Title: Harper's Round Table, April 7, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: March 12, 2018 [eBook #56726]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, APRIL 7, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xvii.—no. 858. | two dollars a year. |

There are in every community young men to whom life at the desk or behind the counter is unutterably dreary and unattractive, and who long for some out-of-door occupation which shall, if possible, contain a spice of excitement. These young men can be divided into two classes—first, those who, if they get a chance to try the life for which they long, will speedily betray their utter inability to lead it; and, secondly, those who possess the physical capacity and the peculiar mental make-up necessary for success in an employment far out of the usual paths of civilized occupations. A great many of these young men think of ranching as a business which they might possibly take up, and what I am about to say is meant as much for a warning to one class as for advice to the other.

Ranching is a rather indefinite term. In a good many parts of the West a ranch simply means a farm; but I shall not use it in this sense, since the advantages and disadvantages of a farmer's life, whether it be led in New Jersey or Iowa, have often been dwelt upon by men infinitely more competent than I am to pass judgment. Accordingly, when I speak of ranching I shall mean some form of stock-raising or sheep-farming as practised now in the wilder parts of the United States, where there is still plenty of land which, because of the lack of rainfall, is not very productive for agricultural purposes.

The first thing to be remembered by any boy or young man who wishes to go West and start life on a cattle ranch, horse ranch, or sheep ranch is that he must know the business thoroughly before he can earn any salary to speak of, still less start out on his own accord. A great many young fellows apparently think that a cowboy is born and not made, and that in order to become one all they have to do[Pg 550] is to wish very hard to be one. Now, as a matter of fact, a young fellow trained as a bookkeeper would take quite as long to learn the trade of a cowboy as the average cowboy would take to learn the trade of bookkeeper. The first thing that the beginner anywhere in the wilder parts of the West has to learn is the capacity to stand monotony, fatigue, and hardship; the next thing is to learn the nature of the country.

A young fellow from the East who has been brought up on a farm, or who has done hard manual labor as a machinist, need not go through a novitiate of manual labor in order to get accustomed to the roughness that such labor implies; but a boy just out of a high-school, or a young clerk, will have to go through just such a novitiate before he will be able to command a dollar's pay. Both alike will have to learn the nature of the country, and this can only be learned by actual experience on the ground. Again, the beginner must remember that though there are occasional excitement and danger in a ranchman's life, it is only occasional, while the monotony of hard and regular toil is not often broken. Except in the matter of fresh air and freedom from crowding, a small ranchman often leads a life of as grinding hardness as the average dweller in a New York tenement-house. His shelter is a small log hut, or possibly a dug-out in the side of a bank, or in summer a shabby tent. For food he will have to depend mainly on the bread of his own baking, on fried fat pork, and on coffee or tea with sugar and no milk. Of course he will occasionally have some canned stuff or potatoes. The furniture of the hut is of the roughest description—a roll of blankets for bedding, a bucket, a tin wash-basin, and a tin mug, with perhaps a cracked looking-glass four inches square.

He will not have much society of any kind, and the society he does have is not apt to be over-refined. If he is a lad of a delicate, shrinking nature and fastidious habits, he will find much that is uncomfortable, and will need to show no small amount of pluck and fortitude if he is to hold his own. The work, too, is often hard and often wearisome from mere sameness. It is generally done on horseback even on a sheep ranch, and always on a cow ranch. The beginner must learn to ride with indifference all kinds of rough and dangerous horses before he will be worth his keep.

With all this before him, the beginner will speedily find out that life on a Western ranch is very far from being a mere holiday. A young man who desires to start in the life ought, if possible, to have with him a little money—just enough to keep body and soul together—until he can gain a foothold somewhere. No specific directions can be given him as to where to start. Wyoming, most of Montana, the western edge of the Dakotas, western Texas, and some portions of the Rocky Mountain States still offer chances for a man to go into the ranch business. In different seasons in the different localities business may be good or bad, and it would be impossible to tell where was the best place to start. Wherever the beginner goes, he ought to make up his mind at the outset to start by doing any kind of work he can. Let him chop wood, hoe, do any chore that will bring him in twenty-five cents. If he is once able to start by showing that he is willing to work hard and do something, he can probably get employment of some kind, although this employment will almost certainly be very ill paid and not attractive. Perhaps it will be to dig in a garden, or to help one of the men drive oxen, or to do the heavy work round camp for some party of cow-punchers or lumberers. Whatever it is, let the boy go at it with all his might, and at the same time take every opportunity to get acquainted with the kind of life which he intends ultimately to lead. If he wishes to try to ride a horse, he will be given every chance, if for no other reason than that he will continually meet men whose ideas of fun are met by the spectacle of a tenderfoot on a bucking bronco.

By degrees he will learn a good deal of the ways of the life and of the country. Then he must snatch the first chance that offers itself to take a position in connection with the regular work of a ranch. He may be employed as a regular hand to help cook on the ranch wagon, or taken by a shepherd to do the hard and dirty work which the shepherd would like to put off on somebody else. When he has once got as far as this his rise is certain, if he is not afraid of labor, and keeps a lookout for the opportunities that offer. After a while he will be given a horse himself, and employed as a second-rate man to do the ordinary ranch work.

Work on a sheep ranch is less attractive but more profitable than on any other. A good deal of skill must be shown by the shepherd in managing his flock and in handling the sheep dogs; but ordinarily it is appallingly dreary to sit all day long in the sun, or loll about in the saddle, watching the flocks of fleecy idiots. In time of storm he must work like a demon and know exactly what to do, or his whole flock will die before his eyes, sheep being as tender as horses and cattle are tough.

ON A CATTLE RANCH—AN UNRULY STEER.

ON A CATTLE RANCH—AN UNRULY STEER.

With the work of a cow ranch or horse ranch there comes more excitement. Every man on such a ranch has a string of eight or ten horses for his own riding, and there is a great deal of exciting galloping and hot riding across the plains; and the work in a stampede at night, or in line-riding during the winter, or in breaking the fierce little horses to the saddle, is as exciting as it is hard and dangerous. The wilder phases of the life, however, are steadily passing away. Almost everywhere great wire fences are being put up, and no small part of the cowboy's duty nowadays is to ride along the line of a fence and repair it wherever broken. Moreover, at present the business of cattle or horse raising on the plains does not pay well, and, except in peculiar cases, can hardly be recommended to a boy ambitious for his future.

So much for the unattractive reality of ranch life. It would be unfair not to point out that it has a very attractive side also. If the boy is fond of open-air exercise, and willing to risk tumbles that may break an occasional bone, and to endure at need heat and cold, hunger and thirst, he[Pg 551] will find much that is pleasant in the early mornings on the great plains, and on the rare days when he is able to take a few hours' holiday to go with his shot-gun after prairie-chickens or ducks, or, perchance, to ride out with a Winchester rifle to a locality where on one of his working days he has seen a small band of antelope standing in the open, or caught a glimpse of a deer bounding through the brush. There is little temptation to spend money, unless he is addicted to the coarsest kind of dissipation, and after a few years the young fellow ought to have some hundreds of dollars put up. By this time he should know all about the business and the locality, and should be able to gauge just what he can accomplish.

For a year or two perhaps he can try to run a little outfit of his own in connection with his work on a big ranch. Then he will abandon the latter and start out entirely on his own account. Disaster may overtake him, as it may overtake any business man; but if he wins success, even though of a moderate kind, he has a pleasant life before him, riding about over the prairie among his own horses or cattle or sheep, occasionally taking a day off to go after game, and, while working hard, not having to face the mere drudgery which he had to face as a tyro. The chances are very small that he will ever gain great wealth; and when he marries and has children of his own there are many uncomfortable problems to face, the chief being that of schools; but for a young man in good health and of adventurous temper the life is certainly pleasanter than that of one cooped up in the counting-room, and while it is not one to be sought save by the very few who have a natural liking for it and a natural capacity to enjoy it and profit by it, still for these few people it remains one of the most attractive forms of existence in America.

The big Anchor rested on the smooth green lawn in front of the house, all glistening in the sunshine with its new coat of white paint, and there was nothing about it to show how it had once taken a very important part in the lives of the youngsters who were even then playing around on the grass not far away. But the old Bo's'n came along one day, and he knew the story, and as near as I can remember it, this is what he said the Anchor told him:

I came out of the ground a great many years ago, and my appearance at the time was somewhat crude. I was put on a train and taken to a place where they gave me a bath, and afterwards I was melted, hammered, and pounded until it seemed as if my last days had come. I had a chance to cool off after this ordeal, however, and a new suit of galvanized clothing was given to me. I felt very proud a few days later as I lay in state at the door of a large ship-chandler's shop on South Street in New York city. Frequently men who passed by in the crowd would stop to look at me, and some of them would remark upon my beauty and my strength, which made me expand with pride and give them one of my brightest looks. Those were the days, you must remember, when I was new and foolish, for up to that time I had never seen the ocean, except for the occasional glimpses I caught over the corner of the dock and through the tangle of shipping.

Spring came, and all was hurry and bustle in the shop behind me. One particularly fine morning a truck backed up against the sidewalk, and some men loaded me on to it, and took me away and transferred me to a steam-freighter, which landed me the next day at Newport. Soon afterward I was shipped to the bow of a large schooner yacht. As long as I live I shall never forget how the Captain and the mate looked me over; and as they patted my arms and flukes they remarked that I was very well made. Mr. Summerville, the owner of the yacht, also came forward to admire me, and after him ran two of the prettiest children I had ever seen. Laying his hand upon my arm, he said:

"Children, this is the new Right Bower. We all place a great deal of dependence upon him."

I was so much overcome at this that I could not speak, but I extended my palm and gave them my very best bow.

I did not meet my associate Anchor until several days afterwards, since he was on duty at the bottom of the bay; but the Chain, to which he was very much attached, gave me his respects. A few days after my arrival, my future chum, Patent Link Chain, came aboard, and we were introduced by the mate. Patent Chain extended his shackles in a friendly way, and I grasped them firmly in my ring. Little did we foresee the many trials before us.

It is needless for me to relate how I nearly fainted when thrown overboard for the first time, and how my dear friend Patent Chain never lost his hold upon me. Nearly all my duty was at night, for I was very much stronger than the Port Bow Anchor. There was another Anchor on board, called Kedge, but my partner and I did not take very kindly to him, as he seemed to be stuck up, and spent most of his time aft. We therefore let him severely alone, and we learned that he remarked to the Chains one day that the Kedge family were called upon to do duty only on special occasions, and to be rowed about in small boats.

The Chains of this yacht for some reason never seemed to get along very well together, and frequently when two of them were on duty at the same time they would get in a tangle, and the mate would have to go out on the bob-stay and chastise them with a marlinspike before they could be separated. But, as my friend Patent Chain frequently remarked, the other chain was very common and had a bad heart. Events proved his opinion was well founded.

We were on a cruise toward Maine when the turning-point in my life occurred. As we sailed along one day I heard the mate say that bad weather was ahead. That evening we came to anchor early in a sheltered bay, and night came on dark and stormy. The wind increased, and sighed and moaned in the rigging. Port Anchor had gone overboard several hours before, but they soon found it necessary to send me down with him. I felt a kind of foreboding of evil as I plunged into the water, and when I reached the bottom I sank one of my arms as deeply into the mud as possible, and groped with my fluke for solid rock. Patent Chain told me he had not reached for such a length before, and he added that the Kedge had been brought forward in case he might be needed.

The storm increased to a hurricane, and soon Port Anchor cried out to me that he felt his strength was giving way. Poor fellow! he seemed to realize that he was too old to stand the terrific strain that he was now being called upon to endure, and his Common Chain couldn't be counted on to hold. Already some of the links were making preparations to part. I called back words of cheer, but received no reply, and a moment later I experienced a terrible shock, for Common Chain had broken, and poor old Port Anchor had been left to his fate in the mud. I felt myself dragged through the stones and the rocks along the bottom, and wondered what was going to happen, for my good friend Patent Chain was telling me that they were praying on deck that I might hold. Little Kedge sank down near me, and tried hard to get a grip on the rocks, but he was so small that he could do but little. Patent Chain shrieked in agony that he was being torn apart, but entreated me at the same time to make final and desperate efforts to save the yacht. Up above the Captain, the mate, and the crew were working frantically to get the storm try-sail set, and they had lashed two hempen cables to Patent Chain so that he could go out further. In the mean time, however, I had found a ledge of rocks, to which I seized with my flukes as well as with my stock, and Patent Chain, spreading himself full length in the mud, clung to the bottom.

How long this dreadful tension lasted I shall never know, but it seemed years to me. It was probably only a few hours. And when I was finally assisted to the surface by old Windlass the next morning, I found the yacht was under way in tow, and headed for the nearest shipyard. She had sustained considerable damage from the hurricane, and as I reached the deck I was surrounded by awed and sympathetic faces. Everyone said I had saved the yacht; and that is why I am placed here and why I am so well treated.

he cavalry has always been the most popular branch of army service in song and story, and, beyond doubt, in the mind of the public. To a boy who has a leaning towards military things it has an absolute fascination, and if he likes a horse (and what boy does not?) it is his choice beyond all others.

In New York city there exists a troop of boy cavalry that has been drilling and exercising faithfully, and under such able direction that it may be taken as a model for what a boys' organization of this kind should be. Soldiering means really serious work, whether it is in the service of a State, a country, or merely entered into for the love of it, and a boy who has not the proper spirit cannot long remain a member of "Troop A" Cadets. It is astonishing to find how quickly and how well the boy recruit learns to ride, how much he learns about a horse, and how his muscles and his eye and his self-reliance develop under the drill. The writer has seen riding that no cowboy need be ashamed of done by a boy of fourteen who a year before had never thrown his leg over anything but a Shetland-pony, and many of the young troopers never mounted a horse at all until they first made their appearance in the tan-bark ring of the troop riding-school. If a boy is a "muff," he does not stay at it long; it takes a lad with the "proper stuff" in him, as the riding-master tells you, to stand the thumping and sometimes the falls of the first month's drill. A horse is a very complicated piece of machinery to the novice, and he must be managed by the eye, the whole body, and the mind. He knows when the rider on his back is timid or determined, and he often acts accordingly. Horses have an individuality that bicycles haven't, and the young trooper must learn to govern besides learning merely to guide and "stay on."

But to take in order what a boy cavalryman must learn. In the first place he must be strong and willing, and quick to listen; that is a great thing—listening. He will find out a great deal about himself, and if he has the right stamina and spirit he improves in every way most wonderfully.

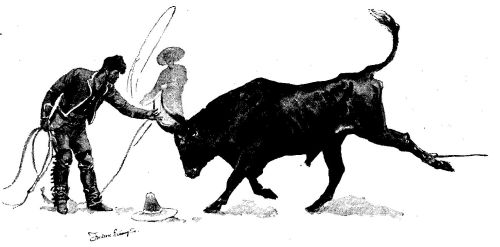

DRESS PARADE.

DRESS PARADE.

As soon as the recruit has been proposed for membership, which is done in the same way it is done in the National Guard—that is, his name is proposed by two members in good standing, then voted on by a committee, and lastly by the whole troop—as soon as all this is done he takes his first lesson. It is not on horseback—that comes later—but on foot; the setting-up exercise has to be gone through with. This is quite a trial, for it means standing erect, and going through various exercises with the arms, the legs, the whole body; bending over with knees stiff, and touching the ground until he wonders where so many aching muscles come from.

Then he learns the facings and marchings, a good deal like an infantryman. But at last a sabre is put in his hand, and he is taught to use it, standing firm on his out-stretched legs, and making wonderful cuts and points to right and left—"cut at head, cut at body, at infantry, at cavalry," etc., over and over. At first some of his wonderful strokes in strange directions would cleave his horse in two, and others would relieve him of his head or mayhap his tail; but soon he learns the proper positions of all these things, and acts as if he were on horseback. When this has been accomplished he is taught the drill with the carbine, loading and firing, and the manual on foot. The lieutenant in charge of the cadets informed me that boys learn quicker and improve much more rapidly than grown men in all this, and that they seldom remain in the "awkward squad" for any length of time. But now comes the riding, and a great deal more; for the cavalryman must look after his own mount, and be able to saddle and bridle.

The first lesson means much. It is a good thing that grace does not count, for it is hard to be graceful or at ease on a bumping, thumping nag with nothing on his back but a blanket. In a little time one learns to hang on with the knees and balance with the body, and then it looks more like fun—the instructor lets go of the bridle-rein and ceases his everlasting words of advice, and the recruit "goes it alone." When he sits in a saddle after undergoing a long course of tan-bark drill, he feels as comfortable as if he was in a chair, and wonders how he ever thought it hard to do.

IN COLUMN OF FOURS.

IN COLUMN OF FOURS.

Now comes the drill on horseback at a walk, a trot, and a gallop. If the horse is an old hand he helps the new trooper out amazingly; he seems to understand the orders, and whisks into place and dresses into line promptly as could be wished for.

After the trooper gets out of the awkward squad for[Pg 553] good and all, the drills become exciting; every meeting is a series of games on horseback; he learns to cut at the ball on the wooden post—"the Turk's head"; he slashes at imaginary enemies afoot and mounted; he learns "tent-pegging," which is riding full tilt down the arena at a wooden peg driven into the ground, which he endeavors to pick up on the point of his sabre, and soon he becomes part of his horse. It is exciting to see three troopers playing the "ribbon chase." One of them has a knot on his right arm, and the other two (they are all mounted without saddles) try to get this ribbon off. It can only be taken off from the left side, and they play tag and manœuvre every which way to get a position. If the one who is "it" is clever, he dodges and doubles, turns and backs, and if he can keep his ribbon for three minutes he wins. But the others push him hard, and here it is where good riding tells. I have seen a little shaver who had to be helped up on to a fifteen-hand horse do some riding that would be credit to a Comanche Indian. They wrestle—these boy troopers—on horseback, and I have seen one leap from his own horse astride that of his opponent, and then succeed in dismounting him. All this brings out the best thing in a boy; it teaches him to be self-reliant and quick in judgment, and it makes his big brother feel proud of him—if he has a big brother.

WRESTLING.

WRESTLING.

When they grow old enough (most of them are between fifteen and seventeen) they generally get into the troop itself, and their preliminary work puts them on a par with the best of the older troopers.

Of course it costs something to organize and maintain a squadron of mounted men, and the members pay yearly dues which cover the expense of horse hire. Their uniforms they own themselves, and they cost about twelve dollars.

In any good-sized town or city it is perfectly possible for a number of boys, with the help of their fathers, to organize such a troop if they go about it in earnest and work in a systematic way.

First of all a competent instructor must be obtained, and every one should realize that money cannot be judiciously saved in his salary. He should be the best man obtainable after a somewhat extended search. Usually he is an old cavalry officer, or perhaps some cavalry officer who has retired. Such men are to be had after some search, and apart from their knowledge of cavalry movements they are valuable because they take a personal interest in all that has to do with their work.

Having secured the instructor a hall is then necessary, and this is by far the most difficult thing to find of the whole outfit. Few towns and not many cities have any hall the ground-floor of which can be used for horses. If the troop is to be a serious affair, and it is impossible to organize one unless it is to be serious, the cheapest way in such cases is to build a huge shed with the earth for a flooring. Here is a proportionately large expense, and the result is that most cavalry cadet troops will have to be formed under the auspices of National Guard troops, which already have armories for cavalry practice.

Once you have an armory and an instructor, the rest is merely detail. Much objection is made of late to military drill and the encouragement of the love of war. Boy troopers have nothing to do with war. They should not wish to fight, even to grow up to fight some day, except in defense of their country. There is no more question of war in a cadet troop than there is in a bicycle club. It is merely that the discipline, the training, the exercise that are good for boys can be obtained in this healthy, manly way, and cannot be obtained with equal efficiency in any other way.

It was only half past eight when the search party left Greenfield, but it would be no darker at midnight. The two negroes who led the way down the avenue and out into the public road carried blazing lightwood knots—that is, long thick pieces of "fat" pine cut from the heart of the tree, and, when lighted, burning for hours with a fierce flame fed by the turpentine and resin which were the sap of the tree.

Close behind the torch-men rode Mr. Grigsby, the dogs trotting beside him, and almost upon his horse's heels was the "top gig" containing the Major and Mr. Tayloe. The scene was striking and even solemn, and except that the Major and his companion now and then exchanged a sentence in subdued tones, not a word was uttered until they arrived at the open space surrounding the school-house. There Mr. Grigsby dismounted and Major Duncombe and Mr. Tayloe got out of the gig. The negroes were left with the horses, Mr. Grigsby and the Major taking their torches.

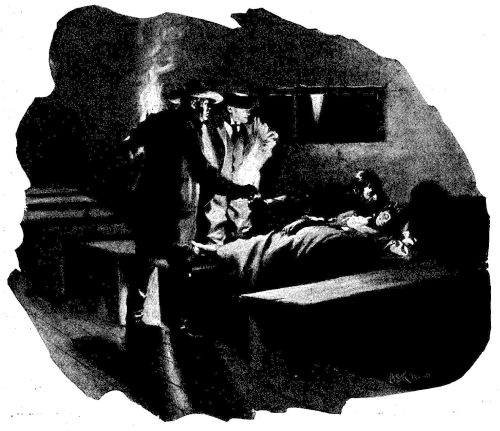

They trod lightly, and the soaked ground made no noise under their feet. Pushing the door further open, they entered, holding their torches high to throw the light into the room. The glare reached the figure of the sleeping girl in the far corner, and with a whispered congratulation to the father, the Major led the way to her. She lay upon her side, facing them, her head pillowed upon her book, her hand under her cheek. She slumbered soundly and sweetly, not stirring when the full blaze of the fat pine struck her closed eyelids.

At the second glance both men exclaimed in horror. Coiled right across her naked ankles and feet was what looked like a striped gray and brown rope. The spectators knew it instantly for a moccasin snake, next to the rattlesnake and copperhead the most deadly of Virginia reptiles. Attracted by the warmth of the child's body, he had curled himself up for his nightly rest, and, raising an ugly head, hissed viciously as the light was reflected from a pair of wicked eyes. Then, instead of striking at the unconscious sleeper, he dropped to the floor and glided swiftly under the benches to a darker corner. Mr. Grigsby sprang after him and planted his heel upon his head. Had he missed him or put his foot upon any other part of the snake, he must have been bitten. He ground his heel into the creature's head with all his might until the convulsed body, that had wrapped itself about his leg and writhed up and down like a curling whip lash, ceased to twist and quiver.

"Bravely done!" said Mr. Tayloe, in honest admiration. "But you ran a great risk."

"I did not think of that," answered the Scotchman, briefly.

He was deadly pale, and his jaw was rigid. The sweat dropped from his chin as he stepped off the dead snake and turned back to the bench where his child lay. It was strange that the exclamations and stamping had not aroused her. Had she been bitten, and was this heavy sleep the stupor of death? The same thought was in the minds of the others while they watched him in breathless silence. He knelt down by the still figure and laid his hand gently upon her head.

"DAUGHTER! FATHER'S LASSIE!" HE SAID, HIS LIPS CLOSE TO HER EAR.

"DAUGHTER! FATHER'S LASSIE!" HE SAID, HIS LIPS CLOSE TO HER EAR.

"Daughter! Father's lassie!" he said, his lips close to her ear.

His voice was husky and unnatural, but she knew it in her sleep. Her eyes unclosed slowly upon his face, and widened as she saw Major Duncombe and Mr. Tayloe behind him. Still dreaming, she smiled slowly and lifted her hand to wave it. It was all a part of the examination day. She was still "playing ladies."

"You do me too much honor, I assure you, sir," she murmured.

She had not been bitten by the moccasin. But for the necessity of ascertaining this, she would not have been told what danger she had escaped. Short work was made with explanations, and no time was lost in hurrying her from the place. Major Duncombe lifted her with his own hands to her seat in front of her father upon his broad-backed horse, and insisted upon sending one of the torch-bearers all the way home with them. Flea was wrapped to her heels in a shawl that had been put into the gig by Mrs. Duncombe's order. It was soft and fluffy and thick, and the folds felt like a caress to her chilled limbs. Her father's arm held her close to his breast; her head lay against his strong shoulder—how strong and safe she had never guessed until now.

Flea never forgot that ride and her awed enjoyment of each feature of it. Her father's silence did not surprise her. He was never talkative, and assured by his gentleness at the moment of her awakening, and the clasp of his arm about her now, that he was not displeased, she was glad to lean back in his embrace and indulge the fancies born of the night's event. She was almost sorry when the dogs ran before them as they neared the house, and the clamor of the welcome they received from the dogs who had staid at home drew out Chaney and Dick from the kitchen, and was the signal for the opening of the front door. It was full of heads, seen blackly against the lighted interior, and Mrs. Grigsby's high-pitched voice rang out, shrilly: "Got her, 'ain't you, pa?"

"Ay, ay! all's right!" he answered.

Carrying the muffled form in his arms, he walked up the path leading from the yard gate, into the house, and set her down before the chamber fire as he might a roll of carpet.

"Don't you look too funny!" laughed Bea, as Flea began to disengage herself. "Lor'! if you 'ain't got on Mrs. Duncombe's winter shawl!"

"An' trouble enough she has given, I'll be boun'!" scolded the mother, heedless of her husband's gravity and silence. "I should 'a' thought yer pa would 'a' left you at Greenfiel' 'tel mawnin'."

"Peace, wife," interposed Mr. Grigsby, sternly. "All of you come in here and be still."

They trooped into the chamber, Chaney, Dick, and the Greenfield negro bringing up the rear, all curiosity and expectation, subdued by his tone and action. For he had taken a well-worn Prayer-book from the mantel shelf, and was turning the leaves while he spoke. Finding what he sought there, he put out his arm to draw Flea to his side, and knelt with her in the middle of the room.

"Let us pray!"

Everybody knelt where he or she chanced to be standing—Mrs. Grigsby by the cradle of her sleeping baby, Bea and Calley at the foot of the bed, Dee before a chair, the negroes crouching upon the floor. The candles flared and guttered, the blaze in the fireplace was beaten this way and that by the damp wind pouring in through the open doors, the drip and dash of the rain without were a low accompaniment to the father's voice, weighted with emotion. While he prayed he kept his hand upon Flea's head.

"Almighty God and Heavenly Father, we give Thee humble thanks that Thou hast been graciously pleased to deliver from great danger the child in whose behalf we bless and praise Thy name in the presence of Thy people. Grant, we beseech Thee, O gracious Father, that she, through Thy help may both faithfully live in this world according to Thy will and also may be partaker of everlasting glory in the life to come, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen."

When all had risen he told in few and strong words where and how he had found the child, now sobbing with excitement in his arms.

"Now," he concluded, "we will talk no more of this matter to-night, and I will have no questions asked this child. She is tired and nervous. In nothing is she to blame. We have great cause for thankfulness for her safety. Mother, have you had supper while we were away?"

He never called her "ma." Flea was the only one of the children who imitated him in this respect. Mrs. Grigsby was fussy, and in many things foolish, but she obeyed her husband's orders in not questioning the runaway, and wiping her eyes more than was quite necessary, led the way[Pg 555] meekly to the dining-room. It was an unusually silent meal, the father setting the example of saying little while he ate. When supper was over he kissed Flea, which he seldom did to any of the children, and bade her, "Go right up to bed," and not to forget to say her prayers.

"And you, Beatrice, when you go up, do not talk to her. She needs rest and sleep."

He was a sensible man, and his behavior on this occasion was what seemed wise and becoming according to his judgment. If he had intended to establish poor Flea in her dignity as an important personage, and stuff her head with absurd notions, he could not have done it more surely. When her bare feet trod the short crooked staircase leading to her bedroom, it was with the measured pace of one who has a position to fill and means to fill it. She was almost surprised that the glass to-night reflected the face she was used to seeing in it.

Bea followed her shortly, brimming over with curiosity and resolution to hear all there was to tell.

"Say," she said, in a half-whisper, coming up to her sister, "how big was the moccasin? It must have felt mighty heavy on your feet. What did pa kill him with?"

Flea looked at her with owl-like seriousness, and laid her finger upon her lip.

"Don't be a fool!" returned the other, contemptuously. "Pa can't hear us."

Whereupon the newly made heroine lifted her hand and pointed upward, rebukingly.

"God can hear you," was what she meant.

"Bah!" sneered Bea. "You needn't preach to your betters. Keep your old story to yourself. I ain't a-going to put up with your airs. Mother ain't, neither. Any runaway nigger can go to sleep in the woods and wake up with a snake lyin' 'longside o' him. 'Tain't as if you had done anything."

This was rough talk, but Flea was, in her own opinion, so high above her sister's level that she could afford to despise it. Long after Bea had fallen asleep the younger girl lay listening to the drip, drop, drip, of the rain overhead, her cheeks on fire, her brain in a whirl, and her eyelids feeling as if they were buttoned back and would not shut.

She was a heroine. The former life had slipped off and away from her as her friend the moccasin had shed his skin last spring. She must recast her thoughts and her manners, make them over through and through in order to live up to her new character. She hoped the rain would hold up by morning, so that she could go to church.

In imagination she saw how every head would turn toward her when she should walk up the aisle. How people would stare and nudge one another during the service, and crowd around her when it was over! Perhaps—and she thrilled all over with merely thinking of it—Mr. Slaughter, the rector, would return thanks publicly for her deliverance. It would be just like Major Duncombe to ask him to do it. A church prayer, said in a white surplice, with all the congregation saying "Amen" at the end, was not too great an honor for a girl who had had an adventure.

That was what the Major had said—"an adventure." She went carefully over every word of his speech, remembering each word.

"We are only too thankful to an overruling Providence that our little heroine's adventure was not also a catastrophe, Mr. Grigsby."

He had rolled it out in a grand, solemn way, quite as he read prayers every morning and night at Greenfield.

Everything had conspired to turn the little maid's brains topsy-turvy. Her head felt actually light at her awakening from the sound sleep that had finally overcome her. There was a queer strained aching all through her, and she had never been crosser in her life.

It was still raining. The ground was sodden; the trees drooped miserably under the weight of wet leaves; the sky was one sullen, obstinate cloud, heaviest and most obstinate toward the west faced by her bedroom windows.

No church or Sunday-school to-day. No show of her famous self to an admiring congregation. Dreams and hopes came down with a cruel thump to the realities of every-day home life. True, she put on, of her own accord, stockings and shoes, and there were always clean clothes for Sunday, but there were week-day clothes, and there were fried middling and corn bread for breakfast, just as if nothing had happened. The coarse food stuck in her throat; the common crockery—white, with fluted green edges—the pewter spoons, the tin coffee-pot, the heavy grayish-blue mug out of which she drank her "hot-water tea" (i.e. milk and water sweetened), had not offended her taste yesterday, or ever before. Now they were disgusting and humiliating.

"You ain't eatin' nothin'!" remarked the mother, as the girl sat back in her chair after a vain attempt to behave as usual. "Do you feel sick?"

"No, ma'am. I'm just not hungry. I don't know why. I reckon I'll go up stairs and lie down."

"Let her alone. She'll be all right after a while," said her father, as her mother began to scold, and Flea got herself out of the room as quickly as possible.

She could never be all right in this house, she was sure. Nobody understood, or sympathized with her. She was stifled and cramped. So far as the discouraged heroine could foresee, every day to come would be like this and all those that had gone by—all rag carpet, and green-edged crockery, and sugar-raggy babies, and Bea's old frocks made over and let down, and fault-finding—

"Flea!" screamed her mother, from the bottom of the stairs, "ain't you coming down to-day? Here's your sister with all the things to wash up and put away."

Flea was lying face downward on the unmade feather bed, dry-eyed and wretched, when the call came. In sinking and sickness of heart she obeyed the summons, the very click of her shoes on the stairs expressive of unwillingness. Nothing she had read or heard of heroinic behavior helped her to go through with the drudgery of scraping plates, rinsing, washing, and wiping crockery and pewter.

"I don't see why mother don't use her silver spoons every day," she grumbled to Bea, wiping and laying down a pewter spoon disdainfully.

"She's goin' to leave 'em to me when she dies," returned that prudent young person. "I'm glad she doesn't wear 'em out, or maybe get one of 'em lost, before then."

There were only six teaspoons in all, and Mrs. Grigsby kept them in a locked drawer. It was all of a piece with the mean, skimpy, tiresome round of her daily life. There was no help for it—none.

The day dragged on more wearily and slowly than ever day had gone before. Her father could have told her, if she had confessed her misery to him, that much of it was the reaction after last night's excitement. As she did not speak of it, he paid little or no attention to her sober face and unwonted silence. She performed her share of dish-washing, table-setting, and table-clearing listlessly, but without complaint, and when not thus employed spent most of her time upstairs. Nobody asked what she did there; still less was anybody concerned to know what she felt there.

Dee—which is by interpretation David—had had a stupid day too. The Grigsby Sunday rules bore hard upon story books and toys, and an active boy of ten was soon at the end of his resources. His mother had scolded him a dozen times for making a noise and getting in her way, and boxed his ears twice.

After the last buffet Dee took refuge in the barn and the society of Dick and the horses. His father would not have approved of it, but his father was not at home. Coming in at dusk, the boy stole up stairs on tip-toe and peeped into his sister's room. The sun was fighting bravely with the bank of clouds on the horizon, and the world was bathed in lurid mist. By this flushed fogginess Dee could see Flea lying in a sort of crumpled heap on the floor by the window. She started up at the noise he made in entering.

"What do you want?" she demanded, crossly.

"You needn't get mad about it," returned her brother. "I'm just sick of Sunday, and I reckon you are too. Monday's worth fifty of it, if you do have to go to school. Ma's cross as two sticks, and pa's gone to look after things up at 'the house,' and Bea's on her high horse, and the young[Pg 556] ones are worse'n a pack of bees for noise 'n' swarmin'." He sat down sociably upon the floor by his sister. "I say, Flea, what you s'pose you were sparred for?"

"Spared for? What are you talking about?"

"Dick says that Chaney says that ma says you were sparred for somethin' real big. Hadn't 'a' been for that, the moccasin would 'a' bit you sure, and you'd been dead before anybody could 'a' got to you for to draw the p'ison out. What you s'pose they meant? What you goin' to do?"

Flea sat upright, looking straight out of the window. As Dick stopped speaking she raised the sash and let in a wave of warm, sweet, damp air. The pink light streamed in with it, flooding the girl's figure and face. Her hair was tousled, and the dust of the bare boards had mixed with her tears to streak her cheeks. Yet the boy stared at her, open-mouthed and puzzled. Light that did not come through the window shone in her face; her eyes were two stars; her fingers were knotted tightly upon one another.

"You are sure that you are not fibbing, Dee? Did they really say that?"

"Certain sure. And Dick says it's true as gawspil. He know'd a baby oncet they thought was clean dead, and all on a suddint it come to, and sot up 'n' walked—like a maracle, you know. And his mother, she said right straight off, 'He will be somethin' wonderful.' And so he was. He fit in the las' war, an' killed, oh, thousands of the British, but girls can't fight, you know. That's 'cause why I arsked you what you s'posed you could 'a' been sparred for."

Flea put her arm about her brother's neck, and pulled the rough head to her shoulder. She and apple-cheeked, slow-witted Dee always got on well together.

"I love you, Dee," she said, in a gush of tenderness. "No matter how great a lady I get to be—and I'm going to be something very great some day—you and I will always be good friends. You won't tell anybody if I tell you a secret?"

The much-impressed Dee gave the desired promise.

"Then—I'm a heroine, Dee!"—sinking her voice—"a sure-enough heroine. And wonderful, beautiful things always happen to heroines. Like Miranda, and Olivia, and Portia, and Cordelia, and Perdita, and Juliet, and Hermione, and Rosalind, and ever and ever so many more ladies I've read about. I'll tell you about some of them to-morrow. They are not Sunday stories, you know."

Neither, for that matter, was that Sunday talk into which she now launched, holding the boy spellbound while the sun went down clear, and the bright clouds grew pale, then dark. Into Dee's greedy ears she poured the tales of what she meant to do and to be in the wondrous To-Come of her dreams.

The talk with her brother, the hopes rekindled by it, and his faith in her and her future made the out-goings of the unhappy day to rejoice. She laid her head upon her pillow that night in tolerable content with home and kindred. They had sung hymns together, as was the Sunday-night custom, and recited each a psalm and three questions in the Church Catechism to their father, who had then granted them the treat of a long story of his early life in Glasgow.

No misgivings as to to-morrow held her eyes waking as she nestled down under the patch-work coverlet she and Bea had put together and helped their mother quilt last winter. The school-room would be her own territory. As the only girl in the school who knew Mr. Tayloe, and had been particularly recommended to him by his patron (she had borrowed that word from an English story-book), she would be foremost in his esteem. In "playing ladies" before sleep got fast hold of her she saw herself introducing less-favored scholars to his favorable notice.

"My sister Beatrice, Mr. Tayloe," she would say. Perhaps he would answer, "I hope she is as intelligent and industrious as her sister."

Flea's was a generous nature, but she did feel that that would pay off Bea well for certain things she had said to her in days past. As for Dee, who was dull at his lessons, her heart warmed and yearned over him in the thought of the good she could do him through her influence with the teacher. Mr. Tayloe looked as if he might be severe with a dull pupil. She would stand between Dee and trouble. He was such a loving little fellow, and her best crony, even if he did not care for books.

Bea was going to wear a white frock to school if the weather were warm enough. Flea's frock, a brown calico with round white spots on it, with an apron of the same, was new and strong and clean. As the prize scholar she could afford to be indifferent to dress. One of these days she would make people who now laughed at her plain clothes open their eyes with her satins—and—laces—and—India cotton stockings—and—oh yes! the pink sash should be just the color of a peach blossom—and—have—fringed—

Flea was clean off to Slumberland, where nobody expects to dream of sensible and probable happenings.

The commander of the revenue-cutter had received from his Lieutenant a detailed description of the sloop Fancy, together with what information that officer had gathered concerning her destination, lading, and crew. As a result of this interview it was determined to guard all passages leading to the upper sound; and during the hours of darkness the cutter's boats, under small sail, cruised back and forth across the channels on either side of Vashar Island, one of which the sloop must take. They showed no lights, and their occupants were not allowed to converse in tones louder than a whisper. While half of each crew got what sleep they might in the bottom of the boat, the others were on watch and keenly alert. In the stern-sheets of each boat was an officer muffled in a heavy ulster as a protection against the chill dampness of the night.

The night was nearly spent and dawn was at hand when the weary occupants of one of these patrol-boats were aroused into activity by two bright lights that flashed in quick succession for an instant well over on the western side of their channel which was the one known as Colros Passage.

"It is a signal," said the officer, as he headed his boat in that direction. "Silence, men! Have your oars ready."

Shortly afterwards another light appeared on the water in the same general direction, but further down the channel. It showed steadily for a minute, and was then lost to view, only to reappear a few moments later. After that its continued appearance and disappearance proved most puzzling, until the officer solved the problem to his own satisfaction by saying:

"The careless rascals have come to anchor, and are sending their stuff ashore in a small boat. That light is the lantern they are working by; but I wouldn't have believed even they could be so reckless as to use it. Douse that sail and unship the mast! So. Now, out oars! Give 'way!"

As the boat sprang forward under this new impulse, its oars, being muffled in the row-locks, gave forth no sound save the rhythmic swish with which they left the water at the end of each stroke.

The row was not a long one, and within five minutes the boat was close to the mysterious light. No sound came from its vicinity, nor was there any loom of mast or sails through the blackness. Were they close to it after all? Might it not be brighter than they thought, and still at a distance from them? Its nature was such that the officer could not determine even by standing up, and for a few moments he was greatly puzzled. He could now see that the land was at a greater distance than a smuggler would choose to cover with his small boats when he might just as well run his craft much closer. What could it mean?

Suddenly he gave the orders: "Way enough! In oars! Look sharp there for'ard with your boat-hook!"

The next moment the twinkling light was alongside, and its mystery was explained. It was an old lantern lashed to a bit of board, that was in turn fastened across an empty half-barrel. A screen formed of a shingle darkened one side of the lantern so that, as the floating tub was turned by wind or wave, the light alternately showed and disappeared at irregular intervals.

That the Lieutenant who was the victim of this simple ruse was angry goes without saying. He was furious, and could he have captured its author at that moment, the ingenious person might have met with rough usage. But there seemed little chance of capturing him, for although the officer felt certain that this tub had been launched from the very smuggler he was after, he had no idea of where she now was, nor of what direction she had taken. All he knew was that somebody had warned her of danger in that channel, and that she had cleverly given him the slip. He could also imagine the "chaff" he would receive from his brother officers on the cutter when they should learn of his mortifying experience.

When, after cruising fruitlessly during the brief remainder of the night, he returned to his ship and reported what had taken place, he was chaffed, as he expected, but was enabled to bear this with equanimity, for he had made a discovery. On the shingle that had shaded the old lantern he found written in pencil, as though for the passing of an idle half-hour, and apparently by some one who wished to see how his name would look if he were a foreigner:

"Philip Ryder, Mr. Philip Ryder, Monsieur Philippe Ryder, Signor Filipo Ryder, Señor Félipe Ryder, and Herr Philip Ryder."

"It's the name of the young chap who led me such a chase in Victoria, and finally gave me the information I wanted concerning the sloop Fancy," said the Lieutenant to his commanding officer, in reporting this discovery.

"Which would seem to settle the identity of the sloop we are after, and prove that she is now somewhere close at hand," replied the commander.

"Yes, sir; and it also discloses the identity of the young rascal who is responsible for this trick, though from his looks I wouldn't have believed him capable of it. He is the one I told you of who was so scented with cologne as to be offensive. I remember well seeing the name Philip Ryder on his dunnage-bag."

The sun was just rising, and at this moment a report was brought to the cabin, from a mast-head lookout, to the effect that a small sloop was disappearing behind a point a few miles to the southward.

"It may be your boat, and it may be some other," said the commander to the third Lieutenant. "At any rate, it is our duty to look him up. So you will please get under way again with the yawl, run down to that point, and see what you can find. If you meet with your young friend Ryder either afloat or ashore, don't fail to arrest and detain him as a witness, for in any case his testimony will be most important."

The Fancy had hauled out of her snug berth soon after sunset that same night, and fanned along by a light breeze, held her course to the southward. Both our lads were stationed forward to keep a sharp lookout, though with a grim warning from Captain Duff that if either of them fell overboard this time, he might as well make up his mind to swim ashore, for the sloop would not be stopped to pick him up.

"Cheerful prospect for me," muttered Alaric. "Never mind, though, Mr. Captain, I'm going to desert, as did the Phil Ryder of whom you seem so fond. I am going to follow his example, too, in taking your first mate with me."

As on the previous night, the lads found an opportunity to talk in low tones; and filled with the idea of inducing Bonny to leave the sloop with him, Alaric strove to convince him of the wickedness of smuggling.

"It is breaking a law of your country," he argued; "and any one who breaks one law will be easily tempted to break another, until there's no saying where he will end."

"If we didn't do it, some other fellows would," replied Bonny. "The chinks are bound to travel, and folks are bound to have cheap dope."

"So you are breaking the law to save some other fellow's conscience?"

"No, of course not. I'm doing it for the wages it pays."

"Which is as much as to say that you would break any law if you were paid enough."

"I never saw such a fellow as you are for putting things in an unpleasant way," retorted the young mate, a little testily. "Of course there are plenty of laws I couldn't be hired to break. I wouldn't steal, for instance, even if I was starving, nor commit a murder for all the money in the world. But I'd like to know what's the harm in running a cargo like ours? A few Chinamen more or less will never be noticed in a big place like the United States. Besides, I think the law that says they sha'n't come in is an unjust one, anyway. We haven't any more right to keep Chinamen out of a free country than we have to keep out Italians or anybody else."

"So you claim to be wiser than the men who make our laws, do you?" asked Alaric.

Without answering this question, Bonny continued, "As for running in a few pounds of dope, we don't rob anybody by doing that."

"How about robbing the government?"

"Oh, that don't count. What's a few dollars more or less to a government as rich as ours?"

"Which is saying that while you wouldn't steal from any one person, you don't consider it wicked to steal from sixty millions of people. Also, that it is perfectly right to rob a government because it is rich. Wouldn't it be just as right to rob Mr. Vanderbilt or Mr. Astor, or even my—I mean any other millionaire? They are rich, and wouldn't feel the loss."

"I never looked at it in that way," replied Bonny, thoughtfully.

"I thought not," rejoined Alaric. "And there are some other points about this business that I don't believe you ever looked at, either. Did you ever stop to think that every Chinaman you help over the line at once sets to work to throw one of your own countrymen out of a job, and so robs him of his living?"

"No; I can't say I ever did."

"Or did it ever occur to you that every cargo of opium you help to bring into the country is going to carry sorrow and suffering, perhaps even ruin, to hundreds of your own people?"

"I say, Rick Dale, it seems to me you know enough to be a lawyer. At any rate, you know too much to be a sailor, and ought to be in some other business."

"No, Bonny, I don't know half enough to be a sailor; but I do know too much to be a smuggler, and I am going to get into some other business as quick as I can. You are too, now that you have begun to think about it, for you are too honest a fellow to hold your present position any longer than you can help. By-the-way, what would happen if a cutter should get after us to-night?"

"That depends," replied the first mate, sagely, glad to feel that there were some legal questions concerning which he was wiser than his companion. "They might fire on us, if we didn't stop quick enough to suit 'em, and blow us out of the water. They might capture us, clap us into irons, and put us into a dark lock-up on bread and water. The most likely thing is that we would all be sent to the government prison on McNeits Island."

"And I suppose if we ever got out we would always be watched and suspected," suggested Alaric, who had listened to all this with almost as much dismay as though it were an actual sentence. "Well, I'll never be caught, that's all. I'll drift away in the dinghy first." In saying this the boy threatened to do the most desperate thing he could think of.

"I believe I'd go with you," said Bonny. "Now, though, I must go and get ready our private signal, for we are getting close to the most dangerous place."

Bonny walked aft, exchanged a few words with Captain Duff, and then disappeared in the cabin, where he remained for some minutes. When he again came on deck he bore a box in which was a lighted lamp provided with a bright reflector. Only one side of the box was open, and this space the lad carefully shielded with his hat. The sloop was just entering Colros Passage, between Vashar Island and the mainland, and was nearer the western shore than the other.

Holding his box as far down as he could reach over the landward side of the vessel, Bonny turned its opening toward the shore, and allowed the bright light to stream from it for a single second. Then by quickly reversing the box the light was made to disappear. A moment later it was shown again, this time with a piece of red glass held in front of the lamp. This red light, after appearing for a single second, was also made to vanish, and another quick flash of white light took its place. A minute or so later the whole operation was repeated, and the white, red, and white signal was again flashed to the wooded shore. At the fourth time of displaying the signal it was answered by two white flashes from the shore.

There was a moment of suspense, and then Bonny exclaimed, in a low tone, "Great Scott! They're after us!"

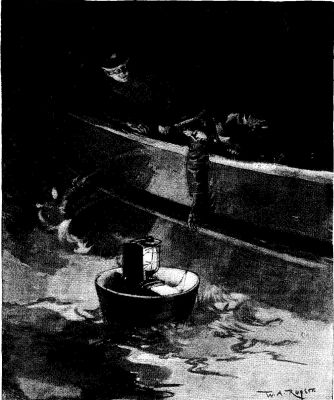

BONNY'S INVENTION STARTED ON ITS JOURNEY.

BONNY'S INVENTION STARTED ON ITS JOURNEY.

Extinguishing his light, he again dived below, this time into the forecastle. When he reappeared he bore the float and lighted lantern already described. Alaric had noticed this queer contrivance the day before, and while wondering at its object, had amused himself by idly scribbling on a smooth shingle that he found inside the tub. Now this same shingle was hastily lashed to the lantern, and the whole affair was launched overboard. At the same time the sloop was put about, and leaving this decoy light floating and bobbing behind her as though it were in a boat, she sped away toward the eastern side of the channel.

When Bonny rejoined Alaric at the lookout station he asked, with a chuckle: "What do you think of that for a scheme, Rick? It's my own invention, and I've been longing for a chance to try it every trip; but this is the very first time we have needed anything of the kind. I only hope the light won't get blown out, or the whole business get capsized before the beaks capture it. My! how I'd like to see 'em creeping up to it, and hear their remarks when they find out what it really is!"

"What does all this flashing of lights and setting lanterns adrift mean, anyway?" asked Alaric, who was much puzzled by what had just taken place.

"Means there's a revenue-boat of some kind waiting for us in the channel, and that we are dodging him. The lights I showed made our private signal, and asked if the coast was clear. Skookum John didn't get on to 'em at first, or maybe he wasn't in a safe place for answering. When he saw us and got the chance, though, he flashed two lights to warn us of trouble. Three would have meant 'All right, come ahead'; but two was a startler. It was the first time we've had that signal; also it's the first chance I've had to test my invention."

Ever since leaving the dancing light Bonny had not been able to take his eyes from it, so anxious was he to discover whether or not it served the purpose for which it was intended. It grew fainter and smaller as the sloop gained distance on her new course. Then all at once it seemed to rise from the water, and an instant later disappeared.

"They've got it, and lifted it aboard," cried Bonny, delightedly; and in his exultation he called out, "The beaks have doused the glim, Cap'n Duff!"

"Douse your tongue, ye swab, and keep your eyes p'inted for'ard!" was the reply muttered out of the after darkness.

"What an old bear he is!" muttered Alaric, indignantly.

"Yes; isn't he?—a regular old sea bear? But I don't mind him any more than I would a rumble of imitation thunder. I say, though, Rick, isn't this jolly exciting?"

"Yes," admitted the other, "it certainly is."

"And you want me to quit it for some stupid shore work that'll make a fellow think he's got about as much life in him as a clam?"

"No, I don't; for I am certain there are just as exciting things to be done on shore as at sea, and if you'll only promise to come with me, I'll promise to find something for you to do as exciting as this, and lots honester."

"I've a mind to take you up," said Bonny, "and I would if I thought you had any idea how hard it is to find a job of any kind. You haven't, though, and because you got this berth dead easy you think you'll have the same luck every time. But we must look sharp now for another light from Skookum John."

By this time the sloop had again tacked, and was headed diagonally for the western shore.

"Who is Skookum John?" asked Alaric.

"Skookum? Why, he's our Siwash runner, who is always on the lookout for us, and keeps us posted."

"What is a Siwash?"

"Well, if you aren't ignorant! 'Specially about languages. Why, Siwash is Chinook for Indian. There's his light now! See? One, two, three. Good enough! We've given 'em the slip once more, and everything is working our way."

As it grew lighter Bonny pointed out the now distant masts of the cutter they had so successfully passed a short time before, and said, with a cheerful grin: "There's the old kettle that thought she could clip the Fancy's wings, and bring her to with a round turn."

Captain Duff laid all the blame of their late arrival on poor Alaric.

"If it hadn't been for your fool antics of two nights ago," he said, "we'd made this port a good hour afore sun this morning. You're as wuthless as ye look, and ye look to be the most wuthless young swab I ever had aboard ship, barring one. He was another just such white-faced, white-handed, mealy-mouthed specimen as you be. Couldn't eat ship's victuals till I starved him to it, and finally got me into the wust scrape of my life. Now I shouldn't be one mite surprised if you'd put me into another hole mighty nigh as deep. So you want to quit your nonsense and 'tend strictly to business, or I'll make ye jump. D'ye hear?"

Alaric acknowledged that he heard, and then walked forward to light the galley fire.

The sloop rounded a long point and came to anchor in a wooded cove, apparently as wild as though they were its discoverers. A couple of Chinamen, who had evidently camped there all night, waited to greet their countrymen on the beach, to which Bonny at once began to transfer his passengers, a few at a time, in the dinghy. As fast as they were landed they were led back into the woods and started toward Tacoma, which was but a few miles distant.

Alaric managed to get his canvas bag on deck unseen by Captain Duff, and slip it into the dinghy as the boat was about to make its last trip.

"Hide it on shore for me, Bonny," he said.

"All right; I will if you'll promise not to skip until we've had another talk on the subject."

"Of course I promise; for I'm not going without you."

"Then perhaps you won't go at all," laughed Bonny.

So the bag was taken ashore and concealed in a thicket a little to one side, and Bonny came back to prepare breakfast, for which Alaric had the water already boiling.

When this meal was nearly ready, and as the boys were sniffing hungrily at the odors of coffee and frying meat, Captain Duff suddenly appeared on deck.

"Go up on that point, you foremast hand—I can't remember your thundering name—and watch the cutter while me and the mate eats. After that one of us'll relieve ye. Ef she moves, or even shows black smoke, you let me know, d'ye hear?"

Alaric managed to secure a couple of hard biscuits with which to comfort his lonely watch, and then Bonny set him ashore.

Picking up his bag and carrying it with him, the boy clambered to the point, and selecting a place from which he could plainly see the cutter, began his watch, at the same time munching his dry biscuit with infinite relish. Much of the water intervening between him and the cutter was hidden from view by nearby undergrowth, and the necessity for scanning it never occurred to him.

After a while Bonny came to relieve him and allow him to go to breakfast.

"Have you really made up your mind to desert the ship?" asked the young mate, noticing that Alaric had his bag with him.

"Yes, I really have," answered the other, "and you will come with me, won't you, Bonny?"

"I don't know," replied the latter, undecidedly. "Somehow I can't make it seem right to desert Captain Duff and leave him in a fix. Seems to me we ought to stay with him until he gets back to Victoria, anyway. Besides, I'd lose my wages, and there must be nearly thirty dollars due me by this time. But you go along to your breakfast, and after that we'll talk it all over. Haven't seen anything, have you?"

"No, not a sign, but— Hello! What's that?"

"Caught, as sure as you're born!" cried Bonny, in a tone of suppressed excitement.

Then the two lads, peering through the bushes, watched a boat, flying the flag of the United States Revenue Marine and filled with sturdy bluejackets, enter the cove and dash alongside the smuggler Fancy.

he recent article from my pen on the "Riddle of the Bluets," and which showed the important significance of its two forms of blossoms, suggests that a few more similar expositions of the beautiful mysteries of the common flowers which we meet every day in our walks, and which we claim to "know" so well, may serve to add something to the interest of our strolls afield. It is scarcely fair to assert that familiarity can breed contempt in our relations to so lovely an object as a flower, but certain it is that this every-day contact or association, especially with the wild things of the wood, meadow, and way-side, is conducive to an apathy which dulls our sense to their actual attributes of beauty. Many of these commonplace familiars of the copse and thicket and field are indeed like voices in the wilderness to most of us. We forget that the "weed" of one country often becomes a horticultural prize in another, even as the mullein, for which it is hard for the average American to get up any enthusiasm, and which is tolerated with us only in a worthless sheep pasture, flourishes in distinction in many an English or Continental garden as the "American velvet plant."

The extent of our admiration often depends upon the relative rarity of the flower rather than upon its actual claims to our appreciation. The daisy which whitens our meadows—the "pesky white-weed" of the farmer—we are perfectly willing to see in the windrows of the scythe or tossed in the air by the fork of the hay-maker. The meed of our appreciation of the single blossom becomes extremely thin when spread over a ten-acre lot. How rarely do we see a bouquet of daisies on a country table? And yet, strange inconsistency! the marguerite of our goodwife's window-garden, almost identical with the daisy and not one whit prettier, is a prize, because it came from the "florist's," and cost twenty-five cents, with five cents extra for the pot.

A certain thrifty granger of the writer's acquaintance was recently converted from the error of his attitude toward the "tarnal weeds and brush." He was one of the tribe of blind, misguided vandals who had always deemed it his first duty "after hayin'" to invade with his scythe all the adjacent roadside, to "tidy things up," reducing to most unsightly untidiness that glorious wild garden of August's floral cornucopia, that luxuriant tangle of purple eupatorium, the early asters, goldenrod, vervains, wild-carrot, and meadow-rue.

He was converted in the sanctuary, where one August Sabbath he beheld by the side of the pulpit, dignified by a large beautiful vase, a great bouquet of this very tall purple thoroughwort, meadow-rue, and wild-carrot of his abomination, and which had actually fallen before his scythe on the evening previous. "Well, there!" he exclaimed; "I didn't realize they was so pretty!"

The beauty of the commonplace often requires the aid of the artist as its interpreter, a fact which Browning realized when he expressed, through Fra Lippo Lippi:

"We're made so that we love

First when we see them painted, things which we have passed

Perhaps a hundred times, nor cared to see."

An illustration of the truth of this axiom was afforded in a recent incident in my experience. Sitting at the open window of my country studio one summer day, engaged in making a portrait of a common weed, a friendly farmer, chancing "across lots," seeing me at work, sauntered up to "pass the time o' day." As he leaned on the window-sill his eye fell upon the drawing before me.

"My!" he exclaimed, "but ain't that pooty?"

"What!" I retorted,[Pg 561] "and will you admit that this drawing of a weed is pretty?"

"Yes, your draft thar is pooty, but you artist fellers alliz makes 'em look pootier 'n they ought to."

So much for the mere attributes of manifest outward beauty without regard to consideration of "botany" or the structural beauty of the flowers. The "botanist" finds beauty everywhere, even among the homeliest of Flora's hosts. But in the light of the "new botany," which recognizes the insect as the important affinity of the flower—the key to its various puzzling features of color, form, and fragrance—every commonest blossom which we thought we had "known" all our lives, and every homely weed scarce worth our knowing, now becomes a rebuke, and offers us a field of investigation as fresh and promising as is offered by the veriest rare exotic of the conservatory; more so, indeed, because these latter are strangers in a strange land, and divorced from their ordained insect affinities. The plebeian daisy now becomes a marvel of a flower indeed—five hundred wonderful little mechanisms packed together in a single golden disk. The red clover refuses to recognize us now unless properly introduced by that "burly bumblebee" with which its life is so strangely linked.

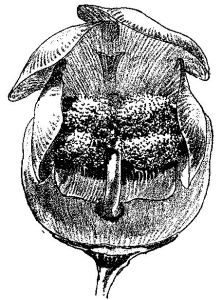

The barn-yard weeds need no longer be considered uninteresting and commonplace, because their mysteries have not yet been discovered, and I can do no better in my present chapter than to select one of their number and redeem it from its hitherto lowly place among them—one of the homeliest of them all, and whose blossoms are scarce noticed by any one except a botanist.

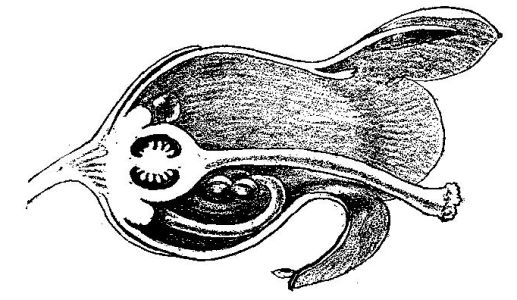

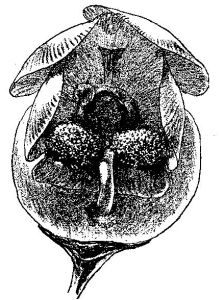

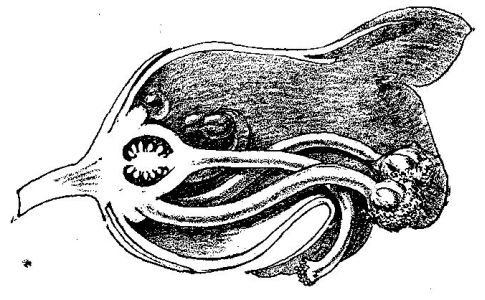

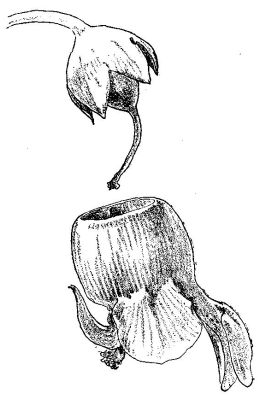

In my initial illustration is shown a sketch of the Figwort, or scrophularia, a tall spindling weed, with rather fine luxuriant leaves, it is true, but with a tall, curiously branching spray of small insignificant purplish-olive flowers, with not even a perfume, like the mignonette, to atone for its plainness. But it has an odor if not a perfume, and it has a nectary which secretes the beads of sweets for its pet companion insects, which in this instance do not happen to be bees or butterflies, but most generally wasps of various kinds, as these insects are not so particular as to the quality of their tipple as bees are apt to be. But the figwort has found out gradually through the ages that wasps are more serviceable in the cross-fertilization of its flowers than other insects, and it has thus gradually modified its shape, odor, and nectar especially to these insects.

Let us then take a careful look at these queer little homely flowers, and for the time being consider them as mere devices—first, to insure the visit of an insect, and second, to make that insect the bearer of the pollen from one blossom to the stigma of another. Here we see a flower with three distinct welcomes on three successive days.

A. First Day's Welcome—Stigma at the Doorway.

A. First Day's Welcome—Stigma at the Doorway.

A¹. First Day—Sectional View.

A¹. First Day—Sectional View.

B. Second Day's Welcome.—Stigma bent downward beneath

two withered Stamens at Doorway.

B. Second Day's Welcome.—Stigma bent downward beneath

two withered Stamens at Doorway.

B¹. Second Day—Sectional View.

B¹. Second Day—Sectional View.

C. Third Day's Welcome.—Four Stamens at Doorway.

C. Third Day's Welcome.—Four Stamens at Doorway.

D. Fourth Day.—Fall of Blossom. Its Mission fulfilled.

D. Fourth Day.—Fall of Blossom. Its Mission fulfilled.

E. Fifth Day.—Pod Enlarging.

E. Fifth Day.—Pod Enlarging.

The flower bud usually opens in the morning, and shows a face as at A, which must be fully understood by looking at the side section shown at A¹.

The anthers and pollen are not yet ripe, but the stigma is ready, and now guards the doorway. To-morrow morning we shall see a new condition of things at that doorway, as seen at B and B¹. The stigma has now bent down out of the way, while two anthers have unfolded on their stalks and now shed their pollen at the threshold. The third morning, or perhaps even sooner, the other pair come forward, and we see the opening of the blossom as at C. Blossoms in all these three conditions are to be found on this cluster.

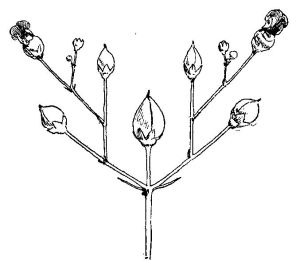

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

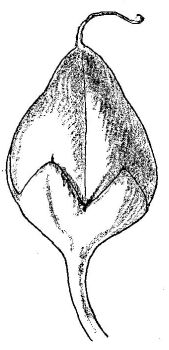

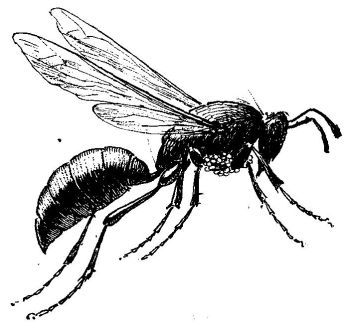

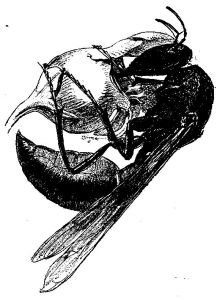

A small wasp is now seen hovering about the flowers, and we must now turn our attention to him as seen in Figs. 1, 2, and 3. The insect alights, we will assume, on a blossom of the second day (Fig. 1), clinging with all his feet, and thrusting his tongue into the heads of nectar shown at A¹ and B¹. He now brings his breast or thorax, or perhaps the under side of his head, against the pollen, and is thoroughly dusted with it. Leaving the blossom, we see him in flight, as at Fig. 2, and very soon he is seen to come to a freshly opened flower, which he sips as before. The pollen is thus pushed against the projecting stigma, as shown at Fig. 3, and thus, one by one, the flowers are cross-fertilized.

The stigma, after receiving pollen, immediately bends downward and backward, as shown in B¹, to give place to the ripening anthers, and shortly after the last pair of them have shed their pollen, the blossom, having then fulfilled its functions, falls off, as shown at D. This may be on the afternoon of the third day, or not until the fourth. If not visited by insects it may chance to remain the longer time; but more than one tiny wasp gets his head into such a blossom, and is surprised with a tumble, his weight pulling the blossom from its attachment.

The result of that pollen upon the stigma is quickly seen in the growing ovary or pod, which enlarges rapidly on the few succeeding days, as in E.

Many species of hornets and wasps, large and small, are to be seen about the figwort blooms, occasionally bees, frequently bumblebees, which usually carry away the pollen on the under side of their heads.

Who shall any longer refer to the figwort as an "uninteresting weed"?

SINGULAR METHOD OF BRANCHING AND FLOWERING.

SINGULAR METHOD OF BRANCHING AND FLOWERING.

"It seems to me, Grandpop, that you have had every kind of exciting experience except a fight with Indians," said Ralph Pell.

Captain Sterling laughed. "Don't be so sure that I haven't had that kind thrown in too by way of variety, my boy," answered the old sailor.

Ralph was all agog in an instant. "There, Grandfather, I know you must have a story to tell about them, or you wouldn't answer me in that way; so please tell it, and I'll learn to box the compass backwards to-morrow to repay you," cried the eager lad.

"All right, Ralph," was the pleased rejoinder; "it's a bargain. And now for my yarn:

"When the California gold fever set the world aflame 'way back in '49, I caught the craze, and determined to dig a big fortune out of old Mother Earth in short order, instead of reefing topsails in winter gales of wind and chewing upon salt junk for a living; so I shipped in a big vessel named the San Juan, that had loaded mining-tools for a cargo, and set sail for the Golden Gate.

"Three months after leaving New York we dropped anchor off San Francisco; but it was not then the great city of to-day, with thousands of noble buildings, paved streets, and electric lights, but a town of tents and hovels thrown together on either side of rough wagon-tracks, and these streets were only here and there faintly lit up at night by the sickly glow of smoky lamps and tallow candles that shone out from the open doorways and the turned-back flaps of dirty canvas huts.

"Although all hands had considerable money due them in the way of wages, it was counted as nothing compared with the bags of gold nuggets that we confidently expected to possess later on, so we all dropped overboard one night while the officers were asleep, and swam ashore. Each man had carefully retained a portion of the advance money paid to him before sailing, in order to buy a shovel, pickaxe, and provisions, and as the miners' stores always remained open until late at night, we supplied ourselves with what we required immediately after landing, and by sunrise were well on our way into the interior, safe from pursuit and capture as deserters.

"Our outfit was the most meagre, but it had taken every cent we had to purchase it, for pickaxes and shovels were five dollars each, and the provisions, which were of the poorest quality, were paid for at a corresponding price.

"There was no mistaking the way to the gold regions, for the trail was defined clearly enough in the way of broken-down and abandoned wagons of every variety, while small straggling parties and large organized companies either passed or were passed by us every few miles. Everybody and everything was colored with the magic suggestion of gold; even the atmosphere seemed to taste of the precious yellow metal, and there was but one thought, one ambition, one incessant subject of conversation from the gray-haired man to the youngster trotting along by his side, and that was gold! gold! gold!