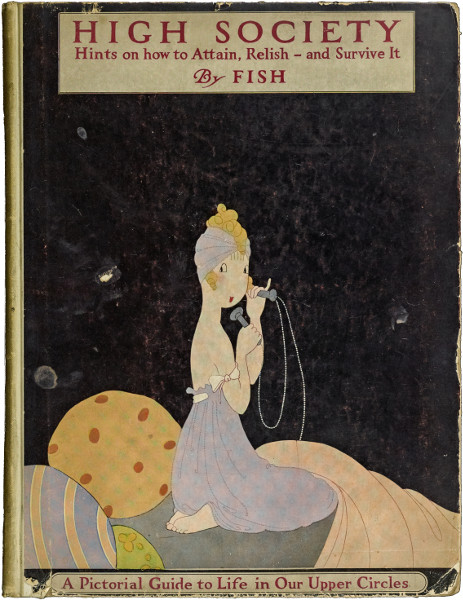

Title: High society

Advice as to social campaigning, and hints on the management of dowagers, dinners, debutantes, dances, and the thousand and one diversions of persons of quality

Illustrator: Anne Harriet Fish

Author: George S. Chappell

Frank Crowninshield

Dorothy Parker

Release date: March 14, 2018 [eBook #56739]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by ellinora, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

STOP!

No reader will be permitted to pass beyond this page who is not actually in society. This book is not for those who dwell in the gloom of mere respectability, or the blaze of sheer wealth. It is a pasturage intended solely for those who bask in the sunlight of the smartest society.

Those whose social standing could conceivably be classed with that of brewers, green-grocers, minor poets, munition magnates, linen drapers, provincial actors, and cubist sculptors, must not trespass within these covers.

BUT—

If your name appears in all the Social Directories; if you are a member of six or eight fashionable clubs; if you never plan a dinner without unpotting a pound or so of pâté de foie gras; if you never witness an opera except from an opera box; if you never go to the city except in an imported motor-car, why then just knock at the title page, open the door, walk in, take off your monocle—or your turreted tiara—and make yourself perfectly at home.

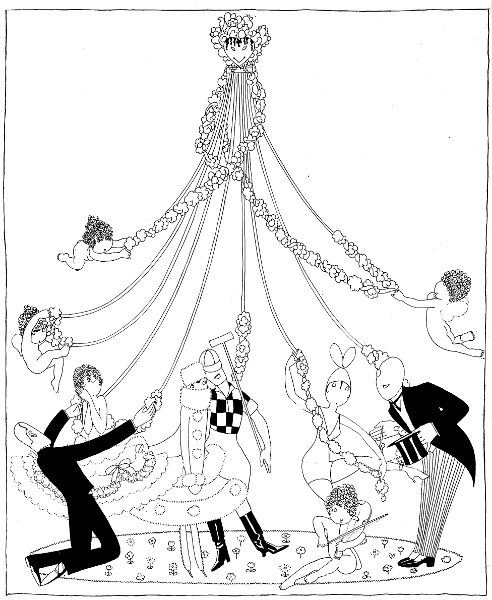

Elucidating the Little May-Pole

Festival on the following page

The artist is the director, the book a many-colored whirligig. Group after group revolves before us, while the artist smiles with an arch, faintly satiric smile, pointing out to us the weaknesses of the participants in this sacred social world, a delightfully gay throng, constantly occupied in singing, cajoling, feasting, playing, and dancing. Each of the characters in this book recognizes only one duty toward himself—not to be bored—and one law toward his neighbors—not to bore them. The wheel of the merry-go-round turns again; color is blurred with color; figure succeeds figure. Montez, Monsieur, montez, Madame. The show begins.

The Drawings by

FISH

The Prose Precepts by

DOROTHY PARKER

GEORGE S. CHAPPELL

and

FRANK CROWNINSHIELD

G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS · NEW YORK and LONDON

The Knickerbocker Press

A HINT TO HIGHWAYMEN

Copyright, 1915, 1916, 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, by the

VANITY FAIR PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC.

Copyright, 1920, by G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS

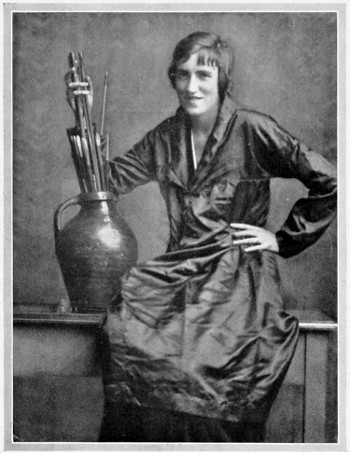

When, in the summer of 1914, certain remarkable drawings of social life, by a new hand, began to appear, in Vanity Fair in New York, and in The Tatler in London, people all over the world stared at them, amazed, amused, admiring. Then they stared at each other, demanding, with one voice: “Who, under the sun, is Fish?”

Meantime, a tall, slender young girl of twenty-two was drawing the pictures that were helping to keep laughter alive during those dark days—and troubling very little indeed as to whether Fame’s wandering searchlight would ever find her out.

That girl was “Fish,” deemed to-day, by many critics, the most distinguished of satirical black-and-white illustrators.

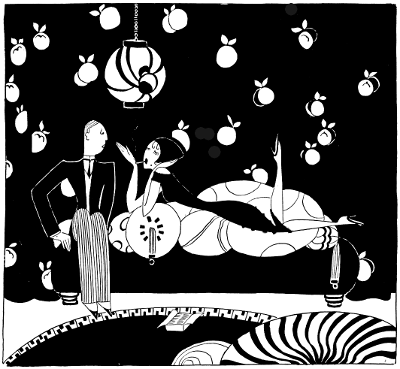

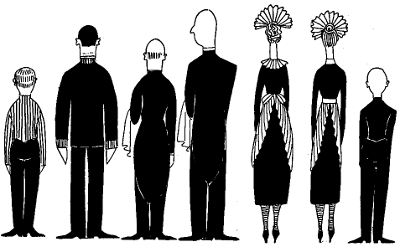

Miss Fish has created, on that miraculous drawing-board of hers, a complete human society, as original and amusing as the worlds of George Du Maurier and Charles Dana Gibson. It is a world populated by young-old matrons, astoundingly mature young girls, Victorian lady remnants, resplendent captains of industry, pussy-footing English butlers, amourous nursemaids, race touts, yearning young lovers, swanking soldiers, blank and vapid bores, bridge-playing parsons, and middle-class millionaires. But, for all its sophistication, it is a world of innocence. The creatures in it are of a touching simplicity, an incredible naïveté. Fish is one of the only caricaturists who has ever done this sort of satire without malice—who has ever treated the poor, misguided children of this world as if they were really children.

But there is beauty in her extraordinary gallery, as well as caricature. The patterns on her flappers’ gowns are like laces and hangings by Beardsley; a Pomeranian lying on a rug, becomes a patch of elegant scrollery, like a detail in a Japanese print. There is no trace at all, in her drawings, of the hackneyed conventions of illustration: everything in them is presented through the medium of an original feeling for form. Even her profiteering millionaires become designs made up of deft and satisfying curves. Her sketches are creations not only of a clever and sophisticated intelligence, but of a true artist.

Photograph by Malcolm Arbuthnot

“FISH”

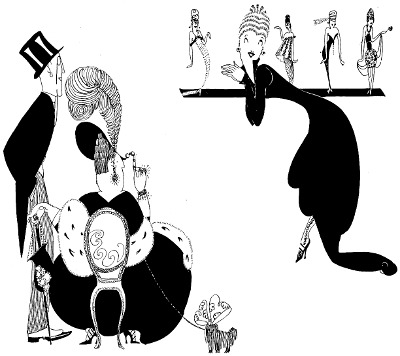

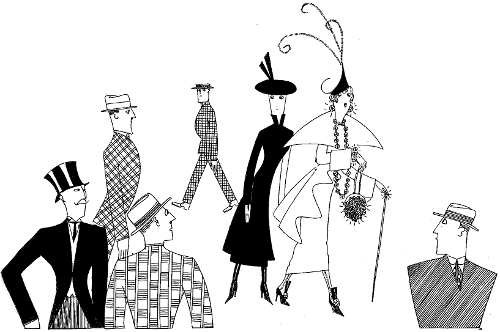

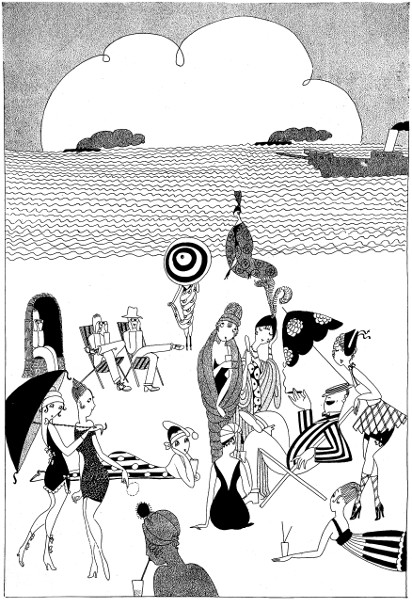

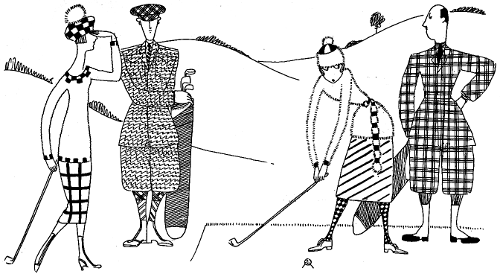

In depicting fashionable society Miss Fish is perhaps at her best, for the reason that the spectacle which seems to interest her most is that pageant of “smart” types that race, as if by magic, to her drawing-board, from every haunt of social life—from opera boxes, ballrooms, race-meets, cabarets, smart supper parties, dinners of state, musicales, and the thousand and one happy backgrounds against which the contemporary beau monde is wont to pose and posture.

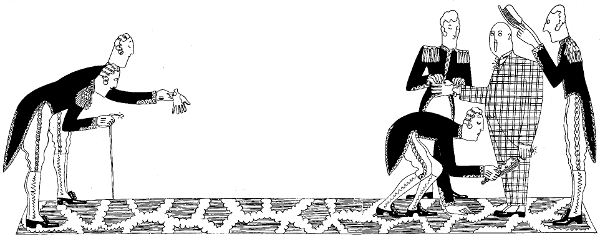

In the pages of this book the reader will meet only with Miss Fish’s social creations: the double-decked dowagers, the amateur vampires, the horsey horsemen, the diabolically clever little débutantes, the tango addicts, the incurable bridge-players, the worn-out week-end hostesses, and the myriad types of human beings that seem perpetually to haunt the portals of our most exalted society.

For six years, Miss Fish’s sketches have appeared, in America, only in Vanity Fair. For the past two years the British public has only seen her work in Vogue (the British edition), and in The Patrician,—the English edition of Vanity Fair. All the drawings in this book appear here with the permission of Condé Nast, the publisher of Vogue, Vanity Fair, and The Patrician.

The Editor.

HIGH SOCIETY

[2]

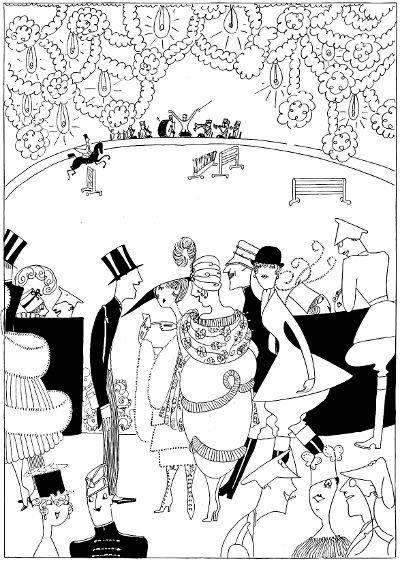

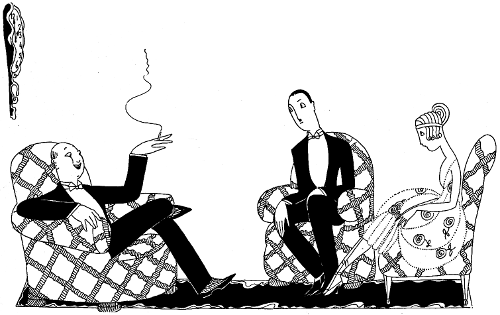

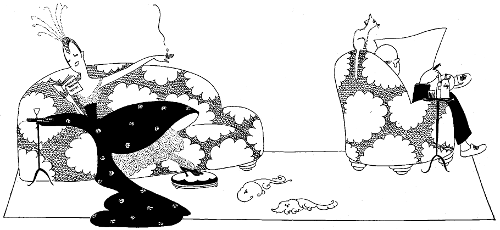

Here we see the horse show in full blast. Here you will see everybody happy, everybody occupied, scandals energetically and effectually discussed, meetings arranged in whispers, society reporters calling everybody by their wrong names, and everybody paying the strictest attention to everything about them—except the horses.

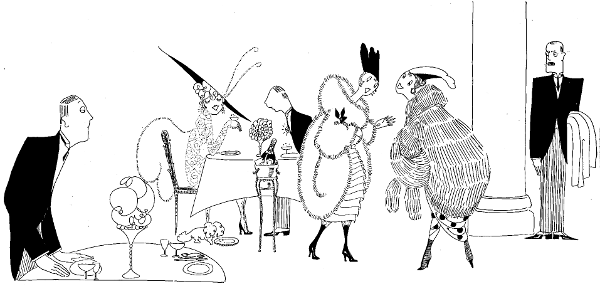

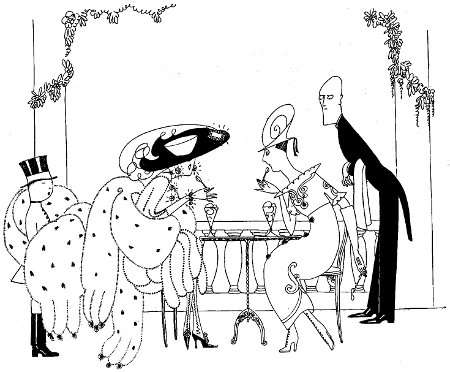

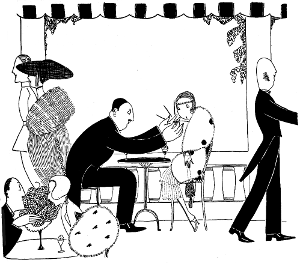

The season in the restaurants has opened strong. And the worst of it is that the ladies will spend all their time in these blessed robbers’ dens. Tell a woman that her place is in the home and—but you wouldn’t do anything as rude as that, would you? There are two other discouraging things about women in a restaurant: first, that they won’t ever go home, and second, that they won’t ever sit down. Here we see a tragedy illustrating both of these points. Muriel, who long ago finished her luncheon simply will not join the gentleman in the hallway (the one who looks a little like President Wilson), although the poor creature has been waiting for twenty minutes. And her charming little vis a vis, Esmé by name (the one with the lap dog that looks like a three-leaved clover), has, on her side, been keeping her fiancé standing at attention for a similar period of time—and, all because the two dears have such thrilling and wonderful things to talk about.

[3]

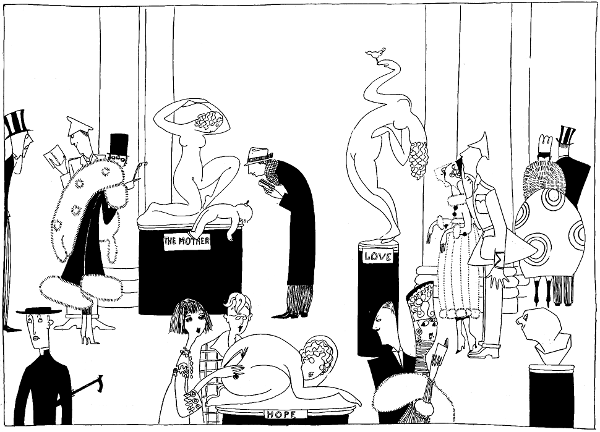

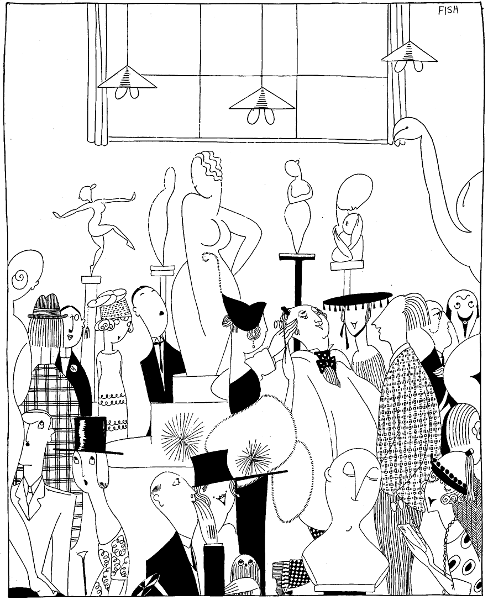

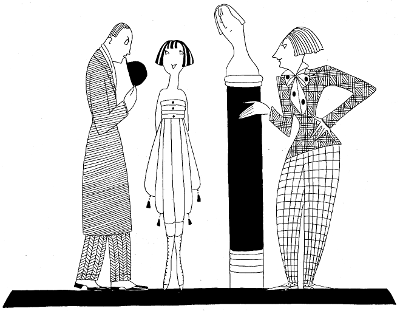

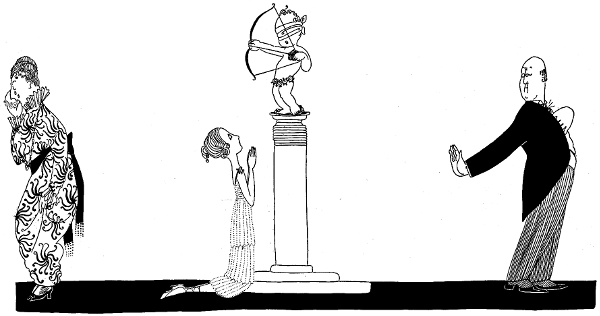

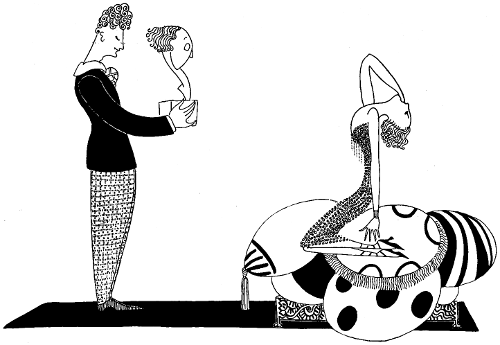

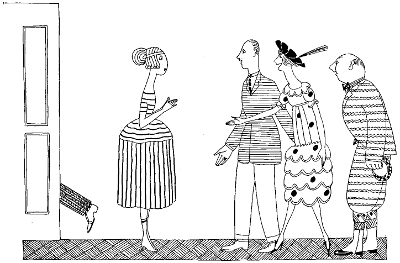

Below we see the opening of the Vorticist Sculpture Salon, a debauch in marble that always brings out a full quota of the artistic cognoscenti of the town. Bohemia always appears in goodly numbers at these charming little revels in stone. The extraordinary thing about much of the new sculpture is that it looks like illustrations for those wonderful books on hygiene, in which ladies’ are taking their matutinal exercises—by correspondence, of course. Take, for instance, the case of the delicate little gem entitled “Love” in this illustration. Captain De Pluyster who is viewing it in company with his fiancée, Miss Corinna Walpole, is listening to her: “Oh, that’s an easy one. I do that twenty times, every morning, just before my bath.”

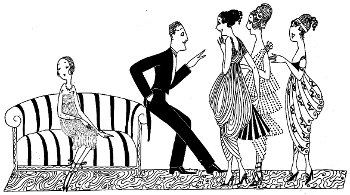

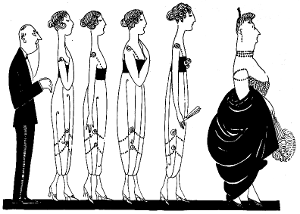

Perhaps the most delightful social occasion of all—at least as far as married men are concerned—is the winter Fashion Fête at Luciline’s select little dressmaking establishment. In the picture, you will observe a married gentleman, accompanied by his gross tonnage. The poor man is not at all listening to Mme. Luciline; no, he is gazing wistfully and, with eyes aflame, toward the wholly divine young ladies who, every season, do so much toward making the happy modes and unmaking the unhappy marriages. “How different would have been my life,” he reflects, “had I met one of those limp and sinuous sirens before I took up with my Henrietta.”

[4]

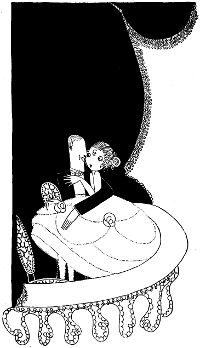

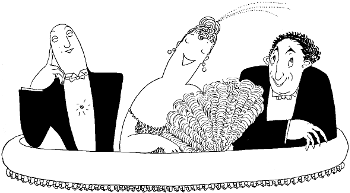

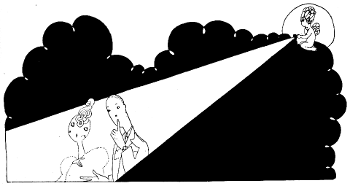

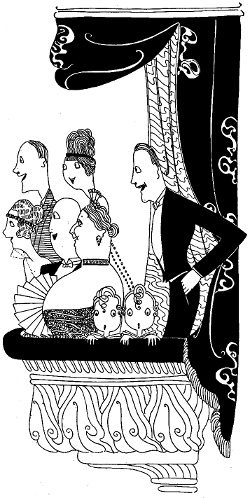

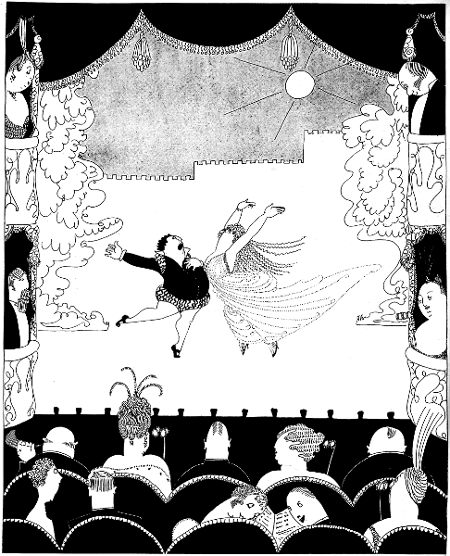

For upward of a generation, now, operatic and musical matters have gone along much as usual at our opera house. It’s always dangerous to be different, or original, or diverting. Literally, the only novel thing that has happened at the opera this season is that the director’s box, which has always been empty, was, at one performance last week, tenanted by a young gentleman in our best society, along with a tiny little friend of his. To see this usually dim, untenanted cave so decoratively occupied was a welcome change in the monotony of a somewhat uneventful season.

Below, you will behold a little scene in Pneumonia Alley otherwise known as the lobby of the opera. It is here that all of our best people gather, after the opera, and wait for hours for their flunkeys and limousines. Fashionable personages are really much cleverer than mere people are wont to suppose. After twenty years of hard study, they have finally devised a system by which—after the opera—they can wait around in the lobby for their motors and reach their houses only an hour later than they would if they left by the main door and picked up a passing taxi.

[5]

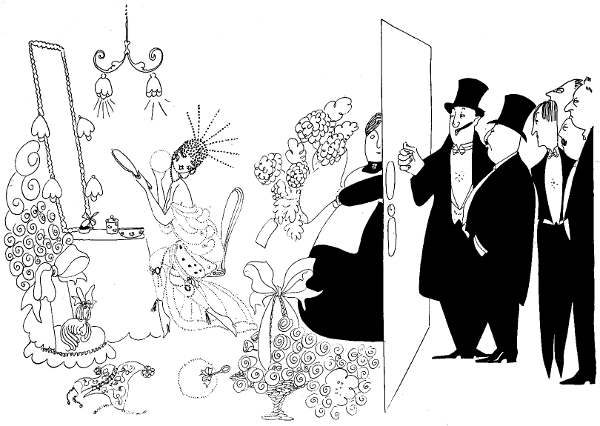

One of the great tragedies of life is that men and women have a way of saying pleasant things to your face, and truthful things behind it. Nowhere is this practice more prevalent than in grand opera. Above, for instance, you will observe a portrait of Signor Enrico Scottinelli, buttering with fair words the bewitching soprano. Nothing could exceed the sweetness of his remarks to her, during the opera. You know the remarks we mean: “Your eyes are radiant arrows in my soul. Your lips are torments to my heart. Look at me, and an eagle lifts my feet; kiss me, and pansies blossom in my breast.” It’s all very operatic and charming, but, back of the scenes—oh my!—what a difference!—“You call yourself an artist! You, who paid a press agent for every line you ever got in a newspaper! You who were hissed at Monte Carlo. You, who are only kept on here at the opera in order to save storage charges on your body at the warehouse! A singer! Ha! ha! ha! Why don’t you go back to washing? An artist! Corpo di Bacco! Why don’t you go back to scrubbing floors? You, who stand there dressed up like Marguerite! Where is your fur, where are your claws, where are your shiny yellow eyes, cat that you are!” All of this, disheartening and saddening as it is, only proves that social amenities at the opera are very much as they are with us all in real life.

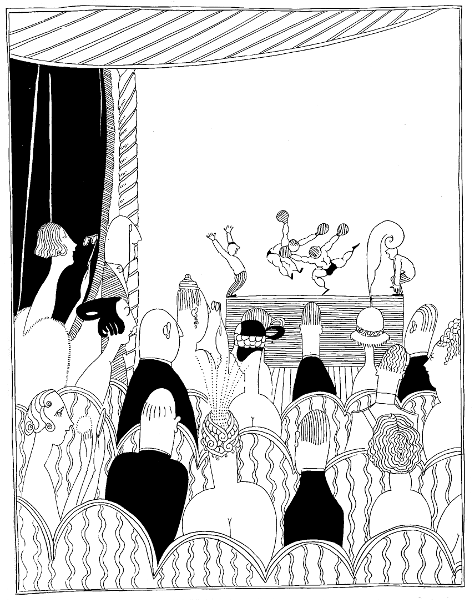

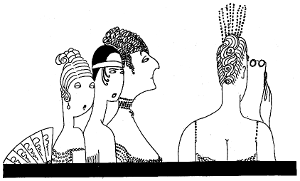

Why is it, we wonder, that the people in the first tier boxes at the opera always seem like human beings. Even their tiaras, feathers, and red Indian facial accoutrements, fail wholly to remove them from the category of living creatures. But the inhabitants of the second tier boxes are, somehow, a race apart. Their faces, figures, fans, hair, and bodily habiliments all somehow take on a strange, wild note. “Are they human?” we ask ourselves, “or are they merely some wax figures which we, as children were wont to admire?” In the sketch we see a group of these second-tier creatures suffering intensely under the spell of the director’s baton.

[6]

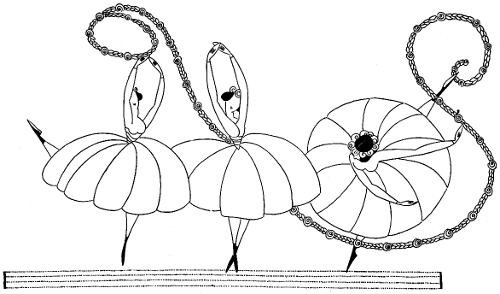

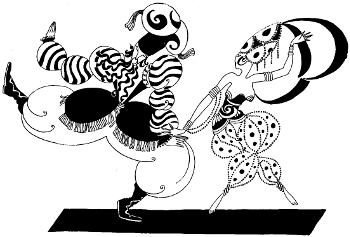

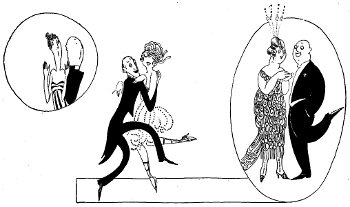

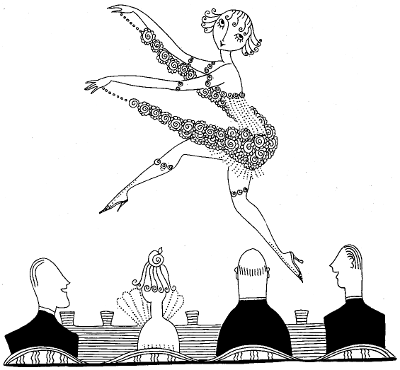

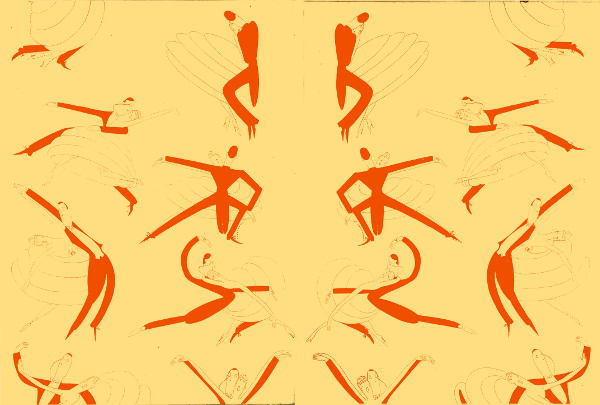

Above is pictured a bright moment from the Ballet of the Rosebud—one of the lighter, sweeter forms of ballet. The plot concerns the love of the Rosebud for the South Wind—the sex interest is always developed early in these little dramas—and it shows how he subsequently leaves her ruthlessly—as it’s against the rules for any ballet to end happily. This scene shows a Trio of Spring Flowers, in action.

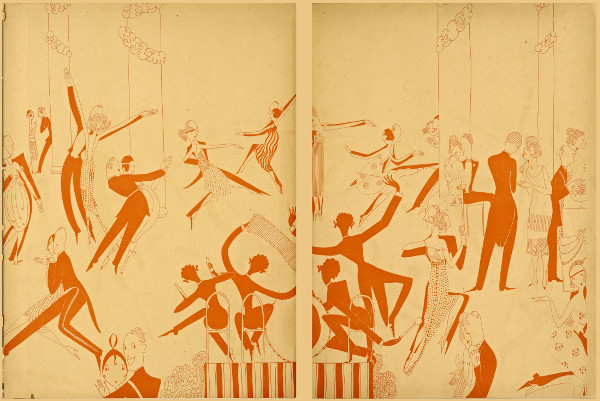

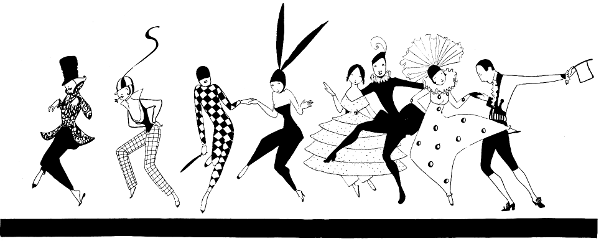

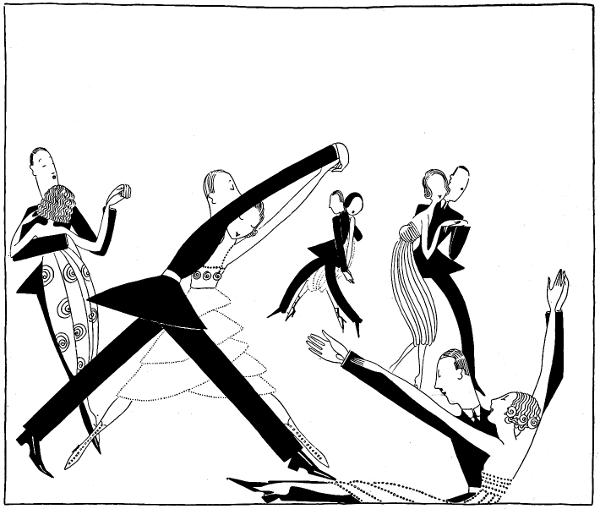

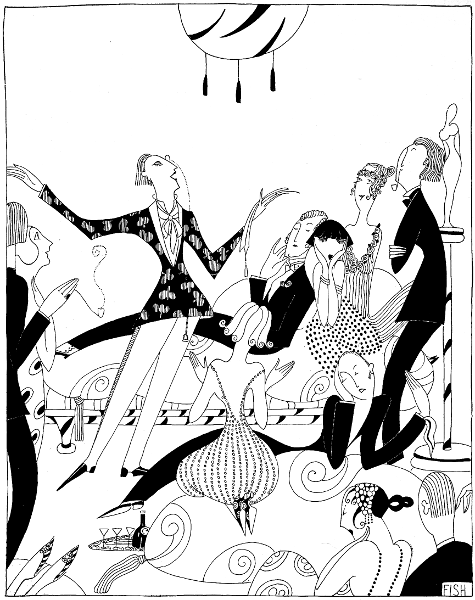

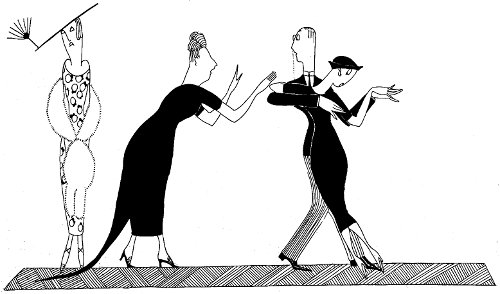

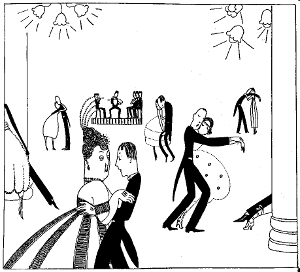

Below is an intimate glimpse of any gathering any evening, anywhere in the, broadly speaking, civilized world. Now that the war is really over, something had to be found to keep all the men interested,—so the dance habit has come back more strongly than ever. If he can only have seven or eight hours of fox-trotting every evening, a young man will get so that he hardly misses his bayonet practise at all.

In spite of sporadic outbursts of protest from non-dancing editors of hearth-side magazines, the dance craze is still going strong. In fact, it’s more violent than it ever was; it is no longer a mere craze—it has reached the point of frenzy. Any kind of dance goes (whether in Rome, Madrid, New York, Paris or London) from the intricacies of the Russian ballet on the stage of the opera, to the simple little fox trot in the privacy of your own home. Joy has never been so completely unconfined as it is this season; everybody is going on—and on—with the dance. You simply can’t get away from it. No matter where you go, some form of dancing is sure to come into your life, someone is certain to appear suddenly and dance with, beside, in front, or all over you.

[7]

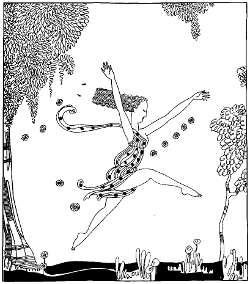

Somebody once got all worked up about dancing and called it the poetry of motion; if you want to go right along with the idea, you might speak of barefoot dancing as the vers libre of motion. No one is quite certain of what it’s all about. The lady in this sketch, a disciple of the art, has left home to run wild in the park at dawn, in a little dance called “The Birth of the Crocus.”

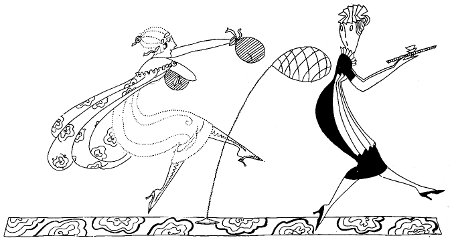

A quiet corner of the Ballet Russe—one of the calmest moments in the company’s entire repertory. Both the lady and gentleman are, of course, stars of the Imperial Ballet of Moscow—they always are. Any male dancer wearing trick red boots, and any female dancer whose costumes are designed by Bakst, instantly becomes a star of the Imperial Theatre of Moscow. This is a scene from “The Golden Vodka,” a drama all about the love of the Princess Soviet for Nikailovitch, the handsome samovar.

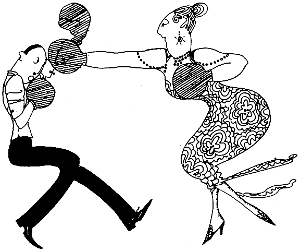

This is what some euphemist has delicately called “ballroom dancing.” It occurs at least once in the course of every musical comedy and variety show. The male half of the cast seems forever looking for an opportunity to toss his partner out into the orchestra. Perhaps it’s the element of uncertainty about this sort of dancing that makes it so popular with the public; you never know at just what moment it’s going to prove too much of a strain for the male member of the team, or when the lady in the case is going to land, with a pretty informality, in your lap.

The Dance of Salome seems never to lose its popularity—perhaps the secret of its appeal is the sweet, wholesome joyousness of it all. It requires very few properties. All a girl needs, to give her own version of Salome’s famous specialty, is a plated silver platter, a papier maché head, and the usual lack of costume.

[8]

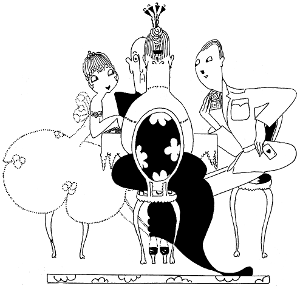

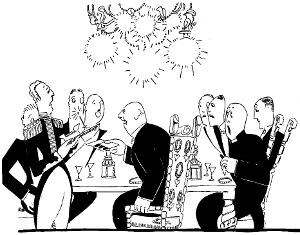

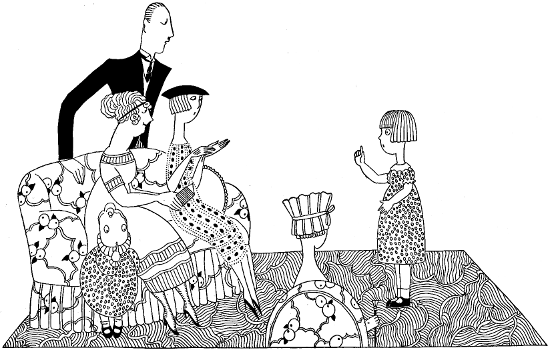

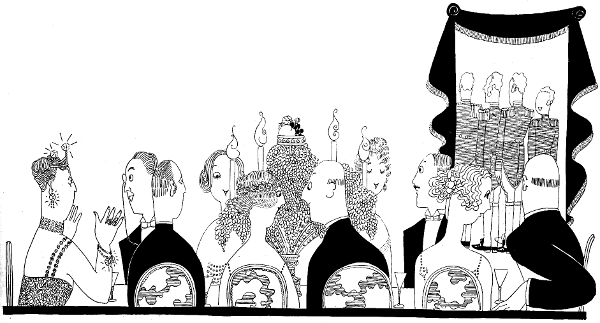

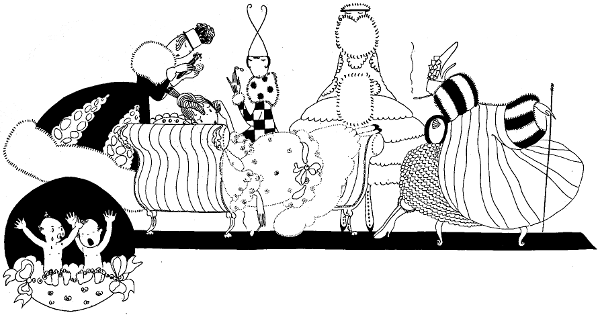

The T. Pennypacker Higgingbothams reached the metropolis, a short while ago, from the social ooze of the Texas oil fields. They wanted to break into society, but, alas, a fondness for eating and a fortune of twenty millions were all that they had to do it with. These pictures mirror their progress in the frigid marble-and-gold society of our inhospitable city. They are here shown at their first important dinner—a little repast of eight—at their palace, a palace which, architecturally considered, is a cross between the Temple of Karnak and Charing Cross Station. They are wisely beginning their social climb among the intellectual set. Brains are the best things to climb on until you got fairly high up, when you can safely discard them.

Reading from left to right, T. Pennypacker Higgingbotham; Marietta Pillsbury Powyss, author of “The Fear of Love,” “More Than Kisses”; Frederick von Nippelzow, Professor of Czech, and the Slav and Bulgar languages at Oxford; Miss Sophronisba Ottway, Japanese lacquer worker, Etruscan embosser, designer of Indian art-jewelry; Guido Bruno Pfaff, lecturer on Malthusianism, Mendelism and sea worms; Babette La Rue, smock designer, garden-stick maker, flower-pot varnisher, book-end painter, art stenciler and jig-saw artist; Bliss Merriweather Gow, play-reader, author of nine Shakespearean masques, creator of a ballet entitled “The Birth of Passion”; and, finally, the dazed Hostess, about to go down for the third time.

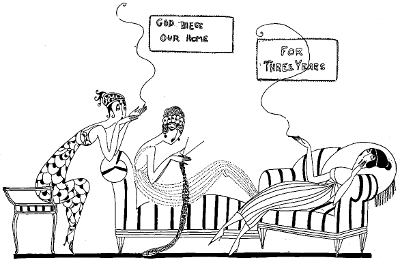

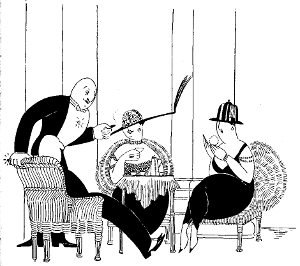

The Higgingbothams were told that they could do nothing without a social secretary. They accordingly engaged Miss Audrey De Vere, a young lady of lineage. Audrey smokes, drinks, and plays “poker”: she also knows how to get first-night tickets at the theatres and an outside table at a cabaret. She can mix eleven different kinds of cocktails with only one bottle of gin, one lemon, two bottles of Vermouth and a single olive. She is engaged to a war hero—her vis-a-vis at this table. The dinner has been cleared away and Audrey and her friends have just finished a little session with the cards. Net result: the T. Pennypacker Higgingbothams are minus the value of one small Texas oil well.

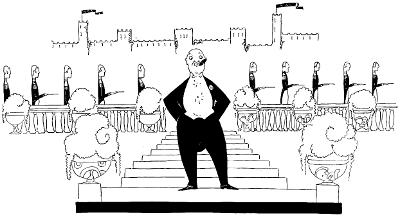

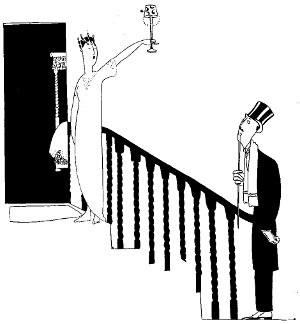

Front elevation of Mr. and Mrs. H. at the head of the grand stairway leading to the gold organ room in their palace. Mr. and Mrs. H. are expecting forty more or less strangers to dine with them. Gold favors will be found under the napkins. Twenty pairs of footmen’s calves, in wood, have just been successfully adjusted by the H’s footmen, in the magenta and gold dining room, brought, at some expense, from Verocchio’s palace in Venice.

[9]

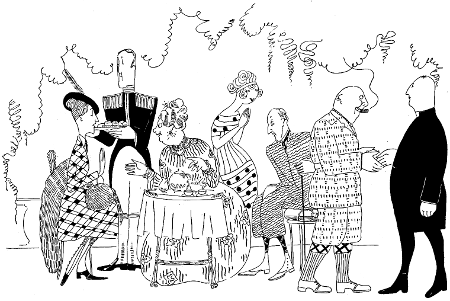

The Higgingbothams have not, on the whole, been very successful in their attacks on the smart set, so they are at present engaged in entertaining Bohemia. Here you see a section of it let loose in the Verocchio dining-room. Reading from left to right: Mr. H., somewhat at a loss to know how to manage the bright young thing on his left; Miss Tessie Truefitt, artists’ model, understudy to a barefoot dancer, poses for Jo Davidson; Le Roy Eastman, socialist, drawing room anarchist, author of “The Red Flag in Spain,” lectures on Government Ownership of Women; Theda B. Small, film vampire, the worst woman in the city, rolls her own cigarettes, never wears stockings; Archibald Witherspoon Troutt, fashion artist, introduced the hoop in men’s evening coats, is suing Lady Duff Gordon for stealing his ideas (note the Byron collar and the Hero tie); Polly Pym, keeps a restaurant in the Apache region—paper napkins, waiters in red shirts, pipe smoking allowed, eau de quinine served from straw bottles, choral singing and recitations; Aristede Le Blanc, French Impressionist, paints with a palette knife; and, finally, poor Mrs. H., speechless at the wild and wanton scene around.

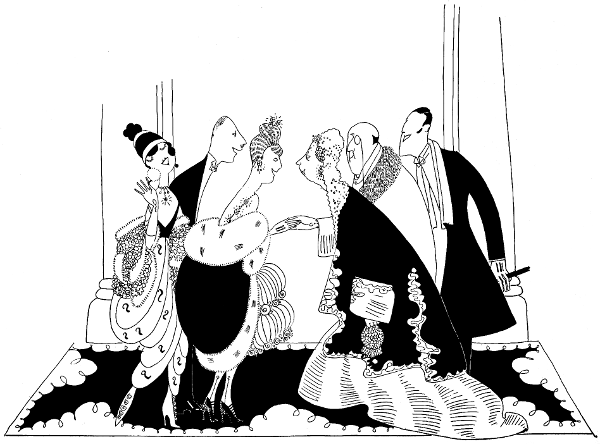

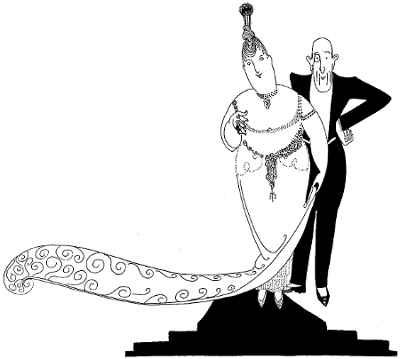

The Higgingbothams have had bad luck with their dinners and have now decided to try nothing but little suppers after the opera. Here we behold them with Mr. and Mrs. Lestranges, who compose the thickest part of the social cream. The Higgingbothams have at last arrived. They have a loge at the opera and know so many great people that they can perfectly well afford to discard all their intellectuals, social secretaries and Bohemians—all of them now unnecessary and de trop. The Lestranges have already refused three courses at supper and are now engaged in inspecting the little Escargots, à la Melba.

Mr. Higgingbotham has at last been permitted to join an ancient social club. He is here enjoying a bottle or two of his famous private stock, Veuve Clicquot, 1883, gray label, silver foil: only two cases in the world—and Mr. Higgingbotham owns them both.

[10]

A type of honeymoon which is not seen very much now is the War Brand. The lady mooner in the sketch below (she is the one leaning against the tree) is Colonel of the First Daffodils, and, of course, the flower of the regiment. The gentleman mooner is the Captain of the 7th Scotch Sodas. They are taking their honeymoon in little slices, between drills, as it were; not a bad system, as it prevents the happy young warriors from becoming fed up with the sweetness of love.

Oh, honeymooners, do you remember the little creeper-covered cottage to which You and She planned to fly immediately after the Voice had breathed o’er Eden? It was millions of miles from home, that little rose-colored paradise, and there wasn’t to be any telephone, and letters were not to be forwarded, and mother couldn’t annoy you, and you were going to pick heartsease in the garden,—and then you found you couldn’t afford it, and so you settled in a suburban villa in solitary exile.

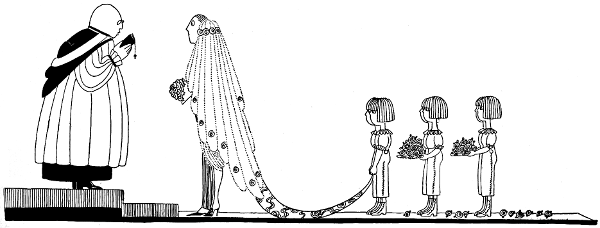

The moment in the honeymoon, which is pictured below, is technically known as the enfin seuls. The parents have been banished, the best man is still in wine; the bridemaids are at the photographer’s, the footmen have gone to chase up the entrée, and the lovers are at last alone with their J-HOY. What a blissful moment! Six months later a moment like this is a bit of a bore. Any third person then, even a dun from the tailor, would be welcome, for love, alas, is like caviare; a little indigestible—unless consumed in very small portions.

[11]

The yachting honeymoon is always a mistake. If anybody offers you a yacht for your honeymoon don’t accept it. The trouble with the ocean, for social purposes, is that it has no kind of taxi service. Take the case of Mr. and Mrs. Boodle-Beauty, who would have died of loneliness if it hadn’t been for bridge. Fortunately, a cook and a sailor knew their way about the card deck. Hearts would come into the bridegroom’s hand, but, with the bride, everything was diamonds.

Showing the bride and groom at the station just before the departure of the Eden express. Note the almost amorous gentleness with which the sentimental porters are caring for the slippered luggage. Good luck to you, happy newlyweds, before you pass into the Beatific Blue! Good luck, and here’s hoping that the train is a limited express, with no “stop-overs” in Nevada.

Of course, most honeymoons take place at hotels. Such wonderful food, and such dim, religious corners in the corridors. And it makes letters home so ridiculously easy. “Dear Mamma, and all: Arthur and I arrived last night. So, so happy. We are very comfortable. Arthur tries to be very cruel, but, so far, I have had no trouble in sitting on him.”

[12]

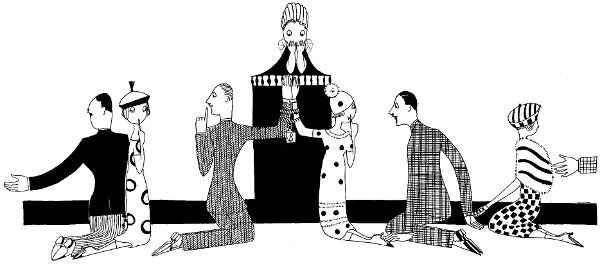

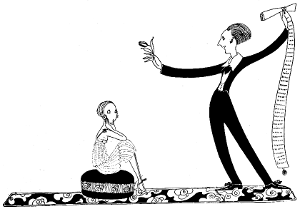

New York, and other American cities, have lately had a visiting procession of foreign poets. Robert Nichols, W. B. Yeats, Siegfried Sasson, John Drinkwater and Lord Dunsany have given ringing poetry recitals, and added greatly to their laurels. Here we have the latest arrival from English shores, Lonsdale Thornditch, the young poet, who finds compensation for the indifference of the British public by reciting his verse to the appreciative audience of America. With the present rate of exchange, and everything, Mr. Thornditch feels very well compensated. He is here seen in the futuristic salon of Mrs. Updike Jones, in New York, reading from his still-unpublished volume, “Skeletons in Scarlet.” His poems are most effective when read aloud, as may be judged from observing the prostrate illuminati about him. We cannot see why this pretty idea of lending literati to other lands should not be taken up by America. Why not redeem America’s literary debt and introduce the people of England to the joys—and even horrors—of the imported poetry recital.

[13]

There was a time when one visited the Natural History Museums to observe Nature’s latest vagaries in the shape of undeveloped amoebæ in bowls, rudimentary horns on recently unearthed amphibians, and models of funny little puffins, and green lizards, who had gone wrong while still in a pre-natal state.

Now one may see all these little jokes of Mother Nature at any fashionable exhibition of ultra modernist sculpture. The city is full of them. You are probably familiar with them. Here, for instance, are a few, which have been named by their creators as follows—reading from left to right—along the very top row: “The Birth of Love,” “Portrait of My Wife,” “Study of a lady,” “Fruitage,” “Inhibited Motherhood” and, finally, “The Death of Libido.”

[14]

Mr. John R. Blivvins, of America, one of the leading figures in that noble band of munitions factory owners who did such yeoman service—for themselves—all through the great conflict. However, even though peace is here, there is still work to be done,—Mr. Blivvins is about to crash in on British Society. By way of a start in the right direction, he has purchased—at 10 per cent discount for cash—an ancestral estate equipped with all the modern conveniences, including built-in butlers, hot and cold running footmen at all hours, and a resident bishop. Everything goes with the estate but the title, and Mr. Blivvins looks to his attractive daughter, Angelica, to furnish that, by marrying one.

Up to this moment, everything has gone along beautifully. Angelica has worked up a visiting Duke to the proposal point, and Mr. Blivvins has behaved so conservatively that the dinner guests are on the verge of accepting him. And then he had to wreck the entire works. Led away by too conscientious attention to the products of the ancestral wine-cellar, Mr. B. is, with unfortunate geniality, insisting that the footman try one of his best cigars. The Duke might overlook this, but the footman—never.

This moment marks the dawn of a new life for the Blivvins family. Their future seems to be practically assured. Angelica, the one and only daughter, has got in some deadly work on one of the local Dukes, who has been pressed into coming down for the week-end. To make it all delightfully homelike, the Duke has brought along his sister, one of the most unmarried noble-women in the entire United Kingdom. This charming little domestic scene shows the arrival of the guests, just at tea time. Angelica is going strong with the Duke (his is the third figure from the right—the clean-cut, red-blooded lad of barely seventy summers). Mr. Blivvins is welcoming the bishop to the little circle—a bishop is always so ornamental when draped gracefully around a tea-table.

[15]

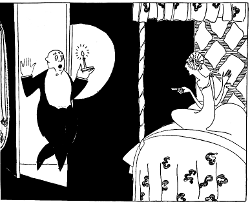

This picture does not show the great moment in any one of our popular farces,—it is far more tragic than that. It shows how Mr. Blivvins—always an artist at that sort of thing—has managed to get himself disliked. In an absent-minded moment—all life’s bitter tragedies happen in such moments—our hero has mistaken a door, and walked into the room where the Duke’s sister has retired to her chaste repose. The noble vestal is defending her honor at the point of a curling-iron, shrieking, “Stop, villain, or I fire.”

The snappy little evening’s entertainment—Mr. Blivvins takes his guests on a personally conducted tour of the picture galleries, proudly pointing out all of his ancestral portraits—that came with the house, when he bought it. Of course, a little of that sort of thing is perfectly ripping, but, after the first eight miles, picture galleries seem to pall a bit. The Duke’s sister is plainly bored.

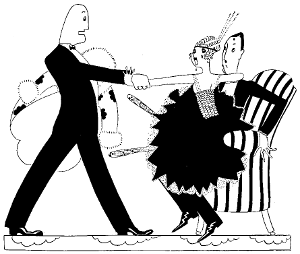

Things are looking considerably brighter here. Angelica has had the inspiration of injecting a little jazz into the Duke’s attentions. After all, dukes are but human; they can’t hold out against a jazz. The noble antique has dropped forty years from his age, and is dancing with all the abandon of a chorus man. Nothing could be sweeter, so far as Angelica’s proud parents are concerned, but the bishop and the Duke’s sister,—oh, Heavens!

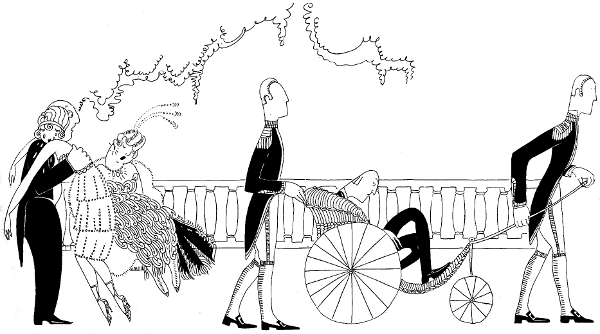

And this is the hideous conclusion of the whole affair. The Duke is indubitably not as young as he used to be, and the jazz dance has brought on a complete breakdown. He has to be ignominiously led away to Mortgaged Towers, the ducal estate, in a bath chair. The Blivvins family plumbs the utmost depths of gloom—and all bets on Angelica’s marriage into the British peerage have been officially declared off.

[16]

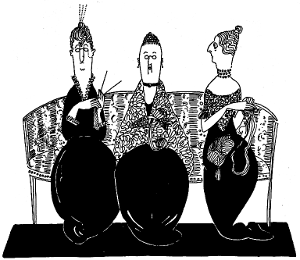

A view of the extreme left wing of the balcony, during a piano recital by the newest Russian prodigy. The members of this exclusive little group simply don’t know how they would ever get along without music. If it weren’t for music, they would be absolutely powerless to express their souls. Nothing is over their heads. Debussy to them is just like nothing at all to you or me, and they whistle catchy little tunes by Rimsky-Korsakoff in their bath-tubs. They are shown here still a trifle spent with enthusiasm after the pianist has obliged with one of his own compositions, entitled, “Dance of the Ghouls.”

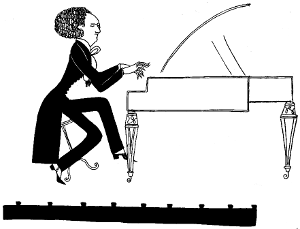

The world-famous pianist, who was once told that he had a Beethoven-like brow and has been dressing the part ever since. He can only manage to work in one concert annually; the rest of his time is taken up in making phonograph and pianola records, posing for heavily shadowed photographs, paying premiums for the insurance on his hands, and lending atmosphere and tone to the more exclusive studio teas.

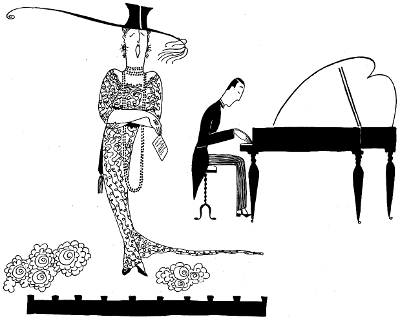

The society soprano—always a feature of the programme for the charity concert. It is pretty to see how gladly she volunteers her services for such events; there is no false modesty about it, no hanging back, no making excuses, no insistence on being coaxed, no niggardliness as to encores. No, she steps right forward, brings her music, supplies her own accompanist, and just lets herself go. She is here portrayed at work, rendering, by her own request, “Baby’s Boat’s the Silver Moon.”

[17]

The little dear has been appearing in public for the last four years—she is soon to celebrate her seventh birthday—and has played in every country in Europe, before all the royalty worth knowing, adding materially to the uneasiness of the crowned heads. This wonder-kiddie, as her press-agent so affectionately calls her, never had a lesson in her life; it’s a gift. It has also proved to be a gift to the father of the phenomenon—he hasn’t done a day’s work in years.

The male, broadly speaking, duet—a great favorite with concert audiences. They go in strongly for the brighter, cleaner school of song; they are particularly good in those ballads about shepherds and shepherdesses, named Colin and Phyllis. They also get in some really great work on the botanical numbers; those heartbreaking ditties with the mild sex interest, all about the love of the violet for the rose.

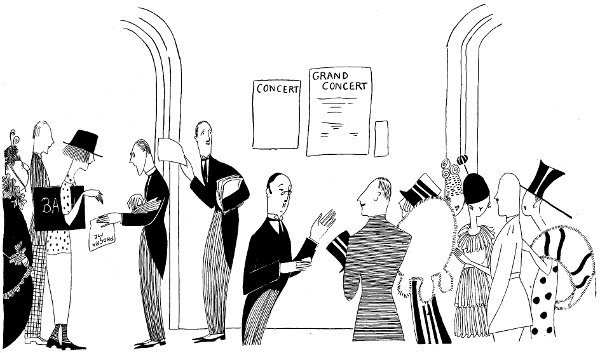

A pack of concert-hounds about to corner their prey—straining at their leashes in the foyer of the concert hall, just before the performance gets under way. All the best-known types of the species are here represented, from the strange beings who are here because they like this sort of thing, to the pitiful creatures who have to come—because their wives like it.

[18]

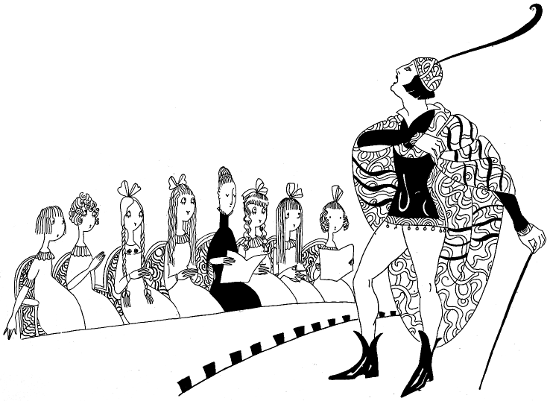

What a topsy-turvy old world it is. And how its recent antics have upset our very highest Society! For a smart young Johnny to-day, Peace hath its horrors just as well as War. Imagine being a Penniless Peer, as was young Algernon Wemyss (of Wimbledon) when sterling-exchange suddenly established its low-visibility record. But, did the brave lad falter? Well, hardly. With only his coronet for capital, he strolled into the pleasant supper parties, of the musical comedy field, finally playing, with great success, the title-role in “The Ideals of Algy,” two of which he may be seen embracing as he takes his first step toward rehabilitating the shattered fortunes of his proud old family.

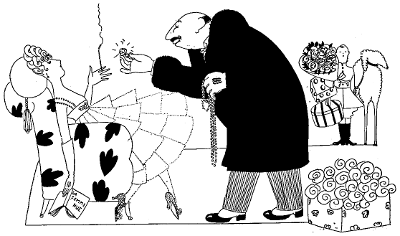

But there was, to Algy, something raffish about the stage. Once on his financial feet again, he realized that the smartest possible form of trade, for a chap with his tastes, is that of the creator of lovely frocks for lovely maidens. And—no sooner said than done! In less than two weeks Algy was known, far and wide, as the man who made Poiret take to French brandy. Algy’s little shop was a rendezvous for every fair lady with any pretensions to chic. But alas! he hopelessly offended his very best customer, Mlle. Nini Latouche, of the Opera. Nini had him black listed everywhere, with the result that the shutters were soon up at Algy’s.

[19]

It is something of a drop from the frills of fashion to the grease and grime of being a fashionable chauffeur; but needs must when the problem of high living drives. Having owned cars all his life, Algy naturally spoke the language perfectly and found no difficulty in landing a job with Abraham Ashurst, the Mattress King. Unfortunately, Algy became much less interested in the mechanism of his car than in the personality of its daily occupant—Miss Annabelle Ashurst who simply doted on ignitions, and everything connected with speed, including the chauffeur. Observing, from his classic portico, that Algy was more of a magneto than a man-servant, father Abraham banished him forthwith from his richly upholstered bosom.

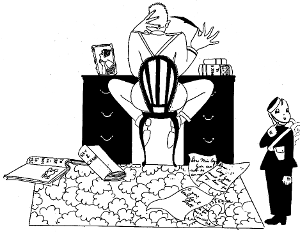

And now we see Algy in that darkest hour which comes before dawn—joyless and jobless, and yet still able to derive a certain bitter amusement from a new game of solitaire which he plays exclusively with unpaid bills. The idea is to work the things into two piles, in one of which the certificates of indebtedness shall equal the accounts receivable in the other. We may add that, in this pathetic pastime, Algy has just failed to go game for the thirty-seventh time.

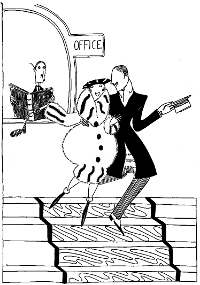

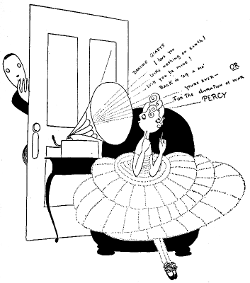

Hurrah for Algy! Like an inspiration came his last and best idea, to capitalize his nimble feet and become a dancing instructor. Below, you see him at the turning-point of his career, just as the maid is informing him that a fabulously rich Miss Detworthy has arrived for her first instruction. Note the enraptured expression of Miss D. (the lady with the circular marks on her gown). Note the appreciative glance of our hero. And so, at last, Algy is able to witness the triumph, in his unhappy life, of Romance, Laughter, and Love.

[20]

As the subsequent series of ringside flash-lights indicates, all the world’s fashionable fair ones have taken up the maidenly art of self-defense. Everybody’s doing it—both in London and New York. The Wilson family is a typical example. Dainty Millicent, shown at right, is prominently mentioned to win the Junior cup. No more breakfast in bed for Milly. Vanished, the boredom of banting. An eight o’clock round with the punching bag and the girl’s day has really begun.

On the right is Millicent’s mama, who, as the picture clearly shows, is rapidly rounding into championship form. Her sparring partner, kind-hearted old Harry Wilson, who is both outweighted and outranged, labors under the added disadvantage of being, in private life, the lady’s husband. The male half of the bout is plainly covering-up. One false blow,—a cross-counter to any one of his adversary’s chins, for example,—and Harry could be haled into the nearest court on a charge of mass murder.

Showing how the smartest dowagers of the sea lion class are waking up to the need of fighting their way into the bear-cat class. It’s only in play, of course, but it’s wicked play.

Below, we see little sister Grace, home from school for the holidays and, of course, mad about boxing, as all the rest of society is. The young parson, bless his pale pink soul, has inquired about the extra-curriculum activities of Grace’s schoolmates, not for a moment expecting that the answer to his innocent interest would be a blow in the Adam’s-apple. This, Grace explains, is the favorite blow of M. Carpentier. An intriguing phase of the tragedy is the delight of old Mrs. Brown, who sits in the right-hand, ring-side armchair, and who has secret designs on the parson—in the shape of her daughter, the adjacent young person who looks a little like a turban-ed turkey’s-egg.

[21]

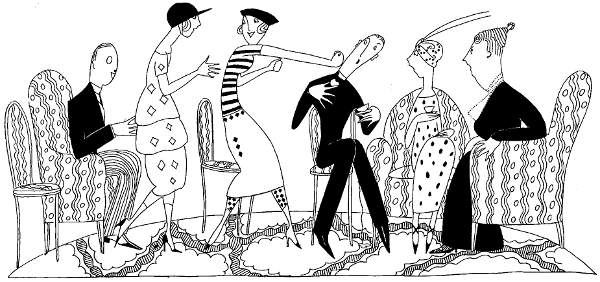

Just now boxing is all the rage in the great and wicked metropolis. Set-to’s happen in the best regulated sets. Nothing, for instance, could have kept the last Sutherby dinner-party awake, after ten, had it not been the perfectly arranged post-prandial entertainment provided by these thoughtful hosts. In spite of an abundance of wines, Lucullan dishes, triple extract of mocha, and an orchestra of twelve saxophones, the party was dying on its feet, until Madame S. escorted the guests to the ballroom where a ring greeted their eyes. From that point on, the weary guests came out of their slumbers, and gaiety reigned supreme.

[22]

The unexpected is always interesting but it is sometimes frightfully disturbing, as well. For instance, here is Miss Emily Rivington, who has gone to a dance and has just remarked, over her left shoulder, to her friend Lucille Taplow—“I ask you, my dear, have you ever seen anything more hideous than this room?” Of course, the poor child was entirely unaware of the fact that her hostess had pussyfooted her way into the room just in time to receive, point blank, the full force of little Emily’s remarks.

If Algy Appleton’s fiancée had shown him something easy to understand in the way of art—like an insurance calendar or the cover of a seed catalogue—he might have been able to murmur something intelligent, but when, in the presence of the sculptor, she led him up to a portrait of herself done in the most modern manner, the poor boy’s mental motor went absolutely dead.

[23]

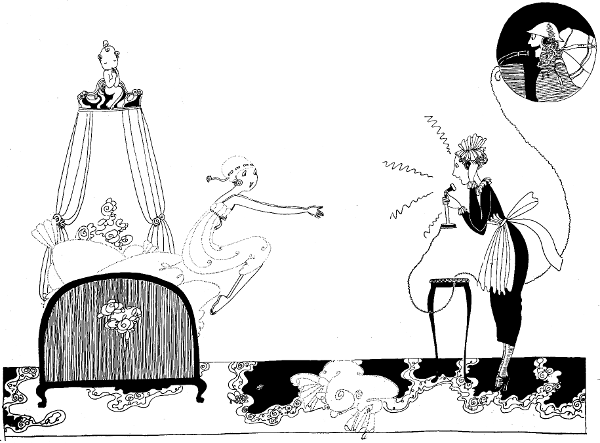

What is a modern ménage without its little affaire de coeur? Surely, those whose hearts still find room for romance will pity the plight of charming Mrs. Francklyn Sunderland who finds herself, as it were, between two fires, one of which warms the slippers of her home-loving husband, while the other crackles over the telephone in the burning words of Mrs. S.’s latest and very best beau. Mrs. S.’s situation is rapidly growing desperate. Query! What should she do?

Marian Holworthy’s right-hand dinner neighbor is the guest of honor and a tremendous genius of some sort, but, for the life of her, Marian cannot think what his specialty is. She has tried him on Art, Music, and Literature without eliciting more than a grunt and is wondering whether she ought to ask him, right out, whether he works for a living.

Poor penniless Dick Wadleigh is in a dreadful fix. He has promised that he will tender his heart and hand to Loretta Lorillard, the rich sister of his over-seas American chum. And now he is gazing upon the lady for the first time and finding that she is, socially and physically speaking, a dud. Just to make things pleasanter, brother Lorillard is hoarsely whispering: “Do it now, old boy, do it now.”

[24]

Having tried everything else at least once, our hero feels that it is only fair to see if there’s anything in matrimony, so he has set forth in quest of something really good in the way of a wife. He is here shown at the conclusion of his affair with Mirabel, a debutante with every qualification of the Perfect Helpmate. But just as everything was getting pleasantly arranged he discovered her secret vice—she is a slave to free verse. She pours out her soul in unfettered rhythms for a whole evening and, really, he never could have anything like that in the house.

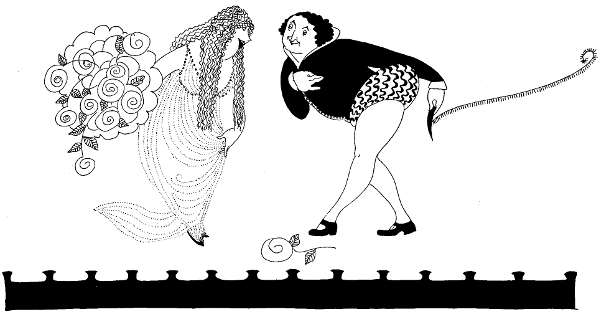

The next event in the series is Phyllis, who specializes in Early Victorian work—blushes, swoons, down-cast eyes, dropped handkerchiefs, and all the rest. Our hero was just about to fall a prey to her appealing femininity and beg her to name the bridesmaids. And then they chanced to drop in at an informal little sparring match, and he caught a glimpse of Phyllis’ inner nature (Phyllis is here pictured in action). Our hero is painfully realizing that this effectually shatters his dream of a sunny married life.

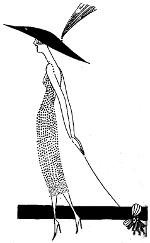

Reader, let us present Chloe, Exhibit C in our hero’s collection of possibilities. From the moment he met Chloe he was intrigued; he followed her about doggedly, always pining to see more of her. Alas, he got his wish when he invited her to the opera, and she appeared in her new Paris gown. Although he feels that, after seeing her in the dress, the ethical thing to do would be to marry her, he cannot help insisting on having a little illusion left—so he regretfully passes out of her life.

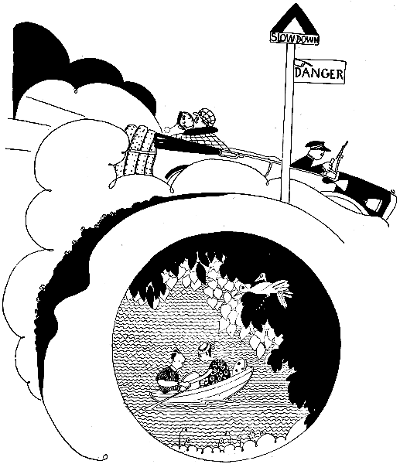

The next in the batting order is Daphne, who appeared, for a time, to be the Ultimate One. In fact, it was all practically settled until she invited our hero to accompany her on a little jaunt in her aeroplane. He felt that there were few lengths to which he wouldn’t go on the ground, but up in the air was unmistakably something else again; so he progressed easily to the next young siren on the list.

[25]

And then there was Peggy. Really, he couldn’t have found a more perfect helpmate than Peggy—civil to her parents, pleasant to have around a bridge table, fond of children and potted plants. Nothing could have been sweeter—until she took him out motoring. He is here registering a silent vow that if he ever gets home all in one piece, he will never permit himself to so much as gaze upon his adorable little Peggy again.

By turning your head just a trifle to the left, you will got a rather good idea of Dolores, the next to crash in our hero’s youthful affections. He was in a fair way to get all worked up over Dolores’ vamping specialties—until in a confidential moment she laid bare her strange, exotic, Ballet Russe sort of soul to him.... After that he knew that things between them twain could never be the same again.

And just below is the end of the whole affair; trying out a half-dozen of the most efficient sirens of his acquaintance, our hero finally marries Mary, who rates about minus 30 in looks, brains, and charm. No one has ever discovered why the veteran of countless affairs always eventually marries a complete physical and intellectual blank. As the proverb so aptly puts it, matrimony does make strange bedfellows.

[26]

Perhaps the sweetest time in a girl’s life is that roseate moment when she gets her first divorce. It is a time that comes but once to a girl. When at last her final decree arrives, she stands, in innocent wonder, on the threshold of a new life. What pretty, girlish dreams are hers as she goes out into the great world in search of a minister, so that she can start things all over again.

Only the shortage of white paper prevented the artist from prolonging the above idea indefinitely. It is the motif for a frieze entitled “Matrimony”—rather a quaint little conception, isn’t it? If you are at all married—or even if you are only an innocent bystander—you will get the idea without a struggle. As soon as divorce mercifully looses one set of shackles, a change of partners is rapidly effected, new bonds are formed—and there they are, right back at the very beginning again.

There is, unfortunately, a bad hitch in the process of obtaining a divorce. They haven’t perfected the method, as yet—it needs a lot of working over. This having to wait about for months or years is really too tiresome; it cuts in so on one’s time. Why, any really earnest worker, going on the schedule of a forty-four-hour week, could be married and divorced three or four times over in the time it now takes a lady to be legally free from only one husband.

[27]

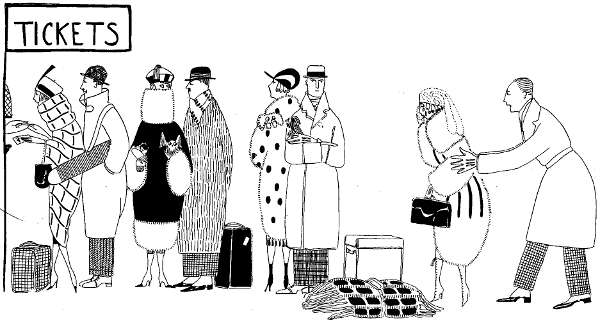

Any time that you want to see a bit of life, go to an American railway station and watch the outgoing trains to Nevada. Several ticket agents have to be constantly on duty in the window where both-way tickets to Reno are sold; one man couldn’t keep up with the rush of trade. A typical line at the ticket office is shown here—it is considered de rigueur for husbands to accompany their outgoing wives to the train. If you are contemplating a jaunt to the nation’s reconstruction center in the near future, it is a bit safer to book seats several weeks ahead.

It is so nice for the new bridegroom to meet his wife’s collection of former husbands. It is something for him to look forward to, all through the honeymoon. These little gatherings are so delightfully home like—it is reassuring to feel that you are all members of the same club.

This little scene is the sort of thing that divorce leads to,—hope springs eternal, and all that. A divorce simply gets one into the right frame of mind for a fresh start in matrimony. After all, Nature will have its own way; there’s nothing like love—it is the passion to which the best divorce lawyers attribute their success.

[28]

Bores may be met with at all times of the day, but none bores so blightingly as he who bores at breakfast. Who more completely spoils a déjeuner than the hideous male shown above who absolutely refuses to pick up his cues in the sweet little matutinal dialogue?

Mrs. Ormsby-Jones, at right, represents that class of almost unbearable bores whose social slogan is “Never take no for an answer,” a group otherwise known as the “Come-Monday-Tuesday-Wednesday-Class.” The Newly-Wed Pangborns, at the other end of the wire, have already fought off three different dinner suggestions from Mrs. O.-J. and can only think of death from apoplexy as an avenue of escape. But is Mrs. O.-J. down-hearted? Never! “Well, then, how about Thursday?” she asks sweetly.

In ancient times, Spartans used to expose their infants on the mountains to test their toughness. The people at Mrs. Willoughby’s tea are wishing that this test had been tried on little Gladys, who has been exhibited by her enthusiastic mother and made to recite La Fontaine’s “Maître Corbeau” in the original Ollendorf. Major Radcliffe, who possesses only military French, is seriously considering going over the top—with Gladys as his objective.

[29]

A bore of tremendous calibre is the plutocratic person who enjoys what psychologists call “acute caste-consciousness.” Take Mrs. Eric Appledorn, for instance, who is the lady shown above with a map of the Amazon River appliquéd on her façade. Can’t you imagine how it bores Dorothy Dobbee, whose nearest approach to car-ownership is a pair of yellow goggles, to be told of the six Rolls-Royces which Mrs. Appledorn has bought for her children?

If I were little Ouija, I should certainly tip the table over on that insufferable blighter who, at every meal, demands a special menu of gluten bread, goldfish wafers, and prunes. “Nothing acid!” he cried; “Nothing starchy! Nothing albuminous! No sugar! Have you saccharine?” Geska, the maid, has no idea what saccharine is, but she is willing to try ground glass on this creature—at a venture.

To end a day of perfect boredom, it is only necessary to go to the theatre with a person who has seen the play before and tells the plot to all those within earshot. At the big moment, pictured at the right, he has just crashed into the silence by assuring the Wilberforce girls that Vera, the heroine, isn’t really killed at all. “Just wait until the next act,” he says cheeringly, “she shoots him then.”

[30]

If you are at all interested in tracing the love interest back to its very beginnings, all you have to do is to visit the nearest park, any bright Spring morning. Little scenes like this are going on all over the place; any member of the younger set, between the ages of two and five, can give you all the information you may require on just how wonderful nature really is. There is only one difference between love and any other contagious disease: once you have had the other disease, you are immune from a second attack.

When first love takes the form of hero worship, there is practically nothing that can be done about it. The case illustrated below is almost at the last stage, as is shown by the patient’s complete loss of appetite. The object of her maiden dreams is her mother’s guest, a returned big-game hunter—one of those bronze-skinned, clean-limbed outdoor men. Really, these people with clean limbs and chiseled features ought not to be at large; they get a young girl’s innocent inhibitions and major complexes all tangled up.

Don’t dwell too long on the picture above, gentle reader; if you have any heart at all, you will just break down and have a good hard cry. This is one of the bitterest phases of first love—the case of the adolescent moth and the professional flame. The youth is at that tender age where he classes all women under thirty-five as crude, and all unmarried women as uninteresting. The lady in the case is just about old enough to be a nice, understanding great-aunt. She is graciously allowing the youth to pour out his heart to her in a series of home-made sonnets,—after all, his little stunt helps to pass away the time until her next dance.

[31]

The great romantic tragedies are no more tragic than an affair like this; for sheer bitterness, the epic of little Gladys and her adored Unknown makes “Romeo and Juliet” look like a bedroom farce. While walking in the park with her nurse, little Gladys, up to that moment but a headless slip of a girl, comes face to face with her fate—her Soul-Mate, her Ineffable One, her Man. It is love at first sight; but the anguished lovers are torn asunder almost immediately. The cruel nurse drags the stricken heroine home to her nap, while the Unknown’s father insists that he must deport himself like a little Man.

And now we must witness the futile yearnings of the youth who has fallen in love with the most popular débutante of the season. He is virtually in a state of shell-shock. The thing has hit him so hard that all power of speech has completely left him. It is seldom that love affects anyone this way, in later life. You just take these little things as all in the day’s work, after you’ve had a few years’ experience with them.

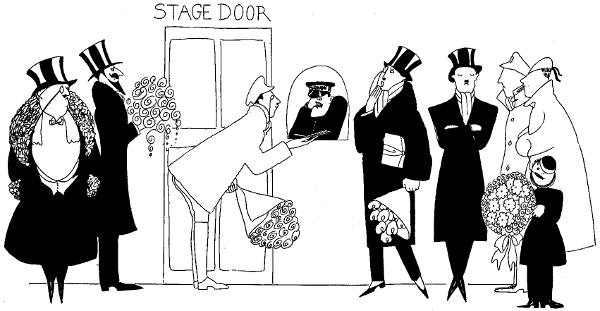

Here is an experience that comes but eight or ten times to a young girl—her worship of the dramatic hero. There are few purer forms of love than these idylls, and few more lucrative emotions—from the box-office standpoint. The youthful worshippers, chastely chaperoned by a vestal, attend every matinée, to bask in the glances of their idol. All their childish pennies are scraped together to buy the front row seats. It’s just the old, old story—it’s the woman that pays, and pays, and pays.

[32]

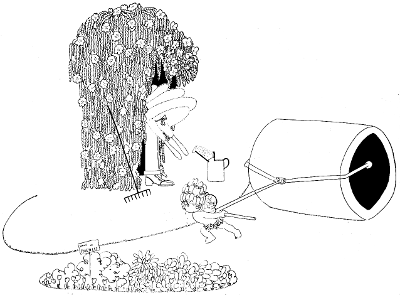

Gardening is always an extremely popular sport,—some people do so love to get close to nature. Of course, there are many who won’t have anything to do with this sport; they remember that all the trouble in the world started in a garden. It is not at all difficult to become a highly accomplished gardener. All it requires is a study of that invaluable text-book “How to Know What Makes the Wild Flowers Wild.”

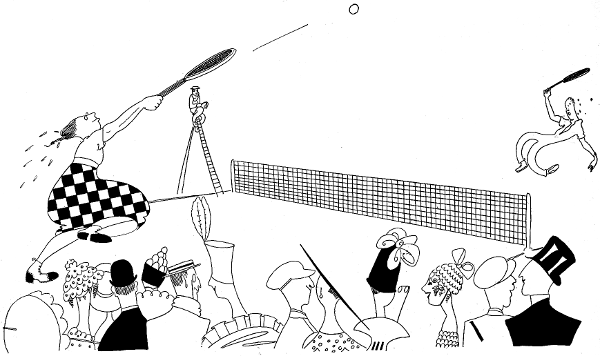

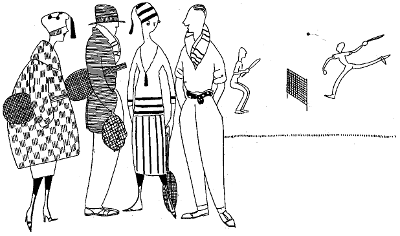

Lawn tennis is one of those sports that are very popular among the onlookers. Ladies who can’t tell a tennis racket from any other noise, and gentlemen who never have been able to understand why the players stand on different sides of the net, are most enthusiastic tennis spectators, never missing any of the big matches. Oh, well, history has proved that there always has been a certain deadly fascination in watching one’s fellow creatures suffer needlessly.

[33]

Golf, that greatest of all reasons why men leave home, has become a delightful indoor sport. All butlers count as hazards, and footmen may not be removed from the course. Mr. Reginald Vere de Vere, one of our best known after-dinner golfers, is here portrayed demonstrating that fine shot he nearly made on the eleventh hole.

Are you one of those who have always believed that a punt is the lowest form of wit? If you are, you must change your views, for punting is bound to happen at all the smartest wet places. All our dowagers and dancing men are delighted with the sport. It’s so pleasant to fish from a punt,—some people do so love to angle for anything that seems to be in the social swim.

The clergy is going in for croquet more strenuously than ever before. It is indeed splendid exercise; there is no better way of developing the vocabulary. The reverend gentleman on the right really should not hit his adversary over the head with his mallet. He should know that whoever hits his opponent with a mallet loses his next turn. The correct thing to do is to hit him with one of the stakes.

[34]

Four members of the feline, velvet-pawed, low-springing, meat-eating, Cat family, shown in the act of trepanning little Angela, the sweet, blonde, yielding, and wholly worshipful being who is seated on the sofa before you. There is not one single nasty thing that the felines have forgotten to say about Angela, a girl who never did a wrong thing—except that she allowed Destiny to make her attractive to married men.

Here we see the ideal mother, the chatelaine type, a type upon which so many poets, novelists, and music hall singers have dilated. The future of the race is hers. It is a trifle hard to tell—whether she is a futurist sofa pillow or a marble parquet floor. This type of lady is always irresistible to the clergy, especially when they are of the Protestant persuasion. As will be observed, upon a closer scrutiny of the lady and her biological factor—the union has been fruitful.

Always devoted to calla lilies, rhythmic (or self-expression) dancing, and loose-fitting Greek robes. She usually displays an abnormal interest in what’s what on the buffet. Leave this type of girl alone with a tableful of truffles, pâtés, mushrooms, macaroons, queen olives, peaches, and chocolate éclairs, and the place, after a bit, will look like Bapaume, after the German evacuation.

[35]

Cupid just leads her around from one dark corner to another and from one brave man to another. She lives exclusively upon little pencilled notes, chocolate bon bons, pressed violets, Percy Shelley, moonlight, and the strains of the guitar. Dangerous to a man in his first season. Equally dangerous to a man in the bald-headed fifties, but particularly dangerous to a man who is tottering on the brink of the grave.

You know the kind. She simply won’t let you alone. Picking on you, all day long. She starts right in on you at breakfast, along with the coffee and the toast. She always gets up early and comes down all dressed and ready for a good day’s nagging. There is no known form of temperament so horrible, so poisonous, so soul-blighting—and so certain to marry. Oh, wives and mothers, what a lesson this picture should be to you.

A frequent and highly commendable type of womanhood. She always knows exactly what she wants—which is usually something under the classification of Jewels. Furthermore, she knows how to get it, and she knows where to go for it. In short, she is a ferret.

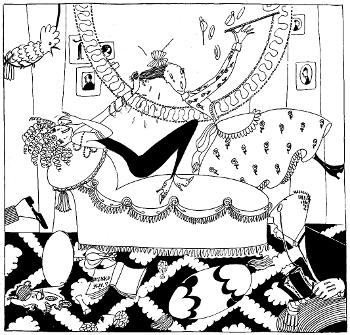

Last, but most frequently met with of all, we behold the artistic temperament. By that we mean the lady who feels things so keenly, suffers so acutely, and kicks so ferociously, that we know instinctively, on observing her, that she is passionately devoted to ART. Have you noticed that they always wear clinging robes and are very rude to their maids?

[36]

The self effacing hostess is a very popular brand. If it weren’t for her week-end parties, society never could catch up with its correspondence. She isn’t in the least entertaining—and she mercifully doesn’t try to be. She thoughtfully effaces herself, and leaves you in your room after supplying each guest with crested paper, assorted pens, and unused stamps. Spending a week-end at her house is much the same thing as spending it in the writing room of the Ritz.

The absent-minded hostess has ruined many a promising young week-end by her unfortunate affliction. She can never quite remember just what people she has asked for the week-end and she will go and ask a bishop, at the last moment. Of course, bishops are a splendid institution and you really couldn’t want anything nicer around a cathedral, but, at a week-end party, when all the tired guests are having their relaxation, a bishop is about as welcome as an outbreak of beri-beri.

The hostess who is so musical is one of those blessings that we could all get along without. She is always exploring among the fauna of Bohemia and capturing some particularly wild specimen. Her guests spend the week-end, like Daniel, in a lion’s den. There is no let-up to the atrocities. The guests sit in horror, thinking of the things they might be doing in the city, while a hairy conscientious objector does unmentionable things to a piano.

[37]

The well-meaning hostess is one of the lowest forms. She insists upon everybody’s getting together and having a jolly time. She can’t call it a week-end till each of her guests has committed at least one parlor trick. She is here portrayed in her favorite pursuit of dragging an inoffensive guest to the piano, insisting that she just knows he sings. People spend exactly one week-end at her place; after that, “Very important business keeps me away. So sorry.”

The perfect, or disappearing, hostess is rare. She always invites the One Person you want to spend the week-end with, and then lets nature take its course. She has a perfectly bearable house surrounded by really wonderful grounds. This hostess appears occasionally at dinner, but at all other times she vanishes completely, leaving things to the careful supervision of the faithful family gardener, who has probably seen more biological history in the making than any man in the county.

The gilded hostess has one of those rustic cottages, where her guests rough it over Sunday surrounded by vintage champagne, Swiss butlers, liveried footmen. The sketch—from life—shows a guest’s retreat to the city, after a week-end’s bridge; note how effectively the footmen decorate the sketch with palms.

[38]

In the good old ante-bellum days, scenes like this were every-day occurrences in the life of Mr. J. Wallingford Smith,—inventor and sole owner of Smith’s Slenderizing Stays—They Lace on the Side. Mr. Smith simply could not call it a day unless at least five male menials were involved in the process of getting him dressed. All his puttings on and takings off were personally attended to by these motherly creatures. And then, just as everything was going nicely, the world had to get mixed up in that dreadful war, so that poor Mr. Smith now has to adjust his jewelry without a corps of specially trained liveried attendants.

Portrait impression—from memory—of Mr. and Mrs. J. Wallingford Smith, motoring in their third-best Rolls-Royce, just about two weeks before the Kaiser turned on the war. Note the attendant chauffeur and footman—Mr. and Mrs. Smith wouldn’t dream of going out without two men on the box. But things aren’t what they used to be. The chauffeur and footman now own their own motors—after two years in the provision business.

This scene, almost too terrible to look upon, is absolutely true—it’s not one of those faked war pictures at all. It reveals the hideous, dreadful privations, that the war brought upon some of us. It shows the bitter anguish of the J. Wallingford Smiths as they watched a battalion of their footmen, chauffeurs, butlers, valets gardeners, coachmen, grooms, house detectives, and resident photographers departing for the Saar Valley. How silent and lonely the house has seemed, the past year, without these brave youths!

[39]

Conscription was the mother of invention—Mrs. Smith recently conceived the brilliant idea of engaging a mere stripling to understudy for the footman who was removed by the war. Someone simply has to carry the family ermines around—you can’t expect a lone lady to do it all by herself. The accompanying picture graphically portrays the new footman in action—playing the part of a movable human coat-room.

And now, even Mrs. Smith’s maid has gone and done it—she decided to remain permanently in the Woman’s Motor Corps. The uniform is so much more becoming than those trying maid’s costumes. She is pictured with her latest and very best Young Man.

Fate seems to be against the unhappy Smiths—it’s not even on speaking terms with them. Even that good idea of Mrs. Smith’s about engaging a child footman didn’t work out. The boy wonder was really too immature—he couldn’t overhear even the simplest stories without blushing—so Mrs. Smith had to resort to a maid to accompany her around the city. But, judging from her expression, she is a trifle dismayed by the number and ardor of Mrs. Smith’s casual acquaintances.

[40]

Advice to the Lovelorn

What Every Girl Should

Know, Before Choosing

a Husband

Advice to the Lovelorn

What Every Girl Should

Know, Before Choosing

a Husband

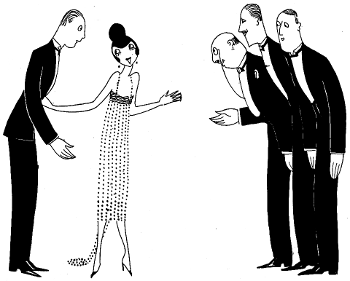

The love interest really must come into the life of every young girl. There’s no use talking, she simply can’t get along without it. Her mother may weep, and her father may become dramatic about it, but a girl should remember in choosing a husband, that it’s the first step that counts in matrimony. After a girl has once been married, a second, third or even a fourth husband are simple matters. It’s the first one that’s tricky. Getting a husband is rather like getting the olives out of a bottle—after you get the first one, the rest come easily.

Every girl is likely to be dazzled by the radiance of the Social Light. He shines in ball-rooms, and in the frontline trenches of tea-fights; he fox-trots with passionate abandon, he is the life and soul of every dinner party, but, around the house he is, unfortunately, something else again. The trouble with these Social Lights is that they simply can’t live without a group of admiring females about them.

There is a time in every girl’s life—usually around Spring—when she falls in love with the Professional Poet. He wears his hair in the manner made popular by Irene Castle, and he believes in free speech, and free verse, and free love, and free everything. His favorite game is reading from his own works—such selections as his “Lines to an Un-moral Tulip.” This type of poet does not go in very strongly for marriage—it cramps his style—with the other ladies.

[41]

Then there is the Futurist Artist. He is really a great factor in a girl’s education: he can show her how, at a glance, to tell the difference between a Matisse painting and a Spanish omelette, and he knows just what the vorticists are trying to prove. He dresses like the property artist in musical comedies and he is simply ripping at designing costumes—he tells you how Lucile is battling to engage him if he would only descend to commercialism. Avoid them, girls, avoid them! They always have a past!

There is unquestionably much to be said on the side of the Munitions Millionaire, as a husband. The course of true love certainly does run much more smoothly if it’s travelled in a Rolls-Royce. Such trifles as diamond tiaras, Russian sables, chintz-lined limousines, and ropes of pearls help Love’s young dream along considerably. The only trouble with a Munitions Millionaire is that his neck is a little too much inclined to bulge over the back of his collar.

But, after all, there’s no use in advising a girl what to do and what not to do, in choosing a husband. The safest way is just to let Nature take its course. She needn’t worry about the thing at all,—she is sure to know the Leading Man, the moment he makes his entrance. He doesn’t even have to be near her—if she just knows he’s back from patrol duty in a distant land, and on the telephone, the cosmic urge will make her break all existing running broad jump records, in order to get to the telephone.

[42]

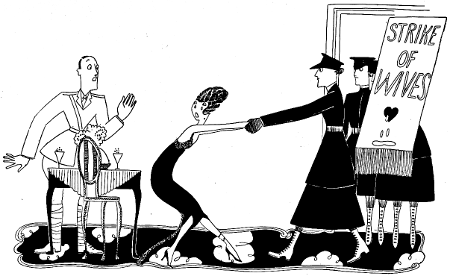

It’s getting so that the members of the widely advertised working classes get up in the morning, look out of the window, and say, “This looks like a nice, warm day—let’s strike for something.” This little habit of going on strike is like the cosmic urge, or the wanderlust, or the young man’s fancy, or any of those things; it gets under way at any time of year, and there’s simply no stopping it. Here is a harrowing scene, one of the fearful tragedies incident to the strike of the nursemaids. The nurse, just called out by her union, is returning her charges to mother, a lady with whom they have but the merest bowing acquaintance, thus utterly spoiling the lady’s afternoon.

It’s only a question of time before the down-trodden husbands form a union and strike for freedom. They have come to realize that bitter truth of married life—it’s always the man who pays, and pays, and pays. Street-cleaners, ship-builders, riveters, gasfitters, and all other laborers claim the right to a forty-four hour week and every evening and Sunday off, with no questions asked—why not husbands? Here is one of the agitators of the Industrial Husbands of the World, shown in the act of uprising.

Even the hairdressers are getting into the spirit of the times, and pledging themselves to strike while the curling-iron is hot. They have found that there is really very little in this silly idea of a life on a Marcel wave. Observe this terrible catastrophe—the striker is throwing down his badge of labor and going out, leaving his unfortunate client with half her hair as art intended it to be, and half of it in the unfinished state in which nature left it.

[43]

A strike of wives may be called at any time; many wives have been threatening to walk out for months. The thing is likely to prove rather embarrassing. Here, for instance, is the case of a member of the wives’ union, whose husband has just returned from five years’ service in the East. In the midst of her enthusiastic welcome, she has been called out by three quite unfeeling delegates of her union.

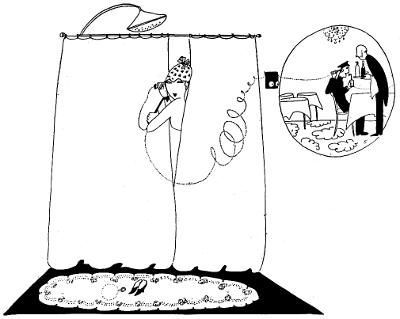

The maids are at last coming around to the modern way of thinking—that in unions there is strength. Here is an intimate glimpse of what will happen if they ever start striking. The maid is obeying the first law of all agitators,—-be sure to strike at the most inconvenient time. She is leaving her employer, so to speak, sunk—just on the point of throwing up the sponge and going down for the third and last time.

There are many terrible things in this world, as someone has so cleverly said, but the worst of all would be a strike of footmen. Why, all social life would be completely paralyzed by it. Just see what a cruel thing it would be. The footmen in this case are striking for shorter hours, higher wages, and looser liveries; they have walked out in the middle of the caviarre, leaving the guests face to face with starvation—and, what is worse, face to face with each other.

[44]

Having your portrait painted, in the good old days, used to be a comparatively simple matter. It was as much a part of a woman’s social duties as going to the opera, or having her hair marcelled. All you needed was a black evening gown, a lap-dog, a cheque for $10,000, and an appointment at the studio of Mr. John Sargent.

It used to be considered awfully radical and just the least bit Bohemian, to have your portrait done by a bearded foreigner like Monsieur Chartran,—local talent was simply nowhere. It was always obligatory, while posing for the portrait, to bring along a trained aunt, to keep off draughts and gentlemen callers. When the canvas was done, you could almost always tell, in six guesses, who the portrait was intended to be.

[45]

But having one’s portrait merely painted isn’t being done any more. The thing to do now is to lease a sculptor, and have him do a simple little portrait in marble, and call it “Mrs. ...—a Mood.” Prospective sitters for modernist busts should remember never to show surprise at the finished product. Never behave like the lady in the sketch; remember that only novices faint on seeing the completed masterpiece. The thing to do is to clasp the hands, gaze yearningly at the ceiling and murmur in passionate undertones, “It is wonderful—but wonderful! The feeling, the soul, the ego—how could you know?”

If you want to go that far, you can have your portrait done by one of the cubist sculptors, who are causing such a furor—among themselves. Just ask the first sculptor you meet at dinner if he won’t do a bust of you; he is sure to be a cubist. He will only be too glad to oblige with a charming trifle, looking rather like an egg after a hard Easter, and to name it “Arrangement: Mrs. B.”

But the sculpture of the young Roumanian refugee artiste, now so plentifully in our midst, is the very farthest one can get in modern portraiture. The gifted sculptress specializes in soul portraits. Naturally, every woman loves to have a little statue of her soul, somewhere around the house. The completed statue, always in the nude, bears the title “My Soul, in Passing: Nocturne.”

In case you haven’t decided just which school you want to employ in creating your portrait, here is a cross-section of our artistic Bohemia. It is a most representative group of sculptors at their recent notable dinner. The noble spirit, at the extreme right is Henri Pryzmytioff, the Post-Futurist Sculptor delivering a long and most impassioned talk on “The Sculpture of Day After To-morrow—and Why.”

[46]

Everyone has a pet superstition, and pretty Madeleine Templeton’s is that if a girl sleeps on her love-letters she is sure to dream of him who is to be her true, true love. Unfortunately, Madeleine has so many tender missives from so many true loves that she is positively uncomfortable and can not sleep at all. She has tried counting her fingers, counting her sheep and counting her admirers, but all is in vain. She is now desperately wondering if she ought to try the modern society method of marrying her true loves, one by one, until the right husband finally turns up.

Helen de Peyster’s favorite fear complex is the fatal number Thirteen! And yet, what is she to do when, having rejected a dozen proposals, along comes handsome Harry Radcliffe, with wealth, position and a personality that causes her heart to miss like a faulty motor. And now the Fates have spoken, indicating plainly that hearts are trumps and that she should undoubtedly follow her partner’s lead. “Am I doomed?” asks Helen, “Simply because Harry is the thirteenth man to propose to me? That’s what I want to know—am I doomed?”

Because Clarice Vanderhoff almost fainted when her fiancé, Teddy Ashhurst, spilled the salt, Ted naturally placated the Unknown Gods by throwing a handful of the offending seasoning over his left shoulder with his right hand. This is undoubtedly very pleasing to the Fates and Goddesses of Chance, but hardly as agreeable to the charming Mrs. Drexel-Drexel who, quite naturally, objects to being salted, like an almond—particularly in public.

It is an established fact, in the mind of Annabelle Armitage, who is shown on our left, that she will wed the first man who meets her gaze on St. Valentine’s morn. She has not yet looked down, nor has Tony Galati, who does the Armitage roses, looked up, but Fate is plainly staging another of those elopements in high society with a stirring last act in which the pleasant news is broken to the present Signora Galati, in Calabria, and the seven little Galatis.

[47]

It is certainly hard on a hostess to have her dinner party spoiled by a social contretemps, yet that is what happened at Mrs. Aspinwall’s when her imported and important authoress, Patience Bitgood, fainted dead away in mid-sweetbread, at the sight of crossed knives beside her plate. This is one of the worst omens of a relentless Nemesis, and foretells a solid year of hard luck.

The new moon is a lovely sight, but, of course, it is absolutely fatal to look at it through glass, a fact well known by Eric Appledorn, who, we may say, is not as simple as he looks. “Come into the garden, Maud,” he murmurs, “and let us go out through the dining room so that we may be sure to gaze on Luna over your lovely right shoulder!” Something in Maud’s eyes tells us that she will follow the red line of romance to its usual and pleasant destination.

[48]

Musical comedy audiences are always notable for the rapt attention they pay to the evening’s entertainment. The male students of the drama, in particular, seem to be ever on the lookout for good lines—especially those of the ladies of the chorus. Above is shown a loge-ful at that standing-room-only success, “The Girl on the Nightboat.”

This is a scene from that realm of outer darkness—the moving picture theatre. The audiences are the thing that make moving pictures move. Observe how intent they are upon the thrilling scenes reeling out before their very eyes. The stirring picture now on the screen shows the inhabitants of Nova Scotia tinning salmon. Only two people—in the back row—fail to register interest in the scenes before them,—those two are, nevertheless, true devotees of the cinema theatres.

You can always tell, by looking at the audience, just who is holding the center of the stage. When the masculine half of the audience occupies itself in reading the corset advertisements in the programmes or in looking restlessly about while the feminine half strains to catch every word—then you can be sure that the marcelled hero, in the jet-buttoned evening clothes, with the velvet collar, is standing in the spotlight and singing, or talking, rhapsodically about the age-old passion of LOVE.

[49]

The war was really responsible for a great many unfortunate occurrences, as so many observant people have already pointed out. Here, for instance, is the case of two returned Lieutenants who, in their year’s stay in Germany, have managed to pick up a good working knowledge of the French language. By way of celebrating their home-coming, they have been invited to see the latest imported French farce—and find that they can understand every word of it. In the future, they will only patronize domestic products.

This is one of those delightful little occasions where the children are given their annual holiday treat. All their existing ancestors, in a body, take them to the Hippodrome. For weeks before the eventful evening, their parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles go about suffering intensely saying what a fearful bore it is going to be and how they dread it, but they really must go through with it—it means so much to the kiddies. Here is the party, shown in action,—observe the deadly boredom of the grown people and the hysterical hilarity of the little guests of honor.

As we explained just a few minutes ago, a glance at the audience will show you what’s going on, on the stage. When the ladies are reading the notes in the programme, or in studying the components of the complexion of the woman in the stage box, while the attention of the gentlemen is riveted on the stage—then you know that the chorus girls have undulated on.

[50]

Of course, you were thrilled when they—your week-end guests—accepted your invitation; and you were tremendously glad to see them when they arrived; and you enjoyed every minute of their stay,—but, oh, Lady, Lady,—wasn’t the most exquisite moment of all that when you and your consort waved a fond farewell to them and the back axle of their Rolls-Royce? Week-ends are wonderful, but, wasn’t Tennyson clever when he said that parting is such sweet sorrow!

The chief horror of every week-end is the lady guest who comes without a maid, borrows the hostess’s, monopolizes her wholly and leaves the hostess marooned in her boudoir, unnerved, unnoticed, and unhooked. This migratory blight always wears a gown out of which she can only escape with the aid of Harry Houdini. In the meantime, below stairs, the pommes-soufflés have collapsed and—which is a great deal more important—the cook is getting ready to do likewise.

There is something about family relationships that always wrecks the entente-cordiale which should exist between guest and host. For instance, there is your wife’s brother, who, warmed by heavy inroads on your vintage Scotch, invariably tells you how little he thought of you when he first met you, and how broken up his family were over the wedding. Only the sacred rites of hospitality stand between this repulsive and misguided being and the honors of a sudden death.

[51]

The statement that “old friends are best” was never made by a lady who has endured the highwayman methods adopted by her old school-chum, or knew-you-as-a-child type of visitor. Reverting to habits, this little house-breaker rifles her hostess’s bureau and chiffonier with the avowed intention of wearing each garment which the hostess has not had the foresight to put on.

In this picture, we have a fiendish friend who, after boring you all day with his silence and devastating dullness, suddenly wakes up, about 11.30 P.M., and begins to tell you about his salmon-fishing trip. After the details of what his camp outfit consisted of, we see him, as the clock strikes two, beginning to play his second salmon, and still going fairly strong.

Have you ever lived, for a dozen odd years, next to some utterly impossible neighbors whom you have carefully snubbed, avoided and ignored only to have a well-meaning idiot, who happens to be your guest over Sunday, lead them joyously into your home with an air of triumphant discovery, as if he had done you the greatest sort of favour.

[52]

There are only six kinds of wives. They are all shown on these two pages, but only one of them can be—on a crossed heart—warmly recommended. Fortunately marriage—which is at best but a primitive substitute for friendship—is becoming less and less fashionable, so that every year fewer of our young society leaders are sacrificed on the wedding pyre. This is especially true among clever people. And now, reader, here is our first exhibit in wives, a very terrible kind, to be sure. She is known as the DEVOTED wife. She loves—and watches out for—her husband, especially in the early morning hours. Note the restraint exercised by our artist in refusing to introduce a cuckoo clock, a device usually inevitable in pictures of this kind.

Here we see a living embodiment of Model No. 2—the BIJOU DOLL. She is often a blonde, but always a deceiver. Despite persistent complaints—by husbands—against wives of this model, the demand for them continues to be brisk. She always has a serious grievance against Fate! Why is it that her husband is so groundlessly jealous? Is it her fault if his men friends pester her and bother the life out of her? Was it her plan to share a chair with Mr. Reginald Stuart? And how absurd her husband is to carry on in that ridiculous way, just because, being tired, she had to sit somewhere, and, as there was nothing else to sit on, the thought suddenly flashed on her: Why not sit on Mr. Stuart?