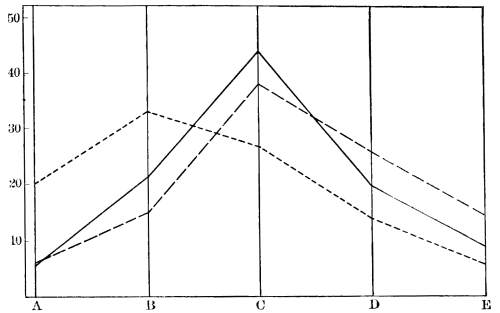

The full-drawn lines are proportional in length to the number of units offered in academic subjects; the dotted lines, to technical subjects

Title: Introduction to the scientific study of education

Author: Charles Hubbard Judd

Release date: April 2, 2018 [eBook #56903]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MWS, Adrian Mastronardi, Les Galloway and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

BY

CHARLES HUBBARD JUDD

PROFESSOR OF EDUCATION AND DIRECTOR OF THE SCHOOL

OF EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

GINN AND COMPANY

BOSTON · NEW YORK · CHICAGO · LONDON

ATLANTA · DALLAS · COLUMBUS · SAN FRANCISCO

COPYRIGHT, 1918, BY CHARLES HUBBARD JUDD

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

219.9

The Athenæum Press

GINN AND COMPANY · PROPRIETORS ·

BOSTON · U.S.A.

iii

This book is the result of eight years of experimentation. In 1909 the Department of Education of The University of Chicago abandoned the practice of requiring courses in the History of Education and Psychology as introductory courses for students preparing to become teachers. For these courses it substituted one in Introduction to Education and one in Methods of Teaching. This move was due to the conviction that students need to be introduced to the problems of the school in a direct, concrete way, and that the first courses should constantly keep in mind the lack of perspective which characterizes the teacher-in-training.

In the years that have elapsed since 1909 the conviction has gained almost universal acceptance in normal schools and colleges of education that the History of Education is not a suitable introductory course. Psychology has grown in the direction of a scientific discussion of methodology, and the demand for a general introductory discussion of educational problems from a scientific point of view has often been expressed by teachers in normal schools and colleges. In this period the writer has had frequent opportunity to try out various methods of presenting such an introductory course. The results of this experience are presented in this volume, which is designed as a textbook for students in normal schools and colleges in the first stages of their professional study.

iv

The teacher who uses this book can expand the course to double the length here outlined by introducing schoolroom observation and supplementary reading. The questions and references offered at the end of each chapter and the references in the footnotes are intended to facilitate such further work. A set of questions is given in the Appendix as a guide to classroom observation.

The obligations which the author has incurred in the preparation of the book are numerous. Almost every member of the Department of Education of The University of Chicago has at some time or other given the course to a division of students, and all have contributed suggestions and criticisms with regard to the organization of material. Special obligations should be noted in this connection to Professors J. F. Bobbitt, S. C. Parker, F. N. Freeman, H. O. Rugg, and W. S. Gray. To Professor E. H. Cameron the author is under obligation for suggestions made after reading the manuscript. To the authors and publishers whose works have been drawn upon for extensive and numerous quotations, special thanks are due for courteous permission to use their material. Finally, it is to the students who have from year to year passed through this course that the largest obligation should be acknowledged because of the suggestions which their reactions have given to the writer.

C. H. J.

Chicago, Illinois

v

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. EXTENDING THE PUPIL’S VIEW OF THE SCHOOL | 1 |

| The pupil’s view limited. Conservatism in the community as a natural consequence. Demand for a broad scientific study. Beginnings of the science of education. Effectiveness of studies of retardation. A study of high-school courses. An experimental analysis of a fundamental subject. A study of the relation of education to general social life. The scientific study of educational problems. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER II. SCHOOLS OF OTHER COUNTRIES AND OF OTHER TIMES | 14 |

| The comparative and historical methods. The American textbook method of teaching. Independence of thought based on reading. European schools caste schools, American schools truly public. Influence of European schools on the educational system of this country. Report of the visiting committee of Taunton in 1801. Adoption of the German model. Results of the adoption of the German example. The reorganization of American schools. Origin of the high school. Education of girls. Higher education free. American public schools secular. The school system and its domination of the teacher. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER III. EDUCATION AS A PUBLIC NECESSITY | 32 |

| The primitive attitude one of neglect. Compulsory education. Compulsion of communities. Later stages of compulsory legislation. American education to 1850. Compulsory attendance. Obstacles to enforcement of compulsory attendance. Newer legislation recognizing complexity of problems of attendance. Supervision a necessary corollary to compulsion. Higher education and public control. Public control adequate only when directed by science. Fiscal problem typical. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER IV. INVESTING PUBLIC MONEY IN A NEW GENERATION | 46 |

| The cost of educating an individual. Total school expenditures in the United States. Cost a determining consideration in school organization. viRelation of school expenditures to other public expenses. Urgent demands for economy and efficiency. Expenditures in relation to wealth. Costs of different levels of education. Costs of different subjects of instruction. Costs of classes of different sizes. Salaries. Books and supplies. The meaning of financial organization and educational accounting. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER V. DELEGATING RESPONSIBILITY FOR CARRYING ON SCHOOLS | 63 |

| Class instruction given over to the teacher. Supervision. Sketch of development of a school system. The community slow to delegate school control. Limits of authority and responsibility not clear. Statement by a public educating association. What is a representative board of education? The functions of a board of education. How a good board gets the work done. Making the machine work smoothly. Report of committee of superintendents. Obsolete administration system. Status of superintendency varies. District control discarded system of school administration. An effective substitute to be discovered. Dangers of this period of adjustment. Organization under scientific principles. Control of school work through tests. A study of the building needs of a city. The errors of democracy. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER VI. THE SCHOOL BUILDING | 78 |

| The building as an evidence of a community’s educational views. Contrasts in plans of rural schools. Contrasts in urban elementary schools. A high-school building of the early type. The hygiene of lighting. The hygiene of ventilation and heating. Hygienic equipment. Relation of equipment to the course of study. Modern school construction and costs. The Gary plan for distributing pupils and enlarging the scope of school work. Requirements to be met when the Gary plan is adopted. The construction of consolidated schools. Comparative statistics. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER VII. GROUPING PUPILS IN CLASSES | 96 |

| Transition to problems of internal organization. Economy a first motive for grouping. Social influence an important motive. Grouping in the one-room school. Courses of instruction in relation to the problem of grouping. New problems of grouping in large schools. Fundamentally different views on the curriculum. The ungraded class in graded schools. Cases where failures show the urgency of the grading problem. Efforts to adjust instruction to pupils. Readjustments of the curriculum. Problems of grouping in high school. Illegitimate reasons for promoting pupils. Experiments and studies which aim to supply both individual instruction and class instruction. Arrangement of the materials of instruction. Exercises and readings. vii | |

| CHAPTER VIII. THE TRADITIONAL CURRICULUM AND ITS REORGANIZATION | 113 |

| Importance of a study of the curriculum. The specialized curriculum of higher schools. Problems of generalizing a specialized curriculum. Traditional character of mathematics courses in high schools. Suggestions of new subjects. Present-day social demands. Traditional neglect of industrial education on the part of the public. The demand for revision of the curriculum. Summary. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER IX. SPECIALIZED EDUCATION VERSUS GENERAL EDUCATION | 127 |

| Present-day wavering between specialized and general training. The theory of separate schools for different classes of people. Statement of principles. Public demand for a new curriculum. Commercial courses in high schools. Agricultural high schools. Part-time courses. Various types of trade schools. The Manhattan Trade School, New York City. Practical applications as parts of academic courses. Studies of social activities. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER X. EXTENSION OF SCHOOL ACTIVITIES | 141 |

| A general social movement. Credit for home activities. Bulletin for teachers: home credits. Relation of home work to traditional school work. After-school classes and vacation classes. Continuation classes for adults. Demonstrations as means of economic and social improvement. Entertainment as part of the educational program. Associations aimed directly at the improvement of schools. Correspondence schools. Principles required to systematize educational activities. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XI. PRINCIPLES INFLUENCING THE ORGANIZATION OF THE CURRICULUM | 156 |

| Necessity of practical decisions in spite of confusion. The doctrine

of discipline. The doctrine of natural education in the form of the

doctrine of freedom. Concentration and interest. Popular attitude

toward discipline. Examples of discipline and freedom. Natural

education and recognition of individual differences. Natural education

as training for life. Training in the methods of knowledge and

general training. Examples of views on formal training. Prominence

of curriculum in determining quality of instruction. Bases for

judging curriculum and syllabi. Formal discipline and transfer of

training. Relation of subjects to maturity of pupils. Summary.

Exercises and readings.

viii |

|

| CHAPTER XII. INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES | 170 |

| Adaptation of curriculum to individual pupils. Low grades of intelligence. Differentiated courses. Tests of general intelligence. Exceptionally bright pupils. Sex differences. Differences in industrial opportunity for the sexes and corresponding demands for training. Household arts as extras. Demand for new courses for girls. Individual differences which appear during training. Democratic recognition of individual differences. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XIII. PERIODICITY IN THE PUPIL’S DEVELOPMENT | 184 |

| Recognition of periodicity in present organization. The meaning of infancy. The period before entering school. The primary period one of social imitation. The period of individualism. Early adolescence as a period of social consciousness. The new school adapted to adolescence. Later adolescence a period of specialization. The reorganized school system. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XIV. SYSTEMATIC STUDIES OF THE CURRICULUM | 197 |

| The curriculum based on authority versus the living curriculum. Older subjects products of long selection. Social needs and the curriculum. Systematic studies as devices for facilitating evolution of the curriculum. A study of representative adults. A study of current references. A study of the mistakes of pupils. Prerequisites for higher courses. Administrative studies. Need of broad, coöperative studies. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XV. STANDARDIZATION | 212 |

| Tests and measurements of products. Earlier standards based on opinion. Objective and exact standards. Beginnings of the movement. Handwriting scales. Speed as a correlate of quality. Standards, personal and impersonal. Social standards versus imposed standards. Comparison through exact measurement. Records as a basis of standardization. Studies of oral reading. Studies dealing with other subjects. Mechanical aspects the first to be standardized. Standardization and the science of education. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XVI. METHODS | 229 |

| Meaning of the term “method.” Meaning of the term “device.” Personal methods and devices. Supposed conflict between methods and subject-matter. Two examples of modern methods. Object ixteaching. Laboratory method in physics. Spread of the laboratory idea. Reaction against the question and answer method. Inefficient methods of study. Organizing a school for supervised study. Organizing subject-matter for supervised study. Experiments in method. Method as a subject of scientific tests. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XVII. CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT | 242 |

| Intellectual progress and social conditions. Social training general. Types of social organization. Social control through anticipation. Organization of routine. Punishments and rewards. Larger social organization. Attempts to classify unruly members of the social group. Impersonal discipline. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII. SELECTED ADMINISTRATIVE PROBLEMS | 254 |

| Programs and marks. The total school day. The class period. Physiological fatigue. Conditions like fatigue. Practical precepts based on study of fatigue. Administrative considerations controlling length of the class period. Adjustment of work within the period. Adjustment of credits. The problem of grading. Experiments with grading systems. The study of marks as an introduction to a study of the school system. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XIX. PLAY | 266 |

| Motives for cultivation of physical powers. Earlier attitude toward play. Play as natural behavior. Periods in the development of play. Play as natural education. Social necessity of recreation. Play as physical education. The school and play. Surveys of children’s play in cities. Systematizing instruction in play. Survey of recreational facilities. Play as part of the regular school program. Slow spread of modern attitude toward play. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XX. HEALTH SUPERVISION | 279 |

| The relation of health to school work. Treatment of pathological cases. School luncheons. Control of home feeding. Public attention to nutrition of children. Control of contagion. The school health department. Difficulties of introducing health instruction. Health as a subject of instruction and as a mode of life. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XXI. SCIENTIFIC SUPERVISION | 289 |

| Evolution of the demand for supervision. The principal. Other supervisory officers. Lack of public appreciation of central problems. Managerial training in relation to democracy. The purpose of the present discussion. Studies of the community. Selection xand management of teachers. Standardization by measurement of results. An example of public recognition of the need of efficiency measurements. Scientific studies and central supervision. Scientific supervision. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XXII. THE SCIENCE OF EDUCATION | 299 |

| Scientific methods of studying schools. Definition through enumeration of methods. The history of educational theory and practice. Courses in psychology. Educational psychology. Statistical studies. The experimental method. Extension of use of psychological methods. Studies of retardation. School experiments and laboratory studies. Examples throughout earlier chapters. Studies of administrative problems. Method of comparison. Records necessary to scientific study. Subdivisions of the science of education. Rapid expansion of the science of education. Definition of the science of education. Exercises and readings. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII. PROFESSIONAL TRAINING OF TEACHERS | 308 |

| Increasing demand for professional training. American normal schools. American demands on secondary-school teachers. German training of secondary-school teachers. New courses in colleges and universities for secondary-school teachers. The requirements of a standardizing association. The California requirements the most advanced in the United States. Continuation training of school officers. Specialized training for administration. Contributions to the science of education. Exercises and readings. | |

| APPENDIX | 321 |

| INDEX | 327 |

xi

| FIGURE | PAGE | |

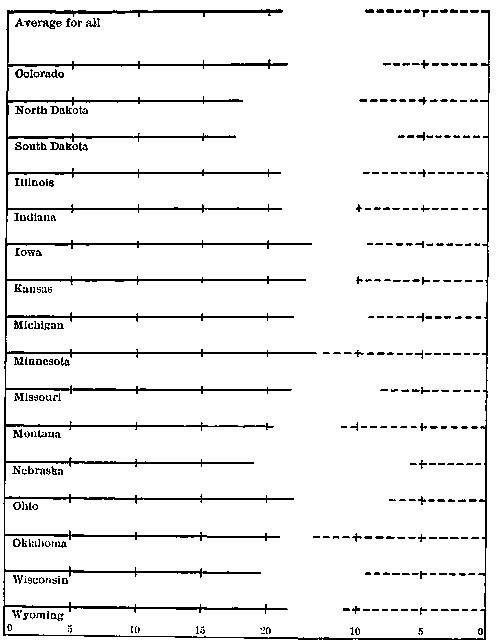

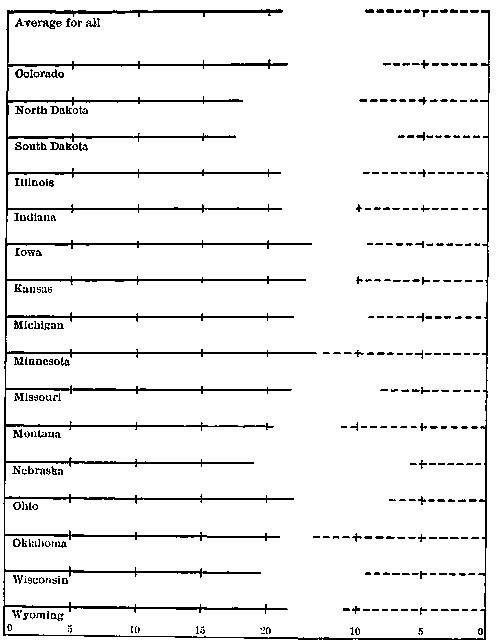

| 1. | Average number of high-school units in the approved schools of the various states of the North Central Association | 6 |

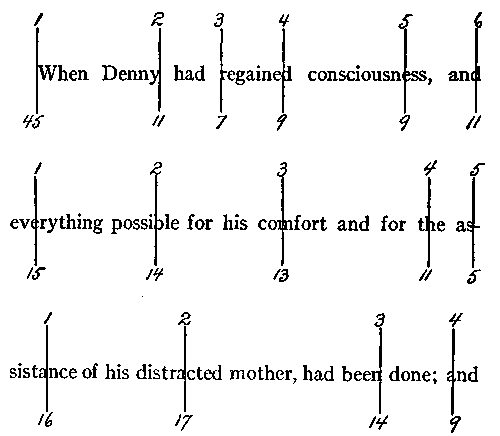

| 2A. | Pauses made in silent reading | 8 |

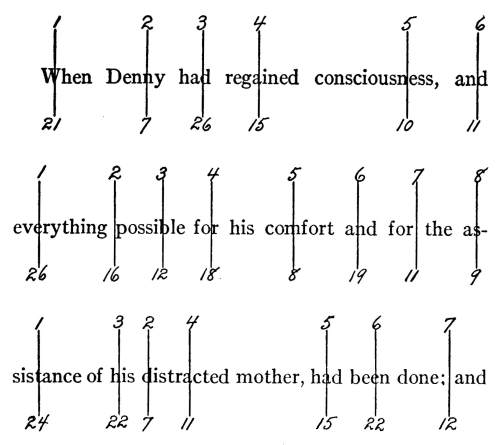

| 2B. | Pauses made in oral reading | 9 |

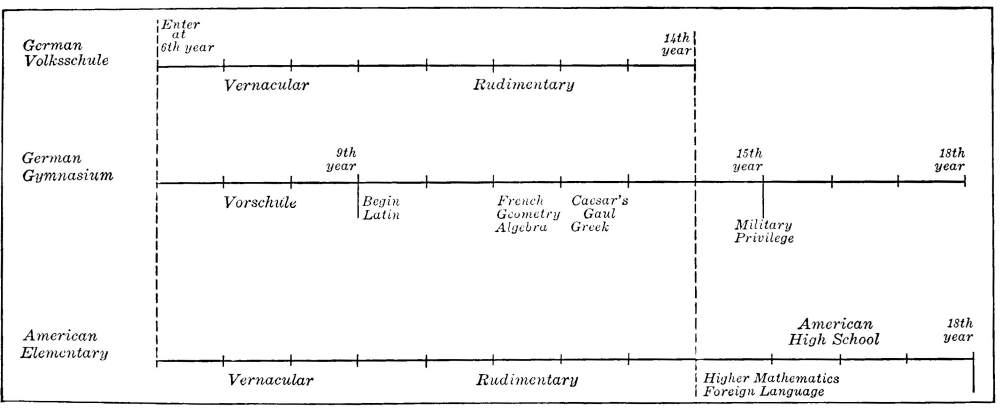

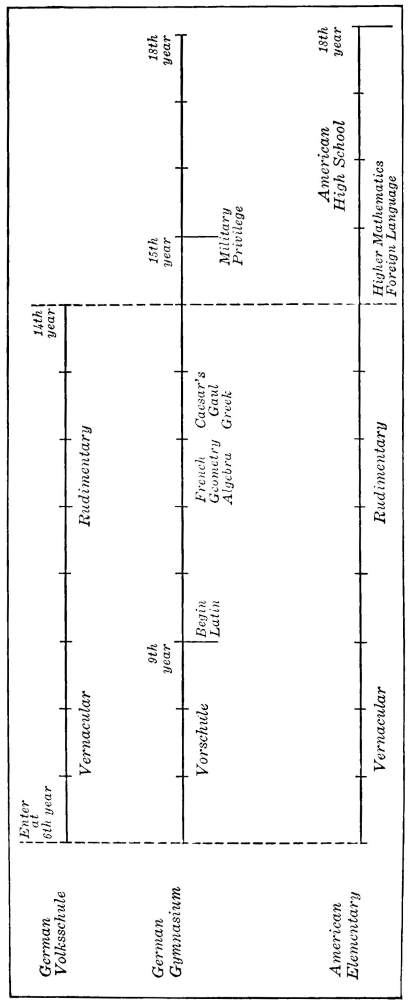

| 3. | Diagram showing the organization of German schools and American schools | 18 |

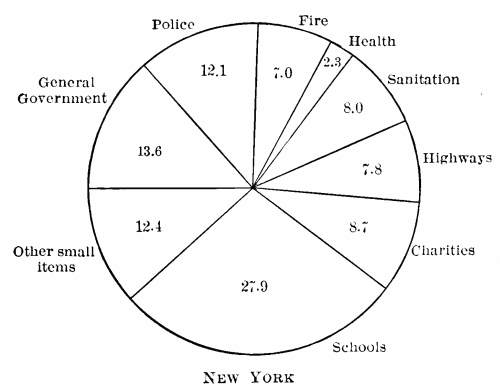

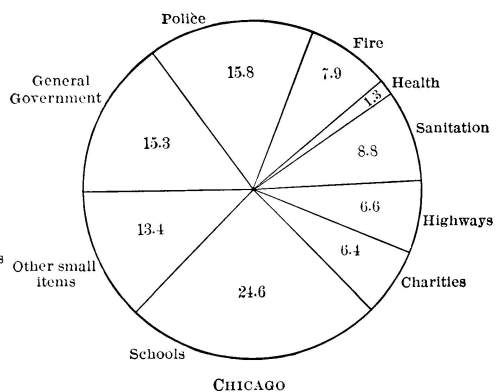

| 4. | Proportion of public money spent for public schools and other items | 50 |

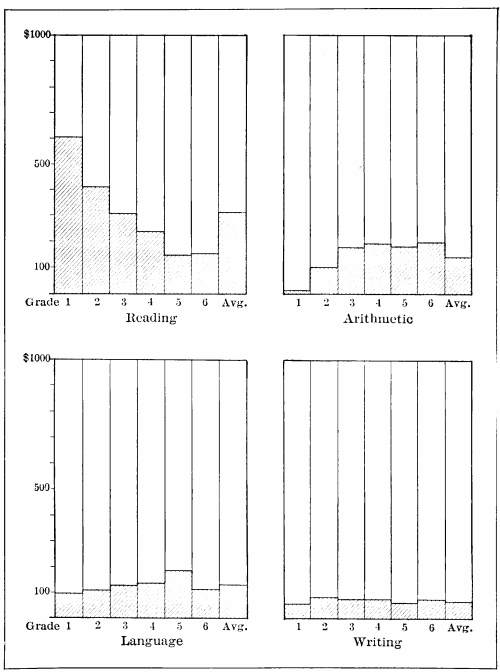

| 5. | Distribution in the various grades of each thousand dollars expended for instruction | 59 |

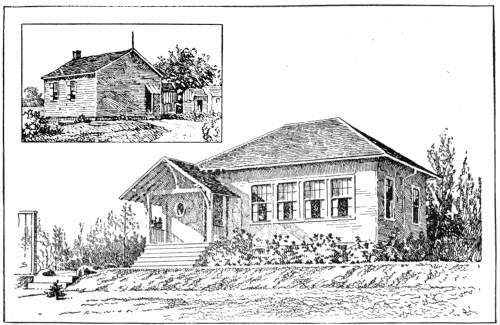

| 6. | Floor plan of a typical school building of the old style | 79 |

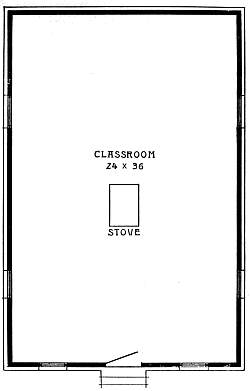

| 7. | Floor plan of a well-arranged one-teacher rural school of minimum cost | 80 |

| 8. | An old and a new rural school | 81 |

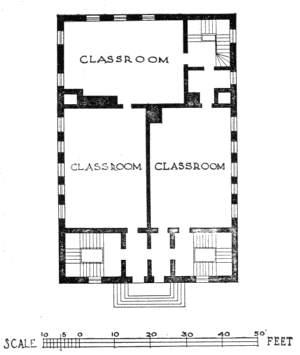

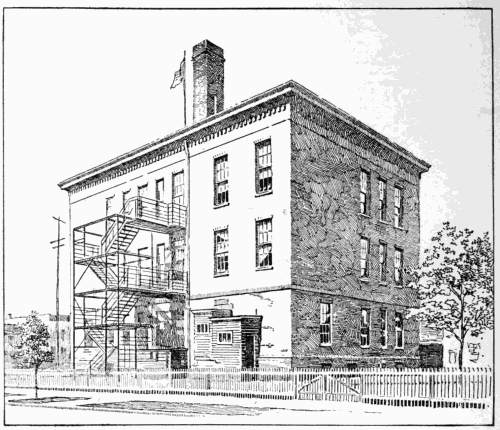

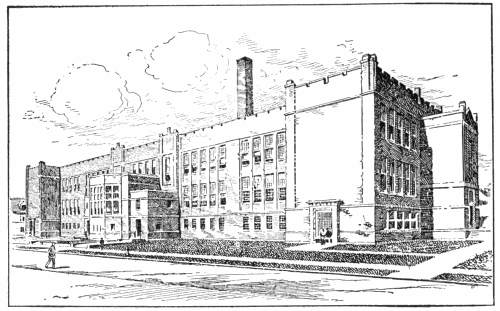

| 9A. | Ground plan of Alabama School | 83 |

| 9B. | Exterior of Alabama School | 83 |

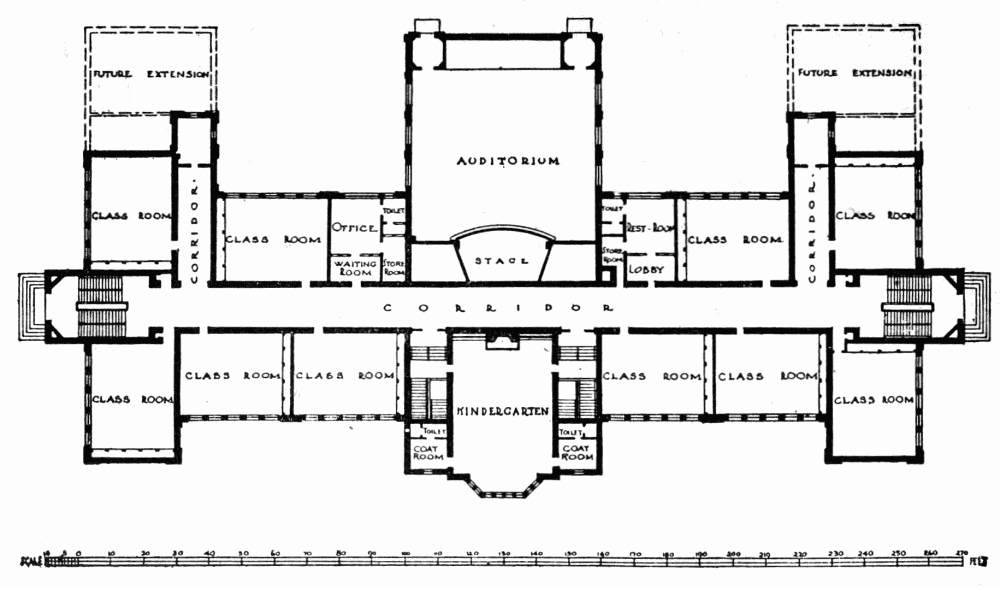

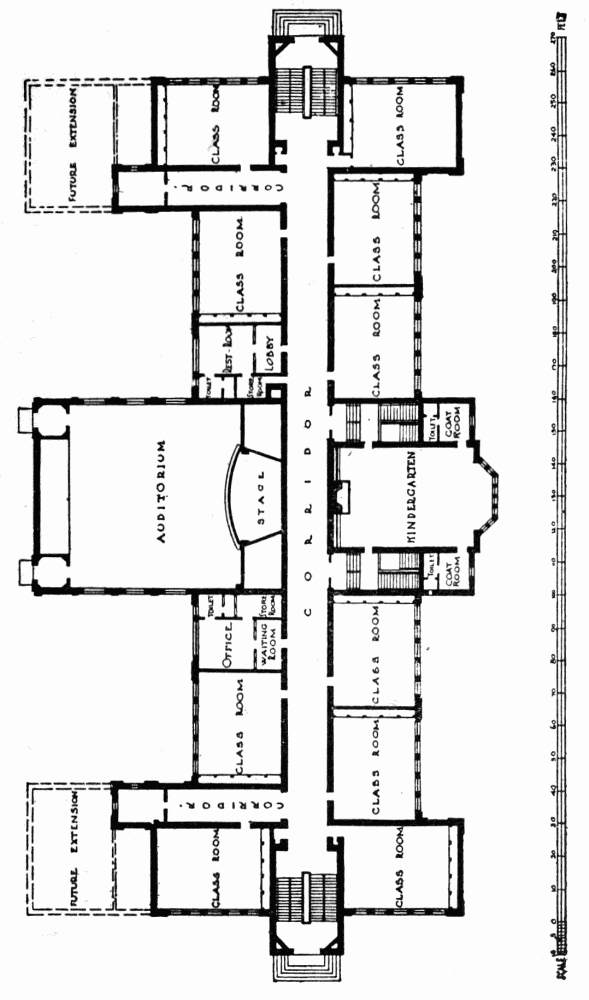

| 10A. | Ground plan of Empire School | 84 |

| 10B. | Exterior of Empire School | 84 |

| 11. | Record of nonpromotions and failures in Cleveland, 1914 | 103 |

| 12. | Enrollment in private vocational schools and in public high schools of Chicago | 133 |

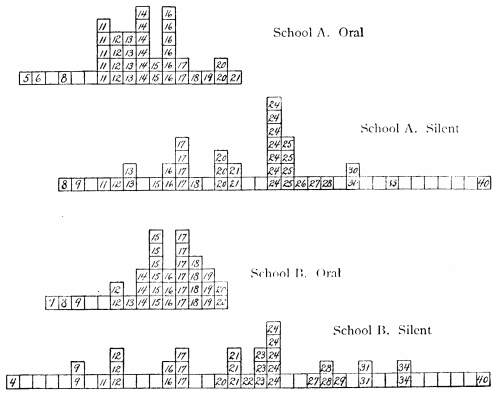

| 13. | Individual differences in the number of lines read in a minute by pupils in the fifth grades of two schools | 181 |

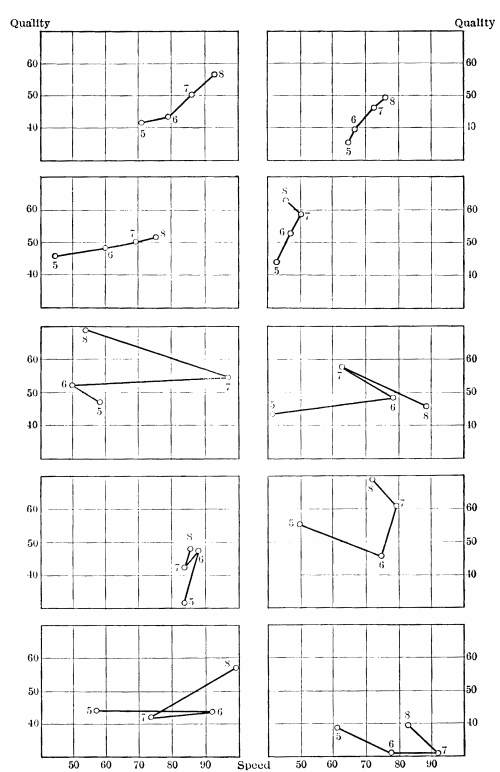

| 14. | Average quality and average speed of handwriting of pupils of the four upper grades in ten schools | 218 |

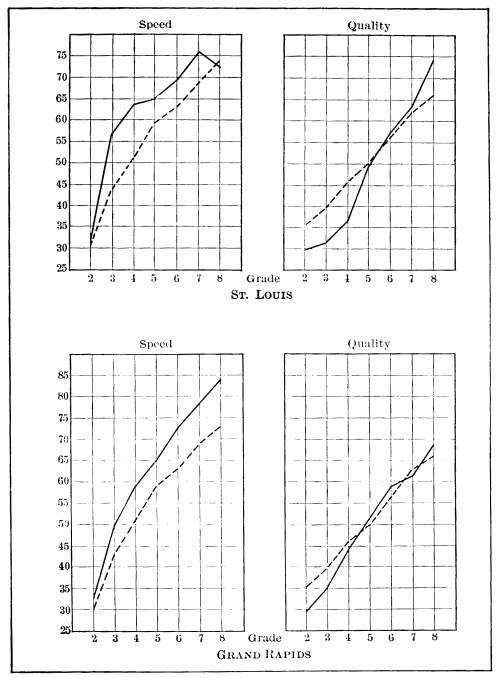

| 15. | Speed and quality of handwriting | 223 |

| 16. | Distribution of grades in various Harvard classes | 263 |

xii

| TABLE | PAGE | |

| I. | Expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools compared for a period of years, including also a comparison of population for the same periods | 48 |

| II. | Per cent of total governmental cost payments devoted to various city departments | 51 |

| III. | Cost per pupil in elementary schools and high schools in selected cities | 55 |

| IV. | Cost, per thousand student hours, of instruction in high schools in the various subjects of the curriculum | 57 |

| V. | The portion of each thousand dollars spent for instruction in each subject in each of the first six elementary grades | 58 |

| VI. | Percentages of failures in the chief subjects of instruction in the five high schools of Denver in June, 1915 | 107 |

1

THE SCIENTIFIC STUDY OF EDUCATION

Most people think of school matters from the pupil’s point of view. When they learned arithmetic and grammar, or later when they studied algebra and Latin, each course was presented to them as though it were a perfect system. The teacher did not confide in them that arithmetic probably ought to be revised by the omission of many of its topics, that formal grammar is a very doubtful subject, and that both algebra and Latin are on the point of losing their places as required subjects. The pupil sees the front of the school scenery; the machinery behind is known only to those who conduct the performance.

It would be possible to multiply indefinitely examples which show that the pupil’s view of the school is very limited. What pupil understands the duties of the principal or the superintendent, or of the still more remote and mysterious board of education? Where does the daily program come from? Who decides about textbooks? Why are school buildings commonly planned with large study-rooms? Most of these questions are never thought of by pupils. Everything in school life seems to have a kind of inevitableness which raises it above question or even consideration.

2

The narrowness of the pupil’s view would have less serious consequences if it were not for the fact that the pupil becomes in mature life a member of a board of education or adopts teaching as his profession. Then trouble results, because there is machinery which must be kept running if schools are to be efficient, and this machinery suffers if intrusted to the hands of those who do not understand its complexities.

One school superintendent, who encountered vigorous opposition to the introduction of changes in the course of study, wrote as follows:

The average American citizen whose schooling was limited to the primary and grammar grades looks with reverence upon the subjects there taught, and refuses to concur in a change of the course of study for the elementary school. Associated with the average citizen is a heavy percentage of the teaching faculty of both elementary and high schools throughout the country.1

Another superintendent, who was more successful in bringing about reforms, makes this statement:

People are more conservative in their attitude towards educational innovations than toward new adjustments to meet the demands of changing modern life in any other field of activity. Each adult is inclined to overvalue the particular type of training he received and to regard with suspicion any change which will tend to discredit this sort of training received at such an expenditure of time and money. The schools are, therefore, the last institution to respond to the changing demands of modern life.2

3

If schools are to be progressive and efficient, they must be studied very much more broadly and comprehensively than they can be from the pupil’s point of view. The suggestion naturally arises that this broader study is a part of the professional duty of the teacher. So it is; but it will not be enough merely to exhibit the intricacies of education to teachers. The whole community must be shown by scientific methods that the school is a complex social institution, and that its conduct, like the conduct of every other social institution, requires constant study and expert supervision. In this movement of opening the eyes of the community to the needs and nature of education, the school officers must be leaders; but their methods must be impersonal and exact.

During recent years the demand for a thorough and comprehensive study of schools by scientific methods has led to a number of investigations which can be offered as an optimistic beginning of a science of education. It would, indeed, be far beyond the truth to assert that science has settled all the problems of teaching and of school organization. There is, however, a very respectable body of fact which has been clearly enough defined so that it can in no wise be set aside. In certain details the requirements of a scientifically valid educational scheme are known and can be described. The method of studying schools can safely be said to be established. It is the work of the future to take up, now this problem, now that, and by progressive stages to work out a complete science of school management and classroom organization.

It will be the purpose of subsequent chapters to define fully certain of the leading problems with which the science of education deals. The remainder of this chapter will be4 devoted to a brief statement of certain typical studies, which will make more concrete and definite the contention that the pupil’s view of schools is narrow and that the teacher’s view must be extended, as must also that of the community at large, if educational conditions are to be improved.

First, we may refer to investigations which have been made of the rate of promotion of pupils through the grades.

Whenever a pupil fails to complete the work of a grade in the appointed time, it is evident that there is some kind of maladjustment. The pupil may be incompetent to do the work required of him because he is mentally deficient. On the other hand, it may be that the work is ill chosen and in need of revision. The following statement from one of the leading students of education in the United States describes with clearness the problem and the progress made in meeting it.

Just ten years ago the distinguished superintendent of schools of New York called attention to the fact that 39 per cent of the children in the schools of that city were above the normal ages for their grades. This aroused widespread investigation, which showed that similar conditions obtained in other cities throughout the country. Soon studies of this phase of educational efficiency showed that the same conditions which resulted in our schools being crowded with retarded children also prevented a large proportion of these children from ever completing the elementary grades.

About seven years ago this became one of the most widely studied problems of educational administration, and in the past four it has been one of the prominent parts of the school surveys. During the entire period hundreds of superintendents throughout the country have been readjusting their schools to better the conditions disclosed.

In these seven years the number of children graduating each year from the elementary schools of America has doubled. The5 number now is three quarters of a million greater annually than it was then. The only great organized industry in America that has increased the output of its finished product as rapidly as the public schools during the past seven years is the automobile industry.

It is probable that no other one thing so fundamentally important to the future of America as this accomplishment of our public schools has taken place in recent years. There is every evidence that this is the direct result of applying measurements to education. If the school survey movement now under way can produce other results at all comparable with this one, we need have no fear for the outcome.3

The quotation does not tell us how the reform has been worked out. That is a long story. In some cities better teachers were needed and have been employed. In a great number of cases the course of study has been revised. Sometimes smaller classes have been provided. So on through a long list of details, one might enumerate the reforms which have resulted from a careful study of the one fact that pupils in the schools were older than they normally should be.

A second type of study can be borrowed from the reports of the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools. This Association has as its practical purpose the inspection of the secondary schools and colleges of the northern states from Ohio to Colorado. The inspectors of high schools in seventeen states brought together in the report of 1916 a number of exact statistics regarding 1128 approved schools.4 One set of these facts may be selected for special comment.

6

7

The number of units, or courses, offered in high schools has increased rapidly in recent years. Especially marked is the addition to the school program of technical subjects, such as home economics, manual training, and commercial courses. The report here under discussion states that in all the approved schools of the association there is an average of 21.13 academic units, that is, units in such subjects as languages, history, mathematics, science, and English; and an average of 9.41 units in technical or vocational subjects.

When we examine the individual states, we find that Minnesota, which has a large state fund, much progressive legislation on high schools, and a vigorous state department of education, shows averages of 23.87 academic units and 12.65 units of vocational subjects. South Dakota, where the school system is new and economic conditions are much less favorable, has averages of 17.62 academic units and 6.46 vocational units. The more striking differences are those which arise not from economic conditions but from clearly indicated differences in educational policy. Ohio has an average of 22.24 academic units, which is high, and an average of only 7.26 vocational units, which is low. On the other hand, Kansas has 22.9 academic units, or just about the same as Ohio, and 10.13 units in vocational subjects.

Finally, if we carry the comparison into still further detail by examining the schools in a single state, we find in Ohio one city with a high school of 870 students offering 18 academic units and 5 vocational units, while in another city, where the student body numbers 710 students, the school offers 24 academic units and 22 vocational units.

The comparisons are illuminating in several respects. It is probable that most communities are ignorant of the fact that their own high schools differ from others. The publication of definite facts with regard to the practices of schools would stimulate wholesome thinking on school problems. The whole life of a school depends in very large measure on8 the course of study. When there are such wide divergences as are here indicated, there is clear evidence of differences in educational policies in different states and communities. At the present time the accepted policies are often the products of tradition or accident. They should be made subjects of careful study and either confirmed or revised.

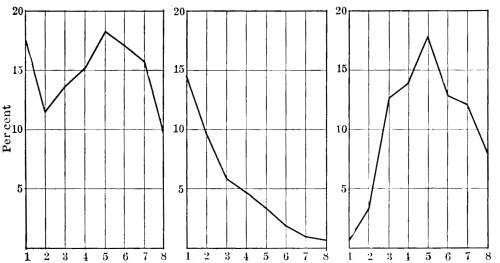

As a third type of scientific study we may take certain recent laboratory investigations of reading. Reading is the most important subject taught in the schools; yet there9 are the widest differences in the results secured with different pupils. It is the duty of the schools to find out what constitutes the difference between good readers and bad readers, in order that both classes may be improved.

The method of these studies consists in photographing the reader’s eyes as they travel along printed lines. The number and length of the pauses are thus determined. It is found in general that competent readers see more at a glance than do poor readers. Furthermore, it is found that different types of reading are radically different; thus there is a marked difference between oral and silent reading. The importance of distinguishing these two types of reading10 lies in the fact that most of the teaching of reading in the elementary schools is by means of the oral method. Most of the demands of later life, and all of the demands made upon pupils when they study textbooks in geography and history and the other subjects of the school course, call for ability in silent reading. The results of investigations can be briefly stated in the following averages: the average numbers of pauses per line in oral reading for adults, high-school pupils, and elementary-school pupils, reading passages of different grades of difficulty, are 8.2, 8.6, and 8.1, while the corresponding averages for silent reading are 6.5, 7, and 6.3. These figures mean that the eye makes more pauses along a printed line when the reader is reading orally than when he is reading silently. Oral reading is therefore a more laborious, difficult form of reading. Furthermore, the time spent in each pause is greater in oral reading. The averages in thousandths of a second for oral reading for the three classes of readers are 380.8, 372.9, 398, while the corresponding figures for silent reading are 308.2, 311.1, and 314.5 These figures show that oral reading is slow as well as laborious.

It would require more discussion than is appropriate at this point to bring out the full meaning of such facts as these. Enough appears on the surface of the results, however, to make it quite evident that the school ought not to emphasize oral reading in the upper grades as it does to-day. The daily oral-reading drill in the seventh and eighth grades imposes on the pupils a slow, clumsy form of reading at a time when they ought to be cultivating the power of rapid silent reading.

It is by means of investigations of this kind that each of the subjects of instruction is being examined, and as a result11 schoolwork is increasingly developing effective methods of cultivating children’s intellectual powers. The work of analyzing each of the subjects will be slow and will require the coöperation of many investigators, but in several subjects, especially in the elementary schools, an encouraging beginning has been made.

A fourth and final example can be borrowed from studies made in the city of Minneapolis of the opportunities for trade training in that city, of the number of workmen needed in each of the trades, and of the kind of preparation required for efficiency in each branch of labor. An industrial and educational survey of the community was undertaken for the specific purpose of adapting educational organization to the practical needs of the community.6 Such a study recognizes the fact that the school is but one among many social institutions and that the school must find its proper place in community life through a thorough scientific study of other more general social activities.

Here, again, it is by no means asserted that the solution of the problem of training workers for the industries has been found. It can, however, be stated with complete assurance that both the school and the community will proceed with greater intelligence if the facts are carefully canvassed in advance.

The spirit of patient, detailed scientific study is more and more dominating the schools. There are some who,12 impatient at the labor involved in such studies, would rush forward to radical experimentation. Fortunately, even such rash reformers are becoming convinced that they need to keep records of their results in order to prove the success of the changes which they have made. As a result, they too are taking on some of the forms of science, though they do not adopt the full program of patient study of conditions.

The result of a scientific movement such as is under way in education will be the cultivation of a broader conception than was ever possible from any individual point of view. The pupil’s view is narrow because he comes in contact with the school only at the point of application of educational methods to his own life. The scientific view of education is broad because it places the school in its proper relations to other social activities, because it defines the relation of the pupils and teachers to one another and to the material used for instruction, and because it opens up all the results of school work to full inspection and evaluation. This broad scientific view is the one which the teacher and the community at large should adopt.

EXERCISES AND READINGS

In every school certain changes are introduced from time to time in spite of the conservatism of the community. Let the student find examples of (1) new courses of study, (2) new methods of appointing or promoting teachers, or (3) new forms of organization, such as the junior high school or departmental teaching. After discovering innovations, let him find how they were brought about.

What are the usual forms of school records and reports known to the student? How could records be made of more value? Suggest methods of presenting the facts of daily attendance so that they can be readily interpreted by a community. What are some of the interpretations that ought to be put on failures and nonpromotions in different kinds of cases? Is repetition of a13 course desirable for a pupil who has failed? Are failures more common in required courses than in elective courses? When a required course is described as essential to the education of everyone, what is meant?

Let the student test his own rates of reading. How should a college class differ from a high-school class in ability to read? Go to a library or study-room and watch the people read. Report the differences between individuals.

The readings which are most stimulating to students who have never faced the problems of school organization are those which call in question present school practices.

Dewey, John. The School and Society. The University of Chicago Press. This is one of the most stimulating demands for a reorganization of the school which has ever been written.

Rousseau, Jean Jacques. Émile. D. Appleton and Company. This is a book of great historical significance. It is an indictment of formalism in education and a vigorous advocacy of naturalism.

Spencer, Herbert. Essays on Education. D. Appleton and Company. This is a demand for a thorough reform of the school curriculum. It is now nearly sixty years old, but it is modern in its spirit.

14

The scientific methods of studying school problems, which were illustrated in the last chapter, can be supported and supplemented by a comparison of the schools of the present with the institutions of earlier times, and by a comparison of the schools of different countries with one another. Such comparisons seldom serve as an adequate basis for the reorganization of school practices, because the conditions in one generation and in one country are so unlike those of others that direct transfer of methods of procedure is dangerous. Comparison serves, however, to set in clear perspective the characteristics which distinguish each situation from every other. If an American wishes to see the school system with which he is familiar from a new point of view, the comparative method furnishes a kind of outside station from which he may look back and see facts which were by no means clear in their meaning when viewed from near at hand.

One very impressive difference between the schools of the United States and the schools of Europe is to be found in the fact that class exercises in our schools are commonly based on assignments in textbooks, while in Europe the chief method of instruction is oral exposition by the teacher. The word “recitation,” which is often employed in describing15 a classroom exercise, is an American term. It originated at the period when devotion to the textbook was even greater than it is now,—when the pupil was expected to repeat verbatim the passage from the text. In British books on education the word “recitation” appears only when referring to American practices, and usually takes the form “the American recitation.” In the German educational vocabulary the word has no equivalent.

The unique American method of reciting lessons learned out of a book can be contrasted with the European method by taking a concrete case. If one goes into a geography class in a German school, one finds in the hands of the pupils no book, except that in the schools for the richer classes there may be an atlas; commonly the wall map serves. The teacher lectures on some section of the country, and follows the lecture by questions which the pupils answer. The advantages of the European method are that the pupils become trained, attentive listeners, and are able in answering questions to talk coherently for long periods, imitating the continuous discourse of the teacher. The disadvantages are that the information supplied is limited by the individual teacher’s training, and the pupils cultivate little or no independence in the collection and sifting of information. The influence of the teacher is always dominant—often oppressively so.

The contrast here pointed out is one of fundamental importance. It can be adequately understood by a study of the history of American schools. When the colonists came to New England they were bent on securing for every individual independent personal contact with the truth. They had left their European homes because there dominating authority always stood between the individual and the16 sources of truth. One of the first acts of the colonists, therefore, was to provide for the training of every boy and girl in that power which would make him or her independent, especially in religion. The early legislation shows unequivocally this motive. Thus in 1650 Connecticut passed a law which had a preamble very much like that of the Massachusetts law of 1647. The preamble is as follows:

It being one chief project of that old deluder, Satan, to keep men from a knowledge of the Scriptures, as in former times, keeping them in an unknown tongue, so in these latter times, by persuading them from the use of tongues, so that at least, the true sense and meaning of the original might be clouded by false glosses of saint-seeming deceivers; and that learning may not be buried in the grave of our forefathers [the court decreed that whenever a township increased to fifty householders they should employ someone] to teach all such children as shall resort to him, to write and read.

So strictly did the early schools devote themselves to reading that arithmetic and, in some cases, even writing were neglected in the exclusive cultivation of the one art of reading. Later generations of American teachers and pupils have experienced a great expansion of the content of the course of study, but the method of instruction has always been predominantly the reading method. The large number of supplementary readers used in history, in geography, and in nature study keep up the traditions of a school which was from the first a reading school.

The social consequences of this emphasis on reading can be seen in the fact that public opinion in America is controlled largely by an appeal to the people through reading matter. The importance of this kind of public opinion can hardly be overemphasized. In a democracy there must be ability to form independent opinions, and this is possible only where there is the widest training in reading.

17

A second characteristic of the school system of the United States which distinguishes it from the systems of Europe is described by the phrase, coined in England, “the educational ladder.” There is no limit in the American system to the possibility offered the individual pupil of going on to higher institutions. The boy or girl who has completed the elementary course can go on to the high school and from the high school to the college and university. This is not true anywhere in Europe. There the school systems are sharply divided into two wholly different and distinct lines of advancement. The children of the common people go to one school; the children of the aristocracy and richer classes go to a different school. The school for the common people is limited in time and opportunity, and does not lead into the universities. Thus the Volksschule of Germany, which gave instruction before the war to 92 per cent of the total school population, is an eight-year school, teaching only the common branches. The pupil who enters the Volksschule cannot look forward to entering any one of the professions or any civil-service position. He cannot be transferred from the upper grades of this common school into the secondary school. The common school of Germany is a social instrument for the perpetuation of a caste system. The common people know their place because they learn it when they enter school.

18

19

The European school for the aristocracy, on the other hand, is organized from its earliest years with a view to preparing its pupils for the higher callings. It is difficult for the American to understand how distinct this school is from the common school. The term “secondary school” is sometimes applied in educational writings to both the high school of the United States and the aristocratic schools of Europe. But the secondary school of Europe is entirely different from our high school. It takes little children in the lower grades and carries them through. Thus the German Gymnasium takes boys of the age of six. These are received into what is called a Vorschule, or preliminary school. After three years in the preliminary school the pupil begins his nine-year course in preparation for the university. In some of the states of the German Empire the pupil may be transferred into the Gymnasium from the earliest grades of the common school, but from this point on there is no commerce whatsoever, in teaching staff, in course of study, or in pupil constituency, between the common school and the school of the aristocracy. The division in France is quite as strict. In England transfer in the later years of the common-school course can be made, but only on the basis of examinations.

The social consequences of such a division within the school system need no detailed exposition. The hard-and-fast lines of caste are drawn very deep in any country where the boys and girls are marked from the beginning of their training by separation in opportunity.

It is not enough that we should see this contrast, however; we must learn its fuller meaning by looking into the history of our own school system. The fact is that we have not broken entirely away from the traditions of Europe. Our elementary school was borrowed directly from the Volksschule of Germany, and many of the readjustments which we are making to-day are nothing less than efforts to shake ourselves free from that disjointed scheme of education.

The time of this borrowing of the German Volksschule is clearly marked in our history. In the first three decades20 of the nineteenth century American schools were at a low level of development. A vivid picture of conditions in 1801 can be given by quoting from one of the earliest school reports that we have. The superintendent of the city of Taunton, Massachusetts, in a recent report reproduced this interesting historical document, of which we may quote certain sections in order to show the kind of school organization which prevailed at that date.

REPORT OF THE VISITING COMMITTEE OF TAUNTON IN 1801

The committee chosen by the town to inspect the schools beg leave to report their situation and examination....

January 6th, 1801. Your committee visited a school kept in Rueben Richmond’s house instructed by Mrs. Nabby Williams of 32 scholars. This school appeared in an uncultivated state the greater part of the scholars.

On the 26 of Feb., visited Mrs. Nabby Williams’ school the second time and found that the scholars had made great proficiency in reading, spelling, writing and some in the grammar of the English language.

Nov. 10th, the committee visited and examined two Schools just opened; one kept in a school house, near Baylies works, of the number of 40 scholars, instructed by Mr. Philip Lee. This School we found to have made but small proficiency in reading, spelling and writing, and to be kept only six or seven weeks; upon inquiry why it should be taught no longer, we were informed that the ratio of school money for this School was and had been usually expended in paying the Master both for his service and board, and in purchasing the fire wood which is contrary to the usual custom of the town.

The other School, visited the same day, was kept near John Reed’s consisting of the number of between 30 and 40 Scholars instructed by Mr. William Reed; This School, being formed into regular classes, appeared to have made a good and pleasing proficiency in reading, spelling, writing, some in arithmetic and others in the Grammar of the English language. This Schoo21l’s share of school money is expended to pay the Master for his service only, so that the School will be continued three months.

On the 8th day of December they visited a School kept in a School house near Seth Hodges, in number 30 Scholars instructed by Mr. John Dunbar. This School appeared in a good way of learning, and to be kept four months.

On the 22nd of December your Committee visited two more Schools just opened, one in a School house near Samuel Pett’s of the number of 40 scholars instructed by Mr. Rufus Dean, and to be kept three months. This School appeared to be in a promising way of learning in reading spelling and writing and to be regularly taught.

The other School is kept in the home of Mr. Paul Chase and taught by Mr. Nicolas Stephens, consisting of 30 Scholars, and appears quite in a good way of learning especially in Spelling for scarcely a word passed a scholar misspelled, in writing some did very well and others in arithmetic appeared attentive.

January 8th, 1801 visited two Schools for the first time, one in the home of Mr. William Hodges of the number of 37 Scholars, instructed by Mr. Lovet Tisdale, the other in the home of Mr. Daniel Burt, of the number of 25 Scholars, instructed by Mr. Benjamin Tubbs. These Schools appeared in good order and attentive to their learning.

Feby. 26th, visited Mr. Dean’s School 2 times, the Scholars were crowded into a small room, the air was exceedingly noxious. Many children were obliged to tarry at home for want of room and though the school was kept only a few weeks they were deprived of its advantages. A want of books was the complaint. The committee were anxiously desirous that this evil might have a remedy and were of opinion it may be easily done. The Scholars appeared to increase in knowledge & claim our approbation.

March 5th, visited two schools, one kept at Mr. Aaron Pratt’s of the number of 30 scholars instructed by Mr. Philip Drown. This school appeared quite unimproved and uncultivated in reading and spelling, some of them did better in writing. This uncultivated state did not appear to be from a fault in the children22 but, as your committee were informed, from the disadvantage of having had masters illegally qualified for their instruction; of which class is their present master unauthorized by law.7

The situation here described was typical of all the settled towns. How much worse it was in sparsely settled districts one can easily imagine. Briefly put, one can say that up to 1830 schools throughout the country held short sessions in the middle of the winter when the pupils were otherwise unoccupied with home demands. There was no supervision except by visiting committees, no course of study, little or no material equipment, and small outlook for a higher education.

During the decade 1830-1840 there was an effort, especially in Massachusetts under the leadership of Horace Mann and in Michigan under John Pierce, to improve the common schools. In an illuminating historical treatise on this subject Mr. F. F. Bunker has reproduced some of the evidences that the changes made at that time in the schools of America were largely influenced by German models. The following quotations indicate how the movement began:

Charles Brooks, a man whose influence in Massachusetts was great, and who may be said to have prepared the way for the work of Horace Mann, did very much to disseminate knowledge respecting the Prussian system. He was primarily interested in establishing a normal school after the Prussian model, yet, during the campaign which he carried on for this purpose between the years 1835 and 1838 he did not limit himself to the consideration of the normal school alone, but sought to acquaint the people with the details of the German system of elementary education as well. His account of the return trip from England, which he made in company with Dr. H. Julius, of Hamburg, indicates the esteem in which he held the Prussian system:

23

A passage of 41 days from Liverpool to New York (with Dr. Julius) gave me time to ask all manner of questions concerning the noble, philosophical, and practical system of Prussian elementary education. He explained it like a sound scholar and a pious Christian. If you will allow the phrase, I fell in love with the Prussian system, and it seemed to possess me like a missionary angel.

Just at the time that Charles Brooks was laboring so diligently to incorporate in the Massachusetts system the results of Prussian experience, another man, John D. Pierce, in Michigan, also an enthusiastic believer in the preëminence of the Prussian organization, was laying the foundation for an educational system in his own State and building into it the best features of Prussian practice. It was mainly because of his suggestions to the chairman of the committee on education in the convention that framed the State government in 1835 that the article in the constitution respecting education was framed and provision made for the office of superintendent of public instruction. Mr. Pierce was appointed to the superintendency in 1836 and at once began the work of preparing a plan for a complete school system.

Before framing his recommendations, which were submitted in 1837 and which were approved for the most part, he visited the schools of New England, New York, and New Jersey. Prior to this, however, he had learned of the Prussian system through an English translation of Cousin’s report. This report of Cousin’s was first made known to the English-speaking people by Sir William Hamilton, who, in the Edinburgh Review, July, 1833, commended the report highly and quoted at considerable length therefrom. The next year (1834) that part of the report which treated of Prussian practice was translated into English by Mrs. Sarah Austin and appeared in London. A New York edition of the same translation was issued in 1835 and widely distributed. It was a copy of this edition which, falling into Mr. Pierce’s hands, profoundly influenced him in framing the system he later submitted to the Michigan Legislature. In describing his entrance into public life Mr. Pierce speaks of this circumstance:

About this time (1835) Cousin’s report of the Prussian system, made to the French minister of public instruction, came into my hands and it24 was read with much interest. Sitting one pleasant afternoon upon a log on the hill north of where the courthouse at Marshall now stands, Gen. Crary (chairman of the convention committee on education) and myself discussed for a long time the fundamental principles which were deemed important for the convention to adopt in laying the foundations of our State. The subject of education was a theme of special interest. It was agreed, if possible, that it should make a distinct branch of the government, and that the constitution ought to provide for an officer who should have this whole matter in charge and thus keep its importance perpetually before the public mind.

Mr. Pierce’s indebtedness to Prussia for many of the ideas which he worked out in the system which he organized is thus set forth by a later superintendent of the Michigan system, Francis W. Shearman, who, writing in 1852, said:

The system of public instruction which was intended to be established by the framers of the constitution (Michigan), the conception of the office, its province, its powers, and duties were derived from Prussia.8...

It is a striking fact that all this borrowing had to do with the common school. Nor was it inappropriate at that period that emphasis should be on the school for the common people. In the young states there was relatively little higher education, and the need was great for an improvement of the common schools.

The consequences of this borrowing were momentous for our history. There are two characteristics which our American schools of elementary grade took on in imitation of the German model, which characteristics have determined in large measure their subsequent development down to the present. In the first place, the German common school was strictly a vernacular school, and, in the second place, it dealt only with rudimentary subjects. The Gymnasium, or the school for the aristocracy, was not a vernacular school.25 Latin and Greek and modern foreign languages were taught in even the lower grades of the Gymnasium. Furthermore, the Gymnasium alone taught such “higher” subjects as the higher mathematics, while the common school confined itself exclusively to arithmetic as the rudimentary branch of mathematics. In point of time the German Volksschule, as noted above, conducted a course eight years in length. The pupils completed this course at fourteen years of age, when they were confirmed in the Church.

The common school was the institution which America borrowed in 1830-1840. The common school was set up in the United States as an eight-year school devoted exclusively to the vernacular and to rudimentary subjects. But the American system developed. The length of the school year increased, and the number of pupils who are ambitious to go on into the higher schools has enormously increased. In 1917 we were told by the Commissioner of Education of the United States that more than 1,300,000 of the young people in this country were in the high schools. Even now, however, the eight-year vernacular rudimentary school of Germany has its stamp on our American life. As a rule our American schools do not permit a pupil to study foreign languages in the lower school, even when we know that he is going on to high school. The general exclusion of languages is due to the tradition that the elementary school is a vernacular school, not to inability on the part of pupils to learn languages. We will not permit algebra to be taught in the elementary school, because algebra is not a rudimentary subject. To be sure, we have had a hard time trying to keep arithmetic in its position of exclusive domination of the elementary course. We have grafted into the arithmetic all kinds of economic information about insurance and banks and foreign exchange. We have exercised our ingenuity to the limit in inventing examples of a complicated sort in order to keep the pupils26 in the upper grades at work in arithmetic. But through it all we have been kept from a rational development by adherence to the tradition of the German common school,—the tradition which treats higher subjects as the exclusive property of the aristocracy.

The day of reform is, however, at hand. Social pressure has gradually been making it evident to all that in America the elementary school cannot be a caste school. The people are demanding that pupils who are to have only a limited schooling be admitted to some of the higher subjects. Furthermore, there are enough pupils who go on into the high school to make it evident that the American scheme should be organized not with a view to distinguishing between the elementary school and the high school, but with a view to combining the two into a continuous institution.

Within the last five years there has spread rapidly a movement known as the junior-high-school movement, or the intermediate-school movement. This is essentially a reform of the seventh, eighth, and ninth grades, and consists, first of all, in the introduction into the course of study of material which formerly belonged to the high school. In the second place, this movement recognizes the maturity of pupils in a variety of ways. It adopts a form of discipline which throws responsibility on them. It departmentalizes the teaching and offers electives, thus securing the advantages of specialization. The movement promises to reorganize our whole school system in such a way as to give us a new kind of national education. America has at the present moment a closer approximation to a continuous educational ladder than any other country, but the ladder needs a little splicing. With the present enthusiasm for national development the splicing is likely to be facilitated.

27

The foregoing statements extracted from the history of the elementary school may be supplemented by references to the history of the high school. The first schools of secondary grade in this country were patterned after the classical secondary schools of England. The Boston Latin School and the Hopkins Grammar School of New Haven are examples of early foundations of the kind in question. These schools were vestibules to the colleges, and the boys who attended them—for they were schools for boys—were looking forward to one of the learned professions, usually, in the early days, to the clergy.

The Latin school charged tuition, as do all the European secondary schools to-day. It was an exclusive school. It was not a part of the popular movement toward general education. In an important sense it was a vocational school and illustrates the general fact of history that higher schools always had a vocational motive back of their organization, whereas the people’s schools of elementary grade were at first always missionary enterprises intended to spread religious training rather than vocational training.

Parallel with the Latin school and growing out of an entirely different motive was another institution which was very much more genuinely American in its character. This was the academy. The academy was often a boarding school to which boys and girls alike went for an extension of their education. Later the village in which the academy was situated took it over or made arrangements to pay for all the pupils, and it became a free academy.

There were some other experiments in the extension of school opportunities. In New England, the oldest and economically most forward section of the country, a ninth grade was added to the elementary school. There are to-day in Maine, and to some extent in other New England28 states, elementary schools with a nine-year course. But the ninth grade never succeeded. It was cramped by the German definition of the elementary school as a vernacular and rudimentary school. To try to spend nine years rather than eight on the three R’s was not productive. The academy, on the other hand, knew no limits of this kind. It reveled in such subjects as French and music and literature and history.

At last the Latin school and the academy fused in the American high school, and the high school took its place at the end of the elementary-school course. The influence of the academy in determining this form of organization was very great, for the academy was from the first connected with the elementary school, while the Latin school was in its early days an institution quite separate from the common school both in its organization and purpose.

These sketches of school history could be supplemented by other discussions. Perhaps it will be well to comment briefly on the unique American attitude toward the education of girls. In Europe girls have only very recently been given opportunities of higher education, and even now the opportunity is limited to the few. We have undoubtedly made the mistake in this country, in our enthusiasm for equality of opportunity, of administering to girls a course of study originally designed for their brothers. In due time we shall learn how to give to girls an education suited to their needs, but there can never be any question among us about the wisdom of a higher education for women.

It has also been noted incidentally that with us all education is free. This has not been attained without much discussion and much legislation. We shall later have an29 opportunity to treat more at length the fiscal policies of American schools. At this point it is enough to note that American schools are what they are because they are free.

An interesting contrast can be drawn here between the practice in England and in the United States. In England vast sums of money make a free education accessible to certain selected individuals. The higher schools are not free to all comers, as ours are, but a bright boy—it is usually only the boy—who can pass a competitive examination is given a stipend, which provides his tuition and often enough more to get books and, if necessary, pay for transportation. The English theory is that it is the duty of the public to pay for selected boys, but not for boys in general. To the American it seems a little hazardous to select the leaders of the nation by competitive examinations given to eleven-year-old boys. On the other hand, the English think of our plan as wasteful because we postpone selection longer than they think we should. The contrast here pointed out is enough to draw our attention to the unique attitude of American schools, which are free to all and in this sense far more democratic than the higher schools of any European country.

Finally, we may point out that our schools are secular. Some of our own fellow countrymen do not believe in secular schools. We are familiar with the practice of organizing parochial schools. France and England have in recent years purchased secularization of their schools after long and bitter controversy. Germany gives instruction in religion as an important part of every course of study. In some sections of Germany the distinction between religious beliefs is carried into the school organization in such a way that one finds public schools set aside for the children of this and that sect. In all schools the pupil has a right to instruction in his own particular type of religion.

30

In the United States the complete democratization of the schools has been possible because differences in religion have been rigidly excluded. There is a common body of knowledge which can be administered in public schools without involving religion. The decision for such a separation was made long ago in this country and is one of the characteristic facts in our school system as well as in our general civic life.

The facts outlined in this chapter ought to create in the mind of the reader a vivid notion of what is meant by the words “school system.” The schools of America or any other country have a kind of colossal personality. The teacher who teaches a fifth grade or a sixth grade or a high-school class does not determine the character of the education given at these points in the system. To be sure, the teacher can do his or her work effectively or inefficiently. The special methods employed may be well or ill adapted to their ends. But above and beyond the individual teacher is the system which controls the pupil’s progress in many subtle ways and determines all the main lines of his training. The teacher who would succeed must understand this larger influence. Especially is it necessary that the teacher who aims to contribute to the rational development of the system through the scientific study of detailed problems become acquainted with the present characteristics of the system and comprehend something of the conditions which have produced these characteristics.

EXERCISES AND READINGS

Among textbooks there are such striking differences that the student will be able after even a superficial analysis to see that their authors had very different ideas about the use of texts. Find31 a textbook which is intended to give the pupil a start in a study rather than a complete discussion of the subject. Find a text which is intended to be learned rather than merely read. What parts of a textbook are addressed to the teacher and constitute teaching devices rather than material for students?

Contrast the ways in which different teachers use textbooks. Are there teachers who neglect the book very largely? When should a teacher lecture? Find specific examples of lessons which can best be taught (1) by questions and answers, (2) by written work, and (3) by lectures.

With regard to a given high school it is important to find out when it was established. What was its first course of study?

With regard to courses for girls, it is interesting to inquire how far classes in an elective system are chosen by boys and how far by girls. Why are conditions as they are?

The foregoing questions are asked on the assumption that the contrasts presented in the chapter are of value only when they make students keenly aware of the facts in their own environment. The facts of history are valuable chiefly because of the light they throw on the present.

Brown, E. E. Making of our Middle Schools. Longmans, Green, & Co. This is the only history of American secondary schools.

Bunker, F. F. “Reorganization of the Public School System,” in Bulletin No. 8, United States Bureau of Education, 1916. This shows how our present school system was organized.

Farrington, F. E. French Secondary Schools. Longmans, Green, & Co.

Farrington, F. E. The Public Primary School System of France. Teachers College.

Judd, C. H. “The Training of Teachers in England, Scotland, and Germany,” in Bulletin No. 35, United States Bureau of Education, 1914.

Monroe, W. S. “Development of Arithmetic as a School Subject,” in Bulletin No. 10, United States Bureau of Education, 1917. This bulletin tells of the origin of the present methods of teaching arithmetic.

Parker, S. C. The History of Modern Elementary Education. Ginn and Company. This is a very good summary of the facts regarding the development of American schools.

32

One does not have to go far from the door of any educational institution to find people who look on reading and writing—to say nothing of higher forms of education—as luxuries rather than necessities. There is the parent who is willing to take his child out of school for the sake of the wage which the child can earn. There is the negligent parent, often himself illiterate, who is utterly unconcerned about the education of his sons and daughters. Another kind of example appears in the boy or girl who goes out into the trades after a limited schooling and fails to keep up the type of intellectual activity which was cultivated in the school. Many a child who has been taught through years of instruction how to read makes very little use of his training in mature life.

An appeal to the history of civilization reveals the fact that there was a time when the opinion prevailed that education was unnecessary for the common man. The earliest schools were for the aristocracy and for the professional classes. Schools for all the people are of comparatively recent date.

In striking contrast with this attitude of neglect and indifference is the fact that to-day there are laws in all the civilized countries of the world compelling children of every social grade to attend school. Society as a whole does not33 share the slight esteem of reading exhibited by the man who takes his child out of school. Indeed, society has gone so far as to set aside that man’s judgment and to assume control of the child to the extent of insisting that the rudiments of an education shall be made universal.

Society still leaves it to the individual to decide whether he is to study higher branches. One may take algebra or not as one elects, but not so with arithmetic. The common interests of our common life dictate that everyone shall be able to count and to make accurate numerical statements. People must know some arithmetic; they must be able to read, or they are a menace to public comfort and safety.

The full acknowledgment of the fact that education is a public necessity has developed gradually. History shows us the steps by which this fact has been recognized in legislative action. The first step was the adoption of laws requiring communities to provide schools. We may put the matter in terms of contemporary conditions by referring to communities which would to-day be backward in this matter if it were not for state control. Thus there are sparsely settled districts or poor districts which cannot afford good schools, or, indeed, any kind of a school. The state is vitally interested in seeing to it that the untoward conditions in these regions do not deprive the children of an education. In the later years of their lives the children from these districts will surely scatter to other parts of the state. They will be less productive than they would have been if they had been educated. It is much more economical for the state as a whole to take a hand in the training of the children than to have to support even a small number of dependent adults during the unproductive period of later life when the consequences of poor schooling appear.

34

In some cases the delinquency of a community is due not to economic stress but to shortsighted frugality. Here again the higher authority of the larger community must take control and force the backward group to give the children such training as will bring them to reasonable productivity.

The earliest legislation on this matter is of the type which was quoted in the last chapter, where reference was made to the Connecticut law of 1650. Such legislation was addressed to the community and enjoined on it the obligation to provide schools.

Such compulsion of the community was followed, but at a much later date, by legislation compelling the child to attend school; and finally the period was reached in the midst of which we live to-day, when the state is taking a hand in the supervision of schools for the purpose of insuring as high and as uniform a grade of education as it can afford.

The first period of our national life, during which we were very gradually evolving the conception of a need for public education and were setting up the requirement of schools in every community, extended down to the decade before the Civil War. Professor Cubberley has given a very illuminating description of this period, from which we may quote the following extracts:

During the early decades of the nineteenth century, schools and the means of education made little progress. There were among the founders of our states certain far-seeing men who wished for general public education, but it was well along toward the middle of the century before these men represented more than a hopeful minority in most of our states, and in the South little was done until after the Civil War....

35

To be illiterate was no reproach, and it was possible to follow many pursuits successfully without having received any other education than the education of daily work and experience. A large proportion of the people felt that those who desired an education should pay for it. As the Rhode Island farmer expressed it to Henry Barnard in 1844, it would be as sensible to propose to take his plough away from him to plough his neighbor’s field as to take his money to educate his neighbor’s child. Others felt that at most free education should be extended only to the children of the poor, and for the rudiments of learning only. Still others felt that all forms of education would be conducted best if turned over to the various religious and educational societies of the time. A system of public instruction maintained by general taxation, such as we to-day enjoy, would not only have been declared unnecessary, but would have been stoutly resisted as well. The best schools, and often the only schools, were private schools supported by the tuition fees of those who could afford to use them, and most of these were more or less directly under church control.

Not until after the beginning of the nineteenth century was education regarded at all as a legitimate public function....

The different humanitarian movements which arose after 1820, and which, among other things, demanded public tax-supported schools for all, had not as yet made themselves felt. The people were poor, and indifferent as to education.

Gradually, and only after great effort, this condition of apathy and indifference was changed to one of active interest, though the change took place but slowly, and differed in point of time in different parts of the country. The Lancastrian system of monitorial instruction (by which a single teacher with the assistance of his best students, called monitors, taught hundreds of pupils), introduced into this country from England about 1806, for the first time made an elementary school training for all seem possible, from a financial point of view....

The idea that free education was a right, and that universal education was a necessity, began to be urged and to find acceptance. The land grants of Congress to the new states for the benefit of common schools greatly stimulated the movement. The published reports of those who had visited Pestalozzi’s school in36 Switzerland, and had examined the new state school system in Prussia, were extensively read. The moral and economic advantages of schools were set forth at length in resolutions, speeches, pamphlets, magazines, and books.

Just when this change took place cannot be definitely stated. Roughly speaking, it began about 1825 and was accomplished by 1850 in the Northern states. It was a gradual change rather than a sudden one, though rapid advances were at times made. The movement everywhere was greatly stimulated by the educational revival inaugurated by Horace Mann in Massachusetts in 1837. In the Southern states, with one or two exceptions, little was accomplished until after the Civil War and the Reconstruction Period were over. Almost everywhere it took place only after prolonged agitation, and ofttimes only after a bitter struggle. The indifference of legislatures, the unwillingness of taxpayers to assume the burdens of general taxation, the small sense of local responsibility, the satisfaction with existing conditions, the old aristocratic conception of education, the pauper and charity-school idea, and frequently the opposition of denominational and private schools,—all of these had to be met and overcome. The referendum was tried in a number of states, and sometimes more than once; in others, the question of free schools became a vital political issue....

By 1850, the principle of tax-supported schools had been generally accepted in all of the Northern states, and the beginnings of free schools made in some of the Southern states. Six state normal schools had been established, a number of states had provided for State Superintendents of Common Schools and for ex-officio State Boards of Education, and the movement for state control of education had begun. It may be said that it had not become a settled conviction with a majority of the people that the provision of some form of free education was a duty of the state, and that such education contributed in a general way, though just how was not at that time clear, to the moral uplift of the people, to a higher civic virtue, and to increased economic returns to the state. A new conception of free public education as a birthright of the child on the one hand, and as an exercise of the state’s inherent right to self-preservation and improvement on the other, had taken37 the place of the earlier conception of schools as merely a coöperative effort, based on economy, and for the instruction of youth merely in the rudiments of learning.9