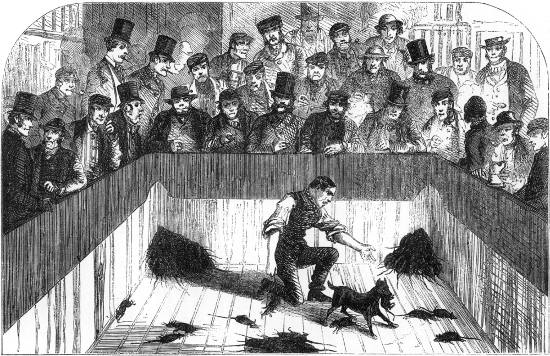

RATTING—“THE GRAHAM ARMS,” GRAHAM STREET.

[From a Photograph.]

Title: London Labour and the London Poor, Vol. 3

Author: Henry Mayhew

Release date: April 27, 2018 [eBook #57060]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Henry Flower, Suzanne Lybarger, the booksmiths

at eBookForge and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

In the html version of this eBook, images are linked to higher-resolution versions of the illustrations.

A Cyclopædia of the Condition and Earnings

OF

THOSE THAT WILL WORK

THOSE THAT CANNOT WORK, AND

THOSE THAT WILL NOT WORK

BY

HENRY MAYHEW

THE LONDON STREET-FOLK

COMPRISING

STREET SELLERS · STREET BUYERS · STREET FINDERS

STREET PERFORMERS · STREET ARTIZANS · STREET LABOURERS

WITH NUMEROUS ILLUSTRATIONS FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

VOLUME THREE

| First edition | 1851 |

| (Volume One only and parts of Volumes Two and Three) | |

| Enlarged edition (Four volumes) | 1861-62 |

| New impression | 1865 |

THE STREET-FOLK.

| PAGE | |

| The Destroyers of Vermin | 1 |

| Street-Exhibitors | 43 |

| Street-Musicians | 158 |

| Street-Vocalists | 190 |

| Street-Artists | 204 |

| Exhibitors of Trained Animals | 214 |

| Skilled and Unskilled Labour | 221 |

| Garret-Masters | 221 |

| The Coal-Heavers | 234 |

| Ballast-Men | 265 |

| Lumpers | 288 |

| The Dock-Labourers | 300 |

| Cheap Lodging-Houses | 312 |

| The Transit of Great Britain and the Metropolis | 318 |

| London Watermen, Lightermen, and Steamboat-Men | 327 |

| London Omnibus-Drivers and Conductors | 336 |

| London Cab-Drivers | 351 |

| London Carmen and Porters | 357 |

| London Vagrants | 368 |

| Meeting of Ticket-of-Leave Men | 430 |

| PAGE | |

| Rat-Killing at Sporting Public-Houses | 7 |

| Jack Black, Rat-Killer to Her Majesty | 11 |

| Punch’s Showman, with Assistant | 45 |

| Guy Faux | 63 |

| Street-Telescope Exhibitor | 81 |

| Street-Acrobats Performing | 93 |

| Street-Conjuror | 117 |

| Circus-Clown at Fair | 132 |

| Street-Performers on Stilts | 150 |

| Old Sarah | 160 |

| Ethiopian Serenaders | 190 |

| Interior of Photographer’s Travelling Caravan | 207 |

| A Garret-Master, or Cheap Cabinet-Maker | 225 |

| Gang of Coal-Whippers at work below Bridge | 241 |

| Coal-Porters filling Waggons at Coal-Wharf | 261 |

| Ballast-heavers at Work in the Pool | 279 |

| Lumpers Discharging Timber-Ship in Commercial Dock | 297 |

| A Dinner at a Cheap Lodging-House | 314 |

| Thames Lightermen tugging away at the Oar | 333 |

| Cab-Driver | 351 |

| Street Ticket-Porters with Knot | 364 |

| Vagrant in the Casual Ward of Workhouse | 387 |

| Vagrant, from the Refuge in Playhouse-Yard, Cripplegate | 406 |

| Vagrant, from Asylum for the Houseless Poor | 423 |

| Meeting of Ticket-of-Leave Men | 430 |

In “the Brill,” or rather in Brill-place, Somers’-town, there is a variety of courts branching out into Chapel-street, and in one of the most angular and obscure of these is to be found a perfect nest of rat-catchers—not altogether professional rat-catchers, but for the most part sporting mechanics and costermongers. The court is not easily to be found, being inhabited by men not so well known in the immediate neighbourhood as perhaps a mile or two away, and only to be discovered by the aid and direction of the little girl at the neighbouring cat’s-meat shop.

My first experience of this court was the usual disturbance at the entrance. I found one end or branch of it filled with a mob of eager listeners, principally women, all attracted to a particular house by the sounds of quarrelling. One man gave it as his opinion that the disturbers must have earned too much money yesterday; and a woman, speaking to another who had just come out, lifting up both her hands and laughing, said, “Here they are—at it again!”

The rat-killer whom we were in search of was out at his stall in Chapel-street when we called, but his wife soon fetched him. He was a strong, sturdy-looking man, rather above the middle height, with light hair, ending in sandy whiskers, reaching under his chin, sharp deep-set eyes, a tight-skinned nose that looked as if the cuticle had been stretched to its utmost on its bridge. He was dressed in the ordinary corduroy costermonger habit, having, in addition, a dark blue Guernsey drawn over his waistcoat.

The man’s first anxiety was to show us that rats were not his only diversion; and in consequence he took us into the yard of the house, where in a shed lay a bull-dog, a bull-bitch, and a litter of pups just a week old. They did not belong to him, but he said he did a good deal in the way of curing dogs when he could get ’em.

On a shelf in this shed were two large dishes, the one containing mussels without the shells, and the other eels; these are the commodities in which he deals at present, so that he is properly what one would call a “pickled-eel seller.”

We found his room on the first-floor clean and tidy, of a good size, containing two bedsteads and a large sea-chest, besides an old-fashioned, rickety, mahogany table, while in a far corner of the room, perhaps waiting for the cold weather and the winter’s fire, was an arm-chair. Behind the door hung a couple of dog-leads, made of strong leather, and ornamented with brass. Against one side of the wall were two framed engravings of animals, and a sort of chart of animated nature, while over the mantel-shelf was a variety of most characteristic articles. Among these appeared a model of a bull-dog’s head, cut out of sandstone, and painted in imitation of nature—a most marvellous piece of ugliness. “He was the best dog I ever see,” said the host, “and when I parted with him for a ten-pound note, a man as worked in the New Road took and made this model—he was a real beauty, was that dog. The man as carved that there, didn’t have no difficulty in holdin’ him still, becos he was very good at that sort o’ thing; and when he’d looked at anything he couldn’t be off doin’ it.”

There were also a great many common prints about the walls, “a penny each, frame and all,” amongst which were four dogs—all ratting—a game cock, two Robinson Crusoes, and three scripture subjects.

There was, besides, a photograph of another favourite dog which he’d “had give him.”

The man apologised for the bareness of the room, but said, “You see, master, my brother went over to ’Merica contracting for a railway[2] under Peto’s, and they sends to me about a year ago, telling me to get together as many likely fellows as I could (about a dozen), and take them over as excavators; and when I was ready, to go to Peto’s and get what money I wanted. But when I’d got the men, sold off all my sticks, and went for the money, they told me my brother had got plenty, and that if he wanted me he ought to be ashamed of hisself not to send some over hisself; so I just got together these few things again, and I ain’t heard of nothing at all about it since.”

After I had satisfied him that I was not a collector of dog-tax, trying to find out how many animals he kept, he gave me what he evidently thought was “a treat”—a peep at his bull-dog, which he fetched from upstairs, and let it jump about the room with a most unpleasant liberty, informing me the while how he had given five pound for him, and that one of the first pups he got by a bull he had got five pounds for, and that cleared him. “That Punch” (the bull-dog’s name), he said, “is as quiet as a lamb—wouldn’t hurt nobody; I frequently takes him through the streets without a lead. Sartainly he killed a cat the t’other afternoon, but he couldn’t help that, ’cause the cat flew at him; though he took it as quietly as a man would a woman in a passion, and only went at her just to save his eyes. But you couldn’t easy get him off, master, when he once got a holt. He was a good one for rats, and, he believed, the stanchest and tricksiest dog in London.”

When he had taken the brute upstairs, for which I was not a little thankful, the man made the following statement:—

“I a’n’t a Londoner. I’ve travelled all about the country. I’m a native of Iver, in Buckinghamshire. I’ve been three year here at these lodgings, and five year in London altogether up to last September.

“Before I come to London I was nothink, sir—a labouring man, an eshkewator. I come to London the same as the rest, to do anythink I could. I was at work at the eshkewations at King’s Cross Station. I work as hard as any man in London, I think.

“When the station was finished, I, having a large family, thought I’d do the best I could, so I went to be foreman at the Caledonian Sawmills. I stopped there a twelvemonth; but one day I went for a load and a-half of lime, and where you fetches a load and a-half of lime they always gives you fourpence. So as I was having a pint of beer out of it, my master come by and saw me drinking, and give me the sack. Then he wanted me to ax his pardon, and I might stop; but I told him I wouldn’t beg no one’s pardon for drinking a pint of beer as was give me. So I left there.

“Ever since the Great Western was begun, my family has been distributed all over the country, wherever there was a railway making. My brothers were contractors for Peto, and I generally worked for my brothers; but they’ve gone to America, and taken a contract for a railway at St. John’s, New Brunswick, British North America. I can do anything in the eshkewating way—I don’t care what it is.

“After I left the Caledonian Sawmills I went to Billingsgate, and bought anythink I could see a chance of gettin’ a shilling out on, or to’ards keeping my family.

“All my lifetime I’ve been a-dealing a little in rats; but it was not till I come to London that I turned my mind fully to that sort of thing. My father always had a great notion of the same. We all like the sport. When any on us was in the country, and the farmers wanted us to, we’d do it. If anybody heerd tell of my being an activish chap like, in that sort of way, they’d get me to come for a day or so.

“If anybody has a place that’s eaten up with rats, I goes and gets some ferruts, and takes a dog, if I’ve got one, and manages to kill ’em. Sometimes I keep my own ferruts, but mostly I borrows them. This young man that’s with me, he’ll sometimes have an order to go fifty or sixty mile into the country, and then he buys his ferruts, or gets them the best way he can. They charges a good sum for the loan of ’em—sometimes as much as you get for the job.

“You can buy ferruts at Leadenhall-market for 5s. or 7s.—it all depends; you can’t get them all at one price, some of ’em is real cowards to what others is; some won’t even kill a rat. The way we tries ’em is, we puts ’em down anywhere, in a room maybe, with a rat, and if they smell about and won’t go up to it, why they won’t do; ’cause you see, sometimes the ferrut has to go up a hole, and at the end there may be a dozen or sixteen rats, and if he hasn’t got the heart to tackle one on ’em, why he ain’t worth a farden.

“I have kept ferruts for four or five months at a time, but they’re nasty stinking things. I’ve had them get loose; but, bless you, they do no harm, they’re as hinnocent as cats; they won’t hurt nothink; you can play with them like a kitten. Some puts things down to ketch rats—sorts of pison, which is their secret—but I don’t. I relies upon my dogs and ferruts, and nothink else.

“I went to destroy a few rats up at Russell-square; there was a shore come right along, and a few holes—they was swarmed with ’em there—and didn’t know how it was; but the cleverest men in the world couldn’t ketch many there, ’cause you see, master, they run down the hole into the shore, and no dog could get through a rat-hole.

“I couldn’t get my living, though, at that business. If any gentleman comes to me and says he wants a dog cured, or a few rats destroyed, I does it.

“In the country they give you fourpence a rat, and you can kill sometimes as many in a farmyard as you can in London. The most I ever got for destroying rats was four bob, and[3] then I filled up the brickwork and made the holes good, and there was no more come.

“I calls myself a coster; some calls theirselves general dealers, but I doesn’t. I goes to market, and if one thing don’t suit, why I buys another.

“I don’t know whether you’ve heerd of it, master, or not, but I’m the man as they say kills rats—that’s to say, I kills ’em like a dog. I’m almost ashamed to mention it, and I shall never do it any more, but I’ve killed rats for a wager often. You see it’s only been done like for a lark; we’ve bin all together daring one another, and trying to do something as nobody else could. I remember the first time I did it for a wager, it was up at ——, where they’ve got a pit. There was a bull-dog a killing rats, so I says,

“‘Oh, that’s a duffin’ dog; any dog could kill quicker than him. I’d kill again him myself.’

“Well, then they chaffed me, and I warn’t goin’ to be done; so I says,

“‘I’ll kill again that dog for a sov’rin.’

“The sov’rin was staked. I went down to kill eight rats again the dog, and I beat him. I killed ’em like a dog, with my teeth. I went down hands and knees and bit ’em. I’ve done it three times for a sov’rin, and I’ve won each time. I feels very much ashamed of it, though.

“On the hind part of my neck, as you may see, sir, there’s a scar; that’s where I was bit by one; the rat twisted hisself round and held on like a vice. It was very bad, sir, for a long time; it festered, and broke out once or twice, but it’s all right now.”

“The rat, though small, weak, and contemptible in its appearance, possesses properties that render it a more formidable enemy to mankind, and more injurious to the interests of society, than even those animals that are endued with the greatest strength and the most rapacious dispositions. To the one we can oppose united powers and superior arts; with regard to the other, experience has convinced us that no art can counteract the effects of its amazing fecundity, and that force is ineffectually directed against an animal possessed of such variety of means to elude it.

“There are two kinds of rats known in this country,—the black rat, which was formerly universal here, but is now very rarely seen, having been almost extirpated by the large brown kind, which is generally distinguished by the name of the Norway rat.

“This formidable invader is now universally diffused through the whole country, from whence every method has been tried in vain to exterminate it. This species is about nine inches long, of a light-brown colour, mixed with tawny and ash; the throat and belly are of a dirty white, inclining to grey; its feet are naked, and of a pale flesh-colour; the tail is as long as the body, covered with minute dusky scales, thinly interspersed with short hairs. In summer it frequents the banks of rivers, ponds, and ditches, where it lives on frogs, fishes, and small animals. But its rapacity is not entirely confined to these. It destroys rabbits, poultry, young pigeons, &c. It infests the granary, the barn, and the storehouse; does infinite mischief among corn and fruit of all kinds; and not content with satisfying its hunger, frequently carries off large quantities to its hiding-place. It is a bold and fierce little animal, and when closely pursued, will turn and fasten on its assailant. Its bite is keen, and the wound it inflicts is painful and difficult to heal, owing to the form of its teeth, which are long, sharp, and of an irregular shape.

“The rat is amazingly prolific, usually producing from twelve to eighteen young ones at one time. Their numbers would soon increase beyond all power of restraint, were it not for an insatiable appetite, that impels them to destroy and devour each other. The weaker always fall a prey to the stronger; and a large male rat, which usually lives by itself, is dreaded by those of its own species as their most formidable enemy.

“It is a singular fact in the history of those animals, that the skins of such of them as have been devoured in their holes have frequently been found curiously turned inside out, every part being completely inverted, even to the ends of the toes. How the operation is performed it would be difficult to ascertain; but it appears to be effected in some peculiar mode of eating out the contents.

“Besides the numbers that perish in these unnatural conflicts, they have many fierce and inveterate enemies, that take every occasion to destroy them. Mankind have contrived various methods of exterminating these bold intruders. For this purpose traps are often found ineffectual, such being the sagacity of the animals, that when any are drawn into the snare, the others by such means learn to avoid the dangerous allurement, notwithstanding the utmost caution may have been used to conceal the design. The surest method of killing them is by poison. Nux vomica ground and mixed with oatmeal, with a small proportion of oil of rhodium and musk, have been found from experience to be very effectual.

“The water-rat is somewhat smaller than the Norway rat; its head larger and its nose thicker; its eyes are small; its ears short; scarcely appearing through the hair; its teeth are large, strong, and yellow; the hair on its body thicker and longer than that of the common rat, and chiefly of a dark brown colour mixed with red; the belly is grey; the tail five inches long, covered with short black hairs, and the tip with white.

“The water-rat generally frequents the sides of rivers, ponds, and ditches, where it burrows and forms its nest. It feeds on frogs, small fish and spawn, swims and dives remarkably fast, and can continue a long time under water.”[1]

In Mr. Charles Fothergill’s Essay on the Philosophy, Study, and Use of Natural History (1813), we find some reflections which remind us of Ray and Derham. We shall extract a few paragraphs which relate to the subject in hand.

“Nothing can afford a finer illustration of the beautiful order and simplicity of the laws which govern the creation, than the certainty, precision, and regularity with which the natural checks in the superabundant increase of each tribe of animals are managed; and every family is subject to the operation of checks peculiar to the species—whatever it may be—and established by a wise law of the Most High, to counteract the fatal effects that might arise from an ever-active populative principle. It is by the admirable disposition of these checks, the contemplation of which is alone sufficient to astonish the loftiest and most comprehensive soul of man, that the whole system of animal life, in all its various forms, is kept in due strength and equilibrium.

“This subject is worthy of the naturalist’s most serious consideration.”

“This great law,” Mr. F. proceeds, “pervades and affects the whole animal creation, and so active, unwearied, and rapid is the principle of increase over the means of subsistence amongst the inferior animals, that it is evident whole genera of carnivorous beings amongst beasts, birds, fish, reptiles, and insects, have been created for the express purpose (?) of suppressing the redundancy of others, and restraining their numbers within proper limits.

“But even the natural checks are insufficient to restrain the effects of a too-rapid populative principle in some animals, which have, therefore, certain destructive propensities given to them by the Creator, that operate powerfully upon themselves and their offspring, as may be particularly observed in the natural history of the rabbit, but which is still more evidently and strikingly displayed in the life and economy of the rat.

“It has been calculated by Mr. Pennant, and there can be no doubt of the truth of the statement, that the astonishing number of 1,274,840 may be produced from a single pair of rabbits in the short space of four years, as these animals in their wild state breed seven times in a-year, and generally produce eight young ones each time. They are capable of procreation at the age of five or six months, and the doe carries her burthen no more than thirty days.

“But the principle of increase is much more powerful, active, and effective in the common grey rat than in any other animal of equal size. This destructive animal is continually under the furor of animal love. The female carries her young for one month only; and she seldom or never produces a less number than twelve, but sometimes as many as eighteen at a litter—the medium number may be taken for an average—and the period of gestation, though of such short continuance, is confined to no particular season of the year.

“The embraces of the male are admitted immediately after the birth of the vindictive progeny; and it is a fact which I have ascertained beyond any doubt, that the female suckles her young ones almost to the very moment when another litter is dropping into the world as their successors.

“A celebrated Yorkshire rat-catcher whom I have occasionally employed, one day killed a large female rat, that was in the act of suckling twelve young ones, which had attained a very considerable growth; nevertheless, upon opening her swollen body, he found thirteen quick young, that were within a few days of their birth. Supposing, therefore, that the rat produces ten litters in the course of a year, and that no check on their increase should operate destructively for the space of four years, a number not far short of 3,000,000 might be produced from a single pair in that time!

“Now, the consequence of such an active and productive principle of increase, if suffered continually to operate without check, would soon be fatally obvious. We have heard of fertile plains devastated, and large towns undermined, in Spain, by rabbits; and even that a military force from Rome was once requested of the great Augustus to suppress the astonishing numbers of the same animal overrunning the island of Majorca and Minorca. This circumstance is recorded by Pliny.

“If, therefore, rats were suffered to multiply without the restraint of the most powerful and positive natural checks, not only would fertile plains and rich cities be undermined and destroyed, but the whole surface of the earth in a very few years would be rendered a barren and hideous waste, covered with myriads of famished grey rats, against which man himself would contend in vain. But the same Almighty Being who perceived a necessity for their existence, has also restricted their numbers within proper bounds, by creating to them many very powerful enemies, and still more effectually by establishing a propensity in themselves, the gratification of which has continually the effect of lessening their numbers, even more than any of their foreign enemies.

“The male rat has an insatiable thirst for the blood of his own offspring; the female, being aware of this passion, hides her young in such secret places as she supposes likely to escape notice or discovery, till her progeny are old enough to venture forth and stand upon[5] their own energies; but, notwithstanding this precaution, the male rat frequently discovers them, and destroys as many as he can; nor is the defence of the mother any very effectual protection, since she herself sometimes falls a victim to her temerity and her maternal tenderness.

“Besides this propensity to the destruction of their own offspring, when other food fails them, rats hunt down and prey upon each other with the most ferocious and desperate avidity, inasmuch as it not unfrequently happens, in a colony of these destructive animals, that a single male of more than ordinary powers, after having overcome and devoured all competitors with the exception of a few females, reigns the sole bloody and much-dreaded tyrant over a considerable territory, dwelling by himself in some solitary hole, and never appearing abroad without spreading terror and dismay even amongst the females whose embraces he seeks. In this relentless and bloody character may be found one of the most powerful and positive of the checks which operate to the repression of this species within proper bounds; a character which attaches, in a greater or less degree, to the whole Mus genus, and in which we may readily perceive the cause of the extirpation of the old black rats of England, Mus rathus; for the large grey rats, having superior bodily powers united to the same carnivorous propensities, would easily conquer and destroy their black opponents wherever they could be found, and whenever they met to dispute the title of possession or of sovereignty.”

When the young rats begin to issue from their holes, the mother watches, defends, and even fights with the cats, in order to save them. A large rat is more mischievous than a young cat, and nearly as strong: the rat uses her fore-teeth, and the cat makes most use of her claws; so that the latter requires both to be vigorous and accustomed to fight, in order to destroy her adversary.

The weasel, though smaller, is a much more dangerous and formidable enemy to the rat, because it can follow it into its retreat. Its strength being nearly equal to that of the rat, the combat often continues for a long time, but the method of using their arms by the opponents is very different. The rat wounds only by repeated strokes with his fore-teeth, which are better formed for gnawing than biting; and, being situated at the extremity of the lever or jaw, they have not much force. But the weasel bites cruelly with the whole jaw, and, instead of letting go its hold, sucks the blood from the wounded part, so that the rat is always killed.

Considering the immense number of rats which form an article of commerce with many of the lower orders, whose business it is to keep them for the purpose of rat matches, I thought it necessary, for the full elucidation of my subject, to visit the well-known public-house in London, where, on a certain night in the week, a pit is built up, and regular rat-killing matches take place, and where those who have sporting dogs, and are anxious to test their qualities, can, after such matches are finished, purchase half a dozen or a dozen rats for them to practise upon, and judge for themselves of their dogs’ “performances.”

To quote the words printed on the proprietor’s card, “he is always at his old house at home, as usual, to discuss the fancy generally.”

I arrived at about eight o’clock at the tavern where the performances were to take place. I was too early, but there was plenty to occupy my leisure in looking at the curious scene around me, and taking notes of the habits and conversation of the customers who were flocking in.

The front of the long bar was crowded with men of every grade of society, all smoking, drinking, and talking about dogs. Many of them had brought with them their “fancy” animals, so that a kind of “canine exhibition” was going on; some carried under their arm small bull-dogs, whose flat pink noses rubbed against my arm as I passed; others had Skye-terriers, curled up like balls of hair, and sleeping like children, as they were nursed by their owners. The only animals that seemed awake, and under continual excitement, were the little brown English terriers, who, despite the neat black leathern collars by which they were held, struggled to get loose, as if they smelt the rats in the room above, and were impatient to begin the fray.

There is a business-like look about this tavern which at once lets you into the character of the person who owns it. The drinking seems to have been a secondary notion in its formation, for it is a low-roofed room without any of those adornments which are now generally considered so necessary to render a public-house attractive. The tubs where the spirits are kept are blistered with the heat of the gas, and so dirty that the once brilliant gilt hoops are now quite black.

Sleeping on an old hall-chair lay an enormous white bulldog, “a great beauty,” as I was informed, with a head as round and smooth as a clenched boxing-glove, and seemingly too large for the body. Its forehead appeared to protrude in a manner significant of water on the brain, and almost overhung the short nose, through which the animal breathed heavily. When this dog, which was the admiration of all beholders, rose up, its legs were as bowed as a tailor’s, leaving a peculiar pear-shaped opening between them, which, I was informed, was one of its points of beauty. It was a white dog, with a sore look, from its being peculiarly pink round the eyes, nose, and indeed at all the edges of its body.

On the other side of the fire-place was a white bull-terrier dog, with a black patch over the eye, which gave him rather a disreputable look. This animal was watching the movements of the customers in front, and occasionally, when the entrance-door was swung back, would give a growl of inquiry as to what the fresh-comer wanted. The proprietor was kind enough to inform me, as he patted this animal’s ribs, which showed like the hoops on a butter-firkin, that he considered there had been a “little of the greyhound in some of his back generations.”

About the walls were hung clusters of black leather collars, adorned with brass rings and clasps, and pre-eminent was a silver dog-collar, which, from the conversation of those about me, I learnt was to be the prize in a rat-match to be “killed for” in a fortnight’s time.

As the visitors poured in, they, at the request of the proprietor “not to block up the bar,” took their seats in the parlour, and, accompanied by a waiter, who kept shouting, “Give your orders, gentlemen,” I entered the room.

I found that, like the bar, no pains had been taken to render the room attractive to the customers, for, with the exception of the sporting pictures hung against the dingy paper, it was devoid of all adornment. Over the fireplace were square glazed boxes, in which were the stuffed forms of dogs famous in their day. Pre-eminent among the prints was that representing the “Wonder” Tiny, “five pounds and a half in weight,” as he appeared killing 200 rats. This engraving had a singular look, from its having been printed upon a silk handkerchief. Tiny had been a great favourite with the proprietor, and used to wear a lady’s bracelet as a collar.

Among the stuffed heads was one of a white bull-dog, with tremendous glass eyes sticking out, as if it had died of strangulation. The proprietor’s son was kind enough to explain to me the qualities that had once belonged to this favourite. “They’ve spoilt her in stuffing, sir,” he said; “made her so short in the head; but she was the wonder of her day. There wasn’t a dog in England as would come nigh her. There’s her daughter,” he added, pointing to another head, something like that of a seal, “but she wasn’t reckoned half as handsome as her mother, though she was very much admired in her time.

“That there is a dog,” he continued, pointing to one represented with a rat in its mouth, “it was as good as any in England, though it’s so small. I’ve seen her kill a dozen rats almost as big as herself, though they killed her at last; for sewer-rats are dreadful for giving dogs canker in the mouth, and she wore herself out with continually killing them, though we always rinsed her mouth out well with peppermint and water while she were at work. When rats bite they are pisonous, and an ulcer is formed, which we are obleeged to lance; that’s what killed her.”

The company assembled in “the parlour” consisted of sporting men, or those who, from curiosity, had come to witness what a rat-match was like. Seated at the same table, talking together, were those dressed in the costermonger’s suit of corduroy, soldiers with their uniforms carelessly unbuttoned, coachmen in their livery, and tradesmen who had slipped on their evening frock-coats, and run out from the shop to see the sport.

The dogs belonging to the company were standing on the different tables, or tied to the legs of the forms, or sleeping in their owners’ arms, and were in turn minutely criticised—their limbs being stretched out as if they were being felt for fractures, and their mouths looked into, as if a dentist were examining their teeth. Nearly all the little animals were marked with scars from bites. “Pity to bring him up to rat-killing,” said one, who had been admiring a fierce-looking bull-terrier, although he did not mention at the same time what line in life the little animal ought to pursue.

At another table one man was declaring that his pet animal was the exact image of the celebrated rat-killing dog “Billy,” at the same time pointing to the picture against the wall of that famous animal, “as he performed his wonderful feat of killing 500 rats in five minutes and a half.”

There were amongst the visitors some French gentlemen, who had evidently witnessed nothing of the kind before; and whilst they endeavoured to drink their hot gin and water, they made their interpreter translate to them the contents of a large placard hung upon a hatpeg, and headed—

About nine o’clock the proprietor took the chair in the parlour, at the same time giving the order to “shut up the shutters in the room above, and light up the pit.” This announcement seemed to rouse the spirits of the impatient assembly, and even the dogs tied to the legs of the tables ran out to the length of their leathern thongs, and their tails curled like eels, as if they understood the meaning of the words.

“Why, that’s the little champion,” said the proprietor, patting a dog with thighs like a grasshopper, and whose mouth opened back to its ears. “Well, it is a beauty! I wish I could gammon you to take a ‘fiver’ for it.” Then looking round the room, he added, “Well, gents, I’m glad to see you look so comfortable.”

The performances of the evening were somewhat hurried on by the entering of a young gentleman, whom the waiters called “Cap’an.”

“Now, Jem, when is this match coming off?” the Captain asked impatiently; and despite[7] the assurance that they were getting ready, he threatened to leave the place if kept waiting much longer. This young officer seemed to be a great “fancier” of dogs, for he made the round of the room, handling each animal in its turn, feeling and squeezing its feet, and scrutinising its eyes and limbs with such minuteness, that the French gentlemen were forced to inquire who he was.

There was no announcement that the room above was ready, though everybody seemed to understand it; for all rose at once, and mounting the broad wooden staircase, which led to what was once the “drawing-room,” dropped their shillings into the hand of the proprietor, and entered the rat-killing apartment.

“The pit,” as it is called, consists of a small circus, some six feet in diameter. It is about as large as a centre flower-bed, and is fitted with a high wooden rim that reaches to elbow height. Over it the branches of a gas lamp are arranged, which light up the white painted floor, and every part of the little arena. On one side of the room is a recess, which the proprietor calls his “private box,” and this apartment the Captain and his friend soon took possession of, whilst the audience generally clambered upon the tables and forms, or hung over the sides of the pit itself.

All the little dogs which the visitors had brought up with them were now squalling and barking, and struggling in their masters’ arms, as if they were thoroughly acquainted with the uses of the pit; and when a rusty wire cage of rats, filled with the dark moving mass, was brought forward, the noise of the dogs was so great that the proprietor was obliged to shout out—“Now, you that have dogs do make ’em shut up.”

The Captain was the first to jump into the pit. A man wanted to sell him a bull-terrier, spotted like a fancy rabbit, and a dozen of rats was the consequent order.

The Captain preferred pulling the rats out of the cage himself, laying hold of them by their tails and jerking them into the arena. He was cautioned by one of the men not to let them bite him, for “believe me,” were the words, “you’ll never forget, Cap’an; these ’ere are none of the cleanest.”

Whilst the rats were being counted out, some of those that had been taken from the cage ran about the painted floor and climbed up the young officer’s legs, making him shake them off and exclaim, “Get out, you varmint!” whilst others of the ugly little animals sat upon their hind legs, cleaning their faces with their paws.

When the dog in question was brought forth and shown the dozen rats, he grew excited, and stretched himself in his owner’s arms, whilst all the other animals joined in a full chorus of whining.

“Chuck him in,” said the Captain, and over went the dog; and in a second the rats were running round the circus, or trying to hide themselves between the small openings in the boards round the pit.

Although the proprietor of the dog endeavoured to speak up for it, by declaring “it was a good ’un, and a very pretty performer,” still it was evidently not worth much in a rat-killing sense; and if it had not been for his “second,” who beat the sides of the pit with his hand, and shouted “Hi! hi! at ’em!” in a most bewildering manner, we doubt if the terrier would not have preferred leaving the rats to themselves, to enjoy their lives. Some of the rats, when the dog advanced towards them, sprang up in his face, making him draw back with astonishment. Others, as he bit them, curled round in his mouth and fastened on his nose, so that he had to carry them as a cat does its kittens. It also required many shouts of “Drop it—dead ’un,” before he would leave those he had killed.

We cannot say whether the dog was eventually bought; but from its owner’s exclaiming, in a kind of apologetic tone, “Why, he never saw a rat before in all his life,” we fancy no dealings took place.

The Captain seemed anxious to see as much sport as he could, for he frequently asked those who carried dogs in their arms whether “his little ’un would kill,” and appeared sorry when such answers were given as—“My dog’s mouth’s a little out of order, Cap’an,” or “I’ve only tried him at very small ’uns.”

One little dog was put in the pit to amuse himself with the dead bodies. He seized hold of one almost as big as himself, shook it furiously till the head thumped the floor like a drumstick, making those around shout with laughter, and causing one man to exclaim, “He’s a good ’un at shaking heads and tails, ain’t he?”

Preparations now began for the grand match of the evening, in which fifty rats were to be killed. The “dead ’uns” were gathered up by their tails and flung into the corner. The floor was swept, and a big flat basket produced, like those in which chickens are brought to market, and under whose iron wire top could be seen small mounds of closely packed rats.

This match seemed to be between the proprietor and his son, and the stake to be gained was only a bottle of lemonade, of which the father stipulated he should have first drink.

It was strange to observe the daring manner in which the lad introduced his hand into the rat cage, sometimes keeping it there for more than a minute at a time, as he fumbled about and stirred up with his fingers the living mass, picking out, as he had been requested, “only the big ’uns.”

When the fifty animals had been flung into the pit, they gathered themselves together into a mound which reached one-third up the sides, and which reminded one of the heap of hair-sweepings in a barber’s shop after a heavy day’s cutting. These were all sewer and water-ditch[8] rats, and the smell that rose from them was like that from a hot drain.

The Captain amused himself by flicking at them with his pocket handkerchief, and offering them the lighted end of his cigar, which the little creatures tamely snuffed at, and drew back from, as they singed their noses.

It was also a favourite amusement to blow on the mound of rats, for they seemed to dislike the cold wind, which sent them fluttering about like so many feathers; indeed, whilst the match was going on, whenever the little animals collected together, and formed a barricade as it were to the dog, the cry of “Blow on ’em! blow on ’em!” was given by the spectators, and the dog’s second puffed at them as if extinguishing a fire, when they would dart off like so many sparks.

The company was kept waiting so long for the match to begin that the impatient Captain again threatened to leave the house, and was only quieted by the proprietor’s reply of “My dear friend, be easy, the boy’s on the stairs with the dog;” and true enough we shortly heard a wheezing and a screaming in the passage without, as if some strong-winded animal were being strangled, and presently a boy entered, carrying in his arms a bull-terrier in a perfect fit of excitement, foaming at the mouth and stretching its neck forward, so that the collar which held it back seemed to be cutting its throat in two.

The animal was nearly mad with rage—scratching and struggling to get loose. “Lay hold a little closer up to the head or he’ll turn round and nip yer,” said the proprietor to his son.

Whilst the gasping dog was fastened up in a corner to writhe its impatience away, the landlord made inquiries for a stop-watch, and also for an umpire to decide, as he added, “whether the rats were dead or alive when they’re ‘killed,’ as Paddy says.”

When all the arrangements had been made the “second” and the dog jumped into the pit, and after “letting him see ’em a bit,” the terrier was let loose.

The moment the dog was “free,” he became quiet in a most business-like manner, and rushed at the rats, burying his nose in the mound till he brought out one in his mouth. In a short time a dozen rats with wetted necks were lying bleeding on the floor, and the white paint of the pit became grained with blood.

In a little time the terrier had a rat hanging to his nose, which, despite his tossing, still held on. He dashed up against the sides, leaving a patch of blood as if a strawberry had been smashed there.

“He doesn’t squeal, that’s one good thing,” said one of the lookers-on.

As the rats fell on their sides after a bite they were collected together in the centre, where they lay quivering in their death-gasps!

“Hi, Butcher! hi, Butcher!” shouted the second, “good dog! bur-r-r-r-r-h!” and he beat the sides of the pit like a drum till the dog flew about with new life.

“Dead ’un! drop it!” he cried, when the terrier “nosed” a rat kicking on its side, as it slowly expired of its broken neck.

“Time!” said the proprietor, when four of the eight minutes had expired, and the dog was caught up and held panting, his neck stretched out like a serpent’s, staring intently at the rats which still kept crawling about.

The poor little wretches in this brief interval, as if forgetting their danger, again commenced cleaning themselves, some nibbling the ends of their tails, others hopping about, going now to the legs of the lad in the pit, and sniffing at his trousers, or, strange to say, advancing, smelling, to within a few paces of their enemy the dog.

The dog lost the match, and the proprietor, we presume, honourably paid the bottle of lemonade to his son. But he was evidently displeased with the dog’s behaviour, for he said, “He won’t do for me—he’s not one of my sort! Here, Jim, tell Mr. G. he may have him if he likes; I won’t give him house room.”

A plentiful shower of halfpence was thrown into the pit as a reward for the second who had backed the dog.

A slight pause now took place in the proceedings, during which the landlord requested that the gentlemen “would give their minds up to drinking; you know the love I have for you,” he added jocularly, “and that I don’t care for any of you;” whilst the waiter accompanied the invitation with a cry of “Give your orders, gentlemen,” and the lad with the rats asked if “any other gentleman would like any rats.”

Several other dogs were tried, and amongst them one who, from the size of his stomach, had evidently been accustomed to large dinners, and looked upon rat-killing as a sport and not as a business. The appearance of this fat animal was greeted with remarks such as “Why don’t you feed your dog?” and “You shouldn’t give him more than five meals a-day.”

Another impatient bull-terrier was thrown into the midst of a dozen rats. He did his duty so well, that the admiration of the spectators was focussed upon him.

“Ah,” said one, “he’d do better at a hundred than twelve;” whilst another observed, “Rat-killing’s his game, I can see;” while the landlord himself said, “He’s a very pretty creetur’, and I’d back him to kill against anybody’s dog at eight and a half or nine.”

The Captain was so startled with this terrier’s “cleverness,” that he vowed that if she could kill fifteen in a minute “he’d give a hundred guineas for her.”

It was nearly twelve o’clock before the evening’s performance concluded. Several of the[9] spectators tried their dogs upon two or three rats, either the biggest or the smallest that could be found: and many offers as to what “he wanted for the dog,” and many inquiries as to “who was its father,” were made before the company broke up.

At last the landlord, finding that no “gentleman would like a few rats,” and that his exhortations to “give their minds up to drinking” produced no further effect upon the company, spoke the epilogue of the rat tragedies in these words;—

“Gentlemen, I give a very handsome solid silver collar to be killed for next Tuesday. Open to all the world, only they must be novice dogs, or at least such as is not considered pheenomenons. We shall have plenty of sport, gentlemen, and there will be loads of rat-killing. I hope to see all my kind friends, not forgetting your dogs, likewise; and may they be like the Irishman all over, who had good trouble to catch and kill ’em, and took good care they didn’t come to life again. Gentlemen, there is a good parlour down-stairs, where we meets for harmony and entertainment.”

The proprietor of one of the largest sporting public-houses in London, who is celebrated for the rat-matches which come off weekly at his establishment, was kind enough to favour me with a few details as to the quality of those animals which are destroyed in his pit. His statement was certainly one of the most curious that I have listened to, and it was given to me with a readiness and a courtesy of manner such as I have not often met with during my researches. The landlord himself is known in pugilistic circles as one of the most skilful boxers among what is termed the “light weights.”

His statement is curious, as a proof of the large trade which is carried on in these animals, for it would seem that the men who make a business of catching rats are not always employed as “exterminators,” for they make a good living as “purveyors” for supplying the demands of the sporting portion of London.

“The poor people,” said the sporting landlord, “who supply me with rats, are what you may call barn-door labouring poor, for they are the most ignorant people I ever come near. Really you would not believe people could live in such ignorance. Talk about Latin and Greek, sir, why English is Latin to them—in fact, I have a difficulty to understand them myself. When the harvest is got in, they go hunting the hedges and ditches for rats. Once the farmers had to pay 2d. a-head for all rats caught on their grounds, and they nailed them up against the wall. But now that the rat-ketchers can get 3d. each by bringing the vermin up to town, the farmers don’t pay them anything for what they ketch, but merely give them permission to hunt them in their stacks and barns, so that they no longer get their 2d. in the country, though they get their 3d. in town.

“I have some twenty families depending upon me. From Clavering, in Essex, I suppose I have hundreds of thousands of rats sent to me in wire cages fitted into baskets. From Enfield I have a great quantity, but the ketchers don’t get them all there, but travel round the country for scores of miles, for you see 3d. a-head is money; besides, there are some liberal farmers who will still give them a halfpenny a-head into the bargain. Enfield is a kind of head-quarters for rat-ketchers.

“It’s dangerous work, though, for you see there is a wonderful deal of difference in the specie of rats. The bite of sewer or water-ditch rats is very bad. The water and ditch rat lives on filth, but your barn-rat is a plump fellow, and he lives on the best of everything. He’s well off. There’s as much difference between the barn and sewer-rats as between a brewer’s horse and a costermonger’s. Sewer-rats are very bad for dogs, their coats is poisonous.

“Some of the rats that are brought to me are caught in the warehouses in the City. Wherever there is anything in the shape of provisions, there you are sure to find Mr. Rat an intruder. The ketchers are paid for ketching them in the warehouses, and then they are sold to me as well, so the men must make a good thing of it. Many of the more courageous kind of warehousemen will take a pleasure in hunting the rats themselves.

“I should think I buy in the course of the year, on the average, from 300 to 700 rats a-week.” (Taking 500 as the weekly average, this gives a yearly purchase of 26,000 live rats.) “That’s what I kill taking all the year round, you see. Some first-class chaps will come here in the day-time, and they’ll try their dogs. They’ll say, ‘Jimmy, give the dog 100.’ After he’s polished them off they’ll say, perhaps, ‘Hang it, give him another 100.’ Bless you!” he added, in a kind of whisper, “I’ve had noble ladies and titled ladies come here to see the sport—on the quiet, you know. When my wife was here they would come regular, but now she’s away they don’t come so often.

“The largest quantity of rats I’ve bought from one man was five guineas’ worth, or thirty-five dozen at 3d. a-head, and that’s a load for a horse. This man comes up from Clavering in a kind of cart, with a horse that’s a regular phenomena, for it ain’t like a beast nor nothing. I pays him a good deal of money at times, and I’m sure I can’t tell what he does with it; but they do tell me that he deals in old iron, and goes buying it up, though he don’t seem to have much of a head-piece for that sort of fancy neither.

“During the harvest-time the rats run scarcer you see, and the ketcher turns up rat-[10]ketching for harvest work. After the harvest rats gets plentiful again.

“I’ve had as many as 2000 rats in this very house at one time. They’ll consume a sack of barley-meal a week, and the brutes, if you don’t give ’em good stuff, they’ll eat one another, hang ’em!

“I’m the oldest canine fancier in London, and I’m the first that started ratting; in fact, I know I’m the oldest caterer in rat-killing in the metropolis. I began as a lad, and I had many noble friends, and was as good a man then as I am now. In fact, when I was seventeen or eighteen years of age I was just like what my boy is now. I used at that time to be a great public charakter, and had many liberal friends—very liberal friends. I used to give them rat sports, and I have kept to it ever since. My boy can handle rats now just as I used to then.

“Have I been bit by them? Aye, hundreds of times. Now, some people will say, ‘Rub yourself over with caraway and stuff, and then rats won’t bite you.’ But I give you my word and honour it’s all nonsense, sir.

“As I said, I was the first in London to give rat sports, and I’ve kept to it ever since. Bless you, there’s nothing that a rat won’t bite through. I’ve seen my lads standing in the pit with the rats running about them, and if they haven’t taken the precaution to tie their trousers round with a bit of string at the bottom, they’d have as many as five or six rats run up their trouser-legs. They’ll deliberately take off their clothes and pick them out from their shirts, and bosoms, and breeches. Some people is amused, and others is horror-struck. People have asked them whether they ain’t rubbed? They’ll say ‘Yes,’ but that’s as a lark; ’cos, sometimes when my boy has been taking the rats out of the cage, and somebody has taken his attention off, talking to him, he has had a bite, and will turn to me with his finger bleeding, and say, ‘Yes, I’m rubbed, ain’t I, father? look here!’

“A rat’s bite is very singular, it’s a three-cornered one, like a leech’s, only deeper, of course, and it will bleed for ever such a time. My boys have sometimes had their fingers go dreadfully bad from rat-bites, so that they turn all black and putrid like—aye, as black as the horse-hair covering to my sofa. People have said to me, ‘You ought to send the lad to the hospital, and have his finger took off;’ but I’ve always left it to the lads, and they’ve said, ‘Oh, don’t mind it, father; it’ll get all right by and by.’ And so it has.

“The best thing I ever found for a rat-bite was the thick bottoms of porter-casks put on as a poultice. The only thing you can do is to poultice, and these porter bottoms is so powerful and draws so, that they’ll actually take thorns out of horses’ hoofs and feet after steeplechasing.

“In handling rats, it’s nothing more in the world but nerve that does it. I should faint now if a rat was to run up my breeches, but I have known the time when I’ve been kivered with ’em.

“I generally throw my dead rats away now; but two or three years since my boys took the idea of skinning them into their heads, and they did about 300 of them, and their skins was very promising. The boys was, after all, obliged to give them away to a furrier, for my wife didn’t like the notion, and I said, ‘Throw them away;’ but the idea strikes me to be something, and one that is lost sight of, for the skins are warm and handsome-looking—a beautiful grey.

“There’s nothing turns so quickly as dead rats, so I am obleeged to have my dustmen come round every Wednesday morning; and regularly enough they call too, for they know where there is a bob and a pot. I generally prefers using the authorised dustmen, though the others come sometimes—the flying dustmen they call ’em—and if they’re first, they has the job.

“It strikes me, though, that to throw away so many valuable skins is a good thing lost sight of.

“The rats want a deal of watching, and a deal of sorting. Now you can’t put a sewer and a barn-rat together, it’s like putting a Roosshian and a Turk under the same roof.

“I can tell a barn-rat from a ship-rat or a sewer-rat in a minute, and I have to look over my stock when they come in, or they’d fight to the death. There’s six or seven different kinds of rats, and if we don’t sort ’em they tear one another to pieces. I think when I have a number of rats in the house, that I am a lucky man if I don’t find a dozen dead when I go up to them in the morning; and when I tell you that at times—when I’ve wanted to make up my number for a match—I’ve given 21s. for twenty rats, you may think I lose something that way every year. Rats, even now, is occasionally 6s. a-dozen; but that, I think, is most inconsistent.

“If I had my will, I wouldn’t allow sewer ratting, for the rats in the shores eats up a great quantity of sewer filth and rubbish, and is another specie of scavenger in their own way.”

After finishing his statement, the landlord showed me some very curious specimens of tame rats—some piebald, and others quite white, with pink eyes, which he kept in cages in his sitting-room. He took them out from their cages, and handled them without the least fear, and even handled them rather rudely, as he showed me the peculiarities of their colours; yet the little tame creatures did not once attempt to bite him. Indeed, they appeared to have lost the notion of regaining their liberty, and when near their cages struggled to return to their nests.

In one of these boxes a black and a white rat were confined together, and the proprietor, pointing to them, remarked, “I hope they’ll[11] breed, for though white rats is very scarce, only occurring in fact by a freak of nature, I fancy I shall be able, with time and trouble, to breed ’em myself. The old English rat is a small jet-black rat; but the first white rat as I heard of come out of a burial-ground. At one time I bred rats very largely, but now I leaves that fancy to my boys, for I’ve as much as I can do continuing to serve my worthy patrons.”

As I wished to obtain the best information about rat and vermin destroying, I thought I could not do better now than apply to that eminent authority “the Queen’s ratcatcher,” and accordingly I sought an interview with Mr. “Jack” Black, whose hand-bills are headed—“V.R. Rat and mole destroyer to Her Majesty.”

I had already had a statement from the royal bug-destroyer relative to the habits and means of exterminating those offensive vermin, and I was desirous of pairing it with an account of the personal experience of the Queen of England’s ratcatcher.

In the sporting world, and among his regular customers, the Queen’s ratcatcher is better known by the name of Jack Black. He enjoys the reputation of being the most fearless handler of rats of any man living, playing with them—as one man expressed it to me—“as if they were so many blind kittens.”

The first time I ever saw Mr. Black was in the streets of London, at the corner of Hart-street, where he was exhibiting the rapid effects of his rat poison, by placing some of it in the mouth of a living animal. He had a cart then with rats painted on the panels, and at the tailboard, where he stood lecturing, he had a kind of stage rigged up, on which were cages filled with rats, and pills, and poison packages.

Here I saw him dip his hand into this cage of rats and take out as many as he could hold, a feat which generally caused an “oh!” of wonder to escape from the crowd, especially when they observed that his hands were unbitten. Women more particularly shuddered when they beheld him place some half-dozen of the dusty-looking brutes within his shirt next his skin; and men swore the animals had been tamed, as he let them run up his arms like squirrels, and the people gathered round beheld them sitting on his shoulders cleaning their faces with their front-paws, or rising up on their hind legs like little kangaroos, and sniffing about his ears and cheeks.

But those who knew Mr. Black better, were well aware that the animals he took up in his hand were as wild as any of the rats in the sewers of London, and that the only mystery in the exhibition was that of a man having courage enough to undertake the work.

I afterwards visited Jack Black at his house in Battersea. I had some difficulty in discovering his country residence, and was indebted to a group of children gathered round and staring at the bird-cage in the window of his cottage for his address. Their exclamations of delight at a grey parrot climbing with his beak and claws about the zinc wires of his cage, and the hopping of the little linnets there, in the square boxes scarcely bigger than a brick, made me glance up at the door to discover who the bird-fancier was; when painted on a bit of zinc—just large enough to fit the shaft of a tax cart—I saw the words, “J. Black, Rat Destroyer to Her Majesty,” surmounted by the royal initials, V.R., together with the painting of a white rat.

Mr. Black was out “sparrer ketching,” as his wife informed me, for he had an order for three dozen, “which was to be shot in a match” at some tea-gardens close by.

When I called again Mr. Black had returned, and I found him kneeling before a big, rusty iron-wire cage, as large as a sea-chest, and transferring the sparrows from his bird-catching apparatus to the more roomy prison.

He transacted a little business before I spoke to him, for the boys about the door were asking, “Can I have one for a penny, master?”

There is evidently a great art in handling birds; for when Mr. Black held one, he took hold of it by the wings and tail, so that the little creature seemed to be sitting upright and had not a feather rumpled, while it stretched out its neck and looked around it; the boys, on the contrary, first made them flutter their feathers as rough as a hair ball, and then half smothered them between their two hands, by holding them as if they wished to keep them hot.

I was soon at home with Mr. Black. He was a very different man from what I had expected to meet, for there was an expression of kindliness in his countenance, a quality which does not exactly agree with one’s preconceived notions of ratcatchers. His face had a strange appearance, from his rough, uncombed hair, being nearly grey, and his eyebrows and whiskers black, so that he looked as if he wore powder.

Mr. Black informed me that the big iron-wire cage, in which the sparrows were fluttering about, had been constructed by him for rats, and that it held over a thousand when full—for rats are packed like cups, he said, one over the other. “But,” he added, “business is bad for rats, and it makes a splendid havery; besides, sparrers is the rats of birds, sir, for if you look at ’em in a cage they always huddles up in a corner like rats in a pit, and they are a’most vermin in colour and habits, and eats anything.”

The ratcatcher’s parlour was more like a shop than a family apartment. In a box, with iron bars before it, like a rabbit-hutch, was a white ferret, twisting its long thin body with a snake-like motion up and down the length of its prison, as restlessly as if it were a miniature polar bear.

When Mr. Black called “Polly” to the ferret, it came to the bars and fixed its pink eyes on him. A child lying on the floor poked its fingers into the cage, but Polly only smelt at them, and, finding them not good to eat, went away.

Mr. Black stuffs animals and birds, and also catches fish for vivaria. Against the walls were the furred and feathered remains of departed favourites, each in its glazed box and appropriate attitude. There was a famous polecat—“a first-rater at rats” we were informed. Here a ferret “that never was equalled.” This canary “had earned pounds.” That linnet “was the wonder of its day.” The enormous pot-bellied carp, with the miniature rushes painted at the back of its case, was caught in the Regent’s Park waters.

In another part of the room hung fishing-lines, and a badger’s skin, and lead-bobs and curious eel-hooks—the latter as big as the curls on the temples of a Spanish dancer, and from here Mr. Black took down a transparent-looking fish, like a slip of parchment, and told me that it was a fresh-water smelt, and that he caught it in the Thames—“the first he ever heard of.” Then he showed me a beetle suspended to a piece of thread, like a big spider to its web, and this he informed me was the Thames beetle, “which either live by land or water.”

“You ketch ’em,” continued Mr. Black, “when they are swimming on their backs, which is their nature, and when they turns over you finds ’em beautifully crossed and marked.”

Round the room were hung paper bags, like those in which housewives keep their sweet herbs. “All of them there, sir, contain cured fish for eating,” Mr. Black explained to me.

“I’m called down here the Battersea otter,” he went on, “for I can go out at four in the morning, and come home by eight with a barrowful of freshwater fish. Nobody knows how I do it, because I never takes no nets or lines with me. I assure them I ketch ’em with my hands, which I do, but they only laughs increderlous like. I knows the fishes’ harnts, and watches the tides. I sells fresh fish—perch, roach, dace, gudgeon, and such-like, and even small jack, at threepence a pound, or what they’ll fetch; and I’ve caught near the Wandsworth ‘Black Sea,’ as we calls it, half a hundred weight sometimes, and I never took less than my handkerchey full.”

I was inclined—like the inhabitants of Battersea—to be incredulous of the ratcatcher’s hand-fishing, until, under a promise of secrecy, he confided his process to me, and then not only was I perfectly convinced of its truth, but startled that so simple a method had never before been taken advantage of.

Later in the day Mr. Black became very communicative. We sat chatting together in his sanded bird shop, and he told me all his misfortunes, and how bad luck had pressed upon him, and driven him out of London.

“I was fool enough to take a public-house in Regent-street, sir,” he said. “My daughter used to dress as the ‘Ratketcher’s Daughter,’ and serve behind the bar, and that did pretty well for a time; but it was a brewer’s house, and they ruined me.”

The costume of the “ratketcher’s daughter” was shown to me by her mother. It was a red velvet bodice, embroidered with silver lace.

“With a muslin skirt, and her hair down her back, she looked wery genteel,” added the parent.

Mr. Black’s chief complaint was that he could not “make an appearance,” for his “uniform”—a beautiful green coat and red waistcoat—“were pledged.”

Whilst giving me his statement, Mr. Black, in proof of his assertions of the biting powers of rats, drew my attention to the leathern breeches he wore, “as were given him twelve years ago by Captain B——.”

These were pierced in some places with the teeth of the animals, and in others were scratched and fringed like the washleather of a street knife-seller.

His hands, too, and even his face, had scars upon them from bites.

Mr. Black informed me that he had given up tobacco “since a haccident he met with from a pipe. I was smoking a pipe,” he said, “and a friend of mine by chance jobbed it into my mouth, and it went right through to the back of my palate, and I nearly died.”

Here his wife added, “There’s a hole there to this day you could put your thumb into; you never saw such a mouth.”

Mr. Black informed me in secret that he had often, “unbeknown to his wife,” tasted what cooked rats were like, and he asserted that they were as moist as rabbits, and quite as nice.

“If they are shewer-rats,” he continued, “just chase them for two or three days before you kill them, and they are as good as barn-rats, I give you my word, sir.”

Mr. Black’s statement was as follows:—

“I should think I’ve been at ratting a’most for five-and-thirty year; indeed, I may say from my childhood, for I’ve kept at it a’most all my life. I’ve been dead near three times from bites—as near as a toucher. I once had the teeth of a rat break in my finger, which was dreadful bad, and swole, and putrified, so that I had to have the broken bits pulled out with tweezers. When the bite is a bad one, it festers and forms a hard core in the ulcer, which is very painful, and throbs very much indeed; and after that core comes away, unless you cleans ’em out well, the sores, even after they seemed to be healed, break out over and over again, and never cure perfectly. This core is as big as a boiled fish’s eye, and as hard as a stone. I generally cuts the bite[13] out clean with a lancet, and squeege the humour well from it, and that’s the only way to cure it thorough—as you see my hands is all covered with scars from bites.

“The worst bite I ever had was at the Manor House, Hornsey, kept by Mr. Burnell. One day when I was there, he had some rats get loose, and he asked me to ketch ’em for him, as they was wanted for a match that was coming on that afternoon. I had picked up a lot—indeed, I had one in each hand, and another again my knee, when I happened to come to a sheaf of straw, which I turned over, and there was a rat there. I couldn’t lay hold on him ’cause my hands was full, and as I stooped down he ran up the sleeve of my coat, and bit me on the muscle of the arm. I shall never forget it. It turned me all of a sudden, and made me feel numb. In less than half-an-hour I was took so bad I was obleeged to be sent home, and I had to get some one to drive my cart for me. It was terrible to see the blood that came from me—I bled awful. Burnell seeing me go so queer, says, ‘Here, Jack, take some brandy, you look so awful bad.’ The arm swole, and went as heavy as a ton weight pretty well, so that I couldn’t even lift it, and so painful I couldn’t bear my wife to ferment it. I was kept in bed for two months through that bite at Burnell’s. I was so weak I couldn’t stand, and I was dreadful feverish—all warmth like. I knew I was going to die, ’cause I remember the doctor coming and opening my eyes, to see if I was still alive.

“I’ve been bitten nearly everywhere, even where I can’t name to you, sir, and right through my thumb nail too, which, as you see, always has a split in it, though it’s years since I was wounded. I suffered as much from that bite on my thumb as anything. It went right up to my ear. I felt the pain in both places at once—a regular twinge, like touching the nerve of a tooth. The thumb went black, and I was told I ought to have it off; but I knew a young chap at the Middlesex Hospital who wasn’t out of his time, and he said, ‘No, I wouldn’t, Jack;’ and no more I did; and he used to strap it up for me. But the worst of it was, I had a job at Camden Town one afternoon after he had dressed the wound, and I got another bite lower down on the same thumb, and that flung me down on my bed, and there I stopped, I should think, six weeks.

“I was bit bad, too, in Edwards-street, Hampstead-road; and that time I was sick near three months, and close upon dying. Whether it was the poison of the bite, or the medicine the doctor give me, I can’t say; but the flesh seemed to swell up like a bladder—regular blowed like. After all, I think I cured myself by cheating the doctor, as they calls it; for instead of taking the medicine, I used to go to Mr. ——’s house in Albany-street (the publican), and he’d say, ‘What’ll yer have, Jack?’ and I used to take a glass of stout, and that seemed to give me strength to overcome the pison of the bite, for I began to pick up as soon as I left off doctor’s stuff.

“When a rat’s bite touches the bone, it makes you faint in a minute, and it bleeds dreadful—ah, most terrible—just as if you had been stuck with a penknife. You couldn’t believe the quantity of blood that come away, sir.

“The first rats I caught was when I was about nine years of age. I ketched them at Mr. Strickland’s, a large cow-keeper, in Little Albany-street, Regent’s-park. At that time it was all fields and meaders in them parts, and I recollect there was a big orchard on one side of the sheds. I was only doing it for a game, and there was lots of ladies and gents looking on, and wondering at seeing me taking the rats out from under a heap of old bricks and wood, where they had collected theirselves. I had a little dog—a little red ’un it was, who was well known through the fancy—and I wanted the rats for to test my dog with, I being a lad what was fond of the sport.

“I wasn’t afraid to handle rats even then; it seemed to come nat’ral to me. I very soon had some in my pocket, and some in my hands, carrying them away as fast as I could, and putting them into my wire cage. You see, the rats began to run as soon as we shifted them bricks, and I had to scramble for them. Many of them bit me, and, to tell you the truth, I didn’t know the bites were so many, or I dare say I shouldn’t have been so venturesome as I was.

“After that I bought some ferruts—four of them—of a man of the name of Butler, what was in the rat-ketching line, and afterwards went out to Jamaicer, to kill rats there. I was getting on to ten years of age then, and I was, I think, the first that regularly began hunting rats to sterminate them; for all those before me used to do it with drugs, and perhaps never handled rats in their lives.

“With my ferruts I at first used to go out hunting rats round by the ponds in Regent’s-park, and the ditches, and in the cow-sheds roundabout. People never paid me for ketching, though, maybe, if they was very much infested, they might give me a trifle; but I used to make my money by selling the rats to gents as was fond of sport, and wanted them for their little dogs.

“I kept to this till I was thirteen or fourteen year of age, always using the ferruts; and I bred from them, too,—indeed, I’ve still got the ‘strain’ (breed) of them same ferruts by me now. I’ve sold them ferruts about everywhere; to Jim Burn I’ve sold some of the strain; and to Mr. Anderson, the provision-merchant; and to a man that went to Ireland. Indeed, that strain of ferruts has gone nearly all over the world.

“I never lost a ferrut out ratting. I al[14]ways let them loose, and put a bell on mine—arranged in a peculiar manner, which is a secret—and I then puts him into the main run of the rats, and lets him go to work. But they must be ferruts that’s well trained for working dwellings, or you’ll lose them as safe as death. I’ve had ’em go away two houses off, and come back to me. My ferruts is very tame, and so well trained, that I’d put them into a house and guarantee that they’d come back to me. In Grosvenor-street I was clearing once, and the ferruts went next door, and nearly cleared the house—which is the Honourable Mrs. F——’s—before they came back to me.

“Ferruts are very dangerous to handle if not well trained. They are very savage, and will attack a man or a child as well as a rat. It was well known at Mr. Hamilton’s at Hampstead—it’s years ago this is—there was a ferrut that got loose what killed a child, and was found sucking it. The bite of ’em is very dangerous—not so pisonous as a rat’s—but very painful; and when the little things is hungry they’ll attack anythink. I’ve seen two of them kill a cat, and then they’ll suck the blood till they fills theirselves, after which they’ll fall off like leeches.

“The weasel and the stoat are, I think, more dangerous than the ferrut in their bite. I had a stoat once, which I caught when out ratting at Hampstead for Mr. Cunningham, the butcher, and it bit one of my dogs—Black Bess by name, the truest bitch in the world, sir—in the mouth, and she died three days arterwards at the Ball at Kilburn. I was along with Captain K——, who’d come out to see the sport, and whilst we were at dinner, and the poor bitch lying under my chair, my boy says, says he, ‘Father, Black Bess is dying;’ and had scarce spoke the speech when she was dead. It was all through the bite of that stoat, for I opened the wound in the lip, and it was all swole, and dreadful ulcerated, and all down the throat it was inflamed most shocking, and so was the lungs quite red and fiery. She was hot with work when she got the bite, and perhaps that made her take the pison quicker.

“To give you a proof, sir, of the savage nature of the ferruts, I was one night at Jimmy Shaw’s, where there was a match to come off with rats, which the ferrut was to kill; and young Bob Shaw (Jim’s son) was holding the ferrut up to his mouth and giving it spittle, when the animal seized him by the lip, and bit it right through, and hung on as tight as a vice, which shows the spitefulness of the ferrut, and how it will attack the human frame. Young Shaw still held the ferrut in his hand whilst it was fastened to his lip, and he was saying, ‘Oh, oh!’ in pain. You see, I think Jim kept it very hard to make it kill the rats better. There was some noblemen there, and also Mr. George, of Kensal New-town, was there, which is one of the largest dog-fanciers we have. To make the ferrut leave go of young Shaw, they bit its feet and tail, and it wouldn’t, ’cos—as I could have told ’em—it only made it bite all the more. At last Mr. George, says he to me, ‘For God’s sake, Jack, take the ferrut off.’ I didn’t like to intrude myself upon the company before, not being in my own place, and I didn’t know how Jimmy would take it. Everybody in the room was at a standstill, quite horrerfied, and Jimmy himself was in a dreadful way for his boy. I went up, and quietly forced my thumb into his mouth and loosed him, and he killed a dozen rats after that. They all said, ‘Bravo, Jack, you are a plucked one;’ and the little chap said, ‘Well, Jack, I didn’t like to holla, but it was dreadful painful.’ His lip swole up directly as big as a nigger’s, and the company made a collection for the lad of some dozen shillings. This shows that, although a ferrut will kill a rat, yet, like the rat, it is always wicious, and will attack the human frame.

“When I was about fifteen, sir, I turned to bird-fancying. I was very fond of the sombre linnet. I was very successful in raising them, and sold them for a deal of money. I’ve got the strain of them by me now. I’ve ris them from some I purchased from a person in the Coal-yard, Drury-lane. I give him 2l. for one of the periwinkle strain, but afterwards I heard of a person with, as I thought, a better strain—Lawson of Holloway—and I went and give him 30s. for a bird. I then ris them. I used to go and ketch the nestlings off the common, and ris them under the old trained birds.

“Originally linnets was taught to sing by a bird-organ—principally among the weavers, years ago,—but I used to make the old birds teach the young ones. I used to molt them off in the dark, by kivering the cages up, and then they’d learn from hearing the old ones singing, and would take the song. If any did not sing perfectly I used to sell ’em as cast-offs.

“The linnet’s is a beautiful song. There are four-and-twenty changes in a linnet’s song. It’s one of the beautifullest song-birds we’ve got. It sings ‘toys,’ as we call them; that is, it makes sounds which we distinguish in the fancy as the ‘tollock eeke eeke quake le wheet; single eke eke quake wheets, or eek eek quake chowls; eege pipe chowl; laugh; eege poy chowls; rattle; pipe; fear; pugh and poy.’

“This seems like Greek to you, sir, but it’s the tunes we use in the fancy. What we terms ‘fear’ is a sound like fear, as if they was frightened; ‘laugh’ is a kind of shake, nearly the same as the ‘rattle.’

“I know the sounds of all the English birds, and what they say. I could tell you about the nightingale, the black cap, hedge warbler, garden warbler, petty chat, red start—a beautiful song-bird—the willow wren—little warblers they are—linnets, or any of[15] them, for I have got their sounds in my ear and my mouth.”

As if to prove this, he drew from a side-pocket a couple of tin bird-whistles, which were attached by a string to a button-hole. He instantly began to imitate the different birds, commencing with their call, and then explaining how, when answered to in such a way, they gave another note, and how, if still responded to, they uttered a different sound.