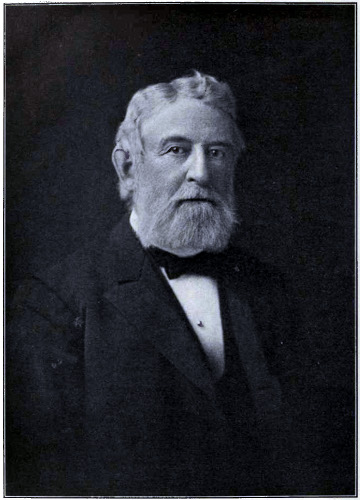

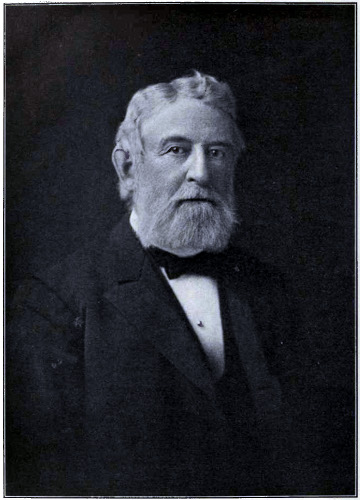

Joshua L. Baily.

President Pennsylvania Prison Society, 1907.

See page 15.

1

Title: The Journal of Prison Discipline and Philanthropy (New Series, No. 46, January 1907)

Author: Pennsylvania Prison Society

Release date: May 5, 2018 [eBook #57090]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Larry B. Harrison, Wayne Jammond and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from images made available by the

HathiTrust Digital Library.)

i

ii

When we consider that the obligations of benevolence, which are founded on the precepts and example of the Author of Christianity, are not canceled by the follies or crimes of our fellow-creatures, and when we reflect upon the miseries which penury, hunger, cold, unnecessary severity, unwholesome apartments, and guilt (the usual attendants of prisons) involve with them, it becomes us to extend our compassions to that part of mankind who are the subjects of those miseries. By the aid of humanity their undue and illegal sufferings may be prevented; the link which should bind the whole family of mankind together under all circumstances, be preserved unbroken; and such degree and modes of punishment may be discovered and suggested as may, instead of continuing habits of vice, become the means of restoring our fellow-creatures to virtue and happiness. From a conviction of the truth and obligations of these principles, the subscribers have associated themselves under the title of “The Pennsylvania Prison Society.”

For effecting these purposes they have adopted the following Constitution:

The officers of the Society shall consist of a President, two Vice-Presidents, two Secretaries, a Treasurer (who may be an undoubted first-class Trust and Safe Deposit Company regularly chartered by the State or National Authorities), and two Counselors.

The Committee on Membership in the “Acting Committee” shall be the nominating committee of the Society, whose duty it shall be after careful consideration to nominate members of the Society most suitable in their judgment for the above named offices. The officers and the Acting Committee shall be chosen by ballot, at the Annual Meeting of the Society, which shall be on the fourth Thursday in the First month (January) of each year and they shall continue in office until their successors are elected. A majority of the whole number of votes cast shall be necessary to the choice of any nominee for office.

In case an election for any cause shall not be held at the time above mentioned, it shall be the duty of the President to call a Special Meeting of the Society, within thirty days for the purpose of holding such election, of which at least three days’ notice shall be given.

The President shall preside in all meetings, and subscribe all public acts of the Society. He may call special meetings whenever he may deem it expedient, and shall do so when requested in writing by five members. In his absence one of the Vice-Presidents may act in his place.

The Secretaries shall keep fair records of the proceedings of the Society, and shall conduct its correspondence.

The Treasurer shall pay all orders of the Society or of the Acting Committee, signed by the presiding officer and the Secretary, and shall present a statement of the receipts and expenditures at each stated meeting of the Society, and an annual report at the annual meeting in the First month (January).

All capital moneys, investments, securities and property belonging to the Society may be placed in the care and custody of such trust company as the Society may by resolution direct, for safe keeping and for the collection of the income and principal thereof.

All investments and re-investments of capital money shall be made by direction of at least three members of the Finance Committee of the Society.

All bequests and life subscriptions which may be received shall be safely invested, the income only thereupon to be applied to the current expenses of the Society.

iii

iv

Joshua L. Baily.

President Pennsylvania Prison Society, 1907.

See page 15.

1

2

The 120th Annual Meeting of “The Pennsylvania Prison Society” was held on the afternoon of the First month (January), 24th, 1907, with Samuel Biddle as Chairman, and Geo. S. Wetherell as Secretary. The Minutes of the 119th Annual meeting were read and approved, after which the Treasurer presented his report.

Memorials on the death of the President, Geo. W. Hall, and the First Vice-President, the Rev. James Roberts, D. D., were submitted and ordered spread on the Minutes.

The officers and the members of the Acting Committee for 1907 were elected (See next page).

Article IV of the Constitution as amended was adopted.

The Editorial Committee was directed to print 7,500 copies of the Journal, and to make such alterations and additions as might be necessary.

Editorial Committee for 1907: Rev. R. Heber Barnes, Chairman; Rev. J. F. Ohl, Deborah C. Leeds, Joseph C. Noblit, Dr. William C. Storkes.

Persons receiving the Journal are invited to correspond with, and send any publications on Prison and Prison Discipline, and articles for the Journal to the Chairman of the Editorial Board, 600 North Thirty-second Street, Philadelphia, Pa., or S. W. Cor. Fifth and Chestnut Streets.

The National Prison Congress of the U. S. for the past eight years designated the fourth Sunday in October annually as Prison Sunday. To aid the movement for reformation, some speakers may be supplied from this Society. Apply to the chairman of that Committee.

👉 John J. Lytle, S. W. Cor. Fifth and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, is the General Secretary of the Society, giving especial attention to the Eastern Penitentiary.

👉 Frederick J. Pooley is Agent for the County Prison, appointed by the Prison Society. Address mail to 500 Chestnut Street, Office of Pennsylvania Prison Society.

3

President

JOSHUA L. BAILY

Vice-Presidents

Rev. HERMAN L. DUHRING, D. D. Rev. F. H. SENFT

Treasurer

JOHN WAY

Secretaries

JOHN J. LYTLE FREDERICK J. POOLEY

Counselors

Hon. WM. N. ASHMAN HENRY S. CATTELL

| Members of the Acting Committee | ||

|---|---|---|

| P. H. Spelissy, | Miss C. V. Hodges, | A. J. Wright, |

| John H. Dillingham, | Rebecca P. Latimer, | Charles H. LeFevre, |

| Dr. Emily J. Ingram, | Rev. Floyd W. Tomkins, | Mrs. E. M. Stillwell, |

| William Scattergood, | Samuel L. Whitson, | Solomon G. Engle, |

| Mrs. P. W. Lawrence, | Harry Kennedy, | Richard H. Lytle, |

| Mary S. Whelen, | Layyah Barakat, | Charles P. Hastings, |

| Isaac Slack, | Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Rev. C. Rowland Hill, |

| William Koelle, | William E. Tatum | Isaac P. Miller |

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Mary S. Wetherell, | Elias H. White, |

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | George S. Wetherell, | John Smallzell, |

| William T. W. Jester, | Henry C. Cassel, | Jacob Hoffman, |

| Mrs. Horace Fassett, | Albert Oetinger, | John D. Hampton, |

| William F. Overman, | Rev. Philip Lamerdin, | Charles McDole, |

| Deborah C. Leeds, | David Sulzberger, | Jonas G. Clemmer, |

| J. Albert Koons, | Mrs. E. W. Gormley, | Susanna W. Lippincott, |

| George R. Meloney, | Frank H. Longshore, | John A. Duncan. |

| Joseph C. Noblit, | Rev. H. E. Meyer, | |

| Visiting Committee for the Eastern State Penitentiary: | ||

| John J. Lytle, | Harry Kennedy, | Rev. Solomon G. Engle, |

| P. H. Spellissy, | Layyah Barakat, | Charles P. Hastings, |

| John H. Dillingham, | Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Rev. F. H. Senft, |

| Isaac Slack, | William E. Tatum, | Rev. C. Rowland Hill, |

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Mary S. Wetherell, | Isaac P. Miller, |

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | George S. Wetherell, | Elias H. White, |

| William T. W. Jester, | Albert Oetinger, | John Smallzell, |

| Deborah C. Leeds, | Henry C. Cassel, | Jacob Hoffman, |

| Mrs. Horace Fassett, | Rev. Philip Lamerdin, | John D. Hampton, |

| George R. Meloney, | David Sulzberger, | Susanna W. Lippincott, |

| Joseph C. Noblit, | Frank H. Longshore, | Charles McDole, |

| Rebecca P. Latimer, | Rev. H. E. Meyer, | Jonas G. Clemmer. |

| Samuel L. Whitson, | Charles H. LeFevre, | |

| Visiting Committee for the Philadelphia County Prison: | ||

| F. J. Pooley, | Mrs. E. M. Stillwell, | George S. Wetherell, |

| Deborah C. Leeds, | William T. W. Jester, | Layyah Barakat, |

| Miss C. V. Hodges | Mrs. P. W. Lawrence, | John A. Duncan, |

| David Sulzberger, | Mrs. Horace Fassett, | Susanna W. Lippincott. |

| Rev. H. E. Meyer, | Mary S. Wetherell, | |

| For the Holmesburg Prison: | ||

| F. A. Pooley, | Isaac Slack, | David Sulzberger. |

| Layyah Barakat, | ||

| For the Chester County Prison: | ||

| William Scattergood, | Deborah C. Leeds, | |

| For the Delaware County Prison: | ||

| Deborah C. Leeds. | ||

| For the Western Penitentiary and Allegheny County Prison: | ||

| Mrs. E. W. Gormley. | ||

| For the Counties of the State at Large: | ||

| Mrs. E. W. Gormley, | Deborah C. Leeds, | Frederick J. Pooley, |

| Layyah Barakat. | ||

| For the House of Correction: | ||

| F. J. Pooley, | Layyah Barakat, | Isaac Slack. |

| Deborah C. Leeds, | David Sulzberger, | |

4

| On Library: | ||

|---|---|---|

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | F. J. Pooley. |

| On Accounts: | ||

| Charles P. Hastings, | Albert Oetinger, | John Smallzell. |

| Editorial Committee: | ||

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Deborah C. Leeds, | Dr. William C. Stokes. |

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Joseph C. Noblit, | |

| On Membership in the Acting Committee: | ||

| Dr. William C. Stokes, | Albert Oetinger, | Charles P. Hastings. |

| George S. Wetherell, | Elias H. White, | |

| On Finance: | ||

| George S. Wetherell, | David Sulzberger, | William Scattergood, |

| A. J. Wright. | ||

| On Employment of Discharged Prisoners: | ||

| Isaac Slack, | John D. Hampton, | Mrs. Horace Fassett, |

| Albert Oetinger, | Rev. H. L. Duhring, D. D., | John A. Duncan, |

| William Koelle, | Frederick J. Pooley, | Mrs. P. W. Lawrence. |

| Henry C. Cassel, | ||

| Auditing Committee: | ||

| Joseph C. Noblit, | John H. Dillingham. | |

| On Police Matrons in Station Houses: | ||

| Mrs. P. W. Lawrence, | Dr. Emily J. Ingram, | Mary S. Wetherell. |

| On Prison Sunday: | ||

| Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Rev. F. H. Senft. |

| Rev. H. L. Duhring, D. D., | Rev. Philip Lamerdin, | |

| On Legislation: | ||

| Rev. J. F. Ohl, | Joseph Noblit, | William Scattergood. |

| Rev. H. C. Meyer, | Rev. R. Heber Barnes, | |

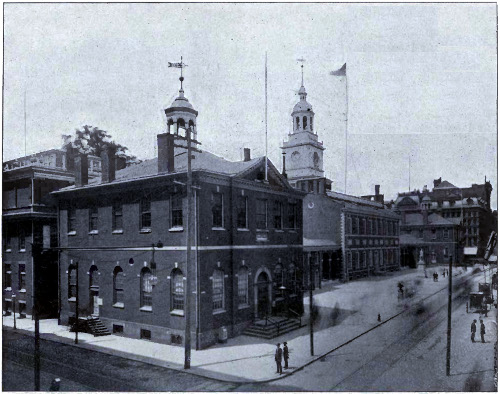

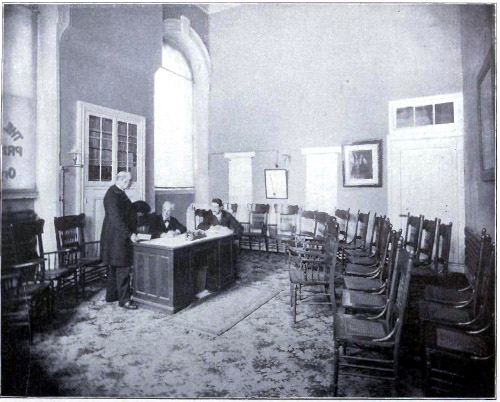

The Pennsylvania Prison Society.

Exterior of Office, S. W. Cor. Fifth and Chestnut Streets.

5

In submitting this, my Seventeenth Annual Report, it is with renewed feelings of devout thankfulness to my Heavenly Father that He has spared my life through another year, and given me the health and strength to perform a service so near and dear to my heart.

In one respect the work of the Pennsylvania Prison Society is unique. Besides the General Secretary, whose labors are confined chiefly to the Eastern Penitentiary, and the Agent for the County Prison, the Society has an “Acting Committee” of fifty members, who by two legislative enactments have the rights of official visitors. The first of these acts became operative in 1829. This was supplemented by the act approved March 20, 1903, which is as follows:

To make active or visiting committees, of societies incorporated for the purpose of visiting and instructing prisoners, official visitors of penal and reformatory institutions.

Section I. Be it enacted, etc., That the active or visiting committee of any society heretofore incorporated and now existing in this Commonwealth for the purpose of visiting and instructing prisoners, or persons confined in any penal or reformatory institution, and alleviating their miseries, shall be and are hereby made official visitors of any jail, penitentiary, or other penal or reformatory institution in this Commonwealth, maintained at the public expense, with the same powers, privileges, and functions as are vested in the official visitors 6 of prisons and penitentiaries, as now prescribed by law: Provided, That no active or visiting committee of any such society shall be entitled to visit such jails or penal institutions, under this act, unless notice of the names of the members of such committee, and the terms of their appointment, is given by such society, in writing, under its corporate seal, to the warden, superintendent or other officer in charge of such jail, or other officer in charge of any such jail or other penal institution.

Approved—The 20th day of March, A. D. 1903.

The foregoing is a true and correct copy of the Act of the General Assembly No. 48.

Under the rights thus conferred those members of the Acting Committee of the Pennsylvania Prison Society assigned to the Eastern Penitentiary visit prisoners in their cells. It is found that this personal work of Christian men and women is productive of good results. In the privacy of the cell hearts and lives are laid open, impressions are made, resolutions are formed, and changes are brought about that under a less personal and individual system of treatment would be well-nigh impossible. The corridor for female prisoners is in charge of a matron, and is regularly visited by women members of the Acting Committee.

During the past year I made over three hundred visits to the Penitentiary; and have had more than three thousand personal interviews with men. Those who need it receive a complete outfit of new clothing on their discharge. But looking after the physical well-being of a man when he leaves I regard as the least important of my duties. I ascertain what his past has been, what his prospects are for the future, and in what way he can be aided in carrying out the good resolutions he may have formed. Thus with good advice and helpful service the man is again given an opportunity to rehabilitate himself.

Besides caring for those just discharged, the General Secretary and the Agent of the County Prison also extend aid to men who have been released for some time, but who have failed to secure employment. This is done at the relief station maintained near the Penitentiary, which is open every morning. 7 Here men who are found to be really deserving are supplied with meal tickets, lodging-room rent, and goods to sell.

The total amount expended during the past year from the Fund for Discharged Prisoners was $3,795.56. Tools were given to men to the amount of $69.16.

As heretofore, Divine services were held in the different corridors each First Day morning under the direction of the Moral Instructor, the Rev. Joseph Welsh. The speakers were supplied by the Local Preachers’ Association of the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Protestant Episcopal City Mission, and the Lutheran City Mission.

The Sunday Song Services at 4 P. M. by choirs from different churches, arranged for by the Rev. H. L. Duhring, D. D., Superintendent of the Protestant Episcopal City Mission, were continued during the year.

I am greatly indebted to all the officers and overseers of the Penitentiary for their uniform courtesy and their valuable assistance in the prosecution of my work. Charles C. Church has proved himself to be an able and efficient warden, to whose administrative ability and genial manner the discipline and good order of the institution are chiefly due.

From the Annual Report of the Penitentiary I gather the following statistics:

| POPULATION | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | Colored | Total | |||

| Males | Females | Males | Females | ||

| Remaining from 1905 | 859 | 13 | 257 | 13 | 1,142 |

| Committed during 1906 | 303 | 8 | 111 | 9 | 431 |

| —— | — | — | — | —— | |

| Total population | 1,162 | 21 | 368 | 22 | 1,573 |

| Discharged during 1906 | 336 | 6 | 96 | 5 | 443 |

| —— | — | — | — | —— | |

| Remaining at the close of 1906 | 826 | 15 | 272 | 17 | 1,130 |

| THE DISCHARGES WERE AS FOLLOWS: | ||

|---|---|---|

| By | Commutation Law | 406 |

| “ | Order of Court | 7 |

| “ | Department of Justice | 8 |

| “ | Order of Huntingdon Reformatory | 4 |

| “ | Pardon | 3 |

| “ | Suicide | 1 |

| Died | 14 | |

| —— | ||

| Total | 443 | |

| Average daily population, 1906 | 1,144 |

| Largest number in confinement during year | 1,175 |

| Smallest number in confinement during year | 1,103 |

8

| (1) SCHOOL | |

|---|---|

| No. of Convicts. | |

| Attended public school | 348 |

| Attended private school | 8 |

| Attended public and private school | 6 |

| Never went to school | 69 |

| — | |

| Total | 431 |

| (2) EDUCATION | |

| Read and write | 312 |

| Read and write imperfectly | 56 |

| Illiterate | 63 |

| — | |

| Total | 431 |

| (3) TRADES | |

| Number having trades | 159 |

| Number having no trades | 272 |

| — | |

| Total | 431 |

| Number idle at time of arrest | 116 |

| (4) AGE OF CONVICTS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | White | Colored | Total | ||||

| From | 15 | to | 20 | years | 31 | 14 | 45 |

| “ | 21 | “ | 25 | “ | 74 | 34 | 108 |

| “ | 26 | “ | 30 | “ | 61 | 36 | 97 |

| “ | 31 | “ | 35 | “ | 53 | 14 | 67 |

| “ | 36 | “ | 40 | “ | 31 | 7 | 38 |

| “ | 41 | “ | 45 | “ | 26 | 6 | 32 |

| “ | 46 | “ | 50 | “ | 15 | 3 | 18 |

| “ | 51 | “ | 55 | “ | 11 | 2 | 13 |

| “ | 56 | “ | 60 | “ | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| “ | 61 | “ | 65 | “ | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| “ | 66 | “ | 70 | “ | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Above 70 years | 1 | 1 | |||||

| — | — | — | |||||

| Total; | 311 | 120 | 431 | ||||

| (5) CONVICTIONS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First | Conviction | 268 | |||

| Second | “ | 1st | time | here | 63 |

| “ | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 31 |

| Third | “ | 1st | “ | “ | 16 |

| “ | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 11 |

| “ | “ | 3d | “ | “ | 8 |

| Fourth | “ | 1st | “ | “ | 8 |

| “ | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 4 |

| “ | “ | 3d | “ | “ | 1 |

| “ | “ | 4th | “ | “ | 1 |

| Fifth | “ | 1st | “ | “ | 2 |

| “ | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 2 |

| “ | “ | 3d | “ | “ | 1 |

| “ | “ | 4th | “ | “ | 2 |

| “ | “ | 5th | “ | “ | 19 |

| Sixth | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 3 |

| “ | “ | 3d | “ | “ | 2 |

| Seventh | “ | 2d | “ | “ | 2 |

| “ | “ | 6th | “ | “ | 2 |

| Eighth | “ | 5th | “ | “ | 1 |

| Eleventh | “ | 3d | “ | “ | 1 |

| Fifteenth | “ | 7th | “ | “ | 1 |

| — | |||||

| Total | 431 | ||||

| PARENTAL RELATIONS AT 16 YEARS | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parents living | 295 | |

| Mother living | 65 | |

| Father living | 38 | |

| Parents dead | 33 | |

| — | ||

| Total | 431 | |

| CONJUGAL RELATIONS | ||

| Single | 254 | |

| Married | 152 | |

| Widowed | 25 | |

| — | ||

| Total | 431 | |

| NUMBER HAVING CHILDREN | ||

| Number having children | 112 | |

| Number of children | 301 | |

| NATIVITY | ||

| Born in the United States | 346 | |

| Foreign born | 85 | |

| — | ||

| Total | 431 | |

| Of the foreign born, naturalized | 31 | |

| Of the foreign born, Not naturalized | 54 | |

| — | ||

| Total | 85 | |

| RECEPTIONS CLASSIFIED AS TO DISTRICTS | ||

| Received from Manufacturing Districts | 161 | |

| Received from Mining Districts | 70 | |

| Received from Agricultural Districts | 200 | |

| — | ||

| Total | 431 | |

The following figures were gathered by the Moral Instructor, the Rev. Joseph Welsh, in his interviews with the prisoners admitted during the year: 10

| Total number received during the year | 431 |

| Number who attended Sunday School | 286 |

| Number who attended Church | 232 |

| Number who were members of Church | 157 |

| Number who were abstainers from use of liquor | 63 |

| Number who were moderate users of liquor | 159 |

| Number who were intemperate users of liquor | 170 |

| Number who were users of tobacco | 356 |

| Number who gambled with cards | 29 |

| Number who gambled on horse races | 11 |

| Number who visited immoral women | 158 |

| Number who kept mistresses | 2 |

This Prison still keeps up its record as a well managed institution. Unfortunately, the Convict Department at Holmesburg is somewhat overcrowded, and it is to be regretted that funds have not yet been provided by the City Councils for additional corridors, so that each man could be separately confined as the law provides. It is admitted by the advocates both of the separate and of the congregate system, that those awaiting trial should be strictly separated. To place a first, and especially a young offender, with a hardened criminal, simply means the production of another criminal, and places the State itself in the position of committing a wrong against one of its own citizens.

Frederick J. Pooley, one of the Secretaries of the Society and Agent at the County Prison, is more untiring than ever in his efforts for the betterment of those incarcerated in Moyamensing, at Tenth and Reed Streets, and in the New County Jail (Convict Department), at Holmesburg. He visits both institutions during five days in the week, seeks to aid men temporally and morally, is instrumental in having cases brought to speedy trial, and in some cases even looks after the destitute families of prisoners. At Moyamensing, women members of the Acting Committee also visit in the Women’s Department.

During the year 1906 there were received at the County Prison, Tenth and Reed Streets:

| White males | 17,085 |

| White females | 2,180 |

| Black males | 3,106 |

| Black females | 1,005 |

| Total committed, 1906 | 23,376 |

| Total discharged, 1906 | 23,452 |

After trial many were sent to Holmesburg. 11

The Associated Committee of Women on Police Matrons in Station Houses meets monthly with three representatives from each of a number of the charitable associations of Philadelphia. On this Committee, the Pennsylvania Prison Society is represented by Mrs. P. W. Lawrence, Dr. Emily J. Ingram and Mary S. Wetherell. The following is the report of the Committee for the past year:

The Committee on Police Matrons held ten regular and one special meeting during the year ending December 31, 1906.

The membership of this Committee is now twenty-one women who represent seven societies, namely, the Pennsylvania Prison Society, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Civic Club, New Century Club, Young Women’s Christian Association, Christian League, and Mothers’ Club. The usual attendance is from eight to twelve members. Reports are received from all the Matrons at each meeting. There are twenty-two. The fourteenth district (Germantown) was supplied with a Matron in March, 1906. The effort is made that each Matron shall receive at least one visit a month. The meeting of the Conference of Charities in Philadelphia in May last brought us unusual interest in the work of Police Matrons elsewhere, and we formed a permanent committee to secure knowledge of it in other cities, and comparison of methods with them. At several meetings of this year, four Matrons at a time were invited to meet with the Committee, and offer suggestions and state experiences requiring help and study. The Needle Work Guild coöperates with the Committee for supplying clothing to the Matrons for their use with needy women and children under their care. Mrs. Fletcher, our Senior Matron, completed her twentieth year of service, and was given a reception by the Committee, at which the Directors and other officials were present. In this time she has had 9,000 women and 2,900 children under her care. The Director of Public Safety, Robert McKenty, has been especially interested in an effort to give personal help to erring women and girls, and extends every facility for our communication with such, by directing the Lieutenants to coöperate with our efforts to redeem them from disgrace and despair. The numbers given in our reports are, of course, from twenty-two districts only. There are fourteen others without Matrons, where many women and children are received. We have been 12 assured that a Matron will be appointed in West Philadelphia very soon, and there is also a prospect of more effective systematic work in coöperation and supervision of this branch of police administration.

(Except as to totals and conditions when received, statistics cannot be made absolutely accurate, especially as to “Nationality and Disposal.”)

| Women under care from January, 1906, to January, 1907 | 9,295 |

| Arrested | 7,475 |

| Lost or seeking shelter | 379 |

| Mothers | 2,898 |

| Intoxicated | 3,679 |

| White | 6,502 |

| Colored | 2,288 |

| Disposals. | |

|---|---|

| Discharged with and without fines | 2,074 |

| Sent to Reformatories | 672 |

| House of Correction | 923 |

| County Prison | 2,255 |

| Americans | 5,320 |

| Foreigners | 2,934 |

| Children under care from January, 1906, to January, 1907 | 6,839 |

| Arrested | 3,417 |

| Lost or ran away | 2,846 |

| White | 5,497 |

| Colored | 651 |

| Brought with parents | 468 |

| Disposals. | |

| Sent home | 4,695 |

| S. P. C. C. and Aid Society | 387 |

| Charities and Reformatories | 449 |

| House of Detention and Juvenile Court | 572 |

William Scattergood, President of the Board of Inspectors, makes weekly visits to this prison, and reports it in good condition. It is considered a model prison. Deborah C. Leeds, a member of the Acting Committee, has also visited it during the year.

Deborah C. Leeds has visited this prison several times during the year, and reports it a well conducted institution. 13

Mrs. E. W. Gormley, Superintendent of the Prison and Jail Department of the W. C. T. U., is also a member of the Acting Committee of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, and as such an official visitor to the penitentiaries, county jails and reformatories of the Commonwealth. We are highly favored in having a member who is doing efficient work in the western part of the State.

This institution for discharged female prisoners was established and is under the supervision of Mrs. Horace Fassett, who is an official visitor at the Eastern Penitentiary and the County Prison. She writes: “The Door of Blessing goes steadily on in its good work under its noble matron, Gertrude Brown. Since January, 1906, fifty women and four babies were sent there from our County Prison, the House of Correction, and the Eastern Penitentiary. All of these were placed in situations in the country, mostly on farms. Some have returned to go to better positions, some have remained, and very few have gone back to their old life. The Door of Blessing is a home for these dear children in every sense of the word—a haven of rest and peace. All love it and look forward to their afternoons out, that they may go there and have supper with the matron and tell her of their joys and sorrows, to which she listens with loving sympathy. Six women were sent to their homes, their families being willing to receive them after a short stay at the Door of Blessing.”

This institution extends help to men discharged from the Eastern Penitentiary and the County Prison. It provides board and shelter for these, gives them employment in broom-making, for which they receive compensation, and seeks to bring all who enter it under the saving power of the Gospel. The efficient Superintendent is Frank H. Starr, who makes every effort to place men in situations when they leave the Home.

This is under the care of the Protestant Episcopal Church. A large number of men from the Penitentiary and County Prison have been sent there for meals and lodgings, sometimes only for a few days, and at other times for a week or two until they could obtain work. 14

During the year a number of men have been sent to this place from the Eastern Penitentiary. Mrs. Booth always receives such with a warm welcome, and often obtains good situations for them.

In the early part of October, 1906, the Committee on Prison Sunday sent out a circular letter, urging the observance of October 21st as Prison Sunday, to thirty-three hundred ministers of the Methodist Episcopal, the Presbyterian, the Baptist, the Lutheran, the Protestant Episcopal, and the Reformed Churches in Pennsylvania, and to six hundred daily and weekly newspapers.

From the Minutes

MEMORIALS OF DECEASED MEMBERSGeorge W. Hall

George W. Hall, former member of the State Legislature and of City Councils, a well-known financier, and President of the Pennsylvania Prison Society, passed away on December 14, 1906, in the 77th year of his age. He was a member of the Franklin Institute, a director of the School of Design for Women, a director of the Home for Feeble Minded Children at Elwyn, a member of the St. Andrew’s Society, a trustee of the Second Presbyterian Church, and an inspector of the Philadelphia County Prison.

It seems proper that there should be a minute of record of one who for years has been an active member, besides being a life member of the Society. He spent much time in looking after the welfare of the prisoners at the County Prison, Tenth and Reed Streets, and at Holmesburg, where he will be greatly missed.

May this minute be recorded and a copy sent to the surviving members of his family.

Rev. James Roberts, D. D.

Rev. James Roberts, D. D., was born at Montrose, Scotland, December 25, 1839.

He came to this country with his parents at an early age, and was graduated from the Princeton Theological Seminary in 1868. His first charge was at Coatesville, Pa., where he remained until 1885, when he took charge of the Church at Darby, Pa. After remaining there ten years he accepted a call to Lambertville, N. J. On leaving this charge he became Superintendent of the Mercer Home for Aged and Retired Ministers, which position he filled until called suddenly from earth on September 27, 1906. His genial, affectionate ways widened the circle of his friends, who were found among all classes. It is with sincere sorrow that our Society records the departure of another of its most honored members and Second Vice-President.

Resolved, That this minute be entered on our records and a copy thereof with our sympathies be sent to the bereaved family.

The Pennsylvania Prison Society. 15

I close my report with the earnest wish that the Pennsylvania Prison Society may constantly widen its scope of operations and grow in efficiency and usefulness as it grows in years.

The work I have performed during not only the last, but for many years, has been very dear to my heart, and I have felt that I have had an especial call to the service. Conscious, however, of my need continually of Divine guidance in all that I have done in His name, I have earnestly sought for that wisdom which will enable me to do all for Him.

With sincere desire that I may be a humble instrument in His hands in winning souls unto Christ, this report is respectfully submitted.

Joshua L. Baily was elected President of The Pennsylvania Prison Society at the annual meeting, January, 1907. His membership in the Society dates from 1851 and he is the oldest member now living. For a number of years he was a member of the Acting Committee and a regular visitor of the Eastern Penitentiary. His great interest in prison discipline induced him, some years ago, to visit voluntarily all the penitentiaries in the Atlantic States, as well as some of those in the States of the Central West, and he visited also many of the County Prisons in Pennsylvania and other States. His interest in correctional institutions was further shown by ten years’ service on the Board of Managers of the House of Refuge.

Mr. Baily has been no less actively interested in charitable institutions, having been for more than fifty years a manager of The Philadelphia Society for the Employment and Instruction of the Poor, of which he is now President. He was one of the founders, and for eighteen years the President of The Philadelphia Society for Organizing Charity. He is also a member and manager of a number of other benevolent societies, so that by reason of long experience, in both correctional and charitable service, Mr. Baily comes to the Presidency of the Prison Society well equipped for the duties devolving upon him. Although still engaged in mercantile business, Mr. Baily gives a large portion of his time, as well as his means, to benevolent purposes, and devotes thereto a degree of vigor, both mental and physical, quite unusual in one of his advanced years. 16

The National Prison Association met in its annual Congress, in the Senate Chamber of the State Capitol, at Albany, N. Y., on the evening of September 15, 1906. The meeting was called to order by the Chairman of the Local Committee, Mr. James F. McElroy, and prayer was offered by the Rev. W. F. Wittaker, D. D., pastor of the First Presbyterian Church.

The Hon. Julius E. Mayer, Attorney-General, represented the Governor in the address of welcome in behalf of the State, and the Mayor of Albany, the Hon. Charles H. Gans, spoke for the city. The Rev. Dr. Frederick Howard Wines made the response, in which he dwelt in reminiscent vein on some of his experiences since the first meeting of the Association, and spoke especially of the leading men who were connected with it during its early history. Dr. Wines advocated three reforms: 1, the abolition of the “sweating” or “third-degree” system, which he called an outrage on the rights of prisoners; 2, the reorganization of the jury system, so that juries could no longer be selected by the “Gang” for the express purpose of defeating justice; and 3, the dismissing of small misdemeanants on their own recognizance, instead of crowding the jails with these.

Dr. Wines then introduced the President of the Association, the Hon. Cornelius V. Collins, Superintendent of Prisons of New York State.

Mr. Collins, after alluding briefly to the purposes and work of the Association, rehearsed the part his own State had taken in the development of plans for the scientific treatment of criminals. Having traced the successive steps in prison reform, in which he showed that New York State had taken the lead, he said:

“Public sentiment has always called for the education and training of the young. How much more important and of what inestimable value is the saving of the adult. Situated as we are here, at the gateway of the republic, we admit at Ellis Island more than a million new people each year. Vital statistics 17 in New York City gave 59,000 births last year, only 11,000 of which were of American parentage. Austria, Russia and Italy each sent us 200,000 immigrants last year. What is more natural than that many of them, wholly unacquainted with our country, our language and our laws, should in their first effort at living in the land of liberty run counter to our laws and find their way to prison. Surely they do come, and the number is constantly increasing. There are now 12,000 convicts in the prisons of this State, made up largely from this cosmopolitan army of ignorance and superstition. This is the problem we have to solve in New York State, and while it is no doubt a fact that our State will always have more than others, it is nevertheless true that every State in the Union will have this class of prisoners to deal with in increasing numbers as time goes on.”

Superintendent Collins detailed the good that followed the separation and classification of prison inmates into groups or grades and the training of the mental faculties through the plan of education in vogue in New York State prisons. The labor and industrial training provided in connection with mental training was spoken of and a plea was made for the indeterminate sentence. In conclusion Superintendent Collins made a timely argument in favor of a reform in county jails. In this connection he said:

“We who are familiar with the facts know that many convicts are received at the prisons who are morally poisoned and contaminated while awaiting trial in the jails by the intimate association with confirmed and degraded criminals which is permitted in these institutions. This is especially true of the younger class of offenders, who come to the jail having respect for authority and dread of confinement. At no period of their penal term are they so susceptible to external influences. If at this period a practical reformatory influence is exerted upon them, their correction can in most cases be accomplished, but if they are left in idleness and subject to the evil influences of degraded companions their respect for law is soon destroyed, and they become hardened and defiant and accept the theories and ambitions of the confirmed criminals as their own. Thus the man who enters jail in such condition that proper treatment would readily turn him from his criminal course often reaches the prison a most discouraging subject for its reformatory system.

“For the interest of society, as well as the protection of young offenders, the jail system should be corrected. The jail buildings are improved and the prisoners are better fed than 18 they were fifty years ago; otherwise the system remains practically the same. Its conspicuous defects still exist. No chain is stronger than its weakest link; the extensive schemes of penal administration in the several States have their fatally weak part in their jails. Genuine and effective organization in the United States for the salvation of criminals and alleged criminals must take heed of these facts, which are notorious.

“May I now suggest that a committee, to be called, if you please, the Committee on Plan and Scope, be appointed at this session of the Prison Congress to consider the following recommendations:

“First. A rational and uniform system of jail administration.

“Second. A uniform system of education for prison officers.

“Third. A uniform system of education for convicts.

“Fourth. So far as possible, a uniform system of prison discipline.

“Fifth. A uniform system of classification.

“Sixth. A uniform system of parole, and a careful consideration of all other matters that in their judgment would tend to make further reforms in the treatment of the criminal classes.

“This committee to make a report of their conclusions at the session of 1907.”

The Congress, deeply impressed by Mr. Collins’ recommendations, subsequently appointed a strong committee to report at the next meeting on the jail system in the United States.

The Conference Sermon was preached by the Rt. Rev. William Crosswell Doane, D. D., LL. D., Bishop of the Diocese of Albany, in the Cathedral of All Saints, where the delegates attended in a body. The Bishop’s text was Matt. 25:36, “I was in prison and ye came unto me.” He said in part: “Almost by an instinctive impulse these words come first to the mind of the preacher at such a service, and by a striking and happy coincidence this service falls upon the Sunday when our Book of Common Prayer appoints for the second morning lesson the chapter which ends with this intense expression of our Lord, containing, I think, the seed principle 19 upon which the noble work of this Association was founded and has been carried on. Last year the preacher took the earthly ministry of our dear divine Lord as the pattern of this work, ‘Who went about doing good.’

“I am only supplementing and carrying along the line of his thought when I ask you to think of the divine Master as giving not the pattern only, but the principle of your work. There is no contradiction in the double presentation of our Lord’s personality along this as along so many other lines. He is so essentially by His incarnation in our human nature that we bring Him to those to whom we minister in His name and find Him in those to whom we bring Him. And in either of these sides the truth is set forth and enforced that the object of all Christian service, whether it be the work of Christianity in religious teaching, or the work of Christianity in the administration of civic affairs, is not the violent denunciation or vindictive infliction of punishment upon a sinner, but the offer of help and the opportunity of reform. The Prison Reform Association may well claim that it describes and expresses in its name the purpose for which in Christian lands prisons exist. ‘He came not to condemn the world, but to save it.’ ‘The Son of Man has come to seek and save the lost.’

“Curiously enough, whatever technical differences may lie in the use of the various words prison and gaol and reformatory, there is one that stands out as having in its root meaning the very thought of that on which we are dwelling, because the penitentiary is certainly the place where men are led and drawn, through real penitence, to seek and find pardon and peace.

“I am not losing sight of the purpose of imprisonment both to stamp crime as crime and to protect society from the criminal. I am only advocating the thought of reform for which this Association stands. If a man is a murderer condemned to die, then there is the overwhelming duty and responsibility of bringing him to repentance, that he may die forgiven. If he is serving a sentence indeterminate or for a fixed time, then surely the influence and effort of prison discipline must be not to harden him into sullen hatred of law and of all that the law stands for, not in a harbored purpose to revenge himself in some way, when once he is free, upon the society which has condemned him; but to waken in him such a sense of shame as shall force him back to the possibility of self-respect, and bring him to that point of realized 20 wrong by means of which he shall ‘come to himself.’ That is the Master’s own description of the prodigal son. Far as he had strayed from his father’s house, he had strayed farther from his real self, the self of his innocent childhood, the self of his home and surroundings, the self of his true nature, and it was when the true man wakened in him that, coming first to himself, he came next to his father’s house.

“In this recognition of the criminal’s sin there must be enforced the discipline of penalty, and of penalty as punishment, but it must be carefully dealt with, so as in no sense to convey the thought of retribution or of vindictive retaliation. The strides of progress which have been made in the last century and a half under the methods of such real reformers as Howard and Wines (whom, as a boy, I remember very well), and Elizabeth Fry and Dorothy Dix, have, among other things, set the stamp of this idea in the fact that capital punishment, which used to be inflicted for many crimes, is reserved to the one for which it was divinely ordered, and from which, I trust, it will never be taken away, namely, the sin of shedding another’s blood. Meanwhile, more and more, in the selection of wardens, in the appointment of chaplains, in the abolition of the fearful cruelties of physical torture, in the decent sanitation of prisons, we have grown more and more to realize that the condemned criminal is to be treated as a man who needs protection, systematic discipline, the training of the prison, to protect him from himself, to put into him the purpose and set before him the possibility of a better life, rather than to humiliate and crush him into desperation and despair. It is quite true that no amount of legislation and no method of enforcing laws can make a man moral, but it is also true that the law which defines and punishes sin deters men from the commission of crime, and when the criminal is condemned and sentenced and his punishment begins, only the power of religion can reach him to convince him of his sin, to convert him from his habits, to reach the motives of his life, to change the tendency of his will, to form in him new habits, to give him the spiritual help by which his conscience may be enlightened and his character changed.

“And there are certain human, natural, physical reasons for the right attitude to the convicted criminal which more than warrant us in assuming it as the groundwork and motive of our dealings with him. It is told, I think of an English bishop, seeing a criminal drawn in a tumbril to execution on Ludgate Hill, in London, that he said, ‘There go I but for 21 grace.’ Somehow I know it is true that now and then men whose lives have been surrounded from childhood up to the very moment of their fall with the best influences, suddenly lapse into great sin. We have instances in the last year which have startled and staggered communities, men in places of trust who have betrayed it, and have either been flung down from the position of confidence and honor or fallen themselves, and found in flight or in suicide the fatal termination of what has seemed to be a career of honorable service. I am bound to say a word even for these. I believe the vindictive personalities which have assailed some of these men are in some cases absolutely unjust.

“There ought to be, thank God, there is, more and more in the great movements in our cities, a strong, set effort of prevention, which is far better than cure. The prisons will be emptier when we have reached the root and reason of crime. If we can control the use of liquor and stop at least its excess; if we can stamp out the curse of drunkenness; if we can more and more arrest the degradation of our slums; if we can train up a race of children in surroundings of physical healthfulness, of moral decency and dignity; and still better, if we can instil into them from earliest childhood the principles and pattern of Jesus Christ, we shall have begun, at the right end, the restoration and the reformation of humanity. Meanwhile, until all these movements have ripened into some result, it becomes us to remember from what sources and in what surroundings the grown-up criminal has come; to realize how far we, by our neglect and indifference, have been responsible for them; and to reach out the helping hand of deep sympathy and pity in the effort to reclaim, to restore and to reform.

“The great revealed truth of universal redemption is full of grace and help. Still more, the truth of individual indwelling of the Christ in us, the hope of glory. It is true that in a way this is a doctrine, a dogma, as people say who think of a dogma as a tyrannical imposition upon their intellectual liberty; but it is truer still that, like many another thing which we call dogma, it is a fact on which depends not merely our holding right faith in Jesus Christ as the God-man, but on which also depend the method and the hope and the value of our dealing with humanity at large or with the individual man. It has in it besides the very highest human hope possible for you and me, that in the great day of eternal decision there shall be for us who have recognized Jesus in those to 22 whom we ministered here the full revelation and manifestation of His glorious God-head, with the word of ‘well done’ and welcome into ‘the kingdom prepared for us from the foundation of the world.’”

At many churches of the city various phases of the work of the Association were presented by delegates to the Congress. At the Cathedral Mr. Thomas M. Osborne, President of the George Junior Republic, Auburn, N. Y., spoke on “The True Foundations of Prison Reform”; Mr. George B. Wellington, of Troy, on “The Duty That We Owe the Convict”; and Prof. Henderson, of Chicago, on “Preventive Work with Children.” The latter maintained that the proper training of a child to keep it from becoming a criminal began before it was born. Crime was not a heritage, but criminal tendencies sometimes were. Judge Lindsay, the great enthusiast in behalf of children, had said that the Juvenile court was organized to keep children out of jail, but that now the problem was to keep children out of the Juvenile court. The problem is to get back to childhood, back to infancy. Babyhood determined whether there should be a large or a small criminal class. Place the child from earliest infancy into such a physical environment and under such mental and spiritual influences as will produce the habit of right living.

The meeting was called to order by President Collins and opened with prayer by the Rev. Thomas D. Anderson. After the appointment of committees and other routine business, the Wardens’ Association went into session. In the absence of the President, Mr. N. N. Jones, Iowa State Prison, Fort Madison, his address was read by Mr. Frank L. Randall, Minnesota, who had been called to the chair. The paper was a compact statement of the warden’s relation to current prison reform. With reference to prison labor it showed how small a portion of the total product is contributed by prisoners. Regarding the relation of discipline to reformation, the writer said: “Discipline is the medium through which all reform becomes effective. The attitude of the warden toward reform should be sympathetic and receptive.”

A paper on “Prison Labor,” by the Hon. John T. McDonough, 23 Ex-Secretary of State, was listened to with considerable interest, because Mr. McDonough, as a member of the Constitutional Convention of 1894, had much to do with framing the constitutional amendment wiping out the contract labor system and prohibiting the sale of prison-made goods in the open market. Under the present laws of New York no work can be done by convicts in competition with outside labor. Whatever is made in the prisons of the State must “be disposed of to the State or any political division thereof, or for or to any public institution owned or managed and controlled by the State, or any political division thereof.” At the same time every inmate of the several State prisons, penitentiaries, jails, and reformatories in the State, who is physically able, must be set to work. By a strong array of figures and apparently favorable comparisons Mr. McDonough undertook to demonstrate the merits and success of the new system. In replying to the paper, Dr. Barrows maintained that in spite of the law several thousand prisoners in the jails and penitentiaries of the State are supported in idleness.

Mr. John E. Van De Carr, Superintendent of the New York City Reformatory of Misdemeanants, on Hart’s Island, read a paper in which he gave an account of said institution and its work. This reformatory, which is the only one in the United States solely for misdemeanants, is the child of Greater New York’s charter. By that charter it became the duty of the Commissioner of Correction “to cause all criminals and misdemeanants under his charge to be classified as far as practicable, so that youthful and less hardened offenders shall not be rendered more depraved by association with and the example of the older and more hardened,” and “to set apart one or more of the penal institutions in his department for the custody of such youthful offenders.” By an act of the Legislature, passed in 1904, the charter of the reform school on Hart’s Island was amended, and the institution was continued and known after January 1, 1905, as “The New York City Reformatory of Misdemeanants.” To this “any male person between the ages of sixteen and thirty, after conviction by a magistrate or court in the city of New York of any charge, offense, misdemeanor, or crime, other than a felony, may be committed for reformatory treatment.” The time of such imprisonment, which must not exceed three years, but must continue at least three months, is terminated by the Board of Parole, which consists of nine commissioners who serve without compensation for a term of one year. The 24 first three rules under the system by means of which an inmate may work out his release on parole (which is determined by merit marks based on demeanor, labor, and study) are as follows: 1. All inmates enter the New York City Reformatory of Misdemeanants in the second grade. 2. If such inmate shall obtain 900 merit marks he shall thereafter enter the first or highest grade. 3. If such inmate shall violate any rules of the Reformatory, or shall in any way be disobedient or ungovernable, he shall be reduced to the third or lowest grade; and no such inmate shall reënter the second grade unless he shall have obtained 300 merit marks. When an inmate is eligible for release on parole, and is so recommended by the superintendent, he is placed on parole in charge of a parole officer for a period of six months, provided he has a home to go to, or employment whereby he can become self-sustaining. Should he violate his parole at any time, the Board of Parole has power to revoke the same and cause his rearrest and reimprisonment as if said parole had not been ordered. To make the system effective, the spiritual welfare of the inmates is faithfully cared for by the Catholic, Protestant, and Hebrew chaplains of the Department of Correction; mental training is provided for by a teacher from the Board of Education; and six different trade-schools furnish industrial instruction. The results so far have proved very satisfactory, the conduct of over eighty-three per cent. of those paroled being reported as satisfactory. “Our experience has already convinced us,” declares the superintendent, “that the modern ideas on this subject are purely scientific, and not sentimental, and that many sent to prison should first be placed in some reformatory where the class of institution in which they should justly be detained could safely be determined. We also feel that it may become necessary to extend the minimum term of three months to a longer period. A sentence is really not reformatory if the minimum is three months; at least the reformation is but temporary. Permanent reformation requires the teaching of a trade, and a trade cannot be learned in that time, although we have accomplished surprising results in that period. To secure the greatest good to the boy, the trades taught should be those that are best paid, namely, the building trades.”

The principal address of the afternoon was by Mr. Warren F. Spalding, Secretary of the Massachusetts Prison Association, 25 on “Principles and Purposes of Probation.” He said in part:

“The probation system is the natural outgrowth of modern theories regarding the treatment of lawbreakers. The acceptance of the proposition that the State should reform and reclaim the offender led to the establishment of reformatories. Later it was realized that some might reform without imprisonment, even in a reformatory, and the probation officer became their supervisor and custodian. His functions are to investigate cases and report regarding past offenses, if any; general character, home, dependents, etc., and the probability of reformation without imprisonment, and he must visit probationers and help them in the work of self-reformation.

“Probation is better than imprisonment for suitable cases, because it saves the offender from the prison stigma, while it keeps him under restraint, controlling his companionships, compelling him to work and support those dependent upon him.

“The probation officer has custodial as well as supervisory powers, and may surrender the probationer for misbehavior. Probation turns the attention of its subject to the future rather than the past. Punishment deals with one past act. Probation deals with the future—with the establishment of character. It puts the emphasis upon what the probationer must do, not upon what he has done.

“Probation as a means of securing reformation has an excellent record. Punishment has failed in a great proportion of its cases. It is only reasonable that the records of the two systems shall be compared. If the law of the survival of the fittest is to prevail in this domain, it is certain that the use of probation is destined for increase, and the use of imprisonment to decrease, as a method of dealing with those who have broken the laws. It will be adopted more and more generally because it succeeds, while imprisonment will be more generally abandoned because it fails.”

Papers were also read by Mr. H. F. Coates, Alliance, Ohio, on “Probation for First Offenders,” and by Samuel J. Barrows, New York, on “The Organization of Probation Work.” Mr. J. G. Phelps-Stokes, New York, spoke on “The Justice of Probation.” Charlton T. Lewis once said: “We are not dealing with acts, but with actors; not with crimes, but with the men who have committed them.” A man is largely the creature of environment. Too often we overlook the fact that crime is not always chargeable to the individual, but to his surroundings. If punishment is to be just, we must know that he who 26 is punished is justly punished. Some of the prolific causes of a criminal career are evil associates, street training, and bad homes. Do we ask as we should, whether those now in prison had such favorable surroundings as the reputable portion of society? How many children grow up without proper home training! Their parents must go out to hard work to the neglect of the children. There is no play for the child except under evil influences; and in New York alone there are 85,000 children deprived of the benefits of a public school education because of deficient school accommodations. Among those who can go to school, truancy is not uncommon. The recreation which every child needs is found by many in saloons, dance halls, cheap theatres, and other demoralizing places. The stress of hard work and long hours also makes it impossible for many parents to care properly for their children. Do we wonder that under such circumstances only harmful influences come to them? Punishment is just only in proportion to culpability; and yet how many have no opportunity to learn what is right or wrong!

The conditions to which first offenders are subjected in many prisons are simply appalling. Hundreds are thrown in with the vilest beings and the most hardened criminals, and are, in addition, obliged in the majority of prisons to endure a living death by reason of the most unsanitary surroundings. It is horrible to sentence a man, woman or child, not only to moral degradation, but to a physical death as well. Imprisonment as a corrective and deterrent is a failure. Punishment can have but two justifications: the correction of the offender, and the protection of society. Probation, on the other hand, at least results in making one refrain from such criminal acts as will send him to prison.

The speaker of the evening was Mrs. Maud Ballington Booth, of the Volunteers of America, who delivered a most eloquent and sympathetic address on “The Hopeful Side of Prison Work.” Mrs. Booth began her work among “her boys” behind the bars ten years ago, at the time of the division in the Salvation Army, which resulted in the formation of the Volunteers of America. To-day she is everywhere known among prisoners and ex-convicts as “The Little Mother.” Mrs. Booth said in part: “I am not here to instruct wardens and chaplains, nor have I come to represent myself, but the work of the organization for which I stand. I see before me another 27 audience to-night, namely, those behind the bars. All I know regarding this work is from within the walls, and I speak, therefore, from the standpoint of the prisoner. I was always told that the task with criminals was a hopeless one, but I have learned to know better. People who talk like that have never been behind the walls of a prison. The theorist looks upon convicts as men who are generally unredeemable. Not so the wardens and chaplains and other prison workers, who have had practical experience. No man or woman would be any good among prisoners without hope. Where there is life there is hope. I do not forget the crime or the stain, and am not a sentimentalist regarding the reformation of criminals; but I firmly believe that no one has fallen so low as to be absolutely beyond redemption. Many of those behind the bars have from earliest childhood never known anything of human or divine love; but have only been cuffed about in the world. Bring these the touch of sympathy, and tell them something of the Father’s love and of the Saviour’s power to save, and you again bring hope into their lives. This must be the foundation of our work within the prison; and where those who have served their time come out, it is love again—mother love, if you please—that must direct their course. In dealing with the convict, our first endeavor must be to enkindle new hope within his heart; and toward the ex-convict the public must assume a better attitude. Finally, if we leave God out we shall not succeed.”

This day of the Congress had been set apart by the New York State Prison Department for an excursion to beautiful Lake George. At 8.30 o’clock over three hundred delegates left Albany by special train. On arrival at Lake George the steamer Horicon was boarded, and after a sail of several hours on the lake, the excursionists were landed at “The Sagamore,” where a basket luncheon was served, after which the meeting of the Chaplains’ Association was held, the Rev. William J. Batt, D. D., of the Massachusetts State Reformatory, in the chair.

After a brief paper by the Rev. W. E. Edgin, Chaplain of the Indiana State Reformatory, Jeffersonville, on “Soul-Winning in a Reformatory,” and an address by Prof. Edward Everett Hale, the president introduced Mr. Joseph F. Scott, 28 of the Elmira Reformatory, whose admirable paper on “The Chaplain from the Warden’s Point of View,” we here reproduce in full:

“Because prisoners are men, they have the same impulses, motives, hopes, and aspirations, and are susceptible to the same influences and amenable to the same forces as other men, though possibly in a less degree. Because some men are prisoners they need the same inspiration, faith, strength, and courage that other men find themselves in need of.

“In the prison of which I am superintendent, there are burglars, pickpockets, and thieves of every description. There is no law on the statute books that has not its offenders there, and they are thought of and spoken of by people in general as such. But when the parents of one of these write me, they say, ‘My son’; or if the brother or sister write, they say, ‘My brother’; and I believe if it were possible for me to hear the words of the Father in Heaven, concerning one of these, they would be, ‘My son,’ or the words of Jesus, ‘My brother.’ Should not our words be the same?

“If I had a son of my own I should insist upon such rules of diet, sleep, and exercise as would insure to him a healthful body and a good constitution, such education, necessary to a well-disciplined mind, such works or pursuits to assure success in life; such disciplinary and moral training as would build up a stable character; all to the end that his place in life would be that of a useful citizen. The need of the prisoner and the prison discipline brought to bear upon him need be nothing more, and should be nothing less than this. He needs physical development, mental quickening, industrial training, discipline and moral instruction, if he is to be returned to society a self-sustaining and useful citizen; and no prison is doing its proper work that does not in some way afford means for these essential elements of discipline.

“The moral instruction is the especial work of the prison chaplain, and he should be given that freedom of action and breadth of scope to make his work efficient. I believe that Christianity is the greatest moral force in the lives of men to-day, because it has humanity as the basis of its ethics. It has come down through the years as a forming, transforming and reforming force in the lives of men, and I believe it is to go on through the ages until selfishness shall have been uprooted, and men brought closer and closer together; when we shall love our neighbor and be willing to work for him as for ourselves, and will do unto others as we would be done 29 by; when we shall live in one great fraternal organization; when wars, and robberies, and strife shall cease and poverty shall be no more; when the strong shall carry the burden of the weak, and succor the unfortunate, and men will live together in brotherly love, under a Christian socialism or in the New Jerusalem, or such designation as you may please to give it. This force, which has accomplished and is to accomplish so much for the world, we cannot deny a place in transforming the lives and characters of prisoners, to that of upright living.

“The prison chaplain, in his work among prisoners, should thoroughly believe that these great Christian forces which have done so much for the world are applicable to the men under his charge and are as efficient in their lives as in the lives of other men; and any Christian clergyman, desirous of helping his fellow men and entering into the service of the Lord and humanity, and of placing himself where he can do the most good, should not hesitate to accept a prison chaplaincy; and a call to such a place should be in his mind equal to the call to one of the best churches in the land.

“It is not my purpose to give a detailed outline for the work of a prison chaplain. No two men can perhaps be successful and do their work in the same way; but every person connected with the prison, be he superintendent, warden, or chaplain, or other officer, should seek every inspiration and good example and ideal within his possibilities, and then simply be his natural self in dealing with the prisoners’ needs.

“When I was superintendent of the Massachusetts Reformatory at Concord, it was the custom there to avail ourselves of the services of the students from Andover Theological Seminary. One student, fresh from his work in the seminary, came into my office one day and asked me what he should do in the prison. I told him that if I were to get some one to do what I wanted done, I would probably get some one else, but that I expected him to go into prison, mingle freely with the prisoners, and find something, some place where he thought he could be of use to them, and give those qualities in himself that he thought would be of the most help. And that is what I would say to a prison chaplain entering the work. Where one is strong another may be weak, and each should work along those lines where he himself feels that he can do the greatest good. The compensation of a prison chaplain should be sufficient to command the services of clergymen of high attainments, and to support themselves and families in a comfortable way. And never should a chaplaincy be looked 30 upon as a place for a broken-down clergyman, or one who has failed in other fields of activity. The chaplain should be given, as I have previously said, sufficient latitude and freedom of action in the prison to carry on the work in such lines as he himself feels that he can be of the greatest service. Therefore, the superintendent, or warden, should not place upon the chaplain such routine duties as will interfere with his doing this. It is recognized by all that the Sabbath is the special day for the chaplain’s work. I believe that we should go further than this, and set aside to him some portion of each day for such religious work as he deems best. He should not be burdened with such work as supervising inmates’ correspondence, the library, teaching school, or the many routine duties which are foisted upon him in many instances, unless he feels that they may be avenues through which he may do his best work.

“If there was one injunction of the Saviour which has given more impetus to Christianity in the world than another, it was His last, ‘Go ye, therefore, and teach all nations,’ or, as found in the other gospel, ‘Go ye into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature.’ I believe this injunction is especially applicable to prisoners, and that the chaplain, first of all, should be a teacher, and his intercourse with the prisoners should be in the form of teaching. Most prisoners are without the truth, and they need to be instructed in the truth, and my experience is that most of them are desirous of learning the truth. And I believe that no chaplain ever failed to interest or impress prisoners when he preached to them a sermon teaching them the simple gospel. I have never failed to see, in a prison chapel, the attention of the men arrested by the simple reading of the gospel, or anything pertaining to the life or teachings of Jesus Christ, or the explanation, by the chaplain, of what those simple truths and teachings consist in. I believe that any chaplain makes a mistake when he goes before his congregation of prisoners with other subjects than the simple gospel, if he thinks thereby to awaken greater interest in other ways.

“Phillips Brooks, when he used to visit the institution at Concord, it was said, never varied his sermons one jot or tittle in presenting them to the prisoners of that reformatory, than in giving them to his cultured congregation in Trinity Church, and he never failed to instruct, impress, and move his congregation of prisoners as no other man to whom I ever listened. And that leads me to the point that I believe that 31 all religious services in a prison should be carried through with the same care on the part of the clergyman, and with the same dignity with which he would conduct the services in any church. The ritual of the church service always appeals to prisoners. The services of the mass, or the ritual of the synagogue, never fail in receiving the reverent attention of the devotees of those faiths; and my observation is that prisoners always respond to those services in which they themselves are largely participants. Congregational singing, responsive readings, repetition of Psalms and the Lord’s Prayer are usually entered into with interest and satisfaction.

“The prison chaplain should be keen in his appreciation of human nature, in dealing with the individual prisoner, that he may see the good that exists in each prisoner with whom he comes in contact, and work upon that side of his character. Humanity is much alike the world over. Race and condition have not so much influence upon the characteristics as we sometimes believe. In the modern American prison will be found prisoners from nearly every nationality under the sun. Their methods of evil are about the same, and they all respond to the same influences, and are actuated by the same motives, each as the other; and the prison chaplain who has learned this, and has learned that there is always something in every prisoner which he can draw out and develop, is well on the road to successful dealing with them. It is not so much the work of the superintendent, warden, or chaplain, to make over a man into something else, as it is to develop him along the lines of his better self.

“When the Saviour called the fishermen, Peter and Andrew, to be his disciples, he did not say to them, ‘Follow me, and I will make you into great orators, or great preachers,’ but, ‘I will make you fishers of men.’ So, when we approach the prisoner, we should not ask him to be something different from himself, but should try to bring out and develop his better self; by holding before his vision the ideal Man, which is Jesus, and the ideal society, which is Christianity in its perfection.”

The evening session was again held in the Senate Chamber of the Capitol. The first address was made by Mr. Frederick G. Pettigrove, Chairman of the Massachusetts Board of Prison Commissioners, on “What a Central System May Do to Promote the Efficiency of Prison Methods.” 32

“A world-famous essayist and statesman said that a complete theory of government would be a noble present to mankind, but he added, it is a present that one could neither hope nor pretend to offer. We are forced to remember this limitation when we examine the various systems of prison government and attempt to suggest remedies for the deficiencies in them. I shall try to show that in whatever way the prisons are governed there are certain reformatory methods and agencies that can be made much more effective and available by the aid of a central system than by being left entirely to local administration. I shall make no attack upon any system, because it would be unjust and ungracious not to remember the great service that has been rendered to the State by the able and philanthropic men and women who have devoted their services to the prisons, and have striven to lift them from mere places of detention to a condition of high public service.

“If all the corrective methods that are now stamped with the approval of public sentiment could be maintained to the best advantage in a single prison, there would be no need of any central authority. It could not be contended that a general board would be any wiser in appointments than the local boards of management. Nor could there be any larger or more humane interest in the affairs of a particular prison, than is shown by the supervisors who have only one prison under their charge. But it would be manifestly impossible, in the larger States at least, to include in a single establishment all the various agencies that are needed for the discipline, the training and the treatment of prisoners; and it is therefore essential that different places should be provided to furnish opportunities best suited to the capacities and the needs of the widely differing individuals.

“The managers of one prison cannot command a knowledge of all the prisons as well as a central board, and if the methods that are now employed are to be used for the greatest good, and to be made available for the largest number of offenders, there must be some general authority to rearrange and reassign prisoners after they have been committed.

“I have no intention here of proposing that the State should take absolute control of all the penal institutions, or even that the authority of all boards of management should be measurably disturbed; but only that some central board should so far possess authority over all the penal establishments as to be enabled to make a rearrangement that would promote efficiency of effort.

“In order to show how such a degree of centrality might be sufficient for large reforms let me outline briefly what I believe 33 would be the best method of classification of prisoners if all suitable facilities could be given by the legislature:

“I would recommend the establishment of one receiving prison for all persons convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to hard labor; in this place prisoners would be held under continual observation for a period long enough to allow the authorities to decide where the prisoner would apparently be likely to receive the most benefit, or where he could be kept with the most advantage to the State.

“As accessories to this place I would provide departmental prisons, in each of which some particular element of instruction or discipline or treatment should be brought to the highest possible degree of efficiency, such as schools for the illiterate, the manual-training school and schools for trade instruction.

“Another department should be assigned to those who are mentally weak, so that they could be put constantly under special guardianship. There are in the prisons, as we all know, many persons who, while not so far below the normal intelligence as to warrant the experts in declaring them to be insane, are nevertheless incapable of performing any useful work or of taking any benefit from prison agencies. In most States provision has been made for the removal of prisoners who are actually insane to an asylum specially provided for that class; but so far there has been no similar establishment created for the safe detention of prisoners who are found to be so far deficient in intelligence as to need the sort of treatment that is given in the schools for the feeble-minded.

“Another humane department would be a hospital prison, an establishment that should combine the needed safeguards for custody with all the essential features for the most scientific and skillful treatment of the different ailments. To be sure it would be necessary to maintain a small infirmary in each prison for emergency cases, but all cases requiring long and continuous treatment would be removed to the hospital prison.

“The last stage of all in such a plan as I outline should be a prison where the guardianship over the prisoner would be relaxed by degrees, so that he could approach his freedom in such a way as to regain some degree of self-reliance.

“To make the general plan of a classified prison system harmonious and effective, the particular place of imprisonment should not be unalterably fixed at the outset. In effect to-day the court in Massachusetts does not absolutely determine the place of imprisonment. The central board has the power to make transfers from one prison to another, with the single exception 34 that no person can be put into the state prison from another place.

“I have seen in other places, however, many prisoners who manifestly belonged in the state prison.

“It would be needless to recite cases of inequitable sentences that show the need of classification. As a type of many others I mention one instance where, through lack of knowledge of the prisoner’s antecedents, a justice sentenced to the reformatory a man who had been six times under imprisonment, including a term in the state prison, and as far as one human being can judge of another, had shown himself incapable of amendment or unwilling to accept the means of reformation.

“Information that may be immediately available to the prison authorities when the prisoner is committed, so that they can assign him to his fit place, is in most cases lacking when the prisoner is before the court. The needed adjustment of prisoners I think could be made by a central authority having all places within its purview, after conference with the prison officials.