Title: The Autobiography of Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Smith, Baronet of Aliwal on the Sutlej, G.C.B.

Author: Sir Harry George Wakelyn Smith

Editor: G. C. Moore Smith

Release date: May 5, 2018 [eBook #57094]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, MWS, Bess Richfield and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

| First Edition (2 vols.) | December, 1901. |

| Reprinted | January, 1902. |

| Reprinted | February, 1902. |

| Reprinted | April, 1902. |

| One Vol. Edition | September, 1903. |

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

LIEUTENANT-GENERAL

Sir Harry Smith

BARONET OF ALIWAL ON THE SUTLEJ

G.C.B.

EDITED

WITH THE ADDITION OF SOME SUPPLEMENTARY CHAPTERS

By G. C. MOORE SMITH, M.A.

WITH PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET

1903

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS, LIMITED,

LONDON AND BECCLES.

The Life of Sir Harry Smith here offered to the public consists of an Autobiography covering the period 1787 to 1846 (illustrated by notes and appendices), and some supplementary chapters contributed by myself on the last period of Sir Harry’s life (1846-1860). Chapter XXXI. carries the reader to the year 1829. This, it is interesting to remark, is a true turning point in the life of the great soldier. Till then he had seen warfare only on two continents, Europe and America (the Peninsula, France, the Netherlands, Monte Video, Buenos Ayres, Washington, New Orleans); from that date onwards the scene of his active service was Africa and Asia. Till 1829 his responsibility was small; after 1829 he had a large or paramount share in directing the operations in which he was engaged. This difference naturally affects the tone of his narrative in the two periods.

The Autobiography (called by its author “Various Anecdotes and Events of my Life”) was begun by Sir Harry Smith, then Lieutenant-Colonel Smith, [vi]at Glasgow in 1824. At that time it was only continued as far as page 15 of the present volume. On 11th August, 1844, when he had won his K.C.B., and was Adjutant-General of Her Majesty’s Forces in India, he resumed his task at Simla. He then wrote with such speed that on 15th October he was able to tell his sister that he had carried his narrative to the end of the campaign of Gwalior, that is, to 1844 (p. 490). Finally, on 7th September, 1846, when at Cawnpore in command of a Division, he began to add to what he had previously written an account of the campaign of the Sutlej, which had brought him fresh honours. This narrative was broken off abruptly in the middle of the Battle of Sobraon (p. 550), and was never completed. Accordingly, of Sir Harry Smith’s life from February, 1846, to his death on 12th October, 1860, we have no record by his own hand.

The Autobiography had been carefully preserved by Sir Harry’s former aide-de-camp and friend, General Sir Edward Alan Holdich, K.C.B., but, as it happened, I was not myself aware of its existence until, owing to the fresh interest awakened in Sir Harry Smith and his wife by the siege of Ladysmith early in 1900, I inquired from members of my family what memorials of my great-uncle were preserved. Sir Edward then put this manuscript and a number of letters and documents at my disposal. It appeared to me and to friends [vii]whom I consulted that the Autobiography was so full of romantic adventure and at the same time of such solid historical value that it ought no longer to remain unpublished, and Mr. John Murray, to whom I submitted a transcription of it, came at once to the same conclusion.

My task as Editor has not been a light one. In Sir Harry’s letter to Mrs. Sargant of 15th October, 1844,[1] he says of his manuscript, “I have never read a page of it since my scrawling it over at full gallop;” and in a letter of 14th January, 1845, “Harry Lorrequer would make a good story of it. You may ask him if you like, and let me know what he says of it.” It is clear from these passages that Sir Harry did not contemplate the publication of his story in the rough form in which he had written it, but imagined that some literary man, such as Charles Lever, might take it in hand, rewrite it with fictitious names, and so fashion out of it a military romance. The chapters[2] on Afghanistan and Gwalior, already written, were, however, of a serious character which would make them unsuitable for such treatment; and the same was the case with the chapters on the Sikh War, afterwards added. Whether Lever ever saw the manuscript I do not know; at any rate, the author’s idea was never carried out.

It is obvious that now that fifty years have passed, some of the reasons which made Sir Harry suggest such a transformation of his story are no longer in force. The actors in the events which he describes having almost all passed away, to suppress names would be meaningless and would deprive the book of the greater part of its interest. And for the sake of literary effect to rewrite Sir Harry’s story would be to destroy its great charm, the intimate relation in which it sets us with his fiery and romantic character.

The book here given to the public is not indeed word for word as Sir Harry wrote it. It has often been necessary to break up a long sentence, to invert a construction—sometimes to transpose a paragraph in order to bring it into closer connexion with the events to which it refers. But such changes have only been made when they seemed necessary to bring out more clearly the writer’s intention; the words are the author’s own, even where a specially awkward construction has been smoothed; and it may be broadly said that nothing has been added to Sir Harry’s narrative or omitted from it. Such slight additions to the text as seemed desirable, for example, names and dates of battles,[3] have been included in square brackets. In some cases, to avoid awkward parentheses, sentences of [ix]Sir Harry’s own have been relegated from the text to footnotes. Such notes are indicated by the addition of his initials (“H. G. S.”).

Sir Harry’s handwriting was not of the most legible order, as he admits, and I have had considerable difficulty in identifying some of the persons and places he mentions. Sometimes I have come to the conclusion that his own recollection was at fault, and in this case I have laid my difficulty before the reader.

I have not thought it my duty to normalize the spelling of proper names, such as those of towns in the Peninsula and in India, and the names of Kafir chiefs. Sir Harry himself spells such names in a variety of ways, and I have not thought absolute consistency a matter of importance, while to have re-written Indian names according to the modern official spelling would have been, as it seems to me, to perpetrate an anachronism.

I have, indeed, generally printed “Sutlej,” though Sir Harry frequently or generally wrote “Sutledge;” but I have kept in his own narrative his spelling “Ferozeshuhur” (which is, I believe, more correct) for the battle generally called “Ferozeshah.” Even Sir Harry’s native place (and my own) has two spellings, “Whittlesey” and “Whittlesea.” In his narrative I have preserved his usual spelling “Whittlesea,” but I have [x]myself used the other, as I have been taught to do from a boy.

Perhaps it is worth while to mention here that Sir Harry’s name was strictly “Henry George Wakelyn Smith,” and it appears in this form in official documents. But having been always known in the army as “Harry Smith,” after attaining his knighthood he stoutly refused to become “Sir Henry,” and insisted on retaining the more familiar name.[4] As the year of his birth is constantly given as 1788, it is worth while to state that the Baptismal Register of St. Mary’s, Whittlesey, proves him to have been born on 28th June, 1787.

While the documents put into my hands by Sir Edward Holdich enabled me to throw a good deal of additional light on the events recorded in the Autobiography, I thought it a prime duty not to interrupt Sir Harry’s own narrative by interpolations. Accordingly I have thrown this illustrative matter into Appendices. In some of these, especially in his letters to his wife of 1835 (Appendix iv.), one sees the writer, perhaps, in still more familiar guise than in the Autobiography.

But I had not merely to illustrate the period of Sir Harry’s life covered by his Autobiography; I [xi]had a further task before me, viz. to construct a narrative of the rest of his life (1846-1860), including his Governorship of the Cape (1847-1852). For the manner in which I have done this, I must crave indulgence. At the best it would have been no easy matter to continue in the third person a story begun by the main actor in the first, and in this case the letters and personal memoranda, which were tolerably abundant for Sir Harry’s earlier years, suddenly became very scanty when they were most required. Accordingly, for much of Sir Harry’s life I had no more sources to draw on than are accessible to anybody—histories, blue-books, and newspapers. I can only say that in this situation I have done the best I could. My chief difficulty was, of course, in dealing with the time of Sir Harry’s command at the Cape. It would have been inconsistent with the scope of the whole book to have attempted a systematic history of the colony or of the operations of the Kafir War. At the same time I could not enable my readers to form an estimate of Sir Harry’s conduct at this time without giving them some indication of the circumstances which surrounded him. If I am found by some critics to have subordinated biography too much to history, I can only hope that other critics will console me by finding that I have subordinated history too much to biography.

Amid a certain dearth of materials of a private [xii]kind, I do congratulate myself on having been able to use the packet of letters docketed by Sir Harry, “John Bell’s and Charlie Beckwith’s Letters.” General Beckwith was an earlier General Gordon, and his letters are so interesting in matter and so brilliant in expression that one is tempted to wish to see them printed in full. Perhaps some readers of this book may be able to tell me of other letters by the same remarkable man which have been preserved.

The latter part of this book would have been balder than it is, if it had not been for the help I have received from various friends, known and unknown. I must express my thanks in particular to the Misses Payne of Chester, who lent me letters addressed to their father, Major C. W. Meadows Payne; to Mrs. Thorne of Chippenham, who lent me letters addressed to her father, Major George Simmons; to Mrs. Fasson, daughter of Mr. Justice Menzies of the Cape, and Mr. W. F. Collier of Horrabridge, who gave me their reminiscences; to Colonel L. G. Fawkes, R.A., Stephen A. Aveling, Esq., of Rochester, Major J. F. Anderson of Faringdon, R. Morton Middleton, Esq., of Ealing, Captain C. V. Ibbetson of Preston, Mrs. Henry Fawcett, my aunt Mrs. John A. Smith, Mrs. Farebrother of Oxford, Mr. B. Genn of Ely, Mr. Charles Sayle of Cambridge, Mr. G. J. Turner of Lincoln’s Inn, Mr. A. E. Barnes of the Local Government Board, [xiii]the Military Secretary of the War Office, and others, for kind assistance of various kinds. I am indebted to my cousins, Mrs. Lambert of 1, Sloane Gardens, S.W., and C. W. Ford, Esq., for permission to reproduce pictures in their possession, and to General Sir Edward Holdich for much aid and interest in my work in addition to the permission to use his diary of the Boomplaats expedition. Lastly, my thanks are due to my brothers and sisters who assisted in transcribing the Autobiography, and in particular to my sister, Miss M. A. Smith, who did most of the work of preparing the Index.

I shall feel that any labour which I have bestowed on the preparation of this book will be richly repaid if through it Harry and Juana Smith cease to be mere names and become living figures, held in honour and affection by the sons and daughters of the Empire which they served.

G. C. MOORE SMITH.

Sheffield,

September, 1901.

For some of the corrections now introduced I am indebted to Lieut.-Col. Willoughby Verner, Rifle Brigade, and to the Rev. Canon C. Evans, late Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge.

G. C. M. S.

University College, Sheffield,

April, 1902.

| REGIMENTAL RANK. | |

| Second Lieutenant, 1st Battalion 95th Regiment | 8 May, 1805 |

| Lieutenant | 15 Aug. 1805 |

| Captain | 28 Feb. 1812 |

| Major, unattached | 29 Dec. 1826 |

| Lieut.-Colonel, unattached | 22 July, 1830 |

| Lieut.-Colonel, 3rd Foot | 13 May, 1842 |

| Lieut.-Colonel, unattached | 25 Aug. 1843 |

| Colonel, 47th Foot | 18 Jan. 1847 |

| Colonel, 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade | 16 April, 1847 |

| Colonel, 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade | 18 Jan. 1855 |

| ARMY RANK. | |

| Major | 29 Sept. 1814 |

| Lieut.-Colonel | 18 June, 1815 |

| Colonel | 10 Jan. 1837 |

| Local rank of Major-General in the East Indies | 21 Aug. 1840 |

| Major-General | 9 Nov. 1846 |

| Local rank of Lieut.-General in South Africa | 1847-1852 |

| Lieut.-General | 20 June, 1854 |

| STAFF APPOINTMENTS. | |

| Peninsular War. | |

| A.D.C. to Colonel T. S. Beckwith | Oct. 1810 |

| Brigade Major, 2nd Brigade, Light Division under Major-General Drummond, Major-General Vandeleur, Major-General Skerrett, and Colonel Colborne successively | Mar. 1811 to the end of the war, Mar. 1814 |

| Washington Expedition. | |

| D.A.G. to Major-General R. Ross | 1814 |

| New Orleans Expedition.[xvi] | |

| A.A.G. to Major-General Sir E. Pakenham | 1814 |

| Military Secretary to Major-General Sir J. Lambert | 1815 |

| Waterloo Campaign. | |

| Brigade-Major, afterwards A.Q.M.G. to 6th Division (Major-General Sir J. Lambert and Major-General Sir Lowry Cole successively) | 1815 |

| [Returns to his regiment.] | |

| Occupation of France. | |

| Major de Place of Cambray | 1815-1818 |

| [Returns to his regiment.] | |

| Glasgow. | |

| Major of Brigade to Major-General Sir T. Reynell (commanding Western District) and Lieut-General Sir T. Bradford (Commander-in-Chief in Scotland) successively | 1819-1825 |

| [Returns to his regiment.] | |

| Nova Scotia. | |

| A.D.C. to Lieut.-General Sir James Kempt, Governor | 1826 |

| Jamaica. | |

| D.Q.M.G. under Lieut.-General Sir John Keane, Governor | 1827 |

| Cape of Good Hope. | |

| D.Q.M.G. under Lieut.-General Sir Lowry Cole, Lieut.-General Sir B. D’Urban, Major-General Sir G. T. Napier, Governors, successively | 1828-1840 |

| Chief of the Staff under Sir Benjamin D’Urban in the Kafir War | 1835 |

| India. | |

| A.G. to Her Majesty’s Forces, under Lieut.-General Sir Jasper Nicolls and Lieut.-General Sir Hugh Gough, Commanders-in-Chief, successively | 1840-1845 |

| Sikh War. | |

| In Command of the 1st Division Infantry | 1845-1846 |

| Cape of Good Hope.[xvii] | |

| Governor and Commander-in-Chief | 1847-1852 |

| Home Staff. | |

| In Command of the Western Military District | 1853-1854 |

| In Command of the Northern and Midland Military Districts | 1854-1859 |

STEPS IN THE ORDER OF THE BATH.

| C.B. for Waterloo | 1815 |

| K.C.B. for Maharajpore | 1844 |

| G.C.B. for Aliwal and Sobraon | 1846 |

An Authentic Narrative of the Proceedings of the Expedition under ... Craufurd until its Arrival at Monte Video, with an Account of the Operations against Buenos Ayres.... By an Officer of the Expedition (1808).

Sir William F. P. Napier: History of the War in the Peninsula.

Sir H. E. Maxwell: Life of Wellington.

Sir William H. Cope: History of the Rifle Brigade (1877).

Edward Costello: Adventures of a Soldier (1852).

A British Rifleman (Major George Simmons’ Diary), edited by Lt.-Colonel Willoughby Verner (1899).

Sir John Kincaid: Random Shots by a Rifleman.

Sir John Kincaid: Adventures in the Rifle Brigade.

Recollections of Rifleman Harris (1848).

Surtees: Twenty-five Years in the Rifle Brigade (1833).

Colonel Jonathan Leach: Rough Sketches in the Life of an Old Soldier (1831).

A Narrative of the Campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans. By an Officer (1821).

Charles Dalton: The Waterloo Roll Call (1890).

George McC. Theal: History of South Africa, vol. iv. (1893).

R. Godlonton: A Narrative of the Irruption of the Kafir Hordes into the Eastern Province of the Cape of Good Hope, 1834-5 (1836).

Sir J. E. Alexander: Narrative of a Voyage, etc. (1837). This work contains in vol. ii. a history of the Kafir War of 1835, with illustrations.

H. Cloete: The Great Boer Trek.

The War in India. Despatches of Viscount Hardinge, Lord Gough, Major-General Sir Harry Smith, Bart., etc. (1846).

J. D. Cunningham: History of the Sikhs.

McGregor: History of the Sikhs.

[xx]General Sir Chas. Gough and A. D. Innes: The Sikhs and the Sikh Wars (1897).

J. W. Clark and T. McK. Hughes: Life of Adam Sedgwick.

Harriet Ward: Five Years in Kaffirland.

J. Noble: South Africa (1877).

A. Wilmot and J. C. Chase: Annals of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (1869).

Alfred W. Cole: The Cape and the Kaffirs (1852).

W. R. King: Campaigning in Kaffirland (with illustrations), (1853).

W. A. Newman: Memoir of John Montagu (1855).

Correspondence of General Sir G. Cathcart (1856).

Earl Grey: The Colonial Policy of Lord John Russell’s Administration (1853).

Blue-Books: Cape of Good Hope (1830-1852).

M. Meille: Memoir of General Beckwith, C.B. (1873).

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Monte Video and Buenos Ayres, 1806-7 | 1 |

| II. | With Sir John Moore—Battle of Coruña, 1808-9 | 14 |

| III. | Back to the Peninsula under Sir Arthur Wellesley, 1809 | 18 |

| IV. | Campaign of 1810—The 1st German Hussars | 24 |

| V. | Campaign of 1810—Battle of the Coa | 28 |

| VI. | Campaign of 1811 | 41 |

| VII. | Campaign of 1812: Storming of Ciudad Rodrigo | 55 |

| VIII. | Campaign of 1812: the Storming of Badajos—Harry Smith’s Marriage | 61 |

| IX. | Campaign of 1812: Battle of Salamanca—Occupation of Madrid—Retreat to Salamanca | 75 |

| X. | Campaign of 1812: Retreat to the Lines of Torres Vedras—Winter of 1812-13 | 84 |

| XI. | Campaign of 1813: Battle of Vittoria | 93 |

| XII. | Campaign of 1813: Advance to Vera | 104 |

| XIII. | Campaign of 1813: In the Pyrenees—General Skerrett—Combat of Vera—Fight at the Bridge, and Death of Cadoux | 113[xxii] |

| XIV. | Campaign of 1813: Colonel Colborne—Second Combat of Vera | 129 |

| XV. | Campaign of 1813: Battle of the Nivelle | 140 |

| XVI. | Combat of the 10th December—Harry Smith’s Dream and the Death of his Mother | 152 |

| XVII. | Campaign of 1814: Battle of Orthez—Anecdote of Juana Smith | 162 |

| XVIII. | Campaign of 1814: at Gée, near Aire—Battle of Tarbes—Battle of Toulouse—end of the War | 170 |

| XIX. | Harry Smith parts from his Wife before starting for the War in America | 182 |

| XX. | Voyage to Bermuda—Rendezvous in the Chesapeake—Battle of Bladensburg and Capture of Washington—Harry Smith sent Home with Dispatches | 191 |

| XXI. | Harry Smith once more in England—Reunion with his Wife in London—Interview with the Prince Regent—Dinner at Lord Bathurst’s—A Journey to Bath—Harry Smith introduces his Wife to his Father—Visit to Whittlesey—He receives Orders To return to America under Sir Edward Pakenham | 209 |

| XXII. | Sails with Sir Edward Pakenham on the Expedition against New Orleans—Reverse of 8th January, 1815, and Death of Pakenham—Sir John Lambert succeeds to the Command, appoints Harry Smith his Military Secretary, and withdraws the Force | 226 |

| XXIII. | Capture of Fort Bowyer—Disembarcation on Ile Dauphine—End of the American War—Visit to Havana and Return-Voyage [xxiii]to England—News of Napoleon’s Return to Power—Harry Smith at his Home at Whittlesey | 248 |

| XXIV. | Harry Smith and his Wife start together for the Waterloo Campaign—Ghent—Battle of Waterloo | 263 |

| XXV. | Juana’s Story | 281 |

| XXVI. | March to Paris—Harry Smith Quartermaster-General of the Reserve—He becomes Lieut.-Colonel and C.B.—The 6th Division moved from Neuilly to St. Germain—the Duc de Berri as a Sportsman—On the Reduction of the 6th Division Harry Smith rejoins his Regiment as Captain—March to Cambray—He is made Major de Place of that Town | 290 |

| XXVII. | Cambray, 1816-1818—Sport and Gaiety—The Duke of Wellington—Harry Smith receives a Visit from his Father | 301 |

| XXVIII. | Return to England (1818)—Harry Smith rejoins his Regiment—Shorncliffe—Gosport—Discharge of the Peninsular Veterans | 317 |

| XXIX. | Glasgow (1819-1825)—Radical Disturbances—Harry Smith once more on the Staff as Major of Brigade—George IV.’s Visit to Edinburgh—Harry Smith revisits Paris—He rejoins his Regiment in Ireland | 324 |

| XXX. | 1825-1828: Harry Smith accompanies his Regiment to Nova Scotia—Sir James Kempt—Harry Smith parts with his old Regiment On Being Appointed Deputy Quartermaster-General in Jamaica—He has to deal with an Epidemic of Yellow Fever among the Troops—Appointed Deputy Quartermaster-General at the Cape of Good Hope | 338 |

| [xxiv]XXXI. | After staying Three Weeks at Nassau, Harry Smith and his Wife sail for England, and after a Miserable Voyage land at Liverpool—He visits London and Whittlesey, and leaves England (1829), not to return till 1847 | 351 |

| XXXII. | Voyage to the Cape—Military Duties and Sport, 1829-1834—Sir Benjamin D’Urban succeeds Sir Lowry Cole as Governor of the Colony | 359 |

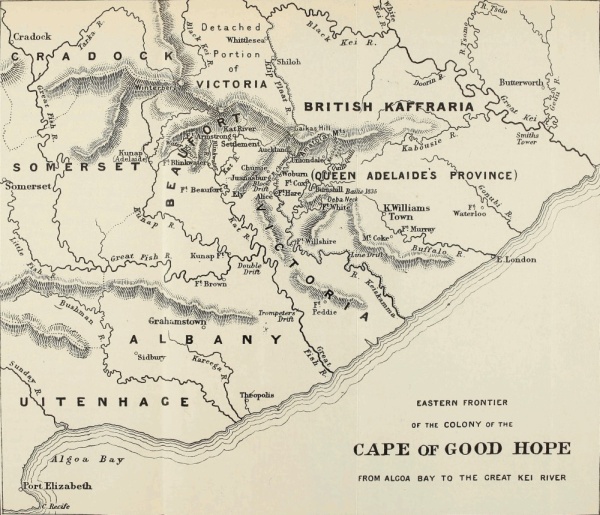

| XXXIII. | Outbreak of a Kafir War—Harry Smith’s Historic Ride to Grahamstown—On his Arrival he proclaims Martial Law—Provides for the Defence of the Town—Attacks the Kafirs and rescues Seven Missionaries | 369 |

| XXXIV. | Harry Smith Chief of the Staff under Sir Benjamin D’Urban—He makes Two Forays into the Fish River Bush and One into the Umdizini Bush—The Force under Sir B. D’Urban marches from Fort Willshire to the Poorts of the Buffalo, from whence Harry Smith makes another Foray | 382 |

| XXXV. | Over the Kei into Hintza’s Territory—War declared against Hintza—His Kraal being destroyed the Chief comes in, and agrees to the Terms of Peace—He remains as a Hostage with the British Force, which marches back to the Kei—Harry Smith marches under Hintza’s Guidance into his Territory to recover the Stolen Cattle—Near the Xabecca Hintza tries to escape, and is shot | 390 |

| [xxv]XXXVI. | March across the Bashee to the Umtata and back to the Bashee—Death of Major White—Difficult March from the Bashee to rejoin Sir B. D’Urban on the Kei—Annexation of the Territory called the “Province of Queen Adelaide,” and Founding of its Capital, “King William’s Town”—Return of the Governor to Grahamstown | 408 |

| XXXVII. | Harry Smith left in Command of the New “Province of Queen Adelaide” at King William’s Town—Death of Lieutenant Bailie—Harry Smith joined by his Wife—Forays on the Kafirs—Conclusion of Peace | 420 |

| XXXVIII. | Harry Smith’s Attempts at civilizing the Kafirs—The Chiefs made British Magistrates—A Census taken—A Police Force established—A Great Meeting of Chiefs—Witchcraft forbidden—A Chief punished for Disobedience—A Rebellious Chief awed into Submission—Agriculture and Commerce introduced—Nakedness discountenanced—Burial of the Dead encouraged—Buying of Wives checked—Hopes of a General Conversion to Christianity | 430 |

| XXXIX. | Lord Glenelg orders the Abandonment of the Province of Queen Adelaide, and appoints Captain Stockenstrom to succeed Harry Smith on the Frontier—Grief of the Kafirs at the Change—Journey of Harry Smith and his Wife to Cape Town—He is exonerated by Lord Glenelg, and receives Testimonials for his Services to the Colony—Leaves Cape Town [xxvi]June, 1840, on being appointed Adjutant-General of the Queen’s Army in India | 452 |

| XL. | Voyage from Cape Town to Calcutta—Harry Smith’s Disappointment at not receiving the Command in the Afghan War—His Criticism of the Operations | 469 |

| XLI. | Sir Hugh Gough succeeds Sir Jasper Nicolls as Commander-in-Chief in India—Affairs in Gwalior—Battle of Maharajpore—Harry Smith made K.C.B. | 480 |

| XLII. | Affairs in the Punjaub—Sir Henry Hardinge Succeeds Lord Ellenborough as Governor-General—Outbreak of the First Sikh War—Battle of Moodkee | 497 |

| XLIII. | Battle of Ferozeshah (or Ferozeshuhur) 21st December, 1845, and Resumed Battle of 22nd December—The Army moves into Position at Sobraon | 507 |

| XLIV. | Sir Harry Smith detached from the Main Army—He reduces the Fortresses of Futteyghur and Dhurmcote—Combines with Colonel Phillips at Jugraon, and after changing his Route To Loodiana encounters the Enemy at Budowal, and loses Some Part of his Baggage—He relieves Loodiana, and, being reinforced and the Enemy having retreated, occupies his Position at Budowal | 523 |

| XLV. | The Battles of Aliwal and Sobraon—End of Sir Harry Smith’s Autobiography | 536 |

| [xxvii]XLVI. | (Supplementary.) Honours and Rewards, and Knitting of Old Friendships | 554 |

| XLVII. | (Supplementary.) In England once more—A Series of Ovations—London, Ely, Whittlesey, Cambridge—Appointed Governor of the Cape of Good Hope | 571 |

| XLVIII. | (Supplementary.) South Africa in 1847—Sir Harry’s Reception at Cape Town and on the Frontier—End of the Kafir War—Extension of the Boundaries of the Colony and Establishment of the Province of “British Kaffraria”—Visit to the Country beyond the Orange and to Natal—Proclamation of the “Orange River Sovereignty”—Triumphant Return to Cape Town—Disaffection among the Boers in the Sovereignty—Expedition thither and Battle of Boomplaats—Return to Cape Town | 582 |

| XLIX. | (Supplementary.) The Question of the Establishment of a Representative Assembly in the Cape Colony—The Convict Question—Kafir War—Recall of Sir Harry Smith—His Departure from the Cape | 609 |

| L. | (Supplementary.) Again in England—Last Years, 1852-1860 | 652 |

| APPENDIX I.—Diary of the Expedition to Monte Video, etc., 1806-7 | 691 | |

| APPENDIX II.—Some Family Letters preserved by Harry Smith with Particular Care | 700 | |

| APPENDIX III.—Memorandum addressed to Sir B. D’Urban on the Diet and Treatment of Soldiers in Confinement [xxviii] | 715 | |

| APPENDIX IV.—Extracts from Harry Smith’s Letters to his Wife during the Kafir War, 1835 | 718 | |

| APPENDIX V.—Address of Colonel Smith to the Caffer Chiefs, 7th January, 1836 | 760 | |

| APPENDIX VI.—Extracts from Sir Harry Smith’s Letters from India, to his Sister, Mrs. Sargant | 766 | |

| APPENDIX VII.—Sir Harry Smith’s Recall from the Cape— | ||

| A. Earl Grey’s Despatch | 782 | |

| B. Sir Harry Smith’s “Memoranda” in Reply | 787 | |

| APPENDIX VIII.—Sir Harry Smith’s Paternal and Maternal Ancestry | 794 | |

| INDEX | 795 | |

| Sir Harry Smith (From a picture painted by Levin about 1856.) |

Frontispiece | |

| Sir Harry Smith’s Birthplace, Whittlesey (From a photograph by A. Gray, Whittlesey, 1900.) |

To face p. | 156 |

| Juana Smith (From a picture painted in Paris in 1815.) |

" | 218 |

| St. Mary’s, Whittlesey (From a photograph by A. Gray, Whittlesey, 1900.) |

" | 260 |

| Lieut.-Colonel Harry Smith (From a picture painted in Paris in 1815.) |

" | 294 |

| John Smith (Sir Harry Smith’s Father) (From a picture painted by J. P. Hunter in 1837.) |

" | 314 |

| Cape Town and Table Mountain (From a lithograph, 1832.) |

" | 370 |

| Map to illustrate the Sutlej Campaign, 1845-6 | " | 498 |

| Plan of the Battle of Aliwal | " | 536 |

| “Aliwal,” Sir Harry Smith’s Charger (From a picture painted by A. Cooper, R.A., 1847.) |

" | 576 |

| Government House, Cape Town (From a lithograph, 1832.) |

" | 584 |

| Map of South Africa, 1847-1854 | " | 594 |

| Plan of the Field of Action at Boomplaats | " | 600 |

| Map of the Eastern Frontier of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (Seat of the Kafir War, 1850-1853) | " | 620[xxx] |

| Lady Smith (From a drawing by Julian C. Brewer, 1854.) |

" | 658 |

| Sir Harry’s Chapel (in St. Mary’s Church, Whittlesey) (From a water-colour by Mrs. B. S. Ward.) |

" | 684 |

Arms granted to Sir Harry Smith in 1846.

They are thus described by Sir Bernard Burke:—

Arms—Argent, on a chevron between two martlets in chief gules, and upon a mount vert in base, an elephant proper, a fleur-de-lis between two lions rampant, of the first: from the centre-chief, pendant by a riband, gules, fimbriated azure, a representation of the Waterloo medal.

Crest—Upon an Eastern crown or, a lion rampant argent, supporting a lance proper; therefrom flowing to the sinister, a pennon gules, charged with two palm-branches, in saltier, or.

The supporters are a soldier of the Rifle Brigade and a soldier of the 52nd Regiment.

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF

Lt.-Gen. Sir Harry Smith,

BARONET OF ALIWAL, G.C.B.

Written in Glasgow in 1824.—H. G. Smith.

I was born in the parish of Whittlesea and county of Cambridgeshire in the year [1787]. I am one of eleven children, six sons and five daughters. Every pains was taken with my education which my father could afford, and I was taught natural philosophy, classics, algebra, and music.[5]

In 1804 the whole country was en masse collected in arms as volunteers from the expected invasion of the French, and being now sixteen years of age, I was received into the Whittlesea troop of [3]Yeomanry Cavalry, commanded by Captain Johnson. During this year the Yeomanry in the neighbourhood patrolled through Norman Cross Barracks, where 15,000 French prisoners were kept, when the Frenchmen laughed exceedingly at the young dragoon, saying, “I say, leetel fellow, go home with your mamma; you most eat more pudding.” In the spring of 1805 the Whittlesea Yeomanry kept the ground at a review made by Brigadier-General Stewart (now Sir W. Stewart), when I was orderly to the General, who said, “Young gentleman, would you like to be an officer?” “Of all things,” was my answer. “Well, I will make you a Rifleman, a green jacket,” says the General, “and very smart.” I assure you the General kept his word, and upon the 15th [8th?] May, 1805, I was gazetted second lieutenant in the 95th Regiment Riflemen,[6] and joined at Brabourne Lees upon the 18th of August. A vacancy of lieutenant occurring for purchase, my father kindly advanced the money, and I was gazetted lieutenant the 15th September [August?], 1805. This fortunate purchase occurred when the 2nd Battalion of the corps was raising and the [4]officers had not been appointed, by which good luck twenty-seven steps were obtained by £100.

In the summer of 1806 a detachment of three Companies was directed to proceed from the 2nd Battalion of the corps from Faversham to Portsmouth, there to embark and form part of an army about to proceed to South America under the command of Sir Samuel Auchmuty. This detachment was under the command of Major Gardner, and I was appointed Adjutant, a great honour for so young an officer.[7] The army sailed for America, touching at Plymouth, Falmouth, Peak of Teneriffe, and Rio Janeiro, at which place it stayed one week to take in water, stores, etc., and, covered by the detachment of Riflemen, landed within a few miles of Monte Video upon the 16th of January, 1807. Some skirmishing took place the whole day with the light troops of the enemy. Upon the 17th and 18th the army halted for the artillery, stores, etc., to be landed. The outposts (Riflemen) were employed both of these days.

Upon the 19th the army moved forward, and a general action took place, the result of which was most favourable to the British, and a position was taken up in the suburbs of Monte Video. Upon the 20th the garrison made a most vigorous sortie in three columns, and drove in our outposts, and a heavy and general attack lasted for near two hours, when the enemy were driven to the very walls of the place. The [5]Riflemen were particularly distinguished on this occasion.

The siege of Monte Video was immediately commenced, and upon the morning of the 3rd of February, the breach being considered practicable, a general assault was ordered in two columns, the one upon the breach, the other an escalade. Both ultimately succeeded. Not a defence was destroyed nor a gun dismounted upon the works. The breach was only wide enough for three men to enter abreast, and when upon the top of the breach there was a descent into the city of twelve feet. Most of the men fell, and many were wounded by each other’s bayonets. When the head of the column entered the breach, the main body lost its communications or was checked by the tremendous fire. Perceiving the delay, I went back and conducted the column to the breach, when the place was immediately taken. The slaughter in the breach was enormous owing to the defence being perfect, and its not being really practicable. The surrender of this fortress put the English in the possession of this part of the country.

I was now afflicted with a most severe fever and dysentery, and owe my life to the kind attentions of a Spanish family in whose house I was billeted. My own relations could not have treated me with greater kindness. My gratitude to them can never be expressed or sufficiently appreciated.[8]

In the autumn[9] an outpost was established on the same side of the river as Monte Video, but nearly opposite to Buenos Ayres, at Colonia del Sacramento. This had formerly belonged to the Portuguese. It was situated on a neck of land, and a mud wall was carried from water to water. There were no guns up, and in one place a considerable breach. One particular night a column of Spaniards which had crossed the river from Buenos Ayres stormed this post, and were near carrying it by surprise had it not been for the valour of Scott and his guard of Riflemen, who most bravely defended the breach until the troops got under arms. The enemy were not pursued, as their numbers were not known and the night was dark. Why this breach was not repaired one cannot say, [7]except that in those days our commanders understood little of the art of war, and sat themselves down anywhere in a state of blind security without using every means to strengthen their posts. Experience taught us better.

The enemy did not re-cross the river, but took up a position about fourteen miles from Colonia, in which Colonel Pack (afterwards Sir Denis Pack), who commanded the British force, resolved to attack them. The column consisted of three companies of Riflemen, the 40th Regiment, two 6-pounders, and three light companies. It marched upon the night of [6-7 June], and arrived in sight of the enemy at daylight in the morning. They were drawn up on an elevated piece of ground, with a narrow but deep, muddy, and miry river in their front. Their cavalry formed a right angle upon the right of their infantry and they had seven guns upon the left. The Rifle Brigade covered the troops whilst crossing the rivulet, and in about twenty minutes by a rapid advance the position was carried, the enemy leaving behind him his guns, tents, stores, etc., with a great quantity of ammunition. In the destroying of the latter poor Major Gardner and fourteen soldiers suffered most dreadfully from an explosion. Some flints had been scattered upon the field; the soldiers took the shot to break the cartridges, and thus the whole blew up. About two hundred shells also exploded. The army at a short distance lay down, and not an individual was touched. Colonel Pack, with his [8]army, the captured guns, etc., returned to Colonia in the evening.[10]

A considerable force having arrived under General Whitelock, who took the command, the army was remodelled and embarked in August [really on the 17th of June], 1807, to attack Buenos Ayres. The post of Colonia was abandoned, and the three companies of the 2nd Battalion Rifle Brigade were embodied with five of the 1st just arrived from England, and I was appointed adjutant of the whole under the command of Major McLeod. The army landed upon [28 June], and was divided into two columns, the one consisting of the light troops under General Craufurd, and of a heavy brigade, the whole under Major-General Leveson-Gower. [Some uncomplimentary epithets are here omitted.] His column was one day in advance of the main body commanded by General Whitelock in person. His orders were to march up to the enemy’s outposts and take up a position. In place of obeying his orders, General Leveson-Gower immediately attacked the enemy in the suburbs of Buenos Ayres, and drove them in with great loss, leaving their cannon behind them. Having thus committed himself, in lieu of [9]following up the advantage he had gained and pushing forward into Buenos Ayres, which would have immediately surrendered, he halted his column and took up a position. The enemy recovered from his panic, and with the utmost vigour turned to and fortified the entrances of all the streets. (Buenos Ayres is perfectly open on the land side, but has a citadel of some strength within the town and upon the river. The houses are all flat-roofed, with a parapet of about three feet high.) The day after the affair alluded to, General Whitelock with his column arrived. The next day he reconnoitred the enemy, drove in their outposts, and partially invested the city. Some very heavy skirmishing took place in the enclosures, the fences consisting of aloe hedges, very difficult to get through, but making excellent breastworks. The Rifle Corps particularly distinguished themselves.

Upon the [5 July] the whole army attacked in four columns. The men were ordered to advance without flints in their musquets, and crowbars, axes, etc., were provided at the head of the column to break open the doors, which were most strongly barricaded. It must be stated that the streets of Buenos Ayres run at right angles from each other. Each street was cut off by a ditch and a battery behind it. Thus the troops were exposed to a cross fire. The tops of the houses were occupied by troops, and such a tremendous fire was produced of grape, canister, and musquetry, that in a short time two columns were nearly annihilated [10]without effecting any impression. The column I belonged to, under Brigadier-General Craufurd, after severe loss, took refuge in a church, and about dusk in the evening surrendered to the enemy. Thus terminated one of the most sanguinary conflicts Britons were ever engaged in, and all owing to the stupidity of the General-in-chief and General Leveson-Gower. Liniers, a Frenchman by birth, who commanded, treated us prisoners tolerably well, but he had little to give us to eat, his citadel not being provisioned for a siege. We were three or four days in his hands, when, in consequence of the disgraceful convention entered into by General Whitelock, who agreed within two months to evacuate the territory altogether and to give up the fortress of Monte Video, we were released. The army re-embarked with all dispatch and sailed to Monte Video. Our wounded suffered dreadfully, many dying from slight wounds in the extremity of lockjaw.

The division of troops I belonged to sailed upon [12 July], under the command of Brigadier-General Lumley. I confess I parted from the kind Spanish family, who during my illness had treated me with such paternal kindness, with feelings of the deepest sorrow and most lively gratitude. The old lady offered me her daughter in marriage and $20,000, with as many thousand oxen as I wished, and she would build me a house in the country upon any plan I chose to devise.

Now that I am brought to leave the fertile [11]plains of the Plate, let me make some little mention of its climate, soil, and productions. Its summer is, of course, in January; during this time it is very hot. Still you have a sea breeze and a land breeze, which is very refreshing. During the rainy seasons the weather is very tempestuous. The climate altogether is, however, most mild and salubrious. Corn of all descriptions grows with the least possible care. The fertile grass plains are immense. The country is not a dead flat, but undulated like the great Atlantic a few days after a gale of wind. Upon these plains thousands of oxen and horses are grazing; they are so thick that were an individual ever entangled amongst them he would be lost as in a wood. These animals are, however, all the property of individuals, and not wild as supposed, and each horse and ox is branded. You could buy a most excellent horse for two dollars (I gave ten for one, he being very handsome, which was a price unheard of before), a cow and calf one dollar, a pair of draft oxen five (they are thus dear in consequence of being trained). The country abounds in all sorts of wild fowl and innumerable wild dogs, which nature must have provided to eat the carcases of the slaughtered cattle, many of which are killed merely for their hides, a few of the prime pieces alone being made use of for food. The marrow is usually also taken and rendered into bladders, with which they cook everything, using it, in short, as we use butter, which makes their dishes very palatable. The native inhabitants, called [12]“peons,” or labourers, are a very superior race of men, almost Patagonians, are beautiful horsemen, and have a peculiar art of catching horses and oxen by what is termed the “lasso.” This is a leathern thong of about thirty feet resembling the lash of a hunting-whip. An iron ring is at one end, through which the other end is passed, by which means a noose is formed; the end is then fastened to the girths of the horse. The lasso is collected in the man’s hand, he swings it circularly round his head, and when the opportunity offers, he throws it over the head of the animal he wishes to catch. He is sure of his aim; the noose draws tight round the animal’s throat, and he is of course choked, and down he drops.

In killing bullocks they are very dexterous. The moment the bullock finds himself caught he begins to gallop round; the end being fast to the saddle, the horse turns gradually round so that he is not entangled. A second peon with his lasso gallops after the bullock, and throws his lasso round the hind leg above the hough and rides in a contrary direction to the other horseman, consequently the bullock is stretched between the two horses. The riders jump off and plunge their knives into the bullock, and other persons are employed to dress it, etc.

The fleet separated in a gale of wind off the Azores. During this gale the transport I was in carried away its rudder. Our captain had kept so bad a reckoning we ran four hundred miles after he [13]expected to make the Lizard. In the chops of the Channel we fell in with the Swallow, sloop of war, to whom we made a signal of distress, and she towed us into Falmouth Harbour [5 Nov.]. It blew the most tremendous gale of wind that night. A transport with the 9th Dragoons aboard was wrecked near the Lizard, and this would inevitably have been our fate had we not been towed in by the sloop of war. The rudder was repaired, we were driven into Plymouth, and in the middle of December anchored at Spithead, where we delighted to have arrived. However, to our great mortification, we were ordered to the Downs, there to disembark.

I obtained leave of absence, and was soon in the arms of a most affectionate family, who dearly loved me. My mother’s delight I shall never forget. There are feelings we possess in our youth which cannot be described. I was then only nineteen. My brothers and sisters were all well, and every moment called to my recollection some incident of juvenile delight and affection.

I stayed in this happy land of my sires for two months, when I was ordered to join. The Regiment was then quartered at Colchester. Although there were many subalterns present who were senior to me, I had given to me, for my exertions abroad as Adjutant, the command of a Company. This was the act of my kind and valued friend Colonel Beckwith, whom I shall have occasion frequently to mention in these memoirs, but never without feelings of affection and gratitude. The Company was in very bad order when I received it, which Colonel Beckwith told me was the reason he gave it me. I now procured a commission for my brother Tom, who was gazetted over the heads of several other candidates.

In the summer [spring] of 1808 10,000 men were ordered to Sweden under the command of Sir J. Moore. Three Companies of the Rifle Brigade under Major Gilmour were to form part of the expedition. By dint of great exertion I was appointed Adjutant to this detachment. We marched to Harwich to embark. When the fleet was collected, we anchored [15]a few days in Yarmouth roads. The fleet arrived at Gottenburgh [on 7 May], blowing a heavy gale of wind. The harbour of this place is most beautiful. The army never landed, but the men were drilled, embarking and disembarking in flat-bottomed boats. I jumped against three regiments, 95th, 43rd, and 52nd, and beat them by four inches, having leaped 19 feet and 4 inches.

Commenced at Simla, Himalayas, 11th Aug. 1844—H.G.S.

At this period Napoleon announced his unjust invasion of Spain, and Sir John Moore’s army was ordered to sail and unite with the forces collecting on the coast of Portugal for the purpose of expelling Junot’s army from Lisbon. On approaching the mouth of the Mondego, a frigate met us to say Sir Arthur Wellesley’s army had landed in Mondego and pushed forward, and that Sir John Moore was to sail for Peniche, and there land on arrival. The battle of Vimiera had been fought [21 Aug. 1808], and the Convention was in progress. Sir John Moore’s army landed one or two days after the battle and took the outposts. The three Companies to which I was Adjutant joined Colonel Beckwith and the headquarters of the Regiment, and I was appointed to Captain O’Hare’s Company (subalterns Smith, W. Eeles, Eaton).

After the embarcation of the French army, an army was formed under Sir John Moore for the aid of the Spaniards, and it moved on the frontier of Alemtejo.

The 95th were quartered in Villa Viciosa, in an elegant palace. I occupied a beautiful little room with a private staircase, called the Hall of Justice. I was sent by Sir Edward Paget to examine the fort Xuramenha and report upon it, the fords of the Guadiana, etc., near the important fortress of Badajos.

In the autumn of this year (1808), Sir John Moore’s army moved on Salamanca. As I could speak Spanish, I was employed by Colonel Beckwith to precede the Regiment daily to aid the Quartermaster in procuring billets and rations in the different towns, and various were the adventures I met with. The army was assembled at Salamanca, and never did England assemble such a body of organized and elegant troops as that army of Sir John Moore, destined to cover itself with glory, disgrace, victory, and misfortune. The whole of this campaign is too ably recorded by Napier for me to dwell on. I shall only say that never did corps so distinguish itself during the whole of this retreat as my dear old Rifles. From the severe attack on our rear-guard at Calcavellos [3 Jan. 1809], where I was particularly distinguished, until the battle of Coruña, we were daily engaged with a most vigorous and pushing enemy, making most terrific long marches (one day 37 miles). The fire of the Riflemen ever prevented the column being molested by the enemy; but the scenes of drunkenness, riot, and disorder we Reserve Division witnessed on the part of the rest of the army are not to be described; it was truly awful and heartrending [17]to see that army which had been so brilliant at Salamanca so totally disorganized, with the exception of the reserve under the revered Paget and the Brigade of Guards. The cavalry were nearly all dismounted, the whole a mass of fugitives and insubordinates; yet these very fellows licked the French at Coruña like men [16 Jan.]. The army embarked the following day. I shall never forget the explosion of a fortress blown up by us—the report cannot be imagined. Oh, the filthy state we were all in! We lost our baggage at Calcavellos; for three weeks we had no clothes but those on our backs; we were literally covered and almost eaten up with vermin, most of us suffering from ague and dysentery, every man a living still active skeleton. On embarcation many fell asleep in their ships and never awoke for three days and nights, until in a gale we reached Portsmouth [21 Jan.]. I was so reduced that Colonel Beckwith, with a warmth of heart equalling the thunder of his voice, on meeting me in the George Inn, roared out, “Who the devil’s ghost are you? Pack up your kit—which is soon done, the devil a thing have you got—take a place in the coach, and set off home to your father’s. I shall soon want again such fellows as you, and I will arrange your leave of absence!” I soon took the hint, and naked and slothful and covered with vermin I reached my dear native home, where the kindest of fathers and most affectionate of mothers soon restored me to health. [11]

In two months I rejoined the Regiment at Hythe. From Hythe we marched for Dover, where we embarked for Lisbon [25 May] to join the Duke’s[12] army. Having landed at Lisbon, we commenced our march for Talavera. On this march—a very long one—General Craufurd compiled his orders for the march of his Brigade, consisting of the 43rd, 52nd, and 95th, each upwards of 1000 strong. These orders he enforced with rigour (as it seemed at the moment), but he was in this way the means of establishing the organization and discipline of that corps which acquired for it its after-celebrity as the “Light Division.”

We had some long, harassing, and excessively hot marches. In the last twenty-eight hours we [19]marched from Oropesa to Talavera, a distance of fourteen Spanish leagues (56 miles), our soldiers carrying their heavy packs, the Riflemen eighty rounds of ammunition. But the battle of Talavera was thundering in our ears, and created a spirit in the Brigade which cast away all idea of fatigue. We reached the sanguinary field at daylight after the battle [29 July], greeted as if we were demi-gods by all the gallant heroes who had gained such a victory. We took up the outposts immediately, and some of us Riflemen sustained some heavy skirmishing. The field was literally covered with dead and dying. The bodies began to putrefy, and the stench was horrible, so that an attempt was made to collect the bodies and burn them. Then, however, came a stench which literally affected many to sickness. The soldiers were not satisfied with this mode of treating the bodies of their dead comrades, and the prosecution of the attempt was relinquished. After our stay at Talavera [29 July-3 Aug.], during which we were nearly starved, the army commenced its retreat, passing the bridge of Arzobispo in the most correct and soldier-like manner, our Brigade forming the rear-guard. The army retired on Deleytosa, the Light Brigade remaining in a position so as to watch the bridge of Almaraz. Here for three weeks we were nearly starved [6 Aug.-20 Aug.], and our position received the name of Doby Hill.[13] We marched every evening [20]and bivouacked so as to occupy the passage of the Tagus, and at daylight returned to our hill. Honey was plentiful, but it gave dysentery. My mess—Leach’s Company (Leach, Smith, Layton, and Bob Beckwith)—were not as badly off as our neighbours. We had a few dollars, and as I could speak Spanish, I rode into the lines of the Spanish troops, where I could always purchase some loaves of bread at a most exorbitant price. With this and some horrid starved goats we lived tolerably for soldiers in hard times. The army retired into quarters—the headquarters to Badajos, our Division (which had added to it Sir Rufane Donkin’s Brigade, the 45th, 87th, and 88th Regiments) to Campo Mayor [11 Sept.], where sickness and mortality commenced to an awful extent. On our reaching the frontier of Portugal, Castello de Vidi, wine was plentiful, and every man that evening had his skin full.

During the period we were at Campo Mayor [11 Sept.-12 Dec.], the Hon. Captain James Stewart and I got some excellent greyhounds. We were always out coursing or shooting, and were never sick a day; our more sedentary comrades many of them distressingly so. The seven right-hand men of Leslie’s Company died in the winter of this year.

While at Campo Mayor the convalescents of my Light Brigade were ordered to our old fortress, called Onguala, on the immediate frontier of Portugal, and opposite to Abuchucha, the frontier of Spain. They consisted of forty or fifty weakly men. I was first for Brigade duty, and I was sent in command, with a Lieut. Rentall of the 52nd Regiment and my brother Tom, who was sick. I knew this country well, for we had had some grand battues there, and shot red deer and wild boars. So soon, therefore, as I was installed in my command, lots of comrades used to come from Campo Mayor to breakfast with me and shoot all day. On one occasion Jack Molloy, Considine, and several fellows came, and while out we fell into the bivouac of a set of banditti and smugglers. We hallooed and bellowed as if an army were near us. The bandits jumped on their horses and left lots of corn-sacks, etc., in our hands; but on discovering our numbers, and that we fired no balls (for we had only some Rifle buttons pulled off my jacket), being well armed, they soon made us retreat. This, after my friends returned to Campo Mayor, so disconcerted me that I made inquiry about these same rascals, and ascertained there were a body of about twenty under a Catalan, the terror of the country. I immediately sent for my sergeant (a soldier in every sense of the word) to see how many of our convalescents he could pick out who could march at all. He soon returned. He himself and ten men, myself, Rentall, and my sick brother Tom (who [22]would go) composed my army. I got a guide, and ascertained that there were several haunts of these bandits; so off I started. We moved on a small chapel (many of which lone spots there are in all Roman Catholic countries), at which there was a large stable. On approaching we heard a shot fired, then a great and lawless shouting, which intimated to us our friends of the morning were near at hand. So Pat Nann and I crept on to peep about. We discovered the fellows were all inside a long stable, with a railed gate shut, and a regular sentry with his arms in his hand. They were all about and had lights, and one very dandy-looking fellow with a smart dagger was cutting tobacco to make a cigar. Pat and I returned to our party and made a disposition of attack, previously ascertaining if the stable had a back door, which it had not. I then fell in our men very silently, Mr. Rentall being much opposed to our attack, at which my brother Tom blew him up in no bad style of whispering abuse, and our men went for the gate. The sentry soon discovered us and let fly, but hit no one. The gate was fast and resisted two attempts to force it, but so amazed were the bandits, they [never] attempted to get away their horses, although their arms were regularly piled against the supports of the roof of the stable, and we took twelve banditti with their captain, a fine handsome fellow, horses, etc. His dagger I sent to my dear father. I sent my prisoners on the next day to Campo Mayor, galloping ahead myself, in an awful funk lest General Craufurd [23]should blow me up. However, I got great credit for my achievement in thus ridding the neighbourhood of a nest of robbers; and the captain and five of his men (being Spaniards) were sent to Badajos and sentenced to the galleys for life, being recognized as old offenders. The remainder received a lesser punishment. My men got forty Spanish dollars each prize money, the amount I sold the horses for. I bought for forty dollars the captain’s capital horse. The men wanted me to keep him as my share, but I would not. Dr. Robb, our surgeon, gave sixty Spanish dollars for a black mare. Thus ended the Battle of the Bandits.

In the winter of this year [12 Dec. 1809] we marched towards the northern frontier of Portugal. We marched towards Almeida, and were cantoned in villages to its rear—Alameda, Villa de Lobos, Fequenas, not far from the Douro. Here too was good shooting and coursing; but I was not permitted to be idle. We moved into Spain [19 Mar. 1810], and at Barba del Puerco had a most brilliant night attack, in which Colonel Beckwith greatly distinguished himself.

At Villa de Ciervo a detachment of one sergeant and twelve Hussars (1st German) were given me by General Craufurd to go right in among the French army, which had moved on Ciudad Rodrigo and then retired. Many are the hairbreadth escapes my Hussars and I had, for we were very daring; we were never two nights in the same place. One night at Villa de Ciervo, where we were watching a ford over the Agueda, two of my vedettes (two Poles elegantly mounted) deserted to the enemy. The old sergeant, a noble soldier, came to me in great distress. “O mein Gott, upstand and jump up [25]your horse; she will surely be here directly!” I was half asleep, with my horse’s reins in my hand, and roared out, “Who the devil is she?” “The Franzosen, mein Herr. Two d——d schelms have deserted.” So we fell back to the rear of the village, sitting on our horses the remainder of the night, every moment expecting the weakness of our party would cause an attempt to cut us off. At daylight we saw fifty French dragoons wending their way on the opposite bank to the ford. I immediately got hold of the padre and alcalde (priest and magistrate), and made them collect a hundred villagers and make them shoulder the long sticks with which they drive their bullock-carts and ploughs, which of course at a distance would resemble bayonets. These villagers I stationed in two parties behind two hills, so that the “bayonets” alone could be seen by the enemy. Then with my sergeant and ten Hussars (two having deserted) I proceeded to meet the enemy, first riding backwards and forwards behind a hill to deceive him as to my numbers. The French sent over the river about half their number. I immediately galloped up to them in the boldest manner, and skirmished advancing. The enemy were deceived and rapidly retired, and I saved the village from an unmerciful ransacking, to the joy of all the poor people.

At this period General Craufurd had officers at two or three of the most advanced vedettes where there were beacons, who had orders to watch the enemy with their telescopes, and, in case of any [26]movement, to report or fire the beacon. I was on this duty in rather a remote spot on the extreme left of our posts. The vedette was from the 1st Hussar picquet. These men would often observe a patrol or body of the enemy with the naked eye which was barely discernible through a telescope, so practised were they and watchful. Towards the evening my servant ought to have arrived with my dinner (for we officers of the look-out could take nothing with us but our horse and our telescope), but he must have missed his way, and as my appetite was sharpened by a day’s look-out, I began to look back, contrary to the vedette’s idea of due vigilance. He asks, “What for Mynheer so much look to de rear?” I, sad at the fast, “Hussar, you are relieved every two hours. I have been here since daylight. I am confounded hungry, and am looking out for my servant and my dinner.” “Poor yonge mans! but ’tis notings.” “Not to you,” said I, “but much to me.” “You shall see, sir. I shall come off my horse, you shall up clim, or de French shall come if he see not de vedette all right.” Knowing the provident habits of these Germans, I suspected what he was about. Off he got; up get I en vedette. With the greatest celerity, he unbuckled his valise from behind his saddle, and took out a piece of bacon (I had kept up a little fire from the sticks and bushes around me), from a cloth some ground coffee and sugar, from his haversack some biscuit, and spread on the ground a clean towel with knife, fork, and a little [27]tin cup. He had water in his canteen—his cooking-tin. He made me a cup of coffee, sliced some bacon, broiled it in the embers, and in ten minutes coffee, bacon, biscuit were ready and looked as clean as if in a London tavern. He then says, “Come off.” Up he mounts, saying, “Can eat. All you sall vant is de schnaps.” I fell to, and never relished any meal half so much; appetite was perfect, and the ingenious, quick and provident care of the Hussar added another to the many instances I had witnessed of this regiment to make them be regarded, as indeed they were, as exemplary soldiers for our emulation.

My servant soon after arrived. The contents of his haversack I transferred to my kind friend the Hussar’s, and half the bottle of wine, on which the Hussar remarked, “Ah, dat is good; the schnaps make nice;” and my servant put up his valise again for him. I was highly amused to observe the momentary glances the Hussar cast on me and my meal, for no rat-catcher’s dog at a sink-hole kept a sharper look-out to his front than did this vedette. In the whole course of my service I never was more amused, and nothing could be more disinterested than the Hussar’s conduct, which I never forgot.

Soon after this the French invested Ciudad Rodrigo, and regularly commenced the siege. The Light Division (into which fell the three regiments 43rd, 52nd, and two Battalions of Rifles, 1st and 3rd Portuguese Caçadores, the latter under Elder, a most brilliant Rifle officer), 1st Hussars, 14th Light Dragoons, 16th Light Dragoons occupied Gallegos, Exejo, etc., our advanced post being at Marialva, on the road to Ciudad Rodrigo. During the whole siege our alerts were innumerable, and at Marialva we had several very smart skirmishes, but so able were Craufurd’s dispositions, we never lost even a vedette.

The French were in the habit of patrolling over the Agueda with cavalry and infantry, about 30 Dragoons and 200 foot. General Craufurd determined to intercept one of these patrols [10 July], and [moved out with] the cavalry, 1st Hussars, 14th and 16th Light Dragoons, and Light Division. It may now be asked, Was it necessary to take out such a force to intercept so small a party? Certainly. Because the enemy might have crossed the Agueda to support the patrols. We were all [29]moved to where directed, the infantry were halted, some of the cavalry moved on. At grey daylight the patrols of the enemy appeared, their Dragoons some way in advance of the infantry. The patrol was very incautiously conducted (not like our 1st Hussars), and the Dragoons were taken in a moment. The infantry speedily retired to an eminence above the ford and formed square. Craufurd ordered them to be attacked by the cavalry, and several right good charges were made; but the French were steady, the dead horses in their front became a defence, and our cavalry never made the slightest impression. Craufurd never moved one of us. The charges of cavalry ceased for a few seconds—the fields around were high-standing corn. The gallant fellow in command gave the word, “Sauve qui peut.” In a moment all dispersed, ran through the standing corn down to the banks of the river, and were saved without the loss of a man. The officer was promoted on his arrival in his camp.

Our loss was very considerable. Poor Colonel Talbot of the 14th (commanding) killed, and a lot of men. I and Stewart, Adjutant of the Rifle Brigade, asked leave to go ahead, and we saw it all. Indeed, it was in sight of the whole division. Had two Companies of ours only been moved to threaten the ford, the enemy would have laid down their arms. Such a piece of soldiering as that morning presented the annals of war cannot produce.[14]

While we were at a village called Valde Mula, in the neighbourhood of Fort Concepcion, that most perfect little work was blown up [21 July]. It was the neatest fortification I ever saw (except the Moro in the Havana subsequently), and the masonry was beautifully executed.

After the fall of Ciudad Rodrigo, which made a brilliant defence, our advanced line fell back to the Dos Casas, and in front of Alameda we had a brilliant affair with the French, in which Krauchenberg 1st Hussars and McDonald Royal Artillery greatly distinguished themselves. The 3rd Caçadores were this day first under fire, and behaved nobly. After this our advanced posts were retired behind the Dos Casas to cover Almeida. While Massena prepared his army to invade Portugal and besiege Almeida, we were daily on the alert and had frequent skirmishes. General Craufurd, too, by a variety of ruses frequently made the whole French army turn out.

In the early morning of the 24th of July (I was on picquet with Leach and my Company that night) the enemy moved forward with 40,000 men. Our force, one Brigade of Horse Artillery, three Regiments of cavalry, five of infantry, were ordered by the Duke to remain as long as possible on the right bank of the Coa, where there was a bridge over the river on the road from Almeida into Portugal to Celerico and Pinhel, posting ourselves between the fortress and the bridge, so as to pass over so soon as the enemy advanced in force. In place of [31]doing this, Craufurd took up a position to our right of Almeida, and but for Colonel Beckwith our whole force would have been sacrificed. Fortunately a heavy rain had fallen, which made the Coa impassable except by the bridge, which was in our possession, and the enemy concentrated his force in one rush for the bridge [24 July].

During the Peninsular War there never was a more severe contest. The 43rd lost 17 officers and 150 men, my Regiment 10 officers and 140 men. When we passed the bridge my section was the rear-guard of the whole, and in a rush to drive back the enemy (with whom we were frequently absolutely mixed), my brother Tom and I were both severely wounded, and a Major Macleod, a noble fellow, afterwards killed at Badajos, put me on his horse, or I should have been taken. The enemy made several attempts to cross, but old Alister Cameron, Captain in the Rifle Brigade, had posted his Company in a ruined house which commanded the bridge, and mainly contributed to prevent the passage of the enemy, who made some brilliant attempts. The bridge was literally piled with their dead and they made breastworks of the bodies. On this day, on going to the rear wounded, I first made the acquaintance of my dear friend Will Havelock,[15] afterwards my whipper-in, who was joining the 43rd fresh from England, with smart chako and jacket. I had a ball lodged in my ankle-joint, a most painful wound. We were sent to Pinhel, [32]where the 3rd Division was seven leagues from the action, the nearest support (?). Sir Thomas Picton treated us wounded en princes.

The wounded were ordered to the rear, so as to embark on the Mondego at Pinhel. In collecting transport for the wounded, a sedan chair between two mules was brought, the property of some gentleman in the neighbourhood, and, fortunately for me, I was the only person who could ride in it, and by laying my leg on the one seat and sitting on the other, I rode comparatively easy to the poor fellows in the wretched bullock-cars, who suffered excruciating agony, poor brother Tom (who was very severely wounded above the knee) among the rest. This little story will show what wild fellows we were in those days. George Simmons’ (1st Rifles) bullocks at one stage had run away. As I was the spokesman, the surgeon in charge came to me in great distress. I sent for the village magistrate, and actually fixed a rope in my room to hang him if he did not get a pair of bullocks (if the Duke of W. had known he would have hung me). However, the bullocks were got, and off we started. The bullocks were not broken, and they ran away with poor George and nearly jolted him to death, for he was awfully wounded through the thick of the thigh. However, we all got down to Pinhel [31 July], and thence descended the Mondego by boats, landing every night. At one house a landlord was most insolent to us, and Lieut. Pratt of the Rifles, shot [33]through the neck, got very angry. The carotid artery must have been wounded, for it burst out in a torrent of blood, and he was dead in a few seconds, to our horror, for he was a most excellent fellow. On the same bed with me was a Captain Hull of the 43rd Regiment with a similar wound. I never saw any man in such a funk.

On our reaching the mouth of the Mondego, we were put on board a transport. In the ship with me was a stout little officer, 14th Light Dragoons, severely wounded, whose thigh afterwards disgorged a French 6-lb. shot. On arrival in Lisbon [7 Aug.] we were billeted in Buenos Ayres, poor Tom and I in awful agony in our miserable empty house. However, we got books, and I, although suffering, got on well enough. But poor Tom’s leg was in such an awful state he was sent home. George Simmons’s wound healed.[16] My ball was lodged on my ankle-joint, having partially divided the tendo Achillis. However, we heard of the army having retired into the celebrated lines of Torres Vedras, and nothing would serve us but join the Regiment. So our medical heroes very unwillingly sent us off to [34]Belem, the convalescent department under Colonel Tucker, 29th Regiment, a sharp fellow enough. When I, George Simmons, and Charlie Eeles, 3rd Battalion, just arrived sick from Cadiz, waited on him to express our desire to join, he said, “Oh, certainly; but you must be posted to do duty with convalescents going up the country.” I was lame and could not walk. George Simmons cantered on crutches, and Charlie Eeles was very sick. However, go or no go, and so we were posted to 600 villains of every Regiment in the army under a long Major Ironmonger of the 88th (afterwards of Almeida celebrity, when the garrison escaped). We marched in a day [7 Oct.]. On the first day’s march he pretended to faint. George Simmons, educated a surgeon, literally threw a bucket of water over him.[17] He recovered the faint, but not the desire to return; and the devil would have it, the command devolved on me, a subaltern, for whom the soldiers of other corps have no great respect, and such a task I never had as to keep these six hundred rascals together. However, I had a capital English horse, good at [35]riding over an insubordinate fellow, and a voice like thunder. The first bivouac I came to was the Guards (these men were very orderly). The commanding officer had a cottage. I reported myself. It was raining like the devil. He put his head out of the window, and I said, “Sir, I have 150 men of your Regiment convalescent from Belem.” “Oh, send for the Sergeant-major,” he very quietly said;—no “walk in out of the rain.” So I roared out, “We Light Division men don’t do duty with Sergeant-majors, nor are we told to wait. There are your men, every one—the only well-conducted men in 600 under my charge—and these are their accounts!” throwing down a bundle of papers, and off I galloped, to the Household man’s astonishment. That day I delivered over, or sent by officers under me, all the vagabonds I had left. Some of my own men and I reached our corps that night at Arruda, when old Sydney Beckwith, dear Colonel, said, “You are a mad fool of a boy, coming here with a ball in your leg. Can you dance?” “No,” says I; “I can hardly walk but with my toe turned out.” “Can you be my A.D.C.?” “Yes; I can ride and eat,” I said, at which he laughed, and was kind as a brother; as was my dear friend Stewart, or Rutu, as we called him, his Brigade Major, the actual Adjutant of the Regiment.

That very night General Craufurd sent for me, and said, “You have come from Sobral, have you not, to-day, and know the road?” I said, “Yesterday.” “Well, get your horse and take this letter [36]to the Duke for me when it is ready.” I did not like the job, but said nothing about balls or pains, which were bad enough. He kept me waiting about an hour, and then said, “You need wait no longer; the letter won’t be ready for some time, and my orderly dragoon shall take it. Is the road difficult to find?” I said, “No; if he keeps the chaussée, he can’t miss it.” The poor dragoon fell in with the French patrol, and was taken prisoner. When the poor fellow’s fate was known, how Colonel Beckwith did laugh at my escape!

At Arruda we marched every day at daylight into position in the hills behind us, and by the ability of Craufurd they were made impregnable. The whole Division was at work. As Colonel Beckwith and I were standing in the camp one day, it came on to rain, and we saw a Rifleman rolling down a wine-cask, apparently empty, from a house near. He deliberately knocked in one of the heads; then—for it was on the side of a rapidly shelving hill—propped it up with stones, and crept in out of the rain. Colonel Beckwith says, “Oh, look at the lazy fellow; he has not half supported it. When he falls asleep, if he turns round, down it will come.” Our curiosity was excited, and our time anything but occupied, so we watched our friend, when in about twenty minutes the cask with the man inside came rolling down the hill. He must have rolled over twenty times at least before the rapidity disengaged him from his round-house, and even afterwards, such was the impetus, he rolled over several times. [37]To refrain from laughing excessively was impossible, though we really thought the noble fellow must be hurt, when up he jumped, looked round, and said “I never had any affection for an empty wine-cask, and may the devil take me if ever I go near another—to be whirled round like a water-mill in this manner!” The fellow was in a violent John Bull passion, while we were nearly killed with laughing.

When Massena retired, an order came to the Light Division to move on De Litte, and to Lord Hill to do the same on our right at [Vallada?]. This dispatch I was doomed to carry. It was one of the utmost importance, and required a gallop. By Jove, I had ten miles to go just before dark, and when I got to Colborne’s position, who had a Brigade under Lord Hill, a mouse could not get through his works. (Colborne was afterwards my Brigadier in the Light Division, and is now Lord Seaton.) Such a job I never had. I could not go in front of the works—the French had not retired; so some works I leaped into, and led my noble English horse into others. At last I got to Lord Hill, and he marched immediately, night as it was. How I got back to my Division through the night I hardly know, but horse and rider were both done. The spectacle of hundreds of miserable wretches of French soldiers on the road in a state of starvation is not to be described.

We moved viâ Caccas to Vallé on the [Rio Mayor], where our Division were opposite Santarem. The next day [20 Nov.] the Duke came up and [38]ordered our Division to attack Santarem, which was bristling on our right with abattis, three or four lines. We felt the difficulty of carrying such heights, but towards the afternoon we moved on. On the Duke’s staff there was a difference of opinion as to the number of the enemy, whether one corps d’armée or two. The Duke, who knew perfectly well there were two, and our move was only a reconnaissance, turned to Colonel Beckwith. “Beckwith, my Staff are disputing whether at Santarem there is one corps d’armée or two?” “I’ll be d——d if I know, my Lord, but you may depend on it, a great number were required to make those abattis in one night.” Lord Wellington laughed, and said, “You are right, Beckwith; there are two corps d’armée.”[18] The enemy soon showed themselves. The Duke, as was his wont, satisfied himself by ocular demonstration, and the Division returned to its bivouac. Whilst here, Colonel Beckwith was seized with a violent attack of ague.

Our outposts were perfectly quiet, although sentries, French and English, were at each end of the bridge over the Rio Mayor, and vedettes along each bank. There was most excellent coursing on the plains of Vallé, and James Stewart and I were frequently out. Here I gave him my celebrated Spanish greyhound, Moro, the best the world ever produced, with a pedigree like that of an Arab horse, bred at Zamora by the Conde de Monteron; but the noble dog’s story is too long to tell here. [39]In one year Stewart gave me him back again to run a match against the Duke of Wellington’s dog. But the siege of Ciudad Rodrigo prevented our sports of that description. Colonel Beckwith going to Lisbon, and I being his A.D.C., it was voted a capital opportunity for me to go to have the ball cut out from under the tendon Achillis, in the very joint. I was very lame, and the pain often excruciating, so off I cut.

Soon after we reached Lisbon, I was ordered to Buenos Ayres to be near the surgeons. A board was held consisting of the celebrated Staff Surgeon Morell, who had attended me before, Higgins, and Brownrigg. They examined my leg. I was all for the operation. Morell and Higgins recommended me to remain with a stiff leg of my own as better than a wooden one, for the wounds in Lisbon of late had sloughed so, they were dubious of the result. Brownrigg said, “If it were my leg, out should come the ball.” On which I roared out, “Hurrah, Brownrigg, you are the doctor for me.” So Morell says, “Very well, if you are desirous, we will do it directly.” My pluck was somewhat cooled, but I cocked up my leg, and said, “There it is; slash away.” It was five minutes, most painful indeed, before it was extracted. The ball was jagged, and the tendonous fibres had so grown into it, it was half dissected and half torn out, with most excruciating torture for a moment, the forceps breaking which had hold of the ball. George Simmons was present, whose wound had [40]broken out and obliged him to go to Lisbon.[19] The surgeon wanted some linen during the operation, so I said, “George, tear a shirt,” which my servant gave him. He turned it about, said, “No, it is a pity; it is a good shirt;” at which I did not —— him a few, for my leg was aching and smoking from a wound four or five inches long. Thank God Almighty and a light heart, no sloughing occurred, and before the wound was healed I was with the regiment. Colonel Beckwith’s ague was cured, and he had joined his Brigade before I could move, so when I returned to Vallé he was delighted to see his A.D.C.