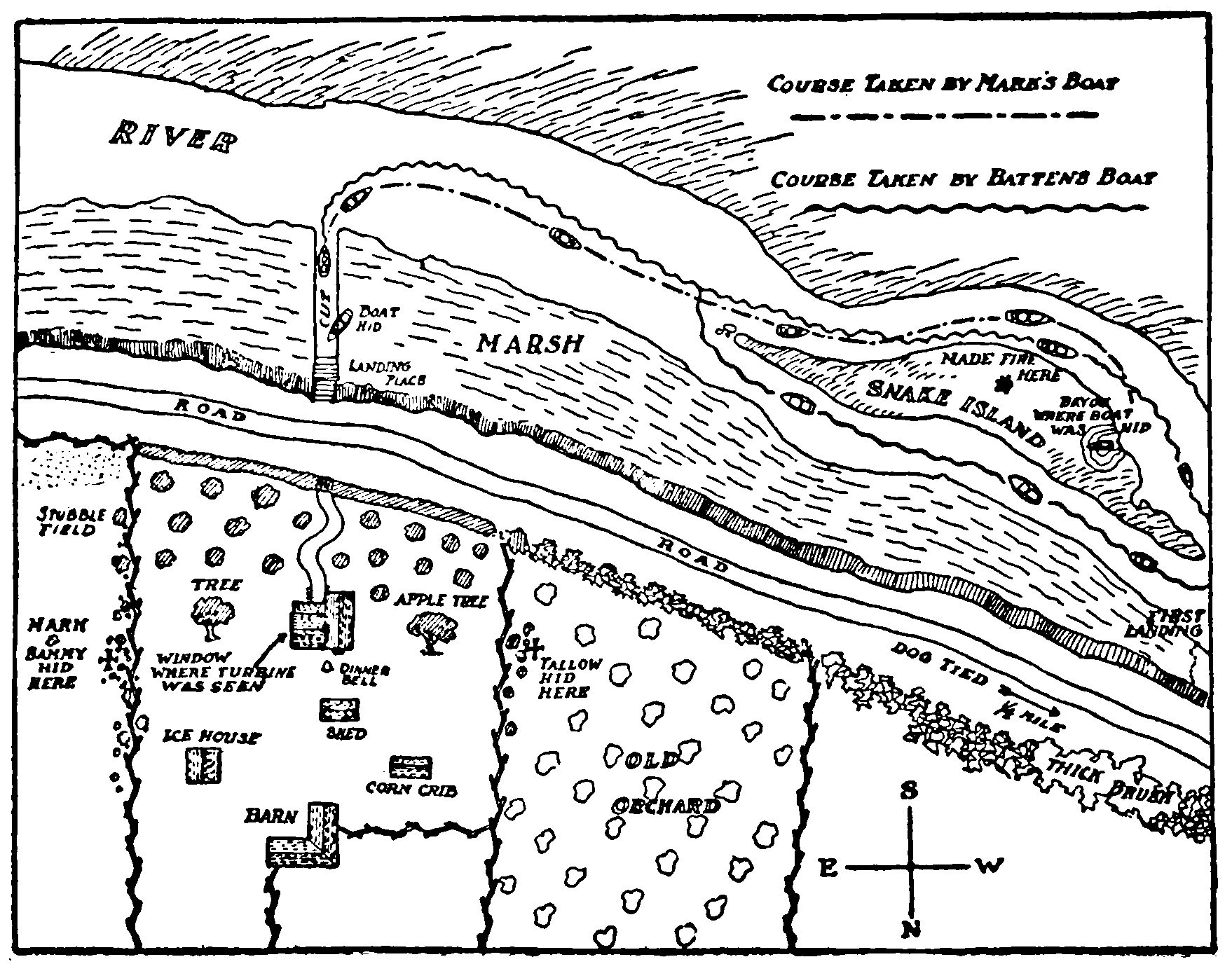

“GO FOR BATTEN. I’M RIGHT HERE, AND I’LL LOOK AFTER BILL”

Title: Mark Tidd: His Adventures and Strategies

Author: Clarence Budington Kelland

Illustrator: William Wallace Clarke

Release date: May 15, 2018 [eBook #57165]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

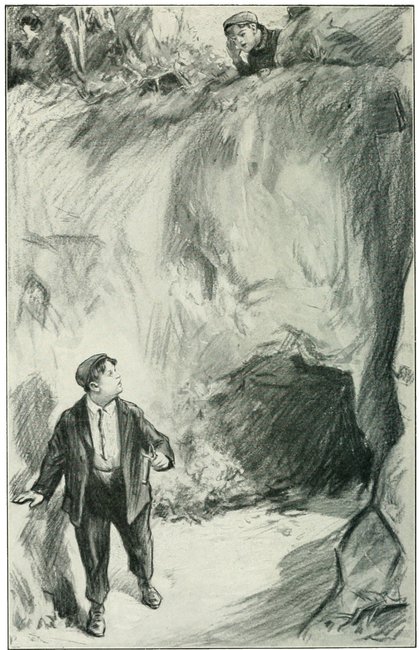

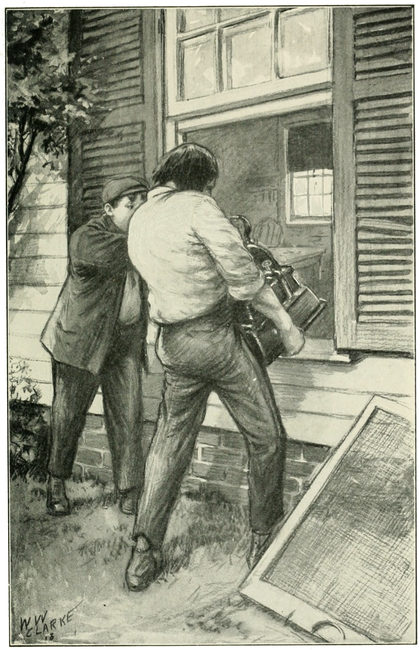

“GO FOR BATTEN. I’M RIGHT HERE, AND I’LL LOOK AFTER BILL”

“GO FOR BATTEN. I’M RIGHT HERE, AND I’LL LOOK AFTER BILL”

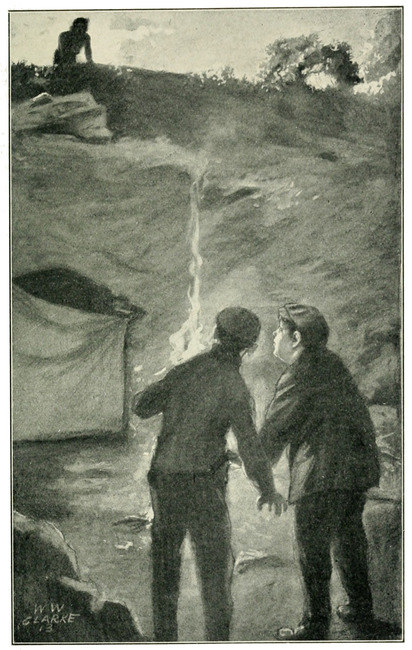

THERE, CROUCHING ON THE BROW, WAS THE FIGURE OF A MAN

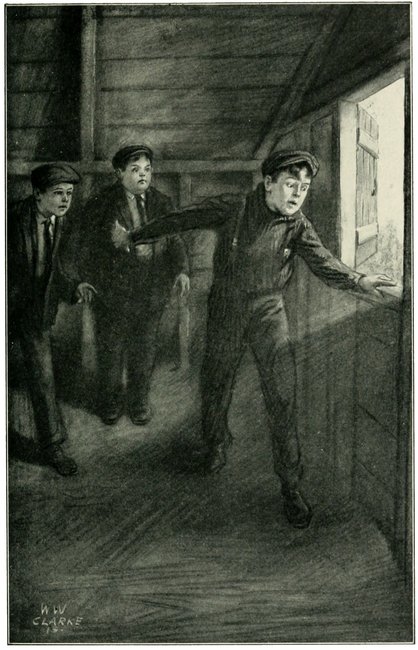

“FELLERS, THE GUARD’S GOT LOOSE, AND HE’S WAITIN’ FOR US TO COME DOWN”

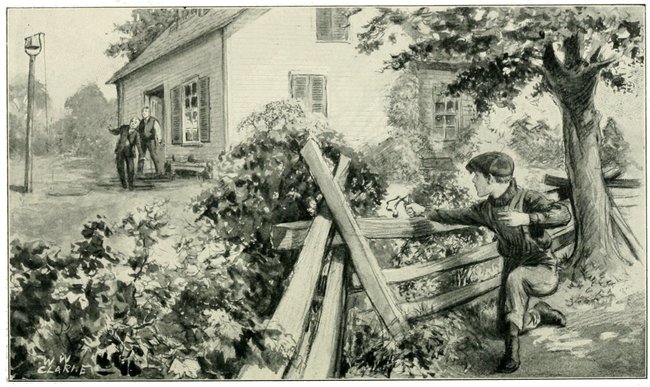

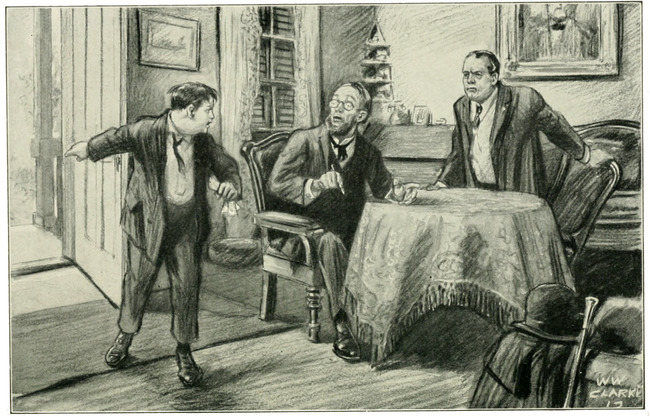

“JUST RUNG TWICE RIGHT UNDER MY NOSE”

SAMMY GRUNTED WHEN HE GOT THE FULL WEIGHT OF IT

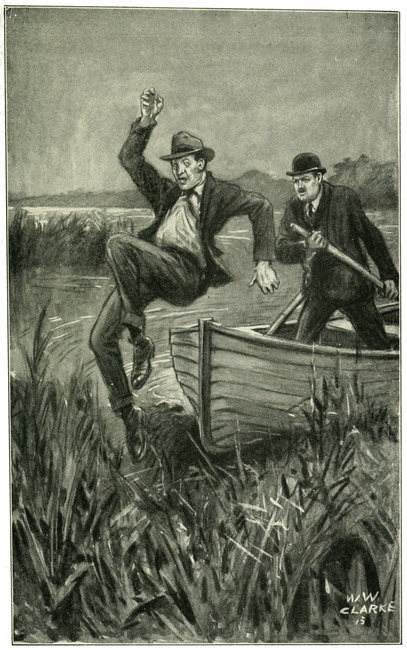

HE LET OUT A YELL AS LOUD AS A LOCOMOTIVE WHISTLE

“YOU GIT RIGHT OUT OF HERE! G-G-GIT!”

My name is Martin—James Briggs Martin—but almost everybody calls me Tallow, because once when I was younger I saw old Uncle Ike Bond rubbing tallow on his boots to shine them, and then hurried home and fixed mine up with the stub of a candle and went to school. I guess it couldn’t have smelled very good, for everybody seemed to notice it, even teacher, and she asked me what in the world I’d been getting into. After that all the boys called me Tallow, and always will, I guess.

I tell you about me first only because I’m writing this account of what happened. Mark Tidd is really the fellow I’m writing about, and Mark’s father and mother, and the engine Mr. Tidd was inventing out in his barn, and some other folks who will be told about in their places. I helped some; so did Plunk Smalley and Binney Jenks, but Mark Tidd did most of it. Mark Tidd sounds like a short name, doesn’t it? But it isn’t short at all, for it’s merely what’s left of Marcus Aurelius Fortunatus Tidd, which was what he was christened, mostly out of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, a big book that Mr. Tidd was so fond of reading that he never read much of anything else except the papers.

Mark Tidd was the last of us four boys to move to Wicksville. I was born there, and so was Plunk Smalley, but Binney Jenks moved over from Sunfield when he was five. Mark he didn’t come to town until a little over a year ago, and Plunk and me saw him get off the train at the depot. I guess the car must have been glad when he did get off, for he looked like he almost filled it up. Yes, sir, when he came out of the door he had to squeeze to get through. He was the fattest boy I ever saw, or ever expect to see, and the funniest-looking. His head was round and ’most as big as a pretty good-sized pumpkin, and his cheeks were so fat they almost covered up his eyes. The rest of him was as round as his face, and Plunk said one of his legs was as big as all six of Plunk’s and Binney’s and mine put together. I guess it was bigger. When Plunk and me saw him we just rolled over and kicked up our legs and hollered.

“I hope he’s goin’ to live in Wicksville,” says Plunk, “’cause we won’t care then if a circus never comes.”

A fat boy like that is a good thing to have in a town, so when things sort of slow down you can always go and have fun with him. At any rate, that was what we thought then. It seemed to us that Marcus Aurelius Fortunatus Tidd was a ready-made joke put right into our hands for us to fool with, but afterward we changed our minds considerable.

Mark’s father and mother got off the train after him, and his father said something to him we couldn’t hear. Mark waddled across the platform to where Uncle Ike Bond’s bus stood waiting, and Plunk and me listened to hear what he would say.

“D-d-do you c-carry p-p-p-passengers in that b-bus?” Yes, sir, he said it just like that!

Well, Plunk he looked at me and I looked at him, and he soaked me in the ribs and I smashed his hat down over his eyes, we were so tickled. If we had been going to plan a funny kid we couldn’t have done half so well. We’d have forgot something sure. But nothing was forgot in Mark Tidd, even to the stutter.

Old Uncle Ike looked down off his seat at Mark, and his eyes popped out like he couldn’t believe what they saw. He waited a minute before he said anything, sort of planning in his mind what he was going to say, I guess. That was a way Uncle Ike had, and then he usually said something queer. This time he says:

“Passengers? What? Me carry passengers? No. I’ve just got this bus backed up here to stiddy the depot platform. The railroad comp’ny pays me to do it.”

Mark Tidd he looked solemn at Uncle Ike, and Uncle Ike looked solemn at him. Then Mark says, respectful and not impertinent:

“If I was to sit here and hold down the p-p-platform could you drive my folks? I could keep it from m-m-movin’ much.”

Uncle Ike blinked. “Son,” says he, “climb aboard, if this here rattletrap looks safe to you, and fetch along your folks. We’ll leave the platform stand without hitchin’ for wunst.”

At that me and Plunk turned to look at the fat boy’s father and mother. Mr. Tidd was a long man, upward of six foot, I guess, and not very wide. His shoulders kind of sloped like his head was too heavy for them, and his head was so big that it was no wonder. His hair was getting gray in front of his ears where it showed under his hat, and he had blue eyes and thin cheeks and a sort of far-off, pleasant expression, like he was thinking of something nice a long ways away. He was leaning against a corner of the station reading out of a big book and paying no attention to anybody. Afterward I found out the book was Gibbon’s Decline and Fall, and that he always carried it around with him to read in a little when he got a spare minute.

Mrs. Tidd wasn’t that kind of person at all. As soon as Plunk and me looked at her we knew she could make bully pies, and wouldn’t get mad if her fat boy was to sneak into the pantry and cut a slice out of one of them in the middle of the afternoon. You could tell she was patient and good-natured, but, all the same, she wasn’t the kind you could fool. If you came home with your hair wet it wouldn’t do any good to tell her somebody threw a pail of water on it. She was looking around to see what she could see, and I bet she didn’t miss much.

The fat boy he motioned to her to come to the bus, and she spoke to her husband. He looked up sort of vague, nodded his head, and came poking across the platform, holding his book in front of him and reading away as though he hadn’t a minute to spare, and clean forgot all about the valise he’d set down beside him.

“Jeffrey,” says Mrs. Tidd, “you’ve forgot your satchel.”

He shut his book, but kept his finger in the place, and looked all around him. Pretty soon he saw the satchel and nodded his head at it. “So I have,” he says, “so I have,” and went back to get it.

Then all of them got into Uncle Ike’s bus, and he stirred up his horses who had been standing ’most asleep, with heads drooping, and they went rattling and banging up the street. When Uncle Ike’s bus got started you could hear it half a mile. I guess it was all loose, for it sounded like a hail-storm beating down on a tin roof.

“Wonder where they’re goin’?” says Plunk.

“You got to do more’n wonder if you’re goin’ to find out,” I says, and started trotting after the bus. It wasn’t hard to keep it in sight, because Uncle Ike’s horses got tired every little while and came to a walk.

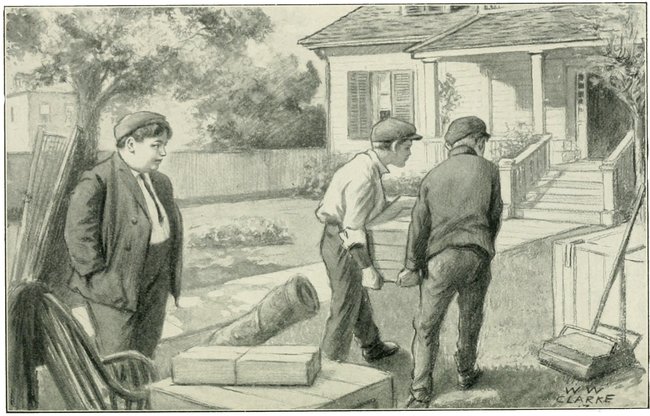

They stopped at the old Juniper house that had been standing vacant for six months, ever since old man Juniper went to Chicago to live with his daughter Susy’s oldest girl that had married a man with a hardware store there. The yard was full of boxes and packing-cases and furniture all done up with burlap and rope.

“They’re goin’ to live here,” Plunk yells; and I was as glad as he was. The benefits of having a stuttering fat boy living near you aren’t to be sneezed at by anybody.

We found a shady place across the street and watched to see what would happen. It’s always interesting to watch other folks work, especially if what they’re doing is hard work, and I guess carrying furniture and trunks and boxes is about as hard as anything.

Mrs. Tidd was ready for work before anybody else. She came to the door with a big apron on and a cloth tied around her hair, and the way she sailed into things was a caution. It seemed like she jumped right into the middle of that mess, and in a minute things were flying. Mr. Tidd came next with his book under his arm and stood in the stoop looking sort of puzzled. Mrs. Tidd straightened up, and then sat down on a packing-box.

“Jeffrey Tidd,” she said, not sharp and angry, but kind of patient and rebuking, “go right back into the house and take those clothes off. I knew if I didn’t stay right by you you’d get mixed up somehow. Will you tell me why in the world you changed from your second-best clothes to that Sunday black suit to move furniture?”

Mr. Tidd he looked pretty foolish and felt of his pants as though he couldn’t believe they were his best ones.

“That does beat all,” he said. “It does beat all creation, Libby. I wonder how these clothes come to be on me?”

“If you didn’t have ’em on under your others, which ain’t impossible, you must have changed into ’em.”

“My best suit!” he said to himself, shaking his head like you’ve seen the elephant do at the circus, first to one side and then to the other. “My best clothes!”

“Maybe I’d better come along and see you get into the right ones this time,” Mrs. Tidd suggested.

“I guess you don’t need to, Libby. I’ll take these off and hang ’em in the closet, and I’ll hang my second-best ones up, too. Then I’ll put on what’s left. That way I can’t go wrong.” He went off into the house, and Mrs. Tidd flew at the piles of stuff again.

Pretty soon the fat boy came around the side of the house with a quarter of a cherry pie in his hand and the juice dripping down faster than he could suck it off.

“Marcus,” his mother called, “take holt of this bundle of bed-slats and carry ’em up to the front room.”

Mark he grabbed them with one hand and hunched them up under his arm so that one end dragged on the ground, walking off slow and eating pie as he went. It took him quite a while to get back. I could see him look across the street at Plunk and me as he came down the steps. He stopped a minute, sort of thinking.

After a while Mr. Tidd came back again.

“Put the Decline and Fall down somewheres so you can use both hands, Jeffrey,” his wife says. And he did it as meek and obedient as could be. Between them they carried a hair-cloth sofa in after she had told Mark to fetch along some medium-sized boxes.

Mark stooped over one, and we could hear him grunt.

“Hello, Skinny,” Plunk yells. “Git your back into it and h’ist. That’s the way to lift.”

The fat boy straightened up and looked at us quite a while. Then he sat down on the box and called, “I bet the two of you can’t l-l-lift it.”

“I’ll bet,” says Plunk, “we kin lift it. I’ll bet we kin carry it from here to the standpipe and back without lettin’ her down wunst.”

“Braggin’ don’t carry no b-boxes.”

The way he said it sort of made me mad. “Come on, Plunk,” I says; “lets show this here hippopotamus whether we kin carry it or not.” And we went running across the street.

“Where d’you want it put?” I says.

“No use you tryin’. You couldn’t g-git it up.”

“Git holt,” I says to Plunk. “Now, Mister What’s-your-name, where’s it go?”

“Up-stairs in the hall; but you b-b-better not try. It’s too heavy for you.”

Plunk and me took that box up-stairs a-flying and ran down again.

“There,” I says. “Now kin we carry it?”

He stuck up what there was to his nose. “One ain’t nothin’. I carried the hull twelve out when we was movin’ in fifteen mum-minutes.”

“If you did,” I says, “Plunk and me can carry ’em in in twelve.”

He just laughed.

“Doggone it,” I says, “we’ll show you, you’re so smart.”

“Can’t d-d-do it.”

“You ain’t the only kid that can carry things,” Plunk says, with a scowl.

Mark he pulled out a little silver watch and held it in his hand. “Twelve m-minutes, was it? Can’t do it. I’ll keep time.”

Well, Plunk and me went at those boxes like sixty, and the way we ran them up-stairs was a terror to cats. When the last one was up we were panting and sweating and most tuckered out. Mark looked off his watch when we came out with a sort of surprised expression. “You kids is stronger than I figgered. You did it in eleven minutes and a half.”

“Sure,” I says.

“But them boxes wasn’t very heavy. You can’t carry that big box, by j-jimminy!”

Plunk and me was good and mad, and if anybody’d seen the way we hustled that big box in they wouldn’t have believed their eyes.

“That’s perty good,” says Mark. “Wouldn’t thought it of you kids. Must be stronger here in Wicksville than over to Peckstown where I come from.” He stopped a minute. “I can’t lift that big rockin’-c-c-chair myself.”

“Huh!” snorted Plunk. “That’s a easy one.” And in we wrastled with the chair.

We weren’t going to have any strange kid think we weren’t up to all he was, so we stayed right there all the afternoon, and I guess we proved pretty conclusively we could carry. And that wasn’t all: we proved we could last. I bet we carried two-thirds of the Tidds’ furniture in. When it was all done we sat down on the fence to pant and rest. Mark’s mother called him.

“I got to go to s-s-s-supper,” he says. “Come again when you feel s-s-strong.” And then he went into the house.

Plunk and me sat still quite a while. I began to think about it and think about it, and I could see Plunk was thinking, too. In about fifteen minutes I looked over at him and he looked over at me.

PLUNK AND ME WAS GOOD AND MAD

“How many things did that fat kid carry in?” I says.

“I didn’t see him carry anythin’.”

“Neither did I.”

We thought quite a spell more. Then I said to Plunk, “I guess maybe we better not do too much braggin’ about how much an’ how long we kin carry.”

He grinned kind of sickly. “This here Mark Tidd,” he says, “ain’t nobody’s fool—leastways, not on Mondays, which is to-day.”

When we got better acquainted with Mark Tidd he read a book called Tom Sawyer to us. I guess he got his idea of making us work out of that; he was always taking schemes out of books.

Mrs. Tidd was just the kind of person I thought she would be. She cooked lots of things and cooked them good; and, no matter how often Mark wanted to eat, she never said a word. Plunk and Binney Jenks and me got to going there a lot, and there was always cookies and pie and things. Of course, we didn’t go specially to eat, but knowing we’d get something wasn’t any drawback. I liked Mrs. Tidd, and sort of admired her, too. She was always working at something and managing things and keeping track of Mr. Tidd and Mark. I never heard her complain, and I don’t remember ever seeing her sit down except in the cool of the evening after supper.

I don’t want you to get the idea that Mr. Tidd was lazy or shiftless, because he wasn’t. He was just queer, and his memory was as long as a piece of string, which is the way we have in Wicksville of saying there was no knowing just how long it really was. Lots of times I’ve seen Mr. Tidd start out to do a job of work and forget all about it before he got a chance to commence. He was sure to forget if Mrs. Tidd didn’t take the Decline and Fall away from him before he went out of the door. Even that didn’t make it certain, because something to think about might pop into his head all of a sudden, and if it did he had to sit down and think about it then and there. He was a machinist complicated by inventions. Every time he saw you doing anything he’d stop right there and invent a better way for you to do it; and mostly the new ways he invented wouldn’t work.

It was an invention that had brought all the Tidds to Wicksville. Mark told us about it. It seems like Mr. Tidd had been inventing a new kind of machine or engine or something that he called a turbine. He’d been working on it a long time, making pictures of it and figuring it out in his head, but he never had a chance to get right down to business and actually invent it till a little while before they came to our town. Then an aunt of his up and died and left him some money. He quit his job right off and came to Wicksville, where it was quiet and cheap, to finish up doing the inventing. When he got it done he wouldn’t need a job any more because it would make him rich. We used to go out in the barn, where he was tinkering away, and watch him for hours at a time, and he never paid any more attention to us than as if we weren’t there at all. But he was careful about other folks and wouldn’t let them step a foot inside of the door. He was afraid somebody would see what he was up to and go do it first, which would have been a mean trick.

Mr. Tidd wasn’t what you call suspicious; he wasn’t always expecting somebody that he knew to do something to his engine, and I guess any man that had wanted to could have got into the workshop and looked it all over to his heart’s content by talking to Mr. Tidd for an hour or so and listening to him tell about the Roman Empire, and how it split down the middle and went all to smash. He was the kind-heartedest man in the world, I guess, and never could see any bad in any one—not in any one he really saw. He had a sort of far-away idea that there was bad folks, and that some of them might want to steal his invention, but if he had seen a man crawling through a window of the barn he’d have found some excuse for him. Anybody could fool him—that is, they could have if Mrs. Tidd hadn’t been there; but she kept her eye on him pretty close and saw to it he didn’t let any strangers come fooling around. If everybody had been as careful as she was this story wouldn’t have happened.

The real beginning of things didn’t look like anything important at all. It happened one afternoon when Mark Tidd and Plunk and Binney and me were hanging around the depot platform waiting for the train to come in. We didn’t expect anybody we knew to come, and there wasn’t any reason for our being there except that there wasn’t any reason for our being anywhere else. Plunk and I sat on one of those baggage-trucks that run along straight for a while and then turn up a hill at the end; Binney sat on a trunk; and Mark was on the platform, because that was the safest place for him and wouldn’t break down. It was hot and sleepy, and we wished we were somewheres else or that something exciting would happen. It didn’t, so we just sat there and talked, and finally we got to talking about Mr. Tidd’s engine. We’d seen him tinkering around it, and he’d told us about it, so we were interested.

“Wouldn’t it be great,” says Binney, “if it worked when he got it done! Us fellers could say all the rest of our lives that we knew intimate a inventor that was as big as Edison.”

We never had thought about that part of it before; but what Binney said was so, and we got more anxious than ever for things to turn out right.

“If it does,” says Plunk, “Mark’ll be rich, and maybe live to the hotel. Think of bein’ able to spend a dollar ’n’ a half every day for nothin’ but meals and a place to sleep.”

Mark he didn’t say anything, because he was drowsy and his head was nodding.

“Mr. Tidd says it’ll reverlutionize the world,” Binney put in. “He says if them Romans had had one of his gas-turbines the empire never’d have fell.”

“If it goes, nothin’ else’ll be used to run automobiles. If Mr. Tidd sold a engine for ev’ry automobile in the United States I guess he could afford livin’ to the hotel. I’ll bet he could own a automobile himself.”

“And they’ll use ’em in fact’ries and steamboats, ’cause they kin be run with steam same as with gasolene.”

“And won’t be more’n a twentieth as big as engines is now.”

We kept on talking and describing what we thought Mr. Tidd’s turbine would do and guessing how long it would be before he was ready to try it to see if it went. We was so interested we never noticed a man sitting a little ways off on a trunk. Pretty soon we did notice him, though, for he got up deliberate like and stretched himself and looked around as if he didn’t see anything, including us. Then his eyes lit on Mark, and he kind of grinned. He lighted a cigar and came walking over toward us.

“How about this train?” he asks, like he wasn’t much interested but wanted to talk to pass away the time. “Is it generally much behind?”

“Not much,” I says. “I ain’t known it to be over a hour late for two weeks.”

“Live here?” he asks, with another grin.

I nodded, but didn’t say anything out loud.

“Pretty quiet place for boys, isn’t it?”

“It ain’t what most folks’d call excitin’.”

After a minute he says: “I used to live in a little town like this when I was a boy, and I remember there wasn’t very much to do. I used to hang around the carpenter shop watching the carpenters work, and around the machine shop seeing how the machinists did things. It was pretty interesting. I suppose you do the same here.”

“We-ell, it ain’t exactly a machine shop we hang around.”

“Oh,” he says, “what is it?”

“It’s a—a—”

Just then Mark seemed to wake up sudden He grunted and interrupted what I was going to say, and then did the saying himself. “It’s a b-barn,” he says.

“Oh,” says the man, “a barn? What do you watch in the barn? The horses?”

“No. Ain’t no h-h-horses.” Then he half shut his eyes like he was going to take another nap.

The man didn’t say anything for a spell. “I was always interested in machines when I was a boy,” he says, at last. “Any kind of a machine or engine got me all excited. But we didn’t have as fine machines then as you do now. They’re making improvements and inventing new things every day. Some day they’re going to invent something to make locomotives better—something along the turbine line, I expect. Know what a turbine is?”

I was just going to say yes, when Mark woke up again. “Yes,” he says, “a t-t-turbine is a climbin’ vine that grows over p-porches.”

The man kind of strangled and looked away. “No,” he says in a minute, “I guess you got it mixed up with woodbine.”

“Maybe so,” says Mark.

We heard the engine whistle, and the man hurried off to see about his baggage. The train pulled in and pulled out again and left us sitting on the platform wondering what to do next. Mark stood up slow and tired and yawned till it seemed like his head would come off.

“Fellers,” says he, “you gabble like a lot of geese. Looked like that man was more’n ord’nary interested in engines.”

“’Spose he heard what we was talking about?”

Mark looked at me disgusted. “Tallow,” says he, “don’t go layin’ down in no pastures, ’cause a muley cow ’thout horns’ll come and chaw a hunk out of your p-p-pants.”

“I guess I ain’t so green,” I told him, but he only grinned.

“Let’s go swimmin’,” says Binney.

Mark shook his head and looked solemn. “Go ahead if you want to. No swimmin’ for me; it’s Friday, and I stepped on a spider this mornin’.”

Plunk busted out laughing. “Haw,” he says, “believin’ in signs. I ain’t superstitious.”

Mark looked at him and blinked. “I ain’t superstitious, but I don’t b’lieve in takin’ extra chances. Probably there ain’t nothin’ in it, but you can’t never tell.”

That illustrates better than I can tell what kind of a fellow Mark Tidd was—cautious, looking on all sides of a thing he was thinking of doing, always trying to figure plans out ahead so nothing disagreeable could happen. I don’t want you to think he was a coward, because he wasn’t, but he never ran his head into trouble that could be dodged ahead of time.

We all started for the river, because it would be cooler there even if we didn’t go in, but on the way Mark found a four-leaf clover, and a white cat ran across the road in front of us, so he figured it out that if there was any bad luck about Friday and killing a spider those two good-luck signs had knocked the spots off it.

Mark Tidd wasn’t given much to exercise, but that isn’t saying he couldn’t stir around spry if there was some good reason. He never wanted to play baseball or tag or anything where you had to run, and usually when a game was going on he’d be lying under a tree reading a book. He said it was a lot easier reading about a game than playing it, and more interesting than watching the kind we played. He read a good deal, anyhow, mostly, I guess, because you can sit so still to do it, and rest at the same time if you want to; and it was surprising the things he got to know about that were useful to us. Seemed like almost everything we wanted to do Mark would have read about some better way of doing it, and that’s how we came to get up the K. K. K., which stands for Ku Klux Klan.

We were all sitting in Tidd’s yard where the shade of the barn fell, and nobody had said anything for quite a spell. I was beginning to want to do something, and it was easy to see that Plunk and Binney were wriggling around uneasy like; but Mark he lay with his little eyes shut tight, looking as peaceful and satisfied as a turtle on a log. All of a sudden the idea popped into my head, and I yelled right out, “Let’s git up a secret society.”

Mark opened one eye and sort of blinked at me, and Plunk and Binney sat up straight.

“What’ll we call it?” Binney wanted to know.

“Who’ll be officers?” Plunk asked.

“I dunno,” I says, sharp like, because they seemed to think I ought to have the whole thing planned out for them to do without their lifting a hand.

Mark rubbed his eyes and rolled over on his side. “What’s the main thing about a s-secret society?” he asks.

“Payin’ dues,” I says, quick.

“Havin’ somethin’ to eat,” Binney guessed.

“Naw,” Mark grunts, contemptuous. “The main thing about a secret society is the s-s-secret.”

We could see in a minute that he was right about that.

“So,” he went on, “if we’re goin’ to have a secret society the first thing is to git a s-s-secret to have.”

“I don’t know no secret,” Binney said, shaking his head hard.

“Nor me,” said Plunk.

I thought a minute, because I knew a couple of secrets, but they were secrets I didn’t calculate to tell anybody, least of all Mark and Plunk and Binney; so I just shook my head, too.

“We’ll make a secret,” Mark told us.

“How?” I wanted to know, because I didn’t see how you could go to work to make a secret, but I might have known Mark would find a way.

“Did you ever hear of the K-k-k-ku K-k-k-klux K-k-k-klan?”

“What?” I asked.

He said it over again.

“I didn’t git it that time,” I told him. “Sounds like a tongue-tied hen tryin’ to cackle.”

Mark sort of scowled at me and did it all over, but not one of us could make a thing of it.

“Write it,” I said; “that’s the only way we’ll ever git it.”

At first he wasn’t going to do it, but we argued with him that it wasn’t any use spoiling a good thing like a secret society just because he couldn’t mention plain a name he wanted to tell us; so at last he wrote it down on a piece of paper. What he wrote was Ku Klux Klan.

“It don’t make no sense,” Binney said. “What language is it, anyhow? Dutch?”

“It ain’t no language. It’s a name.”

“Oh.”

“Of the most p-p-powerful secret society that ever was.”

“I reckon it was over in Russia or somewheres. It sounds like it.”

“It was right here in the United States.”

“Hum,” I said, because that name didn’t sound a bit like the United States to me.

“It was after the war.”

“The Spanish War?”

“No. The North and South war.”

“Oh.... That one. What was it for?”

“For protection. They went ridin’ around at night rightin’ wrongs and scarin’ folks and runnin’ things in general. They wore white sheets over their heads.”

“Gee. Honest?”

“It’s in the histories.”

“And it was secret?”

“The most secret thing ever was. Even men in it didn’t know who one another was.”

“Let’s have one,” Plunk yelled, squirming around like he was sitting on an ant’s nest. “I kin git a sheet.”

“Who’s goin’ to b’long?” I said; and then we all looked at one another.

“Nobody but us four,” Binney whispers, because he’s beginning to feel secret already. There wasn’t any argument to that, so we agreed to be a Ku Klux Klan, and to have our secret meeting-place in a little cave up across from the island where the swimming-hole was. It wasn’t much of a cave. Just a little round room dug out of the hill by somebody a long time ago. I couldn’t stand up straight in it, and when we four was all inside there wasn’t much room left—not with Mark Tidd taking up the space he did.

Well, each of us got a sheet and hid it there, and we kept potatoes to bake and an old frying-pan and a kettle and other things like that in case of emergency, for there was no knowing what might come up with an organization like ours, and we knew we had to be ready. Mark made up passwords and grips and secret signs; and we had an alphabet all of our own that we could write letters to one another in, which was fine, even though there never seemed to be anything very secret to write. But there come to be later on, and there was a time when we was glad of the cave and the potatoes and the frying-pan. But that wasn’t until the next spring, and lots of things happened before then.

I guess maybe it was a month after we organized the Klan when the stranger came to town. We were cooking dinner up at the cave that day—a black bass, four perch, and a couple of blue-gills, with baked potatoes—and we were just scouring the dishes with sand when we looked down and saw Uncle Ike Bond come ambling along the river. Uncle Ike drove the bus when it was necessary and fished the rest of the time, which was most of the time; and he caught fish, too; lots of them. I guess he got a good many on night lines.

Binney Jenks yelled down at Uncle Ike, and he looked up to see who it was. When he recognized Mark Tidd he sat down sort of tired on a log and motioned for us to come. He was a great friend of Mark’s since the day the Tidds moved to town; and he let on to folks that Mark was the smartest boy in Wicksville, which I wouldn’t be surprised if he was.

We all went down the hill, three of us running, and Mark panting along behind and puffing and snorting.

“Expectin’ any visitors?” Uncle Ike asked of Mark.

“No,” said Mark, and sat down.

“Um!” grunted Uncle Ike.

He pulled out his pipe and fussed at it with his jack-knife before he filled it and lighted up. “Looks kinder like you was goin’ to have some,” he said.

Mark didn’t answer anything or ask questions, because if you do Uncle Ike is apt to shut up like a clam and not tell you another thing. He waited, knowing Ike’d tell on if there was anything to say. The old man puffed away for a spell and then asked:

“Father’s makin’ some sort of a whirligig, ain’t he?”

“Yes. He’s inventin’ a e-e-engine.”

“Um!” grunted Uncle Ike. “Calc’late it’s wuth anythin’?”

Mark nodded yes.

“Feller come in on the mornin’ train that seemed tolerable int’rested in sich whirligigs,” said Uncle Ike. “He allowed to set onto the seat with me and asked was I acquainted in town—me! Asked was I acquainted in town!” It was hard for me to tell whether this made Uncle Ike mad or tickled him. He was that way, and you never could make him out. Sometimes when he was maddest he looked most tickled, and when he was most tickled he looked maddest.

“I allowed as how I knowed a few of the citizens by sight and more’n a dozen to speak to,” Uncle Ike went on, “and then he up and begun wantin’ to know. When folks gits to the wantin’-to-know stage on short acquaintance I git to the don’t-want-to-tell stage, and Mister Man didn’t collect no amazin’ store of knowledge, not while he was a-ridin’ on my bus.”

He stopped talking and looked at Mark, and Mark looked at him. Then Uncle Ike winked at Mark. “If I was a smart boy,” he said, “and a stranger feller come to town snoopin’ around and askin’ questions about whirligigs, I’d sorter look into it, I would. And if that stranger feller was askin’ about the i-dentical kind of a whirligig my father was makin’ in the barn and calc’latin’ to git rich out of I’d look into it perty close. And if my father was one of these here inventor fellers that forgits their own names and would trust a cow to walk through a cornfield I’d be perty sharp and plannin’ and keep my eye peeled. That’s what I’d do, and I ain’t drove a bus these twenty years for nothin’, neither. The place to git eddicated,” he said, “is on top of a bus. There ain’t nothin’ like it. There’s where you see folks goin’ away and comin’ home, and there’s where you see strangers and actors and travelin’-men, and everybody that walks the face of the earth. Colleges is all right, maybe, for readin’ and writin’, but when it comes to knowin’ who you kin depend on and who you got to look out for the bus is the place.”

“Did he ask about f-f-father?” Mark wanted to know.

“He didn’t mention him by name,” said Uncle Ike, grinning. “But he says to me, says he, ‘This is a nice town,’ says he, ‘and a town that looks as if there was smart folks in it. It’s lettle towns like this,’ he says, ‘that inventors and other great men comes from,’ says he. ‘Have you got any inventors here?’ he asks.

“‘There’s Pete Biggs,’ I says. ‘He’s up and invented a way to live without workin’.’

“‘Is that all?’ he asks, kind of disappointed.

“‘Wa-al,’ I says, like I was tryin’ hard to remember, ‘I did hear that Slim Peters invented some kind of a new front gate that would keep itself shut. But ’twan’t no go,’ I says, ‘’cause Slim he had to chop down the gate with a ax,’ I says, ‘the first time he wanted to go through it. It was a fine gate to stay shut,’ I says, ‘but it wa’n’t no good at all to come open.’

“‘Ain’t there anybody here tryin’ to make an engine?’ he put in.

“‘Engine?’ says I. ‘Engines is already invented, ain’t they? What’s the use inventin’ when some other feller’s done it first?’

“‘I mean a new kind of an engine,’ he says, ‘a kind they call a turbine?’

“‘Oh,’ says I. ‘I ain’t met up with no engines like that, not in Wicksville. We ain’t much on fancy names here, and I guess if a Wicksville feller had invented anythin’ he wouldn’t have named it that—he’d ’a’ called it a engine right out.’

“‘Umph!’ says the feller, like he was mad, and then got out at the hotel. I stopped long enough to see him talkin’ with Bert Sawyer, so it’s likely he knowed all Bert did inside of ten minutes. And that’s all there was to it.” He looked at Mark with his eyes twinkling.

Mark got up kind of slow, blinking his eyes and looking back at Uncle Ike.

“I guess I’ll go home,” he said.

Uncle Ike slapped his knee and laughed a rattling kind of laugh way down in his throat. “There,” he whispered, like he was talking confidential to Binney and Plunk and me, “what’d I tell you? Hey? What’d I tell you? Don’t take him long to make up his mind, eh? Quicker’n a flash; slicker’n greased lightnin’!”

We went off up the hill after Mark, leaving Uncle Ike sitting on the log laughing to himself and slapping his leg every minute or so. He sat there till we were out of sight.

Mark was pretty quiet walking along, thinking hard what to do, or whether he had better do anything; but finally he seemed to make up his mind and hurried off faster than I ever saw him walk before. And it was a warm day, too. We turned into his yard, and as we went through the gate he jerked his thumb toward the back yard.

“You w-w-wait there,” he stuttered. “I may want you.” Then he went in the front door.

As we walked by we looked through the window and saw the stranger sitting in the parlor talking to Mr. Tidd, and he was nodding and smiling and being very polite; or, anyhow, it seemed that way to me. I always was sort of curious, so I stopped close to the window and listened, while Plunk and Binney went on around the house. I guess it isn’t very nice to listen that way, but I never thought of that until it was all over.

Mr. Tidd was talking.

“Yes, sir,” he was saying, “the world don’t hold another book like this. The title says it’s The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, but it’s about more than that. Why, it’s about everything. It don’t matter what happens, you can find the answer to it in Gibbon.... Yes, sir, The Decline and Fall is the greatest book of ’em all.”

“I agree with you entirely, Mr. Tidd, entirely. It has been some time since I read the book, sir, but I have been promising myself that pleasure—and profit—for several months. I shall read it again, sir, as soon as I get home.”

“You will never regret it,” said Mr. Tidd, and patted the book in his lap.

Somehow the stranger’s face seemed familiar to me, but for a while I couldn’t place him. Then all of a sudden it came to me: he was the man we saw on the depot platform who asked about turbines. I almost yelled out loud to Mark.

I listened again and heard the stranger say:

“I’m in the engineering business, Mr. Tidd, and that’s why I came to see you. I heard you were working on some sort of a machine, and, as my company always wants to keep in touch with the latest developments of mechanics and engineering, I dropped in to have a chat with you.”

“Yes, yes,” said Mr. Tidd; but it was plain he was thinking about something else.

“It happens often,” said the stranger, “that men like yourself, who have valuable ideas, lack the money to carry them out. Very frequently my company, if the idea seems all right, advances the money to carry on experiments.”

“Money,” said Mr. Tidd, vaguely. “Oh yes, money. I don’t need money. No. I have all the money I need.”

The stranger looked disappointed, but he didn’t say anything about it.

“You’re fortunate,” he told Mr. Tidd, “but maybe there’s something else I could do for you.”

“Not as I know of. Don’t seem like I needed a thing, but I’m much obliged, much obliged.”

“What is the nature of the work you are doing?” asked the man. I didn’t think he liked to come right out with the question that way, but probably he couldn’t invent any other way to get at it.

“It’s a turbine,” said Mr. Tidd, right off, and his eyes began to shine. “It’s a practical turbine for locomotives and automobiles and power-plants and what not. Why, sir, this engine of mine will stand on a base no bigger than a cook-stove and develop two hundred horse-power; and it will be reversible. I have a new principle, sir, for the application of steam; a new principle, it is—” He stopped suddenly, shook his head, and said, with a patient sort of smile, “My folks don’t like to have me talk too much about it.”

“Of course,” agreed the stranger, who had been leaning forward and edging farther toward the front of his chair, with interest. “Of course. It is never wise to discuss such things too freely. How far has your work progressed?”

“Not far, not far. In the experimental stages. I have something to show for my work—nothing to boast of, but enough. Enough to make me sure.”

“I should be very interested to look over your workshop,” suggested the stranger. “I always like to see how a thorough machinist has things arranged.”

At that I ducked and ran around the house, and just a moment later Mark came tiptoeing out of the kitchen door. He held up his finger for us to be still and then motioned for us to follow him to the barn.

In the barn he grabbed up a lot of drawings and stuffed them into my hands.

“Here. Take these and hide back of the f-f-fence.”

Then he gave Binney and Plunk some funny-looking pieces of steel to carry, and snatched some other things himself, and we all sneaked out through the back gate and crouched down behind the fence out of sight.

“Father’s goin’ to s-show him the shop,” whispered Mark. “I guess the feller was fixin’ to git a squint at these things. If he was it’s all right, and if he wasn’t no harm’s done.”

In about two shakes of a lamb’s tail Mr. Tidd and the stranger came out of the shop and went inside. We had our ears to the wall and could hear how Mr. Tidd was being taffied by the man, and we could tell by the way he answered back that he was getting to like the stranger more and more every minute. Butter wouldn’t melt in that man’s mouth. He was as full of compliments as an old grist-mill is of rats.

After a while we heard Mr. Tidd say:

“I dunno’s there’d be any objection to your lookin’ at my drawin’s and patterns and stuff. ’Twon’t do no harm, I calc’late.”

The man didn’t say anything, and pretended he wasn’t paying attention. We could hear Mr. Tidd moving around, and then he stopped still, and I knew he was scratching his head, though I couldn’t see him, because he always scratches his head when he can’t figure out just what’s going on.

“I swan,” he said, kind of vague and wondering, “I’d ’a’ bet I left them things right here; I’d ’a’ bet a cookie. But they ain’t here—not a sign of ’em. Now, ain’t that the beatenist? I must ’a’ carted ’em off some place without thinkin’. Um! Hum!... Where’n tunket could it ’a’ been?”

“What seems to be the matter?” asked the stranger, and his voice sounded anxious to me. It did to Mark, too, because he nudged me.

“I’ve up and mislaid my drawin’s and things,” said Mr. Tidd, sounding like he was apologizing. “Ain’t that the dumbest thing! I’m always a-layin’ things around and forgettin’ ’em.”

“Surely they must be in the shop some place,” suggested the stranger.

Again we could hear Mr. Tidd rummaging around, but it wasn’t any use. “No,” he said, “no, they ain’t here. I wonder if I could ’a’ left ’em down to the grocery.”

“What would you be doing with them at the grocery?”

“Nothin’ that I know of, but I might have tucked ’em under my arm and gone just the same. Like’s not I did. Wa-all, I’m sorry I can’t show ’em to you, but maybe they’ll turn up to-morrow.”

“I’ve got to leave on the late train,” said the stranger.

“Too bad,” said Mr. Tidd, his mind still wondering where his things were. “Too bad.” And with that he forgot all about the stranger and went out of the barn and off up the street talking to himself and scratching his head. The stranger looked after him and bit his lips; then he grinned like the joke was on him, and he went, too.

“Well,” I asked Mark, “what now?”

“We’ll put ’em right back,” he said, grinning, “and dad won’t know but what he just overlooked ’em.”

We fixed everything like it was, and then we went down-town to see what we could find out about the stranger.

He was in the hotel when we got there, and it was easy to get out of Bert Sawyer all he knew about him. His name was Henry C. Batten, and he lived in Pittsburg. He was a traveling man for the International Engineering Company, Bert thought, and later we found out it was so, because he left one of his cards in his room and Bert found it.

We sat on the hotel steps until Uncle Ike Bond’s bus rattled up to carry folks to the late train. The stranger squeezed through the door and sat down in a corner, looking as if he wasn’t pleased with things in general. Uncle Ike winked at Mark.

“How’d you make out?” he whispered.

Mark went up close and told him all about it, and Uncle Ike like to have fallen off the seat laughing.

“What’d I tell you?” he chuckled to nobody in particular. “Ain’t he a slick one? Ain’t he? Slicker’n greased pole I call him, eh?”

Then he gathered up the lines, but stooped over again to whisper, “If ever this thing gits where you need help from Uncle Ike Bond just up and say so in his hearin’, and we’ll see what a eddication got on top of a bus is good for.”

I didn’t see what good he could ever do anybody, but that just shows how you can be mistaken in folks.

Right up till snow was on the ground the Ku Klux Klan used to meet in the cave. We would go up there Saturday mornings, all coming by different roads, and when we met there would be passwords and signals and grips and all sorts of secret things. After a while we got so many signs that a fellow had to be pretty careful what he was up to so as not to be telling the other members he was in deadly peril, or that a secret meeting was called at once, or something else, because almost everything we did had a meaning. For instance, if I was to reach around and scratch my back when Mark or Plunk or Binney were looking, that meant that I had to speak to them right away about something important; and if one of us shoved both hands in his pockets at once that meant to look out because enemies were watching. All our signals were simple things like that that wouldn’t be noticed. Mark got most of them up, and I guess there were more than a hundred things to be remembered.

We used to sit in the cave and wish there were some real wrongs being done that we could right, or that we had some kind of a powerful enemy, or that there was a mean, miserable whelp that we could visit at night with our white sheets on and tie him to a tree and frighten him into being a good citizen; but there weren’t any, and we had to take it out in making believe. But that was almost as much fun.

We had one sign that was never to be used except when we were desperate and needed help and succor, and that was to untie your necktie and tie it up again. But the best one of all was the jack-knife sign, and it was a dandy, because there were so many ways of using it. If one of us met the other and said “Lemme take your jack-knife,” that was one way; or if you sent a note by somebody else with the word jack-knife in it, or anything like that. But the best way was the one to be used if you were a captive, or if enemies were surrounding the cave and you wanted to have your comrades rally around you. Nobody would ever suspect it. All you had to do was to meet somebody, a farmer or a man fishing or any one, and give him your knife and tell him please to give it to any one of the society. As soon as that one got the knife he had to collect the others and make for the cave as fast as he could. It worked bully. Lots of times I’ve sent my little brother over to Mark’s with my knife, and dozens of times Mark or Binney or Plunk have sent their knives to me. Once Binney sent his by his father, who was going past my house. I don’t believe the real, original Ku-Kluxers had a better sign than that.

The cave was up on the side hill like I told you, and looked down on the river. I told you, too, how Uncle Ike Bond was always fishing when he could get time, which was most always, and he used to come past almost every time we were there. After a while it got so he’d stop to talk to us or we’d go down to talk to him. Finally one day he grinned, knowing-like, and asked what we were doing there so much.

We looked at one another, and then Mark reached around and scratched his back. That meant, of course, that he had to speak about something important right away, so we got up and told Uncle Ike we’d be back in a minute. He grinned and nodded.

We went off out of earshot, and Mark Tidd whispered:

“Uncle Ike’s a pretty good f-f-friend, ain’t he?”

We said yes, he was.

“I think he’s catchin’ on that we’re up to somethin’.”

“Maybe so,” I said.

“Let’s make him a m-member. Then he can’t give us away. Besides, he’d be a pretty valuable one, anyhow.”

We talked it over awhile, and it was decided unanimous to make him a Ku-Kluxer, so we went back to where he was sitting.

“Uncle Ike,” says Mark, “can you keep a secret?”

“Wa-all, I hain’t never been tempted very hard, but I guess I can keep one good enough for ordinary purposes.”

“This is the secretest thing that ever was,” says Binney.

“Um!” says Uncle Ike. “You don’t tell!”

“We’re the Ku Klux Klan,” says Plunk, to save Mark the trouble of stuttering so many k’s.

“And we want you to join if you’ll take the oath.”

“Sure,” says Uncle Ike. “I’ve always hankered to b’long to somethin’ secret, but I hain’t never seemed to git around to it.”

Mark recited the oath, and Uncle Ike swore to it solemn as could be. He seemed real glad to be a member. After that we spent most of the afternoon teaching him our secret signs and tokens and things. He said he didn’t think he could learn all of them, but that a few dozen of the most important would do. He seemed particular delighted with the jack-knife sign.

“But looky here,” he said, shaking his finger in our faces, “don’t go workin’ any of them signs on me unless you mean ’em in earnest. You young fellers kin fool with ’em as much as you want to, but don’t go sendin’ me no jack-knives till you git where you need my help and need it bad. I’m too old to go gallivantin’ around chasin’ wild geese.”

After that he stopped to our meetings more often than ever, and pretty nearly every time he’d have a big bass, or maybe a nice mess of pan-fish for us to cook for our dinner. We were all glad we made him a member.

All this while Mr. Tidd was working steady on his turbine, and it was getting nearer and nearer to being ready for a trial to see if the model would work and do what he thought it was going to do. He didn’t do anything else but work in the barn and read the Decline and Fall and forget things. I mean he didn’t have any job, but lived on money that he had in the bank. If it hadn’t been for that he’d have had to go on being a machinist all the rest of his life, and probably wouldn’t ever have had time to do any inventing.

With all his forgetting and absent-mindedness and inventing he was one of the most patient men. I never heard him speak sharp, and, no matter what happened, good or bad, he took it just the same, not seeming much disturbed; and always simple and kind-spoken to everybody. He always would stop to answer questions or explain things or just talk to us boys if we came into the shop, and never told us to get out or quit bothering him. Nothing bothered him. But Mrs. Tidd wasn’t that way. She’d worry and worry, and sometimes when she was flying around up to her ears in work she’d out with something cross, not meaning it at all, but letting it fly off the tip of her tongue. But she was never short with Mr. Tidd and never exasperated with him, no matter what he forgot or did wrong.

All four of us—that is, Mark and Plunk and Binney and me—went out to Mr. Tidd’s shop to ask if Mark could come with us and camp Friday night and Saturday and Saturday night and Sunday at our cave. The rest of us had asked and could go if we wanted to. We wanted to, but we didn’t want to without Mark.

Mr. Tidd was tinkering and filing and fussing around with some little parts of his turbine, and we had to speak two or three times before he heard us; then he turned around surprised-like and said, “Bless my soul, bless my soul,” as if we had just come from a thousand miles away in an airship. He laid down his tools and leaned his arm on his bench and stared at us a minute. Then he said “Bless my soul” again and reached for his handkerchief.

“You’ve got it tied around your neck,” Binney told him.

Mr. Tidd felt and found it where Binney said. “Well, well,” he sort of whispered. “However come that there?”

“Pa,” began Mark, “can I go camping at the cave? The fellers are goin’.”

“Camping,” said Mr. Tidd; “camping at the cave? To be sure—at the cave. Um! What cave?”

“Our cave,” we all said at once.

We told him all about it, and he was as interested as could be, asking questions and nodding his head and smiling, just like he wanted to go to the cave himself.

“Can I go, pa?” Mark asked, when we were through.

“Far’s I’m concerned you can,” said Mr. Tidd, “but you better ask your ma. She sort of looks after such things. I guess she looks after everything; and, Mark, when you ask her see if she knows where my shoes are. I swan I couldn’t find ’em this mornin’ when I came out—couldn’t find hide nor hair of ’em. It does beat all how things get lost.”

Mrs. Tidd was dusting the parlor when we went in, and had a cloth tied around her hair. She was just flying around, poking behind things and into corners and going as fast as if she had to have it all done in two minutes.

“Ma,” Mark says, poking his head through the door, “can I go campin’ with the fellers?”

“No,” says Mrs. Tidd, without turning her head. Then she stopped a second and felt of her hair. “What’s that you say?”

Mark asked her again, and we chipped in and explained.

“Was ever such a boy!” she said to herself. “Here I got all the cleanin’ and dustin’, and bread in the oven. Will you be careful and cover up good at night and not get into any mischief?”

Mark nodded.

“What you going to have to eat?”

I told her we’d bake potatoes and have fish and one thing another.

“You sha’n’t do no sich thing—gain’ without proper food!” And off she flew to the kitchen and got a basket in a jiffy. Into it she put a big chunk of ham, and a loaf of bread and some butter, and a whole pie and half a chocolate cake, and what was left of a pot of baked beans. “There,” says she, “I guess that’ll keep you from starvin’.”

We said good-by and started for the door, but she came running after us. “Mark,” she says, “you take these gray blankets, and, mind you, bring them back again or you’ll hear from me.” Then she kissed him and flew back to her dusting again.

We had all of our things in the front yard, and it didn’t take us any time to get them packed on our backs and start for the river. It was only about half an hour’s walk, but it took us a little longer to get there on account of Mark, who wanted to rest every little while; but it wasn’t really resting he wanted; it was a piece of his mother’s cake. We ate it all up before we got to the cave at all.

We got at the cave from the top of the hill and threw our things down on the slope in front. It was a little chilly in the shade, so Mark told us to gather wood for a fire while he packed things away the way they ought to be. I guess we were gone twenty minutes. When we came back everything was just where we left it, and Mark was standing looking into the cave with his face wrinkled up like it gets when he’s puzzled.

“Been workin’ hard, ain’t you?” sings out Plunk.

Usually Mark would have said something back, but this time he didn’t. He turned around and asks, “Have any of you been here since last Saturday?”

Nobody had.

“S-somebody’s been in the cave.”

“How do you know?” I asked him.

“Things been moved around, and some p-p-potaters is gone,” he stuttered.

“Let’s look,” says Binney; and we all crowded in. Mark knew where everything ought to be, even if we didn’t, and he told us just what had been touched and what hadn’t. “He used the f-fryin’-pan,” he grumbled. “Look!”

Sure enough, there was the frying-pan with grease sticking to the bottom, and we never left it that way.

“Wonder who it could have been?” says Plunk.

“Maybe it was Uncle Ike,” guessed Binney.

“No,” says Mark, “he’d ’a’ cleaned the pan.”

That was right. We knew he wouldn’t leave any dirty dishes around.

Well, it kind of upset us. Of course, the cave wasn’t ours, and anybody could come into it that wanted to, but nobody ever did. It was such a little cave that it didn’t amount to much to look at, and it was quite a climb; and now here was somebody poking into our things, and it made us pretty sore.

“Probably some feller come along fishin’ and happened onto it,” Binney guessed.

It didn’t do any good to bother about it, so we set to work and packed our things away and got a fire ready to light. In front of the cave was a little patch of sand—white sand crumbled off the sandstone that the cave was carved out of, I guess—and it was there we had our fires and did our cooking. Mark always fixed the fires, because he knew how to pile the sticks and get them to blazing even if the wind was blowing like sixty. Now he was crouched down ready to strike a match when all of a sudden he said something like he was startled.

“What’s matter?” I asked him.

He didn’t answer, but bent over and looked at something in the sand. Somehow I felt shivery all at once without any reason, and walked over where he was to see what he was looking at. There in the sand was some kind of a footprint; it was a bare foot, but big, bigger than two ordinary men’s feet, with the toes growing sort of sideways. I looked at Mark, and he looked at me.

“What made it?” I whispered. For a minute it didn’t seem safe to speak out loud.

“I dunno,” says Mark, with his eyes big and his face serious. “Looks like a man if the toes weren’t on sideways.”

We called Plunk and Binney, but they couldn’t make anything out of it, so we built the fire good and big, just in case it was some kind of a wild animal. We knew animals were afraid of fire.

It was Binney who thought about the frying-pan. “It must be a man, or it wouldn’t have used the pan,” he says.

That was right. Animals don’t cook. Plunk drew a long breath. “Maybe it’s a wild man,” he said, trembly voiced.

“Like there was with that circus last summer,” I said, remembering the pictures in front of the tent of seven men catching a thing all hair and beard, with skins on it for clothes, and big teeth. We all got closer to the fire.

“Bosh!” snorts Mark; but his voice was a little dry, and he didn’t look any too comfortable. “There ain’t any wild men.” But he didn’t believe it and we didn’t believe it.

“What had we better do?” asks Binney.

“Nothing,” says Plunk, letting on he wasn’t afraid. “It won’t hurt anybody even if it is a wild man. And, besides, there are four of us.”

That wasn’t so very encouraging, judging from the size of the footprint. Anything with a foot as big as that could take four boys at a bite.

“Had we better stay?” Binney was pretty scared and showed it.

“Of course,” Plunk told him. “We ain’t babies. We got to stay.”

We couldn’t very well back down after that. I expect every one of us was willing enough to pack up and go, but nobody would start it, so we sat close to the blaze and talked about other things, and made believe to one another that wild men were the last thing in the world we’d ever think of running away from.

It began to get dark, and we cooked supper. It wasn’t a very cheerful meal because every once in a while one of us would stop to listen and ask, “What was that?” There were lots of noises, like there always are in the woods, but they never seemed so shivery before. The moon didn’t come up till late, and it was dark as a pocket except where our fire lighted things up for a few feet.

“We ought to have a gun,” said Plunk, after we had been quiet a long time.

“Bosh!” said Mark. “Let’s go to b-b-bed.”

“We got to have a guard,” says Binney. “The Ku Klux Klan wouldn’t camp without a sentinel.”

We agreed to that. The night was divided into watches, and we drew pieces of stick to show who would watch first. I drew the shortest piece, and the other fellows went into the cave and wrapped themselves up in their blankets. I sat out by the fire, and I can tell you it was pretty lonesome and scary.

After a while I could hear Mark snoring inside the cave, and it made me sort of mad. Anybody would think he’d been brought up next-door neighbor to a wild man or whatever kind of a thing it was that went around leaving marks in the sand a foot long, with the toes turned toward the side. I crept over to the opening and looked in. All three of them were asleep, and if I felt lonely and skittish before I pretty nearly went into a panic now. The fire was going good, but I threw on more wood just to have something to do and to light up farther into the woods.

Pretty soon the moon came up, and that made it seem chillier. It was as if the light was cold—it looked as if it was. I edged closer to the fire, where the blaze almost scorched my shins, and crouched there, with my heart beating thump, thump, and my insides feeling as if they were shriveling together for lack of anything to hold them out like they ought to be. I looked at my watch, hoping my turn on guard was over. Only a little more than a half-hour of it was gone!

The moon got higher, and the woods, instead of just being black as if a curtain was hanging all around me, got shadowy, and the shadows moved. Give me black darkness any time to the kind where there are patches of light and patches of shadows that keep shifting and oozing around; when the woods look that way you feel certain something is hiding and watching you in the places where the light isn’t.

I got the hatchet and put it between my knees, but it didn’t make me feel much better. I tried whittling, but I couldn’t keep my eyes on it; they wanted to wander around to see if anything was sneaking up on me. I thought about lots of things, and one of them was that if ever I got home it would take a lot of persuading to get me camping out at night again.

Another half an hour went by, and it seemed as if my hours would never pass. Nothing happened, but sometimes I wished it would. Being afraid something will happen is worse than the thing itself if it comes.

I guess it was about half-past ten when the funniest feeling came over me. It’s hard to tell just what it was, but more than anything else it felt as if somebody’s eyes were bearing on my back, watching and watching; and it felt as if the eyes were bright and as if they’d shine in the dark if I was to turn and look at them. I sat for more than five minutes before I could get up courage to look. When I did I couldn’t see a thing, but, all the same, I was as sure as anything that something had been looking at me.

About fifteen minutes later I heard a noise; it was just as if somebody had slipped on the hillside and scrambled for a minute before he could catch his feet. It might have been a stray sheep, or maybe a coon roaming around in the moonlight, but it didn’t sound like it to me; it sounded bigger and stronger. It was so very still afterward that I was more afraid than ever, because if it had been a sheep I’d have heard him running away, and even a coon would have made some sort of a racket. No, I says to myself, it’s something hiding and sneaking around with an eye on us; it’s the thing that used our pan and stole our potatoes and left that track in the sand.

That was all that happened during my watch, but I was glad when it came time to wake Mark to take my place. He came out rubbing his eyes and blinking at the light.

“Talk to me a minute,” he yawned, “till I git awake.”

We talked a spell, but I didn’t say anything about the noise or that I thought something had been watching me. When he was awake so he wouldn’t doze off again I went in and snuggled into my blanket. I was afraid at first I wouldn’t be able to get to sleep, but before I really got to worrying about it I was gone; and I didn’t dream, either.

In the morning none of us had much to say about his watch during the night. By the looks of the others I’m sure they were just as afraid as I was, but they weren’t letting on and neither was I. Besides, it seemed sort of foolish with the sunlight shining bright through the trees and the water glittering and the birds chittering all around. The woods didn’t look as if there could be anything fearsome or dangerous in them; wild men seemed a long ways away and nothing to worry about, anyhow. What would a wild man be doing right outside of Wicksville? If there was one somebody would have seen it and talked about it before we got there.

We fished all day and played Indian and fixed up a raft out of a couple of old logs and poled ourselves around. In the afternoon we went over on the island and gathered about a bushel of butternuts apiece, but they weren’t any good, having laid all winter.

“We’ll have h-h-ham for supper,” Mark said. “We kin warm it up, and it’ll be pretty good with fish.”

We poled the raft across, carrying our nuts, and made for the cave. Mark went to work building the fire again, Plunk and Binney gathered wood, while I riffled around inside getting things ready for the cooking. I found most of the stuff all right, because Mark had put it away, and he always puts things away careful, but when it came to the ham I couldn’t put my hand on it to save my life.

“Where did you put that ham?” I sang out to Mark.

“Right in that jar,” he told me, “next to the basket.”

“It ain’t here,” I called, after I had looked again to make sure.

“It’s got to be,” says he, his voice a little excited, “because I put it there.”

“Well, it ain’t. Come and see for yourself.”

He came in and rummaged around, but not a sign of the ham could he discover. His face was sober when he looked up at me and says, “Is anythin’ else m-missin’?”

Together we went over the things. Everything was there till we got to the bread. All together we had four loaves. We’d used most of one, and there ought to have been three left, but there wasn’t. There were only two.

“Did you hear anything last night?” asks Mark, sharp-like.

“Yes,” I says. “Did you?”

“I ain’t sure, but I th-thought so.”

“I felt somethin’ watchin’ me,” I told him. “Seemed like its eyes was just borin’ into me when my back was turned.”

“Um!” he grunts. “See anythin’?”

“No.”

“Me neither.”

“There’s somebody prowlin’ around, that’s sure. That ham didn’t git tired of stayin’ an’ run off alone.”

Mark grinned. Then he looked solemn again and nodded.

“Don’t seem very dangerous, though—stealin’ ham. Maybe somebody’s playin’ a joke on us.”

“Nobody’d hang around all night and all day for this much joke.”

He admitted that was right. “But ’tain’t no wild man,” he insisted. “There ain’t none.”

“I dunno,” I says.

And then Binney and Plunk came along with their arms stacked full of wood.

Mark and I kept quiet before them, but we arranged that we’d keep watch to-night by twos instead of all alone. “It’ll be more sociable,” I says; and they jumped at the idea.

Mark and I were to stand guard the first part of the night, and Binney and Plunk would be on watch till morning. That was the way it was fixed. About nine o’clock they turned in, and we went out by the fire.

“Let’s be sure there’s enough wood,” I said to him. “I’d sort of hate to be left out here in the dark.”

He grunted, but I noticed he looked at the pile pretty careful, and even dragged in some pieces that were lying within reach.

For maybe an hour we got along fine. Not a thing happened, and we found lots of things to talk about. We got to figuring about his father’s turbine and what it would do and how much money Mr. Tidd would make out of it, and it sounded pretty important. Some day we were sure there’d be big shops in Wicksville where the engines would be manufactured, and Mark would be general manager when he got through college, and all the rest of us would have good jobs. I was going to be a mechanical engineer some day, so Mark agreed to put me in charge of that department. We figured his father would make maybe four or five thousand dollars in a single year.

“If he m-makes anything,” said Mark.

“But he’s goin’ to.”

“He ain’t got it patented yet.”

“What of it?”

“If somebody got holt of his idee, or stole his drawin’s and got it patented f-f-first, he’d never git a thing out of it.”

“Not a dollar?”

“Not a dollar. There’s always folks tryin’ to steal inventions. Most inventors git cheated out of their money or s-some-thin’.”

THERE, CROUCHING ON THE BROW, WAS THE FIGURE OF A MAN

“Your father better be pretty careful, then,” I says.

“Careful!” grunts Mark. “You know how careful he is—and that feller was in town again.”

“No,” I says, surprised, for I’d never heard of it before.

“He was, but f-father was out of town. He didn’t git no satisfaction.”

“I bet he’s sneakin’ around Wicksville just a-tryin’ to gouge that invention out of your father,” I says.

Mark didn’t answer, and sat so quiet I turned to look at him to see what was the matter. He was sitting stiff, leaning forward a little and staring at the face of a big rock half-way down the hill. There was a shadow on it, and it was the shadow of a man’s head.

The moon was shining bright and throwing shadows just like it did the night before. I noticed now that a big shadow was right over us, reaching down the hill to the rock, where it ended in the head. It looked big as an elephant. Mark sucked in his breath, and we looked at each other. Then we both turned slow and looked up the hill. There, crouching on the brow, was the black figure of a man, like he was on his hands and knees staring over at us. His head stood out sharp, and we could see his hair was long and bushy, standing out on all sides just like some kind of South Sea Island savages that there are pictures of in the geography. There wasn’t any doubt about his being big. It was the whoppingest head I ever saw, and the shoulders matched it for size.

All of a sudden as we looked the man wasn’t there. It seemed like he melted right away under our eyes, and we never heard a sound.

“It was—nothing but a man,” I whispered, trying to persuade myself there wasn’t any danger.

“Yes,” Mark whispered back, “but what k-kind of a man?”

When we got to thinking about his size and how long and bushy his hair was, and especially about that queer footmark with the toes pointing to one side, we couldn’t make head or tail of him, except that there was something mighty strange, and that it would be a good thing to keep out of his way. I tell you it wasn’t fun sitting there a couple of miles from a house, without a gun, and with a giant of a man like that prowling around watching you and intending to do nobody knew what.

“Shall we tell the others?” I asked.

Mark thought a minute. “No,” he says. “’Twon’t do no good. We’ll keep mum.”

That is what we did. When our watch was over we waked Plunk and Binney, and they came out to the fire yawning and stretching. We turned in.

I don’t know when it was, but I was woke up by a yelling and hollering outside the cave. Mark and I jumped out, and there were Plunk and Binney screeching as if they were scared to death and throwing blazing chunks of wood out among the trees after a big black figure that ran and leaped and crashed down the hill and out of sight.

“What was it?” I said, shaking Binney by the shoulder.

“I—I guess,” he said, shaking like a leaf, “that it was a goriller. He didn’t look like anythin’ else.”

A gorilla! Come to think of it, it might be a gorilla, but where in time would one of them come from?

Anyhow, there was no more sleep that night. We all sat up together and kept the fire roaring and blazing as bright as we could. We weren’t troubled again.

In the morning Binney says, while we were getting breakfast, “I guess we better go home.”

Plunk didn’t say anything, and I waited for Mark.

“I ain’t goin’ home,” he says. “I’m goin’ to f-find out what it is. Will you stay with me, Tallow?”

“Sure,” I says, but I didn’t want to a bit.

That sort of shamed Plunk and Binney into staying, so nobody went home.

“And, rem-member,” Mark warned us, “this is a secret. We ain’t to say a word to nobody.”

So we were sort of forced to stay by Mark to help him find out what was prowling around in the woods. He was a queer fellow, Mark was. I know he was as afraid as any of us, but he was curious, and when he got curious to know anything you couldn’t scare him away nohow.

“Have you hatched a scheme?” I asked Mark, after we’d scoured off the dishes and cleaned up in front of the cave.

“I got a scheme, but I don’t like it much.”

“Won’t it work?”

“I guess it’ll work.”

“What’s wrong with it, then? You want one that’ll work, don’t you?”

“I ain’t sure,” says he, with a grin. “Sometimes it ain’t desirable to c-catch what you’re after. I dunno just what I’d do with a wild man if I was to get him.”

“You might sell him to a circus,” says Binney, who always took things serious, and couldn’t see a joke if the point was printed out for him.

“What’s the scheme?” I was getting pretty impatient to know.

“Make believe we’ve gone away,” says Mark. “Then he’ll come prowlin’ around. Three of us go over to the island and holler and raise a r-racket. One will stay in the cave. He’ll think we’re all gone.”

“It’s a good scheme,” I says, “for the feller that stays in the cave.”

“That’s the trouble,” Mark grins.

“Who d’you think’ll be fool enough to stay in the cave to catch Mister Wild Man?”

“Me,” says Mark.

“You dassen’t.”

“That’s what I’m wonderin’,” he owns up.

We sat a while without saying a word, then Mark clicks his teeth and says, “I’m goin’ to try it.”

“You ain’t,” I says. “He’ll bust you in two.”

“I don’t b’lieve so. At any rate, I don’t in daylight.”

“You ain’t foolin’?”

“N-no.”

“And you want us to go over to the island and kick up a row like there was four of us, so’s he’ll think nobody’s here?”

“Yes.”

“Come on, fellers,” I says. “If Mark’s gump enough to play he’s bait in a bear-trap I guess we can kick up his racket for him.” We got up and started down hill, leaving Mark in front of the cave looking after us sort of regretful. We weren’t more than half-way down before I began to feel on bad terms with myself. Somehow it didn’t look just right to go off deserting Mark, especially after binding ourselves to stick together in whatever peril come when we made up the Ku Klux Klan.

“Wait a minute,” I told Binney and Plunk. “This ain’t no way to do. You fellers got to yell loud enough for four; can you do it?”

“I guess so,” says Plunk. “Why?”

“’Cause I’m goin’ back to stick with Mark,” I grunted, kind of sharp. “There ain’t nobody in Wicksville goin’ to say I ain’t got as much sand as Mark Tidd.”

“I sha’n’t go back,” Binney says. “I didn’t ask him to stay.”

“Me too,” agreed Plunk.

“Nobody asked you to go back. Somebody’s got to do the hollerin’ on the island, ain’t they? Well, all you got to do is sound like a whole picnic. Now git.”

I went back up the hill cautious and sneaking and sat down just back of Mark. He didn’t hear me till I slipped, and then the way he jumped reminded me of a big rubber ball bounding.

“Whillisker!” he panted, “but you scairt me!”

“Too bad. If I scairt you what’ll the wild man do?”

He grinned kind of sickly. “What you doin’ here?”

“I come to stay,” I says. “Plunk and Binney can make enough row.”

He looked pretty thankful, but tried not to show it. “There ain’t no need,” he says.

“If you don’t want me I’ll git out,” I told him.

He grinned again. “I dunno’s I’d go as far’s kickin’ you out. If you’re g-goin’ to stay let’s git inside the cave.”

We went inside and fixed ourselves as comfortable as we could at the far end, in a sort of recess we’d dug out to put things in, with a piece of canvas hanging down over it, and all the talking we did was in whispers. Somehow we didn’t either of us think of many things to say. I remember after about half an hour of it that I wished if any wild man was coming he’d hurry and have it over with, because my legs were getting cramped. But he didn’t come.

Through the mouth of the cave we could hear Plunk and Binney raising a racket that sounded as if all the kids in Wicksville were mixed up in one big fight.

“They’re doin’ fine,” whispers Mark.

“Yes,” I says, “and I bet they’re enjoyin’ it more’n I am this.”

It began to look as if Mark’s scheme wasn’t any good, for we sat there more than two hours, and I was sure my legs would snap off if I moved, they were so stiff.

“Come on,” I whispered, “let’s get out of this. Nobody’s comin’.”

“Hus-ss-ssh!”

I listened. Sure enough, there was something moving around outside, slow and cautious. We could hear twigs crackling, and once in a while a sort of scuffling like feet moving through dried grass. Mark’s eyes were fastened on the opening through a slit in the canvas, and they were pretty nearly as big as saucers. When you think how small his eyes usually were you can guess how excited he was now. Probably I looked about the same; I know my heart hammered, and I got that empty feeling like I had in the night, and I wished I was seven miles away with a company of soldiers. But I wasn’t any place but right there, and I had to make the best of it.

The sounds came nearer and nearer and nearer until whoever made them was right outside. Then the opening was darkened, and we could see a big head and shoulders that were as broad as the hole. The head stopped and peered around to make sure nobody was there. We were way in the corner; it was pretty dark, and the canvas was in front of us. So there wasn’t much chance of his seeing us or finding us. He mumbled something to himself and crept way in. I almost hollered right out. He was the biggest man I ever saw, and wild-looking. We couldn’t see his face very well, but he was ragged, and his hair was long and frowsy—and we were alone with him in a little cave, and nobody to help within a couple of miles.

He crawled in on all fours and began fumbling around on the other side of the cave where we had kept the bread. I felt Mark heave himself up, and then saw him creep out of the blankets and across the floor until he was between the door and the wild man. It took more nerve than I had, but, though he was as pale as a sheet, he kept right ahead. He stood still, kind of doubtful, getting up his courage to do something and figuring out just what he was going to do. I felt around for something heavy I could use if worse came to worst.

Mark opened his mouth once, but not a sound came. He shut it again and felt of his throat; then he made his voice sound as deep and heavy as he could and sort of barked: “Hey! W-what you do-doin’ here?”

The wild man jumped so he cracked his head against the roof and turned around rubbing it. For the first time we got a good look at his face when the light from outside struck it fair. I expected he was going to leap right at Mark till I saw his face; and then, somehow, I felt sorry for him and not afraid a bit, for it was the most scared face I ever saw—yes, sir, scared! He fairly cowered against the wall.

“Don’t hurt Sammy. Poor Sammy. Sammy’s hungry,” he whimpered.

Mark and I both giggled, we were so relieved. Mark spoke to him again like he was stern and displeased.

“What you stealin’ our stuff for? Hey?”