Title: Mark Tidd in the Backwoods

Author: Clarence Budington Kelland

Illustrator: William Wallace Clarke

Release date: May 22, 2018 [eBook #57197]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

It all started just before school was out. One afternoon when I got home mother showed me a letter from Uncle Hieronymous, who lives in the woods back of Baldwin, on the Middle Branch of the Père Marquette River. I never had seen him, but he and mother wrote to each other quite often, and I guess she’d been telling him a good deal about me, that’s Binney Jenks, and Mark Tidd and Tallow and Plunk. Of course, Mark Tidd was most important. He always thought us out of scrapes. So what did this letter of his do but invite us all to come up to his place and stay the whole summer if we wanted to?

As soon as I read it I was so excited I had to stand up and prance around the room. I couldn’t sit still.

“Can we go, ma? Can we go?” I asked, over and over again, without giving her a chance to answer.

Ma had been thinking it over, because she said yes right off. Ma never says yes to things until she’s had a chance to look at them from all sides and knows just what the chances are for my coming out alive. “You can go if the other boys can,” she told me, and I didn’t wait to hear another word, but went pelting off to Mark’s house.

Mark was in the back yard talking to his father when I got there, and I burst right in on them.

“Can you go?” I hollered. “D’you think you can go?”

“L-l-light somewheres,” says he. “You’re floppin’ around l-l-l-like Bill Durfee’s one-legged ch-chicken.”

“Can you go to my uncle Hieronymous’s? We’re asked in a letter. The whole kit and bilin’ of us. Up in the woods. Right on a trout-stream. In a log cabin.” I broke it all up into short sentences like that, I was so anxious. After a while Mark got it all out of me so he understood it, then he turned to his father.

“C-c-can I go, father?” he asked.

Mr. Tidd, though he’d got to be rich, was just as mild and sort of dazed-like and forgetful as ever—and helpless! You wouldn’t believe how helpless he was.

“Way off into the woods?” says he. “Fishin’ and sich like? Um-hum. ’S far’s I’m concerned, Mark, there hain’t a single objection, but, Mark, I calc’late you better see your ma. She sort of looks after the family more’n I do.... And if she lets you go, son, I’ll give you a new set of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall to take with you. You’ll enjoy readin’ it evenin’s.” With that he took out of his pocket a volume of old Gibbon and sat himself down on the back steps to read it. He was always reading that book and telling you things out of it. After I’d known him a year I most knew it by heart.

We went right up-stairs to where Mrs. Tidd was making her husband a shirt on the sewing-machine. She didn’t have to make him shirts, because they had money enough from the invention to buy half a dozen to a time if they wanted to. But Mrs. Tidd, she says there ain’t any use buying shirts for a dollar and a half when you can make them twice as good for fifty cents and a little work. That was her all over.

Mark called to her from the door. “Ma,” he said, “can I go—”

She didn’t let him get any further than that, but just says sharp-like over her shoulder: “There’s a fresh berry-pie on the second shelf. Can’t you see I’m so busy I dun’no’ where to turn?”

“But, ma,” he says again, “I d-d-d-don’t want pie. I want to g-go—”

“No,” says she, “you can’t.” Just like that, without finding out where he wanted to go or anything; but that didn’t scare us a mite, for we knew her pretty well, I can tell you. In a second she turned around and wrinkled her forehead at us. “Where you want to go?” she rapped out.

Mark started in to tell her, but he stuttered so I had to do it myself. I explained all about it in a jiffy. She thought a minute.

“It’ll get you out from underfoot,” she says, “and keep us from being et out of house and home. I guess if the others can go you can.”

You always could depend on Mrs. Tidd to be just that way. She was so busy with housekeeping or something, and had her head so full that she didn’t get to understand what you said at first and always said no just to be safe, I guess. But I never knew her to refuse Mark anything that he had any business asking. For all her quickness we fellows thought a heap of her, I want to tell you.

When the Martins and Smalleys found out we could go they let Tallow and Plunk come along, so there we were. We fixed it to leave the day school was out and to stay just as long as we could hold out.

We started the day we planned. At first we thought we’d take a lunch, but Mrs. Tidd set her foot down.

“You’ll need a hot meal,” she told us, “so you go right into the dining-car when you get hungry.” Then she gave Mark the money for our dinners, and we all kissed our folks good-by and got on the train.

It was pretty interesting riding along, and we enjoyed it fine till we got to Grand Rapids. We had to change there for Baldwin, and from then on the ride began to get tiresome. We tried a lot of things to pass away the time, but nothing helped. I guess it was because we were so anxious to get into the woods. We went along and along and along. I hadn’t any idea Michigan was so big. After a while a colored man came in and yelled that dinner was ready in the dining-car. Mark began to grin. It looked like he was ready for the dinner. So was I, and the other fellows didn’t hold back much. We went in and sat down at a little table. Each of us got a card that told what there was to eat. There were so many things it was hard to make up our minds, but finally we hit on the idea of every fellow taking something different, and so we got a look at more of it than we would any other way. We were about two-thirds through eating when all at once that car acted like it had gone crazy. I looked at the other three, and you never saw folks with such scared expressions in all your life. Their eyes bulged out, their mouths were open.

Well, sir, we just rose right up out of our chairs; that is, all of us did but Mark Tidd, and he was so wedged in he couldn’t. It started with a crack that we could hear above the roaring of the train, then the car sagged down at the front end and began to bump and jump and wabble back and forth like a boat in a storm. We hadn’t time to get scared—only startled. Then the car went over—smash! I don’t believe anybody ever got such a jolt. The next thing I knew I was kicking around in a mess of rubbish with my head down and my feet up. Busted tables and dishes and chairs and folks were all scrambled on top of me. First off I thought sure it was the end of me, but I didn’t hurt any place, and when my heart settled down below my Adam’s apple I began squirming around to get loose.

I remember the first thing I thought about was its being so still. Nobody was hollering or groaning or anything. It surprised me and sort of frightened me. I squirmed harder and wriggled a table off me and pushed a chair away from the back of my neck. Then I sat up. You never saw such a sight. The car was lying on its side, and the lower side where I was was nothing but a jumble of things and people. And the whole jumble looked like it was squirming.

Next I thought about Mark Tidd. He was so fat and heavy I was afraid he’d be smashed all to pieces. I tried to call him, and at the third try I got out his name.

“Mark,” says I, faint-like, “are you hurt?”

Over to the left of me, under a dining-table with its legs spraddled up, I heard a grunt—a disgusted grunt. It was a familiar grunt, a grunt that belonged to Mark.

“H-h-hurt,” says he, sarcastic-like, but cool as a cucumber, only stuttering more than usual. “H-h-hurt! Me? Naw; I’m comfortable as a ulcerated t-t-tooth. Hey, you,” says he to somebody down under the rubbish, “quit a-kickin’ me in the s-s-stummick.”

I knew he was all right then, and began figgering about Tallow Martin and Plunk Smalley. In a minnit both of them came sort of oozing out from amongst things looking like they’d sat down for a friendly chat with a cyclone.

“Mother’ll be mad about these pants,” says Plunk.

“There hain’t much pants left for her to get mad about,” says Tallow, angry-like and rubbing at his shoulder. “What you want to do is get a barrel.”

“W-what you want to do,” says Mark Tidd, “is g-git me out of here. There’s a feller keeps k-k-kickin’ me in the ribs and somebody t-t-tried to ram a table-leg into my e-e-ear.”

Folks was digging their way out all around us now, and nobody seemed hurt particular, though some was making an awful fuss, specially a stout lady that had lost a breastpin. We began mining for Mark, and pretty soon we got down to where we could see him. He was the beat of anything I ever saw. Somehow he’d wriggled so as to get his head on a soft leather bag that somebody’d brought into the diner—most likely some woman. One arm was pinned down, but the other was free, and what do you think he was doing with it? Eating! Yes, sir; eating! He had two bananas in his pocket that he’d grabbed off the table just before the smash-up, and there he lay, gobbling away as calm as an iron hitching-post. It made me mad.

“You’d eat,” says I, “if Gabriel was tooting his horn!”

“D-d-didn’t know what was goin’ to h-happen,” says he, “so I th-thought I’d g-git what enjoyment there was t-t-to it.”

We hauled him out, and it took all three of us. Heavy? I bet he weighs two hundred pounds. We got his head and shoulders free first and tried to drag the rest of him from under, but he wouldn’t drag. Why, each one of his legs weighs as much as I do. He has to have all his clothes made special. I bet I could rip one of his pant-legs down the front, put sleeves in it, and wear it for an overcoat.

While we were tugging away at him somebody outside began smashin’ the door, and pretty soon three or four men crawled in and began helping folks out. One of them came over to us and looked down at Mark.

“Hum,” says he. “Didn’t know there was a side-show aboard.”

That made Mark kind of mad.

“Mister,” says he, “this is the f-f-f-first wreck I was ever in, and I want to en-enjoy it. So I’d rather b-be pulled out by a f-f-feller that’s more polite.”

The man laughed. “Didn’t mean to offend you,” he said. “Beg your pardon. Naturally I’m one of the politest men in Michigan, but, you see, I was shaken up considerable by the wreck.”

Mark grinned. “All right,” says he. “Go ahead. I’ve got about all the f-fun there is out of bein’ tangled up here.”

The four of us hoisted him up and set him on his feet. He shook himself like you’ve seen a dog do when it comes out of the water, blinked around him to see what there was to see—and then took another banana out of his pocket and began to skin it absent-mindedly.

The man threw back his head and laughed fit to kill. “You sure are a cool one,” he says.

“Don’t do any good to g-g-get excited,” says Mark. “There’s always enough o-other folks to do that. Anybody hurt?”

“Haven’t found anybody yet. It’s a regular miracle.”

Mark looked at Tallow and Plunk and me and shook his head. “You’re the fellers that d-d-don’t b’lieve in luck,” says he. “Now I g-g-guess you won’t make fun of my carryin’ a horseshoe.” And he pulled one out of his pocket. “Found this jest as we was gittin’ on the train,” he says to the man, “and l-look what it’s done!”

“I’ll never travel again without a horseshoe,” he says. “Let’s get out of here—we’re the last ones.”

“Got to git my hat,” says Mark.

That was just like him. When he did a thing he did it thorough. If there’d been any danger and he ought to have got out he would have gone. He never took chances he didn’t have to; but there wasn’t any danger, so he wouldn’t go until he took along everything that belonged to him. It took us twenty minutes to locate our stuff. The man helped us, laughing all the time. He seemed to think he was having a lot of fun. I sort of liked him, too. He was jolly and good-natured and pretty good-looking.

When we got outside I said to Mark, so the man couldn’t hear, “Nice feller, ain’t he?”

“Too g-good-natured,” says he.

“You’re mad ’cause he made fun of you.”

“’Tain’t that. He’s one of these f-f-fellers that make a business of bein’ p-pleasant. Maybe he’s all right, b-but if I was goin’ to have much to do with him I’d k-keep my eye on him.”

“Huh!” says I; but after a while you’ll see Mark wasn’t so far wrong, after all. I never saw such a boy for seeing into folks. He could almost always guess what kind of a person anybody was.

We stood around a minute, getting our breath and sort of calming down. Then we watched the trainmen digging baggage and valuables out of the car and finding owners to fit them. That wasn’t very interesting, so we went and sat down on the bank beside the track and commenced to wonder how long we would have to stay there.

“Probably have to wait for a train from Grand Rapids,” Tallow said.

Mark got up and looked down the track. “G-g-guess they can crowd us in th-them.”

Just then the good-natured man who helped us out of the wreck came along, grinning like he’d found a quarter on the sidewalk.

“Hello!” says he. “Any the worse for wear?”

“No,” says Plunk.

“Camping?” says he.

“Sort of,” says I. “Goin’ to stay at my uncle’s cabin.”

“Whereabouts?” he asked.

“We git off at Baldwin,” I told him.

“Good fishing?” he wanted to know.

“My uncle says it’s bully.”

He sat down alongside of us. “My name’s Collins,” says he—“John Collins.”

He sort of waited, and then I introduced everybody, beginning with Mark Tidd, then Tallow Martin, who was next to him, then Plunk Smalley, and last of all Binney Jenks, which is me.

We talked considerable and speculated on how long we would have to wait and wished there was a lunch-counter handy—especially Mark. Maybe twenty minutes went along before we saw the conductor and yelled at him to know if we were going to have to stay all night.

“Better hustle up to the day coaches,” says he. “I guess we can pull out pretty soon.”

When we got in the car it was pretty crowded, but we four got seats together. Mr. Collins had to take half of a seat quite a ways off from us. I could tell by the way Mark’s eyes looked that he was glad. For some reason or another he’d taken a dislike to the man. I couldn’t see why, because he seemed to me to be pleasant enough for anybody.

I noticed that Mark had a piece of paper in his hand, crumpled up into a ball.

“What’s that?” I asked him.

“D-dun’no’. Picked it up outside.”

“Nothin’ but a piece of paper, is it?”

“Looks so, but you n-n-never can tell.” He opened it up, and it wasn’t anything but a sheet of a letter. The writing began right in the middle of a sentence where the man who wrote it had finished one page and started another. I looked over Mark’s shoulder and read it.

“—peculiar old codger,” it said. “You’ll have to be careful how you handle him. He’ll smell a mouse if you don’t step pretty softly, and then the fat will be in the fire. You haven’t the description of the land, so here it is. Keep it safely, and bring back a deed. It will be the best day’s work you ever did.” Then came some letters and figures that we didn’t understand, but we did understand them later. They looked mysterious and like a cipher code—“The S. 40 of the N. W. ¼ of Sec. 6, Town 1 north, R. 4 west.” Then the letter was signed by a man named Williams J. Partlan.

“Wonder what it means?” I asked.

“Dun’no’,” says Mark. “Guess I’ll s-s-save it and find out.”

Now, that was just like Mark. He didn’t just wonder what these letters and figures meant and then throw away the paper; he saved it so he could study it out or ask somebody who could explain it to him. He was the greatest fellow for looking into things he couldn’t understand you ever heard of.

It was hot and dusty, and pretty soon it began to get dark. First I knew Mark began slumping over against me until he almost squeezed me out of the seat, and then he began to snore. I poked him with my elbow, but it didn’t do any good. Once Mark Tidd gets to sleep it would take more than my elbow to wake him up. I bet he’d have slept right through the wreck and been picked out of it without ever missing a snore. After a while the conductor came through and called “Baldwin. Change for Manistee, Traverse City, and Petoskey.” At that I had to wake Mark, so I put my mouth close to his ear and hollered. He lifted a big fat hand and tried to brush me away like I was a fly. I hollered again and poked him a good one in the ribs. He grunted this time, and with another poke and a holler he half opened his eyes and wiggled his head from one side to the other like he was displeased about something.

“We’re coming to Baldwin,” said I. “Wake up.”

“I d-d-don’t care,” says he, stuttering like anything, “if we’re c-c-comin’ to Jericho with the walls a-tumblin’ down.”

But in a minnit he roused up, and as soon as he really got it through his head what was going on he was as wide awake as anybody.

After a little the train stopped at Baldwin, and we scrambled out, lugging our suit-cases. Out of the tail of my eye I saw Mr. Collins getting off, too. Well, sir, we got off at a little depot, smaller than the one at Wicksville. Down a little piece was a building with lights on it, and that was all. There wasn’t any town that we could see, nothing but the two buildings.

“B-b-bet it’s a lunch-counter,” says Mark.

“Makes no difference if it is,” says I. “We got to find my uncle, and you got to come along. If you don’t we never will find him, for you’re all he’s got to go by. I never saw him, you know. When mother wrote we were coming she told him to look out for the fattest boy he ever saw, and that the rest of us would be along with you.”

“Huh!” says Mark, disgusted-like.

We stood in front of the depot, looking around and waiting for uncle to come up and speak to us. Pretty soon we saw a man come along squinting at everybody and looking into corners and stretching his neck to see around people. He was a tall man, so tall his head come almost on a level with the top of the door. He had a mustache, too—the biggest one I ever saw, with ends that poked out past his cheeks and then swerved down until they almost touched his shoulders. He didn’t have any hat on, and his overalls didn’t come within six inches of reaching his shoes. I most laughed out loud.

When he came to us he stopped and looked and looked. It was mostly at Mark.

“Hum!” says he, after a minnit. “Fattest boy I ever see.... Fattest.... Boy.” He reached out an arm as long as a fence-rail and pointed at Mark. “You’re him,” says he, and chuckled to himself. “Now, hain’t you him?” He didn’t wait for an answer, but said a little poetry. I found afterward he made it up on the spot.

Then he grinned the mostly friendly grin you ever saw.

“Hieronymous Alphabet Bell is my name,” says he, “and I’m a uncle. Yes, sir. You wouldn’t think to look at me I was an uncle, but I am. My nephew’s name is Jenks. Does any one of you happen to be named Jenks?”

“I’m him, uncle,” says I.

He stuck out his hand to me, and I shook with him.

“Howdy, nephew,” says he. “Pleased to make your acquaintance.” He was that polite! “What’s his name?” he asked, pointing to Mark Tidd.

I told him, and they shook hands. After that he shook hands with Tallow and Plunk and acted like he was tickled to death to see us. When he’d done shaking hands once he commenced with me and did it all over again.

“Boys!” says he, making an exclamation of it. “I don’t like boys. I jest despise boys. You can see I do, eh? Can’t you, now? Tell it by my manner. They’re nuisances, so they be, but I can tame ’em. No monkey-shines, mind, or look out for Uncle Hieronymous Alphabet Bell.” After he said this he leaned up against the side of the depot and laughed and shook and slapped his hand against his thigh, but without making a sound. In a minnit he straightened up and recited another little poem:

Mark was looking at Uncle Hieronymous with his eyes bunging out, as interested as could be. His little eyes, almost hidden by his fat, were twinkling away, and I could see right off that he liked uncle. That made me glad, for I liked uncle, too. There was something that made you sort of sorry for him. I guess it was because he was so glad to see us fellows. It made you think maybe he was pretty lonesome.

“Come on,” says he. “I got an engagement with Marthy and Mary, so I got to hustle. Don’t like to break no engagements.”

“Girls?” I asked, feeling sort of offish about it.

“No,” says he, “not exactly girls; nor yet exactly wimmin.” And that was all he’d say about them.

We followed him over to a railing where he’d hitched his horse and wagon. As soon as he came within earshot of the horse he began talking to him just like anybody’d talk to folks.

“Good evenin’, Alfred,” says he; and I thought that was a funny name for a horse. “I’m back again,” he says, “a-bringin’ with me three medium-sized boys and one boy that is a little mite—say about a hundred pounds—over the medium.” He turned to us. “Come over here,” he says, “and see you act your politest. I want you should be acquainted with Alfred. Step right up. Alfred, this here is my nephew, Binney Jenks.”

Alfred lifted his head and bobbed it down in as fine a bow as you ever saw, and he did the same thing when he was introduced to the other three.

“Be we glad to have visitors, Alfred?”

Alfred bobbed his head three times and whickered the most pleased whicker I ever heard a horse give.

Uncle turned to us solemn. “It’s all right, fellers,” says he. “I was a mite bothered till you’d met Alfred and I found out what he thought about you. If Alfred had took a dislike to you I don’t know what I ever would have done. Alfred and Marthy and Mary sort of runs me, so to speak. The way they boss me around is surprisin’ the first time you notice it.”

We all climbed in the wagon with our baggage, and uncle leaned over the dash-board so Alfred could hear better.

“He’s a leetle deef,” uncle told us. Then he spoke to the horse. “Alfred,” says he, “I calc’late we better be startin’ if you feel you’ve got rested. I don’t want to hurry you, but if you feel you’re ready, why, jest go ahead.”

Alfred turned his head as though he wanted to see everybody was in, then he sort of sighed and began to go up the road slow as molasses.

Pretty soon we came to the town, which was about a half a mile away from the depot and the hotel. We went through it without stopping, and then turned out into the country. In a few minutes we were right in the woods; not woods of great big trees, but woods of little trees. There wasn’t anything but woods any place, and uncle said it was that way for miles and miles.

“Nothin’ but jack-pine and scrub-oak,” says he. “Timber’s gone—butchered off. Once,” says he, “you could walk through here for days and never git away from the pine.”

We drove and drove and drove. In places it was so dark we couldn’t see Alfred’s tail, but he knew the way, and if it hadn’t been for bumps and holes that jarred and joggled us we would all have been asleep before we got to uncle’s house.

But we got there at last, and it was a log cabin. The front door was in the back, and there wasn’t any back door in the front. What I mean is that there wasn’t but one door, and that went into the kitchen.

“I figgered out,” says uncle, “that the place folks wanted to git most often was the kitchen, especial after comin’ off the river, so there’s where I put the door.” Then he recited another poem:

He led us through to the front of the house, where there was a bed and two cots for us. “Now,” says he, “git to bed. Breakfast’s at four, and Mary and Marthy’ll be all wrought up to see you. Good night,” says he, and off he went.

We were so tired we didn’t stop to talk, but just tumbled into bed and were off to sleep in a minute.

Most likely we would have slept till noon that first morning at uncle’s place, but he didn’t let us. Uncle had an idea that day began as soon as you could see to get around without a lantern, and it didn’t seem to me that I had finished slapping a mosquito that buzzed around me before I went to sleep when somebody jerked the cover off me and yelled, “Grub-pile.” I got one eye open enough to see Uncle Hieronymous standing there grinning like all git out, and Mark and Tallow and Plunk squirming around disgusted in bed.

“Bacon’s frizzlin’,” says uncle. “I let you oversleep this mornin’, figgerin’ you was wore out. Come a-runnin’! Git up! Why, it’ll be noon in a matter of eight hours!”

There was a smell of something coming in from the kitchen that waked me up quick. I got my feet out on the floor and looked over at Mark Tidd. He was sitting on the bed, with his pudgy nose pointing to the door and sniffing away with the happiest expression I ever saw on his face. Part of the smell was bacon, and part of it was frying potatoes, but the best of it was something else better than both of them put together, and I couldn’t make out what it was.

“Hungry?” says Uncle Hieronymous.

Mark answered him. “I c-c-could eat the tail of the whale that s-s-swallered Jonah,” says he.

We dressed in a hurry so we could get nearer to that smell. By the time we were washed uncle had everything on the table, and we rushed at it like we’d been fasting for forty days and forty nights. Then we saw where the best part of the smell came from. It was little fish all brown and crisp outside—a heaping platter of them.

“Troutses,” says Uncle Hieronymous. “Leetle speckled troutses. Ketched by me personal right in my front yard, so to speak. Got ’em special for you jest before startin’ to the station.” Then he made up another little poem:

Nobody said another word until there wasn’t a thing left on the table but little heaps of fish-bones. Uncle moved back his chair and grinned, and we all grinned back at him. We felt just like grinning. I don’t know when I’ve felt so good.

“Marthy and Mary is waitin’ to get acquainted with you,” uncle says. “They’re peculiar, Marthy and Mary is—most exceedin’ly peculiar—so you want to be p’tic’lar how you act. I wouldn’t have Marthy and Mary get a bad idea of your mannerses for anythin’.”

He shut the door tight and then went to the window.

“Marthy!” says he, as loud as he could yell. “Mary! Comp’ny to the house. Hey, Marthy! Hey, Mary!”

Well, sir, we didn’t know what to expect, but in a minnit two pure-white cats came hustling out from among the underbrush with their tails sticking straight up in the air and the most interested expression on their faces you ever saw.

“Come here to the winder,” says uncle to me. He put his head out and spoke to the cats. “Marthy and Mary,” says he, “this here young person is my nephew, Binney Jenks. Git the name—Binney Jenks.”

The cats both says “Miau,” and reared up on their hind legs with their fore paws against the house.

Uncle Hieronymous sort of drew back. “Don’t come a-jumpin’ up here,” he says. “I won’t have it. You know better’n that, both of you. This here is Mark Tidd,” he went on, “and this is Tallow Martin, and this is Plunk Smalley.”

It didn’t seem to me the cats was much interested in us, but uncle seemed to think they were all excited over our being there.

“Ree-markable cats,” says he. “Intelligent! Oh, my, hain’t they intelligent! Why, boys, the amount of brains them cats has got would s’prise the legislature down to Lansing.”

He went to the stove and got some fish out of the frying-pan. “Marthy and Mary,” he says, important and dignified-like, “I’m a-goin’ to celebrate this here occasion by feedin’ you troutses. Troutses hain’t made for cats, except by way of markin’ important happenin’s. Chubs and perches is for cats, with maybe a bass or a pickerel, but troutses is for men almost exclusive. Here’s one for you, Marthy, and here’s one for you, Mary—and bear in mind, both of you, that you’re much obleeged to these here boys. Lemme hear you say much obliged.”

Martha and Mary both said “Miau,” but I guess it was because they wanted the fish uncle was dangling over their noses.

“There,” says he, drawing himself up as proud as a turkey-gobbler—“there. Intelligent, eh? Never saw cats like that before, I bet.”

The cats sailed into that fish as enthusiastic as we boys had a little while before. Uncle gave each of them a couple. When they were through he spoke to them again.

“That’s all,” he says. “I hain’t goin’ to give you no more and be responsible for ruinin’ your stummicks. Now go on off. D’you hear me? Go on off and catch mouses so’s I can come out.”

“C-c-can’t you go out while they’re there?” Mark wanted to know.

Uncle looked at him astonished. “What? Me? Go out with them two cats?” He shook his head two or three times and looked at Mark regretful-like. “I’m s’prised at you, Mark Tidd. O’ course not. Never. Why,” says he, “you can’t never tell what cats’ll do—especially white cats.” He wagged his head again. I most laughed right there. Think of it! Uncle Hieronymous was afraid of his cats.

Marthy and Mary trotted off out of sight as obedient as could be, and uncle unlocked the door. It was our first look outside. Right in front of the house, which was made of logs, was a little stream. You could hear it gurgling and pouring along, and it sounded as pleasantly and neighborly as could be. All around was woods. The house sat in the middle of a clearing a couple of hundred feet wide, and beyond that all you could see was trees, trees, trees. The clearing was on a little rise of ground, and from the door you could look off across the brook for miles over what looked like a kind of swamp—not a squashy, boggy swamp, but a damp swamp where trees grew, and where, most likely, there was bears and maybe deer.

“Have you lived here always, uncle?” I asked him.

“Always? Me? Not always, not always, by any means. Fifteen years ago I lived up in what they call the copper country now. Yes, sir, right amongst it, so to speak, only I wasn’t minin’. Not me. I owned a forty of timber and logged it a spell. Then along come a feller and offered me a price for it, and I up and sold to him. Yes, sir, sold out bag and baggage. No I didn’t, neither.” He commenced to laugh kind of as if there was a joke on somebody. “Friend of mine, he advised me I should keep the mineral rights, and, by gum! I own ’em to this very day. Me! Mineral rights. Haw!”

“What’s m-m-mineral rights?” It was Mark asked him of course. None of the rest of us cared a whoop what mineral rights were, but Mark wasn’t that way. You never could go mentioning anything strange around him without being made to put in a spell explaining it.

“Mineral rights,” says Uncle Hieronymous, “is the rights to the minerals and metals and sich a-hidin’ in the ground under a piece of prop’ty. One feller can own the trees, another can own the land, and another can own whatever happens to be found under the land. And that’s what I own yet. Haw! If somebody was to up and find a di’mond-mine on that al’ forty, who in the world would it b’long to? Why, to me, Hieronymous Alphabet Bell, and to nobody else that walks on two laigs.”

Mark nodded that he understood, and then Uncle Hieronymous wanted to know what we figured on doing that day.

“L-l-let’s explore,” says Mark.

“We’ll git lost,” says I.

“Shucks. We won’t go b-b-back into the woods. We’ll just go along the b-b-brook.”

“Good idee,” says uncle. “Get acquainted with the neighborhood, so to speak. Whenever you git back’ll be time to eat. If you get lost whistle like this,” and he showed us a whistle that went, “Wheet, wheet, wheet, whee, hoo.” “Reg’lar old lumber-camp signal,” he says.

“D-don’t you want to come?” Mark asked him.

“Me? Goodness, no! Couldn’t spare the time. Couldn’t spare a minnit. Got a lot of thinkin’ to do to-day, and consid’able newspaper-readin’, to say nothin’ of washin’ dishes and catchin’ a mess of fish. No, I don’t guess I got any time to spare. Why, there’s things I’ve been plannin’ to think about for weeks, and puttin’ off and puttin’ off. I picked to-day to study over ’em, and it’s got to be done. I got to git out there and lay onto my back and figger out what I’d ’a’ done if ever I’d got elected to Congress, and what keeps one of these here airyplanes up in the air; and another important p’int is why dogs wag their tails when they’re tickled and cats when they’re mad. You kin see I got my hands full.

he finished up. “Them that thinks and writes it down,” he says, “is authors and poets and philosophers, and them that jest thinks is loafers.”

We were just getting ready to start out when a man that uncle called Billy came driving up in a rickety buggy. As soon as he got in sight he began to yell at us, but we couldn’t understand what he was talking about. When he got close to the house he drew up and yelled louder than ever:

“Feller name of Collins here?”

“No,” says uncle, scratching his chin. “We got a lot of names around, but Collins hain’t one of ’em. Maybe some other’ll do.”

“It’s a telegraft,” says Billy, “and a dummed funny one, too. None of the boys around town could make head or tail to it. Collins was the name. Left word to the hotel he was goin’ to stop somewheres on the Middle Branch. Mighty funny telegraft. Wisht I knowed what it was about.”

“Maybe he’s up to Larsen’s,” says uncle. “I’ve knowed folks to stop there that wouldn’t hesitate a minnit to get telegrafts. Why, Billy, a feller there got a express parcel once.”

Billy held a yellow envelope in his hand and shook his head at it. “Dummed peculiar!” he says. “The only words of sense to it is that somebody’s comin’ t’ meet him. Want to see it?”

“Dun’no’s I do, Billy,” says Uncle Hieronymous. “I got most too much to figger about now without havin’ more added unnecessary.”

“Mysterious, I call it,” Billy says, and shook up his horses. “You bet you I’m a-goin’ to ask the feller what’s the meanin’ of it.”

We watched Billy till he went out of sight around a bend in the sandy road; then Mark Tidd, with his little eyes twinkling the way they do when he sees something more than ordinary funny, says: “We b-b-better get started. There’s consid’able j-jungle to explore.”

Right off we knew Mark was going to pretend we were over in Africa or somewheres plugging along through a forest where the foot of white man had never trod or shot a gun or built a fire. [Note, by Mark Tidd: Must have been a trained foot.]

“I’ll g-go first,” says Mark. “Binney, you be the r-rear-guard. Plunk will watch to the right, and Tallow to the l-left.”

So we started up-stream, keeping close to the water for fear of getting lost.

“Keep your eye p-peeled for boa-constrictors,” says Mark. “Right here we don’t need worry about n-n-natives, ’cause this part of the jungle is full of b-big snakes. Natives is terrified of snakes. If you begin to f-f-feel funny, lemme know. More’n likely it’ll be a boa-constrictor t-tryin’ to charm you. They kin do it. Yes, sir, they kin sit off a hundred feet and look at a man with them b-beady eyes of their’n and ch-ch-charm you so’s you can’t move.”

It made us sort of shiver, because you never know what you’re going to bump into in the woods, especially woods you don’t know anything about. I never heard of any boa-constrictors in Michigan, but that wasn’t any reason why some couldn’t be there. There’s lots in South America, and if one took a notion to crawl up to Baldwin I couldn’t see anything to stop him. It would be quite a crawl for an ordinary snake, but a boa-constrictor, being so big, ought not to have much trouble about it.

“I’ll be glad,” says I, “when the Panama Canal is done.”

“Why?” Mark asked.

“’Cause boa-constrictors won’t be able to get acrost it,” I says. “It’ll be a purtection to the folks of the United States against the savage beasts that live in the Amazon jungles when they’re to home.”

Mark grinned. “I hain’t n-never heard that exact reason given,” says he, “for buildin’ a canal, b-b-but I dun’no’ but it’s as good as a lot of others.”

We went hiking along for another half an hour. All of a sudden Mark stopped and held up his finger. “S-s-s-savages,” he whispered. In a jiffy we were all lying on our stummicks in the high grass, for, sure enough, we could hear a splashing in the stream that meant somebody or something was coming down toward us.

Almost without breathing we waited. Nearer and nearer the sound came, until a man showed up around the bend. He was wading right in the stream and flopping a fish-pole back and forth in the most ridiculous way you ever saw. He’d snap his line ahead till it touched the water and then snap it back and then snap it ahead again. Just like cracking a whip it was.

“Acts crazy,” I says to Mark.

“Crazy nothin’,” he says. “That’s the way you c-c-cast a fly. He’s trout-f-f-fishin’.”

“Oh,” says I, and watched him, more interested than ever. I’d heard about fly-casting, but somehow I hadn’t expected to see anybody actually doing it. The man was maybe a hundred yards off, but we could see he had funny boots on that came way up under his shoulders. There was a little net hanging from his belt, and a basket with a cover over his shoulder. Pretty soon I heard Mark grunt surprised-like.

“What’s matter?” I asked him.

“Know who he is?” Mark asked.

I looked close. The sun came through a place in the trees and shone right on his face, and I recognized the man. It wasn’t anybody in the world but the Mr. Collins that helped us pull Mark out of the wreck.

“It was him the t-t-telegraft was for,” Mark says to himself.

In five minutes Collins was almost in front of us. The water was to his waist, and he was wading slow. All of a sudden he stopped and pulled his pole up into the air. About thirty feet ahead of him something splashed in the water, and I could see his pole was bent way over.

“He’s g-g-got one,” Mark says, excited.

Sure enough, he had. It looked like a big one the way it pulled and jumped and sloshed around. Collins reeled and splashed around considerable himself, all the time getting closer to where we were. Then before you could say “Bingo” he stepped on something slippery—a smooth stone, I guess—and let out a yell. His feet went up and he went down ker-splash! For a second he floundered around like a hog in a puddle, throwing water all over the scenery, but he scrambled back onto his feet, with his pole still in his hand.

“He h-held it out of water all the t-t-time,” says Mark, sort of admiringly. “He’s the stick-to-it kind.”

It’s the way a fellow acts when he’s alone that counts. Collins might have got mad and shook his fist and talked strong language, but he didn’t. He just grinned kind of sheepish and went right on working with his fish till he got it close to him. Then he grabbed his little net and scooped it up.

“Whoop!” says he, taking it in his hand. “Ten inches, and speckled!”

Mark stood up. “D-do you always catch ’em that way?” he asked. “I never fished for trout, but if it’s n-n-necessary to dive after ’em I calc’late I’ll st-stick to perch.”

Collins grinned first and then said: “Hello! What you doing here?”

“Explorin’,” says Mark.

“Stopping near?”

Mark jerked his thumb back toward Uncle Hieronymous’s.

“Who with?”

“His uncle,” says Mark, pointing to me.

Collins looked more than ordinary interested. “Lemme see, you told me his name back on the train, didn’t you? I don’t remember it.”

“D-d-don’t b’lieve I did,” says Mark.

“It’s Hieronymous Alphabet Bell,” says I, and Mark reached out with his foot and kicked me. The grass was so high Collins couldn’t see him do it.

“Oh,” says Collins, and he waded to shore. “Want to see my fish?”

We looked at it. It was a beauty, slender and graceful-like, with pretty red spots all down its sides.

Collins sat down and talked to us about fish and bears and deer and the woods, and then, the first we knew, he’d got the conversation around to Uncle Hieronymous. Mark looked at me and scowled, but I couldn’t see why.

“He lives all alone, mostly,” I told Collins, when he asked.

“I hear he’s quite an interesting character,” Collins said. “Guess I’ll stop in and see him on my way down-stream. He won’t chase me out, will he?”

I was just going to tell him uncle would be glad to see him when Mark spoke up:

“D-d-dun’no’s I’d disturb him to-day,” says he. “He’s doin’ somethin’ special, and he’s apt to take a dislike to anybody that in-interrupts him.”

“Oh,” says Collins. “I better put it off, then.”

“Calc’late so,” says Mark.

“Well, guess I’ll start along. I’m going to be here a few days—up at Larsen’s. Come to see me.”

We said we would, and he started on down the stream.

As soon as he was out of sight Mark got up quick—quicker than I’ve seen him move in a dog’s age—and ran down-stream maybe fifty feet, and then, right at the edge of the water, he stooped over and picked something up. From where I was I could see it was yellow. He sat right down and put it on his knee and began smoothing it out. We hurried over to see what he was up to.

“What you got?” Tallow asked.

Mark grinned and held up a yellow piece of paper.

“Telegraft,” says he. “G-guess it’s the one Billy b-b-brought.”

“Collins drop it?” I wanted to know.

“I hain’t seen n-nobody else go by,” says Mark.

“What’s it say?”

He’d got it all smoothed out now, and, though it was sopping wet and the ink had run quite a lot, he could read it. For a minnit he didn’t say a word, but he had the most peculiar look on his face.

“Well?” says I.

He handed it over. At first I couldn’t make head or tail of it. The last words were plain enough—“Coming by first train”—and the name that was signed was Billings, but the first part was Chinese to me. All the same, it kind of reminded me of something.

“Huh!” says I. “What’s it about?”

Mark pulled another paper out of his pocket and handed it to me. It was the sheet of letter he picked up near the wreck.

“C-c-c-compare ’em,” says he, with a peculiar grin.

I did, and the figures and letters were the identical same: “The S. 40 of the N. W. ¼ of Sec. 6, Town 1 north, R. 4 west.” I was a mite startled, but, for all that, I couldn’t see what there was to be startled about. I guess it was the way Mark acted.

“There’s s-somethin’ up,” says he. “I bet a penny it’s got somethin’ to do with your uncle.” He pinched his cheek and squinted his eyes like he always does when he’s thinking, and then wagged his head.

“I don’t l-like his looks. He’s too dummed g-g-good-natured.”

“But what’s it all about?”

“How do I know?” he says, impatient. “I got to find out what these letters and figgers mean, hain’t I? Then maybe I can sort of git an idee what he’s thrashin’ around for.”

He got up and stuffed both pieces of paper into his pocket.

“Let’s finish exploring and g-git back,” says he. “I’m beginnin’ to g-g-git hungry.”

When we got home Uncle Hieronymous was laying flat on his back by the side of the stream, with his eyes shut and the pleasantest smile on his face. He looked like everything he wanted in the world had walked right up and sat down in his lap. When he heard us coming he sat up and sort of wriggled his eyes to get them wide open, and made a funny motion at us with his hands. Then, right off, he made up a leetle poem:

He got up slow, kind of one piece of him at a time, it looked, and then said:

“Hungry, eh? I bet you. What’ll you eat? Will you have beefsteak, chicken-pie, strawberry short-cake, noodel soup, or bacon and eggs?” He reached around and scratched the back of his neck and winked one eye at the house. “If I was four boys with hollows into their stummicks I’d pick out bacon and eggs, I would. ’Cause why? ’Cause that’s what they’re goin’ to get. Now, each one of you take your choice.”

“N-n-name over those things again, please,” Mark asked him.

Uncle did it as patient as could be. Mark thought careful, going over every one in his mind, then, as solemn as a screech-owl, he says, “I guess b-b-bacon and eggs look best to me.”

Uncle nodded and looked at the rest of us. We spoke up for bacon and eggs right off without thinking over the other things, which seemed to satisfy Uncle Hieronymous all right.

“Will you have ’em baked, b’iled, fried, or stewed?”

“Fried, p-p-please,” says Mark. “Once on the top and once on the b-bottom.”

The rest of us took the same, and uncle went in to start a fire and begin his cooking. While he was at it we walked over to the little tumbledown barn off at a corner of the clearing. It looked as if something big and powerful had come along and given it a push, because it was all squee-geed. Boards were off, and what shingles were left stayed on the roof because they wanted to and not because they had to. Mark peeked inside.

“W-what’s that?” he wanted to know.

The rest of us crowded around and then pushed inside. It was pretty dim in there, but as soon as our eyes got used to it we could see a long white thing laying across the beams above our heads.

“Looks like a boat,” says I.

Tallow Martin lighted a match and held it up so we could see. Sure enough it was a boat—a canoe.

“W-wonder what it’s doing here,” says Mark.

“Let’s ask Uncle Hieronymous,” I says.

So we went off to the house, where uncle was standing over the stove, breaking an egg into a frying-pan.

“’Tain’t ready yet,” says he, as we came into the kitchen.

“We was just out in the barn,” I says, “and we saw a canoe up on the beams. Does it belong to you?”

“Well, now, lemme see. Does that there curi’us leetle boat b’long to me or not? Now, does it? If you was guessin’ how would you guess?”

“I’d guess it did,” I says.

“Then,” says he, “you’d be wrong, for it don’t. At any rate, it didn’t, last time I looked at it. But canoes is peculiar critters—no tellin’ what it’s up and done regardin’ its ownership in nigh onto two months.”

“Can we use it, uncle?”

“Use it? You don’t mean git into the thing on the water? Into that there tipsy, oncertain, wabbly leetle boat? Would you dast?”

“S-s-sure,” says Mark. “I learned to paddle one two years ago.”

“Then,” says uncle, “I guess nobody’ll objec’ serious to fussin’ around in it. Feller left it here two years ago and hain’t never called for it. Go ahead, boys, and do your worst.”

The egg had been sizzling away in the frying-pan. Uncle poked at it with a fork, and then, quicker than a wink, he took hold of the handle of the pan, gave it a little flip, and, would you believe it, that egg turned over just as neat and settled down on its face. I heard Mark chuckle. Uncle looked sort of surprised.

“D-d-do you always turn them like that?” Mark asked.

“How would a feller turn an egg?” uncle wanted to know.

“Well,” says Mark, “after seeing it done like that I don’t know’s there’s any way quite so g-g-good. Anyhow, n-n-none so interestin’.”

In about five minutes the eggs, with fried potatoes and bacon and coffee, were ready, and we put them where they were wanting to go. Uncle gathered up what was left, and when he had shut the door tight he called Martha and Mary and gave it to them.

“Can we get the canoe down now?” I asked uncle.

“You can git it down any time you want to exceptin’ yestiddy. I don’t allow nobody to do anything yestiddy around this house. No, sir. Not a single, solitary thing. That’s how set in my ways I am.”

We all went out to the barn, uncle bringing a ladder with him. He set it up against a beam, and in no time the canoe was down on the ground.

“Kind of a slimpsy-lookin’ thing,” he says, disgusted-like.

“Where’s the p-p-p-paddles?” Mark wanted to know.

“Under the bed,” says uncle, and I ran to get them.

We hauled the canoe down and put it in the water, but right away it began to leak, so we dragged it out again and asked uncle for some paint. He said green paint was all he had. Mark allowed that green paint wasn’t exactly suitable for a canoe, but any paint was better than no paint, so uncle got a can and a brush off a shelf in the kitchen and brought them out to us.

We put the canoe up on a couple of logs and started in to paint, but after we had been at it a couple of minutes Uncle Hieronymous shook his head and grunted. Then he recited another poem:

Then he took the brush away from Tallow, who had it at that particular minute, and told us to clear out while he did a job of painting that would be a credit to the state of Michigan, even if the Governor were to come along to see it, with all the legislature marching in circles around his hat-brim.

We decided to explore down-stream this time. Just as we were starting out from the house Billy came driving along with a fat man on the seat beside him. Not just a big man, but a man that was as fat as Mark Tidd. Billy called to us and waved his hand, and we waved back. Then we started out.

“C-c-couldn’t mistake that feller on a d-d-dark night,” says Mark.

“It ain’t apt to matter whether we do or not,” I told him.

“N-n-n-never can tell. He’s the man that’s comin’ to help out Collins. Wish I knew what those letters and figures in that telegram were about.”

“Oh, come on, and forget about that. Let’s find out what kind of country is down that way.”

To go down-stream we had to take a path through heavy underbrush. Most of the time we had to force our way because the bushes were trying to cover the path. It wasn’t very light, and it was boggy. About a hundred yards ahead we came to a little brook that emptied into the Middle Branch, with two saplings across it for a bridge. I was going ahead. No sooner had I stepped my foot off the far end of the bridge than something began to thrash around and rustle the reeds right under my feet, and all of a sudden a little animal about as big as a dog, or maybe a cat, jumped up and whisked out of sight. He scared me almost out of my wits.

“What was that?” says I.

“That,” says Mark, “was a f-f-full-grown g-grizzly bear.”

“G’wan!” says I. “There ain’t no bears around here.”

“Maybe not,” says Mark, in a whisper, “but there’s something else.” He pointed, and there, across the stream, not more than a couple of hundred feet off, were two little deer and a big one.

Well, it startled all of us. Somehow until then we didn’t realize we really were in the woods—the real, genuine, wild woods where big animals might be. I thought over what I’d said about bears and sort of changed my mind.

“You can’t tell,” I whispered back; “maybe there is bears.”

The deer smelled us, I guess, and off they went, running with the funniest, jumpiest gait you ever saw.

“Did you notice,” asked Mark, “that he asked w-w-who we were?”

“Who asked?” Tallow wanted to know.

“The f-fat man in Billy’s wagon. I could see him asking Billy.”

“Huh!” says I, and on we went.

After a while the ground got higher, and about two miles down we came to a place where the banks of the stream were maybe forty or fifty feet high. Then the stream widened out into a big pool and curved off to the right. It was a dandy place. We sat down, with our feet hanging over, and looked at the water. I noticed some black spots that moved around here and there toward the lower end of the pool where there wasn’t any current, and after a while I got it through my head they were fish—trout. Great big fellows they were. I showed them to the other three, and we sat looking at them, watching how they stayed right around that spot, having a sort of fish meeting, I guess.

The sun was shining bright right down on the water, so that we could see to the bottom where the current didn’t make a ripple. It was pretty deep in spots, too, where the water rushing down had scooped out a hole. It swept around that corner faster than anywhere above.

“Here comes somebody,” says Tallow, and, sure enough, down-stream waded a man, casting away just like we had seen Collins do in the morning. He was an old man—we could tell by the way he carried his shoulders—and he looked tall. He came along, paying no attention to anything but his casting, wading right in the middle of the stream. We watched him without saying anything until he was almost under us.

“If he don’t look out he’s going to wade right into that hole,” says Plunk Martin, but nobody thought to do anything except Mark, and he yelled down:

“L-l-look out, mister. You’re goin’ to s-s-step into a hole.”

The man stopped, looked up, took another step, and sort of stumbled. Then he recovered his balance and waded to shore, but his landing-net had got loose from his belt and was floating down without his noticing it.

“You’ve lost your net,” Tallow yelled.

The old gentleman started after it, but the water got deeper and the current dragged at him pretty strong. He was going to keep on, though, until Mark called to him again.

“It’ll lodge right there in the b-b-brush-heap,” he says.

We all scrambled down the bank to where the old gentleman was. He smiled at us pleasant-like, and said: “Much obliged, boys. I’d have got a good ducking if it hadn’t been for you, and a ducking is no joke at my age.”

“There,” says Mark, “your net’s c-c-caught. Go get it, Binney.”

I scrambled around the shore to the brush-pile and crawled out to where the net was. It was easy to get.

“Camping around here?” asked the old gentleman. I guess he was close to seventy, because his hair and mustache were white as could be. He was a nice-looking old gentleman, with blue eyes that looked like they were twinkling at you, and a big nose. Not a homely nose, but a big one that looked as though he amounted to something.

“We’re staying with my uncle Hieronymous,” I told him.

He sat down on the bank to talk with us. It turned out his name was Macmillan and that he was a lawyer in Ludington, which is about forty or fifty miles farther, and on the shore of Lake Michigan. Right off when he said he was a lawyer Mark was interested. I could see it by the way he squinted his little eyes and pulled on his fat cheek.

“M-m-mister Macmillan,” says Mark, “I want to show you s-somethin’.”

“All right, my son, go ahead.”

“I want to f-f-find out what it is, because it may b-be important.”

“Let’s have a look, then.”

Mark took a paper out of his pocket and gave it to Mr. Macmillan. “I’ve been wonderin’ w-w-what kind of a cipher that is,” says he, “or w-w-what it is if it isn’t a cipher. It m-m-means somethin’.”

“‘The S. 40 of the N. W. ¼ of Sec. 6, Town 1 north, R. 4 west.’ Hum. Does look mysterious, doesn’t it. But, my son, like a lot of things that look mysterious, it isn’t so a bit when you know about it. That is nothing but the description of land. You know there has to be some way of describing every farm, no matter what its size or shape may be, so that everybody will know just where to find it. Well, this cipher, as you call it, describes a farm of forty acres that is the northwest part of Section Six of township number one west of range seventeen. That’s all. Did you think it was telling where hidden treasure was hidden?”

Mark shook his head. “Maybe ’tis,” says he, and all the afternoon we couldn’t get another word out of him.

The rest of us talked with Mr. Macmillan and listened to stories about where he’d fished and hunted, and all about how this part of the state used to be a great pine forest that was butchered off and floated down-stream to the mills. I tell you it was interesting. It began to get late before he was half through, and he had to start for the place where his team was hitched.

“If you come to Ludington,” says he, “drop in to see me.”

We said we surely would.

“And you, young man,” says he to Mark, “when you have any more mysteries to clear up just let me know.”

Mark nodded as sober as could be. Anybody would think he expected to have a couple of mysteries every day.

Mr. Macmillan went off, and we turned back home. As soon as we got in sight of the house we saw uncle had company.

Two men were sitting on the steps, and uncle, tilted back in a chair, was facing them. Nobody seemed to be saying anything as we came up. When we were right close uncle turned and grinned at us.

“Comp’ny, boys,” says he. Then he poked his finger at one visitor. “Jerry Yack,” he says, and Jerry jerked his head. Uncle prodded at the other man. “Ole Skoog,” he says, and Ole jerked his head just like Jerry did. Uncle clean forgot to mention our names at all. It was pretty much of a one-sided introduction, I thought.

We sat down, and nobody said a word. I could see Mark Tidd studying Ole and Jerry and sort of shaking his head over them like he couldn’t make them out. They did nothing but sit and look straight in front of them. They looked like twin brothers, both big and bulging with muscle, both with china-blue eyes and pale hair and cheeks that showed pink through the sunburn.

“Are they brothers?” I whispered to uncle.

“Brothers? Who? Them fellers? Naw. They’re Swedes. That’s what makes ’em look alike. All Swedes look alike. Didn’t you know that? Why, Binney, over in Sweden, where they come from, each feller wears a tag with his name on it. Only way to tell ’em apart. Heard once of a feller losin’ his tag and wanderin’ around for days without bein’ able to find out who he was. When he did find out he found out wrong and had to be somebody else besides himself all the rest of his life. It’s worryin’ about that happenin’ that makes all Swedes so melancholy.”

“Oh!” says I. Mark’s little eyes were opened up wide, and he was staring at uncle like all git-out. Couldn’t quite make up his mind if uncle was fooling us or not.

About fifteen minutes later Jerry Yack hunched his shoulders and moved around uneasy-like. He opened his mouth once and shut it again. Opened it and shut it another time. Then he coughed. Seemed it took all that work to get ready to say something.

“Ay tank,” says he, “ay bane goin’.”

Ole looked up and did considerable wriggling himself. After a while he got ready to speak: “Ay tank,” he says, “ay bane goin’, too.”

They both looked at uncle with their blue eyes wide open like babies. Uncle didn’t say anything. After quite a spell Jerry got around to speak again. He asked a question of uncle.

“W’at you tank? Eh? You bane goin’—yess, or you bane goin’—no?”

Uncle shook his head and recited a poem that made Ole and Jerry look puzzled as anything:

He waggled his head at us boys. “That hain’t neither exactly nor precisely the fact,” says he; “it’s you boys got to decide. Ole and Jerry here come to git me to help ’em a week or so on the river. Loggin’. Jerkin’ logs out of the river-bed. River-bed’s covered with timber farther down. It’s timber that sunk in the old lumberin’-days, and there’s a heap of it. They got a scow with a derrick onto it. What think?”

“H-h-how do you git the logs out?” Mark wanted to know.

Right off his curiosity got to working.

“Poke around with a pike-pole till you find a log. Git a chain fast around her, start your engin’ goin’, and jerk her out with the derrick. Pile ’em on shore.”

Mark nodded like he understood. “How came the logs to be in the river?” he asked.

“Got water-logged and sunk when rafts was runnin’ down,” says Uncle Hieronymous. “Now, you four git together and decide if I can go. I’ll be gone maybe two weeks. Dun’no’ jest where I’ll be, but somewheres on the river below. Plenty of grub in the house, plenty of fish in the stream. Nothin’ to hurt you. How about it, eh?”

“Go, far’s I’m concerned,” I told him.

“M-m-me too,” says Mark; and the rest joined in.

“Won’t be afraid?” asked Uncle Hieronymous. “Sure? Don’t mind bein’ alone with Marthy and Mary, eh? Now be sure. Don’t forgit them two white cats when you’re thinkin’ it over.”

“We hain’t f-f-forgot ’em,” says Mark. Then he up and asked another question. “What I’m wonderin’,” he says, “is, did Mr. Skoog and Mr. Yack ask you all that themselves or did they bring it written in a l-l-l-letter?”

“They—fetched—a—letter,” he wheezed.

Mark nodded. “I d-d-didn’t b’lieve they could have s-s-said it all,” he says.

“When you going?” I asked.

“Right after we eat,” says uncle, and with that he got up and commenced getting supper. In half an hour all seven of us were crowded around the little table, and I want to say if Ole and Jerry couldn’t talk they could eat. If all Swedes eat like they did I bet the farmers in Sweden have to raise whopping big crops to have enough to go around.

After supper Jerry and Ole got a buckboard out of the barn and hitched their horse to it. Uncle threw in a canvas bag of clothes and climbed in.

“If you git to needin’ anything you kin git it up to Larsen’s, I guess,” uncle said. He was going to say something else, but right in the middle of it the old horse jumped all his feet off the ground and started down the road a-kiting. Uncle and Ole and Jerry came pretty nearly being left behind. They all keeled over in a heap, with arms and legs waggling in the air, and there wasn’t any good reason why all of them weren’t jounced out on the ground in the first fifty feet. But they weren’t. Finally Ole got to his feet and caught hold of the lines. He pulled and sawed and yelled, but on the old horse went until he jumped out of sight around a bend in the road. I heard Mark Tidd chuckle.

“B-b-bet those Swedes never started anywhere as quick as that b-b-before,” he says.

I looked at him sharp. He had his sling-shot in his hand.

“Did you shoot the horse?” I asked, sort of provoked, because it didn’t look like a polite thing to do.

He nodded yes.

“What for?” I asked.

He pointed up the road toward Larsen’s, and there, coming along as fast as they could walk, were Collins and the fat man we saw in Billy’s wagon that afternoon. “Th-th-that’s why,” says Mark.

“What have they got to do with it?”

“I got a sort of f-f-feelin’ I don’t want those f-f-fellows to see your uncle Hieronymous. Dun’no’ jest why, but that’s the way I f-f-feel.”

“Well,” says I, “they won’t see him for a couple of weeks now.”

“Not if you f-f-fellers don’t blab where he is,” says Mark.

“You needn’t worry,” I says, sharp-like. “Guess we can keep our mouths shut if there’s any need.”

“May be no need,” says he, “but k-k-keep ’em shut, anyhow.”

We watched the fat man and Mr. Collins. They were headed for our house, all right. I don’t know why, but right there I began to feel that maybe Mark Tidd had stumbled onto something that wasn’t just exactly the way it ought to be. It was hard to believe it, though, for Mr. Collins was such a pleasant, jolly sort of a man, and the fat man looked so good-natured he wouldn’t brush a fly off his bald spot for fear of hurting its feelings. But things did look peculiar. That letter and telegram and the way Mr. Collins seemed to want to meet Uncle Hieronymous made it look as if they were in the woods for something more than a fishing-trip.

Mr. Collins called to us when he was quite a ways off. “Hello, fellows!” says he. “Had any luck to-day?”

We shook our heads. In a minnit they were in the clearing and in another were standing right by us.

“My friend, Mr. Jiggins, boys,” says Mr. Collins, and then he went over all our names careful. “He’s come up to fish, but I don’t believe there’s room enough for him in the stream. Do you?”

“Well,” says Mark, “him and me would f-f-fill it perty full.”

It was the first time I ever heard Mark Tidd joke about his own fatness, and it surprised me considerable. But he had a reason, most likely. He usually had a reason for what he did.

“Been having visitors?” asked Mr. Collins.

“Visitors?” says Mark, and looked as dull as a sheep. You wouldn’t have thought, to look at him then, that he knew enough to spell fish without putting a “g” in it.

“Oh, I just saw somebody drive away.”

“Yes,” says Mark. “Went p-p-perty fast, too.”

“Did seem to be in a hurry,” says Mr. Jiggins.

Mark winked at me, and it was a minnit before I understood what he wanted. Then I knew it must be something about uncle, and there was only one thing about him right then, which was that he was gone away. I guessed Mark wanted me to tell it.

“It was my uncle Hieronymous,” I says, and Mark nodded his head, satisfied.

“Going to town?” asked Mr. Jiggins.

“Dun’no’,” says Mark. “He d-d-didn’t say.”

“Be gone long?”

“Won’t be b-b-back to-night,” Mark stuttered.

Mr. Collins looked at Mr. Jiggins, and Mr. Jiggins looked at Mr. Collins.

“We thought we’d drop in and call on him,” says Collins.

“Too bad he’s gone,” I says. “Come again.”

“We’ll do that,” says Jiggins; but he looked pretty disappointed, and I noticed him eying the road back to Larsen’s. So did Mark. His little eyes twinkled kind of mean.

“Quite a walk d-d-down here, ain’t it?” he asked, with his face solemn. “Dun’no’s I’d care to walk it for n-n-nothin’.”

“Dun’no’s I would, either,” said the fat man, pretty short. “Let’s start back,” he says to Collins.

“When uncle gets back I’ll tell him you were here,” I promised, and they said thank you.

“L-l-let’s git something to eat,” says Mark, and the way he stuttered to get it out was a caution. I’ve noticed he stutters worse when he’s hungry than when he isn’t. “I’ll cook,” says he, “if you fellers will wash the dishes.”

There’s no denying Mark was a good cook. He ought to be, for there never was anybody who thought more about eating than he did. He was always hanging around the kitchen watching his mother, and I’ll bet there never was a girl who could make better baking-powder biscuits than he did that night. There were some raspberries Uncle Hieronymous had found time to pick, and lots of ordinary stuff like fried potatoes and ham.

“T-t-to-morrow,” says Mark, “I’ll make a pie.” He stood looking out of the window, thinking a minute. Then he turned sudden-like, and frowned so his forehead got all ridgy. “Careless,” says he. “Here we are, surrounded by hostiles, and the c-c-c-canoe right there under their eyes. N-n-never would be there in the mornin’. Hain’t you f-f-f-fellers read any books? Don’t you know folks fixed like we are always hide their canoe? Well, you b-b-better git right at it.”

“It’s all paint,” says Plunk Smalley.

“P-p-p-paint!” Mark says, disgusted as could be. “What’s p-paint against losin’ our boat? Where’d we be if we lost it, I’d like to know? Hundreds of m-m-miles from civilization. Our only hope of gittin’ back alive is that b-boat.”

Off we went in a hurry, I can tell you. It seemed real. That was a way Mark had: he could make the games you played with him seem like you were doing the things in earnest. We took that canoe, paint and all, and hid it down the path that ran through the underbrush. We piled limbs of bushes all around it, hid the paddles near, and then went back to the house.

“That was a narrow escape,” Mark says. “Wish we had it provisioned, but it don’t look possible. We can p-p-put blankets and things in it, anyhow.”

We did. We put blankets and matches and cooking-things near the canoe just as if we expected we might have to run to it for our lives any second. That didn’t satisfy Mark. He made us fix up a pack full of canned things and potatoes and flour and salt so we could grab it and be off without waiting even to think. And all the time we thought it was just a game. We thought he was playing, while Mark never said a word, but just let us go on thinking so. He wasn’t playing, though. He was looking ahead and getting ready if an emergency came up. Afterward he told me he wasn’t sure we would ever need the boat, but there was just a chance, and if that chance happened we’d need it bad and quick. So he got it ready. That’s why folks always have found it so hard to beat Mark Tidd. He’d sit and figure and figure and guess what might happen, and when he’d guessed every possible thing that could manage to come about he’d get ready for every one of them.

By the time the canoe was all ready it was almost dark. It was the first we’d thought about spending the night all alone in the cabin, way off miles from anybody, and I’ll admit I began to feel pretty funny. I noticed everybody else was getting quiet and not saying much and looking every once in a while into the woods. It was chilly and still.

“L-l-let’s go to bed,” Mark says, after a while.

“Shall—shall we have a guard?” Tallow says, hesitating-like.

“No need,” Mark says.

I began to think I would like to have somebody big—somebody big and so strong that knew so much about the woods. If some one like that had been there to sleep alongside of us not one of us would have worried a mite. But he wasn’t, so we had to do without.

We put out the lights and locked the door, and after quite a while we all went to sleep.

The next day we didn’t do much but fuss around. Plunk and Tallow tried fishing for trout with angleworms, but they got only one, and he was a rainbow. Mark found a shady spot and read all the time he wasn’t cooking or eating, and I got out Uncle Hieronymous’s draw-shave and found a piece of seasoned hickory he had stowed away. First off I didn’t know what I’d make of it, but after I’d figured a spell I decided it would be a bow and arrow. I was pretty handy with tools, and this wasn’t the first bow I ever made, by any means. It took me all day to finish it and half a dozen arrows, so my time was filled up all right.

“Tell you what let’s do,” says I, at the supper-table. “Uncle said there was a lake about a mile off with bass and perch in it. What’s the matter with digging some worms and hiking there early in the morning? Maybe we can catch a mess for dinner.”

“G-g-good idea,” says Mark. “Then let’s get there by daylight.”

We took a spade and went out back of the barn to dig worms. The ground was pretty dry, but by digging over about an acre we got a half a canful.

“Think it’s enough?” I asked.

“All you can g-g-get has got to be enough,” says Mark, which was perfectly true. Anyhow, if we got one fish for every worm we would have more than we could eat.

Uncle had an old alarm-clock that would still run considerable. I wouldn’t go so far as to say it would run just right, but it had two hands and a face, and it ticked. That ought to be enough for any clock. And it did alarm. I should say it did! It went off like the crack of doom.

“What time’ll I set her for?” I asked.

“’Bout two o’clock,” says Tallow.

Mark grunted. “Two n-n-nothin’,” he stuttered. “Three’s plenty early.”

Then we went to bed. We didn’t seem to be as nervous that night as we had been the night before, which was pleasant. I don’t like to be scared. It is one of the most disagreeable things that happen to me. I was just dozing off when Mark spoke to me.

“Those f-f-fellers was here to-day,” he says.

“What fellers?” I asked, cross-like, because I didn’t like being roused up.

“C-C-Christopher Columbus and George W-W-W-Washington,” he says, disgusted. “Who’d you think?”

“You mean Collins and the fat man?”

He grunted: “Uh-hup. While you was back of the barn whittlin’,” he says. “They went off disappointed. Seems like that f-f-fat feller don’t care much for walking.”

“What did you tell them?”

“Told ’em your uncle wouldn’t be b-b-back ’fore night.”

“Oh, go on to sleep,” Tallow snorted, from his bed; and so Mark and I kept quiet, and the first thing I knew I was being waked up by the worst racket I ever heard. It scared me so I jumped out of bed way into the middle of the room. For a minnit I couldn’t make out what was going on. It might have been a bear tearing down the house or an attack by Indians, for all I could make out. Then I got really waked up and recognized it was the old alarm-clock. It didn’t seem like I’d been to sleep at all, and it was so dark a black cat would have looked sort of gray if it had come into the room. The other fellows were stirring around.

“Time to get up,” I says.

“Doggone that clock,” says Tallow.

I guess that’s what we all thought, but nobody was willing to be the first one to back out, so we lighted a lamp and dressed. My, but it was chilly! When we opened the door and started outside it was like to frost-bite our ears. And everything was wet with dew; my feet were soaked before I’d gone a hundred feet.

I don’t know what time it really was. Maybe it was three o’clock, but if it was, three is a heap earlier than I ever imagined it could be. Why, it was as dark as midnight. We stumbled around and found the road. It was about a mile up the road to the bridge, and maybe a half a mile across the stream to the lake. We came near missing it altogether in the dark, and we would have if it hadn’t been for the sound of a frog splashing into the water. We turned off and fumbled down to the shore, and there we were. We might as well have been home, for we never could find the boat uncle told me about in that blackness, so we just sat down and grumbled. It was pretty uncomfortable, I want to tell you. All the fun there is crouching down in the dark on the shore of a lake you can hardly see, with your feet wet and shivers chasing each other up and down your back, can be put in your ear.

“Who thought of this?” Tallow growled.

“Binney,” says Plunk.

“Who wanted to get up at two?” I asked right back, and they didn’t have another word to say.

We huddled around, all fixed to quarrel. It got a little lighter, but not enough to do any good, and by that time we were hungry. Tallow mentioned he was, and Mark—the only one in the crowd to think ahead—pulled a bag out of his pocket with sandwiches and store-cookies in it. We gobbled them and felt a bit better.

Just as it began to get sort of grayish we heard wagon-wheels in the road. Right off Mark started a game. He figured we’d feel better if we had something to think about, I guess.

“Hist!” says he. “The p-p-pirates!”

We all kept so still you couldn’t even hear us breathe.

“If they f-f-find us here in their lair,” says Mark, “it’ll be all day with us. Have you got the diamonds s-s-safe, Binney?” he whispered.

“Yes,” says I, feeling of some pebbles in my pocket, “I got ’em.”

“Maybe they’ll pass without seein’ us,” Tallow guessed.

But the wagon stopped. It stopped right alongside of where we were, and somebody spoke.

“Fine time of the day to get a man out,” he says. “Might have had four hours’ sleep yet.”

“Never mind,” says another voice, sort of laughing; “you’ll be all right as soon as they start biting.... That boat Larsen told us about ought to be right near here.”

“Let it stay,” grumbled the other man. “I ain’t going to stir out of this wagon till it’s light enough for me to see to get around without busting my neck. A man of my size ain’t a cat, to run along on the top of a fence.”

“Here, have a smoke. That’ll cheer you up. It’ll be plenty light in fifteen minutes, Jiggins.”

Mark nudged me. I thought the voices were familiar, but as soon as that name Jiggins was mentioned I knew it was Mr. Collins and the fat man.

“Lay low,” says Mark, “and listen. That’s the pirate chief.”

We listened.

“We want to get back to Larsen’s by nine o’clock,” said Jiggins. “Our friend with the name ought to be home by this time, and I don’t want to hang around this forsaken hole in the woods all summer.”

“Hieronymous Alphabet Bell,” says Collins. “That is quite some name. Wonder where he got it?”

“Don’t care where he got it. What I’m worrying about is, will we get him?”

“Sure,” says Collins. “He’s probably forgotten he ever owned forty acres in the Northern Peninsula, and if he remembers it he won’t think about retaining the mineral rights when he sold it.”

“You never can tell about these old codgers. Some of ’em are wiser than they look.”

“Well,” says Collins, “we’ve got to land him. It means considerable to you and me, eh? To think of the old codger living here in the backwoods when he is the owner of one of the finest bits of copper property in the state! I don’t suppose there’s any telling what that land is worth as it stands.”

“You can bet it’s worth considerable, or the company wouldn’t be so anxious to get hold of it. Anyhow, it would be enough to make our friend Hieronymous richer than he ever dreamed of being.”

“Well, he won’t ever know it. Seems kind of mean, sometimes, to gouge an old fellow, but I suppose business is business. He’s as happy without it, likely.”

“We haven’t got it yet,” snapped Jiggins, “and you want to move pretty cautious. Remember, you’re a friend of a farmer who bought that piece to farm on. Remember he’s a peculiar old fellow who wants to feel nobody else has any right whatever in the land he lives. That’s why he wants to get the mineral rights Mr. Hieronymous Alphabet owns. Remember that. It ought to fool him, all right, but you can’t ever tell. We mustn’t offer him too much, or he’ll get to thinking. Two hundred is the highest, I should say.”

“Two hundred’s plenty. There’s no need to waste money, anyhow.”

Mark Tidd was holding onto my arm. As Collins and Jiggins went on talking I could feel him getting more and more excited by the way his fingers dug into me. I hadn’t any idea he was so strong in the hands, but I began to think he’d take a chunk right out of me.

“Quit it,” I says, in a whisper.

“D-d-did you hear?” he asked, stuttering so he could hardly get the words out.

“Yes,” says I.

Just then Plunk Smalley, who always was doing something at the wrong minnit, had to lean forward suddenly and bang his head against a stump.

“Ouch!” he hollered.

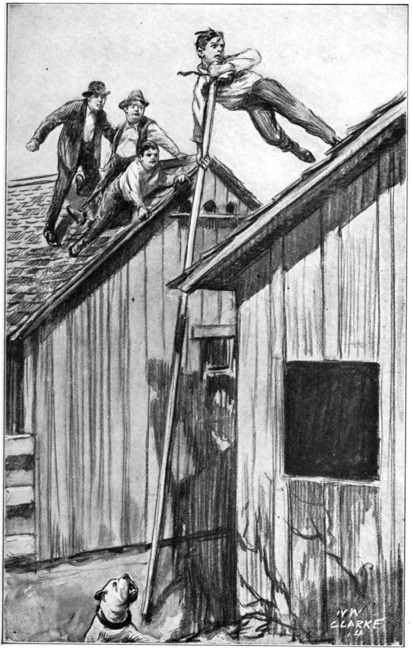

The talk in the wagon stopped in a second, and I heard somebody leap to the ground and come jumping toward us. Of course, it was Collins, because the fat man never could have moved so fast. We were in a nice place—all sitting on the ground, without the slightest idea where to run without getting mired or tangled up in the underbrush. But we did our best. Everybody took a different direction, and you could hear folks floundering wherever you listened. The fat man had got down and was coming after us too.