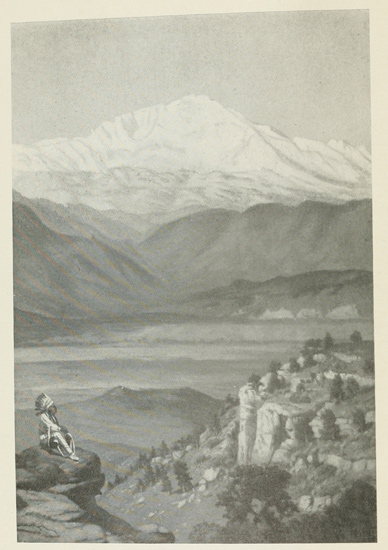

Pike's Peak

From a painting by Charles Craig

Title: The Indians of the Pike's Peak Region

Author: Irving Howbert

Release date: June 2, 2018 [eBook #57252]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Melissa McDaniel and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/indiansofpikespe00howbuoft |

Including an Account of the Battle of Sand

Creek, and of Occurrences in El Paso

County, Colorado, during the War

with the Cheyennes and Arapahoes,

in 1864 and 1868

By

Irving Howbert

Illustrated

The Knickerbocker Press

New York

1914

Copyright, 1914

BY

IRVING HOWBERT

| PAGE | |

| The Tribes of the Pike's Peak Region | 1 |

| Trails, Mineral Springs, Game, etc. | 27 |

| The Indian Troubles of 1864 | 75 |

| The Third Colorado and the Battle of Sand Creek | 93 |

| A Defense of the Battle of Sand Creek | 114 |

| A Defense of the Battle of Sand Creek—Continued | 147 |

| The Indian War of 1868 | 187 |

| FACING PAGE | |

| Pike's Peak | Frontispiece |

| Ouray | 60 |

| Colonel John M. Chivington | 117 |

| Governor John Evans | 123 |

For the most part this book is intentionally local in its character. As its title implies, it relates principally to the Indian tribes that have occupied the region around Pike's Peak during historic times.

The history, habits, and customs of the American Indian have always been interesting subjects to me. From early childhood, I read everything within my reach dealing with the various tribes of the United States and Mexico. In 1860, when I was fourteen years of age, I crossed the plains between the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains twice, and again in 1861, 1865, and 1866; each time by ox- or horse-team, there being no other means of conveyance. At that time there were few railroads west of the Mississippi River and none west of the Missouri. On each of these trips I came more or less into contact with the Indians, and during my residence in Colorado from 1860 to the present time, by observation and viii by study, I have become more or less familiar with all the tribes of this Western country.

From 1864 to 1868, the Indians of the plains were hostile to the whites; this resulted in many tragic happenings in that part of the Pike's Peak region embracing El Paso and its adjoining counties, as well as elsewhere in the Territory of Colorado. I then lived in Colorado City, in El Paso County, and took an active part in the defense of the settlements during all the Indian troubles in that section. I mention these facts merely to show that I am not unfamiliar with the subject about which I am writing. My main object in publishing this book is to make a permanent record of the principal events of that time.

So far as I know, the public has never been given a detailed account of the Indian troubles in El Paso County during the years 1864 and 1868. At that time there was no newspaper published in the county and the few newspapers of the Territory were small affairs, in which little attention was given to anything outside of their immediate localities. The result was that news of tragic happenings in our part of the Territory seldom passed beyond the borders of our own county.

I have thought best to begin with a short account of the tribes occupying the Pike's Peak ix region prior to the coming of the white settler, adding to it extracts from the descriptions given by early explorers, together with an account of the game, trails, etc., of this region. All these facts will no doubt be of interest to the inhabitant of the present day, as well as of value to the future historian.

I took part in the battle of Sand Creek, and in many of the other events which I mention. Where I have no personal knowledge of any particular event, I have taken great pains to obtain the actual facts by a comparison of the statements of persons who I knew lived in the locality at the time. Consequently, I feel assured of the substantial accuracy of every account I have given.

In giving so much space to a defense of the battle of Sand Creek, I am impelled by an earnest desire to correct the false impression that has gone forth concerning that much maligned affair. Statements of prejudiced and unreliable witnesses concerning the battle were sent broadcast at the time, but except through government reports, that only few read, never before, to my knowledge, has publicity been given to the statement of the Governor of the Territory, telling of the conditions leading up to the battle, or to the sworn testimony of the colonel in command at the engagement, or x of the officer in command of the fort near which it was fought. That the battle of Sand Creek was not the reprehensible affair which vindictive persons have represented it to be, I believe is conclusively proven by the evidence which I present.

I. H.

Colorado Springs,

November 1, 1913.

The

Indians of the Pike's Peak

Region

It would be interesting to know who were the occupants of the Pike's Peak region during prehistoric times. Were its inhabitants always nomadic Indians? We know that semi-civilized peoples inhabited southwestern Colorado and New Mexico in prehistoric times, who undoubtedly had lived there ages before they were driven into cliff dwellings and communal houses by savage invaders. Did their frontier settlements of that period ever extend into the Pike's Peak region? The facts concerning these matters, we may never know. As it is, the earliest definite 2 information we have concerning the occupants of this region dates from the Spanish exploring expeditions, but even that is very meager. From this and other sources, we know that a succession of Indian tribes moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains during the two hundred years before the coming of the white settler, and that during this period, the principal tribes occupying this region were the Utes, Comanches, Kiowas, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and Sioux; and, further, that there were other tribes such as the Pawnees and Jicarilla Apaches, who frequently visited and hunted in this region.

The Jicarilla Apaches are of the Athapascan stock, a widely distributed linguistic family, which includes among its branches the Navajos, the Mescalaros of New Mexico, and the Apaches of Arizona. Notwithstanding the fact that they were kindred people, the Jicarillas considered the latter tribes their enemies. However, they always maintained friendly relations with the Utes, and the Pueblos of northern New Mexico, and intermarriages between members of these tribes were of frequent occurrence. The mother of Ouray, the noted Ute chief, was a Jicarilla Apache.

From the earliest period, the principal home of the Jicarilla Apaches was along the Rio Grande 3 River in northern New Mexico, but in their wanderings they often went north of the Arkansas River and far out on the plains, where they had an outpost known as the Quartelejo. By reason of the intimate relations existing between the Jicarillas and the Pueblo Indians, this outpost was more than once used as a place of refuge by members of the latter tribes. Bancroft, in his history of New Mexico, says that certain families of Taos Indians went out into the plains about the middle of the seventeenth century and fortified a place called "Cuartalejo," which undoubtedly is but another spelling of the name Quartelejo. These people remained at Quartelejo for many years, but finally returned to Taos at the solicitation of an agent sent out by the Government of New Mexico. In 1704, the Picuris, another Pueblo tribe, whose home was about forty miles north of Santa Fé, abandoned their village in a body and fled to Quartelejo, but they also returned to New Mexico two years later. Quartelejo is frequently mentioned in the history of New Mexico, and its location is described as being 130 leagues northeast of Santa Fé. In recent years the ruin of a typical Pueblo structure has been unearthed on Beaver Creek in Scott County, Kansas, about two hundred miles east of Colorado Springs, which, in 4 direction and distance from Santa Fé, coincides with the description given of Quartelejo, and is generally believed to be that place.

Aside from the Jicarilla Apaches, the Utes, living in the mountainous portion of the region now included in the State of Colorado, were the earliest occupants of whom there is any historical account. They were mentioned in the Spanish records of New Mexico as already inhabiting the region to the north of that Territory in the early part of the seventeenth century. At that time, and for many years afterward, they were on peaceable terms with the Spanish settlers of New Mexico. About 1705, however, something occurred to disturb their friendly relations, and a war resulted which lasted fifteen to twenty years, during which time many people were killed, numerous ranches were plundered, and many horses stolen. Although the Utes already owned many horses, it is said that in these raids they acquired so many more that they were able to mount their entire tribe. During that time various military expeditions were sent against the Utes as well as against the Comanches, who had first appeared in New Mexico in 1716. In 1719, the Governor of New Mexico led a military force, consisting of 105 Spaniards and a large number of Indian auxiliaries, 5 into the region which is now the State of Colorado, against the hostile bands. The record of the expedition says that it left Santa Fé on September 15th and marched north, with the mountains on the left, until October 10th. In this twenty-five days' march the expedition should have gone far beyond the place where Colorado Springs now stands. Although the expedition failed to overtake the Indians, the latter ceased their raids for a time, but their subsequent outbreaks showed that their friendship for the New Mexican people could not be entirely depended upon, although they mingled with them to such an extent that a large portion of the tribe acquired a fair knowledge of the Spanish language.

The Utes were an offshoot of the Shoshone family, the branches of which have been widely distributed over the Rocky Mountain region from the Canadian line south into Mexico. It is now generally conceded that the Aztecs of Mexico and the Utes belong to the same linguistic family. It is probable that in the march of the former toward the south, many centuries ago, the Utes were left behind, remaining in their savage state, while the Aztecs, coming in contact with the semi-civilized nations of the South, gradually reached the state of culture which they had 6 attained at the time of the conquest of Mexico by the Spaniards. I am firmly of the opinion that these Indians, and in fact all the Indians of America, are descendants of Asiatic tribes that crossed over to this continent by way of Bering Strait at some remote period. These tribes may, however, have been added to at various times by chance migrations from Japan, the Hawaiian and South Sea islands. It is known that in historic times the Japanese current has thrown upon the Pacific Coast fishing-boats, laden with Japanese people, which had drifted helplessly across the Pacific Ocean. It is, therefore, fair to assume that what is known to have occurred in recent times might also have frequently occurred in the remote past, and if this be so, the intermarriage of these people with the native races would undoubtedly have had a decided influence upon the tribes adjacent to the Pacific Coast. There seems to be no reason why the people of the Hawaiian Islands should not have visited our shores, as those islands are not much farther distant from the Pacific Coast than are certain inhabited islands in other directions. These same conclusions have been reached by many others who have made a study of the question.

The National Geographic Magazine of April, 7 1910, contained an article written by Miss Scidmore on "Mukden, the Manchu Home," in which she says:

When I saw the Viceroy and his suite at a Japanese fête at Tairen, whither he had gone to pay a state visit, I was convinced as never before of the common origin of the North American Indian and the Chinese or Manchu Tartars. There before me might as well have been Red Cloud, Sitting Bull, and Rain-in-the-Face, dressed in blue satin blankets, thick-soled moccasins, and squat war-bonnets with single bunches of feathers shooting back from the crown. Manchu eyes, Tartar cheek-bones, and Mongol jaws were combined in countenances that any Sioux chief would recognize as a brother.

The Ute Indians were well-built, but not nearly as tall as the Sioux, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, or any of the tribes of the plains. Their type of countenance was substantially the same as that of all American Indians. They were distinctly mountain Indians, and that they should have been a shorter race than those of the plains to the east is peculiar, as it reverses the usual rule. Might not this have been the result of an infusion of Japanese blood in the early days of the Shoshones when their numbers were small? And possibly from this same source came the unusual ability of the Utes in warfare. 8

As Indians go, the Utes were a fairly intelligent people. They had a less vicious look than the Indians of the plains, and as far as my observation goes, they were not so cruel. They ranged over the mountainous region from the northern boundaries of the present State of Colorado, down as far as the central part of New Mexico. Their favorite camping-place, however, was in the beautiful valleys of the South Park, and other places in the region west of Pike's Peak. The South Park was known to the old trappers and hunters as the Bayou Salado, probably deriving its name from the salt marshes and springs that were abundant in the western part of that locality.

Game was to be found in greater abundance in the South Park and the country round about than in almost any other region of the Rocky Mountains, and for that reason its possession was contended for most strenuously year after year by all the tribes of the surrounding country. For a time in the summer season, the Utes were frequently driven away from this favorite region by the tribes of the plains who congregated in the South Park in great numbers as soon as the heat of the plains became uncomfortable. However, the Utes seldom failed to retain possession during most of the year, as they were remarkably good 9 fighters and more than able to hold their own against equal numbers.

In point of time, the Comanches were the next tribe of which we have any record, as inhabiting this region. These Indians also were a branch of the Shoshone nation. They led the procession of tribes that moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains during the seventeenth and the first half of the eighteenth centuries. When first heard of, they were occupying the territory where the Missouri River emerges from the Rocky Mountains. Later, they were driven south by the pressure of the Sioux Indians and other tribes coming in from the north and east. For a while they occupied the Black Hills, and then were pushed still farther south by the Kiowas. They joined their kinsmen the Utes in raids upon the settlements of New Mexico in 1716, and it was to punish the Comanches as well as the Utes, that the Governor of New Mexico, in 1719, led the military expedition into the country now within the boundaries of Colorado. In 1724, Bourgemont, a French explorer mentions them under the name of the Padouca, as located between the headwaters of the Platte and Kansas rivers, but later accounts show that before the end of that century they had been pushed south of the 10 Arkansas River by the pressure of the tribes to the north.

During the stay of the Comanches in this region, they were for a time friendly with the Utes, and the two tribes joined each other in warfare and roamed over much of the same territory, but later, for some unknown reason, they for a time engaged in a deadly warfare. The old legend of the Manitou Springs mentions the possible beginning of the trouble. The incident around which the legend is woven, may be an imaginary one, but it is a well-known fact that long and bitter wars between tribes resulted from slighter causes. It is said that a long war between the Delawares and Shawnees originated in a quarrel between two children over a grasshopper.

The Comanches were a nation of daring warriors, and after their removal to the south of the Arkansas River, they became a great scourge to the settlements of Texas and New Mexico, finally extending their raids as far as Chihuahua, in Mexico. As a result of these operations, they became rich in horses and plunder obtained in their raids, besides securing as captives many American and Spanish women and children. One of their most noted chiefs in after days was the son of a white woman who had been captured in Texas 11 in her childhood, and who, when grown, had married a Comanche chief. The Government arranged for the release of both the American and Spanish captives, but in more than one instance women who had been captured in their younger days refused to leave their Comanche husbands, notwithstanding the strongest urging on the part of their own parents.

Following the Comanches came the Kiowas, a tribe of unknown origin, as their language seems to have no similarity to that of any of the other tribes of this country. According to their mythology, their first progenitors emerged from a hollow cottonwood log, at the bidding of a supernatural ancestor. They came out one at a time as he tapped upon the log, until it came to the turn of a fleshy woman, who stuck fast in the hole, and thus blocked the way for those behind her, so that they were unable to follow. This, they say, accounts for the small number of the Kiowa tribe.

The first mention of this tribe locates them at the extreme sources of the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers, in what is now central Montana. Later, by permission of the Crow Indians, they took up their residence east of that tribe and became allied with them. Up to this time they possessed no horses and in moving about had to depend solely 12 upon dogs. They finally drifted out upon the plains; here they first procured horses, and came in contact with the Arapahoes, Cheyennes, and, later, with the Sioux. The tribe probably secured horses by raids upon the Spaniards of New Mexico, as the authorities of that Territory mention the Kiowas as early as 1748, while the latter were still living in the Black Hills. It may not be generally known that there were no horses upon the American continent prior to the coming of the Spaniards. The first horses acquired by the Indians were those lost or abandoned by the early exploring expeditions, and these were added to later by raids upon the Spanish settlements of New Mexico. The natural increase of the horses so obtained gave the Indians, in many cases, a number in excess of their needs. Previous to acquiring horses, the Indians used dogs in moving their belongings around the country. As compared with their swift movements of later days this slow method of transportation very materially limited their migrations.

By the end of that century, the Kiowas had drifted south into the region embraced by the present State of Colorado, probably being forced to do so by the pressure of the Sioux, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes, who were at that time advancing from the north and east. As the Kiowas advanced 13 southward, they encountered the Comanches; this resulted in warfare that lasted many years, in the course of which the Comanches were gradually driven south of the Arkansas River. When, finally, the war was terminated, an alliance was effected between the two tribes, which thereafter remained unbroken. In 1806, the Kiowas were occupying the country along the eastern base of the mountains of the Pike's Peak region. From Lieut. Zebulon Pike's narrative, we learn that James Pursley, who, according to Lieutenant Pike, was the first American to penetrate the immense wilds of Louisiana, spent a trading season with the Kiowas and Comanches in 1802 and 1803. He remained with them until the next spring, when the Sioux drove them from the plains into the mountains at the head of the Platte and Arkansas rivers. In all probability their retreat into the mountains was through Ute Pass, as that was the most accessible route. In the same statement Lieutenant Pike mentions Pursley's claim to having found gold on the headwaters of the Platte River. By the year 1815, most of the Kiowas had been pushed south of the Arkansas River by the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, but not until 1840 did they finally give up fighting for the possession of this region. 14

The Cheyennes and Arapahoes were of the Algonquin linguistic family, whose original home was in the New England States and southern Canada. When first heard of, about 1750, the Cheyennes were located in northern Minnesota. Later, about 1790, they were living on the Missouri, near the mouth of the Cheyenne River. Subsequently they moved west into the Black Hills, being forced to do so by the enmity of the Sioux. Here they were joined by the Arapahoes, a tribe of the same Algonquin stock, and from that time on the two tribes were bound together in the closest relations.

Beginning about 1800, these two federated tribes, accompanied by some of the Sioux, with whom they had made peace, gradually moved southward along the eastern base of the Rocky Mountains. Dr. James, the historian of Long's expedition which visited the Pike's Peak region in 1820, mentions the fact that about four years previous there had been a large encampment of Indians on a stream near Platte Cañon, southwest of Denver, which had assembled for trading purposes. It appears that the Cheyennes had been supplied with goods by British traders on the Missouri River, and had met to exchange these goods for horses. The tribes dwelling on the fertile plains of the Arkansas and Red rivers 15 always had a great number of horses, which they reared with much less difficulty than did the Cheyennes, who usually spent the winter in the country farther to the north, where the cold weather lasted much longer and feed was less abundant. After many years of warfare with the Kiowas, the Cheyennes and Arapahoes were victorious, and by a treaty, made in 1840, secured undisputed possession of the territory north of the Arkansas River and east of the mountains. As this was only eighteen years before the coming of the whites, the Cheyennes and Arapahoes could not rightfully claim this region as their ancestral home. The country acquired by the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, through their victory over the Kiowas, embraced a territory of more than eighty thousand square miles. As in those two tribes there were never more than five thousand men, women, and children, all told, the area was out of all proportion to their numbers.

Early in 1861, the Government made a treaty with the Cheyennes and Arapahoes by which these tribes gave up the greater part of the lands claimed by them in the new Territory of Colorado. For this they were to receive a consideration of four hundred and fifty thousand dollars, to be paid in fifteen yearly installments, the tribes 16 reserving for their own use a tract about seventy miles square located on both sides of the Arkansas River in the southeastern part of the Territory.

From the time of their first contact with the whites, the Cheyennes and Arapahoes were alternately friendly or hostile, just as their temper or whim dictated upon any particular occasion. With the old trappers and hunters of the plains, the Cheyennes had the reputation of being the most treacherous and untrustworthy at all times and in all places, of any of the tribes of the West. The Arapahoes, while occasionally committing depredations against the whites, were said to be somewhat different in temperament, in that they were not so sullen and morose as the Cheyennes, and were less treacherous and more open and trustworthy in their dealings. This estimate of the characteristics of the two tribes was fully confirmed in our contact with them in the early days of Colorado.

The Cheyennes were continuously hostile during the years 1855, 1856, and 1857, killing many whites and robbing numerous wagon-trains along the Platte River, which at that time was the great thoroughfare for travelers to Utah, California, Oregon, and other regions to the west of the Rocky Mountains. In 1857, the Cheyennes were severely 17 punished in a number of engagements by troops under command of Colonel E. V. Sumner of the regular army, and as a result, they gave little trouble during the next five or six years.

In the early days, the Arapahoes came in touch with the whites to a much greater extent than did the Cheyennes. The members of the latter tribe usually held aloof, and by their manner plainly expressed hatred of the white race. Horace Greeley, in his book describing his trip across the plains to California in 1859, tells of a large body of Arapahoes who were encamped on the outskirts of Denver in June of that year, because of the protection they thought it gave them from their enemies the Utes. I saw this band when I passed through Denver in June of the following year.

The Sioux were one of the largest Indian nations upon the American continent. So far as is known, their original home was upon the Atlantic Coast in North Carolina, but by the time Europeans began to settle in that section they had drifted into the Western country. Their first contact with the white race occurred in the upper Mississippi region. These white people were the French explorers who had penetrated into almost every part of the interior long before the English had made any serious attempt at the exploration of 18 the wilderness west of the Allegheny Mountains. The friendly relations between the French and the Sioux continued for many years, but when the French were finally supplanted by the English in most localities, the Sioux made an alliance with the latter which was maintained during the Revolutionary War, and continued until after the War of 1812. Subsequent to the year 1812, the Sioux gradually drifted still farther westward, and not many years later their principal home was upon the upper Missouri River. The recognized southern boundary of their country was the North Platte River, but on account of their friendly relations with the Cheyennes and Arapahoes, the Sioux often wandered along the base of the mountains as far as the Arkansas River, and, being at enmity with the Utes, they frequently joined the Cheyennes and Arapahoes in raids upon their common enemy.

While the Pawnees seldom spent much time in this region, they often came to the mountains in raids upon their enemies the Sioux, Cheyennes, Arapahoes, and Kiowas and upon horse-stealing expeditions. The Pawnees were members of the Caddoan family, whose original home was in the South. In this they were exceptional, since almost every other tribe in this Western country came 19 from the north or east. From time immemorial their principal villages were located on the Loup Fork of the Platte River and on the headwaters of the Republican River, about three hundred miles east of the Rocky Mountains. The Pawnees were a warlike tribe and extended their raids over a very wide stretch of country, at times reaching as far as New Mexico. They carried on a bitter warfare with the Sioux, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes, and at times were engaged in warfare with almost every one of the surrounding tribes. They were a courageous people, and were generally victorious, where the numbers engaged were at all nearly equal. The Spaniards of New Mexico became acquainted with this tribe as early as 1693, and made strenuous efforts to maintain friendly relations with them; with few exceptions these efforts were successful.

In 1720, the Spanish authorities of New Mexico learned that French traders had established trading stations in the Pawnee country, and were furnishing the Indians with firearms. This news greatly disturbed the Spaniards and resulted in a military expedition being organized at Santa Fé, to visit the principal villages of the Pawnees for the purpose of impressing that tribe with the strength of the Spanish Government, and thus to 20 counteract the influence of the French. The expedition started from Santa Fé in June of that year. It was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Villazur, of the Spanish regular army, and was composed of fifty armed Spaniards, together with a large number of Jicarilla Apache Indians as auxiliaries, making the expedition an imposing one for the times. The route taken, as nearly as I can determine from the description given in Bancroft's history of New Mexico, was northerly along the eastern base of the mountains, passing not very far from where Colorado Springs is now located. After reaching the Platte River, at no great distance east of the mountains, the expedition proceeded down the valley of that stream until it came in contact with the Pawnees, but before a council could be held, the latter surprised the Spaniards, killed the commanding officer, and in the fight that ensued almost annihilated the party. The surviving half-dozen soldiers, who were mounted, saved themselves by flight. Not yet having acquired horses, the Pawnees could not pursue them. These survivors, after untold hardships, reached Santa Fé a month or two later to tell the tale. Another instance of a Spanish force visiting the Pawnees occurred in 1806. When Lieutenant Pike on his exploring tour visited 21 the Pawnees on the Republican River in September of that year, he found that a Spanish military force had been there just ahead of him. This force had been dispatched from Santa Fé to prevent him from exploring the country north of the Arkansas River, to which the Spanish Government insistently laid claim. However, the expedition failed of its purpose, inasmuch as it marched back up the Arkansas River to the mountains, and returned to Santa Fé without having seen or heard of Lieutenant Pike.

When Colonel Long on his exploring expedition visited this tribe in 1819, he found the Pawnees mourning the loss of a large number of their warriors who had been killed in an encounter with the Cheyennes and Arapahoes in the region adjacent to the Rocky Mountains. It seems that ninety-three warriors left their camp on the Republican River and proceeded on foot to the mountains on a horse-stealing expedition. The party finally reached a point on the south side of the Arkansas River, having up to that time accomplished nothing. Here they were discovered and attacked by a large band of Cheyennes and Arapahoes. During the fight that followed, over fifty of the Pawnees were killed; but the attacking party suffered so severely that after the fighting had continued for a 22 day or more, they were glad to allow the surviving Pawnees, numbering about forty, to escape. Most of the latter were wounded and it was with difficulty that they succeeded in reaching their homes.

All the tribes that I have mentioned were purely nomadic, and, aside from the Pawnees, depended entirely upon game for a living.

The Pawnees were the only tribe that engaged in agriculture. Their summer camps were generally located at some favorable spot for growing corn, beans, pumpkins, and other vegetables. They usually remained at such place until their crops were harvested, when they made large excavations in the ground in which they stored their grain and vegetables for future use. After covering the excavation they carefully obliterated all evidence of it, in order to prevent discovery. They would then go off on hunting expeditions, returning later in the winter to enjoy the fruits of the summer's toil of their squaws—for the warrior never degraded himself by doing any labor which the squaw could perform. Their habitations, when staying any length of time in one locality, were made of poles, brush, grass, and earth, and were more durable structures than the lodges used by the other tribes of the plains. 23

The Utes, Comanches, Kiowas, Sioux, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes used the conical wigwam, which was easily erected and quickly taken down. The conical wigwam consisted of a framework of small pine poles about two and one-half inches in diameter and twenty feet in length. In its erection, three poles were tied together about two or three feet from the smaller end; the three poles were then set up, their bases forming a triangle sufficiently far apart to permit of a lodge about twenty feet in diameter. The remaining sixteen to eighteen poles used were then placed in position to form a circle, their bases about four feet apart and their tops resting in the fork of the three original poles. Among the plains Indians, where buffalo were plentiful, the covering for this framework consisted of buffalo skins which had been tanned and sewed together by the squaws. It was so shaped that a flap could be thrown back at the top, leaving an opening through which the smoke could escape, and another at the bottom for use as a door. The bottom of this covering was secured by fastening it to small stakes driven into the ground. All of the bedding, buffalo robes, and other belongings of the Indians were taken into the wigwam and piled around the sides; a small hole was then dug in the center of the 24 earthern floor, in which the fire was built. In taking down the tents, preparatory to moving about the country, the squaws removed the covering from the framework, and folded it into a compact bundle; they took the poles down and laid them in two parallel piles three or four feet apart, and then led a pony in between them. The upper end of each pile was fastened to the pack-saddle, leaving the other end to drag upon the ground. Just back of the pony's tail the covering of the tent was fastened to the two sets of poles, on top of which the babies and small children were placed. In this way the Indians moved their camps from place to place. The squaws did all the work of making these tent coverings, procuring the poles, setting up the tents, and taking them down. The warrior never lifted his hand to help, as it was beneath the dignity of a warrior to do any kind of manual labor.

Among the favorite camping-places of the Indians in El Paso County, Colorado, the region extending along the west side of Cheyenne Creek just above its mouth was probably used most frequently. There were evidences of other camping places at different points farther up the creek, that had been used to a lesser extent. Their tent-poles, 25 in being dragged over the country, rapidly wore out, and for that reason the Indians of the plains found it necessary to come to the mountains every year or two to get a new supply. The thousands of small stumps that were to be seen on the side of Cheyenne Mountain at the time of the first settlement of this region gave evidence that many Indians had secured new lodge poles in that locality. It is probable that this was the reason why their tents were so often pitched in the valley of Cheyenne Creek, and undoubtedly this is the origin of the name by which the creek is now known.

On account of its close proximity to the country of the Utes, the Indians of the plains must necessarily have had to come to this locality in very considerable force and must at all times have kept a very sharp lookout in order to avoid disaster. It is known that the Utes maintained pickets in this vicinity much of the time. In the early days, any one climbing to the top of the high sandstone ridge back of the United States Reduction Works at Colorado City might have seen numerous circular places of defense built of loose stone, to a height of four or five feet, and large enough to hold three or four men comfortably. These miniature fortifications were placed at intervals 26 along the ridge all the way from the Fountain to Bear Creek and doubtless were built and used by the Utes. From these small forts, the Indian pickets could overlook the valley of the Fountain, the Mesa, and keep watch over the country for a long distance out on the plains. At such times as the Utes maintained sentinels there it would have been difficult for their enemies to reach this region without being discovered. 27

The principal Indian trail into the mountains from the plains to the northeast of Pike's Peak came in by way of the Garden Ranch, through what used to be known as Templeton's Gap. It crossed Monument Creek about a mile above Colorado Springs, then followed up a ridge to the Mesa; then it went southwest over the Mesa and across Camp Creek, passing just south of the Garden of the Gods; from there it came down to the Fountain, about a mile west of Colorado City, and there joined another trail that came from the southeast up the east side of Fountain Creek. The latter trail followed the east side of the Fountain from the Arkansas River, and crossed Monument Creek just below the present Artificial Ice Plant in Colorado Springs, from which point it ran along the north side of the Fountain to a point just west of Colorado City, where it crossed to the south side, then up the south side of the 28 creek to the Manitou Springs. From this place it went up Ruxton Creek for a few hundred yards, then crossed over to the west side, then up the creek to a point just below the Colorado Midland Railway bridge; thence westward up a long ravine to its head; then in the same direction near the heads of the ravines running into the Fountain and from a quarter to a half of a mile south of that creek for two miles or more. The trail finally came down to the Fountain again just below Cascade Cañon and from there led up the Fountain to its head, where it branched off in various directions.

The trail I have described from Manitou to Cascade Cañon is the famous old Ute Pass trail which undoubtedly had been used by various tribes of Indians for hundreds of years before the discovery of America. We know it was used later for many generations by the Spanish explorer, the hunter, the trapper, and the Indian until the white settler came, and even after that by occasional war-parties, up to the time the Indians were driven from the State of Colorado. Marble markers were placed at intervals along this trail by the El Paso County Pioneer Society in the summer of 1912. This trail and those leading into it from the plains were well-traveled roads and gave indication of long and frequent use. 29

Dr. Edwin James, botanist and historian of Long's expedition, who visited the Pike's Peak region in 1820, says:

A large and much frequented road passes the springs and enters the mountains running to the north of the high peak.

He says of the principal spring at Manitou:

The boiling spring is a large and beautiful fountain of water, cool and transparent and aërated with carbonic acid. It rises on the brink of a small stream which here descends from the mountains at the point where the bed of this stream divides the ridge of sandstone, which rests against the base of the first granitic range. The water of the spring deposits a copious concretion of carbonate of lime, which has accumulated on every side, until it has formed a large basin overhanging the stream, above which it rises several feet. The basin is of snowy whiteness and large enough to contain three or four hundred gallons, and is constantly overflowing. The spring rises from the bottom of the basin with a rumbling noise, discharging about equal volumes of air and of water, probably about fifty gallons per minute, the whole kept in constant agitation. The water is beautifully transparent, has a sparkling appearance, the grateful taste and exhilarating effect of the most highly aërated artificial mineral water.

In the bottom of the spring a great number of beads and other small articles of Indian adornment were found, having unquestionably been left there as a sacrifice or present to the springs, which are regarded 30 with a sort of veneration by the savages. Bijeau, our guide, assured us he had repeatedly taken beads and other adornments from these springs and sold them to the same savages who had thrown them in.

Mr. Rufus B. Sage, who describes himself as a New Englander, after passing through this region in 1842, published a book giving his experiences and observations. In speaking of the Fontaine qui Bouille Creek, now known as the Fountain and of the Manitou Springs, he says:

This name is derived from two singular springs situated within a few yards of each other at the creek's head, both of which emit water in the form of vapor, with a hissing noise; one strongly impregnated with sulphur and the other with soda. The soda water is fully as good as any manufactured for special use and sparkles and foams with equal effervescence. The Arapahoes regard this phenomenon with awe, and venerate it as the manifestation of the immediate presence of the Great Spirit. They call it the "Medicine Fountain" and seldom neglect to bestow their gifts upon it whenever an opportunity is presented. These offerings usually consist of robes, blankets, arrows, bows, knives, beads, moccasins, etc., which they either throw into the water, or hang upon the surrounding trees.

Sometimes a whole village will visit the place for the purpose of paying their united regard to this sacred fountain.

The scenery in the vicinity is truly magnificent. A valley several hundred yards in width heads at the 31 springs, and overlooking it from the west in almost perpendicular ascent tower the lofty summits of Pike's Peak, piercing the clouds and reveling in eternal snow. This valley opens eastward and is walled in at the right and left at the mountain's base by a stretch of high table-land surmounted by oaks and stately pines, with now and then an interval displaying a luxuriant coating of grass. The soil is a reddish loam and very rich. The trees, which skirt the creek as it traces its way from the fountain, are generally free from underbrush, and show almost as much regularity of position as if planted by the hand of art. A lusty growth of vegetation is sustained among them to their very trunks, which is garnished by wild flowers during the summer months, that invest the whole scene with an enchantment peculiar to itself.

The climate, too, is far milder in this than in adjoining regions, even of a more southern latitude. "'Tis here summer first unfolds her robes, and here the longest tarries"; the grass, continuing green the entire winter, here first feels the genial touch of spring. Snow seldom remains upon the ground to exceed a single day, even in the severest weather, while the neighboring hills and prairies present their white mantlings for weeks in succession.

As the creek emerges from the mountains, it increases in size by the accession of several tributaries, and the valley also expands, retaining for a considerable distance the distinguishing traces above described.

The vicinity affords an abundance of game, among which are deer, sheep, bear, antelope, elk, and buffalo, together with turkeys, geese, ducks, grouse, mountain fowls, and rabbits. Affording as it does such magnificent32 and delightful scenery, such rich stores for the supply of human wants both to please the taste and enrapture the heart; so heavenlike in its appearance and character, it is no wonder the untaught savage reveres it as a place wherein the Good Spirit delights to dwell, and hastens with his free-will offerings to the strange fountain, in the full belief that its bubbling waters are the more immediate impersonation of Him whom he adores.

And there are other scenes adjoining this that demand a passing notice. A few miles from the springs, and running parallel with the eastern base of the mountain range, several hundred yards removed from it, a wall of coarse, red granite towers to a varied height of from fifty to three hundred feet. This wall is formed of an immense strata planted vertically. This mural tier is isolated and occupies its prairie site in silent majesty, as if to guard the approach to the stupendous monuments of Nature's handiwork, that form the background, disclosing itself to the beholder for a distance of over thirty miles.

Lieut. John C. Frémont, who visited the springs in 1843, while on his second expedition, was just as enthusiastic about them. He says:

On the morning of the 16th of July we resumed our journey. Our direction was up the Boiling Springs River, it being my intention to visit the celebrated springs from which the river takes its name, and which are on its upper waters at the foot of Pike's Peak.

Our animals fared well while we were on this stream, 33 there being everywhere a great abundance of grass. Beautiful clusters of flowering plants were numerous, and wild currants, nearly ripe, were abundant. On the afternoon of the 17th, we entered among the broken ridges at the foot of the mountain, where the river made several forks.

Leaving the camp to follow slowly, I rode ahead in the afternoon, in search of the springs. In the meantime, the clouds, which had been gathering all the afternoon over the mountains, began to roll down their sides, and a storm so violent burst upon me that it appeared I had entered the store house of the thunder storms. I continued, however, to ride along up the river until about sunset, and was beginning to be doubtful of finding the springs before the next day, when I came suddenly upon a large, smooth rock about twenty feet in diameter, where the water from several springs was bubbling and boiling up in the midst of a white encrustation, with which it had covered a portion of the rock. As it did not correspond with the description given me by the hunters, I did not stop to taste the water, but dismounting, walked a little way up the river, and passing through a narrow thicket of shrubbery bordering the stream, stepped directly upon a huge, white rock at the foot of which the river, already becoming a torrent, foamed along, broken by a small fall.

A deer which had been drinking at the spring was startled by my approach, and springing across the river bounded off up the mountain. In the upper part of the rock, which had been formed by the deposition, was a beautiful, white basin overhung by currant bushes, in which the cold, clear water bubbled up, kept in constant motion by the escaping gas, and overflowing 34 the rock which it had almost entirely covered with a smooth crust of glistening white.

I had all day refrained from drinking, reserving myself for the springs, and as I could not well be more wet than the rain had already made me, I lay down by the side of the basin and drank heartily of the delightful water.

As it was now beginning to grow dark, I rode quickly down the river on which I found the camp a few miles below. The morning of the 18th was beautiful and clear, and all of the people being anxious to drink of these famous waters, we encamped immediately at the springs and spent there a very pleasant day.

On the opposite side of the river is another locality of springs which are entirely of the same nature. The water has a very agreeable taste, which Mr. Preuss found very much to resemble that of the famous Selter spring in the Grand Duchy of Nassau, a country famous for wine and mineral waters.

Resuming our journey on the morning of the 19th, we descended the river, in order to reach the mouth of the eastern fork which I proposed to ascend. The left bank of the river is here very much broken. There is a handsome little bottom on the right, and both banks are exceedingly picturesque, a stratum of red rock in nearly perpendicular walls, crossing the valley from north to south.

Lieut. George F. Ruxton, an officer of the British Army, who was seeking the restoration of his health by roughing it in the Rocky Mountains, camped at the Manitou Springs for a number of months in the early part of 1847. 35

Writing of his trip from Pueblo up the Fontaine qui Bouille in the month of March of that year, and of his stay at the springs afterwards, he says:

The further I advanced up the creek and the nearer the mountains, the more advanced was the vegetation. As yet, however, the cottonwoods and the larger trees in the bottom showed no signs of life, and the currant and cherry bushes still looked dry and sapless. The thickets, however, were filled with birds and resounded with their songs, and the plains were alive with prairie dogs, busy in repairing their houses and barking lustily as I rode through their towns. Turkeys, too, were calling in the timber, and the boom of the prairie fowl at rise and set of sun was heard on every side. The snow had entirely disappeared from the plains, but Pike's Peak and the mountains were still clad in white.

On my way I met a band of hunters who had been driven in by a party of Arapahoes who were encamped on the eastern fork of the Fontaine qui Bouille [Monument Creek]. They strongly urged me to return, as, being alone, I could not fail to be robbed of my animals, if not killed myself. However, in pursuance of my fixed rule never to stop on account of Indians, I proceeded up the river and camped on the first fork for a day or two, hunting in the mountains. I then moved up the main fork on which I had been directed by the hunters to proceed, in order to visit the far famed springs, from which the creek takes its name. I followed a very good lodge-pole trail which struck the creek before entering the broken country, being that used by the Utes and Arapahoes on their way to the 36 Bayou Salado. Here the valley narrowed considerably, and turning an angle with the creek, I was at once shut in by mountains and elevated ridges which rose on each side of the stream. This was now a rapid torrent tumbling over the rocks and stones and fringed with oak and a shrubbery of brush. A few miles on, the cañon opened into a little shelving glade and on the right bank of the stream, raised several feet above it, was a flat, white rock, in which was a round hole where one of the celebrated springs hissed and bubbled with its escaping gas. I had been cautioned against drinking this, being directed to follow the stream a few yards to another, which is the true soda spring.

I had not only abstained from drinking that day, but with the aid of a handful of salt, which I had brought with me for the purpose, had so highly seasoned my breakfast of venison, that I was in a most satisfactory state of thirst. I therefore proceeded at once to the other spring, and found it about forty yards from the first and immediately above the river, issuing from a little basin in the flat, white rock, and trickling over the edge into the stream. The escape of gas in this was much stronger than in the other, and was similar to water boiling smartly.

I had provided myself with a tin cup holding about a pint, but before dipping it in I divested myself of my pouch and belt, and sat down in order to enjoy the draught at my leisure. I was half dead with thirst, and tucking up the sleeves of my hunting shirt, I dipped the cup into the midst of the bubbles and raised it, hissing and sparkling, to my lips. Such a draught! Three times without drawing a breath was it replenished and emptied, almost blowing up the roof of my mouth with its effervescence. It was equal to the very 37 best soda water, but possesses that fresh, natural flavor which manufactured water cannot impart.

The Indians regard with awe the medicine waters of these fountains, as being the abode of a Spirit who breathes through the transparent water, and thus by his exhalations causes the perturbation of its surface. The Arapahoes especially attribute to this water god, the power of ordaining the success or miscarriage of their war expeditions, and as their braves pass often by the mysterious springs when in search of their hereditary enemies, the Utes, in the "Valley of Salt," they never fail to bestow their votive offerings upon the water sprite, in order to propitiate the Manitou of the fountain and insure a fortunate issue to their path of war. Thus at the time of my visit, the basin of the spring was filled with beads and wampum and pieces of red cloth and knives, while the surrounding trees were hung with strips of deer skin, cloth, and moccasins; to which, had they been serviceable, I would most sacrilegiously have helped myself. The signs, too, around the spring, plainly showed that here a war dance had been executed by the braves, and I was not a little pleased to find that they had already been here and were not likely to return the same way; but in this supposition I was quite astray.

The large spring referred to by Dr. James, Sage, Frémont, Ruxton, and the other writers whom I have quoted, is the one now enclosed and used by the bottling works at Manitou. Ruxton says the two springs were intimately connected with the separation of the Comanche and the Snake, or 38 Ute tribes, and he gives the following legend concerning the beginning of the trouble:

Many hundreds of winters ago, when the cottonwoods on the Big River were no higher than an arrow, and the red men, who hunted the buffalo on the plains, all spoke the same language, and the pipe of peace breathed its social cloud of kinnikinnik whenever two parties of hunters met on the boundless plains—when, with hunting grounds and game of every kind in the greatest abundance, no nation dug up the hatchet with another because one of its hunters followed the game into their bounds, but, on the contrary, loaded for him his back with choice and fattest meat, and ever proffered the soothing pipe before the stranger, with well-filled belly, left the village,—it happened that two hunters of different nations met one day on a small rivulet, where both had repaired to quench their thirst. A little stream of water, rising from a spring on a rock within a few feet of the bank, trickled over it and fell splashing into the river. To this the hunters repaired; and while one sought the spring itself, where the water, cold and clear, reflected on its surface the image of the surrounding scenery, the other, tired by his exertions in the chase, threw himself at once to the ground and plunged his face into the running stream.

The latter had been unsuccessful in the chase, and perhaps his bad fortune and the sight of the fat deer, which the other hunter threw from his back before he drank at the crystal spring, caused a feeling of jealousy and ill-humour to take possession of his mind. The other, on the contrary, before he satisfied his thirst, 39 raised in the hollow of his hand a portion of the water, and, lifting it towards the sun, reversed his hand and allowed it to fall upon the ground,—a libation to the Great Spirit who had vouchsafed him a successful hunt, and the blessing of the refreshing water with which he was about to quench his thirst.

Seeing this, and being reminded that he had neglected the usual offering, only increased the feeling of envy and annoyance which the unsuccessful hunter permitted to get the mastery of his heart; and the Evil Spirit at that moment entering his body, his temper fairly flew away, and he sought some pretense by which to provoke a quarrel with the stranger Indian at the spring.

"Why does a stranger," he asked, rising from the stream at the same time, "drink at the spring-head, when one to whom the fountain belongs contents himself with the water that runs from it?"

"The Great Spirit places the cool water at the spring," answered the other hunter, "that his children may drink it pure and undefiled. The running water is for the beasts which scour the plains. Au-sa-qua is a chief of the Shos-shone; he drinks at the head water."

"The Shos-shone is but a tribe of the Comanche," returned the other; "Waco-mish leads the grand nation. Why does a Shos-shone dare to drink above him?"

"He has said it. The Shos-shone drinks at the spring-head; other nations of the stream which runs into the fields. Au-sa-qua is chief of his nation. The Comanche are brothers. Let them both drink of the same water."

"The Shos-shone pays tribute to the Comanche. 40 Waco-mish leads that nation to war. Waco-mish is chief of the Shos-shone, as he is of his own people."

"Waco-mish lies; his tongue is forked like the rattlesnake's; his heart is black as the Misho-tunga [bad spirit]. When the Manitou made his children, whether Shos-shone or Comanche, Arapahoe, Shi-an, or Pā-né, he gave them buffalo to eat, and the pure water of the fountain to quench their thirst. He said not to one, Drink here, and to another, Drink there; but gave the crystal spring to all, that all might drink."

Waco-mish almost burst with rage as the other spoke; but his coward heart alone prevented him from provoking an encounter with the calm Shos-shone. He, made thirsty by the words he had spoken—for the red man is ever sparing of his tongue—again stooped down to the spring to quench his thirst, when the subtle warrior of the Comanche suddenly threw himself upon the kneeling hunter, and, forcing his head into the bubbling water, held him down with all his strength, until his victim no longer struggled, his stiffened limbs relaxed, and he fell forward over the spring, drowned and dead.

Over the body stood the murderer, and no sooner was the deed of blood consummated than bitter remorse took possession of his mind, where before had reigned the fiercest passion and vindictive hate. With hands clasped to his forehead, he stood transfixed with horror, intently gazing on his victim, whose head still remained immersed in the fountain. Mechanically he dragged the body a few paces from the water, which, as soon as the head of the dead Indian was withdrawn, the Comanche saw suddenly and strangely disturbed. Bubbles sprang up from the bottom, 41 and rising to the surface, escaped in hissing gas. A thin vapoury cloud arose, and gradually dissolving, displayed to the eyes of the trembling murderer the figure of an aged Indian, whose long, snowy hair and venerable beard, blown aside by a gentle air from his breast, discovered the well-known totem of the great Wan-kan-aga, the father of the Comanche and Shos-shone nation, whom the tradition of the tribe, handed down by skillful hieroglyphics, almost deified for the good actions and deeds of bravery this famous warrior had performed when on earth.

Stretching out a war-club towards the affrighted murderer, the figure thus addressed him:

"Accursed of my tribe! this day thou hast severed the link between the mightiest nations of the world, while the blood of the brave Shos-shone cries to the Manitou for vengeance. May the water of thy tribe be rank and bitter in their throats." Thus saying, and swinging his ponderous war-club (made from the elk's horn) round his head, he dashed out the brains of the Comanche, who fell headlong into the spring, which, from that day to the present moment, remains rank and nauseous, so that not even when half dead with thirst, can one drink the foul water of that spring.

The good Wan-kan-aga, however, to perpetuate the memory of the Shos-shone warrior, who was renowned in his tribe for valour and nobleness of heart, struck, with the same avenging club, a hard, flat rock which overhung the rivulet, just out of sight of this scene of blood; and forthwith the rock opened into a round, clear basin, which instantly filled with bubbling, sparkling water, than which no thirsty hunter ever drank a sweeter or a cooler draught. 42

Thus the two springs remain, an everlasting memento of the foul murder of the brave Shos-shone, and the stern justice of the good Wan-kan-aga; and from that day the two mighty tribes of the Shos-shone and Comanche have remained severed and apart; although a long and bloody war followed the treacherous murder of the Shos-shone chief, and many a scalp torn from the head of the Comanche paid the penalty of his death.

In telling of the great quantities of game in this region, Ruxton says:

Never was there such a paradise for hunters as this lone and solitary spot.

Game abounded on every hand. Bear, elk, deer, mountain sheep, antelope, and grouse were in abundance in the surrounding mountains and valleys. Of buffalo there were few except in the valleys west of Pike's Peak and in the Bayou Salado, or South Park, as it is now known.

Ruxton further says:

It is a singular fact that within the last two years the prairies, extending from the mountains to one hundred miles or more down the Arkansas, have been entirely abandoned by the buffalo; indeed, in crossing from the settlements of New Mexico, the boundary of their former range is marked by skulls and bones, which appear fresher as the traveler advances westward and towards the waters of the Platte.

The evidences that Ruxton here mentions were 43 still apparent twelve or fourteen years later, when the first settlers of this region arrived. Buffalo skulls and bones were scattered everywhere over the plains, but live buffalo could seldom be found nearer than one hundred miles east of the mountains.

The reason for this has been variously stated, some claiming that a contagious disease broke out among the buffalo in the early forties, which virtually exterminated those along the eastern base of the mountains. Others say that about that time there was a tremendous snowfall in the early part of the winter which covered the whole country along the eastern base of the mountains to a depth of six to eight feet, and that as a result all the buffalo within the region of the snowfall starved to death during the following winter. It is very possible that the latter reason may have been the true one, as a heavy fall of snow in the early part of the winter is not unknown. In the winter of 1864-1865 the antelope of this region nearly starved to death, owing to a two-foot fall of snow, on the last day of October and the first day of November, 1864, which covered the ground to a considerable depth for most of the winter.

While it is true that there were no buffalo in 44 this immediate region at the time Ruxton was here, nor afterwards, it is well-known that they had been fairly plentiful in earlier years. Lieutenant Pike tells of killing five buffalo the day he reached the present site of Pueblo in 1806, and a day or two afterwards he killed three more on Turkey Creek, about twenty miles south of where Colorado Springs now stands, and saw others while climbing the mountains in his attempt to reach the "high point," as he calls it, now known as Pike's Peak.

In 1820, Long's expedition, on its way from Platte Cañon, killed several buffalo on Monument Creek, a few miles south of the Divide; and later, while camped on the Fountain a short distance below the site of the present city of Colorado Springs, killed several more.

Sage says that in 1842, during a five days' stay at Jimmy's Camp (ten miles east of the present city of Colorado Springs), he "killed three fine buffalo cows."

After Ruxton had been camped near Manitou Springs for two or three weeks, while out hunting one day, he ran across an Indian camp, which startled him very much. No Indians were in sight at the time, but later he got a glimpse of two carrying in a deer which they had killed. The 45 next morning Ruxton concluded that as a matter of safety, he had better remove his camp to some more secluded spot. The following day a fire was started on the side of the mountain to the south of the springs, which rapidly spread in every direction. He says:

I had from the first no doubt that the fire was caused by the Indians who had probably discovered my animals, and thinking that a large party of hunters might be out, had taken advantage of a favorable wind to set fire to the grass, hoping to secure the horses and mules in the confusion, without risk of attacking the camp.

In order to be out of reach of the fire, Ruxton moved his camp down the Fontaine qui Bouille six or seven miles. He says:

All this time the fire was spreading out on the prairies. It extended at least five miles on the left bank of the creek and on the right was more slowly creeping up the mountainside, while the brush and timber in the bottom was one mass of flame. Besides the long, sweeping line of the advancing flame the plateaus on the mountainside and within the line were burning in every direction as the squalls and eddies down the gullies drove the fire to all points. The mountains themselves being invisible, the air from the low ground where I then was, appeared a mass of fire, and huge crescents of flame danced as it were in the very sky, until a mass of timber blazing 46 at once exhibited the somber background of the stupendous mountains.

The fire extended towards the waters of the Platte upwards of forty miles, and for fourteen days its glare was visible on the Arkansas River fifty miles distant.

The testimony of Ruxton bears out information I have from other sources, that a large portion of the great areas of dead timber on the mountainsides of this region is the result of fires started by the various Indian tribes in their wanderings to and fro. Old trappers say that the Utes frequently went out upon the plains on horse-stealing expeditions; that when they had located a camp of their enemies, they would stealthily creep in among their ponies in the night, round them up, and start off towards the mountains with as many as they could hastily gather together. They were sure to be pursued the following morning when the raid had been discovered, and often the Utes with the stolen herd would find their pursuers close after them by the time they reached the mountains. In that case, they knew that if they followed up Ute Pass they were likely to be overtaken, but by crossing over the northern point of Cheyenne Mountain and on to the west along a trail that ran not very far distant from the route now followed 47 by the Cripple Creek Short Line, they could much more easily elude their pursuers. If, when west of Cheyenne Mountain the Utes found their enemies gaining upon them, they would start a timber fire to cover their retreat. These fires would, of course, spread indefinitely and ruin immense tracts of timber. This is doubtless one of the principal reasons why our mountainsides are so nearly denuded of their original growth of trees. These horse-stealing raids were no uncommon occurrence. Colonel Dodge, in his book Our Wild Indians, tells of one made by the Utes in 1874, which was daring as well as successful. He says:

A mixed band of some fifteen hundred Sioux and Cheyennes, hunting in 1874, went well up on the headwaters of the Republican River in search of buffalo. The Utes found them out and a few warriors slipped into their camp during the night, stampeded their ponies at daylight, and in spite of the hot pursuit of the Sioux, reached the mountains with over two hundred head.

Ruxton frequently mentions the Ute Pass, and states that it was the principal line of travel to and from the South Park for all the Indian tribes of this region at the time of his arrival, as well as previous thereto. 48

There was another much-used trail into the South Park which entered the mountains near the present town of Cañon City. It led in a northwesterly direction from the latter place, and reached the South Park proper near Hartsell Hot Springs. This route was used by the Indians occupying the country along the Arkansas River and to the south of it. In addition to the two principal trails, there were others of lesser note, as, for example, that over the north end of Cheyenne Mountain, and one west of the present town of Monument; but these were difficult and were not used to any great extent.

In 1806, Lieutenant Pike attempted to lead his exploring expedition over the Cañon City trail, but evidently had a very poor guide, and, as a result, lost his way very soon after leaving the Arkansas River. They wandered about through the low mountains west of the present mining camp of Cripple Creek, and finally reached the Platte near the west end of Eleven-Mile Cañon where the river emerges from the South Park. He mentions having found near that point a recently abandoned Indian camp which he estimates must have been occupied by at least three thousand Indians.

Thomas J. Farnham, on his way to Oregon in 49 1839, passed through the South Park, reaching it from the Arkansas River by the trail already described. He tells of his trip, in a rudely bound little book of minutely fine print, published in 1843. In recounting his journey from the Arkansas River to the South Park, he frequently mentions James Peak as being to the east of the route he was traveling. Previously, when encamped on the Arkansas River, below the mouth of the Fontaine qui Bouille, he speaks of the latter stream as heading in James Peak, eighty miles to the northwest; he also states that one of the branches of the Huerfano originates in Pike's Peak, seventy to eighty miles to the south. This brings to mind the fact that previous to about 1840 the peak that we now know as Pike's Peak was known as James Peak. Major S. H. Long, who was in command of the expedition that explored the Pike's Peak region in 1820, gave it this name in honor of Dr. James, who is supposed to have been the first white man to ascend it. After about 1840, this name was gradually dropped and Pike's Peak was substituted.

Farnham was very much pleased with the South Park, and says of it, after describing its streams, valleys, and rocky ridges:

This is a bird's-eye view of Bayou Salado, so named 50 from the circumstance that native rock salt is found in some parts of it. We were in the central portion of it. To the north and south and west its isolated plains rise one above another, always beautiful and covered with verdure during the months of spring and summer. A sweet spot this, for the romance of the future as well as of the present and past. The buffalo have for ages resorted here about the last days of July from the arid plains of the Arkansas and the Platte; and hither the Utes, Cheyennes and Arapahoes, Black Feet, Crows and Sioux of the north, have for ages met and hunted and fought and loved, and when their battles and hunts were interrupted by the chills and snows of November, they separated for their several winter resorts.

How wild and beautiful the past, as it comes up fledged with the rich plumage of the imagination! These vales, studded with a thousand villages of conical skin wigwams, with their thousands of fires blazing on the starry brow of night! I see the dusky forms crouching around the glowing piles of ignited logs, in family groups, whispering the dreams of their rude love, or gathered around the stalwart form of some noble chief at the hour of midnight, listening to the harangue of vengeance or the whoop of war that is to cast the deadly arrow with the first gleam of morning light.

Or, may we not see them gathered, a circle of old braves, around an aged tree, surrounded each by the musty trophies of half a century's daring deeds. The eldest and richest in scalps rises from the center of the ring and advances to the tree. Hear him!

"Fifty winters ago when the seventh moon's first horn hung over the green forests of the Ute hills, myself 51 and five others erected a lodge for the Great Spirit on the snows of the White Butte and carried there our wampum and skins, and the hide of a white buffalo. We hung them in the Great Spirit's lodge and seated ourselves in silence till the moon had descended the western mountain, and thought of the blood of our fathers that the Comanches had killed when the moon was round and lay on the eastern plains. My own father was scalped, and the fathers of five others were scalped, and their bloody heads were gnawed by the wolf. We could not live while our father's lodges were empty and the scalps of their murderers were not in the lodges of our mothers. Our hearts told us to make these offerings to the Great Spirit who had fostered them on the mountains, and when the moon was down and the shadows of the White Butte were as dark as the hair of a bear, we said to the Great Spirit: 'No man can war with the arrows from the quiver of thy storms. No man's word can be heard when thy voice is among the clouds. No man's hand is strong when thy hand lets loose the wind. The wolf gnaws the heads of our fathers and the scalps of their murderers hang not in the lodges of our mothers. Great Father Spirit, send not thine anger out. Hold in thy hand the winds. Let not thy great voice drown the death yell while we hunt the murderers of our fathers.' I and the five others then built in the middle of the lodge a fire, and in its bright light the Great Spirit saw the wampum and the skins and the white buffalo hide. Five days and nights I and five others danced and smoked the medicine and beat the board with sticks and chanted away the powers of the great Medicine Men, that they might not be evil to us and bring sickness into our bones. Then 52 when the stars were shining in the clear sky, we swore (I must not tell what, for it was in the ear of the Great Spirit), and went out of the lodge with our bosoms full of anger against the murderers of our fathers whose bones were in the jaws of the wolf and went for their scalps, to hang them in the lodges of our mothers." See him strike the aged tree with his war-club; again, again, nine times. "So many Comanches did I slay, the murderers of my father, before the moon was round again and lay upon the eastern plains."

Farnham, continuing, says:

This is not merely an imaginary scene of former times in the Bayou Salado. All the essential incidents related happened yearly in that and other hunting-grounds, whenever the old braves assembled to celebrate valorous deeds of their younger days. When these exciting relations were finished, the young men of the tribe who had not yet distinguished themselves were exhorted to seek glory in a similar way; and woe to him who passed his manhood without ornamenting the door of his lodge with the scalps of his enemies.

This valley is still frequented by these Indians as a summer haunt, when the heat of the plains renders them uncomfortable. The Utes were scouring it when we passed. Our guide informed us that the Utes reside on both sides of the mountains,—that they are continually migrating from one side to the other,—that they speak the Spanish language,—that some few half-breeds have embraced the Catholic faith,—that the remainder yet hold the simple and sublime faith of their forefathers, in the existence of one great, creating, and sustaining Cause, mingled 53 with the belief in the ghostly visitations of their deceased Medicine Men, or Diviners;—that they number one thousand families.

He also stated that the Cheyennes were less brave and more thievish than any of the other tribes living on the plains.

Farnham's description of the incantations practiced by the Utes is in the main probably true; the information on which it was based was doubtless obtained from his guide.

Ruxton tells of the use of the trail west of the present town of Monument by a war-party of Arapahoes on their way to the South Park to fight the Utes. In the night the band had surprised a small company of trappers on the head of Bijou Creek, killing four of them and capturing all of their horses. The following morning two of the trappers, one of whom was slightly wounded, started in pursuit of the Indians, intending if possible to recover their animals. They followed the trail of the Indians to a point in the neighborhood of the present town of Monument where they found that the band had divided, the larger party, judging from the direction taken, evidently intending to enter the mountains by way of Ute Pass. The other party, having all the loose animals, started across the mountains by the pass to 54 the west of Monument, probably hoping to get the better of the Utes by coming in from two different directions. The trappers followed the latter party across the first mountains where they found their stolen animals in charge of three Indians. The trappers surprised and killed all three of them, recaptured their animals, and then hurried on to the Utes, giving such timely warning as enabled them to defeat the Arapahoes in a very decisive manner.

The battles in the South Park and on the plains between the contending tribes were seldom of a very sanguinary nature. If the attacking Indians happened to find their enemies on level ground, they would circle around them just out of gunshot at first, gradually coming closer, all the time lying on the outside and shooting from under the necks of their ponies. These ponies were generally the best that the tribe afforded and were not often used except for purposes of war. While engaged in battle, the Indians seldom used saddles, and in place of bridles had merely a piece of plaited buffalo-hide rope, tied around the under jaw of the pony. If the defending party was located in a fairly good defensive position, the battle consisted of groups of the attacking party dashing in, firing, and then dashing out again. 55 This was kept up until a few warriors had been killed or wounded and a few scalps had been taken; then the battle was over, one side or the other retreating. With an Indian, it was a waste of time to kill an enemy unless his scalp was taken, as that was the evidence necessary to prove the prowess of the warrior. Engagements of the kind I have mentioned have occurred in almost every valley in and around the South Park at some time during the hundreds of years of warfare that was carried on in that region.

Frémont, on his return trip from California, during his second exploring expedition, crossed the Rocky Mountains by way of Middle Park, then across South Park, reaching the Arkansas River near the present town of Cañon City. On his way through the South Park he witnessed one of these battles, in describing which he says: