E-text prepared by MWS, Wayne Hammond,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

i

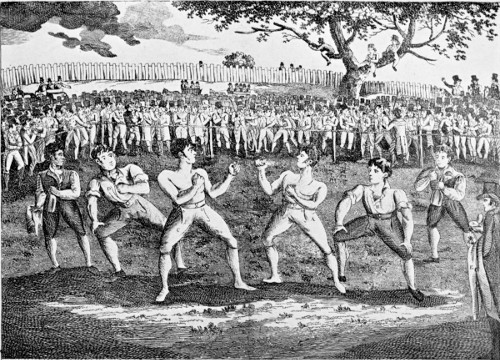

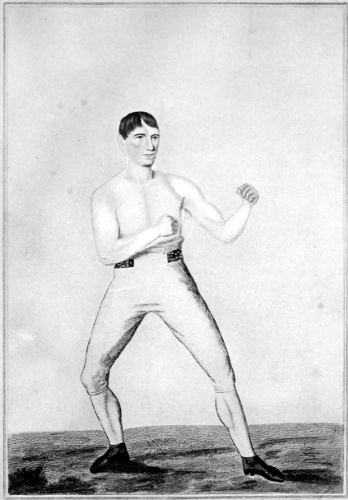

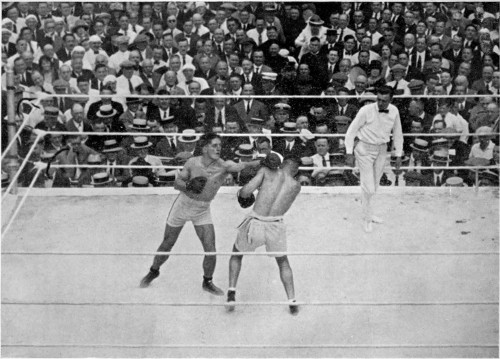

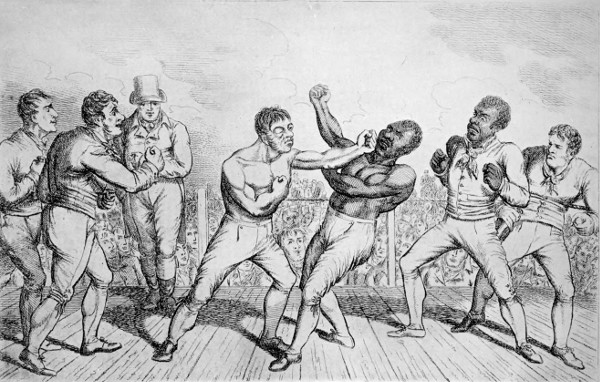

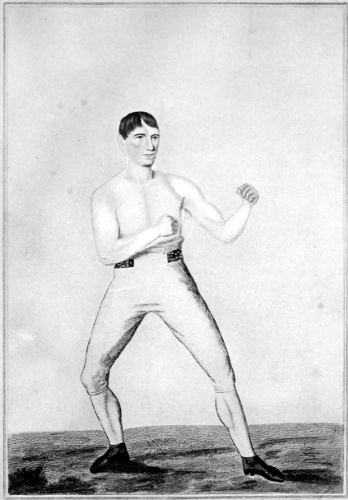

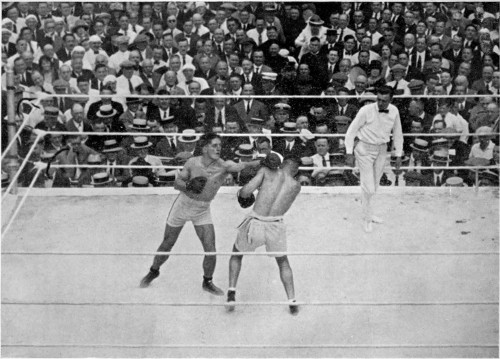

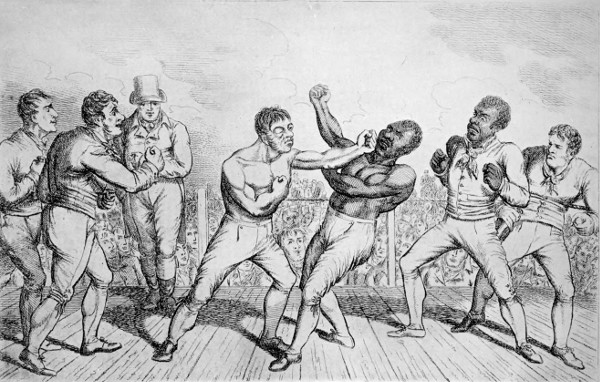

Frontispiece.

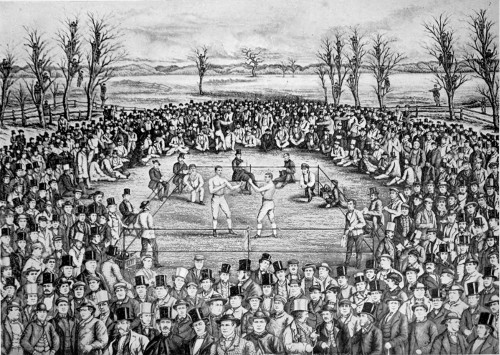

“The Close of the Battle, or the Champion Triumphant. 1. Round.—Sparring for one minute, Cribb made play right and left, a right-handed blow

told slightly on the body of Molineux, who returned it on the head, and a rally followed, the Black knocked down by a hit on the throat. 2.—Cribb

showed first blood from the mouth, a dreadful rally, Cribb put in a good body-hit, returned by the Moor on the head. Closing, Cribb thrown. 3.—Cribb’s

right eye nearly closed, another rally, the Black deficient in wind receives a doubler in the body. Cribb damaged in both eyes and thrown. 4.—Rally,

hits exchanged. Cribb fell with a slight hit and manifested first weakness. 5.—Rallying renewed. Cribb fell from a blow and received another in falling.

6.—The Black, fatigued by want of wind, a blow at the body-mark doubles him up, and is floored by a hit at great length. 7.—Black runs in intemperately,

receives several violent blows about the neck and juggler, falls from weakness. 8.—Black rallies, Cribb nobs him, gets his head under his left arm, and

just fibbed till the Moor fell. 9.—Black runs in, met with a left-handed blow which broke his jaw, and fell like a log. 10.—Black, with difficulty, made

an unsuccessful effort and fell from distress. 11.—This round ended the fight. Black received another knock-down and unable again to stand up.”

ii

iii

KNUCKLES AND GLOVES

BY THE SAME AUTHOR:

GLAMOUR

CAKE

UNOFFICIAL

THE COMPLETE GENTLEMAN

THE TENDER CONSCIENCE

FORGOTTEN REALMS

MAX BEERBOHM IN PERSPECTIVE

MAX BEERBOHM IN PERSPECTIVE

THE COMPLETE AMATEUR BOXER

THE COMPLETE AMATEUR BOXER

iv

KNUCKLES AND GLOVES

BY

BOHUN LYNCH

WITH A PREFACE BY

SIR THEODORE COOK

Illustrated

LONDON: 48 PALL MALL

W. COLLINS SONS & CO. LTD.

GLASGOW MELBOURNE AUCKLAND

v

Copyright

First Impression, October, 1922

Second Impression, November, 1922

Manufactured in Great Britain

vi

To H. G. B. L.

Though I deplore the pain you felt

When you had broken my command,

And I had taken you in hand,

Planting my blows beneath your belt,

I like to think of future years

When skin that’s fair shall change to brown,

When ‘listed in a fairer fight,

You shall return to others’ ears

Blows straightly dealt with left and right,

Blows you encountered lower down!

vii

PREFACE

In the brickwork of a well-known London house, not far from

Covent Garden, there is a stone with the date, 1636, which was

cut by the order of Alexander, Earl of Stirling. It formed part

of a building which sheltered successively Tom Killigrew, Denzil

Hollis, and Sir Henry Vane; and that great kaleidoscope of a quack,

a swordsman, and a horse-breaker, Sir Kenelm Digby, died in it.

Within its walls was summoned the first Cabinet Council ever

held in England, by Admiral Russel, Earl of Orford. Its members

belonged to a set of jovial sportsmen, of whom Lord Wharton

and Lord Godolphin may be taken as excellent types. About the

same time, out of the mob that peoples Hogarth’s pictures, out

of the faces with which Fielding and Smollett have made us

familiar, and in a society for which Samuel Richardson alternately

blushed and sighed, arose the rough but manly form of Figg, the

better educated but equally lusty figure of Broughton, who first

taught “the mystery of boxing, that truly British art” at his

academy in the Haymarket in 1747.

But, unfortunately, the beginnings of prize-fighting, or

boxing for money with bare fists, were more romantic than its

subsequent career, for it lived on brutality and it died of boredom.

The house near Covent Garden has become the National Sporting

Club. Knuckles have been replaced by gloves. To-day we see

Carpentier knock his man out scientifically in less than a single

round, instead of watching Tom Sayers, with one arm, fighting

the Benicia Boy, and only getting a draw after two hours and

twenty minutes. Mr. Bohun Lynch’s description of the battle

is one of the best I have ever read, and he gives full credit to each

man for the fine spirit shown throughout an encounter in which

neither asked for mercy and neither expected any.

On the afternoon of June 16, 1904, there was sold in King

viii

Street, Covent Garden, the belt presented to J. C. Heenan (who

was called the Benicia Boy from the San Francisco workshops,

where he was employed) after the great fight was over. It was

a duplicate of the championship belt, and it bore the same title

as that presented at the same time to Sayers: “Champion of

England.” The price it fetched in 1904 was, I fear, a true

reflection of the interest now taken in its original owner and his

pugilistic surroundings; and it is difficult to recall the celebrity

of both from those past years when Tom Sayers seemed to share

with the Duke of Wellington the proud title of Britain’s greatest

hero. But it is not really so astonishing when we remember that

the plucky little Hoxton bricklayer stood to the youth of his era

as the gamest representative of almost the only form of sport the

larger public knew or cared about. In days when golf, lawn-tennis,

cricket, football, and the rest not only multiply our sporting

stars almost indefinitely, but attract crowds numbered by scores

of thousands to applaud them, we do not seem to pitch upon the

boxer as our especially typical representative of national sporting

skill. There may be other reasons for that, too. English boxers

seem to have only retained their characteristic style long enough

to hand it on to others; they then proceeded to forget it. When

Jem Mace left off boxing in England he went to Australia, and in

Sydney he taught Larry Foley, who in turn educated Peter Jackson,

Fitzsimmons, Hall, Creedon, and Young Griffo. The first two

handed on the lighted torch to the United States. The result

was soon obvious. When the Americans came over they beat us

at all weights from Peter Jackson downwards, and they beat us

because they had learnt from us what one of the best exponents

of the art has called “velocity and power of hitting combined

with quickness and ease of movement on the feet”; I should like

to add to that, “the straight left,” or as it is more classically

known, “Long Melford.”

No doubt the best of the old fighters now and then produced

a fine and manly example of human fortitude and skill. “If I

were absolute king,” wrote Thackeray in a famous Roundabout

Paper after the Sayers and Heenan fight, “I would send Tom

ix

Sayers to the mill for a month and make him Sir Thomas on

coming out of Clerkenwell.” I am tempted in this connection

to reproduce what must be one of the few letters Tom Sayers ever

wrote. It was caused by a public discussion after his famous

fight, which is little short of amazing when we look back at it.

The newspapers were filled with frenzied denunciations, Parliament

angrily discussed the question, Palmerston quoted, with

every sign of satisfaction, a French journalist who saw in the

contest “a type of the national character for indomitable perseverance

in determined effort,” and then (cannot you see his smiling

eyes above the semi-serious mouth?) proceeded to draw a contrast

between pugilism and ballooning, very much to the disadvantage

of the latter. A correspondent wrote to the Press inquiring

indignantly whether it were true that the Duke of Beaufort, the

Earl of Eglinton, and the Bishop of Oxford had attended “this

most disgraceful exhibition.” Tom Sayers, roused to unwonted

penmanship, retorted in the Daily Telegraph as follows:—“In

answer to your correspondent, I beg to state that neither bishop

nor peer was present at the late encounter. It is from a pure

sense of justice that I write you this. I scarcely think it reasonable

that such repeated onslaughts should be made on me and my

friend, Heenan. Trusting you will insert this in your widely-circulated

and well-regulated journal, allow me to remain, yours

faithfully, Thomas Sayers, Cambrian Stores, Castle Street,

Leicester Square, April 21, 1860.” The Stock Exchange had

given him a purse of a hundred guineas that afternoon, so you

need scarcely wonder at the urbanity of his language. In the

House of Commons, meanwhile, the Home Secretary had been

calling forth cheerful expressions of hilarity by reminding those

members who had witnessed the battle that they might be indicted

for misdemeanour, though he was pleased to add that fighting

with fists was in his opinion better than the use of the bowie-knife,

the stiletto, or the shillelagh.

I can remember Mr. Lynch’s boxing for his University, and

the severe discomfort he occasioned his Cambridge adversary;

and when I recall the many excellent books (on different subjects)

x

which he has previously given us, I see in him an author who has

not only the knowledge but the skill to produce that requisite

blend of literature and experience which can alone commend the

subject of his volume to the English-speaking public. I wish I

could claim as much myself. But I suffered from the educational

advantage of having a younger brother who knocked me down

(and often “out”) with the greatest kindliness and persistence

whenever we put on the gloves together; and being overmuch

puffed up with pride at finding I could stand so much of it, I

rashly took on a guardsman so considerably my superior that

after three rounds I was never allowed to box again, and had to

quench my thirst for personal combat in ensuing years with foil

and duelling-sword. My brother died suddenly of a fever when

he was in training under Bat Mullens for the Amateur Championship,

and only twenty-one. He was six feet three and thirteen

stone stripped, and I never saw an amateur I thought his better

until Hopley came into the ring for Cambridge; and no one

ever knew how good Hopley was, for no one ever stood in the

ring with him for more than two minutes, and he retired, like

St. Simon (I mean, of course, the Duke of Portland’s thoroughbred)

as undefeated as he was unextended.

Another very good fight in Mr. Lynch’s book (and I have

never read a better analysis of the technical “knock-out” than

the one he gives on page 126) is that between Peter Jackson and

Frank Slavin. I saw it, so I can correct a slight verbal error

(foreseen in his own footnote) in Mr. Lynch’s pages. Mr. Angle

(I have his letter before me) did not say “Fight on” at that

dreadful moment when the packed house could scarcely breathe;

when Slavin was tottering blindly to and fro, refusing to give

in; when Peter looked out at us appealingly, with the native

chivalry that shone through his black skin, and evidently hated

to continue. The referee’s quiet syllables, “Box on,” sounded

like a minute-gun at sea, and in a few moments it was all over.

When Slavin was brought round in his dressing-room, and told

he had been knocked out, he muttered, “They’ll never believe

that in Melbourne.”

xi

There must have been something about the old prize-ring

which we have lost to-day, or it would never have inspired such

good literature or attracted such brilliant men in its support.

Byron’s screen in Mr. John Murray’s drawing-room is far from

the only testimony to that dazzling poet’s love of fighting. Hazlitt

was almost equally attracted. Perhaps the most grisly passage

even in the pages of De Quincy is that episode in the first part of

“Murder as One of the Fine Arts,” where the fight between

the amateur and the baker of Mannheim (with its result) is vividly

described. The best pages of Borrow, too, gain their best inspiration

from the same source. I often seem to recall that pair of dark

eyes flashing in a fair face shaded by hair that was prematurely

touched with grey; lips full and mobile, as quick with Castilian

phrases to a Spanish landlord as with Romany to Jasper

Petulengro, or with English to the fruit-woman on London

Bridge; the queer, fascinating, mystical, honest mixture of a man,

with something of the Wandering Jew, a good deal of Don

Quixote, a touch of Melmoth, a sound flavouring of Cribb and

Belcher, who was George Borrow. Under his magic guidance

you step into the air which fanned the elf-locks of the Flaming

Tinman. He loved the heroes of the Ring like brothers. “He

strikes his foe on the forehead, and the report of the blow is like

the sound of a hammer against a rock.” The sentence stands

unmatched in all the annals of pugilism. The battle of his father

with Big Ben Brain in Hyde Park was an abiding memory to him;

and, apart from the famous encounter in the Dingle, the son did

almost as well; and all his life nothing moved him to such instant

eloquence as boxing, except horses.

Mr. Lynch, with all his knowledge of the art, and all his

sympathy with the best qualities in the men whose combats he

portrays, cannot conceal from us that on the whole the old

prize-ring was brutal and the modern “pugilistic contest”

between professionals has very little that is attractive. Yet he is

right both to put them on record and to tell the truth about them

without fear or favour. For at the very heart of their foundations

is an ineradicable and a noble instinct of the human race. Even a

xii

Dempsey, earning several thousand pounds a minute, may be

dimly conscious that he is building better than he knows.

Professionals in any game who attain a height of skill which

gives them a practically unlimited market for what they have to

sell, can scarcely be blamed by stockbrokers who gamble on a

falling market, or by profiteers who battened on the war. Even

the modern professional boxer cannot do permanent harm to the

true atmosphere of the great game in which he shines briefly like

a passing meteor. It is pages like these from Mr. Lynch that

should inspire the professional to give us his best and leave

aside the worst in what is, after all, only an epitome of life,

a show in which the blows are seen instead of hidden, in which

rewards or losses are known to all the world instead of silently

concealed. There is a spirit in Boxing which nothing can

destroy, and while we cherish it among amateurs, the professional

will never be able to defile it.

Mr. E. B. Michell, an old pupil of my father’s, and the only

boxer who ever held three of the amateur championships at

different weights, is still with us; and I should still do my best

to prevent any friend from wantonly attacking him. Like all

real fighters, he has always been the kindliest of men, the most

difficult to provoke to extremes. But any one who has managed

to extract from his diffidence those few occasions when he had to

use his fists, because no other course was possible, will realise

that boxing is not merely a splendid form of recreation, but one

of the finest systems of self-defence ever developed by persistent

effort.

Julian Grenfell’s famous poem, “Into Battle,” was written

in the Trenches the day after he had fought the champion of his

division in France; and there were few who read it who did not

recall that previous victory of his over Tye, the fireman, which

will never be forgotten in Johannesburg. Three times he was

laid on his back. In the third round he knocked the fireman

out, “and he never moved for twenty seconds.... I was 11 st.

4 lb., and he was 11 st. 3 lb. I think it was the best fight I shall

ever have.” He found a better in the Ypres Salient, and again he

xiii

wrote:—“I cannot tell you how wonderful our men were, going

straight for the first time into a fierce fire. They surpassed my

utmost expectations. I have never been so fit or nearly so happy

in my life before.” For such men it is impossible to sorrow.

These brothers and their comrades were taken from us in the full

noon of their splendid sunlight; and on its fiercest throb of high

endeavour the brave heart of each one of them stopped beating.

Their memories stand, to me, for all that may be meant, achieved, or

promised in such courage, such endurance, aye, such instantaneous

cataclysm as Mr. Bohun Lynch’s chapters at their best recall.

His tale has obviously a sordid side, yet more evidently a brutal

one. But the red thread of honourable resolution runs through

the warp and woof of it; and these are not days when we may

dare to minimise the value of the pluck that conquers pain.

THEODORE A. COOK.

June, 1922.

xiv

NOTE

Certain passages in this book, notably in the

Introduction, and in the second part, dealing with

recent contests, are substantially based, and in some

instances literally culled, from articles which I wrote

for The Daily Chronicle, The Field, Land and Water,

The Outlook, and The London Mercury, and to the

editors of these journals I owe my best thanks for

much kindness and consideration.

xv

CONTENTS

xvii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

xviii

xix

INTRODUCTION

Sports and games may be classified as natural and artificial.

Running, jumping, and swimming, for example, are natural

sports, though, to be sure, much artifice is required to assure in

them especial excellence. In these simple instances it is merely

directed to avoid waste of energy. Boxing is one of the artificial

sports, and has never been, like wrestling, anything else. In the

far distant past the primitive man, with no weapon handy, no doubt

clutched and hugged and clawed at his immediate enemies, just

as children, who are invariably primitive until they are taught

“better,” clutch and claw to-day. That natural and instinctive

grasping and hugging was the forefather of subtle and tricky

wrestling, whether Greek, Roman, or North-country English,

but as far as we can discover the earliest use of fisticuffs was for

sport alone. It may seem natural to hit a man you hate, but it is

only second nature, and any one but a trained boxer is apt to seize

him by the throat. The employment of fists as weapons of offence

and of arms for shields developed from the sport. As such, too,

it is very effectual, especially when combined with a knowledge of

wrestling, but only when the enemy is of similar mind. I am

informed by a former Honorary Secretary of the Oxford University

Boxing Club, who from this point of view ruthlessly criticised

a former book of mine on the subject, and who has spent many

years in close contact with uncivilisation, that boxing is of extremely

little value against a man with a broken bottle or a spanner—let

alone an armed cannibal.

The praises of boxing as a practical means of self-defence have

been, perhaps, too loudly sung. A boy at school may earn for

himself a certain reputation, may establish a funk amongst his

fellows owing to his quickness and agility with or without the

gloves; but in practice he seldom has a chance of employing his

xx

skill against his enemies. On the other hand, a small boy who

comes in contact for the first time with another’s skill (or even

brutality) receiving a blow in the face, invariably cries, “Beastly

cad!” because a blow in the face hurts him.

You have to accept this convention of sportsmanlike warfare,

like others, before you can make it work. And the Love of Fair

Play of which we have heard so much in the past is quite artificial

too. It is not really inherent in human nature. Like other

moralities it has to be taught, and it is very seldom taught with

success. Let us say, not unreasonably, that you begin to take an

interest in boxing as a boy. You hear about various fights—at

least you do nowadays, and you want to imitate the fighters, just

as in the same way but at a different moment you want to be an

engine-driver, or an airman, or the Principal Boy in Robinson

Crusoe, when your young attention is drawn to such occupations.

When I was a small boy (if, in order to illustrate a point, a short

excursion into autobiography may be forgiven me), the last flicker

of the Prize-Ring had, so to put it, just expired, and glove-fighting

was not then perhaps a pretty business. A curiosity which,

not being skilled in the science and practice of psycho-analysis,

I can only ascribe to spontaneous generation, and the fact that

Tom Sayers once invested my mother, then a little girl, with his

champion’s belt at a village fair—this curiosity impelled me to

desire, from a railway bookstall, the purchase on my behalf of a

shilling book called The Art of Self-Defence, by one Ned Donelly.

It was, I believe, the very first work of its peculiar and spurious

kind—that is, a handbook with or without merit (this one had

several, notably that of brevity), written by a sporting reporter

and inscribed by the pugilist. I had some difficulty in getting that

gift, but when I did I devoured the book from gray paper cover

to cover. I knew it almost all by heart once. I remember now

that Ned Donelly said he had fought under the auspices of Nat

Langham, and I wondered what auspices meant, and I wonder

now if Ned Donelly knew. Later, in the mid-nineties, Rodney

Stone appeared in the pages of “The Strand Magazine,” and Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle, whilst admitting that rascality was known in

xxi

connection with the Prize-Ring, yet showed how the Great

Tradition of the British Love of Fair Play in the face of the most

reprehensible practices maintained itself. All literature which

touched the subject, all conversation with elder persons led me to

believe that this desire of Fair Play was inseparable from the

British composition (though seldom found outside these islands),

and that if one had a quarrel at school an adjournment was immediately

made to some secret trysting-place, where boys formed a

ring, a timekeeper and referee were appointed, and you and your

opponent nobly contended until one—the one who was in the

wrong, of course—gave in.

It wasn’t until I wished to have a fair, stand-up fight with

another boy—with a succession of other boys—that I found a

somewhat serious flaw in the great Tradition, and that at one

of the “recognised” public schools. The other boy might or

might not stand up straight in front, but half a dozen other boys

would invariably hang on behind—me. In the end I managed to

bring off two fair fights, one with another boy of like mind who,

cold-blooded and conversational, walked with me to a secluded

field; the other by means of a ruse. I had challenged this adversary

again and again. With derision, he refused to fight me.

Once I attacked him in public, but was very soon made to see

sense, as well as stars, for he hit me at his own convenience whilst

his partisans held my arms. The merits of the quarrel I entirely

forget. You may be sure that they were trivial. I will readily

admit that both of us were horrible little beasts (though I admit

it the more readily of him) in the certain knowledge that boys of

our age, excepting those who happen to read this, almost always

are. So I waited my opportunity, and one evening I caught my

enemy alone reading a paper on a notice-board. I came behind

him with stealth, and I kicked him hard, and I then ran away.

And he did exactly what I had, rather confidently, expected him

to do. He thought me an arrant coward, and he followed fast.

I led him to a safe and secluded passage, well lit, at the top of some

stairs where there was just room for a close encounter. We should

not be interrupted by any one. I waited for him to get on a level

xxii

with me. I have seldom enjoyed anything so much as the next

two minutes or so. I hated that boy very much. The score

against him was a long one. Moralists (who are always dishonest

in their methods of propaganda) tell us that revenge turns to

gall and bitterness.... Oh, does it? The sheer physical delight

in thrashing some one I hated, some one rather bigger and heavier

than myself, too, which made it all the better, has lived on in sweet

retrospect. There was no “hearty handshake” or anything

pretty of that sort. It was simple, downright bashing, and it was

delicious. And, not to please the moralist but to record a fact,

the air really was cleared. We did shake hands afterwards, and

all rancour was gone—at least from me: and for ever after we were

quite, though perhaps coldly, civil to each other, and my late

adversary is now a Lieutenant-Colonel, D.S.O., and I think (but

am not sure) C.M.G.

The Love of Fair Play, then, where hate is involved, needs a

great deal of teaching. I am not trying, in the instance quoted

above, to make a case for myself as a lover of fair play in those

days. The difference between my enemy and me was chiefly a

difference in vanity. He was content to annoy me without risk

of hurt or chance of glory. I was ready to stake a bit in order that

my victory should be complete for my own smug self-satisfaction.

He was the practical fellow: I was the sentimentalist.

Boxing of a kind is the earliest artificial sport of which we

have any record, and the earliest record, and from the literary

point of view, the best of all time is, though we are not concerned

with it here, Greek.

As far as can be discovered there is no tale of any boxing between

the gradually debased sport of the ancients and the institution

of the British Prize-Ring early in the eighteenth century. And it

was not until a hundred years or more later that boxing began to

take its place as a topic in polite letters. Under that head it is

difficult to include Boxiana, or Sketches of Antient and Modern

xxiii

Pugilism, from the days of the renowned Broughton and Slack to the

championship of Crib. This was written by Pierce Egan, the

inventor of “Tom and Jerry,” and dedicated to Captain Barclay,

the famous trainer of pugilists. The first volume was published

in 1818. Egan, like many later writers, was often upon the

defensive, and was ever upon the alert to find excuses for the

noble art. He constantly drew attention to the fact that, whilst

Italians used stilettos and Frenchmen engaged in duels à la mort,

the Briton has the good sense to settle a dispute with his fists.

Egan frankly disliked refinement, but he does recognise in boxing

something better than refinement.

The same point of view is implicit in M. Mæterlinck’s discussion

of modern boxing.1

“... synthetic, irresistible, unimprovable blows. As

soon as one of them touches the adversary, the fight is ended,

to the complete satisfaction of the conqueror, who triumphs

so incontestably, and with no dangerous hurt to the conquered,

who is simply reduced to impotence and unconsciousness

during the time needed for all ill-will to evaporate.”

To return to Pierce Egan, Blackwood’s Magazine for March,

1820, goes in (if the prevalent metaphor of precisely a hundred

years later may be allowed) off the deep end in reviewing

Boxiana:—

“It is sufficient justification of Pugilism to say—Mr.

Egan is its historian.... He has all the eloquence and

feeling of a Percy—all the classical grace and inventive

ingenuity of a Warton—all the enthusiasm and zeal of a

Headley—all the acuteness and vigour of a Ritson—all the

learning and wit of an Ellis—all the delicacy and discernment

of a Campbell; and, at the same time, his style is

perfectly his own, and likely to remain so, for it is as inimitable

xxiv

as it is excellent. The man who has not read Boxiana

is ignorant of the power of the English language.”

If ever responsible overstatement reached the border-line of

sheer dementia it is here. But for the sake of politeness, let us

content ourselves with saying, further, that the reviewer’s enthusiasm

got the better of his judgment. What matters to us now is

that Pierce Egan made a record of the old Prize Ring which is

invaluable. So that we are not concerned so much with his

literary distinction as with his accuracy as a chronicler, and, as

other records of contemporary events are either scarce, or, as in

some cases, totally lacking, it is not easy to check his accounts.

From internal evidence, we know at the first glance at Boxiana

that we must be careful; for Egan shouts his praises of almost

all pugilists upon the same note. And all of them cannot have

been as good as all that! This author was a passionate admirer

of the noble art and of the men who followed it, and it is his

joyous zeal (apart from the matters of fact which he tells us) that

make him worth reading. For the rest we must regard him as

we are, nowadays, prone to regard most historians, and make

such allowance as we see fit for inevitable exaggerations. That,

on one occasion at least, he was deliberately inaccurate, we shall

see later on.

There was a delightful simplicity about the old boxing

matches. The men fought to a finish; that is, until one or other

of them failed to come up to the scratch, chalked in the mid-ring,

or until the seconds or backers gave in for them, which last

does not appear to have happened very often. A round ended

with a knock-down or a fall from wrestling, and half a minute

only was allowed for rest and recovery.

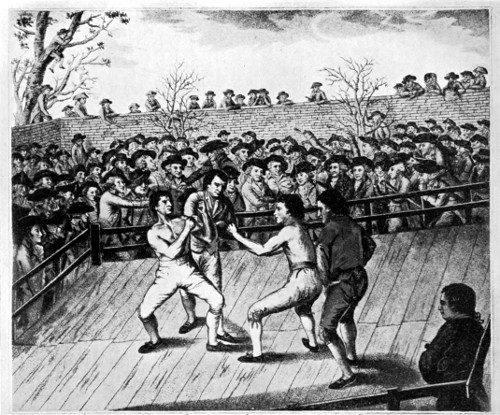

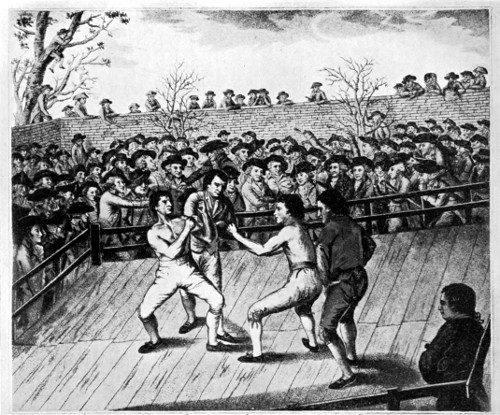

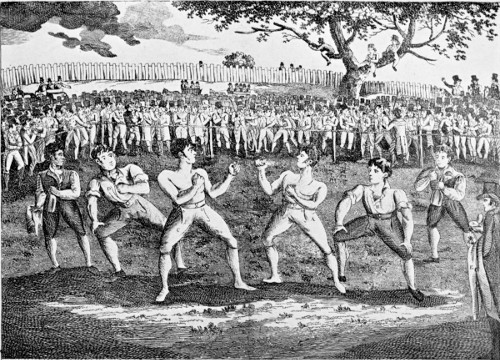

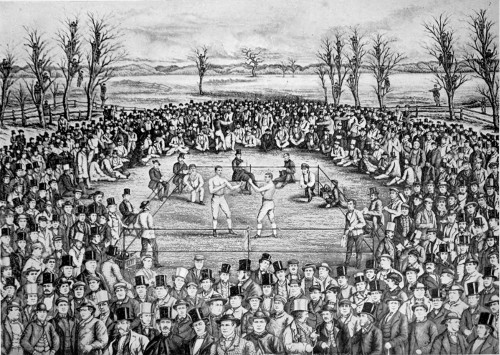

One of the illustrations in this book is taken from a print of

the original Rules governing Prize-Fights, “as agreed by several

gentlemen at Broughton’s Amphitheatre, Tottenham Court Road,

August, 16th, 1743.”

These Rules were as follows:—

I.—That a square of a Yard be chalked in the middle of the

xxv

Stage; and on each fresh set-to after a fall, or being from the

rails, each Second is to bring his Man to the side of the Square,

and place him opposite to the other, and until they are fairly set-to

at the Lines, it shall not be lawful for one to strike at the other.

THE RING

RULES

TO BE OBSERVED IN ALL BATTLES ON THE STAGE

I. That a square of a Yard be chalked in the

middle of the Stage; and on every fresh set-to

after a fall, or being parted from the rails, each

Second is to bring his Man to the side of the

square, and place him opposite to the other, and

till they are fairly set-to at the Lines, it shall not

be lawful for one to strike at the other.

II. That, in order to prevent any Disputes, the time

a Man lies after a fall, if the Second does not bring

his Man to the side of the square, within the space

of half a minute, he shall be deemed a beaten Man.

III. That in every main Battle, no person whatever

shall be upon the Stage, except the Principals and

their Seconds; the same rule to be observed in bye-battles,

except that in the latter, Mr. Broughton

is allowed to be upon the Stage to keep decorum,

and to assist Gentlemen in getting to their places,

provided always he does not interfere in the Battle;

and whoever pretends to infringe these Rules to

be turned immediately out of the house. Every

body is to quit the Stage as soon as the Champions

are stripped, before the set-to.

IV. That no Champion be deemed beaten, unless

he fails coming up to the line in the limited time,

or that his own Second declares him beaten. No

Second is to be allowed to ask his man’s Adversary

any questions, or advise him to give out.

V. That in bye-battles, the winning man to have

two-thirds of the Money given, which shall be

publicly divided upon the Stage, notwithstanding

any private agreements to the contrary.

VI. That to prevent Disputes, in every main Battle

the Principals shall, on coming on the Stage, choose

from among the gentlemen present two Umpires,

who shall absolutely decide all Disputes that may

arise about the Battle; and if the two Umpires

cannot agree, the said Umpires to choose a third,

who is to determine it.

VII. That no person is to hit his Adversary when

he is down, or seize him by the ham, the breeches,

or any part below the waist: a man on his knees

to be reckoned down.

As agreed by several Gentlemen at Broughton’s Amphitheatre,

Tottenham Court Road, August 16, 1743.

Reproduced by permission of “The Field.”

II.—That, in order to prevent any Disputes, the time a Man

lies after a fall, if the Second does not bring his Man to the side

of the square, within the space of half a minute, he shall be deemed

a beaten Man.

III.—That in every Main Battle, no person whatever shall

be upon the Stage, except the Principals and their Seconds; the

same rule to be observed in bye-battles, except that in the latter

Mr. Broughton is allowed to be upon the Stage to keep decorum,

and to assist Gentlemen in getting to their places, provided always

he does not interfere in the Battle; and whoever pretends to

infringe these Rules to be turned immediately out of the house.

Everybody is to quit the Stage as soon as the Champions are

stripped, before the set-to.

IV.—That no Champion be deemed beaten, unless he fails

coming up to the line in the limited time, or that his own Second

declares him beaten. No Second is to be allowed to ask his

Man’s adversary any questions, or advise him to give out.

V.—That in Bye-battles, the winning man have two-thirds

of the Money given, which shall be publicly divided upon the

Stage, notwithstanding private agreements to the contrary.

VI.—That to prevent Disputes, in every Main Battle the

Principals shall, on coming to the Stage, choose from among the

gentlemen present two Umpires, who shall absolutely decide all

Disputes that may arise about the Battle; and if the two Umpires

cannot agree, the said Umpires to choose a third, who is to determine

it.

VII.—That no person is to hit his Adversary when he is down,

or seize him by the ham, the breeches, or any part below the

waist; a man on his knees to be reckoned down.

It will be seen that all contingencies are by no means covered

by these regulations, but in those days far more was left to the

xxvi

judgment and discretion of the Umpires and the Referee. Spectators,

even “interested” onlookers who had plunged on the

event, were usually willing to abide by their decisions; and, as

a general thing, though there was more elbow-room for rascality

than in later times, the men fought fairly. Anyhow, Egan says

that they did.

Whether the death of bare-knuckle fighting is to be mourned

is not a question to be dealt with in the first chapter. As George

Borrow observed very many years ago, “These are not the days

of pugilism,” and without attempting any discussion of the rights

and wrongs of the general problem, we may yet read the annals

of the Ring and draw our own conclusions from particular instances.

The “days of pugilism” are unlikely to return.

It is not, indeed, until we come to George Borrow that we find

the praises of boxing sung as a sport, as an outlet for energy, as

pure good fun. It is true that, being Borrow, he tells us in Romany

Rye of a character who regarded it “as a great defence against

Popery.” But Borrow, when he left Popery alone, had a splendid,

“Elizabethan” and full-blooded view of life, whether he was

concerned with the pleasures of milling or the “genial and

gladdening power of good ale, the true and proper drink of

Englishmen.”

“Can you box?” asks the old magistrate in Lavengro.

“I tell you what, my boy: I honour you.... Boxing is,

as you say, a noble art—a truly English art; may I never

see the day when Englishmen shall feel ashamed of it, or

blacklegs and blackguards bring it into disgrace! I am a

magistrate, and, of course, cannot patronise the thing very

openly, yet I sometimes see a prize-fight.”

“All I have to say,” Borrow continues later on in

Lavengro, “is, that the French still live on the other side of

the water, and are still casting their eyes hitherward—and

that in the days of pugilism it was no vain boast to say,

that one Englishman was a match for two of t’other

race.”

xxvii

What would he have said had he lived to see a French

champion? The two words, “boxing” and “Frenchman,”

within half a mile of each other, so to put it, made a stock

joke in those days and for long after, even to within recent

memory.

Borrow had the true boxer’s joy in a fight for its own sake,

the violent exercise, the sense of personal contest which is more

manifest in fisticuffs than in any other sport.

“Dosta,” says Jasper Petulengro, “we’ll now go to

the tents and put on the gloves; and I’ll try to make you

feel what a sweet thing it is to be alive, brother!”

The following is his account of the crowd at a prize-fight,

the encounter itself being dismissed in a few lines:—

“I think I now see them upon the bowling-green, the

men of renown, amidst hundreds of people with no renown

at all, who gaze upon them with timid wonder. Fame,

after all, is a glorious thing, though it last only for a day.

There’s Cribb, the Champion of England, and perhaps the

best man in England: there he is with his huge, massive

figure, and a face wonderfully like that of a lion. There

is Belcher, the younger ... the most scientific pugilist who

ever entered a ring.... Crosses him, what a contrast!

Grim, savage Skelton, who has a civil word for nobody and

a hard blow for anybody—hard! one blow, given with the

proper play of his athletic arm, will unsense a giant. Yonder

individual, who strolls about with his hands behind him,

supporting his brown coat lappets, undersized, and also looks

anything but what he is, is the King of the Lightweights,

so-called—Randall! the terrible Randall, who has Irish blood

in his veins: not the better for that, nor the worse; not far

from him is his last antagonist, Ned Turner, who, though

beaten by him, still thinks himself as good a man, in which

he is, perhaps, right, for it was a near thing; and a better

xxviii

‘shentleman,’ in which he is quite right, for he is a Welshman....

There was—what! shall I name the last? Ay,

why not? I believe that thou art the last of all that strong

family still above the sod, where may’st thou long continue—true

species of English stuff, Tom of Bedford—sharp as

Winter, kind as Spring.

“Hail to thee, Tom of Bedford.... Hail to thee, six-foot

Englishman of the brown eye, worthy to have carried a

six-foot bow at Flodden, where England’s yeomen triumphed

over Scotland’s king, his clans and chivalry. Hail to thee,

last of England’s bruisers, after all the many victories which

thou hast achieved—true English victories, unbought by

yellow gold....”

Borrow wrote of the Prize-Ring in its decline and of its best

days from a greater distance than did Egan, and his perspective

is therefore truer. Still we do learn a great deal from Boxiana

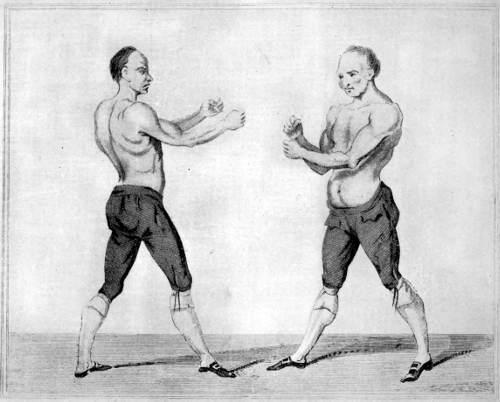

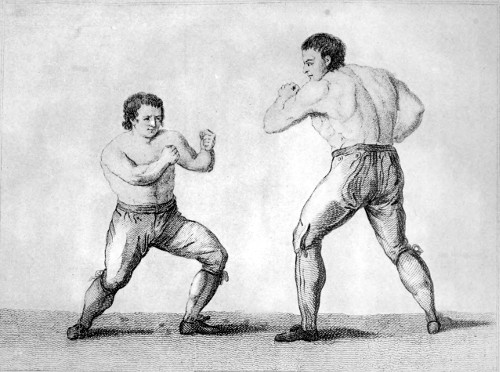

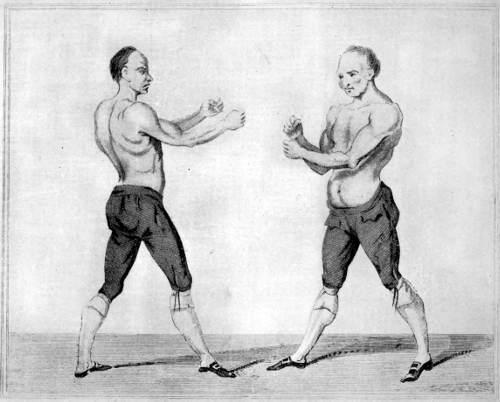

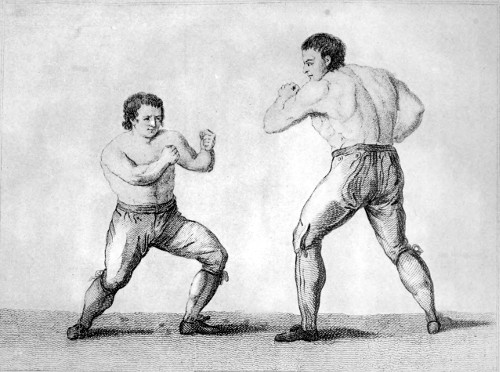

of the old giants; whilst contemporary engravings, some of which

will be found here, give us, more or less faithfully, the attitudes

of the fighters. Whether the artists observed the same fidelity

in regard to the muscular development of the principals we must

decide from our own experience. It is often said that if men were

to train themselves to this herculean scale they would be so muscle-bound

as to be almost immobile.

At the beginning of Volume III. of Boxiana, Egan tells us of

the extraordinary physique of the fighter.

“The frames, in general, of the boxers are materially

different, in point of appearance, from most other men; and

they are also formed to endure punishment in a very severe

degree.... The eyes of the pugilists are always small; but

their necks are very fine and large; their arms are also muscular

and athletic, with strong, well-turned shoulders. In general,

the chests of the Boxers are expanded; and some of their

backs and loins not only exhibit an unusual degree of strength,

but a great portion of anatomical beauty. The hips, thighs,

xxix

and legs of a few of the pugilists are very much to be admired

for their symmetry, and there is likewise a peculiar ‘sort of

a something’ about the head of a boxer, which tends to give

him character.”

And he adds a footnote: “The old Fanciers, or ‘good judges,’

prefer those of a snipe appearance.”—(An appearance which

obviously could not long have been maintained!)

Of scientific boxing, as we understand it, there was comparatively

little; though in the hey-day of the Prize-Ring (roughly

speaking, the first quarter of the nineteenth century) the foundations

of the exact science were well laid. However, the chief

qualifications for a good pugilist were strength and courage, even

as they are to-day. But, besides hitting, the fighters might close

and wrestle, and many a hard battle was lost by a good boxer

whose strength was worn out by repeated falls, falls made the

more damaging when a hulking opponent threw himself, as at

one time he was allowed to do, on top of him.

The other principal differences between old and modern

boxing were these: it was one of a man’s first considerations to

hit his antagonist hard about the eyes, so that they swelled up

and he could not see. Men strong and otherwise unhurt were

often beaten like that. Secondly, bare knuckles, in hard repeated

contact with hard heads, were apt to be “knocked up” after a

time. The use of gloves, though it probably makes a knock-out

easier and quicker, obviates these two difficulties. However,

even with the heavy “pudden” of an eight-ounce glove, the

danger to the striker, though much lessened, is not entirely

avoided, and I once put out two knuckles of my left, at the same

time breaking a bone at the back of my hand in contact with an

opponent’s elbow with which he guarded his ribs. This sort

of accident is very rare.

The chief interest in the fights described by Pierce Egan

and by others lies in their records of magnificent courage, for—there

is really no way out of it—the old Prize-Ring was, by the

prevalent standards of to-day, a somewhat brutal institution.

xxx

Horrible cruelty was seen and enjoyed, not as a rule the cruelty

of the two men engaged, fair or foul as may have been their

methods, but of their backers and seconds, who, with their money

on the issue, allowed a beaten man, sorely hurt, to go on fighting

on the off-chance of his winning by a lucky blow. Sometimes

their optimism was, within the limits of its intention, justified, and

an all but beaten man did win. Really, that sort of thing happens

more often in modern boxing, especially amateur boxing, to-day,

than it did in the Prize-Ring, and this is due, not to the callousness

of referees, but to their perspicacity. A thoroughly experienced

referee understands exactly how much a man can endure, particularly

when he has seen the individual in question box before.

He knows that he is not nearly so much hurt and “done” as he

looks, or rather as the average spectator thinks he looks; and he

gives him his chance. And, suddenly, to the wild surprise of

every one, except, perhaps, the referee, he puts in a “lucky”

blow and knocks out an opponent who had hitherto been “all

over” him.

On the other hand, a backer sometimes did withdraw his

man in the most humane fashion when he had been badly

punished, and very often to the deep resentment of the boxer

himself, who, left to his own devices, would have fought on so

long as his weakening legs would obey his iron will.

One more word upon the subject of “brutality” may be

forgiven me. Again and again has it been said, but never too

emphatically, how seldom it is that the men themselves were to

blame. It is the hangers-on, the parasites, the vermin of sport,

outside the ring, the field, the racecourse, who never risked nor

meant to risk a broken nose or a thick ear, who are out for money

and for money alone, by fair means for choice (as being on the

whole the better policy), but by foul means readily enough rather

than not at all—these are the men who bring every institution

upon which they batten into bad repute. Certainly the broken

ranks of this army were occasionally recruited from the less

successful or the more dissipated but quite genuine fighters, just

as the hired bully is not unknown amongst the boxers of to-day.

xxxi

But the real villain, the man who gets the money out of rascality,

does so, if possible, with a whole skin.

The Prize-Ring served its turn. For nearly a hundred years—that

is, roughly, from 1740 to 1840—it was a genuine expression

of English life. Right or wrong as may have been the

methods used, it was spontaneous. After that, if we except

individual encounters, it was forced, laboured, and in vain. The

spontaneity was gone. In his Preface to Cashel Byron’s Profession,

Mr. Shaw tells us that pugilism was supposed to have died of

its own blackguardism: whereas “it lived by its blackguardism

and died of its intolerable tediousness.”

That is very true, but it must be remembered that the tediousness

sprang very largely from the blackguardism—that is to say,

towards the end of the bare-knuckle era the men used to stand

off from each other, doing as little damage as possible and earning

their money as easily as might be. Moreover, men who fought

a “cross” were, particularly in the latter half of the nineteenth

century, seldom good enough actors to appear beaten with any

degree of plausibility, when they could, in fact, have continued

fighting: and the result was that they stood about the ring, sparring

in a tentative fashion, wrestling now and again, and wasting

time, waiting for an opportunity to fall with some show of reality.

Thackeray, however, who, according to Mr. Shaw, loved a prize-fight

as he loved a fool, appeared to think that the sport died of hypocritical

respectability. There is, of course, plenty to be said upon both

sides; and Thackeray’s opinions will be more closely discussed in the

chapter dealing with the fight between Sayers and Heenan.

Of one disease or another, or of several complications, the

Prize-Ring died, and from its dust arose the gradually improving

sport of glove-fighting, the boxing of to-day.

The aim of this book is to cover the ground of bare-knuckle

fighting and of modern professional boxing from the inception

of the Ring to the present day, by making notes upon a number

of representative battles in their chronological order.

xxxii

1

PART I

KNUCKLES

2

3

CHAPTER I

JOHN BROUGHTON AND JACK SLACK

The first Boxing Champion of England of whom any record has

been handed down to us was Figg. Fistiana or The Oracle of

the Ring gives his date as 1719. Strictly, however, his title to fame

rests more securely on his excellence with the cudgel and small-sword

than on fisticuffs, and the real father of the ring was John

Broughton, who was Champion from 1738 to 1750.

Broughton had a famous place of entertainment known as

the Amphitheatre, in Hanway Yard, Oxford Road, near the site

of a like establishment that had been kept by Figg. Here, with

pit and gallery and boxes arranged about a high stage, displays

of boxing were given from time to time, and here it was that

sportsmen first learned to enjoy desperate struggles between man

and man.

As has already been shown, Broughton formulated the rules

which for many years to come were to govern fighting, and which,

much as they leave to the imagination as well as to the discretion

of officials, tell us with the utmost simplicity the conditions under

which men fought.

For eighteen years John Broughton was undisputed Champion

of England. That probably meant very little, for boxing had

not yet become popular and its science was in its extremest infancy.

I would gladly make the foolish and unprofitable bet that if

Broughton, in his prime and with his bare fists, could be transplanted

to these latter days, he would not stand for one minute

before Joe Beckett with the gloves on. (That is less of a handicap

than it sounds to any boxer who has never used his bare knuckles.)

Broughton’s fight with Slack can by no standard be called

great, but it has its peculiar importance in showing us how a

4

certain degree of skill hampered by over-confidence and lack of

training may be at the mercy of courage, strength, and enterprise.

Broughton’s knowledge of boxing, compared with the science of

Jem Belcher and Tom Spring, must have been negligible; but

years of practice must have taught him something. As far as we

can gather, Slack knew less than a small boy in his first term at

school. He was a butcher by trade, and one day at Hounslow

Races he had “words” with the champion, who laid about him

with a horse-whip. Thereupon Slack challenged Broughton,

and the fight took place at the Amphitheatre on April 10th, 1750.

There was nothing elegant about Jack Slack. His attitude

was ugly and awkward, he was strong and healthy but quite

untrained in our meaning of the word. He only stood 5 feet 8½

inches but weighed close upon 14 stone—nearly as much as his

antagonist, who was a taller man. Broughton was eager for the

fight or for the money to be derived from it. He regarded Slack

with the utmost contempt and made no sort of preparation. So

afraid was he that the butcher might not turn up at the last minute

that he gave him ten guineas to make sure of him! The betting

was 10-1 on Broughton when the men appeared in the ring.

After all, as boxing went in these days, he did know something

about defence, and he was master of two famous blows, one for

the body and one under the ear, which were said to terrify his

opponents.

Slack stood upright, facing his man, with his right rigidly

guarding his stomach and his left in front of his mouth. But

that was only at the beginning. Directly he got into action Slack

speedily forgot his guard. The art of self-defence was unknown

to him, his was the art of bashing. He was a rushing slogger

against whom a cool man’s remedy is obvious. But he was also a

glutton for punishment, and almost boundless courage and staying

power, or “bottom,” as they used to call it in those days. Regardless

of the plain danger of doing so, he charged across the ring at

Broughton, raising his hands like flails. Slack was noted for

downward chopping blows and for back-handers, neither of

which are or ever have been really successful. Broughton met this

5

wild charge in the orthodox manner with straight left and right,

propping off his man in such a way that the attacker’s own weight

was added to the power of the blows. For two minutes or so

Slack was badly knocked about. Then they closed for a fall

and Broughton’s great strength gave him the advantage. But he

was getting on in years and was untrained and in flesh. The

effort of wrestling with a man of his own ponderous weight made

his breath come short, and when next they faced each other across

their extended fists the first dullness of fatigue already weighed

on the old champion. He was a slow man, and had been used to

win his fights by the slow and steady method of wearing down his

antagonists. Slack was harder and stronger than he had supposed,

but of course he would beat him—this ungainly slogger who

didn’t know enough to avoid the simplest blow. But Slack, the

rusher, was a natural fighter which, when all’s said, is a very good

sort of fighter indeed. He liked the game—the fun of it, the

sport of it. In spite of his bulk he was pretty hard. Standing

square to his man with the right foot a little forward, he had no

fear of his great reputation, he was quite untroubled by the stories

of that terrible blow beneath the ear. He went for Broughton

with a will. He would give him no time to remember his ring-craft.

He would take cheerfully all that was coming on the way,

and sooner or later he would get past the champion’s guard.

And presently Slack jumped in and landed a tremendous blow

between Broughton’s eyes. And the champion’s face was soft

from good living. He had not been hit like that for many a year.

Both his eyes swelled up at once.

The spectators saw that Broughton was dazed. He seemed

stupid and slow—not himself at all. And—they could not understand

this—he hesitated and flinched before his man. The Duke

of Cumberland, who was his chief patron, could hardly believe

his eyes. Broughton afraid? Broughton, from whom all others

flinched away, who stood so boldly and straight before his man,

who, though slow and heavy, was so sure and never gave ground?

Slack stood away for a moment and Broughton came forward

with his hands before him, feeling his way. Then the people saw

6

that his eyes were entirely swollen up and closed. The man

was blind.

The Duke was slower than the others.

“What are you about, Broughton?” he shouted to him.

“You can’t fight. You’re beat.”

To which Broughton replied, vaguely turning his head about

as though uncertain from which quarter his backer’s voice had

come,—

“I can’t see my man, your Highness. I am blind—not

beat. Only put me in front of him and he’ll not win yet.”

But Slack dashed in again and Broughton could not ward off

a blow. Still strong, quite unbeaten in the literal sense of the

word, he had to give in. It was an accident in the game and yet

it was a part of the game. The whole fight was over in fourteen

minutes.

In order to compare those days with these, it is interesting

to know that tickets for the Amphitheatre on this occasion cost

a guinea and a half, whilst the money taken at the door besides

fetched £150. Slack, as winner, was given the “produce of the

house,” which in all amounted to £600. When we have in mind

the difference in the value of money then and now, we must

realise that even in the early days of the Prize-Ring a successful

boxer stood to win a considerable sum. The chief difference in

his earning capacity lay in the fact that bare-knuckle fights were

necessarily less frequent than the softer encounters of to-day.

Nor was the sport widely popular at that time, the patrons and

spectators being chiefly confined to publicans and other good

sinners.

7

CHAPTER II

TOM JOHNSON AND ISAAC PERRINS

It is character and knowledge of character, which, together with

strength and skill, makes boxing champions to-day. And we are

inclined to think that the psychological element in fighting came

in only within the day of gloves, and rather late in that day.

Certainly the old records of the early Prize-Ring are of brawn and

stamina, skill and courage rather than of forethought and acutely

reasoned generalship, but there are exceptions, and one of the

most noteworthy is that of Tom Johnson.

Johnson (whose real name was Jackling) was a Derby man,

who came to London as a lad, and worked as a corn porter at Old

Swan Stairs. For a heavyweight champion he was very small—short,

rather: for he stood but 5 feet 9 inches. He must, however,

have been made like a barrel, for he weighed 14 stone, and

the girth of his chest was enormous. A story is told of how

Johnson when his mate fell sick carried two sacks of corn at each

journey up the steep ascent from the riverside and paid the man

his money, so that the boxer’s amazing strength earned the double

wage.

The best known and probably the fiercest of Johnson’s

battles was with Isaac Perrins, who stood 6 feet 2 inches and

weighed 17 stone. It is not probable that boxers trained very

vigorously in those early days, so that the weights may be misleading.

Contemporary prints, however, certainly give the

impression of men in hard condition. Perrins, a Birmingham

man, is said to have lifted 8 cwt. of iron into a wagon without

effort.

The fight took place at Banbury in Oxfordshire on October

22, 1789. The men fought (it is interesting to know when we

8

think of the prizes of the present day) for 250 guineas. Two-thirds

of the door money went to the winner, one-third to the

loser. The men fought on a turfed stage raised five feet above

the ground.

Johnson’s method had always been to play a waiting game,

to try to understand his opponent’s temperament, to take no

avoidable risks. He knew that he was a good stayer, so he was

accustomed to use his feet and to keep out of distance until he had

sized up his man. He would always make rather a long but

certain job of a fight than a quick but hazardous one.

Johnson’s greatest trouble was his passionate temper, which

was largely the cause of his downfall two years later in his fight

with Big Ben Brain. Isaac Perrins, who had the name of a good-natured

giant, was the first to lead. He ... “made a blow,”

Pierce Egan tells us, “which, in all probability, had he not have

missed his aim, must have decided the contest, and Johnson been

killed, from its dreadful force.” But Johnson dodged the blow

and countered with a terrific right-hander which knocked Perrins

down. At that time prize-fighters stood square to each other

with their hands level, ready to lead off with either. And in that

position a man naturally fell over much easier than from the solid

attitude of a few years later till the present time.

The next three rounds were Johnson’s, for Perrins was shaken

by his first fall. Then Perrins gathered himself together, and by

sheer weight forced himself, regardless of the blows that rained

on him, through the smaller man’s guard and knocked him down.

And for several rounds in his turn Perrins was the better. He cut

Johnson’s lip very badly, so that he lost blood, and the betting for

some time remained in his favour.

Tom Johnson by this time had the measure of his man. The

usual waiting game would not serve now. He must not only

wait, but he must keep away, and in order to keep away, he must

run away. This may not have been wholly admirable from a

purely sporting point of view, but we must forgive Johnson a

good deal (and as we shall see there really was a good deal to

forgive) on account of his inches. “He had recourse,” says Egan,

9

“to shifting”—that is, he kept out of the way for as long as

possible, and then, as by the rules of the Prize-Ring a round

only ended when one of the men went down, probably closed and

let Perrins throw him.

But the spectators approved of this method no better than

they would to-day, and there was a good deal of murmuring

against Johnson. At last Perrins, unable to reach his nimble-footed

antagonist, began to mock at him. “Why!” he exclaimed

to the company at large, “what have you brought me here?

This is not the valiant Johnson, the Champion of England: you

have imposed upon me with a mere boy!”

At this Johnson was stung to retort, for he was no coward

and was but fighting in the only way which his size allowed.

Moreover, Perrins’s observation roused his dander, and he blurted

out, “By God, you shall know that Tom Johnson is here!”

and immediately flew at his man in a passion of rage and planted

a terrific blow over his left eye, so that it closed almost at

once.

This incident nearly decides for us that Perrins was not

much of a boxer. A wild charge of that sort, particularly by a

much smaller man, is seldom difficult to frustrate. And the

opinion of the crowd began to veer round. Those who had put

their money on Perrins began to hedge.

Undaunted by his closed eye, Perrins pulled himself together

in the next round and returned as good as he had got, closing

Johnson’s right eye. And so for a while the fight remained level.

Many rounds and very short ones. A half-minute’s rest between.

Much hard punishment given and got, but a great deal of it not of

a kind obvious to the inexpert spectator. Quite apart from short-arm

body-blows which are sometimes apt to elude observation,

there was wrestling for a fall with which far more rounds ended

than with falls from a blow. The effort to throw is exhausting

enough, but to be thrown and for a heavy man to fall on top of

you is terribly wearing. And though the strength of these two

men was prodigious, yet Johnson was the closer knit of the two,

from a boxer’s point of view the better made.

10

Now when they had fought forty rounds, Johnson was confident

and happy, but he knew that he was pitted against a lion-hearted

man who was by no means yet worn out. Suddenly he

got an opening for a clean straight blow with all his weight behind

it. This was a right-hander, which struck Perrins on the bridge

of his nose and slit it down as though it had been cut with a

knife.

The odds were now 100-10 on Johnson, but he had by no

means won the fight. Perrins was boxing desperately, striving

with his great superiority in reach to close Johnson’s remaining

eye. He knew very well that many a fight had been won like

that, an otherwise unhurt man being forced to throw up the

sponge because he was totally blinded by the swelling of his eyes.

In the forty-first round Johnson either slipped down or deliberately

fell without a blow and Perrins and his backers claimed the victory.

If Johnson did actually play this very dirty trick to gain time and

have a rest, he deserved to lose. We don’t know what actually

happened. The records merely state that he fell without being

hit. But the umpires allowed it because that contingency had not

been covered in the articles of agreement made before the fight.

Perrins now changed his method, attacking his man with

chopping blows presumably on the back of the neck and head,

and back-handed blows which are seldom efficacious. These

puzzled Johnson at first, and he took some of them without a

return until he learned the knack and guarded himself. And

Perrins’s strength now began to go: while Johnson, who for a

few rounds had seemed tired, began to improve again. But yet

he never began the attack. He left that always to the giant. In

fact, Johnson did everything to save himself and to make his

man do most of the work. Then Perrins, who had lunged forward

with a terrific blow, fell forward, partly from his own impetus,

and partly from weakness. Johnson, who had stepped aside

from the blow, watched him and as he fell hit him in the face with

all his might, at the same time tumbling over him. After that

Perrins was done. Every round ended by his falling either from

a blow or from sheer weakness. Johnson hit him as he pleased,

11

with the consequence that Perrins’s face was fearfully damaged,

“with scarce the traces left of a human being.” But he refused

to give in, and round after round his seconds brought him to

the scratch, when he swayed and staggered and struggled for

breath and tried to fight on. His pluck in this battle was the

inspiration of the Prize-Ring for ever afterwards. More than

once Johnson, still strong, sent in tremendous blows which would

utterly have finished lesser men, but Isaac Perrins held on until

his friends and seconds gave in and refused to let the good fellow

fight any more. The match had lasted for an hour and a quarter,

during which sixty-two rounds had been fought.

In many ways it was an unsatisfactory fight, but for cunning

(if rather low cunning) on one side and magnificent courage and

determination on the other, it must be counted one of the greatest

combats of the old days.

12

CHAPTER III

RICHARD HUMPHRIES, DANIEL MENDOZA, AND JOHN JACKSON

The Jews in this country have taken very kindly to boxing, both

as spectators and as principals, throughout the annals of the

Ring, both in the days of bare knuckles and in later times down

to the present day, there has generally been a sprinkling of good

fighting Israelites. And the first Jew of any note as a boxer

became Champion of England.

The battles for which Daniel Mendoza was most famous were

the succession, four in number, in which he engaged Richard

Humphries. The first of these was negligible, being but a “turn-up”

or pot-house quarrel at the Cock, Epping. This took

place in September of 1787, but it led to a pitched fight between

these men for a purse of 150 guineas at Odiham, in Hampshire,

in the following January.

Like many prominent fighters, Mendoza was finely developed

from the waist upwards, with a big chest and a show of muscle

in the arms, but his legs were weaker. He was five-foot seven

in height. Humphries was an inch taller and rather better built.

He was known as the “Gentleman Boxer” because of his pleasant

manners and sporting behaviour generally. Both were men of

proved courage. As may be imagined from the Epping incident,

there was no love lost between them.

They fought on a twenty-four foot stage erected in a field,

but, since the day was wet, the boarded ring from the first proved

to be a hindrance to good boxing.

At first the men were both very cautious. Mendoza, always

a little inclined to attitudinise and to pose for effect, swaggered

about the ring until he saw an opening when, lunging forward

with a mighty blow he slipped and fell. On coming up again

13

Mendoza got a little nearer to his man and hit him twice, the

second blow knocking Humphries down. In the next round they

closed and Humphries was heavily thrown. Already it seemed

certain that Mendoza was the better boxer, though Humphries

was very strong and full of pluck. And for a quarter of an hour

of hard fighting his pluck was fully needed. Mendoza throughout

that time attacked him with the utmost violence, knocking

him down or throwing him with consummate skill, so that the

betting was strongly in the Jew’s favour. Then happened one of

those curious and unsatisfactory incidents for which Broughton’s

Rules, at all events, had no remedy. Mendoza had driven his

antagonist, blow following blow, right after left, across the ring

to the side, which appears on this occasion to have been railed

and not roped. A smashing right had all but lifted Humphries

off the stage, and for a moment he hung over the rail quite helpless

and at Mendoza’s mercy. Instantly taking advantage of his

position, the Jew sent in a terrific right-hander at Humphries’s

ribs which, had it landed, would almost certainly have knocked

him out of time and so finished the fight. But Tom Johnson,

who was acting as Humphries’s second, leapt forward and caught

Mendoza’s fist in his own hand.

The Jew’s followers immediately sent up a shout of “Foul!”

which was reasonable enough. Indeed, by modern rules there

would be no question at all. Humphries would have been immediately

disqualified for his second’s interference. But the old

rules were elastic and the umpires on this occasion decided that

Johnson was justified, as his man should be considered “down.”

Whether they had any ulterior motive, such as the desire to see

the fight run its natural length, one cannot say. But we do know

that human nature has altered remarkably little in a hundred

and fifty years, and to-day a referee, not of the first rank, will

often stretch a debatable point in order “not to spoil sport,” or

because it would be a pity if the public failed to get their money’s

worth out of the moving pictures taken of the fight.

Hitherto, owing to the wet and slippery boards, Humphries

had been severely handicapped. He now took off his shoes and

14

fought in his silk stockings. But with these, too, he found it

difficult to keep his footing and after a round or two his seconds

provided him with a pair of thick worsted stockings to put over

them. In these he could stand firm, and shortly afterwards his

great courage began to be rewarded, for Mendoza flagged a little,

and Humphries picked him clean off his feet and threw him with

terrible force to the ground. The Jew came down on his face,

cutting his forehead severely and bruising his nose. Coming up

for the next round, Mendoza was plainly hurt and shaken, and

thenceforward his antagonist showed himself the better man.

Mendoza went down before a terrific body-blow, while in the

next round he fell from a left-hander on the neck which nearly

knocked the senses out of him. Then, coming up again, he

dashed at Humphries and hit him with all his flagging power in

the face, but he slipped and toppled over from the impetus of his

own rush and fell down on the boards with his leg awkwardly

twisted under him. In doing this he sprained a tendon, and

knowing that further effort was quite useless, he gave in. A

moment later he fainted in the ring and was carried away. So

Humphries’s victory on this occasion was due, finally, to an

accident. The whole battle was finished in half an hour, and

“never was more skill and science displayed in any boxing match

in this kingdom,” wrote the chronicler, Pierce Egan, with his

customary exaggeration.

Prone as human nature ever is, now as then, to judge by

net results, Mendoza’s reputation nevertheless suffered little

from this defeat. On the contrary, he had boxed so well and had

shown so much courage that he had, if anything, enhanced it.

It was seen that he was a much quicker man than Humphries

and that he was far better at close quarters. On the other hand,

Mendoza was not a really hard hitter.

After this battle the winner wrote a note to his backer and

patron, Mr. Bradyl, which delightfully summed up the situation:—

“Sir,—I have done the Jew, and am in good health.

“Richard Humphries.”

15

But a number of sportsmen were by no means satisfied that

Humphries had “done” the Jew on his own merits. They fully

realised that accident had materially helped in that “doing,”

and accordingly were ready to back the Jew again. The two men

being quite willing, a match was arranged and was eventually

fought in Mr. Thornton’s park, near Stilton, in Huntingdonshire,

on May 6th, 1789. For this encounter, popular excitement being

very great, a sort of amphitheatre was built with seats piled tier

on tier around the ring. It held nearly 3000 people. This, too,

was an unsatisfactory fight, but has to be chronicled because it

illustrates very vividly some of the causes which nearly a hundred

years later finally brought the Prize-Ring to ignominy, and

because, also, it shows how mixed are human motives and emotions

during severe physical strain.

The men squared up to each other, and Humphries made the

first attack, but Mendoza stopped the blow neatly and sent in a

hard counter which knocked his antagonist down. The second

and third rounds ended in exactly the same way. The Jew’s

confidence was complete, his speed remarkable. He had learned

to hit no harder, but he certainly hit more often than Humphries.

For about forty minutes Mendoza had much the best of it, taking

his adversary’s blows on his forearm, instantly replying with his

quick, straight left, or closing and throwing Humphries.

The feeling of impotency, of long effort continuously baffled,

finds the breaking point of a boxer’s pluck much sooner than

severe punishment relieved by a successful counter from time to

time. Humphries was tired, but not seriously hurt. In the

twenty-second round Mendoza struck at him, but he avoided

the blow and dropped. He did not slip. As the Jew’s fist came

towards him he made the almost automatic movement which

should ensure its harmlessness, but at the same moment he

deliberately made up his mind to take the half minute’s rest then

and there. Or perhaps that was instinctive too. The human

mind flits quickly through the processes or stages of intention

and comes to a certain conclusion. Humphries wanted to gain

time and fell without a blow. Now the articles of agreement

16

expressly stated that if either man fell without a blow he should

lose the fight. And the cries of “Foul!” from the crowd and

especially from Mendoza’s corner were natural enough. But

Humphries and his backers claimed the fall a fair one because

Mendoza had struck a blow, though it had not, as a matter of

fact, landed. The partisans on either side wrangled and argued,

and finally a general fight seemed almost inevitable. Above the

yelling and cursing of the crowd and in the general confusion, the

umpires could scarcely be heard. Sir Thomas Apreece, Mendoza’s

umpire, naturally shouted that it was a foul and that Humphries

was beaten. Mr. Combe, the other umpire, held his tongue,

refusing to give an opinion. That should have been sufficient.

But Mendoza’s second lost his temper and shouted across the

ring to Tom Johnson, who was once again seconding Humphries,

that he was a liar and a scoundrel. This observation may not

have been strictly to the point, but the point (save that of the

jaw) is the last consideration when feeling runs high on notable

public occasions. Johnson said nothing and began to cross the

ring in his slow, heavy way, looking very dangerous. But a

diversion interrupted a promising bye-battle, for Humphries

stood up and called on Mendoza to continue fighting, carrying

the war, as it were, into the enemy’s country by taunting him with

cowardice. Mendoza was willing enough, but his backers held

him back. Humphries then threw up his hat and challenged the

Jew to a fresh battle, and at last they fell to again. And yet again

Mendoza showed himself the better man, knocking Humphries

down twice in succession. For half an hour the second act of this

drama continued indecisive, though Mendoza was evidently the

better and more skilful man. He now punished Humphries

severely, closing one of his eyes, severely cutting his forehead

and lip. He had little in return, though Humphries had put

in some heavy body-blows at close quarters which had made

the Jew wince. But throughout the second half of the fight

Humphries fought with perfect courage and even confidence.