Title: "The One" Dog and "The Others": A Study of Canine Character

Author: Frances E. Slaughter

Illustrator: Augusta Guest

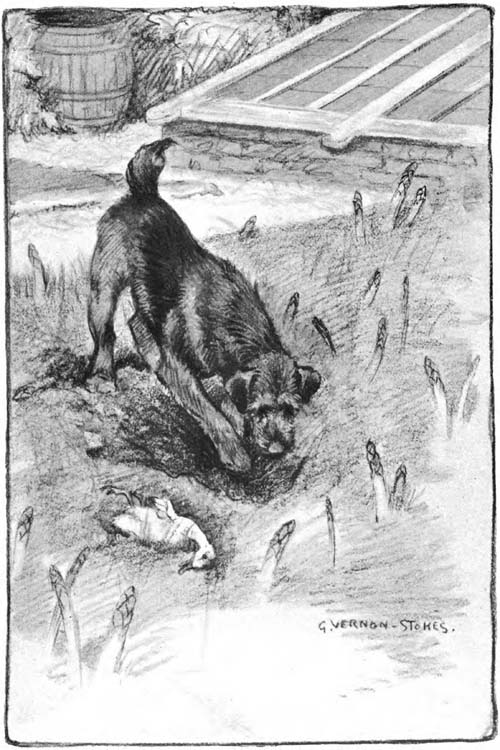

G. V. Stokes

Release date: June 24, 2018 [eBook #57384]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by MFR, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by the Google Books Library Project (https://books.google.com)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the Google Books Library Project. See https://books.google.com/books?id=QLErAQAAMAAJ&hl=en" |

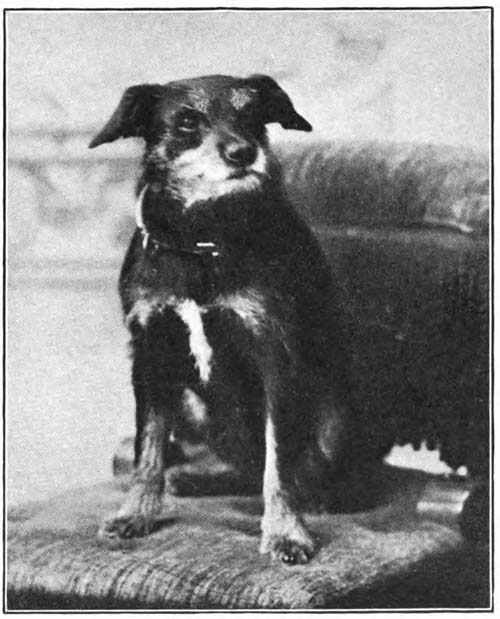

BANDY

“THE ONE” DOG

AND

“THE OTHERS”

A Study of Canine Character

BY

FRANCES SLAUGHTER

ILLUSTRATIONS BY

AUGUSTA GUEST AND G. VERNON STOKES

AND FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1907

Copyright, 1907, by

Longmans, Green, and Co.

All Rights Reserved

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

“My dog is perfection in character and disposition, and in intelligence he cannot be beaten.”

These words give the attitude of mind of the large body of dog lovers, whether in England or America, or in whatever remote corner of the earth they may be found. For is not every human convinced in the inner recesses of his mind of the immense superiority of his own canine favourite to all others of his race? Yet some there are who only cherish this delusion in the sanctity of their unspoken thoughts, while with the unfettered license of a fine freedom they look out on the world of dogs with what appears, at least to themselves, to be an unbiassed and independent judgment. Thus while in confidential parley with ourselves we play with our unshaken faith in the gifts and performances of our own special dog friend, we present a bold front of open-minded justice when we are asked to listen to the deeds of other dogs.

Such an attitude is all that I can hope for from those who read these simple studies of dog life. The interest of the unvarnished anecdotes, that have been collected at first hand, will be intensified by the thought of the[Pg viii] very superior cleverness of “The One” dog in similar circumstances, as against “The Others,” whose gifts must always seem quite painfully mediocre in comparison.

But to all our dog friends we have duties in proportion to the response they make to the influences of mind and affection we bring to bear on them. While we cherish “The One,” may we never forget that every instinct of humanity demands from us a careful discrimination of the rights of “The Others” in the battle of life.

| Page | |

| Introduction | xiii |

| BOOK I—Life Histories | |

| The Child of the House | 3 |

| The Diplomatist | 32 |

| The Professor | 44 |

| The Soldier of Fortune | 69 |

| The Artistic Thief | 87 |

| BOOK II—Studies and Stories | 105 |

| INDEX | 269 |

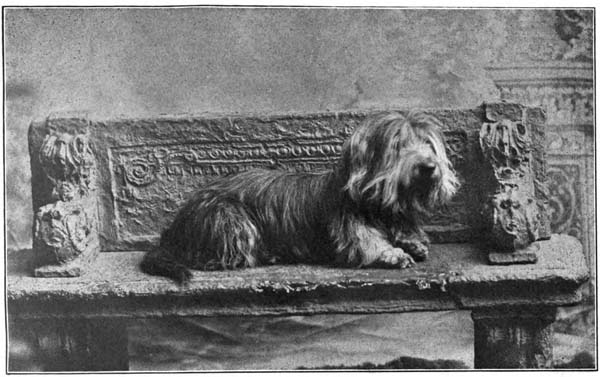

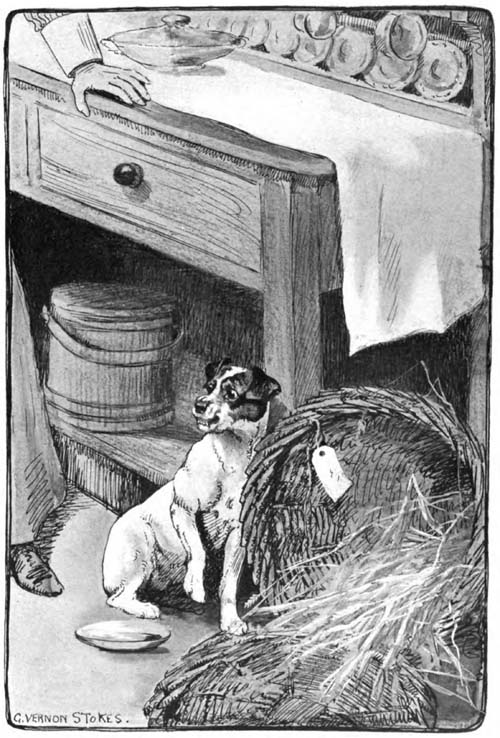

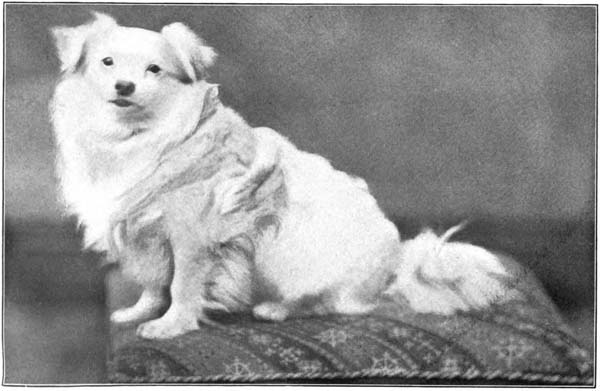

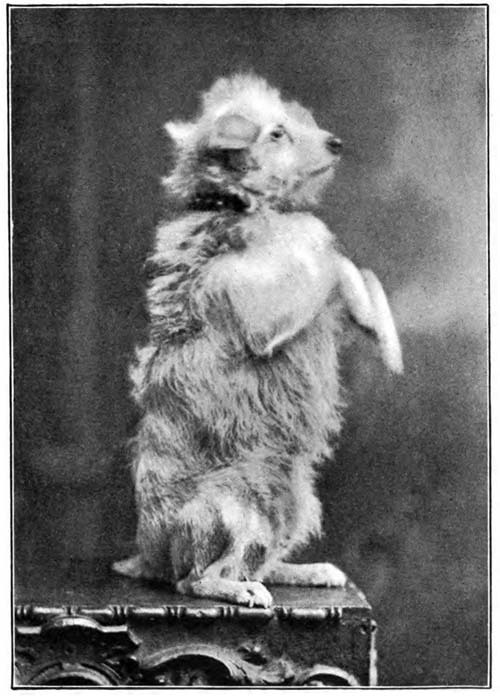

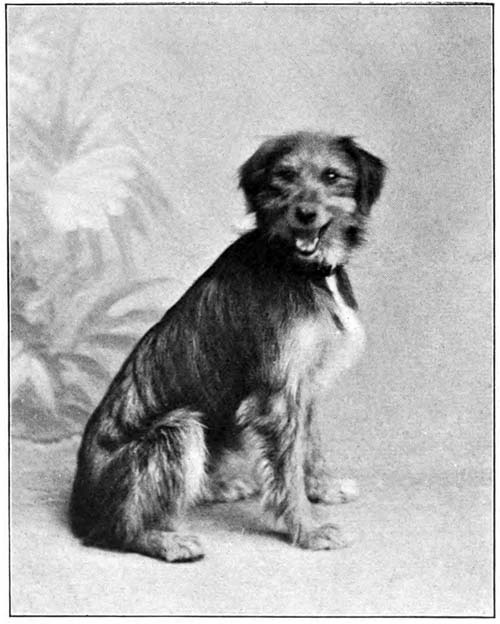

| Bandy | Frontispiece |

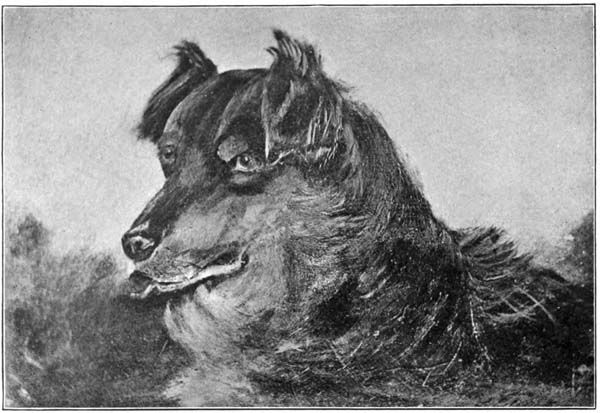

| The Child of the House | Facing page 4 |

| The Diplomatist | “ “ 32 |

| The Professor | “ “ 46 |

| The Soldier of Fortune | “ “ 70 |

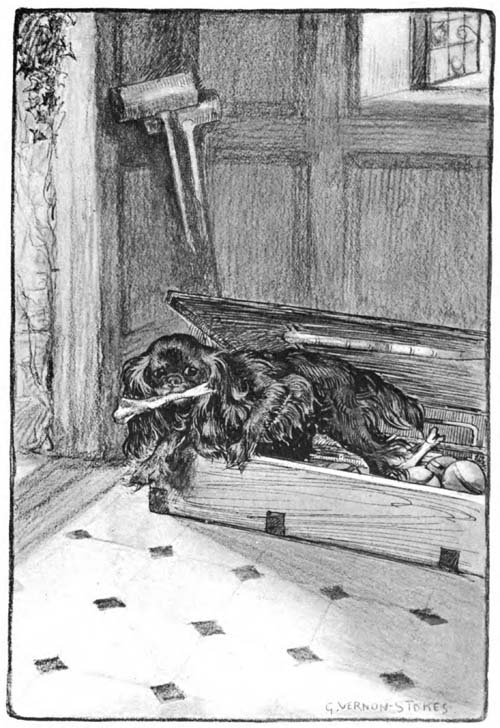

| The Artistic Thief | “ “ 96 |

| Suspicion | “ “ 120 |

| Mr. Guest’s Hounds, 1900 | “ “ 134 |

| “Conscience Makes Cowards of us” | “ “ 150 |

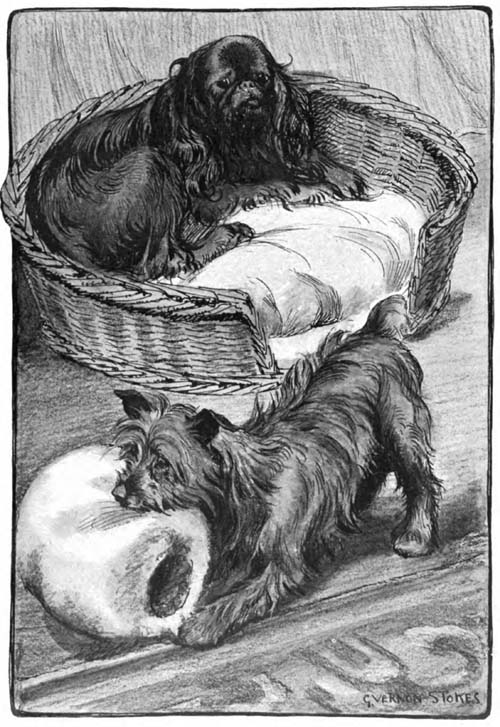

| The Invalid and his New Friend | “ “ 166 |

| Bobbie | “ “ 180 |

| Billy | “ “ 188 |

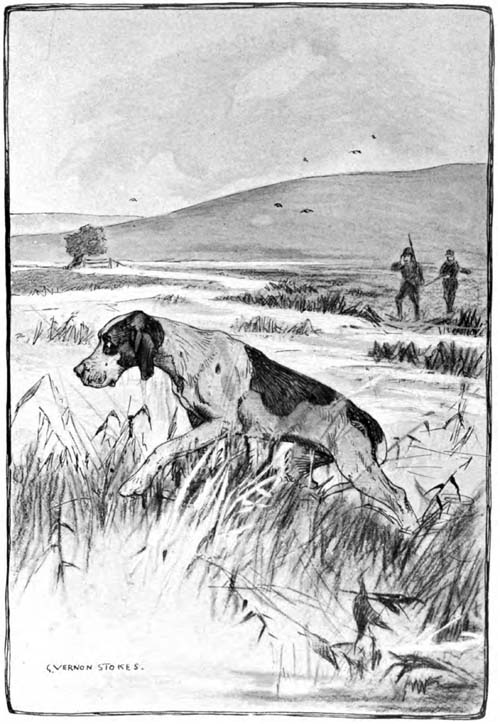

| “Are they Coming?” | “ “ 198 |

| Bobbins | “ “ 204 |

| Boy | “ “ 208 |

| Bettina Corona | “ “ 212 |

| A Sunday Morning’s Work | “ “ 232 |

| Bosky | “ “ 244 |

| Jimmy | “ “ 248 |

“THAT creature’s best that comes most near to man” may in truth be spoken of the dog. Nearest to man in the daily experiences of domestic life, he shares the joys and disappointments that are the lot of his owner. Under man’s influence the dog’s intelligence has been trained to meet the requirements of the environment that is now his. In what a wonderful way he responds to the demands of the civilised conditions of his life, those know who bring the light of their higher intelligence to bear on the study of his character. The more we study the dog, the better we shall understand his kinship to us in the realms of mental and moral feeling, and the more clearly we shall appreciate the barriers that cut him off from the experiences of our own higher life.

In the Life Histories of five dogs I have gathered facts that give the distinctive characteristics that marked each one off from his fellows. With these dogs I have had exceptional advantages of learning from their owners the special marks of character that distinguished them. The results of this study I have made the groundwork of my book. The anecdotes of many other dogs, that are given to illustrate more fully individual traits of character, have all been collected at first hand, and, so far as I know, have never before appeared in print.

[Pg xiv]The only exceptions are those I have taken from Miss Serrell’s book “With Hound and Terrier in the Field.” As editor of this book I am able to vouch for the truth of the many and charming stories that are scattered broadcast through it, and with the author’s permission I have given a few that bear on the subject of my own work. Two other stories, one of which is taken from the delightful study of the first Earl of Lytton, written by his daughter, Lady Betty Balfour, and a quotation from Mrs. Draycott’s interesting Sketches of Himalayan Folk Lore, are the only ones that have been already given to the public.

We know that long ages of companionship with man have made the dog our fellow in sympathy and intelligence in a way that is impossible to any other member of the brute creation. Yet even he has not lost the marks of the old wild life that was once his. But it is a long step back from the inmate of our twentieth century home, where the surroundings given by advancing civilisation and moral development have the marks of ages of progress, to the primeval conditions of the life of our favourite’s ancestors. Far be it from me to dogmatise as to what those old conditions of life were. They are lost in the obscurity of the past, and we listen with respect when men of science tell us of the conditions that obtained in bygone ages, though not always with entire acceptance of the inferences they draw.

Few, however, will dispute the probability that the ancestor of the dog—wolf, jackal, or of whatever type he may have been—lived in a pack and thus had the aids of community life to train his intelligence and fit him for the struggle of existence among his fellows. It is[Pg xv] only the question of his mental development that concerns us here, and we have authority for saying that a higher development of intelligence obtains among the members of a community than among those who in solitary freedom meet the dangers and fight the difficulties of life without such help from others of their kind.

In the study of jackals, of wolves and of hounds that hunt in packs, we see the clearest traces of the old life lived in the forests and the plains, where man had not as yet entered into a struggle with nature on his own account. We find now, as in the past, evidence of the sympathy that is at the root of all social instincts, governing the life of the community. Without the loyalty to a recognised code of conduct and morals, that may be said to be the foundation of social life, no body of animals living a common life could survive. Where there is community of interests there must be a common working for the general good, or the band will be scattered and fall a prey to its enemies. But the sympathy that is quick to warn of coming trouble and give assistance when misfortune has fallen, to help the weak and to encourage the wavering, links the members of a society together in the strongest possible bonds. It is this that will strengthen them collectively to withstand attacks against which individually they will have no chance. Such a tie must have enabled the ancestors of our domestic dogs to preserve life and to hand on a position in the tribal company to their offspring.

The training the dog had received as a member of the pack, when man rough and uncivilised as he then was, became his companion in the struggle for life, was the source of his value to the human. In hunting, in the[Pg xvi] guarding of his master’s property, the dog found his place in the life of his owner, and since those early days of association in the wilds, the rise and progress of the human race has marked the gradual amelioration of the condition of the dog. It is sounding a high note, perhaps, to say that the history of the development of canine intelligence has advanced step by step with the history of the civilisation of the human race. Yet I venture to think that the facts bear out the statement.

In the rude life of our forbears the dog was primarily valuable in the daily quest for food, and as the conditions of life were rough and uncertain for his master, so also were they for him. Yet the dog had reached another stage of life from the days when in the primeval pack he had roved the forests untouched by the influence of man. Obedience to the customs of the canine clan had given place to the service and companionship of the human master, and from this point his history is closely woven with the fortunes of the human race.

Not only were his speed and scenting powers made use of in the chase, but his courage and fidelity were recognised and valued in the protection of his master’s home. A step further in the course of the domestication of the dog, and we find that his mental development is subject to varying influences as his powers are used primarily as a guardian or as a hunter. The sheep dog and the guardian of the house are brought more directly under the influence of their owner’s home life, while the dog used chiefly for hunting remains more under the conditions of his primeval state. Yet the hunting dogs, of which the hounds of to-day are the representatives, were also subject to the will and to a certain extent[Pg xvii] followed the rise in fortune of their masters. It is among these members of the canine race that we must look for the community life that is the modern rendering of their old tribal conditions.

With the spread of civilisation, and above all with the rise of Christianity, the dog came gradually to be recognised as having claims, not only on his master’s forbearance, but as possessing rights of his own in the common life of master and servant. The faithful creature who showed such wonderful aptitude in guarding his master’s flock in the field, and was such a sympathetic and intelligent companion in his home, had a claim to be treated with the kindness and consideration that was due from his owner to all—whether man or beast—who gave him faithful service.

We have only to compare the position of the dog among Mohammedans or Hindoos in the present day with the conditions of his life in England and America to see what Christianity has done for him indirectly. He is saved from needless suffering, tended in sickness, and housed and fed so that his physical and mental powers can reach their highest point of development. He thus attains a far higher level in the life history of his race than is possible to his half-starved, cowed, and miserable brothers in Eastern lands.

To the Mohammedan he is an unclean creature, and by him is treated with a disregard of the amenities of intercourse between man and beast that goes far to make him the outcast in mind and manners that he is in the conditions of his outward life. The tumultuous troop of pariahs that rush out from an Indian village, to the discomfort of the English rider enjoying his[Pg xviii] morning gallop, show in appearance and disposition marks of the neglect in which their life from its earliest day is passed. With the Hindoo the dog is safe from active ill treatment, and while in health and strength may share the conditions of his master’s life. But when sickness, or accident, or old age overtakes him, not a hand will be lifted in his service. Though some simple, timely aid might save the poor brute nameless suffering, and even give him years in which to serve his master in the future as he has done in the past, his Hindoo owner will show the fatalistic indifference to his sufferings that is one of the marks of the followers of his strange creed. The dog’s time has come, and the man who will vex his soul if inadvertently he crush the life from the tiniest of creeping insects, will show a perfect disregard of the claims of the animal who has served him with all the love and fidelity of his heart and the strength of the best years of his life.

But in Western lands where Christian ethics have put the finishing touch to the gentler influences of a progressive state of civilisation, the dog’s rights as a living, sentient being are regarded as they never have been in the course of the world’s history. True, there are bright spots in the past as there are direful blemishes in the present, that on the one hand bring discredit on the vaunted progress of human development, and on the other throw the glamour of a strange acceptance of moral responsibility to the dumb creation on the men of far-off days, but these are the exceptions that go to prove the truth of the general statement.

As man advances in civilisation and grows more restrained in the habits and manners of his life, his mind[Pg xix] develops, and one of the first signs of his progress is his respect for life as such. The dog, as his constant companion, feels most, in the realm of animal life, the change in his masters outlook. He is treated with ever increasing gentleness and comprehension. For as one sign of a mind of low type, or of a low order of development is an incapacity for sympathy with an intelligence either lower or higher than its own, so with the expanding powers of man’s mind he is able more and more to enter into the workings of his dog’s mind. As his own powers of sympathy and insight grow larger and deeper, he awakens an ever increasing response from the answering echoes in the dog’s mind. Here then we may bear in mind that if the dog had not the inherent capacity to respond, there could be no channel of communication with the larger outlook of the human mind as developed in man.

But if the development of human and canine intelligence has each in its degree and order followed the same line, the mental characteristics of the two races must be akin. It is only, indeed, from the starting-point of reading our own processes of mind into the mind of our humble friend that we can form the slightest conception of the meaning of his actions, which in their expression so closely resemble our own under the same conditions. Surprise, anger, joy, grief, resentment, and the emotions that go to make up the round of our own daily experience, find their counterparts in the dog. It is from analogy with the states of mind that in our own case evoke these expressions that we reason of the feelings and impulses that stir the mind of the dog and give rise to similar manifestations of feeling. On no[Pg xx] other ground can we even attempt to fathom the workings of his mind.

If then the dog be our kinsman in the realm of mind, though his standing be on a lower level than our own, are we not bound, in return for the unwavering devotion he shows us, to give him the best guardianship and care that our own higher powers give us the means of using for his benefit? It is to the realisation of this truth that I hope my studies of the dog may help.

Having thus stated the views with which I approach the study of the dog’s mind and character, I must turn for a moment to the sources from which I have drawn the anecdotes that have given me the materials on which I have worked.

Of the five Life Stories that form the First Book, “The Child of the House” was my own devoted companion for over twelve years. Of the other dogs that I have selected for fuller notice, Bruce, “The Diplomatist,” was the property of Mr. T. F. Dale, whose writings on animals and sport are well known both in England and America. Bandy, “The Professor,” belonged to Mr. H. Richardson, who was senior master at Marlborough School, where Bandy’s merry little life, though not untouched by tragedy, was passed. Jack, “The Soldier of Fortune,” was owned by Miss Serrell, whose life-long love of dogs and horses is shown in her book “With Hound and Terrier in the Field.” Miss Helen Dale was the mistress of Jet, “The Artistic Thief,” one of a long line of fascinating little spaniels that have been among her home friends.

When I come to the subject of the many shorter anecdotes that have been given me so freely, not only[Pg xxi] by my personal friends, but by many whom I have never had the pleasure of meeting, I can only say that my gratitude is very great for the kindly help afforded me from all sides. Without the numberless stories told me by Miss Serrell, I could never have hoped to collect enough for the purposes of the book. To her and to Miss Helen Dale I also owe special thanks for reading the proofs for me and making many valuable suggestions.

Miss Dale has also given me many shorter stories, and her brother, Mr. T. F. Dale, has done the same. Others who have contributed to my little store, and have most kindly lent me photographs of many of the dogs mentioned, are Mrs. Arthur Dugdale, Miss Rose Southey, Mrs. Bruce Steer, and Miss Edith Gilbertson, and through these friends I would convey my thanks to the strangers who have helped me at their request.

Frances Slaughter.

March, 1907.

THE “ONE DOG” AND

“THE OTHERS”

“THE One” of all dogs for me was a long, low Skye of the old-fashioned drop-eared kind. In breed and build he was just what I had always said I would not have as a house dog, yet I never regretted the weakness that forbade me to send the forlorn little stranger away. He had no eventful history, and though I am persuaded that no other of his kind was ever quite so intelligently sympathetic and altogether lovable as he, I have nothing to relate of him that “The Others” will not outdo at every turn. Yet for me he is the one apart, and his memory has all the fragrance of richest perfumes from friendship’s garden.

It is in his life, and in those of my friends’ dogs, whose life histories I have written, that I have found the data for such thoughts and fancies concerning our relations with the dog, and of the various pleasures, pains, and obligations that result therefrom, which I hope my readers may share with me.

[Pg 4]The summer in which Mr. Gubbins came to me, I had a lady staying with me, who was also a great lover of dogs. A brother of this friend it was, who brought the little aristocrat with the strangely incongruous name to ask a temporary shelter, while his owner looked out for a suitable home for him. This man, another keen dog-lover, had seen and admired the beautiful young Skye at a country house where he was staying. He made friends with the timid, shy animal, who belonged to no one in particular in the house, and when the visitor left, the terrier was offered to him. He could not find it in his heart to refuse, so he brought it to his sister to take care of. I may say that at the time I had a Basset hound and a bulldog, both of which slept in my room at night

When this friend came into my study, where his sister and I were sitting, my astonishment was great to see a long, grey, hairy creature, of which nothing could be distinguished but his magnificent coat, slip in at the door behind the visitor. After a short pause, during which the bright eyes hidden behind a cloud of hair were doubtless taking in the bearings of the situation, the terrier made straight for the long, low chair at the further end of the room, where I was sitting, and curled himself up behind it. My other dogs were in the garden, and there was no one to dispute the refuge with him. He submitted quietly to caresses, but was evidently so frightened that he was soon left in peace, while the reason of his advent was explained.

The Child of the House

GUBBINS

He had gone as a puppy to his late owners, from his[Pg 5] breeder Mr. Pratt, whose long-haired Skyes were at one time well known in Hyde Park, where their master took them for their daily exercise. These dogs were bred with the nicest care, and the strain that came from Lady Aberdeen’s kennels had been preserved. Pratt, who was a butler, living with a family on the Bayswater side of the Park, was devoted to his dogs, but as he could not keep a great number of them, and doubtless looked to making his hobby a profitable investment, the puppies were sold at a remunerative price.

In the case of my own favourite, he had gone early to his country home, and, not having been trained to the house, he was put in the charge of a gamekeeper to have his education completed. This man, whose very name I do not know, had little idea of the gentleness required for successful training. He was harsh and ill-tempered, and the shy, wild little creature, who all his life long was one of the most sensitive of his kind, was years before he recovered from the experiences of those early months. He was cowed and frightened, and, not having the bright merry little ways of puppyhood, he won no favour from any member of the family when he was sent up to the house with his first hard experience of life behind him. He crawled about the grounds by himself, and only asked to be left alone and unnoticed, so that he might escape the rough usage that he associated with intercourse with the superior being. The long grey form was creeping over a wide expanse of lawn, looking a dejected enough specimen of his race, when the visitor saw him from his bedroom[Pg 6] window, and was struck by his great beauty. When Gubbins left with his new owner he accepted the experiences of the journey by road and rail with the dejected submission that only gradually gave place to a real joy in living as he began to forget what harsh words and blows, and the chilling guardianship of kindly but unloving owners, were like.

For the first weeks he was regarded as my visitor’s property, and for a few nights he slept in her room. But in spite of this, and of the constant presence of my own dogs with me, he attached himself to me from the first. He spent long hours curled up behind my study chair, or, if he could gain entrance to my bedroom, he would lie contentedly under the bed. I took very little notice of him, as I did not wish to become fond of him, and was only anxious that he should find a good home before my visitor left me. But very soon Gubbins would follow the other dogs when they rushed up or downstairs in front of me, and he and the Basset being of unusual length of body and shortness of limb, my friend always used to call the procession, “dog by the yard.” Gubbins was so quiet and harmless that the others from the first seemed to accept him as not worth disputing with. When I was busy in my study I soon got into the habit of putting down my hand to pat the little hairy ball that was sure to be within reach, for the garden gambols of the other dogs had as yet no attraction for him. Then one night he got into my room, and was so reluctant to be taken off to his usual quarters that he was allowed to stay, and[Pg 7] from that time to almost the end of his long life he never slept away from me when I was at home.

By the time my friend’s visit came to an end I had begun to wonder if I could ever give him up. As no suitable home offered, and the weeks passed, Gubbins carried the citadel by assault by reason of an illness he had at the very time I had a friend seriously ill in the house. Between my duties in the sick-room I made hurried visits to the suffering dog, who spent his time by the now deserted chair in my study. He would eat nothing but what I gave him, and by his touching trust in, and affection, for me he fairly won my heart.

It was not long after this that Gubbins had his first and only taste of show life. I had been asked to support a dog show in the neighbourhood, and consequently entered him and another of my dogs, Gubbins at that time being about three years old. On the morning of the show, he was taken and delivered over to the authorities, as I was not able to go myself till later in the day. When I entered the show ground I made my way at once to the place where the Skyes were benched, but could see nothing of my dog. The attendants could give me no tidings of him, and it was a kindly stranger who, overhearing my inquiries, at last told me he had seen a Skye in the pet dog section of the show, and he added, “the sooner he was taken away he thought the better.” I hastened to act on the suggestion, and to my great annoyance found my poor Gubbins, looking the picture of misery,[Pg 8] benched in a place only large enough for a dog half his length and size. He was, indeed, so stiff and cramped when I took him out that he could hardly stand. The man in charge of the benches was quite deaf to my assertion that it was cruelty to put a dog in a place so obviously unfit for him, and in spite of the absurd mistake that had been made he tried to refuse to allow me to move him. To this, not unnaturally, I paid no heed, but taking Gubbins with me I told the man I would see the secretary about the matter. When I found this functionary, a much harassed individual, who seemed far from being at home at his duties, I was told curtly that he supposed the mistake was mine in entering the dog for a wrong class! In any case it was against the rules of the show for a dog to be taken from the benches until the judging was over. Nevertheless Gubbins did not return to his martyrdom, and it took him many days to recover from the effects of the combined foolish treatment, and the terror he had suffered at finding himself among strangers. I decided that any honours he might win would be dearly bought, as it was clear his early experiences had made him unfit for show life, and I always refused to let him try his fortune again.

My other dogs were sent to new homes when I gave up my house, but Gubbins became a great traveller, and accompanied me everywhere in the wanderings of the next few years. At first he was quiet as a mouse when taken by carriage or train, and I had no anxiety as to his ever wandering from me, even in the most crowded[Pg 9] thoroughfares. But as his nature recovered its tone, and a bright, joyous, and independent outlook on life became habitual to him, he grew wilful and over confident that my protection was sufficient to rescue him from any trouble. Yet he was three months in my house before he lost the habit of keeping himself hidden from view, and was, as I have said, always concealed behind or under some article of furniture. The slightest accidental touch of a foot, even the gentlest, was enough to make him flee in terror, and for hours afterwards he would not come out from his shelter, or respond to any caresses. Almost to the end of his life, until sight and hearing were impaired, he always rushed into the most secluded corner he could find whenever strangers came into the room, and no blandishments would draw him out while they remained.

I thought at first that his spirit had been so utterly broken that he would never recover, but would always need the care lavished on a semi-invalid. But gradually and surely he began to show the natural fearlessness of his disposition and the bright playfulness that afterwards distinguished him. Little by little he gained courage, and secured his place as first favourite in the house. I do not think, however, that he was ever quite happy while the other dogs remained, though he thoroughly enjoyed his daily scamper with them.

After his first illness he would never feed in the outhouse where the dogs’ dinner was made ready for them. Daily complaints came to me that Gubbins would not touch his food, and though if I went out[Pg 10] and petted and encouraged him he would begin to eat heartily, the instant I turned away he stopped, and no one could induce him to take another mouthful. I said sternly that he must be left till natural hunger forced him to give up the fancy, and it was only when I found how thin and weak he was getting that one day I ordered his previously rejected food to be brought into the dining room. The bowl was put down on a newspaper, spread out for a tablecloth. Gubbins watched the proceedings with interest, and then with much tail wagging, fell on the food with a will and quickly disposed of it. Never after this did he attempt to go near the other dogs when they were feeding, but at breakfast time curled himself up near the spot where his bowl had been placed, and waited till it was brought to him. That I do not shine as a disciplinarian with my pets must, I fear, after this be conceded, for there are drawbacks to feeding a long-haired dog on your dining-room carpet. It only needed a day or two to show Gubbins that manners in the house were not quite on a level with those of the dogs’ feeding-place. As soon as the last mouthful of food was disposed of, a kennel duster was brought into play to remove the remains of the meal from the long hair about the mouth and at the tips of the beautiful ears. After the first time or two he showed his appreciation of the new régime by standing quietly with his head over the dish where he had just finished eating, and if he was not attended to immediately he would look round to see the cause of the delay.

[Pg 11]His enormously thick coat required the most careful daily grooming, and the time spent on this was not an unmixed pleasure to Gubbins. For some time he submitted quietly, as he did to everything else that was asked of him, but by the time he had won his place in the dining room, and the kitchen regions had become unknown ground to him, he sometimes showed resentment at the treatment his tangled locks entailed on him.

The first serious difference of opinion I had with him came over his refusing a piece of toast he had asked for at breakfast. As he had asked for it, he must be made to eat it. But each time the usually coveted dainty was put before him his tongue came out, and with a contemptuous flick sent it rolling over the floor. He was told it must be eaten, and a mutinous determination not to obey was shown in the pose of his head, for one can hardly speak of expression where the face, even to the eyes, was entirely covered with thick, falling hair. But the whole contour of his form expressed a great refusal, and it was felt that a lesson of obedience must be given.

When the meal came to an end the toast was again offered and rejected, and before I left the room Gubbins was fastened to the leg of the table, and I told him the toast must be eaten before he would be released. While the maid was clearing away the breakfast things Gubbins lay perfectly quiet, but as soon as he found himself shut in alone he began to call and struggle. I went in more than once to see if the dispute was at an end, but no, there lay the rejected morsel, and Gubbins would have none of it. When the hour arrived for the daily[Pg 12] walk great sounds of unrest came from the room, and once more looking in I found, to my astonishment, the dog had actually succeeded in dragging the fairly large dining table quite out of its place, in the direction of the door. A chorus of angry barks showed his displeasure, but there still lay the uneaten toast. At this moment, while the door was standing open, the other dogs came into the hall on their way out. “Is Gubbins to come with us?” asked their guardian. “No,” I answered. “If he will not eat the toast he must be left at home.”

Behind the bundle of hair I could just see two bright eyes fixed on my face. The front door opened, and the other dogs rushed out. Gubbins sat up, listening intently, and when he found the others were actually going without him he looked round for the object of contention, flung himself upon it, swallowed it, and then rushed barking to the end of his tether, demanding to be set free. Needless to say this was done, but the excited, quivering dog turned for one second to give my hand a dainty, propitiatory lick before he rushed off wildly in pursuit of the others.

The lesson was remembered, but all through life, from this point, a wilful determination to have his own way was one of his characteristics. This I attribute to the reaction from the harsh treatment of his early days, and though it is probable that with firmer discipline it might have been overcome, I found it impossible to resort to harsh measures when he was only just coming out from the shell of nervous dread that had seemed to wrap him round from all the enjoyments of life. I fear I[Pg 13] hailed the first exhibitions of will as an indication of his recovery to a normal state. A sharp word from me, if given at a sufficiently early stage, would always restrain him, but to others he was not so obedient, and I fear soon learned to trade on the fact that under no circumstances would he be beaten. A flick of a handkerchief he took with stoicism from others, but from my hands it had all the effect of a stronger punishment. He would crawl away, and lie, a picture of dejection, for an hour or more. He was left to feel himself in disgrace, until he would presently come creeping to my feet for the pat of forgiveness that restored him to life and animation.

His devotion to me never wavered, and after each of his severe illnesses I thought I saw a closer attachment show itself in many ways. What, perhaps, was the greatest proof of his unwavering loyalty was that during the last six months of his life, when he was sixteen years of age, nearly blind and partially deaf, and in a state that required him to be carried up and downstairs, and otherwise attended to, I was not able to have him in my room at night, and his care passed greatly into the hands of others. To his guardians he was very affectionate, and especially to the friend who watched over him with the most devoted care, and to whom Gubbins looked for the greatest enjoyment of his life—his daily walk. But there could be no doubt in the mind of any one who was with him, that no one was likely to displace his mistress from the warmest corner of his heart.

He always showed the nicest appreciation of the capacity and duties of those who took care of him. When[Pg 14] he was already so feeble that he was generally carried from one room to another, I was astounded to find he realised that I was not strong enough to do this. His knowledge was all the more extraordinary because when in stronger health, I had been in the habit of lifting and carrying him on occasions. But one night when the maid who always carried him into the dining room, and for whom he waited as a matter of course if she was not there when I went to dinner, was absent, Gubbins came out of his basket as soon as I moved and crawled into the other room after me. The following night his attendant was at home, so Gubbins stayed quietly in his basket as usual till she came to fetch him. Often afterwards the same thing happened, and during the whole of the time after his powers had failed he never once appealed to me to lift him. He would make the most determined efforts to mount the garden steps if I was with him, though he never attempted to do so if he was with any one else, but would lie down and wait to be fetched if he was not lifted at once.

At one time when I had him in lodgings, the maid who attended on him was with me, and always carried him up and down the two flights of stairs that led to my bedroom. When the maid was going home for a month’s holiday I wondered what I should do with him. I did not think he could get up by himself, and did not want to call a strange maid to my assistance. At bed-time I went to the stairs as if I expected him to follow me, and the little thing worked his way up with a sideways motion after me, stopping on the landing for a rest,[Pg 15] and then finishing the journey. In the morning he followed me down, though this was really a dangerous proceeding, and I had to prevent his taking a roll to the bottom by holding him up with his lead fastened to his collar. This performance was repeated as a matter of course every night and morning for the month, and when the maid returned I told her that Gubbins had learned to go upstairs by himself, and that while he could do so I preferred him not to be carried. When she came to fetch him, therefore, for the night, she told him to follow her, and he went out of the room after her obediently. At the foot of the stairs, however, he laid down, and turning a deaf ear to her calls he quietly waited for her to come back and pick him up.

That under any circumstances Gubbins could refuse his walk I did not believe, till one day I found him lying on the front doorstep, and refusing to move at the entreaties of his prospective companion, the reason being that he had discovered I was about to leave the house. This was when he had been with me about a year, for up to that period he had shown himself equally willing to go out with me or any other of his friends. After this he would never go until he was sure that I was not going out, and many a time he insisted on being let into my study to see if I was there, before he would leave the house. If nothing in my dress suggested a walk he would go off and immediately give himself up to the joys of the coming expedition. When at one time I used to go out in the early morning before breakfast, at a certain stage in my dressing operations Gubbins would[Pg 16] always come up to investigate what boots and skirt I had on. If his sensitive little nose told him those were in use that he connected with a walk, he began to bark and jump round me, as if wild with joy, for he knew that he would go too. But if he recognised the skirt in which I usually cycled he crept away dejectedly, for on these occasions I always left him at home. Although his speed would have enabled him to keep up easily with the bicycle, I have always thought it mistaken kindness to allow a dog to go at the stretch of his powers while he keeps in touch with carriage or bicycle, as the prolonged tension is likely to injure the natural action of heart and lungs.

One day, when there was illness in the house, the volley of barks and wild gambols with which Gubbins showed his joy at an approaching walk could not be allowed. I felt a little doubtful if the exuberance of his joy could be kept within due limits, and in any case I knew I was the only person likely to be able to restrain him. When the moment arrived for putting this to the test I knelt down by him, and turning his little head up I put my finger on my lips and in a low, hushed voice told him he must be quiet. He saw I was dressed for walking and knew what was in store. He was, however, evidently impressed, and opening the room door quickly I cautioned him again, and to my great relief only one little half strangled bark escaped before we were safely outside the hall door. Yet he tore down the stairs in his usual headlong manner when excited, and was quivering with eagerness for the coming joy.

[Pg 17]After this I was always able to make him go out quietly by the same means, and in a house where he stayed with me for some weeks he learned that under no circumstances was barking allowed indoors. He consequently won golden opinions from the old lady whose feelings he thus spared. But that he felt the long restraint irksome, he would show by a petulant twist of his head from under my hand, when I made one of my many appeals to him to remember the caution. His self control happily lasted to the end of the visit, though I never felt inclined to put it to the same test again.

It was one of the most interesting studies I have ever had, to watch the gradual unfolding of Gubbins’s mind as he threw off the terrors of the past. His strong affection was, as I have said, the first point that showed itself. Then his intelligent appreciation of the ways of the household, and his own place in it, was little by little made plain, and with it came the manifest determination to stand on his rights. It was not, however, till he had been with me for some four years that he began the system of signs and sounds that stood to him in the place of language.

There were certain biscuits kept for Gubbins as a treat when he had behaved with decorum in the dining room, where he used to lie in a corner during meals. These biscuits were known in the household as “Peter Burrs,” owing to the correction given me in the matter of pronunciation by a worthy country grocer, when I stated my wish for “Petits Beurres.” The tin containing these dainties was generally taken from the sideboard by[Pg 18] one of ourselves, just before we left the table. Gubbins was always all attention, and at the movement to fetch the tin, he would come out of his corner and bark rapturously. But one day a friend brought me the wrong tin by mistake, and Gubbins, who had been all eagerness as usual to watch for its advent, sat down quietly and did not attempt to come up for the usual offering. It was this conduct that led me to notice the mistake that had been made, for the tins were almost alike in size, though different in colour. The dog’s appreciation of the mistake before we had recognised it, caused such amusement that while this friend was staying with me she often tested Gubbins’s discernment by bringing out the wrong tin purposely. Never was he deceived, though one day he rushed up and barked once before he noticed the tin, but as soon as he saw it he sat down and waited for the mistake to be rectified.

It was when he stole to my side during luncheon, and made his presence known by a delicious little low sound of entreaty, that his language sounds began. I was so delighted with the effort that I took to making him say it before he had one of his much loved biscuits given to him. “Ask, Gubbins,” he was told, and the little entreating sound came as a preliminary to business. Very soon he learned to use the signal to draw attention to any want, such as the need for water, or the opening of a door. Whenever his water dish was empty Gubbins would first call attention to the fact by lying full length in front of it, with his head touching the dish. If this[Pg 19] did not succeed he would look round to see why he was not being attended to, and if I was—or pretended to be—wholly immersed at my writing table he would cry quietly to himself,—a little complaining noise that could not be overlooked in its gentle persistence. Once or twice I tested him further to see what would happen, and when Gubbins found that my denseness was not to be pierced by any ordinary means he came up to me and, resting his head against me, “asked.” Then he walked back to his water dish and lay down as before. That here there was a very intelligent adaptation of means to end is evident.

The daily bone thrown to Gubbins was of course a great delight, and once I tried the same experiment that Mr. Herbert Spencer made with his Skye, and with the same result. A string was fastened to the bone and Gubbins had his usual play with it, a necessary part of which was for him to stand growling over it and dare any of his friends to take it from him. This nearly always brought some one on to the lawn to play the part of robber. It was enough for one of his friends to advance gently towards him saying, “Is that for me, Gubbins?” for the little thing to seize it in his mouth and run to a distant part of the lawn, where the performance was repeated. If his friends did not go on playing the game I have known Gubbins to leave his bone and come to ask them to see it out, and only when his spirits had exhausted themselves would he settle down to the enjoyment of the dainty, secure in the knowledge that no one would be allowed to interfere[Pg 20] with business. But to return to the experiment. Gubbins was just settling down to the serious part of the performance when I pulled the string and drew the bone gently away. Gubbins gave a startled look at it as it receded slowly, then as it lay still he approached with every sign of caution and stretched out one fat paw. Still there was no movement, and relief and confidence were now expressed in his bearing. Then I jerked the bone to some distance. Gubbins fairly turned tail and fled to me for protection. The sense of the unknown, conditions of which he had no previous experience, terrified him, as did the growling of thunder or the presence of strangers in his own home.

In matters where Gubbins was on known ground his courage was beyond dispute and often brought him into peril. No dog was too large or too strong to call forth hostile demonstrations, if he happened to excite his ire. I well remember the horror with which, on hearing the well-known rush and growl that signalised Gubbins’s dislike of another dog, I turned to see the ridiculous little creature hanging on to the nose of a huge St. Bernard. With one angry toss of his mighty head the larger dog could have broken the spine of his tormentor. Happily the monster seemed too astonished at the onslaught of the hairy mass to do anything beyond give a very gentle swaying motion of the head, which swung Gubbins’s long body from side to side; for even hanging as the latter was at full length, his hind limbs were well off the ground, and he must have made one of his marvellous springs to fasten on the[Pg 21] head as he did. Presently his teeth loosened and he dropped from his perilous perch, and he certainly owed his life to the remarkable gentleness of his victim.

Before Gubbins had walked off his excess of spirits in exercise he often gave these mad rushes, sometimes, I grieve to say, at humans. Any unsavoury specimen of the genus tramp always roused his mischief, and so, alas! did any gentle, fragile looking old lady or gentleman who could be depended on to receive his onslaught with a sufficient display of terror to make it worth while. Many were the scrapes from which he was not always rescued with the honours of war, and countless were the apologies made on his behalf. But after his maddest exploit the absurd little bundle of hair would come meekly to my feet, and generally by his very appearance disarm the sufferers. At such a moment caresses from the stranger’s hand were suffered with deceptive meekness, and were evidently taken as the necessary consequence of the previous joy. That the loud bark which would have fitted a dog ten times his size, and the sudden rush at the heels of a passing stranger, were sufficiently alarming, is clear, and a leather lead was soon fastened promptly to his collar whenever a human approached who long experience had taught me was one likely to be singled out by Gubbins as a vent for his excitement. His teeth never came into play, and this showed it was simply the fun of the thing that appealed to him, and not the hostile feeling that often prompted his attacks on fellow dogs.

Gubbins was the most humanly intelligent of all the[Pg 22] dogs I have ever owned, and so far as his powers of mind went they appealed perfectly to the same level of expression of our own. While his trust and love were unwavering, his sympathy with anything in the shape of suffering or sorrow was undoubted. He would never leave me of his own free will, if he knew I was in trouble, though it could only have been by the tone of my voice that he discovered there was anything amiss. In the case of physical illness it was the same, and he would lie for hours on the foot of my bed, to which on these occasions he always “asked” to be permitted to jump.

The highest exercise of intelligence he ever showed was prompted by his love, and the amount of reasoning power that led to the successful carrying out of his stratagem shows what a narrow boundary there is between the highest efforts of the animal mind and those where human intelligence begins. I was suffering at the time from malaria, a legacy from a fairly long sojourn in India, and it was decreed by the friend who had taken charge of my sick-room that Gubbins was not to be allowed to disturb me. This lady, who was herself one of Gubbins’s most faithful friends, and was regarded by him with the warmest affection, told him after breakfast that he was not to come to me. That he fully understood what she said he showed by the dejected way in which he turned from her and crawled into his basket. The dining-room door was then shut on him, the back stairs were cut off by two heavy doors, and the passage from the top of the front stairs led past my friend’s bedroom before my own could be reached.[Pg 23] From her bedroom, where the visitor sat writing with her door open, she could hear if any of the household should go into the dining room and set Gubbins at liberty. Besides, the flop, flop with which he always jumped from step to step of the stairs was clearly audible over all that part of the house, and this gave her confidence that he could not, in any case, get up without her hearing him.

But the dining-room door had not been fastened securely, and though it was a heavy oak door Gubbins managed to work it open. He then crept upstairs without a sound, and therefore in a very different way to that in which he usually mounted, stole past the open bedroom door, without betraying his presence, and putting his head close to the crack of my door gave one of his tiniest “asks.” So low was it that the watcher in the adjoining room heard nothing. At first I did not realise what had happened, and thought the voice reached me from a distance. But when a repetition came, the peculiar guarded sound of the faint call struck me, and at the third time I knew that by some means Gubbins had found his way to me. Entering into the spirit of the enterprise I opened the door softly and let him in. Without any of the usual manifestations of joy with which he was wont to greet me, he slipped past, and without waiting for the permission he always asked he sprang on the bed and curled himself round with a sigh of content. Then the drowsiness of fever overcame me, and I dozed for some hours, Gubbins also sleeping peacefully at my feet.

[Pg 24]When at last my friend appeared, her relief at the sight of the hairy bundle on the bed was great. She told me that a search had been made for him all over the place, both indoors and out, as soon as it was discovered that he had escaped from the dining room. My room had not been thought of, as she felt certain he could not have come upstairs without being heard by her.

The amount of thought and caution exercised by the dog in carrying out his plan was remarkable. After making use of the great muscular strength of his sturdy forepaws in getting open the door of his prison, he had to get upstairs in a way that would not betray his presence. How he managed this we could not understand at the time, but years afterwards I saw him, when still weak from a severe illness, crawl up with a sideways, crab-like motion that explained what he had done to attain his ends in the heyday of his youth and strength. Placing his forepaws on the step above him he hitched his hind quarters up sideways, as his length could only thus be supported on the step, the depth of the stairs not being more than half his length. In this way there was no noise, but he still had to pass the watcher’s open door and convey the fact of his presence to me without letting her know. This accomplished successfully, he did not forget the need for caution when he had made good his entrance, but with a silent caress to my feet, and much wagging of the tail he left his usual mode of welcome severely alone, and, secure of my understanding and abetting, even took possession of one of his most[Pg 25] prized rewards, only rarely accorded, by jumping on to the bed without the preliminaries of permission asked and granted that were always insisted on.

Here he showed a clear appreciation of the difficulties of carrying out his plan, and who shall say what was passing in his brain as he stole softly upstairs, passed his friend’s open door without disclosing his presence, and then, with all the precautions a human could have used, succeeded in communicating with me? Not less remarkably did he show his appreciation of the dangers so far conquered, when he exercised needful self-restraint in the expression of his greeting, and sank down at last with a sigh of content as he realised that all was well.

We are told by an eminent writer on the psychology of animals that the feeling of shame stands very high in the development of the emotional powers. In Gubbins its manifestation was very apparent. A flick of the handkerchief or a sharp word from me changed his whole aspect in a second, unless, indeed, the excitement of some forbidden pleasure had taken him in too firm a grip, and the enterprise on which he had started had to be carried out at all costs. But once the excitement passed, shame for his misdeed followed, and was shown in the same way a child will do in the same circumstances, up to the verge of speech. On one occasion, when I was from home all day, the maid in whose charge he had been left neglected to attend to him. The shame-faced little dog that met me on my return, and who put his head in my hand and cried softly, told me that some trouble had happened for which he was not to blame. In the same[Pg 26] way when he was suffering from illness that caused occasional attacks of sickness, if by chance he was shut in a room when misfortune overtook him, although he knew he would not be punished for what was not his fault, he could not have shown more shame at the occurrence if he had dreaded chastisement.

Gubbins was a little gentleman in all his ways and feelings, his one lapse from propriety of manners being the rushes by which he helped to work off the excitement of his walks. He could always be depended on to preserve a neutral attitude towards any stranger staying in the house, if I performed a sort of introduction by putting my hand on my visitor’s arm and telling Gubbins that he or she was my friend. The same course had to be adopted with a new maid, and if a fearless pat was then given him by the new-comer, I knew that as long as that person was in the house there would be no trouble. But if, on the other hand, the slightest fear of him was shown, it behoved me to be careful, for if that maid came in his way when he was under the influence of any excitement such as that of his daily walk, there would be the same attempts to upset her equanimity by which he distinguished himself out of doors. No use of the teeth, but just the communication of his own excitement to one who his instincts told him could be relied on to respond. To secure the clatter of a fallen tray, or the headlong rush of a frightened maid downstairs, while he stood growling and barking at the top, as if ready to tear her in pieces, gave him, I grieve to say, under such circumstances, the liveliest enjoyment. But[Pg 27] when he was shut up to reflect on his misdemeanours, by whatever process these were brought home to him, an unmistakable feeling of shame was displayed as soon as he had recovered his normal state.

The abject depression with which he crept from view one very wet autumn, the first time his long coat was clipped about his legs and the under part of the body, took a long time to recover from. For days a remark on his appearance, or a laugh at his expense by any visitor, would cover him again with shame. His self-respect had been wounded, and the same feeling was shown when he was taken out for a walk the first time after a severe illness. The poor weak dog could only totter along for a very short distance. But on the way he met another dog, and as soon as Gubbins saw him approaching, the change in his demeanour was instantaneous. With head and tail erect, and a general air of alertness and strength, he passed his rival, walking on the tips of his toes, as he was wont to do in better times. A few steps carried him triumphantly past, and then, the excitement over, the poor little invalid collapsed as suddenly as he had pulled himself together, and rolled over helpless in the dust. Could any animal without a sense of the ego, the personal I, show such a keen sense of the respect due to himself?

A quite marvellous knowledge of time was shown by my favourite. I am not speaking of the hours of feeding, for such knowledge is doubtless due to the promptings of the natural appetite. But how for some months he always knew when the clock pointed to half-past nine I[Pg 28] have never been able to ascertain. A lady who was living with me as my secretary at the time was a warm friend of Gubbins, and was accepted by him as such. This lady was not in good health, and used to retire to bed before the rest of the party. In about a week Gubbins constituted himself the guardian of her health in this respect. If she did not move promptly at the half hour he roused himself, came out of his basket, and, sitting at her feet, barked until she got up and said good-night. The performance was so much appreciated that after this Gubbins’s reminder was waited for, and though there was no clock within hearing that struck the half hour, nor so far as we knew any sound that could tell the time, Gubbins was never more than a few minutes either before or after. He would go and sit close at the lady’s feet, lift his head and fix his brown eyes on her face, and bark his signal for her to go. There seemed no reason for him to wish her to leave, as no sooner had she gone from the room, than he went back to his basket and curled himself up to wait for the dispersal of the other members of the family. With no one else did he ever do anything of the same kind.

At one time when I was living in the country, the same inscrutable knowledge of the hour of seven in the evening was shown by him. Once or twice he was taken for a run across the valley below the house to the post, just before the dinner hour at seven-thirty. After that he was always on the look out at seven o’clock, and as soon as he associated the little expedition with one member of the household, he found him out and kept close[Pg 29] to him as soon as the hour arrived. Once, when the dinner hour had been advanced, the letters were taken earlier, and Gubbins had not come in from his rambles in the garden and could not be found. He was watching, however, when the messenger returned, and showed that he understood what had happened by taking up his position in good time the following day on a point in the drive where the two ways from the house met, and without passing which no one could leave the place. Often after this he would sit there watching, instead of coming into the house, as he clearly understood that from that spot he had a full command of the situation.

As the gradual unfolding of Gubbins’s mind had been an unfailing source of interest, so was the preservation of his natural characteristics when his powers began to fail. He enjoyed his life almost to the end, and through the last long day of suffering found comfort in the care and affection that were lavished on him. Although for some time his eyesight had almost gone and his hearing was impaired, and other disabilities of old age were upon him, he still went nearly mad with joy at the prospect of a walk, still took a certain modified, though always mischievous, pleasure in making others share his excitement, and made his sense of smell serve for the loss of his other faculties in a quite marvellous way. He always recognised his old friends, and it was a characteristic of his throughout life that he never forgot a single person whom he had once accepted as a friend. It might be months or even years before he saw them again, but he never failed to recognise them.

[Pg 30]Various were the names bestowed on him by his many friends at different times. From the absurd “Mr. Gubbins,” he was called by the still more unsuitable title of “Scrub.” This led to a mild joke of a friend of mine, who always inquired after him by the formula, “And how is Ammonia?” A very dear old lady, the mother of the friend through whom Gubbins came to me, spoke of him as “The caterpillar,” moved thereto by the sight of the long dark form that used to steal across her drawing room to find a hidden corner, when he was staying with me in her house. In the inner circle of his home he became “The Hairy Angel” or “The Fascinating Fiend,” according to the nature of his disposition at the moment.

But these names belong to the time of his youth and strength; his beauty he kept to a surprising degree up to the very day of his death. It was touching to see him in his later years, and especially during the last six months when he was all but blind, finding his way about the house by the help of his nose. I have often watched him come into my study when he was looking for me. The room is a double one, and he used to feel for the side of the arch that forms the division, then feel about for the couch that stands on one side of the inner room. From there he touched my bureau, and thence worked about till he found my chair, which was often at some little distance. No sooner did his nose touch the chair than he hurried to the front of it to see if I was sitting there, and feeling the full helplessness of continuing his search if I was not in my usual place, he would curl himself[Pg 31] up beside it and cry quietly. I have watched him do this while I stood by the bookshelves in the back room, though I had to be careful he did not find me out, as he came in by the door in that room.

To the last the watchful little head would come up in his basket, and a warning growl give notice of the presence of a stranger, and in his feeble way he guarded his beloved mistress to the end. When the little life went out from the suffering body it left a blank that for those who loved him best can never be filled, but—

“Ung Roy, ung Loy, ung Chien”

BRUCE, a beautiful black and tan collie, had the appearance of a gentleman and the finished manners of one accustomed to the usages of society. In the days of his prime he won many honours in the show ring, though his points were not those required by modern fashion. His head was too broad for present-day judges, but this gave space for the brains that made Bruce the most charming of companions. He was light in build, strong, and full of grace and activity, and his beauty he retained almost to the end of his life. His colour, as I have said, was black and tan, the latter a bright golden hue, that was very striking. His eyes were clear and brown, and wonderfully expressive, and over each was a bright tan spot. His ears were half prick, the points of which almost met over his forehead, when he stood to attention. His ruff was magnificent, and had it had the ring of white decreed by fashion Bruce would have carried all before him on the show bench. As it was, the only touch of white about his coat was at the tip of his grand brush, for to speak of it as a tail seems almost an indignity.

The Diplomatist

BRUCE

But it was the high-bred finish of his manners that won Bruce his many friends. In his home circle he was[Pg 33] always gentle and affectionate, though he had the finest grades of distinction in his regard. Any member of the family had a general place in his affections, but that underneath this was a subtle difference in his feelings was shown by his behaviour towards them. To the servants of the house he was always polite, and to the older ones who were admitted to the confidence and respect of their employers, he was even affectionate. But he never gave them the outbursts of unrestrained affection that in moments of excitement he would shower on his special friends in the family circle. Being a great favourite with the servants, he was always something of a tyrant with them, and clearly thought that one of their chief duties in life was to wait on him.

His politeness to visitors was invariable. If he saw strangers coming to the house he would accompany them to the drawing room, and as soon as they were seated would gravely offer a beautiful silky paw. In the same way he would be ready, when they took their leave, to escort them to the front gate, and there once again offer a paw in farewell. This was always a very taking performance of his, and if the departing visitor, after duly accepting the offered salute, said to him, “That is a very cold good-bye, Bruce,” he would instantly offer the other paw in token of good-will. The strangest thing about his attention to visitors was that no one had instructed him, and it was not till Bruce’s hand-shaking was talked of as quite a feature of a call at the house that his master taught him to offer the right paw in salutation. This he learnt as quickly as[Pg 34] any other lesson, and with its accomplishment the last touch of polish had been given to Bruce’s society manners.

Bruce came from a large kennel when he was two years old. His pedigree and former history were unknown, and Bruce started in life with only his good looks, his intelligence, and his perfect manners to depend on. When he came to his new home he responded instantly to individual affection and attention, and showed a very strong sense of his personal rights. His master at that time owned another collie, also a house dog, who answered to the name of Lassie. From the day of Bruce’s advent the two dogs took it in turns to pass the night in their master’s bedroom. Bruce always respected the arrangement, and on the nights when it was not his turn to have the place of honour he would curl himself up contentedly on the mat put ready for him in the hall; but Lassie would often try to steal a march on him. She would lay her plans in advance, and creep upstairs before her master retired, and trust to possession to bring her through. As soon as Bruce discovered her tactics he would rush up after her, and do his best to pull her downstairs. Ejected with ignominy from the bedroom, Lassie would still make a fight for it, and entrenching herself on the landing do her best to stand her ground. The commotion of course attracted their master, who would take Lassie by the collar and lead her in disgrace down to her allotted sleeping place in the hall. Bruce would sit smiling at the top of the stairs and watch her down, wagging his[Pg 35] tail and giving every sign of complacent satisfaction at having won the day.

It was in his dealings with humans that Bruce showed his talent in diplomacy. He often paid visits with his master, and never failed to bestow the cream of his attention on the most important person present. He singled out his host or hostess and made good his place with them before he took the slightest heed of any one else. His greatest triumph was during a visit to his master’s grandmother. For some reason his owner felt obliged to take him, though the old lady was by no means an indiscriminate dog-lover, and was wont to declare that she “liked dogs in their proper place.” Many were the talks held in the family before Bruce’s departure as to what his reception was likely to be. Did he understand and take his measures accordingly? The result seemed to justify the supposition. In any case, on arriving at the house he settled the matter once for all. Without a word being said to him he went straight to his hostess’s room, and arriving there before his master he sat down in front of the old lady, and, with a grace that instantly won her heart, offered first one silky paw and then the other for her acceptance. By the time his owner arrived Bruce was reaping the first fruits of his diplomacy in the petting and admiration of his new friend. Bruce’s “proper place” after that was any spot he chose in the house, and he was given a warm invitation to repeat his visit when he left.

While he was still new to the show bench he exercised his tact, by getting a man he knew to stay by him,[Pg 36] as presumably he felt lonely among so many strange faces. The man was the village schoolmaster near Bruce’s home, and so far had always been treated with polite indifference by him. As the schoolmaster was making a round of the benches he felt a touch on his arm, and there was Bruce with a most amiable expression of countenance holding out a paw to him. The man responded to the advances made to him, and Bruce, all anxiety to please, managed to make him stay by him till one of his own family arrived. The reason of his amiability was then apparent, for Bruce promptly relapsed into his former indifference, and his visitor was allowed to depart without any further notice being taken of him.

When Bruce was more used to the show bench he manifested the most lively appreciation of having been singled out for honours. If no card fell to him he curled himself up on his bench, put his brush over his head, and slept quietly till all was over. But when he had secured a card his demeanour was very different. He sat up with an alert and self-satisfied air, and though as a rule he did not make advances to strangers outside his home, he now seemed possessed with a universal benevolence. He always attracted attention, and to all who admired him he instantly offered to shake a paw in the most affable manner. He used indeed to hold a levée, and thoroughly enjoyed the unwonted importance of his position. So long as he was in the show grounds his general friendliness lasted, but once outside his show manner was dropped and he became chary of notice by strangers.

[Pg 37]He never, however, resented advances being made to him unless he was startled. Being nervous and high strung, any sudden rough movement he disliked, and under such circumstances would give a snap to mark his displeasure. He never used his teeth, for he was by no means uncertain in his temper. To other dogs he was usually gentle, but a collie he would always go for. Many were the scrapes he got into in consequence, and when his master had cured him of the trick of making the attack, he would invariably pass a collie with such wanton provocation written in his bearing that the other dog, stirred out of his self-control, always made for him.

Bruce’s enjoyment of practical jokes was great. When a walk was in prospect, his delight was to rush into the hall, and, snatching his collar and lead from their place on the hat-stand, hastily throw them into hiding. A glance at Bruce’s smiling face was enough to tell his master what had happened. Intense enjoyment was displayed by the watching dog, while a search for the missing collar was made. But Bruce’s paws were long, and the place he had selected was not always easy to find. Then his anxiety for the coming joy of the walk would carry all before it, and moving suddenly to the place of concealment he would seize the collar and fling it at his master’s feet. The superior and slightly supercilious way in which he brought to light the hidden thing said as plainly as any speech, “If you are so stupid that you cannot find it, I suppose I must help you.” In the summer he would sometimes change his tactics, and taking[Pg 38] the collar and lead in his mouth, would jump a fence or hedge, and lie just out of reach on the other side. If the moment for a joke was not well chosen, and there seemed any danger of his being left behind to enjoy it by himself, he was speedily at his companion’s feet, asking, with an eloquence none the less to be understood because it was mute, to be forgiven and taken out.

His greatest joy was to have stick or umbrella confided to his care during the walk. Solemnly, and with a great show of appreciating the duties of his position, Bruce would walk decorously by the side of the owner of his trophy. But not for long. There would be a sudden flash, and Bruce would disappear over some obstacle where he could not be followed, and after a race round the orchard or field into which he had hurled himself, he would reappear with nothing in his mouth. With expectancy written all over him he waited for the order to “Go, seek.” Obediently he flew the hedge and proceeded to hunt for the missing stick. But the result was always the same. He could not find it. Again and again the same process would be gone through, and no one could look more guileless than Bruce when he returned to tell of his want of success. Sometimes the only way to stop the game was to walk on and leave him to himself, on which he would go directly to the spot where the stick was lying hidden, take it up, and go on decorously as before, carrying it in his mouth.

Bruce acted as if the secrets of the family circle were an open book to him, or at any rate those that concerned himself. As he and Lassie, whatever their private differences,[Pg 39] would always unite against a common foe, their master found his walks disturbed by the frequent altercations that arose in the course of them. He announced, therefore, that for the future he would only take out one at a time, and as he was going that day to a town about a mile off, he gave orders that Bruce was to be shut up before he started. Bruce at the time was lying quietly on the hearthrug, and in a short time he got up and went to the door, and was let out into the garden. His master thought no more about him, and later in the day started for his walk, taking Lassie with him. When he had almost reached the town he was struck by the resemblance to Bruce of a dog sitting in the middle of a patch of grass, where three roads met. His own way lay past the spot, and he soon found that Bruce was waiting there for him too far from the house to be taken back, and thus securing his walk. One of his exploits seems almost beyond the realm of the possible, but I can vouch for the truth of the facts as I give them. His master was in the habit of going away on business, and leaving his home on one day, he nearly always returned on the next. On one occasion, however, he said that he should return the same night, and in order to do this he would come by another railway line and reach a station he very rarely used, at 10.30. Bruce as usual was with him when he talked of his plans. That evening when Bruce was let out for his evening run he disappeared, to the consternation of the other members of his family. He was searched for in all directions, but no tidings could be[Pg 40] heard of him, and great was the rejoicing when at eleven o’clock he returned. The household had been waiting up for the master, but he did not arrive. The next day he came back by the way he had intended to come the previous day, and he had no sooner alighted from the train than one of the porters who knew him came up and said, “Your dog was here looking for you last night, sir. He saw the train in and seemed to expect you, and when he found you were not here he went off. He would not let any of us touch him.” On arriving at home his master heard of Bruce’s absence the night before, and the chain of evidence seemed complete. Not so the explanation. Bruce’s presence at the station was vouched for by a perfectly disinterested person, who could not have known any of the circumstances attending his master’s journey. The dog’s absence from home at the time was undoubted, so also was his presence when his master stated his plans, but how it was that Bruce was ready to welcome the expected traveller at the station I cannot pretend to explain. It is quite one of the most inexplicable efforts of a dog’s intelligence that I have ever met with.

Though for fifteen years Bruce lived with his family, his life was not without vicissitudes. After a time his master took up an appointment in India, and Bruce had to be left behind. He passed into the care of his master’s brother and sister, with whom he was already on affectionate terms. In his new home, however, he did not have the first place, as a very remarkable spaniel was already in possession. Bruce, with his usual ready tact,[Pg 41] though with chastened feelings, took the second place. The cook in his new home was an old servant, whom he had known in his first days of acquaintance with the family. She had indeed passed through various stages in the household, and from nursery maid in “the old house” had risen to be cook to the “young master and mistress.” For Bruce, Harriet had simply a passion. He could never do wrong for her, and in return she was decidedly tyrannised over by him.

But in Nottingham, where Bruce’s lot was now cast, the townspeople appreciate a good dog. So one day Bruce disappeared, and all inquiries about him were unavailing. His guardians gave him up, but Harriet never lost hope and always declared that he would come home. Every night this devoted woman sat up till the small hours of the morning, watching and listening, and with a saucepan of hot soup ready for the wanderer. On the third or fourth night, she heard a feeble call at the front door, and rushing up she found Bruce, with a fragment of dirty rope round his neck. The dog seemed at almost the last stage of exhaustion, and staggering in he was taken to the kitchen fire, and without moving from his place he lapped up a little warm soup, and slept the sleep of exhaustion for twenty-four hours.

Why he should have been so worn out was never explained, as from “information received” it turned out that he had spent his time in a street of small houses not a mile away from his home. His experiences, whatever they may have been, were never forgotten by him, and[Pg 42] from that time he showed a disposition to bite every ill-dressed man who approached him.

After five years’ absence Bruce’s master returned, and Bruce on hearing his voice looked at him attentively and then gave him the modified form of affectionate greeting that showed he recognised him as one of the family. The dog seemed puzzled, and the dim memories that stirred in the back of his mind led him to follow his old master to his bedroom at night. There he lay down quietly, and it was not till his master was in bed that the far-off echoes of past days became clear, and with a cry Bruce suddenly hurled himself on the bed and covered his astonished owner with caresses.

When the time came for another long parting Bruce took the matter of his future guardianship into his own hands by attaching himself so lovingly to his master’s father that his decision was accepted without demur. Alas, Bruce never saw his master again, for old age and infirmities were upon him, and before another return from India the old dog had passed away.