Junior

Classics

THE·YOUNG·FOLKS’

SHELF·OF·BOOKS

P·F·Collier·&·Son Corporation

New York

Title: The Junior Classics, Volume 9: Stories of To-day

Editor: William Patten

Release date: July 16, 2018 [eBook #57522]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR, For Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Junior

Classics

THE·YOUNG·FOLKS’

SHELF·OF·BOOKS

P·F·Collier·&·Son Corporation

New York

The

Junior Classics

SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY

WILLIAM PATTEN

MANAGING EDITOR OF THE HARVARD CLASSICS

INTRODUCTION BY

CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D.

PRESIDENT EMERITUS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

WITH A READING GUIDE BY

WILLIAM ALLAN NEILSON, Ph. D.

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

PRESIDENT SMITH COLLEGE, NORTHAMPTON, MASS., SINCE 1917

VOLUME NINE

Stories of To-day

P. F. COLLIER & SON CORPORATION

NEW YORK

Copyright, 1912

By P. F. COLLIER & SON

Copyright, 1918

By P. F. COLLIER & SON

“Brother Rabbit’s Cradle,” Joel Chandler Harris; Copyright, 1904, by McClure, Phillips & Co. “A Story of Decoration Day for the Little Children of To-day,” Elisabeth Harrison; Copyright, 1895, by Elizabeth Harrison. “The Taxes of Middlebrook,” R. S. Baker; “The Cure of Fear,” N. Duncan; “A Christmas Adventure,” J. E. Chamberlin; “Chased by the Trail,” Jack London; “Big Timber Beacon,” J. L. Mathews; “How Hilda Got a School,” Lelia Munsell; “The Second String,” J. B. Connolly; “Holding the Pipe,” A. W. Tolman; “The Travelling Doll,” Evelyn S. Barnett; “The Idea That Went Astray,” Pauline C. Bouvé; “Gravity Gregg,” I. O. Rankin; “Jonnasen,” D. L. Sharp; “In the Oven,” R. W. Child; “On a Slide-Board,” R. Barnes; “On a Tight Rope,” A. W. Tolman; “The Call of the Sea,” F. Palmer; “Down the Incline,” C. N. Hood; “Drasnoe Pipe-Line,” A. S. Pier; “Manuk Del Monte,” R. Thomas; Copyright, 1898, 1903, 1904, 1905, 1906, 1907, 1908, 1909, by Perry Mason Co. “The Fore-Room Rug,” Kate Douglas Wiggin; Copyright, 1895, by Kate Douglas Riggs; used by permission of and by arrangement with the publishers, Houghton, Mifflin Company. “The Imp and the Drum,” Josephine Daskam Bacon; From “The Imp and the Angel,” Copyright, 1901, 1907, by Charles Scribner’s Sons. “The Foreman,” S. E. White; Copyright, 1903, by S. S. McClure Co.; 1904, by Stewart Edward White. “The Cost of Loving,” F. O. Bartlett; Copyright, 1912, by P. F. Collier & Son. “Ladybird,” Edith Barnard; Copyright, 1906, by P. F. Collier & Son. “The Gray Collie,” Georgia W. Pangborn; by permission from “Interventions”; Copyright, 1911, by Charles Scribner’s Sons. “Cressy’s New Year’s Rent,” Albert Lee; Copyright, 1896, by Harper Bros.

Acknowledgments of permissions given by authors and

publishers for the use of copyright material

appear in Volume 10

MANUFACTURED IN U. S. A.

TC

| PAGE | |||

| Brother Rabbit’s Cradle | Joel Chandler Harris | 7 | |

| The Little Baxters Go Marketing | Tudor Jenks | 18 | |

| A Story of Decoration Day for the Little Children of To-day | Elizabeth Harrison | 23 | |

| The Taxes of Middlebrook | Ray Stannard Baker | 30 | |

| The Cure of Fear | Norman Duncan | 43 | |

| A Christmas Adventure | J. E. Chamberlin | 55 | |

| Chased by the Trail | Jack London | 66 | |

| Big Timber Beacon | John L. Mathews | 79 | |

| How Hilda Got a School | Lelia Munsell | 90 | |

| The Imp and the Drum | Josephine D. Bacon | 99 | |

| The Second String | James B. Connolly | 116 | |

| Holding the Pipe | Albert W. Tolman | 128 | |

| The Travelling Doll | Evelyn Snead Barnett | 137 | |

| The Doll Doctor | E. V. Lucas | 152 | |

| The Idea that Went Astray | Pauline C. Bouvé | 168 | |

| Gravity Gregg | Isaac Ogden Rankin | 171 | |

| Jonnasen | Dallas Lore Sharp | 179 | |

| In the Oven | Richard W. Child | 186 | |

| On a Slide-Board | Robert Barnes | 192 | |

| The Call of the Sea | Frederick Palmer | 201 | |

| On a Tight Rope | Albert W. Tolman | 213 | |

| Down the Incline | Charles Newton Hood | 220 | |

| The Cost of Loving | Frederick O. Bartlett | 225 | |

| Ladybird | Edith Barnard | 241 | |

| The Drasnoe Pipe-Line | Arthur Stanwood Pier | 255 | |

| Manuk Del Monte | Rowland Thomas | 269 | |

| The Man Without a Country | Edward Everett Hale | 279 | |

| The Foreman | Stewart E. White | 315 | |

| The Gray Collie | Georgia W. Pangborn | 328 | |

| The Fore-Room Rug | Kate Douglas Wiggin | 340 | |

| Cressy’s New-Year’s Rent | Albert Lee | 359 | |

| [4]Mr. O’Leary’s Second Love | Charles Lever | 370 | |

| The Rose and the Ring | William M. Thackeray | 389 | |

| I. | Shows How the Royal Family Sat Down to Breakfast | 393 | |

| II. | How King Valoroso Got the Crown, and Prince Giglio Went Without | 397 | |

| III. | Tells Who the Fairy Blackstick Was, and Who Were Ever So Many Grand Personages Besides | 402 | |

| IV. | How Blackstick Was Not Asked to the Princess Angelica’s Christening | 407 | |

| V. | How Princess Angelica Took a Little Maid | 410 | |

| VI. | How Prince Giglio Behaved Himself | 415 | |

| VII. | How Giglio and Angelica Had a Quarrel | 423 | |

| VIII. | How Gruffanuff Picked the Fairy Ring Up, and Prince Bulbo Came to Court | 429 | |

| IX. | How Betsinda Got the Warming-Pan | 436 | |

| X. | How King Valoroso Was in a Dreadful Passion | 443 | |

| XI. | What Gruffanuff Did to Giglio and Betsinda | 447 | |

| XII. | How Betsinda Fled, and What Became of Her | 456 | |

| XIII. | How Queen Rosalba Came to the Castle of the Bold Count Hogginarmo | 462 | |

| XIV. | What Became of Giglio | 466 | |

| XV. | We Return to Rosalba | 480 | |

| XVI. | How Hedzoff Rode Back Again to King Giglio | 488 | |

| XVII. | How a Tremendous Battle Took Place, and Who Won It | 493 | |

| XVIII. | How They All Journeyed Back to the Capital | 503 | |

| XIX. | And Now We Come to the Last Scene in the Pantomime | 509 | |

| There was no going Home for him, even to a prison |

| The Man Without a Country |

| Frontispiece illustration in color from the painting by Nella F. Binckley |

| A Gush of water followed, burying the sled and washing the dogs from their feet |

| Chased by the Trail |

| From the drawing by George Giguère |

| “I’m not your doctor. I’m a doll’s doctor.” |

| The Doll Doctor |

| From the drawing by Carton Moorepark |

| “Three of us were riding down the Slope of the great, grassy Hills” |

| Manuk Del Monte |

| From the drawing by W. H. D. Koerner |

| “Does Mr. Cressy live here?” |

| Cressy’s New-Year’s Rent |

| [6]From the drawing by Edwin J. Meeker |

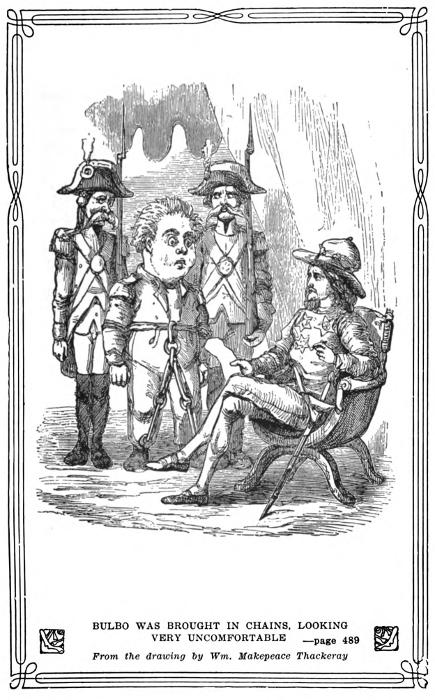

| Bulbo was brought in Chains, looking very uncomfortable |

| The Rose and the Ring |

| From the drawing by Wm. Makepeace Thackeray |

| And the gloomy procession marched on |

| The Rose and the Ring |

| From the drawing by J. H. Tinker |

“I wish you’d tell me what you tote a hankcher fer,” remarked Uncle Remus, after he had reflected over the matter a little while.

“Why, to keep my mouth clean,” answered the little boy. Uncle Remus looked at the lad, and shook his head doubtfully. “Uh-uh!” he exclaimed. “You can’t fool folks when dey git ez ol’ ez what I is. I been watchin’ you now mo’ days dan I kin count, an’ I ain’t never see yo’ mouf dirty ’nuff fer ter be wiped wid a hankcher. It’s allers clean—too clean for ter suit me. Dar’s yo’ pa, now; when he wuz a little chap like you, his mouf useter git dirty in de mornin’ an’ stay dirty plum twel night. Dey wa’n’t sca’cely a day dat he didn’t look like he been playin’ wid de pigs in de stable lot. Ef he yever is tote a hankcher, he ain’t never show it ter me.”

“He carries one now,” remarked the little boy with something like a triumphant look on his face.

“Tooby sho’,” said Uncle Remus; “tooby sho’ he do. He start ter totin’ one when he tuck an’ tuck a notion fer ter go a-courtin’. It had his name in one cornder, an’ he useter sprinkle it wid stuff out’n a pepper-sauce bottle. It sho’ wuz rank, dat stuff wuz; it smell so sweet it make you fergit whar you[8] live at. I take notice dat you ain’t got none on yone.”

“No; mother says that cologne or any kind of perfumery on your handkerchief makes you common.”

Uncle Remus leaned his head back, closed his eyes, and permitted a heart-rending groan to issue from his lips. The little boy showed enough anxiety to ask him what the matter was. “Nothin’ much, honey; I wuz des tryin’ fer ter count how many diffunt kinder people dey is in dis big worl’, an’ ’fo’ I got mo’ dan half done wid my countin’, a pain struck me in my mizry, an’ I had ter break off.”

“I know what you mean,” said the child. “You think mother is queer; grandmother thinks so too.”

“How come you to be so wise, honey?” Uncle Remus inquired, opening his eyes wide with astonishment.

“I know by the way you talk, and by the way grandmother looks sometimes,” answered the little boy.

Uncle Remus said nothing for some time. When he did speak, it was to lead the little boy to believe that he had been all the time engaged in thinking about something else. “Talkin’ er dirty folks,” he said, “you oughter seed yo’ pa when he wuz a little bit er chap. Dey wuz long days when you couldn’t tell ef he wuz black er white, he wuz dat dirty. He’d come out’n de big house in de mornin’ ez clean ez a new pin, an’ ’fo’ ten er-clock you couldn’t tell what kinder clof his cloze wuz made out’n. Many’s de day when I’ve seed ol’ Miss—dat’s yo’[9] great-gran’mammy—comb ’nuff trash out’n his head fer ter fill a basket.”

The little boy laughed at the picture that Uncle Remus drew of his father. “He’s very clean, now,” said the lad loyally.

“Maybe he is an’ maybe he ain’t,” remarked Uncle Remus, suggesting a doubt. “Dat’s needer here ner dar. Is he any better off clean dan what he wuz when you couldn’t put yo’ han’s on ’im widout havin’ ter go an’ wash um? Yo’ gran’mammy useter call ’im a pig, an’ clean ez he may be now, I take notice dat he makes mo’ complaint er headache an’ de heartburn dan what he done when he wuz runnin’ roun’ here half-naked an’ full er mud. I hear tell dat some nights he can’t git no sleep, but when he wuz little like you—no, suh, I’ll not say dat, bekaze he wuz bigger dan what you is fum de time he kin toddle roun’ widout nobody he’pin’ him; but when he wuz ol’ ez you an’ twice ez big, dey ain’t narry night dat he can’t sleep—an’ not only all night, but half de day ef dey’d ’a’ let ’im. Ef dey’d let you run roun’ here like he done, an’ git dirty, you’d git big an’ strong ’fo’ you know it. Dey ain’t nothin’ mo’ wholesomer dan a peck er two er clean dirt on a little chap like you.”

There is no telling what comment the child would have made on this sincere tribute to clean dirt, for his attention was suddenly attracted to something that was gradually taking shape in the hands of Uncle Remus. At first it seemed to be hardly worthy of notice, for it had been only a thin piece of board. But now the one piece had become four pieces, two long and two short, and under the deft[10] manipulations of Uncle Remus it soon assumed a boxlike shape.

The old man had reached the point in his work where silence was necessary to enable him to do it full justice. As he fitted the thin boards together, a whistling sound issued from his lips, as though he were letting off steam; but the singular noise was due to the fact that he was completely absorbed in his work. He continued to fit and trim, and trim and fit, until finally the little boy could no longer restrain his curiosity. “Uncle Remus, what are you making?” he asked plaintively.

“Larroes fer ter kech meddlers,” was the prompt and blunt reply.

“Well, what are larroes to catch meddlers?” the child insisted.

“Nothin’ much an’ sump’n mo’. Dicky, Dicky, killt a chicky, an’ fried it quicky, in de oven, like a sloven. Den ter his daddy’s Sunday hat, he tuck ’n’ hitched de ol’ black cat. Now what you reckon make him do dat? Ef you can’t tell me word fer word an’ spellin’ fer spellin’ we’ll go out an’ come in an’ take a walk.”

He rose, grunting as he did so, thus paying an unintentional tribute to the efficacy of age as the partner of rheumatic aches and stiff joints. “You hear me gruntin’,” he remarked—“well, dat’s bekaze I ain’t de chicky fried by Dicky, which he e’t ’nuff fer ter make ’im sicky.” As he went out the child took his hand, and went trotting along by his side, thus affording an interesting study for those who concern themselves with the extremes of life. Hand in hand the two went out into the fields,[11] and thence into the great woods, where Uncle Remus, after searching about for some time, carefully deposited his oblong box, remarking: “Ef I don’t make no mistakes, dis ain’t so mighty fur fum de place whar de creeturs has der playgroun’, an’ dey ain’t no tellin’ but what one un um’ll creep in dar when deyer playin’ hidin’, an’ ef he do, he’ll sho be our meat.”

“Oh, it’s a trap!” exclaimed the little boy, his face lighting up with enthusiasm.

“An’ dey wa’n’t nobody here fer ter tell you,” Uncle Remus declared, astonishment in his tone. “Well, ef dat don’t bang my time, I ain’t no free nigger. Now, ef dat had ’a’ been yo’ pa at de same age, I’d ’a’ had ter tell ’im forty-lev’m times, an’ den he wouldn’t ’a’ b’lieved me twel he see sump’n in dar tryin’ fer ter git out. Den he’d say it wuz a trap, but not befo’. I ain’t blamin’ ’im,” Uncle Remus went on, “kaze ’tain’t eve’y chap dat kin tell a trap time he see it, an’ mo’ dan dat, traps don’ allers sketch what dey er sot fer.”

He paused, looked all round, and up in the sky, where fleecy clouds were floating lazily along, and in the tops of the trees, where the foliage was swaying gently in the breeze. Then he looked at the little boy. “Ef I ain’t gone an’ got los’,” he said, “we ain’t so mighty fur fum de place whar Mr. Man, once ’pon a time—not yo’ time ner yit my time, but some time—tuck’n’ sot a trap fer Brer Rabbit. In dem days, dey hadn’t l’arnt how ter be kyarpenters, an’ dish yer trap what I’m tellin’ you ’bout wuz a great contraption. Big ez Brer Rabbit wuz, it wuz lots too big fer him.

“Now, whiles Mr. Man wuz fixin’ up dis trap, Mr. Rabbit wa’n’t so mighty fur off. He hear de saw—er-rash! er-rash!—an’ he hear de hammer—bang, bang, bang!—an’ he ax hisse’f what all dis racket wuz ’bout. He see Mr. Man come out’n his yard totin’ sump’n, an’ he got furder off; he see Mr. Man comin’ todes de bushes, an’ he tuck ter de woods; he see ’im comin’ todes de woods, an’ he tuck ter de bushes. Mr. Man tote de trap so fur an’ no furder. He put it down, he did, an’ Brer Rabbit watch ’im; he put in de bait, an’ Brer Rabbit watch ’im; he fix de trigger, an’ still Brer Rabbit watch ’im. Mr. Man look at de trap an’ it satchify him. He look at it an’ laugh, an’ when he do dat Brer Rabbit wunk one eye, an’ wiggle his mustache, an’ chaw his cud.

“An’ dat ain’t all he do, needer. He sot out in de bushes, he did, an’ study how ter git some game in de trap. He study so hard, an’ he got so errytated, dat he thumped his behime foot on de groun’ twel it soun’ like a cow dancin’ out dar in de bushes, but ’twan’t no cow, ner yit no calf—’twus des Brer Rabbit studyin’. Atter so long a time, he put out down de road todes dat part er de country whar mos’ er de creeturs live at. Eve’y time he hear a fuss, he’d dodge in de bushes, kaze he wanter see who comin’. He keep on an’ he keep on, an’ bimeby he hear ol’ Brer Wolf trottin’ down de road.

“It so happen dat Brer Wolf wuz de ve’y one what Brer Rabbit wanter see. Dey wuz perlite ter one an’er, but dey wan’t no frien’ly feelin’ ’twix um. Well, here come ol’ Brer Wolf, hongrier dan a chicken-hawk on a frosty mornin’, an’ ez he come[13] up he see Brer Rabbit set by de side er de road lookin’ like he done lose all his fambly an’ his friends terboot.

“Dey pass de time er day, an’ den Brer Wolf kinder grin an’ say, ‘Laws-a-massy, Brer Rabbit! what ail you? You look like you done had a spell er fever an’ ague; what de trouble?’ ‘Trouble, Brer Wolf? You ain’t never see no trouble twel you git whar I’m at. Maybe you wouldn’t min’ it like I does, kaze I ain’t usen ter it. But I boun’ you done seed me light-minded fer de las’ time. I’m done—I’m plum wo’ out,’ sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. Dis make Brer Wolf open his eyes wide. He say, ‘Dis de fus’ time I ever is hear you talk dat-a-way, Brer Rabbit; take yo’ time an’ tell me ’bout it. I ain’t had my brekkus yit, but dat don’t make no diffunce, long ez youer in trouble. I’ll he’p you out ef I kin, an’ mo’ dan dat, I’ll put some heart in de work.’ When he say dis, he grin an’ show his tushes, an’ Brer Rabbit kinder edge ’way fum ’im. He say, ‘Tell me de trouble, Brer Rabbit, an’ I’ll do my level bes’ fer ter he’p you out.’

“Wid dat, Brer Rabbit ’low dat Mr. Man done been had ’im hired fer ter take keer er his truck patch, an’ keep out de minks, de mush-rats an’ de weasels. He say dat he done so well settin’ up night after night, when he des might ez well been in bed, dat Mr. Man prommus ’im sump’n extry ’sides de mess er greens what he gun ’im eve’y day. Atter so long a time, he say, Mr. Man ’low dat he gwineter make ’im a present uv a cradle so he kin rock de little Rabs ter sleep when dey cry. So[14] said, so done, he say. Mr. Man make de cradle an’ tell Brer Rabbit he kin take it home wid ’im.

“He start out wid it, he say, but it got so heavy he hatter set it down in de woods, an’ dat’s de reason why Brer Wolf seed ’im settin’ down by de side er de road, lookin’ like he in deep trouble. Brer Wolf sot down, he did, an’ study, an’ bimeby he say he’d like mighty well fer ter have a cradle fer his chillun, long ez cradles wuz de style. Brer Rabbit say dey been de style fer de longest, an’ ez fer Brer Wolf wantin’ one, he say he kin have de one what Mr. Man make fer him, kaze it’s lots too big fer his chillun. ‘You know how folks is,’ sez Brer Rabbit, sezee. ‘Dey try ter do what dey dunner how ter do, an’ dar’s der house bigger dan a barn, an’ dar’s de fence wid mo’ holes in it dan what dey is in a saine, an’ kaze dey have great big chillun dey got de idee dat eve’y cradle what dey make mus’ fit der own chillun. An’ dat’s how come I can’t tote de cradle what Mr. Man make fer me mo’ dan ten steps at a time.’

“Brer Wolf ax Brer Rabbit what he gwineter do fer a cradle, an’ Brer Rabbit ’low he kin manage fer ter git ’long wid de ol’ one twel he kin ’suade Mr. Man ter make ’im en’er one, an’ he don’t speck dat’ll be so mighty hard ter do. Brer Wolf can’t he’p but b’lieve dey’s some trick in it, an’ he say he ain’t see de ol’ cradle when las’ he wuz at Brer Rabbit house. Wid dat, Brer Rabbit bust out laughin’. He say, ‘Dat’s been so long back, Brer Wolf, dat I done fergit all ’bout it; ’sides dat, ef dey wuz a cradle dar, I boun’ you my ol’ ’oman got better sense dan ter set de cradle in der parler,[15] whar comp’ny comes’; an’ he laugh so loud an’ long dat he make Brer Wolf right shame er himse’f.

“He ’low, ol’ Brer Wolf did, ‘Come on, Brer Rabbit, an’ show me whar de cradle is. Ef it’s too big fer yo’ chillun, it’ll des ’bout fit mine.’ An’ so off dey put ter whar Mr. Man done sot his trap. ’Twa’n’t so mighty long fo’ dey got whar dey wuz gwine, an’ Brer Rabbit say, ‘Brer Wolf, dar yo’ cradle, an’ may it do you mo’ good dan it’s yever done me!’ Brer Wolf walk all roun’ de trap an’ look at it like ’twas ’live. Brer Rabbit thump one er his behime foots on de groun’ an’ Brer Wolf jump like some un done shot a gun right at ’im. Dis make Brer Rabbit laugh twel he can’t laugh no mo’. Brer Wolf, he say he kinder nervous ’bout dat time er de year, an’ de leas’ little bit er noise ’ll make ’im jump. He ax how he gwineter git any purchis on de cradle, an’ Brer Rabbit say he’ll hatter git inside an’ walk wid it on his back, kaze dat de way he done done.

“Brer Wolf ax what all dem contraptions on de inside is, an’ Brer Rabbit ’spon’ dat dey er de rockers, an’ dey ain’t no needs fer ter be skeer’d un um, kaze dey ain’t nothin’ but plain wood. Brer Wolf say he ain’t ’zactly skeer’d, but he done got ter de p’int whar he know dat you better look ’fo’ you jump. Brer Rabbit ’low dat ef dey’s any jumpin’ fer ter be done, he de one ter do it, an’ he talk like he done fergit what dey come fer. Brer Wolf, he fool an’ fumble roun’, but bimeby he walk in de cradle, sprung de trigger, an’ dar he wuz! Brer Rabbit, he holler out, ‘Come on, Brer Wolf; des hump yo’se’f, an’ I’ll be wid you.’ But try ez[16] he will an’ grunt ez he may, Brer Wolf can’t budge dat trap. Bimeby Brer Rabbit git tired er waitin’, an’ he say dat ef Brer Wolf ain’t gwineter come on he’s gwine home. He ’low dat a frien’ what say he gwineter he’p you, an’ den go in a cradle an’ drap off ter sleep, dat’s all he wanter know ’bout um; an’ wid dat he made fer de bushes, an’ he wa’n’t a minnit too soon, kaze here come Mr. Man fer ter see ef his trap had been sprung. He look, he did, an’, sho’ nuff, it ’uz sprung, an’ dey wuz sump’n in dar, too, kaze he kin hear it rustlin’ roun’ an’ kickin’ fer ter git out.

“Mr. Man look thoo de crack, an’ he see Brer Wolf, which he wuz so skeer’d twel his eye look right green. Mr. Man say, ‘Aha! I got you, is I?’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Who?’ Mr. Man laugh twel he can’t sca’cely talk, an’ still Brer Wolf say, ‘Who? Who you think you got?’ Mr. Man ’low, ‘I don’t think, I knows. Youer ol’ Brer Rabbit, dat’s who you is.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Turn me outer here, an’ I’ll show you who I is.’ Mr. Man laugh fit ter kill. He ’low, ‘You neenter change yo’ voice; I’d know you ef I met you in de dark. Youer Brer Rabbit, dat’s who you is.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘I ain’t not; dat’s what I’m not!’

“Mr. Man look thoo de crack ag’in, an’ he see de short years. He ’low, ‘You done cut off yo’ long years, but still I knows you. Oh, yes! an’ you done sharpen you mouf an’ put smut on it—but you can’t fool me.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Nobody ain’t tryin’ fer ter fool you. Look at my fine long bushy tail.’ Mr. Man ’low, ‘You done tied an’er tail on behime you, but you can’t fool me. Oh, no, Brer Rabbit![17] You can’t fool me.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Look at de ha’r on my back; do dat look like Brer Rabbit? Mr. Man ’low, ‘You done wallered in de red san’, but you can’t fool me.’

“Brer Wolf say, ‘Look at my long black legs; do dey look like Brer Rabbit?’ Mr. Man ’low, ‘You kin put an’er j’int in yo’ legs, an’ you kin smut um, but you can’t fool me.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Look at my tushes; does dey look like Brer Rabbit?’ Mr. Man ’low, ‘You done got new toofies, but you can’t fool me.’ Brer Wolf say, ‘Look at my little eyes; does dey look like Brer Rabbit?’ Mr. Man ’low, ‘You kin squinch yo’ eye-balls, but you can’t fool me, Brer Rabbit.’ Brer Wolf squall out, ‘I ain’t not Brer Rabbit, an’ yo’ better turn me out er dis place so I kin take hide an’ ha’r off’n Brer Rabbit.’ Mr. Man say, ‘Ef bofe hide an’ ha’r wuz off, I’d know you, kaze ’tain’t in you fer ter fool me.’ An’ it hurt Brer Wolf feelin’s so bad fer Mr. Man ter sput his word, dat he bust out inter a big boo-boo, an’ dat’s ’bout all I know.”

“Did the man really and truly think that Brother Wolf was Brother Rabbit?” asked the little boy.

“When you pin me down dat-a-way,” responded Uncle Remus, “I’m bleeze ter tell you dat I ain’t too certain an’ sho’ ’bout dat. De tale come down fum my great gran’daddy’s great gran’daddy; it come on down ter my daddy, an’ des ez he gun it ter me, des dat-a-way I done gun it ter you.”

Paul Baxter was too small to be head of the family. He was only seven, while his sister was five, and Paul thought she had a great deal to learn. Mrs. Baxter was the rest of the family, for the father had sailed away with the fishing fleet one foggy morning, and the fleet came back without one boat, and that boat was John Baxter’s. They all thought he was drowned, but they were wrong, as you will see. Meanwhile you must pretend you don’t know he is alive, or else you can’t understand what an unhappy time Mrs. Baxter was living through, and how much rested on Paul’s little shoulders while he considered himself the head of the family.

The worst time had not come yet, for the father had saved some money, and he had not been missing more than about two weeks. Mrs. Baxter knew that the money would soon be gone, so she was saving every cent she could.

On the day before Thanksgiving, she told Paul and his sister Kate that “until their father came home again” (for she would not speak as if he were lost), they must be very careful, and so their Thanksgiving dinner would have to be a very plain one.

“No turkey?” Kate asked.

“No, dear,” said their mother, “unless you and Paul can catch one somewhere in the street.”

They knew this was a joke, for they lived in South Street, New York City, where trucks rumbled about all day.

Paul felt he must get a turkey for a reason Mrs. Baxter didn’t know. As John Baxter was bidding Paul good-bye the night before he sailed, Paul had asked whether he would be back for Thanksgiving.

“I think so, my boy, but one can’t be sure. If I shouldn’t, you must see to the Thanksgiving dinner, and carve the turkey. Will you?”

“Yes,” said Paul, very proud, and now how could he, if there was none to carve? Paul made up his mind that it was his business to see that the family had a turkey. Paul had some money in his own small cast-iron bank. And he knew it was right for him to do what he liked with his savings. He had already offered them to his mother, and she had told him they were of no use to her. Kate, too, had some money in her bank; it was just like Paul’s except that there was a “K” on the door, made with a red pencil.

While their mother was clearing away the breakfast, Paul beckoned to Kate and proposed that they should put their money together and surprise mother with the biggest, fattest, finest bird in the market.

Kate feared the bird would cost too much.

“Nonsense, child,” said Paul, grandly; “why, I have more than seventy-five cents. How much have you?”

“Twenty-eight, I think,” said Kate.

“Well, then!” Paul answered; “that’s more’n a[20] dollar. You can buy ’most anything for a dollar, child.”

They opened the banks, and counted the money three times, to make sure. It came out different every time, but they had about one dollar and fifteen or eighteen cents. It was all in small pieces and looked enough to buy an elephant. Paul tied it all up carefully in the corner of his handkerchief.

Then, after they had helped their mother to tidy the rooms, they got permission to go to market for her. She told them what to buy, and Paul was glad when his mother told them to get some cranberries for sauce, and a plum-pudding that came in a tin can. With their turkey, what a feast these would make!

The market was not far away, but it was so crowded that Paul and Kate had to hold hands tight. For a long time they could get no attention, but at last, by pulling one of the marketmen’s aprons, Paul made him listen. Paul bought all the things on their list, and then said, proudly:

“Please show me some of the biggest turkeys.”

The marketman, pointing to a long row, remarked:

“There they are—all weighed and marked. Pick out the one you want.”

Paul examined the tickets stuck on the turkeys—$2.20, $3.50, $2.40, $4.00 (he was a perfect giant of a gobbler!) and so on. Paul felt a lump in his throat, he was so disappointed! Then little Kate made it worse by pointing to the very biggest and saying, “Oh, Paul, buy that!—it’s the best of all!”

Paul whispered to her, “It costs four dollars.[21] Isn’t that awful? The cheapest one is two dollars! What can we do?”

Kate shook her head. Then she had a bright idea.

“I know!” she said. “If we can’t have the biggest, let’s get the very littlest that ever was! It will be cunning, and that will make mamma laugh.”

“But I don’t see any very little ones,” Paul replied.

“Ask the man,” Kate urged.

It was some time before Paul could get the man’s attention, and then the question was put.

“The littlest turkey?” repeated the marketman, with a grin. “That’s a queer order, now. Why do you want the littlest one, my boy?”

“’Cause we’re buying it for mamma,” said Kate eagerly. “She can’t get one at all, because papa’s gone away, and he may not come back, and we got the money out of our banks, and we’ve only one dollar and fifteen cents, and we can’t have the biggest, you see.”

“Hello!” said the marketman, “here’s a talker for a little one! Haven’t I seen you before?”

“Yes, sir,” Kate answered. “I’m Katie Baxter, and I used to come with papa.”

“You Jack Baxter’s girl?” asked the marketman, stooping down and picking the child up.

“Yes, sir,” said Kate, “but please put me down.” But instead the man called to a marketman in the next stall,

“See here O’Neil, this is the Baxter girl. She’s come with another little kid to buy the littlest turkey for her mother. They’ve got the money out[22] of their banks, and it’s a dollar fifteen. Can’t we fill the order?”

“Well, I guess we can,” said the other marketman heartily. “We’ll send them a bird—with the stuffing, too!”

“It’ll be all right,” said the first marketman, putting little Kate on her feet again. “Give me the number, and we’ll send the bird around to-morrow.”

Paul gave the number, untied the money from his handkerchief, and away they went through the noisy street home.

Paul and Kate had hard work to keep the secret of their marketing, but they did, all that day, and the next.

About four o’clock there was a knock at the door, and when the door was opened, there was nobody there. But there was something. A big, big market-basket, and in it was the giant turkey, and on the turkey’s breast a piece of paper, saying:

“From the friends of John Baxter to Mrs. Baxter and the little Baxters, hoping they’ll enjoy their Thanksgiving.”

And that wasn’t all, for the turkey, when Mrs. Baxter came to prepare it, was stuffed with silver dollars.

Then Mrs. Baxter cried; and Paul and Kate were puzzled by that. But she was thankful, for she told them so.

When the great bird was properly browned and smoking, Paul took his place ready to carve. He had just raised the knife and fork when the door opened and a big, hearty sailor came in, saying:

“Here, here, young man, this won’t do! That is my place!”

And, of course, it was John Baxter; and the turkey was not nearly so hot by the time he had been hugged and kissed (meaning John Baxter, of course), and had told how his boat had been sunk, but he and his mates picked up by a steamer.

That was a Thanksgiving dinner.

Next day John Baxter took his boy and girl down to the market, and they made another giving of thanks to the marketmen, and that is a good ending to the story, isn’t it?

There is one more thing. The marketmen would not take back their silver, and so it went into the bank—a real bank this time—for Paul and Kate.

I want you to listen to a sad, sweet story to-day, and yet one that ought to make you glad—glad that such men have lived as those of whom I am going to tell you. It all happened a good many years ago, in fact so long ago that your fathers and mothers were little boys and girls in kilts and pinafores, some of them mere babies in long clothes.

One bright Sunday morning in April the telegraph wires could be heard repeating the same[24] things all over the land, “Tic, tic; tictic; t-i-c; tic, tictic;—tic, t-i-c, tic; t-i-c; tic, t-i-c; t-i-c, t-i-c, tic,” they called out, and the drowsy telegraph operators sat up in their chairs as if startled by the words the wires were saying.

“Tic, t-i-c, tic; tictic; tic, tictic; tic; t-i-c, tictic;—tic, tic; t-i-c, tic,” continued the wires, and the faces of the telegraph operators grew pale. Any looker-on could have seen that something dreadful was being told by the wires.

“Tic, t-i-c, tic; tictic; tic, tictic; tic; t-i-c, tictic;—tic, tic; t-i-c, tic,” again repeated the wires. There was no mistaking the message this time. Alas, alas, it was true! The terrible news was true! Even the bravest among the operators trembled.

Then came the rapid writing out of the fearful words that the slender wires had uttered, the hurrying to and fro; and messenger boys were seen flying to the great newspaper offices, and the homes of the mayors of the cities, and to the churches where already the people were beginning to assemble. For the deep-toned Sabbath church bells high up in the steeples had been ringing out their welcome to all, even the strangers in their midst—“Bim! Baum! Bim!” they sang, which everybody knew meant, “Come to church, dear people! Come! Come! Come!” And the people strolled leisurely along toward the churches—fathers and mothers and little ones, and even grandfathers and grandmothers. It was such a bright, pleasant day that it seemed a joy to go to the house of God and thank Him for all His love and care. So one family after another filed into their pews while the[25] organist played such soft, sweet music that everybody felt soothed and quieted by it.

Little did they dream of the awful words which the telegraph wires were at that very moment calling out with their “Tic, t-i-c, tic; t-i-c; tic, t-i-c; t-i-c, t-i-c, tic;—Tic, t-i-c, tic, tictic, tic, tictic; tic; t-i-c; tictic.”

The clergymen came in and took their places in the pulpits. In each church the organ ceased its wordless song of praise. The congregation bowed and silently joined with all their hearts in the petitions which the clergyman was offering to the dear Lord, Father of all mankind, Ruler of heaven and earth. Some of them softly whispered “Amen” as he asked protection for their homes and their beloved country. Did they know anything about the danger which even then hung over them? Perhaps they did.

In many of the churches the prayer was over, the morning hymn had been sung, when a stir and bustle at the door might have been noticed, as the messenger boys, excited and out of breath, handed their yellow envelopes to the ushers who stood near the door ready to show the late comers to unoccupied seats. First one and then the other ushers read the message, and from some one of them escaped, in a hushed whisper, the words, “Oh, God! Has it come to this!”

And all looked white and awe-struck. The head usher hurried tremblingly down the aisle, and without waiting for the clergyman to finish reading the announcements of the week, laid the telegram upon the pulpit desk.

The clergyman, somewhat surprised at such an interruption, glanced at the paper, stopped, gasped, picked it up, and re-read the words written upon it, as though he could not believe his own eyes. Then he advanced a step forward, holding on to the desk, as if he had been struck a blow by some unseen hand. The congregation knew that something terrible had happened, and their hearts seemed to stop beating as they leaned forward to catch his words.

“My people,” said he in a slow, deliberate tone, as if it were an effort to steady his voice, “I hold in my hand a message from the President of the United States.” Then his eyes dropped to the paper which he still held, and now his voice rang out clear and loud as he read, “Our Flag has been fired upon! Seventy-five thousand troops wanted at once. Abraham Lincoln.”

I could not make you understand all that took place the next week or two any more than the little children who heard what the telegram said, understood it. Men came home, hurried and excited, to hunt up law papers, or to straighten out deeds, saying in constrained tones to the pale-faced women, “I will try to leave all business matters straight before I go.” There was solemn consultations between husbands and wives, which usually ended in the father’s going out, stern-faced and silent, and the mother, dry-eyed but with quivering lips, seeking her own room, locking herself in for an hour, then coming out to the wondering children with a quiet face, but with eyes that showed she[27] had been weeping. There were gatherings in the town halls and in the churches and school houses all over the land. The newspapers were read hurriedly and anxiously.

And when little Robert looked up earnestly into his grandmamma’s face and asked, “Why does mamma not eat her breakfast?” grandmamma replied, “Your papa is going away, my dear.” And when little Robert persisted, by saying, “But papa goes to New York every year, and mamma does not sit and stare out of the window, and forget to eat her breakfast,” then mamma would turn solemnly around and say, “Robert, my boy, papa is going to the war, and may never come back to us. But you and I must be brave about it, and help him get ready.” And if Robert answered, “Why is he going to the war? Why does he not stay at home with us? Doesn’t he love us any more?” then mamma would draw her boy to her and putting her arms around him, and looking into his eyes, she would say, “Yes, my darling, he loves us, but he must go. Our country needs him, and you and I must be proud that he is ready to do his duty.”

Then Robert would go away to his play, wondering what it all meant, just as you would have wondered if you had been there.

Soon the papas and uncles, and even some of the grandfathers, put on soldiers’ uniforms, and drilled in the streets with guns over their shoulders, and bands of music played military music, and the drums beat, and crowds of people collected on the street corners, and there were more speeches, and[28] more flags, and banners, and stir, and excitement. And nothing else was talked of but the war, the war, the terrible war.

Then came the marching away of the soldiers to the railway stations, and then the farewells and cheers and waving of handkerchiefs and the playing of patriotic airs by the bands of music, and much more confusion and excitement and good-bye kisses and tears than I could tell you of.

Then came the long, long days of waiting and praying in the homes to which fathers and brothers no longer came, and silent watching for letters, and anxious opening of the newspapers, and oftentimes the little children felt their mamma’s tears drop on their faces as she kissed them good-night—their dear mamma who so often had sung them to sleep with her gay, happy songs—what did it all mean? They could not tell.

And all this time the fathers, brave men as they were, had been marching down to the war. Oftentimes they slept on the hard ground with only their army blankets wrapped around them, and the stars to keep watch over them, and many a day they had nothing to eat but dry bread and black coffee, because they had not time to cook more, and sometimes they had no breakfast at all because they must be up by daybreak and march on, even if the rain poured down, as it sometimes did, wetting them through and through.

What were such hardships when their country was in danger?

Then came the terrible, terrible battles, more[29] awful than anything you ever dreamed of. Men were shot down by the thousands, and many who did not lose their lives had a leg shot off, or an arm so crushed that it had to be cut off. Still they bravely struggled on. It was for their beloved country they were fighting, and for it they must be willing to suffer, or to die.

Then a hundred thousand more soldiers were called for, and then another hundred thousand, and still the bloody war continued. For four long years it lasted, and the whole world looked on, amazed at such courage and endurance.

Then the men who had not been killed, or who had not died of their sufferings came marching home again, many, alas, on crutches, and many who knew that they were disabled for life. But they had saved their country! And that was reward enough for their heroic hearts. Though many a widow turned her sad face away when the crowd welcomed the returning soldiers, for she knew that her loved one was not with them, and many little children learned in time that their dear fathers would never return to them.

War is such a terrible thing that it makes one’s heart ache to think of it.

Then by and by the people said, “Our children must grow up loving and honoring the heroic men who gave their lives for their country.” So in villages and towns and cities monuments were built in honor of the men who died fighting for their country. And one day each year was set apart to keep fresh and green the memory of the brave soldiers;[30] and it has been named “Decoration Day,” because on this day all the children, all over the land, are permitted to go to the graves of the dead soldiers and place flowers upon them.

Up above the pines on the edge to the east the sun was rising and the air smelled of the woods, of the warm sand of the roadsides, of the perfect May morning. Three men in the quaint garb of pioneer foreigners came down the lane from the shoemaker’s house and turned into the road. Before they had gone many paces old Peter Walling stopped abruptly.

“There is a warning,” he said in Norwegian.

The eyes of the two others followed swiftly to his pointing. In the midst of the sand a twig of willow had been stuck. The top was split, and it held upward a bit of soiled paper. Old Peter seemed undecided whether to touch the message or not, but Halstrom, the shoemaker, plucked it from the stick, and scowled as he tried to make out its meaning. Presently he handed it to his son.

“What does it say, Eric?” he asked.

The message was in English, printed with a lumberman’s coarse pencil, and a rude attempt had been made to draw a skull and cross-bones at the top of the paper. Eric read it slowly, translating into Norwegian as he went along:

“Be Ware! All Norwegans and Sweeds are hereby WARNED not to go to the Town Hall under PENALTY of DEATH.”

It was signed in big letters, “By Order of the Committee.”

Eric Halstrom looked up and laughed shortly. “Well,” he said, “it means us,” and he tucked the message away with some care in his pocket.

“We may need it,” he added.

The two older men were silent for a moment. Then Peter Walling spoke faintly: “If there is going to be trouble—if there is danger—”

The old shoemaker straightened his bent shoulders and his eyes flashed angrily. “Peter Walling, will you go or will you stay? I thought we had settled this question once for all.”

“I’ll go, Jens—yes, yes, I’ll go,” answered Walling, hurriedly, but his lips protested under his beard.

Halstrom turned without a word and hobbled down the road, determination speaking from every nervous hitch of his twisted frame. He was small and crippled, and in all his life he had never been able to do the work of a strong man. But there was that in his blue eyes which made him a leader in Thingvalla. He had cobbled in the old country, and he had cobbled in this new Northwest among the pines, and every peg he drove had clinched a thought. He was not educated in English; he had emigrated too late for that, but he had seen to it that his son made the best of the scant schooling of a new land, and better still, he had taught him some of the wisdom that comes to a cobbler who thinks.

Eric stood almost six feet tall. His hair was as[32] yellow and curly as a rope end, and his eyes were blue and steady. Although barely twenty years old, he had learned by the hard knocks of a pioneer country how to take care of himself, both with his big right arm and with his tongue.

Over ten miles of sand-hills and corduroy, through vast forests of pine as yet barely notched with the clearings of settlers, the three men came at last in sight of the town hall, the shoemaker and his son in front, and old Peter Walling behind, muttering his fears. The town hall was a log shack, one story high, with a single large room.

As the three approached, they could see that the road was full of men and teams. The men were moving about, and talking with the boisterous pleasantry of backwoodsmen who do not often meet. They had gathered this spring morning for the annual session of the board of review—the board that was to make the final equalization of the taxes on the property of the township. Eric looked anxiously to see if there were any others present from the Thingvalla settlement, or, indeed, any Scandinavians, but he could not see even one.

“They are all afraid,” the shoemaker said, bitterly. “They have come to a free country, and they don’t know how to be free.”

But the New Antrim settlement was out in force. Eric heard the jolly voices of the young Irishmen, and he knew well that they were spoiling for a fight. Thingvalla was in one corner of the township, New Antrim was in the other, and between the settlements stretched unbroken forests of pine and implacable bitterness. It was one of those settlement[33] differences so common in the backwoods, and the more unfortunate for being unfounded. New Antrim was sure that Thingvalla was trying to control the township, and Thingvalla was equally sure that New Antrim was escaping its share of taxation. And that was the condition on this bright May day, when the three from Thingvalla came down with the warning in Eric’s pocket.

“They are too many!” muttered old Peter Walling, tremulously.

They saw Calvin Donohue and his men sporting in the sunshine. Donohue was the man in the otter cap, immensely broad and brawny of shoulders, long of arms and square of chin. He talked in a big, jolly voice; from where they stood they could hear him laugh.

O’Rourke, Callahan and some of the younger men were trying their strength on a huge iron soap-kettle that stood in front of the blacksmith shop. They were testing their muscles to see which could lift it from the ground with one hand. There were few who could do it, but Calvin Donohue put it as high as his shoulder as if it were only a feather. Others were pitching quoits with horseshoes, and one group was watching a pulling contest between O’Rourke and Davy, who were sitting, feet to feet on the ground, tugging on a crowbar.

The shoemaker, who had been resting by the roadside, now rose, and without a word set off down the hill toward the crowd, with his chin thrown up and his eyes looking neither to the right nor to the left.

The moment the men of New Antrim saw them,[34] a gleeful shout went up. Here was new sport for them. A powerful man in a lumberman’s red jacket seized a heavy oak swingletree from the blacksmith’s door, sprang out into the road, and shouted:

“Come on, boys, we’ve got ’em!”

Eric and his father did not stop, but old Peter Walling wavered, then turned and ran back up the road as fast as his legs could carry him. It was two against thirty, but the two stood their ground. While they were exchanging challenges, a man opportunely stepped from the doorway of the town hall and began to rap on the logs with a stake, announcing that the board had been called to order.

At once there was a rush for the benches, and Eric and his father reached the door without opposition.

The shoemaker made as if to enter, but Jim O’Rourke barred the door with his arm.

“No Swedes admitted,” he said, gruffly.

The shoemaker, paying no attention to the order, again endeavored to enter. He was thrown back violently, and if it had not been for Eric, he would have fallen. The shoemaker tried to speak, but his English was hopelessly confused and broken. Eric was white to the lips, but he controlled himself.

“We are citizens of this township,” he said, “and we have a right in this meeting.”

“Go wan!” was the answer. “We won’t have any foreigners here.”

“We are as much Americans as you are!” responded Eric, hotly.

“Be cool,” cautioned the shoemaker, in his native tongue.

“I tell you, Jim O’Rourke,” continued Eric, more steadily, “there’s no need of our quarrelling this way, and if you’d let us explain we’d show you why we should all be friends—”

“Friends! Let me give you a friendly hint. You get out of here double-quick.”

By nature the Scandinavian is peaceable. He hates fighting as much as he loves his home; and yet, for being slow to wrath, he is the more terrible when roused. Eric took one step forward and drove up O’Rourke’s arm with a stinging blow that sent him spinning into the room. Then he and his father entered. O’Rourke, recovering himself, rushed upon Eric and dealt him a terrific blow in the breast. The two men were just closing in a desperate encounter when Caxton, the chairman, rose, ordering silence and preparing to enforce his decree with a stout oak stake.

“What’s the trouble here?” he demanded, when quiet had been restored.

“We are citizens of this township,” said Eric, panting, “and we have a right to attend this meeting. This man tried to shut us out.”

Caxton paused a moment.

“Put out the Norsks!” roared a voice.

“No,” said Caxton. “They have a right to be here and to be heard on the subject of their taxes.”

“Thank you!” said Eric, eagerly. “I want to explain—”

“You will be given a chance in due time,” was the answer, given so coldly that it indicated the[36] chairman’s position against them beyond a doubt. There were many whispered threats, but Eric and his father firmly stood their ground. The business of the board of review is to hear the complaints of those who think they have been unfairly taxed. Apparently there were to be few complaints at this meeting. An old man who spoke with the unmistakable inflection of the Irishman commended the assessment and praised the assessor. He thought every one in the township had been satisfied. He was pleased to know that this was so. As he sat down, a small, loosely jointed man, with fiery red hair, rose from his chair.

He wore a diamond shirt-stud which, if genuine, would have purchased every stitch of personal apparel in the room. He drawled pleasantly in his talk. Every one knew him. His name was William P. Ketchum, or more familiarly, Billy Ketchum. Eric’s eyes fastened hard upon him and watched him as a catamount might watch a squirrel, and with much the same motive.

Billy Ketchum was the representative of the great logging concern of Miller, Knees & Dye, which owned all the pine lands in the township, and, indeed, in nearly all the county. He complimented the assessor in his softest manner, he complimented the board down from Caxton to Severn, through Holt, and then he complimented them up again from Severn to Caxton. He mentioned New Antrim and brought in a deft reference to the shamrock and the old sod, and then—he suddenly caught the eye of Eric Halstrom burning at him above the heads of the crowd. For a single instant he seemed[37] trying to pull himself together, and then he went on with his pleasant drawl:

“As representing the largest taxpayers in Middlebrook,” he said, “I am deeply interested in its welfare. We pay our taxes gladly, knowing that they have been honestly levied and that they will be honestly collected—”

At this Eric Halstrom came shouldering nearer, with the shoemaker close behind him.

“It’s not so!” Eric gasped, excitedly. “I tell you it’s not so. He’s the man who’s caused all the trouble.”

“I was not aware,” put in Billy Ketchum, in his smoothest voice, “that you allowed your meetings to be broken up by a brawling—”

His last words were drowned in shouts, and it was some moments before Mr. Caxton, pounding on the table, could restore peace.

Calvin Donohue whispered in the chairman’s ear, and Mr. Caxton said aloud to Eric, “We’ll hear what you have to say right away.”

The shoemaker pushed Eric forward eagerly. The boy stood up before the crowd, blushing and stammering. His big hands fumbled in his pockets and his tongue refused to stir. He had not been particularly afraid to face the assembled forces of New Antrim in the road, but he was afraid to make a speech.

“I—I wanted to—explain about the taxes,” he stammered.

“So I suppose,” was Mr. Caxton’s cool reply.

Eric pulled a piece of chalk out of his pocket and looked round.

“I—I’ve got to have something to write on,” he said, at which the New Antrimites shouted with laughter.

If it had not been for the wise old shoemaker at that moment, Eric would have been lost, laughed to defeat. Nothing will floor a speaker more quickly than the wit of an Irish audience. But the shoemaker spoke in Norwegian. Eric turned quickly; he was only a step from the door. There, outside in the sand, stood the old iron kettle. He stooped, picked it up, and set it on a bench, which the shoemaker had swung into place. It was all done so swiftly that New Antrim forgot its fun in its astonishment.

And when Eric drew a big white square on the kettle with his chalk, a voice rose hoarsely from the back of the room:

“Well, I’ll be jiggered!”

At that all the Irishmen laughed, and then sat still again, out of respect, being “jiggered.”

Eric divided the white square into many smaller squares. In one corner he drew a number of crosses; in the opposite corner he did the same. One of these groups of crosses he labeled T.

“That is the Thingvalla settlement,” he said, “and this—is New Antrim.”

Then he swept his hand between the two and glanced at Billy Ketchum. “And all this in here is the pine owned by Miller, Knees & Dye.”

The shoemaker whispered in his ear, and he turned to the chairman, and said in a sterner voice: “I want to show who is to blame for all this trouble between the settlements.”

“We are not dealing with quarrels,” was the response. “We are here to equalize taxes.”

“That’s it, that’s what I want to do. I want to show that the taxes aren’t equal.”

Then he fumbled in his pocket and drew out a much-folded paper. With this to support him, he forgot all about himself, and talked rapidly and earnestly.

He told how he had figured up all the land owned by the Scandinavians of Thingvalla, and all that owned by New Antrim, and all that owned by the lumber company.

“Thingvalla has two thousand two hundred and forty acres in farms; New Antrim has two thousand nine hundred and twenty acres,” he explained, “while the lumber company has more than twelve thousand acres of pine. Thingvalla is assessed at an average of four dollars and sixty cents an acre; New Antrim is assessed at four dollars and fifteen cents an acre—a little less, but not enough to count. But here is this lumber company assessed for only one dollar and ninety cents an acre—”

Here Billy Ketchum sprang excitedly to his feet. “But this is wild land—not a foot of it is cultivated. I tell you such a comparison is unfair—”

“Yes, but your pine is worth more to the acre than our farms with all our crops and buildings on them.”

“I tell you—”

“I know!” broke in Eric, excitedly. “I tell you, I know! Look here—”

He drew from his pocket a pack of little strips of paper, each with a section map at the top, upon[40] which different “forties” of land were checked up in red and blue pencil.

He turned again to the table and marked out a square about midway between the settlements.

“Here’s section ten, township forty, range twelve. Last fall I was hired to go over this land with the company’s explorer, and estimate the pine. We travelled together for two months, counted all the trees, and estimated the number of feet of lumber they would make. That pine as it stands is worth from four dollars to six dollars a thousand feet, and some of the single forties have more than two hundred thousand feet of timber on them. That makes a cash value of from eight hundred dollars to twelve hundred dollars—or twenty dollars to thirty dollars an acre—and that’s more than the best improved farm in this county is worth—”

“I tell you—” roared little Billy Ketchum, wild with excitement.

“And you know it,” added Eric. “Here are these slips, which will prove just what I say. They are the company’s own valuation of its property. You can see for yourselves that our farms are assessed for more than twice as much as this pine land, although it is worth five or six times as much. And that will show you who is dodging taxes. Billy Ketchum says that he represents the biggest taxpayers in the township, and that he is well contented with the assessment. Of course he is contented, but he is wrong about representing the largest taxpayers. As the assessments now are, we represent the biggest taxpayers—and we are not contented, for we pay ten times the taxes that we[41] should. All I ask is that the assessments be fair, and Thingvalla and New Antrim will not quarrel.”

Billy Ketchum, purple of face, tried in vain to make himself heard, but the Irishmen of New Antrim drowned him out of the discussion. The explorer’s slips were passed back and forth and referred to the diagram on the iron kettle, and for a few moments pandemonium reigned.

“What’s more,” shouted Eric, in the flush of victory, “I can prove that Billy Ketchum is at the bottom of this quarrel!”

There was silence again.

“If it hadn’t been for him, we’d have been good friends to-day. He’s kept us enemies so that we couldn’t get together and assess the pine lands as they ought to be assessed.”

Ketchum sprang to his feet.

“It’s not so!” he shouted. “We’ve been perfectly fair to every one. Why should I mix up in neighborhood quarrels?”

He poured out an impassioned speech, the drawl all gone, and the words crowding so fast that he could hardly utter them plainly. He called the Irishmen “Billy” and “Calvin” and “Pete” familiarly, and spoke of their warm friendship, but somehow they did not rouse to enthusiasm as he had expected. They were thinking.

Presently Eric made himself heard again.

“Who left that warning in the Thingvalla road last night?” he asked, facing Ketchum.

“Who? How should I know?”

At this, New Antrim leaned forward to a man with curiosity. Eric drew out the warning and[42] told where he had found it. Then he passed it gravely to Mr. Caxton.

“Billy Ketchum left that in the road,” said Eric. “He did it to keep us away from the meeting. He tried to make us think that the New Antrim settlement was against us. He had found out that I knew the real value of those pine lands.”

Again Billy hopped up. “I dare him to prove it, Mr. Chairman! I didn’t come here to be insulted. I tell you—I dare him to prove it!”

“Well, I will,” said Eric, coolly.

At that the shoemaker stepped round behind the table and picked up a long, slender, paper-covered roll and handed it to Eric. Eric held it up, and pointed to Ketchum’s name written upon it, for it was a roll of maps. Ketchum rushed at Eric and tried to grasp his property, but Eric brushed him aside.

Then he unrolled the manila covering of the maps a few inches and held it up. One corner was torn off. He took the warning notice from Mr. Caxton’s desk and held it in the place of this torn corner. It fitted perfectly.

“My father happened to see this when he came in,” explained Eric. “What more proof do you want?”

For a moment the room was still. Then the same deep voice which had spoken once before burst out:

“I’ll be jiggered!”

Calvin Donohue turned to Billy Ketchum and said, none too pleasantly:

“You get out! We can manage our own affairs!”

Callahan suggested taking him out triumphantly in the iron kettle, but Billy disappeared with such haste they could not catch him.

Then the whole assembly took up seriously the problem of assessments, and before the day was out, the township of Middlebrook was equalized, and the taxes of the settlers, New Antrim and Thingvalla alike, were cut down to their just proportions, no more, no less, and the pine lands were assessed strictly in accordance with Eric’s estimate slips.

Like many another snug little harbor on the northeast coast of Newfoundland, Ruddy Cove is confronted by the sea and flanked by a vast wilderness; so all the folk take their living from the sea, as their forebears have done for generations.

It takes courage and a will for work to sweeten the hard life of those parts, which otherwise would be filled with dread and an intolerable weariness; and Donald North, of Ruddy Cove, was brave enough till he was eight years old. But after that season he was so timid that he shrank from the edge of the cliffs when the breakers were beating the rocks below, and he trembled when the punt heeled to a gust.

Now he was a fisherman’s son, and in the course[44] of things must himself be a paddle-punt fisherman; thus the mishap which gave him that great fear of the sea cast a dark shadow over him.

“Billy,” he said to young Topsail, on the unfortunate day, “leave us go sail my new fore-an’-after. I’ve rigged her out with a grand new mizzens’l.”

“Sure, b’y!” said Billy. “Where to?”

“Uncle George’s wharf-head. ’Tis a place as good as any.”

Off Uncle George’s wharf-head the water was deep—deeper than Donald could fathom at low tide—and it was cold, and covered a rocky bottom, upon which a multitude of starfish and prickly sea-eggs lay in clusters. It was green, smooth and clear, too; sight carried straight down to where the purple-shelled mussels gripped the rocks.

The tide had fallen somewhat and was still on the ebb. Donald found it a long reach from the wharf to the water. By and by, as the water ran out of the harbor, the most he could do was to touch the mast tip of the miniature ship with his fingers. Then a little gust of wind crept round the corner of the wharf, rippling the water as it came near. It caught the sails of the new fore-and-after, and the little craft fell over on another tack and shot away.

“Here, you!” Donald cried. “Come back, will you?”

He reached for the mast. His fingers touched it, but the boat escaped before they closed. He laughed, hitched nearer to the edge of the wharf, and reached again. The wind had failed; the little[45] boat was tossing in the ripples, below and just beyond his grasp.

“I can’t cotch her!” he called to Billy Topsail, who was back near the net-horse, looking for squids.

Billy looked up, and laughed to see Donald’s awkward position—to see him hanging over the water, red-faced and straining. Donald laughed, too. At once he lost his balance and fell forward.

This was in the days before he could swim, so he floundered about in the water, beating it wildly, to bring himself to the surface. When he came up, Billy Topsail was leaning over to catch him. Donald lifted his arm. His fingers touched Billy’s, that was all—just touched them. Then he sank; and when he came up again, and again lifted his arm, there was half a foot of space between his hand and Billy’s. Some measure of self-possession returned. He took a long breath, and let himself sink. Down he went, weighted by his heavy boots.

Those moments were full of the terror of which, later, he could not rid himself. There seemed to be no end to the depth of the water in that place. But when his feet touched bottom, he was still deliberate in all that he did.

For a moment he let them rest on the rock. Then he gave himself a strong upward push. It needed but little to bring him within reach of Billy Topsail’s hand. He shot out of the water and caught that hand. Soon afterward he was safe on the wharf.

“Sure, mum, I thought I was drownded that time!” he said to his mother, that night. “When[46] I were goin’ down the last time I thought I’d never see you again.”

“But you wasn’t drownded, b’y,” said his mother, softly.

“But I might ha’ been,” said he.

There was the rub. He was haunted by what might have happened. Soon he became a timid, shrinking lad, utterly lacking confidence in the strength of his arms and his skill with an oar and a sail; and after that came to pass, his life was hard. He was afraid to go out to the fishing-grounds, where he must go every day with his father to keep the head of the punt up to the wind, and he had a great fear of the wind and the fog and the breakers.

But he was not a coward. On the contrary, although he was circumspect in all his dealings with the sea, he never failed in his duty.

In Ruddy Cove all the men put out their salmon-nets when the ice breaks up and drifts away southward, for the spring run of salmon then begins. These nets are laid in the sea, at right angles to the rocks and extending out from them; they are set alongshore, it may be a mile or two, from the narrow passage to the harbor. The outer end is buoyed and anchored, and the other is lashed to an iron stake which is driven deep into some crevice of the rock.

When belated icebergs hang offshore a watch must be kept on the nets, lest they be torn away or ground to pulp by the ice.

“The wind’s haulin’ round a bit, b’y,” said Donald’s[47] father, one day in spring, when the lad was twelve years old. “I think ’twill freshen and blow inshore afore night.”

“They’s a scattered pan of ice out there, father,” said Donald, “and three small bergs.”

“Iss, b’y, I knows,” said North. “’Tis that I’m afeared of. If the wind changes a bit more, ’twill jam the ice agin the rocks. Does you think the net is safe?”

It was quite evident that the net was in danger, but since Donald had first shown signs of fearing the sea, Job North had not compelled him to go out upon perilous undertakings. He had fallen into the habit of leaving the boy to choose his own course, believing that in time he would master himself.

“I think, zur,” said Donald, steadily, “the net should come in.”

“’Twould be wise,” said North. “Come, b’y, we’ll go fetch it.”

So they put forth in the punt. There was a fair, fresh wind, and with this filling the little brown sail, they were soon driven out from the quiet water of the harbor to the heaving sea itself. Great swells rolled in from the open and broke furiously against the coast rocks.

The punt ran alongshore for two miles keeping well away from the breakers. When at last she came to that point where Job North’s net was set, Donald furled the sail and his father took up the oars.

“’Twill be a bit hard to land,” he said.

Therein lay the danger. There is no beach along that coast. The rocks rise abruptly from[48] the sea—here, sheer and towering; there, low and broken.

When there is a sea running, the swells roll in and break against these rocks; and when the breakers catch a punt, they are certain to smash it to splinters.

The iron stake to which Job North’s net was lashed was fixed in a low ledge, upon which some hardy shrubs had taken root. The waves were casting themselves against the rocks below, breaking with a great roar and flinging spray over the ledge.

“’Twill be a bit hard,” North said again.

But the salmon-fishers have a way of landing under such conditions. When their nets are in danger they do not hesitate. The man at the oars lets the boat drift with the breakers stern foremost toward the rocks. His mate leaps from the stern seat to the ledge. Then the other pulls the boat out of danger before the wave curls and breaks. It is the only way.

But sometimes the man in the stem miscalculates—leaps too soon, stumbles, leaps short. He falls back, and is almost inevitably drowned. Sometimes, too, the current of the wave is too strong for the man at the oars; his punt is swept in, pull as hard as he may, and he is overwhelmed with her. Donald knew all this. He had lived in dread of the time when he must first make that leap.

“The ice is comin’ in, b’y,” said North. “’Twill scrape these here rocks, certain sure. Does you think you’re strong enough to take the oars an’ let me go ashore?”

“No, zur,” said Donald.

“You never leaped afore, did you?”

“No, zur.”

“Will you try it now, b’y?” said North quietly.

“Iss, zur,” Donald said, faintly.

“Get ready, then,” said North.

With a stroke or two of the oars Job swung the stem of the boat to the rocks. He kept her hanging in this position until the water fell back and gathered in a new wave; then he lifted his oars. Donald was crouched on the stern seat, waiting for the moment to rise and spring.

The boat moved in, running on the crest of the wave which would a moment later break against the rock. Donald stood up, and fixed his eye on the ledge. He was afraid; all the strength and courage he had seemed to desert him. The punt was now almost on a level with the ledge. The wave was about to curl and fall. It was the precise moment when he must leap—that instant, too, when the punt must be pulled out of the grip of the breaker, if at all.

He felt of a sudden that he must do this thing. Therefore why not do it courageously? He leaped; but this new courage had not come in time. He made the ledge, but he fell an inch short of a firm footing. So for a moment he tottered, between falling forward and falling back. Then he caught the branch of an overhanging shrub, and with this saved himself. When he turned, Job had the punt in safety; but he was breathing hard, as if the strain had been great.

“’Twas not so hard, was it, b’y?” said Job.

“No, zur,” said Donald.

Donald cast the net line loose from its mooring, and saw that it was all clear. His father let the punt sweep in again. It is much easier to leap from a solid rock than from a boat, so Donald jumped in without difficulty. Then they rowed out to the buoy and hauled the great, dripping net over the side.

It was well they went out, for before morning the ice had drifted over the place where the net had been. More than that, Donald North profited by his experience. He perceived that if perils must be encountered, they are best met with a clear head and an unflinching heart.

That night, when he thought it over, he was comforted.

In the gales and high seas of the summer following, and in the blinding snowstorms and bitter cold of the winter, Donald North grew in fine readiness to face peril at the call of duty. All that he had gained was put to the test in the next spring, when the floating ice, which drifts out of the north in the spring break-up, was driven by the wind against the coast.

Job North, with Alexander Bludd and Bill Stevens, went out on the ice to hunt seal, and the hunt led them ten miles offshore. In the afternoon of that day the wind gave some sign of changing to the west, and at dusk it was blowing half a gale offshore. When the wind blows offshore it sweeps all this wandering ice out to sea, and disperses the whole pack.

“Go see if your father’s comin’, b’y,” said Donald’s[51] mother. “I’m gettin’ terrible nervous about the ice.”

Donald took his gaff—a long pole of the light, tough dogwood, two inches thick and shod with iron—and set out. It was growing dark, and the wind, rising still, was blowing in strong, cold gusts. It began to snow while he was yet on the ice of the harbor, half a mile away from the pans and clumpers which the wind of the day before had crowded against the coast.

When he came to the “standing ice,”—the stationary rim of ice which is frozen to the coast,—the wind was thickly charged with snow. What with dusk and snow, he found it hard to keep to the right way. But he was not afraid for himself; his only fear was that the wind would sweep the ice-pack out to sea before his father reached the “standing edge.” In that event, as he knew, Job North would be doomed.

Donald went out on the standing edge. Beyond lay a widening gap of water. The pack had already begun to move out.

There was no sign of Job North’s party. The lad ran up and down, hallooing as he ran; but for a time there was no answer to his call. Then it seemed to him he heard a despairing hail, sounding far to the right, whence he had come. Night had almost fallen, and the snow added to its depth; but as he ran back, Donald could still see across the gap of water to that great pan of ice, which, of all the pack, was nearest to the standing edge. He perceived that the gap had considerably widened since he had first observed it.

“Is that you, father?” he called.

“Iss, Donald!” came an answering hail from directly opposite. “Is there a small pan of ice on your side?”

Donald searched up and down the edge for a detached cake large enough for his purpose. Near at hand he came upon a thin, small pan, not more than six feet square.

“Haste, b’y!” cried his father.

“They’s one here,” he called back, “but ’tis too small! Is there none there?”

“No, b’y! Fetch that over!”

Here was a desperate need. If the lad was to meet it, he must act instantly and fearlessly. He stepped out on the pan, and pushed off with his gaff.

Using his gaff as a paddle—as these gaffs are constantly used in ferrying by the Newfoundland fishermen—and helped by the wind, he soon ferried himself to where Job North stood waiting with his companions.

“’Tis too small,” said Stevens. “’Twill not hold two.”

North looked dubiously at the pan. Alexander Bludd shook his head in despair.

“Get back while you can, b’y,” said North. “Quick! We’re driftin’ fast. The pan’s too small.”

“I think ’tis big enough for one man and me,” said Donald.

“Get aboard and try it, Alexander,” said Job.

Alexander Bludd stepped on. The pan tipped fearfully, and the water ran over it; but when the weight of the man and the boy was properly adjusted,[53] it seemed capable of bearing them both across. They pushed off.

When Alexander moved to put his gaff in the water the pan tipped again. Donald came near losing his footing. He moved nearer the edge, and the pan came to a level. They paddled with all their strength, for the wind was blowing against them, and there was need of haste if three passages were to be made. Meanwhile the gap had grown so wide that the wind had turned the ripples into waves, which washed over the pan as high as Donald’s ankles.

But they came safe across. Bludd stepped quickly ashore, and Donald pushed off. With the wind in his favor, he was soon once more at the other side.

“Now, Bill,” said North, “your turn next.”

“I can’t do it, Job,” said Stevens. “Get aboard yourself. The lad can’t come back again. We’re driftin’ out too fast. He’s your lad, an’ you’ve the right to—”

“Iss, I can come back,” said Donald. “Come on, Bill! Quick!”

Stevens was a lighter man than Alexander Bludd, but the passage was wider, and still widening, for the pack had gathered speed.

When Stevens was safely landed, he looked back.

A vast white shadow was all that he could see. Job North’s figure had been merged with the night.

“Donald, b’y,” he said, “you got to go back for your father, but I’m fair feared you’ll never—”

“Give me a push, Bill,” said Donald.

Stevens caught the end of the gaff and pushed the lad out.

“Good-by, Donald!” he said.

When the pan touched the other side, Job North stepped aboard without a word. He was a heavy man. With his great body on the ice-cake, the problem of return was enormously increased, as Donald had foreseen.

The pan was overweighted. Time and again it nearly shook itself free of its bad load and rose to the surface.

North stood near the center, plying his gaff with difficulty, but Donald was on the extreme edge. Moreover, the distance was twice as great as it had been at the first, and the waves were running high, and it was dark.

They made way slowly, and the pan often wavered beneath them; but Donald was intent upon the thing he was doing, and he was not afraid.

Then came the time—they were but ten yards off the standing edge—when North struck his gaff too deep into the water. He lost his balance, struggled desperately to regain it, failed—and fell off. Before Donald was awake to the danger, the edge of the pan sank under him, and he, too, toppled off.

Donald had learned to swim now. When he came to the surface, his father was breast-high in the water, looking for him.

“Are you all right, Donald?” said his father.

“Iss, zur.”

“Can you reach the ice alone?”

“Iss, zur,” said Donald quietly.

Alexander Bludd and Bill Stevens helped them[55] up on the standing edge, and they were home by the kitchen fire in half an hour.

“’Twas bravely done, b’y,” said Job.

So Donald North learned that perils feared are much more terrible than perils faced. He has a courage of the finest kind, in these days, has young Donald.

Having lived all his fourteen years in New York City, making occasional visits to his grandfather’s house in Connecticut, Horace Mason had often sighed for an adventure, and lamented because life in the eastern part of the country is so tame and uninteresting. It had certainly never occurred to him that the chance for a pretty thrilling adventure existed in the quiet country neighborhood in which his grandfather lived.

About a week before Christmas Horace’s mother took him to his grandfather’s farm for the holidays—he had seldom been there in winter.

The weather became remarkably cold and rough, but Horace found pleasure in walking about woods and pastures in rubber boots and ulster, and noting how odd the familiar scenes looked when covered with snow and ice, instead of dressed in green.

A tree was to be set up on Christmas Eve in the old homestead; but Uncle John, on the afternoon of the twenty-third, brought in for the celebration a rather scraggly little red cedar, brown rather than[56] green, which Horace deemed totally unfit for the dignity of a Christmas celebration.

“Why didn’t you get a fir balsam, with a nice even top to it?” Horace asked his uncle.

“Don’t grow around here.”

“But there are some over in the Big Swamp,” said Horace.

“Never noticed ’em,” said Uncle John.

Horace said nothing to this, because he was aware that he had often noticed things about the region, in the way of trees, plants and birds, which were apparently quite unobserved by the residents.

“You won’t be offended if I go after one to-morrow, will you, Uncle John?”

“Bless your heart, no!”

The next morning a blizzard raged. Horace, looking out, saw nothing but the whirling fine snow; the wind rattled all the shutters on the old house; it shook the building to its very foundations.

Horace thought it would be great fun to go out into this storm, with ulster, high rubber boots, and cap over his ears, looking for a Christmas tree in the Big Swamp. It did not occur to him that he needed to get his mother’s permission for the expedition, and it certainly did not occur to her that the boy would start out in such a storm.