Title: The Bookbinder in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg

Author: Thomas K. Ford

Contributor: John M. Hemphill

C. Clement Samford

Release date: July 30, 2018 [eBook #57609]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

An Account of his Life & Times, & of his Craft

Williamsburg Craft Series

WILLIAMSBURG

Published by Colonial Williamsburg

MCMXC

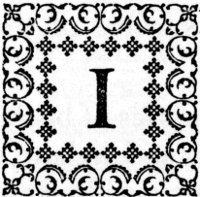

In October 1770 the inventory of the personal estate of Lord Botetourt, His Majesty’s Governor General of Virginia, contained a catalogue of books in the library at the Palace, made after his death by his executors. The shelves held over three hundred volumes. Today this library has been recreated by Colonial Williamsburg using the inventory list and other information on books in print at that time. The actual library of Lord Botetourt was sent back to England—and was lost at sea.

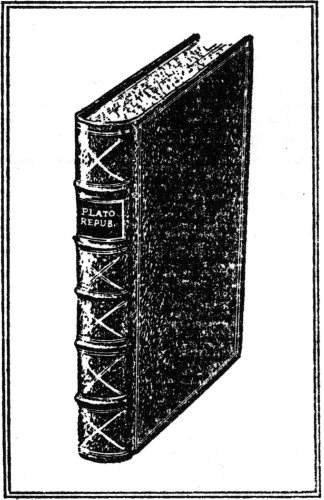

Much about the Governor can be deduced from the books he owned—plus a few he had borrowed and neglected to return. His interests ranged over the whole field of human knowledge, with particular emphasis on history, literature, law, and politics. However, it is not with the substance but with the form of these volumes in the renewed library that we are concerned. For us the important fact 2 is that, with a few exceptions, they are eighteenth-century books in eighteenth-century bindings.

The visitor who pauses only for a moment to look at them will see that most of them share certain outward characteristics:

They are bound in leather, with brown calfskin predominant;

Their spines are crossed by a number of horizontal ridges;

The title (abbreviated) usually appears in gold leaf on a small panel of colored leather glued to the spine, and sometimes the author’s name, too;

The spine may also bear a moderate amount of decorative gold tooling; and

The sides of the volumes, where visible, are likely to display “blind” tooling, which means ornamental indentations in the surface of the leather, made without gold leaf.

These are the five most noticeable characteristics of books bound in the eighteenth century in England or in England’s North American colonies. Standards of workmanship were on the whole higher in the mother country, but binders on both sides of the Atlantic used the same basic methods of bookmaking.

The techniques of bookbinding, in fact, had not changed much for a very long time. Men like William Parks, John Stretch, and Thomas Brend bound books in eighteenth-century Williamsburg in essentially the same way as had their predecessors in medieval monasteries a thousand years before.

Incidentally, among bookbinding craftsmen one does not mention “machine binding”; to the true binder there is no true binding except by hand. The machines of a modern 3 bindery do not “bind” a book according to the craft tradition, but “case” it. Therefore, the words “bind,” “bookbinding,” “bound books,” and so on whenever used in this pamphlet always refer to the traditional hand operation, never to the machine process or product. And “bookbinder” herein is always the hand craftsman, never the machine operator.

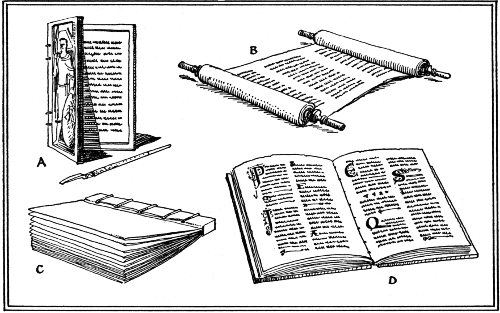

Man learned to write long before he learned to make paper. Smooth stones, clay tiles, and wax tablets, among other surfaces, were early precursors of scratch-pads and typewriter bond. Later, but before the modern form of a paged book developed, written records were most often kept on long rolls of papyrus, parchment, or vellum—the latter two being much alike.

The lines of writing sometimes ran the entire length of these rolls, sometimes they ran crossways, and sometimes they paralleled the long edge but were divided into columns. The third arrangement is still used in Jewish scrolls of the law, which are kept on rollers, one at each end.

Such a long strip could, however, be folded accordion-like instead of being rolled up. If the folds were made between the columns of writing, each column became a page and the whole began to resemble the book we are familiar with today.

At first these rudimentary books were protected by wooden boards pasted to the first and last pages. As a next step holes were stabbed through every page near the left-hand fold, and a cord or thong laced through the holes held the “accordion” together along one side.

By the fifth century a method had come into general use of sewing individually folded sheets together one by one, not to each other but to a series of flexible “hinges.” These were usually narrow strips of leather—four, five, or sometimes six depending on the height of the book—laid across the folded edges of the pages. Linen thread sewed through the folds and around each cross-strip in turn held the pages 4 firmly in place. Wooden boards affixed to the thongs as well as pasted to the first and last pages protected the whole, sometimes with the help of metal clasps and even locks.

These methods of preserving written material have now largely been superseded by the printed and bound or machine-cased book: (A) Diptych or hinged tablet of wood, ivory, or the like, often carved, whose inner surfaces of wax carried writing impressed by the stylus. (B) Scroll with columnar writing on a pair of rollers. (C) Japanese “orihon,” accordion-folded and bound along one side. (D) Codex or early form of book, an illuminated manuscript protected between thin boards; our word “book” comes from the German for beech (Buch), a wood often used for this purpose.

To guard the leather crossbands and linen thread from exposure and wear, it then became customary to cover the spine of the book with a wide, vertical strip of leather. Later, for better appearance and greater protection, the leather covering was extended partway onto the boards (the so-called “half-binding” of the medieval period) and then all the way.

Thus was developed and perfected the bound book: a collection of folded sheets sewn together flexibly and protected between covers. Its physical structure was largely the creation of monastic craftsmen of the early Middle Ages, just as its literary content throughout that period was most often religious scripture or comment.

Speaking only of quality of materials and workmanship, a book may be bound just as well in a simple cover as in an ornate one. Fine binding does not require adornment. It does require the services of a man of high skill and matching integrity, whose handiwork will inevitably display the quiet beauties of intrinsic quality.

But in the hands of men who possess the spark of creative artistry, bookbinding can be more than pure craft work. Although the binder’s decorative tools are forever prefixed, each to reproduce its own set and simple pattern, they are infinitely flexible in the ways they can be combined. It is not the tool that makes a binding beautiful or ugly, but the hand that holds the tool—and even more the mind and eye that guide the hand. The history of bookbinding is studded with the names of men who were true artists in leather. For them the most rewarding commission a customer could give was a simple order to dress some work of lasting worth in a binding of appropriate beauty.

In the Middle Ages all books were rare and valuable. Each volume was entirely lettered by hand and its pages were customarily “illuminated” with elaborately drawn initial letters and gilded marginal decorations. The binding of such a book was likely to be as painstakingly ornate as were its pages, and a few bindings were quite valuable in themselves. Before full leather covers became standard, the boards of some manuscript volumes—especially for a church altar or a royal library—might even be encased in beaten gold or silver and encrusted with enamel and semiprecious stones.

The invention of printing from type, as everyone knows, had extremely far-reaching consequences on the spread of public education and enlightenment. It had also some effects that were not so desirable. In the didactic phrase of the Encyclopedia Britannica, “Printing brought small books, cheap books, ugly books.”

Now it cannot be denied that most books today are smaller than the great manuscript tomes of the monastic scholars. They are cheaper, too. But it would be wrong to say that all books bound since Johann Gutenberg’s day have been ugly. To be sure, introduction of the printing press increased the flow of work to the bindery. But if the binder could no longer lavish time and care on every volume, he could still devote high artistry to an occasional book, steady craftsmanship to all.

Innumerable examples from the hands of many binders since the fifteenth century attest that the cover of a printed book can be as beautiful as that of a manuscript book. The names of Nicholas Eve, Clovis Eve, “Le Gascon” (otherwise unknown), and Geoffrey Tory of sixteenth-century France, and Padeloup and Le Monnier in the eighteenth century, deserve mention. In England bindings are not as easily identified with their binders, but the names of Thomas Berthelet, royal binder to Henry VIII, and above all Samuel Mearne, binder to Charles II, stand out. Roger Payne was England’s most distinguished binder in the eighteenth century.

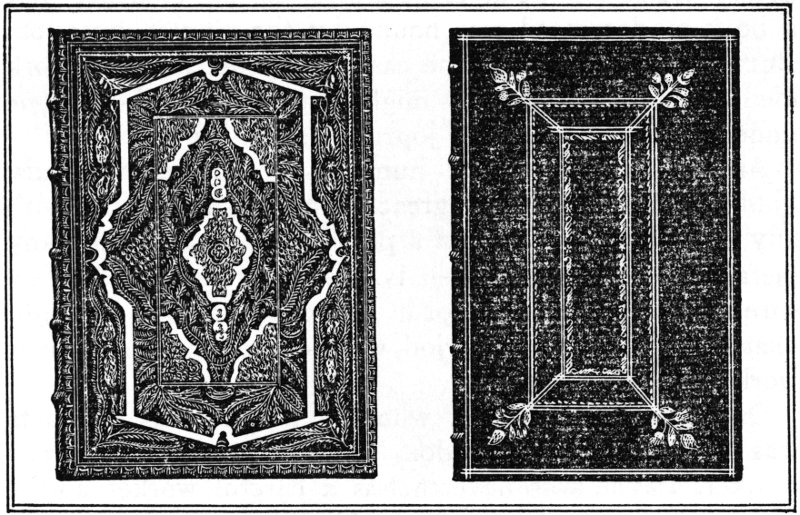

Before the fifteenth century, European binders usually had worked ornamentation into leather “in blind,” that is, without gold leaf. The technique of applying gold seems to have been perfected by Islamic leatherworkers of Mediterranean Africa, and brought from Morocco to Europe via Spain and Italy. Sixteenth-century French binders carried this kind of adornment to a peak of intricate tooling and lavish gilding. Their English counterparts, while they imitated the French, tended to favor simpler designs and less gold leaf. In the late seventeenth century and continuing through the eighteenth, straight lines rather than curves became characteristic of English work.

For example, the broken lines of the “cottage” style credited to Samuel Mearne resembled an outlined roof and walls. Later the “Cambridge” style became popular in England. It consisted of a vertical panel of thin lines 7 (fillets) on the sides of the book, with flower or leaf ornaments (fleurons) at the corners and perhaps in the center, and a narrow lace border around the boards. The example illustrated indicates that colonial binders continued to favor the Cambridge design until well into the eighteenth century.

Left, “cottage” style decoration on a 1674 Bible, bound in the shop of Samuel Mearne of London. Right, “Cambridge” style binding on a copy of Muscipula printed in 1728 by William Parks in Annapolis and bound by him.

Around 1760 a Dutch binder developed a method of treating leather with acid to give it a marbled appearance, and other binders lost no time in prying the secret away from him. First among binders in England to learn the technique was an émigré German, John Baumgarten, who made the most of his advantage. As Thomas Jefferson wrote to Robert Skipwith in 1771, books “bound by Bumgarden in fine Marbled bindings” cost 50 per cent more than in plain bindings.

In addition to national styles and local designs that developed at various times and places, certain binders perfected individual patterns of their own. In some cases 8 these were so unique as to be almost certain evidence that a book so decorated was bound by the man in question. But not always. As in the case of Samuel Mearne, work identified with the master might actually have been done under his instruction by a journeyman in his shop.

Among the very large number of eighteenth-century bindings that survive, the great difficulty is to identify with any certainty the binder of a particular volume. In many instances—perhaps most—it is impossible to be absolutely sure on this point. Except in France, binders of the eighteenth century, or any period, who signed or labeled their work were relatively rare.

One English craftsman who did identify his products was Roger Payne of London. An eccentric and a heavy drinker, Payne was nevertheless a careful worker and a creative artist in the bindery. His books are beautifully adorned with patterns built up with small tools that he designed and cut himself. In many of the books he bound, Payne included a detailed account of his work. The following statement, copied in part from a Bible now owned by Princeton University, is a good example:

Letter’d in ye most exact manner, exceeding rich small Tool Gilt Back of a new pattern studded in Compartments. The outside finished in the Richest & most elegant Taste Richer, & more exact than any Book that I ever Bound. The insides finished in a new design exceeding elegant. Bound in the very best manner sew’d with silk on strong and neat Bands. The Back lined with Russia Leather under the Blue morrocco. Cover very strong & neat Boards....

Although some colonial binders labeled their products, none of the several Williamsburg bookbinders of colonial days followed Roger Payne’s admirable precedent. Examples of the work of some of them, however, have been identified beyond doubt through direct or circumstantial 9 evidence—the latter often derived by processes resembling police detection.

Clues to the identity of a binder may be found in various facets of printing and binding: shop records of orders filled, materials used, and wages paid; place and date of publication as given on title pages; watermarks in the paper; and recurrent decorative patterns. Even contemporary newspaper advertisements may throw light on the matter.

The watermark of paper made in William Park’s paper mill near Williamsburg. It represents the coat of arms of the Virginia colony. This tracing is taken from Rutherford Goodwin, The William Parks Paper Mill at Williamsburg (Lexington, Va., 1939), in which he tells how the watermark was once described by a New Englander as resembling two men in long underwear with a basket of fish between them. The parallel vertical lines are the “chain lines” characteristic of handmade “laid” paper.

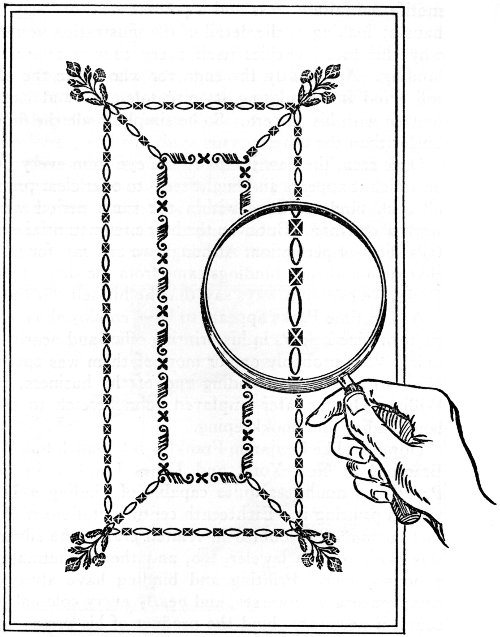

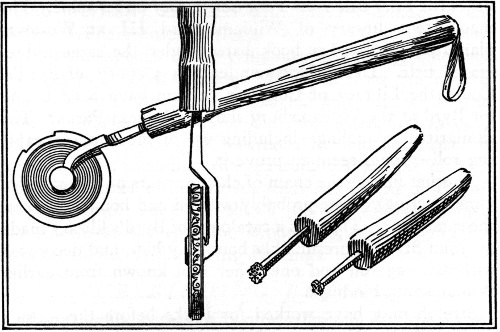

Evidence of every kind has been used in tracing out the story of the bookbinding craft in Williamsburg. The surest clues, especially in tracking down and identifying individual bindings, have been the distinctive footprints left by the binders’ decorating tools. Archaeological excavations on the site of the Printing Office have yielded examples of these tools, some for stamping letters and 10 others for impressing the gilded decoration that made the eighteenth-century bookbinder’s products as attractive as they were useful.

Under the eye of microscope and enlarging camera even mass-produced typewriters reveal slight irregularities that are unique to each machine. The brass stamps and rolls used by eighteenth-century binders for working decorations into leather were all made by hand. Because of some imperfection in workmanship or simply because ornamental dies were not supposed to duplicate each other, each tool had its own peculiarities. Very often the distinguishing characteristics of the impressions they made are visible to the naked eye.

Two such telltale tools—both “rolls” or wheel-like tools used to make continuous border patterns—proved especially useful in tracing the history of Williamsburg bookbinders and bindings. The trail of one can be followed through the ownership of successive binders for nearly three-quarters of a century. Another shows up again and again throughout a fifty-year period. Similar clues left by other tools were also helpful in the detective process, but cannot be dealt with in this brief account.

For convenience we shall call the two chief telltales the “Mousetrap” roll and the “egg” roll. They serve almost as indexes to the rest of our story. The impressions made by the original tools, and the “smoke imprint” made by modern recuttings of the same tools, are shown in the accompanying illustration.

The Mousetrap roll owes its name to the publication on which it made its first known appearance, a Latin poem entitled Muscipula, which means “mousetrap.” Its pattern, alternating two rather conventional motifs, is not particularly noteworthy in appearance. Nevertheless, the impression it made was not duplicated by any other roll.

This representation of a book cover shows one of the chief clues followed in tracing the tools used and books bound by Williamsburg binders. It shows the design on a copy of the Statutes and Charter of the College of William and Mary printed in Williamsburg in 1736 by William Parks and bound in his shop. The College itself is in Williamsburg, of course, but this volume is in the John Carter Brown Library at Providence, Rhode Island, and another like it in design is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, England. The illustration was made (except for the magnification) as a smoke imprint of twentieth-century tools cut in the same pattern as the originals. The inner panel of the Cambridge style decoration was made by the “Mousetrap” roll that Parks brought with him from Annapolis. The intermediate rectangle, made by the “egg” roll, reveals the elongated oval that reappeared on other books connected with Parks and his successors in the Williamsburg printing offices. The corner fleuron also appeared on earlier Parks bindings.

The egg roll is no more unusual as a pattern, but gains distinction from the fact that its built-in signature is an obvious mistake. It also alternates two conventional motifs, a Maltese cross and a pointed oval or “egg.” Perhaps by looking at the detail of the illustration you can see why this tool identifies itself every time it appears on a binding. Apparently the engraver who made the original roll erred in calculating its circumference and came out uneven with his pattern. So he simply made the final oval longer than the others.

Once seen, the flaw jumps to the eye from every binding on which it appears and might seem to offer clear proof that all such bindings done within the same period were the work of one man. But even the best circumstantial evidence falls short of perfection. Although we can say, for instance, that such-and-such bindings came from the shop of William Parks, we cannot always say that he himself did the work.

At one time Parks appears to have employed as many as eight or nine helpers in his printing office and nearby paper mill. Very probably one or more of them was specifically hired to handle the binding end of the business, just as William Hunter later employed John Stretch to do both bookbinding and bookkeeping.

However, like Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, William Bradford in New York, and James Franklin in Boston, Parks was doubtless quite capable of binding a book as well as printing it. Eighteenth-century craftsmen of every sort customarily doubled in related crafts: the silversmith was likely to be a jeweler, too, and the cabinetmaker also a house-joiner. Printing and binding have always been complementary processes, and nearly every colonial printer could, if necessary, bind the product of his press.

A great many colonial printers also published weekly newspapers, in whose columns they advertised the job-printing services and stationery wares they had to offer. The colophon of the Virginia Gazette of October 1, 1736, for instance, specified that it was printed in Williamsburg “by W. PARKS. By whom Subscriptions are taken for 13 this Paper, at 15 s. per Annum: and BOOK-BINDING is done reasonably, in the best Manner.”

The first successful printer in Virginia, Parks had been public printer to the colony of Maryland before he moved to Williamsburg in 1730. One of the early publications issued by his Annapolis shop, in 1728, was the aforementioned book of Latin verse, and the three surviving copies are all decorated in the same Cambridge pattern and all with the roll we have named the Mousetrap roll.

The Complete Mariner, a manuscript volume of navigational exercises with a title page printed in Williamsburg in 1731, was doubtless one of the first products of Parks’s shop in Williamsburg. Its cover was handsomely decorated in blind with the Mousetrap roll and with two other ornaments that also were used on books issued by Parks’s Annapolis shop and later on bindings done in Williamsburg.

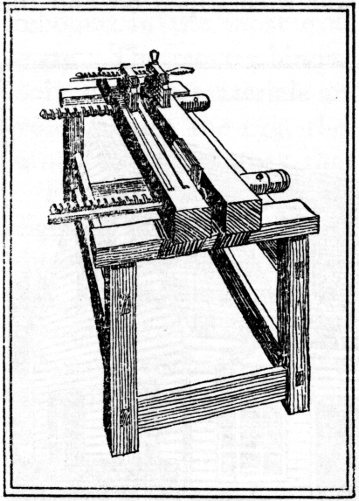

Rolls and small stamps used in the Williamsburg bindery. The gap in the outer edge of the fillet roll permits the binder to start and stop his impression cleanly. Both rolls and stamps must be heated for use and pressed into the leather quite hard.

In 1736 Parks published the Charter and Statutes of the 14 College of William and Mary, in Virginia. Three copies survive in their original bindings. Two of these—one in England, one in America—bear the marks of both the Mousetrap roll and the egg roll in the simple pattern illustrated on page 11. The third is more elaborately decorated, with many small impressions of other tools, but around the edge is the telltale egg roll.

Many of the same tools used on this third copy of the William and Mary Charter, including the egg roll around the border, reappear on one copy of a book printed nearly a decade later in New York. This was Daniel Horsmanden’s account of a Negro conspiracy to burn New York City. The copy in question, now in the Library of Congress, bears the brief title New York Conspiracy on its spine. The magnificent library of William Byrd III at Westover plantation included a book listed under the same abbreviated title. Daniel Horsmanden was a cousin of Byrd’s. Could the Library of Congress volume have been bound for Byrd at the Williamsburg shop of William Parks? The similarities in tooling—including use of the unmistakeable egg roll—would seem to prove it.

Another link in the chain of clues appears on the cover of a manuscript volume probably written and bound at about the same time. This was a catalogue of Byrd’s library made by John Stretch, presumably bound by him, and decorated with the egg roll and one other tool known from earlier Williamsburg bindings.

Stretch may have worked for Parks before the latter’s death in 1750. He was in the employ of Parks’s successor, William Hunter, for a number of years. Presumably he bound the books that issued from Hunter’s press during this period as well as the blank record books that were a staple item of Hunter’s business. One of these blank books was used by George Washington for copies of his letters and invoices from 1755 to 1765—and it, too, was decorated with the egg roll.

One of the few printed books known to have come from 15 Hunter’s shop was a new edition of the William and Mary Charter, printed in 1758. One copy that survives in original covers has another roll also used on the Washington letter book and small ornaments used on both the earlier edition of the Charter and on the New York Conspiracy, plus design similarities to both of these and to the Stretch catalogue of Byrd’s library.

A daybook kept by William Hunter during the first two years of his proprietorship of the shop carries the trail a bit farther. A daybook was simply a running record of each day’s transactions of all kinds, more often called a “journal” nowadays. It would certainly have been bound right in the shop, and this daybook bears the impress of a stamp previously identified with Parks’s Annapolis and earliest Williamsburg imprints.

Another daybook of the Williamsburg printing office also survives in original binding. It dates from the time of Hunter’s successor, Joseph Royle, and almost beyond question was also bound in the shop where it was used. Its cover, not surprisingly, was tooled in blind with two of the familiar rolls, including the egg roll. A volume of York County records also survives from the period of Royle’s proprietorship. Its cover shows the impressions of three old standbys: the egg, the Mousetrap, and a third roll seen on earlier Williamsburg bindings.

If the outside covers of two printing office daybooks can add a few bits to our story, the inside pages should be a gold mine of information about bookbinding in colonial Williamsburg. And so they are.

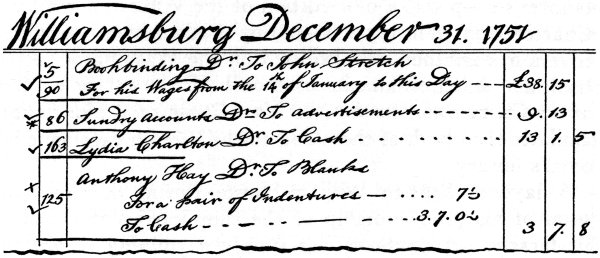

Hunter’s daybook for the period from July 1750 through June 1752 and Royle’s covering most of 1764 and all of 1765 tell a great deal about the quantity and variety of binding work they did, the prices they charged, and a little about the wages they paid. Hunter, for example, at the end of 1751 entered payment of 38 pounds 15 shillings 16 against the bookbinding account “To John Stretch For his Wages from the 14th of January to this Day.” Thus, from this source, Stretch earned 15 shillings sixpence a week.

A part of a page from William Hunter’s daybook for the Williamsburg Printing Office, especially redrawn for this booklet. Notice the entry for bookbinding wages paid to John Stretch.

The kinds of bookbinding done in the shops of Hunter and Royle—and doubtless also by the other Williamsburg printers, about whose business we lack detailed information—can be divided into three main groups: edition binding, custom binding, and the manufacture of blank record books. As a sideline, they also made and sold pocketbooks, letter cases, and other kinds of pocket cases.

In volume of work done in Hunter’s shop, and probably in many other colonial binderies, the manufacture and sale of blank books was easily of first importance. Obviously these were not printed books—although the pages of some of them were ruled by hand in advance of binding. They were letter-copy books, account books, and record books of various kinds used by everyone who was at all systematic about his business affairs.

Accounts kept “after the Italian manner,” as described in John Mair’s Book Keeping Methodiz’d (about 1750), called for ten different books. The three chief ones were a “wastebook” in which transactions were jotted down at the time they took place, a permanent “journal” or “daybook” 17 into which they were transcribed in a more stately hand when time permitted, and a “ledger” containing in final and complete form all accounts pertaining to the business. Subsidiary records described by Mair were the cash book, book of charges and merchandise, book of house expenses, factory or invoice book, sales book, bill book, and receipt book.

Hunter’s daybook shows entries covering sales of all the principal varieties and many of the subsidiary forms. In fact, entries pertaining to “blank books,” “legers,” “alphabets,” “journals,” “account books,” “day books,” “waste-books,” and the like far outnumber all other binding entries together. Royle’s daybook, which seems to have been kept on a somewhat different basis—perhaps less meticulously—than Hunter’s, lists proportionately fewer such entries compared to those for binding printed volumes.

One might expect that business record books would have been bound sturdily, but in plain and cheap dress. Sometimes they were, but often they were just as well finished as were printed books, usually in good quality calfskin, sometimes in vellum or parchment. Ledgers in particular were large and heavy books; since they got steady usage, they needed to be made of the best materials and workmanship for the sake of durability. And custom usually led to a certain amount of decoration on even the most utilitarian volume. The result was that blank books were often as fine in outward appearance as those from the press—and sometimes more costly, because of the larger skins needed to cover them.

Not a few of the books sold by William Hunter and presumed to have been made up by him or John Stretch brought a price of a pound or more. This was, as we have seen, a good deal more than Stretch earned in a week. The most imposing price charged to any of Hunter’s customers was the 3 pounds 10 shillings John Hall paid for “a large Record Book Imperial.”

All eighteenth-century paper was manufactured by hand, 18 and sheets of various sizes and kinds bore such designations as pot, foolscap, pro patria, crown, demy, royal, super royal, imperial, atlas, and elephant. These names referred to supposedly standard sizes, but actual dimensions were neither precise nor unchanging. In seventeenth-century England a sheet of “demy” measured about 10 by 15½ inches. The English paper of the same name today is 17½ by 22½ inches.

This increase in dimensions of paper took place gradually, and as the size of sheets grew the size of pages could also grow. A result was that folio books became too large to be handy while quarto and octavo formats, which were more economical to print, gained popularity among both printers and book buyers.

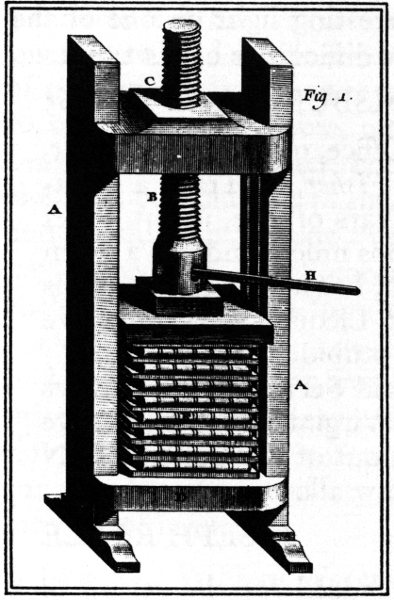

This engraving from the French eighteenth-century encyclopedia of Denis Diderot shows the interior of a bookbindery of the time, and some of the equipment used. The operations under way in the shop are (a) “smashing” folded signatures flat on a stone anvil; (b) sewing signatures together on the stitching frame; (c) trimming the edges of a book before the covers are put on; and (d) squeezing a stack of finished books in a standing press.

Some idea of the volume of binding done in Hunter’s establishment during the two years covered by his daybook 19 may be gathered from the partial figures for supplies charged to binding. These included £56 17s. 6d. for paper and £250 13s. 9½d. for other binding materials, chiefly calf and sheepskins, gold leaf, and pasteboard. In physical quantity the totals are again incomplete but indicative: at least 140 dozen skins and more than a ton of pasteboard.

These materials, of course, went to the binding of printed as well as blank books. As their daybooks show, the binding of books to order was a steady source of income for both Hunter and Royle—and doubtless for Royle’s successors as it had been for Hunter’s predecessor. Custom work included the rebinding of worn books, the lettering and application of title panels, and perhaps some binding of books the printer bought in flat sheets, already printed, from London or from another colonial printer.

The fact that custom binding and rebinding accounted for a prominent share of the work done by Williamsburg binders indicates that Governor Botetourt was not the only man in Virginia before the Revolution who owned and cherished books. According to one estimate, there were at least 1,000 private libraries with at least 20,000 volumes altogether before the colony was one hundred years old. Another study of 100 such collections, including the largest, calculated their average size at 106 titles (possibly twice that many volumes).

The average is high because the study included such very extensive libraries as those of William Byrd II, Robert Carter, and Ralph Wormeley. Nearly half of the libraries in the group studied had fewer than twenty-five titles. However, most Virginia gentlemen of the planter aristocracy owned at least an armful of books.

An occasional book in any such collection might have been written by the owner himself. Hunter stitched a manuscript volume for Nathaniel Walthoe, Esqr., and Royle bound a handwritten book for John Blair. What these gentlemen had written that deserved such care can only be guessed at. Both were officials, so the books might well 20 have been public records of some kind. On the other hand, perhaps the content was less prosaic: poetry, maybe, or something like the “list of Horse Matches” that Royle bound for the Hon. John Tayloe at two shillings.

Music books, volumes of collected pamphlets and magazines, a “cyphering book” for Mrs. Jane Vobe, keeper of the King’s Arms Tavern, and dozens of similar items in the Hunter and Royle daybooks account for only a portion of custom binding, however. The book most often bound to order was the Bible, closely followed by the Anglican prayer book. Hunter bound a number of Bibles for 6 shillings, but charged 12 shillings for a “large Church Bible” and 50 shillings for one “neatly bound in Turkey.” “Turkey,” “levant,” and “morocco” leathers were all goatskin, each taking its name from the region where it was tanned.

Here are a few entries from Royle’s daybook during mid-1765, selected not only because they show the binder’s price list, but also because the customer’s name or occupation, or his preferences in reading matter and binding, or his concern for the intellectual advancement of the fair sex may be of interest:

| [shillings/pence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| June 11 | William Waters, Binding Corelis Sonate, lettd ... 4to | 8/9 | |

| June 19 | Hon. John Blair, Binding Amelia [County] rent roll. folio | 15/- | |

| June 27 | George Davenport, Binding Mrs Ballard’s Prayer Book | 3/9 | |

| Col Robert Bolling, Binding Councel of Trent, folio, gilt & Letter’d 15/- Do ... Baconi Historia, Henrici Septimi, do 2/6 | 17/6 | ||

| Thomas Jefferson, Do History Virginia, 4to | 8/9 | ||

| July 3 | Col Robert Bolling Junr Lettering Pope’s Works, 9 Vols for Miss Sally Waters | 5/7½ | |

| Aug. 28 | Revd David Mossom, Binding a Bible 5/- | ||

| John Gilchrist, Ditto Love Elegies 2/- | 7/- | ||

| Aug. 31 | James Anderson, Blacksmith Binding a Quarto Bible. in ruff Calf | 10/- | |

An advertisement Royle placed in the Maryland Gazette for May 2, 1765, throws an interesting light on one of the characteristic labor-management difficulties of his time:

WILLIAMSBURG, April 23, 1765

Ran away from the Printing-Office, on Saturday Night, a Servant Man named George Fisher, by Trade a Book-Binder, between 25 and 26 Years of Age, about 5 feet 5 Inches high, very thick, stoops much, and has a down Look; he is a little Peck-pitted, has a Scar on one of his Temples, is much addicted to Licquor, very talkative when drunk, and remarkably stupid.

Whoever apprehends the said Servant, and conveys him to the Printing-Office, in Virginia, shall have Five Pounds Reward, and if taken out of the Colony, TEN POUNDS, beside what the Law allows.

JOSEPH ROYLE

This seems a generous reward indeed for the return of a man of Fisher’s unendearing qualities. Not that Fisher, a transported convict, was untalented in his way. “Conveyed” to Williamsburg and lodged in the gaol, he escaped at the end of July, both from custody and from history.

The third principal variety of work done in the Williamsburg binderies was edition binding—the stitching and uniform covering of a whole run of books printed in the same shop. Session laws of the Virginia Assembly, and periodical codifications of them printed in editions of 1,000 copies or more constituted the bulk of edition binding for Parks and his successors.

Shortly before his death Parks had agreed to print and 22 bind 1,000 copies of the 1748 revision of the Virginia code “with the Arms of Virginia stampt on each book.” Along with the other assets and liabilities of the printing office, Hunter took over this contract, which called for the volumes to be finished by June 10, 1751. In October of that year however, he felt obliged to defend himself with the following notice in the Virginia Gazette:

☞ The Subscribers to the Virginia Laws, as well as the Public Magistrates, having loudly complain’d of their long Delay, and thrown the Blame of it entirely on the Printer; it is judg’d necessary to assure them, That they have been printed near four Months, and that their Publication has been in no wise retarded through his Neglect, but for Want of the Table; the Gentleman appointed to draw it up, not having yet compleated it—— Those subscribers who are in immediate Want of them, on paying a Pistole, may have them Stitch’d for present Use, which they may afterwards have bound when the Table is printed, making it up the Subscription Price.

When he worked on a number of books at the same time, the binder ordinarily moved them in groups through the various binding processes. Thus a group of books, all damp and needing to be pressed, could be put into such a standing press as this, with “press boards” between each one. While this group dried out the next was being glued up, and so on.

Nearly twenty years later a subsequent collection of Virginia laws caused a different kind of trouble for three of Hunter’s successors in Williamsburg. The job of printing and binding 1,000 copies of the great volume was too much for the public printer, William Rind, to handle alone. So he undertook it jointly with the partnership of Alexander 23 Purdie and John Dixon. Their order for leather to cover the books was answered by a shipment from London of “Nasty dirty little skins” that could neither be used nor returned. Eventually the skins rotted on the wharf at Yorktown, while the printers had to ask reimbursement from the House of Burgesses.

Although William Parks published a number of books under his own imprint, just as he had done in Annapolis, Hunter, Royle, and their successors seem to have been much less active in this phase of the printing and binding business. Those who were public printers continued to issue the Virginia laws and other public compilations, proclamations, and the like. Also, they annually printed small pocket almanacs, usually only stitched and covered in paper, which sold in considerable numbers each December and January.

The several Williamsburg printers who followed Royle left no daybooks or other records that have yet come to light. What little we know of their bookbinding activities comes from their advertisements in the various Virginia Gazettes. (At one time three separate weekly papers were issued in Williamsburg by rival printers, all called the Virginia Gazette!) Here are some typical samples:

GENTLEMEN may now be supplied, on short notice, at the Printing Office, Williamsburg, with BLANK BOOKS of all sizes, ruled or unruled, and bound either in Calf or Vellum. OLD BOOKS also new bound, and any thing in the BOOK BINDING business executed in the cheapest and best manner.

Virginia Gazette Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, Printers March 14, 1766

BLANK Bills of Exchange, Bonds, Bills of Lading, and all other Blanks, may be had of William Rind, at the New Printing-Office, near the CAPITOL. Gentlemen 24 may also be supplied with all Sorts of Blank Books; and old Books are neatly and expeditiously Bound, at a reasonable Rate.

Virginia Gazette William Rind, Printer May 30, 1766

A COMPLETE ASSORTMENT OF

All Kinds of STATIONARY,At Dixon & Hunter’s Printing Office:

BEST Writing Paper, Imperial, Royal, Medium, Demy, Thick and Thin Post, Propatria and Pot, by the Ream, or smaller quantity; Gilt, Plain, and Black Edge Paper for Letters; Parchment; Inkpowder; best large Dutch Quills and Pens; red and black Sealing-Wax and Wafers; Memorandum Books; Red Ink, in small Vials; Red Inkpowder; Pounce and Pounce-Boxes; Black Lead Pencils; all Sizes of neat Morocco Pocket Books; all Sorts and Sizes of Pewter Inkstands; best Edinburgh Inkpots, for the Pocket; best Playing Cards. —— Legers, Journals, Day-Books, and all Sorts and Sizes of Blank Books for Merchants Accounts or Records. Blanks of all Kinds for Merchants, County Court Clerks, &c. &c. &c.

☞ Old BOOKS new BOUND, and all Kinds of BOOK-BINDING done at this Office, either in the NEATEST or CHEAPEST Manner, according to Directions; and where any Thing in the PRINTING BUSINESS is expeditiously performed, on moderate Terms.

Virginia Gazette John Dixon and William Hunter Jr., Printers March 18, 1775

THOMAS BREND,

BOOKBINDER and STATIONER,HAS for SALE, at his shop at the corner of Dr. Carter’s large brick house, Testaments Spelling Books, Primers, Ruddiman’s Rudiments of the Latin Tongue, Watts’s Psalms, Blank Books, Quills Sealing-Wax, Pocket-Books, and many other articles in the Stationery way. Old books rebound; and any Gentlemen who have paper 25 by them and want it made into Account Books, may have it done on the shortest notice.

Virginia Gazette John Clarkson and Augustine Davis, Printers August 19, 1780

Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, who placed the first of these advertisements, were the successors of Joseph Royle in the shop on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg that had passed down from William Parks to William Hunter to Royle to Purdie. Their Virginia Gazette was the direct continuation of the paper founded by Parks in 1736. We are not too surprised, therefore, to find the egg roll reappearing once more on the covers of several copies of a book printed by Purdie and Dixon in 1774.

The name of Thomas Brend brings to a conclusion the known list of bookbinders who worked in Williamsburg before the Revolution. Brend emigrated from England to Annapolis in 1764 and set up in trade there. It seems probable that he moved to Williamsburg with William Rind in 1766 or arrived shortly afterward. Rind was the Annapolis printer whom Jefferson and some other patriots had induced to come to Virginia. They hoped Rind’s press would offset the impact of Joseph Royle’s, which they thought was too much in the governor’s pocket.

Jefferson was among the men for whom Brend bound books, as were St. George Tucker of Williamsburg and other persons less known to history. This work, however, he did in Richmond, where he moved after the capital of Virginia had been changed to that city in 1780. There he did most of his work, including the covers of many books of public records, as an independent binder.

On an account book of the state auditor for 1785 appears the familiar egg roll. How it got into Brend’s possession no one can say, since he was presumably not in the direct line of succession from Parks through Hunter and Royle. Somehow he did acquire tools from the succession, for the trail of detection comes full circle in 1799. In that year in Richmond 26 Thomas Brend rebound Jefferson’s collection of the laws of Virginia, using to decorate the board edges the same Mousetrap roll that William Parks had used in Annapolis in 1728.

Although this small pamphlet does not pretend to be a thorough manual on how to bind your own books, anyone seeking a hobby might well consider bookbinding. The procedures are simple, the necessary tools and materials need not cost a great deal, and the satisfactions one can take in the production of his own fine bindings should be obvious.

What we can do here is to describe only the basic tools, equipment, and procedures that would have been used by a Williamsburg craftsman in binding a book in the most usual dress of colonial times. The practicing binder, of course, would have had a comparative wealth of tools and materials with which to turn out—by the time-honored and still-used procedures—bindings in greater number and variety of finish. The following lists represent the minimum essentials for binding a book.

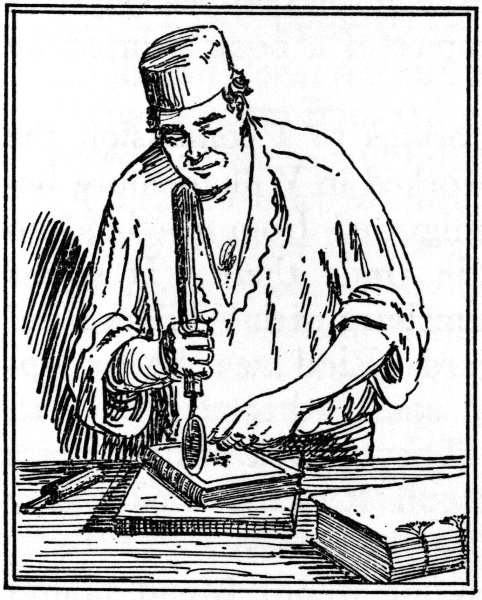

When the time comes for applying decoration to a binding, the bookbinder—here using a single-fillet roll—can exercise his artistic imagination or follow a traditional pattern.

Materials

Tools & Equipment

The printer’s job was done when the flat sheets of paper came off his press, each sheet containing four or more printed pages arranged so that folding would bring the pages into proper sequence. The binder’s first task was to fold the 28 sheets into “signatures” of four, eight, twelve, or sixteen pages.

Sheets folded once—into two leaves, a four-page signature—made a large-format book called a “folio.” Two folds in each sheet made eight-page signatures and “quarto” books. Three folds gave “octavo” volumes of sixteen-page signatures. A different arrangement of folds produced twelve pages in a signature and a “duodecimo” book. For any number of folds, however, a bone or ivory folder—a thin, smooth blade—was essential for rapid and accurate work. And it came in handy for a number of other binding operations, too.

After he had folded all the printed sheets, the binder gathered a full set of signatures in the proper order to make the book. On his stitching frame—which was simply a four-piece vertical framework, the upper crosspiece adjustable in height—he stretched four to six leather thongs or pieces of hemp cord. With needle and strong linen thread he then stitched the signatures, one after another, through their center folds to each of the crossbands. The sewing frame held them parallel to each other and at right angles to the pages.

These bands gave bound books their flexibility and created the ridges across the spine characteristic of most of them. The stitch used in sewing the signatures to the bands was about as simple as could be, but it cannot be duplicated by any machine yet devised. The crossbands and the stitching together were the keys to the all-but-everlasting durability and the flat opening of the well-made book.

The binder next squared up the back of the book and applied glue to it. When dry, he put the book in the trimming press and trimmed the fore edge, head, and tail, then with his backing hammer rounded off the spine. Having cut the boards just a bit larger than page size, he punched holes through them close to their back edges. These holes he spaced in pairs to match the position of the bands, which he laced through the holes, pasted firm, and pounded smooth.

Very little the binder had done so far would be visible in the finished product. But at this point he could begin to put his artistry on display. Selecting silk thread in two colors to suit his taste, he bound a narrow piece of leather across both the top and bottom of the spine, completely covering them with something like a buttonhole stitch. These “headbands” added little to the strength but much to the appearance of a book. Careful binders said that a book should no more be seen in a library without headbands than a gentleman should appear in public minus a collar.

In the “trimming press and plough,” the bound pages of a book are clamped between the heavy horizontal beams of the press while a knife held in the plough slides back and forth, planing the exposed edge of the book smooth and even.

Next came the “drawing on” of the cover. The binder cut a piece of calfskin approximately ¾ inch larger all around than the covers of the book opened out flat, and with his skiving knife pared the margins of the leather very thin. After the leather had been well soaked with water on the outer or grain side and with paste on the inner side, the binder carefully molded it around the spine and smoothed it onto the boards—being careful not to stretch it. The pared margins were then turned in and the volume, except for minor touches and drying, was finally ready to be decorated.

Having decided on the pattern of decoration he wished to apply, the binder heated the appropriate brass tools to “blind in” the design. The tools had to be hot enough to make a sharp impression in the leather, but not hot enough 30 to burn it. Each had to be pressed into the leather with just the right weight—not too much and not too little—to produce the desired effect.

If the pattern was also to be gilded, the binder prepared a solution of white-of-egg, called “glair,” and painted it into the blind impressions. Having laid gold leaf thereon, he again pressed the same heated tools carefully in the same indentations. The excess gold was then wiped off and the leather cleaned with diluted vinegar and dressed with a good leather dressing.

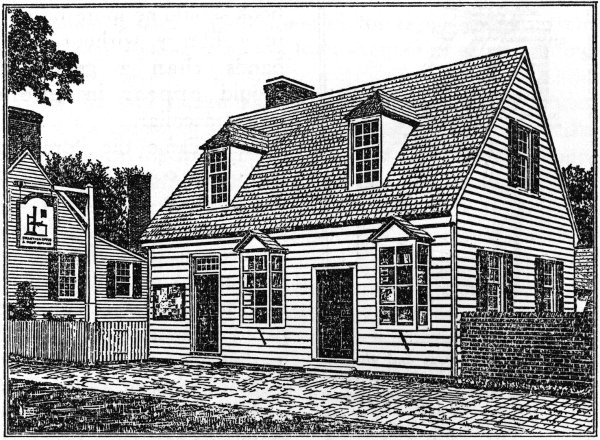

This is the Printing Office in Williamsburg, restored to look as it did in the eighteenth century when it was occupied in succession by William Parks, William Hunter, Joseph Royle, Alexander Purdie, and John Dixon with his partners William Hunter, Jr., and Thomas Nicolson.

Finally, the endpapers were pasted down to the insides of the boards and the book was complete. It took perhaps eight to ten hours of actual working time for a single volume, but spaced over as much as two weeks to allow drying time between processes.

Just as the printing office of William Parks and his successors stood on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg two centuries ago, so it stands again today on its original site. Again today it includes a bindery where gentlemen and ladies may bespeak books to be bound or rebound in the most exact manner and the most elegant taste. The master binder assures his patrons that he uses only the best materials and can, if they so wish, decorate a volume with the egg, the Mousetrap, or any other roll or ornament in his stock that pleases their fancy.

For he not only uses the same kinds of tools used in the eighteenth century; some of them are actually recut to produce replicas of the old patterns. And his methods of work, too, are the same that were employed in this shop by men who put sturdy covers on the volumes of William Byrd II, Thomas Jefferson, and Norborne Berkeley—otherwise titled Lord Botetourt.

Those who may be interested in pursuing further either the historical or the handicraft aspects of bookbinding will find the following list useful. Most of these books also include bibliographies or reading lists.

Susan Stromei Berg, comp., Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg Imprints. New York: Clearwater Publishing Co., 1986.

Vito J. Brenni, Bookbinding: A Guide to the Literature. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1982.

Edith Diehl, Bookbinding, Its Background and Technique. 5th ed. rev. Port Washington, N. Y.: Kennikat Press, 1965.

Hannah D. French, Bookbinding in Early America: Seven Essays on Masters and Methods. Worcester: American Antiquarian Society, 1986.

David Muir, Binding and Repairing Books by Hand. New York: Arco Publishing Co., 1977.

Howard M. Nixon, Five Centuries of English Bookbinding. London: Scholar Press, 1978.

Matt T. Roberts and Don Etherington, Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books: A Dictionary of Descriptive Terminology. Washington, D. C.: Library of Congress, 1982.

C. Clement Samford and John M. Hemphill II, Bookbinding in Colonial Virginia. Williamsburg, Va.: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1966.

Walters Art Gallery, The History of Bookbinding, 525-1950 A.D. Baltimore: The Trustees of the Walters Art Gallery, 1957.

Lawrence C. Wroth, The Colonial Printer. Portland, Me.: Southworth-Anthoensen Press, 1938.

Laura S. Young, Bookbinding and Conservation by Hand: A Working Guide. New York: R. R. Bowker Co., 1981.

The Bookbinder in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg was first published in 1959 and previously reprinted in 1964, 1970, 1973, 1978, and 1986. Written by Thomas K. Ford, editor of publications at Colonial Williamsburg until 1976, it is based largely on a monograph prepared jointly by C. Clement Samford, then the master bookbinder, and John M. Hemphill II, a member of the Department of Research. The monograph has been published as Bookbinding in Colonial Virginia (Williamsburg Research Studies, 1966).