By AGNES GIBERNE, Author of “Sun, Moon and Stars,” “The Girl at the Dower House,” etc.

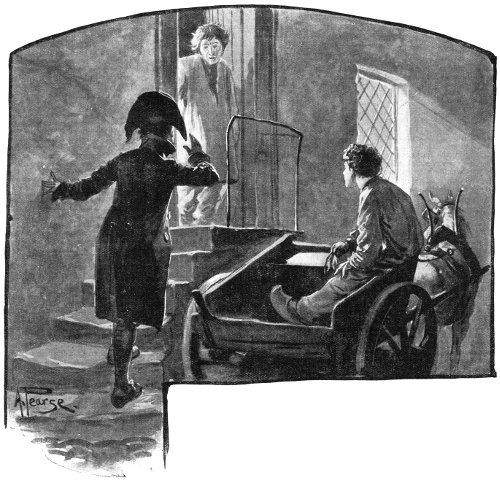

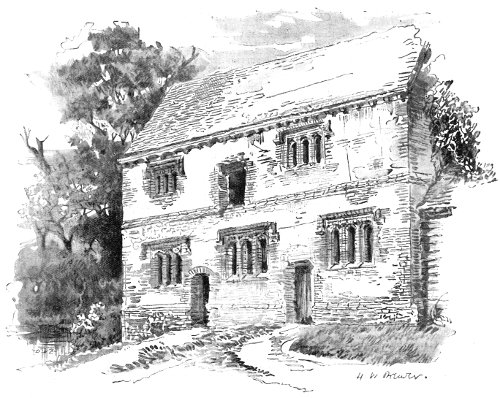

“PUTTING UP THE PONY AND CART AT

A WAYSIDE INN.”

All rights reserved.]

{386}

CHAPTER XXV.

ROY BARON A FUGITIVE.

On the

edge of a

little clearing

in the

centre of the wood

stood a small

square charcoal-burner’s

cottage,

built of stone.

Near behind might be seen a good-sized

outhouse or woodhouse; and to one side

was the pile of slowly-burning charcoal.

Round and about were heaps of unsightly

rubbish and of blackened moss.

Nobody seemed to be within or at

hand. Jean opened the cottage door

without difficulty; and when they had

passed through, he bolted it in their

rear.

Then in the darkness he found his

way to a corner, struck a light with flint

and steel, made a “dip” to burn, and

groped anew. The one window was

closely shuttered.

Roy flung himself upon a small

bench, glad to get his breath, and

watched the other’s doings curiously.

“Are we to stop here?” he asked.

“But if the gendarmes come?”

“We must circumvent them,

M’sieu.”

“How? What are you going to

do?”

Jean was too busy to reply. He produced

a blouse, such as would be worn

by a French labouring lad, with shirt

and trousers to match, and brought

them to Roy. “M’sieu must change

his clothes,” he said. “Rest afterwards.”

“All right,” once more assented Roy,

though the cottage was swimming and

his ears were buzzing with fatigue. He

stood up, and promptly divested himself

of what he wore, to assume a different

guise. Jean brought from the same

corner a small bottle of dark liquid,

which he mixed with a little water in a

basin, and then dyed Roy’s hair and

eyebrows, thereby altering his look to

such an extent that even his mother

might almost have passed him by. Roy

laughed so much under this operation,

as to discompose the operator.

“Tenez, M’sieu! Taisez-vous, donc,

s’il vous plait! M’sieu, I entreat. I

assure Monsieur it is no matter for

laughter.”

“If you knew what it is to

be free again, you’d laugh

too,” declared Roy, and then

his merriment passed into a

big yawn. “But I’m awfully

sleepy.”

“Deux minutes, and Monsieur

shall rest. Monsieur is

hungry.”

Monsieur undoubtedly was,

though the craving to lie down

was even greater than the

craving to eat. Jean handed

him a hunch of bread and

cheese and a glass of milk;

and while Roy was occupied

with the same, he proceeded

to array himself in holiday

costume. He donned an old

and shabby but once gorgeous

coat, with standing collar and

gay buttons, which, as he informed

Roy, had many long years before

been the best holiday coat of his esteemed

grandfather.

“I go to the wedding of my niece,”

he remarked, with so much satisfaction

that, for a moment, Roy really thought

he meant it. “Does Monsieur perceive?

And Monsieur will be the boy—Joseph—who

goes with me in the little cart.”

“But where is the little cart?”

“All in good time, M’sieu. Now we

have for the moment to get rid of these

things.”

Jean rolled the discarded clothes into

a bundle, with which he disappeared out

of the cottage for a few minutes. Roy

conjectured that he might have buried

it in the bushes, or under heaps of black

rubbish, abundance of which lay ready

to hand. Jean then took Roy into the

outhouse, which was more than two-thirds

full of heavy logs and faggots

of wood—the winter supply—piled

together.

“Am I to get underneath all that,

Jean?”

“Oui, M’sieu. The gendarmes will

not easily find you there.”

“And you too?”

“Non, M’sieu. I betake myself to

the soupente.”

The soupente in a French cottage is

a kind of upper cupboard, a small

corner cut off from the one room, near

the ceiling, descending only half-way

to the ground, and reached by a ladder.

“And if they find you there——”

“M’sieu, if they find me, they will not

know me—see, in this dress! I am not

like the Jean who chopped wood at

Bitche. And I hope then to draw their

attention from M’sieu! Voyez-vous?”

Roy wrung his hand. “I don’t know

what makes you so good to me,” the

boy said huskily. “I—I don’t think

it’s fair upon you, though. And—I

can’t think why!”

“It is not difficult to tell M’sieu

why!” Jean looked abstractedly at

the roof of the wood-hut. “It is for the

sake of my mother—for the sake of that

kind Monsieur le Capitaine, who would

not leave her unhappy. Does M’sieu

remember—how Monsieur le Capitaine

regarded my mother that day?”

Roy remembered—and understood.

“Now, Monsieur! We may not lose

time. The light grows fast.”

Jean pulled down and hauled aside

logs and masses of wood, making a kind

of little cave or hollow far back, where

Roy could creep in and lie close to the

wall. Jean wrapped round him an old

coat, for warmth; and then, when he

had laid himself down, threw light

black rubbish over him as an additional

security, before carefully heaping up

anew the logs and faggots, till not the

faintest sign remained of any human

being beneath. Jean did his utmost to

deface all tokens that the wood-pile had

been disturbed.

“M’sieu must lie still,” he said.

“On no account must M’sieu move or

speak. If by chance I should have to

go away, M’sieu must wait till nightfall,

when the cart will come to take

M’sieu elsewhere.”

“But I say, Jean—you must not get

into trouble for me,” called Roy, his

voice sounding far and muffled.

“Bien, M’sieu. Trust Jean to do

his best. Can M’sieu breathe easily?”

“Rather stuffy, but it’s all right.”

“Au revoir, M’sieu. I go to the

soupente. M’sieu will remain in the

bûcher, till I or my friend come again.”

Then silence. Jean returned to the

cottage, where he rinsed the basin which

had been used for dyeing purposes, put

things straight, unbolted the front door,

climbed up into the little soupente,

drawing the ladder after him, and there

laid himself flat, under a pile of loose

rubbish. Soon he was or pretended to

be asleep.

Roy’s sleep was no pretence. Despite

his hard bed, and the “stuffiness” of

the limited atmosphere which he had to

breathe, despite fear of gendarmes and

risks of discovery, he was very soon

peacefully sound asleep, and knew no

more for the next two hours.

Something roused him then. In a

moment he was wide awake; his heart

thumping unpleasantly against his side.

The gendarmes had come.

Roy of course could see nothing; he

could only hear; and he heard a good

deal more than might have been expected

from his position, since his

senses were quickened by the exigency

of the moment. Also, the men made a

good deal of noise, after the manner of

gendarmes. Roy imagined that three

or four of them must be there.

They made their way first into the

cottage, surprised to find the door on

the latch, and nobody within. The fact

of finding the door thus tended to allay

their suspicions, as Jean had hoped.

On the face of matters, nothing was

less probable than that fugitives hiding

within should not so much as have

drawn the bolt. They walked round

the one room, knocking things about

a little. One of them looked vaguely

about for a ladder, but seeing none

he did not trouble himself further as to

the soupente.

Then they left the cottage, and

entered the bûcher, where the wood

was solidly and firmly piled together,

as for the winter’s use. No signs here

of human life. Roy below the pile lay

motionless, every faculty concentrated

into listening. One of the men kicked

down a few faggots, and another pulled{387}

at a log. To Roy it sounded as if they

were making their way to where he

was. But the search stopped at last,

after what seemed to Roy a small century

of suspense, and they took themselves

off. He heard them mount their horses

and trot away.

“Safe!” murmured Roy, and in his

heart there was a fervent “Thank

God!” not spoken in words.

He wondered whether Jean would

come to him; but Jean remained

absent; and Roy obeyed orders, staying

where he was. Presently he

dropped asleep again, and remembered

nothing more for hours.

How many hours he had no means of

knowing. Where he lay, he was in

pitch darkness. When he woke, he

had the consciousness which we often

have after sleep, of a considerable time

having elapsed; but whether it was

now morning or afternoon or evening

he could not even guess. He only

knew that he was growing frightfully

weary of his constrained position, longing

to get out and exert himself. To

sleep more was not possible. He

waited, minute after minute, wondering

if the long slow day would ever come

to an end. At length a voice sounded—

“M’sieu!”

“All right,” called Roy.

“Can M’sieu wait a little longer? I

hope to get Monsieur out soon—after

dark. It is not safe before then.”

“I’ll wait, Jean. Only as soon as

possible, please.”

“Oui, M’sieu.”

Jean disappeared anew. Roy put a

question, and had no answer. He was

wildly hungry, but there was nothing to

be done except to endure.

The wisdom of Jean’s caution became

apparent. Before darkness settled down

the same party of gendarmes again

galloped up and sprang to the ground.

They walked as before through cottage

and shed, once more kicking the furniture

about. This time one of them found the

ladder, went up it, and stepped inside the

soupente; but Jean had betaken himself

to another hiding-place outside the

cottage, and the search bore no fruit.

The men entered the wood-hut again,

in a perfunctory manner, knocking

down a log or two carelessly, and using

one to another rough language as to

the escaped prisoner, which boded no

gentle treatment for Roy should he fall

into their clutches. Then they vanished,

and silence settled down anew upon the

scene.

“Not likely to come again, I hope,”

murmured Roy. “O I am tired of

this!”

One more hour he had to endure; and

then came the welcome sound of Jean

removing the wood-piles.

“Can M’sieu stand?” asked Jean.

Roy crept out slowly, made the effort,

and fell flat. Jean pulled him up, and

held him on his feet.

“All right, I’m only stiff,” declared

Roy. “They won’t come back, I

suppose.”

“Non, M’sieu.”

“Why, it’s night, I declare! Been

so dark in there, I didn’t know the

difference between night and day.

There, now I can walk.” Roy managed

to reach the cottage on his own limbs

unassisted. “What a desperately long

day it has been.”

“M’sieu has found it wearying, sans

doute.”

“But as if that mattered! As if

anything mattered—only to get away

safely!” Roy said energetically.

“Jean, you are a good fellow! Is

this for me to eat? I’m as hungry as

a bear! Jean, I shall always think

better of Frenchmen for your sake.”

“Yet M’sieu will doubtless fight us

one day.”

“I shall fight Buonaparte, not the

French nation. I like some of your

people awfully—some at Fontainebleau,

and some at Verdun. And Mademoiselle

de St. Roques most of all.”

“Oui, M’sieu. M’sieu had better

eat.”

“All right, I’m eating, and you must

too. Oh, lots of French have been as

good and as kind to us détenus as they

possibly could be. And I only know

one single lodging-house keeper who

behaved like a brute. Most of them

have been just the other way. Why,

they have kept on lodgers month after

month, out of sheer kindness, when they

couldn’t pay anything because no money

reached them from England. I know

all that! And I like the French—only

not Boney!”

Jean smiled to himself.

“Cependant, M’sieu, the army of the

Emperor is made of French soldiers.”

“Can’t help that,” retorted Roy.

“And they can’t help it either, poor

fellows—most of them. I say, this

cheese is uncommonly good. Where

did you manage to hide it away, so as

to keep it from the gendarmes? Jean,

were you long at Bitche? Tell me

about it.”

Jean was cautious. He evidently

preferred not to enter into details. It

was better for Roy’s own sake that he

should not know too much. It seemed,

however, that on Jean’s arrival at

Bitche, he had found one of the gendarmes

to be an old acquaintance; and

through this gendarme, not through his

soldier-friend, he had obtained a temporary

post in the fortress. A man who

did rough work, chopping and carrying

wood and so on, had fallen ill and had

gone home for a fortnight to a neighbouring

village. Meanwhile, Jean was

allowed to undertake his work.

This gave Jean a good opportunity to

study the fortress and to make himself

acquainted with the surrounding country.

He did not fully explain to Roy the

maturing of his plans during that fortnight,

nor precisely what those plans

had been. The careful manner in which

he avoided speaking of his soldier-friend

made Roy pretty sure that the said

friend had had some sort of hand in

aiding his escape; but he put no more

questions in this direction. Jean had

had two or three glimpses of Roy from

time to time; but he had held carefully

aloof, until he saw his way to action.

Then he contrived to be sent into the

yard just when the better class of

prisoners was assembled there; and the

rest Roy knew.

“Why was I sent to that upstairs

room?” demanded Roy.

“M’sieu, there were doubtless reasons.

It is sometimes best that one should not

know all the reasons that may exist,”

observed Jean meditatively. “What if,

perhaps, somebody had known of the

intended escape, and had tried by that

means to save M’sieu from danger?”

“Jean, was it you?”

“Non, M’sieu!”—decidedly. But

whether Jean spoke the truth on this

point, whether Jean might or might not

have had a hand in the wire-pulling

which led to that event, Roy had no

means of knowing. He felt that further

questioning would be unfair. He had

but to be thankful that he was free.

By the time hunger and thirst were

satisfied, Roy’s spirits had risen to

a pitch unknown to him during eight

months past. Then, the land being

shrouded in darkness, a rough little cart

drawn by a rough little pony and driven

by a charcoal-burner came to the door.

Roy spoke a few grateful words to him,

as well as again to Jean, for their

generous help. After which, he and

Jean started in the cart, taking a small

lantern with them.

This next stage of the journey meant

quicker and easier advance than that of

the night before. The pony was both

strong and willing; and all through the

hours of darkness they were getting

farther and farther away from Bitche.

By dawn of day the fear of pursuit was

immensely lessened. Even if the gendarmes

had overtaken them, they would

hardly have suspected the odd figure in

a smart old coat and ancient cocked hat

of being the temporary wood-chopper at

Bitche, or the black-haired boy in a

rough blouse of being their prisoner,

Roy Baron.

For greater safety, both that day and

the next, they found a retired spot in

which to hide, letting the pony loose to

browse and rest on some rough ground,

or putting up it and the cart at a wayside

inn, and calling for it later. One

way and another, the dreaded pursuit

was eluded; and, as day after day went

by, Roy felt himself indeed free and on

the road for Home.

“Why should you not come with me

to England, Jean? I can promise you

that you’d be well looked after there by

my friends,” urged Roy. He had

grown sincerely fond of this kind,

thoughtful Frenchman.

They were now fast nearing the coast,

and their next halting-place was to be

at a farm-house within sight of the sea.

There they would have to remain until

an opportunity should occur for Roy to

cross the Channel. Since he had no passport

he could not attempt to journey by

the ordinary routes. But even here Jean’s

resources did not fail, and the owners of

the said farmhouse were near relatives

of his own.

“Non, M’sieu. I should feel strange

in another country. Also—have I not

promised to let Monsieur le Capitaine,

and Monsieur votre Père, and Madame

votre Mère, hear of your safety? Could

I disappoint them?”

“But, I say, will it be safe for you to{388}

go back to Verdun? What if they find

out that you have helped me to get

away?”

“They will not find out, M’sieu. It

was known that I should leave Bitche

that night—and my friends will have

diverted suspicion from me. Moreover,

it is no such hard matter to make a little

disguise of myself—if need be.”

Then they reached the farm, and Roy

found himself among friends, ready all

to shield him for Jean’s sake. It was

decided that he should work as a boy

upon the farm, sufficiently to draw no

attention upon himself, since the waiting

for a passage might be long. Roy was

willing to be or to do anything, if only

he might at last escape to England.

The farmer’s eldest son, a soldier by

conscription in the army of Napoleon,

had been a prisoner in England; and

he, like Roy, had made his escape,

getting safely back to France. Roy,

immensely interested in this story, plied

the farmer and his wife with questions

as to the experiences of the young fellow

in an English prison—questions which

they were not loath to answer. They

had, of course, the whole story at their

fingers’ ends.

It was at a place called “Norman’s

Cross” that their Philippe had been

confined—somewhere not far from the

eastern coast of England. About seven

thousand prisoners of war, chiefly

Frenchmen, were there kept under close

surveillance. The prison and the barracks

were built on high land, healthy

enough—yes, certainly, as to that, the

farmer said—with plenty of fresh air.

And the prisoners were guarded more

by sentinels in all directions, than by

fortifications, walls, moats, or dungeons.

“Not like Bitche!” interjected Roy.

Well, no, certainly—Monsieur spoke

correctly. The place—Norman’s Cross,

and the old farmer made a funny sound

of these two words—was not precisely

like Bitche. As to arrangements,

Philippe had had no fault to find with

the food provided. It was good of its

kind; and cooks were chosen from

among the French prisoners by themselves,

being paid for their work of

cooking by the English Government.

Also, when Philippe fell ill, he found the

hospital well managed. A school for

prisoners was kept going; and several

billiard-tables as well as other amusements

were provided.

But, ah, the poor Philippe, he had

been unhappy in captivity! Was it not

natural? Had not Monsieur himself

experienced the same? He had longed

to be free—to return to his own country

once more. And though on the whole

the prisoners had been fairly well treated,

at all events in that particular place, yet

of course there had been cases of

roughness and of harsh treatment.

Moreover, there was much to make a

prisoner sad—the desperate gaming, the

perpetual duelling, among his fellow-prisoners

were of themselves sufficient.[1]

So, after more than a year of captivity,

always more and more hopeless, with no

token of the war drawing to a close, he

had at last resolved to make his escape.

And, through great dangers, privations,

difficulties, he had actually succeeded.

Where was Philippe now? Ah—pour

cela—he had rejoined his regiment, and

was again at his old occupation. Fighting,

fighting—who could say for how

long? Perhaps to be again taken

prisoner, and once again to be at

Norman’s Cross! Who could foretell?

(To be continued.)

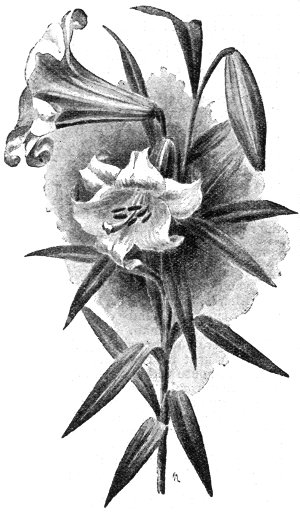

PRACTICAL AIDS TO THE CULTURE OF LILIES.

By CHARLES PETERS.

Japan is the home of lily culture. Not only

are the Japanese Islands rich in native lilies,

but their inhabitants, imbued with a love of

flowers, which to our Western minds is almost

incomprehensible, have introduced into their

country all the prominent plants of Eastern

Asia. And with a knowledge which we

possess in but a small degree, they have

modified and beautified both their own plants

and those that they have introduced from

foreign countries.

The culture of the lily in Japan has reached

a high stage of development, and most of

our best varieties of lilies owe their origin to

Japanese gardeners.

Foremost among the lilies of Japan is the

one which bears the name of its native place.

Lilium Japonicum Odorum is one of the very

finest of the lilies, and in the strength of its

perfume it is absolutely without a rival.

The true L. Japonicum, or, as it is now more

generally termed, L. Japonicum Odorum is

but little known in England, but an allied

species, L. Brownii, is well known, and though

not grown so frequently as it should be, it is

deservedly popular.

It has always been a question whether

L. Japonicum and L. Brownii are but varieties

of the same plant. Certainly there is a great

similarity between them, but there are points

in which the two plants differ and these

differences are very constant.

In Dr. Wallace’s little book on lily culture

the differences between these two lilies are

detailed in tabular form, and for ourselves we

are fully convinced that L. Brownii and

L. Japonicum are distinct but very nearly

allied species.

The bulb of L. Japonicum is white or

yellowish, but never brown. The scales are

narrow and are very loosely connected with

the base. The bulb is always rather loose and

the scales divergent, but good bulbs have a

very firm centre. The bulb of L. Brownii is

usually reddish and the scales are broad. The

base is very small, and the whole bulb has a

curious and very characteristic shape.

The shoot of L. Japonicum is greener and

blunter than that of L. Brownii. The shoot

of the latter lily very much resembles thick

asparagus.

During growth it is easy to distinguish

between these two lilies, for the stem of

L. Japonicum is green, while that of L. Brownii

is brown.

There is not very much difference in the

flowers of these lilies. L. Brownii often bears

three blossoms, and in one case, recorded in

The Garden, five blossoms upon one stem.

Two blossoms are very frequently present on

the same stem. We have never known L.

Japonicum to bear more than one blossom on

each shoot.

The flowers of L. Japonicum are a rich{389}

custard yellow while they are opening, but in

the fully expanded blossom the colour of the

interior is a rich creamy white. The pollen

is reddish brown. The exterior of the perianth

is thickly streaked with chocolate colour.

The scent of this flower is very strong,

resembling that of the Jasmine.

The flowers of L. Brownii never show the

deep yellow colour which is present in the

partially opened buds of L. Japonicum. The

pollen is deep brown and the exterior of the

blossoms is more streaked with brown than

are those of L. Japonicum. We cannot

recognise any difference in the smell of these

two lilies, but Dr. Wallace contends that the

smell of L. Brownii is only moderately strong,

like that of L. Longiflorum; while other

authors have denied to L. Brownii any scent

whatever!

There is but little reason in the naming of

any plant nowadays, and the foolish and

unscientific methods of naming plants after

some person who has discovered, or described,

or who has often done nothing more than

bought a specimen of the plant, is unfortunately

very rife. Scientists have tried and are

still trying to put down this absurd nomenclature,

but they are thwarted in every way by

gardeners and others. Mr. Jones, Nurseryman,

has just flowered a lily. He does not know

its name. What does he do? Does he trouble

to find out if the plant is known to science?

Not he! He labels it Lilium Jonesii. Mrs.

Smith, a very aristocratic lady and a great

patron of Mr. Jones, comes along, sees, admires

and buys that lily. She asks Mr. Jones to

send her the plant, and it arrives labelled,

“Lilium Jonesii var. Smithii.” So much for

gardeners’ floral nomenclature!

Can anyone tell us who is the Mr. Brown

after whom L. Brownii is named? As far as

we can find out that gentleman is quite

unknown to science. Perhaps some wag

might suggest that the name originated

through ignorance. The man who discovered

the lily—or rather who thought he had

discovered it, for the plant has been cultivated

in Japan for centuries—perceiving that the

colour brown was very characteristic of the

flower, wanted to name the lily with a Latinised

version of “The Brown Lily,” but his

classical education, having been somewhat

neglected, he knew not the Latin for brown,

so he named the plant Lilium Brownii or

Browni to cloak his ignorance.

As no one is certain of the origin of the

name Brownii, so no one knows the original

habitat of this species. All our specimens

come from Japan, but it is very doubtful

whether it is a native of that land.

Have you ever seen a clump of L. Brownii

in flower? Last July there was a bed of this

lily at Kew in full blossom, and as the weather

had been remarkably suitable to the plant, and

its blossoms had not been injured by rain, the

sight of that bed was one of the loveliest

sights we can remember.

This lily has lately become more popular

than formerly, but it is very far from enjoying

that universal admiration which it amply

deserves. One reason for its comparative

scarcity is its tendency to degenerate, a

tendency which we strongly suspect is due to

improper culture.

It is usually stated that this lily should be

grown in very light sandy soil. We have

grown it in such a soil and also in a strong,

well-manured, peaty loam—a soil as different

from a light sandy soil as can be well imagined.

Those lilies grown in the light soil became

diseased and died without flowering. Those

in the heavy soil grew strong and very tall,

never showed any trace of disease, and each

spike produced two perfect blossoms.

The depth of the colour of the exterior of

the blossoms varies with the amount of light

in which the lily is grown. Specimens grown

indoors usually have a pure white exterior.

The blossoms are very tender and are often

cankered by rain at the flowering time.

Both L. Brownii and L. Japonicum make

admirable pot plants, and their blossoms last a

long time as cut flowers.

The variety of L. Brownii called Leucanthum

lacks the brown coloration of the blossoms.

We cannot distinguish it from the ordinary

variety when grown indoors. There are several

other so-called varieties.

All the lilies which we have described are

natives of Asia, but now we come to one which

inhabits our own continent.

Lilium Candidum, the white, or Madonna,

or St. Joseph’s Lily, is unquestionably the lily.

And when we mention the lily, this is the

plant which is usually meant.

Common as this lily has been in English

gardens for very many centuries, it is not a

native plant, and has very rarely escaped from

cultivation. We have only once seen this lily

growing wild. This was in a wood in Surrey,

and it was probably a garden escape. There

was but one spike of blossoms in 1895 when

we first saw it. Next year it produced one

solitary flower, but since that period it has

entirely disappeared.

Why this lily has never become wild in

England is not very obvious, for though it

never seeds in our Island, it very rapidly

increases by off-sets formed round the bulbs,

and hundreds of these must be thrown away

yearly.

Perhaps it is that the lily is not really hardy

in our climate, and though it will flourish when

tended in the garden, it is unable to hold its

own in the strife with our native plants.

Where the white lily will grow, it is one of

the loveliest of garden plants. Always better

where it has been long established and undisturbed

for years, it is in old gardens that this

lily is seen in perfection.

Unlike the lilies we have already considered,

the Lilium Candidum bears from

four to thirty blossoms on each stem. It is

true that one very rarely sees an umbel of more

than ten blossoms, but a plant bearing only

this number is a very marked feature in a

garden.

This lily differs from every one of its

colleagues in many points. Its bulb which

we figured in our first part is very characteristic.

About the end of October the white

lily begins to throw up an autumn crop of

leaves. This alone marks it off from all other

lilies, for though one or two species do sometimes

send up a stray leaf or two in autumn,

none of them do so regularly. But with L.

Candidum the autumn leaves are never absent,

and they remain green and fresh till long after

the flower shoot has appeared.

The flowers of the white lily are very

different from those of L. Longiflorum and

its allies. They are very short, widely-expanded

and very numerous. The pollen is

yellow. The flowers have a pleasant though

rather strong perfume.

Though this plant has been grown for

centuries in gardens, there are but few varieties

of it.

One variety named Aureo-Marginatis has

its leaves bordered with golden-yellow and the

autumn growth looks very striking in winter.

Three other varieties are recognised.

Monstrosum or Flora-pleno, has double

flowers. But the flowers themselves never

develop, the bracts becoming a greenish-white.

It is an ugly and worthless plant and

is deservedly neglected. The two other

varieties are called peregrinus and striatum.

In the latter the flowers are streaked with

purple. Neither variety is of any value.

The white lily is one of the oldest of all

garden plants. It was certainly cultivated by

the Romans, and is in all probability the origin

of the “Fleur de Lys.”

If you turn up L. Candidum in any book of

gardening, you will find something like this:

“The Lilium Candidum will grow anywhere,

provided the soil is of a light sandy nature.”

If you follow this advice, you will probably lose

every one of your plants.

We cannot, alas, tell you how to grow this

lily to perfection, for the simple reason that

we cannot do so ourselves. We can only tell

you how not to grow it and how we have

obtained moderate success.

The bulbs must be planted early in autumn.

It is best to plant them in late August or

early September. If you defer planting till

December or later, the bulbs will not produce

an autumn crop of leaves, they will not send

up a flower spike next season, and will probably

lie rotting in the ground.

Except in very exceptional circumstances this

lily will not flower well the first year it is

planted, for it needs several years to accustom

itself to new surroundings.

When once this plant is established and

flowers well, it should never be disturbed.

The bulbs should be planted about a foot

deep. Often when the bulbs have been in the

ground for some years, they will work their

way to the surface. Even if this happens it

is best to leave them alone, if they flower well.

But if the blossoms begin to deteriorate,

take up the bulbs and replant them.

Now about the soil. L. Candidum won’t

grow in sand and does not like a sandy soil at

all. It must have a rich moderately heavy

loam of good depth. It is in the black heavy

loam of the Thames valley that we have seen

this lily at its best. It likes lime in the soil,

but dislikes peat.

If this lily is grown in light sandy soil, it

grows beautifully till about the middle of May.

Disease then commences and kills all your

lilies with rapid strides, so that out of one

hundred spikes you may get perhaps three

half-rotten flowers. This has been our

experience of growing this lily in the orthodox

way, and we have lost very many hundreds of

flowers through following the generally

received opinions.

Lilium Candidum makes a fairly good pot-plant,

if the pot in which it is placed is very

deep.

This plant is grown in nearly every cottage

garden, and is very cheap to purchase. About

ten shillings a hundred is the ordinary price of

the bulbs.

Since we wrote our account of the diseases

of lilies we have heard of a new method of

treating the bulbs of Lilium Candidum, when

year after year the spikes become diseased.

The bulbs are washed and then baked in a cool

oven. We have heard that though this method

does, to a certain extent, check the disease, it

very materially interferes with the growth and

blossoming of the plant.

Resembling L. Candidum in the form and

number of its flowers, but differing from it in

almost every other particular, the next lily,

“The Lily of Washington,” is a species which

taxes the resources of the lily-growers to their

utmost.

Lilium Washingtonianum is the first lily

which we meet with from the great Western

Continent. It inhabits California and the

North West, growing upon the rocks and

mountain slopes of its native home.

The bulb of this lily is different from that of

any other. It is long, oblique, and rhizomatous.

Its peculiar ovoid shape is due to the fact that

it grows at one end only. The flower-spike

always appears from near the growing end.

The far end of the bulb gradually decays as

the near end grows. Bulbs of this lily are

often five or six inches long and two inches

broad. The only other lily which bears a bulb

in any way resembling this is L. Humboldti, a

native of the same places.

The leaves of L. Washingtonianum are{390}

arranged in whorls, and are quite different from

any other Eulirion except Lilium Parryi, the

next species.

The flowers are borne in a dense raceme.

Good specimens often bear as many as twenty

or thirty blossoms, but only too commonly

but one or two flowers are borne on each stem.

Individually the flowers are not much, being

small, thin, and of a pale purple, fading to the

deeper shades of purple. The pollen is yellow.

There is a variety of this species, called

Purpureum, in which the flowers are upright.

In this type the upper flowers look upwards,

the middle ones are horizontal and the lower

flowers droop. Although the variety is called

Purpureum, the flowers are by no means

always purple, but vary from pure white to

deep violet.

Beautiful as this lily is when seen in perfection,

we cannot regard it otherwise than as

a fraud. It is one of the most difficult to

grow; it is very liable to disease; it rapidly

degenerates, and it is expensive. The bed of

these lilies at Kew was the least effective of

all the groups of lilies.

If you wish to grow this lily, you must

carefully study its native climate, and the

habits of the plant when at home.

It is a moderately hardy lily, but will not

stand excessive frosts. Neither will it stand

great heat. For this reason the bulbs should

be planted very deeply. In its native land the

bulbs live at the depth of twelve to thirty

inches below the surface, and though we do

not recommend so great a length as the latter,

twelve inches should be the minimum depth

at which the bulbs are planted.

A very rich soil is required, but sharp

drainage is essential. The latter may be

obtained by mixing gravel with the soil.

Whatever you do, the lilies will probably

fail, or if they do live, they will give you one

or two poor blossoms to repay you for your

trouble.

In pots the culture of this lily is rather more

satisfactory. The pots must be of good depth

and sharp drainage is essential.

The last group of the Eulirions contains

three lilies which possess drooping bell-like

flowers.

Lilium Parryi is an American species coming

from the same place as L. Washingtonianum.

It is a little lily with citron-yellow coloured

blossoms and deep orange pollen-grains.

The blossoms, of which there are rarely more

than three on each stem, are small but pretty

and curious.

L. Parryi should be grown in the same way

as L. Washingtonianum. It is a difficult

plant to flower, but is more satisfactory than

its showy ally.

It is rather a rare plant and has not been

grown in England for very long.

The second of the drooping Eulirions is also

yellow. It is a native of Nepaul and takes its

name, L. Nepaulense, from its native place.

This lily in its growth resembles the other

Himalayan lilies, especially Lilium Wallichianum.

It is not very commonly grown in

this country, but it is an interesting species

and deserves more attention than it has

received.

It grows at the height of five and ten

thousand feet, and so should prove as hardy

in our gardens as L. Giganteum has done.

But its hardiness, as far as we are concerned,

remains to be proved.

The flowers are about the size of those of

L. Candidum, but are of a deep yellow colour,

deeply striped and spotted on the interior with

rich purple. The flowers are drooping and

somewhat resemble those of L. Giganteum in

form, but they are shorter, thicker and more

revolute. We have never seen more than two

flowers on one stem. It requires similar treatment

to L. Wallichianum.

In The Garden for April 19th, 1890, was reproduced

a plate of “Lilium Napaulense var.

Ochroleuceum.” If this plate is accurate, this

variety is indeed a fine lily, being yellowish-white

on the exterior with a deep primrose

inside. To our minds this plate recalls

L. Brownii more than any other variety of

lily that we are conversant with.

We must also go to a plate in The Garden

for the last of the nodding Eulirions. This

lily is L. Lowi, and hails from Burmah.

It resembles L. Nepaulense in shape and

growth, but the flowers are white, densely

spotted with rich claret-colour on the interior.

We have never seen the plant, and though

we tried hard to obtain a bulb of this species

we were unsuccessful in our quest. So of its

culture we know nothing.

(To be continued.)

By RUTH LAMB.

PART VI.

CORN OR STRAW.

“Let us draw near with a true heart.”

Hebrews x. 22.

I think we may spend an hour profitably,

my dear girl friends, in contrasting the fair-seeming

part of our lives with that which is

real, true, and thorough.

It is good to be real in all things. True to

the core. In thought, word, and deed to be

the same human being as we wish our friends

to think us. On this subject of reality I will

tell you a story to begin with.

I dare say most of us joined in harvest

thanksgiving services after we returned home

last autumn; probably many of you joined in

preparing for them, and in arranging the

offerings sent by the congregations.

It was in autumn, but not this year, and in

city and village churches the “Feast of Ingathering”

was being kept. Daily songs of

thanksgiving were going up to the God of

harvest, in acknowledgment of the bounteous

provision He had made to supply the wants of

the teeming millions dependent on Him for

their daily bread.

A number of young people, mostly girls,

were busily engaged in decorating a church

for the Harvest Festival services on the

following day. Flowers, fruit, vegetables,

loaves of all sizes and corn in sheaves, or

shaped into miniature stacks, had been sent in

abundance. The poorest members of the congregation

were not the least willing givers.

They could not offer hot-house grapes or fruits

that were costly to mature, but they brought of

their best from cottage gardens and in no

stinted measure. The clean, ruddy carrots,

white turnips, cauliflowers in their nest of

green leaves, with other homely vegetables, the

best of their kind, added much to the picturesqueness

of the offerings.

The pulpit and font were bordered with

green moss on which were pretty devices in

scarlet berries, and below these hung a fringe

of oats, dainty-looking, light and graceful as

lace. There was a foot of this fringing to

finish when the material ran short.

“More oats wanted,” said the worker.

“Bring me some, please.”

But none were forthcoming.

“You have used them all,” was the answer.

“I cannot fill this space with anything else.

The design would be spoiled. There seemed

to be any quantity of oats, but this fringe takes

so much. Who will give us some more?”

Nobody seemed to know and time was

precious. At last a girl spoke, though in a

rather shamefaced way and in a hesitating tone.

“I know who would give us a bundle of

oat straw. We could pick out the best pieces

and by mixing them in with the unthreshed

corn, the length could be made up. There

would be some undoing and working up again,

but I don’t think anybody would notice the

difference.”

There was a short uncomfortable silence,

soon broken by the tremulous voice of the

youngest helper present—a mere child.

“Oh, we must not, we must not do that.

It would be horrid to pretend to give the

best corn that has been grown, to try and

show God how thankful we are, and then for

Him to see that there is ever so much empty

straw amongst it. It’s all very well to say

that we could make the fringe look as if it

were real corn and nobody would find out,

but God would know, and——”

The child speaker could not utter another

word. The trembling voice broke into a sob

that was more eloquent than the simple words

which had however gone home to the hearts

of the elder ones present.

“You are right, Nelly darling,” said one

of these as she drew her little friend to her

side and kissed her tenderly. “There must

be no ornamental shams amongst our thank-offerings

to God. We should not like our

neighbours to know that a portion of the fringe

ought to be labelled ‘Only straw,’ should we?”

“No, indeed,” was the answer from all the

rest, and one said, “How could we bear to

look at it and think that it was a miserable

counterfeit? Better no fringe than straw

where corn should be.”

To this all the workers heartily assented.

I do not remember how the little difficulty

was got over, but I know it was not by the

substitution of straw and empty husks for

corn. I know, too, that all present learned a

solemn lesson from the child who, out of the

fulness of her heart, spoke on the side of truth.

It was indeed a question of truth or untruth,

reality or pretence, which had so stirred

the young speaker. The child’s words and

the circumstances under which they were

uttered have often recurred to my mind during

intervening years, and I believe that in repeating

them I shall have done good service

to you, my dear girl friends.

Does not the very thought of that little

scene suggest self-examination? Are we not

inclined to ask ourselves how much of what

we may well call “straw” is mingled with

our offerings to God? When we kneel with

every appearance of devotion and even our

lips repeat the familiar words of praise, is our

worship always what it seems to be? Do not

you and I know that often, when the knee has

been bent and the head bowed in apparent

reverence, and when our lips have moved in

prayer or response, or our voices have rung

out tunefully in psalm or hymn, our hearts

have had little share in our seeming worship?

It has been a poor, mechanical thing in

which true reverence, penitence, faith and the

spirit of love, thankfulness and praise, have

been almost entirely absent. It has seemed to

our neighbours like true corn, but has been

mostly empty straw. I say mostly, because it{391}

would be hard to think that there was no

reality in it. Even amongst the straw cast

aside from the threshing machine, a few grains

of corn will always be found, each of which

contains the germ of a new and fruitful life.

If, in looking into our own hearts, we find

out the poverty of our worship, the barrenness

of our life service, the vast proportion of

coldness and indifference when compared with

the little spark of genuine love to God and

man which finds a place there, we cannot help

acknowledging that only a grain of true corn

is to be found here and there, amid the poor

straw of our daily lives.

Let us, nevertheless, take courage. A

single grain of true wheat may be the fruitful

parent of grand harvests to come—of a

handful of grain at first, each corn of which,

fructifying in turn, will yield more and more

until, as the years pass on, whole fields of

waving gold will mark their increase.

Look carefully, dear ones, for the little

grains of true corn in your natures. The

little grain of love to God will grow if you

let your hearts dwell on the thought of His

great love for you. If we do not think about

it we cannot realise it, but when we do, we

are so filled with a sense of its vastness, that

the living grains of love, gratitude, thankfulness,

praise, joy and longing to prove our love

by service, all fructify and become the parents

of glorious harvests in our future lives.

God’s love is such a generous love. He

gives everything to His children. In Christ,

God has given to you and me the very best

that even He could give. “Shall He not

also with Him freely give us all things?”

“No good thing will He withhold from them

that walk uprightly.”

Seeing then that God has given us the best

gift of all, and that all good things are

promised us on the one condition that we

walk uprightly, does it not become us to

expel all that is false from our worship and

our lives? To be true to the core? To let

words and actions be the harvest springing

from the living grain of holy love in our

hearts, watched, watered, cherished, guarded

assiduously, lest it should die and our worship

become a mere outward thing—straw, in

place of true corn, the poor sham which

human eyes could not detect, but the worthlessness

of which is known to Him who is of

purer eyes than to behold evil or to “look

upon iniquity”?

When we think of it, does it not seem

strange that “feigned lips,” wandering

thoughts, outward reverence without any real

adoration, can be permitted to pass current in

our minds? We know that, in God’s sight,

one little act of kindness done for His sake,

one spark of love fanned into a flame which

illumines the life of a fellow creature who is

sitting in darkness and the very shadow of

death; one honest effort after righteousness;

one sentence of true prayer uttered with a

sense of need by longing lips; one note of

true, spontaneous praise and thanksgiving

from a grateful heart; one cry for strength,

light and needed grace, spoken in the fewest

words that can express desire; each and all of

these, though small in a sense, are precious

and will not be forgotten. Mere grains they

may be, but they are living grains—the seeds

whence come grand harvests to God’s glory

and our own good.

I have taken the higher and more important

part of our subject first, but we will come

down to a lower level and speak a little about

carrying the same spirit of truth and thoroughness

into our everyday work.

I hope we all feel that we ought to render

of our very best to God, and to do this with

full sincerity of purpose and of heart. Surely

the same spirit should enter into all our

dealings and intercourse with our neighbour.

Whatever work may be entrusted to us, do

not let us think how little will pass muster,

but what is the best we can do, and then

resolve on doing this.

We must never forget that whoever truly

loves God will love his neighbour also, and

will prove this in daily life and intercourse.

I want you, my dear girl friends, to be

animated by this spirit in the home, whether

you are a daughter or one who, in serving,

serves also the Lord Christ. In the work-room

too, where so much of the character and

success of the employer depends on the

thoroughness and conscientiousness of the

workers.

Do not give the mother, the mistress, or

the outside employer cause to complain that

you put no heart into your work, or that, if

you can do it without immediate loss to

yourself, you will bestow less pains upon the

portion which is below the surface and not

likely to be so carefully examined as the rest.

To act in such a manner is to render the merest

eye-service. It is giving straw from which

nearly all the golden grain has been taken away.

It is fair-seeming, but unreal and untrue.

Little things sometimes illustrate important

lessons. Some time ago, two girls undertook

to dress a couple of dolls which were exactly

alike and intended as presents for twin sisters,

seven years old. Both were equally anxious

to give pleasure to the little people, but they

set about it in different ways. Each had the

same amount to spend on clothes, which was

not to be exceeded, but the details were left

to themselves.

The one chose her materials less for show

than for real fitness, and said to her friend,

who was lost in choice amongst remnants of

rich silks, “My doll is going to be just a little

girl, not a fine lady.”

“My fine lady will be the more attractive,”

said the other. “Both the children will

want it, and that will be the worst of it all.”

The other did not answer, but set diligently

to work, and gave time, pains, and patience

in no stinted measure. She made complete

sets of beautifully finished little garments,

both for day and night wear. Every string

and button was in the right place, and every

article could be taken off and put on as easily

as a real child’s. All would bear washing

and be none the worse for it.

The second girl bought rich silk for a frock,

dainty boots, and tiny silk stockings, and

succeeded in making a little picture hat,

evening cloak and dress in suitable style.

Altogether the lady doll made a distinguished

appearance; but below the shining dress there

were the poorest shams for garments, which,

once taken off, would not be worth replacing.

Naturally, both children at first turned

longing eyes on the gaily-attired doll, and

seemed anxious to possess it. But the

unselfish nature of one triumphed, and whilst

her sister grasped the showy toy, she whispered,

“I’ll have the other, please!” and lifted her

rosebud mouth to kiss the giver.

We know the endless joy a child finds in

playing “little mother.” She never tires of

dressing and undressing her doll, of setting up

a washing day for its garments, or smoothing

them with a tiny iron—under supervision.

The little twin maidens soon decided that

the doll, whose clothes could be treated exactly

like their own, was a treasure indeed, and the

curly heads bent over it, shared in maternal

cares, and found delightful occupation therein

for many a day.

The fine garments were, after all, but as

straw in comparison with corn. They were

just to be looked at and admired, then put

aside. They gave the “little mother” no

change. She could do nothing for a fine lady.

To the girl who had given of her best, the

sight of the children’s pleasure was reward

enough. As to the other, she said, “I meant

well, you did well; but I have learned a

lesson. Even a child soon finds out the

difference between what is thorough and what

has only a fair outside. I saw my gaily-dressed

toy lying neglected, whilst one ‘little

mother’ was hushing her sham baby to sleep

and the other child was folding away its day

clothes. They saw my eyes turning towards

my neglected handiwork, and, fearing I should

be hurt, one said, ‘She’s very nice to take

out for a walk; but she’s a fine lady, you

know, not a baby to nurse, and her things

won’t take off, so we can’t put her to bed.’

I said to myself, ‘No more shams even in doll

dressing. My work shall be real all through.’”

So the fine lady was not without use after

all. As to the other doll, it did more than

give pleasure. It was a mute lesson which

seemed to be always saying, “If a thing is

worth doing at all, it is worth doing well.”

It was an example of neatness, orderliness,

industry and ungrudging labour to the small

people, who were taught by those about them

to take care of what had cost so much

painstaking to produce.

I think I hear one of you ask, “Has not

straw its value also? Could it be done without?

Is it not necessary for the production

of the grain itself?”

Certainly it is a most valuable thing and

fills a most important place. It could be

ill spared from Nature’s storehouse. Its

uses are manifold, and would take long to

enumerate. You will remember that, at the

very beginning of our talk this evening, we

showed the straw in use, along with the

grain it held, both as an offering and a

decoration in the house of God. It was only

when it was proposed to put straw in place

of “the full corn in the ear,” that it was

objected to as an empty sham.

There is a great deal of straw mixed with

our social intercourse that might well be

thrown aside, and there are other cases in

which we should be sorry to part with it.

The visits which are paid merely because we

owe them, without the slightest wish to see

the individual and only to get rid of a feeling

of debt, are straw of one kind.

We have all heard the remark, “I got

through such a number of calls to-day. It

was so fine that nearly everybody was out, as

I thought they would be.”

The calls made in the expectation and hope

of finding our acquaintances out, are surely a

kind of social straw that we could well

dispense with. The invitation given, not

because a guest is really wanted, but because

it “would not do to leave her out,” is straw

of the same kind.

But there are many kind words said and

little thoughtful actions performed which are

only straw, in a sense; but we should miss

them sadly if they were omitted.

Supposing that one of you received two

gifts of equal intrinsic value at the same time.

A curt line or a telegram announced the one,

a lovingly-worded letter, or kind expressions

uttered in a tone and with a look of good will

accompanied the other. In neither case would

the value of the gift be affected; but—oh,

what a difference there would be in the feelings

of the receiver!

The prettily-worded letter or message would

linger in the memory and the pleasant smile

would be recalled whenever the gift was in

sight. They were but the straw that enfolded

it, but it was precious straw which had its

right place and value.

Much that I have said to-night, dear girls,

is intended to suggest thought—not to exhaust

the subject, for that would be difficult. But

I trust it will help us all to discriminate

between the false and the true, the thorough

and the fair-seeming, and strengthen our determination

to give of our best to God above all,

and, for His sake, to our neighbour also.

(To be continued.)

{392}

{393}

Now that the guitar has again become a

favourite and fashionable instrument, many

girls are searching out and bringing to light

guitars which their mothers, aye, and even

their grandmothers, played on in days gone

by, and they endeavour once more to awake

the long silent strings (if any survive) with

more or less musical and unmusical results.

Presuming that our readers have learnt the

rudiments from their master or mistress, or

even if they have found them out themselves

from such clear tutors as De Marescot’s (Metzler),

or Madame Sidney Pratten’s (Boosey),

they will find themselves soon able to undertake

the accompaniments in a collection of

twelve songs arranged for the guitar with

much taste and discrimination in album form

(1s. 6d.), by Lily Montagu (J. Williams).

These include Schubert’s “Who is Sylvia,”

Godard’s “Song of Florian;” songs by

Cowen, Cellier and A. Horrocks, who sets

Charles Kingsley’s wistful lines:—

“I once had a sweet little doll, dears.”

The poor damsel was lost in the heath one

day, and, after bitter lamentation, she was

found a terrible wreck long after by her faithful

mistress, to whom

“... for old sake’s sake, she is still, dears,

The prettiest doll in the world.”

Most of us have gone through the triste era

of our girl-life, when we were obliged to

confess to ourselves that we had “grown too

big for dolls.”

Vol. I. of Alfred Scott Gatty’s well-known

plantation songs (Boosey) are now published

for guitar, and they “go” capitally.

There are some duets for two guitars by

Madame Pratten, and their effect is quite

charming; we think too that Messrs. Schott

still have the old but delightful Opus 87, by

Joseph Küffner, namely, twelve (short) duos

for two guitars for the use of beginners.

To those who wish to add the many Spanish

graces there are to their guitar playing, we

thoroughly recommend a really clever little

3s. book, particularly dealing with this difficult

subject for description. It is entitled “Brilliant

Effects on the Guitar,” by Edith Feilden

(J. Blockley). Most teaching photographs

show the hands in different positions on the

guitar, and its dainty exterior is so gaily and

well coloured by a representation of the

Spanish flag, that it is attractive for a gift

book. It is to be obtained of Miss Feilden,

Feniscowles House, Scarborough.

Mary Augusta Salmond.

By A MAJOR’S DAUGHTER.

It was not because I am a major’s daughter

that an invitation came to me one bright

autumn morning, but because I was the

curate’s wife. We were seated at breakfast

when the “command” to meet their Excellencies

was handed up. Just like the

proverbial curate’s family we were laying in a

foundation of stirabout, only our porridge was

swimming in thick yellow cream, and was

daintily served. On the table, besides, was the

purest heather honey, a few golden peaches,

and hot rolls of crispy bread.

“Thank goodness! a clergyman is always

in full dress!” quoth the dear curate, as he

pulled down his silk M.B. waistcoat. “But

you, my dear Eileen, had better meditate on

chiffons.”

And meditate I did, until I was fairly

puzzled. There was the white silk, and the

pink one, the yellow brocade, with its beautiful

train, and the simple muslin. I was very

young at the time, and dearly loved finery.

The real vital question of suitability turned

on what the invitation meant. Were Lord

and Lady L—— coming as royalty, or simply

as themselves? The duchess alone could

interpret her card, and so to the duchess I went.

“Did you not notice that R.S.V.P. was

omitted? Put on feathers and veils, and

your best bib and tuckers,” said the dear old

hostess. “’Tis as King and Queen their

Excellencies come.”

So, of course, the yellow brocade it had to

be, with its low neck, and short topaz-trimmed

sleeves.

Now, though the curate’s wife was fairly

well-to-do in the world, the curate would keep

no carriage. It was quite out of the question

to drive in a pony-trap to the Castle, so the

duchess “loaned” one of her own state

chariots! She did more, a few hours before

dinner-time a square box was handed in at

the Clergy House, containing a mass of copper-coloured

William Allen Richardsons, arranged

in the newest mode by the duchess’s head-gardener.

Most of the house-party were assembled in

the huge drawing-room when Mr. Giles,

accompanied by his attendant satellites, threw

open the door and announced—

“The Reverend and Mrs. Smith.”

It was blazing, too, with electric light, and

sweet with perfume as I walked forward, to

be encouragingly greeted by my dear old friend

and patron.

“Their Excellencies are not down yet,” she

said kindly; “but you are just in time——”

With this, the door was suddenly flung

open again, and everyone stood up, whilst

something like a cannon-ball plunged into the

room! It was the Lord-Lieutenant! I

found out, during the course of the evening,

that this was his way of hurrying in, in

order that the company might re-take their

seats as soon as possible. A few more

seconds, then a vision of loveliness in white

satin and crystal, and a whole stomacher of

magnificent pearls, walked in. It was sweet

Lady L——. There were no introductions,

and every usual order of procession into the

dining-room was reversed. For the duchess

went in first, leaning on the Lord-Lieutenant’s

arm, immediately followed by the Duke, leading

her Excellency. The rest of the company—thirteen

couples—followed in stately order,

the curate’s wife being last with some insignificant

honourable.

But she had her revenge! Her husband

was the first to speak, as he was called upon

by a rap to say grace, and she found herself on

Lord L——’s right hand. In order to show

why she was there, I must explain that the

royal chairs were placed in the centre of the

long table, not at each end, and that their

Excellencies and our hosts occupied the middle

of the room. In a few minutes I had time to

notice that their own footmen stood behind

the regal party, but that the rest of us were

served by the duke’s servants.

What a sight was that whole party! Every

earl wore his star, and every countess her

coronet. Jewels galore glittered everywhere.

All the same, the most striking-looking man

there was the curate, in his plain black dress,

with his beautiful face just as usual—calm and

radiant and spirituelle.

I do not think that dinner was quite a

success, though a chef had been engaged to

cook it and two others at a fee of £100. The

game was burned, and the ice-puddings were in

lumps. There were long pauses between the

rêlêves, and an ominous wait before all the

twelve courses were handed round. I was so

much taken up with the scene that I frequently

laid down my knife and fork, even before I

had tasted the morsels set before me, and

found everything whisked away in a second.

Nearly two hours that dinner occupied.

Then, from behind a palm, our hostess nodded

to the other end of the table, and his Excellency

stood up. For this moment I had

waited in fear and trembling. I knew we had

to make the tour of that long table, then back

out of the room, for royalty must never see

behind the scenes.

I had practised a sweeping curtsey before

the pier-glass at home. I had gracefully

backed from before it over and over again,

but when my turn came I grew the colour of

my copper roses, and nearly tumbled over my

train.

Nobody seemed to notice, however, not

even James Giles, the major-domo, so I was

fairly cool by the time the duchess took me

by the arm to introduce me to her Excellency.

“It is as good as a presentation at Court,

my dear,” she whispered, “and will give you

the entrée.”

I had often rehearsed this scene, and in

imagination had seen Lady L—— standing up

stately, and receiving the curate’s wife very

frigidly. Behold the contrary.

Seated on a stool before the blazing fire,

with all her lovely dress crumpled up under

her, Lady L—— was “roasting her bones,” as

she said. She jumped up like a girl when the

duchess led me towards her; and I really

think she admired the yellow brocade.

“I hope I shall soon see you at Court,” she

said pleasantly, as I kissed her hand. “And

your husband too. The brave stand made by

the Church of —— in all her difficulties makes

us value every one of her clergy and their wives,

even if they are bits of girls like yourself.”

Then she laughed, and I laughed, and we

found out we had each a beautiful home-ruler

at home about the same age, who ruled us

with a rod of iron. So we had a pleasant chat

until I forgot I was the curate’s wife and she

her Excellency.

Suddenly the cannon-ball shot in again,

in a great hurry, and we rose to our feet. A

few presentations had been made to him in the

dining-room, and soon everyone was chatting

like ordinary folk over coffee cups and cream.

About eleven o’clock cards were got out, and

the curate and “his reverence’s honoured

lady” left. I nearly backed into Mr. Giles

as I did so, and he very nearly laughed, but

not quite. I never saw Giles laugh.

As we were driving home under the big

elms and pines, we kept silence awhile. The

first remark came, of course, from me.

“I’m very hungry,” in a plaintive voice.

“And I’m starving,” was the response, as

the curate slipped his arm round his little

wife’s yellow brocade waist.

“American crackers and apples?” I suggested.

“And a big fire,” said his reverence, drawing

my furs closer round me. “You are frozen.”

So, over a blazing fire in our bedroom, we

ate crackers and apples to fill the vacuum left by

curiosity even after a vice-regal dinner-party.

{394}

By JESSIE MANSERGH (Mrs. G. de Horne Vaizey), Author of “Sisters Three,” etc.

CHAPTER XXIV.

t was one o’clock

in the morning

when a carriage

drove up to the

door of the Larches,

and Mrs.

Asplin alighted,

all pale, tear-stained,

and

tremulous. She

had been nodding

over the fire

in her bedroom

when the young

people had returned

with the

news of the

tragic ending

to the

night’s festivity,

and

no persuasion

or argument

could induce

her to wait

until the next

day before flying

to Peggy’s side.

“No, no!”

she cried. “You

must not hinder

me. If I can’t

drive, I will

walk! I would

go to the child to-night if I had to crawl

on my hands and knees! I promised

her mother to look after her. How could

I stay at home and think of her lying

there? Oh, children, children, pray for

Peggy! Pray that she may be spared,

and that her poor parents may be spared

this awful—awful news!”

Then she kissed her own girls, clasped

them to her in a passionate embrace,

and drove off to the Larches in the

carriage which had brought the young

people home.

Lady Darcy came out to meet her,

and gripped her hand in eager welcome.

“You have come! I knew you would.

I am so thankful to see you. The doctor

has come, and will stay all night. He

has sent for a nurse——”

“And—my Peggy?”

Lady Darcy’s lips quivered.

“Very, very ill—much worse than

Rosalind! Her poor little arms! I

was so wicked, I thought it was her

fault, and I had no pity, and now it

seems that she has saved my darling’s

life. They can’t tell us about it yet,

but it was she who wrapped the curtain

round Rosalind, and burned herself in

pressing out the flames. Rosalind kept

crying ‘Peggy! Peggy!’ and we

thought she meant that it was Peggy’s

fault. We had heard so much of her

mischievous tricks. My husband found

her lying on the floor. She was unconscious;

but she came round when they

were dressing her arms. I think she

will know you——”

“Take me to her, please!” Mrs.

Asplin said quickly. She had to wait

several moments before she could control

her voice sufficiently to add, “And

Rosalind, how is she?”

“There is no danger. Her neck is

scarred, and her hair singed and

burned. She is suffering from the

shock, but the doctor says it is not

serious. Peggy——”

She paused, and the other walked on

resolutely, not daring to ask for the

termination of that sentence. She crept

into the little room, bent over the bed,

and looked down on Peggy’s face

through a mist of tears. It was drawn

and haggard with pain, and the eyes

met hers without a ray of light in their

hollow depths. That she recognised

was evident, but the pain which she

was suffering was too intense to leave

room for any other feeling. She lay

motionless, with her bandaged arms

stretched before her, and her face looked

so small and white against the pillow

that Mrs. Asplin trembled to think how

little strength was there to fight against

the terrible shock and strain. Only once

in all that long night did Peggy show

any consciousness of her surroundings,

but then her eyes lit up with a gleam

of remembrance, her lips moved, and

Mrs. Asplin bent down to catch the

faintly-whispered words—

“The twenty-sixth—next Monday!

Don’t tell Arthur!”

“‘The twenty-sixth’! What is that,

darling? Ah, I remember—Arthur’s

examination! You mean if he knew

you were ill, it would upset him for his

work?”

An infinitesimal movement of the

head answered “Yes,” and she gave

the promise in trembling tones—

“No, my precious, we won’t tell him.

He could not help, and it would only

distress you to feel that he was upset.

Don’t trouble about it, darling. It will

be all right.”

Then Peggy shut her eyes and wandered

away into a strange world, in

which accustomed things disappeared,

and time was not, and nothing remained

but pain, and weariness, and mystery.

Those of us who have come near to death

have visited this world too, and know the

blackness of it, and the weary waking.

Peggy lay in her little white bed and

heard voices speaking in her ear, and

saw strange shapes flit to and fro.

Quite suddenly as it appeared, a face

would be bending over her own, and as

she watched it with languid curiosity

wondering what manner of thing it

could be, it would melt away and vanish

in the distance. At other times again

it would grow larger and larger, until

it assumed gigantic proportions, and

she cried out in fear of the huge, saucer-like

eyes. There was a weary puzzle

in her brain, an effort to understand,

but everything seemed mixed up and

incomprehensible. She would look

round the room and see the sunshine

peeping in through, the chinks of the

blinds, and when she closed her eyes

for a moment—just a single, fleeting

moment—lo! the gas was lit, and someone

was nodding in a chair by her side.

And it was by no means always the

same room. She was tired, and wanted

badly to rest, yet she was always rushing

about here, there, and everywhere,

striving vainly to dress herself in clothes

which fell off as soon as they were

fastened, hurrying to catch a train to

reach a certain destination; but in each

instance the end was the same—she

was falling, falling, falling—always

falling—from the crag of an Alpine

precipice, from the pinnacle of a tower,

from the top of a flight of stairs. The

slip and the terror pursued her wherever

she went; she would shriek aloud, and

feel soft hands pressed on her cheeks,

soft voices murmuring in her ear.

One vision stood out plainly from

those nightmare dreams—the vision of

a face which suddenly appeared in the

midst of the big grey cloud which

enveloped her on every side—a beautiful

face which was strangely like, and yet

unlike, something she had seen long,

long ago in a world which she had well

nigh forgotten. It was pale and thin,

and the golden hair fell in a short curly

crop on the blue garment which was

swathed over the shoulders. It was

like one of the heads of celestial choirboys

which she had seen on Christmas

cards and in books of engravings, yet

something about the eyes and mouth

seemed familiar. She stared at it

curiously, and then suddenly a strange,

weak little voice faltered out a well-known

name.

“Rosalind!” it cried, and a quick

exclamation of joy sounded from the

side of the bed. Who had spoken?

The first voice had been strangely like

her own, but at an immeasurable

distance. She shut her eyes to think

about it, and the fair-haired vision