Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXXVI, No. 2, February 1850

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: August 19, 2018 [eBook #57733]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net

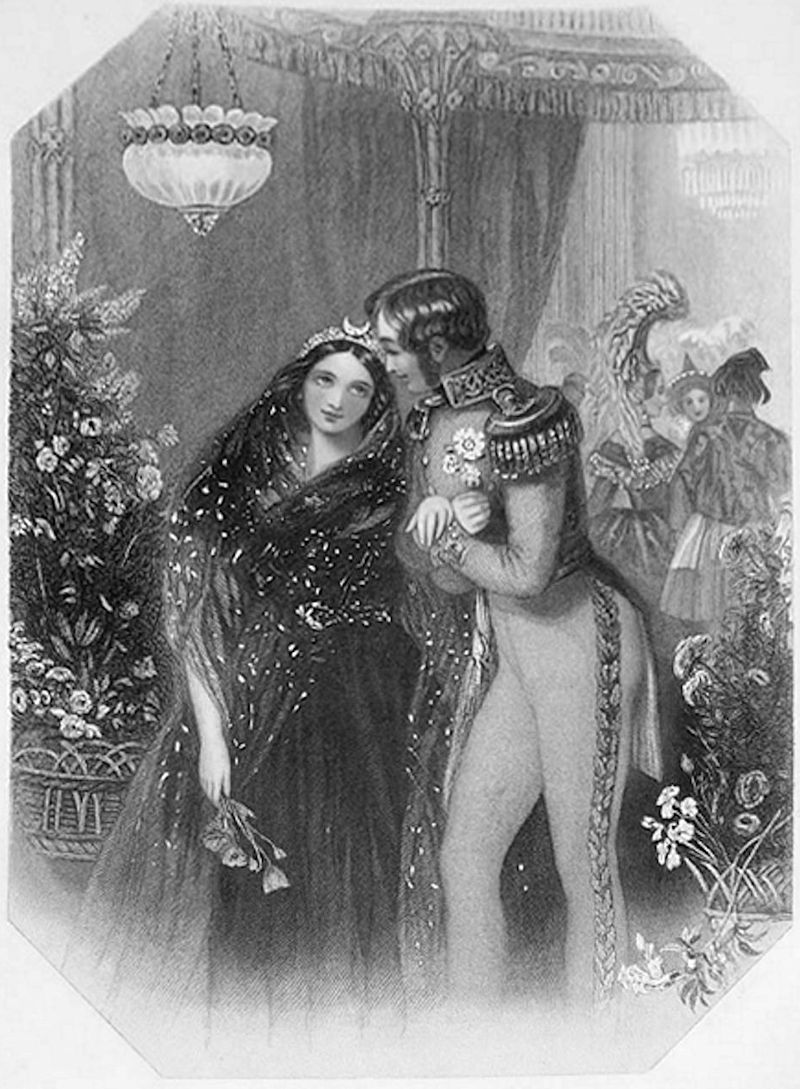

THE VALENTINE.

Engraved expressly for Graham’s Magazine by W. E. Tucker.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXVI. February, 1850. No. 2.

Table of Contents

Fiction, Literature and Articles

Poetry, Music, and Fashion

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXVI. PHILADELPHIA, February, 1850. No. 2.

The flowers which cold in prison kept

Now laugh the frost to scorn.

Richard Edwards. 1523.

Among the ancient manuscripts in the British Museum there is one of Saxon origin, written by Ethelgar, a writer of some note in the tenth century. Commenting on the months, he speaks of February, which he calls Sprout kele, because colewort, a kind of cabbage, which was the chief sustenance of the husbandmen in those days, began to yield wholesome young sprouts during this month. Some centuries after, this name was modernized by the Romans, who offered their expiatory sacrifices at this season of the year, and called Februalia. Frequently during this month the cold is abated for a short time, and fine days and hasty thaws take the place of rigid frost. From this peculiarity, this month has often been called by ancient writers by the expressive name of “February fill dike.”

Clare’s verses are sweetly descriptive of this changing season —

The snow has left the cottage top;

The thatch moss grows in brighter green;

And eaves in quick succession drop,

Where pinning icicles have been;

Pitpatting with a pleasant noise,

In tubs set by the cottage door;

While ducks and geese, with happy joys,

Plunge in the yard-pond brimming o’er.

The sun peeps through the window pane;

Which children mark with laughing eye:

And in the wet street steal again,

To tell each other Spring is nigh:

Then, as young Hope the past recalls,

In playing groups they often draw,

To build beside the sunny walls

Their spring-time huts of sticks and straw.

And oft in pleasure’s dreams they hie

Round homesteads by the village side,

Scratching the hedgerow mosses by,

Where painted pooty shells abide;

Mistaking oft the ivy spray

For leaves that come with budding Spring,

And wondering in their search for play

Why birds delay to build and sing.

The mavis-thrush with wild delight

Upon the orchard’s dripping tree,

Mutters, to see the day so bright,

Fragments of young Hope’s poesy:

And dame oft stops her buzzing wheel

To hear the robin’s note once more,

Who tootles while he pecks his meal

From sweet-briar hips beside the door.

The frost often returns after a few days, and binds Nature with his iron hand. In Great Britain, where the Spring is much earlier than with us, February is remarkable for what is termed the “runs” of moles.

Le Count, a French naturalist, records some interesting notices of the nature of moles, (an animal not very common in this cold climate,) as well as the speed at which they travel through their underground galleries. He observes, “They are very voracious, and die of hunger if kept without food for twelve hours. They commence throwing up their hillocks in the month of February, and making preparations for their summer campaign, constructing for themselves runs in various directions, to enable them to escape in case of danger; and also as a means of procuring their food. These runs communicate with one another, and unite at one point; at this centre the female establishes her head-quarters, and forms a separate habitation for her young, taking care that both shall be on a higher level than the runs, and as nearly as possible even with the ground, and any moisture that may penetrate is carried off by the runs. This dormitory, if it may be so styled, is generally placed at the foot of a wall, or near a hedge or a tree, where it has less chance of being broken in. When so placed, no external embankment gives token of its presence; but when the soil is light a large heap of earth is generally thrown over it. Being susceptible of the slightest noise or vibration of the earth, the mole, in case of surprise, at once betakes itself to its safety runs.”

We sometimes, though rarely, find the snow-drops, “fair maids of February,” as they are called, peeping through their mantle of snow, and the gentle aconite, with its

“Green leaf furling round its cup of gold,”

giving life and animation to the otherwise dank and desolate border. Leigh Hunt in describing this month says, “If February were not the precursor of Spring, it would be the least pleasant month in the whole year, November not excepted. The thaws coming so suddenly produce freshets, and a clammy moisture, which is the most disagreeable of winter sensations.

Various signs of returning Spring—

——songful Spring—

Whose looks are melody,

occur at different times during this month. The month of February in England may well be compared to the month of April in America.”

The author of “The Sabbath” thus vividly paints the sterility of this month, and its effects upon the “rural populace.”

All outdoor work

Now stands; the wagoner, with wish-bound feet,

And wheel-spokes almost filled, his destined stage

Scarcely can gain. O’er hill, and vale, and wood,

Sweeps the snow-pinioned blast, and all things veils

In white array, disguising to the view;

Objects well known, now faintly recognized;

One color clothes the mountain and the plain,

Save where the feathery flakes melt as they fall

Upon the deep blue stream, or scowling lake,

Or where some beetling rock o’er jutting hangs

Above the vaulty precipice’s cove.

Formless, the pointed cairn now scarce o’ertops

The level dreary waste; and coppice woods,

Diminished of their height, like bushes seem.

With stooping heads, turned from the storm, the flocks

Onward still urged by man and dog, escape

The smothering drift; while, skulking at aside,

Is seen the fox, with close down-folded tail,

Watching his time to seize a straggling prey;

Or, from some lofty crag, he ominous howls,

And makes approaching night more dismal fall.

During this month, the increasing influence of the sun is scarcely felt, till we approach the end, then hoping, watch from day to day the lengthened minutes as they pass, to usher in Spring’s holy charms.

———

BY AGNES L. GORDON.

———

It chanced upon a pleasant day,

In charming summer weather,

That Wit and Beauty sallied forth

To take a stroll together.

And as they idly roamed along,

On various themes conversing,

Young Beauty, somewhat vain, began

Her wondrous powers rehearsing.

And much she dwelt upon the charms

Her outward form adorning,

And seemed to feel herself supreme,

All other merit scorning.

This roused the ire of sparkling Wit,

Who keenly thus retorted:

“Your claim, though easily advanced,

Requires to be supported.

“Mark yon bright bird that wings his flight

Athwart the sunny skies,

Let each on him display our skill,

To catch him as he flies.

“Your chance is first, for well I know,

And own the pleasant duty,

That Wit in every age must yield

Due precedence to Beauty!”

Young Beauty smiled, and charmed the bird

With softened strains alluring,

And bound him with a silken chain,

More brilliant than enduring.

She placed the captive in a net,

Entwined of many flowers,

And with a merry, mocking smile,

Bade Wit now try his powers.

Then from his feathered quiver Wit

A silver arrow drew,

With perfect and unerring aim

He pierced the net-work through.

The bird released, on eager wing

Soared upward to the skies;

A second arrow reached his breast —

He fell—no more to rise!

Beauty looked sore dismayed, to see

Her snare thus incomplete.

When gallant Wit the trophy raised,

And laid it at her feet.

“Could we but journey hand in hand,”

He said to Beauty, smiling,

“No prey could e’er escape my shaft,

Who saw your charms beguiling.

“But since the stern decrees of fate

Our union thus opposes,

And you so oft my arrows blunt,

Beneath a weight of roses;

“Remember, Beauty’s charms will fade,

Despite each fond endeavor,

And strong, well tempered shafts of wit

Her chains will often sever.”

A TALE OF HUMBLE LIFE.

———

BY H. HASTINGS WELD.

———

The father of Ellen O’Brien was a small farmer, whose situation when the child began to think at all, seemed to her the realization of all that is happy, and all that is cheerful in this world. Children do think very early; much earlier than their elders suspect. But happily for them they are easily contented. They look at the bright side, and unconscious of the superior advantages, and the greater comforts of others, have no temptation to discontented comparisons, and no motive for uneasy envy.

Ellen’s earliest memory of marked and positive happiness—that is to say, of an incident which conferred particular pleasure, was connected with a child—a very small child. She remembered how her father told her to “make a lap, now,” and placed the wee thing upon the knees which she prepared with much ado to receive it. She was told that this was her little brother, her own little brother; and she hugged it in troubled happiness, almost afraid to touch, lest she should hurt it. She gazed upon it with that undefined feeling of mingled awe and pleasure with which little children regard less children. She looked at its fragile hands and wondered, if she took them in hers, whether they would fade or drop to pieces, like the delicate blossoms which she had often killed with kindness. And when it cried—oh, but she was astonished! That such a little thing should be so ungrateful while she coddled and cared for it, and nursed it ever so tenderly, was more than she could well endure. She thought it well deserved, and ought to have a whipping, only that a whipping might hurt it—and that she would not consent to.

It was, however, not a great while before a safe acquaintance grew up between the new comer and Ellen. He was called Patrick, after his father, and his father’s father before him. Ellen was three years his senior. That difference in their ages would have been a wonder; only that it was explainable. Another little Patrick, his predecessor, was “called home,” as his father said, “before he had scarce a taste of the world at all.” And Ellen, from hearing so often of the other little Patrick, and from her indistinct memory of a baby that she saw one day, as if in a dream, and did not see any more, learned to think of infants as of little things that would die if they were not carefully watched. And this Patrick she was resolved should not slip away for want of attention from his sister; therefore she nursed him as carefully as if that had been her sole vocation.

The wonder about babies grew less as Ellen grew older. At first, in her childish little heart, she thought every little baby must be a little Patrick, and that no new one could come while there was another about. But familiarity destroys marvels. She found there could be little Phelims and Terrences as well as Patricks, Bridgets and Kathleens as well as Ellens. Child after child lifted its clamorous voice for food and nursing in Patrick O’Brien’s cottage, until at last when he was asked respecting his children, he was fain to count them upon his fingers. And he always began with Ellen and his thumb—Paddy came next, and the formula was—“There’s Ellen, then little Paddy that was called early, then Paddy that is now—sure Ellen and Paddy are the thumb and forefinger to us. What would the mother do without them, at all?”

Ellen grew to a fine, stout girl, with a cheerful open face when you spoke to her—but there was a shade of care and thought over it when in repose, which you may often see in the oldest daughter of a poor man. She moved and acted as if while the tribe who had exhausted the family names of the O’Briens were born children to her mother, she was born before them for a deputy mother to them all. Legs and arms were all over the cottage, in all sorts of places where they shouldn’t be, and she jerked them out of harm’s way, with a half-petulant dexterity which was pleasant to observe. Tow-heads and shock-heads popped up continually, and she pushed them aside with a “there now, wont you be aisy!” which was musical, with a very little discord. And there was an easy and natural carelessness of authority and half rebellion in obedience, which was truly puzzling to strangers, but which gave no discomposure to Ellen or to her mother. Indeed, Mrs. O’Brien sat, the centre of her offspring, with the most contented air in the world, plying her knitting needles with easy assiduity, and dismissing child after child from her arms, as they severally grew out of her immediate province and into Ellen’s. Or she bustled, if there was bustling to do, with perfect indifference, it might seem, to one who did not know her, as to whether there were children in the house or not.

But sometimes her interference became necessary as a measure of last appeal, and she came down on them with hearty whacks which were invariably poulticed with a word or two, half scolding and half good-natured wit. The children were thus reconciled to the propriety and necessity of certain summary inflictions, which at the same time they took care to avoid, when it could be done without too much trouble. Often there were voices heard in a higher key than is considered proper in a drawing-room, and sometimes there was a debouchment of children out at the door, and a consequent squealing of little pigs, and fluttering of chickens before it; which showed the mother’s activity at ejection. But no drawing-room ever sheltered more gentle hearts, and no mother of high degree ever followed a scolding with more patience than Mrs. O’Brien did. There was no malice in her, and a half-laugh stood ever in her eye, as she looked out at the door on the living miscellanies she had put in motion, and said—“Sure you can’t turn a hand, or step any place at all, for pigs, chickens and childer!”

There is often more room in the heart than in the house. The O’Briens began to feel themselves crowded—or rather to feel the inconvenience of too many sitters for their stools, without knowing precisely—or rather without permitting themselves to acknowledge what caused their discomfort. There were too many mouths for the potatoes, as Patrick senior and his wife were at last compelled to admit in their matrimonial committee of ways and means, and the question now became, how could they diminish the one, or increase the other. The lesser fry were out of the question. Nothing could be done in the way of removing them; nor did the thought occur to father or mother, who loved the children with true Irish hearts; that the smaller children were in the way, or that any of the little ones could possibly be spared, if the lord-lieutenant himself wanted a baby. So they began canvassing at the other end of the long list.

“There was Ellen,” said the father, doubtfully.

“Ellen! Sure you’ll not be putting her away, and nobody to mind the childer? What is the wages, I’d like to know, would make her place good to us?”

And Ellen, it was decided, was a fixture.

“There is Paddy,” said the mother with some hesitation. “Sure he’s a broth of a boy, and it is time he should do for himself—it is. It’s little in life he’s good for here, anyway.”

The father did not think so. Many were the little “turns” that Paddy cheerfully undertook, but all of them could not in conscience be made to appear to amount to an indispensable service, or any thing like it.

“Look at him now?” said the mother. And they looked at Pat, whose all good-natured face, unconscious that it was the subject of observation, bloomed like a tall flower amid the lesser O’Briens who clustered about him.

“Sure there’s a tribe of them!” said O’Brien.

“But look at Paddy! He’s the moral of yourself at his age, Patrick; with the same niver-a-thought, lazy look!”

It was questionable whether the wife’s affectionate reminiscence was a compliment or not; and an expression of sad humor, between a smile and a scowl, passed over O’Brien’s face, as he regarded his elder son, the heir to his personal beauties and accomplishments—and to his cast off clothes. It was of little use the latter were, for the father usually exacted so much of them, that when they descended to the son, sad make shifts were necessary to keep up in them any show of integrity, however superficial. And the stitches which were hurriedly taken between whiles, by his mother, had a comprehensive character which brought distant parts of the garments into a proximity very far from their original intention. The difference in size between father and son permitted a latitude in this respect, and the gathering together of the fabric produced an appearance more picturesque than elegant. As to the extra length of the garments that soon corrected itself, and Paddy junior’s ankles presented a ring of ragged fringe; or a couple of well-developed calves protruded in easy indifference. Indeed he was a broth of a boy, good natured and “bidable,” as he was ragged and careless. It was time that his good properties should be made available—and that some of the other young ones should have a chance at their father’s wardrobe.

——

It was a sad thing to part with Paddy. But necessity knows no law, and he was apprenticed to a farmer with more land and fewer children than Patrick O’Brien. And it was no less sore to Paddy to leave the homestead, than for his brothers and sisters and father and mother to give up the “moral of his father.” Those whose hearts are not united by a community in privation, and whose easy lives present no exigencies in which they are compelled to feel with and for each other, can separate without tears, and be re-united without emotion. But the few miles of distance which were now to be placed between little Paddy and the cot where he was born, seemed to him almost an unbounded desert; and the going away from home, though for so small a journey, was equivalent to banishment. He took a sorrowful review of all the familiar objects which had been his companions from his birth. There was not a scratch on the cabin walls that did not seem to him as a brother; not a mud-hole around the premises that was not as an old familiar friend. But he manfully tore himself from all; and it was with no little sensation of independence that he felt that henceforth he was really to earn his own living, and to eat bread which should not diminish the breakfasts of the rest. There were other circumstances too, as yet undeveloped, which aided him in becoming reconciled. The inmates of the new home were not strange to little Paddy, and one of them, in especial, he had a childish weakness and fondness for. It is not our intention to say that Paddy and little Norah knew any thing about what boarding-school misses call undying affection; for such nonsense was beyond their years, and schools were above their opportunities. But leave we Paddy to establish himself in his new home, while we return to the O’Briens.

Sorrow a bit of difference they soon found, did Paddy’s absence make in the consumption of food. The potatoes were as extensively devoured as ever, and little Paddy’s hand-turns were much missed. His bright face gone left a blank which nothing seemed to fill; though Mrs. O’Brien, blessings on her, as far as enumeration went, soon made up the same tale that there was before Paddy’s extradition. There was a half thought in the father’s mind of christening the new comer Paddy also, since the removal of his favorite boy was like death to him; and he really began to feel as if names would run short if the wearers were not duplicated. This notion, however, was over-ruled by the bright face of Pat himself, who came at the first opportunity to bid the new brother good-morning.

“Which of the childer is that wid you, Paddy?” said his mother, who had removed with her knitting to the bed in the dark corner.

“Sure it’s none of our childer at all,” said Paddy, while Norah blushed for the first time in her life, and both had the first glimpse of a new revelation. “It’s only the master’s Norah. I thought may be, the walk would be lonely.”

Mrs. O’Brien looked on the consequences of her own fear of loneliness—consequences which had multiplied around her, till an hour’s solitude, asleep or awake, had become one of the never-to-return joys which the song sings of. She had a prophetic dream of a similar destiny for Paddy and Norah, but said nothing to put precocious notions into children’s heads. Ellen did not half like her brother’s bringing a stranger home with him—and she would have let Norah perceive her displeasure, but her heart was too kind to do any body a willing disservice. Norah was soon put at ease—almost. But the double visit was not repeated till long afterward. Meanwhile Norah and Paddy were “set to thinking.” That visit, made in the innocence of their hearts robbed those hearts of a portion of that innocence. Before, they had been as a new brother and sister—now as they grew in years constraint increased between them. At last, resolved upon what he called a better understanding, Paddy forced Norah to confess in words what he might easily have taken for granted. And they pledged themselves, young as they were, to a life of privation, and the same chance of more mouths than food, which had been Paddy’s own idea of a household ever since he could remember—his experience in the new home excepted.

Paddy went home one evening without Norah, fully resolved to divulge what he had determined on, in set words—a labor he might have saved himself, for it was all guessed long before. His time was out now in a few months, and he had resolved, as soon as one bondage was concluded to enter into another. In the years that he had been away, he had visited home too often to be surprised at the changes which had taken place. Ellen looked old—she seemed the mother of her brothers and sisters, for care fast brings the marks of years. And the mother, tall, gaunt and thin, looked as if she might have been the grand-parent of the children around her. Patrick senior was better saved, but time showed its marks on him too; and those not light ones. He was more peevish than formerly; he retained the same black pipe longer in service, and kept it, too, in use more constantly, for there was scarce an hour of the day when its fragrance was not issuing. And as strong tobacco is too apt to require strong accompaniments, we are compelled to acknowledge that Patrick O’Brien was contracting a taste for less harmless potations than buttermilk.

Poor and content is rich. Poor and discontented is poor indeed. Ellen felt the infection of unhappiness, and the very children seemed to have grown miserable. Squalor and negligence had marked the whole household, and Paddy had learned to make his visits unpleasant performances of duty, instead of the hilarious occasions that they once were. It was no wonder that he preferred a quiet evening in his second home, where he could sit and watch Norah’s busy fingers, rather than a visit to his own father’s house; for there cracked and dissonant voices jarred harshly, children cried, and the welcome which he once met had changed to the utterance of mutual complaints, and perhaps to unsuspended jarrings among those whom he loved.

There seemed a spell on the place. Ellen said—“Sure there’s no luck here any more.” And a neighbor, who had a son over sea, put a new thought in her head. Ellen was often desired to act as amanuensis to answer his letters. If her epistles were not clerkly they were written as dictated, and it may be shrewdly suspected that the person to whom they were written liked them none the less, that he detected the handwriting, though they were signed, “your affectionate mother.” Such a paradise as American letters revealed to her, could not fail to make her own discomforts worse by contrast. But the paradise was to her for a long time a thing unhoped for, unthought of. At last a new resolution occurred to her.

“Sure, mother,” she said one day, “we’d better be in Ameriky.”

The mother smiled at the impossibility. But Ellen had set her heart on it. She was the prop of the house—the only one in it, indeed, who had any strength or determination left. Need we say she carried her point? She reasoned father and mother into the desirableness of the change, and they could but acknowledge that any thing would be preferable to their present situation. The correspondence to which she had access furnished her with arguments, and the will once found for the enterprise, the way presented no longer insuperable obstacles. All had been discussed, and the journey was fully determined upon, when Paddy reached the cottage with his plans in his head—selfish plans, Ellen afterward said they were.

“Sure,” cried she as he entered, “here’s Patrick, too, will go with us.”

“To be sure I will—where?” answered Paddy, delighted once more to find his home cheerful.

“To Ameriky, Patrick,” said his father, taking the pipe from his mouth to watch his son’s face. The son looked sad, astonished, and bewildered. It was all new to him, and he could make no reply, save to repeat —

“A-mer-iky!”

“To be sure,” said Ellen. “What’ll we wait here for, doing no good at all? There’s Phelim may be president, and Mike a djuke, and Terrence a parliament man, and Bridget may marry a lord, and—”

“And Ellen?” inquired Patrick, with a quizzical look, which contrasted curiously with his wo-begone expression.

“Sure the best of the land will be hers,” said her mother. “Hasn’t she been the born slave of the whole of ye’s? She didn’t go away from her mother’s side, not she, for betther board and keeping!”

“Mother!” expostulated Paddy.

“More she didn’t,” continued the mother, vexed at her son’s cool reception of their good news as she deemed it. “She didn’t find new young mates, and forget the mother that bore her!”

“Mother!” said Patrick, “ye sent me away, ye know ye did. Sure I’d not gone to the Queen’s palace asself, but ye sent me away, so you did.”

“Thrue for you, Patrick!” said Ellen, breaking in to keep the peace. “Thrue for you; and more be token of that we’ll welcome you back again. Your service is up, come Easter, and then we’ll all cross the wide sea together!”

Poor Patrick! All the various modes in which he had conned over his intended communication were put to flight in a moment. This was no time to speak of any such proposals—for with half an eye to such a contingency, Patrick knew his mother had spoken. Never had the way back seemed so long to Patrick as it did that night. He had committed himself by no engagement to go with his family to the new land over sea; but he saw that they all chose to take his going for granted. The children supposed it of course, thinking of nothing else; and the elders deemed it the best way to admit no question. Norah listened in vain that night for Paddy’s cheerful whistle as he neared the house. She wondered, and fell asleep. But there was no sleep for Patrick.

Norah was too diffident to ask Patrick how he sped the next day—but didn’t she burn to know! At length, and with a very sad face, he told her all except his mother’s covert and undeserved reproaches. Norah listened with a tear in her eye, for she could not dissemble. She did not interrupt him, and when he ceased, she said:

“Sure you’ll go with them, Patrick, dear!”

“Sure I’ll do no such thing, Norah, darling!” And he hugged her to his heart with a suddenness which she could not foresee, and an energy she could not resist, had she wished it.

——

Norah was satisfied. There is no denying that. But how was Paddy to satisfy his father and mother and Ellen? How was he to explain to the little O’Briens that they were going to America and brother Patrick was to remain behind? Never was a worse day’s work done for Norah’s father than Patrick’s that day, we are very sure. Never was a poor fellow so dissatisfied with himself. A few days before, all seemed to promise to falsify the adage that the course of true love never did run smooth. And now never was stream so ruffled.

“ ’Tis but a word and all’s over,” he said to himself, as he turned his head homeward the next evening, prepared to face the worst. But his fears whispered that there would be more than one word or two, and those high ones; and by the time he had reached his father’s door, all his courage was gone again. When he entered he found the good wife there who had the son over sea. She was fully installed as one of the council, since she also had resolved upon crossing the water. All the various items and charges of the voyage were calculated, and Paddy was counted as one of the party—not without lamentations, which he arrived in season to hear, that he had grown too tall to be counted as one of the “childher.”

It was a desperate case, and there was nothing for it but desperate courage. “Mother,” said Patrick, “and father, and Ellen, and you childher, you’ve pushed the thing so far that you drive me to tell you all, once and forever, that I cannot go!”

Patrick senior let his pipe fall with astonishment. The mother turned pale with sorrow and displeasure. Ellen arose, and going to Patrick’s side—he had not taken a seat—drew him out of doors. They walked a few steps from the house in silence, and reaching a tree paused there. Patrick folded his arms, and leaning against it, bowed his head and stood in troubled silence. Ellen placed her hands upon his, and never a word was spoken till, when she felt her brother’s hot tears fall upon her hand, she cried:

“Sure, Paddy, you are not going to leave us now!” And she fell upon his neck and clung to him with the evidences of earnest and frantic affection.

“Indeed, indeed, Ellen darling, it is you that leave me. It is you that go away from the land where God has been good to us, to seek a new home and new friends over sea. I cannot go there with you, Ellen; indeed I can’t.”

“And what will this land be to you, Paddy dear, but a land of strangers—no mother, no father, no sister nor brother in it? Where’ll be the hearth side that you’ll find a home at? Come, brother, with the rest of us, where father will lift up his head again and mother be happy!”

“Amen to their happiness, Ellen, and yours too. Go your ways without me. Sure I’ve given my word on it, and must tarry to take care of my own home, sister dear.”

“Is it that you mean!” cried Ellen, starting back indignant. “And shall we plough the seas while you cling to her apron-string! Will you be as easy in your undutiful bed, while the mother that bore you is tossed on the ocean, and the sister that toiled for you is down, down in the deep sea, maybe? Oh, Patrick! by the days of your wee, wee childhood, come along with us now. Is it thus, selfish as you are, that you lose all natural affection? Didn’t the clargy tell us, only Sunday was a week, to honor father and mother?”

“Thrue for you, Ellen. But who would be our father and mother, if our father had not left his father and mother to clave to his wife? Oh, go along with you, Ellen, to break my heart so, and my word of words given to Norah that I will stay with her and cherish her—for better for worse!”

Ellen said no more. Patrick did not re-enter the house, but proceeded homeward—to the place which was now doubly home to him, since the home of his childhood was about to be broken up. But the efforts of his mother to change his determination did not cease, and many a half-altercation he had with his family in his now frequent visits. Still, though strongly tempted to yield, he never would give full consent, and the sight of Norah reassured him in his resistance. The few weeks that remained between the fixing upon the purpose of emigration and the day of departure, were a long, long time to Patrick, and a season of sad trouble; and he could not speak with freedom to any of his distress. Norah was high-spirited, and the bare suspicion of the manner in which her name was bandied, and her love for Patrick all but cursed at the house of his father, would have led her to forbid Patrick ever to speak on the subject to her again. With slow reluctance the family gave way to Patrick’s resolute determination, and ceasing unkind reproaches, loaded him with tenderness, that much more affected his determined spirit. The day of parting came at last, and Norah herself proposed that she should accompany her betrothed to take leave of his kindred. It was a dangerous thing for him to suffer, Patrick knew; but how could he avoid it? And what would he have thought of her, too, had she not proposed it?

Unmixed and bitter was the grief with which Patrick’s kindred took leave of him to commence their long journey. They sorrowed as persons who should see his face no more; and without extravagance or hyperbole, the passion of grief which they felt and exhibited may be termed heart-rending. Scarce a word did they give to Norah. The mother looked on her almost with aversion, and the father scarce heeded her presence at all. Ellen only said:

“Cherish him, Norah—love him, for you see what he foregoes for you. God forgive him if he is wrong, and me if he is right.”

——

They were gone. Norah thought it was but natural, at first, that Patrick should be sad, for the interview which she had witnessed made her unhappy too. But she was not well pleased that his gloom continued. Weeks and months passed, and still Patrick had not resumed his former light-heartedness. Nor did there appear any indication of its return to him. The wedding day, to which he once looked forward with continual expectation, and of which, at one time, he daily spoke, he now seemed to dread and scarcely mentioned. And when he did speak of it, it was with a forced appearance of interest. Norah was offended at his coldness, and as he did not press, as formerly, a positive and early date, you may be sure that she did not increase in impatience for the nuptials to which Patrick appeared to be growing daily more indifferent. He thought her ungrateful that she did not duly estimate the sacrifice he had made for her; and she considered him weak-minded that he had over-estimated his affection for her, and undervalued his own kin, and was now repenting. Patrick was indeed more miserable than he had ever been in his life before. Not a word had he heard from his connections in many long months; and what Ellen said to him under the tree before his father’s door, now haunted him—“Shall we plough the seas while you cling to her apron-strings? Will you be easy in your bed, when the mother that loves you is tossed on the sea, and the sister that toiled for you is drowned?” By day these words haunted him, and by night his mother and sister rose out of the sea to come to his bedside. And truly, when he waked in a cold perspiration of terror from these visions, it was hard to persuade him that they were not true; and that the sea had not verily given up its dead to reproach him.

“Norah, dear,” he said at length one evening, as they sat alone, “my heart is broke, so it is.”

She answered with a look in which deep sorrow mingled with all her old affection. Nor did she resist, when he drew her to his side, and placed her head against his bosom. He felt that he could not say what he must when her eyes met his. So she nestled lovingly to him while he sat long in silence. She guessed, but would not ask, what he wished to say, and at length he continued:

“Every morning when I wake it is to hear what they said to me, when I wouldn’t go with them. And every night when I lie down, sure the clatter of that leave-taking drives sleep away. And when the eyes shut for very weariness, and I have cried myself into a troubled slumber, it is no rest. Sometimes my mother comes to me, Norah, and sometimes my sister. I know that they come from the deep, deep sea, for they are all dripping wet. Never a word do they say with their mouths, but their eyes, Norah. God save us, what was that?”

Norah had caught his contagious horror, and clung closer to him, as they both shivered with terror. It was many minutes before Patrick could resume his narrative, but after a trembling pause he proceeded:

“They come to me, Norah, and I know it’s them. When I wake, don’t I feel the cold water of the sea chilling my temples? The saints save us, Norah, from such visiters to our bridal bed! You think me changed and that my heart is turned, and my manner is unkind—but, Norah dear, what will I do, what can I do?”

“It’s all your sick fancy, Patrick—and maybe your conscience is not easy,” said Norah, shaking off the spectral influence of Paddy’s dreams. “It’s all your own notion, Paddy dear. Your mother and all of them are well and happy—barring that they feel the loss of you as much as you do their absence. And I know their consciences are not easy, Patrick, for the hard words they said to you must leave a deep wound in their own hearts. You must go to them, Patrick.”

“What, Norah, and leave you!”

“And why not? Sure, Paddy dear, you’re not worth a body’s having now, and that’s the truth. You are not the same lad that you were at all, and what will I do with such a man? It’s a long lane that has no turn, and all will come right by and by.”

“Norah!”

“Well!”

“Wouldn’t you go with me too?”

“Sure I thought you’d be asking that, Patrick. Ellen said you were selfish—and wasn’t it the truth she said! Will you change the load from your heart to mine? Haven’t I a father and mother, and sisters too? Will I give them up and go away, because you can’t give yours up? It isn’t reason, Patrick.”

In vain did our hero strive to alter Norah’s determination. Her arguments were unanswerable, and he was fain to submit. After many days’ irresolution he resolved, but still not without doubts and misgivings, to follow his parents to America. The resolution was taken, the spectral appearances which had annoyed him ceased. He was half-tempted to retreat from his purpose, but Norah gave him no encouragement, and his nocturnal visiters threatened to renew their visits; so that he was fain to adhere to his resolve, and take a steerage passage to the great entre-pot of the New World—New York.

Great was his amazement upon arriving there to find that it was a place so large, and one of many large places; and that to inquire for his family there was of as little utility as it would be to ask for his master’s dog in Dublin. It was a sad trial to Patrick that he had come to a strange land, he verily believed, to no purpose. But it was necessary for him to do, or starve, and finding employment he worked, with a heavy heart it is true, but not without hope. Chance—or we should better say Providence—directed him to a priest, to whom he related his difficult position and almost extinguished hopes. The kind father was struck with his tale, and, after a moment’s pondering referred to his record of priestly acts, and sure enough, there he found the name of Ellen O’Brien—O’Brien no longer!

“Mighty easy it was then, for her to come over,” shouted Pat, forgetting his Reverence. Fine talk hers to me about selfishness, and drowning, and all that. Very pleasant it was, no doubt of it, to write and read them long letters. But it has given me the first trace of them anyhow, and that’s something.

With this clue the persevering young Irishman was not long in tracing the party to their late stopping-place—late, for they were there no longer. He followed to Albany, and there again lost the scent; for a party of poor emigrants are not so easily followed. Again he heard of them in Buffalo; away, it seemed to him, at the verge of the world; and again he pursued.

“Sure he would find them now,” he said, “if it was only to have a fly at that traitor, Ellen—God bless her!”

In Buffalo he was once more disappointed, for from Buffalo they had flitted also. “It’s the Wandering Jew Ellen has married, no doubt,” he said, “to lead me this dance, and she to rate me so. Wait till I find them once more.”

Time would be unprofitably spent in tracing all poor Patrick’s journeyings, including many an excursion from the main routes. Wherever the sinews of his countrymen were busy upon public works and other enterprises, in which the labor of the sturdy Hibernian is found so valuable, there Patrick wandered—and patient perseverance at last was rewarded. He had traced out an impromptu village on a rail-road truck, where the delvers had put up cabins which they would sorrow to leave. As he looked curiously through the little settlement, he was startled to hear his own name shouted, and in a moment more one of his many brothers had him by the neck, with a hug as stifling as if he had taken lessons in the new country of one of those undisputed natives—the black bear.

Patrick had much ado to stop his brother’s clamor, that he might surprise the others. And he was astonished moreover to find little Phelim, for he it was, with a Sunday face on in the middle of the week. This mystery was solved when they reached the cabin; for there was a gathering in honor of the first Patrick of the new generation, who had that day, during the priest’s visit in his round on the works, been first empowered to answer to his name like a Christian.

“It’s this you were up to, is it?” shouted Patrick, bursting upon them. “I thought it wasn’t entirely to make Phelim a president, and Michael a djuke, that you come over!”

Tears, shouts of laughter, frolic, pathos, poetry, and prose most unadorned, made up the delightful melange at that unexpected meeting.

——

Patrick found that his family had indeed made a happy change. There was no gainsaying that. And he himself experienced no difficulty in procuring employment; but he was far from being so well content as the others. He wrote to Norah upon his arrival at New York, and again when he had found his father and mother; and he wanted sadly to invite her to join him in America. But for the same reason that he did not return to Ireland, he dared not ask her to come over; for if he could not leave his friends how could she hers? He would have gone “home,” as he persisted in calling it, but, strange to say, Ellen was not in the least humbled in her exactions by the fact of her own marriage. She loved Pat better than any body in this world, her own husband and her own child not excepted, and it was with a feeling of wrong that she heard or thought of his loving any one else, or being beloved by any.

Sad news began now to come from the old country. The O’Brien’s had no letters; but others had, and the newspapers were full of the dreadful destitution and the deaths from starvation in Ireland. Now poor Patrick was worse afflicted than he had been by separation from his parents. Tidings came of starvation and death in houses the inhabitants of which he knew were wealthier far than Norah’s father; and he feared and dreaded that she might even want for a bit of bread, while he rolled in plenty. Had he pursued his own inclination he would have posted back—but Ellen said—“Don’t think of such a thing! Is it mad you are? When there’s people dying there of the hunger will you go snatch the bread from their mouths? Or will you go ‘home,’ as you call it, and feed the three kingdoms from your own pocket?” Patrick was hurt—and he thought of the two Norah was far the better comforter.

Deep indeed was the distress that rested upon unhappy Ireland. And Patrick’s fears for his friends at home were but too well founded. Sickness and famine invaded the district in which Patrick was born; and though his old master at first was bountiful to those around him, stern necessity at last brought its admonition that he must hold his hand. There is distress that opens the heart; but when it comes to dividing your living with your neighbor, to become at last fellow in his need, the instinct of self-preservation chills charity. Nevertheless, the good farmer gave—and gave a day too long; for the time came when he could count his own scanty provision in food and in purse. Impoverished, he learned at last to suffer and to sicken. He buried his wife out of his sight, and his children sunk one after another into the grave. He denied himself bread to feed his famishing family—almost rejoicing, while the dead lay unburied in his house, that with the release of child after child, the need of food and the wail of hunger diminished. And now at last Norah and himself only remained of all that happy household; and they had but to prepare their last food and die. The immense demand which had been made upon the charitable had proved too great for the supply; and men had ceased at last to think it a strange thing that people died of hunger.

Often did Norah think in her distress of him who was now far away. And heartily she rejoiced for his sake, that he had not remained to add another claimant on the public charity, to the thousands who pleaded unavailingly for it. But it was sad to think that he must one day hear that her he loved had sunk into the grave, the last of her house, for to death she firmly looked as the only hope of release from suffering.

A footstep broke the silence; but it hardly disturbed her revery. It was the kind ecclesiastic who had been present at the death of her mother and her brothers—who had seen her sister’s eyes closed, and to whom she herself looked, at no distant day for the last offices of the church. His frequent visits had become part of her daily experience, but she saw now that his face wore something more than the usual calm expression. She looked up inquiringly, and he placed in her hands a letter, addressed to his care for her.

She knew the handwriting, and could scarce command firmness to break the many seals and wafers with which over caution had secured the letter. It was from Patrick, and enclosed more money than she had before seen for many weeks. “Now, God be praised,” she cried, “my father shall find comfort again!”

“He has found it, daughter!” said the priest in a solemn voice from the bedside. Norah hurried there, to receive, in the last faint smile, a father’s inaudible blessing.

Need we say that the good priest gave Norah sound advice: to wit, that the money which she had received were better expended in finding her way to Patrick, than in protracting a weary existence in the place now so sad to her. Ellen’s welcome was not the least hearty which Norah received; and all agree that there was a Providence in the events which guided Patrick before her to America. Norah is cherished as one of the “childher,” and Mrs. O’Brien insists that her mistake at the bedside years before, was only a bit of prophecy, for her heart always yearned to Norah as one of her own. All are well pleased; and though a shade of sorrow for her kindred is habitual to the countenance of Mrs. Norah O’Brien, it adds to the sweetness of its expression, and is a better look, in its resignation, than one of discontent or of vacuity.

As to the young cousins in the neighborhood, we leave their statistics to the next census. They have proved jewels of comfort to Grandfather Patrick, who, though quite infirm, is still useful to “mind the childer;” while Mrs. O’Brien, the grandmother, labors like Sisyphus to keep little feet in hose, with no hope that her work will ever cease while her breath lasts, or her fingers can ply a needle.

———

BY R. H. STODDARD.

———

I’ve lost my little May at last;

She perished in the Spring,

When earliest flowers began to bud,

And earliest birds to sing;

I laid her in a country grave,

A rural, soft retreat,

A marble tablet o’er her head

And violets at her feet!

I would that she were back again,

In all her childish bloom;

My joy and hope have followed her,

My heart is in her tomb;

I know that she is gone away,

I know that she is fled,

I miss her everywhere, and yet

I cannot make her dead!

I wake the children up at dawn,

And say a simple prayer,

And draw them round the morning meal,

But one is wanting there;

I see a little chair apart,

A little pin-a-fore,

And Memory fills the vacancy,

As Time will—nevermore!

I sit within my room, and write

The lone and weary hours,

And miss the little maid again

Among the window flowers;

And miss her with her toys beside

My desk in silent play,

And then I turn and look for her,

But she has flown away!

I drop my idle pen and hark,

And catch the faintest sound;

She must be playing hide-and-seek

In shady nooks around;

She’ll come and climb my chair again.

And peep my shoulder o’er,

I hear a stifled laugh—but no,

She cometh nevermore!

I waited only yester night,

The evening service read,

And lingered for my idol’s kiss,

Before she went to bed,

Forgetting she had gone before,

In slumbers soft and sweet,

A monument above her head,

And violets at her feet!

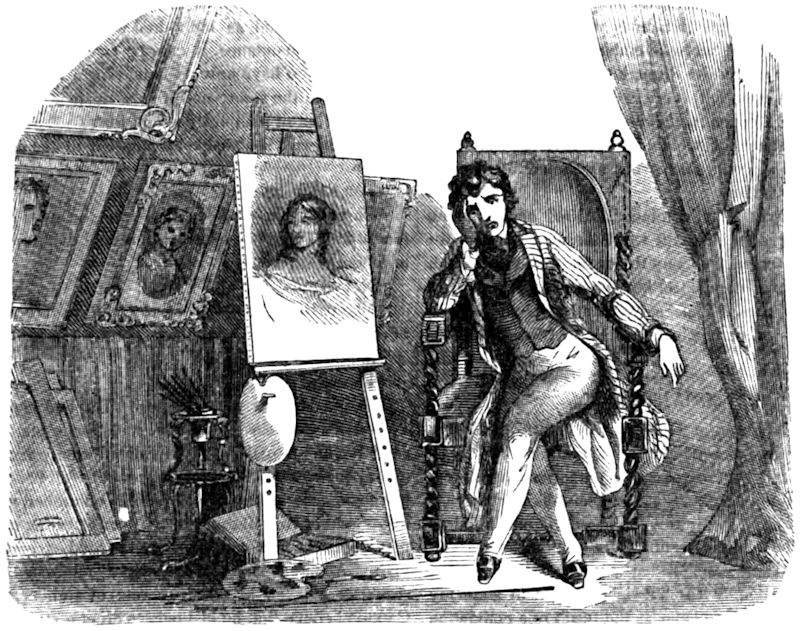

OR THE STRUGGLE FOR INDEPENDENCE.

———

BY T. S. ARTHUR

———

(Continued from page 8.)

Clara, as has been seen, fell into a thoughtful, sober state of mind, after the interview with her husband, in which she mentioned the fact of having five thousand dollars in stocks. Something in the manner of Alfred troubled her slightly. When he came home in the evening she experienced, in meeting him, the smallest degree of embarrassment; yet sufficient for him to perceive. Like an inflamed eye to which even the light is painful, his morbid feelings were susceptible of the most delicate impressions. A mutual reserve, unpleasant to both, was the consequence. Ellison imagined that his wife had, on reflection, become satisfied of his baseness in seeking to obtain her hand in marriage because of her possession of property, and the change in his manner which this feeling produced, naturally effected a change in her. From that time their intercourse became embarrassed, and both were unhappy.

A few days after Clara had informed her husband of the fact that she possessed five thousand dollars in stocks, she brought him the certificates which she held, and placing them in his hands, said,

“You must take care of these now.”

“What are they?” he asked, affecting an ignorance that did not exist, for the instant his eyes rested on the papers he understood what they were.

“Certificates of the stock about which I told you.”

Ellison handed them back quickly, and with a manner that could not but wound the feelings of his wife, saying at the same time,

“Oh, no, no! I don’t want them. Draw the interest yourself as you have been doing.”

“I have no further need of the money,” replied Clara, in a voice that had acquired a sudden huskiness. “Our interests are one you know, Alfred, and you take care of these matters now.”

But, the young man, acting under a perverse and blind impulse, positively refused to keep the certificates.

“I’d rather you would draw the money as you have been doing,” said he, his voice much softened and his manner changed. “It may be weakness in me, but I feel sensitive on this subject.”

Ellison’s evil genius seemed to have him in possession.

“On what subject?” inquired Clara, in a tone of surprise.

“On the subject of your property,” replied Ellison, with a want of delicacy the very opposite of his real character.

If a cold hand had been laid upon the bosom of Clara, she could not have experienced a more sudden chill. She made no reply. Ellison perceived, in an instant, the extent of his error. Like a man struggling in the mire, every moment seemed but to plunge him deeper. A more painful reserve followed this brief but unhappy interview. Deeply did the young man regret not having taken the certificates when they were handed to him. That was his only right course. But they were presented unexpectedly, and the first suggestion which came was that the act was more compulsory than voluntary on the part of his wife.

The subject was not alluded to again, but it was scarcely for a moment out of the thoughts of either Clara or her husband. When the half-yearly interest became due, which was in the course of a week, Clara drew the money. It amounted to the sum of one hundred and fifty dollars.

“You will not refuse this, I hope?” said she smiling, as she handed him what she had received. “It is the half-yearly interest on our stock.”

Alfred was a little wiser by experience.

“I have no particular use for it just now,” was his reply. “Suppose you keep it and pay our board every week as long as it lasts. Twenty-four dollars will be due to-morrow.”

“Very well, just as you like, Alfred. If you should want any of it, you must help yourself. You will find it in my drawer.”

“I’ll call on you if I should get out of pocket,” was replied to this in a playful tone of voice.

Both felt relieved. But it grew out of the fact that Ellison had been able to disguise his real feelings, and this was but a false security. There was a certainty, however, about the means of paying the weekly charge for boarding, that was a great relief to the mind of Ellison, and which enabled him the better to hide his real feelings from his wife. Happily for him, the four pictures which had been talked about were ordered. He completed them in about five weeks, and received two hundred dollars, the price agreed upon. One hundred of this sum he paid to the friend who had loaned him the money to lift the obligation that was felt to be so oppressive. Fifty of what remained he placed in the hands of Clara, playfully saying to her as he did so, that she must be his banker. The remark was timely and well expressed, and it had its effect both upon his own mind and that of his wife. But the source of trouble lay too deep to be easily removed.

Seek to disguise it as he would, Ellison could not hide from himself the fact, that he had suffered a great disappointment. Often and often, would come back upon him his old dream of the sunny clime of art and music, and he would feel the old, irrepressible longing to visit the shores of Italy. At last, it was some months after his marriage, he said to Clara, something favoring the remark —

“I don’t think I shall ever be happy until I have seen the galleries of Rome and Florence.”

Clara looked surprised at this remark, it was so unexpected, for no intimation of such a feeling had ever been breathed ere this by her husband.

“Why do you wish to go there?” she naturally inquired.

“To took upon the glorious old masters,” replied Ellison. “I will never be any thing in my art until I have studied them.”

“You think too meanly of your present attainments,” said Clara. “N—— has been to Italy, but with all his study of the old masters he has not half the ability as an artist that you possess.”

“It isn’t in him, Clara,” replied Ellison with some warmth. “He might study in the galleries of Florence forever, and not make a painter.”

“There are many specimens and copies of the old masters in our city,” remarked Clara, “could you not find aid from studying them?”

“No, no—or at least but little,” said Ellison coldly. He had hoped that his wife would feel favorable, at least, to a visit to Italy, even though it might not at the time be practicable. But her evident opposition to the thing chilled his over-sensitive feelings.

“Ah me!” sighed the young artist to himself, when alone, “I am free in nothing!”

Other thoughts were coming into utterance, but he checked and drove them back. As for Clara, she was utterly unconscious of what was in the mind of her husband. Could she have understood his real feelings, she would have sacrificed even her natural prudence and forethought, and cheerfully proposed to sell the stock they possessed in order that they might visit Italy and spend a year or two in that classic region. But a reserve had already been created, and Ellison, in particular, kept secret more than half of what was passing in his mind, while he imagined his wife to have thoughts and feelings to which she was a total stranger. He said no more about Italy, for it was plain to him that she would oppose the measure if suggested; and, as she had brought him a few thousands, she of course had a right to object.

Fortunately for the young artist, the four pictures which he had painted gave excellent satisfaction. In fact, they were his best works. The mind, when smarting under pain, often acts with a higher vigor, while the perceptions acquire a new intensity; and this was the real secret of his better success. The pictures pleased so well that they brought him other sitters, and he was able, some time before Clara’s instalment of interest was exhausted, to place more money in her hands. The fact of doing this was always a relief to his mind. It was a kind of tacit declaration of independence. From that time both his work and his ability increased, and he was able to make enough to meet, with the aid of his wife’s income, the various expenses to which he was subjected, and to pay off the few obligations that were held against him. But he was not happy. No man can be who forfeits, by any act that affects the whole of his after life, his self-respect; and this Ellison had done. In spite of his better judgment, he would permit himself to see in Clara’s words, looks and conduct, a rebuke of the mercenary spirit that first led him to seek her favor. Nothing of this was in her heart. But guilt makes the mind suspicious.

——

The young artist worked on with untiring assiduity—he was toiling for independence. Never, since his marriage, had he breathed the air with the freedom of former times. The reaction of his often strange manner—his days of reserve—had been felt by his wife, and the effect upon her was plainly to be seen. With a perverseness of judgment, hardly surprising under the circumstances, he attributed the change in Clara to her suspicions as to the purity of his motives in seeking an alliance. In the meantime, he had become more intimately acquainted with her relatives, none of whom he liked very well. Her oldest brother interfered a good deal in the suit which he was engaged in defending on behalf of his wife; and by much that he said, left the impression that he did not think Ellison’s judgment sound enough in business matters to advise a proper course of action.

This fretted the sensitive and rather irritable young man, and, in a moment when less guarded than usual, he told him that he felt himself fully competent to manage his own affairs, and hoped that he would not, in future, have quite so much to say about things that did not concern him. The brother was passionate, and stung Ellison to the quick by a retort in which he plainly enough gave it as his opinion that before five years had gone by, his sister’s property would all be blown to the winds through his mismanagement. This was little less than breaking Ellison on the wheel. He turned quickly from his cool, sneering opponent, and never spoke to him afterward. Piqued, however, by the taunt, he proposed to Clara that they should visit the West, and remain there for as long a time as it was necessary to personally look after their interests. He could paint there as well as at the East; and might possibly do better for a time. To this Clara’s only objection was the necessity that it would involve for disposing of some of their stock, in order to meet the expense of removal, and the sustaining of themselves, if Alfred should not readily obtain employment as an artist, thus lessening the amount of their certain income.

“But see how much is at stake,” replied Alfred. “All may be lost for lack of a small sacrifice.”

“True,” said Clara, in instant acquiescence. “You are right.”

But when the proposed movement of Ellison and his wife became known, her relatives had a good deal to say about it. George Deville, the oldest brother, whose feelings now led him to oppose any thing that he thought originated with Alfred, pronounced it as preposterous.

“Why don’t Ellison go himself?” said he. “What does he expect to gain by dragging Clara out there?”

“You surely are not going off to Ohio on such an expedition,” was his language to his sister.

“Yes,” she replied to him, mildly, “I am going.”

“What folly!” he exclaimed.

“George,” said Clara, in a firm, dignified manner, “I must beg of you not to interfere in any way between my husband and myself. In his judgment I am now to confide, and I do it fully. We think it best to go and see personally after our own interests.”

“But Clara—”

“Pardon me, George,” interrupted the sister, “but I must insist on your changing the subject.”

Deville became angry at this, and as he turned to go away, said something about her being beggared by her “husband’s fooleries,” in less than five years.

It so happened that Ellison entered at this moment, and heard the insulting remark. It was with an effort that he kept himself from flinging the brother, in a burst of unrestrained passion, from the room. But he controlled himself, and recognised him only by an angry and defiant scowl. As Deville left the room, Clara burst into tears, and placing her hands over her face, stood weeping and sobbing violently. Alfred’s mind was almost mad with excitement. He did not speak to his wife at first, but commenced walking hurriedly about the room, sometimes throwing his arms over his head, and sometimes clasping his hands tightly across his forehead. But, in a little while, his thoughts went out of himself toward Clara, and he felt how deeply pained she must be by what had just occurred. This softened him. Approaching where she still stood weeping, he took her hand and said,

“We would have been happier, had you been penniless like myself.”

The tears of Clara ceased flowing almost instantly. In a few moments she raised her head, and looking seriously at her husband, asked,

“Why do you say that, Alfred?”

“No such outrage as the present could, in that case, ever have occurred.”

“If George thinks proper to interfere in a matter that does not in the least concern him, we need be none the less happy in consequence. I feel his words as an insult.”

“And so they are. But they do not smart on my feelings the less severely. Lose your property! He shall know better than that, ere five years have passed.”

“Don’t let it excite you so much, Alfred. His opinion need not disturb us.”

“It has disturbed you, even to tears.”

“It would not have done so, had not you happened to hear what he said. This was what hurt me. But as we have provoked no such interference as that which my brother has been pleased to make; and, as we are free to do what we think right, and competent to manage our own affairs, I do not see that we need feel very unhappy at what has occurred.”

“If you have any doubts touching the propriety of doing what I suggested, let us remain where we are,” said Ellison.

“I have no doubts on the subject,” was Clara’s quick reply. “I think that where so much property is in danger, that we ought to take all proper steps to protect our interests; and it is impossible for us to do this so well at a distance as we could if on the spot where the contest is going on. When you first proposed it, I did not see the matter so clearly as I do now.”

Preparations for a temporary removal to the West were immediately commenced; and in the course of a few weeks they were ready for their departure. There was not a single one of Clara’s relatives who did not disapprove the act, nor who did not exhibit his or her disapproval in the plainest manner. This, to Alfred, was exceedingly annoying, in fact, coming as it did on his already morbid and sensitive feelings, actually painful.

“They shall see,” he said to himself, bitterly, “whether I squander her property! If I don’t double it in five years, I’m sadly mistaken.”

This was uttered without there being any clearly defined purpose in the young man’s mind; but it was in itself almost the creation of a purpose. From that moment he became possessed with the idea of so using his wife’s property as to make it largely reproductive. He studied over it every day, and remained awake, with no other thought in his mind, long after he had laid his head upon his pillow at night.

With five hundred dollars in cash, obtained through the sale of five shares of stock, Ellison and his wife started for the West on the errand that we have mentioned. Clara looked for an early return, but Alfred left his native city with the belief that he would never go back there to reside; or if so, not for many years. Plans and purposes were dimly shadowing themselves forth in his mind, as yet too indistinct to assume definite forms, yet absorbing most of his thoughts. For the time all dreams of Italy faded, and in vague schemes of money-making, he forgot the glories of his art.

The place of their destination was a growing town, numbering about six thousand inhabitants. Near this lay the five hundred acres of land in dispute. On arriving, they took lodgings at a hotel, and, in due time, sent for the agent who had charge of the property. He informed them as to the state of affairs, and assured them that all was going on as safely as possible. The case had been called at the last term of court, but was put off for some reason, and would not be tried for three months to come, when they hoped to get a decision. If favorable or adverse, an appeal would be made, and a year might probably elapse before a final settlement of the questioned rights could be obtained.

Ellison hinted at their purpose in visiting the West. The agent said, in reply, that their presence would not in the least affect the case. It would be as safely managed if they were in Europe.

“That is all easily enough said,” remarked Alfred, after he was alone with his wife; “but I am disposed to think differently. Every man ought to understand his own business, and watch its progress.”

In this view Clara fully acquiesced; and they made their arrangements to reside in the West for at least some months to come. In the course of a week or two Ellison announced himself as an artist from the East, whose intention it was to pass a short time in D——. He arranged a studio, and made all needful preparation for sitters; but, during the first two months of his residence there, not an individual came forward to be painted. Expenses were going on at the rate of about fifteen dollars a week, with a good prospect of their being increased ere long. This was rather discouraging, and it may be supposed that the young artist was in no way comfortable under the circumstances. By this time he had become so well acquainted with the state of the case pending, as to be pretty well satisfied that his presence would be of no great utility in securing a favorable termination of the affair. If he had come to the West alone, a week’s personal examination of the position of things would have enabled him to see their entire bearing, and to understand that his presence was in no way necessary.

This conviction, to which the mind of Ellison came reluctantly, did not by any means help him to a better state of feeling. He had closed his studio at the East, just as he was beginning to get sitters enough to secure a pretty fair income, and was in a strange place, where people were yet too busy in subduing nature’s ruder features to think much of the arts. He was the only painter in town; yet he did not receive an order. Occasionally one and another called at his rooms, looked at his pictures, asked his prices, and talked about having some portraits taken. But it never went beyond this.

Steadily the sum of money they had brought with them diminished, and nothing came in to supply the waste. To go back again was, to one of Ellison’s temperament, next to impossible; and even if he returned, he felt now no certainty of being able to do so well as when he left. His unhappiness, which he could not conceal, troubled Clara, who understood its ground. He was talking, one day, in a desponding mood, of his doubtful prospects, when Clara said to him,

“There is no need, Alfred, of your feeling so troubled. We have enough to live on, certain, for the next four or five years, even if you do not paint a portrait; to say nothing of the property in dispute, which will, without doubt, come, with a clear title, into our possession before a very long time.”

“All very true,” replied Alfred. “But that consideration doesn’t help me any. I cannot see your property wasting away without feeling unhappy. It is for me to increase it; whereas, now, I am the cause of its diminution.”

“Alfred, why will you talk thus?” said Clara, in a distressed tone of voice. “Why will you always talk of my property? When I gave you myself, did not all I possessed become as much yours as mine?”

Alfred sat silent.

“We need not remain here,” resumed Clara, “any longer than it will be useful.”

“I cannot go back to Philadelphia,” said Alfred, quickly. “At least not until the business upon which we came has reached a favorable termination.”

Clara did not ask why he said this; for she comprehended clearly his feelings.

“We needn’t return there,” she replied. She said this, notwithstanding her own desire to go back was very strong. “In Cincinnati, artists are encouraged. We can go there.”

“Yes, or to one of the cities lower down the river. Any thing rather than return to the East with your property lessened a single dollar.”

“It is wrong for you to feel so, Alfred—very wrong,” said Clara. “We ought always to let a conviction of having acted from right motives sustain us in every position in life. Here, and only here, is the true mental balance.”

Alas for Ellison! the lack of this very conviction was at the groundwork of his inquietude. The property that now caused him so much trouble was the first thing that drew him toward his wife; and all the alloy that had mixed itself with his happiness came from this source. Had she not been the possessor of a dollar, and had he been drawn toward her for her virtues alone, their minds would have flowed together as one, and, in the most perfect union, they would have met and overcome whatever difficulties presented themselves. But all was embarrassment now, rendered more oppressive through the morbid pride of the young man, who felt every moment as if a window were about to open in his breast, so that his wife could see the baseness of which he had been guilty. This very effort at concealment but awakened a suspicion of what was there.

The conversation continued, Alfred getting in no better state of mind, until Clara became so hurt, or rather distressed, by many things said by her husband, that she could not control her feelings and gave vent to them in tears. Thus, as week after week went by, the causes of unhappiness rather increased than diminished.

——

Ellison had been in D—— three months, and was about leaving for Cincinnati, when his lawyer called on him, and stated that he was authorized by the opposing counsel to say, that the plaintiffs in the case were willing to withdraw their suit if one hundred acres of the land in question were relinquished.

“At the same time,” remarked the lawyer, in giving this information, “it is but right for me to state my belief that the offer comes as the result of a conviction that the claim urged for the ownership of the property has no chance of a favorable termination.”

“Yet the suit may be continued for two or three years,” said Ellison.

“Yes, and they can put you to a great deal of trouble and expense.”

“And there is at least a doubt resting on the issue.”

“There is upon all legal issues.”

“Then I think we had better accept the compromise.”

“You must decide that for yourself,” said the lawyer.

“How long will the question be open?”

“For some days, I presume.”

“Very well. I will see you about it to-morrow, or at latest on the day after.”

Clara, on being informed of the new aspect the case had assumed, fully agreed with her husband that the offer of a settlement had better be met affirmatively; and this being done, the suit was withdrawn, and they were left in the peaceable possession of some four hundred acres of excellent land. The costs were nearly two hundred dollars. This made it necessary to part with more of their stock, which was effected through their agent at the East. Five more shares were sold.

The termination of this suit wrought an entire change in the views and purposes of Ellison. A residence in the West of three months had brought him in contact with people of various characters and pursuits, all eagerly bent on money-making. Towns were springing up as if by magic, and men not worth a dollar to-day were counting their thousands to-morrow. The spirit of enterprise was all around him; and it was hardly possible for him to remain unaffected by what was in the very atmosphere that he was breathing.

“Let me congratulate you on the happy termination of your suit,” said an individual with whom Ellison had some acquaintance, a day or two after all was settled. “You have now as handsome a tract of land as there is in the state; and if you manage it aright, will make out of it an independent fortune.”

This language sounded very pleasant in the ears of Ellison.

“You know the tract?” said he.

“Oh yes! Like a book. I’ve traveled over every foot of it. There is a hundred thousand dollars worth of timber on it.”

“Not so much as that.”

“There is, every dollar of it. Not as fire-wood, of course.”

“In lumber, you mean.”

“Exactly.”

The man’s name was Claxton. He had come to D——, about a year previously, with some six thousand dollars in cash, and as full of enterprize and money-loving ambition as a man could well be. The town was growing fast, and the supply of lumber, which a saw-mill of very limited capacity was turning out, so poorly met the demand, that prices ranged exceedingly high. A large landholder, whose interests were seriously affected by this high rate of lumber, made Claxton believe that he had only to erect a steam saw-mill, capable of turning out, per day, a certain number of feet of boards and scantling, and his fortune was made. Without stopping to investigate the matter beyond a certain point, and taking nearly all the statements made by the individual we have named for granted, Claxton ordered a steam-engine from Pittsburg, rented a lot of ground on the bank of the river, and forthwith commenced the erection of his mill. As soon as the citizens of D—— understood what he was about, there were enough of them to pronounce his scheme a foolish one, in which he would inevitably lose his money. But he had made all the calculations—had anticipated, like a wise man, all the difficulties; and knew, or thought he knew, exactly what he was about. It was nearly a year before he had his mill ready. By this time he was not only out of funds, but out of confidence in his scheme for making a fortune. In attempting to put his mill in operation, some of the machinery gave way, and the same result happened at the next trial. Thus expense was added to expense, and delay to delay. In the mean time, the owner of the other mill had been spurred on by the approaching competition, to increase its capacity, and was turning out lumber so fast as to cause a reduction in the price.

So soon as Claxton became aware of the fact that Ellison’s suit had come to a favorable termination, he conceived the idea of getting off upon the young artist his bad bargain with as little loss to himself as possible, and he had this purpose in his mind when he congratulated him so warmly on his release from the perplexity and uncertainty of the law.

“Trees standing in the forest, and lumber piled up ready for use in building,” said Ellison, in reply to Claxton’s suggestion, “are very different things.”

“Any man knows that. But, in the conversion of the trees into lumber, lies the means of wealth. There is not an acre of your land that will not yield sufficient lumber to bring three hundred dollars in the market.”

“Are you certain of that?” inquired Ellison.

“I know it. The tract is very heavily timbered.”

“Three hundred dollars to the acre,” said Ellison, musing; “four hundred acres—three times four are twelve. That would make the lumber on the whole four hundred acres worth over a hundred thousand dollars!”

“I know it would. And you may rest assured that the estimate is not high. I only wish I had your chances for a splendid fortune.”

“How is this lumber to be made available?” asked Ellison.

“Cut and manufacture it yourself. You’ll find that a vast deal more profitable than painting pictures. You can see that this is one of the best situated towns in the West. The supply of lumber has always been inadequate for building purposes, and, in consequence, its prosperity has been retarded. Reduce the price by a full supply, and houses will go up as by magic, and the value of property rise in all directions. At present, you could not get over fifteen dollars an acre for your land if you were to throw it into market. But go to work and clear it gradually, sawing up the timber into building materials, and, in ten years, such will be the prosperity of the place, growing out of the very fact of a full supply of cheap lumber, that every acre will command fifty dollars.”