Title: Ideals in Art: Papers Theoretical, Practical, Critical

Author: Walter Crane

Release date: September 5, 2018 [eBook #57852]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

WORKS BY WALTER CRANE

THE BASES OF DESIGN. With 200 Illustrations, many drawn by the author. Third Edition. Crown 8vo, 6s. net.

LINE AND FORM. A Series of Lectures delivered at the Municipal School of Art, Manchester. With 157 Illustrations. Third Edition. Crown 8vo, 6s. net.

THE DECORATIVE ILLUSTRATION OF BOOKS, OLD AND NEW. With 165 Illustrations. Fourth Edition. Crown 8vo, 6s. net.

LONDON: GEORGE BELL AND SONS

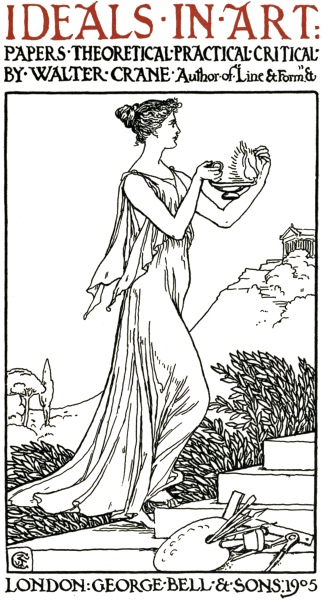

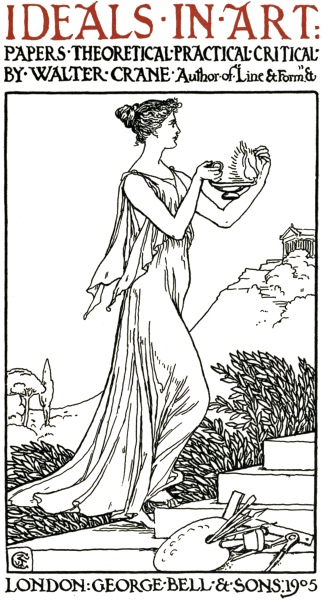

IDEALS·IN·ART:

PAPERS·THEORETICAL·PRACTICAL·CRITICAL·

BY·WALTER·CRANE·Author·of·“Line&Form”.Et

LONDON:GEORGE·BELL·&·SONS:1905

v

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

vi

The collected papers which form this book have been written at different times, and in the intervals of other work. Most of them were specially addressed to, and read before the Art Workers’ Guild, as contributions to the discussion of the various subjects they deal with; so that they may be described as the papers of a worker in design addressed mainly to art workers. They are not, however, wholly or narrowly technical, and the point of view frequently bears upon the general relation of art to life.

Some of the papers were delivered as lectures to larger audiences, and others have appeared as articles, mostly in journals devoted to art.

Of the former, the one upon the Arts and Crafts movement was prepared for and read as one of a series of lectures given during a recent exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, and is now for the first time printed in its entirety.

The “Thoughts on House-Decoration” was read before the convention of the National Association of Master Painters and Decorators recently held at Leicester.

vii “The Influence of Modern Social and Economic Conditions on the Sense of Beauty” was the substance of an address at the opening of a debate on that question at a meeting of the Pioneer Club.

The paper on “The Progress of Taste in Dress” was written for “The Healthy and Artistic Dress Union,” and appeared in their journal “Aglaia.” The article on Mr. Chesterton’s book appeared in “The Speaker”; that on “The Teaching of Art” in “The Art Journal.”

The notes on “Gesso” work appeared in an early number of “The Studio,” and I have to thank the editor, Mr. Charles Holme, for kindly allowing me to reprint it here, and also for the loan of the blocks used for the illustrations, both for this and others of the papers.

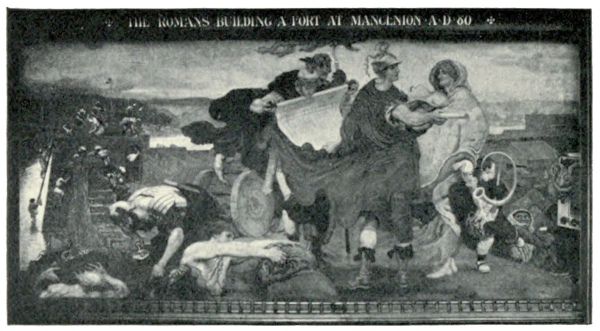

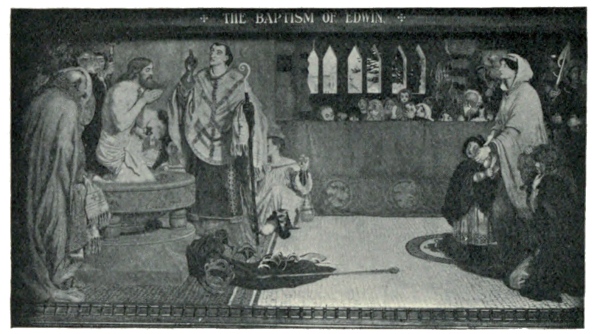

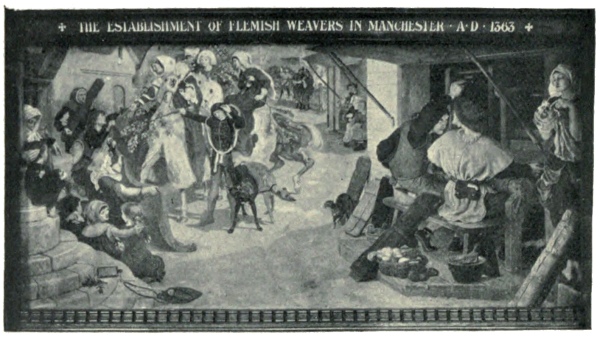

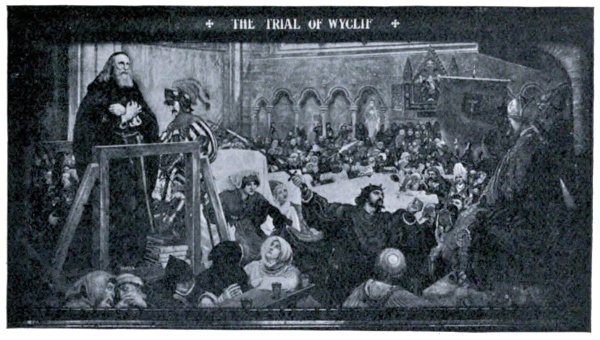

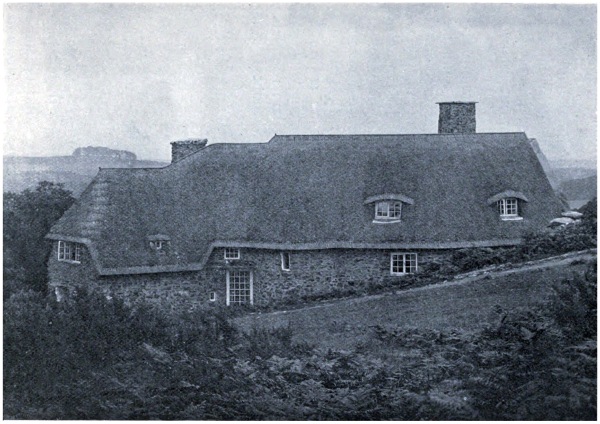

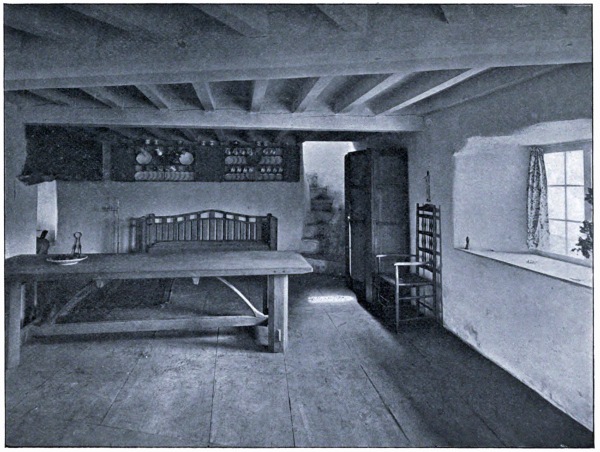

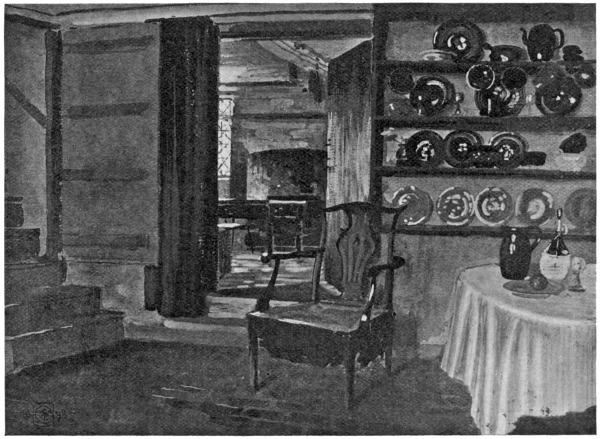

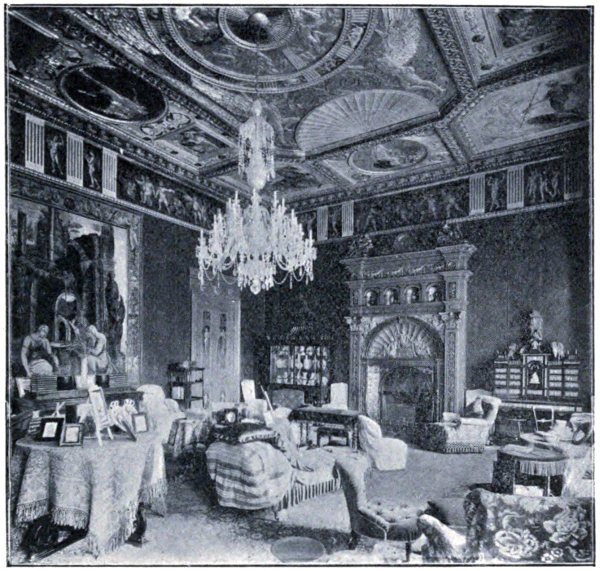

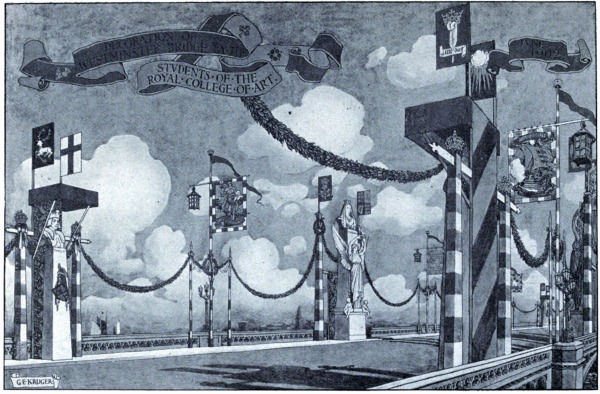

My best thanks are also due to Mr. Ernest Gimson for the loan of photographs of his cottage at Stoneywell; to the Earl of Pembroke for enabling me to obtain those of the double cube room at Wilton; to Mr. Charles Rowley, and Mr. Charles W. Gamble of the Municipal School of Technology, Manchester, for photographs of the Madox Brown frescoes; to Mr. Augustus Spenser and Mr. FitzRoy, the Principal and the Registrar of the Royal College of Art, for their help in obtaining for me the examples of the work of the students given; and to Mr. Arthur P. Monger for the care he took in photographing them; also to Mr. Kruger of the Royal College, for the use of his admirable drawing of the decorations ofviii Westminster Bridge, which appeared in “The Magazine of Art,” and is now reproduced by permission of Mr. M. H. Spielmann and Messrs. Cassell.

I should like to add a note or two on some of the illustrations, on other points not commented upon in the papers.

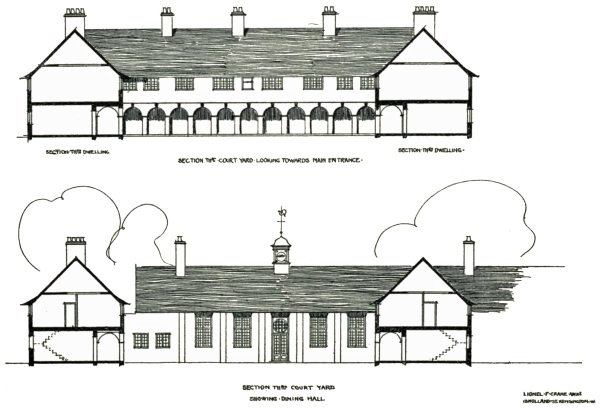

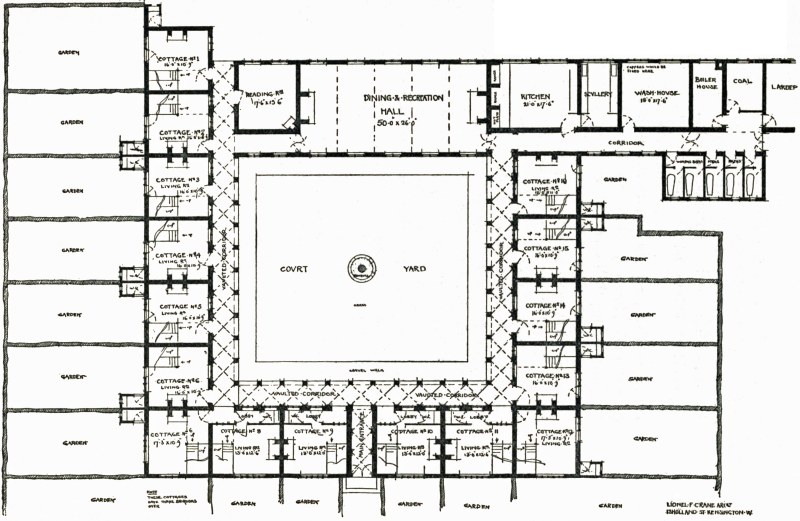

The sketch plan and elevation of a collective dwelling (at page 116), for which I am indebted to my architect-son, is offered as a suggestion of what could be done in this way on very simple lines. Each tenant in such a collective dwelling would have his private house or cottage, with the advantage of the use of the common dining-hall, and the service of a collective kitchen; also a general reading-room, and to these rooms a vaulted way with an open arcade on the side next the quadrangle would enable each tenant to reach this part of the building under cover from his own dwelling, which comprises a private garden, as well as the use of the common quadrangle.

From the architectural point of view grouped dwellings, upon some such principle as here suggested, would undoubtedly lend themselves to artistic and pleasant treatment, and would mitigate the depressing effect of the monotonous rows of squat dwellings intended for our workers’ homes, and the mean sameness of the streets, which are spreading around our great towns in every direction, only, it is to be feared, to form slums in the future.

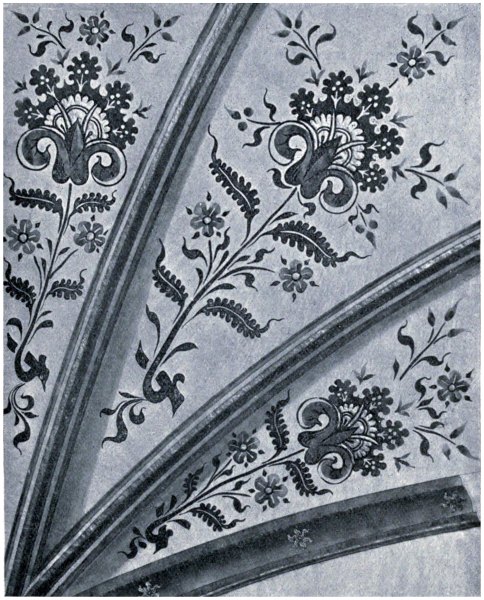

In regard to Manchester, spoken of on page 119, another practical step has been taken inix the much-needed direction of school-decoration. Through the public spirit of Mr. Grant, one of her citizens, who has found money enough to start the work, students of the Municipal School of Art are enabled to carry out on a large scale mural paintings upon the upper walls of the class-rooms in one of the principal primary schools. The subjects have been enlarged from some of my coloured book designs such as “Flora’s Feast.” Such work might not only be made to bear most helpfully on the general work of education, but in itself be an important side of school influence, since by means of large simple typical mural designs great historical events and personages, as well as natural form, might be made familiar to the eyes of children at the same time that their sense of beauty and imaginative faculties were appealed to.

Local history might in this way be preserved also. In this connection one was glad to see the other day at Hoxne (the ancient Eagles-dune) in Suffolk the school-house connected with the history of the place by having a figure of St. Edmund carved as a finial of the chief gable, with a relief in stone let into the wall beneath, illustrating the incident of the saintly king being taken by the Danes at the bridge, while an inscription mentions that the building marks the spot, and the date of his death in 870.

WALTER CRANE.

YEW TREE FARM,

September, 1905.

x

| PAGE | |

| OF THE ARTS AND CRAFTS MOVEMENT: ITS GENERAL TENDENCY AND POSSIBLE OUTCOME | 1 |

| OF THE TEACHING OF ART | 35 |

| OF METHODS OF ART TEACHING | 58 |

| NOTE ON TOLSTOI’S “WHAT IS ART?” | 69 |

| OF THE INFLUENCE OF MODERN SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONDITIONS ON THE SENSE OF BEAUTY | 76 |

| OF THE SOCIAL AND ETHICAL BEARINGS OF ART | 88 |

| OF ORNAMENT AND ITS MEANING | 102 |

| THOUGHTS ON HOUSE-DECORATION | 110 |

| OF THE PROGRESS OF TASTE IN DRESS IN RELATION TO ART EDUCATION | 171 |

| OF TEMPORARY STREET DECORATIONS | 192 |

| OF THE TREATMENT OF ANIMAL FORMS IN DECORATION AND HERALDRY | 203 |

| OF THE DESIGNING OF BOOK-COVERS | 225 |

| OF THE USE OF GILDING IN DECORATION | 237 |

| OF RAISED WORK IN GESSO | 247 |

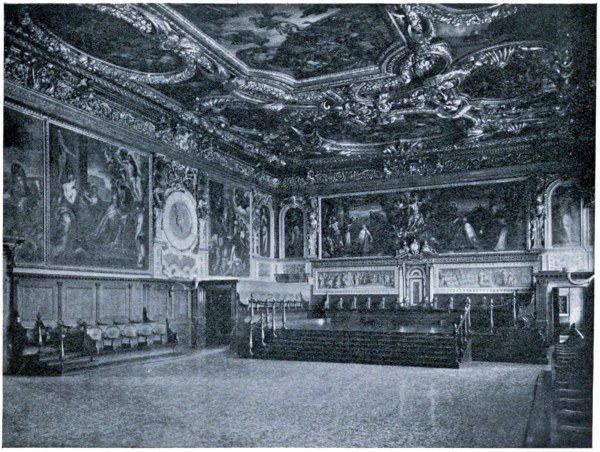

| THE RELATION OF THE EASEL PICTURE TO DECORATIVE ART | 265 |

| A GREAT ARTIST IN A LITERARY SEARCHLIGHT | 273 |

| INDEX | 283 |

xi

| PAGE | |

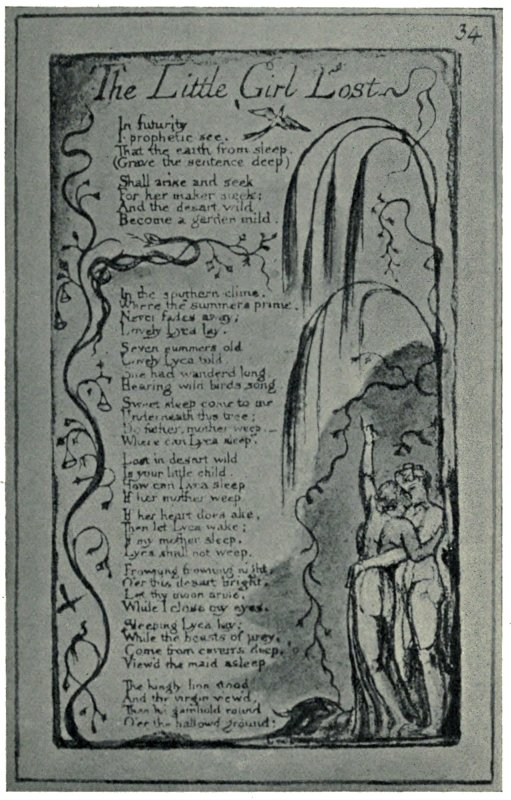

| Page from Blake’s “Songs of Experience” | 5 |

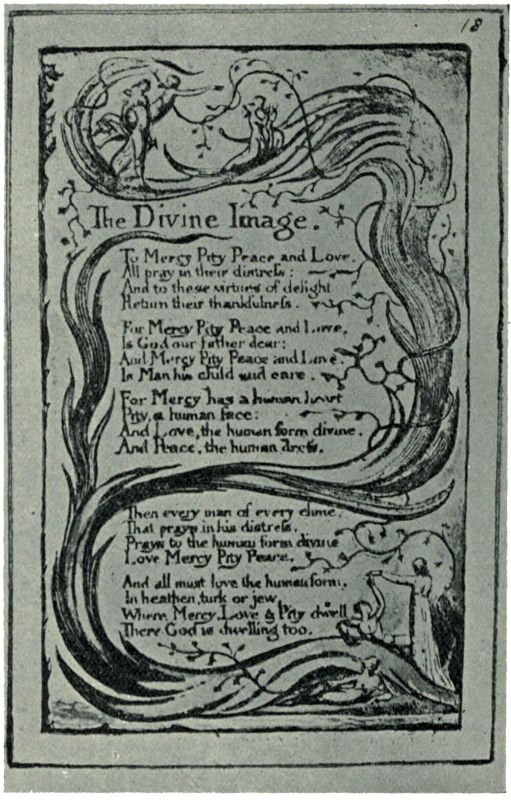

| Page from Blake’s “Songs of Innocence” | 6 |

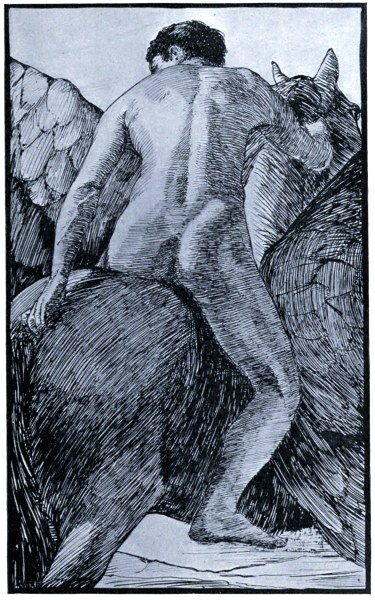

| Wood engravings by Edward Calvert | 7, 8 |

| Illustrations to Tennyson: | |

| The Ballad of Oriana, by Holman Hunt | 9 |

| The Palace of Art, by D. G. Rossetti | 10 |

| The Bride (from “The Talking Oak”), by Sir J. E. Millais | 11 |

| Manoli, by Frederick Sandys | 13 |

| Royal College of Art, Students’ Designs: | |

| Figure Composition, Frederigo Barbarossa, by Lancelot Crane | 37 |

| Time Studies, by H. Parr | 38, 39 |

| Time Studies of Figures in Action | 41 |

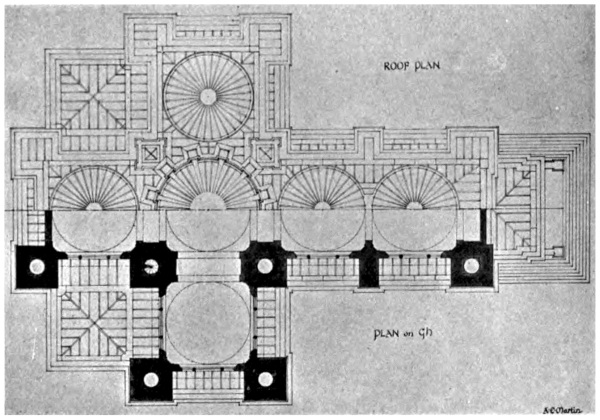

| Design and Plan of a Domed Church, by A. E. Martin | 42 |

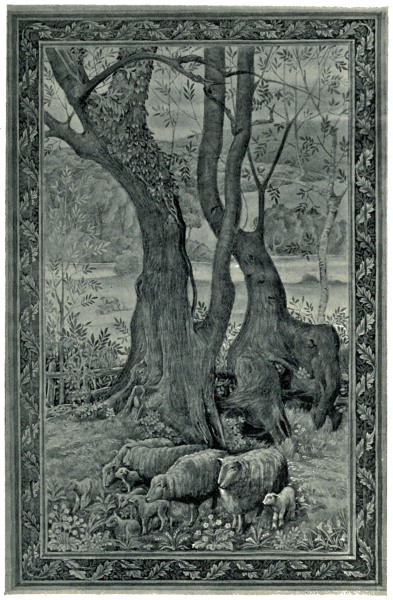

| Design for Tapestry, by E. W. Tristram | 43 |

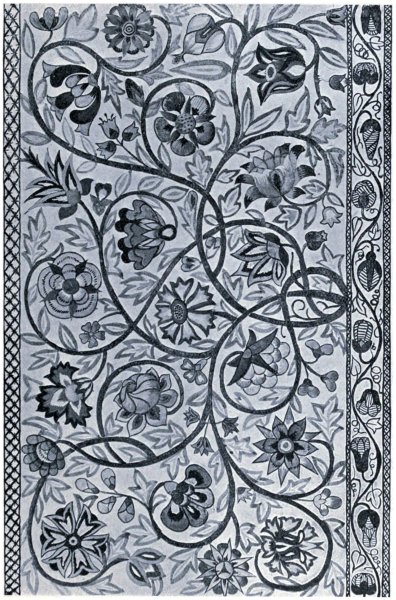

| Design for Embroidery, by Miss E. M. Dunkley | 45 |

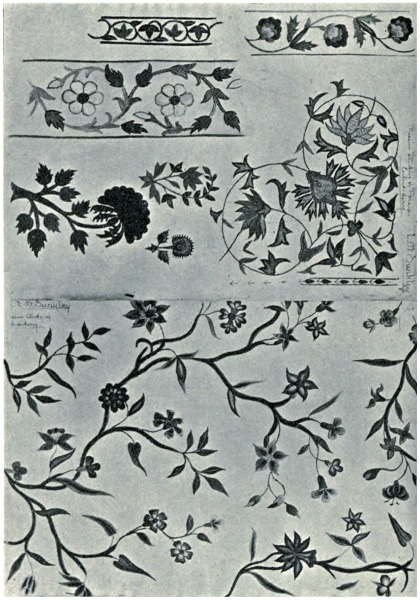

| Museum Studies in Embroidery, by Miss E. M. Dunkley | 46 |

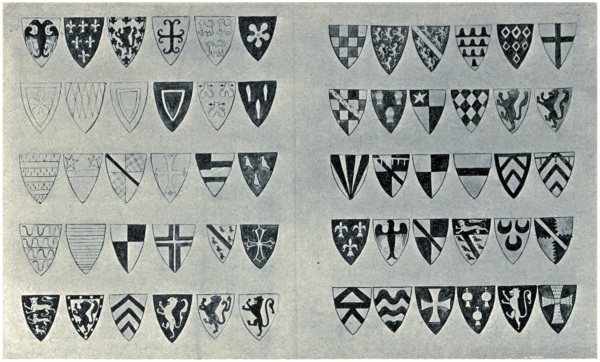

| Sheet of Heraldic Studies, by Miss C. M. Lacey | 47 |

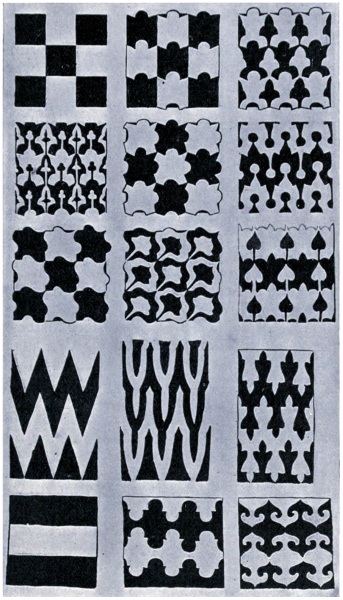

| Studies in Counterchange, by W. G. Spooner | 49 |

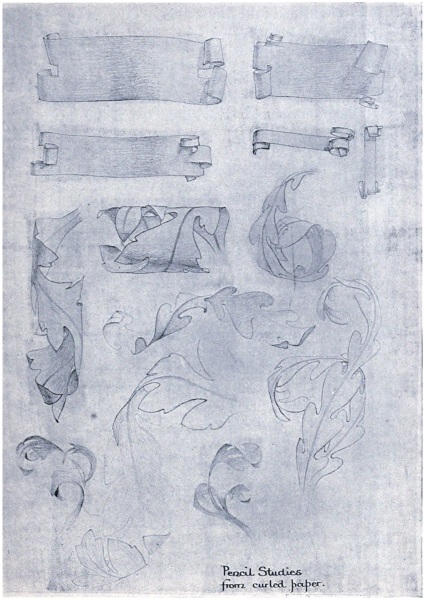

| Studies of Scroll Forms, by W. G. Spooner | 51 |

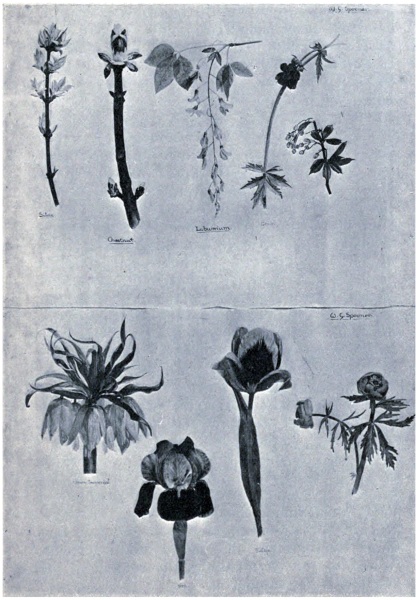

| Studies of Plant Forms, by W. G. Spooner | 53 |

| Pen Drawings, by H. A. Rigby | 55, 57 |

| Cabinet, designed and decorated in Gesso, by J. R. Shea | 59 |

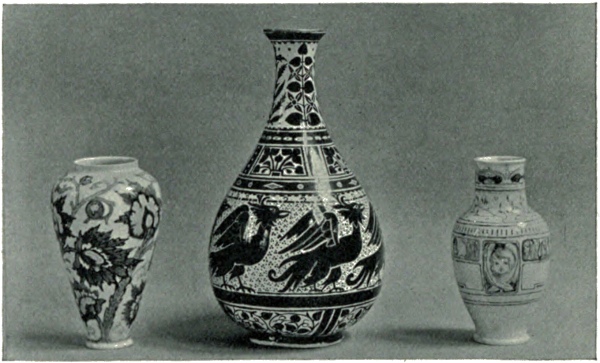

| Group of Pottery, designed and executed by the Students | 60 |

| Wood Carving, by J. R. Shea | 61 |

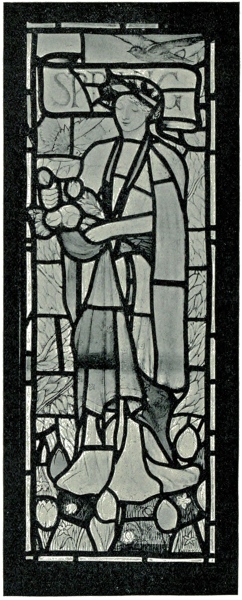

| Stained Glass Panel, designed and executed by A. Kidd. | 62xii |

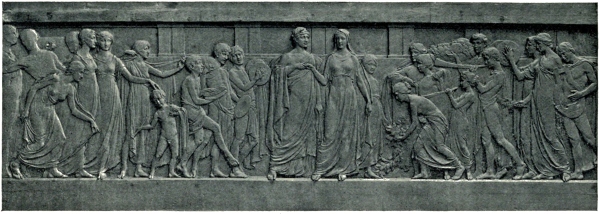

| Frieze, by James A. Stevenson. | 63 |

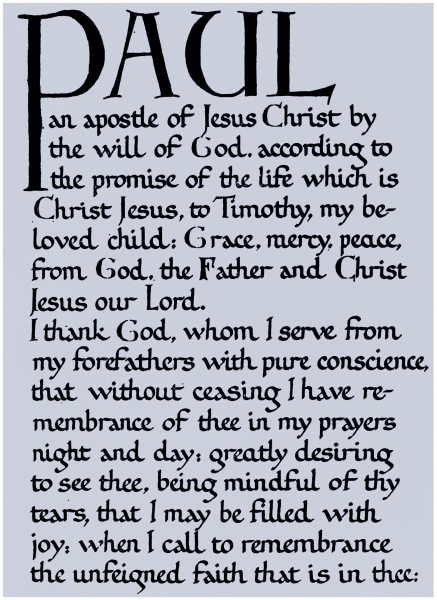

| Page of Text, written by J. P. Bland | 65 |

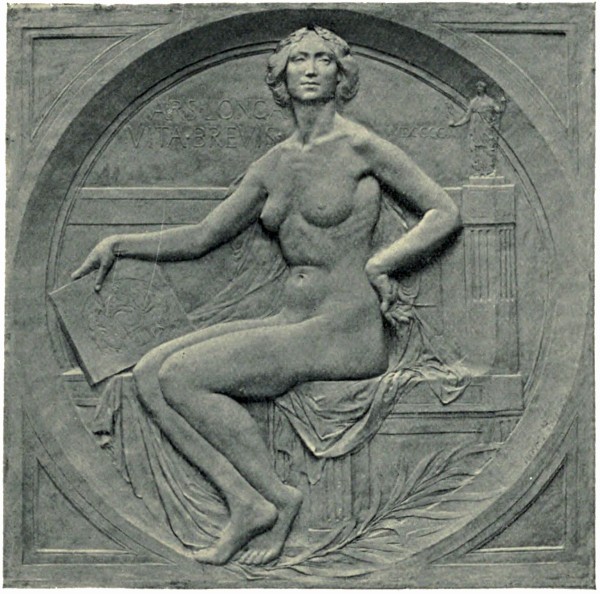

| Panel by Vincent Hill | 67 |

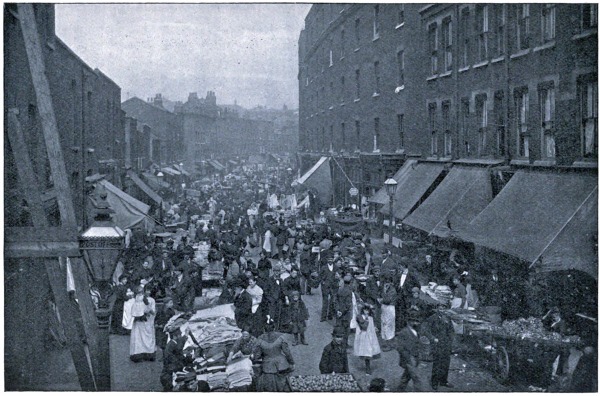

| Wentworth Street, Whitechapel | 79 |

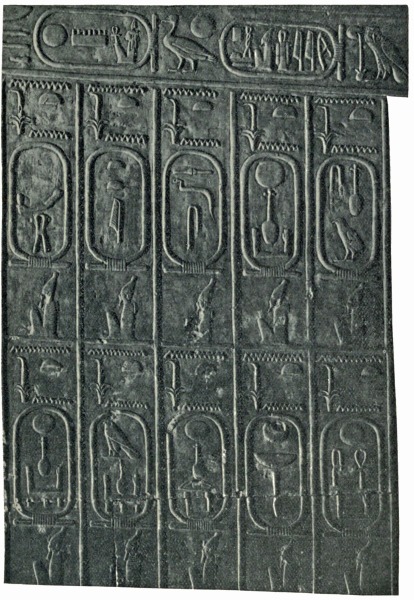

| Egyptian Hieroglyphics as a Wall Decoration (Temple of Seti, Abydos) | 89 |

| Greek Cylix (Peleus and Thetis) | 105 |

| Sketch for Collective Dwelling, by Lionel F. Crane | 116 |

| Plan of Collective Dwelling, by Lionel F. Crane | 116 |

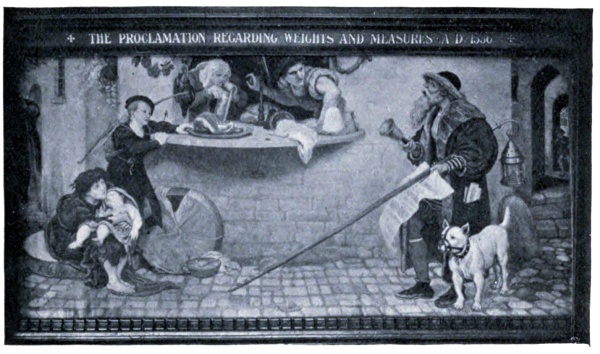

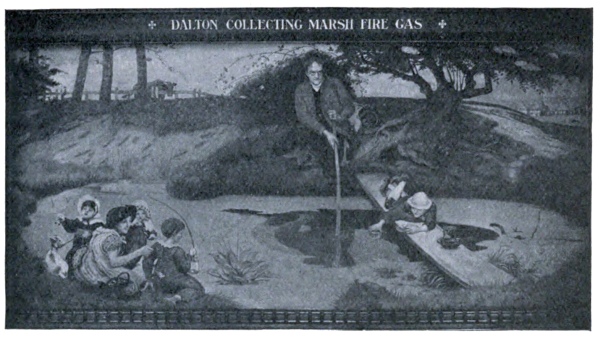

| Frescoes by Ford Madox Brown in the Town Hall, Manchester | 118, 119 |

| View in Bournville | 123 |

| Cottages at Bournville, designed by Alex. W. Harvey | 123 |

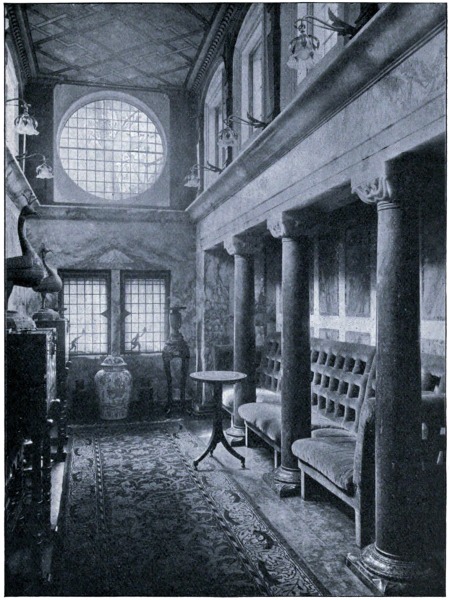

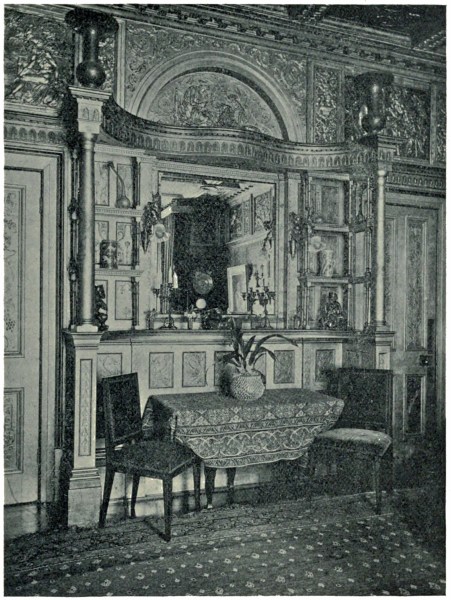

| Interior, 1a, Holland Park, designed by Philip Webb | 131 |

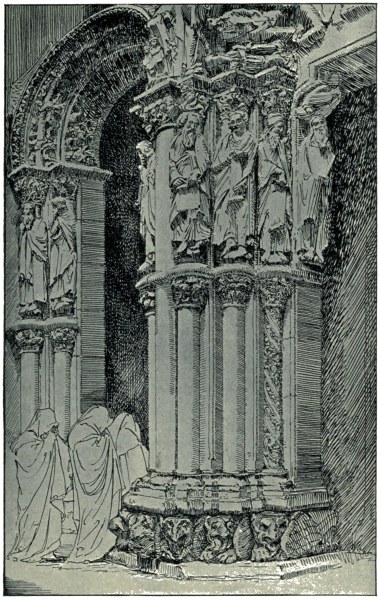

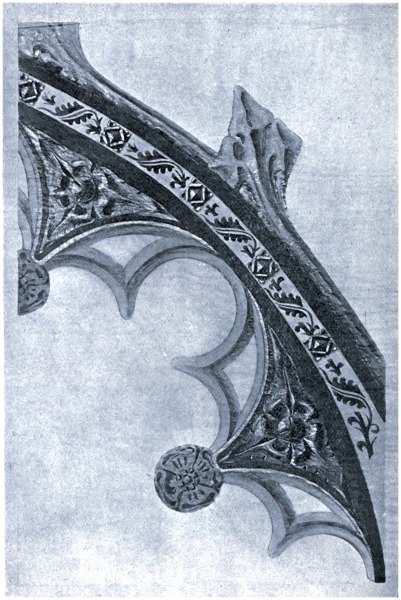

| Ranworth Rood Screen, Norfolk (from Drawings by W. T. Cleobury) | 133, 134, 135, 137, 138, 139, 141, 143 |

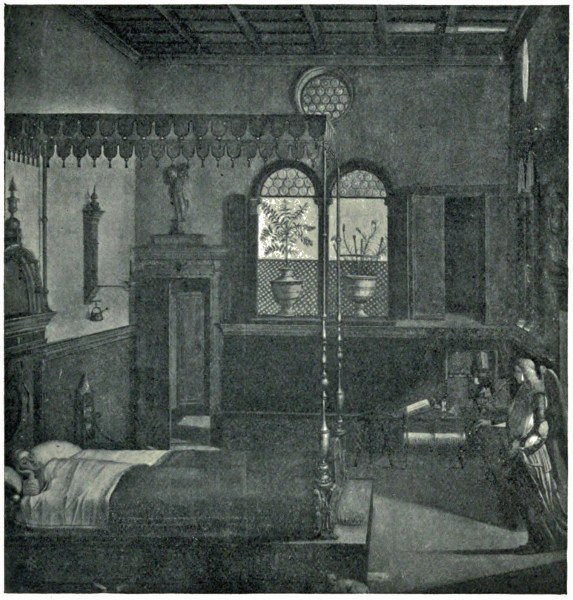

| Lucas van Leyden, “The Annunciation” | 145 |

| Carpaccio, “The Dream of St. Ursula” | 147 |

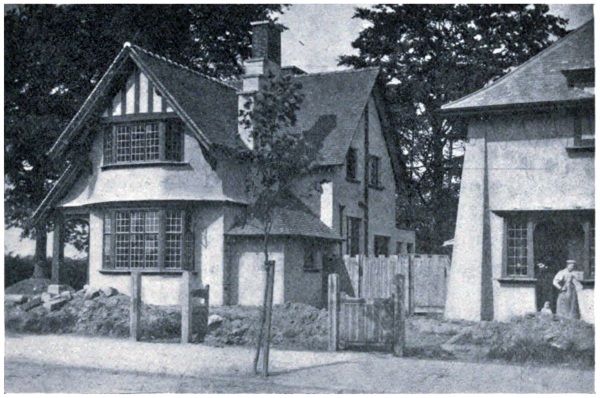

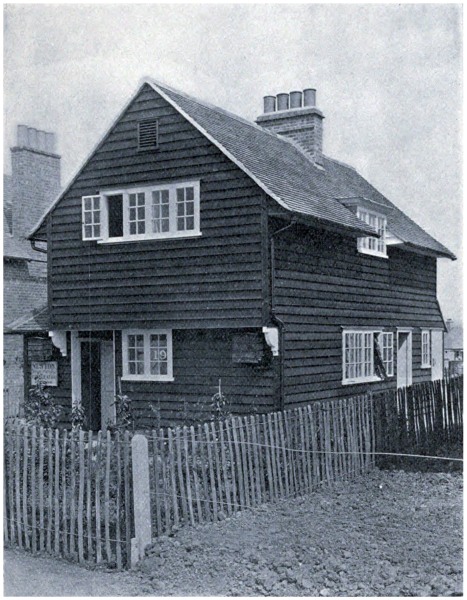

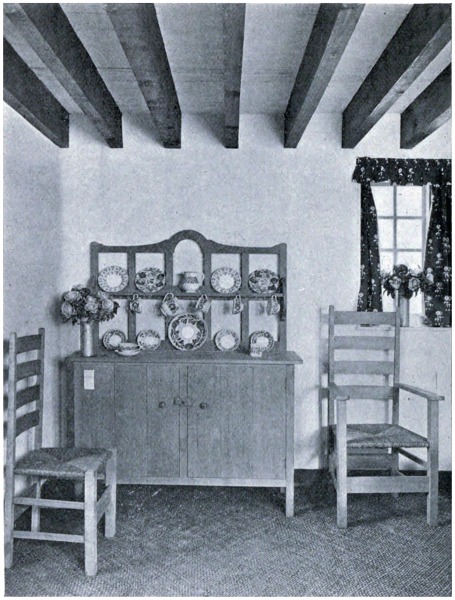

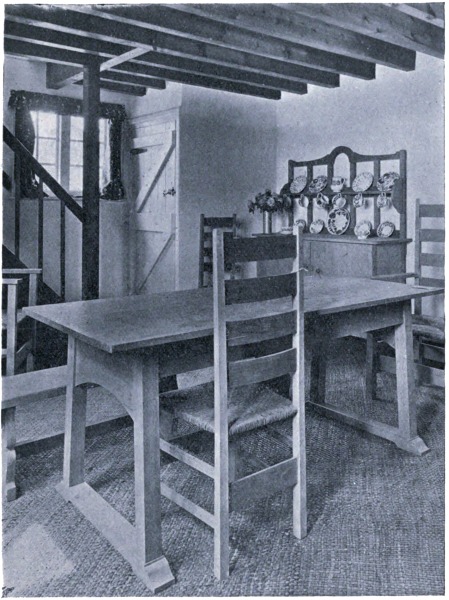

| Cottage in the Garden City, Letchworth, Herts, designed by Lionel F. Crane | 149, 150, 151 |

| Stoneywell Cottage, designed by Ernest W. Gimson | 153, 155 |

| Old English Farmhouse Interior (from a Sketch by Walter Crane) | 157 |

| Combe Bank, Sevenoaks, the Saloon, decorated by Walter Crane | 159 |

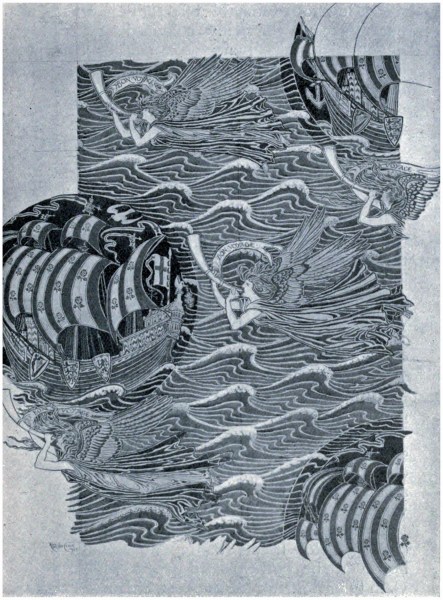

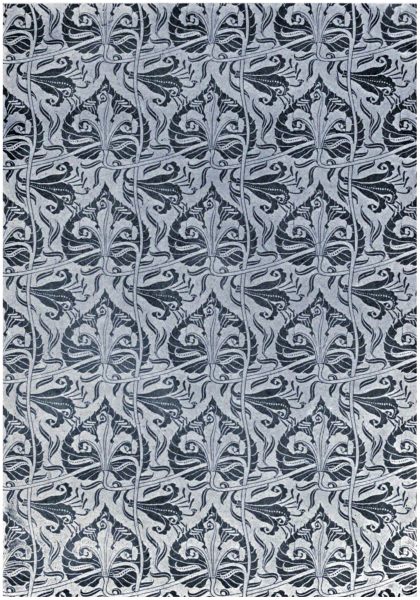

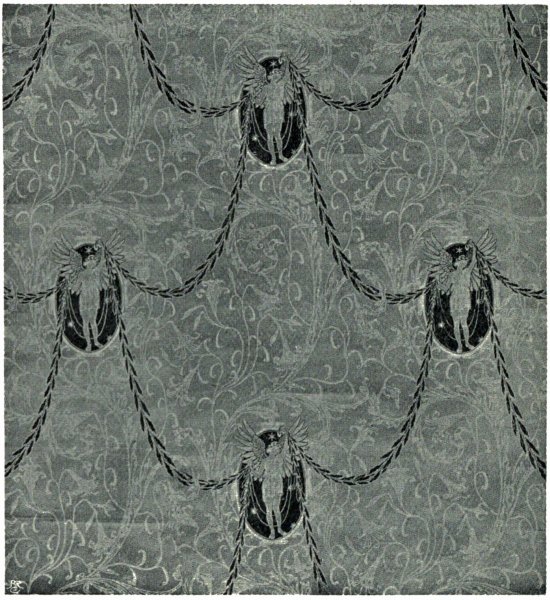

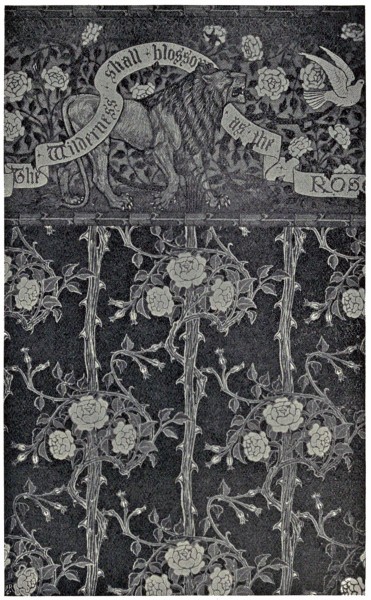

| Printed Cretonne Hangings, designed by Walter Crane | 160, 161 |

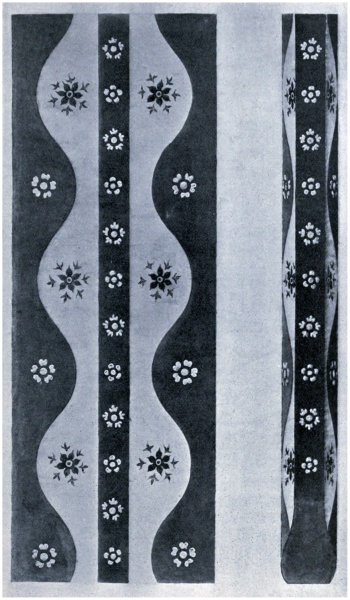

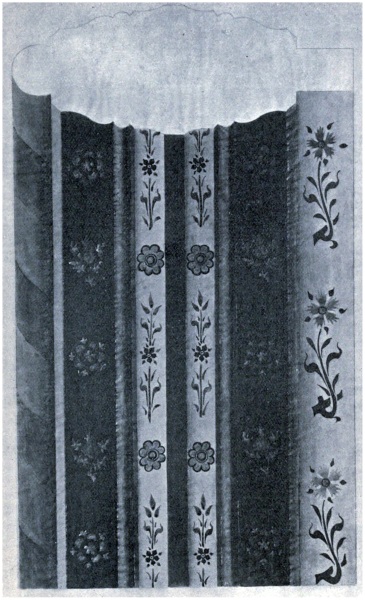

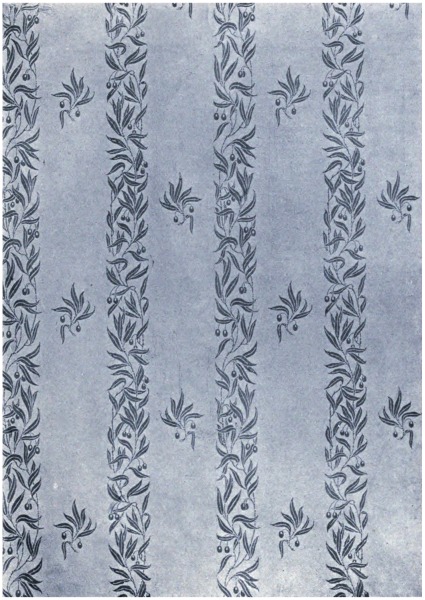

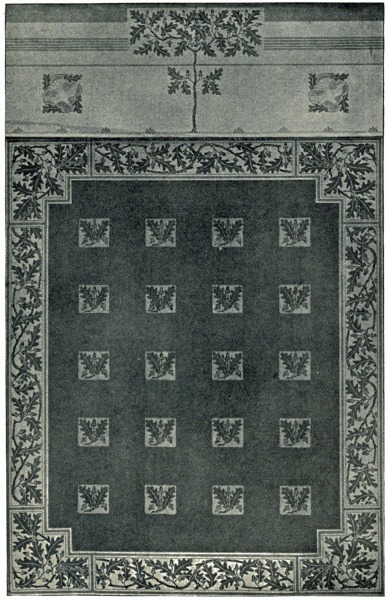

| Wall-papers, designed by Walter Crane | 163, 164, 165, 167, 168, 169 |

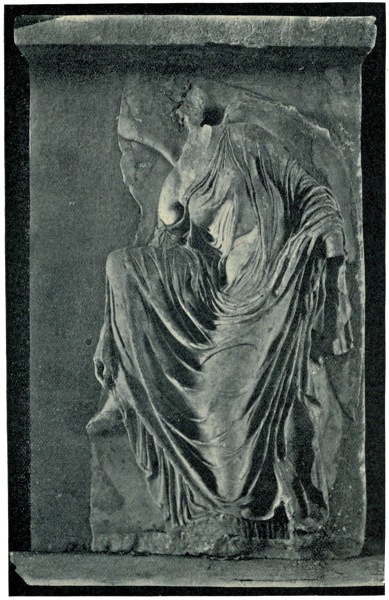

| Greek Drapery (Temple of Nike Apteros, Athens) | 173 |

| Types of Artistic Dress | 177 |

| Types of Children’s Dress | 179 |

| Types of Working Dress | 181 |

| Hungarian Peasant Costumes | 182, 183 |

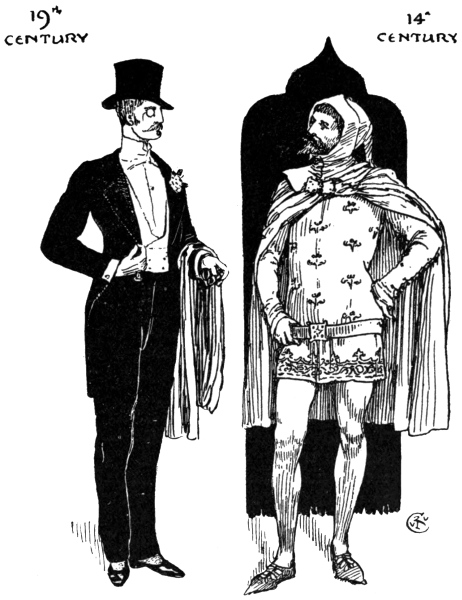

| A Contrast. Modern and Mediaeval Simplicity | 187 |

| Decoration of Westminster Bridge, by the Students of the Royal College of Art (from a Coloured Drawing by G. E. Kruger) | 195 |

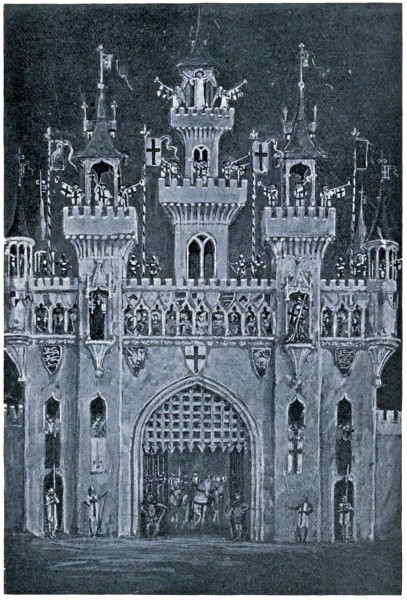

| Suggestion for a Temporary Gatehouse at Temple Bar, by Walter Crane | 197xiii |

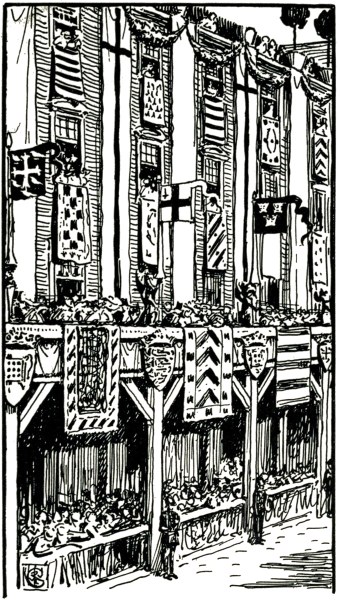

| Temporary Street Decoration | 199, 201 |

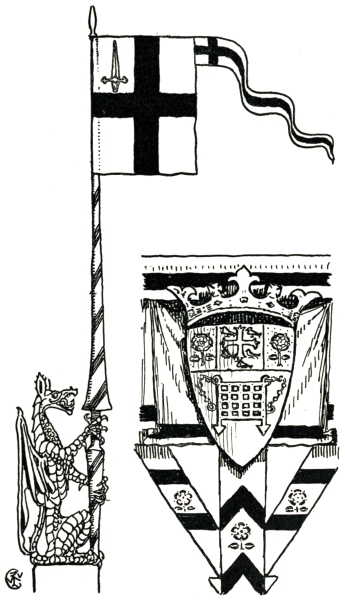

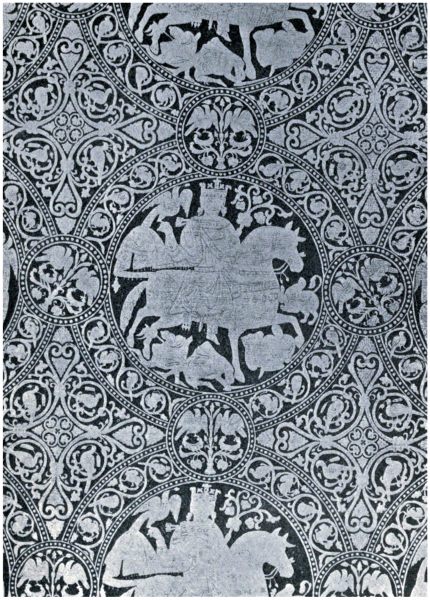

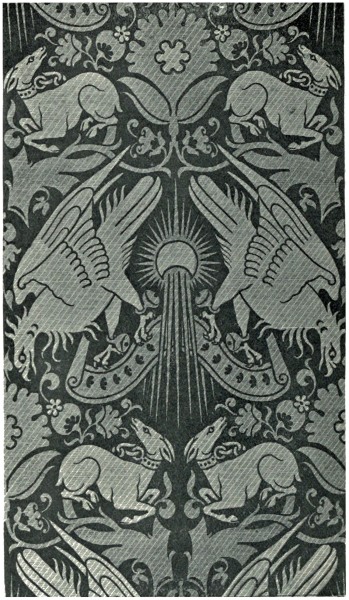

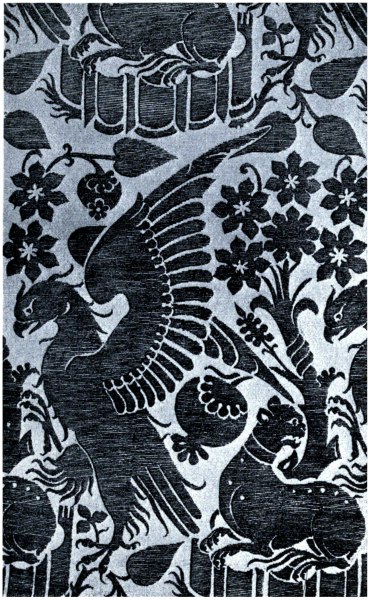

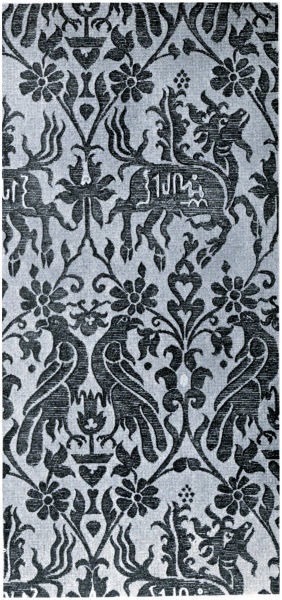

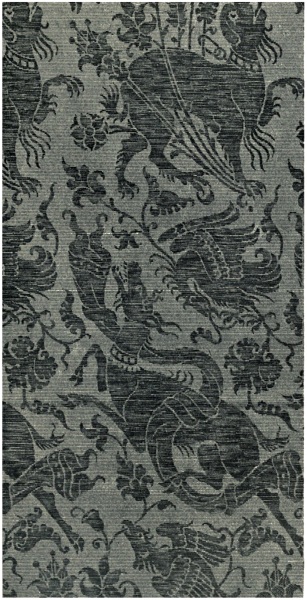

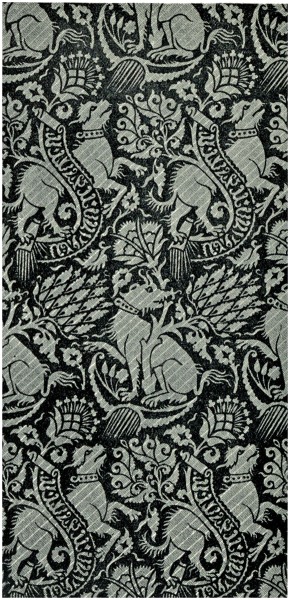

| Royal Mantle from the Treasury of Bamberg | 205 |

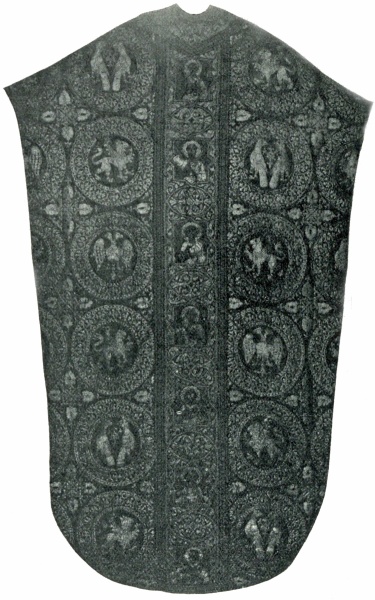

| Chasuble from the Cathedral of Anagni | 206 |

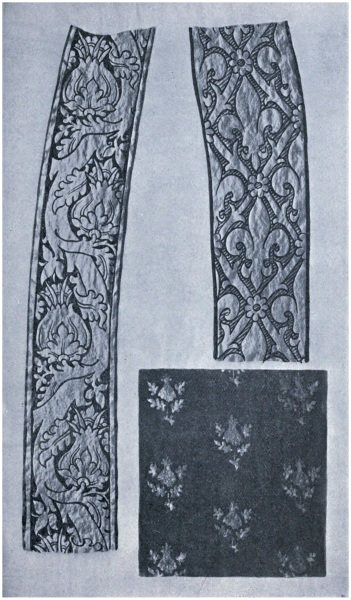

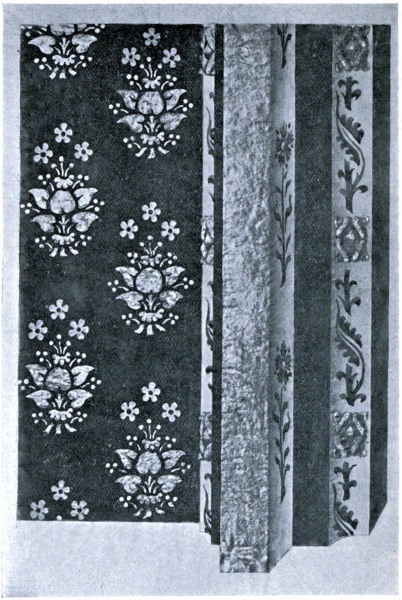

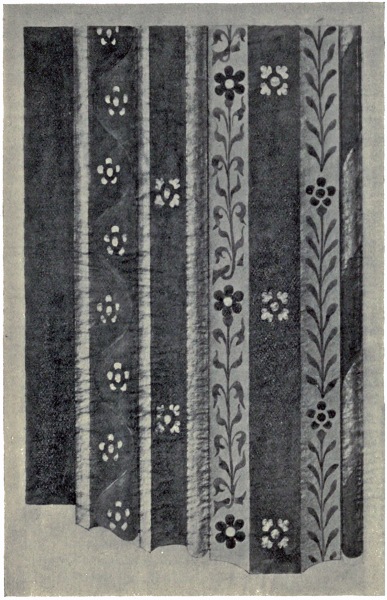

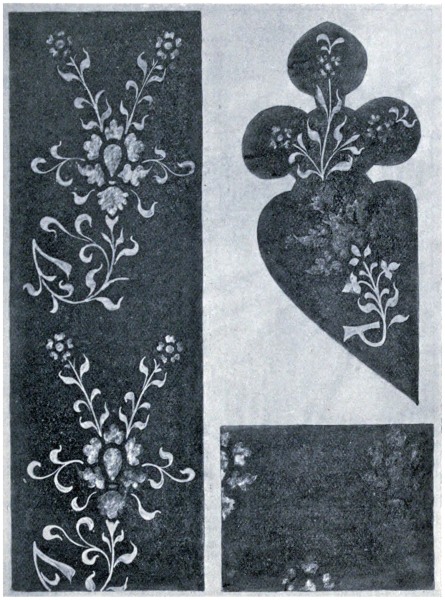

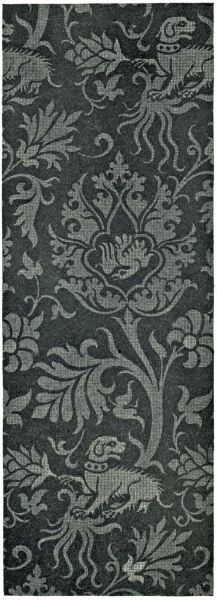

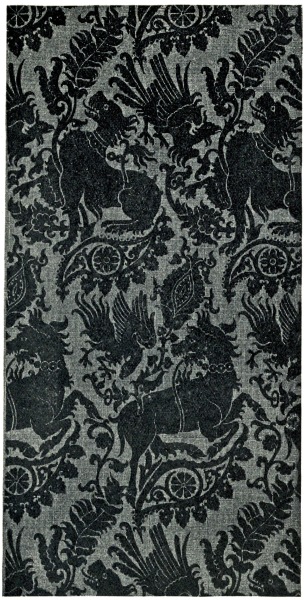

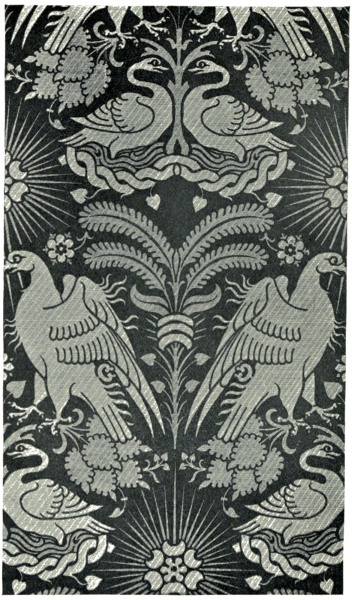

| Sicilian Silk Patterns (XIVth century) | 207, 208, 209, 210, 211, 212, 213, 214 |

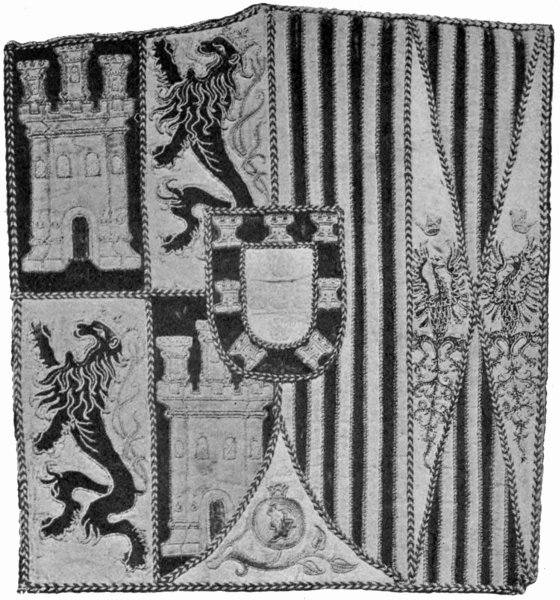

| Embroidered Tabard in the Archaeological Museum at Ghent | 215 |

| Details from the Embroidered Tabard | 216, 217, 218 |

| Robe of Richard II (from the picture at Wilton House) | 219 |

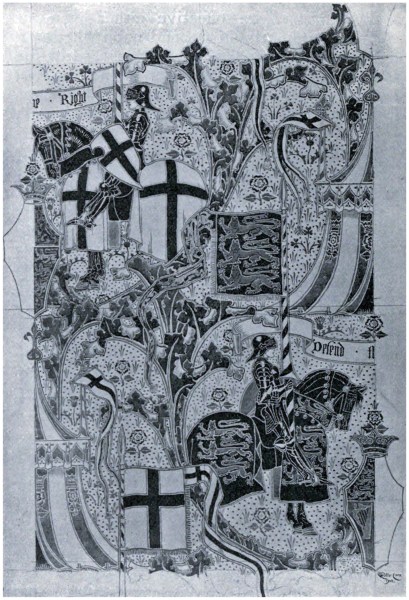

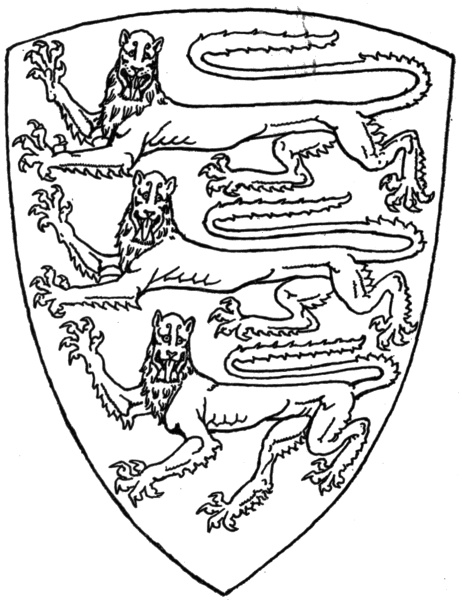

| The Lions of England, designed by Walter Crane | 220 |

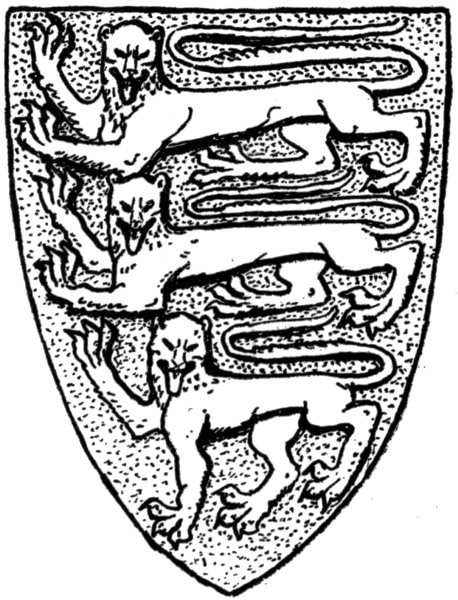

| Heraldic Lion, designed by Walter Crane | 221 |

| The Lions of England (from the Tomb of William de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, Westminster Abbey) | 222 |

| Equestrian Figure with Heraldic Trappings (from the Tomb of Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster, Westminster Abbey) | 223 |

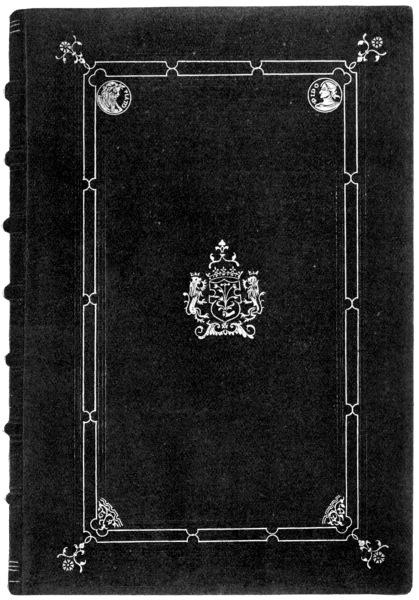

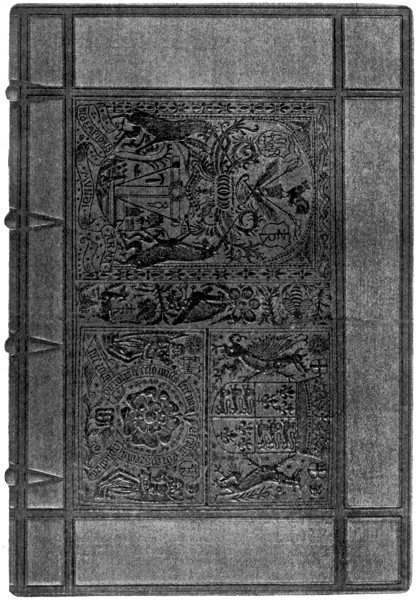

| Binding in black morocco, with Medallions and Coat of Arms, by Thomas Berthelet | 227 |

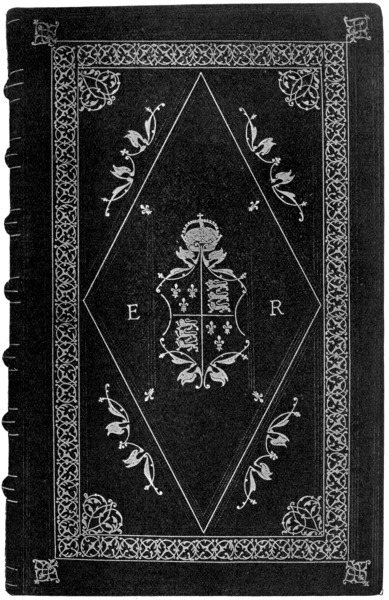

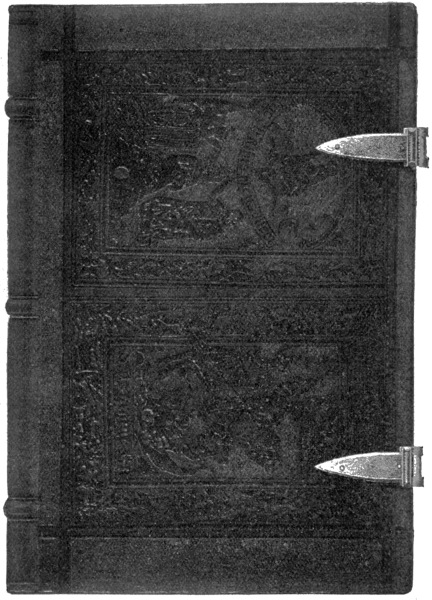

| Binding in black morocco, with Arms of Edward VI, by Thomas Berthelet | 229 |

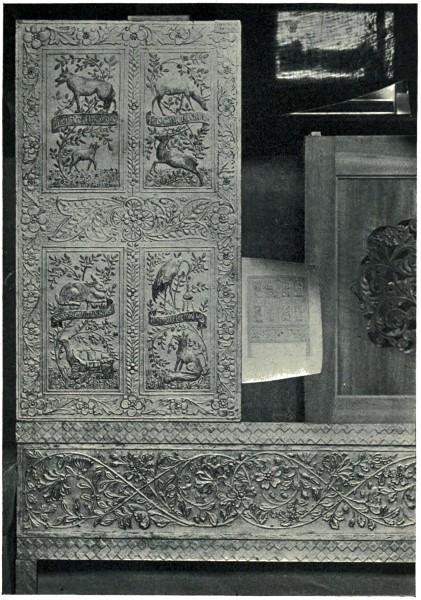

| Binding in stamped calf, with emblematical designs | 231 |

| Binding of oak boards covered with stamped calf, by John Reynes | 233 |

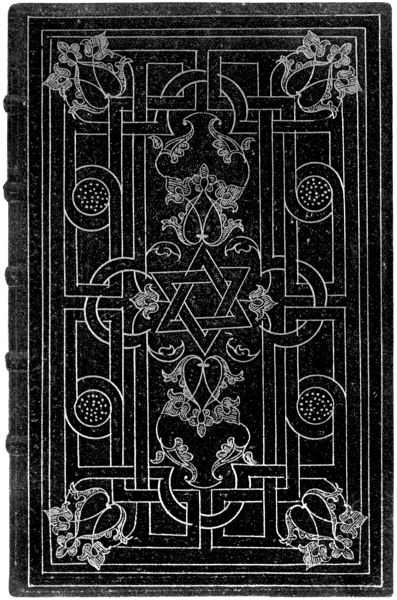

| Binding in brown calf, inlaid, by the Wotton Binder | 235 |

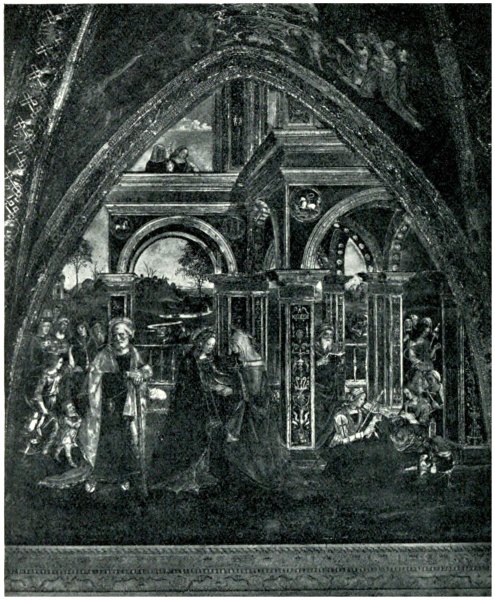

| Appartamenti Borgia, Vatican, showing Pinturicchio’s “Salutation,” etc. | 238 |

| Detail from Pinturicchio’s “Salutation,” with enrichments in Gesso | 239 |

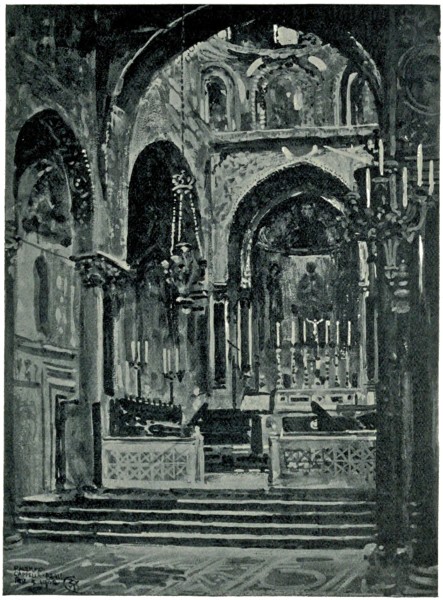

| Palermo, Cappella Reale (from a Water-colour Sketch by Walter Crane) | 241 |

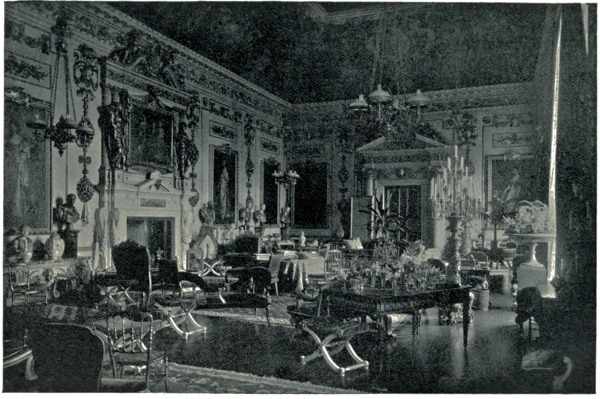

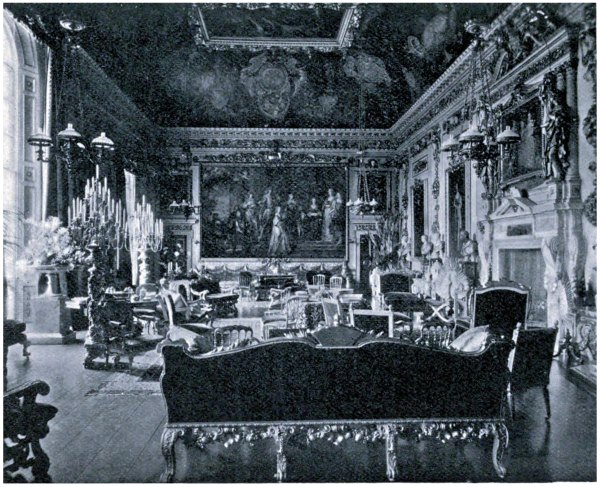

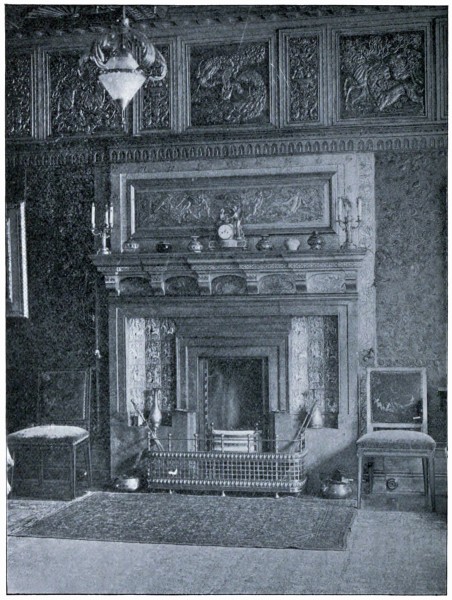

| The Double Cube Room, Wilton House | 243, 245 |

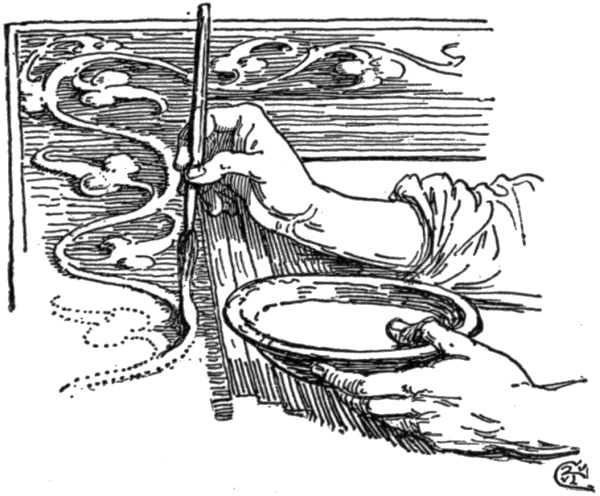

| Method of Working with the Brush in Gesso | 249 |

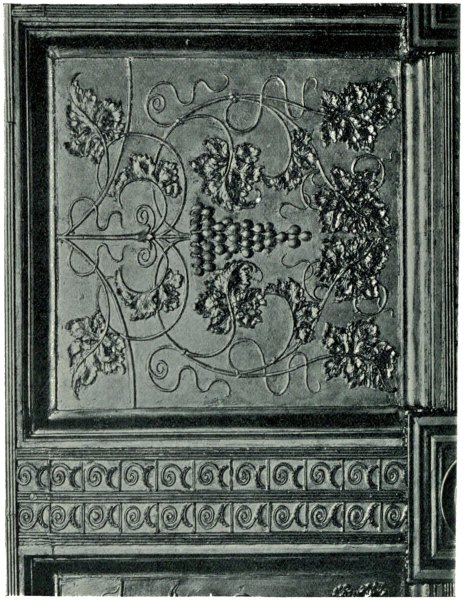

| Filling for Picture Frame in Gesso Duro, designed by Walter Crane | 250 |

| Design for a Bell-pull, modelled in Gesso, by Walter Crane | 251 |

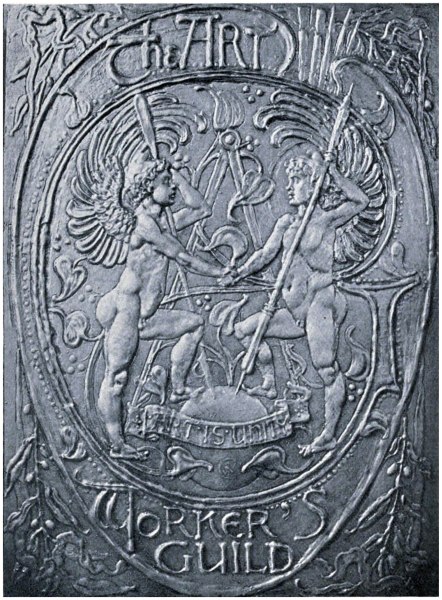

| Gesso Panel, design for the Art Workers’ Guild, by Walter Crane | 253 |

| The Dance (Frieze Panel in Gesso), designed by Walter Crane | 254xiv |

| Picture Frame in Oak with Gesso filling, designed by Walter Crane | 255 |

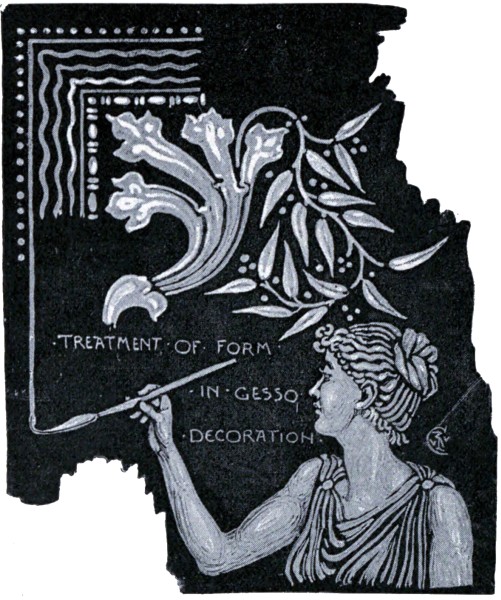

| Treatment of Form in Gesso Decoration, by Walter Crane | 256 |

| System of Modelling with the Brush in Gesso | 257 |

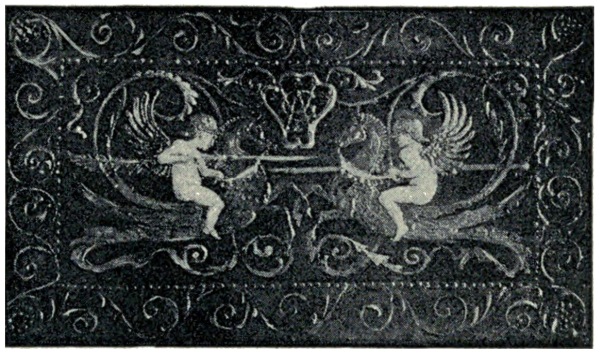

| Gesso Decoration at 1a, Holland Park, by Walter Crane, the woodwork by Philip Webb | 258, 259, 260, 261 |

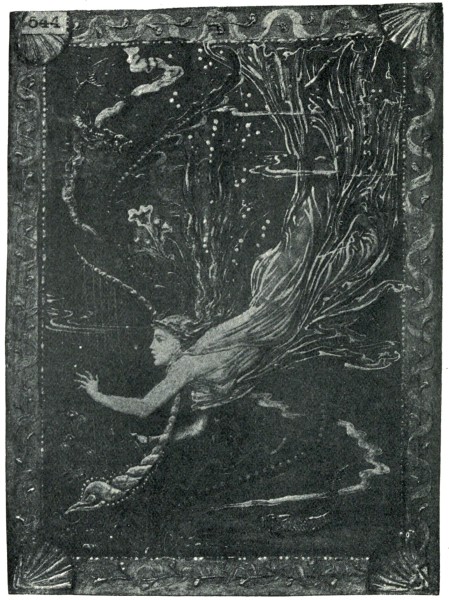

| Panel in Gesso, tinted with lacquers and lustre paint, designed by Walter Crane | 262 |

| Panel in Gesso, tinted with lacquer, designed by Walter Crane | 263 |

| Pictorial Decoration (Ducal Palace, Venice) | 271 |

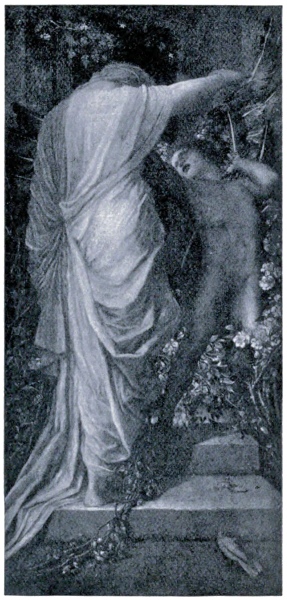

| “Love and Death,” by G. F. Watts, R.A. | 275 |

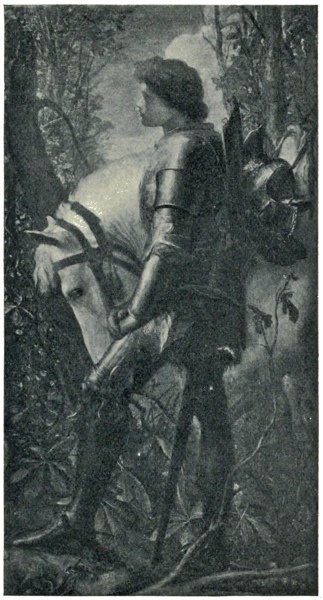

| “Sir Galahad,” by G. F. Watts, R.A. | 277 |

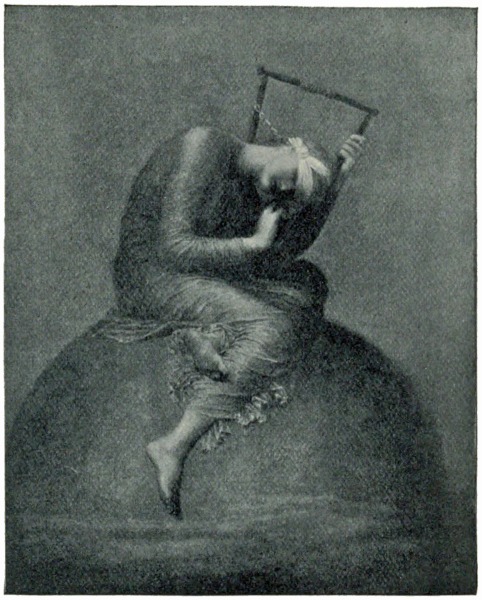

| “Hope,” by G. F. Watts, R.A. | 279 |

1

It seems a strange thing that the last quarter of the nineteenth—or what I was going to call our machine-made—century should be characterized by a revival of the handicrafts; yet of the reality of that revival there can now be no manner of doubt, from whatever point we date its beginnings, or to whomsoever we may trace its initiation.

Indeed, it seems to me that the more we consider the characteristics of different epochs in the history of art, or of the world, the less we are able to isolate them, or to deal with them as phenomena by themselves, so related they seem to what has gone before them, and to what succeeds them, just as are the personalities associated with them; and I do not think this movement of ours will prove any exception to this rule.

Standing as we do on the threshold of a new century—which so often means a new epoch in2 history, if not in art—it may, perhaps, be allowable to look back a bit, as well as forward, in attempting a general survey of the movement. Like a traveller who has reached a certain stage of his journey, we look back over the region traversed, losing sight, in such a wide prospect, and in the mists of such a far distance, of many turns in the road, and places by the way, which at one time seemed important, and only noting here and there certain significant landmarks which declare the way by which we have come.

To take a very rapid glance at the phases of decorative art of the past century, we see much of the old life and traditions in art carried on from the eighteenth century into the early years of the nineteenth, when the handicrafts were still the chief means in the production of things of use or beauty. The luxurious excess of the later renascence forms in decoration, learned from France and Italy (though adopted in this country with a certain reserve), corrected by a mixture of Dutch homeliness, and later by French empire translations of Greek and Roman fashions in ornament, often attained a certain elegance and charm in the gilded stucco mirror frames and painted furniture of our Regency period, which replaced the more refined joinery, veneer, and inlaid work of Chippendale and his kinds.

Classical taste dominated our architecture, striving hard to become domesticated, but looking chilly and colourless in our English gray climate, as if conscious of inadequate clothing.

This Greco-Roman empire elegance gradually3 wore off, and turned to frigid plainness in domestic architecture, and to corpulency in furniture, as the middle of the century was approached, when the old classical tradition in furniture, handed on from Chippendale, Sheraton, and Hepplewhite, seemed to be suddenly broken into by wild fancies and fantastic attempts at naturalism in carving, combined with a reckless curvature of arms and legs supporting (or supported by) springs and padding. Drawing-rooms revelled in ormolu and French clocks, vast looking-glasses, and the heavy artillery of polished mahogany pianos, while Berlin-wool-work and anti-macassars in crochet took possession of any ground not occupied by artificial flowers, and other wonders, under glass shades.

The ’51 Exhibition was the apotheosis of mid-nineteenth century taste, or absence of taste, perhaps. The display of industrial art and furniture then, to judge from illustrated catalogues and journals of the period, seemed to indicate that ideas of design and craftsmanship were in a strange state. The new naturalism was beginning to assert itself, but generally in the wrong place, and in all sorts of unsuitable materials. Those were the days when people marvelled at the skill of a sculptor who represented a veiled figure in marble so that you could almost see through the veil!—but that was “Fine Art.” Industrial art was in a very different category, yet it was influenced by fine art, and, generally, greatly to its disadvantage. We had vignetted landscapes upon china and coalboxes, for instance, and Landseer pictures on4 hearth-rugs—and our people loved to have it so.

These things were done, and more also, in the ordinary course of trade, which flourished exceedingly, and no one bothered about design. If furniture and fittings were wanted, the upholsterer and ironmonger did the rest.

Yet was it not in the “fifties” that Alfred Stevens made designs for iron grates? so that there must have been one artist, at any rate, not above giving thought to common things. Designers like Alfred Stevens, and his followers Godfrey Sykes and Moody, certainly represented in their day a movement inspired chiefly by a study of the earlier renascence, and an honest desire to adapt its forms to modern decoration. Their work, though suffering—like all original work—deterioration at the hands of imitators, showed a search for style and boldness of contour and line, touched with a certain refined naturalism which gives the work of Alfred Stevens and his school a very distinct place. It was mainly a sculptor’s and modeller’s movement, and represented a renascence revival in modern English decorative art; and through the work of Godfrey Sykes and Moody, in association with the government schools of art, it had a considerable effect upon the art of the country.

But I think many and mixed elements contributed to the change of feeling and fashion which came about rather later, in which perhaps may be traced the influence of modes of thought expressing themselves also in literature and5 poetry, as well as the study of different models in design.

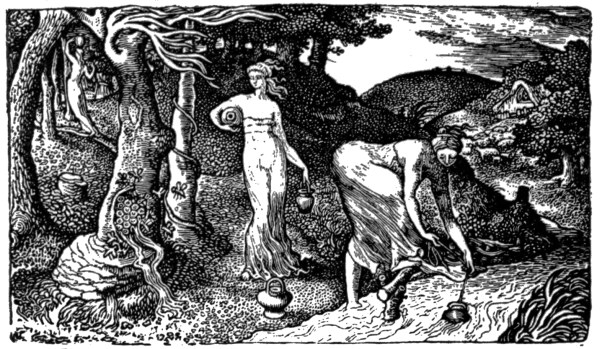

Wood Engravings by

Edward Calvert

The Return Home

Wood Engravings by

Edward Calvert

The Flood

One cannot forget that the early years of the

nineteenth century were illuminated by the6

inspiration and clearness of inner vision were

expressed in so individual a form with such

fervour of poetic feeling and social aspiration,

both in verse and design, in the books engraved7

8

9

and printed by himself which remain the remarkable

monument of his neglected genius.

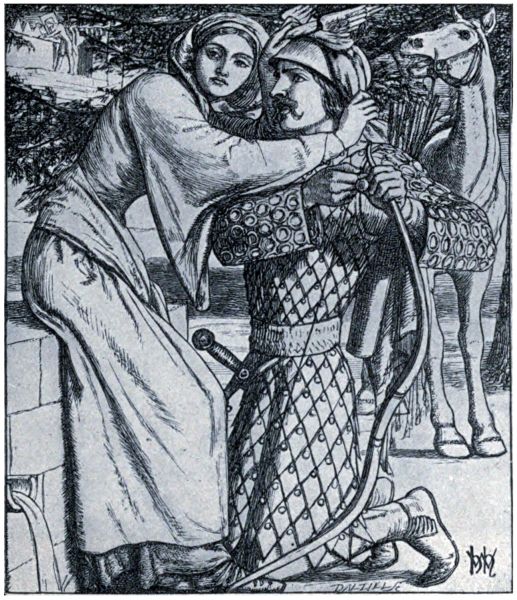

Illustrations to Tennyson

“The Ballad of Oriana.” By Holman Hunt

The group of artists associated with him, too, such as Edward Calvert and Samuel Palmer, marked an epoch in English poetic illustration, associated with wood engraving and printing, of very distinct character and beauty, the influence of which may be seen at the present day in some of the woodcuts of Mr. Sturge Moore.

The more conscious classical designs of Flaxman10 and Stothard were colder, but graceful, and mark a period from which we seem more widely separated than from others more remote, yet seemingly nearer in sentiment.

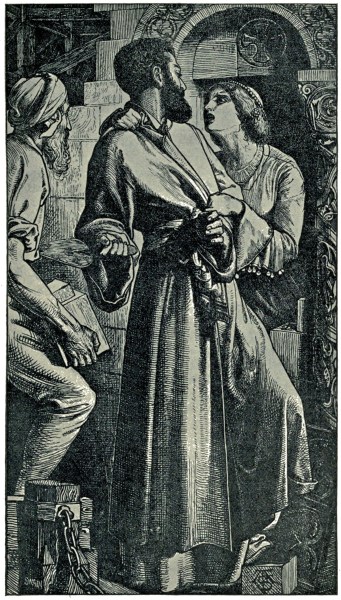

Illustrations to Tennyson

“The Palace of Art.” By D. G. Rossetti

Quite a different kind of sentiment was fostered by the writings of Scott upon which so many generations have been fed, but they had their effect in keeping alive the sense of romance and interest in the life of past days, still further enlightened by the researches of antiquarians, and the increased study of the Middle Ages, and above all of Gothic architecture. All these must be considered as so many tributary streams to swell the main current of thought and feeling11 which carried us on to the artistic revival of our own times.

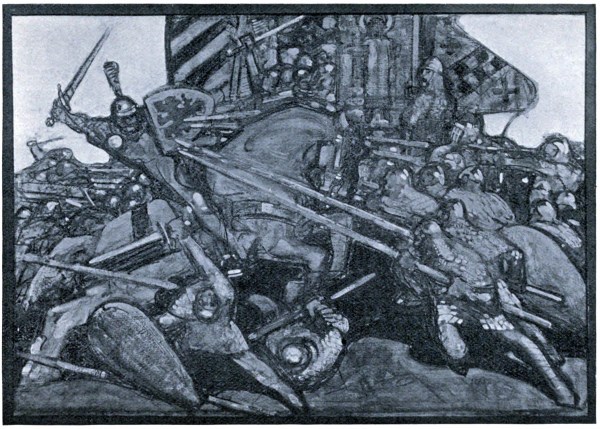

Illustrations to Tennyson

The Bride (from “The Talking Oak”). By Sir J. E. Millais

The poetry of Tennyson, with its sense of colour, sympathy with art and nature, and the romance of the historic past, its thoroughly English feeling, and its revival of the Arthurian Legend, and its association (in the Moxon edition of 1857) with the designs of some of the12 leading pre-Raphaelite painters must be counted if not as a very strong influence upon, at least as an evidence and an accompaniment of that movement.

The names of Ford Madox Brown, of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, of William Holman Hunt, at once suggest artists of extraordinary individuality, remarkable decorative instinct, and carefulness for, and scholarly knowledge of, beautiful and significant accessories of life, of which all have not only given evidence in their own craft of painting, but also as practical designers.

The name of another remarkable artist must be mentioned, that of Frederick Sandys, contemporary with the pre-Raphaelites, imbued with their spirit, and following their methods of work. A wonderful draughtsman and powerful designer, who in all his work shows himself fully alive to beauty of decorative design in the completeness, care, and taste with which the accessories of his pictures and designs are rendered. His powers of design and draughtsmanship are perhaps best shown in the illustrations engraved on wood which appeared in “Once a Week,” “The Cornhill Magazine,” and elsewhere, which were shown with the collections of the artist’s work at the International Society’s last exhibition at the New Gallery, and at the Winter Exhibition at Burlington House in the present year (1905).

Manoli. By Frederick Sandys

From “The Cornhill Magazine”

In some quarters it appears to be supposed

that the pre-Raphaelite movement consisted entirely

of Rossetti, and that to explain its development

you have only to add water—or caricature.13

14

It is extraordinary to think in what

uncritical positions professional critics occasionally

land themselves.

I cannot understand how any candid and fairly well-informed person can fail to perceive that the pre-Raphaelite movement was really a very complex movement, containing many different elements and the germs of different kinds of development in art.

If it was primitive and archaic on one side, it was modern and realistic on another, and again, on another, romantic, poetic, and mystic; or again, wholly devoted to ideals of decorative beauty.

The very names of the original members of the brotherhood, to say nothing of later adherents, suggest very marked differences of temperament and character, and these differences were reflected in their art.

The stimulating writings of Ruskin must also be counted a factor in the movement, in his recognition of the fundamental importance of beautiful and sincere architecture and its relation to the sister arts: in his enthusiasm for truer ideals both in art and life: in the ardent love of and study of nature so constantly, so eloquently expressed throughout his works.

Despite all controversial points, despite all contradictions—mistakes even—I think that every one who has at any time of his life come under the influence of Ruskin’s writings must acknowledge the nobility of purpose and sincerity of spirit which animates them throughout.

15 It is the fashion now in some quarters to undervalue his influence, but at all events it was at its best a wholesome and stimulating influence, provocative of thought, and no man must be held accountable for the mistakes or misapplications of his followers—the inevitable Nemesis of genius.

It was an influence which certainly had practical results in many ways, and not least must be counted its influence upon the life, opinions and work of the man to whose workshop is commonly traced the practical revival of sincere design and handicraft in modern England—I need hardly say I mean William Morris.

It is notable that at the outset the initiation of that practical revival was due to a group of artists, including the names already mentioned, and although in later days the practical direction of the work fell into the hands of William Morris, the fact that the enterprise had the sympathy and support of the leading artists of the pre-Raphaelite School must not be forgotten.

Indeed, it is said that the initiative or first practical proposal in the matter came from D. G. Rossetti, and it must be remembered that originally the main object of the firm was to supply their own circle with furniture and house decorations to suit their own tastes, though the operations were afterwards extended to the public with extraordinary success. The work, too, of the group was strengthened on the architectural side by such excellent designers as Mr. Philip Webb, who, in addition to architectural and constructive work of all kinds is16 remarkable for the force and feeling of his designs of animals used in decorative schemes, both in the flat and in relief.

The hare and hound in the frieze of the dining-room at South Kensington Museum are early works of his, as well as the woodwork of the room.

The study of mediaeval art had, however, been going on for many years before, and books of the taste and completeness of those of Henry Shaw, for instance, had been published, dealing with many different provinces of decorative art, from alphabets to architecture. The well engraved and printed illustrations of these works afforded glimpses even to the uninitiated of the wonderful richness, invention and variety of the art of the Middle Ages—so long neglected and misunderstood—while the treasures of the British Museum in the priceless illuminated manuscripts of those ages were open to those who would really know what mediaeval book-craft was like.

Then, too, the formation of the unrivalled collections at South Kensington, and the opportunities there given for the study of very choice and beautiful examples of decorative art of all kinds, especially of mediaeval Italy and of the earlier renascence, played a very important part both in the education of artists and the public, and helped with other causes to prepare the way for new or revived ideas in design and craftsmanship.

The movement went quietly on at first, confined almost exclusively to a limited circle of17 artists or artistically-minded people. It grew under the shadow of the atrocious Franco-British fashions of the sixties, now (or recently) so much admired, crinolines and all, in some quarters, because I suppose they are so old-fashioned.

Independent signs of dissatisfaction with current modes, however, were discernible here and there. It was, I think, about this time that Mr. Charles L. Eastlake (late Keeper of the National Gallery) who was trained as an architect, published a book called “Hints on Household Taste,” in which he says somewhere: “Lost in the contemplation of palaces we have forgotten to look about us for a chair.” This seemed to indicate a reaction against the exclusive attention then given to what were called “the Fine Arts.”

Associations were formed for the discussion of artistic questions of all kinds, and I mind me of a certain society of art students which used to meet in the well-known room at No. 9, Conduit Street, the existence of which indicated that there were thought and movement in the air among the younger generation and new ideas were on the wing, many of them carrying the germs of important future developments. Even outside Queen Square there were certain designers of furniture and surface decorations not wholly absorbed by trade ideals, who maintained a precarious existence as decorative artists.

There were architects, too, of such distinction and character as Pugin, William Burges, and Butterfield, who were fully alive to the value of18 mediaeval art, and were bold experimenters as well as scholars and enthusiasts in their revival of the use of mural decoration in colour.

Mr. Norman Shaw’s work, which has so much influenced the newer architectural aspects of London, comes later, and is more distinctly and intimately related to our movement, which it may here be said has owed much of its strength to its large architectural element.

There were, of course, builders and decorators in those days, but the genus “decorative artist” was a new species as distinct from the painter and paper-hanger.

While these, and the historic, the landscape, the animal, and genre painter had their exhibitions, were recognized, and some of them duly honoured at times, decorative artists and designers may be said to have had nowhere to lay their heads—in the artistic sense—so they laid their heads together!

The immediate outcome of this sympathetic counsel took the form of fireside discussions by members of a society of decorative artists founded by Mr. Lewis F. Day, strictly limited in number, called “the Fifteen.” This small society was in course of time superseded, or rather absorbed, by a larger body known as the Art Workers’ Guild, which contained architects, painters, designers, sculptors, and craftsmen of all kinds, and grew and increased mightily; it has since thrown out a younger branch in the Junior Art Workers’ Guild.

Guilds, or groups of associated workers were also formed for the practice and supply of certain19 handicrafts, and societies like that of the Home Arts and Industries Association organized village classes in wood-carving, pottery, metal-work, basket-making, turning, spinning, and weaving linen, embroidery, and other crafts.

These efforts, mostly due to a band of enthusiastic amateurs, must all be counted, if not always satisfactory in their results, yet as educational in their effects, and as creating a wider public interested in the handicraft movement, and therefore as adding impetus to that movement, which in 1888—the year of our own society’s foundation—even rose to the height of—or extended to the length of—a “National Association for the Advancement of Art in Relation to Industry” (such was its title) which actually held congresses in successive years in Liverpool, Edinburgh, and Birmingham—as if they were scientists or sectarians. Members of our society were more or less connected with these developments.

All this time we had, as we still have, a Royal Academy of Arts. But somewhere in the early eighties arose certain bold, bad men who—not satisfied with an annual picture-show of some two thousand works or so, always fresh—desired to see a national exhibition of art which should comprise not only paintings, sculpture, and architectural water-colours, but some representation of the arts and handicrafts of design.

Another plank in this artistic platform was the annual election of a selection and hanging committee out of and by the whole body of artists in the kingdom. This movement attracted20 a considerable number of adherents, largely among the rising school of painting, until it was discovered that several of the leaders desired to belong to the garrison of the fortress they proposed to attack.

The Arts and Crafts section of this movement, mostly members of the Guild aforesaid, seeing their vision look hopeless in that direction, then withdrew, and formed themselves into the present Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, with power to add to their number. And I think they gathered to themselves all the artists and craftsmen of standing who were sympathetic and willing to subscribe to their aims.

We may note here that since the directors of the Grosvenor Gallery in its Winter Exhibition of 1881 arranged a collection of designs for decoration, including cartoons for mosaic, tapestry, and glass, no attempt to show contemporary work of the kind had been made.

We were, however, but few at first, and but few of us widely known, and with limited influence. William Morris and Burne-Jones did not join us until we had fairly organized ourselves and defined our programme, though their works from the first have enriched our exhibitions.

The initial steps were laborious and difficult and the process of organization slow, each step being carefully debated. Suitable premises seemed at one time impossible to procure, the demands of an ordinary picture-gallery being by no means suited to the mixed displays of an arts and crafts exhibition, so little so, indeed,21 that it was proposed to hire a large old-fashioned London mansion in order to group our exhibits in better relation.

Time, however, seemed to help us somewhat, as, during the period of our formation the New Gallery was opened—emerging in marble and gilding from its whilom dusty chrysalis as an abandoned meat market—and here, in the autumn of 1888, as may be remembered, supported by a courageous list of guarantors we opened our first exhibition.

I think we were fully conscious that an exhibition is at the best necessarily a very imperfect thing, and should probably even agree that it was a necessary evil. An exhibition of such various elements as an arts and crafts show brings together has its own particular difficulties.

One cannot place fragmentary pieces of decorative art in their proper relation, and relation is of the essence of good decorative art.

We are driven to a sort of compromise, finding practical difficulties in the way of logical systems—such as the grouping according to kind, or the grouping according to authorship—and have resorted to a mixed method with a view to the best decorative ensemble with the materials at hand—with the result, I fear, of hurting the feelings of nearly everybody concerned—but that is the common fate of exhibition committees.

Having had the honour of being president during the first three years of the society’s existence I had occasion to state its objects and22 principles as far as I understood them, and as these are set forth in our Book of Essays it does not seem necessary to repeat what is there written, but a short re-statement of the chief points may not be out of place here.

We desired first of all to give opportunity to the designer and craftsman to exhibit their work to the public for its artistic interest and thus to assert the claims of decorative art and handicraft to attention equally with the painter of easel pictures, hitherto almost exclusively associated with the term art in the public mind.

Ignoring the artificial distinction between Fine and Decorative art, we felt that the real distinction was what we conceived to be between good and bad art, or false and true taste and methods in handicraft, considering it of little value to endeavour to classify art according to its commercial value or social importance, while everything depended upon the spirit as well as the skill and fidelity with which the conception was expressed, in whatever material, seeing that a worker earned the title of artist by the sympathy with and treatment of his material, by due recognition of its capacity, and its natural limitations, as well as of the relation of the work to use and life.

We sought to trace back ornament to its organic source in constructive necessity.

We asserted the principle that the Designer and Craftsman should be hand in hand, and work head with hand in both cases, so that mere redundancy of ingenious surface ornament on the one hand, or mechanical ingenuity in executive23 skill on the other, should not be considered as ends in themselves, but only as means to ends, neither the one nor the other being tolerable without controlling taste.

But how assign artistic credit to nameless workers? One can hardly expect artistic judgement and distinction without artistic responsibility, and, according to the usual methods of industrial exhibitions, individual designers and craftsmen were concealed under the general designation of a firm.

We therefore asked for names of responsible executants—those who had contributed in any way to the artistic character of the work.

This seemed a simple and obvious request, but there has probably been more difficulty over this one point than over any other of our programme.

But here we encounter the sharp corner of an economic question, as is so often the case in pursuing a question of principle in art—a question touching the position and artistic freedom of the workman. A workman, one perhaps of many who contribute to the production of a piece of modern craftsmanship, is in the hands of the firm that exhibits the work. It is to the commercial interest of the firm to be known as the producer of the work, and it must be therefore out of good nature or sense of fairness, or desire to conform to our conditions, when the name of the actual workman is given, who so long as he is in the employ of a firm is supposed to work exclusively in that firm’s interest. Complaints have been made that the workman whose24 name is given on an exhibited work may be tempted away to work for a rival firm,—an interesting illustration of the working of our system of commercial competition.

Yet, if a workman is worthy of his hire, the good craftsman is surely worthy of due personal credit for his skill, and if superior skill has a tendency to increase in market value, we need not be surprised, either as employers or private artists, seeing that in either case we should consider it fair to avail ourselves of such increase.

I think the question must be honestly faced. As it is, owing to accidents, intentional omissions, or inadvertencies, our cataloguing in this respect has not been so complete as one could wish, and we are necessarily dependent in respect to these particulars upon our exhibitors.

Our exhibition for the first three years was annual. With the election of William Morris as President a change of policy came in, and it was considered advisable to limit ourselves to triennial exhibitions. This was partly because the organization of a yearly exhibition put a considerable strain and responsibility upon a voluntary executive, and consumed a considerable amount of the thought and time of working artists; partly also from the consideration that more interesting shows would result if held after a three years’ interval, giving time for the production of important work. It must be said, however, that artistic production of constructive and decorative work was then in fewer hands, and it was impossible to foresee the increase of activity in the arts and crafts, or the steady25 support of an interested, if comparatively limited, public which we have enjoyed.

Looking back at the general character of our exhibitions, it is interesting to note certain lines of evolution in the development of design and the persistence of certain types of design. Now even in the work of a single artist, the character of his design is seen to undergo many changes in the course of his career, as he comes under various different influences. Some are more, some are less variable, but a man’s youthful work differs considerably from his mature work, as his later work will again differ from his mature work. While there is life there must be movement, growth, and change, let us tie ourselves down as narrowly as we will. But even apart from this, the process of evolution may be seen and felt in the conception and construction of a design before it finally leaves our hands. We get the germ of an idea, and in adapting it to its material and purpose it is necessarily modified. Even in the character and quality of its line and mass it is added to or taken away from in obedience to our sense of what is fit and harmonious.

If, then, this process takes place with the individual, how much more with many individuals developing either on one line or many? How much more shall we discern this trend of evolution in the sum and mass of work after the passage of years?

To the superficial observer the work of a group of men more or less in sympathy in general aim is apt to be labelled all alike,26 whereas among that very group we may discern tendencies and sympathies in reality most diverse.

Now it seems as regards general tendencies in design in our movement that, after a period of a rich and luxuriant development of ornament, a certain reaction has taken place in favour of simplicity and reserve. It is probably a perfectly natural desire for repose after a period of excitement. And even where pattern is used the character of the form is much more restricted and formal as a rule. There is a tendency to build upon rectangular or vertical lines and to allow larger intermediary spaces.

The same desire for severity and simplicity in a more marked degree is to be observed in furniture design and construction. In fact, throughout all the recent work in the larger kinds of decoration and craftsmanship, this aim at simplicity and severity of line and general treatment is pronounced. This probably reflects the same feeling observable in recent domestic architecture, wherein a search for proportion and style, with simplicity of line and mass seem to influence the designer, and an appropriate use of materials rather than ornamental detail. But in one direction richness and artistic fancy seems to have found a new field, and it is a province which in our earlier exhibitions had hardly any representation at all, I mean jewellery and gold and silversmith’s work and the art of enamelling, which show an extraordinary development, and may be claimed as a distinct and direct result of the new artistic27 impulse in the handicrafts. In these arts there is obviously very great scope for individuality of treatment, for invention, for fancy, and taste.

It was in the year 1887 that, at the invitation of Mr. Armstrong (the then Director for Art at the Science and Art Department) a French artist-craftsman (the late M. Louis Dalpeyrat of Limoges1) gave a series of demonstrations in enamelling at the South Kensington schools. Among the band of interested students was Mr. Alexander Fisher, who took up the work seriously; his accomplishment is so well known and so many workers in enamelling owe their first instruction to him that he has been called the father of the recent English revival in this beautiful craft.

1 I am indebted to Mr. Armstrong for some interesting particulars as to this. It appears that M. Louis Dalpeyrat was employed to make copies of some of the pieces of enamel in the South Kensington Museum, which he did very skilfully, and these copies were used for circulation among provincial museums and schools of art. Mr. Armstrong obtained sanction for M. Dalpeyrat to give a series of demonstrations in enamelling to a class of twelve students from the National Art Training School (now the Royal College of Art), and these were given in the metallurgical laboratory in the College of Science, where the plaques were fired, Prof. Roberts Austen having given permission. There was no grant at that time for technical instruction.

I ventured to say on some occasion in the early days of our movement that “We must turn our artists into craftsmen, and our craftsmen into artists.”

Well, certainly the first part of the sentence has been fulfilled in a remarkable way, since the movement is chiefly notable for the number28 of artists who have become craftsmen in a variety of different materials.

In the second, transformation has not taken place to the same extent, which may, perhaps, be more or less accounted for by the consideration of those economic questions before spoken of, in so far as they apply to the workman.

As a rule the workman has been specialized for a particular branch of work, or a particular subdivision of a branch of workmanship; he seldom can acquire an all-round knowledge of a craft, and is seldom able to take a complete or artistic view of his work, as a whole, as he never produces a complete whole under the conditions of the modern workshop or factory.

Then, too, English workmen have been trained to look upon mechanical perfection and mechanical finish as the ideal, and it is impossible to set up a different ideal in a short time.

It must be remembered, also, that, as a class, the modern workman is engaged in a great economic struggle—an industrial war, quite as real, and often as terrible in its results as a military one—to raise his standard of life, or even to maintain it amid the fluctuations of trade, and, as a rule, he is not in a position to cultivate his taste in art.

Let us hope that the new schools of design under the Technical Education Board will have their effect, as they undoubtedly offer new and better practical opportunities to young craftsmen than have been available before.

Such schools as the Central School of Arts and29 Crafts, under the London County Council, may be regarded as a direct outcome of the movement, and it is a remarkable fact that its teachers are composed principally of members of our society and committee, to whom the organization of the classes was due.

Besides, if the artist has learned of the craftsman, there must be a good deal of education going on quietly in the studios and workshops of those aforesaid artist-craftsmen, wherein the craftsman learns in his turn of the artist, and here again must spring good results.

Sound traditions of design and workmanship should be of enormous help in starting students on safe paths, and preventing that painful process of unlearning from which so many earnest students and artists have suffered in our days. Such traditions, however, should never be allowed to crystallize or hinder new thought and freedom of invention within the limits of the material in which the designer works, for living art exhibits a constant growth and evolution; and though in some cases the process of evolution in an artistic life may appear to take rather the form of degeneration, the important thing is to preserve life with its principle of growth, without losing balance, and above all, sense of fitness and beauty.

If beauty and utility are our guides in all design and handicraft, we can hardly go wrong. If our design is organic both in itself and in its incorporation with constructive necessity—if it, springing out of that necessity, expresses the joy of the artist, and is truly the crown of the30 work, making the dumb material vocal with expressive line and form, or colour, it must at least be a thing having life, character, sincerity, and these are important elements in the expression of new beauty.

Along with the formation of discussion clubs and societies of designers and craftsmen, the tendency to form Guilds of Handicraft, whether they are a new form of commercial enterprise, or consist, as they frequently do, in the first place, of a group of artists and craftsmen in genuine sympathy working together with assistants, must be noted as another sign of the influence of the movement; as also the influence of certain types of design upon ordinary trade production.

It is even asserted that—I quote from a trade journal on a recent Arts and Crafts exhibition—“the arts and crafts movement has been the best influence upon machine industry during the past ten years”—that “while we have sought to develop handicrafts beside it on sound and independent lines, we have succeeded in imparting something of the spirit of craftsmanship to the best kind of machine-work bridging over the former gulf between machinery and tools, and quickening machine-industry with a new sense of the artistic possibilities that lie within its own proper sphere.”

Let us hope so, indeed.

Certainly we cannot hope that the world, just yet, will beat its swords into ploughshares, or its spears into pruning-hooks, still less that it will return to local industry and handicraft for31 all the wants of life, or look solely to the independent artist and craftsman to make its house beautiful. The organized factory and the great machine industries will continue to work for the million, as well as for the millionaire, under the present system of production; but, at any rate, they can be influenced by ideas of design, and it must be said that some manufacturers have shown themselves fully alive to the value of the co-operation of artists in this direction. Those who desire and can command the personal work of artists in design and handicraft are now able to enlist it, and this demand is likely to increase, and therefore industrial groups or guilds of this kind may increase.

If such groups of workers, or workers in the different handicrafts could by combination in some way still further counteract or control purely commercial production, by raising certain standards of workmanship and taste, and in the special branches of handicraft look after the artistic interests of their members generally, their power and influence might be much extended, especially if such guilds could be in some sort of friendly relation, so that they could on occasion act together, combining their forces and resources, for instance, for special exhibitions, or representations, such as masques and pageants, of the kind recently presented by the Art Workers’ Guild at the Guildhall of the City of London.

Such shows, uniting as they do all kinds of design and craftsmanship in the embodiment of a leading idea, are a form of artistic expression32 which may be regarded as the latest outcome of the movement, and may have a future before it.

I think that by such means, at all events, artistic life would be greatly stimulated, and artistic aims and ideals better understood—especially in their relation to social life.

And, surely, art has a great social function, even though it may have no conscious aim but its own perfecting.

Even in its most individual form it is a product of the community—of its age, and it is always impossible to say how many remote and mixed elements are combined to form that complex organism—an artistic temperament.

Every age looks eagerly in the glass which art and craftsmanship hold up, even if it is only to find itself reflected there. But it not only seeks reflection, it seeks expression—the expression of its thought and fancy, as well as its sense of beauty, and the successful artist is he who satisfies this search.

It seems, too, that every age, probably even each generation, has a different ideal of beauty, or that, perceiving a different side of beauty, each successively ever seeks some new form for its expression. This is the movement of growth and life, the sap of the new idea rising in the spring-time of youth through the parent stem, bursting into new branches and putting forth leaves; the green herb springing from the dead leaves—the new ever striving with the old.

It is always possible for a society to narrow down, or to widen. It may consider its true33 work lies in the exposition chiefly of the work of one school, and would be perfectly justified in so thinking, so long as that school maintained its vitality and power of growth.

On the other hand, it might determine to have no prejudices on the subject of school or style, but welcome all good work after its kind.

Such points are largely controlled by considerations of available space and determination of scope, and are usually settled by the effective strength of the view which has the majority. There might even be something to be said, given unlimited space, and security against financial loss, for placing every work sent in to such exhibitions, but keeping the selected work in a distinct section.

“Here,” we might say, “is the material we had to deal with, and here is our selection,” and so make the exhibition an open court of appeal. These are questions for the future. We have, as a society, even in our comparatively short life, lived long enough to see great gaps in the ranks of English design. Great names, great leaders have passed from the roll of our membership, but not their memory, or the effect and value of their work.

We are left to carry on the twin-lamp of Design and Handicraft as best we may. If we bear that lamp with steady hands, fully alive to the necessity of continual life and freedom of movement in art, while conscious of the value of preserving certain historic traditions, founded upon real artistic experiences, and the necessities of material and use, we may yet, I hope,34 be of service in our exhibition and other work, if we succeed in comprehending within our membership the best elements of both new and old, in maintaining the highest standard of taste and workmanship, and in placing, so far as we are able, the best after its kind, in our honest opinion, before the public.

35

The teaching of Art! Well, to begin with, you cannot teach it. You can teach certain methods of drawing and painting, carving, modelling, construction, what not—you can teach the words, you can teach the logic and principles, but you cannot give the power of original thought and expression in them.

Of course a man’s ideas on the subject of teaching necessarily depend upon his general views of the purport and scope of art.

Is Art (1) a mere imitative impulse—a record of the superficial facts and phases of nature in a particular medium? or, is it (2) the most subtle and expressive of languages, taking all manner of rich and varied forms in all sorts of materials, under the paramount impulse of the selective search for beauty?

Naturally, our answer to the question what should be taught, and how to teach it depends upon our answer to these questions. But the greater includes the less, and, though one may be biassed by the second definition given above, it does not follow that the first may not have its due place in a course of study.

36 The question, then, really is, what is the most helpful course of study towards the attainment of that desirable facility of workmanship, that cultivation of the natural perception, feeling, and judgement in the use of those elements and materials in their ultimate expression and realization of beauty?

And here we have to stop again on our road, and ask what is this quality of beauty, and whence does it come?

Without exactly attempting a final or philosophical account of it, we may call it an outcome and efflorescence of the delight in life under happy conditions. The history of art and nature shows its evolution in ever varying degree and form, constantly affected by external conditions, and modified by place and circumstance, following, in the development of the sensibility to ideas and impressions of beauty, through the refinement of the senses and the intellect, much the same course as the development of man himself as a social and reflective animal.

As we cannot see colour without light, neither can we expect sensibility to beauty to grow up naturally amid sordid and depressing surroundings.

Royal College of Art: Painting School under Prof. Gerald Moira

Sketch for Figure Composition. “Frederigo Barbarossa.” By Lancelot Crane, A.R.C.A.

To begin with, then, before we can have art

we must have sensibility to beauty, and before

we can have either we must have conditions

which favour their existence and growth. We

must have an atmosphere. A condition of life

where they come naturally, with the colours of

the dawn and the sunset; where the common

occupations are not too burdensome, and the37

38

anxiety for a living not too great to leave any

surplus energy or leisure for thought and creative

impulse; where the cares of an empty life, and

the deceitfulness of riches do not choke them;

where art has not to struggle, as for very life,

for every breath it draws, and ask itself the why

and wherefore of its existence.

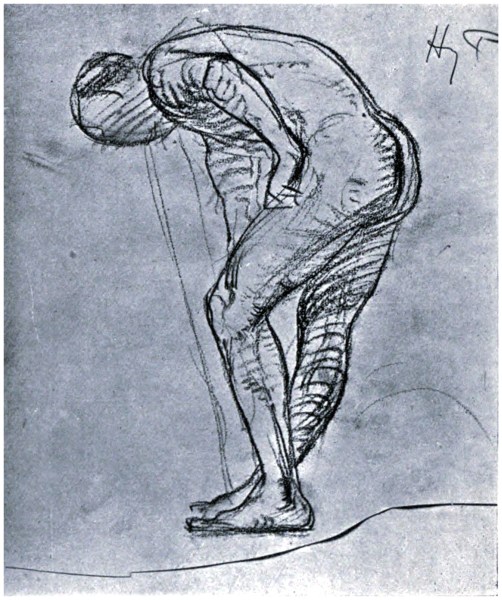

Royal College of Art: Painting and Life School under Prof. Moira

Time Study. By H. Parr

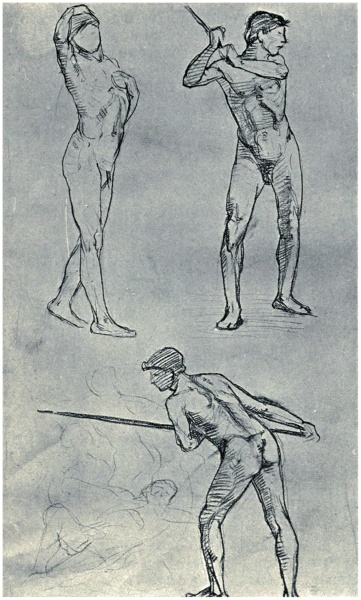

Royal College

of Art:

Painting and

Life School

under Prof.

Moira

Time

Studies of

Figures in

Action.

By

H. Parr

For art is not an independent accidental unrelated39

40

phenomenon, but is the result, as we

find it in its various manifestations, of long

ages of growth, and co-operative tradition and

sympathy.

Seeking beautiful art, organic and related in all its parts, we turn naturally to places and periods of history which are the culminating points in such a growth. To Athens in the Phidian age, for instance; to almost any European city in the Middle Ages; to one of our own village churches, even, where the nineteenth-century restorer has not been; to Venice or Florence in the early renascence, rather than to modern London or Paris. But even limiting ourselves to our own day we have got to expect far more from the man who has worked from his youth up in what we call “an atmosphere of art,” even if it is only that of the modern painter’s studio, than from a mill hand, say, trained to some one special function, perhaps, in some process of machine industry, whose life is spent in monotonous toil and whose daily vision is bounded by chimney-pots and back-yards.

A pinch of the salt of art and culture at measured intervals, will never counteract the adverse and more prominent influence of the daily, hourly surroundings on the eye and mind. It is hopeless if one hour of life’s day says “yes,” if all the other twenty-three say “no” continually.

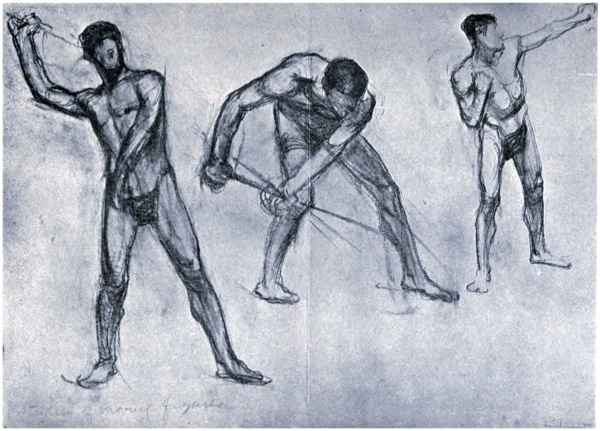

Royal College of Art: Painting and Life School under Prof. Moira

Time Studies of Figures in Action

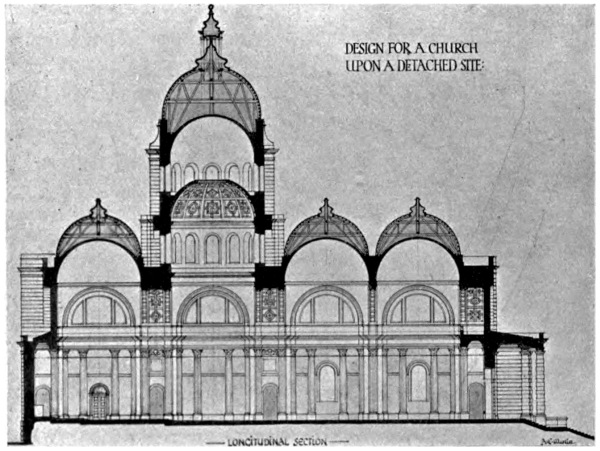

Royal College of Art:

Architectural School

under Prof. Beresford Pite

DESIGN FOR A CHURCH UPON A DETACHED SITE

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Design for

Tapestry.

By E. W.

Tristram

Our fundamental requirements then, are a

sympathetic atmosphere, a favourable soil and

climate for the raising of the seed of art in its

fullest sense; which means, practically, a reasonable41

42

43

44

human life, with fair play for the ideas and

senses, and good for the drama of the eye. To

how many is this now possible?

Granting this, however, would go a long way towards solving the next problem—What to teach? for we should then find that art was not separable from life.

Children are never at a loss what to learn, or what to teach themselves, when they see any manner of interesting work going on and have access to tools and materials. They gather at the door of the village blacksmith, or at the easel of the wayside painter. Demonstration is the one thing needed—demonstration, demonstration, always demonstration. This is, perhaps, at the bottom of the present strong determination to French modes on the part of our younger painters. You can learn this part of the painting business because you can see it done. You could learn any craft if you saw it done, and had ordinary aptitude. But it does not follow that there is no art but painting, and that impressionism is its prophet.

It might be said almost that the modern cabinet or competitive gallery picture, unrelated to anything but itself, and not always that, has destroyed painting as an art of design.

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Design for

Embroidery.

By Miss

L. M.

Dunkley

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Museum

Studies in

Embroidery.

By Miss

L. M.

Dunkley

Royal College

of Art:

Design

School

under Prof.

Lethaby

Sheet of

Heraldic

Studies.

By Miss

C. M. Lacey

I would, therefore, rather begin with the constructive,

and adaptive, side of art. Let a student

begin by some knowledge of architectural construction

and form. Let him thoroughly understand

the connection, both historic and artistic,

between art and architecture. Let him become

thoroughly imbued with a sense of the essential45

46

47

48

unity of art, and not, as is now so often the case,

be taught to practise some particular technical

trick, or meaningless elaboration; or be led to

suppose that the whole object of his studies is

to draw or paint any or every object from the

pictorial point of view exclusively. Let the two

sides of art be clearly and emphatically put before

him, which may be distinguished broadly

as: (1) Aspect, or the imitative; (2) Adaptation,

or the imaginative. Let the student see

that it is one thing to be able to make an accurate

presentment of a figure, or any object, in its

proper light and shade and relief in relation to

its background and surroundings; and quite another

to express them in outline, or to make

them into organic pieces of decoration to fit a

given space.

Then, again, he should perceive how the various media and materials of workmanship naturally determine the character and treatment of his design, while leaving ample range for individual choice and treatment.

Royal College

of Art:

Design

School

under

Prof.

Lethaby

Studies in

Counterchange.

By

W. G.

Spooner

The constructive and creative capacity may

exist in a high degree without any corresponding

power of drawing in the pictorial sense, and

considerable proficiency in some of the simpler

forms of various handicrafts, such as ornamental

modelling in relief, wood-carving, and repoussé

work, is quite possible of attainment by quite

young people; whereas the perception of certain

subtleties in pictorial methods of representation,

such as perspective, planes, and values, and the

highly selective sense which deals with them are

matters of matured mental perception, as well49

50

as technical experience and practical skill. The

same is true as to power of design. It is a

question of growth.

So that there are natural reasons for a primary training in some forms of handicraft, which, while affording the same scope for artistic feeling, present simpler problems in design and workmanship, and give a tangible and substantial foundation to start with.

In thus giving the first places in a course of study in art to architecture, decorative design, and handicraft we are only following the historic order of their progress and development. When the arts of the Middle Ages culminated in the work of the great painters of the earlier Renascence, their work showed how much more than makers of easel pictures they were, so that a picture, apart from its central interest and purpose was often a richly illustrated history of contemporary design in such things.

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Studies of

Scroll

Forms.

By

W. G.

Spooner

Now, my contention is, that whereas a purely

pictorial training, or such a training as is now

given with that view, while it often fails to be

of much service in enabling a student to paint a

picture, unfits him for other fields of art quite

as important, and leaves him before the simplest

problem of design helpless and ignorant; while

a training in applied design, with all the forethought,

sense of beauty and fitness, ingenuity

and invention it would tend to call forth, would

not only be a good practical education in itself,

but would enormously strengthen the student

for pictorial work, especially as regards design

and the value of line, while he would get a clear51

52

apprehension of the limitations of different kinds

of art, and their analogies.

In studying form, if we model as well as draw, we enormously increase our grasp and understanding of it, and so it is as regards art generally that studies in every direction will be found to bear upon and strengthen us in our main direction.

I should, therefore, endeavour to teach relatively—to teach everything in relation not only to itself, but to its surroundings and conditions; design in relation to its materials and purpose; the drawing of form in relation to other forms; the logic of line; pictorial colour and values in relation to nature but controlled by pictorial fitness.

The ordinary practice of drawing and study from the human figure—the Alpha and Omega of all study in art—does not seem sufficiently alive to the help that may be gained by comparative anatomy. We should study the figure, not only in itself and for itself, but in relation to the forms of other animals, and draw the analogous parts and structures, side by side, not from the anatomist’s point of view but the artist’s. We should study them in life and action no less.

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Studies of

Plant Form.

By W. G.

Spooner

54 Now a word as regards action. We have been recently told that artists have been fools since the world began in their manner of depicting the action of animals, or rather animals in action, but it was by a gentleman who (though I fully acknowledge the value and interest of Mr. Muybridge’s studies and discoveries) did53 not appear to have distinguished between moments of arrested action, and the action represented, which is the sum of those moments. Instantaneous photographs of animals in action will tell you whereabouts their legs are found at a given moment, but it is only when they are put in a consecutive series, and turned on the inside of a horizontal wheel before the eye that they represent action, and then it is illusion, not art. Now the artist has to represent or to suggest action without actual movement of any kind, and he has generally succeeded not by arresting the literal action of the moment, but by giving the sum of consecutive moments, much as the wheel does, but without the illusory trick. His business is to represent, not to imitate. Art after all is not science or analysis, or we might expect fidelity to the microscope on the part of our painters and draughtsmen. Until we all go about with photographic lenses in our heads instead of eyes, with dry plates or films instead of retinas, we shall, I fancy, still be interested in what artists have to say to us about nature and their own minds, whether instantaneous impressions, or the long result of years.

This is only one of the many questions which rise up at every step in the study of art, and I know of no system of teaching which adequately deals with them. No doubt our systems of teaching or attempting to teach art want constant overhauling, like most other systems. When we are overhauling the system of life itself, it is not wonderful.

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Pen Drawing. By H. A. Rigby

I do not, of course, believe in any cast-iron55

56

system of education from any point of view. It

must be varied according to individual wants

and capacities. It must be made personal and

interesting or it is of little good; and no system,

however efficient, will manufacture artists in

anything: any more than the most brilliant

talents will do away with the necessity of passionate

devotion to work, careful thought, close

observation and constant practice which produce

that rapid and intimate sympathy of eye

and hand, and make them the responsive and

delicate interpreters of that selective and imaginative

impulse which results in Art.

57

Royal College of Art: Design School under Prof. Lethaby

Pen Drawing. By H. A. Rigby

58

Methods of teaching in art are, I take it, like most other human methods, of strictly relative value, depending at all times largely upon the current conception of the aims, purpose, and province of art.

As this conception necessarily alters from time to time, influenced by all sorts of subtle changes in the social organism (manifesting themselves in what we call Taste), as well as by fundamental economic conditions, so the ideas of what are the true methods in art teaching change also.

Naturally in a time when scepticism is so profound as to reach the temerity of asking such a question as “What is art?” there need be no perceptible shock when inquiries are instituted as to the best methods of art teaching. As important witnesses in the great case of the position of art in general education, or commercial interests v. the expansion of the human mind and the pleasure of life—methods of art teaching have to be put in the box. What do they say?

Well, have we not the good old (so-called) Academic methods always with us?

59

Royal College of Art: Design School Craft Classes, Gesso, under Mr. G. Jack

Cabinet designed and decorated in Gesso. By J. R. Shea

60 The study of the antique by means of shaded drawings, stumped or stippled “up to the nines” (if not further), leading on to equally elaborate life-studies, which somehow are expected to roll the impressions of eight, ten, or more sittings into one entirety—and wonderfully it is done, too, sometimes.

Royal College of Art: Design School Craft Classes, Pottery under Mr. Lunn

Group of

Pottery designed

and

executed by

the Students

Are we not led to these triumphs through the winsome defiles of freehand and shaded drawing from the cast, perhaps accompanied by cheerful model drawing, perspective puzzles, and anatomical dissections, and drawings of the human skeleton seen through antique figures, which seem to anticipate the Röntgen rays?

“The proper study of mankind is man,” but according to the Academic system it is practically the only study—study of the human frame and form isolated from everything else.

No doubt such isolation, theoretically at least, concentrates the attention upon the most difficult61 and subtle of all living organisms; but the practical question is, do these elaborate and more or less artificial studies really give the student a true grasp of form and construction? Are they not too much practically taken as still-life studies, and approached rather in the imitative spirit?

Royal College

of Art:

Design

School Craft

Classes,

Wood-Carving,

under

Mr. G. Jack

Wood-Carving by J. R. Shea

Then, again, such

studies are set and pursued

rather with the

view to equipping the

student with the necessary

knowledge of a

figure painter. They

are intended to prepare

him for painting anything

or everything

(and generally, now,

anything but something

classical) that can be

comprehended or classified

as “an easel picture”—that

is to say,

a work of art not necessarily

related to anything

else. It is something

to be exhibited

(while fresh) in the62

63

64

open market with others of a like (or dis-like)

nature, and, if possible, to be purchased and

hung in a gallery, or in the more or less darkness

of the private dwelling—“to give light

unto them that are in the house.”

Royal College of Art: Design School Craft Classes, Stained Glass, under Mr. C. W. Whall

Panel designed and executed by A. Kidd

Royal College of Art: Modelling School under Prof. Lanteri.

Frieze by J. A. Stevenson

Works of sculpture (or modelling as she is generally practised) may not fare any better (privately) in the end, when one remembers the busts placed back to the windows, or the marble statue forced to an unnatural whiteness by purple velvet hangings—but, certainly, the methods of teaching seem more in relation to the results.

To begin with, a sculptor’s or modeller’s figure (unless a decorative group or an architectural ornament) is isolated and has no background; and it is undoubtedly a severe test of skill and knowledge to model a figure in clay in the round from the life. Some are of the opinion that it is more difficult to model perfectly a basso-relievo, but there is no end to the work in the round.

I am really inclined to think that ever since the Italian Renascence the sculptor’s and modeller’s art and aims have dominated methods of art teaching generally, and have been chiefly responsible for what I have termed the Academic method, which seems mainly addressed to the imitation of solid bodies in full relief, or projection in light and shade on a plane surface, which method indeed in painting, at least, is quite opposed to the whole feeling and aim of Decorative art.

Royal College

of Art:

Design

School,

Instructor in

Lettering

Mr. Johnson

Page of Text, written by J. P. Bland

In architecture, on the classical and Academic

method, the young student is put through the65

66

five orders, and is expected to master their subtle

proportions before he can appreciate their artistic

value, and with but a remote chance of

making such knowledge of practical value, in a

country and climate to which such architectural

features are generally unsuitable.

Our methods of art teaching have sailed along in this stately way from time immemorial. Does not Burlington House stand where it did?

At all events a new spirit is abroad, since the arts and handicrafts of design have asserted themselves.

Methods of art teaching in relation to these must at any rate be definite enough. Each craft presents its own conditions and they must be signed, sealed, and delivered at the gate, before any triumph or festival is celebrated within.

Such conditions can be at least comprehended and demonstrated; materials can be practised with and understood, and even if invention in design can never be taught, on the negative side there are certain guides and finger-posts that may at least prevent lapses of taste, and loss of time.

The designer may learn what different means are at his disposal for the expression of line and form; for the colour and beauty of nature, recreated in the translucent glass or precious enamel, or speaking through the graphic printed line or colour of the wood-block—eloquent in a thousand ways by means of following the laws of certain materials in as many different arts.

What are the qualities demanded of a designer in such arts? quickness of invention and67 hand, power of direct definition of form. The expressive use of firm lines; sensitive appreciation of the value of silhouetted form, and the relief and effect of colours one upon another; perception of life and movement; knowledge of the growth and structure of plants; sense of the relation of the human form to geometric spaces, and power over its abstract treatment, as well as over the forms of the fowls of the air and beasts of the field.

Royal College of Art: Modelling School under Prof. Lanteri

Panel by Vincent Hill

This is a glimpse of the vista of the possibilities of teaching methods opened up by the68 arts of design, and in so far as those arts are understood and practised and sought after as important and necessary to the completion of a harmonious and refined life, so will our methods of art instruction have to adapt themselves to meet those new old demands.

69

Count Tolstoi’s book is, for the most part, a very fierce and trenchant attack upon modern, as well as some ancient art, from the point of view of a social reformer and an ascetic and iconoclastic zealot. In a true Christian spirit he denounces nearly everybody and everything, and indeed, metaphorically speaking, and to his own satisfaction at least, first sacks and burns the houses of the aesthetic philosophers from Baumgarten to Grant Allen, flinging their various definitions of beauty to the winds; and he proceeds to make a bonfire of the most eminent names and works, both ancient and modern, and including Sophocles, Euripides, Æschylus, Aristophanes, Dante, Tasso, Milton, Shakespeare; Raphael, Michael Angelo’s “Last Judgement,” parts of Bach and Beethoven; Ibsen, Maeterlinck, Verlaine, Mallarmé, Puvis de Chavannes, Klinger, Böcklin, Stück, Schneider, Wagner, Liszt, Berlioz, Brahms, and Richard Strauss;—no English need apply, I was about to say, but he includes Burne-Jones. And then, waving his torch, he points70 to the regeneration of art in the re-organization of Society, tempered by the opinion of the plain man and—leaves the question still burning.

Of an ideal of beauty in art he will have none. Beauty appears to his ascetic mind (or mood) as something synonymous with pleasure, and therefore more or less sinful and to be avoided: yet, realist as he appears to be at times, he is quite as vague and idealistic as the idealists he scorns when he speaks of a “Christian art” which is to take the place of modern corruptions. Tolstoi’s view of art, too, is practically limited to literature, the drama, music, painting, and sculpture. (I am afraid he did not know of the Art Workers’ Guild when he wrote his book, and seems ignorant of William Morris and the English movement.)

Only towards the end of the work (p. 171) does he mention “ornamental” art, or rather he speaks of “ornaments” (including “China dolls”) and remarks that such as these “for instance, ornaments of all kinds are either not considered to be art, or considered to be art of a low quality. In reality” (however, he says), “all such objects, if only they transmit a true feeling experienced by the artist and comprehensible to everyone (however insignificant it may seem to us to be) are works of real good Christian art.”

He then becomes aware, recalling his denial of “the conception of beauty” as supplying “a standard for works of art” that he is in an inconsistent position, and turns round and says that71 “the subject-matter of all” kinds of ornamentation consists not in the beauty, but in the feeling (of admiration of, and delight in, the combination of lines and colours) which the artist has experienced and with which he infects the spectator. This seems to be a cumbrous and roundabout way of saying that the thing is admired because it is beautiful.