Margeret loved them too.

Title: Master Simon's Garden: A Story

Author: Cornelia Meigs

Illustrator: Frances White

Release date: September 18, 2018 [eBook #57925]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from images made available by the HathiTrust

Digital Library.)

Margeret loved them too.

| I | The Edge of the World |

| II | Master Simon’s Pilgrimage |

| III | Roofs of Gold |

| IV | The Gospel of Fear |

| V | By Candlelight |

| VI | The Schoolhouse Lane |

| VII | Goody Parsons on Guard |

Old Goody Parsons, with her cleanest white kerchief, her most sorrowful expression of face and her biggest brown basket, had gone down through the village and across the hill to tell Master Simon what a long, hard winter it had been and how her cupboard was as bare, indeed, as Mother Hubbard’s own. Now, as she made her way up the stony path again, her wrinkled old face was wreathed in smiles and her burden sagged heavily from her arm, for once more it had been proved that no one who came hungry to Master Simon’s door ever went away unsatisfied. He had piled her basket high with good things from his garden, his wife had added three loaves of freshly baked bread and a jar of honey, and his little daughter Margeret had walked part of the way up the hill to help the old woman on her homeward road.

“Good-bye to you, little Mistress,” Goody Parsons called after her when they parted at last, “and may the blessings on your dear father and mother be as many as are the good gifts in my basket.”

Margeret, since her father needed her, did not wait to reply, but scampered away down the path again. The old woman stood on the hill-crest looking down at the scattered houses of the little Puritan town, at the spreading, sloping meadows and the wide salt marshes growing yellow-green under the pleasant April sunshine.

“These hills and meadows will never look as fair to me as those of England,” she sighed, “but after all it is a goodly land that we have come to. Even if there be hunger and cold and want in it, are there not also freedom and kindness and Master Simon?”

The little town of Hopewell had been established long enough to have passed by those first terrible years when suffering and starvation filled the New England Colonies. There were, however, many hard lessons to be learned before those who knew how to live and prosper in the Old World could master the arts necessary to the keeping of body and soul together in the New. Men who had tilled the rich smooth fields of England and had followed the plough down the furrows that their great-grand-fathers had trod before them, must now break out new farm lands in those boulder-strewn meadows that sloped steeply down to the sea. Grievous work they surely found it, and small the returns for the first hard years. Yet, whenever food or fire or courage failed, the simplest remedy in the world for every trouble was to go in haste to Master Simon Radpath. His grassy meadow was always green, his fields rich every harvest time with bowing grain, his garden always crowded with herbs and vegetables, and gay the whole summer long with flowers, scarlet and white and yellow.

The old woman who had been his visitor to-day watched Margeret’s yellow head disappear down the lane, and then turned to rest her basket on the rude stone wall, not because the burden was too heavy for her stout old arm, but because she heard footsteps behind her and she did dearly love to stop a neighbour on the road for a bit of talk.

“Good morrow, friend,” she cried out, almost before she saw to whom she was speaking.

Her face fell a little when she discovered that it was only Samuel Skerry, the little crooked-backed shoemaker who lived with his apprentice in a tiny cottage, one field away from Master Simon’s garden. A scowling, morose fellow the shoemaker was, but Goody Parsons’ eager tongue could never be stopped by that.

“Spring is surely coming at last, neighbour,” she began, quite undisturbed by Skerry’s sullen greeting. “Here is another winter gone where it can trouble old bones no longer.”

“Spring indeed,” snarled the shoemaker, in his harsh voice, “why, the wind is cold as January and every key-hole in my house was shrieking aloud all last night! Where see you any Spring?”

“I have been, but now, to visit Master and Mistress Radpath,” she returned, “and their garden is already green, with a whole row of golden daffodils nodding before the door.”

“Ah,” answered her companion, “trust Master Simon to have some foolish, useless blossoms in his garden the moment the sun peeps out of the winter clouds. Does he never remember that so much time spent on what is only bright and gaudy is not strictly in accord with our Puritan law?”

“It was with herbs from that same garden that he healed you and many of the rest of us during that dreadful season of sickness,” retorted Goody Parsons, “and did you not lie ill for two months of that summer and yet have a better harvest than any year before, because he had tended your fields along with his own?”

“Ay, and preached to me afterwards about every nettle and bramble that he found there, as though each had been one of the seven deadly sins. No, no, I like not his ways and I am weary of all this talk of how great and good a man is Master Simon. I fear me that all is not well in that bright-flowering garden of his.” The shoemaker nodded craftily, as though he knew much that he would not tell.

Goody Parsons edged nearer. She was grateful to that gentle-voiced, kind-faced Master Simon who had helped her so often in trouble; she loved him much but, alas, she loved gossip more.

“Tell me what they say, good neighbour,” she coaxed.

Samuel Skerry was provokingly silent for a space.

“They say,” he said at last, “that in that garden—beyond the tulip bed—behind the hedge—”

“Yes, yes!” she gasped as he paused again.

“There is Something hid,” he concluded—“Something that no one of us ever sees but that neighbours hear, sometimes, crying aloud.”

“But what is it?” she begged to know, in an agony of curiosity.

“Hush, I will whisper in your ear,” he said. “It were not meet to speak such a thing aloud.”

Goody Parsons bent her grey head to listen, and started back at the shoemaker’s low-spoken words.

“Ah, surely that can not be true of so good a Puritan!” she cried in horror.

“You may believe me or not, according to your will,” returned the shoemaker testily. “You were there but now; did you hear naught?”

Loyalty to her dear Master Simon and love of giving information struggled for a moment in the Goody’s withered face, but at last the words simply burst from her.

“I did hear a strange cry,” she said. “Ah, woe is me to think ill of so good a man! Come with me toward my house, Neighbour Skerry, and I will tell you what the sound was like.”

So off the two went together, their heads bent close, their lips moving busily, as they gossiped with words that were to travel far.

Only Master Simon, his wife and his daughter, Margeret, knew the real reason why his garden and fields had greater success than any other’s, knew of the ceaseless labour and genuine love that he expended upon his plants and flowers. Margeret loved them also, and would often rise early and go out with him to weed the hills of Indian corn, water the long beds of sweet-smelling herbs or coax some drooping shrub back to life and bloom. It was pleasant to be abroad then, when the grey mists lying over the wide, quiet harbour began to lift and turn to silver, when the birds were singing in the great forest near by and the dark-leaved bayberry bushes dropped their dew like rain when she brushed against them. Then she would see, also, mysterious forms slipping out of the dark wood, the graceful, silent figures of the friendly Indians, who also got up before the dawn and came hither for long talks with their good friend, Master Simon. They brought him flowers, roots and herbs that grew in this new country, while he, in turn, gave them plants sprung from English seed, taught them such of the white men’s lore as might better their way of living and offered much sage counsel as to the endless quarrels that were always springing up among them between tribe and tribe.

“It is strange and not quite fitting that those heathen savages should follow you about like dogs,” the villagers used to tell him, a little jealous, perhaps, that he should be as kind to his red-skinned friends as he was to his Puritan comrades. But Master Simon would only smile and go on his way, undisturbed by what they said.

When the long, warm evenings came and Margeret and her mother brought their spinning wheels to the doorstep that they might use the last ray of daylight for their work, Master Simon would labour beside them, tending now the roses and the yellow evening-primroses before the cottage. And he would tell, as he worked, of those other primroses that grew in English lanes, of blossoming hedge-rows and soaring larks and all the other strange beauties of that dear country across the sea. Sometimes Margeret’s mother would bend her head low over her spinning to hide the quiet tears, as he told of the great, splendid garden where he had learned his skill with plants and herbs, a garden of long terraces and old grey sundials and banks of blooming flowers. It was there that he and she had walked together in the moonlight, and had planned, with hearts all unafraid, for the day when they should be married and should set sail for that new land that seemed so far away. But there was no sadness or regret in Master Simon’s heart.

“Some day,” he would say, straightening up from his work and looking about him with a happy smile; “some day we shall have just such another garden planted here in the wilderness, at the very edge of the world that white men know.”

This year, however, as he and Margeret planted the garden in unsuspecting peace of mind, there was strange talk about them running through the village. Much as the good Puritans had left behind them in England, there was one thing that was bound to travel with them beyond the seas, their love of gossip about a neighbour. The whispered words of Samuel Skerry had travelled from Goody Parsons to those who dwelt nearest her, and from them to others, until soon the whole town was buzzing with wonder concerning Master Simon’s garden and that secret thing that lay hidden in its midst. There were many people who owed him friendship and gratitude for past kindness, but there was not one who, on hearing the news, could refrain from rushing to the nearest house and bursting in with the words:

“Oh, neighbour, have you heard—?” the rest always following in eager whispers.

Thus the talk had gone the rounds of the village until it reached the pastor of the church, where it fell like sparks into tow.

“I was ever mistrustful of Simon Radpath,” cried the minister, Master Hapgood, when he heard the rumour. “That over-bright garden of his has long been a blot upon our Puritan soberness. Others have their door-yards and their garden patches, yes, but these sheets of bloom, these blazes of colour, I have always said that they argued something amiss with the man. He had also an easy way of forgiving sinners and rendering aid to those on whom our community frowned, that I liked none too well. Now we know, in truth, what he really is.”

And off he set, post-haste to speak to the Governor of the Colony about this dreadful scandal in Hopewell.

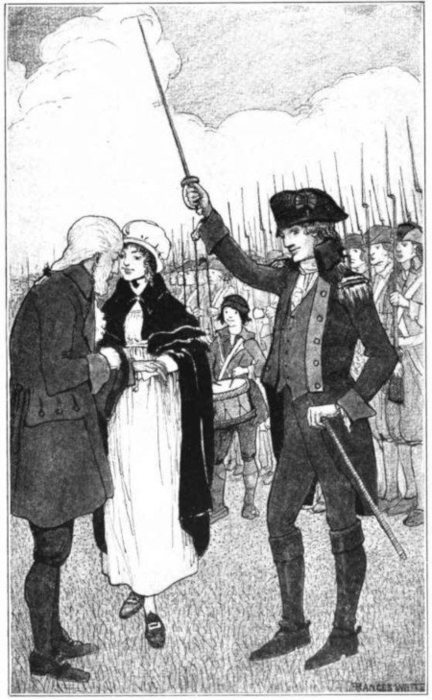

Trouble, therefore, was coming upon Master Simon on that pleasant morning of late May when Margeret went out to swing on the white gate and listen to the robins singing in the linden tree. It was trouble in the form of a stern company of dark-clad men, who came striding down the lane beneath the young white-blooming apple saplings. There were the church deacons, the minister, the Assistants and the great Governor himself, come to inquire into this business of the garden and its mysteries. Beside the Governor walked a stranger, a famous preacher from Scotland, whose strictness of belief and fierce denunciations of all those who broke the law, were known and dreaded throughout New England. Margeret dropped off the gate and ran full of wonder and alarm to tell her father.

It seemed, however, that the thoughts of these sober-faced public officers were not concerned entirely with Master Simon and his wickedness. The Governor bore a letter in his hand and was discussing with his friend from Scotland, Master Jeremiah Macrae, the new and great danger that was threatening the Colony. The friendly Indians, the peaceable Wampanoags, were becoming restless and holding themselves aloof from their former free intercourse with the people of the settlements. Other tribes more fierce and savage than they, were pressing upon them and crowding them more and more into the territory occupied by the whites. The Wampanoags, it was said, were being harassed by the Mohegans, old and often-fought enemies, while they, in turn, were being driven from their homes by the terrible Nascomi tribes, who dwelt far away but were so war-like and cruel that their name had ever been used as a bye-word to frighten naughty Indian babies into good behaviour. Should such an avalanche of furious red-skinned warriors descend upon them, what could the little Colony of Puritans, with its four cannon and only fifty fighting-men, do to defend their lives and the homes that they had built with such courageous toil?

It was small wonder, then, that all the beauty and freshness of the full-flowering Spring could not arouse the heavy thoughts of the Governor and his companions. Then, at the turn of the lane, they came in sight of a strange group, so sinister and alarming that the whole company stood still and more than one man laid his hand on his sword. Full in the way stood three tall, silent Indians, mightier of limb and fiercer of aspect than any the white men had ever seen before, their hawk-like faces daubed with gaudy colours and their strange feathered war-bonnets sweeping to their very heels. A trembling Wampanoag, brought as interpreter, advanced at the bidding of his imperious masters and strove vainly to find words with which to repeat his message.

“Come,” said the Governor, “speak out. What can these strangers have to say to us?”

The interpreter, after more than one effort, managed to explain as he was ordered. These Indians had come from far away across the mountains and were of those dreaded Nascomis, a branch of the terrible Five Nations. They had heard of the new settlers and had come to look at their lands, intending, if they found them too good for aliens, to return later with all their warriors and drive the white men forth.

“And true it is that they will do so,” added the Wampanoag, dropping from halting English into his own tongue when he found that one or two of those present could understand him. “There is no Indian of our tribe who does not hear all his life terrifying stories of these Nascomis, and of how, once in long periods of time, they change their hunting grounds and have no mercy on those who dwell in the land of their desire.”

The Governor, in spite of the deep misgiving that all knew must be weighing at his heart, spoke his answer with unmoved calm.

“We will have speech with you later,” he said through the interpreter, “for the present we have grave business with Master Simon Radpath. If you wish you may follow and come afterward to my house where we will treat further of this errand of yours.”

The Indians, with unchanging faces, turned and walked down the lane beside the Puritan company. They talked together in their strange guttural language, pointing out this or that peculiarity of the white men’s dress and seeming to regard them with far less of awe than mere curiosity. It was a short and bitterly uncomfortable journey that brought the gathering of elders, in small humour for any kindness of heart, to Master Simon’s gate.

As Margeret stood beside her father, greeting these unexpected and disturbing guests, she happened to glance across the sunlit field and saw Skerry, the shoemaker, and the boy who was his apprentice, standing before the door of their cottage. The little cobbler was shading his eyes with his hand and watching the dark procession as eagerly as though he had some deep concern in their errand. The ragged boy, however, seemed to have no interest in the matter, or no liking for it, since he stood with head turned away, staring down at the blue harbour and the wide-winged, skimming sea-gulls. The little girl observed them for only one moment, the next, and all her thoughts were drowned in wonder and alarm at the Governor’s words.

“It has come to our ears, sir,” he was saying sternly, “that you have here a garden too gay for proper Puritan minds, a place too like the show gardens of the Popish monasteries, or of the great lords that dwell amid such sinful luxury in England. In this Colony men and women have sat in the stocks for wasting precious hours over what shows only beauty to the eye and brings no benefit to the mind and heart. But what is that?” he broke off abruptly, sniffing suddenly at a vague sweet perfume that drifted down the May breeze.

“Please, sir, ’tis hawthorn,” said Margeret, who was losing her terror of the Governor in curiosity at the sight of the Indians. “There was but a little sprig that Father brought from England, grown now to a great, spreading bush.”

A sudden change came over the Governor’s stern face. Had he a stabbing memory of wide, smooth English meadows, yellow daffodils upon a sunny slope and hedges sweet with hawthorn blossom in the Spring? None of the Pilgrims ever spoke of the homesickness that often assailed their steadfast hearts, but, as the Governor and Master Simon looked into each other’s eyes, each knew of what the other was thinking. It was of some much loved and never forgotten home in England, perhaps, some bit of woods or meadow or narrow lane leading up a windy hill. The offending garden would have been in a fair way toward being forgiven had not the Scotch minister come forward and plucked the Governor by the sleeve.

“See, see!” he said, pointing. “Just look yonder.”

Truly that was no sight for sober Puritan eyes! There beside the linden tree was a great bed of tulips, a blaze of crimson and gold, like a court lady’s scarf or the cloak of a king’s favourite. Against the green of the hedge, the deep red and clear yellow were fairly dazzling in the sunshine. The Governor scowled and drew back.

“Of what use,” cried the minister in his loud harsh voice. “Of what use on earth can be such a display of gaudy finery?”

There were three members of that company who could answer him. The Indian ambassadors, laughing aloud like children, dropped upon their knees before the glowing flower bed, plucked great handfuls of the brilliant blossoms, filled their quivers, their wampum belts and their blankets with the shining treasure and turned to gaze with visible awe at the owner of all these riches.

“Do you not see,” said Master Simon to the minister, an unsubdued twinkle in his eye, “that there is nothing permitted to grow upon this good, green earth that has not its use?”

“Such a flaunting of colour,” said the Governor severely, yet perhaps with the ghost of a smile held sternly in check, “has not our approval. Now I would see what lies behind that hedge.”

Little Margeret looked up at her father and turned pale; even Master Simon hesitated and was about to frame an excuse, but it was too late. A shrill, terrible scream arose from behind the thick bushes.

“There, there, did I not tell you?” cried one of the deacons, and the whole company pressed forward into the inner garden.

They saw, at first, only a smooth square of grass, rolled and cut close like the lawns in England. Four cypress trees, dug up in the forest and trimmed to some semblance of the clipped yews that grace formal gardens, stood in a square about the hewn stone column that bore a sundial. Quiet, peaceful and innocent enough the place seemed—but there again was that terrible scream. Out from behind a shrub came strutting slowly the chief ornament of the place, Margeret’s pet, Master Simon’s secret, a full-grown, glittering peacock. Seeing a proper company of spectators assembled, the stately bird spread its tail and walked up and down, turning itself this way and that to show off its glories, the very spirit of shallow and empty vanity. For pure amazement and horror, the Governor and his companions stood motionless and without speech.

But if the Englishmen were frozen to the spot, it was far otherwise with the Indians. They flung themselves upon their faces before the terrifying apparition, they held up their hands in supplication that it would do them no harm. Then, after a moment of stricken fear and upon the peacock’s raising its terrible voice again, they sprang to their feet, fled through the gate and up the lane, and paused not once in their headlong flight until they had disappeared into the sheltering forest. The Governor drew a long breath, caught Master Simon’s eye and burst into a great roar of laughter.

“You have done us a good turn, you and your silly, empty-headed bird,” he said, “though I was of a mind for a moment to put it to death and to set you in the pillory for harbouring such a creature of vanity. Yet for the sake of his help against a dreaded foe, you shall both be spared. Now see that you order your garden more soberly and that no further complaints come to my ears.”

He turned to go.

“If you please, may we keep the tulips?” begged Margeret, curtseying low, her voice shaking with anxiety.

“Yes, little maid,” was the gracious answer, “you may keep your tulips since you cannot use them for gold as those poor savages thought they could. And go, pluck me a branch of that hawthorn blossom that smells so sweet. It grew—ah, how it grew in the fair green lanes of my own dear Nottinghamshire.”

With the sprig of hawthorn in his grey coat, and with a bow to Margeret as though she had been some great lady, the Governor passed out into the lane followed by all his company, deacons, Assistants and Master Hapgood. Only the minister, Jeremiah Macrae, lingered inside the gate. Suddenly he lifted both his arms toward heaven and spoke out loudly in his great, harsh voice. With his dark cloak flying about him and his deep-set eyes lit by a very flame of wrath, he looked to Margeret like one of the prophets of old, such as were pictured in her mother’s great Bible. She trembled and crept nearer to her father.

“Think not, Simon Radpath,” the minister thundered, “that, although you have won the Governor’s forgiveness by a trick, there the matter ends. Woe be unto you, O sinful man, unless you destroy the gaudy vanity of this wicked garden. Change your ways or fire and sword shall waste this place, blood shall be spilled upon its soil and those who come after you shall walk, mourning, among its desolate paths.”

Margeret gasped with terror, but Master Simon, though a little pale, stood his ground undaunted.

“I, too, have made a prophecy concerning my garden,” he answered. “It is carved yonder about the edge of the sundial, and the climbing roses are reaching up to cover the words for it will be long before their truth is proved. It may be that this spot will see flame and sword and the shedding of blood, for new countries and new ideas must be tried in the fire before they can live. But my prophecy is for peace and growth, yours for war and destruction—a hundred years from now men shall know which of us spoke truly.”

“‘A hundred years from now,’” repeated the minister scornfully. “Think you that, after the half of that time, there will be any man who remembers you, or your words, or your garden?”

He strode across the lawn, plucked aside roughly the trailing rose-vines at the edge of the sundial and read the words carved deep in the grey stone. Then, with no comment, nor any word of leave-taking, he went out through the gate and up the lane. Margeret stood long watching him as he climbed the steep path. His figure looked very black in the clear, white sunshine, very ill-omened and forbidding even as it grew small in the distance and finally vanished over the crest of the hill.

In spite of Master Macrae’s ominous words, all was for a time quiet and at peace in Master Simon’s pleasant, sunny garden. Peace prevailed also among the Colonists and their Indian allies, the rumours of warfare slowly died away and, while Spring grew into summer, and summer glowed and bloomed and faded into autumn, everywhere in the little Colony were happiness and contentment. The fields were yellow with abundant grain, the apple-trees bent with a generous load, the sacks of dried peas and the great golden pumpkins were piled high upon the floor of the public granary. There would be no want and famine this winter!

Margeret walked beside her father down through the field where he had been piling the rustling cornstalks into tall heaps like Indian wigwams. She stopped often to hearken to the cawing of the crows, who were gathering their band and making ready to go South, and to watch a busy chipmunk carrying grain and nuts to his store-house under the wall.

“I would that all the world were as bright and happy as this corner of it,” said Master Simon, as he paused in his work to look down over the sloping meadows to the shining waters of the harbour and the rude little fishing-boats coming to anchor. “But look,” he added, “who is that yonder in our garden beckoning us to come quickly? It is the pastor, Master Hapgood, and two Indians with him, while the other—why, it is the Governor himself! What can be amiss now? Since our peacock has been banished to England, I can think of naught else for which we may be brought to justice.”

It was indeed the Governor, anxious-faced and troubled in mien, who came forward to meet them.

“One of the same Nascomi ambassadors has come hither again,” he said, “to ask some favour of us. That much I can make out from the interpreter, but for the rest, his message is so strange and his English words so few that we have come to you, who understand the Wampanoag tongue better than does any other, to learn what he would say. Further, I think that his errand has somewhat to do with you.”

Master Simon turned his quick, bright eyes upon the Indian interpreter.

“Speak on,” he said, and listened with a face growing graver and more disturbed with every word the Wampanoag and the Nascomi uttered. He turned at last to the Governor.

“They speak of a terrible pestilence,” he explained, “a scourge that has visited the Nascomis and has already slain a goodly number. I have heard often from the Indians hereabout of these plagues, by which many times whole tribes, even entire nations have been swept away.”

“But what wants the fellow with us?” inquired the Governor.

“He has come to beg that we pray to our god for their deliverance,” said Master Simon at last.

“What?” cried the pastor. “To our God? Is it possible that these Nascomis are Christians?”

“No,” returned Master Simon slowly, “he speaks not of the God we know. He begs us to pray for him to that shining god with the terrible voice and a hundred glittering eyes, that walked in this garden six months since and struck such terror to the hearts of himself and his companions. He says that they have asked in vain for help from their own gods and he has come all this long and perilous way to make his prayer, poor savage, to my banished peacock.”

The Governor’s face grew dark with trouble, but the minister’s became suddenly transformed with a fury of righteous anger. It was not for nothing that he had listened to the now famous Jeremiah Macrae and his fierce threatenings of Heaven’s vengeance.

“Simon Radpath,” he cried, striving to thunder forth his words as did the great minister, but succeeding only a scant half as well; “Simon Radpath, you have committed the most grievous sin known to the human race. You have led a man, nay, a whole nation into idolatry, into worshipping as a god that vain iniquitous creature you so wickedly harboured here.”

“But please, sir, they were heathen already,” faltered little Margeret, stirred to fearful boldness by all this wrath against her father.

“That matters not,” was the stern reply. “He has aided and increased their heathenism, so that their last state is worse than their first. Heaven alone can tell what punishment he should suffer for so unspeakable a wrong.”

“Heaven, sir,” said Master Simon, speaking slowly and quietly; “Heaven has also given me the opportunity to make reparation. Margeret, go tell your mother to fetch my great cloak and to gather such things as I need for a journey, and to put into a basket all the herbs that are drying up among the rafters. Many times have I talked with the Indians about these pestilences and pondered upon what might have power to check them: now I will put my knowledge to the test. I will go back with the Nascomi messenger to see how I can help his afflicted people.”

Hurriedly obedient, but with her whole heart crying out in protest, Margeret ran to the house to do her errand. Her mother, rising from her spinning wheel, quickly made the necessary preparations, although scarcely understanding their purpose. Puritan women in those troubled times had learned to act promptly and without asking for explanations. When they came forth from the house, bearing bundles and the big basket, the same little group still stood, unmoving by the gate, while the pastor, holding up his hand, was speaking loudly, as though in the pulpit.

“And if you die far away amid that godless nation,” he was saying, “it will be only Heaven’s judgment upon you and the vanities of this wicked garden.”

Then it was that of a sudden, Master Simon’s quiet manner dropped from him.

“Cease your preaching of death and destruction, Master Hapgood,” he cried, “and go, rather, up into your meeting-house yonder and pray. Pray with all your might to that God who once walked in a Garden, that He will spare me for this people’s need, so that they may learn that when they come hither to ask for help from Him and us, they do not ask in vain.”

Thus he spoke and then, in a moment, was gone. A hurried kiss to Margeret and to her mother, a sign to the Indians, and the little party set off, up the steep lane, across the boulder-strewn clearing and into the forest. Margeret ran panting behind them for a little way, then, blinded with weeping, stumbled over a stone and lay sobbing in the grass. A strong arm came about her and lifted her up.

“Do not fear, little maid,” said the Governor’s great voice, grown strangely gentle now. “God will not suffer so brave and good a man as your father to perish. He will come safe back to you again.”

It was thus that Master Simon went into the wilderness, leaving behind him, in the little house on the hillside, two very heavy, loving hearts.

“Will he come back? Will he come back?” seemed to Margeret to be the refrain that sang through every one of the autumn sounds, the creaking of the grain-carts, the blows of the threshing-flails, the thumping of the batten in the busy loom.

Many friendly neighbours, remembering past kindnesses, brought in what was left of Master Simon’s harvest, gathered a store of fire wood, banked the house with earth and leaves and made all ready against the cold. More than once the Governor came to offer his respects to Mistress Radpath and to bid her and her little daughter be of good cheer—events that made the villagers stare, for a visit from the Governor was an awesome thing. Master Hapgood, the pastor, came also many times to ask for news, although he seemed not yet to know whether he should praise Master Simon’s courage or continue to condemn his wickedness.

The Scottish minister, Master Jeremiah Macrae, was still in the Colony, preaching vehemently up and down the land, crying to the people to repent of their grievous sins before it was too late. Many a time, so it came to the ears of Hopewell, had he denounced Master Simon, his garden and all that grew therein. From town to town he went, until all of New England began to stir uneasily under the lash of his bitter tongue.

“He may do good and he may do ill,” said their neighbour, Goodman Allen, to Mistress Radpath. “We are used to being called to account for our sins and there is no one among us, Heaven knows, that can be called perfect. But this man, when I listen to his preaching, tempts me to be more of a sinner than less of one, so sure is he that we are all condemned to eternal punishment together. His words are more than even a good Puritan can bear, he threatens us with Heaven’s wrath until we grow weary and indifferent, while with his tales of hellfire he frightens the children so that they are afraid to go to bed alone.”

Margeret shivered as she stood listening to their honest neighbour’s words. It was quite true that the strange minister had haunted her own dreams for many a night.

“Some folk,” the man went on, “say that he speaks like one of the prophets of old, come back to earth again. But I say,” here he dropped his voice and glanced anxiously about the shadowy kitchen; “I say that he may not be a prophet, but the Devil himself that we have in our midst. We will mark well his words concerning Master Simon’s garden, and if they come true, then will we know what to think.”

It appeared to Margeret, through all that autumn, that the world went very much awry. It was only a part of the general sadness of all things that, when she went one day to carry a basket of apples to Goody Parsons, she found the old woman sitting on the bench before her door in the pale autumn sunshine, weeping bitterly. The climbing rose that she had brought with her from England and that had grown to the very top of her cottage door, had drooped all summer and now trailed forlornly across the grey logs, dead beyond any doubt.

“Great, fragrant white roses it bore,” said the old woman, choking over her words, “roses that I carried in my hand the day I was married, and that my three daughters carried too, on their wedding days, each in her turn. The dearest memory that I have is of our little cottage in Hertfordshire, where the beehives stood in a long, sun-warmed row beside the hedge and the rose vine climbed to the very eaves, covering the whole wall with leaf and blossom. And now my rose is dead, a punishment, I can well see, for the harm I did your good father by means of my idle, gossiping tongue.”

“But listen,” Margeret said, “do you not remember that my father once told you that this rose was finer than any in our garden and you gave him some of the shoots to plant among our own? We have one now, climbing high on our house wall and the others I know are still growing down by the hedge. So to-morrow you shall have a new plant of the very same rose, to grow as tall and bloom as gaily as the last.”

“Bless me now,” cried Goody Parsons, a smile breaking through her tears. “You are your father’s own good daughter, little Mistress, and have almost made me happy again. But I never can be quite so until I can forget the harm my chattering has done or until I see Master Simon come safe home out of that terrible wilderness.”

The new little rose took most kindly to the transplanting that Margeret so skilfully accomplished, and stood strong and sturdy beside the door, its twigs still green long after the leaves had fallen from the trees and the misty Indian summer had taken possession of the land.

“I believe that when Spring comes it will grow as fast as that stocking you are knitting,” laughed Margeret one day, when she came to inspect its progress.

The old woman nodded and smiled.

“I hope to see it climb to the top of my door again before I die,” she answered. “Heaven grant me time for that and to end my evil gossiping ways. Do you know that neighbour Allen—” she checked herself suddenly and added, with a sigh, “There I go again! Take heed, my lass, and see how hard it is to mend a fault when you have grown old.” And she closed her lips with firmness and fell to knitting furiously.

Margeret could not forbear laughing again and was still smiling to herself as she took her way across the hill. The leafless woods stood black and bare against a pale yellow sky, and a little thin new moon hung low behind the treetops. She was surprised to find herself so happy to-night, as though in such a fair world there could not be so much of trouble and sadness as she had thought. Just where her path skirted the forest’s edge she caught sight of a dark figure moving among the black shadows of the tree-trunks, and presently she saw it come out of the wood and go down the lane before her.

“Is it Samuel Skerry?” she wondered, as the form, vague in the twilight, turned into the path that led to the shoemaker’s cottage. “But no, it is too tall for the cobbler, it must be that boy who lives with him. What has he been seeking in the wood? The fruits and berries are all gone and he had no gun. I wonder!”

Her idle speculations did not, however, last long, for as soon as she reached home and fell to telling her mother of Goody Parsons and the rose, her thoughts of the shoemaker’s apprentice were swept away.

She had a visit from him, nevertheless, some weeks later, a visit that surprised her more than the coming of the Governor himself. Early one bitter windy morning, as she knelt shivering on the hearth trying to blow the reluctant fire into flame, there came a knock at the outer door. Upon the threshold, that was banked deep with the first heavy snow, stood the ragged boy who dwelt at Samuel Skerry’s. His teeth were chattering and his fingers trembling with the cold, but his dark blue eyes were shining with excitement.

“There has been a fox in your hen house these three nights past,” he said, “and so I arose early this morning and see, here he is.”

The body of the red marauder trailed over his arm, its great brush dragging limply in the snow. It had been with helpless dismay that Margeret and her mother had noticed the loss of their fowls, so that this news brought relief indeed.

“Oh, thank you, thank you!” she cried. “But I fear your watch has been a bitter cold one. Come in and warm yourself, you must be well-nigh frozen.”

The boy hesitated.

“My master, the shoemaker—” he began, but Margeret interrupted him, borrowing the stern manner she had seen her mother use on similar occasions.

“Come in at once,” she commanded, and when he shyly obeyed she shut the door behind him lest he escape.

He sat down upon the stool in the chimney corner and, when she once more attempted to blow the fire, took the bellows gravely from her and in a moment had the flames leaping high, flooding the kitchen with ruddy light. Margeret filled her pewter bowl brimful with steaming porridge and watched with pleasure as her guest ate with unconcealed hunger. She brought bread and cheese and a cup of milk which she set upon the bench beside him, and then busied herself about the kitchen lest she should seem to be staring at her unwonted visitor. Each eyed the other shyly when occasion offered, but looked away quickly when their glances happened to meet. He seemed to be watching her golden hair shining in the firelight, while she, by peeping into the old round mirror that hung upon the wall, could see how black were his hair and eyelashes and how dark blue were the eyes with which he stared at her when her back was turned. She felt friendly enough and anxious to put her companion at his case, and so, apparently, did he, but neither knew what to say and so the meal was finished in silence. It was Mistress Radpath’s footstep on the stair that roused him suddenly to speech.

“Oh, I must go,” he cried, springing up. “Samuel Skerry will be awake and waiting for me this long time. He will want to strike me for my delaying.”

And out of the door he sped, in greater terror, it seemed however, of Margeret’s mother than of his master, the shoemaker. The little girl, watching him through the window as he crossed the white field, realised suddenly that she had not even thought to ask his name. Often after that day she wondered who he could be, and many times looked wistfully across the waste of snow toward the neighbouring cottage. Although she saw him now and then, passing in and out of the distant doorway, he did not come near their house again. Goodman Allen’s wife, who came to sew with Mistress Radpath, dropped a bit of gossip concerning him.

“We are all wondering who that shoemaker’s apprentice can be,” she said. “He is no kin of Samuel Skerry’s, of that you may be sure, for he is far too pleasant-faced and gentle-mannered. The town officer went to ask, as was his duty, but could get no information from the boy’s master. Skerry said the lad was named Roger Bardwell, that he would answer for him and that was all. We all wonder where the boy can have come from; there is not one of us who does not like him.”

That, it seemed, was the sum of Hopewell’s knowledge of the shy, ragged, handsome lad.

Early in December there came, suddenly, a furious storm of wind and snow, that covered the fields, blocked the roads and drifted so deep about the houses that many of them were buried to the very eaves. It was the worst that the Colonies had ever known in all of their short history. For three days the gale shrieked about the staunch little cottages and roared down the chimneys, while those who dwelt within toiled unceasingly to build the fires up and keep the bitter cold at bay. When finally the storm had died away, when paths had been dug and people were able to go to and fro again, the strangest news suddenly went racing through the village. The Scotch minister, who had been upsetting the peace of all New England, had disappeared. He had set forth, people said, on a journey from Boston to Salem, travelling alone as was his custom, and, save for one man who had met him at the edge of the forest, struggling along in the face of the rising gale, no mortal eye had ever seen him again. That he had lost his way and perished among the drifts, was easy enough to believe, but the good people of Hopewell had another thing to say.

“The Devil came to take his own again,” many of them declared openly, for in those rough times the Devil was a more familiar figure than in later days and more than one of the Pilgrim Fathers laid claim to having seen him, horns and hoofs and tail and all. And while some folk were not quite so free-spoken as to agree with the opinion of their bolder neighbours, yet they too shook their heads and said:

“Watch Master Simon’s garden, there will his burning words be proven, whether true or false.”

For the thought that, unspoken, filled to the brim every good heart in Hopewell was:

“Where was Master Simon through all that bitter storm and will he ever come back to tend his garden again? We can spare a dozen Scotch ministers, but never one Simon Radpath.”

December, January and February went by, each one, it seemed to Margeret, covering the span of a year. March slipped past with roaring winds and melting snows, then came April and Spring again. Listlessly she watched the apple trees grow green, saw the warm pink of the Mayflowers showing under the brown leaves and heard the returning birds calling to one another in the meadow. Once she had loved all these things, but what did they matter now if Master Simon was never to see them again?

Then, one night, she was awakened suddenly by—she knew not what. Was it the moonlight, dropping in shining white squares upon the rough floor of her room? Was it a far-off dog barking in the village? No, it was something different, the sound of footsteps, hushed, but so many in number that even above the slight noises of the night they must still be heard. She sprang from her bed and ran to the window. Down the lane came a strange procession, slim dark figures moving almost without a sound, Indian after Indian, in numbers that seemed to have no end, while, in the midst, came her own dear father, leaning on the arm of the tall warrior at his side. At the very last came an Indian boy, carrying a ragged bundle and the very basket into which she had put the herbs so many months ago. There was something so absurd in seeing even her basket come home safe from that far journey that she laughed out loud in the midst of the moonlit silence.

It was a quiet that, however, did not last long. Dogs barked, doors flew open, voices cried out, “Welcome home, Master Radpath,” and eager stumbling feet, hastily shod in heavy boots, came running down the stony paths. The weary traveller was brought in to be warmed, fed and embraced; a messenger was sent in haste to the house where the Governor lodged that night. Through all the village spread the news that Simon Radpath had come home and that with him had journeyed a great chief of the Nascomis, to smoke the pipe of everlasting peace with the white settlers. Early in the morning the town-crier was despatched to spread the tidings through the whole district.

What a proud moment it was for Margeret when she heard this great official’s huge, deep voice crying from the crossroads:

“Hear ye, good people all! Master Simon Radpath is come safe and sound to his home again.”

It was a prouder moment still when she went, on the next Sabbath, up to the meeting-house and, sitting among the women, could see her father opposite in his place of honour, with many glances turning sidewise to gaze at him as the hero of the day. Samuel Skerry, from his bench near the door, was regarding him from under scowling brows, but the boy beside him followed Master Simon’s every movement with eager, worshipping eyes. Proudest of all was Margeret when the pastor ascended into the pulpit and gave public thanks to God that “their good comrade, who had made a far journey into the wilderness, who had ministered successfully to a stricken people and who had brought about a momentous treaty of peace, had come safe home again to his Puritan companions, to his wife and daughter and to his little garden on the hill.

“There be some of us,” he ended, “who thought that garden was blessed and some who thought it was accursed, and I, as Heaven is my witness, am not yet certain whether it is or no. But of one thing we can be sure, since it is plain to all eyes to-day, that Simon Radpath is the truest and bravest Pilgrim of us all.”

“Have a care, little Mistress, there are duck eggs in that basket.”

The warning, called forth anxiously by Goodwife Allen, leaning over her half-door, was quite unheeded by rebellious Margeret, who hurried out of the gate, swinging her burden quite as recklessly as before.

She felt herself to be in a very rash mood that morning, for was she not already in disgrace both at home and abroad? She had committed a very terrible offence on the day before, the Sabbath, after she had been sitting long on the hard bench in the meeting-house, shuffling her feet, kicking her heels together and watching the sand of the pulpit hourglass drop slowly, grain by grain, as though it would never mark the sermon’s end. When Master Hapgood, as though in absence of mind, had turned the glass over, a signal that his talk would last for perhaps an hour more, she had heaved a long, loud sigh that resounded, in a pause of the speaker’s, to the furthest corner of the meeting-house. Many of the Puritan maids giggled openly, and more than one man, including Master Simon, smiled behind his hand, although the pastor’s black frown would have made any but the most abandoned child bow her head in shame. Yet even to her mother’s sorrowful chiding on the way home, Margeret had not replied meekly as a Puritan maid should.

This morning, when she had been sent with a bundle of herbs to Goodwife Allen’s and had been directed to come quickly home again, she was openly loitering on the road and planning to stop when she reached the wide, sunny marsh and gather some of the gorgeous wild flowers that she had noticed when she passed. She was weary, she told herself, of all these strict rules, never to run and romp in the lanes, never to wear gay ribbons or bright dresses, always to sit quiet on the hard benches through the long, long, Sunday sermons. Presently, as she reflected thus and swung her basket in time to her rebellious thoughts, one of the duck eggs rolled over the edge and smashed in the dusty road.

“I don’t care,” cried Margeret, stamping her foot, although there was no one to hear or see. “I don’t care!”

She might just as well have broken them all for, when she reached home, an hour later, laden with an armful of bright marsh flowers, her mother asked her for the eggs and she suddenly recollected that she had set the basket down upon a tussock as she waded in the swamp and had left it there.

“There is no time to go back to seek it now,” was all Mistress Radpath said.

Margeret knew that she ought to declare that she was sorry, but naughtiness and impatience seemed to have fastened upon her that day and she kept silent.

“Bring out your spinning-wheel, my child,” said her mother a little later. “Neighbour Deborah Page is ill and we must spin for her as well as ourselves to-day.”

The little girl had just seen her father go past the door with his gardening tools on his shoulder and had been planning to follow and help him work among the flowers in the warm June sun. It was a pleasant day of clean-washed air and fresh salt breezes, one that she could scarce bear to think of spending within doors. She obeyed her mother very reluctantly, brought her wheel from its corner and sat down to spin. Her fingers were clumsy and her temper short so that in a moment she had tangled her thread and jerked the treadle so roughly that it snapped. Her mother’s look of mute reproach was more than she could bear.

“I care not at all,” she cried loudly and bitterly. “I wanted to break the hateful wheel. Little girls must play sometimes!”

So saying, she rushed out of the door slamming it to behind her. She saw Master Simon standing on the path, looking gravely and sorrowfully after her, but she did not give him time to speak. Taking refuge behind the great hawthorn bush she buried her face in the grass and burst into hot, angry tears.

After she had cried for some time and had, in part at least, washed away her wrath, she sat up to look about her and to wonder how, after all, she could have been so wicked. Across the meadow, filled with bobolinks, she could look down to the harbour where the full June tide was running in. A little boat, sailed she knew by Roger Bardwell, the shoemaker’s apprentice, in such moments as he could steal from his harsh master, was flying joyously before the gay, warm wind. She could sniff a bewildering sweetness that filled the air, for the linden tree had bloomed the day before, driving Mistress Radpath’s bees nearly mad with joy. She had heard them humming in the branches nearly the whole night through and to-day again their song was loud in her ears. Indeed, as she listened, the buzzing and whirring grew so insistent that she began to realise something had happened.

“Why,” she exclaimed, “I believe that they are swarming.”

Leaving her refuge behind the hawthorn bush, she peeped over the hedge of the little enclosed garden where the sundial stood and where the peacock had once dwelt. Yes, there beyond, under the apple trees stood her mother, with eager eyes and cheeks pink with excitement, as she held up the new hive and sought to lure the bewildered bees within. The air seemed full of their black whirring little bodies, which bye and bye, however, gathered close and finally settled in a huge dark mass, hanging from the linden tree like some strange, gigantic fruit. Then must Mistress Radpath exercise all her wiles, find the queen-bee and persuade her to enter the hive, to be followed at last by her train of black, buzzing courtiers.

“Now that was as skilfully managed as ever I saw it!” exclaimed Master Simon. “Scarce could I have done better myself.”

He chuckled as he spoke for it was a well-known joke in the household that Master Simon, although equal to any other emergency that might arise, could not come in too great haste to call Mistress Radpath, once the bees swarmed. He took the hive from her now and bent to kiss the successful bee-mistress before he went to put it in place beneath the apple-trees.

“Goody Parsons says I shall never have true skill until I learn to whisper charms and spells over the hives, as she does,” returned Mistress Radpath. “She says—but oh, my spinning, I shall never have it done!”

She went quickly into the house, leaving Master Simon to set the hive in its place at the end of the long row that stretched across the back of the garden. Some of the hives, those that had been brought from England, were trim and blue-painted, the others were roughly framed out of wood cut in the forest. It chanced that the one just put into place was the best and most elaborate of all, for it had a pane of glass in its side through which one could see the newcomers already turning to the work that would result in the building up of a golden honeycomb. Margeret, her anger almost forgotten now, slipped across the grass and stood at her father’s side, watching too. As she came near he murmured to himself a line that she had heard him quote before:

“Father,” she said, putting her hand into his and speaking hesitatingly, as she was not quite sure how she would be received, “what do those words mean and where did you first hear them?”

She was quite astonished when, for answer, Master Simon burst into a hearty laugh.

“My child,” he said, “that is almost the very question that was asked me forty years ago by my elderly Aunt Matilda of whom I was that moment thinking. And with that scowl upon your face, you look not unlike the severe dame herself as she asked it.”

“Ah, tell me about it,” begged Margeret, the scowl disappearing and the last of her anger quite swept away. She loved her father’s stories, especially those that had to do with his boyhood and that fierce and redoubtable Aunt Matilda.

Master Simon turned to the bench under the linden tree, at the edge of the little enclosed garden, and took her upon his knee.

“And so,” he queried, “that gust of temper is all gone by and you are willing to be friends with your father and mother again? What was it that put you into such a sudden passion? I did not know that you hated so to spin.”

“It was not just the spinning,” returned Margeret, hanging her head. “It was because I was weary of working so much and being so dull and sober. It was because”—here was so terrible a confession that she could scarce bring it forth—“because I did not like to be a Puritan maid and did not want to be good.”

Her father only laughed and held her close.

“We all of us have that same thought at times,” he said, “and in every heart there stirs, now and then, an impatience with the strict and bare Puritan life. We, who, when children, saw some of the glitter and gorgeousness of that golden age in England, the reign of Queen Elizabeth, cannot but feel a longing, sometimes, for that splendid pomp and show from which we have turned aside. It would be odd did not the echoes of our hidden desire still sound in the hearts of our sons and daughters. I can never forget how the great Queen once made a royal progress through the town near which I dwelt, and how I ran in the dust beside her procession, staring with all my eyes at the glittering array. Such shining soldiers, such ladies clad in velvet and cloth of gold, such heavy banners fluttering in the hot air! No Queen in a fairy tale could have shown a more splendid picture. And when I went back to the cottage where I lived with my uncle and aunt, saw him in his dark coat and Aunt Matilda in her scant grey dress, and looked about at the bare walls and the rough furniture, then I, like you, felt suddenly that it was a dreary business this of trying to be a good Puritan. Yet the following of our faith is not all, thank Heaven, in wearing a sober coat and going to meeting six hours every Sabbath.”

“Did you ever see the Queen again?” asked Margeret.

“Yes, I saw and spoke with her once, when I was still a little boy and she was an old woman. How I chanced to see her, and how my staid uncle broke through our strictest Puritan law, are both parts of the story that I was to tell you. Well, we will have the story first and then talk a little further of this grievous business of being a Puritan.

“You must remember,” he began, as Margeret nestled closer against his arm, “since I have told you so often, that all through my boyhood I lived with my uncle at the edge of a great, wonderful garden that belonged, not to any of the people thereabout, but to the English Crown. It was there that Queen Bess, when she was but the Princess Elizabeth Tudor, had lived when she was a girl. There, too, my father, Robert Radpath, who was heir to the neighbouring estates, used to play with her when they were children and up to the time when she became Queen. He never saw her after that day when she set off to London to assume the crown, but he was always loyal in her service and she stood ever his friend. He sailed on many of those long voyages for which Queen Elizabeth’s reign is famous; he and others of her brave sailors risked much that her flag should fly in distant, unknown corners of the world. When my father became a Puritan and the persecuting laws bore so heavily upon all of that faith that even the Queen’s interest seemed powerless to save him, she appointed him upon a mission to China, to bear a message from her to that far country’s mighty ruler. From that voyage he never returned.

“I was a very little boy at the time of his going, but I remember him well and remember, too, the day the royal messenger came with a letter written in the Queen’s own hand ‘To my good friend and old comrade, Robin Radpath.’ He brought also a gorgeously be-ribboned and red-sealed packet that was to be delivered to ‘The Right, High, Mighty and Invincible Emperor of Cathaye,’ with Elizabeth’s signature upon it, written very large for the better reading of a monarch who knew only Chinese. In three days my father had sailed away in one of her great high-prowed ships, sailed to meet disaster in some unknown sea, for he never came home again.”

“And that was how you came to dwell with your uncle?” asked Margeret, for of this portion of her father’s life she never had heard before.

“Yes, my mother being dead, her brother took me to his house where I lived henceforth with him and his sister, my Aunt Matilda. My father’s Puritanism had cost him his estates, but my uncle, a humble man, had escaped the persecution that had, so far, struck only at the great lords. A rigid follower of the rules of his faith was my uncle, but my Aunt Matilda—ah, her strictness and severity left his far behind. He feared no man on earth, yet of his sister he was as afraid as was I.

“After all these years I cannot quite recollect how it befell that my uncle took me with him on a journey to London, it may have been only because I begged so hard to go. Even less can I tell you how he came to do the thing that almost above all else is forbidden to Puritans, to witness a show of play-actors. We were passing down a narrow crowded street when I saw a sign beside a gateway, a great placard setting forth that here within was to be enacted ‘A new play by Master William Shakespeare, The Chronicle History of King Henry the Fifth, and His Glorious Victory of Agincourt.’ I pulled my uncle’s arm to call his attention, he hesitated, passed by the gate, came back again and finally, muttering ‘Say naught of this to your aunt,’ led me within.

“It was a strange sight for the eyes of a little Puritan boy fresh from the country, the rough platform of the stage, the open space before it where stood a motley crowd of the common folk of London, the rows of boxes, and finally the gaily dressed actors who strode forth upon the boards. I believe rain fell upon us as we stood there, and that the sun came out and disappeared again, but to all that I gave little heed, for my heart and soul and eyes were with the gallant King Henry, speeding away to France. It was a play full of clashing arms, of ringing war-cries and hard-fought battles, yet in the midst of it there was one who came forth to describe the higher blessings of a peaceful kingdom, likening it to a beehive, with each member doing his appointed task and having joy in his work. It was thus he spoke of the bees, ‘Singing masons building roofs of gold.’ When the play was over, my uncle led me out, blind and deaf to the sights and sounds of London, only those stirring words ringing in my ears as they do still.”

“And did your Aunt Matilda ever find you out?” inquired Margeret, hot on the trail of the rest of the story.

“My uncle made me promise again never to tell her,” Master Simon continued with a chuckle, “but he might have known that a little boy, so full of one idea as I was of that play, must spill the news abroad somehow. It was the day after our return that I was playing on the grass before our cottage while my aunt sat knitting in the doorway. Suddenly she asked:

“‘Simon, what is it that you are muttering?’

“She spoke so quickly and sharply that I, lost in a maze of dreams that I scarce understood, had no better wit than to tell her the line that was running through my head.

“‘Singing masons,’ she snapped. ‘What means that? There are no such words in the Bible and you have no business to be reading aught else. Where heard you that, Simon?’

“I had my scattered wits collected now, and I pretended not to hear.

“‘I think it is time I fed the hens,’ I said with sudden dutifulness. ‘See, the sun is almost down.’

“‘Not until you answer me,’ she directed, but again I feigned not to hear and hurried across the grass. I heard her get up to follow and then I ran as fast as my short legs would permit.

“‘Simon,’ she called after me, and I trembled lest I be caught and made to confess. I doubt whether she had the least suspicion of my uncle’s iniquity, or whether it was more than her curiosity that had become so roused. But well I knew that once she asked a question she was bound to have an answer.

“Across the poultry yard I fled, despair in my heart, for I heard her footsteps coming close behind. I remember thinking that I could hide almost anywhere, being so little, but that the sun was so low that my great long shadow would betray me wherever I sought shelter. So I climbed the palings that bordered my uncle’s ground, crossed the lane and squeezed through the hedge into the great garden over the way. Far off I could still hear my aunt’s shrill, high voice calling ‘Simon, Simon.’

“I have told you much of that garden, little Margeret, but never, never can I tell you enough; of the spreading trees, the pleached walks that were cool long tunnels in the summer’s heat, and of the high, dark hedges, through whose arches I could glimpse such wealth of colour and sunshine that it seemed I must be peeping into Paradise. I had walked there with my father when I was a tiny boy, and could still remember his tales of how he used to play there with the Princess Elizabeth, and how it was in the little enclosed garden at the centre, still called the Queen’s Garden, that the news had come that the English throne was hers. We often went there together to see the clipped yew-trees that the English gardeners call ‘maids-of-honour’ and to watch the old, old peacock trail his shabby feathers across the grass. The yews, my father said, had been named by the Princess after her own maids-of-honour, and one in particular that would grow thin and straggling in spite of the gardener’s care was called, after an unfortunately ugly and sharp-tempered lady of her company, ‘Mistress Abigail Peckham.’ After my father’s death I used to play there still, although my aunt did not greatly approve. The gardeners—there were but few of them now, and all of them old, because the Queen came almost never to this estate of hers—were kind to me and taught me all I know of flowers and growing things.

“Had I not been in such haste to escape my aunt I should have noticed a group of people at the distant gate, men on horseback and women in hoods and cloaks as though they had come on a journey. I took small heed of them, however, my only thought being that in the Queen’s little garden I should be safe from pursuit, since there scarce any person save myself ever seemed to enter. Yet this time, as I came panting through the hedge, I started back in amazement for there was some one there. A tall woman stood beside the bench and, as she turned toward me, I saw that her hair was red and her skin yellow and wrinkled like old parchment. She was wrapped in a great, grey riding cloak, although between its folds I could catch the glitter of jewelled embroideries and velvet slashed with gold.

“‘Robin!’ she cried out when she saw me and then, in a moment added, ‘No, no, Robin has long been dead.’

“‘My name is Simon,’ I told her, ‘and I dwell with Master Parrish of this village,’ for so I had been taught to say.

“She scarcely seemed to hear me, but stood looking about, her face working oddly as though she wished to weep but had well-nigh forgotten how. Thinking to cheer her, and wishing to show off the garden which I had begun to think of as my own, I touched her arm and pointed to the foremost yew-tree, lank and awkward after all the years.

“‘That,’ I said, ‘is the Lady Abigail Peckham.’

“She looked at me in startled wonder.

“‘How came you to know that, boy?’ she asked sharply.

“‘My father told me,’ I answered, and, going from one to another of the maids-of-honour, I named them all, ‘Cecelia, Eleanor, Gertrude and Anne.’

“‘There is no one but my old play-fellow who ever heard those names,’ she said, the stiffness of her manner melting suddenly. ‘You must be the son of Robin Radpath.’

“‘And you,’ I answered boldly, for her smile had put me quite at ease, ‘must be the great Queen Elizabeth of England.’

“‘Ay,’ she returned, ‘a queen who has outworn her time and who has come back to look once more before she dies upon the place where, of all her life, she was the happiest.’

“She began to move to and fro across the grass, seeming to greet each flower and shrub as though it were an old friend. Suddenly, however, she turned to me again.

“‘Are you of your father’s faith?’ she inquired.

“‘Yes,’ I told her. ‘I am a Puritan.’

“‘You say it boldly, boy,’ she said. ‘Are you not afraid? No, you would scarce be your father’s son, did you show fear. Ah, when I was young, I also was not afraid. I made men do as I willed and I forced a measure of tolerance upon my people. Now I am an old woman, bullied by my Ministers of State, who will not believe that until you let men worship as they will there can be no peace.’

“Then she took my hand and spoke so gravely and earnestly that I can never forget her words.

“‘Hark ye, lad,’ she said, ‘you shall bear a message from the age that is past to the age that is to come, a truth that an old woman has learned in tears and that the next generation, mayhap, must learn in blood. It is that the Gospel of Fear fills no churches, that no terror of imprisonment, pain or death will ever drive men from the religion they hold to be the true one. We of the Church of England have made our mistake and well-nigh learned our sorry lesson, but will you of the Puritan faith have eyes to see more clearly, or will you, too, sow the Gospel of Fear for a bitter reaping?’

“I was but a little boy, Margeret, when I listened to those words, but I shall remember them as long as ever I live. Here in the New England, where we are planting our fields and gardens with all of what we loved best in the Old, we are planting too, as I can see, something more than gardens, the seeds of a new country and a new life. Yet sometimes I fear that in our laws there is too much of harshness and severity, that our faith is more a terror of God’s wrath than a love for His kindness, that we also are planting deep the Gospel of Fear for a sorrowful reaping. It may be I am wrong and that man of fierce speech who cursed my garden was right after all. But, mistaken or not, we are doing a work that will some day prove to be a great one, so that we should all labour happily together like ‘singing masons building roofs of gold.’ That, to my mind, is what it is to be a Puritan. So shall we, Margeret, so easily grow weary of our task merely because the life seems bare and the labour long?”

“No, no,” she cried, slipping from his knee and flinging her arms about his neck, “and if you will come in and mend my spinning wheel, I will set about doing my share this very minute. But do you think that my work for others might some day be a little greater than mere spinning and something not—not quite so dull? Must I wait until I am old to do more than that?”

Her father laughed cheerily.

“No, you need not wait until you are old,” he said, “but it does no harm to be spinning while the greater adventure is tarrying on the way. Who knows, it maybe in waiting for you only just around the corner of the next year.”

The sun stood high overhead as they went up the path together, while through the drone of the bees and the subdued twitter of the birds in the drowsy noonday, Margeret could hear the whirr of her mother’s busy wheel. If all the toilers of hand and heart were like Mistress Radpath and Master Simon, the roofs of gold would soon be built to the very clouds.

The higher task and the larger adventure were nearer to Margeret Radpath than she had thought. Neither she, nor her mother nor Master Simon as they went about their work through all those busy summer months had even a vague dream of what the first days of autumn would bring forth. Hopewell, falling ever into more placid ways with each year of quiet and prosperity, had begun to forget the excitements of its earlier history and to cease talking even of the strange vanishing of Jeremiah Macrae. It seemed, as it always does in peaceful times, as though nothing could ever again stir the calm order of the passing days.

If there was any one who had an inkling of what disturbing matters were in store it was the silent, shabby Roger Bardwell who did Samuel Skerry’s errands, helped to mend Hopewell’s rows of broken shoes and who, in spite of his shyness and the evil reputation of his master, seemed to have won the good will of all who knew him. It began to be that people bringing boots to be mended asked that the apprentice do the work instead of the cobbler himself for, as Goodwife Allen said:

“That surly Skerry makes me feel that with every stitch he puts into the leather he has sewed in a poisoned thought of me and mine.”

At first the shoemaker took such requests as ill-naturedly as you would expect of so sour tempered a man; later he would merely shrug his shoulders and say:

“If the boy wishes to do twice as much work as his master, what have I to say? So be it you pay me the money I care not who bears the labour.” For it was well known that Skerry loved money almost as much as he hated his fellow men.

Throughout this summer it began to happen more and more often that villagers, coming to ask for Roger Bardwell, found only the scowling master-cobbler, and on their inquiring where the boy might be were told that “he was off in the forest somewhere, wasting the precious minutes that might otherwise be turned into good silver coin.”

“Ay, coin for you but not for him,” Goody Parsons retorted one day. “When you pay the boy no wages you have no just cause for complaint if now and then he steals a moment for himself.”

“A moment!” snarled Skerry. “Why, he is often gone for a whole day and a night and sometimes more. He used to waste his time sailing a boat down yonder on the bay, but now he has given up even that pastime for these endless expeditions into the wood.”

“Tell me, friend, what errand takes him there and for such long spaces of time,” inquired the Goody eagerly. “Tell me and I vow I will whisper it to no one.”

The shoemaker rocked back and forth upon his stool in silent, ill-natured glee.

“And this is the dame who had sworn to give over gossiping,” he exclaimed. “No, you would not whisper it, you would shout it louder than could the town crier himself. Therefore I will not tell you.”

“I think you do not know,” returned Goody Parsons with spirit, and she flounced out of his workshop with as much haughtiness as her still old joints would permit. She left Skerry muttering and frowning over her remark, which had evidently come nearer to the truth than he liked. It was not often that the shoemaker’s crafty curiosity failed to penetrate the most hidden mysteries, but in this matter of his helper’s absence he seemed to have met with distinct failure. Whatever it was that took Roger Bardwell so often to the forest, whatever it was that made his blue eyes more serious and his face more sober every day, no questioning or spying on his master’s part served to draw the secret from him.

Margeret Radpath saw him seldom, but even on those rare occasions she noticed how much graver and more troubled he seemed to be as time went by. Was Samuel Skerry so cruel to him, she wondered; was life within the same four walls with the shoemaker’s rasping tongue so hard to bear? She wished often that she might know the truth of the matter and whether she or her father could be of any help.

She was sent one day with Master Simon’s great snow boots that must be mended before the winter, and she tried, all the way across the field, to summon courage enough to offer Roger some word of sympathy and friendship. The shoemaker’s cottage, with its wide-spreading eaves and small deep windows looked somehow of a very lowering and forbidding aspect, as she made her way with failing spirit up the stone-flagged pathway to its door. It had been built almost the first of the cottages of Hopewell, not by Samuel Skerry, but by a stout-hearted weaver, one of the earliest settlers. He had gone now to dwell in Salem but throughout the first and most troubled years of the Colony’s history he had lived here all alone. There was a tale that once an Indian, whom the weaver had made an enemy, had come there in the night seeking to kill the white man who was so bold as to dwell by himself. The weaver, a man of mighty strength, had overpowered the Indian, had cut the web from his loom and had bound his struggling foe to the great armchair that stood by the fire. Then he had calmly mounted once more to his high bench, had set up his weaving and had toiled busily the whole night through, singing as he worked. Neighbours came in the morning and, at the weaver’s orders, released the Indian who slunk off into the forest inspired with a wholesome dread of these mad white men who feared nothing. Margeret thought, as she came up the path, that the cottage looked like just the place where stirring things might have happened in the past and might some day happen again.

On peeping in through the open door she saw that the loom had never been taken down and that even the weaver’s great armchair still held its place before the fire. It seemed dark within, after the bright sunshine outside, but she could make out the figure of Roger Bardwell bending over the shoemaker’s bench in the further corner of the room. His work lay unfinished on his knee and his face was buried in his hands. Utter weariness and despair spoke in his whole attitude. He sprang up quickly, however, when he heard her footstep and greeted her with his shy smile.

“Why, Mistress Margeret,” he was beginning, when he was interrupted by the opening of the back door of the cottage and the abrupt entry of Samuel Skerry.

“So,” said the shoemaker to Margeret, “you have an errand here? Then state it quickly, for ours are busy days and time means good money.”

Dismayed at his harsh tone, Margeret quickly drew the heavy boots from under her arm.

“These are worn in the soles and are to be mended,” she said. “My father says that—”

Skerry broke out in sudden anger as though he could not bear even the mention of Master Simon.

“A pest on you and your father!” he cried. “Do I not hear enough in the village of Master Simon this and Master Simon that, without having to see his own daughter coming to my house to tell me what I should do? Begone from my door and come not here again with your chattering and your tempting my boy into idleness.”

Margeret made no delaying but turned at once to flee. Roger, however, followed her beyond the door and spoke hastily in an undertone.

“You must not mind the shoemaker’s sharp words, little Mistress,” he reassured her. “He seems indeed to bear ill will toward your father, but still I sometimes see him at our door, watching Master Simon in his garden with a look so gentle, almost wistful, that I know not what to think. The boots shall be mended safely, and when they are done I will bring them back. I fear that the scant welcome you have received will make you desire little to come hither again.”

“When he brings the boots,” Margeret reflected, as she walked back through the field, “my father must question him and perhaps can find a way to help him.”

It was just then the season for candle making, the task that Margeret loved above all others of the year. Beyond Master Simon’s garden was a stretch of waste land reaching down to the water’s edge, where grew in a thick tangle, the dark bayberry bushes that so many of the Puritans had thought best to root out of their fields. Master Simon, however, had kept his and had found that from their abundant fruit could be made the green, sweet-smelling tapers that were of such service through the long winter. Tallow was still scarce in the little Colony, and wax candles brought from England far too costly, so this was a brave discovery indeed. Every autumn when the first tang of frost was in the air, all the children of Hopewell gathered to pick Master Simon’s bayberries and a merry task they made of it. Then, for days after, would come the sorting of the fruit, the boiling and skimming and the dipping of the wicks. Slowly the candles would take shape until the moment that was to Margeret a breathlessly exciting one when the first pair were placed in the copper candlesticks on the mantel and were lighted to see if all had been properly done and the tapers burned clear, steady and fragrant as they should.