Cut 1.

Tepoztla.

Title: Mexican Copper Tools: The Use of Copper by the Mexicans Before the Conquest; and the Katunes of Maya History, a Chapter in the Early History of Central America, With Special Reference to the Pio Perez Manuscript.

Author: Philipp J. J. Valentini

Contributor: Juan Pío Pérez

Translator: Stephen Salisbury

Release date: September 24, 2018 [eBook #57961]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Julia Miller and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

| Page. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mexican Copper Tools | 5 | |

| The Katunes of Maya History | 45 | |

| Note by Committee of Publication | 47 | |

| Introductory Remarks | 49 | |

| The Maya Manuscript and Translation | 52 | |

| History of the Manuscript | 55 | |

| Elements of Maya Chronology | 60 | |

| Table of the 20 Days of the Maya Month | 62 | |

| Table of the 18 Months of the Maya Year | 63 | |

| Table of Maya Months and Days | 64 | |

| Translation of the Manuscript by Señor Perez | 75 | |

| Discussion of the Manuscript | 77 | |

| Concluding Remarks | 92 | |

| Sections of the Perez Manuscript Expressed in Years | 96 | |

| Table of Maya Ahaues Expressed in Years | 100 | |

| Results of the Chronological Investigation | 102 | |

| Page. | |

|---|---|

| Copper Axes in the Arms of Tepoztla, Tepoztitla And Tepozcolula | 12 |

| Copper Axes, the Tribute of Chilapa | 13 |

| Copper Axes and Bells, the Tribute of Chala | 14 |

| Mexican Goldsmith Smelting Gold | 18 |

| Yucatan Copper Axes | 30 |

| Copper Chisel Found in Oaxaca | 33 |

| Mexican Carpenter’s Hatchet | 35 |

| Copper Axe of Tepozcolula | 36 |

| Copper Axe of Tlaximaloyan | 36 |

| Copper Tool, Found by Dupaix in Oaxaca | 37 |

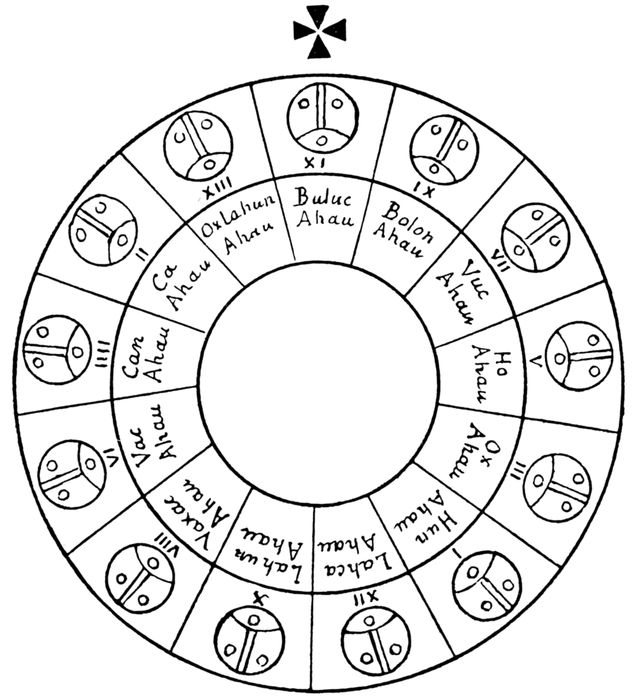

| Maya Ahau Katun Wheel | 72 |

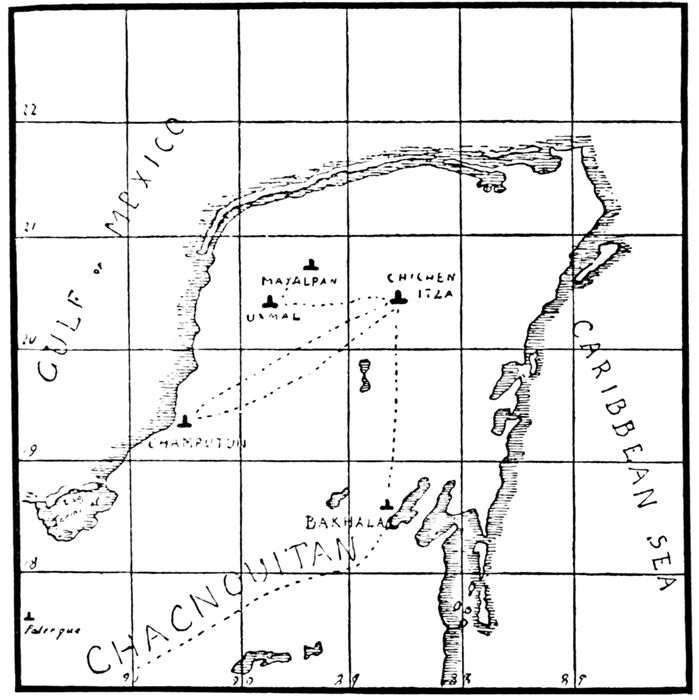

| Map Showing the Movement of the Mayas, As Stated In The Manuscript | 78 |

| Footnote | |

| Yucatan Axe, From Landa | 17 |

| Indian Battle Axe, From Oviedo | 19 |

The subject of prehistoric copper mining, together with the trade in the metal and the process of its manufacture into implements and tools by the red men of North America, has engaged the attention of numerous investigators.

It was while listening to an interesting paper on prehistoric copper mining at Lake Superior, read by Prof. Thomas Egleston before the Academy of Sciences, of New York, March 9, 1879, that the writer was reminded of a number of notes which he had made, some time previous, on the same subject. These notes, however, covered a department of research not included in the lecture of that evening. They were collected in order to secure all the material extant in relation to the copper products of Mexico and Central America. Nevertheless, this treatment of a subject so germain to ours, could not help imparting an impulse to a rapid comparison of the results of our own studies with those of others. It brought to light striking agreements, as well as disagreements, which existed in connection with the copper industries of the two widely separated races. On the one hand it appeared that both of these ancient people were unacquainted with iron; both were trained to the practise of war, and, strange to say, both had invariably abstained from shaping copper into any implement of war, the metal being appropriated solely to the uses of peace.

But, on the other hand, whilst the northern red man attained to his highest achievement in the production of the 6axe, the native of Central America could boast of important additions to his stock of tools. He possessed copper implements for tilling the fields, and knew the uses of the chisel. Besides, when he wished to impart to the copper a definite form, he showed a superior ingenuity. The northern Indian simply took a stone, and by physical force hammered the metal into the required shape. But the skilled workman of Tecoatega and Tezcuco, subjecting the native copper to the heat of the furnace, cast the woodcutter’s axe in a mould, as well as the bracelets and the fragile earrings that adorned the princesses of Motezuma.

Therefore, in view of the recently increasing interest shown in archæological circles, respecting everything relating to Mexico, the writer deemed it worth while to revise the notes referred to.

As to the fact that the early Mexicans used instruments of copper, there can be no doubt. The brevity of the statements respecting these instruments is nevertheless very perplexing. The accounts of the Spanish chroniclers, indeed, afford a certain degree of satisfaction, but they leave us with a desire for fuller information. We should have felt more grateful to these authorities if, out of the thousand and more chapters devoted to the glorious deeds of the “Castellanos and Predicadores,” they had written one in which they had introduced us to the Mexican work-shop, exhibiting the weaver, the paper-maker, the carpenter, the goldsmith, and the sculptor, and initiating us into the devices and methods respectively employed; describing the form and shape of the tools they used, and giving an account of all those little details which are indispensable for achieving any technical or artistical results.

Yet, as it exists, the desired information is incomplete, and, for the present at least, we can only deplore its brevity. In looking for aid from other quarters we feel still more perplexed. No specimen of any copper or bronze tool, apparently, has been preserved, and we are thus prevented 7from determining whether the axes or chisels mentioned by the Spanish authors were of the same shape as ours, or whether the natives had contrived to give them a peculiar shape of their own. Finally, no definite hint is given whether the kind of copper metal, which they called “brass or bronze,” was copper with the natural admixtures of gold, silver, tin, or other tempering elements, or whether the Mexicans had themselves discovered the devices of hardening, and combined the elements in due conventional proportions.

All these questions are of the highest interest, and claim an answer. Our most renowned authorities for Mexican archæology and history, Humboldt, Prescott and Brasseur de Bourbourg,[1] pass over this subject without giving any desired satisfaction. They do not go much farther than to repeat the statements furnished by the writers in the same language as they received them.

These early statements will form the principal portion of the material out of which we weave the text of our discussion. In order that the reader may be better prepared to enter into our reasoning and judge of the correctness of our conclusions, we shall, in translation, place the statements of these authors below the text, in the form of foot-notes; though, in cases where it is believed that the reader may desire to see the originals, the Spanish text is given. Considerable help has been derived from a source hitherto very little consulted, that of the native paintings, which represent copper implements. As will be seen, they make up, to a certain extent, for the deficiency of the latter in collections. The cuts we give are of the same size as those we find copied in the Kingsborough Collection.

8We shall speak first of those localities whence the natives procured their copper and their tin; secondly, of the manner in which they used to melt metals; thirdly, consider whether the metal was moulded or hammered; and fourthly, discuss the various forms into which their tools appear to have been shaped.

That the natives of the New World collected and worked other metals besides gold and silver, seems to have become known to the Spaniards only after their entrance into the city of Mexico, A.D. 1521. During the first epoch, in which the West India Islands and the Atlantic coasts of South and Central America were explored and conquered, no specimen of utensils, tools or weapons, made of brass or copper, was discovered to be in the possession of the inhabitants. So also in Yucatan, Tlascalla, and on the high plateau of Anahuac, where mechanics and industry were found to have a home, and where the native warrior exhibited his person in the most gorgeous military attire, their swords, javelins, lances and arrows, showed that concerning the manufacture of arms they had, so to speak, not yet emerged from the Stone-Age. And finally, when brass, copper, tin, and even lead, were seen exposed for sale in the stalls of the market-place of Mexico, it was noticed to the great astonishment of the conquerors, that these metals had exclusively served the natives for the manufacture of mere instruments of peace.

The Spanish leader communicates these facts to his emperor in these few words:[2]—“Besides all kind of merchandise, I have seen for sale trinkets made of gold and silver, of lead, bronze, copper and tin.” Almost the same expressions are used in the memoirs of his companion, 9Bernal Diaz de Castillo:[3]—“And I saw axes of bronze, and copper, and tin.” Under the influences of such a revelation the hearts of the distressed Spaniards must have been elated with joy and courage, when they saw not only a prospect of replacing the arms which their small band had lost, but also the source from which to equip the faithful Indian allies of Tlascala in an efficient manner. Immediately after having taken firm foothold on the conquered ground, Cortes 10ordered the goldsmiths of Tezcuco to cast eight thousand arrow-heads of copper, and these weapons were made ready for delivery within a single week.[4] At the same time, too, the hope to have a supply of cannon made was presented to the conqueror’s mind. The only question was from whence to procure a sufficient quantity of the material necessary to carry out this design.

Copper is found to-day in nearly all the states of the Mexican Republic. We abstain, therefore, from quoting the localities. But as far as our information goes, no writer or historian has stated where Cortes and before him the natives themselves found it. To investigate this matter might be of direct utility, at least. We intend to use a source hitherto little explored, but which for the history of Mexico is of greatest importance, the picture tables, called the Codices Mexicana. These collections contain representations of their historical, religious, social and commercial life. The writer of this article has made himself familiar with these sources, expecting to find in them disclosures about the location of the ancient copper mines, as soon as he could discover what copper was called in the language of the natives. The answer comes in this connection.

The Mexicans had the habit of giving a name to their 11towns and districts from the objects which were found in abundance in their neighborhood. Therefore, copper regions ought to bear a name which related to this mineral.

In Lord Kingsborough’s Collection, Vol. V., pages 115–124, there are two printed alphabetical indices of the names of all the towns, whose hieroglyphic symbol, or, as we term it, whose coat of arms, is represented in the Codex Mendoza, to be found in Vol. I. of the same collection, pages 1–72. This Codex is arranged in three sections. The first shows the picture-annals of the ancient Aztec-Kings, and the cities which they conquered (pages 1–17). The second reproduces again the coats of arms of these cities, but gives in addition the pictures of all the objects of tribute which these cities had to pay. The third section exhibits an illustration of how Mexican children were trained from infancy up to their 15th year. Sections first and second will claim our interest, exclusively.

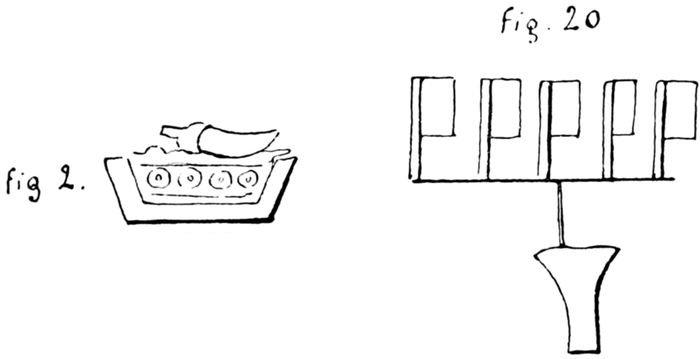

Copper, we learn from the Dictionary of Molina[5] was named in the language of the Nahoa speaking natives, tepuzque.[6] Upon searching in the above quoted Codices, we find three names of towns which are compounds of this 12word tepuzque. Their names appear in the following form: Tepoztla, Vol. I., page 8, fig. 2, and the same name on page 26, fig. 13. Tepoztitla, page 42, fig. 10, and Tepozcolula, page 43, fig. 3.

The cuts 1, 2, 3 and 4, are faithful reproductions of the coats of arms belonging to these towns.

Cut 1.

Tepoztla.

Cut 2.

Tepoztla.

Cut 3.

Tepoztitla.

Cut 4.

Tepozcolula.

There cannot be any doubt as to the meaning of the objects represented by these pictures. They mean axes. Their handles appear in a curved form, the blades at their cutting edges are somewhat rounded, and the tenons of the blades are inserted below the top of the handles. Both handles and blades are painted in a reddish brown color, the wood as well as the copper.

The differences between the pictured representations are the following: Cuts 1, 2, and 4, show the axes growing out from the top of a mountain, whilst the axe of cut 3 appears by itself. Further, the axes of cuts 1 and 2, those of Tepoztla, show something applied to the handle, which in cut 1 we recognize to be a single bow-knot, and in cut 2 the same girdle with a bow-knot, yet wound about a dress of white color, embroidered with red spots. A notable difference, however, will still be noticed between the form of the axes in cuts 1, 2, 3, and that in cut 4, or Tepozcolula. We shall speak of this latter, on a later page, as an instrument very closely related to the other axes.

13By means of these pictures we arrive at the knowledge of the following facts: Copper was undoubtedly found in the neighborhood of the three named cities. Moreover, copper in these cities was wrought into axe-blades. Finally, the axe will turn out to be the symbol used for copper, in general.

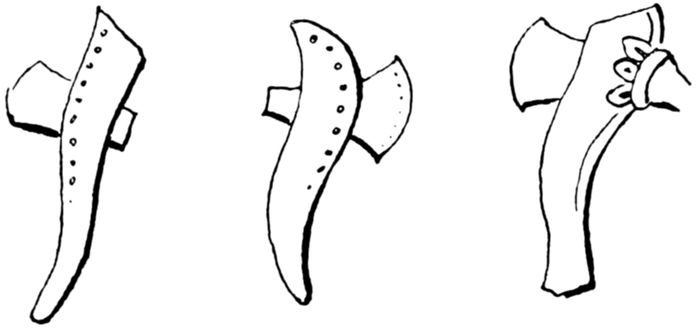

Let us accept these facts and see whether this picture for the symbol for copper does not return on other pages of the same Codex, and thereby gain more information on the subject. We notice the picture of the axe-blade reappearing on the pages 39 and 42. Both happen to bear the same number, that of figure 20, and both belong to the same section of the Codex which contains the pictures of the tributes paid by the conquered towns. Cut 5 is a reproduction of fig. 20, page 39, Codex Mendoza. It shows the metal axe without a handle hanging on a thread from a line upon which we see five flags are painted. Moreover, at the left side is a little picture. A flag in Mexican symbol writing signifies the number twenty.[7]

Cut 5.

Town of Chilapa.

14We may therefore conclude that by this combination one hundred copper axes are indicated. The question now arises, what city may have paid this tribute of copper axes? The painter has not only omitted to connect directly these flags and axe with one of the various coats of arms that are grouped in their neighborhood, but even, if he had done so, the student, still unacquainted with the art of explaining pictures, would be unable to make out the name of the city, embodied in the picture of the coat of arms. We will overcome this difficulty by consulting the interpretation of the Codex Mendoza, which is printed on the pages 39–89 of Vol. V., Kingsb. Collection. There, on page 73, the suggestion is given that the tribute objects refer to the town of Chilapa, whose coat of arms (fig. 2), as we shall notice on the cut, consists of a tub filled with water, and on whose surface the chilli-fruit appears, better known as the Spanish red pepper chilli, red pepper, atl, water, pa, in or above. For this reason we learn that the town of Chilapa was tributary in 100 axes.

Cut 6.

Town of Chala.

In like manner we may proceed with the definition of the picture found on page 42, fig. 20. The copy given in cut 6, shows 80 blades of copper axes in fig. 20, and besides 40 little copper bells in fig. 19, and the interpretation, Vol. V., page 76, informs us that it was the town of Chala, fig. 26, which had to pay this kind of tribute.

Therefore, the towns of Tepoztla, Tepoztitla, Tepozcolula, and, besides, those of Chilapa and Xala, must be considered to have been connected, in 15one way or the other, with copper mining, copper manufacture, and the tribute of the same.[8]

A few words on the procuring of the metal from localities where it was discovered by the natives, may find a suitable place here. Mining, as we understand it to-day, or as the Spaniards understood it already at the time of the conquest, was not practised by the natives. Gold and silver were not broken from the entrails of the rocks. They were collected from the placeres by a process of mere washing. No notice at all has come down to us how copper was gathered. We can, however, easily imagine, that whenever by a chance outcropping a copper vein or stratum became visible, they probably broke off the ore or mineral to a depth easy to be reached, and only selected the most solid pieces. It is evident that the results of such superficial mining must have been very trifling, certainly not greater than would barely suffice for the fabrication of the most necessary tools. Herein we will find an explanation, why this people, though possessing the metal and the technical skill, nevertheless did not use it for the manufacture of arms. The production could not have been abundant enough to supply the whole nation or even the professional soldier with metal weapons. They preferred therefore, to continue in the ignorance of the Stone-Age.

16Where the Mexicans found the lead that was seen in the market-place, nay, even the purposes for which they might have used it, we have been entirely unable to learn. Lead in the language of the Nahoas, is called temeztli (telt stone, metzli moon), moon stone, a name picturesque and characteristic, as were most of those which stand in the list of objects that belong to the realm of nature. Not a single picture referring to lead can be found in the Mexican Codices. The same must also be said of tin, the name of which was amochictl, a word seemingly Nahoatl in form, but whose root was probably derived from a foreign language. It will be gratifying, however, to learn from the pen of the great conqueror Cortes himself, where the natives, and afterwards his followers, found their tin. To quote the language of Cortes,[9] “I am without artillery and weapons, though I have often sent money to obtain them. But as nothing drives a man to expedients so much as distress, and as I had already lost the hope that Your Royal Majesty might be informed of this, I have mustered all my strength to the utmost in order that I might not lose what I have already obtained with so much danger and sacrifice of life. I have therefore arranged to have men immediately sent out in search of copper, and in order to obtain it without delay I have expended a great amount of money. As soon as I had brought together a sufficient quantity, I procured a workman, who luckily was with us, to cast several cannons. Two half-culverines are now ready, and we have succeeded as far as their size would permit. The copper was indeed all ready for use, but I had no tin. Without tin I could do nothing, and it caused me a great deal of trouble to find a sufficient quantity of it for these cannons, for some of our men, who had tin plates or other vessels of that kind, were not willing to part with them at any rate. For this reason 17I have sent out people in all directions searching for tin, and the Lord, who takes care of everything, willed graciously that when our distress had reached its highest point, I found among the natives of Tachco[10] small pieces of tin, very thin and in the form of coins.[11] Making further investigations I found that this tin, there and in other provinces was used for money, also that this tin was obtained from the same province of Tachco, the latter being at a distance of 26 leagues from this town. I also discovered the locality itself of these mines. The Spaniards whom I despatched with the necessary tools brought me samples of it, and I then gave them orders that a sufficient quantity should be procured, and, though it is a work of much labor, I shall be supplied with the necessary quantity that I require. While searching for tin, according to a report from those skilled in the subject, a rich vein of iron-ore was also discovered.

Now supplied with tin I can make the desired cannons, and daily I try to increase the number, so that now I have already five pieces ready, two half-culverines, two which are still smaller, one field-piece and two sacres, the same that I brought with me, and another half-culverine which I purchased from the estate of the Adelantado Ponce de Leon.”

In the above report of Cortes, therefore, we are informed of the name of the locality where tin was found and dug by the natives. So we have the facts established that both copper and tin[12] were dug by the natives, that there was a 18traffic, in them at that time, that Cortes himself succeeded in getting at the mines from which they were extracted, and that he had not been mistaken in his former recognition of their display for sale in the public market.

But before these ores could be shaped into the above named commercial forms, it is clear that they still needed to undergo a process of smelting. As to the peculiar mode of smelting pursued by the natives, we have not been able to find any distinct reference in the writings of the chroniclers. It does not appear that the ancient Mexicans understood the method of the Peruvians of melting their copper in furnaces exposed to the wind on the lofty sierras, but we may form for ourselves an idea of how they proceeded from a picture in Codex Mendoza, page 71, fig. 24.

Cut 7 gives a faithful reproduction.

Cut 7.

Smelting Gold.

In the midst of an earthen tripod, surrounded by smoke and flames, we perceive a small disk of a yellow color. Our attention is called to the peculiar mark imprinted on the surface of the disk. Upon searching in Lord Kingsborough’s Collection, Vol. V., page 112, plate 71, where the interpretation of the little picture is given, we learn, that the man sitting by the tripod, is meant to be a goldsmith. Hence we conclude the disk must be understood to mean a round piece of gold, and that very probably the mark printed on it, was the usual symbolical 19sign for gold.[13] At the right of the tripod sits a man wrapped in his mantle, no doubt the master of the work-shop; for the addition of a flake flying from his mouth, as the typical sign for language or command, gives us a right to suppose that we have before us the so-called temachtiani, or master of the trade. At the left side crouches the apprentice, tlamachtilli. He holds in his right hand 20a staff, one end of which is in his mouth and the other is placed in the crucible. Tlapitzqui, in the Nahoatl language means at the same time a flute player and a melter of metal. This etymological version therefore conveys the idea, that the staff held by the smelter signifies a pipe or tube used for increasing heat by blowing the fire, as the staff is similar to a long pipe or flute and is held in the 21mouth of the workman. In his left hand he holds a similar staff, but there is no means of recognizing whether it is a stick for stirring the embers, or a tube to be used alternately with the other. Now, we shall be permitted to draw a conclusion from this process of smelting gold as to the manner of smelting copper. The process must have been exactly the same with both. For, if the Mexican goldsmith, with the aid of a blowpipe, was able to increase the heat of the fire to such a degree as to make gold fusible, a heat which requires 1,100° C., he cannot have found greater difficulties in melting copper, which requires nearly the same degree of heat; and tin, which is far more easily fusible, could have been treated in the same way.

Melting was followed by casting into forms or moulds, and these moulds must have been of stone. This might be concluded from the language of Torquemada and Gomara.[14] The words “by placing one stone above another 22one” are too clear to leave the least doubt as to what the author meant. This process will account for the absolute identity we had the opportunity to observe existing between certain trinkets of the same class, coming chiefly from Nicaragua and Chiriqui. No specimens of a mould, however, have come to our view, or have been heard of as existing in any collection, probably because whenever they were met by the “huaqueros,” they did not recognize them as such, and threw them away.

The scanty knowledge we have of all these interesting technical details will not be wondered at, if we consider that we derive it from no other class of writers than from unlearned soldiers, and monks unskilled in the practical matters of this world. But still, the principal reason for this want of information is that the Mexican artist was as jealous in keeping his devices secret, as the European. They also formed guilds, into which the apprentices were sworn, and their tongues were bound by fear as well as interest. Let us quote only one instance. The Vice-King 23Mendoza reports to the Emperor[15] that he offered to pardon one of those workmen, if he would disclose how he was able to counterfeit the Spanish coins in so striking a way. But the native preferred to remain silent and was put to death.

Here is the place for asking the question: Would not the early Mexicans, aside from their practice of casting the above metals, have employed also that of hammering? Our reply would be emphatically in the negative, if taking the expression “hammering” in its strict meaning, which is that of working with the hammer. The writers of the Conquest have left the most explicit testimony, that the natives, only after the arrival of the Spaniards became acquainted with this instrument, and with the art of using it for working high reliefs out of a metal sheet. Moreover, the native vocabulary has no word for the metal hammer as it is commonly understood. Yet the wooden mallet was known, the so-called quauhololli, and used by the sculptors. In the gradual education of mankind in technical knowledge, beating of metals, of course, must have preceded casting. The ancestors of the early Mexicans, at a certain epoch, stood on the same low stage of workmanship as their more distant northern brethren. But when the inventor of the mould had taught them how to multiply the objects most in demand, by the means of this easy, rapid and almost infallible operation, we must not imagine that he had done away entirely with the old practice of beating and stretching metal with a stone. The practice, in certain cases, would have been maintained: as for instance, when a diadem, a shield, or a breastplate was to be shaped, and on occasions when the object to be made required the use of a thin flat sheet of metal. Such objects are not only described by the writers, but are also represented by the 24native painters. A specimen of such a kind is mentioned, which on account of its extraordinary beauty, workmanship and value left a deep impression on the conquerors. It was the present which Motezuma made to Cortes at his landing, on the Culhua coast, “the two gold and silver wheels;” the one, as they said, representing the Sun, the other the Moon. According to the measures they took of them, these round discs must have had a diameter of more than five feet. It is preposterous to imagine that round sheets of this size should have been the product of casting.[16]

We pass on now to discuss the various tools which we have reason to think were cast in copper or in bronze, by the early Mexicans.

The axe stands in the first place. Cortes, we shall remember, omitted to specify any of the objects which he saw exposed for sale in the market-place. Not so his companion, Bernal Diaz. He, after a lapse of 40 years, when occupied with the writing of his memoirs, has no recollection of other tools, which he undoubtedly must have seen, except the much admired bronze axes. Specimens of these were sent over to Spain in the same vessel on which the above mentioned presents to the Emperor were shipped. At their arrival at Palos, Petrus Martyr of the Council House of the Indies was one of the first to examine the curiosities sent from the New World, and to gather from the lips of the bearers their verbal comments. His remarks on the axes he had seen, are “with their bronze axes and hatchets, cunningly tempered, they (the Indians) fell the 25trees.” There are three expressions in this passage which will claim our attention. First, we learn that two classes of axes were sent over, one of which Martyr recognized as a “secūris” the other as a “dolabra” hence a common axe, and another which was like a pick or a hoe. Further on we shall give an illustration of these axes, taken from the pictures of the natives, when we are to recur again to this subject. Our author, in the second place, describes the two axes as of bronze, for this is the English rendering of the Latin expression: aurichalcea. Thirdly, we learn, that the blades were “cunningly tempered” or “argute temperata.” This language requires explanation.

The attentive reader will remember what has been said respecting Cortes and Bernal Diaz, whether they recognized the bronze objects in the market as a mixture of copper and tin, of themselves, or whether they had been inquisitive enough to ask for information, and in consequence learned that it was a common practice among the workmen to mix these two metals, in certain proportions, in order to produce a harder quality of copper. The latter hypothesis seems to gain a certain corroboration from Martyr’s language. For there cannot be the slightest doubt as to what he meant when putting down the words “cunningly tempered.” He wished to express the idea, that he had positive grounds for the conviction, that the metal of which the axes were made, was not a natural but an artificial product. What grounds for this conviction he had, he does not, however, communicate to his reader.

Our author has the well deserved reputation of being one of the fullest authorities for all that concerns the discovery and conquest of the western hemisphere. Of all, however, that he has written, the pages containing the landing of Cortes in Yucatan, and the entrance of the Spaniards in the capital of Motezuma, appear to have been the most attractive to the general reader and the student; these pages being torn and soiled in the existing copies of his original 26Latin, as well as of its translation into foreign languages. We mention this circumstance, for it is not without a certain bearing upon our question. It proves how confidently the reading public has drawn upon the author’s statement, and how eagerly students have sought to digest his amazing accounts, quite unsuspicious, however, of the errors in dates as well as facts; admiring rather than criticizing the pompous phraseology of his mediæval Latin, or his often very suggestive but somewhat flighty speculations. In Petrus Martyr, therefore, we may recognize the originator of the widespread theory that the Mexicans possessed the secret of manufacturing bronze in the highest perfection and in accordance with metallurgical rules. We are, however, forewarned. The statement is of importance, and must be weighed before accepting it. We fear it will fail like many genial but unsupported inspirations, of which our author was susceptible. If we ask whence he derived the notion that the bronze tools were “argute temperata” we shall find that he failed to give any authority. Petrus Martyr, whom we often find quoting the full names and special circumstances by the aid of which he gathered the material for his historical letters, does not follow this laudable practice on this occasion, even though the matter was one of importance to investigators like himself. For these instruments of bronze, and many other tools sent over, must have been, in another way, still more interesting to him than the objects of industry themselves. These tools afforded the most palpable proof of an independent industry practised by that strange people beyond the sea; they were a key perhaps also to the riddle, how it was possible to perform those marvels of workmanship. This silence of Petrus Martyr respecting the details of the “argutia” which he professes that the natives employed in manufacturing their bronze is so much the more striking, since we find him enlarging a long while upon their manufacture of paper; and he shows himself correctly informed respecting that 27process. It is clear that the one was as well worth detailing as the other. Therefore we cannot help expressing the suspicion, that whilst he had correct information respecting the one, he had none respecting the other.

It would, however, be venturing too much to reject so important a statement merely on the grounds alleged. In order to save it, we could fairly say, that he omitted his references through carelessness. Accepting this position, let us then seek to ascertain, who his informants might have been, and chiefly inquire what they were able to tell him about the manufacture of bronze in Mexico.

The circumstances accompanying the arrival of the precious gifts from the capital at the Camp of Cortes, their shipping and unlading at Palos, and their registration at the custom-house, are perfectly known. From them we gather the following points: First, no Spaniard had yet set foot in the interior, they were still loitering on the shores of Vera Cruz, where the embassies of Motezuma made their appearance. Hence, they were still shut off from the opportunity of inspecting the workshops of Tezcuco, Mexico and Azcapotzalco, the centres from which this special class of merchandise was spread over the whole isthmus. Cortes, who had many reasons for hastening the transfer of the precious treasures to the ships, without much delay despatched one of them, intrusting two of his friends, Montejo and Puerto Carrero, with the mission of presenting to the Emperor the report of his startling discoveries and the presents coming from the new vassal-king. Petrus Martyr, indeed, mentions these two cavaliers, as being Cortes’ messengers, and it is highly probable that it was from their lips that he gathered among other correct information also that about the manufacture of paper. The special kind of paper he describes, is one which was manufactured and used exclusively on the coast of Yucatan and Vera Cruz, not the paper of the maguey-plant which grows on the high plateaus, but that of the amatl-tree, a native of the 28tierra caliente. Being in the very country where this kind of paper was manufactured, the Spanish writers, therefore, had the opportunity of hearing how paper was made, even, possibly, of seeing the process itself, which they had not enjoyed in the case of bronze. Could they have got the information from the mouths of the embassadors? We know they held shyly aloof. The intercourse was very ceremonious, and difficult besides, since the conversation passed through the two native languages, and we cannot fairly imagine that the technical question of manufacturing bronze should have become one of the topics of inquiry. Moreover, we do not believe that special attention would have been paid to these bronze implements, if we consider the overpowering impression which the richness and rareness of the other objects must have caused them. Finally, would they not have believed the yellow metal to be gold? since they dreamt of nothing else, and were far from imagining that the opulent ruler of Mexico would have made their Emperor a present of poor bronze tools.

We are not able to offer any conclusive evidence against the remarkable statement made by Petrus Martyr. We are fully aware how many positive proofs are required to render it totally invalid. But we deemed it to be our duty not to withhold from our readers the many grave doubts we entertain against its too ready acceptance. We have still to add, that this statement stands isolated and without support in the whole literature of the Conquest. His contemporary writers, indeed, occasionally speak of copper axes that were tempered by an alloy. None of them, however, goes so far as he, to impute to the early Mexicans the preparation of an artificial bronze, as was so manifestly implied by the words, argute temperatis.

The passages which speak about the axes used by the natives are cited below[17]. Three kinds are mentioned, stone, 29copper and bronze axes. The first of them must have been in use among such tribes as lived outside of the circle of Mexican trade and civilization, or among those which intentionally held themselves aloof. For its retention and use the complete absence of ores in certain districts may have had a decided influence, as for instance was the case with the peninsula of Yucatan.[18] The shape of the Yucatecan 30blades and that of the handle and the adjustment of both, at least as far as is shown (see cut 8) by the pictures of the Dresden Codex, which are of genuine Yucatecan origin, appear to have been identical with those of the interior of Anahuac.

Cut 8.

Axes of Yucatan.

Among the copper and bronze axes noted below, those of Nicaragua appear to have been of an uncommonly rich alloy of gold. The reader will smile at Herrera’s account of the shrewdness shown by the native ladies in keeping for themselves the plates of pure gold they were attired with, and burdening the soldiers of Gonzales with heavy metal axes.[19] The axes mentioned by Gomara, undoubtedly came 31from the mines of Anahuac, since their alloy was not only gold, but tin and silver. Gomara is the first who notes the chisel and the borer.

Let us further ascertain, what Father Sahagun[20] is able to tell us about Mexican metal tools. As a teacher of the young native generation, he made it his life’s task to teach his pupils all that concerned the religious belief, the history and the industry of their forefathers. We extract from Lib. 10, Cap. 7, the following passages and translate them as literally as possible: “The goldsmith is an expert in the selection of good metal. He knows how to make of it whatever he likes and does it with skill and elegance. He is conversant with all kinds of devices, and all this he does with composure and accuracy. (Con medida y compas). He knows how to purify the ore, and makes plates of silver as well as of gold 32from the cast metal. He knows likewise how to make moulds of carbon (moldes de carbon), and how to put the metal into the fire in order to smelt it. The unskilful goldsmith does not know how to purify the silver, he leaves it mixed up with the ashes, and has his sly ways in taking and stealing something of the silver.” Further on in Cap. 24: “he who is a trader in needles (agujas), casts, cleans, and, polishes them well; he makes also bells (cascabeles), filters (aguijillos), punches (punzones), nails (clavos), axes (hachas), hatchets (destrales), cooper’s adzes (azuelas), and chisels (escoplos).”

In these two passages is summed up all that we sought to gather piecewise from the writers of the Conquest, on our special question. A few new features, however, are cropping out in this enumeration of implements, which give rise to the suspicion, that the goldsmith is described, not as he worked before the year 1521, but as he had perfected himself and enlarged his technical knowledge through the intervention of Spanish mechanics, in the year of Sahagun’s writing, about 1550. We mean the moulds of carbon, the nails,[21] and the cooper’s adze, of which we read in Sahagun exclusively, and of which no pictures or other evidences of their ante-Spanish existence have been preserved.

Pictures of needles frequently occur in the Mexican paintings. But it is understood that they are without an eye, the introduction of our sewing needle having been an 33actual revelation to the natives. The head of a Mexican needle, or rather pin, was full, and split like that of an animal’s bone. The borer, certainly, had no handle or spiral point. Of all these stitching, piercing and drilling instruments nothing has been preserved, in kind.

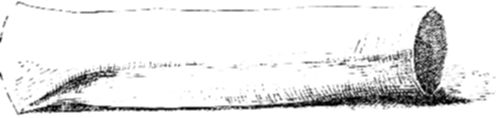

Cut 9.

Copper Chisel found in Oaxaca.

A chisel of copper was, however, discovered by Captain Dupaix[22] near the city of Antequera (in Oaxaca). We give a faithful fac-simile of it in cut 9. It is described by the discoverer in the following words: “There are also many chisels of red copper found in the neighborhood of this city, a specimen of which I possess, and will show in the illustrations. Its length is seven inches, and the thickness is one square inch (sic), and one side is edged, and this edge is a little dull, showing that it had been in use. We do not know the temper they gave to these instruments in order to employ them in their labors and in their arts, or to give the wood or possibly the stone a regular form.”

We do not know if this chisel is still preserved in the Museum of Mexico, to which it was presented by Captain Dupaix. If not, we hope to be somewhat indemnified by another specimen of bronze chisel, of which we are now in pursuit, and which according to description is similar in form and composition to the one spoken of. Señor Andrez Aznar Perez, now in New York, ploughed up such a tool 34about twelve years ago, on his plantation near the river Tzompan in Tabasco, at the depth of nearly 12 inches. It was entirely solid, and had a slightly rounded edge, about an inch in length, and he offers to have it brought from Yucatan for further examination.

From the illustration of Captain Dupaix and the description of Mr. Perez, we can for the moment only conclude that the ancient Mexican chisel was similar in its form to that which our stone-masons now make use of.

In regard to the form of ancient Mexican axes, we gave a general idea at the beginning of this essay, but we have still several details to discuss. In the illustrations the curved wooden handle will no doubt appear remarkable. The Mexican painters were such faithful imitators of what they saw, that we cannot presume they would have indulged in what was an essential alteration of the object to be copied. If the handle of the axe was curved, they would have copied it curved, and thus it appears not only in the Mexican but also in the Yucatecan picture codices.

Those acquainted with the practical handling of axes, and with felling trees, know that a curved handle must increase the swinging power of an axe to a considerable degree, and to have used this form is a remarkable instance of Mexican technical craft and cunning. It would be worth while to investigate whether this use of a curved handle was exclusively confined to the natives of Central America, or had passed beyond its boundaries, north as well as south.

We further learn from the pictures, that not the blade of the axe, but the handle had an opening at a certain distance from the top, into which the blade was fitted.

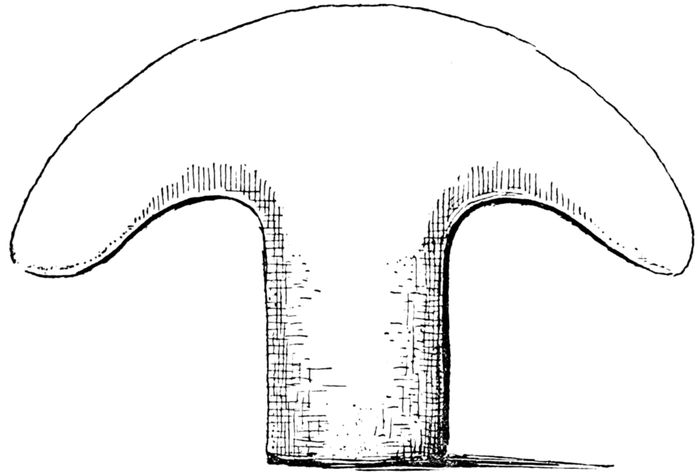

The specimens represented in the cuts 1, 3, 5, 6, 8, appear to be common chopping axes. In the coat of arms of the town of Tepozcolula (see cut 4), however, as already pointed out, the form of the axe differs from those of Tepoztla and Tepoztitlan. In order to obtain a correct idea of these particular kinds of axes, we invite the reader to 35compare it with another picture (Cod. Mendoza, page 71, fig. 77), and which we give in cut 10. The shape of the axes themselves are evidently alike, in the one as well as in the other picture, only that in cut 10 the axe is not in connection with the coat of arms, but is held by a man who is at work dropping or squaring the branch of a tree, from which chips are flying off. This kind of axe, evidently, served a different purpose from those chopping axes of Tepoztla. It was the hatchet used by the carpenter. Thus reads the explanation given in Kingsb. Coll., Vol. V., page 112.

Cut 10.

Mexican carpenter.

This instrument is of the most extravagant form. Were it not for the authentic interpretation of the picture and the accessories we should not be able to make out what kind of object it represented, and least of all that it was a hatchet.

Let us examine its construction. The wooden handle has the shape of all the Mexican and Yucatecan axes,—that of a somewhat curved club. But instead of its being chopped off at the top, the handle extends farther and is bent down to an angle of about 45 degrees. On the head of this bent top a deep notch is visible, into which the blade of a little axe is fixed, being fastened by a tongue or string wound three times around. Thus, when a blow was struck, we can presume, the head of the tenon would not move, from the resistance it met from the bottom of the notch. Thus much the picture proves, and we cannot learn anything more of this instrument. We only presume that in order to get a durable handle, they sought a curved branch, and that this branch came generally from one particular class of trees. The word Tepozcolula signifies, properly, the town in which copper was bent, tepuzque (copper), and coloa (to bend), but we learn from our picture, that the 36natives understood these words to signify the town where the curved handles were manufactured, which seems to be corroborated by another picture which we found for the coat of arms of the town of Tepozcolula, Cod. Mendoza, pl. 45, fig. 5, in which the painter (see cut 11) has laid a special stress upon this curving of the handle, by shaping the end of the handle into an exaggerated spiral form.

Cut 11.

Tepozcolula.

There existed also a town, in which carpenter’s work was the chief occupation of the inhabitants. This is to be inferred from the coat of arms belonging to the town of Tlaximaloyan, cut 12, Cod. Mendoza, pl. 10, fig. 5.

Tlaxima signifies to work as a carpenter, and tlaximalli a chip of wood. The “little” axe of copper, found by Dupaix at Quilapa, and of which he gives an illustration not differing from the known shapes of all axes, is very probably a specimen of this carpenter’s axe (see Dupaix, Vol. II., 3d Expedition, Planche II., fig. 4).

Cut 12.

Town of Tlaximaloyan.

It is but natural to think that being in possession of the large chopping axe, the invention of the small hatchet would have become incomparably easier than that of this awkward carpenter’s tool. We are, however, too little informed to judge or to criticize its construction and rather incline to think that these people had reasons of their own for giving it the form it has. It must have been the one which Sahagun called “destral,” or carpenter’s hatchet.[23]

We can still offer another form of copper tool once used 37by the natives. Dupaix[24] discovered the original near the same town where he had found the chisel. Below is a copy of his drawing in cut 13:

Cut 13.

Copper Tool, found by Dupaix in Oaxaca.

The edge of this tool will be noticed to have a curve belonging to the circumference of a circle. The cutting blade is 10 inches wide. Like the axes, it has a tenon by which it could be fastened to an opening in a wooden handle. It will appear from closer description that it was too thin to have been used for heavy operations. Let us consult the narration of the explorer: “This instrument is of red and very pure copper, and when touched it gives out a sonorous sound. The metal is not hammered but cast. It is of not much weight, symmetrical, and of graceful shape. The contours 38are regular and resemble those of an anchor. It is flat on both sides, the portion serving as a handle (or tenon) is a little thicker and slopes towards the edge, which cuts as well as a chisel. An Indian, named Pascual Baltolano, from the village of Zocho Xocotlan, half a mile distant from this city of Antequera, a few months ago, when tilling his field met with an earthen pot which contained 23 dozen of these blades, their quality, thickness and size being a little different from each other. This gives rise to the supposition that there existed various moulds, by means of which these specimens were multiplied and cast. They did not differ greatly from that which I possess. We meet here with a great difficulty, which is to determine to what usage these instruments were destined,—to agriculture or mechanics, as instruments of sacrifice or a variety of offensive weapon that was fixed in the point of a lance? That which is certain, however, is that they are found in abundance in this province and that merchants buy these metals from the Indians and rank them high on account of the superior quality of the ore.” On proceeding in his expedition, the same author reaches the village of Mitla, where in the parochial church he receives the following disclosure on the purpose of the before-mentioned tools: “One day, when hearing mass in Mitla, I noticed an ancient picture, which represented (San.) Isidro, the patron of the laborers, and saw him painted holding in his right hand a pole armed with the problematic blade. I therefrom conclude, that like the ancient Indians, the native laborers of to-day have adopted this instrument as a distinctive mark of their profession, and that instead of being an instrument of death it must be viewed as one for giving life.” This explanation agrees satisfactorily with what could be inferred from its size and its peculiar shape, and if we imagine the tenon bent and in this form fastened to the top of a pole we should possibly have discovered a certain garden instrument of which the Spaniards spoke as always used by the natives, the uictli, or coa, hoe. It was never described in 39particular, nor could we discover it in the pictures, but Molina’s translation of uictli with “coa” which is hoe, tells the story.

There is still something more in this passage of Dupaix, that is worth considering. Among the 23 dozen of the instruments contained in the earthen pot, and of which he was informed that they were similar in shape to that which he had found, it is clear that there must have been a great number of very diminutive size; otherwise we cannot conceive how so many of them would have been placed in the pot, at all. Let us take advantage of this suggestion and suppose Dupaix’s engraving, cut 13, reduced to a diminutive size. We make thereby a little figure, and we cannot deny that it looks like a Greek Tau. Of such a Greek Tau, formed from copper, and used by the natives as money at the time of the Conquest mention is made by the chroniclers.[25] They may be right, but with the understanding that these copper pieces were not manufactured for the purpose of serving as coin, but as tools, which of course, came into market and became objects of barter, as we read the copper bells also did, besides grains of the cacao fruit, bales of cotton, axes and other articles of common necessity.

Thus much, and no more, we were able to glean from the early literature of the Conquest and from the paintings of the natives. As we anticipated at the outset, the testimony bearing on copper industry among the early Mexicans is altogether incomplete and lacks that fulness of description in which those writers indulge when treating topics of social 40customs, religious rites, or monstrous idols. In but few instances the pictures gathered from the codices illustrate the dim suggestions and the doubtful wording of the Spanish text, so as to give at least a general idea of the localities where the copper ores were obtained, of the process of smelting, of the moulds that were used, and the objects or tools that were produced by these means.

One point however we think we have come very near deciding, and one which when collecting our notes was constantly in mind, namely: Whether the Mexican bronze was to be viewed as an artificial or a natural product? There was a great doubt concerning this question caused by the first notices respecting the composition of the bronze. The expressions of Cortes and Bernal Diaz were of so condensed a character that we were at a loss how to reduce them to their elementary meaning, and the doubt was not removed when examining apart each of the subsequent writers on the same subject. But when putting their statements together, a certain basis, at least, could be obtained, from which to deduce a settled opinion. From the combined statements we learned that the bronze found among the natives contained a rich basis of copper, which was mixed either with gold, or with silver, or with tin, and we might infer from this variety of admixtures, that the natives manufactured their laton according to a fixed method. But, on the contrary, as the three metals named are always found to be the steady components of Mexican copper ore, we are led to the presumption, that these ores were worked in their unaltered condition, just as nature had produced them. It is not indeed meant to teach thereby, that the native did not appreciate the fact, that copper of a deep red was softer than that of a lighter color. Whenever they had to manufacture a chisel and had a choice between the two qualities, we are certain they would have employed the lighter metal for this purpose. But we hardly believe that they considered the light metal 41to be a composition of the red colored copper with either silver, gold or tin. This belief would involve a presupposition of metallurgical science in the early Mexicans, that we have not the least knowledge they had ever attained to. On the other hand, however, there is a strong reason for the belief, that they recognized this light metal to be related to the red copper. For if they had thought this bronze or laton to be a separate kind of metal, they would have had a separate name for it, as they had for all the other metals, from the gold down to the tin, and even to the cinnabar. Bronze would have been called tepuzque as was copper, but probably—with the addition descriptive either of color or of hardness.

We were unable to discover one single hint, from which to infer that they possessed the knowledge of hardening copper by dipping the hot metal into water. This is a hypothesis, often noted and spoken of, but which ranges under the efforts made for explaining what we have no positive means to verify or to ascertain.

Though we have gained so little from our researches, this little, however, we hope may incite others to extend their investigations, and thus render the path clearer which we have tried to explore into this field of prehistoric industry. The most substantial proofs and contributions may be expected from our fellow-students in Mexico. They dwell upon the ground which was the scene of this ancient industry. They are also in a continuous contact with a numerous indigenous race, which despite of European attempts to improve their working facilities, still tenaciously cling to their old usages and fashions. Our Museums are overcrowded with Mexican idols, pottery, and flint arrow-heads. One specimen of an ancient tin-borer, one of a copper axe or hoe, or of a bronze chisel would be counted as a very welcome and valuable acquisition.

The Publishing Committee are glad of the opportunity to print another paper from the pen of Professor Valentini. His previous contributions have been favorably received by some of the most competent judges. He is always ingenious and suggestive, taking care to sustain his views by adequate collateral information, and leaving an impression of earnestness and thoroughness, even though the reader should not be able always to see the way through his bold inferences to the important conclusions deduced from them.

It seems apparent that new phases of opinion respecting the position in the world’s history held by the races occupying the central portions of the American Continent may be looked for in the near future. Or rather, perhaps, it may be claimed that vestiges of ancient and independent culture, of revolutions, conquests, and changing dynasties, extending back to a remote period of time, which have hitherto simply excited and bewildered travellers and explorers, bid fair to be subjected to tests and comparisons derived from wider and closer observation, for which the means are accumulating, and from which definite results are anticipated.

It is remarkable how one tidal wave of investigation after another has, at different eras, invaded and receded from these regions, carrying from them more or less of the fragments of their architectural, monumental, and pictorial records—the sources of doubtful and unsatisfactory interpretation. The Spanish chroniclers; the scientists of the period of Humboldt and his contemporaries; the French government and the learned societies of France, uniting their efforts to render effective the honest but undisciplined enthusiasm of Brasseur de Bourbourg; all have experienced a subsidence of interest arising mainly from a want of success in yielding a sufficiently plausible solution of a mysterious subject. The death of Brasseur, the fall of Maximilian, and the political distractions of the French government and people, are not alone the causes of suspended action on the part of the learned bodies of France. They deemed it prudent to discredit the judgment and correctness of their own agent. One at least of Brasseur’s Commission publicly disavowed responsibility for his opinions; and his attempt to interpret 48the Codex Troano by means of the alphabet of Bishop Landa was pronounced by themselves to be a failure.

How signally the explorations of Del Rio, of Dupaix, of Galindo, and of De Waldeck, failed to make a permanent impression on the public mind! How soon the illustrated narrative of Stephens became in a measure disregarded, and even his reliableness questioned! How completely the nine ponderous folios of Lord Kingsborough’s extensive collection fell dead from the press, until the great work to which he had devoted his life and his entire fortune sold in the market for less than a single useless production of Increase or Cotton Mather! We have seen the elaborate and learned essays of Gallatin upon Mexican civilization slumbering with the long sleep of the Ethnological Society; the Geographical Society cautious about travelling out of the routes of regular expeditions; even the sardonic “Nation,” assumed arbiter in literature, politics, and science, and always ready for caustic criticism, hesitating to venture far beneath the surface of these important inquiries. The ill-fated Berendt has perished in the midst of his unfinished labors; and, lastly, one of the most purely philosophical investigators of Indian habits and history reasons in a direction opposed to the antiquity and extent of aboriginal civilization.

If there is to be a renewal of interest in Mexican archæology, and a revived consciousness of something more to be gained from the relics of culture among the early races of this continent (a meaning in its mystical remains that has not been developed), our Society may claim its share in the re-kindling or fostering of the newly excited impulse. In saying this we do not overlook the preparation which recent studies of the general condition of prehistoric races has created for such investigations; but, in this particular field, it has had the fortune to draw special attention to certain regions and opportunities of research. This has been due to the earnest and liberal exertions of one of its members, who, some years since, passed a winter in Yucatan, and has kept up a correspondence with friends and acquaintances there.[26] He embodied his observations and experiences in a report on behalf of the Council rendered in 1876. He has since endeavored to promote the operations of Dr. and Mrs. Le Plongeon in the actual field, and has assisted in preparing the papers of Professor Valentini for our publications, providing illustrations in all cases when practicable. The Report of the Council in the present number of “Proceedings” is largely devoted to an account, by the writer[27] of a visit to the city of Mexico, and his observations upon the country and its history. More than twelve years ago, in January, 1868, a generous member of the Society[28] had the forethought to establish a department of the library composed of books relating to Spanish America, beginning with the gift of Lord Kingsborough’s mammoth publication, and others, for the 49specialty of antiquities, and accompanied by a pecuniary foundation for future growth. The importance of a provision for this particular purpose becomes daily more conspicuous as attention is directed to that portion of the continent.

It is gratifying to perceive that such movements, with the greater activity in publishing its “Anales” on the part of the Museo Naçional de México, and the issue of such publications as that of Prof. Rau by the Smithsonian Institution,[29] and the private work of Mr. Short,[30] are not without their influence.

The scheme, which, although not fully matured, we have reason to believe a real one, of sending an expedition to some of the original Mexican provinces for a thorough exploration, at the cost of a wealthy citizen of New York, the results to be printed in the North American Review, may be regarded as one of the fruits of the “Renaissance.”

In the ensuing discussion an attempt is made to explain the so-called “Katunes of Maya history.”

The Manuscript which bears this name is written in the Maya language, and its discovery is of comparatively recent date. At its first publication in 1841 it could not fail to attract the attention of all those who were engaged in the study of ancient American history, because it unveiled a portion of the history of Yucatan, which had been till then entirely unknown and seriously missed. At that date only a scanty number of data, loosely described, and referring to an epoch removed from the Spanish conquest of the Peninsula by only a few decades, had appeared as the sole representatives of a long past, in which the builders of the ruined cities undoubtedly must have lived an eventful life, not to be counted by a few generations, but by a long and hardly calculable number of centuries. This vacuum of time the manuscript promised to fill out. Though it did not offer a history conceived in the common acceptation of the 50word, the brief epitome of events which it presented, began by telling us of the arrival of foreigners from distant lands, who, step by step succeeded in conquering the Maya soil and who were brought into significant connection with the name as well as the fall of cities now lying in ruins over the whole country.

As to the authenticity of the events reported, they have been received by many students with a confidence and faith rarely manifested when discoveries of such importance are brought to light. As to the form in which they were presented, the author seemed to exhibit neither the skill of a professional nor the clumsiness of an occasional forger. If on the one hand the gaps he left betrayed a defective memory, this circumstance should be held rather as an indication of his credibility. The material from which his information was derived, we might add, was extensive, and much of it was probably lost when he gave the account at a later period of his life.

The events communicated being in themselves of the highest interest, rose in importance from the fact that they were arranged in successive epochs. A chance was thereby given to calculate the long space of time that intervened between the arrival of the ancient and of the modern conquerors. This difficult task was attempted by the fortunate discoverer himself, Señor Juan Pio Perez, of Yucatan, accompanied by a learned discussion on ancient Maya chronology. His calculation furnishes the sum of 1392 years, the first initial date to be assigned to the year 144 A. D., and the last to 1536 A. D.

When, some years ago we undertook to examine the argument of Señor Perez we were not at all astonished by the great antiquity of the date he had drawn from the Maya Manuscript. For, nearly at the same time, we had reached similar results in an attempt made to utilize certain records which Ixtlilxochitl (1590), and Veytia (1760), (Kingsborough Collection, Vols. 8 and 9), have left regarding the earliest chronology of the Nahuatl tribes. By adopting a more 51rational method of computation than these Mexican writers had followed, we were unable to withstand the conclusion, that the Nahuatl people who were immediate territorial neighbors of the Mayas, considered the year 258 A. D. the earliest date of their arrival on and occupancy of the Mexican soil. Thus we had reached in this line of investigation very nearly the same results with the Nahuatl as Señor Perez with the Maya chronology, and the suspicion began to dawn upon us that these two neighboring people might, possibly, have stood in a still closer than a mere territorial connection.

These results, however, were only of a very problematical nature. They were derived from written reports, which, after all, could not be regarded as unquestionable authority. But they received a strong confirmation from a discovery we made later on the so-called Mexican Calendar Stone. In our discussion of this monument we believe that we have given ample proof of the fact, that its principal zone contains a sculptured record, showing a series of numerical symbols, from the computation of which the year 231 A. D. resulted as that which the Nahuatls had accepted as the first date of their national era.

Records presented in stone and compiled by the nation whose history they convey, must always be considered the most authentic evidence of historical truth. Now, were we also so fortunate as to possess some Maya monument, similar to the Mexican Calendar Stone, and were we also able to decipher it, we should thereby have the means for determining whether Maya chronology extended back to an epoch different from that of the Nahuatl, or to one identical with it. That such a monument once existed we have no doubt. That it may still exist, we have no reasonable grounds for denying the possibility. It remains, however, still to be discovered and to be interpreted. But since the fortunate discovery has not yet been made, we must rest satisfied for the present with conclusions derived from extant written records. The only manuscript of this character thus far 52brought to light, is that said to have been found at Mani,[31] which was translated by Señor Perez from the Maya language, and accompanied by a very valuable chronological interpretation.

Since the close revision we undertook of the latter, brought out very striking coincidences of early Maya dates with those of the Nahuatl, and especially with that indicated on the Calendar Stone, we thought it worth while to reprint the manuscript, to discuss its contents again, and to arrange them under new points of view. Regarded by itself, the manuscript, indeed, might seem of only doubtful value in settling an important chronological question. But the comparison of its earliest date with that of the Nahuatl monument will enhance the value of each of them, because they may be considered as corroborative of each other.

Note.—This Manuscript has also an introduction and close, which Señor Perez has not published, because the dates specified occurred in the Spanish epoch, and consequently were of no interest to the Maya student.

In the interest of authenticity it is much to be regretted that neither the name of the author, his residence, nor the date when the Manuscript was written, are known to us, and we are also ignorant of other matters of moment; whether the Manuscript is an original or a copy, or how often copied, or by what family or person it may have been preserved before it came into the hands of Don Juan Pio Perez. That Yucatecan gentleman had retired from Mérida, the capital, to the District of Peto, to devote himself to his favorite studies, the ancient language and the history of his nation. The unusual interest that he showed in this direction, united to his influential position as first officer of 56the district, enabled him to obtain many small manuscript documents known to have been written by the natives in their vernacular language, the Maya, soon after the time of the conquest, which, for the most part, contained historical reminiscences of the time of the supremacy of their ancestors. Among these manuscripts there was a so-called Chilam Balam Calendar, which, in the form of an appendix, contained, besides, the outlines of the primitive history of Yucatan. It was, indeed, but a brief epitome of historical events, accompanied by the corresponding dates. But its value consisted in the circumstance that these dates were catalogued according to successive epochs; and it required only slight inspection to disclose the fact that they extended back to a period not very distant from our Christian Era.

This was a discovery to the learned world as welcome as any that could be made. It was unique in its kind. All attempts, thus far, had vainly sought to learn something about the history of the builders of those palaces and temples with whose ruins the peninsula was covered at the date of the arrival of the Spaniards, and which pointed to a long past and to the unceasing activity of a numberless population, which, while it was skilled in the most important branches of art and industry, and familiar with a luxury such as only ancient Asia and India had displayed, was yet governed by a despotic and hierarchical power. The native, when asked whose work the ruins were, would answer nothing but that they owed their origin to men who, in ancient times, had immigrated from far distant countries.

The Manuscript disclosed at once the history of these strange immigrants, showed the progressive march of the conquest, and the contemporaneous foundation of the largest cities then in ruins, and furnished in the Maya language the chronology of each event and its corresponding epoch. By means of his extensive antiquarian knowledge Señor Perez made an exact translation of this Manuscript into Spanish, and afterwards undertook a critical interpretation 57of its contents, and accompanied the whole with an introductory explanation of the system of ancient Maya chronology.

In the midst of these labors he was surprised by the arrival of the celebrated American traveller and archæologist, John Lloyd Stephens, and was induced to entrust to him a copy of the MSS. and interpretations to be embodied in his work on Yucatan, in order to bring them more fully before the world. His wishes were scrupulously complied with, and the Spanish translation has been rendered into literal English by Mr. Stephens in “Incidents of Travel in Yucatan,” vol. I., Appendix, pages 434–459, and vol. II., Appendix, pages 465–469.

Mr. Albert Gallatin, who, of all American students, has made himself most thoroughly acquainted with what remains of the historical elements of the Nahuatl and Maya people, has brought together the results of his investigations in a lecture published in the “Transactions of the American Ethnological Society,” New York, 1858, vol. I., pages 104–114. The information therein contained attests an entire familiarity with the method pursued by Señor Perez in his commentary, without, indeed, undertaking any severe criticism of it. In our opinion Mr. John L. Stephens and Mr. Gallatin are the only Americans who have recognized Señor Perez’s merits in an unequivocal manner, and have brought them to the knowledge of the world.

This is all we could learn about the Manuscript, nor have we been able to form a supposition, much less to discover in the text itself any clue to the source from which the unknown Maya author could have drawn his data. At the end of the Manuscript Señor Perez gives his opinion that the whole was written from memory, because it must have been done long after the conquest, and after Bishop Landa had publicly destroyed much of the historical picture-writing of the Mayas by an auto-da-fé, and because the whole narration is so concise and condensed that it appears more like an index than a circumstantial description of events.

58These opinions of Señor Perez might cast a well grounded suspicion on the authenticity of the manuscript. We shall try to remove such doubts, at once, by presenting the following considerations. We do not believe that Bishop Landa succeeded in burning the entire treasures of Maya literature at the notorious auto-da-fé in the town of Mani in 1561. The authorities[32] to which we have access describe the number of the destroyed objects so precisely that we have every reason to confide in their correctness. We read of 5,000 idols of different size and form, 13 large altar stones, 22 smaller stones, 197 vessels of every form and size, and lastly of 27 rolls (sic) on deerskin covered with signs and hieroglyphics, given to destruction at that time and place. We may believe that the terrorism exercised by Bishop Landa had a powerful influence on the minds and on the newly converted consciences of the natives, and the Bishop no doubt used every possible means to get into his hands as much as he could of what he considered to be “cabalistic signs and invocations to the devil.” But we can never believe that these 27 rolls represented the entire Maya literature, collected for hundreds of years with the greatest care and held sacred by the natives. Such a wholesale destruction would have been an impossibility. We could refer to a similar occurrence that took place in Mexico; and though Bishop Zumarraga has the bad reputation of having destroyed all the picture treasures of the Nahuatls by an auto-da-fé, there were notwithstanding so many of them in existence soon after his time in the possession of native families that Ixtlilxochitl, Tezozomoc, and others, were able to build up their detailed accounts of the primitive history of their country from these original sources. Possibly numbers of them may have been preserved among the Maya tribes, for only under such favorable conditions could Cogolludo, Villagutierre and Lizana have obtained 59the valuable information and material which form the chief interest of their labors and researches, and which enabled also Pio Perez in the year 1835, to discover material from which to interpret so complete a description of the system of Maya chronology. Nay, even, we have a suspicion that Bishop Landa may have laid aside the most important part of these records, or what was the most intelligible to him, for we cannot comprehend how he would have been able without these pictures before his eyes to present in his work the symbols for the days so correctly, and also those for the months, or how otherwise he could have written his work in Spain, so far removed from all sources of information and from consultation with the natives.

No reason, therefore, exists why the Maya author should not have remained in possession of some painting, which exhibited the annals of his forefathers. If, however, he was compelled to write his “Series of Katunes” from memory, there is no reason for not relying on the accuracy of his retentive faculties alone. The noble Indians, and he belonged undoubtedly to this class, were very particular in training their sons to learn by heart songs expressing the glorious deeds of their ancestors. It is a fact attested by the Spanish chroniclers, that these songs were recited publicly in the temples and on solemn religious occasions. They were the only kind of positive knowledge with which we know the brains of the Indian pupils were burdened. In either case, therefore, the accuracy of the written Maya report needs not be doubted, at least not on the grounds alleged. Had it been composed in the Spanish language instead of Maya, we should have viewed this circumstance with a more critical eye. But as the native under Spanish rule expressed it in his native language, this kind of loyalty appears to us to give a certain warranty of dealing with a man who described the traditions of his oppressed race, and who wished to perpetuate its memory by handing down to posterity the principal events of the past history of his nation.

60At this place, we should not like to omit pointing out an interesting suggestion which the clear headed and sagacious author, Señor Eligio Ancona[33] made in his before mentioned work, that Bishop Landa and the author of the Manuscript agree so often in their mention of historic dates, in the manner as well as the matter, as to lead to the idea that both drew their information from the same source. Whatever be its origin, we agree with the views of Señor Perez, that, in spite of the deficiency and breaks occurring in the Manuscript, it deserves critical attention as the only document thus far discovered that gives information of the early history of Yucatan.

It is impossible to understand the Manuscript before obtaining a knowledge of the division of time prevalent in Yucatan before the Spanish Conquest. Señor Perez has the incontestable merit of having been the first to lay before the world not only the chief points of the system but also all the technical details. Before his time but little was known of Maya chronology. From the great historic works of Torquemada, Herrera and Cogolludo, we learn only that the Mayas, in conformity with the Mexicans, held that the solar year was composed of 360 days, and when these were passed they added 5 days more as a correction. We are told that both nations divided their years into 18 months, and their months into twenty days each. As to the longer periods of time, however, we hear of certain differences. While the Mexicans had an epoch of 6152 years which they divided into 4 smaller periods, the so called Tlapilli, each of 13 years, the Mayas counted a great epoch of 260 years, the so called Ahau Katun, subdivided into 13 smaller periods each of 20 years, with the simple name Ahau. This period of 20 years was according to Cogolludo[34] subdivided again into what he calls lustra of 5 years each, but he does not give the native name of this division.

62The discovery of the Manuscript, no doubt, induced Señor Perez to make a systematic and detailed sketch of the early native chronology of his country. We shall mention only the most interesting and important of his details and refer the reader for the rest to Stephens’ work already mentioned. The names of the 20 days in the month are as follows:—

| 1 | Kan. |

| 2 | Chicchan. |

| 3 | Quimij. |

| 4 | Manik. |

| 5 | Lamat. |

| 6 | Muluc. |

| 7 | Oc. |

| 8 | Chuen. |

| 9 | Eb. |

| 10 | Been. |

| 11 | Gix. |

| 12 | Men. |

| 13 | Quib. |

| 114 | Caban. |

| 215 | Edznab. |

| 316 | Cavac. |

| 417 | Ahau. |

| 518 | Ymix. |

| 619 | Yx. |

| 720 | Akbal. |

63The 18 months were as follows:—

| 1 | Pop (16th of July.) |

| 2 | Uoo (5th of August) |

| 3 | Zip (25th of August). |

| 4 | Zodz (14th of September). |

| 5 | Zeec (4th of October). |

| 6 | Xal (24th of October). |