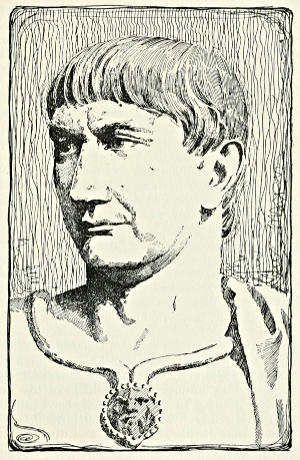

MOMMSEN

Title: The historians' history of the world in twenty-five volumes, volume 06

the early Roman Empire

Editor: Henry Smith Williams

Release date: October 17, 2018 [eBook #58124]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note: As a result of editorial shortcomings in the original, some reference letters in the text don’t have matching entries in the reference-lists, and vice versa.

MOMMSEN

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME VI—THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Press of J. J. Little & Co.

Astor Place, New York

| VOLUME VI | |

| THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE | |

| PAGE | |

| The Early Roman Empire: A Sketch, by Dr. Otto Hirschfeld | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |

| The Scope, the Sources and the Chronology of the History of Imperial Rome | 15 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| The Empire and the Provinces (15 B.C.-14 A.D.) | 25 |

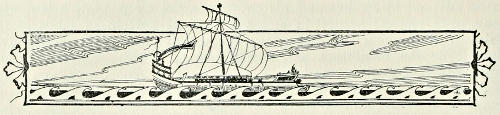

| Augustus makes Egypt his private province, 43. Administration of the provinces, 47. Army and navy under Augustus, 49. | |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

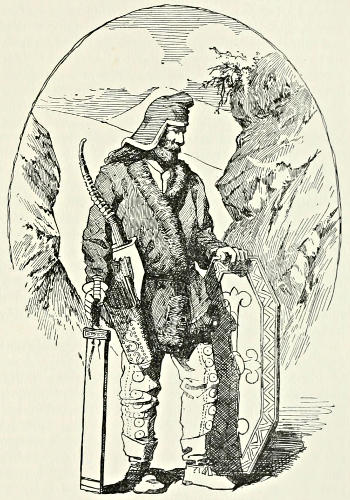

| The German People and the Empire (16 B.C.-19 A.D.) | 56 |

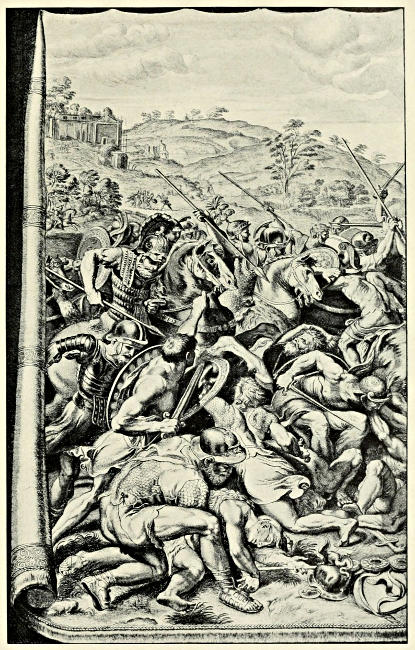

| The German War of Independence against Rome, 59. The battle of Teutoburg Forest, 64. The campaigns of Germanicus, 69. Victories of Germanicus, 71. Gruesome relics in Teutoburg Forest, 72. The return march, 72. Battling with Arminius, 74. Germanicus recalled to Rome, 76. End of Marboduus and Arminius, 76. | |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| The Age of Augustus: Aspects of its Civilisation (30 B.C.-14 A.D.) | 78 |

| Empire is peace, 78. Comparison between Augustus and Napoleon III, 80. The Roman Empire compared with modern England, 84. The Roman constitution, 86. Augustus named imperator for life, 87. The imperator named Princeps Senatus and Pontifex Maximus, 88. Tightening the reins of power, 90. Panem et Circenses: Food and games, 91. Pauperising the masses, 92. Games: Gladiatorial contests, 94. Races and theatricals, 96. Novum seculum: The new birth for Rome, 97. Literature of the Golden Age, 101. Merivale’s estimate of Livy, 107. Livy as the [viii]artistic limner of the Roman people, 109. The spirit of the times, 112. | |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| The Last Years of Augustus (21 B.C.-14 A.D.) | 116 |

| The personal characteristics of Augustus, 120. A brief résumé of the character and influence of Augustus, 129. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| The Immediate Successors of Augustus: Tiberius, Caligula, and Claudius (14-54 A.D.) | 133 |

| Tiberius (Tiberius Claudius Nero Cæsar), 133. Expeditions of Germanicus; victory of Idistavisus, 134. Early years of successful government by Tiberius, 134. Death of Germanicus; external affairs, 136. Internal government, 142. Velleius Paterculus eulogises Tiberius, 148. The fall of Sejanus, 151. Tacitus describes the last days of Tiberius, 154. Suetonius characterises Tiberius, 156. Merivale’s estimate of Tiberius, 157. The character of the times, 159. Caligula (Caius Julius Cæsar Caligula), 160. Suetonius describes Caligula, 163. Claudius (Tiberius Claudius Drusus Cæsar), 168. The misdeeds of Messallina described by Tacitus, 171. The intrigues of Agrippina, 176. Tacitus describes the murder of Claudius, 178. The character of Claudius, 179. The living Claudius eulogised by Seneca, 180. The dead Claudius satirised by Seneca, 181. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| Nero: Last Emperor of the House of Cæsar (54-68 A.D.) | 184 |

| Nero (Claudius Cæsar Drusus Germanicus), 184. Corbulo and the East, 186. The Roman province of Britain, 188. The war with Boadicea, Queen of the Iceni, 190. Britain again a peaceful province, 193. Burrus and Seneca, 194. Octavia put to death, 196. The great fire at Rome; persecution of the Christians, 199. Conspiracy met by cruelty and persecution, 202. Personal characteristics of Nero, according to Suetonius, 206. Merivale’s estimate of Nero and his times, 208. Nero in Greece, 215. Nero’s return to Italy and triumphant entry into Rome, 218. Discontent in the provinces, 219. Galba is saluted imperator by his soldiers, 220. The death of Nero, 223. | |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and the Three Flavians (68-96 A.D.) | 225 |

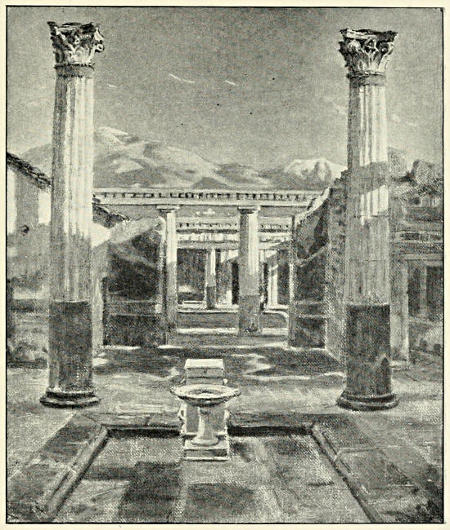

| Galba (Servius Sulpicius Galba), 225. Otho (M. Salvius Otho), 226. Vitellius (Aulus Vitellius), 228. Vespasian (T. Flavius Sabinus Vespasianus), 231. Vespasian performs miracles and sees a vision, according to Tacitus, 232. Vespasian returns to Rome, 233. Titus continues the Jewish war, 234. Josephus describes the return [ix]of Titus and the triumph, 236. The empire in peace, 240. Banishment and death of Helvidius, 241. Sabinus and Epponina, 242. The character and end of Vespasian, 243. A classical estimate of Vespasian, 244. Personality of Vespasian, 246. Titus (T. Flavius Sabinus Vespasianus II), 247. The destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum, 250. Pliny’s account of the eruption, 253. Agricola in Britain, 255. The death of Titus, 255. Domitian (Titus Flavius Domitianus), 257. Suetonius on the death and character of Domitian, 261. A retrospective glance over the government of the first century of Empire, 262. | |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| The Five Good Emperors: Nerva to Marcus Aurelius (96-180 A.D.) | 267 |

| Nerva (M. Cocceius Nerva), 267. Trajan (M. Ulpius Trajanus Crinitus), 268. The first Dacian war, 269. Trajan dictates terms to Decebalus, 271. The second Dacian war, 273. Oriental campaigns and death of Trajan, 274. The correspondence of Pliny and Trajan, 276. Trajan’s column, 277. Hadrian (P. Ælius Hadrianus), 280. The varied endowments of Hadrian, 281. Hadrian’s tours, 282. Hadrian as builder and administrative reformer, 284. Personal traits and last days of Hadrian, 286. Renan’s estimate of Hadrian, 288. Hadrian as patron of the arts, 289. Antoninus (Titus Aurelius Antoninus Pius), 290. Renan’s characterisation of Antoninus, 292. Marcus Aurelius (M. Ælius Aurelius Antoninus), 294. The plague and the death of Verus, 296. Border wars, 296. The revolt of Avidius, 299. An imperial tour and a triumph, 300. Last campaigns and death of Aurelius, 303. Merivale compares Aurelius and Alfred the Great, 305. Gibbon’s estimate of Marcus Aurelius and of the age of the Antonines, 305. | |

| CHAPTER XXXVII | |

| The Pagan Creeds and the Rise of Christianity | 307 |

| Stoicism and the Empire, 308. Christians and the Empire, 313. The Christian and the Jew, 315. Religious assemblies of the Christians, 317. Christianity and the law, 318. The infancy of the Church, 320. Persecutions under Nero, 321. Persecution under Trajan and the Antonines, 324. | |

| CHAPTER XXXVIII | |

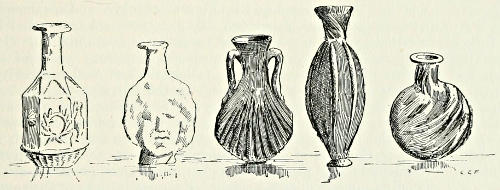

| Aspects of Civilisation of the First Two Centuries of the Empire | 329 |

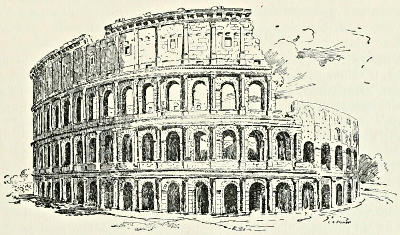

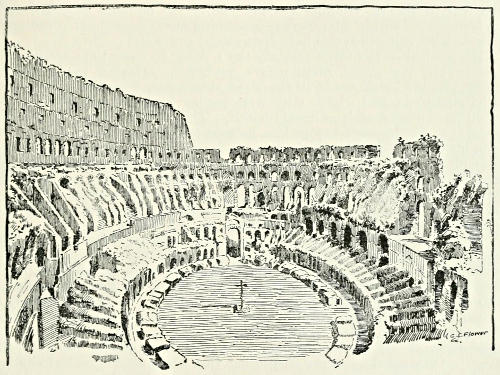

| The spirit of the times, 329. Manners and customs, 335. Suppers and banquets, 339. The circles, 342. Public readings, 345. Libraries and book-making, 346. The ceremony of a Roman marriage, 349. The status of women, 352. Paternal authority and adoption: The slavery of children, 356. The institution of slavery, 359. Games and recreations, 367. The Roman theatre and amphitheatre, 370. Sheppard’s estimate [x]of the gladiatorial contest, 375. | |

| CHAPTER XXXIX | |

| A Half Century of Decline: Commodus to Alexander Severus (161-235 A.D.) | 377 |

| Commodus, 378. Cruelties and death of Commodus, 379. Pertinax (P. Helvius Pertinax), 382. Julianus (M. Didius Severus Julianus), 383. Severus (L. Septimius Severus), 385. Conquests of Severus, 387. Caracalla (M. Aurelius Antoninus Caracalla), 391. Macrinus (M. Opilius Macrinus), 393. Elagabalus (Narius Avibus Bassianus), 395. Dion Cassius on the accession and reign of Elagabalus, 396. Alexander Severus (M. Aurelius Alexander Severus), 400. Renan’s characterisation of the period, 403. | |

| CHAPTER XL | |

| Confusion Worse Confounded: The Second Half of the Third Century of Empire (235-285 A.D.) | 406 |

| Maximin (C. Julius Verus Maximinus), 408. Rival emperors and the death of Maximin, 409. Pupienus (M. Clodius Pupienus Maximus), Balbinus (D. Cælius Balbinus), and Gordian (M. Antonius Gordianus), 411. Philip (M. Julius Philippus), 412. Decius (C. Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius), 413. Gallus (C. Vibius Trebonianus Gallus), 414. Æmilianus (C. Julius Æmilianus), 414. Valerian (P. Licinius Valerianus) and Gallienus (P. Licinius Gallienus), 415. Gallienus (P. Licinius Gallienus), 417. The thirty tyrants, 418. Claudius (M. Aurelius Claudius), 420. Aurelian (L. Domitius Aurelianus), 421. Aurelian walls Rome and invades the East, 422. Zosimus describes the defeat of Zenobia, 423. The fall of Palmyra, 424. Aurelian quells revolts; attempts reforms; is murdered, 426. Tacitus (M. Claudius Tacitus), 427. Probus (M. Aurelius Probus), 428. The Isaurian robbers, 430. Carus, Numerianus and Carinus, 431. | |

| CHAPTER XLI | |

| New Hope for the Empire: The Age of Diocletian and Constantine (286-337 A.D.) | 433 |

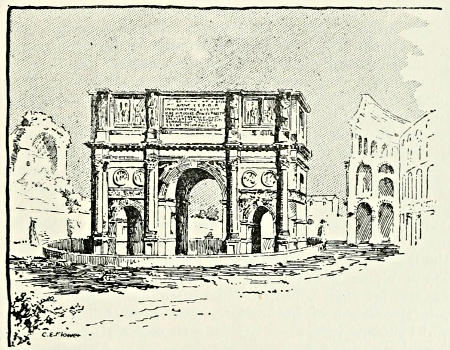

| Diocletian appoints Maximian Co-Regent, 433. The fourfold division of power, 434. Diocletian persecutes the Christians, 436. Abdication of Diocletian and Maximian; the two new Cæsars, 437. Strife among the rulers, 438. Constantine wars with Maxentius, 439. Struggle between Constantine and Licinius, 442. The long truce between the emperors: Reforms of Constantine, 445. Constantine and Licinius again at war, 447. Constantine besieges Byzantium, 448. Constantine, sole ruler, founds Constantinople, 450. The old metropolis and the new: Rome and Constantinople, 453. Character of Constantine the Great, 454. Constantine and Crispus, 457. The heirs of Constantine, 460. The aged Constantine and the Samaritans, 462. Last days of Constantine, 465. | |

| CHAPTER XLII | |

| The Successors of Constantine to the Death of Julian (337-363 A.D.) | 466 |

| War of the Brother Emperors, 469. Constantius and Magnentius, 470. Constantius [xi]sole emperor, 472. The fate of Gallus, 476. Constantius and Julian, 477. The Quadian and Sarmatian wars, 478. Sapor’s invasion of Mesopotamia, 479. Julian in Gaul, 481. Julian repulses the Alamanni and the Franks, 483. Expedition beyond the Rhine, 485. Julian as civic ruler, 486. The jealousy of Constantius, 488. Julian acclaimed Augustus, 491. Constantius versus Julian, 493. The death of Constantius; Julian sole emperor, 497. The religion of Julian, 498. Julian invades the East, 499. A battle by the Tigris, 503. The pursuit of Sapor, 505. Julian’s death, 508. | |

| CHAPTER XLIII | |

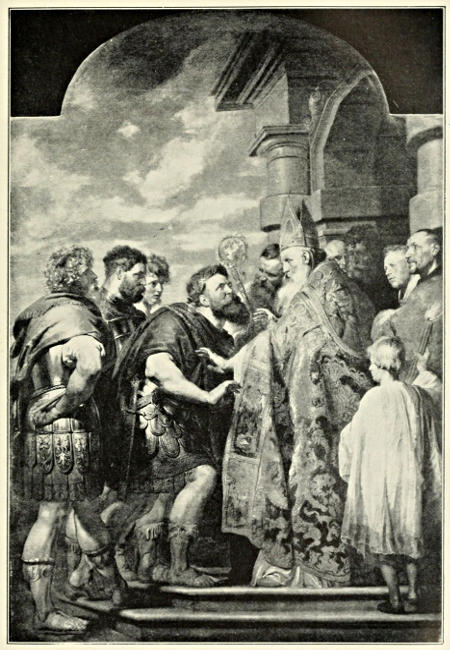

| Jovian to Theodosius (363-395 A.D.) | 510 |

| Election of Jovian (Flavius Claudius Jovianus), 510. Sapor assails the Romans, 511. The humiliation of the Romans, 512. Valentinian and Valens, 516. Invasion of the Goths in the East; battle of Hadrianopolis and death of Valens, 520. Valens marches against the Goths, 523. Theodosius named Augustus, 525. Virtues of Theodosius, 528. Tumult in Antioch, 529. The sedition of Thessalonica, 531. Theodosius and Ambrose, 532. Last days of Theodosius, 534. | |

| CHAPTER XLIV | |

| The Division of the Empire (395-408 A.D.) | 535 |

| Arcadius and Honorius succeed Theodosius, 535. Alaric invades Greece, 543. | |

| CHAPTER XLV | |

| The Goths in Italy (408-423 A.D.) | 550 |

| Alaric invades Italy, 550. Honorius retires to Ravenna; Attalus named Emperor, 556. Attalus deposed; Rome sacked by Alaric, 559. Death of Alaric; succession of Atawulf, 564. Constantine and Gerontius; Constantius, 566. | |

| CHAPTER XLVI | |

| The Huns and the Vandals (423-455 A.D.) | 572 |

| The Gothic historian Jordanes on the battle of Châlons, 587. The invasion of Italy; the foundation of Venice, 591. The retreat of Attila, 592. | |

| CHAPTER XLVII | |

| The Fall of Rome (430-476 A.D.) | 598 |

| The Barbarian Emperor-makers, 610. A review of the Barbarian advance, 618. A fulfilled augury, 623. Breysig’s observations on the fall of the Roman Empire [xii]in the West, 623. | |

| APPENDIX A | |

| History in Outline of Some Lesser Nations of Asia Minor (283 B.C.-17 A.D.) | 626 |

| APPENDIX B | |

| The Roman State and the Early Christian Church | 629 |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 643 |

| A General Bibliography of Roman History | 645 |

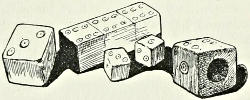

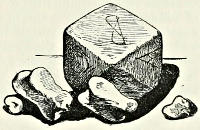

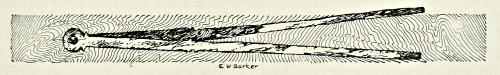

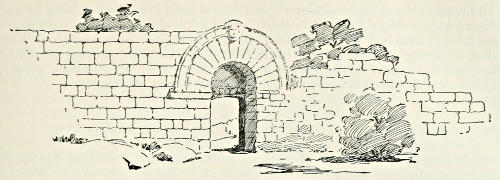

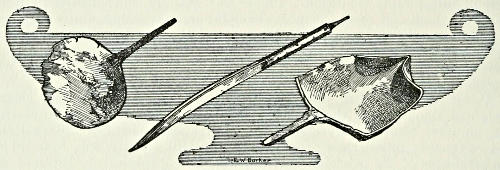

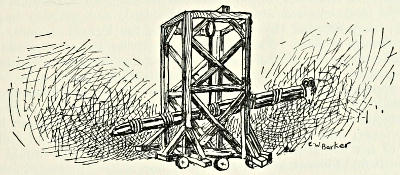

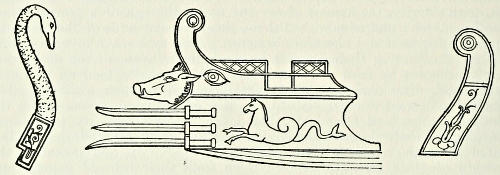

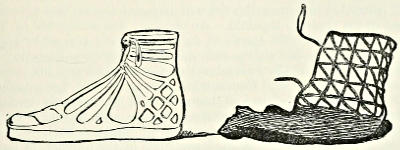

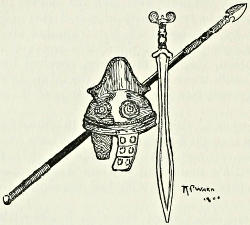

Roman Trophies

Written Specially for the Present Work

By Dr. OTTO HIRSCHFELD

Professor of Ancient History in the University of Berlin

The words “The Age of the Roman Empire is a period better abused than known,” written by Theodor Mommsen half a century ago, no longer contain a truth. To his own illuminative and epoch-making works we owe it, in the first instance, that this period, so long unduly neglected and depreciated, has come into the foreground of research within the last decade or two, and has enchained the interest of the educated world far beyond the narrow circle of professed scholars. Edward Gibbon, the only great historian who had previously turned his attention to this particular field, and whose genius built up the brilliant Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire on the sure foundation laid ready to his hand by the vast industry of the French scholar Le Nain de Tillemont, chose to confine himself, as the title of his work declares, to giving a description of the period of its decay. By so doing he did much to confirm, though he did not originate, the idea that the whole epoch of the Roman Empire must be regarded as a period of deterioration, and that the utmost to which it can lay claim is an interest of somewhat pathological character, as being the connecting-link between antique and mediæval times, and between the pagan and the Christian world. And when we look upon the picture sketched by that incomparable painter of the earlier days of the empire, Tacitus, where scarcely a gleam of light illumines the gloomy scene, we may well feel justified in the opinion that the only office of this period is to set forth to us the death-struggle of classical antiquity, and that no fresh fructifying seeds could spring from this process of corruption.

And, as a matter of fact, it cannot be denied that even the best days of the Empire can hardly with truth be spoken of as the prime of Rome. There is a dearth of great names, such as abound in the history of Greece and the early history of Rome. Julius Cæsar, the last truly imposing figure among the Romans, does not belong to it; he laid the foundations of this new world, but he was not destined to finish his work, and not one of his successors came up to the standard of this great prototype. Individual character falls into the[2] background during the empire, even the individuality of the Roman people; its history becomes the history of the antique world, and an account of the period between the reigns of Augustus and Constantine can, in its essence, be nothing other than the history of the world for the first three centuries after Christ.

It is easy to understand how Niebuhr, whose enthusiastic and lifelong labours were devoted to the history of ancient Rome, should have coldly turned aside from the period of imperial rule and cherished no desire to carry his history beyond the fall of the republic. Certainly it would be unjust to judge of his attitude towards the first-named period from the brief lecture with which he concluded his lectures on Roman history, but we shall nevertheless do no injustice to his undying merits by maintaining that in his heart of hearts he felt no sympathy with it. For it is not possible to conjure up a mental picture of the civilisation and condition of the empire from the scanty and imperfect records of literary tradition, a tradition that is not sufficient even for the first century, and fails us almost completely with regard to the second, and even more with regard to the third. Nothing can make up for this deficiency except an exhaustive study of monuments, and, more especially, of inscriptions, but this Dis Manibus literature, as he was pleased to call it, was a thing which Niebuhr, in spite of his many years of residence in Rome, neither cared for nor understood. For this we can hardly blame him, because, while the subject of coins had received admirable treatment at the hands of Joseph Eckhel, the inscriptions were hardly accessible for scientific purposes till long after Niebuhr’s death.

It is difficult for a later generation to realise the condition of epigraphic research before the critical compilation of the Corpus inscriptionum Latinarum had put an end to the frightful state of things that prevailed in this study, discredited as it was by all sorts of forgeries. But when we see the insuperable difficulties with which a scholar of the first rank, like Bartolommeo Borghesi, had to contend in collecting and sifting the boundless abundance of materials for the researches on the subject of the history of the empire, which he planned on so vast a scale and carried through with such admirable acumen; when we see how the chief work of his life came to nought for lack of any firm standing-ground whatsoever, we can easily understand that Niebuhr should have preferred not to venture on such dangerous ground.

From every part of the earth where Roman feet have trod, these direct witnesses to the past arise from the grave in almost disquieting abundance: the inexhaustible soil of Rome and its immediate vicinity has already yielded more than thirty-five thousand stones; we possess more than thirty thousand from other parts of Italy; and the number of those bestowed upon us by Africa, which was not opened up to research until the last century, is hardly smaller. Again, the Illyrian provinces, Dalmatia first and foremost, but Roumania, Bulgaria, and Servia, all in their degree, and even Bosnia, almost unknown ground till a short time ago, have become rich mines of discovery in our own days, thanks to increased facilities of communication and to the civilisation which has made its way into those countries.

There is, no doubt, much chaff that has attained to an unmerited longevity in these stone archives, much that we would willingly let go by the board. But one thing is certain: that only out of these materials—which[3] of late have been singularly supplemented by the masses of papyri discovered in Egypt—can a history of the Roman Empire be constructed; and that any one who addresses himself to the solution of a problem of this kind without exact knowledge of them, though he were as great a man as Leopold von Ranke, must fall far short of the goal within reach. What can be done with such materials has been shown by Mommsen in the masterly description of the provinces from the time of Cæsar to the reign of Diocletian, given in the fifth volume of his History of Rome, a volume which not only forms a worthy sequel to those which preceded it, but in many respects marks an advance upon them, and makes us all the more painfully aware of the gap which we dare scarcely hope to see filled by his master hand.

What is the secret of the vivid interest which the Roman Empire awakens even in the minds of those who feel little drawn towards the study of antiquity? It is, in the first place, undoubtedly because this period is in many respects more modern in character than any other of ancient times; far more so than the Byzantine Empire or the Middle Ages. It is a period of transition, in which vast revolutions came about in politics and religion and the seed of a new civilisation was sown. Its true significance is not to be found in the creation of a world-wide empire. Republican Rome had already subdued the East in her inexorable advance; Macedonia and Greece, Syria, Asia, Africa, and, finally, Egypt, had fallen into her hands before the setting up of the imperial throne.

In the West, again, Spain and the south of Gaul had long been Roman when Julius Cæsar started on the campaign which decided the future of Europe, and pushed the Roman frontier forward from the Rhone to the Rhine. The sway of Rome already extended over all the coasts of the Mediterranean, and the accessions made to her dominions during the period of imperial rule were comparatively insignificant. The Danubian and Alpine provinces were won for the Roman Empire by Augustus, Britain was conquered by Claudius, Dacia and Arabia by Trajan, beside the conquests which his successor immediately relinquished. Germania and the kingdom of Parthia permanently withstood the Roman onset, and the construction of the Upper Germanic and Rætian Limes by Domitian was an official recognition of the invincibility of the Germanic barbarians. The counsel of resignation, given by Augustus to his successors out of the fulness of his own bitter experience, warning them to keep the empire within its natural frontiers, i.e., the Rhine, Danube, and Euphrates, was practically followed by them, and Hadrian did unquestionably right in breaking altogether with his predecessor’s policy of expansion and refusing to expose the waning might of the empire to a continuous struggle to which it was no longer equal.

The great work of the empire, therefore, was not to conquer a world but to weld one into an organic whole, to foster civilisation where it existed and to be the instrument of Græco-Roman civilisation amongst the almost absolutely uncivilised nations admitted into the Orbis Romanus: and up to a certain point it actually accomplished this pacific mission, which proceeded with hardly a pause even under the worst of tyrants. Its task, however, varied greatly in various parts of its world-wide field.

In the East, permeated with Greek culture, though by no means denationalised, the Romans scarcely made an attempt to enter into competition[4] with this superior civilising agency, and, except as the medium of expression of the Roman magistrates, the Roman language played a very subordinate part there.

The art and literature which flourished in this soil during the days of empire are, with insignificant exceptions, as Greek in form and substance as in the preceding centuries. In the great centres of culture in the East, in Antioch and Alexandria, the Roman government and the Roman army have left visible traces, but there is nothing to lead us to suppose that they profoundly affected, far less metamorphosed, the Græco-Oriental character of those cities. Ephesus, the capital of Asia and the seat of the Roman government, was no more Romanised than Ancyra or Pergamus. The only exception is Berytus, “the Latin island in the sea of Oriental Hellenism”; there, in the Colonia Julia Augusta Felix, where the colonists were Roman legionaries, grew up the famous school of jurisprudence, where Ulpian, the great jurist of Syrian descent, may have had his training; a school which ministered abundant material to the editors of the Codex Theodosianus, and whence professors were summoned by Justinian to co-operate with him in the compilation of the code which cast Roman law into its final shape. In general, the Roman Empire received much from the East both of good and evil, but gave it practically no fresh intellectual impulse; its chief contribution to Græco-Oriental civilisation was the establishment of order, the guarantee of personal safety, and the advancement of material prosperity.

The case was very different in the West, where Rome was called upon to accomplish a great civilising mission, and where the ground had been prepared for her in very few places by an indigenous civilisation. In the south of Gaul, indeed, the Greek colony of Massilia had for six centuries been spreading the Greek language and character, Greek coinage and customs, by means of its factories, which extended as far as to Spain, and a home had thus been won for Hellenism on this favoured coast, as in southern Italy. Cæsar, with the far-seeing policy that no sentimental considerations were suffered to confuse, was the first to break the dominion of the Greek city, which had so long been in close alliance with Rome, and so to point the way to the systematic Romanisation of southern Gaul.

The Phœnician and Iberian civilisation of Africa and Spain was even less capable of withstanding the irresistible advance of Rome. The names of cities and individuals have indeed survived there as witnesses to the past, and the Phœnician language held its ground in private life for centuries, but the Roman language and Roman customs made a conquest of both Africa and Spain in the course of the period of imperial rule. The same holds good, and in the same degree, of Dalmatia and Noricum, less decidedly of Rætia and the Alpine provinces. In Mœsia, where a vigorous Greek civilisation had made itself at home in the trading stations on the Black Sea, the process of Romanisation was not completely successful, and in the northeastern parts of Pannonia it was never seriously taken in hand. But even Dacia, though occupied at so late a date, and though the colonists settled there after the extermination or expulsion of its previous inhabitants were not Italians, but settlers from the most diverse parts of the Roman Empire, was permeated with Roman civilisation to an extent which is positively astonishing under the circumstances.

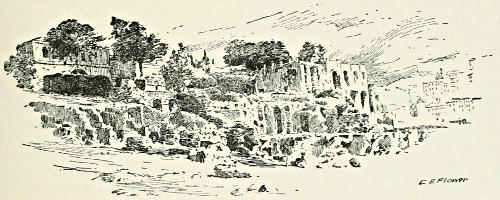

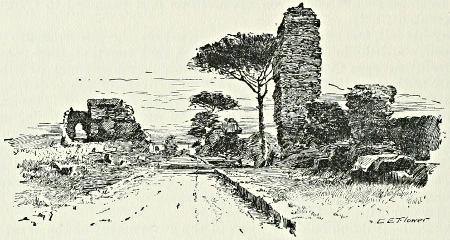

In Britain alone the Romanising process proved altogether futile, in spite of the exertions of Agricola, and the country remained permanently a great military camp, in which the development of town life never advanced beyond the rudimentary stage. Even in Gaul, which had been conquered by Cæsar, it proceeded with varying success in the various parts of the country, making most headway in Aquitaine, though not till late, and less even in middle Gaul, where the Roman colony of Lugdunum, the metropolis of the three Gallic provinces, alone reflected the image of Rome in the north. But even at Augustodunum (Autun), which was a centre of learning in the early days of the empire no less than at the point of transition from the third century to the fourth, Roman civilisation reached the lower ranks of the population as little as in other parts of Gaul. Moreover, in the Gallic provinces, which were conquered by Cæsar but not organised by his far-seeing political genius, the old civitates and pagi were not superseded, as in the Narbonensis, by the Italian municipal system, and the Celtic language did not wholly die out in middle Gaul till the time of the Franks.

The civilisation of western Belgica was even more meagre; while in the eastern portions of the country, in the fertile valleys of the Moselle and Saar, thickly studded with villas, we come upon a curious mixed Gallico-Roman civilisation of which the graceful descriptions of Ausonius and the lifelike sculptures of the Igel column, and the Neumagen bas-relief afford us a lively picture.

Trèves, above all, bears witness to the vigour of Roman civilisation in these parts, though it did not attain its full development until the fourth century. The Romanising of Gaul would no doubt have proceeded far more energetically had not the country been emptied of Roman troops from the time it was conquered. The immense efficacy of the Roman legions as agents of civilisation has been demonstrated—even more clearly than on the Danube—on the banks of the Rhine, where the Roman civilisation which centred about the great camp-cities struck deep root, although it had not strength to survive the fierce storms of the wandering nations which have since raged over that region.

The value of the Roman work of civilisation was most profoundly realised by those who witnessed it in their own country, and no writer has given more eloquent expression to this feeling than a late Gallic poet in the verses in which he extols the blessings of Roman rule:

But what Rome did for these countries was repaid her a hundred-fold. No country took so prominent a part in the literature of the empire as Spain. She gave birth to the two Senecas, to Lucan, Martial, and Quintilian (not to speak of lesser men): that is to say to the originator of modern prose and the champion of Ciceronian classicism. From Africa come the versatile Apuleius and the pedantic Fronto, as well as the eloquent apologists of Christianity, Tertullian, Cyprian, and Augustine. Gaul early exercised a strong influence on the development of rhetoric, and in the latter days of the empire became a seat of Roman poetic art and study. Even more striking is the fact that Spain and Africa gave birth to Trajan, Hadrian, and Septimius Severus, men who, widely as they differed in character and purpose, were the principal factors in the evolution of the empire.

Had the age of the empire been merely a period of decay, it certainly would not have had the strength to accomplish a work of civilisation which is practically operative in Latin countries to this day. And as a matter of fact, nothing can be less correct than such an assertion, witnessing, as it does, to a very slight acquaintance with the period in question. Rather must we say that republican Rome would not have been equal to the task; a new empire had to arise, upon a fresh basis, stable at home and strong abroad, assuring and guaranteeing legal protection and security throughout the world, in order to accomplish this pacific mission. The Roman body politic was in the throes of dissolution; in a peaceful reign of half a century Augustus created it anew, and if his work does not bear the stamp of genius, if we cannot exonerate it from the charge of a certain incompleteness, yet with slight modifications it held the Roman empire together for three centuries, and stood the test of practical working. Had Julius Cæsar lived longer, had he been destined to see the realisation of his great projects, he would no doubt have built up a work of greater genius and more homogeneous character, but it is an open question whether it would have proved equally lasting after the death of its creator. Great men make the history of the world, and determine the course of events, but the potent and arbitrary personality, which would fain conjure present and future to serve its will, imposes fetters on the course of subsequent development which later generations cannot and will not endure.

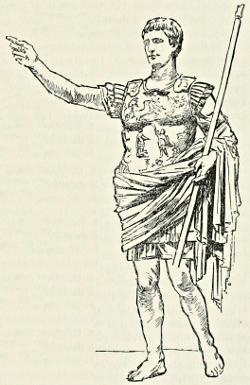

Augustus gave Rome a new system of government—an imperial system. The old Roman constitution, originally intended for a city, admirable as it was, could no longer serve as the basis of a state that had become a world-wide empire; it had, moreover, been completely shattered in the conflicts of the last century of the republic. To restore the republic was impossible, its obsequies had been celebrated on the fields of Pharsalia and Philippi. After the battle of Actium, which merely decided whether the name of the emperor should be Antonius or Octavian, and, possibly, whether the centre of the new empire should lie in the East or the West, the only question which could arise was that of the form, not of the essential character, of the new creation.

There can be no doubt that Julius Cæsar would have ascended the throne of Rome as absolute imperator after his return from the Parthian expedition, and Octavian as well had it in his power to claim sovereignty without limitation of any kind, for the whole army and fleet were under his command; but he rested content with a more modest title and took the reins of government, not as imperator but as princeps. He did not found a monarchy but a diarchy, as it has been aptly styled, in which the power was to be permanently divided between the emperor and the senate. It was a compromise with the old republic, a voluntary constitutional limitation of the sovereign prerogative by which all the rights pertaining to the people and the senate—legislation no less than legal jurisdiction, the right of coinage no less than the levy of taxation, the disposal of the revenue and expenditure of the state, and finally (after the accession of Tiberius and ostensibly in compliance with a clause in the testamentary dispositions of Augustus), the appointment of magistrates—were to appertain, under well-defined rules, in part to the princeps and in part to the senate. The empire was to be elective, as the old Roman monarchy had been; the nomination to the throne was to proceed from the senate, but on the other hand the supreme command[7] of the army and fleet was vested in the emperor in virtue of his proconsular authority, which extended over all parts of the empire outside the limits of the city of Rome. The legions were quartered in the provinces under his jurisdiction, while in those governed by the senate, with a few exceptions which soon ceased to be, all that the governors had at their disposal was a very moderate force of auxiliary troops.

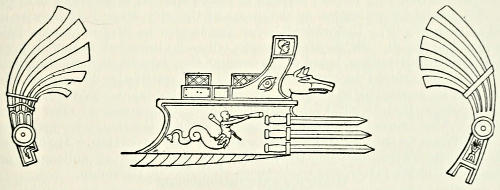

Roman Trophies

We have no reason to doubt the honesty of Augustus’ intentions, but it is obvious that all the prerogatives of the senate insured it a fair share in the government only so long as the sovereign chose to respect them. The reign of terror under his successors sufficed to set in the most glaring light the absolute impotence of the senate when opposed to a despot, and overturned the neatly balanced system of Augustus. It is easier, we cannot but confess, to blame the author of this system and to demonstrate its impracticability than to put a better in its place. For can it be supposed that if Augustus had set up an absolute monarchy such as Cæsar contemplated, the Romans would have been spared the tyranny of a Caligula or a Nero? Again, if Augustus had handed over to the senate even a share in the command of the army, would the empire have been so much as possible, or would he not immediately have conjured up the demon of civil war? Nor was the co-operation of the senate in the government altogether a failure; it proved salutary under emperors such as Nerva and his successors. The history of all ages goes to prove that chartered rights are of no avail against despots, and what guarantee is there in modern monarchies for the maintenance of a constitution confirmed by oath, except the conscience of the sovereign, and, even more, the steadfast will of the nation, which will endure no curtailment of its rights?

But the Roman nation existed no more, and in the senate under the empire a Cineas would now have seen, not a council of kings, but, like the emperor Tiberius, an assemblage of men prepared to brook any form of servitude. If it had been possible to give legal representation to the Roman citizens in Italy and the romanised provinces, the system devised by Augustus might have been destined to enjoy a longer lease of life. The emperor Claudius, who had some sensible ideas intermingled with his follies, would have admitted Gauls of noble birth to the senate, as Julius Cæsar had done. We can read in Tacitus of the vehement opposition with which this proposal was received by the senators, who would not hear of any diminution of their exclusive class privileges; and even the Spaniard Seneca has nothing but angry scorn for the defunct emperor who wanted to make the whole world a present of the rights of Roman citizenship and “to see all Greeks, Gauls, Spaniards, and Britons, in the toga.”

And yet this would have been the only way to infuse fresh sap into the decaying organism, to maintain the vital forces of the senate, to establish the government of the empire on a broader basis, and to bind the nations which had been subdued by the sword to the empire with indissoluble ties. It is true that by the so-called jus Latii which Vespasian bestowed upon the whole of Spain as a testimony to the Romanisation of the country, the magistrates, and after the second century the town-councillors, of such cities as did not enjoy full rights of citizenship, were admitted to the ranks of Roman citizens, a very sensible measure, though of benefit to a limited circle only, by which the best elements of provincial society became Roman citizens.

Full rights of citizenship were also bestowed on the peregrine soldiers when they entered the oriental legions, and on the Vigiles at Rome, and the soldiers of the fleet and auxiliary forces on their discharge. But from the reign of Antoninus Pius onwards this important privilege was not accorded, as before, to the children of these soldiers, but churlishly confined, with few exceptions, to the men themselves; and the bestowal consequently lost its virtue as an agency for the assimilation of the population of the empire; and when, two hundred years after the death of Augustus, the son of the emperor Septimius Severus, who himself had broken with all the national traditions of Rome, granted Roman citizenship to all subjects of the empire, as we are informed (though by authorities which greatly exaggerate the scope of the measure), it was no longer felt as a political privilege but as the outcome of a greedy financial policy.

The reorganisation of the government by Augustus, open to criticism as it is in many respects, was a blessing to the Roman Empire. The view which prevailed under the republic, that the provinces had been conquered only to be sucked dry by senators and knights, governors and tax-farmers, in league or in rivalry of greed (we have one example out of hundreds in Verres, condemned to immortality by the eloquence of Cicero), this view was laid aside with the advent of the empire, and even if extortion did not wholly cease in the senatorial provinces, yet the provincial administration of the first two centuries A.D. is infinitely superior to the systematic spoliation of the republic. The governors are no longer masters armed with absolute authority, constrained to extort money as fast as possible from the provincials committed to their charge in order to meet debts contracted by their own extravagance and, more especially, by that bribery of the populace which was indispensable to their advancement. They are officials under strict control, drawing from the government salaries fully sufficient to their needs. It was a measure imperatively called for by the altered circumstances of the time and fraught with most important consequences to create, as Augustus did, a class of salaried imperial officials and definitively break with the high-minded but wrong-headed principle of the republic by which the higher posts were bestowed as honorary appointments, and none but subordinate officials were paid, thus branding the latter with the stigma of servitude.

It is true that the cautious reformer adopted into his new system of government the old names and the offices which had come down from republican times, with the exception of the censorship and the dictatorship, which last had long been obsolete. But these were intended from the outset to lead but a phantom existence and to take no part in the great task of imperial administration. Augustus drew his own body of officials from the knightly[9] class, and under the unpretentious titles of procurator and præfect practically committed the whole administration of the empire to their hands, reserving, apart from certain distinguished sinecures in Rome and Italy for the senators the præfecture of the city, all the great governorships except Egypt, and the highest commands in the army. The handsome salaries—varying in the later days of the empire from £600 to £3,600 ($3,000 to $18,000)—and the great influence attached to the procuratorial career, which opened the way to the lofty positions of præfect of Egypt and commander of the prætorian guards at Rome, rendered the service very desirable and highly esteemed.

While the high-born magistrates of the republic entered upon their one year’s tenure of office without any training whatsoever, and were, of course, obliged to rely upon the knowledge and trustworthiness of the permanent staff of clerks, recorders and cashiers in their department, there grew up under the empire a professional class of government officials who, schooled by years of experience and continuance in office and supported by a numerous staff recruited from the imperial freedmen and slaves, were in a position to cope with the requirements of a world-wide empire. These procurators, some as governors-in-chief of the smaller imperial provinces, some as assistants to the governors of the greater, watched over the interests of the public exchequer and the emperor’s private property, or looked after the imperial buildings and aqueducts, the imperial games, the mint, the corn supply of Rome and the alimentary institutions, the legacies left to the emperors, their castles and demesnes in Italy and abroad—in short, everything that fell within the vast and ever widening sphere of imperial government. Meanwhile the exchequer of the senate dwindled and dwindled, till it finally came to be merely the exchequer of the city of Rome.

The government department which underwent the most important change was that of taxation. And there, again, Augustus with the co-operation of his loyal colleague and friend Agrippa carried out the decisive reform which stood the test of time till at least the middle of the second century in spite of mismanagement and the exactions of despots, and secured the prosperity of the empire during that period. While the indirect taxes, the vectigalia, continued in the main to be levied on the easy but (for the state and still more for its subjects) unprofitable plan of farming them out to companies of publicans, which had come down from republican days—though the publicans were now placed under the strict supervision of the imperial procurators—the tributa, which was assessed according to a fixed scale partly in money and partly in kind, the poll-tax and the land-tax were thenceforth levied directly by government officials, and the extortionate tax-farmers were finally banished from this most important branch of the public service.

A necessary condition of such a reform was an accurate knowledge of the empire and its taxable capacity. The census of the whole world did not take place at one and the same time, as the apostle Luke supposed, but the census of Palestine which he records certainly formed part of the survey of the Roman Empire which was gradually proceeded with in the early days of imperial rule, and by which the extent of the country, the nature of the soil, and the number and social position of its inhabitants, were ascertained as a basis for taxation and recruiting. In an inscription found at Berytus an[10] officer records that by the command of Quirinus, who as governor of Syria took the census of Palestine mentioned by St. Luke, he had ascertained the number of citizens in Apamea in Syria; and numbers of his comrades must in like manner have been employed on this troublesome business in every part of the empire.

According to these statistics the land-tax and the poll-tax, the chief sources of revenue in the empire, were assessed. The latter affected only those who did not possess full rights of citizenship and was always regarded as a mark of subjection in consequence; the burden of the former fell upon all land in the provinces unless by the jus Italicum, which was most sparingly conferred, it was placed on the same footing as the soil of Italy, which was exempted from the tax. But even Italian soil ultimately lost its immunity from taxation; and the introduction of the land tax into Italy, which formed part of Diocletian’s reform in this department, marks the reduction of this country, privileged above all others in the constitution of Augustus, to the level of the provinces.

Unfortunately taxation in the early days of the empire is one of the most obscure of subjects, as our sources of information yield nothing much until the reign of Diocletian. But the great discoveries of papyri and quantities of receipt-shards (the so-called ostraca) recently made in Egypt have already thrown some light upon the widely extended and complicated administration of the country, and we may hope for further instruction from the land of the Ptolemies, which exercised a stronger influence than any other upon the administration of the Roman Empire.

We might say much more concerning the reforms by which Augustus and his successors transformed the character of the whole empire; of the organisation of the standing army practically created by Cæsar, which in manifold formations compassed about the motley population of the universal empire of Rome with a firm bond; of the imperial coinage which made the denarius and the Roman gold piece legal tender throughout the Roman world and either did away with local coinage or restricted it to private circulation in the place where it was struck (with the sole exception of Egypt, which occupied a peculiar position in this as in other respects); of the institution of an imperial post, which, though it served almost exclusively the purposes of the magistrates and was long a heavy burden on the provincials, is nevertheless a landmark in the history of international communication; of the opening up of remote provinces by the extended network of roads, on the milestones of which nearly all the emperors since Augustus inscribed their names, especially Trajan, Hadrian, Severus, and Caracalla; of the alimentary institutions originated by Nerva (one of the few government institutions for the public welfare in ancient times), which were intended to subserve both the maintenance of the citizen class and the furtherance of agriculture in Italy. We should gladly dwell upon the further development of Roman law by the council of state organised by Hadrian, after Augustus the greatest reformer on the imperial throne, and on the redaction of the edictum perpetuum carried out at his command by Salvius Julianus, whose full name and career we have but recently learned from an inscription found in Africa, which paved the way for a common law for the whole empire and prepared the great age of jurisprudence at the beginning of the third century, when the springs of creative power in art and literature were almost wholly dried up. But within the narrow limits of this brief survey we must refrain from this, as from a description of the prosperity and decline of the highly developed municipal life of the period, and a sketch of the history of[11] the empire at home and abroad, and of its intellectual life. One question, however, cannot be left altogether without answer—the question of the attitude of the imperial government towards alien religions, and, above all, towards Christianity. A detailed examination of the position of Christianity in the Roman Empire by the authority best qualified to speak on the subject[1] will be found in another part of this work, and I can therefore confine myself in this place to a brief notice.

Paganism is essentially tolerant, and the Romans always extended a full measure of this toleration to the religions of the nations they conquered. The early custom of transferring to Rome the tutelary divinity of any conquered city in the vicinity is a practical expression of the view that any addition to the Roman pantheon (which had begun to grow into a Græco-Roman pantheon by the admittance of Apollo and the Sibyls and had actually been such since the war with Hannibal) must be regarded simply as an addition to the divine patrons of Rome. In the main this view was adhered to under the empire, although Augustus formulated more definitely the idea of a Roman state religion and closed the circle of gods to whom worship was due on the part of the state. But we have evidence of the spirit of tolerance and the capacity for assimilation characteristic of the age in the wide dissemination of the Egyptian cults of Isis and Serapis, especially in the upper ranks of society, and still more in the worship—deep rooted among the masses and spread abroad over the greatest part of the earth—of the Persian Mithras, whom Diocletian and his co-regents praised in the great Danubian camp of Caruntum as the patron of their dominion. Even the Phœnician gods of Africa and the Celtic gods of Gaul and the Danube provinces were allowed to survive by identification with Roman divinities of a somewhat similar character, and in the outlandish surnames bestowed upon the latter; although the names of the great Celtic divinities disappear from the monuments—a matter in which the government undoubtedly had a hand. So many barbarians, says Lucian the scoffer, have made their way into Olympus that they have ousted the old gods from their places, and ambrosia and nectar have become scanty by reason of the crowd of topers; and he makes Zeus resolve upon a thorough clearance, in order unrelentingly to thrust forth from Olympus all who could not prove their title to that divine abode, even though they had a great temple on earth and there enjoyed divine honours.

In view of the lengths to which the Romans carried the principle of giving free course to every religion within the empire so long as its professors did not come into conflict with the government officials or tend to form hotbeds of political intrigue, such as were the schools of the Druids, how did it come to pass that the Christian religion, and to a less extent the Jewish religion also, were assailed as hostile and dangerous to the state?

It is the collision between monotheism and polytheism, between the worship of God and—from the Jewish and Christian point of view—the worship of idols. The great crime which Tacitus lays to the charge of the Jews, that which brought upon the Christian the imputation of atheism, was contempt for the gods, i.e., the gods of the Roman state. And this denial was not only aimed at the gods of the Roman pantheon; it applied[12] in equal measure to the emperor-god, to whom all subjects of the empire, whatever other religion they professed, were bound to erect altars and temples in the capitals of the provinces, and everywhere do sacrifice; who, conjointly with and above all other gods, in both East and West, demanded that supreme veneration which constituted the touch-stone of loyalty. To refuse this was necessarily regarded as high treason, as crimen læsæ majestatis, and prosecuted as such. It is true that the monotheistic Jews, after the destruction of their national independence, were allowed by law to exercise their own religion on condition of paying the temple dues in future to the Capitoline Jupiter, and penalties were attached only to conversion to the Jewish religion, especially in the case of Roman citizens. But it is evident that they very skilfully contrived to avoid an open rupture with the worship of the emperor no less than with the national religion of Rome; for history has no record of Jewish martyrs who suffered death for their faith under the empire.

Roman Trophies

It was otherwise with Christianity; from the outset, and more particularly after the ministry of Paul, the great Apostle of the Gentiles, which determined the whole course of its subsequent development, it had come forward as a universal religion, circumscribed by no limitations of nationality and gaining proselytes throughout the whole world, an ecclesia militans, resolved to break down all barriers set up by human power and the rulers of this world in order to bear the new faith to victory. Here no lasting compromise was possible. After the reign of Trajan he who did not deny the faith and adore the pagan gods and the image of the emperor had to pay the penalty of an obduracy incomprehensible to the Roman magistrates, by death as a traitor. Singularly enough, it was this emperor, so averse to persecution and self-deification, who outlawed Christianity in the Roman Empire by the verdict that the Christians should not be hunted out, but, when informed against and convicted, should be punished unless they renounced their faith; and most of his successors—though not without exceptions, among whom Hadrian, Severus Alexander, and Philip must be numbered—adopted the same line. It may be that even then they had a presage of the danger to the Roman state that would arise from this international religion which had originated in the East, which declared all men, even slaves, to be equal before God, and was in its essence socialistic; at least it is difficult to explain on any other grounds the profound hatred to which Tacitus, the greatest intellect of his time, gives vent in his description of the prosecution of Christians under Nero.

As a matter of fact the spread of Christianity in Asia had by that time attained considerable proportions, as is evident from the report sent by Pliny[13] to Trajan and from other records; and as early as the reign of Domitian it had made its way in Rome even to the steps of the throne. But there was certainly no man then living who would have thought it possible that this despised religion of the poor was destined to conquer the world-wide empire, and this disdain is the only explanation we can find for the fact that the first general persecution of the Christians—for the local outbreaks of persecution under Marcus Aurelius, Severus, and Maximinus, confined as they were to a narrow circle, cannot be so called—did not take place until about the middle of the third century. Tertullian may have described too grandiloquently the enormous advance of Christianity throughout the empire; it is nevertheless beyond controversy that by the beginning of the third century it had become a power which serious-minded rulers, solicitous for the maintenance of a national empire, might well imagine that their duty to their country required them to extirpate with fire and sword. In this spirit Decius waged war against Christianity, and so did Diocletian, who assumed the surname of Jovius, after the supreme divinity of Rome, as patron of the national paganism. But it was a hopeless struggle; only ten years later Constantine made his peace with the Christian church by the Milan edict of toleration, and shortly before his death he received baptism.

With Constantine the history of ancient Rome comes to an end; the transference of the capital to Byzantium was the outward visible sign that the Roman Empire was no more. The process of dissolution had long been at work; symptoms thereof come to light as early as the first century, and are frightfully apparent under the weak emperor Marcus, whose melancholy Contemplations breathe the utter hopelessness of a world scourged by war and pestilence. The real dissolution of the Roman world, however, did not take place until the middle of the third century. The empire, assailed by barbarians and rent asunder by internal feuds, became the sport of ambitious generals who in Gaul, Mœsia, and Pannonia, placed themselves at the head of their barbarian troops; the time of the so-called Thirty Tyrants witnesses the speedy disintegration of the recently united West.

Nor could the strong emperors from the Danubian provinces check the process of decay. Poverty fell upon the cities of Italy and the provinces, whose material prosperity and patriotic devotion had been the most pleasing pictures offered by the good days of the Roman Empire; seats in the town council and municipal offices, once passionately striven after as the goal of civic ambition, as the election placards at Pompeii testify, now found no candidates because upon their occupants rested the responsibility of raising taxes it was impossible to pay; the way was paved for the compulsory hereditary tenure of posts and trades indispensable to the government. Agriculture was ruined, and documents dating from the third century and the end of the second, which have been recently brought to light in parts of the empire remote from one another, describe with affecting laments the want and hardships endured by colonists and small landholders in the vast imperial demesnes. The currency was debased, silver coins had depreciated to mere tokens, salaries had to be paid for the most part in kind, public credit was destroyed.

The desolation of the land, no longer tilled in consequence of the uncertainty of possession amidst disorders within and without; a steady decrease of the population of Italy and the provinces from the end of the second century[14] onwards; famine, and a prodigious rise in the cost of all the necessaries of life, which it was a hopeless undertaking to check by any imperial regulation of prices, are the sign-manual of the time. The army, from which Italians had long since disappeared, liberally interspersed with barbarian elements and no longer held together by any interest in the empire and in an emperor who was never the same for long together, was no longer capable of coping with the Goths and Alamanni who ravaged the Roman provinces in all directions; the right bank of the Rhine and the Limes Germanicus and Limes Ræticus, laboriously erected and fortified with ramparts and castellae, fell a prey to the Germans in the middle of the third century. A Roman emperor meets a shameful death in captivity among the Parthians; Dacia, Trajan’s hard-won conquest, has to be abandoned and its inhabitants, who were spared by the enemy, transplanted to the southern bank of the Danube.

Towards the end of the third century the cities in Gaul were surrounded with substantial walls, Rome itself had to be fortified against the attacks of the barbarians, and was once more provided with a circumvallation, as in the days of hoary antiquity, by one of the most vigorous of her rulers. Diocletian ceased to make the Eternal City his capital, and realised in practice the idea of division into an Oriental and Occidental world which had stirred the minds of men three centuries before. His successor put a final end to the Roman Empire; but all he had to do was to bury the dead.

[1] [See Professor Harnack’s article on Church and State on page 629.]

Roman Trophies

Professor Hirschfeld has pointed out that there is a general misconception as to the true meaning of later Roman history and that the time of the Roman Empire is, in reality, by no means exclusively a period of decline. In point of fact, there were long periods of imperial history when the glory of Rome, as measured by its seeming material prosperity, by the splendour of its conquests, and the wide range of its domination, was at its height. But two prominent factors, among others, have served to befog the view in considering this period. In the first place, the fact that the form of government is held to have changed from the republican to the monarchial system with the accession of Augustus, has led to a prejudice for or against the age on the part of a good share of writers who have considered the subject. In the second place the invasion of Christianity during the decline of the empire has introduced a feature even more prejudicial to candid discussion.

Yet, broadly considered, neither of these elements should have had much weight for the historian. In the modern sense of the word the Roman commonwealth was never a democracy. From first to last, a chief share of its population consisted of slaves and of the residents of subject states. There was, indeed, a semblance of representative government; but this, it must be remembered, was continued under the empire. Indeed, it cannot be too often pointed out that the accession to power of Augustus and his immediate successors did not nominally imply a marked change of government. We shall have occasion to point out again and again that the “emperor” was not a royal ruler in the modern sense of the word. The very fact that the right of hereditary succession was never recognised,—such succession being accomplished rather by subterfuge than as a legal usage,—in itself shows a sharp line of demarcation between the alleged royal houses of the Roman Empire and the rulers of actual monarchies. In a word, the Roman Empire occupied an altogether anomalous position, and the power which the imperator gradually usurped, through which he came finally to have all the influence of a royal despot, was attained through such gradual and subtle advances that contemporary observers scarcely realised the transition through which they[16] were passing. We shall see that the senate still holds its nominal power, and that year by year for centuries to come, consuls are elected as the nominal government leaders.

Nevertheless, it is commonly held that posterity has made no mistake in fixing upon the date of the accession of Augustus as a turning-point in the history of the Roman commonwealth. However fully the old forms may have been held to, it is only now that the people in effect submit to a permanent dictator. The office of dictator, as such, had indeed been abolished on the motion of Mark Antony; but the cæsars managed, under cover of old names and with the ostensible observance of old laws, to usurp dictatorial power. There was an actual, even if not a nominal, change of government. This change of government, however, did not coincide with any sudden decline in Roman power. On the contrary, as just intimated, the Roman influence under the early cæsars reached out to its widest influence and attained its maximum importance. Certainly, the epochs which by common consent are known as the golden and the silver ages of Roman literature—the time, that is to say, of Augustus and his immediate successors—cannot well be thought of as periods of great national degeneration. And again the time of the five good emperors has by common consent of the historians been looked on as among the happiest periods of Roman history. In a word the first two centuries of Roman imperial history are by no means to be considered as constituting an epoch of steady decline. That a decline set in after the death of Marcus Aurelius, some causes of which were operative much earlier, is, however, equally little in question. Looking over the whole sweep of later Roman history it seems difficult to avoid the conclusion that the empire was doomed almost from the day of its inception, notwithstanding its early period of power. But when one attempts to point out the elements that were operative as causes of this seemingly predestined overthrow, one enters at once upon dangerous and debatable ground. At the very outset, as already intimated, the prejudices of the historian are enlisted pro or con by the question of the influence of Christianity as a factor in accelerating or retarding the decay of Rome’s greatness.

Critics have never tired of hurling diatribes at Gibbon, because his studies led him to the conclusion that Christianity was a detrimental force in its bearing on the Roman Empire. Yet many more recent authorities have been led to the same conclusion, and it is difficult to say why this estimate need cause umbrage to anyone, whatever his religious prejudices. The Roman commonwealth was a body politic which, following the course of all human institutions, must sooner or later have been overthrown. In the broader view it does not seem greatly to matter whether or not Christianity contributed to this result. That the Christians were an inharmonious element in the state can hardly be in question. As such, they cannot well be supposed to have contributed to communal progress. But there were obvious sources of disruption which seem so much more important that one may well be excused for doubting whether the influence of the early Christians in this connection was more than infinitesimal for good or evil. Without attempting a comprehensive view of the subject—which, indeed, would be quite impossible within present spacial limits—it is sufficient to point out such pervading influences as the prevalence of slavery, the growing wealth of the few and the almost universal pauperism of the many fostered by the paternal government, and the decrease of population, particularly among the best classes, as abnormal elements in a body politic, the influence of which sooner or later must make themselves felt disastrously.

Perhaps as important as any of these internal elements of dissolution was that ever-present and ever-developing external menace, the growing power of the barbarian nations. The position of any nation in the historical scale always depends largely upon the relative positions of its neighbour states. Rome early subjugated the other Italian states and then in turn, Sicily, Carthage, and Greece. She held a dominating influence over the nations of the Orient; or, at least, if they held their ground on their own territory, she made it impossible for them to think of invading Europe. Meantime, at the north and west there were no civilised nations to enter into competition with her, much less to dispute her supremacy. For some centuries the peoples of northern Europe could be regarded by Rome only as more or less productive barbarians, interesting solely in proportion as they were sufficiently productive to be worth robbing. But as time went on these northern peoples learned rapidly through contact with the civilisation of Rome. They were, in fact, people who were far removed from barbarism in the modern acceptance of the term. It is possible (the question is still in doubt) that they were of common stock with the Romans; and if their residence in a relatively inhospitable clime had retarded their progress towards advanced civilisation, it had not taken from them the racial potentialities of rapid development under more favourable influences; while, at the same time, the very harshness of their environment had developed in them a vigour of constitution, a tenacity of purpose, and a fearless audacity of mind that were to make them presently most dangerous rivals. It was during the later days of the commonwealth and the earlier days of the empire that these rugged northern peoples were receiving their lessons in Roman civilisation—that is to say, in the art of war, with its attendant sequels of pillage and plundering.[2] Those were hard lessons which the legions of the cæsars gave to the peoples of the north, but their recipients proved apt pupils. Even in the time of Augustus a German host in the Teutoberg Forest retaliated upon the hosts of Varus in a manner that must have brought Rome to a startling realisation of hitherto unsuspected possibilities of disaster.

It has been pointed out that the one hope for the regeneration of Rome under these conditions lay in the possibility of incorporating the various ethnic elements of its wide territories into one harmonious whole. In other words, could Rome in the early day have seen the desirability—as here and there a far-sighted statesman did perhaps see—of granting Roman citizenship to the large-bodied and fertile-minded races of the north, removing thus a prominent barrier to racial intermingling, the result might have been something quite different. We have noted again and again that it is the mixed races that build the great civilisations and crowd forward on the road of human progress. The Roman of the early day had the blood of many races in his veins, but twenty-five or thirty generations of rather close inbreeding had produced a race which eminently needed new blood from without. Yet the whole theory of Roman citizenship set its face against the introduction of this revivifying element. The new blood made itself felt presently, to be sure, and the armies came to be recruited from the provinces. After a time it came to pass that the leaders—the emperors even—were no longer Romans in the old sense of the word. They came from Spain, from Illyricum, and from Asia Minor. Finally the tide of influence swept so strongly in the direction of Illyricum that the seat of Roman influence was transferred to the East, and the Roman Empire entered a new phase of existence. The[18] regeneration was effected, in a measure, by the civilisation of the new Rome in the East; but this was the development of an offspring state rather than the regeneration of the old commonwealth itself. Then in the West the northern barbarians, grown stronger and stronger, came down at last in successive hordes and made themselves masters of Italy, including Rome itself. With their coming and their final conquests the history of old Rome as a world empire terminates.

It is the sweep of events of the five hundred years from the accession of Augustus the first emperor to the overthrow of Romulus Augustulus the last emperor that we have to follow in the present volume. Let us consider in a few words the sources that have preserved the record of this most interesting sequence of events.

Reference has already been made to the importance of the monumental inscriptions. For the imperial history these assumed proportions not at all matched by the earlier periods. It was customary for the emperors to issue edicts that were widely copied throughout the provinces, and, owing to the relative recency of these inscriptions a great number of them have been preserved.

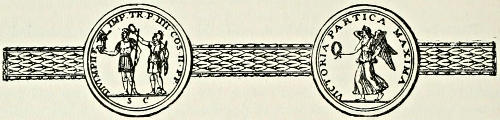

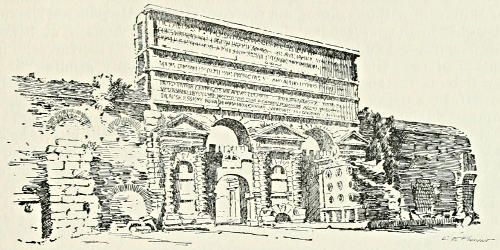

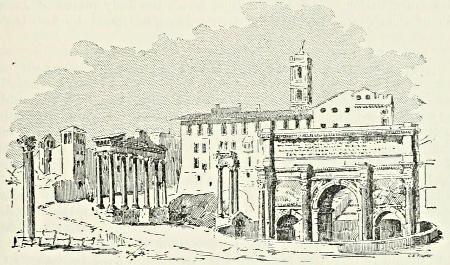

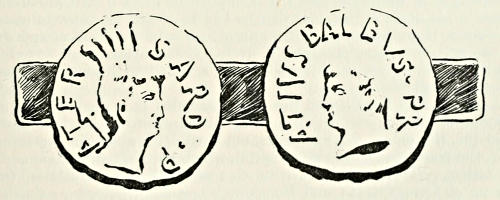

As a rule, these inscriptions have only incidental importance in the way of fixing dates or establishing details as to the economic history. On the other hand, such a tablet as the Monumentum Ancyranum gives important information as to the life of Augustus, and such pictorial presentations as occur on the columns of Trajan and Marcus Aurelius are of the utmost importance in reproducing the life-history of the period. For mere matters of chronology—having also wider implications on occasion—the large series of coins and medals is of inestimable importance. Without these various inscriptions, as has been said, many details of imperial history now perfectly established must have remained insoluble.

Nevertheless, after giving full credit to the inscriptions as sources of history, the fact remains that for most of the important incidents that go to make up the story, and for practically all the picturesque details of political history, the manuscripts are still our chief sources. The authors whose works have come down to us are relatively few in number, and may be briefly listed here in a few words. For the earliest imperial period we have the master historian Tacitus, the biographer Suetonius, the courtier Velleius Paterculus, and the statesman Dion Cassius. As auxiliary sources the writings of Martial, Valerius Maximus, Pliny, and the Jewish Wars of Josephus are to be mentioned. For the middle period of imperial history Dion Cassius and Herodian, supplemented by Aurelius Victor and the other epitomators, and by the so-called Augustan histories or biographies, are our chief sources. After they fail us, Zosimus and Ammianus Marcellinus have the field practically[19] to themselves, gaps in their work being supplied, as before, by the outline histories. Details as to these writers will be furnished, as usual, in our general bibliography.

29. Temple of Janus closed for the third time. 28. Senate reduced in numbers. 27. Octavian lays down his powers; is given the proconsular imperium for ten years, and made commander-in-chief of all the forces with the right of levying troops, and making war and peace. He receives the title of Augustus. Provinces divided into senatorial (where no army was required) and imperial where troops were maintained. 23. Proconsular imperium conferred on Augustus with possession of the tribunicia potestas. 20. War against the Parthian king, Phraates. Tigranes reinstated in his kingdom of Armenia. 19. Cantabri and Astures (in Spain) subdued. 15. Rætia and Noricum subjugated by Drusus and Tiberius and included among the Roman provinces. 12-9. Campaigns of Drusus in Germany and subjugation of Pannonia by Tiberius. 4 B.C. Birth of Jesus. 4 A.D. Augustus adopts his stepson Tiberius. 9. Illyricum, having rebelled, is reduced by Tiberius. Arminius, the chief of the Cherusci, a German tribe, annihilates a Roman army under Quintilius Varus. 14. Tiberius, emperor. Germanicus, nephew of Tiberius, quells the revolted legions on the Rhine and makes war on the German tribe of the Marsi. 15. Germanicus invades Germany a second time and captures the wife of Arminius (Hermann). 16. Battle of the Campus Idistavisus. Arminius defeated by Germanicus. 17. Recall and death of Germanicus. 23. Prætorian cohorts collected into one camp outside Rome on the suggestion of Sejanus, who now exercises great influence over Tiberius. 31. Sejanus put to death with many of his friends. 37. Caligula succeeds Tiberius. 41. Murder of Caligula. Claudius succeeds. 42. Mauretania becomes a Roman province. 43-47. Britain subdued by Plautius and Vespasian. 43. Lycia becomes a province. 44. Judea becomes a province. 54. Claudius poisoned by his wife Agrippina and succeeded by her son Nero. 55. Nero poisons his step-brother Britannicus. 58. Domitius Corbulo sent against the Parthians and Armenians. 59. Agrippina murdered by Nero’s orders. 61. Suetonius Paulinus represses the revolt of Boadicea in Britain. 62. Nero murders his wife Octavia. 63. Parthians and Armenians renew the war. The Parthians finally sue for peace. The king of Armenia acknowledges his vassalage to Rome. 64. Destruction of great part of Rome by fire, said to have been started by Nero’s command, but attributed by him to the Jews and Christians. First persecution of the Christians. 65. Piso conspires against Nero. The plot is discovered. 66. First Jewish War. Vespasian sent to conduct it. 68. Gaul and Spain revolt against Nero, who commits suicide.

68. Galba, Otho, and Vitellius succeed each other as emperors. 69. Vespasian, the first Flavian emperor, proclaimed by the soldiers. Vitellius put to death. The aristocratic body purified and replenished. Official worship restored. Public works executed. Reforms in the army and the finances, and the administration generally. Batavian revolt under Claudius Civilis. 70. Fall of Jerusalem. Batavian revolt quelled by Cerealis. 71. Cerealis becomes governor of Britain. 78. Agricola begins his campaigns in Britain. 79. Titus, the second Flavian emperor. Pompeii and Herculaneum destroyed by an eruption of Vesuvius. 80. Agricola reaches the Solway Firth. 81. Domitian, the third Flavian emperor. 83. War with the Chatti. 84. Caledonians under Galgacus defeated by Agricola, who completes the conquest of Britain. 86. Dacian invasion of Mœsia. 87. Dacians defeat a Roman army. 90. Peace with the Dacians. 93. Antonius Saturninus, governor of upper Germany, revolts. The rebellion is put down and his papers are destroyed. Domitian executes the supposed accomplices of Saturninus and begins a series of cruelties. Philosophers expelled from Rome. Persecutions of Jews and Christians. 96. Nerva succeeds on the murder of Domitian, and introduces a policy of mildness. 98. Trajan, emperor. 101-102. Dacians attacked and overthrown by Trajan. 106. Dacians finally subdued by Trajan. Their country becomes a Roman province. 114. Parthian War undertaken to prevent the Parthian king from securing the Armenian crown to his family. 116. Parthian War ends with the incorporation of Armenia, Mesopotamia, and Assyria amongst the Roman provinces. Trajan dies on his return. Many public works were executed in this reign. 117. Hadrian, emperor. He abandons Trajan’s recent conquests. 118. Mœsia invaded by the Sarmatians and Roxolani. Hadrian concludes peace with the Roxolani. The Sarmatian War continues for a long time. 120-127. Hadrian makes a tour through the provinces. 121. Hadrian’s wall built in Britain. 132. Edictum perpetuum, or compilation of the edictal laws of the prætors. 132-135. Second Jewish War, beginning with the revolt of Simon Bar Kosiba. Many buildings were erected in Hadrian’s reign. 138. Antoninus Pius, emperor. He promotes the internal prosperity of the empire, and protects it against foreign attacks. 139. British revolt suppressed by Lollius Urbicus. Wall of Antoninus (Graham’s Dyke) built. 161. Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, joint emperors. 162-165. Parthian War. It terminates in the restoration of Armenia to its lawful sovereign and the cession of Mesopotamia to Rome. 163. Christian persecution. 166. A barbarian coalition of the Marcomanni and other tribes threatens the empire. Both emperors take the field against them. 169. Lucius Verus dies. 174. Victory over the Quadi. Miracle of the Thundering Legion. 175. Avidius Cassius proclaims himself emperor, and makes himself master of all Asia within Mount Taurus. He is assassinated. 178. War with the Marcomanni renewed.