Title: Public and Private Life of Animals

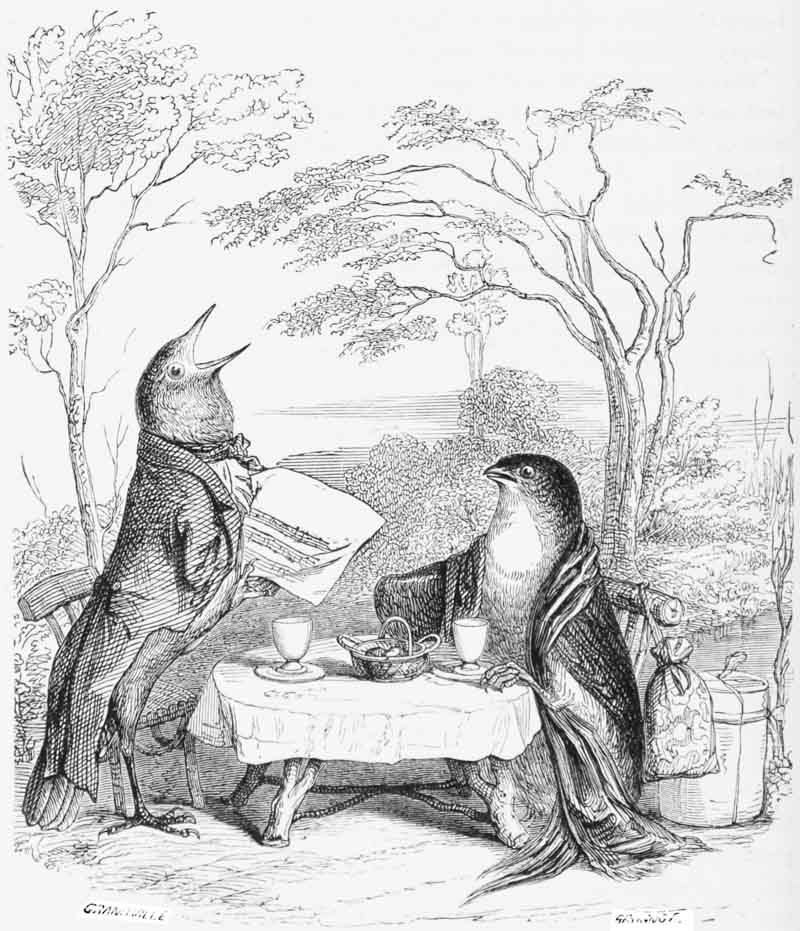

Editor: P.-J. Stahl

Adapter: J. Thomson

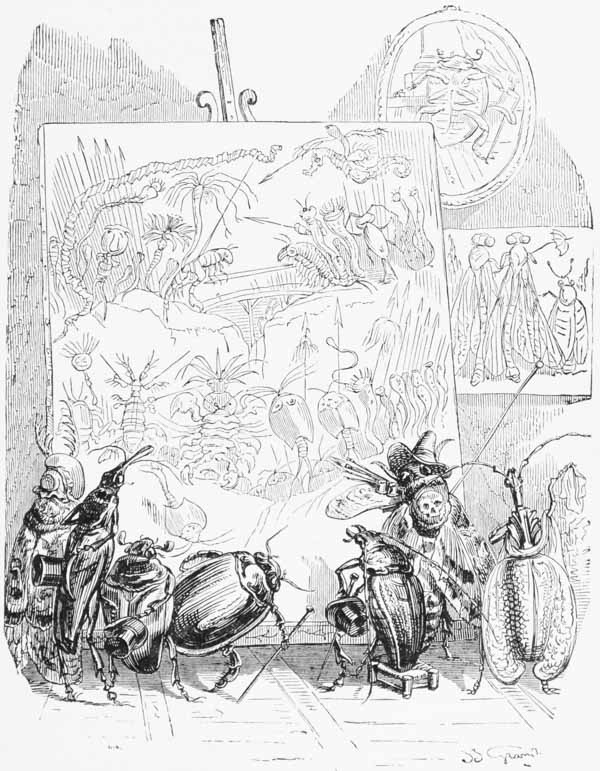

Illustrator: J. J. Grandville

Release date: October 31, 2018 [eBook #58214]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, RichardW, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

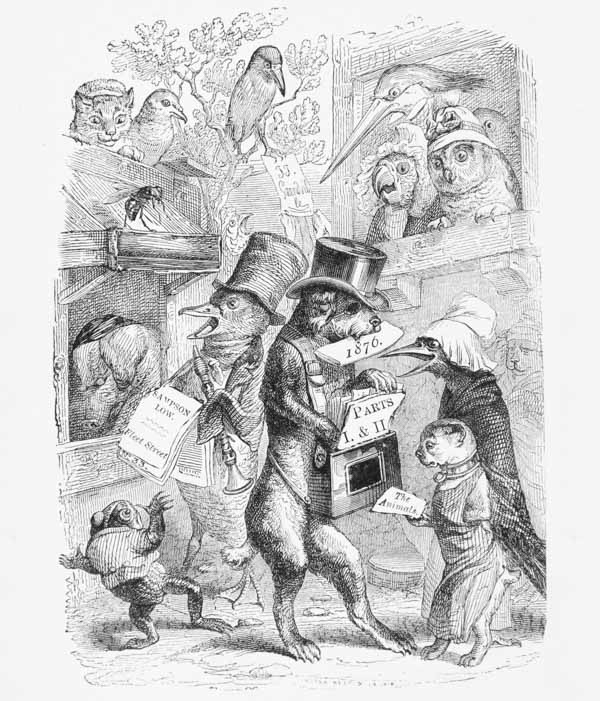

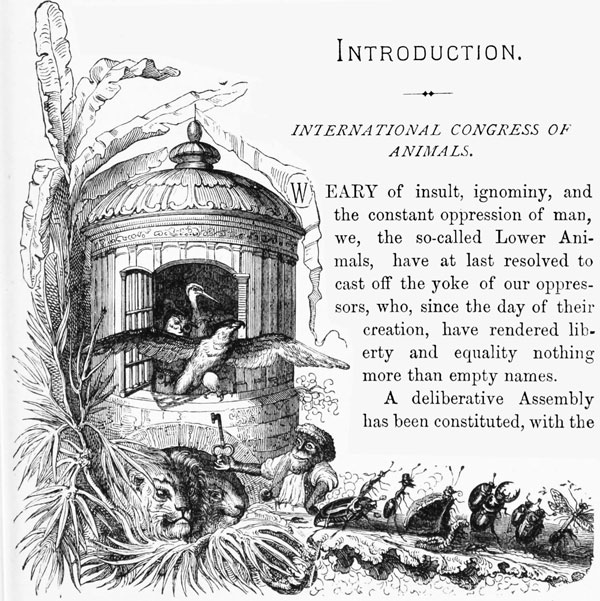

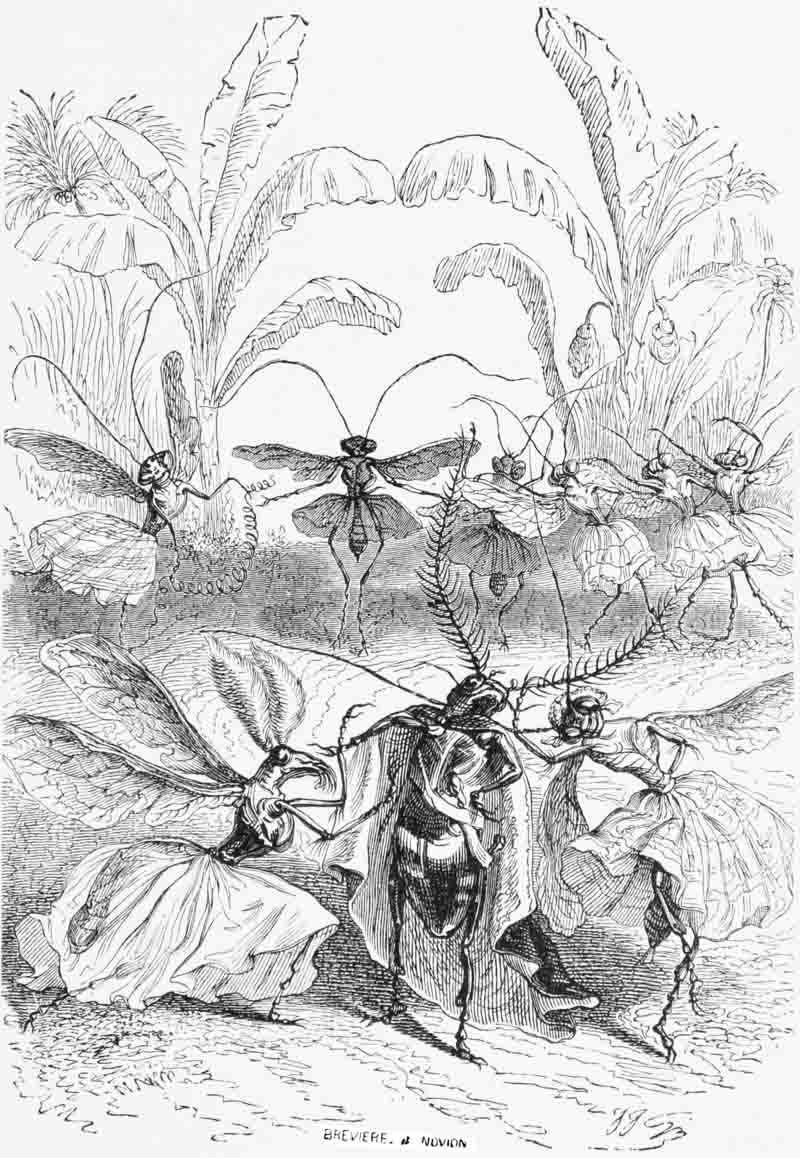

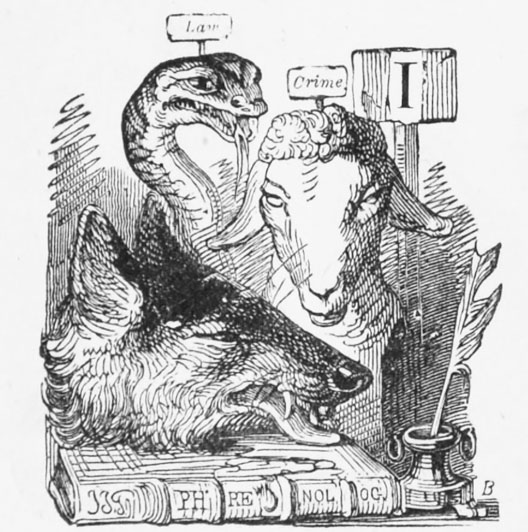

![Public and Private Life of Animals. London. 1876. [Artist: Brevier S.]](images/i000-03.jpg)

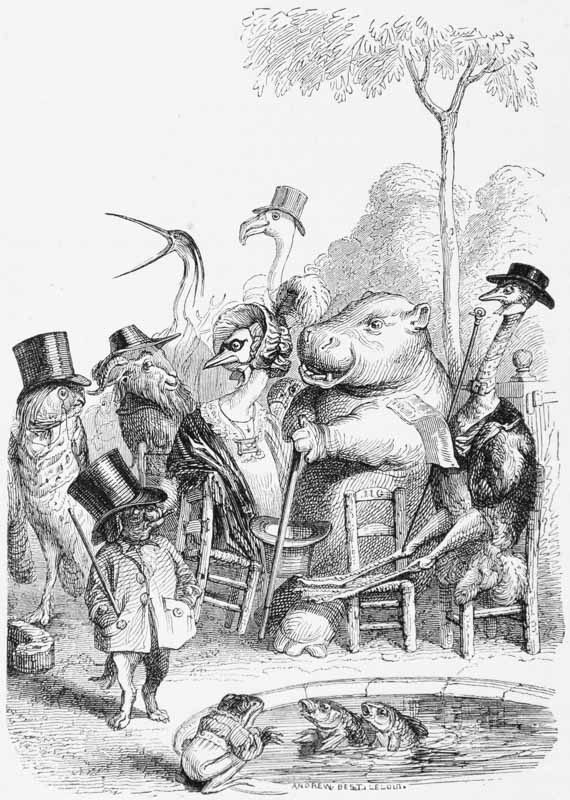

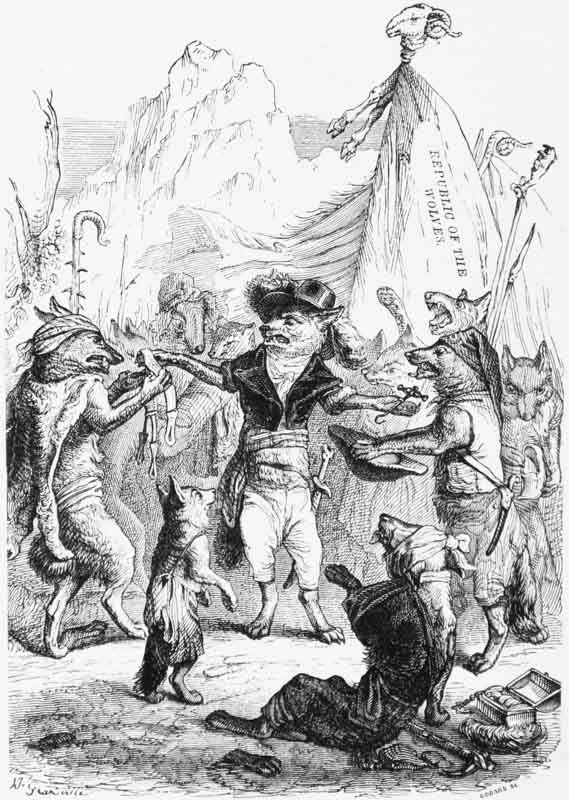

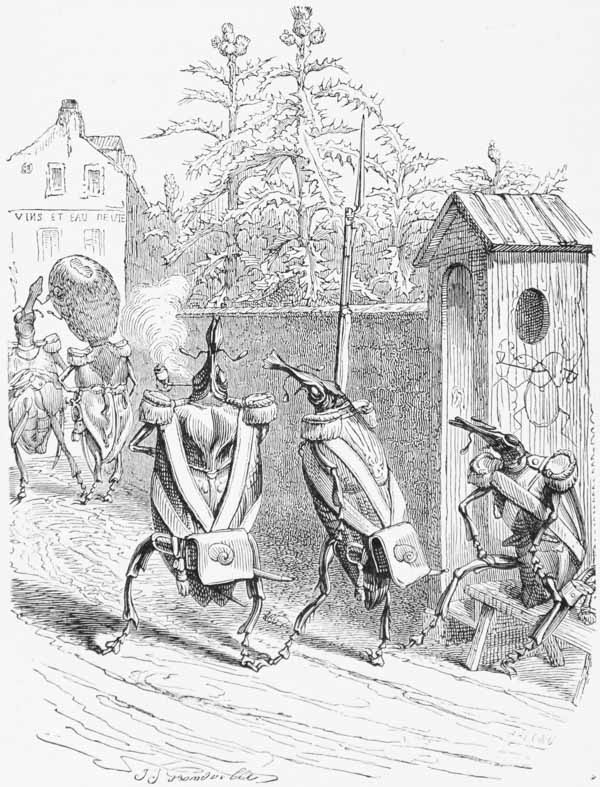

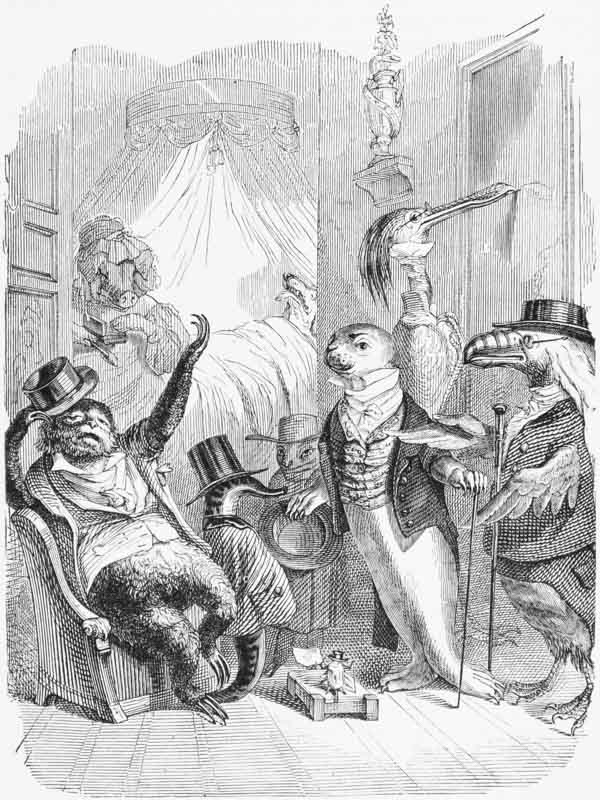

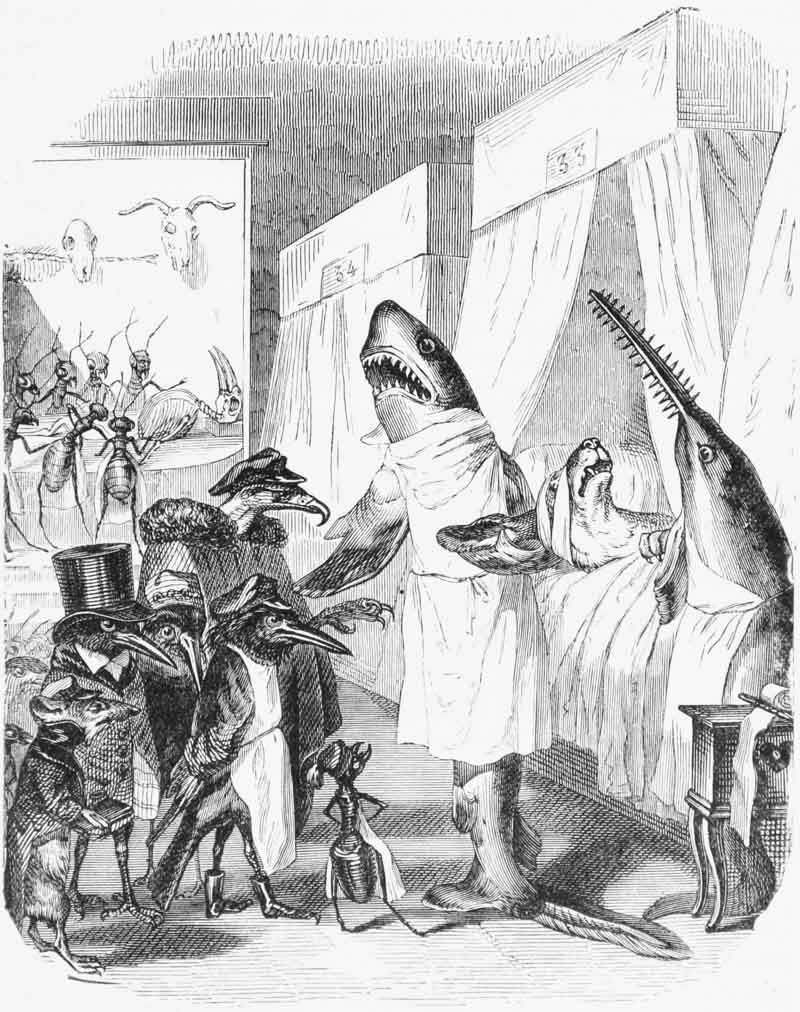

WEARY of insult, ignominy, and the constant oppression of man, we, the so-called Lower Animals, have at last resolved to cast off the yoke of our oppressors, who, since the day of their creation, have rendered liberty and equality nothing more than empty names.

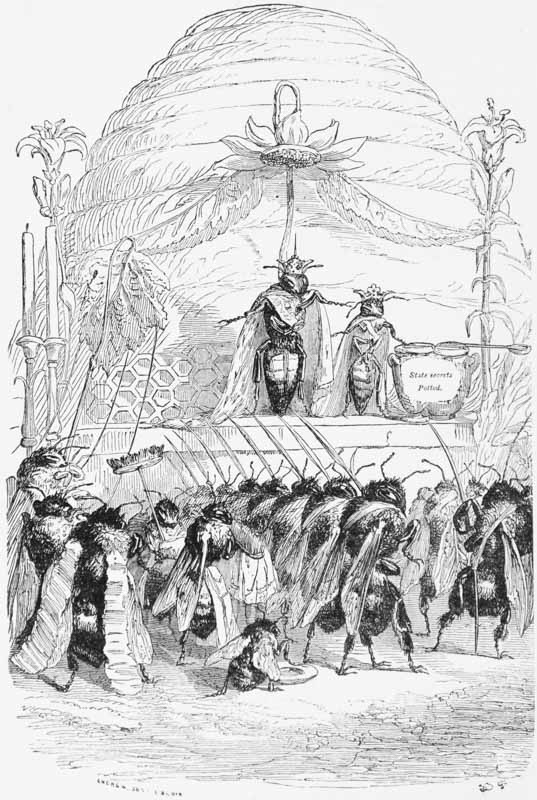

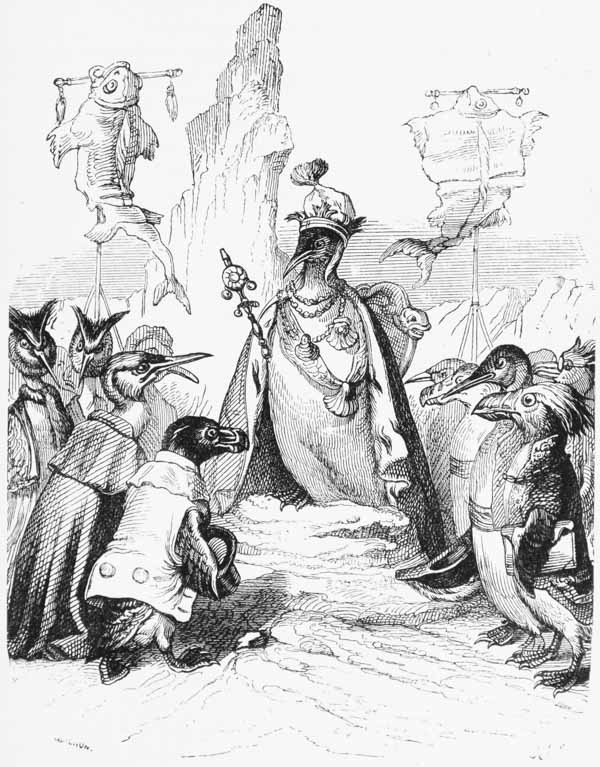

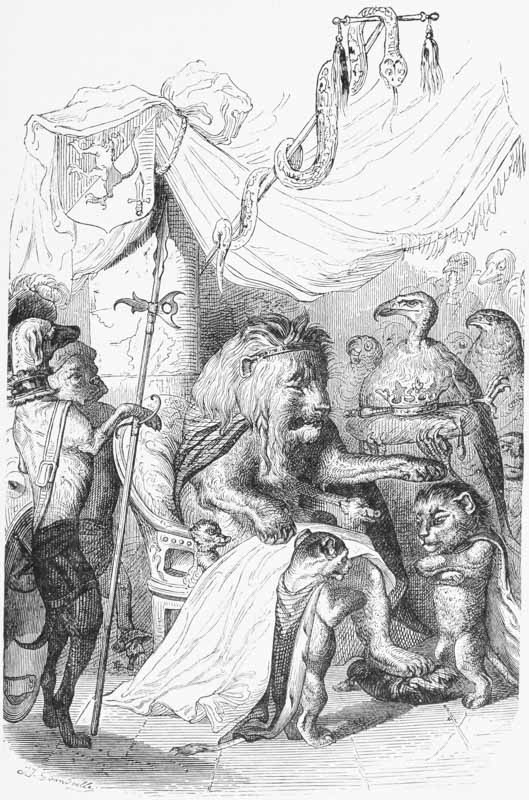

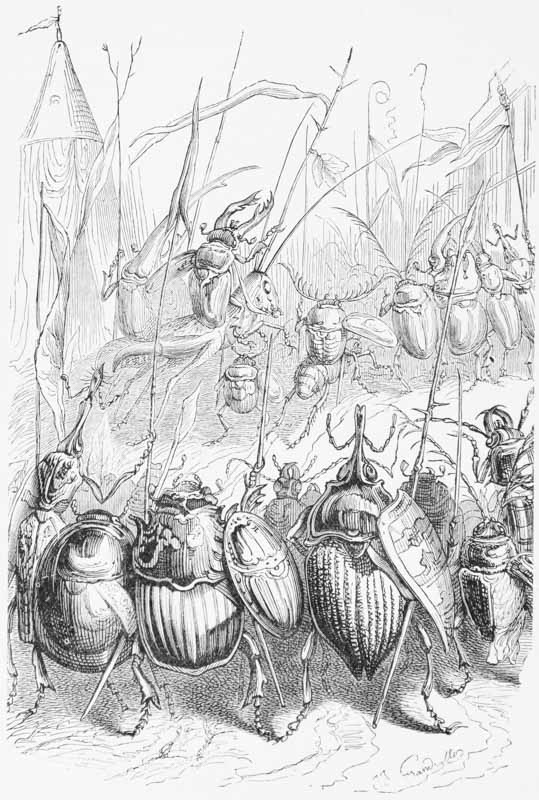

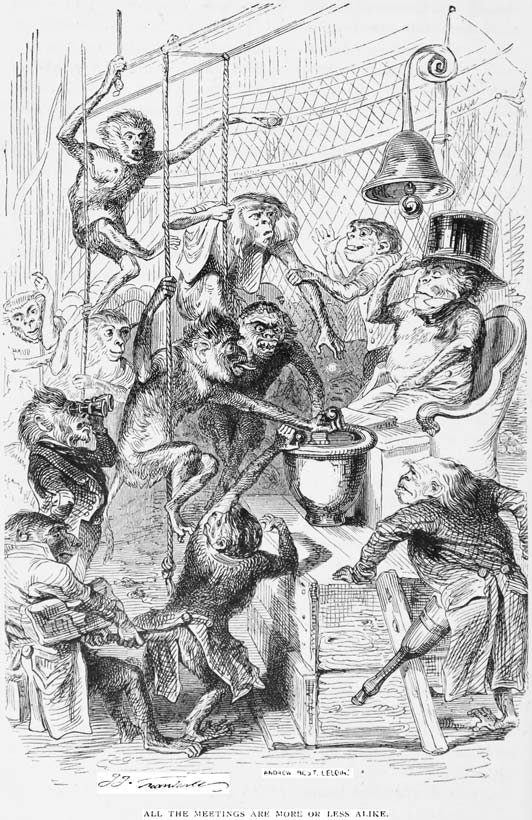

A deliberative Assembly has been constituted, with the full sanction of the Great Animal Powers, to whom we look with confidence for that guidance and support which will enable us to carry out the measures framed for our advancement.

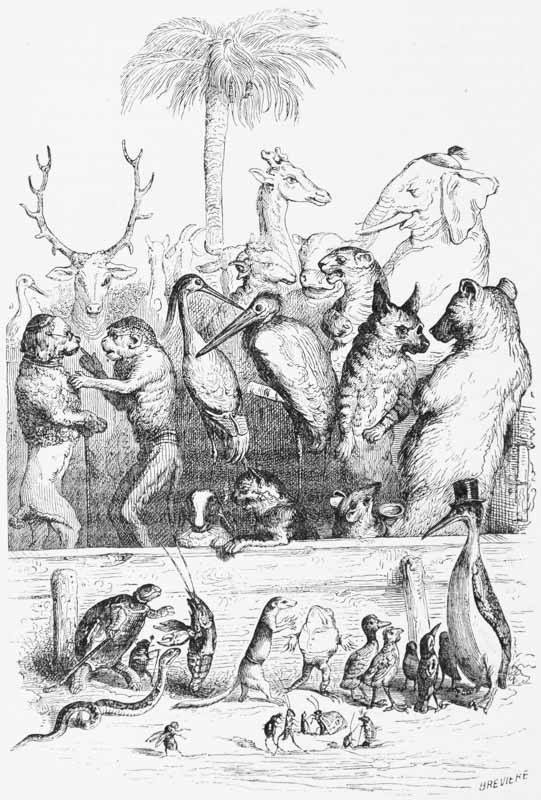

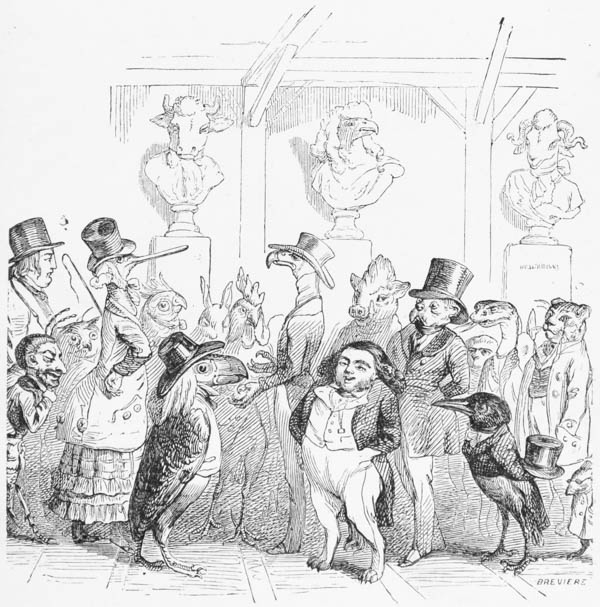

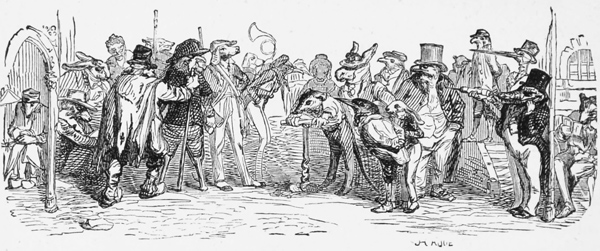

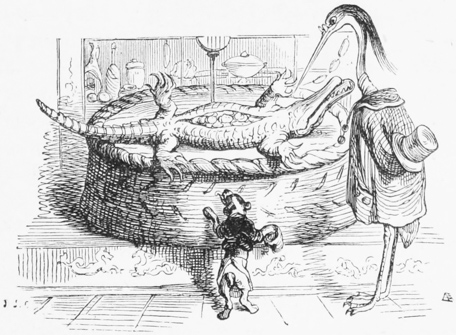

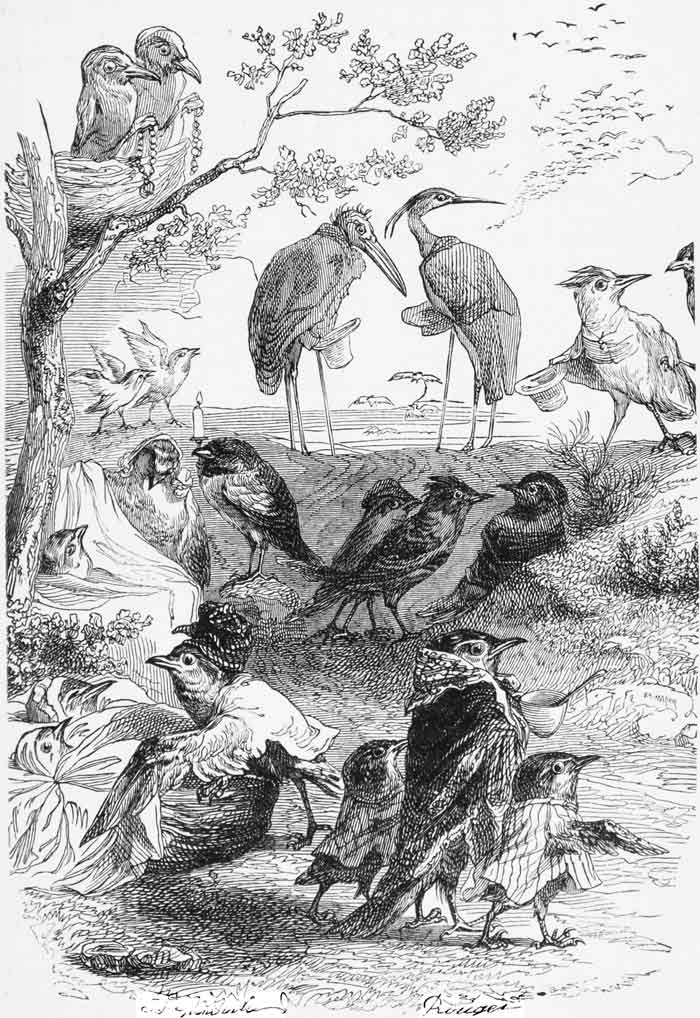

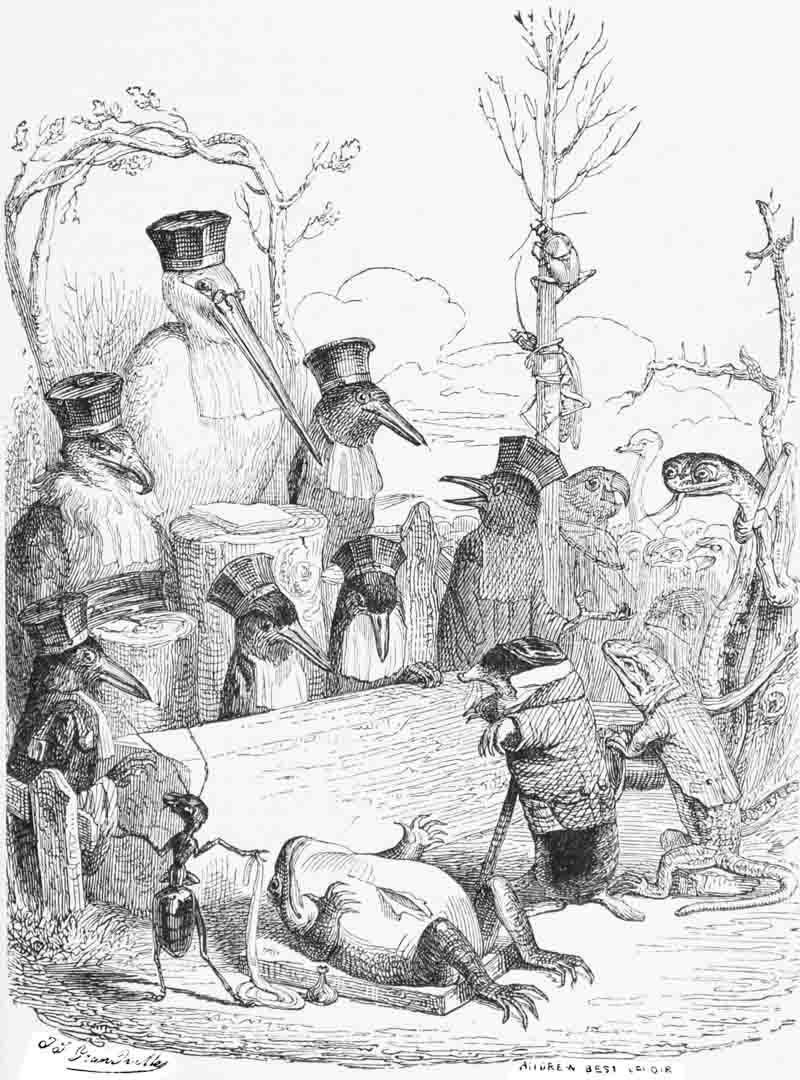

The Assembly has been already convoked. Its first sitting took place, on a lovely spring morning, on the green sward of the Jardin des Plantes. The spot was happily chosen to secure a full attendance of the animals of all nations. In justice to ourselves, let it be known that the proceedings were conducted with the harmony and good manners which the brutes have made peculiarly their own.

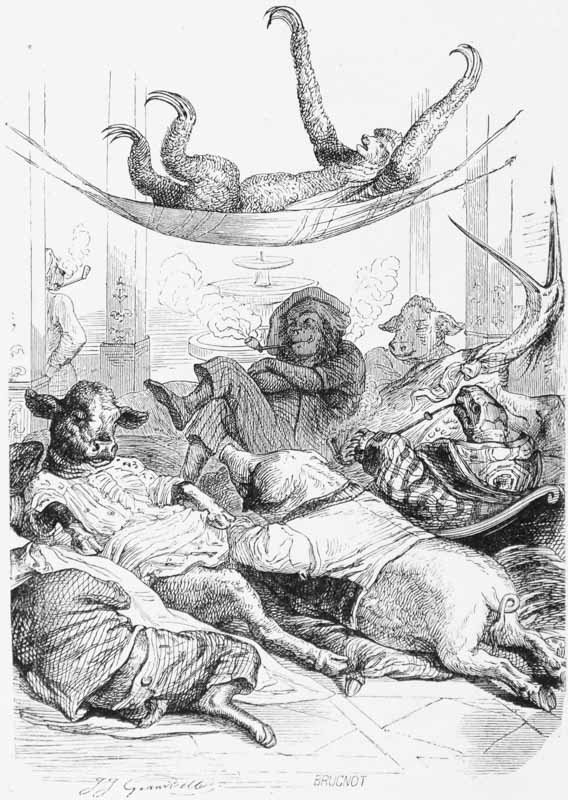

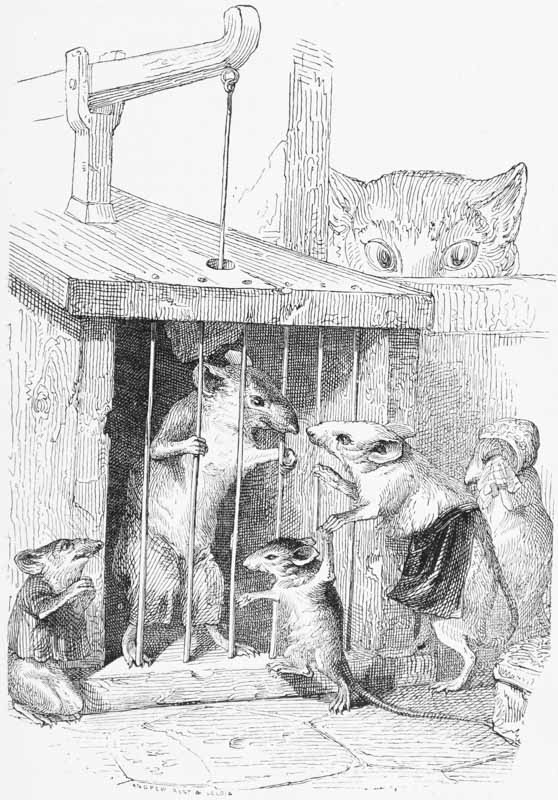

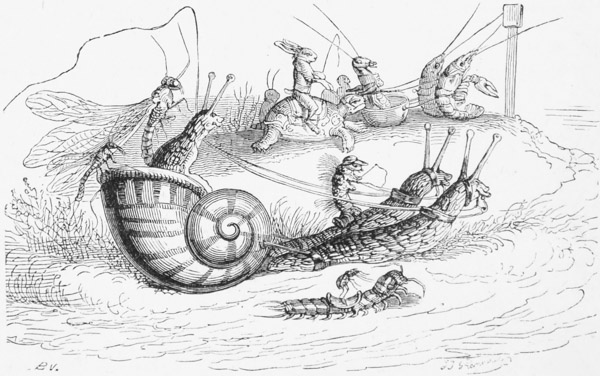

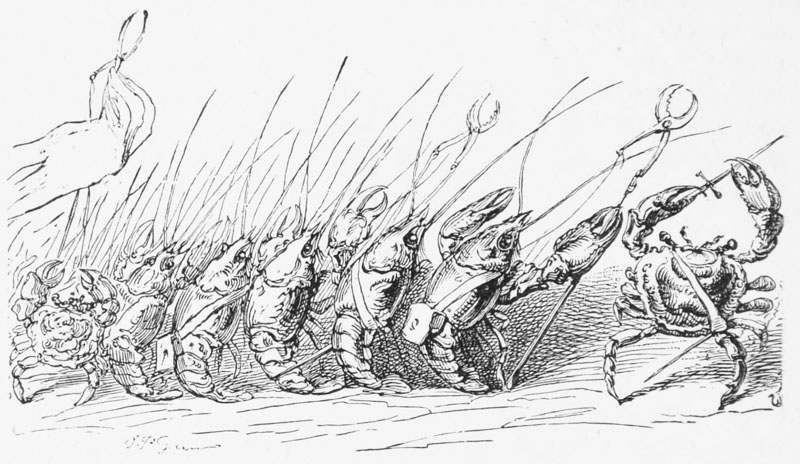

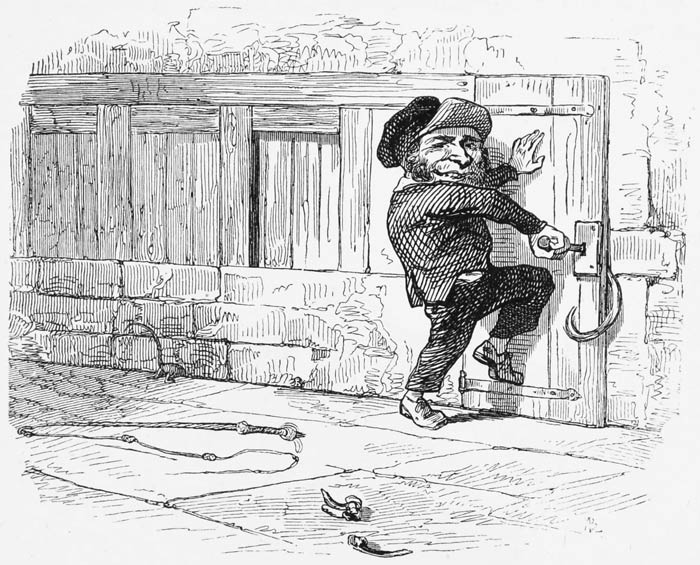

An Orang-outang, fired by his love of liberty, mastered the mechanism of locks, and at night, while the great world slept, opened the iron gates to the prisoners, who walked gravely out to take their seats. A large circle was formed, the Domestic Animals on the right, the Independent Wanderers on the left, and the Molluscs in the centre.

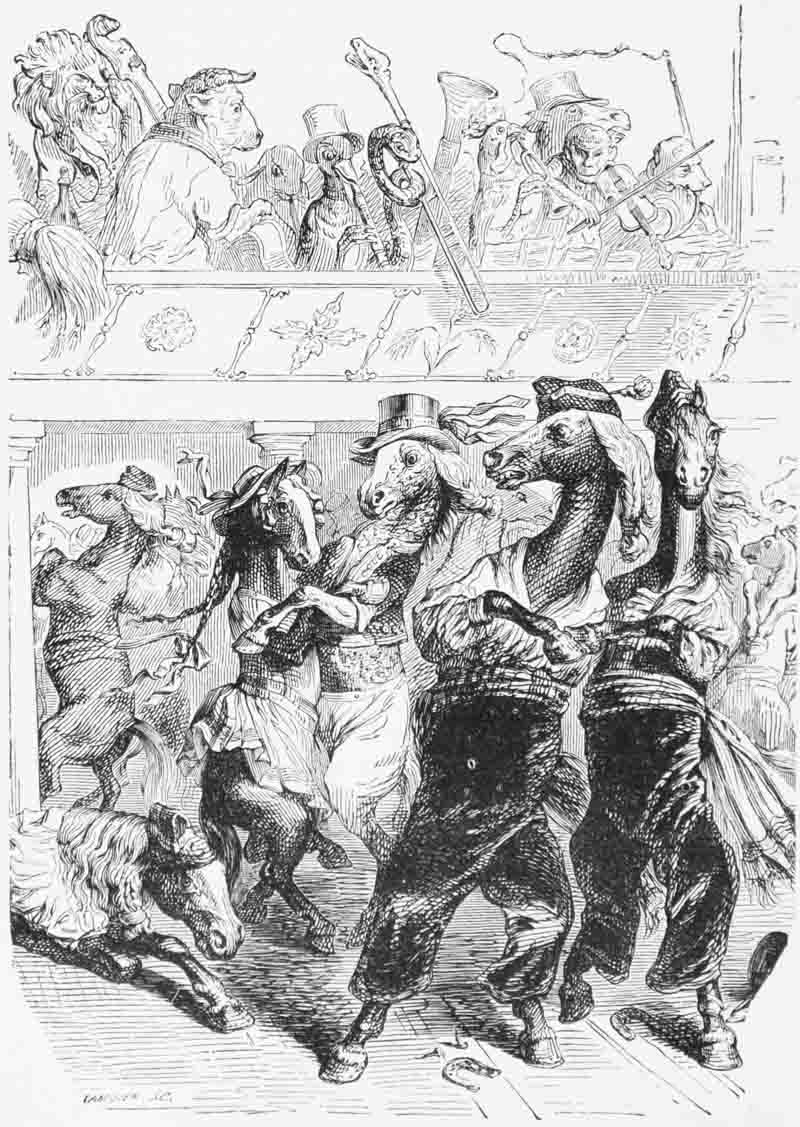

The rising sun, struggling through the gloom, fell upon a scene at once imposing, and full of great historic interest. No assembly of men that ever met on earth could possibly display a more masterly control of passion than did the non-herbivorous and carnivorous members of their powerful instincts. The Hyæna became almost musical, while the notes of the Goose were full of deep pathos.

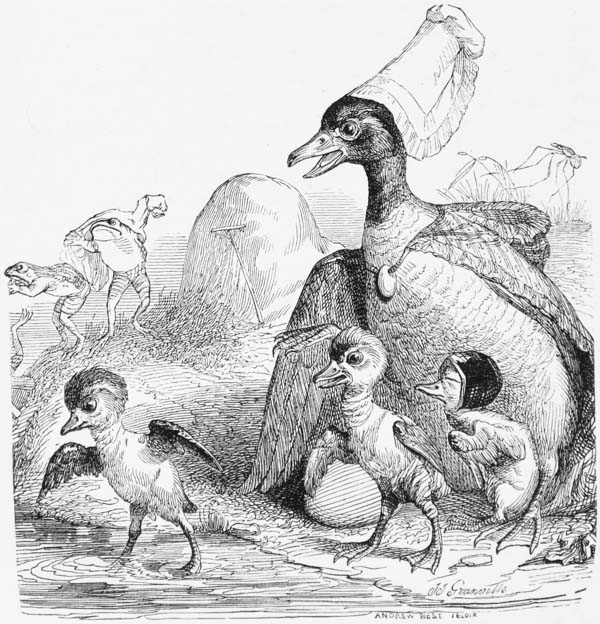

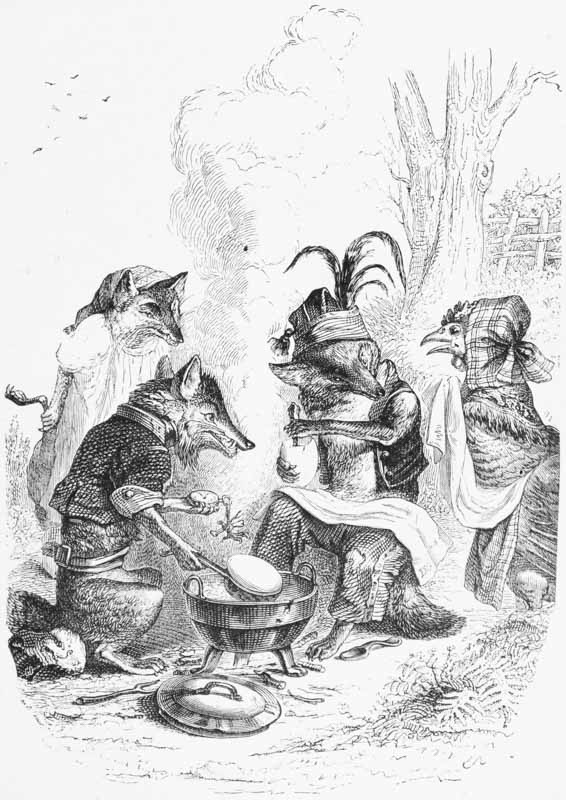

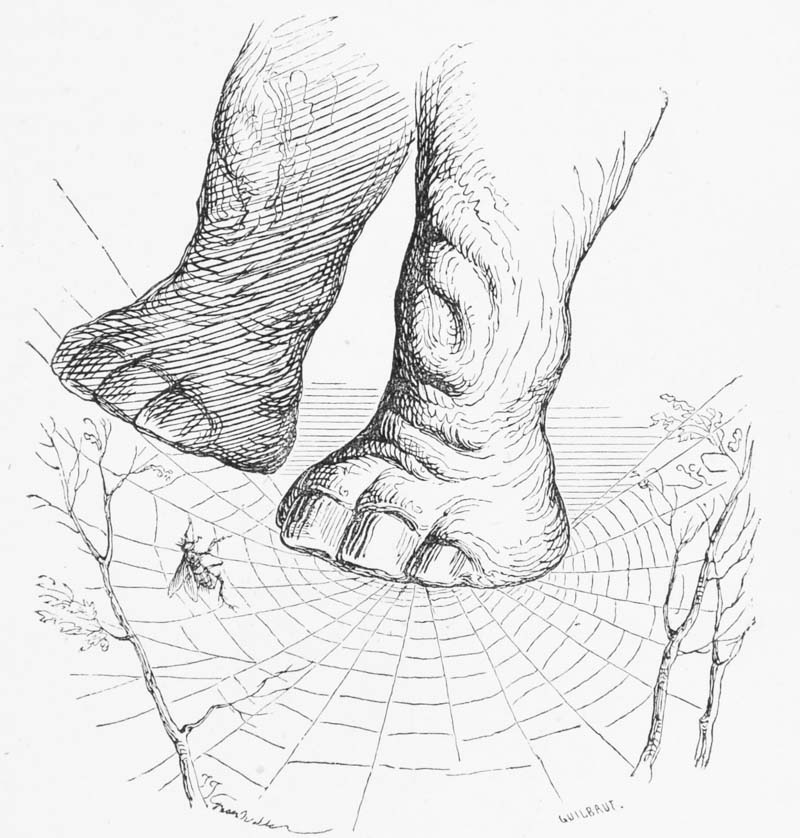

The opening of the Congress was marked by a scene most touching. All the members embraced and kissed each other, in one or two instances with such fervour as to lead to the effusion of blood. In the interests of the Animal Kingdom, it must be recorded that a Duck was strangled by an overjoyed Fox, a Sheep by an enthusiastic Wolf, and a Horse by a delirious Tiger. As ancient feuds had existed between the families, these events were clearly referable to the power of ancestral usage, and the joy of reconciliation. A Barbary Duck chanted a solemn dirge over the body of her companion, who had fallen in the cause of freedom. Before resuming her seat, the member for Barbary made an eloquent speech, urging the Congress to overlook the accidents, and proceed with the orders of the day. At this moment an unfortunate Siamese Ambassador Elephant was about to propose the abolition of capital punishment. Being a devout Buddhist, he advocated the preservation of life in every form. Unluckily for his doctrine, he had placed his huge foot on a nest of Field-mice, killing both parents and children. A young Toad drawing his attention to the melancholy fact overwhelmed him with remorse.

In simple courtesy to the reader, we must state that the report of the proceedings was obtained from a Parroquet, whose veracity may be trusted, as he only repeats what he has heard. We crave permission to conceal his name. Like the ancient senators of Venice, he has sworn silence on State affairs. In this instance alone he has thrown off his habitual reserve.

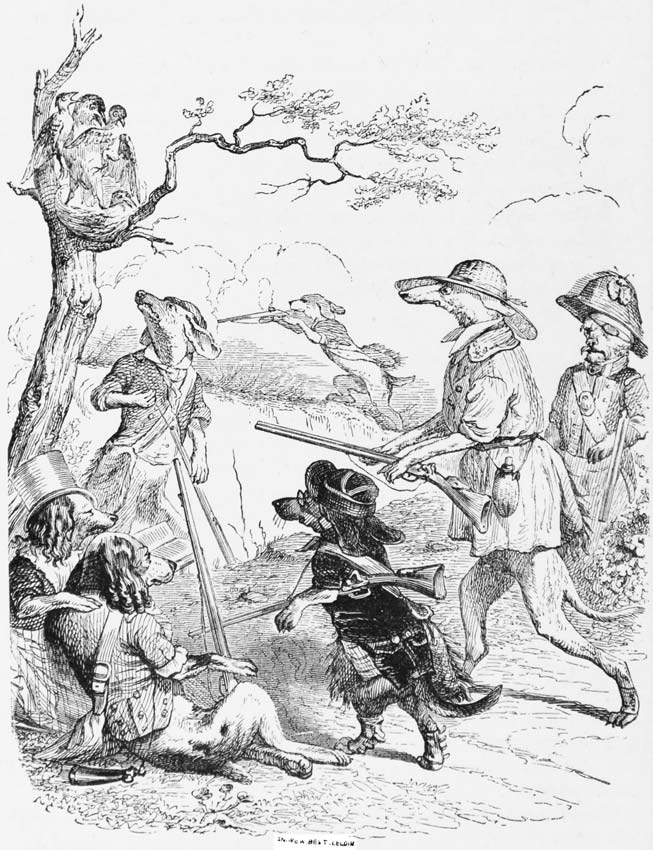

Nomination of President.—Questions relative to the suppression of man.—The members of the Left vote for war, the Right for arbitration.—Discussions in which the Lion, Tiger, Horse, Nightingale, Boar, and others take part.—The opinion of the Fox, and what came of it.

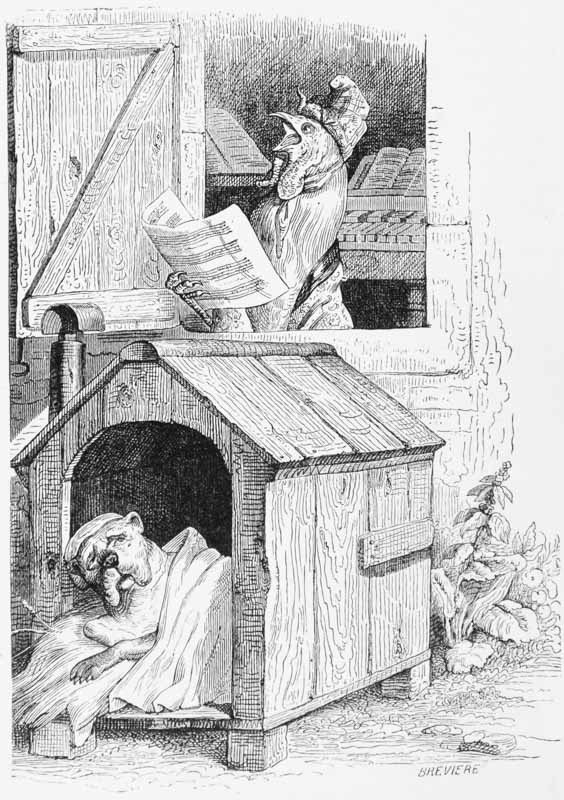

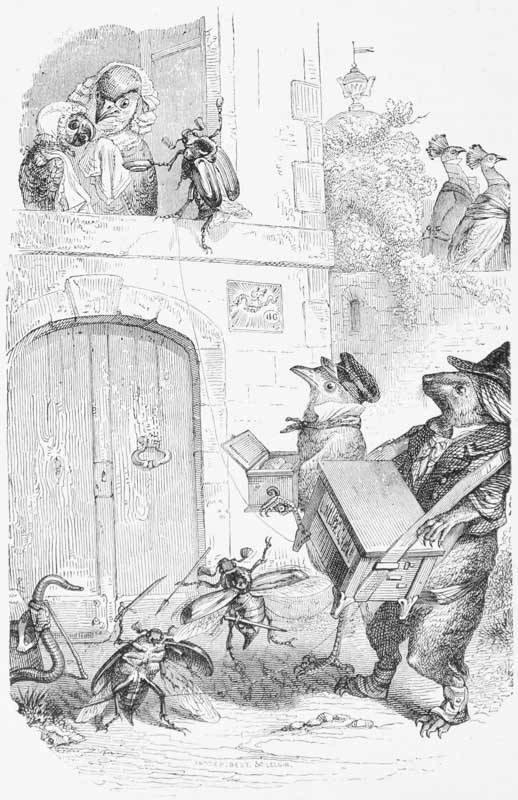

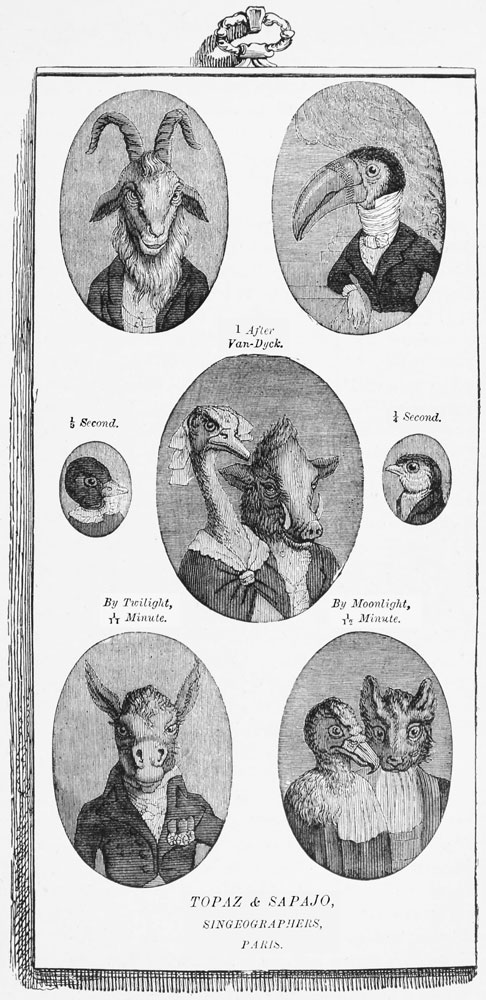

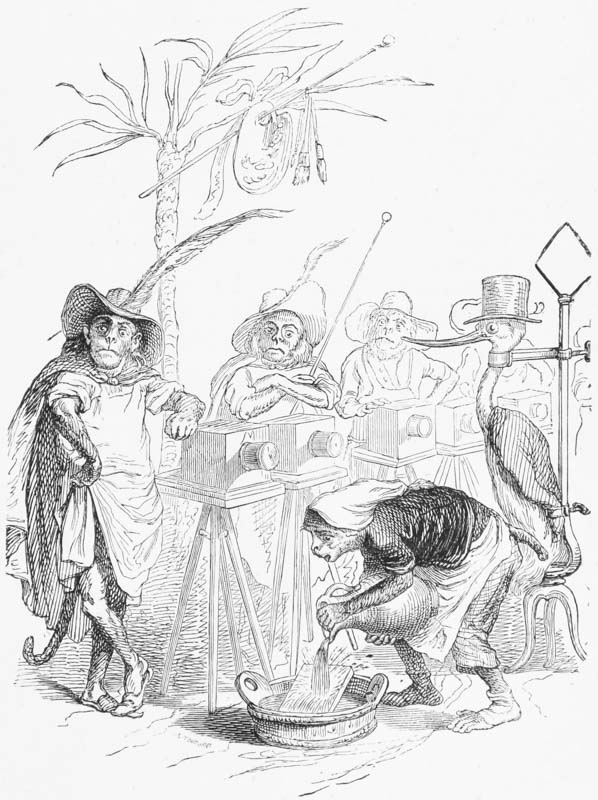

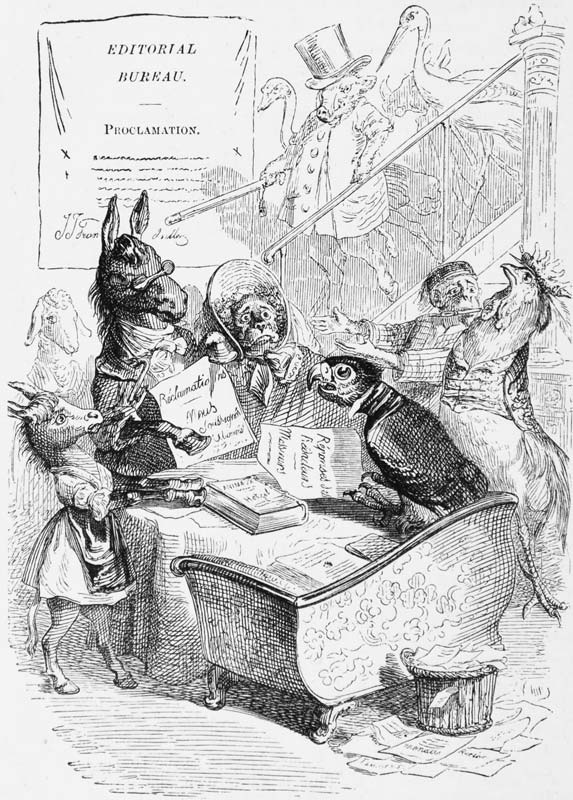

This publication is edited conjointly by the Ape, Parroquet, and Village Cock.

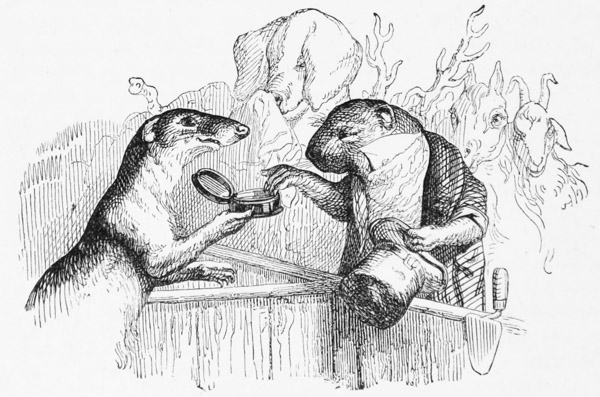

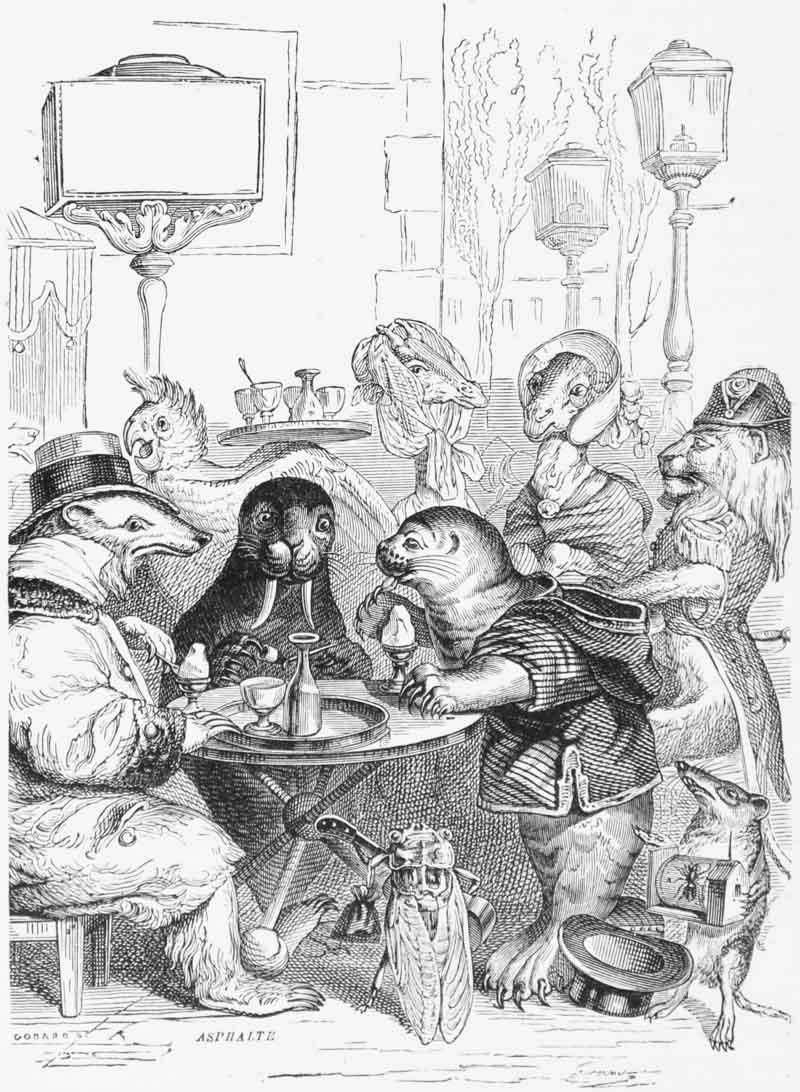

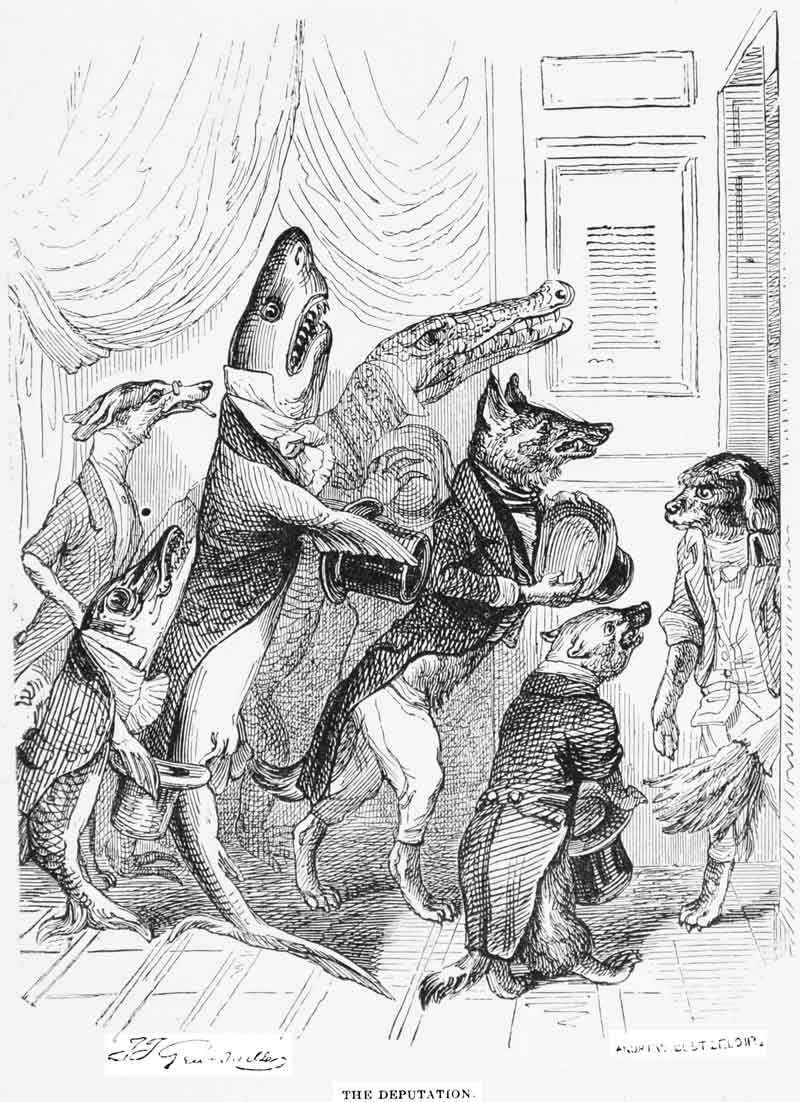

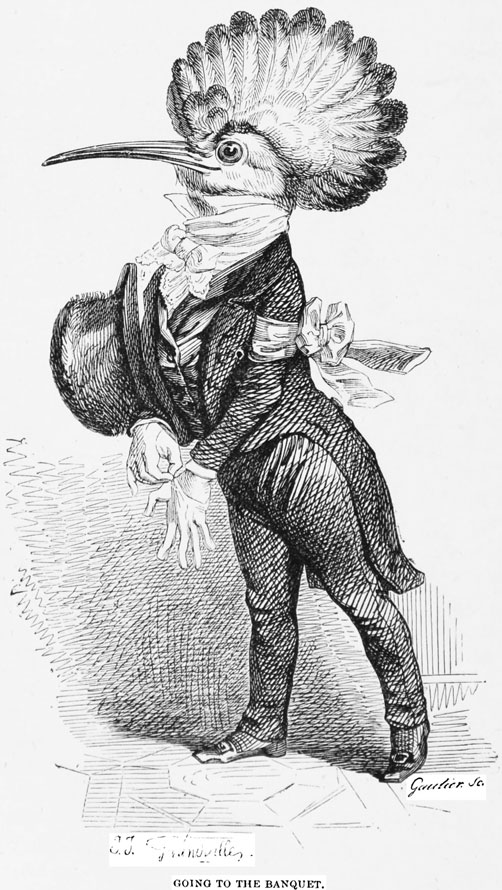

The garden paths are thronged with powerful deputies from the menageries of London, Berlin, Vienna, New York, and St. Petersburg. The Congress promises to be the most successful ever held in Paris. The death of a great French author, who devoted his pen to Natural History, has cast a gloom over the garden. The cultured animals wear crape, while the bolder spirits, proudly disdaining such symbols of grief, drop their ears and drag their tails along the ground. Here and there distinguished parties are hotly discussing the formation of the Congress, the framing of rules, and the choice of President. The Wolf sits beneath a tree, intently gazing on the Ape, whose careful attire and well-poised eye-glass proclaims man’s far-off cousinship to his family.

The Chameleon considers the get-up of the Ape a graceful tribute to his human kinsman.

The Wolf suggests that “to ape is not to imitate!”

The Snake in the grass hisses.

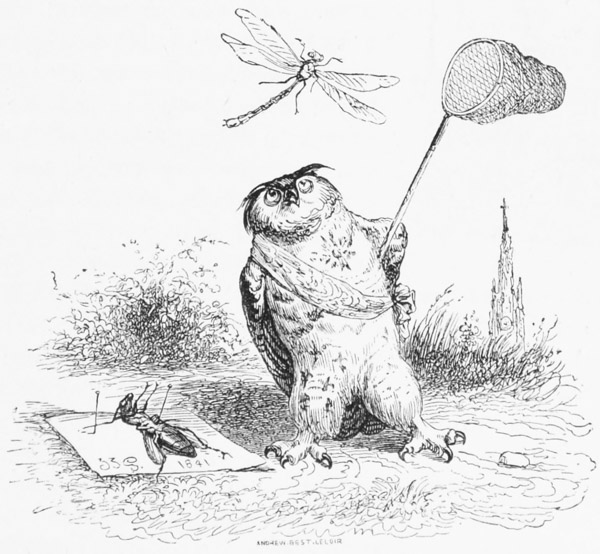

An erudite Crow croaks from his perch, “It would be extremely dangerous to follow in the footsteps of man,” and quotes the well-known line, “Timeo Danaos et dona ferentes.” He is loudly congratulated on the happy quotation by a German Owl, well versed in the dead languages.

The Buzzard devoutly contemplates the two scholars, while the Mocking-bird jeeringly remarks, “One way of passing for a learned biped is by talking to others of things they do not understand.”

The Chameleon blushes, and then looks blue. At this moment the Marmot awoke, to pronounce life a dream. “A dream?” said the Swallow, “nay, rather a journey.” The Ephemera gasped out, “Too brief, too brief,” and died.

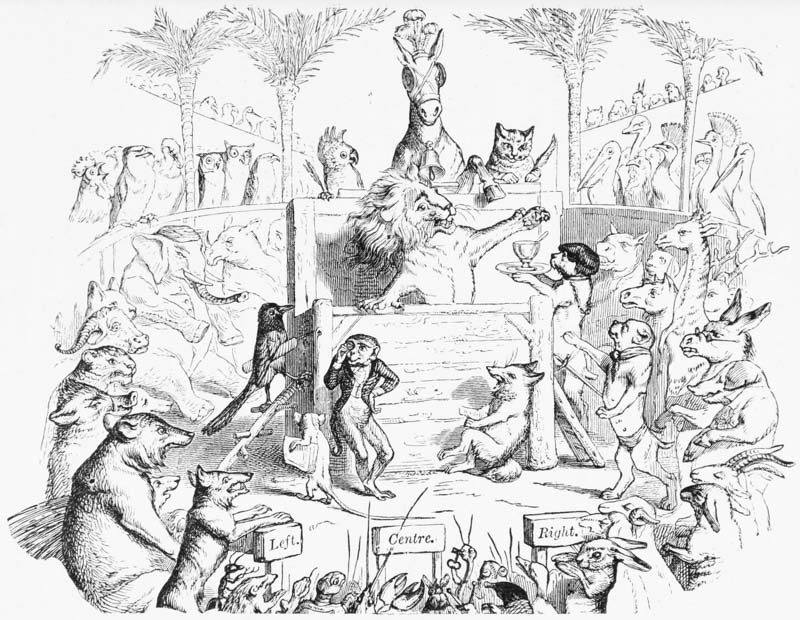

The question of the Presidency brings the scattered groups to the centre of the garden, and to business. When all are seated and expectant, the Ass brays out silence, quite needlessly, as the only audible sound was caused by a Flea sneezing in his ear. His supporters had prepared a speech for him, and his assurance, gravity, and weight obtained him a hearing. It was whispered that the honourable member was about to move that his ancient policy of progressing backward should be steadily kept in view. The orator, so adjusting his ears as to catch the faintest murmur of applause, flourished his tail impressively, and proceeded—

“Fellow-quadrupeds, and brother brutes of all climes and conditions, the question of the Presidency of this noble Assembly is one of primary importance. In order to lift the burdens from your backs, as the lineal descendant of Balaam’s ass, I offer myself as candidate for the position, hedged round as it is with difficulty and danger. It is needless to remind you of the hereditary attributes which qualify me for the office of President—firmness verging on obstinacy, patience under affliction, and a rooted determination to kick against all opposition.” Here the speaker was interrupted by the Wolf, who protested against the presumption of this slave of man. Stung to the heart, the honourable Ass was about to indulge his time-honoured habit of kicking up his heels, when he was called to order by the Bear.

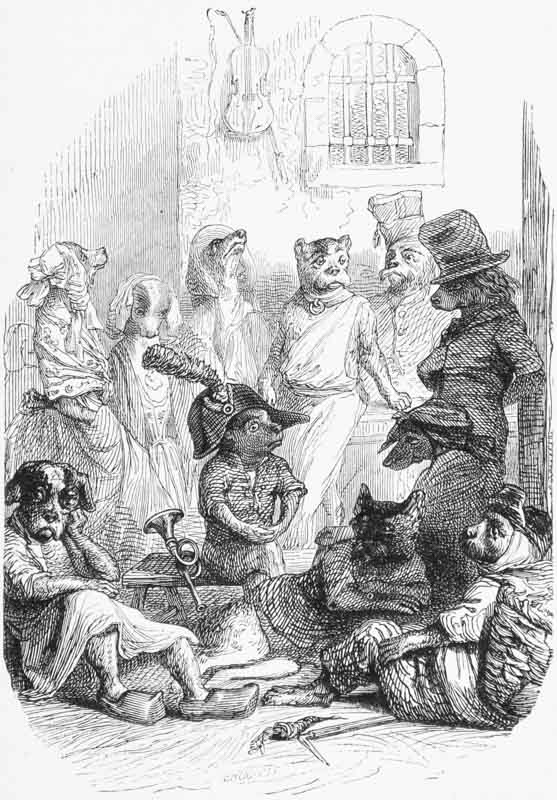

“Brothers,” said the Bear, “let not the heat of party feeling, added to the stifling air of Paris, compel me to return to my native climb, the North Pole. There my suffering has been great, but in the Arctic Circle I can grin and bear it as becomes my nature. Here, in a circle so refined, such brawling is only fit for men whose fiery tempers dry up the fountain of their love.” The Seal trembled at the sound of the dreaded voice.

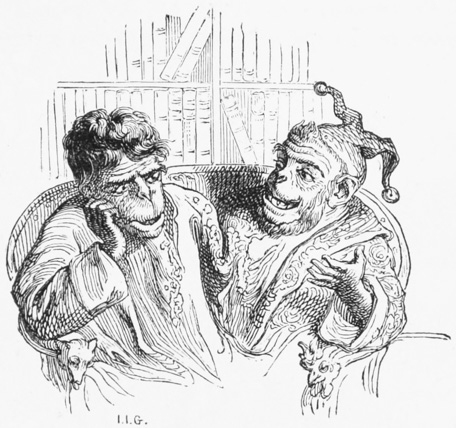

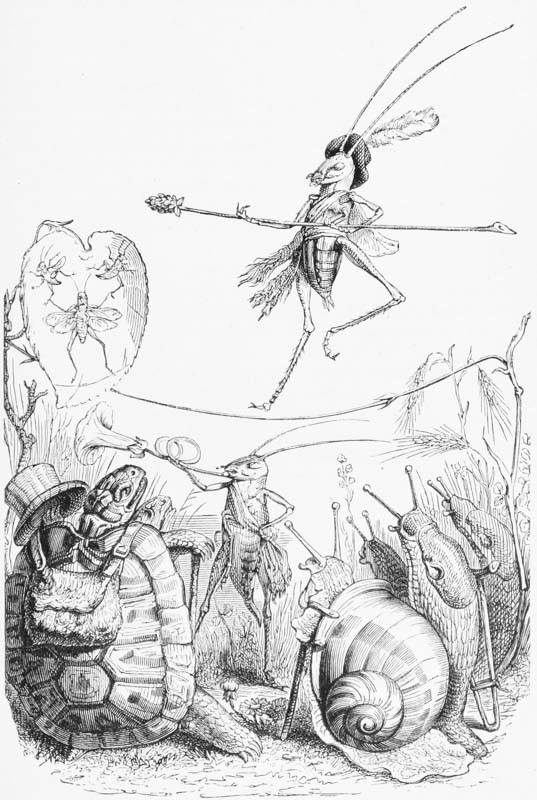

The Lion roared and restored order, while the Fox unobserved slipped into the tribune, and in a brief but subtle speech so eulogised the Mule—who carried a useful appendage in the shape of a bell—that he was chosen President.

The Mule takes the chair, and the tinkling of his bell is followed by silence broken for an instant by the Watch-dog—who fancied himself at his master’s door—gruffly inquiring, “Who’s there?”

The Wolf casts a scornful glance at the poor confused brute.

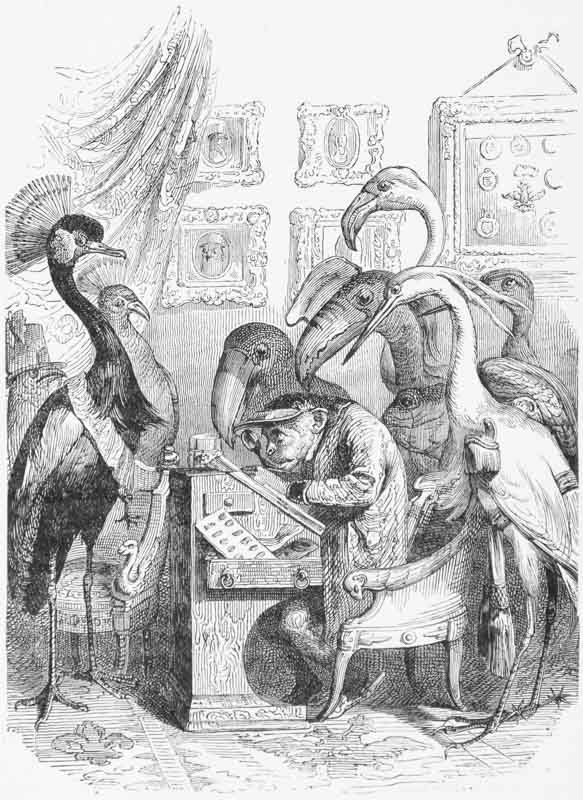

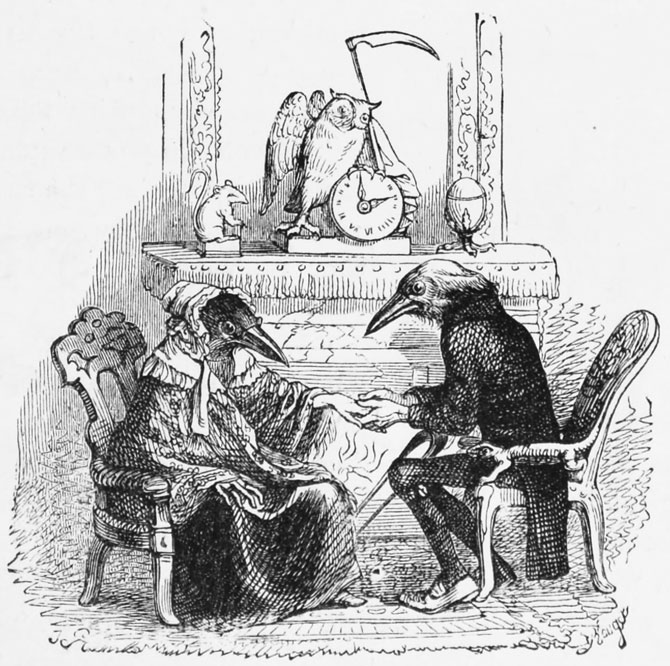

The Parroquet and Cat, preparing quills supplied by the Goose, seat themselves at the table as Secretaries.

The Lion ascends the tribune with imposing gravity; “shaking the dewdrops from his mane,” he denounces in a voice of thunder the tyranny of mankind, and continues: “There is but one way of escape open for all! Fly with me to Africa, to the sweet solitudes of boundless deserts and primeval forests, where we can hold our own against the inroads of degenerate humanity! Far from sheltering walls man is powerless against the noble animals I see around me. Cities are men’s refuge, and few there are of the lion-hearted among them, if I may use the expression” [ironical cheers from the Tiger], “who would meet us face to face in our native wilds.” The speaker concluded with a glowing picture of the proud independence of animal life in Africa.

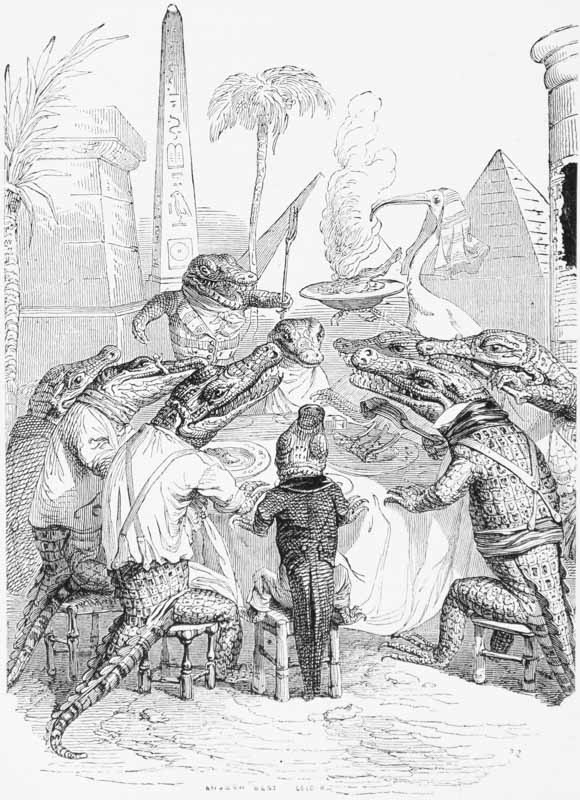

The Elephant advocated emigration to Central Africa. “It is a land,” said he, “where teeth and tusks are excellent passports, and where every traveller ought to carry his own trunk full of water.” This latter remark was objected to by the Hippopotamus, who held that water would be more useful if left in swamps and rivers.

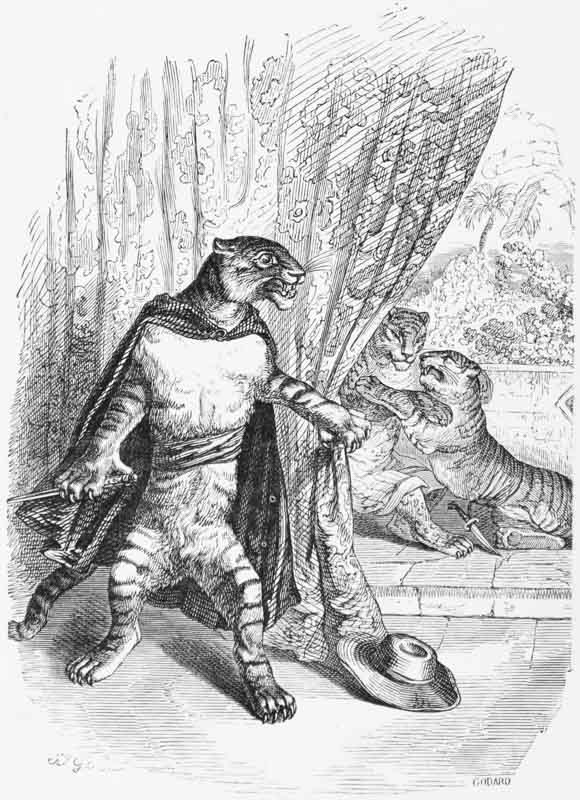

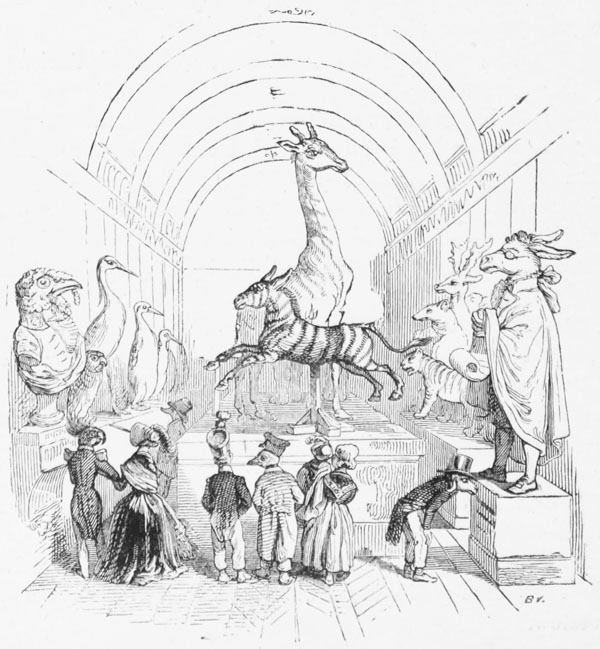

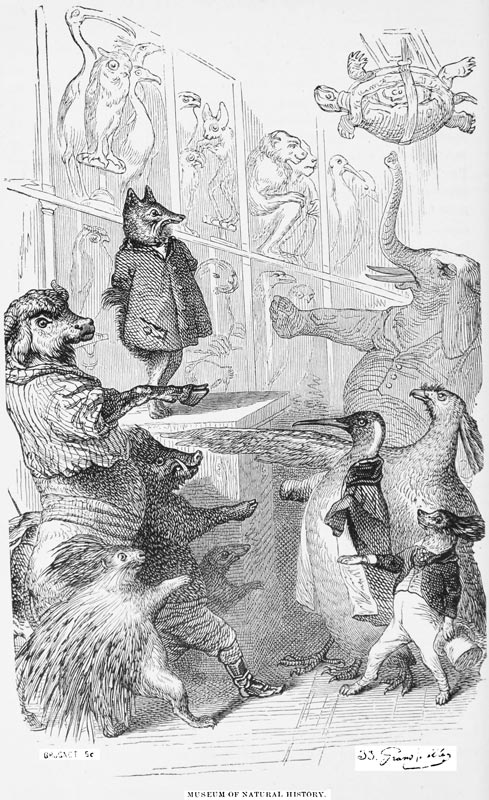

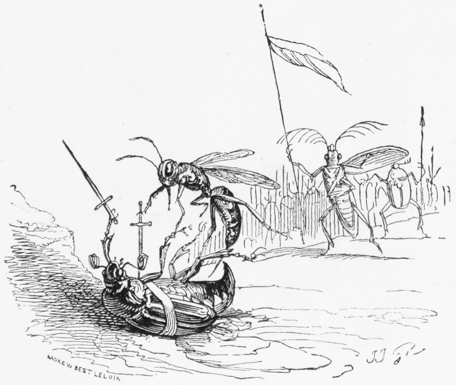

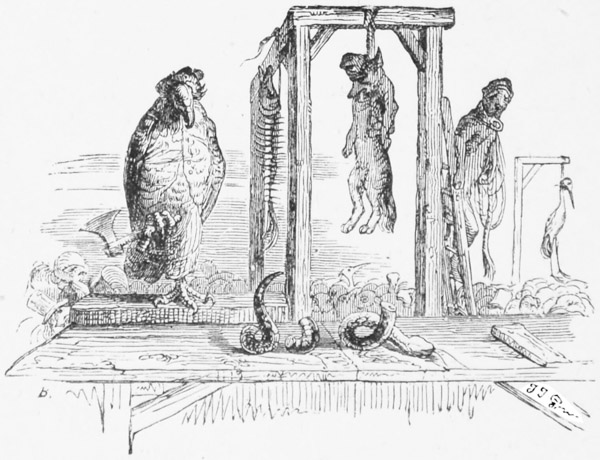

Hereupon the Dog protested that nothing could equal city life, and was put down by the Tiger, Wolf, and Hyæna. As for the Tiger, with a terrific howl he leaped into the tribune bellowing out, “War! blood! Nothing short of the utter extermination of man will establish the security of the Animal Kingdom. Great generals seize great occasions. Did not Rabbits undermine Tarragona? Did not liquor conquer Alexander the Great? The doom of the human race is sealed, its world-wide sway ended! The savage despots have driven us from our homes, hewn down our forests, burned our jungles, ploughed up our prairies, scooped out the solid world to build their begrimed cities, lay their railroads, warm their thin blood, roast our flesh for food. Torturing, slaying, and playing the devil right and left, men have trod the skins of my ancestors under foot, worn our claws and teeth as talismans, poisoned us, imprisoned us, dried and stuffed us, and set us to mimic our bold natures beside mummies in museums. Down with them, I say! Down with the tyrants!” Here the orator paused, he caught sight of a tear glistening in the eye of a lamb, his teeth watered, and his claws crept out at sight of this gentle tribute to his eloquence.

“Well may you weep, sweet one. He, man, robbed your mother of her fleece to clothe his guilty limbs, stole her life and devoured her, head and all. But why recall our wrongs? Is it not enough that he deprived us of our birthright? The world was ours before his advent, and he brought with him misery, confusion, death!” The Tiger concluded with an appeal to all beasts of prey to fight for liberty.

An old Race-horse, now a poor hack, begged permission to say a few words.

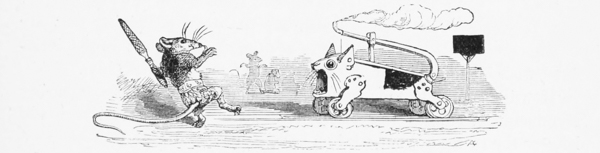

“Noble beasts, I must confess myself more familiar with sporting life than politics, or with the questions under discussion. I have, in my day, lived in clover; latterly the neglect and brutality of my human taskmasters have caused me much suffering. I am descended from a noble stock, the bluest blood of the turf circulates in my veins; but alas! I disappointed my first owners, and was soon sent adrift on the world. I was yoked in the last Royal Mail on the road, and earned my hay gallantly, until the accursed railways ruined my prospects. I beg humbly to move the abolition of steam traffic, and that the influential members of Congress should send me to grass, that I may end my days in the green fields, enjoying some State sinecure. Depend upon it, no one is more deserving of your sympathy and support than the reduced member of a noble family.”

The President was so moved by this appeal, that he left the chair, announcing an interval of ten minutes.

The tinkle of the bell summons the delegates to their places, which they take with a promptitude that bears witness to their zeal.

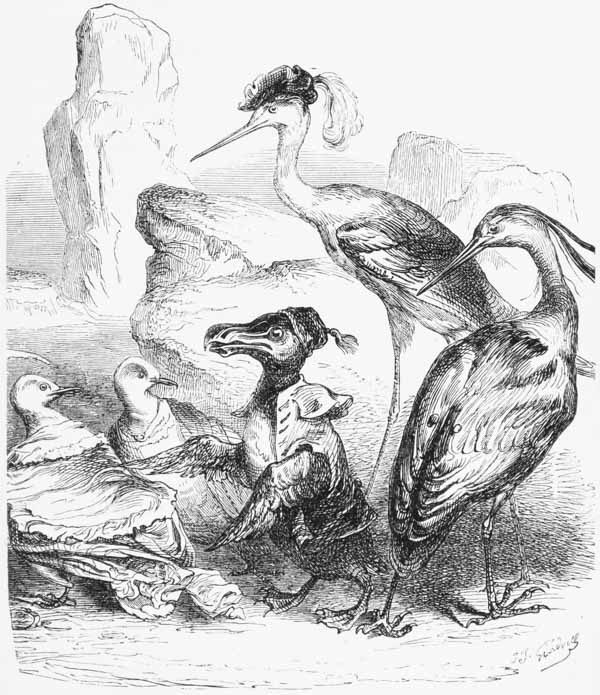

The Nightingale alights on the tribune, and in a gush of melody prays for bluer heavens and serener nights. He is called to order, as, notwithstanding the purity of his notes, he had proposed no tangible measure of reform. The Ass takes exception to the songster’s low notes, as wanting in asinine richness.

A modest Camel from Mecca proposes that men should be taught to use their legs in place of the backs of higher animals. This proposal is greeted with the applause of equine animals, including the President, who, discovering that the claims of this distinguished foreigner had been overlooked, inquires as to the future of Turkish finance.

The Camel replies with much good sense, “There is one God, and Mahomet is his prophet!”

The Pig here gave it out as her opinion that trouble will never end until men are compelled to abjure the faith of Mahomet, respect Pigs, supply unlimited food and drink, and abolish sanitary law, so as to give nature free scope to expand.

An old Boar—accused by his foes of wandering about farmyards—complimented the Pig on her good taste, suggesting, at the same time, that the absence of sanitary law might tend to poison the political atmosphere. Mrs. Pig protested against insinuations calculated to mix up piggeries with politics.

The Fox, who had been taking notes, ascended the tribune and commenced—

“It is with great satisfaction that I rise to offer one or two remarks on the able speeches of the honourable members of this Congress. Before reviewing the various propositions, I take this opportunity of saying, that never throughout my diplomatic career have I witnessed harmony more perfect. Never has there been a more profound display of unanimity of sentiment than in the wagging tails of this wise assembly. The tail is the chief attribute coveted by man. [‘Right you are,’ growled an old Sporting-dog]. That by the way; to return to business, nothing could be nobler than the proposal of the Lion to establish and defend our animal commonwealth in Africa. It must not, however, be forgotten that that continent is distant, and inaccessible to many useful members of the Congress, industrial animals, who might succumb to savage warfare or malaria.

“The allusion of the Dog to the joys of city life is not without interest; but he is the slave of man. Mark his collar, inscribed with some barbarous name!” The subject of comment scratches his ear, and the Mocking-bird observes that his ears must have been cropped to imitate man.

“For an instant—carried away by the tide of his eloquence—I shared the ardour of the Tiger, and almost lent my voice to the war-cry. War is very good for those who escape; but it leaves in its train orphans and widows to be provided for by the survivors. Therefore it is not an unmixed good, more especially as right does not always triumph.

“The reasoning of the Pig is both good and bad, and like that of the Boar, is more calculated to affect pork than progress.

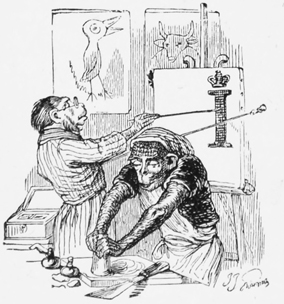

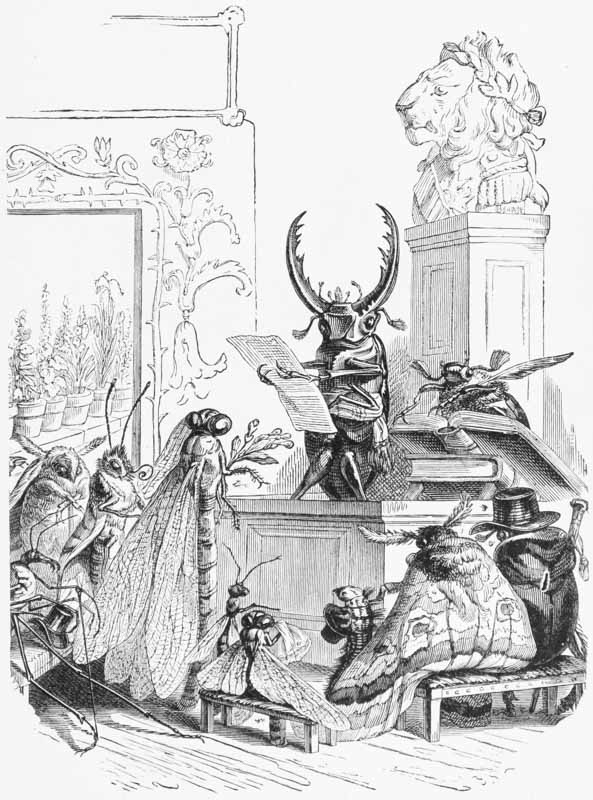

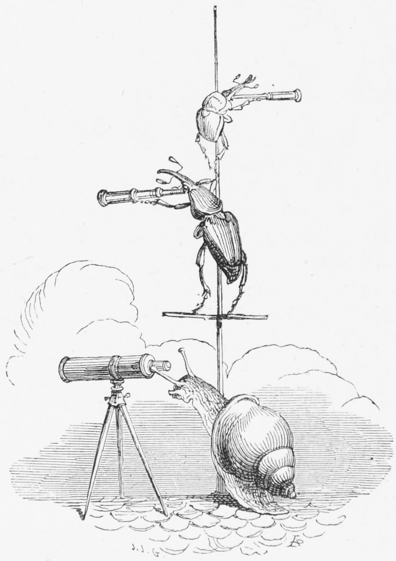

“I take you all to witness that peace, war, and liberty are alike impossible for all. We are all agreed that evil exists somewhere, and that something must be done. [Loud cheers.] I have now the honour to propose a new, untried remedy. [Great excitement.] The only reasonable, lawful, and sacred course to follow is to struggle for knowledge. Why not take a leaf from human experience, and employ the Press to make known our wants, aspirations, customs, and usages, our public and private life.

“Naturalists imagine they have done all when they have analysed our blood, and endeavoured to find out the secret of our noble instinct from our physical organisation.

“We alone can relate our griefs, our patience under suffering, and our joys—joys so rare to creatures on which the hand of man has pressed so heavily.” The speaker paused to conceal his emotion. He continued: “Yes, we must publish our wrongs.

“A word to the ladies. The circle which they most adorn is that of home, and to them must we look for information—jotted down in leisure-hours—on domestic subjects. Let them eschew politics. A lady politician is a creature to be avoided. I have further to crave the indulgence of this noble assembly in submitting the following articles—

“Article 1st.—It is proposed to vote unlimited funds to carry out the ‘Illustrated Public and Private History of Animals,’ the funds to be invested in Turkish Securities and Peruvian Bonds.”

A Member of the Left proposes to take charge of the money-bag.

The Mole suggests that the funds should be sunk in certain dark mining companies, of which he is an active director.

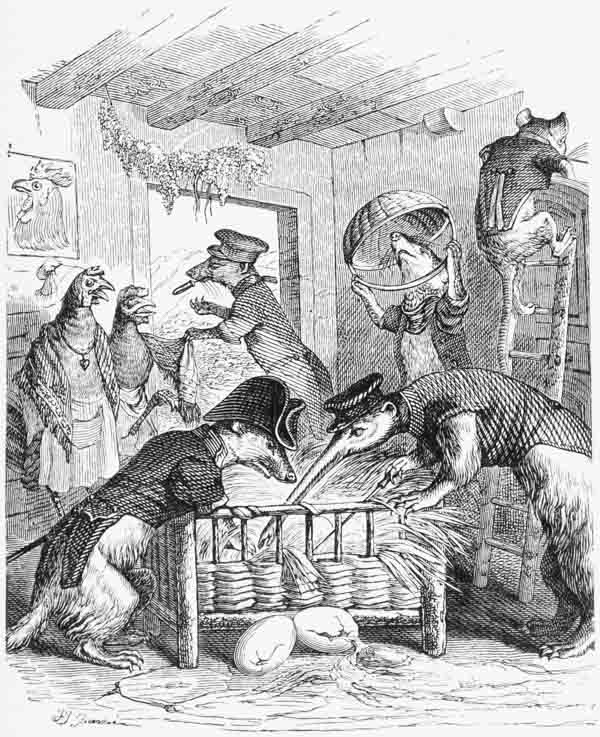

This proposal is negatived by the Codfish, who is of opinion that they would be safer at the bottom of the sea, as molehills have hitherto proved unremunerative. A Hen came forward with her Chickens, saying, as she had a number of little bills standing open, and which must be honoured, she would take part of the coin as a temporary loan, and do her best to lay golden eggs.

This suggestion was referred to a select committee, and here the matter dropped.

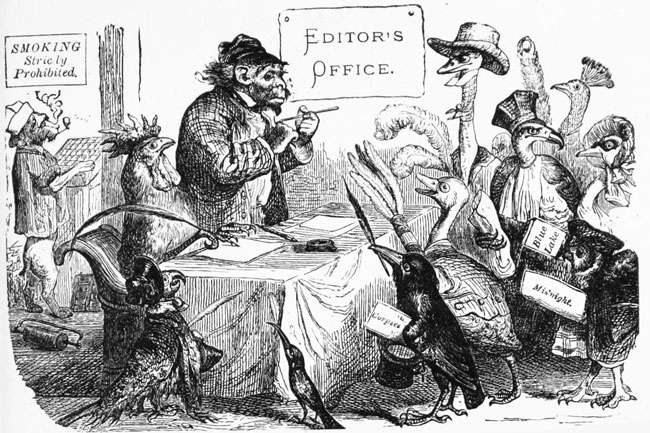

“Article 2d.—The Journal of the Animals must combat ignorance and bad faith, the joint enemies of truth. The entire matter to be edited by competent brutes, in order to disarm criticism.

“Article 3d.—Men must be employed to perform the drudgery of printing.

“Article 4th.—The Fox must find an intelligent philanthropic publisher.”

Here the Fox shook his head dolefully, and said he would try. “I have,” he continued, “imposed on myself the severest task of all, as the profits of publication must, for a long time, be absorbed in corrections, discounts, and advertising.”

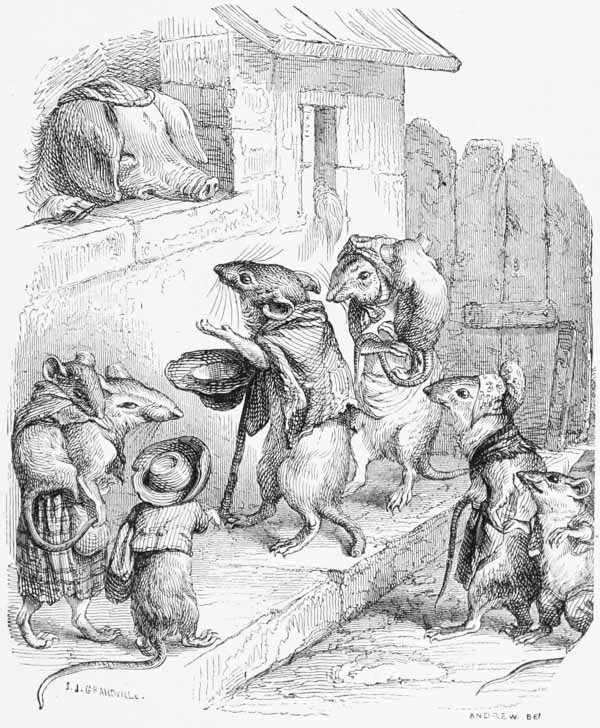

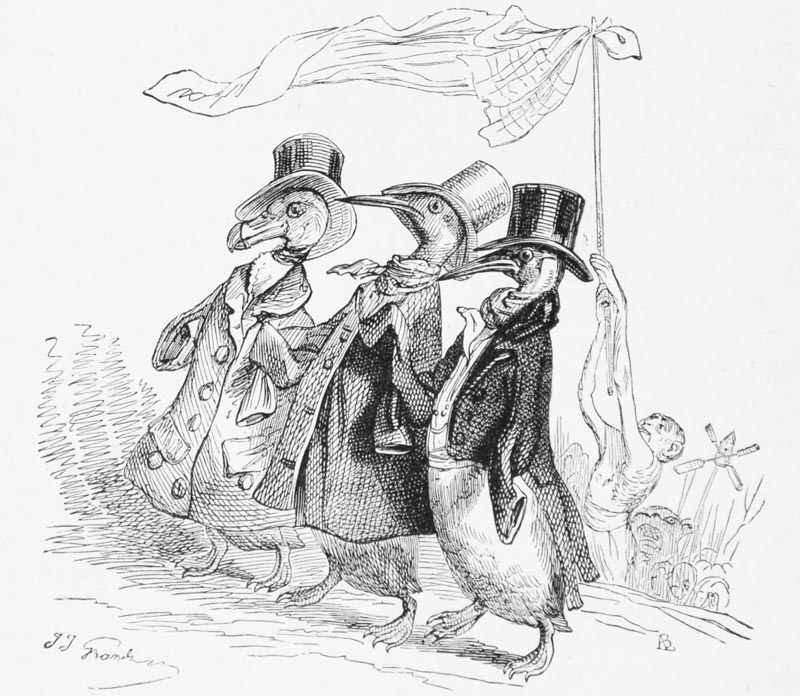

A vote of confidence passed in favour of the speaker’s integrity and ability closed the proceedings. Before the Assembly broke up, it was announced, amid loud applause, that the Ape, Parroquet, and Village Cock would enter at once on their duties as Editors in Chief of the “Public and Private Lives of Animals,” and that the work would open with the “History of a Hare.”

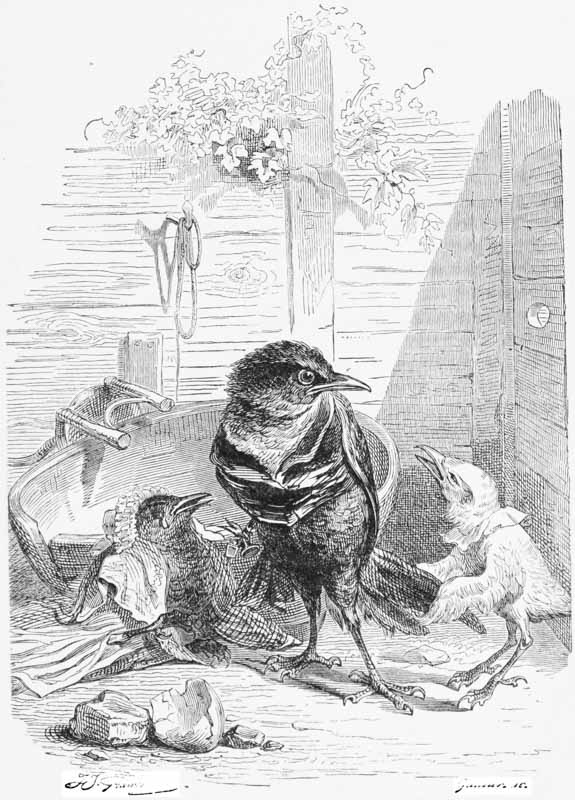

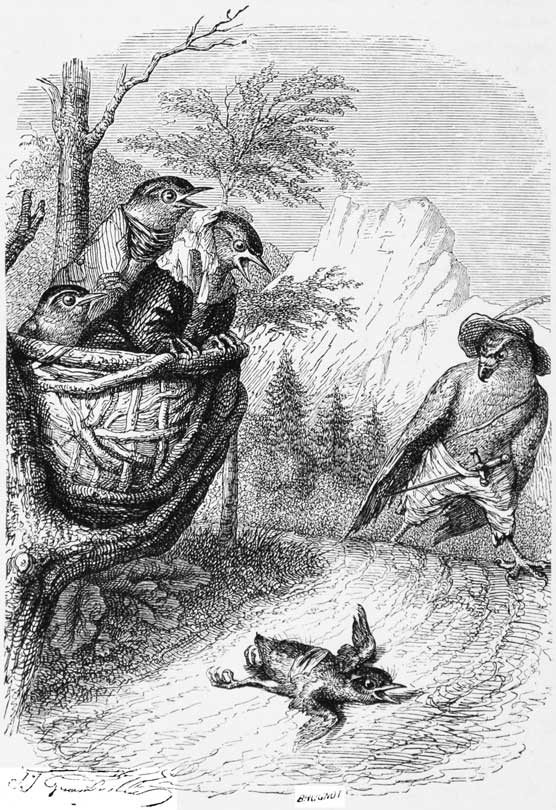

In which the Magpie begins.—Some preliminary reflections by the Author of this history.—The Hare is made prisoner.—The Hare’s theory of courage.

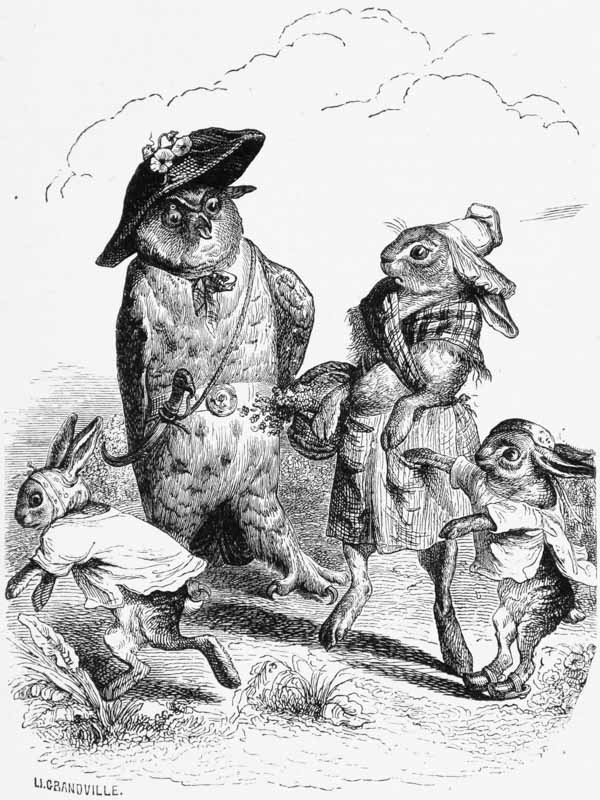

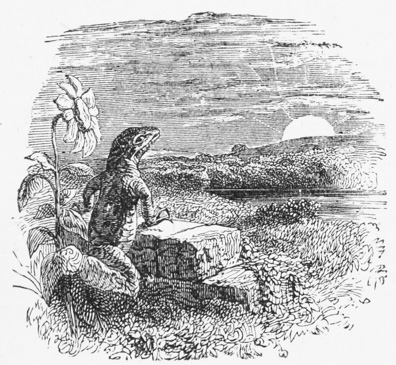

ONE day last week, as I stood on the branch of an old tree, meditating on the closing lines of a poem I was about to dedicate to my race, my attention was arrested by a Leveret running at full speed across a field. He turned out to be a personal friend of my own, great-grandson of the hero of this tale.

“Mr. Magpie,” he cried, quite out of breath, “grandfather lies yonder in a corner of the wood. He sent me to call you.”

“Good child,” I said, while I patted his cheek with my wing, “go your grandfather’s errands, but do not run so fast, else you will come to an untimely end.”

“Ah!” he replied, sadly, “love feels no fatigue. But come to one who needs your counsel. My grandfather is ill, bitten by the keeper’s dog.”

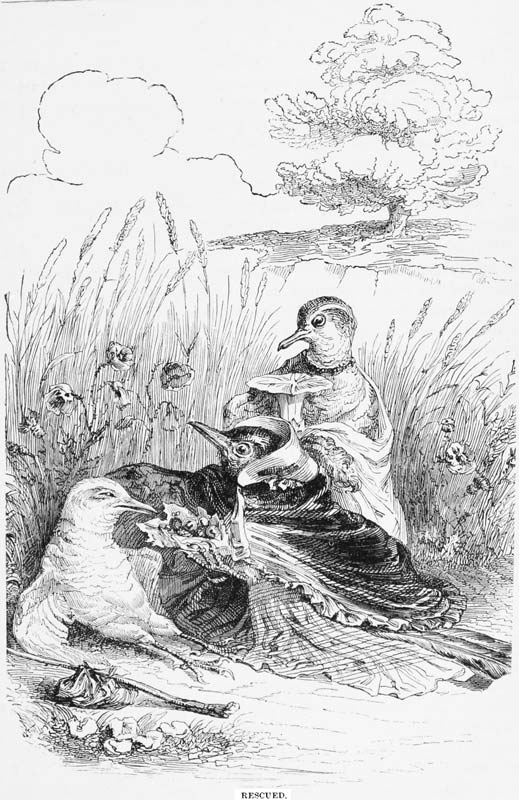

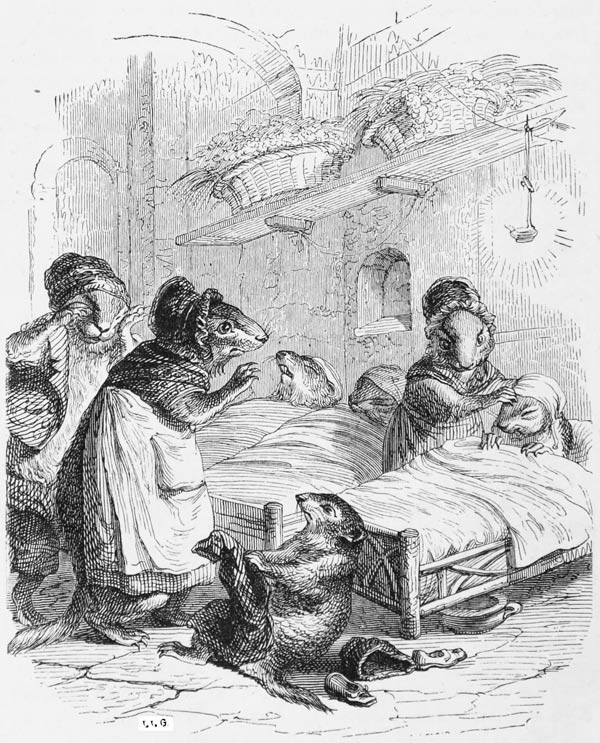

Repairing at once to the scene of the disaster, I found my old friend suffering intense pain from a wound in his right foot, which he carried slung in a willow-band. His head was also bandaged with soothing leaves brought by a neighbourly Deer.

Blood still flowed, affording fresh testimony of man’s tyranny.

“My dear Magpie,” said the venerable sufferer, whose face, although grave even to sadness, had lost nothing of its original simplicity, “our lot in this world is, at best, an unhappy one.”

“Alas!” I replied, “we encounter fresh tokens of our misery every day.”

“I know,” he continued, “that one ought always to be on one’s guard, and that the Hare is never certain to die peacefully in his form. The campaign begins badly. Here am I, perhaps blind of an eye, and certainly lamed so that a Spaniel might easily outrun me. Worse than all, I am told the shooting begins in a fortnight. I must therefore put my affairs in order, and leave the history of a short, but not uneventful life, to posterity to profit by. When mingling in the society of the world, one is constrained to observe a polite and prudent silence, and to disguise one’s true sentiments. But in prospect of death, brought face to face with the last enemy, one can never hope to win his clemency by polished lying and hypocrisy. My tale will therefore be unreserved and true. Besides, in bequeathing a valuable history to posterity there is a satisfaction in feeling that one’s influence will live, and prove a real power in the world long after the author’s death.”

I had the greatest difficulty in making him understand that I was quite of his opinion, for during his imprisonment he had become very deaf, and what rendered it still more disagreeable was that he obstinately denied being so. How many times have I not cursed the unnatural life which bereft him of hearing! I said in a loud tone, “It is a noble ambition to live one’s life over again in one’s works, and the history you are about to give to the world should enable you to face death calmly, as immortal fame may take the place of life. In any case, the book ought to see the light; it can do no harm.” He then told me that his troubles had been great. The wound in his right foot had prevented his using the pen. He tried to dictate to his grandchildren, but they, poor little ones, had only learned how to eat and sleep. It had occurred to him to teach his eldest child to commit the story to memory, and thus hand it down from father to son. “But,” he added, “oral traditions are never trustworthy; and as I have no desire to become a myth like the Great Buddha, or Saint Simon, I beg you will act as my amanuensis. My history would then, sir, reflect the lustre of your genius.”

Wishing to invest this, the most important and perhaps the last act of his life, with due solemnity, he retired for a few seconds. Being a learned Hare, he thought it necessary to commence with a quotation.

These two lines by Racine were splendidly rendered by the erudite speaker.

The eldest grandchild left his accustomed sport, and respectfully seated himself on his grandfather’s knee. The second, who was passionately fond of stories, pricked up his ears, while the youngest sat up, prepared to divide his attention between the narrative and a cabbage-leaf he was eating. The old Hare, seeing that I was waiting, began thus—

“My secret, my dear children, is my history. May it serve you as a lesson, for Wisdom does not come to us; we must travel by long and tortuous ways to meet her. I am ten years old—so old, indeed, that never before, in the memory of Hares, has so long a term of life been granted to a poor animal. I was born in France, of French parents, in May 1830; there, behind that oak, the finest tree in the beautiful forest of Rambouillet, on a bed of moss which my good mother had lined with her softest fur. I can still recall those beautiful nights of my infancy when simply to live was to be happy, the moonlight seemed so pure, the grass so tender, and the wild thyme and clover so fragrant. Life was to be clouded, but not without its gleams of sunshine. I was gay then, giddy and idle as you are. I had your age, your thoughtlessness, and the use of my four feet. I knew nothing of life; I was happy, yes, happy! in ignorance of the cruel fate that may at any moment overtake us. It was not long before I became aware that the days, as they followed each other, were only alike in duration; some brought with them burdens of sorrow that seemed to blot out the joy from life.

“One day, after scampering over these fields, and through the woods, I returned to sleep by my mother’s side (as a child ought to do). At daybreak I was rudely awakened by two claps of thunder, followed by the most horrible clamour. . . . My mother, at two paces from me, lay dying, assassinated! . . . ‘Run away,’ she cried, and expired. Her last breath was for me! One second had taught me what a gun was in the cruel hands of man. Ah, my children! were there no men on earth, it would be the Hares’ paradise. It is so full of riches. Its brooks are so pure, its herbs so sweet, and its mossy nooks so lovely. Who, I ask you, could be happier than a Hare, if the good God had not, for His own wise ends, permitted man to oppress us? But alas! every medal has a reverse face; evil is always side by side with good, and man by the side of the brute. Would you believe it, my dear Magpie—I have it on the best authority—that man was originally a godlike animal?”

“So it is said,” I replied, “and he has himself to thank for his present condition.”

“Tell me, grandfather,” said the youngest; “in the field yonder were two little Hares with their sister, and a large bird that wanted to prevent them passing. Was that a man?”

“Be quiet,” said her brother; “since it was a bird, how could it be a man? If you want grandfather to hear, you must scream, and that will frighten the neighbours.”

“Silence!” cried the old Hare, who perceived they were not listening. He then inquired, “Where was I?”

“Your mother had just died, and you had fled.”

“Yes, to be sure. My poor mother, she was right; her death was only a prelude to my own suffering. It was a royal hunt that day, and a horrible carnage took place. The ground was strewn with the slain; blood everywhere, on the grass and underwood; branches, broken by bullets, lay scattered about; and the flowers were trodden under foot. Five hundred victims fell on that dreadful day. One cannot understand why men should call this sport, and enjoy it as a pastime.

“My mother’s death was well and speedily avenged. It was a royal hunt, but it was the last; he who held the gun, I am told, passed once more through Rambouillet, but not as a sportsman.

“I followed my mother’s advice, and, for a hare only eighteen days old, ran bravely; yes, bravely! If ever, my children, you are in danger, fear nothing, flee from it. It is no disgrace to retreat before superior force. Nothing annoys me more than to hear men talk of our timidity and cowardice. They ought rather to admire and imitate the tact which prompts us to use our legs, being ignorant of the use of arms. Our weakness makes the strength of boastful men and brutes.

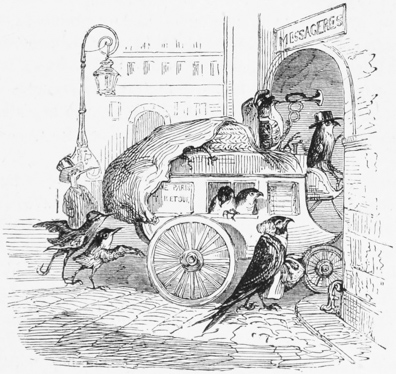

“I ran until I fell quite exhausted, and became insensible. When I recovered consciousness, judge of my terror! I found myself no longer in the green fields, but shut up in a narrow prison, a closed basket. My luck had deserted me, and yet it was something to know I was still living, as it is said death is the worst of all evils, being the last. But men rarely release their prisoners. My mind therefore became a prey to bitter forebodings, as I had no notion of what might become of me. I was shaken by rough jolts, when one, more severe than the others, half-opened my prison door, and enabled me to see that the man on whose arm it was suspended was not walking, yet a rapid motion carried us along. You, who as yet have seen nothing, will find it hard to believe that my captor was mounted on a horse. It was man above, and horse beneath. I could never make out why such a strong, noble creature should, like a dog, consent to become the slave of man—to carry him to and fro, and be whipped, spurred, and abused by him. If, like the Buddhists, we were to believe in transmigration after death, it would all come right at last, and we some day, as men, would have our time of torturing animals. But the doctrine, my children, is more than doubtful. I, for one, have no faith in it.

“My captor was a magnificent creature—the king’s footman.”

The Revolution of July, and its fatal consequences.—Utility of the Fine Arts.

AFTER a brief but impressive pause, a shadow seeming to settle on his fine features, my old friend resumed the thread of his narrative.

“I offered no resistance. It was my fate, and I accepted it calmly. Among men, every one is more or less the servant of another, the only difference being in the kind of services rendered. Once within the pale of civilisation, I was forced to accept its degrading obligations. The king’s lackey was my master.

“As good luck would have it, his little girl, who had taken me for a cat, became my friend. It was soon settled that I was to be killed. My mistress pleaded for my youth and beauty, and the pleasure which my society afforded her. Her chief delight was in pulling my ears, a familiarity which I never resented. My patience won her heart, and I felt grateful to her for her kindness to me.

“Women, my children, are infinitely superior to men; they never go hunting hares, men are their game!

“I would have suffered patiently, had I seen the faintest prospect of escape; but I dreaded the pitiless bayonet of the guard at the gate of the Louvre.

“In a small room in Paris, beneath the shade of the Tuileries, I often watered my bread with my tears. This bread of slavery seemed, oh! so bitter, and so difficult to get over, for my heart was full of the green fields and sweet herbs of freedom. No abode on earth can be more dreary than a palace when one is compelled to remain within its gilded walls. The gold and glitter soon grow dim when compared with the blue sky and free earth, the delight of God’s creatures.

“I tried to while away the time by gazing out of the window, but this only rendered my bondage all the more galling. I began to hate the monotony of my new life. What would I not have given for one hour’s liberty, and a bit of thyme. Often was I tempted to throw myself from the window of my prison, to take one desperate leap, and live or die for freedom. Believe me, my children, happiness seldom dwells within palace walls.

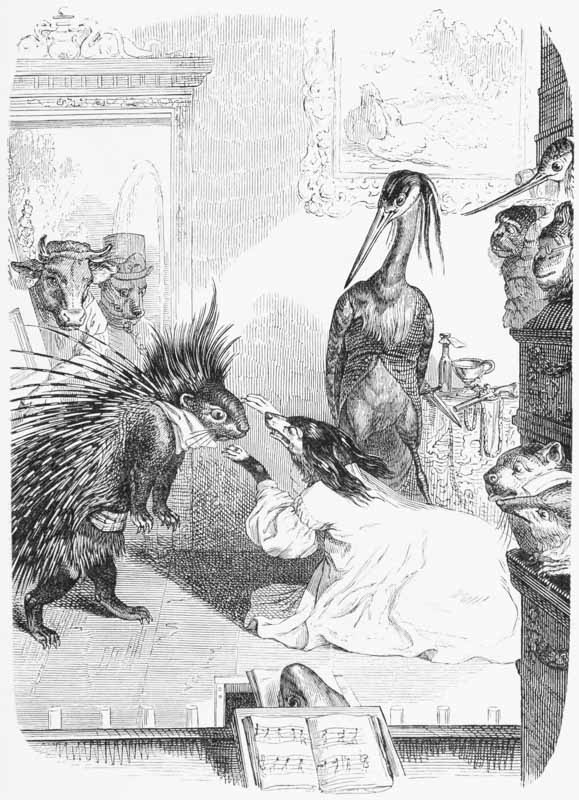

“My master, in his position as royal footman, had little to occupy his leisure; his chief duties consisted in posturing, and wearing a suit of gaudy clothes. From his lofty point of view my education seemed extremely defective; he therefore set himself the task of improving me, that is, rendering me more like himself. I was obliged to learn a number of exercises by a process of torture as ingenious as it was devilish, the lessons becoming more and more degrading. O misery! I was soon able to do the dead hare and the living hare, at the slightest sign from my master, as if I were a mere dog. My tyrant, encouraged by the success I owed to the rigour of his method, added to this series of lessons what he termed an accomplishment: he taught me the art of fiendish music. In spite of the terror I felt at the noise, I was soon able to perform a passable roll on the drum. This new talent had to be displayed every time any member of the royal family left the palace.

“One day, it was Tuesday, July 27, 1830 (I shall never forget that date) the sun was shining gloriously. I had just finished beating the roll for Monsieur the Duke of Angoulême. My nerves were always irritated by contact with the donkey’s skin of the drum. All at once I heard guns going off. They seemed to be approaching the Tuileries from the side of the Palais Royal.

“Dear me! I thought, some unfortunate hares have had the imprudence to show themselves in the streets of Paris, where there are so many dogs and guns and sportsmen. But then I reflected that most of the latter were picturesque, not real sportsmen, who had never shot a hare. The dreadful recollection of the hunt at Rambouillet froze me with fright. What could hares possibly have done to man to bring down such vengeance upon them? I instinctively turned to my mistress to implore her protection, when I beheld her face filled with terror greater than my own. I was about to thank her for the pity she felt for me, when I perceived that her fear was only personal, that she was thinking very little indeed about me, and very much about herself.

“These gun-shots, each detonation of which congealed the blood in my veins, were fired by men on their fellows. I rubbed my eyes, I bit my feet till they bled, to assure myself I was not dreaming. I can only say, like Orgon—

“The need that men have for sport is so pressing, that in the absence of other game they take to shooting each other.”

“It is dreadful to think of the depravity of human nature,” the Magpie replied. “I am positively obliged to hide myself towards evening, to escape the last shot of some passing sportsman, whose only reason for not firing at a magpie would be to save his gunpowder. In all probability, the wretch who might bring me down would not think even me good enough to eat.”

“What is still more singular,” said my friend, “is that men glory in this butchery, and a great ‘bag,’ filled with victims, is considered something to be proud of. I shall not weary you with the full history of the Revolution of July, although many details remain unrecorded. A Hare, although a lover of freedom, would hardly be accepted as an historian.”

“What is a revolution of July?” inquired the little Hare, who, like all children, only listened now and then when any word struck him.

“Will you be quiet?” said his brother; “grandfather has just told us that it is a time when every one is frightened.”

“I shall content myself by telling you that the struggle continued three whole days. My ears were torn with the mingled noise of drums, cannon, the whistle of the bullets, and the sound of fierce strife, that filled Paris like the breaking of angry waves on a rocky shore.

“While the people fought and barricaded the streets, the Court was at St. Cloud. As for ourselves, we passed a fearful night at the Tuileries. Our terror seemed to prolong the darkness. When the dawn came at last, the firing was renewed, and I heard that the Hôtel de Ville had been taken and retaken. I no doubt would have felt grieved at all this had I been able to go away like the Court, but that was not to be thought of. On the morning of the 29th a dreadful tumult was heard under the windows, followed by the booming of cannon, and dull crash of iron balls. ‘It is finished, the Louvre is taken,’ cried my master; and clasping the little girl in his arms, he disappeared. It was then eleven o’clock. When they had gone, I realised that I was alone and helpless, but then it occurred to me, there being no one here, I have no enemies, and my courage rose with the reflection. The men outside might kill each other, and thus expend their ammunition as fast as they chose—so much the worse for men, and the better for Hares.

“I was hidden beneath the bed, for the room was invaded by soldiers, who cried in a strange tongue, ‘Long live the King.’ ‘Cry away,’ I said, ‘it is easy to see that you are not Hares, and that the king has not been making game of you.’ Soon the ‘redcoats’ disappeared, and a poor man—a scholar, I believe—came and sought shelter in my room. He had no taste for war; he therefore deposited himself in a cupboard, where he was soon discovered by a crowd of bloodstained ruffians, who searched everywhere, crying ‘Liberty! long live Liberty!’ as if they had hoped to find it in some odd corner of the Tuileries. After fixing a flag out of the window, they sung a striking song, commencing—

Some of them were black with powder, and must have fought as hard as if they had been paid for it. I thought that these poor begrimed creatures, as they kept continually shouting ‘Liberty!’ must have been imprisoned in baskets, or shut up in small rooms, and were rejoicing in their freedom. I felt carried away by their enthusiasm, and had advanced three steps to join in the cry of ‘Liberty!’ when my conscience arrested me with the question, ‘Why should I?’

“During these three days—would you believe it, my dear magpie?—twelve hundred men were killed and buried.”

“Bah!” I said, “the dead are buried, but not their ideas!”

“Hum!” he replied.

“Next day my master came back: he had not shown himself for twenty-four hours. He was changed—he had ‘turned his coat,’ an operation which cost him a pang, as he had made a good thing out of the king’s livery. Men turn their coats as easily as the wind turns the weathercock on yonder spire. It is a mean artifice, to which we could not descend without spoiling our fair proportions.

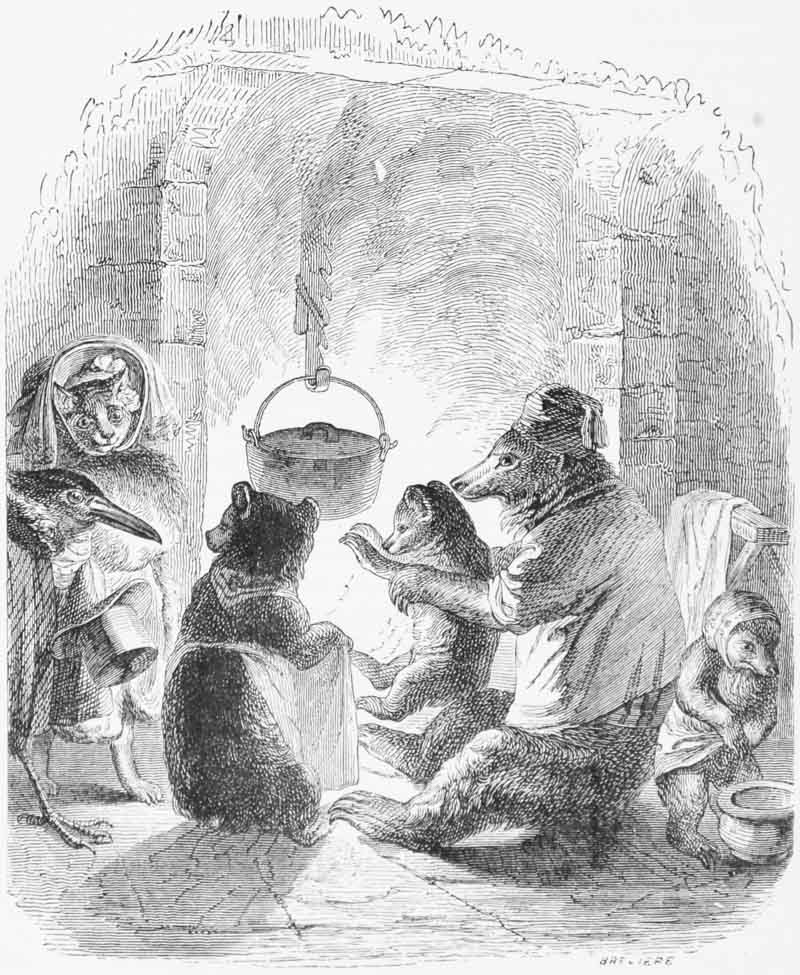

“I learned from my master’s wife that there was now no king. Charles X. had gone never to return, and the worst of all was, that they themselves were ruined. You observe, the downfall of the king was viewed selfishly, not as a national calamity, but simply as an event which blighted their own fortunes. That is the way of men. Secretly I rejoiced at the disaster, as it rendered my emancipation possible. Alas! my dear little Hares, Hares propose, and man disposes. Have no faith in the liberty born of the blood and agony of revolution. The change wrought by strife only embittered my lot. My master, who had never been taught any useful occupation, was reduced to living on his wits, which served him so badly, as to leave him often without bread. He was brought to such straits as we Hares are when the snow lies heavy on the ground. I have seen his poor child weeping for the food that men often find so difficult to procure. Be thankful, my children, that you are not men; and that you can feed on the simple herbs as nature has provided them. Although suffering from hunger, I felt many a bitter pang for my little mistress. If the rich only knew the appetite of the poor, they would be afraid of being devoured. I more times than once saw my master eye me with ferocity. A famished man has no pity; I believe he would almost eat his own children. You will readily understand, therefore, that my life was in the greatest danger. May you ever be kept from the peril of becoming a stew.”

“What is a stew?” inquired the little Hare in a loud voice.

“A stew is a Hare cut up and cooked in a pan. A great man once said that our flesh is delicious, and our blood the sweetest of all animals; but he adds that we seem to be aware of our danger, as we sleep with our eyes open.” At this reply the audience became so quiet, that one might have heard the grass growing.

“Nothing can ever make me believe,” cried the old Hare, much moved by the recollection of that incident in his life, “that Hares were created to be cooked, and that man cannot employ himself better than by eating animals in many respects superior to him. I owe my life to the misery that reduced me to skin and bone, and to the timely word of my mistress who pleaded for my life, that I might still display my accomplishments. ‘Ah!’ said my master, striking his forehead and looking dramatic, as Frenchmen always do in joy or sorrow, ‘I have an idea’—that was for him a sort of miracle. From that day I became a public character, and the saviour of the family.”

Public and political life.—His master becomes his charge.—Glory nothing but a wreath of smoke.

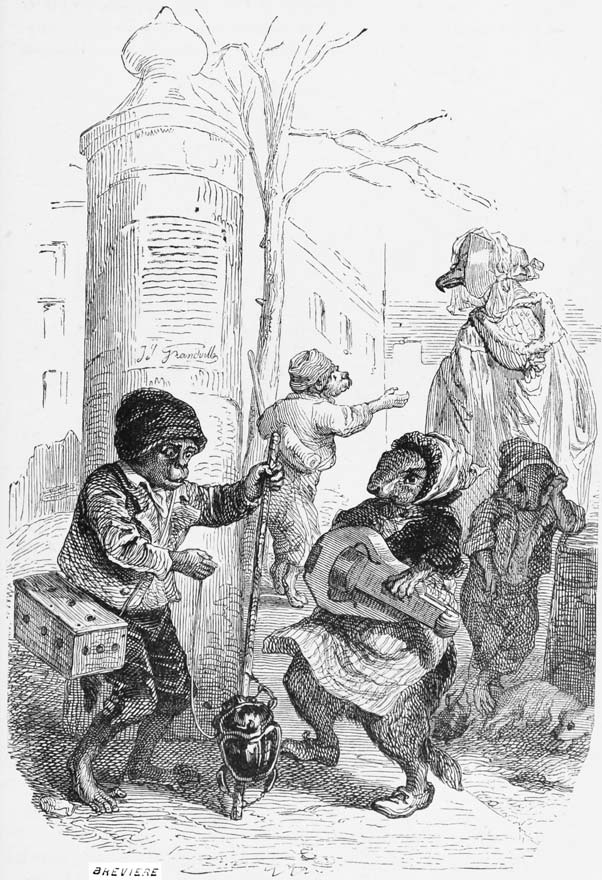

“I SOON discovered my destiny. It was not the Tuileries! My master had made a little house of four boards, which he set up in the Champs Elysées, and there, beneath the blue sky, I, a denizen of the forest of Rambouillet, was exhibited in public at the cost of my proper pride, natural modesty, and health. I well remember my master’s words just before I made my début.

“ ‘Bless Heaven!’ he said, ‘that after profiting by your more than ordinary education, you have fallen into the hands of such a master. I have trained you and fed you for nothing. The moment has now arrived for you to prove to the world your noble sense of gratitude. When I caught you, you were rustic and uninstructed. The airs and graces which you have acquired were taught you for your amusement. Now they will enable us to enter upon a glorious and lucrative career. It has always been understood that men, sooner or later, reap the fruits of their disinterestedness. Remember that from this day our interests become one. You are about to appear before a people, the most polished, proud, and difficult to please, and all that is required of you is to please everybody. Be careful never to mention King Charles, and all will go well, as crime and injustice have been abolished. Do your part, and I will relieve you of the task of receiving the money. We shall never make millions; but the poor manage to live upon less.’

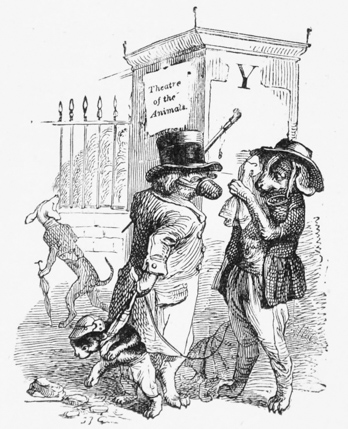

“ ‘Ah me!’ I said to myself, ‘what a modest speech! My master is a bold tyrant; to hear him, one would think that I had voluntarily relinquished my liberty, and besought him to snatch me away from all that was dear to me in life.’ For all that, my début was a most brilliant affair; I became the rage of Paris. During three years I beat the roll-call for the Ecole Polytechnique, Louis Phillipe, La Fayette, Lafitte, for nineteen ministers, and for Napoleon the Great. I learned—go on writing, my dear Magpie—to fire cannon.

“For a long time, by great good luck, I never mistook one name for another, and never once abused the trust of those depending on me. My master praised my probity, and declared me incorruptible.

“During my public career I paid some attention to politics. In the Oriental question I felt deeply interested. It was at last settled by diplomatic subtlety, to the satisfaction of the Hares of all nations. In the East the Hare has been an object of great political importance. It may be as well here to record my conviction that there is no reason to dread the immediate development of the power of the Ottoman Empire, or to give credence to the report that a cure has been discovered for the moral and physical obliquity of Mongolian eyes.

“To continue my narrative. Once, at the close of a long fatiguing day, I had just finished the fiftieth representation, and obtained numerous cheers and coppers. The two candles were nearly burned out, when my master insisted on my firing a number of guns. I felt fagged and stupid. At the words, ‘A salute for Wellington,’ I ought to have refused to fire; but bang went the gun. I was accused of treachery by the crowd, who hurled my master, show and all, into the middle of the road. As for myself, I fell pell-mell with money, candles, and theatre. St. Augustine and Mirabeau were right when they said, each in his own way, ‘That glory is nothing but a wreath of smoke,’ or like a candle that may be extinguished by the slightest breath of adversity. Happily, fear gave me courage. Amid the tumult I sought safety in flight. Hardly fifty feet from the scene of my fame, I still heard the clamour of the angry crowd. About to cross the road at a single bound, I was caught between the legs of some one, who, like myself, seemed to be fleeing from the fray. My speed was so rapid, and the shock so violent, that I rolled into the ditch, carrying the owner of the legs with me. My doom was sealed, I thought. Men are far too proud not to resent being brought low by a poor Hare. My life will be sacrificed!”

“Birds of a feather flock together.”—Our hero secures the friendship of a subaltern Government Clerk.—An unfortunate death.—Good-bye to Paris.

“I COULD hardly believe my eyes—this man, of whom I was in the greatest dread, was himself as frightened as if the devil had got between his legs. Good, I said, my lucky star has not left me. This old gentleman seems to have adopted my theory of courage. Both being naturally timid, we will constantly agree. ‘Sir,’ I whispered, in my softest and most reassuring tones, ‘I am unused to addressing your fellow-men, but I make bold to speak to you, as, if we are not blood relations, we are at least brothers by sentiment. You are afraid, you cannot deny it! and your emotion renders you all the more worthy in my eyes.’

“At that moment a carriage passed, and by its light I perceived that the stranger I had brought down was the wise man who hid himself in the cupboard in the Tuileries, and who had been one of the most attentive of my audience. He had a man’s body, it is true, but from his honesty, and the gentle expression of his face, I felt certain that his ancestors had belonged to our race. His joy was great when, regaining his habitual calm, he recognised in me his favourite actor. ‘The fear,’ he said, ‘that seized upon me is infinitely worse than its cause.’ These words seemed to me to sound the very depths of profundity. I felt, for the first time, a true attachment, and permitted my new friend to carry me away. I soon discovered that he was extremely humble and poor, being employed as a sub-Government clerk. He was bent less by age than by his constant habit of saluting every one, by his care to keep his head lower than his superiors, and by his duty, which consisted in doing the work of those above him, as well as his own. Next to his son, who bore a close resemblance to him, he loved what he called his garden, a small box of earth at the window, and a few flowers, which opened with the sun. They were the little censers of his worship, whose fragrance ascended to heaven with his morning prayers.”

“ ‘My dear sir,’ said one of our neighbours, an actor more successful in life than my master, ‘you are far too modest; you do not make enough of yourself. I was once modest like you, but I cured myself of that grave defect. Do as I did—compel the world to accept you at your own value. Speak louder; bluster about; give yourself full voice and swagger. It is wonderful how it tells, although the voice owes its depth to the emptiness within, and the swagger to the fact that without it your natural endowments would never lift you from the gutter.’

“The world is always liberal with advice to the poor; but my master preferred his humble position to all the riches and fame that might be acquired by becoming an impostor, whose energies would always be strained to enable him to crow lustily from his own dunghill.

“Our life was a very regular one. The father left early for his office, and his son for school. I was left alone in charge of our room, and should have felt dull had not the quiet and rest their peculiar charm after the fatigues of my life in the Champs Élysées. After the day’s work we were all united at our evening meal, a most frugal one. I was, indeed, often afraid of being hungry. They would have shared their last crust with me. It is always so with the poor. I felt nearer God in this little room than I had done since I left the green fields; I noticed so many acts of self-denying love.

“One day my master came home very much agitated, and burying his head in his hands, exclaimed, ‘My God! they talk of another change of Ministry; if I lose my place, what will become of us? We have no money!’ ‘My poor father,’ said the son, ‘I will work for you. I am big, and can make money.’ ‘No, my boy, you are still young, and know nothing of the world.’ ‘But, father,’ he continued, ‘why not go to the king, and ask him for money?’ My master said, ‘They are only beggars who live upon their miseries; and besides, the king has his own poor relations to provide for.’

“Since the rich have always their poor relations, why have not the poor their rich ones?”

“Tell me,” said the little Hare, who had slipped behind her grandfather, so as to shout into his ear; “You talk of king and ministers—who are they?”

“Be quiet,” replied the old Hare, “it cannot be of any consequence to you who or what the king is. It is not yet certain whether he is a person or a thing. As to the ministers, they are the gentlemen who cause others to lose their places, until they have lost their own.”

“Ah me!” said the little one, much satisfied with his explanation; “never let it be said that it is useless to speak seriously to children.”

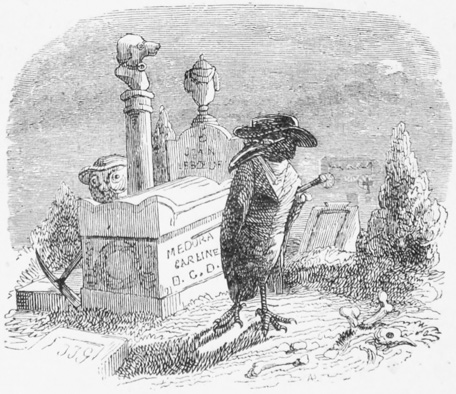

“The fatal day came at last. My master lost his place by a change of Ministry, and soon after died of a broken heart. His poor son was not long in following him to the grave. I was left alone in the empty room, as everything was taken and sold to meet the funeral expenses. I should myself have been sacrificed had I not escaped after nightfall, and sped through the streets of Paris, scarcely halting to take breath until beyond the Arc de l’Étoile. There I paused for a moment, casting a look of compassion on the great city wrapped in slumber beneath a dark cloud, that shut out heaven from its view.”

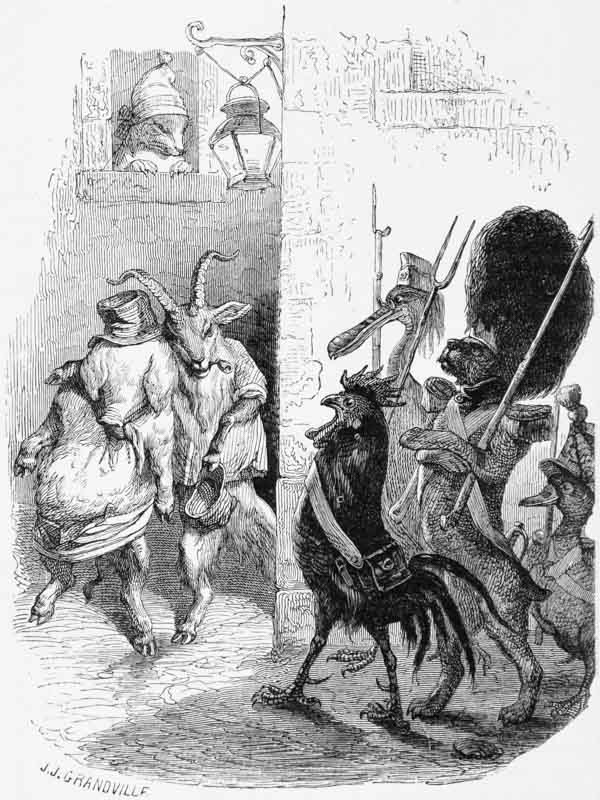

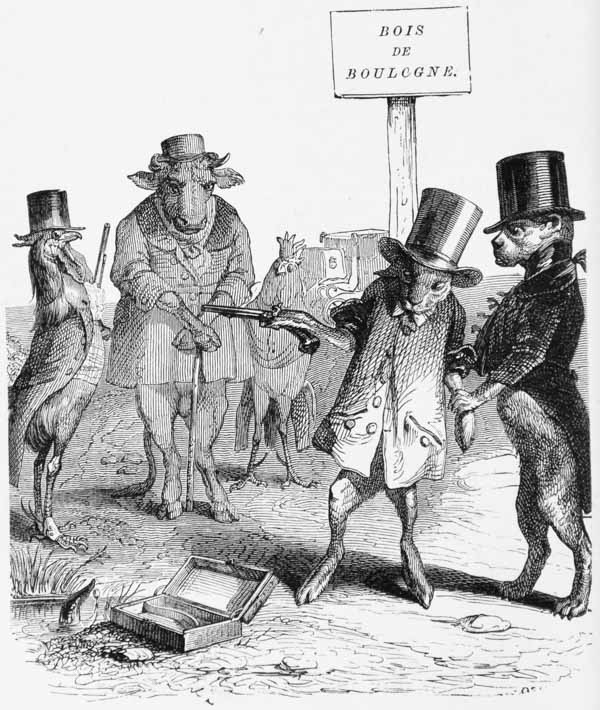

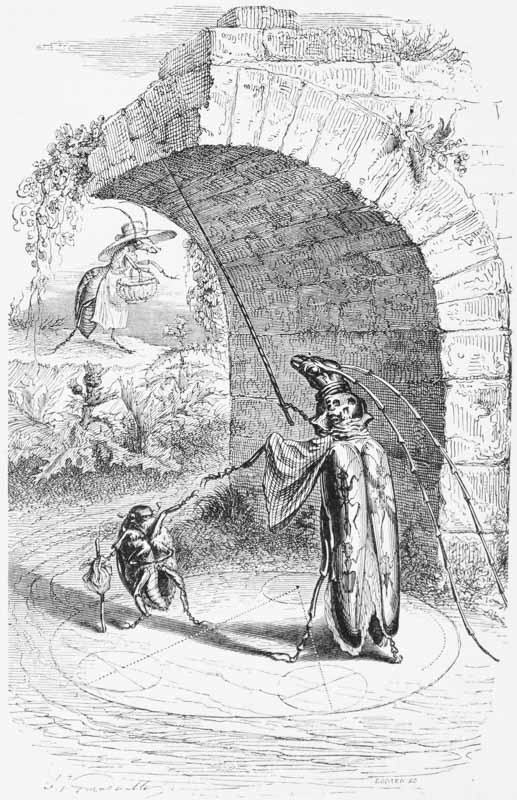

Return to the fields.—The worthlessness of men and other animals.—A Cock, accustomed to the ring, provokes our hero.—Duel with pistols.

“I SOON reached a wood, and felt my chest expand with the pure air. It was so long since I beheld the full extent of the sky, that I seemed to look upon it for the first time. The moonlight was bright, and the night-breeze laden with a banquet of fresh odours that it had caught up about the fields and hedgerows. Endowed by nature with an acute sense of smell, nothing could be more delicious to a weary Hare than the fresh fragrance of grass and thyme. Each breath I inhaled filled me with the fond memories of my childhood, which passed into my dreams as I slept in the open air. Early next morning I was roused by the clang of steel. Two gentlemen were fighting with swords, and appeared to me determined to kill each other; however, when they were tired of fencing, they walked off quietly arm-in-arm. Other combatants followed, but not one fell, and no blood was spilt in these affairs of honour, after nights of gambling and debauchery.

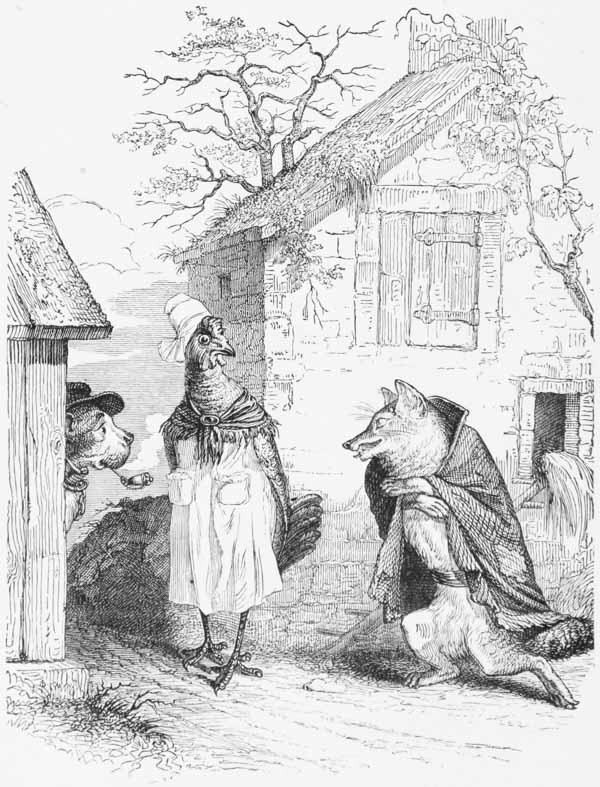

“Journeying onward until within sight of a village, I fell in with a Cock. As I had been cooped up in a town, and seen nothing but men and women for so long, this bird interested me greatly. He was a fine fellow, high on his legs, and carried his head as if he could not bend his neck. He had quite a martial bearing, reminding one of a French soldier.

“ ‘By my comb!’ he exclaimed, ‘I hope you will know me again. I never came across a Hare with such a stock of assurance.’

“ ‘What!’ I replied, ‘may I not admire your fine proportions. I have been so long in Paris, I have quite forgotten the grandeur of nature.’

“Would you believe it? Although my answer was so soft and simple, yet the fellow was offended, crowed like to split my ears, and cried, ‘I am the Cock of the village, and it shall never be said that a miserable Hare can insult me with impunity.’

“ ‘You astonish me,’ I continued, ‘I never intended to insult you.’

“ ‘I have nothing to do with your intentions. Every insult ought to be wiped out with blood. I am rather badly off for a fight, and I shall have much pleasure in giving you a lesson in good manners. Choose your arms.’

“ ‘I would rather die than fight. Let me pass—I am going to Rambouillet to rejoin some old friends.’

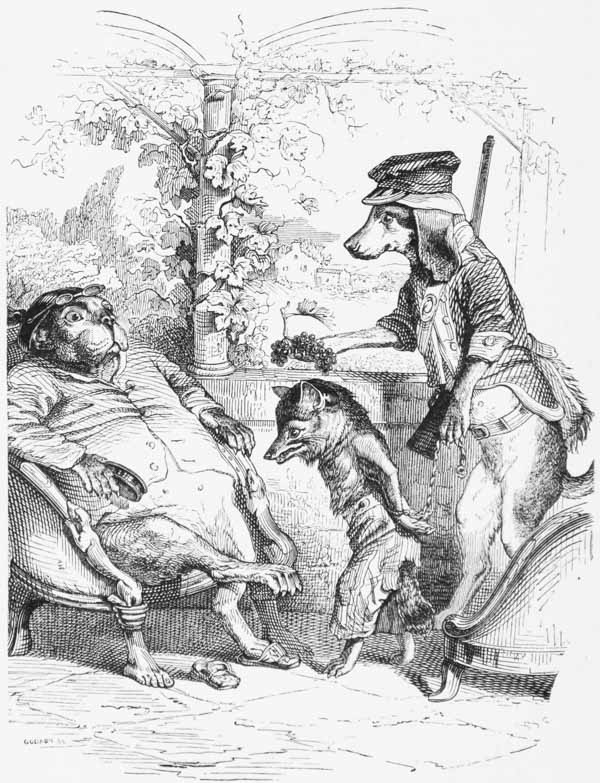

“ ‘Fight you must, else I will put a ball through you. Here are an Ox and a Dog, who will serve as seconds. Follow me, and do not attempt to escape.’

“What could I do? flight was impossible—I obeyed. Then addressing the seconds, I said, ‘Sirs, this Cock is a professed duellist. Will you stand by and see me assassinated? I have never fought, and my blood will be on your heads.’

“ ‘Bah!’ said the Dog, ‘that is a trifle. Everything must have a beginning. Your simple candour interests me. I will stand by you. Now that I am certain of you, it concerns my honour that you should fight.’

“ ‘You are extremely polite, and I am touched with your goodness; but I would rather deny myself the pleasure of having you witness my death.’

“ ‘Hear him, my dear Ox,’ cried my adversary. ‘In what times do we live? Has it positively come to this, that cowardice, impudence, and low-bred nature are to triumph over all that is chivalrous and noble in the world?’

“The pitiless Ox bellowed with rage. The Dog, taking me aside, said in a soothing tone, ‘It makes little odds in the end how one dies; and between us two, I don’t half like this Cock. Believe me, I heartily wish you success. Were I a sporting Dog, you might doubt my sincerity, but I have settled down to a country life, that would be quiet were it not for the early crowing of your foe, who permits no one in the village to sleep after daybreak.’

“ ‘I shall never be able to get through it,’ I replied, half dead.

“ ‘You have the choice of weapons. Choose pistols, and I will load them.’

“ ‘In the name of all that is canine and good,’ I said, ‘try and arrange this affair.’

“ ‘Come, make haste,’ cried the Cock. ‘Enter this copse! One of us will never leave it!’ he added.

“At these words I felt a cold chill run through me. As a last resource, I reminded the Ox and Dog of the law against duelling.

“ ‘Those laws are made by cowards,’ they replied.

“I endeavoured to work upon the tenderest feelings of my adversary’s nature by inquiring what would become of his poor hens should he fall. All was in vain. Twenty-five paces were marked off; the pistols were loaded, and we took our places.

“ ‘Are you used to this arm?’ said the Dog.

“ ‘Alas! yes; but I have neither aimed at nor wounded any one.’ As good luck would have it, I had to fire first.

“ ‘Take good aim,’ said the Dog, ‘I detest this fellow.’

“ ‘Why on earth, then, don’t you take my place? Are you still at enmity with me,’ I said to my foe. ‘Let us kiss and forget all.’

“ ‘Fire!’ he replied, cursing fearfully.

“This roused me. The Ox retired and gave the signal; I pressed the trigger, and we both fell—I, from emotion, and the Cock from the ball that pierced his heart.”

“ ‘Hurrah!’ cried the Dog.

“ ‘Silence, gentlemen,’ I said, ‘this is no time for rejoicing.’ But he was a jolly dog, and light-hearted.

“ ‘Bravo!’ said the Ox, ‘you have rendered a public service. I shall be glad if you will dine with me this evening. The grass is particularly tender in this neighbourhood.’

“I declined the invitation and said, ‘May the blood of this miserable bully be upon your heads. Gentlemen, good morning.’

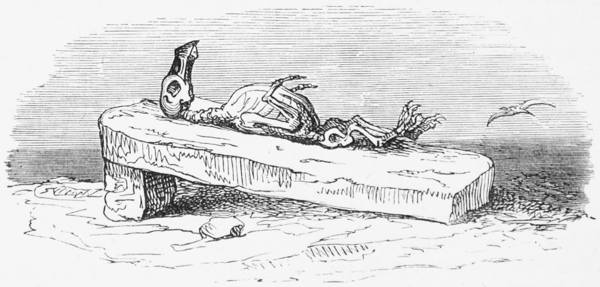

“My journey to Rambouillet was, as you may be certain, a sad one. It was long before the dread image of my dead enemy vanished from my eyes. The freshness and beauty of nature at last acted as a balm to my spirits; and ere I reached the forest, with all its souvenirs of my youth, my troubles were forgotten. Some months after my return, I had the pleasure of becoming a father, and soon after a grandfather. You know the rest, my dear children, so now you are at liberty.” At these words his audience awoke.

“Since my return, my dear Magpie, I have had leisure for reflection, and have come to the conclusion that true happiness is not to be found in this world. If it does exist at all, it is most difficult to attain, and the most fleeting possession of our animal nature. Philosophic men without number have wasted their lives in vainly attempting to discover some clue to the mystery, and all to no purpose. Some of them would fain have us believe that they had nearly created a heaven for themselves where self-love had only set up its own image as its god. Other men demand happiness of heaven as if it were a debt owed them by its Divine Ruler, and probably the wisest section settle down to enjoy the pleasures which life undoubtedly affords, and to make the best of ‘the ills that flesh is heir to.’

“I believe, on the whole, that our lives, although they have their disadvantages, are pleasanter than the lives of men, for this reason. The present is to us everything. We live for to-day. Men live for to-morrow. The to-morrow that is to be brimful of joy. Alas! thus human hope is carried on through all the days of life; but the joy is never realised, and the hope goes with men beyond the grave.”

PARISIAN Sparrows have long been recognised as the boldest of the feathered tribe. Thoroughly French, they have their follies, and their virtues to atone for them; but above all, they have been for many generations objects of envy to the birds of foreign climes. This latter reflection is sufficient to account for all the calumnies heaped upon them by their enemies. They who dwell amid the splendour of the capital, are a happy tribe. As for myself I am one of the number of distinguished metropolitan birds. Of a naturally gay disposition, an unusually liberal education has lent gravity to my appearance. I have been fed on crumbs of philosophy; having built my nest in the spout of an illustrious writer’s dwelling. Thence I fly to the windows of the Tuileries, and compare the anxieties of the palace and the fading grandeur of kings, with the immortal roses, budding in the simple abode of my master, which will one day wreathe his brow with an undying glory.

By picking up the crumbs that have fallen from this great man’s table, I myself have become illustrious among the birds of my feather, who, after mature deliberation, have appointed me to select the form of government calculated to promote the welfare of sparrows. The task implied is a difficult one, as my constituents never remain long on one perch, chattering incessantly when their liberty is threatened, and fighting among themselves almost without cause.

The birds of Paris, ever on the wing, have many of them settled down to thinking, and are now giving their attention to such subjects as religion, morality, and philosophy.

Before residing in the spout—in the Rue de Rivoli—I made my escape from a cage in which I had been imprisoned for two years. Every time I felt thirsty, I had to draw water to amuse my master, one of those bearded animals who would have us believe they are the lords of creation. As soon as I regained my liberty, I related my sad story to some friends in the Faubourg St. Antoine, who treated me with great kindness. It was then, for the first time, I observed the habits of the bird-world, and discovered that the joy of life does not consist in simply eating and drinking. I was led to believe that even the life of the sparrow has higher ends, and to form convictions which have added greatly to my fame.

Many a time have I sat on the head of one of the statues of the Palais Royal, where I might be seen with my plumes ruffled, my head between my shoulders, and, with one eye closed on the world, reflecting on our rights, our duties, and our future. Grave questions forced themselves upon me. Where do sparrows come from? Where do they go to? Why can’t they weep? Why don’t they form themselves into societies like crows? Why don’t French sparrows settle everything by arbitration, since they enjoy such a sublime language?

Great changes were taking place around; houses were supplanting gardens, and depriving birds of the insects and grubs found in the shrubs and soil. The result, as might have been expected, was to draw the line still more markedly between the rich and poor, and to set up “caste” as it exists among certain types of the human race. The sparrows in the densely-populated quarters were reduced to living on offal, while the aristocracy fed daintily, and perched as near heaven as the trees of the Champs d’Elysées would allow them.

This defective constitution could not last long; one half of the feathered tribe chirping joyously in the fulness of their stomachs, surrounded by superb families, and the other half brawling and clamouring for filthy refuse. The latter, driven to desperation, determined indeed to use, if need be, their horny beaks to improve their social condition.

With this laudable object in view, a deputation waited on a bird who had lived in the Faubourg St. Antoine, and assisted at the taking of the Bastille. This bird was appointed to the command of the sufferers, who organised themselves into a body, each one feeling the necessity of implicit obedience.

Judge of the surprise of the Parisians who beheld thousands of small birds ranged on the roofs of the houses in the Rue de Rivoli; the right wing towards the Hôtel de Ville, the left on the Madeleine, and the centre on the Tuileries. The aristocratic birds, seized with panic-fear at sight of this demonstration, and dreading the loss of their power and position, despatched a fledgling of their number to address the rioters in these words:—“Is it not well that we should reason together and not fight?”

The rioters turned their eyes upon me. Ah! that was one of the proudest moments of my life: I was elected by my fellow-citizens to draw up a charter to conciliate all, and settle differences among the most renowned sparrows in the world, sparrows who for a moment were divided on the question “how to live,” the eternal backbone of political discussions.

Those birds in possession of the enchanting abodes of the capital, had they any absolute right to their property? Why and how had caste become established? Could it last? Were perfect equality established among Parisian sparrows, what form would the new government assume? Such were the questions asked by both parties. “But,” said the hedge-Sparrows, “the earth and all its riches should be equally divided.” “That is an error,” said the privileged ones; “we live in a city, and are subject to the restraints, as well as to the refinement, of society; whereas you in your condition enjoy greater freedom, and ought to content yourselves with the hedgerows and fields, and all that satisfies untutored nature.”

Thereupon a general twittering threatened to lead to hostilities, but the popular tumult with sparrows, as with man, is the labour-pangs of national deliverance, and brings forth good. A proposition was carried, to send an intelligent bird to examine the different forms of government. I had the honour of being selected for the post, and at once started on my mission. What would one not sacrifice for his country? To tell the truth, the position was one which conferred both dignity and emolument. Let me now lay the report of my travels as an humble offering on the altar of my country.

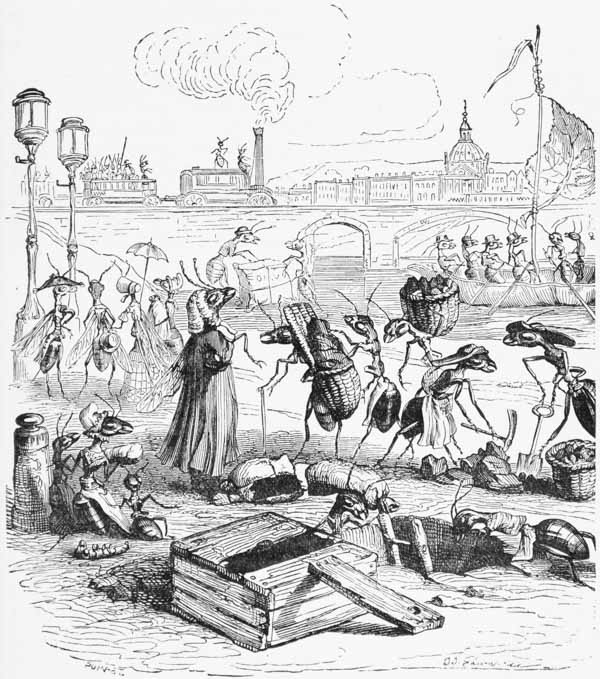

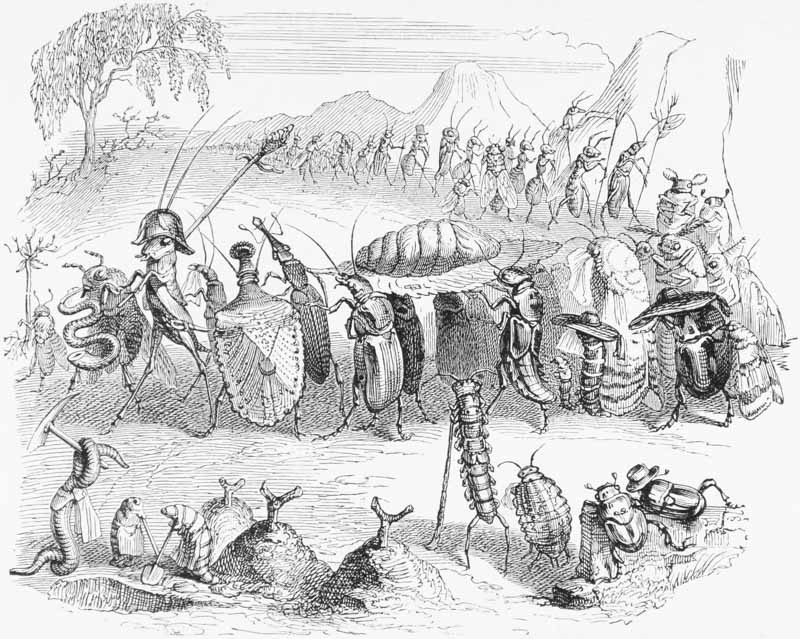

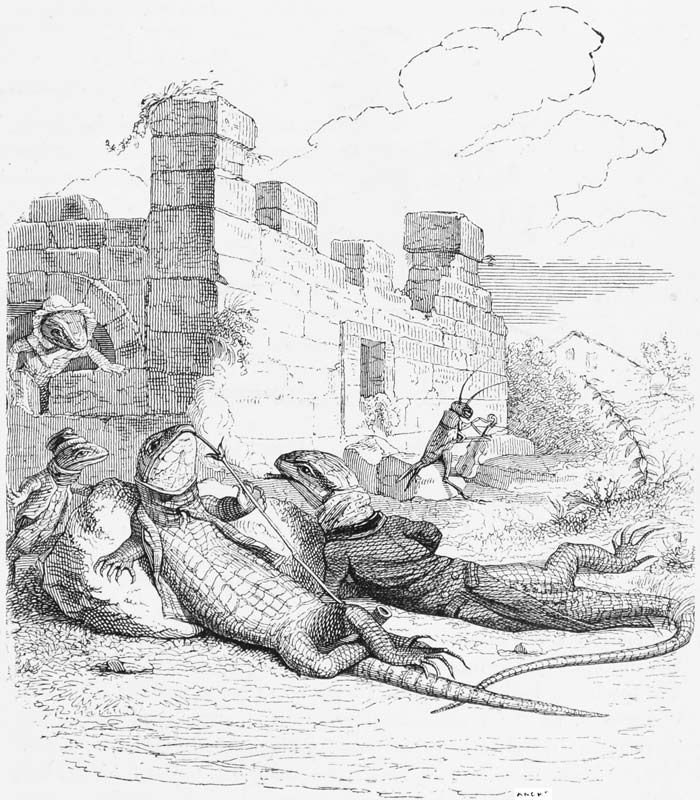

After traversing the sea, not without difficulty and danger, and experiencing many of those adventures which take the place of genuine information in modern books of travel, I arrived at an island called Old Frivolity. Why it should be termed old I could never make out, as it is said that the world was created all at once. A Carrion-Crow, whom I met, pointed out the government of the ants as a suitable model, so you may understand how eager I was to study their system, and discover their secrets. On my way I fell in with scores of ants travelling for pleasure. They were all of them black and glossy, as if newly varnished, but utterly devoid of individuality, being all alike. After, indeed, one has seen a single ant, one knows all the others. They travel coated with a liquid which keeps them clean. Should one meet an ant in his mountains, on the water, or in his city-dwelling, his get-up is irreproachable. Care is even bestowed on the cleanliness of his feet and mandibles. This affectation of outward purity lowered them in my estimation. I inquired of the first ant I met, “What would happen to you were you for an instant to forget your careful habits?” He made no answer; I discovered, indeed, that they never exchange a word with any one to whom they have not been formally introduced. I fell in with an intelligent Coralline of the Polynesian Ocean, who informed me that she had been arrested by the fishes when engaged in raising the coral-foundation on which a new continent was to repose. She mentioned a curious fact relating to the government of the ants, namely, that they confer the right upon their subjects to annex all new lands as soon as they appear above sea-level. I now found out that Old Frivolity was so named to distinguish it from New Coral-reef Island. I may mention in passing, that these are private confidences, and caution my noble constituents not to abuse them.

As soon as I set foot on the island, I was assailed by a troop of strange animals—government servants—charged with introducing you to the pleasures of freedom, by preventing you carrying certain contraband objects you had set your heart upon. They surrounded me, compelled me to open my beak in order that they might look down my throat in case I should be carrying prohibited wares inland. As I proved to be empty, I was permitted to make my way to the seat of the government, whose liberty had been so lauded by my friend the Crow.

Nothing surprised me more than the extraordinary activity of the people. Everywhere were ants coming and going; loading and unloading provisions. Palaces and warehouses were being built; the earth, indeed, was yielding up all its finest materials to aid them in the construction of their edifices. Workmen were boring underground, making tunnels to relieve the traffic on the surface of the island. So much taken up, indeed, was every one with his own business, that my presence was not noticed. On all sides, ships were leaving laden with ants for the colonies, or with merchandise destined for foreign shores; vessels were crowding into the ports, bearing produce from distant parts of the world; messages were flashing from agents abroad, telling merchants of the abundance of products that might almost be had for the lifting. So clever are these ants in everything connected with commerce, that whenever they receive a message, they send off their vessels, laden with cheap wares which they sell to weak races at the highest market prices. Some semi-savage nations assert that the strong drink the ants export is too potent, and that the narcotic they extract from a certain plant, which is watered by the sweat of a servile race, affords a powerful stimulant to national decay,—is, in fact, a physical and moral poison. To this, diplomatists reply that the trade is lucrative, that there is a demand for the narcotic, and that so long as the demand lasts the ants must supply it at their own price. There are those among them who abhor this traffic, and condemn it as a moral slave-trade, in so far as the effect of the narcotic on its consumers is to render them its bondsmen for life. These ants, curiously enough, profess the Christian religion, and send propagandists to all parts of the world. For all that, I soon found out that many of them are idolaters, worshipping gods made of gold by themselves, and set up in shrines called banks; other idols, called “consolidated funds,” railway stocks, and generally sound investments, yield their owners a temporal good, and enable them to “live in clover.” Other idols, again, when sunk in foreign loans and spurious companies, rebel and bring down all sorts of calamities on the widows and orphans of the most industrious ants of the island. There are those among them, whose avocation it is to make these images out of clay with such attractive ingenuity that, when set up to public gaze, worshippers flock to the shrines and take their glitter for pure gold; these gods are for “raising the wind,” but they sometimes bring down a storm and are overthrown, crushing in their fall thousands of poor devotees.

In the midst of the general activity I noticed some winged ants; and, singling out one, inquired of the guard, “Who is that ant standing unemployed while all the others are labouring?”

“Oh,” he replied, “that is a noble lord. We have many such as he, patricians of our empire.”

“What is a patrician?” I asked.

“They are the glory of the land,—fellows with four wings who fly about in the sun, and are at their wits’ end to know how to pass the time most pleasantly.”

“Can you yourself ever hope to become a patrician if you work hard?”

“Well, no; not exactly. The wings of patricians are natural; they run in the families, so to speak. But artificial wings may be ingrafted by the sword of the sovereign for distinguished service; these, however, are never strong enough to enable the wearer to soar clear of his plebeian fellows into the high heaven of aristocracy. I must tell you that some of the four-winged order are almost indispensable to the state; they nurse the national honour, and plan our campaigns.”

The noble ant who had caused my inquiries was coming towards us. The common ants made way for him; these working ants of the lower order are extremely poor, possessing absolutely nothing. The patricians, on the other hand, are rich, having palaces in the ant-hills, and parks, where flies are reared for their food and sport.

The ants display the tenderest regard for their offspring; and to the care bestowed upon the training of the young they attribute their national greatness. It is astonishing to see the neuters watching over the young. In place of sending—as some of our Parisian sparrows do—their callow-brood to be nursed by birds of prey, they themselves tend the orphans. They, indeed, live for them, sheltering them from the cold winds that sweep their island, watching for the fitful gleams of sunshine to lead them out. These ant-neuters watch with pride the growth of the young lives, and the development of the instinct for war and conquest in the young brood; not alone the conquest of lands and races, but the mastery over the elements of nature that informs them how to brave the worst storms, and build their wonderful ant-hills. These nurses, although tender-hearted, are proud, and will unflinchingly buckle the swords on to their favourites, and send them away to fight for fame, or die for their country. From the point of view of a philosophical French sparrow, all this seemed to me strangely conflicting, and on the whole a sign of defective national character. At this moment the patrician ascended one of the city fortifications and said a few words to his subordinates, who at once dispersed through the ant-hill; and in less time than I take to write I noticed detachments issuing from the stronghold, and embarking on straw, leaves, and bits of wood. I soon learned that news of a defeat had arrived from abroad, and they were sending out reinforcements. During the preparations, I overheard the following conversation between two officers:—

“Have you heard the news, my lord, of the massacre of the innocents by the savages of Pulo Anto?”

“Yes; we shall have to annex the territory of these painted devils, and teach them the usages of civilisation.”

“I suppose it must be so; our fellows will have some rough work in the jungle, and the expedition to punish a handful of barbarians will cost no end of money, and some good lives.”

“As pioneers of progress, we must be prepared to sacrifice something for the common good, and our men are in want of active service. Besides, Pulo Anto is a rich island, and will yield a good revenue.”

This last remark was very much to the point, so conclusive, indeed, as to satisfactorily terminate the dialogue. Will it pay? is the final question which settles all the transactions of this military and mercantile race. I imagined that the noble lord spoke of the “common good” in the sarcastic tone peculiar to his nation. This phrase meant the immediate benefit of the Ant kingdom, and the ultimate disappearance from the face of the earth of a weak neighbour. The ants carry the process of civilising a savage nation to such a degree of refinement, that the subliming and re-subliming influences of contact gradually cause the destruction of the dross of savagedom and the annihilation of race. It seemed to me that what the ants happen to like they look upon as their own, and make it their own if it suits their convenience. They extend their empire, and carry warfare and commerce into the ant-hills of their weaker neighbours. They wax stronger and richer year by year, while the nations with which they trade, many of them, grow weaker and poorer.

I remarked to an officer that the aggressive policy of his government was much to be reprobated.

“Well,” he replied, “there may be truth in what you say, but we must obey the popular voice, open new fields for our commerce, and keep our army and navy employed.”

“You, sir, call this fulfilling a divine mission; a foreign war is a sort of god-send to keep the fighting ants employed. You go on the principle of the surgeon who cuts up his patients to keep his hand in, and his purse full. Such work ought to be left to the butcher.”

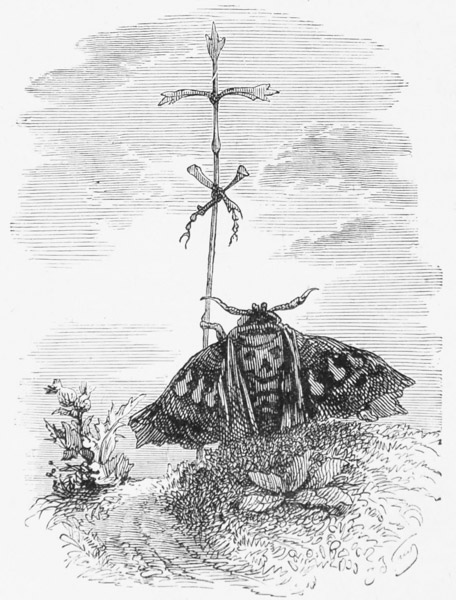

“Oh no; you labour under a great mistake. I own we do something in the way of vivisection, just as would the skilful surgeon to increase his knowledge, and enable him to heal the festering sores of humanity. When we find pig-headed ants or deaths-head moths”——

“What are pig-headed ants?”

“A species of insect devoid alike of reason and all the nobler qualities which we ourselves possess. I say, when we find them, it becomes our duty to use strong measures to raise their condition, or remove them out of our way.”

“Just as a physician who fails to effect a cure would feel justified in killing his patient?”

“Again, sir, you misapprehend my meaning. It is the custom of Parisian sparrows, when they clamour for liberty, equality, and fraternity, to kill each other, in order to purify the government. Having no real grievances at home, we find it convenient to redress our wrongs and seek for sweets abroad. Thus we preserve our independence, and confer a benefit on the world at large. My time is precious—good morning!”

My noble constituents will readily understand how I stood petrified at the audacity of this fighting ant, who stoutly maintained that might alone was right, and that his corrupt form of government ought, forsooth, to be set up as a model.

I had it in my mind to tell him that the chief successes of his foreign policy were effected by the subtile diplomacy of maintaining intestine divisions in foreign states. In this way the time of their enemies is fully occupied, and their strength weakened.

But he retreated before superior force, well knowing that his arguments must be crushed by the criticism of a Philosophical French Sparrow.

I afterwards learned that the officer had retired to his property in the country, “there,” as the ants would say, “to practise those virtues God has imposed upon our race.”

The only good points about the government of Old Frivolity lie in the protection extended to the meanest subjects, and the way they manage the working neuters, in making them pull together to effect great ends. This latter would prove a great element of danger were it introduced among ingenious Parisian sparrows.

I started much impressed with a sense of the perfection of this oligarchy, and the boldness of its selfish measures, and left regretting that in governments, as in individuals, close scrutiny reveals many defects.

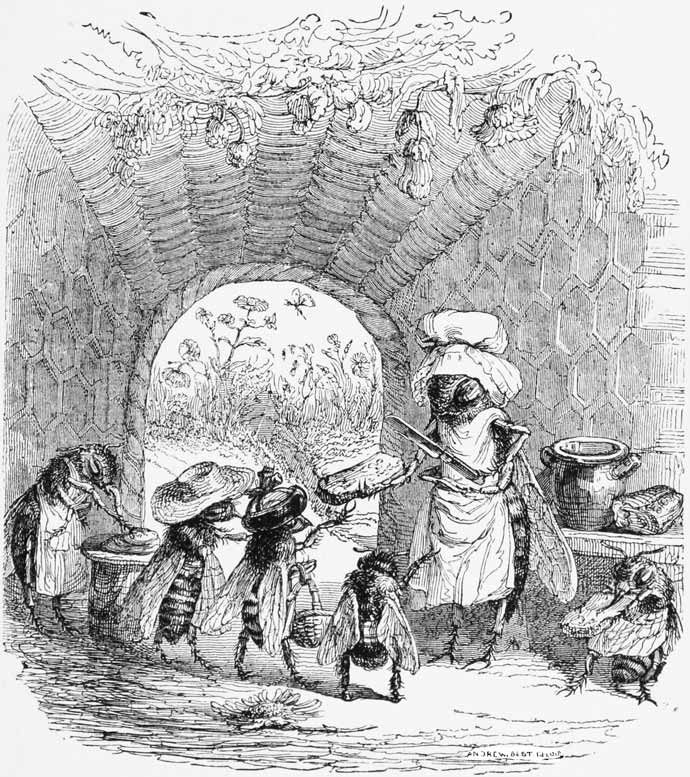

Profiting by what I had seen in the Ants’ empire, I resolved in future to observe more closely the habits of the tribes, before trusting myself to princes or nobles. On reaching this new dominion I stumbled against a bee bearing a bowl of honey.

“Alas!” he exclaimed, “I am lost.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Do you not see I have spilt the queen’s soup, happily the cup-bearer, the Duchess of Violets, will attend to her immediate wants. I should die of grief if I thought my faults would not be repaired.”

“How came you to worship your queen so devoutly? I come from a country where kings and queens and all such human institutions are held in light esteem.”

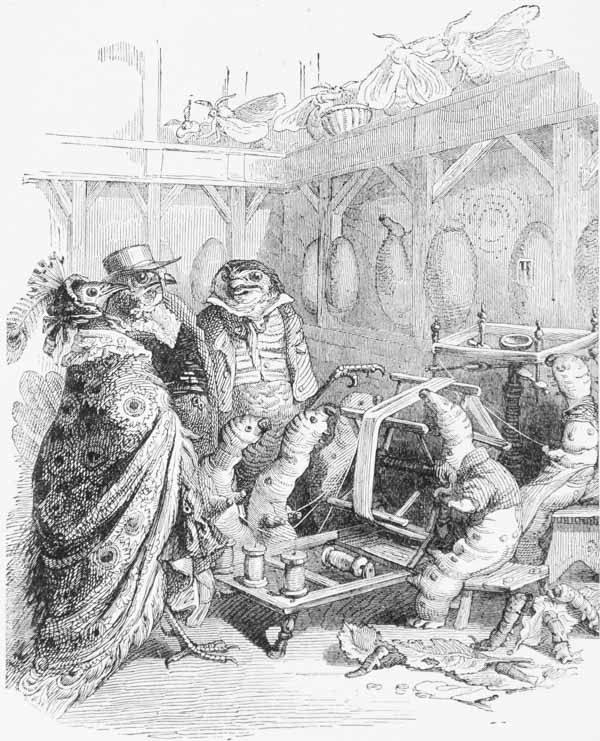

“Human!” cried the Bee; “know, bold Sparrow, that our queen and our government are divine institutions. Our queen rules by divine prerogative. Without her wise rule we could not exist as a hive. She unceasingly occupies herself with our affairs. We are careful to feed her, as we are born into the world to adore, serve, and defend her. She has her sons and daughters for whom we rear private palaces. The latter are, too frequently, wedded to hungry, petty princes, who thus claim our service and support.”

“Who is this remarkable queen?”

“She is,” said the Bee, “Tithymalia XVII., a woman endowed with rare wisdom; she can scent a storm afar off, and is careful to lay in stores for severe winters. It is said also that she has treasures in foreign lands.”

Here a young foreign prince came forward, and cautiously inquired if we thought any of the young ladies of royal blood likely to want a husband.

“Prince,” said the working Bee, “have you not heard of the ceremonies and preparations for departure? If you wish to court any daughter of Tithymalia you had better make haste. You are well enough in your appearance, although you could do with a new coat.”

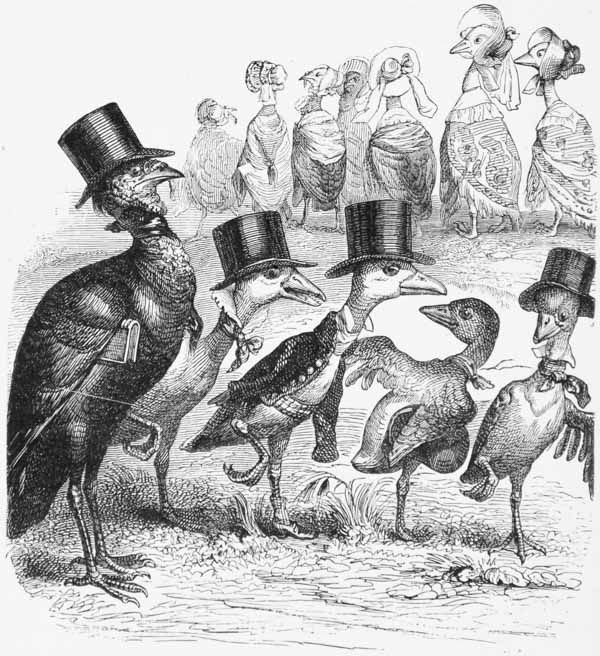

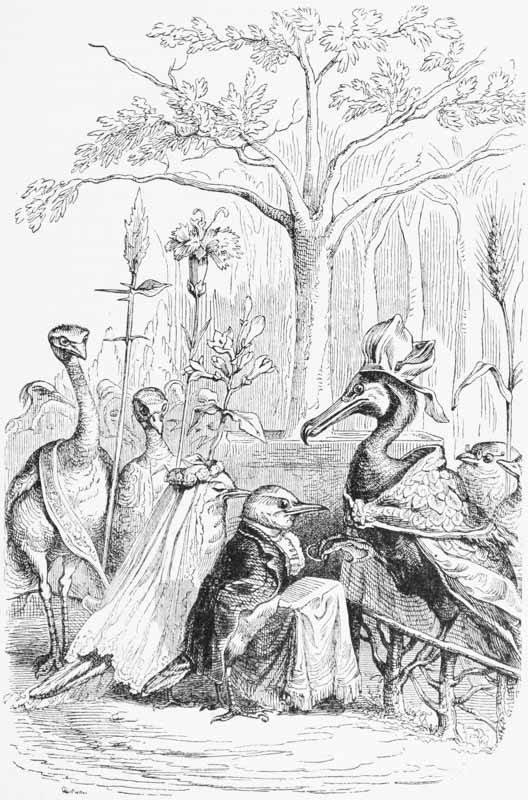

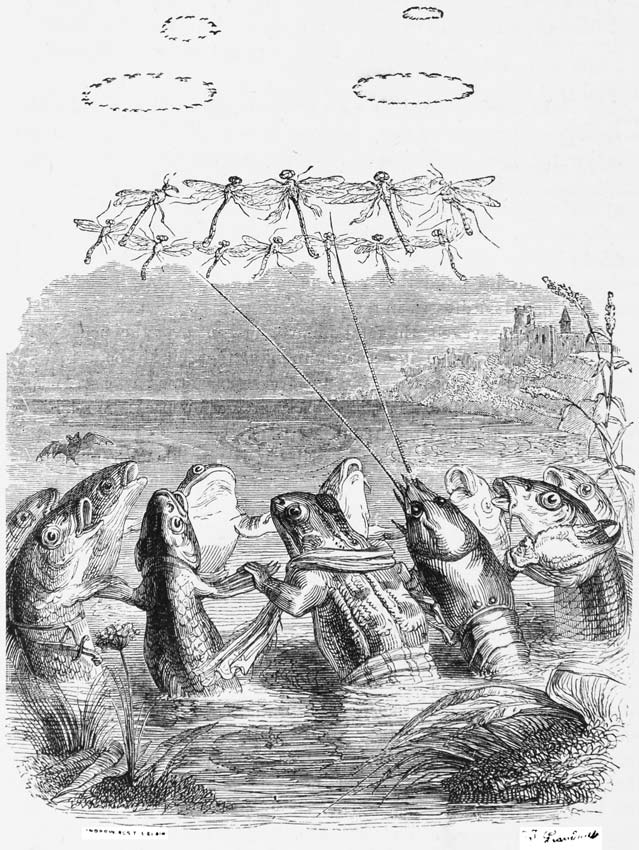

I beheld a splendid spectacle. One of the princesses was about to be married. The pageant on which I gazed must have a powerful effect on the vulgar imagination, and wed the people to the memories and superstitions which are about the only links uniting the higher with the lower orders of society.

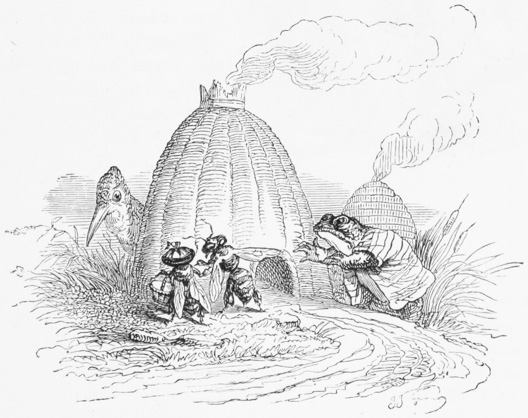

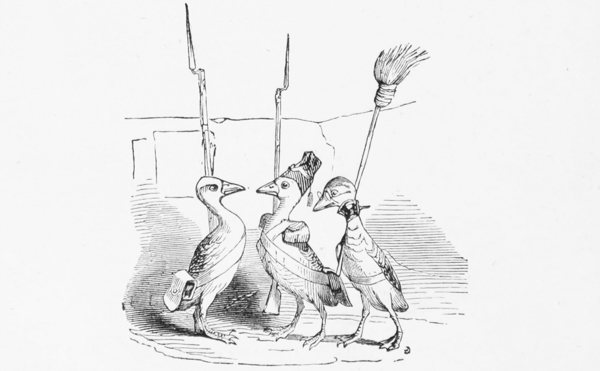

Eight drummers in yellow and black jackets left the old city called Sadrach—from the name of the first Bee who preached social order; these were followed by fifty musicians, all of them so brilliant that one might have said they were living gems. Next came the bodyguards armed with terrible stings. They were two hundred strong. Each battalion was headed by a captain, wearing on his breast the order of Sadrach—a small star of beeswax. Behind them came the queen’s dusters, headed by the grand duster, then the grand tooth-pick-bearer, cup-bearer, eight little cup-bearers, and the mistress of the Royal House, with twelve train-bearers, and lastly, the young queen, beautiful in her maidenly grace, her true modesty. The wings which shone with great splendour had never yet served for flight. The queen-mother accompanied her, robed in velvet, aglow with diamond-dust. Musicians followed humming a hymn of praise composed for the occasion. After the band came twelve other old drones, who seemed to me to be a sort of national clergy. They were all alike one to the other, and buzzed uniformly and monotonously. About ten or twelve thousand bees marched from the hive, upon the edge of which stood Tithymalia, and addressed these memorable words to the multitude:—

“It is always with a new pleasure that I witness your flight, as it secures the tranquillity of my people, and that”——She was here interrupted by an old drone who was afraid of the queen using unparliamentary language—at least so I thought. Her Majesty continued—“I am certain that, trained by our habits of thrift and industry, you will serve God and spread the glory of His name on the earth which He has so enriched with honey-yielding flowers. May you never forget the honour due to your queen, and to the sacred principles of our government. Think that without loyalty there is anarchy, that obedience is the virtue of good bees, that the strength of the state depends upon your fidelity. Know that to die for your queen and the church is to give life to your land. I give you my daughter Thalabath as queen. Love her well!”

This eloquent speech was followed by loud buzzing.

As soon as the young people had left with the queen, the poor prince I had noticed buzzed around them, saying, “Oh most noble Tithymalia, unkind fate has bereft me of the power of making honey, but I am versed in economics, so if you have another daughter with a modest dowry, I”——

“Do you know, prince,” said the grand mistress of the Royal House “that with us the queen’s husband is always unfortunate. He is looked upon as a sort of necessary evil, and treated accordingly. We do not suffer him to meddle with the government, or live beyond a certain age.”

But the queen heard his voice and said, “I will befriend you, you can serve me; you have a true heart, you shall wed my daughter, and lend your pious aid to the work of our kingdom.”