Title: A Book of the United States

Editor: Grenville Mellen

Release date: December 9, 2018 [eBook #58447]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse, Sue Clark, Brian Wilcox, and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

In Part II. the chapter sequence skips number XV. in both the Contents and body with no actual omission of text.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Four wide tables in the Appendix may not display completely in handheld devices using the epub or mobi formats.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and have been accumulated in a table at the end of the text.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes have been accumulated in a table at the end of the book and are identified in the text by a dotted underline and may be seen in a tool-tip by hovering the mouse over the underline.

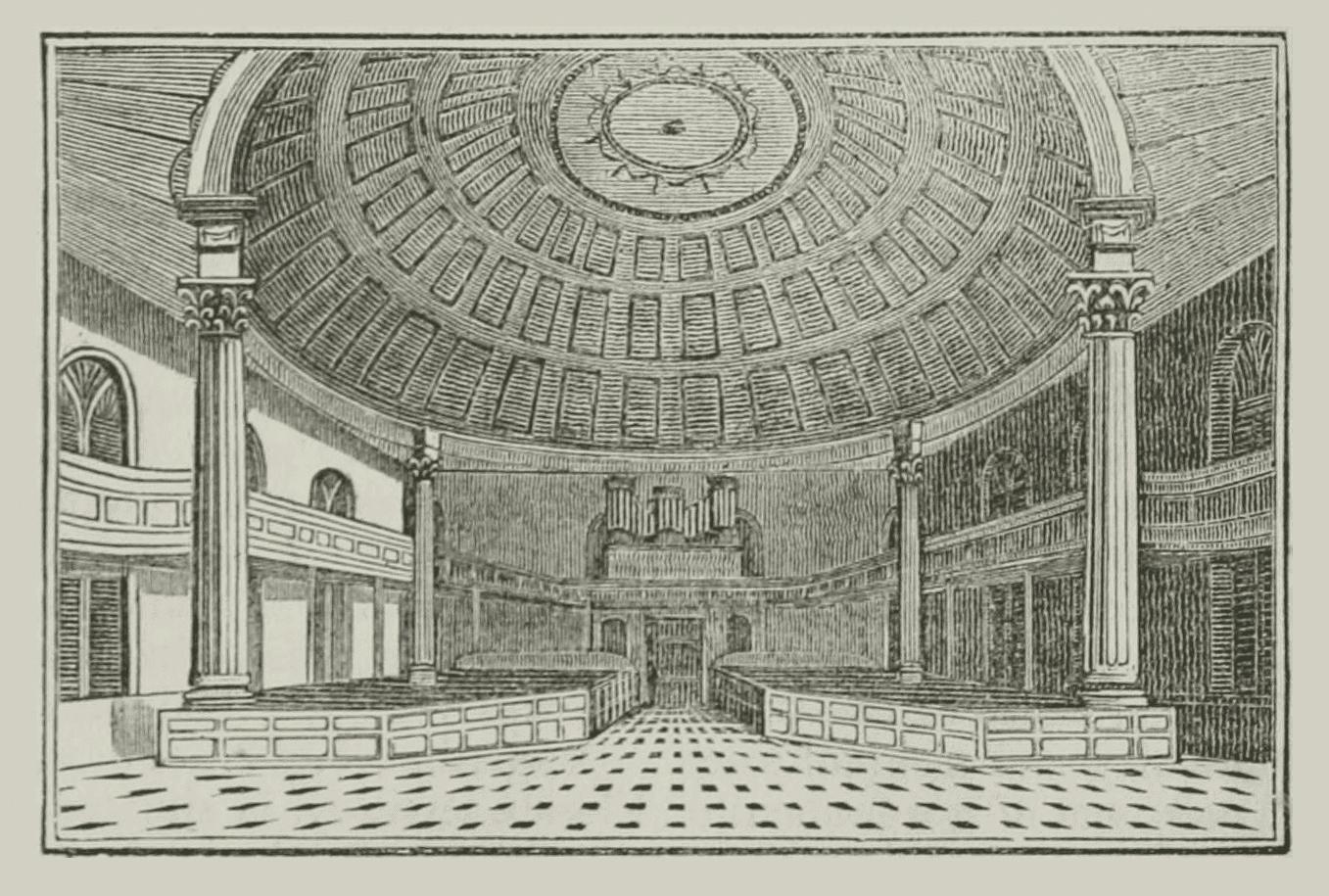

Hall of Representatives ... Washington.

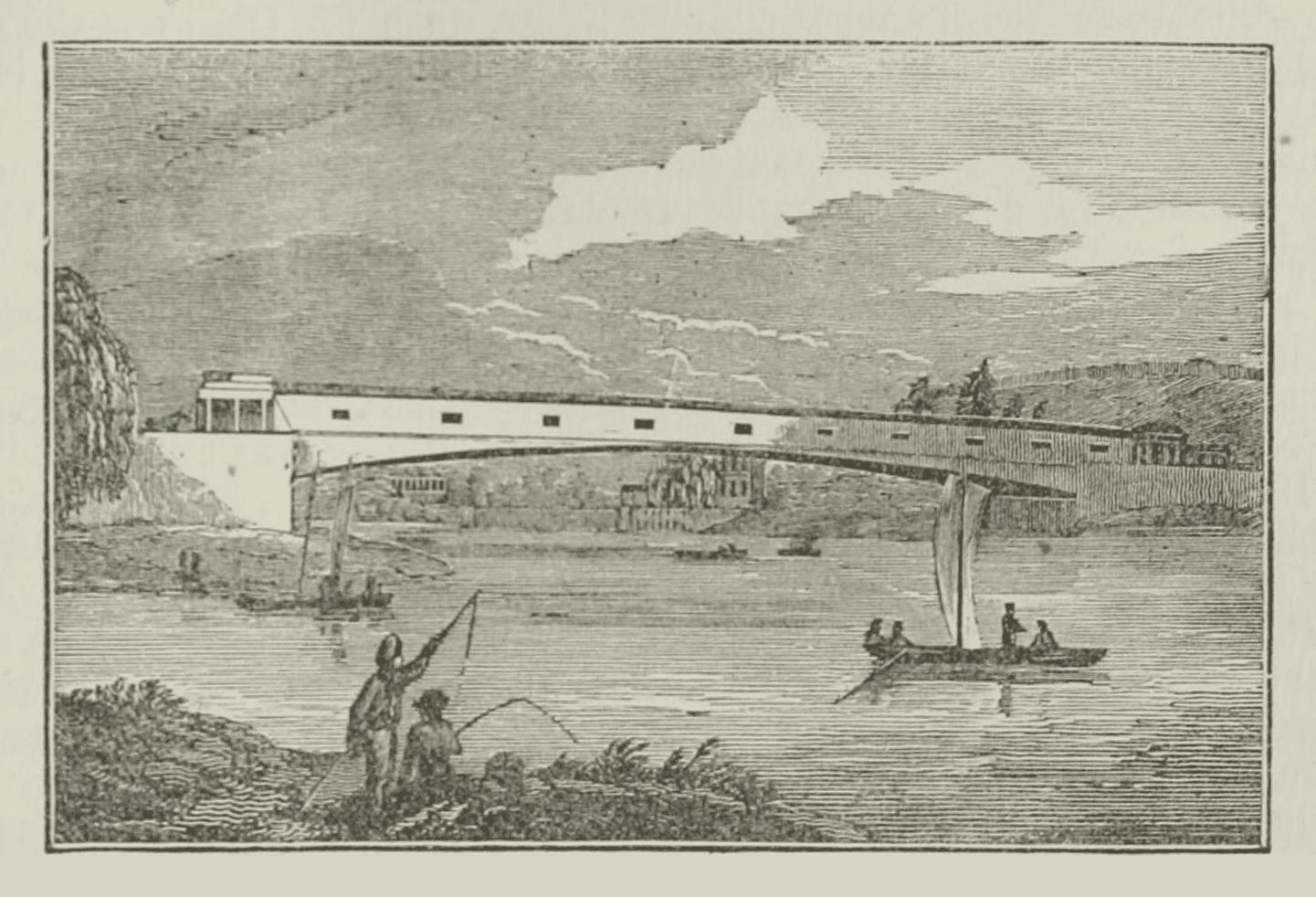

Bridge and Rapids near Falls of Niagara.

A

BOOK OF THE UNITED STATES.

EXHIBITING ITS

GEOGRAPHY, DIVISIONS, CONSTITUTION, AND GOVERNMENT;

|

INSTITUTIONS, AGRICULTURE, COMMERCE, MANUFACTURES, RELIGION, EDUCATION, POPULATION, NATURAL CURIOSITIES, RAILROADS, CANALS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS, |

MANNERS AND FINE ARTS, ANTIQUITIES, LITERATURE, MINERALOGY, BOTANY, GEOLOGY, NATURAL HISTORY, PRODUCTIONS, &c. &c. &c. |

AND PRESENTING

A VIEW OF THE REPUBLIC GENERALLY,

AND OF THE

INDIVIDUAL STATES;

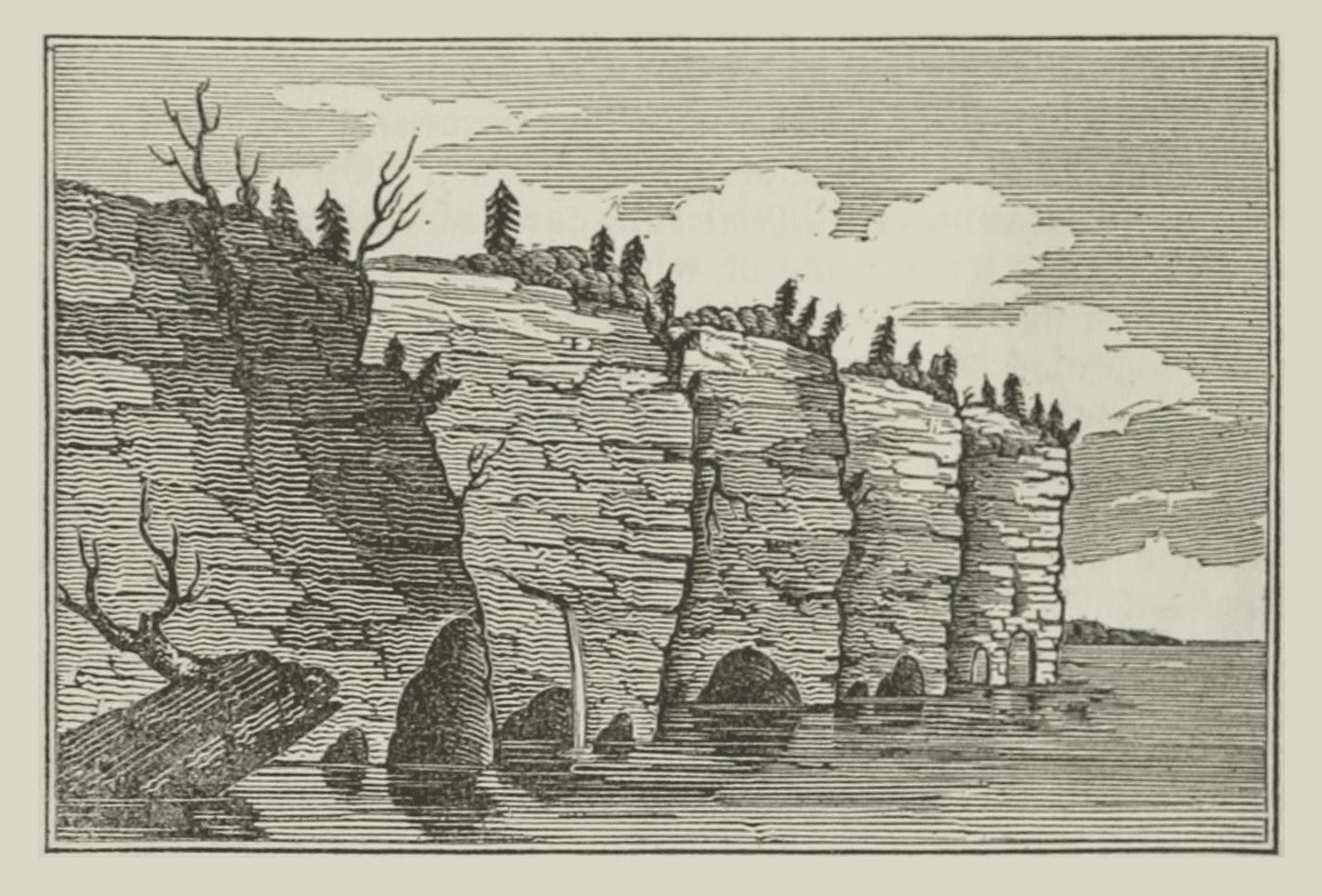

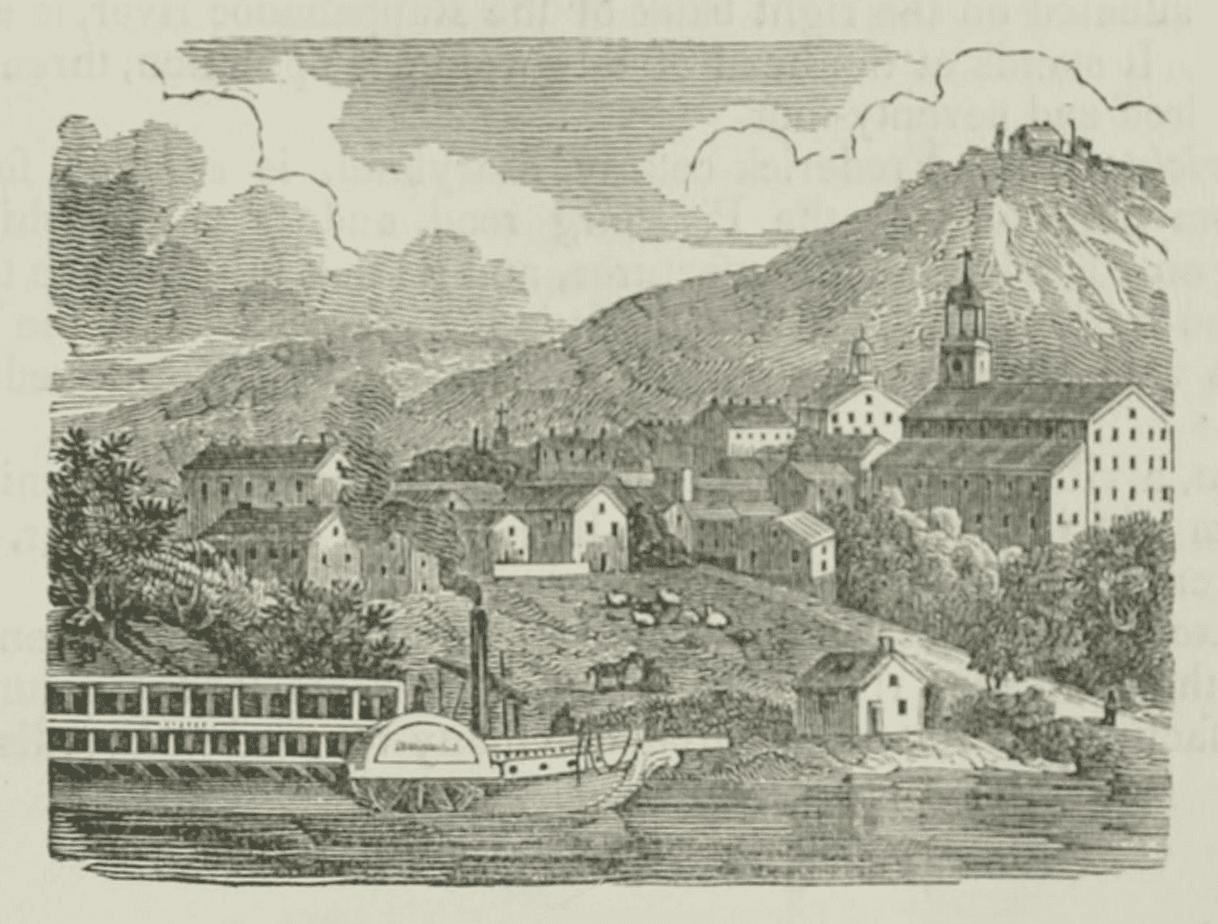

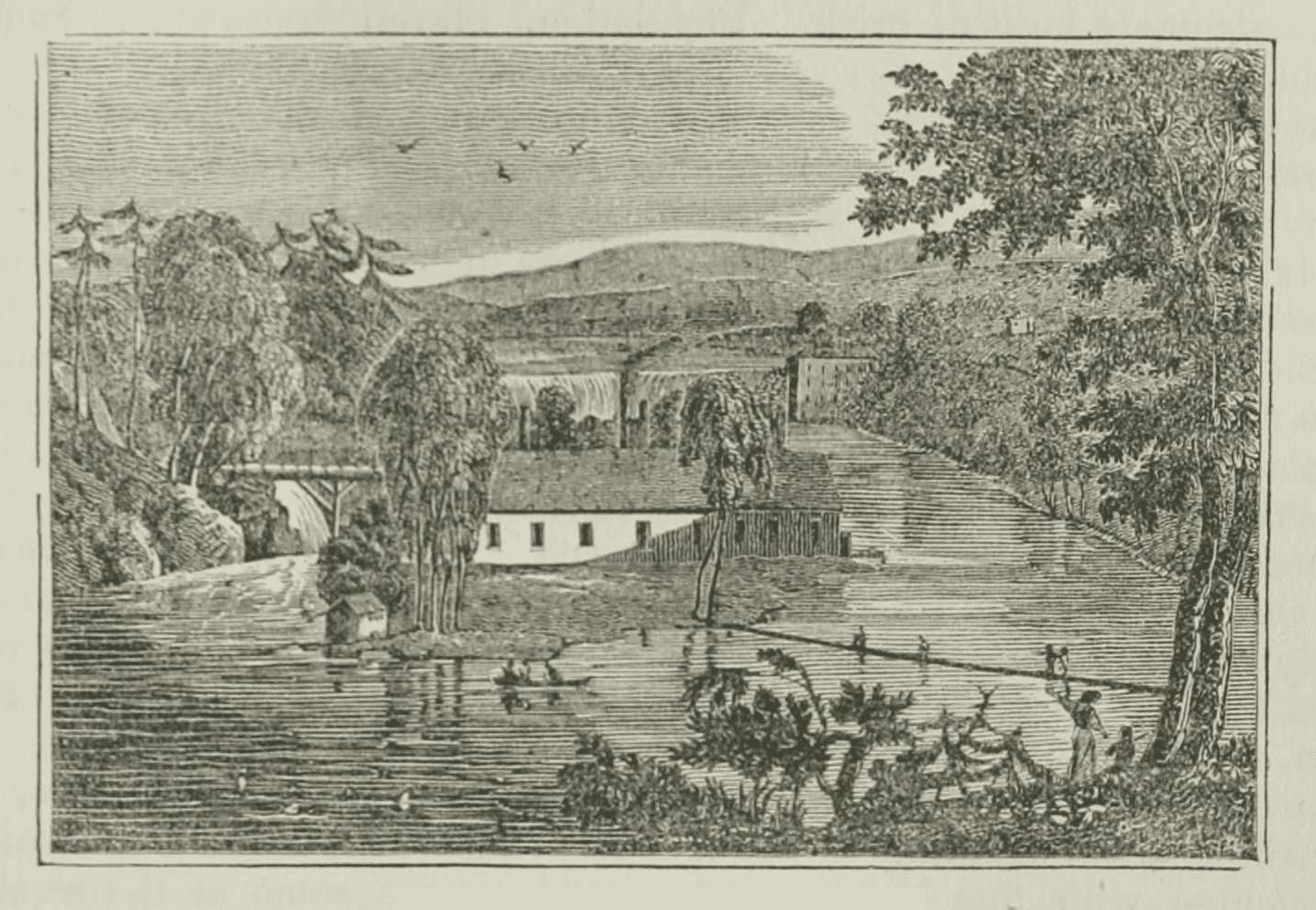

View on the Mississippi.

TOGETHER WITH A CONDENSED

HISTORY OF THE LAND,

FROM ITS FIRST DISCOVERY TO THE PRESENT TIME.

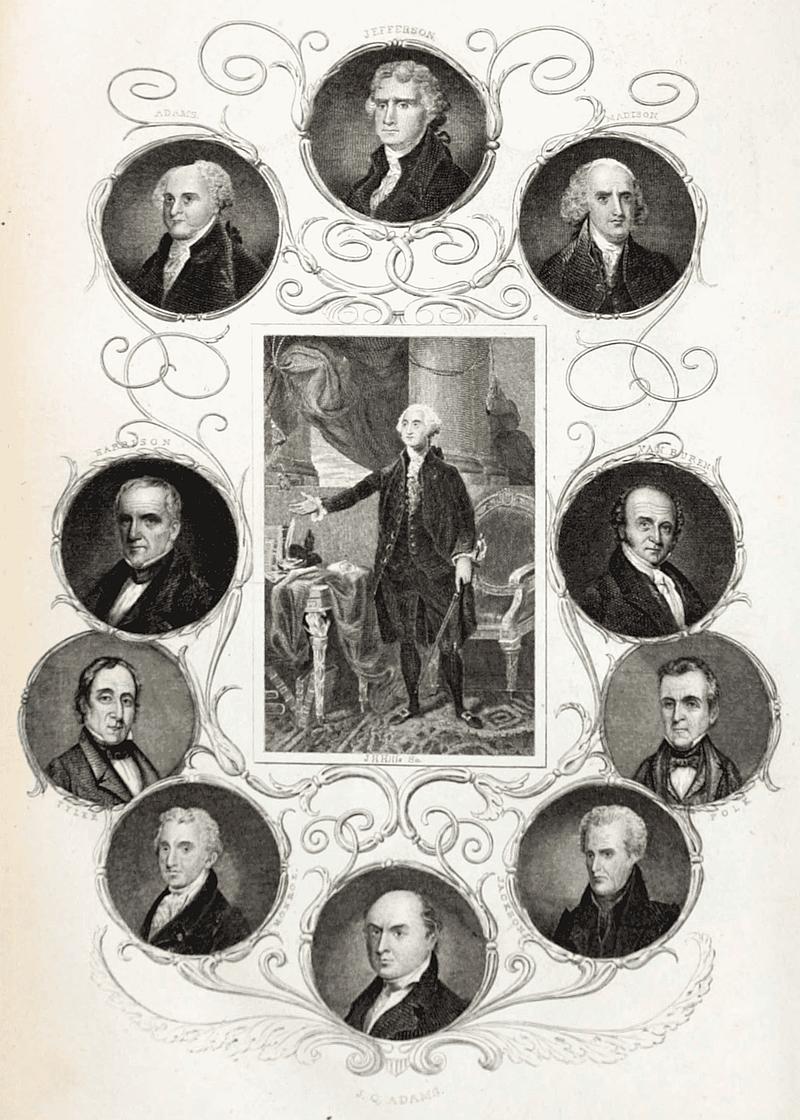

THE BIOGRAPHY

OF ABOUT TWO HUNDRED OF THE LEADING MEN:

A DESCRIPTION OF THE

PRINCIPAL CITIES AND TOWNS;

WITH

STATISTICAL TABLES,

RELATING TO THE RELIGION, COMMERCE, MANUFACTURES, AND VARIOUS OTHER TOPICS.

EDITED BY

GRENVILLE MELLEN

WITH ENGRAVINGS OF CURIOSITIES, SCENERY, ANIMALS, CITIES, TOWNS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS, &c.

HARTFORD:

PUBLISHED BY A. C. GOODMAN & CO.

1852.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1839, by

GRENVILLE MELLEN,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of Massachusetts.

IN presenting this volume to the American public, the introductory remarks in which we shall indulge will be few and general, as the book is one of that kind that speaks with singular plainness for itself, and seems to us to require little upon the prefatory page in the way of explanation, either with reference to its character considered collectively, or in detail.

The chief object in preparing this work has been to furnish something which should be found to embrace those subjects which are of abiding interest and importance to all classes. It has been a wish to present such matters, as well as could be done in the compass allowed, as are of interest to all classes of readers, and an acquaintance with which is desirable for our own citizens especially.

Directed by these intentions, it is hoped that the efforts to bring a valuable and attractive volume before the public may have proved successful; and that, viewed with reference to the subjects of which it treats, this may be called, emphatically, a book for this country, exhibiting, at one view, a picture of the Republic in its physical, political, and social conditions, so drawn and colored as to present in pleasant relief its most striking and peculiar features.

Simplicity was a leading object in the preparation of the work. By such object it was natural to be guided, when it was remembered that the pages were designed for the general eye and for all classes. This quality was allowed to govern, in a great degree, both in the thought and style; and if, in any case, it may have been carried to a point beyond the fortunate one, it will be believed, we presume, that the fault, if it be such, is upon the better side.

In some instances interesting historical accounts are retained and enlarged upon, from a consideration of the universally popular character which such accounts generally possess. It is not known, however, that they are referred to or dwelt upon in such a manner as to induce the charge of credulity beyond that very pardonable degree which all well disposed and good natured, and we may add, well informed, writers and readers are ever ready to meet.

Frequent references are made to able and prominent writers, in connection with the several important subjects which are here introduced; and such extracts are given, as, it is thought, will best illustrate and enforce them. This course, with most readers, is an acceptable one, and in a work of this nature it is the best that can be pursued, frequently, to accomplish, within reasonable limits, the design of the undertaking.

To enlarge would seem to be useless. The volume must speak for itself, and bear its recommendation within. It is hoped, with the several sketches of the Republic which it intends to present, under its different aspects, it may prove an agreeable and instructive one to the community.

We had intended to have annexed a list of the writers consulted and extracted from in the course of the volume; but we believe the references in the pages will supersede the necessity of a more particular notice. It would be unjust, however, not to mention our especial obligation to the excellent View of the United States by Mr. Hinton, of which we have made the freest use throughout the volume.

New York, June, 1839.

PART I.

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY.

CHAP. I. Mountains

CHAP. II. Valleys

CHAP. III. Prairies and Plains

CHAP. IV. Rivers

CHAP. V. Cataracts and Cascades

CHAP. VI. Lakes

CHAP. VII. Springs

CHAP. VIII. Caverns

CHAP. IX. Islands

CHAP. X. Capes and Peninsulas

CHAP. XI. Bays, Harbors, Sounds, and Gulfs

CHAP. XII. Oceans

CHAP. XIII. Soil

CHAP. XIV. Climate

CHAP. XV. Minerals

CHAP. XVI. Animals

CHAP. XVII. Botany

CHAP. XVIII. Geology

CHAP. XIX. Natural Curiosities

PART II.

POLITICAL GEOGRAPHY.

CHAP. I. Political and Geographical Division

CHAP. II. Cities and Towns

CHAP. III. Agriculture

CHAP. IV. Manufactures

CHAP. V. Commerce

CHAP. VI. Rail-roads

CHAP. VII. Canals

CHAP. VIII. Government

CHAP. IX. Convention

CHAP. X. Indian Tribes

CHAP. XI. American Antiquities

CHAP. XII. Religion

CHAP. XIII. Manners and Amusements

CHAP. XIV. Penitentiary System

CHAP. XVI. Literature and Education

CHAP. XVII. Fine Arts

CHAP. XVIII. Banking System

CHAP. XIX. Biographical Sketches

CHAP. XX. History

BOOK OF THE UNITED STATES.

PART I.

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY.

THOUGH embracing in its extent several elevated ranges of great length and breadth, the territory of the United States cannot be considered as a mountainous country. The land along the whole line of the seacoast is level for a considerable distance into the interior. The breadth of this level tract expands from fifty miles in the north-east extremity, gradually, as we advance to the south-west, till in the state of Georgia, it has attained an extent of near two hundred miles. Beyond this the land gradually rises into mountains, which are much more remarkable for their length and breadth, than their height. They sometimes consist of numerous parallel ridges rising successively behind each other; at other times they run into knots; and sometimes they recede from their parallel direction into what are called spurs. These ranges or belts of mountainous country, though receiving a vast number of different appellations, are most usually known by the name of the Alleghanies. The long continuity of this chain has obtained it the name of the Endless Mountains, from the northern savages. The French and Spaniards, who first became acquainted with it in Florida, applied to it through its whole extent the name of Apalachian, which is still retained by a considerable river of that country.

The general course of the Alleghanies is about north-east and south-west; east of the Hudson they are scattered in irregular groups, without any very marked direction.

The range of the Rocky or Chippewan Mountains divides the waters which flow east into the Missouri and Mississippi, from those which flow west into the Pacific Ocean, and are a continuation of the Cordilleras of Mexico. Their longitude is about one hundred and twelve west, and they terminate in about seventy north latitude. Along the coast of the Pacific is another range which seems to form a step to the Rocky Mountains. It extends from the Cape of California along the coast to Cook’s Inlet, generally rising to no great height in the southern portion. In the northern part, La Perouse states that it is ten thousand feet high, and at its northern extremity is Mount Elias, eighteen thousand feet high, and the loftiest peak of North America.

The White Mountains in New England, largely considered, are the principal ranges running north-east and south-west, projecting from the main ridge that forms the boundary of the United States, and separates the waters of the St. Lawrence from those that run south through the Northern States. The highest ridge is that called the White Mountain Ridge in New Hampshire, running from south to north, the loftiest summits of which are Monadnock, a hill of an abrupt and striking character, Sunapee, Kearsarge, Carr’s Mountain, and Moosehillock. Towards the north of the state, these eminences rise to a much higher elevation, and are known specifically by the name of the White Mountains.

White Mountains.

White Mountains.

These are the loftiest mountains in the United States, east of the Mississippi. They lie between the Connecticut and Androscoggin rivers on the north-east and west, and the head-waters of the Merrimack on the south sixty or seventy miles from the coast; yet their white summits are visible from many miles at sea. They extend about twenty miles from south-west to north-east, and their base is eight or ten miles broad.

Mount Washington is the highest of all the White Mountains, being six thousand two hundred and thirty-four feet above the level of the sea. Next to Mount Washington in height is Mount Adams, then Jefferson, then Madison, all more than five thousand feet high; there are several besides these, though none so elevated. The country around and among the mountains is very wild and rough, and the mountains themselves are difficult of access. The east side of Mount Washington rises at an angle of forty-five degrees. The lower part of the mountain is covered with thick woods of spruce and fir trees, with deep beds of moss beneath. Heavy clouds of vapor often rest upon the mountain, and fill the moss with water, which cannot be exhaled or dried up by the sun on account of the woods, and therefore it breaks out in numerous springs which feed the streams from the mountain. The trees are short and stunted higher up the mountain; soon there are only bushes; then instead of bushes are vines; the last thing that grows is winter grass mixed with moss; the summit is entirely bare of vegetation. There is a plain from which the last height of Mount Washington rises to the height of fifteen hundred feet. This elevation or pinnacle is composed of huge grey rocks. Reaching the top much fatigued and out of breath, the traveller is instantly master of a boundless prospect, noble enough to pay him for his labor. The Atlantic dimly seen through a distance of sixty-five miles, the Vermont Mountains on the west, the southern and northern mountains of New Hampshire, Lake Winnipiseogee, ponds, streams, and towns, without number, all form a great impressive picture.

The road from the seacoast to the mountains passes along the head stream of the Saco, which rises among these mountains, and breaks through them at a place known by the name of the Notch, a narrow defile extending two miles in length between two large cliffs, apparently rent asunder by some vast convulsion of nature.

‘The sublime and awful grandeur of this passage baffles all description. Geometry may settle the heights of the mountains; and numerical figures may record the measure; but no words can tell the emotions of the soul, as it looks upward, and views the almost perpendicular precipices which line the narrow space between them; while the senses ache with terror and astonishment, as one sees himself hedged in from all the world besides. He may cast his eye forward or backward, or to either side; he can see only upward, and there the diminutive circle of his vision is cribbed and confined by the battlements of nature’s ‘cloud-capped towers,’ which seem as if they wanted only the breathing of a zephyr, or the wafting of a straw against them, to displace them, and crush the prisoner in their fall. Just before our visit to this place, on the 26th of June, 1826, there was a tremendous avalanche, or slide, as it is there called, from the mountain which makes the southern wall of the passage. An immense mass of earth and rock, on the side of the mountain, was loosened from its resting place, and began to slide towards the bottom. In its course, it divided into three portions, each coming down, with amazing velocity, into the road, and sweeping before it shrubs, trees, and rocks, and filling up the road, beyond all possibility of its being removed. With great labor, a pathway has been made over these fallen masses, which admits the passage of a carriage. The place from which the slide, or slip, was loosened, is directly in the rear of a small, but comfortable dwelling-house, owned and occupied by a Mr. Willey, who has taken advantage of a narrow, a very narrow interval,—where the bases of the two mountains seem to have parted and receded, as if afraid of coming into contact,—to erect his lone habitation: and, were there not a special Providence in the fall of a sparrow, and had not the finger of that Providence traced the direction of the sliding mass, neither he, nor any soul of his family, would ever have told the tale. They heard the noise, when it first began to move, and ran to the door. In terror and amazement, they beheld the mountain in motion. But what can human power effect in such an emergency? Before they could think of retreating, or ascertain which way to escape, the danger was passed. One portion of the avalanche crossed the road about ten rods only from their habitation; the second, a few rods beyond that; and the third, and much the largest portion, took a much more oblique direction. The whole area, now covered by the slide, is nearly an acre; and the distance of its present bed from its former place on the side of the mountain, and which it moved over in a few minutes, is from three quarters of a mile to a mile. There are many trees of large size that came down with such force as to shiver them in pieces; and innumerable rocks, of many tons’ weight, any one of which was sufficient to carry with it destruction to any of the labors of man. The spot on the mountain, from which the slip was loosened, is now a naked, white rock; and its pathway downward is indicated by deep channels, or furrows grooved in the side of the mountain, and down one of which pours a stream of water, sufficient to carry a common saw-mill.

‘From this place to the Notch, there is almost a continual ascent, generally gradual, but sometimes steep and sudden. The narrow pathway proceeds along the stream, sometimes crossing it, and shifting from the side of one mountain to the other, as either furnishes a less precarious foothold for the traveller than its fellow. Occasionally it winds up the side of the steep to such a height, as to leave, on one hand or the other, a gulf of unseen depth; for the foliage of the trees and shrubs is impervious to the sight. The Notch itself is formed by a sudden projection of rock from the mountain on the right or northerly side, rising perpendicularly to a great height,—probably seventy or eighty feet,—and by a large mass of rock on the left side, which has tumbled from its ancient location, and taken a position within twenty feet of its opposite neighbor. The length of the Notch is not more than three or four rods. The moment it is passed, the mountains seem to have vanished. A level meadow, overgrown with long grass and wild flowers, and spotted with tufts of shrubbery, spreads itself before the astonished eye, on the left, and a swamp or thicket, on the right, conceals the ridge of mountains which extend to the north: the road separates this thicket from the meadow. Not far from the Notch, on the right hand side of the road, several springs issue from the rocks that compose the base of the mountain, unite in the thicket, and form the Saco river. This little stream runs across the road into the meadow, where it almost loses itself in its meandering among the bogs, but again collects its waters and passes under the rock that makes the southerly wall of the Notch. It is here invisible for several rods, and its presence is indicated only by its noise, as it rolls through its rugged tunnel. In wet seasons and freshets, probably a portion of the water passes over the fragments of rock, which are here wedged together, and form an arch or covering for the natural bed of the stream.

‘The sensations which affect the corporeal faculties, as one views these stupendous creations of Omnipotence, are absolutely afflicting and painful. If you look at the summits of the mountains, when a cloud passes towards them, it is impossible for the eye to distinguish, at such a height, which is in motion, the mountain, or the cloud; and this deception of vision produces a dizziness, which few spectators have nerve enough to endure for many minutes. If the eye be fixed on the crags and masses of rock, that project from the sides of the mountains, the flesh involuntarily quivers, and the limbs seem to be impelled to retreat from a scene that threatens impendent destruction. If the thoughts which crowd upon the intellectual faculties are less painful than these sensations of flesh and blood, they are too sublime and overwhelming to be described. The frequent alterations and great changes, that have manifestly taken place in these majestic masses, since they were first piled together by the hand of the Creator, are calculated to awaken “thoughts beyond the reaches of the soul.” If the “everlasting hills” thus break in pieces, and shake the shaggy covering from their sides, who will deny that

“This earthly globe, the creature of a day,

Though built by God’s right hand, shall pass away?—

The sun himself, by gathering clouds oppressed,

Shall, in his silent, dark pavilion rest;

His golden urn shall break, and, useless, lie

Among the common ruins of the sky;

The stars rush headlong, in the wild commotion,

And bathe their glittering foreheads in the ocean?”

‘Reflection needs not the authority of inspiration to warrant a belief, that this anticipation is something more than poetical. History and philosophy teach its truth, or, at least, its probability. The melancholy imaginings which it excites are relieved by the conviction that the whole of God’s creation is nothing less

“Than a capacious reservoir of means,

Formed for his use, and ready at his will;”

and that, if this globe should be resolved into chaos, it will undergo a new organization, and be re-moulded into scenes of beauty, and abodes of happiness. Such may be the order of nature, to be unfolded in a perpetual series of material production and decay—of creation and dissolution—a magnificent procession of worlds and systems, in the march of eternity.’1

A few weeks after the slide mentioned in the above description, a disaster occurred which occasioned the destruction of the interesting family to which allusion is there made.

The afternoon had been rainy, and the weather continued so till eleven o’clock in the evening, when it cleared away. About the same hour, a great noise was heard, at the distance of several miles like the rushing down of rocks and much water from the mountains. The next morning, the people, at Conway, could perceive that some disaster, of no ordinary character, had happened, by the appearance of the mountains on each side of the road. On repairing to the spot, they found the house of Mr. Willey, standing near the Notch, unhurt, but destitute of any of the family. It is supposed that they left it in their fright, and were instantly swept away, and buried under the rocks and earth which were borne down by the freshet. This family consisted of Mr. Willey, his wife, five children, and two hired men, all of whom were suddenly swept from time to eternity, by this lamentable disaster. Had they remained in the house, they would probably have been safe.

The central and western parts of Maine are mountainous. The highest mountains are the Katahdin, situated near the centre of the state, the Speckled, Bald, Bigelow, and Ebeeme mountains. The range between the rivers Hudson and Connecticut, and this last and lake Champlain, is called the Green Mountains, an appellation which it has received from its perpetual verdure, being covered on its western side with hemlock, pine, spruce, and other evergreens. These mountains are from ten to fifteen miles wide, much intersected with valleys, and abounding in springs and streams. Vegetation decreases on approaching their summits; the trees diminish in size, and frequently terminate in a shrubbery of spruce and hemlock, two or three feet high, with branches so interwoven as to prevent all passage through them. The sides of the mountains are generally rugged and irregular; some of them have large apertures and caves. Their tops are coated with a compact and firm moss, which lies in extensive beds, and is sometimes of a consistency to bear the weight of a man without being broken through. These mosses absorb a great deal of moisture, and afford wet and marshy places, which in the warm season are the constant resort of water fowl. The loftiest summits are Killington Peak, near Rutland; Camel’s Rump, between Montpelier and Burlington, and Mansfield Mountain, a few miles farther north, all which are more than three thousand five hundred feet above the level of the sea. Ascutney, a single mountain near Windsor, is three thousand three hundred and twenty feet in height.

The range called Green Mountains in Vermont, enters the west part of Massachusetts from the north, and forms the Hoosac and Tagkannuc Ridges, which run nearly parallel to each other south, into Connecticut. The most elevated peaks of the Tagkannuc Ridge are Saddle Mountain in the north, four thousand feet high, and Tagkannuc Mountain in the south, three thousand feet. No summits of the Hoosac Ridge much exceed half these elevations. Mount Holyoke, in the neighborhood of Northampton, commands a prospect of the highest beauty; the waters of the Connecticut wind about its base, giving fertility and wealth of vegetation to the surrounding country. On its top a shanty is erected, in which refreshments are kept for the visitors who at favorable seasons make this excursion in great numbers.

There are two distinct chains belonging to the Alleghany range in the state of New York, the Catskill and the Wallkill. The Catskill, which is the most northern, is the continuation of the proper Alleghany or western chain; the eastern is called, by some geographers, Wallkill.

A visit to the Catskill is a favorite excursion of northern travellers, and several days may be spent very agreeably in examining the grand and romantic scenery of the neighborhood. Pine Orchard is a small plain, two thousand two hundred and fourteen feet above the Hudson, scattered with forest trees, and furnished with an elegant house of great size. Immediately below is seen a wild and mountainous region, finely contrasting with the cultivated country beyond, which presents every variety of hill and valley, interspersed with town, hamlet, and cottage.

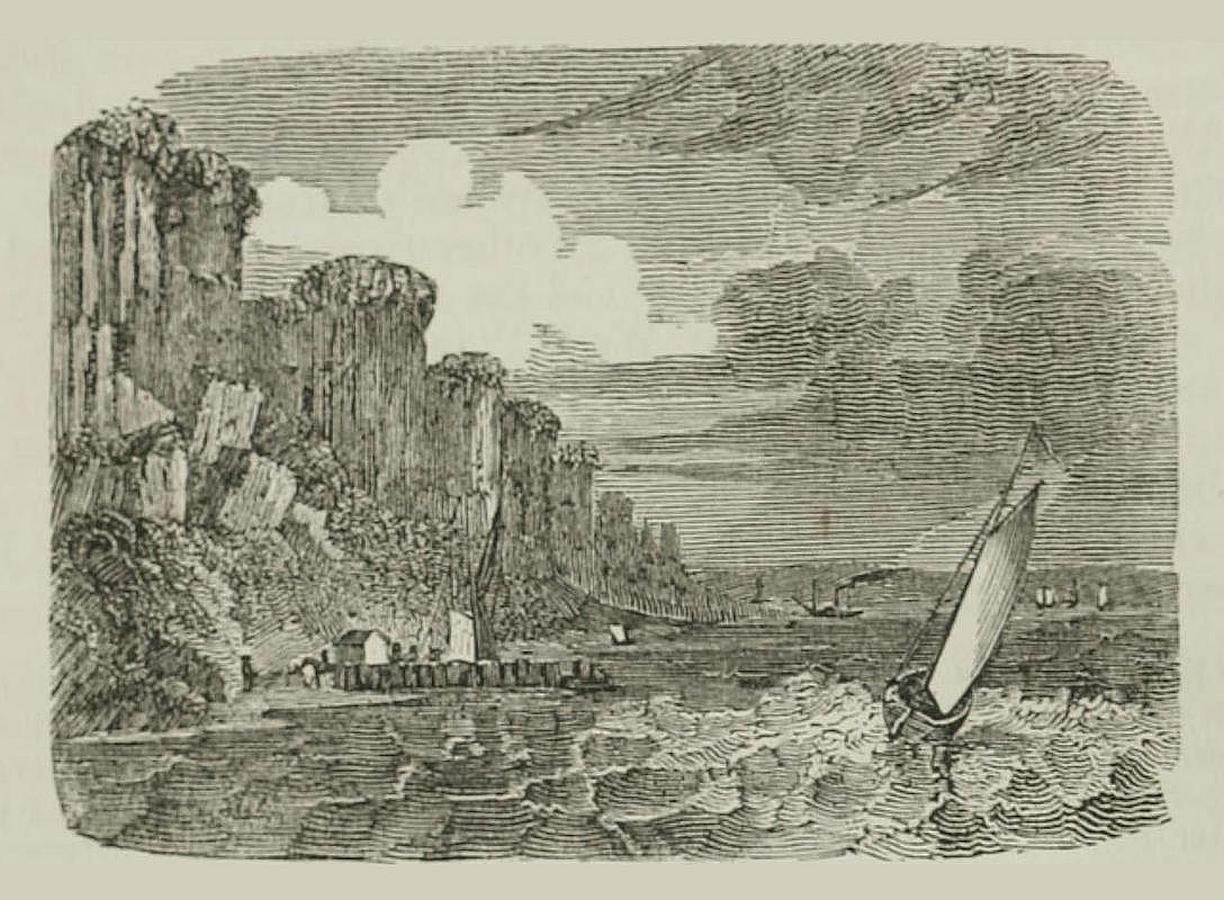

The hills of Weehawken are on the west side of the Hudson, nearly opposite the city of New York.

Weehawken.

The Highlands of the Hudson, or Fishkill Mountains, which first appear about forty miles from New York, are marked for their sublimity and grandeur, and interesting from their connection with many great events of the revolution. This chain is sixteen miles in width, and extends twenty miles along both sides of the Hudson. The height of the principal has been estimated at one thousand five hundred and sixty-five feet. The Peruvian Mountains consist of a lofty tract in the northern part of New York, being round the sources of the Hudson, and separating the waters of Lake Champlain from those of the St. Lawrence. They received their name from the supposition that they contained mineral treasures. Their loftiest summit, called Whiteface, is about three thousand feet above the level of Lake Champlain.

Highlands.

The Apalachian chain in Pennsylvania spreads to its widest limits, and covers with its various ranges more than one half of the state. The greatest width of the chain equals two hundred miles. It consists of parallel ridges sometimes little distant from each other, and at other times with valleys twenty or thirty miles broad lying between them. The range nearest the coast is called the South Mountain, and is a continuation of the Blue Ridge of Virginia. This, however, is hardly a distinct ridge, but only an irregular series of rocky, broken eminences, sometimes disappearing altogether, and at others spreading out several miles in breadth. These eminences lie one hundred and fifty or two hundred miles from the sea, and their height does not exceed one thousand two hundred feet above the surrounding country. Beyond these are the Kittatinny or Blue Mountains, which extend from Maryland to New Jersey across the Susquehanna and Delaware. Farther westward are the ridges bearing the names of the Sideling Hills, Ragged Mountains, Great Warrior Mountain, East Will’s Mountain, till we come to the Alleghany Ridge, the highest range, and from which this whole chain has in common language received the name of the Alleghany Mountains. The highest summits are between three and four thousand feet above the level of the sea. West of the Alleghany are the Laurel and Chesnut Ridges.

These mountains are in general covered with thick forests. The Laurel Mountains are overgrown on their eastern front with the tree from which they are named. The wide valleys between the great ridges are filled with a multitude of hills, confusedly scattered up and down. The tops of the ridges sometimes exhibit long ranges of table land, two or three miles broad; some of them are steep on one side, and extend with a long slope on the other. These mountains are traversed by the great streams of the Susquehanna chain, and the head-waters of the Ohio.

The Wallkill, which crosses the Hudson at West Point, forty miles below the Catskill, is the continuation of the Blue Ridge, or Eastern Chain, which is the most general appellation for the extensive ridge which fronts the Atlantic. The eastern and western ranges run parallel to each other, south-west, till on the frontiers of North Carolina and Virginia they unite in a knot which has been called the Alleghany Arch, because the principal chain embraces there in a curve all its collaterals from the east. A little farther to the south, but still in North Carolina, a second knot unites all the collateral ridges from the west, and forms a culminating point of heads of rivers. The second bifurcation stretches south-west and then west, and the name of the 2Cumberland Mountains through the whole state of Tennessee, while the proper Alleghany Chain, left almost alone, continues its course to the south-west, and completes the boundary of Georgia and the two Carolinas. From the Alleghany Arch, there are three principal ridges or ramifications of the Alleghany, running north-east and nearly parallel to each other, namely, the Alleghany Proper, the North Mountain, and the Blue Ridge. Of the last ridge the highest summits are the Otter Peaks. The elevated district of South Carolina presents seven or eight mountains running in regular directions, the most distinguished of which is the 3Table Mountain. Mr. Jefferson, with peculiar felicity of illustration, called the range of the Alleghanies the spine of the United States separating the eastern from the western waters, and the whole of the territory from the Mississippi to the Atlantic into three natural divisions, materially differing from each other in climate, configuration, soil, and produce; namely, the coast, the mountains, and the western territory.

In extent, in elevation, and in breadth, the Rocky Mountains far exceed the Alleghanies of the Eastern States. Their mean breadth is two hundred miles, and where broadest, three hundred. Their height must be very great, since, when first seen by Captain Lewis, they were at least one hundred and fifty miles distant. On a nearer approach, the sublimity of the prospect is increased, by the appearance of range rising behind range, each yielding in height to its successor, till the most distant is mingled with the clouds. In this lofty region the ranges are covered with snow in the middle of June. From this last circumstance, these ranges have been sometimes denominated the Shining Mountains—an appellation much more appropriate than that of the Rocky or Stony Mountains, a property possessed by all mountains, but peculiar to none. The longitudinal extent of this great chain is immense, running as far north-west as sixty degrees north latitude, and perhaps to the Frozen Ocean itself. The snows and fountains of this enormous range, from the thirty-eighth to the forty-eighth degree of northern latitude, feed, with never-failing supplies, the Missouri and its powerful auxiliary streams.

Table lands at the foot of the Rocky Mountains.

In endeavoring to explore these Alpine heights, and the sources of the Red and Arkansaw rivers, Captain Pike and his party were bewildered amidst snows, and torrents, and precipices. The cold was so intense, that several of the party had their limbs frostbitten, and were obliged to be abandoned to their fate, by Pike and his surviving companions. In a lateral ridge, separating the valley of the Arkansaw from that of the Platte river, in north latitude forty-one degrees, is a remarkable peak, called the Great White Mountain; so remarkable, indeed, as to be known to all the savage tribes for hundreds of miles round, and spoken of in terms of admiration by the Spaniards of New Mexico, and which formed the boundary of their knowledge to the north-west. The altitude of this peak was taken on the base of a mile by Pike, and found to be ten thousand five hundred and eighty-one feet above the level of the meadow at its foot; and the height of this latter was estimated at eight thousand feet above the level of the sea; in all, eighteen thousand five hundred and eighty-one feet of absolute elevation; being six thousand feet higher than the peak of Teneriffe, by Humboldt’s measurement; or two thousand eight hundred and ninety-one feet short of that of Chimborazo, admitting the elevation of this last to be twenty-one thousand four hundred and seventy-two feet. Captain Pike and his companions never lost sight of this tremendous peak, unless in a valley, for the space of ten weeks, wandering amongst the mountains. What is the elevation at the sources of the Missouri can only be matter of mere conjecture. The level of the river, where they left their canoes, could not be less than six thousand feet above the sea; but how high the mountains rose above this point the narrative does not inform us, and hardly gives us any data to decide. The central chain, as usual, is marked in the map as highest, and covered with snow during the whole year. The latitude is between forty-five and forty-seven degrees; and between these parallels, in Europe, the lower limit of perpetual congelation is fixed at from nine to ten thousand feet above the level of the sea; and it can hardly be supposed that the summits of this snowy range were less than eight thousand five hundred or nine thousand feet high, making a reasonable allowance for the greater coldness of the American continent. Captain Clarke allows this central range to be sixty miles across, and that the shortest road across the different ranges is at least one hundred and forty miles, besides two hundred miles more, before we can reach a navigable river. In their first passage across these tremendous mountains, the American party suffered every thing which hunger, cold, and fatigue, could impose, during three weeks. They were compelled to melt the snow for their portable soup; many of their horses (which they used for conveying their baggage, or for riding,) were foundered by falls from precipices; the men became feeble through excessive toil, and sickly from want of food, as there are no wild animals in these inhospitable regions; and, but for an occasional meal of horse flesh, the whole party must have perished. In returning home from the mouth of the Columbia, their state was little better. Having again come in sight of the mountains, in the middle of May, they attempted to pass them but in vain, on account of the snow, which lay from six to ten feet deep, and were obliged to return, and rest in the plains to the twenty-fourth of June. These mountains are, therefore, a far more formidable barrier to the Pacific, than the Alleghanies to the back country, and can be passed with great difficulty only for three months in the year, namely, from the latter end of June to the latter end of September.

We are indebted to the Missouri Advocate for the following account of General Ashley’s discoveries in this quarter. He considers it quite possible to form a route across this formidable barrier to the Pacific Ocean. The route proposed, after leaving St. Louis, and passing generally on the north side of the Missouri river, strikes the river Platte, a short distance above its junction with the Missouri; then pursues the waters of the Platte to their sources, and, in continuation, crosses the head-waters of what General Ashley believes to be the Rio Colorado of the west, and strikes, for the first time, a ridge or single connecting chain of mountains, running from north to south. This however presents no difficulty, as a wide gap is found apparently prepared for the purpose of a passage. After passing this gap, the route proposed falls directly on a river, called by George Ashley the Buenaventura, and runs from that river to the Pacific Ocean. The face of the country, in general, is a continuation of high, rugged, and barren mountains; the summits of which are either timbered with pine, quaking-asp, or cedar; or, in fact, almost entirely destitute of vegetation. Other parts are hilly and undulating; and the valleys and table-lands (except on the borders of water-courses, which are more or less timbered with cotton-wood and willows,) are destitute of wood; but this indispensable article is substituted by an herb, called by the hunters wild sage, which grows from one to five feet high, and is found in great abundance in most parts of the country. The sterility of the country generally is almost incredible. That part of it, however, bounded by the three ranges of mountains, and watered by the sources of the supposed Buenaventura, is less sterile; yet the proportion of arable land, even within those limits, is comparatively small; and no district of the country visited by General Ashley, or of which he obtained satisfactory information, offers inducements to civilized people, sufficient to justify an expectation of permanent settlement. The river visited by General Ashley, and which he believes to be the Rio Colorado of the west, is, at about fifty miles from its most northern source, eighty yards wide. At this point, General Ashley embarked and descended the river, which gradually increased in width to one hundred and eighty yards. In passing through the mountains, the channel is contracted to fifty or sixty yards, and so much obstructed by rocks as to make its descent extremely dangerous, and its ascent impracticable. After descending this river about four hundred miles, General Ashley shaped his course northwardly, and fell upon what he supposed to be the sources of the Buenaventura; he represents those branches as bold streams, from twenty to fifty yards wide, forming a junction a few miles below where he crossed them, and then emptying into a lake (called Grand Lake,) represented by the Indians as being forty or fifty miles wide, and sixty or seventy miles long. This information is strengthened by that of the white hunters, who have explored parts of the lake. The Indians represent, that at the extreme west end of this lake, a large river flows out, and runs in a westward direction. General Ashley, when on those waters, at first thought it probable they were the sources of the Multnomah: but the account given by the Indians, supported by the opinion of some men belonging to the Hudson Bay Company, confirms him in the belief, that they are the head-waters of the river represented as the Buenaventura. To the north and north-west from the Grand Lake, the country is represented as abounding in salt. The Indians west of the mountains are remarkably well disposed towards the citizens of the United States; the Eutaws and Flatheads are particularly so, and express a great wish that the Americans should visit them frequently.

A large number of lateral ranges project to the south-east, east, and north-east of the main range. Where the Missouri enters the plains, is the most eastern projection; and from where the Jaune leaves the snowy range, there is a lateral range, running more than two hundred miles south-east, which is intersected by the Bighorn river. As these mountains have not yet been explored by the eye of geological science, it is impossible to say any thing respecting their component parts; but, from every thing that we can learn from Pike and Clarke, they seem to be chiefly granitic. No volcanoes have yet been discovered amongst them; but strange unusual noises were heard from the mountains, by the American party, when stationed above the falls of the Missouri. These sounds seemed to come from the north-west. ‘Since our arrival at the falls,’ says the narrative, ‘we have repeatedly heard a strange noise coming from the mountains, a little to the north of west. It is heard at different periods of the day and night: sometimes when the air is perfectly still and unclouded, and consists of one stroke only, or of five or six discharges in quick succession. It is loud, and resembles precisely the sound of a six pounder at the distance of three miles. The Indians had before mentioned this noise like thunder, but we had paid no attention to it. The watermen also of the party say, that the Pawnees and Ricaras give the same account of a similar noise made in the Black Mountains, to the westward of them.’ Again, near the same place, it is afterwards said: ‘They heard, about sunset, two discharges of the tremendous mountain artillery.’ Not a word more occurs upon the subject; but we know that similar explosions take place among the mountains near the head of the Washita, and among the mountains of Namhi, near the sources of the Red river.

In our present state of ignorance respecting these mountains, it is impossible to give a solution of this phenomenon, though it may proceed from some distant volcano, which, like Stromboli, may be in a state of constant activity, but more irregularly. It is well known that the sounds of volcanoes are heard at very great distances, as at Guatimala, where the sound of the volcano of Cotopaxi was distinctly heard, though more than two hundred and twenty miles distant. Some indications of volcanoes had been seen by the American party, when ascending the river, about sixty miles below the mouth of the Little Missouri, where they passed several very high bluffs on the south side, one of which had been lately a burning volcano, as the pumice stones lay very thick around it, and emitted a strong sulphureous smell. Similar appearances are mentioned by Mackenzie, as taking place among the Rocky Mountains on their eastern side, in north latitude fifty-six and one hundred and twenty degrees west longitude. ‘Mr. Mackay,’ says he, ‘informed me, that in passing over the mountains, he observed several chasms in the earth that emitted heat and smoke, which diffused a strong sulphureous stench.’ From all these circumstances combined, it is natural to infer that the sound proceeds from some very distant and unknown volcano.

On the west side of the Mississippi, and about midway between the Rocky Mountains and the Alleghanies, lies a broad range of mountains, called the Ozarks, six or seven hundred miles in length, about one hundred broad, and having an elevation varying from one to two thousand feet above the sea. This range of low mountains, which is penetrated by two branches of the Mississippi, the Arkansas and Red river, was nearly altogether unknown till within these few years. It is parallel with the range of the Alleghanies, making an angle of about forty degrees with the great range of the Andes. As far as the Ozarks have yet been explored, the granites and older primitive rocks are found at the lowest part, being surmounted by those of more recent formation. The reverse of this is observed in the Rocky Mountains. A similar range of broken and hilly country commences on the Ouisconsin river and extends north to Lake Superior. It is called the Wisconsin or Ouisconsin Hills.

GENERAL REMARKS ON MOUNTAINS.

Mountains are supposed by naturalists to have different origins, and to date their commencement from various periods. Those which form a chain, and are covered with snow, are accounted primitive, or antediluvian. They greatly exceed all other mountains in height; in general their elevation is very sudden, and their ascent steep and difficult. They are composed of vast masses of quartz, destitute of shells, and of all organized marine matter; and appear to descend almost perpendicularly into the body of the earth. Of this kind are the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Himmaleh ranges, the Atlas, and the Andes. Another class are of volcanic origin. These are either detached or surrounded with groups of lower hills, the soil of which is heaped up in disorder, and consists of gravel and other loose substances. Among these are Mount Ætna and Vesuvius. A third class of mountains, whether grouped or isolated, are such as are composed of stratified earth or stone, consisting of different substances of various colors. The interior consists of numerous strata, almost horizontally disposed, containing shells, marine productions, and fish bones in great quantities. The strata of mountains which are lower and of more recent date, sometimes appear to rise from the side of primitive mountains which they surround, and of which they form the first step in the ascent.

The mountains in Asia are the most elevated and imposing in the world. Of these the Himmaleh chain is the highest; one of its peaks, Dhawalaghiri, reaching the altitude of twenty-eight thousand and ninety-six feet, and several exceeding twenty-four thousand. Africa has some extensive chains of mountains, but the altitudes of only a few have been ascertained. Mont Blanc is the highest summit of Europe, reaching an elevation of fifteen thousand seven hundred and thirty-five feet. The Andes of South America present the most striking and stupendous features; cataracts, volcanoes, and immense chasms of an almost perpendicular descent. Chimborazo, the highest point of the Andes, reaches twenty-one thousand four hundred and sixty-four feet; in many places the peaks rise to upwards of twenty thousand feet, though in others they sink to less than one thousand.

In general, all the chains of mountains in the same continent, seem to have a mutual connection more or less apparent; they form a sort of frame-work to the land, and appear in the origin of things to have determined the shape which it was to assume; but this analogy, were we to generalize too much, would lead us into error. There are many chains, which have very little, or, rather, no affinity to each other. Such are the mountains of Scandinavia and of Scotland, mountains as independent as the character of the nations who inhabit them.

| 1. | Long’s Peak, the highest of the Rocky Mountains, Missouri Territory | 12,000 |

| 2. | James’s Peak, of the Rocky Mountains, Missouri Territory | 11,500 |

| 3. | Inferior peaks of the Rocky Mountains, varying from 10,700 to | 7,200 |

| 4. | Mt. Washington, the highest of the White Hills, New Hampshire | 6,234 |

| 5. | Inferior peaks of the White Hills, varying from 5,328 to | 4,356 |

| 6. | Moosehillock Mt., Grafton County, New Hampshire | 4,636 |

| 7. | Mansfield or Chin Mt., Chittenden County, Vermont | 4,279 |

| 8. | Camels’ Rump, Chittenden County, Vermont | 4,188 |

| 9. | Shrewsbury Peak, Rutland County, Vermont | 4,034 |

| 10. | Saddleback Mt., Berkshire County, Massachusetts | 4,000 |

| 11. | Table Mountain, Pendleton District, South Carolina | 4,000 |

| 12. | Peaks of Otter, Bedford County, Virginia | 3,955 |

| 13. | Killington Peak, Rutland County, Vermont | 3,924 |

| 14. | Round Top, the highest of the Catskill Mountains, New York | 3,804 |

| 15. | High Peak, one of the highest of the Catskill Mountains, New York | 3,718 |

| 16. | Grand Monadnock, Cheshire County, New Hampshire | 3,718 |

| 17. | Manchester Mountain, Bennington County, Vermont | 3,706 |

| 18. | Ascutney Mountain, Windsor County, Vermont | 3,320 |

| 19. | Ozark Mountains, Arkansas Territory, average height | 3,200 |

| 20. | Wachuset Mountain, or Mount Adams, Worcester County, Mass. | 2,990 |

| 21. | Whiteface Mountain, Essex County, New York | 2,690 |

| 22. | Kearsarge Mountain, Hillsborough County, New Hampshire | 2,460 |

| 23. | Alleghany Mountains, average height | 2,400 |

| 24. | Porcupine Mountains, Chippeway County, south of Lake Superior | 2,200 |

| 25. | Cumberland Mountains, average height | 2,200 |

| 26. | Moose Mountain, New Hampshire | 2,008 |

| 27. | New Beacon, the highest of the Highlands, New York | 1,658 |

THE Valley of the Mississippi is the largest in the world; and differs from any other of very great extent, in the peculiar distinctness of its outline. It is bounded south by the gulf of Mexico, west by the Rocky Mountains, north by the great lakes of British America, and east by the Apalachian Mountains. Its general surface may be classed under three distinct aspects; the thickly timbered, the barren, and the prairie country. This valley extends from the twenty-ninth to the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, and exhibits every variation of temperature from the climate of Canada to that of Louisiana. It is a wide extent of level country, in which the various rivers, inclosed between two chains of mountains three thousand miles apart, find a common centre, and discharge their waters into the sea by a single channel. Geologically considered, this immense valley presents every where the aspect of what is called secondary formation. Its prevailing rocks are carbonate of lime, disposed in the most regular lamina, masses of limestone, in which seashells or organic remains are imbedded, retaining their distinct and original form. At every step, is presented the aspect of a country once covered by lakes or seas. The soil, stones, and exuviæ of lake or river formation, are, to all appearance, of comparatively recent origin. In the alluvial soils, to the depth of from twenty to an hundred feet, are found pebbles, smoothed by the evident attrition of waters, having the appearances of those masses of smoothed pebbles that are thrown on the seashore by the dashing of the surge. Leaves, branches, and logs are also found at great distances from the points where wood is seen at present, and at great depths below the surface. In the most solid blocks of limestone, split for building, deers’ horns and other animal exuviæ are found incorporated in the solid stone.

‘From its character of recent formation,’ says Mr. Flint, ‘from the prevalence of limestone every where, from the decomposition which it has undergone, and is constantly undergoing, from the prevalence of decomposed limestone in the soil, probably, results another general attribute of this valley—its character generally for uncommon fertility. We would not be understood to assert, that the country is every where alike fertile. It has its sterile sections. There are here, as elsewhere, infinite diversities of soil, from the richest alluvions, to the most miserable flint knobs; from the tangled cane brakes, to the poorest pine hills. There are, too, it is well known, towards the Rocky Mountains, wide belts that have a surface of sterile sands, or only covered with a sparse vegetation of weeds and coarse grass. But of the country in general, the most cursory observer must have remarked, that, compared with lands, apparently of the same character in other regions, the lands here obviously show marks of singular fertility. The most ordinary, third rate, oak lands, will bring successive crops of wheat and maize, without any manuring, and with but little care of cultivation. The pine lands of the southern regions are in many places cultivated for years, without any attempts at manuring them. The same fact is visible in the manner in which vegetation in this country resists drought. It is a proverb on the good lands, that if there be moisture enough to bring the corn to germinate, and come up, they will have a crop, if no more rain falls until the harvest. We have a thousand times observed this crop continuing to advance towards a fresh and vigorous maturity, under a pressure of drought, and a continuance of cloudless ardor of sun, that would have burned up and destroyed vegetation in the Atlantic country.

‘We have supposed this fertility to arise, either from an uncommon proportion of vegetable matter in the soil; from the saline impregnations mixed with the earth, as evidenced in the numberless licks, and springs of salt water, and the nitrous character of the soil, wherever, as in caves, or under buildings, it is sheltered from moisture; or, as we have remarked, from the general diffusion of dissolved limestone, and marly mixtures over the surface. In some way, spread by the waters, diffused through the soil, or the result of former decomposition, there is evidently much of the quickening and fertilizing power of lime mixed with the soil.’

The greatest length of the Valley of the Missouri is twelve hundred miles, its greatest breadth seven hundred. In the direction of the western rivers, the inclined plain of the Missouri extends eight hundred miles from the Chippewayan Mountains, and rather more than that distance from south to north, from the southern branches of the Kansas, to the extreme heads of the northern confluents of the valley. Ascending from the lower verge of this widely extended plain, wood becomes more and more scarce, until one naked surface spreads on all sides. Even the ridges and chains of mountains partake of these traits of desolation.

The celebrated valley called the American Bottom extends along the eastern bank of the Mississippi to the Piasa Hills, four miles above the mouth of the Missouri. It is several miles in width, and has a soil of astonishing fertility. It has all the disadvantages attending tracts of recent alluvion, the most valuable parts of it being liable to be swept away by the current of the Mississippi. ‘But the inexhaustible fertility of its soil,’ says Major Long, ‘makes amends for the insalubrity of the air, and the inconvenience of a flat and marshy situation, and this valley is undoubtedly destined to become one of the most populous parts of America. We were formerly shown here a field that had been cultivated, without manure, one hundred years in succession, and which when we saw it, (in August, 1816,) was covered with a very luxuriant growth of corn.’

The Ohio Valley is divided by the river into two unequal sections, leaving on the north-west side eighty thousand, and on the south-east one hundred and sixteen thousand square miles. The river flows in a deep ravine five hundred and forty-eight miles long in a straight line, and nine hundred and ninety-eight by the windings of the stream. In its natural state the Ohio valley, with the exception of the central plain, was covered with a dense forest. Open savannahs commence as far east as the sources of the Muskingum. Like the plain itself, those savannahs expand to the westward, and on the Illinois open into immense prairies. This valley may be regarded as a great plain inclining from the Apalachian system of the north-west, obliquely and deeply cut by the Ohio and its numerous confluents, into chasms from an elevation of four hundred feet to nearly the level of the streams. On the higher parts of the valley, the banks of the river rise by bold acclivities which wear almost a mountainous aspect. This boldness of outline imperceptibly softens in descending the Ohio, and on approaching the Mississippi, an extent of level woodland bounds the horizon. Ascending the rivers of the south-east slope, the scenery becomes more and more rugged, until it terminates in the ridges of the Apalachian chains: if the rivers of the north-west slope are followed, on the contrary, we find the landscape broken and varied near the Ohio, but around their sources flat and monotonous.

The Valley of the Hudson varies extremely in its width, being in some places contracted to the immediate neighborhood of the stream; in others extending forty miles. On the borders of the river the land is generally elevated. The Mohawk is bordered by two long ranges of hills presenting little variety of aspect. In the early part of its course it flows through extensive flats. The valleys of the Susquehanna and its branches are remarkably irregular. These streams traverse the whole width of the Apalachian chain of mountains, sometimes flowing in wide valleys between parallel ranges for fifty or sixty miles in a direct course, and at other times breaking through the mountain ridges. The valleys between the different ranges of the great chain extending throughout Pennsylvania are often twenty or thirty miles in width with a hilly or broken surface.

Valley of the Mohawk.

The only large valley in North Carolina lies between the Blue Ridge, and a parallel range called the Iron, Bald, and Smoky Mountains. It runs north-east and south-west, is one hundred and eighty miles in length, and from ten to forty in width.

The valleys of the small rivers of Tennessee are singularly beautiful and fertile, surpassing all others of the same description in the Western States. The valleys of the Cumberland and Tennessee differ little from the alluvions of the other great rivers of the west.

The Valley of the Connecticut is one of the most celebrated valleys of the United States for its fertility and beauty. It is a large tract of land extending from Long Island sound to Hereford Mountains in Canada, five miles beyond the forty-fifth degree of latitude. In the largest sense, it is from five to forty-five miles in width, and its surface is composed of a succession of hills, valleys and plains. The interval lands begin about twelve or fourteen miles from the mouth of the river. These are formed by a long and continued alluvion. The tributary streams of the Connecticut run every where through a soft and rich soil, considerable quantities of which, particularly the lighter and finer particles, are from time to time washed into their channels, by occasional currents springing from rains and melted snows. Wherever the stream moves with an uniform current these particles are carried along with it; but where the current is materially checked, they are in greater or less quantities deposited. In this manner a shoal is formed at first, which afterwards rises into dry land; this is almost invariably of good quality, but those parts which are lowest are commonly the best, as being the most frequently overflowed, and therefore most enriched by successive deposits of slime. Of these parts, that division which is farthest down the river is the most productive, consisting of finer particles, and being more plentifully covered with this manure. In the spring these grounds are almost annually overflowed. In the months of March and April, the snows, which in the northern parts of New England are usually deep, and the rains, which at this time of the year, are generally copious, raise the river from fifteen to twenty feet, and extend the breadth of its waters in some places a mile and a half or two miles. Almost all the slime conveyed down the current at this season, is deposited on these lands, for here, principally, the water becomes quiescent, and permits the earthy particles to subside; this deposit is a rich manure; the lands dressed with it are preserved in their full strength, and being regularly enriched by the hand of nature, cannot but be highly valuable. Nor are these grounds less distinguished by their beauty. The form of most of them is elegant; a river passing through them becomes, almost of course, winding; the earth of which they are composed is of a uniform texture, the impressions made by the stream upon the border are also nearly uniform; hence this border is almost universally a handsome arch, with a neat margin, frequently ornamented with a fine fringe of shrubs and trees.

Nor is the surface of these grounds less pleasing; their terraced forms and undulations are eminently handsome, and their universal fertility makes a cheerful impression on every eye. A great part of them is formed into meadows which are here more profitable, and every where more beautiful than lands devoted to any other culture; here they are extended from five to five hundred acres, and are every where covered with a verdure peculiarly rich and vivid. The vast fields also which are not in meadow, exhibit all the productions of the climate, interspersed in parallelograms, divided only by mathematical lines, and mingled in a charming confusion. In many places, large and thrifty orchards, and every where forest trees standing singly, of great height and graceful figures, diversify the landscape. Through its whole extent this valley is almost a continual succession of delightful scenery. The Connecticut is one of the most beautiful rivers in the world; the purity, salubrity and sweetness of its waters, the frequency and elegance of its meadows, its absolute freedom from aquatic vegetables, the enchanting elegance and grandeur of its banks, sometimes consisting of a smooth and winding beach, here covered with rich verdure, there fringed with bushes, now crowned with lofty trees, and now formed by the intruding hill, the rude bluff, and the shaggy mountain; these are objects which no description can equal.

GENERAL REMARKS ON VALLEYS.

Valleys are formed by the separation of chains of mountains or of hills. Those which are formed between high mountains, are commonly narrow and long, as if they had originally been only fissures dividing their respective chains, or for the passage of extensive torrents. The angles of their direction sometimes exhibit singular symmetry. In the Pyrenees there are said to be valleys whose salient and re-entrant angles so perfectly correspond, that if the force which separated them were to act in a contrary direction, and bring their sides together again, they would unite so exactly that even the fissure would not be perceived. There are some highly situated valleys containing rivers and lakes which have no outlets or streams. Most high valleys have their surface upon a level with the summits of the secondary mountains in the neighborhood. The lower valleys widen as they recede from the secondary mountains from which they originate, and gradually lose themselves in the plains. Their opposite angles correspond regularly, but are very obtuse.

The sort of narrow passage by which we enter into these high valleys is called a pass or defile. Between Norway and Sweden is one of these passes, formed by several masses of rock cut by nature into the shape of long parallelograms, and which have between them a passage shut in by perpendicular walls. This pass is near Skiærdal; another of the same kind is at Portfeld, or the Mountain of the Gate. These openings exactly resemble those by which the Hudson passes through successive chains of mountains, which seem desirous of checking its course. The Cordilleras of the Andes present the most stupendous passes of this kind that are known; they are from four to five thousand feet deep.

The valleys of the Hudson and Connecticut are equalled by few in the old world for natural beauty and romantic scenery. Of the valleys of Europe, that of the Rhine is most celebrated; and is only more interesting than the Hudson on account of its old historical associations, its populous cities, and the picturesque ruins and massive monuments of architecture which frown upon its banks.

ONE of the most remarkable features of the western country consists in its extensive prairies or savannahs, which prevail in all the vast region between the Alleghany and the Rocky Mountains, and also to the west of the Rocky Mountains. When seen from the summits of the Mexican and the Rocky Mountains, they seem absolutely boundless to the view. They are not to be considered merely as dead flat, but undulating into gentle swelling lawns, and expanding into spacious valleys, in the centre of which is always found a little timber, growing on the banks of the brooks and rivulets of the finest water. Pike, who viewed them from the summit of the Blue Mountain, under the source of the Arkansaw, says, ‘the unbounded prairie was overhung with clouds, which seemed like the ocean in a storm, wave piled on wave, and foaming; while the sky over our heads was perfectly clear, and the prospect was truly sublime.’ In these vast prairies the soil is dry, sandy, with gravel; but the moment we approach a stream, the land becomes more humid, with small timber. It is probable that these steppes or prairies were never well wooded, as, from the earliest ages, the aridity of the soil, having so few water-courses running through it, and these being principally dry in summer, no sufficient nourishment has been afforded to the growth of timber. In all timbered land, the annual discharge of the leaves, with the continual decay of old trees and branches, creates a manure and moisture, which are preserved from the heat—the sun not being permitted to direct his rays perpendicularly, but to shed them only obliquely through the foliage. But in Upper Louisiana, a barren soil, dried up for eight months in the year, presents neither moisture nor nutriment for the growth of wood.

These vast plains of Louisiana, near the upper courses of the Arkansaw, with its tributary streams, and the head-waters of the Kanzas, White and Grand Osage rivers, may become in time like the sandy deserts of Africa; ‘for,’ says Pike, ‘I saw in my route, in various places, tracts of many leagues, where the wind had thrown up the sand in all the fancied forms of the ocean’s rolling waves, and on which not a single speck of vegetation appeared.’ From this circumstance Pike deduces the following remark: ‘From these immense prairies may arise a great advantage to the United States, namely, the restriction of our population to some certain limits, and thereby a continuation of the Union. Our citizens being so prone to rambling, and extending themselves on the frontiers, will, through necessity, be compelled to limit their extent on the west to the borders of the Missouri and Mississippi; while they leave the prairies, incapable of cultivation, to the wandering and uncivilized aborigines of the country.’ These prairies, from the borders of the Mississippi, on the east, to the base of the Mexican Alps on the west, rise with a continually increasing acclivity for many hundred miles, till, at the base of the mountains, they attain an elevation of eight thousand feet, as we are informed by Pike, which is greater than the elevated level of the great desert of Gobi, on the north-west of China, estimated by Du Halde to be five thousand five hundred and eleven feet above the level of the sea, or the great arid desert, to the north of the cape of Good Hope, traversed by the Orange river, and lately visited by the Rev. Mr. Campbell, the elevation of which is estimated by Colonel Gordon at six thousand five hundred and sixty-one feet above the level of the sea. In addition to the aridity of the Louisiana prairies, they are so impregnated with nitre, and other salts, as to taint the waters that flow in various directions. Pike says, that for leagues together, they are covered with saline incrustations; and a number of tributary streams descending into the Arkansaw and Kanzas rivers are perfect salines; and beyond the river Platte, as we are informed by Colonel Lewis, the lands are not only destitute of timber, but even of good water, of which there is but a small quantity in the creeks, and even that is brackish. The same saline incrustations pervade the prairies on the Upper Missouri; and the same want of timber, little or no dew, with very little rain, continues till the neighborhood of the mountains.

The calcareous districts, which form the great portion of the region west of the Alleghanies, present certain tracts entirely divested of trees, which are called barrens, though capable of being rendered productive. The cause of this peculiarity has not been accurately examined. Those parts of this region which are elevated three or four hundred feet, and lie along deeply depressed beds of rivers, are clothed with the richest forests in the world. The Ohio flows under the shade of the plane and the tulip tree, like a canal dug in a nobleman’s park; while the lianas, extending from tree to tree, form graceful arches of flowers and foliage over branches of the river. Passing to the south, the wild orange tree mixes with the odoriferous and the common laurel. The straight silvery column of the papaw fig, which rises to the height of twenty feet, and is crowned with a canopy of large indented leaves, forms one of the most striking ornaments of this enchanting scene. Above all these, towers the majestic magnolia, which shoots up from that calcareous soil to the height of more than one hundred feet. Its trunk, perfectly straight, is surmounted with a thick and expanded head, the pale green foliage of which affects a conical figure. From the centre of the flowery crown which terminates its branches, a flower of the purest white rises, having the form of a rose, and to which succeeds a crimson cone. This, in opening, exhibits rounded seed of the finest coral red, suspended by delicate threads six inches long. Thus, by its flowers, its fruit, and its gigantic size, the magnolia surpasses all its rivals of the forest.

The following excellent description of the prairie country is from the pen of Mr. James Hall. ‘That these vast plains should be totally destitute of trees, seems to be an anomaly in the economy of nature. Upon the mind of an American, especially, accustomed to see new lands clothed with timber, and to associate the idea of damp and silent forests with that of a new country, the appearance of sunny plains, and a diversified landscape, untenanted by man, and unimproved by art, is singular and striking. Perhaps if our imaginations were divested of those associations, the subject would present less difficulty; and if we could reason abstractly, it might be as easy to account for the existence of a prairie as of a forest.

‘It is natural to suppose that the first covering of the earth would be composed of such plants as arrived at maturity in the shortest time. Annual plants would ripen, and scatter their seeds many times before trees and shrubs would acquire the power of reproducing their own species. In the mean time, the propagation of the latter would be likely to be retarded by a variety of accidents—the frosts would nip their tender stems in the winter—fire would consume, or the blasts would shatter them—and the wild grazing animals would bite them off, or tread them under foot; while many of their seeds, particularly such as assume the form of nuts or fruits, would be devoured by animals. The grasses, which are propagated both by the root and by seed, are exempt from the operation of almost all these casualties. Providence has, with unerring wisdom, fitted every production of nature to sustain itself against the accidents to which it is most exposed, and has given to those plants which constitute the food of animals, a remarkable tenacity of life; so that although bitten off, and trodden, and even burned, they still retain the vital principle. That trees have a similar power of self protection, if we may so express it, is evident from their present existence in a state of nature. We only assume that in the earliest state of being, the grasses would have the advantage over plants less hardy, and of slower growth; and that when both are struggling together for the possession of the soil, the former would at first gain the ascendancy; although the latter, in consequence of their superior size and strength, would finally, if they should ever get possession of any portion of the soil, entirely overshadow and destroy their humble rivals.

‘We have no means of determining at what period the fires began to sweep over these plains, because we know not when they began to be inhabited. It is quite possible they might have been occasionally fired by lightning, previous to the introduction of that element by human agency. At all events, it is very evident that as soon as fire began to be used in this country by its inhabitants, the annual burning of the prairies must have commenced. One of the peculiarities of this climate is the dryness of its summers and autumns. A drought often commences in August, which, with the exception of a few showers towards the close of that month, continues throughout the season. The autumnal months are almost invariably clear, warm, and dry. The immense mass of vegetation with which this fertile soil loads itself during summer, is suddenly withered, and the whole surface of the earth is covered with combustible materials. This is especially true of the prairies where the grass grows to the height of from six to ten feet, and being entirely exposed to the sun and wind, dries with great rapidity. A single spark of fire, falling any where upon these plains at such a time, would instantly kindle a blaze, which would spread on every side, and continue its destructive course as long as it should find fuel. Travellers have described these fires as sweeping with a rapidity which renders it hazardous to fly before them. Such is not the case; or it is true only of a few rare instances. The flames often extend across a wide prairie, and advance in a long line. No sight can be more sublime than to behold in the night a stream of fire of several miles in breadth, advancing across these wide plains, leaving behind it a black cloud of smoke, and throwing before it a vivid glare which lights up the whole landscape with the brilliancy of noonday. A roaring and cracking sound is heard like the rushing of a hurricane. The flame, which in general rises to the height of about twenty feet, is seen sinking and darting upwards in spires, precisely as the waves dash against each other, and as the spray flies up into the air; and the whole appearance is often that of a boiling and flaming sea, violently agitated. The progress of the fire is so slow, and the heat so great, that every combustible object in its course is consumed. Wo to the farmer whose ripe cornfields extend into the prairie, and who suffers the tall grass to grow in contact with his fences! The whole labor of the year is swept away in a few hours. But such accidents are comparatively unfrequent, as the preventive is simple, and easily applied.

‘It will be readily seen, that as soon as these fires commenced, all the young timber within their range must have been destroyed. The whole state of Illinois, being one vast plain, the fires kindled in different places, would sweep over the whole surface, with a few exceptions, of which we are now to speak. In the bottom-lands, and along the margins of streams, the grass and herbage remain green until late in the autumn, owing to the moisture of the soil. Here the fire would stop for want of fuel, and the shrubs would thus escape from year to year, and the outer bark acquire sufficient hardness to protect the inner and more vital parts of the tree. The margins of the streams would thus become fringed with thickets, which, by shading the ground, would destroy the grass, while it would prevent the moisture of the soil from being rapidly evaporated, so that even the fallen leaves would never become so thoroughly dry as the grass of the prairies, and the fire here would find comparatively little fuel. These thickets grow up into strips of forests, which continue to extend until they reach the high table-land of the prairie; and so true is this, in fact, that we see the timber now, not only covering all the bottom-lands and hill sides, skirting the streams, but wherever a ravine or hollow extends from the low grounds up into the plain, these are filled with young timber of more recent growth. But the moment we leave the level plane of the country, we see the evidences of a continual struggle between the forest and the prairie. At one place, where the fire has on some occasion burned with greater fierceness than usual, it has successfully assailed the edges of the forest, and made deep inroads; at another, the forest has pushed out long points or capes into the prairie.

‘It has been suggested that the prairies were caused by hurricanes, which had blown down the timber and left it in a condition to be consumed by fire, after it was dried by laying on the ground. A single glance at the immense region in which the prairie surface predominates, must refute this idea. Hurricanes are quite limited in their sphere of action. Although they sometimes extend for miles in length, their track is always narrow, and often but a few hundred yards in breadth. It is a well known fact, that wherever the timber has been thus prostrated, a dense and tangled thicket shoots up immediately, and, protected by the fallen trees, grows with uncommon vigor.

‘Some have imagined that our prairies have been lakes; but this hypothesis is not tenable. If the whole state of Illinois is imagined to have been one lake, it ought to be shown that it has a general concavity of surface. But so far from this being true, the contrary is the fact; the highest parts of the state are in its centre. If we suppose, as some assert, that each prairie was once a lake, we are met by the same objection; as a general rule, the prairies are highest in the middle, and have a gradual declivity towards the sides; and when we reach the timber, instead of finding banks corresponding with the shores of a lake, we almost invariably find valleys, ravines, and water-courses depressed considerably below the general level of the plain.

‘Wherever hills are found rising above the common plane of the country, they are clothed with timber; and the same fact is true of all broken lands. This fact affords additional evidence in support of our theory. Most of the land in such situations is poor; the grass would be short, and if burned at all, would occasion but little heat. In other spots, the progress of the fire would be checked by rocks and ravines; and in no case would there be that accumulation of dry material which is found on the fertile plain, nor that broad, unbroken surface, and free exposure, which are necessary to afford full scope to the devouring element.

‘By those who have never seen this region, a very tolerable idea may be formed of the manner in which the prairie and forest alternate, by drawing a colored line of irregular thickness, along the edges of all the water-courses laid down on the map. This border would generally vary from one to five or six miles, and often extend to twelve. As the streams approach each other, these borders would approach or come in contact; and all the intermediate spaces not thus colored would be prairie. It would be seen that in the point formed by the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi, the forest would cover all the ground; and that, as these rivers diverge, and their tributaries spread out, the prairies would predominate.’