Title: Harper's Young People, July 11, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: December 12, 2018 [eBook #58457]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 141. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, July 11, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Toby coaxed and scolded, and scolded and coaxed, but all to no purpose. The monkey would clamber down over the end of the tent as if he were[Pg 578] about to allow himself to be made a prisoner, and then, just as Toby would make ready to catch the rope, he would spring upon the ridge-pole again, chattering with joy at the disappointment he had caused.

The visitors fairly roared with delight, and even the proprietors, whose borrowed property was being destroyed, could not help laughing at times, although there was not one of them who would not have enjoyed punishing Mr. Stubbs's brother very severely.

"He'll break the whole show up if we don't get him off," said Bob, as the monkey tore a larger hole than he had yet made, and the crowd encouraged him in his mischievous work by their wild cheers.

"I know it; but how can we get him down?" asked Toby, in perplexity, knowing that it would not be safe for any one of them to climb upon the decayed canvas, even if there were a chance that the monkey would allow himself to be caught after his pursuer got there.

"Get a long pole, an' scrape him off," suggested Joe; but Toby shook his head, for he knew that to "scrape" a monkey from such a place would be an impossibility.

Bob had an idea that if he had a rope long enough to make a lasso, he could get it around the animal's neck and pull him down; but just as he set out to find the rope, Mr. Stubbs's brother settled the matter himself.

He had torn one hole fully five inches long, and commenced on another a short distance from the first, when the thin fabric gave way, the two rents were made one, and down came Mr. Monkey, only saved from falling to the ground by his chin catching on the edges of the cloth.

There he hung, his little round head just showing above the canvas, with a bewildered and at the same time discouraged look on his face.

Toby knew that it would be but a moment before the monkey would get his paws out from under the canvas, and thus extricate himself from his uncomfortable position. Running quickly inside the tent, he seized Mr. Stubbs's brother by his long tail, pulling him completely through, and the mischievous pet was again a prisoner.

It was a great disappointment to the boys on the outside when this portion of the circus was hidden from view; but it was equally as great a relief to the partners that the destruction of their tent was at last averted.

After the excitement had nearly subsided, and Toby was reading his pet a lesson on the sin of destructiveness, Reddy arrived with the materials for making his circus poster—a sheet of brown paper, a bottle of ink, and a brush made by chewing the end of a pine stick.

He began his work at once. It was a long task, but was at last accomplished, and when the partners went to their respective homes that night, the following placard adorned one side of the tent:

On arriving at the house, Toby secured Mr. Stubbs's brother so that he could not liberate himself, after which he ran into the house to inquire for Abner.

The news this time was more encouraging, for the sick boy had awakened thoroughly refreshed after his long sleep, and had asked how the work on the tent was getting on. Aunt Olive thought Toby could see him, and after promising that he would not remain very long, or allow Abner to talk much, he went upstairs.

The crippled boy was lying in the bed bolstered up with pillows, looking out of the window that commanded a view of the tent, and evidently puzzled to know whether the large sheet of brown paper which he saw on one side was there as an ornament, or to serve some useful purpose.

Toby explained to him that it was the poster Reddy had made, and then told him all that had been done that day toward getting ready for the great exhibition which was to dazzle the good people of Guilford, as well as to bring in a rich reward, in the way of money, to the managers.

Abner was so interested in the matter, and seemed so bright and cheerful when he was talking about it, that Toby's fears regarding his illness were entirely dispelled. He came to the conclusion that Abner had simply been tired, as Aunt Olive had said, and that he would be better than ever by morning.

This belief was strengthened by the doctor, who came while Toby was still with his friend, and who, in answer to a question, said, cheerily:

"Of course he'll be all right; he may not be quite smart enough to go out to-morrow, but before the week is ended I'll guarantee that you'll have hard work to keep him in the house."

Toby's heart was light again as he attended to his evening's work; and when he met Joe, on his way to the pasture, he laid plans for the coming exhibition with a greater zest than he had displayed since the matter was first spoken of.

Now that the tent was up, and Abner on the sure and rapid road to recovery, Toby thought it quite time that Mr. Stubbs's brother should be taught to take some part in the performance. Joe was of the same opinion, and they decided to commence the education of the monkey that very night, giving him two or three lessons each day until he should be thoroughly trained.

The cows were not exactly hurried on the way home that night; but they were not allowed to loiter by the road-side when they saw particularly tempting tufts of grass, and as soon as they were in the barn Mr. Stubbs's brother was taken to the tent.

He was in anything rather than a good condition for training, for he evidently remembered his frolic of the afternoon, and was anxious to repeat it. Toby thought he could be made to leap through hoops as a beginning of his circus education, and all the energies of the boys were bent to the accomplishment of this.

But the monkey was either remarkably stupid or just then determined to take no part in the show, for although Joe held the hoops until his arms ached, and Toby coaxed and scolded until he was hoarse, Mr. Stubbs's brother could not be persuaded even to attempt a leap.

"It's no use to try any more to-night," said Toby, impatiently, when it was nearly dark inside the tent, and his pet was showing signs of anger. "We'll commence the first thing in the mornin', an' I guess he'll do it."

"I'd whip him if I was you," said Joe, who was thoroughly tired, and angry at the monkey's obstinacy. "If you would give him a good switchin', he'd know he'd got to do it."

"I wouldn't whip him if he never did anything," said Toby, as he hugged his pet tightly, almost as if he feared Joe might attempt, as one of the partners in the enterprise, to whip the unwilling performer.

"'Tain't my monkey, so I ain't got nothin' to say about it," and Joe was impatient now; "but if he was mine, I'll bet he'd do what I told him to."

It seemed almost as if Mr. Stubbs's brother knew what had been said about him, for he nestled close to Toby, hiding his face on the boy's neck in a way that would have prevented his master from whipping him even if he had been disposed so to do.

"We'll put him in the shed, and I guess he'll be good[Pg 579] enough to-morrow," said Toby, cheerfully; and then, after fastening the flag in the front of the tent in such a way that the wind would be kept out, if nothing more, he and Joe walked toward the house, discussing the question of the kind of tickets they should use at the show.

While they were yet some distance from the wood-shed in which Mr. Stubbs's brother was lodged, Aunt Olive called Toby to come quickly to the house.

"You put him in the wood-shed, an' fasten him in snug," said Toby, as he handed the monkey to Joe, and started for the house at full speed.

Now Joe knew perfectly well where Mr. Stubbs's brother was kept; but as he had never seen him put away for the night, he was uncertain whether he should be tied there, or simply shut in. It hardly seemed to him that Toby would leave the monkey tied up by the neck all night, so he set him comfortably on a bench, and carefully shut the door.

Toby had been called to go to the druggist's for some medicine, and he came out of the house in such haste, calling to Joe to follow him, that nothing more was thought of the insecurely prisoned monkey.

When Toby returned it was so late that Uncle Daniel advised him to go to bed if he had any desire to be "healthy, wealthy, and wise," and he obeyed at once.

Positive that Abner was on the road to recovery, sure that all his work had been done, and with nothing to trouble him, it was not very long that Toby lay awake after he was once in bed.

It seemed to him that he had been sleeping a long while, when he was awakened by the sound as of some one hunting around in his room; and before he had time to call out, the candle was lighted, showing that the intruder was Uncle Daniel, only partially dressed, and in a high state of excitement.

"What is it? What's the matter?" asked Toby, in alarm, thinking at once of Abner, and fearing that something had happened to him.

"Hush!" said Uncle Daniel, warningly; "don't make a noise, for some one is trying to get into the hen-house, an' I am going to make an example of him. I suppose it's one of the tramps who went by here to-day, an' I want to find that gun I saw in here yesterday."

There was such a weapon in Toby's room, or at least what had once been a gun was there, for a hired man whom Uncle Daniel had employed left it there. It had been an army musket, and appeared to have been used as a collection of materials to repair other guns with, for the entire lock, ramrod, and at least four inches of the stock had been taken away, leaving it a mere wreck of a gun.

"It's up there in the corner behind the wash-stand," said Toby, coming out of the bed as quickly as if he had tumbled out, and alarmed at the thought of burglars. "It ain't no good, Uncle Dan'l, for there's only a little of it left."

"It will do as well for me as a better one," said Uncle Daniel, grimly. "I don't want to shoot anybody, only to give them a severe fright, and perhaps capture them."

"Then what'll you do with 'em?" asked Toby in a whisper, almost as much alarmed by Uncle Daniel's savage way of speaking as by the thought of the burglars.

"I don't know, Toby boy—I don't know. The tramps do trouble me greatly, an' I'd like to make an example of these; but I suppose they must be hungry, or else they wouldn't try to get into the hen-house. I guess if we catch one we'll give him a good breakfast, and try to persuade him to go to work like an honest man."

Uncle Daniel's anger usually had some such peaceful ending, as Toby knew; but he did look blood-thirsty as he stood there in his shirt sleeves, with one stocking on, and his night-cap covering one ear and but a small portion of his head, while he handled the invalid gun recklessly.

By the time he was ready to go in search of the supposed chicken thief, Aunt Olive, looking thoroughly frightened, came into the room with his other stocking and his boots in her hand, insisting that he should put them on before he ventured out.

It must have been a very tame burglar who would have continued at his work after the lights had warned him that the inmates of the house were aroused; but Toby did not think of that. He saw that Aunt Olive had armed herself with the fire-shovel, that Uncle Daniel kept a firm hold of the gun even while he was trying to put his boots on, and he was frightened by the warlike preparations.

Toby put on his trousers and shoes as quickly as possible, and when Uncle Daniel was ready to start, he stationed himself directly behind Aunt Olive—a position which he thought would afford him a fair view of what was going on, and at the same time be safe.

"Now be careful of that gun, Dan'l, an' don't go so far that they can hurt you, for there's no telling what they will do if they find out you mean to catch them;" and Aunt Olive looked quite as badly frightened as did Toby.

"There, there, Olive, don't be alarmed," said Uncle Daniel, soothingly. "They will probably run as soon as they see the gun, and that will end it. I only hope that I can catch one," and Uncle Daniel went down the stairs as determined and savage-looking a man as ever started in search of a supposed chicken thief.

Aunt Olive insisted on carrying the candle, though Uncle Daniel urged that it would not be possible for him to surprise the burglars if she held this light as a warning; but she had no idea of allowing him to go out where there was every probability that he would be in danger, unless she could see what was going on.

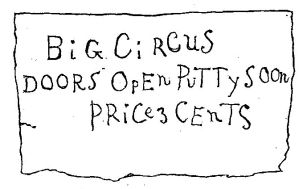

In the month of May, 1765, an advertisement appeared in London announcing that a concert would be given at Hickford's Rooms, Brewer Street, Golden Square, "for the benefit of Miss Mozart, aged thirteen, and Master Mozart, of eight years of age, prodigies of nature, a concert of music, with all the overtures[2] of this little boy's own composition."

Suppose one had been able to go to that concert in May, 1765. It would have been a charming sight. I am sure there was a great deal of jostling about of Sedan-chairs and footmen; and in the spring twilight—they gave concerts earlier then than now—the gorgeously dressed ladies and gentlemen must have looked very much like a picture. Let us follow them into the "rooms."

We find ourselves in a large well-lighted hall, with chairs and benches, and a big platform containing some instruments and a good harpsichord. Then out comes old Papa Mozart, a dignified gentleman from Salzburg, leading a child by each hand, one a charmingly pretty little girl in the quaint dress we are reviving to-day; the other, a boy of eight, of the most striking grace and beauty, and dressed like a little court gentleman, that is, with knee-breeches, silken hose, shoe-buckles, a little satin coat with lace ruffles, and a little sword at his side.

The little boy makes his bow to the enthusiastic audience; he sits down to the piano, and forthwith begins one of his own sweet, child-like, yet harmonious compositions. Then Nannerl plays. Presently the two young prodigies vanish, the fine audience move away, the lights are out, and the boy's London fame has begun. As we go through dingy Golden Square to-day, a hundred and fifteen years[Pg 580] later, we think of all the music he left for us to hear and feel and play between that night when he played "his own little compositions," and the day of his early death, in 1791, at the age of thirty-five years.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born at Salzburg in 1756. His father had possessed musical talent, but in him it was genius. At three years of age he learned to play; before he was five he had composed a great many little melodies, which his father wrote down for him. I remember seeing in the studio of an English artist in London,[3] himself the son of a great musician, a picture representing the baby Mozart, a charming little figure, leading a visionary choir of angels. It seemed to me the very embodiment of what Mozart must have been as a child—beautiful, fascinating, angelic, and a musician to his very soul.

His sister Anna, or "Nannerl," as she was called, also played marvellously, and when the children were very young their father started with them on a concert tour, during which they played in London. Everywhere they went they were fêted and caressed in a way which would have spoiled even Mozart's sweet, sunny nature, but for his father's watchful care.

Innumerable presents were made them, some of rich jewelry. This their father insisted upon keeping in a box, only allowing them to take it out on rare occasions and enjoy looking at it for a little while.

It was during that London visit that the father fell ill. They were in lodgings in Chelsea, which was then an open country with blooming gardens and green lanes. The little Mozarts had to keep very quiet during this illness of their father's. The harpsichord was closed, and the children took to running about the pretty suburban place, no doubt enjoying the rest from practicing. But it was during this enforced idleness that Mozart composed his first symphony (Opus 15). He was then in his tenth year. Think of the amount of scientific knowledge as well as the genius the boy must have possessed! Soon after, they gave more concerts, playing among other things duets for four hands on the harpsichord, which was then (in 1765) a great novelty.

During the latter part of the London visit a series of entertainments were given at home, where for two shillings and sixpence people could come and "test the youthful prodigies at the harpsichord." They were lodging in a quaint old inn down in the part of London known as Cornhill, and there they delighted hundreds of admiring and curious visitors.

Passing from this time of sunny though precocious childhood to a boyhood in which he worked indefatigably, we find Mozart in Italy, studying, composing, performing, and writing the most delightful letters home, chiefly to his dear Nannerl, who was by this time more devoted to domestic duties than music.

One of the most interesting experiences of the Mozarts took place in 1775. The Elector of Bavaria had invited Mozart to write an opera for the Carnival, and so when the work was completed—La Tinta Giardiniera—the father and son, with pretty Nannerl, set off for Munich, where court life was then very gay.

In the old market-place of Munich lived a very respectable widow, and Nannerl was lodged there, the father and son having to go nearer to the court. It must have been a delightful visit. Nannerl was all excitement about the opera, and her brother darted in and out half a dozen times a day to report progress. Finally the grand night came. The opera-house was crowded to excess; the court was there in full splendor, and Mozart, the youthful maestro, fine, in a new suit of lace and satin, sat by his father's side, with Nannerl, waiting not a little timidly, no doubt, for the performance to begin. The success was tremendous. The boy—for he was scarcely more in years—became the object of the wildest enthusiasm, and from that hour his musical fame was established.

But we must not feel that all Mozart's days were so cloudless and so joyful. Times of anxiety and heart-sickness were not wanting in his short and busy life. The little family circle was so centred in Mozart that when he started out on a second tour, and the father could not accompany him, the mother left her household duties to Nannerl and set forth with her son. An adoring fondness for his parents was one of the most lovely traits in Mozart's beautiful nature. On this trip he wrote home with pride how careful he was of his mother, and she, good woman, watched him tenderly, giving up everything to his pleasure and profit.

He spent the winter in Mannheim, where his letters show how very busily he was employed. He writes that he rose early, "dressed quickly," and after breakfast composed until twelve; then wrote until half past one, when he dined. At three he began to give lessons, which continued until supper-time; after which he read, unless he was among his friends. Of course he had a large circle wherever he was, but in Mannheim during this winter he formed friendships which shadowed all his life.

The Weber family were there—brilliant musicians, agreeable, and witty. There were five daughters, and Mozart straightway fell in love with the eldest, Aloysia—a beautiful girl, who was studying for the stage. She was well pleased with the young composer's attentions, and he went to Paris half, or, as he considered it, wholly engaged. That was a sad visit to Paris. His mother, wishing to economize for her son's sake, took rooms in a cold, poor quarter of the town, and there fell ill with a fatal disorder. Poor Mozart wrote home the most pathetic letters. We can fancy how he tried to save her, but it was in vain. The careful, tender, self-sacrificing mother faded from his life, her last thoughts being to commend this beloved son to God's keeping.

Full of sadness, the poor young fellow hastened to[Pg 581] Mannheim, where he hoped Aloysia Weber would console him. She had gone to Munich, and thither he followed her. There the true selfishness of the Weber family was shown to him. They had become prosperous, and Mozart, although famous, was far from being rich, so that the family of his betrothed received him coldly. Aloysia herself scarcely listened to the first words he said. He had entered the Weber parlor full of hope and anxiety to see his future wife and tell her the story of his sorrow. He must have looked noble and manly, with the tenderness of his grief in his handsome face, but Aloysia turned aside coldly—there were others there, to whom she talked. Mozart hesitated a moment, and then seating himself at the piano, sang in his rich clear voice: "Ich lasse das Mädchen das nicht will" (I leave the maiden who leaves me). And before the evening was over, the engagement was at an end.

We could wish that his intimacy with the Webers had also ended, but later he renewed acquaintance with them, and in spite of much opposition from his anxious father and Nannerl, he married Constanza, Aloysia's younger sister. With her he tried to be happy, but even in his tenderest letters we see that she was ill-tempered, cold, and selfish. But Mozart's nature was so uniformly sweet that it took a great deal to make him positively wretched, and unkind he could not be.

When he was in the midst of many worries, one summer, he used to ride out every morning for exercise, and leaving his wife sleeping, he never failed to pin a little note to her pillow, that she might find it on awaking. It was always a sweet word of love and care for her, and it is hard to think Constanza was not worthy of it.

There is so much to tell of Mozart, I wish that we might linger an hour more over his sweet story. His successes were so many that it is hard to think of him as so often in trouble about money.

In 1791 his beautiful opera of The Magic Flute was produced with tremendous success at Vienna. Constanza came on to hear it, and was thoroughly frightened by Mozart's altered looks. He was ashy pale, worn, and thin. She seems to have been full of a really tender feeling for him then. He was writing his famous mass, the "Requiem," and continued it even after he took to his bed, and while Constanza sat beside him watching with tears the feeble hand at work, he told her that his heart and soul were full of thoughts of the dear Lord who had died for him.

The Magic Flute was drawing crowded houses, while Mozart lay dying not far off. In the evenings he would time the performance, saying to Constanza and her sister Sophie, and some musical friends always with him, "Now they are singing this or that part."

The day before his death he read over the score of the Requiem, and asked the friends near him to try and sing it with him. They did so, Mozart coming in with his part in a sweet faint voice. Suddenly, at the Lacrimosa, he burst into tears, and laid down the score for the last time. That evening he murmured to Constanza, "Oh, that I could once more hear my Magic Flute!"

Constanza glanced at Roser, a musician who was with them, and, blinded by his tears, Roser sat down to the piano, and sang one of Mozart's favorite airs. It was almost the last sound his closing ears received. The next morning, Sunday, December 5, 1791, at the age of thirty-five, Mozart died.[4]

He left behind him so many works that I hardly know which to speak of first. His operas, Don Giovanni, Figaro, and The Magic Flute are known and prized all the world over; but besides there are the masses, the sonatas, the symphonies, and the quartettes. In the sonatas especially the young pianist may find the greatest advantage. As reading they are admirable, and for practice with four hands I know of nothing better, unless it be some of Haydn's quartettes.

STRATEGY.

STRATEGY.

Jack and I made up our minds to catch a woodchuck. We were spending the summer down on the east end of Long Island, and judging from the number of cauliflowers eaten by them, the woodchucks were abundant; so we determined to catch one.

Farmer Brown, to whom we applied for advice, told us to "grab him by the tail as he went into his hole." This sounded so easy that we decided to try it at once. We found, however, after two or three days of patient waiting, that the woodchuck absolutely refused to go into his hole while we were within grabbing distance.

We then set steel-traps in the burrows, but with no effect. We wandered around the fields armed with an old musket, and succeeded only in wasting a large quantity of powder and lead. We tried to drown one out, and after blistering our hands by carrying pails of water, were told that "a woodchuck hasn't lived in that burrer for two years." We were disappointed, but not discouraged.

"Let's set the rabbit trap," said Jack one morning as we were planning for the day's campaign.

So we carried the rabbit trap, which was a great box with a swinging door, up to the hedge back of the barn, and set it. Farmer Brown laughed at us, and said,

"Ef you see a 'chuck, put for the nearest hole; ef you git thar before him you can stop him from goin' in."

This plan seemed so much more exciting than any other, that we spent that afternoon and the next day looking for a stray woodchuck. Toward evening our patience was rewarded by the sight of a woodchuck in the middle of a field. Jack and I had by that time learned the location of the holes as well as the owners themselves, and we both started for a burrow in the hedge.

The woodchuck saw us, and made for the same burrow. He hadn't so far to go, and was evidently in a great hurry. Jack managed to arrive just in time to throw his hat in the mouth of the hole, thinking to bar the progress of the woodchuck. Vain hope! On came the woodchuck, and dived into the burrow, carrying Jack's hat with him. I just reached the spot in time to see the brown stump of a tail vanish, and hear Jack exclaim,

"I wonder what he is going to do with my hat?"

The loss of Jack's hat cast a damper upon our hunting for the afternoon, and it was not until after supper that we thought of the rabbit trap. When we reached it, it was sprung, and there was a sound of scratching inside that showed plainly something was trying to escape. We carried the trap carefully down to the barn, and opened it, so as to let our prize into a large barrel.

Our happiness was complete: it was a large woodchuck. What had tempted him to go into the trap I am sure I can't tell. Probably he was a victim of his own curiosity. At any rate, we had him safe and sound in the barrel, and after we had covered it with a board we went to our beds very much elated over our success.

The next morning we rose early, and went to the barn to see our prize. There he was in the barrel, his little eyes gleaming with rage, and signifying his disapproval of our proceedings by a series of short, sharp barks. Suddenly a brilliant idea struck me.

"Let's shut the doors; then let him out on the floor, and have some fun with him," I said.

Jack agreed, and we soon had every door and window but one securely fastened. This window was, fortunately for me, overlooked in our haste to have our fun.

We turned the barrel over, and out sprang a very angry woodchuck. He started directly for Jack, and that youth, with an agility which I had never given him credit for, scrambled into the oats bin. The animal then turned his undivided attention to me, and I dashed around the barn, the woodchuck in pursuit.

Every nail in the barn seemed to stand out and take a hold upon some portion of my clothing, and it was rapidly being reduced to fragments. Jack jumped out of the bin to assist me, but only succeeded in making the confusion worse. With a jump, the woodchuck fastened his teeth on Jack's arm. Luckily he only bit through the sleeve of his loose blue flannel shirt. Thoroughly frightened, Jack grasped a rope which hung from one of the rafters, and swung himself out of reach.

At that moment I spied the open window, and in a second more I was out. Jack was hanging on the rope with a tenacious grip, and the woodchuck was trotting around trying to find an avenue of escape. I ran to the door and threw it open. A dark form whizzed past me, and Jack dropped from the rope. We had had enough woodchuck for one summer.

"What on airth hev you boys been a-doin'?" inquired Farmer Brown as we entered the house.

"Been having some fun with a woodchuck," replied Jack, a little sheepishly.

Farmer Brown laughed, and remarked, as he took a second look at our torn clothes and flushed faces,

"Wa'al, I don' know, but it kinder looks as ef the woodchuck had been a-hevin' fun with you."

And when I think the matter over, I am rather inclined to be of the same opinion.

A little wandering sunbeam

Came sliding down the sky;

To seek another home below,

It left its home on high.

On baby Mary's head it lit—

Our gentle little one;

Her eyes grew blue as heaven's hue,

Her ringlets like the sun.

Its home it made with her; and since,

Though quiet as a mouse,

Her smile is like the day: she is

Our sunbeam in the house.

"Not a fire-cracker," Mr. Marden had said, looking around on his half-dozen boys—"not a single fire-cracker, nor pin-wheel, nor rocket this year, boys. You come pritty nigh burnin' up the hull town last Fourth, an' I don't want to run no more sech risks. Enj'y yourselves as well's you can other ways 'n that. Now mind!"

That was how and why—because of this interdiction of everything that goes to make a Fourth of July different from a fourth of August or any other day—the boys happened to think of going up the river fishing.

They were down on the river-bank, lying at full length on the green grass, when Jed Harden said, meditatively, tossing a pebble into the water, "There'll be no fun staying here, boys, 'thout we can fire off things."

Bud Rose laughed. He could never be serious. "It's because we fired off Jennings's barn last Fourth that everybody's so down on our celebrating this year," said he. "I wonder how the old thing got afire, anyhow?"

"Easy enough," rejoined Jed; "there was a heap of straw all round it, and I don't s'pose we were over 'n' above careful. The old shanty wasn't worth ten cents, but it came near burning up everybody else's buildings."

"So it did. After all, I don't blame folks much. There ain't such a sight of fun in snapping crackers, anyhow."

"But what shall we do?"

Charley Stevens looked up then. All this time he had not spoken, but lay gazing out on the river. "I move[Pg 583] we go fishing up on Beaver Brook," said he. "Start before daylight, and stay till after dark."

"Second the motion. Hooray!"

All was animation now. The boys sat bolt-upright. Charley laughed. "Moved and seconded that we, the stirring youth of Brayton, celebrate to-morrow by going fishing. All who favor this will please say—"

"Ay!"

"The motion is unanimously carried," said Charley, shaking back his hair.

I think it was myself. So would you if you could have heard that roaring assent. There was no half-way work with the Brayton boys. They were all on hand the next morning, with their lunch baskets, not exactly before daylight, but sufficiently early; and they could not resist the temptation to give several prolonged whoops as they shoved the old scow out from shore.

"That'll let 'em know we're 'round," laughed Charley Stevens. "There, boys, back up. I've left my pails."

"What pails?"

"Why," said Charley, "I promised to save some of the smallest fish, if they weren't hooked too much, for Laurie's aquarium, and I brought along a couple of pails to keep 'em alive in. There they are on the bank. Backwater."

"Nonsense!"

But Charley was firm; and Jed and Bud and Vet, who were taking the first turn at the paddles, pulled a rod or two back to the shore, not without a little grumbling, and brought away the pails. Afterward they all had very good reason to remember and be thankful for this. Then they pulled steadily away up the river, through the light fog which the rays of the morning sun had not yet scattered, trolling their lines, and catching a few fish by the way.

"I would have brought a frying-pan," said Dean Marden, pulling in a speckled trout, "but father said 'twouldn't do to make a fire this weather. Everything's dry as tinder."

"And Beaver Brook isn't more'n two miles from the village, through the woods," said Charley, meditatively. "Wind blows right that way, too."

"It's four miles by the river, if it's an inch," said Vet Adams; for the river certainly made a wide detour.

"It's crooked as a ram's horn," declared Jeff Gammon, wiping the perspiration from his face. "A fellow has to pull all the way round Robin Hood's barn to get anywhere."

Charley laughed. "We're almost to the mouth of the brook now," said he. "There's the old pine."

And in a few minutes the scow, propelled by three pairs of stout arms, swept grandly around the point of land and into Beaver Brook, on one side, just as a light birch-bark canoe, holding two men, shot out on the other side.

"Indians!" exclaimed Charley, in a tone of great disgust. "There's a camp of 'em down the river somewhere. We won't get any fish here, boys."

Charley was right. They fished for half an hour, waiting patiently for a nibble, which they did not get.

"We'll have to go further up the brook," said Charley; and accordingly the old scow was once more set in motion.

How pleasant it was! They ran along in the shade of the willows that skirted the brook, their paddles dipping lazily, and their fishing-lines trailing in the deep still water. It was very warm in the sun, but there was a smart breeze blowing, and a prospect of showers later on.

Suddenly Charley felt a jerk on his line that, taking him unawares, nearly pulled him off his seat.

"Gracious! boys, hold on," he said, in an excited whisper. "I've got a ten-pounder."

It was not half of that, nor had Charley got his fish; but the paddles were quickly and quietly shipped. Charley pulled in a nice trout, and Bud Rose another.

"Ain't they beauties!"

"We're right in a school of 'em," said Bud, rebaiting his hook. "I say, fellows, ain't this a long chalk better'n fire-works?"

For no matter how many times a country boy may have been a-fishing, nor how many fish he may have caught, the sport must always be exciting.

An exclamation of alarm from one of their number, as Bud finished speaking, startled the boys; and they were a good deal more startled, and not a little provoked, to see Charley catch up one of the heavy paddles and plunge it into the water with a long sweeping stroke, the impetus of which sent the scow forward a dozen feet.

"Now look here!"

"Boys," cried Charley, flushed and anxious in a minute, "we may have the fire-works yet. See there!"

Around a bend in the stream a thin blue line of smoke was seen curling up through the trees, and even as the boys gazed, it appeared to increase in volume and density.

"The Indians must have left it!" exclaimed Charley, hurriedly. "Boys—"

There was no need nor time for words. Instantly the two remaining paddles were seized, and the scow was headed up and around the bend. It came to them all in a flash how strong the wind was blowing from the west; that the woods of Dunn Township, altogether proprietors' land, adjoined Brayton, extending to the top of the hill that overlooked the village; and each boy's heart turned pale at the prospect.

"It's all black growth, too," groaned Charley, "and full of old dry tops, where they've been lumbering year after year—just a regular tinder-box. This wind'll carry fire from it a mile anyway. Pull, boys, pull!"

And they pulled. But the fire was getting under good headway when they reached the spot. The smoke was rolling up blacker and thicker, and through it the boys could see the red flickering tongues of flame.

"Take the pails—your hats—anything that'll hold water," cried Charley, "and wet your jackets—wet yourselves all over."

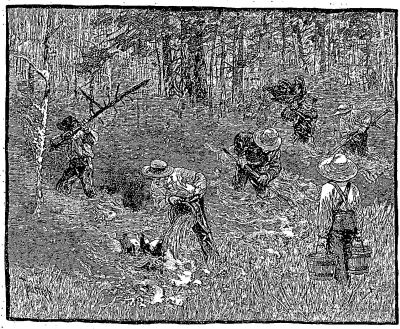

"PAILFUL AFTER PAILFUL OF WATER WAS DASHED UPON THE FIRE."

"PAILFUL AFTER PAILFUL OF WATER WAS DASHED UPON THE FIRE."

He was obeyed. Pailful after pailful of water was dashed upon the fire, which had been built beside an old dry pine stub; and they were really subduing it, when a sudden tempestuous flurry of wind scattered the burning embers in all directions; and presently, before the boys were able fairly to realize that the mischief had been done, a dozen tiny puffs of smoke started up around. In reality everything was dry as tinder.

"We've got to fight it—fight it hard, boys," said Charley, between his gritted teeth. "I'd like to wring the necks of those Indians."

Well, and how they battled the fire that scorching July day! They stamped it out; they smothered it with earth; they dashed water over it; they stifled it with their wet jackets, blistering faces, hands, and feet without for a moment minding the pain. More than once they were sure they had conquered, and made the woods ring with a shout of triumph, only to see, almost before the echoes died away, another puff of smoke starting up, and another. Their throats were parched, and rattled when they tried to speak, and their eyes were smarting and inflamed with the smoke.

"It's no use, boys; we can't do it," one or another would say; and then they would fall to work with greater vigor than before, if that were possible.

It was no boys' play, I can tell you. For two long hours they fought the flames, with blistering hands and faces begrimed with smoke and cinders. And when they saw the fire was gaining inch by inch, they worked still.

"We'll do all we can," panted Charley. "Oh, boys, why won't it rain! The thunder-clouds all go round. Oh, boys!"

As he spoke, a long fiery tongue lapped at the foot of a[Pg 584] dry tree, and the flames went up, up, to the top, with a hissing, rushing roar which turned the boys' hearts sick with dread.

"It's gone," said Charley. "We can't do any more."

But at the same moment came a growl of distant thunder. A dense, black cloud was growing in the west. Through it there darted a vivid gleam of light.

"Thunder and lightning!" yelled Bud. "Up, boys, and at it again! We'll have plenty of help before long."

So it proved. The cloud swept over the sky with surprising rapidity, and in a very short time the rain fell in sheets. And out in the storm, the thunder crashing, and the lightning playing about them, stood ten smoke-blackened, drenched boys, with little rivers of rain wearing channels down their sooty faces, hurrahing with might and main. If a few tears of thankfulness and relief mingled with the rivers of rain, I do not think any boy need have been at all ashamed of them.

"Well," said Charley, "we've had our Fourth-of-July fire-works with a vengeance." This was when the rain had nearly ceased falling, and the boys had embarked for home.

"We've had the fire anyhow," laughed Bud, plying his paddle leisurely.

"And I'm sure we've had the work."

"You don't suppose 'twill start up again?", asked Jed Marden, looking behind a little anxiously, as the old scow moved slowly down the stream.

"No," answered Charley, and he drew a deep breath of relief; "it can't after such a soaking. But 'twas a close shave, I tell you, boys."

So the towns-people thought when they heard the story.

"'Twas a fust-rate day's work for us," said Mr. Marden at the corner grocery next morning. "Nothin' on earth would ha' saved the place ef the fire'd come through there. It's somethin' to brag about. I'm proud o' the boys—I am so."

"They've paid up for burning Jennings's old barn," said Mr. Stevens, carefully weighing out four ounces of tea.

"So they hev," assented Mr. Marden.

And so the good folks of Brayton have each and every one of them resolved that next year the boys shall have such a Fourth-of-July celebration as Brayton has never yet seen.

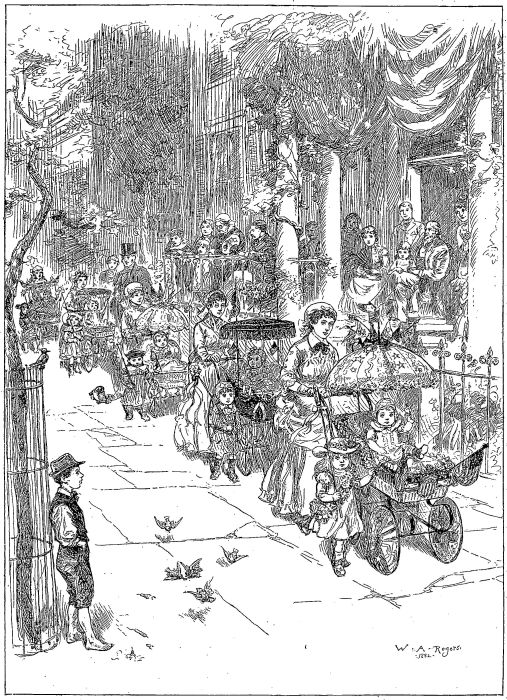

The gay parade of little folk shown in our picture takes place every Fourth of July at Dayton, Ohio—a pretty town on the banks of the Miami River.

It originated, we believe, in the brain of a patriotic little nurse-maid, who, with two or three companions; on a Fourth of July some years ago, trimmed their carriages with flags and streamers, and gayly tripped around the block in Indian file. The babies were delighted, and the nurse-maids flattered at the attention they received on every hand, and not one little boy on the entire route so far forgot himself as to fire a cracker under the babies' carriages or throw a torpedo at their protectors.

Every year, with one exception, the little procession has wended its way along the sidewalk, with constantly increasing numbers, the pioneer babies taking the lead.

But on a hot summer day one year, when the little carriages were almost ready, and busy hands were putting on their holiday attire, one of the three children fell ill and passed away. Its empty carriage told so mournful a story that the other nurses sadly put by the flags and trimmings, and the flowers and wreaths drooped and withered.

The next year, when the flowers were blooming over the silent little pioneer, all the baby carriages in town were put in commission at least a week before the Fourth. Every scrap of nickel plate was burnished to the highest degree of polish, and lingering roses on the later bushes were carefully guarded to preserve them to grace the occasion.

In the cool of the evening, when the small boys were about tired of exploding mines, disfiguring their faces, and making that awful din incident to the day, and were beginning to count up their sky-rockets, pin-wheels, and red lights, the gay procession moved down the broad flagged walk.

At the head was the pretty nurse who had originated the affair, pushing before her a wicker carriage trimmed with roses, and gay with flags and emblems and gilded stars, from the wheels to the lace-trimmed canopy. Nestling in its gorgeous carriage was a somewhat bewildered but very happy baby. A tiny boy, as guard of honor, accompanied each little carriage, carrying in his hand a wand to charm away stray fire-crackers from their path.

Porticoes and balconies were crowded with the babies' friends as the procession passed by and faded into a pretty recollection of silvery laughter, waving flags, crowing babies, and happy nurse-maids and children.

THE BABIES' FOURTH-OF-JULY PROCESSION.

THE BABIES' FOURTH-OF-JULY PROCESSION.

Little John worked in a barrel factory in the thriving town of E——, in Pennsylvania.

Piling staves or rolling barrels all day long is not very enjoyable work, but Johnnie did not grumble: no, indeed, he was too happy to get even the hardest and dullest work to do. He wanted to go to school, and his aunt had said if he could save money enough to buy books and clothes, he might go. He was delighted with this permission, and clattered down-stairs, three steps at a time, to hunt up Pat, his friend and confidant, who would double his happiness by sharing it.

Pat was a newsboy on the railroad, a cheery, good-natured Irish lad, whose mother had died years ago, when he was but a blue-eyed baby. The new mother that came into the little whitewashed cabin by the railroad was too busy with her pigs, her garden, and her own little ones to pay much attention to Pat at first; though by-and-by she thought there was no room for him in the little home. Poor Pat! he had a hard time finding any place where there was room for him. At last Johnnie persuaded his aunt to let the forsaken Irish boy share his bed. They had been firm friends, sharing their boyish griefs and joys with the complete sympathy of childhood; they were brothers in heart, if not in name.

Johnnie and Pat were industrious, contented, and happy. During the day they worked on the cars and in the factory, but in the evening the kind aunt taught them the common-school studies. Both boys eagerly longed for the time when they could enjoy fuller advantages for education.

Pat saw his way but dimly, but Johnnie's happiness seemed near at hand. It was a touching sight to see the two boys once or twice a week bring out their store of savings. No miser ever thrilled at the sight and touch of heaps of gold as those two boys at their paltry handful of silver and copper.

It was about a month before school began, and yet Johnnie had not saved quite the desired amount.

One evening he came rushing home waving his hat and dinner pail to his aunt, who stood in the doorway.

"Oh, auntie, I have enough now," he shouted joyfully.

Her motion for silence and the look on her face lowered his glad voice.

"What is the matter? Are you ill? Has anything happened to Pat?" he hurriedly asked.

"Come in and sit down, and I will tell you," she replied.

A strange sickening odor of some drug filled the house; there was an unusual stir in the front room. Johnnie's heart sank within him. He listened with terror-stricken face to the terrible news. An accident on the road; Pat was hurt; they were amputating his arm; they feared he would die.

His face grew whiter and whiter as each detail of the horror grew upon his mind. He buried his face in his hands, and sat motionless a long, long time.

After a time he went softly into the house, into the room where Pat lay still unconscious.

"Pat, dear Pat," he sobbed, laying his wet face against the one colorless hand.

Here he remained until he heard the doctor's step in the hall, when he withdrew to the shadow of the curtain, dreading yet longing to hear his words. How his heart leaped with joy to know that Pat might live, though a cripple. His dear, dashing, frolicksome Pat a cripple!

All night long Johnnie sat with his eyes on the pallid young face. He was trying to think out some plan for helping him. A firm, happy look dawned on his grave, thoughtful face. He seemed to have solved a part of his hard problem.

Toward morning Pat opened his eyes and looked around in a dazed sort of way. He tried to rise, but was too weak. Slowly he recalled the accident, the pain, and the darkness. What came then? Looking around in a helpless, wistful manner, he saw Johnnie's big eyes shining on him through falling tears. He moved his left hand around to find the right one. Alas! it was gone. Turning his face to the wall, the hot tears slipped quickly down from his closed eyes.

It was a long day for the boys, Johnnie at his toilsome labor in the factory, and Pat at home thinking, thinking, thinking, trying to find some gleam of brightness, some way of self-help in the future.

Going home that night Johnnie bought an orange and a picture for his friend. He endeavored to be more than usually cheerful in his manner that evening. Pat was trying too, but it was such a faint smile that he gave that Johnnie had hard work to keep back the tears.

"But I did," he triumphantly said to his aunt. "I never mean to make Pat feel badly any more if I can help it. Oh, auntie"—this very eagerly—"may I let Pat take my money and go to school? I can wait a little longer, and Pat will help me in the evenings."

His aunt touched his sunshiny head tenderly. "You know best, my dear boy. It is your money. Use it to satisfy your own heart."

It was some time before Pat was well again, but after the first few days' struggle he never murmured. He seemed to accept and make the best of his circumstances. Every evening Johnnie remembered to bring him some token of his love—a banana, a paper, a bunch of gay flowers, or a box of bonbons; for his money was now all for Pat—his dear helpless Pat.

At last the eventful day arrived when Pat was to be up and dressed. Johnnie started home with more than usual speed, eager to see and congratulate him.

He had frequently noticed boys playing near and on a small tank used for mixing paint. They used to stir this, and inhale the fumes, which gave them a kind of half-dizzy but pleasant kind of feeling. It was rather a dangerous play, and Johnnie usually coaxed the boys away, and endeavored to persuade them not to return. As he was passing the tank this evening he saw two little boys leaning over it, and just at that moment one of them fell face downward into the tank; the other little boy sank down upon the steps, too much stupefied to render any assistance. Dropping his pail, Johnnie sprang up the steps, and into the tank. There was only a small quantity of liquid in it, but quite enough to cover the unconscious boy. Johnnie lifted him up, and called loudly for help. It soon came, for there were others who had seen the boy fall, though too far away to render the assistance that Johnnie did. For some time it was feared that the little victim would not revive.

After a while, however, they had the satisfaction of seeing him open his eyes. Johnnie wanted to go home now; he knew that his aunt and Pat were anxiously awaiting him. He was deliberating what to do, when a carriage drove up, and a lady and gentleman hurriedly alighting, came up to the still half-unconscious child. Johnnie heard one child cry, "Mamma!" and saw the look of glad recognition light up the face of the other, and then he was off with all speed for home. As he approached the house he saw his aunt, and—yes, it was, it was—Pat standing in the doorway, looking anxiously toward the factory. He waved his hat, and hastened forward yet faster, stopping at the gate quite out of breath from excitement, but looking so happy and smiling that their fears were calmed at once.

"Oh, I am so glad to see you, Pat! Don't touch me, auntie dear; I am all over paint and benzine. Just wait until I change my clothes and I will tell you all about it," he said, as he disappeared upstairs.

But the great surprise and pleasure came the next day. Johnnie had gone to work as usual, and was not expected home until evening. About noon, however, he entered the kitchen where his aunt was working.

"Come, aunt, into the room where Pat is. I have something nice to tell you."

But when there he could say nothing. He just put in her hand a crisp check for two hundred dollars.

"Oh. Johnnie! now you can go to school too," shouted the delighted Pat.

"What does it mean, dear?" asked his aunt, gazing in wonder at the check, at Johnnie, and then at the check again.

"The manager gave it to me this morning. It was his little boy who fell into the tank yesterday. He had heard about my wanting to go to school, and about Pat, so he gave me this. Oh, dear auntie! do you suppose anybody was ever so happy as I am? Here is the manager's carriage too. I am to have a half-holiday, and take you both out riding. Come, we will have some dinner, and then go down the deep hollow road."

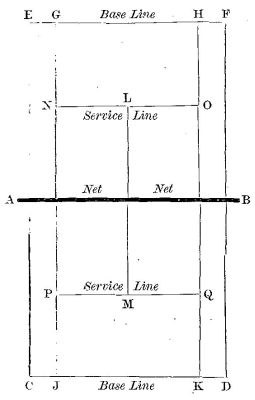

In an article on lawn tennis published in Young People last summer we pointed out how the game might be indulged in with a very small outlay of money—how some of the implements, indeed, might be of home manufacture and yet be serviceable. Accordingly we were obliged to limit the court to a size which the net supplied with cheap tennis sets would admit. As the game has now become so popular that it is likely to be, if it is not already, the game of games, we will take our readers a little further, and show them how to lay out a full-sized court both for single and double games.

As the double court measures 78 feet by 36, the lawn should be not less than 100 feet by 50, and the court should be laid out as in the accompanying diagram.

First, stake out the base line, E to F, 36 feet, with your string. Then carry it along the line F to D, 78 feet, and in the same manner make the line E to C, 78 feet. Then connect C, D, and if your figure is a parallelogram, this last line should be the same length as E to F, namely, 36 feet.

The whole area of the two courts is now marked out. Next for the divisions.

The single courts are of the same length as the double, but only 27 feet wide, that is 9 feet less than the double. Mark out, therefore, the positions of G and H, which will be 4½ feet from E and F respectively; and in the same manner, and at the same distances from the side lines, mark the positions of J and K. Then extend your string from G to J, and from H to K.

Now for the net, which is shown by the broad line A to B, extended three feet on each side of the boundary of the court. From the net line measure 21 feet to N, O, P, Q respectively, and join N and O, P and Q. These last lines are 27 feet long: divide them in half, so that the distance from N to L, for instance, is 13½ feet, and mark the line L to M.

You will think, and rightly, that if you are to stake all these lines at the same time with string, you will require several hundred feet of string; but this is not necessary. Cut sixteen stakes about six inches long, sharpened at one end and broad at the other, so that they can be easily driven into the ground and yet not easily be trodden out of sight. As you measure off each point you will drive a stake to mark it; thus you will need as many stakes as there are letters in the diagram.

As the court on the one side of the net is exactly similar to that on the other, if you grow tired of measuring and driving stakes, you may mark the lines of the one court before completing the laying out of the other. This you must do with "whitening" and a brush not less than two inches wide. Each line that is to be marked must be shown by a string stretched over it as a guide: otherwise the lines will be far from straight. As each line is finished, the string is taken up and used to guide the marking of the next line. Care should be taken to mark all the lines equally distinct, and to renew them as they get worn out.

Here is a handy table of distances from point to point in the diagram.

| Double court | { Base line E to F = 36 feet. |

| { Side line F to D = 78 feet. | |

| { Side line E to C = 78 feet. | |

| { Base line C to D = 36 feet. | |

| Single court | { Base line G to H = 27 feet. |

| { Base line J to K = 27 feet. | |

| { Side line G to J = 78 feet. | |

| { Side line H to K = 78 feet. | |

| Service court | { Net to service lines = 21 feet. |

| { Central line, L to M = 42 feet. | |

| Between net posts | A to B = 42 feet. |

Among all the races and religions of India there are none more curious than the Parsees. They are sometimes called Fire-Worshippers, on account of their reverence for the sun, and consequently of the fire that comes from it. The founder of their religion was Zoroaster, who was supposed to have brought fire from heaven, and placed it on their altars, and to this day it is kept burning in their temples.

The Parsees belonged originally in Persia, and were persecuted by the Saracens more than a thousand years ago, so that many of them embraced the Mohammedan religion. The few that clung to the worship of the sun were driven into the most barren parts of the country, or compelled to leave it altogether. Many settled in the province of Guzerat in Hindostan, bringing the sacred fire with them. They were again persecuted by the Mohammedans, but for the last two hundred years have enjoyed religious freedom.

It is thought that there are about two hundred thousand of them now in India. In Bombay alone there are seventy thousand Parsees, and the rest are principally in Guzerat and along the western coast. They are intelligent and enterprising, pay great attention to the education of their children, give liberally to all public charities, and their merchants are considered the shrewdest business men in the world. More than three-fourths of the business of Bombay is in their control, and for this reason the place is often called "the City of the Parsees."

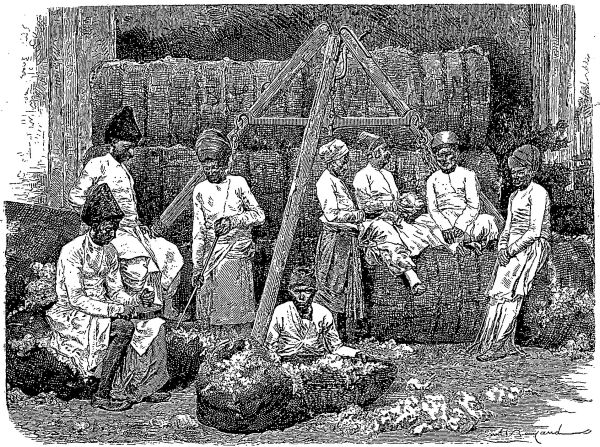

PARSEE MERCHANTS BARGAINING FOR COTTON.

PARSEE MERCHANTS BARGAINING FOR COTTON.

The cotton market of Bombay is an excellent place in which to study these strange people, and in the height of the season it is often crowded with them. They go among the bales and bags of cotton examining the fibre, and talking busily with each other in their efforts to buy or sell. When making a bargain they are rarely in a hurry, and it is not an unusual sight to see a couple of them seated on[Pg 588] a bale of cotton, each with a sample in his hands, arguing with great earnestness over a difference of a few cents on a transaction amounting to thousands of dollars. From the closeness of their bargains they are sometimes called "the Jews of the East." It has been said that the Israelites of Europe can not compete successfully with the Parsees in matters of trade.

These people adhere to the dress of their ancestors. Their ordinary costume consists of a white frock falling below the knee, over trousers of the same material, and for head-coverings they wear a curiously shaped hat of spotted muslin, without a brim. Their priests wear a hat of the same shape, but of pure white, the rest of their dress being similar to that of the ordinary Parsee. They take care of their poor so thoroughly that a Parsee beggar is never seen. The men rarely accompany their wives in public, and very few Europeans have ever seen the inside of a Parsee house, so as to learn the domestic life of the family. Parsee boys and girls are frequently very handsome, but their beauty fades while they are yet young. Their parents are very fond of them, and a father will often deny himself many things in order to spend freely on the education or amusement of his children.

Notwithstanding their habit of driving close bargains, the Parsee merchants have a high reputation for honesty. They may be a long time closing a transaction, but when the word has been given, they adhere closely to their agreements. The wealthiest men of Bombay are among the Parsees, and they are as noted for their charities as for their great fortunes. One of these merchants, who had gained an enormous fortune in trade with China, devoted the closing years of his life to works of charity. He connected the island of Bombay with the mainland by a causeway at his own expense, he built and endowed two hospitals, and he gave a large amount of money for the relief of British soldiers during the Crimean war. The Queen conferred on him the honor of knighthood, and afterward made him a baronet. Since his death his son has inherited not only the title but the charities of his father.

The Parsees do not bury or burn their dead like the Hindoos and Mohammedans around them, but expose the bodies to be eaten by birds. One of their most prominent merchants explained this custom as follows:

"We consider fire sacred, and would not use it for burning the dead, as the Hindoos do, or for any other ignoble office. The earth is the mother of mankind, and the producer of the fruits and other things on which we live, and the burial of the dead would be a defilement and an injury. Cemeteries are everywhere considered unhealthy, and our mode of sepulture is open to none of the objections that are made to cremation or burial."

The Parsees are not by any means confined to Bombay and its vicinity; there are several Parsee houses in Calcutta, Madras, and other cities of India, and they can also be found in Hong-Kong, Shanghai, Yokohama, and other cities of Asia. Some of the Bombay houses have branches in London, and a few in New York and San Francisco, and year by year their business is spreading throughout the world. Twelve hundred years ago they numbered but a few thousand refugees; now they have become an influential people, respecting the religions of others, but clinging tenaciously to their own. The sacred fire burns in their temples, as it has burned for centuries, and from present indications it will continue to glow for many centuries to come.

A naughty little city boy was taken to a farm,

To spend the summer holidays, away from heat and harm;

Where he could roll upon the grass, or chase the little chicks,

Or tease the piggies in the pen by poking them with sticks.

To pull the peacock's feathers out to him was lots of fun;

The geese stretched out their necks and hissed, and made him turn and run;

He didn't dare to plague the dog, for fear that he would bite;

But he was in all sorts of scrapes from morning until night.

One day he climbed a cherry-tree that in the garden grew,

Because it was the very thing he'd been told not to do;

The cherries they were red and ripe, and tasted very sweet—

That naughty boy he swallowed them as fast as he could eat.

But when he'd eaten all he could, and scrambled down again,

He sat upon the ground, and soon began to scream with pain;

And when at last the doctor came he very grimly said,

"Give him a dose of castor-oil, and put him right to bed."

"It isn't nice," said his mamma, "to lie in bed all day;

I hope 'twill be a lesson, Tom, and teach you to obey."

Tom promised solemnly no more that cherry-tree to climb;

And his mamma was very sure he meant it—at the time.

So many lads have written to Our Post-office Box asking for advice and information as to how to build a cheap canoe, that Messrs. Harper & Brothers have just reprinted in a circular the article on this subject which appeared in Harper's Young People April 27, 1880. Messrs. Harper & Brothers will mail the circular and working plans to any address on receipt of a three-cent postage stamp.

Warm Weather.—Why, of course, dears. But we need the sunshine to ripen the corn, and make the apples round and red, and paint the yellow pears, and kiss the green grapes until they grow large and purple. Let me tell you a secret. It isn't worth while to fan, and fan, and keep saying "Oh, dear! I wish a breeze would come! When will this heat be over?" Neither is it a good plan to drink a great deal of ice-water. The more you drink, the more you will want. Try to forget the heat, and get some pleasant thing to do, sitting in the coolest place you can find. Paint a picture, draw some Wiggles, make a puzzle for Harper's Young People, or write a letter to Our Post-office Box; help auntie dust the parlor, gather flowers to fill the vases, read an interesting book, arrange your specimens or stamps, or tell a story to please your little sister. If you do something that you like to do, or that will make others happy, the warm day will be gone before you know it.

Fort Bayard, New Mexico.

I am a little boy eight years old. I have taken Young People for over a year. I like New Mexico very much. I have a little burro (that is Mexican for donkey) that I ride or drive. My father has three deer-hounds and one stag-hound. One of the deer-hounds is mine; I call him Thor. The names of the rest of the hounds are Hilda, Maida, and Jarl; Jarl is the stag-hound. Day before yesterday Hilda was hooked by a cow, Thor had a cut in his foot, and Jarl had a sliver in his leg two inches long. When Jarl was a puppy, he had a bad fall from a railroad trestle. Papa was going to shoot him, but one of the soldiers said, "Don't shoot, sir; he is all right." We have a pointer called Roy. I have been to the Santa Rita copper mines, and have seen the stamps that they crush the ore with. I take German lessons from the librarian of the Twenty-third Infantry. My mother has twelve hens—two sitting, and two with little chickens. I have nothing more to tell about now, but I will write again. I liked "Toby Tyler" and "Tim and Tip," and I like "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" very much; and oh, I liked "Scrap" so much! and "The Boys' Tea Party" was splendid. I would like to send my love to the Postmistress.

W. Swift M.

The Postmistress sends you hers in return.

Glassborough.

I have begun to make a collection of curiosities, and have three butterflies, one moth, a hornets' nest, and two birds' nests; in them are three eggs. My only pet is a kitten named Bunthorne, but I am lamenting the loss of a horned toad from Mexico. It refused to eat, and after three months of captivity it quietly died. They are called by the Mexicans el taurusita del Vergita, meaning the little bull of the little Virgin.

P.S.—Will you tell me the difference between a maiden and a spinster?

H. S. W.

What a pity about the poor toad! Perhaps he pined for home.

Any unmarried woman is a maiden. A spinster is a person who spins. In olden times the young ladies of the family used to spin and weave the household linen, and so they were called spinsters. Really a maiden and a spinster are the same.

Gallipolis, Ohio.

I am a little girl twelve years old. I have been taking Harper's Young People two years, and like it very much. I have been afflicted for years, and have to walk on crutches. I have two sisters, who are away at school; a week more and they will be at home, and I will be happy. I have a canary-bird; his name is Pedro. The bottom of his cage dropped out, and he flew away, and was gone a day and night; a boy caught him, and brought him back to me. I have a tortoise-shell cat and kitten. The old cat is named Spot, and the kitten Hot. I will exchange twelve foreign and United States stamps for the same number of gilt cards or glass buttons. I have a button string of over a thousand glass buttons; I have also six hundred cards.

Mary V. Cox.

Although you have to walk on crutches, you have happy times, I am sure, for a contented heart triumphs over all difficulties.

Sherburne Four Corners, New York.

I am a girl twelve years old, and am not very large for my age. I have five sisters and one brother. Two of my sisters are married, and each has a little boy. The oldest boy is four years old, and the youngest is not two weeks old yet. My birthday was last May, on Decoration-day. I am collecting cards, and now have 370. We have four horses and two colts; and I have a very nice cat.

Fannie A. H.

A very little girl with a very big hat,

And a dear little boy with a pail,

They were going to the beach to play in the sand,

And then off with papa for a sail.

Little Confectioners.—Several little girls have asked me to give them some receipts for making chocolate caramels and other candies. I hope they will remember that in candy-making, as in other cooking, it is necessary to be very exact in measuring the different ingredients; neither sugar nor flavoring can be left to chance. And the little cook must keep a sharp eye on her fire, and watch her pan and its contents, so as to remove them at just the right moment. Sugar must be made into a syrup by adding water to it, and boiling it until it is smooth and thick. It is then called clarified sugar.

Chocolate Caramels.—Dissolve four ounces of chocolate in as little water as possible, and add it to one pound of clarified sugar, stirring it for a few minutes before taking it off. If you wish a richer caramel mixture, then take half a pound of chocolate, two cups of sugar, half a cup of milk, and a small lump of butter. Scrape the chocolate in the milk, add it to the boiled sugar, and stir in the butter. When your caramels are done pour them into a flat pan or a sheet of tin which you have oiled or buttered, so that they will not stick fast to it. When cool enough to be dented with the finger, cut the caramels into the shape you desire with a knife. If you do not eat your caramels on the day they are made, keep them in a tightly closed jar.

Everton taffy is a favorite with children. It is made in this way:

Everton Taffy.—Melt three ounces of butter in a brass skillet, and add one pound of brown sugar; boil the mixture over a clear fire until the syrup, when dropped into cold water, breaks between the teeth without sticking to them. Pour it into pans which have been rubbed with buttered paper, and set it away to cool. If you wish, you may add the grated rind of a lemon when the sugar is half done.

Plain Taffy.—Boil a quart of molasses slowly for half an hour over not too fierce a fire, stirring it constantly. Add to it half a tea-spoonful of bicarbonate of soda (baking-soda). Try the candy by dropping a spoonful in cold water. If brittle, it is done.

You may, if you wish, make molasses candy very white by pulling it in your hands, first flouring them or buttering them, so that the candy will not stick fast to your fingers.

Now, dear little housekeepers, although I have given you these receipts, I do not advise you to spend a great deal of time in candy-making in midsummer. I would rather hear that you had been riding on the hay, or gathering apples, fishing with your brothers, or going over the hills for blackberries. But if you do make candy, be sure to write me word whether or not it turns out finely and tastes good.

Weatherford, Texas.

I am a little boy seven years old. I have never been to school yet, but I learn at home. I like my books very much. I had several nice books given to me, and I have read them all but one. I have just had a nice trip with my papa, going on the Texas and Pacific Railroad to Colorado City. It is in Western Texas, on the Colorado River. The river was very high, and I saw some horses swim across it. I saw a great many prairie-dogs. They burrow in the ground, and have a rattle-snake, an owl, and a rabbit with them. I also saw a panther. I wanted a prairie-dog for a pet, and a gentleman promised to send me one. I see where little Susie has told you about her pet, a horned toad. There are a great many of them here. They do not hop like a toad, but run almost as fast as a lizard. I catch them, and put them in the garden to destroy the bugs. My pet is a little rat terrier named Snip. I saw a little printing-office at Colorado City, where a paper called the Nut-Shell is printed. It is about as large as a big sheet of writing-paper. Its editor is Johnny Tolar, a boy about fifteen years old. I take it and Harper's Young People. I wrote this letter by myself, and then got mamma to show me the mistakes.

Howard L.

I will first tell where Fort Pickens is. It is on Santa Rosa Island. The island is surrounded by the Gulf of Mexico and Pensacola Bay, and is a large uninhabited island. On the 25th of May the Presbyterian Sabbath-school from Pensacola gave a picnic. We left the wharf for Fort Pickens about half past nine. We had a very nice time going over; we played games and talked all the way over. We arrived at the Fort at about ten or half past ten o'clock. As soon as we had landed, we went right to the Fort, where we staid for about half an hour resting, after which we walked through the Fort. We then went back to where our parasols and baskets were. We got our parasols, and started with a few other girls and boys to walk round the parapets of the forts. A few boys and girls went over to the Gulf to gather shells, but it was so warm that I thought it best to wait until afternoon before I went over to the Gulf. About twelve o'clock we went into one of the large, cool case-mates and danced and decorated our hats with ferns and wild flowers gathered inside the Fort. At one o'clock we had dinner, which we enjoyed very much. We had everything necessary to eat at a picnic. After dinner we spent the time until half past two much the same as in the morning. At half past two a crowd of ladies, gentlemen, and children went over in a sail-boat to Barrancas to visit the light-house. I did not go over with them for fear of getting seasick. After I had seen the boat leave the wharf I went back to the Fort, where I met several girls who were going over to the Gulf. I went with them. When we got over to the Gulf we pulled off our shoes and stockings and went in wading. When tired of that we walked up the beach gathering shells, until we thought it time to go back to the Fort. After a sail on the Gulf we returned to Pensacola, and arrived there about half past six. We were very tired.

Nannie L. W.

Washington, D.C.

I am a little girl six years old. I have no brother nor sister, but have as many as six dolls. Fanny is nearly as old as I am. Her nose is almost flat. I keep Etta dressed all up pretty. Santa Claus has had two big books made with my Harper's Young People. I hope he won't forget to call for them again this year. I have taken them every one. I have a blackboard; I print, and can add and take away. I am in the Second-Reader. Mamma and I are going to Maine next month to stay till it is real cool here. There we go out fishing. We pick blueberries, blackberries, and cranberries. I have four little cousins who go from here. We all have the same grandpa and grandma. We ride on the hay, and dig clams. Papa will go down to bring us home. Every Tuesday night he reads me the stories from Harper's Young People. I like the letters very much, and everything in them. When papa sees a letter from his little girl, he will open his eyes. I have never been to school. I think Toby Tyler is just as nice as any other of my friends. I am wondering if you will have room for this in my Harper's Young People; it is a very long letter.

One of your little girls, Olive E. B.

Thank you, dear, for printing your letter so beautifully.

Hartford, Connecticut.

An amusing game which I have seen played is the following: Take four handkerchiefs and tie them like dolls, to represent four persons; then tie a thread to each, and put them (the threads) over the chandelier, and give each thread to a person, who must try to conceal himself behind a door or something else; and then, while some one plays on the piano, those who have the threads keep them jerking, letting the dolls hang so that they come down to the floor. If well done, it is quite a good representation of dancing.

S.

Lexington, Kentucky.

As I have not seen a letter from Lexington, I thought I would write one. I have two little puppies; one is named Sport, and the other Preston. I have a hen, and she lays eggs. I have a little brother, and he is named Hugh. He has two kittens; one is a Maltese, and one a common cat. I can ride a bicycle, and last year I took the certificate at the fair for good riding.

E. Sayre C.

Waukesha, Wisconsin.

I am twelve years old, and have taken the Young People from the beginning. I like it very much; I can hardly wait a week for it to come, because the continued stories all leave off in such interesting places.

I haven't any pets to tell you about, for they all died. I had five cats, a mother and four little ones, and some one killed the mother, and two[Pg 591] little dwarfs, as I called them, had to be drowned, because they could not live without her; then one of the remaining two fell into the well and drowned itself, and the horse stepped on the other one; so that is the fate of my five cats.

My mamma, papa, and little brother have all been to California, and left me here with some friends; they were gone nearly a year, and sometimes I felt very lonesome. My brother is ten years old, and we have a nice big yard to play in. My brother's name is Earle, and we both like "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" very much.

Winnie W.

Admirer.—Newfoundland is pronounced with the accent on the first syllable. I do not know who wrote the exercise in alliteration which you mention. It is clever, but you could no doubt compose an equally excellent one yourself. Whether to use plain or ornamental note-paper is a matter to be decided by your own taste. The exquisite little butterfly painted by yourself in the corner of your sheet is a decided addition to the beauty of your letter. I would not waste such decorations on an envelope, however, as that has to pass through many hands, and is less private than the inclosure.

Violet S.—Your teacher has discovered a very pleasant way of teaching her pupils how to write compositions. Although most schools are now taking their summer recess, I will state her method. She takes ten words from a lesson which the girls have recently studied, and writes them on the blackboard, after which she gives them fifteen minutes with their slates and pencils. At the end of fifteen minutes each is asked for her composition.

The smallest black-and-tan terrier in the world is supposed to belong to a lady in Chicago. It weighs from a pound to a pound and a half. Its skin is like the finest silk, its eyes project like marbles, its legs resemble lead-pencils, and its feet are the most perfect and curious things alive. It reposes in a basket lined with gold and cardinal satin, wears a collar studded with diamonds and emeralds, with "Baby Mine," its pet name, on a gold plate tipped with a gold bell, and is fed from a saucer of Dresden china.

Bettie.—Keep powdered borax on your wash-stand, and use it when washing your hands; it will make them soft and white. Lemon juice is also good to whiten the hands. But the Postmistress does not object to a healthy brown color in summer either on hands or face.

This article on the making of anagrams, which we ask you to read carefully, was prepared by a gentleman who has had a great deal of experience with puzzles and puzzlers. Perhaps you will try your own skill in transposing sentences after this ingenious fashion:

In a former issue of Young People a writer told the younger readers of the old-fashioned amusement of making anagrams on the names of acquaintances and public characters. The author gave several illustrations of famous anagrams made many years ago; but there have been some truly wonderful anagrams published in this country during the last four or five years, and I shall endeavor to give you a few of the most interesting ones.

There is a certain understanding among contributors to puzzle columns that an anagram is a word, name, place, or event so transposed that it will relate in some way to the original subject; while if merely so transposed that it will produce other words not relative to the original, it is called a transposition; but transpositions are usually made of a single word, as, for instance, the following by a lady of Toledo, Ohio, who signs herself "Mazie Lane":

"Transpose a musical anthem grand,

And find a picture by a red man's hand."

The answer is Motet—Totem.

Here is one by a young man of Boston, who signs himself "Sphinx":

"Gay, pretty flowers of the spring,

Transposed will stipulators bring."

Answer: Primroses—Promisers.