![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Certain delightful English towns, with glimpses of the pleasant country between

Author: William Dean Howells

Release date: December 26, 2018 [eBook #58540]

Most recently updated: January 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

A few minor typographical errors have been corrected. List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

WITH GLIMPSES OF THE PLEASANT

COUNTRY BETWEEN

W. D. H O W E L L S

ILLUSTRATED

HARPER & BROTHERS PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK AND LONDON

1906

{ii}

| Copyright, 1906, by Harper & Brothers. —— All rights reserved. Published October, 1906. |

NO American, complexly speaking, finds himself in England for the first time, unless he is one of those many Americans who are not of English extraction. It is probable, rather, that on his arrival, if he has not yet visited the country, he has that sense of having been there before which a simpler psychology than ours used to make much of without making anything of. His English ancestors who really were once there stir within him, and his American forefathers, who were nourished on the history and literature of England, and were therefore intellectually English, join forces in creating an English consciousness in him. Together, they make it very difficult for him to continue a new-comer, and it may be that only on the fourth or fifth coming shall the illusion wear away and he find himself a stranger in a strange land. But by that time custom may have done its misleading work, and he may be as much as ever the prey of his first impressions. I am sure that some such result in me will evince itself to the reader in what I shall have to say of my brief stay with the{2} English foster-mother of our American Plymouth; and I hope he will not think it altogether to be regretted.

My first impressions of England, after a fourth or fifth visit, began even before I landed in Plymouth, for I decided that there was something very national in the behavior of a young Englishman who, as we neared his native shores, varied from day to day, almost from hour to hour, in his doubt whether a cap or a derby hat was the right wear for a passenger about landing. He seemed also perplexed whether he should or should not speak to some of his fellow-passengers in the safety of parting, but having ventured, seemed to like it. On the tender which took us from the steamer to the dock I fancied another type in the Englishman whom I asked which was the best hotel in Plymouth. At first he would not commit himself; then his humanity began to work in him, and he expressed a preference, and abruptly left me. He returned directly to give the reasons for his preference, and to excuse them, and again he left me. A second time he came back, with his conscience fully roused, and conjured me not to think of going elsewhere.

I thought that charming, and I afterwards found the hotel excellent, as I found nearly all the hotels in England. I found everything delightful on the way to it, inclusive of the cabman’s overcharge, which brought the extortion to a full third of the just fare of a New York cabman. I do not include the weather, which was hesitating a bitter little rain, but I do include the behavior of the customs officer, who would do not more than touch, with averted eyes, the contents of the single piece of baggage which he had me open. When it came to paying the two hand-cart men three shillings for{3} bringing up the trunks, which it would have cost me three dollars to transport from the steamer to a hotel at home, I did not see why I should not save money for the rest of my life by becoming naturalized in England, and making it my home, unless it was because it takes so long to become naturalized there that I might not live to economize much.

It was with a pleasure much more distinct than any subliminal intimation that I saw again the office-ladies in our hotel. Personally, they were young strangers, but officially they were old friends, and quite as I had seen them first forty years ago, or last a brief seven; only once they wore bangs or fringes over their bright, unintelligent eyes, and now they wore Mamie loops. But they were, as always, very neatly and prettily dressed, and they had the well-remembered difficulty of functionally differencing themselves to the traveller’s needs, so that which he should ask for a room and which for letters and which for a candle and which for his bill, remains a doubt to the end. From time to time with an exchange of puzzled glances, they unite in begging him to ask the head porter, please, for whatever it is he wants to know. They all seem of equal authority, but suddenly and quite casually the real superior appears among them. She is the manageress, and I never saw a manager at an English hotel except once, and that was in Wales. But the English theory of hotel-keeping seems to be house-keeping enlarged; a manageress is therefore more logical than a manager, and practically the excellence of English hotels attests that a manager could not be more efficient.

One of the young office-ladies, you never can know which it will be, gives you a little disk of pasteboard with the number and sometimes the price of your room{4} on it, but the key is an after-thought of your own. You apply for it on going down to dinner, but in nearly all provincial hotels it is safe to leave your door unlocked. At any rate I did so with impunity. This was all new to me, but a greater novelty which greeted us was the table d’hôte, which has nearly everywhere in England replaced the old-time dinner off the joint. You may still have that if you will, but not quite on the old imperative terms. The joint is now the roast from the table d’hôte, and you can take it with soup and vegetables and a sweet. But if you have become wonted to the superabundance of a German steamer you will not find all the courses too many for you, and you will find them very good. At least you will at first: what is it that does not pall at last? Let it be magnanimously owned at the outset then, while one has the heart, that the cooking of any English hotel is better than that of any American hotel of the same grade. At Plymouth, that first night, everything in meats and sweets, though simple, was excellent; in vegetables there were green things with no hint of the can in them, but fresh from the southerner parts of neighboring France. As yet the protean forms of the cabbage family were not so insistent as afterwards.

Though we dined in an air so cold that we vainly tried to warm our fingers on the bottoms of our plates, we saw, between intervening heads and shoulders, a fire burning blithely in a grate at the farther side of the room. It was cold there in the dining-room, but after we got into the reading-room, we thought of it as having been warm, and we hurried out for a walk under the English moon which we found diffusing a mildness over the promenade on the Hoe, in which the statue of Sir Francis Drake fairly basked on its pedestal. The old

sea-dog had the air of having lifted himself from the game of bowls in which the approach of the Spanish Armada had surprised him, and he must have already arrived at that philosophy which we reached so much later. In England it is chiefly inclement in-doors, but even out-doors it is well to temper the air with as vigorous exercise as time and occasion will allow you to take. Another monument, less personally a record of the Armada, balanced that of Drake at the farther end of the Hoe, and on top of this we saw Britannia leading out her lion for a walk: lions become so dyspeptic if kept housed, and not allowed to stretch their legs in the open air. We had no lion to lead out; and there was no chance for us at bowls on the Hoe that night, but we walked swiftly to and fro on the promenade and began at once to choose among the mansions looking seawards over it such as we meant to buy and live in always. They were all very handsome, in a reserved, quiet sort; but we had no hesitation in fixing on one with a balcony glassed in, so that we could see the sea and shore in all weathers; and I hope we shall not incommode the actual occupants.

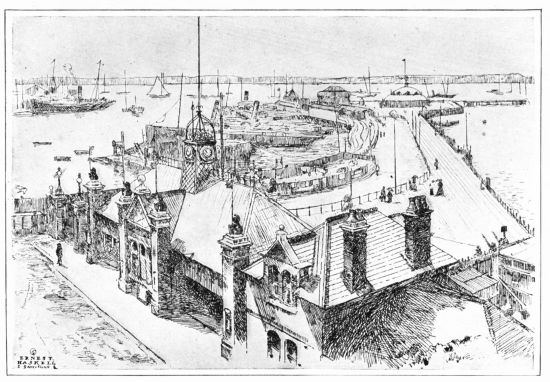

The truth is we were flown with the beauty of the scene, which we afterwards found as great by day as by night. The promenade, which may have other reasons for calling itself as it does besides being shaped like the blade of a hoe, is a promontory pushed well out into the sound, with many islands and peninsulas clustered before it, or jutting towards it and forming a safe roadstead for shipping of all types. Plymouth is not a chief naval station of Great Britain without the presence of war-ships in its harbor; and among the peaceful craft at anchor with their riding-lights showing in the deeps of the sea and air one could distinguish the huge kraken{6} shapes of modern cruisers and destroyers, and what not. But like the embattled figures of the marine and land-going soldiery, flirting on the benches of the promenade with females as fearless as themselves, or jauntily strolling up and down under the moon, the ships tended to an effect of subjective peacefulness, as if invented merely for the pleasure of the appreciative stranger. We were, at any rate, very glad of them, and appreciated the municipal efforts in our behalf as gratefully as the imperial fortifications of the harbor. It must be confessed at once, if I am ever to claim any American superiority in these “trivial, fond records,” which I shall never be able to help making comparative, that in what is done by the public for the public, we are hardly in the same running with England. It is only when we reflect upon our greater municipal virtue, and consider how the economies of our civic servants in the matter of beauty enable them to spend the more in good works, that we can lift up our heads and look down on what England has everywhere wrought for the people in such unspiritual things as parks and gardens, and terraces and promenades and statues. I could have wished that first evening, before I committed myself to any wrong impression or association, that I had known something more, or even anything at all, of the history of Plymouth. But I did not even know that from the Hoe, and possibly the very spot where I stood, the brave Trojan Cirenæus hurled the giant Goemagot into the sea. I was quite as far from remembering any facts of the British civilization which has always flourished so splendidly in the fancy of the native bards, and which has mingled its relics with those of the Roman, not only in the neighborhood of Plymouth, but all over England. As for the facts that Plymouth had been harried through{7}out the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries by the incursions of the French; that it was the foremost English port in the time of Elizabeth; that Drake sailed from it in 1585 to bring back the remnant of Raleigh’s colony from Virginia; that one hundred and twenty-seven English ships waited in its waters to meet the Spanish Armada; that it stood alone in the West of England for the Parliament in the Civil War; that Charles II. had signified his displeasure with it for this by building to overawe it the entirely useless fortress in the harbor; and that it was the first town to declare for William of Orange when he landed to urge the flight of the last Stuart: I do not suppose there is any half-educated school-boy but has the facts more about him than I had that first night in Plymouth when I might have found them so serviceable. I could only have matched him in my certainty that this was the Plymouth from which the Mayflower sailed to find, or to found, another Plymouth in the New World; but he could easily have alleged more proofs of our common conviction than I.

At sunset, which they have in Plymouth appropriately late for the spring season and the high latitude, there had been a splotch of red about six feet square in the watery west, promising the fine weather which the morning brought. It also brought more red coats and swagger-sticks in company with the large hats and glaring costumes which had not had so good a chance the night before, whether we saw them in our walk on the Hoe, or met them in the ramble through the town into which we prolonged it. Through the still Sunday morning air there came a drumming and bugling of religious note from the neighboring fortifications, and while we listened, a general officer, or perhaps only a colonel, very tight in the gold and scarlet of his uniform,{8} passed across the Hoe, like a pillar of flame, on his way to church. But I do not know that he was a finer bit of color, after all, than the jet-black cat with a vivid red ribbon at her neck, which had chosen to crouch on the ivied stone-wall across the way from our hotel, in just the spot where the sun fell earliest and would lie longest. There was more ivy than sun in Plymouth, that is the truth, and this cat probably knew what she was about. There was ivy, ivy everywhere, and there were subtropical growths of laurel and oleander and the like, which made a pleasant confusion of earlier Italy and later Bermuda in the brain, and yet was so characteristic of that constantly self-contradictory England.

Many things of it that I had known in flying and poising visits during fifty years of the past began to steal back into my consciousness. The nine-o’clock breakfast, of sole and eggs and bacon, and heavy bread and washy coffee, was of the same moral texture as the sabbatical silence in the pale sunny air, which now I remembered so well, with some weird question whether I was not all the while in Quebec, instead of Plymouth, and the strong conviction at the same time that this was the absurdest of obsessions. The Hoe was not Durham Terrace, but it looked down on a sort of Lower Town from a height almost as great, and the spread of the harbor, with a little help, recalled the confluence of the St. Lawrence and the St. Charles. But the rows of small houses that sent up the smoke of their chimney-pots were of yellow brick, not of wood or gray stone, and their red roofs were tiled in dull weather-worn tints, and not brilliantly tinned.

Why, I wonder, do we feel such a pleasure in finding different things alike? It is rather stupid, but we are always trying to do it and fatiguing ourselves with the

sterile effect. At Plymouth there was so much to remind me of so much else that it was a relief to be pretty promptly confronted on the Hoe with something so positive, so absolute as a Bath chair, which at the worst could only remind me of something in literature. A stubby old man was tugging it over the ground slowly, as if through a chapter of Dickens; and a wrathful-looking invalid lady sat within, just as if she had got into it from a book. There was little to recall anything else in the men strolling about in caps and knickerbockers, with short pipes in their mouths, or, equally with short pipes, wheeling back and forth on bicycles. There were a few people in top-hats, who had unmistakably the air of having got them out for Sunday; though why every one did not wear them every day in the week was the question when we presently saw a shop-window full of them at three and sixpence apiece.

This was when we had gone down into the town from the Hoe, and found its quiet streets of an exquisite Sunday neatness. They were quite empty, except for very washed-up-looking worshippers going to church, among whom a file of extremely little boys and girls, kept in line and kept moving by a black-gowned church-sister, gave us, with their tender pink cheeks and their tender blue eyes, our first delight in the wonderful West-of-England complexion. The trams do not begin running in any provincial town till afternoon on Sundays, and the loud-rattling milk-carts, bearing bright brass-topped cans as big as the ponies that drew them, seemed the only vehicles abroad. The only shops open were those for the sale of butter and eggs and fruit and flowers; but these necessaries and luxuries abounded in many windows and doorways, especially the flowers, which had already begun to arrive everywhere by tons{10} from the Channel Islands, though it was then so early in March. It is not the least of the advantages which England enjoys that she has her Florida at her door; she has but to put out her hand and it is heaped with flowers and fruits from the Scilly Isles, while the spring is coming slowly up our way at home by fast-freight, through Georgia and the Carolinas and Virginia.

So many things were strange to me that I might have thought I had never been in Plymouth before, and so many things familiar that I might have fancied I had always been there. The long unimpressive stretches of little shops might have been in any second-class American city, which would likewise have shown the same exceptional number of large department stores. What it could not have shown were the well-kept streets, the reverently guarded heritage from the past in here and there a bit of antique architecture amid the prosperous newness; the presence of lingering state in the mansions peering over their high garden wall, or standing withdrawn from the thoroughfares in the quiet of wooded crescents or circles.

I doubt if any American city, great or small, has the same number of birds, dear to poetry, singing in early March, as Plymouth has. That morning as we walked in the town, and that afternoon as we rode on our tram-top into the country, they started from a thousand lovely lines of verse, finches and real larks, and real robins, and many a golden-billed blackbird, and piped us on our way. Overhead, in the veiled sun, circled and swam the ever-cawing rooks, as they jarred in the anxieties of the nesting then urgent with them. They were no better than our birds; I will never own such a recreant thing. If I do not quite prefer a crow to a rook, I am free to say that one oriole or redbird or

hermit-thrush is worth all the English birds that ever sang. Only, the English birds sing with greater authority, and find an echo in the mysterious depths of our ancestral past where they and we were compatriots.

Viewed from the far vantage of some rising ground the three towns of Plymouth, Stonehouse, and Devonport, which have grown together to form one Plymouth, stretch away from the sea in huge long ridges thickly serried with the gables, and bristling with the chimney-pots of their lines of houses. They probably look denselier built than they are through the exaggerative dimness of the air which lends bulk to the features of every distant prospect in England; but for my pleasure I would not have had the houses set any closer than they were on the winding, sloping line of the tram we had taken after luncheon. It was bearing us with a leisurely gait, inconceivable of an American trolley, but quite swiftly enough, towards any point in the country it chose; and after it had carried us through rows and rows of small, low, gray stone cottages, each with its pretty bit of garden at its feet, it bore us on where their strict contiguity ceased in detached villas, and let us have time to look into the depths of their encompassing evergreenery, their ivy, their laurel, their hedges of holly, all shining with a pleasant lustre. So we came out into the familiar provisionality of half-built house-lots, and at last into the open country quite beyond the town, with green market-gardens, and brown ploughed fields, patching the sides of the gentle knolls, laced with white winding roads, that lost their heads in the haze of the horizon, and with woodlands calling themselves “Private,” and hiding the way to stately mansions withdrawn from the commonness of our course.

When the tram stopped we got down, with the other{12} civilian persons of our tram-top company, and with the soldiers and the girls who formed their escort, and hurried beyond hearing of the loud-cackling, hard-mouthed, red-cheeked, black-eyed young woman, whom one sees everywhere in some form, and in whose English version I saw so many an American original that I was humbled with the doubt whether she might not have come out on the Mayflower. There were many other people more inoffensive coming and going, or stretching themselves on the damp new grass in a defiance of the national rheumatism which does not save them from it. At that time, though, I did not know but it might, and I enjoyed the picturesqueness of their temerity with an untroubled mind. I noted merely the kind looks which prevail in English faces of the commoner sort, and I thought the men better and the women worse dressed than Americans of the same order. Then, after I had realized the prevalence of much the same farming tradition as our own, in the spreading fields, and holloed my fancy up and away over the narrow lines climbing between them to the sky, there was nothing left to do but to go to town by a different tram-line from that which brought us. The man I asked for help in this bold enterprise had a face above the ordinary in a sort of quickness, and he seemed to find something unusual in my speech. He answered civilly and fully, as all the English do when you ask them a civil question, without the friendly irony with which Americans often like to visit the inquiring stranger. Then he stopped short, checking the little boy he was leading by the hand, and said, abruptly, “You’re not English!”

“No,” I said, “we’re Americans,” and I added, “From New York.”

“Ah, from New York!” he said, with a visible rush of{13} interest in the fact that it never afterwards brought to another English face, so far as I could see. “From New York! Americans!” and he stood clutching the hand of the little boy, while I felt myself in the presence of a tacit drama, which I have not yet been able to render explicit. Sometimes I have thought it not well to try. It might have been the memory of sad experiences which had left a rancor for our country in his heart, and held him in doubt whether he might not fitly wreak it upon the first chance American he met. Again I fancied it might have been the stirring of some long-deferred hope, some defeated ambition, or the rapture of some ideal of us which had never had the opportunity to disappoint itself. I only know that he looked like a man above his class: an unhappy man anywhere, and probably in England most unhappy. I stupidly hurried on, and after some movement to follow me he let me leave him behind. Whoever he was or whatever his emotion, I hope he was worthy of the sympathy which here offers itself too late. If I could I would perhaps go back to him, and tell him that if he sailed for New York he might never find the America of his vision, but only a hard workaday world like the one he was leaving, where he might be differently circumstanced, but not differently conditioned. I dare say he would not believe me; I am not sure that I should believe myself, though I might well be speaking the truth.

The next day being Monday, it was quite fit that we should go to work with the rest of the world in Plymouth, and we set diligently about the business of looking up such traces of the Pilgrim Fathers as still exist in the town which was so kind to them in their great need of kindness. I will not pretend that the pathetic story recurred to me in full circumstance during our search for{14} the exact place from which the Mayflower last sailed, when after she had come with her sister ship, the Speedwell, from Holland to Southampton, and then started on the voyage to America, she had been forced by the unseaworthiness of the Speedwell to put back as far as Plymouth. Mr. W. E. Griffin, in his very agreeable and careful little book, The Pilgrims in their Three Homes, is able only to define the period of their stay there as “some time,” but he tells us that the disappointed voyagers “were treated very kindly by the people of the Free Church, forming what is now the Grange Street Chapel, the Mayflower meanwhile lying off the Barbican.” The weather was good while the two ships stayed, but when they sailed again the Speedwell returned to London with some twenty of the homesick or heart-sick, while all her other people stowed themselves with their belongings in the little Mayflower as best they could, and she once more put out to sea: a prison where the brutal shipmen were their jailers; a lazar where the seeds of death were planted in many that were soon to fill the graves secreted under the snow of the savage shore they were seeking.

I believe it was the visiting association of American librarians who caused, a few years ago, a flag-stone in the pavement of the quay where the Mayflower lay to be inscribed with her name and the date 1620, as well as a more explicit tablet to be let into the adjacent parapet. Perhaps our driver could have found these records for us, or we could have found them for ourselves, but I am all the same grateful for the good offices of several unoccupied spectators, especially a friendly matron who had disposed of her morning’s stock of fish, and had now the leisure for indulging an interest in our search. She constituted herself the tutelary spirit{15} of the neighborhood, which smelt of immemorial catches of fish, both from the adjacent market and from the lumpish, quaintly rigged craft crowding one another in the docks and composing in an insurpassable picturesqueness; and she directed us wherever we wanted to go.

The barbican of the citadel from which the Mayflower sailed, before there was either citadel or barbican, is no great remove from the Hoe, which may justly enough boast itself “the first promenade in England,” but it is quite in another world: a seventeenth-century world of narrow streets crooking up hill and down, and overhung by the little bulging houses which the pilgrims must have seen as they came and went on their affairs with the ship, scarcely bigger than the fishing-boats now nosing at the quay where she then lay. Whatever it was in the Mayflower’s time, it is not a proud neighborhood in ours, nor has it any reason to be proud; for it is apparently what is indefinitely called a purlieu. At one point where I climbed a steep thoroughfare to look at what no doubt unwarrantably professed to be a remnant of “Cromwell’s castle,” I met an elderly man, who was apparently looking up truant school-children, and who said, quite without prompting, “This used to be ’ell upon earth,” with something in his tone implying that it might still be a little like it. We could not get into the ruin, the solitary who tenanted its one habitable room being away on a visit, as a neighbor put her head out of a window opposite to tell us.

Probably the traveller who wishes for a just impression of the Plymouth of 1620 will get it more reliably somewhat away from the immediate scene of the Mayflower’s departure. There are old houses abundantly overhanging their first stories, after the seventeenth-century fashion, in the pleasanter streets which keep{16} aloof from the water. If he is more bent upon a sense of modern Plymouth he will do best to visit her group of public edifices, the Guild Hall, the Law Courts, the Library, and see all that I did not see of the vast shipping which constitutes her one of the greatest English ports, and the government works which magnify her importance among the naval stations of the world.

It is always best to leave something for a later comer, and I may seem almost to have left too much by any one whom I shall have inspired to linger in Plymouth long enough after landing to get his sea-legs off. But really I was continually finding the most charming things. The very business aspects of Plymouth had their charm. I saw a great prosperity around me, but there was no sense of the hustle which is supposed alone to create prosperity with us. I dare say that below the unruffled surface of life there is sordid turmoil enough, but I did not perceive it, and I prefer still to think of Plymouth as the first of the many places in England where the home-wearied American might spend his last days in the repose of a peaceful exile, with all the comforts, which only much money can buy with us, cheaply about him. He could live like a gentleman in Plymouth for about half what the same state would cost him in his own air, unless he went as far inland as the inexpensive Middle West, and then it would be dearer in as large a town. He could keep his republican self-respect in his agreeable banishment by remembering how Plymouth had held for the Commonwealth in Cromwell’s time, and the very name of the place would bring him near to the heroic Plymouth on the other shore of the Atlantic. I speak from experience, for even in my two days’ stay with the mother Plymouth I had now and then a vision of the daughter Plymouth, on the elm-shaded slopes of

her landlocked bay, filially the subordinate in numbers and riches with which she began her alien life. Still of wood, as the English Plymouth is still of stone, and newer by a thousand years, she has an antiquity of her own precious to Americans, and a gentle picturesqueness which I found endearing when I first saw her in the later eighteen-sixties, and which I now recalled as worthy of her lineage. Perhaps it was because I had always thought the younger Plymouth would be a kind dwelling-place that I fancied a potential hospitality in the elder. At any rate I thought it well, while I was on the ground, to choose a good many eligible residences, not only among the proud mansions overlooking the Hoe, but in some of the streets whose gentility had decayed, but which were still keeping up appearances in their fine roomy old houses, or again in the newer and simpler suburban avenues, where I thought I could be content in one of the pretty stone cottages costing me forty pounds a year, with my holly hedge before me belting in a little garden of all but perennial bloom.

We had chanced upon weather that we might easily have mistaken for climate. There was the lustre of soft sunshine in it, and there was the song of birds in the wooded and gardened pleasaunces which opened in several directions about the Hoe, and seemed to follow the vagarious lines of ancient fortifications. Whether weather or climate, it could not have been more suitable for the excursion we planned our last afternoon across that stretch of water which separates Plymouth from the seat of the lords who have their title from the great estate. The mansion is not one of the noble houses which are open to the public in England, and even to get into the grounds you must have leave from the manor-house. This will not quite answer{18} the raw American’s expectation of a manor-house; it looks more like a kind of office in a Plymouth street; but if you get from it as guide a veteran of the navy with an agreeable cast in his eye, and an effect of involuntary humor in his rusty voice, you have not really so much to complain of. In our own case the veteran’s intelligence seemed limited to delivering us over at gates to gardeners and the like, who gave us back to his keeping after the just recognition of their vested interests, and then left him to walk us unsparingly over the whole place, which had grown as large at least as some of our smaller States, say Connecticut or New Jersey, by the time we had compassed it. We imagined afterwards that he might have led us a long way about, not from stupidity, but from a sardonic amusement in our protests; and we were sure he knew that the bird he called a nightingale was no nightingale. It was as if he had said to himself, on our asking if there were none there, “Well, if they want a nightingale, let ’em have it,” and had chosen the first songster we heard. There were already songsters enough in the trees about to choose any sort from, for we were now in Cornwall, and the spring is very early in Cornwall. There were primroses growing at the roots of the trees in the park; in the garden closes were bamboos and palms, and rhododendrons in bloom, with cork-trees and ilexes, springing from the soaked earth which the sun damply shining from the spongy heavens could never have dried. The confusion of the tropical and temperate zones in this air, which was that of neither or both, was somewhat heightened by the first we saw of those cedars of Lebanon which so abound in England that you can hardly imagine any left on Lebanon. It was a dark, spreading tree, with a biblical seriousness and an oriental poetry of aspect, under{19} whose low shelving branches one might think to find the scripturalized childhood of our race. The gardens, whether English or French or Italian, appealed to a more sophisticated consciousness; but it had all a dim, blurred fascination which words refuse to impart, and the rooks, wheeling in their aërial orbits overhead, seemed to deepen the spell with the monotony of their mystical incantations. There were woodland spaces which had the democratic friendliness of American woods, as if not knowing themselves part of a nobleman’s estate, and which gave the foot a home welcome with the bedding of their fallen leaves. But the rabbits which had everywhere broken the close mossy turf with their burrowing and thrown out the red soil over the grass, must have been consciously a part of the English order. As for the deer, lying in herds, or posing statuesquely against the sky on some stretch of summit, they were as absolutely a part of it as if they had been in the peerage. A flag floated over the Elizabethan mansion of gray stone (rained a fine greenish in the long succession of springs and falls), to intimate that the family was at home, and invite the public to respect its privacy by keeping away from the grounds next about it; and in the impersonal touch of exclusion which could be so impersonally accepted, the sense of certain English things was perfected. You read of them all your life, till you imagine them things of actual experience, but when you come face to face with them you perceive that till then they have been as unreal as anything else in the romances where you frequented them, and that you have not known their true quality and significance. In fiction they stood for a state as gracious as it was splendid, and welcomed the reader to an equal share in it; but in fact they imply the robust survival, in commer{20}cial and industrial times, of a feudal condition so wholly obsolete in its alien admirer’s experience that none of the imitations of it which he has seen at home suggest it more than by a picturesqueness almost as provisional as that of the theatre.

What the alien has to confess in its presence is that it is an essential part of a system which seems to work, and in the simpler terms, to work admirably; so that if he has a heart to which the ideal of human equality is dear, it must shrink with certain withering doubts as he looks on the lovely landscapes everywhere in which those who till the fields and keep the woods have no ownership, in severalty or in common. He must remember how persistently and recurrently this has been the history of mankind, how, while democracies and republics have come and gone, patrician and plebeian, sovereign and subject, have remained, or have returned after they had passed. If he is a pilgrim reverting from the new world to which the outgoing pilgrims sailed, there to open from the primeval woods a new heaven and a new earth, his dismay will not justly be for the persistence of the old forms which they left behind, but for the question whether these forms have not somehow fixed themselves as firmly and lastingly in his native as in his ancestral country. I do not say that any such anxieties spoiled the pleasure of my afternoon. I was perhaps expecting to see much more perfect instances of the kind, and I was probably postponing the psychological effect to these. It is a fault of travel that you are always looking forward to something more typical, and you neglect immediate examples because they offer themselves at the outset, or you reject them as only approximately representative to find that they are never afterwards surpassed. That was the case with our hotel,{21} which was quite perfect in its way: a way rather new to England, I believe, and quite new to my knowledge of England.

It is a sort of hotel where you can live for as short or as long a time as you will at an inclusive rate for the day or week, and always in greater comfort for less money than you can at home, except in the mere matter of warmth. Warm you cannot be in-doors, and why should not you go out-doors for warmth, when the subtropical growths in the well-kept garden, which never fails to enclose that kind of hotel, are flourishing in a temperature distinctly above freezing? They always had the long windows, that opened into the garden, ajar when we came into the reading-room after dinner, and the modest little fire in the grate veiled itself under a covering of cinders or coal-siftings, so that it was not certain that the first-comer who got the chair next to it was luckiest. Yet around this cold hearth the social ice was easily broken, and there bubbled up a better sort of friendly talk than always follows our diffidence in public places at home. Without knowing it, or being able to realize it at that moment, we were confronted with a social condition which is becoming more and more general in England, where in winter even more than in summer people have the habit of leaving town for a longer or a shorter time, which they spend in a hotel like ours at Plymouth. There they meet in apparent fearlessness of the consequences of being more or less agreeable to one another, and then part as informally as they meet. But as yet we did not know that there was that sort of hotel or that we were in it, and we lost the earliest occasion of realizing a typical phase of recent English civilization.{22}

THE weather, on the morning we left Plymouth, was at once cloudy and fair, and chilly and warm, as it can be only in England. It ended by cheering up, if not quite clearing up, and from time to time the sun shone so brightly into our railway carriage that we said it would have been absurd to supplement it with the hot-water foot-warmer which, in many trains, still embodies the English notion of car-heating. The sun shone even more brightly outside, and lay in patches much larger than our compartment floor on the varied surface of that lovely English country with which we rapturously acquainted and reacquainted ourselves, as the train bore us smoothly (but not quite so smoothly as an American train would have borne us) away from the sea and up towards the heart of the land. The trees, except the semitropical growths, were leafless yet, with no sign of budding; the grass was not so green as at Plymouth; but there were primroses (or cowslips: does it matter which?) in bloom along the railroad banks, and young lambs in the meadows where their elders nosed listlessly among the chopped turnips strewn over the turf. Whether it was in mere surfeit, or in an invincible distaste for turnips, or an instinctive repulsion from their frequent association at table, that the sheep everywhere showed this apathy, I cannot make so sure

as I can of such characteristic features of the landscape as the gray stone cottages with thatched roofs, and the gray stone villages with tiled roofs clustering about the knees of a venerable mother-church and then thinning off into the scattered cottages again.

As yet we were not fully sensible of the sparsity of the cottages; that is something which grows upon you in England, as the reasons for it become more a part of your knowledge. Then you realize why a far older country where the land is in a few hands must be far lonelier than ours, where each farmer owns his farm, and lives on it. Mile after mile you pass through carefully tilled fields with no sign of a human habitation, but at first your eyes and your thoughts are holden from the fact in a vision of things endeared by association from the earliest moment of your intellectual nonage. The primroses, if they are primroses and not cowslips, are a pale-yellow wash in the grass; the ivy is creeping over the banks and walls, and climbing the trees, and clothing their wintry nakedness; the hedge-rows, lifted on turf-covered foundations of stone, change the pattern of the web they weave over the prospect as your train passes; the rooks are drifting high or drifting low; the little streams loiter brimful through the meadows steeped in perpetual rains; and all these material facts have a witchery from poetry and romance to transmute you to a common substance of tradition. The quick transition from the present to the past, from the industrial to the feudal, and back again as your train flies through the smoke of busy towns, and then suddenly skirts some nobleman’s park where the herds of fallow deer lie motionless on the borders of the lawn sloping up to the stately mansion, is an effect of the magic that could nowhere else bring the tenth and{24} twentieth centuries so bewilderingly together. At times, in the open, I seemed to be traversing certain pastoral regions of southern Ohio; at other times, when the woods grew close to the railroad track, I was following the borders of Beverly Farms on the Massachusetts shore, in either case recklessly irresponsible for the illusion, which if I had been in one place or the other I could have easily reversed, and so been back in England.

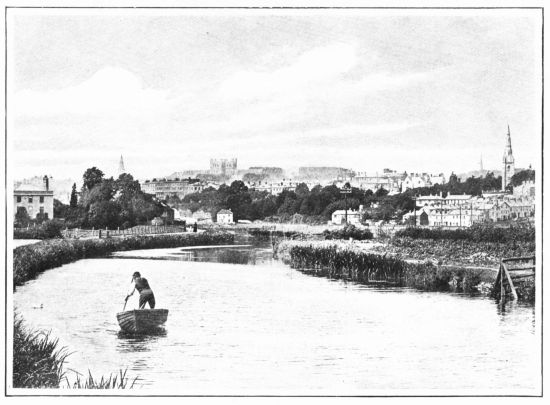

The run from Plymouth to Exeter is only an hour and a half, but in that short space we stopped four or five minutes at towns where I should have been glad to have stopped as many days if I had known what I lost by hurrying on. I do not know it yet, but I know that one loses so greatly in every sort of high interest at all the towns one does not stop at in England that one departs at last a ruined, a beggared man. As it was we could only avert our faces from the pane as we drew out of each tempting station, and sigh for the certainty of Exeter’s claims upon us. There our first cathedral was waiting us, and there we knew, from the words which no guide-book fails to repeat, that we should find “a typical English city ... alike of Briton, Roman, and Englishman, the one great prize of the Christian Saxon, the city where Jupiter gave way to Christ, but where Christ never gave way to Wodin.... None other can trace up a life so unbroken to so remote a past.” Whether, when we found it, we found it equal to the unique grandeur imputed to it, I prefer to escape saying by saying that the cathedral at Exeter is more than equal to any expectation you can form of it, even if it is not your first cathedral. A city of scarcely forty thousand inhabitants may well be forgiven if it cannot look an unbroken life from so remote a past as Exeter’s.

“IN EXETER OUR FIRST CATHEDRAL WAS WAITING US{25}”

Chicago herself, with all her mythical millions, might not be able to do as much in the like case; when it comes to certain details I doubt if even New York would be equal to it.

I will not pretend that I was intimately acquainted with her history before I came to Exeter. I will frankly own that I did not drive up to the Butt of Malmsey in the hotel omnibus quite aware that the castle of Exeter was built on an old British earthwork; or that many coins, vases, and burial-urns dug up from such streets as I passed through prove the chief town of Devonshire to have been built on an important Roman station. To me it did not at once show its Romano-British origin in the central crossing of its principal streets at right angles; but the better-informed reader will recall without an effort that the place was never wholly deserted during the darkest hours of the Saxon conquest. The great Alfred drove the Danes out of it in 877, and fortified and beautified it, and Athelstan, when he came to Exeter in 926, discovered Briton and Saxon living there on terms of perfect amity and equality. Together they must have manned the walls in resisting the Northmen, and they probably united in surrendering the city to William the Conqueror after a siege of eighteen days, which was long for an English town to hold out against him. He then built the castle of Rougemont, of which a substantial ruin yet remains for the pleasure of such travellers as do not find it closed for repairs; and the city held for Matilda in the wars of 1137, but it was finally taken by King Stephen. In 1469 it was for the Red Rose against the White when the houses of Lancaster and York disputed its possession, and for the Old Religion against the New in the time of Henry VIII.’s high-handed reforms, when the Devonshire and Cornish men fought for the{26} ancient faith within its walls against his forces without. The pretender Perkin Warbeck (a beautiful name, I always think, like a bird-note, and worthy a truer prince) had vainly besieged it in 1549; and in the Civil War it was taken and retaken by King and Parliament. At some moment before these vicissitudes, Charles’s hapless daughter Henrietta, who became Madame of France, was born in Exeter; and in Exeter likewise was born that General Monk who brought the Stuarts back after Cromwell’s death.

The Butt of Malmsey had advertised itself as the only hotel in the cathedral close, and as we had stopped at Exeter for the cathedral’s sake we fell a willing prey to the fanciful statement. There is of course no hotel in the cathedral close, but the Butt of Malmsey is so close to the cathedral that it may have unintentionally confused the words. At any rate, it stood facing the side of the beautiful pile and getting its noble Norman towers against a sky, which we would not have had other than a broken gray, above the tops of trees where one nesting rook the less would have been an incalculable loss. One of the rooms which the managers could give us looked on this lovely sight, and if the other looked into a dim court, why, all the rooms in a cathedral close, or close to a cathedral, cannot command views of it.

We had of course seen the cathedral almost before we saw the city in our approach, but now we felt that the time spent before studying it would be time lost and we made haste to the great west front. To the first glance it is all a soft gray blur of age-worn carving, in which no point or angle seems to have failed of the touch which has blent all the archaic sanctities and royalties of the glorious screen in a dim sumptuous harmony of figures and faces. Whatever I had sceptically read,

and yet more impatiently heard, of the beauty of English cathedrals was attested and approved far beyond cavil, and after that first glance I asked nothing but submissively to see more and more of their gracious splendor. No wise reader will expect me to say what were the sculptured facts before me or to make the hopeless endeavor to impart a sense of the whole structure in descriptions or admeasurements. Let him take any picture of it, and then imagine something of that form vastly old and dark, richly wrought over in the stone to the last effects of tender delicacy by the miracles of Gothic art. So let him suppose the edifice set among leafless elms, in which the tattered rooks’-nests swing blackening, on a spread of close greensward, under a low welkin, where thin clouds break and close in a pallid blue, and he will have as much of Exeter Cathedral as he can hope to have without going there to see for himself; it can never otherwise be brought to him in words of mine.

Neither, without standing in that presence or another of its kind, can he realize what the ages of faith were. Till then the phrase will remain a bit of decorative rhetoric, but then he will live a meaning out of it which will die only with him. He will feel, as well as know, how men built such temples in an absolute trust and hope now extinct, but without which they could never have been built, and how they continued to grow, like living things, from the hearts rather than the hands of strongly believing men. So that of Exeter grew, while all through the tenth and eleventh centuries the monks of its immemorial beginning were flying from the heathen invasions, but still returning, till the Normans gave their monastery fixity in the twelfth century, and the long English succession of bishops maintained the cathedral{28} in ever-increasing majesty till the rude touch of the Tudor stayed the work that had prospered under the Norman and Plantagenet and Lancastrian kings. If the age of faith shall extend itself to his perception, as he listens to the afternoon service in the taper-starred twilight, far back into the times before Christ, he may hear in the chanting and intoning the voice of the first articulate religions of the world. The sound of that imploring and beseeching, that wailing and sighing, which drifts out to him through the screen of the choir will come heavy with the pathos of the human abasing itself before the divine in whatever form men may have imagined God, and seeking the pity and the mercy of which Christianity was not the first to feel the need. Then, if he has a sense of the unbroken continuity of ceremonial, the essential unity of form, from Pagan to Roman and from Roman to Anglican, perhaps he will have more patience than he otherwise might with the fierce zeal of the fanatics who would at last away with all ceremonial and all form, and would stand in their naked souls before the eternal justice and make their appeal direct, and if need be, through their noses, to Him who desireth not the death of a sinner.

Unless the visitor to Exeter Cathedral can come into something of this patience, he will hardly tolerate the thought of the Commonwealth’s-men who deemed that they were doing God’s will when they built a brick wall through it, and listened on one side to an Independent chaplain, and on the other to a Presbyterian minister. It is said that they “had great quiet and comfort” in their worship on each side of their wall, which was of course taken down directly after the Restoration. For this no one can reasonably grieve; and one may of course rejoice that Cromwell’s troopers did not stable

their horses in Exeter Cathedral. They forbore to do so in few other old churches in England, but we did not know how to value fully its exemption from this profanation in our first cathedral. We took the fact with an ignorant thanklessness from our guide-book, and we acquiesced, with some surprise, in the lack of any such official as a verger to instruct us in the unharmed monuments. The printed instructions which we received from the placard overhanging a box at the gate to the choir did not go beyond the elementary precept that we were each to put sixpence in it; after that we were left free to look about for ourselves, and we made the round of the tombs and altars unattended.

The disappointment which awaits one in English churches, if one’s earlier experience of churches has been in Latin countries, is of course from the want of pictures. Color there is and enough in the stained windows which Cromwell’s men sometimes spared, but the stained windows in Exeter are said to be indifferent good. In compensation for this, there are traces of the frescoing which once covered the walls, and which Cromwell’s men neglected to whitewash. They also heedlessly left unspoiled that wonderful Minstrel’s Gallery stretching across the front of the choir, with its fourteen tuneful angels playing forever on as many sculptured instruments of stone. For the rest the monuments are of the funereal cast to which the devout fancy is pretty much confined in all sacred edifices. There is abundance of bishops lying on their tombs, with their features worn away in the exposure from which those of many crusaders have been kept by their stone visors. But what was most expressive of the past, which both bishops and crusaders reported so imperfectly, was the later portrait statuary, oftenest of Elizabethan ladies and their lords,{30} painted in the colors of life and fashion, with their ruffs and farthingales worn as they were when they put them off, to rest in the tombs on which their effigies lie. It is not easy to render the sense of a certain consciousness which seemed to deepen in these, as the twilight of the closing day deepened round them in the windows and arches. If they were waiting to hold converse after the night had fallen, one would hardly have cared to stay for a share in their sixteenth-century gossip, and I could understand the feeling of the two dear old ladies who made anxiously up to us at one point of our common progress, and asked us if we thought there was any danger of being locked in. I did my poor best to reassure them, and they took heart, and were delightfully grateful. When we had presently missed them we found them waiting at the door, to thank us again, as if we had saved them from a dreadful fate, and to shake hands and say good-bye.

If it were for them alone, I should feel sensibly richer for my afternoon in our first cathedral. But I think my satisfaction was heightened just before we left, by meeting a man with a wheelbarrow full of coal which he was trundling through “the long-drawn aisle and fretted vault” to the great iron stoves placed on either side of the nave to warm the cathedral, and contribute in their humble way to that perfect balance of parts which is the most admired effect of its architectural symmetry. As he stopped before each stove and noisily stoked it from a clangorous shovel, the simple sincerity of this bit of necessary house-keeping in the ancient fane seemed to strike a note characteristic of the English civilization, and to suggest the plain outrightness by which it has been able to save itself sound through every age and fortune. The English have reared a civic edifice more{31} majestic than any the world has yet seen, but in the temple of their liberty and their loyalty a man with a wheelbarrow full of coal has always been frankly invited to appear when needed. It is this mingling of the poetical ideal and the practical real which has preserved them at every emergency, and but for his timely ministrations church and state would alike have fared ill in the past. He has kept both habitable, and to any one who visits cathedrals with a luminous mind the man with the wheelbarrow of coal will remain as distinctly a part of the impression as the processioning and recessioning celebrants coming and going in their white surplices, with their red and black bands; or even the singing of the angel-voiced choir-boys, who as they hurry away at the end of the service do not all look as seraphic as they have sounded. There is often indeed something in the passing regard of choir-boys less suggestive of the final state of young-eyed cherubim than of evil provisionally repressed.

I do not say that I thought all this before leaving the cathedral in Exeter, or till long afterwards. I was at the time rather bent upon seeing more of the town, in which I felt a quality different from that of Plymouth though it pleased me no better. The manageress of the Butt of Malmsey had boasted already of the numbers of nobility and gentry living in the neighborhood of the little city, where, she promised, we should see ten private carriages for every one in Plymouth. I did not keep count, but I dare say she was right. What was more to my crude pleasure was the sight of the many Tudor, and earlier than Tudor, houses in the High Street and the other streets of Exeter, with their second stories overhanging their first, to that effect of baffle in the leaded casements of their gables which we fancy in the eyes of{32} stout gentlemen who try to catch sight of their feet over the intervening bulge of their waistcoats. They are incomparably picturesque, those Tudor houses, and as I had afterwards occasion to note from some of their interiors, they mark a beginning of domestic comfort, which, if not modern on the American terms, is quite so on the English.

To the last, I had always to make my criticisms of the provision for the inner house in England, but my conviction that the English had little to learn of us in providing for the inner man began quite as early as in my first walks about Exeter, where the most perverse American could not have helped noting the abundance and variety of the fruits and vegetables at the green-grocers’. Southern Europe had supplied these better than Florida and California supply them with us at the same season in towns the size of Exeter, or indeed in any less luxurious than our great seaboard cities. Counting in the apples and oranges from South Africa and the Pacific colonies of Great Britain, we are far out of it as to cheapness and quality. Then, no place in England is so remote from one sea or another as not always to have the best and freshest fish, which as the dealers arrange them with an artistic eye for form and color, make, it must be owned, a more appetizing show than the thronging shapes of carnage which start from the butchers’ doors and windows, and bleed upon the sidewalk, and gather microbes from every passing gust. There is something peculiarly loathsome in these displays of fresh meat carcases all over England, which does not affect the spectator from the corded and mounded ham and bacon in the grocers’ shops, though when one thinks of the myriads of eggs needed to accompany these at the forty million robust English breakfasts every morn{33}ing, it is with doubt and despair for the hens. They seem equal to the demand upon them, however, like every one and everything else English, and they always lay eggs enough, as if every hen knew that England expected her to do her duty.

We sauntered through Exeter without a plan, and took it as it came in a joy which I wish I could believe was reciprocal, and which was at no moment higher than when we found at the corner of the most impressive old place in Exeter the office of a certain New York insurance company. As smiling fate would have it, this was the very company in which I was myself insured, and I paused before it with effusion, and shook hands with the actuary in the spirit. In the flesh, if he was an Englishman, he might not have known what to do with my emotion, but with Englishmen in the spirit the wandering American always finds himself cordially at home. One must not say that the longer they have been in the spirit the better; some of them who are actually still in the flesh are also in the spirit; but a certain historical remove is apt to relieve friends of that sort of stiffness which keeps them at arm’s-length when they meet as contemporaries. At the other end of Bedford Circus, where I had my glad moment with the insurance actuary, I found myself in the presence of that daughter of Charles I., the Princess Henrietta, who was born there near three hundred years ago, and whose life I had lately followed with pathos for her young exile from England, through her girlhood in France, and through her unhappy marriage with the King’s brother Monsieur, to the afternoon of her last day when she lay so long dying in the presence of the court, as some thought, of poison. I could not feel myself an intrusive witness at that strange scene, which{34} now represented itself in Bedford Circus, with the courtiers coming and going, and the doctors joining their medical endeavors with the spiritual ministrations of the prelates, and the poor princess herself taking part in the speculations and discussions, and presently in the midst of all incontinently making her end.

I suppose it would not be good taste to boast of the intimacy I enjoyed with the clergy in the neighborhood of the cathedral, by favor of their translation into a region much remoter than the past. Without having the shadow of acquaintance with them and without removing them for an instant from their pleasant houses and gardens in the close at Exeter, I put them back a generation, and met them with familiar ease in the friendly circumstance of Trollope’s many stories of cathedral towns. I am not sure they would have liked that if they had known it, and certainly I should not have done it if they had known it; but as it was I could do it without offence. When we could rend ourselves from the delightful company of those deans, and canons, and minor canons, and prebendaries, with whom we really did not pass a word, we went a long idle walk to an old-fashioned part of the town overlooking the Exe from the crest of a hill, where certain large out-dated mansions formed themselves in a crescent. We instantly bought property there in preference to any more modern neighborhood, and there our subliminal selves remain, and stroll out into the pretty park and sit on the benches, and superintend the lading and unlading of the small craft from foreign ports in the old ship-canal below: the oldest ship-canal in the world, indeed, whose beginnings Shakespeare was born too late to see. We do not find the shipping is any the less picturesque for being much entangled in the net-work of railroad lines (for{35} Exeter is a large junction), or feel the sticks and spars more discordant with the smoke and steam of the locomotives through which they pierce, than with the fine tracery of the trees farther away.

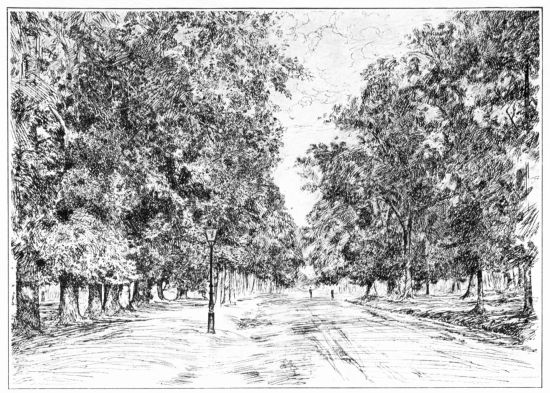

I was never an enemy of the confusion of the old and new in Europe when Italy was all Europe for me, and now in England it was distinctly a pleasure. It is something we must accept, whether we like it or not, and we had better like it. The pride of the old custodian of the Exeter Guildhall in the coil of hot-water pipes heating the ancient edifice was quite as acceptable as his pride in the thirteenth-century carvings of the oaken door and the oak-panelled walls, the portraits of the Princess Henrietta and General Monk, and the swords bestowed upon the faithful city by Edward IV. and Henry VII. I warmed my chilly hands at the familiar radiator while I thawed my fancy out to play about the medieval facts, and even fly to that uttermost antiquity when the Roman Præetorium stood where the Guildhall stands now. Still, I was not so warm all over but that I was glad to shun the in-doors inclemency to which we must have returned in the hotel, and to prolong our stay in the milder air outside by going a drive beyond the city into the charming country. I do not say that the country was more charming than about Plymouth, but it had its pleasant difference, which was hardly a difference in the subtropical types of trees and shrubs. There were the same evergreens hedging and shading, too deeply shading, the stone cottages of the suburbs as we had seen nearer the sea; but when we were well out of the town, we had climbed to high, rolling fields, which looked warm even when the sun did not shine upon them; there were brown bare woods cresting the hills, and the hedge-rows ran bare and brown between{36} the ploughed fields and the verdure of the pastures and the wheat. Behind and below us lay the town, clustering about the cathedral which dwarfed its varying tops to the illusion of one level.

We had driven out by a handsome avenue called, for reasons I did not penetrate, Pennsylvania Road. Stately houses lined the way, and the wealth and consequence of the town had imaginably transferred themselves to Pennsylvania Road from the fine old crescent where we had perhaps rashly invested; though I shall never regret it. But we came back another way, winding round by the first English lane I had ever driven through. It was all, and more, than I could have asked of it in that quality, for it was so narrow between the tall hedges, which shut everything else from sight, that if we had met another vehicle, I do not know what would have happened. There was a breathless moment when I thought we were going to meet a market-cart, but luckily it turned into an open gateway before the actual encounter. There must be tacit provision for such a chance in the British Constitution, but it is not for a semi-alien like an American to say what it is.

We were apparently the first of our nation to reach Exeter that spring, for as we came in to lunch we heard an elderly cleric, who had the air of lunching every day at the Butt of Malmsey, say to his waiter, “The Americans are coming early this year.” We had reasons of our own for thinking we had come too early; probably in midsummer the old-established cold of the venerable hostelry is quite tolerable. If I had been absolutely new to the past, I could not have complained, even in March, of its reeling floors and staggering stairways and dim passages; these were as they should be, and I am not saying anything against the table. That again was{37} better than it would have been at a hotel in an American town of the size of Exeter, and it had a personal application at breakfast and luncheon that pleased and comforted; the table d’hôte dinner was, as in other English inns, far preferable to the indiscriminate and wasteful superabundance for which we pay too much at our own. It is of the grates in the Butt of Malmsey that I complain, and I do not know that I should have cause to complain of these if I had not rashly ordered fire in mine. To give the grate time to become glowing, as grates always should be in old inns, I passed an hour or two in the reading-room talking with an elderly Irish gentleman who had come to that part of England with his wife to buy a place and settle down for the remnant of his days, after having spent the greater part of his life in South Africa. He could not praise South Africa enough. Everything flourished there and every one prospered; his family had grown up and he had left seven children settled there; it was the most wonderful country under the sun; but the two years he had now passed in England were worth the whole thirty-five years that he had passed in South Africa. I agreed with him in extolling the English country and climate, while I accepted all that he said of South Africa as true, and then I went up to my room.

With the aid of the two candles which I lighted I discovered the grate in the wall near the head of the bed, and on examining it closely I perceived that there was a fire in it. The grate would have held quite a double-handful of coal if carefully put on; the fire which seemed to be flickering so feebly had yet had the energy to draw all the warmth of the chamber up the chimney, and I stood shivering in the temperature of a subterranean dungeon. The place instantly gave evidence of being{38} haunted, and the testimony of my nerves on this point was corroborated by the spectral play of the firelight on the ceiling, when I blew out my candles. In the middle of the night I woke to the sense of something creeping with a rustling noise over the floor. I rejected the hypothesis of my bed-curtain falling into place, though I remembered putting it back that I might have light to read myself drowsy. I knew at once that it was a ghost walking the night there, and walking hard. Suddenly it ceased, and I knew why: it had been frozen out.{39}

THE American who goes to England as part of the invasion which we have lately heard so much of must constantly be vexed at finding the Romans have been pretty well everywhere before him. He might not mind the Saxons, the Danes, the Normans so much, or the transitory Phœnicians, and, of course, he could have no quarrel with the Cymri, who were there from the beginning, and formed a sort of subsoil in which conquering races successively rooted and flourished; but it is hard to have the Romans always cropping up and displacing the others. He likes well enough to meet them in southern Europe; he enjoys their ruins in Italy, in Spain, in France; but the fact of their presence in Britain forms too great a strain for his imagination. By dint of having been there such a long time ago they seem to have anticipated any novelty there is in his own coming, and by having remained four hundred years they leave him little hope of doing anything very surprising in a stay of four months. He is gnawed by a secret jealousy of the Romans, and when he lands in Liverpool, as he commonly does, and discovers them in possession of the remote antiquity of Chester, where he goes for a little comfortable mediævalism before pushing on to wreak himself on the vast modernity of London, he can hardly govern his impatience. Their ves{40}tiges are less intrusive at Plymouth and Exeter than at Chester, but still I think the sort of American I have been fancying would have been incommoded by a sense of them in the air of either place, and, if he had followed on with us to Bath, would have found no benefit from the springs which they frequented two thousand years earlier, so fevered must have been his resentment.

The very beginnings of Bath were Roman, for I suppose Prince Bladud is not to be taken as serious history, though he is poetically important as the putative prototype of King Lear (I believe he had also the personal advantage of being a giant), and he is interesting as one of the few persons who have ever profited by the example of the pigs. Men are constantly warned against that, in every way, but Prince Bladud, who went forth from his father’s house a leper, and who observed the swine under his charge wallowing in the local waters and coming out cured from his infection, immediately tried them himself, and recovered and lived to be the father of an unnatural family of daughters. By inspiring Shakespeare with the theme of his great tragedy, he was the first to impart the literary interest to Bath which afterwards increased there until it fairly rivalled its social and pathological interest. But the Romans have undoubtedly a claim to the honor of building a city on the site of the present town; under their rule it became the favorite resort of the gayety which always goes hand in hand with infirmity at medicinal springs, and if you dig anywhere in Bath, now, you come upon its vestiges. A little behind and below the actual Pump Room, these are so abundant that, if you cannot go to Herculaneum or Pompeii, you can still have a fair notion of Roman luxury from the vast tanks for bathing, the stone platforms, steps, and{41} seats, the vaulted roofs and columns, the furnaces for heating the waters, and the system of pipes for conveying it from point to point. The plumbing, in its lavish use of material, attests the advance of the Romans in the most actual and expensive of the arts; and the American invader must recognize, with whatever of gall and bitterness, that his native plumbers would have little to teach those of the conquerors who possessed Britain two thousand years before him.

If he had been coming with us from Exeter the morning we arrived, he might, indeed, have triumphed over the Romans in the comfort of his approach, for, after all, there are few trains like the English trains to give you a sense of safety, snugness, and swiftness. I like getting into them from the level of the platform, instead of climbing several steps to reach them, as we do with ours, and I like being followed into my compartment by one of those amiable porters who abound in English stations, and save your arms from being pulled out of their sockets by your hand-baggage. They are the kindest and carefullest of that class whom Lord Chesterfield nobly called his unfortunate friends, and who in England are treated with a gentle consideration almost equal to their own, and as porters they are so grateful for the slightest recompense of their service. I have seen people give them twopence, for some slight office, or nothing when they were people who could not afford something; but I never saw an English porter’s face clouded by the angry resentment which instantly darkens the French porter’s brow if he thinks himself underpaid, as he always seems to do. It did not perceptibly matter to the English porter whether he followed me into a first-class or a third-class carriage, and it was from a mere love of luxury and not from the hope of{42} gratifying any sense of superiority to the fellow-being with my hand-baggage that I ended by travelling first-class for short hauls in England. On the expresses, like those from London to Edinburgh, you can make the journey third-class in perfect comfort, and with no great risk of overcrowding, but not, I should say, in the way-trains.

We had come third-class from Plymouth to Exeter in a superstition preached us before leaving home, that everybody now went third-class in England, that to go first-class was sinfully extravagant, and that to go second-class was to chance travelling with valets and lady’s-maids. But in coming on from Exeter we thought we would risk this contamination, and, not realizing that the first-class rate was no greater than ours with the cost of a Pullman ticket added, I boldly “booked” second-class. But so far from finding ourselves in a compartment with valets and lady’s-maids, in whose company I hope we should have avouched our quality by promptly perishing, we were quite alone, except for the presence of a lady who sat by the window knitting, knitting, knitting. She did not look up, but from time to time she looked out, till our interchanges of joy in the landscape seemed to win upon her, and then she looked round. Her glance at the member of our party whose sex seemed to warrant her in the overture was apparently reassuring. She asked if we would like the window closed, and we pretended that we would not, but she closed it, and then she arranged her needles in her knitting, and folded her knitting up, and put it firmly away in her bag, and began to talk. Evidently she liked talking, but evidently she liked listening, too, and she let us do our share of both in confirming the tacit treaty of amity between our nations. She spoke

of the Americans, not as cousins, but as brothers and sisters; and I began to be sorry for all the unkind things I had said of the English, and mutely to pray that she might never see them, however just they were. She had been in America, as well as most other parts of the world, and we tried hard for some mutual acquaintance. Our failure did not matter; we were friends for that trip and train at least, and when we came to Bristol, where our own party was to change, we were fain to run away from our tea in the restaurant to take the hand held out to us from the window of her parting train.

It was very pretty, and we said, If the English were all going to be like that! I do not say that they actually were, and I do not say they were not; but no after-experience could affect the quality of that charming incident, and all the way from Bristol to Bath we turned again and again from the landscape, that lay soaking in the rains of the year before, and celebrated our good-fortune. We were still in its glamour when our train drew into Bath; and in our wish to be pleased with everything in the world to which it rapt us, we were delighted with the fitness of the fact that the largest buildings near the station should be, as their signs proclaimed, corset-manufactories. We read afterwards that corset-making was, with the quarrying of the Bath building-stone, the chief business interest of the place, as such a polite industry should be in a city which was for so long the capital of fashion. Our pleasure in it was only less than our joy in finding that our hotel was in Pulteney Street, where the Allens of “Northanger Abbey” had their apartment, and where Catherine Morland had so often come and gone with the Tilneys and the Thorpes, and round the farthest corner{44} of which the dear, the divine, the only Jane Austen herself had lived for two years in one of the large, demure, self-respectful mansions of the neighborhood.

Our hotel scarcely distinguished, and it did not at all detach itself from the rank of these handsome dwellings; and everything in our happy circumstance began at once to breathe that air of gentle association which kept Bath for a fortnight the Bath of our dreams. There was a belief with one of us that he had come to drink the waters, but an early consultation with possibly the most lenient of the medical authorities of the place, who make the doctors of German springs seem such tyrannous martinets, disabused him. Since he had brought no rheumatism to Bath, his physician owned there was a chance of his taking some away; but in the mean time he might go once a day to the Pump Room, for a glass of the water lukewarm, and be a little careful of his diet. A little careful of his diet, he who had been furiously warned on his peril at Carlsbad that everything which was not allowed was forbidden! But he found that the Bath medical men said the same thing to the patients whom he saw around him, at the hotel, doubled up with rheumatism, and eating and drinking whatever their stiffened joints could carry to their mouths. All the greater was the miraculous virtue of the waters, for the sufferers seemed to make rapid recovery in spite of themselves and their doctors. There were no lepers among them, and since Prince Bladud’s day few are noted as having resorted to Bath; but there is rheumatism enough in England to make up the defect of leprosy, and the American, who had come with only a mild dyspepsia, found himself quite out of the running, or limping, with his fellow-invalids.

He had apparently not even brought an American{45} accent with his malady, and that was a disappointment to one of the worst sufferers, who constantly assured him, in a Scotch burr so thick that he had to be begged to speak twice before he could be understood, that he was the only American without a twang whom he had ever met. The twangless dyspeptic wished at times to pretend that he was only twangless in British company, and that when his party went to their rooms they talked violently through their noses till they were out of breath, as a slight compensation for their self-denial in society. But, upon the whole, the Scotch gentleman was so kind and sweet a soul, and seemed, for all his disappointment, to value the American so much as a phenomenon that he forebore, and in the end he was not sorry.