Transcriber's Note:

Inconsistent hyphenation and spelling in the original document have

been preserved. Obvious typographical errors have been corrected.

In many cases, Bancroft uses both "u" and "v" to spell an

author’s name. Examples include:

- Villagutierre and Villagvtierre

- Mondo Nuovo and Mondo Nvovo

- Villagutierre and Villagvtierre

- Aluarado and Alvarado

- Gvat. and Guat.

- Cogolludo and Cogollvdo

- Vetancurt and Vetancvrt.

Other archaic letter substitutions include b for v, i for y,

x for j, i for j, ç or c for z and vice versa. These have been

left as printed.

Possible printers errors include:

- Quauhtemoctzin or Quauhtemotzin

- Verrazano or Verrazzano

- Bartolomeo or Bartolommeo

- Fricius or Frisius

- Gatinara or Gattinara

- Veitia and Veyia

- Loaysa and Loaisa

- Fitz-Roy and FitzRoy

- Cohuanococh and Cohuanacoch

- Ahpotzotzil or Ahpozotzil

- embassadors or ambassadors

- unincombered or unencumbered

- Albitez or Albites

- Lucayos or Lucayas

- Castelhanus or Castelhanos

- Quauhtemali or Quauhtimali.

The book cited as "Meer oder Seehanen Buch" should be "Meerhanen

oder Seehanen der Königen von Hispanien", a chapter about (not by)

Columbus. The same correction applies to the entry for "Löw

(Conr.)"

The book cited as "Delaporte. Reisen Eines Franzosen oder

Beschreibung." has an incomplete title. The complete title is

"Reisen Eines Franzosen Oder Beschreibung Der Vornehmsten Reiche

In Der Welt."

The book cited as "Santarem (M. le Vicomte), Memoire sur la

question ..." has an incomplete title. The complete title is

"Memoire sur la question de savoir á quelle époque que L'Amérique

Meridionale a cessé d'être représentée dans les cartes

géographiques comme une île d'une grande étendue."

The punctuation in Footnote IX-8 was left as printed.

Italics in the footnote citations were inconsistently applied by the

typesetter.

Accents and other diacritics are inconsistently used.

This volume contains references to the previous five volumes of this work.

They can be found at:

THE WORKS

OF

HUBERT HOWE BANCROFT.

VOLUME VI.

HISTORY OF CENTRAL AMERICA.

Vol. I. 1501-1530.

SAN FRANCISCO:

A. L. BANCROFT & COMPANY, PUBLISHERS.

1883.

Entered according to Act of Congress in the Year 1882, by

HUBERT H. BANCROFT,

In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

All Rights Reserved.

PREFACE.

During the year 1875 I published under title of

The Native Races of the Pacific States what purports

to be an exhaustive research into the character and

customs of the aboriginal inhabitants of the western

portion of North America at the time they were first

seen by their subduers. The present work is a history

of the same territory from the coming of the Europeans.

The plan is extensive and can be here but briefly explained.

The territory covered embraces the whole of

Central America and Mexico, and all Anglo-American

domains west of the Rocky Mountains. First given

is a glance at European society, particularly Spanish

civilization at about the close of the fifteenth century.

This is followed by a summary of maritime exploration

from the fourth century to the year 1540, with

some notices of the earliest American books. Then,

beginning with the discoveries of Columbus, the

men from Europe are closely followed as one after

another they find and take possession of the country

in its several parts, and the doings of their

successors are chronicled. The result is a History

of the Pacific States of North America, under

the following general divisions:—History of Central

America;

History of Mexico;

History of the North

Mexican States;

History of New Mexico and Arizona;

History of California;

History of Nevada;

History

of Utah;

History of the Northwest Coast;

History

of Oregon;

History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana;

History of British Columbia, and History of

Alaska.

Broadly stated, my plan as to order of publication

proceeds geographically from south to north, as

indicated in the list above given, which for the most

part is likewise the chronological order of conquest

and occupation. In respect of detail, to some extent

I reverse this order, proceeding from the more general

to the more minute as I advance northward.

The difference, though considerable, is however less

in reality than in appearance. And the reason I hold

sufficient. To give to each of the Spanish-American

provinces, and later to each of the federal and independent

states, covering as they do with dead monotony

centuries of unchanging action and ideas, time

and space equal to that which may be well employed

in narrating north-western occupation and empire-building

would be no less impracticable than profitless.

It is my aim to present complete and accurate

histories of all the countries whose events I attempt

to chronicle, but the annals of the several Central

American and Mexican provinces and states, both

before and after the Revolution, run in grooves too

nearly parallel long to command the attention of the

general reader.

In all the territorial subdivisions, southern as well

as northern, I treat the beginnings and earliest development

more exhaustively than later events. After

the Conquest, the histories of Central America and

Mexico are presented on a scale sufficiently comprehensive,

but national rather than local. The northern

vii

Mexican states, having had a more varied experience,

arising from nearer contact with progressional

events, receive somewhat more attention in regard to

detail than other parts of the republic. To the

Pacific United States is devoted more space comparatively

than to southern regions, California being

regarded as the centre and culminating point of this

historical field.

For the History of Central America, to which this

must serve as special as well as general introduction,

I would say that, besides the standard chroniclers and

the many documents of late printed in Spain and elsewhere,

I have been able to secure a number of valuable

manuscripts nowhere else existing; some from the

Maximilian, Ramirez, and other collections, and all of

Mr E. G. Squier's manuscripts relating to the subject

fell into my hands. Much of the material used

by me in writing of this very interesting part of the

world has been drawn from obscure sources, from

local and unknown Spanish works, and from the

somewhat confused archives of Costa Rica, Honduras,

Nicaragua, Salvador, and Guatemala.

Material for the history of western North America

has greatly increased of late. Ancient manuscripts

of whose existence historians have never known, or

which were supposed to be forever lost, have been

brought to light and printed by patriotic men and

intelligent governments. These fragments supply

many missing links in the chain of early events, and

illuminate a multitude of otherwise obscure parts.

My efforts in gathering material have been continued,

and since the publication of The Native Races

fifteen thousand volumes have been added to my collection.

viii

Among these additions are bound volumes

of original documents, copies from public and private

archives, and about eight hundred manuscript dictations

by men who played their part in creating the

history. Most of those who thus gave me their testimony

in person are now dead; and the narratives of

their observations and experiences, as they stand recorded

in these manuscript volumes, constitute no

unimportant element in the foundation upon which

the structure of this western history in its several

parts must forever rest.

To the experienced writer, who might otherwise

regard the completion of so vast an undertaking within

so apparently limited a period as indicative of work

superficially done, I would say that this History was

begun in 1869, six years before the publication of The

Native Races; and although the earlier volumes of the

several divisions I was obliged for the most part not

only to plan and write, but to extract and arrange my

own material, later I was able to utilize the labors of

others. Among these as the most faithful and efficient

I take pleasure in mentioning Mr Henry L. Oak, Mr

William Nemos, Mr Thomas Savage, Mrs Frances

Fuller Victor, and Mr Ivan Petroff, of whom, and

of others, I speak at length elsewhere.

Of my methods of working I need say but little

here, since I describe them more fully in another place.

Their peculiarity, if they have any, consists in the

employment of assistants, as before mentioned, to

bring together by indices, references, and other devices,

all existing testimony on each topic to be treated.

I thus obtain important information, which otherwise,

with but one lifetime at my disposal, would have been

ix

beyond control. Completeness of evidence by no

means insures a wise decision from an incompetent

judge; yet the wise judge gladly avails himself of all

attainable testimony. It has been my purpose to give

in every instance due credit to sources of information,

and cite freely such conclusions of other writers as

differ from my own. I am more and more convinced

of the wisdom and necessity of such a course, by which,

moreover, I aim to impart a certain bibliographic

value to my work. The detail to be encompassed appeared

absolutely unlimited, and more than once I

despaired of ever completing my task. Preparatory

investigation occupied tenfold more time than the

writing.

I deem it proper to express briefly my idea of what

history should be, and to indicate the general line of

thought that has guided me in this task. From the

mere chronicle of happenings, petty and momentous,

to the historico-philosophical essay, illustrated with

here and there a fact supporting the writer's theories,

the range is wide. Neither extreme meets the requirements

of history, however accurate the one or

brilliant the other. Not to a million minute photographs

do we look for practical information respecting

a mountain range, nor yet to an artistic painting of

some one striking feature for a correct description.

From the two extremes, equally to be avoided, the

true historian will, whatever his inclination, be impelled

by prudence, judgment, and duty from theory

toward fact, from vivid coloring toward photographic

exactness. Not that there is too much brilliancy in

current history, but too little fact. An accurate record

of events must form the foundation, and largely the

x

superstructure. Yet events pure and simple are by

no means more important than the institutionary development

which they cause or accompany. Men,

institutions, industries, must be studied equally. A

man's character and influence no less than his actions

demand attention. Cause and effect are more essential

than mere occurrence; achievements of peace

should take precedence of warlike conquest; the condition

of the people is a more profitable and interesting

subject of investigation than the acts of governors,

the valor of generals, or the doctrines of priests.

The historian must classify, and digest, and teach as

well as record; he should not, however, confound his

conclusions with the facts on which they rest. Symmetry

of plan and execution as well as rigid condensation,

always desirable, become an absolute necessity

in a work like that which I have undertaken. In

respect to time and territory my field is immense.

The matter to be presented is an intricate complication

of annals, national and sectional, local and personal.

That my plan is in every respect the best

possible, I do not say; but it is the best that my

judgment suggests after long deliberation. The extent

of this work is chargeable to the magnitude of

the subject and the immense mass of information

gathered rather than to any tendency to verbosity.

There is scarcely a page but has been twice or thrice

rewritten with a view to condensation; and instead

of faithfully discharging this irksome duty, it would

have been far easier and cheaper to have sent a hundred

volumes through the press. The plan once

formed, I sought to make the treatment exhaustive

and symmetrical. Not all regions nor all periods are

portrayed on the same scale: but though the camera

xi

of investigation is set up before each successive topic

at varying distances, the picture, large or small, is

finished with equal care. I may add that I have attached

more than ordinary importance to the matter

of mechanical arrangement, by which through title-pages,

chapter-headings, and indices the reader may

expeditiously refer to any desired topic, and find all

that the work contains about any event, period, place,

institution, man, or book; and above all I have aimed

at exactness.

We hear much of the philosophy of history, of the

science and signification of history; but there is only

one way to write anything, which is to tell the truth,

plainly and concisely. As for the writer, I will only

say that while he should lay aside for the time his

own religion and patriotism, he should be always ready

to recognize the influence and weigh the value of the

religion and patriotism of others. The exact historian

will lend himself neither to idolatry nor to detraction,

and will positively decline to act either as

the champion or assailant of any party or power.

Friendships and enmities, loves and hates, he will

throw into the crucible of evidence to be refined and

cast into forms of unalloyed truth. He must be just

and humble. To clear judgment he must add strict

integrity and catholicity of opinion. Ever in mind

should be the occult forces that move mankind, and

the laws by which are formulated belief, conscience,

and character. The actions of men are governed by

proximate states of mind, and these are generated

both from antecedent states of mind and antecedent

states of body, influenced by social and natural environment.

The right of every generation should be

xii

determined, not by the ethics of any society, sect, or

age, but by the broad, inexorable teachings of nature;

nor should he forget that standards of morality are a

freak of fashion, and that from wrongs begotten of

necessity in the womb of progress has been brought

forth right, and likewise right has engendered wrongs.

He should remember that in the worst men there is

much that is good, and in the best much that is bad;

that constructed upon the present skeleton of human

nature a perfect man would be a monster; nor should

he forget how much the world owes its bad men. But

alas! who of us are wholly free from the effects of

early training and later social atmospheres! Who

of us has not in some degree faith, hope, and charity!

Who of us does not hug some ancestral tradition, or

rock some pet theory!

As to the relative importance of early history, here

and elsewhere, it is premature for any now living to

judge. Beside the bloody battles of antiquity, the

sieges, crusades, and wild convulsions of unfolding

civilization, this transplanting of ours may seem tame.

Yet the great gathering of the enlightened from all

nations upon these shores, the subjugation of the

wilderness with its wild humanity, and the new empire-modelling

that followed, may disclose as deep a significance

in the world's future as any display of army

movements, or dainty morsels of court scandal, or the

idiosyncrasies of monarchs and ministers. It need

not be recited to possessors of our latter-day liberties

that the people are the state, and rulers the servants.

It is historical barbarism, of which the Homeric poems

and Carlovingian tales not alone are guilty, to throw

the masses into the background, or wholly to ignore

xiii

them. "Heureux le peuple dont l'histoire ennuie,"

is an oft repeated aphorism; as if deeds diabolical

were the only actions worthy of record. But we of

this new western development are not disposed to

exalt brute battling overmuch; as for rulers and generals,

we discover in them the creatures, not the creators,

of civilization. We would rather see how nations

originate, organize, and unfold; we would rather examine

the structure and operations of religions, society

refinements and tyrannies, class affinities and antagonisms,

wealth economies, the evolutions of arts and

industries, intellectual and moral as well as æsthetic

culture, and all domestic phenomena with their

homely joys and cares. For these last named, even

down to dress, or the lack of it, are in part the man,

and the man is the nation. With past history we may

become tolerably familiar; but present developments

are so strange, their anomalies are so startling to him

who attempts to reduce them to form, that he is well

content to leave for the moment the grosser extravagances

of antiquity, howsoever much superior in interest

they may be to the average mind. Yet in the old

and the new we may alike from the abstract to the

concrete note the genesis of history, and from the

concrete to the abstract regard the analysis of history.

The historian should be able to analyze and to generalize;

yet his path leads not alone through the enticing

fields of speculation, nor is it his only province to

pluck the fruits and flowers of philosophy, or to blow

brain bubbles and weave theorems. He must plod

along the rough highways of time and development,

and out of many entanglements bring the vital facts

of history. And therein lies the richest reward.

"Shakspere's capital discovery was this," says Edward

xiv

Dowden, "that the facts of the world are worthy

to command our highest ardour, our most resolute

action, our most solemn awe; and that the more we

penetrate into fact, the more will our nature be quickened,

enriched, and exalted."

That the success of this work should be proportionate

to the labor bestowed upon it is scarcely to

be expected; but I do believe that in due time it will

be generally recognized as a work worth doing, and

let me dare to hope fairly well done. If I read life's

lesson aright, truth alone is omnipotent and immortal.

Therefore, of all I wrongfully offend I crave beforehand

pardon; from those I rightfully offend I ask no

mercy; their censure is dearer to me than would be

their praise.

xv

CONTENTS OF THIS VOLUME.

CHAPTER I.

INTRODUCTION.

SPAIN AND CIVILIZATION AT THE BEGINNING OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY. |

| PAGE. |

| General View—Transition from the Old to the New Civilization—Historical

Sketch of Spain—Spanish Character—Spanish Society—Prominent

Features of the Age—Domestic Matters—The New

World—Comparative Civilizations and Savagisms—Earliest Voyages

of Discovery |

1 |

CHAPTER II.

COLUMBUS AND HIS DISCOVERIES.

1492-1500. |

| Early Experiences—The Compact—Embarkation at Palos—The Voyage—Discovery

of Land—Unfavorable Comparison with the Paradise

of Marco Polo—Cruise among the Islands—One Nature Everywhere—Desertion

of Pinzon—Wreck of the Santa María—The Fortress of

La Navidad Erected—Return to Spain—Rights of Civilization—The

Papal Bull of Partition—Fonseca Appointed Superintendent of the

Indies—Second Voyage—Navidad in Ruins—Isabela Established—Discontent

of the Colonists—Explorations of the Interior—Coasting

Cuba, and Discovery of Jamaica—Failure of Columbus as Governor—Intercourse

with Spain—Destruction of the Indians—Government

of the Indies—Diego and Bartolomé Colon—Charges against the

Admiral—Commission of Inquiry Appointed—Second Return to

Spain—Third Voyage—Trinidad Discovered—Santo Domingo

Founded—The Roldan Rebellion—Francisco de Bobadilla Appointed

to Supersede Columbus—Arbitrary and Iniquitous Conduct of

Bobadilla—Columbus Sent in Chains to Spain |

155 |

CHAPTER III.

DISCOVERY OF DARIEN.

1500-1502. |

| Rodrigo de Bastidas—Extension of New World Privileges—The Royal

Share—Juan de la Cosa—Ships of the Early Discoverers—Coasting

xvi

Darien—The Terrible Teredo—Wrecked on Española—Spanish

Money—Treatment of Bastidas by Ovando—Accused, and Sent to

Spain for Trial—He is Immediately Acquitted—Future Career and

Character of Bastidas—The Archives of the Indies—The Several

Collections of Public Documents in Spain—The Labors of Muñoz

and Navarrete—Bibliographical Notices of the Printed Collections

of Navarrete, Ternaux-Compans, Salvá and Baranda, and Pacheco

and Cárdenas |

183 |

CHAPTER IV.

COLUMBUS ON THE COASTS OF HONDURAS, NICARAGUA, AND COSTA RICA.

1502-1506. |

| The Sovereigns Decline either to Restore to the Admiral his Government,

or to Capture for him the Holy Sepulchre—So he Sails on a Fourth

Voyage of Discovery—Fernando Colon and his History—Ovando

Denies the Expedition Entrance to Santo Domingo Harbor—Columbus

Sails Westward—Strikes the Shore of Honduras near Guanaja

Island—Early American Cartography—Columbus Coasts Southward

to the Darien Isthmus—Then Returns and Attempts Settlement at

Veragua—Driven thence, his Vessels are Wrecked at Jamaica—There

midst Starvation and Mutiny he Remains a Year—Then he

Reaches Española, and finally Spain, where he shortly afterward

Dies—Character of Columbus—His Biographers |

202 |

CHAPTER V.

ADMINISTRATION OF THE INDIES.

1492-1526. |

| Columbus the Rightful Ruler—Juan Aguado—Francisco de Bobadilla—Nicolás

de Ovando—Santo Domingo the Capital of the Indies—Extension

of Organized Government to Adjacent Islands and Mainland—Residencias—Gold

Mining at Española—Race and Caste in

Government—Indian and Negro Slavery—Cruelty to the Natives—Spanish

Sentimentalism—Pacification, not Conquest—The Spanish

Monarchs always the Indian's Friends—Bad Treatment due to Distance

and Evil-minded Agents—Infamous Doings of Ovando—Repartimientos

and Encomiendas—The Sovereigns Intend them as

Protection to the Natives—Settlers Make them the Means of Indian

Enslavement—Las Casas Appears and Protests against Inhumanities—The

Defaulting Treasurer—Diego Colon Supersedes Ovando as

Governor—And Makes Matters Worse—The Jeronimite Fathers

Sent Out—Audiencias—A Sovereign Tribunal is Established at

Santo Domingo which Gradually Assumes all the Functions of an

Audiencia, and as such Finally Governs the Indies—Las Casas in

Spain—The Consejo de Indias, and Casa de Contratacion—Legislation

for the Indies |

247

xvii |

CHAPTER VI.

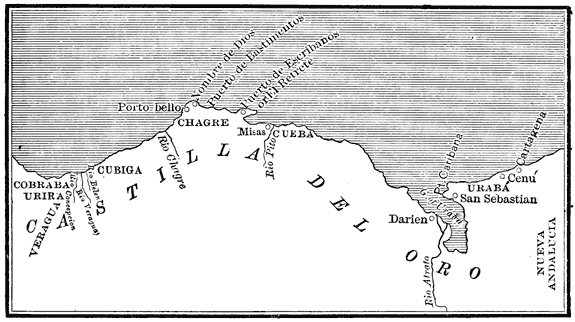

THE GOVERNMENTS OF NUEVA ANDALUCÍA AND CASTILLA DEL ORO.

1506-1510. |

| Tierra Firme Thrown Open to Colonization—Rival Applications—Alonso

de Ojeda Appointed Governor of Nueva Andalucía, and Diego de

Nicuesa of Castilla del Oro—Hostile Attitudes of the Rivals at Santo

Domingo—Ojeda Embarks for Cartagena—Builds the Fortress of San

Sebastian—Failure and Death—Nicuesa Sails from Veragua—Parts

Company with his Fleet—His Vessel is Wrecked—Passes Veragua—Confined

with his Starving Crew on an Island—Succor—Failure at

Veragua—Attempts Settlement at Nombre de Dios—Loss of Ship

Sent to Española for Relief—Horrible Sufferings—Bibliographical

Notices of Las Casas, Oviedo, Peter Martyr, Gomara, and Herrera—Character

of the Early Chroniclers for Veracity |

289 |

CHAPTER VII.

SETTLEMENT OF SANTA MARÍA DE LA ANTIGUA DEL DARIEN.

1510-1511. |

| Francisco Pizarro Abandons San Sebastian—Meets Enciso at Cartagena—He

and his Crew Look like Pirates—They are Taken back to San

Sebastian—Vasco Nuñez de Balboa—Boards Enciso's Ship in a Cask—Arrives

at San Sebastian—The Spaniards Cross to Darien—The River

and the Name—Cemaco, Cacique of Darien, Defeated—Founding of

the Metropolitan City—Presto, Change! The Hombre del Casco Up,

the Bachiller Down—Vasco Nuñez, Alcalde—Nature of the Office—Regidor—Colmenares,

in Search of Nicuesa, Arrives at Antigua—He

Finds Him in a Pitiable Plight—Antigua Makes Overtures to

Nicuesa—Then Rejects Him—And Finally Drives Him Forth to

Die—Sad End of Nicuesa |

321 |

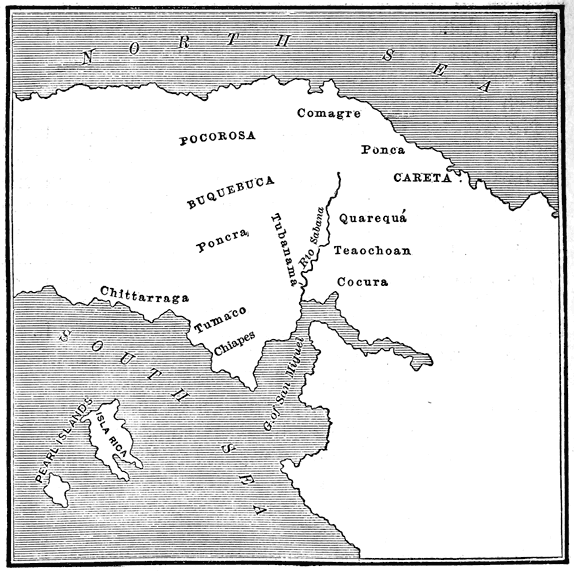

CHAPTER VIII.

FACTIONS AND FORAGINGS IN DARIEN.

1511-1513. |

| The Garrison at Nombre de Dios—Subtle Diplomacies—Vasco Nuñez

Assumes Command—Enciso, his Life and Writings—The Town

and the Jail—Rights of Sanctuary—Valdivia's Voyage—Zamudio's

Mission—Expedition to Coiba—Careta Gives Vasco Nuñez his

Daughter—Ponca Punished—Jura, the Savage Statesman—Visit of

the Spaniards to Comagre—Panciaco Tells Them of a Southern

Sea—The Story of Valdivia, Who is Shipwrecked and Eaten by

Cannibals—Vasco Nuñez Undertakes an Impious Pilgrimage to the

Golden Temple of Dabaiba—Conspiracy Formed by the Natives to

Destroy Antigua—Fulvia Divulges the Plot—Darien Quieted—Vasco

Nuñez Receives a Royal Commission—Serious Charges—Vasco

Nuñez Resolves to Discover the Southern Sea before He is

Prevented by Arrest |

337

xviii |

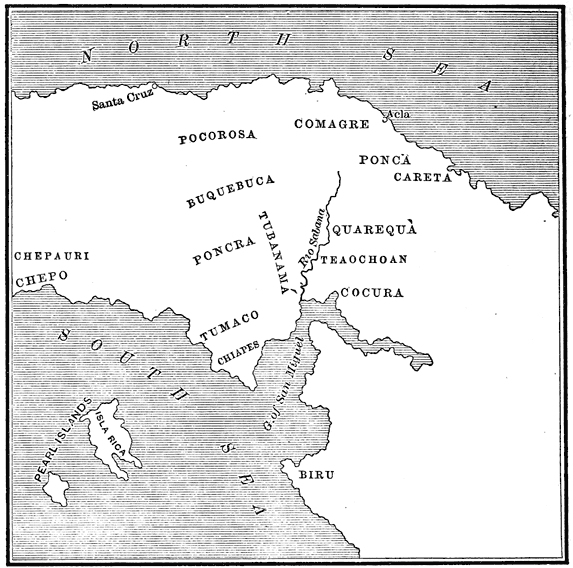

CHAPTER IX.

DISCOVERY OF THE PACIFIC OCEAN.

1513. |

| Departure of Vasco Nuñez from Antigua—Careta's Welcome—Difficulties

to be Encountered—Treacherous Character of the Country—Historical

Bloodhounds—Ponca Reconciled—Capture of Quarequá—First

View of the Pacific from the Heights of Quarequá—The

Spaniards Descend to Chiapes—Take Formal Possession of the South

Sea—Form of Taking Possession—The Names South Sea and Pacific

Ocean—Further Discoveries—Perilous Canoe Voyage—Gold and

Pearls in Profusion—Tumaco Pacified—The Pearl Islands—The

Return—Teoca's Kindness—Ponca Murdered—Pocorosa Pacified—Tubanamá

Vanquished—Gold, Gold, Gold—Panciaco's Congratulations—Arrival

at Antigua |

358 |

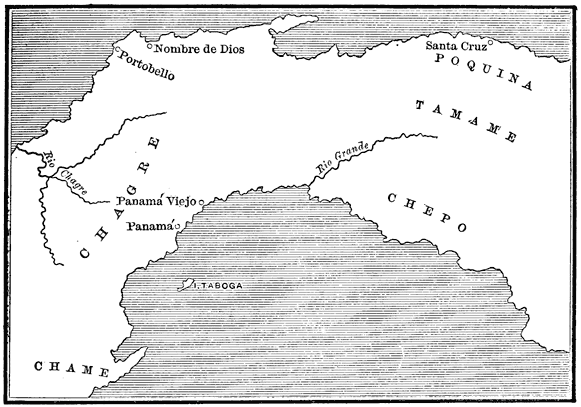

CHAPTER X.

PEDRARIAS DÁVILA ASSUMES THE GOVERNMENT OF DARIEN.

1514-1515. |

| How the Discovery of a South Sea was Regarded in Spain—The Enemies

of Vasco Nuñez at Court—Pedrarias Dávila Appointed Governor—Departure

from Spain and Arrival at Antigua—Arbolancha

in Spain—Pedrarias Persecutes Balboa—The King's Requirement

of the Indians—Juan de Ayora Sent to Plant a Line of Fortresses

between the Two Seas—Which Work He Leaves for Wholesale

Robbery—Bartolomé Hurtado Sent to Bring in the Plunder—Disastrous

Attempts to Violate the Sepulchres of Cenú—Expedition

of Tello de Guzman to the South Sea—The Site of Panamá Discovered—The

Golden Temple of Dabaiba Once More—Gaspar de Morales

and Francisco Pizarro Visit the South Sea |

386 |

CHAPTER XI.

DARIEN EXPEDITIONS UNDER PEDRARIAS.

1515-1517. |

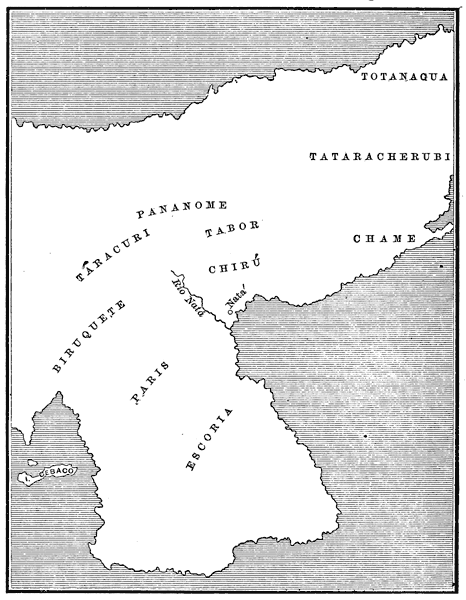

| Gonzalo de Badajoz Visits the South Sea—What He Sees at Nombre de

Dios—His Dealings with Totonagua—And with Tataracherubi—Arrives

at Natá—The Spaniards Gather much Gold—They Encounter

the Redoubtable Paris—A Desperate Fight—Badajoz Loses his

Gold and Returns to Darien—Pedrarias on the War-path—He Strikes

Cenú a Blow of Revenge—Acla Founded—The Governor Returns Ill

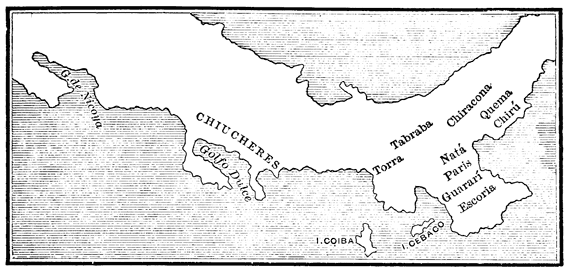

to Antigua—Expedition of Gaspar de Espinosa to the South Sea—The

Licentiate's Ass—Robbery by Law—Espinosa's Relation—A

Bloody-handed Priest—Espinosa at Natá—He Courts the Acquaintance

of Paris—Who Kills the Ambassadors—Hurtado Surveys the

Southern Seaboard to Nicoya—Panamá Founded—An Aboriginal

Tartarus—Return of Espinosa's Expedition |

412

xix |

CHAPTER XII.

THE FATE OF VASCO NUÑEZ DE BALBOA.

1516-1517. |

| Affairs at Antigua—Different Qualities of Pacification—Complaints of

Vasco Nuñez to the King—A New Expedition Planned—Vasco Nuñez

Made Adelantado and Captain-general of the South Sea—Pedrarias

Keeps Secret the Appointment—Reconciliation of Balboa and Pedrarias—Betrothal

of Doña María—Vasco Nuñez Goes to Acla—Massacre

of Olano—The Municipality of Acla Established—Materials

for Ships Carried across the Mountains—Difficulties, Perils,

and Mortality—Balboa at the Pearl Islands—Prediction of Micer

Codro, the Astrologer—Rumored Arrival of a New Governor at

Antigua—Meditated Evasion of New Authority—The Infamy of

Garabito—Vasco Nuñez Summoned by Pedrarias to Acla—His

Journey thither—Trial and Execution |

432 |

CHAPTER XIII.

DECLINE OF SPANISH SETTLEMENT ON THE NORTH COAST.

1517-1523. |

| Dishonesty the Best Policy—Pedrarias Stigmatized—His Authority Curtailed—Quevedo

in Spain—He Encounters Las Casas—The Battle of

the Priests—Oviedo Enters the Arena—Business in Darien—The

Interoceanic Road Again—Its Termini—Pedrarias and Espinosa at

Panamá—The Licentiate Makes another Raid—The Friars of St

Jerome have their Eye on Pedrarias—The Cabildo of Antigua Shakes

its Finger at Him—Continued Attempts to Depopulate the North

Coast—Albites Builds Nombre de Dios—Lucky Licentiate—Arrival

and Death of Lope de Sosa—Oviedo Returns and Does Battle with

the Dragon—And is Beaten from the Field |

460 |

CHAPTER XIV.

GIL GONZALEZ IN COSTA RICA AND NICARAGUA.

1519-1523. |

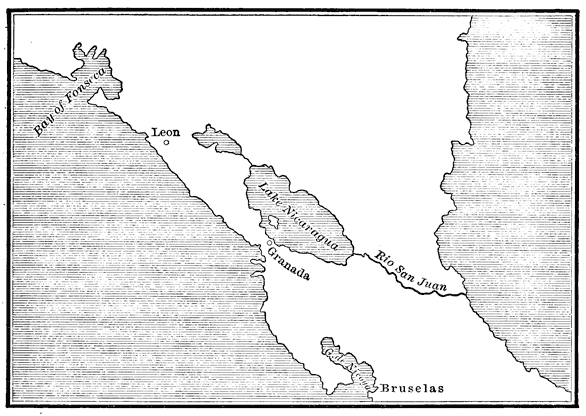

| Andrés Niño and his Spice Islands—Fails to Obtain Authority to Discover—Applies

to Gil Gonzalez Dávila—Agreement with the King—Royal

Order for the Ships of Vasco Nuñez—Pedrarias Refuses to

Deliver Them—Gil Gonzalez Transports Ships across the Mountains—Embarks

from the Pearl Islands—Gil Gonzalez Proceeds by

Land and Niño by Sea—Visit to Nicoya—And to Nicaragua—The

Captain-general Converts many Souls—And Gathers much Gold—Fight

with Diriangen—Nicaragua Apostatizes—The Spaniards Terminate

the Discovery and Hasten to their Ships—Niño's Voyage to

Fonseca Bay—Return to Panamá |

478

xx |

CHAPTER XV.

SPANISH DEPREDATIONS ROUND PANAMÁ BAY.

1521-1526. |

| European Settlement on the West Coast of America—Progress of Panamá—Laws

Respecting Spanish Settlements in America—Final

Abandonment of Antigua—Administration of the South Sea Government—Piracy

upon Principle—Pascual de Andagoya Explores Southward—Conquers

Birú—Return to Panamá—Colonies of Veragua and

Chiriquí—The Chieftain Urracá Takes up his Abode in the Mountains

and Defies the Spaniards—Pizarro, Espinosa, Pedrarias, and

Compañon in vain Attempt his Overthrow—Building of Natá—Compañon

as Governor—Hurtado Colonizes Chiriquí—Conspiracy—Capture

and Escape of Urracá—Several Years more of War |

495 |

CHAPTER XVI.

THE WARS OF THE SPANIARDS.

1523-1524. |

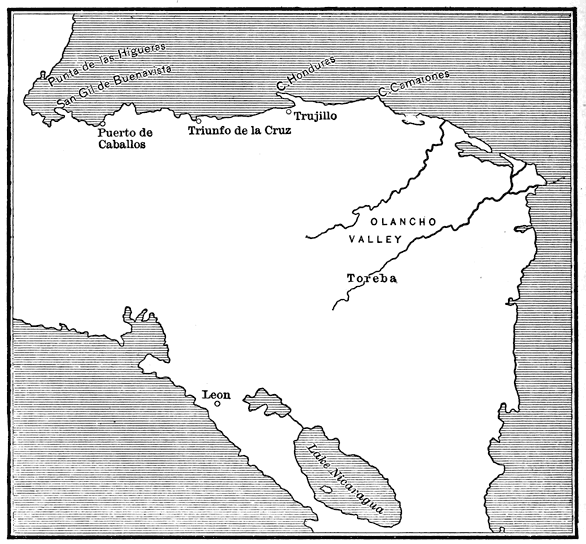

| Oviedo in Spain—He Secures the Appointment of Pedro de los Rios as

Governor of Castilla del Oro—Pedrarias Determines to Possess

Nicaragua—He Sends thither Córdoba, who Founds Brusélas, Granada,

and Leon—And Carries a Ship across the Land from the

Pacific to Lake Nicaragua—He Makes a Survey of the Lake—Informed

of Spaniards Lurking thereabout—Development of the

Spanish Colonial System—Gil Gonzalez Escapes with his Treasure

to Española—Despatches Cereceda to Spain with Intelligence of his

Discovery—Sails from Santo Domingo to the Coast of Honduras—Arrives

at Puerto Caballos—Founds San Gil de Buenavista—Encounters

Hernando de Soto—Battle—Cristóbal de Olid Appears—Founds

Triunfo de la Cruz |

511 |

CHAPTER XVII.

COLONIZATION IN HONDURAS.

1524-1525. |

| Cortés in Mexico—Extension of his Conquests—Fears of Encroachments

on the Part of Spaniards in Central America—Cristóbal de Olid Sent

to Honduras—Touching at Habana, He is Won from Allegiance to

Cortés—Triunfo de la Cruz Founded—Olid as Traitor—Meeting with

Gil Gonzalez—The Wrath of Cortés—Casas Sent after Olid—Naval

Engagement in Triunfo Harbor—Casas Falls into the Hands of Olid,

Who is soon Captured by the Captive—Death of Olid—Return of

Casas to Mexico—Trujillo Founded—Interference of the Audiencia

of Santo Domingo |

522

xxi |

CHAPTER XVIII.

MARCH OF CORTÉS TO HONDURAS.

1524-1525. |

| Doubts concerning Casas—Cortés Tired of Inaction—Determines to Go

in Person to Honduras—Sets out with a Large Party—Arrives at

Goazacoalco—The Gay Army soon Comes to Grief—The Way Barred

by Large Rivers and Deep Morasses—Scarcity of Provisions—Sufferings

of the Soldiers—The Trick of the Merchant-cacique—Killing

of the Captive Kings—Apotheosis of a Charger—Fears of Rebellious

Spaniards Dissipated on Nearing Nito |

537 |

CHAPTER XIX.

CORTÉS IN HONDURAS.

1525-1526. |

| He is Master of all the Miseries there—Miasma and Deep Distress—Exertions

of Cortés in Behalf of the Colonists—A Vessel Appears

with Provisions—Cortés Sends out Foragers—He Seeks a Better

Locality—Sandoval at Naco—Others Settle at Caballos—Cortés at

Trujillo—Vessels Sent to Mexico, Cuba, and Jamaica—Troubles in

Mexico—Cortés Irresolute—Starts for Mexico—Is Driven back by a

Storm—Pacification of Adjacent Pueblos—Cortés Sends Presents to

Córdoba—Shall Cortés Make himself Master of Nicaragua?—Arrival

of Altamirano—Return of Cortés to Mexico |

566 |

CHAPTER XX.

PEDRARIAS REMOVES TO NICARAGUA.

1525-1527. |

| Córdoba Meditates Revolt—Soto and Compañon Object—Their Flight—Pedrarias

Nurses his Wrath—Secret Motives for his Departure for

Nicaragua—Córdoba Loses his Head—The Governor Covets Honduras,

and Comes to Blows—The Indians Follow the Example—Bloody

Scenes—Pedrarias Interrupted in his Reverie—Pedro de los

Rios Succeeds as Governor at Panamá—His Instructions and

Policy—Residencia of Pedrarias—Triumphant Result |

584 |

CHAPTER XXI.

RIVAL GOVERNORS IN HONDURAS AND NICARAGUA.

1526-1530. |

| Colonial Policy—Salcedo Displaces Saavedra in the Government of Honduras—Saavedra's

Escape—Pedrarias' Envoys Trapped—Salcedo

Invades Nicaragua—His Cruelty and Extortion—Distress among the

Colonists—Rios also Presents Claims, but is Discomfited—Pedrarias

Follows Triumphant—Salcedo's Ignominious Fate—Estete's Expedition—Slave-hunting

Profits and Horrors—Gladiatorial Punishment of

Revolted Natives—Pedrarias' Schemes for Aggrandizement—He

Grasps at Salvador and Longs for Peru—Both Elude Him—Further

Mortification, and Death—Character of the Conquerors |

597

xxii |

CHAPTER XXII.

MARCH OF ALVARADO TO GUATEMALA.

1522-1524. |

| Rumors in Mexico concerning the Country to the South-eastward—Pacification

in that Quarter—The Chiefs of Tehuantepec and Tututepec—At

the Gate of Guatemala—Summary of Aboriginal History—Allegiance

and Revolt—Preparing of an Expedition—Delayed by the

Troubles at Pánuco—A Second Army Organized—The March—Subjugation

of Soconusco—The Taking of Zapotitlan |

617 |

CHAPTER XXIII.

CONQUEST OF GUATEMALA BEGUN.

February-March, 1524. |

| Overtures of Kicab Tanub to the Lords of the Zutugils and Cakchiquels—Death

of the Quiché King—Tecum Umam his Successor—Gathers a

Great Army—Intrenches Himself at Zacaha—Passage of Palahunoh

by the Spaniards—A Skirmish—A Bloody Engagement—Quezaltenango

Established—The Army Advances on Xelahuh—The City

Deserted—Battle of Xelahuh—Tecum Umam Slain—Forcible

Proselyting |

632 |

CHAPTER XXIV.

DOWNFALL OF THE QUICHÉ NATION.

April, 1524. |

| Utatlan, Capital of the Quichés—Its Magnificence—The Royal Palace

and Pyramidal Fortifications—Private Apartments and Gardens—Plan

to Entrap the Spaniards—A Feast Prepared—The Enemy

Invited—The Treachery Discovered—Masterly Retreat of Alvarado—The

Quiché King and Nobles Entrapped—They are Made to

Gather Gold—And are then Destroyed—Utatlan Burned and the

Country Devastated—Subjugation of the Quichés Complete |

643 |

CHAPTER XXV.

THE CAKCHIQUELS AND ZUTUGILS MADE SUBJECTS OF SPAIN.

April-May, 1524. |

| March to the Cakchiquel Capital—With a Brilliant Retinue King Sinacam

Comes forth to Meet the Spaniards—Description of Patinamit—Occupation

of the Cakchiquel Capital—Expedition against Tepepul,

King of the Zutugils—The Cliff City of Atitlan—A Warm Battle—Entry

into the Stronghold—Reconciliation and Return to Patinamit—Love

Episode of Alvarado |

652

xxiii |

CHAPTER XXVI.

EXPEDITION TO SALVADOR.

1524. |

| Campaign against Itzcuintlan—A Rough March—The Town Surprised—Desperate

Defence—Alvarado Determines to Explore still farther

South—Crossing the River Michatoyat—The Spaniards Come to

Atiquipac, Tacuylula, Taxisco, Nancintlan, and Pazaco—The Towns

Deserted—Poisoned Stakes and Canine Sacrifice—Enter Salvador—Moquizalco

and Acatepec—Battles of Acajutla and Tacuxcalco—Blood-thirstiness

of this Conqueror—Entry into Cuzcatlan—Flight

of the Inhabitants—Return to Patinamit |

663 |

CHAPTER XXVII.

REVOLT OF THE CAKCHIQUELS.

1524-1525. |

| Return of the Allies to Mexico—Founding of the City of Santiago—The

Cakchiquels Oppressed beyond Endurance—They Flee from the

City—Difficulty in again Reducing Them to Subjection—Reinforcements

from Mexico—Campaign against Mixco—Capture of that

Stronghold—Fight with the Chignautecs—Superhuman Valor of a

Cavalryman—Conquest of the Zacatepec Valley—Expedition against

the Mames—Defeat of Can Ilocab—Entry into Huehuetenango—Siege

of Zakuléu—Surrender of Caibil Balam |

678 |

xxiv

AUTHORITIES QUOTED

IN THE

HISTORY OF CENTRAL AMERICA.

Aa (Pieter vander), Naaukeurige Versameling. Leyden, 1707. 30 vols.

Abaunza (Justo), El Senador Director Provisorio a sus Compatriotas. Agosto

5 de 1851. [Leon, 1851.] folio.

Abbott (John S. C.), Christopher Columbus. New York, 1875.

Abbott (John S. C.), History of Hernando Cortez. New York, 1855.

Acosta (Joaquin), Compendio Histórico del Descubrimiento, etc., de la Nueva

Granada. Paris, 1848.

Acosta (Josef de), De Natvra novi orbis libri dvo. Salmanticæ, 1589.

Acosta (Josef de), De Procvranda Salvte indorvm. Salmanticæ, 1588.

Acosta (Josef de), Historia Natural y Moral de las Yndias. Sevilla, 1590.

[Quoted as Hist. Ind.]

Acosta (Josef de), The Naturall and Morall Historie of the East and West

Indies. London, n.d. [1604]. [Quoted as Hist. Nat. Ind.]

Adams (C. B.), Catalogue of Panama Shells. New York, 1852.

Aguiar y Acuña (Rodrigo de), Svmarios de la Recopilacion general de las

Leyes de las Indias. Madrid, 1628.

Aguilar (Manuel), Memoria sobre el cultivo del Café. Guatemala, 1845.

Ahumada (Augustin de), Nicaragua, Dec. 24, 1755. MS.

Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sitzungsberichte, Abhandlungen. Berlin, 1859

et seq.

Alaman (Lúcas), Disertaciones sobre la Historia de la República Mejicana.

Méjico, 1844-9. 3 vols.

Alaman (Lúcas), Historia de Méjico. Méjico, 1849-52. 5 vols.

Albolario y Periquillo. [San Salvador, 1852.] folio.

Albornoz, Carta al Emperador, 15 Dic. 1525. In Icazbalceta, Col. Doc., tom.

i.; Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xii.

Album Mexicano. Mexico, 1849 et seq.

Album Semanal, San Jose, 1856 et seq.

Alcanzada (Victoria), Discursos Pronunciados, Abril 29 de 1863. Managua,

1864. folio.

Alcedo (Antonio de), Diccionario Geográfico Histórico. Madrid, 1786-9. 5 vols.

Alegre (Francisco Javier), Historia de la Compañia de Jesus en Nueva España.

Mexico, 1841. 3 vols.

Allen (Bird), Sketch of the Eastern Coast of Central America. In Lond. Geog.

Soc., Jour., 1841. vol. xi.

Almagro, Informacion. In Col. Doc. Inéd., tom. xxvi.

Almy (John J.), Report on Chiriquí. [New York], 1859.

Altos Los, Manifiesto documentado que el Gobierno, etc. Guatemala, 1849.

folio.

xxvi

Alvarado (Gonzalo de), Memoria. MS.

Alvarado (Hernando de), and Joan de Padilla, Relacion del descubrimiento

del mar del sur. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. iii.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Asiento y Capitulacion, in Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col.

Doc., tom. xvi.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Cartas Varias desde 1534 hasta 1541. MS. folio.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Fundacion de Gracias á Dios, 1536. In Pacheco and

Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xv.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Lettres de Pedro de Alvarado à Fernand Cortes. In

Ternaux-Compans, Voy., serie i., tom. x.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Real Cedula a Pedro de Alvarado, 16 Abril, 1538.

In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xiv.

Alvarado (Pedro de), Relacion hecha a Hernando Cortés, 28 de Julio, 1524.

In Barcia, Historiadores Prim., tom. i.

Alvares (Pedro), Navigation. 1520. In Ramusio, Viaggi, tom. i.

Alzate y Ramirez (José Antonio), Gacetas de Literatura de Mexico. Mexico,

1790-4. 3 vols.; and Puebla, 1831. 4 vols.

Amador de los Rios (José), Vida y Escritos de Oviedo. In Oviedo, tom. i.

America, Descripcion de la America meridional y Septentrional. (Madrid,

1809.) MS. folio.

America, Disertacion sobre varias cuestiones interesantes pertenecientes à los

negocios de America. Madrid, 1821.

America ó examen general de la situacion politica. Northampton, 1828.

America: or a General Survey of the Political Situation. Philadelphia.

America: or an exact description of the West-Indies. London, 1655.

America Settentrionale e meridionale. Torino, 1836.

America, The Progress and Prospects. New York (1855).

America Central, Gaceta Oficial. Managua, 1849 et seq.

America Central, Reclamacion de la Intervencion de Alej. Macdonald. Leon,

[1842.]

American Almanac. Boston, 1830 et seq.

American Annual Register. New York, etc., 1825 et seq.

American Antiquarian Society, Proceedings. Worcester, 1820 et seq.

American Geographical Society, Bulletin. New York, 1874 et seq.

American Notes and Queries. Philadelphia, 1857 et seq.

American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia, 1819 et seq.

American Quarterly Register and Magazine. Philadelphia, 1848 et seq.

American Quarterly Review. Philadelphia, 1827 et seq.

American Register. Philadelphia, 1807 et seq.

American Review. Philadelphia, 1811 et seq.

American State Papers. Boston, 1817 et seq.

American and Foreign Christian Union. New York, 1850 et seq.

Amérique Centrale, Colonisation du District de Santo-Thomas, Guatemala.

Paris, 1844.

Amoretti (Charles), Primo Viaggio intorno al Globo ... fatta dal Antonio

Pigafetta. Milano, 1800.

Andagoya (Pascual de), Carta al Rey, 22 Oct., 1534.

Andagoya (Pascual de), Narrative of the Proceedings of Pedrarias Dávila.

London, 1865.

Andagoya (Pascual de), Relacion de los sucesos de Pedrárias Dávila. In

Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. iii.

Anderson (Adam), Historical and Chronological deduction of the origin of

Commerce. London, 1801. folio. 4 vols.

Anderson (Young), Eastern Coast of Central America, Report 1839. London,

1839.

Andrews (W. S.), Illustrations of West Indies. London, n.d. folio.

Andrino (J. E.), Remitido á la Gaceta de Salvador 20 Julio, 1853. San

Salvador, 1853. folio.

Annales des Voyages. Paris, 1809-14. 24 vols.

Annals of British Legislation. London, 1856 et seq. 4to.

xxvii

Annals of Congress. (1st to 18th Congress.) Washington, 1834-56. 42 vols.

Annual Register. London, 1758-1807. 47 vols.

Anson (George), A Voyage round the World. London, 1756.

Antonelli (Juan Bautista), Instruccion hecha por el Ingeniero para San Juan

de Ulúa. 15 Mar., 1590. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xiii.

Antunez y Acevedo (Rafael), Memorias Históricas. Madrid, 1797.

Apiano (Pedro), Cosmographia corregida y añadida por Gemma Frisio.

Anvers, 1575.

Apianus (Petrus), Cosmographicus Liber, Landshutæ, 1524.

Apianus (Petrus), Introductio geographica Petri Apiani, Ingolstadii, 1533.

Appleton's Handbook of American Travel. New York, 1867.

Appleton's Illustrated Handbook of American Travel. New York, 1857.

Aragon (Antonino), La Victoria de Coatepeque. San Salvador, 1863.

Arana (Thomas Ignacio), Relacion de los estragos, y rvynas de Guathemala.

Guathemala, 1717. folio.

Arancel de los derechos, que se han de llevar en las dos Secretarias. Madrid,

1749.

Arancel de 1720. In Reales Ordenes, tom. iii.

Archenholtz (J. M. von), History of the Pirates, etc., of America. London, 1807.

Arellano (Jose N.), Oracion funebre, 26 Oct., 1846. Guatemala, 1846.

Arévalo (Faustino), Laudatio funebris eminentissimi Francisci Antonii de

Lorenzana. Romæ [1804]. folio.

Arévalo (Rafael de), Coleccion de Documentos Antiguos del Archivo de Guatemala.

Guatemala, 1857.

Arévalo (Rafael de), Libro de Actas del Ayuntamiento de Guatemala. Guatemala,

1856.

Ariza (Andrés), Comentos de la Rica y Fertilisima Provincia de el Darien.

1774. MS. 4to.

Armin (Th.), Das Alte Mexiko. Leipzig, 1865.

Arosemena (Justo), Examen sobre la Franca comunicacion, Istmo de Panama.

Bogotá, 1846.

Arrangoiz (Francisco de Paula de), Mejico desde 1808 hasta 1867. Madrid,

1871-2. 4 vols.

Arricivita (J. D.), Crónica Seráfica y Apostolica. Madrid, 1792. folio.

Arrillaga (Basilio D.), Informe que dieron los Cónsules. Mexico, 1818. 4to.

Arriola (D. J. de), Ilegitimidad de la Administracion Barrios. [Leon, 1862.]

Artieda, Pacificacion de Costa Rica. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc.,

tom. xv.

Asher (G. M.), Life of Henry Hudson. London, 1860.

Astaburuaga (Francisco S.), Repúblicas de Centro-America. Santiago, 1857.

Atitlan, Requête de plusieurs chefs. In Ternaux-Compans, série i., tom. x.

Atlantic Monthly. Boston, 1858 et seq.

Audiencia de Santo Domingo, Cartas. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc.,

tom. i.

Auger (Edward), Voyage en Californie. Paris, 1854.

Aurrecoecha (José Maria de), Historia sucinta é imparcial de la marcha que

ha seguido en sus convulsiones políticas la América Española, etc.

Madrid, 1846. 4to.

Avery (William T.), Speech in U. S. House of Rep., Jan. 24, 1859. Washington,

1859.

Avezac (Martin), Hylacomylus. Paris, 1867.

Avezac (Martin), In Nouvelles Annales des Voyages, tom. cv.; tom. cvi.;

tom. cviii.; tom. cx.; also Soc. Geog., Bulletin, tom. xiv.

Avila y Lugo, Descripcion de las Yslas Guanajas, 1639.

Ayetta, Informe, in Provincia del Santo Evangelio. 8 Mar., 1594.

Ayon (Tomas), Apuntes sobre algunos de los acontecimientos. Nicaragua,

etc., 1811 et seq.

Ayon (Tomas), Consideraciones sobre la cuestion de Limites Territoriales.

Managua, 1872.

Ayon (Tomas), Speech, Feb. 1, 1862. San Salvador, 1862.

xxviii

Bagatela (La), Agosto 19, 1851 et seq. [Granada.]

Baily (John), Central America; describing Guatemala, Honduras, Salvador,

Nicaragua, and Costa Rica. London, 1850.

Balboa (Vasco Nuñez de), Cartas. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom.

ii.; Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. iii.

Balboa (Vasco Nuñez de), Los Navíos.

Bancroft (George), History of the United States. Boston, 1870, et seq.

Bancroft (Hubert Howe), Native Races of the Pacific States. New York,

1875. 5 vols.

Banks (James), On the Cotton of Honduras and Yucatan, n.pl., n.d.

Barcia (Andrés Gonzalez de), Historiadores Primitivos de las Indias Occidentales.

Madrid, 1749. folio. 3 vols.

Bard (Samuel A.), Waikna; or, Adventures on the Mosquito Shore. [By

E. G. Squier.] New York, 1855.

Barrionuevo, Informacion hecha en Panamá al navío Concepcion. 7 Abril,

1534. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. x.

Barrios (Gerardo), A los pueblos del Salvador, Segundo manifiesto. San Salvador,

1863.

Barrios (Gerardo), Discurso ante el Cuerpo Legislativo del Salvador, Febrero

1, 1860. San Salvador, [1860.]

Barrios (Gerardo), El porqué de la caida de Barrios. San Salvador, 1863.

Barrios (Gerardo), Manifesto of. Nueva York, 1864.

Barrios (Gerardo), Presidente Legitimo de la Republica del Salvador. Panama,

1863.

Barrios (Gerardo), Relaciones con el Gobierno de Nicaragua. Managua, 1860.

Barrios (José Rufino), General en Gefe, á los Pueblos del Salvador, Mayo 8,

1876. San Salvador, 1876.

Barrow (John), The Life, Voyages, and Exploits of Admiral Sir Francis Drake.

London, 1843.

Barrundia (José), Discurso Pronunciado, Setiembre 15, 1850. San Salvador,

[1850.]

Bastidas (Rodrigo de), Asiento que hizo con sus Majestades Católicas, 5 Junio,

1500. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. ii.

Bastidas (Rodrigo de), Informacion de los Servicios. In Pacheco and Cárdenas,

Col. Doc., tom. ii.

Bastide (M. de), Mémoire sur un Nouveau Passage. Paris, 1791.

Bates (H. W.), Central America, The West Indies, and South America.

London, 1878.

Batres (Manuel de), Relacion de las fiestas reales. Guatemala, 1761.

Baxley (Willis), What I saw on the West Coast of South and North America.

New York, 1865.

Bay Islands, Copy of Queen's warrant for erecting into a British Colony, etc.

London, 1856. folio.

Bayle (Pierre), Dictionnaire Historique et Critique. Rotterdam, 1720. folio.

4 vols.

Beaumont, Pablo de la Purísima Concepcion, Crónica de la Provincia de S.

Pedro y S. Pablo de Mechoacan, MS.; also Mexico, 1873-4. 5 vols.

Beccatini (Francisco), Vida de Carlos III. Madrid, 1790.

Beechey (F. W.), Address at the Anniversary Meeting of the Royal Geographical

Society, 26th May, 1856. London, 1856.

Beechey (F. W.), Narrative of a Voyage to the Pacific, 1825-8. London,

1831. 2 vols.

Behaim (Martin), Globe—Humboldt's Essay on the Oldest Maps. MS. folio.

Bejarano (Félix Francisco), Informe hecho por el Gobernador de Veragua.

1775. MS.

Belcher (Edward), Narrative of a Voyage round the World, 1836-42. London,

1843. 2 vols.

Belize, Copy of a letter, Nov., 1836, to S. Coxe, defining boundary. London, 1856.

Belize, Packet Intelligencer. Belize, 1854 et seq.

Belknap (Jeremy), American Biography. Boston, 1794.

xxix

Bell (Chas N.), Remarks on the Mosquito Territory. In Lond. Geog. Soc.

Jour., vol. xxxii.

Bell (James), A System of Geography. Glasgow, 1836. 6 vols.

Bell (John), Speech in Senate of the U. S., February 26, 1856. Washington, 1856.

Belly (Félix), À Travers L'Amérique Centrale. Paris, 1867. 2 vols.; also

Paris, 1870. 2 vols.

Belly (Félix), Carte d'Etude pour le tracé et le profil du Canal de Nicaragua.

Paris, 1858.

Belly (Félix), Durchbruch des Amerikanischen Continents. Paris, 1859.

Belly (Félix), Le Nicaragua. Paris, 1870. 2 vols.

Belly (Félix), Protesta del Señor Don Félix Belly. Leon, 1869.

Belot (Gustave), La Vérité sur le Honduras. Paris, n.d.

Benton (Joseph A.), Speech in U. S. Senate, March, 1826. Washington City, 1826.

Benton (Thomas H.), Abridgment of Debates in Congress, 1759-1856. New

York, 1857-63. 16 vols.

Benton (Thomas H.), Thirty Years' View U. S. Senate. New York, 1854. 2 vols.

Benzoni (Girolamo), History of the New World. (Hakl. Soc. ed.) London, 1857.

Benzoni (Girolamo), La Historia del Mondo Nuovo. Venetia, 1572.

Berendt (C. H.), Report of Explorations in Central America. In Smithsonian

Report, 1867.

Berendt (Hermann), Analytical Alphabet for Mexican and Central American

Languages. New York, 1869.

Berenger, Collection de tous les Voyages faits autour du Monde. Paris,

1788-9. 9 vols.

Bergaño y Villegas (Simon), La Vacuna. Canto dirigido á los Jóvenes.

Nueva Guatemala, 1808.

Bergaño y Villegas (Simon), La Vacuna y Económica Política. Nueva Guatemala,

1808.

Bergomas (Jacobo Philippo), Nouissime historiarũ omniũ. Venetiis, 1503.

Bergomas (Jacobo Philippo), Supplementi Chronicarum ab ispo mundi exordio.

[Venet., 1513.]

Berlanga, Pesquisa, Sobre conducta de Pizarro, 1535. In Pacheco and Cárdenas,

Col. Doc., tom. x.

Bernal Diaz. See Diaz del Castillo (Bernal).

Betagh (William), A Voyage round the World. London, 1757.

Beulloch, Le Mexique en 1823. London, 1824. 2 vols.

Biblioteca Americana. London, 1789.

Biblioteca Mexicana Popular y Economica, Tratados. Mexico, 1851-3. 3 vols.

Biddle, Memoir of Sebastian Cabot. London, 1831.

Bidwell (Chas. Toll.), The Isthmus of Panamá. London, 1865.

Bigland (John), A Geographical and Historical View of the World. London,

1810. 5 vols.

Bilboa (Francisco), Iniciativa de la America. Paris, 1856.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. Edinburgh, 1817 et seq.

Blagdon (Francis Wm.), The Modern Geographer. London, n.d. 5 vols.

Blasquez, Opinion. In Chiapas, Documentos Originales. MS.

Blewfields, Documentos Interesantes sobre el Atentado. San Salvador [1848].

Blomfield (E.), A General View of the World. Bungay, 1807. 4to. 2 vols.

Boddam Whetham (J. W.), Across Central America. London, 1877.

Bogotá, Gaceta de la Nueva Granada. Bogotá, 1843 et seq.

Bogotá, Gaceta Oficial. Bogotá, 1848 et seq.

Boletin de Noticias. San Salvador, 1851 et seq.

Boletin del Ejercito. Santa Ana, 1851 et seq.

Bonnycastle (R. H.), Spanish America. London, 1818. 2 vols.

Borbon (Luis de), Ciudadanos. Mexico, 1820.

Bordone (Benedetto), Libro di Benedetto Bordone nel qual si ragiona de tutte

l'Isole del mondo. Vinegia, 1528.

Borthwick (J. D.), Three Years in California. Edinburgh, 1857.

Borthwick (J. D.), In Hutchings' California Magazine, vol. ii.

Boss (V. D.), Leben und Tapffere Thaten der See Helden. Nürnberg, 1681.

xxx

Bossi, Vita di Colombo. Milan, 1818.

Bourgoanne, Travels in Spain. In Pinkerton's Col. Voy., tom. v.

Boyle (Frederick), A Ride across a Continent. London, 1868. 2 vols.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Bibliothèque Mexico-Guatémalienne. Paris, 1871.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Histoire des Nations civilisées du Mexique et de

l'Amérique Centrale. Paris, 1857-9. 4 vols.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Lettres pour servir d'Introduction à l'Histoire primitive

des Nations Civilisées de l'Amérique Septentrionale. Mexico, 1851. 4to.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Manuscrit Troano. Etudes sur le système graphique

et la langue des Mayas. Paris, 1869-70. 4to. 2 vols. (Mission Scientifique,

Linguistique.)

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Notes d'un Voyage dans L'Amérique Centrale. n.pl., n.d.

Brasseur de Bourbourg, Recherches sur les Ruines de Palenqué. Avec les

Dessins de M. de Waldeck. Paris, 1866. folio. 1 vol. text; and 1 vol. plates.

British Railway. Remarks on, from Atlantic to Pacific from Gulf of Honduras.

London, 1849.

British Sailor's Discovery, or the Spanish Pretensions refuted. London, 1739.

Brouez (M. P.), Une Colonie Belge dans L'Amérique Centrale. Mons, 1846.

Brown (A. G.), Speech in U. S. Senate, March 12-13, 1856. n.pl., n.d.

Bryant, What I saw in California. New York, 1849.

Bryant (William Cullen), History of the United States. N.Y. 1876-81. 4 vols.

Buccaneers of America. See Esquemelin.

Buitrago (P.), Carta, Agosto 26 de 1851. MS. folio.

Bülow (A. von), Der Freistaat Nicaragua. Berlin, 1849.

Burgoa (Francisco de), Geografica Descripcion de la Parte Septentrional, del

Polo Artico de la America (Oaxaca). Mexico, 1674. 4to. 2 vols.

Burke (Edmund), An Account of European Settlements in America. London,

1808, 4to; also editions London, 1760, 2 vols.; London, 1770, 2 vols.

Burney (James), A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea.

London, 1803-16. 4to. 4 vols.

Burton (R.), The English Heroe: or, Sir Francis Drake revived. London,

1687; also edition London, 1710.

Burwell (William M.), Memoir Explanatory of the Transunion and Tehuantepec

Route. Washington, 1851.

Bury (Viscount), Exodus of the Western Nations. London, 1865. 2 vols.

Buschmann (Johann Carl Ed.), Über die Aztekischen Ortsnamen. Berlin,

[1853.] 4to.

Bussière (Th. de), L'Empire Mexicain. Paris, 1863.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Apuntes para la Historia del Gobierno del General

Santa-Anna. Mexico, 1845.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Cuadro Historico de la Revolucion Mexicana.

Mexico, 1823-7. 5 vols.; also Mexico, 1832-46. 6 vols.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Diario de lo especialmente occurrido en Mexico,

Sept. de 1841 à Junio de 1843. Mexico, 1841-3. MS. 4to. 4 vols.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Historia del Emperador D. Agustin de Iturbide

(Continuacion del Cuadro Historia). Mexico, 1846.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Materiales para la Continuacion del Cuadro

Historico. Mexico, 1833-9. MS.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Medidas para la Pacification de la America

Mexicana. MS. 1820.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Memorandum, ó sea Apuntes de lo principalmente

occurrido en Mexico. Mexico, 1844-7. MS.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Resistencia de la Córte de España. México, 1833.

Bustamante (Cárlos María de), Voz de la Patria. Mexico, 1828-31. 3 vols.

Bustelli-Foscolo (Comte), La Fusion Républicaine du Honduras et du Salvador

en un seul état. Paris, 1871.

Butler (J. D.), The Naming of America. Madison, 1874.

Byam (George), Wanderings in some of the Western Republics of America.

London, 1850.

Byam (George), Wild Life in the Interior of Central America. London, 1849.

xxxi

Cabañas (T.), El Presidente, Marzo 2, 1852. [Comayagua, 1852.]

Cabañas (Trinidad), Soldado de la Patria, Agosto 27 de 1853. Santa Rosa,

1853. folio.

Cabañas y la Paz, Proclamacion de los Democratas. Deciembre 2 de 1851.

San Salvador, 1851.

Cabeza de Vaca (Alvar Nuñez), Relation. Translated from the Spanish by

Buckingham Smith. New York, 1871. 4to.

Cabildo de Guatemala. Informe al actual Prelado. Guatemala, 1827.

Cabot, Navigatione di Sebastiano Cabota. In Ramusio, Viaggi, tom. ii.

Cabrera Bueno (Joseph Gonzalez), Navegacion Especvlativa, y Practica.

Manila, 1734. folio.

Cabrera (Paul Felix), Beschreibung einer alten Stadt in Guatimala. Berlin,

1832.

Cadamosto (Alvise), La Prima Nauigatione, etc. Vicenza, 1507; also in Ramusio,

Viaggi, tom. i.

Cadamosto (Alvise), La Seconda Navigatione. In Ramusio, Viaggi, tom. i.

Cadena (Felipe), Breve Descripcion de la noble ciudad de Santiago. Guatemala,

1858.

Cadena (Fr. Cárlos), Descripcion de las reales exequias que á la tierna

memoria de nuestro augusto y católica monarca el Sr. D. Cárlos III.

Guatemala, 1789. 4to.

Caicedo (J. M. Torres), Union Latina. Paris, 1865. 4to.

Caldas (Sebastian Alvarez Alfonso Rosica), Carta sobre la conqvista de las

Provincias del Lacandon. Goatemala, 1667. folio.

Calendario Manual y Guia de Forasteros. Mexico, 1811 et seq.

Calle (Juan Diez de la), Memorial, y Noticias Sacras, y Reales del Imperio de

las Indias Occidentales. n.pl., 1646.

Calle (Juan Diez de la), Recopilacion. n.pl., 1646.

California Newspapers. (Cited by name and date.)

Calvo (Charles), Annales Historiques de la révolution de l'Amérique latine.

Paris, etc., 1864-67. 5 vols.

Calvo (Charles), Recueil Complet des Traités. Paris, 1862-7. 16 vols.

Calvo (Joaquin Bernardo), Memoria presentada por el Ministro de Relaciones.

San José, 1852, 1854.

Camp (David W.), The American Year-Book. Hartford, 1869 et seq.

Campaño (Estanislao), Oracion Funebre en los Funerales del General Jose Maria

Cañas. San Salvador, 1860.

Campbell, A Concise History of Spanish America. London, 1741.

Campe, Historia del Descubrimiento y Conquista de America. Madrid, 1803.

3 vols; also Mexico, 1854. Madrid, 1845.

Campo (Rafael), Contestacion a la segunda replica impresa en San Salvador

en la imprenta Nacional. Leon, 1873.

Campo (Rafael), Contestacion á la Primera replica á los libelistas del Salvador

en Nicaragua. San Salvador, 1871.

Canal or Railroad between the Atlantic and Pacific. Report of February 20,

1849. Washington, 1849.

Cancelada (Juan Lopez), Ruina de la Nueva España. Cadiz, 1811. 4to.

Cancelada (Juan Lopez), Telégrafo Mexicano. Cadiz, 1814 et seq.

Cancellieri (Francisco), Dissertazioni sopra Cristoforo Colombo. Roma, 1809.

Cancellieri (Francisco), Notizie storiche e Bibliografiche di Christoforo Colombo.

Roma, n.d.

Candé (de Moussion), Notice sur le Golfe de Honduras. Paris, 1850.

Capron (E. S.), History of California. Boston, 1854.

Carazo (Manuel José), Informe del Ministro de Hacienda, 1852. San Jose, 1852. 4to.

Carbo (Pedro), Question entre L'Angleterre et les Etats-Unis. Paris, 1856.

Cardona, Memorial sobre descubrimientos en California. In Pacheco and

Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. ix.

Carmichael (John), Letter on the Destruction of Greytown. Liverpool, 1856.

Carranza (Domingo Gonzalez), A Geographical Description of ... the West

Indies. London, 1740.

xxxii

Carrasco, Carta, Nicaragua, sobre reformas. In Pacheco and Cárdenas, Col.

Doc., tom. v.

Carrera (Rafael), A Los Jefes, Oct. 30, 1863. San Salvador, 1863.

Carrera (Rafael), Manifiesto, Junio 22, 1854. [Guatemala, 1854.]

Carrera (Rafael), Origen y Nacimiento. Guatemala, 1844. MS.

Carrera and Morazan, Coleccion de Noticias de Centro America. Guatemala,

1846.

Carreri (Gemelli), Viaggio, etc.

Carreri (Gemelli), Voyage de. In Berenger, Col. Voy., tom. ii.

Carriedo (Juan B.), Estudios Históricos y Estadisticos. Oaxaca, 1850. 2 vols.

Carta de la Reina, in Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. iii.

Cartas de Indias. Madrid, 1877. folio.

Cartier, Prima Relatione di Iacqves Carthier. In Ramusio, Viaggi, tom. iii.

Caruette (La Pere), Lettres Inédites sur la Nouvelle Granada. In Nouvelles

Annales des Voyages, tom. cxlv.

Casaus y Torres (Ramon), Relacion de las exequias que se hicieron en la

Santa Iglesia Catedral. Guatemala, 1846.

Cash (T. M.), The Panama Fever. In Overland Monthly, vol. i.

Casorla (J. R.), Cultivo del Café. Panamá, 1878.

Cass (Lewis), Speech in U. S. Senate, Jan. 28, 1856. Washington, 1856. 8o. 16 pp.

Cass (Lewis), Speech on the Clayton-Bulwer treaty, January 11, 1854.

Washington, 1854.

Castañeda, Informe. In Col. Doc. Inéd., tom. xxvi.

Castellanos (Juan de), Elegías de Varones ilustres de Indias. Madrid, 1857.

Castellon (Francisco), A los Pueblos de Centro-America. Agosto 23, 1851.

[Comayagua, 1851.]

Castellon (Francisco), Al Publico, Deciembre 8, 1853. [Leon, 1853.]

Castellon (Francisco), Al Publico, Febrero 10, 1854. San Salvador, 1854.

Castellon (Francisco), Calumnia Atroz. Leon, 1851.

Castellon (Francisco), Discurso Pronunciado, Junio 11 de 1854. n.pl., 1854.

Castellon (Francisco), Documentos relativos á la Cuestion de Mosquitos. San

Salvador, 1852.

Castellon (Francisco), Documentos Relativos á la Legacion de Nicaragua y

Honduras. Granada, 1851. folio.

Castillo, Carta sobre la pacificacion de Tierra Firme. Julio 1, 1527. In Pacheco

and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xii.

Castle (William), A Short Discovery of Coast and Continent of America. In

Voyages, Col. (Churchill), vol. viii.

Castro Diario. In Doc. Hist. Mex., 1st series, toms. iv., v., vi.

Cava, Testimonio del Estado de Despoblacion de Honduras, 1536. In Pacheco

and Cárdenas, Col. Doc., tom. xiv.

Cavanilles (Antonio), Historia de España. Madrid, 1860-3. 5 vols.

Cavo (Andres), Los Tres Siglos de Mexico. Mexico, 1836-8. 3 vols.

Cedulario. A Collection mostly MSS. folio. 3 vols.

Celis, Camino de Honduras á Guatemala, 1539. In Pacheco and Cárdenas,

Col. Doc., tom. xiv.

Central America, American Anxieties, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Article, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, British Aggression in. n.pl., n.d.

Central America, British Colony. (32d Cong., 2d. Sess., Senate Report 407.)

Washington, 1853.

Central America, Clayton and Bulwer Convention-Correspondence. London,

1856.

Central America, Coasts. [Candé, Notice sur le Golfe.] n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Correspondence of the Department of State, Accompanying

Message of the President of the U. S., December, 1855.

Central America, Correspondence with the late Mr Wallerstein. London,

1856. folio.

Central America, Correspondence with the United States Respecting. London,

1856. folio.

xxxiii

Central America, Disputes with America, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Further Correspondence with the United States. London,

1856. folio.

Central America, Great Britain and the United States, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Messages of the President of the United States. Jan., 1853,

Dec., 1853, May, 1856.

Central America, Miscellaneous Documents on Politics, n.pl., n.d. folio.

Central America, Mosquito King and British Queen, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Mr Crampton and the American Question, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Pamphlets. 9 vols.

Central America, Question in United Service Magazine, April, 1856.

Central America, Recent Travels in. In Blackwood's Magazine, 1858.

Central America, Report of Committee on Foreign Relations. (32d Cong.,

2d Sess., Report of Committee 407.)

Central America, Reviews, n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Ruined Cities of. n.pl., n.d.

Central America, Tarifa de Aforos para la Exaccion de Derechos. n.pl., 1837.

Central America, Unexplored Regions of. New York, 1868.

Central America in Congress. 1858. A Collection.

Central American Affairs, 1856. A Collection.

Central American Affairs, Documents relative to. Washington, 1856.

Central American Constitutions.

Central American Notes. Scrap Book.

Central American Question. Correspondence concerning the Arbitration.

[Washington, 1856.]

Central American Commercial and Agricultural Company. Brief Statement.

London, 1839.

Centro America, A los Honorables Representantes del Congreso. [Comayagua],

Nov. 6, 1852. folio.

Centro America, A los Pueblos. [Various dates, 1851-2.]

Centro America, Consideraciones establecer Gno. jeneral. Setiembre 13, 1852.

[Tegucigalpa, 1852.] folio.

Centro America, Convencion Provisional de los Estados. Guatemala, 1839.

Centro America, Correspondencia respecto á la Isla del Tigre. [San Jose,

1849.] folio.

Centro America, Escrito que Demuestra Conviene Establecer un Gobierno

Nacional, Noviembre 10, 1845. San Salvador, 1845.

Centro America, Estatuto Provisorio de la Republica, 13 Octubre, 1852.

Tegucigalpa, 1852.

Centro America, Extractos Sueltos de varios libros de la Coleccion de

Muñoz. MS. 1545-55. folio.

Centro America, Ley Orgánica de la Hacienda Federal de la Republica.

San Salvador, 1837.

Centro America, Ministerio de Hacienda, Febrero 27, 1837. MS. folio.

Centro America, Ministerio de Relaciones, Agosto 22, 1836. MS. folio.

Centro America, Necesidad Urjente de la Reorganizacion. Paris, 1848.

Centro America, Otras reflexiones sobre reforma politica. Philadelphia,

1833.

Centro America, Para Conocimiento de los Estados Confederados, Enero 26,

1852. [Comayagua, 1852.] folio.

Centro America, Para conocimiento de los pueblos, Febrero 20, 1853. [Tegucigalpa,

1853.] folio.

Centro America, Por Disposicion del Gobierno Jeneral, Julio 31, 1851. [Leon],

1851.

Centro America, Proposicion (A la Asamblea Nacional, Octubre, 1852). Tegucigalpa,

1852.

Centro America, Proposicion que el Sr. Representante por el Salvador Don

J. Barrundia. [Leon, 1851.]

Centro America, Provisorio de la Republica, Noviembre 20, 1852. [Comayagua,

1853.] folio.

xxxiv

Centro America, Pueblos Todos de Centro America, Marzo 2, 1853. Tegucigalpa,

1853. folio.

Centro America, Reflecciones Dedicadas á las Lejislaturas de los Estados.

Enero 1, 1853. San Vicente, 1853.

Centro America, Representacion National, Octubre 8, 1851. San Salvador,

1851.

Centro America, Secretaría del despacho relaciones, Enero 21, 1851. [Chinandega,

1851.] folio.

Centro America, Secretaría del despacho relaciones, Marzo 31, 1851. [Leon,

1851.] folio.

Centro America, Situation de Centro America. Articulos Publicados en

Gaceta de Guatemala, Nos. 83-90. Managua, 1863.

Centro Americano, A Los Americanos, Junio 15, 1850. [Leon, 1850.] folio.

Centro Americano, A Los Americanos. Honduras, 1853. folio.

Centro Americano, A Periodical. Guatemala, 1825 et seq.; also A Weekly.

Guatemala, 1833 et seq.

Centro Americano. Los Leoneses, Agosto 15, 1851. Leon, 1851. folio.

Centro Americana, Pacto de la Confederation. Comayagua, 1842.

Centro Americano, Unos Nacionalistas, Set. 5, 1852. [Tegucigalpa, 1852.] folio.

Cerezeda (Andrés de), Carta al Rey, Enero 20, 1529. MS. 1529. folio.

Chambers' Edinburgh Journal. London, 1834 et seq.

Chamorro (Fernando), Documentos que Esclarecen la Muerte. Leon, 1863.

Chamorro (Fernando), Sobre la Cuestion de Nacionalidad y los Libelos del Señor

Zeledon. Setiembre 25, 1862. Granada, 1862.

Chamorro (Fruto), Mensaje del Director Supremo de Nicaragua, Enero 22,

1854. Managua, 1854.

Chamorro (Pedro Joaquin), Discurso Pronunciado. Managua, 1871.

Champagnac (J. B. J.), Le Jeune Voyageur en Californie. Paris, n.d.

Charencey (M. le Cte de), Le Percement de l'Isthme de Panama. Montagne,

1859.

Charlevoix (Fr. Nav. de), Histoire de l'Isle-Espagnole. Paris, 1730.

Charlevoix (Fr. Nav. de), Histoire de la Nouvelle France. Paris, 1744. 4to.

3 vols.

Charpentier (Eugene), Projet D'Exposition Universelle a San-Salvador. Paris,

1867.

Chateaubriand (de), Congrès de Vérone. Paris, 1838. 2 vols.

Chavez (Gabriel de), Relacion de la provincia de Meztitlan. MS. 1579. folio.

Chevalier (Emile), Des Travaux Entrepris à L'Isthme de Panama. In Soc.

Géog., Bulletin, series iv., tom. iv.

Chevalier (Michel), L'Isthme de Panamá. Paris, 1844.

Chiapas, Documentos Originales para la historia de Chiapas. MS.

Chiapas, Segundo Trimestre de los hechos Notables de la Asamblea Departamental

de Chiapas. Guatemala, 1845.

Chica, Restitution de los Chamelcos. In Chiapas, Documentos Orig.

Chimalpain, Hist. Conq. See Gomara (Francisco Lopez de), Hist. Mex.

China and Japan, A Sketch of the New Route. San Francisco. 1867.

Chiriquí, Copiador de oficios del Gobierno con la Lejislatura provincial. MS.

1854.

Chiriquí, Libro de actas de la cámara provincial ... en sus sesiones extraordinarias.

MS. 1851.

Chiriquí, Ordenanzas de la Cámara. MS. 1849 et seq. folio.

Chiriquí Real Estate Company, By-laws and other documents. MS. 1854-6.

Chiriquí, Reglamento que la cámara provincial de ... decreta para su régimen

interior. MS. 1849.

Chiriquí Improvement Company. Abstract of Privileges and Titles, n.pl.,

n.d. folio.

Chiriquí Improvement Company, A Collection.

Chiriquí Improvement Company, Possessions, n.pl., n.d.

Chiriquí Improvement Company, Reports. New York, 1856.

Chiriquí Province, n.pl., n.d.

xxxv

Chronica compendiosissima. Antwerp, 1534.

Circumnavigation of the Globe, An Historical Account. Edinburg, 1837.

Cladera (Christobal), Investigaciones Históricas. Madrid, 1794.

Clark (Sam), Life and Death of Sir Francis Drake. London, 1671.

Clavigero (Francesco Saverio), Storia Antica del Messico. Cesena, 1780. 4to.

4 vols.

Clavigero (Francesco Saverio), Storia della California. Venezia, 1789. 2 vols.

Clay (J. B.), Speech in U. S. House of Rep., February 7, 1859. Washington,

1859.

Clayton (John M.), Speech in U. S. Senate, April 19, 1850. Washington, 1853.

Clement (Claudio), Tablas Chronologicas. Valencia, 1689.

Cleveland (Daniel), Across the Nicaragua Transit. [San Francisco, 1868.] MS.

Cloquet (Martial), Rapport sur Santo-Thomas de Guatemala. Bruxelles, 1844.

Cobbett's Register. London, 1802-34. 67 vols.

Cockburn (John), A Journey over land from the Gulf of Honduras to the

Great South-Sea. London, 1735.

Codman (John), The Round Trip. New York, 1879.

Coffin (Charles Carleton), The Story of Liberty. New York, 1879.

Coffin (Charles E. B.), Letter to the Chiriquí Improvement Company. New

York, 1859.

Coffin (James Henry), Winds of the Globe. Washington, 1876. 4to.

Coggeshall (George), Second Series of Voyages, 1802-41. New York, 1852.

Cogolludo (Diego Lopez), Historia de Yucathan. Madrid, 1688. folio.

Cojutepeque, La Municipalidad y Vecindario de la Ciudad Leal de. San

Salvador, 1863.

Coleccion de Documentos Inéditos para la Historia de España. Madrid,

1842-73. 59 vols.

Colmenares (Rodrigo de), Memorial Presentado al Rey sobre á poblar Urabá.

In Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. iii.

Colombel, Report on Golfo Dulce. n.pl., n.d.

Colombia, Constitution de la République. In Ancillon, Mélanges.

Colombia, Diario Oficial. Bogotá, 1872 et seq.

Colombia, Acta de la instalacion del Congreso Constituyente de Colombia

del año de 1830. Cartagena, 1830.

Colombia, Constitucion de los Estados-Unidos de Colombia, sancionada el 8

de Mayo de 1863. Panamá, 1875.

Colombia, La Diputacion del Cauca en el Congreso de 1876. Bogotá, 1876.

Colombia, Leyes y Decretos del Congreso Constitucional de la Nueva Granada.

n.p., n.d.

Colombia, Leyes y Decretos expedidos por el Congreso Constitucional de 1839.

Bogotá, 1839.

Colombia, Memorias. [Different departments and dates.]

Colombia, Nos los representantes de las provincias del centro de. Bogotá,

1831. folio.

Colombia, Partes relativos al Ataque y Rendicion de la Plaza de Manizáles.

Medellin, 1877.

Colombo (Fernando), Historie della vita, e de' fatti dell' Ammiraglio D.

Christoforo Colombo suo Padre. Venetia, 1709.

Colon (Fernando), La Historia de el Almirante D. Christoval Colon, su Padre.

In Barcia, Historiadores Prim., tom. i. [Translation in Pinkerton's Col.

Voy., vol. xii.; and in Kerr's Col. Voy., vol. iii.]

Colon (Diego), Memorial a el Rey 1520. London, 1854.

Colón y Larriátegui (Felix), Juzgados Militares de España y sus Indias.

Madrid, 1788-97. 5 vols.

Colonial Magazine. London, 1840-41. 6 vols.

Colton's Journal of Geography. New York, 1867.

Columbus (Christopher), Cartas. In Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. i.

Columbus (Christopher), Copia de la Lettera. Venetia, 1505.

Columbus (Christopher), Cuarto y Ultimo Viage. In Navarrete, Col. de

Viages, tom. i.

xxxvi

Columbus (Christopher), Die vierdte Reise so vollenbracht hat. In Löw,

Meer oder Seehanen Buch, p. 6. Cologne, 1598.

Columbus (Christopher), Epistola Christofori Colom: cui etas nostra multũ

debet: de Insulis Indie supra Gangem nuper inuentis. M.cccc.xciij.

Columbus (Christopher), Navigatio. In Grynæus, Novvs Orbis.

Columbus (Christopher), Primero Viage. In Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. i.

Columbus (Christopher), Segundo Viage de. In Navarrete, Col. de Viages,

tom. i.

Columbus (Christopher), Tercer Viage. In Navarrete, Col. de Viages, tom. i.

Comercio, Libre Reglamento. In Reales Ordenes, tom. iii.

Concilios Provinciales Mexicanos. 1o, 2o, 3o, y 4o; 1555, 1565, 1585, 1771.

The original MS. Records. folio. 5 vols.; also editions Mexico, 1769;