![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Cordova: A city of the Moors

Author: Albert Frederick Calvert

Walter M. Gallichan

Release date: February 4, 2019 [eBook #58831]

Most recently updated: January 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

THE SPANISH SERIES

CORDOVA

THE SPANISH SERIES

EDITED BY ALBERT F. CALVERT

Seville

Murillo

Cordova

The Prado

The Escorial

Spanish Arms and Armour

In preparation—

Goya

Toledo

Madrid

Velazquez

Granada and Alhambra

Royal Palaces of Spain

Leon, Burgos, and Salamanca

Valladolid, Oviedo, Segovia, Zamora, Avila, and Zaragoza

A CITY OF THE MOORS BY

ALBERT F. CALVERT AND

WALTER M. GALLICHAN

WITH 160 ILLUSTRATIONS

LONDON: JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

NEW YORK: JOHN LANE COMPANY MCMVII

{iv}

{v}

Edinburgh: T. and A. Constable, Printers to His Majesty

To

THE DUKE OF SOTOMAYOR

Lord High Chamberlain to H.M. the King of Spain, etc.

My dear Duke,

Some of the pleasantest of my many pleasant memories of Spain are associated with, as indeed they were derived from, the sympathy you have displayed in my work and the great kindness I ever received from the Duchess of Sotomayor and yourself. For these, I hope, sufficient reasons—not as one who seeks to liquidate a heavy debt of hospitality, but rather rejoices in his obligations—I beg you to accept this dedication and permit me to associate your illustrious name with this modest volume.

I am,

My dear Duke,

Your obliged and ever grateful,

ALBERT F. CALVERT.

{vii}{vi}

It would be unnecessary to enlarge upon the reasons for including a study of Cordova in this series of Spanish Handbooks: indeed a series of this description would be incomplete without it. The beautiful, powerful, and wise Cordova,—‘the City of Cities,’ ‘the Pearl of the West,’ ‘the Bride of Andalus,’ as the Arabian poets have variously named it,—the ancient capital of Mohammedan Spain, is still one of the most curious and fascinating monuments of this singularly interesting country.

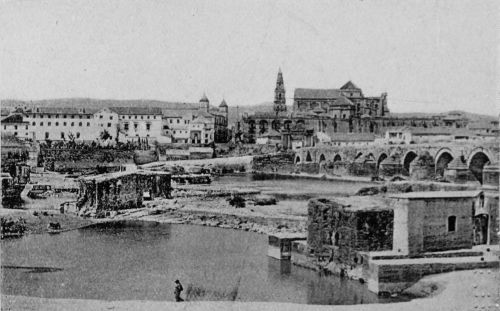

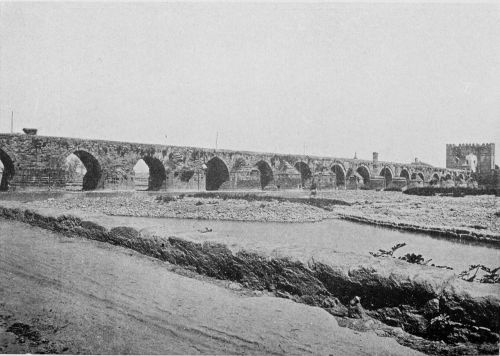

Much water has flowed under the sixteen arches of the bridge which spans the Guadalquivir since ‘Cordova was to Andalus what the head is to the body, or what the breast is to the loin’; the Moorish city of the thirty suburbs and three thousand mosques, whose fame once obscured the glory of ancient Damascus, is no longer the centre of European culture. ‘The brightest splendour of the world’ has been lost in centuries of neglect and decay, and the new{viii} light of a modern civilisation has not shone upon the remains of its mediæval grandeur.

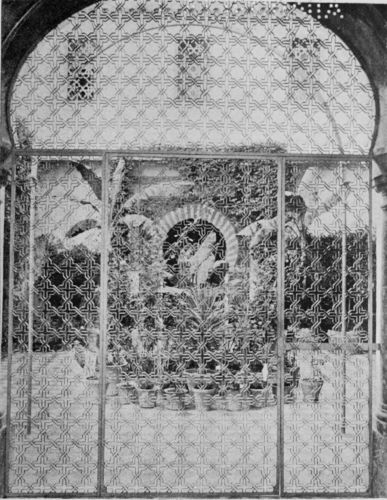

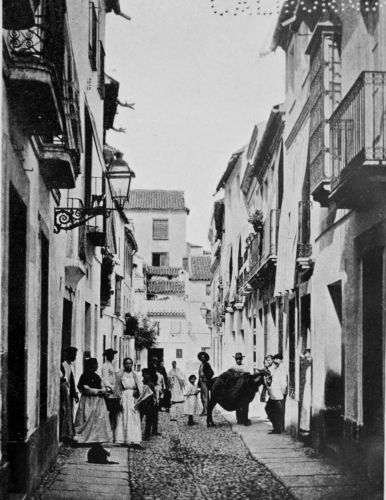

But the Cordova of the great Khalif is still the most African city in Spain; its mosque remains to give us a clearer and fuller idea of the power and magnificence of the Moors than anything else in the Peninsula, not excepting even the Alhambra; and in its narrow, uneven streets and mysterious, silent patios, in the gold and crimson of its fragrant gardens, the student and the artist may find unending interest and enchantment.

In selecting the illustrations for this book, the authors have endeavoured to provide both for the antiquary and the lover of the beautiful; for those whose acquaintance with Spain must be made through the medium of the printed page, and for those more fortunate readers who will, we hope, find this book a memento of their wanderings in Andalusia.

ALBERT F. CALVERT.

WALTER M. GALLICHAN.

{ix}

Many of the photographs included in this volume, other than those taken by myself, were supplied by Messrs. Rafael Garzon of Granada, Senan and Gonzalez of Granada, Hauser and Menet of Madrid, Ernst Wasmuth of Berlin, publisher of Uhde’s Baudenkmaeler in Spanien und Portugal, and Eugen Twietmeyer of Leipzig, publisher of Junghändel’s Die Baukunst Spaniens, and I take this opportunity of acknowledging their kind permission to reproduce them in this volume.

A. F. C.

{1}

An impression of colour, heat, and somnolence grows upon the stranger as he rambles through the bright alleys and sunlit plazas of Cordova. He may be neither painter, poet, nor antiquary; yet the opulence of vivid, almost garish tones, the romance that lingers about the Moorish courtyards and the perfumed gardens, and the surviving, pervasive suggestion of age, will stimulate his senses and imagination. For one who is capable of deeper and more subtle impressions, the old city will seem as a consummation of desire and a realisation of fanciful dreams. The spell of Orientalism will hold him; the splendours of The Arabian Nights will be brought before his vision; and he will conjure shapes of sultan, wizard, genii, and sage, and see the lovely retinue of fair women within the palaces of the swarthy potentates.{2}

Music of reed and string will delight his ears; and loitering by the walls, on the banks of the swirling Guadalquivir, he will hear the selfsame song of the bulbul which brought joy and sadness to dark, inscrutable eyes in olden days. He will watch the blue shadows of mosque and tower, and see the sun lavish gold on roof and turret, while his eye will be dazzled by the hues of balconies, by the hot geranium, the gay dabs of drying garments, hanging like flags against the ardent sapphire of the Andalusian sky.

Framed in the arch of a city gateway, he will see a lovely vista of vineyard, olive-crowned hillock, and meditative, grey sierra, rising to the blue.

He will pace the silent square at night, and discourse with Seneca. His ears will drink in the stoic counsels of Lucan, and his brain will grapple with the problems laid down by the sagacious Averroes. He will hear the Moslem call to prayer, and stand to gaze upon the band of the devout filing into the Mezquita.

Clamours of battle will assail him, the clash of sword and shield will startle his slumber, and the night will tremble with the triumphant roar of the fierce, invading Goths. And in hours, fragrant with the scent of flowers—placid in contempla{3}tion of the simple happiness of Cordova’s youths and maidens in the Court of Oranges—he will weave romances of the ancient life, when the town was the seat of the cultured, the home of the arts, and the sanctuary of the pious.

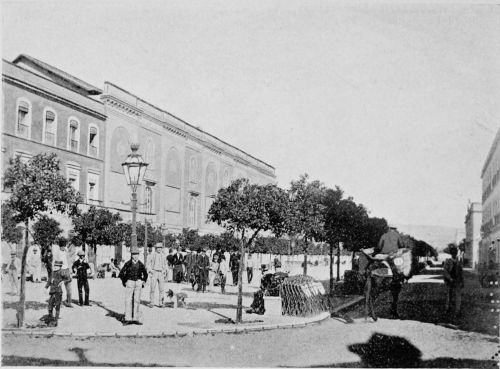

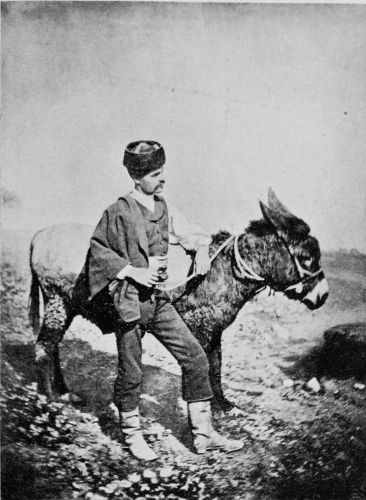

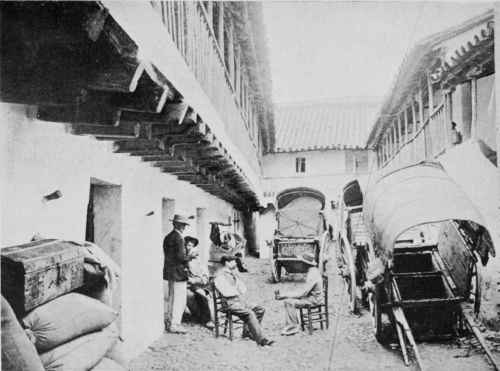

Doubtless the Cordova of to-day subsists like other towns upon the industry and the commercial energy of its inhabitants. There are shops and hotels in the streets; there are signs of handicrafts and of common daily employments. But there is no bustle, no indication of a strenuous existence for the people, and the siesta is long and undisturbed. There is a market, but its produce and merchandise do not suggest the wealth and commerce of earlier days. The consumo, or customs officer, levies his tax upon almost everything which the hard-faring peasants bring into the town, and we have seen a conflict between one of these officials and a countryman over a single live pigeon. The peasant questioned the tax, and the officer explained the case with the flat of his sword-blade. This incident is characteristic of Andalusia, and perhaps it may throw a light upon the discontent which is apt, at times, to manifest itself violently among the agricultural population of Spain.

Certainly there are days of markets and ferias{4} when Cordova arouses itself, and trains of mules and asses creep into the place, and flocks may be seen in the streets. Wine, oil, and fruit are produced in the environs, and grain-crops flourish on the plain. In mediæval times Cordova was famed for its mart, where silk and grain were sold. The district still bears repute for its horse-breeding, but the stock has suffered deterioration through injudicious selection. An anonymous American writer, who was here in 1831, speaks of the horses of Cordova as the finest in Spain, and asserts that they are the descendants of the pure Arabian breed. One still notes many good horses. It is said that the water from the Guadalquivir is as nourishing for horses as is the barley of certain districts of Spain.

The banishment of the Moors hastened the decay of Cordova. For a period the region was almost stripped of its population, and grass grew in the plazas and patios of the town. To-day the inhabitants number about fifty thousand, and though Cordova wears an air of lethargy, the grass does not spring up in the streets. There seems to be just enough human activity to keep the town alive, and it is not wholly, as Henry O’Shea described it, ‘a city of the dead.’ A certain measure of prosperity is assured for{5} Cordova by the attraction of its antiquity, which brings strangers from many lands to visit the magnificent Mezquita.

The Spaniard is not a passionate enthusiast of modernity. He is conservative, and zealous and proud of his ancient towns, and it is quite probable that the bulk of the natives of Cordova prefer that the atmosphere of the place shall remain mediæval. And we who resort to Cordova to reflect upon its past grandeur, and to imbue ourselves with the spirit of the Moorish days, are assuredly satisfied that it has not been modernised and marred during the years that have intervened between the great vandalism after the expulsion of the Arabs and the present time. We are glad to think that all which remains of majesty and beauty is now carefully cherished and respected.

Toledo and Avila, both Moorish towns, display an austerity fascinating by reason of its very grimness. Cordova is beautiful by comparison, partly on account of its situation in a fertile district, and partly because its houses are white flower-decked, and cheerful in aspect. It is more voluptuous than these fortified towns of Castile. The climate is southern, the air softer, and the buildings are less stern in colouring and less{6} menacing in appearance. In Cordova, flowery courts invite you with a smile; in Toledo, frowning gates and barred doors forbid your entrance. Toledo reminds us that the Moors were warriors and conquerors, bent upon aggression and the extension of territory; in Cordova one thinks of the race as sages, artists, worshippers, poets, and lovers. The palm-trees planted by Abd-er-Rahman, ‘The Servant of the Merciful God,’ the tropical flowers and fruits, the mosque, and the fountains, give impress of the milder, pacific, quietly joyous life of the Moors. We recall the words of the wise ruler: ‘Beautiful palm-tree! thou art, like me, a stranger in this land; but thy roots find a friendly and a fertile soil, thy head rises into a genial atmosphere, and the balmy west breathes kindly among thy branches.’

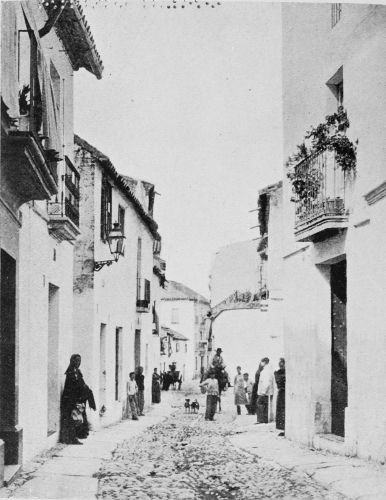

By these signs we learn to love Cordova as the sanctuary of learning and devotion rather than as the citadel of the valiant. It is essentially Oriental. Look at the streets—narrow, crooked, and shady, for, having no horse vehicles, the Arabs had no need for wider thoroughfares. The roofs of the houses project and screen the alleys from the sun. Cordova is clean and bright in contrast to Toledo. The streets are free from garbage; the interiors of the houses{7} are frequently cleansed, and flowers are grown by rich and poor. Fruits are cultivated in and around the town, and one may pluck the fig, orange, lemon, date, peach, plum, pomegranate, strawberry, and almond.

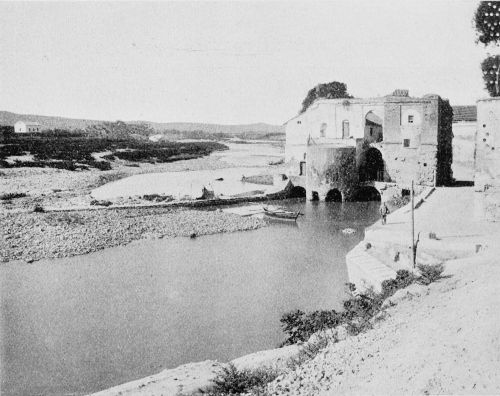

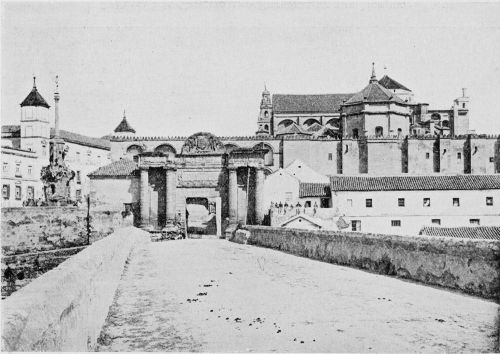

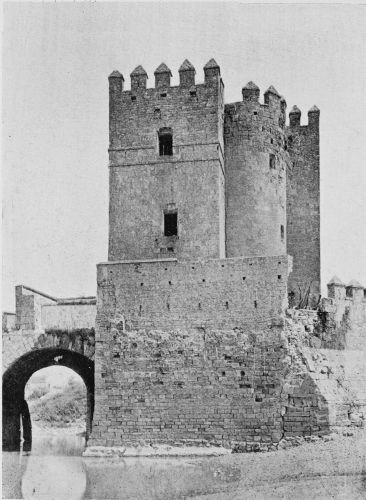

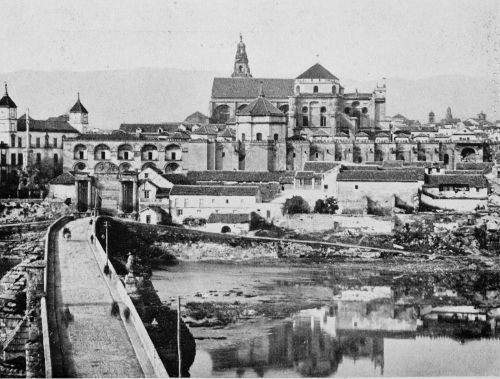

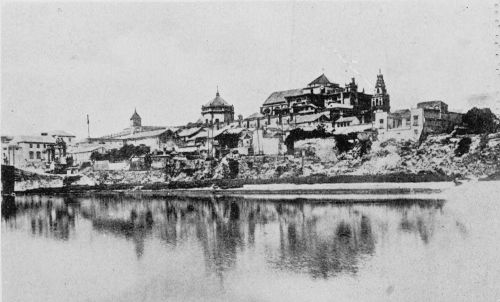

Standing on the massive bridge which spans the Guadalquivir, one looks upon the mosque, the city walls, and towers of churches. The Campo de la Verdad forms a broad promontory washed by the river, and we see quaint Morisco water-mills, and the lever nets of fishermen. There are seventeen arches to the bridge, which is of Moorish design, standing upon piles constructed by the Romans. In the distance rises the range of the Sierra Morena, a savage wilderness of rock, ravine, and crag, haunted by the boar, deer, and lynx. Winding through rich meadowland, the Guadalquivir flows, now in swift shallows, and then in slow deeps, which from certain points of view resemble landlocked pools. The river is wide, but not of great depth. Its flood is stained brown from the soil through which it flows, and at times, when the mountains pay their tribute of swollen streams, the Guadalquivir speeds in a turbid current, filling its banks to the brim.

There is a lonely majesty about this tawny river which for many leagues of its course flows through a desolate, deserted plain. It has but few trees upon its banks; but here and there are stretches of brushwood tenanted by nightingales. The stork visits the silent reaches to fish for eels. Upon its brown banks grows the cold grey cactus. The river breeds barbel, tench, and big eels, and in the summer shad ascend from the sea.

In Roman times the Guadalquivir was navigable as far as Cordova, but to-day the channels have silted up. A few salt pools in the plains show that the sea once covered large tracts of this part of Andalusia. The river is now tidal for some miles above Seville, and ships of heavy tonnage can reach that port. In the middle and upper reaches the river is unfrequented; it waters grassy wastes and fertile vegas, and murmurs by groves of olives in its course by Andujar and Cordova.

Antillon, a Spanish writer, accuses the Cordovese of ignorance and coarse manners. We encountered neither of these qualities during our stay in the old town. Cordova has its mendicants, whose eyes are keen for the advent of visitors, and the boys are somewhat troublesome in their voluntary capacity as guides to the{9} sights of the place. But the natives of Cordova are sedate, picturesque folk, showing no discourtesy to the stranger, but rather a disposition to assist him.

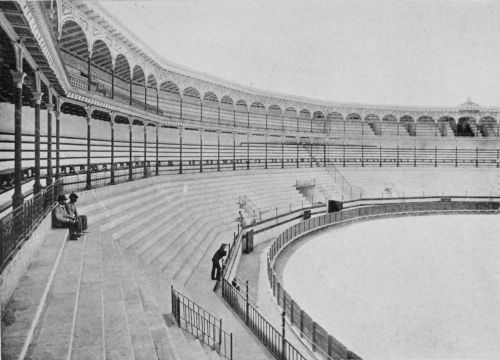

There are three principal hostelries—the Suiza and the Oriente are the visitors’ houses; but those who desire a purely Spanish environment may find quarters at the little Victoria, which has a very charming patio, gay with flowers. There are several good cafés. For amusement there is the Grand Teatro, a large house, in which we saw The Barber of Seville performed. There is, of course, a bull-ring, the Plaza de Toros of every town in Spain. The chief fights are held during the ferias of May and September.

But Cordova is the town of dreams, memories, and meditations rather than of exuberant gaiety. It is a Mecca of the artistic and the studious. For garish pleasure, sparkling society, and excitement one must go to Seville, Malaga, or Cadiz. There is a serene solemnity in Cordova, though it is by no means a gloomy city. The mosque is the attraction and the wonder of the city, and sacred temples do not dispose to hilarity. Cordova is eloquent of the gorgeous, heroic past, and its stones contain sermons upon human{10} destiny and the insecurity of empires. It is a garden city, antiquated, improgressive, tenacious of the ancient spirit, and abounding in beauty of form and colour.

Cordova contains only the remnants of its pristine magnificence, but these are marvellous and precious. The city once boasted of fifty thousand resplendent palaces, and a hundred thousand inferior houses. Its mosques numbered seven hundred, and the cleanly Moors built nine hundred public baths. The city stretched for ten miles along the banks of the Guadalquivir, flanked with walls, battlements, and towers, and approached by guarded gates. The common folk spoke in phrases of poetry; there were no illiterates. Art in every branch flourished in the city; there were hosts of craftsmen working in brass, gold, and clay. The libraries were huge, and hither came men of science, philosophers, poets, and students of all subjects to glean from the store of the world’s accumulated thought.

Throughout Europe the mention of Cordova brought yearning to the hearts of the cultured and studious, and men suffered hardship and stress to pay pilgrimages to this source of learning. Many who journeyed hither echoed the{11} words of Ibn Sareh, the poet, which he uttered upon entering the seat of wisdom: ‘God be praised; I am in Cordova, the abode of science, the throne of the Sultans!’ Seville was ‘the gem,’ ‘the pearl’ of Andalusia; Cordova was called ‘the Bride.’ El-Makkari, the Moorish chronicler, rehearses many of the poetical tributes paid by Moslem writers to the splendid city. Setting forth the culture of the city, he adds, in one place: ‘The Cordovans were further celebrated for the elegance and richness of their dress, their attention to religious duties, their strict observance of the hours of prayer, the high respect and veneration in which they held their mosque, their aversion to wine and their destruction of wine-vases wherever they found any, their abhorrence of every illicit practice, their glory in nobility of descent and military enterprise, and their success in every department of the sciences.’

Such were the inhabitants of Cordova at the time when the city was the great capital of the Mohammedan empire. Seville and Toledo yielded pre-eminence to Cordova, and men spoke in veneration of its four great wonders: the immense and gorgeous mosque, the bridge over the Guadalquivir, the city of Ez-Zahra, situated{12} in the suburbs, and the sciences which were studied in the colleges.

When we read the ancient annals and grow absorbed by the story of Cordova’s past, we can scarcely realise that the town and its inmates were real things. The place and the people seem to belong to the realm of fairy romance; the city seems one of dreams, and the natives pass as in a pageant of the imagination. And yet we may enter the sacred mih-rab, commune with the ghosts of warrior and philosopher, and stand where Tarik stood when he wrested the prized capital from the Goths.

Tangible evidence of a superb civilisation surrounds us in Cordova. We see examples of early Moorish architecture brought to its highest artistic manifestation in the mosque. We listen in vain for the voices of teachers, the song of the singers and poets, and the call of the muezzin to devotion; but we tread in the footsteps of the long-vanished Moor, and read his story in the noble lines, chaste embellishments, and gorgeous details which his skilful hands produced.{13}

Probably a city of the Carthaginians once stood upon the ground now covered by Cordova. Phœnicians, Greeks, Trojans, and Tyrians battled in their day for the rich spoil of Spain, and the armies of Carthage ravaged the whole of the country. Rome wrought the downfall of the Carthaginian dominion in Bœtica (Andalusia) and Lusitania (Spain). In A.D. 205 the Romans began to lay hands on the Iberian Peninsula, and after long strife they conquered all the land save the territory of the indomitable Basques of the rocky north.

At Corduba (Cordova) the Romans established a capital of Hispania Ulterior, and the city was one of importance and prosperity. Under Cæsar it became the chief town of Bœtica. According to Plutarch, the government of Spain was given to Julius Cæsar after his prætorship, and he ruled firmly and justly over Portugal and Andalusia. The conquering emperor resided in{14} Corduba, and it was here that he was first attacked with epilepsy.

Beneath the rule of Rome Andalusia prospered. Roads, bridges, and aqueducts were constructed; cities were enlarged and founded, industries were developed, and the wealth of the country increased. This spell of peace and progress was broken by the conflict between Cæsar and Pompey, and Spain was the scene of some of their fiercest battles. With the decay of Roman greatness and valour, Bœtica was overrun by the hosts of the Goths from northern and eastern Europe. Like beasts of prey these hordes despoiled the Roman cities, shattering temple and amphitheatre, and laying waste fertile farms and abundant orchards. Rome yielded its last hold upon fair Bœtica; the Goths seized upon the land, and split it up into territories ruled by warriors. The invaders were ruthless in their destruction; they aimed at removing every trace of the Roman civilisation, and unfortunately they were successful in accomplishing an almost universal demolition of building, monument, and statue.

Cordova was one of the residences of the Gothic kings. It was known as Kordhobah among the Goths. There is little doubt that it{15} was a city of considerable opulence; for when it was sacked by the Moors it yielded gorgeous robes, embroidered with gold flowers, fine chains of gold, strings of pearls, and quantities of emeralds and rubies. The sway of Ludherick, or Roderick, King of the Goths, was first menaced by Tarif the Berber. Roderick was in dispute with the Lord of Ceuta, a city on the Strait of Gibraltar, and this quarrel exposed him to the attack of the covetous territory-hunters of northern Africa.

While Roderick and the Lord of Ceuta contended, Tarif, the redoubtable leader of the Berber army, landed in Spain, with a force of one hundred cavalry and four hundred foot-soldiers. Tarif appears to have solicited reinforcements, in order to meet the Goths at better odds. A force under Tarik was then sent by Musa Ibn Noseyr, with the object of capturing Andalusia. As Tarik was crossing the sea, he beheld an apparition of Mohammed, surrounded by armed Arabs. The Prophet bade the General take cheer, saying: ‘Take courage, O Tarik, and accomplish what thou art destined to perform.’ The vision was accepted by the anxious Tarik as an omen of victory. He rallied his soldiers, and marched upon Cordova, which was the royal{16} citadel of Roderick. The Gothic king, upon the tidings of the invasion, came from the north with his army to the capital, and commanded his officer Theodemir to advance and encounter Tarik.

Roderick was at this time striving with the sons of Witiza, the preceding monarch, for his claim to certain territories. Count Julian and Bishop Oppas sided with the princes, and a large number of the people stood to their cause. The advent of the forces of Musa served as an opportunity for the sons of Witiza to strike a blow at Roderick, their powerful enemy. They decided to join the army of Tarik, and to oppose the Gothic rule.

The combined hosts of Tarik and the sons of Witiza encamped to the south of Cordova, after taking Algeciras. Meanwhile the Moorish commander wrote to his superior for more troops, for Roderick boasted of a large and valorous following. The great encounter between the Goths and the Moors was enacted on the plain of Guadalete. Roderick came to the field in a litter, carried by two mules, and over his head was a brilliantly jewelled canopy. Aided by the disaffected princes and their adherents, Tarik made a terrific onslaught upon the ranks of the Goths.{17} It has been recounted by Moorish historians that Tarik himself went into the thick of the fight, and killed Roderick with his sword. This account is, however, doubted by El-Makkari, who asserts that after the battle Roderick could not be found alive or dead.

The victory was mighty and complete for the Moors. Upon the news of Tarik’s success, his compatriots began to pour into the country, for the purpose of colonisation, and in the expectation of enrichment in a land which had yielded fortune to Carthaginian, Roman, and Visigoth. But Cordova was still secure in the keeping of the Christians, though Roderick had been defeated. Naturally the victorious Tarik yearned to win fresh laurels, and his design was upon the great capital of the Goths, the remaining stronghold of the routed defenders of Bœtica.

The general selected for the attack upon Cordova was Mughīth Ar-rumi. At the direction of Tarik, this warrior rode, with seven hundred horsemen, to lay siege to the city. Some of the Moorish chroniclers state that Tarik himself led the expedition against the capital; but Mughīth appears to have been the leader upon whom the conduct of this important movement fell.

Advancing within a short distance of Cordova,{18} the force encamped in a forest, and remained cautiously in hiding. At this time many parts of Andalusia, which are now wholly bare of trees, were well wooded. The foolish destruction of the forests came later, under the Christian rule, the reason for the wholesale felling of timber being that trees harbour birds, and that birds feed upon seed and grain.

Concealed in a dense pinewood, Mughīth Ar-rumi saw the coveted city almost within his grasp. But the walls were high, stoutly fortified, and formidable, and the defenders were reputed valiant and stubborn. Scouts from the Moorish army were sent to view the defences of the city. They met a shepherd, and from him they extracted the intelligence that the chief residents of Cordova had quitted, and fled to Toledo for protection. By threat or bribe, the spies also gathered from the shepherd that there was one weak spot in the city walls. With this information they returned to the ambush, and acquainted Mughīth with that which they had learned.

The Moorish commander bade his warriors prepare for a night attack upon the city. Darkness and a heavy shower of hail favoured the stealthy approach of the horsemen to the walls,{19} the hail drowning the sound of the horses’ hoofs. A halt was called. Mughīth ordered an inspection of the walls, enjoining a close watch for sentries. The advance party reported that no sentinels were to be seen at their posts, and that the city seemed deep in slumber. Upon this the shepherd quietly conducted the soldiers to the weakest point of the embattlements, where grew a big fig-tree. One of the Moors clambered into the topmost branch of the tree, and contrived to gain the summit of the city wall. Unrolling the coils of his turban, Mughīth threw one end to the man, who used it as a rope to assist his comrades in scaling the barrier.

The entrance into the city was achieved quietly and with little loss of time. With scarcely any effort of resistance, the startled inhabitants fled from their houses, and, headed by the Governor, rushed to a church for safety. The edifice proved a veritable fastness for a large number of the people. Mughīth Ar-rumi was baffled. His only course was to cut off all approach to and egress from the church, trusting that starvation would compel the imprisoned populace to yield. But he was unaware that a conduit brought water underground to the building, and that the defenders were probably able to hold out{20} for some time, having provided themselves with rations for a state of siege.

A negro, who managed to find a way into the church, was sent as a spy. This man immediately fell into the hands of the besieged, who were at first alarmed by his appearance. They had never seen a human creature with a skin of ebony and hair of wool. Mistaking the hue of the black man’s skin for uncleanliness, they washed and scrubbed him with great pains. But, greatly to their wonder, the black covering refused to leave the man’s skin, and they at length ended the prolonged ablutions. In seven days the much-scrubbed negro made his escape. To Mughīth he reported the conduit. Whereupon the general promptly cut off the supply of water, and thought to bring the people to instant surrender. He was, however, disappointed, for the band in the church still bravely held out and defied him.

The extremest measure was at length employed by the impatient Moor. For three months the refugees had resisted all endeavour to eject them or to starve them into submission. The church was fired, and the luckless defenders had no choice between instant death and yielding. They rushed from the flames, and the Governor{21} of the city was taken captive. The church was afterwards known as ‘The Church of the Burning.’

So fell the Kordhobah of the Gothic kings. The palace became the residence of Mughīth, who lived there until he had decided upon the future government of the city. Before leaving Cordova, the Moorish general appointed the Jewish residents the rulers of the city. Thus the oppressed and plundered Hebrew came into possession, and rose to the position of autocratic director of those who had bitterly persecuted him. This affront to the dignity of the proud Goths was doubtless grievous to them in the hour of their defeat. But it was a shrewd policy of rulership on the part of Mughīth Ar-rumi.

Whether certain of the Moorish writers of this period are correct in relating that Tarik was before the walls of Cordova, we are not able to say. It is written that he came with an army, and after waiting nine days in impatience, being unable to force an entry, he departed, and left Mughīth to capture the city.

Cordova was now made subject to the Khalif of Damascus; but in 756 it was independent, under the rule of Abd-er-Rahman I. According to El-Makkari, Ayub was the first to establish{22} the capital of the territory of Andalus at Cordova.

Mughīth, the capturer of Cordova, was not only an intrepid soldier, he was a scholar and poet, and a lover of the arts. After the taking of the city he went to Damascus, but returned to Cordova and lived in the palace.{23}

Abd-er-Rahman, a brave prince of a family that had ruled Damascus, was born in troubled times in the camp before that city. Es-Deffah had seized upon the throne; the family of the Omeyyads was hurled from power. While under sentence of death for his attempt to restore the fortunes of his family, Abd-er-Rahman passed a period of wandering among Arab herdsmen. His dream was of Andalusia, where the supporters of the Omeyyads were still numerous and powerful; and by dint of energy and enthusiasm the young prince contrived to form a corps of one thousand Arabs.

Abdulmalek Ibn Kattan, who had usurped rulership in Cordova, had been defeated by the adventurous Balj at the head of a troop of Syrians. The luckless Abdulmalek, after falling into the hands of Balj, was crucified in a field outside Cordova, with a hog on one side and a dog on the other. Until recovered by friends{24} and removed for burial, the body of the conquered sultan was left upon the cross as a menace to his followers.

But Balj enjoyed only a short spell of power, for at the end of eleven months he was forced to encounter the redoubtable prince of the Omeyyads, whose army of Arabs was largely augmented by fierce partisans in Spain.

Marching upon Cordova, Abd-er-Rahman besieged the city. Balj was wounded, and his injuries caused his death. From this time, for about three centuries, the capital of Andalusia was held by the Omeyyad line, and during this rule the city reached the highest stage of its might and magnificence. The Arab writers state that the independent khalifate of Cordova was founded by Abd-er-Rahman I., after conquering Yusuf, who reigned in the city. Yusuf resisted the Omeyyad troops outside the walls of Cordova, and, being worsted, he retired. Abd-er-Rahman then entered the city, and appointing the command to Abu Othman, went in pursuit of the remnant of Yusuf’s army. Meanwhile Yusuf counter-marched, returned to Cordova, and assailed Abu Othman, promising him future security for himself and his relatives if he would surrender.

It is said that Othman refused to accept the{25} terms of surrender. But eventually Yusuf and Abd-er-Rahman came to an agreement, and both monarchs lived in the city (A.D. 757) in amity. The treaty was, however, afterwards broken by Yusuf, who left his palace, collected a force, and made war in Andalusia. He was frustrated by the Governor of Seville, but after the conflict Yusuf escaped to Toledo. Here he was recognised in the street, and murdered, by spies who hoped to receive reward for their fealty to Abd-er-Rahman. Yusuf’s head was sent to Cordova, and nailed to an arch of the bridge, together with the head of his son.

Upon attaining the throne, Abd-er-Rahman began to turn his energies to the development of Cordova. He had a passion for building. A new palace arose, mosques and baths were erected, and an aqueduct was constructed to bring pure water from the mountains. In 786 Abd-er-Rahman supervised the building of the huge and splendid Mezquita.

In character the first Omeyyad ruler was humane, eloquent, and brave. He had red hair, a fresh skin, and high cheek-bones. His form was tall and supple, and he was fond of exercise, especially the sport of falconry. His dress was always of white linen, and he lived simply.{26}

There are, however, blots upon the reputation of Abd-er-Rahman I. He was of violent temper, and subject to strong prejudices. His treatment of Abu Othman, Temain, and other allies, who had assisted him in gaining power, was not generous. He reigned for over thirty-three years, and was buried in Cordova.

Hisham, son of Abd-er-Rahman, succeeded in the government of Cordova. He was esteemed as a wise king, and under his direction the work of building and adorning the Mezquita was continued. Hisham founded schools for teaching the Arabic language, and he restored the long bridge over the Guadalquivir.

The next ruler was Hakem, who continued the work of enlarging and improving the mosque. This sovereign was soon confronted with the trials of a rebellion in the city, and a very grievous period of famine. A poet of Cordova wrote:

Hakem was the first king to give regular pay to the army. He left a family of twenty boys and twenty girls, and the throne descended to one of his sons, Abd-er-Rahman {27}II.

The fourth Omeyyad sultan was an encourager of poets, painters, and philosophers. Abu Meruan, the illustrious historian, lived in this reign, and Ziryāb, the distinguished musician, was a court favourite. When Ziryāb was on his way to the city of culture and the arts, his royal patron went out to receive him with honour and pomp. Being himself a poet and a passionate worshipper of music, Abd-er-Rahman II. was a true friend of all artists.

Ziryāb, the composer, was singularly versatile. We read that he invented a new process for making linen white, that he introduced asparagus into Andalusia, invented a crystal ware, and taught the use of leather beds.

It is interesting to learn that the harem of the second Abd-er-Rahman contained several cultured women. One of these was Tarūb, a favourite concubine, to whom the monarch addressed these lines:

Another beauty of the court was Kalam, a woman of learning. She recited poetry and was gifted in music.{28}

We may pass over the somewhat uneventful period of rule under Mohammed and Abdullah, and enter upon the reign of the illustrious Abd-er-Rahman III. (912-961), the greatest of the Omeyyads, and the most enlightened of the trio of monarchs bearing his name. This was the crowning, the most glorious, hour of Cordova’s splendour. The Moors were in possession of almost the whole of Spain. Draw a line on the map of the country from the north-eastern limit of the Pyrenees to Coimbra, north of Lisbon, and you will divide the region of the conquered Iberians of the Biscayan mountains from the kingdom of the Mohammedans. All the districts below the line were governed by the Moors. In 1360 only Granada remained as the remnant of Moorish might in Spain.

Abd-er-Rahman III. lived in a gorgeous palace in the northern quarter of Cordova. This was but one of the sumptuous houses of the city in the height of its grandeur, for, on the authority of several chroniclers, there were fifty thousand palaces in Cordova, besides three hundred mosques. One of these palaces was known as Damascus; others were called the Palace of the Garden, the Palace of Contentment, and the Palace of Flowers. The glitter of Cordova shone{29} afar throughout the Moslem world. Ibn Said, the historian, wrote a full description of ‘the beauties of the kingdom of Cordova,’ containing information concerning the population, industries, and buildings of the fair and opulent city. The water from the aqueduct was collected in a large reservoir, in which stood the image of a lion, covered with gold, and having jewels for the eyes. The stream poured in at the hind part of the lion, and gushed from the mouth, and the overflow ran to the Guadalquivir.

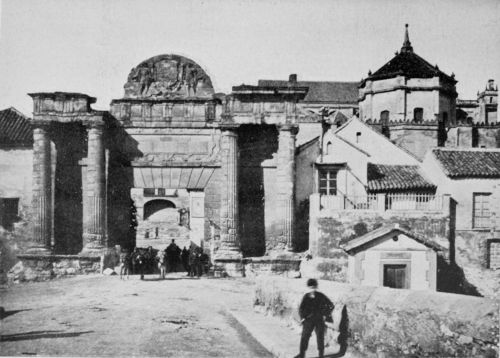

A palace upon arches was built over the river. Dimascus, the chief palace, had roofs supported by marble columns, and dazzling floors of mosaics. Walls surrounded the city, which was approached by beautiful gates, bearing such names as Bab Koriah (the Gate of Coria), Bábu-el-Tamen (the Gate of the Gardens), and Bábu-el-Jemi (the Gate of the Great Mosque).

The wise, the studious, and those skilled in the arts and the crafts flocked to Cordova during the reign of Abd-er-Rahman III. Surrounded by the learned in his splendid palace, the great Khalif lived in an atmosphere of thought and beauty. Literary men came nightly to recite their stories to the sultan and his nobles, musicians played their compositions, and masters{30} of science expounded their theories and discoveries.

Amid the counsels of the intellectual and the prudent Abd-er-Rahman ruled with discretion, justice, and tolerance; Spain had reached the height of its civilisation. The land was made to yield of its richest; fruits and flowers of the tropics flourished; the steeds of Arabia were bred in the vales around the city; workers in clay, wood, and metals plied their crafts with loving industry; and the world wondered at this spectacle of might, culture, and peace.

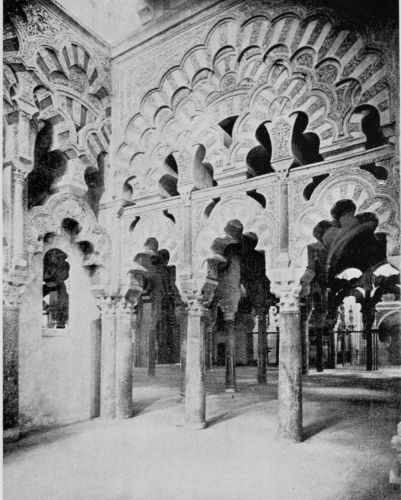

It was Abd-er-Rahman III. who caused the building of Medinat-Ez-Zahra, a city situated at a distance of four miles and a third from Cordova. This marvellous suburb contained markets, taverns, baths, and institutions of learning. A stupendous mosque was erected. El-Makkari speaks of the magnificent palace, wherein the Khalif was served by an army of servants; the gardens, and the fishponds teeming with well-fed fish, who were regaled with a daily allowance of twelve thousand loaves of bread.

Forty years were spent in the making of Ez-Zahra. Ten thousand workmen and three thousand horses and mules were employed in the labour. The columns came from Carthage,{31} Rome, and Constantinople; the walls and roof of the palace were of marble adorned with gold.

Upon viewing the majestic city, a Moorish writer cried: ‘Praise be to God Most High for allowing His humble creatures to design and build such enchanting palaces as this, and who permitted them to inhabit them as a sort of recompence in this world, and in order that the faithful might be encouraged to follow the path of virtue, by the reflection that, delightful as were these pleasures, they were still far below those reserved for the true believer in the Celestial Paradise.’

When the messengers of Constantine came to Ez-Zahra, they were awed and made speechless by the majestic grandeur of the palace. Alas! to-day not a vestige of Medinat-Ez-Zahra survives. The ruthless Berbers razed the fair city to the ground in 1010, leaving not a stone to remind the beholder of its past glory.

The last Abd-er-Rahman possessed a love of ceremony and splendour. He built palaces, mosques, and halls to appease this passion of ostentation; and we read that when potentates journeyed to seek his presence, he caused elaborate buildings to be erected for their nightly reception along the route. In reading of the{32} Mezquita, we shall see how much of his time and wealth were devoted to improving and embellishing the great structure.

Upon the city of Ez-Zahra Abd-er-Rahman spent huge sums from the treasury. It was built to please one of his concubines, after whom it was named, and a statue of the fair favourite was carved in relief over the chief gateway. The palaces were of massive plan and beautiful design. Dark hills formed the background to the city, and referring to the situation Ez-Zahra said: ‘See, O master, how beautiful this girl looks in the arms of yonder Ethiopian.’ The sombre hills were, however, an eyesore to Abd-er-Rahman, and he proposed to remove them; but this feat of engineering was not carried out, and to relieve the blackness of the slopes the Sultan caused them to be planted with fig and almond trees.

Hakem II., who succeeded Abd-er-Rahman, was a just ruler, distinguished for his humility. He was a zealous ascetic, and he passed laws condemning the use of wine. To enforce abstinence from the juice of the grape, he rooted up the vineyards. We shall see later how this Khalif devoted himself to enriching the Mezquita.

We have now reached the reign of the power{33}ful Almanzor, or Almansur, a romantic and ambitious personage, who came to Cordova as a poor student. During the days of his poverty he made a scanty livelihood by writing letters, and became the protégé of Aurora, mother of Hisham II. After attaining this post, he appears to have made quick advance towards preferment, for he was soon appointed kadi of a town, and obtained a position as a civil servant in the city of Seville. Returning to Cordova, he paid homage to his patroness Aurora, and gave her costly gifts. His next appointment was as master of the mint, and we learn that he built himself a mansion of silver.

Almanzor’s career was a fight for power. He won general esteem by his prowess as a soldier, and in the wars with the Christians he triumphed in fifty-six battles. Even when stricken by illness, Almanzor went to the field in a litter, and directed the movements of his force in their attacks on the infidels. Always scheming for authority, he contrived to usurp rule in Andalusia. The attainment of his desire did not yield him complete felicity, for he once wept at the thought that war would one day destroy his sway and level his magnificent palace.

Under Almanzor Cordova grew in might and{34} was still regarded as the wonder of the Moslem world. The Vizier was a man of culture, a clever diplomatist, and a valorous soldier. Conde says that in battle ‘he resembled a raging panther, leaping on the prey and thirsting for blood.’ In times of peace he held poetical tournaments, rewarding the victorious poets with heavy prizes of money for their verses. Almanzor was the founder of Ez-Zahirah, a town which grew up in the vicinity of Ez-Zahra. It contained a resplendent palace, which was two years in the building. Here the monarch maintained a court, and received foreign potentates, with much ceremony and parade of wealth.

Cordova saw the first signs of impending decadence when Almanzor died, and his son Muzaffar came in to rule. Under Almanzor the glory of the city reached its culmination. ‘Do not make war on these people, for by the Lord we have seen the earth yielding them its hidden treasures,’ was the counsel of the Sclavonian ambassadors, after they had sojourned in Cordova, and seen the wonders and riches of Ez-Zahra and Ez-Zahirah displayed before their dazzled eyes. Vast were the resources and the armaments of these three marvellous cities, and famous for valour were their sons. Almanzor forged{35} thousands of blades and spears, and the yield of his shield manufactory was twelve thousand in one year.

And yet power, pomp, learning and the arts—all decayed with the waning of the great Omeyyad dynasty. The ripe fruit of this fine civilisation seems to have rotted rapidly. Such social science as the Moors possessed could not save it from destruction; the arts of war, in which the makers of Kordhobah were so excellent, failed against the inexorable march of decadence. Boastful imperialism and luxury ate out the heart of the city, till it could not withstand the savage Berber mob. Complete disorder prevailed, palaces were wrecked, mosques were pillaged, treasure looted, gardens laid waste, and the largest library in the world was ransacked and plundered.

We can scarcely form a conception of all the beauteous edifices, the noble works of artist and craftsman, that perished in this last upheaval. Almanzor’s palace was ruthlessly burned to the ground. The city claimed to be an independent republic. Robbers swarmed in the holy fanes, and murderers rushed red-handed through the streets.

In A.D. 1010 the Berbers attacked Ez-Zahra,{36} and killed its defenders with savage ferocity. Even within the mosque the fugitive citizens were not safe from the swords of the invading barbarians. Led by Ibn Hishaim Ibn Abd-l-Jabbar, the rebels swooped upon Cordova. The glorious art treasures of Ez-Zahirah were seized by the troops, and the mansions were destroyed by fire. Baghdad and other towns of the east became the storehouses of the jewels, plate, books, and pictures which were stolen from Cordova; and the uncultured horde came into possession under the leadership of Suleyman. Only vestiges of Cordova’s pristine grandeur survived this period of frenzied rapine.

Lamentable was the fall of this centre of wisdom, virtue, refinement, and the arts. Nothing could restore its majesty and pre-eminence. Misruled by discordant factions, Cordova lingered moribund, a sad spectacle of shattered might. It has never regained a tithe of its former supremacy. The drowsy city lives on its memories of greatness.

In 1235 Ferdinand III.—the doughty Christian warrior San Fernando—took the city at the point of the sword, and reclaimed it from the alien heretic.

Spain rejoiced at this capture of the capital of{37} Moorish power. It was a triumph for the soldiers of the Cross. Most of the vanquished Cordovans took refuge in Granada; the ‘reconciled’ sullenly accepted the conditions imposed upon them, and remained in the city. Such was the downfall of the Khalifs. The Christians established rule in the despoiled capital; the mosque was purified from its taint of the Moslem, and dedicated to the worship of God and the Virgin, and one by one the hundreds of baths fell into disuse, for cleanliness was not a canon of the victorious faith.

The coming of San Fernando only hastened the process of disruption in Cordova. War was the chief business of the Spaniard at this age, and handicraft was despised as something unworthy of a true Castilian caballero. All the possibilities of reconstruction and restoration were neglected by the Christians, who were more concerned with expelling the Moors and shattering every relic of their rule, than in making reasonable use of the resources and the crafts which they had developed and brought to perfection. The remnant of the Moors still remained the designers, craft-workers, and agriculturists, but their arts and their husbandry steadily declined. No great and beautiful buildings were reared on the ashes of{38} Cordova, excepting the Christian additions to the Mezquita, which was consecrated in the name of the Vírgen de la Asuncíon.

The militarist Spaniards had no time to devote to trade, the cultivation of the vegas, and the extension of learning. Buildings which had been the joy of the Moors were permitted to crumble, or were pulled down to supply material for the erection of squalid dwellings. Grim ruin descended upon fair Cordova; melancholy decay succeeded its long era of growth and prosperity. The admirable irrigation system, which had made the meadows lush and the land fecund, was left unused, and the vineyards and plots were neglected. Briars and weeds gained supremacy in the fertile valley; the earth became impoverished and barren. The beautiful horses of Arab breed, which were reared by the Moors, deteriorated in stamina and grace, and degenerate cattle roamed the plains by the Guadalquivir. Forests planted by the makers of Cordova were felled; the country was rendered bare of foliage and shade.

In the seventeenth century the population of the city had been reduced to about seventy thousand inhabitants, and the number of its residents steadily dwindled after the expulsion{39} of the Moors. There are now about fifty thousand people in Cordova. In the tenth century three hundred thousand persons dwelt in the city and its surroundings.

The Mezquita, the bridge, the mosque of Almanzor and the ruins of the Alcazar stand as eloquent examples of the Cordova of Almanzor: not a stone survives of the luxurious palaces, whose names suggest Oriental splendour and the joy of life. We can but imagine the charm of the Palace of Contentment and the Palace of the Diadem, and the loveliness of the scented gardens that delighted sultans and sultanas, and the sages and the poets of the far-famed ‘Bride of Andalusia.’

Hushed is the voice of the muezzin: no longer can men sit entranced at the strains of the musicians, or listen to the recitals of the doctors and the poets. But the same notes of the nightingale drift on the perfumed breeze of evening, and the hawks still sail and soar above the minaret. And in the Court of Oranges, girls of erect and Moorish mien bear Oriental pitchers on their heads, as they resort to the fountain for water; while through the open door of the Mezquita one may scent the incense, and see the tangled vista of Arabic arches; or, standing upon{40} the many-arched bridge, watch the selfsame umber river which legions upon legions of dusky warriors crossed to victory.

Thus Cordova, though in a sense dead, still lives and speaks. Its stones are vividly reminiscent of the days of the Moors; the atmosphere is mysteriously impressive, and the features of its natives have still the Arab cast, while in their customs and their speech traces of the Moor survive.

With the triumph of San Fernando came the steady disintegration of the high civilisation of Cordova, and its history from the day of victory onwards is one both mournful and instructive. The expulsion of the Arab artisans was an error of policy which the more intelligent Cordovese quickly recognised, for soon after the restoration of the city into the hands of the Spanish sovereigns, many of the inhabitants proposed to request the king to permit six per cent. of the Moors to remain in Cordova. This petition was, however, lightly regarded by the Governor, and it does not appear to have come under the attention of Ferdinand. Later on, the citizens, finding that trade was rapidly declining, begged that a few aged Moors might be allowed to stay in the city, and to ply their trade of harness-makers.{41}

The neglect of the staple industries of Cordova after the Christian reconstruction is an object-lesson upon the paralysis of the arts and crafts which characterises the Castilian influence during this period. It seems almost incredible that the Spaniards had forgotten the art of harness-making, or that the natives of Cordova refused to soil their fingers in any sort of labour. But what other inferences can be drawn from the proposed petitions that a small number of the Moriscos might be retained as mechanics? It appears evident that the only occupations deemed fitting for an Andalusian of that day were ecclesiastic or military. There was only the choice between the church and the army.

An observant traveller, the Chevalier de Bourgoanne, who made a tour of Spain in 1797, writes of the melancholy decay of Cordova. ‘In so fine a climate,’ says the Chevalier, ‘in midst of so many sources of prosperity, it (Cordova) contains no more than 35,000 inhabitants. Formerly celebrated for its manufactories of silks, fine cloths, etc., it has now no other industrious occupations but a few manufactories of ribbons, galoons, hats and baize.{42}’

When Abd-er-Rahman I. seized upon the citadel of the Gothic Christian kings, he found the Cordovese split up into various sects, such as the Gnostics, Priscillianists, Donatists, and Luciferians. These cults were, however, united in their detestation of the new creed of the East, which the victors sought to impose upon them. It is quite clear from the records of the more impartial Spanish historians, that the Sultan was a man of tolerant mould and a respecter of justice. His ambition was to erect a temple, which would rival in magnificence those of Baghdad, Jerusalem, and Damascus, and approach in sanctity to the fane of Mecca itself.

The Christian church in Cordova stood upon the site of the former Roman religious edifice dedicated to Janus, and upon this situation Abd-er-Rahman desired to rear his great mosque. Autocrat though he was, the monarch strove to maintain the conditions upon which the inhabi{43}tants had surrendered. He might have broken faith, and annexed the Christian building and the ground upon which it stood. But he honourably offered to buy the church and the plot from the conquered people. The negotiations of purchase were placed in the hands of the Sultan’s favourite secretary, Umeya Ibn Yezid.

At first the Christians refused to sell their cherished basilica, which had been divided into a temple of the faith of Christ and a fane for the worship of Allah. Here, in separate portions of the building, the conquerors and the conquered murmured their prayers and repeated their praises to their deities. How the Cordovese were induced to relinquish the church cannot be explained by any historical evidence that we are able to obtain from the writings of Arabians and Spaniards. Some authors have suggested that the Christians of Cordova were disheartened by adversity and the assaults of Islam upon their creed, and that they yielded to the suasion and counsels of Umeya Ibn Yezid, and sold their tabernacle to the invaders. At any rate it is manifest that Abd-er-Rahman won in the end, and that he was able to forward his project without showing violence to the natives of Cordova.

No doubt the Christians preferred to worship{44} in their own buildings rather than to share the basilica with the infidels, and this preference may have influenced their spiritual leaders in meeting the request of the sultan and his agent. Under the terms of transference, the Cordovese were permitted to reconstruct the edifice formerly dedicated to St. Faustus, St. Januarius, and St. Marcellus, three martyrs whom they deeply revered. Immediately upon the conveyance of the church and its site to Abd-er-Rahman, the work of erecting the gorgeous mosque was begun with much enthusiasm and at the expenditure of huge sums of money. The Khalif was rich. Besides the treasure wrested from the Goths during the wars, he extracted a tithe upon the produce of the land and on manufactures. A tax was also laid upon every Christian and Jew in Andalusia. Beyond this, the Moorish kings were greatly enriched by the acquisition of the valuable mines of Spain, the quarries of marble, and other sources of wealth. From these revenues Abd-er-Rahman and his successors, Hisham, Abd-er-Rahman II., the greatest of the dynasty and the third of the line—and lastly, the extravagant Al-manzor—lavished heavy sums upon the designing, construction, and costly adornment of the Mosque.

The power of the first Khalif of Cordova was{45} supreme and undisputed. He was the sole spiritual and temporal head of the people, ‘the Commander of the Faithful.’ Subservient to him were the walis who ruled in the provinces. Abd-er-Rahman’s despotism made upon the whole for charity, tolerance, and justice. The accounts of his persecutions have been coloured by pious historians, and bear the stamp of a natural hostility to the conqueror and his religion. One or two of the more accurate Spanish writers assert that, at the most, only forty persons were martyred in Cordova under the Omeyyad sway; and, according to Morales, these victims sought persecution.

To court sufferings at the hands of the Moors was deemed a noble virtue in the breast of the devout Christians. We may recall the story of Santa Teresa of Avila, who, as a child, wandered from the city with her little brother to seek persecution in the country of the infidels. Whatever may be charged against the Khalifs of the family of Omeyya, it cannot be asserted that their policy after the conquest was one of tyrannous subjugation. They undoubtedly levied taxes and imposts upon the Goths, and confiscated their lands, after a campaign of destruction and aggression; but as victors they{46} displayed magnanimity, and sought to heal the wounded spirit of the vanquished.

The attitude of Abd-er-Rahman I. towards the Christian population of Cordova was, therefore, clement and conciliatory. Under his sovereignty there dawned an age of prosperity and advancement. The work of building the resplendent Mezquita employed thousands of artisans and labourers. This vast undertaking led to the development of all the resources of the district. Durable stone and beautifully veined marbles were quarried from the Sierra Morena and the surrounding regions of the city. Metals of various kinds were dug from the soil, and factories sprang up in Cordova amid the stir and bustle of an awakened industrial energy. A famous Syrian architect made the plans for the Mosque. Leaving his suburban dwelling, the Khalif came to reside in the city, so that he might personally superintend the operations, and offer proposals for the improvement of the designs. We are told that Abd-er-Rahman moved about among the workers, directing them during several hours of every day. The monarch was growing old. It was the longing of his heart to witness the final achievement of his great scheme before death overtook him.{47}

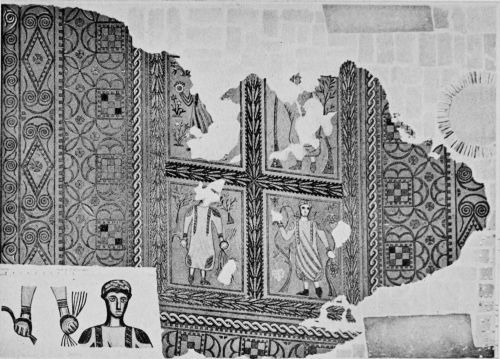

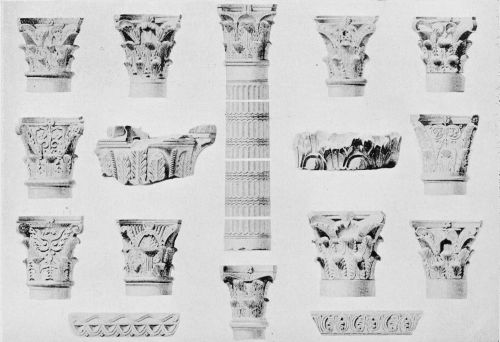

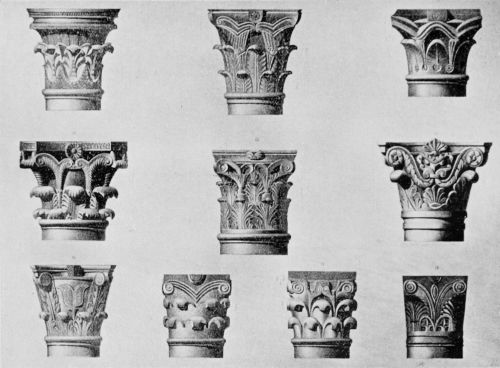

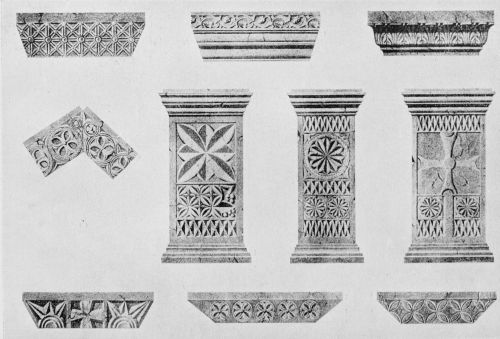

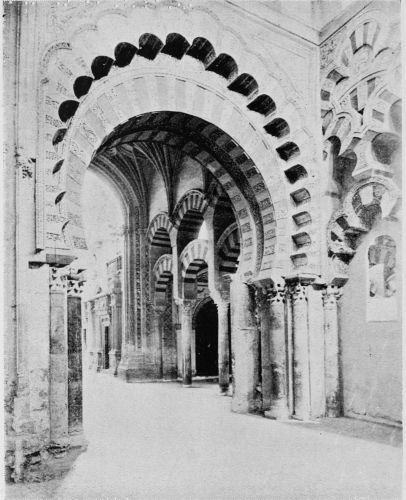

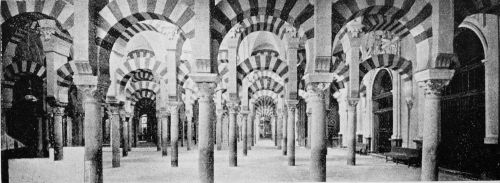

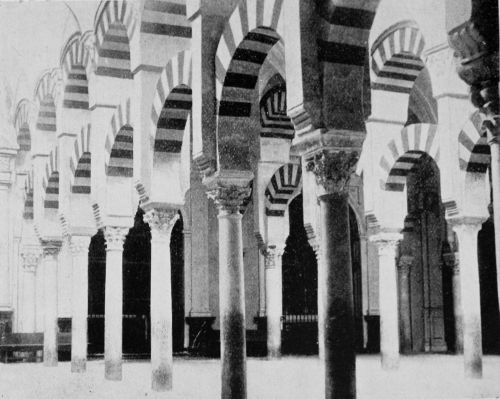

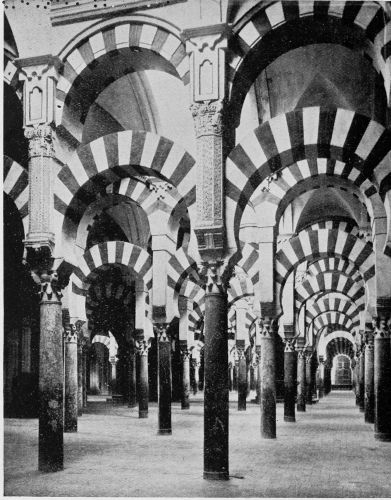

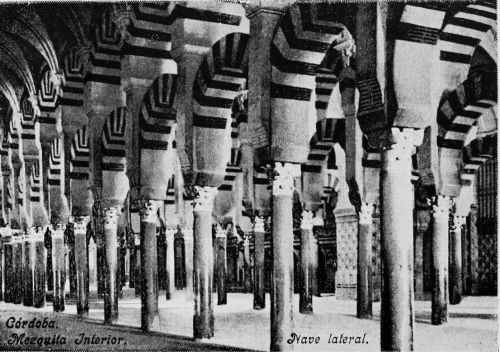

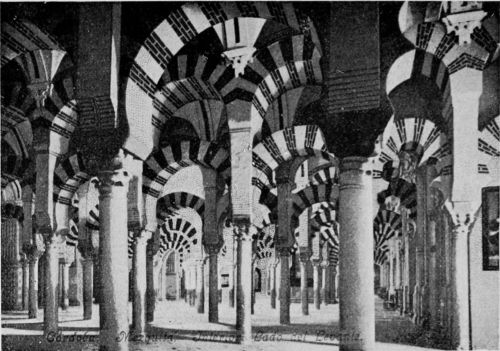

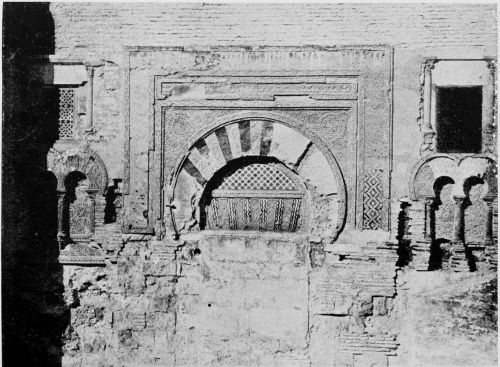

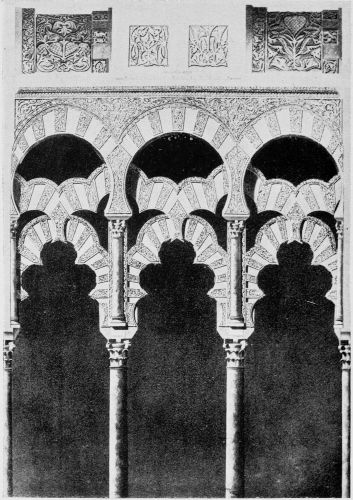

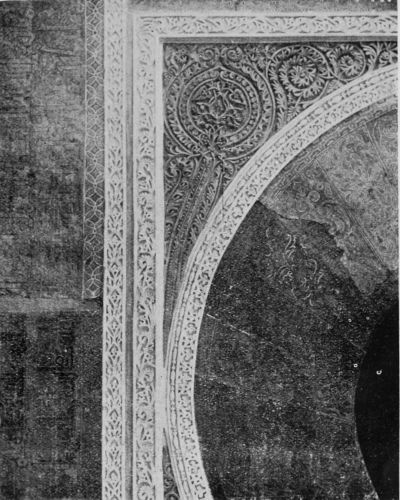

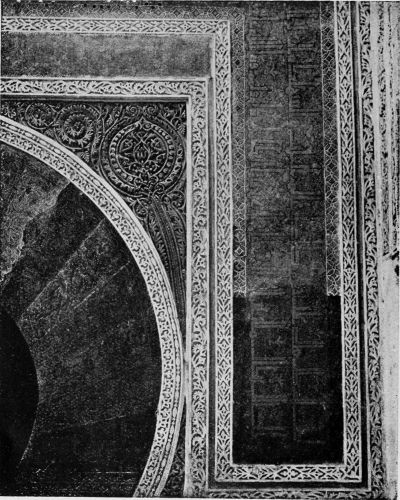

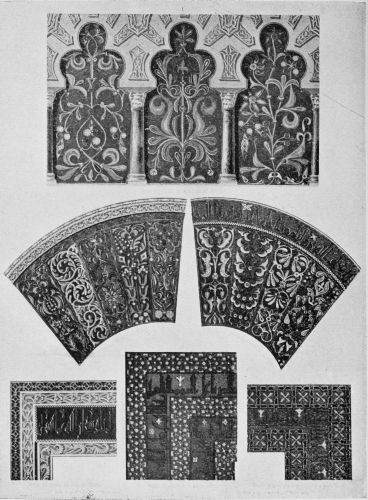

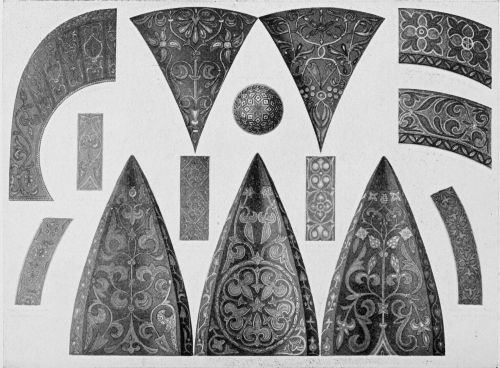

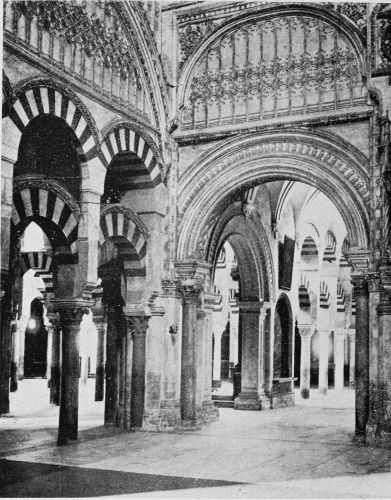

In planning the Mosque the architects incorporated a number of Roman columns with choice capitals. Some of the columns were already in the Gothic structure; others were sent from various quarters of Spain as presents from the governors of provinces. Ivory, jasper, porphyry, gold, silver, copper, and brass were used in the decorations. Marvellous mosaics and azulejos were designed. Panels of scented woods were fastened with nails of pure gold, and the red marble columns were said to be the work of God. The primitive part of the building, reared under the direction of Abd-er-Rahman I., was that bordering the Court of Oranges. Later, the immense temple embodied all the styles of Morisco architecture in one noble composition.

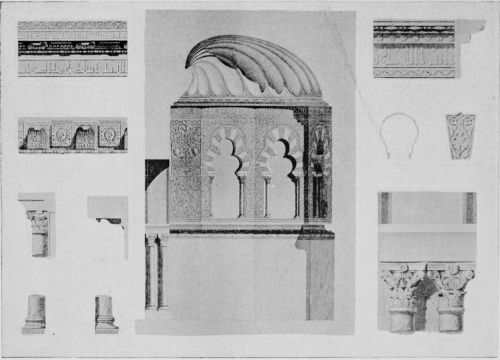

The first Khalif of Cordova did not survive to witness the completion of the Mosque. He died in the Alcazar long before the work was finished, and committed the task to his son Hisham. The prince carried on the work with zealous devotion. Upon his father’s death in 788, the building covered only a small part of the ground now occupied by the Mosque and its later additions. Hisham I. built the tower for the muezzin, and the fretted gallery for the women worshippers, and added much to the Zeca, or{48} House of Purification, erected by Abd-er-Rahman.

The Court of Ablutions was laid out by the first Khalif, and occupied the ground of the present Court of Oranges. In constructing the Mosque, the founders adapted the basilica form of building to the new worship. During the Omeyyad dynasty the original building was constantly enlarged and improved, and fresh decorations were added up to the time of Almanzor. Each Khalif vied with his predecessor in beautifying the temple. The pristine building was finished ten years after the planning under Abd-er-Rahman I., that is, during the reign of Hisham I., who conducted the labour with the utmost expedition. Marbles of spotless white were chosen for the innumerable columns. Arrazi, an Arab writer, speaks of the valuable wine-coloured marble, obtained from the mountains of the district, which was much used in embellishing the naves of the Mosques of Cordova and Ez-Zahra.

The solemnity and beauty of the ceremonies in the House of Purification can only be imagined. Every day saw the celebration of the tazamein, or purification of the devout, before entering the holy structure, and six times daily the alicama,{49} or call to prayer, was shouted by the muezzin from the summit of the minaret. No shoes were permitted to defile the sanctuary; the worshippers entered barefooted. From its sacred shadow all Jews were excluded, and restrictions guarded the approach of women, except the privileged royal brides.

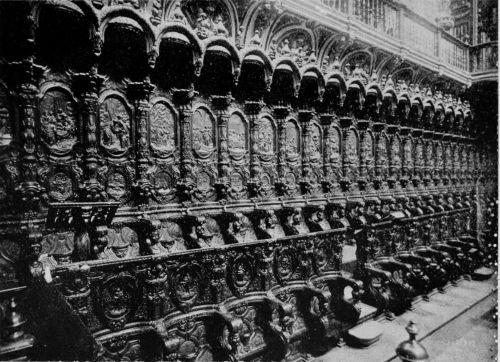

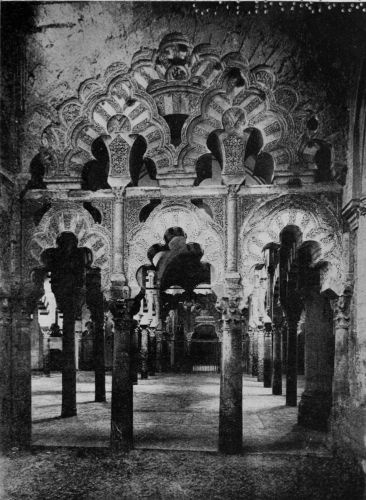

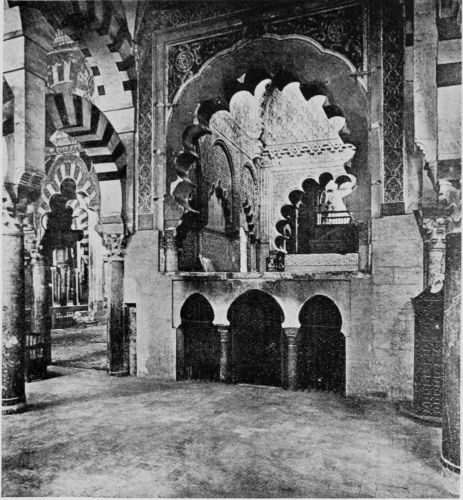

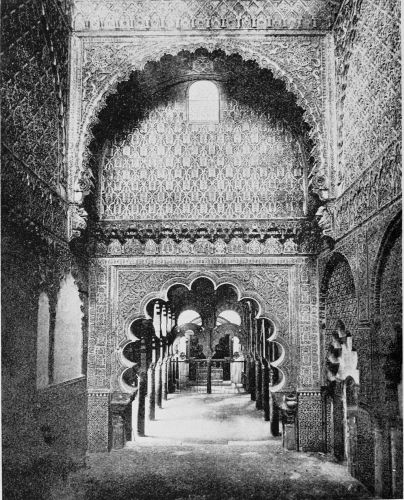

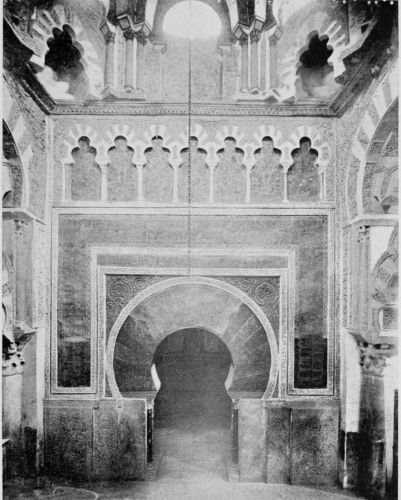

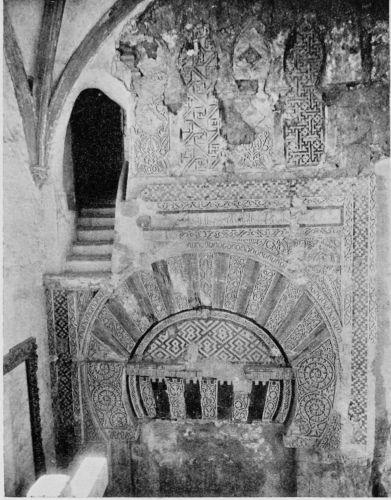

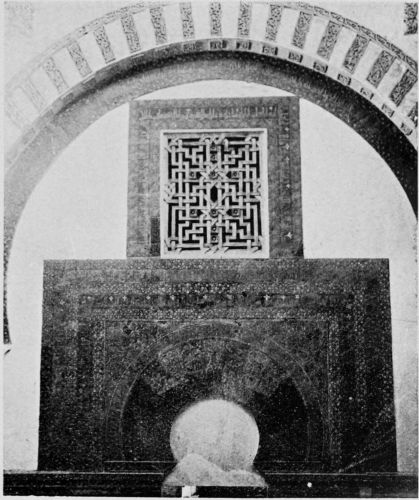

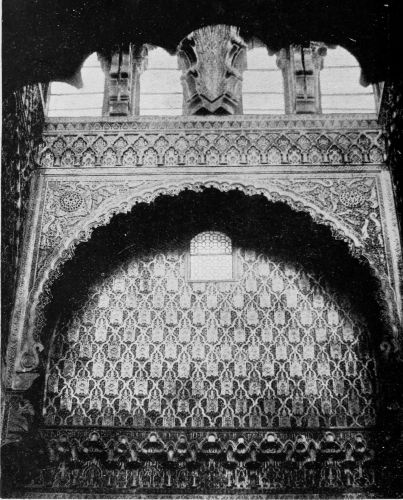

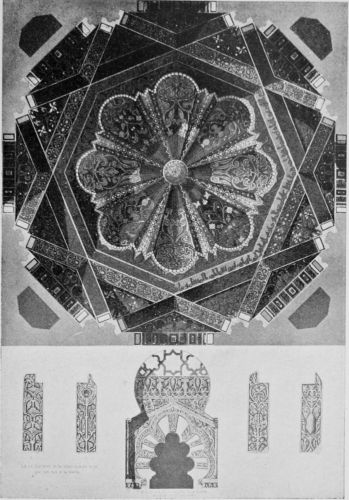

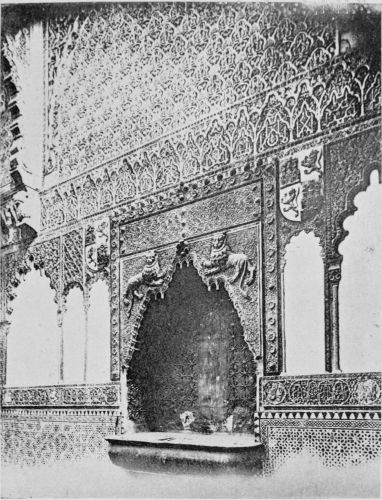

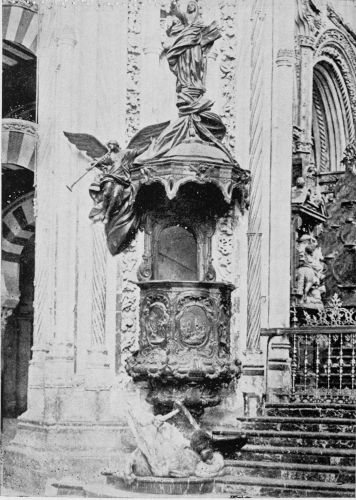

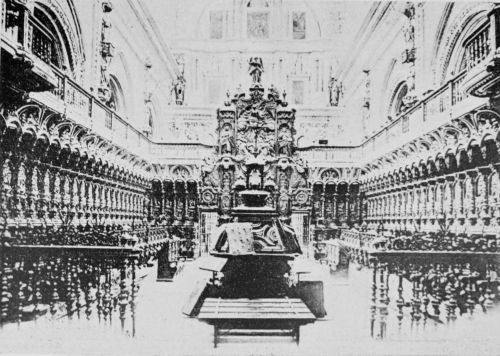

The interior glittered with gold, silver, precious stones, mosaics, and hundreds of lamps of brass. By the side of the priest stood a mighty wax candle, and the scent of the burning aloes, ambergris, and perfumed oils in the lanterns drifted through the tangled arches of the long naves. Some of the brass lamps were made out of bells taken from Christian churches. The pulpit was seven years in the making. It was of ivory, ebony, sandal, aloe, and citron wood, with nails of gold and silver. Eight artists lavished their skill upon the designing and adorning of this pulpit. In the wondrous mih-rab the walls were of pure gold. A copy of the Koran in a gold case, set with pearls and rubies, was kept in the pulpit. It was taken away by Abu-Mohammed on one of his campaigns, and was finally lost to the faithful.

The building of the Mosque began in 785 or 786, and throughout the rule of the Omeyyad{50} monarchs there were constant additions to the Zeca of Abd-er-Rahman I. As Cordova grew, and strangers flocked to the city from North Africa and Arabia, it was found necessary to provide a larger edifice for the worshippers. In the time of Abd-er-Rahman II., the House of Purification was enlarged by the addition of several aisles, two porches were added, and a new mih-rab was constructed. The columns were gilded at this period at the direction of the Sultan. During the reign of Mohammed I. the work was continued; the walls and portals were improved, and the maksurrah, or railed sanctum for the Khalif, was also built. The ruler attended the services in great pomp on Fridays, approaching the Mosque by an underground passage from his palace.

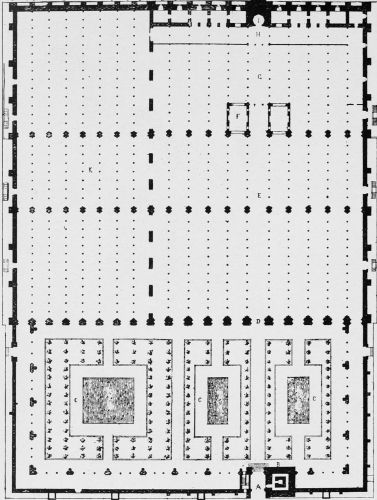

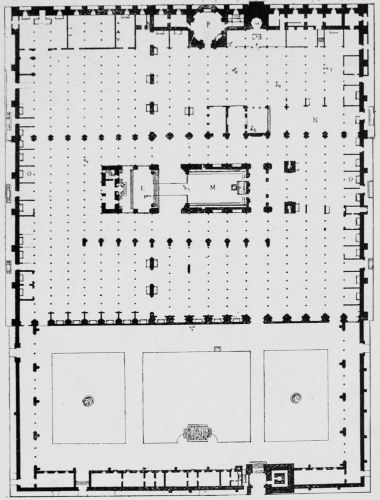

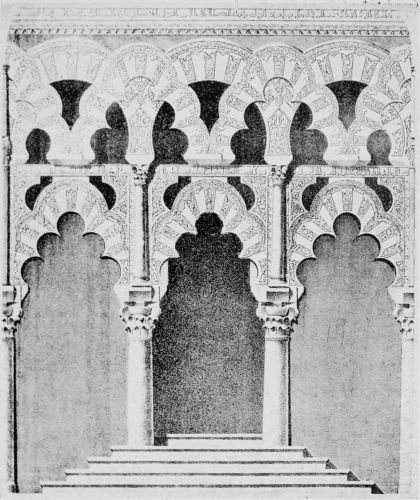

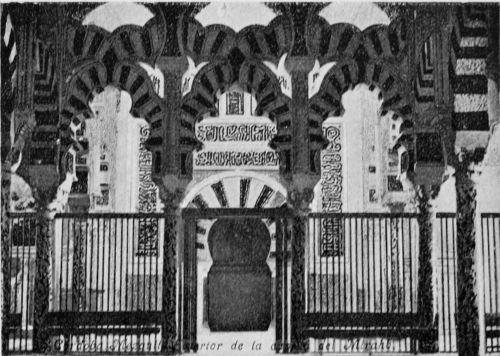

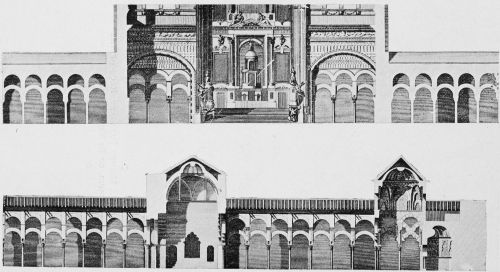

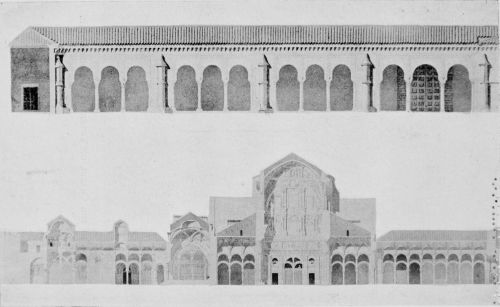

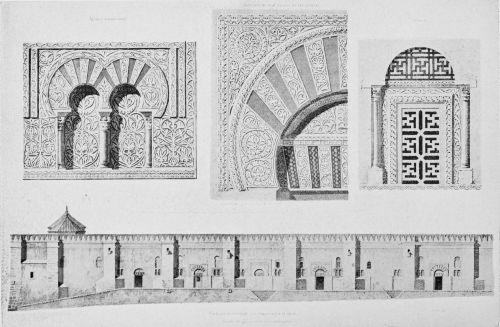

Hisham’s temple covered an area of 460 feet from north to south, and 280 feet from east to west. It was flanked by stout, fortified walls, with watch-towers and a tall minaret. The number of the outer gates was nine, and of the inner doors eleven. These doors led to the same number of naves within the Mosque. The court had spacious gates on the north, west, and east sides, and fountains for the purification of the pious. The naves were eleven in number,{51} stretching from north to south, and these were crossed by twenty-one smaller naves running from east to west.

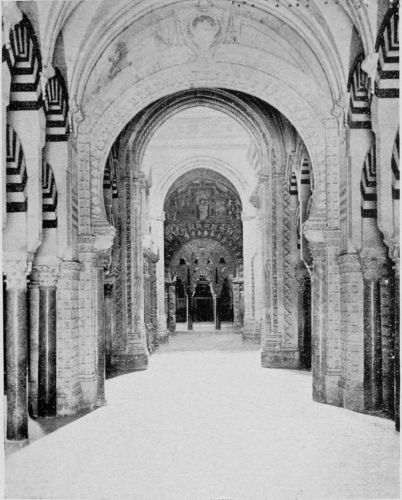

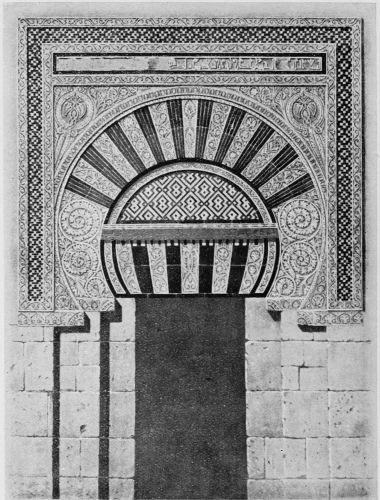

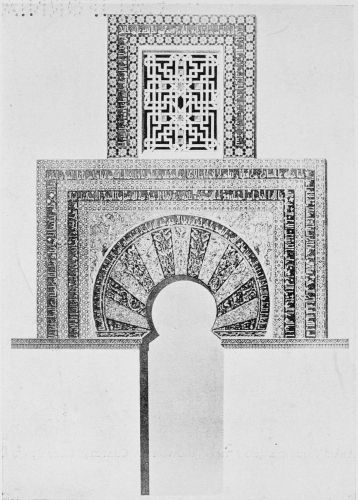

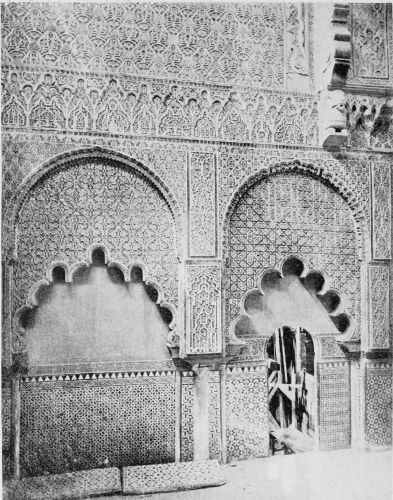

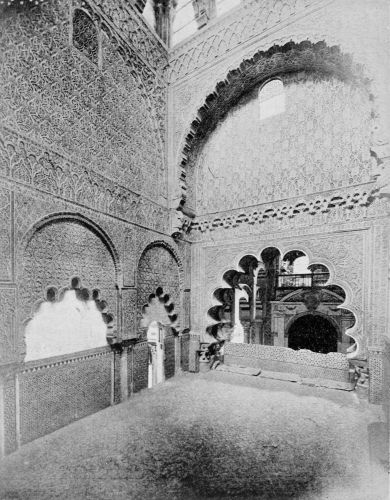

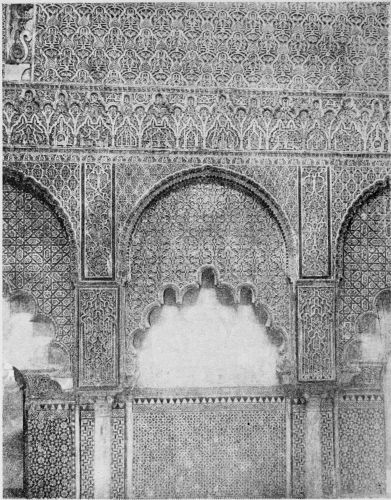

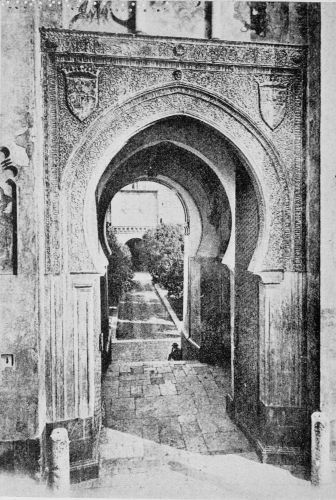

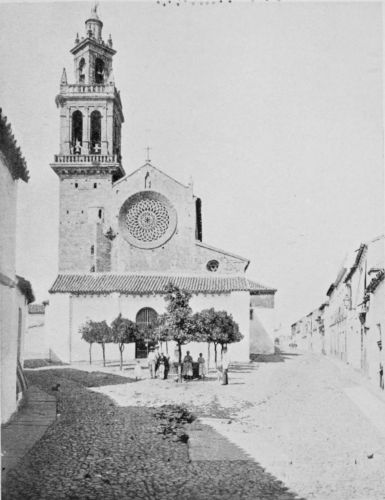

In the Mezquita of Cordova we see the first examples of the true Arabian architecture, whose purity was lost at a later date in the style of the Almohades. The Estilo Sarraceno, or earlier style of design and decoration, has an example in the beautiful Puerta del Perdon of the Mosque of Cordova. We learn that by the year 1282 the fashion in form and adornment had so greatly changed, that the Moors who then remained in the city appeared unable to follow the tradition of their craft in decorating the interior of the cathedral. Even in the reign of Almanzor, the specific style of the Arabs was giving place to less beautiful conceptions of line and decoration. Nevertheless, it is generally admitted that the Mosque is the finest example in Europe of the Moorish religious edifice. It maintains uniformity in the plan of its construction, while the dimensions are enormous, and the adornment elegant and characteristic of the art of Islam in the flower of its might and magnificence.

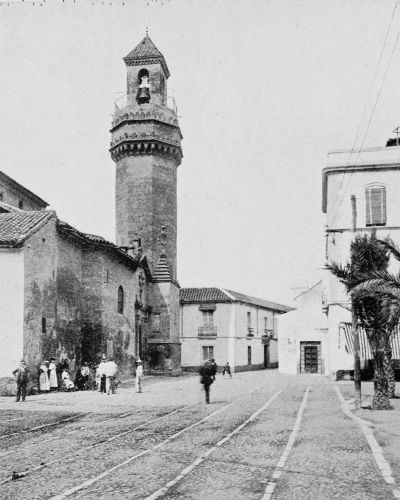

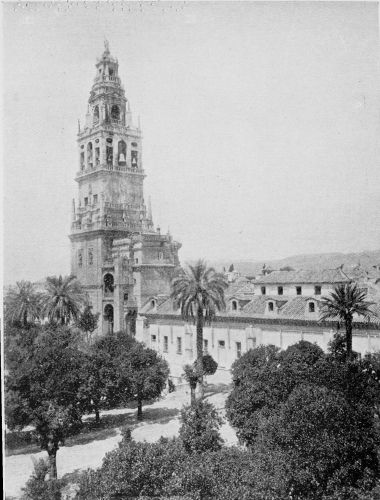

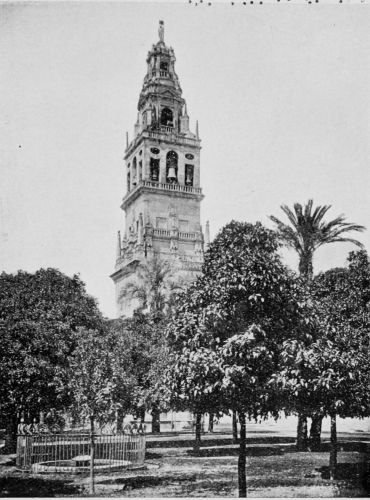

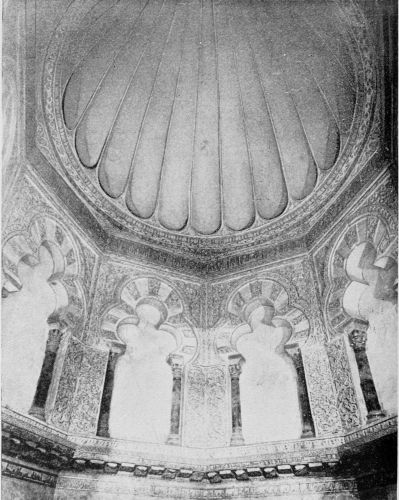

Abd-er-Rahman III. assumed his title of Khalif with the style of En-Nāsir li-dīni-llāh, ‘the Defender of the Faith of God,’ added to{52} the Mosque a new tower, and renovated the ancient façade. The minaret contained two staircases, which were built for the separate ascent and descent of the tower. On the summit there were three apples, two of gold and one of silver, with lilies of six petals. The minaret is four-faced, with fourteen windows, having arches upon jasper columns, and the structure is adorned with splendid tracery.

Long before the final stages in the history of the Omeyyad builders, the Moslem temple of Cordova was deemed one of the greatest marvels of architecture in the world. The chroniclers and poets of the period unite in applauding the zeal of the sovereigns who expended such vast treasure in furthering the glory of Allah by the erection of this sumptuous and dazzling tabernacle. Abúlmothanne, the poet, wrote of the Mosque: ‘To it the pilgrims resort from all parts of the world, as if it were the sacred temple of Mekka. Indeed, its mih-rab, when examined, will be found to contain rokn (angles) as well as makárn (standing-place).’ And another singer proclaimed that the Mosque, which was consecrated to God, was ‘without equal in the world.’

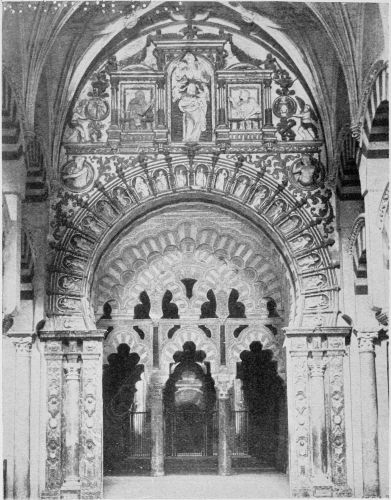

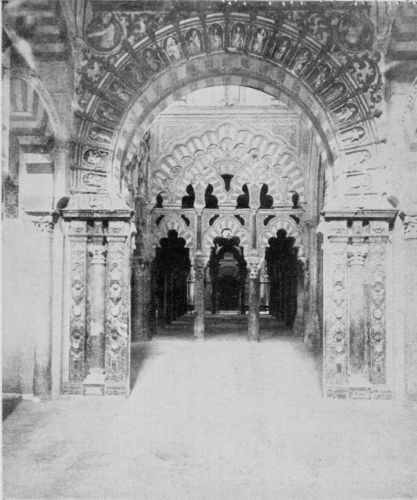

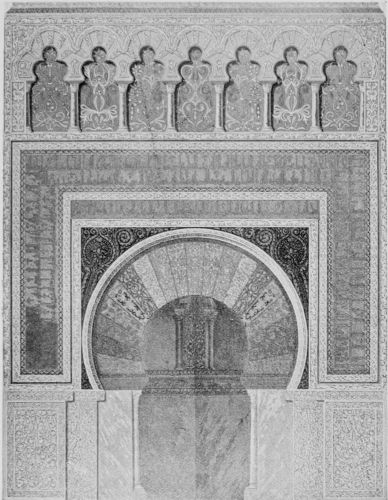

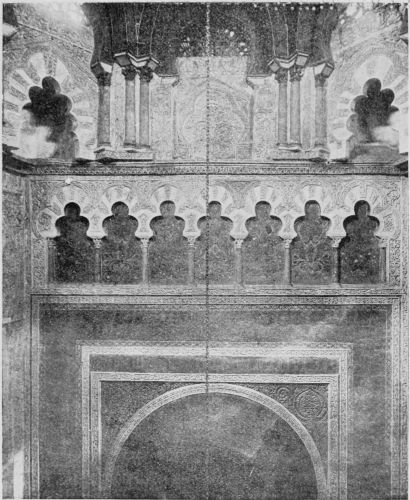

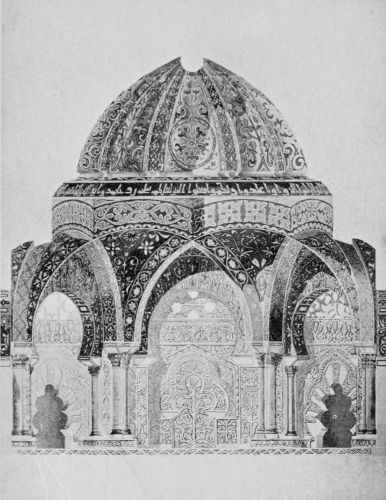

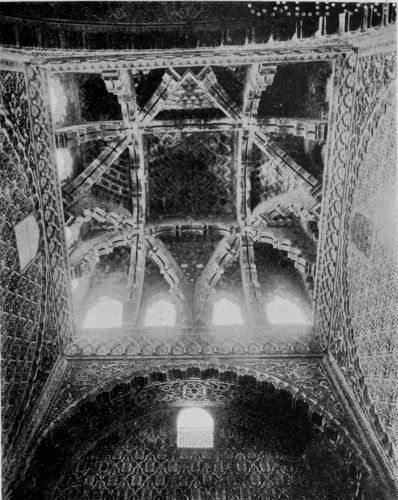

Hakem II., Al-Mostansir-billáh, greatly increased the size of the building. This just and{53} cultured ruler caused the construction of the third mih-rab, which was over four years in the making and rivalled all the previous work in this gorgeous part of the Mosque. The new sanctuary was crowned with a splendid cupola, and the marvellous mosaics of foseyfasa were introduced. Hakem also designed a fresh maksurrah for the Sultan, a space enclosed by an ornate wooden fence or screen, which was beautifully domed in the Byzantine style.

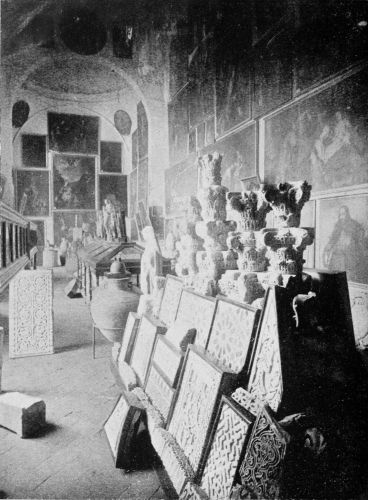

Hakem II. was not only occupied in extending and adorning the interior of the Mezquita. During his busy reign in Cordova, the immense library was enlarged by contributions of manuscripts upon all subjects, gathered from every part of the civilised nations. But the library, with its unique treasures of Oriental lore, and its works of science in many languages, was lost to the world upon the wrecking and downfall of the city. The fruit of Hakem’s devotion remains, however, in the most gorgeous and lovely embellishments of the Mosque. This Khalif also built an alms-house adjoining the temple, and quarters for the residence of the preachers and officials of the house of worship.

The style introduced by Hakem II. is seen in the Puerta Murada, in the holy mih-rab, and the{54} part once occupied by the maksurrah. This sovereign delighted in rich colouring, in splendour and daring in the construction of delicate columns to heavy arches, and in the extension of the fantastic arched naves. He almost doubled the size of the Mezquita by the extensions on the south side.

Under Almanzor there was no slackening in the enthusiasm which the Omeyyad family exhibited in improving Cordova and extending and beautifying its famous House of Purification. The part added to the Mosque by Almanzor is that behind the altar, to the left, when entering by the Door of Pardon. The enlargement during this Khalif’s rule was towards the east. New rows of columns, numbering eight, were added, giving a fresh sense of vastness to the aisles and vistas of interlaced arches.

The great Mosque was completed in the time of Almanzor, and its completion was the presage of the decline of Arab power in Spain. In extent the building now measures 394 feet by 360 feet. Almanzor put the finishing touches to the work which Abd-er-Rahman I. began. For generations architects, designers, artists, masons, and metal-workers had lovingly toiled to produce a triumph of art.

The Mosque was finished. Almanzor sought{55} to improve upon the designs and bewildering brilliance displayed in the labour of preceding reigns; but it is doubtful whether his endeavours heightened the splendour of the structure, or gave fresh lustre to the building that stood in the days of Hakem II. It is agreed among the authorities upon Moorish art that Almanzor’s contributions to the edifice show evidence of a decline in taste, and a waning of the æsthetic sense of the Arab-Byzantine schools of designers and craftsmen.

When Almanzor died, the Mosque was 742 feet in length from north to south, and 472 feet in width from east to west. It was encompassed by battlemented walls, with towers of irregular height. The south wall was the highest, and it had nineteen towers. The total number of the watch-towers was forty-eight, and the majority of these have survived.

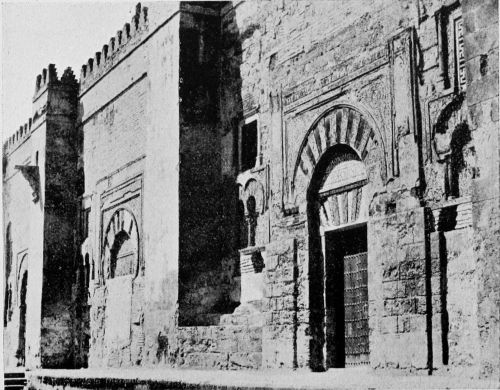

In the stressful days when the Moorish colonisers sought to possess the whole of the Iberian Peninsula, Cordova was stoutly fortified, and the Mosque was protected by this unscalable wall. This barrier of stone is over six feet thick, and designed to withstand the most violent battering. The defences of the sanctuary are very picturesque; there is a subject for the{56} painter at every tower and corner; but they are perhaps a little less wonderful than the grim walls of Avila, or the sombre parapets of brown Toledo. They are made of durable stone, which is marvellously preserved. Many times have these battlements shuddered at the shouts of the fierce besiegers and the determined defenders; often have their stones been stained with the blood of Goth and Moor.

To-day, in the shadow of the walls, we stroll and look upon the calm vistas, the plain, and the cold grey slopes of the sierras, and see the beggars shrinking from the blinding glare of the sun, prone upon the ground in their tatters, in the cool shelter which the tall towers yield. The Mosque dreams, as all things dream in ancient Spain. Its solid outer walls have defied the ravage of storms and wars. They remain weird monuments of Oriental strength, placid and somewhat mournful in their magnificent sufficiency.{57}

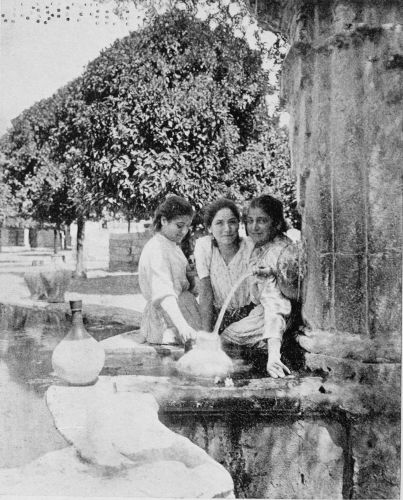

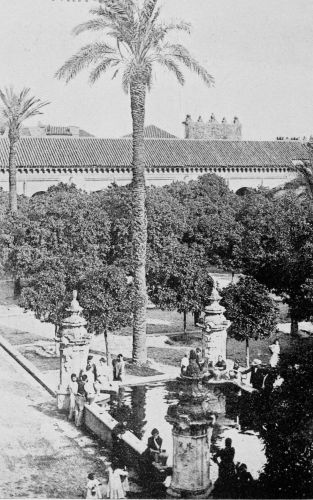

The Court of Oranges is shaded on one side by the oldest parts of the Mosque. It is much larger than the Orange Court, or Patio de los Naranjos, of the cathedral of Seville. Here was once the Court of Ablutions, the place where the faithful purified themselves before venturing within the Mezquita. The fountains, five in number, remain to remind us of the original character of the courtyard. Women come here to fetch water from the clear springs. They carry tall jars upon their hips, or upon their heads, and loiter by the fountain to gossip.

This quiet court invites the aged and the idler. It is cool and gratefully shaded, and when the orange-trees are in bloom a fragrance pervades the place. The priests who officiate in the cathedral spend the hours of leisure here, pacing in pairs up and down, as they smoke their cigarettes. Now and again, one notes the{58} lover waiting for his fair one amid the fountains and the palms.

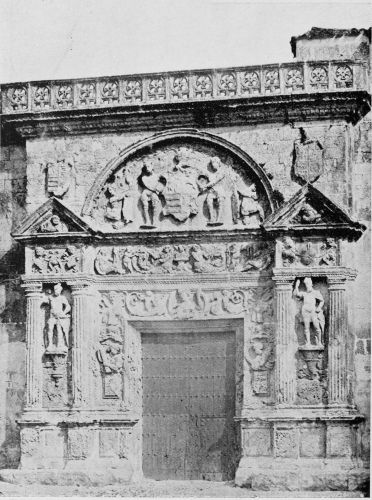

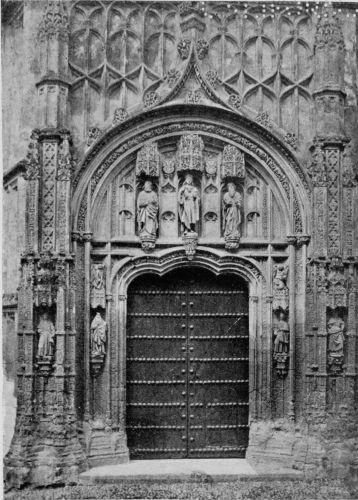

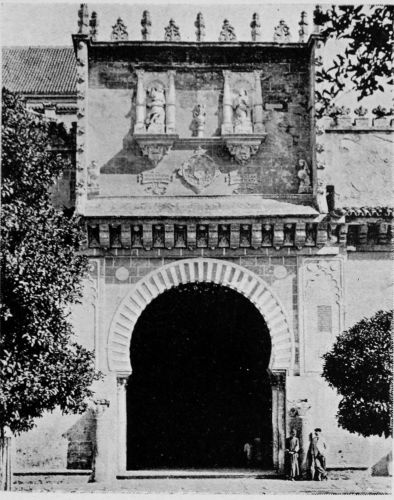

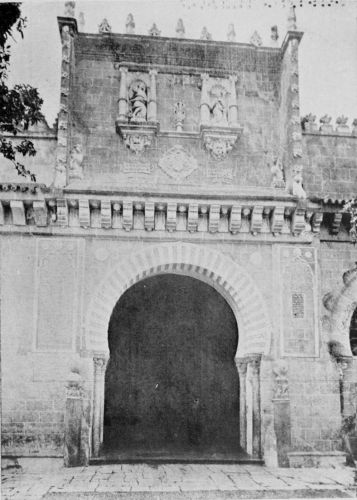

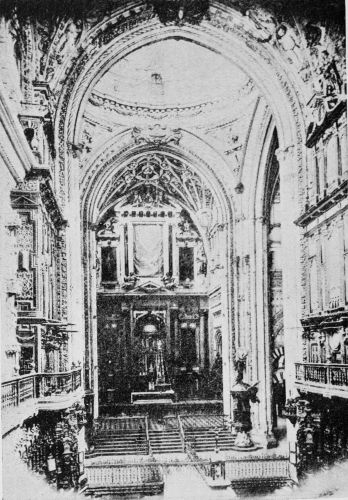

Once there were nineteen beautiful gateways leading into the Court of the Oranges, and these were uniform with the nineteen aisles. We enter by the Puerta de los Palmas, facing the Puerta del Perdon. The sumptuous Gate of Pardon at once attracts us. It is over twenty feet high, with the characteristic horseshoe arches and the elaborate Oriental ornamentation. But this is not the ancient gate; it dates from the Christian recapture of Cordova, and is constructed in imitation of the Arabian work. It is surmounted by a belfry. The upper part of the horseshoe arches is exceedingly ornate, and on either side are coats of arms. The structure is in the Estilo Sarraceno. There are massive doors, coated with copper, upon which are inscriptions. Above the door are poorly painted frescoes.

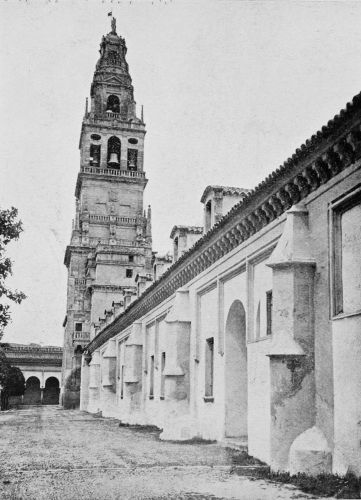

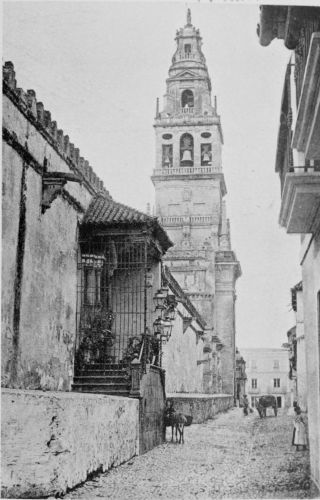

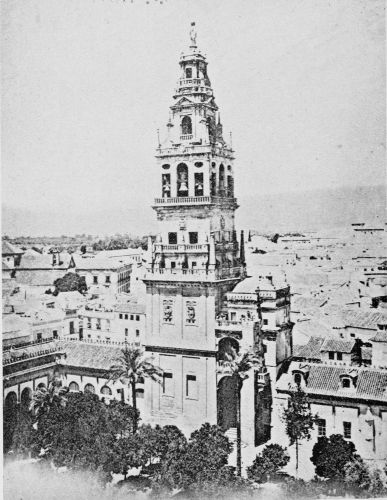

The Bell Tower erected in place of the old minaret of Abd-er-Rahman III. is not Moorish. It was designed by Hernan Ruiz, one of the Christian architects who planned the cathedral. This tower is interesting as a later monument, but it is not in harmony with the Mosque. It rises higher than the former minaret, is more pretentious, and is out of character with the{59} surroundings. On the top is a figure of San Rafael.

The Court of Oranges is over four hundred feet long and more than two hundred feet in breadth. There was a destruction of many of the trees during a violent storm about seventy years ago, and some of the orange-trees were not replaced. The courtyard has quiet cloisters on three sides, with pillars and arches in the Gothic style.

One side of the Patio de los Naranjos is occupied by the Mosque, and it is here we see the finest exterior work of the time of Abd-er-Rahman I. and Hisham. The portions added by Almanzor are behind the altar to the left, when entering by the Gate of Pardon. In the main the impression that one gains in the Court of Oranges is distinctly Moorish. The fountains, the trees, the fine doors of the Mosque, the walls, the gate on the eastern side, and the inscriptions are purely Oriental. For the rest there has been tampering. The hand of the ‘restorer’ can be traced, and the Bell Tower is an affront upon the old edifice.

Four of the fountains were originally constructed by Hakem II., when he had spent his energy upon improving the interior of the Mezquita.{60} The two founts in the east were for the ablution of the women; the two in the west for the purification of the men. The fountains were scooped out of single blocks of marble, brought from one quarry. To bring these huge masses of marble to their positions in the Court of Oranges, it was necessary to make a sloping road. The fountains were drawn by oxen, and borne upon heavy carts, and seventy beasts were required for each team. When the tanks were set in their places, the water streamed in through the great aqueduct of Abd-er-Rahman I., and the surplus went to fill other fountains in the city.

There was no sparing of the toil of man or beast in the days when the Omeyyads reigned in Cordova, for each Khalif seemed eager for the completion of his share of work upon the Mezquita. The army of Morisco labourers was augmented by a host of Christian captives, and we read that these unfortunates were employed to carry stone upon their heads. We can imagine the files of Christians, each man bending under his burden, compelled to toil in the upraising of a mighty temple to the glory of Islam. But the pendulum swings, and time brings its changes in the fortunes of Moor and Christian. At a later period it is the Mudejar,{61} the ‘reconciled’ Moor, who supports the cumbrous loads upon his head, and does the bidding of the Catholic in the construction of the cathedral. And out of all this labour and sweat, hewing of stone, forging of metal, carving of wood and ivory, beating of gold and silver, and laying on of choice, imperishable colours, we have the composite fane of to-day—the Christian cathedral enfolded in the more wondrous structure of the Mohammedan Mosque. Surely there are questions that flash upon the mind as we sit in the Orange Court, and listen to the throb of the bell calling the Christians to prayer within the ancient Mezquita of the Omeyyads!

But the Cordovese do not appear to ponder upon Time’s fantastic transformations. They muse of other things—the affairs of the hour—and regard the Mezquita as an excellent asset to their slumbrous and impoverished city. Every stranger within their walls is looked upon as a sightseer; and what should he come to see but the famous Mosque? And so the boys in the street, offering their services as guides through the labyrinthine white alleys, point ahead and cry: ‘Mezquita, Mezquita.’ For the building is not known as the cathedral; it is still called the Mosque, although it has been reconsecrated and{62} dedicated to the worship of God and the Virgin Mother.

Climb to the top of the tower and look around upon the bleached houses of the city, the curving river, the dull green of the olive thickets, the yellow grain fields, and the grey ridges of the mountains. Everything is sharp, clear-cut in the unpolluted air, and glowing in the brilliant sunshine of the south. The thoroughfares are like a network, tangled and mazy. Carthaginian hosts crossed those sierras to conquer this coveted territory from the Iberians. Then came the legions of Rome, to expel the settlers and to found Corduba. Here stood the great temple of Janus in the days of Seneca and Lucan, the arena, the schools, and the institutions of a powerful and cultured people. But all these fell with the inrush of the Goths from the north, those intrepid warriors, fanatical as they were fearless; and Cordova saw the ruin of the Roman civilisation, and the inception of a new faith and a new social order.

The scene changes constantly; the action of the drama is vivid. Again the invading flood sweeps over Andalusia. The swarthy Moors advance in battle array to the walls of the city, and the affrighted Cordovese fly to their churches{63} for hiding. Again there sounds the clash of weapons and the shouts of combatants. And Islam prevails; the Christian cathedral is given to the Moors, and the Mezquita takes its place.

For centuries the Omeyyad rules in Cordova, and shapes the city to his fashion, obliterating almost every trace of the preceding orders, creeds, and customs. These are the palmy days, whose memorial lies below us in the Mosque, and the bridge over the Guadalquivir. These are the days that made Cordova a name familiar in the ears of the civilised nations, the days of power, splendour, and learning, whose glory shone throughout the world. The new Mecca arose; the creed of the East conquered, and Iberia was transformed to the guise of the Orient. And as the Moorish sway spread, and the conquered Christians conformed to the new traditions, and the country prospered, men thought that this state was sound and stable, and probably final and perfect.

But the pendulum swung again; the dominion of Islam was threatened by enemies within and without. History repeated itself; Time worked its inevitable revenge, and a lustier race made profit from the decadence of the Morisco civilisation. Spain arose and turned upon her oppressor,{64} and the streets of Cordova were once more drenched with the blood of Moor and Christian. This proud Bell Tower stands as a symbol of the reconquest, and of the decline of Cordova.

Christian Spain rejoiced in her change of fortune. The crusaders set themselves to demolish and to upheave. They abandoned the wholesome habits of the Moors; the baths were destroyed by the hundred as useless relics of the detested Mohammedan. Temples, colleges, and palaces were thrown down. Science, the arts, and letters were neglected. We have read how trade forsook Cordova, and how the light of learning was almost extinguished. Gone were the cultured days of Abd-er-Rahman III., and the resplendent pomp of Almanzor. The Mecca of the West had fallen; the fate of Roman Corduba had come upon it. There was no revival, no uprising of the ruins from the ashes that could remake Cordova in the semblance of its old self. Vestiges alone remained to remind the beholder of the grandeur and the glory of the Mohammedan domination. A misdirected imperialism, an irrational conception of greatness, wrought the wreckage of the ‘Bride of Andalus’ after her recapture by the Christian Spaniards.{65}

Before the rise of Mahomet, the architecture of the Arabs was almost devoid of those specific characters that we find in the later work of Omeyyad designers and artists. The pristine Arabian edifices were built as though the tent served as the model for the architects of this nomadic race. But in the great Mosque of Omar at Jerusalem we have the first example of a new and vigorous development of the art of architecture. The minaret, or praying-tower, was invented by Alwalid, and other distinctive features of the Moorish or Saracenic style were introduced in religious buildings.