Title: Harper's Young People, July 25, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: February 4, 2019 [eBook #58832]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| ST. ELIZABETH OF THURINGIA. |

| UP THE CREEK. |

| SEA-ANEMONES. |

| "THE MINUTE-HAND OF THE CLOCK." |

| MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER. |

| A RACE FOR LIFE. |

| TRAPPING TORUPS. |

| HOW THEY HELPED THE DEACON. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iii.—no. 143. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, July 25, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

On a beautiful hill near the town of Eisenach, Germany, there stands an ancient castle, famous in history for the many remarkable events which have taken place within its walls.

It is called the Wartburg, and it was here, in 1521, that Martin Luther found shelter and protection after his return from the Diet of Worms. Within the secure walls of the old castle he spent a peaceful year, laboring on the translation of the Bible, which has brought light and joy to so many hearts. The room where he worked, with the table, book-case, and other furniture, is still carefully preserved.

The Wartburg is one of the oldest castles in North Germany. It was built about the middle of the eleventh century, by Count Lewis, a very powerful lord in Thuringia. It is said that one day the Count was out hunting, when a deer that he was pursuing led him to the foot of a steep rocky hill, where it plunged up the cliffs, and disappeared in the thick forest. The Count stopped, surrounded by his followers, and declared that although the hill had robbed him of the desired game, it should, in its turn, become his fortress and stronghold. This was a bold declaration, for the hill was the property of another Count, and it was against the laws of the great German empire that a man should build on soil which was not his. But Count Lewis had thought of this. He had twelve trusty knights, and at his command they worked many hours in the darkness, carrying soil in baskets from the lands of their master to the top of the hill, until enough was collected upon which to build a castle. Then Count Lewis went boldly to work, and erected the fortress which still crowns the heights above Eisenach.

The counts of Thuringia after this made the Wartburg their home, and it was here that St. Elizabeth passed her life in holy deeds. Her true history is that she was a daughter of a King of Hungary, and was born at Pressburg in 1207. When very young she was betrothed to Lewis, son of Count Hermann of Thuringia, and brought to the Wartburg to be educated. As she grew to womanhood she became remarkable for her charitable deeds, and the family of her young husband complained bitterly that she was wasting his property. Not long after her marriage her husband died while absent in the great army of the Crusaders, and Elizabeth with her three little children was driven away from the Wartburg, and compelled to beg for bread in the neighboring villages. But the people loved her so much that her husband's family were soon forced to restore her rights. The hardships she suffered, and the sacrifices she made, were too heavy for her to bear, and in 1231 she died, when only twenty-four years old. Four years after her death she was made a saint by Pope Gregory IX., and a multitude of beautiful legends were wreathed about her memory. Poets sung her praises, and the poor who had received food and clothing from her gentle hands remembered her loveliness and kindness through many generations.

A German poet of the thirteenth century wrote a life of St. Elizabeth in verse, which contains some pretty legends about her birth and life. In 1207 Count Hermann of Thuringia called a grand meeting of poets and minstrels at the Wartburg, and offered a prize to him who should compose the best poem. From far and near came poets to the competition, and a vast assemblage of noble lords and ladies were gathered to hear them sing the quaint ballads of that olden time. One evening the company were all in the great balcony of the castle, when, a poet, pointing with prophetic finger to the setting sun, declared that a daughter was at that moment born to the King of Hungary, who would become the wife of the son of Count Hermann, and whose wondrous virtue and charity would be remembered through all coming ages. Count Hermann at once dispatched messengers to the court of Hungary asking for the hand of the baby princess for his son, and the betrothal at once took place.

Another beautiful legend is about St. Elizabeth and the roses. Soon after Elizabeth's marriage to Lewis, the son of Count Hermann, a terrible famine came upon Thuringia. There was no bread, and the poor people of the country were compelled to eat roots and wild herbs to keep from starving. Their sufferings touched the tender heart of Elizabeth, and she commanded that bread should be baked in the great kitchens of her castle, which she daily distributed to the poor with her own hands. It is said that the lives of many hundreds of people were saved by her bounty. Her husband's family begged him to put a stop to this waste, as they called it, and to forbid his wife from any longer feeding the poor. It is said that he yielded to the wishes of his mother and sisters, and declared that no more bread should be sent out from the castle. So far the story is true. Now comes the pretty legend which has ever since caused St. Elizabeth to be pictured with roses in her hands.

Her kind heart could not rest while the poor people around her were dying of hunger. With a basket filled with bread she would go from the castle and distribute her bounty among the poor who crowded around her. One day when starting on this mission of charity, her basket on her arm, she met her husband, who stopped her, and sternly demanding what she carried in the basket, tore off the mantle which covered it. To the astonishment of both the basket appeared filled with fragrant roses, and on the forehead of Elizabeth, shone a glittering cross. Her husband was so overcome by what he recognized as a miracle that he gave orders that in future her noble charities should be done with perfect liberty, and he himself did all in his power to aid her in the generous task.

"It's a mighty good thing for us, Mort Hopkins, we took such an early start."

"Say, Quill, what do we want of those rollers?"

"Guess you'll find out 'fore we get the Ark around the dam."

"That's so. All ready? Shove her, now. Here we go. Don't she travel!"

"Mort, what was that long word you went to the foot on yesterday?"

"Me-an-der-ing."

"And you called it 'mean-drying,' and spelled it wrong. Tell you what, we're just going to meandrew now 'fore we get back."

"Guess Taponican Creek'll give us all the twists we want. It's as crooked as a ram's horn."

"Tisn't much wider some places, but the Ark will squeeze through 'most anywhere."

It would not, indeed, have required much of a flood to float a skiff of that size; but she was a pretty one, and it was no work at all for two stout boys of from twelve to thirteen years of age to "pole her along." There was not enough water where they now were to encourage the use of oars, but a pair of them lay in the stern, beside the fishing-poles and the bait and luncheon.

The day was one of those truly wonderful Saturdays that come to country boys in summer, and Mort Hopkins and Quill Sanders had all but slighted their breakfasts to get the early start they were now so pleased with.

"Mort, if Taponican Creek runs out of Pawg Lake, we'll find the place where it does."

"Guess we will. It's there, somewhere."

"We won't stop to fish along."

"No, sir! Not one of the boys knows where we're going."

"If they'd ha' known, they'd all have come, and chucked the Ark jam-full."

Mere passengers were not wanted on board of a ship that was clearly bound on a voyage of discovery. Extra cargo of any kind would have been bad for the fortunes of such a vessel.

The boys did not pole their boat up stream for more than twenty minutes before they came to a place where the banks gave the Taponican room to spread itself. Of course the wider it spread what water it had, the thinner the water became.

Right in the middle of a sparkling field of gurgling ripples the Ark ran suddenly aground.

"Overboard, Quill!" shouted Mort. "Guess Columbus had to wade before he found much."

"Noah didn't."

"His ark had a roof on it."

"Shove her, now. There she goes."

Their trousers were rolled up about as high as they would go, and the water was not very cold. The Ark drew less when its entire crew was out of it.

"Ah! ugh! Crab."

"Nipped you, did he? Oh, phew! what a clam shell! Stepped right down on it. Catch your crab?"

"He let go. Can't see him. Didn't he give my heel a dig, though! They're the ugliest, sassiest—"

"Jump in. She'll float now."

"Shove, or she'll go back, and get aground again."

"There's the dam. Now we've got a job on hand."

The dam was not a high one, but no two boys of their size could have lifted the Ark over it. Quill Sanders had thought of that, and the little craft was pulled ashore at a spot where farmers coming to the mill drove down to water their horses.

"There's just a good road all around from here to the pond. Now for the rollers, Mort."

Two bits of round poles, about three inches thick and four feet long, were a great help in getting the Ark up the slope, but it was slow work for all that. No man in Corry Centre could have hired any two small boys to undertake it. Quill and Mort did it all the more eagerly because no living being would have given them a cent for doing it.

The miller came out, indeed, to shout after them:

"Hullo, boys, what're ye up to?"

"Going to Pawg Lake," said Quill, proudly. "Your old dam's in the way, and we're a-dodgin' 'round it."

"Pawg Lake! I declare! Do ye spect to ever git back agin?"

"Guess we do," said Mort. "Bring you anything when we come?"

"Ye-es. Fetch the lake right along. Bring me the upper eend of the creek. You'll find it lyin' right there."

"Guess we will," said Mort. "Now, Quill, h'ist her. Shove!"

How they did shove! But the old miller came out into the road and took the Ark by the head, and after that about all the boys had to do was to change the rollers forward as the strong-armed fat old fellow dragged the light skiff along.

"There, boys. You're a plucky brace of spring chickens. In with her, now. She's afloat agin."

"Thank you, Mr. Getty."

"Don't forget to fetch me back Pawg Lake, when you find it. An' the crooked eend of the creek."

"Crooked?" said Quill. "Tell you what, I guess we'll have to meandrew pretty much all the way."

"Andrew what? Oh yes. Guess you will. Go it! Good-by."

Off they went, and now their time had come for actual rowing. The upper pond of Corry Centre was well known to be a deep one. It was wonderfully, perilously far from its smooth surface to the home of the eels on its weedy bottom in some places. It lay in a narrow valley, however, between the slopes of steep hills, and it was long rather than wide.

"Isn't this a big thing, Mort? I was never out on any such voyage as this before. Were you?"

"Don't believe anybody else ever was. Not around here. It's a new thing."

"Wonder what the boys'll say? Mort, we might hold on here long enough to catch a fish or two."

"No, sir-ree! We'll just meandrew till we get to Pawg Lake."

They were pulling nicely along just then, quite a distance above the mill and near the eastern shore of the pond, when a clear, pleasant voice sang out to them:

"Hey, boys! Put me across the pond, please?"

The manner and the accent of that hail were offensively correct and polite, and there at the edge of the woody bank stood a young man of middle size. He carried a joint rod instead of a fish-pole; he had a sort of butterfly net on a stick, and everything about him was nice and expensive to that degree which always arouses the hostility of country village boys. Still, these two were on their good behavior that morning, and their hearts were a little warm over the conduct of Mr. Getty. The Ark was pulled ashore and the stranger was taken on board.

"Straight across, please. Nice boat you have. Capital fun for bright young fellows like you. Spending your day out of school on the water? Good idea."

"Course it is," said Mort, but Quill Sanders added:

"I say, mister, got any fish in your basket yet?"

"Not one, my boy. No luck at all this morning."

"Guess you won't catch any 'round here, with all that there fancy rigging."

"Think not? Ah, here we are. Put me ashore. Will a dime apiece do?"

He held out a couple of bits of shining silver as he spoke, but he had already stirred the pride of the crew of the Ark.

"No, thank you," said Quill Sanders. "We're on a voyage of discovery. We won't take pay for any kindnesses we do to the natives we meet."

"You don't say! Voyage of discovery. New World. All that sort of thing. Arctic circle. North Pole. Sandwich Islands."

"No, sir-ree!" exclaimed Mort. "We're bound for Pawg Lake. All the way up the Taponican."

"That's this mighty stream, I suppose, and Pawg Lake is at the mysterious end of it. Boys, it isn't of any manner of use. I'm not a native. Only stopping in the village for a week. You've got to take me on board the—the what's her name?"

"The Ark," said Mort, with much dignity, "and we're not calling for passengers."

"Passengers? Oh no, I'm one of the crew. I'd ship before the mast if there was one. Just let me take those oars and work my watch on deck. Then I'll go below while you take yours."

He had again seated himself, even while he was speaking, and Mort Hopkins hardly knew why he didn't resist the sudden seizure of those oars.

Then there came a surprise to both of them, for the stranger made the Ark spin around, and get her head up stream, and glide away over the water, after a fashion to which she was entirely unaccustomed.

"Quill," said Mort, "he can row."

"Mister," said Quill, "did you bring any lunch with you?"

"I did, my young friend. I am provisioned for the voyage. Is it a long one?"

"All the way up Taponican Creek, and it just meandrews."

"You don't say! Have to tack around the short corners,[Pg 612] and all that sort of thing. Are the natives at all dangerous?"

"Never been there," said Mort, "'cept once, when father and Uncle Hiram and the Dutch house-painter went to Pawg a-fishin', and took me along."

"Did they catch anything?"

"Guess they did; but they had things to catch 'em with. Something better than that there whip-stalk and a spool o' thread."

"They were wise men. We will see what we can do when we get there. Nice boat this is. I can make her meandrew all the way. If we don't discover something, it won't be our fault."

"He just can row," began Quill to Mort, but at that moment the stranger began to pull a little more slowly, and they could hardly believe their ears. He struck into a ringing, musical song that kept time with the oars. That was surprise enough, but what made it bad was that they could not understand one word he was singing.

"Quill," whispered Mort, "I was pop sure he wasn't born in this country. He's a foreigner."

They were out of the pond now, and there was no question whatever of the crookedness with which the creek wound its way in and out among the pastures and meadows. There was nowhere a very strong current, and the boys were a little surprised to find their favorite stream at once so deep and so narrow. Its character was very different from any it was able to earn below the pond and down through the village.

"It's awful clean, though," said Quill, "and there's any amount of trees and bushes along the banks."

"Boys," exclaimed the stranger at last, "I'm going to try one of these shady hollows for a trout. Quill, you take an oar, and paddle me along slowly into that black-looking cove up yonder. I'll show you something new. Mort, you get back into the stern."

"He knows our names," muttered Mort.

But it was no fault of theirs if he did not. He gave Quill a few more directions, and then he stood well forward, with the light graceful rod they had called a "whip-stalk" poised in his right hand. The wind was gently blowing up stream, and the stranger said, very quietly:

"That'll do. Steady, now."

And then they heard the faint hum of the reel on his rod, and a gossamer flight of fine line, with three little bits of fuzzy things at the end of it, each about the size of a small gray moth, dropped on the water as light as thistle-down.

It was a beautiful cast, if the boys had but known it, and the flies alighted in a spot of dark water almost under the bank, where a little eddy made a faint ripple on the surface.

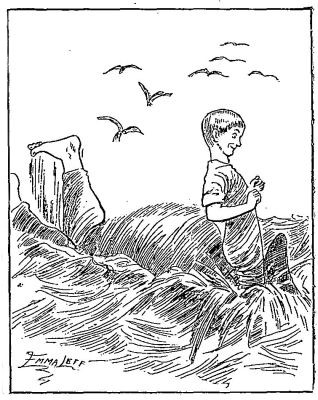

"SOMETHING BRIGHT AND VIGOROUS SPRANG CLEAR OUT OF THE

WATER."

"SOMETHING BRIGHT AND VIGOROUS SPRANG CLEAR OUT OF THE

WATER."

Splash! Something bright and vigorous sprang clear out of the water!

"Struck! I'll get him. Steady, Quill; don't pull a stroke. He's a heavy one this time. I must give him all the line he wants. He's off up stream."

How that reel did buzz, and how the excited boys did watch the motions of their new acquaintance!

"He'll run all the way to Pawg," said Mort.

"Not with that hook in him," said Quill. "See! he's a-winding him up again."

The reel was a "multiplier," and the line came in swiftly enough, for the fisherman had "snubbed" his victim, and turned him toward the boat. Out and in, again and again, went the line, but at last the boys had seen the prize, and knew it was a bigger speckled trout than they supposed Taponican contained.

"Here he comes! Now for the net!"

Both his young friends had long since decided that that machine was designed for "catching minnies," but now its round loop was skillfully thrust under the exhausted fish, as he allowed himself to be dragged alongside. No strain on the slender line. Only a quick, easy "lift," and then a beauty of a trout, more than a pound in weight, lay flopping on the bottom of the Ark.

"Whoop! hurrah!"

"Isn't he a buster?"

"Just look at his spots, Quill."

"We never catch 'em, 'cause they feed on flies, and you have to scoop 'em in."

"Now, boys, more fun."

They were ready for it, and there was plenty of it all the way to Pawg. The trout were biting freely, and every eddy and circling pool on which the interesting stranger's flies alighted yielded up its share of glittering spoil.

"This is your lake? Upon my word, it's a pretty one. There's an island right out in the middle. Boys, we must go and discover that island. It'll be a good place to eat our lunch in. Did you know it was about time for seamen like us to eat something? It hadn't occurred to me before, but I am as hungry as a bear!"

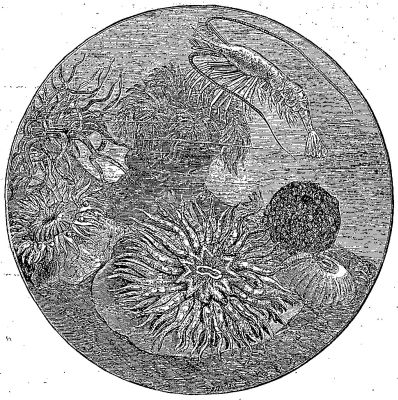

Many of you, no doubt, have learned, when at the sea-shore, the delight of climbing over wet rocks covered with slippery sea-weed, and peering into the little pools left between the stones to see if the great waves have dropped any treasures from the ocean. Those who have enjoyed this pleasure will gladly recall the sparkling pools, carpeted with rich-colored sea-weeds which half conceal the timid animals that live there.

In such pools the rocks, the shells, and the sea-weeds all have richer tints from the bright water that covers them, and one who loves beautiful things will linger beside the pools as if gazing into enchanted gardens.

On searching these rock pools we should find many curious animals. None would interest us more than the sea-anemone, though when we find it hiding in some dark corner, with its tentacles all drawn in, and looking like a soft brown lump, it may not promise much beauty.

The sea-anemone adheres firmly to the rocks, so we will not pull it off. If we watch long enough we shall see it begin to rise in the middle, and from the summit will creep out, very slowly and softly, beautiful tentacles like a wreath around the top. It is now that this singular animal looks like a flower, and deserves the name that it possesses. I think, though, it is not so much like the anemone as it is like a chrysanthemum or some other flower with a great many petals. You would be charmed with the delicate light-colored tentacles waving gently in the water.

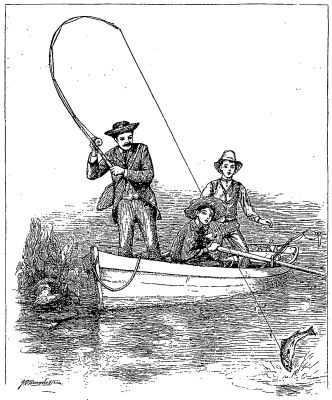

Fig. 1.—Stomach and Chambers of Sea-Anemone.

Fig. 1.—Stomach and Chambers of Sea-Anemone.

In the middle of the tentacles is the mouth, leading into a hollow sac, which is the stomach. The remainder of the body is divided by partitions from top to bottom into open chambers. In Fig. 1 you will see the stomach at a, and the chambers at b.

There is an opening at the bottom of the stomach through which the food passes after being digested. Sea-water also enters the body through the stomach, and both the water and the nourishment circulate freely through the chambers. Each tentacle is a hollow tube connected at its base with one of the chambers, and readily filled with water. Here we have an explanation of the mysterious manner in which the sea-anemone swells itself out and then shrinks away again. The body and tentacles are enlarged by drawing in water to fill them, and when they are suddenly contracted the water is forced out through the mouth.

The sea-anemone has no hard skeleton whatever; all parts of the body are soft, like a stiff jelly. It can draw its tentacles in out of sight, and it will do so upon the slightest alarm, rolling itself into an ugly lump like the one we found. Allow it to remain quiet for a while, however, and it will blossom out as gorgeously as ever.

When any little crab, or worm, or small fish brushes past the tentacles, the lasso-cells are darted out to paralyze it, and the tentacles seize the prey and pass it to the mouth. The bones or shells which remain after the meal are thrown out from the mouth. The tentacles hold the prey tightly, so that even cunning crabs can not escape, and you know it is not the easiest thing in the world to catch a crab and hold it.

Sea-anemones are greedy creatures. It takes a great deal of food to satisfy their appetites, and their mouths can be extended to receive quite large animals. They eat mussels and cockles by sucking the body out of its shell. Great numbers of sea-anemones, in their turn, are devoured by other animals, their soft bodies offering little resistance.

Fig. 2.—Cluster of Anemones.

Fig. 2.—Cluster of Anemones.

The variety of color in these animals is almost endless. Some of them are rich olive and chocolate colors, or purple dotted with green. One beautiful species has violet tentacles pointed with white; another, red tentacles speckled with gray. This one spreads out its green arms edged with a circle of dead white, while that one opens a milk-white top circled with a border of pink. In Fig. 2 is a cluster, of beautiful anemones. The two small ones at the right show how these creatures look when closed.

Some sea-anemones which live in exposed situations are of a dull, dusky brown, covered with rough warts, while animals of the same species, living in deep water,[Pg 614] where there is less need of concealment, have smooth skins adorned with brilliant tints of rose, scarlet, or light green. This is a beautiful provision of Nature for protecting the little creatures by rendering them inconspicuous when left upon rocks by the retreating waves.

The number of eggs produced by sea-anemones seems almost incredible. A single animal is said to throw out three hundred eggs in one day. The eggs are little jelly-like lumps which are formed on the inside of the partitions, and are thrown out from the mouth. After swimming about by means of hair-like appendages called cilia, they settle on some solid body and begin to grow. Sometimes the young ones remain within the body of the parent until their tentacles have grown. They are then ready to settle down soon after reaching the water.

Sea-anemones increase by budding as well as by eggs. At the lower edge of the body little round knobs are sometimes formed, which separate from the parent and grow into perfect animals. If the tentacles or other parts of the body are removed, new tentacles soon grow in their places. If an individual is torn in pieces, each fragment has the power of forming for itself a mouth and throwing out tentacles, and becoming a new sea-anemone, perfect in all its parts.

Most species live in holes among the rocks, attached to stones or shells, over which they slide in a clumsy manner. They are especially fond of deep dark grottoes, and when they have taken full possession of such a place, they may be found clinging to the sides and roof of the cave, and displaying their charms without reserve. Although they do not enjoy the glare of the bright sun, they expand best in mild, clear weather, and remain closed when the sea is rough and stormy.

A few of these animals float on the ocean. One sea-anemone is fond of a roving life, and having no very good means of travelling about, it attaches itself to the back of a certain kind of crab, and accompanies the crab in all its wanderings. There seems to be an attraction between the two, and one is rarely seen without the other.

Another species is mostly found clinging to the shell of a whelk, but for certain good reasons it never clings to a living one. The whelk burrows in the sand. This would be disagreeable and inconvenient to the anemone, so it prefers a dead shell which has been taken possession of by a hermit-crab, and henceforth travels about with the crab. We would scarcely look for affection in a crab, but it has been said that the hermit grows fond of its companion, and that when it has outgrown its shell and has selected a new one, it will carefully lift the anemone from the old home and place it on the new one, "giving it several little taps with its big claws to settle it."

I hope that none of you will fail to hunt up these lovely rock pools when you have an opportunity. The pleasure of a visit to the sea-shore is greatly increased by an interest in the strange forms of animal life which we see there and nowhere else. A glass jar filled with sea-water is often a source of great delight. In it you may drop any strange-looking object that has excited your curiosity. Perhaps this strange object may prove to be some odd little animal which is not yet dead, but which will revive with the touch of the life-giving water.

Most of these animals are timid, but they will expand when they are left perfectly still. In this way we may watch their habits and their hidden beauties. Sea-anemones do nicely in such an aquarium, and as they cling to the side of the jar, we can observe all parts while they are in action. By far the pleasantest way to learn about them is to let them tell their own story. The water must be changed frequently, for impurities are constantly passing from the bodies of even these delicate animals. They will soon die if placed in fresh-water.

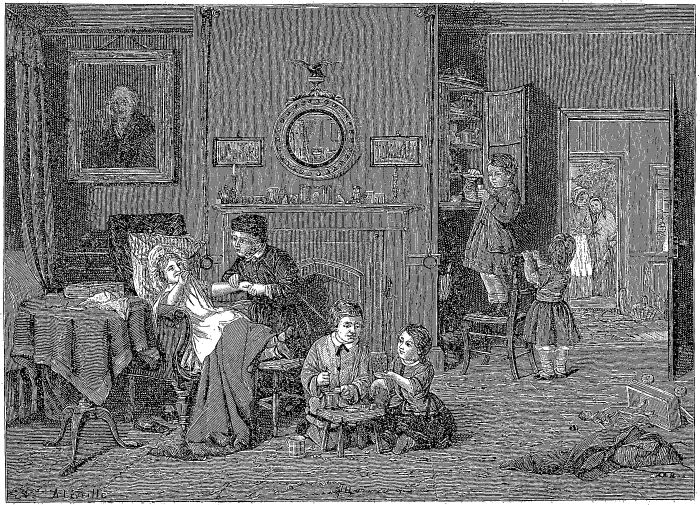

"Kaspar, thou little rogue, how often shall I tell thee not to meddle with that clock?"

"I was only watching the wheels go round, father," said a sturdy little fellow in a soiled leathern jacket, starting up with a half-mischievous look in his blue eyes.

"And what hast thou to do with the wheels, eh? Suppose this clock is stopped or put wrong some day by one of thy tricks, what shall I, Hans Scheller, custodian of St. Martin's Church, say to the Town Council? Dost thou know what birch porridge is, thou rogue? Beware, or I'll give thee such a taste of it as shall make thee go round faster than the wheels."

Poor Hans was indeed kept in constant terror by his inquiring son's uncontrollable habit of going wherever he ought not. The old Church of St. Martin was a famous play-ground for any boy, with its shadowy aisles, and countless pillars, and tall towers, and deep niches, and half-ruined battlements; and the worthy custodian, when he awoke from his after-dinner nap in his little room at the foot of the great clock tower, never knew whether he should find his hopeful boy hiding behind the altar-screen, trying to blow the organ bellows, playing hide-and-seek among the pinnacles of the roof, or sitting astride of a carved spout a hundred and sixty feet above the pavement.

All this, however, might have been forgiven; for the old custodian was really as fond of his "little rogue" as the boy, with all his wildness, was of him. But the one thing that Hans could not pardon was the danger caused by his son's restless inquisitiveness to his beloved church clock. It was his pride and glory to be able to tell every one that during the whole forty years that he had been in charge of the "St. Martin's Kirche," the clock had never stopped or gone wrong; and nothing would convince him that it was not by far the finest clock in the whole world.

"Don't tell me of the big clock of Strasburg Cathedral," he would say, with an obstinate shake of his gray head. "Could it go forty years on end, think you, without the slightest deviation? No, that it couldn't, nor any other clock on the face of the earth except this one."

Mindful of Kaspar's inquiring turn of mind, his father, having to do some marketing in the town the day after our hero's stolen visit to the clock, locked the door of the tower, and took the key along with him.

"No harm can happen now," he muttered; "and, in any case, I shall be back before he gets out of school."

But, as ill-luck would have it, the teacher was called away by some business that afternoon, and the boys got out of school more than an hour earlier than usual. Kaspar, finding his father gone, went straight to the door of the clock tower, and looked rather blank on discovering that it was locked. But he was not one to be easily stopped when he had once made up his mind. Getting out upon the roof, and crawling along a cornice where only a cat or a school-boy could have found footing, he crept through an air-hole right into the clock-room.

For some time he was as happy as a child in a toy shop, running from one marvel to another, until at length he discovered another hole, and thrusting his head through it, found himself looking down upon the market-place through the face of the clock itself. But when he tried to withdraw his head again, it would not come.

It was such a queer scrape to be in that Kaspar was more inclined to laugh than to be frightened; but suddenly a thought struck him which scared him in earnest: his neck was in the track of the minute-hand, which, when it reached him, must inevitably tear his head off!

Poor Kaspar! it was too late now to wish that he had left the clock alone. He tried to scream for help, but with his neck in that cramped position, the cry that he gave was scarcely louder than the chirp of a sparrow. He struggled desperately to writhe himself back through the hole; but a piece of the wood-work had slipped down upon the back of his neck, and held him like a vise.

On came the destroyer, nearer and nearer still, marking off with its measured tick his few remaining moments of life. And all the while the sun was shining gayly, the tiny flags were fluttering on the booths of the market, and the merry voices of his school-fellows who were playing in the market-place came faintly to his ears, while he hung there helpless, with Death stealing upon him inch by inch. His head grew dizzy, and the measured beat of the ticking sounded like the roll of a muffled drum, while the coming hand of the clock looked like a monstrous arm outstretched to seize him, and the carved faces on the spouts seemed to grin and gibber at him in mockery. And still the terrible hand crept onward, nearer, nearer, nearer.

"What can that thing in the clock face be?" said a tourist below, pointing his spy-glass upward. "Why, I declare it looks like a boy's head!"

"A boy's head!" cried a gray-haired watchmaker beside him (one of Hans Scheller's special friends), snatching hastily at the glass as he spoke. "Why, good gracious! it's little Kaspar. He'll be killed! he'll be killed!" And he rushed toward the church, shouting like a madman.

The alarm spread like wild-fire, and before Klugmann, the watchmaker, had got half-way up the stairs leading to the tower, more than a score of excited men were scampering at his heels. But at the top of the stair they were suddenly brought to a stand-still by the locked door.

"It's locked!" cried Klugmann in tones of horror, "and Hans must have taken the key with him, for it isn't here."

"Never mind the key," roared a brawny smith behind him. "Pick up that beam, comrades, and run it against the lock. All together now!"

Crash went the door, in rushed the crowd, and Kaspar, now senseless from sheer fright, was dragged out of his strange prison just as the huge bar of the minute-hand actually touched his neck. And so it fell out that poor old Scheller, coming home for a quiet afternoon nap, found the door of the tower smashed in, his son lying in a swoon, and his little room crowded with strange men all talking at once.

But from that day forth Kaspar Scheller never meddled with the church clock again.

For an hour this tantalizing work was continued, and the pursuers were nearly exhausted. Leander, who was naturally a very slow-moving boy, was more quickly tired than the others. When for at least the twentieth time they thought they had the monkey within their grasp, and he darted to the top of one of the tallest trees, Leander declared he could not take another step, even though the life of the monkey and the success of the circus depended upon it.

Of course it was not to be thought of that they should leave their band there exhausted and alone, so Toby decided they should rest as long as Mr. Stubbs's brother remained in the tree, and it was determined to occupy the time by eating the luncheon Aunt Olive had prepared.

During the last ten minutes of the chase Leander's face had worn a very gloomy expression; but it lightened wonderfully when the package of food was opened, and Toby helped him to a large slice of bread and meat.

Nor was Leander the only one who looked with favor upon the food. Mr. Stubbs's brother had been a close observer of all that was going on at the foot of the tree in which he had taken refuge, and he showed every disposition to make one of the eating party.

Seeing his evident hunger, Toby was sure it would be possible to capture the monkey by means of the food, and he walked around the trunk of the tree, holding a piece of gingerbread temptingly in his fingers.

The monkey came down from branch to branch, as if he had decided to allow himself to be made a prisoner for the sake of the food; but just as Toby was about to seize him, he jumped back with a cry that sounded much as if he were laughing at the disappointment he had caused.

Then Joe tried his skill, coming about as near success as Toby had done; and Leander was roused to action by the new phase the chase had assumed. He too held out some food in order to give Mr. Stubbs's brother the impression that all he had to do was to come and get it.

In thus trying the coaxing plan, all three of the boys got on one side of the tree, while the greater part of their provisions was on the opposite side.

The monkey descended again, first toward one boy and then toward another, as if it were his purpose to allow all three to catch him, and all were equally certain they were about to succeed, when Mr. Stubbs's brother suddenly ran along the branches toward the food. Before it was possible for any of the boys to intercept him, he had dropped to the ground, seized two of the very largest pieces of cake, and was up in the tree again so quickly that but for the cake he had in his paws it might have been doubted whether or not he had been on the ground at all.

Now Mr. Stubbs's brother could laugh at his pursuers, if it is possible for a monkey to laugh; for, without any thanks to them, he had a trifle more than his share of the provisions, and was still at liberty.

"It ain't any use," said Joe, in despair, as he threw himself on the ground, and attacked the luncheon savagely. "I don't believe we shall ever get him; an' if we don't, it won't be much use for us to have our show, for every real circus has a monkey."

"We must catch him," replied Toby, mournfully, looking up into the tree where his pet sat eating the stolen food with the greatest possible enjoyment. "I wouldn't go home an' leave him here if I had to stay all night."

"One might watch here while the others went back to the village an' got every feller there to come out an' help," suggested Leander, who was famous for having ideas so brilliant that no one could carry them into execution.

"We're goin' away from home all the time this way," said Toby, after he had studied the matter carefully, without paying any attention to the suggestion made by Leander; "now let's get a little ways the other side of the tree, an' when he comes down again he'll have to go toward home. Even if we can't catch him, perhaps we can drive him into the village."

Even Leander could see the wisdom of this plan, and the party moved their luncheon and themselves to the side of the tree opposite to that on which they had approached it.

Of course there was nothing to do but wait Mr. Stubbs's brother's pleasure in the matter, and he seemed to be in no haste to make a move. He ate his cake in the most leisurely fashion possible, and then appeared to be wonderfully interested in the leaves, for he would spend several minutes pulling one apart, probably to see how it was made.

But he was obliged to come down at last, and he chose the time just as Leander had settled himself comfortably for a nap, which did not tend to make the band regard him with additional favor.

As Toby had thought, the monkey started back in the direction they had come; and as he was going toward home, they did not make any effort to hurry him. If they could not catch him, they could at least drive him, and they were satisfied to let him go as slowly as he chose—a plan which met with hearty approval from Leander.

For some time Mr. Stubbs's brother moved along as if it were his greatest desire to be back at Uncle Daniel's again, and then Toby saw him run along swiftly as if he had found something under a tree which interested him greatly.

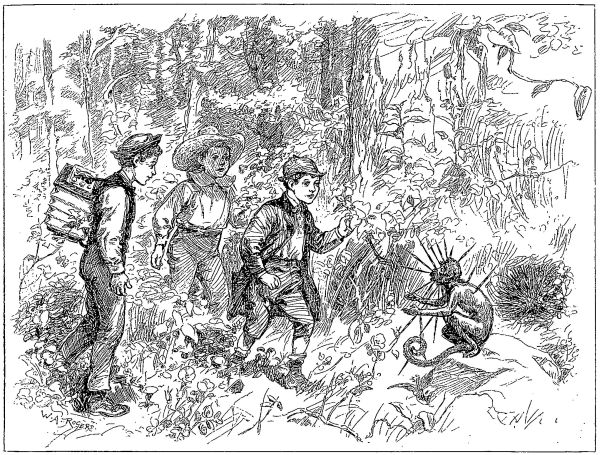

Afraid that the monkey had done this simply to avoid being driven, and that he might dart through the under-brush and get in the rear of them again, Toby ran forward quickly; but before he had taken more than a dozen steps he heard piercing shrieks, which evidently came from the monkey, while the commotion among the bushes indicated that a struggle of some kind was taking place there.

With but one thought, and that for the safety of his pet, Toby ran ahead regardless of the bushes that tore his clothing and scratched his face. A struggle was going on, as he saw when he pulled the branches of the trees away, and Mr. Stubbs's brother was getting decidedly the worst of it.

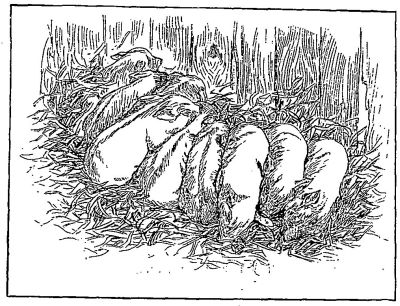

A small, prickly ball curled up at the foot of the tree, and the monkey striking at it savagely with his paws, while porcupine quills were sticking in his face and body, told the whole story.

The monkey had seen the porcupine, and, much to his discomfort, had tried to make that animal's acquaintance. As every boy knows, when one of these animals is attacked it immediately rolls itself up into a ball, with the quills or spines sticking straight out, and the attacking party generally gets plentifully supplied with them in a very short time.

It was some moments before Toby could persuade his pet to stop trying to inflict punishment when he was getting the greater part himself; but he pulled him away at last, and the porcupine, unrolling himself with a grunt of satisfaction, trotted away into the bushes.

There was no disposition on the part of Mr. Stubbs's brother to run away again. He stood there looking as sad and discouraged as a monkey ought to look who had commenced his day's work by stealing ducks, and concluded it by fighting a porcupine.

MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER AFTER HIS ENCOUNTER WITH THE

PORCUPINE.

MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER AFTER HIS ENCOUNTER WITH THE

PORCUPINE.

The quills stood out from his face, making him look as if sadly in need of shaving, while on almost every inch of his body there was one of these natural weapons, giving him a decidedly comical appearance.

As he stood there holding out his paws to Toby as if asking him to extract the spines, and squinting down now and then at those in his face, the boys did not try to restrain their laughter, which appeared to make the inquisitive monkey very angry.

He screamed and scolded in the shrillest tones until Toby set about picking out the quills for him, and Joe took a firm hold of his collar to make sure he should not escape when he was relieved from the effects of his introduction to the porcupine.

PLAYING DOCTOR.

PLAYING DOCTOR.

I dare say you have often seen Assam on the map, and have often tasted Assam tea. The tea gardens are a very pretty sight at certain seasons of the year. I would like to send you a photograph of my garden. From the high ground near we can see the far-off Himalayas, with their snow-clad summits gleaming brightly in the sun.

"Far off the old snows, ever new,

With silver edges cleft the blue—

Alone, aloft, divine."

But I am quite sure you won't care to hear about snowy mountain-tops, and unspeakable sunsets, and other glories of the Himalayan Alps, but boy-like will want to know if I have had any adventures since I came out. This is a great country for wild beasts of all sorts. Not long ago I was walking in the garden with a friend of mine; we were moving along slowly and chatting, when suddenly my friend shouted out something which I could not understand, and vanished like—a lamp-lighter. I looked around to see if there was anything to account for such an unceremonious leave-taking, when, turning the corner, I too was aware of two great bears that barred the way. It was an awkward predicament, and I must confess I was somewhat taken aback, and did not quite know what to do. However, after a good stare, the bears relieved me of all further anxiety by taking themselves quietly off.

Completely unarmed as I was, I was only too thankful to see them safely off the premises.

The other day I had a still more unpleasant adventure; and this time, as before, among the principal actors in the scene was an angry bear. I went to see a friend of mine, a neighboring planter, who lived some miles away. I had a friend staying with me; we went in a small pony-cart; I drove, my friend sat alongside me, and behind was the syce, or native groom. The first part of our return journey was accomplished without any mishap. When, however, we came to the last part of the journey—the last mile or so, I should say, was simply a roadway cut through the jungle—we were surprised to hear a low grunting noise, and a rustling in the ditch that ran alongside the road—a noise as of some large beast forcing himself through the thick undergrowth.

We in front took but little notice of it, under the impression that it was a pig or dog, or something of the kind. You can imagine my horror, and amazement when I felt myself convulsively grasped by the syce, and heard him whispering in agonized tones, "He'll have me off in a minute, sahib, if you don't drive on quickly." Turning round as I best could under the circumstances, I saw a huge bear lumbering along, now on his hind-legs, now on all fours, every now and then making ineffectual "scoops" at the frightened syce on the backseat with his ugly-looking fore-paws.

With a smart cut across the back and a word of encouragement, I started the pony off at his best pace. On he galloped, as fast as ever he could lay his little legs to the ground; but Bruin was not to be denied, and we could not, do what we would, shake him off.

It was a most exciting race. I had to keep cool, for on me, the driver, all depended, and the least mistake on my part might have cost us our lives.

After racing along for some distance in this way, with the bear now alongside us, now close behind us, by some fortunate accident one of our coats fell out on to the road. Bruin instantly halted to have a sniff, but after a moment's pause he was under way again, and before long had overhauled us. Once more "ding, dong, ding, dong, we galloped along," racing for very life. Every turn of the wheels was bringing us nearer home, and if our pony could only last the distance, there was still a good chance for us. As we thus raced along, with the bear hustling after us, so close that we could hear his heavy breathing, my "solah topee" (hat) fell off, and Bruin once more stopped to have a sniff.

All honor to that hat! Had its brim been less broad, the wind would not have taken it off. Had the wind not taken it off, who can tell what our fate would have been? The pony was nearly exhausted; his speed was slackening, and in a moment the bear would have had us in his clutches.

But that moment's delay in Bruin's frantic chase saved us. Heavily I plied the whip upon our unfortunate pony's back. A few leaps carried us forward another hundred yards, and our bungalow came in sight. The bear realized that he was beaten, and slunk off into the jungle, leaving us to go home in peace. We were very thankful to get out of it so well. When our friends were told that we had been chased by a bear they could hardly believe it, but the story is true for all that. Three lives were saved by the puff of wind that blew away my hat.

"Say, boys, I have an idea," Charlie Swan announced one morning as he was sitting on the porch of the farm-house where he and his cousins were spending the summer.

"Let's have it," said Jack, one of the cousins.

"Well, it's just this. You know the pond is full of torups. I believe we boys can have some fun catching them."

"Pooh!" interrupted Jack, "we've had that idea for a long time. How are you going to do it?"

"With a trap," answered Charlie, looking very wise.

"Who ever heard of trapping terrapin?"

"I don't see why it can't be done."

"What kind of a trap would you use?"

"Come out to the shop, and I'll show you," replied Charlie.

While the boys are in the shop I will explain, for the benefit of my readers who do not live near the water, what a torup is. It is a member of the turtle family, and closely resembles the far-famed terrapin of Chesapeake Bay, but it differs from the terrapin in that it lives in either fresh or salt water, rather preferring the fresh, and burying itself in the mud for a greater part of the time. Consequently its flesh acquires a muddy flavor that many people do not like. The torup has all the ferocity of the snapping-turtle, and when aroused will display wonderful agility in jumping at its enemies. In common with the rest of the turtle family, it has the peculiarity, as the Irishman expressed it, of "living a long time after it's dead." I have seen one bite through a lead-pencil six hours after the head had been separated from the body. Another trait of the torup, which Charlie meant to take advantage of in making his trap, is that he will crawl into anything or under any log beneath which he can possibly force himself, resistance only seeming to make him more obstinate in the accomplishment of his purpose.

Before long Charlie and his cousins came out of the shop, carrying with them the trap. It was only a box about three feet long, two feet high, and eighteen inches wide. He had taken out one end, and fastened it to the top by two strong hinges, so that it opened inward. About half-way down each side he had driven two pegs, so that the door could be pushed in, but not out. On the bottom were nailed several strips of old iron.

"I don't see how you are going to work it," said Walter, as he followed Charlie toward the pond.

"Well, I'll explain," replied Charlie. "You see that this door is so hung that the torup can push it in and go in, but can't push it out after he gets in."

"Yes."

"Now I shall put a few old bones, with some meat on them, in the box for bait. The torup will smell them, will push up the door, and crawl into the box; then when he tries to get out again, he finds that he can't."

"All right," replied the boys, and in a few minutes Charlie was with them at the edge of the pond, putting the bones in the further end of the box. They sunk it carefully, and Charlie drove a stick on each side, so that it could not be tipped over or dislodged from its place. Nothing now remained to be done but to wait until the next morning.

When the morning came they rushed to the pond, Charlie full of confidence, and his cousins rather disposed to make fun of his trap. When they tried to lift it into the boat they found it quite heavy, and Charlie exclaimed, joyfully, "Its full!"

"Yes, full of water," replied Jack, scornfully.

"We will see," replied Charlie, as he lifted the box into the boat. In a moment more he pulled out the two pegs, and the door swung outward. Out tumbled four large torups.

"Well, I never!" exclaimed Jack, in surprise. The torups manifested their dissatisfaction by snapping viciously as the boys came near them.

After that the box was set several times with varying results, and the boys did a good work in destroying a large number of torups; for not only do they make it almost impossible for fish to live in a pond, but they will also destroy young ducks by catching them by the feet and dragging them beneath the water, where they devour them alive.

"Cherries? I should say so! There's no end to 'em—trees are loaded, and red's a burning-bush. I was by there to-day."

It was an intensely eager voice, and Davy Kent, the speaker, ended his little speech with an expressive smack of the lips.

"He'd never miss the few we'd take, would he, boys?" That was Ned Rogers. It was upon a straw pile behind Mr. Rogers's barn that the boys were holding an earnest consultation.

"Miss 'em? No, not if we took twice as many as we will."

"A bushel will be enough to treat the whole crowd, won't it?"

"Oh, any amount."

"Now see here, boys"—and Clem Goodrich lifted himself into a sitting posture and knit his brows thoughtfully as he spoke—"I think—isn't this—doesn't it seem a little bit like stealing? Don't you suppose he'd give us a few if we were to ask him? It looks to me—"

But right here Clem's mild voice was drowned in a roaring, boisterous chorus.

"It's not staling, me boy," said Con O'Brien, with the faintest brogue in the world; "it's only helping ourselves to a few cherries, that otherwise might spoil for want o' the picking, and so be wasted intirely. And if Deacon Gammon don't know it, he'll be none the wiser, for he's got piles and hapes more'n he can take care of. Ten to one he'll be obliged to us for helping him out a little—he isn't a bad old gintleman at heart, you know. And it's for the fun of it as well as the ating we take 'em, and that's the truth."

"So 'tis," echoed a good many of the boys.

As for Clem, he gazed into Con's serious face doubtfully, yet, it must be confessed, very willing to be convinced.

"I suppose you know best," said he—"you fellows that have lived here all your lives."

"Of course," laughed Jerry Parker. "Why, my father says he always plants an extra melon seed for us boys as well as for the bugs."

So they reasoned away their doubts and made their plans; and somehow, before the little party broke up, each boy had pretty nearly succeeded in persuading himself that he would be doing the Deacon a favor by helping him make away with a small portion of his fruit. All the same, Ned Rogers couldn't resist a little feeling of guilt, not unmingled with dread, when his father said at the tea table that evening: "I wonder what Deacon Gammon thought of that mow of early-cut timothy? He was up to look at it this afternoon."

Nobody could tell what the Deacon thought of the hay, for nobody had seen him. But Ned was thinking that he would give something to know just at what time in the afternoon the Deacon came to look at that haymow.

That was what he said to his friends when they met next night all ready for the proposed raid on the Deacon's cherries. There were not a few blank faces in the little crowd when he told his story.

"He might have heard us if he was there when we were talking," said Ned, beating a lively tattoo on the bottom of his basket. "I don't say he did, but he might."

"Oh, pshaw!" exclaimed Con O'Brien. "The Deacon's deaf a little, and I don't believe he could hear what we were a-saying. Why didn't you go round, me boy, to the straw hape, and see if you could hear yourself into the bar-rn?"

A shout went up at that, which, to be sure, was exactly what Con wanted, since there is nothing better than a jolly-sounding laugh to put a boy on good terms with himself and everybody else.

"It's all right," said he. "Come on, now, and don't you be afraid o' nothin'."

Not a boy among them was afraid; but a good many of them couldn't keep their hearts from fluttering in a very queer way when they came, with their baskets and bags, to the gap in Deacon Gammon's orchard wall. The orchard was near the house, and the cherry-trees were scattered about among the apple-trees in a hap-hazard fashion. The house looked dark and still.

"It's just as I told you," whispered Con O'Brien, triumphantly. "The Deacon and his wife have gone to prayer-mating, and the coast is clear. 'Rah for we! Look at 'em, me boys!"

They did more than look at the great, delicious, clustering cherries, hanging from boughs which bent low down with their weight. They pulled them by handfuls, and bags and baskets were rapidly filled.

"But there don't look to be any less 'n there was when we begun," said Con, with a merry chuckle. "Now, boys, isn't this a big help to the old gintleman? He'd niver get away with 'em alone, sure."

There was no sound except the voices of the frogs in the marsh under the hill while the work went briskly on. It was when the boys were nearly ready to leave that they heard a voice in the direction of the Deacon's domicile:

"I don't know, but I'll walk out and see."

"It's ould Mrs. Gammon herself!" sounded Con's excited whisper. "Go for the gap, me boys, and don't spill your cherries over. Go, now!"

They were all only too ready to obey. Away they skurried, with long leaps, like frightened rabbits, through the orchard grass to the break in the wall. But they did not go beyond it. Up rose the Deacon on the other side, as cool—so Jerry Barker afterward said—as a frozen cucumber.

"Good-evening, boys," said he. He took off his hat as he spoke, and by the light of the moon the boys could see that he was making a desperate effort to keep his face straight. "Now I'm— Hold on there! Stop!"

For Con and Ike Harris had started to run. They stopped, however. There was nothing else to do when the Deacon spoke in that way, and they knew it.

"Let's see," said the Deacon, reaching toward Ned[Pg 620] Rogers's basket, which was forthwith handed over to him with great alacrity—"let's see how many you've got."

He examined every boy's load in turn carefully and in silence, and all the while the boys looked into each other's faces without speaking. Oh! if the moon would but go under a cloud!

When the Deacon had finished his inspection, he spoke again, kindly, and with a pleasant smile:

"Now, boys, I'm much obliged to ye. I've laid out to go to town with a load o' truck to-morrow, an' I was wonderin' how I'd get my cherries picked. I'm reely obliged to ye, and I'll be more so if ye'll carry 'em to the house for me."

Not a boy felt like disobeying. Not one but silently picked up his burden of cherries and marched along before the Deacon to the house and into the porch.

"Set 'em right down here," directed Deacon Gammon, cheerily, "an' I'll see to 'em 'fore long. Now, boys, ye've worked consider'ble hard, an' you want some supper. Come in an' have some cherry pie an' cheese."

Every boy's face said he would rather die, and there was a sound of murmured negatives.

"Yes, you will," said the Deacon; "you've worked well, an' deserve your supper. Right in to the kitchen now, right in! Mother's a-waitin' for ye."

So she was—kind, motherly Mrs. Gammon. And there was a table loaded with goodies waiting for them too—sandwiches, and plum-cake, and cherry pie, and cherry tarts, and cherries—cherries everywhere.

"Good-evening," said Mrs. Gammon, beaming upon the boys.

"Take some chairs," ordered the Deacon, behind them; "and set right up and have some cherry pie and sech."

The boys wondered whether they were awake or dreaming as they filed shamefacedly past Mrs. Gammon, hats in hand, and took seats at the well-spread table.

"Now help yourselves," said the Deacon's wife. And each boy in his heart wondered if she knew, and hoped she didn't. But they helped themselves readily enough; and at length, between the Deacon's funny stories and the delicious cherry pie, they came as near to enjoying themselves as was possible under the circumstances.

"You ain't eat scarcely anything," said the Deacon, when the boys finished their meal. "Have some cherries? No cherries? Ho! ho! ho!"

"Now, father!" expostulated his wife, mildly, and then the boys knew she knew.

"I don't s'pose I'd ought to," said the Deacon; and he walked to the head of the table, and stood there looking down at his young guests with a queer little smile. "I ain't much of a speechifier," said he, "but I want to ask you boys a question. Which would ye rather be, when ye get ready to take your fathers' places, honest men or rogues?"

Every boy caught his breath. The old eight-day clock in the corner ticked painfully loud.

"The man'll be nigh about the same as the boy," went on the Deacon. "Now which'll you be, boys, rogues or honest men?"

"Hon—honest men," cried Con O'Brien.

Later on he said he couldn't help it, with the Deacon looking at him, and the Deacon's wife wiping her glasses in that anxious way; but he meant it all the same. And they all followed his lead, as they ever did, every boy.

"That's right," said Deacon Gammon—"that's just right; and we won't say another word about it."

"No, don't," said his wife.

But, after all, it was Con O'Brien who said the right thing in the right place, as he picked up his basket, which wasn't entirely empty, in the porch.

"Whenever you want any help about picking your cherries, Deacon Gammon, call on us," said he. "We'll be sure to come when you sind for us, and we won't come before, honest Injun!"

"That's right," said the Deacon—"that's right."

Then his eyes twinkled, as the boys filed out into the night. "Edward," said he to Ned Rogers, "tell your father that's the best mow of timothy I ever saw."

"It's just the way I thought," cried the boys, when they got out of the Deacon's hearing, "just exactly."

AN UNWELCOME VISITOR.

AN UNWELCOME VISITOR.

Middletown, Virginia.

A very dear friend of mamma's sent Young People to me as a Christmas present. I enjoy the stories so much! and am now very much interested in "Mr. Stubbs's Brother." I think the pictures lovely. I am saving every number carefully. Mamma intends having them bound. I see the little girls have been writing about their pets. We have a German canary; he sings by lamp-light. His name is Paul Pry. I am a minister's daughter, and live in the beautiful Valley of Virginia. This is my first attempt at letter-writing. I am ten years old, and would love to see my letter in Our Post-office Box.

M. Blanche M.

Huntsville, Alabama.

I have no pets to write about, but I will tell you of my nice trip. I went to Nashville and Columbia to play in the Huntsville Amateur Opera Company. I appeared as one of the little Dragoon Guards. The name of the play is Patience. Sir. G. is the director, and my papa is Bunthorne. Let me thank Mr. Otis for his nice story of "Mr. Stubbs's Brother." I grow so impatient for the paper each week. I am nine years old.

Edwin L. W.

Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

On the 6th of June my papa, mamma, and I went on the State Editors' Excursion to Washington and Mount Vernon. We arrived at Washington at half past one, and at the depot we were met by our friend Mr. Read, of the Patent-office. After resting awhile, we went around the city to see the sights until dinner-time, which was half past four. At nine o'clock that evening I went with my papa and mamma to the formal reception which the President gave the editors. Being a little girl, I felt shy, and almost slipped past him, but he said, "I don't want this little miss to pass me." So the secretary of the association took me, and told him who I was. He then shook hands with me very pleasantly, so I'm no more shy of the President.

The next morning we took the steamboat Corcoran to go to Mount Vernon. I liked the ride very much; it was very pleasant down the river. On entering the grounds the first thing visited was the tomb of Washington, and there we stood and looked and looked at the marble caskets that hold the bodies of George and Martha Washington. Mamma reached through the iron bars and got some pebbles that were put there for visitors to take. The next place we came to was the old tomb of Washington. We went down into it, and there we chipped some splinters off the old door frame. The mansion we came to next, and entered the hall, and there we saw the key of the Bastile (which is a very large key) in a glass case. The first room we entered was the state dining-room, and there a gentleman explained the different interesting things that were in the house. In this room, in a glass case, is a stone model of the Bastile. We then came into the east parlor; in it was what I thought was an old-fashioned piano, but I was told that it was a harpsichord. We next entered the west parlor; then the dining-room, in which was a large fire-place. From there we went into the kitchen, where there was a table spread, with old-fashioned dishes, knives, and forks. We then went upstairs, and entered the room where Washington died. The bed was very wide. We also saw the room of Martha Washington, and that of Eleanor Custis. Her bed was so high that she had to have three steps to go up to it. Lafayette's room and the guest-chamber were the two prettiest rooms in the house. All the rooms have the same furniture that they had in Washington's day. We went to the attic, and up into the cupola, and had a good view of the beautiful Potomac and the country around. A gentleman took a hen's egg out of a nest in the old brick barn. I gathered a bunch of clover heads and daisies from the yard.

What I like best at Mount Vernon are the grounds and the river-bank, where I would so much enjoy running and playing. I used to think that Washington was a very plain man, but since I have been at his home I have changed my mind, and now think that he liked fine things too. We started back to Washington city about two o'clock, and reached there in time for our dinner, which we enjoyed very much after our day of sight-seeing.

Next day we went into the Patent-office, the Treasury Department, the Smithsonian Institution, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, the Agricultural Building, the Post-office, and the Capitol. All these buildings are very large and handsome, and contain many interesting and wonderful things. In the Dead-letter Office we met an old gentleman who was very kind to me. He said:

"Little girl, are you a Sunday-school girl, and what school do you go to?"

My answer was, "To the Second Presbyterian, of Carlisle."

The next morning we started for home. I was glad to get there, for I was tired, though I enjoyed Washington very much.

Maud Z.

This is a very charming letter to have been written by a little sight-seer who is not yet eight years old. The description of your pleasant day at Mount Vernon, little Maud, will please hundreds of other girls, and boys too, who have not yet been there, but hope some day to go and see the place which was once the home of the Father of his Country.

Blanchard, Ontario.

I am the eldest of six. I was thirteen years old on Midsummer-day, so I thought I would write to the Post-office Box of Harper's Young People. I have taken it since March, 1882. A lady teacher from Chicago spent her vacation with us last summer, and while here her little sisters sent her several numbers of Young People. I thought them just splendid. After going home she sent me a number now and again, but I wanted one every week, so my little cousin and I together sent for it. I have never been out of Canada, but my grandpa has been twice round the world, and I listen with much interest when he speaks of the various countries he has visited. We have a pretty school, and a nice walk to it through a wood by the side of a creek. There are wild flowers in the bush, and you may think what nice bouquets we gather. We all go to school. My papa is a farmer, and we have lots of cattle and horses and many feathered fowls. I must not forget to tell you the nice little present I got from Chicago on my birthday. The same dear friend sent me a pretty needle-book made by one of the Sisters of Charity in Chicago. I prize it highly. They tell me Ontario is very much like the State of New York. Have you ever, dear Postmistress, been in Ontario? Everything is lovely here; all nature seems alive. I have quite a number of pets: three cats (Bessie, Tom Barney, and Jennie), two pet lambs (Jack and Tom), and a shaggy little dog named Tip, the best of all. I think I will now close my letter by sending kind wishes to you and to my little cousins over the line.

M. Blanche D.

No, dear Blanche, I have never visited your pleasant home, but your description is so vivid that I can see with my eyes shut the pretty school-house, the walk by the creek, and the grove where the wild flowers bloom. What a number of pets you have to care for!

Mainhouse, Kelso, Roxburghshire, Scotland.

I am a little boy eight and a half years old, and I have a little brother nearly six. Our father and mother are in India, and we live with our grandpapa in the country. We have two Belgian rabbits, and I call mine Bunny, and John's Brownie. We have a pony named Sambo. There is a large retriever dog whose name is Don. We receive Harper's Young People every week from our uncle and aunt who live in America, and we like it very much. I like "The Talking Leaves." We have a canary, and he sings all day long. We have each a garden, and there are pretty flowers, and we like working in them after lessons are over. We do not go to school; auntie gives us our lessons. I write this letter myself, and John writes his name after mine.

Robert B. P. and John D. P.

Papa and mamma in India must be very much pleased with the letters they receive from their little sons if they are written as plainly and as well expressed as this one.

I am thirteen years old, and love Harper's Young People. We have great fun with a bear that lives near us; he is a young cub. We had a little rabbit and a pet canary, but a wicked old cat killed them both. I have a small but elegant stamp book, with 135 stamps in it; I would like offers for it. I am soon going to learn telegraphy. Could you tell me how all the people got their names?

Harry B. Wilson,

77 Pearl St., Chelsea, Mass.

Some names were given, in the first place, because of the occupation of the person with whom the family began. In all ages smiths have been very useful, and society would not have known what to do without them; so it comes to pass that a great many people bear the name of Smith. Wilson was originally Will's son, Johnson John's son, and so on. Sometimes a number of soldiers and retainers took the name of their chief, in the old warlike days, when a castle was defended by a great many warriors, and the lord of the castle in his turn protected whole villages of women and children. Some names are in memory of places, of rivers, or mountains where battles took place. Some are called after favorite colors. The history of surnames is very curious, and you will be interested if you look into it carefully.

I am glad you are about to study telegraphy.

Brookhaven, Mississippi.

I was much pleased with the letter from the little girl in Germany, for I want to know all about music. I am thirteen years old, and have been taking lessons five years. I play Jael's Faust, Sonnambula, Rigoletto, etc., and I am very anxious to go to Germany, the father-land of music. I am studying German and French, and taking lessons on the violin. My papa says I may go there some day if I study hard. I think our country is the grandest one on the globe, but still I would like to cross the ocean and study under such professors and composers as Joachim Raff, Frau Clara Schumann, and the violinist Hermann. I am sure they would inspire me to do more. "M. W." has certainly heard of our Edison and his wonderful electric light. I have been to Spanish Fort, in New Orleans, and seen the light; it is so brilliant that one almost imagines it is a smaller sun in the sky. Then, too, we have here the telephone and the audiphone, and these are only a few of the modern inventions.

Katie B. J.

You are certainly a very busy little woman, Katie. I hope your desire to go to Germany may be gratified. But do not forget health in your wish for improvement.

Wheeling, West Virginia.

I am a little girl eight years old. I have two dolls, and I love them very much. This is the first letter I have ever written. I have a canary-bird, and it is a beautiful singer. It is very tame. Once I was leaning over the cage, and before I noticed it birdie was pulling my hair. I have two sisters, Bessie and Florrie. My grandpa has a dog named Ben. He is very much afraid of fire-crackers. He spent Fourth of July behind the pantry door. We could not coax him out, even to feed him.

Lillie J. F.

No wonder the poor dog did not know what to make of such a fuss as the fire-crackers made. Your birdie is very cunning.

Columbus, Ohio.

I am eleven years old. My uncle gave me your paper for my birthday present, and I think it was a nice present. I have always read the letters in Our Post-office Box, and I thought I would write one too. I notice that all the little girls tell about their pets. I have a little turtle for my pet. It likes to eat flies; it will take them in its mouth, and eat them fast. My turtle is very small. Mamma said that I must take it back to the river, because it might die. Our schools are all out now, and I passed for the C. Grammar. We have a great many canaries, and I have a beautiful Java finch: it has a bright red bill, and it says tat, tat, all the day long. Good-by.

Winnie S.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

I am very fond of pets, and have nine canaries, six of which I raised myself. Any little girl or boy may do the same, with care and patience. Mamma has two goldfinches. One of them she brought from Europe last summer. I don't like Europe as well as I do America. I was very homesick while I was in those countries where no English is spoken. I could not even find out what I wanted to eat by looking at the bills of fare. We are going soon to my grandma's beautiful country home near Niagara Falls, where I expect to be very happy.

Katharine H.

Conway, Massachusetts.

I am a little girl six years old. I live in a house where my great-grandpapa lived. There are high hills here, and a pretty little brook, and it has speckled trout in it; and we live in the shadow of big trees that my great-uncles planted when they were little boys. The birds come and sing in the trees, and little red squirrels chase each other through them, and bring nuts and eat them in the trees. My uncle says, when he was a little boy, and lived here, a red squirrel with a bushy white tail lived in these same trees, and he tried to catch it in a trap, but could not. I hope I will see one some time. I have two little kittens and a pet lamb. The lamb goes to the pasture now, but at night comes and bleats for us to feed him. And when it is almost dark, a whip-poor-will comes and sings to us. The laurel is now in bloom on the hills, and is both pink and white, and is very pretty. We sent some of it in a box to Chicago. I went a mile to school, and studied reading, spelling, writing, and arithmetic, but the school is closed now. My uncle sends me Harper's Young People. It comes on Tuesdays, and I like it very much. I am glad when Tuesday comes. I enjoy the Toby Tyler stories, and read them the first thing. I like to read about Jimmy Brown. He is a naughty boy but very funny. My mamma says I must not like the naughty boys, and I will try not to, but I read about them.

Florence R. H.

Oxford, Indiana.

I am a little girl eleven years old. My birthday was on the 23d of May; I received several nice presents. I have two little brothers. Johnnie, the oldest, is five years, and Norman is eleven months old, the dearest and sweetest little baby,[Pg 623] I think, that ever was. I go to school in the winter, but we do not have summer school. I am sorry, for I love to go to school. We have Sunday-school half a mile from here. I think we live in a very nice place. A small grove is north of the house and barn, and Big Pine Creek is on the east. I often go fishing. The creek has been pretty high several times this spring and summer, almost a quarter of a mile wide just east of the house. My grandma gave me a little canary. His name is Billy; he is a great pet, and a very sweet singer, and also a great fighter. He will bite our fingers, and look very savage; and when he sings he nearly always gets under his swing, and makes it go with his head, and thus keeps time with it.

Zua E. T.

Germantown, Pennsylvania.

I am a little girl of thirteen, and my brother and I take Harper's Young People, and have done so for nearly two years. I think "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" is very nice, but I think "Toby Tyler" was better. I am now staying at my cousin's, and we thought it would be very nice to write to you. I have lived in America for only six years, as I was born on the island of St. Thomas, in the West Indies, where we had no winter, and I never saw snow until I came here. I thought it came down in great lumps, and I was very much surprised to see it falling in flakes. I have a dear little sister six years old whose name is Annie, but we call her Pansy, Nannie, or any other pet name we choose. She had a kitten, which she named Tabby, and when we moved, papa put him in a bag and sent him to the other house, but the next day he ran away. I am having the volume of 1881 bound, so as not to lose any of the numbers.

Eliza M. S.

A quart of pins, hair-pins, and needles was lately found in the nest of a mouse when some workmen tore down the piazza of an old hotel in Massachusetts. So that accounts for some of the pins which are always disappearing. They were taken away by a foolish little mouse, and could not have made a very soft bed for her family.

Louie Le B.—We will lay your little friend's pretty poem aside until cold weather comes round again. Thank you for sending it.

A Feast in Tahiti.—We are sometimes ready to imagine that we know better how to decorate our houses and dinner tables than the people do who live in the far-off East. But Miss C. F. Gordon-Cumming, who was invited to a feast in Tahiti, has given a very beautiful description of the style of entertainment. It would be hard to find anything prettier:

"Good Queen Pomare had lately died, and the islanders were in mourning for her. At the same time they were welcoming her successor, King Ariiane, with demonstrations of joy. He was making a royal progress over his domains, and stopping at Paea, he and his suite dined in the town-hall. Dinner was laid for three hundred guests. At one end was a table where the chiefs had prepared to entertain the royal party, and other tables had been spread by the families of the neighborhood for themselves and their friends. The building was decorated with palms and tree-ferns, and festooned all over with deep fringe made of hybiscus fibre dyed either yellow or white. There must have been miles of this fringe wreathed about the hall.

"On sitting down, the table seemed to have a series of white marble vases arranged along the centre. On looking closely, these vases turned out to be lumps of the thick, fleshy stalk of the banana near the root. They were of the purest white. In them were stuck branches of the thorny wild lemon-tree, and on each thorn were fastened bunches of gay artificial flowers, either made of colored leaves, or of the silken white fibre of the arrow-root, or of bamboo fibre. From some of the banana vases floated silvery plumes of aerial film like fairy ribbons. This was the snowy reva-reva, extracted from young cocoa-palm leaves. The worker who produces this lovely gossamer keeps a split stick stuck in the ground at her side; into its cleft she fastens one end of each ribbon as she peels it. It is so very light and soft that but for this precaution the first faint puff of air would blow it away.

"When the feast was at an end, the guests adorned their hats with these graceful plumes, and with the pretty, fanciful flowers. Then everybody adjourned to the grassy shore, and seated there, they watched the golden moon rising above the calm sea, while companies of glee-singers filled the air with soft, sweet music."

We would call the attention of the C. Y. P. R. U. this week to the article on "St. Elizabeth of Thuringia," by Mrs. Helen S. Conant, and to "Sea-Anemones," by Miss Sarah Cooper. The boys will learn how to help the ducks and fishes to an easier life in shady ponds by reading Mr. Allan Forman's article entitled "Trapping Torups."