![[Image of the book's cover unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: Colour Decoration of Architecture

Author: James Ward

Release date: February 7, 2019 [eBook #58840]

Most recently updated: January 24, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

|

List of Illustrations (etext transcriber's note) |

COLOUR DECORATION OF

ARCHITECTURE

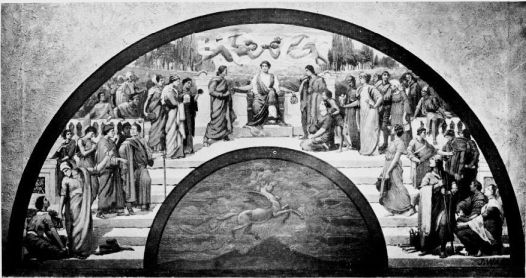

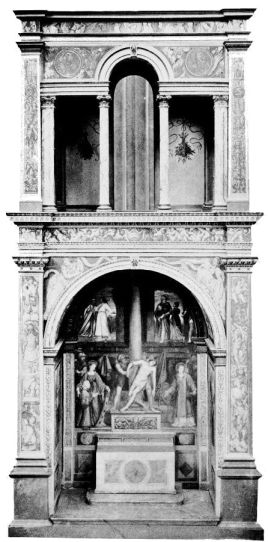

Frontispiece.]

Plate I.—Sketch Design for a Wall Decoration in Fresco.

Fame Rewarding the Arts and Sciences.

TREATING ON COLOUR AND DECORATION OF THE INTERIORS

AND EXTERIORS OF BUILDINGS. WITH

HISTORICAL NOTICES OF THE ART AND

PRACTICE OF COLOUR DECORATION

IN ITALY, FRANCE, GERMANY

AND ENGLAND. FOR THE

USE OF DECORATORS

AND STUDENTS

BY

JAMES WARD

AUTHOR OF “PRINCIPLES OF ORNAMENT,” “HISTORIC ORNAMENT,” “COLOUR HARMONY

AND CONTRAST,” “PROGRESSIVE DESIGN,” “FRESCO PAINTING,” ETC.

WITH TWELVE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR AND

TWENTY-TWO IN HALF-TONE

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

1914

{iv}

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

BRUNSWICK STREET, STAMFORD STREET, S.E.,

AND BUNGAY, SUFFOLK.

{v}

This book is written with the view that it may be of practical service to the decorator, student and craftsman, who may be engaged in the practice and art of colour decoration, as applied to the interiors and exteriors of public buildings, churches, and private dwellings. I trust also it will be of some value to all who take an interest in the decoration of their own houses. The people of our own countries have been so unaccustomed to coloured buildings for the last three or four hundred years that a strong prejudice against the use of colour in architecture has been developed and is maintained even at the present day. Though we may all love colour, there are very few amongst us who have the courage to advocate its use in the decoration of buildings. We visit Italy, France, Germany, and the East, and admire the many and beautifully decorated churches, palaces, city halls and other public and private buildings, but the lessons we may have learned are lost to us, for we come back to our country to still hug our ancient prejudice against the use of colour, and are contented with the greyness of life, and with the dreariness and drab of our great manufacturing cities.

It is fashionable just now for many of our educated classes to talk largely on art and decoration on public platforms, and to air their artistic views in newspapers and magazines, but when it comes to a{vi} question of the practical application of their preaching and writing, they are found wanting, their courage seems to evaporate, as they think they have done their duty in the advancement of art by simply talking about it. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in England there was a school of living art, and five or six centuries previous there was one in Ireland. Is it too much to expect these golden ages of art to return to us? We hope not, but before they do, art must become a common thought with the people, which can hardly be said to be the case at present.

I have included in this work some brief historical reviews of colour decoration in Italy, France, Germany and England, not so much on historical lines, but in order to offer to the decorator and student some account of the styles, methods and practice of the art under consideration in the countries named, and in hopes that what I have written in respect to these matters may prove of practical value to the readers of this book.

I desire to thank the Authorities of the Victoria and Albert Museum, The Dublin National Museum, the Dean of St. Alban’s Cathedral, and Mr. William Davidson, L.R.I.B.A., Architect, Edinburgh, for their kind permission to use the illustrations acknowledged to them in this work.

J. Ward.

“I cannot consider Architecture as in anywise perfect without Colour.”

Ruskin: Seven Lamps of Architecture.

THE History of Art testifies, in all its great periods, to the keen delight that artists, decorators, and architects have taken in the study of colour, and its expression in certain harmonious proportions and arrangements for the decoration of buildings. Colour was obtained for the adornment of a building by the use of marbles, metals, enamelled bricks and floor mosaics, which may be classed as permanent colouring, and structural in character, or it was applied, as in painting, wall mosaics, and stained glass. Architects were not content with leaving their buildings in grey and drab, for in such periods of the past, no building was considered complete without its final application of colour decoration.{2}

Nature, for the solace of mankind, has made most of her works beautiful, by dressing them in coloured garments. Birds, insects, stones, gems, trees, flowers and “weeds of glorious feature”; the countless phases of the earth, the sea, and the sky with its clouds, when rosy-fingered at the dawn, when sunlit in noon-day beauty, or when fringed with the gold and crimsoned fires of the dying day, afford the clearest evidence that nature delights in rich and bright, as well as in quiet schemes of colour harmony. Therefore, if true art is built on the solid ground of nature, colour cannot well be divorced from it, for although certain uncoloured artistic creations are legitimate enough, they come under the head of illustrations, or are portions of coloured schemes of decoration, for colourless art, like colourless nature, is almost a contradiction in terms.

Even a whitewashed wall, when left some time to the weather, will be eventually changed into a variegated surface having delicate tints or suggestions of almost every colour. We might also illustrate nature’s dislike to monotonous uniformity of tone if we select any other colour, however brilliant or intense, instead of white. The doors and windows of a house may be painted, for example, in a uniform colour of the rankest and crudest green imaginable, but if left long enough to the effects of the weather, this harsh colour will be transformed to a beautiful and variegated harmony of numerous and closely{3} related tones, varying perhaps from greys to emerald greens and peacock blues, or in other words the rank and uniform harshness of the original colour will be eventually oxidised and bleached into a colour harmony of variegated beauty.

From our knowledge of the changes in colour made by sunshine and storm on outside painting and on whitewash, it might be suggested that a country cottage with white walls should have the doors and other woodwork, such as window shutters and frames, painted in a strong and rich green, and the window sashes in vermilion. Such a cottage should have a roof of thatch, or failing that, a red-tiled roof. In a few months after the cottage was painted it would lose any supposed harshness of colour that it might have had when first done, and would afterwards present a pleasant note of subdued richness of colour, that would be in complete harmony with the country or landscape around it. But if the cottage must have a slate roof, and if its walls are of red brick, then the doors, window shutters and frames should still be painted green, slightly inclining to yellow, but the window sashes should be painted white.

As regards the outside painting of the modern “concrete” cottages and villas, which are now contributing so much to the deepening of the grey and gloom of town and country, nothing short of the addition of inlaid panels of mosaic, or tile decoration, and the most brilliant colours imaginable{4} on the woodwork will serve to relieve the dreary and leaden-hued monotony of the Portland cement walls.

If we love to see colours in nature and in pictures, why should we not also love to see a beautiful, a commonplace, or even any badly designed building decorated in pleasant schemes of harmonious colouring? We are quite prepared to hear the modern critic, as well as the modern “cubist,” reply to this, that “art is art because it is not nature,” that “it is absurd for an artist to worship, or to represent Beauty,” or they may use any other convenient shibboleth, to protest against the representation of nature in art either in form or colour.

The question may be asked, “Why are the outsides of our modern buildings practically colourless?” when we know that during the ancient, medieval, and the early Renaissance periods the exteriors, as well as the interiors of all buildings were strongly coloured, either by the means of using natural marbles, metal-work, tiles, mosaics, or by painted decorations. Many notable examples of colour decoration, both exterior and interior, it is true, have been executed in modern times, but modern nations are still very timid in the use of colour, especially in regard to its application to the exterior of buildings. We are not yet quite emancipated from the white, grey, or drab effects, but we must at least be thankful for the note of colour in the red{5} brick, and occasional red-tiled roof of the modern dwelling-house.

Our lack of colour appreciation has generally been laid to the charge of Puritanism, but this has been hitherto chiefly associated with the white-washing of church interiors. Cromwell, or rather his fanatical followers, have had a deal to answer for as iconoclasts, but at the same time it must be remembered that Cromwell was a friend of artists, and a patron of the arts in his day, and we certainly are indebted to him for the preservation of Raffaelle’s Cartoons, the masterpieces of that great painter, which he hid in safety in the cellars of Hampton Court Palace during the troubles of the Civil War. Since Cromwell’s time, however, colour decoration has crept into many of our public buildings, and some buildings in England were treated in colour thirty or forty years ago; but to-day, and we can hardly blame Cromwell for this, figuratively speaking, it may be said that a fresh colour-destroying wave of whitewash is sweeping over the country, which is now blotting out the former efforts of our old decorators.

The interiors of most of our public buildings are generally of an indescribable drab colour, if they are not painted white. It requires some courage to decorate properly in colour, as well as experience and ability, but it is very humiliating to find that notwithstanding our plentiful supply of decorative artists, the majority of our public buildings are{6} painted in the style which we find frequent in bathrooms. The white of the bathroom has certainly something to recommend it. It looks decidedly clean, when it is freshly done, and has an air of great humility. Many people advocate white because, they say, it is safe, that is, because it relieves them of the solving of a colour problem; some museum authorities recommend it because they say that it is the best contrasting background for the objects and examples. The palace and the ballroom people advocate it because they think that ladies’ dresses and Court uniforms look best against it, but all these reasons are just the ones that an artist would put forward to prove that white is not the best background for museum objects, and should not be used for the walls of a state assembly-room.

Dark, or strongly coloured objects in a museum look doubly darker against white walls, so that often you cannot see the beauty of their forms or the modelling and colour value of their surface details unless you get your eye quite close to them, which is sometimes impossible. On the other hand, suitably coloured and decorated walls often bestow a certain charm on the objects and examples by enhancing their beauty and preciousness, and by linking them together with the decoration, avoiding that mechanical and cold effect of isolation which many objects present on the colourless and undecorated walls of some museums.

As regards ballrooms, or state assembly-rooms,{7} white walls make the worst kind of backgrounds for dresses and uniforms, as they afford too great a contrast with brightly coloured ones, and in the case of white dresses no contrast at all.

There is evidently a strong objection to the use of colour for the decoration of our public buildings; it is avoided as if it were an unholy thing, something desperately wicked, like the “scarlet and purple” trappings of the unhallowed lady of Babylon. Yet we see that the Almighty has clothed His glorious creation in thousands of tints of lovely colours, and on the other hand we find that Nature uses white very sparingly indeed. We moderns, however, live an artificial life, we are always in such a hurry that we have neither time nor inclination to learn the lessons we should learn from Nature; and besides, we are more or less obsessed with a puritanical pride, like the pride which apes humility, so in our indifference to the beauty of colour we seek for salvation in whitewash and plenty of it.

Perhaps, however, the Italian architect, Palladio, who flourished in the sixteenth century, was really more responsible than Puritanism for the fashion of colourless buildings, for he was one of the first who regarded colour as an evil thing, as he has said that “white was more acceptable to the Gods,” an absurd statement, if he believed that the Gods were responsible for the colouring of Nature. It may be safely stated that the fashion of colourless buildings had its inception in Europe in Palladio’s time, for previous{8} to this date, which ushered in the decadence of the Renaissance, all the interiors and exteriors of buildings were decorated in colour from the earliest historic times. Any ancient building that had any architectural pretensions was not only coloured, but treated in the richest and brightest colours known to the decorator, and such colours were applied in their full strength. In the present day we have got so much accustomed to the absence of colour in architecture that when we do see the rare example of a richly coloured interior—exterior colouring is out of the question—which is not often, we must admit, we may be shocked by the novelty of it, and though we may secretly admire the daring of the decorator, we should be accused of our bad taste if we ventured to give it our unqualified approval.

Much as we all love colour, we seem to be afraid to get too far away from white, or very pale and neutral tints, in decoration. We appear to be too timid, or anxious not to offend the Palladian taste of the public. On the other hand, in the matter, for example, of church decoration, we are extraordinarily inconsistent, for we tolerate and encourage the employment of the most daring combinations of colour in stained-glass windows, and yet, as a rule, leave the rest of the architecture colourless and cold, so that in the majority of our churches the walls and ceilings look more chilly and cheerless in contrast with the brilliant glories of their stained-glass windows. The majority of our churches are a kind

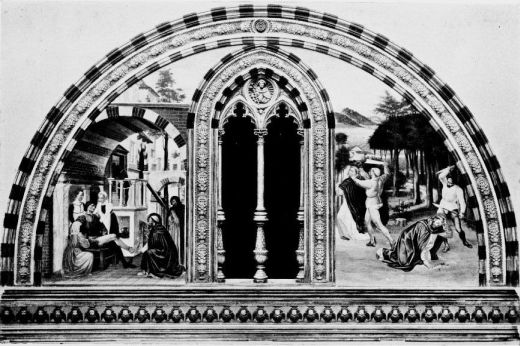

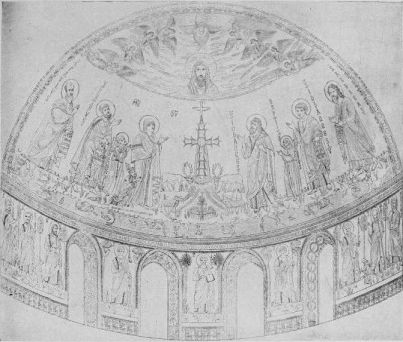

To face p. 9.]

[National Museum, Dublin.

Plate 2.—Frescoes in the Chapel of St. Peter Martyr, Church of St. Eustorgio, Milan.

(From portion of the model in the National Museum, Dublin.)

of reflex of the present general aspect of many medieval ones that have had their former decoration sacrilegiously scraped off their piers, walls, ribs, and ceiling vaults, and so deprived of their former beauty and comeliness.

Architecture is the mother of the arts and crafts, and she certainly looks all the happier when accompanied by her children, Sculpture and Painting, but when they are absent from her, her dignity is not augmented or enhanced by her saddened expression of loneliness that accentuates the coldness of her isolation.

We suppose that no one objects to the fashion of filling church windows with coloured glass; on the contrary, we should be thankful that in these modern times this reminiscence of ancient colour expression still remains to us, but why do we draw the line at coloured windows? Why are we not more consistent, and colour also the rest of our churches, interiors and exteriors as well, with coloured marbles, mosaic, or painted decoration? Seeing that we tolerate and admire colour decoration in stained-glass windows, there seems to be no legitimate reason why we should not have panels of coloured mosaic, enamelled terra-cotta or tiles, fresco, or coloured marbles as vehicles of colour decoration in churches as well as stained glass. Any of these materials or methods of decorative colour expression might well be used in the carrying out of designs for memorials {10}of our departed friends, and would be quite as effective for such purposes as stained glass. But who has ever seen or heard of a fine mosaic, or a fresco executed or painted on the walls of a church to the memory of somebody in particular? If we adopted and employed mosaics or frescoes as memorials of the dead, as well as stained-glass windows, we would still be exercising a pious duty to our departed friends, and at the same time would be assisting to make the Temple of the Living God more comely and beautiful by adding some of the necessary colour finish to the walls of the church.

In a church at Birmingham there are a series of most beautiful windows in the chancel-end of the building, designed by Burne-Jones, that are magnificent in their glory of flaming crimson hues, and are superb examples of the artist’s composition and design. One regrets, however, to find that the decoration of this church is typical of the usual embellishment of the modern House of Prayer, which generally begins and ends in the chancel windows.

IT has been said that Architecture may be compared to a book, and that Sculpture and Painting are the illustrations which serve to explain the text and decorate the volume. It might be argued, however, that the text of the written book may be in itself a work of art, and therefore not require any explanatory illustrations or decorations. To a certain extent this may be quite true, but on the other hand a book will be more valuable, more useful, and more complete, as well as being more beautiful, by having the additional interest of a well-designed and appropriate setting of artistic and explanatory illustrations to embellish the text. And just as the written matter of the book should not be regarded as a mere background for the illustrations and decoration, neither should the architecture be so designed as to appear only as a background for the sculpture and painting, for the building is the important thing, but sculpture, painting, and ornamental decoration should be certainly employed to explain the architecture, to symbolise the use of the building,{12} and to give additional interest and beauty to the fabric.

Colour in architecture ought to be employed in a structural sense, that is, it ought to be so used that it may help out, or confirm, the logical and indispensable features of a building that give to it the essential qualities of repose and stability, and the tones of colour, if judiciously selected and applied, will explain at a glance the various forms, features, divisions and sub-divisions of the architecture more rapidly and better than could possibly be hoped for in, say, a colourless or undecorated building. Therefore, in the diffused and somewhat darkened light of interiors the proper application of colour is of inestimable value, as an explanatory help in revealing the structural lines, the profiling of the mouldings, and the proportions of the architecture.

It is quite possible to decorate interiors in colour schemes of austere and extreme simplicity, in delicacy, in brilliancy, or in rich and full-toned splendour, in accordance with the nature and uses of the building, provided that we do not interfere with the essential quality of repose. In order that this important attribute of good architecture may be secured and maintained it is evident that neither sculptural nor coloured decoration should occur in isolated spots of interiors; they should not be dotted about, or applied here and there on walls, ceilings, pillars, mouldings, or other places, but should appear as essential and integral parts of the natural growth{13} of a broad decorative scheme. It does not follow from this that certain parts of a building, such as the ceiling, the frieze, capitals of columns and the chancel-end or sanctuary of a church should not be more honoured by having a richer application of colour and ornament than the other parts of the building, but the inference is, that the latter should also be intelligently treated in colour and decoration, in a subordinate way, so that they will assist in the gradual leading up to the richer wealth of the more honoured and salient parts, and so become indispensable factors in promoting the unity of the entire scheme of decoration.

Coloured decoration which is only applied here and there in the interior of a building gives a spotty effect that is more than often futile and artificial. In the matter of church decoration it appears in our own country that just now it is more or less the custom to decorate the chancel-end of a church with a wealth of carving, stained glass, and richly-coloured ornamentation, and to leave the rest of the interior plain and colourless. We may be grateful, however, to find that the universal delight in colour, one of those things which we had “loved long since and lost awhile,” is now revealing itself in modern days after centuries of absence, and is expressing itself, timidly, and in isolated spots, but perhaps as time goes on it will spread again slowly, and let us hope surely, from one end of the building to the other.

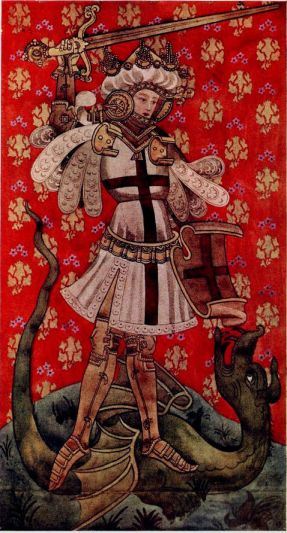

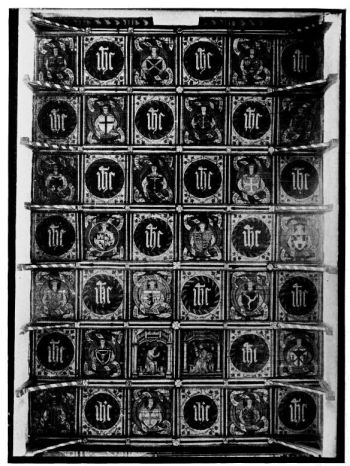

We must admit that a fine eye for colour is a{14} natural gift as much as a fine perception for form and proportion, or as a fine ear for music, but a love for all these things may be inspired in us from the work and teachings of the great masters of former ages, and certainly a love for colour from the teachings of nature and the great schools of painting and decorative art. That there was a golden age of decorative painting in England in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries we know from the remaining fragments of colour and decoration on the rood-screens and other parts of our old churches, and though the wall decorations have almost disappeared, the examples of painting which still remain on some of this old woodwork clearly testify to the importance of the English school of painting of the period mentioned.

We are more fortunate in our remaining possession of some of the finest stained glass in the world, which was designed and set up during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance times in England, and these rich and splendid “jewels set in silver setting” are a further proof of the keen delight of our early English decorators and craftsmen in the production of refined and beautiful colour.

Many people ridicule the colouring of the Middle Ages as inharmonious and barbarous. Such absurd ideas in respect to the use of colour by the old decorators may have been derived from the knowledge that in early times the artist’s palette was limited to three or four colours, besides black and white, and

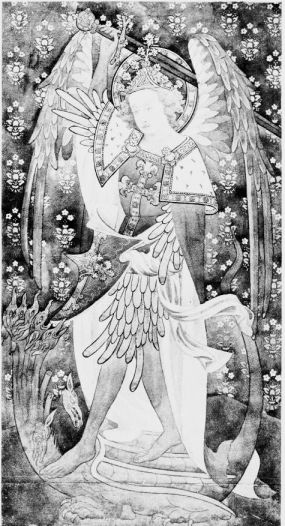

To face p. 14.]

[From a Water-colour by W. Davidson.

Plate 4.—Saint Michael.

(From a Painting on the Rood Screen, Ranworth Church: English, Early Sixteenth Century.)

that these colours, such as red, blue, green and yellow, were applied, in decoration, in their full strength, as undoubtedly they generally were. But it ought to be remembered that, however crude the colours may be, it is their arrangement, quantity, and proportion as to surface area in the scheme of decoration, that makes, or mars, the harmony, and not their individual strength, purity or crudeness. The early decorators hardly ever used broken tones or half-tones in their colour arrangements, and perhaps this largely accounts for the mistaken views that some hold in regard to the decorative colouring of the Middle Ages. There is of course a great beauty in broken-toned colouring, which is in much favour in modern decoration, but it is not a matter of much difficulty to harmonise such broken tones and tints. A greater difficulty is to harmonise an arrangement of colours in their full strength of hue, a task for a great colourist; but this we know has often been done successfully in all the best periods of art, and it certainly was done by the old decorators of the Middle Ages in painting, mosaic, enamels, and stained glass, in spite of the limitation of their palette, or, shall we say, because of it?

In all the great periods of art there was certainly the keenest delight in colour. It is difficult for some of us to believe that the Parthenon and other Greek temples, and also all of our old cathedrals were at one time highly coloured, but they certainly were{16} so shortly after they were built. The modern prejudice against the use of colour in architecture set in about the same time that sculpture also became, like painting, an independent art, which was about the beginning of the decadence of the Renaissance, at the end of the sixteenth century.

The architect, sculptor and painter should confer together, and if possible work in harmony with each other, so that when a cathedral, a church, a city hall, or any other public building is about to be erected, the complete scheme of the finished decoration should be formulated when the plans are being made. At any rate, the architect should always determine and keep in mind the style and nature of the subsequent colour effect and decoration, and so design his building in accordance with such preconceived ideas. That would be the ideal way to plan a building, after the uses of the structure were clearly defined, but unfortunately we are aware that the cases are few and rare in which the architect is enabled to do this, or that he lives long enough to see his ideas carried out. We might point out one notable instance of modern work where the architect’s original ideas of the decoration are now being carried out, namely, in the new cathedral at Westminster. When planning this important building the architect thought out, very carefully, what the methods and nature of the colour finish were to be, and it is interesting and gratifying to find that the{17} decoration of the brick shell of the building, including the main walls, the chapel, the crypt, and the sanctuary, are now being finished with a coloured marble sheathing, and with splendid mosaics, all of which he had made provision for in his original design.{18}

WHEN treating any building in colour, importance should be given obviously to the emphasising, and not to the effacement of the structural features, but when the building is deficient in such features, or very poor in this respect, it is the duty of the decorator to provide, in some measure, for this deficiency by dividing, for example, the large plain surfaces into panels, friezes, dadoes, spandrels, or other subdivisions, by the use of painted bands and lines, which may take the place of mouldings, but these painted bands and fillets should be treated flatly, and not in imitation of relief mouldings. These enclosing bands around panels, or large wall and ceiling subdivisions, may in certain cases be decorated with simple repeating patterns of ornament, and in others, if necessary, left in plain tints of colour. If, however, there should happen to be some permanent structural features, such as marble columns and entablatures, or woodwork in oak or mahogany, etc., already in the interior, and whose natural surfaces must be preserved, it follows then

that the decorator must arrange his scheme of colour, not only to harmonise with the natural colour of these permanent structural features, but he must modify his colouring so that it will in no way overpower the colour of the permanent material, and so weaken the appearance of its structural character. On the other hand, great care should be taken to use only such tones in the colours as will prevent these permanent architectural features from having the undesirable effect of an extreme isolation in the building.

Whatever scale of colour is used in a building there should be a strict maintenance of its relationship between all the great divisions and subdivisions. The colourings of the latter may be treated as a sort of echo, in lower tones, of those of the former, but not so subdued as to give sharp contrasts. Every feature of the architecture, major or minor, should be well defined and balanced in colour harmony, so as to keep the general effect free from any startling abruptness or discordance, in order that they may all contribute to, and so preserve, the necessary breadth of treatment.

The principal or broad contrast in the colour scheme should be between the structural and non-structural parts, or the active parts such as columns, piers, ribs and cornices, and the inert surfaces, such as panels, ceilings, walls, vaults, and spandrels. The more intense and forcible expressions of colour relief ought to be used on selected portions of the{20} structural forms, if they are not already of natural coloured materials, in order to unite them together, to give them a vigorous expression of life, and to emphasise their importance in the building.

There are no parts of a building that lend themselves to a more varied treatment in colour and decoration than the main walls of an interior, and this diversity depends on the character, architectural style and uses of the building. It is obvious that the same treatment cannot well be given to the walls of a church, a theatre, a concert or an assembly room, and a private residence, though it often is done. Nor can an interior, like that of a public hall or palace, that may have such architectural features as columns, pilasters, and well-marked panellings, either of marble, stone, or of wood construction, be treated in a similar manner to that which may be proper for the walls of a room which may be devoid of any architectural features.

Then, again, we have to consider, before we set about the planning of the colour or decoration of a wall, whether it is to be partly covered with pictures in frames, or if great surfaces are to be coloured which will have nothing placed or hung upon them, or if the large surfaces are already divided into panels, or if the wall is to have a dado and a frieze, if there are already hangings or window curtains of

a certain colour, and the carpet and furniture likewise. We may also have to decide whether our wall colouring is to be a harmony of analogy, or closely related colour tones, in accordance with the above objects in the room—that would be the simplest and safest method of colour treatment for the walls—or if it is to be a harmony of contrast in colour, which offers a more difficult problem, but if well done, would be more effective and interesting.

There are two other questions regarding the colour treatment of walls, or rather of interior colouring generally, which for the sake of argument we might consider, though they are of very little importance, and certainly have nothing like the importance which some decorators attach to them. We are told that before we begin the colouring of a room we are to ask ourselves “What is the aspect?” and also, “Is the room to be used mostly in the day, or mostly at night?” The questions seem logical enough, but we might well say in reply, that as regards the aspect of a room, what does it really matter whether the colouring is in a harmony of cool or warm, light or dark, arrangements of colour, provided we do obtain a harmony? Again, in our own countries, where we get so few days of long sunshine, is it really a matter of importance to decorate a room with a southern aspect in any way different from one with a northern aspect? The greatest decorators of the finest periods never seemed to trouble themselves much about aspects. They{22} were more interested in producing good decoration, and in the planning of fine colour schemes. As regards the decoration and colouring of a room for day, or for night uses, we may say at once, that if we except the interiors of theatres, there are hardly any rooms, in either public or private buildings and residences, that are not used both in the day and at night, so we may safely disregard the problem of colouring that is to be viewed by artificial light, for in nine cases out of ten, at least, ordinary interiors are seen, and ordinary rooms used, both in the day and night. It is best, therefore, to arrange our colour schemes so that they will look harmonious in the daylight, and such colouring will not suffer much by artificial light, provided the room is well lighted by electric or incandescent gas lamps, and is not in a state of low illumination, or semi-darkness.

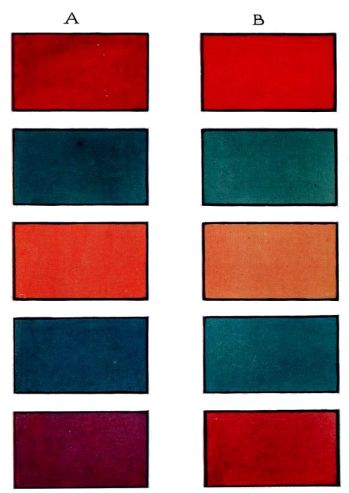

We shall say something later on in reference to the changes which some colours undergo when seen in artificial light. (Plate 13.)

We offer a few suggestions for the general colouring of walls in rooms of an ordinary residence or in public buildings, namely:—If a red is decided upon it should be of a deep pink slightly broken or toned with a very little blue and yellow; if the colour is to be of a yellowish tone, it ought to be pale and golden inclining to a light brown; if blue it should be of a pale greenish blue, or of any tint between that and a greyish ultramarine; a deep blue tone should never be used for large wall spaces.

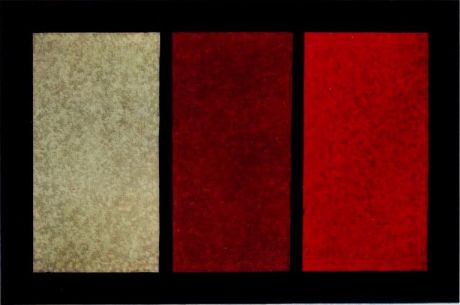

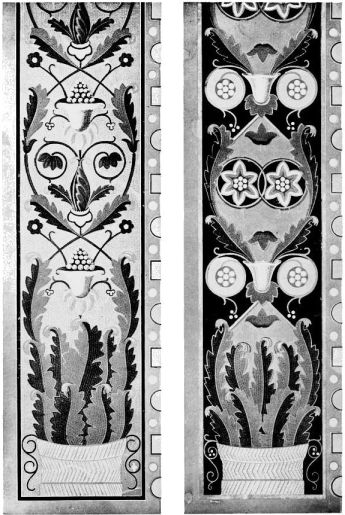

PLATE VII

THREE SUGGESTIONS OF COLOUR TINTS FOR PAINTED WALLS OR PAPER-HANGINGS, AS BACKGROUNDS FOR FRAMED PICTURES

If greens are to be used in large spaces they should be, if pale, more pure in colour than in the case of deep greens; the latter tones should be less pure and more grey, in order to avoid rankness of hue.

These suggestions apply to the colours of either painted walls, or to the tints of paperhangings, if the latter be used as wall-coverings. Large expanses of wall surfaces when painted in a single tint have usually a dry and uninteresting appearance; to avoid this, and at the same time to give the wall the effect of being treated in a single tone of colour, the surface, after being painted in the chosen colour, should have another thin application of a tint, slightly lighter, or darker than the previous coating, stippled over the latter, or the thin, and different, shade of colour may be applied with the brush, and immediately after the application it should be partially wiped off with clean rags. This operation will give the wall surface a slightly mottled and lively appearance, and will remove the dead and monotonous uniformity usually seen on painted walls when the work is finished in the more solid and flat methods of execution. (See Plate 7.)

We give as suggestions of colours the three examples on Plate 7, which we think suitable as background tints for the walls of rooms on which pictures would be hung. Any of these colours might be used on the walls of a picture gallery or in rooms that contained pictures in gold or in black frames, either for the colour tints of paint, if used,{24} or for the tints of paperhangings, but for choice we think the brownish tinted—middle illustration—would be on the whole the most satisfactory of the three. If the walls are to be painted they should be finished in a stippled manner, as described above, but if a paperhanging is used the stippled effect would be obtained by a very small self-coloured, lighter or darker pattern, or by some other method of superimposed lines or dots on the red, brown, or grey-green ground.

When decorating curved surfaces, such as vaulted ceilings, domes, or the semi-dome of an apse, when they are not sectionally divided by mouldings, or archivolts, it is extremely difficult to preserve the proper appearance of their sections or surfaces, especially when they are treated pictorially, or with a diaper, or all-over-pattern of ornament. In such cases it is necessary, as the custom was with the majority of the old mosaic artists and fresco painters, to subdivide these vaulted or domed ceilings into proportionate parts, running either in a vertical or in a horizontal direction, by bands, or lines, thus supplying the needed substitute for mouldings or relief divisional lines. Even if these bands and lines were left out, and the decoration designed in a series of horizontal, vertical, or arched divisions, forming rows of figures or ornament, an appearance{25} of constructive stability would be given to the scheme of decoration and so prevent any confusion as to the true section of the vaulted surface.

When a ceiling of a large hall or of a church is to be decorated, whether the surface be flat or curved, it is generally necessary to interpose a band of colour, either plain, or with a pattern on it, between the cornice, ribs, or archivolts and the field or panel, so that the structural abruptness between these features may be modified and softened, and that an artistical alliance may be created between the colouring of the panel and that of the cornice under the flat ceiling, or between the ribs and the vaulted surface, respectively.

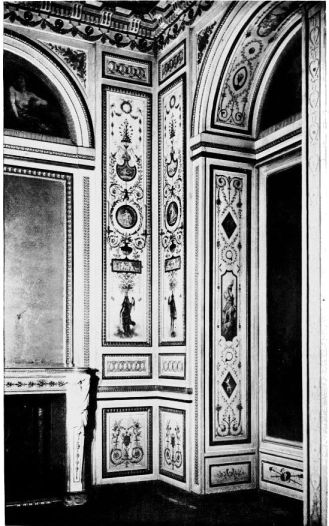

The ceilings of interiors, whether flat or vaulted, provide admirable fields for colour and decoration. The greatest attention was given to them by the artists of the Italian Renaissance. Even when the rest of the interiors were simple or almost plain, in regard to decorative treatment, the ceiling was hardly ever neglected. (Plate 21.) Some of the finest Italian art is found on the ceilings of the churches and palaces. For example, Michel Angelo’s masterpiece in painting was the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel; there are also Raffaelle’s ceiling decorations in the Stanze of the Vatican; Pinturrichio’s richly-coloured ceilings in the Borgia Apartments, and those of his in the “Sala Piccolomini” at Siena, in the choir of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome, in Santa Maria Maggiore at Spello, and in the Chapel{26} of the Sala di Cambio at Perugia, where he worked with Perugino. Many important ceiling decorations were painted by Raffaelle’s pupils, Giulio Romano, Perino del Vaga and Giovanni da Udine, in the palaces at Mantua, the Villa Madama, some in Venice and Genoa, others in the Vatican and in the Castel Angelo, at Rome, etc. There is also the ceiling of elaborate panelling, in which figure subjects alternate with arabesques in the Chapel of the Palazzo Vecchio at Florence, painted by Ridolfo Ghirlandaio. Ceilings of a later date, heavy in their mouldings and ornamentation, exist in the churches and palaces of Venice, and other places, which were painted with pictorial subjects by Paul Veronese and Tintoretto. The list of Italian painted ceilings would be almost endless, and we have only mentioned a few to point out the importance attached to ceiling decoration in Italy. The Italian ceilings were usually moulded, and were divided into a series of panels, lozenged-shaped, square, oblong, and circular, and where the relief mouldings did not exist, the decorator supplied their place by bands and enclosing lines, or even in some cases by feigned mouldings in colour, and sometimes by low relief stucco. Most of the ceilings were coloured in the brightest possible tints, and gold was also freely used, not only for heightening the salient parts of mouldings and carved enrichments, but often as backgrounds to the pictorial work and ornamental patterns. The gold backgrounds were in most cases

slightly toned with a glaze of warm transparent brown, or were treated with a fine mesh-like pattern of crossed lines, to enrich and also to modify the raw brilliancy of the gold. Another effective way of using gold was the common employment of gold stars and spots over bright red or blue backgrounds. This was usually done in cases where gold was used in the bands, or in ornament on the bands, which surrounded the panels having the bright-coloured backgrounds.

If one may be permitted to criticise the splendid Italian painted ceilings, it might be pointed out that, generally speaking, the rich and deep colouring was in many cases too dark, which often produced a lowering effect in this architectural feature of the room, especially in cases where the ceiling was only of a moderate height. It is only very lofty ceilings that can safely be treated in strong and moderately dark colours, and in proportion to the lowness of a ceiling the colouring should tend to become lighter in scale. The greatest weight or strength of colour on a flat ceiling should be kept in the corners, and near the cornice. This will help to give a more raised appearance to the centre, or at least it will determine, in an effective manner, the more perfect flatness of the surface, as all flat ceilings have a tendency to appear lower in the centre than at the sides. The general colour scheme of a ceiling should be arranged with due regard to even distribution, not only of the colour values, but of the{28} tints and hues, and if gold is used great care must be taken that it is also evenly distributed, so as to prevent any spottiness that would be due to the inequality of its application; in short a perfect balance of the colours and gold must be maintained respectively, although it may not be necessary to have a mechanical symmetry either in the colouring, ornamental patterns, or in the infilling of the panels, or other subdivisions.

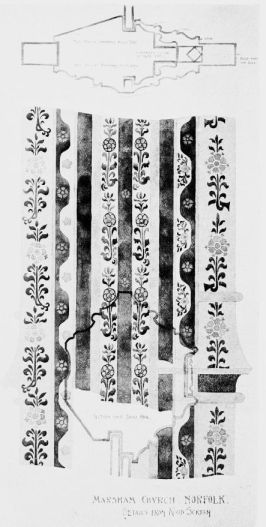

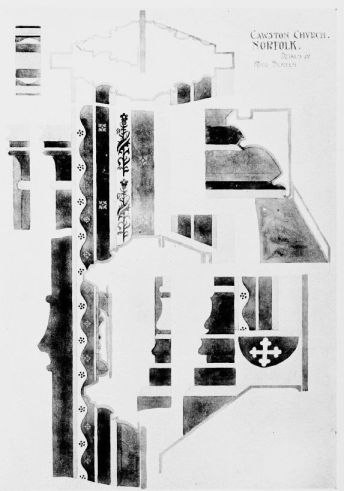

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of the architectural styles are the mouldings, so much so, that a building having no mouldings is almost, if not entirely, devoid of architectural expression; it may be classed as a structure, but hardly as true architecture, for the style, and even the date of a building may be often determined by the design of its mouldings alone. Ruskin has said, “Never give mouldings separate colours,” but he adds that “he knows this is heresy.” He is right if he means that the individual members of a group of mouldings should not be “picked out” in too decided or separate colours. What should be avoided is the possible danger of detaching them too much from each other. Contrasting colours should be used sparingly, and only to distinguish the larger and more structural members from those of the smaller ones. Simple explanation of their contours only is

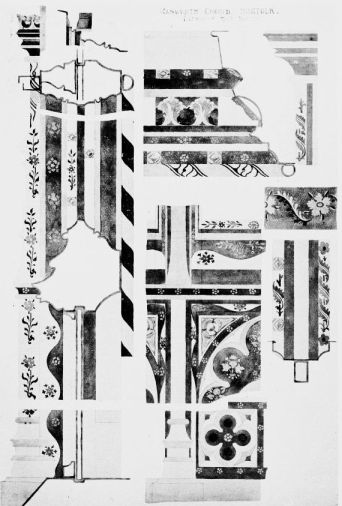

To face p. 28.]

[From a Drawing by W. Davidson.

Plate 9.—Decorated Mouldings.

(From the Rood Screen, Ranworth Church: English. Early Sixteenth Century.)

wanted, and not any appearance of detachment. As a rule, the more numerous and elaborate the group of mouldings the less contrast in their colour treatment is required. But, on the other hand, if a well-balanced colour harmony is obtained by treating a group of mouldings in separate colours, provided there is no appearance of detachment, and that the effect of harmonious unity of colour as a leading motive is secured, then we should say that this particular treatment would be justified. There are many instances where groups of mouldings have been treated in strong contrasting colours, in work of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which are examples of successful colouring.

The cornice in an ordinary room should be treated in colour as part of the wall, and not as belonging to the ceiling, for the cornice is the crown of the wall, and is not part of the ceiling. The value of a cornice in a room, as an architectural feature, is to soften the harsh divisional line between the ceiling and the wall, but this effect is destroyed if the cornice is left white or coloured like the ceiling, and not treated in colour to show that it belongs to the wall. As a general rule, the deep and recessed hollows in the cornice should be coloured fairly strong, as weak tints are lost or become grey when they are in shadow, but large{30} spaces, such as coved hollows, that happen to be well lighted, should not be treated so strongly in colour. Prominent edges and fillets of the cornice mouldings should be either light in colour or gilt.

The frieze of a public hall, assembly-room, or of a room in an ordinary house, is an architectural feature which always forms a fine field for colour and decoration, in sculpture or in painting. In the earliest, and in all great periods of art, the frieze was that part of the building which received the richest treatment. The best art of the ancient Mesopotamian nations was lavished on the coloured enamelled friezes, and the chief glory of the Parthenon was its sculptured frieze. The treatment, where pictorial or ornamental, admits of more elaboration in design and a richer application of colour than any other part of the room. (Plate 10.) If an interior has an important frieze decoration, it is not so necessary to have much colour or decoration on the ceiling. When tinting the cornice mouldings over the frieze it is extremely important that the dominant colours in the frieze should be “echoed” in some of the members of the cornice.

A frieze is of more architectural value in a room than a dado, for it is sufficient of itself to give an architectural aspect to a room; but if there is a dado it would obviously be coloured somewhat darker

than the walls, whether it was in wood, or only as a painted feature, and its moulding or “chair rail” would be coloured so as to harmonise with the dado, because it is also the crown or cornice of that feature.

As regards the debatable question of the imitation of relief mouldings and other architectural features on painted walls and ceilings, there are many precedents for doing so, some of which we will speak of further on, but this can only be successfully done when the decorator has a good knowledge of architecture and knows exactly what to do, like Michel Angelo when he divided the plain surface of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel into panels and niches by means of imitative structural forms and mouldings, in order to separate and enclose his magnificent painted series of scriptural subjects, prophets and sibyls. The imitation of architectural features in painted light and shade may not be logical, but when a great artist does such things, we are obliged to accept them without much criticism, as we accept the work of a great poet who makes his own grammar.

The question of whether to paint in colour the woodwork such as doors, window-frames and wainscoting of interiors, or to leave them in the natural colour of the wood, depends chiefly on the kind of{32} wood employed in their construction. It would be wrong, for example, to advise the painting or colouring of the more valuable kinds of wood such as oak, mahogany, walnut, ebony, or any rare kind of wood, in any way other than that which would deepen or make richer the natural tone of the material by the application of a varnish, and of such a varnish as would only intensify the natural beauty of the wood, but not produce anything like a polished surface. It would be better to accept the natural colour of such woods, and to scheme the colouring of walls and ceiling to harmonise with the colour of the woodwork in such cases, especially if in addition to the door and window-framing there happened to be a considerable amount of wainscoting or wood panelling in the room.

In the medieval and earlier periods, however, whether in churches, palaces, or in smaller houses, even the more valuable woods, especially oak, were always painted and decorated in colours. The natural colour, or the rarity of valuable woods, did not as a rule prevent them from being treated in colour like the other parts of the buildings. Romanesque and Gothic wooden ceilings and rood-screens, though constructed of oak or other hard woods, were invariably treated in colour and partly gilt.

The simplest and perhaps the more satisfactory way of treating the woodwork of an ordinary room in colour would be in selected tones of the colour which appears on the larger wall spaces, but whatever

the hue that may be used on the woodwork it should be of two or three shades of the selected colour, forming a harmony of closely related tones. (See Plates 6 and 11.) The woodwork may be in some cases of a different scheme of colouring from the walls, as in such instances where there is a dado of wood or a wainscot of wood panelling, but where the doors or windows appear as isolated features in large wall spaces, the most satisfactory way of treating them in colour is to paint them in analogous tones of the wall colour. If gold occurs in the frieze or on the cornice mouldings, the fillets, or smaller members of the door frames and panel mouldings should also be gilt.{34}

THE colouring of the exteriors of important buildings should be, if possible, effected by the use of the constructive materials, such as stone, marble, granite and coloured terra-cotta in conjunction with panels and friezes, etc., of enamelled tiles or mosaic, and even in the case of less pretentious buildings a good deal might be done by ordinary painting. Stucco plastered exteriors, however, should not necessarily be painted in a uniform stone colour. Stone and soft bricks get black in cities, but hard bricks retain their colour much better. A highly polished material, such as granite or marble, does not go well with freestone, owing to the violent contrast between the polished and dull surfaces; also, any highly polished surface reflects light in such a way that to the sight the form is often altered. Granite polished with emery brings out the natural colour without giving a glaze to it, and is therefore better for an outdoor effect. Bronze sheathing on doors and bronze window and door framing, when it is not too dark{35} in tone, goes well with a grey granite building, and when such a building has some panels of mosaic, or of coloured marble, such as “opus Sectile,” the colour scheme is very effective. These materials are now being used very much in some important buildings in the continental cities.

In using coloured marbles, the best effects, as a rule, are obtained when two kinds only are used together, or merely one colour with white, such as black and white, red and white, green and white or purple and white. The finest early Italian marble altars, pulpits, and monuments generally conform to one of these simple colour arrangements. The principal parts of these works are executed in white marble and have only one coloured marble introduced for columns, pilasters, friezes, and panels at the bases and pediments. It may be mentioned that the white marble of these monuments is yellowish in tone, and the black somewhat greenish, thus producing a soft and mellow effect. At Palermo and Naples there is a great deal of marble work of the later Renaissance and modern times which has inlaid floral arabesques in various coloured marbles, such as black, brown, orange and red, all in combination, the greater part of which is unsatisfactory as it lacks repose, owing to the harshness of the contrasting colours.

A notable exception to the use of two, or at most three, kinds of marble in combination is seen {36}in the magnificent “opus Alexandrinum” floor pavements, and in other marble work of the Byzantine buildings, where three kinds have been used, namely, porphyry, serpentine and white, with sometimes little portions of yellow, but the purple of the porphyry and the green of the serpentine, with their variegated tints, are colours which are in complete accordance with each other, and the effect of this arrangement is always pleasant and harmonious.

There is every reason why public buildings should be erected in natural or artificially coloured materials. Such coloured materials would not be more expensive than the grey, drab, and white stone and marble which is now used so much for exterior elevations. If we cannot have rich colouring on the outsides of our public buildings, we might at least be permitted to have schemes of colour that would present quiet and restrained harmonies, so that, even in a modest degree, they would contribute to our pleasure by counteracting some of the greyness and gloom that overshadows and often conceals the architectural beauty of many buildings in our large towns and cities.

Architects and sculptors, as a rule, are responsible for the appearance of the exteriors of buildings, and they only in exceptional cases appear to have a love for colour, but they should remember that colour appeals, if not to everybody, to a considerably large section of the public, which includes {37}both cultured and uncultured people, who can appreciate a coloured building, but are not much interested in seeing a colourless exterior.

Some of the simplest and inexpensive examples of exterior structural colouring may be obtained by the use of red brick, and common stone dressings on the façade of a building, if to this could be added some notes of grey-blue in terra-cotta, or tiles, in bands, borders, or in panels. Mosaic in panels would be better still, but we leave that out on the score of expense. Such an example as this colour arrangement may be seen in many buildings in Florence, Milan, and in the northern towns of Italy. We might mention one, that of the front of the Hospital of the Innocents, in Florence, which is a yellow-red brick elevation with severe columns and arches of a warm-coloured stone, and in the spandrels between the arches are the grey-blue and white roundels of Delia Robbia glazed earthenware, the whole effect being a pleasant and warm colour arrangement, and besides being extremely simple, it is certainly very effective, and an admirable example of structural colouring.

At Verona, Venice, and many other places in Italy there are fine examples of this style of exterior colouring where the red bricks give the dominant tone, whether terra-cotta or stone be used for the dressings, or glazed earthenware heraldic panels, mosaic, or fresco are added to give the balance of blue, or other sharper notes of pure colour, that may be required to complete the harmony.{38}

It is a matter well known that in Northern Germany, Belgium, Holland, and in England red brick buildings with stone and terra-cotta dressings and sculptured work were erected as manor houses, palaces, and every kind of public building, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, most of which were fine examples, not only of architecture, but of exterior colouring.

The front of the Doge’s Palace at Venice is an example of suitable application of colour to public buildings. The sculpture and mouldings are in white marble, and the wall surface has a chequered pattern of marble slabs of a pale rose colour and white Istrian stone.

Fresco paintings and mosaic have often been employed in Italy on the exteriors of churches and palaces. There is a beautiful bit of heraldic painting, alternating with cardinals’ hats placed in squares, on a wall behind the Duomo of Verona. This, however, and nearly all exterior wall paintings have suffered very much by the weather in course of time, and such decoration has no chance of lasting compared with the colour of the more permanent materials of stone, marble, tiles, or mosaic.

In Germany, much more than other countries, exterior colour-painting and decoration has always found great favour. Even to-day the exteriors of many buildings, especially hostelries and restaurants, are painted as they were in the sixteenth century.{39} A great revival of colour decoration took place in Germany, as it did also in France, about the middle of the last century. We shall consider this at more length when making an historical survey of the subject in later chapters, and endeavour to describe some of the methods and principles of colour decoration adopted and carried out by the old decorators of England and the continental nations. Before leaving, however, this portion of our subject it may be useful and interesting to notice an important example of Venetian exterior polychromy of the late medieval period.

The building in question is known as the Ca’ D’Oro, or “Golden House,” so called on account of the great quantity of gilding that it formerly had on its façade. This building must have been erected on the site of a former medieval palace, for the rebuilding of it was begun in 1424, contemporary with that of the Piazzeta façade of the Ducal Palace at Venice. The architect or “stone-mason” was Giovanni Buon, who was assisted by his son, Bartolomeo, the palace being erected for a nobleman named Marino Contarini, at St. Sophia on the Grand Canal. The existing documents, which consist of the original memoranda of Contarini, dated 1431-2, and preserved among the papers of the Procurators of St. Mark’s, give in detail the orders for the gold and colours, and how they were to be used in the decoration of the façade. From these and also from the traces of the colour and gold which Signor G.{40} Boni found on parts of the building in 1885, we are enabled to form an estimate of the polychromatic decorations of this medieval palace, which may serve as an illustration of the external colour-decoration of the period.

From these evidences we find that the balls of Istrian stone which decorated the embattlements were gilt, also the carved mouldings, the abacus of each capital, lions, shields, dentels, rose-flowers, and other salient points of the carvings. The backgrounds of capitals, soffits, some shields and bands were painted ultramarine blue, “fine azure ultramarine, in such a manner that it may last longer” (that is, twice coated). The blue ground of the soffits was studded with small golden stars. It is interesting to note how all the stonework was painted in the early times, when it is mentioned that all the red stones of the façade and the red dentels were to be painted with oil and varnish in still deeper tones of red, “so that they will look red.” It appears that this was done in order to give a look of uniformity to the red Verona Broccatello marble, which, being composed of the detritus of ammonites, had a variegated, or patchy-like appearance when newly cut, and therefore its effect, when new, did not find favour in the eyes of the decorator, as perhaps he thought that in its virgin state its appearance disturbed the broad colour effect he was aiming for. The crowning cornice was painted with white lead and oil, and also in a like manner the roses and{41} vines on the façade. The backgrounds of the latter carved decoration, and that of the fields of the cusps of the window tracery and of the cornice foliage were painted black, in order to give the effect of penetration.

The parts of the façade which were painted white were those of bluish or yellowish Istrian stone, the natural colour of which the Venetians did not like, so they generally obliterated it with a coating of white paint. In the memoranda it is also stated that the stone battlements were to be “painted and veined, to make them look like marble.”

The imitation of marbles and woods by painting the commoner stone, or inferior wood in simulation of the more costly materials, though rightly condemned as a common practice by purists has, however, been largely practised by the decorators of primitive Greece, Pompeii, Rome, and of the East, as well as of the Renaissance and later periods. The old decorators had no scruples in regard to the painting of plaster or common stone to make it look like marble; but generally in such examples the imitation was more strictly confined to objects and surfaces where the more costly materials would have been used if sufficient means had been available to procure them.

The modern practice of imitating a costly wood by graining an inferior one hardly ever obtained in the earlier periods; the old decorators often enough{42} painted all kinds of wood in any arbitrary way or colour, but they did not grain them to simulate other woods. Although the imitation of wood by graining is not practised so much to-day as it was in the Victorian time, there is still a good deal of it done. Even worse than this is the modern practice of erecting wooden columns and entablatures as shop fronts, especially those of public-houses and gin-palaces, in simulation of a stone construction, which may be an excusable sham, but there is no reason why this stone construction in wood should be painted to imitate costly marble, which only makes a double sham. We can call to mind the instance of some large and heavy doors in a Government building of this country, which are, of course, made in panelled wood, but have been painted to imitate grey granite! The reader can think that the limit of imitative painting is here reached, if he can imagine the deception that is presented of two slabs of heavy granite swinging on hinges.

In the case of the Ca’ D’Oro battlements, and of similar imitations of marble in the painted decoration of late medieval buildings in Venice, we can see the expression of a striving after the rich effects of colour that were obtained in the earlier Byzantine architecture by the use of the real marbles, which were employed to give the structural and permanent colour to edifices built in that style. It ought to be remembered that the Venetian Gothic architecture, more especially in colouring—and we might safely{43} say all Venetian art of later periods with its rich and beautiful colour—was strongly influenced by the splendour of Byzantine and Eastern colouring, as expressed in the mosaics, enamels, and richly-coloured marbles that were used so much to line the walls inside and outside of the Byzantine churches and palaces.

Although such coloured decoration as that of the façade of the Ca’ D’Oro might be classed as a decadent and artificial system, in so far as it was an imitation, or an attempt in applied colour at the survival of the more permanent Byzantine coloured architecture, still the general effect of the colour scheme, where full-toned blues, reds, black, white, and gold were frankly employed, must have been extremely rich and interesting, when seen in the radiant sunshine, and reflected in the waters of the Grand Canal. We might add that the colouring of this medieval palace, in common with that employed on all Venetian buildings of that time, was also in a great measure a reflex of the powerful and sensuous colouring of the East, which strongly influenced, if it was not indeed the chief source of the distinctive colour harmony that was the crown and glory of Venetian art.{44}

JUST as the aims of the painter of pictures are quite divergent from those of the decorator, so is the use of colour in the representation of natural objects and of natural phenomena divergent from that of the latter’s in his employment of tints in coloured decoration. The painter of pictures is at liberty to use unlimited tints and shades of one colour, or of any number of colours, to represent the facts or effects of nature in realistic or in imaginative art, that is to say, he can make the greatest possible use of gradation both in colour and in light and shade, but the decorator is limited in the matter of colour gradation, and still more limited in the matter of light and shade, to the use of a few tints of closely related tones, and, as a rule, he must use them in a series of flat tints, with little or no light and shade, and which may or may not be separated from each other by contours or outlines of neutral or different colours.

The aim of the decorator is to beautify surfaces{45} by the use of colour, so he selects or creates his tints and shades, which may be of extremely rich and deeply saturated hues, heightened perhaps with the addition of silver or gold, or he may use schemes of sober tints of broken colours; but the aim of the picture painter is to respect the colouring of nature and to produce another kind of beauty, which if not always strictly imitative of natural forms and facts in colour and drawing, must at least show that its foundations are laid on the solid ground of nature. Colour is therefore used by the artist-painter in a limited sense, in so far as it is imitative of any particular scene or natural effect which he may desire to record, but the choice of the decorator is unlimited, for he can always invent his own colour schemes. And as the latter is justified in disregarding shadows and gradation in the rendering of his decorative forms, even when they are derived from nature, he is equally free to use any colour in an arbitrary way on such forms instead of their natural or local colour, provided that it does not interfere with the harmony and balance of his colour scheme. The old Gothic glass painters, for example, who produced some of the finest coloured glass, did not hesitate to colour the feet or the hands of their figures a vivid green, a crimson, or a brilliant blue, though the other flesh portions of the same figure would be in the natural colour, if they found it necessary to have any of those colours in such parts of the design where the feet or hands happened to{46} be. Although we should not agree with this arbitrary colour treatment of natural forms, it only emphasises the fact that the old designers looked upon their figure compositions as simply units or integral parts of the general colour scheme, and nothing more or less than legitimate decoration.

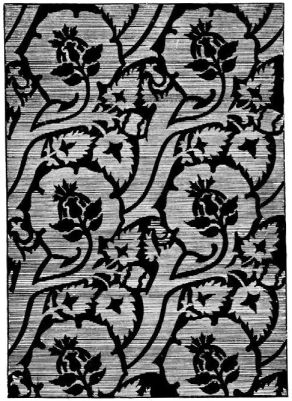

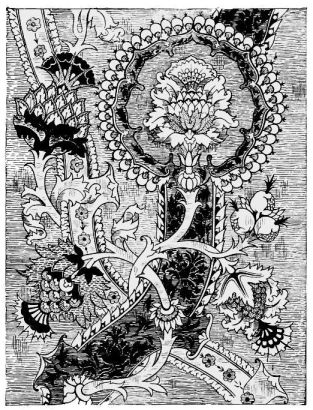

The decorator may design his ornamental forms on the bases of natural ones, and may, by colouring them in tints suggested by nature, produce a beautiful decorative work, which indeed has often been done. Still, he is free to frankly disregard the natural or local colour of such forms if the latter does not suit his purpose, and may use any other colours that will enable him to produce the best effect and most satisfactory decoration. In any case there should be no attempt to imitate either the colouring or forms of nature in a realistic sense, however much he may make use of suggestions from natural forms and objects. If purely natural forms, such as those of birds, animals, or the human figure are introduced into decoration, they should be firmly outlined in some neutral colour in order to show that they are only intended as portions of the decorative scheme and not in the sense of realistic representations. Accurate representations of natural forms and photographic realism should be avoided in decoration. If the Byzantine mosaicists had drawn, or could have drawn, their figures better, they might have produced worse decoration, and might have failed to express the essentials of decorative art.{47}

The greater part of modern polychrome decoration, not only on buildings but on nearly every description of handmade objects or manufactured goods that have pretensions to artistic claims, is only misapplied painting which has usurped the place of true decoration. This kind of semi-pictorial work came into vogue about the beginning of the seventeenth century in Italy and France, and gradually spread and developed in other European countries, so to-day there is still a great demand for this kind of art which is neither genuine decoration nor painting. Interior surfaces of buildings, textile hangings, carpets, all kinds of pottery, and almost every kind of object that presents a surface for decoration is treated with naturalistic transcripts of flowers, birds, animals, the human figure, as well as copies of landscapes and architectural views, all represented in a pictorial manner with more or less merit, but all misapplied work. Such meretricious merchandise is welcomed and purchased by a very large section of the public, who are unable to distinguish between true and false decoration.

Decoration in Monochrome.—The simplest form of coloured decoration is monochromatic, that is, where one colour is used or where several tints of any one colour are used. This kind of colour treatment is often very satisfactory for the walls, ceilings, and woodwork of any ordinary room, where the pictures on the walls, the carpet, hangings, furniture{48} and ornamental objects all combine to furnish the sharper and more contrasting colour notes that may be required. In such monochromatic decoration lighter and darker shades of the selected colour are used, the lighter and less intense tints being spread over the larger spaces, while the more intense and purer shades would be on the mouldings and on the smaller subdivisions of the architecture. The choice of the particular colour selected for any monochromatic scheme will in a measure depend on the uses of the room as well as on the decorative taste and feeling for colour. Monochromatic colouring may be enlivened by the use of gold in narrow lines or in small quantities, such as in the gilding of the fillets of door mouldings and cornices, etc.

Use of gold in decoration.—Gold should not be used in large quantities in any scheme of decoration, except in backgrounds where it would be partially covered with ornamentation, or else it will be liable to lose its precious quality, and so look vulgar and common. Where gold is used in great quantities, such as we see in the gaudy gold and white decoration of some state assembly-rooms, it completely loses its quality of preciousness, and in proportion to the increase of the quantity used, it becomes cheap-looking and appears more like brass than gold. If gold must be used lavishly in the decoration of state rooms it ought to be toned down with some transparent brown colour which would tend to make it still richer, and would destroy the tinselly or brassy{49} appearance which large masses of gilding always present to the eye. Where gold was used in backgrounds of figure or ornamental compositions by the Italian artists, its natural glare was usually toned down either by having a net-work of lines, or a fine tracery pattern, or sometimes a fine diaper or checker pattern painted on it in black or dark brown. Also the surface, previous to the gilding of it, was sometimes prepared with a rough texture, in order to prevent it from having the objectionable shine that is common to the gilding of smooth surfaces, and to enable the spectator to see the real colour of the precious metal. Gold grounds look better when the surface is slightly curved, for all gilded flat surfaces, unless modified by one of the methods we have mentioned above, will either appear glaringly bright or very dark according to the position from which they are seen. It may also be mentioned that gold has in common with white, or very pale colours, the effect of spreading, so that thin lines, or delicate tracery patterns in gold, on a dark, or moderately dark coloured ground, always appear to look broader than they really are, this being due to the spreading effect of light which is reflected to the eye by the brilliancy of gold, or white.

Coloured decoration on gold grounds ought to be outlined in black, or some very dark colour, in order to prevent the gold from overpowering the {50}colour and making it look ineffective. When highly relieved enrichments are gilt, the ground behind them may be “picked out” in strong colour, such as vermilion, deep cobalt blue, or black in cases where an effect of penetration is desired, but in proportion to the lowness of the relief the background colouring may be lessened in strength or intensity. It must be pointed out, however, that ornament in very low relief, if gilded, will require a more strongly coloured background than in the case of ornament that may be simply coloured, but not gilt.

The small interval, or concord of closely related tones.—It might be suggested that the natural development, or sequence of purely monochromatic colouring to a full and rich polychromy would be of that kind of colour harmony which is known as the small interval, which, in decoration, is expressed by the concord of closely related colour tones. It may be also defined as a harmony of colour analogy, a kind of gradation where colours and their tints are separated by a little distance or interval from each other in the chromatic circle. The colouring of natural objects and phenomena afford endless examples of the small interval. The plumage of birds, wings of insects, foliage of trees and plants, flowers, shells, some minerals, and the sunset sky may be mentioned as some of the illustrations of this kind of harmonious colour gradation, where the various tints and shades of closely related colours are cunningly arranged by nature in delicate, yet decided contrasts, not of hue, but of analogous tones.{51} For example, a green-blue may pass into a violet-blue, by a gradual series of separated tints, but the latter colour must be kept at the shade of violet just before it is overcome by red, and the former must not be overpowered by yellow. The colour of a peacock’s neck-plumage affords a good illustration of this kind of green-blue to violet-blue colouring by gradation of shades. A similar gradation is where an orange-red passes gradually into a crimson-red, but neither yellow in the first-named colour nor blue in the crimson must be permitted to overcome them. The decorator being concerned with the use of broken colours—that is, pure colours modified by mixture of black, white or grey—for the covering of large spaces such as walls, ceilings and woodwork panels, can therefore adopt the principle of the small interval in architectural colouring with advantage and success, by using any group of closely related colours for his scheme; and further, if he desires to intensify or enliven the latter, he can do so by the use of small quantities of other contrasting colours introduced in the cornice, frieze or mouldings, or in lines, bands and other forms of painted ornamentation, and, if necessary, the whole of the decoration might be heightened by gilding.

Coloured decoration on coloured grounds.—The use of coloured grounds, and especially those of contrasting colours, postulates the more complex forms of polychromatic decoration, where a good number of{52} widely separated tints and shades of various colours are employed in any one scheme.

In polychromatic schemes of colouring there are certain laws which must be respected, regarding the relation of one colour to another, their modification of tint or shade, as affected by their position, and the strength or weakness of the light which illuminates them, however much may be left to the good taste and feeling for colour which the decorator may possess. All these essentials have to be considered, for it is not so much a question of rich and glowing colour schemes, or sober, quiet and subdued arrangements, but to obtain a harmonious colour finish in either. The decorator must aim for, and if possible obtain, a proper balance of colour, not so much for the achievement of uniformity, as for that of unity and repose. In order to obtain unity he must therefore see that even in the most complex polychromy a perfect balance of the colours is the first consideration, and of the utmost importance. In decoration we have both colour and form, but colour in decorative art is the more important of the two. A certain balance is looked for in ornamental or pictorial fillings of panels, for example, or even in the secondary ornamentation of painted bands, stiles, and other minor surfaces, but the repetition of exactly similar forms on such surfaces is by no means essential, but on the contrary produces monotony. In the matter of colour the case is reversed, for it is very important that there should be a decided repetition of

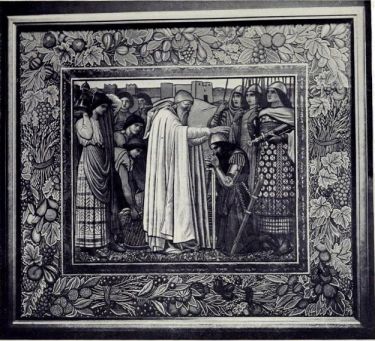

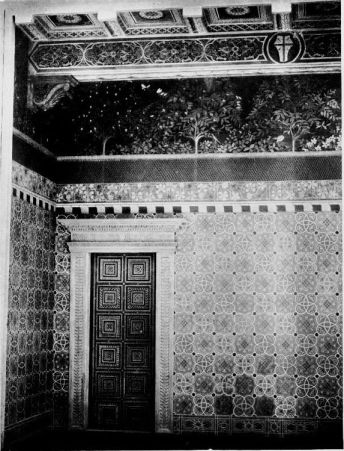

To face p. 52]

[Victoria and Albert Museum.

Plate 12. From the Cartoon of the Mosaic in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

(Melchizedek Blessing Abraham. By Sir W. B. Richmond, K.C.B., R.A.)

colour, even to the point of symmetry, in architectural colouring, if the balance is to be maintained. There must be “echoes” or “recalls” of the same, or very similar, tints and shades in ceilings, walls, woodwork, and other parts of interior colouring if the qualities of good decoration, such as breadth, repose, and rhythm are to be secured. The rhythm of colour in decoration is of far more importance than that of the ornamental forms.

These laws and principles apply to all kinds of architectural decoration and their colour schemes, but if possible with more force to the richer and more complex polychromy, where pure and intense colours are employed with others of lesser intensity, together with gold, silver, white and black.

Contours, or outlines.—Coloured ornament or pictorial decoration on coloured grounds ought to be outlined, especially so if the ornament or decoration does not differ much in colour from that of the ground. Even colours that greatly contrast with each other ought to be outlined to prevent them from having the appearance of mixing with each other, for most colours will not show their true value unless they are outlined with a neutral one such as black, white or gold, or with some lighter or darker colour than their own. The general rule is, that if the superimposed ornament is of a lighter colour than the ground, provided that it is not excessively light, it should be outlined with a still{54} lighter colour, but if darker than the ground, the outline should be still darker.

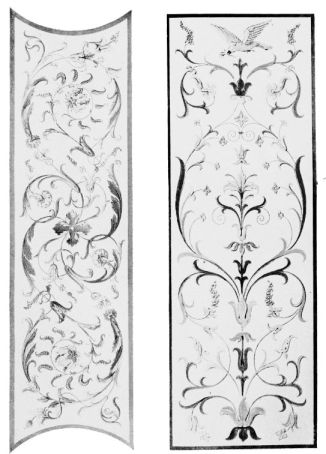

Certain ornamental compositions, such as arabesques that are painted in light and shade on a coloured or gold ground, may not require decided contours. The absence of outlines on such ornament is not so detrimental to them as it would be to decoration that is painted in flat tints, because such arabesques or tracery are sufficiently relieved by their light and shade treatment, and are usually painted in dark and intense colours, if the background is white or light in tint, and on dark-coloured grounds they are generally executed in lighter and brighter colours on the dark ground.