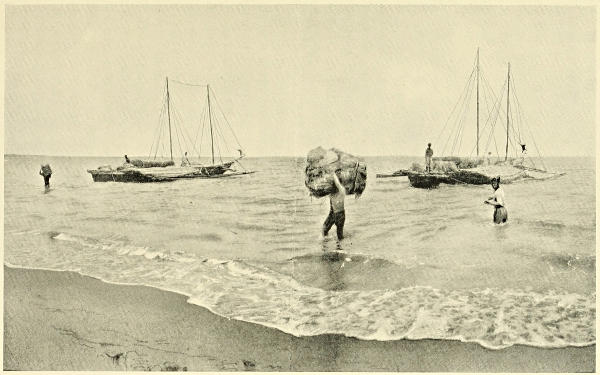

Discharging Hemp from Paraos (Native Boats).

Title: An Englishwoman in the Philippines

Author: Mrs. Campbell Dauncey

Release date: February 11, 2019 [eBook #58863]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

AN ENGLISHWOMAN IN THE PHILIPPINES

First Edition July 1906

Reprinted October 1906

AN ENGLISHWOMAN

IN THE

PHILIPPINES

BY MRS CAMPBELL DAUNCEY

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY

1906

Printed in Great Britain

In the following letters, written during a stay of nine months in the Philippine Islands, I tried to convey to those at home a faithful impression of the country I was in and the people I met. Since I came home I have been advised to collect and prepare certain of my letters for publication, and this I have done to the best of my ability, though with considerable misgivings as to the fate of such a humble little volume.

It is impossible to mention the Philippine Islands, either in daily life in the country itself, or in describing such life, without reference to the political situations which form the topic of most conversations in that uneasy land. On this subject also I wrote to the best of my power, faithfully and impartially; for I hold no brief for the Americans or the Filipinos. I merely aimed at a plain account of those scenes and conversations, generally written within a few hours of my observing them, which, it seemed to me, would best convey a true and unbiassed impression of what I saw of the Philippines as they are.

| PAGE | |

| LETTER I. MANILA |

|

| Journey from Hong Kong. First sight of the Philippine coast. Manila Bay. The Pasig River. A drive through the streets. Old Manila. Spanish influences. Manila hotels. The Virgin of Antipolo. Inter-island steamers. | 1 |

| LETTER II. FROM MANILA TO ILOILO |

|

| Beautiful islands. Coin divers. A glimpse of Cebú. The hemp industry. The Island of Mactan. Magellan. A curious record in orthography. Fellow-passengers. Soldiers and school-teachers. American theories. Social and racial equality. The Filipino race. | 8 |

| LETTER III. FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF ILOILO |

|

| Arrival at Iloilo. Situation of Guimaras and Negros. The Island of Panay. Climate. House-hunting. Native methods. Conant coinage. Philippine houses. | 15 |

| [viii]LETTER IV. A PHILIPPINE HOUSE—AMERICAN PRICES—NATIVE SERVANTS—FURNITURE |

|

| We find a house. Domestic architecture. The Azotea. Results of American extravagance. Iloilo shops. Filipino servants. Settling down. Chinese shops. Furniture. “Philippines for the Filipinos.” Rumours of the Custom House. | 22 |

| LETTER V. HOUSEKEEPING IN ILOILO |

|

| Housekeeping. Strange insects. Chinese bread. The washerwoman. Domestic etiquette. A hawker of orchids. | 33 |

| LETTER VI. A WASTED LAND |

|

| The road to Molo. Picturesque scenes. Custom House methods. An unpleasant surprise. Philippine trading firms. An over-zealous law. The Philippine bed. Christmas Eve. The tropic dawn. Christmas Day. The water-supply. Food and drink. Scarcity and high prices. Book-learning versus agriculture. | 42 |

| LETTER VII. CUSTOMS AND DRESS OF THE NATIVES |

|

| A Filipino Fiesta. The national hero. Doctor Rizal and his work. A languid festival. A musical people. Dress of the native women. Piña muslin. Dress of native men. Scrupulous cleanliness. A walk on the beach. Gorgeous colouring. | 50 |

| [ix]LETTER VIII. SOCIAL AMUSEMENTS |

|

| A ball at the Spanish Club. The Rigodon. Curious costumes. Bringing in the New Year. A painful interlude. Position of Eurasians. New Year’s Day. The suburbs of Iloilo. Filipino children. | 57 |

| LETTER IX. TARIFFS—INSECTS |

|

| More Custom House surprises. Official blunders. House-lizards. Roof-menageries. Anting-anting. Snakes. Cicadas. Ants. Cockroaches. Mosquitoes. | 66 |

| LETTER X. A FILIPINO THEATRE—CARABAOS |

|

| Dramatic clubs. The Iloilo theatre. An amusing experience. An operetta. The Jaro road. Carabaos. An evening scene by the river. The fashionable paseo. | 74 |

| LETTER XI. SOME RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN OCCUPATION |

|

| Heat and drought. Bathrooms. A handsome cow-boy. Cost of living. Military manners. Camp Josman. The Government of the Philippines. A “pull.” An arbitrary tax. The Plaza Libertad. Effects of fire and bombardment. Story of the American occupation. Unwelcome saviours. A pretty garden. The “unemployed.” Scale of wages. A Philippine cabstand. Filipino dignity. A charming scene. | 82 |

| [x]LETTER XII. CHINESE NEW YEAR—LABOUR CONDITIONS—A CINÉMATOGRAPH SHOW |

|

| The Chinese New Year. Question of Chinese labour. A cinématograph entertainment. Unpleasant habits. An interesting audience. Diplomatic warfare. A half “’cute” native. A Filipino philosopher. Tropical rain. | 95 |

| LETTER XIII. SOME INFLUENCES OF CLIMATE, SCENERY, AND RELIGION |

|

| The Rainbow. Sugar industry. A beautiful view. Unchanging charms. “Always afternoon.” The fascination of the East. Missionaries. A keen advocate. La Iglesia Filipina Independiente. | 103 |

| LETTER XIV. VOYAGE TO MANILA |

|

| A journey to Manila. The mail steamer. Food for Esquimaux. A comfortable night. Dream Islands. Dress for Europeans. Manila. The harbour. Curious reasoning. American hustling. A charming house. The Luneta. | 110 |

| LETTER XV. AN OFFICIAL ENTERTAINMENT |

|

| Evening on the Pasig River. Malacañan Palace. An evening fête. The Arms of the Philippines. “The Gubernatorial party.” “Manila at a glance.” The Gibson Girl. An amusing episode. A drive in Manila. The fashions. Manila shops. A market for the best diamonds. A “mixed” wedding. | 120 |

| [xi]LETTER XVI. MANILA AND ITS INHABITANTS |

|

| The suburbs of Manila. Hawks. A nursery-garden. Orchids. By the bandstand in the evening. Manila society. A city of cards. Intramuros. Americanised Filipinos. The American Ideal. Blind pride. Bilibid prison. Arts and crafts. The “Exposition” and the inquiring voter. The Philippine sky. A steamer on fire. A procession of death and degradation. “Sport.” A visit to Malacañan. A beautiful woman. Some lovely embroideries. Manila prices. Mr Taft and his Chinese servants. | 128 |

| LETTER XVII. DEMOCRACY AND SOCIETY IN MANILA |

|

| A Mestizo party. Seeking for democracy. And finding aristocracy. A shopping expedition. Chinese enterprise. Bridge again. A devotee and enthusiast. | 143 |

| LETTER XVIII. THE RETURN VOYAGE AND MY COMPANIONS |

|

| Home letters. The Simla of Manila. The return journey to Iloilo. A crowded ship. My cabin-mate. Filipino schoolboys. The first-fruits of the American Ideal. Filipino manners. Some Filipino views. Philippine Spanish. Dawn at the mouth of the Iloilo River. Expensive religion. Wonderful costumes. Lax port authorities. A hearty welcome home. | 151 |

| [xii]LETTER XIX. A BAILE—A NEW COOK AND AMERICAN METHODS |

|

| Carnival festivities. Lenten relaxations. A Palais Royale farce at the Filipino Club. “Hiawatha.” At a baile. A walk through the town. A Chinese graveyard. A troublesome cook. Wily native ways. A change of staff. Municipal marvels. Noblesse oblige. | 161 |

| LETTER XX. FILIPINO INDOLENCE—A DROUGHT |

|

| The rising thermometer. A Filipino watering-cart. A harrowing story. The Filipino employé. Mañana. A demonstration in racial equality. More drought. A new acquisition. | 169 |

| LETTER XXI. THE WHARVES—AN OLD SPANIARD |

|

| Roofs of Philippine houses. A walk along the quay. Chinese sailors. A mistaken policy. Native shops. Curious cigars. Desolate mud-flats. One of the results of high wages. A Spanish courtier. Los Indianos. A cause for panic. | 174 |

| LETTER XXII. A TRIP TO GUIMARAS—AN ASTONISHING PROPOSAL—HOUSEBUILDING |

|

| A little trip on the sea. Marvellous scenery. The ship of the Ancient Mariner. Coast villages. A band in the Plaza. Oriental tastes. The difference of Eastern and Western minds. Little comedies. How we drive in Iloilo. An importunate visitor. Strange American customs. A peaceful scene in the sunset. Building a house. | 182 |

| [xiii]LETTER XXIII. A TROPICAL SHOWER—OUR SERVANTS—FILIPINO CUSTOMS |

|

| The mails. A good butler. “The inevitable muchacho.” Palm Sunday. Negritos. Curly hair. Beggars. A Filipino funeral. | 191 |

| LETTER XXIV. EASTER FESTIVITIES |

|

| Easter holidays. Superfluous precautions. A gruesome procession. The Funeral of Christ. Rival religionists. A midnight pageant. A pretty procession. Happy children. A dull baile. | 195 |

| LETTER XXV. A DAY AT NAGABA |

|

| A trip to Nagaba. A native house. The “Philippine cuckoo.” Nipa thatch. Ylang-Ylang. A swimming-bath. A stroll along the rocks. A fisherman’s hut. Country-folk. The village. Pig-scavengers. The fire-tree. The tuba man. Mistaken temperance enthusiasts. Cocoanut-growing. | 202 |

| LETTER XXVI. THE MONSOON—AN ITALIAN OPERA COMPANY |

|

| Love-birds. Traces of the Filipino mind. The S.-W. Monsoon. Typhoons. A horrible custom. A wandering Opera Company. Increasing heat. | 210 |

| [xiv]LETTER XXVII. A WEEK-END AT NAGABA |

|

| The departure for Nagaba. An amusing landing. Morning on the beach. A fish corral. Trading vessels. A native kitchen. Betel-nut. A row up the river. Up in the woods. A magnificent prospect. Wild fruits. A primitive hut. The simple life. The American theory of education before food. Wanted a Colonial Office. Harlequins of crab-land. The tropic night. Fishing by torchlight. A parao. Skilful sailorising. Home again. | 215 |

| LETTER XXVIII. A LITTLE EARTHQUAKE, AND AN OPERA COMPANY UNDER DIFFICULTIES |

|

| A slight earthquake. Grand opera under difficulties. Barbaric laughter. The exodus to Hong Kong. Vagaries of the Monsoon. | 226 |

| LETTER XXIX. AN EVENING ON THE RIVER—RIVAL BISHOPS |

|

| Evening on the Iloilo River. Pleasant natives. A cocoanut-grove. The bolo. Green cocoanut. Salt pits. More trouble with the Customs. The verdict of Solomon. A hopeless grievance. Curiosities of taxation. Religious enthusiasm. Rival bishops. The Cardinal Delegate and the Aglipayano Monsignore. The Plaza at Jaro. A handsome old belfry. The Angelus. Peace and goodwill. | 231 |

| [xv]LETTER XXX. PHILIPPINE SANITATION—DECORATION DAY |

|

| The coolness of 90°. A letter from Benguet. Expense of travelling. Baby mongeese. Native neighbours. The sanitary control. An appeal to verguenza. An ill-kept town. An inhuman custom. The new hospital. Decoration Day. Digging up American soldiers. Unwholesome sentimentality. | 239 |

| LETTER XXXI. MR TAFT—TROPICAL SUNSETS—UNPLEASANT NEIGHBOURS—FILIPINO LAW |

|

| News of the coming of Mr Taft and his party. Miss Alice Roosevelt. A simple-minded damsel. Relaxing wind. By the Molo road. A lovely scene. An Eurasian household. A melodrama. And a farce. A flitting. Filipino justice. | 247 |

| LETTER XXXII. OUR MONGEESE—A FIRE—THE NATIVE EDUCATION QUESTION |

|

| A distressing malady. Habits of my mongeese. An alarm of fire. A strange state of affairs. “Arbitrary race-distinctions.” Undemonstrable theories. | 255 |

| LETTER XXXIII. A PAPER-CHASE—LACK OF SPORTS—PREPARATIONS FOR MR TAFT |

|

| A paper-chase. Lack of sports. Ladies astride. A problem for Mr Taft. Amusing headlines. Sad little pets. | 260 |

| [xvi]LETTER XXXIV. TRYING HEAT—AN AMERICAN PROSPECTOR—NEW LODGERS—BARGAINING FOR PIÑA |

|

| Damp heat. An enterprising millionaire. New neighbours. A happy household. Buying piña muslin. | 265 |

| LETTER XXXV. DECLARATION DAY—THE CULT OF THE FLAG—A PROCESSION, FESTIVITIES, AND A BALL |

|

| Declaration Day. The cult of the Stars and Stripes. An angry critic. The procession. American officers. Methods of horsemanship. A cruel vanity. American soldiers. The Veteran Army of the Philippines. “Little brown brothers.” Representative parades. Celebrations in the Plaza. Strange developments of athletics. A melancholy contrast. Official ball at the Gobierno. An ardent anti-Taftite. An amusing assembly. Unconventional bandsmen. A keen pro-Filipino. An ill-bred Mestiza. Balancing a quilez. Some of the drawbacks of civilisation. | 270 |

| LETTER XXXVI. COCK-FIGHTING—PULAJANES |

|

| A sad loss. The Filipino and his fighting-cock. Tricks of the ring. Off to the front. Peace and prosperity. A horrible story. A plague of flies. A slovenly guest. The poll-tax and some of its workings. | 286 |

| [xvii]LETTER XXXVII. A PEARL OF GREAT PRICE |

|

| Philippine flowers. A town of swamps. Monotonous scenery. Hawking a pearl. Pearl fisheries. Plentiful fish-supply. | 292 |

| LETTER XXXVIII. AGRICULTURAL POSSIBILITIES |

|

| A Gymkhana on the beach. An alfresco domestic servant agency. Road-mending. The foreign cemetery. Justice for the white man. Treatment of servants. The Filipino tiller of the soil. Wasted opportunities. A terrible disease. Some native fruits, and some more wasted opportunities. A welcome invitation. | 295 |

| LETTER XXXIX. A LAST DAY AT NAGABA—THE “SECWAR” |

|

| Farewell to Nagaba. The three-card trick. The Secret Police. A pleasant sail. Through the village. A native shop. Corn pone. An Anglipayano church. An idyll. Filipino coffee. Lack of American enterprise. A strange word. The coming of the Secwar. Human mosquitoes. A familiar type of character. | 301 |

| LETTER XL. PREPARATIONS |

|

| Preparations for the Patron Saint. Arcadian animals. Mr Taft’s intentions. Determined patriots. A famous phrase. The blessings of a free press. American altruism. Political Pecksniffs. The spell of indolence. | 310 |

| [xviii]LETTER XLI. THE FESTIVITIES |

|

| The Comitiva Taft. A reception that failed. Unappreciative guests. The decorations. A culinary treat. A call in the dark before the dawn. Gay streets. The visitors. “Miss Alice.” Mr Taft. The “Taft smile.” Looking for equality. A well-instructed journalist. Floats. Some strange banners. Mr Taft’s opinions. An amusing contre-temps. A very informal reception. A little mistake in tact. The banquet. Disappointed admirers. A haphazard feast. The mermaid. Speeches. A fiery patriot. Instructive applause. A splendid orator. Mr Taft’s mission. Two critics. | 315 |

| LETTER XLII. WEIGHING ANCHOR |

|

| An Iloilo hotel. A faithful servant. Complaisant Americans. Echoes of the visitation. Skilful reporting. A disappointed well-wisher. | 337 |

| LETTER XLIII. HOMEWARD BOUND |

|

| A pleasant prospect. Comfortable quarters. Chop-sticks. A happy little slave. The Chinese pigtail. An unspoilt Filipino. The dignity of the white man. The dregs of East and West. A last whiff of the sugar-camarins. | 342 |

| Index. | 347 |

| Discharging Hemp from Paraos (Native Boats) | To face page 10 |

| A Filipino Girl, aged 10—A Casco (Barge) | ” 14 |

| Old Spanish Houses at Molo | ” 20 |

| The Back of our House, showing Azotea and Outbuildings | ” 24 |

| Filipino Servants | ” 28 |

| Riding a Carabao | ” 78 |

| Spanish Architecture in the Philippines: An Old Church at Daraga | ” 89 |

| Manila—Malacañan Palace | ” 120 |

| Manila—The Escolta | ” 126 |

| A Street in Manila, showing the Electric Tram | ” 129 |

| Manila—The Luneta | ” 130 |

| Bird’s-Eye View of Inland Suburbs of Manila | ” 138 |

| A Philippine Pony | ” 174 |

| Native Houses | ” 204 |

| The Track of a Typhoon | ” 210 |

| A Filipino Market-Place | ” 218 |

| [xx]A Three-Man Breeze off Guimaras—A Parao | ” 222 |

| A Palm Grove | ” 232 |

| Cathedral and Belfry at Jaro | ” 236 |

| A Suburb of Iloilo | ” 242 |

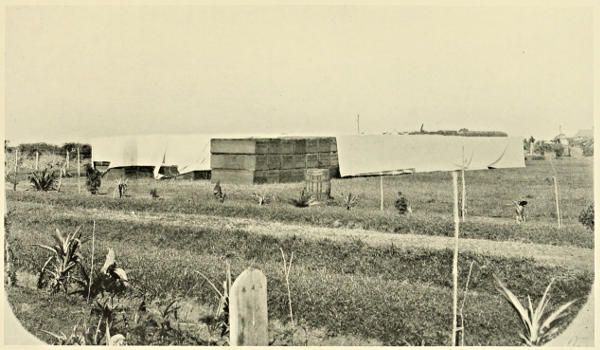

| Awaiting Shipment—Coffins containing Bones of American Soldiers stacked in Malate Cemetery, Manila | ” 244 |

| A Village Cock-Fight | ” 287 |

| Watering Carabaos | ” 293 |

| A Filipino Fish-Market | ” 294 |

Manila, 27th November 1904.

We arrived here early yesterday morning from Hong Kong, after three days of rather a horrible sea voyage, as the steamer was more than crowded, the weather rough, and we carried a deck cargo of cattle. These conditions are not unusual, however, in fact I believe they are unvarying, as the 362 miles of sea between here and Hong Kong are always choppy, and the two mail steamers that ply to and fro, the Rubi and the Zafiro, are always crammed full, and invariably carry cattle.

The poor beasts stood in rows of pens on the main deck, each fitting tightly into his pen like a bean in a pod; many of them were ill, and one died. We watched the simple funeral with great interest, for the crew hoisted the dead animal by means of a crane, with a rope lashed round its horns, standing on the living beasts on each side to do it; but they had a good deal of difficulty in extracting the body from its pen, in which it was wedged sideways by two live neighbours, who stubbornly resented the whole affair. Finally, with a great deal of advice and swearing, the[2] carcase was slung over the side, and it looked very weird sailing down the ship’s wake in the sunset.

That was the only event of the voyage, till we sighted Luzon, the biggest and most northern of the Philippines, some time on Saturday afternoon—this is Monday, by-the-bye.

The Zafiro kept all along the coast, which loomed up dim and mountainous, but we could not see anything very clearly, for the atmosphere was thick and hazy. Here and there on the darkening mountain sides a column of smoke rose up very straight into the evening air, and I was told they came from forest clearings, but we saw no signs of human habitation. A man who had been many years in the Philippines, and was returning to what had become his home, told me that such fires on the mountain sides had been used a great deal as signals between the insurgents during the Spanish and the American wars, and had been made to indicate all manner of gruesome messages.

About two in the morning, the Zafiro arrived at Manila and anchored in the bay, and when it was light, about five o’clock, we came up on deck and looked round, but the land lies in a section of so vast a circle that one does not realise it is a bay at all. The morning was very dull and grey; hot, of course, but overcast, and the sea calm and grey like the sky. The city of Manila lay so nearly level with the water that it was almost out of sight, just a long low mass, rather darker than the sea. Far, far away inland a faint outline of mountains was perceptible, but Manila is built, for the most part, on a mud-flat at the mouth of a broad river called the Pasig. This is a curious river, only 14 miles long, coming from a big lake called the Laguna de Bayo, but yet it is wide and[3] deep enough at the mouth for 5000-ton steamers to anchor at the wharves and turn in the stream.

About seven o’clock, or earlier, our friends’ launch came out for us, and in this little craft we steamed up the mouth of the Pasig, past rows and rows of steamers anchored at the quays, and hundreds of huge native barges covered over with round roofs of brown matting. I noticed numbers of brilliantly green cabbages floating down the stream, sitting on the water like lilies, with long brown roots trailing behind, and thought a cargo of vegetables had been wrecked, but was told these are water plants drifting down from inland bays up the river. They are the most extraordinary plants, of intensely crude and violent emerald, and make a marvellous dash of colour amongst the grey and brown shipping on the yellow, muddy water.

We landed at a big wharf, right in the town, and close to streets with shops, all looking strangely European after China and the Straits, the whole place reminding me more of the suburbs of Malaga or the port of Las Palmas than any other places I can think of. Here a carriage was waiting for us, and we drove all through the outskirts of the town, till we came out upon the bay again, and saw the open sea, where our friends’ house is situated in a quarter called Ermita. All Manila is divided into quarters, or wards, with curious Spanish or Filipino names—Malate, Pasay, Intramuros, Binondo, etc., and many names of Saints.

The days get very hot here after eight o’clock, whether the sun happens to be shining or not, so I did not go out until the cool of the evening, and spent the day in the house, unpacking and resting, and trying to forget the smell of those cattle. Never again, I am sure, shall I linger with pleasure near the door of a byre!

Everyone here goes about in diminutive victorias,[4] very like the Italian carrozza, and all the horses are tiny ponies, the result of a cross between the little Chinese horse and a small Spanish breed. They are sturdy little beasts, and remarkably quick trotters, with thick necks, and look pretty if they are well kept; but some of those in the hired carriages are very poor little creatures, though they tear about with incredible loads of brown-faced natives.

We drove about the town, which all looks as if it had been put up in a hurry. There are no indications of antiquity outside Intramuros, the old Spanish Manila, founded in 1571, which stands, as its name signifies, within walls—crumbling grass-grown old walls, very high, and with a deep moat.

This Walled City, as the Americans called it, is the town the British took under General Draper in 1762, and these are the walls our ships bombarded at the same time, under Admiral Cornish, papa’s great-uncle. When we were at home, it seemed strange that just before I came to the Philippines, I should inherit the lovely old emerald ring which the priestly Governor of Manila gave to the Admiral, when the former was a prisoner of war in the British Fleet, during the few days we held the Philippines, before we gave them back to Spain. But when I was actually under the walls they fought for, I looked at the old ring, and the coincidence seemed stranger still. I wished it were a magic emerald that I could rub it lightly, and summon some mysterious spirit which would tell me all the old ring had seen and heard. But now, Old Manila is only a backwash leading to nowhere, for the modern town has spread itself all up the banks of the Pasig River.

Our way did not lie through the Walled City, but along outside it, down a broad avenue, bordered[5] by handsome trees, over a bridge across the Pasig, and into the town of shops and streets. The whole place looked dull, grey, ugly, and depressing, and after Hong Kong it seemed positively squalid. Big houses like the magnificent stone palaces of Hong Kong, would be impossible here on account of the frequent earthquakes, but such buildings as there are look mean and dilapidated, and the streets are badly paved or not at all, weeds grow everywhere; in fact, there is a sort of hopeless untidiness about the place that is positively disheartening, like going into a dirty and untidy house. I think a great deal of the hopelessness, too, consists in the air of the natives, who appear small and indolent after one’s eye has become accustomed to the tall, fine figures of the busy Chinamen.

I was particularly struck with the fact that I saw no traces of anything one is accustomed to think of as Spanish—no bright mule-trappings, or women with mantillas, or anything gay and coloured, and the houses are not built round patios. I was told that the reason of this is that the Spaniards who settled in the Philippines all came from the north of Spain, from Biscaya, and of course the Spain one knows and thinks of as Spanish is Andalusia and the South, with the wonderful glamour and poetry of the Moorish influence.

In the course of our drive we went to a certain bridge to see a religious procession, and as we got near the place where it was to pass, the streets were crowded with people, and there were triumphal arches scattered about, all looking quite pretty in the rosy-pink glow of the sun, which was just beginning to set. We pulled up in a mass of carriages and traps on one side of the bridge, and waited an hour or more for the procession, which was then about three hours overdue.

While we waited there, we met and talked with a Mr —— whom I mentioned to you before as having come out from England in the same series of steamers as ourselves. He told us that he was putting up at the best hotel in Manila, which, he said, was haphazard and dirty beyond belief. We said we had had the same account from other people, and considered ourselves more than lucky to be staying with friends.

“Yes,” he said, “you are in luck, for you can’t imagine what a Manila hotel is like. And yet it is full of decent people. I wonder why they can’t run a better one.”

It does seem odd when one comes to think of it, because, though Manila is off the tourist track of the world, and there is no reason for any mere traveller to come here, still, people do come sometimes, and anyhow there are the Americans themselves, who want a shelter of some sort, and that nation has the reputation of being accomplished connoisseurs in the matter of hotels. One would imagine that a good hotel would be the first thing they would demand or establish, but they have been here six years now, and the Manila hotels are still a byword for unutterable filth and discomfort.

Well, about this procession, the occasion of which was the bringing down to Manila of a very sacred image, called the Virgin of Antipolo, from the town of Antipolo, which is inland, to deposit her in some church in Manila. She had been four hundred years in Antipolo, and was a very precious and much-battered relic, so her journey was a great event, and the procession had been travelling, by road and river, ever since before the dawn.

At last the long lines of people began to appear, crawling over the bridge in the last grey shadows. It proved to be a very dull affair, simply consisting of endless files of the faithful, carrying unlighted[7] candles, with every now and then a band of music, and every now and then a group of paper lanterns carried on poles, or some gaudy banner, and all moving along to the accompaniment of a weird, unearthly chant. This kind of thing went on and on, and after an hour we got tired of it, and drove away without having seen the actual image, which was, we were told, a little, armless, wooden figure, dressed in a stiff tinsel robe, perched up on an immense high platform, decorated with lamps and flowers, and surrounded by priests chanting, and acolytes swinging censers.

We are to sail for Iloilo to-day, after lunch, having got a permit to go in the Kai-Fong, of the China Steam Navigation Company. We were to have come in this same steamer from Hong Kong, as I told you at the time, in which case we should have gone in her right through to Iloilo, touching here and at Cebú, but we received the telegram too late, an hour or so after she had left, and as we were told to start at once, we followed by that pleasing craft the Zafiro.

By this manœuvre we have clashed with a vexatious local law that forbids foreign (i.e., not American or Filipino) steamers to convey passengers from Island to Island of the Philippines, so we had to apply for this special permit, as they say the regular mail steamers, which ply between Manila and Iloilo, are exceedingly dirty and uncomfortable. They are owned by a Spanish Company, trading under the American flag. However, it is all settled now, in favour of the English boat, and we sail this afternoon.

I have only caught a passing glimpse of Manila, but I hope to be able to tell you more about it later on, as I have been invited to come back and pay a visit to our friends here in a month or two’s time.

S.S. “Kai-Fong,” China Sea, December 1, 1904.

I hear there will be a mail going out from Iloilo to-morrow, the day we arrive, so I will write you a letter to go by it, that you may not be disappointed—six weeks hence!

We left Manila at three o’clock on Monday, in lovely sunshine, and had a delightful voyage through scenery which was simply a miracle of beauty. The sky was intensely blue, with little white clouds; the sea calm and still more intensely blue, dotted with dreams of islands, some mauve and dim and far away, some nearer and more solid-looking, and a few quite close, so that we could see the great forests of bright green trees and the grassy lawns, which cover the hills and clothe the whole islands down to long, white, sandy beaches, with fringes of palm trees.

The islands are volcanic, mountainous, and of all shapes and sizes, from Luzon, which is nearly the size of England,[1] and Mindanao, which is larger still, down to tiny fantastic islets, but all rich, green, fertile—even a rock poking its head out of the brilliant sea, has its crown of green vegetation. I don’t know at what size an island ceases to be an island and becomes a mere rock, but anyhow, there are two thousand Philippines considered worth enumerating.

I noticed very few signs of cultivation, or even of human habitation, but was told that even if there were villages in sight, they would be difficult to distinguish, unless we passed close to them, as they are built of brown thatch, and placed amongst the trees. Here and there was a little group of white buildings, generally, in fact always, clustering round a huge church. We passed quite close to some of the islands, so that we saw the trees and beaches clearly, but even those at a distance were very distinct, and I was particularly struck with the absence of colour-perspective, for the islands some way off, if they were not so far away as to look mauve, were just as brilliantly green as those close at hand. One after another, like a ceaseless kaleidoscope, these fairy islands slipped past all day—in fact, as I write, I can hardly keep my attention on my letter, the scenery is so wonderful and so constantly varying.

We got to Cebú, which is the chief town of the island of that name, at six o’clock on Wednesday morning, and anchored just off the town, which appeared as a flat jumble of grey corrugated iron roofs and green trees, rather shut in by high mountains close behind. On account of these hills, they say Cebú is much hotter than Iloilo, as the latter town lies open to the Monsoons.

These are the chief towns of the Philippines: Manila, the capital, in Luzon; Iloilo, in Panay; and Cebú, in Cebú; and that is the order they come in as to size, though between the two provincial towns there is endless rivalry on the subject of importance. In fact they are a sort of local Liverpool and Manchester—bitterly jealous, and yet pretending to despise each other. There was a P. and O. cargo steamer anchored not far from us, the first ever seen at Cebú, and everyone seemed very proud of the event.

When we went on deck, we saw a couple of canoes, hollowed out of big tree trunks, circling round, and containing natives dressed in loin-cloths, offering to dive for coins, in the approved fashion, west of Port Saïd. They were fine young men, yellowy brown in colour, and they made a great deal of noise, but did not dive very well. After breakfast some of C——’s friends came off in a launch and took us ashore, when we drove in the usual little victoria, drawn by two small ponies, to the British Vice-Consulate, a large house on the borders of the town, where the Vice-Consul, Mr Fulcher, entertained us royally.

Here I followed the same programme as I did at Manila, resting in the cool house all the long, hot day, and driving out in the evening at about five o’clock, when the sun had begun to go down. We drove all through dim streets, with a gorgeous sunset fading in the sky, and I could not make things out very distinctly, but could see that we were passing along ramshackle, half-country roads with overshadowing trees, and every now and then we passed a row of little open shops with bright lights in them, and natives squatting about. There are no bazaars in this country, by-the-bye, only little mat-shed shops where food is sold.

That was all I saw of Cebú, as I did not go out this morning, and we sailed in the afternoon. When we came down to the wharf to get on board, the tide, or the Port Doctor, had allowed of the Kai-Fong, drawing up to the wharf, so we came on board up a plank, when one had to look at the ship instead of the water on each side! The ship was very busy getting a cargo of hemp into one of the holds, hemp being the peculiar produce of the Island of Cebú and the opposite ones of Samar and Leyte, all long-shaped islands lying almost parallel in the middle of the Archipelago.

The hemp comes on board in great oblong bales, looking like oakum, and a man told me it was the fibre of a plant like a banana tree, which the natives split and shred very skilfully, and then it is dried and done up in bales, and “that is all there is to it,” as the Americans say.

Opposite the town of Cebú is a long, low island called Mactan, where the great Portuguese Navigator Magellan was killed in the year 1521. The story is that the natives of the islands, finding Magellan invincible, and believing him to be enchanted, lured the great explorer away by treachery to the little island of Mactan, where they had prepared a pit covered with branches, such as they use to trap wild pigs. Magellan fell into this trap, whereupon the savages rushed out of their hiding-places and shot him in the joints of his harness with poisoned arrows, and one bold man finally finished him off with a spear. They poison their arrows to this day as they did then, by dipping the tip into a decomposed human body.

There is a monument to Magellan on the spot where he died, but we did not have time to go and see it, so I had to be content with looking at a photograph, which gave me a very good idea of the quaint old three-decker edifice of grey stone, tapering to a column at the top. The real and original spelling of Mactan is as I have written it, but it is now altered to Maktan, and for this change there is a very curious reason, dating from the days, some ten years ago, when the Filipinos, headed by a patriot of the name of Emilio Aguinaldo, revolted against the authority of Spain. The chief element in the uprising was a secret society, called the Katipunan, the device of which, on flags and so forth, was K K K, and to make this fact memorable, or to prove his power, Aguinaldo ordered the hard letter C to be replaced[12] by K in all names in the Philippines, making Mactan, Maktan; Capiz, Kapiz; Catbologan, Katbologan, and so on. This alteration the Americans, some think unwisely, have not taken the trouble to abandon, so the revolutionary spelling remains a monument of the success of disloyalty, to say nothing of the names having thus lost all philological significance.

We are now passing round the north end of the Island of Cebú, for Panay lies to the westward, in a rough parallel. Sometimes the north passage is taken, and sometimes the south, according to the wind and current. The currents are very strong between these islands—all the Philippine Islands, I mean, and in many places the sea is always rough, in fact it is very seldom really calm anywhere, I believe.

Our fellow-passengers are all Americans, half of them military, officers and privates, who address each other in most unceremonious fashion, and the rest school-teachers. A most appropriate and characteristic company, as the American scheme out here is to educate the Filipino for all he is worth, so that he may, in the course of time, be fit to govern himself according to American methods; but at the same time they have ready plenty of soldiers to knock him on the head, if he shows signs of wanting his liberty before Americans think he is fit for it. A quaint scheme, and one full of the go-ahead originality of America.

I can understand the conduct of the free and easy soldiers, for such equality is not inconsistent with American social theories; but what puzzles me is the use of these astounding pedagogues, who are honest, earnest, well-meaning folk, but their manners are those of ordinary European peasants. And as to the language they speak and profess, it is so unlike English that literally I find it difficult[13] to catch their meaning when one of them speaks to me direct, and quite impossible when they talk to each other. Yet I could forgive them their dreadful lingo, if only they would not use the same knife indiscriminately to lap up yolk of egg, or help themselves to butter or salt. Of course these good people are fresh from America, and utterly ignorant of all things and people outside their native State (such ludicrous questions they ask!), but quite apart from that, and the hopeless blunders they must make on that account, it seems a pity that such rough diamonds should represent to these natives the manners and intellect of a great and ruling white nation.

But here comes the most curious phenomenon of all, for I am told that the United States does not pose as either “white” or “ruling” in these islands, preferring, instead, to proclaim Equality, which seems a very strange way to treat Malays, and I find myself quite curious to see how the theory works out. I only hope it won’t mean that we shall have unmanageable servants and impudence to put up with. Our friends in Manila told me ominously that housekeeping was “difficult,” and I begin to wonder if Equality has anything to do with it!

They are a funny little people, these Filipinos, the women averaging well under 5 feet, with pretty, slender figures and small hands and feet. The original race was a little, fuzzy-headed, black people, remnants of which are still to be found in the mountains and in the smaller islands, but the Filipino, as one sees him, is the result of Malay invasions. Up in the north, in Luzon, the Malays are a race or tribe called Tagalo, but all this part of the Archipelago is called Visaya, and the people Visayans. Of these broad outlines there are many subdivisions of type of course, in the way that[14] physique is different even in different counties in so small a space as England; but the average Filipino is the same everywhere. The Filipinos (by which are meant the Tagalos and Visayans) are, as nearly as one can say, a short, thick-set people, with yellowy-brown skins, round, flat faces, very thick lips, which frequently jut out beyond the tip of the nose, and more bridge to the same said nose in proportion to the amount of foreign blood in the owner’s veins. It is not easy to lay down any very definite rule about their appearance though, as the race is so hopelessly mixed with Spanish, Chinese, European—every nation under the sun, that it is difficult to say what is a Filipino face. One feature they have in common, and that is magnificent, straight, jet-black hair, which the women turn back from the forehead, where it makes a roll so thick that it looks as if it must be done over a pad, while they twist the back high up, in shiny coils. The men look as if their thick mops were cut round a basin, and they have no beards and moustaches—I mean they can’t grow any, not that they don’t want them! As far as I have seen, they appear to be very lazy, and to talk a great deal. They are not a bit like the Chinese or Japanese in any way, unless they happen to have a strain of that blood in them, and even then the resemblance is only physical, for though the type may be varied, the universal character remains unalterable.

I forgot to tell you that at Cebú we “collected” C——’s dog, a dear old brown person, with one of the sweetest faces I ever saw, who answers to the name of Tuyay, which is the Visayan for Victoria. I really must leave off writing now, as it is long past time to “turn in,” though I feel as if I could write on for hours, there is so much to tell you.

Iloilo, December 4, 1904.

We arrived here on Friday last (the 2nd), and I at once sent off a letter to you, written on board the Kai-Fong, which letter ought to reach you some time in the middle of January.

We are so glad to be at the end of this long journey—exactly seven weeks from London—seven weeks to the very day, for we left London on a Friday and got here on a Friday; and all that time we have been travelling steadily, and have seen so much that it seems years already since we left home. I hope you got all the letters I wrote on the way? One each from Gibraltar, Marseilles, Port Saïd, Aden, Colombo, Singapore, Penang, Hong Kong, Manila, and lastly, Cebú. I give you this list because I always have a fixed conviction that letters posted on a sea voyage seldom turn up, as the last one sees of them is going over the side in a strange land, in the clutches of some oily, dark person, who swears he will spend the money one has given him in stamps. I try to believe him, but he, like Victor Hugo’s beggar, thinks he has to live somehow, I suppose.

Well, so here we are at last on our “Desert Island,” as you call it—which is really a vast and fertile country, with several big towns, of which this is the chief and largest.

We got in at dawn as usual, the run from Cebú (which I notice the Americans call See-boo) being[16] about twelve hours, so our first view of the Island of Panay and the town of Iloilo was in the early morning light, from the deck of the steamer, which lay, waiting for pratique, in the “roads,” at the mouth of a river. We saw a long, flat, dark-green coast line, with a high range of purple mountains far inland, and the town of Iloilo, like Manila, almost imperceptible, as it lies so low on the mud-flats of a big estuary. It did not look at all inviting, just a line of very green trees, with some grey iron roofs amongst them, and it seemed as if it must be baking hot, but, as a matter of fact, the very flatness and the direction of the mountains keep the place cool, for, as I told you before, it lies exposed to the N.-E. and S.-W. Monsoons, the great arbiters of fate in the China seas.

On the map you may find marked a small island called Guimaras, which is about 4 or 5 miles off, but in this air it looks so close that trees and houses can be seen over there with the naked eye, and yesterday evening, in driving down a street of Iloilo and seeing Guimaras at the end, I thought it was part of this island at the end of the road!

Guimaras is very small, with low, pointed hills, covered with forests, as are all these islands; and behind it, 7 miles further away, lies the big island of Negros, the mountains of which loom up, a dim, pale purple outline behind bright green Guimaras, making one more of these marvellous colour effects. One of the high peaks we see is a volcano called Malaspina or Canloon, which is 4592 feet high, and only half quiescent. At any rate, if we cannot actually see it, there is such a volcano in Negros. There are plenty of volcanoes in the Philippines, twenty-three of them all told, and that fact and the frequent earthquakes give an uncomfortable impression, as of a thin crust of rocks and trees over vast subterranean fires.

Here, in Panay, the mountains are 20 miles inland, away to the west—a long range of peaks and serrated ridges, behind which the sun sets with magnificent effects. From the foot of the mountains the land stretches away quite flat, watered by big rivers, and where one of these streams forms a wide estuary, this town is built, as I told you, on the mud, in the same way that Manila stands on the mud-flats of the Pasig.

The first settlement of white men in Panay was only a Spanish garrison, inside a fort built in the days when a few Spaniards in armour lurked under shelter from the poisoned arrows of the savage natives, while now and then a priest ventured out to see what a little talk and baptism would do towards making life more pleasant for everyone concerned.

When the island became more civilised, or settled, or subdued, or all three, a town called Jaro (pronounced Hahro) was founded about 3 miles up the river, and became the capital of Panay, but now the tide of commerce has swept down-river, and the chief town is Iloilo, all crammed down at the edge of the sea, with many of its suburbs nothing more nor less than sandy beach. It is a big town, with long, straggling streets, and the houses, all two stories high, with grey corrugated iron roofs, stand apart, separated by little bits of garden with palms and flowering trees, which makes it quite pretty, in spite of all the buildings being totally devoid of any architectural beauty whatsoever.

At present the N.-E. Monsoon is blowing, and everyone is anxious to point out to me how deliciously cool the weather is, and it is certainly not so overpowering as I had expected, but all the same I find it quite hot enough to be pleasant and a little over. Though there is no dew, the nights are refreshing—almost cold by contrast with[18] the day, and the evenings charming, while the early mornings are simply delicious. Dawn begins at half-past five, and by six the sun is up, but the air is exquisite till about half-past eight, when it begins to get too hot for anything but shade and fans, if one has any choice. I think the average Fahrenheit now is 83°, but as life here is adapted to such temperature, you must not think that means anything like what 83° would be in England. Still, when all is said and done, it is very hot, and if this is what they call “winter,” I am only thankful that I have not plunged at once into “summer.” This “winter” goes on till March, and then the weather begins to get hotter and hotter till June, when the Monsoon shifts to the S.-W., and the rainy season begins.

Four months dry and cool; four months dry and hot; four months wet and hot—that is the climate over most of the Philippine Islands, but it varies in sequence in different places—areas is a better word—and on the Pacific seaboard the seasons are quite reversed, so that it is rainy there when it is dry here. By rain and dry, however, I gather that a great deal of drought or a long, steady rain is not meant, for all during the dry season there are heavy showers, and everything remains green, while in the wet season there are spells of fine weather. Now I think I have described to you all I can of Iloilo till I see more of the place, but I know how anxious you will be to have some idea of what it is like.

We are busy house-hunting, which is a tedious and toilsome business, as there is not such an institution as a house agency—you allow a rumour to get about that you want a house, and then people tell other people to tell you where an empty building, such as you say you want, is to be found.[19] Then you go off and “find” the house—a matter, usually, of infinite difficulties and sometimes quite impossible, as the Filipino cab-drivers don’t know the names of the streets, or the numbers, or the names of the people. The best plan is, get into a rickety old trap and let the man drive about, while you lean out and ask for the house you started out to find, and end by seeing another one with se aquila (to let) written up, and stopping as near to it as the driver can pull up his pony, and getting out there instead.

Having thus “found” a house, you set to work to “find” the owner of it, who is probably at the club, or a cock-fight, or playing cards; and when he, or she, appears, you ask—and this is quite necessary—if the house is to let; for the board does not signify much, as they seldom take the trouble to remove one when once it has been put up. Most of the boards are obligingly going through the process of removing themselves, one nail at a time.

When the house really is to let, you ask the rent, and whatever the answer is you throw up your hands in horror, and declare it is muy caro (very dear), and that you will give half, calling assorted Saints to testify to all the drawbacks which make the house unfit for human habitation at any price.

Then a long argument ensues, for the people never really want to lose a tenant, as they know there is no lack of choice, for trade is very bad, and so many houses stand empty. All the same, the rates and taxes are appallingly high, and the rents are preposterous for this sort of town, and for the accommodation offered. Moreover you have a strangely lazy, supercilious, half-bred sort of people to deal with, who would rather keep a house empty and say they must have 100 dollars[20] a month and starve, than take 50 for it and live on the fat of their land.

The money here is a dollar currency called Conant, which is worth 2s. 1d.—half the American dollar. This is the Philippine currency, and is named after its inventor, an American called Conant, and I wish he had invented a cheaper unit, for 10 Conant dollars, or pesos, as they are called, are nothing to spend, whereas the equivalent, an English guinea, is an important sum, and represents four times the spending value of 10 pesos. It is a silver currency, dollars and notes, and the coins have rather a pretty design of a man sitting looking at the sea, surrounded by most amusing inscriptions. For instance, the 5-cent, piece is: “Five Centavos,” and underneath is “Filipinas.” Why not “Five cents.” and “Philippines,” or else “Cinco centavos, Filipinas?” Why such mongrel? One can only suppose it is the notion of Equality coming out in some mysterious way by meeting the natives half-way in Spanish, which, by-the-bye, is not their native language, and only a few of them speak it at all.

The houses here, as I said before, are all two-storied, the upper part of wood, and the lower of stone or concrete. The floors are of long planks of hard, dark, native woods, which the servants polish with petroleum pads on their feet, sliding about till the surface is like brown glass. The walls are merely wooden partitions, painted white or green, and in the corners of the rooms appear the big tree trunks to which the house is lashed, sometimes just painted white like the walls, or encased in a wooden cover. The word “lashed,” I must tell you, is not a figure of speech, as the houses really are tied together with bejuco, rattan (a strong, fibrous vine), so as to allow sufficient play for earthquakes, which, it appears, are so[21] frequent in these islands as to be in no way remarkable.

The “windows” are really the greater part of each side of the house left open and fitted with shutters, sliding in grooves. Even with these “windows” closed against rain or sun the rooms remain cool, as the shutters are composed of wooden slats a little apart. Inside these is another set for very rainy weather, made of small square panes, each filled with a very thin, white, pearl oyster shell.

Taken all round, the Philippine houses are very pretty, and capable of a great deal of decoration, though, of course, one does not want any draperies or many ornaments about in such a climate, where such superfluities would simply become the homes and nurseries of clouds of mosquitoes and other small fry, besides being unendurably hot even to look at.

At first it appears very odd to see houses without chimneys and rooms without fireplaces, though I can’t think why they have none, as it must be very difficult to keep the houses dry in the wet Monsoon.

Iloilo, December 10, 1904.

I am sure you will be pleased to hear that we have already found a house to suit us, in fact we are quite charmed with it, and can’t be too thankful that we did not hastily take any of the others we saw. C—— went to look at some on Tuesday, but on the way he saw this one, and liked it so much that he at once came back for me to look at it, and I went off to inspect, even in the middle of the day! I agreed with him in thinking the house charming, so we took it at once—or as soon as we had finished the preliminary pantomime with the Filipino landlady, a pleasant woman, married to a Spaniard.

The house is in one of the two nicest streets, a little out off the town, on the spit of land formed by the estuary and the open sea. These two streets run parallel, but as the spit gets narrower they leave off, and end in the Government Hospital, the Cavalry Corral (stables), some Government buildings, and diminish gradually to a long road, a house, some barren land, a few palms, a pilot’s hut, a little bit of beach, some pebbles, and one small crab.

Our house faces S.-W. on a garden, and the back is all open to the river and the N.-E. Monsoon—the most important consideration here, for houses that do not get the wind are stifling and unhealthy.[23] We saw two or three that would have suited us very well, but for the fact that they stood the wrong way, or because the through draught was impeded by some tree or building outside.

The house we have taken is in the usual style, such as I described to you in my last letter, and in one-half of the lower part lives our Spanish landlord, while in the other half, rather vault-like, se aquila. The lower parts of the houses are unhealthy, because of the malarial gases arising from the soil, and the damp, so no one lives in the basements if they can afford anything else.

The upper part of this house we are going to live in is quite a separate dwelling, as it is approached by an outside staircase, coming up upon an open balcony running round three sides of the upper story. The balcony is a great charm, and very few of the houses have this addition. I thought that the Spaniards would have made open balconies the fashion out here, but was very much surprised to see none, and can only attribute the lack of them to the fact that the settlers came from the North, in the same way that the houses have no patios, and so forth. A roofed balcony like this is not only a delightful lounge, but it keeps the house very cool, besides catching a lot of the heavy rains, and it seems incomprehensible that any sane person could build a house in this climate without one. Verandahs are, of course, quite unknown, but I daresay there is a reason for all this in the terrible Typhoons which sweep over these islands, and would make short shrift of any fancy out-works.

We come into a big hall at the back of the house, with the outer side almost all (with shutters) open to the estuary, and the front portion of the house is the sala. Off these two, open five rooms, all large and airy, and freshly painted white. In many of the houses the top of each room has a deep[24] frieze in the shape of a pretty wooden grill, a Chinese fashion, which allows the air to circulate freely through the house—to say nothing of the remarks of the dwellers! We have not got this extra luxury, which I suppose has not been considered necessary in so airy a house.

At the back is what is called the Azotea, which in this case happens to be built over the house below. It is a big, sloping, concrete floor, on which are built the kitchen, bathroom, store-room, etc.—all very compact, and quite away from the house, and not coming between us and the wind. In this, again, some of the houses we saw were impossible, for the outbuildings on the Azotea were placed so that they stopped the draught through the house. You may think I am a little foolish on the subject of a current of air, but I assure you I am not, for in a position with no draught the pores of the skin open like so many sluices, and one’s head begins to throb.

So that is our house, which, after genuine Spanish haggling, we got for 50 pesos a month, a sum working out at about £60 a year, a very low rent indeed out here. In fact, when we set out and said we meant to give no more than 50 dollars a month for a house, we were simply laughed at, and at first were almost inclined to think it could not be done, but when we saw the numbers of houses standing empty in all the nice streets, we stuck to our sum, and are very glad now that we did so. A Spaniard or Mestizo (Eurasian) would not dream of giving more than thirty for a house like the one we have taken, but an American would give a hundred. That is where the trouble comes in—in making the people understand that we don’t mean to grind them down, nor, on the other hand, to pay foolish sums, but to give the right value for what we get.

You know the way Americans go about in Europe spending the unit, which is lower than their own, like water, with no sense of value? And how they raise prices wherever they go! Well, they have done the same thing here, and an American woman, who was talking to me the other day, told me it was now beginning to be apparent to them what a mistake they had made, and they bitterly regretted having made the Philippines as expensive as America, but that it was very difficult for them to go back now to the more reasonable scale, for as soon as a Filipino found out you were an American, nothing would move him from American prices. Poor thing, she was very bitter about it, and I felt very sorry for her (as well as rather alarmed for myself), for the sums she was paying in rent and wages to live at all in Iloilo, would have kept her in comfort in London or Paris.

Well, when we had settled on the house, we drove straight to the shop-streets of the town—or rather, street, for there is only one with shops, the principal thoroughfare, called the Calle Real. Some of the shops have quite big, handsome windows of plate glass, with wonderful things displayed in them, but when you get inside you find they are, like the shop window in Browning’s poem, only “astonishing the street,” and beyond the window there is nothing but a large half-empty hall, where a few languid, sallow Eurasians stand trimming their nails behind long, untidy counters. These are the Spanish, Filipino, and German shops; but the Chinese are just the reverse, with no show in the little low window, and the inside a small, poky room, crammed with everything any human being ever invented, and kept by energetic, slant-eyed men who simply won’t let you go without buying something.

The principal shop, however, is the great[26] Store, which is kept by an English firm called Hoskyn & Co., and is said to be the best in the islands, and there we bought elemental necessaries, in the way of a few pieces of furniture, some groceries, china, glass, and so forth, at prices, when translated into shillings, to turn one faint with dismay. It was maddening to think of the lovely things we could have got for the same money at home, nevertheless these were very cheap for the Philippines, for this is a notoriously cheap “store,” which can afford to sell at low prices, as they have such an immense business, even being able to compete with the shops in Manila, where they send all manner of life’s necessaries. Though I am once more reminded of papa’s remark that he never realises what a curse human life has become till he reads through a store list.

When we had done our shopping, we came back to the house and unpacked our new household goods as they came in, hung lamps, and so on, and all that day worked hard at the house. At intervals prospective servants kept dropping in, for servants are secured here in much the same way as houses—people tell other people about the opportunity, and the news flies about in servant-land.

All shapes and sizes of Filipinos loomed on the balcony at intervals, and drifted into the hall and stood watching us till we had time to attend to them. In this country all the doors stand always open for coolness, and there are no bells, and when you go to a house you walk in at the door and sing out for a servant. Some people go so far as to have a hand bell at the top of the stairs, but the whole system seems to me ridiculous, so I have persuaded C—— to invest in a door bell, which he is going to fix to the main door into the hall.

We were unpacking and going about the house,[27] and every now and then we would come upon a silent figure waiting, just waiting, anywhere, leaning up against something, and perfectly indifferent to time or place. This stamped him as a candidate. To each one C—— put first of all the question:

“Can you speak English?”

And when the man said “Yeees, sair,” he was refused without any further parley, for nothing will induce us to take servants who can understand what we are saying, which would make life impossible in these open houses. Besides that, when they speak English it means they have been with Americans, who spoil the Filipino servants dreadfully with their well-meant notions of equality, and give ridiculous wages as well. In the Spanish days a Filipino head-servant got 5 or 6 pesos a month, and the peso then was the Mexican dollar, which is only about two-thirds of the Conant unit. It was, and is, riches to them, but so changed are these things now, that we are considered wonderful because we have found a mayordomo or head boy willing to come to us for 10 pesos a month and a second boy for 6. An American would give them twice as much, if not more, which would simply turn them into drunkards, or gamblers, or both, or worse.

All the Philippine servants are men, as all over the East, though some women do have a native maid; but as all the women I have met do nothing but complain of the laziness and uselessness of these handmaidens, I have no idea of saddling myself with such a burden.

The two men we have engaged are about twenty years of age, but it is always very difficult to tell how old Filipinos are, as they look old when they are young and young when they are old. They can give no particular account of[28] themselves, these two, and have unaccountably mislaid their little books of references; but we are taking them on the recommendation of their faces, which are nice, and that is just as good a standard to go by in a Filipino as in anyone else! One is a native of Guimaras; the other a Tagalo, from Luzon; and both are short, thick-set, sturdy-looking fellows who ought not to give us much trouble with falling ill. Half the time here the servants are ill with fever, or colds, or heaven knows what, for it is a race without much stamina.

One of the most aggravating characteristics of the Filipinos is the way they murmur, for they have naturally very soft voices, which become positively a whisper with shyness and awe. The English people here adopt the custom, which prevails throughout the East, of calling their servants “boys,” but the Americans use the Spanish word muchacho, and that is unfortunate, as they give all vowels the narrow, English value, making it this word muchaycho. It sounds so odd, this lack of ear, and quite alters some of the Spanish names—such as saying Cavyt for Cavite (the naval port of Manila), Caypiz for Capiz (a town in Panay), and so on, and though they pronounce Jaro exactly the same as the English town of Harrow, thank goodness they don’t go so far as to call this place Eye-low-Eye-low!

But I am wandering away from the servants, and I have not yet introduced the cook to you. We had less trouble to get this treasure than the others, as all the natives cook well by instinct—at least, they know how to make the best of what food there is to be had, which is all one wants. This particular chef is a shrivelled, pock-marked person, about 4 feet[29] 6 in height, with an array of immense teeth, and an air of intense importance; this last characteristic being funny or annoying according to the mood one happens to be in oneself. His wages are 15 pesos a month, and as he is a married man, or says so, he is to live with his family in the town.

And that was the end of the first day, and a very long and fatiguing one in this climate.

When we came back next morning we found that the boys, who had been left in charge of the house and what furniture we had fixed up, had already swept and polished the floors, which made an immense difference to the appearance of the place, and the lamps were filled and trimmed. There is electric light in the town, but it is so very bad, and is the cause of so much complaint, that all have to supplement their expensive electricity with oil lamps before they can read. We are, therefore, not going to have it put on, though it would be quite easy, as the wire passes over us from next door. The efficiency and intelligence of the new servants pleased us very much, but all the same we observed cautiously to each other: “New brooms sweep clean.”

We left the new brooms still sweeping, and went off to the shops again, and once more spent important and heart-breaking sums on the bare necessities of life. This time it was furniture, at the shop of a Chinese Eurasian, where we got a lot of things that look very nice, though they are not anything wonderful in the way of wood; but in these light, open houses with no fires and no carpets, it is not necessary to have such rich-looking furniture as at home. If one likes to spend still more money, there are beautiful things to be had made from magnificent hard Philippine woods, but the high price of labour,[30] the poverty everywhere, and lack of capital and enterprise, have made these hard-wood things so dear that they are luxuries. The ordinary furniture is, in spite of the cent.-per-cent. import duties, either made out of Oregon pine, or else imported ready made from Vienna; but an insect called buc-buc, with which the country abounds, eats these soft pine woods, though it will not touch the native mahogany, teak, ebony, etc. It is not as if this Philippine timber were swept off for export, for no trade is done with it as no cheap labour is to be had, and splendid trees just decay in the crowded forests on the hills.

For our sala we invested in basket furniture, a necessity in this heat, for padded chairs or cushions would be unendurable. The bamboo and rattan, of which Chinamen would make all sorts of pretty chairs and couches for a few pesos a piece, grow plentifully here, but in the Philippines such articles are only to be had at three times the price, as they are imported from China, for the Filipinos are too lazy and stupid to make anything of the materials given them by “el buen Dios,” and if they did, the scale of wages, set by the American Government, would make the things even more expensive than those imported. So the reeds rot, and the woods rot; and we, for our part, cannot cease to regret that we did not, while we were in Hong Kong, invest in some of the cheap and beautiful furniture we saw there, but we took local advice and forbore to import anything into this land of prohibitive tariffs; though now we discover that, tariffs and all, we should have found it cheaper to have brought the things with us.

All this expense of life springs from the accepted interpretation of the maxim, “Philippines[31] for the Filipinos,” which saying was invented by the late (and first) Governor-General of the Philippines, a man of the name of Taft, who is now Secretary of War in the United States. I suppose the idea caught on in America, and the good people there, whose opinion controls affairs in this country, which they have never seen, think that prohibitive tariffs and the exclusion of cheap Chinese or Japanese labour, must be a good thing for these depopulated islands if it is a benefit to the overcrowded U.S.A.

As a matter of fact, when applied to an indolent, indifferent race, the result is stagnation and starvation prices, which is a terrible state of affairs in a hot country like this, where food and labour ought to be plentiful and cheap, or nothing will pay. I can’t think that the Americans really believe the Filipinos to be as high a development of the human race as they are themselves; but since they wish, with the best intentions, to allow the Filipinos to benefit by American systems of government, these Malays must first learn the A B C of such a system. Whether they are capable of profiting by such lessons, or whether they are so foreign to the essence of this race as to ruin it, remains to be demonstrated.

Well, I must get back to the house again, and the end of the story is that we moved into our house on Thursday, the 8th, and slept here that night. We were able to do this so soon, as people have been very kind in lending us things—sheets and towels from one, table-linen from another, and so on—but all the same I wish our cases would come, as there is such a responsibility about other people’s gear.

À propos of these same cases, we are rather uneasy in our minds about them, as we are beginning to hear alarming rumours of Customs duties[32] to be paid. Wedding presents used to be exempt, but quite lately duties were levied on them, and I am afraid we shall have to pay for our own things, which is a bore, not to say rather a blow.

We got through all our trunks, etc., that we had with us with a perfunctory opening of one box, a few questions, and the signing of papers, the only trouble being C——’s gun, which they took away, and he will not be able to get a licence, or allowed to have it out of the Customs House before he finds two “bonds” of 100 dollars each. That is, in clear English, he must find two people who are prepared to bet the American Government 100 dollars each that he is not going to sell the gun to an Insurgent.

So, barring the gun anxiety, we got our boxes in all right, and are told it would have gone equally well with the cases had we had them with us, but as they are coming out by freight, they will be subject to the duties. However, the authorities tell us it will not be very severe—C—— went and inquired about it, as he said he would rather not take our spoons and forks and things out of bond, but would prefer to send them back to Hong Kong rather than pay a large sum. So, all things considered, C—— is not reassured, so he has arranged to have the cases sent here unopened and in bond; and is going to open them, in bond, at the Custom House, and have the contents appraised before he decides what to do with them. The only reasonable hope is that many of the contents, such as plate, may be exempt, or very lightly taxed, as they are articles that could not possibly be produced in the Philippines; but when I mentioned this to a Customs official, he replied that such an idea had nothing to do with the system of taxation.

This is a fearfully long letter, but even now I feel I have not told you half I wanted to.

Iloilo, December 17, 1904.

We are settling down very comfortably into our charming house, which we like more and more, and are continually congratulating ourselves on our luck in having found such a nice home.

There is nothing special to tell you about since I last wrote, so I will try to give you some idea of my housekeeping, of which I think I have not yet told you anything beyond just mentioning how many servants we have.

I find that the cook—he with the important manner and the big teeth—has been an under-cook in an American hotel, or what he is pleased to call an American hotel, by which I take it he means one of the saloons or eating-houses in the town. So far, however, he has proved himself a very good cook indeed, which is even more necessary here than anywhere else, for food in the Philippines has but little variety, and is not nourishing at its best. Every morning I give this person a peso and a half, with which he goes off to the market and buys whatever takes his fancy, or, more probably, what is to be had, which generally takes the form of an incredibly small and thin fowl—alive; one or two little fish; some green peppers or egg-plants, and always a few very small, half-ripe tomatoes. With these and with help from the store-room, he concocts a very good lunch and dinner, and, doubtless, makes a good thing[34] out of it, but most cooks charge 2 dollars for the same menu, and he really provides for us very well. I supply tea, salt, butter, lard, tinned fruits, potatoes, macaroni—in fact all the dry provisions usually kept in a store-room, I don’t know what is the technical name for them.

The store-room (dispensa, they call it), where these treasures are hoarded up, is a very nice little dark cabin, with shelves all round, which I made the boys clean out and wipe everywhere with petroleum, an excellent precaution against the numberless and extraordinary animals with which one has to share the house. I got tall glass jars for protection against cockroaches, and tins to keep mice off, and wire-netting for rats, and naphthaline to astonish the scorpions and spiders; and last, but by no means least, a good strong padlock for human beings! When the tins and bottles were all arranged, they looked very home-like.

We get up at half-past five or six, and I give one of the boys 20[2] cents, with which he goes out and buys bread for the day at the shop of some Chinaman down the street. It is necessary to get small daily supplies of everything, for food will not keep. Some people have told me fearful anecdotes about the horrors perpetrated by the Chinamen in the making of their bread, and these faddists have theirs made at home, but the Chinese bread tastes quite good, and is much more light and digestible than that made by the house-cooks. As our cook has cooked for Americans, he knows how to make the hot cakes which are the great feature of American breakfasts, but we won’t have them, for they are deadly anywhere, especially in the tropics.

After our seven o’clock breakfast, which consists[35] very largely of eggs, and after C—— has gone to the office, I open the door of the dispensa and serve out the day’s supplies; but this routine was not brought about without a struggle, for at first the cook persisted in coming to me intermittently all day long to ask for things. At least, he invented wants, but I had an idea his only object was the key of the dispensa, as these Filipinos have a full measure of the cunning of the brown-faced person all the world over. However, I disappointed him about that, always leaving whatever I was doing to go and open the door and get out what he wanted, at the same time remarking, as best I could, that if he did not ask for things at the proper time he must do without them. Then once or twice I carried the threat into effect, and when he heard what C—— had to say about the dinner, that cured him. Everyone tells me doleful tales about the way the muchacho or boy robs them, so I thought it would be better to start from the first by giving as few opportunities as possible for trouble of this sort.

In the morning the servants’ food is also given out, each one getting an allowance of rice (for which purpose we lay in a large sackful), and this they boil and eat with some tiny fish which they buy for themselves with a few extra cents I give them. I believe it is unheard-of extravagance to give the extra money; and I never measure out the rice, but let them take it, for, after all, it is all the poor souls live on. All over the Philippines the natives of all classes live almost entirely on rice, which formerly used to be grown in all the islands, but rinderpest destroyed many of the carabaos (buffaloes), which worked the soil, and high wages and heavy taxes have wrought even greater havoc, so that now[36] the supply nearly all comes from China. You see, high wages are offered in the towns, and what with that and the unsuitable education they receive, the country-people all flock into the towns, and the country places are empty. It is on the coast, in the towns, that rice is so much eaten, for inland the staple food is camote (sweet potato); so the country-people think rice a luxury, and the town’s-people eat camote as a treat.

When I wrote last, I don’t think the staff was completed by the washerwoman, was it? A person with a huge, almost black, pan face came and stood in the picture of blue sky and green palm-branches framed in the doorway, dressed in a skirt formed of a tight fold of red cloth and a muslin bodice with huge sleeves (the native costume), holding a big black umbrella in one hand, and muttering in an undertone, while she kept one dull, rolling eye on Tuyay, who was disposed to growl and sniff.

We were at breakfast at the time, and as we ate we conversed patiently with her till we found that this person wanted to be taken on as a lavandera at 20 pesos a month, which is about twenty-six guineas a year. This offer we refused with imprecations, and we added that we would not give more than 10.

She melted away, murmuring, from the front door, and presently reappeared at the back door (both opening upon the hall, but at different ends), and murmured afresh. I must tell you, by-the-bye, that, following a very general custom here, we use one end of the hall as dining-room, though there is a room which has been used for that purpose, but it looks on the alley between this house and the next, and is not so cool as the hall.

After more conversation, we decided to engage this pan-faced individual at 12 pesos a month as a stop-gap, till we should be able to find some more intelligent woman, and there and then I gave her a bagful of soiled linen, and off she went.

Next day at lunch she suddenly reappeared, perfectly cow-like and stolid, leaning up against the door-post and murmuring so that C—— simply got wild with her, and would have thrown everything on the table at her head, I believe, if I had not been there.

As the cook is the only one of the servants who speaks above a whisper, he was sent for, and he told us that pan-face wanted soap, starch, and charcoal. All the washing is done in cold water at some well, it appears, and they only want a little charcoal to put in the iron. So C—— wrote an order, a vale they call it, upon Hoskyn’s for soap, a box-iron, starch, and charcoal, and away went the new lavandera.

But we had not seen the last of her, for the next day she came again, at breakfast this time, and murmured again, clutching the bulgy gamp and leaning against the door-post. This time the cook told us she wanted tin tubs, and C—— gave a sort of roar as he asked her when the devil she was going to begin the washing, but she only looked more hopelessly stupid, and her face became more like a gorilla’s. At last she got her vale for tubs, and off she went—but about mid-day she reappeared, on the balcony, outside the front door, with the tubs, huge tin baths, sitting beside her.

C—— managed to control himself sufficiently to ask her if there was anything the matter with the tubs, and she was understood to say no, but she only wanted to show us she had got tubs; and she melted away.

Next afternoon I was told the lavandera had arrived, so I went out to tell her the señor would soon be in and ready to listen to her, though I really had some doubt about the latter statement, but I found her undoing a huge bundle of washing—all finished and ready! And such beautiful work, C——’s white linen suits done to perfection, my frocks and blouses like new—I never saw clothes look more fresh and lovely. It was a pleasant surprise.