Title: Harper's Young People, August 1, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: February 16, 2019 [eBook #58896]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| vol. iii.—no. 144. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS. New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, August 1, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

Author of "Toby Tyler," "Tim and Tip," etc.

It was quite a task to extract the porcupine quills from Mr. Stubbs's brother, because the operation was painful, and he danced about in a way that seriously interfered with the work.

But the last one was out after a time, and the monkey was marched along between Joe and Toby, looking very repentant now that he was in his master's power again.

"I tell you what it is," said Joe, sagely, after he had walked awhile in silence as if studying some matter, "we'd better get about six big chains an' fasten Mr. Stubbs's brother to the tent; 'cause if we keep on tryin' to train him, he'll keep on gettin' loose, an' before he gets through with it, we sha'n't have any show left."

"I think that's the best thing we can do," panted Leander; "'cause if all hands of us has to start out many times like this, some of the boys will come up while we're off, an' pull the tent down."

"We can tie him in the tent, and have him for a wild man of Borneo," suggested Joe.

"I guess we won't train him," replied Toby, rather sorry to deprive his pet of the pleasure of being one of the performers, and yet fearing the trouble he would cause if they should try to make anything more than an ordinary monkey out of him.

The pursuit had led the boys farther from home than[Pg 626] they were aware of, and it was noon when, weary and hungry, they arrived at the tent, where they found the other party, who had given up the search some time before. They had travelled through the woods without hearing or seeing anything of the runaway, and had returned in the hope that the others had been more successful.

Leaving Mr. Stubbs's brother in charge of the partners, who, it was safe to say, would now take very good care to prevent his escape, Toby hurried into the house to see Abner.

The sick boy was no better, Aunt Olive said, neither did he appear to be any worse—he was sleeping then; and, after eating some of his dinner at the table, and taking the remainder in his hands, Toby went out to the tent again.

He found his partners indulging in an animated discussion as to when the performance should be given.

Reddy was in favor of having it within two or three days at furthest; Bob thought that, as Mr. Stubbs's brother was not to be one of the performers, there was no reason for delay.

All the others were of the same opinion, but Toby urged them to wait until Abner could take part in it.

To this Bob had a very reasonable objection: in two weeks more school would begin, and then, of course, the circus would be out of the question. If their first exhibition should be a success, as it undoubtedly would be, they could give a second performance when Abner should get well enough to attend it; and that would be quite as pleasing to him as for all the talent to remain idle while waiting for his recovery.

Toby felt that his partners asked him to do only that which was fair. The circus scheme had already done Abner more harm than good, and, as he did not seem to be dangerously sick, it would be unkind to the others to insist on waiting.

"I'd rather Abner was with us when we had the first show," said Toby; "but I s'pose it'll be just as well to go ahead with it, an' then give another after he can come out."

"Then we'll have it Saturday afternoon; an' while Reddy's fixin' up the tickets, Ben an' I'll get the animals up here, so's to see how they'll look, an' to let 'em get kinder used to the tent."

Reddy was a boy who did not believe in wasting any time after a matter was decided upon, and almost as soon as Toby consented to go on with the show, he went for materials with which to make posters and tickets.

His activity aroused the others, and all started out to bring in the animals, leaving Toby to guard Mr. Stubbs's brother and the tent. The canvas would take care of itself, so long as it was unmolested, but the other portion of Toby's charge was not so easily managed. After much thought, however, he settled the monkey question by tying Mr. Stubbs's brother to the end pole, with a rope long enough to allow him to climb nearly to the top, but short enough to keep him at a safe distance from the canvas.

By the time this was done, Ben arrived with the first installment of curiosities. His crowing hen he had under his arm, and Mrs. Simpson's three-legged cat and four kittens he brought in a basket.

"Joe's got a cage 'most built for the hen, an' I'll fix one for the cat this afternoon," he said, as he seated himself on the basket, and held the hen in his lap.

"You can't fix it if you've got to hold her," said Toby, as he brought from the barn a bushel basket, which was converted into a coop by turning it bottom side up, and putting the hen underneath it.

Ben was about to search the barn for the purpose of finding some materials with which to build the cat's cage, when a great noise was heard outside, and the two partners left the tent hurriedly.

"It's Bob an' his calf," said Ben, who had got out first, and then he started toward the new-comers at full speed.

It was Bob and his calf; but the animal should have been mentioned first; for it seemed very much as if he were bringing his master, instead of being brought by him. In order to carry his cage of mice and lead the calf at the same time, Bob had tied the rope that held this representative of a grizzly bear around his waist, and had taken the cage under his arm. This plan had worked well enough until just as they were entering the field that led to the tent, when Bob tripped and fell, scaring the calf so that he started at full speed for the barn, of course dragging the unfortunate Bob with him.

Sometimes on his face, sometimes on his back, screaming for help whenever his mouth was uppermost, and clinging firmly to the cage of mice, Bob was dragged almost to the door of the tent, where the frightened animal was finally secured.

"Well, I've got him here, an' I hain't lost a single mouse," said Bob, as he counted his treasures before even scraping the dirt from his face.

Ben and Toby led the calf into the tent after some difficulty, owing to the attempts of Mr. Stubbs's brother to frighten him, and then they did their best to separate the dirt from their partner.

In this good work they had but partially succeeded, when Reddy arrived with a large package of brown paper, and his cat without a tail. This startling curiosity he carried in a bag slung over his shoulder, and from the expression on his face when he came up it seemed almost certain that the cat's claws had passed through the bag and into her master's flesh.

"There," he exclaimed, with a sigh of relief, as he threw his live burden at the foot of the post to which Mr. Stubbs's brother was tied. "I've kept shiftin' that cat from one shoulder to the other ever since I started, an' I tell you she can scratch as well as if she had a tail as long as the monkey's."

It surely seemed as if the work of building the cages had been too long neglected, for here were a number of curiosities without anything in which they could be exhibited, and the audience might be dissatisfied if asked to pay to see a cat in a bag, or a hen under a bushel basket.

Toby spoke of this, and Bob assured him that it could easily be arranged as soon as all the partners should arrive.

"You see, we've got to carry Mrs. Simpson's cat an' kittens home every night, 'cause she says the rats are so thick she can spare her only daytimes, an' we don't need a cage for her till the show comes off," said Bob, as he bustled around again to find materials.

Mr. Stubbs's brother demanded his master's attention about this time, owing to his attempts to make friends with the calf. From the time that this peaceful animal, who was to be transformed into a grizzly bear, had been brought into the tent, the monkey had tried in every possible way to get at him, and the calf had shown unmistakable signs of a desire to butt the monkey. But the ropes which held them both had prevented the meeting. Now, however, Bob detected Mr. Stubbs's brother in trying to bite his rope in two, and it was considered necessary to set a guard over him.

Reddy was already busily engaged in painting the posters, despite the confusion that reigned, and as his work would keep him inside the tent, he was chosen to have general care of the animals—a task which he, without a thought of possible consequences, accepted cheerfully.

Leander and Joe came together, the first bringing his accordion, and four rabbits in a cage, and the last carrying five striped squirrels in a pasteboard box.

Leander was the only one who had been thoughtful enough to have his animals ready for exhibition, and the[Pg 627] cage in which the long-eared pets were confined bore the inscription, done in a very fanciful way with blue and red crayons: "Wolves. Keep off!"

This cage was placed in the corner near the band stand, where the musician could attend to his musical work and have a watchful eye on his pets at the same time.

Reddy had been busily engaged in painting a notice to be hung up over the calf; and as he fastened it to the barn just over the spot where the animal was to be kept, Bob read, with no small degree of pride in the thought that he was the fortunate possessor of such a prize:

Then the artist went back to his task of painting posters, while the others set to work, full of determination to build the necessary number of cages, if there was wood enough in Uncle Daniel's barn.

They found timber enough and to spare; but as it was not exactly the kind they wanted, Toby proposed that they should all go over to the house, explain the matter to Aunt Olive, and ask her to give them as many empty boxes as she could afford to part with.

As has been said before, Aunt Olive looked upon the circus scheme with favor, and when she was called upon to aid in the way of furnishing cages for wild animals, she gave the boys full permission to take all the boxes they could find in the shed. They found so many that they were able to select those best suited to the different animals, and yet have quite a stock to fall back upon in case they should make additions to their menagerie.

Every boy should know how to swim, and it should be a part of every boy's early education. But even good swimmers are exposed to the danger of drowning; and to show what to do for an apparently drowned person is the object of this article. When life is supposed to be extinct, proper exertions will often restore the circulation, and establish breathing. It is estimated that a minute and a half's submersion is sufficient to cause death by drowning, and hence the necessity of rescuing a person from the water as quickly as possible, and using restorative measures promptly, is very great.

As soon as the body is taken from the water, the feet and lower part of the body should be elevated, and the head allowed to hang down, that the water may be allowed to run out of the throat and mouth as much as possible; then the clothing should be removed from the upper part of the body, exposing the chest. The person should then be placed upon his back, with a roll of clothing or something else convenient to form a pillow, upon which the shoulders should rest. Then some one present should take hold of the arms just below the elbow, and slowly raise them above the head, so that the elbows may nearly touch on a line parallel with the body; then as slowly bring down the arms to the side of the chest, pressing the elbows firmly against the ribs. This movement must be repeated many times, alternately extending the arms, and replacing them by the side. The object is to cause expansion and contraction of the chest walls, and thus mechanically causing the entrance of air into and exit from the lungs.

It is advisable, also, to see that the tongue has not fallen back into the mouth, and in case it has done so, to seize it with the thumb and finger, and draw it forward. Dashing cold water in the face may also be tried. The feet and legs should be rubbed dry, and kept warm by wrapping in dry clothing or blankets if they can be obtained.

When the least sign of breathing is seen, the exertion should be actively continued, and pressure made upon the chest wall at short intervals to aid the expulsion of the air in the lungs, and allow fresh air to enter. If ammonia is available, it should be poured on a handkerchief, and held at a little distance from the nose at occasional intervals; and when the breathing is established, if brandy or some other stimulant, as whiskey or alcohol even, can be procured, a small quantity, say half a tea-spoonful in a tea-spoonful or two of water, should be cautiously given, and repeated in fifteen minutes.

After animation is restored, the person should be wrapped up warmly in blankets, and seclusion should be observed.

Efforts such as these are often rewarded with success, and no one recently taken from the water should ever be given up as drowned until they are faithfully tried. It is never safe for a boy to go in swimming alone, for unforeseen accidents may occur, such as cramps, or entanglement in weeds. Some other hidden danger may spring up, as unexpected force of current, or great depth of water, and then it is safer by far to have help within calling distance.

In cities, swimming-schools supply the place which nature affords to the boy in the country. The feeling of security which a knowledge of the art of swimming secures to its possessor compensates for all the danger and trouble one is exposed to in acquiring it.

[Continued from page 612, No. 143, Harper's Young People.]

They knew, but the very excitement of it kept them silent, and Quill again gave up the oars to the stranger. He made short work of that stretch of smooth, sunny water, and the Ark's original crew were proud of her. It seemed but a few minutes before she ran almost up on shore in a little cove of the thickly wooded islet.

"Magnificent! Ours by right of discovery. Boys, we must have a fire. You go for loose sticks and things, while I kindle one."

What could they do but shout their loudest, and dart away after supplies of fire-wood?

"He's got some matches," said Quill. "He's lighting a piece of paper. He's kindling some brush."

He was certainly a very remarkable man for two boy-boatmen to meet on a cruise like the one in question, for, even while the bright blaze leaped out through the first black smudge of smoke, he burst into another foreign song.

The stranger was standing by his fire, fanning it with his wide-brimmed straw hat, and his closely trimmed curly head was bare. They could guess that he was not more than twenty, and he was a very handsome young fellow, if his clothes had not been so fine.

"This is great," he muttered to himself. "First piece of genuine out-and-out fun I've had since I got here. Hullo, what's this?"

There had been an unnoticed rustle among the trees and bushes to the right of him.

"Please, sir, we—we—we're—are—are—all drownded."

The words came out all broken to pieces by childish sobs, and there stood a pretty little barefooted girl of eight or nine summers looking up at him. Her rosy face was wet with tears, and the larger share of her dress looked as if it were wet with Pawg Lake water.

"Drowned, my dear? Is that so? Were you drowned?"

"N-n-n-o—no, sir."

"Were any of the rest drowned?"

"N-n-n-o, sir, but Aunt Sally can't make the boat swim, 'cause there's come a hole in it."

"That's awful. Tell Aunt Sally to bring it to me, and I'll mend it."

"She—she can't come. She's lost one of her shoes."

"Is that so? We must go and hunt for that shoe."

"We did hunt, and she got her feet wet. It's in the mud. 'Way down."

"Boys, come on. We've got a shipwreck."

"Hear that, Quill?"

"See that girl, Mort? There's something happened. Come on."

They stopped as they went by to throw their armfuls of sticks and bark on the fire, and then they dashed after their dandy fisherman, who was already following the eager leading of the wet little girl. She was in a desperate hurry, and she led the way almost straight across the islet. This did not contain more than a couple of acres of rocks and trees, and was easy to cross; but there on the northern shore was a scene which both Mort Hopkins and Quill Sanders understood at a glance.

A large, square-nosed, rickety-looking old punt of a boat was pulled part way up on a log at the water's edge, and anybody could see that one of her worn-out bottom boards had fallen away bodily from its proper place.

"There's no sort of float in that thing," said Quill to Mort.

"No, sirree; she's done for."

"One, two, three, four, five, besides my little wet messenger," remarked their grown-up friend. And then he added: "I declare! A young lady!"

They saw him color slightly, too, as a tall, well-dressed, and quite pretty girl of seventeen or near it slowly arose from the rock on which she had been sitting. She did not come forward, and she was blushing, and Quill whispered:

"Mort, where's her other shoe?"

"Lost it, I guess. They're awfully shipwrecked. Let's rescue 'em."

"Hush! Hear that fellow talk. She's telling him all about it."

There was very little to tell. She had taken her sister and niece and some little girls who were visiting them out for a boat ride on Pawg Lake. They all lived near the head of it. The girls danced about. The boat began to leak. She rowed to the islet because it was nearest. She tried to fix the loose board, and it came all the way off. They had been there for hours. Nobody on shore knew where they were.

"How many mothers are anxious?" asked the dandy fisherman.

"Three, and quite a number of aunts and uncles and fathers."

"We must put you ashore at once, then. I really can not doctor that boat. Boys, may I land them in the Ark?"

"Why, that's what we came for," said Quill Sanders, a little vaguely.

"What they came for?" said the young lady, with one foot a trifle behind the other.

"Exactly," said the fisherman. "All the way from I don't know where. I'm only a foremast hand. They are the captains and owners. Will you walk over? No, please, I'll bring the Ark around here."

"Thank you, I wish you would."

"Come on, boys. This is better fun than catching trout."

"Well, it is," said Mort.

"Mister," remarked Quill, "if we all crowd into the Ark, we'll sink her."

"We must look out for that. You and Mort stay here, and I'll row the girls ashore, and come back after you."

"Capital idea! We'll take her right around, and rescue 'em all."

They did so; but just as they were pulling to the beach where the old punt lay, Mort came out of a sort of thoughtful fit, and said, suddenly:

"Guess it won't do, Quill. You and I'll stay and take care of the island, while he puts the girls ashore."

"I don't care. Let him."

The pretty young lady was the first to remark upon the small size of the Ark, and received for reply:

"She's withered a good deal since Noah's time. If you'll take the stern seat, I'll try and stow the rest in. The boys have volunteered to wait here for me."

"We shall crowd your boat."

"Not at all; but there will be no room for them to dance out any of the bottom boards. The passengers must keep still. Is it of any use to fish around for your shoe?"

"No, sir. It's in the mud. I stepped out in a hurry. It came off."

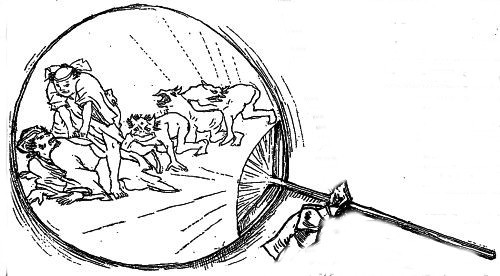

THE SHIPWRECKED PARTY RESCUED BY THE "ARK."

THE SHIPWRECKED PARTY RESCUED BY THE "ARK."

"I see. Yes. Glad you took better care of the other. I'm sorry for that shoe. Now, children—young ladies, I mean—if you don't want another shipwreck, and all to be drowned again, you'll keep still till we get ashore. If any of you wish to speak to me, call me Ham. All the rest of the Ark's original crew have gone somewhere."

Away he pulled, and Quill Sanders and Mort Hopkins sat on the shore and watched him, until the former exclaimed:

"Mort, we might as well save the time. Let's go and eat something."

"It's a big thing, Quill. We'll have an awful time getting home."

The fire was blazing finely, and the two young discoverers found their appetites all they could ask for. They even discussed the propriety of cooking a trout or so, but decided that it would be better to catch some fish for themselves. There were plenty of promising places along shore, but the results astonished them.

"Mort," said Quill, at the end of ten minutes, "did you ever know fish to bite this way?"

"Never. Got another. Here he comes—perch. What's yours?"

"Hurrah! it's a pickerel."

Not a very heavy one, but in he came, and the excitement of that next hour of Pawg Lake fishing made it seem a wonderfully short one.

"Quill," said Mort, "there he comes."

"I knew he'd bring the boat back."

"Of course he would."

There he was in a few minutes more, smiling as ever, and remarking, "Come along, boys; you are both wanted at Ararat."

"Where?" said Quill.

"Where the Ark landed her passengers. Come along. I'm a dove, with no end of olive branch in my mouth."

They gathered their fish, and hurried into the boat, while he explained that the long absence of that shipwrecked young lady and her younger companions had stirred up a tremendous excitement along the shores of Pawg Lake, and that their rescue was no small affair.

"I have been kissed by any number of mothers and aunts, and have had to shake hands with quite a large body of men. You boys must come and take your share."

"Don't you do it, Quill," said Mort. "Let's go right home."

"Yes, mister. I say, give me the oars, and I'll start for the creek."

"Couldn't think of it, my young friends. I gave my word I would bring you ashore."

There was no help for it, and in what seemed to them a terribly short time Quill and Mort were the centre of a crowd of people in a big farm-house. They were compelled to eat again until they could not eat any more; but Quill remarked, in a whisper:

"Glad none of 'em hugged me, Mort. That woman looked like it."

The whole subject of the voyage of discovery came out, and when dinner was over—it was supper too, and almost anything else—and the boys declared they must set out for home, a big man, who owned the farm-house, and was father of the young lady and her sister, and uncle of the wet little girl, got up and said:

"Home? Of course. Come on, boys. I've fixed all that."

So he had; for there was the largest kind of a lumber wagon, with the Ark already in it, and a man holding the horses, ready to start.

"That's our boat," said Quill.

"So it is," said the dandy fisherman. "I'm going with you. It's the first voyage of discovery that ever went home overland, ship and all."

"Quill," whispered Mort just then, "either she's found her shoe, or she had another pair."

The young lady was blushing remarkably all the while they were getting into the wagon, and the fisherman said "good-by" for the crew of the Ark.

When they reached Corry Centre, the driver pulled up in front of the village tavern.

"Here's your trout," said Quill, as their strange friend sprang lightly out.

"Keep 'em—keep 'em. Best day's fun I ever had. I'm coming down to hunt you boys up to-morrow. Good-by. Take care of the Ark."

"Good-by!" they both shouted as they were hurried away. But they had to turn at once and answer the driver's question about where he was to go next.

They were glad enough to get home safe and sound; but even when the Ark was once more floating in Taponican Creek, near the bridge, Quill and Mort had to look hard at her and at each other, and then at the trout and their own strings of Pawg Lake fish, before they could quite make up their minds that they had not been dreaming a good deal that splendid Saturday.

"ME'S SICK."

"ME'S SICK."

How many of the young people have ever heard the story of that simple-hearted, brave soldier of Napoleon's empire, so long known as the "First Grenadier of France"?

Born in the provinces, La Tour d'Auvergne received a thorough military schooling, and entered the army when quite young.

Throughout a career of nearly twoscore years, he served ever with fidelity and distinction, yet always refused the promotion which was constantly offered him, preferring, as he said, the familiar duties of the grenadier to even the glories of a marshal.

His wishes were, in a measure, respected. He held always the rank of Captain, though eventually his command equalled in numbers almost ten regiments.

After his death, which occurred in action, there was instituted in the regiment with which he had been connected, and by the express directions of Bonaparte himself, a most touching tribute to his faithful service. His name had never been stricken from the roll, and at its call, upon the daily parade, the oldest veteran present would step forward, and saluting, answer, "Died on the field of battle."

The details of his history show that his life was well worthy the honors thus paid to his memory, and many incidents are told of him which illustrate his unselfish devotion to the profession he loved so well.

Upon one occasion, being on furlough, he paid a visit to an old friend in a section of the country as yet remote from actual war.

While there, he learned that a detachment of several hundred Austrians, having in view the prevention of a certain important movement of the French, was on the march to a spot where this purpose could be easily accomplished. To reach this they must pass through a narrow defile, guarded by an old stone tower, which was garrisoned by perhaps half a company of French soldiers.

To warn these of their danger in time to prepare for defense was the aim of our hero, and putting up a slender store of provisions, he started off.

To his dismay he found on arriving at the tower that his comrades had been only too well warned already, and had fled, even leaving their muskets and a goodly supply of ammunition behind them.

He knew that if the Austrians could be held in check long enough to allow the completion of the French manœuvre, by that time tower and pass would be of little use to either side. He determined, single-handed, to make the fight against a regiment.

There were many conditions which favored the successful carrying out of this brave resolve. The tower could be approached only through a narrow ravine, in which but two or three men could walk abreast, and as he was abundantly supplied with arms, the grenadier did not despair of at least partial success. He barricaded the doors, carefully loaded all the muskets, which he placed in convenient positions for instant handling, made a good meal off the food he had brought with him, and then sat down to await the enemy.

He was unmolested until near dawn, when unusual sounds without announced the Austrians' approach.

They halted at the mouth of the defile, and almost immediately an officer, bearing a flag of truce, appeared with a demand for surrender.

D'Auvergne answered the call, replying that "the garrison would defend itself to the last," and the messenger, little suspecting that the entire garrison was comprised in the person of the single soldier who stood before him, retired.

A small cannon was shortly after brought to bear upon the tower; but our grenadier made such good use of his weapons that half a dozen of the Austrians lay wounded upon the ground before they could fire a single shot. Finding this mode of attack ineffectual, an assault was ordered; but as the head of the column came within range of the tower, so deadly a fire was poured upon it that it was ordered back amid great confusion.

Two further attacks were made, with like results, and when night fell, the solitary grenadier was still in possession of his stronghold, and unhurt, while nearly fifty of the enemy were either killed or wounded.

Sunset brought a second summons to yield, with an intimation that, if refused, a regular siege would be entered upon, and kept up until hunger should compel submission.

Deeming the twenty-four hours which had elapsed sufficient time for the accomplishment of the French move, D'Auvergne returned answer that the garrison would surrender the following morning if allowed safe-conduct to the French lines, and permission to retain its arms. These terms, after a little parley, were acceded to.

At daybreak on the morrow, accordingly, the enemy were drawn up to receive the vanquished garrison.

The door of the tower opened, and a soiled and scarred veteran, literally staggering under the weight of as many muskets as he could carry, walked slowly between the ranks, and depositing his load at the feet of the Colonel, saluted. To the surprise of the latter, no one followed.

"But where is the garrison, grenadier?" asked he.

"Sir, I am the garrison," replied the soldier.

For a moment astonishment held the Austrian dumb; then ordering his command to present arms, and raising his cap, "Grenadier, I salute you," said he: "so brave a deed is without parallel."

The desired escort was provided, and with it was sent a dispatch relating the whole affair.

When the circumstance became known to the Emperor, the offer of promotion was renewed, and again declined, and D'Auvergne remained to the day of his death simply the "First Grenadier of France."

"Where's your Tom Matthews, Ned?" said Phil Hartshorn. "Here it is half past nine by my watch, and he was to be on hand at nine sharp."

As he spoke a little freckled boy came panting up to them, saying: "Tom says as how he can't go up 'Corua to-day nohow. He's sick with suthin I've forgot the name of. He's awful sorry, and said if yer'd only hold on till to-morrer, he'd go; and he thinks it'll be a sight better day, too, for he's 'most sure there'll be a thunderin' big shower to-night."

"Nonsense!" said Dick; "there isn't one chance in a million of a shower; sky is as clear as a bell."

"But," says Arthur, "there are no two ways about it. Mother said we were not to go if Tom Matthews were not here."

"You don't suppose mother really meant that?" said his brother Phil.

"Now, Cousin Arthur," said Dick, "you just put that conscience of yours to sleep as fast as you can.

"'Hush-a-by, conscience, on the tree-top,

Dear Mrs. Hartshorn would never say stop.'"

"But, Arthur," interrupted Ned, "she wouldn't care if she knew how many times I've been up Chocorua. Why, I've been to the top thousands of times. I know the way just as well as Tom."

Though Arthur's duty was as clear to him as at first, he decided to take Dick's advice, and silence his conscience.

Half an hour later they were climbing up the steep side of the mountain, laden with the tent, provisions, and other necessaries for their night's encampment.

Chocorua is one of the most difficult of the New Hampshire hills to ascend, not so much on account of its height as its rocky and steep outline. To Ned Brown, however, accustomed to scrambling over the hills of his native place, it was simply a very tiresome walk; but to the three city boys, who for the first time were spending part of their vacation among the mountains, it was a novel and rough experience. Nevertheless, their spirits did not flag, and about two o'clock they had reached the rocky summit, as tired and hungry a set of boys as you ever saw.

They soon found a comfortable spot, where they threw themselves down at full length, and at Dick Harris's suggestion pitched into the eatables which Mrs. Brown had put up for them.

After a while Ned exclaimed: "Look here, boys, you can't spend the whole afternoon eating. Just clap two or three doughnuts into your pockets, and come along. We've got to get ready for the night."

"Wait a week," said Dick, "until I take one more drink of coffee; then we'll go and explore the country."

"Can't you remember, Ned, where you generally pitch your tent?" said Arthur.

"Tom Matthews pretty much always bosses that business," answered Ned.

"I guess we can find as good a place as Tom Matthews," said Phil. "There it is now, right ahead—don't you see?—down in that hollow under that tall tree."

"All right; let's make for it, then," said Ned. "We haven't any time to lose."

Some hours later Ned called out: "Now that everything is ready for the night, you shall have a high old supper. You needn't any of you put your fingers in the pie either. I'm goin' to make a regular lumberman's pudding. Dick, just hand me that tin plate, will you?"

"No, sir, I can't even do that; it might be putting the very finger into the pie, or rather pudding, which would spoil the whole. I am not going to run any such risk."

"That's too thin—a capital excuse for laziness—but I can do it myself fortunately. First, you see, I cut a slit in this stick, and slip the edge of the plate into it, and that makes a tip-top spider. Next I put in some pieces of fat pork, and am goin' to fry them over this blazin' fire. When the pork is done, I'll take that out, and crumb this pilot-bread into the fat."

"What a mess!" the boys all exclaimed. "You don't expect us to eat that stuff, do you?"

"You needn't trouble yourselves; I can eat every bit of it. Wait till I sprinkle white sugar all over it thick and heavy, and then it is done. Come, do you want any, or shall I eat it all myself?"

"As Caterer Brown has made it, we won't hurt his feelings by refusing," said Arthur. "Hand it along."

"Well, Ned," said Phil, "this is capital. Do they teach cooking in your school, or has Miss Parloa been in this part of the country?"

"Oh, last winter when I camped out up North with father and the other lumbermen, they used to make this 'most every night, and I tell you it tasted mighty good."

After supper the boys whiled away the time telling stories. The most interesting one was the legend of Chocorua, the Indian chief after whom the mountain was named.

Chocorua had a son, a boy of ten or twelve years, who often visited the house of a white man who lived in Albany, at the foot of the mountain. One day while there he accidentally ate some food which had been prepared for a fox, and soon after died. This brought out the Indian spirit of revenge in Chocorua, so that he watched his opportunity, and when the father was away, killed the wife and children. Cornelius Campbell, the father, though a white man, was not a Christian, and the same revengeful spirit took possession of him. Not long after, Chocorua, while standing on the edge of a precipice, was shot by Campbell. He lived only a few moments, uttering fearful curses against the white men. He was never buried, but his bones were left to whiten on the rocks.

All Ned's talk tended to make the boys ready to start at every sound, and Arthur inwardly began to wish he had not disregarded the warning voice he had heard in the morning. Even the other boys felt a little dismal; but they all forced out loud exclamations over the pleasure of the day, and the moment after they had dropped on their bed of pine boughs were all sound asleep.

The clouds which, unnoticed by the boys, had been forming behind the hills, gathered heavily in a threatening mass over the mountain-peak, the air trembled with peal after peal of rolling thunder, the sky was brilliant with lightning flashes which sent gleams of intense and livid light over the white cliffs. Still the boys slept on. The furious storm-clouds gradually dropped lower and lower, until at last they burst in one torrent of hail and rain. Every hollow was fast filling up, until the one in which our boys were encamped became as it were the bed of a pool, and the white canvas of their tent seemed like the tip of a sail flapping in the wind.

One of those fearful claps of thunder which seem to shake the whole earth, and which are heard only among the mountains, at last roused the boys. In terrible alarm, they waded from their tattered tent, just in time to see the tall tree near whose roots they had been sleeping hewn into fragments by the glistening blade of the axe which the angry storm was wielding. For a moment they gazed on each other with mute horror, then, as with one voice, exclaimed, "Where's Ned?"

They wildly called "Ned! Ned! Ned Brown!" but there was no answer. They groped back for him in the darkness, lighted only by the uncertain flashes, which were growing less and less frequent; but the tent had been swept away, and their fire wholly extinguished, so they had nothing to guide them to the exact spot of their former encampment. For hours they searched in vain. Drenched and chilled, weary and bruised, at length, as day dawned, they found themselves in a dense forest, with no path and no guide.

"What shall we do?" said Arthur. "Why did we come? I will never do what I know to be wrong again."

"'No use to cry for spilled milk,'" said Dick, trying to speak cheerfully, while his face contradicted his words.

"Let us get out of these woods and down this mountain if we possibly can," said Arthur. "Then, if we don't find Ned, we can send some one up for him who knows something about the way."

"All right," said Phil. "It don't look as if we should have anything to eat till we do get down, and I'm 'most starved. Hark! What's that noise? I do believe that's a bear's growl. He is coming nearer, surely."

"Pshaw! nonsense! it isn't a bear; it's only the rustling of the leaves," said Dick.

But every little while some noise would cause them to fear that some wild animal was on their track.

Several times they were stopped by a precipice so steep that no human foot could descend it, and were obliged to retrace their course and seek another less difficult way.

Just at dusk they reached a farm-house, where, as it was on the opposite side of the mountain from their boarding place, they were obliged to spend the night.

Oh, what a night it was! The heavy supper after the long fast made them ill, and every limb was aching with pain and fatigue. Then the terrible anxiety about Ned! What might he not be suffering alone on the mountain, and what report could they give to his mother when they made their way back to the boarding-house? Surely three boys were never more severely punished for disobedience. Never again would Dick sing,

"Hush-a-by, conscience, on the tree-top."

When morning came three miserable-looking objects[Pg 632] dragged themselves up to the gate of the old boarding-house. But who was that walking up and down the piazza at such a troubled pace?

Nobody less than Ned, who was fretting himself half crazy waiting for the party who had arranged to go in search of three lost boys. Ned had been more fortunate than they, for after the wash-out, which had separated him from his companions, he had happily strayed into the very path which led home.

Presently Mrs. Hartshorn came out, but after one good look at the party she apparently concluded that they needed no word of reproof from her. Conscience had evidently preached every effective sermon, for which the experience of the past thirty-six hours had supplied a powerful text.

You'd think such a small boy would not know

How to get back if he should go

Without his mother so far away

Beyond the garden fence to play.

But he lays a trail of daisies white,

That gleam in the grass like stars at night;

So running home he can never stray,

With the scattered daisies to show the way.

"Why, Millie, where did you get that bird-skin which you wear in your hat?"

"I am sure I do not know, papa. But it is very seldom you take notice of my hats, and I am very glad that for once I am wearing one which interests you. Mamma bought the bird somewhere down town; I did not ask her where. I think he is just lovely; don't you?" and off came Millie's hat for the Professor's inspection. "Only see his breast, so bright that it almost looks to be on fire, and just above it his throat as white as a patch of snow! Isn't he perfectly splendid?"

Her father had taken the hat in his hand, and was examining the bird with an expression of face that showed he was thinking of something more than what was before him. He stood so long without speaking that Millie broke out in her usual lively manner:

"Why, papa, I never saw you look at a girl's hat so closely before—mine or any one's else. I have had handsomer hats than that, and you did not say a word about them. The bird is very beautiful, I know, but what do you see so wonderful in him?"

"I was wondering how he could come here, my child. You do not know where your mother bought the skin, but do you know where the bird lives?"

"No, sir, not at all. I have no doubt you do, but I never thought of it. Did you ever see them in their native country?"

"Yes, Millie, I have seen them often. The species is African; I saw them very often in South Africa—once, I recollect, at Zanzibar, and on the West Coast I have seen them in Senegambia and at the mouth of the Gaboon. Shall I tell you where I first saw the bird?—for I can never forget it, and the sight of this skin brought back that day to me so forcibly, that for a moment I forgot where I was."

"Oh! do, papa, do. You know how I rejoice in the stories. What a favorite hat this will be!"

"Let us go into the library, then, where I can show you an engraving that I have. Please hand me the russet-leather portfolio from that lower drawer. See, I have opened at once to the very one I wished to find. It will give you an excellent idea of the two bright little kingfishers that I saw that day on the west bank of the Nile."

"The Nile, papa! I wonder if mine came from the Nile? Only think of my Nile-bird hat!"

"That I can not tell, Millie. But before I go on with my story it is well that you should know something about the family of birds to which this one belongs, for he has many relatives, and they are scattered in almost all countries, and one at least of them has been famous among poets for two thousand years. Did you ever hear or see the expression used of halcyon days, meaning days of great prosperity and happiness?"

"Yes, sir, I recollect it was in one of the pieces of poetry we read only last week in school, and I wondered at the time what it meant, and I intended to ask you."

AFRICAN KINGFISHERS.

AFRICAN KINGFISHERS.

"I will tell you. This little bird of the drawing and of your hat is a kingfisher, and the kingfishers are found, as I explained, in almost all parts of the world. We have one species, not at all uncommon, throughout the United States, which is known in the books as the belted kingfisher. Our little African here, you see, is not larger than a sparrow, but his belted brother is almost as large as a common pigeon, and well do I recollect what a time a lot of us had, when I was a boy about twelve years old, in trying to get at the nest of a pair of them. Kingfishers the world over build their nests in deep burrows which they make in river-banks and similar places. Eight of us gathered one Saturday, with[Pg 633] Tom Perkins—a stout boy of fifteen—for a sort of Captain, and Charlie Mason for Lieutenant. We worked all that day, and then nearly until night, of the following Saturday, before we found the end of the burrow. Tom said he really thought we should dig across Deacon Moseley's farm and out into Widow Whitman's pasture lot. It was sixteen feet and a half that the birds had burrowed into a very hard bank of clay.

"This was our American species, whose name is Ceryle alcyon; but all about the shores of the Mediterranean a similar smaller species is found which by the old Latins was called Alcyon or Halcyon, though in ornithological works, now it is named Alcedo hispida. Most absurd stories have always been told concerning it. It was said to have the power of preventing storms, of keeping the sea perfectly quiet, so that while the female was sitting on her eggs the weather was always calm and peaceful, and you see readily how the word halcyon came therefore to have in poetry the meaning to which I have referred. Of course this was all foolishness, but it was only one of[Pg 634] many tales which have been told about that very bird, and some of which I have no doubt are believed by ignorant people to this day."

"Is he a handsome bird, papa, like this one in my hat?"

"Oh no; on the contrary, he is of quite plain plumage. You must not fancy that our species or the European possess any such brightness of color. Now look at the picture again. You see both the male and the female. Notice, by-the-way, that they are sitting near the mouth of their burrow. Look at those long crest feathers. They are shining blue, almost like the sky, with light ashy green spots, while the jet-black ones fairly sparkle on their blue background. And then his blazing red lower surface, with his white throat and that enormous bill of bright vermilion, makes such an assemblage of brilliant color as you seldom see."

"Let me get the map, papa, and then please show me just where you found my little bird."

"That is right, Millie; you will be more interested the more definitely you fix the knowledge. How well I remember that day. It seems as though it had been but yesterday. Among all the rivers of the world, there is not one which can be compared with the Nile. It does not seem like any other water. There's a sort of magic about it. All the time that I spent there I felt myself living in dreamland rather than in anything that belonged to this life and this world. It is not the river itself, for I have seen a number of much finer and grander streams of water in other countries. The Danube or the Ganges can either of them surpass it, while here in America I could select half a dozen which are more than its rivals. But any one of them I always felt that I could understand. They were beautiful, they were grand, with charming banks and forests and fields and cities, but there was nothing strange about them. They seemed like other parts of the world. But the Nile is not like them; it never looked to me like a reality. Everything about it was so mixed with mystery that if I had waked any morning and found that there was no Nile to be seen where I saw it the night before, I should have thought it was all right.

"All around me were monuments and temples and houses so old that those who built them had died and been forgotten hundreds and perhaps thousands of years before the earliest history of which we have any knowledge commenced. Who were those people? I could tell how they looked, for there were their figures and faces carved on the stones, but—who were they? Where did they come from? Negroes, Asiatics, Egyptians, such as were about me every day; there they were carved, and sometimes painted, on the ruins, and I used to wander around and wonder, and dream, and wonder, and it was in the midst of just such wondering as that that a little kingfisher flashed upon me, and it is not strange that I remember him. Do you see the First Cataract, Millie, on the river?"

"Yes, here it is. P-h-i-l-a-e, Philæ; is that it?"

"That is the name of an island there with some extremely beautiful ruins upon it. Few travellers ascend the river further; they stop there and return; but I did not; I continued on to the south a long distance. One day, just before I reached the Second Cataract, I had stopped on the west bank of the river to rest my men for an hour or two. It was a burning hot afternoon, perfectly calm, with the sun blazing down on the white sand of the desert and on the glass-like water of the river, until it was enough to almost fry one's brain. Three or four palm-trees grew at this point, and it was their shade which had induced me to stop; but I found to my great delight that what was probably a temple had formerly stood there, and some of the fragments still remained. One of these fragments represented a human figure seated. The head was gone, and one arm; the other arm was perfect, with the hand lying on the knee, and I began to make a drawing of the whole.

"Just as in my drawing I reached the hand, and was sketching its shape on the paper, a little blue and red bird passed me, with a cry somewhat like the one you may hear any morning from our American species, and swinging up he perched himself on the very hand which I was drawing at the moment. It was a lovely little kingfisher. He sat there but a moment, and then darted to a hole in the river-bank, which he entered, and which I knew must contain his nest. It was such a burrow as our American species makes, and forthwith came back to my mind the time when I was a boy, and when Tom and Charlie and the rest of us worked so hard at digging toward Deacon Moseley's lot.

"I watched till the little fellow came out. Then he flew away, and I soon lost sight of him. His name is Corythornis cyanostigma, and the sight of another here in your hat carried me away so completely that for the moment I almost fancied I was on the Nile again, the association was so powerful."

"Well, papa, I am very glad of it. I will wear him only a day or two, and then I will take him out and give him to you, and get mamma to put something else in his place. You may be sure I shall never forget my Nile-bird hat. But did you not say that there are kingfishers found in other countries? I suppose they must be like this, even if they are not so beautiful."

"Yes, there are; and I must tell you of one most remarkable species, Millie—remarkable for his voice, though not for any beauty of color. We will call him Dacelo gigas—gigas meaning very large, for he is a great clumsy bird. He lives in Australia. The first night I ever spent there 'in the bush'—which means out in the wild country—I was waked just before daylight by a most outrageous racket in the thicket close to me. I started up in some fright, and roused a man near me. 'Oh, go to sleep; that is nothing but a jackass.' But as we were where a donkey would not be likely to come, I could not tell what to make of it, and I did not go to sleep, and by-and-by I heard him again and again, but my comrades paid no attention to the sound, and so I said nothing further.

"After breakfast I took my gun, and started out to look for birds. Among others I shot a great coarse-looking kingfisher, larger than a crow; and when I returned to camp, the man whom I had roused in the morning remarked, as I laid out my game: 'There, you have got him. That is the very fellow that you heard this morning. We always call him the laughing jackass.' And often after that I heard their harsh cry, like laughing and braying together."

I didn't like that little French village. Thad and I were at our wits' end to find some way to amuse ourselves. There wasn't any river to row on, nor any hills to climb, and not a single person we could talk to out of the family.

Then you sort of felt as if you were a lunatic in an asylum; for instead of fences, every house had a high stone wall around it; that is, every house except the one where we boarded, which was surrounded by an iron railing, with the bars just far enough apart to make it look like a cage in a menagerie. At least this is what Thad said it reminded him of, and sometimes I used to see him tearing up and down behind it, playing he was an African lion. I didn't tell him it was silly, because once in a while I turned panther myself. It was an awfully poky town.

About three times every day Thad and I used to beg father to go somewhere else, but he always said, "Have patience, boys." I wonder if anybody ever counted the[Pg 635] number of times fathers and mothers say, "Have patience"? If it's as tiresome to say as it is to listen to, I feel sorry for them.

Well, one morning when they both were out driving, and the landlady had gone to market, and there was nobody at home but the French cook and us boys, I was that sorry for Thad, not to mention how awfully dull I was myself, that I felt I must do something. So I called Thad down-stairs, and told him I'd invent a new play for him.

"We can use the fence just the same for a cage," I explained, "and you're to be a tiger a keeper's trying to tame. I'll be the keeper, and at first you must snap at me through the bars; but I'll look you straight in the eye all the time (that's the way keepers do), and then all of a sudden I'll open the door, rush into the cage, and you'll be tamed."

Thad said that would be fun, and then I got father's cane, and we both went out into the front yard. Hardly anybody ever walked on that street, so I wasn't afraid of being interrupted.

I went outside, shutting the gate behind me, and Thad having curled himself up close to the railing, pretending to be asleep, I began operations by poking him with my stick.

At first he only gave a low growl (I wasn't sure whether tigers growled or howled, but I told him a growl would do); but when the cane slipped and tickled him under the arm, he jumped up, and neither growled nor howled, but screamed, until I was obliged to remind him that he wasn't a wild-cat.

"But tickling's no fair," he cried, still squirming a little.

"All right," I answered, beginning my taming operations, and keeping my eye on him in a way that I think really began to frighten him.

Then he started racing up and down inside the fence, I after him on the outside, until we were both quite out of breath, and then he stood still, and snapped at me between the bars.

We were right by the gate, and while he had his head out, pretending to gnaw my stick, I suddenly let go of it, and slipping through the gateway, rushed up behind him before you could say "Jack Robinson."

"Now you must turn around, and we'll look at each other for a minute, and then you'll give in," I cried, making believe crowd into a corner of the cage.

"But I can't turn round," exclaimed Thad. "I can't get my head out."

"Why, how did you get it in, then?" I replied, stepping up to examine into matters. "Twist it the other way."

Thad thereupon obediently gave a fresh tug, but all in vain; his head remained stuck between the bars like a cow's in the patent stalls.

I was scared then, and never thinking about tigers, took him by the neck, and tried my best to get him free; but I couldn't. Then he set up a very unbeastlike yell, which brought the French cook out of the house, with a bunch of garlic in her hand.

When she saw what had happened, she screamed louder than Thad. The noise they both made together was something frightful, while I ran first one side of the fence, then the other, wondering dismally if we'd have to live in that town always because Thad couldn't get his head out.

If we'd had any neighbors except a deaf old man, a woman who never left her bed, and two young men who went to work three miles away, I suppose we'd soon have had a crowd around us, but as it was, nobody appeared but a little girl with a hunk of bread, the sight of which caused Thad to stop hollowing, and declare that we must bring him something to eat.

When I had opened and shut my mouth several times, pointing my finger down it and then at Thad, the cook comprehended what was wanted, and rushing outside of the fence, put that bunch of garlic right under my brother's nose.

"Pah!" he exclaimed, and wrenched his head back so suddenly that I half expected to see both his ears drop off.

"Oh dear," I groaned, "if he can't free himself with such a jerk as that we can never get him out at all."

Then recollecting that Thad hated the smell of garlic as much as I did, and seeing that the cook was still trying to feed him with it, I motioned sternly toward the house, and ordered her to "departez," which wasn't hard to say, as you just take an English word and put a little French end to it.

She understood me at once, and seemed to feel quite insulted, for she walked straight back to the kitchen, slamming the gate after her.

The next minute somebody slapped me on the shoulder, and turning, I jumped as if I had seen a ghost, for it was Thad, and I was at least five feet from the fence. You see, when the gate was open the space between those two particular bars was a little smaller than when it was shut. Thad and I might have remained in that pickle for any length of time, he screaming at the top of his voice, and I dancing around him in agony. Who knows how long it would have taken us to find out that all we had to do was to shut the gate, if that woman hadn't got mad and given it such an awful slam?

Small fingers always want to be kept busy. No matter how warm the weather is, they can not lie comfortably quiet, but must be doing something. Why not try a little rustic-work, setting up a good-natured rivalry with florists and landscape gardeners? It will require the boys and girls both—the boys to do the heavy work, and the girls to supply the grace and minor ornamentation.

Rustic-work is a term that by general consent is now applied to all structures of wood the forms and surfaces of which are left in their natural shape, or covered with material such as bark, cones, fungi, etc.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 is an excellent example of nature's rustic-work. How kindly the golden-rod, blackberry, Virginia creeper, and ferns have ranged themselves about the old stump to increase the picturesque beauty of its decay!

Now imagine this stump transplanted to a lawn or garden with its wealth of wild plants and shrubs, while in strong contrast to these are planted in the hollow of the stump a variegated mass of drooping vines, and the most beautifully marked and colored of the so-called "foliage" plants. Truly no imported and expensive jardinet (small garden) of highest artistic workmanship was ever made that could compare with this of nature's wild and cultivated beauty.

There are thousands and thousands of just such stumps that with a little care and trouble might easily be converted into beautiful lawn and garden adornments.

When digging out such a stump, the ground must be well excavated from about and under the main roots, which are sawn (not chopped) off about one foot below the surface of the ground. In replanting the stump, try to imitate all the natural features of the ground surrounding it, even to rocks and toad-stools. The latter are not poisonous unless eaten, and are very picturesque.

The best soil for filling in the spaces about the roots and the bottom of the stump is the black and rich "vegetable mould" found in all old woods. Next to this comes peat,[Pg 636] which can be obtained from dried-up ponds and ditches, only care must be taken to crush it fine, and mix with it about one-third of ordinary garden soil; otherwise it will be apt to cake after rains.

When setting up a stump jardinet it is the easiest thing in the world to establish at the same time a small menagerie. Tree-toads, common garden-toads, all varieties of land-snails, field-mice, chipmunks, can be induced to make their homes in and about your stump if they are well treated and cared for.

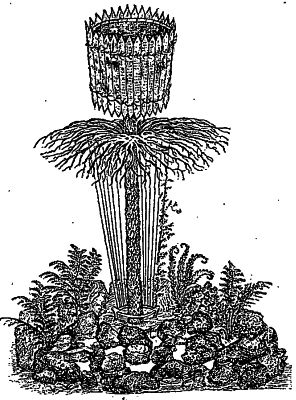

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

To set up a successful stump menagerie, little nooks must be formed under the roots by means of stones so placed together as to leave open spaces of various sizes. These must connect with one another, as shown in Fig. 2. When covered with earth, these chambers are entered by means of runs which connect with the under-ground chambers. All creatures that set up a home in these chambers will have a good time if you do not dig them out every other day, "just to see, you know, how they are getting along."

But now let us imagine that no such rotted-out and picturesque stump is to be obtained. There is still quite an easy way to make a jardinet.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

First obtain from a grocer a half butter-keg, which will cost about twenty cents. Wash it out thoroughly with hot water to cleanse it of all salt, that might prove injurious to growing plants. In the bottom bore a number of small holes, and place a layer of broken flower-pots or pieces of charcoal two inches in depth. The holes are for the purpose of draining off all surplus water. The layer of charcoal is to prevent the soil at the bottom of the tub from being carried away through the draining holes. If these precautions are not taken, the earth in the tub will "sour," and the roots of the plants will rot. Next obtain a log of wood of rough exterior, and also some rough bark. The tub must be fastened to the top of the log, as shown in Fig. 3, and the latter firmly planted in the desired spot. The bark must be nailed to the tub so as to join and match the bark on the stump.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

On dead and decaying white-birch-trees many kinds of fungi are to be obtained, and at the bases of very old trees many varieties of lichens. These, when fastened to the jardinet as shown in Fig. 4, produce a very natural and picturesque effect. About the base of the jardinet rude-shaped stones are piled up. The spaces of earth between the rocks are dug out to the depth of from one-half to three-quarters of a foot. These are technically known as "pockets," and are for the reception of vegetable mould. The rookery is now in condition for planting with cultivated and wild ferns, and also low-growing varieties of plants. The tub is also filled with mould, and planted with "foliage" plants and vines.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5 is a jardinet, vinery, and fernery combined. The upright post is of red cedar or locust, with the bark on. A square piece of board two inches in thickness is nailed on top of the post, and on this is placed a half butter-tub, on which pointed slats half an inch thick and two inches wide are nailed. These slats are painted green, and a light and graceful trimming of rustic vinery is tacked on near the top and bottom of the slat-work. Instead of slats, straight rustic branches split in half and pointed at both ends can be used.

The branch-work consists of a circle of branches of drooping habit, the ends or stocks of which are both nailed and bound with wire or stout twine, so as to support the weight of vines when they reach it from the tub above and the trellis below. The twine-work for the vines consists of gray or green twine. There is a twine sold by florists by the name of "invisible twine," which is of a light green color, and is used for training vines; this is far superior to the white cotton cord generally used, which always looks cheap and inartistic, and in course of time frays out and breaks. But this cheap cord can be made very durable and pleasing in color by running it through hot yellow bees-wax in which has been mixed any of the cheap chrome greens.

A small wooden hoop is securely fastened to the bottom of the post close to the ground by means of four wooden hooks; to this hoop the lower ends of the twine are securely fastened; the upper ends are tied to the branch-work, which helps to retain them in a drooping position. To obtain the best results and light and graceful effects, always plant Madeira or cypress vines; avoid the fancy gourds and other heavy climbers, as they are apt to break down the twine-work during heavy storms. At the base of the structure a heavy rockery is massed, containing numerous pockets. In these, ferns and the English ivy and the so-called German ivy are planted.

All rustic-work should present the appearance of solidity and durability, and must be strongly put together. Never use in any way marine forms or material in conjunction with rustic-work or rockery. They are entirely out of keeping and harmony with nature, and indicate a great want of taste. Nothing can exceed the ugliness of a bordering of clam or oyster shells, or Florida conch shells; they are worse than calcimined or white-washed rocks.

A bright little Jap is Tommi Taroo,

And he swings on a piece of round bamboo;

For round bamboo is the very best thing

That a boy can use as a seat for a swing.

He lives in the town of Hiogo—

A very nice place to live, you know,

Because it's such fun to go to Kobé,

The city of strangers, just over the way:

A city of Yankees and English too—

Comical fellows to Tommi Taroo—

French and Dutch and Portuguese,

And many another from over the seas.

Fish-day, fish-day in Hizen;

Fish for the women, but not for the men;

Fish for the girls, but not for the boys.

To-day only women know fishermen's joys.

And all on account of Queen Jungu,

Who once caught a fish as fishermen do;

The fish said, "Go and conquer Corea,"

And this she did within a year.

And that is the reason the girls to-day

Are all out fishing, instead of at play;

And I think the fish they show to you

Is as fine as that of Queen Jungu.

Lu-wen lived in Hakodadi;

Lu-wen was a little laddie.

Lu-wen's head was nicely shaved.

He was very well behaved.

Suzume was Lu-wen's mother;

Nakamura was his brother.

Very fine was Nakamura,

And his dress was silk of Surah.

His umbrella and his fan

Were the largest in Japan.

Once he gave them to Lu-wen,

But bade him bring them back again.

This Lu-wen was glad to do

When he'd gone a block or two;

For people left their tea and soy

To stare at him, and call out, "Halloo, big umbrella! where are you going with that little boy?"

Three little Satsumas and old Satsuma,

Or four Satsumas in all,

Laid aside their tasks, and put on their masks

For a grand Matsuri ball.

They howled and growled, and acted like

Wild animals born and bred.

To make an impression they formed a procession,

With old Satsuma ahead.

Just then the clown, of all the town

The funniest man to be found,

Jumped on to the back of the first of the pack,

And merrily rode him around.

Now, when he begun, they thought it was fun,

And acted as though they'd gone mad,

Until old Satsuma, in very bad humor,

Said, "Enough of this thing we have had."

Eight little girls of Japan,

All running as fast as they can

For fear she'll be late,

Each one of the eight

Is running as fast as she can.

Did you ever see children so fat?

In Japan, though, they say, "What of that?"

To be fat is a duty;

It adds to your beauty.

And that is the reason they're fat.

This dear little Mabel,

She isn't quite able

To say what it is has gone wrong;

But she looks in the glass.

And the shadow-frowns pass

O'er a face that is sweet as a song.

She is thinking of Lizzie,

Whose hair is so frizzy.

She wishes her own could be cut;

But papa, only said

When she showed him her head,

"What, spoil it, my darling?—tut! tut!"

The other day, as the Postmistress was driving down a pretty rural road, she came upon a farm-house which stood all alone. It was late in the afternoon, and there was nobody stirring about the place; doors and windows were closed; the dog was asleep beside his kennel; the gray cat, with two kittens cuddling close to her, was taking a nap on the mat by the front door; and it was as quiet as could be all around, until—peep! peep! cluck! cluck!—there came suddenly in view the prettiest brood of chicks in the world; thirteen of them, dears, and every one as white as swan's-down. The little snowy puff-balls were taking an airing with their sober cream-colored mamma, and the Postmistress will not soon forget how cunning Mrs. Hen and her family looked. Pray, Daisy and Mattie, Freddy and Guy, have you a dainty brood of chicks at your house? And why haven't you sent the Postmistress word about them?

Danby Four Corners, Vermont.

I am a little boy nine years old, and will be ten the 9th of August. I have a calf and a canary-bird and a little kitten. I go to school almost every day. I have an auntie who sends me the money to buy Harper's Young People. I hope she will send money every year. My grandma sends me a little pin-money every month. I have over fifty dollars in the bank. I have no father, and my mamma is poor. I can't think of any more to write this time.

Robert.

When you are a man, as you will be one of these days, you will be able to work for your dear mamma. She is not very poor if she has a good and loving son ten years old. I am glad to hear that you do not spend for toys and candies all the money grandma sends you, but save some of it for future use.

Rockport, Massachusetts.

As I have never seen a letter in Our Post-office Box from Rockport, I thought I would write one to tell you how much I enjoyed reading "Toby Tyler," and how much I like "Mr. Stubbs's Brother." I have a dear little baby sister nearly eight months old. Her name is Mattie. We think she is the prettiest baby in the world. Mamma says that every one thinks the same of their baby, so I suppose all are satisfied. I am twelve years old, and go to the Grammar School. My studies are arithmetic, reading, spelling, history, grammar, and geography. I take music lessons twice a week. My sister and I are much interested now in reading the works of C. C. Coffin. I like The Story of Liberty, Old Times in the Colonies, Boys of '76, and Winning his Way the best.

Annie L. B.

You could not read better books, dear, than those you mention. Boys of '76, in particular, should be in the library of every American child.

Sullivan, Indiana.

I am a little girl ten years old. I have a Maltese cat; its name is Mallie. I have three chickens. One of them is a bantie. My sister Libbie gave it to me. Its name is Chickie, and the other two are Dick and Topie. My papa gave me Harper's Young People for a Christmas present. My sister Effie took it two years, and now I am taking it. I wrote a letter once before, and it was not published. Oh, I hope this one will not be put in a pigeon-hole! We have a pea-fowl. We call him Sancho, because he speaks the word so plainly, and mamma thinks he tries to be like Sancho Panza. I am taking music-lessons, and learning to ride on horseback, and when papa leaves the old gentle horse at home we go out riding. I have two sisters and one brother. I signed the red-ribbon pledge. I think Jimmy Brown's stories are very nice.

Maggie A. C.

Cahto, California.

A little girl, a subscriber of Harper's Young People, thinks all the little girls should say something, to Mr. Harper to tell him how pleased we are every week to receive our paper. I wish every little girl could have as nice a time as I do, fishing for trout. Away out here where we live is a creek that has fish in it. Brother and I go fishing every Saturday, and I enjoy the sport very much. Brother Ed cut down a tree which was one hundred and fifty feet tall, and in the top of it was a rat's nest. We thought it strange that a rat would go so high to build its nest. I brought the little rats home, but they died.

Sophia R. (aged seven.)

That was a very ambitious rat, little Sophie. It was just as well the rat babies did not live; they would have been very troublesome pets. Do you ever forget to come home to dinner when you are waiting for the trout to bite? That is what a little friend of mine does sometimes.

Montclair, New Jersey.

I want to tell you about my pets. In the first place, we have two canaries; mine is Dick, and Dandy belongs to my brother Willie. Dicky was bought for me, but Dandy came to us. One Sunday morning papa was reading, and Dicky hung on the piazza. We suddenly heard two canaries singing, and looking to see what was the matter, we saw a strange bird eating Dick's seed. He was willing to be caught, and papa gave him to Willie. Dick and he sing together a great deal now. Dick was once carried down into the cellar in the mouth of Henry, our cat, who laid him on the coal-bin, and was just preparing to eat him when the girl came down and took him up-stairs. We did have a mocking-bird too—his name was Jack—but he died. A horrid cat came in one dark night and frightened poor Jackie to death. Another pet is a dog, whom we call Chaucer. He is five years of age, and we have had him since he was two weeks old.

Effie E. H.

What a good thing the birdie was rescued in time from the clutch of Madame Puss, who can not help being a hunter, as it is her nature.

Pensacola, Florida.

I am a little boy nine years old. I like to read about Mr. Stubbs's Brother, and I watch every week for Young People to come. I have two dear sisters. Mary, aged five, who is in Jacksonville with our grandma, and Ethel, who is the sweetest and the prettiest baby in the State. My papa is the principal of the High School here. I am going to take lessons on the piano from my mamma this summer. It is nice to walk down to our lovely bay, and see it full of ships from all countries.

Alfred McC. W.

Indianapolis, Indiana.

Papa says if I want to be pretty sure to have my first letter published in Young People's Post-office Box, I must write something new and interesting. As I have read or had read to me by mamma all the letters since Young People started, and do not remember having heard anything about railroads, I will tell you about them. Papa works in a railroad office, and often takes me with him on trips out on the road, and into the shops and yards, and has taught me the difference between a journal and an axle, a truss-rod or hog-chain and a stay-chain, and other parts of a car. I have seen an engine in the shops all taken apart, the wheels all out from under it, and all the bright Russia iron stripped off the boiler, which left it a dull, rusty-looking piece of hollow iron, for they take out the front end and flue sheets and flues, and you can see clear through back to the fire-box, and all cold; so unlike an engine when fired up and full of steam, coupled to a train, ready to pull it out when the conductor says, "All aboard!" I would like to tell you about a ride I took on an engine at night, but I am afraid I have made my letter too long now. I am eight years old, and mamma helped me to spell the hard words.

Re.

Write again, little bright-eyed Re, and tell us about your ride. We would like to hear from you.

Little Johnny Jump-up,

Under the trees,

Laughing in the sunshine,

Nodding to the breeze.

Little Johnny Jump-up,

Some folks call him Pansy;

Johnny doesn't care a bit—

Follow out your fancy.

Poor little Daisy, with ruffles and tucks,

Has to sit still, lest she spoil her fine dress.

Dear little Rose, in a calico gown,

And a checked gingham pinafore, plaided and brown,

Is the happier girlie, I guess.

"I can paint pictures," says sweet little Nell;

"I study music," says darling Estelle;

"I ride my pony," cries dear little Lou.

Here's our wee Margie, and what can she do?

Bless her, the good little sister at home:

"I take care of baby and brother Jerome."

When you think you are hungry.

And are not quite sure,

Then candy or cake, dears,

The hunger will cure.

But when you've been playing,

We'll say by the brook,

And fishing with pins, dears,

Instead of a hook,

Then good bread and butter,

A generous slice;

For boys and for girls, dears,

There's nothing so nice.

New Haven, Connecticut.

I am a little girl nine years old. I have a little pet kitten. The mother and she played beautifully together, until two great dogs came in the yard, and she ran to protect her kitten; but instead of killing the kitten, they killed the mother. This is all I am going to write to-day.

Nelly M. F.

Indeed, dear Nelly, I am very sorry for the fate of your poor cat. Could nobody save her from her enemies? She had the true mother spirit. Even a timid bird will grow brave, and fight to defend its fledglings if they are attacked.

San Antonio, Texas.

We have a little farm three miles from San Antonio, and we borrow a little donkey, or burro, as the Mexicans call it, to go out there; and you would be amused to see us. Mamma bought us a saddle, and the good old man who loans us the burro has a little dog-cart. Sometimes we use the saddle, and sometimes the cart, and away we go. It would remind you of Punchinello and his horse and black cat on his way to Paris. When the little donkey concludes to go fast, and when he wants to go slow, we are very much at his mercy, for he does as he pleases. We go out to the farm, and swim, and hunt eggs for papa, and gather wild flowers to bring mamma; and, dear Postmistress, we caught three little mocking-birds, and have them in a cage. We would send them to you if we could; and if we go to New York, as we think we will, we will bring them to you. Mamma told us we were very naughty indeed to take the little birdies, and asked us how we would like to be kidnapped and carried from home. Then we were very sorry we had taken them, and wanted to carry them back; but she said it was too late then; that the poor mother had probably gone away when she found her babies stolen. So we promised mamma not to take a bird again, and we will keep our word, for when we took them we did not think a mother bird would grieve as our mamma would if we were stolen. The mocking-birds sing any song, and if they hear any one play on the piano, they will whistle the same tune; and one used to call like the little chickens, and papa hunted everywhere, thinking some little chick had lost its mother, when what should he see but a mocking-bird on the gate, making the same noise a little chick does when its mother is out of sight!