Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XXXI, No. 5, November 1847

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: February 20, 2019 [eBook #58926]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins, Chelsea Laird & the online

Distributed Proofreaders Canada team at

https://www.pgdpcanada.net from page images generously

made available by Google Books

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXI. Nov, 1847. No. 5.

Contents

| Fiction, Literature and Articles | |

| Reminiscences of Watering-Places | |

| The Village Doctor (continued) | |

| Ida Bernstorf’s Journal | |

| The Islets of the Gulf (continued) | |

| The Last Adventure of a Coquette | |

| The Three Calls | |

| Kitty Coleman | |

| The Silver Spoons | |

| Game-Birds of America.—No. VII | |

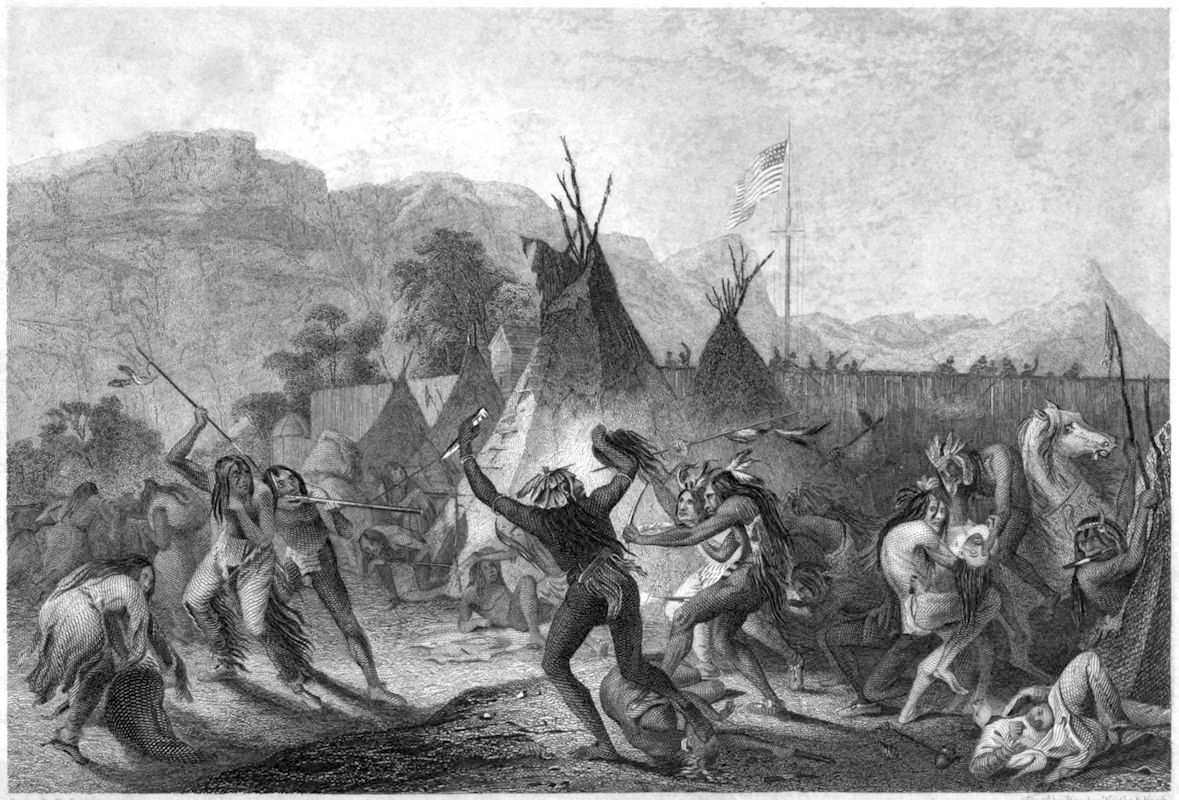

| Fort Mackenzie | |

| Review of New Books | |

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XXXI. PHILADELPHIA, NOVEMBER, 1847. No. 5.

———

BY FRANCIS J. GRUND.

———

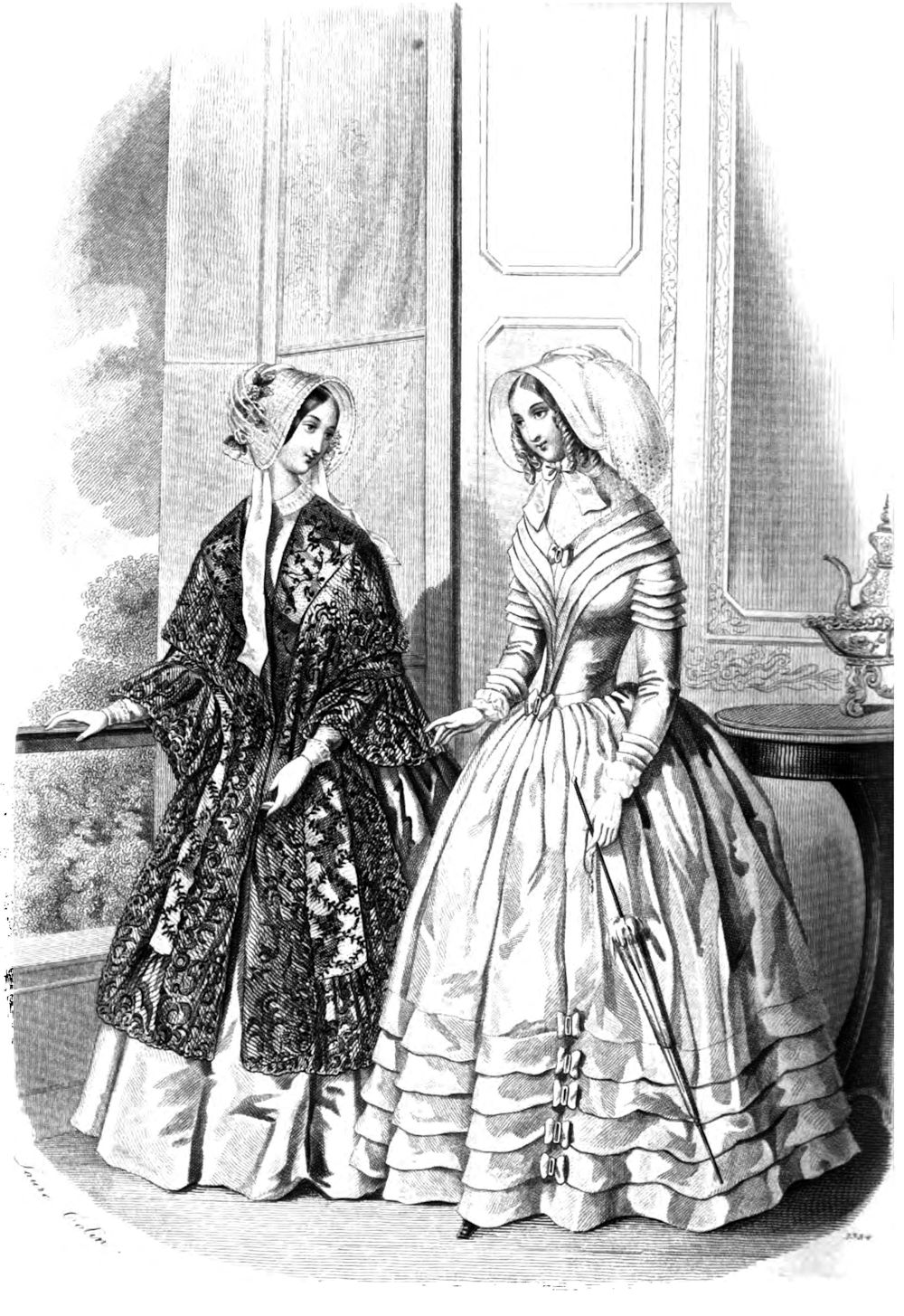

Whatever our political independence may be, we are slavish imitators of Europe in every thing appertaining to society. We may boast of being republicans—we may beard England and France, conquer the Mexicans and annex Cuba, but we dare not get up a coat or a pantaloon, or a morning-dress, or a peignoir of a lady, without first waiting for the fashion plates of Paris. What is taste but a sense of the fitness of things—the intuition of propriety—and why should we not lay claim to it as well as other nations. John Bull, in that respect, is a much more remarkable man; not only is he stock-English at home, but an Englishman wherever he goes—in Canton and St. Petersburgh, in Constantinople or Paris—wherever he sojourns he founds, or assists in founding, an English colony, governed by English laws, English fashions, English tastes, and all the substantial customs of his foggy and smoky island. Nothing tempts him to forego his Anglicism. He breakfasts on a steak in India, as he does on Ludgate Hill, and has made the establishment of butchers’ shops in the Asiatic possessions of England an important item of legislation;—he has established coffee-houses in Paris, where you get, par excellence, a biftec à l’anglaise—he has established Hotels d’Angleterre in every habitable town and village of Europe, and he has colonized the world with English shoemakers, tailors, and other artisans of every description. Let him go where he may, he prefers the productions of his country to every other, and even deals in preference with his countrymen, though he knows they cheat him. He would rather be circumvented by his own countrymen than pay an additional frank to a Frenchman.

Wherever half a dozen English families are congregated, there is a loyal English association for the preservation of the purity of English manners, English patriotism, and the holy and essential connection of Church and State. As a matter of course, whenever they can afford to pay for a preacher, they have their English chapel, and if a nobleman happens to get among them, they have their English genealogies, their court and their toadies. In former days they were at least obliged, when traveling, to study French, or some other European language, but since English is spoken all over the world, from the lady in the drawing-room to the garçon of the hotel and the café, the incoherent monosyllables of which English conversation is usually composed, will answer for an overland journey to Calcutta. Even in this country the English remain attached to their habits and customs, and to the fashions of their own modern Babylon.

Alas! it is not so with us. We imitate the whole world; we are the slaves of fashions set by other people, and yet, we are the only country on earth which has a written declaration of independence.

But the worst of it is, that in imitating Europe, we select generally that which is least fit for our use, and omit those laudable customs and manners which, being founded on the experience of centuries, give to the old continent the only real advantage it has over us. We copy aristocratic prudery and exclusiveness, and omit the graceful provenance of the higher orders, wherever their rank or title is not drawn into question, and the agreeable equality which is the essential charm of society. We cannot unbend for a single moment—we carry our personal dignity, our wealth, and our connections into the humblest walk of life, and by that very means deprive ourselves of a thousand little enjoyments which constitute the great aggregate of human happiness.

I will here allude only to one instance—the manner in which we spend our summers. Our summers are, in general, hotter than those of Europe and, in consequence, drive a much larger portion of the population into the country and to the watering-places. The facilities of locomotion, too, are very great, and traveling comparatively cheap; because we are in a habit of doing it in caravans, whether it be by rail-roads[1] or in floating palaces. How delightfully might we not spend the warm season, and the delicious autumn which follows, if we only knew how!

In Europe there are two kinds of watering-places: those where baths are taken or waters drunk for the use of health, and those which, being delightfully situated, attract crowds of visiters merely for the purpose of agreeable pastime. The waters of the Pyrenees, of the Tyrol, and some of the Brunnens of Germany, belong to the former class; but by far the greatest number are properly comprised under the head of “Baths of Luxury and Amusement.” And, indeed, it is a luxury to use such baths in such places, and surrounded by such comforts! Among the model waters of the world are those of Germany. They unite in themselves all the advantages of the others, and surpass them in the profundity of thought and research with which they are organized and embellished. There is a high, lofty enthusiasm in that hardy race of Germans, which one would not naturally seek behind those listless blue eyes, flaxen hair, drum heads and quadrangular faces, which have won for them the characteristic appellation of têtes-carrées; and yet how beautifully are their classic lore, their wild romanticism, and their modern merriment, illustrated at their Brunnens! They are complete little worlds in themselves—miniature planets, scarcely perturbed by the revolutions of other bodies. In a week you can pass through the whole of them, from Hesse Homburg and Baden-Baden to Wiesbaden, Emms and Langenschalbach, and yet each of these bears a distinct physiognomy, and is complete within itself. Wonderful totality of the Germans—harmonious agreement of taste, fancy and reality, to be found at a German watering-place, and no where else in Germany! The republicanism and philosophy of the Germans, driven from the residences of princes, have taken refuge at the Brunnens, where they have established the democracy of high life—the cosmopolitism of education and good breeding, and the individual independence which is sometimes in vain sought in other commonwealths! I will give here, by way of example, a short description of the principal advantages of Baden-Baden—deservedly the most fashionable watering-place now in Europe—to show what a fashionable resort of that land can be made; and of what improvements our own are capable, if people had a mind to be free and easy, at least as long as the thermometer ranges from eighty to a hundred.

I shall not trouble my readers with a description of the various routes that lead to Baden from Paris, London, or any other place they choose to start from. They will find it laid down on every map of Germany, not far from Strasburg and the Rhine, and the postillions in their high-boots, leather inexpressibles, short-jackets and glazed hats, with bright brass bugles dangling to their sides, on which they often charm their horses and annoy their English passengers, are so accustomed to the road that they are sure to carry you there within the time prescribed by law, (4 miles to the hour,) if you will promise not to disappoint them with the drink-geld. A German postillion gets money merely for drink, and hence his douceur is called drink-money—the English translation of the above idiom. This only I will say: that if you take the rail-road from Carlsruhe to Baden-Baden, you have already a foretaste of the comforts that await you. Of course you take first class cars, balanced on extra steel springs, where, stretched on a rose-wood sofa, carved à la Renaissance, with a large looking-glass before you, and an elegant table between, you may either read, take notes, take a collation or enjoy an agreeable tête-à-tête, as taste or opportunity may prompt you. These cars are never crowded, and you are in them as in a lady’s boudoir, treading softly on the carpet. Instead of the shrill whistle, the hunter’s, respectively the postillion’s bugle, apprises you of your arrival, the door is opened, and the conductor, doffing his cap with the Grand Ducal arms, informs you that you have reached the place of your destination. There is no trouble about the luggage, which is all marked and registered, and sent to your hotel by the agents of the road, for another drink-geld, regulated by a tariff.

And now as to the hotels, of which there are about twenty or thirty in the place. The first question is: how large an apartment do you want? Do you require two, three, four, five, six or more rooms? with the windows looking into the garden or on the street? There are some rooms higher up with a fine view of the mountains—some with a balcony, &c. These rooms are not merely places to sleep in; they are as completely furnished as those of your own house, with large glasses, sofas, lounges, fauteuils, and every convenience of the town or residence you have just left. You are in the country without missing any of the comforts of the city. There are two excellent tables d’hôte, one at an early and one at a late hour, (5 o’clock,) to suit your habits; breakfast in your rooms when you ring; supper from seven or eight in the evening till four or any o’clock the next morning, à la carte. Of course when you dine in your room you command your dinner à la carte also, but you better leave that to the taste of your host. Every hotel has baths attached to it, which you may command at any hour, and physicians who explain to you their effect on the constitution, and with whom you may advise as to your case. If you dine at the table d’hôte you are sure to have a band of music, which has at least the effect of promoting conversation, if it does not refresh your memory with the most popular pieces of the last opera. There is no public parlor; but the accommodations are such that you may receive your friends in your own room. The public parlor is the Conversation House, or Kursaal, where you see every body—not only “the boarders of your hotel,” but the whole society of the place, which meets there twice a day, and is to the visiters of Baden what the capitol in Washington is to strangers in that city. This, of course, prevents the formation of cliques or sets, or coteries that are, for instance, formed at Saratoga, in regard, God save the mark! to the boarding-place you may be at, and enables you to be in good society without being observed; meeting your acquaintances, and yet obliged to recognize none unless you choose to do so. During the season there are some two or three thousand people every day at the Conversation House, which, of an evening, I can compare to nothing better than the levee of our President, with this exception only, that there is less of a jam, and of course less confusion.

The Conversation House itself is a very tasteful and elegant building; and some idea may be formed of the costliness of its furniture, when I state that the painting of the walls of a single saloon in it has cost fifty thousand francs. There are music and dancing, concerts and theatrical representations connected with the Conversation House, and only one marplot, which the government is about to suppress—the gaming-table. The principal games played are Rouge and Noire, or trente et quarante, Roulet and Hazard, introduced lately from Crockford’s. But it is not considered good taste to gamble, though there is usually a large gallery of spectators; and a lady at the gaming-table is, indeed, a most sorry spectacle. Every body has a right to enter the Conversation House gratis, from the time it is opened till it is closed; provided the person, male or female, is properly dressed; and it is the fashion to be dressed as simply as possible, and for the ladies never to wear diamonds. Balls and concerts are given in separate rooms by subscription; but even there it is considered bad taste and absolutely vulgar, to appear in full dress. I have seen Prince Gallitzin waltzing with the Duchess of Béthune, he dressed in a linen jacket, and she wearing red morocco shoes! The only hair-dress which is not absolutely ridiculous in a lady, consists of natural flowers. It is the intention that all shall enjoy themselves equally, and that nothing shall provoke remarks. The height of vulgarity, in a watering-place, is to be distinguished. It is understood that all social obligations and distinctions are suspended or cancelled at the watering-place, and that no obligation there incurred need be recognized in the city. There is, therefore, no fear of making disagreeable acquaintances, and the agreeable ones must be renewed in town.

But what I have thus far stated is but half the real pleasure enjoyed at a German watering-place, or the comfort that you can find there, if you like to stay there for a season. In that case you had best hire an étage (a whole floor of a house, usually from five to ten rooms, with a kitchen, &c.) or a whole house for yourself, all which you find already furnished with kitchen utensils, crockery, silver, in short, every thing that you have left at home, with even servants, if you desire, to wait on you; all by the week, month, or the whole season. In a similar manner may you hire your carriage by the day, week, month, or season, your saddle-horse, or a donkey to ride over the mountains. You are, in fact, surrounded by every convenience of London or Paris, and yet, in half an hour’s drive, amidst the peasantry of the most laughing villages of Germany.

Baden is not without its Italian Corso. Every afternoon, that is from 6 o’clock till dark, ladies and gentlemen drive from Baden to Lichtenthal, a distance of not more than two English miles, but which, by art, is so arranged as to convey the idea of a much longer jaunt. You drive all the time through a most beautiful alley of horse-chestnuts; but you are not fatigued with the tiresome monotony of a straight line, and its diminishing perspective. The line you follow is serpentine, with unequal curves on both sides, so as to lengthen your course and still keep you in the valley bounded on both sides by semi-circular mountains. In this manner you enjoy every possible scenery, and every advantageous position to view it. Now the old castle, which you have just left, again bursts on your sight; then the landscape seems to be changed into an open prairie, bound on both sides by craggy rocks; then you find yourself suddenly traversing a flower-garden, traveling along between rose-bushes raised to the height of from eight to ten feet; and all at once you are again, as if by magic, buried within the dark foliage of a dense oak forest. Thus the scenery varies till you have come to the nunnery of Lichtenthal, where you may alight and take some refreshment in the hotel opposite, or if you are fond of clear, mountain streamlets, taste the cool water of the rills that trickle down the mountains; some blowsy children being always ready to present you with a tumbler-full on a waiter, with a bunch of flowers placed by the side of it, for which you are expected to make a small return. Germany is essentially the country of flowers and music, and you can indulge in both of them, during the season, at Baden-Baden. By the side of the alley of horse-chestnuts, which is wide enough for two or three carriages to drive abreast, there is another for cavaliers on horseback, so that ladies and gentlemen can practice all the arts of refined coquetry whilst admiring the beauties of nature, and enjoying the fragrant air with which this romantic valley is constantly blessed. On the left hand, following the gurgling brook which meanders through the valley, is a gravel-walk, sufficiently near the drive for the promenaders to observe and to be observed, and with its animated groups, much contributing to the variety of the scene. There is no social difference observed between those who drive and those who walk, parties frequently alighting from their carriages to join the pedestrians, and carriages being ready on both ends of the promenade to convey them. Whichever way you turn, social distinctions vanish—the life you lead seems to be all romance; you have left the cares of the world behind you, and are willing to look upon all men as honest and true, and on all women as angels. Neither are you answerable for your doings at the watering-place, except to your own conscience—all that occurs there is a mere episode, you live, as it were, in a parenthesis. What a pretty parenthesis one lives in at Saratoga with a “corps of reporters” at one’s elbow to note one’s acts, and chronicle one’s fancies! But this very freedom from social trammels is often the cause of the most lasting affections, as those trees frequently strike the deepest roots which are early exposed to the blast.

You have now returned from the Corso to the Conversation House, which on one side is leaning against the mountains, having in front a rich park, and under the trees numerous stalls, where ladies may indulge in the entertaining vocation of shopping, to ruin either husbands or gallants. The shops, however, are now closed; the moon has risen, and with her electro-galvanic power, is silvering the old walls of the castle, perched, like an eagle’s nest, on the mountain. As you pass on, her playful light twinkles through the leaves, and paints grotesque figures on ladies’ shawls and bonnets, which are not to be imitated either by Nancy or Paris embroidery, and are handsomest when falling on plain gauze or muslin, slightly veiling the sylph-like forms that flit between the trees.

In front of the Conversation House is the orangery, with the golden fruit of Hesperus suspended from its dark green branches; an ocean of light from lamps placed between the trees, gives a magic appearance to the crowd that floats between them; and a scientific orchestra of from twenty-four to thirty instruments, diffuses harmony through the cool evening breeze, till its melodious notes die with faint echo in the mountains.

In that promenade, though not measuring more than six or eight hundred paces, you seem to take an optical trip through Europe. You hear every language spoken, and behold every possible costume, from the straight-laced Englishman to the turbaned Turk and the ample-folded Armenian. The Italian, French, Spanish, English, Russian, German, and Oriental tongues are here mingling with one another without producing the least confusion, or making any one believe that he is not at home. The Englishman, with his two left hands, so manly in public life, and so peevish and awkward in society, almost unbends; the fiery Spaniard forgets his Prado and the dark eyes of Madrid; the mocking Frenchman leaves off his bons-mots; the Russian thaws from his icy despotism; and the enthusiastic Italian himself swears that this would have been a scene for the love of Petrarca. But the thoughtful German, with his abstractions and enthusiasm running in rich veins deep beneath the surface, flies from the throng, and climbing up the footpath of the mountain, carved in the rock by patient taste, breathes soft vows to willingly listening ears, in the sweet solitude of moonlight.

Connected with the Conversation House is a restaurateur, who is at the same time a limonadier and glacier. There is nothing that the Café de Paris, the Maison d’or, Tortoni, the Rocher de Cancale, or the Trois frères Provençaux can furnish, that you do not find on the carte of this practical epicure; while instead of the glass-boxes in which you are obliged to dine or sup, in Paris, you are here served in a spacious gallery, ornamented with plants and flowers from the four quarters of the globe, a thousand times reflected in gigantic mirrors. Every thing here seems to be arranged by the hands of a kind fairy, and the repasts themselves are served with a promptitude and a precision as if the spirits attending you were obeying the magic wand of an enchanter.

A reading-room and a circulating library are also connected with the establishment. The latter contains the standard works, and the latest publications in English, French, and German you are sure to find there the best; and there is no club in England that can furnish a greater variety of newspapers, English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish journals, with the New York Herald, and the Courier and Enquirer.

It is long past midnight when you return home, but the hotels, and many private residences, are still lit up, and music, that sweet concomitant of life in Germany, is still greeting you as you wind your way through the crooked streets.

In no part of Europe do you see a British peer dining table d’hôte; but the watering-places of Germany make an exception from the rule. I have seen the most aristocratic leaders of the Tory party (that was)—certainly not without a proper train of English toadies—lieutenant-generals in the army of the historical house of S——t, and India nabobs, content with the public ordinary, though the ladies of the party are seldom seen without a dragon. “What is a dragon?” will some of my readers ask. I will explain. A dragon, applied to a young English gentlewoman is what an “elephant” is applied to a German. It consists of an old maiden aunt, or some other distant relation, whose business it is to superintend the conduct of a young lady that is just “out.” Her functions resemble those of the old nurse in Romeo and Juliet, only that she is much more watchful, and seldom or ever to be bribed. If you attempt to corrupt her, you rouse the British lion, or the Dragon of St. George; hence the name, which has been given them by the French. The acerbity of the temper of English dragons renders them generally lean and gaunt; but in Germany, where good nature abounds, they grow fat, though with a dogged obstinacy which is as insulting as it is provoking, they will squat down on the sofa right between you and the lady you wish to entertain; proving a most palpable objection to a tête-à-tête, for which reason they are properly called “elephants.”

The business of an English dragon at a table d’hôte in a German watering-place, is to occupy a seat on that flank of a lady which is threatened with a masculine invasion. As a further precaution, and a sort of second line of circumvallation, the seat next to the dragon is left unoccupied, because they expect a friend at dinner, who is always invited, but who never comes, and for whom no landlord dares to make a charge, be the table ever so crowded. Thus guarded and fortified, a young Englishwoman of family may defy siege or assault from any quarter; in a watering-place, however, it is best not to feel too secure, and to rely not altogether either on the beasts I have just named, or those which are conspicuously displayed on escutcheons.

While upon this chapter, I may as well allude to the fact, that there is no “match-making” at a German watering-place; and that gentlemen, from the extreme freedom of manners which is tolerated, are not expected to pay the debts of their gallantry. A gentleman, having danced or conversed with a lady, or been introduced to her in every form used in society, does not yet acquire a right to call on her; and having even been invited in the place, has not yet received the privilege of making his bow in town. So, then, society is left to its own good sense, and with no other but individual responsibilities. There is no shrewd distinction between elder sons and Tartars;[2] no forced attention to heiresses, and consequently, no arrogant neglect of “poor beauties.” Grace and loveliness enchant by their own charms, and wealth is courted only at the end of the season.

Such is a German watering-place for three months in the year—from the 1st of July to the end of September, though the latter part of that month the place begins to thin; and in the winter these places are nothing but pretty villages, with fine white houses and spacious hotels. A few calculating Englishmen, however, have discovered that living there all the year round would enable them to practice such economy that they might, in the season, cut a very great dash without spending much money in the aggregate. Accordingly, some twenty or thirty families—swallows whose pinions are clipped, and will not admit of yearly migrations—have made their nests there for the winter; and the most forlorn-looking creatures they are, if you get a chance to see them. The men affect to indulge in the chase, and the dowager ladies in a quiet rubber of whist, whilst the young women divide their time between novels and embroidery. No nightingale longs for the return of the seasons as they do; they become true lovers of nature, and prefer the cool evenings of summer to all the gayeties of the carnival.

But I have not yet enumerated all the advantages of German watering-places, and particularly of Baden-Baden. Not only are the drives about the town very handsome, but also those within a circumference of from ten to twenty miles. You may take a drive to the old and the new castle (a new castle in Germany is one which dates from the 16th century) to the Mercury—a sort of watch-tower perched on the summit of the highest mountain in the panorama which surrounds you—to Gernsbach, a delightful village, situated in a romantic valley, through whose apparently quiet bosom a mountain-torrent is rushing, like a wild passion, toward the father of the German streams, old Helvetian Rhine—or to the old chapel—or, if you are fond of wild scenery, to the craggy cliffs of the Black Forest. All these roads are built at an enormous expense, and with great skill through narrow defiles, over precipices, real and artificial, and in a serpentine manner so as to command a variety of views. The roads are as level as the floor of your parlor; a much more direct footpath, resembling the neatest gravel-walk in your garden, conducts pedestrians to the same places.

Wherever you find a beautiful spot, with a commanding sight, there you will find a bench and one or more oak chairs, where you may rest yourself and enjoy the landscape at your ease. Even on the road for carriages a space is left for turning or halting wherever a commanding view presents itself to the eye. In this careful treasuring up of the wealth of nature, the Germans have no equal in Europe. Theirs are the quiet enjoyment of contemplativeness—the dreams, called forth by an ardent love of the great fountains of inspiration. But who is there deriving happiness from bare realities, without reminiscences of the past, or hopes of the future?

The old castle is a ruin of very ancient date, but several rooms in it have been refitted, of course in the style of the middle ages, with huge massive oak tables and chairs, arched windows, with painted glass, and armorial frescos. The old dungeon has been, very properly, transformed into a wine-cellar, the only prisoners being huge casks of hock, and a corresponding number of long-necked bottles. On a writ of habeas corpus, any of these will be brought before you, and you may drink the health of the present Grand Duke—a poor devil of a fellow, whose place ought to have been occupied by Caspar Hauser—or the memory of his worthy ancestors, in the finest room that is left in their old residence. You will also find an excellent restaurant, and a cafetier, who, in the midst of the remnants of past ages, will present you with a carte, the very copy of which you may have seen at Mavart’s, or at the Café Anglais. After dinner you may climb up the old tower, and from the dilapidated loop-holes of the fourteenth century, contemplate the improvements of the nineteenth, as the cars from Carlsruhe rattle over the rails.

There is, indeed, a peculiar pleasure in thus scanning, with a single glance, the vestiges of five successive centuries; to view the past and the present, and to lose oneself in the contemplation of the future. You can almost realize immortality in beholding the works of twenty generations, and the undying spirit that produced them, without having lost one atom of its pristine energy or vigor. The world spirit is ever young, though one generation after another dies in its embrace, each cherishing its own fond hope of everlasting life. The contemplation of the future steels men’s nerves to patient enterprise and heroic valor; but the retrospective is the true element of poetry. The future, from our limited perception, is necessarily shapeless; but the past, aided by distance, stands out in bold relief, and the colossal figures of history animate the scene. They stand on pedestals, animating or warning examples in all times to come. There is a peculiar species of romanticism connected with the remnants of the middle ages. They are nearer to us than the classical ruins of antiquity, and from their immediate connection create stronger sympathies. The spiritualism of the middle ages contrasts advantageously with the materialism of the Greeks and Romans, and has a stronger and more direct hold on our imagination. The ruins of Rome, Athens, and Carthage, lead to a train of reflections which leave you comparatively cold; while the turreted castle and time-defying walls of our own immediate ancestors strike us like reminiscences of our own childhood.

Descending the castled mountain, and taking the road toward the Hunter’s Lodge, the scenery becomes more and more wild; the habitations of men disappear, and pursuing your route some few hours, you find yourself at once transplanted to the most picturesque scenes of the Alleghanies. You are now in the Black Forest, one of the few spots in Europe where you behold primitive oaks, as yet undesecrated by the woodman’s axe, and land which has never been tilled by the ploughman. Here is a little miniature painting, beautifully set in diamond spires and emerald hills on the one side, and the pearly Rhine on the other. Some there are who think the setting more valuable than the picture; but diplomacy has a different opinion on the subject, and has always valued the Black Forest as one of the most important strategical positions of Germany.

There is no sea-bathing in Europe equal in natural grandeur to either Cape May, or Long Branch. The most frequented watering-place of that sort, on the Continent, is Ostende; but the Belgians are the most unpoetical, unamiable people of Europe. With more historic lore than almost any other modern people, their minds are as flat as their soil,[3] and their manners as unsociable as the Spanish hangman, Alba, could have made them. Their religion is petrified, their literature stale, and there is nothing of the ideal in them. It is in the bogs of Flanders where the home-sick Swiss mountaineer is most tempted to commit suicide. Ostende, independent of the beach, which does not compare to our own sea-shore, is extremely dreary. Nothing but sand, sand-hills, and morasses, surround it. It is true, these morasses have been cultivated by the extreme patience and industry of the Flemish peasant, but there is a monotony in their fields and parks, and even in their gardens, which can drive you mad. Every thing answers a useful purpose, but to the imagination it is a dreary waste.

Ostende, during the summer season, is nevertheless a picture of Europe in miniature. You can reach it from England in eight hours, from Brussels in six, from Paris in sixteen, from the Rhine (Cologne) in fifteen. Brighton, on the opposite side of the Channel, is nevertheless a paradise to it, if any thing can be called a paradise where, instead of the primitive manners of the first couple, you meet with the exclusive dampness of English society. But nature has blessed that little Island of Great Britain—the Japan of the European sea—with so many gifts, that the strange organization of its society appears to be less the offspring of that peculiar irony which runs through history, than a means of tempering “the envy of less happier lands,” and making them comparatively content with their fate. Every Continental watering-place is crowded with Englishmen, who come there to enjoy social freedom; those of England are nothing but epitomes of the concentric circles which mark the monotonous orbits of the different classes of English society. The elements do not mingle, form no harmonious groups, and have nothing cheering either for the imagination or the heart.

There is great danger that the society of our own watering-places is gradually copying the model, without having the same uniform, and on that account more endurable standard of division. The different coteries of a large city—the necessary consequence of the difference of refinement and education—need not necessarily conflict with each other; but they are intolerable in a small place, where the distinctions are constantly before your eyes, can hardly be kept up without rudeness. Fancy half a dozen coteries dining at the same table, meeting at least three times a day, and then spending the evening together in the same parlor. It must be a perfect little purgatory, from whose pains there is no respite, except by diving in the broad Atlantic.

|

I purposely avoid the English dandyism “railway.” |

|

Younger sons without fortune.—Remark of the Editors. |

|

I, of course, except the people of Liege and the Ardennes, who are descended from the Gauls, and are only politically united with Flanders and Brabant. |

A ROMANCE OF REAL LIFE.

———

TRANSLATED FROM THE FRENCH BY LEONARD MYERS.

———

(Concluded from page 167.)

I arrived at Montpellier, and was well received by my uncle, who informed me that he had obtained for me an honorable situation. A rich Englishman, very old, nervous and gouty, was desirous of having a doctor constantly beneath his roof, an intelligent young man, who might attend to his disease under the direction of another physician. I had been proposed and accepted. We immediately repaired to the residence of Lord James Kysington. We entered a large and handsome mansion, filled with servants, and having passed through a suite of rooms we were ushered into the cabinet of Lord James Kysington.

Lord Kysington was seated in a large arm-chair. He was a very old man, with a chilling and austere countenance. His hair, which was completely white, contrasted singularly with eye-brows that were still of the deepest black. He was tall and thin, at least as well as I could distinguish through the folds of a large linen surtout, fashioned like a dressing-gown. His hands were hidden in the sleeves, and a white bear’s fur covered his ailing feet. A table stood near him on which were placed several vials containing potions.

My uncle introduced me. “My lord, this is my nephew, Doctor Barnabé,” he said.

Lord Kysington bowed, that is to say, he made an almost imperceptible inclination of his head, as he looked at me.

“He is well instructed,” my uncle resumed, “and I doubt not will prove useful to your lordship.”

A second motion of the head was the only answer my uncle obtained.

“Besides,” added the latter, “having received a good education, he can read to your lordship, or write when you wish to dictate.”

“I shall be obliged to him for it,” Lord Kysington at last replied, and he instantly closed his eyes, either because he was fatigued or that he wished the conversation to cease there; and my uncle took his departure.

I now had time to look about me. Near the window sat a young woman, very elegantly dressed, who was working at a piece of embroidery without at all raising her eyes toward us, as though we were not worthy of her notice. On the carpet at her feet a little boy was playing with toys. At first the young woman did not appear to me pretty, because she had black hair and black eyes, and to be handsome, in my estimation, was to be fair, like Eva Meredith; and then, in my inexperienced judgment, I always associated beauty with a certain air of gentleness. That which I found pleasant to look upon was what I supposed to be a goodness of heart—and it was long before I could confess to myself the beauty of this female, whose bearing was so proud, and whose look so disdainful.

She was, like Lord Kysington, tall, thin, and somewhat pale, and there seemed to exist between them a family resemblance. Their dispositions were too much alike for them to agree well, and they lived together scarcely exchanging a word, certainly not loving each other. The child, too, had been taught to make as little noise as possible; he stepped on tiptoe, and at the least creaking of the floor a harsh look from his mother or Lord Kysington would change him into a statue.

It was too late now to return to my village, but there is always time to regret that which we have loved and lost, and my heart beat faster when I thought of my humble home, my native valley, and liberty.

The following was all I could learn relative to the family I was in.

Lord Kysington had come to Montpellier for the restoration of his health, which had been injured by the climate of the Indies. The second son of the Duke of Kysington, himself only lord by courtesy, he owed to his own talents, and not to birth, his fortune and political position in the House of Commons. Lady Mary was the wife of his youngest brother, and Lord Kysington had chosen her son, his nephew, for his heir. I now began to attend to this old man as zealously as I could, fully persuaded that the most likely method of bettering a bad position was to fulfill even a painful duty.

Lord Kysington always behaved to me with the strictest politeness. A nod would thank me for every care, for every action that relieved him. One day when he appeared to be asleep, and Lady Mary was busy with her work, little Harry climbed on my knees, and finding that we were in a distant corner of the room, he asked me some questions with the artless curiosity of his age, and I, in return, hardly aware of what I was saying, interrogated him as to his relations.

“Have you any brothers or sisters?” I asked.

“I have a very pretty little sister.”

“And what is her name?”

“Oh, she has a charming name, guess it, doctor.”

I know not what I was thinking of. In my own village I had only heard the names of peasants, and they would not have been fit for the daughter of Lady Mary. Madame Meredith was the only well-bred lady I knew, and as the child kept repeating, guess, guess, I answered at random,

“Eva, perhaps.”

We were speaking in a very low tone, but the instant the name of Eva had passed my lips, Lord Kysington suddenly opened his eyes and sat upright in his chair, Lady Mary dropped her work and turned quickly toward me. I was stupefied at the effect I had produced, and gazed at them alternately, without daring to speak another word—some moments elapsed—Lord Kysington fell back in his arm-chair and closed his eyes again, Lady Mary resumed her work, and Harry and myself spoke no more.

For a long time I sat reflecting on this singular incident; afterward, all things having sunk into their usual calm, and silence reigning around me, I rose gently, and was about to leave the room. Lady Mary laid aside her embroidery, passed out before me, and motioned with her hand for me to follow her. As soon as we reached the parlor, she shut the door, and standing before me, her head erect, and her whole countenance wearing the imperious air which was the most natural expression of her features. “Dr. Barnabé,” said she, “will you be so kind as never again to pronounce the name you just now uttered; it is one that Lord Kysington should not hear;” and with a slight inclination she returned to the cabinet and shut the door.

A thousand ideas beset me; this Eva, whose name it was forbidden to mention, was she not Eva Meredith? Was she, then, the daughter-in-law of Lord Kysington? And was I living with the father of William? I hoped, yet doubted, for, in a word, although this name of Eva designated but one person to me, to others it might only be a name, perhaps, common in England.

I did not dare to question, but the thought that I was in the family of Eva Meredith, near the woman who was robbing the mother and orphan of their paternal inheritance, engrossed my mind constantly, both day and night. Often in fancy did I picture the return of Eva and her son to this dwelling, and saw myself asking and obtaining forgiveness for them; but when I raised my eyes, the cold, impassible face of Lord Kysington froze all the hopes of my heart I began to examine that face as if I had never seen it; I endeavored to find in those features some motions, some traces, which might disclose a little feeling. I sought for the soul I wished to move; alas! I found it not. But, thought I, what signifies the expression of the countenance, it is but the exterior cover which is seen with the eye—the meanest chest may be filled with gold! All that is within us cannot be guessed at first sight; and whoever has lived, has also learned to separate his soul and his thoughts from the common expression of his features.

I resolved to clear up my doubts—but what method was I to take? To interrogate Lady Mary, or Lord Kysington, was out of the question. To ask the domestics?—they were French, and but newly engaged. An English valet-de-chambre, the only servant who had accompanied his master, had just been sent to London on a confidential mission. It was to Lord Kysington that I must direct my inquiries. From him would I learn all—from him obtain pardon for Eva. The severe expression of his face had ceased to terrify me. I said to myself, “when in the forest we find a tree to all appearance dead, we make an incision in it to ascertain whether the sap does not still flow beneath the dead bark; so will I test his heart, and try if some feeling be not still within it.” I waited for an opportunity. To await patiently will not bring to pass that which we look for; instead of depending entirely on circumstances, we should avail ourselves of them as they occur.

One night Lord Kysington sent for me; he was in pain. After giving him the attentions requisite, I remained by him to watch the result of my prescriptions. The chamber was gloomy. A wax light shone dimly on the objects in the room; the pale and noble form of Lord Kysington was reclining on his pillow. His eyes were closed; it was his custom, when about to suffer, to collect his moral courage; he never complained, but lay stretched on his couch, straight and motionless as the effigy of a king on his tomb. He usually asked me to read to him, perhaps because the thoughts of the book would occupy his mind, or the monotony of a voice might put him to sleep.

That evening he made a sign to me with his bony hand to take a book and read to him; but I looked for one in vain, for the books and papers had been taken down into the parlor, and all the doors leading to it were fastened, so that I could not obtain one without ringing for it and disturbing the family. Lord Kysington made a gesture of impatience, but he resigned himself, and pointed to a chair for me to take a seat near him. We sat thus for a long while without speaking, almost in darkness, the clock alone breaking the silence with the regular ticking of its pendulum. But sleep came not. Of a sudden Lord Kysington unclosed his eyes, and turning to me, said,

“Speak to me; relate something, I care not what.”

He shut his eyes again, and lay waiting.

My heart beat violently—the time was come.

“My lord,” I said, “I fear I know of nothing that would interest your lordship. I can only speak of myself and the events of my life; and you would wish to hear the history of some great man, or some great event, that might claim your attention. What can a peasant have to descant upon, who has lived content with little, in obscurity and repose? I have scarcely ever been absent from my native village. It is a pretty hamlet in the mountains. Not far off there is a country residence, where I have seen those who were rich, and might have left, and who, nevertheless, stayed there because the woods are thick, the paths covered with flowers, the rivulets clear and dashing over the rocks. Alas! there were two in that house—and soon but one poor, solitary woman remained until the birth of her child. My Lord, this lady spoke the same language as yourself. She was beautiful, as seldom may be seen in England or France; good, as only the angels in heaven can be. She was but eighteen years of age when I left her, fatherless, motherless, and already bereaved of an adored husband; she is weak, delicate, almost sickly, and yet she has need to live—who else will protect her little child?

“Oh! my lord, there are many unfortunate beings in this world. To be unfortunate in the meridian of life, or when old age is creeping on, is doubtless sad, yet there are then pleasant remembrances which tell us that we have played our part, that we have lived our time, and had our joys. But when tears and sorrow come at eighteen, it is sadder still, for we know full well nothing can revive the dead—all that is left is to weep forever. Poor girl! do we see a beggar by the road-side, it is with cold or hunger that he suffers; we give him charity, and do not think of him with sorrow, since he may be relieved; but the only alleviation that could be tendered to this unhappy being, whose heart is bowed and broken, would be to love her—and there is no one near to do her this charity. Ah! my lord, had you but known the handsome young man who was her husband. Barely twenty-three years old, of a noble form, a high forehead—like your own, intellectual and haughty—with deep blue eyes, somewhat thoughtful—yes, somewhat sad; but I knew the reason—it was that he loved his father, his country, and yet must be banished from both. His smile was full of gentleness. Oh! how he would have smiled on his little child had he lived to see him! Yes, he loved it yet unborn; he even took delight in looking at the cradle destined for it. Poor, unfortunate young man! I saw him on a stormy night, in a dark forest, stretched on the damp ground, motionless, lifeless, his garments covered with mire, and his head crushed with a frightful wound, from which the blood still flowed in torrents. I saw—alas! I saw William—”

“You were present, then, at the death of my son!” cried Lord Kysington, rising like a spectre from the pillows that sustained him, and fixing on me his eyes, so large, so piercing, that I drew back in fear; but in spite of the darkness of the room, I thought a tear moistened the eye-lids of the old man.

“My lord,” I replied, “I saw your son dead, and I saw his child born.”

There was a moment’s silence.

Lord Kysington gazed fixedly on me; at last he made a motion, his trembling hand sought mine and pressed it, his fingers then unclasped, and he fell back exhausted.

“Enough, enough, sir!—I suffer!—I have need of repose. Leave me.”

I bowed and withdrew.

Before I left the room Lord Kysington had resumed his accustomed position, his silence, and immobility.

I will not repeat to you, ladies, my numerous and respectful attempts with Lord Kysington; his indecision, his concealed anxiety, and how, at last, his paternal love, awakened by the details of the horrible catastrophe; how the pride of his house, animated by the hope of leaving an heir to his name, ended in the triumph over a bitter resentment. Three months after the scene I have just described, I stood on the threshold of the mansion to receive Eva Meredith and her son, recalled to their family to resume all their rights. It was a joyful day for me.

Lady Mary, who, possessing great command over herself, had dissembled her joy when family dissensions had made her son the future heir of her brother, now concealed still better her regret and anger when Eva Meredith, or rather Eva Kysington, became reconciled with her father-in-law. Lady Mary’s marble-like brow remained without emotion, but how many dark passions lurked within her breast beneath this apparent calm.

I stood, as I have said, at the threshold when the carriage of Eva Meredith (I will continue to call her by that name) drew up in the court-yard. Eva eagerly gave me her hand. “Thanks! thanks, my friend!” she said, and she brushed away the tears that were trembling in her eyes, and taking by the hand her child, a boy three years old, she entered her new home. “I feel afraid,” she said to me. She was the same weak woman, broken down by misfortune, pale, sad, and beautiful, scarcely believing in the hopes of earth, and whose only certainty was the things of heaven. I walked by her side, and, whilst still dressed in mourning, she was ascending the first flight of stairs, her sweet face bedewed with tears, her slender and attenuated form leaning on the balustrade, and with outstretched arm she drew along the child, who walked still slower than herself, Lady Mary and her son appeared at the head of the staircase. She wore a robe of brown velvet, splendid bracelets encompassed her arms, and a light gold chain girt that forehead which would have graced a diadem. Her step was firm, her form erect, and her glance one of pride; and thus did these two mothers meet for the first time.

“Welcome, madame,” said Lady Mary, as she kissed Eva Meredith. Eva made an effort to smile, and answered in an affectionate manner. How could she have dreamt of hatred, she who only knew how to love.

We proceeded toward Lord Kysington’s cabinet. Madame Meredith could scarcely support herself, but she entered first, and advancing several steps, knelt by the arm-chair of her father-in-law. She took her child in her arms and placing him on Lord Kysington’s knees, said,

“It is his son.” And the poor creature wept in silence.

For a long time did Lord Kysington gaze on the child, and as he recognized the resemblance to the features of his lost son, his look became affectionate, and his eyes grew dim with tears. Forgetting his age, the lapse of time, the misfortunes he had experienced, he fancied the happy days were returned when he pressed that son, yet a child, to his heart.

“William! William!” he sobbed. “My daughter!” he added, extending his hand to Eva Meredith.

My eyes were suffused with tears. Eva had now a home, a protector, a fortune. I was happy and wept.

The child, quietly seated on its grandfather’s knee, had evinced no signs of fear or joy.

“Will you love me?” said the old man.

The child raised his head, but made no reply.

“Do you not hear me? I will be a father to you.”

“Excuse him,” his mother said, “he has always been alone; he is still very young, and so many persons frighten him; he will soon, my lord, understand your kind words.”

But I looked at the child; I examined him attentively; I recalled my sinister alarms. Alas! those forebodings were changed into a certainty; the awful calamity Eva had experienced before the birth of her child, had occasioned sad consequences for her infant; none but a mother, in her youth, and love, and inexperience, could have remained so long in ignorance of her misfortune.

And Lady Mary, too, was watching the child at the same time as minutely as myself.

Never, while life remains, shall I forget the expression of her face; she was standing upright, and her piercing eyes were bent on the little William as though they wished to penetrate his very soul; and as she gazed, lightning seemed to flash from her eyes, her lips parted, as if to smile, her breath came short and oppressed, like that of one anticipating a great joy. She looked with straining eyes—hope, doubt, and eager expectation depicted on every feature; at last her acute hatred guessed the worst, a cry of triumph seemed to have escaped from her inmost heart, but no sound issued from her lips. She drew herself up, cast a glance of disdain on her conquered rival, and once more became impassible.

Lord Kysington, wearied with the emotions of the day, sent us all from his cabinet, and continued alone the whole evening.

The next morning, after a night of disquiet, when I descended to Lord Kysington’s room, all the family were assembled round him; Lady Mary held the little William in her arms—it was the tiger holding its prey.

“The beautiful babe,” said she. “See, my lord, this fair silken hair, how bright the sun makes it look! but, dear Eva, is your son always so silent? He has not the vivacity, nor the gayety belonging to his age.”

“He is always pensive,” said Madame Meredith. “Alas! he could not learn to be gay while near me.”

“We will try to amuse him and make him lively,” returned Lady Mary. “Go, my dear child, and embrace your grandfather, tell him that you love him.”

But William did not stir.

“Do you not know how to embrace? Harry, that’s a good boy, embrace your uncle, and set your cousin a good example.”

Harry sprang on Lord Kysington’s knees, threw his arms about his neck, and said,

“I love you, uncle.”

“Now, my dear William,” said Lady Mary.

But William stood without moving, without even raising his eyes to his grandfather.

A tear stole down Eva’s cheek.

“It is my fault,” she said, “I have not educated him rightly.” And she took William on her lap, while her tears fell fast upon his face; he felt them not, however, but fell asleep on the oppressed bosom of his mother.

“Try,” said Lord Kysington, “to make William less shy.”

“I will endeavor,” she replied, in that child-like tone of submission I had so often heard. “I will try, and perhaps I may succeed, if Lady Mary will tell me what she has done to make her son so happy and gay.” And the wo-begone mother looked at Harry, who was playing by Lord Kysington’s chair, and her glance returned to her own poor sleeping babe.

“He suffered even before his birth,” she murmured. “We have both been very unfortunate; but I will endeavor to weep no more that William may become as other children.”

Two days elapsed, two painful days, full of concealed grief, full of a heavy anxiety. Lord Kysington’s brow was care-worn, and his eyes would seek mine, as though to question; but I turned away to avoid answering.

The morning of the third day Lady Mary entered the room with playthings of various kinds, which she had brought for the two children. Harry laid hold of a sabre, and ran up and down the room, uttering shouts of joy. William stood still; he held in his little hands the toys that were given him, but made no effort to use them, nor even looked at them.

“Stay, my lord,” said Lady Mary to her brother, “take this picture-book and give it to your grandson, perhaps his attention will be attracted by the pictures in it.” And she led William to Lord Kysington. The child made no resistance, but walked up to him, then stood still as a statue.

Lord Kysington opened the book, and every eye was turned upon the old man and his grandson. Lord Kysington was sullen, silent, and austere; he turned over several leaves, slowly stopping at every picture, and keeping his eye on William, whose steadfast gaze was not even directed toward the book. Lord Kysington turned over a few more leaves, then his hand became motionless, the book fell from his knees, and a mournful silence prevailed in the room.

Lady Mary approached me, and leant over, as if to whisper in my ear, but said, in a tone loud enough to be heard by all present, “This child is surely an idiot, doctor.”

She was answered by a scream. Eva rose like one thunder-stricken, and snatching up her son, whom she clasped convulsively to her breast—“Idiot!” she cried, while her glance for the first time flashed with indignation, “Idiot!” she repeated, “because he has been unfortunate all his life; because he has witnessed nothing but tears from his birth; because he cannot play like your son, who has ever been surrounded by happiness! Come! come, my child,” said Eva, and she wept bitterly, “come, let us leave these pitiless hearts, that have nothing but harsh words for our calamities.”

And the unhappy mother took her child in her arms, and quickly ascended to her chamber. I followed her. She placed William on the floor and knelt before that little child. “My son! my son!” she sobbed; William came to her, and leaned his head on his mother’s shoulder. “Doctor,” she cried, “he loves me; you see it; he comes to me when I call him; he embraces me; his caresses have sufficed for my tranquillity, for my happiness, sad as that happiness is. Good God! is not this enough! Speak to me, my son; comfort me; find a consoling word, a single word to tell thy despairing mother. Until now I have only thought of gazing on those features so like thy father’s, and wished for silence that I might weep freely; but now, William, I must have words from thy lips. Dost thou not see my tears, my anguish. Beloved child, so beautiful, so like thy father—speak, oh, speak to me!”

Alas! the child did not heed her, and evinced no emotion, no intelligence; a smile alone—a smile horrible to look upon, played upon his lips. Eva buried her face in her hands, and continued kneeling on the floor, sobbing violently.

O! then I prayed heaven to inspire me with consoling thoughts, which might suggest to this mother a ray of hope. I spoke to her of the future, of a cure to be looked for, of a change that was possible, nay, probable. But hope seldom lends its aid to falsehood; and when there is no longer room for it, it changes to despair. A terrible, a mortal shock had been given, and Eva at last comprehended the whole truth.

From that day but one child descended each morning into Lord Kysington’s cabinet; there were two females, but one only seemed to live, the other was silent as the dead; the one said, “my son,” the other never breathed her child’s name; the one bore herself erect and haughty, the other’s head was ever bowed on her bosom, the better to hide her tears; the one brilliant and beautiful, the other pale, and clothed in mourning, the struggle was over—Lady Mary triumphed. Harry was allowed to play beneath Eva’s very eyes; this was cruel. Her anguish was never taken into consideration; each day Harry was brought to repeat his lessons to his uncle. They boasted of his progress. The ambitious mother had calculated every thing that could insure success; and whilst she had soothing words and feigned consolations for Eva Meredith, each moment she contrived to torture her heart. Lord Kysington, disappointed in his dearest hopes, relapsed into that coldness which had terrified me so much; the last spark of love had fled from that heart, closed now as firmly as the stone seals the tomb. Though strictly polite to his daughter-in-law, he had for her no affectionate word. The daughter of the American planter could find no place in his heart but as the mother of his grandson, and that grandson he regarded as one dead. He was more silent and gloomy than ever, regretting, no doubt, that he had yielded to my entreaties, and given his old age a severe trial, so painful, and henceforth so useless.

A year rolled by in this manner, when, on a mournful day, Lord Kysington sent for Eva Meredith, and motioned her to take a seat near him. “Listen to me, madame,” he said, “take courage, and listen to me. I wish to act justly toward you and conceal nothing. I am old and ailing, and must now attend to my worldly affairs. They are sad both for you and myself. I will not speak to you of my chagrin at my son’s marriage; your misfortune has disarmed me on that point. I sent for you to reside with me; I was desirous to see and love, in your son William, the heir of my fortune; on him were based all my dreams of the future and of ambition. Alas! madame, fate has been cruel to us both. The widow and child of my son shall have all that can obtain them an honorable subsistence, but as the master of a fortune, which I have acquired by my own exertions, I have adopted my nephew; and hereafter shall consider him as my sole heir. I am about to return to London, but my house shall still be your home.”

Eva, (so she afterward told me,) for the first time, felt courage take the place of dejection within her; she possessed that becoming strength a noble spirit gives; she raised her head, and if her brow had not the pride of Lady Mary’s, it wore at least the dignity of misfortune.

“Depart, my lord,” she replied, “go! I shall not accompany you. I will not be a witness to the disinheriting of my son. You have been very hasty, my lord, in condemning forever. What can we know of the future? You have very soon despaired of God’s mercy.”

“The future,” said Lord Kysington, “at my age, is all in the passing hour. If I am to act, there is no time for delay—the present moment is my only certainty.”

“Do as you will,” Eva replied. “I will return to the house where I was happy with my husband. I will remain there with your grandson, Lord William Kysington; this name, his only heritage, he shall retain; and though the world may never know it till it is inscribed on his tomb, nevertheless your name is that of my son.”

Eight days from this time Eva Meredith descended the staircase, still holding her son by the hand as when she first entered that fatal house. Lady Mary was behind, a few steps higher up, and numerous domestics gathered together in melancholy silence, were looking on, and regretting that mild mistress driven from her paternal roof.

In quitting this house, Eva left the only beings whom she knew on earth, the only ones from whom she had the right to claim pity; the world was before her, boundless and void—it was Hagar departing for the desert.

“This is dreadful, doctor!” exclaimed the village doctor’s auditors. “Are there, then, lives so completely miserable—and you too have witnessed them?”

“I did witness all,” said Doctor Barnabé; “but I have not yet told you all, allow me to finish.”

Soon after the departure of Eva Meredith, Lord Kysington started for London. Finding myself once more at liberty, I renounced all desire of improving myself—I possessed enough skill for my native village, and I returned to it immediately.

And again we stood in that little white house, reunited as before this two years’ absence; but the time which had passed had augmented the heaviness of misfortune. We neither of us dared to speak of the future, that unknown time of which we have all so much need, and without which the present moment, if it is joyous, passes by with a transient happiness, if sad, with indelible sorrow.

I have never looked on a grief more noble in its simplicity, more calm in its strength, than that of Eva Meredith. She still implored the God who had stricken her. God was for her the unseen Being who could work impossibilities, near whom we commence to hope once more, when the hopes of earth are fled. Her look, that look replete with faith, which had already attracted my attention so forcibly, was riveted on the brow of her boy, as if awaiting the coming of the soul she so fervently prayed for. I cannot describe to you the courageous patience of that mother, speaking to her son, who heard but understood not. I could tell you all the treasures of love, the thoughts, the ingenious tales she endeavored to instill into that benighted mind, which repeated like an echo the last words of the sweet language spoken to him. She told him of heaven, and God, and of his angels; she joined his hands together that he might pray, but she could never make him raise his eyes to heaven.

She attempted in every possible form the first lessons of childhood; she read to her son, spoke to him, tried to divert him with pictures, and sought from music sounds which, differing from the voice, might attract his attention.

One day, making a horrible effort, she related to William his father’s death; she hoped for, expected a tear. That morning the child fell asleep while she was yet speaking to him; tears were shed, but they fell from the eyes of Eva Meredith.

Thus she vainly exhausted every endeavor in a persevering struggle. She labored on that she still might hope; to William, however, pictures were but colors, and words only noise. Nevertheless the child grew, and became remarkably handsome. Any one to have seen him for a moment only, would have called the passiveness of his features’ calmness; but this prolonged, this continued calm, this absence of all sorrow, of all tears, had upon us a strange and melancholy effect. Ah! it must be in our nature to suffer, for William’s eternal smile made every one say “the poor idiot!” Mothers do not know the happiness which is concealed beneath their children’s tears. A tear is a regret, a desire, a fear—in fine, it is the very existence commencing to be understood. William was content with every thing. In the daytime he appeared to sleep with open eyes; he never hastened his steps, nor avoided any danger. He never grew weary, impatient, or angry; and if he could not obey the words spoken to him, he at least made no resistance to the hand which led him.

One instinct alone remained in this nature deprived of all understanding; he knew his mother—he even loved her. He took pleasure in leaning on her lap, on her shoulder—he embraced her. If I detained him for some time from her, he manifested a kind of uneasiness, and when I conducted him to her, without evincing any signs of joy, he became tranquil again. This tenderness, this faint glimmering of reason in William’s heart was Eva’s support—her very life. Through this she found strength to attempt, to hope, to wait. If her words were not understood, at least her kisses were. O! how often she pressed his head between her hands, and kissed his forehead again and again, as though she had hopes that her love might kindle that cold and silent heart. How often, when clasping her son in her arms, did she almost look for a miracle.

Oft times, in the village church, (Eva was of a Catholic family,) kneeling on the stones, before the altar of the Virgin, forgetting every thing beside, she would hold her son in her arms, by the marble statue of Mary, and say—“Holy Virgin! my son is inanimate as this thy image, O! ask of God a soul for my child.”

She gave alms to all the poor of the village; she supplied them with bread and clothing, saying, “Pray for him.” She consoled suffering mothers in the cherished hope that she, too, might be comforted. She dried up the tears of others, that hers also might cease to flow. She was beloved, blessed, venerated by all who knew her; conscious of this, she offered up the blessings of the unfortunate, not in pride, but hope, to obtain grace for her son. She loved to look upon William when he slept, for then he appeared like other children; for an instant, a single moment, perhaps, she would forget the truth, and gazing on those symmetrical features, on that bright hair, on the long lashes which cast their shade on William’s rosy cheek, she felt that she was a mother almost joyfully, almost with pride. God is often merciful even toward them whom he has decreed shall suffer.

It was thus that William’s first years of childhood were passed. He had now reached his eighth year. Then a sad change came over Eva Meredith, which I could not fail to perceive; she ceased to hope; whether her son’s stature (for he had grown tall) rendered his want of intelligence more apparent, or that, like a workman who has labored all the day, in the evening yields to fatigue, the soul of Eva seemed to have renounced the task it had undertaken, and to have become doubly dejected. She now only prayed to Heaven for resignation. She abandoned books, pictures, music, in fine, all the means she had called to her assistance. She became utterly dispirited and silent, but, if possible, still more affectionate to her son. Having ceased hoping that she could afford him the chance of mixing with the world, of acquiring a position in it, she felt that he had now none but her on earth; and she asked of her own heart a miracle, that of augmenting the love she bore him. The poor mother became a slave—a slave to her son; the whole aim of her soul was to keep him from every suffering, from the smallest inconvenience. If a sunbeam shone on him, she would rise, draw the curtains, and produce shade in the place of the strong light which had made him lower his eyes. If she felt cold, it was for William she brought a warmer garment; was she hungry, for William, too, the garden fruits were gathered; did she feel fatigued, for him she brought the arm-chair and downy cushions; in a word, she only lived to guess his every wish and want. She still possessed activity, but no hope. William arrived at the age of eleven, and then commenced a new epoch in Eva’s life. William, amazingly large and strong for his age, had no longer need of the constant cares that are lavished on the first years of life. He was no longer the child, sleeping on his mother’s lap; he walked alone in the garden; he rode on horseback with me; he followed me willingly in my mountain trips; the bird, though deprived of wings, had at last quitted its nest.

William’s misfortune had in it nothing frightful nor even painful to look on. He was a young boy, beautiful as the day, silent and calm—a calmness not belonging to earth, whose features expressed nothing but repose, and whose face was ever smiling. He was neither awkward, nor disagreeable, nor rude; a being living by your side without a question to ask, and who knew not how to answer one. Madame Meredith had not now, to occupy her grief, that need of activity which the mother, as a nurse, always finds; she again seated herself by the window, whence she could see the hamlet and the village spire, on the very spot where she had mourned so deeply for her first William. She turned her face to the exterior air, as though asking the wind which breathed through the trees to refresh her burning temples also.

Hope, necessary cares, each in turn vanished, and now she had only to be vigilant, to watch at a distance, day and night, as the lamps which burn forever beneath the church vaults.

But her strength was exhausted. In the midst of this grief, which had returned when on the point of being healed, through silence and want of occupation, after having vainly tried every effort of courage and hope, Eva Meredith fell into a consumption. In spite of the resources of my art, I saw her weaken and waste away; for what remedy can be given when the disease is of the soul?

Poor stranger! the sun of her own clime, and a little happiness might have restored her; but there was no ray of either for her. For a long time she was ignorant of her danger—for she had no thought of self; but when she could no longer leave her arm-chair, it became apparent even to herself. I could not depict to you her anguish at the thought of leaving William, helpless, with no friends or protector, among such as could not find an interest in him, who should have been loved, and led by the hand like a child. Oh! how she struggled to live! with what eagerness she drank the potions I prepared for her! and she fondly believed in a cure—but the disease progressed. And now she detained William in the house more frequently; she could not bear him to be out of her sight. “Stay with me,” she would say; and William, always contented by his mother’s side, seated himself at her feet. She would gaze on him till a torrent of tears prevented her from distinguishing his gentle form, then she beckoned him still nearer, folded him to her heart, and exclaimed in a species of transport, “O! if my soul, when separated from my body, could enter into that of my child, I could die with pleasure!”

Eva could not persuade herself to despair entirely of the divine mercy; and when every earthly hope had vanished, her loving heart had sweet dreams on which she built new hopes. Good God! it was sad to see that mother dying beneath the very eyes of her son—of a son who could not comprehend her situation, but smiled when she embraced him.

“He will not regret me,” she said, “he will not weep for me, perhaps not even remember me.” And she sat motionless, in mute contemplation of her child, her hand then sometimes seeking mine. “You love him, my friend?” she murmured.

And I told her that I would never leave him till he had better friends than myself.

God in heaven, and the poor village doctor, were the only protectors to whom she confided her son.

Truth is mighty! this widowed being, disinherited, dying by the side of a child who could not even appreciate her love, felt not yet that despair which makes men die blaspheming. No, an invisible friend was near her, whom she seemed to depend on, and would often listen to holy words that she alone could hear.

One morning she sent for me early; she was unable to leave her bed, and with her shrunken hand she pointed to a sheet of paper, on which some lines were traced.

“Doctor, my friend,” she said, in her sweetest tone, “I had not the strength to go on, will you finish the letter?”

I took it up, and read as follows—

“My Lord,—This is the last time I shall ever write to you. Whilst health is restored to your old age, I am suffering and dying. I leave your grandson, William Kysington, without a protector. My lord, this letter is written to remind you of him, and I ask for him rather a place in your affections, than your fortune. Throughout his life he has understood but one thing—his mother’s love; and he must now be deprived of this forever! Cherish him, my lord; he only comprehends affection.”

She had not been able to finish; I added,

“Lady William Kysington has but a few days to live; what are Lord Kysington’s orders in regard to the child who bears his name?

“Dr. Barnabé.”

This letter was sent to London, and we anxiously awaited the answer. Eva never after rose from her bed. William, seated beside her, held his mother’s hand in his the livelong day, and she sadly endeavored to smile on him. On the opposite side of the bed I prepared draughts to mitigate her pain.

She again began to speak to her son, still in hopes that after her death some of her words would recur to his memory. She gave him every advice, every instruction that she would have lavished on the most enlightened being; and turning to me, she would say—“Who knows, doctor, perhaps some day he will find my words in the depths of his heart.”

Some weeks more slipped by. Death was approaching, and however submitted her soul might be, this moment brought the anguish of separation, and the solemn thought of futurity. The curate of the village came to see her; and when he left her, I drew near him, and taking his hand, said, “You will pray for her?”

“I asked her,” he replied, “to pray for me.”

It was the last day of Eva’s life. The sun had set, the window near which she had sat so often, was open. She could see in the distance the spots which had become endeared to her. She clasped her son to her heart, kissing his brow, and his locks, and wept.

“Poor child!” said she, “what will become of you?” and with a final effort, while love beamed from her eyes, she exclaimed, “O! listen to me, William; I am dying—your father, too, is dead; you are now alone on earth—but pray to God. I consign you to Him, who provides for the harmless sparrow on the house-top, He will watch over the orphan. Dear child! look on me—speak to me! Try to comprehend that I am dying, that some day you may think of me!” And the poor mother lost her strength to speak, but still embraced her child.

At that moment an unaccustomed noise aroused me. The wheels of a carriage were rolling over the gravel of the garden-walks. I ran to the steps. Lord Kysington and Lady Mary alighted, and entered the house.

“I received your letter,” said Lord Kysington to me. “I was on the point of leaving for Italy, and I have deviated from my route somewhat in order to decide the fate of William Meredith. Lady William?”

“Lady William Kysington still lives, my Lord,” I answered.

It was with a feeling of pain that I saw that calm, cold, and austere man enter Eva’s chamber, followed by that proud woman, who had come to witness an event so fortunate for herself—the death of her former rival.

They went into the little chamber, so neat and plain, so different from the gorgeous apartment of the mansion at Montpellier. They approached the bed, within the curtains of which Eva, pale and dying, yet still beautiful, held her son folded to her heart. They stood on either side of that bed of sorrow, but found no tender word to console the unfortunate being whose eyes met theirs. A few cold sentences, a few disconnected words escaped their lips. Witnesses, for the first time, of the mournful spectacle of a death-bed, they averted their eyes, in the belief that Eva Meredith could not see nor hear; they were only waiting till she should expire, and did not even assume an expression of kindness or regret.

Eva fixed her dying gaze upon them, and a sudden effort seized upon her almost lifeless heart. She now understood that which she never before suspected—the concealed sentiments of Lady Mary, the profound indifference, the selfishness of Lord Kysington. She at last felt that these were her son’s enemies, not his protectors. Despair and terror were depicted on her wan, emaciated countenance. She made no effort to implore the soulless beings before her, but with a convulsive impulse, she drew William still closer to her heart, and gathering her little remaining strength, she cried, while she impressed her last kisses on his lips, “My poor child! thou hast not a single prop on earth; but God above is good. O, God! come to the assistance of my child!” And with this cry of love, with this last, holiest prayer, her breath fled, her arms unclasped, and her lips remained fixed on William’s brow. She was dead, for she no longer embraced her son—dead! beneath the very eyes of those who to the last had refused to protect her—dead! without giving Lady Mary the fear of seeing her attempt, by a single supplication, to revoke the decree which had been pronounced, leaving her a lasting victory.

There was a pause of solemn silence; no one moved or spoke—for death appals the proudest hearts. Lady Mary and Lord Kysington knelt by the bed of their victim.