Title: The Story of Man In Yellowstone

Author: Merrill D. Beal

Release date: March 18, 2019 [eBook #59092]

Most recently updated: January 25, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Greetings from Wonderland Park Naturalist Merrill D. Beal

THE STORY

of

MAN IN YELLOWSTONE

REVISED EDITION

THE YELLOWSTONE LIBRARY AND MUSEUM

ASSOCIATION

Yellowstone Park, Wyoming

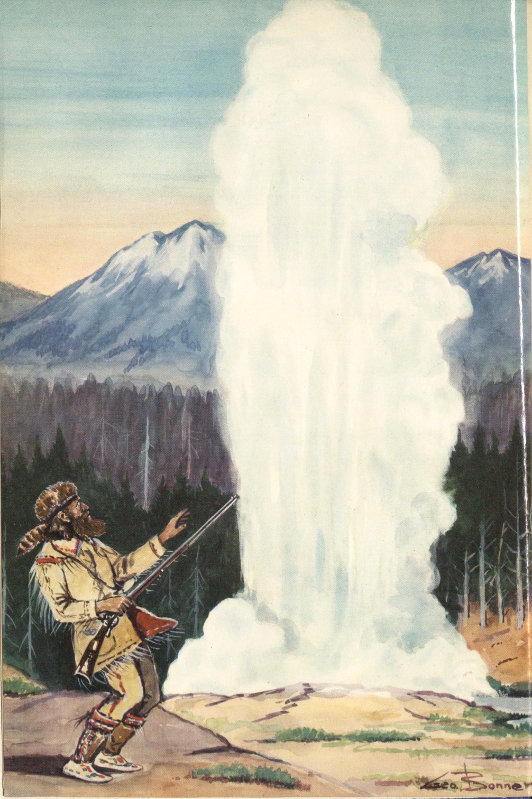

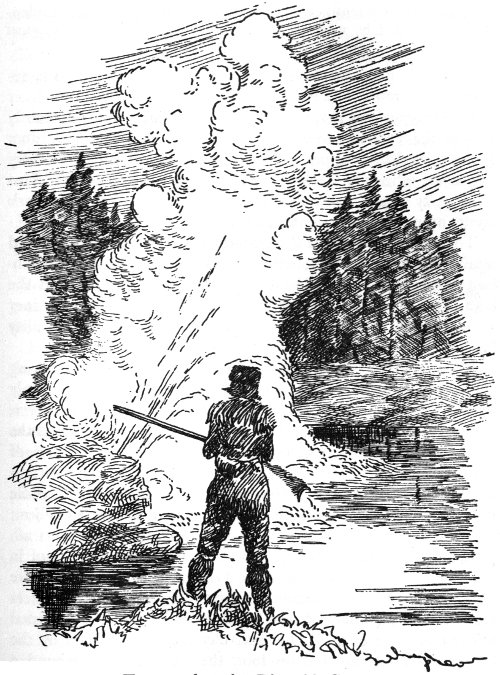

A Yellowstone geyser in action

By

MERRILL D. BEAL

Seasonal Park Naturalist,

Yellowstone National Park;

Professor of History,

Idaho State College

Approved by the National Park Service

Yellowstone Interpretive Series

Number 7

Revised Edition

Illustrated

1960

Published By

The Yellowstone Library and Museum Association

Yellowstone Park, Wyoming

Copyright, 1949

By The Caxton Printers, Ltd.

Caldwell, Idaho

Copyright, 1956

By The Yellowstone Library and

Museum Association

Yellowstone Park, Wyoming

Copyright, 1960

By The Yellowstone Library and

Museum Association

Printed and bound in the United States of America

by the WHEELWRIGHT LITHOGRAPHING COMPANY,

Salt Lake City, Utah

To

The men in the National Park Service Uniform, protectors and interpreters of Yellowstone. Indeed, to all National Park Service personnel and others who subscribe to the purposes for which the area was reserved.

This book is published by the Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, a non-profit organization whose purpose is the stimulation of interest in and the furtherance of the educational and inspirational aspects of Yellowstone’s history and natural history. The Association cooperates with and is recognized by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior, as an essential operating organization. It is primarily sponsored and operated by the Naturalist Division in Yellowstone National Park.

As one means of accomplishing its aims the Association has published a series of reasonably priced books and booklets which are available for purchase by mail throughout the year or at the museum information desks in the park during the summer.

| Number | Title and Author |

|---|---|

| 1. | Wild Animals of Yellowstone National Park by Harold J. Brodrick |

| 2. | Birds of Yellowstone National Park by Harold J. Brodrick |

| 3. | Yellowstone Fishes by James R. Simon |

| 4. | The Story of Old Faithful Geyser by George D. Marler |

| 5. | Reptiles and Amphibians of Yellowstone National Park by Frederick B. Turner |

| 6. | Yellowstone’s Bannock Indian Trails by Wayne F. Replogle |

| 7. | The Story of Man in Yellowstone by Dr. M. D. Beal |

| 8. | The Plants of Yellowstone by W. B. McDougall and Herma A. Baggley |

Orders or letters of inquiry concerning publications should be addressed to the Yellowstone Library and Museum Association, Yellowstone Park, Wyoming.

Yellowstone National Park lives as a cherished memory in the minds of millions of people. Greater still is the number who anticipate a visit to this Wonderland. To nearly all, the Park stands as a symbol of the enrichment of the American way of life. And well it might, because it is a geological paradise, a pristine botanical garden, and an Elysium for wild game. But most important of all, it is a place of recreation for countless thousands who come to find a temporary escape from the pressure of a highly artificial life. Thoughtful people assent to the opinion of Wordsworth:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. —Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathed horn.

After many years of indifference to the claims of nature, the American people are coming into accord with the wise teachings advanced by John Muir more than fifty years ago. Today, legions 8 of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people realize that going to the mountains is like going home. They have found a brief sojourn in the wilderness a necessity of life. There is a balm in the sun, wind, and storm of mountain heights. There is healing in willow parks and gentian meadows. Cobweb cares of the world’s spinning give way before the vibrant touch of Mother Earth when her children venture boldly into unbeaten paths. There they may attune their ears to strange sounds; their lungs respond to pine sap air. Jumping from rock to log, tracing rivers to their sources, brings men up from panting puffs to deep-drawn breath in whole-souled exercise unto a newness of life.

The story of Yellowstone has been told many times, but seldom does one catch that elusive something that so mightily impresses the sensitive visitor. The theme is at once so inspiring and grand, the details so varied and minute, as to challenge one’s finest discrimination to seize upon the major features and bring them into relief. There is still much that is primitive in Wonderland, and in this setting it is appropriate to envision the salient traits of the Old West. Hereabouts was once enacted a colorful panorama of frontier life. There were Indians, trappers, miners, cowboys, rustlers, poachers, soldiers, and settlers. A description of these picturesque people and their ways might bring enjoyment to many. Perhaps the spirit of appreciation that characterizes this history is its chief claim upon the attention of Yellowstone visitors.

This monograph was written for them, and it represents a synthesis of many lectures that evolved in their presence, in the afterglow of Yellowstone campfire programs. Visitors whose enjoyment of life seems particularly enhanced by a visit to the Park may find the reason therefore in those lines:

One impulse from a vernal wood

May teach you more of man,

Of moral evil and of good,

Than all the sages can.

—WORDSWORTH

In the interest of economy of time in reading this history, it is suggested that chapters three, four, and ten might be skimmed. However, a knowledge of the Indians and trappers whose haunts and activities impinged upon the Park area is essential to a full appreciation of Yellowstone National Park in its western setting.

Former Superintendent Edmund B. Rogers and Park Naturalist David de L. Condon gave me access to the records of the Park. Their interest in advancing the knowledge of Yellowstone has been keen and constant.

My Yellowstone Park ranger-colleagues also served as sources of information and occasional critics. It is probable that each of them will be able to identify an element of his own thought or expression in the narrative. As my campfire lectures evolved into a unified monograph, guidance was received from professional historians. They have been more critical than the rangers but not less kind.

At the State College of Washington, Dr. Herman J. Deutsch and Dr. Claudius O. Johnson made the college’s Northwest Collection available. They also joined their colleagues, Dr. W. B. Thorson and Dr. C. M. Brewster, in making many fine and comprehensive criticisms, which combined to strengthen the narrative. Several of my colleagues at Idaho State College gave direction and increased purpose to the discussion of conservation and wild life principles. They are Dr. Ray J. Davis, Albert V. S. Pulling, and DuWayne Goodwin. Dr. Carl W. McIntosh, president of the college, has extended many courtesies. Professor Wallace E. Garets edited the manuscript.

Former Yellowstone National Park Naturalist, Dr. C. Max Bauer, gave encouragement from the inception of the study and reviewed the final draft. Other National Park officials from 12 whom wise council and valuable suggestions were received include Dr. Carl P. Russell, former National Park Supervisor of Interpretation, and Dr. Alvin P. Stauffer, Chief of Research and Survey. The collaboration of J. Neilson Barry was invaluable in the exposition of the discovery phase in the chapter on John Colter. J. Fred Smith, Delbert G. Taylor, and Mr. and Mrs. George Marler have also given material support to this effort.

The illustrations are principally the work of William S. Chapman, North District Ranger.

The support of Yellowstone Park Superintendent Lemuel A. Garrison and Chief Park Naturalist Robert N. McIntyre in bringing forth this Third Edition under the auspices of The Yellowstone Library and Museum Association is indeed appreciated.

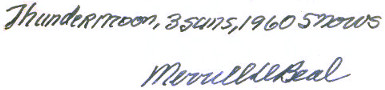

Lastly, gratitude is due my wife, Bessy N. Beal, and our son, David, and his wife, Jean, for the typing of the manuscript and for the rendering of much additional service to this enterprise. MERRILL D. BEAL

IDAHO STATE COLLEGE

POCATELLO, IDAHO

June 10, 1960

It is interesting and significant that this book, telling the story of man in the area of our oldest National Park, should be available soon after a season of record-breaking public use of the area. During the travel year 1948, one million thirty-one thousand five hundred and thirty-one people visited Yellowstone National Park.

The discoverer of The Yellowstone Country early in the nineteenth century, and re-discoverers through the years prior to 1872, as well as all visitors to the Park before the advent of modern highways and automobiles probably gave no thought to the reality and problems of a million visitors a year.

Dr. Beal’s well documented and carefully prepared book brings us through the history of man in a wilderness, through that period of history before annual visitation of a million visitors in that wilderness. Readers will find the story of the before-one-million-visitors-years most interesting. It is a period, especially since the establishment of the National Park in 1872, in which we as a nation were experimenting for the most part in wilderness preservation and, at the same time, encouraging its use. Dr. Beal’s book covers a period in U.S. history when shameful exploitation of natural resources was common practice. The preservation of The Yellowstone Country as a National Park is an action during the period of exploitation, an action of which we can all be proud. The story of man in Yellowstone is a fascinating one. It can also be a challenge to everyone to assume responsibility 14 in continued preservation of Yellowstone National Park so that future generations may benefit from all of the things that unimpaired natural areas can offer by way of recreation, education, and inspiration.

JOHN E. DOERR Former Chief Naturalist, National Park Service

O, give me a bit of the great outdoors

Is all that I ask of you,

Where I may do whatever I like

And like whatever I do.

Where the sky is the boundary up above

And the earth is the measure below,

And the trail starts on where the sun comes up

And ends where the sun sinks low.

Where the wind blows sweet as a baby’s breath,

And the sun shines bright as its eyes,

And the showers come and the showers go

As the tears when the little one cries.

And the brook runs merrily through the glade,

Singing its gladdening song,

And the pine trees murmur their soothing sighs,

Still bearing that song along.

Yes, carry me back to the lake’s white shores

With its deer and its lily pad.

Where the loon calls out into the moonbeams bright

Through the mist on the waters sad.

Let me hear the elk’s far cry

As it sweeps through the forest deep,

Where the silence hangs as over the dead

At rest in eternal sleep.

I’ll pitch my tent by some lonesome pine,

By the rippling water’s edge,

With the great outdoors as my garden,

And the willows round as my hedge.

And surrounded by pretty flowers,

That perfume the gentle breeze,

I’ll idle away the whole long day,

In the shade of my old pine trees.

And I’ll watch on yonder mountain

The colors change with the day,

And I’ll follow each shadow creeping

So silently on its way.

And then I’ll give thanks to God above

And in gratitude I’ll pause,

And I’ll love, not hate, each care that comes

In that great big home—Outdoors.

—FRANK L. OASTLER

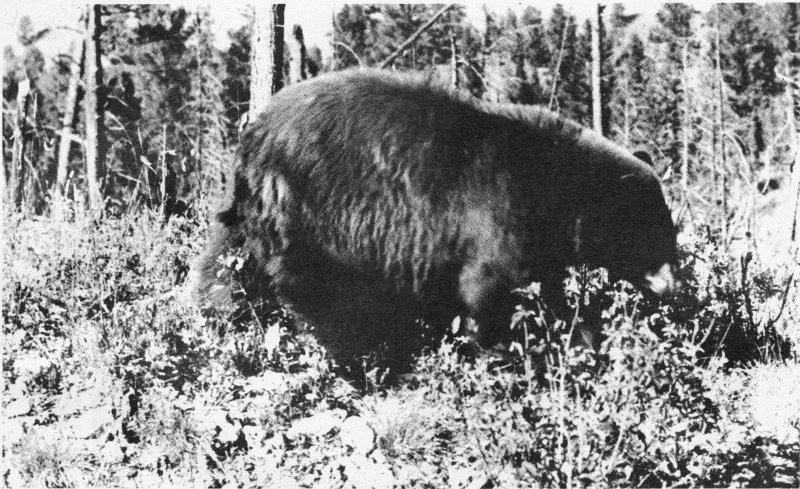

Yellowstone National Park was one of the last regions in the United States to come into the scope of man’s knowledge. This fact is partly responsible for its development as a wild animal retreat. Grizzlies and people do not go well together under natural conditions. Yet nature has bequeathed a rare portion of her treasure upon this enchanting land that forms the crown of the Rockies. Within the confines of what the world calls Yellowstone the visitor may find great and wondrous manifestations of natural handiwork. Indeed, nature seems to have indulged in several grand orgies of creation. Here are lofty mountain majesties and shining rivers of silver and green wind athwart the heights and plateaus like living, breathing things. Everywhere the air is pierced by lodgepole pines. Erect they stand, bristling with fierce determination, while prone beneath their feet lie their uprooted brethren in tangled disorder and various degrees of decay.[1]

The whole plateau is dotted by myriad alpine lakes of surpassing beauty. Surely it is comparable to a vast sponge which receives a five-foot mantle of snow annually. From this precipitation sufficient water is derived to feed a legion of springs and streams. “The altitude renders it certain that winter comes early and tarries 24 late; in fact, it is almost always in sight and liable to drop in any day.”[2]

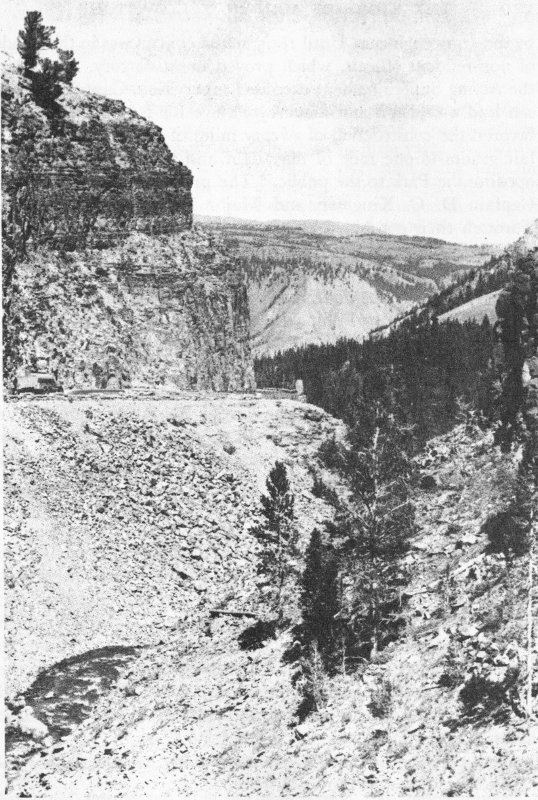

Deep and delicately etched canyons involuntarily shock the visitor as he views their kaleidoscopic grandeur. Massive mountains display their mighty ramparts in a silhouette that is unmistakable and unforgettable. Indeed, some of these serrated spires once served as pilots to the wayfarer; and Indians named them “Pee-ah,” meaning large and permanent.[3] So are they still, mute testaments of the ages.

Surely such an impressive alternation of rivers, forests, lakes, canyons, and mountains is in itself complete. Someone has said, “Yellowstone has everything except a cave and a glacier.” Actually, there are caves and glaciers in the Park’s environs, but the most unique feature of all this Wonderland is its thermal activity. Thousands of hot springs and hundreds of geysers reveal strange secrets of the inner earth. Mammoth Hot Springs Terraces represents the actual process of a mountain turning inside out.

Yellowstone Park is roughly located between longitude 110° W. and 111° W. and latitude 44° N. and 45° N. In respect to Wyoming, the Park is located in the northwestern corner, encroaching slightly upon Montana and Idaho. The area comprehends three thousand, four hundred and seventy-two square miles, and the average elevation is eight thousand feet above sea level. Occupying a central portion of the Rockies’ greatest girth, the Park’s scenic position is most strategic. From the top of Mt. Washburn a majestic rock-ribbed panorama is disclosed. It is indeed a vast area, surrounded by lofty mountain ranges, some of whose towering peaks are reflected in Lake Yellowstone. This comprehensive view reminds one of a gigantic amphitheatre or, from another angle, a colossal orange juicer with the Yellowstone 25 River as its spigot. At the river’s outlet from the Park at North Gate the elevation is five thousand, three hundred and fourteen feet above sea level, whereas the maximum height of eleven thousand, three hundred and sixty feet is achieved on the summit of Eagle Peak on the southeastern boundary.[4] Cartographers have segregated the most conspicuous elevations into seven plateaus, three ranges, four ridges, and several minor units of mountains and hills.[5] Thirty-two mountain peaks loom above the ten-thousand-foot level, and another six exceed the eleven-thousand-foot scale.[6]

The Continental Divide winds among the Park’s southern plateaus in the manner of a serpent. From these circumstances, Yellowstone Park has become truly the wondrous land of water and the source of that life-giving liquid to lands hundreds of miles away in all directions. Nowhere else does water so well display its varied charms. From the Divide’s snowy, timber-rimmed pockets, icy rivulets flow into sylvan pools, thence to rushing rivers with thundering waterfalls. Other water issues from steaming vents and towering geysers connected with the earth’s internal heat and weaves vaporous trails into streams called warm or fire rivers.[7]

Great rivers have their origins in its alpine parks, from whence they follow their devious courses to the several seas. Oh, the rivers of Wonderland, what strength and beauty they possess! There 26 is the Yellowstone itself, arising upon Yount’s Peak and its vicinity among the high Absarokas. It rolls northward through that vast lake of limpid blue referred to by the natives as “the smile of the Great Spirit.” From the famous Fishing Bridge outlet it flows tranquilly again beyond Hayden Valley, but soon it flashes into milk-white cascades, a transitional phase of noisy preparation for its two great falls. These awe-inspiring plunges are one hundred and nine and a sheer three hundred and eight feet, for the Upper and Lower Falls respectively. At each point the river’s mighty volume sets up an awful tumult of sound, earth tremor, and spray in the immediate environs. The river’s pulsating reverberation seems to follow its imprisoned rush along a tortuous path for many miles toward the Missouri.

Another stream arises in the southeast corner of the Park that possesses equal might and great utility. By the natives it was known as “Pohogwa,” or river of the sagebrush plains. The French called it La Maudite Riviere Enragee, meaning accursed, mad river, but American frontiersmen renamed it the Snake.[8] The latter name lacks something of the romance in the others but aptly describes this stream which everywhere exhibits some characteristic of reptilian behavior.

Two other interesting rivers arise in the Park and join a third a hundred miles beyond the northwest boundary of Yellowstone. The Madison’s tributaries derive from meadowlands beyond Upper Geyser and Norris Geyser basins.[9] The Madison is a moss-bottomed stream with lusty aquatic life. The Gallatin, which heads in the range of the same name, has a dashing manner. It has carved its way among forests both living and petrified. Each river follows a parallel course until they merge with the Jefferson at Three Forks. As the triumvirate roll away together, one remembers 27 the unity and friendship that characterized the three men for whom they were named.

Other sinuous streams are the tuneful Bechler, laughing Lamar, and sculpturing Shoshone. These streams possess attractions that appeal to fishermen, hikers, photographers, and artists. In Yellowstone, the two-ocean-drainage courses are almost as intricate and snug as a child’s hands folded in prayer. At either Isa Lake, or Two Ocean Pass, a pebble tossed in one stream would start vibrations upon the “water-nerve endings” of Atlantic and Pacific river systems. In fact, the Yellowstone country is the apex of North America; it is essentially the Great Divide.

Yellowstone’s summer climate is invigorating and delightful. Frequent, but fleeting, rainstorms tend to modify the prevailing atmospheric aridity. Evenings and nights are invariably cool. The highest temperature ever recorded at Mammoth was 92.4°, while the lowest on record was 66° below zero. This record low was taken at Riverside Station near West Gate on February 9, 1933.[10]

Such is the physical setting of this mountainous country. Its western slope was called the land of “Ee-dah-how.” This was a Shoshone exclamation that means “Behold! the sun is streaming down from the mountain tops; it is sunup, time to get up!”[11]

It is expedient that a brief review of early American history should be given as a setting for the major interests in the drama of Yellowstone. The history of Wonderland falls logically into three periods: Archaeological characteristics and association; Modern discovery and exploration; Development as a pleasuring ground by the United States Government.

The greater part of the Yellowstone area was a part of the Louisiana Purchase, whereas that portion under the Snake River drainage appertained to the great Pacific Northwest. All of the territory involved once belonged to Spain. However, the Spanish 28 claim was relinquished in a series of treaties beginning with San Ildefonso in 1800, wherein the province of Louisiana was retroceded to France under the dictation of Napoleon Bonaparte. The balance of Spanish interests above the forty-second parallel was extinguished in favor of the United States in 1819.

American acquisition of Louisiana from France grew out of several considerations. The frontiersmen of the Ohio Valley were chafing under foreign commercial restrictions at New Orleans. The officials of the government were distressed at the prospect of having the strong-willed Napoleon as a neighbor. President Jefferson cogently expressed the general concern by saying, “... from this moment we must marry the British fleet and nation.”[12] However, the alarm was soon dispersed by an eminently successful negotiation. Jefferson had instructed Robert Livingston, the American Minister to Paris, to buy New Orleans and West Florida. The early part of the spring of 1803 found Napoleon hard pressed for money and disgusted with native resistance against his government in Haiti, led by the remarkable Negro, Toussaint L’Ouverture, whom Bonaparte called the “gilded African.” By March, Napoleon realized that the Peace of Amiens was about to be ruptured and war with England resumed. In these circumstances he decided to dispose of his American holdings. This notable decision was effected while His Imperial Majesty was taking a bath. Consequently it was one of the cleanest decisions that he ever made! It was then that the “Little Corporal” directed J. M. Talleyrand to say, “What would you give for the whole of Louisiana?”[13] Livingston, who was a trifle deaf anyway, could hardly believe what he heard. After some parleying the deal was closed by Livingston and Monroe for $15,000,000; of this amount $3,750,000 was diverted to American citizens to meet private claims against the French government. Livingston showed prophetic 29 insight when he said to Monroe, “We have lived long, but this is the noblest work of our whole lives....”[14] More than a dozen states have been carved out of the 827,987 square miles. It is probable that Old Faithful Geyser alone is worth far more than the original purchase price, should good taste allow an assignment of monetary value to such a natural wonder.

Notwithstanding the marvels of this alluring land, Yellowstone lay dormant, forbidding and inhospitable, until the last quarter of the nineteenth century. Why was its call to conquest so long unheeded? Seldom has an area so long ignored made such a phenomenal rise to fame. The answer to this question is fully explored in this narrative.

It is a fairly well-attested fact that America was first discovered by Leif Ericsson about 1000 A.D.[15] However, as Mark Twain put it, “America did not stay discovered,” and therefore Columbus is not to be denied. So it was with Yellowstone. The most significant feature of its early history lies in the inconclusive nature of the early reports concerning its position and character.

Yellowstone’s isolation was not effectively invaded and broken until the decade of 1860. This narrative will explain how early, trapper observations drifted into oblivion, and later, miner excursions faded into indifference. Hence, the first conclusive visitations were those made by the Folsom-Cook party in 1869 and the Washburn-Langford-Doane Expedition of 1870. Why did Wonderland remain unknown to the world so long? Surely the answer is found in its relative inaccessibility. Yellowstone is a sequestered region, mountain-locked by the Absaroka, Teton, Gallatin, Beartooth, and Snowy ranges. Here, then, is a plateau a mile and a half above sea level, encircled by a still loftier quadrangle of rocky barriers. Some of these culminate in peaks and ridges that rise 4,000 feet above the level of the enclosed table land.

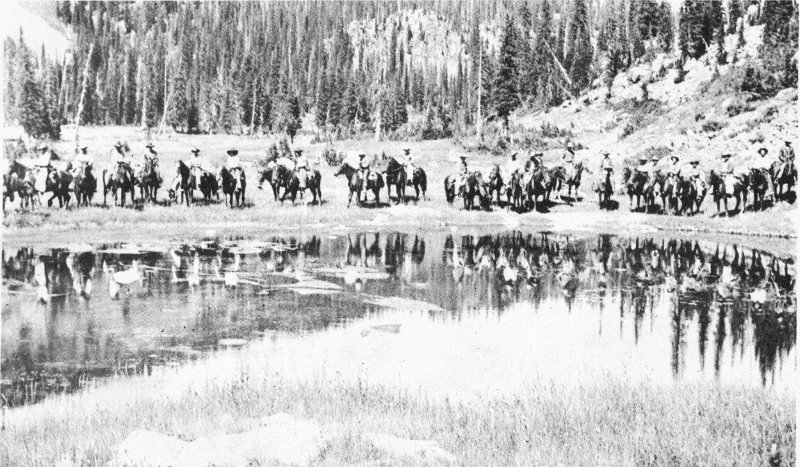

Of course there were a few yawning, ever-difficult canyon approaches, 31 cut by foaming mountain torrents and several high, snow-choked passes suitable for late summer use. However, they were far removed from the principal arteries of pioneer travel, and they still remain apart from the main avenues of trade. Even now, these same bulwarks of nature, and their concomitants of snow and wind, exclude traffic from the region for half the year. Consider, then, the situation when all travel was on foot or horseback, and bases of supply were far away from all approaches to this mountain crown. Adequate mountain exploration necessitated large parties and elaborate outfits in the middle nineteenth century.

From these circumstances it is easy to understand why Lewis and Clark missed Yellowstone. They adhered quite closely to the Missouri River thoroughfare. However, as an incident of an extensive side trip on their return, Clark and a detail of ten took an alternate route that eventually brought them upon the Yellowstone River near the present site of Livingston, Montana.[16] Previously, while at Fort Mandan, they had learned that the Minnetaree Indian name for the river was “Mitsiadazi,” which means Rock Yellow River. The French equivalent, Roche Juane, was also in common use among the Indians and trappers, although when or by whom the name was given is unknown. American trappers called the river “Yallerstone!” A segment of the stream was trapped in 1805 by Antoine Larocque’s party of North West Company trappers. They struck the river at a point twenty trapping days above its mouth, which was reached on September 30.[17]

The fact of the name’s currency is further attested by Patrick 32 Gass’ significant journal entry on July 1, 1806: “Perhaps Capt. Clarke [sic] who goes up the river here, may also take a party and go down the Riviere Juane, or Yellowstone River.”[18] Beyond the Indian stream names, little information concerning the area was ascertained by Lewis and Clark at that time.

While Lewis and Clark did not add any knowledge of Yellowstone Park to their epic-making report, still it was a member of the party who first viewed its exotic beauty. However, before delineating Colter’s discovery, the picture of the Park’s isolation should be explored further.

The first thrust toward the Yellowstone country was made by the French explorer de Verendrye, who came near the northeastern border in 1743 when he crossed the lower Yellowstone River, leaving Wonderland still undiscovered.[19]

By 1810, the Missouri Fur Company established posts on the mouths of the Bighorn and at Three Forks of the Missouri. Notwithstanding these locations, there was little penetration of the “top of the world,” as the Crow Indians called the Yellowstone country. Blackfoot Indian hostility forced the abandonment of the post at Three Forks and in the fall of 1810, Major Andrew Henry, one of the partners, led a small party into the Pacific Ocean drainage. They went up the Madison River, thereby skirting the Gallatin Range which bounds the Park on the west. They crossed a low pass and came upon a beautiful lake. Henry’s name was given the lake (Henrys Lake) and also to its outlet (Henrys Fork of the Snake River), which they followed about forty miles below its debouchment into Snake River Valley. In a pleasant spot some four miles below the present St. Anthony Falls they erected Fort Henry, but they did not prosper there and, feeling discouraged and insecure, abandoned that post. In 1811, Henry released his trappers, and while they returned to the east by various routes all of them missed the Yellowstone region.[20]

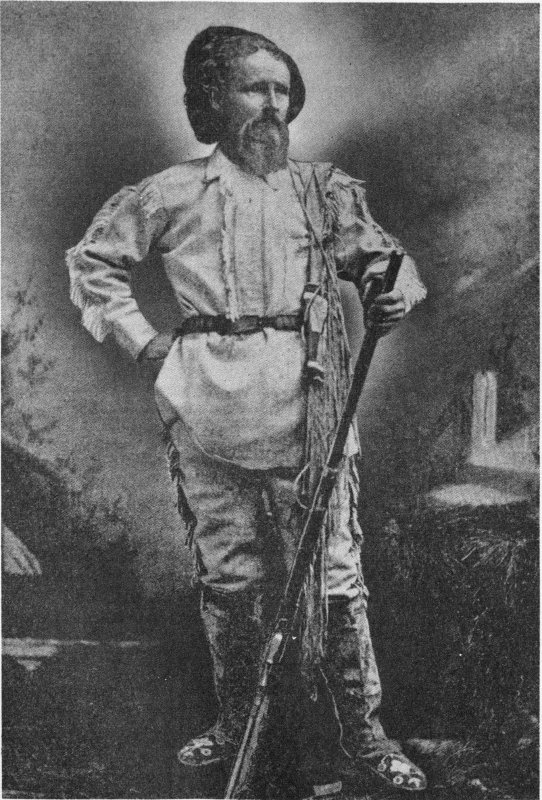

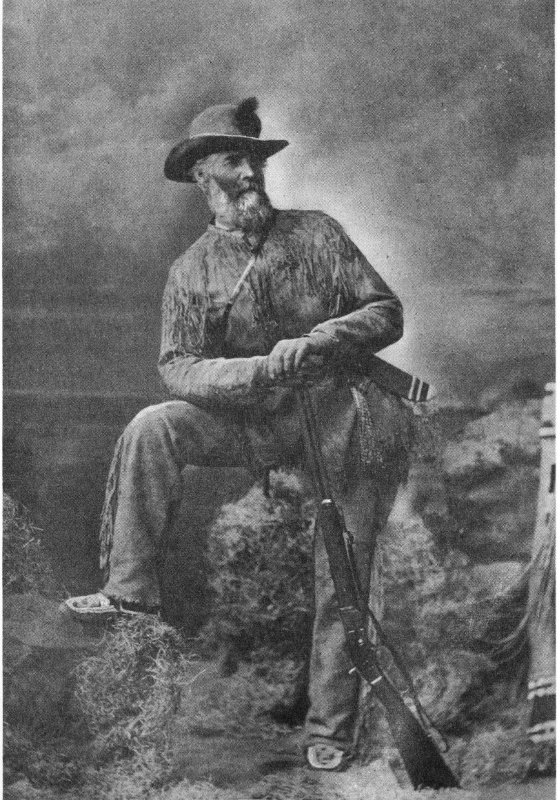

W. S. Chapman

Sacajawea with Lewis and Clark.

As Henry’s men circled eastward a much larger expedition was threading its course between the Wind River Mountains and the Tetons. In 1811, Wilson Price Hunt led the “Overland Astorians,” a band of sixty trappers, toward the Pacific. They reached Henry’s deserted post early in August. It is probable that a member of this party inscribed a rock “calling card” that reads: “Fort Henry 1811 by Capt. Hunt.” This marker is now included in the historical collections of the Yellowstone Park museums. It was found at the fort site in 1933 and donated to the museum by Seasonal Park Ranger-Naturalist Merrill D. Beal.[21] Hunt’s party unfortunately decided to switch from horses to hurriedly-made canoes, which were launched upon Snake River near the fort. The hardship, privation, and recurring peril experienced by this band are among the most severe ever encountered by civilized men. Although they were obliged to separate into three groups in order to subsist each part finally reached the mouth of the Columbia. In 1812, a smaller party called the “Returning Astorians,” under Robert Stuart, probably discovered South Pass.[22]

Notwithstanding the extensive peregrinations of these splendid wayfarers, Lewis and Clark, Andrew Henry, and Wilson Price Hunt, Wonderland, large though it is, remained a place 35 apart. Only one white man had been sufficiently venturesome to gain entrance into the enchanted land.

John Colter was the son of Joseph and Ellen Shields Colter. He was born in or near Staunton, Virginia, probably in 1775.[23] Little is known of Colter’s youth except that the family moved from Virginia to the vicinity of Mayville, Kentucky, when he was about five years old. As John grew to manhood it is evident that he possessed a restless urge to be in the wilderness. An unparalleled opportunity to satisfy this desire came upon the arrival of Captain Meriwether Lewis on his voyage down the Ohio River. From this contact Colter joined the Lewis and Clark Expedition at Louisville, Kentucky, on October 15, 1803.[24] The following spring they were on their way up the Missouri. Doubtless he was already experienced in woodcraft and the use of firearms. Strong, active, and intelligent, he soon won the rank and privileges of a hunter.

Colter’s fitness for the business of exploration was early recognized and universally accepted.[25] For two years he shared the expedition’s many trials and triumphs, but they had obviously failed to satisfy his desire for adventure. Before the explorers returned, intrepid fur traders were moving westward along the great Missouri artery as was their custom. Two Illinoisans, John Dickson and Forest Hancock, were encountered west of the Mandan Indian Villages in what is now the state of North Dakota. They had high expectations of fortunes in fur, and from them Colter caught the trapping fever. This was early in August of 1806. They evidently recognized John Colter as a man after their 36 own hearts and offered to furnish him an equal share of their supplies. Then, and there, they became boon companions, and Colter requested an honorable discharge from government service. This wish was granted with the understanding that no one else would request such consideration.[26]

The government party gave their comrade powder, lead, and other articles that would be useful to him. Is this not evidence that he was in the best possible standing with the company? Indeed, he was an admirable embodiment of the American scout. He was a person of sturdy, athletic frame, above the average height. He was physically quick, alert, enduring, a fine shot, the ideal frontiersman. His greatest asset was an extraordinary coordination of thought and action. This balance, combined with an abundance of energy, made Colter particularly dynamic. Patient and loyal, he performed his duties faithfully. In tribute to him a creek tributary to the Clearwater River, near Lapwai, had already been named Colter Creek. In numerous references to him his associates did not once hint of any mean or selfish act. He was constantly possessed by good temper, and he was of the open-countenanced Daniel Boone type cast.[27] Surely Colter was fully qualified for high adventure because he was, indeed, a two-fisted man with the sinews of a bear and the surefootedness of a cougar. He was wholly unafraid of wild animals, savages, or elements.

From August until the spring of 1807, this trio of Dickson, Hancock, and Colter trapped and traded along the upper Missouri. Then Colter gathered his pelts and started for St. Louis in a canoe. At the mouth of the Platte River, toward the end of June, he met Manuel Lisa.[28] They also struck up a friendship and 37 bargain. Colter was still set for adventure and his new friend had such an assignment. In this meeting the strongest and boldest of the early American trappers of the West met the greatest Missourian trader. Upon hearing Manuel Lisa’s plans, the travel and weatherworn Colter turned westward for the second time, as a member of the Lisa party.

Manuel Lisa proposed the establishment of posts on both sides of the Continental Divide. His plan was to send men along the course of every stream and out among the wandering tribes of Indians, until the commerce of the entire country was in the control of the Missouri Company. He had with him some of the most intrepid Kentucky and Tennessee hunters, rawboned backwoodsmen with their long-barrelled flintlocks, which they usually carried across their knees while on the boat. It was a larger undertaking than any before, and he needed fighters who were experienced and daring from the start.

As they neared the mud-hutted village of the Arickaras the warriors swarmed forth but soon backed up before the leveled muskets of Lisa’s hunters. The traders went ashore and smoked the pipe of peace with the chiefs. This heretofore warlike tribe thereupon became temporarily pacified and sought presents and traffic in scarlet cloth and trinkets. The trappers purchased ponies from these Indians and struck westward toward the Yellowstone Valley. In amazement they viewed the bad lands on the north of the Bighorn. The party arrived at the mouth of the Bighorn River on November 21 and began the building of Fort Raymond, usually called “Manuel’s Fort,” which was their first trading post.[29] They feared the Blackfeet Indians and considered it expedient to abide temporarily in the land of the friendly Crows.

According to the authoritative report of Henry M. Brackenridge, Colter was appointed to carry the news of this undertaking 38 to all the Indian tribes in the south.[30] Since this is an original reference to Colter’s assignment it should be quoted:

He [Lisa] shortly after despatched Coulter [sic], the hunter ... to bring some Indian nations to trade. This man, with a pack of thirty pounds weight, his gun and some ammunition, went upwards of five hundred miles to the Crow nation; gave them information, and proceeded from thence to several other tribes....[31]

Thus, this rugged and dynamic man, now in his early thirties, entered the wilderness on foot and alone, into an area unknown to his race. The journey was a simple business enterprise. As he journeyed southward, he contacted the many Crow clans.

Although practically everyone assumes that John Colter discovered Yellowstone National Park in the early winter of 1807-08,[32] few realize that there is no conclusive evidence to support the claim. Therefore, a review of the proof is essential. The record is brief: Colter did leave Fort Manuel (Raymond) in the fall of 1807.[33] Yet the direction he took is not definitely mentioned, and no incident was specifically recorded of any unique visitation. Still, soon after this journey, Colter related strange tales of weird, natural phenomena.[34] Few of the stories he told were chronicled in detail. However, it is a matter of record that he claimed to have seen a large petrified fish nearly fifty feet long,[35] numerous hot springs and geysers,[36] and a great lake.

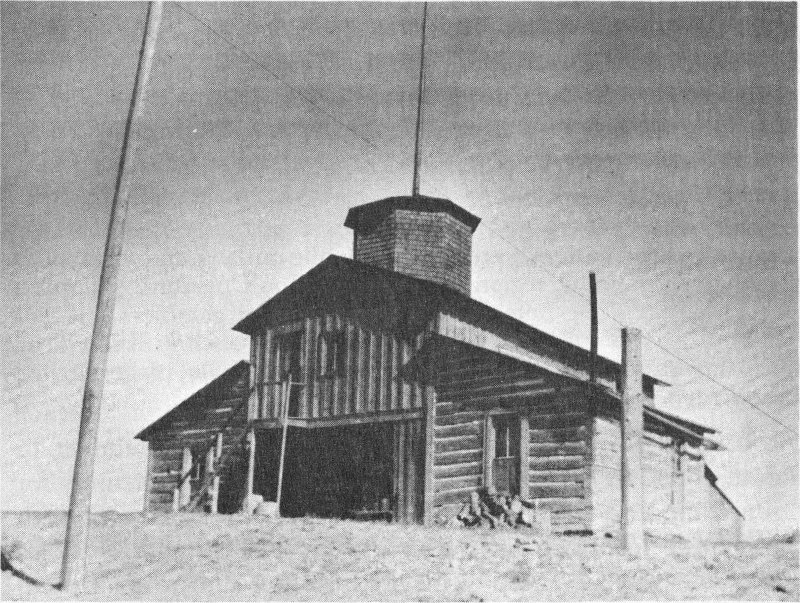

Manuel Lisa’s Fort built in 1807.

Evidence that Colter saw a geyser basin is flimsy indeed. Notwithstanding the uncertainty of Colter’s large travel experience, it is obvious that somewhere, sometime, he saw something that impressed him mightily. He must have waxed enthusiastic, because his recital evoked so much ridicule from the trapper fraternity. For a half a century, everywhere in the West, the mountain men argued and joked pro and con about the mythical marvels of “Colter’s Hell.” By 1837, the story had become common knowledge by reason of the following reference in Washington Irving’s first edition of The Adventures of Captain Bonneville:

A volcanic tract ... is found on ... one of the tributaries of the Bighorn.... This ... place was first discovered by Colter, a hunter belonging to Lewis and Clarke’s [sic] exploring party, who came upon it in the course of his lonely wanderings, and gave such an account of its gloomy terrors, its hidden fires, smoking pits, noxious streams, and the all-pervading “smell of brimstone,” that it received, and has ever since retained among trappers the name of “Colter’s Hell.”[37]

Irving’s description is significant because it is evidence of the “Colter’s Hell” tradition current at that time. However, the location assigned is incorrect. No gloomy terrors or hidden fires exist on Stinking Water (now Shoshone River). As in other explorations 41 of the Colter case, Irving made guesses and assumptions.

Nothing has ever been found that states precisely when or where Colter saw the wonders of Yellowstone. Yet, the fact persisted that sometime between 1806 and 1810, somewhere between the Jefferson and Shoshone rivers he saw them! And strange enough, in the fullness of time, his spacious claims were wholly vindicated. This strange circumstance, therefore, presents the student of early Western exploration with one of the most difficult problems in regional history. Does the full discovery of Yellowstone Park in 1870, ipso facto, prove the tradition of John Colter’s earlier visitation?[38]

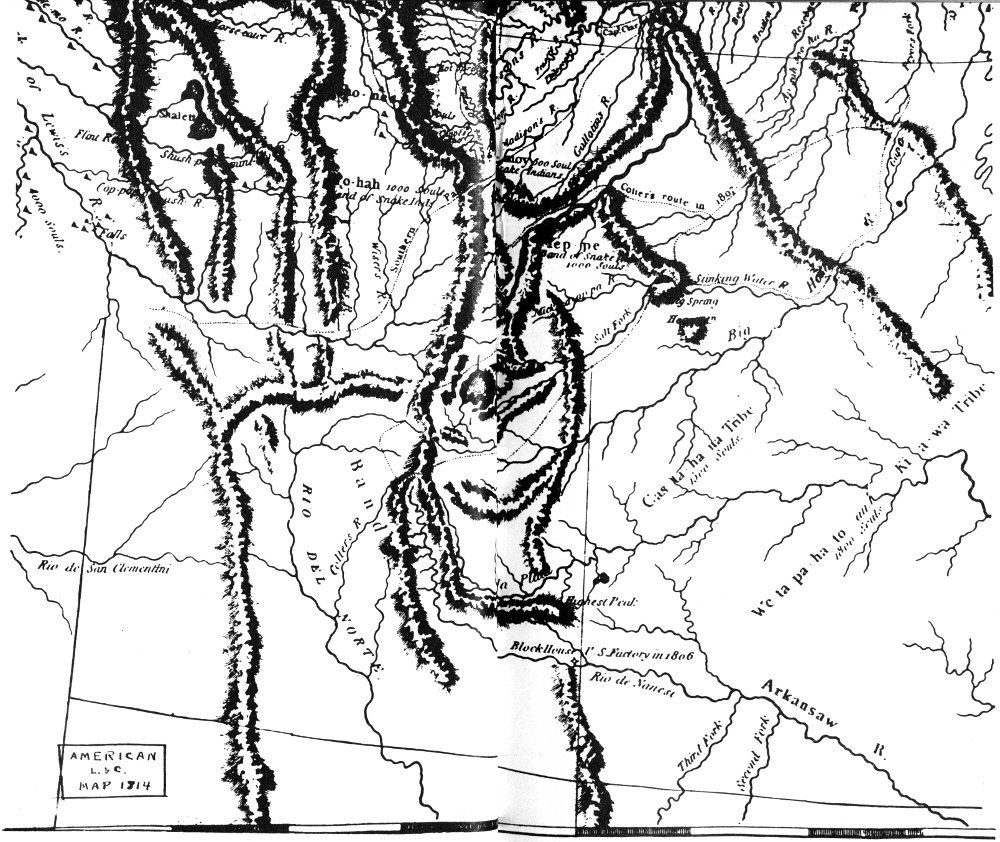

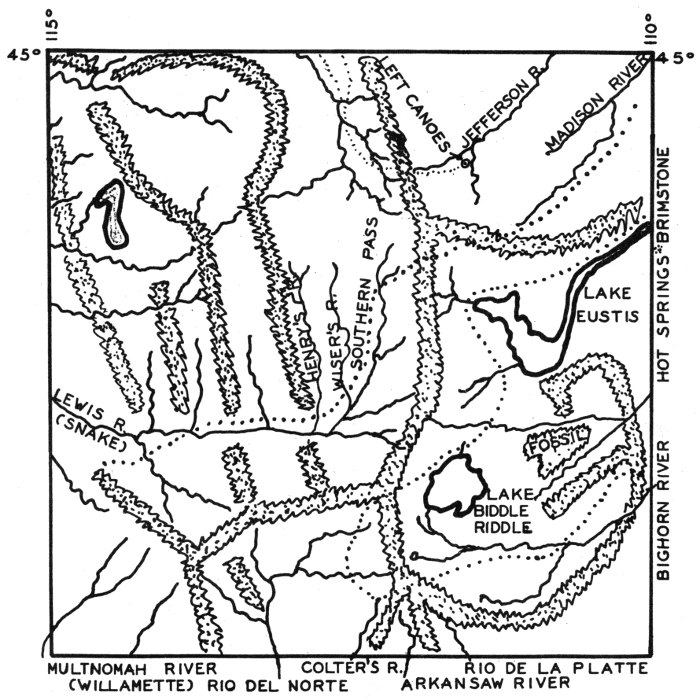

In the Colter case there are only two elements of primary evidence. First, it is a matter of record that he made a journey from Fort Manuel in the fall of 1807 and subsequently returned with an astonishing story of natural wonders. Secondly, a famous map was published in 1814, based upon the compilations of Lewis and Clark. Upon this Map of 1814 appears a dotted line marked “Colter’s Route in 1807.”[39] It is generally assumed that the dotted line actually marks the route of Colter’s journey from Fort Manuel. Although the route charted cannot be accepted literally, it is an important documentary link, worthy of the utmost study. There is little upon the map that would confirm the existence of Yellowstone’s marvels beyond the phrases “Boiling Spring,” and “Hot Spring Brimstone,” but every trapper encountered boiling springs and waters impregnated with bubbling gases having sulphurous odors. These were not unusual. 42 Hence, there is nothing indicated along that dotted line that would guarantee anything extraordinary.[40]

Still, the known facts of Colter’s journey toward the headwaters of the Bighorn in the fall of 1807 and the representation of his extensive exploration to the west, a part of which is now Yellowstone National Park, upon the Map of 1814 is highly significant. For one thing, it proves that William Clark, who supplied the map sheets to Samuel Lewis,[41] the Philadelphia cartographer, was particularly impressed by Colter’s journey, otherwise it would not have been incorporated upon this very important document.

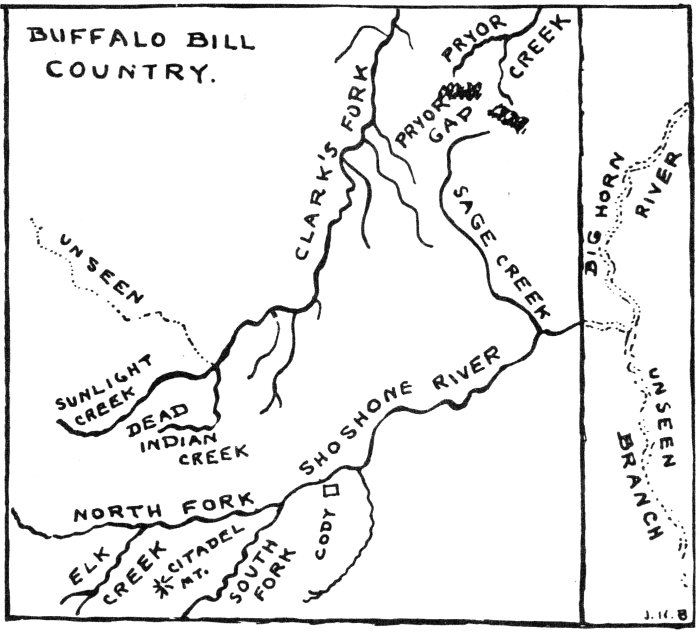

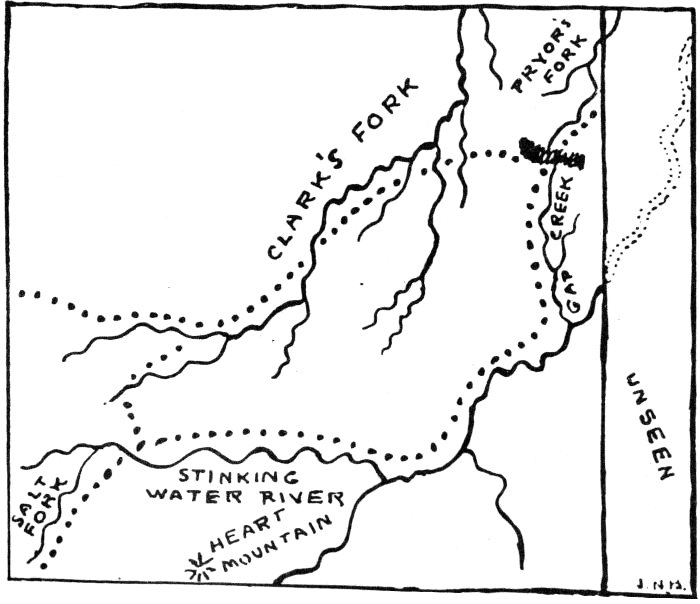

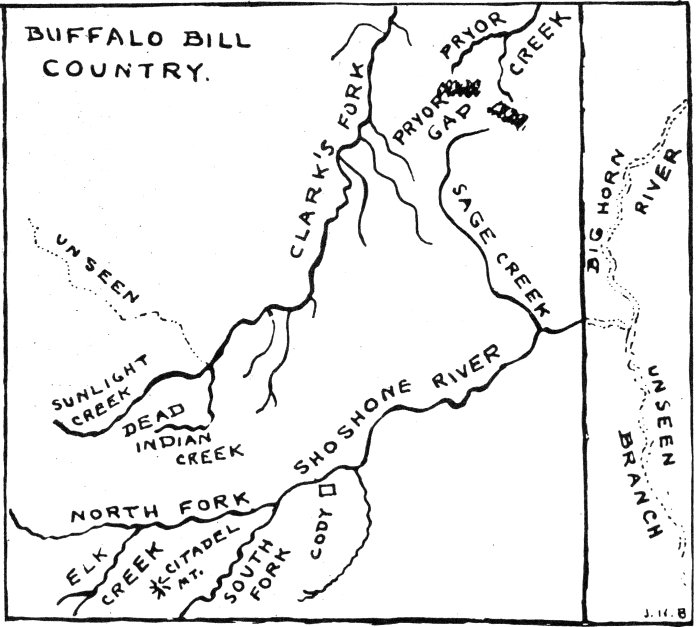

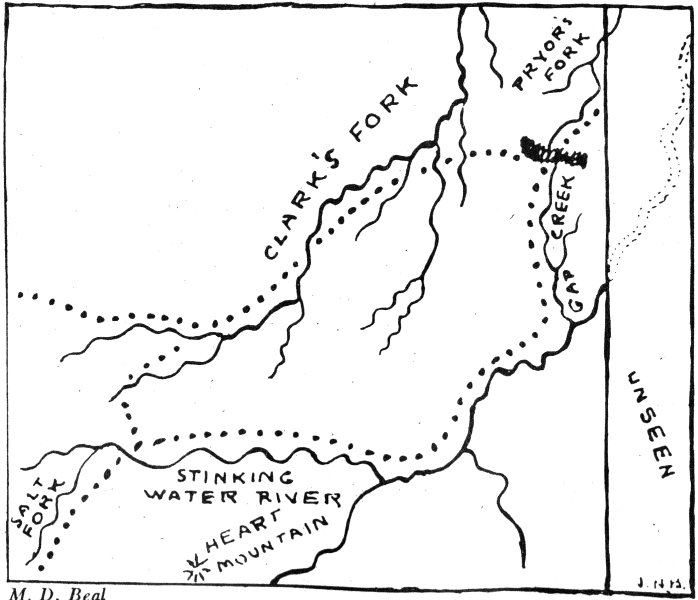

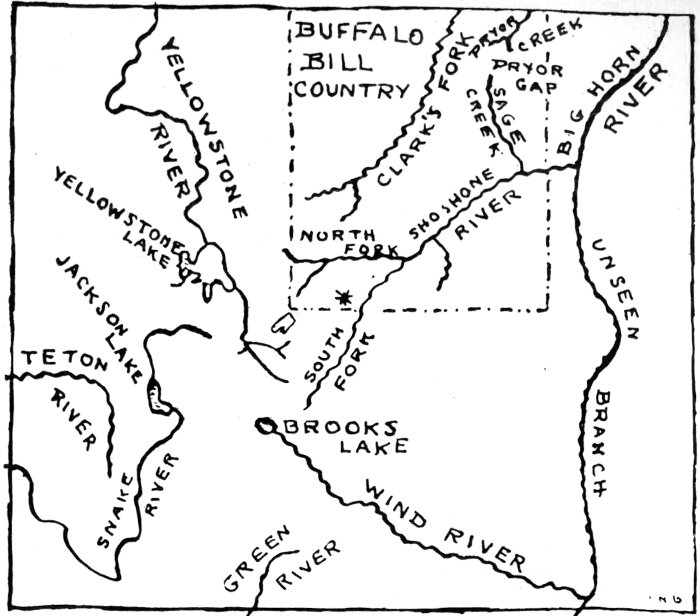

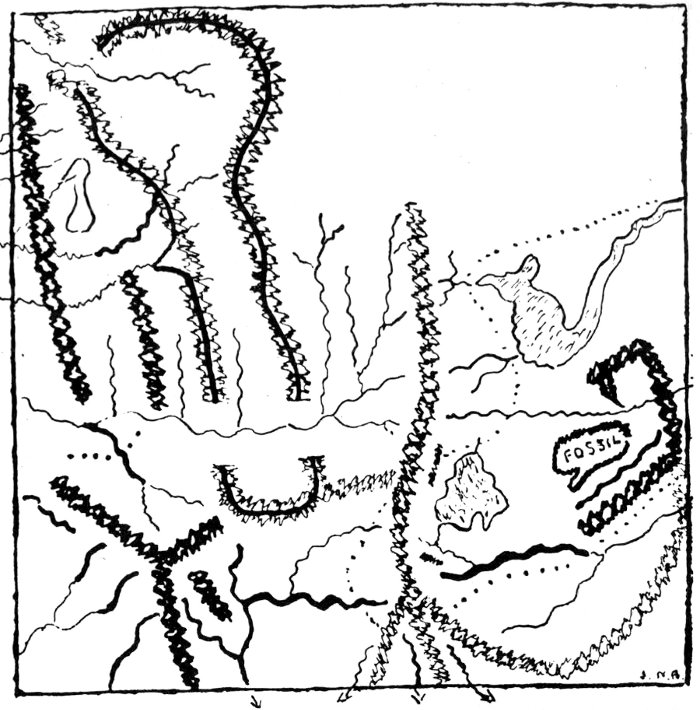

According to this map, John Colter traveled in a southwesterly direction from the mouth of the Bighorn River.[42] He must have mapped the area because his route cast of the Absaroka Range (Yellowstone’s eastern boundary) conforms so accurately with existing geographic conditions that his journey to the Park’s border may be followed like tracks in the snow. From Fort Manuel he ascended Pryors Fork some fifty miles to Pryors Gap.[43] Passing through this opening, he crossed westward to Clarks Fork, which he ascended to Dead Indian Creek. From there he evidently quartered a divide to the south, which brought him upon a river called Mick-ka-appa, where he first smelled sulphur. So he renamed the stream Stinking Water River. It is known today as the North Fork of Shoshone River. In ascending this stream, Colter quickly gained elevation, and in a hanging valley about midway up the range he found a clan of Indians for whom he was obviously searching. On the Map of 1814 they are identified as “Yep-pe, Band of Snake Indians, 1000 Souls.”

From these denizens of both prairie and mountain, Colter undoubtedly first learned of the Yellowstone marvels. The acquisition of this interesting information at a point in relatively close proximity to the features, together with other favorable conditions, impelled him to project an exploration of the “enchanted land.” After listening to eloquent descriptions of the natural phenomena nothing could be more natural than for such an adventurous explorer to experience an intense desire to visit the country. Remember, his mission of informing the clans concerning the establishment of Fort Manuel at the mouth of the Bighorn River had been performed. Now he was on his own with leisure time on his hands. Although the season was advanced, late November often finds the Park open for travel. Tribal accounts describing a vast wilderness of multiform grandeur made the restless trapper burn with curiosity. One can easily envision him weighing the factors of distance, time, and the known hazards, until he struck a favorable balance. His sign talk in council with the chiefs could probably be sifted out and summarized in these terms: “Less than two hundred miles ... the trails are known by your scouts, and they are still open.... A matter of five or six suns ... your horses are fat and strong ... game is plentiful.... Well, what are we waiting for?”

Such an appraisal of the situation is in complete accord with the known realities. Colter was an experienced explorer; he knew how to conduct an expedition. This procedure eliminates the element of foolhardiness so conspicuous in the usual picture visualized of a solitary trapper on snowshoes, wending an uncertain course among river labyrinths running in various directions, mountain ranges of interminable lengths, and gargoylian lakes. Instead, the enterprise now conforms to a standard characteristic of Colter’s levelheaded courage and judgment. Of course he may have gone alone and on foot, but if so why, after leaving the Yellowstone country, did he depart from the straight-of-way down Clarks Fork toward Fort Manuel and head back to the 44 Yep-pe village as the map so clearly shows? Logic insists that Indian scouts were with him, or at least that he had borrowed a horse from them, which he was obliged to return. Thus, Colter’s famous journey into the land of scenic mystery was efficiently accomplished late in November. With the aid of Yep-pe Indian leaders, if not under their guidance, he had gone where no white man had ever been before, and he still reached Manuel’s Fort in good season, or else the Map of 1814 would not have been inscribed “Colter’s Route in 1807.”

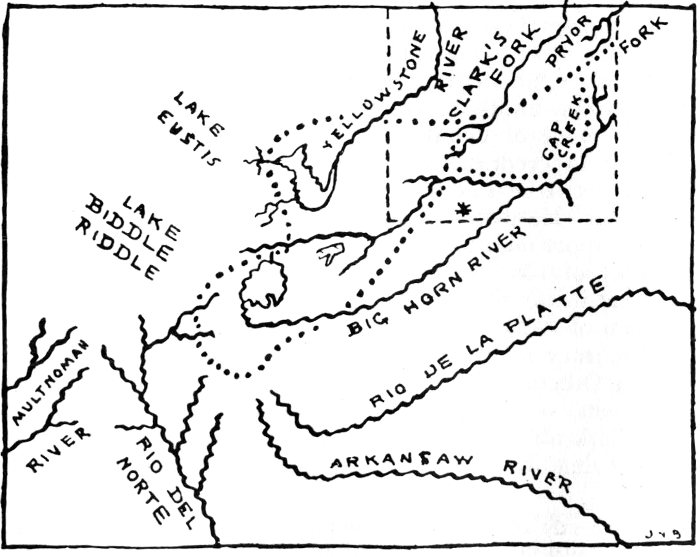

But, where precisely in Yellowstone Park did Colter travel? This question poses an extremely difficult problem in research. (The serious student will find the many ramifications involved in the problem explored more fully in the Appendix.) Unfortunately the dotted line appearing on the Map of 1814, marked “Colter’s Route in 1807,” is of no help whatever in answering the question. In fact, the map complicates the problem because the geography depicted on the western loop, or so-called Yellowstone Park section of the map, is wholly fictitious. Unlike the valid section east of the Absarokas, the western section bears no similarity to anything in Yellowstone Park, Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, America, the world, or the moon! It is, in fact, a plat of bogus geography comparable only to the kind found in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. In short, it is obvious that “Colter’s Route in 1807,” beyond the Yep-pe village, was not properly described because it depicts him as visiting the drainage of all the river systems within a radius of five hundred miles of that Indian encampment. The most obvious errors in that part of the map which impinges upon the western section of this so-called “Colter’s Route” are:

(1) Three Forks are shown to the northeast instead of northwest.

(2) Lake Biddle, usually identified as Jackson Lake, could only be Brooks Lake and be on the Bighorn drainage. Jackson 45 Lake lies due south about fifty miles, on the other side of the Continental Divide.

(3) The Rio Del Norte (Green River of the Colorado) is far and away to the south. It is grotesquely misplaced.

(4) The South Fork of Snake River is not depicted, neither is the Jackson Lake area.

(5) Upper Yellowstone River is not shown, and Lake Eustis (presumed to be Lake Yellowstone) is fantastic in all respects.

In view of these egregious errors it is a monumental mistake to insist, as so many authors in effect have done, that Colter was a human helicopter who hopped all over the Rocky Mountains in connection with his Yellowstone exploration. Actual geography and common sense prove that he could not possibly have made such an extensive journey, particularly so late in the season. Just as certainly, geography and common sense attest that in traveling a normal western loop essential to yield conformity with the map’s figure eight[44] Colter would have seen precisely the type of country the Map of 1814 does not depict, but which, nevertheless, is actually there! A normal half circle would have brought him upon the Upper Yellowstone River, South Fork of Snake River, Yellowstone Lake, and the thermal areas at Thumb of Lake and Hayden Valley. These paint pots, hot springs, and geysers, particularly Dragon’s Mouth and Mud Volcano, satisfy the descriptions he made and easily meet the requirement of the terms on the map, “Boiling Spring,” “Hot Springs Brimstone,” and also Washington Irving’s reference “... of gloomy terrors, hidden fires, smoking pits, noxious streams....” In effect, these areas alone would qualify as “Colter’s Hell.”

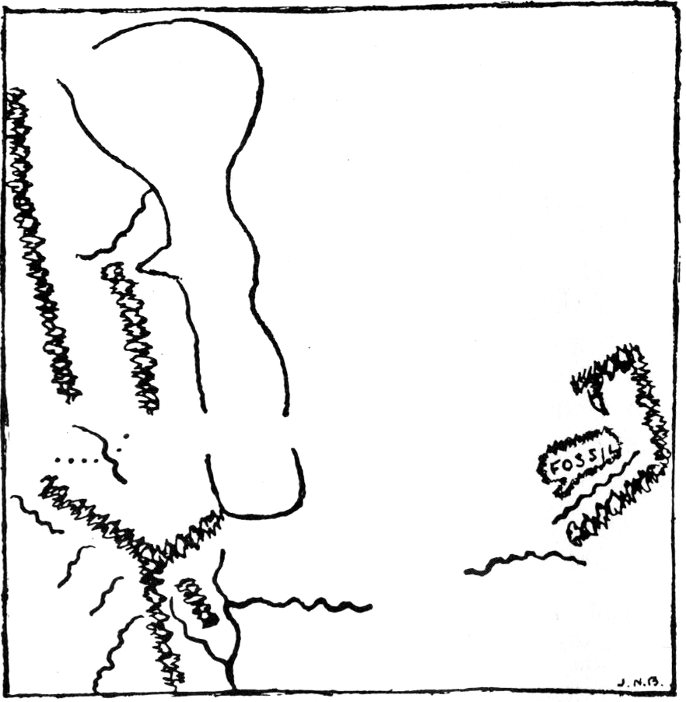

J. N. Barry

Eastern section of Colter’s route.

A true sketch of the Cody, Wyoming, area as it is mapped today.

The east sector of Colter’s route as depicted on the Map of 1814. Note the conformity with actual geography. The only material difference is in names.

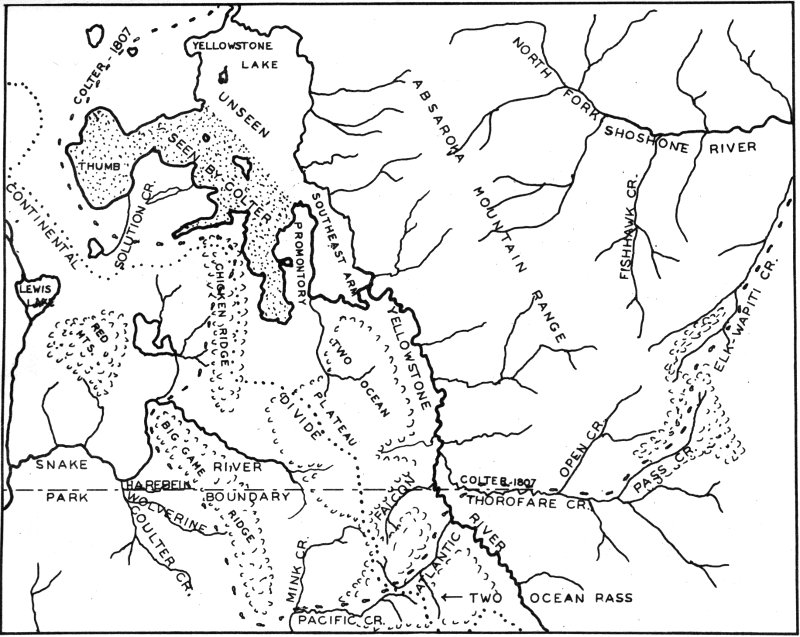

It is now possible to accurately sketch both parts of Colter’s famous journey. Firstly, from Fort Manuel he reached the Yep-pe Indian camp and returned to the mouth of the Bighorn River where Fort Manuel was built, exactly as the map depicts. It is because of the accuracy of this section of the Map of 1814 that Colter’s Yellowstone course may be now traced like tracks in the snow. Secondly, from the Yep-pe Indian camp, Colter ascended “Elk-Wapiti Creek” to its source; then crossing a range he came upon a mitten-shaped mountain, which he labeled “fossil.”[45] From this landmark he probably descended Pass Creek to Thorofare Creek, which he followed to the Upper Yellowstone River. Then he ascended Atlantic Creek and crossed the Continental Divide at Two Ocean Pass. From here he descended Pacific Creek, skirted Big Game Ridge, and crossed the South Fork of Snake River, within the present confines of the Park. Thence, along Chicken Ridge, from whence he could frequently view South Arm, he headed toward Flat Mountain Arm, crossed Solution Creek, and struck West Thumb.[46] The validity of this itinerary is wholly sustained by the genuine features of this area as they appear upon the Map of 1814. Indeed, the route seems obvious and indisputable in view of the actual conditions existing. There are alternative routes within certain limitations. On a crude map where there are numerous similar streams various combinations are possible.[47]

Section from map of 1814 depicting Lewis and Clark route. Its legend reads: “A map of Lewis and Clark’s Track, Across the Western Portion of North America, From the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean; By Order of the Executive of the United States in 1804, 5, 6. Copied by Samuel Lewis from the Original Drawing of Wm. Clark.”

Leaving West Thumb, Colter circled the Lake to its outlet and followed it to the Hayden Valley thermal area. Dragon’s Mouth and the Mud Volcano were undoubtedly features contributing to the impression he carried away and transmitted to others. Even the “Hot Springs Brimstone” characterization on the Map of 1814 mildly suggests violent thermal activity. The phrase also suggests that Colter mapped a geyser basin.[48]

Colter’s return route from Hayden Valley supplies the final link in the figure eight. To reach the Yep-pe Indian camp he might have veered to the northeast, crossed Yellowstone River at a ford below Dragon’s Mouth, and ascended Pelican Creek or one of the tributaries of the Lamar River. After crossing the Absarokas, he evidently descended one of the creeks that empty into Clarks Fork. No one on earth can be certain about this part of his journey. There is no reference anywhere, and the Map of 1814 gives no clue. Still, he did reach a tributary of Clarks Fork, which he followed to its junction with Dead Indian Creek, thence to the Yep-pe band. As stated above, Colter left the Yep-pe village in returning to Fort Manuel by a different route than the one that brought him there. This fact, together with his return to the Yep-pe Indian camp, is of the first importance in assessing the validity of Colter’s Yellowstone discovery.

While Colter’s journey in Yellowstone proper was not comprehensive, still he was definitely oriented and reasonably precise. Truly, Colter crossed the eastern and central parts of Yellowstone’s Wonderland, and he observed its features closely. Companions were duly apprised of these marvels. Members of the Lisa party thereafter referred to the region as “Colter’s Hell.” In May, 1810, when he reached St. Louis, William Clark was officially informed. It was then that Clark believed in Colter’s story and passed it on to Nicholas Biddle and Samuel Lewis who 51 were in Philadelphia. Notwithstanding considerable misapprehension as to facts, Colter’s journey was nevertheless depicted after a fashion on the remarkable Map of 1814. Upon this evidence alone, John Colter became accredited as the first white man to enter the Yellowstone Park country, hence its first discoverer. Here, indeed, was a man worthy of making a great discovery. He was a dreadnaught, if there ever was one; completely self-reliant; unafraid of forests, deserts, rivers, or mountains, including all of their denizens; yet withal, a serious-minded person of integrity. He is entitled to everlasting credit in the field of western geographical exploration.

Eventually, Colter found himself back in Lisa’s Fort. He had discovered the interesting Two Ocean Pass across the Rocky Mountains into the Snake River drainage. He was the first white man to touch upon the northeastern perimeter of majestic Jackson Hole country. Then, as the climax of all, he was the first to climb still higher and gaze upon the marvels of a never-to-be-forgotten land. Has it ever been the fortune of any other man to explore such a vast domain of virgin territory? It is a strange paradox that, accustomed as mountain men were to impressive manifestations of nature, Colter’s relation of Yellowstone’s wonders only won him the distinction of a confirmed prevaricator.[49]

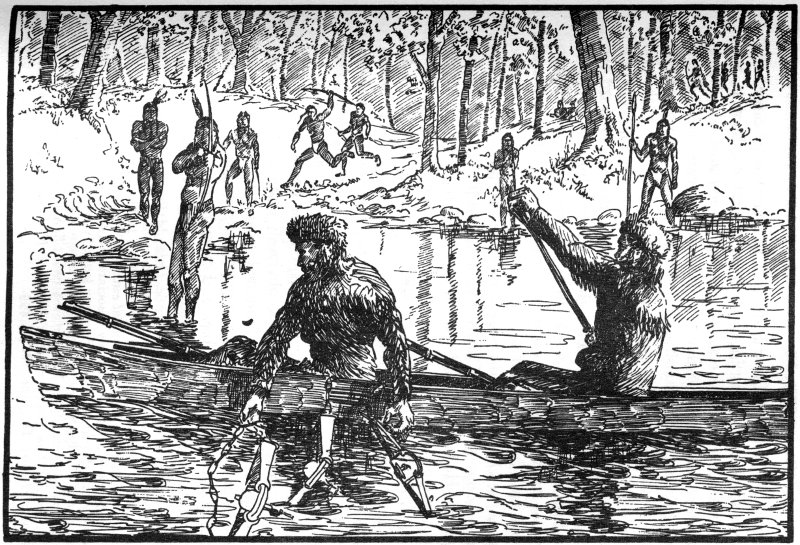

While Colter’s experience after 1807 has little bearing upon the history of Yellowstone, it is a part of the heritage of the Old West and therefore essential for the unity of the narrative.[50] In 52 the autumn of 1808, Colter and a companion named Potts invaded the hunting grounds of the Blackfeet Indians in the vicinity of Three Forks forming the Missouri. Early one morning they were setting a line of traps along either the Jefferson, Madison, or Gallatin rivers, about a day’s travel from their point of junction.[51] As they were silently paddling the canoe, they heard a resounding noise that resembled the muffled pounding of feet. Colter was apprehensive about Indians, and since perpendicular banks obstructed their view he advised hiding. However, his impulsive companion accused him of cowardice; why run from buffalo? Almost within the moment a band of “Black Devils” burst through the thicket into full view. Colter kept cool and rowed for the bank. As they drew closer to the enemy, Potts dropped his paddle and picked up his rifle. This gesture was interpreted as an act of defiance by the Blackfeet braves. A stalwart savage leaped into the water and snatched Potts’ rifle out of his hands. Whereupon, with an air of mastery that Indians respect, Colter stepped to the bank, wrested the weapon from the warrior’s grasp, and returned it to Potts.

W. S. Chapman

Colter and Potts under attack.

The Blackfeet were now swarming through the brush, but Colter, calm and poised, raised his hand palm forward in the peace signal. Potts, now convinced that flight was the only hope, nosed the canoe toward mid-stream. Suddenly a bowstring twanged, and Potts cried out, “Colter, I’m wounded.” Colter urged him to come ashore, but instead he leveled his rifle at an Indian and fired. Instantly a score of arrows entered his body or, in Colter’s language, “he was made a riddle of,” and he slumped lifeless in the canoe.[52] Calm and flintlike Colter stood his ground. As the chief sized up the situation, a dozen warriors identified the survivor as the white man who raised havoc among them in a battle with a band of Crow Indians.[53] This knowledge caused the braves to clamor for setting him up as a mark to shoot at, but their chief interfered. He stood in great dignity and said, “This is a brave warrior. We will see how bravely he can die.”[54] Then, seizing the victim by the shoulders, he asked him if he could run fast. To this query Colter replied with a chop-fallen air that he was slow. Actually, he was an excellent sprinter. Several hundred Indians swarmed about, working up their emotions toward the victim. First they denuded him, then motioned him to move forward perhaps a hundred yards, from whence he was signalled to run toward a “v” shaped open prairie of some six miles expanse. Colter had drawn a chance to save himself if he could! He accepted the challenge and resolved to make the most of it. As the war whoops sounded, Colter was away with the dash of an antelope. He bounded and ran until his lungs burned within him, and he ruptured a blood vessel in his nose. On he sped, mile after mile, until the chorus of Indian yells grew fainter and fainter. All of Colter’s muscles cried out for a moment’s respite. He looked around and beheld a spear-armed warrior some twenty yards behind him, coming fast to split him in two. Upon impulse, Colter whirled in his tracks, and running obliquely, gave the signal for mercy. The reply was a thrust spear, but the brave made a false step, stumbled, and fell. He was obviously astonished at Colter’s gory appearance. The badly launched spear struck in the ground and was broken off. In a surge of hope and strength, the powerful Colter lunged like a stag at bay, and overpowering the Indian, he seized the barbed half and impaled his fallen foe to the earth!

If the Blackfeet had possessed a spirit of chivalry they would have called quits to this ordeal by running and combat. Here was a man who had outrun the cream of the redskin sprinters and, unarmed, had slain an armed warrior. Surely such a performance should have won the captive’s freedom. But the Blackfoot code made no allowance for heroic behavior in the enemy.

On came the braves, more ruddy than usual by reason of their exertions and more fleet than normal because of the caliber of the quarry. Colter needed no spear now; he fairly vaulted until he gained the river bank, and diving into the stream he concealed himself under a jam of driftwood or beaver dam that impinged upon an island. Here he secreted himself while they howled and thrashed about for hours, yelling, as Colter said, “like a legion of devils.” When darkness came, like an angel of mercy, he dragged his aching body from its watery prison, silently swam across the river, and started the second excruciating lap in his race for life.[55] Manuel Lisa’s Fort was two hundred miles away.

After seven days of hiding and nights of painful travel and exposure he found his way through Bozeman Pass and eventually reached the fort at the mouth of the Bighorn. During this “ordeal by travel” he had no sustenance other than roots known as psoralea esculenta, or sheep sorrel.[56] Again there was momentary disposition among the trappers to question Colter’s veracity, but the evidence was unimpeachable, and it was written plainly where all might see. He seemed only a shadow of his former self.

According to James, even this terrible experience did not daunt the lion-hearted trapper, “Dangers seemed to have for him a kind of fascination.”[57] Colter could not reconcile himself to the loss of 56 the traps he had dropped in the river during the attack. Soon after his recovery, he ventured again into the forbidden Three Forks region. At his first night’s camp he was attacked, but he contrived to escape. Whereupon, he vowed to his maker that he would never return.[58]

Acting upon this resolution Colter started his third voyage down the Missouri. While he was resting in one of the upper Minnetarre villages, probably in September of 1809, Manuel Lisa arrived. The Three Forks country was his destination and Colter must show him the way.

By midwinter a strong detachment was on its way, headed by Pierre Menard as bourgeois commander, Andrew Henry as field captain, and John Colter as guide. The party arrived at Three Forks on April 3, 1810 and built a post. Within a fortnight the Blackfeet attacked. Five trappers were killed, and most of the horses and equipment disappeared. It was a crushing blow to the enterprise, and for Colter, the final straw. James states that Colter came into the fort, spoke of his promise to God, repented of his foolhardy return, and said, “If God will only forgive me this time and let me off I will leave the country day after tomorrow and be d——d if I ever come into it again.”[59] Several days later he and a companion slipped through the Indian lines and in due time reached Fort Manuel. From there the two men departed for St. Louis in a dugout and reached that frontier capital on the last day of May. They had negotiated the distance of 2,500 water miles in the incredible time of thirty days.[60] Is it any wonder that other trappers referred to “Colter’s large experience”?

For over five years he had been among barbarian people, and of certain torments he had more than enough. His life had been 57 one of hard toil and high adventure; now he would seek peace and quiet.

Captain Meriwether Lewis had passed away, but William Clark was a person of authority. He was Brigadier General of Militia and Superintendent of Indian Affairs. To Clark, Colter gave geographical data, a part of which appeared on the map published in 1814 in the Biddle-Allen edition of the journals. Colter was unable to collect the wages due him as a member of the famous expedition so he brought suit against the Lewis estate and secured partial compensation. His trapping claims for services to Thomas James were unavailing as the latter could not collect from the fur company. While in St. Louis attending to this vexatious business he undoubtedly related his experiences to General William Clark. The latter, in turn, passed the story along to John Bradbury, the English scientist, and James M. Brackenridge, an American author. Such men accepted his report at face value. Concerning him, James wrote, “His veracity was never questioned among us.”[61] Lesser people were more incredulous, and Colter’s reputation suffered accordingly.

Colter took up a tract of bounty land on the south bank of the Missouri in the vicinity of Dundee village, Franklin county. There the great wanderer, with his bride Sally, turned to the prosaic routine of farming. Wilson Price Hunt’s expedition found him there and offered him a position as guide. Bradbury said he accompanied them for several miles, balancing in his mind the charms of his bride against those of the Rocky Mountains. However, the life of steady habits won, but not for long, as he died of jaundice in 1813.

During the subsequent half century Colter’s reputation evolved 58 by degrees through the following stages: bare-faced prevaricator, devil-take-care mountain roamer, accidental discoverer of Yellowstone National Park. From the present perspective he appears much more than a scout and explorer. He was something of an economist and prophet, because he is said to have told Henry M. Brackenridge that where he had been, “a loaded wagon would find no obstruction in passing over the Rocky Mountains.”[62]

On Yellowstone maps a single conspicuous feature commemorates Colter’s work. It is Colter’s Peak near the southeastern point of Yellowstone Lake. May it ever stand aloof, towering and quite inaccessible; a fitting monument to a gallant scout. Such a man should never be forgotten because he was master of the untamed West.

A description of the Indian background is an integral part of all early American history. An appreciation of the “Old West” is impossible without an understanding of the Indian problem.

Yellowstone was not the original homeland of any distinct Indian tribe. In comparatively recent time, probably about 1800, it became the refuge for a small and degenerate band of Tukuarika, or sheep-eating Indians. They had formerly lived in the Montana and Dakota country but had been driven into seclusion by the powerful Blackfoot nation. The several branches of Shoshones residing in Yellowstone environs were Bannocks, Snakes, Tukuarikas, and Flatheads. The Crows came from other Indian sources. All of these Indians possessed certain racial characteristics of the red race. In view of various conflicting ideas, a few observations about the people as a whole are expedient.

Indians are human beings possessing the sensibilities and emotions of white men. However, their manner of living and conception of life has been relatively low. Even so, it is difficult to generalize upon them as a people. As Chief Washakie once said, “Indians very much like white men—some good, some bad.” It is generally conceded that they were proud, so haughty in fact that they lacked that quality of mind so essential to progress or adjustment, humility or teachability. They could not learn because they would not admit that they lacked anything. They were 60 the “chosen people.” Originally they looked upon the hard-working white people as slaves and referred to them by no other name.

As a rule Indian braves were arrogant lords, not to be degraded by menial toil. It was enough for them to expose themselves to the hardships of fighting and hunting. They would proudly bring home the trophies of war and the hunt. They were also diligent in caring for their weapons and horses in preparation for future exploits. Much leisure time was expended upon personal ornamentation and in talking about the news of the day and affairs of the tribe. The Indians’ inordinate pride was revealed in every movement. The men in particular possessed a free and easy bearing. This natural grace of action was probably facilitated by their practice of living in a semi-nude condition.[63]

Indians were much more cunning and adroit than the wildest game. They were fleet and stealthy, deceitful and cruel. To gain an advantage over prey or an enemy by strategy was their greatest joy and constituted the primary requisite for leadership. To be mentioned by one’s tribesmen as a great warrior or a cunning horse thief was the highest ambition of an Indian, and many were past masters at both these hazardous hobbies. The greatest among them was the one with the most “coups” to his credit, such as scalps, stolen horses, and captured enemies. Making coups entitled the brave to wear an eagle feather in his hair and emblazon it upon his robe; by this token he was distinguished for heroic action.[64]

On the whole they were revengeful and vindictive. If an injury, real or fancied, were done to them by a particular person, it was a solemn duty to retaliate either against him or someone else. Many cases can be adduced to sustain this principle. In 1809, 61 a trapper named Carson accepted a banter from a band of Arickaras to shoot among their enemy Sioux, who were across the Missouri a half mile away. The reckless trapper shot and killed one of the Sioux warriors. The following year three white men were slain by the Sioux to expiate this crime. The Indian code demanded blood for blood, the more the better. They were seldom inclined toward chivalry; mercy had no part in their code. It was hard, relentless, and primitive. By the strong hand they lived, and by the strong arm only were they awed. Forays, feuds, battles, that was the life! They painted, dressed, danced, and prayed for war.

And yet, in a way, they had poetic souls. The beauty and grandeur of nature revealed itself in their dignified bearing. Many were majestic in appearance, poised of manner, and eloquent in speech. Some of them were gifted storytellers who entertained their hearers. Others were great speakers who instructed them in the legendary lore of the tribe. Still others were artists, musicians, skilled artisans in many lines; and there were medicine men.

Tribal organization was based upon the family unit, which was monogamous, except in the case of the chief men who usually had several wives. The chief’s lodge occupied a central position in the village, with other leaders’ abodes surrounding. The women, too, observed a style of dress in keeping with their respective stations. Heredity in leadership was unknown; men became chiefs by reason of their cunning and courage in war, wisdom in council, and generosity toward the tribesmen.[65]

In the matter of economics most mountain Indians were novices. It is undoubtedly true that early American settlers received important initial aid from the Indians in raising crops. They taught the whites how to raise the very products that still constitute the backbone of American production: maize, potatoes, 62 tobacco, cotton, squash, and beans. But instead of improving along with the settlers, they generally preferred the ways of their fathers. They did not lack the means for the production and preservation of food so much as the energy and ability to anticipate future necessity.

In the Rocky Mountains, where nature was quite inhospitable (without irrigation), the natives were even less thrifty than elsewhere. When food was plentiful they would gormandize to the uttermost, living contentedly. When confronted by famine they would languish in starvation. Natural forces battered them roughly. There was fasting, but there were buffalo brains and tongues too—earth’s supreme dish!

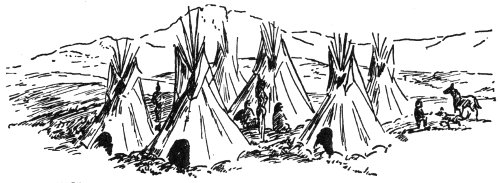

W. S. Chapman

Mountain Indian clan.

The women and girls were practically slaves to their husbands and brothers. They were inured in hardships and possessed much forbearance and self-denial. Their homemaking work was arduous. They dressed all game and gathered nuts, berries, fuel, and roots. They made bows, arrows, lodges, travois, and clothing. The packing and moving, striking lodges and general routine was women’s work.[66] There was never the slightest disposition to complain among them; in fact, they were inclined to despise a brave 63 who departed from the usual patterns. He would be called “old woman” and his squaw, if any, often received a castigation. Maidens were required to be modest, wear robes at all times, and look seriously upon life. Marriages were arranged by parents with the consent of near relations. The desires of the young people were given consideration, if reasonable, but the decision was made by the girl’s father.

Meat was the mainstay of life among Indians, and a considerable supply was available before white men came. In spite of inadequate weapons, the natives had numerous effective methods of securing wild game. Most hunters were masters of what was called the cabalistical language of birds and beasts. By this means they were able to approach many animals closely and slay them. Bison were sometimes driven into natural arenas where a gory slaughter ensued. Occasionally these great beasts were maneuvered into runs, from which they were stampeded pellmell over a precipice.[67] Generally they were simply chased and shot down at full gallop. This procedure required great dexterity in loading and discharging weapons. Of course the hunter’s full attention was given to the target because his hunting horse took care of himself. He anticipated every move of the prey. With eyes flashing, nostrils distended, and foam flowing from his mouth, the trained steed sprang after the deceptive buffalo in swift execution of his master’s will.

The war horse was even more highly prized than a hunter. Animals of exotic appearance had double or treble value over ordinary steeds and were claimed by the chiefs. The proud warrior went to as much pains to adorn his horse as he did himself. Nothing could induce him to neglect or mistreat his favorite.

In their palmy days, the Indians largely confined their efforts to pursuit of big game. In later years they had reluctant recourse to smaller animals. Rabbits were encircled—sometimes by a chain 64 of fire. Ground squirrels were drowned out, and all types of animal life were utilized for food. The products of the buffalo, deer, elk, antelope, goat, bear, beaver, and numerous small animals and fish gave them strength for the pursuit of more game and the enemy. Many different combinations of meat, roots, nuts, and berries were known to the Indians. Pemmican was a mixture of pounded dried meat, grease, and service berries. When properly prepared and packed in skins this food would keep indefinitely.[68]

The camas and yamp plants were the Indian’s bread. These roots are about an inch in diameter, and they have a sweetish taste while fresh, but they are more palatable when baked in earthen ovens. Either of these roots contains nutriment sufficient to support life, and often mountain Indians were obliged to subsist on this slender fare.

From a white man’s viewpoint the dominant element in Indian religion was superstition. A stark animism prevailed in every cult. They believed that the different animals had either good or evil spirits and that they should be revered or feared according to their nature. The sun in particular was an object of worship. Each young man diligently sought his own strong medicine. The ritual varied but usually involved solitude, exertion, fasting, and extreme exposure. During this vigil the youth received a new name and a symbol of power. In due time these signs of maturity were manifest among the tribe and a status therein was secured.

Illness and death were attributed to the influence of evil spirits. The chief remedy for sickness was the sweat house. This was a mystic shrine both for temporal and spiritual blessing. The health seekers would rub their bodies with the tips of fir boughs, and thus the steam would effectively penetrate their bodies in a few minutes. Several sweats, each followed by a dip in a stream, constituted a bath, except when the spiritual interest predominated. 65 In that case the votary might remain in the sweat house for hours or even days.

In respect to amusement Indians had unusual interest. That they were stoical at all times is an erroneous idea. They laughed and joked and engaged in many games.[69] Their singing was largely extemporaneous, accompanied by instruments of the crudest type. A horse race had tremendous appeal for the “bucks,” who sometimes gambled away everything they possessed, including their wives and children. In general, the social life of Indians was notable for its excesses. Certain seasonal festivals were held in which the element of worship was interwoven with hilarity. Before going upon a hunt the Indians were wont to clothe some of the hunters in hides of the game, buffalo, or elk. These “bucks” would then cavort around in the manner of the game desired. In all this there was an air of expectancy and supplication.

Smoking was another semi-sacred ceremony by which oaths and agreements were secured. A ritual was usually observed. They relied heavily upon innumerable supernatural symbols and routines.

Such were the general characteristics and customs possessed by all of the mountain Indians. A marked degree of differentiation among them would justify a brief description of each. Of course these differences are only apparent to the discerning eye. Factors of physiognomy, dress, and speech are recognizable upon close observation.[70] However, it is not an easy matter to express these different characteristics in words.

The Bannocks (also Bannacks)— This name is derived from the Shoshoni word “bamp,” which means “hair,” and “nack,” which signifies “a backward motion.” It is also said that these Indians made cakes from acorn flour, pulverized grasshoppers, and currant jelly which so resembled the Scotch bannock cake 66 in shape and flavor that some Scotch trapper applied this name to the tribe. There were approximately two thousand Bannocks in 1810, and they claimed the country southwest of Yellowstone. It was this tribe which made a deep trail across Yellowstone in going to and returning from their buffalo hunts. Bannocks were tall, straight, athletic people, possessed of more physical courage than most Indians. In a defensive way they were the most warlike of all Indians.

The Shoshoni or Snake Indians— This tribe of natives lived in the upper Snake River Valley. According to Alexander Ross, the Snake Indians were so named because of their characteristic quick concealment of themselves when discovered. “They glide with the subtility of the serpent.” However, Indians interpreted the word “Shoshoni” as meaning “inland.”[71] Father DeSmet stated: “They are called Snakes because in their poverty they are reduced like reptiles to the condition of digging in the ground and seeking nourishment from roots.”[72] They lived in peace with the Flatheads and Nez Percés in the north and were at war with the Blackfeet, Crows, Bannocks, and Utahs. The Snakes were dependable participants in the trappers’ rendezvous so often held in the Green River Valley in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. TyGee was a leading chief during much of the nineteenth century. The Targhee Forest was named after this Snake chieftain. They were a short, very dark, heavy-set people, with small feet and hands but large chests and shoulders. Their disposition was quite peaceful and friendly toward other people, although they were very suspicious. They were excellent horsemen and good fighters when aroused. The whole nation consisted of about a thousand, but it was broken into bands, some of which were vital and murderous while others, such as the “Diggers,” were degraded and impoverished. Their great and constant occupation was to obtain food, and they were disposed to eat almost anything.

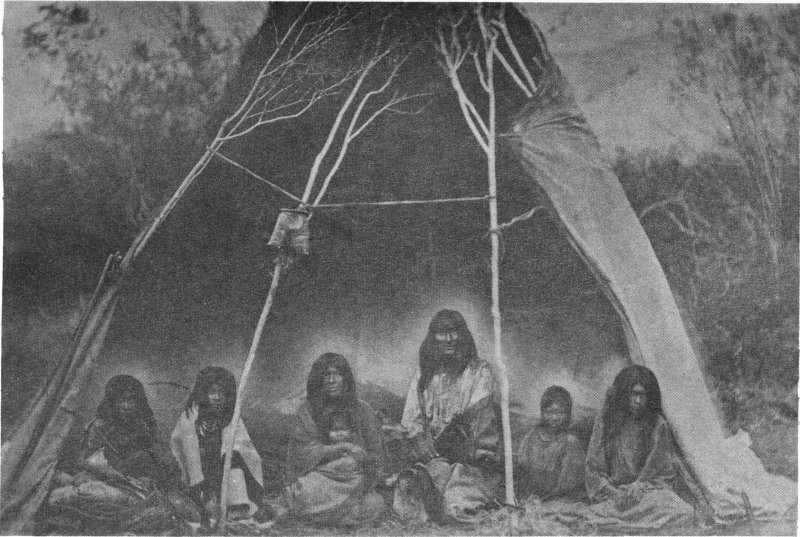

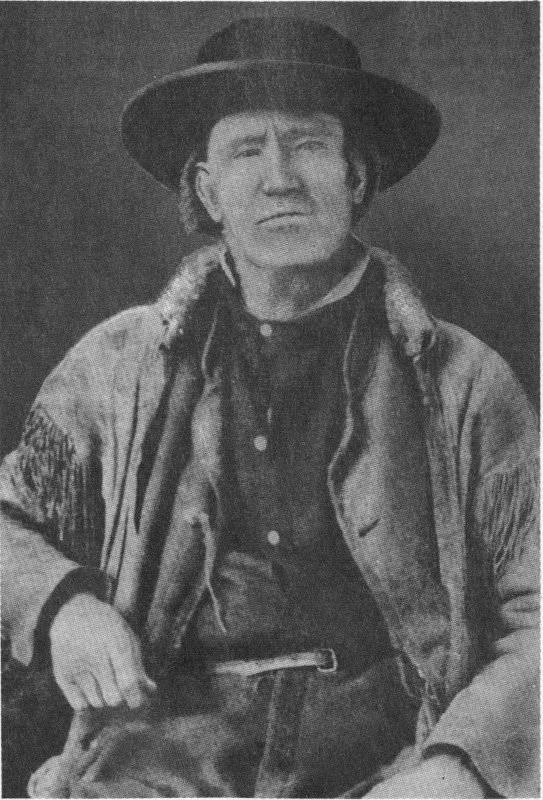

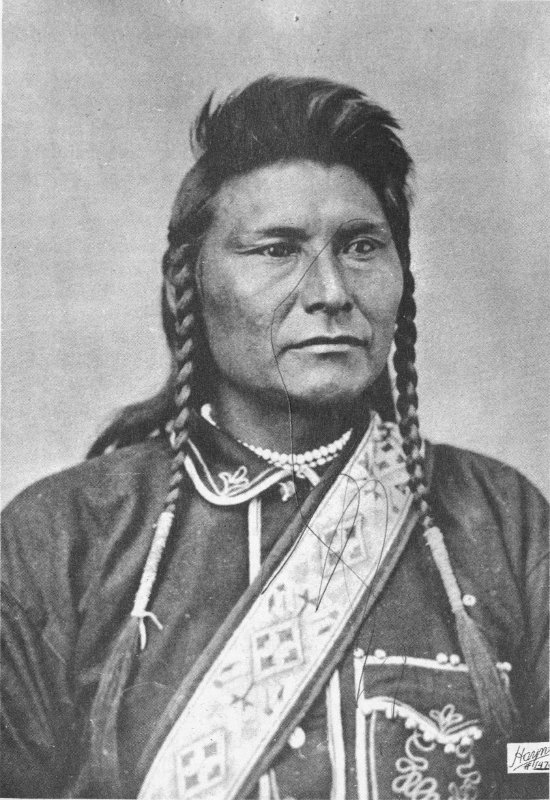

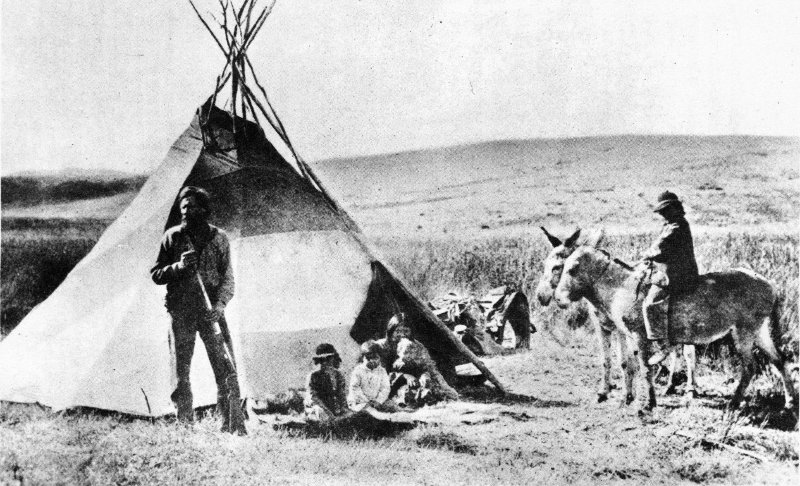

Photo by W. H. Jackson

Family of Sheepeater Indians

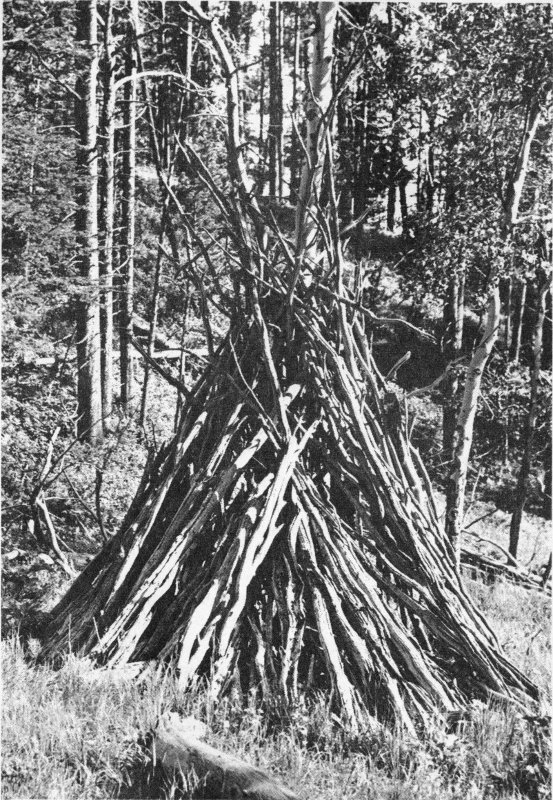

Tukuarikas or Sheepeater Indians— “Tuku” means “mountain sheep” and “arika,” “eat,” or “Sheepeater.” They were a slender, wiry people who possessed neither ponies nor firearms but used bows and arrows effectively. They wore furs and skins and lived among the rocks in the Gardner River canyon in Yellowstone and in the Salmon River Mountains of central Idaho. There were some two hundred Indians in the Yellowstone tribe. Their main support was from game and fish. These Indians did not possess any distinctive culture of their own, but, hermit-like, they seemed concerned only to carry on by themselves until further notice.

The Flatheads— This tribe lived in western Montana. The Flatheads roamed the prairie between Glacier National Park and the Bitter Root Range. Lake Flathead was their favorite rendezvous. These Indians supposedly derived their name from an ancient practice of shaping or deforming the head during infancy. However, in 1830, Ferris claimed that not one living proof of that practice could be found among them. They called themselves “Salish” and spoke a language remarkable for its melody and simplicity. They were noted for humanity, forbearance, and honesty. They were certainly one of the few tribes in the Rocky Mountains who could boast that they never killed or robbed a white man nor stole a single horse.

The Blackfeet— This was a branch of the great Algonquian Nation. They were the Ishmaelites of the west; indeed, they were the most “teutonic” of all American Indians. Their hands were against every man, and the hands of all men, both red and white, were against them.[73] Their habitat was the Marias River Valley in Montana, but they were known as the devils of the mountains 68 and prairies. All who knew them agreed with trader Bird’s observation made to Kenneth McKenzie: “When you know the Blackfeet as well as I do you will know that they do not need any inducements to commit depredations.” They were always hostile and predatory, and their wanderings were most extensive. The tribal name, meaning “Siksi,” “black,” and “kah,” “foot,” alluded to feet made black by roving through the ashes of regions devastated by fires. The Blackfeet were great meat eaters and because of their energy they were generally well supplied. They had horses and guns from an early time, and they wore leather clothing, often highly decorated with beadwork.