GENEALOGICAL CHART FOR EARLIEST HISTORY OF ISLAM.

Names of Khalifas are in black letters; their order in Khalifate is indicated by prefixed Roman numerals; all dates after A.D. 622 are A.H.

Title: Development of Muslim Theology, Jurisprudence, and Constitutional Theory

Author: Duncan Black MacDonald

Release date: March 26, 2019 [eBook #59135]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Fritz Ohrenschall and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Semitic Series

DEVELOPMENT OF

MUSLIM THEOLOGY, JURISPRUDENCE

AND CONSTITUTIONAL THEORY

By DUNCAN B. MACDONALD, M.A., B.D.

SERIES OF HAND-BOOKS IN SEMITICS

EDITED BY JAMES ALEXANDER CRAIG

PROFESSOR OF SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES AND

HELLENISTIC GREEK IN THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

Recent scientific research has stimulated an increasing interest in Semitic studies among scholars, students, and the serious reading public generally. It has provided us with a picture of a hitherto unknown civilization, and a history of one of the great branches of the human family.

The object of the present Series is to state its results in popularly scientific form. Each work is complete in itself, and the Series, taken as a whole, neglects no phase of the general subject. Each contributor is a specialist in the subject assigned him, and has been chosen from the body of eminent Semitic scholars in Europe and in this country.

This Series will be composed of the following volumes:

I. Hebrews. History and Government. By Professor J. F. McCurdy, University of Toronto, Canada.

II. Hebrews. Ethics and Religion. By Professor Archibald Duff, Airedale College, Bradford, England. [Now Ready.

III. Hebrews. The Social Life. By the Rev. Edward Day, Springfield, Mass. [Now Ready.

IV. Babylonians and Assyrians, with introductory chapter on the Sumerians. History to the Fall of Babylon. By Dr. Hugo Winckler, University of Berlin. [In Press.

V. Babylonians and Assyrians. Religion. By Professor J. A. Craig, University of Michigan.

VI. Babylonians and Assyrians. Life and Customs. By Professor A. H. Sayce, University of Oxford, England. [Now Ready.

VII. Babylonians and Assyrians. Excavations and Account of Decipherment of Inscriptions.

VIII. Syria and Palestine. Early History. By Professor Lewis Bayles Paton, Hartford Theological Seminary. [Now Ready.

IX. Development of Muslim Theology, Jurisprudence and Constitutional Theory. By Professor D. B. Macdonald, Hartford Theological Seminary. [Now Ready.

The following volumes are to be included in the Series, and others may be added:

X. Phœnicia. History and Government, including Colonies, Trade, and Religion.

XI. Arabia, Discoveries in, and History and Religion until Muhammad.

XII. Arabic Literature and Science since Muhammad.

XIII. The Influence of Semitic Art and Mythology on Western Nations.

The Semitic Series

DEVELOPMENT OF

Muslim Theology, Jurisprudence

and Constitutional Theory

BY

DUNCAN B. MACDONALD, M.A., B.D.

SOMETIME SCHOLAR AND FELLOW OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

GLASGOW; PROFESSOR OF SEMITIC LANGUAGES IN

HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1903

Copyright, 1903, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

Published; March, 1903

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

MEMORIÆ

MATRIS SACRVM

It is with very great diffidence that I send out this book. Of the lack and need of some text-book of the kind there can be little doubt. From the educated man who wishes to read with intelligence his “Arabian Nights” to the student of history or of law or of theology who wishes to know how it has gone in such matters with the great Muslim world, there is demand enough and to spare. Still graver is the difficulty for the growing body of young men who are taking up the study of Arabic. In English or German or French there is no book to which a teacher may send his pupils for brief guidance on the development of these institutions; on the development of law there are only scattered and fragmentary papers, and on the development of theology there is practically nothing. But of the difficulty of supplying this need there can be even less doubt. Goldziher could do it fully and completely; no other Arabist alive could approach the task other than with trepidation. The following pages therefore form a kind of forlorn attempt, a rushing in on the part of one who is sure he is not an angel and is in grave doubt on the question of folly, but who also sees a gap and no great alacrity on the part of his betters toward filling it. One thing, however, I would premise[viii] with emphasis. All the results given here have been reached or verified from the Arabic sources. These sources are seldom stated either in the text or in the bibliography, as the book is intended to be useful to non-Arabists, but, throughout, they lie behind it and are its basis. By this it is not meant that the results of this book are claimed as original. Every Arabist will recognize at once from whose wells I have drawn and who have been my masters. Among these I would do homage in the first instance to Goldziher; what Arabist is not deep in his debt? With Goldziher’s influence through books I would join the kindred influence of the living voice of my teacher Sachau. To him I render thanks and reverence now for his kindly sympathy and guidance. Others in whose debt I am are Nöldeke, Snouck Hurgronje, von Kremer, Lane—many more. Those who are left of these will know their own in my pages and will be merciful to my attempts to tread in their steps and to develop their results. What is my own, too, they will know; into questions of priority I have no desire to enter. Foot-notes which might have given to each scholar his due have been left unwritten. For the readers of this book such references in so vast a subject would be useless. Such references, too, would have in the end to be made to Arabic sources.

More direct help I have to acknowledge on several sides. To the atmosphere and scholarly ideals of Hartford Seminary I am indebted for the possibility of writing such a book as this, so far from the ordinary theological ruts. Among my colleagues Professor[ix] Gillett has especially aided me with criticism and suggestions on the terminology of scholastic theology. Dr. Talcott Williams, of Philadelphia, illumined for me the Idrisid movement in North Africa. One complete sentence on p. 85 I have conveyed from a kindly notice in The Nation of my inaugural lecture on the development of Muslim Jurisprudence. Finally, and above all, I am indebted to my wife for much patient labor in copying and for keen and luminous criticism in planning and correcting. With thanks to her this preface may fitly close.

Duncan B. Macdonald.

Hartford, December, 1902.

⁂ As it has proved impracticable to give in the body of the book a full transliteration of names and technical terms, the learner is referred for such exact forms to the chronological table and the index. In these hamza and ayn, the long vowels and the emphatic consonants are uniformly represented, the last by italic.

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | 3 |

| PART I CONSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT |

|

| CHAPTER I | |

| From Death of Muhammad to Rise of Abbasids | 7 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| To Rise of Ayyubids | 34 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| To Present Situation | 50 |

| PART II DEVELOPMENT OF JURISPRUDENCE |

|

| CHAPTER I | |

| To Close of Umayyad Period | 65 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| To Present Situation | 91 |

| [xii]PART III DEVELOPMENT OF THEOLOGY |

|

| CHAPTER I | |

| To Close of Umayyad Period | 119 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| To Foundation of Fatimid Khalifate | 153 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| To Triumph of Ash‘arites in East | 186 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Al-Ghazzali | 215 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| To Ibn Sab‘in and End of Muwahhids | 243 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| To Present Situation | 266 |

| APPENDICES | |

| I. Illustrative Documents in Translation | 291 |

| II. Selected Bibliography | 358 |

| III. Chronological Table | 368 |

| INDEX | 373 |

| Page | 30, | line 5, | for al-Mukanna read al-Muqanna. |

| ” | 86, | l. 19, | for first Khalifa read second Khalifa. |

| ” | 201, | l. 26, | for tasalsal read tasalsul. |

| ” | 237, | for Mansell read Mansel. | |

| ” | 267, | l. 30, | for Haqqari read Hakkari. |

| ” | 299, | l. 10, | for Mushriqs read Mushriks. |

| ” | 300, | l. 4, | for kalimatan ash-shahada read kalimata-sh-shabada. |

| ” | 325, | l. 23, | for wihdaniya read wahdaniya. |

| ” | 339, | l. 11, | for ihtiyaz read ihtiyaj. |

Transcriber’s Note: The errata have been corrected.

In human progress unity and complexity are the two correlatives forming together the great paradox. Life is manifold, but it is also one. So it is seldom possible, and still more seldom advisable, to divide a civilization into departments and to attempt to trace their separate developments; life nowhere can be cut in two with a hatchet. And this is emphatically true of the civilization of Islam. Its intellectual unity, for good and for evil, is its outstanding quality. It may have solved the problem of faith and science, as some hold; it may have crushed all thought which is not of faith, as many others hold. However that may be, its life and thought are a unity.

So, also, with its institutions. It might be possible to trace the developments of the European states out of the dying Roman Empire, even to watch the patrimony of the Church grow and again vanish, and yet take but little if any account of the Catholic theology. It might be possible to deal adequately with the growth of that system of theology and yet never touch either the Roman or the civil law, even to leave out of our view the canon law itself. In Europe the State may rule the Church, or the Church may rule the State; or they may stand side by side in somewhat dubious amity, supposedly taking no[4] account each of the other. But in Muslim countries, Church and State are one indissolubly, and until the very essence of Islam passes away, that unity cannot be relaxed. The law of the land, too, is, in theory, the law of the Church. In the earlier days at least, canon and civil law were one. Thus we can never say in Islam, “he is a great lawyer; he, a great theologian; he, a great statesman.” One man may be all three, almost he must be all three, if he is to be any one. The statesman may not practice theology or law, but his training, in great part, will be that of a theologian and a legist. The theologian-legist may not be a man of action, but he will be a court of ultimate appeal on the theory of the state. He will pass upon treaties; decide disputed successions; assign to each his due rank and title. He will tell the Commander of the Faithful himself what he may do and what, by law, lies beyond his reach.

It was, then, under the pressure of necessity only that the following sketch of the development of Muslim thought was divided into three parts. By no possible arrangement did it seem feasible to treat the whole at once. Intolerable confusions and unintelligible complications would, to all appearance, be the result. As the most concrete and simple side, the development of the state is taken first. Second, on account of the shortness of the course which it ran, comes the development of the legal ideas and schools. Third comes the long and thrice complicated thread of theological thought. It is for the student to hold firmly in mind that this division is purely mechanical and for convenience only; that it[5] corresponds to little or nothing in the real nature of the case. This will undoubtedly become clear to him as he proceeds. He will meet with the same names in all three divisions; he will meet with the same technicalities and the same scholastic system. A treatise on canon law is certainly different from one on theology, but each touches the other at innumerable points; their authors may easily be the same; each will be in great part unintelligible without the other. He must then labor to merge these three sections again into one another. His principal helps in this, along with diligent parallel reading, will be the chronological table and the index. In the table he will watch the succession of men and events grouped from all the three sections; from the index he will trace the activities of each man in these different spheres. The index, too, will give him the technical terms and he will observe their recurrence in historical, legal, and theological theory. Further, it will serve him as a vocabulary when he comes to read technical texts.

But, again, another warning is necessary. The sketch given here is incomplete, not only in details but in the ground that it covers. Important phases of Muslim law, theology, and state theory are of necessity passed over entirely. Thus Babism is not touched at all and the Shi‘ite theology and law hardly at all. The Ibadite systems have the merest mention and Turkish and Persian mysticism are equally neglected. For such weighty organizations the Darwish Fraternities are most inadequately dealt with, and Muslim missionary enterprise might well be treated[6] at length. Guidance on these and other points the student will seek in the bibliography. It, too, makes no pretence to completeness and consists of selected titles only. But it will serve at least as an introduction and clew to an exceedingly wide field. And it may be well to state here, in so many words, that no work can be done in this field without a reading knowledge of French and German, and no satisfactory work without some knowledge of Arabic.

And, again, this sketch is incomplete because the development of Islam is not yet over. If, as some say, the faith of Muhammad is a cul-de-sac, it is certainly a very long one; off it many courts and doors open; down it many peoples are still wandering. It is a faith, too, which brings us into touching distance with the great controversies of our own day. We see in it, as in a somewhat distorted mirror, the history of our own past. But we do not yet see its end, even as the end of Christianity is not yet in sight. It is for the student, then, to remember that Islam is a present reality and the Muslim faith a living organism, a knowledge of whose laws may be of life or death for us who are in another camp. For there can be little doubt that the three antagonistic and militant civilizations of the world are those of Christendom, Islam, and China. When these are unified, or come to a mutual understanding, then, and only then, will the cause of civilization be secure. To aid some little to the understanding of Islam among us is the object of this book.

The death of Muhammad and the problem of the succession; the parties; families of Hashimids, Umayyads and Abbasids; election of Abu Bakr; nomination of Umar; his constitution; election of Uthman; Umayyads in power; murder of Uthman; origin of Shi‘ites; election of Ali; civil war; Mu‘awiya first Umayyad; origin of Kharijites; their revolts; Ibadites; development of Shi‘ites; al-Husayn at Karbala; different Shi‘ite constitutional theories; doctrine of the hidden Imam; revolts against Umayyads; rise of Abbasids; Umayyads of Cordova.

With the death of Muhammad at al-Madina in the year 11 of the Hijra (A.D. 632), the community of Islam stood face to face with three great questions. Of the existence of one they were conscious, at least in its immediate form; the others lay still for their consciousness in the future. The necessity was upon them to choose a leader to take the place of the Prophet of God, and thus to fix for all time what was to be the nature of the Muslim state. Muhammad had appointed no Joshua; unlike Moses he had died and given no guidance as to the man who should take up and carry on his work. If we can imagine the people of Israel left thus helpless on the other[8] side of the Jordan with the course of conquest that they must pursue opening before them, we shall have a tolerably exact idea of the situation in Islam when Muhammad dropped the reins. Certainly, the people of Islam had little conception of what was involved in the great precedent that they were about to establish, but, nevertheless, there lies here, in the first elective council which they called, the beginning of all the confusions, rivalries, and uncertainties that were to limit and finally to destroy the succession of the Commanders of the Faithful.

Muhammad had ruled as an absolute monarch—a Prophet of God in his own right. He had no son; though had he left such issue it is not probable that it would have affected the direct result. Of Moses’s son we hear nothing till long afterward, and then under very suspicious circumstances. The old free spirit of the Arabs was too strong, and as in the Ignorance (al-jahiliya), as they called the pre-Muslim age, the tribes had chosen from time to time their chiefs, so it was now fixed that in Islam the leader was to be elected by the people. But wherever there is an election, there are parties; and this was no exception. Of such parties we may reckon roughly four. There were the Early Believers, who had suffered with Muhammad at Mecca, accompanied him to al-Madina and had fought at his side through all the Muslim campaigns. These were called Muhajirs, because they had made with him the Hijra or migration to al-Madina. Then there was the party of the citizens of al-Madina, who had invited him to come to them and had promised[9] him allegiance. These were called Ansar or Helpers. Eventually we shall find these two factions growing together and forming the one party of the old original believers and Companions of Muhammad (sahibs, i.e., all those who came in contact with the Prophet as believers and who died in Islam), but at the first they stood apart and there was much jealousy between them. Then, in the third place, there was the party of recent converts who had only embraced Islam at the latest moment when Mecca was captured by Muhammad, and no other way of escape for them was open. They were the aristocratic party of Mecca and had fought the new faith to the last. Thus they were but indifferent believers and were regarded by the others with more than suspicion. Their principal family was descended from a certain Umayya, and was therefore called Umayyad. There will be much about this family in the sequel. Then, fourth, there was growing up a party that might be best described as legitimists; their theory was that the leadership belonged to the leader, not because he was elected to it by the Muslim community, but because it was his right. He was appointed to it by God as completely as Muhammad had been. This idea developed, it is true, somewhat later, but it developed very rapidly. The times were such as to force it on.

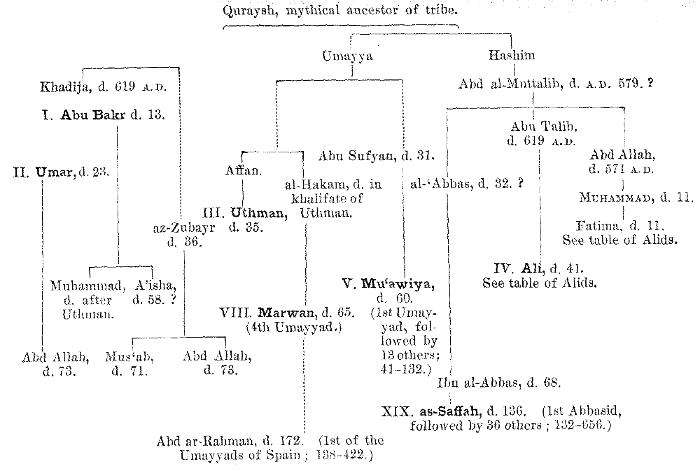

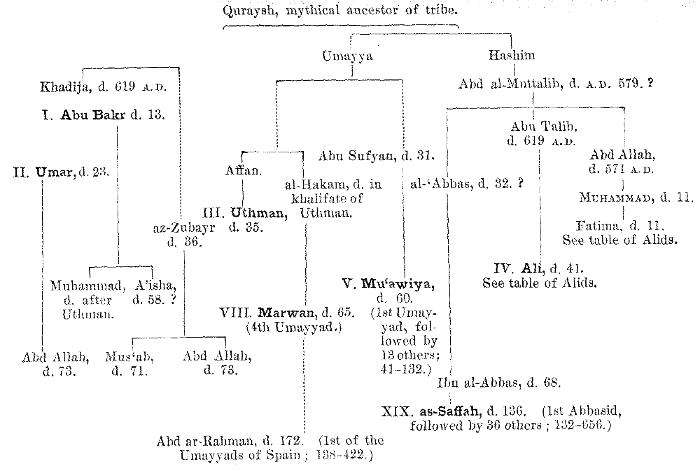

Those, then, were the parties of which account must be taken, but before proceeding to individuals in these parties, it will be well to fix some genealogical relationships, so as to be able to trace the family and tribal jealousies and intrigues that were[10] so soon to transfer themselves from the little circle of Mecca and al-Madina and to fight themselves out on the broad field of Muslim history. For, in truth, in the development of no other state have little causes produced such great effects as here. For example, it may be said, broadly and yet truly, that the seclusion of Muslim women, with all its disastrous effects at the present day for a population of two hundred millions, runs back to the fact that A’isha, the fourteen-year-old wife of Muhammad, once lost a necklace under what the gossips of the time thought were suspicious circumstances. As to the point now in hand, it is quite certain that Muslim history for several hundred years was conditioned and motived by the quarrels of Meccan families. The accompanying genealogy will give the necessary starting-point. The mythical ancestor is Quraysh; hence “the Quraysh,” or “Quraysh” as a name for the tribe. Within the tribe, the two most important families are those of Hashim and Umayya; their rivalries for the succession of the Prophet fill the first century and a half of Muslim history, and the immediately pre-Islamic history of Mecca is similarly filled with a contest between them as to the guardianship of the Ka‘ba and the care of the pilgrims to that sanctuary. Whether this earlier history is real, or a reflection from the later Muslim times, we need not here consider. The next important division is that between the families of al-Abbas and Abu Talib, the uncles of the Prophet. From the one were descended the Abbasids, as whose heir-at-law the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire now claims the Khalifate, and from the other the different conflicting lines of Shi‘ites, whose intricacies we shall soon have to face.

GENEALOGICAL CHART FOR EARLIEST HISTORY OF ISLAM.

Names of Khalifas are in black letters; their order in Khalifate is indicated by prefixed Roman numerals; all dates after A.D. 622 are A.H.

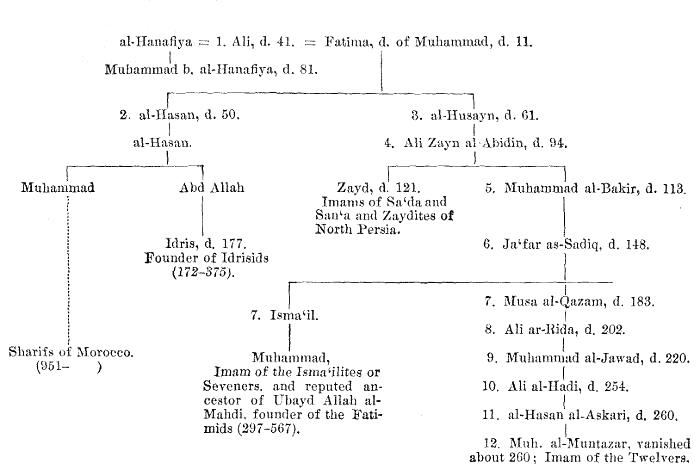

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLE OF ALIDS.

To return: in this first elective council the choice fell upon Abu Bakr. He was a man distinguished by his piety and his affection for and close intimacy with Muhammad. He was the father of Muhammad’s favorite wife, A’isha, and was some two years younger than his son-in-law. He was, also, one of the earliest believers and it is evident that this, with his advanced age, always respected in Arabia, went far to secure his election. Yet his election did not pass off without a struggle in which the elements that later came to absolute schism and revolution are plainly visible. The scene, as it can be put together from Arabic historians, is curiously suggestive of the methods of modern politics. As soon as it was assured that the Prophet, the hand which had held together all those clashing interests, was really dead, a convention was called of the leaders of the people. There the strife ran so high between the Ansar, the Muhajirs and the Muslim aristocrats of the house of Umayya, that they almost came to blows. Suddenly in the tumult, Umar, a man of character and decision, “rushed the convention” by solemnly giving to Abu Bakr the hand-grasp of fealty. The accomplished fact was recognized—as it has always been in Islam—and on the next day the general mass of the people swore allegiance to the first Khalifa, literally Successor, of Muhammad.

On his death, in A.H. 13 (A.D. 634), there followed Umar. His election passed off quietly. He had been nominated by Abu Bakr and nothing remained[14] but for the people to confirm that nomination. There thus entered a second principle—or rather precedent—beside that of simple election. A certain right was recognized in the Khalifa to nominate his successor, provided he chose one suitable and eligible in other respects. Unlike Cromwell in a similar case, Abu Bakr did not nominate one of his own sons, but the man who had been his right hand and who, he knew, could best build up the state. His foresight was proved by the event, and Umar proved the second founder of Islam by his genius as a ruler and organizer and his self-devotion as a man. Through his generals, Damascus and Jerusalem were taken, Persia crushed in the great battles of al-Qadisiya and Nahawand, and Egypt conquered. He was also the organizer of the Muslim state, and it will be advisable to describe part of his system, both for its own sake and in order to point the contrast with that of his successors. He saw clearly what were the conditions under which the Muslims must work, and devised a plan, evidently based on Persian methods of government, which, for the time at least, was perfect in its way.

The elements in the problem were simple. There was the flood of Arabs pouring out of Arabia and bearing everything down in their course. These must be retained as a conquering instrument if Islam were to exist. Thus they must be prevented from settling down on the rich lands they had seized,—from becoming agriculturists, merchants, and so on, and so losing their identity among other peoples. The whole Arab stock must be preserved as a warrior[15] caste to fight the battles of God. This was secured by a regulation that no new lands should be held by a Muslim. When a country was conquered, the land was left to its previous possessors with the duty of paying a high rent to the Muslim state and, besides, of furnishing fodder and food, clothing and everything necessary to the Muslim camp that guarded them. These camps, or rather camp-cities, were scattered over the conquered countries and were practically settlements of Muslims in partibus infidelium. The duty of these Muslims was to be soldiers only. They were fed and clothed by the state, and the money paid into the public treasury, consisting of plunder or rents of conquered lands (kharaj), or the head-tax on all non-Muslims (jizya), was regularly divided among them and the other believers. If a non-Muslim embraced Islam, then he no longer paid the head-tax, but the land which he had previously held was divided among his former co-religionists, and they became responsible to the state. He, on the other hand, received his share of the public moneys as regularly distributed. Within Arabia itself, no non-Muslim was permitted to live. It was preserved, if we may use the expression, as a breeding-ground for defenders of the faith and as a sacred soil not to be polluted by the foot of an unbeliever. It will readily be seen what the results of such a system must have been. The entire Muslim people was retained as a gigantic fighting machine, and the conquered peoples were machines again to furnish it with what was needed. The system was communistic, but in favor of one special caste. The others—the[16] conquered peoples—were crushed to the ground beneath their burdens. Yet they could not sell their land and leave the country; there was no one to buy it. The Muslims would not, and their fellow-co-religionists could not, for with it went the land-tax.

Such was, in its essence, the constitution of Umar, forever famous in Muslim tradition. It stood for a short time, and could not have stood for a long time; but the cause of its overthrow was political and not social-economic. With the next Khalifa and the changes which came with him, it went, in great part, to the ground. The choice of Umar to the Khalifate had evidently been dictated by a consideration of his position as one of the earliest believers and as son-in-law of the Prophet. The party of Early Believers had thus succeeded twice in electing their candidate. But with the death of Umar in A.H. 23 (A.D. 644) the Meccan aristocratic party of the family of Umayya that had so long struggled against Muhammad and had only accepted Islam when their cause was hopelessly lost, had at last a chance. Umar left no directions as to his successor. He seems to have felt no certainty as to the man best fitted to take up the burden, and when his son sought to urge him to name a Khalifa, he is reported to have said, “If I appoint a Khalifa, Abu Bakr appointed a Khalifa; and if I leave the people without guidance, so did the Apostle of God.” But there is also a story that after a vain attempt to persuade one of the Companions to permit himself to be nominated, he appointed an elective council of six to make the choice after his death under stringent conditions, which went all to wreck[17] through the pressure of circumstances. The Umayyads succeeded in carrying the election of Uthman, one of their family, an old man and also a son-in-law of Muhammad, who by rare luck for them was an Early Believer. After his election it was soon evident that he was going to rule as an Umayyad and not as a Muslim. For generations back in Mecca, as has already been said, there had been, according to tradition, a continual struggle for pre-eminence between the families of Umayya and of Hashim. In the victory of Muhammad and the election of the first two Khalifas, the house of Hashim had conquered, but it had been the constant labor of the conquerors to remove all tribal and family distinctions and frictions and to bring the whole body of the Arabs to regard one another as brother Muslims. Now, with a Khalifa of the house of Umayya, all that was swept away, and it was evident that Uthman—a pious, weak man, in the hands of his energetic kinsfolk—was drifting to a point where the state would not exist for the Muslims but for the Umayyads. His evil spirit was his cousin Marwan ibn al-Hakam, whom he had appointed as his secretary and who eventually became fourth Umayyad Khalifa. The father of this man, al-Hakam ibn al-As, accepted Islam at the last moment when Mecca was captured, and, thereafter, was banished by Muhammad for treachery. Not till the reign of Uthman was he permitted to return, and his son, born after the Hijra, was the most active assertor of Umayyad claims. Under steady family pressure, Uthman removed the governors of provinces who had suffered with Muhammad and fought in the[18] Path of God (sabil Allah), and put in their places his own relations, late embracers of the faith. He broke through the Constitution of Umar and gifted away great tracts of state lands. The feeling spread abroad that in the eyes of the Khalifa an Umayyad could do no wrong, and the Umayyads themselves were not backward in affording examples. To the Muhajirs and Ansar they were godless heathen, and probably the Muhajirs and Ansar were right. Finally, the indignation could no longer be restrained. Insurrections broke out in the camp-cities of al-Kufa and al-Basra, and in those of Egypt and at last in al-Madina itself. There, in A.H. 35 (A.D. 655), Uthman fell under the daggers of conspirators led by a Muhammad, a son of Abu Bakr, but a religious fanatic strangely different from his father, and the train was laid for a long civil war. In the confusion that followed the deed the chance of the legitimist party had come, and Ali, the cousin and son-in-law of the Prophet, was chosen.

Fortunately this is not a history of Islam, but of Muslim political institutions, and it is, therefore, unnecessary to go into the manifold and contradictory stories told of the events of this time. These have evidently been carefully redacted in the interests of later orthodoxy, and to protect the character of men whose descendants later came to power. The Alids built up in favor of Ali a highly ingenious but flatly fictitious narrative, embracing the whole early history and exhibiting him as the true Khalifa kept from his rights by one after the other of the first three, and suffering it all with angelic patience. This[19] varies from the extreme Shi‘ite position, which damns all the three at a sweep as usurpers, through a more moderate one which contents itself with cursing Umar and Uthman, to a rejection of Uthman only, and even, at the other extreme, satisfies itself with anathematizing the later Umayyads. At this point the Shi‘ites join hands with the body of orthodox believers, who are all sectaries of Ali to a certain degree. Yet this tendency has been counteracted to some extent by a strongly catholic and irenic spirit which manifests itself in Islam. After a controversy is over and the figures in it have faded into the past, Islam casts a still deeper veil over the controversy itself and glorifies the actors on both sides into fathers and doctors of the Church. An attempt is made to forget that they had fought one another so bitterly, and to hold to the fact only that they were brother Muslims. The Shi‘ites well so-called, for Shi‘a means sect, have never accepted this; but it is the usage of orthodox, commonly called Sunnite, Islam. A concrete expression of any result reached by the body of the believers then often takes the form of a tradition assigned to Muhammad. In this case, it is a saying of his that ten men, specified by name and prominent leaders in these early squabbles, were certain of Paradise. It has further become an article in Muslim creeds, that the Companions of the Prophet are not to be mentioned save with praise; and one school of theologians, in their zeal for the historic Khalifate, even forbade the cursing of Yazid, the slayer of al-Husayn (p. 28 below), and reckoned as the worst of all the Umayyads, because he had been[20] a Khalifa in full and regular standing. This catholic recognition of the unity of Islam we shall meet again and again.

Abandoning, then, any attempt to trace the details and to adjust the rights and wrongs of this story, we return to the fixed fact of the election of Ali and the accession to power of the legitimist party. This legitimist party, or parties, had been gradually developing, and their peculiar and mutually discordant views deserve attention. These views all glorified Ali, the full cousin of Muhammad and husband of his daughter Fatima, but upon very different grounds. There could not but exist the feeling that a descendant of the Prophet should be his successor, and the children of Ali, al-Hasan and al-Husayn were his only grandchildren and only surviving male descendants. This, of course, reflected a dignity upon Ali, their father, and gave him a claim to the Khalifate. Again, Ali himself seems to have made a great and hardly comprehensible impression upon his contemporaries. The proverb ran with the people, “There is no sword save Dhu-l-faqar, and no youth save Ali.” He was not, perhaps, so great a general as one or two others of his time, but he stood alone as a warrior in single combat; he was a poet and an orator, but no statesman. As one of the earliest of the Early Believers, it might be expected that the Muhajirs would support him, and so they did; but the matter went much farther, and he seems to have excited a feeling of personal attachment and devotion different from that rendered to the preceding Khalifas. Strange and mystical doctrines were afloat[21] as to his claim. The idea of election was thrown aside, and his adherents proclaimed his right by the will and appointment of God to the successorship of the Prophet. As God had appointed Muhammad as Prophet, so He had appointed Ali as his helper in life and his successor in death. This was preached in Egypt as early as the year 32.

It will easily be seen that with such a following, uniting so many elements, his election could be brought about. Thus it was; but an evil suspicion rested upon him. Men thought, and probably rightly, that he could have saved the aged Uthman if he had willed, and they even went the length of accusing him of being art and part in the murder itself. The ground was hollow beneath his feet. Further, there were two other old Companions of the Prophet, Talha and az-Zubayr, who thought they had a still better claim to the Khalifate; and they were joined by A’isha, the favorite wife of Muhammad, now, as a finished intrigante, the evil genius of Islam. Ali had reaped all the advantage of the conspiracy and murder, and it was easy to raise against him the cry of revenge for Uthman. Then the civil war began. In the struggle with Talha and az-Zubayr, Ali was victorious. Both fell at the battle of the Camel (A.H. 36), so called from the presence of A’isha mounted on a camel like a chieftainess of the old days. But a new element was to enter. The governorship of Syria had been held for a long time by Mu‘awiya, an Umayyad, and there the Umayyad influence was supreme. There, too, had grown up a spirit of religious indifference, combined with a preservation[22] of all the forms of the faith. Mu‘awiya was a statesman by nature, and had moulded his province into an almost independent kingdom. The Syrian army was devoted to him, and could be depended upon to have no other interests than his. From the beginning of Ali’s reign, he had been biding his time; had not given his allegiance, but had waited for the hour to strike for revenge for Uthman and power for himself. The time came and Mu‘awiya won. We here pass over lightly a long and contradictory story. It is enough to note how the irony of history wrought itself out, and a son of the Abu Sufyan who had done so much to persecute and oppose Muhammad in his early and dark days and had been the last to acknowledge his mission, became his successor and the ruler of his people. But with Ali ends the revered series of the four “Khalifas who followed a right course” (al-khulafa ar-rashidun), reverenced now by all orthodox Muslims, and there begins the division of Islam into sects, religious and political—it comes to the same thing.

The Umayyads themselves clearly recognized that with their accession to power a change had come in the nature of the Muslim state. Mu‘awiya said openly that he was the first king in Islam, though he retained and used officially the title of Khalifa and Commander of the Faithful. Yet such a change could not be complete nor could it carry with it the whole people—that is clear of itself. For more than one hundred years the house of Umayya held its own. Syria was solid with it and it was supported by many statesmen and soldiers; but outside of[23] Syria and north Arabia it could count on no part of the population. An anti-Khalifa, Abd Allah, son of the az-Zubayr of whom we have already heard, long held the sacred cities against them. Only in A.H. 75 (A.D. 692) was he killed after Mecca had been stormed and taken by their armies. Southern Arabia and Mesopotamia, with its camp-cities al-Kufa and al-Basra, Persia and Egypt, were, from time to time, more or less in revolt. These risings went in one or other of two directions. There were two great anti-Umayyad sects. At one time in Mu‘awiya’s contest with Ali, he trapped Ali into the fatal step of arbitrating his claim to the Khalifate. It was fatal, for by it Ali alienated some of his own party and gained less than nothing on the other side. Part of Ali’s army seceded in protest and rebellion, because he—the duly elected Khalifa—submitted his claim to any shadow of doubt. On the other hand, they could not accept Mu‘awiya, for him they regarded as unduly elected and a mere usurper. Thus they drifted and split into innumerable sub-sects. They were called Kharijites—goers out—because they went out from among the other Muslims, refused to regard them as Muslims and held themselves apart. For centuries they continued a thorn in the side of all established authority. Their principles were absolutely democratic. Their idea of the Khalifate was the old one of the time of Abu Bakr and Umar. The Khalifa was to be elected by the whole Muslim community and could be deposed again at need. He need be of no special family or tribe; he might be a slave, provided he was a good Muslim ruler.[24] Some admitted that a woman might be Khalifa, and others denied the need of any Khalifa at all; the Muslim congregation could rule itself. Their religious views were of a similarly unyielding and antique cast, but with that we have nothing now to do.

It cannot be doubted that these men were the true representatives of the old Islam. They claimed for themselves the heirship to Abu Bakr and Umar, and their claim was just. Islam had been secularized; worldly ambition, fratricidal strife, luxury, and sin had destroyed the old bond of brotherhood. So they drew themselves apart and went their own way, a way which their descendants still follow in Uman, in east Africa, and in Algeria. To them the orthodox Muslims—meaning by that the general body of Muslims—were antipathetic more than even Christians or Jews. These were “people of a book” (ahl kitab), i.e., followers of a revealed religion, and kindly treatment of them was commanded in the Qur’an. They had never embraced Islam, and were to be judged and treated on their own merits. The non-Kharijite Muslims, on the other hand, were renegades (murtadds) and were to be killed at sight. It is easy to understand to what such a view as this led. Numberless revolts, assassinations, plunderings marked their history. Crushed to the ground again and again, again and again they recovered. They were Arabs of the desert; and the desert was always there as a refuge. It is probable, but as yet unproved, that mingled with the political reasons for their existence as a sect went tribal jealousies and frictions; of such there have ever been enough and[25] to spare in Arabia. Naturally, under varying conditions, their views and attitudes varied. In the wild mountains of Khuzistan, one of their centres and strongholds, the primitive barbarism of their faith had full sway. It drew its legitimate consequence, lived out its life, and vanished from the scene. The more moderate section of the Kharijites centred round al-Basra. Their leader there was Abd Allah ibn Ibad, and from about the year 60 on the schism between his followers and the more absolute of these “come-outers” can be traced. It is characteristic of the latter that they aided for a time Abd Allah ibn az-Zubayr when he was besieged in Mecca by the Umayyads, but deserted him finally because he refused to join the names of Talha and his own father, az-Zubayr, with those of Uthman and Ali in a general commination. The Kharijites were all good at cursing, and the later history of this section of them shows a process of disintegration by successive secessions, each departing in protest and cursing those left behind as heathen and unbelievers. Characteristic, too, for the difference between the two sections, were their respective attitudes toward the children of their opponents. The more absolute party held that the children of unbelievers were to be killed with their parents; the followers of Abd Allah ibn Ibad, that they were to be allowed to grow up and then given their choice. Again, there was a difference of opinion as to the standing of those who held with the Kharijites but remained at home and did not actually fight in the Path of God. These the one party rejected and the other accepted. Again,[26] were the non-Kharijites Muslims to the extent that the Kharijites might live amongst them and mix with them? This the severely logical party denied, but Abd Allah ibn Ibad affirmed.

From this it will be abundantly clear that the only party with a possible future was that of Ibn Ibad. His sect survives to the present day under the name of Ibadites. Very early it spread to Uman, and, according to their traditions, their first Imam, or president, was elected about A.H. 134. He was of a family which had reigned there before Islam, and from the time of his election on, the Ibadites have succeeded in holding Uman against the rest of the Muslim world. Naturally, the election of the Imam by the community has turned into the rule of a series of dynasties; but the theory of election has always held fast. They were sailors, merchants, and colonizers already by the tenth century A.D., and carried their state with its theology and law to Zanzibar and the coast of East Africa generally. Still earlier Ibadite fugitives passed into North Africa, and there they still maintain the simplicity of their republican ideal and their primitive theological and legal views. Their home is in the Mzab in the south of Algeria, and, though as traders and capitalists they may travel far, yet they always return thither. Any mingling in marriage with other Muslims is forbidden them.

At the opposite extreme from these in political matters stands the sect that is called the Shi‘a. It, as we have seen, is the name given to the party that glorifies Ali and his descendants and regards the Khalifate as belonging to them by right divine. How[27] early this feeling arose we have already seen, but the extremes to which in time the idea was carried, the innumerable differing views that developed, the maze of conspiracies, tortuous and underground in their methods, some in good faith and some in bad, to which it gave rise, render the history of the Shi‘a the most difficult side of a knowledge of the Muslim East. Yet some attempt at it must be made. If there was ever a romance in history, it is the story of the founding of the Fatimid dynasty in Egypt; if there was ever the survival of a petrifaction in history, it is the survival to the present day of the Assassins and the Druses; if there was ever the persistence of an idea, it is in the present Shi‘ite government in Persia and in the faith in that Mahdi for whom the whole world of Islam still looks to appear and bring in the reign of justice and the truth upon the earth. All these have sprung from the devotion to Ali and his children on the part of their followers twelve centuries ago.

In A.H. 40 (A.D. 660) Ali fell by the dagger of a Kharijite. These being at the opposite pole from the Shi‘ites, are the only Muslim sect that curses and abhors Ali, his family and all their works. Orthodox Islam reveres Ali and accepts his Khalifate; his family it also reverences, but rejects their pretensions. The instinct of Islam is to respect the accomplished fact, and so even the Umayyads, one and all, stand in the list of the successors of the Prophet, much as Alexander VI and his immediate predecessors do in that of the Popes.

To Ali succeeded his son, al-Hasan, but his name[28] does not stand on the roll of the Khalifate as usually reckoned. It shows some Shi‘ite tinge when the historian says, “In the Khalifate of al-Hasan,” and, thereafter, proceeds with, “In the days of Mu‘awiya,” the Umayyad Khalifa who followed him. Mu‘awiya had received the allegiance of the Syrian Muslims and when he advanced on al-Kufa, where al-Hasan was, al-Hasan met him and gave over into his hands all his supposed rights. That was in A.H. 41; in A.H. 49 he was dead by poison. Twelve years later al-Husayn, his brother, and many of his house fell at Karbala in battle against hopeless odds. It is this last tragedy that has left the deepest mark of all on the Muslim imagination. Yearly when the fatal day, the day of Ashura, the tenth of the month Muharram, comes round, the story is rehearsed again at Karbala and throughout, indeed, all the Shi‘ite world in what is a veritable Passion Play. No Muslim, especially no Persian, can read of the death of al-Husayn, or see it acted before his eyes, without quivering and invoking the curse of God upon all those who had aught to do with it or gained aught by it. That curse has clung fast through all the centuries to the name of Yazid, the Umayyad Khalifa of the time, and only the stiffest theologians of the traditional school have labored to save his memory through the merits of the historical Khalifate. But even after this tragedy it was not out with the blood of Muhammad. Many descendants were left and their party lived on in strange, half underground fashion, as sects do in the East, occasionally coming to the surface and bursting out in wild and, for long, useless rebellion.

In these revolts the Shi‘a was worthy of its name, and split into many separate divisions, according to the individuals of the house of Ali to whom allegiance was rendered and who were regarded as leaders, titular or real. These subdivisions differed, also, in the principle governing the choice of a leader and in the attitude of the people toward him. Shi‘ism, from being a political question, became theological. The position of the Shi‘ite was and is that there must be a law (nass) regulating the choice of the Imam, or leader of the Muslim community; that that law is one of the most important dogmas of the faith and cannot have been left by the Prophet to develop itself under the pressure of circumstances; that there is such an Imam clearly pointed out and that it is the duty of the Muslim to seek him out and follow him. Thus there was a party who regarded the leadership as belonging to Ali himself, and then to any of his descendants by any of his wives. These attached themselves especially to his son Muhammad, known from his mother as Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiya, who died in 81, and to his descendants and successors. It was in this sect that the most characteristic Shi‘ite views first developed. This Muhammad seems to have been the first concerning whom it was taught, after his death, that he was being preserved by God alive in retirement and would come forth at his appointed time to bring in the rule of righteousness upon the earth. In some of the innumerable sub-sects the doctrine of the deity, even, of Ali was early held, in others a doctrine of metempsychosis, generally among men and especially from one Imam to[30] his successor; others, again, advanced the duty of seeking the rightful Imam and rendering allegiance to him till it covered the whole field of faith and morals—no more was required of the believer. To one of these sects, al-Muqanna, “the Veiled Prophet of Khorasan,” adhered before he started on his own account.

We have seen already that so early as 32 the doctrine had been preached in Egypt that Ali was the God-appointed successor of the Prophet. Here we have its legitimate development, which was all the quicker as it had, or assumed, a theological basis, and did not simply urge the claims to leadership of the family of the Prophet after the fashion in which inheritance runs among earthly kings. That was the position at first of the other and far more important Shi‘ite wing. It regarded the leadership as being in the blood of Muhammad and therefore limited to the children of Ali by his wife Fatima, the daughter of Muhammad. Again, the attitude toward the person of the leader varied, as we have already seen. One party held that the leadership was by the right of the appointment of God, but that the leader himself was simply a man as other men. These would add to “the two words” (al-kalimatani) of the creed, “There is no god but God, and Muhammad is the Apostle of God,” a third clause, “and Ali is the representative of God.” Others regarded him as an incarnation of divinity; a continuing divine revelation in human form. His soul passed, when he died, to his next successor. He was, therefore, infallible and sinless, and was to be treated with absolute, blind obedience.[31] Here there is a mingling of the most strangely varied ideas. In Persia the people had been too long accustomed to looking upon their rulers as divine for them to be capable of taking up any other position. A story is told of the governor of a Persian province who wrote to the Khalifa of his time that he was not able to prevent his people from giving him the style and treatment of a god; they did not understand any other kind of ruler; it was as much as his authority was worth to attempt to make them desist. From this attitude, combined with the idea of the transmigration of souls, the extreme Shi‘ite doctrine was derived.

But though the party of Ali might regard the descendants of Ali as semi-divine, yet their conspiracies and revolts were uniformly unsuccessful, and it became a very dangerous thing to head one. The party was willing to get up a rising at any time, but the leader was apt to hang back. In fact, one of the most curious features of the whole movement was the uselessness of the family of Ali and the extent to which they were utilized by others. They have been, in a sense, the cat’s-paws of history. Gradually they themselves drew back into retirement and vanished from the stage, and, with their vanishing, a new doctrine arose. It was that of the hidden Imam. We have already seen the case of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiya, whom Muslims reckon as the first of these concealed ones. Another descendant of Ali, on another line of descent, vanished in the same way in the latter part of the second century of the Hijra, and another about A.H. 260. Their respective followers[32] held that they were being kept in concealment by God and would be brought back at the appointed time to rule over the world and bring in a kind of Muslim millennium. This is the oriental version of the story of Arthur in Avalon and of Frederick Barbarossa in Kyffhaüser.

But that has led us far away and we must go back to the fall of the Umayyads and the again disappointed hopes of the Alids. By the time of the last Khalifa of the Umayyad house, Marwan II, A.H. 127-132 (A.D. 744-750), the whole empire was more or less in rebellion, partly Shi‘ite and partly Kharijite. The Shi‘ites themselves had, as usual, no man strong enough to act as leader; that part was taken by as-Saffah, a descendant of al-Abbas, an uncle of Muhammad. The rebellion was ostensibly to bring again into power the family of the Prophet, but under that the Abbasids understood the family of Hashim, while the Alids took it in the more exact sense of themselves. They were made a cat’s-paw, the Abbasid dynasty was founded, and they were thrown over. Thus, the Khalifate remained persistently in the hands of those who, up to the last, had been hostile to the Prophet. This al-Abbas had embraced the faith only when Mecca was taken by the Muslims. Later historians, jealous for the good name of the ancestor of the longest line of all the Successors, have labored to build up a legend that al-Abbas stayed in Mecca only because he could there be more useful in the cause of his nephew. This is one of the perversions of early history of which the Muslim chronicles are full.

But the story of the Umayyads is not yet out. From the ruin that overwhelmed them, one escaped and fled to North Africa. There, he vainly tried to draw together a power. At last, seeing in Spain some better prospect of success, he crossed thither, and by courage, statesmanship, and patience, carved out a new Umayyad empire that lasted for 300 years. One of his descendants in A.H. 317 (A.D. 929) took the title of Khalifa and claimed the homage due to the Commander of the Faithful. There is a story that al-Mansur, the second Abbasid, once asked his courtiers, “Who is the Falcon of Quraysh?” They named one after another of the great men of the tribe, beginning, naturally, with his majesty himself, but to no purpose. “No,” he said, “the Falcon of Quraysh is Abd ar-Rahman, the Umayyad, who found his way over deserts and seas, flung himself alone into a strange country, and there, without any helper but himself, built up a realm. There has been none like him of the blood of Quraysh.”

Shi‘ite revolts against Abbasids; Idrisids; Zaydites; Imamites; the Twelvers; constitutional theory of modern Persia; origin of Fatimids; Maymun the oculist; plan of the conspiracy; the Seveners; the Qarmatians; Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi and founding of Fatimid dynasty in North Africa; their spread to Egypt and to Syria; al-Hakim Bi’amrillah; the Druses; the Assassins; Saladin and the Ayyubids.

It is not in place here to deal with all the numberless little Shi‘ite revolts against the Abbasids which now followed. Those only are of interest to us which had more or less permanent effect on the Muslim state and states. Earliest among such comes the revolt which founded the dynasty of the Idrisids. About the middle of the second century the Abbasids were hard pressed. The heavens themselves seemed to mingle in the conflict. The early years of their rule had been marked by great showers of shooting stars, and the end of the age was reckoned near by both parties. Messianic hope was alive, and a Mahdi, a Guided of God, was looked for. This had long been the attitude of the Alids, and the Abbasids began to feel a necessity to gain for their de facto rule the sanction of theocratic hopes. In 143 Halley’s comet was visible for twenty days, and in 147 there were again showers of shooting stars. On the part of the Abbasids, homage was solemnly rendered to the eldest son of al-Mansur, the Khalifa[35] of the time, as successor of his father, under the title al-Mahdi, and several sayings were forged and ascribed to the Prophet which told who and what manner of man the Mahdi would be, in terms which clearly pointed to this heir-apparent. The Alids, on their side, were urged on to fresh revolts. These risings were still political in character and hardly at all theological; they expressed the claims to sovereignty of the house of the Prophet. On the suppression of one of them at al-Madina in 169, Idris ibn Abd Allah, a grandson of al-Hasan, escaped to North Africa—that refuge of the politically disaffected—and there at the far-off Volubilis of the Romans, in the modern Morocco, founded a state. It lasted till 375, and planted firmly the authority of the family of Muhammad in the western half of North Africa. Other Alid states rose in its place, and in 961 the dynasty of the Sharifs of Morocco was established by a Muhammad, a descendant of a Muhammad, brother of the same Abd Allah, grandson of al-Hasan. This family still rules in Morocco and claims the title of Khalifa of the Prophet and Commander of the Faithful. Strictly, they are Shi‘ites, but their sectarianism sits lightly upon them; it is political only and they have no touch of the violent religious antagonism to the Sunnite Muslims that is to be found in Persian Shi‘ism. As adherents of the legal school of Malik ibn Anas, their Sunna is the same as that of orthodox Islam. The Sahih of al-Bukhari (see below, p. 79) is held in especially high reverence, and one division of the Moorish army always carries a copy of it as a talisman. They are really a bit of the second[36] century of the Hijra crystallized and surviving into our time.

Another Shi‘ite line which lasts more or less down to the present day, is that of the Zaydites of al-Yaman. They were so called from their adherence to Zayd, a grandson of al-Husayn, and their sect spread in north Persia and south Arabia. The north Persian branch is of little historic importance for our purpose. For some sixty-four years, from 250 on, it held Tabaristan, struck coins and exercised all sovereign rights; then it fell before the Samanids. The other branch has had a much longer history. It was founded about 280, at Sa‘da in al-Yaman and there, and later at San‘a, Zaydite Imams have ruled off and on till our day. The Turkish hold upon south Arabia has always been of the slightest. Sometimes they have been absolutely expelled from the country, and their control has never extended beyond the limits of their garrisoned posts. The position of these Zaydites was much less extreme than that of the other Shi‘ites. They were strictly Fatimites, that is, they held that any descendant of Fatima could be Imam. Further, circumstances might justify the passing over, for a time, of such a legitimate Imam and the election as leader of someone who had no equally good claim. Thus, they reverenced Abu Bakr and Umar and regarded their Khalifate as just, even though Ali was there with a better claim. The election of these two Khalifas had been to the advantage of the Muslim state. Some of them even accepted the Khalifate of Uthman and only denounced his evil deeds. Further, they regarded it as[37] possible that there might be two Imams at the same time, especially when they were in countries widely apart. This, apparently, sprang from the sect being divided between north Persia and south Arabia. Theologically, or philosophically—it is hard to hold the two apart in Islam—the Zaydites were accused of rationalism. Their founder, Zayd, the grandson of al-Husayn, had studied under the great Mu‘tazilite, Wasil ibn Ata, of whom much more hereafter.

But if the Zaydites were lax both in their theology and in their theory of the state, that cannot be said of another division of the Shi‘ites, called the Imamites on account of the stress which they laid on the doctrine of the person of the Imam. For them the Imam of the time was explicitly and personally indicated, Ali by Muhammad and each of the others in turn by his predecessor. But it was hard to reconcile with this a priori position that an Imam must have been indicated, the fact that there was no agreement as to the Imam who had been indicated. Down all possible lines of descent the sacred succession was traced until, of the seventy-two sects that the Prophet had foretold for his people, seventy, at least, were occupied by the Imamites alone. Further, the number of Hidden Imams was constantly running up; with every generation, Alids found it convenient to withdraw into retirement and have reports given out of their own deaths. Then two sects would come into existence—one which stopped at the Alid in question, and said that he was being kept in concealment by God to be brought back at His pleasure;[38] and another which passed the Imamship on to the next generation. Out of this chaos two sects, adhering to two series of Imams, stand clear through their historical importance. The one is that of the Twelvers (Ithna‘ashariya); theirs is the official creed of modern Persia. About A.H. 260 a certain Muhammad ibn al-Hasan, twelfth in descent from Ali, vanished in the way just described. The sect which looked for his return increased and flourished until, at length, with the conquest of Persia in A.H. 907 (A.D. 1502) by the Safawids—a family of Alid descent which joined arms to sainthood—Persia became Shi‘ite, and the series of the Shahs of Persia was begun. The position of the Shah is therefore essentially different from that of the Khalifa of the Sunnites. The Khalifa is the successor of Muhammad, with a dignity and authority which inheres in himself; he is both king and pontiff; the Shah is a mere locum tenens, and reigns only until God is pleased to restore to men the true Imam. That Imam is still in existence, though hidden from human eyes. The Shah, therefore, has strictly no legal authority; he is only a guardian of the public order. True legal authority lies, rather, with the learned doctors of religion and law. As a consequence of this, the Shi‘ites still have Mujtahids, divines and legists who have a right to form opinions of their own, can expound the original sources at first hand, and can claim the unquestioning assent of their disciples. Such men have not existed among the Sunnites since the middle of the third century of the Hijra; from that time on all Sunnites have been[39] compelled to swear to the words of some master or other, long dead.

This division of the Shi‘ites is the only one that exists in great numbers down to the present day. The second of the two mentioned above came to power earlier, ran a shorter course, and has now vanished from the stage, leaving nothing but an historical mystery and two or three fossilized, half-secret sects—strange survivals which, like the survivals of geology, tell us what were the living and dominant forces in the older world. It will be worth while to enter upon some detail in reciting its history, both for its own romantic interest and as an example of the methods of Shi‘ite propaganda. Its success shows how the Abbasid empire was gradually undermined and brought to its fall. It itself was the most magnificent conspiracy, or rather fraud, in all history. To understand its possibility and its results, we must hold in mind the nature of the Persian race and the condition of that race at this time. Herodotus was told by his Persian friends that one of the three things Persian youth was taught was to tell the truth. That may have been the case in the time of Herodotus, but certainly this teaching has had no effect whatever on an innate tendency in the opposite direction; and it is just possible that Herodotus’s friends, in giving him that information, were giving also an example of this tendency. Travellers have been told curious things before now, but certainly none more curious than this. As we know the Persian in history, he is a born liar. He is, therefore, a born conspirator. He has great quickness of[40] mind, adaptability, and, apart from religious emotion, no conscience. In the third century of the Hijra (the ninth A.D.), the Persians were either devoted Shi‘ites or simple unbelievers. The one class would do anything for the descendants of Ali; the other, anything for themselves. This second class, further, would by preference combine doing something for themselves with doing something against Islam and the Arabs, the conquerors of their country. So much by way of premise.

In the early part of this third century, there lived at Jerusalem a Persian oculist named Maymun. He was a man of high education, professional and otherwise; had no beliefs to speak of, and understood the times. He had a son, Abd Allah, and trained him carefully for a career. Abd Allah, however—known as Abd Allah ibn Maymun—though he had thought of starting as a prophet himself, saw that the time was not ripe, and planned a larger and more magnificent scheme. This was to be no ordinary conspiracy to burst after a few years or months, but one requiring generations to develop. It was to bring universal dominion to his descendants, and overthrow Islam and the Arab rule. It succeeded in great part, very nearly absolutely.

His plan was to unite all classes and parties in a conspiracy under one head, promising to each individual the things which he considered most desirable. For the Shi‘ites, it was to be a Shi‘ite conspiracy; for the Kharijites, it took a Kharijite tinge; for Persian nationalists, it was anti-Arab; for free-thinkers, it was frankly nihilistic. Abd Allah himself[41] seems to have been a sceptic of the most refined stamp. The working of this plan was achieved by a system of grades like those in freemasonry. His emissaries went out, settled each in a village and gradually won the confidence of its inhabitants. A marked characteristic of the time was unrest and general hostility to the government. Thus, there was an excellent field for work. To the enormous majority of those involved in it the conspiracy was Shi‘ite only, and it has been regarded as such by many of its historians; but it is now tolerably plain how simply nihilistic were its ultimate principles. The first object of the missionary was to excite religious doubt in the mind of his subject, by pointing out curious difficulties and subtle questions in theology. At the same time he hinted that there were those who could answer these questions. If his subject proved tractable and desired to learn further, an oath of secrecy and absolute obedience and a fee were demanded—all quite after the modern fashion. Then he was led up through several grades, gradually shaking his faith in orthodox Islam and its teachers and bringing him to believe in the idea of an Imam, or guide in religious things, till the fourth grade was reached. There the theological system was developed, and Islam, for the first time, absolutely deserted. We have dealt already with the doctrine of the Hidden Imam and with the present-day creed of Persia, that the twelfth in descent from Ali is in hiding and will return when his time comes. But down the same line of descent seven Imams had been reckoned to a certain vanished Isma‘il, and this[42] Isma‘il was adopted by Abd Allah ibn Maymun as his Imam and as titular head of his conspiracy. Hence, his followers are called Isma‘ilians and Seveners (Sab‘iya). The story which is told of the split between the Seveners and the Twelvers, which were to be, is characteristic of the whole movement and of the wider divergence of the Seveners from ordinary Islam and its laws. The sixth Imam was Ja‘far as-Sadiq (d. A.H. 148); he appointed his son Isma‘il as his successor. But Isma‘il was found drunk on one occasion, and his father in wrath passed the Imamship on to his brother, Musa al-Qazam, who is accordingly reckoned as seventh Imam by the Twelvers. One party, however, refused to recognize this transfer. Isma‘il’s drunkenness, they held, was a proof of his greater spirituality of mind; he did not follow the face-value (zahr) of the law, but its hidden meaning (batn). This is an example of a tendency, strong in Shi‘ism, to find a higher spiritual meaning lying within the external or verbal form of the law; and in proportion as a sect exalted Ali, so it diverged from literal acceptance of the Qur’an. The most extreme Shi‘ites, who tended to deify their Imam, were known on that account as Batinites or Innerites. On this more hereafter.

But to return to the Seveners: in the fourth grade a further refinement was added. Everything went in sevens, the Prophets as well as the Imams. The Prophets had been Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, Muhammad and Isma‘il, or rather his son Muhammad, for Isma‘il himself had died in his father’s lifetime. Each of these Prophets had had a[43] helper. The helper of Adam had been Seth; of Noah, Shem; and the helper of Muhammad, the son of Isma‘il, was Abd Allah ibn Maymun himself. Between each pair of Prophets there came six Imams—it must be remembered that the world was never left without an Imam—but these Imams had had no revelation to make; were only guides to already revealed truth. Thus, we have a series of seven times seven Imams, the first, and thereafter each seventh, having the superior dignity of Prophet. The last of the forty-nine Imams, this Muhammad ibn Isma‘il, is the greatest and last of the Prophets, and Abd Allah ibn Maymun has to prepare the way for him and to aid him generally. It is at this point that the adherent of this system ceases to be a Muslim. The idea of a series of Prophets is genuinely Islamic, but Muhammad, in Muslim theology, is the last of the Prophets and the greatest, and after him there will come no more.

Such, then, was the system that those who passed the fourth degree learned and accepted. The great majority did not pass beyond; but those who were judged worthy were admitted to three further degrees. In these degrees, their respect for religious teaching of every kind, doctrinal, moral, ritual, was gradually undermined; the Prophets and their works were depreciated and philosophy and philosophers put in their place. The end was to lead the very few who were admitted to the inmost secrets of the conspiracy to the same position as its founder. It is clear what a tremendous weapon, or rather machine, was thus created. Each man was given the amount of light he[44] could bear and which was suited to his prejudices, and he was made to believe that the end of the whole work would be the attaining of what he regarded as most desirable. The missionaries were all things to all men, in the broadest sense, and could work with a Kharijite fanatic, who longed for the days of Umar; a Bedawi Arab, whose only idea was plunder; a Persian driven to wild cries and tears by the thought of the fate of Ali, the well-beloved, and of his sons; a peasant, who did not care for any family or religion but only wished to live in peace and be let alone by the tax-gatherers; a Syrian mystic, who did not know very well what he thought, but lived in a world of dreams; or a materialist, whose desire was to clear all religions out of the way and give humanity a chance. All was fish that came to their net. So the long seed-planting went on. Abd Allah ibn Maymun had to flee to Salamiya in Syria, died there and went to his own place—if he got his deserts, no desirable one—and Ahmad, his son or grandson, took up the work in his stead. With him the movement tends to the surface, and we begin to touch hard facts and dates. In southern Mesopotamia—what is called the Arab Iraq—we find a sect appearing, nicknamed Qarmatians, from one of their leaders. In A.H. 277 (A.D. 890-1) they were sufficiently numerous and knew their strength enough to hold a fortress and thus enter upon open rebellion. They were peasants, we must remember, Nabateans and no Arabs, only Muslims by compulsion, and thus what we have here is really a Jacquerie, or Peasants’ War. But a disturbance of any kind suited the Isma‘ilians. From[45] there the rising spread into Bahrayn and on to south Arabia, varying in its character with the character of the people.

But there was another still more important development in progress. A missionary had gone to North Africa and there worked with success among the Berber tribes about Constantine, in what is now Algeria. These have always been ready for any change. He gave himself out as forerunner of the Mahdi, promised them the good of both worlds, and called them to arms. The actual rising was in A.H. 289 (A.D. 902). Then there appeared among them Sa‘id, the son of Ahmad, the son of Abd Allah, the son of Maymun the oculist; but it was not under that name. He was now Ubayd Allah al-Mahdi himself, a descendant of Ali and of Muhammad ibn Isma‘il, for whom his ancestors were supposed to have worked and built up this conspiracy. In A.H. 296 (A.D. 909) he was saluted as Commander of the Faithful, with the title of al-Mahdi. So far the conspiracy had succeeded. This Fatimid dynasty, so they called themselves from Fatima, their alleged ancestress, the daughter of Muhammad, conquered Egypt and Syria half a century later and held them till A.H. 567 (A.D. 1171). When in A.H. 317 the Umayyads of Cordova also claimed the Khalifate and used the title, there were three Commanders of the Faithful at one time in the Muslim world. Yet it should be noticed that the constitutional position of these Umayyads was essentially different from that of the Fatimids. To the Fatimids, the Abbasids were usurpers. The Umayyads of Cordova, on the other hand,[46] held, like the Zaydites and some jurisconsults of the highest rank, that, when Muslim countries were so far apart that the authority of the ruler of the one could not make itself felt in the other, it was lawful to have two Imams, each a true Successor of the Prophet. The good of the people of Muhammad demanded it. Still, the unity of the Khalifate is the more regular doctrine.

But only half of the work was done. Islam stood as firmly as ever and the conspiracy had only produced a schism in the faith and had not destroyed it. Ubayd Allah was in the awkward position, on the one hand, of ruling a people who were in great bulk fanatical Muslims and did not understand any jesting with their religion, and, on the other hand, of being head of a conspiracy to destroy that very religion. The Syrians and Arabs had apparently taken more degrees than the Egyptians and North Africans, and Ubayd Allah found himself between the devil and the deep sea. The Qarmatians in Arabia plundered the pilgrim caravans, stormed the holy city Mecca, and, most terrible of all, carried off the sacred black stone. When an enormous ransom was offered for the stone, they declined—they had orders not to send it back. Everyone understood that the orders were from Africa. So Ubayd Allah found it advisable to address them in a public letter, exhorting them to be better Muslims. The writing and reading of this letter must have been accompanied by mirth, at any rate no attention was paid to it by the Qarmatians. It was not till the time of the third Fatimid Khalifa that they were[47] permitted to do business with that stone. Then they sent it back with the explanatory or apologetic remark that they had carried it off under orders and now sent it back under orders. Meanwhile the Fatimid dynasty was running its course in Egypt but without turning the people of Egypt from Islam. Yet it produced one strange personality and two sects, stranger even than the sect to which it itself owed its origin. The personality is that of al-Hakim Bi’amrillah, who still remains one of the greatest mysteries that are to be met with in history. In many ways he reminds us curiously of the madness of the Julian house; and, in truth, such a secret movement as that of which he was a part, carried on through generations from father to son, could not but leave a trace on the brain. We must remember that the Khalifa of the time was not always of necessity the head of the conspiracy, or even fully initiated into it. In the latter part of the Fatimid rule we find distinct traces of such a power behind the throne, consisting, as we may imagine, of descendants and pupils of those who had been fully initiated from the first and had passed through all the grades. In the case of al-Hakim, it is possible, even, to trace, to a certain extent, the development of his initiation. During the first part of his reign he was fanatically Muslim and Shi‘ite. He persecuted alternately the Christians and the Jews, and then the orthodox and the Shi‘ites. In the latter part, there was a change. He had, apparently, reached a point of philosophical indifference, for the persecutions of Christians and Jews ceased, and those who[48] had been forced to embrace Islam were permitted to relapse. This last was without parallel, till in 1844 Lord Stratford de Redcliffe wrung from the Porte the concession that a Muslim who apostatized to Christianity should not be put to death. But, mingled with this indifference, there appeared a strange but regular development of Shi‘ite doctrine. Some of his followers began to proclaim openly that the deity was incarnate in him, and it was evident that he himself accepted and believed this. But the Egyptian populace would have none of it, and the too rash innovators had to flee. Some went to the Lebanon and there preached to the native mountain tribes. The results of their labors are the Druses of to-day, who worship al-Hakim still and expect his return to introduce the end of all things. Finally, al-Hakim vanished on the night of February 12, A.D. 1021, and left a mystery unread to this day. Whether he was murdered, and if so why, or vanished of free-will, and if so again why, we have no means of telling. Our guess will depend upon our reading of his character. So much is certain, that he was a ruler of the autocratic type, who introduced many reforms, most of which the people of his time could not in the least understand and therefore misrepresented as the mere whims of a tyrant, and many of which, from our ignorance, are still obscure to us. If we can imagine such a man of strong personality and desire for the good of his people but with a touch of madness in the brain, cast thus in the midst between his orthodox subjects and a wholly unbelieving inner government, we shall perhaps[49] have the clew to the strange stories told of him.

Another product of this conspiracy, and the last to which we shall refer, is the sect known as the Assassins, whose Grand Master was a name of terror to the Crusaders as the Old Man of the Mountain. It, too, was founded, and apparently for a purpose of personal vengeance, by a Persian who began as a Shi‘ite and ended as nothing. He came to Egypt, studied under the Fatimids—they had established at Cairo a great school of science—and returned to Persia as their agent to carry on their propaganda. His methods were the same as theirs, with a difference. That was the reduction of assassination to a fine art. From his eagle’s nest of Alamut—such is the meaning of the name—and later from Masyaf in the Lebanon and other mountain fortresses, he and his successors spread terror through Persia and Syria and were only finally stamped out by the Mongol flood under Hulagu in the middle of the seventh century of the Hijra (the 13th A.D.). Of the sect there are still scattered remnants in Syria and India, and as late as 1866 an English judge at Bombay had to decide a case of disputed succession according to the law of the Assassins. Finally, the Fatimid dynasty itself fell before the Kurd, Salah ad-Din, the Saladin of our annals, and Egypt was again orthodox.