Title: Obstetrical Nursing

Author: Carolyn Conant Van Blarcom

Release date: April 9, 2019 [eBook #59234]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

THE CARESS

From the painting by Gari Melchers

In writing this book on obstetrical nursing I have been influenced by certain steadily deepening impressions which have been received in the course of my contact with maternity work in this country, Canada and England during the past twenty years. It has been borne in upon me, in the first place, that very often there is something akin to bewilderment among those nurses who have been trained to care for patients according to the teachings of one group of obstetricians and who later find themselves nursing the patients of other doctors who hold different, or even opposite views. And not infrequently I have found in the nurses a degree of loyalty to their training which made them sceptical, or even intolerant, of nursing methods which differed from those which they had been taught.

I have become convinced, therefore, that a book on obstetrical nursing which would be helpful to and widen the outlook of all nurses, no matter where nor by whom trained, must of necessity describe the underlying principles of obstetrical nursing and offer a survey of the nursing methods which are employed in maternity wards and hospitals of recognized excellence and in the practice of acknowledged authorities upon obstetrics.

This is, I am aware, a unique attitude, for the present text books on obstetrics for nurses reflect, in each instance, the wishes of one doctor, almost entirely, or advocate the methods employed in one hospital. My experience in teaching obstetrical nursing makes me feel that a parallel description of dissimilar nursing procedures serves to broaden the nurse’s attitude toward her work and her grasp of the entire subject, both because she becomes aware of the fact that methods, other than those with which she is familiar, are employed in hospitals of high standing and because she appreciates the fact that these unfamiliar methods may be as efficacious as those in which she has become expert.

xiiAccordingly I have devoted the better part of the past year and a half to a study of the scope and methods of the present training in maternity nursing in several hospitals, in this country and Canada, in which the obstetrical work is of a conspicuously high character, and have presented a composite of this teaching in the succeeding pages.

But that there might not be apparent inconsistencies in the different methods of maternity care described, I have given an explanation of the purposes and general principles of the care, including nursing, which the nurse is likely to find is given to all obstetrical patients, the country over.

For the sake of simplicity and clarity I have divided the book into seven parts, following an introduction which describes the requisites and opportunities of obstetrical nursing and the importance of the nurse’s own attitude toward her work and her patient. The first two parts, dealing with the normal anatomy and physiology of the female generative tract and the development of the fetus, are designed to supply the nurse with enough technical information to make her ministrations intelligent and effective. In this respect, I have doubtless given less than some nurses will wish and possibly more than others will think necessary, but I have given about the average amount of instruction that is found satisfactory in the training schools of high standing. Four of the succeeding parts are devoted respectively to a description of the nurse’s duties during pregnancy, labor, the puerperium and early infancy. In each of these I have explained, first, the normal physiological processes which take place; then, the nurse’s duties under average conditions and finally, her responsibilities in the event of complications or abnormalities. A separate part is devoted to a description of the organized care and instruction of the maternity patient, by public health nurses, both before and after delivery, which have proved to be satisfactory.

While describing various hospital procedures, I have deemed it of practical importance to explain, in each instance, how similar results might be obtained, with improvised appliances, in a patient’s home whether in a city or a rural community. In xiiishort, I have endeavored to make clear the essentials of obstetrical nursing without regard to the status or location of the patient.

Since the patient’s state of nutrition and her frame of mind are of vital importance throughout pregnancy, labor and the puerperium, I have not only dwelt upon them in all descriptions of the nurse’s duties during these periods but have devoted an entire chapter to a simple explanation of the principles of each of these two important subjects.

My varied contact with obstetrical nurses has convinced me that those nurses who appreciate the never ending wonder and beauty of this miracle of the beginning of a new life, derive peculiar satisfaction from the care of the maternity patient. At the same time, in many hospitals, even where the patients are given the most conscientious care, the nurses are often so nearly overwhelmed by the long, irregular hours and the insistent demands of routine duties, that they do not grasp the significance of the event in which they are participants. Accordingly, I have made a sustained effort throughout the following pages to give the young nurse something of a feeling of reverence for this great mystery of birth.

In the course of my survey of the present training in obstetrical nursing, I have met the warmest generosity on the part of the obstetrical and nursing staffs in all of the hospitals which I have visited. Accordingly, I find it very difficult to find adequate expression for my sense of gratitude to the doctors and nurses of the Montreal Maternity Hospital; the Burnside Obstetrical Department of the Toronto General Hospital; The Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania; Bellevue Hospital; The Long Island College Hospital; The Brooklyn Hospital; The Cleveland Maternity Hospital and to Dr. J. Whitridge Williams and Miss Elsie Lawler for making available the entire resources of the wards, clinics, laboratories and class and lecture rooms at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

I wish to offer an expression of deepest possible appreciation to Dr. John W. Harris for the generosity with which he has given of his time, thought and wide experience in an effort to xivprovide accurate and practical information, and to set a high standard of work and ideals for those nurses who would be influenced by this book. Having taught and lectured to nurses, as well as medical students, for years, Dr. Harris is in a position to give counsel and criticism of peculiar value to a book on obstetrical nursing and he has given these throughout the entire preparation of this book.

Because of their concern with any effort to better the state of mothers and babies, I have been given suggestions, assistance and inspiration with the most selfless generosity by The Reverend Father John J. Burke; Dr. J. Clifton Edgar; Dr. Frederic W. Rice; Dr. J. P. Crozer Griffith; Dr. Caroline F. J. Rickards; Dr. Esther Loring Richards; Dr. E. V. McCollum; Miss Nina Simmonds and Dr. John R. Fraser. Among the many nurses with whom I have conferred, I have met a characteristic spirit of helpfulness which has expressed itself in their eager readiness to pass on to other nurses the benefits of their own training and experience. Those to whom I am especially indebted, for aid and suggestions, are Miss Calvin MacDonald; Mrs. Bessie Amerman Haasis; Miss Robina Stewart; Miss Caroline V. Barrett; Miss Katherine de Long; Miss Jean Gunn; Miss Mary E. Robinson; Miss Sara Cooper; Miss Laura F. Keesey; Miss Chelly Wasserberg; Miss Kate Madden; Mrs. Minnie S. Brown; Miss Anne Stevens; Miss Madge Allison and Miss Katherine Tucker.

To Mrs. Elizabeth Porter Wyckoff I am under heavy obligation for most discriminating editorial assistance and for her farsighted criticisms toward increasing the clarity of the text. And I feel sure that the tender little poem on the miracle of motherhood, which Mrs. Elizabeth Newport Hepburn wrote expressly for this book, will be as warmly appreciated by my readers as it is by me.

I wish to express my deep gratitude to Mr. Max Brodel for his invaluable counsel and guidance in planning and assembling the illustrations to elucidate the text. And I am very grateful to Mr. Gari Melchers for the spirit which I believe is infused into this book through the reproduction of two of his lovely paintings of a mother and baby, and to Mr. Russell Drake for xvhis valuable drawings. I wish further to thank Mr. J. Norris Myers, of The Macmillan Company, for unfailing courtesy and helpfulness in facilitating all matters relating to the publication of this book.

For statistical information I am indebted to Dr. Louis I. Dublin and for authority in offering the scientific background of the teaching I have drawn from “The Practice of Obstetrics” by J. Clifton Edgar; “Obstetrics” by J. Whitridge Williams; “The Diseases of Infants and Children” by J. P. Crozer Griffith and “The Prospective Mother” by J. Morris Slemons.

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preface | xi | |

| Introduction | 3 | |

| PART I. | ||

| ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY | ||

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | Anatomy of the Female Pelvis and Generative Organs | 19 |

| II. | Physiology | 45 |

| PART II. | ||

| THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE BABY | ||

| III. | Development of the Ovum, Embryo, Fetus, Placenta, Cord and Membranes | 61 |

| IV. | Physiology of the Fetus | 84 |

| V. | Signs, Symptoms, and Physiology of Pregnancy | 93 |

| PART III. | ||

| THE EXPECTANT MOTHER | ||

| VI. | Prenatal Care | 111 |

| VII. | Mental Hygiene of the Expectant Mother | 145 |

| VIII. | Preparation of Room, Dressings, and Equipment for Home Delivery | 155 |

| IX. | Complications and Accidents of Pregnancy | 164 |

| PART IV. | ||

| THE BIRTH OF THE BABY | ||

| X. | Presentation and Position of the Fetus | 217 |

| XI. | Symptoms, Course, and Mechanism of Normal Labor | 232 |

| XII. | Nurse’s Duties During Labor | 243 |

| XIII. | Obstetrical Operations and Complicated Labors | 295 |

| xviiiPART V. | ||

| THE YOUNG MOTHER | ||

| XIV. | Physiology of the Puerperium | 317 |

| XV. | Nursing Care During the Normal Puerperium | 323 |

| XVII. | The Nursing Mother | 357 |

| XVII. | Nutrition of the Mother and Her Baby | 368 |

| XVIII. | Complications of the Puerperium | 391 |

| PART VI. | ||

| THE MATERNITY PATIENT IN THE COMMUNITY | ||

| XIX. | Organized Prenatal Work | 405 |

| XX. | Care of the Mother and Baby by Visiting Nurses | 437 |

| PART VII. | ||

| THE CARE OF THE BABY | ||

| XXI. | Characteristics and Development of the Average New-born Baby | 451 |

| XXII. | Nursing Care of the Average New-born Baby | 461 |

| XXIII. | Common Disorders and Abnormalities of Early Infancy | 518 |

| XXIV. | A Final Word | 544 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | ||

| Anatomy and Physiology. | ||

| FIG. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 a. | Normal female pelvis | 21 |

| b. | Normal male pelvis | 21 |

| 2. | Diagram of pelvic inlet seen from above | 22 |

| 3. | Diagram of pelvic outlet seen from below | 23 |

| 4. | Sagittal section of the pelvis | 24 |

| 5. | Two types of pelvimeters | 25 |

| 6. | Diagram showing method of measuring distance between crests, spines and trochanters | 26 |

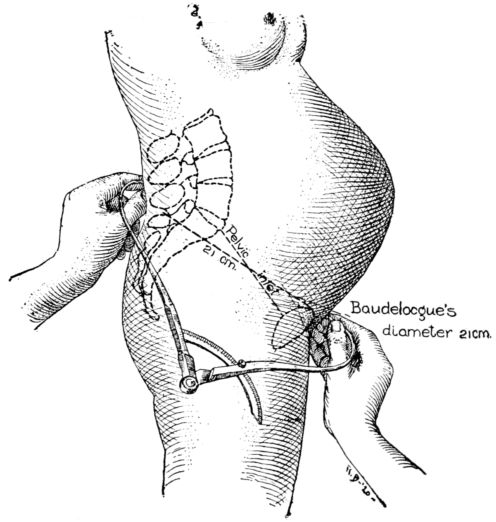

| 7. | Diagram showing method of measuring Baudelocque’s diameter | 27 |

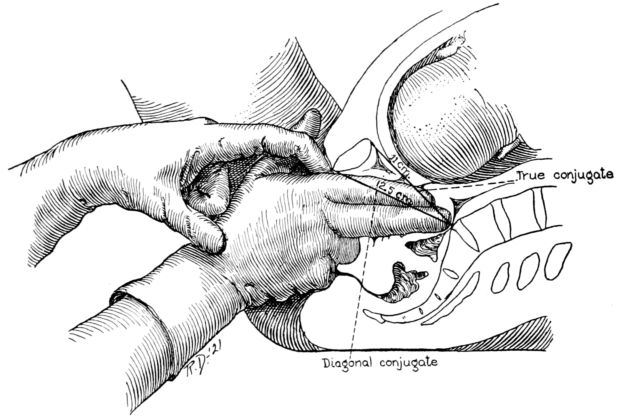

| 8. | Diagram showing method of estimating true conjugate | 28 |

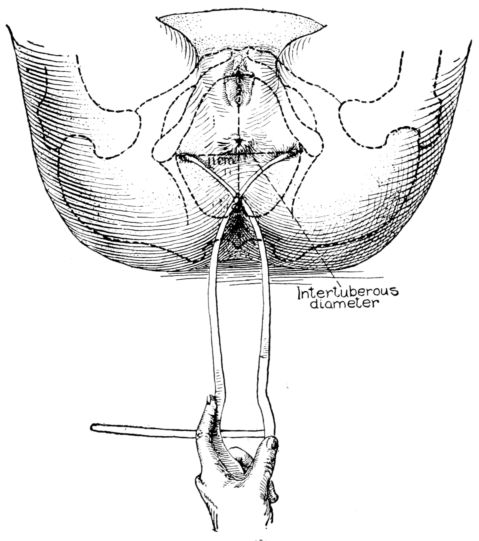

| 9. | Diagram showing method of measuring intertuberous diameter | 29 |

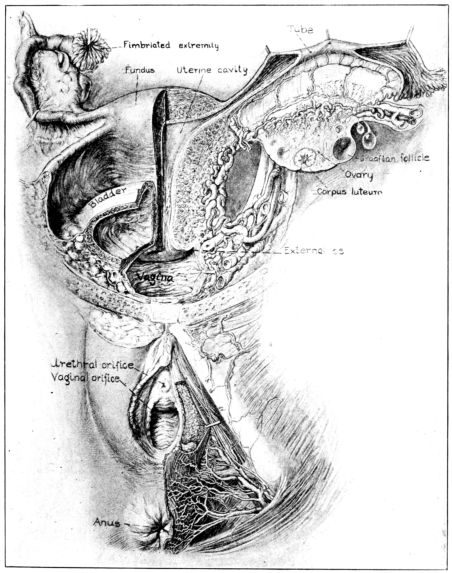

| 10. | Anterior view of external and internal female generative organs | 31 |

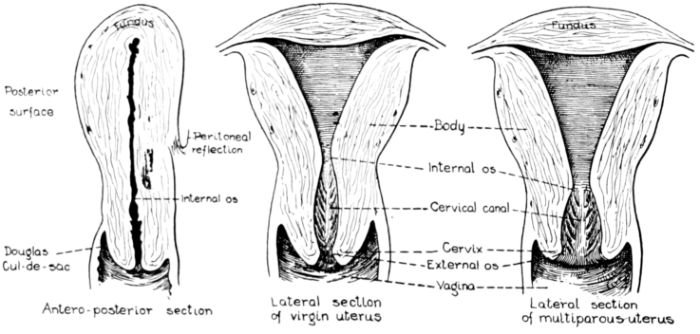

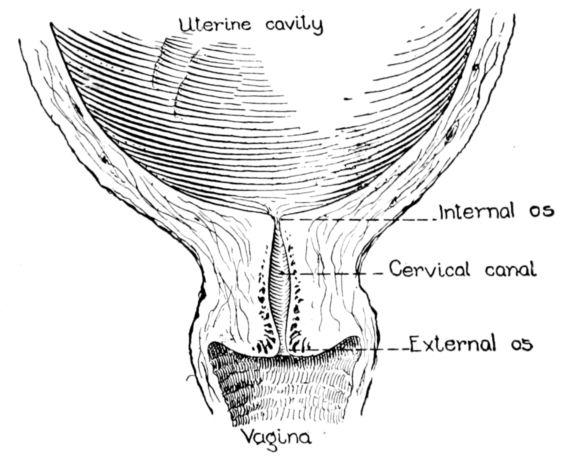

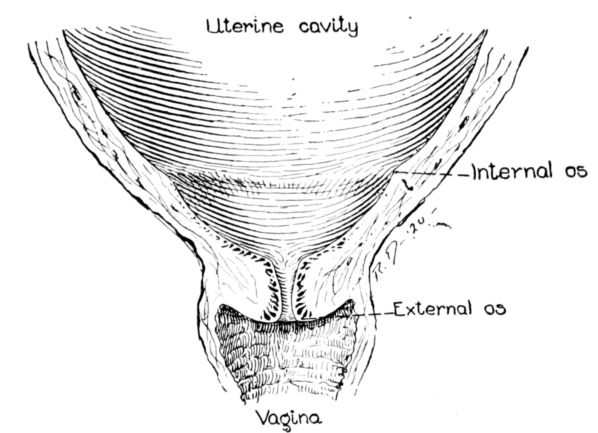

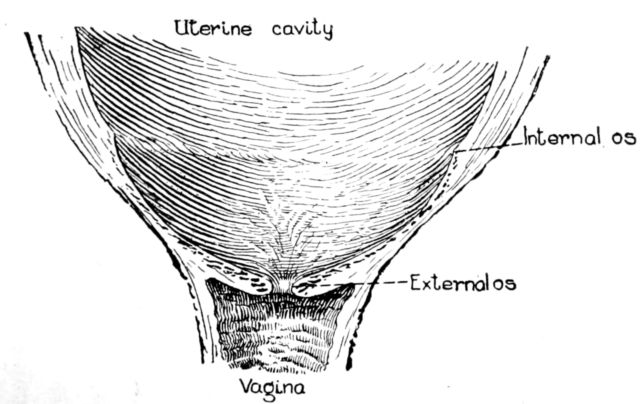

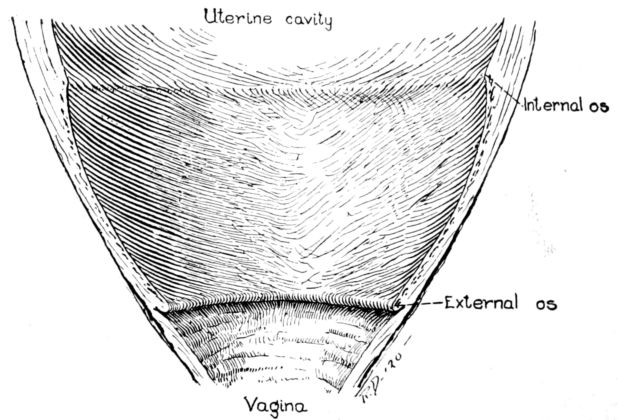

| 11. | Diagrams of sections of virgin and multiparous uteri | 32 |

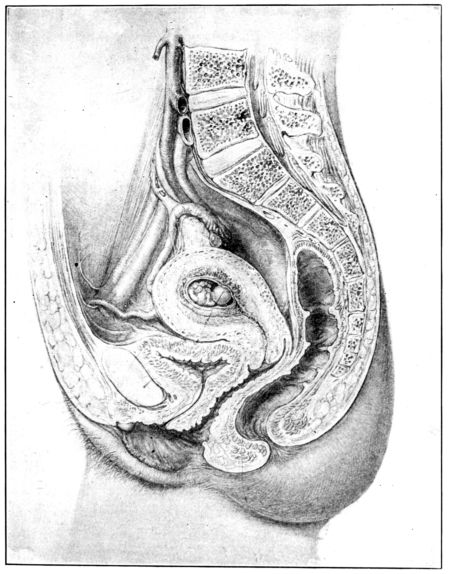

| 12. | Sagittal section of female generative tract | 35 |

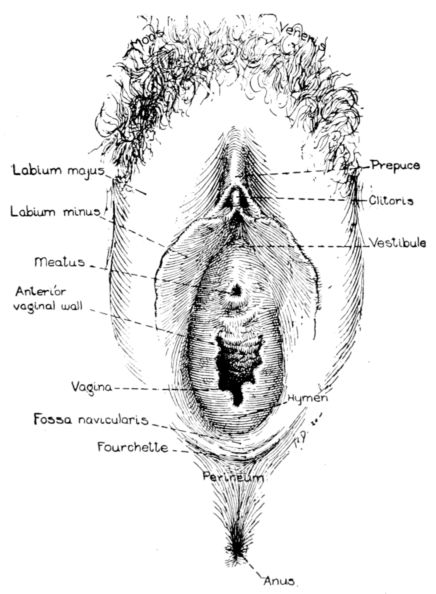

| 13. | Diagram of external female genitalia | 39 |

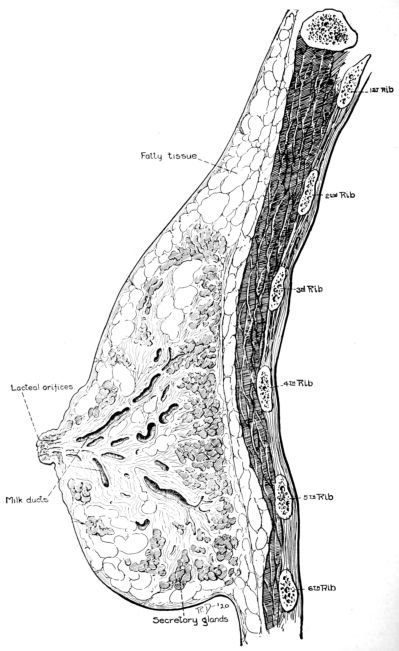

| 14. | Sagittal section of breast | 42 |

| 15. | Front view of breast | 43 |

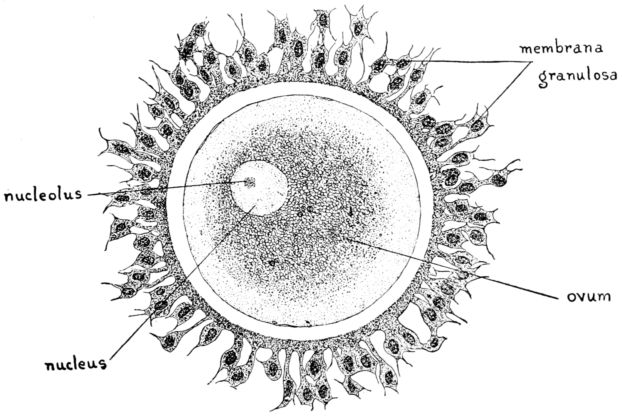

| 16. | Diagram of human ovum | 47 |

| Development of the Baby | ||

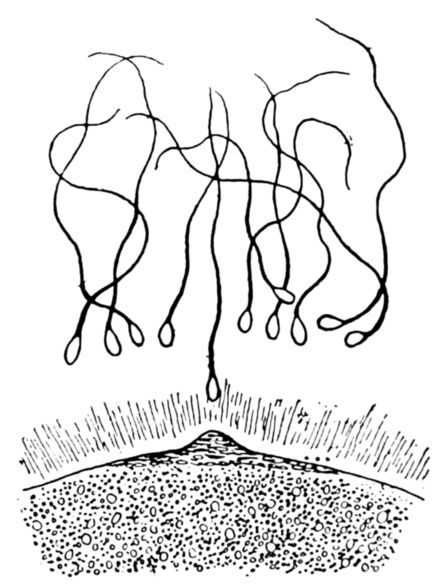

| 17. | Diagram of human spermatozoa | 61 |

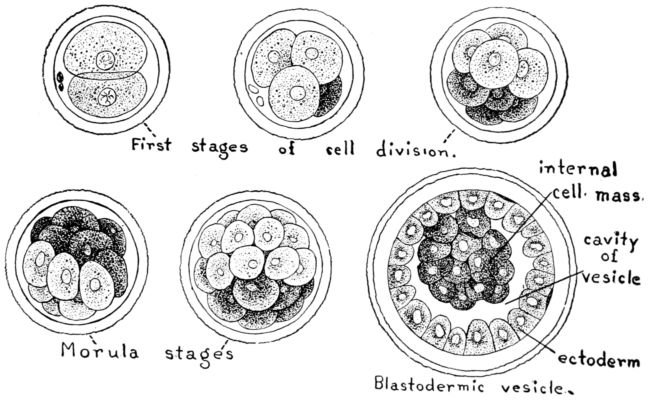

| 18. | Diagram of segmenting rabbit’s ovum | 65 |

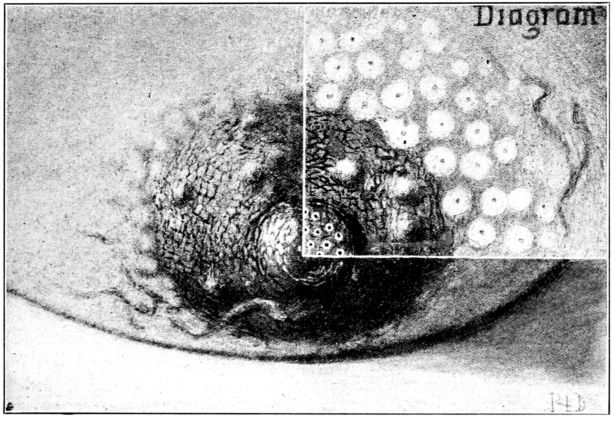

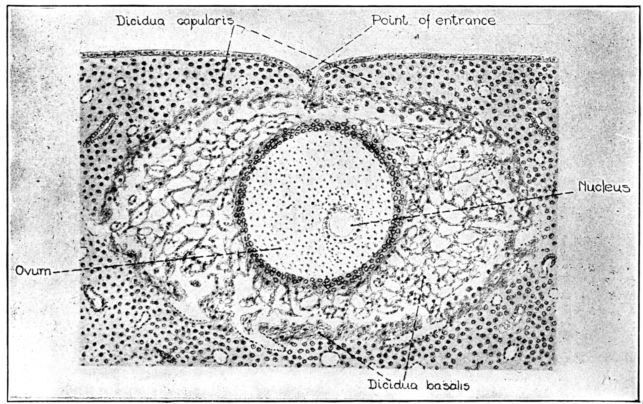

| 19. | Ovum about 13 days old embedded in the decidua | 66 |

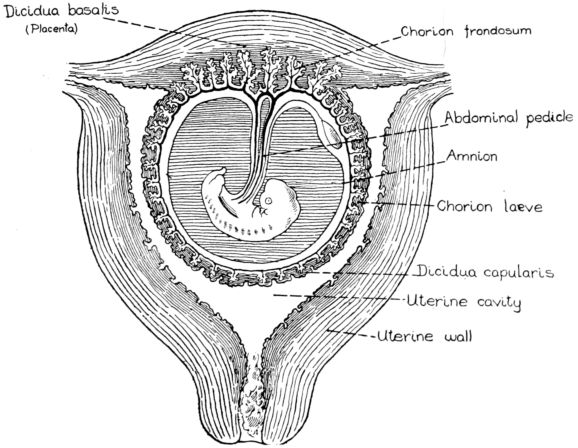

| 20. | Diagram of developing fetus, cord, membranes and placenta in utero | 69 |

| 21. | Diagram of structure of placenta | 71 |

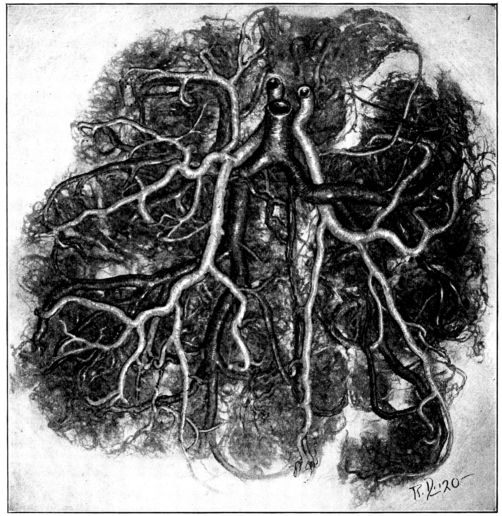

| 22. | Photograph of placental vessels | 72 |

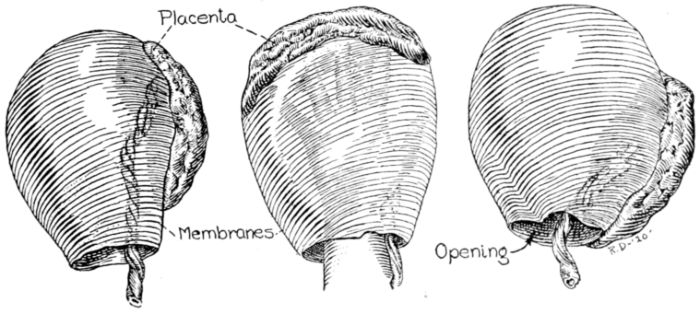

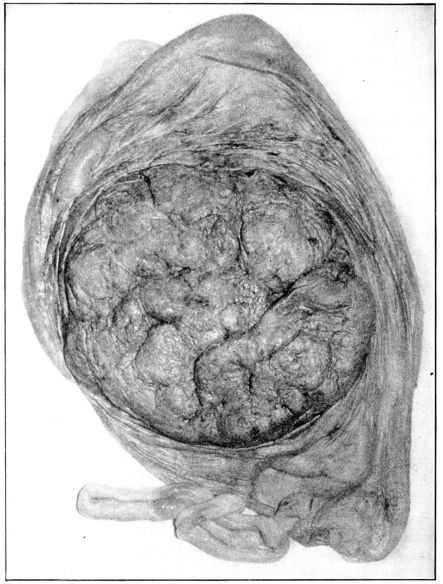

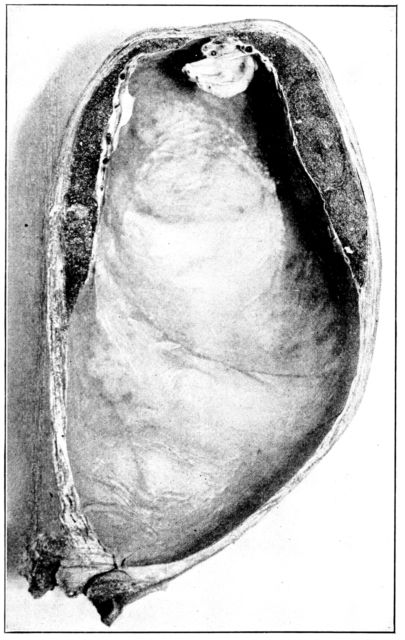

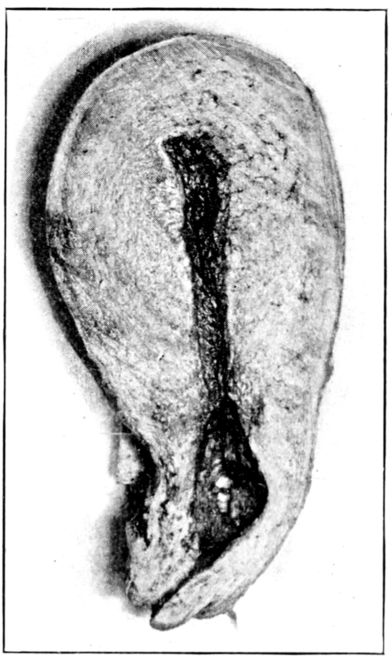

| 23. | Maternal surface of the placenta | 74 |

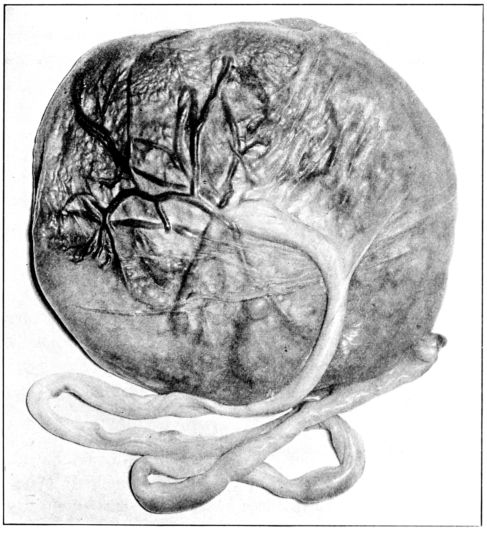

| 24. | Fetal surface of the placenta | 75 |

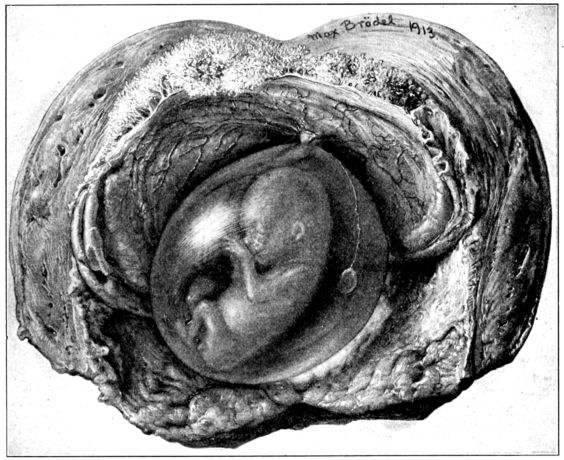

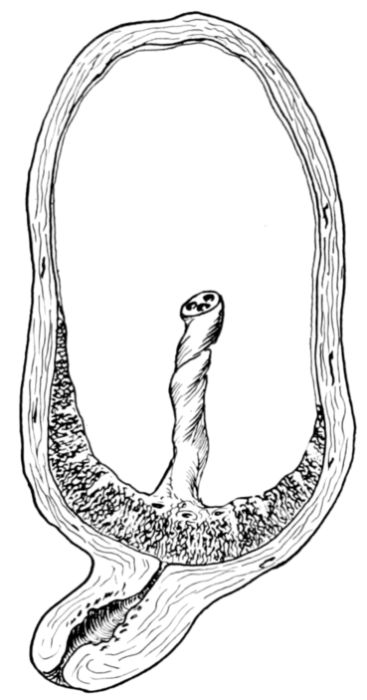

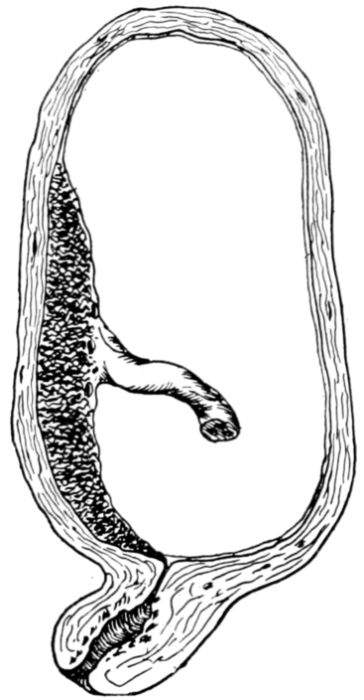

| 25. | Embryo about 5.5 cm. long in amniotic sac | 77 |

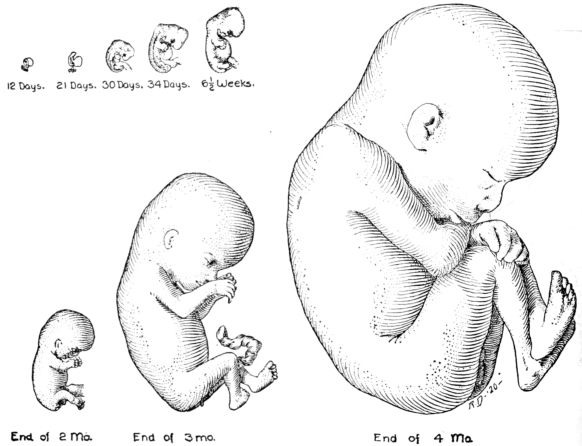

| 26. | Outlines of fetus at different stages | 78 |

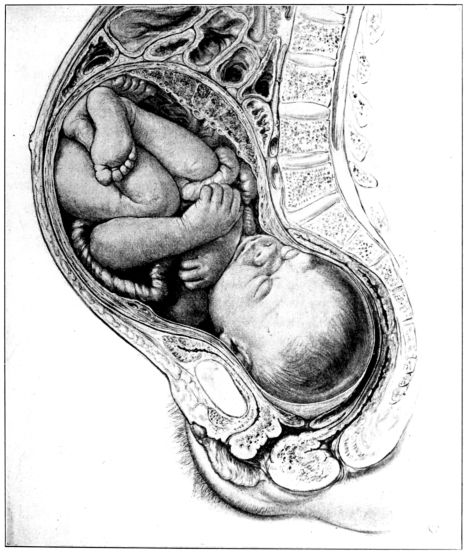

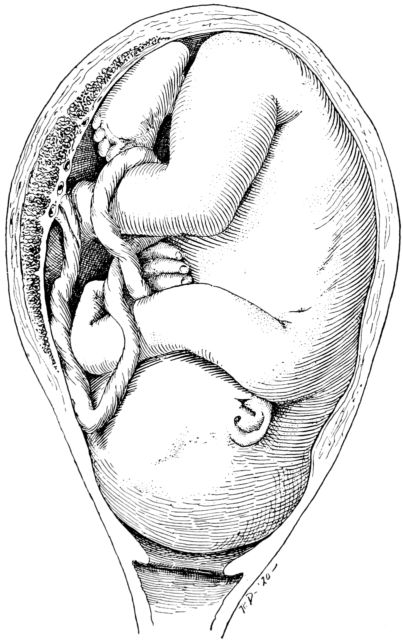

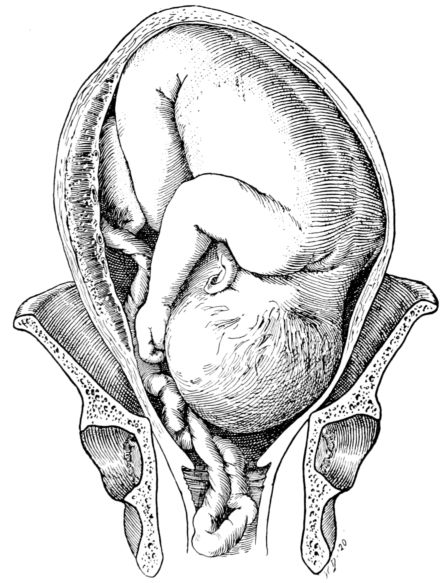

| 27. | Full term fetus in utero | 81 |

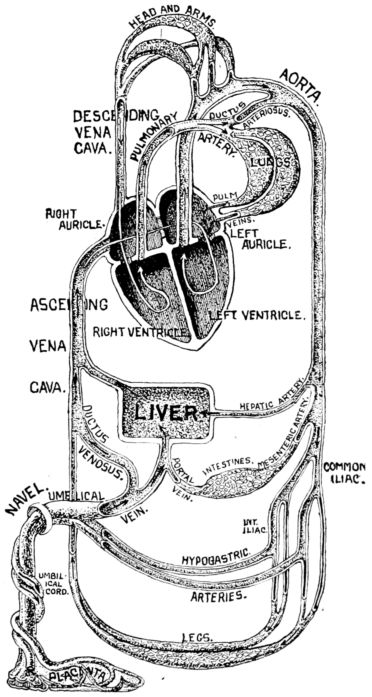

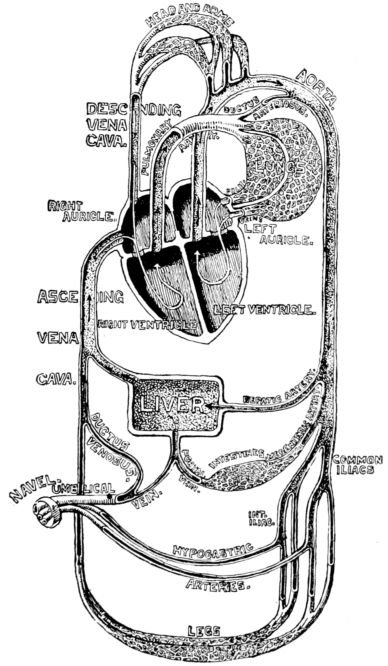

| xx28. | Diagram of fetal circulation | 85 |

| 29. | Diagram of circulation after birth | 87 |

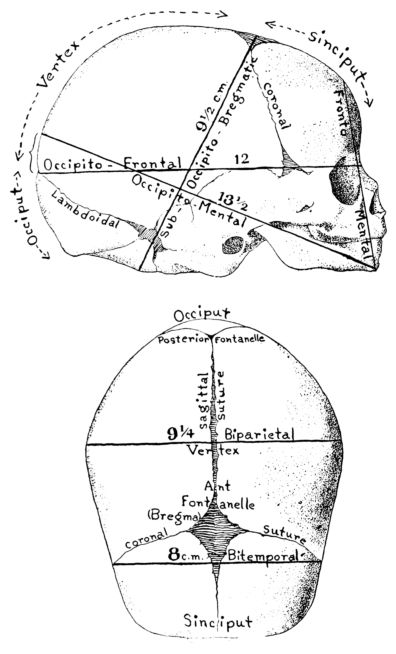

| 30. | Side and top view of fetal skull | 90 |

| The Expectant Mother. | ||

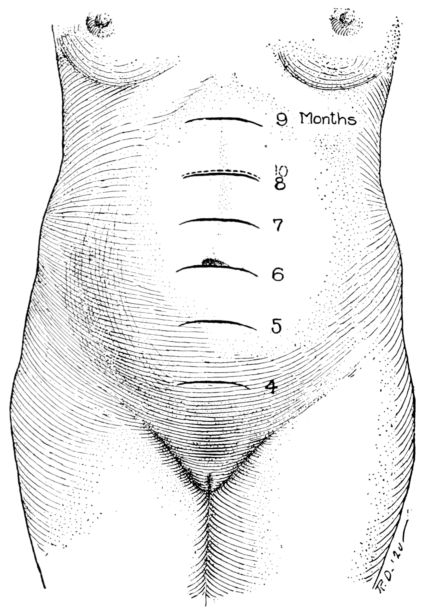

| 31. | Height of fundus at different stages of pregnancy | 94 |

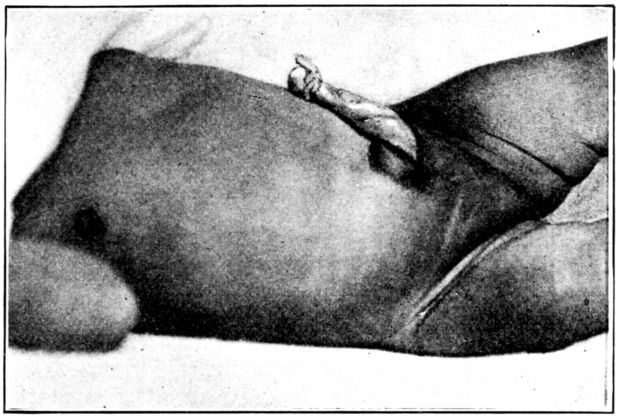

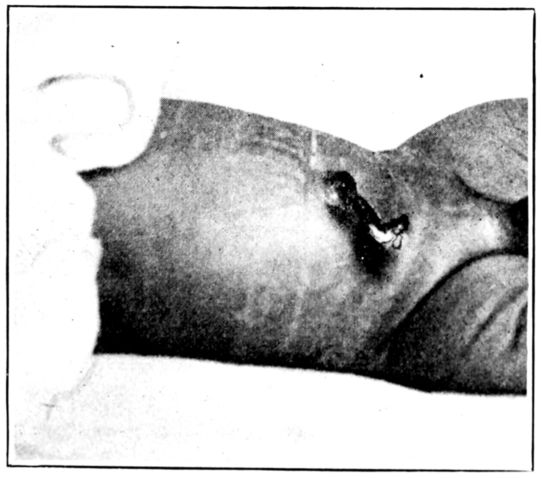

| 32. | Contour of abdomen at ninth month | 95 |

| 33. | Contour of abdomen at tenth month | 95 |

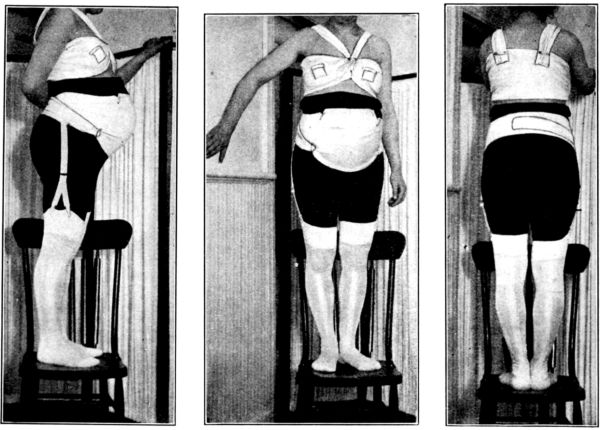

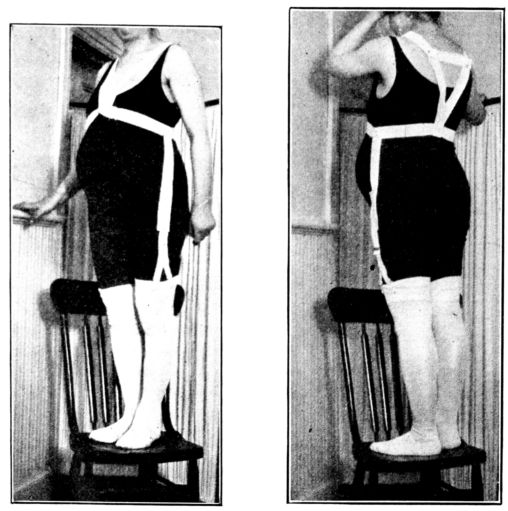

| 34. | Front view of home-made abdominal binder | 123 |

| 35. | Side view of same | 123 |

| 36. | Back view of same | 123 |

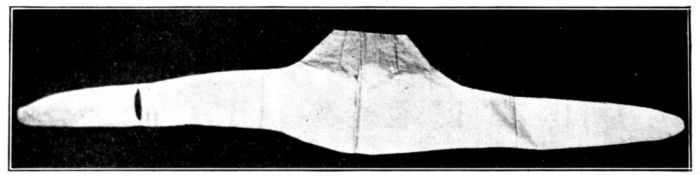

| 37. | Abdominal binder used in above | 124 |

| 38. | Front view of home-made stocking supporters | 124 |

| 39. | Back view of same | 124 |

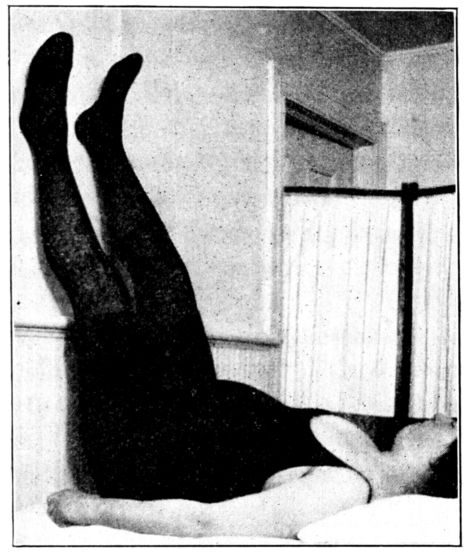

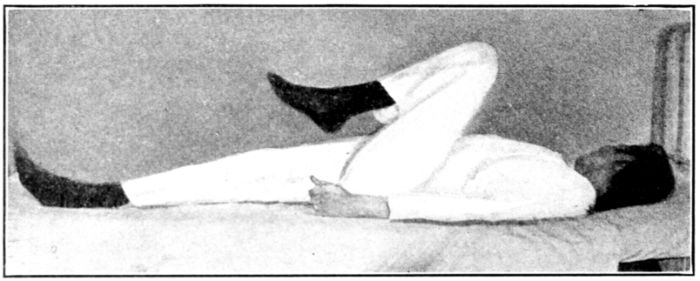

| 40. | Patient in right-angled position to relieve varicose veins | 138 |

| 41. | Elevated Sims position | 139 |

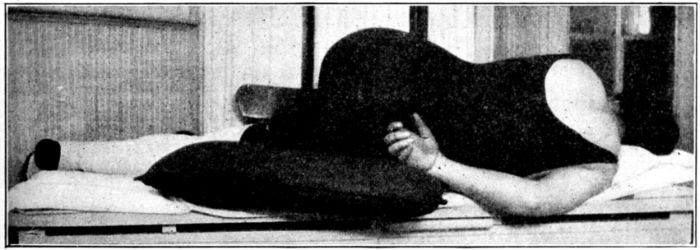

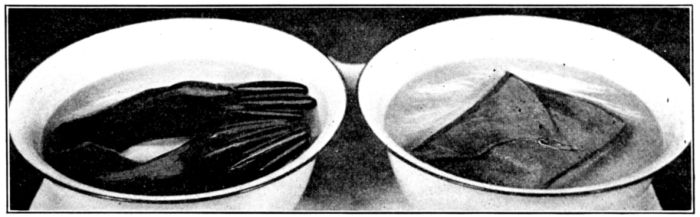

| 42. | Gloves, ready for dry sterilization | 160 |

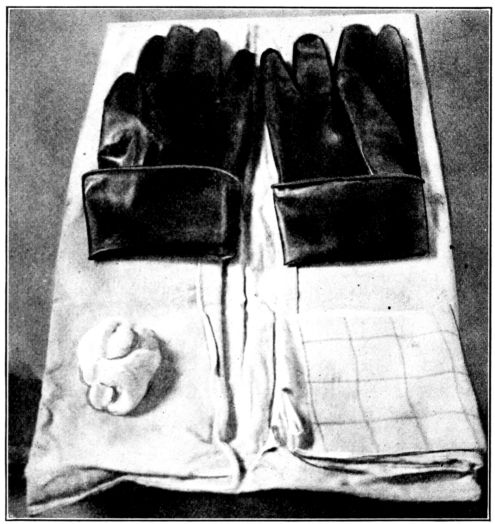

| 43. | Delivery pad of newspapers and old muslin | 161 |

| 44. | Diagram of centrally implanted placenta prævia | 174 |

| 45. | Partial placenta prævia | 175 |

| 46. | Diagram of marginal placenta prævia | 176 |

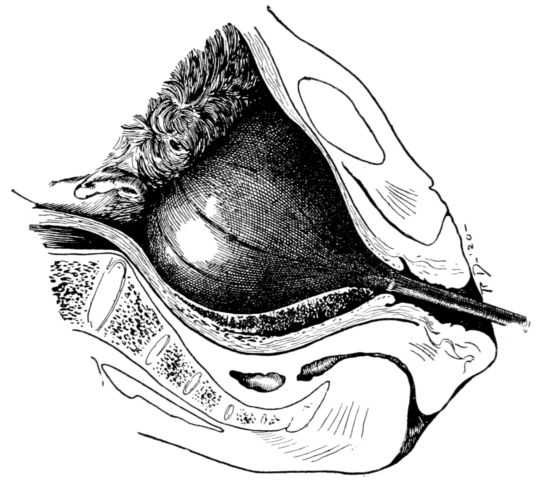

| 47. | Champetier de Ribes’ bag inserted in uterus | 177 |

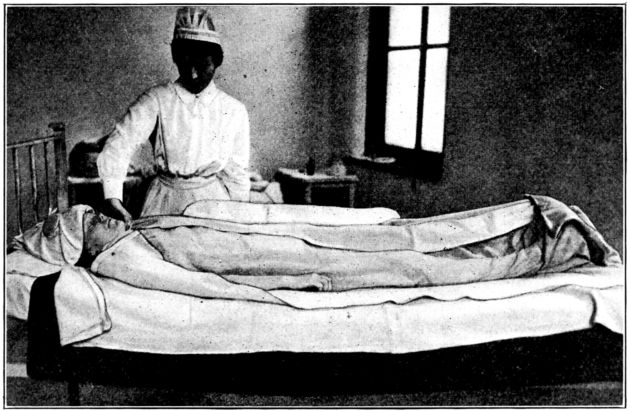

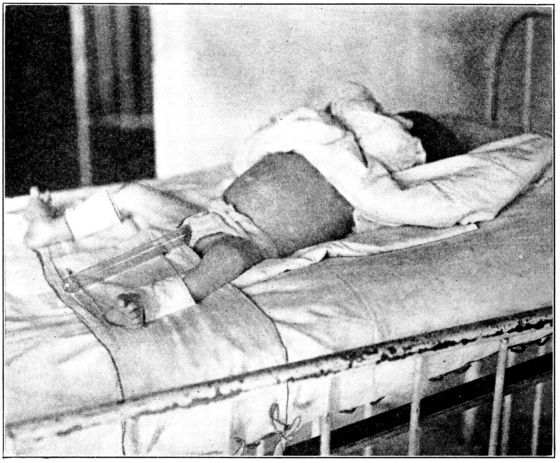

| 48. | Patient in hot pack given with dry blankets | 197 |

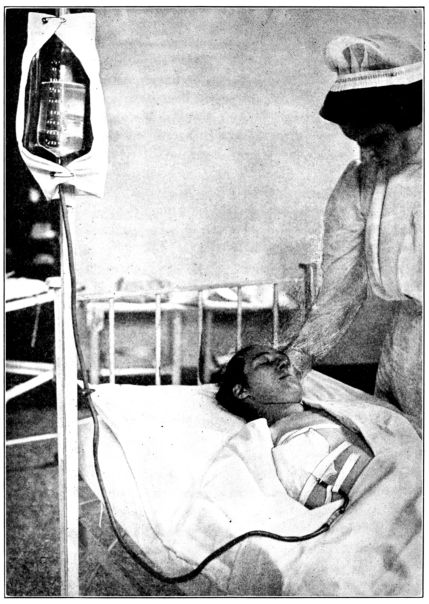

| 49. | Method of giving infusion | 202 |

| The Birth of the Baby. | ||

| 50. | Attitude of fetus in uterus at term | 217 |

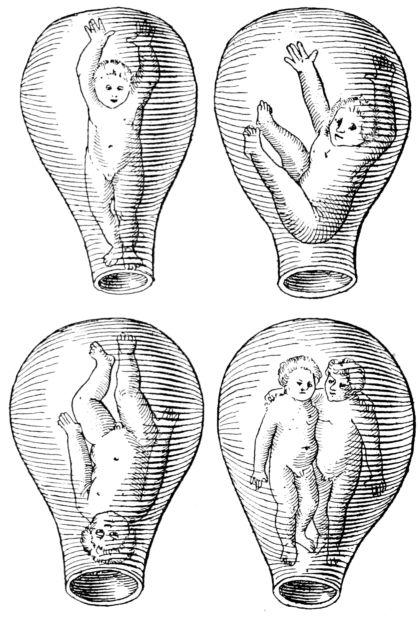

| 51. | Illustration from first text-book on obstetrics | 218 |

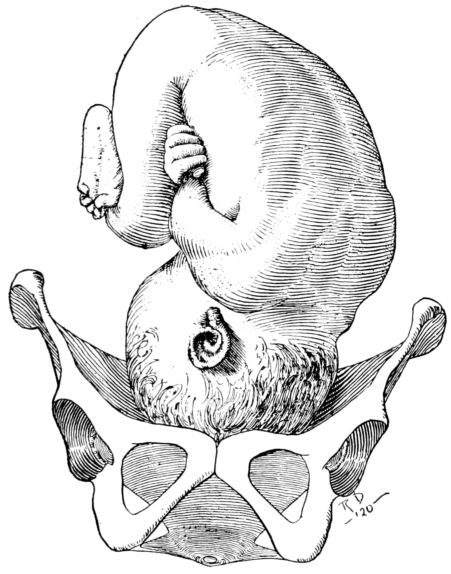

| 52. | Attitude of fetus in breach presentation | 219 |

| 53. | Attitude of fetus in vertex presentation | 220 |

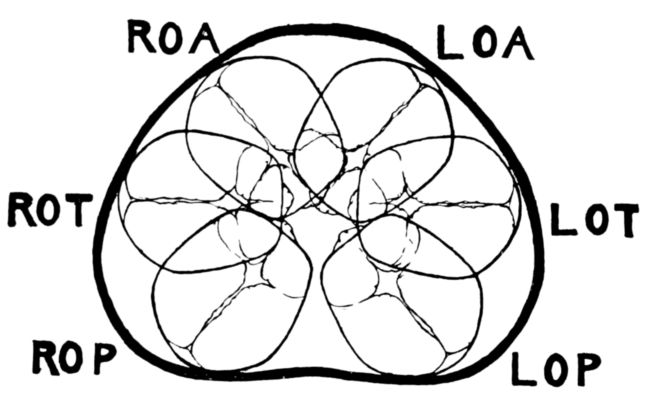

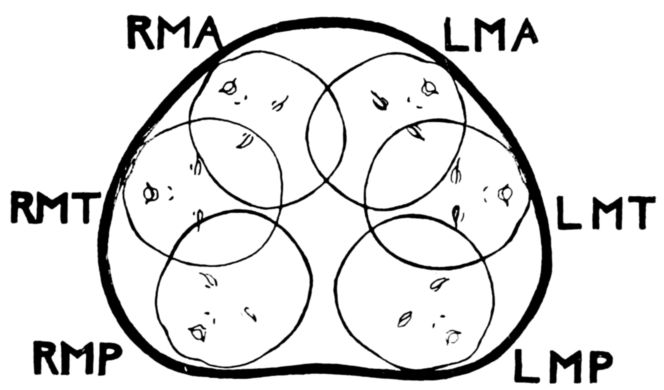

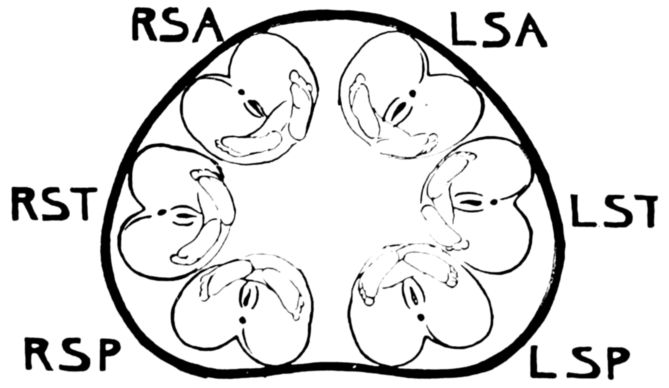

| 54. | Diagram of six positions in a vertex presentation | 222 |

| 55. | Diagram of six positions in a face presentation | 223 |

| 56. | Diagram of six positions in a breech presentation | 223 |

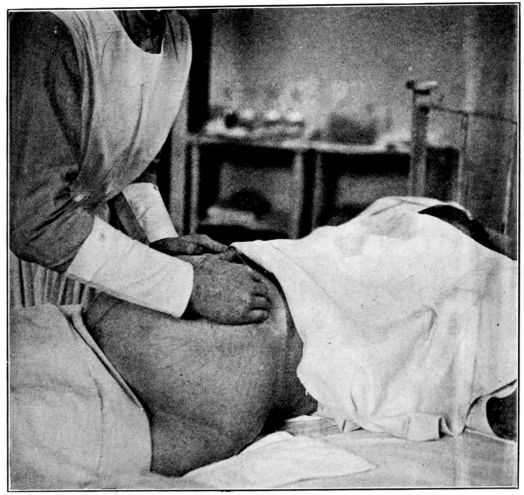

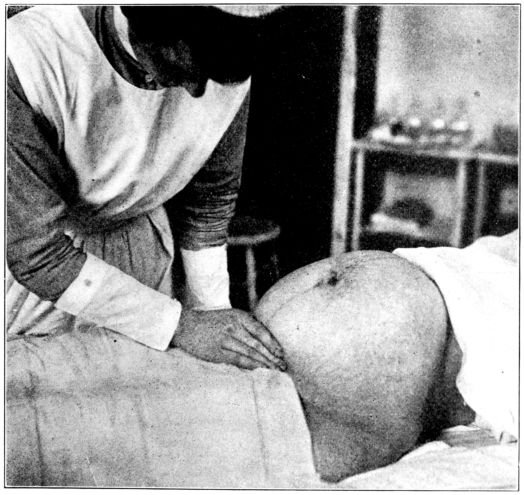

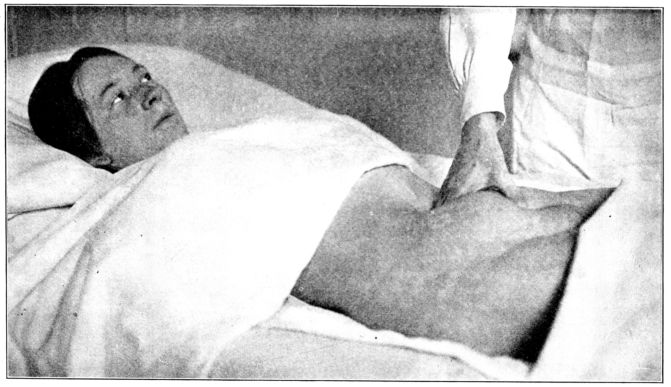

| 57. | First maneuver in abdominal palpation | 225 |

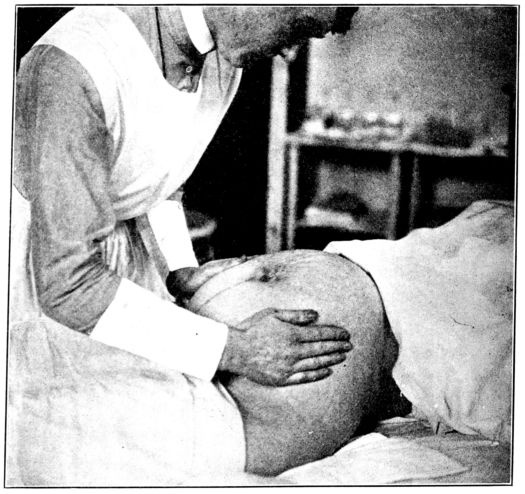

| 58. | Second maneuver in abdominal palpation | 226 |

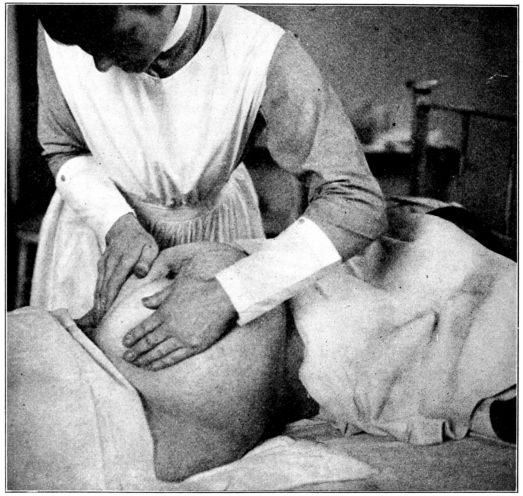

| 59. | Third maneuver in abdominal palpation | 227 |

| 60. | Fourth maneuver in abdominal palpation | 228 |

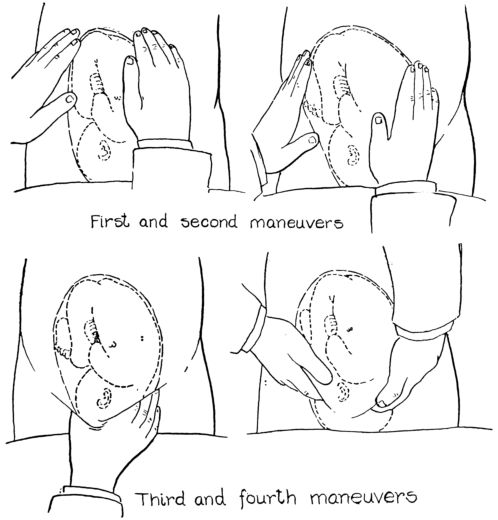

| 61. | Diagrams showing positions of nurse’s hands in four maneuvers of abdominal palpation | 229 |

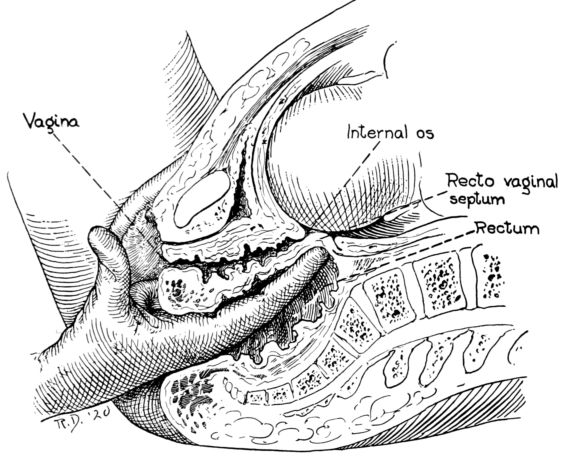

| 62. | Ascertaining position of fetus by rectal examination | 230 |

| xxi63, 64, 65, 66. | Diagrams showing stages of dilatation and obliteration of cervix | 234 |

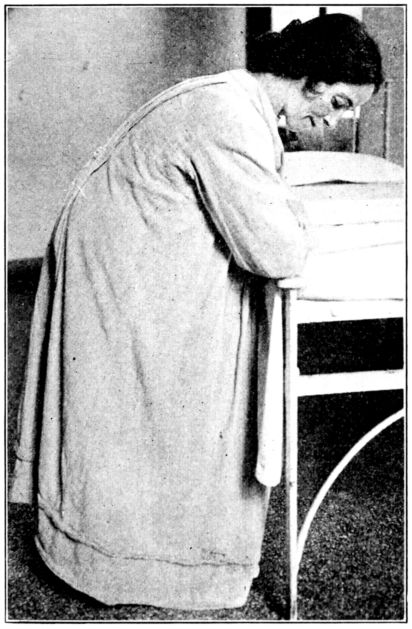

| 67. | Characteristic position of patient during first stage pains | 235 |

| 68. | Diagram indicating rotation and pivoting of head during birth | 236 |

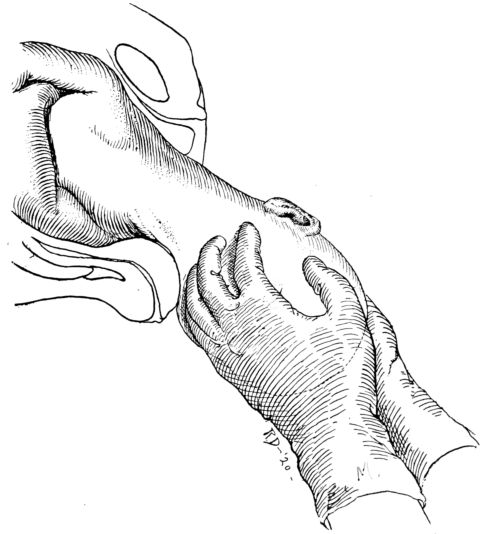

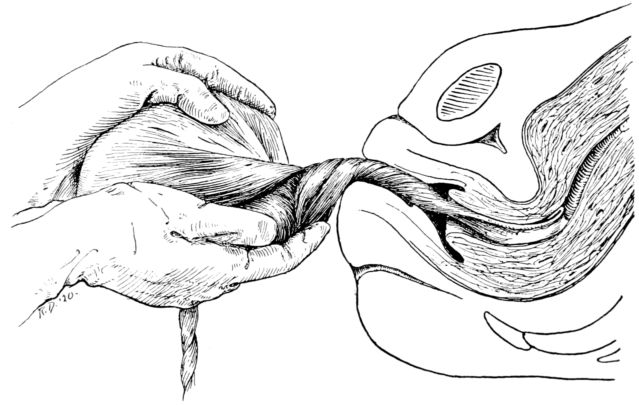

| 69. | Anterior shoulder being slipped from under symphysis | 237 |

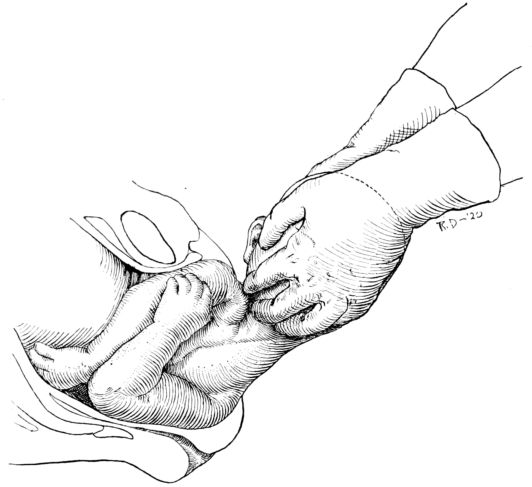

| 70. | Birth of posterior shoulder | 238 |

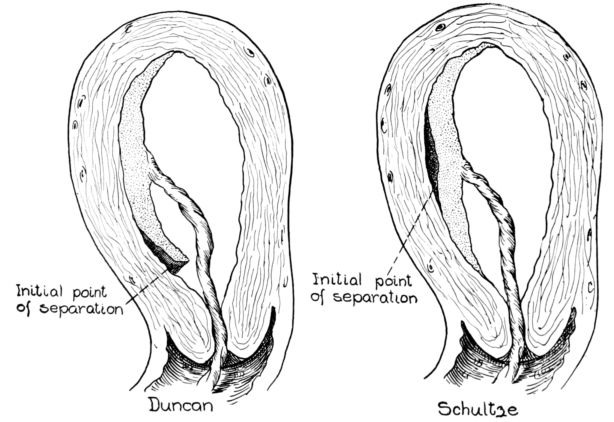

| 71. | Diagrams of Duncan and Schultze mechanisms of placental separation | 239 |

| 72. | Section showing thinness of uterine wall before birth of fetus | 240 |

| 73. | Section showing thickness of uterine wall immediately after labor | 241 |

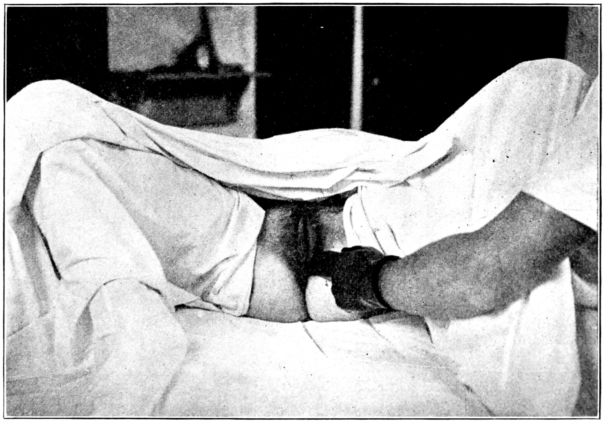

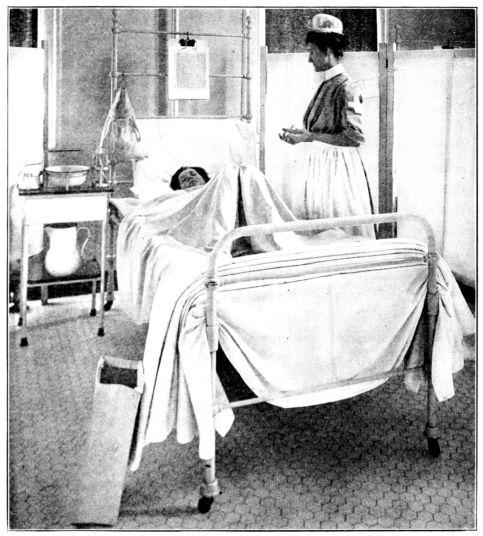

| 74. | Preparing patient for vaginal examination or delivery | 250 |

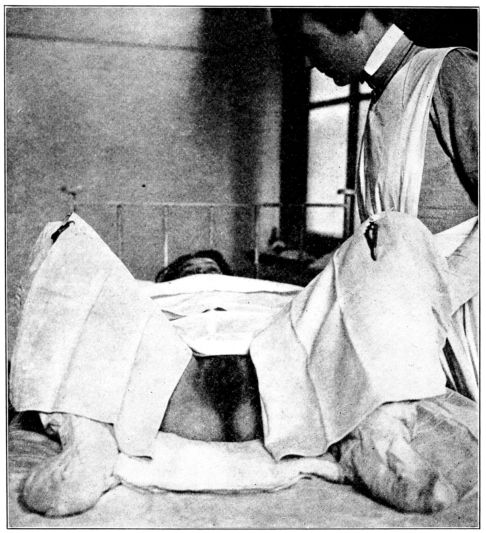

| 75. | Patient draped for vaginal examination | 251 |

| 76. | Wrong and right methods of boiling gloves | 253 |

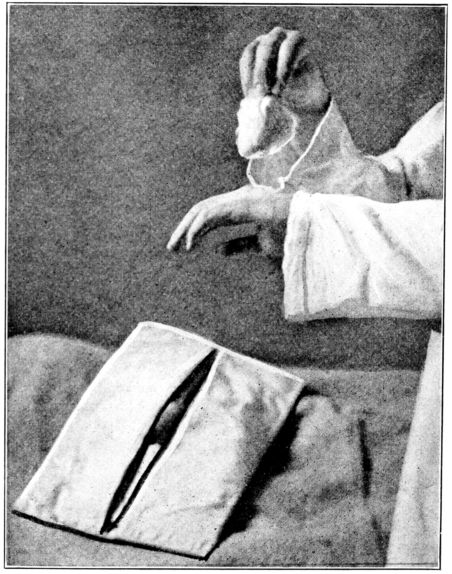

| 77. | Powdering hands before putting on dry gloves | 254 |

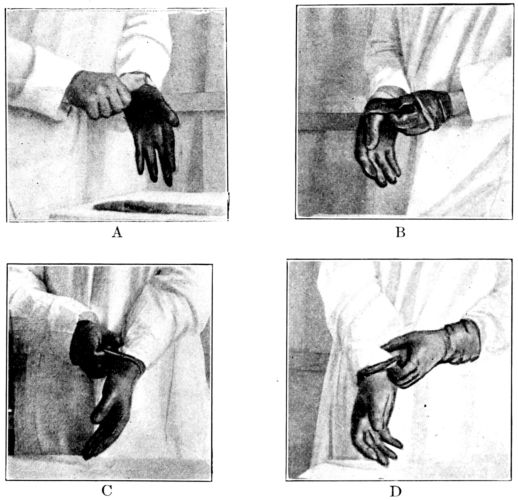

| 78. | Successive steps in proper method of putting on gloves | 255 |

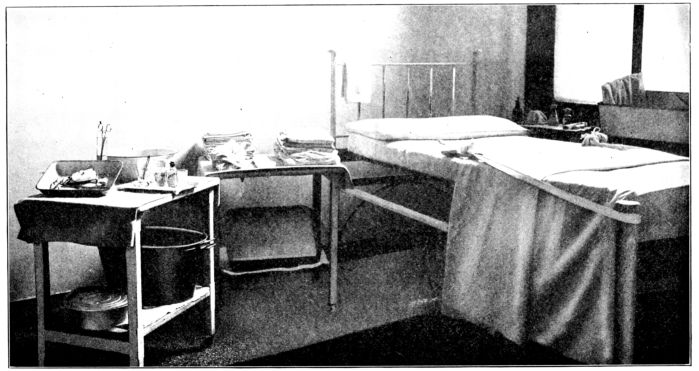

| 79. | Bed and simple equipment ready for normal delivery | 258 |

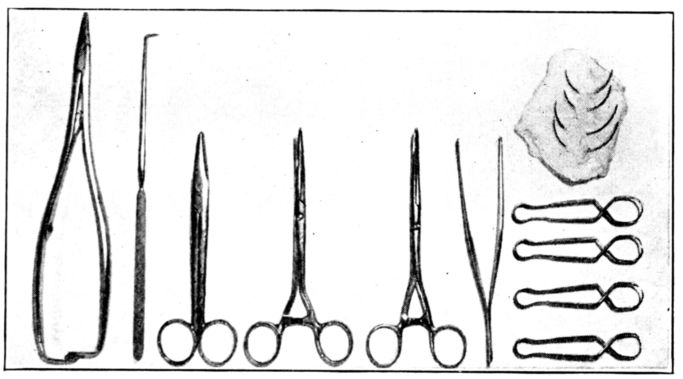

| 80. | Instruments shown in Fig. 79 | 260 |

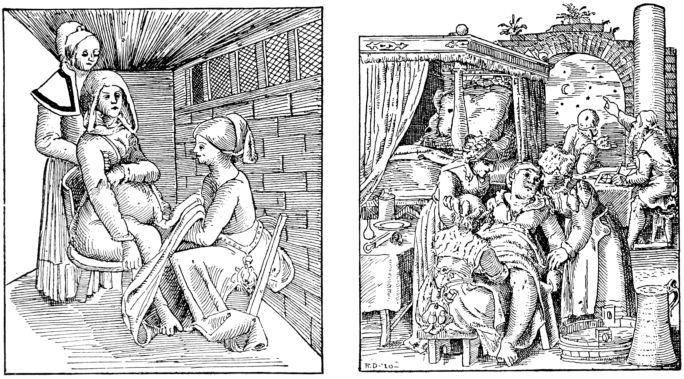

| 81. | Old prints showing early methods of delivery | 261 |

| 82. | Patient draped with sterile dressings for delivery | 262 |

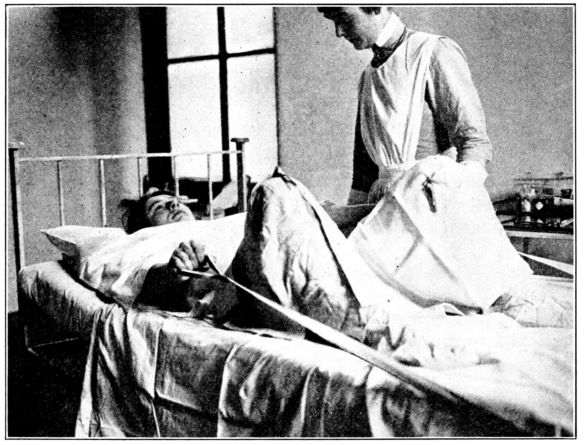

| 83. | Patient pulling on straps while bearing down during second stage | 264 |

| 84. | Palpating baby’s head through perineum | 265 |

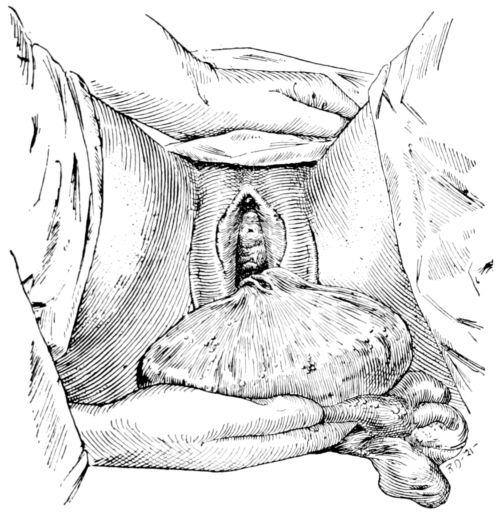

| 85. | Baby’s head appearing at vulva | 266 |

| 86. | Head farther advanced | 267 |

| 87. | Holding back head at the height of a pain | 268 |

| 88. | External rotation following birth of head | 269 |

| 89. | Wiping mucus from baby’s mouth | 270 |

| 90. | Stroking baby’s back to stimulate respirations | 271 |

| 91. | Two clamps on cord after pulsation has ceased | 272 |

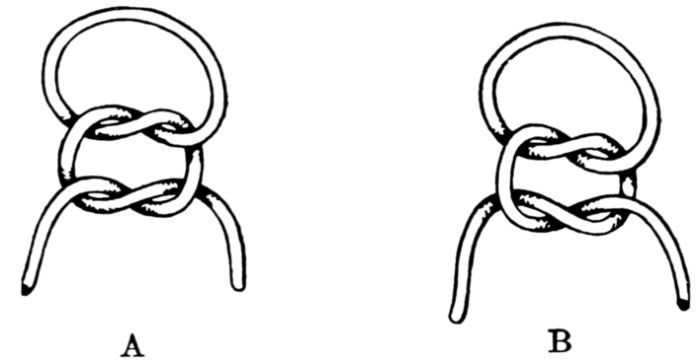

| 92. | Wrong and right method in tying knot in cord ligature | 272 |

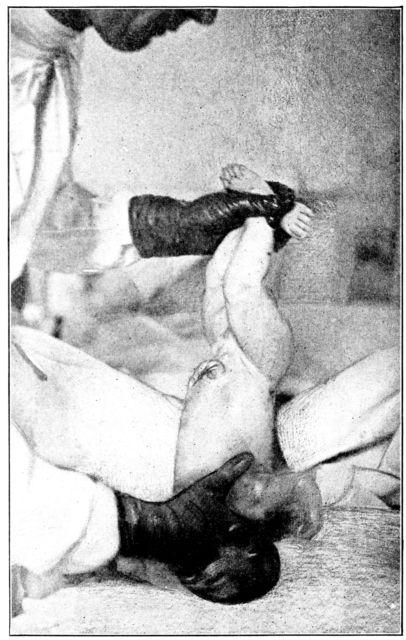

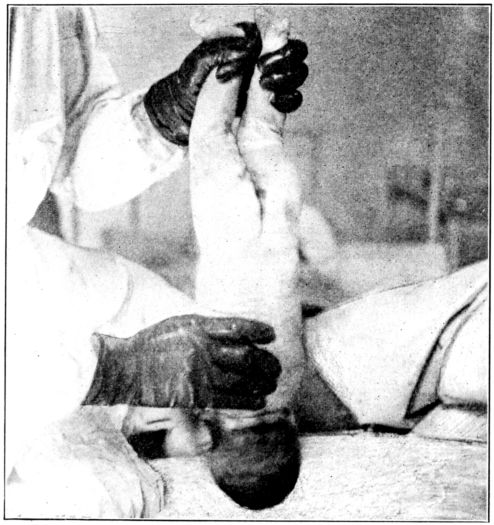

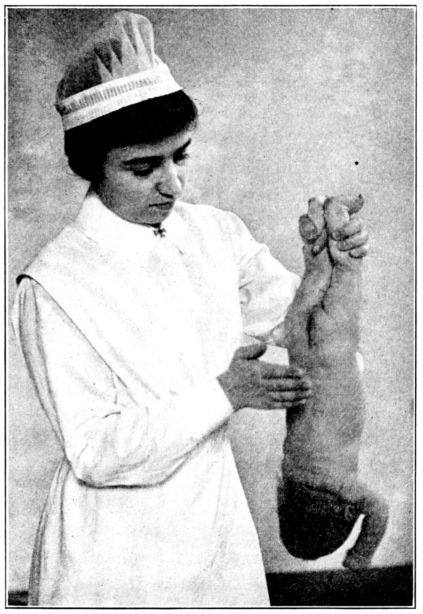

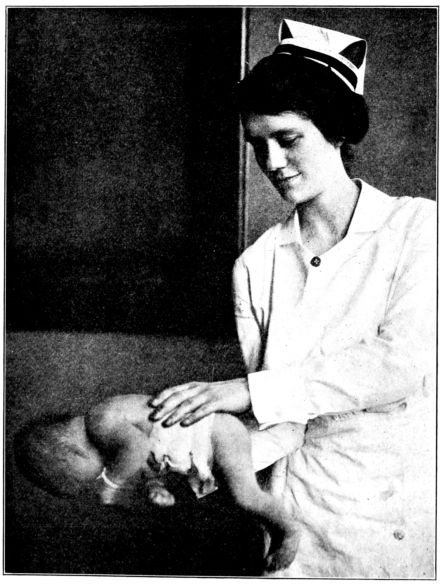

| 93. | Stimulating baby’s respirations | 274 |

| 94, 95. | Stimulating baby’s respirations | 275, 276 |

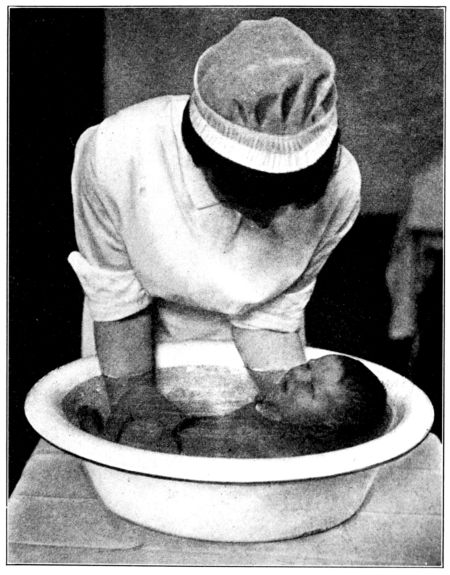

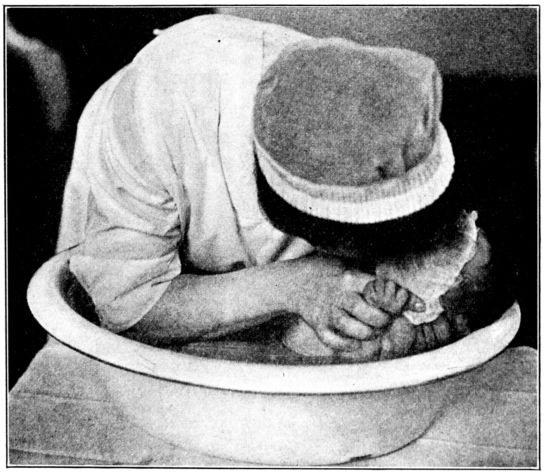

| 96, 97. | Resuscitating baby by holding under warm water | 277, 278 |

| 98. | Resuscitation by means of direct insufflation | 279 |

| 99. | Delivery of the placenta | 280 |

| 100. | Twisting membranes while withdrawing placenta | 281 |

| 101. | Massaging fundus through abdominal wall | 282 |

| 102. | Showing prolapsed cord between head and pelvic brim | 285 |

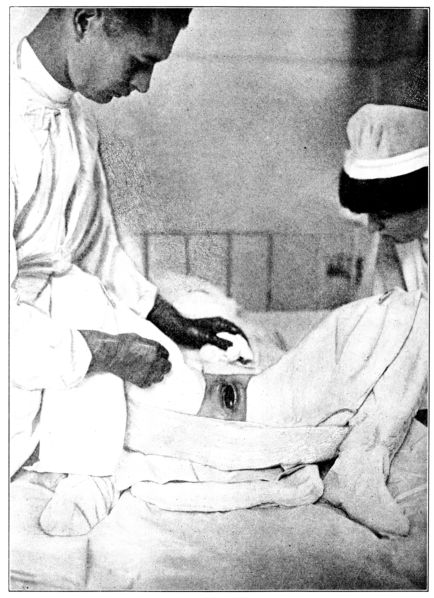

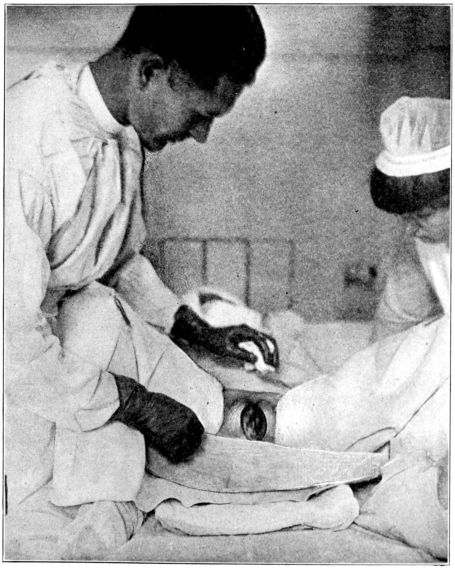

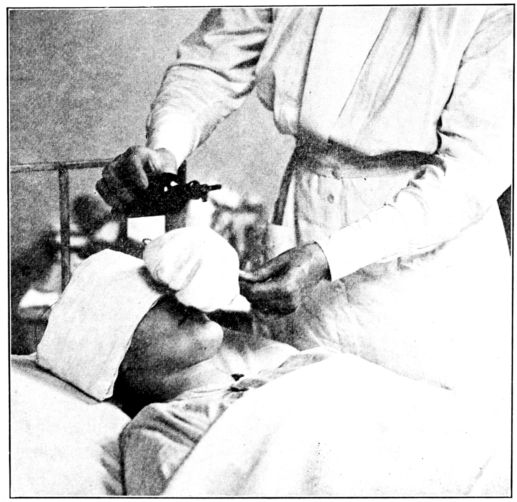

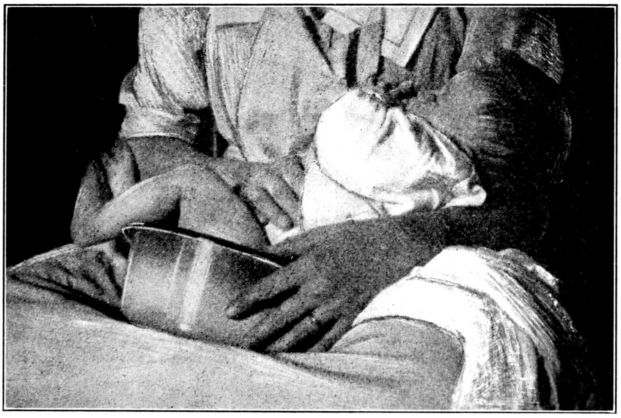

| 103. | Giving chloroform for obstetrical anæsthesia | 287 |

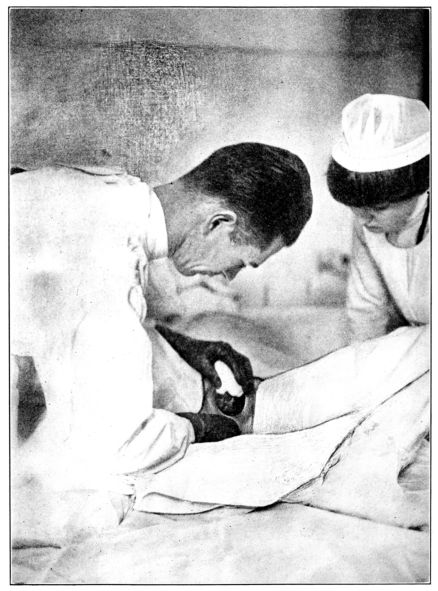

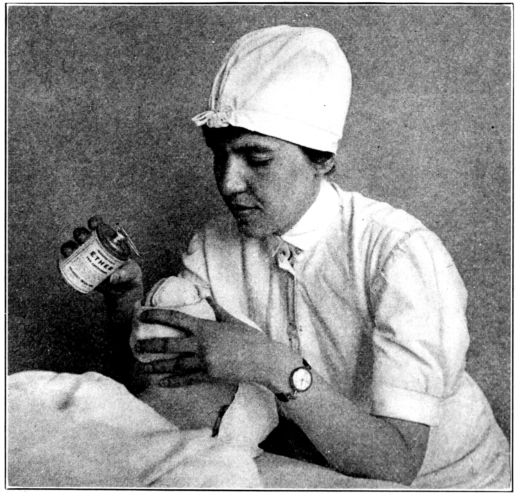

| 104, 105. | Giving ether for obstetrical anæsthesia | 289, 290 |

| 106. | Giving ether for complete anæsthesia | 293 |

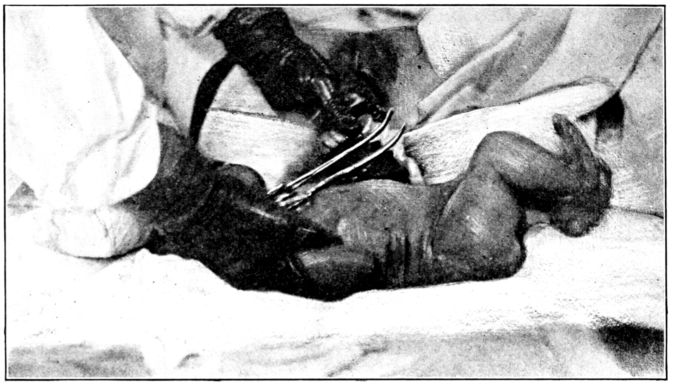

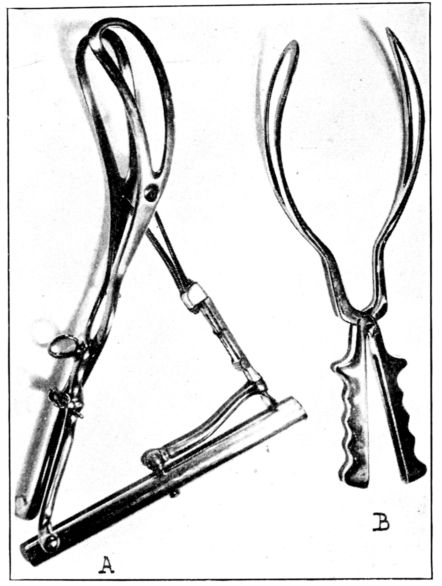

| xxii107. | a. Tarnier forceps, b. Simpson forceps | 301 |

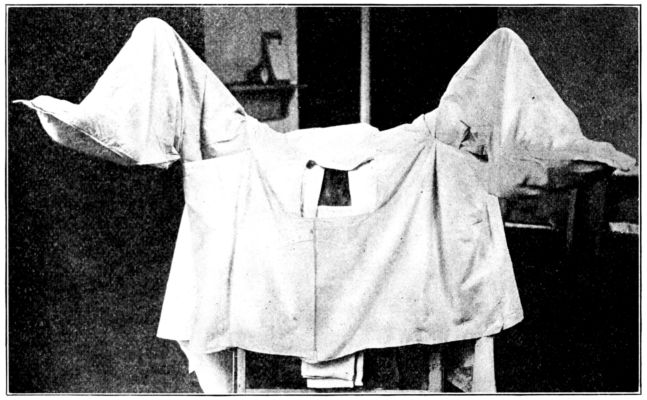

| 108. | Patient in position and draped for forceps operation | 302 |

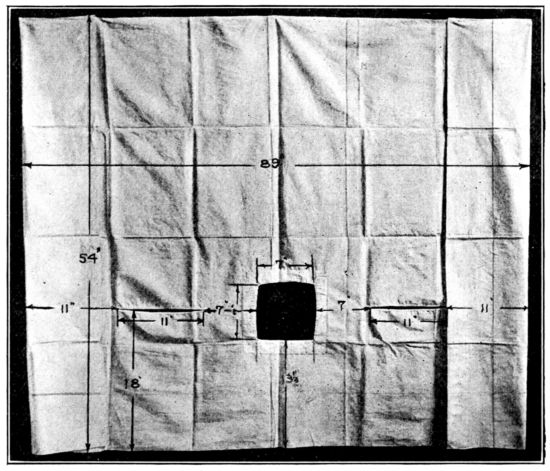

| 109. | Forceps sheet used in Fig. 108 | 303 |

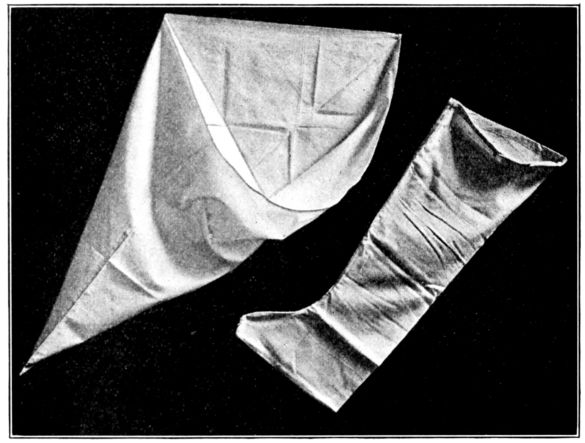

| 110. | Two types of leggings for obstetrical use | 304 |

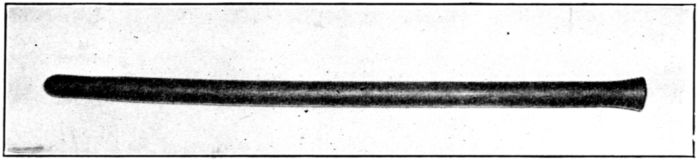

| 111. | Rubber bougie | 311 |

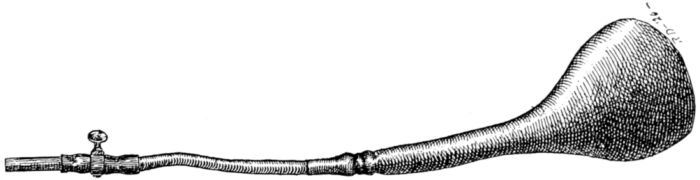

| 112. | Champetier de Ribes’ bag | 311 |

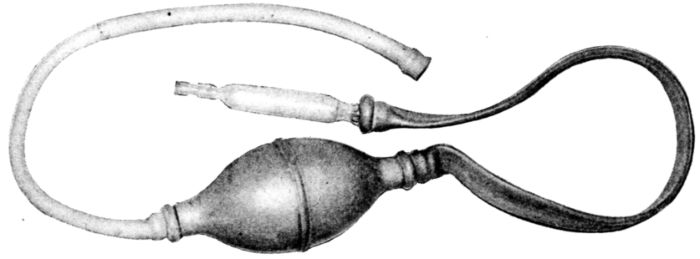

| 113. | Voorhees’ bag | 312 |

| 114. | Bag held in forceps for introduction into uterus | 312 |

| 115. | Syringe for filling above bags after insertion | 312 |

| The Young Mother. | ||

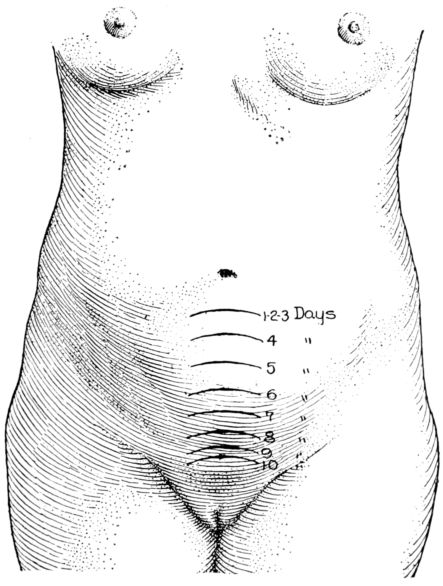

| 116. | Height of fundus on each of first ten days after delivery | 327 |

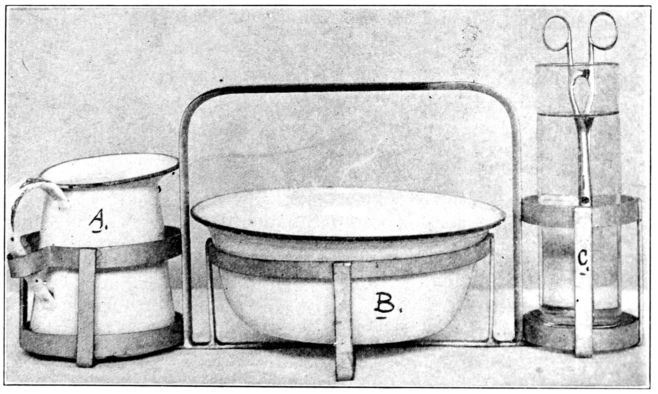

| 117. | Patient draped for postpartum dressing | 336 |

| 118. | Equipment in rack used in Fig. 117 | 337 |

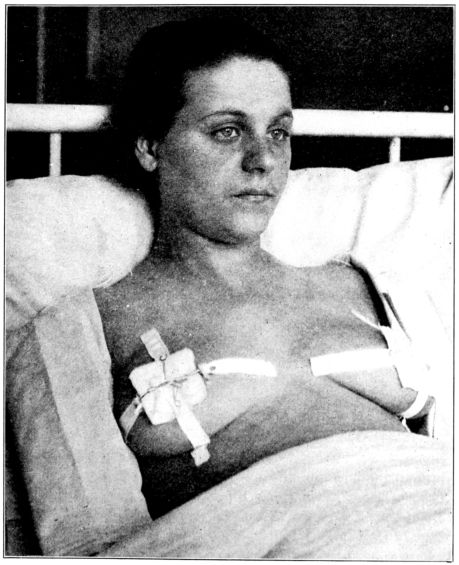

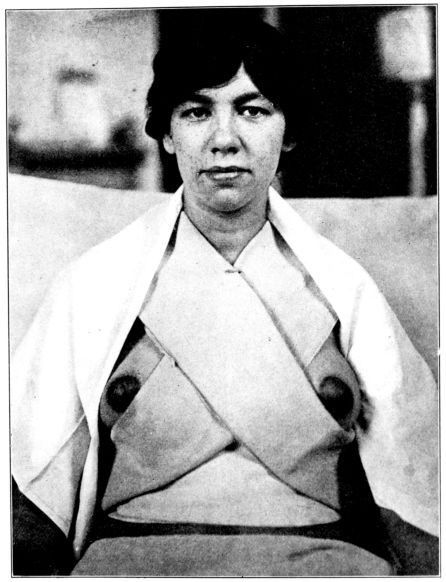

| 119. | Method of covering nipples with sterile gauze | 339 |

| 120. | Baby nursing through a nipple shield | 341 |

| 121. | Nipple shield used in Fig. 120 | 342 |

| 122. | Supporting heavy breasts by means of folded towels | 343 |

| 123. | Ice caps applied to engorged breasts | 344 |

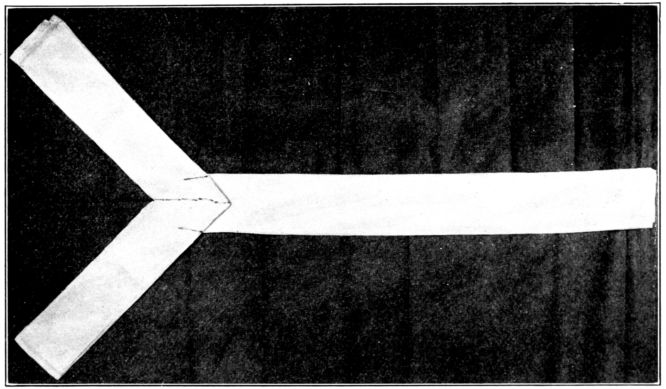

| 124. | Y binder before application | 345 |

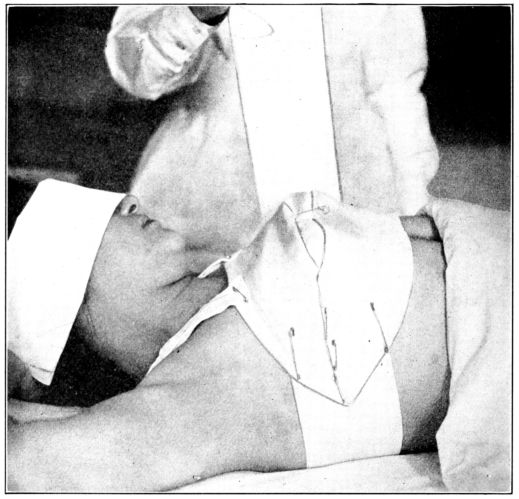

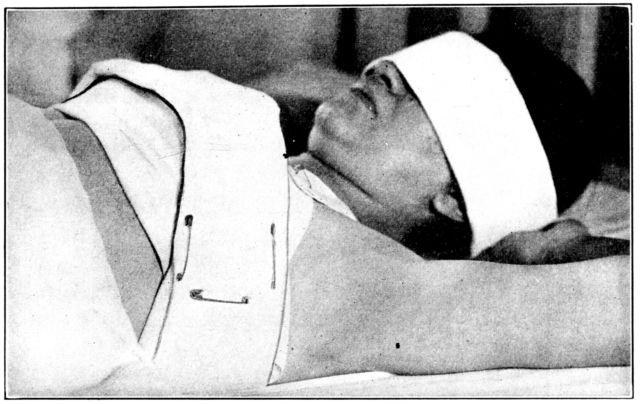

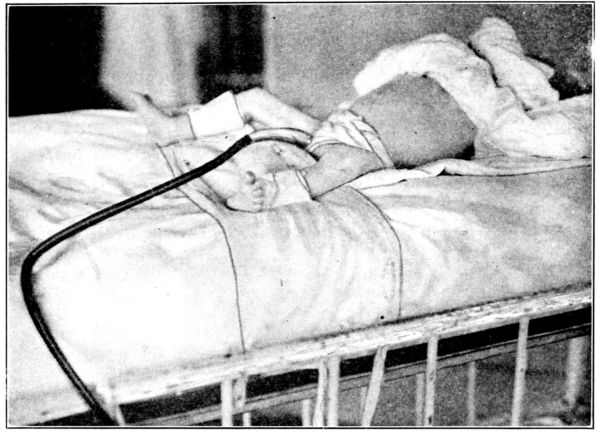

| 125. | Y binder applied | 346 |

| 126. | The same seen from the other side | 347 |

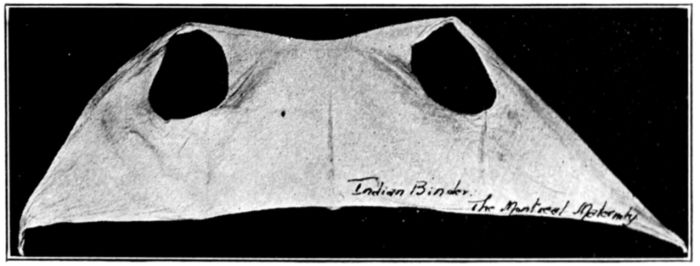

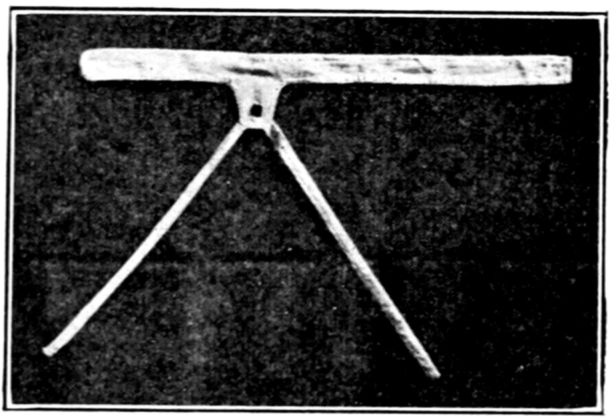

| 127. | Indian binder | 347 |

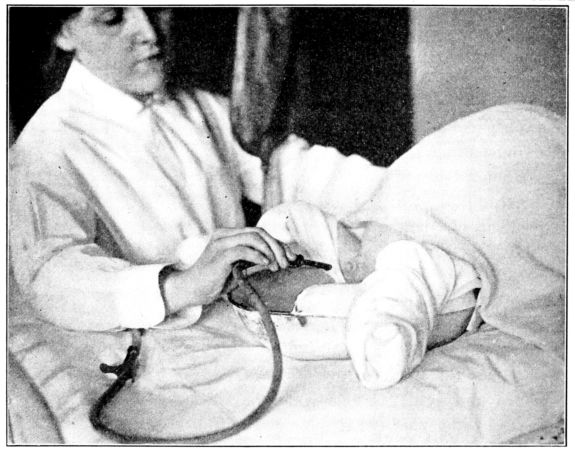

| 128. | Method of stripping | 348 |

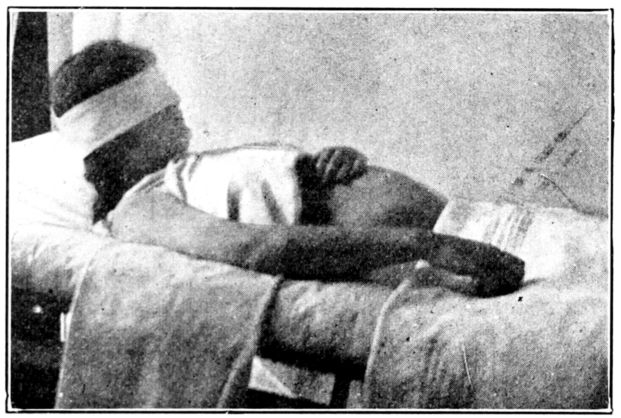

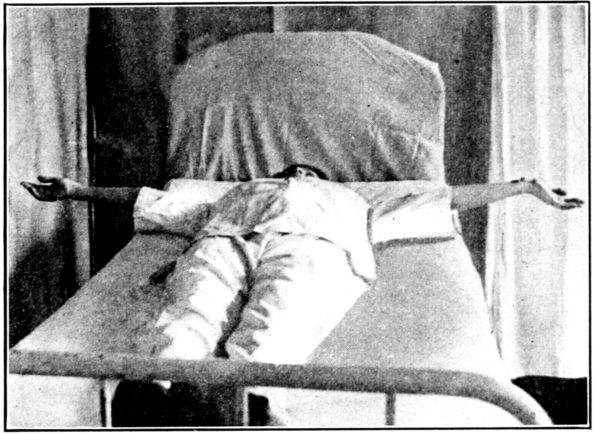

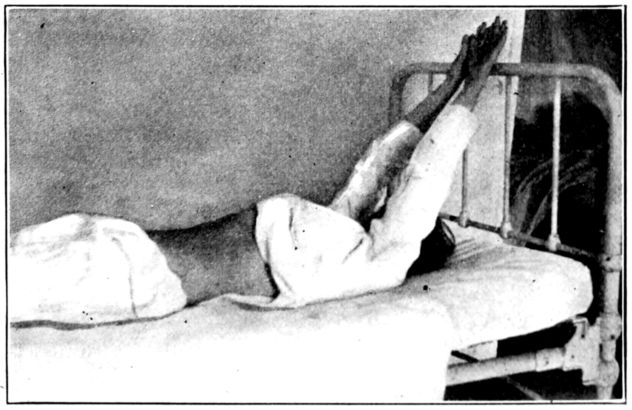

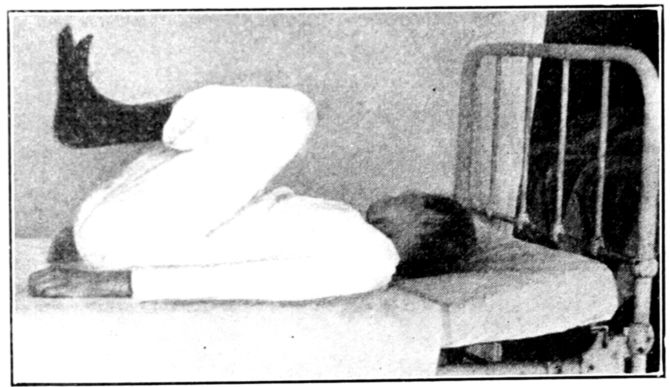

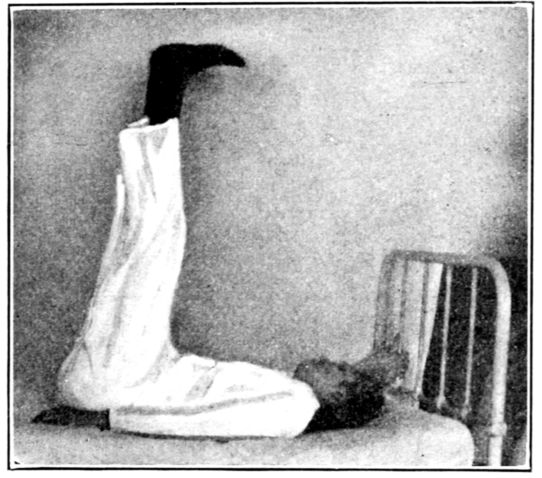

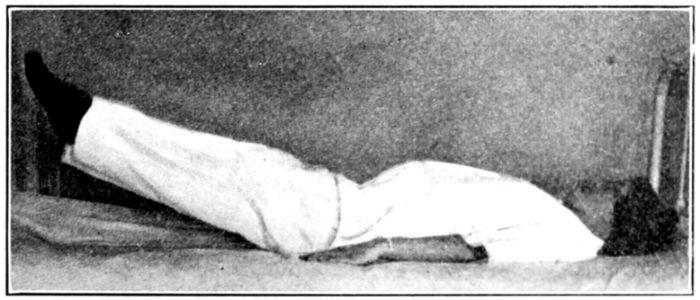

| 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135. | Bed exercises taken during the puerperium | 350 to 353 |

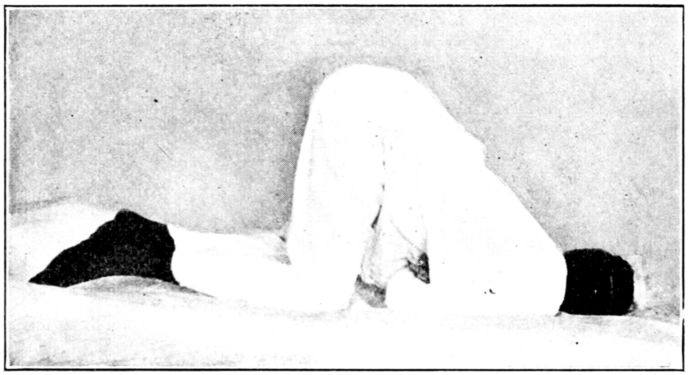

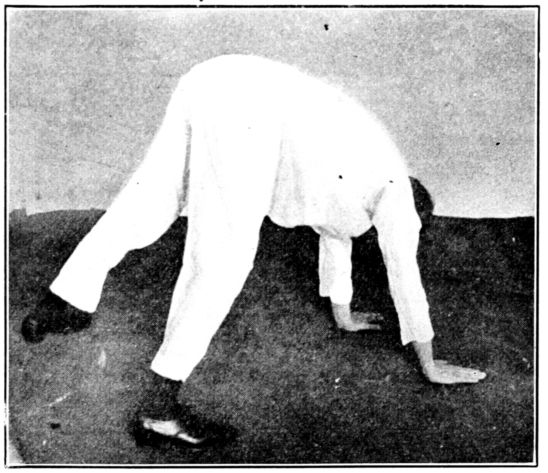

| 136. | Knee-chest position | 354 |

| 137. | Exercising by walking on all fours | 354 |

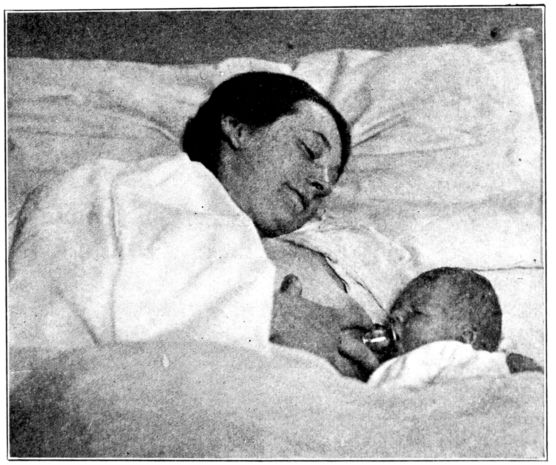

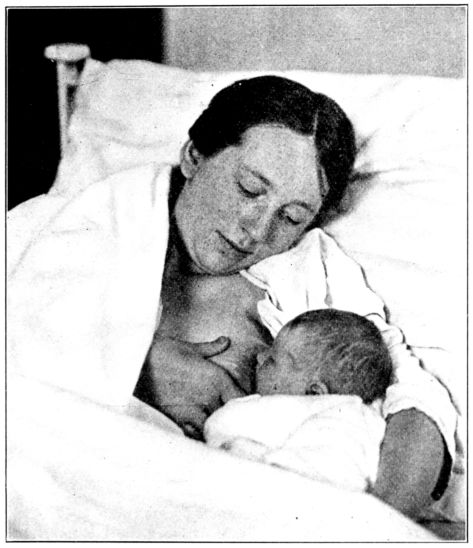

| 138. | Position of mother and baby for nursing in bed | 359 |

| 139. | The Nursing Mother (from a painting by Gari Melchers) | 361 |

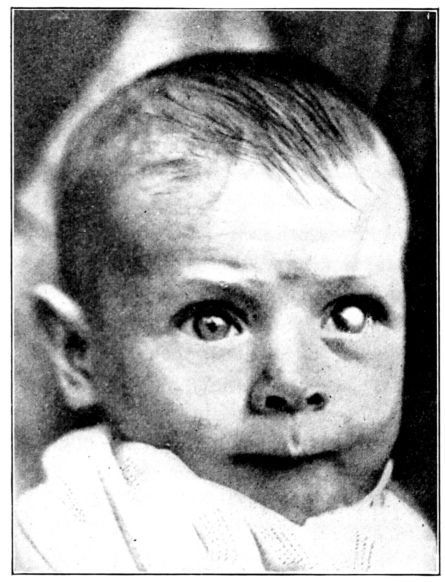

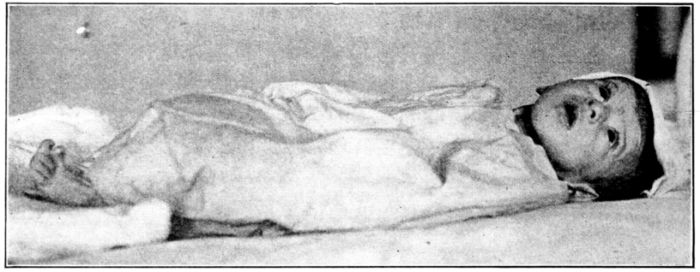

| 140. | Baby partially blind as a result of a faulty diet | 378 |

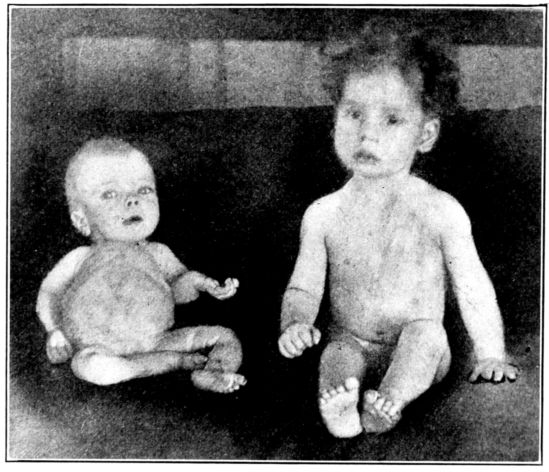

| 141. | Rachitic and normal babies of the same age | 381 |

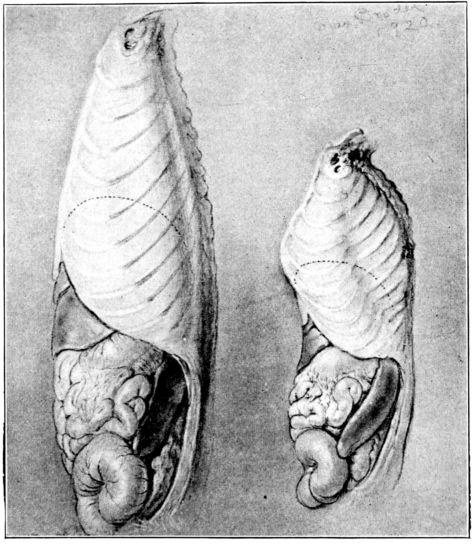

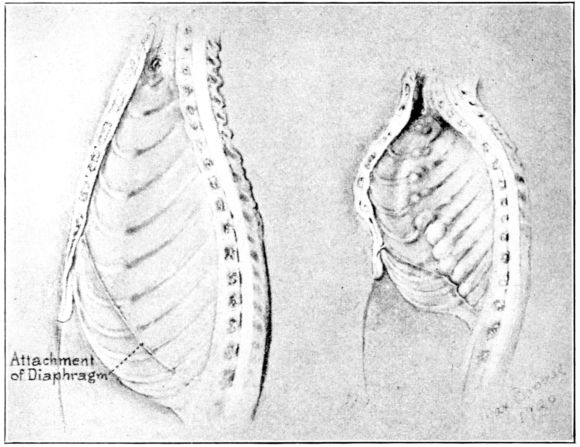

| 142. | Chest walls of normal and rachitic rats of the same age | 383 |

| 143. | Interior of specimens in Fig. 142 | 384 |

| The Maternity Patient in the Community. | ||

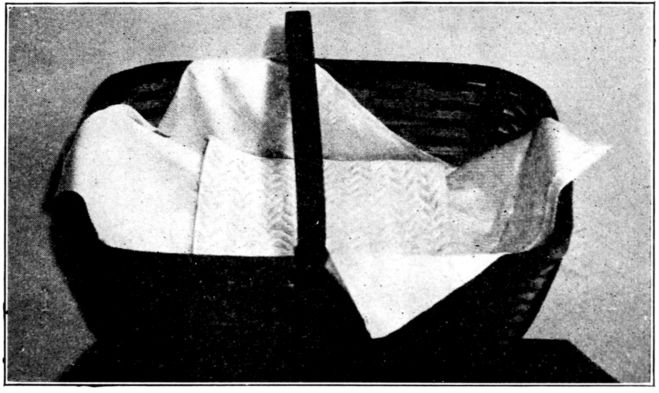

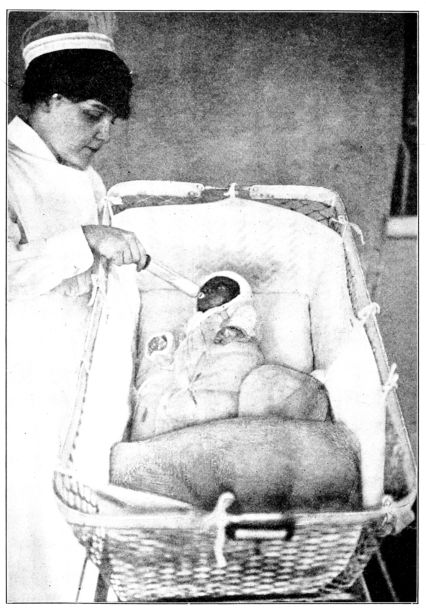

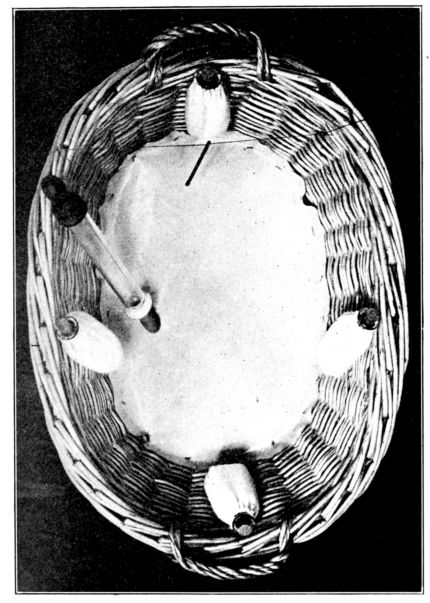

| 144. | Baby’s bed improvised from a market basket | 415 |

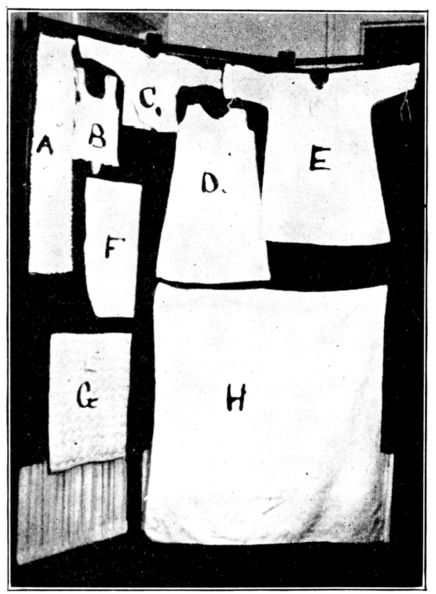

| 145. | Layette recommended to expectant mothers by Maternity Centre Association | 416 |

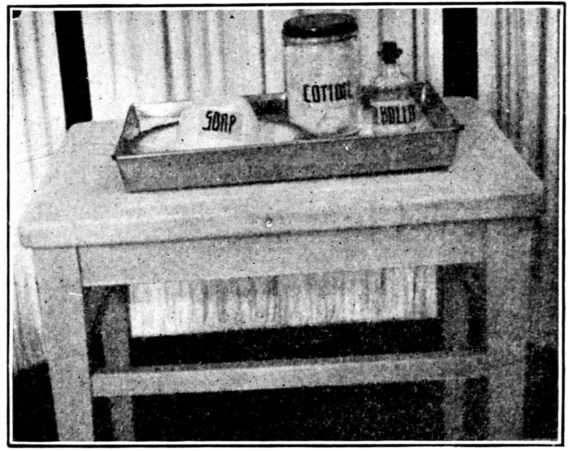

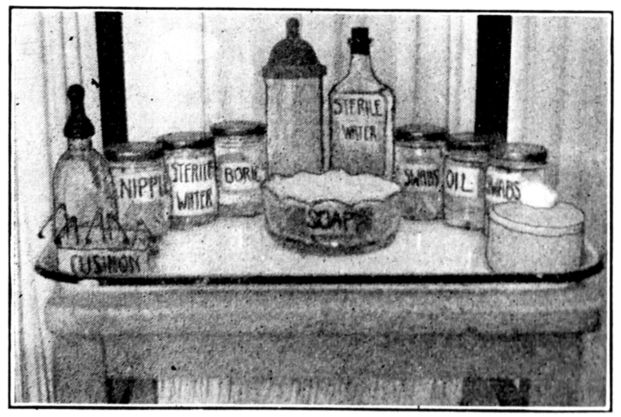

| 146. | Breast tray recommended to expectant mothers by Maternity Centre Association | 417 |

| xxiii147. | Baby’s toilet tray recommended to expectant mothers by Maternity Centre Association | 417 |

| The Baby. | ||

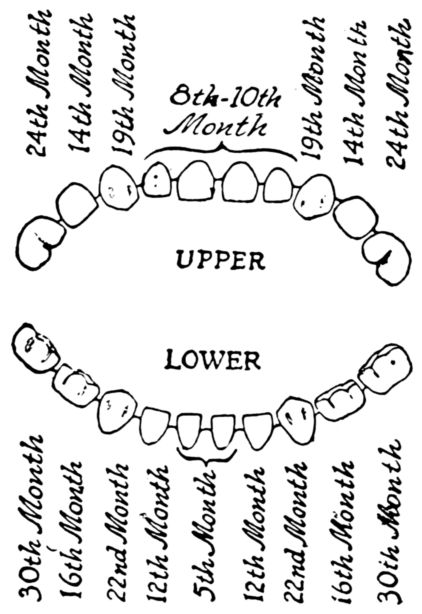

| 148. | Diagram of first teeth | 456 |

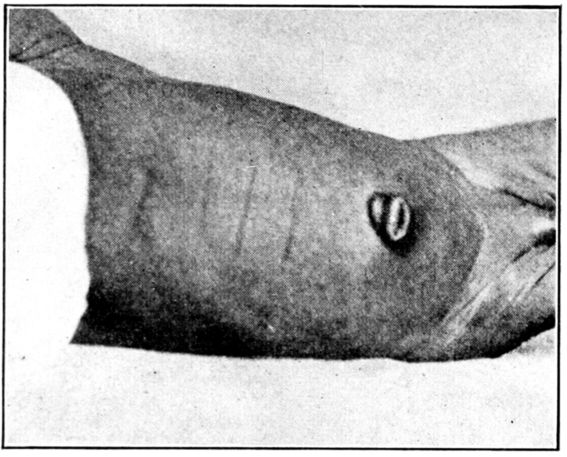

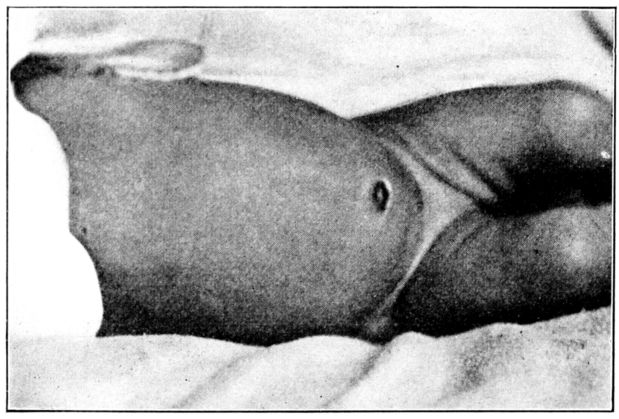

| 149. | Umbilical cord immediately after birth | 457 |

| 150. | The same four days later | 457 |

| 151. | Umbilicus immediately after separation of cord | 458 |

| 152. | Well healed umbilicus | 458 |

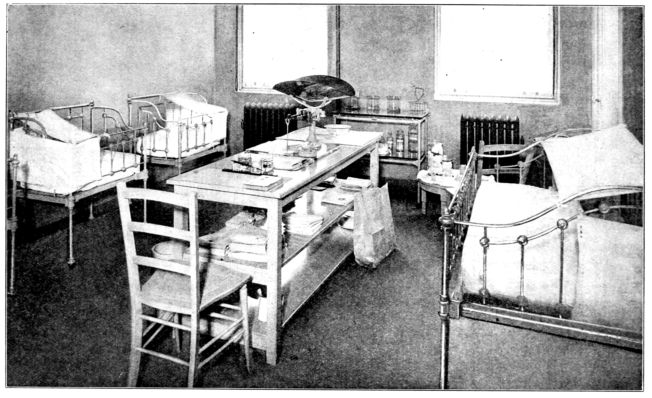

| 153. | Nursery at Manhattan Maternity Hospital | 465 |

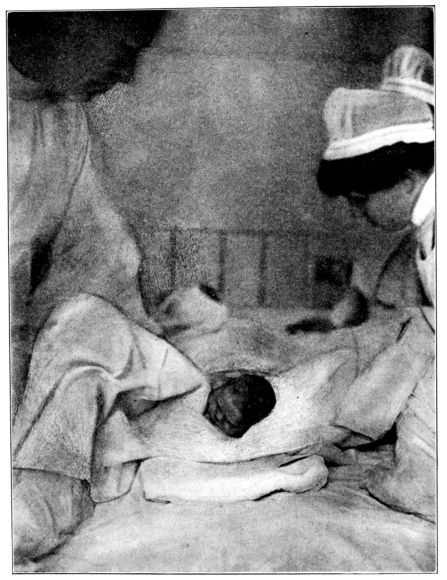

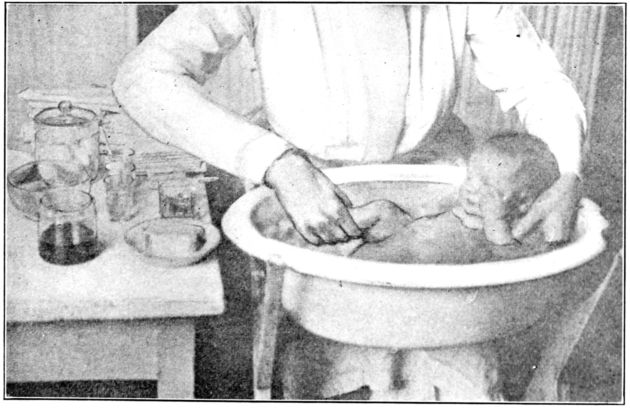

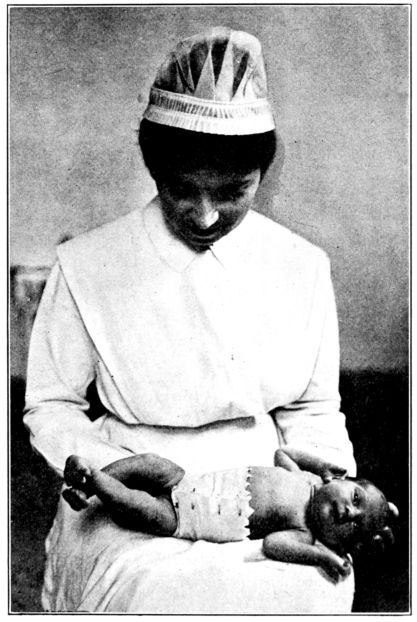

| 154. | Bathing the baby | 467 |

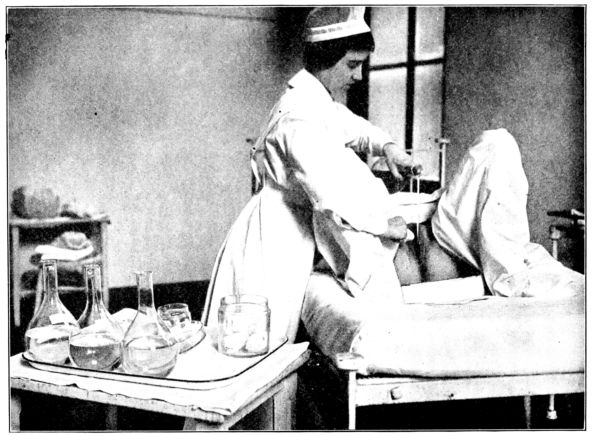

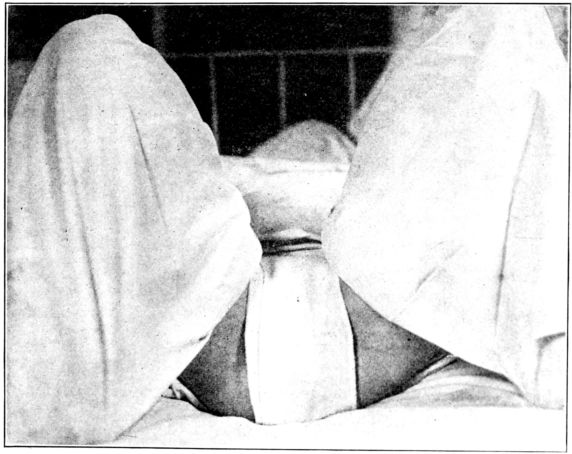

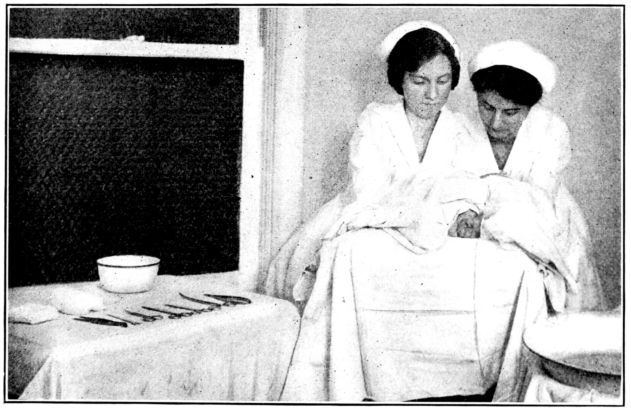

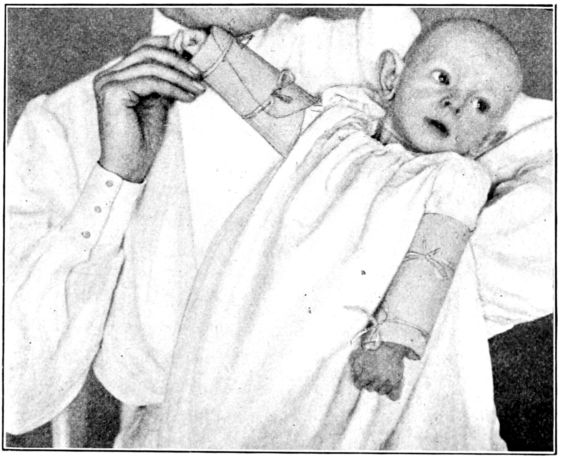

| 155. | Preparation for circumcision | 468 |

| 156. | Baby draped with sterile sheet, in above | 469 |

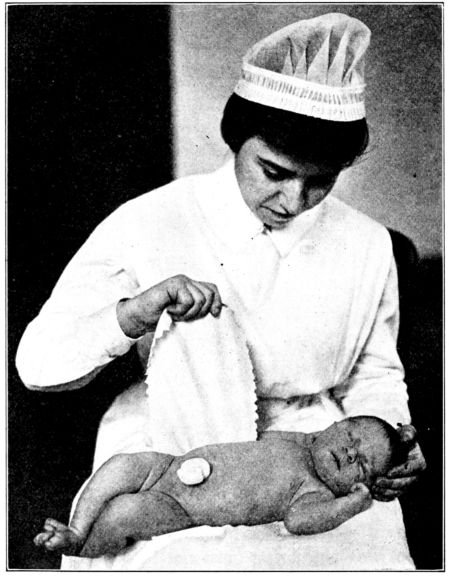

| 157. | Cord dressed with dry sterile gauze | 470 |

| 158. | Abdominal binder applied over cord dressing | 471 |

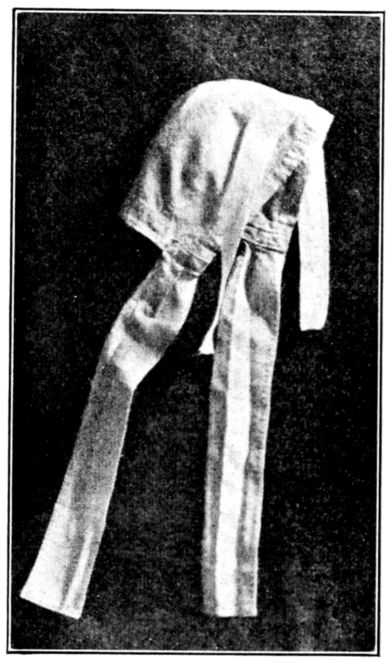

| 159. | Satisfactory baby clothes | 473 |

| 160. | Diagonally folded diaper applied | 474 |

| 161. | Longitudinally folded diaper applied | 474 |

| 162. | Sutton poncho to protect baby for outdoor sleeping | 479 |

| 163. | Training the baby to use a chamber | 481 |

| 164. | Stiff cuffs to prevent thumb sucking | 483 |

| 165. | Hammer cap to prevent ruminating | 484 |

| 166. | Ruminating cap applied | 485 |

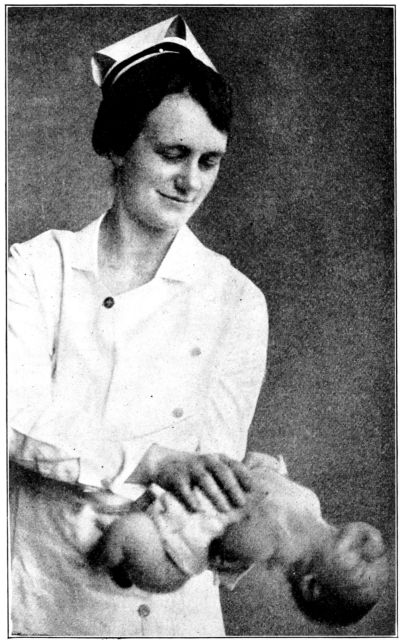

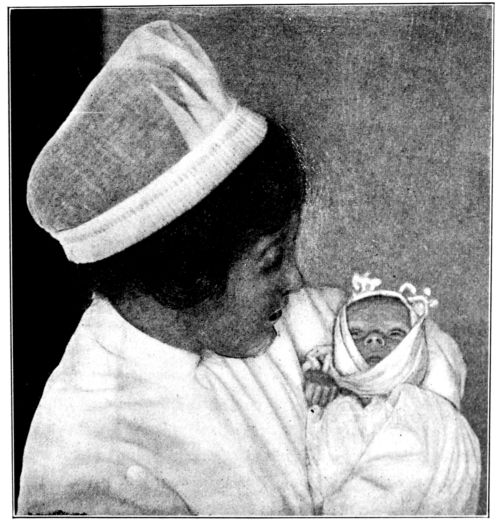

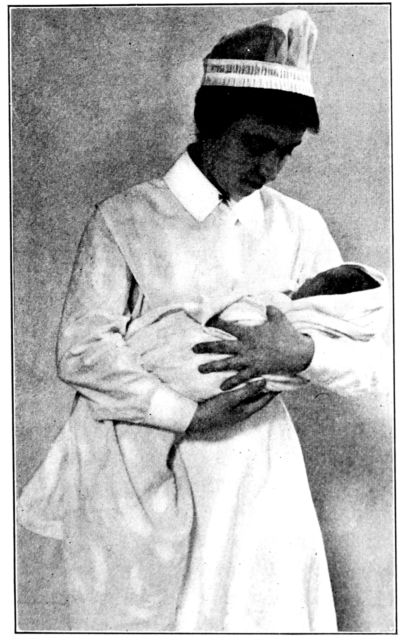

| 167. | Proper method of carrying baby | 487 |

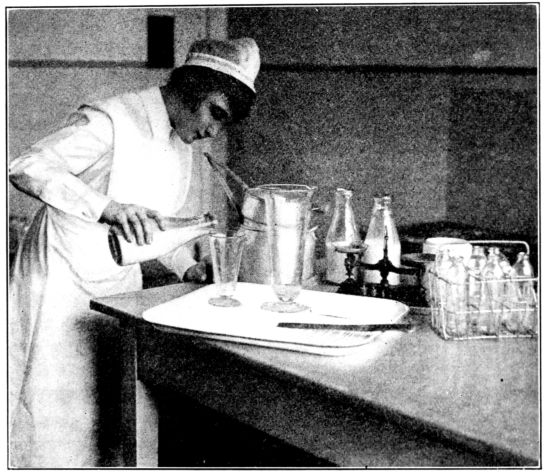

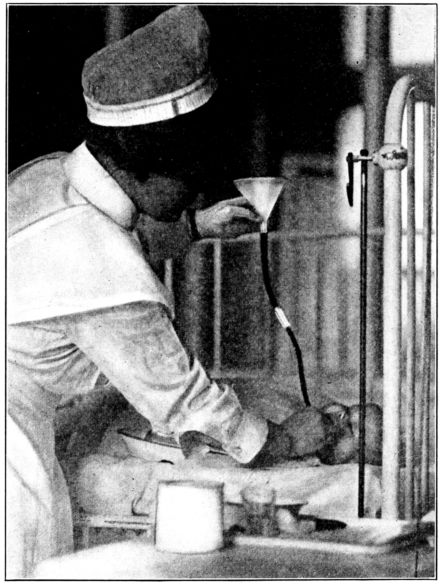

| 168. | Preparing the baby’s milk | 493 |

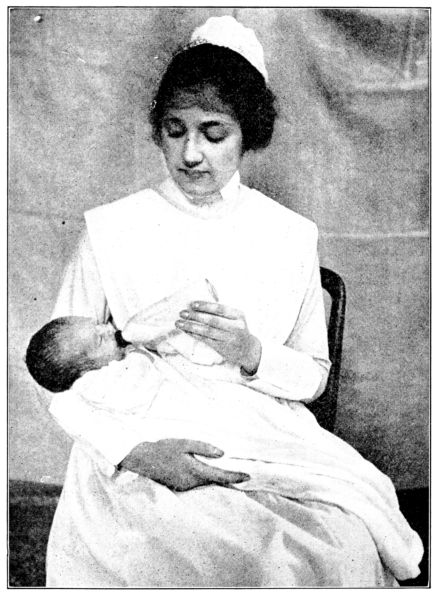

| 169. | Giving the baby his bottle | 496 |

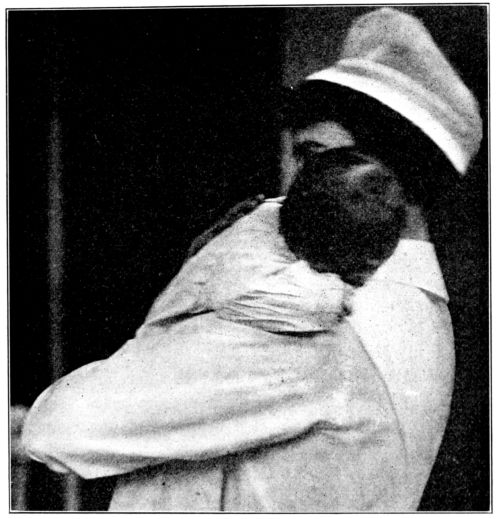

| 170. | Holding baby upright after feeding | 497 |

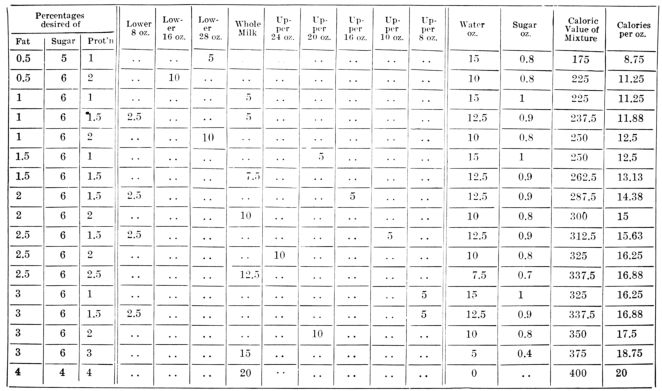

| 171. | Dr. Griffith’s table of fat percentages | 500 |

| 172. | Reverse side of above card | 501 |

| 173. | Baby in a basket ready to travel | 507 |

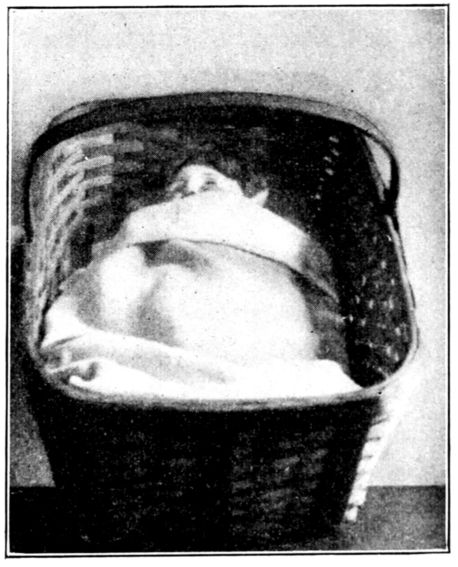

| 174. | Quilted robe with hood for the premature baby | 509 |

| 175. | Premature baby in lined basket, being fed with Boston feeder | 510 |

| 176. | Bed for premature baby improvised from small clothes basket | 511 |

| 177. | Putting the baby in a wet pack | 521 |

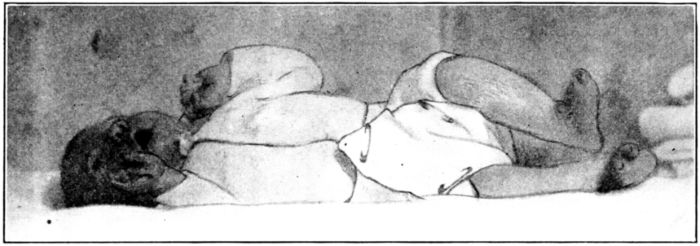

| 178. | Baby in wet pack | 522 |

| 179. | Diagrams showing successive steps in giving the baby a pack | 522 |

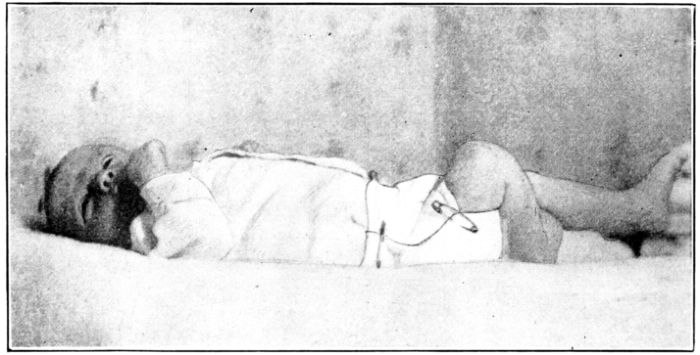

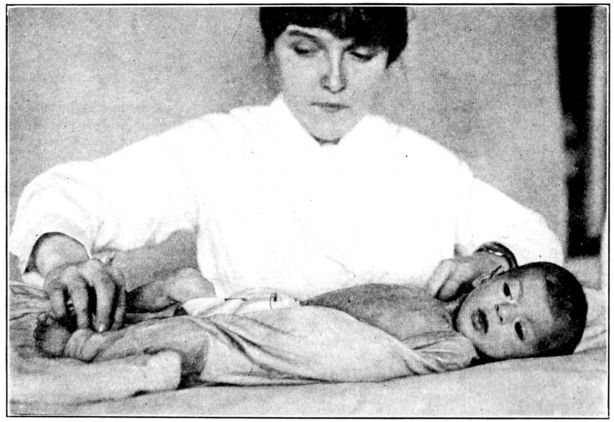

| 180. | Baby wrapped in blanket preparatory to gavage | 523 |

| 181. | Gavage | 524 |

| 182. | Obtaining a fresh specimen of urine from the baby | 526 |

| 183. | Obtaining a 24–hour specimen of urine from the baby | 527 |

| xxiv184. | Band to hold baby’s legs while obtaining specimens of urine | 527 |

| 185. | Belt used to hold tube for specimen | 528 |

| 186. | Giving the baby an enema | 530 |

| 187. | Irrigating the eye with a blunt nozzle | 536 |

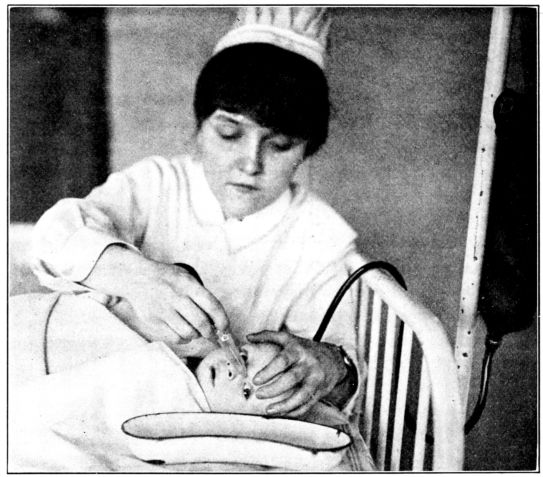

| 188. | Method of holding baby for treating gonorrhœal ophthalmia | 537 |

| CHARTS. | ||

| No. | ||

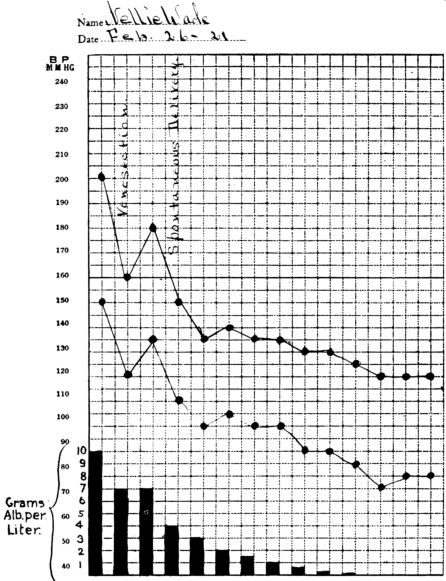

| 1. | Showing drop in blood pressure and albumen, after delivery, in eclampsia | 204 |

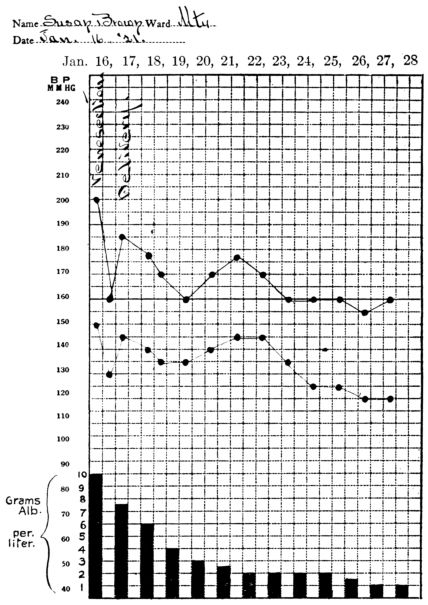

| 2. | Showing persistence of high blood pressure and albumen in the urine, after delivery, in nephritic toxæmia with convulsions | 206 |

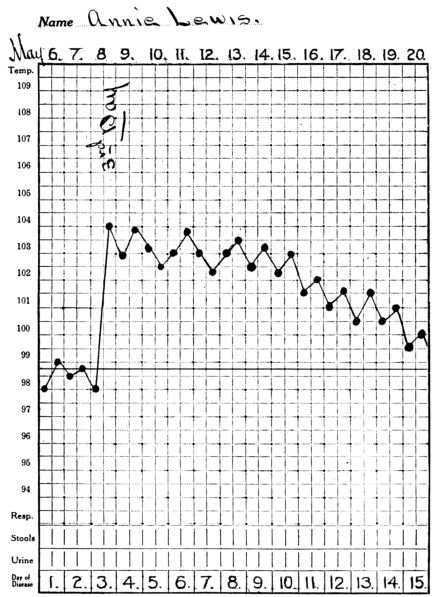

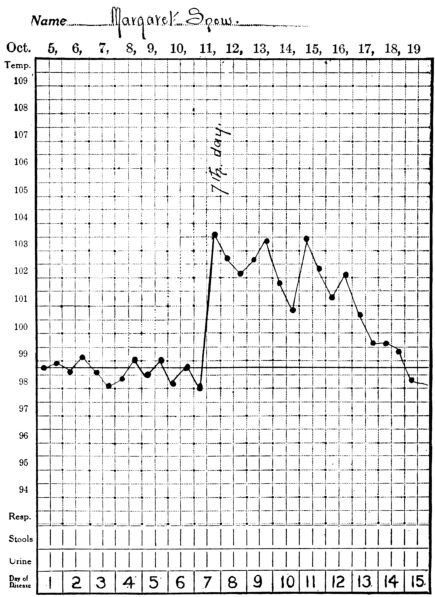

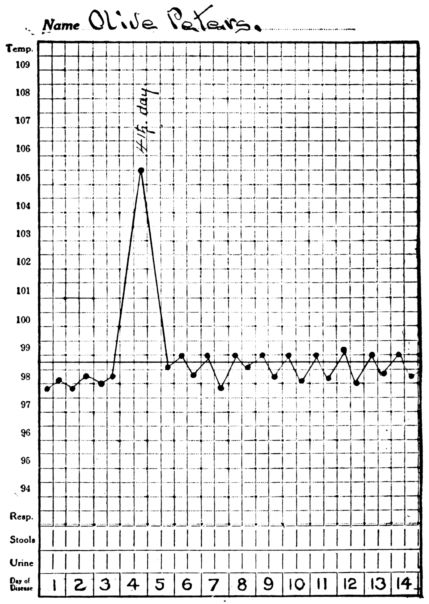

| 3. | Showing temperature curve in streptococcus infection | 397 |

| 4. | Showing temperature curve in gonorrhœal infection | 398 |

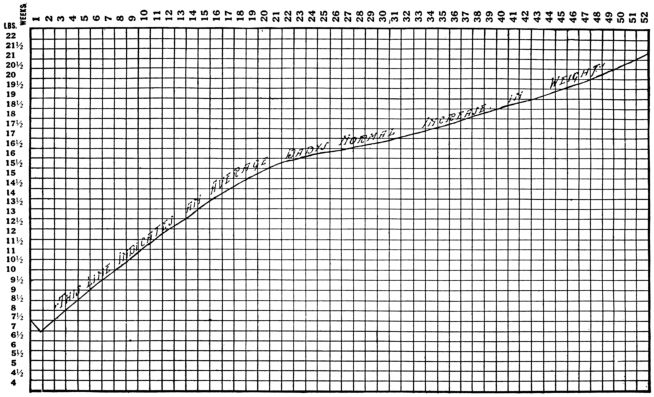

| 5. | Showing normal weekly gain in weight during first year of life | 454 |

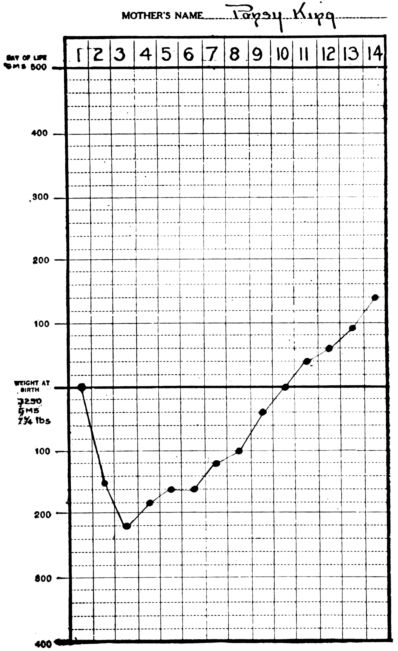

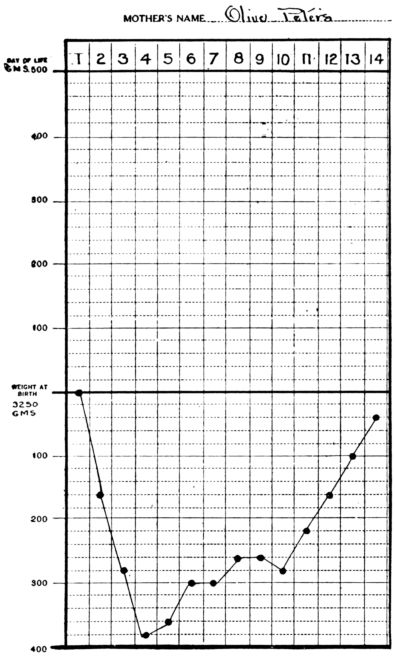

| 6. | Showing normal daily gain in weight during first two weeks | 520 |

| 7. | Showing loss of weight in inanition fever contrasted with No. 6 | 520 |

| 8. | Showing rise in temperature in inanition fever | 520 |

The avowed purpose of care given to the maternity patient to-day is to minimize the discomforts and perils of her pregnancy, labor, and the puerperium, and so safeguard her and her baby that both will emerge from the lying-in period in a satisfactory condition and with a bright prospect of having permanently good health.

The striking difference between obstetrics as practiced to-day, and that of former times, is that it now lays as much stress upon the future health of the mother and baby as it does upon their immediate safety.

Happily, the present-day obstetrician, who assumes the care of an expectant mother, does so with confidence and optimism because of the available knowledge upon which he may draw for her benefit. Progress in the various branches of medicine and nursing is steadily pointing the way toward greater and more effective safeguards for the maternity patient and her baby.

The value of these safeguards is attested to by the satisfactory results of the care which is given to the patients in well conducted hospitals or in their homes by careful physicians; by various out-patient departments and nursing organizations to patients within their reach. These results are in the form of a large proportion of mothers and babies who are well and continue to be well.

That is one view of the matter. Looking at it from another aspect, we discover that more than seven women still lose their lives for each 1,000 births that occur in this country, the actual number varying in different localities. Childbirth is still second to tuberculosis as a cause of death among women between fifteen and forty-five years of age, and in spite of the proved value of care in making maternity a safe adventure, the larger 4proportion of these women die from infection or toxæmia which are almost entirely preventable.

The incredible fact in this connection is that, while there has been a decline in the deaths from such other controllable conditions as typhoid fever and some of the infectious diseases of childhood, there has been an actual increase in deaths from preventable causes associated with child-bearing.

Dr. Dublin estimates that throughout the United States as a whole, during 1920, the total number of deaths due to childbirth was about 20,000.

In addition to the high death rate among mothers the mortality among babies is even greater. Dr. Dublin estimates that out of every 1,000 babies born during 1920, about 85 died before they were a year old, or about 200,000 in the course of the year, and that the large majority of these died from congenital causes, from infection or nutritional disturbances. Another 100,000 babies perish, yearly, through still births. As all of these conditions are preventable to a greater or lesser degree, we have to acknowledge that many babies die whom we know how to save. There is sound reason, therefore, for the belief that proper care would save the lives of about two-thirds of the mothers and half of the babies who now die and half of the babies who are born dead.

And let it be remembered that conditions which destroy life, also destroy or greatly impair health and resistance to disease. Although we may count the number of mothers and babies who fail to survive the too severe test to which they are put during crucial periods in the lives of both, we cannot count, nor even approximately estimate, the number of those who escape death only to be imprisoned in frail, deformed, or diseased bodies. Therein lies much of the tragedy which follows in the wake of neglect—the lifelong handicaps, suffering, and inefficiency that need not have been.

This lack of care is not due to limitations in medical knowledge, for the efficacy of known methods is being constantly demonstrated. And our instant and generous response, the country over, to appeals for help in relieving various forms of need and disaster does not suggest a national cold-bloodedness, 5or even indifference, to needless suffering. But still a legion of mothers and babies die each year from lack of care, and almost at our very thresholds.

Perhaps the root of the difficulty lies in the fact that childbirth, as well as the attendant suffering and death, are so familiar that they are regarded as being normal incidents in the ordinary course of affairs.

One of the most dramatic of all human events, the birth of a new being, is accepted casually, almost without concern, because it is so frequent—so commonplace.

Moreover, we are all accustomed to hearing stressed the fact that child-bearing is not a disease, but is a normal physiological function.

Not so generally, however, do we hear emphasis made upon the equally important facts that there is extreme danger of infection while these physiological functions are in progress, and that they subject the entire organism to such a strain that there results a dangerously narrow margin between health and disease.

Accordingly, too much is expected, or taken for granted, from the provisions which Nature has made to promote these functions, and not enough assistance is given to protect the mother, while they are in course, or to help the immature baby in adjusting himself to the greatest change which he makes during the entire span of his existence.

When the time comes, and it seems to be approaching, that pregnancy, labor, the puerperium and infancy are regarded as crucial periods in the life history, demanding all the preventives and safeguards that all branches of medicine and nursing can offer, these periods will cease to be so enormously destructive of life and health.

We cannot build a strong race with sickly and maimed mothers and babies, and we can scarcely have other than sickly and maimed mothers and babies without care.

Apparently, then, our national health is in a large measure dependent upon good obstetrics and good obstetrics includes good nursing.

Good nursing implies more than the giving of bed baths and medicines, boiling instruments and serving meals. It is more 6than going on duty at a certain time, carrying out orders for a certain number of hours and going off duty again. It implies care and consideration of the patient as a human being and a determination to nurse her well and happily, no matter what this demands.

In carrying on her work, the maternity nurse may be called upon to aid in prenatal supervision and instruction; to prepare for and assist with a delivery, or to give either exclusive or visiting nursing care to a young mother and her baby. These patients may be in a hospital or at home and the home may be of any kind from a palace to a hut or a tenement. The patients may be in a city, a small town, or a rural community, and in the care of doctors whose methods vary widely.

But in spite of the diversity of conditions and the fact that no two will be quite alike, the general need of all of these patients will be the same.

Their need is care, which includes cleanliness in order to prevent infection; suitable food; fresh air and exercise; regular and sufficient rest and sleep; an equable body temperature; early treatment of complications and correction of physical defects. In short, each patient needs to be watched; needs clean care and to practice the approved principles of personal hygiene from the beginning of pregnancy. This without regard to race, color, creed, occupation, status, or location. It means all maternity patients and their babies the country over.

There was a time when the obstetrician first saw his patient in labor or shortly beforehand, and when the care of the baby began at birth or soon afterward.

We know what this tardy attention has cost in human lives and suffering.

We know, too, that among the mothers, abortion, miscarriages, toxæmias, difficult or impossible labors may be largely prevented through prenatal care; while among babies, the enormously high death rate, during the first month of life from causes which begin to operate before birth, convinces us that we must begin to take care of the baby nine months before he is born, if he is to have the greatest benefits of present available knowledge. Such early care reduces still births and injury during labor; it reduces premature births, which is important, 7because the nearer the baby goes to term the better his chance of survival and of good health, and prenatal care also increases the prospects of satisfactory breast feeding.

Although we know that the ideal is to have all maternity patients supervised and instructed entirely by a physician from the beginning of pregnancy and then delivered in a well conducted hospital, it is scarcely probable that this ideal will ever be realized. There will always be patients who cannot afford to employ a doctor for so long a period; there will always be communities in which hospital provisions do not exist or are inadequate. There will always be expectant mothers whom it would be unwise to remove from home, excepting under pressing conditions, because of the influence exerted by their mere presence in keeping the family group intact. And so on, through a number of deterring conditions which will probably never cease to exist, and which will keep the patient at home.

Since patients who are supervised during pregnancy and delivered in hospitals usually recover, the high rate of death and injury, in this country, is to be found among women who are unsupervised before labor and subsequently delivered at home. Accordingly, if this widespread injury is to be reduced, the essentials of the care which is found to be efficacious must be made available for all patients throughout the length and breadth of the land.

Prenatal care, clean deliveries, and intelligent motherhood will go far toward solving the problem of a high maternal and infant death rate, and these require not widespread care, alone, but widespread teaching as well—impressing upon women and their families the importance of care and precautions in connection with childbirth. Important as it is for men to study and inform themselves in regard to the problems of finance and cattle raising, for example, it is still more important for both men and women to study and appreciate the problems of expectant and actual motherhood.

It is in this teaching that the nurse may be immeasurably helpful, in fact is indispensable, for the carrying of approved care into the home and the general teaching of personal hygiene are inextricably bound up with nursing.

8The details of the care and teaching of patients are, of course, specified by a doctor or a medical board, but the effectiveness of the planning, whether for one or several patients, is very largely dependent upon the nurse’s intelligence, interest and conscientiousness, and her ability to teach.

This is borne out by the almost uniform recommendations, made by official bodies, for provisions looking toward the reduction of maternal and infant deaths including as they do the following:

1. The employment of public health nurses. (To give home care or instruction or both.)

2. The establishment of prenatal clinics and baby health centers. (In both of these the nurse aids in supervising and teaching the mother how to take care of herself and her baby.)

3. Trained attendance during labor. (The nurse aids greatly in preparing for and assisting with clean deliveries.)

4. Improved and increased hospital facilities. (There cannot be good hospital work without good nursing.)

5. Prompt and accurate registration of births. (Here, too, the nurse may be helpful by always making sure that the birth has been reported.)

Here is no light task nor mean privilege which is set before the nurse and in order to meet them fitly she must be prepared. The indispensable requisites for nursing and teaching the maternity patient, whether at home or in a hospital, are training, an exacting conscience, and genuine concern for her patient as an individual.

A certain amount of scientific knowledge is necessary, in this as in any other field, to give the nurse an intelligent background and a kind of definiteness and stability to her work. She should be trained in the essentials of general nursing, of surgical nursing and operating room technique, and in the care of babies. She must of necessity know something of the anatomy and physiology of the female generative organs; the physiological adjustments during pregnancy; the development of the baby within the uterus; the normal process, or mechanism, of labor, and the changes which ordinarily take place during the puerperium. 9Such information will make clear to her the reasons for the care which she gives to her patient, and accordingly her care will be more intelligent. And she will be better able to recognize the difference between evidences of normal physiological changes and the symptoms of complications.

Two of the newer branches of medicine—nutrition and mental hygiene or psychiatry—have a more and more apparent relation to the safety and welfare of the maternity patient, and accordingly are of moment to the maternity nurse. For, it must be remembered, it is the purpose of obstetricians to-day to establish future health for their patients as well as immediate safety. The nurse should endeavor to help with all that the doctor attempts to do toward these ends, and in order to help she must understand.

The maternity nurse can scarcely be expected to specialize in nutrition or in psychiatry, but she may give to her patients the practical benefits of many valuable discoveries in these fields. She may not be able to remember, for example, all of the sources and purposes of lime in the diet, nor of each of the protective substances, often referred to as vitamines, but any nurse can remember and be guided by the fact that her patient will not be satisfactorily nourished either before or after the birth of the baby unless she has a varied diet containing milk, eggs, and green vegetables. She also can explain to her patients that faulty dietaries are responsible for the tradition that each child costs the mother a tooth, as well as the fact there may be undernourishment even among babies who are fed at the breast, if the mother’s diet is inadequate.

And though the mass of nurses cannot be expected to grasp all of the intricacies of psychiatry, they may without exception apply one of its most important principles by adopting a warm and sympathetic attitude toward their patients and by this means win their trust and confidence. The restfulness of this; the relaxation and general state of mind that this will engender in a large proportion of patients will exert a definitely beneficial effect upon the physical well-being of the expectant mother, the woman in labor and the nursing mother.

These simple applications of important scientific discoveries 10that relate to the everyday life of her patient—these are things for the maternity nurse to bear in mind. She is nursing a human being who is passing through crucial periods and anything that affects her as a human being affects her as a patient.

Apparently, then, the work of the obstetrical nurse necessitates a training in general nursing and its various branches, in addition to obstetrics, for there seems to be no aspect of nursing which may not, under some condition, have its place in the care of the mother or her baby. All of this training, however, will prepare her for effective work only if she herself has a spirit of eagerness and enthusiasm. But if she has these and even a little training, she may do much.

Accordingly, let the nurse who has been prepared by a general and special training, and who wants to be of the greatest possible service to the maternity patient start by appreciating a few general principles which will be absolutely indispensable to the success of her work. They may be expressed somewhat as follows:

1. Cleanliness—under all conditions, to protect both mother and baby from infection.

2. Watchfulness—for early symptoms of complications in either mother or baby.

3. Adaptability—to the patient, the doctor, and the surroundings.

4. Sympathy—for every mental and physical stress which the patient may suffer.

If the nurse convinces herself of the import of these requirements and is exacting of herself in giving them broad interpretation, she cannot but nurse her patients well.

She will appreciate the invariable need for cleanliness and watchfulness if she will hark back to the fact that our mothers and babies die in distressingly large numbers from infections, toxæmias, and nutritional disturbances, all of which are usually amenable to preventive or early treatment.

In order to be always clean, always watchful, and always ready to execute, both in letter and spirit, the orders of doctors whose methods of treatment will differ, the nurse will need to be very adaptable. She will need to keep a clear head 11and an open mind and to remember always the ends that are being striven for: the immediate safety and the future wellbeing of the mother and the baby. And she may rest assured that, no matter how they vary as to details, all doctors want all of their patients to be given clean care; watched for symptoms of complications; and given good general nursing.

Considering the need for cleanliness in a very broad and practical sense, the nurse will realize that the test of her ability to protect her maternity patients from infection is not what she is able to do in a hospital where there is every facility for clean work. It is not the ability to maintain asepsis in a tiled operating room that counts, where she is aided by sterilizers, basins, and solutions of various kinds and colors, a wealth of ingenious appliances and a corps of co-workers. It is the understanding and imagination which will enable her, perhaps single-handed, to carry the principles of such work into a patient’s home; to do clean work, from the standpoint of avoiding infection, in a mountain hut or a city tenement where everything is dirty.

The nurse will do well to begin to develop her powers of adaptability while she is still in training. She may greatly increase the value of her hospital experience by trying always to understand the purpose of the care which she is giving and trying at the same time to imagine how, in an average home, she would accomplish the results of this or that procedure which is made easy of execution in the hospital by special equipment. She should never lose sight of the fact that she is not being trained solely to conform to any one hospital routine or to become expert in only one method of nursing care. She is being prepared to go out and give nursing care to any young woman and her baby who need it, no matter where or how they are situated or by what methods they are treated.

If conditions are such that the doctor’s orders and the patient’s requirements seem impossible of fulfillment, then the nurse must attempt the impossible and attempt it with confidence of success.

It is clear that the nurse must cultivate adaptability and resourcefulness if she is to give good care to all her patients 12under all conditions. But even the most efficient and intelligent work will not be wholly satisfactory unless it is infused with a spirit of sympathy for the woman as an individual.

The thing that counts in this connection is what the nurse, herself, means to the woman who is facing a very important and mysterious event, who, after every known aid has been given, must still go through a great deal alone, both mentally and physically. It is not helpful to a woman in such a situation to be told that women have borne children since the dawn of Creation and that they all have had pain; that she will have to go through with it, as they have, and that the less fuss she makes about it the better. But it does help her to have the nurse say that she has been with so many women in labor that she knows they suffer intensely, and because she knows it so well she wants to do all that lies in her power to give even a little relief. The nurse may never know just how she has helped and reassured; how a pain was made a little easier to bear, not only by the hand slipped under an aching back, but also by the sympathy that the act conveyed. But she may be sure that she has helped.

In such a connection, the nurse must guard against the mistake of dividing her patients into well defined groups: those who are poor and those who are more favored. If she unfailingly looks for the human being beyond the patient she will find some of the most sensitive and appreciative of women among the simplest and poorest and they will be warmly responsive to a thoughtful, considerate attitude. And at the same time, the patient in comfortable circumstances who seems to be surrounded by all that one could desire, is often pathetically lonely and isolated. She, too, will be appreciative of encouragement and an attitude of concern for her comfort.

Suffering and anxiety make no class distinctions and have a very leveling effect, for prince and pauper, alike, need sympathy when afflicted.

From the standpoint of the nurse herself, there might be discouragement in this description of what is expected of her, and what are her opportunities in this work of caring for mothers and babies, if she did not go straight to the heart of 13the matter and see that all that is needed, after all, is good nursing. She must realize, of course, that good nursing necessitates training and a spirit of such eager service that she will do for her patient all that lies in her perhaps limited power, and then try to learn of still more that she may offer. And she may rest assured that the value of her work will be quite as dependent upon such a spirit as upon her training.

Obstetrical nursing may be defined, with accuracy, as the nursing care of an obstetrical patient, but its true significance is limited only by the nurse’s ability, resourcefulness, and vision. And the more spirituality which pervades this work the more effective will be the nurse’s skilled ministrations and the more satisfying will it all be to her.

This aspect of maternity nursing—what it means to the nurse herself—should be given full recognition, for although the demands which are made upon her are exacting, she will find more than compensating interest and gratification in her work.

It provides a channel of expression for some of her most elemental and deeply rooted impulses. The desire to create exists within most of us, and surely the nurse tastes of the joys of creation when she watches the beautiful baby body grow and develop under her care. And she has a consciousness of patriotic service, too, for while helping to secure the immediate safety and future health of the baby citizen she is helping to build a strong race.

But this work goes still further and offers even more than these.

The average nurse has a deep maternal instinct. She may not be conscious of it as such, but it is this instinct which prompts her to select nursing from the wide range of occupations and professions which are open to her. And it is entirely natural that she should derive great satisfaction from this vicarious motherhood—this giving of her knowledge and skill in service to the woman with a baby in her arms.

The opportunities for self-expression which are open to the nurse who gives this form of service make us wonder if she should not be included in the enviable group of those others 14whose life work is an expression of themselves—the poets and painters; the architects, musicians, and sculptors—those who create and build because of an urge within them. Surely, the spirit and the results of the work of the nurse who thus gives of herself may be ranged with the efforts of those others whose work is an expression of themselves.

16“The body is the crowning marvel in the world of miracles in which we live. Fearfully and wonderfully made, it claims our respect not only because God fashioned it, but because He fashioned it so well—because it is a thing of beauty, a perfection of mechanism.”

CHAPTER I. ANATOMY OF THE FEMALE PELVIS AND GENERATIVE ORGANS. Normal Female Pelvis. Pelvimetry. Female Organs of Reproduction. Internal Genitalia. Uterus. Fallopian Tubes. Ovaries. Vagina. Bladder. Rectum. External Genitalia. Mons Veneris. Labia Majora. Labia Minora. Vestibule. Vaginal Opening. Fossa Navicularis. Bartholin Glands. Perineum. Breasts.

CHAPTER II. PHYSIOLOGY. Puberty. Ovulation. Menstruation. Modifications of Menstruation. Menopause.

The present broad knowledge of the anatomy of the female pelvis has resulted in an enormous reduction in death and injury among obstetrical patients and their babies.

This knowledge of the pelvic anatomy, relating as it does, to both normal and malformed pelves, has made possible a system of taking measurements, termed pelvimetry, which gives the obstetrician a fair idea of the size and shape of his patient’s pelvis. Such information, coupled with observations upon the size of the child’s head, gives a foundation upon which to base some expectation of the ease or difficulty with which the approaching delivery is likely to be accomplished.

Since each patient’s pelvic measurements are considered from the standpoint of their comparison with normal dimensions, it is manifestly important that the obstetrical nurse have a clear idea of the structure of the normal female pelvis, and also of its commonest variations.

Viewed in its entirety, the pelvis is an irregularly constructed, two-storied, bony cavity, or canal, situated below and supporting the movable parts of the spinal column, and resting upon the femora or thigh bones. (Fig. 1, A. and B.).

Four bones enter into the construction of the pelvis: the two hip bones or ossa innominata, on the sides and in front with the sacrum and coccyx behind.

The innominate bones (ossa innominata), symmetrically placed on each side, are broad, flaring and scoop-shaped. Each bone consists of three main parts, which are separate bones in early life, but firmly welded together in adults: the ilium, ischium and pubis. The ilia are the broad, thin, plate-like sections above, 20their upper, anterior prominences, which may be felt as the hips, are the anterior superior spinous processes used in making pelvic measurements. The margins extending backward from these points are termed the iliac crests.

The ischii are below and it is upon their projections, known as the tuberosities, that the body rests when in the sitting position, and which also serve as landmarks in pelvimetry. The pubes form the front of the pelvic wall, the anterior rami uniting in the median line by means of heavy cartilage and forming the symphysis pubis.

The sacrum and coccyx behind are really the termination of the spinal column, the sacrum consisting, usually, of five rudimentary vertebrae which have fused into one bone. It sometimes consists of four bones, sometimes six, but more often of five. The sacrum completes the pelvic girdle behind by uniting on each side with the ossa innominata by means of strong cartilages, thus forming the sacro-iliac joints. The spinal column rests upon the upper surface of the sacrum. The coccyx, a little wedge-shaped, tail-like appendage, which ordinarily has but slight obstetrical importance, extends in a downward curve from the lower margin of the sacrum, to which it has a cartilaginous attachment, the sacro-coccygeal joint. This joint between the sacrum and coccyx is much more movable in the female than in the male pelvis.

We find, therefore, that although the pelvis constitutes a rigid, bony, ringlike structure, there are four joints: the symphysis pubis, the sacro-coccygeal, and the two sacro-iliac articulations. As the cartilages in these joints become somewhat softened and thickened during pregnancy, because of the increased blood supply, they all permit of a certain, though limited amount of motion at the time of labor. This provision is of considerable obstetrical importance, since the sacro-coccygeal joint allows the child’s head to push back the forward-protruding coccyx, as it passes down the birth canal, thus removing what otherwise might be a serious obstruction. And when, as is sometimes necessary, because of a constricted inlet, the pubic bone is cut through (the operation known as pubiotomy), the hingelike motion of the sacro-iliac joint permits of an appreciable spreading of the two hip bones and a consequent widening of the birth canal.

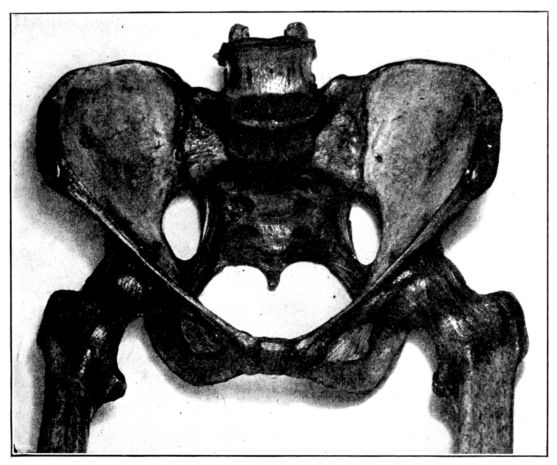

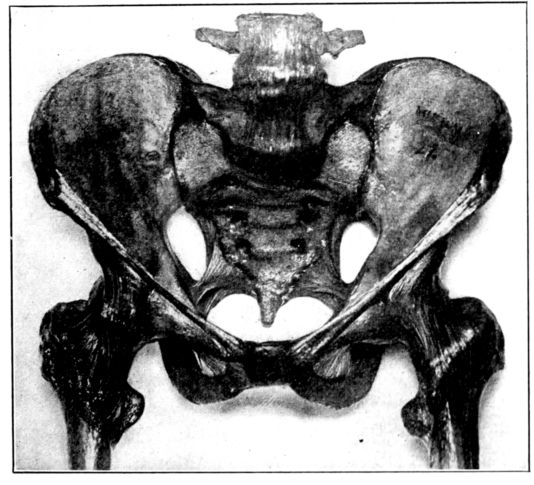

A. Normal female Pelvis.

B. Normal male Pelvis.

Fig. 1.—Normal Pelves. Note the broad, shallow, light construction of the female pelvis, A, as compared with the more massive male pelvis, B.

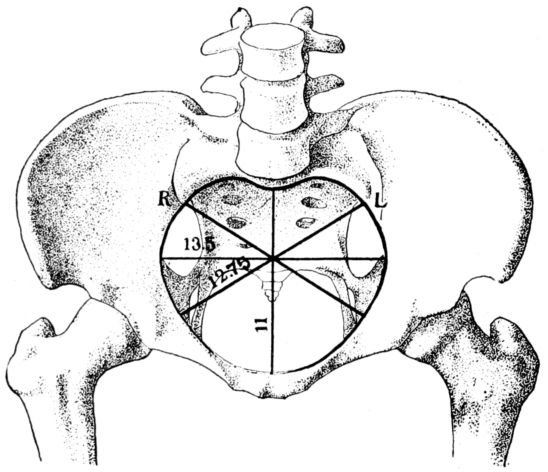

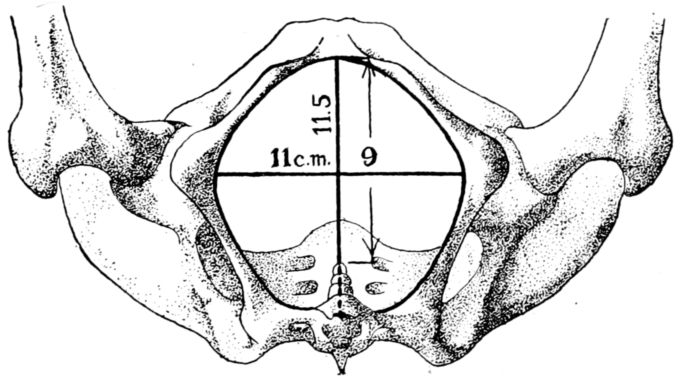

22The pelvic cavity as a whole is divided into the true and false pelves by a constriction of the entire structure known as the brim or inlet. The inlet is not round, its antero-posterior diameter being shortened by the sacro-vertebral joint which protrudes forward and gives the opening something of a blunt, heart-shaped outline. (Fig. 2.)

Fig. 2.—Diagram of the pelvic inlet, seen from above, with most important diameters.

As the pelvis occupies an oblique position in the body, the plane of this brim is not horizontal, but slopes up and back from the symphysis-pubis to the promontory of the sacrum. Being swung upon the heads of the femora, the relation of the pelvis to the entire body differs in the sitting and standing positions. When a woman stands upright, her pelvis is so markedly oblique in its position that she would tip backward but for strong tendons attached to the pelvis and running down the front of the thighs. Added strain upon these tendons during pregnancy may account for some of the apparently undue fatigue experienced by the expectant mother.

The shallow, expanded portion of the pelvis above the brim 23is the large, or false pelvis, its walls being formed by the sacrum behind, the fan-like flares of the ilia on each side, with the incompleteness of the bony wall in front made up by abdominal muscles.

The false pelvis ordinarily serves simply as a support for the abdominal viscera, which do not occupy the true pelvis unless forced down by some such pressure as that caused by tight, or poorly fitting corsets. The false pelvis is of little obstetrical importance, its function during pregnancy being to support the enlarged uterus, while at the time of labor it acts as a funnel to direct the child’s body into the true pelvis below.

Fig. 3.—Diagram of pelvic outlet, seen from below, with most important diameters.

The true pelvis, on the other hand, is of greatest possible obstetrical importance since the child must pass through its narrow passage during birth. It lies below and somewhat behind the inlet; is an irregularly shaped, bottomless basin, and contains the generative organs, rectum and bladder. Its bony walls are more complete than those of the false pelvis, and are formed by the sacrum, coccyx and innominate bones. Its lower margin constitutes the outlet, or inferior strait, and being longer in its antero-posterior dimension than in its transverse measurement, its long axis is at right angles to the long axis of the inlet. (Fig. 3.) A baby’s head, accordingly, must twist or rotate in making its descent through this bony canal, for the long diameter of the head must first conform to one of the long diameters of the inlet, either transverse or oblique, and then turn so that the length 24of the head is lying antero-posteriorly, in conformity to the long diameter of the outlet, through which it next passes.

The posterior wall of the pelvis, consisting of the sacrum and coccyx, forms a vertical curve and is about three times as deep as the anterior wall formed by the narrow symphysis pubis. The structure as a whole, therefore, curves upon itself, resembling a bent tube with its concavity directed forward. (Fig. 4.)

Fig. 4.—Diagram of sagittal section of the pelvis showing curve of the bony canal, with most important diameters.

Thus it becomes apparent that the structure of the pelvis requires the child’s head, not only to rotate in its passage through the birth canal, but also to describe an arc, since the part of the head which passes down the posterior wall travels farther in a given time than the part which passes under the pubis.

This twisting and curving of the birth canal must be appreciated in order to understand the mechanism of labor.

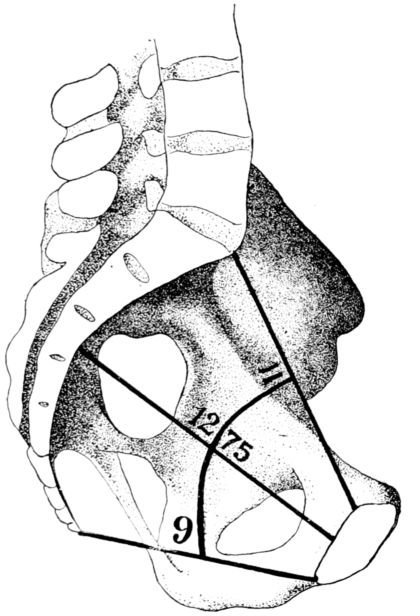

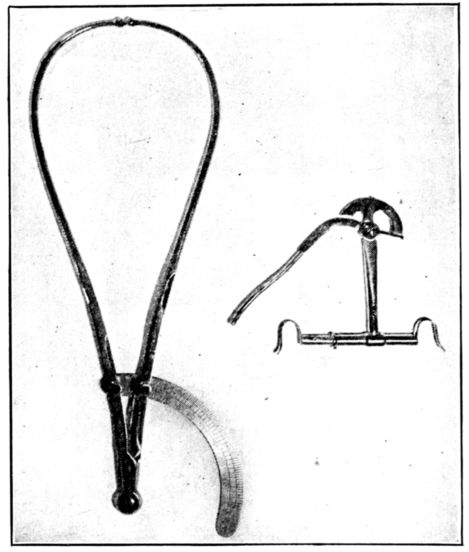

25In considering the question of pelvimetry, we find that there are both external and internal measurements to be taken, all for the purpose of estimating as accurately as possible the shortest diameter of the inlet through which the baby must pass. (Fig. 5.)

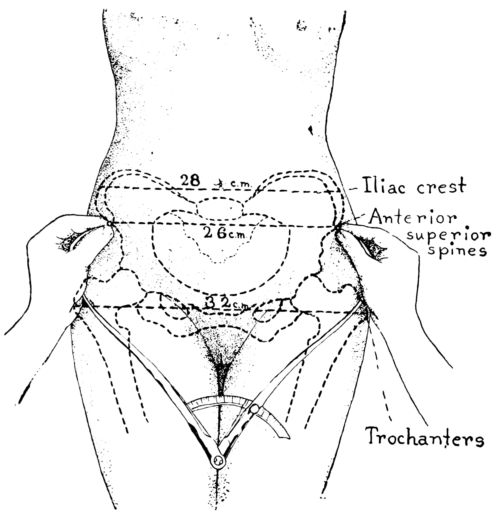

According to a common system of mensuration, the first external measurement is the inter-spinous, the distance between the anterior-superior spines, those bony points which are uppermost as the patient lies on her back. This distance is normally 26 centimetres. (Fig. 6.)

Fig. 5.—Two types of pelvimeters frequently used in taking measurements of the pelvic inlet and outlet.

The second measurement is the inter-crestal, or the distance between the iliac crests, and is normally 28 centimetres.

Baudelocque’s diameter is the third measurement and is taken with the patient lying on her side. (Fig. 7.) It is the distance from the top of the symphysis to a depression just below the last lumbar vertebra. This depression is easily located as it also marks the upper angle of a space just above the buttocks, which in normal pelves is quadrilateral. In malformed pelves this quadrangle may be so misshapen as to become almost a triangle with the apex directed either up or down. This dimension 26is sometimes called the external conjugate and ordinarily measures 21 centimetres.

The fourth measurement is the distance between the great trochanters, or heads of the femora, and normally is 32 centimetres.

All of these measurements, which after all are only approximate, relate to the top of the pelvis and are valuable in that they help in estimating the dimensions of the inlet, which are the important ones, and obviously cannot be measured on a live woman.

Fig. 6.—Diagram showing method of measuring distances between iliac crests and spines and the trochanters.

The inlet has four measurements of obstetrical importance: the antero-posterior, or true conjugate, which is the distance from the top of the symphysis pubis to the prominence of the sacrum, and is normally 11 centimetres; the transverse diameter, which is at right angles to the true conjugate and is the greatest width of the inlet, measuring from a point on one side of the brim to the corresponding point on the other, is normally 13.5 centimetres, and the two diagonal measurements, known respectively 27as the right and left oblique diameters, which are normally 12.75 centimetres.

Although it is very important to the expectant mother that all of these dimensions be of normal length, the length of the true conjugate, or conjugata vera, is of the gravest importance of all because it is the shortest diameter through which the child’s head must pass. If it is shorter than normal, the channel may be too constricted for the full-term baby’s head to pass through comfortably, thus making a spontaneous delivery extremely difficult, or even impossible.

Fig. 7.—Diagram showing method of measuring Baudelocque’s diameter.

The length of the all important, true conjugate is estimated by introducing the first two fingers of one hand into the vagina until the tip of the second finger touches the promontory of the sacrum. (Fig. 8.) The point at which the inner margin of the symphysis then rests upon the forefinger is measured, thus giving the length of the diagonal conjugate. This normally measures 12.5 centimetres or more, and is estimated as being 1.5 centimetres longer than the true conjugate.

28The most important measurement of the outlet is the intertuberous diameter, the distance between the tuberosities of the ischii. This is the shortest diameter through which the child must pass in the inferior strait, and normally measures something more than 8 centimetres, usually about 11 centimetres. (Fig. 9.)

It is possible, by studying such measurements as these, made upon an expectant mother, and comparing them with dimensions which have been accepted as normal, to form a reasonably accurate estimate of the size and shape of her pelvis.

Fig. 8.—Diagram showing method of estimating the true conjugate by measuring the length of the diagonal conjugate.

A delivery may be, and frequently is, accomplished through a pelvis which is not entirely normal in size or shape. But the obstetrician of to-day is closely observant of the patient whose pelvic measurements depart from the normal by more than the accepted margin of safety, and he plans for labor in accordance with the indications in each case.

Disproportion between the measurements of the mother’s pelvis and the size of the child’s head must be considered in this connection. A small pelvis may permit of the spontaneous delivery of a small child, but be too narrow for the passage of a 29full-sized baby, while a woman with a normal pelvis may have an extremely difficult labor because of an unusually large child.

The size and shape of the pelvis is found to vary among different races and in different individuals. And the size and contour of the inlet may be so altered by rickets, lack of proper exercise during early life, or by growths upon the pelvic bones, as to seriously interfere with normal labor.

Fig. 9.—Diagram showing method of measuring the inter-tuberous diameter.

The various kinds of malformed pelves may be loosely classified as generally contracted or small; flat; simple funnel; generally contracted funnel; and the rachitic pelves, both flat and generally contracted. There may be a contracted inlet, or a contracted outlet, or both may occur in the same pelvis.[1]

30Rachitic pelves are common among negroes and not altogether rare among white women.

The normal male pelvis is deep, narrow, rough and massive as compared with the female structure (see Fig. 1.), and the angle of the pubic arch, formed by the two pubic bones, is deeper and more acute in the male than in the female skeleton.

The normal female pelvis, on the other hand, is light, broad, shallow, smooth and large, giving evidence of the infinite wisdom and skill that entered into constructing it for the high purpose it was designed to serve.

The female organs of reproduction are divided into two groups, the internal and the external genitals. With them are usually considered certain other structures: the ureters, bladder, urethra, rectum and the perineum, because of their close proximity (Fig. 10.); and the breasts, because of their functional relation to the reproductive organs.

Internal Genitalia. The internal organs of generation are contained in the true pelvic cavity and comprise the uterus and vagina in the centre, an ovary and Fallopian tube on each side, together with their various ligaments, membranes, nerves and blood vessels and a certain amount of fat and connective tissue.

The uterus is the largest of these organs. In its nonpregnant 31state, it is a hollow, flattened, pear-shaped organ about three inches long, one and a quarter inches wide, at its broadest point, three-quarters of an inch thick and weighing about two ounces.

Fig. 10.—Anterior view of female generative tract, showing both external and internal organs. Drawn by Max Brodel. (Used by permission of A. J. Nystrom & Co., Chicago.)

Ordinarily it is a firm, hard mass, consisting of irregularly disposed, involuntary (unstriped or plain) muscle fibres and connective tissue, nerves and blood vessels. The arrangement 32of the uterine muscle fibres is unique, for they run up and down, around and crisscross, forming a veritable network. This strange arrangement of the fibres is favorable to the growth of the uterine musculature during pregnancy, and a factor in preventing hemorrhage after delivery.

The abundant blood supply to the uterus merits a word. It is derived from the uterine arteries, arising from the internal iliacs, and the ovarian artery from the aorta. The arteries from the two sides of the uterus are united by a branch where the neck and body of this organ meet, thus forming an encircling artery. A deep cervical tear during labor may break this vessel and a profuse hemorrhage occur as a result.

Fig. 11.—Diagrams of sections of virgin and multiparous uteri.

The uterus is covered, front and back, by a fold of the peritoneum, except the lower part of the anterior wall where the peritoneum is reflected up over the bladder. It is lined with a thick, velvety, highly vascular mucous membrane, the endometrium, the surface of which is covered by ciliated, columnar epithelium. Embedded in the endometrium are numerous mucous glands which dip down into the underlying, muscular wall.

The uterus as a whole is comprised of three parts: the fundus, that firm, rounded, head-like part above; the body, or middle portion, and the cervix, or neck, below. It is in the body and cervix that we find the long, narrow uterine cavity, divided by a constriction into two parts. The cavity of the body is little more than a vertical slit, being so flattened from before backward 33that the anterior and posterior surfaces are nearly if not quite in apposition. It is somewhat triangular in shape with an opening at each angle. (Fig. 11.) The lower of these openings leads into the cavity of the cervix through a constriction termed the internal os, while at the cornua, or two upper angles, are the openings into the Fallopian tubes.

The cavity of the cervix is spindle-shaped, being expanded between its two constricted openings, the internal os above and the external os below, which opens into the vagina. The external os in the virgin is a small round hole but has a ragged outline in women who have borne children.

This oblong, muscular body, the uterus, is suspended obliquely in the centre of the pelvic cavity by means of ligaments. In its normal position the entire organ is slightly curved forward, or ante-flexed, the fundus being directed upward and forward and the cervix pointing down and back. This position is affected by a distended bladder or rectum, and also by postural changes in the body as a whole. The cervix protrudes into the anterior wall of the vagina for about one-half inch and almost at right angles, since the vagina slopes down and forward to the outlet.

The upper part of the uterus is held in position by means of ligaments, the lower part being embedded in fat and connective tissue between the bladder and rectum. This more or less of a floating position makes possible the enormous increase in size and upward push or extension of the uterus during pregnancy. The pregnant uterus becomes soft and elastic as it grows. At term it is about a foot long, eight to ten inches wide, and reaches up into the epigastric region. This growth is due in part to the development of new muscle fibres and in part to a growth of the fibres already existing in the uterine wall.

After labor the uterus returns almost, but never entirely, to its former size, shape and general condition.

The Fallopian tubes are two tortuous, muscular tubes, four or five inches long, extending laterally in an upward curve, from the cornua of the uterus and within the folds of the upper margin of the broad ligament, by which they are covered. At their juncture with the uterus, the diameter of these tubes is so small as to admit of the introduction of only a fine bristle, but they 34gradually increase in size toward their termination in wide trumpet-shaped orifices, which open directly into the peritoneal cavity. Finger-like projections called fimbriæ, fringe the margins of these openings.

The mucous lining of the tubes is covered with ciliated epithelium and is continuous with that of the uterus. At the fimbriated extremities of the tubes this lining merges into the peritoneum, the serous lining of the abdominal cavity.

Just here it will be well to say a word about the peritoneum because of the possibility of its becoming infected during labor and the lying-in period, and the very grave consequences of such infection. It is a delicate, highly vascular, serous membrane which both lines the abdominal cavity and covers the abdominal and pelvic organs, which press into its outer surface and are covered much as one’s fingers would be covered by pushing them into the outer surface of a child’s toy balloon. The continuity of this membrane is broken only where it is entered by the Fallopian tubes.

The ovary, the sex gland of the female, is a small, tough ductless gland, about an inch long and three-quarters of an inch wide, or about the size and shape of an almond. It is greyish pink in color and presents a more or less irregular, dimpled surface. An ovary is suspended on either side of the uterus, in the posterior fold of the broad ligament, by which it is partly covered. Its outer end is usually attached to the longest of the fimbriated extremities of the Fallopian tube, the fimbria ovarica, which has the form of a shallow gutter, or groove. The inner end of the ovary is attached to the ovarian ligament, which in turn is attached to the uterus below and behind the tubal entrance.

The ovary consists of two parts, the central part or medulla, composed of connective tissue, nerves, blood and lymph vessels, and the cortex, in which are embedded the vesicular Graafian follicles containing the ova. At birth each ovary contains upwards of 50,000 of these ova, which are the germ cells concerned with reproduction and the process of menstruation.

These ovarian glands perform two vital functions, for in addition to their prime function of producing and maturing the germinal cell of the female, they provide an internal secretion 35which exercises an immeasurably important, though imperfectly understood, influence upon the general well-being of the entire organism.

Fig. 12.—Sagittal section of female generative tract. Drawn by Max Brodel. (Used by permission of A. J. Nystrom & Co., Chicago.)

The vagina is an elastic, muscular sheath or tube, about four inches long, lying behind the bladder and urethra and in front of the rectum. It leads interiorly up and backward from the vulva to the cervix, which it encases for about half an inch. The space between the outer surface of the cervix that extends into the vagina, and the surrounding vaginal walls, is called the fornix. 36For convenience of description, this is divided into four sections or fornices: the anterior, posterior and lateral fornices.

Between the posterior fornix and the rectum a fold of the peritoneum drops down and forms a blind pouch known as Douglas’ cul-de-sac. At this point the delicate peritoneum is separated from the vagina by only a thin, easily punctured, muscular wall. This is a fact of grave surgical significance, for unless instruments and nozzles introduced into the vagina are very gently and skillfully directed, they may easily pierce this thin partition. Septic material may thus gain entrance to the peritoneal cavity and peritonitis result.

The bore of the vaginal canal ordinarily permits of the introduction of one or two fingers. It is somewhat flattened from before backward, and on cross section resembles the letter H. During labor this canal becomes enormously dilated, being then four or five inches in diameter, and permits the passage of the full term child.

The vagina is lined with a thick, heavy, mucous membrane which normally lies in transverse folds or corrugations called rugæ. These folds are obliterated and the lining stretched into a smooth surface as the canal dilates during labor.

Attention must be drawn to the fact that the vagina, cervix, uterus and tubes form a continuous canal from the vulva to the easily infected peritoneum, a fact which makes absolute surgical cleanliness in obstetrics virtually a matter of life or death to the patient.

This muscular tube is lined throughout its entire length with mucous membrane, which, though continuous, changes somewhat in character along its course. The epithelial cells of the lining of the tubes and body of the uterus have hair-like projections, cilia, which maintain a constant waving motion from above downward. The effect of this sweeping current is to carry down toward the outlet any object or secretion which may be upon the surface of the lining of the tubes or uterine cavity. The unfertilized ovum is thus swept down to meet the germ cell of the male and become fertilized.

Along this variously constructed canal, at different periods in the life of the individual, pass the matured ovum, the menstrual 37flow, the uterine secretions, the fetus, the placenta and lochia, (the discharge which occurs during the puerperium).

Although the bladder and rectum are not organs of reproduction, they are contained in the pelvic cavity and lie in such close proximity to the internal genitalia that at least a passing word must be devoted to their description.

The bladder is a sac of connective tissue which serves as a reservoir for the urine and is situated behind the symphysis pubis and in front of the uterus and vagina. Urine is conducted into the bladder by the ureters, two slender tubes running down on each side from the basin of the kidney across the pelvic brim to the upper part of the bladder, which they enter somewhat obliquely, at about the level of the cervix. It is thought that pressure of the enlarged pregnant uterus upon the ureters at this point may be one factor in the causation of pyelitis, a frequent complication of pregnancy. The bladder empties itself through the urethra, a short tube which terminates in the meatus urinarius, a tiny opening in the vulva.

The rectum, the lowest segment of the intestinal tract, is situated in the pelvic cavity behind and to the left of the uterus and vagina. It extends downward from the sigmoid flexure of the colon to its termination in the anal opening. The anus is a deeply pigmented, puckered opening situated an inch and a half or two inches behind the vagina. It is guarded by two bands of strong circular muscles, the internal and external sphincter ani. The skin covering the surface of the body extends upward into the anus where it becomes highly vascular and merges into the mucous lining of the rectum. Pressure exerted during pregnancy by the enlarged uterus is felt in both the rectum and bladder, frequently causing a good deal of discomfort and almost painful desire to evacuate their contents.

The blood vessels in the anal lining just within the external sphincter sometimes become engorged and inflamed, even bleeding during pregnancy, as a result of the pressure exerted by the greatly enlarged uterus. The distended blood vessels, which in this condition are called hemorrhoids, not infrequently protrude from the anus and become very painful.

38After having considered the structure and relative positions of the pelvic organs one is able to picture more clearly the arrangement and disposition of the uterine ligaments, all of which are formed by folds of the peritoneum. They are twelve in number, five pairs and two single ligaments, namely: two broad, two round, two utero-sacral, two utero-vesical, two ovarian, one anterior and one posterior ligament.

The broad ligaments are in reality one continuous structure formed by a fold of the peritoneum, which drops down over the uterus, investing the fundus, body, part of the cervix, and part of the posterior wall of the vagina. It unites on each side of the uterus to form a broad, flat membrane which extends laterally to the pelvic wall, dividing the pelvic basin into an anterior and posterior compartment, containing respectively the bladder and rectum. Between the folds of the broad ligament are situated the ovaries and ovarian ligaments, the Fallopian tubes, the round ligaments and a certain amount of muscle and connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatics and nerves.

The round ligaments, one on each side, are narrow, flat bands of connective tissue derived from the peritoneum and muscle prolonged from the uterus, and containing blood and lymph vessels and nerves. They pass upward and forward from their uterine origin just below and in front of the tubal entrance, finally merging in the mons veneris and labia majora.

The utero-sacral ligaments, of which there is one on each side, arise in the uterus and, extending backward, serve to connect the cervix and vagina with the sacrum.

The utero-vesical ligaments, one on each side, extend forward and connect the uterus and bladder.

The ovarian ligaments, as previously described, are attached to the uterine wall and to the inner end of the ovary, one on each side.

The anterior ligament is a portion of the peritoneum which dips down between the bladder and uterus, forming a pouch. It is known also as the uterine-vesical pouch, or the vesico-uterine excavation.

The posterior ligament is formed in much the same manner by a portion of the peritoneum dipping down behind the uterus, 39in front of the rectum, and forming the recto-vaginal pouch. This is the Douglas’ cul-de-sac previously referred to.

External Genitalia.—The vulva, or external genitalia, are situated in the pudendal crease which lies between the thighs at their junction with the torso, and extends posteriorly from the pubis to a point well up on the sacrum. (Fig. 13.)

The mons veneris is a firm cushion of fat and connective tissue, just over the symphysis pubis. It is covered with skin which contains many sebaceous glands and after puberty is abundantly covered with hair.

Fig. 13.—Diagram of external female genitalia. (Redrawn from Dickinson.)

The labia majora are heavy ridges of fat and connective tissue, prolonged from the mons veneris and extended down and back almost to the rectum, on each side, forming the lateral boundaries of the groove. They are lined with mucous membrane and covered with skin and hair, the latter growing thinner toward the perineum until it finally disappears.

The labia minora are two small cutaneous folds lying between the labia majora on each side of the vagina. Like the larger 40folds, they taper toward the back and practically disappear in the vaginal wall. Their attenuated posterior ends are joined together behind the vagina by means of a thin, flat fold called the fourchette. The labia minora divide for a short distance before joining at an angle in front, thus forming a double ridge anteriorly. In the depression between these ridges is the clitoris, a small, sensitive projection composed of erectile tissue, nerves and blood vessels and covered with mucous membrane. The meatus urinarius is just below the clitoris and between two small folds of the mucous membrane.

The vestibule is the triangular space between the labia minora, and into it open the meatus urinarius, the vagina and the more important vulvo-vaginal glands.