Title: A Vagabond's Odyssey

Author: A. Safroni-Middleton

Release date: April 18, 2019 [eBook #59303]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Whitehead, Linda Cantoni, Barry

Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

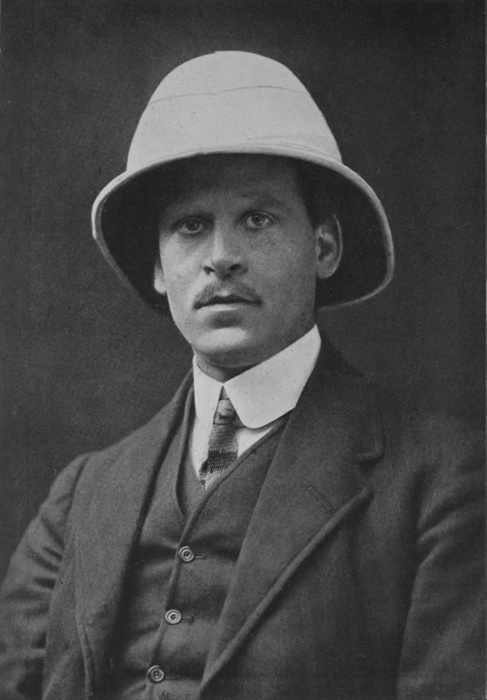

Portrait of the Author

Looking reflectively over this second instalment of my autobiography, I perceive that I am such a genuine vagabond that I have even travelled along in my reminiscences without caring for the material niceties of recognised literary method; so I have gone back over the whole track and tried earnestly to polish my efforts.

It seems quite unnecessary for vagabonds to wear (metaphorically speaking) old trousers with fringed ends to the legs, penniless pockets, dusty boots, an unshaven face and dirty collar, or to give vent to the devil-may-care utterances and all the ungrammatical “politeness” of the phraseology of the grog shanty and bush hotels, when they attempt to live over again on paper the tale of their wandering life. I cannot reform the world into a population of convivial beachcombers, nor would I if I could, out of consideration for future vagabonds, who naturally want the outer spaces of the world for their special province. Neither can I make you believe I could have done better in a literary sense if I had taken more trouble with my book. But I can to some extent reform myself, and at least strive to compete with the literary aristocrats on the slopes of their own cultivated ground. I am sure they will make good company if I succeed, and they will have been my best friends. Yes, I half believe in jumping out of bed on a cold night to hold a candle to the devil! I know that sometimes while you stand shivering you discover that he’s really not such a bad fellow, and the candlelight is likely to give you a glimpse of some faint resemblance in his wrinkled face, some far-off expression of that beautiful old life that he lived ere he sinned, became respectable and fell—banished from heaven.

Life is a terrible contradiction; we are dead because we are born alive. Our very creed is based on the sad fact that the cemetery tablets record the dates of the true beginning of life everlasting. The thundering city is a necropolis wherein multitudes of wandering corpses breathe, with inert souls and thoughts that are like night bats flitting through the sepulchres of our death, with dead eyes and dead mouths that open to cough and even sometimes laugh! My book of reminiscences is (to me at least) like those silent, moss-grey tablets of immortality; but even more wonderful and true (as far as I know), for, while I am dead, I can see my long ago. I can lift the stone slab from the grave in the silent night and gaze on the dead boy’s face, and in a way make the dead eyes laugh and the voiceless mouth mutter and sing in a hollow voice old, far-away songs of love, romance and its comrade, grief. Yes, you and I can see such things. Oh, how ineffably sad to some of us!

You may wonder what all this has to do with the preface to a book of reminiscences. It has a lot to do with the matter, because I am a born vagabond, and the world is incorrigibly respectable!

There are about one hundred pages missing from this book—pages that should have told of the inevitable details of stern existence: those things that all men who are vagabonds experience, such as the stomach-rumbles of hunger, monstrous hopes and misgivings, hospitals and illnesses, and cold nights sleeping out under the coco-palms and gum-trees when the wind suddenly shifts to a shivering quarter. Evil thoughts, heartaches, the tenderest wishes, passionate drums, longings, and memories in the night of a woman’s eyes, the fall before great temptation, atheistical thoughts, curses and religious remorses you will look for in vain. For, after all, I am not brave enough to tell the truth! I might have done so if I had had the friendly, courageous publisher who would not cut them out of the original manuscript. But where is the publisher who would let me hide behind his influential bulk as he risked all and published the truth? Yes, those things which would make the reader recognise the truth by his own responsive thrills.

Well, I will risk my reputation on the opinions of those critics who will be able to read the hundred pages I have left out. For real scallawags do not always leave the worst out only. Moreover, I may be lucky enough to find sympathy, for even critics are sometimes at heart genuine vagabonds, and they may realise that I have turned into the light of other days, the stars, the blue tropical skies, moonlit seas by coral reefs and palm-clad isles, and into the heart of intense dreams, to paint faithfully all that I tell.

Before my North American experiences, which I have recorded in the opening chapters of this book, I had shipped before the mast of a sailing ship, the S——p, at Sydney, N.S.W., intending to go with her round the Horn, and so home to England. But, being unable to tolerate the bullying chief mate and the offal-flavoured fo’c’sle food, I left the boat at ’Frisco and again shipped on an American tramp that was chartered for trading purposes to go cruising in the South Seas, where once more I had many ups and downs, and settled for a few months in the Fiji group and elsewhere. My reminiscences, and many of the incidents of that time, I have told in the second part of the present volume, which opens with “The Charity Organization of the South Seas.”

My South Sea Island legends and fairy tales have never been told elsewhere. I have written them as nearly as possible in the manner in which they were told me by the Samoan children and natives who were my friends. The mythology of the South Seas is unfortunately becoming almost completely forgotten by the natives, who now live under such different conditions, and seem only interested in the creeds, legends and mythology of the Western world.

These experiences of mine are written from memory, and I have as nearly as possible kept them in the order that I lived them; and if they seem far-flung for one as young as I was, let me assure you that hundreds of English boys have had my experiences and could tell this tale.

I am from a family of rovers. My uncles were travellers and explorers. My brothers out of the spirit of adventure all went to sea, and achieved success on sea and land through perseverance. My grandfather in his boyhood went to sea. (I believe he was born at sea. His mother was a lady of the Italian Court, noted for her beauty and an accomplished musician.) He was a direct descendant of Charles, the second Earl of Middleton, whose estates were eventually confiscated by creditors—an evil destiny that has survived right down to the present, it having cropped up in the author’s own affairs.

I hope to follow this volume with another one, wherein I shall tell of my life when I settled for a while among civilised peoples and became respectable, and my serious troubles commenced.

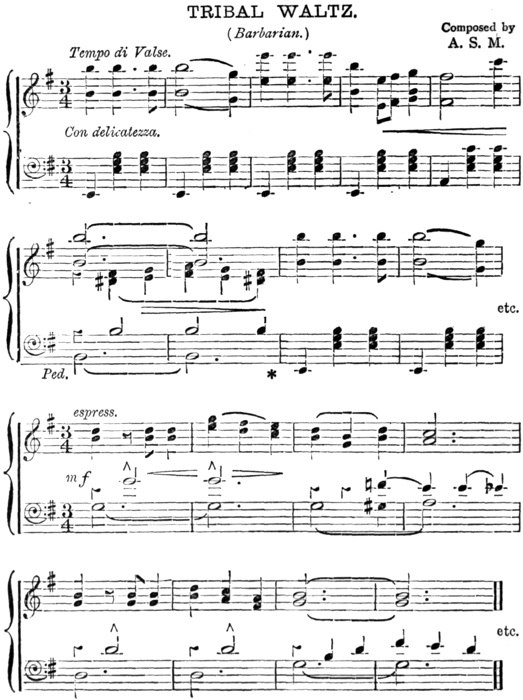

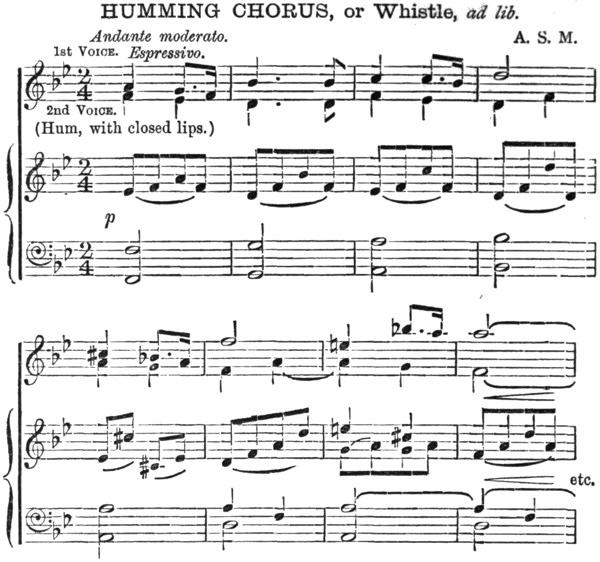

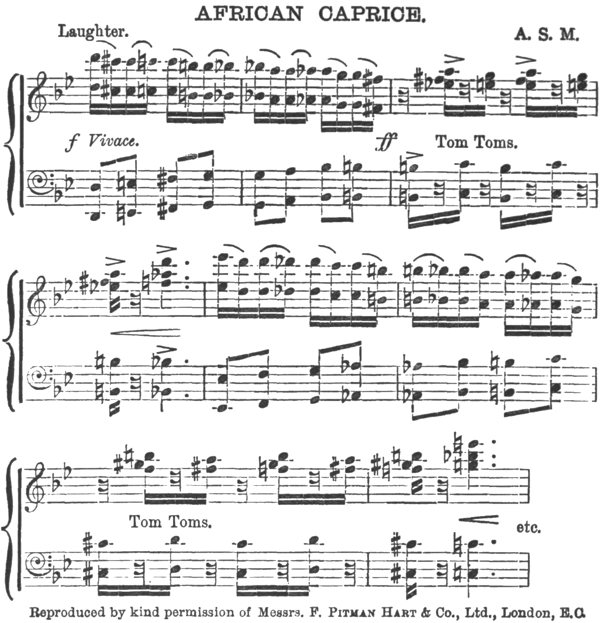

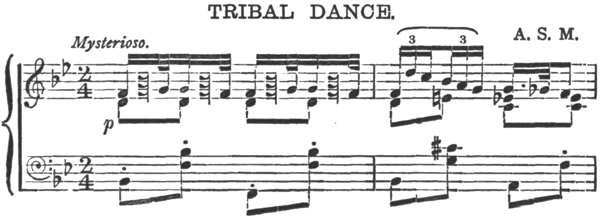

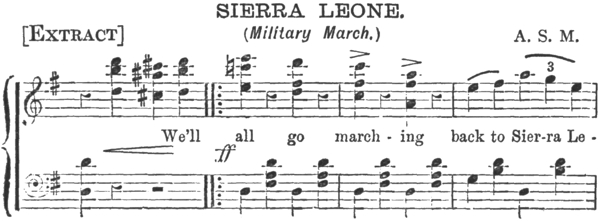

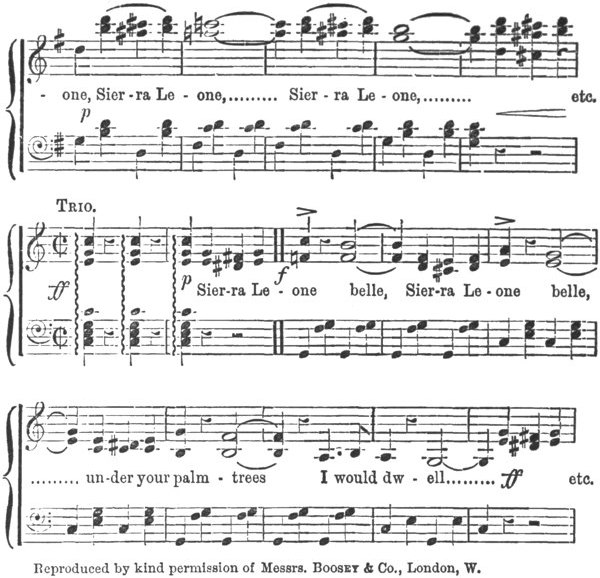

I have to thank Messrs Boosey & Company, of London, for permission to use certain extracts from my military band Entr’actes, Marches, etc., which they have published.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | IN BOSTON | 17 |

| II. | UNITED STATES MILITARY MUSIC | 23 |

| II. | I TRAVEL AND SELL BUG POWDER | 27 |

| IV. | MY BROTHER’S RETURN | 35 |

| V. | HOME | 45 |

| VI. | CHANGES IN SAMOA | 55 |

| VII. | ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON | 69 |

| VIII. | ROBERT LOUIS STEVENSON AND HIS FRIENDS | 83 |

| IX. | HONOLULU | 96 |

| X. | AN INLAND MARCH | 110 |

| XI. | AT SEA | 130 |

| XII. | CIRCULAR QUAY | 140 |

| XIII. | MATENE-TE-NGA | 155 |

| XIV. | MEMORIES AND REFLECTION | 173 |

| XV. | THE LECTURER | 182 |

| XVI. | HOMESICK | 191 |

| XVII. | A NEGRO VIOLINIST | 213 |

| XVIII. | MY MANY PROFESSIONS | 220 |

| XIX. | YOKOHAMA | 230 |

| XX. | BOMBAY | 241 |

| XXI. | AT SEA IN DREAMS | 249 |

| XXII. | I ARRIVE AT THE ORGANIZATION | 261 |

| XXIII. | FATHER ANSTER | 276 |

| XXIV. | BACK AT THE CHARITY ORGANIZATION | 289 |

| XXV. | AT NUKA HIVA | 305 |

| XXVI. | A DECK-HAND ON BOARD THE “ELDORADO” | 311 |

| XXVII. | MY ENGLAND | 325 |

| Portrait of the Author | Frontispiece |

| Hongis Track, Rotorua, N.Z. | 58 |

| Whangarei Falls, North Auckland, N.Z. | 70 |

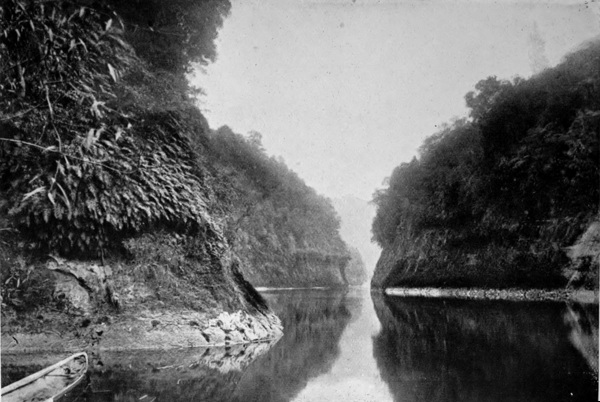

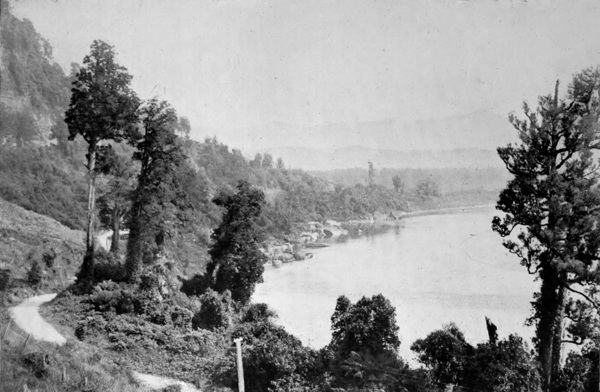

| Wanganui River, N.Z. | 92 |

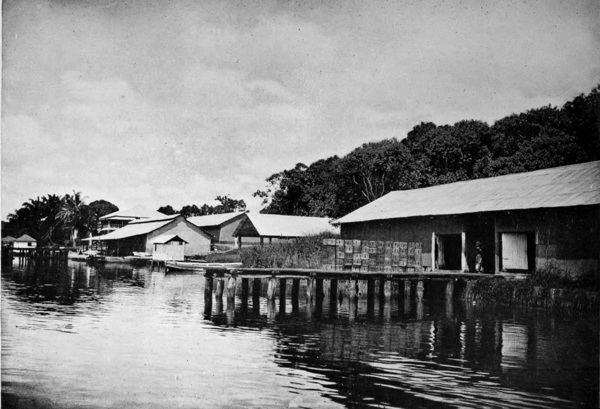

| A River Wharf, West Africa | 118 |

| Kawieri, N.Z. | 142 |

| Whakarewarewa, Rotorua, N.Z. | 148 |

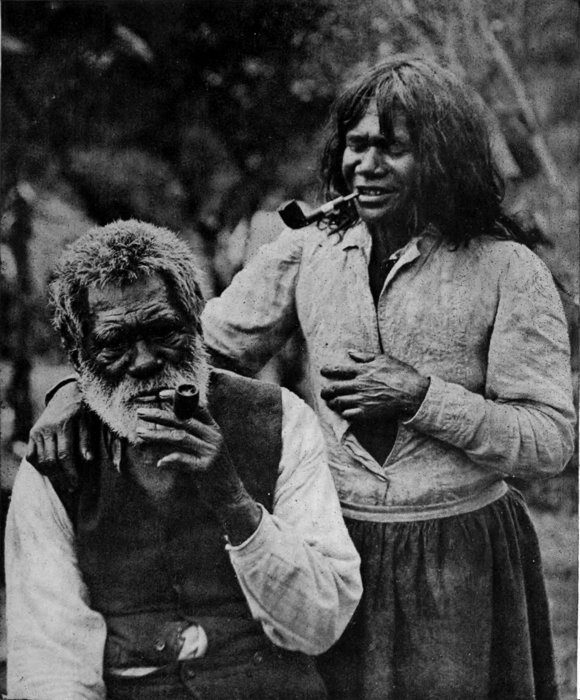

| Old Maori, said to be 105 years old | 152 |

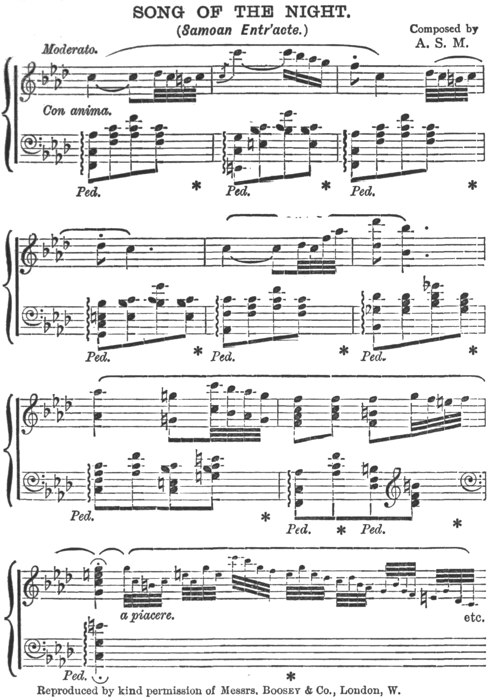

| Half-Caste Maori Girls | 160 |

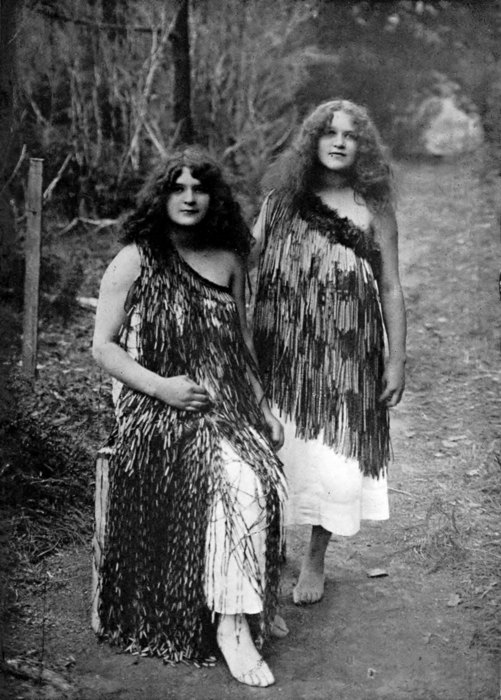

| Lake Rotorua and Mokoia Island, N.Z. | 176 |

| Settler’s Home, Gold Coast | 194 |

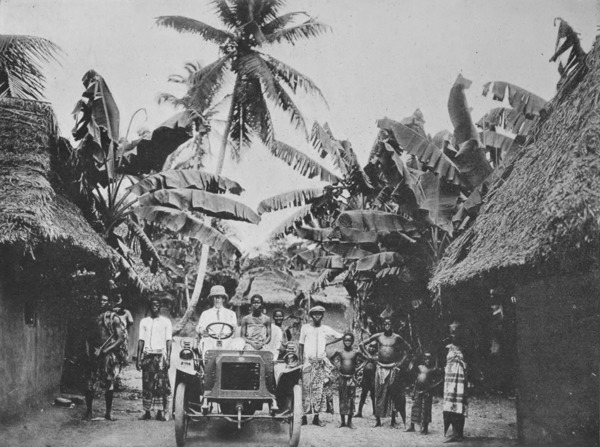

| The First Motor-Car in a Gold Coast Village | 204 |

| River Scene, West Africa | 216 |

| Botanical Gardens, Ballarat | 238 |

| River Scene in New Zealand | 246 |

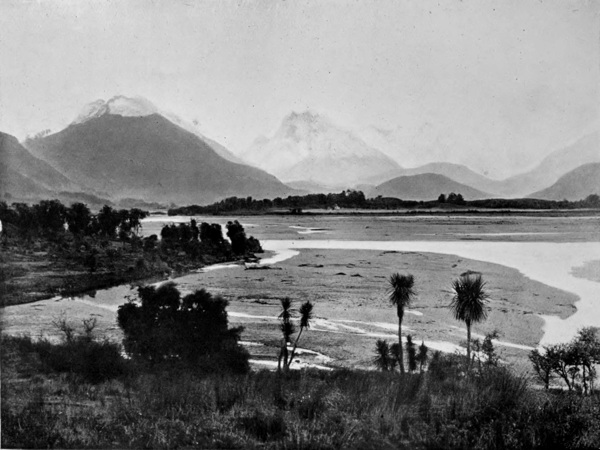

| Dart Valley, Lake Wakatipu, N.Z. | 272 |

The New Zealand photographs are by Mr F. G. Radclife, Whangarei, New Zealand.

In Boston—Song-composing—Looking for a Publisher—How I secured him—I visit Providence—I play in the Military Band—Hard up

IN those old days of my youth an atmosphere of romance gathered from old novels and dreams still sparkled in my head. I am going to tell of the adventures that followed directly on my boyhood, when before the mast I had crossed the seas with eyes athirst for romance, looking for the wonderful, the beautiful in distant lands, in men and in women, and for that opportunity to perform those mighty, world-thrilling deeds that, alas, I have not even yet performed!

After much wandering in search of wealth and fame, following desperate trouble owing to schemes that failed in Australia and the South Sea Islands, I at length caught typhoid fever in San Francisco. With many misgivings I recovered. At last I found myself sitting in a top attic in North America. It was a humble little room, the atmosphere and surroundings the very thing to feed the fire of my aspiring mind, to force one to do better. Its one window-pane was broken; the furniture consisted of an old table, a box chair, a candlestick and my extemporised bed on the floor! I was in Boston, “the Hub of the Universe”! My sea-chest and best suit were in pawn in San Francisco. My money had almost all gone, and my latest grand passion had faded. I had been practising the violin furiously day and night, for I hoped to become the world’s greatest violinist. Yet at heart I still felt triumphant. The world seemed especially mine! One thing only existence lacked—a kindred spirit to stand shoulder to shoulder by my side on some quest for glorious violence, adventurous thrills, voyaging across the uncharted seas of imagination. O too brief, splendid madness of youth!

Far below, outside my window, over the city’s stone-slabbed streets, rattled vehicles, and the hurried, endless battalions of Yankee citizens passed by, seeking fortune or the grave. Gold seemed the incentive to all thrills; human passion, hope and ambition seemed congealed into a mechanical state of steam, electric locomotion, and all that the almighty silver dollars would clink against. I also seemed to have frozen and become a part of the machine which is called civilisation. The songs of sails aloft, the noise of forest winds and soundings across deep waters, had faded from my dreams into a wail of selfishness. Imagination is the soul of the Universe, and grief is its Bible; but, alas, I felt a gross craving for food.

So my ambition to outrival Paganini on the violin had subsided from its state of enthusiastic fire and had left in my heart a dull callousness. One intense wish survived: to get a sound pair of boots and a new suit! Winter snows were only just melting, and much privation had considerably thinned me. I had done many things which I feel remain best untold. Necessity had inspired me with many original and desperate schemes, the latest of which was a determination to compose songs. Music hall hits come, have their day, are whistled and sung by the élite and by the street-arab, and suddenly I thought, why should not I supply the public with those rotten melodies? I would do it on original lines and give the American public something new. Did they not hail as brand-new old melodies that Wellington’s soldiers sung at Waterloo and antiquated strains brought over by the passengers of the Mayflower with one bar reversed and the title altered.

I would jump from my bed at night and, throwing off my “blanket,” which consisted of half-a-dozen old overcoats which my landlady had lent me, write down inspired strains and next day put them to suitable words, words with those sentimental and lascivious suggestions in them that suit the public taste—for the artist in me had sorrowed and become temporarily gross. I sought money more than the applause of musical critics. Boston publishers became familiar with my handwriting. I had about fifty rejected manuscripts with specially printed forms, notices that offered me “their appreciation of my favours, and the editor’s sincere compliments, and by the same post with many regrets they were returning the MSS.” At length I thought my name was getting too well known: I was obliged to seek a nom de plume. With characteristic family cautiousness I hit on a name that was already famous in New York musical circles. My youthful innocence had almost passed, and I vaguely felt that to compete with the world I must deliberately stain myself with its contagion. Often my heart bristled with schemes as multitudinous as quills on a hedgehog’s hide.

I had composed an attractive melody and had placed suitable words to it, but, notwithstanding my famous nom de plume, “Muller,” I had had my manuscripts returned, torn in the post, the editor’s marks indelibly damaging it, and too often a dark stain across the first page that looked suspiciously like editorial tobacco juice.

Things began to look serious. I became, if possible, even thinner. My landlady’s politeness became gross; she thumped the door for rent. I was starving and only had a cake of common yellow soap. With the superhuman energy and pluck of aspiring youth I tried again, imitated the latest hit and sent the manuscript to “D—— & Co.,” of Boston, a small publishing firm in a side street off 6th Avenue. I signed it with my nom de plume; the initials differed by one letter from those of the original owner—I thought this necessary to save legal trouble.

I waited three days. The post brought me no letter, so I wrote to the publisher and said:

“Dear Sirs,—I am an Englishman on tour, and a member of the Carl Rosa Opera Company’s orchestra. I may have to leave Boston at any moment, so, much against my wish, I must worry you for speedy consideration of my manuscript song, Dreams of Eldorado, which I can get publicly performed in London town when I arrive back.”

Two days later, to my great delight, I received a letter asking me to call on D—— & Co. re my manuscript. The very thought of my song reaching engraving and print thrilled me; that I should be published in America at another man’s expense seemed impossible! A Vanderbilt-like feeling pervaded my being. I pawned my violin, paid my landlady a week’s rent and gave the little blue-eyed daughter twenty-five cents to buy sweets with. I could have sung with joy. Next morning at ten-thirty I was to be at the publisher’s office. By night the reaction set in. I became suspicious. Suppose it was all a ruse! For had I not borrowed a famous name? A thousand thoughts haunted me; my musical ability seemed nil. I had no talent. I hummed my melodies over; they seemed ridiculously tuneless. There was no doubt about it: the Boston publishers had seen through my scheme, had held a solemn council, and most probably would be waiting in that office to pounce upon me and charge me with my duplicity, and then God knows what they might do. On the floor all night the old overcoats moved and moved as I restlessly turned in my bed. I was numbed with awful suspicions and possible contingencies. I rose haggard and wretched, and against all my usual instincts sought a saloon and drank twenty-five cents’ worth of rum. With renewed courage I prepared to risk all. At ten o’clock I walked past a brass-plated door with D—— & Co. on it. Three times I passed it and then, walking crabwise, I went in. A little man with a skull-cap on got up and welcomed me. I hurriedly glanced round; the ambushed publishers of my imagination faded as the girl typewriter yawned and clicked away. My erstwhile gloom blossomed to monstrous hopes. Negotiations commenced. “What did I usually ask for my work?” he demanded. I blushed and hastily wiped my nose. “Will fifty dollars do?” I answered. I eventually got five dollars for the song as a preliminary payment on royalties to come. Such royalties! One cent on each copy sold after the first ten thousand advertisement copies had been given away and the second one thousand had repaid the actual expenses of the publication and engraving. Afterwards, too, I found out that to engrave a song of four plates cost the publisher five dollars. I trembled as I clutched the green five-dollar bill. “Will he alter his mind?” was my chief thought. “Does he think I am the great Muller?” The publisher broke in on my thoughts. “Place your name there,” he said, and I signed the imposing agreement, four times the length of my manuscript song.

Readjusting his skull-cap and wiping his spectacles, he began to examine my signature. The weather was cold, but I started to perspire. Was he comparing my signature with Muller’s? It was an awful thought, and with a sickly farewell I bolted!

Hurrying down the main street, I longed to get out of sight with the dollars, but I heard a shout behind me; my assumed name was loudly called: I turned; my heart sank. I nearly fainted: the publisher was running after me. I clutched my money, determined to resist. The new greatness thrust upon me by the sale of my song still remained with me. I could not humiliate my pride and run, though I longed to do so. With his little skull-cap askew, he stood puffing in front of me! I gave one glance to warn him not to get too near my person, and heard him saying: “Oh, excuse me, Mr Muller, I suppose you will be in Boston long enough to correct the proof?”

In a dream I reached my room, packed up my brush and comb, got my violin out of pawn and left Boston for Providence, where my brother lived, who had left England years before. To my great regret I found, when I arrived, that he was away in California. No one seemed to know when he would return. I could not force my way into his bachelor rooms, and so I was once more on the rocks.

I became acquainted with a young Swede who was musical and played the clarionet. Together we fixed up a small orchestra, went out to play at dances and so just managed to exist. We hired a large room in a hall near the Hoyle Buildings in Westminster Street; made our own furniture out of meat tubs and our beds of old overcoats. My violin, with coats doubled on it, made an excellent pillow. With our heads side by side on it we slept as soundly as though we were in the Australian bush. I spent hours each day, and sometimes worked far into the night, practising my violin and reading the lives of great musicians and writers.

My brother, a crack violinist and a well-known journalist in the States, did not return for four or five months, and in the meantime our orchestra failed. My friend and I lived for a time on the free lunches of the grog saloons. North American saloon owners do not allow their customers to starve while they supply them with alcoholic poison, which is, however, fifty per cent. better than English spirit. For Americans are both humane and practical. They know that dead men do not buy rum, so the bars at luncheon hours steam with hot Frankforts, plates of cold meat, cheese and biscuits, provided without any charge to their customers. The honesty of Providence is illustrated by one fact alone—if you buy ten cents’ worth of whisky they hand you a glass and the bottle, that you may help yourself. In London, Australia and the South Seas the grog-keeper would be ruined in a week if he ran his business on those lines! You seldom see a woman in a grog saloon, and never drunk in the streets.

Eventually I secured several jobs at concert halls. The pay was small, but, though other work was to be had, my temperament strongly objected to anything that needed muscular power. To tell the truth, I was ambitious. I longed to raise myself out of the ordinary ruck of things. However, when my Swedish friend got a job out at Pawtucket, digging post-holes, the high wages tempted me and I too started work there. Together we toiled for three weeks. Then once more I started composing, and had several pieces of dance music accepted in my own name. I arranged them as pianoforte solos, and one or two for the violin and piano.

When the weather got warm I sometimes went out to Fort Hill, on the Seekonk river. The prairie-land of Rhode Island survives in variegated patches of miles of beautiful scenery, with rushing rivers, and landscapes dotted by wooden homesteads that remind one of New Zealand and the Australian bush-land.

United States Military Music—The Roger Williams Park—Indians—Rhode Island Scenery and Amusements—Yankees—Experiences—A Miner from California

IN Providence I made friends with a military band conductor. He was a jolly customer, hard up but good-natured and humorous, a real American bandmaster of the old convivial school, kind at heart and fond of good whisky. His greatest virtue was a commonplace one: he would always pay you back anything he borrowed, but unfortunately he was hard up and could not do so. He had every excuse for this, for, as elsewhere, bandsmen, indeed musicians in general, were supposed to be able to live on melody and royalties that might arrive in some remote future. I worked for him, borrowed my comrade’s clarionet and secured a position in the military band. It played in Roger Williams Park, performing on the usual holidays and on sunshiny evenings.

American conductors believe in vigour and fire when they perform, and sacrifice artistic pianissimo to force and go: on the march the bands lift you off your feet through the lilt of the music. The characteristic go-ahead of the Yankees is finely illustrated by the music they perform, and the military bands swing the population along as they march down the streets: men, women and children instinctively fall into line. A Pied-Piper-of-Hamelin fever seizes hold of the citizens; the whole population is suddenly on the march as the band goes by. I played in the band on the Fourth of July, a day celebrated by fireworks and gun-firing. Americans go mad on that date, wear masks and do other hideous things; it’s a kind of Guy Fawkes celebration.

The Roger Williams Park is partly wild and partly cultivated, and artistically laid out with gardens and miniature landscapes that in summer-time are a paradise of flowers. Various kinds of tropical-looking trees abound, in scattered clumps that are haunted at sunset with bright, roving eyes: for springing from bough to bough jump swarms of big, wild, grey squirrels; their brush tails, a foot long, stick up as they jump. The children are their boon companions, and come miles with lumps of cake and bread to feed their tiny, soft playmates; for they are as tame as white mice, spring down from bough to bough and sneak a peanut off your hand, turn, brush your face with their tails and are gone! In a second they are sitting on a skyward twig nibbling away at your gift, safe against the blue sky. I found a nest of them at Pawtucket Falls, a wild, beautiful spot near Rhodes. As I was looking at the fluffy youngsters the mother arrived and, to my astonishment, chased me away.

At Pawtucket Falls, too, I met a group of travelling Indians, menagerie people I think, en route for somewhere. Fenimore Cooper and other Indian tales still interested me, so I talked to them and spoke to “Bull Face,” a grave-looking chief, tawny and wrinkled with years, and clothed in a heavy brown blanket which swarmed with fleas. He spoke English as well as I did; but the South Sea Island breeds are far removed from the Indian tribes, both by blood and habit. I never sought his tribe again. I also saw Indians camping at Ochee Springs; real Indians they were, with squaws attending to their wants as they blinked their eyes and gazed scornfully on the onlookers. Smoking their calamets, dressed in tribal fashion, they inspired me with curiosity. I cannot say that the women were as handsome as I expected, for they had stolid, broad, reddish-brown faces and expectorated frequently as they sucked clay pipes. A pretty little papoose tugged at its mother’s breast, and did not look unlike a South Sea Island baby, excepting that its forehead was high and receding, and it had an impertinent European look. The women carry their suckling babes in a basket on their back: when the babe finishes pulling at the breast it crawls into the basket behind and goes to sleep until the next meal. I saw the papooses of another tribe too; the children looked like little wrinkled old men, and you might have thought that they were small authors sitting on their bundles of unaccepted manuscript, so worried did they look.

Providence is a spacious city; English towns are in the shade compared to it, and seem overcrowded and gloomy. The streets are wide; terraced store buildings on each side tower to the skies. Piazzas shade the pavements and the citizens from scorching sunlight and rain. America has built her cities on the improved plans of the Old World, and so has an advantage over London and our provincial towns. Room to breathe in is the natural birthright of America. Extensive parks, rushing rivers, and relics of primeval scenery surround the city, and divide the suburbs for miles and miles.

No sign of poverty is betrayed by the well-dressed crowds that chatter cheerfully up and down the main streets; street-arabs are unknown. A Mile End woman of London town in rags, with bruised nose and eyes, walking down the street would create a sensation in Providence, and their weekly papers would devote an article to the distressing incident.

Brilliantly lit saloons shine in the evening streets, and regiments of laughing youths and girls hurry to the various depots, bound for the ferry-boats on moonlight trips down the rivers. The bars are closed on Sunday, but men trust men, and more sly rum is drunk on Sunday than weekdays. Niggers with ebony faces mingle with the white population, wearing white collars which support their ears: a shabby nigger has never been seen in Providence. If you shoot a nigger and do not kill him you are in danger of getting six months in the State prison for wasting shot and powder!

Many of the characters you meet in American cities remind you of Englishmen, but you can never really forget that you are in America. No true Yankee with self-respect allows you to quash his opinion. Nothing on earth can beat Providence, Boston, or any state you happen to be in. They will argue for ever; and if you at length say anything that has indisputable conviction in it, a true Yankee will squirt a stream of tobacco juice with the deliberate intention of not missing you.

Things of this kind worry you for a while, but you soon fall into their ways, and if you are smart can outrival them on their own ground; but you have got to be smart. To tell the truth, Americans have good reason to be proud of their states, and really have plenty to blow about.

Literary critics have hinted that Bret Harte discovered his characters in his own imagination. I can on oath dispute that fact. Grim Mr Billy Goat Whiskers, who fought in the North and South wars, draws his munificent pension, chews tobacco and dwells in Providence to-day. You do not meet him everywhere, but he is to be met.

In the grog saloons old miners from California told me their experiences, drew from their pockets photographs of gold nuggets and of gold claims that revealed small white dots in the far background—the tombstones of men who had thwarted them! They were innocent-looking enough, these men scarred with wounds, tropic heat and bad rum. They followed the various occupations that suited aged heroes. One old miner from Alaska suddenly arrived in Providence quite penniless. His name was Cargo. Walking down Z—— Street, he spied the name of Cargo over a sign-writer’s shop, walked straight in, spat on the floor, called the “boss,” and tried to make him believe he was the ancestor of the family of Cargo, and the rightful owner of the business. He was immovable. They expostulated with him; he would not go, so they gave him a job and thus saved legal proceedings in the High Courts of the state, and the expense of regiments of lawyers who would dispute the true owner’s claim to his business.

Providence is full of reminiscent men who tell of adventures that are wide and wonderful.

If you are disinclined to go to the theatre you can always go into a bar and in peace and comfort sit within earshot of some grog-nosed hero of the old school, and find subject matter to outrival the romance of fiction. You must take good care not to let the old fellow know you are listening, otherwise he leaves facts alone and, with ill-concealed pride, makes your blood congeal with vivid descriptions of old days, murder and despair, or your mouth water for a breath of the fortunes that knocked around ere you were born.

I travel and sell Bug Powder—Seeking my Wages—Pork and Beans—Reminiscences of Sarasate—I strive to outrival Paganini—Practising the Violin—I am presented with a Round Robin—My Blasted Ambitions

AS the hot months came round my money gave out. Work was plentiful in the numerous factories that throb and thunder with machinery in Providence, but such work was not congenial to my temperament, and would ruin my fingers for violin-playing, as the post-digging job did. Nevertheless I should have availed myself of the opportunity had no alternative appealed to me. But my friend the conductor was a crank who was always producing some new scheme or invention that would assist him financially and augment his moderate musician’s salary.

One night he came to my diggings beaming with enthusiasm over a plan to make us both rich. He had invented a new bug powder: our fortunes were made; all we had to do was to let the Providence public know the catastrophe that we had ready for these insects. Suburban houses in the States are generally made of wood that is specially suitable for the bug state. So the population of Rhode Island all have one secret; and on dark nights in hot weather candle gleams and shadowy figures can be seen dodging on the windows of the tenements, as restless folk in their nightshirts smash bugs on the wooden walls. I write from experience. They creep down the walls in regiments, and while you sleep eat your eyelids; if you wink they seek crevices, dart into your ears, and prepare for the next attack! Closing your toes together swiftly at night in bed, you can be sure that you have squashed three or four American bugs. I have carelessly glanced at skeletons which I thought were ancient dead bugs on the walls in the room of my new lodgings, and then at midnight I have lit the candle, and down the walls were marching battalions of old bug-skins! They had smelt me, and the regiments on the frontier of my bedstead were already full blown with my blood.

So it is obvious that a good insect powder would be a blessing in Providence.

Well, my Swedish friend and I threw our musical instruments aside, and started on the bug powder business, full of hope. I had several musical compositions that I was ambitious to publish on my own account. I felt that Providence bugs had presented the tide in my affairs which I should take at the flood.

With our pockets stuffed with a thousand bills, advertisements bearing testimonials from American presidents and English royalties who had stayed in America, my comrade and I tramped along with our hearts singing the excelsior song of happiness. We really lived in a paradise of ignorance and youth. “A rose by any other name would smell as sweet” is a true phrase, and happy, though selling bug powder, was equally true of us.

We marched, singing, on the dusty, white track to Narragansett. In the suburban gardens that led to the front doors grew gorgeous flowers. I can still dream that I smell their fragrance, and see the dancing blossoms in the brilliant sunshine. Strange things darted over us, hovered near the blooms and moaned like big humble bees. They were humming-birds, glittering and flashing their vivid colours, outrivalling the flowers with their brilliant feathery garment. The sky was blue as a girl’s eyes, and nearly as beautiful. We delivered the thousand bills and spent the rest of the day by a river. Wild fowl swam across it, and fresh from the eggs, with frightened eyes gleaming, the little ones paddled behind them. For miles the country was strewn with trees and houses, many of them made of wood, and at these especially we left three or four bills and at length disposed of the lot.

When we called on my friend the conductor for a first instalment of twenty dollars for our services we found him out, but after several visits we caught him. He was pleased to hear that we had worked a full week and left five thousand advertisements, but he put off the payment of our wages and borrowed my last five dollars! We haunted him for days; he was seldom home. My comrade and I sweated for miles and miles, seeking him at his various musical engagements; but the man seemed gifted with second sight, for as we knocked at the front entrance he hurried off from the back and vanished. The bug business failed and he moved. Still we demanded our wages by post; for he had left no address, and we hoped that the postal authorities would forward our pleading request. At last we found him. The sound of martial music came down D—— Street: a military band was leading a funeral procession, of some old soldier I suppose. There at the head of the band he blew solo cornet. We dared not approach him, but in our excitement we waved our hands. He winked in a friendly way as he passed on, and the strains of Chopin’s Funeral March faded with our hopes.

Eventually we caught him in a cul-de-sac, got ten dollars out of him and lived on pork and beans for a fortnight. Providence would be indeed stricken without pork and beans. As a rule they are not cooked, or rather baked, at home, but bought in jars, hot from the baker’s oven, ten and twenty-five cents a jar. Crime is scarce in Providence, capital punishment abolished. If a citizen sat down to his meal and discovered no pork and beans, and slew the waiter, he would get off on extenuating circumstances. Well, to revert to the bug powder business, like all my commercial enterprises, it ceased on my receiving the ten dollars, and my employer the bandmaster told me, when I met him a month after, that I had made five dollars more out of the enterprise than he did.

This brings me to another friend, a Sioux Indian, who was married and lived in the next rooms to my own. His wife, a white woman, took in washing and kept him. I used to sit in the evening and listen to his opinion of the States. His whole soul hated the Yankees. I once praised the Americans and their cities. He was down on me in a flash. “I am the true American,” he growled, “and the day will come when we shall get our country back.” I did not argue the point with him; his old wife kept him, and he showed base ingratitude by his opinions. He was educated and well dressed, and revealed to me, by all his conversation, the same kind of spite for the foreigner that I had noticed in the South Seas. Notwithstanding that the States had been peopled by whites so long, still the Yankee was an interloper and the robber of his country. He was not a bad old Indian, and was a friend to me during my stay at his tenement.

Just before I took his rooms I went to Boston to hear H——, a celebrated violinist who was performing there; I was anxious to hear if he was as wonderful as the review notices made him. I do not think I have ever heard such fine playing equalled even. He played Mendelssohn’s concerto, and swayed the legato strain out till it sang like a rivulet of silver song as the deeper notes mellowed to a golden strain as perfect in quality as the sunset lyre-bird of Australia. I have heard Sarasate, Ysaye, Joachim and many others, but no one with a better tone and intonation, except Sarasate, who played like some inspired magician off the concert stage. I heard him play at his villa in Biarritz, where I had the pleasure of receiving a gratuitous lesson from the celebrated maestro. “No, like this,” he said, as I played one of his own compositions: then he lifted his violin to his chin, and looked out of the villa’s latticed window as he played and rippled out a sparkling chain of diamond-pure notes and then literally swooned into the adagio.

I never had the courage to play that particular piece after.

After hearing that violin virtuoso at Boston I became enthusiastic and returned to Providence. The fever was on me. Again I determined to be the world’s greatest violinist! I almost wept at my wasted life on sea and shore. What might I not have been now, thought I, had I been practising the violin all those thousands of days instead of making sailors and South Sea Island savages my comrades? I went to the music stores and purchased the American editions of Petrie’s Studies, and Paganini’s Twenty-four Etudes-Caprices.

In my room, over the old Indian’s, I commenced. At daybreak I jumped each morning off my trestle bed and started practising. At first I tackled the Caprice which is double-stopping throughout. In a week I had got it off. I had long fingers, otherwise I should think it an impossibility. All day I bowed away. My furniture consisted of a music-stand, the Etudes, my bed and me! When I look back and think of my wonderful perseverance, it seems almost incredible. True and wonderful is the energy and happiness that aspiration brings to youth! Day after day I worked away at the studies with almost demon-like fury. Soon my chin had a great scab on it where the violin rested as I ground out the double-stopping sweeps, arpeggios and staccatos. I became thin and haggard-looking. I greedily devoured the lives of great violinists, among them Paganini and Ole Bull; also, after long intervals, pork and beans, as the old Indian below-stairs cooked them. He soon looked upon me as a sad kind of madman. I would gulp down the beans, look at his old grandfather clock and rush upstairs, then once more grind away, determined to make up for lost years. I saw the mighty crowds at concerts TO BE, applauding my wonderful playing! I was a new Paganini. Ah! how I remember it all. Through excessive playing the corns on my finger-tips became so hard that I could not feel the strings! My nervous system was soon wrecked, and my brain became ethereal with dreams—music was the all in all of life. People who did not play the violin were insanely ignorant.

Inspired, I extemporised melodies as I bowed and toiled away during the night hours: the day was not sufficient. The doors of the next tenement would suddenly bang, and strange tappings sound on the walls. I opened the window at midnight. I thought my double-stopping assuredly entranced the neighbours. It was hot weather, their windows were open too. In my imagination I thought I was playing to crowded houses. I heard the applause. Do you think I exaggerate? Believe me, I could never write down the depth, the magnificence, of those enthusiastic dreams. Only those who have felt as I felt, and were once inspired with ambition as I was inspired, will know exactly all that I felt, and all that I dreamed.

One day ten solemn-looking American citizens appeared outside the door of the Indian’s tenement; they wanted to see me. My name was called. I laid the violin down. I had no friends. Had my brother arrived? Strange thoughts flitted through my brain. Had people come as a special convoy to praise my extraordinarily fine playing? I opened the door and, white-faced and tremulous, I stared at a grey-bearded, solemn-looking old man who acted as spokesman. He presented me with a round robin. Fierce faces were looking over his shoulders! Two or three hundred signatures were there, the landlord’s signature looked the boldest! I was either to stop playing the violin or give up the premises and move at once. This was a terrible blow to me. I should lose a day’s practice if I had to tramp about looking for another room. I hated the world. Men were hard and mercenary. Only violinists and musicians had souls. I looked at my violin; it was my dear, abused comrade, and I clung to its reputation more than ever. No mother on earth ever leaned over her child with thoughts that outdid the tenderness of mine as I leaned over my tiny, responsive comrade, silent in its coffin-shaped bed. The dead child of my musical aspirations it seemed to me, for they were gone, and my mighty ambition lay a dead failure. Oh, you aspirants, you musicians and poets of this world, all you who love art for art’s sake, for you, and you alone, I write this. You will understand; you are my brothers. I can wish you more success, but no greater happiness than the delirium, the ecstatic joy that was mine when I sought to become the world’s greatest violinist.

I became melancholy: my incessant practice and irregular meals had, for the time being, destroyed my nerves. I thought of my schooldays and my life at sea, and longed for my boyhood’s days in the Australian bush. I remembered the kingly stockman and his wife, and the surrounding bush loneliness; the leafy gum clumps and the parrots roosting in them; and the hours when I sat on the dead log by the scented wattles in the hollows and watched the fleets of cockatoos like tiny canoes fade away in the sunset. I heard in dreams the laughter of the romping bush children as I raced them down the scrub-covered slopes, and I longed for those ambitionless days to come again.

My Brother’s Return—Scenery—Old Providence—Robert Louis Stevenson—New York—At Sea—The Change

IN August that year I at last received a letter from my brother, telling me he had left California and would arrive in Providence in a few days. I was delighted, for I was then completely on the rocks, having spent all my earnings on buying a violin bow and a stock of music! My comrade the Swede promised to come with me to meet my relative at the station.

The next day we stood on the platform together at eleven o’clock. The telegram said 12.30 P.M., but we were young and eager. We rubbed our hands with joyful anticipation as we stood there anxiously watching. Our funds were low and my brother had performed a miracle—he was a poet and journalist, and had made money out of his profession. When the train steamed in and the saloon car door opened I recognised at a glance the characteristic contour of the family face, though I had not seen my brother since we were children. I rushed forward overjoyed, and the welcome of brotherhood smiled in his expression. Six feet in height, and correspondingly athletic in appearance, he was well able to carry his own portmanteau, but privations and thoughts of affluence from his exchequer inspired me. Impulsively I seized it!

Years of residence in the States seemed to have changed his original nationality and the accent of his speech. He stood smiling before me, a Yankee of the aristocratic type. His keen grey eyes stared at my shabby clothes: the situation was evident to him at a glance. In a store by the civic centre, with an entrance that looked like the south nave of the Crystal Palace, my comrade and I were measured for new suits. Words could not express my gratitude.

With this lightening of my financial cares I felt the dim delirium, the exuberance, the faint revival of my old romantic glamour return; the world seemed beautiful after all.

My Swedish friend was delighted too, and smiled from ear to ear. I can still see his tall, lanky figure, and his merry round blue eyes as he puffs and tootles away on his beloved clarionet. Ah, how happy we were, marching on, carelessly unfulfilling the great promise of youth while we were yet youthful! Yet what is the good of promise fulfilled when youth is gone, when the glamour has faded, and you look through the grim spectacles of reality at the rouged cheeks of blushing truth and beauty? Oh, to remould this scheme of life, and be born old! To travel with Time and grim experiences down the years towards cheerful, glorious youth, back, back to the innocence and beauty of childhood’s dreams! To die full of hope and fond beliefs—and let the true believers travel the other way!

I know not where we went or why we went. I only know that my brother embraced the occasion and caught the vagabond fever; and that our valet, an old Turk (who kept swearing that he wasn’t an Armenian), sang jovial songs that were musically reminiscent of his harem days as he stumbled and struggled behind us, carrying our bundles of fruit, new suits, bouquets of flowers, and my long-wanted expensive copyright Etudes, Petrie’s Violin Studies, and all that sudden and unexpected affluence inspired us to buy.

I recall, too, how we were walking up the brilliantly lighted main street when a negro, who was anxiously watching for the editor of a Providence journal (that had criticised his lodging-house and the lady lodgers who kept such late hours), suddenly whipped out a revolver and fired. The editor had appeared at his door and received a bullet in his face, but he too had a revolver—probably he had been expecting the negro’s compliments—and he fired back and blew all the negro’s front teeth out. The next bullet from the negro’s revolver went through the Violin Studies which I held by my side, and but for the fortunate ricochetting of the bullet I should not now be able to write my reminiscences! I think the negro recovered from his wound and the editor was severely reprimanded for not hitting a vital spot. For the sins of negroes are dwelt upon like the sins of the poor relation, and I must admit that negroes are sometimes almost as bad as white men. There were no moving pictures in those days to perpetuate the episode, but still it is flashed vividly before my mind’s eye. I see the three races of good fellowship, my tall brother and myself, between us my lanky Swede comrade, and, just behind us, straight-nosed Turkey struggling along on bandy legs. Equipped with argosies of youthful dreams, pitching the moon and stars and sun from hand to hand, with rollicking song on our lips we fade away down the uncharted seas of Westminster Street, Providence!—to awaken on dim shores of cold daybreak as once more I kneel and take the sacrament before the grim, mock-eyed old priest—Reality! When I was twenty years and one month old—how long ago it seems!

We visited most of the fashionable places of interest, went almost everywhere, through the Open Sesame of my brother’s liberality. And that is saying a good deal, for theatres and palatial halls of amusement abound. There’s “The Gaiety,” “The Colonial,” “Hippodrome,” “Sans Souci,” “Bijou,” and heaven knows how many more, wherein the cheerful multitudes of R.I. folk scream with laughter and weep over unreal dramas.

I no longer played the monotonous second fiddle in the orchestra of the music hall; we sat, a happy trio, the smiling occupants of orchestral stalls, where I saw the Indian squaw fade to a shadow and die rather than sell her honour; and the American missionary weep over the grave of the half-caste Zulu in Timbuctoo who had died sooner than he would drink rum! Here was no painting of true life, no dramatic, realistic scene showing the besotted derelict who died far away in the isolation of some alien land—the man from nowhere, who took the wrong turning twenty years before, being hurried into his roughly made coffin: then his two lonely comrades watching the sunrise gleam in his dead eyes, and the half-boyish smile on the silent lips, as they place the coffin lid on, and creep along at daybreak, carrying him under the mahogany-trees to the hole by the swamp. They say a prayer and murmur: “Pity, Bill, that we left the bottle of whisky by his bed. Didn’t he rave about someone in the old country? Wonder what ’twas all about. The weather’s hot. Buried him rather quick, eh? Here’s the cross: ‘Bill.’ No name. ‘Died of Fever, Remembered by Us.’”

Moonlight ferry trips, picnics, concerts and songs are as characteristic of Providence as of the South Sea islanders of Samoa and Tonga. One difference divides the Providence population from the islanders—the natives of Providence wear clothes; but the Yankee mechanics outdo the Savaii and Fiji islanders in tobacco-chewing, and can spit over their shoulders with even swifter certitude than my sailor comrades of San Francisco, whom I told you about in my first book of South Sea reminiscences. Boating is an essential feature in their amusements. Rhodes-on-the-Pawtucket is crammed with boats. On sunshiny days thousands of youths and girls paddle and sing away, and never reflect on the time when Red Indian canoes darted in the moonlight over those same waters.

My comrade was still with me, and we got several engagements to play at dances and concerts. My brother was in the ring, so to speak, and so we were received with an enthusiasm that we had greatly missed when we really wanted it. My friend eventually, however, went off to Alaska to some relations. He promised to write to me, but I never heard of him again.

My brother owned, and still owns, I hope, estates called Cranston Heights, an elevated, breezy place. On the hottest day a sleepy wind creeps about them. From that spot you can gaze down into the valleys and see a wall of cliffs about an eighth of a mile long, rising a hundred feet high. There on a large boulder, known as Middleton’s Rock, my brother and I would sit reflectively smoking long Yankee corn-cob pipes, as we reclined, shaded by umbrellas of green-leafed trees from the hot sunlight. We sat there talking and dreaming of years ago when the Indians camped on Cranston Heights. I think my brother could outrival Fenimore Cooper and Cody in his knowledge of Indian history and the legends of the original tribes that owned America. Stone arrow-heads and Indian pottery to this day are often found there, and my brother showed me several relics which were dug out of his estate.

Rhode Island was of course originally an Indian settlement. Forests grew by the rushing rivers, and on the prairie landscapes stood native villages. The dominion was under a King Philip, and the island is sometimes called, for poetical purposes, “Land of King Philip.” The forests have succumbed to the woodman’s axe, though still patches of woods and prairie-land are left, and it was in that clump that I sat and played my violin and dreamed sometimes. Still the beautiful rivers run across the landscapes like veins of silver and gold fluid, glittering under the leafy clumps of beech, maple, hickory and many varieties of trees that resemble tropical types. The waters of those old rivers, like the coming and passing of singing humanity, have long since slipped into the distant seas, but still other waters flow on and are known by the ancient Indian names. The Seekonk river winds through Providence and throws its liquid mass into Narragansett Bay. From Cranston Heights you can see the exquisite scenery that is characteristic of the neighbourhood of Providence; across the valleys the hills fade before the eyes into dreamy distances as sunset floods the horizon. If you are poetical you can see the ghostly camp fires and dead Indian riders galloping and fading into the arched sunset of blood fire. The view reminded me of a South Sea modern shore village, for here and there were dotted bungalows, fenced by trees and green shrub and flowers. Things have altered a good deal since those days, for I have recently visited Providence.

Mr J——, whose palatial bungalow was among them, is one of Rhode Island’s greatest business men, and his commercial success is deserved, through his unassuming philanthropy. He has given a great deal of land, parks and drives to Providence. I think it was in Meshanticut Park, one of his gifts to the city, that I met with an adventure. The weather was hot, and I spied a small lake by some trees. Immediately I undressed and, though my brother expostulated, I dived into the water: the park officials came and arrested me, but my brother explained and I got off with a caution. Years of wild life in the South Seas had taught me to bathe where and when I liked, and I had yet to learn that park lakes in Providence were not as lagoons on the isles of the wild South Seas, wherein the whole population bathe without even the modest fig leaf, gossip, mention the weather and go their ways.

Oaklawn is another pretty spot. I stayed there with some of my brother’s friends, at Wilbur Avenue, I think. There is a little wooden bridge thereabouts, not far from an old stone mill. Near this spot in the old days a great Indian battle was fought, and there by that little bridge my brother would sit for hours, writing his articles for the provincial and New York papers.

It was at Oaklawn Bridge that I sat and told my brother of my various boyish experiences in the South Seas, of the island chiefs, and of my reminiscences of Robert Louis Stevenson, whom I had met at Apia and on ships at sea. My brother was deeply interested in all I told him. He was a great admirer of Stevenson’s work and his perfect literary style. We talked of Stevenson’s easy and careless manner that seemed such a contrast to his perfection and polish in writing. How he did not care a tinker’s curse for the opinion of the conventional world, and loved to shock visitors to Samoa by appearing before them suddenly in old clothes, bare-headed and bootless. I saw him come aboard a ship dressed in that way; and I recalled how, on another occasion, I met him coming down the track inland from Saluafata, the native village. “Hello, youngster,” he said; and, as I was going his way, off we tramped along the track together as he hummed beside me. Then, with the sunset, out came the native children rushing from the forest. Like tiny ghosts they glided, begging, in the shadows at our legs as we strode alone; and as Robert Louis Stevenson threw brass buttons to them, they raced after them, and then, half frightened that he might want to reclaim the prizes, they suddenly disappeared, racing back into the forest. The sunset died behind our backs and the stars crept over the Vaea Mountain top and the dark-branched coco-palms each side of the track; the shadows thickened as the stars brightened. So well do I remember that night that even now I seem to see my companion striding onward beside me, his loose neck-cloth fluttering in the wind that drifts in from the sea, stirring the coco-palms and pungent-smelling forest flowers as it passes. Still I see his ghost-like shadow, the clear eyes, the thin, æsthetic face; still he is humming a folk-song, while his right hand beats the moonlit bush with a stick—and yet he has lain there many years on the top of the Vaea Mountain—his rugged island tomb railed by the dim sky-lines of surrounding tropical seas, his vaulted roof the everlasting sky, studded with the brightest stars, as he lies with his stricken aspirations like some dead Christ of the lost children of the wild, solitary South.

A critic in The Times, reviewing my first book, Sailor and Beachcomber, after writing a column of critical appreciation, finished up by saying: “Mr Safroni-Middleton prides himself on having known Robert Louis Stevenson in the South Seas.” My book has three hundred and four pages: on three of them I spoke of Stevenson; but I fail to see why I should pride myself on knowing him, except in this sense, that I am proud to have met him and to count him among the many men who followed after my own heart.

If he had not died before I returned, a little older, to Samoa, he would have welcomed me as I should have welcomed him; for he had several times expressed a wish that I should call on him and take my violin, but in the foolishness of a boy’s thoughtlessness I did not go. Worldly greatness did not appeal to him, nor did my letters of introduction, for I had none, and he was, I am quite sure, aware of the fact.

Well, to return to my experiences in North America. After a time I left Providence, and then went down the Hudson river bound for New York. There I stayed in a temperance hotel close to the Bowery, and I cannot forget the scene.

Along winding avenues that divide the towering wooden buildings rushed battalions of hurrying legs. The noise of car bells and gongs and the babble of shouting voices assailed my ears. All the races under the sun seemed to have emigrated to that spot to fight in scheming regiments for the almighty dollar. White men, Chinamen, black men, tawny men, yellow men, Armenians, Turks, Germans with thick necks—all were there. Over my head rushed express trains. No space seemed wasted. Indeed the Yankees in their commercial search for gold peg out claims in the sky, claim square miles of stars, as up go their buildings to the heavens. By the second-storey windows on elevated railway tracks crash along the trains. In those days they ran by steam, and the coal-dust showered down your neck and in your eyes as you moved along with the thick crowd below; a crowd so dense that you could shut your eyes, make no effort, and still be propelled along in the mighty rush, as you dreamed of other days of peace and solitude! I went across Brooklyn Bridge by night: swung on mighty steel cables, it dangles in space and has several divisions for vehicles and pedestrians. Below rushed the ferry-boats on the Hudson river, their port-holes ablaze with light, and the sound of music on deck fading as they passed underneath. Across the bridge hurried electric cars, racing along by the mechanical genius of man’s brain, the light of the Universe—the stars switched on to wheels!

I only stayed one week in New York, for I met an old shipmate whom I had sailed with from Sydney. He was on a tramp steamer. One of the deck-hands had gone into hospital, so I yielded to my friend’s persuasion, went on board, secured the job and signed on. For the rest, it is all like a dream now: I can hear the rattle of the rusty chain as they haul the anchor up, and the uncouth, shrill calls of the pulling crew rising above the clamour of the steam winches, just before the tramp steamer moves away from the wharf to put to sea. New York and its babble of voices with their nasal twang, its vast drama of scheming existence in a feverish hurry, fades away and becomes a memory of some monstrous “magic shadow show” lit by the sun far off somewhere across the lone sea miles astern.

The sea routine has commenced: deep down in the stokehold firemen with cadaverous faces turned to the furnace blaze are toiling away. They look like shadows in the flame-lit gloom, like dead men working out their penance in hell. Attired in pants and a sweater only, with their hairy chests steaming with running perspiration, they work furiously. Their conversation is made up chiefly of oaths and forcible criticism on the lack of generosity they found in Bill or Jim, who only stood them ten drinks ashore, after all they had treated them to on that first spree night of the last trip. They are not bad men, and as they spit out the coal-dust in a thick mass from their stained lips, and take a gulp of condensed water to quench their thirst, I feel deeply sorry for them, and realise that they are the unsung heroes of the sea. I look at the row of unshaved faces thrust forward to the roaring fires, and at their shrivelled hands and big arms moving the long steel stoking bars, and wonder at the marvellous strength and virtue of the hard-working ship’s firemen.

On deck, like iced wine to my lips, I drink in the fresh sea breeze. It is dark. I cannot turn in, for I should not sleep, so I go into the fo’c’sle and watch the sailors playing cards, then return on deck and look over the ship’s side. Under the pendulous, curved moon—for it seems to sway to the roll of the rigging—the mate’s form moves to and fro as he tramps the bridge. The sailing ship that we sighted on the weather-side at sunset is now only a tiny travelling star low down on the ocean darkness far astern, where her mast head-light shines.

The weariness of the sea’s monotony is on me; we have been to sea long enough to be half-way across the Atlantic. The weather is much colder. The moon is large and low, and looks like a ghostly arch to the south, for it seems half submerged far away on the edge of the ocean, that seems shivering for miles with silver mystery. Just over the side I watch the mirrored masts and rigging glide along with us as though a ghostly ship is following; and the hours fly and dawn breaks greyly, and once more the tramp steamer is surrounded by blue sky-lines, till sunset sinks to a wild blaze in the western arch of the sky. The sailors go on watch. The cook washes his pots and pans ere he cuts his corns and turns into his bunk.

The wind’s voice murmurs mournfully in the rigging and round the bridge awnings; as the night grows older it swells to a tremendous voice that is really me! for it is the re-echo of my own hearing and dreaming consciousness. I fancy I hear the hounds of death racing across the wild sea moors as shadows dropping from the flying clouds go running over the moonlit sea, and now, as though a door in the sky is opened, the stars and moon are driven and shut away in the outer Universe. For a mighty sheet of storm-cloud slides across the heavens. The world is changed to an infinity of dark and wind, and the one dim figure of the look-out man on the fo’c’sle head. The thundering seas slowly rise with their white crests glowing in the ebon darkness as the brave old tramp steamer, like a frightened thing, stays her way a moment, and shivers as seas strike the weather bow. Then again she pitches onward, as wonderful little men, with bony, haggard faces with weary eyes in them, stare into the furnace fires of the steamer’s bowels, and shovel and stoke to sustain an honest existence, and drink tank water. No wonder they drink beer when they get the chance. I am quite sure I should.

A week later we sighted the cliffs of England, and soon after the sea tramp touched the wharf at Liverpool with a jerk and a shiver, and went to sleep among a forest of masts and funnels till her next trip.

Home—On an Orient Liner—The Orchestra—A Sailing Ship—Paganini—Port Said—Honolulu

AGAIN I am home and meet familiar faces, and enjoy the sweet security of home life and respectability; but soon the flight of time brings its inevitable changes both to my feelings and to those around me. I am no longer the prodigal son and a romantic novelty to the many who welcomed me at my arrival in the monotonous suburb; but nevertheless we are all moody companions in the sad drama of respectability. I had made up my mind to go travelling no more, but my good resolutions have faded away, and my whole soul is centred on inventing the best excuse for my not being able to accept the good position in London that will make me, at last, the respected son of a respected father.

Well, I feel a bit ashamed of my incorrigible personality, and yet how much my soul is burdened with the thought that I must aspire to higher things, and go off to the city each day like Mr W.’s son does, to sit on a stool. I can never be the pride and joy of the family, and as I sit alone and dream I am miserable with dim forebodings. On the back of the chair is my very high white collar and the smart tweed suit, and by my washstand my beloved fiddle. Just over it, on a peg by my bed, is my big-rimmed Australian hat. Alas! that hat speaks of tropical sunshine and coco-palms. I can hear the arguing voices of bushmen in the grog shanty by “Bummer’s Creek,” and the trade wind in the shore banyans as the beachcomber laughs and nudges his pal in the ribs.

I cannot sleep, for the parrots are flying and muttering across the sky of my dreams; I hear the crack of the stock-whips on the slopes as the scampering, flying sheep go racing across my bedroom floor. I close my eyes, and the natives start singing in the Fijian village, and the drums are beating the sunset out ere I am wide awake, through the civilised jingle of the milkman’s cans in the cold, windy street below.

The last dark wintry morning arrives. It has all been settled. I have signed on for a voyage as violinist and assistant purser on the Orient liner the Britannia. I am to catch the 4 A.M. train to London Bridge. How dark and cold it is as I get up and dress, then go up the next flight to kiss my three sisters a last good-bye. They lift their sleepy heads and put their arms around my neck. “Good-bye, Tiggy,” they say once again, as I gently close their bedroom door and go downstairs. My father helps me on with my overcoat, and says very kind words. I try to answer, but my voice sounds husky and I keep placing the wrong arm in my overcoat sleeves. Now comes the greatest task of all, a task that will tax all my courage. I strive to hide my weakness and make a joke about the bad penny turning up again soon, and then neither of us speak, and once again I kiss her lips, the lips of the most beautiful woman this world ever gave me. I hurry down the streets. I am glad it’s dark, for my eyes feel weak, and the windy light of the lamp-posts seem to swim about the street spaces. I am haunted by her face all down the Channel that night, for she caught my soul adrift among the stars ere I was born, and my heart still sings a sad song for the woman who was my mother.

There is a deal of sameness on a large liner’s trip to the colonies. But for the complication of characters among the passengers and crew, and the ports that we put into on the voyage out, the passage would be extremely monotonous.

Forward, near the fo’c’sle, was the glory hole, between decks, wherein slept the crowd of stewards and cooks. They were a jolly lot of men, and when the steerage and fore-cabin passengers had finished their evening meal they would sit on their sea-chests yarning or playing cards far into the night. Sometimes they would sing songs, accompanied by the twang and tinkling of the assistant cook’s banjo; and older men, who were tired out, thrust their fierce faces out of their bunks and swore at being kept awake, as once more the wild chorus of I owe Ten Shillings to O’Grady re-echoed through the “glory hole.” Sleepless passengers up on deck clapped their hands with pleasure to hear the monotony broken, as the big pistons in the engine-rooms throbbed out their incessant pom-pe-te-pom, and the screws thrashed the racing liner across the world. In the morning at four-thirty the men would be dead to the world in their bunks as the second steward started shouting: “Now then, you sleepers! Now then, you sleepers, rise and shine!” or “Come out of it, you young b——!” and so on, as sleepy heads lifted up in the rows of bunks and then dropped helplessly again. Some were romantic boys who had read autobiographies, and some middle-aged men who had sickened of the workman’s train and drifted to sea.

In the evenings I played the violin in the saloon and deck concerts aft, beyond the dividing rope which was the boundary line that told the fore-cabin passengers that they must not approach the élite in the first saloon.

Our orchestra consisted of three violins, ’cello, bass, and the usual brass and wind. I had an easy time, and often till midnight would stand on deck watching the stars and the world of waters below, and listening to the voices of passengers on deck outward bound for Australia, to find fame and fortune—or ill fame.

I became very friendly with a member of our ship’s band, the solo cornet player. He was a quiet, elderly man, turning grey, and had once been a player in the orchestra of the Lyceum Theatre. A fine all-round musician he was too. He would sit on deck after dark, put a mute on his instrument, and extemporise melody and make it sound like a sweet-voiced girl singing softly to herself. He had the real temperament, and had received a first-class musical education.

Nothing reveals character, the intellectual calibre of the instrumental player, so much as the type of composition that makes up his private repertoire. For in that he only plays the compositions which appeal to him. Some are devoid of personality and only perform the stock pieces that are fashionable. Others revel in melody that tells of the light side of life, its gaiety, or the pathos of dramatic existence on the stage, the tragedian’s mock grief before the footlights ere the curtain falls. Others find their musical heaven vaguely expressed by playing those pieces that seem to murmur, as a sea-shell murmurs of the ocean, that indefinable note of poetry, the voice of the unknown, the intense inner life of our existence. My friend was one of the latter kind. He gave me many useful hints which I profited by, (as I often did in my travels), and so received a free musical education, the only music lessons I ever really had.

But for the throb of the engines and thrashing screw, the vessel’s motion, and the stewards’ sea-legs aslant to the deck’s list as they walk the saloons and cabin alley-ways, you could half think you were in some subterannean hotel. Travel on a liner, and the wild poetry of the sailing ships swerving to the swell of travelling seas, the climbing sailors aloft singing their chanteys among the storm-beaten sails, the flying clouds overhead that race the moon, all seem to be something that you dreamed of, or lived through ages ago.

Sea-boots and oilskins seem mythical things that faintly recall your yellow-backed old buccaneer novels, or the days when Drake sailed down the seas.

Officers on the P. & O. liners speak with university polish. “Ay, ay”, “Hold hard!”, “Look out, you son of a sea-cook!”, “Holy Moses!”, “Up she comes”, “All together!”, “Let go!”, “Haul the mainsail up!”. This is all changed now to “Make haste, Mr Pye-Smith” and “Yes, sir, I beg your pardon. What a draught!”. Or a bell tinkles down in the engine-room, and the mammoth liner, like a mighty iron beast, slows obediently to half-speed, stops, or slashes her tail and goes full speed astern, without one song or oath.

The stormy night and head-wind, the huddled group of sailors in oilskins singing their wild chantey, O, O, for Rio Grande, on deck in the windy dark as they bend together and pull while the vast monotone of the ocean becomes the orchestral accompaniment to voices from strong, open, bearded mouths, and your world of stars suddenly veers as the dark canvas sails and yards swerve round; the chief mate shouting, “What the blazing hell—— Ay, there!” as on the wind comes faintly back, “Ay, ay, sir, all clear!”: this smacks more of the sea. Why, on a sailing ship, the very sea-cook at the galley door, amidships, clutching his pans, gazing across the wild, lonely waters, where the leaping, white-bearded waves seem like old misers’ hands plucking at the sunset’s gold, is sheer downright poetry compared with the electric-lighted saloon crowded with munching, over-fed men and women with moving mouths and pince-nez on their respectable noses.

The sailing ship has its rough, uncomfortable side, for well I remember my last trip from ’Frisco round the Horn, when I stood on deck at night, with deadly cramp gripping my legs, my eyebrows frozen together, my nose pinched and blue with cold, the decks awash and our sea-chests afloat in the fo’c’sle and deck-house. I recollect the cook holding on to his pots and pans and swearing as only an old-time boatswain, and that cook, could swear as we begged for a pannikin of hot coffee: stuff that tasted like heaven-sent life-blood to our frozen lips as we two boys drank it. The weather-beaten boatswain in his oilskins and sea-boots went by us in the dark, as great seas came over, singing a song to himself as though he was soliloquising in some quiet bar off the Mile End Road instead of experiencing the wildest weather I have ever seen, or ever want to see.

How I admired those old seafarers! “Fetch that, matey,” they’d say, and off I’d rush, eager to please and obey the orders of Horatio Nelson and Sir Francis Drake, for such men they seemed to me.

In the fo’c’sle at night they’d say: “Get that fiddle out and play to us.” A thrill of boyish pride would go through me to notice their attention and respect as I played my best. Presently they would join in as I played the chanteys they had taught me, Sailing down to Rio or Blow the Man Down. Without removing their pipes or chewing quids, their cracked, hoarse-throated voices would join in.

Deep bass voices two or three had, and as they sat round me on their old sea-chests, and I scraped away to the tuneless, yelling, bearded mouths beneath the dim light of the fo’c’sle oil lamp, I drank in the last breath of the winds of sea romance. I see them now as I dream. There they sit on their sea-chests, oilskins and sea-boots on, with curios from other lands fastened over their bunks around them, as they open their big bearded mouths and sing. How ghost-like their eyes look by the light of the dim lamp, as the hazy tobacco smoke curls thickly to the low roof! Then their hollow voices fade and the visionary “Old Hands” vanish as the last breath of wind blows them like cobweb-fine things through the fo’c’sle door, along the moonlit deck, away seaward for ever as I dream.

How I recall these lonely nights and the sailors moving across the deck in the dark, or climbing aloft like shadows back to the sky. I used to stand alone and gaze over the ship’s side and suddenly feel the intensity of living, as my thoughts half clung hopefully to the stars, like lost, migrating swallows that cling to the rigging of ships far out at sea; and the mighty, moving water all around me seemed to break with its monotone against eternity. I remember lying in my bunk, and by the oil lamp’s light watching the ship’s cockroaches go filing across the photographs of my parents and relatives which I had tacked on my bunk side to remind me of home, though I required no such reminder. Those silent faces intensified the difference between reality and my boyhood’s dream; as a cold breath out of the grave of my beloved, who slept in the seas outside, blew through the door across my face as I dreamed of her—my beautiful dead romance!

Truly, sailing ships have their rough side as well as a wildly romantic one. Rolling down south, with gales behind bringing the seas up like majestic travelling hills as under the poop they go, and she rolls and swerves as the masts sweep across the sky, is the motion of sea poetry. If you are aloft you look down and could swear that she must turn turtle. Telling you this calls back my feelings when I first went aloft as a boy of fourteen years.

The ship was rolling heavily, and as I looked down on deck something seemed to have happened (I turned pale, I’m sure): she was turning right over. I clung on with might and main as the masts and yards went over; death seemed to stare me in the face: like a wild beast I hooked on with fingers, toes and teeth, prepared for the final plunge into the heaving ocean below, when lo! to the mysterious equal pull of gravity she slowly swerved and rose, the rigging jerked and rattled, the jib-boom lifted and the figure-head at the bows lifted her face from the weather-side and went right over to peep at the lee-side. Overjoyed, I looked over my shoulder astern and saw the chief mate yawning on the poop and the man at the wheel quite unconcerned, when I had instinctively thought they were clinging to anything movable, prepared to dive into the ocean when the ship turned clean over. That bronzed, broad-shouldered mate grinned when I stood on the poop. He asked me how I had felt. He was a good sort. He’s dead now and under the sea, missing these many years; and the red-bearded Scotch skipper, who was like a father to me, is worse off, for the last I heard of him was that he was still alive and missing—mentally. “But this won’t buy the baby a frock,” as they say at sea when you go off dreaming and leave your work to yarn. So I must return to the P. & O. liner as she races across the Mediterranean, bound for Suez.