Title: Jack's Two Sovereigns

Author: A. S. Fenn

Release date: April 20, 2019 [eBook #59313]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

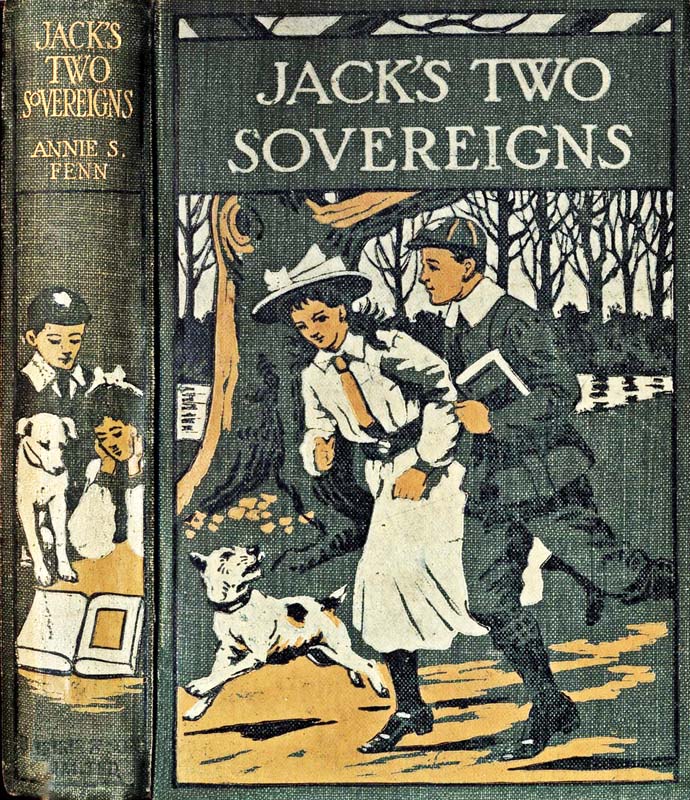

BOB SAVES JEM FROM THE FALLING HOUSE

BY

ANNIE S. FENN

Author of “Little Dolly Forbes” “A Year with Nellie”

“Olive Mount” &c.

ILLUSTRATED

BLACKIE AND SON LIMITED

LONDON GLASGOW AND BOMBAY

| Chap. | Page | |

| I. | Evening at Home, | 5 |

| II. | Money Matters, | 16 |

| III. | Relations, | 27 |

| IV. | Help in Need, | 35 |

| V. | “Stop Thief!” | 43 |

| VI. | Where is Father? | 48 |

| VII. | Morning, | 57 |

| VIII. | Self-reproach, | 64 |

| IX. | An Invalid, | 71 |

| X. | Night, | 81 |

| XI. | A Storm, | 90 |

| XII. | Deserted, | 101 |

| XIII. | Returning Kindness, | 109 |

| XIV. | Reunion, | 115 |

MADGE, do leave those horrid old stockings, and let’s all have a game at ‘Beggar my neighbour.’ It would keep Jem and Jack from quarrelling.”

“I can’t, unless you’ll darn them for me. There are eight pairs, and they ought to be done to-night ready for the morning.”

“Well, take your chair and sit between them, to keep them apart.”

“What’s the use of that? If Jack were here and Jem in Australia, they’d quarrel somehow. How industrious you are to-night, Edie!”

[6]“I am tired.”

“Well, as you’re the only person that’s tired, of course it’s quite fair that you should do nothing.”

“Madge, if you’d asked me civilly to help you, I’d have done so in a minute, but sneering won’t make me, you may be quite sure of that. Why don’t you ask Bessie to do some work?”

“Because she’s younger, and it doesn’t matter so much about her.”

“Madge, get me that little oil-can that your mother uses for the sewing-machine.”

“Yes, father.... Here it is.”

“Madge, there’s baby crying. Run up and rock him to sleep again.”

“Yes, mother.”

The little sitting-room at 15 Buxton Street, Denham Green, seemed a great deal too small to hold such a family party as were now squeezed into it, the above being a few of the remarks flying about there at eight o’clock in the evening. Those gathered in this small space were all members of the Kayll family. There was Mr. Kayll, a little,[7] fair, bald, pleasant-looking man, who was seated at the table with a newspaper before him, on which were spread out tiny wheels, screws, nuts, and cogs of yellowish metal. He had taken the clock to pieces, as it would not go, and was cleaning its works, not seeming to take more notice of the hubbub than if he were stone deaf.

Then there was Mrs. Kayll, a thin, worried-looking woman, who was engaged in putting a patch on the knee of a small and shabby pair of tweed trousers. There was Madge, too, a minute before, but she had gone to baby, and the quiet, regular, “thump, thump” of the cradle rockers could be heard in the room overhead.

The others were so mixed up that it was difficult to distinguish one from another.

That boy with the dark curly hair and mischievous eyes was Jack, aged fourteen, who earned five shillings a week by the labour of his own hands. Beyond him, with his elbows on the table, and his eyes intent on the works of the clock over which his father was busy, was Bob, his elder brother—but[8] no one is likely to remember all these children without a list to look at now and then. Here are their names, ages, and occupations.

Madge, aged sixteen, “mother’s help.”

Bob, aged fifteen, father’s help.

Jack, aged fourteen, a printer’s boy.

Jem, aged thirteen, errand-boy to a chemist.

Edie, aged twelve, school-girl.

Bessie, aged ten, school-girl.

Baby, aged five months. No occupation.

Now, having arrived at a clear understanding, we can get on with the story, and there will be no excuse for anyone mixing up Jack with Jem, Edie with Bessie, or Madge with the baby.

This was the conversation going on between Jack and Jem.

“I do more work for four shillings than you do for five.”

“That you don’t. I work twice as hard as you do any day.”

“Oh, I say! I like that! And you told me yesterday that you’d found time to read Robinson Crusoe all through.”

“I didn’t.”

[9]“Yes, you did.”

“No, I didn’t.”

“Well, perhaps you’ll be good enough to tell me what you did say, then.”

“I said I’d skimmed it.”

“I don’t think you did; but any way, whether you skimmed it, or whether you read it properly, you wouldn’t have done so when anyone was looking, I know.”

“Now, look here, Jem, if you’re going to lecture me, I shall just sew up your coat-sleeves after you’re gone to sleep to-night, and get ready some more little surprises for you. I won’t be lectured by my youngers.”

“Do be quiet and not quarrel, you two boys,” interrupted their mother in a plaintive tone, as she held up her needle between herself and the lamp, the better to see its eye. “It does worry me so. You’ve given me quite a headache.”

Jack was silent at once. Not so Jem.

“Have we, mother?” he said quickly. “I’m so sorry. But I can’t help quarrelling with Jack. He doesn’t give me any peace. Now this morning I went all the way to the[10] shop with a ticket pinned on the back of my jacket, with ‘This side up, with care’ on it, and Jack says that’s to teach me to brush it before I put it on. And yesterday all my pockets were sewn up, to teach me to keep my hands out of them. It doesn’t. It makes me put them in all the more.”

“Jack,” said Mrs. Kayll severely, “don’t do that sort of thing any more. I forbid it. Jokes of that kind may be very funny to you, but they often lead to serious consequences. And it’s not for you to teach Jem what he ought to do, except by setting him a good example.”

Still Jack was silent. He loved teasing and playing tricks, especially on Jem, and was continually getting into grief by this means.

“I sha’n’t stop at Graves’s long,” said the younger boy soon after in a low tone to his brother.

“It’s very stupid of you, then. You don’t know when you’ve got a good place.”

“I know when I’ve got a bad one, though.”

“The fact is,” said Jack, who had an uncomfortable[11] habit of telling people the exact truth to their faces, “you are jealous of me because I get five shillings a week, and you only get four.”

Jem turned of an indignant scarlet.

“I’m not! I wouldn’t be in your shoes for a pound a week, if I knew it; so now, then!”

“Then you would be very selfish, for a pound a week would make you able to help mother ever so much—buy your own clothes and all sorts of things.”

“Oh, you boys! you boys!” sighed Mrs. Kayll. “Father, did you ever hear anything like them?”

“Like them! Oh, dear, yes, lots of times,” he answered in a preoccupied tone, without looking up from his work. “My brother Tom and I were just as bad at their age. I recollect, though,” he added, glancing at his boys for a minute with a twinkle in one eye, “that my father used to cane us both soundly, and send us to our bed-rooms till we apologized.”

“Oh, but we’ll apologize without that,”[12] cried Jack laughing. “Jem, old chap, shake hands, and never mind my fun.”

Jem was quite ready, and there was peace between them for perhaps half an hour.

But though the boys were quiet, the girls were not. Edith and Bessie were at this moment engaged in a playful and good-tempered struggle for the possession of a worn-out doll, which means that the one who had it in her hand was running round the room, jumping over chairs, or scrambling under the table, with the other catching at her frock or pinafore amid deafening shrieks of laughter.

“Hush, children! Play quietly,” said Mrs. Kayll, and the noise stopped for a minute, only to go on again a little later.

At this point Madge walked in again with the baby in its night-dress on her arm, wide awake, and in the best of spirits.

“He wouldn’t go to sleep, mother, and no wonder, so I’ve brought him down, the sweet darling pet. And did he want to come down-stairs and see all the fun? He should, then, that he should, a chickums,[13] and sissy will nurse him while she darns the stockings.”

And she sat down in her old place, and tried to mend the great holes worn by the boys in the heels of their hose, with the little one on her lap jumping, kicking, writhing, and running great risk of being pricked by Madge’s long needle.

Upon this Bessie, a rather pale, fragile-looking little creature, with great thoughtful gray eyes, left the rough play of which she was already growing tired, and set herself to interest and amuse her baby brother, talking nonsense to him, building up houses of cotton-reels on the table, and letting him knock them over, tickling him, kissing his fat cheeks, until he laughed aloud, and made remarks in his own language, such as “Boo, google, coo-coo,” which singular words little Bessie seemed perfectly to understand.

Meanwhile Edie had drawn a chair to the table, and was quite absorbed in a book which she had read at least six times before, and Jack was behind her, secretly pinning her dress to the legs of the chair, in which[14] feat he completely succeeded without arousing suspicion. He then strolled round looking for some fresh diversion, which was easily found. A couple of metal buttons were lying near Mrs. Kayll’s elbow, ready for placing on the garment she was mending. Jack possessed himself of these, and in two seconds they had gone down Jem’s back, and the culprit had to escape from the room to get away from his brother’s vengeance. Jem dashed after, and the scuffle was soon heard going on overhead.

They were a noisy, merry, poor and unlucky family. Loving one another dearly at the bottom of their hearts, but hiding their love as though it were a crime, quarrelling a good deal, and causing much anxiety to Mrs. Kayll, who used to think sometimes that no woman ever had children so hard to manage and so little time for managing them. For Mr. Kayll, though he was the best of husbands and kindest of fathers, and worked hard all his life, had not the gift of “getting on in the world.”

They were all startled into looking up[15] from their various employments by a loud imperative knock at the door.

Madge and the baby went to answer it, and voices were at once heard that sounded more energetic than polite. Before many minutes had passed the girl came back, rather red in the face, and with a paper in her disengaged hand.

“It’s the baker,” she said in an undertone, so as not to be heard in the passage. “He has brought his bill, and he’s so rude, and says he won’t bring us any more bread unless he’s paid to-night.”

“How much?” asked her father, taking the account from her and looking at the amount. “As it happens, I can do it. Here, Madge, pay him, make him receipt it, get rid of him, and tell him he needn’t trouble to call again.”

Madge took the money and did as she was told. But she stood for a minute in the passage after he was gone, before she rejoined the others, and brushed something from her eyelashes.

“Oh, baby,” she whispered, pressing her[16] face to the cool little cheek. “It’s miserable to be poor. I think there’s nothing more wretched in the world.”

In that sentiment all her brothers and sisters would have agreed. They had had few other troubles, and therefore fancied there was nothing so bad as the want of money.

“MOTHER,” said Madge, as she and Mrs. Kayll were making the beds on the next Monday morning, “I wish you would talk to Jem. He is determined to leave his place, and it does seem such a pity.”

“Leave!” cried Mrs. Kayll, stopping in the act of shaking up a pillow. “Why, I thought he liked it so much!”

“So he did at first, but he’s tired of it already, just as he always is, after a month or so.”

[17]Mrs. Kayll sighed wearily, and laid the pillow in its place, taking care that the hole in the much-patched cover should go underneath and out of sight.

“Tiresome boy! He is so unsettled. I’ll talk to him to-night; but it’s not much good when he has once taken a dislike to his work. He’ll never go on with it with any pleasure. I don’t know what would become of us if Jack were the same. Heigh-ho! You children are a constant anxiety to me. We really can’t afford to have Jem at home on our hands just now, when your father’s doing so badly—really I don’t think he ever did so badly before.”

“Yet,” said Madge thoughtfully, straightening the patchwork quilt, made long since by her own hands, “Jem is so good in his way, and seems much more fond of us all than either Bob or Jack, and plays with the children without teasing them like Jack does.”

“Yes, he’s a dear affectionate boy,” sighed her mother, “but I wish his affection made him consider us a little more and himself a little less.”

[18]At this point, as they had finished the bed they were making, Madge picked up the baby—who had been sitting in a corner all the time, contentedly sucking a knob which had come off a chest of drawers, and looking on at his mother and sister while they were busy—and conveyed him into the next room, where he had again to sit with his back to the wall and amuse himself as well as he could.

“Never mind. Don’t get unhappy about it, mother dear,” said Madge in her quiet philosophical way. “As long as we’re all well, that’s the chief thing, isn’t it? Being poor isn’t half so bad as being ill.”

From which it will be seen that, like most other people, Madge saw the world with quite different eyes when she was fresh and bright in the morning, from those with which she looked at it when she was tired and depressed at night.

“Ah, it’s all very well for you, child,” said her mother, who seemed to think poverty was quite bad enough, as she looked at the girl’s worn blue dress, and remembered how hard it had been to make the children look[19] anything like respectable for church yesterday—“It’s all very well for you, but when you come to my age you will wish you too had a little leisure, and need not grind, grind, slave and pinch from year’s end to year’s end. But there, Madgie, it’s of no use grumbling. I don’t really mind, only I get tired of it now and then.”

And she smiled, and then sighed as a few more disagreeable reflections came crowding into her mind. Her husband’s coat was very very shabby, and he ought to have another, just to keep up his character in his business. The coals were getting low, too, and the summer was drawing to its close; there was no saying how soon the days might turn cold. And there was very little food in the larder. She must really turn her thoughts to providing dinner.

“Madge,” she said suddenly, “your father has a sale to-day, and won’t be home to dinner, so we’ll not cook anything but some potatoes, because there’s a jar of nice beef dripping, and you all like potatoes and dripping.”

[20]“Yes, mother,” Madge answered, apparently scarcely giving the matter a thought.

It was well for Mrs. Kayll that her eldest daughter was so amiable and easy of disposition. Nothing came wrong to Madge. She took life quietly, with a kind of stolid good-temper, and was one of those people of whom everyone else expects a great deal, and gets it, without being surprised, or particularly grateful. She worked hard from morning to night, uncomplainingly, and it was not until she was very tired, and had more on her hands than she could do, that she was sometimes led into speaking a little sharply to her young brothers and sisters.

Ever since she left off going to school, Madge had been nurse, cook, needlewoman, and in part teacher, for in so large a family as this, where no servant could be kept, there was always more than enough employment for both her mother and herself, with keeping the house tidy, everyone’s clothes clean and in good repair, preparing meals and clearing them away, and taking care of the baby.

[21]The children who were at school came in for their simple dinner, and ran off again; the afternoon was passed in the same way as usual, with washing up, straightening, and making all comfortable and ready for tea.

To this meal Jack, Jem, and the three girls came home, but Mr. Kayll and Bob were not expected until nine or ten. So the mother poured out tea, and Madge cut bread and dripping for everybody with untiring patience.

Suddenly, in the middle of the meal, Jem remarked in a matter-of-fact tone:

“I’ve left.”

“What?” cried Jack.

“Oh, Jem, you don’t mean that!” exclaimed Mrs. Kayll.

“I do, though; but don’t you bother about it, mother, I’ll soon get something else to do.”

“Jem, you’re a—” began Jack hotly; but his mother touched his lips with her hand.

“Don’t call him names, whatever he’s done, Jack. That won’t do any good. But[22] oh, Jem, it is too bad if you have, when you know how poor we are, and how little your father has had to do lately.”

“But don’t you see, mother,” said Jem, with a rather superior smile, “I mean to get something better, so that I shall be more real help. I’m sure I ought to be making more than four shillings a week, and I believe I can if you leave me alone.”

“Oh, yes,” put in Edie, who always believed in Jem, and took his part against the whole world, “he’ll soon find a better place, where he’ll get on—won’t you, dear? And he has stayed in this one a month now—that’s longer than he was last time, and next time he’ll stay longer still.”

Jack gave a sort of grunt that seemed to express disapproval, and the matter dropped until Bob came in a couple of hours later, very tired and not in the best of tempers in consequence.

“Father’s coming directly, mother,” he said. “I won’t have anything till he comes in, and then we’ll have a bit of supper together.”

[23]He sat down, and Bessie, the smallest and palest of the girls, climbed on his knee, and slipped her arm under his and round his back.

“Well, monster,” he said, for this was his nickname for the slight little creature, “how have you been getting on? Any news?”

“No,” said Bessie, “except that Jem’s left his place.”

“Left? What, have they sent him off?”

“No. He left of his own accord. He was tired of it.”

“Then he’s a miserable, selfish, stupid, useless creature, and for two pins I’d give him a thorough thrashing,” cried Bob. “Do you hear that, Jem?”

Madge tried to check his anger, as her mother was not in the room, but he would not listen to her.

“No, Madgie,” he went on, “I shall let him hear the truth for once in his life, as father’s so easy with him. He doesn’t deserve to have a home to come to when he behaves as he does, caring more for whether he likes his work, or whether he doesn’t, than for seeing[24] mother slave till she’s ready to drop. Do you think she likes toiling from morning to night to keep us all respectable and comfortable, or that father likes shouting himself hoarse all day before he can make people buy things for half what they’re worth, or that Madge enjoys sweeping the stairs and washing up the sauce-pans, or even that Jack or I like our work? You’re the only one that doesn’t seem to think it’s possible to do what you ought, whether you like it or not. You seem to think you were put into the world to enjoy yourself, no matter how inconvenient that may be for other people.”

Jem looked very cast-down, for he was fond of Bob, and liked to have his good opinion. Edie put in a word for him.

“Don’t be too hard on him, Bob. He’s much younger than you, you know.”

“I don’t think it’s possible to be too hard,” he answered. “I’m thoroughly ashamed of him.”

At this point Mrs. Kayll re-entered the room, and directly after the head of the family arrived, Madge having only just[25] finished setting the bread and cheese and cold bacon in readiness. Mr. Kayll was evidently tired out after the day’s hard work, but he had a smile and a nod for each of the young people in turn, and a kiss for his wife, who went to the door to meet him.

While he and his eldest boy ate their supper, Madge put the baby off to sleep in his cradle, and the three little girls said good-night and went to bed, Edie whispering to Jem as she passed him:

“Never mind, old boy, so long as father isn’t angry.”

When they were gone Mr. Kayll took out his purse, which he handed to Jack, with:

“Give that to your mother, Jacky. That’ll set her up for a little while.”

Mrs. Kayll poured the contents into her hand and counted ten sovereigns.

“All for me?” she asked.

“Of course it is. Make much of it. There’s no saying when the next will come.”

Jack took the empty purse to give back to his father, and turned it over in his hands, squeezing it, and pretending to try to find[26] some stray coin that had been overlooked, but really slipping into it two sovereigns of his own, which he had held in his hand for some time, looking out for an opportunity of getting them into his father’s possession without the act being seen.

Poor Jack, who was generally supposed to care very little about his family, had been saving for a long time, depriving himself of anything he could so as to put a little aside from his weekly earnings, and had at last been unable longer to resist the temptation of giving Mr. Kayll a surprise. Yet his face expressed nothing as he handed back the purse, which his father weighed in his hand with mock grief.

“Feels terribly light again,” he said, returning it to his pocket as he believed empty.

Jack laughed inwardly, imagining the expression of his father’s face when he should find the money, and be unable to guess whence it had come. He controlled his mouth, and kept a serious face then, but once or twice afterwards during the evening a[27] stifled chuckle proceeded from him, the meaning of which no one could discover.

Madge had come down again and was just about to put the food away, when there came a timid knock at the front door.

“THAT doesn’t sound like a creditor with a bill to-night,” said Mr. Kayll, laughing and rubbing his hands softly over his knees. “But if so, mother’s ready for him.” And he slapped his pocket meaningly. “Jack, my boy, you go and open. Your sister looks as though she’d done about enough for to-day.”

Jack obeyed. He opened the door rather doubtfully a little way to begin with, and then, hearing and seeing nothing, somewhat wider, when he saw before him a small girl, apparently about as old as his sister Edie.

[28]He looked at her, but she did not speak.

“What do you want?” he asked, after waiting a minute.

“Does Mr. Kayll live here?” she inquired then in a voice that trembled with nervousness.

“Yes, he does.”

“Could I see him?”

“I suppose so. Come in,” said Jack gruffly, and she stepped timidly inside, when he shut the door behind her and put his head into the sitting-room.

“Little girl wants to speak to you, father.”

“Little girl! What little girl? What’s her name?”

“She didn’t tell me.”

“Ask her then, my boy.”

Jack’s head disappeared, but reappeared almost directly, and he said:

“Amy Coleson.”

“Coleson!” repeated his father with a start of surprise. “Tell her to come in here.”

And the next instant Jack ushered in the visitor, who looked at the floor and seemed dazzled by the lamp-light which showed her[29] to be a pretty child with soft yellow hair and fair white skin, but poorly or rather miserably clad in a black frock worn through at the elbows and in many a place beside. She was so thin in the face, too, that it was quite painful to look at her.

Mr. Kayll took her by the hand, drew her to him, and kissed her.

“Well, this is a surprise!” he said. “Little Amy Coleson! Grown exactly like her mother, too, only thinner. Jack, bring her a chair. Mother, isn’t she like what Amy used to be?”

“Very,” said Mrs. Kayll, resting one hand on her husband’s shoulder, and thoughtfully looking at the child. “Dear, dear, how time flies! It must be eight years since we saw her last. Boys, you’ve heard of your father’s cousin Amy. This is her little girl.”

“And where have you dropped from?” Mr. Kayll asked next. “What brings you to us alone at nearly nine o’clock at night?”

“Mother was afraid I shouldn’t find you at home if I came earlier,” said the child, nervously twisting her hands together, and[30] letting her large blue eyes wander from one to another of the wondering faces around her, for Madge and Jem were staring at her without disguise, and Bob and Jack stole furtive glances every now and again.

“And how is mother?” Mr. Kayll asked, beginning to have some suspicion as to the meaning of this visit. “I haven’t even heard from her for years and years.”

“She’s not very well. She never is very well,” was the shy answer. “She always has such a bad cough.”

“And father?”

“Father died a long time ago,” she said simply, with a downward glance at her shabby and ragged black frock.

“Dead! Dear me! Tut, tut, tut!” said Mr. Kayll, very much shocked. “Poor child! Poor little woman! that’s very sad. Dear me!” he repeated, while his wife looked at the wan little figure until the tears came into her eyes. As for Madge, not being able to show her sympathy in any other way, she sat down and drew her little cousin on to her knee.

[31]“Mother sent me,” said Amy Coleson from that perch as she gathered more courage, “to ask you if you would lend us a little money, because we are so dreadfully poor, and—and baby’s so ill;” here her voice trembled, but she recovered herself directly and went on, “and we can’t get her anything she ought to have.”

Mr. Kayll looked grave.

“How old is the baby?” his wife asked.

“Three; but she can’t walk yet. She has never been strong.”

There was something very old and womanly about Amy’s way of saying this that showed plainly how she was her mother’s companion and help, and had lost her childishness in the anxiety of needing money, an anxiety that makes children old before they are grown up.

“And how many more of you are there?” Mrs. Kayll inquired, as her husband seemed to be still thinking.

“There’s Kitty,” she said. “That’s all; mother and Kitty, baby and me. Kitty’s only four.”

[32]“What have you been living on since you lost your father, my dear?” Mr. Kayll asked, suddenly looking up, for he had been staring very hard at the boards of the floor where they were visible through a hole in the carpet.

The little girl coloured faintly.

“Mother used to take sewing, but she has been so ill and so busy nursing baby that she hasn’t been able to do any. We haven’t had any money lately except what I’ve earned, but we can do with very little,” she concluded pathetically. And then guessing at the question that was coming, she added: “I’m a model.”

“A what?”

“I sit for painters to draw and paint me,” she said, “when they want me, but that isn’t always, and the last week or two I haven’t been wanted at all. And mother thought perhaps you’d help us a little until—until—I get something to do again, or mother is better and can take in sewing.”

Mr. Kayll stared at the boards again for a few minutes in silence. The child’s story[33] was a sad one undoubtedly, yet how could he help her with such a large family of his own? But again, when he compared the round healthy faces of his children with that of this pale sharp-featured little creature, and reflected that she was fatherless, and had already to support others by her own efforts, he felt that he could not refuse her request. Fatherless! What would become of his little ones had they not him to work for them?

“Madge,” he said rising, “get the girl a sandwich. She must be hungry after her journey. By the way, where do you come from? Where do you live now?”

“At Wingate Row, Bacton,” she answered.

“But you’re not going back there to-night?”

“Oh, yes, I am!” she said quickly. “I must. It isn’t much after nine, and it’s only half an hour’s walk.”

He asked her one or two more questions, then giving his wife a look that she understood, he led the way from the room, she following, when they had a little private conversation in the kitchen, leaving the visitor[34] to eat the sandwiches Madge brought her, and to be stared at by the wondering boys.

In the kitchen five pounds passed back into Mr. Kayll’s purse, as a result of the few words with his wife. Then they both returned and found Amy Coleson standing up, apparently anxious to be gone.

“Come, my child,” said Mr. Kayll. “I’ll take you home and talk to your mother myself; that will be the best way. When you’re ready I am.”

She coloured up to the roots of her hair with pleasure, for she had begun to think her visit was to have no result at all.

“I am ready now,” she said, raising her face to kiss first Madge, then Mrs. Kayll, and then laying her hand confidingly in his. “Good-bye,” and she glanced at the rest with a nod that was meant for them all at once, and began to move towards the door. Mr. Kayll lingered only to say good-night to the children, as they would be in bed before his return, and looked round at their bright faces with a smile. It was a pleasant picture, one that he would perhaps have looked at yet[35] once more if he had known that he would never enter that room again.

The next minute he and the child were gone. Then began a buzz of talk and wonderment, and Madge cleared away the supper-things with her head so full of other thoughts that she nearly put the cheese into the bread-pan and the loaf away on the same dish with the bacon.

AS Mr. Kayll and Amy Coleson walked towards Bacton, the little girl found her voice, and talked away fast enough in a sober old-fashioned way.

“We live in lodgings, you know, and we owe lots of rent, but Mrs. Smith is so kind, and says she doesn’t mind waiting a bit longer, and she knows we’ll pay it as soon as we can; and sometimes she brings us a little[36] beef-tea for baby, only not very often, because mother don’t much like it, and she don’t let her know how poor we are. Mother can’t bear for anyone to know. When father was alive it was quite different. I remember it very well; we lived at Barnes then, and there was only Kitty beside me until a little while after father died, and then baby came. She’s such a dear little thing with light yellow hair, and talks as plainly as I do nearly, and so patient—oh, she is so patient! But she can’t walk. We’ve tried so hard to teach her to walk, and once when she was stronger she nearly could, but then she got weaker afterwards and forgot it all again.”

Mr. Kayll was silently musing over this, noticing how the child always said “we,” as though she and her mother went together in everything, when a kind of sniff made him look down, and the light from the next gaslamp showed him that his little companion was quietly crying.

“Don’t do that, my dear,” he said kindly. “What’s the use? We’ll hope that the worst of your troubles are over now, though I don’t[37] know that I can help you much. Still, I’ll do what I can.”

Amy hastened to dry her wet eyes, as though ashamed of the tears, gulped down a sob, and in a few minutes spoke as cheerfully as at first.

“You all looked so happy and so bright and comfortable at your home. Such a lot of you, too! It must be nice to have brothers. And that big girl, too; I did like her.”

They walked on again without talking. Mr. Kayll would almost have forgotten his little friend but for the hand holding so tightly to his, and all the more tightly when they met some noisy party of men arm in arm, shouting and singing as they came.

“Are you tired, my dear?” asked Mr. Kayll after a while, as he felt that she lagged slightly behind him.

“Rather,” she answered, quickening her steps for a few minutes, but gradually falling back into her old weary walk, dragging her unwilling feet along, with her shoes, much too large, flapping the pavement at every step. “I have been out all day, and it’s getting so late.”

[38]And as she grew more tired she ceased to chatter. On and on they went along the broad road crowded with foot-passengers, past the shops that were still open and brilliant with flaring gas-jets. Once more only before they reached their destination Amy spoke:

“Isn’t it funny,” she said, looking up at her companion, “to see all these shops and the heaps of people, and to hear them shouting and laughing, and then just to lift up your eyes and there are the stars?”

“Very,” said Mr. Kayll without thinking about it, for he had other matters on his mind; and if he had thought about it, it would have seemed to him the most natural thing that the stars should be overhead all the time.

Amy was silent. It was her private belief that everything was very strange—the world, the people in it, and the sky above; but no one she knew seemed to look upon it in quite the same light.

On and on, then suddenly to the right, and down a darker street for some distance, then[39] to the left, up a narrower turning, and Amy stopped and said:

“This is Wingate Row, and here is our house.”

And a few minutes later Mr. Kayll was in a poorly-furnished room talking to a thin haggard-looking young widow, who was sitting beside a bed on which lay the sick baby with a face as white as the pillow. In the mixed pleasure and sadness of meeting his cousin again after so long an interval, and in such a way, he had no eyes to spare for anything else, and did not see the loving way in which little old-fashioned Amy bent over the invalid, softly kissing her, and whispering, “How are you, baby dear?”

She kneeled by the bed, holding the tiny white fingers, and doubling them up or opening them out, half playfully, half in forgetfulness of what she was doing, as she talked in a low voice meant only for baby’s ears.

“And now, my darling, you’ll soon be better, you know. Very, very soon. Shall I tell you where I’ve been? I’ve seen a lot of[40] boys, and such a nice girl. They called her Madge. Madge! What a funny name, isn’t it?”

“What was she like?” lisped the little thing, twining her fingers in her sister’s wavy yellow hair, and softly pulling.

“Big. Not pretty, but with kind eyes, and she kissed me, and made me sit on her knee as though I had been as little as you, baby. And she gave me some supper, and was so nice. I wish you could see her. She didn’t talk much. I don’t remember that she said anything at all. It was only her way of looking, and holding my hand, and smiling. And there was a big solemn boy, and a smaller one, and a smaller one still. I suppose Kitty has been in bed ever so long, hasn’t she?” And she glanced towards the door of a small inner room that opened out of this one.

The baby nodded.

Meanwhile a long, earnest conversation was going on behind them between their mother and Mr. Kayll. The children did not hear what was said, for it was carried on[41] in undertones, but the chink of coins reached their ears, and Amy’s eyes sparkled.

“If we had plenty of money, baby, how happy we could be, couldn’t we? But perhaps we shouldn’t be as fond of each other then as we are now; do you think we should?”

“Oh, yes, fonder,” said the tiny invalid, still playing with her sister’s curls that fell forward on the bed-clothes.

“I don’t so much wish to be very rich, and to have carriages and all sorts of beautiful things,” Amy went on dreamily, “but, oh dear! I should like always to be able to earn money if I worked hard, and to bring it home to you and mother and Kitty. But there isn’t any work to do. I believe the beggars, and the organ-grinders, and the girls selling flowers get ever so much more than we do. Oh, baby, I think it is funny that some people should have more money than they can possibly spend in all their lives, and we shouldn’t have any.”

The sick child’s blue-veined eyelids slowly closed. She could not understand all this, but the low sweet murmuring talk had[42] soothed her to sleep, with her fingers tangled in the long soft hair.

Amy dared not move for fear of rousing her, and continued to kneel there in silence with her eyes fixed on the sleeping face. Poor baby! Was it likely that she would ever get strong and healthy, here in this narrow, crowded court, where no fresh air ever seemed to come, and very little sunshine was to be seen? Would she not linger on month after month, perhaps year after year, a weak little cripple, who must be carried or wheeled about always, for want of air and sunlight and good things now, before it was too late?

As she wondered in her old, old way, the voices of her mother and Mr. Kayll buzzed on until the buzz became fainter and fainter, as though it were getting further and further away, until it was inaudible in the far distance.

Amy’s head had sunk on the bed, and she was fast asleep.

MR. KAYLL had heard the whole long, sad story of the struggles of his cousin, Mrs. Coleson, to keep her children and herself from starving. He believed that even now she would not have asked for help, but that the illness of her youngest child and her own failing strength had compelled her to do so much against her will. There was no one else to whom she could go, for her only other relation, Mr. Coleson’s mother, although she was well off, was a very hard and proud old lady, who had long ago refused to have anything more to do with her daughter-in-law. In consequence, though he could ill afford it, Mr. Kayll lent her five pounds that he had intended for the use of his own family. With that sum the widow would be able to get on for a while, and he could only hope that she would never be brought quite so low again.

“At least,” he said, as he rose to go, and[44] glanced at Amy as she slept with her head on her tiny sister’s pillow, “you have there a good and helpful little girl, who must be a great comfort to you.”

Mrs. Coleson smiled rather sadly.

“She is of more use than many a grown-up person,” she replied. “Poor Amy! It has been a hard life for her. She has scarcely known what it is to be a child.”

And then farewell for the present was said without disturbing the sleepers, and Mr. Kayll stood once more out under the stars. It was now half an hour after midnight. He heard a clock strike as he started homewards, feeling very sad and grave for him, for he was a man who was nearly always cheerful, even under circumstances that would have made most other people sit down and sigh over the hardness of their fate.

“Poor things!” he said to himself more than once as he went. “How altered! Poor Amy!” And by Amy he meant not the little girl but her mother, whom he had long ago known as a merry happy child, without a care or trouble in the world. It was no[45] wonder Mr. Kayll wished for once in his life with all his heart that he were rich, that he might put poverty and want away from these poor relations of his for ever.

The appearance of the streets had quite changed since he came. The shops were now shut, and the foot-passengers had nearly all gone. Only the policeman was still on his beat, and a few stray late people were hurrying home to bed.

Mr. Kayll thought of his wife sitting up tired and half asleep, and wondering what kept him so long, and this thought made him hasten his steps more and more until he was almost running.

All at once, as he was passing a closed shop, the door was suddenly thrown open, and a man dashed swiftly by him. Without noticing this much, he was keeping up his own steady trot, when he heard someone else running behind him, and the next instant a big powerful man had caught hold of him by the collar, and a voice said in his ear:

“I’ve got one of you at any rate! Police! Thieves!”

[46]Mr. Kayll tried to shake off his grasp, but he found this was impossible, so gave up the attempt and stood still.

“Nonsense! What do you mean? What’s the matter?” he asked.

But the man, who had no hat on, and was not completely dressed, shouted again loudly, “Police! Thieves!” while, unseen by either of them, a third man crept out of the same shop-door, and glided quietly away in the opposite direction. Then two policemen came up, and much to his astonishment and anger Mr. Kayll was given into custody.

“It’s absurd!” he said indignantly. “Why, I haven’t twopence about me anywhere.”

But he might say what he liked; it was all of no use. The man without a hat declared that he had broken into his shop, in company with another man who had escaped.

And this is the paragraph that came out in the papers afterwards:

“Robert Kayll was charged with being concerned, with another man not in custody, in burglariously breaking and entering 4050 Queen Street, Bacton, and stealing two[47] sovereigns, the property of Henry Brown, jeweller. Henry Brown, of 4050 Queen Street, said he saw the house closed on Monday night at half-past eleven o’clock. At about ten minutes to one he was disturbed by a noise down-stairs, and saw two men walking out of the street door. The prisoner was one of the two men. Witness ran after them, caught hold of the prisoner, and called out ‘Police.’ The other man ran away. He held on to prisoner till the police arrived, when he gave him into custody. Witness then examined the premises, and found that a cash-desk had been broken open, and that four pounds had been taken. Two of the missing sovereigns were found on the prisoner.—The prisoner said he was passing the door, and the prosecutor ran out and caught him. He had no idea how the two sovereigns came into his possession. He was committed for trial.”

“JEM, you had better go to bed, and you too, Jack. It’s very late, and I don’t suppose father will be home before twelve. A quarter past eleven! That’s too late for all of you.”

It was Mrs. Kayll who spoke, looking first at the clock and then round at her sleepy children. Madge was nodding, Bob stifling a yawn, and Jack and Jem both appeared much too wide-awake to be natural.

Jem made a grimace.

“Oh, no, do let us stay and hear all about it,” he said in imploring tones.

Jack, however, rose at once.

“All right, mother; good-night.” And he went straight upstairs in the dark, for candles by which to see to undress were a luxury not indulged in by the Kayll children.

“It’s all very well for Jack to go, you[49] know, mother,” said Jem, who was not inclined to yield without an argument, “because he has to be up early and off to work; but I haven’t, until I get something else to do, so I may just as well sit up and keep you company. Send Bob and Madge instead.”

Mrs. Kayll looked up with a slight smile.

“I don’t want any company, thank you,” she told him. “I get quite as much as I need—rather too much, sometimes. And I don’t think it’s good for you to be up till twelve, dear.”

“It won’t hurt me for once,” said the boy quickly.

“Why can’t you go to bed when mother tells you?” muttered Bob, who was preparing to go himself. “What’s the good of bothering her and making such a fuss?”

Jem fired up angrily.

“You be quiet, Bob. Nobody spoke to you. I may stay, mayn’t I, mother?”

“No, no, no,” repeated Mrs. Kayll firmly, shaking her head. “Go to bed, all of you, and get a good rest, ready for the work of[50] to-morrow. Father will be tired, and I’m sure he’d a great deal rather find you all gone and the house quiet. Do go, there’s good children.”

Madge folded up her work, kissed her, and went. Bob followed her example; but still Jem lingered, sitting so silent that his mother thought he had gone, and sewed on industriously until some slight sound he made caused her to start and look up.

“Dear me, Jem! What has come over you? You heard what I said a few minutes ago.”

“I didn’t suppose you’d really mind, mother. Besides, I want to tell father about leaving Mr. Graves’s, and to ask him what I’d better do next.”

“Jem! How thoughtless you are, to be sure! Now, do you think, when father comes in tired, as he certainly will be, between twelve and one at night, he will want to be worried by your affairs? There, no more, Jem. Go along at once.”

Very slowly and reluctantly, and wearing a sulky expression which meant that he thought himself ill-used, Jem departed,[51] though all the time he was so sleepy he had hardly been able to hold his eyes open for a quarter of an hour past.

Edith and Bessie were sleeping soundly when Madge went up. She stood for a few minutes looking at them, as they lay side by side, for there was enough moonlight to show their faces quite plainly to eyes that had grown accustomed to the darkness.

“How pretty they are like that!” thought Madge, with an elder sister’s affection. “What dear little things they are too, in spite of their faults, when one comes to think about it!”

Then she undressed, said her prayers, and crept in beside Bessie, so weary after seventeen hours of hard toil that almost as soon as her head touched the pillow she was in a dreamless sleep.

Before long the whole house was wrapped in a peaceful stillness, as one after another of its occupants lay down and forgot all fatigues, anxieties, longings for money, aches and pains, in pleasant visions or calm unconsciousness.

[52]And the poor mother down-stairs? She drew the lamp nearer, now that there was no one else to share its light, and stitched away at her mending, the click of her needle on the thimble being almost as regular as the “tick-tack” of the little clock on the mantelpiece.

Ungrateful little clock that it was! It had always been treated well and kindly, and wound up every night, in spite of its not telling the exact truth, and now Mr. Kayll had just cleaned it, oiled its works, and set it going again; yet, such is the ingratitude of clocks, it set itself to work to make poor Mrs. Kayll uncomfortable, by compelling her to notice how fast the time was going. It would not even strike twelve quietly, but gave a warning growl first, to attract her attention, and then hammered out twelve distinct “tings,” that sounded twice as loud as usual.

“He must be here soon,” said Mrs. Kayll, taking a fresh needleful of cotton, and trying to go on with her work; but somehow or other the needle would not go in at the right place, and Mrs. Kayll’s head drooped[53] forward slowly more and more, until her chin rested upon her breast.

She, too, was asleep. The clock at once seized this opportunity, and rushed on as fast as it could go, the big hand hurrying round its face and the little one creeping steadily after. Half-past twelve. She did not move. The hands hurried on, and suddenly the tired mother started awake, roused by a loud warning sound, in time to hear it strike “One.”

“Good gracious!” she exclaimed, springing to her feet, rubbing her eyes and staring hard at the clock, before she could believe. “One! How late he is! I must have been nodding.”

She walked up and down the room a few times, to wake herself more thoroughly; and then again tried to go on with her work, thinking meanwhile of the little girl and her sad story.

“They are keeping him long,” she said to herself; “but there’s no saying how much worse he may have found matters than he expected. Possibly they are in such great[54] trouble that he cannot bring himself to leave them. Poor Robert! How worn out he will be!”

Stitch, stitch. And then the drowsiness came back, and the clock made haste, and succeeded in striking two without waking her. She awoke, though, at a quarter past the hour, put away her work, and walked to the door to stand looking out into the street.

It is very painful to wait and wait for someone you expect, who does not come. At first you are surprised, then astonished, then you begin to be anxious, after which, if the expected person is one for whom you care much, you become seriously frightened, and imagine every terrible thing that could possibly have come to pass.

So it was with Mrs. Kayll. At three o’clock she fancied her husband must have been run over, or have met with some other accident, and before long she determined to wait no longer, but to go out and look for him.

She went upstairs, the first thing, bent[55] over the bed where Madge was sleeping, and gently shook her by the arm. The girl opened her eyes in an instant.

“Hush, Madge! Don’t wake the others, pray.”

Madge sat upright, staring at her mother with a bewildered expression.

“Do you hear me, child? Are you awake?”

“Yes, mother. What’s the matter?”

“Father hasn’t come home!”

Madge stared at her still, evidently not quite understanding.

“Why—what time is it?” she whispered.

“A quarter past three or more.”

“Oh, mother!”

“I want you to dress quickly and come down, so that you could open the door if I should miss him, and then I’m going to look for him,” Mrs. Kayll said hurriedly, but without raising her voice above a whisper, so that the others slept on undisturbed.

Madge stepped out on to the floor and began to put on her clothes.

“I don’t think you need be so frightened,[56] mother dear,” she said. “So many things might have kept him. Perhaps the baby that the little girl said was so ill, was worse, and father thought it would be cruel to come away. Or the mother may be worse, so that he could not leave the children. Or perhaps there may be a fire somewhere, and father is stopping to see it. You know how fond father is of looking at fires.”

These solutions of the puzzle had already occurred to Mrs. Kayll, but yet they seemed more possible when suggested by someone else.

“Well, dear, it can’t do any harm for me to go and see. The worst that can happen is that your father may laugh at me for being so anxious about nothing. Come down as soon as you’re ready.”

And, thinking it safer, not to talk there any longer, she went and put on bonnet and shawl, and again took up her position at the front door.

In a few minutes Madge was at her side.

“What are you going to do first, mother?”

“I am going to find the address Amy[57] Coleson gave us—Wingate Row—to see if he is there, and, if not, whether he has been there, and at what time he left. If he comes home, Madge, tell him how it was, and that I am sure to be in soon.”

And with these words her mother hurried away, and the girl was left to keep lonely watch, and to stifle her fears as well as she could. Fortunately for her, Madge had not such a quick imagination as her mother.

IT was Madge’s custom to be up and have the baby dressed at half-past six, and breakfast ready at a quarter past seven, Mrs. Kayll nearly always coming down about the same time as she did, and sharing the work of preparing the meal, though Madge used to try to get it done without waking her. The boys were always the next to make their[58] appearance, as they had to start early for work.

On this particular morning, after the night of useless waiting and watching, the meal was spread, the baby sitting in a corner trying to wear some teeth through his gums by means of a bread-crust, and Madge was sharpening a knife ready for cutting the bread, when Jack descended from above, whistling as he came.

“Morning, old girl,” said he in cheery tones. “What time did father get home?”

His sister was very pale, with red eyelids, and many unmistakable signs of having cried a great deal not long since. Jack was not given to showing much affection—in fact he showed so little that he was not supposed to feel any at all. Therefore it was only “like him” that he should simply stare at her blankly when he observed these signs, and say:

“Hallo! What’s up?”

Madge’s only answer was “Oh, Jack!” in a broken voice, as she turned away her head for a minute.

[59]Jack still stared in wonder. Had father not come home at all? Had—why did Madge look so strange? All at once something much worse than the truth flashed into his mind. The colour left his ruddy face in an instant, leaving it ashy white, and he stood gazing at her, with a sudden horror turning him cold and sick. He could not speak again, but sat down by the table and waited for what was to come.

“Oh, Jack,” she repeated in the same half-choked tones, “poor father!”

The boy tried hard to ask something—“How—what—?” and his lips parted, but no sound came.

“Mother sat up for him till nearly half-past three,” Madge went on, overcoming her emotion enough to be able to cut some bread and butter, and never dreaming for an instant what was passing in her brother’s mind, and what unnecessary misery she was making him suffer. “Then she woke me, and I came down, while she went to try and find out what had become of him.”

The memory of her lonely watch was really[60] in great part what caused Madge’s voice to tremble and her eyes to fill, but as Jack knew nothing of this he was quite unprepared for her next remark:

“And what should you think? He has been taken up by the police for a burglar, and is locked up.”

The boy still said nothing, for he had hard work to keep back a burst of laughter. Locked up! Was that all? And he had been fancying—but here he checked himself, and set his teeth until the desire to either laugh or cry was gone. To Madge’s surprise he turned on her angrily the next moment.

“What on earth is there in that to make such a fuss about? I suppose they’ll soon find out their mistake and set him at liberty again.”

He swallowed some tea, took a bite or two of bread and butter, and, before she had got over her astonishment, had snatched up his cap and run off.

“What an unfeeling boy!” Madge said to herself when he was gone. “He doesn’t seem to care a bit for anybody. How different from Jem!” For Madge was one of those[61] who judge people by their manner and appearance, and are not in the least able to see below the surface.

Then down came Bob and Jem, who had slept the night through, and were quite unprepared to hear that anything uncommon had happened. Madge had to explain again, and after his first surprise was over, Bob’s first thought was for “the mother,” as he called her.

“Where is she?” he asked, as she did not make her appearance.

“I persuaded her to lie down, as she was up all night. And she can’t do anything now but wait.”

“Fancy poor father locked up in the police station!” said Jem, looking inclined to shed tears, which evidence of feeling was set down to his credit by Madge, but had quite the contrary effect on Bob.

“Look here, Jem,” said he sharply, “don’t go and make things worse by behaving like a girl. Set to and find some work, so that mother hasn’t the worry of knowing you’re doing nothing as well as her other troubles.”

[62]“If you think I’m going to stir out of the house before I see father safe back again, you’re very much mistaken. I care more about him than I do about a shilling or two—so there,” Jem returned with a mixture of sulkiness and obstinacy.

Bob shrugged his shoulders, and addressed Madge without taking any more notice of his brother.

“I suppose I had better go to the office as usual, and do the best I can without father, in case he’s wanted,” he said. And he too hurried away.

Then the little girls came down, and had to be sent off to school without being told anything, except that father was out, in accordance with Mrs. Kayll’s wishes, after which there was no one at home but Madge, Jem, the baby, and their mother.

There was so much to do during the morning that the elder sister had no time to be miserable, and somehow Bob’s view of the matter had made her feel much lighter hearted. It was a mistake which would be set right very shortly, and father would come[63] home in the course of the day, and laugh with them over his amusing adventure. She found herself singing over her work later on, after her mother had gone out to be present at the hearing of the case, and would not even be depressed by Jem’s solemn eyes which followed her about full of surprise and reproach.

But her singing did not last long, for baby was extremely fretful, and would not sit on the floor and watch her as usual. He whimpered and fidgeted, and was not in the least amused by Jem’s attempts at playing with him. In short he was so tiresome, for a good-tempered baby, that Madge felt sure he could not be well, and carried him about with her on her left arm, while she dusted the rooms, and made the beds as well as she could with her right hand alone, feeling not a little anxious all the time on the little brother’s account. Suppose he should have “caught something,” how dreadful it would be!

JACK reached home again a little before six, and, just because he was in a fever of anxiety to know whether Mr. Kayll was at home again, kept strong guard over himself, and walked in as coolly as usual, for he found the front door open.

His eyes glanced quickly round the little parlour as he entered. His father was not there, and, moreover, there was such a cloud of gloom upon everyone that the courage he had been keeping up all day suddenly left him, and his heart sank with a leaden weight. What did this mean? What new misfortune had happened?

Tea was spread, for in trouble or joy children at least must eat. Besides, Madge had found relief from mental excitement in going about her usual duties, poor girl. She was now walking to and fro, with the baby lying quietly in her arms, its little face looking[65] very hot and flushed. The child certainly had all the appearance of sickening for some complaint.

Edie and Bessie were just taking their places at the table, hungry enough to be able to look calmly on any prospect but that of being deprived of food. There was plenty of bread and dripping at all events, and they had had but little dinner.

Mrs. Kayll was occupied in trying to console Jem, who would look on the worst side of everything, and was very unhappy in consequence.

“What’s the news?” asked Jack in a low voice of Madge. “What about father?”

“He’s remanded for a week,” said Madge, stopping before him and rocking herself from one foot to the other. “That means that we shall have to get on without him as well as we can for all that time, though I don’t know how we shall manage to do it.”

“But can’t anything be done?”

Madge shook her head.

“It seems not. And mother says she must get a lawyer to defend him, even if we[66] have to live on bread and water; or else there’s no saying what might happen.”

Jack gazed at her silently for a minute. Then he asked:

“Has mother got any money?”

“Yes, but not much. Father gave a lot to those Colesons.”

“H’m. I think we boys ought to be able to earn enough to live on somehow. I can do with very little myself. What’s the matter with baby?”

“I don’t know. He doesn’t seem at all right, poor darling.”

They both looked round, for Mrs. Kayll had come to the table, and was cutting bread, and talking to the little girls meanwhile.

“We must try and not make ourselves unhappy,” she said. “There are so many worse troubles than this. All we have to do is to be patient, and to be as careful as possible over every halfpenny. You three must stay away from school for the present, and Jem must contrive to get something to do, and with one thing and another I daresay we shall get on pretty well.”

[67]“But how was it?” cried Jack. “How could they mistake father for a burglar if he told them his name, and his business, and where he came from, and everything? It’s so absurd.”

“Not altogether so absurd as you think,” his mother answered. “There he was passing the shop that was robbed at a time of night when very few people are out; and though he said he hadn’t a penny about him, when he was searched there were two pounds in his purse. It is very odd, certainly, for though your father took five sovereigns with him, he lent them all to Mrs. Coleson, and he couldn’t account for how he came by those other two in the least. No more can I. If it hadn’t been for them, I believe he would have been here now.”

Jack listened to this with a rapidly paling face. What he had meant for a pleasant surprise had turned out a most unpleasant one after all; his little joke had very likely done all the mischief. He had been denying himself, scraping and saving for months, working extra hours when by that he could[68] earn a few more pence, and all for this! All to send his own father to prison for a week, and to cause a great deal more than what he had saved to be spent on proving him not guilty of theft. As these thoughts came clearly before him, he stole unnoticed from the room, and went upstairs to sit down in a chair by his own bed and cry as he had hardly cried since he was a baby.

Down-stairs his absence was soon noticed.

“Where’s Jack? He must want his tea,” said Mrs. Kayll.

“I think he went upstairs,” said Madge sighing. “He scarcely stopped to hear about father. He takes things very calmly, does Jack.”

Bessie coloured at Madge’s tone, and became her favourite brother’s champion.

“Jack is too sensible to make a fuss when it won’t do any good. He’s as sorry as anybody else, I know.”

“Well, go and tell him to come to tea, Bessie,” said her mother.

The little girl went at once, and found poor Jack with his face in his hands sobbing.[69] She was quite awe-struck, never remembering to have seen him shed a single tear—her brave manly brother, fourteen years old, who if he hurt himself only whistled, if he were scolded took it in silence, if he were ill kept the fact to himself until somebody found it out. Her Jack—crying!

She was half inclined to creep away again, feeling as though she had no business to have found him out, as he had come away here alone. But altering her mind she went and wound her arms round his neck, kissed him, called him her “dear old Jack,” dried his eyes with her own pocket-handkerchief, and cried too.

Jack sobbed on for a few minutes, then suddenly sprang to his feet, dashed his sleeve across his eyes, and tossed back his hair.

“I won’t!” he said. “What’s the good? Don’t tell them, Bessie. I’m worse than a girl!”

“And they all say you don’t care!” murmured his sister half to herself.

“Let them!” Jack returned proudly, pouring out some cold water and washing his face[70] vigorously till the marks of tears disappeared, and the redness was not only in his eyelids but everywhere else as well. “Does it show? Will they suspect me?”

Bessie shook her head.

“There’s no fear of that. If you went down with the tears standing on your cheeks they’d only think you’d been laughing.”

Jack seemed relieved by this view of the case, and stood for a few seconds thinking, whereupon all his composure vanished, his lip quivered, and a fresh rush of tears came to his eyes. He turned quickly away, fighting to keep them back, while Bessie took his hand and held it, puzzled and half frightened.

“Is it all about father?” she asked timidly.

“It’s all,” began the boy, choking back a sob, “because I was such a great stupid idiot! Don’t tell the others, but those two pounds were mine. I worked so hard, and saved them—to please father when he was hard up, and then instead of just giving them to him and saying so, I must put them in his purse for a joke, and make no end of mischief.”

[71]“Never mind, Jack. It can’t be helped. And they can tell the magistrate so, you know, and then it will be all right.”

“Not for a week!” groaned Jack, washing his face again. “There! That’s over!” he added, drying it vigorously. “You won’t see me make such a goose of myself again in a hurry. Bessie, if you tell anyone I’ve been crying I’ll never forgive you.”

“TROUBLES never come singly,” said poor Mrs. Kayll as she took her youngest child from Madge’s arms, and looked uneasily at its flushed face. “If he keeps like this, we must send for the doctor. I can’t understand it at all.”

The time was about half-past six in the morning, and Madge had been holding the child while her mother dressed. Both the[72] mother and daughter had had their rest broken by the baby’s fretfulness, as he woke up and cried at intervals the whole night through, and first one, then the other, had risen to walk about with him, trying to soothe him to sleep.

It was with a sinking heart that Madge lighted the fire and set the kettle on to boil before breakfast. Was everything going wrong all at once? But she put on as cheerful an expression as she could, and nobody expected her to be merry, as it was not in her nature.

Everything felt uncomfortable this morning. The girls were to stay away from school, as their mother did not want to spare the money for them, and with Jem there as well the house seemed too full. Besides, both girls were so anxious to be of use that Madge, in hurrying to and fro, tumbled over them in all directions. They dusted the rooms, they made the beds, they came constantly to Madge with the question, “What shall we do next?” till she was nearly distracted. Yet she racked her brains every time for[73] something for them to do, knowing that they would be still more trouble if they were idle. One idle person was bad enough!

“Jem,” said she, as she washed up the breakfast things, “aren’t you going to see after some work?”

Jem, who was sitting on the table swinging his legs to and fro, and looking very dismal, nodded assent.

“Because, you know, if you could earn ever so little, it would be a help; I suppose Mr. Graves would give you a character.”

“Yes, Madgie,” said the boy; “I’m going soon, but I must wait until baby’s better. I can’t go away while he’s so ill.”

“But you won’t do him any good by staying at home.”

“Perhaps not, but I shouldn’t feel satisfied to be away until I know what’s the matter with him. Besides, I might be wanted, you know.”

Madge compressed her lips, feeling more inclined to be angry at what seemed only selfishness, than to admire him, as she usually did, for his affectionate disposition.

[74]“Bob and Jack are gone,” said she.

“They were obliged. And I don’t think they mind so much,” was the answer.

The day passed very slowly, and everyone seemed to find it too long. Mrs. Kayll came down, and attended to various duties with the baby always in her arms, as she did not care to part with him, even to Madge.

“He keeps just the same,” she said in the afternoon. “I don’t think he looks any worse.”

Madge caressed the little one’s cheek. She felt half inclined to cry when she saw the small face quiver as if with pain.

“He doesn’t understand it, poor little fellow,” she said. “I think he wonders why we don’t help him, and make him feel well again.”

“It’s a good thing father doesn’t know,” said Jem, who was looking on. “How anxious he would be!”

Meanwhile Mrs. Kayll was turning over a question in her own mind. Should she send for the doctor, or should she wait a little longer? She could not afford to pay him, as it had taken more than she knew how to[75] spare to pay for someone to defend her husband—a matter that she had arranged on the previous day. The lawyer who had taken the case in hand had told her she need be under no anxiety, as all was sure to go well. There would be no difficulty in proving that Mr. Kayll had been arrested in mistake, with the evidence of Mrs. Coleson to show where he had been, and that of Jack to explain his possession of the money, while plenty of people could answer for his being a respectable auctioneer, and the last man in the world to be mixed up in a burglary, so that Mrs. Kayll was as much at ease in her mind on that score as she could be while her husband was still detained.

The evening found no change in the baby. He sat up for a few minutes once or twice, amused by something Bessie brought to attract his attention, but his heavy head soon sank back on his mother’s breast, and he would seldom rouse himself and look round.

Bob came in at his usual time, ate his supper, and then went to Mrs. Kayll with an air of determination.

[76]“We can’t let you knock yourself up, old lady,” he said, firmly but gently taking the sick child from her. “You are making yourself ill. Now, sit in the arm-chair and rest—and Madge, get a pillow to make her more comfortable.” And Mrs. Kayll yielded, though she had refused again and again to let Madge relieve her, and dozed off to sleep, while the big, rough boy walked patiently to and fro, to and fro, with his tiny brother cradled in his arms.

The baby seemed fairly comfortable in its new position, and was quiet as long as the regular movement went on. Madge kept the others quiet, and soon sent them to bed, for the poor exhausted mother was now in a sound slumber, and they all felt it a duty not to disturb her rest.

Bob walked on with untiring patience, as one hour crept after another and vanished for ever, refusing Madge’s offers to “take baby,” and trying in a whisper to get her, too, to go to bed. Once or twice he sat down until the child began to be restless, when he went on with his steady pacing as regularly as a machine.

[77]It was nearly three when Mrs. Kayll started up, cramped from sleeping in a chair, and looked in a horrified way at the clock.

“You poor children!” she whispered. “Why didn’t you wake me? Poor boy! how tired you look!” And she kissed Bob’s forehead as she relieved him of his burden. “Come, Madge, we will go upstairs, and get what sleep we can.”

Madge followed her, with a new idea making its way into her slow brain. For the first time she was beginning to see what virtues that we never suspect may be hidden under a rough and uncouth appearance, virtues that only come out when there is trouble or care to call them forth.

The next morning was much like this one over again, until breakfast was finished, and the two boys gone. Jem was still lounging about in idleness, when there came a call from above.

“Madge!”

“Yes, mother.”

“Send Jem for the doctor—quick!”

The boy did not wait to be sent, but[78] snatched up his cap and darted off. His sister ran upstairs.

“What is it, mother? Is he worse?”

The baby was still lying quietly on Mrs. Kayll’s lap—not flushed now, but extremely pale. Madge drew near and spoke to him; but though he opened his eyes he did not seem to see her, but gazed out with a curious blank stare.

“Oh, mother!” cried Madge, clasping her hands, “I don’t believe he knows me. Baby, it’s Madge. Baby!”

Mrs. Kayll’s forehead wrinkled itself into upright lines.

“It’s very strange,” she said slowly. “I am getting rather frightened, though I thought at first this morning that he was better.—No, go away, dears,” for Edie and Bessie were peering in at the door. “I am going to keep him very quiet for the present.”

“Mayn’t we come and kiss him, mother?” asked Bessie imploringly.

“Not yet. Not till the doctor has seen him.”

The little girls went unwillingly back to their work, and Madge knelt on the floor by[79] her mother, still trying to attract the little one’s notice, but in vain.

“Do you think it’s some illness—something catching?”

“I can’t tell, dear. It doesn’t look like it.”

They were silent, listening anxiously for Jem’s return.

“You see, Madge, he won’t eat, and he can’t go on like that. He has hardly swallowed any food since the day before yesterday.”

Before long Jem came flying back, scarlet with running, panting, and out of breath.

“Doctor will come as soon as he can,” he told them—“most likely in an hour or so. Can I do anything, mother?”

“Nothing,” she answered, scarcely taking her eyes from the pallid little face. “Nothing but keep quiet, and get the others to be quiet too.”

Very still the house was for the two hours before the arrival of the doctor, for whom all were so anxiously looking. And all the while the baby lay in that listless state, recognizing nobody. The children spoke in hushed voices,[80] and whispered to each other that they wondered what father would say if he knew, and that they did wish he were at home. For the household pet had scarcely had a day’s illness, and had seldom been even what the nurses call “fractious.”

At last. The doctor had come. He was a thin clever-looking young man, who seemed as though he had known all of them since they were born, and who touched Bessie’s soft hair as he passed her on the staircase, and clapped Jem on the shoulder when he let him in.

He was a long time shut in the bed-room with Mrs. Kayll and the baby. The children, waiting about outside, could hear his voice, as he asked a number of questions, followed by their mother’s low-voiced answers. Then, all at once, he came out, and found their four eager faces waiting for him.

“Nothing catching,” he said smiling. “I’m going to send him some physic, and he’ll be ever so much better to-morrow.”

“HE seemed to think baby had got at something poisonous, and sucked it—paint or dye of some kind,” said Mrs. Kayll afterwards to Madge. “It’s impossible to say he hasn’t, when he puts everything he comes near into his mouth. One can’t always have one’s eye upon him. What do you think, dear? Does he look any worse—or a trifle better? I don’t know myself, I’ve been looking at him so long, but I almost fancy there is a little improvement.”

It was again towards evening, and, so slowly does time seem to go when anything occurs out of the common course of events, the children began to feel as though their father had been absent for years instead of only three days. Madge herself felt almost as though she had grown older in that short time. There were actually lines in her smooth brow as she examined the baby, for[82] the difference she could not see. She kissed the small white hand that lay so listlessly over her mother’s dress, and the thick drops clouded her eyes.

“Oh, baby, baby!” she sighed, with a chill of dread creeping over her, as she found that he still seemed neither to see nor hear. “Mother, I wish it were any one of us but him, for we could at least tell how we felt. I wish with all my heart it was me.”

One by one the children went to say good-night—each more tired by doing nothing in particular than by the usual lessons or work. Each kissed the baby’s white cheek, and stole softly away to bed, scarcely speaking; and again Mrs. Kayll and Madge were left to watch and sleep in turn through the night hours.

There were only three bed-rooms in this little house where the Kaylls lived, for, when people are as poor as they were, they have often to crowd into a small space. In fact, they would not have been able to afford a house to themselves in the outskirts of London, but that they had this one very[83] cheaply from its many disadvantages. For one thing, it was so old that it was not considered very safe, while the one adjoining it was really so unsafe that it had not been inhabited for some time. Then it stood so much below the road that it was damp, and the wall-paper used to peel off in places on the ground floor.

Of the three bed-rooms one belonged to the boys, one to the girls, and the other to Mr. and Mrs. Kayll and the baby.

The boys had gone early to bed that night, Bob and Jack so thoroughly tired out that they quickly fell asleep, the latter to dream that his father came home and caned him well—although Mr. Kayll had never caned anyone in his life, and probably never would—for his foolish little joke which had done so much harm. For, though no one had said a word of reproach to him on the subject since his part in the affair became known, Jack blamed himself bitterly, and was at the bottom of his heart extremely unhappy, but at the same time much too proud to confess the fact, or even to let it be guessed from[84] his manner or appearance. Only Bessie seemed to understand, and was very loving to him in consequence in her shy little way.

Yet, as a matter of fact, though he had helped to bring about this trouble that had fallen on the whole family, Jack was not more unhappy than Jem, who lay long awake, restless and dissatisfied with himself, wishing that he had not thrown away his situation for a mere whim; that he had tried for another; that his father were back; that the baby were not ill; that they were all better off; wishing and wishing, until his wishes gradually faded into uneasy dreams, and his dreams into a complete blank.

In the girls’ room there was one more wakeful still—little Bessie, whose mind was very active, as is often the case with delicate people. She lay wide awake, hour after hour, her small brain busy with one thing after another, until she felt too nervous to lie still, stepped out of bed, and began to dress.

For Bessie had taken it into her head that she was being deceived for her good, and that her little brother was really dying.

[85]“They say he will be better in the morning, and they mean that all his illness will be over, and that he will be a little angel,” she said to herself. “And father will never see him again.”

And the tears crept quietly down her cheeks as she put on her clothes. If she could not sleep it would be better to be up, and then she should hear what was going on. She loved her baby brother so dearly, and perhaps he would never again smile at her, never again prattle to her in his pretty unintelligible way, which she always fancied she understood—she hardly thought anyone understood or loved him as she did. Well, there was one way.

She kneeled down by her bed, folded her hands, and closed her eyes, while her lips moved softly for some time, though she only said the same simple words again and again.

At last she stood up, dried her eyes, and went to the window to look wistfully up at the stars. Poor little Bessie! she loved every one she knew so much that her only great wish was that she and her father, mother,[86] brothers and sisters might all die at once, and so no one be left lonely upon earth.

A sound from down-stairs made her start and go to the door to listen. Somebody was certainly up and moving about. Who could it be? She peered out and saw that her mother’s door was shut, while a streak of light beneath told that a candle was left burning. At the same time from the room occupied by the boys came to her ears something very like a snore.

“Who is it? It can’t be a thief, because he would know that we are too poor to have anything worth stealing. And yet—”