Tom stood up occasionally and chatted with the other two.

Title: Tom Slade on Overlook Mountain

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Illustrator: Howard L. Hastings

Release date: May 5, 2019 [eBook #59439]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

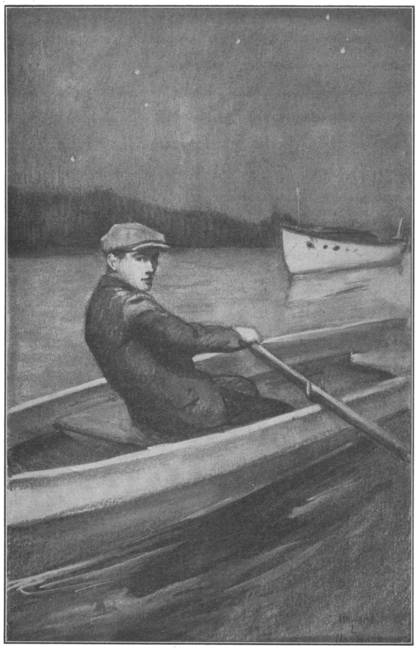

Tom stood up occasionally and chatted with the other two.

| I | TOM |

| II | HERVEY WANDERS INTO THE STORY AND OUT AGAIN |

| III | THE BOAT |

| IV | THE STRANGER |

| V | THE CUP OF SORROW |

| VI | THE UNKNOWN FRIEND |

| VII | IN THE WOODS |

| VIII | THE DERELICT FINDS A PORT |

| IX | AT CAMP |

| X | ON THE TRAIL |

| XI | OUT OF THE PAST |

| XII | ANOTHER GLIMPSE OF THE GOODFELLOW |

| XIII | TOM GETS HIS WISH |

| XIV | THE JOB ON THE MOUNTAIN |

| XV | ON THE WAY |

| XVI | NEW FRIENDS |

| XVII | VOICES |

| XVIII | ON THE JOB |

| XIX | TOM AND NED |

| XX | AN ACCIDENT |

| XXI | THE FACE IN THE STORM |

| XXII | THE OBSCURE TRAIL |

| XXIII | TOM AND AUDRY |

| XXIV | GHOSTS OF YESTERDAY |

| XXV | AT TWILIGHT |

| XXVI | TOM IS TROUBLED |

| XXVII | THE CRIMINAL |

| XXVIII | IN CONFIDENCE |

| XXIX | THE ONLY WAY |

| XXX | THE DEPARTURE |

| XXXI | TIME |

| XXXII | ALONE |

| XXXIII | GOODFELLOW |

| XXXIV | THE BOAT ROCKS |

| XXXV | LAST WORDS |

| XXXVI | HOMEWARD BOUND |

| XXXVII | THE BRIGHT MORN |

| XXXVIII | T. S.—A. F. |

| XXXIX | “HERE’S LUCK” |

If so it chance that you live in the city of New York and should, let us say, stop for a cooling drink of water in the interval of a ball game, pause for a few moments and consider this strange story of old Caleb Dyker and perhaps the water will not taste quite so good to you.

Old Caleb Dyker had never seen the great city of New York; he had never in all his life been away from the little village of West Hurley until he was put out, thrown out, or rather until his little village was taken away from him by the great city of New York.

If it is a good rule never to hit a fellow under your size, then the great city of New York is not a very good scout, for it knocked the poor little village of West Hurley clean off the map.

And that was because the great city of New York wanted a drink of water.

So poor Caleb Dyker, dazed and bewildered at this pathetic eviction from all that was near and dear to him, became a tramp and wanderer. And that is how Tom Slade fell in with him.

Tom Slade himself had something of the spirit of the tramp and wanderer. He was assistant at Temple Camp, the big scout community in the Catskills, and was the hero of every boy who spent the summer there. But he was restless. Perhaps his service overseas had made him so, and at the time of this singular chain of happenings the roving spirit was upon him.

Yet it is unlikely that he would have gone away from Temple Camp, that year at all events, if he had not fallen in with the queer personage who all unwittingly gave impetus to his dormant wanderlust.

It is funny, when you come to think of it, how these two, poor old Caleb Dyker and Tom, first met at a little crystal spring by the wayside where they had both paused for a drink of water. Because, you know, this whole story hinges on a drink of water as one might say....

Poor Tom; of all the ridiculous errands to be on, that one of tramping down to Catskill Landing was the most ridiculous. Because Tom was a poor young fellow, and was no more able to buy the boat than Hervey Willetts (one of the young scouts of camp) was able to give an accurate and rational account of it.

It was really Hervey who started this whole thing, Hervey Willetts who started so many things. In his purposeless wanderings he had roamed to Catskill Landing one day and (as usual) had not returned for dinner.

“Why didn’t you come back for dinner?” asked the young assistant, rather annoyed.

“Slady, Catskill Landing is thirteen miles and you can’t hear the dinner horn that far. Besides, thirteen is an unlucky number.”

“We’ll have to get a radio if we want you to come home for dinner,” said Tom. “We’ll have to broadcast the dinner call.”

“Slady, don’t talk about radios, don’t mention the name; you ought to see the radio on that boat—the big cabin cruiser that’s for sale. I’d like to buy that boat, Slady, it’s a pipperino!” Probably he would have bought it and sailed away to South Africa in it quite alone, but for one trifling reason. The price of the boat was two thousand dollars, and Hervey had exactly two nickels.

“A pretty big pipperino, hey?” asked Tom.

“Oh, about seventy-five feet—well, maybe fifty, say. If I had that boat, Slady, I’d beat it for Japan and I’d come back by way of the Suez Canal. Two thousand bucks, that’s cheap for that boat, Slady. If I had two thousand bucks I’d buy that boat in a minute.

“You would, huh?”

“You tell ’em I would. It’s got everything in it, Slady, bunks, cook stove, compass, everything. Why I’d give a couple of hundred bucks just for that compass alone, I would.”

It is hard to say why Hervey would have paid such a price for a compass since he never cared in which direction he went and when you are climbing a tree or a telegraph pole, you need no compass to inform you that you are going up.

“Why, that rich man must want to give it away, Slady,” Hervey continued. “Two thousand bucks! Why it’s worth about, oh about ten or fifteen thousand anyway—maybe twenty. It’s a regular ocean liner. There’s a ladder up the side and everything; you just grab it and—”

“Oh, you swam out to it?” Tom asked. “It’s anchored off shore?”

“You can just kindly mention that I did. I swam out to it and all around it and everywhere. There’s a no trespassing sign; you just grab hold of that and pull yourself right up, easy as pie.”

“I see.”

“Maybe a lot of us could club together and buy it, hey?” said Hervey.

Tom smiled. If the scouts at Temple Camp could have scared up twenty dollars among them they would have been lucky. “We might club together and buy the anchor,” Tom laughed.

“Don’t miss it, Slady; go down and look it over. You can crawl right in through one of the port-holes—I did; it’s a cinch. Any dinner left?”

“You’d better go and ask Chocolate Drop,” said Tom.

With a stick which he always carried, Hervey removed his outlandish rimless hat, cut full of holes, and revolving it upon the end of the stick sauntered up toward the cooking shack singing,

It was odd how the memorable series of adventures which befell Tom was thus started by that blithesome visitor at camp, whom they called the wandering minstrel. He set fire to Tom’s imagination in the same careless fashion that characterized all his artless, irresponsible acts, and ambled away again leaving poor Tom to his fate.

Tom went down to Catskill Landing to look at the boat. He did not tell any one he was going because he realized the absurdity of a young camp assistant with thirty dollars a week going to inspect a boat which was for sale for two thousand dollars. He just wanted to look at it; a cat can look at a king.

He did not go about his inspection in Hervey’s original way; he secured permission from the man in whose care the boat had been left, and this man rowed him out to the boat which lay at anchor a hundred feet or so from shore.

Tom felt rather embarrassed at finding that some one representing the owner was to accompany him, and he had an unpleasant feeling that the man knew he was not a likely customer.

“They thinking of buying a boat for the camp?” the caretaker asked as they rowed out.

“Oh, I just thought I’d look her over,” said Tom, non-committally. “It’s a bargain, I hear.”

“These rich fellers get tired of their toys, you know,” said the man. “I suppose if that boat was down New York and he advertised her, she’d be snapped up quick enough.”

“Who is the owner?” Tom asked.

“Homer, his name is; folks got a big place near Greendale. Oak Lodge they call it. He’s in Europe now.”

Tom climbed up on the deck of the boat with more reverence for it than ever Hervey Willetts had shown.

It was a cabin cruiser, one of those palatial motor-boats which seem all the more luxurious and attractive for being cosy and small. It had a quaint name, Goodfellow, which somehow seemed appropriate to its combined qualities of snug comfort and sporty trimness. It looked a wide awake, companionable boat.

It seemed to Tom that the owner must be a young man with a predilection for camping, and all the wholesome sport which goes with it, for in the little cabin there were fishing tackle, crab-nets, a tent and all the usual paraphernalia of the scout and adventurer. A mere glimpse at the tiny galley with its oil stove and spotless tins was enough to arouse an appetite.

“It’s a peach all right,” said poor Tom; “it’s a bargain at two thousand, I’ll say that. I wonder why he wants to get rid of it?”

“Got the airplane bug, I guess,” said the man.

“He’s in Europe?” Tom asked.

“Climbin’ mountains in Switzerland; last card I got from him said Loosarne or some such place. If all them mountains was stamped out flat I reckon Switzerland would be as big as the United States. Folks get crazes fer climbin’ them mountains; they got ter go roped together, I hear. What rich folks is after is excitement, I reckon. They go sailin’ on the streets in Veenus, judgin’ from the post cards.”

Tom did not hear these comments on European travel. He was gazing about, feasting his eyes on every enchanting detail and appurtenance of the boat. He derived a kind of foolish comfort from the fact that, the owner being away, the sale of this trim little floating palace could not be consummated for a while at least. Yet he stood a better chance of being struck by lightning than of being able to buy it.

“Well, you couldn’t sell it anyway?” he said in a wistfully, questioning way.

“Couldn’ give no bill o’ sale,” said the man.

“And she won’t go yet then—anyway?”

“Not ’nes she slips her anchor.”

Poor Tom could not drag himself away from the handsome little craft. He vaulted onto the cabin roof and sat with his legs dangling over the cockpit, gazing about at the accessories which spoke so seductively of nautical life; the anchor, the bell, the compass, the brass fog-horn in its canvas cover, the life preservers with Goodfellow printed on them.

Then, like a flash, he ceased his day dreaming and became the practical, alert young fellow that he was. He jumped down off the cabin roof, fully awake to his poverty and the fact that he was wasting this honest man’s time.

“She’s the kind of boat you read about, all right,” he said.

As they rowed shoreward the man gave a little dissertation on boats which Tom later had cause to remember.

“Well, there’s somethin’ about a boat,” he said, “yer fall in love with it. Now nobody ever loved a automobile. I guess that’s why boats is called females in a way of speakin’; named after women and all that. Yer go crazy over a boat. I knowed men, I did, would let their boats rot, ’fore they’d sell ’em. You wouldn’ hear uv nobody doin’ that with a airplane. It’s human natur’, as the feller says.

“You never heered nobody speak affectionate about a automobile, now did yer? Yer heered ’em praise it ’n say it could make the hills ’n all that, but yer never heered nobody speak soft like ’bout one, now did yer? Folks get new autos every year or two, but they stick ter their ole boats.

“When a boat brings a man in out uv a storm he jes’ kind uv loves that boat. He don’t look at his speedometer and say, ‘She done three hundred miles ’n she’s worth that much less.’ No sir, I can show yer half a dozen men ’bout here, up ’n down the river, wouldn’ sell yer their ole scows, no sir, not fer love or money, they wouldn’.

“Take Danny Jellif up here, owns the Daisy; you couldn’ buy the Daisy. ’Cause money don’t count fer nothin’ where there’s love; that’s how I dope it out. Mebbe these rich fellers is different, but not always, I guess. Leastways, yer get ter love a boat, she’s kind uv human. Mebbe Ted Homer is different; he didn’ name her a female name anyway.”

“Oh, lots of girls are good fellows,” said Tom. “Well, I reckon you know more about ’em than I do,” said the man as he rowed.

This was not the case, for indeed Tom knew very little about them. This was his first love affair. He was madly in love with Goodfellow. And it was pathetic that this beauteous damsel of his heart was so far beyond his reach. He was like a pauper in love with a princess and he felt that he would do anything in the world to win her. Anything? Well, most anything....

If Tom Slade owned that boat he would make a cruise down the coast in it. As he hiked back to Temple Camp he thought of what he would do and where he would go and who he would take along—if he only owned that boat. He would rechristen it the—the—the—no, he wouldn’t rechristen it at all; Goodfellow was a crackerjack name, he would call it Goodfellow.

And now as he thought of the name it seemed a particularly happy name for a boat, an inspiration, as Pee-wee Harris would have said. It meant trusty and fair and square, with a true sportsman’s broad code of honor.

Goodfellow. Tom mused upon the name. It suggested pal, it suggested daring, and just a touch of blithesome recklessness. Above all it seemed to Tom to suggest pal. Good scout, good citizen, good pupil, good son, good brother; all good, no doubt, but such names for a boat! “Goodfellow,” said Tom, “that’s one peach of a name.” Could it be that being a good fellow was really better than being any of these other things? Or was it just that the name was blithesome and sportive?

And just then he came upon the stranger. He came upon him at a little crystal spring by the wayside where hikers from Temple Camp often paused for a cooling drink. Out of deference to this little spring, the stone wall which bordered the road had been made to form a semicircle at the spot, leaving the water free to bubble up.

And at this spot, where the cold, hard wall respectfully stepped aside, to allow the spring to make its kindly presence known to the thirsty wayfarer, some flat stones projected from the rough, loose masonry, to form several seats. The Temple Camp boys never used these stone shelves, for by instinct they preferred the top of the wall. Therefore, it looked the more peculiar to Tom to see sitting on one of these hospitable projections the queerest, most wizened looking little old man that he had ever seen.

The little shelf on which he sat was so unobtrusive that he seemed to be sitting on nothing at all, in the very center of the small semicircle of stone wall. He looked like some whimsical statue sitting there with his two shrivelled hands resting on his crazy cane. His old-fashioned steel-rimmed spectacles rested at such a rakish angle on his nose that one of his eyes looked over one lens, while the other looked under the opposite one. And there was a strange, bright stare in his eyes which might once upon a time have suggested shrewdness. The whole whimsical aspect of this funny little old man was emphasized by the fact of his looking straight ahead of him the while he talked; his interest in Tom’s presence seemed quite impersonal.

Tom was nothing if not personal and hearty and, seating himself near this queer personage, he stretched his legs out in front of him, clasped his hands in back of his head, and said, “Well, you taking a rest?”

“It’s all right to drink this water if you want to,” said the old man in a crisp, choppy voice.

“You said it,” laughed Tom; “no germs here, you can bet.”

Then having rested momentarily he kneeled down, drinking out of his cupped hands while the little old man looked straight ahead of him, his withered hands clasped upon his cane.

“You needn’t be ashamed to drink that water,” he said, “it’s honest water; all water that comes out of springs is honest.”

“Well,” laughed Tom as he lifted his cupped hands for another cooling draught, “this water certainly needn’t be ashamed to look anybody in the face.”

The water, indeed, seemed carefree and of a good conscience. It trickled down off Tom’s face and neck as if it had a clean record and not a care in the world. He arose not only refreshed but cleansed. “You bet it’s good, pure water,” he said.

The little old man continued looking straight ahead of him and when he spoke it was with a kind of crisp finality, like an oracle speaking. It amused Tom, and he sat on the ground with his hands clasped around his drawn-up knees, listening to the queerest tirade he had ever heard.

“You never drink out of the Ashokan Reservoir, do you?” the old man asked.

“Well I don’t exactly drink out of the Ashokan Reservoir,” Tom said. “But you know it’s pretty hard to get away from the Ashokan Reservoir when you’re down in New York.”

“New York is a thief,” the old man said.

“Now who’s calling names?” Tom laughed.

“If you drink any water that comes from the Ashokan Reservoir, you’re accessory to a thief,” the old man said. “Drink spring water. Miles and miles of country was stole to make the Ashokan Reservoir. The village where I lived, West Hurley, was wiped out to make the Ashokan Reservoir. My home was took away from me.

“Why did New York have to come way up here for water? That water is poison—it has sorrow in it. If you drink that water you drink a bitter cup of sorrow. Every drink you take of it you’re drinking sorrow. Drink spring water. You’re a young man, don’t mix yourself up with a crime; keep your hands clean.”

“I don’t see how I’m going to keep my hands clean unless I wash them,” Tom laughed; “and down in New York the only way you can wash your hands is to turn on the faucet. What’s the big idea, anyway, Cap?”

“My name is Dyker,” said the old man.

“Mine’s Tom Slade,” said Tom. “You seem to have a grouch against the Ashokan Reservoir. You should worry. I suppose they had to clear away the valley to make room for it. What’s done is done; I wouldn’t let it bother my young life if I were you.”

“I’m seventy-three year old,” said the little old man, “and from the day they drove me out of my house ’til this very minute, I never drank a drop out of that cup of sorrow—”

“It’s a pretty big cup all right,” Tom laughed. “You wouldn’t laugh if you’d ’a’ been put out of your home. On that day I swore I’d never drink a drop of water out of that reservoir, and I kept that vow. I tramped as far as New York City, I did, but not a drop of it did I touch; I bought spring water and drank it. I wouldn’t drink sorrow any more than I’d wash my hands in another’s blood.”

Something in the little old man’s voice caused Tom’s mood of banter to change and he gave a quick glance up at the whimsical, pathetic figure sitting there looking straight ahead across the fields. The withered hands were trembling and the funny rustic cane, memento of the woods and companion of his lonely travels, was shaking as if in very sympathy.

Of a sudden Tom’s heart was touched by this aged wanderer. And then, as if by some new fight, he saw the poor old creature’s crazy vow as something fine and heroic.

To set the vast Ashokan Reservoir at defiance was certainly a conception worthy of one cast in a heroic mould. To go to New York City and still not drink of the supply from that distant sea, was surely something in the nature of a stunt. Right or wrong, sane or insane, this poor little old man was made of strong material, the kind of stuff that heroes and martyrs are made of.

And Tom resolved that he would cease joking with him.

“Well,” said Tom, “where I belong we don’t bother much with the Ashokan Reservoir; we drink spring water at camp. I guess none of these places around here get water from the big reservoir. I belong at Temple Camp. You’ve heard of that place? It’s right in among the hills over there—big boy scout camp, you know.

“You say you’ve been batting around the country for twelve years? That gets me; that’s my middle name, flopping around like a tramp—I don’t mean a tramp,” he added kindly, “but a kind of a vagabond. Wherever there’s adventure, that’s the place for me.”

His voice was cheery, his manner offhand and friendly. It was hard not to like Tom, and it was easy to fall in the way of being confidential with him. He sat there on the ground, his knees up and his hands about them. His pleasant, expectant look seemed to encourage friendliness.

“I’m assistant manager over at the camp,” he said, “and I listen to more blamed troubles every day than you could shake a stick at, kids’ quarrels’ and one thing or another. But I’ll be jiggered if I ever heard any one say anything against the Ashokan Reservoir. I always thought it was a nice big reservoir; I hiked around it once. Pretty big engineering feat, I guess,” he added, in a way that seemed to invite confidences. “It’s a regular young ocean, I’ll say that.”

“I suppose you know the ocean is cruel,” said the old man, looking straight ahead of him.

“Yes, it’s pulled some pretty brutal stuff,” said Tom. “What d’you say we swap yarns?”

There was a moment of silence, broken only by the sound of the crystal water as it bubbled up merrily in its little rocky bed. Whatever dark and criminal record the vast Ashokan Reservoir may have had, this little wayside spring seemed to carry a clear conscience; its murmuring voice was like a lullaby; it seemed as innocent and carefree as a child. And these two, whose lives were destined to be so tragically interwoven, sat there in silence, while the pure, crystal water bubbled up. And for a few moments neither spoke.

“Did you ever get a bird’s-eye view of the reservoir?” the old man asked. “You never seed it from the top of Overlook Mountain, did you?” This was the first mention that Tom had heard of Overlook Mountain, on whose towering summit fate was reserving the greatest adventure, perhaps the greatest test, in all his young life.

“No, I never did,” said Tom. “Is that the mountain where they’re building a big hotel? Or rebuilding one or something or other?”

The old man ignored his question. “You go up there,” he said in his crisp, impersonal way, “and look down from the top and you’ll see the whole reservoir at once—”

“Looks big, huh?”

“You’ll see miles and miles of it, where villages and houses used to be. Old West Hurley used to be down there; it was wiped out. My house where I lived nigh on thirty year was took down. Mother, it killed her just like if you struck her with an axe. Wouldn’ you call that murder? My boy, my grandson, he was drove away with false charges on him—lies. Wouldn’ you call that as bad as kidnapping? Old Merrick, he done that; he was conspirators with ’em. He’s dead ’n where he belongs, he is, but the murderer is still at large.”

“You mean your grandson was accused of murder?” Tom asked cautiously.

“He were, and they was all lies,” said the old man. “But it was that reservoir, and all them engineers from New York that murdered mother.”

“You mean—she was your wife?”

“Thirty years we lived there,” the old man said. “Since I been alone I never touched that water. I don’t mix with murderers.”

Tom could see that the poor old man was shaking with emotion. Whatever grievance, real or fancied, was in his mind, it was by no means clear to Tom. He thought that the old man was not altogether rational. He was rather more interested in the murder which the grandson had been charged with, than with the murder committed by the great reservoir. He was rather more curious about the smaller murderer than the larger one. But it seemed almost hopeless to get a connected and comprehensible narrative out of the poor little old man.

“Who was your grandson accused of killing?” Tom asked.

“That were old Merrick that lived in Kingston. My boy weren’t no more guilty than you are.”

“They actually charged him with it?”

“Lies, all lies,” said old Dyker.

Tom paused in thought. He was not open-minded enough to eliminate a formal accusation from his mind. Who was this poor, little queer old man that his word should be accepted against the weight of an official accusation? And moreover, if the grandson were a fugitive as the old man had said, was not that fact in itself a cause for suspicion against him?

“How old would your grandson be now?” Tom asked.

“Maybe thirty,” the old man said. “He were only a lad when they hatched up the conspiracy against him. I ain’t seed him since. Abney Borden said he seed him once, passed him right by one night near the reservoir, an’ the lad didn’ speak to him. More like it were on’y his ghost, I says. Maybe just his ghost looking for the old house; that’s what I think. Lots of ghosts of the old West Hurley folks comes back lookin’ fer their old homes.”

“Humph,” said Tom as he scrutinized his queer acquaintance musingly. He had about decided that the little old man was not altogether sane. “But the old village, I mean where it was, is under water, isn’t it?” he asked.

“In dry spells they come, them ghosts,” the old man said.

“Eh, huh,” said Tom as if this were an interesting item in the manners and customs of spooks. “They don’t expect the whole reservoir is going to be dried up, do they?”

“The old village is part on the slope of the shore,” the old man said. “When the water gets low in a drought you can see summat of the old place, ends of streets, ruins and such like.”

The old man’s rather disconcerting manner of looking straight ahead of him while he talked, and uttering each observation with a kind of mechanical air of absolute certainty, had the effect of rather squelching Tom. And so in this instance he felt properly rebuked for underrating the intelligence of spooks.

“That’s interesting,” he said; “an old ruined village coming to light now and then. Sort of reminds you of a body floating to the surface, huh?”

“Whose body?” the old man asked crisply.

“Oh, nobody’s body in particular,” Tom said. “I just meant—sort of—you know—like a story as you might say. Sort of the same as if an old ship were to rise up in the ocean. You believe in ghosts,” he added cheerily. “Now there might be such a thing as the ghost of a village, mightn’t there? A dead village? Why sure.”

The idea seemed not to impress the old man. But to Tom’s ready imagination there was something captivating in the thought of some old ship, a gallant bark of former days, rising out of the unknown depths of the ocean, and haunting the endless waste.

He did not indeed, believe in ghosts, yet after all if a village that is long since dead and gone, and withdrawn from the sight of men in its watery grave, occasionally creeps forth, a shrunken, soulless remnant of its former self, an all but intangible shadow of what was once life,—is not that a ghost? And may not one fancy this spectral, silent thing waiting in the concealment of its grave for the releasing drought, even as the shade of some departed human soul waits for the darkness in which it may steal forth? But Tom did not voice these spooky reflections, for the old man’s crisp voice recalled him front his musing.

“The reservoir, that were the murderer,” said old Dyker; “it murdered mother. Whoever done the other murder, it were not my boy. He run away but he were innocent.”

“Never seen him since, huh?” Tom asked kindly.

There was no answer, but Tom could see that the old withered hands trembled on the poor rustic cane. Probably they did not bespeak any new felt emotion, it was just the trembling of aged hands.

It seemed to Tom that his chance acquaintance had said these same things so many times that they had lost all emotional power over him. It was rather the poor little old man’s defiant attitude and a certain sturdiness about him, which somehow reached Tom’s heart. Trembling, dependent hands and a resolution of iron, that was what touched Tom.

“And you’ve just been wandering around the country ever since?” he asked. “Mostly here in the Catskills, I suppose? Sort of a—” Tramp was what he meant but he caught himself in time and said, “Sort of an outdoor bug, hey?”

But the little old man’s thoughts lingered on the main point of his interest. “Dead or alive, he were as innocent as you,” he said.

“Well,” said Tom cheerily, “I’m going to drink his health anyway. Here’s good luck to him wherever he is.” And he kneeled again and took another drink of the innocent, cool, refreshing water.

“What are you doing to-night?” Tom asked, scrutinizing the old man curiously. Then without waiting for an answer he said in his hearty way, “I tell you what you do; come back to camp with me and look us over, knock around there for a day or two and rest up. Nothing but spring water, absolutely guaranteed,” he added pleasantly. “We keep open house at camp, you know, and you’ll be welcome. What d’you say? It’s only about six miles from here across fields.”

“I walked as much as twenty mile a day,” the old man said. “I walked nigh on a thousand mile in the last ten year, I reckon.”

“Well, you’re about due for a little rest,” laughed Tom. “Come on back with me and meet the bunch, they’re just a lot of kids.”

“I travelled one summer with a circus,” the old man said.

“So?” said Tom.

“I sold needles one summer,” the old man added. “I got two dollars for being in a moving picture. You didn’t happen to see that picture?”

“N—no, I didn’t,” Tom answered thoughtfully. The crisp, disinterested way in which the old man enumerated his experiences seemed to preclude the possibility of getting him to discourse upon them. He delivered himself of random items, out of his apparently miscellaneous fund of adventures, in such a choppy way as to seem both amusing and disconcerting.

Tom suspected that his memory might be good enough to recall salient things, but not details. Moreover, it is very hard to discourse familiarly with one who does not look at you. Personal intercourse is quite as much with the eyes as with the voice. Tom had an amused sense of the handicap to conversation in the little old man’s queer way of talking, as if making dogmatic announcements to the world at large.

“Well, let’s stroll down to camp,” he said, rising. “When I meet a person who’s travelled as much as you have, I feel as if I want to know him better. Come on, what do you say we start?”

It was not until this request, accompanied by physical evidence of Tom’s intention to go, that the old man arose and started to accompany him. Tom could then see how small and wizened his companion was. Yet there was an odd contradiction, something grotesque and laughable, in his spry carriage. He was evidently a hardened pedestrian. With each step he jammed his cane down on the ground with a vigor that was quite inspiring. It seemed to bespeak a strength of character out of keeping with his shrivelled little body and his shabby raiment.

As there seemed no hope of responsive conversation with his eccentric companion, Tom tried to beguile him with an account of the Goodfellow.

“Just been down to Catskill to look at a boat,” he said. “Some boat, I’ll say; regular little yacht. Belongs to a fellow named Homer that lives over the river. I’d like to own that boat. Two thousand buys it and it’s giving it away. You know these rich fellows have always got to be getting something new and poor fellows get the benefit—if they’re not too poor.”

“That’s what were offered for my boy,” said the old man. Tom had thought to get away from that topic.

“Two thousand, huh?”

“A man is worth more’n a boat,” said old Dyker.

“Oh sure,” said Tom. “But that boat’s worth a good deal more than two thousand. I’m plum crazy about that boat, it’s got everything on it you can think of. It’s named Goodfellow. Pretty good name, hey?”

“Old Merrick, he were rich,” was all the old man said. Tom construed this as an indirect reflection against young Homer, because he was in the same hated class as the late Mr. Merrick.

As they made their way along, Tom fell to wondering what were the facts about this dark business which the little old man cherished in his memory. It was impossible to get a rational and consecutive account out of him, but evidently a tragedy had occurred some years back and not the least sad effect of it, whatever it was, was that it had set this poor old creature’s wits askew and made him a wanderer.

From his own account he had tramped as far as the metropolis where he must have cut a strange figure with his shabby, rustic clothes and his crazy stick. Tom pictured him trudging down Broadway striking the sidewalk resolutely with his cane, heedless of the gaping throng. No wonder the moving picture people had used him.

Even now, as he trudged along beside him, bent and wizened and pathetic with a hundred dubious signs of lonesome poverty, there was a vigor about him which made him at once both ludicrous and picturesque. His whole being seemed so concentrated on the task of walking that Tom refrained from putting on him the added burden of conversation.

The first crimson glow of sunset was on the summit of the hills to the west and as this faded to the sombre shade of twilight, the countryside seemed suddenly to be pervaded by a stillness which by contrast emphasized every sound along the wayside. The pounding of the old man’s stick upon the stony road seemed more aggressively audible, and Tom glanced amusedly sideways now and again, smiling at his companion’s intentness.

Across the fields a laden hay wagon was lumbering homeward and its towering, disordered burden changed color in the witchery of the twilight as it moved slowly out of the dying golden area. The voices of the men seemed crisp and clear like voices heard across the water. Before the wayfarers, the road seemed clear cut and ribbon-like as it wound away into the black woods.

Here the arched and intertwined boughs made a dim tunnel in which a refreshing coolness was always felt. A shadowy calm—this stretch of a mile or so. It was always dusk in this foliage-covered way and in the twilight it was all but dark. There was the pungent odor of damp leaves and rotting wood.

The slight sound made by travelers here reechoed as if a score of spectral voices were complaining of the strangers’ intrusion into their domain. The place was called Ghost’s Trail and with reason, for one had but to pause where a death’s head was graven on a wayside stone and call aloud, when there answered a wailing chorus out of the solemn depths. It was said that two large rocks were responsible for these ghostly medleys. But some there were who found the explanation in a murder which had once been committed at this lonely spot.

Be this as it might, there was something eery about this sequestered way which afforded a short cut to Temple Camp. The playing of the shadows conjured up queer figures which often seemed like human forms lurking among the trees. Such was Tom’s first impression of a moving object ill-concealed beyond a trunk.

Soon, however, as the travelers came abreast of the tree, there emerged a gaunt figure, surprised into reluctant exposure, and trembling visibly. It was the figure of a youngish man in the last extreme of emaciation and shabbiness, but Tom could make no guess as to his age for before he could glimpse the face the stranger was already hurrying along the path in the direction from which our travelers had come. What Tom did notice with surprise was that old Caleb Dyker stood stark still, staring back at the almost fleeing form.

“You know him?” Tom asked. But his companion did not answer, only stood, as it seemed transfixed, staring at the apparition.

“You know him?” he repeated curiously.

“That you, Joey?” the old man called in the high pitched, broken voice of age. The moment seemed tense though Tom did not know why.

“Joey—that you?”

But the hurrying figure neither turned nor answered.

For a moment Tom’s imagination pictured the stranger as the fugitive grandson and he was conscious of a certain amusement at the likeness of such a meeting to the happenings in a photo-play.

“Know him?” he asked rather anxiously.

“I thought it were Joey Ganley,” the old man said.

“His folks were neighbors of mine in the old village. He went out west, Joey did, when they stole our homes. He done well out there and sent his mother money to build a house in the new village. You didn’t happen to see that house?” The old man did not vouchsafe Tom any details by which Joe Ganley’s fine gift to his mother might be identified.

“N—not to know it,” said Tom. “I haven’t been in West Hurley much.”

“In Woodstock they have crazy artists,” the old man said, apparently forgetting all about the stranger.

“That’s near West Hurley, isn’t it?”

“Some on ’em wears socks two different colors. One of ’em has long hair wanted to paint me in a picture. You don’t happen to know him, do you? He gave me two dollars.”

“I didn’t know the artists over that way were so rich,” said Tom. “No, I don’t know much about the wild artists of Woodstock; I’ve heard about them though. Joey what’s-his-name never came back, did he?”

“He made money and got married and settled down sum’eres out there. He was a foreman.”

“Well then I guess that wasn’t Joey,” said Tom indulgently. The old man just trudged along, jamming his cane down with each step. He seemed to have forgotten all about the stranger.

Nor did the little episode linger in Tom’s mind. But he thought it rather strange that a young man working as a foreman somewhere in the west should have prospered so exceptionally as to be able to send his mother money enough to build a house. And this notwithstanding the fact that he had married and incurred the expense of a home of his own. These things did not perplex him for he was not sufficiently interested, but the thought occurred to him.

Of one thing he felt certain, and that was that it was not the prosperous and filially generous worker in the west whom they had just encountered in this lonesome road. Old Caleb Dyker had been seeing things....

Tom wondered how much of the choppy and disconnected narrative with which this eccentric little old wanderer had beguiled him had any foundation in fact. But he liked old Caleb Dyker, he liked his sturdy way of trudging along and jabbing his cane down on the ground. There was character in that.

He was amused at the old man’s way of making announcements and at his apparent inability to enter into familiar and confidential discourse. There was something whimsical about him which Tom could not explain to himself. Perhaps it was the old man’s habit of taking everything for granted, artists, movie producers, the great metropolis....

He seemed quite content to accompany Tom to camp without manifesting any becoming hesitancy at going there or inquiring about the character of the community which he was to visit. Tom thought his long wanderings must have bred in him the habit of living day by day and of never being greatly surprised at anything. To him his vigorous eccentricity was captivating.

And so they came to Temple Camp. And there, as it turned out, the little weather-beaten derelict, cast adrift by the great, blind, heedless monster of a reservoir, found a home for many weeks to follow.

The scouts of Temple Camp respected his declaration of war against the vast, watery usurper which supplied that other monster, the metropolis, and refrained from making fun of his heroic posture. Old Caleb drank only the fresh, clear, sparkling water which trickled down from its innocent source among the hills. And who shall say that he was not as great in his iron-clad resolve as was the ruthless, seething, grasping Bedlam which he defied?

Old Caleb became a favorite—nay, a pet—at camp, and he was soon adopted as one of its regular institutions. It cannot be said that he was unappreciative but he was so mellowed by time and hardened by a variety of adventures incidental to his roaming life that he seemed incapable of accepting individuals as such. He took the camp and all its people for granted, he seemed unable to distinguish one boy from another, but he appeared to like them all and certainly he was contented.

He possessed, if any one ever did, the unconscious faculty of adapting himself to his surroundings. He gave the impression that he would be quite at home anywhere, that no one could disconcert or abash him.

It was amusing how he failed utterly to take special cognizance of high scout officials who visited camp and who were accustomed to bathing in the sunshine of homage, even of awe. Old Caleb would probably have trudged into the White House or the Vatican without the least hesitancy, jabbing his stick resoundingly on the floor, utterly unconscious of the fame or identity of his host.

This much his eccentricity and wandering life had done for him (and it was no small thing); he would not have distinguished between the Pope and Pee-wee Harris. Perhaps it was just because his mind did not perceive readily enough to make these distinctions. He seemed to be mentally near-sighted. The world was big and he could see it, but individuals he could not see.

He always carried his outlandish stick with him wherever he went as if to be ready for the Ashokan Reservoir in case he met it face to face. But he did not talk much about the matters with which he had beguiled Tom on the day of their first meeting. Nor did the scouts of camp encourage him to talk of these things for indeed they were not greatly interested in his past.

First and last old Caleb did enough odd jobs to earn his board. He was a prime favorite with Uncle Jeb Rushmore, the camp manager, and with that dread potentate before whom every scout did homage, Chocolate Drop, the colored emperor and autocrat of the cooking shack.

Hour after hour old Caleb would sit in a tilted chair outside this holy of holies whittling handiwork with a jack-knife while a continually shifting audience of scouts lolled about on the grass.

He could make boats, and linked wooden chains and even complicated wooden edifices miraculously assembled in bottles. Some of these marvels the scouts put on sale in the neighboring village of Leeds and they were bought by summer boarders and the proceeds turned over to old Caleb. Pop Dyker he came to be called and he seemed to like it, or at least not to care....

And so things might have gone on till the end of the season and old Caleb gone sturdily forth again upon his wanderings if it had not been for a shipment of provisions which had been put off the West Shore train down at Kingston instead of at Catskill, the nearest station to the camp. That was because somebody or other of the name of Templeton lived at Kingston and his home was called Templeton Lodge and in the language of freight men, Templeton Lodge sounds exactly like Temple Camp.

It fell to the young assistant to go down to Kingston and get this business straightened out and, because it concerned food, Pee-wee Harris generously volunteered to accompany him. It was remarkable how many proffers of assistance Pee-wee made in the face of continuous rejection of his services.

The scout who accompanied Tom in the camp flivver was Brent Gaylong, a tall, lanky, wise-looking young fellow, who was in fact a sort of unofficial scoutmaster to a one patrol troop. The two most conspicuous things about him were a dry sense of humor and a pair of spectacles which perched halfway down his nose, giving him a whimsically mature and studious look; they seemed to remove him quite irrevocably from the field of thrilling adventure. Tom liked “Old Doctor Gaylong” as everybody did, for he was good company and an ideal companion for a journey.

Brent Gaylong sat on the middle of his back as he usually did and used the edge of the windshield for a foot rest. Tom drove the car. It was a Ford touring car and on the side of it in gilt letters was printed TEMPLE CAMP, BLACK LAKE, N. Y.

“A Ford’s the only car that has any romance about it, do you know that, Tom?” Brent spoke in his funny, drawling way. “There’s the same difference between the Ford and other cars as there is between a little old tavern and a modern hotel. Suppose somebody were to tell you the Waldorf-Astoria is haunted; you’d just laugh at him.

“The Ford is—you know—what d’you call it—picturesque. The Ford has the adventurous spirit. I’m for the Ford. In all this blamed automobile claptrap, the Ford’s the only car that has any personality. Did you read about that one that crossed the desert of Sahara? I’d rather be in the class with a camel than with a Cadillac. Old Fords especially. People do things with Fords; the Ford’s a good little old pal, shabby and romantic—like old Dyker. He’s a regular little old Ford.”

“You’re so crazy about romance and adventures and things like that,” said Tom in his matter-of-fact way, “would you be interested in a murder?”

“A good one?” Brent drawled.

“An old one,” Tom said. “The murderer is still at large. There was two thousand dollars offered for him but he was never caught. It happened, oh, ten or fifteen years ago.”

“That’s the kind I like,” said Brent. “All murders ought to be ten or fifteen years old. I like one where the wrong man goes up for life and then years after a young lawyer marries his daughter and hunts out the real murderer. New murders I don’t care about.”

“If you’ll be serious for a minute,” said Tom, “I’ll tell you about it and maybe you can help me. It’s got something to do with old Dyker.

“A long time ago his grandson was accused of killing a man in Kingston named Merrick. The old man kind of told me something about it, but you know how he is; it was a kind of a jumble.

“While I’m in Kingston I’d like to find out something about it if I could. Only I don’t just exactly know how. I thought maybe you could help me. About all I know is that an old man named Merrick was killed and that he lived in Kingston. Pop Dyker says his grandson never did it; I guess likely he did, though. Anyway I’d kind of like to find out about it.”

“That’s a cinch,” drawled Brent. “All that it’s necessary to do is to go to one of the newspaper offices disguised as an every-day citizen. It might be well to carry a loaded fountain pen. In an offhand way ask permission to look over the old newspaper files. There you are.”

“Trouble is I don’t know just exactly what year it was, even.”

“One might starve while wandering through the desert files,” said Brent. “Your point is well taken.”

“You make me tired,” Tom complained. “If I knew the year that the old village of West Hurley was moved to make way for the big reservoir—I think that would be the year. You’re so good at arguing and debating and all that,” he added with his characteristic simplicity, “I thought maybe you could help me.”

“Tomasso,” said Brent, “leave it to me. I will track down the murder if not the murderer. If it is hiding in the fastnesses of the Kingston Journal I will find it. Leave everything to me. Mr. Derrick or whatever his name is, shall not escape me even though he is dead. I am a scout and I have the Pathfinder’s badge. You go to the freight station and when you get through come to the office of the Journal. On entering steal cautiously to the file room. If you see me looking over the files do not recognize me unless I adjust my spectacles. That will be the sign that—”

“You make me tired,” Tom said. “Are you really going to do it or not?”

“I am going to do it,” said Brent. “But when you come if I am wearing a false beard do not be surprised. If I tap three times with my fountain pen you will know it is I and that the way is clear. This is a dangerous business, Slade, and we can’t be too careful. Leave all to me.”

“It’s no wonder that Pee-wee Harris calls you crazy,” said Tom.

When Tom entered the newspaper office after attending to the freight matter as well as several errands, he saw Brent sitting on a stool before a high table with a great bound volume of newspapers before him. His lanky legs were drawn up, his feet resting on a high rung of the stool, a pencil was over his ear, and his prosaic spectacles and studious air were so at odds with the adventurous role he had given himself that even sober Tom was fain to smile.

“Shhh,” said Brent, never looking up. “I have it; it was hiding in a Sunday edition. I crept stealthily through the Saturday issue and—”

“No fooling,” said Tom expectantly; “have you really found it?”

He stood at Brent’s side gazing at a heading which seemed to visualize to him the event which old Dyker had recalled in his rambling talk. The hazy reminiscence seemed brutally clear and definite now with this cold announcement before him. And as he read, not only the event was confirmed but the guilt fixed as well.

CRAZED YOUTH KILLS BENEFACTOR, the glaring heading read.

Tom glanced at the top of the yellowed sheet and saw that the issue was of a date fourteen years back. The thing had occurred before Temple Camp was dreamed of and when he was a hoodlum in Barrel Alley.

“Satisfactory?” said Brent in his funny way. Tom did not answer; he was too engrossed in reading.

“Henry Merrick,” the article ran, “was found murdered in his home yesterday. He had been struck with some blunt instrument while in his library and was lying partly under his writing table quite dead when the body was discovered by his aged housekeeper, Miss Martha Wildick, on returning at seven o’clock from a church meeting.

“All indications point to the guilt of one Anson Dyker, a youth of seventeen years who is known to have called at the house between five and five-thirty and who shortly before six o’clock was seen to emerge from a kitchen window and hurry through the thick shrubbery in back of the Merrick home.

“It is known that between five and seven o’clock Mr. Merrick was alone in the house save for the presence of this youth. It is probable that the crime was committed with one or other of several ornate fireplace instruments, for these, a shovel and pair of tongs and poker, were found strewn upon the floor. An overturned chair was the only other indication of a struggle.

“The motive which incited the maddened boy to murder was undoubtedly revenge though he also availed himself of the opportunity for robbery, for a metal strong-box believed by Miss Wildick to have contained several bonds and various notes and securities, and not improbably more than a thousand dollars in cash, was missing. No trace has been found of the boy.”

Tom could hardly read fast enough, “Young Dyker,” the report continued, “was with his grandparents an occupant of a small cottage in West Hurley owned by Mr. Merrick. Investigation reveals that the Dykers have cherished an unreasoning hatred of their landlord from the time he was compelled to notify them that the cottage, an old and humble abode, was to be torn down because of the flooding of the area to make the Ashokan Reservoir.

“When seen this morning, Caleb Dyker, the grandfather, while protesting his grandson’s innocence, declared that Merrick was a scoundrel and had received his just deserts at the hands of his murderer. Caleb admits sending Anson to Kingston yesterday with over two hundred dollars back rental to pay Merrick. This he drew out of the bank resolved to be under no further obligation to the man who was to ‘turn him out’ as he phrased it, from his home of thirty years.”

There was considerably more to this sensational report concerning mainly the suspected whereabouts of the fugitive boy, of whom there was no trace. Articles in issues of the paper immediately following rounded out the story in the original report and Tom read these with breathless interest to a point where the crime was relegated to an inside page and the reports of progress in the matter (or lack of progress) were brief and perfunctory.

From all these diminishing accounts he learned that the Dykers, notwithstanding that they had been in many ways the subjects of their wealthy landlord’s forbearance and benevolence for years, had been seized with a blind wrath against him when he was forced by the government to dispose of his property in the little doomed village. Evidently the Dykers had not perceived his innocence and helplessness in this matter. Simple and ignorant, they had seen him only as they had seen the whole great engineering project; he and it were ruthless destroyers.

There was much in the old newspapers to this purpose. The blind hatred of the Dykers was like the senseless wrath underlying a southern feud. They could see only one fact, and that fact, tragic indeed, obscured every other consideration. They were to be driven from their home.

The boy, susceptible and loyal, imbibed this hatred. Neighbors heard him say that he would like to kill the scoundrel Merrick. It was but a week or two prior to their necessary eviction that old Caleb in a burst of hatred and scornful independence drew out of his small savings the money with which to square his account with his detested landlord.

With this money young Anson had been sent to Kingston. Before starting he had been heard to say, “If he starts talking to me and stringing me with a lot of lies, I’ll kill him.”

That was the sum and substance of the known facts about the horrid crime, tragic sequel of misplaced hatred and vengeance; an instance of that blind, irrational malice so often persisting in the country.

It was easy for Tom to piece out the sad story of ignorant rebellion against the inevitable by these lowly people, of rash and fiery youth, of the grandmother’s broken heart and death, of the grandfather, homeless and lonely, wandering forth into a strange world. Tom pictured him very vividly with his stick and his old crooked spectacles.

And the vast Ashokan Reservoir, subject of his valiant loathing, had crept over its allotted area and finally filled the green valley and covered up the scene of the deserted village and the forsaken, devastated home.

Tom was recalled from his momentary reverie by Brent’s drawling, matter-of-fact tone. “I’m a better Sherlock Nobody Holmes than you thought I was. Look here. I’ve discovered everything but the married-and-lived-happily-thereafter part. Here’s a copy of the paper published only last week. Read that—down there—second column.”

In a paper which Brent pulled from his pocket and laid open on the big, dusty volume with its ancient news, Tom read with fresh interest the following item. It was prefixed by an inconspicuous heading which read, MERRICK OFFER IS PERPETUATED. The brief article ran:

“The death in Albany on Friday last of Horace E. Merrick, well known merchant of the capital city, recalls the tragic murder of his brother, Henry Merrick, in this city more than a decade ago. Henry Merrick, a kind-hearted and generous man, was brutally murdered in his home and all signs pointed to the guilt of a youth whose aged grandparents occupied a cottage owned by Merrick in the old village of West Hurley. The cottage was one of the many buildings necessarily demolished in clearing the area now covered by the reservoir.

“The youth, Dyker by name, was never seen or heard of after the killing. His indictment by the Grand Jury was followed by the offer of two thousand dollars reward for his apprehension by the murdered man’s brother Horace.

“Horace Merrick’s will, leaving the bulk of his property to his son Borden Merrick, provides that the offer of two thousand dollars reward be continued throughout the lifetime of his son and heir. This stipulation seems to have been incorporated in the instrument as a matter of general principle and out of regard for his brother’s memory, as there seems little likelihood of the culprit being brought to justice at this late date.”

“Anything more I can do for you?” asked Brent in his usual manner of quiet ridicule.

“Yes, there is,” said Tom. “Don’t say anything to Pop Dyker about our hunting these things up. Don’t say anything to him at all.”

“I’ll be as silent as the grave,” said Brent. “What do you say we get some lunch?”

To Tom poor old Caleb seemed like a last, faint echo of the upheaval which had changed the face of nature and spelled sorrow in so many lives. He was like a floating timber tossed by the wind and sea, the last stray memento of some ship long since swallowed up in angry waves.

Tom was resolved old Caleb should not know that the offer of a reward for his grandson’s capture was still open. He had hated but he had not killed nor sanctioned killing. Tom had no doubt now of the grandson’s guilt but his better knowledge of the whole affair only strengthened his sympathy and liking for the little old man.

“Poor old codger,” Brent mused as they started back. “I never knew his past history. I suppose a lot of folks lost their homes when the land was cleared for the reservoir.”

“They were paid for them,” said Tom. “I guess a lot of them were glad to get the money.”

“You can’t pay a person for his home,” said Brent. “You can pay him for his house. Some of them tore their houses down, I heard, and carried them off and put them up again in the new village near the shore. That’s some idea, moving a village.

“Do you know,” he added, sprawling one of his legs against the windshield and the other outside the car, “I believe it’s a good idea for a village or a city to move; it gets into a rut sort of and needs a change. It’s bad to stay too long in one place. Now you take Brooklyn for instance, or Jersey City—”

“I often feel as if I’d like to get away and do something else for a while,” said Tom, taking a serious view of Brent’s talk. “I don’t mean give up my job at camp, of course, but just get off on a kind of a—you know.”

“Restless kind of—I know,” said Brent. “Be nice to get off in that boat, huh? The one you were shouting about? Just flop around. I suppose you could bang down south in a boat like that. Start about, oh say in October, and hit Palm Beach for the cold weather. I’d like to go down to Dixie so as to get away from the Dixie songs we have up here. There’s nothing like the water, Slady old boy. If I ever get rich I’m going to have a yacht.”

Tom mused, his thoughts returning fondly to the Goodfellow. “She’s some boat all right,” he said. “Hang it all, now you’ve got me thinking of it again.” Then, after a pause he said, “Like to take a little ride over to the Reservoir and pike around? It would only take an hour or so. I feel kind of restless to-day; I don’t want to go straight back. I’ll show you the boat, too, if you care to see it, when we get back to Catskill. It doesn’t cost anything to look at it,” he added wistfully.

“Anywhere you want to go, Tommy,” drawled Brent. “I’ll look at anything you want to show me.

“That’s very kind of you,” said Tom, glancing amusedly at his companion. Brent reclined in an ungainly posture of complacent ease with a: whimsically observant look on his face as if ready to be interested in anything and everything which did not require any physical exertion. It got on Tom’s nerves a little, but it amused him.

They drove through the clean, pleasant city of Kingston and over the bridge across the Esopus Creek and along the fine, smooth highway which parallels the Ulster and Delaware Railroad. A ride of half an hour or so brought them in sight of the vast, artificial lake which furnishes water to the distant metropolis.

“Pretty big drink of water, hey?” drawled Brent.

“They say it’s forty miles around it,” said Tom. “The dam is way over at the other end.”

They could not see the whole reservoir from the road, but they caught glimpses of it and could form an idea of its long, irregular extent.

Soon they came to the removed and rebuilt village of West Hurley near the shore of the reservoir. Close by, under the water as Tom knew, were the bones of the old dead village, traces of streets, odds and ends of demolished masonry, submerged memorials of the settlement which had once been there.

There was not much to the new village; it must have lost something in the process of removal and revival of the community life. Some of its simple buildings seemed comparatively new. The visitors looked in vain for any signs of actual reconstruction.

“Do you know,” mused Brent in his slow, dry way, “I don’t know why a reconstructed village shouldn’t be just as good as a new one—same as an automobile or a typewriter. I’d kind of like to get a squint under the water though. What do you suppose we’d see?”

“If we were here during a drought,” said Tom, “we’d see things on the sloping shore, that’s what Pop Dyker said.”

“Old village sort of pokes its nose up, hey?”

“Sort of like a ghost,” Tom said.

“Comes up for air,” said Brent. “Well, let’s move along. I guess the new village won’t get its feet wet, it seems to be well back.”

They drove along the road a little farther and up toward Woodstock, which is the habitat of a queer race of poets and artists, and so on in a northeasterly direction till they came to Saugerties and found themselves back on the road which borders the lordly Hudson.

At Catskill they paused for an inspection of the Goodfellow, Brent showing his usual amiable and whimsically passive interest at the prospect of acquaintance with this beauteous damsel of poor Tom’s heart.

Tom was disappointed to find that his friend, the caretaker, had gone away and was not expected to return till late in the autumn. No one seemed to have the boat in charge and Tom (lacking Hervey Willetts’ aggressive genius) was disinclined to venture upon that hallowed deck without permission. Nor was there a rowboat handy in which to circumnavigate the trim little cruiser and view it at close range.

So they contented themselves with a long distance inspection from the shore. The Goodfellow, in Tom’s view, seemed rather the worse for her long period at anchor. She looked neglected. Her white sides were dirty and there was, even from the distant shore, the appearance of neglect about her. She lay well clear of the area of navigation and was safely padlocked to her buoy as Tom could tell by her heavy mooring chain.

A boat is at home in the water and will not deteriorate riding at anchor. But just the same the sprightly Goodfellow seemed to be suffering from the fickleness and neglect of her wealthy young owner. The flag-pole was broken. The awning over the cockpit was torn and its loose shreds flapped in the breeze.

One thing in particular Tom noticed, which seemed quite at variance with the former spick and span appearance of the little cruiser. The port-holes seemed to be covered inside with some dusty looking material, which might have been torn from the ruined awning. Why the caretaker should have thought it desirable to put these makeshift shades in the unoccupied craft, Tom could not imagine. But on second thought it seemed not so surprising. It would confound the curiosity of strangers, boys especially, who might row out and try to peek into the sumptuous little cabin.

Another thing he noticed which he could not so easily explain. This was an area of sooty black at the top of the little smokestack from the galley. Probably it had been there before and he had never noticed it....

On the way to camp he said to Brent, “Seeing her neglected like that only makes me want her all the more.”

“You love her for herself alone,” said Brent in his droll way.

“I read in a book,” said Tom, “that if a fellow wants a thing and wants it bad enough and keeps on wanting it, in the end he’ll get it.”

“That isn’t what you read, Tommy,” said Brent. “You’re thinking of something that Stevenson said; ‘What a man wants, that thing he will get. Or he will be changed in the trying.’ That’s what you’re thinking of, Tommy. A man can have anything he wants if he’s willing to pay the price.”

“Well, I haven’t got the price,” said Tom soberly. He seemed quite simple and unsophisticated beside Brent.

“How do you know you haven’t?” Brent said.

“I know whether I’ve got two thousand dollars or not, don’t I?” Tom said sullenly.

“Yes, but how do you know two thousand dollars is the price?”

“Because the caretaker told me,” said Tom. “What are you trying to do, kid me? You can’t buy a thing if you haven’t got the price, can you? You get on my nerves.”

“I can have the gold trophy cup in the glass case in Administration Shack if I want to pay the price,” Brent drawled. “I can steal it.”

“And you’d go to jail.”

“Sure, that would be the price, Tommy,” said Brent.

On reaching camp, Tom was hailed by that human megaphone, Pee-wee Harris, who advised him in advance that he was wanted in Administration Shack. “There’s a man with a team and there’s a girl and he looks kind of like a cowboy and they want to see you,” Pee-wee shouted breathlessly.

In front of Administration Shack stood a team of stout gray horses hitched to an old-fashioned, one-seated buckboard. On the rear part of this were a couple of barrels and several crates apparently full of provisions. On the seat sat a girl of about eighteen holding the reins. She wore a khaki middy blouse, the sleeves of which were rolled up man fashion exposing deeply tanned arms. Her hat was also of khaki and worn with an unconventional tilt backwards.

A half dozen or so scouts were standing about this antiquated rig, commenting freely on it and volunteering sage observations to each other as to its history, mission and character.

The young lady who sat enthroned upon its seat might have satisfied their frank curiosity on some of these points but she elected to maintain a detached silence. This did not deter the boys from including even her in their speculations.

“I bet she came from out west,” one of them said.

“I bet they belong in a circus,” another ventured.

As Tom approached to enter Administration Shack the girl’s air of studied unconsciousness seemed to become the more intensified. She looked as if she would not have seen Tom even if he had been an elephant. And this notwithstanding that he was far from unpleasing to the eye.

As he passed behind the carriage, however, and up the porch, she availed herself of the opportunity for a furtive glimpse of him while his back was turned. As luck would have it he was just swinging around inside the screen door and he caught her, as it were, red handed. So in the acquaintance which was soon to start, poor Tom had at least this first little preliminary triumph.

In Administration Shack sat a man who might have been the girl’s father or elder brother; he seemed rather young for the one and old for the other. Tom soon learned that he was her brother.

He was a youngish looking man, Tom thought about thirty-three or four, but the fact that he had been for several days unshaved made it difficult to hazard a guess as to his age. He wore a gray flannel shirt and baggy corduroy trousers. He sat in one of the rustic chairs, one leg over the other, and a dilapidated cowboy hat perched upon his knee. He had been talking with Mr. Carleson, the resident trustee and camp executive.

Mr. Carleson wore the negligee camping outfit and he was far from being a parlor scout, but by contrast with the visitor he seemed positively nifty in his “roughing-it” attire. The studied protest against civilized formality made by scouting officials was here put to shame by this romantic looking stranger. He must have long since ceased to think of clothes from any point of view to have reached this negligent simplicity.

“Here he is now,” said Mr. Carleson, alluding to Tom. “Tommy,” he continued, “this is Mr. Ferris, who has charge of the work up on Overlook Mountain. They’re renovating the old hotel up there, you know. Somebody or other gave him the tip that he might find some one here who could help with the woods work, felling timber and all that; sort of an under boss. That the idea, Mr. Ferris?”

“It was the station agent at Catskill that told me about you folks,” said the visitor. “He seemed to think I might find a young fellow here who might like to take a flyer in work along adventurous lines—with pay. Just for a month or two of course. We’re trying to rush things through up there so the place can be re-opened next season. I guess there’s not much chance of that though, not the way things are going.

“We—eh—we lost a dog last week, killed by a wildcat. We went after the wildcat, found a bear that had been killed by a rattlesnake, found the rattlesnake’s nest and killed four of them. That wouldn’t appeal to you, I suppose? I tell that to every likely young fellow, it’s our star adventure, but it doesn’t seem to pull, somehow. My sister thinks she knows where the wildcat hangs out but we haven’t time to go after him.

“Let’s see,” he added, with the effect of wishing to be honest, “we—we have some eagles up there, too. Those are about the only inducements along the line of possible adventure. There’s a precipice you could fall off if you wanted to. Storms are pretty bad up there.

“We’re chopping down trees and building some rustic steps and putting up poles for the ’phone wires and doing a lot of odds and ends outside. What I’m after is a young chap ’bout your age who can boss a little gang of tenderfoots and keep them interested and get some work out of them; keep them from flopping.

“Of course I can’t guarantee the adventures, only the pay, but it’s a pretty wild spot up there. It’s no job in a department store. What I’m after is a young fellow whom I don’t have to manage but who can help manage. Mr. Carleson says you’re an all around scout and fond of adventure. If so I thought you might be interested. We’ll give you just what you’re getting here and any adventures you may have, thrown in—as a sort of a bonus.”

Tom liked this man from the first minute; he was amused at his wistfully hopeful way of setting forth the rather dubious advantages of life on the mountain. He looked inquiringly at Mr. Carleson.

“It’s up to you, Tommy,” said the executive. “If you want to go up there and help these people, we’ll manage to plug along. I know you’re about due for a little change. Maybe it would do you good to get away from the kids for a month or so.”

“You—you didn’t mean for me to go along with you right now, did you?” Tom asked.

“Why—no, and yes,” said Ferris. “Most fellows who promise to come don’t show up. I’ve become sort of superstitious about it. I usually grab them if I can. Of course, you’re not one of the riffraff, but, well, I’d like it a little better if you came along. A bird in the hand, you know. Does it appeal to you?” he added.

“Well, I guess yes,” said Tom.

“My sister outside there has a sort of a joke about them never showing up. She says the kind that are in need of jobs like that are usually the kind you can’t depend on. If I told her you were coming along up next Monday she’d just laugh.”

“Oh, is that so?” said Tom. “Well just for that, I’ll go if you’ll wait ten minutes till I throw some things in a duffel bag. If I wait till Monday the wildcat may die.”

“You’ll start by having the laugh on her,” laughed Mr. Carleson.

So it happened that twice, even before they were introduced, Tom had the laugh on this young damsel of the mountain. First when she relaxed her dignified composure long enough to steal a glimpse of him. And second when he came out ready to start. He enjoyed her slight chagrin in this second matter. As for the stolen glance, poor Tom was too simple in a way, to think twice about that.

The ride to the summit of Overlook Mountain was the longest, slowest, hardest ride that Tom had ever been upon.

From Catskill to West Saugerties it was not so bad, though tedious enough to one accustomed to the sprightly flivver. From West Saugerties they had to go out of their way for several miles in a northwesterly direction till they came to Plaat Clove Post Office. From this settlement they followed the road south over Plattekill Mountain, a laborious enough climb, and so on past Echo Lake, a lonely, wood-embowered sheet of water on the lower reaches of Overlook.

Here began the climb of the rugged monarch on the wild, rock-studded summit of which some enterprising visionary many years back had shown the rashness and hardihood to erect a hotel. It could never have been a pronounced success by reason of its remoteness and inaccessibility.

There are hostelries perched as high as the old Overlook Mountain House but few with such laborious approach. Once it had been damaged by fire and renovated. Sometimes it had been open; often closed. It was and is barnlike and unlovely.

A secret wireless station is said to have been maintained in it during the world war. In its intervals of disuse ghosts, not averse to mountain climbing, are alleged to have patronized it. Counterfeiters and kidnappers are reported to have availed themselves of its remoteness. A disturbing reminder of its insecurity may be seen in the long cables reaching slantingways down from its eaves in every direction to safe anchorage in the rocky ground.

In the woods about it savage beasts can be heard in the night and among the crags of its precipitous eastern face the wild cries of the eagle and the hawk pierce the darkness. Even the homely old Mountain House cannot destroy the effect of primitive wildness under its very shadow.

In the memorable season when these events occurred, some sanguine dreamer with the means to indulge his fancy, had purchased and proceeded on a rather extensive scale to renovate the old structure and to improve its immediate surroundings.

Since the memorable exploit of Christopher Columbus it is unsafe to ridicule an adventurous enterprise, however Utopian, and there is this much, at least, to be said for the work that was started: it gave employment to a miscellaneous crew of workers at a time when work was scarce.

Life on the frowning old mountain with the uncertainties and discomforts attending employment, proved to have no appeal to adventurous youth in the country below. The little band of workers, mostly amateurs, were recruited from distances and localities which gave the work a certain glamor until they experienced something of its rigors and isolation. Then they departed unceremoniously. It was no wonder that Nielson Ferris wanted one real scout to assist in the sometimes disheartening task which he was superintending.

The buckboard seat was not wide enough to accommodate the three, so Tom sat in back with his legs dangling over, and occasionally, by way of stretching himself, stood up behind the seat, holding on to the back and chatting with the other two.

It was a slow, hard pull up the mountain, over a woods road which was hardly more than a trail. Again and again they stopped to rest the struggling horses, and Tom placed stones under the rear wheels.

“How many have you got working up there?” he asked.

“Oh ’bout a dozen just now,” said Ferris. “But only four of them are steadies. They come and go. We’ve got a chauffeur who lost his license and can’t drive; he’s not so bad. We’ve got an inventor who invented a substitute for gasoline; he’s waiting for a law suit to be decided in his favor—fifty thousand bucks I think he expects. He’s good for the summer. We’ve got an ex-soldier; he’s a good worker, but a queer duck.”

“Don’t forget the legitt,” said his sister.

“And we’ve got a legitimate actor,” said Ferris; “he’s a good worker too. Dances, sings and expects to play Hamlet next season.”

“He chops down a tree more artistically than any one I ever knew,” said Miss Audry Ferris. “He bows when he’s finished.”

“All he wants is a little applause,” said Ferris. “You’ll like them, the steadies. The rest are sort of transients. A couple of them aren’t half bad.”

“They won’t like you though,” said Audry.

“Thanks. Why not?” Tom asked.

“They’ll think you’re uppish.”

“That’s news to me,” said Tom. “I was never called uppish before. I don’t see how you can think that.”

“I didn’t say I thought so,” she said. “But your staying in the cottage with us will make them think so. That’s what they’ll say, that you’re uppish. That’s just what Ned Whalen will think; I can just hear him asking, ‘Well, how’s things in the Executive Mansion?’”

“Oh now—” her brother laughed deprecatingly.

“Oh yes, he will,” she said. “That’s exactly what he asked Will Daggett; Will told me so himself. He has that abominable sarcastic way about him. I know just exactly the kind of things he’ll say. Things that make you mad, but that don’t give you a chance to denounce him. I can just hear him now.”

“Nobody wants to denounce him,” soothed her brother.

“I want to denounce him,” the girl said.

“He’s a very good worker,” Nielson urged; “Will said so himself. Good outdoor man too. Get along,” he concluded, addressing the struggling horses. “I can hear you flying off the handle some fine day or other and telling him how you hate him and then I’ll lose the best worker I’ve got.”

“I’m not an idiot,” said the girl. “You seem to know just exactly what I’ll do and say. Have I ever done or said anything?”

“You seem to know just exactly what he’ll do and say,” her brother laughed.

“Who was Will Daggett?” Tom asked by way of generalizing the conversation.

“He was a young gentleman,” said Audry. “And he kept the accounts and stayed in the cottage with us. He went home to prepare for college.”

“He failed to pass last year—g’long, Flossie,” said her brother disinterestedly.

“You’ll see,” said the girl mysteriously, and evidently addressing Tom who was standing behind them holding the back of the seat. “You’ll see for yourself. You’ll be a martyr for living in the cottage.”

“Well I don’t think I’d like that,” Tom said. “Maybe it would be better if I bunked in with the gang; maybe we’d all work better together that way. Especially as I guess most of them are older than I am. Gee, I don’t want them to think I’m a boss.”

“You may be right about that,” said Ferris.

“Then why don’t we all eat with them?” Audry asked.

“Because we’re not in such close touch with them as Mr. Slade will be. He expects to work too.”

“You bet,” said Tom. “Of course I never really bossed a job; at camp I’m a sort of a boss over the kids, I suppose you might say, and I mix up with them, eat with them and all that.”

“That’s entirely different,” the girl said.