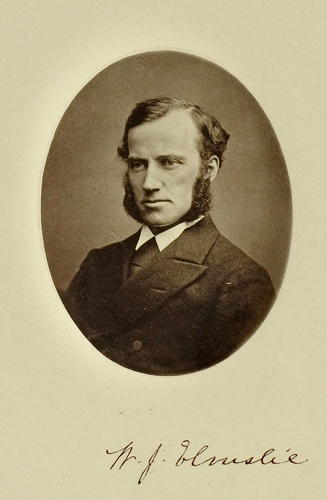

W. J. Elmslie

Title: Seedtime in Kashmir: A Memoir of William Jackson Elmslie

Author: William Jackson Elmslie

Editor: Margaret Duncan Elmslie

W. Burns Thomson

Release date: May 8, 2019 [eBook #59457]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sonya Schermann, Chris Pinfield, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note:

There are variations in the spelling of local words, in the use of hyphens, and in the placement of quotation marks. These have been retained.

Apparent typographical errors have been corrected.

W. J. Elmslie

A MEMOIR

OF

WILLIAM JACKSON ELMSLIE,

M.A., M.D., F.R.C.S.E., ETC,

LATE MEDICAL MISSIONARY, C. M. S., KASHMIR,

BY

HIS WIDOW;

AND

HIS FRIEND, W. BURNS THOMSON,

MEDICAL MISSIONARY.

LONDON:

JAMES NISBET & CO., 21 BERNERS STREET.

1875.

It would have gratified me had this memoir of Dr. Elmslie been placed, at an earlier date, in the hands of his friends; but circumstances, that need not be recorded here, caused delay.

An earnest desire was expressed that it should be published, at the latest, by Christmas; and, in meeting this wish, I have found it impossible to afford Mrs. Elmslie, who is in India, an opportunity of revising the work,–to the value of which she has contributed largely,–prior to its publication; and so I regard myself as responsible for the selection and setting of the matter it contains.

I owe thanks to those who have sent me reminiscences of Dr. Elmslie, or who have accommodated me with the use of letters which they received from him.

I trust this brief memoir of a manly, earnest student; a dutiful son; a devoted medical missionary; and a true, steadfast friend, may be blessed to do good, in answer to the much prayer that has accompanied its preparation.

| PAGE | ||

| I. | EARLY LIFE | 1 |

| II. | SCHOOL AND COLLEGE LIFE | 8 |

| III. | MEDICAL STUDENT LIFE IN ABERDEEN | 17 |

| IV. | MEDICAL STUDENT LIFE IN EDINBURGH | 30 |

| V. | JOURNEY TO INDIA | 45 |

| VI. | FROM CALCUTTA TO KASHMIR | 54 |

| VII. | KASHMIR–ITS PEOPLE, ETC. | 70 |

| VIII. | WORK IN KASHMIR | 87 |

| IX. | WAYSIDE MINISTRIES AND WORK IN AMRITSAR | 117 |

| X. | SECOND YEAR'S WORK IN KASHMIR | 133 |

| XI. | WORK IN CHAMBA | 157 |

| XII. | THIRD YEAR'S WORK IN KASHMIR | 173 |

| XIII. | VISIT TO CALCUTTA, AND WORK IN AMRITSAR | 200 |

| XIV. | FOURTH YEAR'S WORK IN KASHMIR | 209 |

| XV. | WAYSIDE MINISTRIES AND WORK IN KASHMIR | 225 |

| XVI. | THE TRAINING OF NATIVE MEDICAL MISSIONARIES | 238 |

| XVII. | FEMALE MEDICAL MISSIONARIES | 246 |

| XVIII. | HOME VISIT | 251 |

| XIX. | LAST YEAR'S WORK IN KASHMIR | 259 |

| XX. | LAST JOURNEY AND DEATH | 271 |

| XXI. | CONCLUSION | 279 |

MEMOIR.

On the 29th June 1832, the subject of this memoir was born in Aberdeen to James and Barbara Elmslie. Their eldest child, a little girl, had been taken from them shortly before his birth, so the mother called William her "son of consolation," and most tenderly did she cherish this first-born son during the early years of his life. The family was in tolerably comfortable circumstances, as the father a boot-closer, was a clever tradesman, and had plenty of work. William's earliest memories were of a home in which his mother's presence was always pre-eminently felt as the source of comfort and love. Mrs. Elmslie was no ordinary woman. She was blessed with a vigorous intellect, a large measure of common sense, much ingenuity and forethought, and a certain combination of qualities that gave her the power to interest, to warm, to comfort, and to command; and all was pervaded by the spirit of an unostentatious Christianity. Her childhood had been spent among the sea-faring people of Cromarty, amidst those scenes now {2} made familiar to the world by Hugh Miller's sketches of his early home. Her father, William Lawrence, as captain of a vessel which sailed to all parts of the world, had an adventurous history; and the details of his experience, fresh in her own memory, were graphically conveyed to her boy; and it was his delight to sit beside her and listen to these wonderful stories. He thus imbibed much useful information; his imagination was stirred; and the spirit of enterprise unconsciously fostered. The quiet life in Aberdeen was varied by occasional visits to his paternal grandfather at Ballater, and deep and fruitful impressions of the beauties of nature were gained amid the grand mountain scenery of his native land. As William was delicate, when a child, he was not much given to the romps of other boys; but preferred staying beside his mother, who was always to him a treasury of comfort and knowledge.

Having, through industry and economy, succeeded in saving a little money, William's father, with the view of improving his fortune, removed with his family to London; but, as might have been foreseen, the change was not a happy one. A stranger in the mighty crowd of busy men, he soon found that money was not more easily won there than in his native country; and after struggling on for a year, without meeting the hoped for tide of prosperity, his health failed, and he became seriously ill. Worn out with constant watching and care Mrs. Elmslie was seized with typhus fever, of so malignant a type, that their one servant fled from the house in terror. The picture of the little household is most touching. The father is still prostrate through weakness; {3} the mother raves in the delirium of fever; and the only attendant is a child eight years of age! His sense of responsibility; his distress at witnessing so much suffering; and his alarm, caused by the mysterious mutterings of his much loved mother, broke in rudely upon the sweet dreams of childhood, and set him face to face with stern realities. But matters grew worse. A physician had occasionally dropped in upon them, and now his aid is indispensable; but where is he to be found? The servant, who might have told, is gone; the mother is unconscious; and the father does not know; and so the brave boy sallies forth to seek him in the crowded streets of London! As he wanders along he scans eagerly the face of every one who seems like the friend he so much needs, but in vain; the busy stream of human beings rushes past unheeding, and he feels utterly desolate and in despair. Unable longer to bear up, he stands still, his young heart bursting under its accumulated sorrows, and through his tears sends up to heaven the cry, "God help me!" That is the burden of his prayer. The lessons of his mother bear fruit in the hour of trial. Right speedily comes the answer. A passer by stops, asks what is wrong, and the child explains. He is directed to a house close at hand, where he finds not a doctor merely, but a friend,–a friend whose unwearied care and kindness are never to be forgotten. Soon after, William too was prostrated by the dreadful fever; but this good physician watched over him and never remitted his generous kindnesses–which were administered in every needful form–till he saw the little family safely away from the great city on their return to {4} Aberdeen. When Dr. Elmslie arrived in London on his return from India in 1870, one of his first visits was to the house of this friend, but he was not there; and he could not discover whether he still lived, or had gone to reap his reward from Him who said, "Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these, my brethren, ye have done it unto me."

Strange to say, William's father seemed to give himself little thought about the education of his boys, and insisted that William should follow his own humble trade; and so the child was fully set apart to the service of St. Crispin when only nine years of age. It was impossible the slender youth could attempt any heavy kind of work, and so of necessity he stood, in his new calling, on a platform a grade higher than that occupied by the venerable Carey, who boasted that he was only a "cobbler." "He excelled," writes Mr. William Martin, "specially in the finer departments of the work, which required great care and attention; and many a weary hour he spent at it, when other boys were fast asleep, that he might earn sufficient to pay his fees and augment the comforts of the mother whom he loved so well." William soon became so expert that he was able to turn out a greater quantity of first-rate work, in a given time, than almost any competitor. This not only sensibly improved the domestic finance, but won for him a little leisure, which he devoted to his much loved books.

It is good to bear the yoke in one's youth; but it was placed on William so early, and pressed so heavily, that {5} had it not been for the encouragement of his mother, and his own unconquerable energy, he must have remained ignorant of even the rudiments of learning. His mother did all she could to cheer and help him; she often read aloud to him, and got others to read, and in the evenings young friends frequently gave him a share of what they were picking up at school. Thus he struggled on for some six years before he entered the grammar school. Yea, the duties of the trade lay hard upon him all through the time he was at school, and continued even while attending the University; long, indeed, after they ceased to be needful for his own support, for he gained a bursary, and had good private teaching; but as the father's health declined, and his eyesight became weak, the more the work was thrown over on the dutiful son. But his application never flagged. To save time and help himself forward, he used to fix his book in the "clambs" (an instrument employed for holding the leather), and placing them conveniently in front of him, he learned to pick up right quickly a sentence from Zumpt, or a line from Homer, or any other book, and thus he stitched and studied for long weary years; and so successfully, that before he had reached the end of his Art's course, he had gained five prizes in various classes, and a bursary. He used to refer to those days of subjection to his father's will–of hard uncongenial work and repressed desires–as a time of much mental and moral discipline. He learned patience, perseverance, self-control, the value of time, and faithfulness in discharging duty, however irksome. In going through his daily drudgery in {6} obedience to his father, he learned the invaluable lesson that his life must be ruled, not by what is pleasing, but by what is right.

William Elmslie could not recall a time when he was without thoughts, more or less serious, regarding divine things. From his earliest years, his mother earnestly sought to convey to him some of her store of spiritual knowledge, which was her only riches. Many passages of Scripture she repeated to him, till even when a very little boy he knew them as familiar household words. The Westminster Shorter Catechism was rendered precious to him all through life by her simple loving expositions, and her quaint homely illustrations, drawn largely from her own observation and experience. But it was not till he was fourteen years of age that he came savingly to know Jesus. At that time, the instructions of his mother received impressiveness through the faithful dealing of his Sabbath School Teacher, who, in private personal intercourse, pressed upon him the necessity of a new heart. Two passages were made particularly useful at this time, and these were ever after much prized. The first was, "God commendeth his love toward us, in that, while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us" (Rom. v. 8). The second, "Ye know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, that, though he was rich, yet for your sakes he became poor, that ye through His poverty might be rich" (2 Cor. viii. 9). Although at this time, William came in contact with a real living Saviour, his faith was very feeble; but, as it was faith unfeigned, it grew. Religion became more satisfying to him than it had ever been. He got pretty {7} clear glimpses occasionally of his pardon and acceptance in Immanuel; these multiplied and brightened till the settled conviction of his life became–"My beloved is mine, and I am His." He had been a dutiful son all along, but there was now a new principle infused into his obedience that sweetened all the elements of bitterness. He learned, when serving from love to his Father in heaven, that if called to sacrifice in one direction, he reaped joys in another; and that, after all, the way of right is a way of pleasantness and a path of peace.

In 1848 William Elmslie was regularly enrolled as a pupil in the Grammar School of Aberdeen, and never student more eager started in pursuit of knowledge. At that time its Rector was the Rev. Dr. Melvin, whose character and mode of tuition have been made famous as much by their results in the men they helped to mould, as by the graphic description of one of our finest writers. A few sentences from Professor Masson's paper may enable us to trace the kind of influence now brought to bear on William. "I have known many other men," writes the Professor, "since I knew him–men of far greater celebrity in the world, and of intellectual claims of far more rousing character than belong to Latin scholarship; but I have known no one, and I expect to know no one so perfect in his type as Melvin. Every man whose memory is tolerably faithful, can reckon up those to whom he is indebted; and trying to estimate at this moment the relative proportions of influences, from this man and that man, encountered by me, which I can still feel running in my veins, it so happens that I can trace none more distinct, however it may have been marred and mudded, than that stream which, as Melvin gave it, was truly 'honey-wine.'"–(Macmillan's Magazine, 1863, p. 231.) {9}

When William first entered school he only felt in part the power of this remarkable man, but when promoted to the advanced classes, directly under Melvin's care, the enthusiasm of his nature was stirred, and his mind yielded itself to be moulded by him. He owed much of his success at college, and of his power in mastering languages, to the very careful mental training received from Melvin. "He gave us hard work," he said, "but it was intense enjoyment, for one's mind was strengthened, expanded, and in the truest, fullest meaning of the word, educated." During his first year William was often down-cast, for school life was new to him, and he felt himself far behind others of his age. However, he resolved to do his best, and to make the most of the much-prized privileges so long denied him. During holiday time, when others were at play, he was at his books; and not in vain, for at the beginning of his second year he gained by competition a bursary that helped to relieve him from pecuniary anxieties. By the end of the next session he stood high in his classes, and carried off the first prize in Greek. The Rev. Mr. Salmond, Free Church, Barry, one of William's friends at school and college, writes thus of these early days:–"We were close companions and studied very much together in private as well as in public. These were ever-memorable days, rich in generous friendships and affluent also with what should have been most helpful for the up-building of manly moral character and energetic intellectual life, when Dr. Melvin kept the youngest of us in fixed devotion to the genius of the Latin tongue, and when, after the decease of that unique master, Professor {10} Geddes made us all a-glow with his own enthusiasm, and fired us with the classic spirit of Greek. Into what was best, in these buoyant and productive times of earliest mental discipline and most unselfish companionships, William Elmslie threw himself with all his heart, and was a friend to most. His position, too, was in some respects peculiar among us. His seriousness was more marked, and his independent spirit and his determination to do everything for himself, and to make the utmost of his opportunities, had methods of expressing themselves which were altogether his own. Commencing his course at a somewhat more advanced age than most of us, and possessing the advantage of having learned a trade, he used to excite our admiration by the sturdy diligence with which he toiled to support himself, in a way which many a silly youth would have counted beneath him, and also, in truth, our envy at the ability which he had thus acquired to possess himself of books beyond the reach of others. I well remember how ambitious some of us were to get a week's loan of some of his laboriously-earned treasures, and how ready he was to indulge us in that line of things. Thus it happened that, in addition to the text-books usually studied at that stage in Greek and Latin, not a few boys of some thirteen or fourteen years of age voluntarily mastered volumes ordinarily reserved for a later period,–such as "Zumpt's Grammar," "Döderlein's Synonyms," "Ramshorn's Synonyms," the first part of "Jelf's Greek Grammar,"[1] &c. And for a certain measure of the attainments {11} aimed at and made by a good many beyond the stated requirements of the classes in these and other branches, we were indebted not a little to the stimulus of his example as well as to his willingness to help others with his books and counsel. His own acquirements in Latin were very considerable, and to Greek also he took with a burning affection and a determined perseverance, which might have led him on to distinguished results had the opportunity of continuing his studies been given him in Providence. In these youthful days, in short, the great features of character, which appeared subsequently in his work in a distant country, and in taxing circumstances, were the very qualities that constrained respect from all his comrades in school and college,–his readiness to take in hand all kinds of honest labour, manual and mental, his patient dedication to the task of the time, his thirst for knowledge, his zeal in helping others, and the hearty and fearless interest which he displayed all through his course in every decidedly religious movement. This last made him a somewhat outstanding member of our student-circles, and rendered the impression which he left upon his associates a very happy one."

When William got in some measure abreast of his school-fellows in learning, he rejoiced to join them in the playground in every manly sport. His hard work never inclined him to mope. With his whole heart he threw himself into the game. Of cricket he was particularly fond, and the company of which he was a member was called the "Thistle Club." He stood A-1 at bowling. He could not endure those meandering, sneaking balls {12} that creep in upon you at unawares. No; the enemy got fair warning. Drawing himself well up, the body thrown back, and the lips compressed, he took careful aim; then off shot the ball, swift and straight as an arrow; and when he heard the delightsome clatter of the tumbling wickets, he cut a demi-somersault, and sang out merrily, "Nemo me impune lacessit."

It was near the close of William's fourth session at school that the death of the reverend rector took place. He fell paralysed to the ground one day while engaged in his classroom, and William Elmslie was one of the sorrowing pupils who helped to bear the almost lifeless form to his home,–not many days later to be borne thence to its narrow bed in the churchyard. William never ceased to be thankful that so much of his student life had been passed under an influence so beneficial, being deeply conscious of having gained in the Grammar School of Aberdeen such a mental training as enabled him to grapple with, and to overcome, the intellectual difficulties which, in after days, he had to encounter.

In November 1853, he passed from school to college; and with no little pride and pleasure his mother saw him don the scarlet cloak worn by the students of King's College, Aberdeen. "It was there," writes his friend, the Rev. Andrew Ritchie of Coull, "that I first met with William Elmslie. We were students of the same year, and I shared the same room with him in his parents' house. We both worked hard. It was no unusual thing for us to restrict ourselves to five hours' sleep. We engaged a watchman to waken us {13} at three o'clock every morning; and we took it in turn to rise first, kindle the fire, and boil the coffee, which Mrs. Elmslie had made ready the night before. After enjoying a slice of bread and that good, warm coffee, we began our day's work. William was always prayerful and earnest, and from the very first we engaged in devotions together, as well as separately; it was our delight to talk of Christ, and of our desire to devote ourselves to his cause.

"William's work was harder than mine, for his father's failing health and eyesight made him now more and more dependent on his son's exertions. On this account, William undertook an engagement to teach in a school in Aberdeen, and he had also several private pupils. Being a first-rate student, and of gentlemanly manners, he had no difficulty in getting as much employment of this kind as he wished; but the constant hard work and severe study told on his health, and, at the close of the second session at college, he was forced to obey doctor's injunctions, and to seek rest and country air."

He spent some time with relatives in Elgin, and in the neighbourhood of Inverness, and returned, strengthened in mind and body, to take up again the double burden of supporting his parents and maintaining himself at college. Sometimes when his prospects were peculiarly dark, and he needed sympathy, friends took the occasion to urge him to give up the struggle altogether, and turn aside to something that would be immediately remunerative. He had a hard time of it when passing through his philosophical classes. To most honest, earnest students, this is a season {14} of much conflict, and Mr. Elmslie's circumstances did not tend to make the doubts and temptations that usually encompass it easily borne. Sometimes, when he knelt to pray, troop after troop of doubts rushed in upon him, and made such assaults on his long cherished beliefs, that he gradually ceased to plead with God, and entered into regular mental warfare, becoming altogether unconscious of his kneeling posture. Recovering himself, he was shocked at his irreverence; tried to smooth himself down and feel solemn, but in the stillness a withering chill stole over him as if he were encircled by a boundless nothing. The "Eternal Silences" sent very cheerless responses to the groans that burst from his burdened spirit. With keen powers of analysis, and a slight tendency to introspection, it will be believed that such battles were not infrequent. It is needless to ask, in surprise, "But was he not a Christian?" Yes; but a far older and more experienced Christian was so puzzled by the mysteries of Providence that he exclaimed, "As for me, my feet were almost gone; my steps had wellnigh slipped." Mr. Elmslie's feet were on the rock, but he staggered greatly notwithstanding. Through all his varied forms of trial, his mother stood by him to sustain and cheer; and when his philosophic perplexities went beyond her depth, she at least could sympathise and pray. He used to say "that a mother's sympathy, if she had a Mary's faith, was the greatest blessing a young man could possess when first installed into the mysteries of philosophy." The mother and son had, all through, an unwavering conviction that God intended him for a higher form of service than {15} boot-closing, and therefore trials did not discourage so much as might have been expected; for they were regarded as a fatherly discipline; a preparation for future usefulness, upon which they ceased not to ask the Divine blessing.

Having taken his degree in arts, he felt anxious, before deciding on a further course of study, to see something of the world, and to have a change from the scene of so much labour. He therefore gladly accepted a proposal to go abroad as tutor in the family of an Aberdeenshire gentleman, who was to spend the following winter in Italy. It was a curious fact which he sometimes quoted as an instance of God's overruling even our failings as a means of carrying out His own plan of our lives, that this gentleman's choice of him as tutor for his sons was caused by a preference for his handwriting, the very point on which he was most conscious of deficiency.

The year spent in Italy was not one of much enjoyment. William's sensitive nature suffered acutely in this first experience of life among strangers, and his position was rendered more trying and lonely from a misunderstanding between him and the father of his pupils. Nevertheless the lessons in human nature, and the experience of the world gained there, proved invaluable to him ever after.

Here, too, his self-reliance was strengthened, and he gained a firmer conviction of God's power to give him joy and peace, however untoward his outward circumstances might be.

In Florence he had the great privilege of meeting with {16} some very helpful Christian friends, among whom was the Rev. Mr. Hannah, a young Irish clergyman, who had been appointed to minister to the English residents in that lovely city. William spent much of his spare time with this dear servant of God, who was then drawing very near the close of his service on earth, and was fast ripening for glory. The Spirit of God seemed to reveal to him much of what eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither hath it entered into the heart of man to conceive, and for which he was being made ready. To all who then ministered to him much blessing was given, and William richly shared it in a realisation of the unseen and the eternal such as he had never known before. During Mr. Hannah's illness, William agreed to relieve his mind of anxiety by conducting Sabbath services for his little congregation. He read to them some of his favourite sermons, such as Chalmers on "The expulsive power of a new affection;" Caird on the "Solitariness of our Lord's sufferings;" and Maclaren on the "Soul's thirst after God." The Rev. Mr. Macdougall, who relieved him of his position some six weeks later, used laughingly to say that Mr. Elmslie had quite spoiled the people, for they would never listen to any ordinary man's sermons after having enjoyed those intellectual feasts. William returned to England in June 1858, and in London heard an encouraging sermon from the Rev. Dr. Hamilton from a text well suited to his circumstances, "Casting all your care upon Him, for He careth for you."

[1] Mr. Elmslie was not able to purchase such books as the above; he hired them from a bookseller at so much per week.

After his return from Florence Mr. Elmslie's thoughts were directed to the ministry; and having passed the required preliminary examinations, and gained a bursary by competition, he entered the Free Church Divinity College in November 1858. During the session his attention was drawn to the mission field, and as he searched his Bible, for instruction and direction, an element in missionary service so obtruded itself on his notice that it could neither be overlooked nor thrust aside. It became clear to his mind that when the Divine Spirit gave marked prominence, in the New Testament, to the combination of healing with preaching in the planting of Christianity, it was intended to instruct and guide those who, in after ages, might devote themselves to the extension of the kingdom of Christ. He accepted the lesson, and resolved to acquire the power of healing. Instead of attempting to follow the subjective changes through which Mr. Elmslie passed, as his thoughts gradually turned from a pastorate at home, to service as a medical missionary abroad, it may be more instructive to indicate, in a few brief sentences, how the subject of medical missions–the combination of healing with preaching–is presented in the Word of God. The {18} more he studied the infallible missionary guide; and the more he contemplated the perfect Model Missionary–for He hath left us an ensample that we should walk in His steps–the more he became enamoured with the delightful form of service to which he now consecrated his life. But let us, for a moment, turn to the Scriptures. When the disciples of the Baptist approached the Saviour with the inquiry, "Art thou He that should come, or do we look for another? Jesus answered and said unto them, Go and show John again those things which ye do hear and see: the blind receive their sight and the lame walk, the lepers are cleansed, and the deaf hear, the dead are raised up and the poor have the gospel preached unto them" (Matt. xi. 3-5). He healed the sick and preached the gospel and pointed the inquirers to that combination as proof conclusive that He was the Sent of God. The combination was not fortuitous or incidental; it was foretold; and it was a striking way of delivering part of the message He brought us from the Father,–that He came "to bear our sicknesses" and to be "the Saviour of the body." This mode of procedure was wondrously fitted to secure a friendly consideration to his claims among the ignorant, the indifferent, or the hostile; and was full of wisdom and tenderness. It is well to note that this is not a solitary instance of the combination of healing and preaching, got up to settle doubts in the minds of John's disciples. In the life of Jesus it is "use and wont," and their attention is directed to it as a sample of what He is doing every day, and occasionally to such an extent that there is not time "so much as to eat bread," and His {19} relatives think "He is beside Himself." It is not necessary to multiply quotations. One must suffice. "And Jesus went about all Galilee, teaching in their synagogues and preaching the gospel of the kingdom, and healing all manner of sickness and all manner of disease among the people. And His fame went throughout all Syria; and they brought unto Him all sick people that were taken with divers diseases and torments, and those which were possessed with devils, and those which were lunatic, and those that had the palsy; and He healed them" (Matt. iv. 23, 24.).

This combination of healing with the preaching of the gospel is not only largely exhibited in the ministry of Jesus, but was enjoined by Him upon the Apostles who practised it in the home and foreign mission field, during their Master's lifetime and after His ascension to glory. Their commission is particularly clear on this point,–"As ye go, preach, saying, The kingdom of God is at hand. Heal the sick; ... freely ye have received, freely give" (Matt. x. 7, 8). "He sent them (the twelve disciples) to preach the kingdom of God and to heal the sick" (Luke ix. 2). Very similar are the instructions given by the Lord to the seventy home missionaries whom He sent, two and two, into every city whither He Himself would come. "Heal the sick that are therein, and say unto them, The kingdom of God is come nigh unto you."

The case of Paul is very instructive. Most of his life, after his conversion, was spent in pioneering mission work, in which the "healing" element was likely to be of much {20} use, and we find he was endowed with that power in a remarkable degree. In Ephesus, an important heathen centre, where opposition was strong and his difficulties many and great, it is said, "God wrought special miracles by the hands of Paul; so that from his body were brought unto the sick handkerchiefs or aprons, and the diseases departed from them, and the evil spirits went out of them" (Acts xix. 11, 12). An apron or handkerchief having touched the Apostle's body is carried to a sufferer and suffices to effect a cure. This indicates a marvellous latitude for the exercise of the healing power, and yet it is evident there were limitations to it. This great Apostle, who was not a whit behind the chiefest of the apostles, was not able to cure Timothy, though much depended on his enjoying vigorous health. We infer this inability from the fact that Paul left him in his infirmity, and fell back on the very humble "Recipe"–"Take a little wine for thy stomach's sake." Why not heal him right off? Why not send a "handkerchief" to him? Again, we read, "Trophimus have I left at Miletum, sick." Very strange, if there be no restrictions imposed on this power to heal! Why cure Sergius Paulus, a heathen, and leave his Christian friend lying ill? More striking still; Epaphroditus was sick, nigh unto death, and Paul's heart was breaking lest he should die, and he should have sorrow upon sorrow. Why not try the efficacy of the handkerchief here? Paul assuredly would have cured him if he could. There were not many such labourers as Epaphroditus, and so he could ill be spared from active duty; and Paul's affection made sure that everything possible would be done for him, {21} yet the sickness presses on; "nigh unto death" and the apostle's sorrow deepens. These restrictions tend to show that the exercise of the healing power was much limited within the domain of the Church. On the other hand it seemed to enjoy unlimited scope in its approaches to an outlying heathenism. The combination of healing with preaching was plainly intended to be a pioneering agency. "Into whatsoever city ye enter, heal the sick."

The significance of these lessons, as pointing out the path of duty to us, is not weakened by the fact that all the "healing" was performed by supernatural power; for, in those early days, the same power that enabled the missionary to heal enabled him to speak in "an unknown tongue." But the withdrawal of the miraculous from this latter element of missions does not free us from the obligation "to go into all the world," and, by the use of our natural faculties, acquire the ability to speak in foreign tongues. So in regard of the power to heal–it must be now gained by diligent study. The Scriptures thus seem to show very plainly that the best way of reaching the heathen, and, consequently, that the most effective form of mission agency is to combine healing with the preaching of the gospel. Most certainly this was the practice of Christ and the apostles; and it must surely be unwise to disregard the plain teaching of that practice regarding the best means of spreading the gospel. Mr. Elmslie, as we have said, bowed to the Scripture teaching, and resolved to acquire the power of healing–to become a medical missionary. The cause at that time was little known and little esteemed; {22} but he was fully persuaded in his own mind; and this clear conviction helped to uphold him during the storm that burst upon him when he made known his intention to study medicine. To face four years of study, with winter and summer courses, besides the heavy expense of a medical education, seemed madness to his friends, and they vehemently opposed him in his resolution; but hitherto the Lord had helped him, and to be a workman thoroughly furnished for the Master's service appeared to him worth any amount of effort and self-denial. Accordingly he braced himself up to his work. Again he taught in the Academy, received private pupils, stitched the 'uppers' of boots and shoes, and pored over his books. Sixteen hours of work daily was the rule in those busy years. Study was rather a relaxation than anything else. Long-continued custom had begotten a love for it, and obstacles seemed to add a certain zest to his pursuit of knowledge. But during this preparation period there were seasons when the cares of poverty pressed heavily; and faith, hope, and patience required to be in fullest exercise.

At one time, when sorely bestead, he made a journey on foot all the way to Inverness, where a brother of his mother's lived in comfortable circumstances. His purpose was to lay his case before him, and to ask temporary aid, to be restored with interest when God should give him power to win money for himself. He was kindly welcomed, and invited to spend some weeks in the family, but no inquiry was made as to his circumstances, nor was any assistance offered. He could not muster fortitude to {23} break to his uncle the subject of his necessities; and so he returned to Aberdeen with an empty purse and a "full" heart, to work harder, if possible, and to pray more earnestly. Remembering the hopes and the bitter disappointment of that journey, he used to say that a rich man could hardly give greater comfort, or do more good than by extending a helping hand to "a struggling student, really in earnest in his work, and with his Master's service as his dearest aim." These words are in capitals, to express Mr. Elmslie's strong views as to the kind of students to whom help would be a benefit. They must be "struggling" students, who, above all things, love the Master and His work. He came to know that some who had no love for Jesus might take up the profession of religion, to be helped into the profession of medicine. They did not "struggle," and had not the remotest intention to struggle, but were mean enough to accept the fruits of self-sacrifice on the part of others, that they might live in comfort and self-indulgence. He held very strongly that no student with a trace of manliness in him, would accept such help from others, save in real necessity, and then only as an accommodation.

It is necessary to advert to the difficulties with which Mr. Elmslie had to contend, but very pleasing it is to note how cheerily he grappled with them. Writing to his friend, Mr. Ritchie, from Ballater–whither he had gone for rest–in 1859, at a time when dark clouds in abundance clustered around his horizon, he says: "I am living here very much like a hermit. But, for all that, I feel very happy, except now and then when a cloud comes over {24} the horizon of my mind. I then feel a temporary sadness, which, however, soon passes, as when a cloud crosses the disc of the sun. O for another such laugh as we had the first day we were here, it would do us good. It's a delicious thing, a good hearty laugh. You will be thinking I am getting mighty wise, having so much time and inclination for reading. Far from it. It takes a great deal of reading to make one wise. One retains so little of what he reads, that it is a long, long time before the grains of gold gathered assume any considerable bulk." Writing to the same friend a few days later, he says: "I was extremely glad yesterday to see you before me in 'black upon white.'"

"I knew you had been doing business by the address on the envelope–it was so smart and commercial like, as much as to say, Get out of the way, you poor student, you can't transact business like me; what do you think, I am a man with an income of a hundred–a hundred and twenty pounds! every farthing–that's something worth writing. No more two guineas an hour. No more rushing from house to house, like one begging his bread from door to door, in a cold night in December. No, no; nothing so beggarly; I am a little gentleman now, and shall be able to spend my winter evenings within doors as far as is agreeable to my taste. I say I almost saw all that, and a great deal more, depicted on that commercial envelope of yours. And when I opened, I found my most sanguine expectations fully realised; you being the proud master of £120 a year, with twenty-two urchins to drill scholastically. Your bread's baken, Andrew, I said, for {25} the next year, at least. Now I think you acted wisely in accepting the offer, although you should hold the situation only for a year. And I will tell you why. Your responsibility is increased, and that not to such an extent as to crush you under its weight. It's of great consequence, I consider it, to have one's responsibility thus gradually increased. It fits one for a farther increase, when he has successfully carried his previous burden. Why is it that some men, and especially ministers, so completely fail in sustaining the weight of responsibility that is suddenly laid upon their shoulders? Just because their shoulders are strangers to the weight, and the weight is too much for them at first. I suppose you see what I am driving at."

At the election of Lord Rector for the University in 1860, Mr. Elmslie took a somewhat prominent part. In Aberdeen, on such occasions, the votes are given by "Nations,"–a nation representing the students from certain defined districts. They sometimes differed greatly in numerical strength. This year, for example, Mar contained 149 matriculated students, Moray registered only 49, and yet in electoral value, they were equal! On this occasion, two nations voted for one candidate, and two for the other, but there was a majority of 38 students in favour of one of the candidates, so that when the Principal intimated his intention of settling the difficulty by giving his casting vote against the candidate supported by the majority of students, the Mar and Angus nations resolved to dispute said vote as "inexpedient, incompetent, and illegal." Funds were raised to meet the law {26} expenses, and Mr. Elmslie was appointed treasurer. It is amusing to note the carefulness with which, in letter after letter, he impresses on the agents in Edinburgh that he and his companions are not to be held responsible for the payment of a single farthing beyond the monies actually received.

The election was carried against his party, and on the 16th March 1861, the professors and students assembled to hear the Rector's inaugural address. At the close of the preliminary services, when the successful candidate was just going to speak, Mr. Elmslie, being a procurator, ascended the platform, and very deliberately read a protest against the validity of his election. He then, with a low bow, placed the document in the hands of the Principal, and walked out of the room, followed by a considerable number of students. But many of the same party remained to see what was to be the upshot of their proceedings; and not a few, to give impressiveness to their protest, had come to the hall armed with peas, shot, stones, and other such-like persuasive but most illogical arguments, and the result was a "row," prodigiously out of keeping with academic propriety. Although Mr. Elmslie was entirely blameless in regard to these low proceedings, the amount of censure awarded him was singularly liberal. "Nothing," writes his companion in the struggle,–now the Rev. Mr. Mackie of St. Mary's E. C. Dumfries–"nothing could be more alien to Elmslie's feelings and sense of duty than any breach of university discipline. He took no part in it, and restrained it to the utmost of his power." Referring to these student days, {27} Mr. Mackie writes, "My early acquaintance with Mr. Elmslie impressed me equally with esteem for the greatness of his intellect, and the goodness of his heart. He was slow of speech, but swift in judging. Often, when plans were proposed, he would simply say 'No' very slowly, and then render a single reason which left no room for any other reply than 'I see.' He was one of the most satisfactory friends I have ever had in life; for you could count upon him at all times. I cannot recall a single instance in which his counsel seemed to fail me when we were acting together under very trying circumstances, with very few opportunities for consultation. His memory was remarkably tenacious of any agreement as to co-operation, as he was remarkably tenacious of his purposes. One always knew where he would find him."

In the end of July of 1862 he passed his second professional examination. "It was," he writes to Mr Ritchie, "a long, stiff, but I am happy to say, a successful pull. We had nine hours hard work,–to me at least it was hard. There was no little manual work, apart from the mental effort required in summoning up so many facts and putting them together in a connected form. I was exceedingly fortunate in the subject on which I was examined (vivâ voce). I answered the questions as fast as they were put to me, and altogether got on splendidly until I felt sorry when the examinations were ended, because I could not get any longer opportunity of showing off how thoroughly I was 'up.' This was a bit of vanity, but pardonable, I think; was it not? At the close of the examination, on being called into the Senatus Chamber, I was informed by {28} the Dean of the Faculty that I had passed with 'much credit.'"

At an early stage of his studies Mr. Elmslie had heard of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society, an organization which paid the class fees, text books, and cost of licences of young men desiring to prepare themselves for the mission field. The reader is already aware that it was no easy task for Mr. Elmslie to open up his difficulties to others, but pressed by necessity, and encouraged by friends, he laid his case before the society in Edinburgh, and on the 7th May 1860 he got the following reply from the secretary, Dr. Coldstream, "I was instructed to inform you that the committee cannot consent to relax in your favour, their regulations as to residence in Edinburgh, during the Medical Curriculum, and the requiring their students to abstain from private teaching." It is due to the gentleman who sent this official notice to state, that he spoke a word of kindly cheer from himself which helped to lessen the bitterness of disappointment.

"Afflictions are not joyous but grievous;" sometimes, however, they are very profitable: and there is nothing for which Mr. Elmslie gives more frequent or more hearty thanks, than for his "afflictions"–for the very trials, the record of which awakens our sympathy. Soon again he was battling as cheerily with his responsibilities as if he had received no disheartening repulse. Some twelve months after, an influential friend in Aberdeen brought his case a second time before the Board in Edinburgh. This gave rise to a very instructive correspondence, but our present object requires us to cull from it nothing more than {29} the simple fact, that notwithstanding the difficulties mentioned above as lying in the way of his getting help from Edinburgh he did get a grant in aid of £15.

Having passed his second professional examination with honours, he came to the last year of his medical course, rejoicing, as students usually do at that period, in the thought that practically his battle was fought. I was anxious, he writes, "to spend the winter in Edinburgh, as it was in all likelihood my last before going abroad." And so he came south prepared to accept gratefully, as a temporary accommodation, such benefits as the Missionary Society could bestow. Mr. Elmslie feared there might be some risk in coming to attend medical classes in Edinburgh, if he purposed–as he did–to return to Aberdeen for his final examination and degree; but his desire to be even for one season under men like Syme, Simpson, Miller, &c., overcame his hesitation, and in November 1862 he became an inmate of our humble home in the Dispensary in Edinburgh.

It seems becoming to give a brief notice of the society from which Mr. Elmslie got temporary assistance, or rather to permit the society to say a few words for itself. It began in November 1841. Its objects are thus stated: "The objects of the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society shall be to circulate information on the subject of medical missions, to aid other institutions engaged in the same work, and to render assistance at missionary stations to as many professional agents as the funds placed at its disposal shall admit of." After existing for twenty years it thus reports itself: "The Society has now entered upon the twentieth year of its existence. The retrospect is at once humbling and encouraging. Humbling in respect of the small extent to which the objects contemplated have been carried out, and of the imperfections of the machinery now in operation; encouraging, because the principle for which the society had at its formation to contend, has now been generally acknowledged by the friends of missions as a sound one."

The year before Mr. Elmslie came to Edinburgh, this society was amalgamated with another and independent Medical Missionary Society, which, though young in {31} years, gave strong evidence of vitality. The two societies being "germane in their objects," they became one, and after the union, the following prospectus was issued, bearing the imprimatur of the whole directorate:–

"The object of the Society is to promote the propagation of the gospel amongst heathen and other unenlightened people, through the agency of well-qualified medical practitioners, who are either partially supported, or aided by grants of medicines, books, and instruments.

"The society aids and directs the education of promising young men who resolve to devote themselves to medical missionary service.

"It provides for the half of the salary of a medical missionary at Madras, whose labours, extended over four years, have been greatly blessed–5760 persons having received aid last year. This mission deals with a portion of the heathen population of Madras, beyond the direct influence of any other missionary agency.

"The society maintains a dispensary in the Cowgate of Edinburgh, in which religious instruction is combined with medical treatment. During last year this dispensary administered medical aid to 5332 patients, all of whom had the Word of Life set before them. A well-qualified superintendent, with assistants, takes charge of the dispensary, which supplies an admirable training school for the society's students. The attendance at the prayer-meetings, held for persons in their working-clothes, is very encouraging. There are not wanting proofs of these means having been blessed to the awakening and conversion of souls. {32}

"The society organises monthly meetings for the benefit of the medical students attending the Colleges in Edinburgh, who are addressed on various subjects, more or less illustrative of the principles and progress of Christian Missions." Reminding our readers that this refers to the state of matters some twelve years ago, we return to Mr. Elmslie.

The mission work of the dispensary he enjoyed greatly; but only a little of it was permitted to him, or to any of the students, lest they should be diverted from their medical studies. In all mission dispensaries it is the practice, when the patients have assembled, to hold a short religious service with them, which affords an excellent opportunity for commending Christ. It fell to Mr. Elmslie to conduct this service once a week, and it was quite a refreshment to himself to do so; but he was not effective as a speaker on such occasions. There was a monotony in his delivery that disposed to drowsiness, and a want of point and power that surprised those who knew his logical cast of mind, and his varied stores of information. But in another part of the work he was quite an adept. The superintendent, distressed at witnessing large numbers of neglected youths lounging idle about the district where he laboured, resolved to do something for their spiritual benefit, and Mr. Elmslie joyfully assisted. The lads were frightfully wild. On the Sabbath evenings especially, work being suspended, they gathered in the neighbourhood in large and numerous groups. "It was impossible to be indifferent to their presence. Their noisy demonstrations compelled attention; and though we might {33} contrive to pass them, utterly regardless of the interest of their souls, we were obliged to be most considerately mindful of the interest of our own 'shins.' It was not safe to go near them, for they were continually fighting, and wrestling, and plunging about in the most alarming fashion." Fourteen of these lads sat down to tea with Mr. Elmslie every Sabbath night in one of the rooms of the dispensary, and this attractive opening service was followed by a Bible lesson. At first they were inclined to be troublesome, but the quiet firmness with which he grasped the reins made the most reckless feel that opposition was hopeless. His mastery over them was complete; and without any visiting efforts on his part, the attendance was wonderfully regular. Several of his pupils were at least outwardly reformed; and one, it is hoped, got real spiritual blessing. He gave up his evil practices, attended to his business, began to go to church, and became a respectable tradesman. Dropping in at the close of Mr. Elmslie's meeting, as the writer often did, it was a touching sight to witness the band of lawless outcasts kneeling reverently around him, whilst he poured out the deep yearnings of his heart on their behalf to Him who came to seek and to save the lost.

In the household visitation of his patients, Mr. Elmslie soon became a great favourite. He had suffered, being tried, and was therefore able to sympathise with those in trial. Young as he was, he could to some extent use the language of the apostle, "That we may be able to comfort them which are in any trouble by the comfort wherewith {34} we ourselves are comforted of God." He was welcomed amongst the poor not merely as a doctor, but as a friend. The children clung to him, and he had many pets amongst them who amused and refreshed him. "I am very sorry, indeed," he writes of one of these, "to learn that wee Sandy has been taken away from you. He was a great pet of mine, and I think the wee man liked the doctor. I trust Sandy is singing to-day in heaven, not 'There is a happy land, far, far away;' but this is the happy land. I do sympathise with you and Mrs. –– very sincerely, but what is in heaven is certainly not lost. Heaven has now a greater hold upon you, and if Sandy's going away helps to make you think more of Jesus, and to desire and strive to live a godly life, then wee Sandy will not have lived and died in vain."

Mr. Elmslie was usually so wide-awake, that it was not often he was found off his guard. But in the course of this session he was fairly caught napping. The incident is trifling, but it shows how a good and diligent student may get into an awkward predicament through mere thoughtlessness. Mr. David Young and he were grinding in one of the empty rooms of the college. They were overheard discussing a knotty question, when –– laid his hand on Mr. Young's shoulder, and said, "If you will both promise to be good boys, I think I can help you in 'grinding' up that difficult bit." "How?" was at once the inquiry. "Dr. –– has a splendid preparation, and I'm sure he won't object to diligent students seeing it sometimes." (Rather generous, to be obliging with another man's {35} goods!) Next day they were duly introduced into Dr. ––'s sanctum, and the magnificent preparation placed before them. Their friend then withdrew, and they fastened the door on the inside. It was a golden opportunity; but "we had not done much," says Mr. Young, "when a sharp footstep came along the passage towards us. We instinctively held our breath, and looked at each other. The surprise deepened when a key was hastily thrust into the door of our sanctum, but being snibbed, it could not be opened, and Dr. –– went along the passage calling loudly for our obliging friend, who found it necessary to be engaged elsewhere at that moment, and did not appear. Meanwhile I rose and unfastened the door, and Dr. –– soon returning, entered and found us sitting before his model. He held up both his hands, and exclaimed, "What is this? My almost priceless preparation, which I would not allow my most intimate friend to touch!" By this time the culprits were standing; and, after a becoming pause, Elmslie began to sing Miserere, but was cut short at once. "That will do, gentlemen; you may go." They crept out in the meekest attitude possible, and certain uneasy misgivings regarding the propriety of their conduct, suggested some anxious glances behind them during their departure.

The time for his final examination in Aberdeen, in the spring of 1863, drew near, and the hopes and fears that usually agitate students on such an occasion, Mr. Elmslie felt with peculiar force. He knew that the stand he made at the rectorial election had not gained favour for him in the {36} senate; and he feared his coming to attend medical classes in Edinburgh might not be relished by the medical faculty; and therefore, during the whole session, he had studied earnestly. "I never," he said, "studied harder in my life." He did so because he wished to maintain his reputation as a student. How natural, also, that he should desire to see the end of his severe struggle, not to support himself merely, but his little household; and, besides, he longed to be free to go forth, without let or hindrance, to the blessed work of winning souls. Knowing how much depended on this, his last appearance, he says, in another letter, "I studied with might and main." He went in to his examination; he did his best; he thought he had done well, but, to his inexpressible astonishment and grief, he was "plucked,"–an ugly word, but it is the term we students best understand; it comes closest home to our consciousness, and carries in it the concentrated essence of all that is undesirable in our student life;–plucked in Aberdeen in the two subjects which unhappily he had not studied there; rejected in Aberdeen in midwifery, for which, during the session, he won Sir J. Y. Simpson's diploma, and a certificate of merit to boot; rejected in Aberdeen on medical jurisprudence, for which, in Edinburgh, by fair competition, he carried off the gold medal. It is not our province to comment, and we studiously abstain from it; it is ours simply to chronicle; but a single word of sympathy from a personal friend of Elmslie's may not be out of place:–"Dear Elmslie," writes Professor Miller, "I sympathise with you most keenly in your heavy trial.... 'God defend the right,' was a stout and good {37} old battle-cry, and He will." Mr. Elmslie returned to Edinburgh.

On rejoining us in the dispensary, there was much prayer for divine guidance, for it was a time of great perplexity. He was strongly urged to go back to Aberdeen, and take his degree in July. This, it was truly said, was the easiest course, so far as work was concerned. It was certainly the cheapest, and that was a consideration he could well appreciate. For a time he felt the sore pangs of suspense as to the path of duty; but the more he thought over it, the more evident it became, that were he to go back to Aberdeen, so shortly after being publicly rejected, it would appear that he was getting his qualification as a favour, and not as a right, and that all through life a certain suspiciousness or doubtfulness would attach to his degree,–and therefore to his professional standing,–seeing it was so immediately preceded by a "plucking." He could not return to Aberdeen. The following short note to his mother, which is the first he wrote after his rejection, shows the quarter in which he sought support and guidance:–"M. M. Dispensary, 16th May 1863.–Dearest Mother,–I was delighted to get your cheering note, and very glad to hear that you feel comforted in mind, though very lonely. Let us cling close to Jesus, let us draw out of His fulness, and never forget that He cares for us,–for you, and for Stewart, and me–infinitely more than for the flowers which are looking so lovely just now. We may look upon ourselves as belonging truly to Him. May we not, dear mother? Then let us believe that all things will be made to work together for good for us,–even {38} this, sore trial though at present it seems. May God bless and comfort you by His Spirit, dear mother.–Your affectionate son, William."

When it was finally determined that he should take an extra year of study and graduate in Edinburgh, he withdrew as soon as possible from all official connection with the dispensary, and took lodgings in Brown Street; borrowing money from private friends to enable him to meet the responsibilities so unexpectedly thrown upon him. This was, to Mr. Elmslie, perhaps the hardest winter of his life. There was no difficulty, it is true, in finding those who were willing enough to lend to him, but a man must borrow with great hesitation and consideration, who honestly intends to repay, as Mr. Elmslie did; and, besides, one of an independent spirit is the less inclined to borrow the greater his need. Then Mr. Elmslie's mother was feeling so much her loneliness, through his continued absence from home, that he strove to the utmost that she should be comfortable, whatever might become of himself. Friends could not fail to notice that it was to him a season of serious self-denial, and once and again, with the view of moderating the severity of the pressure upon him, found means to convey help to him without letting him know whence it came. These love tokens were accompanied with the single sentence, "Your Father knoweth that ye have need of these things." Soon after the packets reached their destination, he ran along to us to ask us to help him to give God thanks.

Before settling down to the hard study of the winter, he cleared off his first professional examination in the University {39} at Edinburgh, and sent his mother the following account of the appearance he made:–"6 Brown Street, Edinburgh, Nov. 4, 1863. My ever dear Mother,–Bless the Lord with me for His great goodness to me! I have passed (my first professional) at the University of Edinburgh, and more than passed, for the professors passed high encomiums on the excellence of my papers. Prof. Balfour was so satisfied with my paper on botany, that he merely showed me some microscopic preparations, and asked me to name them. Prof. Playfair said my paper on chemistry was so good, that he did not intend to put a single question more. On learning that I had been a pupil of Prof. Brazier's, he said I reflected great credit on my former teacher. Oh, mother, these were little words, but how sweet they were to me! In my heart, all the time I listened to them, I was blessing God for having given me power to write such papers, and thus to corroborate all that had been said in favour of my character as a student. The paper on natural history was without one error, and Prof. Allman, in my viva voce, was fully satisfied with my answers. How thankful I am and ought to be. I don't think I ever studied so hard as during the past five weeks. The subjects to which I had to devote my attention were extensive, and I knew that much depended on my success. The thought of that nerved me. I prayed constantly and earnestly that the Lord would bless my efforts, and He has! ... Please let me have dear Stewart's letter, that I may write him a long answer.... My communion last Sabbath was not so happy as I could have wished; my mind was too exhausted for full enjoyment, but I was enabled {40} to feel myself a sinner, and once more to take Jesus to be my Saviour."

Few could say more truthfully than Mr. Elmslie that he prayed "constantly and earnestly." This session, especially, when labouring to redeem his character as a student from the slur cast upon it by his rejection, he seemed to feel the need of constant waiting upon God. He prayed as much as if study were of little use; he studied as hard as if to pray were vain. He furnished a good illustration of "Praying and Working." This winter he became secretary to the "Medical Student's Devotional Society," and did what he could to promote its interests. There was something touching in Mr. Elmslie's manner in prayer. He spoke in his natural voice, without a trace of the artificial in its tone. His sentences were short and very simple, which gave a child-like character to his supplications; and it was encouraging to note the confidingness with which, in humbleness of spirit, he made known his wants to his Father in heaven.

The following short letter to his mother notes the progress of his studies:–"6 Brown Street, 29th February, 1864. My dearest Mother,–Your last note was very cheering to me. The same post brought me one from Stewart, telling of his safe arrival at his ship, for which I join you in thanking our Heavenly Father. I continue to feel less nervous, and am able to study very hard. God will bless those strenuous efforts, and, as you say truly, dear mother, the time will soon slip away, and we shall see each other again. Take great care of yourself till then, dear mother. My examinations take place early in April, but I don't {41} intend, at present at least, to appear again in Aberdeen till I am doctor of medicine from the university; that can not be till the 1st August. Dr. Candlish is to deliver the first of his course of lectures on the Fatherhood of God to-morrow, and a great treat I expect it to be. We have lost Mr. Dykes; you will be sorry to hear his health has obliged him to leave St. George's, where his preaching was so much appreciated,–and he has gone to rest in Italy for the present. God bless and comfort you with the precious consolations of His Spirit!–Dear mother, your loving son, William."

One subject for prayer which was never omitted was guidance as to his future sphere of labour. Only two of the places brought under his notice require mention–Bombay and Kashmir. Friends interested in the extension of medical missions were exerting themselves to raise £2000, to guarantee a fair start to a medical mission in Bombay; but, till the sum should be completed, even those who looked upon Elmslie as the very man for the sphere, and longed to possess him, had not faith to enter into a definite agreement with him. Gladly would Mr. Elmslie have gone to Bombay, for he considered it one of the most important heathen centres in India, where there was full scope for the exercise of all the gifts and graces wherewith God had blessed him. He more than once spoke of the unbelief that shrunk from fixing him, when the hand of God was so manifest in all the antecedent movements connected with that mission. Kashmir was under his notice for a considerable time. This was also a new mission.

"It was in the year 1862," says the Rev. Mr. Clark, "that the Kashmir Mission was commenced by an address which was sent to the Church Missionary Society, signed by most of the great and good men who then held in their hands the government of the Punjaub. They knew that the best means of benefitting Kashmir was the gift of God's Word, and the exemplification of Christian charity. Kashmir, from the earliest times, had been an outlying province of the Punjaub, and had been made over by us to the present reigning family not twenty years before; and Christian people desired to place within reach of the people in Kashmir the same blessings which they had endeavoured to give to the Punjaub. It was during a journey on the mountain-road between Murree and Abbottabad, that the idea first occurred to Dr. Cleghorn, that Kashmir was one of those countries where the influence of medical skill would greatly avail to aid the introduction of Christ's gospel."

The "Church Missionary Society's Committee of Correspondence, April 5, 1864, resolved–That, adverting to the Christian zeal and extraordinary liberality of the friends of the Society in the Punjaub towards the establishment of the Kashmir Mission, and their judgment of the importance to its success of a medical missionary, this Committee will make the present case an exception to their general practice, and will be willing to enter into communication with Mr. Elmslie, with a view to his appointment to the Kashmir Mission, provided that he is prepared cordially to act upon the missionary principles of the Society." The movement in this country was {43} promoted by Professor Balfour, Dr. Coldstream, and the Rev. G. D. Cullen, all of whom took a kind interest in Mr. Elmslie, and the result was, that he was appointed for five years a lay agent of the Church Missionary Society, and hence his Presbyterianism was not much of a difficulty. But there was a permanent drawback connected with the mission in Kashmir: "He seems," writes Dr. Coldstream "to be somewhat staggered by the rajah's law of exclusion from his possessions for six months of each year; but I have encouraged him to believe, that it may be quite possible for him to find abundance of occupation during that period of exclusion, in territory under British rule or protection."

"I can bear testimony," continues the worthy doctor, "very fully and with confidence, in favour of Mr. Elmslie, as having apparently all the gifts and graces which one desires to see conjoined in a medical missionary."

His medical examinations in Edinburgh, at the College of Surgeons and University, were duly passed with credit (he did "splendidly," he wrote to his mother), and he was capped in August 1864, and there was therefore now no ambiguity circling round his professional Status. Instead of writing to his much-loved mother, he rushed home to enjoy her company during the few weeks he could now afford before sailing for India. The following passage from a letter to Mrs. Coldstream shows the direction of his thoughts at this time:–

"27 Blackfriars Street, Aberdeen, 31st August 1864.–It does greatly gladden my heart to know that you have been making me and my future labours the subject of {44} earnest supplication at the throne of grace. I very much need your urgent petitions in my behalf, for although I have used my prayerful endeavour all along to have myself qualified for the special work to which, I trust, I have been called; nevertheless, when I get but a dim glimpse of the numerous and heavy responsibilities and great difficulties of my future position, as a labourer for Jesus among the benighted heathen, the irresistible exclamation of my heart is, Who is sufficient for these things? Quickly, however, I have the cheering response whispered into the ear of my faith by the loving and sympathising One, 'My grace is sufficient for thee.' I rest in that declaration of our Saviour. My dear mother, I am happy to be able to say, loves the Saviour, and does not grudge to give up a son to work under His banner, who has done so much for her soul. Who would not be willing to give up all to Jesus when He makes the demand? You can easily fancy how very much this willing surrendering of me to the Lord by my dear mother diminishes the sorrow which we mutually feel at the thought of being so far and so long separated. Jesus sweetens everything."

As mentioned by Dr. Elmslie in his letter to Mrs. Coldstream, it greatly lessened the trial of parting from his mother, that she came at length to be willing to give him up to foreign service. Long after his own mind was satisfied that he was called to labour amongst the heathen in distant lands, the mother failed to see that there was any need that her darling son should go so far from home. Sometimes she tried to introduce the subject, to plead with him from her standpoint; but whenever she approached it, he held up his hand, and, with an earnest deprecating gesture cried, "No! mother, no." Having got, as he believed, his marching orders from the "Captain of Salvation," he could not confer with flesh and blood. "Let her tell Jesus," he used to say; "He will put all right," and He did, for she gave him up willingly; and fondly she blessed him. It aggravated the trial on both sides that Mrs. Elmslie's other son–a sailor–was then far away from home; but William did his utmost to arrange for her comfort after his departure. His first note addressed to her after rejoining us in Edinburgh bears date, "Friday night," and was written after special prayer by a few {46} friends, that the Lord would graciously sustain and comfort her: "My dearest mother ... cheer up. I am well, and our loving Father is supporting me graciously in this hour of trial. He will sustain both of us if we lean on His almighty arm. I leave in an hour for London after very laborious work in Edinburgh. Every one is very kind to me. God bless and comfort you.–Your loving son, Willie."

"Southampton, 19th September 1864.–My ever dearest Mother,–When I dropped you my last note I was indeed in a very great hurry, for I had but a few minutes before leaving for London. Dear Mr. Ritchie's coming with me has been a source of great pleasure. I heartily wish he were coming all the way to India. After transacting all my business in London, we went down to Windsor, and spent the remainder of Saturday and Sunday with Uncle Stewart and Emma, who welcomed us most cordially. Vine Cottage is a little paradise of a place, I wish I could transport you to it, dear mother; how much good it would do you. We went to church in old Windsor where we heard a pitiably poor sermon. In the afternoon we went to St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle; there was no sermon, but the music was very grand. I believe most of the members of the choir are professionals....

"I am really well now, dearest mother. I trust you are leaning on God and rejoicing in Him. Rejoice in the Lord alway.–Your ever loving son, Willie."

"Southampton, 20th September 1864, 'Poonah.'–Just about to sail. Sorry about you, dear mother; only kept up by the knowledge that the Lord Himself is with you. {47} Lean hard on the Lord, and may He spare us to meet! The Lord bless you and comfort you. I shall write from Gibraltar in a very few days.–Your ever loving son, Willie."

"Poonah, off the coast of Portugal, Sept. 24.–My ever dear Mother,–We expect to arrive in Gibraltar to-morrow morning, and I cannot let an opportunity pass without posting a few lines for you.

"I have great reason for thankfulness to our gracious Father for all His kindness since I left you. With the exception of one day's sickness, I have kept well even through the heavy swell on the Bay of Biscay....

"I daresay you feel curious to know how I like board-ship life, and who my fellow-passengers are. We have Englishmen, Scotchmen, Irishmen, Dutchmen, and old Indians on board, and among the servants there are natives of India and China. Poor things, they are so looked down upon; I long to be able to speak a kind word to them, and to tell them that God loves them. There are two others in the cabin with me,–one a Christian man, an officer from the Punjaub, who knows the missionaries there. He also knows Dr. F––, and speaks highly in praise of him.

"We have three clergymen with us, one of whom is Archdeacon of Madras, to whom Major R–- proposed that we should have morning prayers, and this has been begun. Only a few have, as yet, attended, but it was pleasant to unite in thanking God for His great goodness, and to claim fulfilment of the promise that where two or three are gathered together in Christ's name, He will be in the midst of them. To-day we had a larger attendance.... {48} My own morning reading is the Bible; I also have had great pleasure in reading 'Gentle Life.' Our usual routine is: at 9, breakfast; 10, prayers; reading till 12, the hour for luncheon; on deck reading or conversing till 4, when the summons to dinner is heard. I must tell you what a fix I was in the first day at dinner. You know what a fear I have of being called on to carve; but where do you think I found my place at table, but right before a dish of fowls! I had to do my best, but have managed to avoid that seat ever since. After dinner there is the same round of reading, talking, or playing chess. I long to be in India, settled to work, for this kind of life is mere vegetating. I mean to begin the study of Hindustani next week: this will be my chief work for some months to come. Pray for me, dear mother. It is a very difficult language; but you remember the miracle of the gift of tongues. The Archdeacon is to preach to-morrow. I am sorry to think we are to arrive at Gibraltar on a Sunday, as I shall not be able to go and explore.

"I shall take up the thread of my story before we reach Malta, so as to have a letter ready for you when the mail goes out....

"Good-night, dearest mother; may you enjoy much of the presence of the good Spirit.–Your ever loving son, Willie."

"Mediterranean Sea, S.S. Poonah, 28th Sept. 1864.–My ever dear Mother,–We have had a very calm and pleasant run from the Rock, but now we are being so roughly tossed by the blue waters of the Mediterranean, that it is with difficulty I can write.... The Archdeacon and captain {49} arranged that worship should be in the evening on Sunday, as there was a great deal of noise and bustle on the morning of the Lord's day. In the evening, accordingly, everything was beautifully arranged. A large awning was spread over the quarter-deck, a box erected as a desk, having in front a large lantern, and the Archdeacon preached a very good sermon from those words, 'What think ye of Christ?'

"After service I had an interesting conversation with a young Dutch lady, who is evidently dying of consumption. She told me she had lived a very thoughtless life, but the glorious light of the Gospel seems to be dawning on her mind. I trust it is so, for her sun is fast setting.... I have begun Hindustani, and am kindly helped by Major R.

"The Lord bless and comfort my dear mother.–Your ever loving son, William."

"To the same.–Yesterday forenoon we arrived at Malta, and I had the pleasure of visiting Valetta, its principal city, which is composed chiefly of military forts of the greatest strength. I am told by military men on board that the island is considered impregnable. Passing along the main street of Valetta, we saw the Governor's palace. The women almost all wore black mantles over their hair, in some cases fastened with flowers. Every second person we met was a priest: there are 1600 in the capital alone. We visited the great Church of St. John's,–a truly magnificent building, so far as costly embellishments go; but it is florid, and not in harmony with the sacred purpose of the edifice. It reminded me of {50} Notre Dame in Paris, but neither of these buildings please me so much as Te Duomo in Florence, of which you have a photograph. A host of importunate beggars besieged us as we entered St. John's,–arrant rogues they seemed, every one of them. The son of Louis Philippe was buried in this church, and over his tomb there is an exquisite piece of sculpture.

"We spent a very interesting afternoon with Mr. Gibb, who took us to see the depot of the British and Foreign Bible Society, the superintendent of which is an old soldier, a soldier of the cross, too, and of the right stamp for such a post. Four thousand Bibles were sold the year before last, and through his laborious exertions no fewer than twelve thousand were disposed of last year. There cannot but be fruit where God's word is sown, accompanied as the sowing is, by many an earnest prayer for the increase. Mr. G. next took us to see the Public Library of Valetta, which belonged originally to the knights of Malta, and in which I saw copies of the writings of the Fathers in Divinity. There is a university in Valetta, and a capital normal school, in which, in addition to a good education, the boys have lessons in shoemaking, printing, and carving....