Title: Wild Animals of North America

Author: Edward William Nelson

Author of introduction, etc.: Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor

Illustrator: Louis Agassiz Fuertes

Ernest Thompson Seton

Release date: May 10, 2019 [eBook #59475]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR, Wayne Hammond and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

379

Copyright, 1918

BY THE

National Geographic Society

Washington, D. C.

Press of Judd & Detweiler, Inc.

381

In offering this volume of “Wild Animals of North America” to members of the National Geographic Society, the Editor combines the text and illustrations of two entire numbers of the National Geographic Magazine—that of November, 1916, devoted to the Larger Mammals of North America, and that of May, 1918, in which the Smaller Mammals of our continent were described and presented pictorially.

Edward W. Nelson, the author of both articles, is one of the foremost naturalists of our time. For forty years he has been the friend and student of North America’s wild-folk. He has made his home in forest and desert, on mountain side and plain, amid the snows of Alaska and the tropic heat of Central American jungles—wherever Nature’s creatures of infinite variety were to be observed, their habits noted, and their range defined.

In the whole realm of scientists, the Geographic could not have found a writer more admirably equipped for the authorship of a book such as “Wild Animals of North America” than Mr. Nelson, for, in addition to his exceptional scientific training and his standing as Chief of the unique U. S. Biological Survey, he possesses the rare quality of the born writer, able to visualize for the reader the things which he has seen and the experiences which he has undergone in seeing them. Each of his animal biographies, of which there are 119 in this volume, is a cameo brochure—concisely and entertainingly presented, yet never deviating from scientific accuracy.

In Mr. Louis Agassiz Fuertes, the National Geographic Society has secured for Mr. Nelson the same gifted artist collaborator which it provided for Henry W. Henshaw, author of “Common Birds of Town and Country,” “The Warblers,” and “American Game Birds,” all of which were assembled in our “Book of Birds.” In the present instance Mr. Fuertes has produced a natural history gallery of paintings of the Larger and Smaller Mammals of North America which is a notable contribution to wild-animal portraiture, and the reproductions of these works of art are among the most effective and lifelike examples of color printing ever produced in this country.

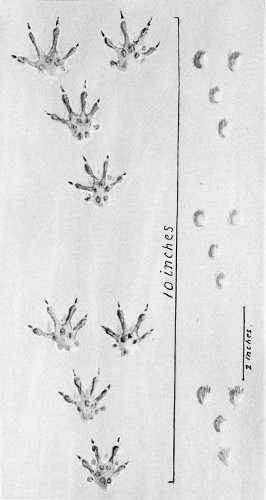

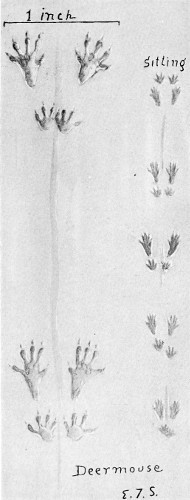

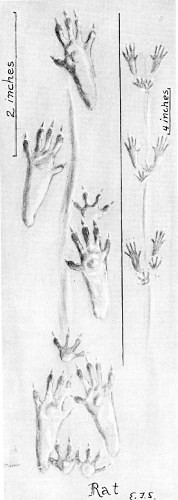

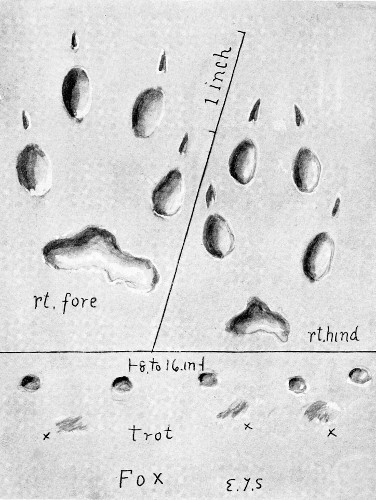

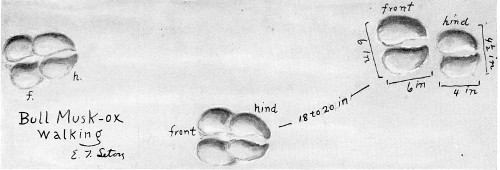

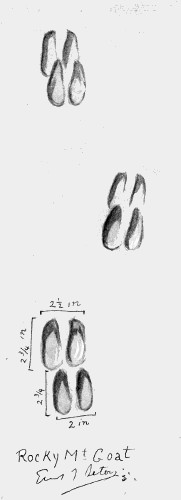

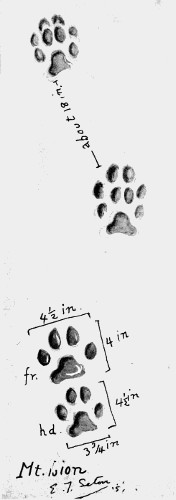

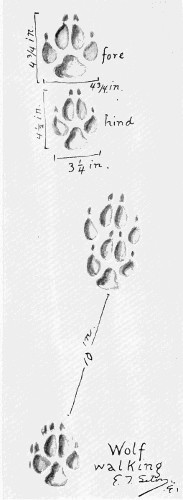

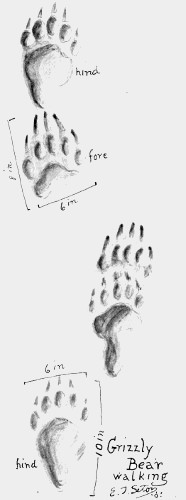

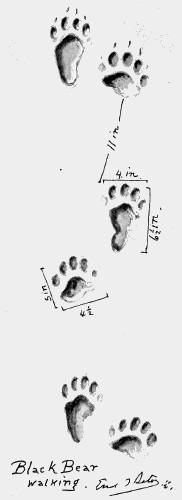

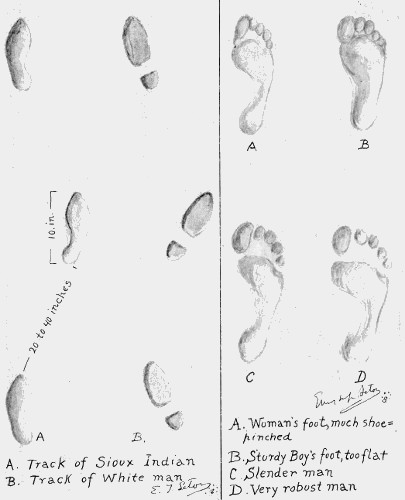

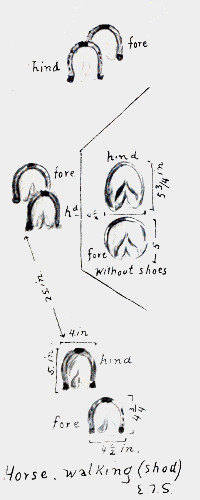

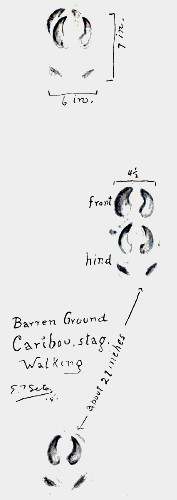

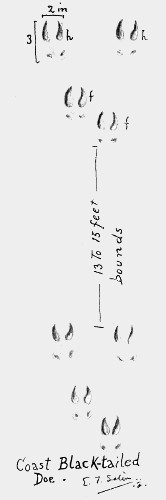

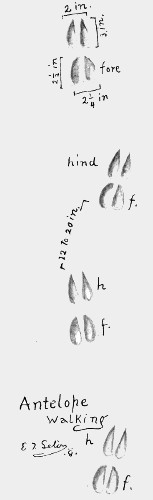

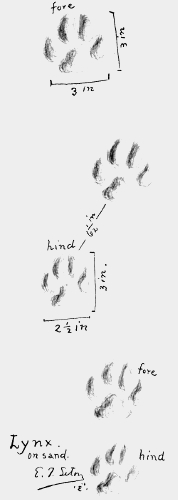

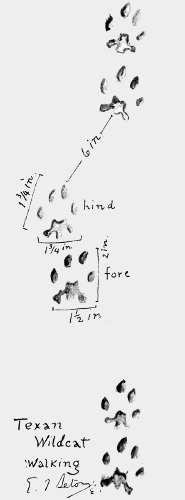

Supplementing the work of Mr. Nelson and Mr. Fuertes is a series of drawings by the noted naturalist and nature-lover, Ernest Thompson Seton, showing the tracks of many of the most widely known mammals.

“Wild Animals of North America” provides in compact and permanent form a natural history for which the National Geographic Society expended $100,000 in the two issues of the Magazine in which the articles and illustrations originally appeared.

(The articles and illustrations in this volume are reproduced from the November 1916, and May, 1918,

National Geographic Magazine. The first page is numbered 385, as it originally appeared

in the Magazine The following pages are numbered in sequence.)

| Text | Color illustration |

Track illustration |

|

|---|---|---|---|

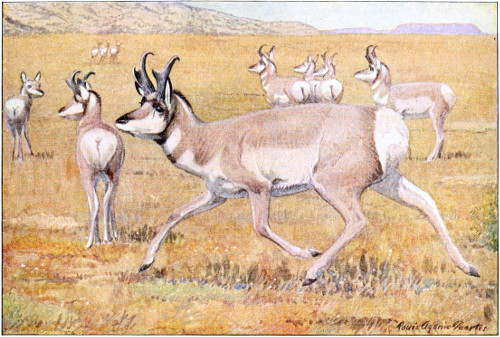

| Antelope, Prong-horn | 452 | 451 | 611 |

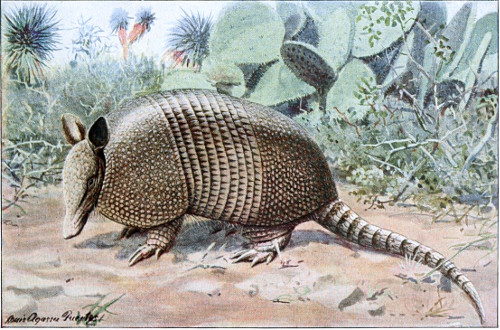

| Armadillo, Nine-banded | 584 | 559 | .. |

| Badger | 420 | 419 | 601 |

| Bat, Big-eared desert | 603 | 567 | .. |

| Bat, Hoary | 598 | 566 | .. |

| Bat, Mexican | 599 | 567 | .. |

| Bat, Red | 596 | 566 | .. |

| Bear, Alaskan Brown (frontispiece) | 441 | .. | .. |

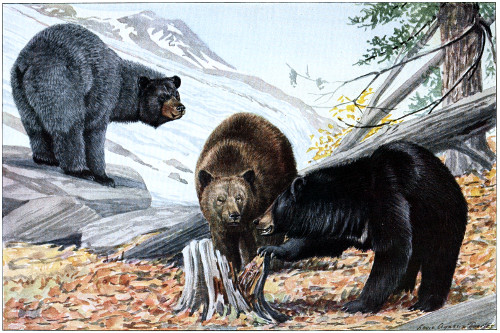

| Bear, Black | 437 | 439 | 608 |

| Bear, Cinnamon, or Black | 437 | 439 | .. |

| Bear, Glacier | 437 | 439 | .. |

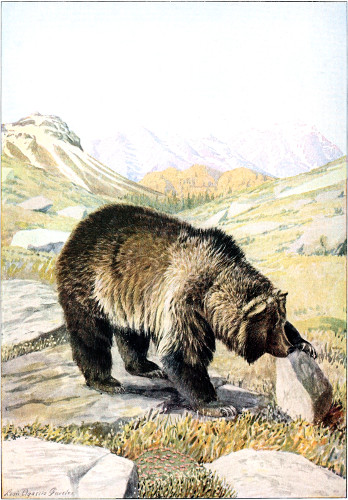

| Bear, Grizzly | 440 | 442 | 608 |

| Bear, Polar | 436 | 438 | .. |

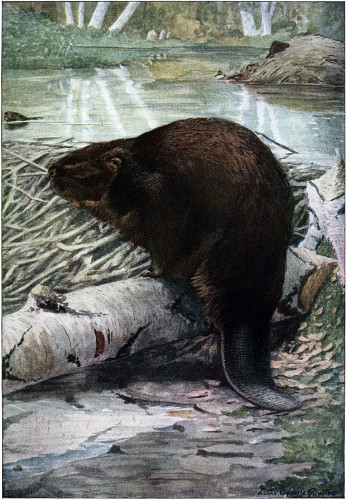

| Beaver, American | 441 | 443 | .. |

| Beaver, Mountain | 529 | 534 | .. |

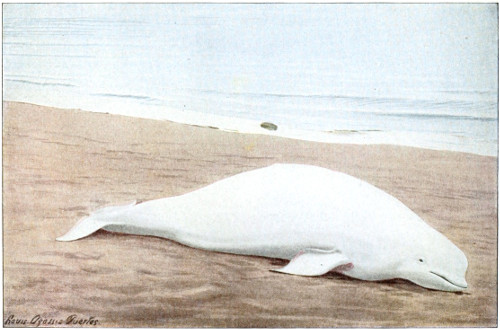

| Beluga, or White Whale | 468 | 470 | .. |

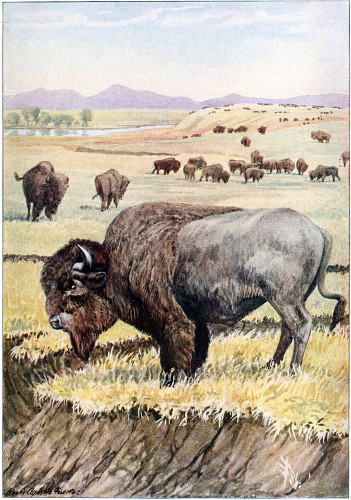

| Bison, American, or Buffalo | 461 | 463 | .. |

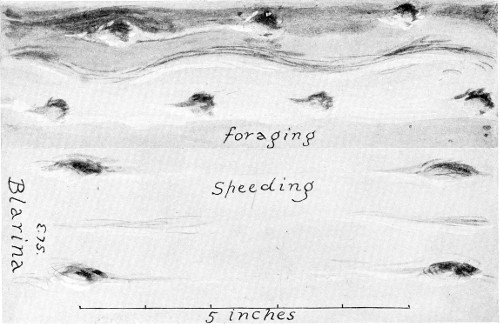

| Blarina | 593 | 566 | 595 |

| Bobcat, or Bay Lynx | 409 | 411 | .. |

| Bowhead | 469 | 471 | .. |

| Buffalo, or American Bison | 461 | 463 | .. |

| Cachalot, or Sperm Whale | 472 | 471 | .. |

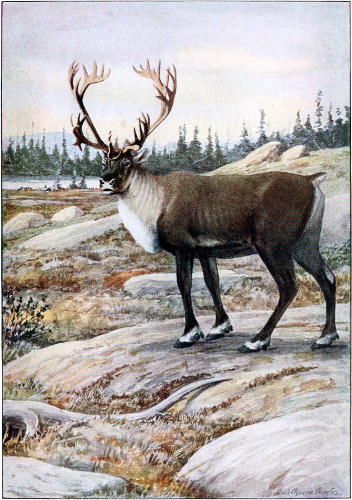

| Caribou, Barren Ground | 460 | 422 | 610 |

| Caribou, Peary | 460 | 422 | .. |

| Caribou, Woodland | 460 | 459 | .. |

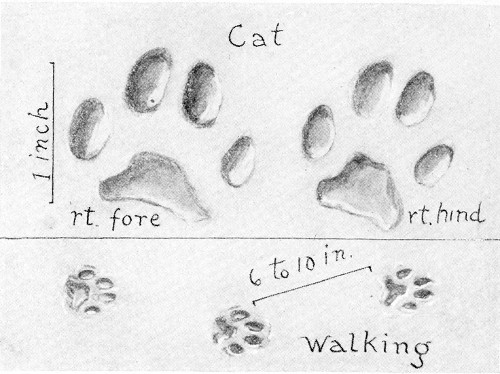

| Cat, Common | .. | .. | 487 |

| Cat, Jaguarundi, or Eyra | 413 | 415 | .. |

| Cat, Ring-tailed | 586 | 562 | .. |

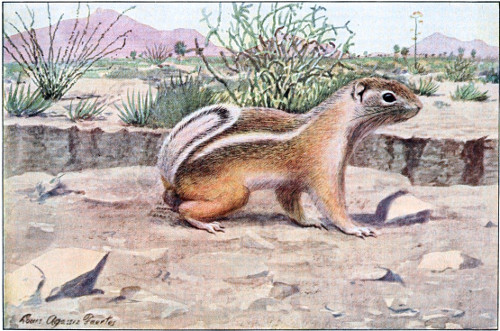

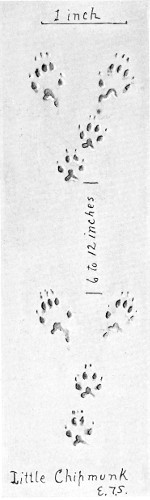

| Chipmunk, Antelope | 545 | 539 | .. |

| Chipmunk, Eastern | 549 | 542 | 580 |

| Chipmunk, Golden | 545 | 542 | .. |

| Chipmunk, Oregon | 552 | 543 | .. |

| Chipmunk, Painted | 553 | 543 | .. |

| Cony, or Little Chief Hare | 494 | 511 | .. |

| Cougar, or Mountain Lion | 412 | 414 | 605 |

| Cow, Common | .. | .. | 594 |

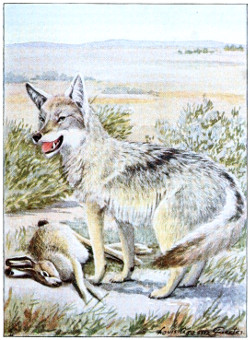

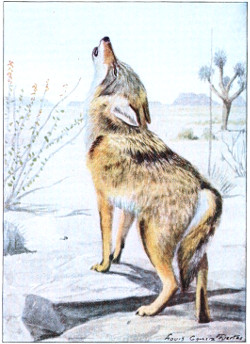

| Coyote, Arizona, or Mearns | 424 | 423 | .. |

| Coyote, Mearns, or Arizona | 424 | 423 | .. |

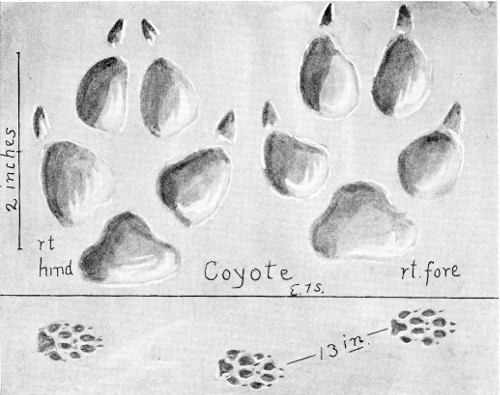

| Coyote, Plains | 424 | 423 | 599 |

| Deer, Arizona White-tailed | 457 | 458 | .. |

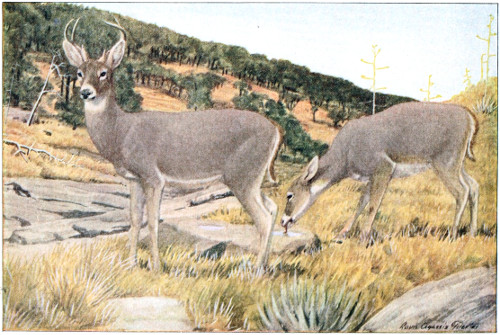

| Deer, Black-tailed | 456 | 455 | 611 |

| Deer, Mule | 453 | 455 | 607 |

| Deer, Virginia | 456 | 458 | .. |

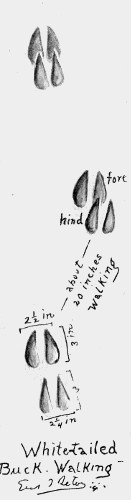

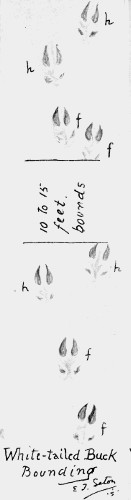

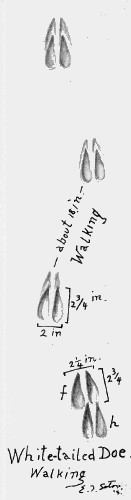

| Deer, White-tailed | 456, 457 | 458 | 606 |

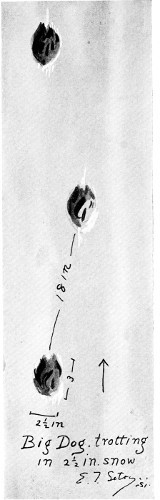

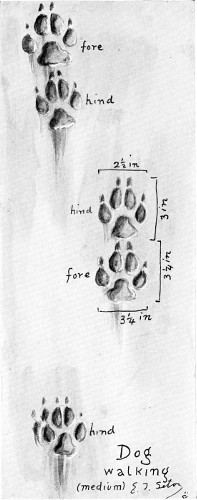

| Dog | .. | .. | 596, 597 |

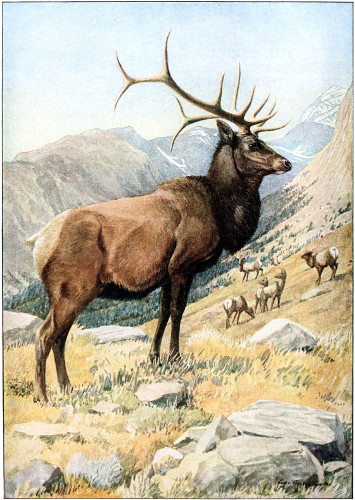

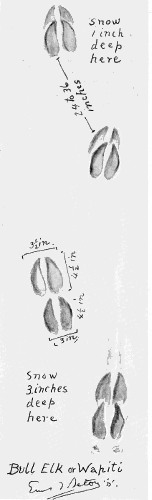

| Elk, American | 453 | 454 | 607 |

| Eyra, or Jaguarundi Cat | 413 | 415 | .. |

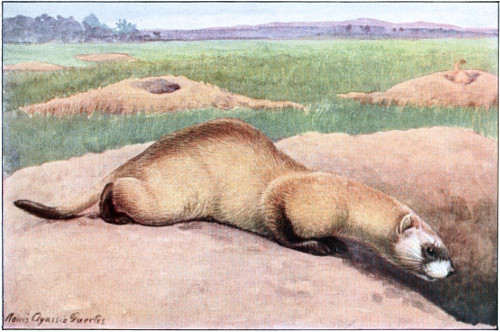

| Ferret, Black-footed | 571 | 551 | .. |

| Fisher, or Pekan | 444 | 446 | .. |

| Footprints, wild folk | .. | .. | 485 |

| Fox | .. | .. | 575 |

| Fox, Alaska Red | 417 | 418 | .. |

| Fox, Arctic, or White | 425 | 426 | .. |

| Fox, Cross | 417 | 418 | .. |

| Fox, Desert | 420 | 419 | .. |

| Fox, Gray | 417 | 419 | .. |

| Fox, Pribilof Blue | 425 | 426 | .. |

| Fox, Red | 416 | 418 | .. |

| Fox, Silver | 417 | 418 | .. |

| Fox, White, or Arctic | 425 | 426 | .. |

| Goat, Bighorn | .. | .. | 604 |

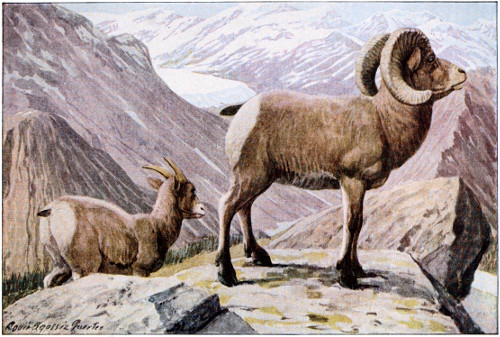

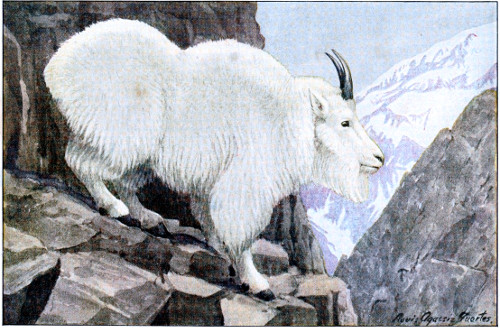

| Goat, Rocky Mountain | 452 | 451 | 604 |

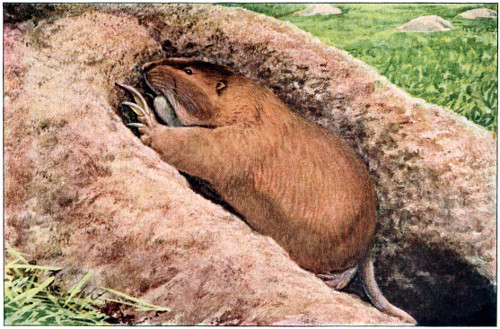

| Gopher, Pocket | 500 | 515 | .. |

| Hare, Arctic | 491 | 510 | .. |

| Hare, Little Chief | 494 | 511 | .. |

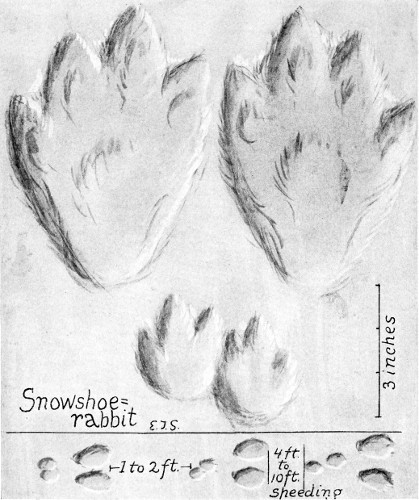

| Hare, Varying | 489 | 507 | 490 |

| Horse | .. | .. | 610 |

| Human footprints | .. | .. | 609 |

| Jaguar | 413 | 414 | .. |

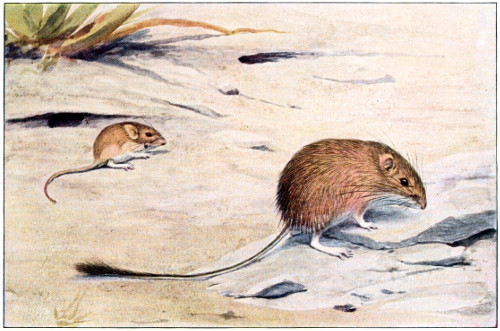

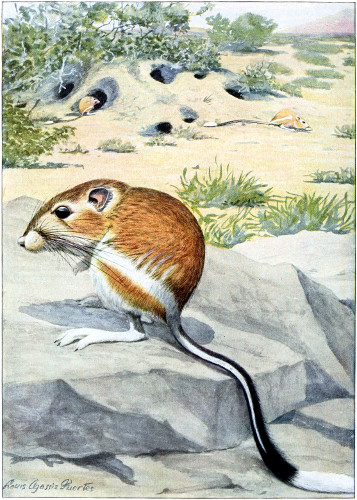

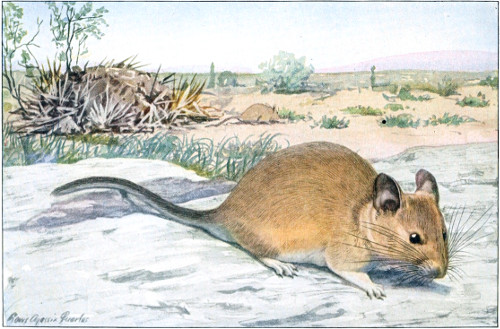

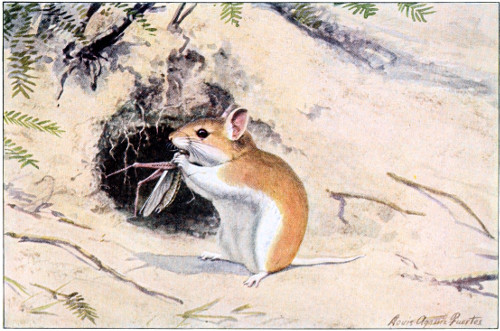

| Kangaroo Rat | 502 | 518 | .. |

| Lemming, Banded | 503 | 519 | .. |

| Lemming, Brown | 504 | 519 | .. |

| Lion, Mountain | 412 | 414 | 605 |

| Lynx, Bay | 409 | 411 | .. |

| Lynx, Canada | 409 | 411 | 612 |

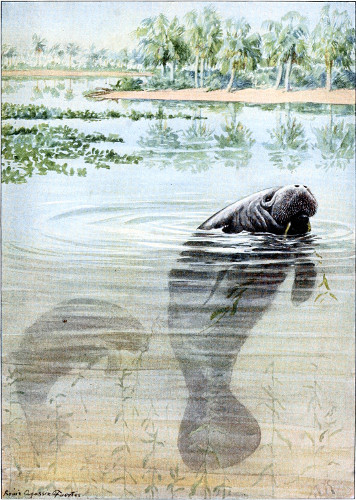

| Manati, Florida | 465 | 467 | .. |

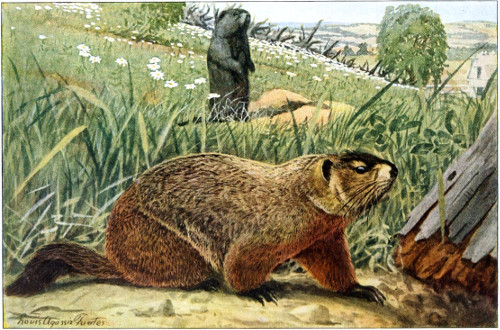

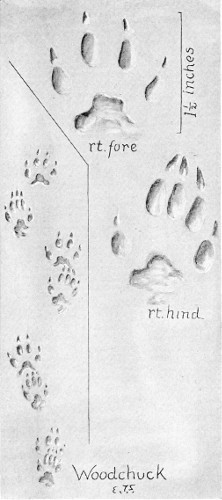

| Marmot, American | 533 | 534 | 578 |

| Marmot, Hoary, or Whistler | 536 | 535 | .. |

| Marten, or American Sable | 576 | 555 | .. |

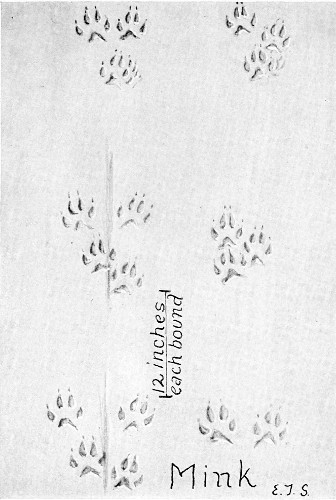

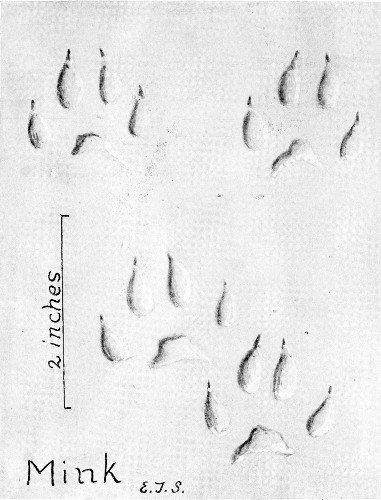

| Mink, American | 575 | 555 | 586, 587 |

| Mole, Oregon | 588 | 563 | .. |

| Mole, Star-nosed | 589 | 563 | .. |

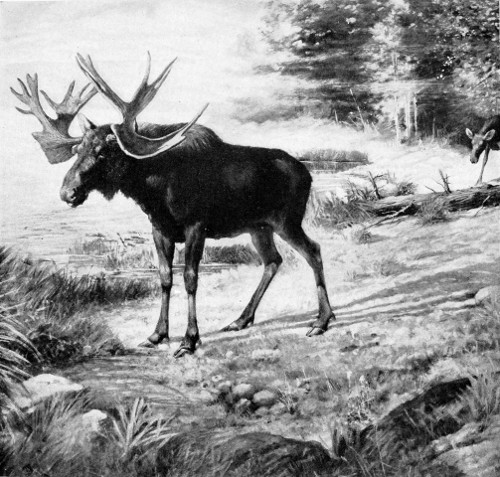

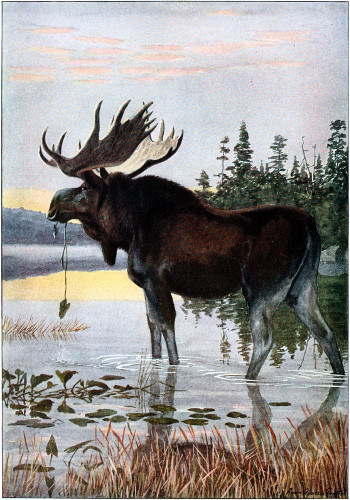

| Moose | 461 | 462 | 602 |

| Mouse, Beach | 524 | 530 | .. |

| Mouse, Big-eared Rock | 525 | 531 | .. |

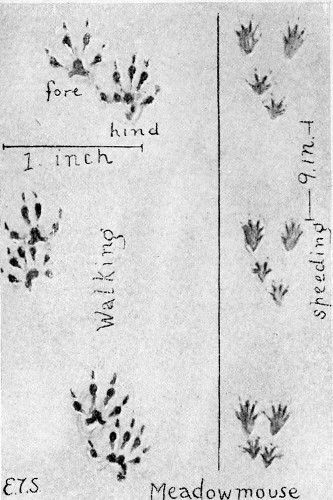

| Mouse Field, or Meadow | 505 | 522 | 495 |

| Mouse, Grasshopper | 520 | 527 | 570 |

| Mouse, Harvest | 517 | 527 | .. |

| Mouse, House | 529 | 531 | .. |

| Mouse, Jumping | 496 | 514 | .. |

| Mouse, Pine | 508 | 522 | .. |

| Mouse, Red-backed | 509 | 523 | .. |

| Mouse, Rufous Tree | 512 | 523 | .. |

| Mouse, Silky Pocket | 497 | 515 | .. |

| Mouse, Spiny Pocket | 498 | 515 | .. |

| Mouse, White-footed | 521 | 530 | 572 |

| Muskhog, or Peccary | 448 | 447 | .. |

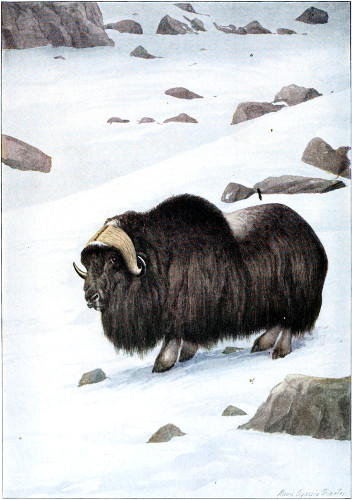

| Musk-ox | 464 | 466 | 600 |

| Muskrat | 513 | 526 | 569 |

| Ocelots, or Tiger-cats | 416 | 415 | .. |

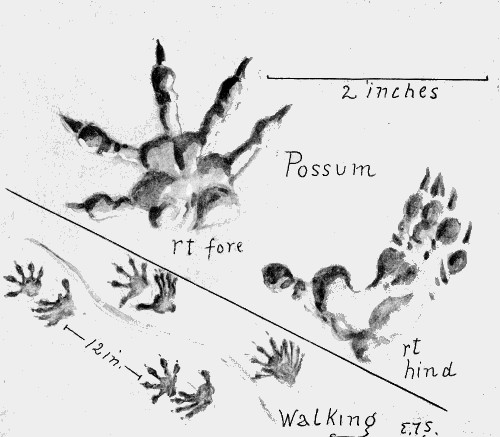

| Opossum, Virginia | 408 | 410 | 588 |

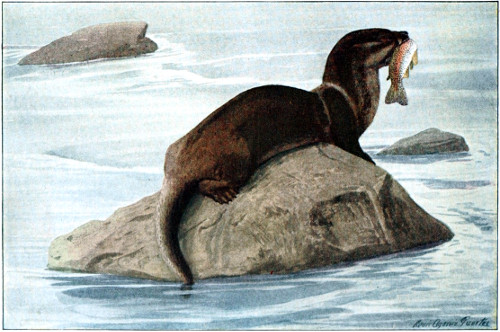

| Otter | 445 | 446 | .. |

| Otter, Sea | 432 | 434 | .. |

| Peccary, Collared | 448 | 447 | .. |

| Pekan, or Fisher | 444 | 446 | .. |

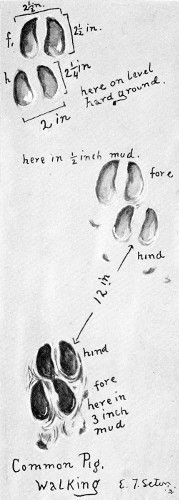

| Pig, Common | .. | .. | 571 |

| Pika, or Little Chief Hare | 494 | 511 | .. |

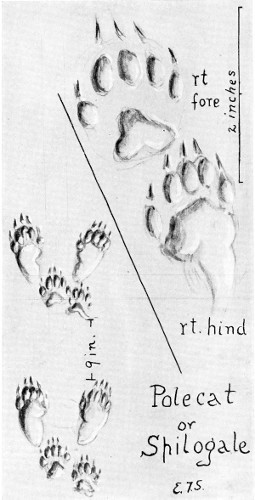

| Polecat, or Spilogale | .. | .. | 593 |

| Porcupine | 495 | 514 | .. |

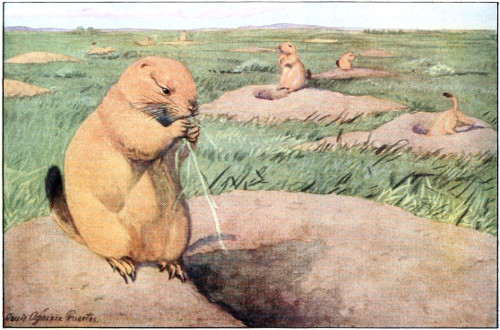

| Prairie-dog | 536 | 538 | .. |

| Quadruped, with biped track: Common cat |

.. | .. | 487 |

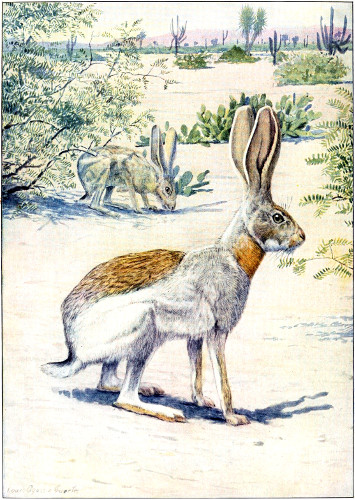

| Rabbit, Antelope Jack | 486 | 506 | .. |

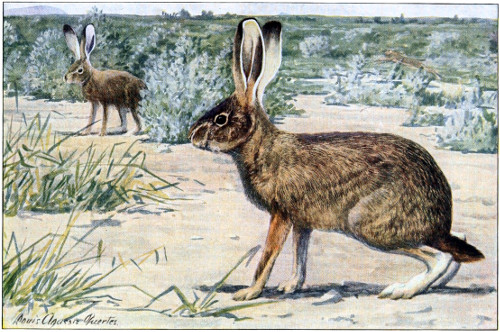

| Rabbit, California Jack | 487 | 507 | .. |

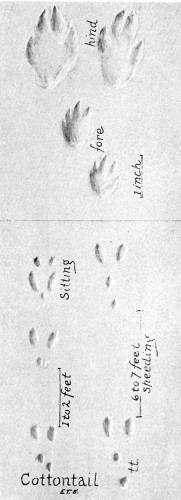

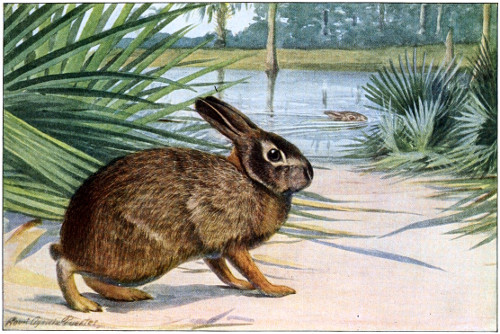

| Rabbit, Cottontail | 492 | 510 | 492 |

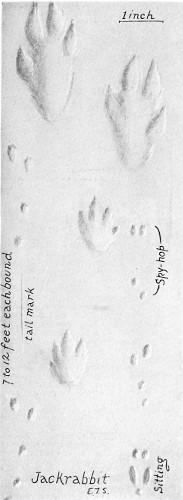

| Rabbit, Jack | .. | .. | 488 |

| Rabbit, Marsh | 493 | 511 | .. |

| Rabbit, Snowshoe | 489 | 507 | 490 |

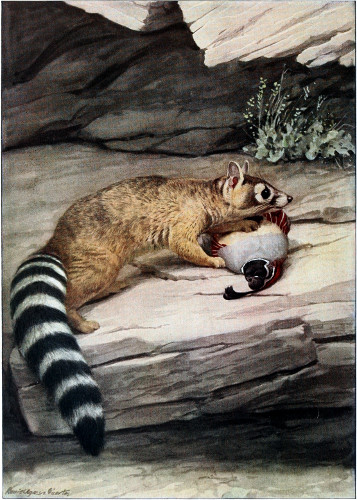

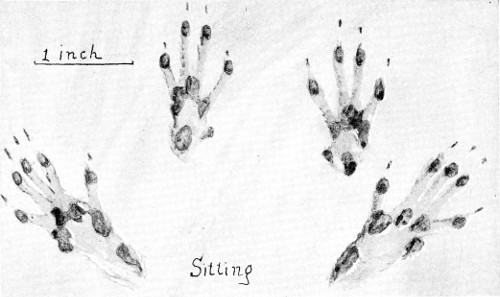

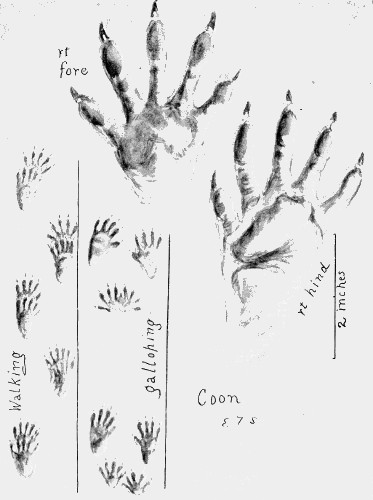

| Raccoon | 408 | 410 | 590 |

| Rat, Brown | 525 | 531 | 574 |

| Rat, Kangaroo | 502 | 518 | .. |

| Sable, American, or Marten | 576 | 555 | .. |

| Sea-elephant, Northern | 432 | 434 | .. |

| Sea-lion, Steller | 429 | 431 | .. |

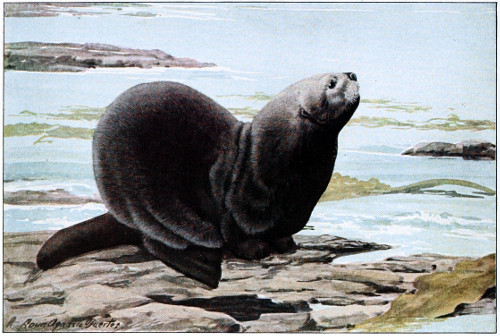

| Seal, Alaska Fur | 429 | 431 | .. |

| Seal, Elephant | 432 | 434 | .. |

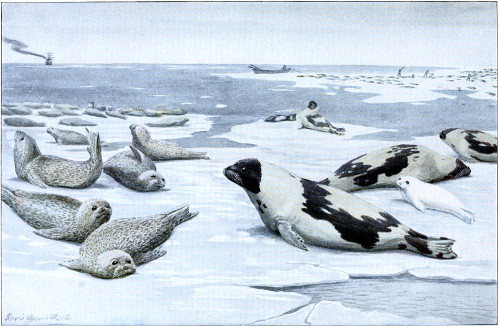

| Seal, Greenland | 433 | 435 | .. |

| Seal, Harbor | 433 | 435 | .. |

| Seal, Harp, or Saddle-back | 433 | 435 | .. |

| Seal, Leopard | 433 | 435 | .. |

| Seal, Ribbon | 436 | 438 | .. |

| Seal, Saddle-back | 433 | 435 | .. |

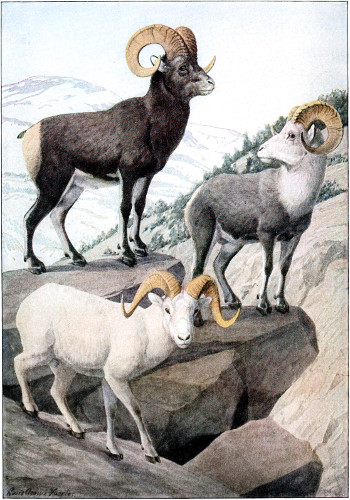

| Sheep, Dall Mountain | 449 | 450 | .. |

| Sheep, Rocky Mountain | 448 | 447 | .. |

| Sheep, Stone Mountain | 449 | 450 | .. |

| Shrew, Common | 591 | 566 | .. |

| Shrew, Short-tailed | 593 | 566 | 595 |

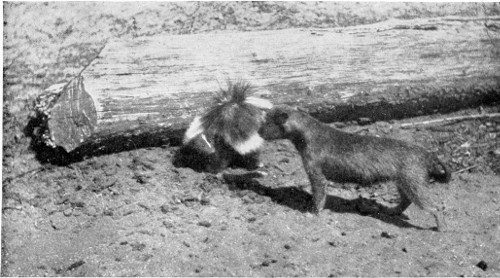

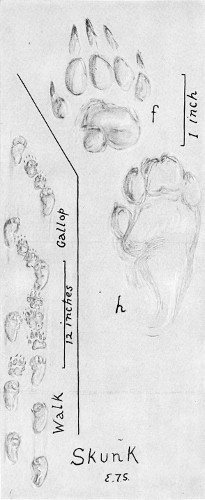

| Skunk, Common | 580 | 558 | 592 |

| Skunk, Hog-nosed | 582 | 559 | .. |

| Skunk, Little, or Polecat | .. | .. | 593 |

| Skunk, Little Spotted | 577 | 558 | .. |

| Squirrel, Abert | 564 | 550 | .. |

| Squirrel, California Ground | 541 | 539 | .. |

| Squirrel, Douglas | 557 | 546 | .. |

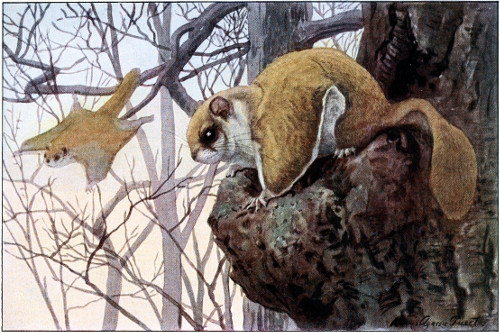

| Squirrel, Flying | 568 | 551 | .. |

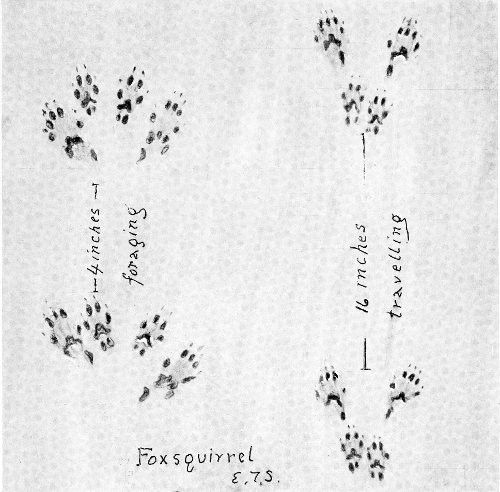

| Squirrel, Fox | 561 | 547 | 581, 582 |

| Squirrel, Gray | 560 | 547 | .. |

| Squirrel, Kaibab | 564 | 550 | .. |

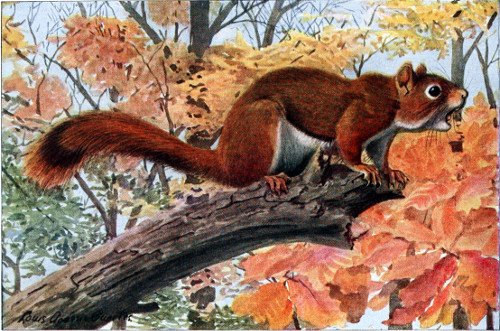

| Squirrel, Red | 556 | 546 | .. |

| Squirrel, Rusty Fox | 561 | 547 | 581 |

| Squirrel, Striped Ground | 540 | 538 | .. |

| Spilogale, or Polecat | .. | .. | 593 |

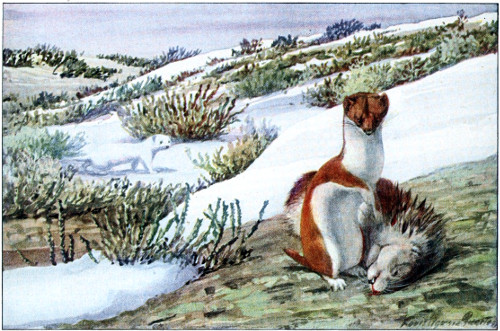

| Stoat, or Large Weasel | 572 | 554 | .. |

| Tiger-cats, or Ocelots | 416 | 415 | .. |

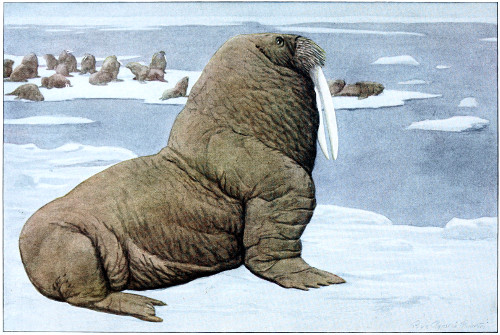

| Walrus, Pacific | 428 | 430 | .. |

| Wapiti, or American Elk | 453 | 454 | .. |

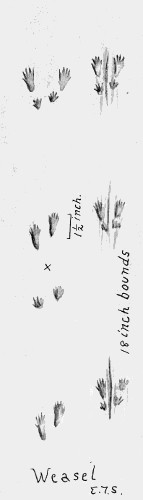

| Weasel | .. | .. | 584 |

| Weasel, Large, or Stoat | 572 | 554 | .. |

| Weasel, Least | 573 | 554 | .. |

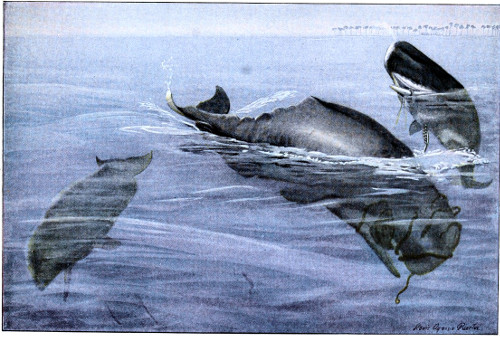

| Whale, Greenland Right | 469 | 471 | .. |

| Whale, Killer | 468 | 470 | .. |

| Whale, Sperm, or Cachalot | 472 | 471 | .. |

| Whale, White, or Beluga | 468 | 470 | .. |

| Whistler, or Hoary Marmot | 536 | 535 | .. |

| Wildcat, Texan | .. | .. | 612 |

| Wolf, Arctic White | 421 | 422 | .. |

| Wolf, Black | .. | 423 | .. |

| Wolf, Gray, or Timber | 421 | 423 | 605 |

| Wolf, Prairie | 424 | 423 | .. |

| Wolf, Timber, or Gray | 421 | 423 | .. |

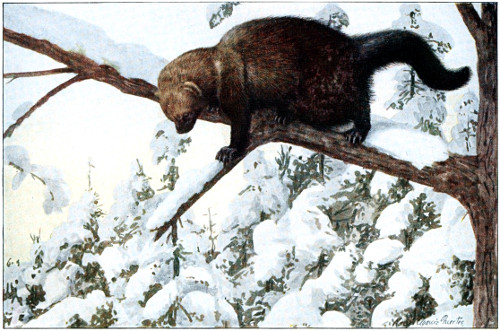

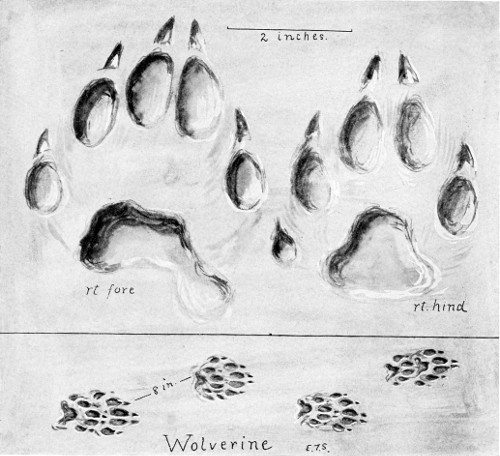

| Wolverine | 428 | 427 | 583 |

| Woodchuck, Common | 533 | 534 | 578 |

| Woodrat | 516 | 526 | .. |

383

384

From a drawing by Louis Agassiz Fuertes Copyright by the National Geographic Magazine, 1916, Gilbert H. Grosvenor, Editor

THE LARGEST CARNIVOROUS ANIMAL EXTANT

THE ALASKA BROWN BEAR

The great brown bear of the Alaska peninsula, Ursus gyas, and his cousin, Ursus middendorffi, of Kodiac Island, are the largest of all bears, as well as the largest carnivorous animals in the world. While sometimes attaining a weight of 1500 pounds, they are, as a rule, inoffensive giants, taking flight at the first sight of man. But when wounded, or surprised at close quarters, they give battle, and their enormous size, strength and activity render them terrific antagonists. The world did not know of the existence of these bears until 1898. During the spring the Alaska brown bear lives upon the salmon which come up the rivers and creeks to spawn, while in the summer and fall they eat the sedge of the lowland flats, grazing like cattle, and varying their diet with small mammals and berries which they find in the hills. The comparatively limited and easily accessible territory in which they live renders their future precarious unless reasonable means for their proper protection are continued. 385

By E. W. NELSON

Chief, U. S. Biological Survey

With Illustrations from Paintings by Louis Agassiz Fuertes

At the time of its discovery and occupation by Europeans, North America and the bordering seas teemed with an almost incredible profusion of large mammalian life. The hordes of game animals which roamed the primeval forests and plains of this continent were the marvel of early explorers and have been equaled in historic times only in Africa.

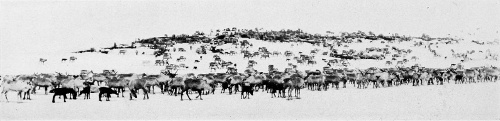

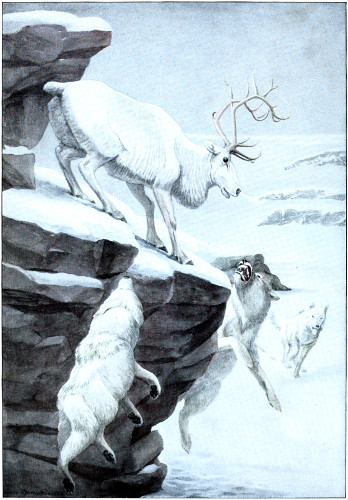

Even beyond the limit of trees, on the desolate Arctic barrens, vast herds containing hundreds of thousands of caribou drifted from one feeding ground to another, sharing their range with numberless smaller companies of musk-oxen. Despite the dwarfed and scanty vegetation of this bleak region, the fierce winter storms and long arctic nights, and the harrying by packs of white wolves, these hardy animals continued to hold their own until the fatal influence of civilized man was thrown against them.

Southward from the Arctic barrens, in the neighboring forests of spruce, tamarack, birches, and aspens, were multitudes of woodland caribou and moose. Still farther south, in the superb forests of eastern North America, and ranging thence over the limitless open plains of the West, were untold millions of buffalo, elk, and white-tailed deer, with the prong-horned antelope replacing the white-tails on the western plains.

With this profusion of large game, which afforded a superabundance of food, there was a corresponding abundance of large carnivores, as wolves, coyotes, black and grizzly bears, mountain lions, and lynxes. Black bears were everywhere except on the open plains, and numerous species of grizzlies occupied all the mountainous western part of the continent.

Fur-bearers, including beavers, muskrats, land-otters, sea-otters, fishers, martens, minks, foxes, and others, were so plentiful in the New World that immediately after the colonization of the United States and Canada a large part of the world’s supply of furs was obtained here.

Trade with the Indians laid the foundations of many fortunes, and later developed 386 almost imperial organizations, like the Hudson’s Bay Company and its rivals. Many adventurous white men became trappers and traders, and through their energy, and the rivalry of the trading companies, we owe much of the first exploration of the northwestern and northern wilderness. The stockaded fur-trading stations were the outposts of civilization across the continent to the shores of Oregon and north to the Arctic coast. At the same time the presence of the sea-otter brought the Russians to occupy the Aleutian Islands, Sitka, and even northern California.

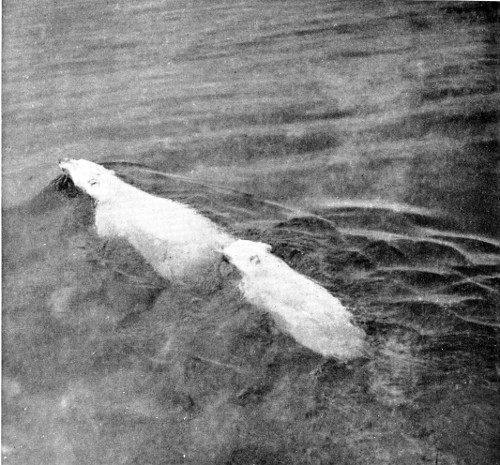

TOWING HER BABY TO SAFETY

When a mother polar bear scents danger she jumps into the water and her cub holds fast to her tail while she tows it to safety. But when no danger seems to threaten she wants it to “paddle its own canoe,” and boxes its ears or ducks its head under water if it insists on being too lazy to swim for itself.

The wealth of mammal life in the seas along the shores of North America almost equaled that on the land. On the east coast there were many millions of harp and hooded seals and walruses, while the Greenland right and other whales were extremely abundant. On the west coast were millions of fur seals, sea-lions, sea-elephants, and walruses, with an equal abundance of whales and hundreds of thousands of sea otters.

A SWIMMING POLAR BEAR

A polar bear when swimming does not use his hind legs, a new fact brought out by the motion-picture camera.

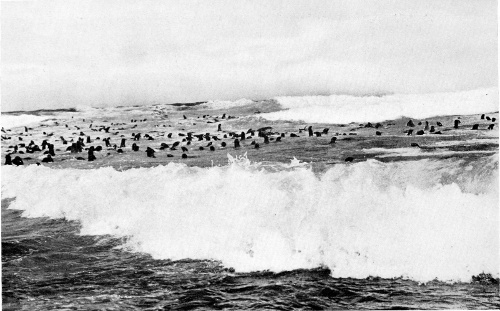

FUR SEAL: FEMALES AND YOUNG PUPS

From the ages of one to four years fur seals are extremely playful. They are marvelous swimmers, and frolic about in pursuit of one another, now diving deep, and then, one after the other, suddenly leaping high above the surface in graceful curves, like porpoises.

Many of the chroniclers dealing with explorations and life on the frontier during the early period of the occupation of America gave interesting details concerning the game animals. Allouez says that in 1680, between Lake Erie and Lake 387 388 389 Michigan the prairies were filled with an incredible number of bears, wapiti, white-tailed deer, and turkeys, on which the wolves made fierce war. He adds that on a number of occasions this game was so little wild that it was necessary to fire shots to protect the party from it. Perrot states that during the winter of 1670-1671, 2,400 moose were snared on the Great Manitoulin Island, at the head of Lake Huron. Other travelers, even down to the last century, give similar accounts of the abundance of game.

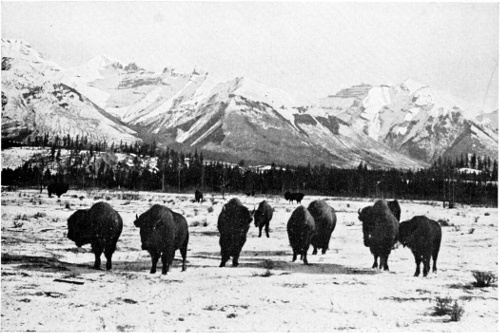

ROAMING “MONARCHS OF THE PLAIN”: BRITISH COLUMBIA

A remnant of the veritable sea of wild life that surged over American soil before the dikes of civilization compassed it about and all but wiped it out.

The original buffalo herds have been estimated to have contained from 30,000,000 to 60,000,000 animals, and in 1870 it was estimated that about 5,500,000 still survived. A number of men now living were privileged to see some of the great herds of the West before they were finally destroyed. Dr. George Bird Grinnell writes:

“In 1870, I happened to be on a train that was stopped for three hours to let a herd of buffalo pass. We supposed they would soon pass by, but they kept coming. On a number of occasions in earlier days the engineers thought that they could run through the herds, and that, seeing the locomotive, the buffalo would stop or turn aside; but after a few locomotives had been ditched by the animals the engineers got in the way of respecting the buffaloes’ idiosyncrasies....

“Up to within a few years, in northern Montana and southern Alberta, old buffalo trails have been very readily traceable by the eye, even as one passed on a railroad train. These trails, fertilized by the buffalo and deeply cut so as to long hold moisture, may still be seen in summer as green lines winding up and down the hills to and from the water-courses.”

Concerning the former abundance of antelope, Dr. Grinnell says: “For many years I have held the opinion that in early days on the plains, as I saw them, antelope were much more abundant than buffalo. Buffalo, of course, being big and black, were impressive if seen in masses and were visible a long way off. Antelope, smaller and less conspicuous in color, were often passed unnoticed, except by a person of experience, who 390 might recognize that distant white dots might be antelope and not buffalo bones or puff balls. I used to talk on this subject with men who were on the plains in the ’60’s and ’70’s, and all agreed that, so far as their judgment went, there were more antelope than buffalo. Often the buffalo were bunched up into thick herds and gave the impression of vast numbers. The antelope were scattered, and, except in winter, when I have seen herds of thousands, they were pretty evenly distributed over the prairie.

A WALRUS BATTLE FRONT: THOUGH FORMIDABLE LOOKING, WITH THEIR LONG TUSKS, THEY ASK ONLY TO BE LET ALONE.

“I have certain memories of travel on the plains, when for the whole long day one would pass a continual succession of small bands of antelope, numbering from ten to fifty or sixty, those at a little distance paying no attention to the traveler, while those nearer at hand loped lazily and unconcernedly out of the way. In the year 1879, in certain valleys in North Park, Colorado, I saw wonderful congregations of antelope. As far as we could see in any direction, all over the basins, there were antelope in small or considerable groups. In one of these places I examined with care the trails made by them, for this was the only place where I ever saw deeply worn antelope trails, which suggested the buffalo trails of the plains.”

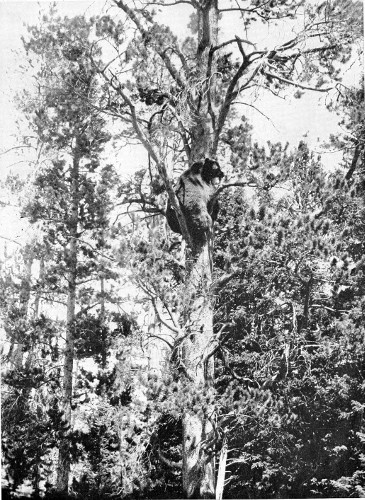

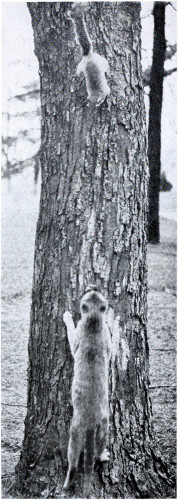

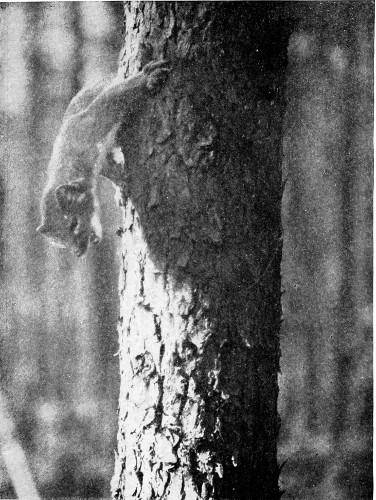

A CINNAMON TREED: YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK

Bruin for the most part is an inoffensive beast, with an impelling curiosity and such a taste for sweet things that he can eat pounds of honey and lick his chops for more.

MOOSE FEEDING UNDER DIFFICULTIES

The moose likes the succulent water plants it finds at the bottom of lakes and sluggish streams, and often when reaching for them becomes completely submerged.

The wealth of animal life found by our forebears was one of the great natural resources of the New World. Although freely drawn upon from the first, the stock was but little depleted up to within a century. During the last one hundred years, however, the rapidly increasing occupation of the continent and other 391 392 393 causes, together with a steadily increasing commercial demand for animal products, have had an appalling effect. The buffalo, elk, and antelope are reduced to a pitiful fraction of their former countless numbers.

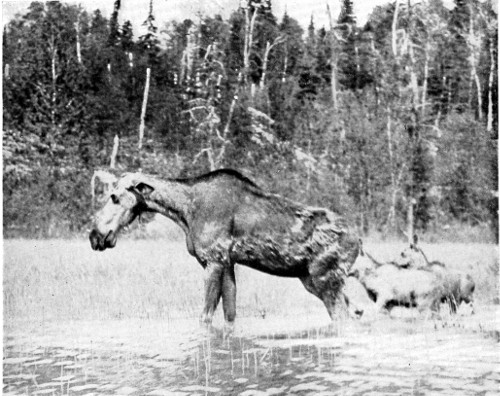

COW MOOSE WITH HER YOUNG

Notice the fold of skin at her neck resembling a bell.

Practically all other large game has alarmingly decreased, and its extermination has been partly stayed only by the recent enforcement of protective laws. It is quite true that the presence of wild buffalo, for instance, in any region occupied for farming and stock-raising purposes is incompatible with such use. Thus the extermination of the bison as a denizen of our western plains was inevitable. The destruction, however, of these noble game animals by millions for their hides only furnishes a notable example of the wanton wastefulness which has heretofore largely characterized the handling of our wild life.

A like disregard for the future has been shown in the pursuit of the sea mammals. The whaling and sealing industries are very ancient, extending back for a thousand years or more; but the greatest and most ruthless destruction of the whales and seals has come within the last century, especially through the use of steamships and bomb-guns. Without adequate international protection, there is grave danger that the most valuable of these sea mammals will be exterminated. The fur seal and the sea-elephant, once so abundant on the coast of southern California, are nearly or quite gone, and the sea otter of the North Pacific is dangerously near extinction.

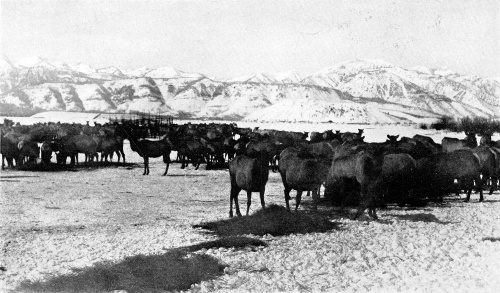

ROCKY MOUNTAIN ELK

They can hold their own in the mountains in summer, but when the deep snows come they are compelled to go down into the valleys. Just before they leave the big bulls travel the mountains from one end to the other, driving old and young before them into the lower country. In case of a hard winter the elk are thin and weak, and then the dreaded wolf makes havoc among them, especially the little calves.

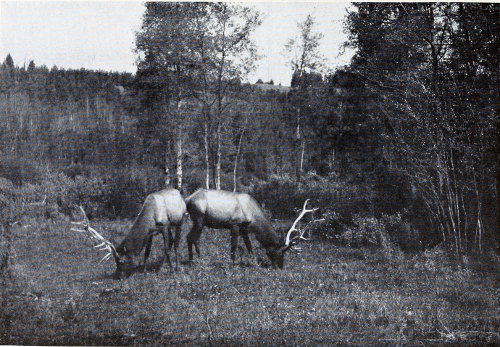

AN UNUSUAL ELK PICTURE

The recent great abundance of large land mammals in North America, both in individuals and species, is in striking contrast with their scarcity in South America, the difference evidently being due to the long isolation of the southern continent from other land-masses, whence it 394 395 396 397 might have been restocked after the loss of a formerly existing fauna.

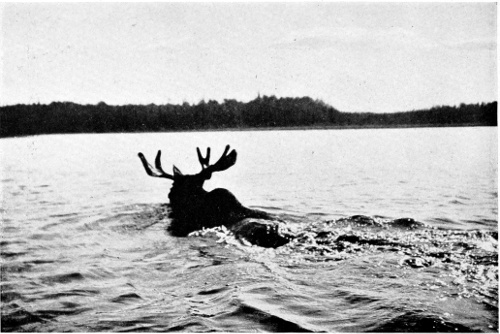

THE MOOSE IS A POWERFUL SWIMMER

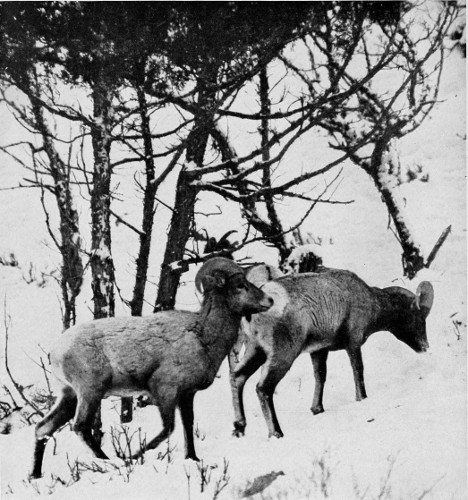

PART OF A HERD OF SIXTY MOUNTAIN SHEEP

They are fed hay and salt daily at the Denver and Rio Grande Railway station at Ouray, Colorado. This picture was taken at a distance of about 10 to 15 feet from the wild animals, which grow quite tame under such friendly ministrations.

A MOOSE THAT LIVED IN NEW JERSEY IN PLEISTOCENE TIMES: CROVALCES

A primitive moose-like form, a nearly perfect skeleton of which was found in southern Jersey some years ago. In size and general proportions the animal was like a modern moose, but the nose was less developed, and the horns were decidedly different in character.

The differences in the geographic distribution of mammal life between North and South America and the relationships between our fauna and that of the Old World are parts of the latest chapter of a wonderful story running back through geologic ages. The former chapters are recorded in the fossil beds of all the continents. While only a good beginning has been made in deciphering these records, enough has been done by the fascinating researches of Marsh, Cope, Osborn, Scott, and others to prove that in all parts of the earth one fauna has succeeded another in marvelous procession.

It has been shown also that these changes in animal life, accompanied by equal changes in plant life, have been largely brought about by variations in climate and by the uplifting and depressing of continental land-masses above or below the sea. The potency of climatic influence on animal life is so great that even a fauna of large mammals will be practically destroyed over a great area by a long-continued change of a comparatively few degrees (probably less than ten degrees Fahrenheit) in the mean daily temperatures.

The distribution of both recent and 398 fossil mammals shows conclusively that numberless species have spread from their original homes across land bridges to remote unoccupied regions, where they have become isolated as the bridges disappeared beneath the waves of the sea.

THEIR LIVING LIES BENEATH THE SNOW

All nature loves kindness and trusts the gentle hand. Contrast these sheep, ready to fly at the slightest noise, with those in the picture on page 396, peacefully feeding in close proximity to a standing express train. Every one appreciates a good picture of a living animal more than the trophy of a dead one!

For ages Asia appears to have served as a vast and fecund nursery for new mammals from which North Temperate and Arctic America have been supplied. The last and comparatively recent land bridge, across which came the ancestors of our moose, elk, caribou, prong-horned antelope, mountain goats, mountain sheep, musk-oxen, bears, and many other mammals, was in the far Northwest, where Bering Straits now form a shallow channel only 28 miles wide separating Siberia from Alaska. 399

INTRODUCING A LITTLE BLACK BEAR TO A LITTLE BROWN BEAR AT SEWARD, ALASKA

“Howdy-do! I ain’t got a bit of use for you!”

“What do I care! You’d better back away, black bear!”

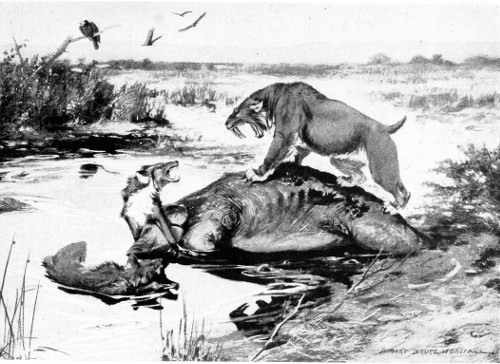

The fossil beds of the Great Plains and other parts of the West contain eloquent proofs of the richness and variety of mammal life on this continent at different periods in the past. Perhaps the most wonderful of all these ancient faunas was that revealed by the bones of birds and mammals which had been trapped in the asphalt pits recently discovered in the outskirts of Los Angeles, California. These bones show that prior to the arrival of the present fauna the plains of southern California swarmed with an astonishing wealth of strange birds and beasts (see page 401).

The most notable of these are saber-toothed tigers, lions much larger than those of Africa; giant wolves; several kinds of bears, including the huge cave bears, even larger than the gigantic brown bears of Alaska; large wild horses; camels; bison (unlike our buffalo); tiny antelope, the size of a fox; mastodons, mammoths with tusks 15 feet long; and giant ground sloths; in addition to many other species, large and small.

With these amazing mammals were equally strange birds, including, among numerous birds of prey, a giant vulturelike species (far larger than any condor), peacocks, and many others.

The geologically recent existence of this now vanished fauna is evidenced by the presence in the asphalt pits of bones of the gray fox, the mountain lion, and close relatives of the bobcat and coyote, as well as the condor, which still frequent that region, and thus link the past with the present. The only traces of the ancient vegetation discovered in these asphalt pits are a pine and two species of juniper, which are members of the existing flora.

There is reason for believing that primitive man occupied California and other parts of the West during at least the latter part of the period when the fauna of the asphalt pits still flourished. Dr. C. Hart Merriam informs me that the folk-lore of the locally restricted California Indians contains detailed descriptions of a beast which is unmistakably a bison, probably the bison of the asphalt pits.

The discovery in these pits of the bones of a gigantic vulturelike bird of prey of far greater size than the condor is even more startling, since the folk-lore of the Eskimos and Indians of most of the tribes from Bering Straits to California and the Rocky Mountain region abound in tales of the “thunder-bird”—a gigantic bird of prey like a mighty eagle, capable of carrying away people in its talons. Two such coincidences suggest the possibility that the accounts of the bison and the “thunder-bird” are really based on the originals of the asphalt beds and have been passed down in legendary history through many thousands of years.

Among other marvels our fossil beds reveal the fact that both camels and horses originated in North America. The remains of many widely different species of both animals have been found 400 in numerous localities extending from coast to coast in the United States. Camels and horses, with many species of antelope closely related to still existing forms in Africa, abounded over a large part of this country up to the end of the geological age immediately preceding the present era.

A REINDEER HERD AT CAPE PRINCE OF WALES, ALASKA: MANY FAWNS ARE TO BE SEEN IN THE HERD, AS THIS PICTURE WAS TAKEN SHORTLY AFTER THE FAWNING SEASON

Then through imperfectly understood changes of environment a tremendous mortality among the wild life took place and destroyed practically all of the splendid large mammals, which, however, have left their records in the asphalt pits of California and other fossil beds throughout the country. This original fauna was followed by an influx of other species which made up the fauna when America was discovered.

At the time of its discovery by Columbus this continent had only one domesticated mammal—the dog. In most instances the ancestors of the Indian dogs appear to have been the native coyotes or gray wolves, but the descriptions of some dogs found by early explorers indicate very different and unknown ancestry. Unfortunately these strange dogs became extinct at an early period, and thus left unsolvable the riddle of their origin.

Before the discovery of America the people of the Old World had domesticated cattle, horses, pigs, sheep, goats, dogs, and cats; but none of these domestic animals, except the dog, existed in America until brought from Europe by the invaders of the New World.

The wonderful fauna of the asphalt pits had vanished long before America was first colonized by white men, and had been replaced by another mainly from the Old World, less varied in character, but enormously abundant in individuals. Although so many North American mammals were derived from Asia, some came from South America, while others, as the raccoons, originated here.

It is notable that the fossil beds which prove the existence of an extraordinary abundance of large mammals in North America at various periods in the past, as well as the enormous aggregation of mammalian life which occupied this continent, both on land and at sea, at the time of its discovery, were confined to the Temperate and Arctic Zones. It is popularly 401 believed that the tropics possess an exuberance of life beyond that of other climes, yet in no tropic lands or seas, except in parts of Africa and southern Asia, has there been developed such an abundance of large mammal life as these northern latitudes have repeatedly known.

THIS REPRESENTS A SCENE AT THE CALIFORNIA ASPHALT PITS, WITH A MIRED ELEPHANT, TWO GIANT WOLVES, AND A SABER-TOOTHED TIGER (SEE PAGE 399).

In temperate and arctic lands such numbers of large mammals could exist only where the vegetation not only sufficed for summer needs, but retained its nourishing qualities through the winter. In the sea the vast numbers of seals, sea-lions, walruses, and whales of many kinds could be maintained only by a limitless profusion of fishes and other marine life.

From the earliest appearance of mammals on the globe to comparatively recent times one mammalian fauna has succeeded another in the regular sequence of evolution, man appearing late on the scene and being subject to the same natural influences as his mammalian kindred. During the last few centuries, however, through the development of agriculture, the invention of new methods of transportation, and of modern firearms, so-called civilized man has spread over and now dominates most parts of the earth.

As a result, aboriginal man and the large mammals of continental areas have been, or are being, swept away and replaced by civilized man and his domestic animals. Orderly evolution of the marvelously varied mammal life in a state of nature is thus being brought to an abrupt end. Henceforth fossil beds containing deposits of mammals caught in sink-holes, and formed by river and other floods in subarctic, temperate, and tropical parts of the earth, will contain more and more exclusively the bones of man and his domesticated horses, cattle, and sheep.

The splendid mammals which possessed the earth until man interfered were the ultimate product of Nature working through the ages that have elapsed since the dawn of life. All of them show myriads of exquisite adaptations to their environment in color, form, organs, and habits. The wanton destruction of any 402 of these species thus deprives the world of a marvelous organism which no human power can ever restore.

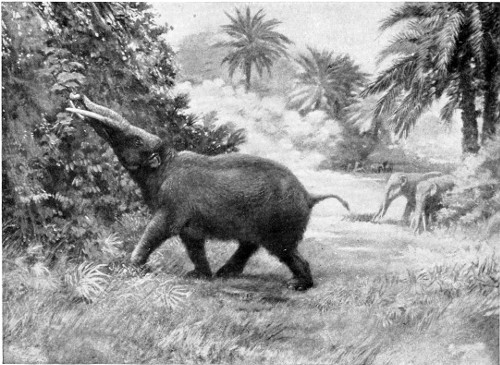

A PRIMITIVE FOUR-TUSKED ELEPHANT, STANDING ABOUT SIX FEET AT THE SHOULDER, THAT LIVED AGES AGO IN THE UNITED STATES (TRICOPHODON MIOCENE)

Fortunately, although it is too late to save many notable animals, the leading nations of the world are rapidly awakening to a proper appreciation of the value and significance of wild life. As a consequence, while the superb herds of game on the limitless plains will vanish, sportsmen and nature lovers, aided by those who appreciate the practical value of wild life as an asset, may work successfully to provide that the wild places shall not be left wholly untenanted.

Although Americans have been notably wasteful of wild life, even to the extermination of numerous species of birds and mammals, yet they are now leading the world in efforts to conserve what is left of the original fauna. No civilized people, with the exception of the South African Boers, have been such a nation of hunters as those of the United States. Most hunters have a keen appreciation of nature, and American sportsmen as a class have become ardent supporters of a nation-wide movement for the conservation of wild life.

Several strong national organizations are doing great service in forwarding the conservation of wild life, as the National Geographic Society, the National Association of Audubon Societies, American Bison Society, Boone and Crockett Club, New York Zoölogical Society, American Game Protective and Propagation Association, Permanent Wild Life Protective Fund, and others. In addition, a large number of unofficial State organizations have been formed to assist in this work.

Through the authorization by Congress, the Federal Government is actively engaged in efforts for the protection and increase of our native birds and mammals. This work is done mainly through the Bureau of Biological Survey of the U. S. Department of Agriculture, which is in charge of the several Federal large-game 403 preserves and nearly seventy bird reservations.

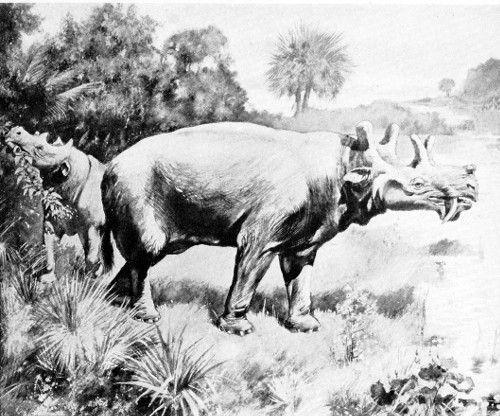

A GROTESQUE CREATURE THAT ONCE LIVED IN THE UNITED STATES (UERTATHERIUM EOCENE, MIDDLE WYOMING)

It had six horns on the head and, in some species, two long canine teeth projecting downward from the upper jaw. The feet were somewhat like those of an elephant, but the skull and teeth resemble nothing on earth today.

On the large-game preserves are herds of buffalo, elk, deer, and antelope. The Yellowstone National Park, under the Department of the Interior, is one of the most wonderfully stocked game preserves in the world. In this beautiful tract of forest, lakes, rivers, and mountains live many moose, elk, deer, antelope, mountain sheep, black and grizzly bears, wolves, coyotes, mountain lions, and lynxes.

Practically all of the States have game and fish commissions in one form or another, with a warden service for the protection of game, and large numbers of State game preserves have been established. The increasing occupation of the country, the opening up of wild places, and the destruction of forests are rapidly restricting available haunts for game. This renders particularly opportune the present and increasing wide-spread interest in the welfare of the habitants of the wilderness.

The national forests offer an unrivaled opportunity for the protection and increase of game along broad and effective lines. At present the title to game mammals is vested in the States, among which great differences in protective laws and their administration in many cases jeopardize the future game supply.

If a coöperative working arrangement could be effected between the States and the Department of Agriculture, whereby the Department would have supervision and control over the game on the national forests, so far as concerns its protection 404 and the designation of hunting areas, varying the quantity of game to be taken from definite areas in accordance with its abundance from season to season, while the States would control open seasons for shooting, the issuance of hunting licenses, and similar local matters, the future welfare of large game in the Western States would be assured.

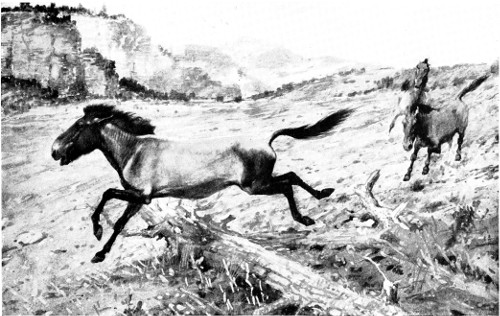

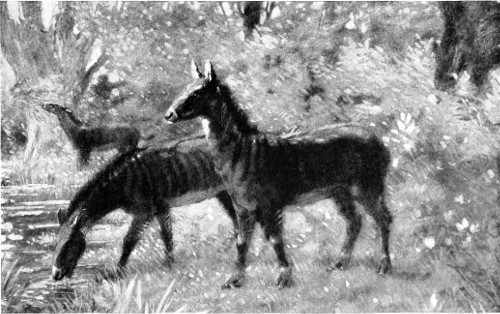

THE PRIMITIVE FOUR-TOED HORSE (EOHIPPUS, LOWER EOCENE, WYOMING)

The so-called four-toed horse, a little creature some 12 inches in height at the shoulder, having four well-defined hoofs on the front foot and three on the hind foot. The animal is not a true horse, but was undoubtedly an ancestor (more or less direct) of the modern form. It must have been a very speedy type, which contributed greatly to the preservation of the species in an age when (so far as we know) the carnivores were rather slow and clumsy.

Under such an arrangement the game supply would be handled on business principles. When game becomes scarce in any restricted area, hunting could be suspended until the supply becomes renewed, while increased hunting could be allowed in areas where there is sufficient game to warrant it. In brief, big game could be handled by the common-sense methods now used so effectively in the stock industry on the open range. At present the lack of a definite general policy to safeguard our game supply and the resulting danger to our splendid native animals are deplorably in evidence. 405

A TRUE HORSE WHICH WAS FOUND IN THE FOSSIL BEDS OF TEXAS: PLEISTOCENE

It is interesting to note that this country was possessed of several species of wild horses, but these died out long before the advent of the Indian on this continent. The present wild horses of our western plains are merely stragglers from the herds brought over by the Spaniards and other settlers. When Columbus discovered America there were no horses on the continent, though in North America horses and camels originated (see text, page 399).

THE FOREST HORSE OF NORTH AMERICA (HYPOHIPPOS MIOCENE)

This animal is supposed to have inhabited heavy undergrowth. It was somewhat off the true horse ancestry and had three rather stout toes on both the fore and hind feet. 406

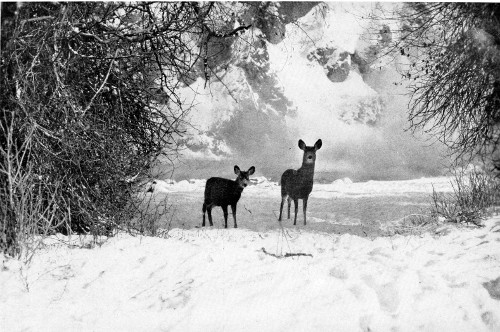

A MONTANA DOE AND FAWN

Observers of those times believed that at the beginning of the last century there were more deer and antelope in the United States than there were buffaloes. If that be true, they were probably more numerous than any domestic animal we have today. 407

THE SPIRIT OF THE WILD

Timorous as a gazelle in the open, brave as a lion when forced to fight, with nerves as quick as lightning and sinews as hard as steel, these denizens of the deep wood match the wind for speed, are unsurpassed for endurance, and yield place to no other species in graceful beauty. 408

The opossums are the American representatives of the ancient order of Marsupials—a wonderfully varied group of mammals now limited to America and Australasia. Throughout the order the young are born in an embryonic condition and are transferred to teats located in an external pocket or pouch in the skin of the abdomen, where they complete their development. The kangaroos are among the most striking members of this group.

Numerous species of opossums are known, all peculiar to America and distributed from the eastern United States to Patagonia. The Virginia opossum, the largest of all the species, is characterized by its coarse hair, piglike snout, naked ears, and long, hairless, prehensile tail. Its toes are long, slender, and so widely spread that its footprints on the muddy border of a stream or in a dusty trail show every toe distinctly, as in a bird track, and are unmistakably different from those of any other mammal.

This is the only species of opossum occurring in the United States, where it occupies all the wooded eastern parts from eastern New York, southern Wisconsin, and eastern Nebraska south to the Gulf coast and into the tropics. It has recently been introduced in central California. Although scarce in the northern parts of its range, it is abundant and well known in the warmer Southern States.

These animals love the vicinity of water, and are most numerous in and about swamps or other wet lowlands and along bottom-lands bordering streams. They have their dens in hollow trees, in holes under the roots of trees, or in similar openings where they may hide away by day. Their food consists of almost everything, animal or vegetable, that is edible, including chickens, which they capture in nocturnal raids.

The Virginia opossums have from 5 to 14 young, which at first are formless, naked little objects, so firmly attached to the teats in the mother’s pouch that they can not be shaken loose. Later, when they attain a coating of hair, they are miniature replicas of the adults, but continue to occupy the pouch until the swarming family becomes too large for it. The free toes of opossums are used like hands for grasping, and the young cling firmly to the fur of their mother while being carried about in her wanderings.

They are rather slow-moving, stupid animals, which seek safety by their retiring nocturnal habits and by non-resistance when overtaken by an enemy. This last trait gave origin to the familiar term “playing possum,” and is illustrated by their habit of dropping limp and apparently lifeless when attacked. Despite this apparent lack of stamina, their vitality is extraordinary, rendering them difficult to kill.

While hunting at daybreak, I once encountered an unusually large old male opossum on his way home from a night in the forest. When we met, he immediately stopped and stood with hanging head and tail and half-closed eyes. I walked up and, after watching him for several minutes without seeing the slightest movement, put my foot against his side and gave a slight push. He promptly fell flat and lay limp and apparently dead. I then raised him and tried to put him on his feet again, but his legs would no longer support him, and I failed in other tests to obtain the slightest sign of life.

The opossum has always been a favorite game animal in the Southern States, and figures largely in the songs and folk-lore of the southern negroes. In addition, its remarkable peculiarities have excited so much popular interest that it has become one of the most widely known of American animals.

Few American wild animals are more widely known or excite more popular interest than the raccoon. It is a short, heavily built animal with a club-shaped tail, and with hind feet that rest flat on the ground, like those of a bear, and make tracks that have a curious resemblance to those of a very small child. Its front toes are long and well separated, thus permitting the use of the front feet with almost the facility of a monkey’s hands.

Raccoons occupy most of the wooded parts of North America from the southern border of Canada to Panama, with the exception of the higher mountain ranges. In the United States they are most plentiful in the Southeastern and Gulf States and on the Pacific coast. Under the varying climatic conditions of their great range a number of geographic races have developed, all of which have a close general resemblance in habits and appearance.

They everywhere seek the wooded shores of streams and lakes and the bordering lowland forests and are expert tree-climbers, commonly having their dens in hollow trees, often in cavities high above the ground. In such retreats they have annually from four to six young, which continue to frequent this retreat until well grown, thus accounting for the numbers often found in the same cavity. Although tree-frequenting animals, the greater part of their activities is confined to the ground, especially along the margins of water-courses. While almost wholly nocturnal in habits, they are occasionally encountered abroad during the day.

Their diet is extraordinarily varied, and includes fresh-water clams, crawfish, frogs, turtles, birds and their eggs, poultry, nuts, fruits, and green corn. When near water they have a curious and unique habit of washing their food before eating it. Their fondness for green corn leads them into frequent danger, for when bottom-land cornfields tempt them away from their usual haunts raccoon hunting with dogs at night becomes an especially favored sport.

Raccoons are extraordinarily intelligent animals and make interesting and amusing pets. 409 During captivity their restless intelligence is shown by the curiosity with which they carefully examine every strange object. They are particularly attracted by anything bright or shining, and a piece of tin fastened to the pan of a trap serves as a successful lure in trapping them.

They patrol the border of streams and lakes so persistently that where they are common they sometimes make well-trodden little trails, and many opened mussel shells or other signs of their feasts may be found on the tops of fallen logs or about stones projecting above the water. In the northern part of their range they hibernate during the coldest parts of the winter, but in the South are active throughout the year.

Raccoons began to figure in our frontier literature at an early date. “Coon-skin” caps, with the ringed tails hanging like plumes, made the favorite headgear of many pioneer hunters, and “coon skins” were a recognized article of barter at country stores. Now that the increasing occupation of the country is crowding out more and more of our wild life, it is a pleasure to note the persistence with which these characteristic and interesting animals continue to hold their own in so much of their original range.

The lynxes are long-legged, short-bodied cats, with tufted ears and a short “bobbed” tail. They are distributed from the northern limit of trees south into the Temperate Zone throughout most of the northern part of both Old and New Worlds. In North America there are two types—the smaller animal, southern in distribution, and the larger, or Canada lynx, limited to the north, where its range extends from the northern limit of trees south to the northern border of the United States. It once occupied all the mountains of New England and south in the Alleghenies to Pennsylvania. In the West it is still a habitant of the Rocky Mountains as far south as Colorado, and of the Sierra Nevada nearly to Mount Whitney.

The Canada lynx is notable for the beauty of its head, one of the most striking among all our carnivores. This species is not only much larger than its southern neighbor, the bay lynx, but may also be distinguished from it by its long ear tips, thick legs, broad spreading feet, and the complete jet-black end of the tail. It is about 3 feet long and weighs from 15 to over 30 pounds. As befits an animal of the great northern forests, it has a long thick coat of fur, which gives it a remarkably fluffy appearance. Its feet in winter are heavily furred above and below and are so broad that they serve admirably for support in deep snow, through which it would otherwise have to wade laboriously.

This animal does not attack people, though popular belief often credits it with such action. It feeds mainly on such small prey as varying hares, mice, squirrels, foxes, and the grouse and other birds living in its domain; but on occasion it even kills animals as large as mountain sheep. One such feat was actually witnessed above timberline in winter on a spur of Mount McKinley. The lynx sprang from a ledge as the sheep passed below, and, holding on the sheep’s neck and shoulders, it reached forward and by repeatedly biting put out its victim’s eyes, thus reducing it to helplessness.

The chief food of the Canada lynx is the varying hare, which throughout the North periodically increases to the greatest abundance and holds its numbers for several years. During these periods the fur sales in the London market show that the number of lynx skins received increases proportionately with those of the hare. When an epizoötic disease appears, as it does regularly, and almost exterminates the hares, there is an immediate and corresponding drop in the number of lynx skins sent to market. This evidences one of Nature’s great tragedies, not only among the overabundant hares, but among the lynxes, for with the failure of their food supply over a vast area tens of thousands of them perish of starvation.

The Canada lynx has from two to five kittens, which are marked with dusky spots and short bands, indicating an ancestral relationship to animals similar to the ocelot, or tiger-cat, of the American tropics. The young usually keep with the mother for nearly a year. Such families no doubt form the hunting parties whose rabbit drives on the Yukon Islands were described to me by the fur traders and Indians of the Yukon Valley.

During sledge trips along the lower Yukon I often saw the distinctive broad, rounded tracks of lynxes, showing where they had wandered through the forests or crossed the wide, snow-covered river channel. Here and there, as the snow became very deep and soft, the tracks showed where a series of leaps had been made. Lynx trails commonly led from thicket to thicket where hares, grouse, or other game might occur. Canada lynxes appear to be rather stupid animals, for they are readily caught in traps, or even in snares, and, like most cats, make little effort to escape.

The bay lynx, bobcat, or wildcat, as Lynx ruffus and its close relatives are variously called in different parts of the country, is one of the most widely distributed and best known of our wild animals. It is about two-thirds the size of the Canada lynx and characterized by much slenderer proportions, especially in its legs and feet. The ears are less conspicuously tufted and the tip of the tail is black only on its upper half. Bobcats range from Nova Scotia and southern British Columbia over practically all of the wooded and brushy parts of the United States except along the northern border, and extend south to the southern end of the high table-land of Mexico.

OPOSSUM

RACCOON

From the earliest settlement of America the 410 411 412 bobcat has figured largely in hunting literature, and the popular estimate of its character is well attested by the frontier idea of the superlative physical prowess of a man who can “whip his weight in wildcats.” Although our wildcat usually weighs less than 20 pounds, if its reputed fierceness could be sustained it would be an awkward foe. But, so far as man is concerned, unless it is cornered and forced to defend itself, it is extremely timid and inoffensive.

CANADA LYNX

BOBCAT (Bay Lynx)

Like all cats, it is very muscular and active, and to the rabbits, squirrels, mice, grouse, and other small game upon which it feeds is a persistent and remorseless enemy. Although an expert tree-climber, it spends most of its time on the ground, where it ordinarily seeks its prey. It is most numerous in districts where birds and small mammals abound, and parts of California seem especially favorable for it. At a mountain ranch in the redwood forest south of San Francisco one winter some boys with dogs killed more than eighty bobcats.

Ordinarily the bobcat seems to be rather uncommon, but its nocturnal habits usually prevent its real numbers being actually known. In districts where not much hunted it is not uncommonly seen abroad by day, especially in winter, when driven by hunger.

The bay lynx makes its den in hollows in trees, in small caves, and in openings among rock piles wherever quiet and safety appear assured. Although a shy animal, it persists in settled regions if sufficient woodland or broken country remains to give it shelter. From such retreats it sallies forth at night, and not only do the chicken roosts of careless householders suffer, but toll is even taken among the lambs of sheep herds.

As in the case of most small cats, the stealthy hunting habits of the bay lynx renders it excessively destructive to ground-frequenting birds, especially to quail, grouse, and other game birds. For this reason, like many of its kind, it is outlawed in all settled parts of the country.

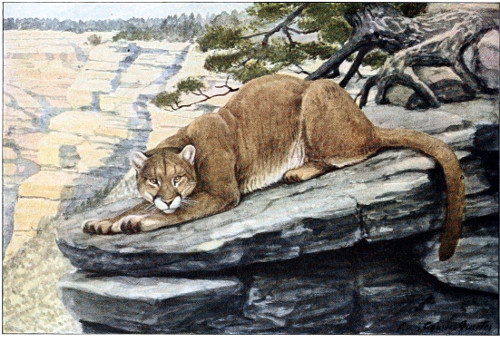

The mountain lion, next to the jaguar, is the largest of the cat tribe native to America. In various parts of its range it is also known as the panther, cougar, and puma. It is a slender-bodied animal with a small head and a long round tail, with a total length varying from seven to nine feet and a weight from about 150 to 200 pounds.

It has from two to five young, which are paler brown than the adult and plainly marked with large dusky spots on the body and with dark bars on the tail. These special markings of the young, as in other animals, are ancestral, and here appear to indicate that in the remote past our plain brown panther was a spotted cat somewhat like the leopard.

No other American mammal has a range equal to that of the mountain lion. It originally inhabited both North and South America from southern Quebec and Vancouver Island to Patagonia and from the Atlantic to the Pacific coasts. Within this enormous territory it appears to be equally at home in an extraordinary variety of conditions. Formerly it was rather common in the Adirondacks of northern New York and still lives in the high Rocky Mountains of the West, where it endures the rigors of the severest winter temperatures. It is generally distributed, where large game occurs, in the treeless ranges of the most arid parts of the southwestern deserts, and is also well known in the most humid tropical forests of Central and South America, whose gloomy depths are drenched by almost continual rain.

A number of geographic races of the species have been developed by the varied character of its haunts. These are usually characterized by differences in size and by paler and grayer shades in the arid regions and by darker and browner ones in the humid areas.

The mountain lion, while powerful enough to be dangerous to man, is in reality extremely timid. Owing to its being a potentially dangerous animal, the popular conception of it is that of a fearsome beast, whose savage exploits are celebrated in the folk-lore of our frontier. As a matter of fact, few wild animals are less dangerous, although there are authentic accounts of wanton attacks upon people, just as there are authentic instances of buck deer and moose becoming aggressive. It has a wild, screaming cry which is thrillingly impressive when the shades of evening are throwing a mysterious gloom over the forests. In the mountains of Arizona one summer a mountain lion repeatedly passed along a series of ledges high above my cabin at dusk, uttering this loud weird cry, popularly supposed to resemble the scream of a terrified woman.

The mountain lion is usually nocturnal, but in regions where it is not hunted it not infrequently goes abroad by day. It is a tireless wanderer, often traveling many miles in a single night, sometimes in search of game and again in search of new hunting grounds. I have repeatedly followed its tracks for long distances along trails, and in northern Chihuahua I once tracked one for a couple of miles from a bare rocky hill straight across the open, grassy plain toward a treeless desert mountain, for which it was heading, some eight or ten miles away.

Although inoffensive as to people, this cat is such a fierce and relentless enemy of large game and live stock that it is everywhere an outlaw. Large bounties on its head have resulted in its extermination in most parts of the eastern United States and have diminished its numbers elsewhere. It is not only hunted with gun and dog but also with trap and poison.

A mountain lion usually secures its prey by a silent, cautious stalk, taking advantage of every cover until within striking distance, and then, with one or more powerful leaps, dashing the victim to the ground with all the stunning impact of its weight. In a beautiful live-oak forest on the mountains of San Luis Potosi I 413 once trailed one of these great cats to the spot where it had killed a deer a short time before, and could plainly read in the trail the story of the admirable skill with which it had moved from cover to cover until it reached a knoll at one side of the little glade where the deer was feeding. Then a great leap carried it to the deer’s back and struck the victim to the ground with such violence that it slid 10 or 12 feet across the sloping ground, apparently having been killed on the instant.

Another trail followed in the snow on the high mountains of New Mexico led to the top of a projecting ledge from which the lion had leaped out and down over 20 feet, landing on the back of a deer and sliding with it 50 feet or more down the snowy slope.

The mountain lion often kills calves, but is especially fond of young horses. In many range districts of the Western States and on the table-land of Mexico, owing to the depredations of this animal, it is impossible to raise horses. Unfortunately the predatory habits of this splendid cat are such that it can not continue to occupy the same territory as civilized man and so is destined to disappear before him.

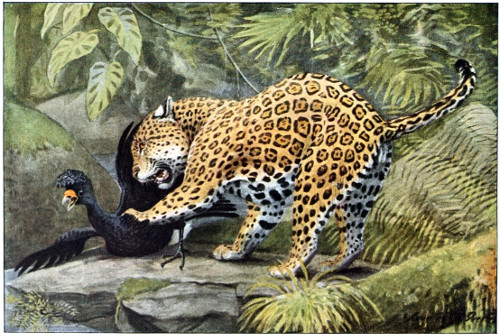

The jaguar, or “el tigre,” as it is generally known throughout Spanish America, is the largest and handsomest of American cats. Its size and deep yellow color, profusely marked with black spots and rosettes, give it a close resemblance to the African leopard. It is, however, a heavier and more powerful animal. In parts of the dense tropical forests of South America coal-black jaguars occur, and while representing merely a color phase, they are popularly supposed to be much fiercer than the ordinary animal.

Jaguars are characteristic animals of the tropics in both Americas, frequenting alike the low jungle of arid parts as well as the great forests of the humid regions. In addition, they range south into Argentina and north into the southwestern United States. Although less numerous within our borders than formerly, they still occur as rare visitants as far north as middle Texas, middle New Mexico, and northern Arizona. They are so strictly nocturnal that their presence in our territory is usually not suspected until, after depredations on stock usually attributed to mountain lions, a trap or poison is put out and reveals a jaguar as the offender. Several have been killed in this way within our border during the last ten years, including one not far from the tourist hotel at the Grand Canyon of Arizona.

Although so large and powerful, the jaguar has none of the truculent ferocity of the African leopard. During the years I spent in its country, mainly in the open, I made careful inquiry without hearing of a single case where one had attacked human beings. So far as I could learn, it has practically the same shy and cowardly nature as the mountain lion. Despite this, the natives throughout its tropical home have a great fear of “el tigre,” as I saw evidenced repeatedly in Mexico. Apparently this fear is based wholly on its strength and potential ability to harm man if it so desired.

Jaguars are very destructive to the larger game birds and mammals of their domain and to horses and cattle on ranches. On many large tropical ranches a “tigrero,” or tiger hunter, with a small pack of mongrel dogs, is maintained, whose duty it is immediately to take up the trail when a “tigre” makes its presence known, usually by killing cattle. The hunter steadily continues the pursuit, sometimes for many days, until the animal is either killed or driven out of the district. It is ordinarily hunted with dogs, which noisily follow the trail, but its speed through the jungle often enables it to escape. When hard pressed it takes to a tree and is easily killed.

Few predatory animals are such wanderers as the jaguar, which roams hundreds of miles from its original home, as shown by its occasional appearance far within our borders. In the heavy tropical forest it so commonly follows the large wandering herds of white-lipped peccaries that some of the Mexicans contend that every large herd is trailed by a tiger to pick up stragglers. Along the Mexican coast in spring, when sea turtles crawl up the beaches to bury their eggs in the sand, the rising sun often reveals the fresh tracks of the jaguar where it has traveled for miles along the shore in search of these savory deposits.

In one locality on the Pacific coast of Guerrero I found that the hardier natives had an interesting method of hunting the “tigre” during the mating period. At such times the male has the habit of leaving its lair near the head of a small canyon in the foothills early in the evening and following down the canyon for some distance, at intervals uttering a subdued roar. On moonlight nights at this time the hunter places an expert native with a short wooden trumpet near the mouth of the canyon to imitate the “tigre’s” call as soon as it is heard and to repeat the cry at proper intervals. After placing the caller, the hunter ascends the canyon several hundred yards and, gun in hand, awaits the approach of the animal. The natives have many amusing tales of the sudden exit of untried hunters when the approaching animal unexpectedly uttered its roar at close quarters.

The eyra differs greatly in general appearance from any of our other cats, although it is one of the most characteristic of the American members of this widely spread family. It is larger than an otter, with a small flattened head, long body, long tail, and short legs, thus having a distinctly otterlike form. It is characterized by two color phases—one a dull gray or dusky, and the other some shade of rusty rufous. Animals of these different colors were long supposed to represent distinct species, but 414 415 416 it has been learned not only that color is the only difference between the two, but also that the two colors are everywhere found together, affording satisfactory evidence that they are merely color phases of the same species.

MOUNTAIN LION

JAGUAR

RED AND GRAY PHASES OF THE JAGUARUNDI CAT, OR EYRA

TIGER-CAT, OR OCELOT

The eyra is a habitant of brush-grown or forested country, mainly in the lowlands, from the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas south to Paraguay. In this vast territory it has developed a number of geographic races.

In southern Texas, where it is often associated with the ocelot, the eyra lives in dense thorny thickets of mesquites, acacias, ironwood, and other semitropical chaparral in a region of brilliant sunlight; but farther south it also roams the magnificent forests of the humid tropics, in which the sun rarely penetrates. It appears to be even more nocturnal and retiring than most of our cats, and but little is known of its life history. The results of thorough trapping in the dense thorny thickets near Brownsville, Texas, indicate that it is probably more common than is generally supposed.

The natives in the lowlands of Guerrero, on the Pacific coast of Mexico, informed me that the eyra in that region is fond of the vicinity of streams, and that it takes to the water and swims freely, crossing rivers whenever it desires. Its otterlike form goes well with such habits, and further information may prove that it is commonly a water-frequenting animal. Its unusual form and dual coloration and our lack of knowledge regarding the life of the eyra unite to make it one of the most interesting of our carnivores.

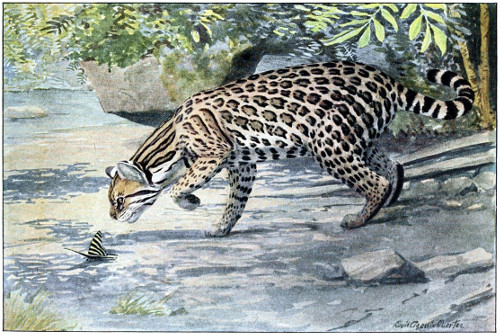

The brushy and forested areas of America from southern Texas and Sonora to Paraguay are inhabited by spotted cats of different species, varying from the size of a large house cat to that of a Canada lynx. Only one of these occurs in the United States. All are characterized by long tails and a yellowish ground color, conspicuously marked by black spots, and on neck and back by short, longitudinal stripes—a color pattern that strongly suggests the leopard.

In the lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas the tiger-cat is rather common, with the eyra-cat, in areas densely overgrown with thorny chaparral. Like most of the cat tribe, it is strictly nocturnal and by day lies well hidden in its brushy shelter. By night it wanders along trails over a considerable territory, seeking its prey. Birds of all kinds, including domestic poultry, are captured on their roosts, and rabbits, wood rats, and mice of many kinds, as well as snakes and other reptiles, are on its list of game.

Its reptile-eating habit was revealed to me unexpectedly one day in the dense tropical forest of Chiapas. I was riding along a steep trail beside a shallow brush-grown ravine when a tiger-cat suddenly rushed up the trunk of a tree close by. A lucky shot from my revolver brought it to the ground, and I found it lying in the ravine by the body of a recently killed boa about 6 or 7 feet long. It had eaten the boa’s head and neck when my approach interrupted the feast.

The first of these cats I trapped in Mexico was captured the night after my arrival, in a trail bordering the port of Manzanillo, on the Pacific coast. The rejoicing of the natives living close by evidenced the toll this marauder had been taking from their chickens.

The tiger-cat is much more quiet and less fierce in disposition than most felines. It excited my surprise and interest whenever I trapped one to note how nonchalantly it took the situation. The captive never dashed wildly about to escape, but when I drew near sat and looked quietly at me without the slightest sign of alarm and with little apparent interest. A small trap-hold, even on the end of a single toe, was enough to retain the victim. On one occasion, while a cat thus held sat looking at me, it quietly reached to one side and sank its teeth into the bark of a small tree to which the trap was attached, and then resumed its air of unconcern.

The tiger-cat brings within our fauna an interesting touch of the tropics and its exuberance of animal life. It is found in so small a corner of our territory, however, that, despite its mainly inoffensive habits, it is certain to be crowded out in the near future by the increased occupation of its haunts.

Red foxes are characterized by their rusty red fur, black-fronted fore legs, and white-tipped tail. They inhabit the forested regions in the temperate and subarctic parts of both Old and New Worlds, and, like other types of animal life having a wide range, they break up into numerous distinct species and geographic races.

In America they originally ranged over nearly all the forested region from the northern limit of trees in Alaska and Canada south, east of the Great Plains, to Texas; also down the Rocky Mountains to middle New Mexico, and down the Sierra Nevada to the Mount Whitney region of California. They are unknown on the treeless plains of the West, including the Great Basin. Originally they were apparently absent from the Atlantic and Gulf States from Maryland to Louisiana, but have since been introduced and become common south to middle Georgia and Alabama.

Wherever red foxes occur they show great mental alertness and capacity to meet the requirements of their surroundings. In New England they steadily persist, though their raids on poultry yards have for centuries set the hand of mankind against them. For a time conditions favored them in parts of the Middle Atlantic States, for the sport of hunting to hounds was imported from England, and the foxes had partial protection. This exotic 417 amusement has now passed and the fox must everywhere depend on his nimble wits for safety.

Since the days of Æsop’s fables tales of foxes and their doings have had their place in literature as well as in the folk-lore of the countryside. Many of their amazing wiles to outwit pursuers or to capture their prey give evidence of extraordinary mental powers.

Their bill of fare includes many items, as mice, birds, reptiles, insects, many kinds of fruits, and on rare occasions a chicken. The bad name borne by them among farmers, due to occasional raids on the poultry yard, is largely unwarranted. They kill enormous numbers of mice and other small rodents each year, and thus well repay the loss of a chicken now and then.

Red foxes apparently pair for life and occupy dens dug by themselves in a secluded knoll or among rocks. These dens, which are sometimes occupied for years in succession, always have two or more entrances opening in opposite directions, so that an enemy entering on one side may be readily eluded. The young, numbering up to eight or nine, are tenderly cared for by both parents.

Although they have been persistently hunted and trapped in North America since the earliest times, they still yield a royal annual tribute of furs. It is well known that the highly prized cross, as well as the precious black, and silver gray foxes are merely color phases occurring in litters of the ordinary red animal. Black skins are so highly prized that specially fine ones have sold for more than $2,500 each in the London market. The reward thus offered has resulted in the development of black fox fur-farms, which have been very successful in parts of Canada and the United States, thus originating a valuable new industry.

By the modern regulation of trapping, foxes and other fur-bearers are destined to survive wherever conditions are favorable. In addition to the economic value of foxes, the location of an occasional fox den here and there on the borders of a woodland tract, the meandering tracks in the snow, and the occasional glimpse of animals cautiously making their rounds add a keen touch of primitive nature well worth preserving in any locality.

The red fox of the Kenai Peninsula, Alaska, and the adjacent mainland is probably the largest of its kind in the world, although those of Kodiak Island and of the Mackenzie River valley are nearly as large. Compared with its relatives of the United States, the Kenai fox is a giant, with heavier, duller-colored coat and a huge tail, more like that of a wolf than of a fox. The spruce and birch forests of Alaska and the Mackenzie Valley are apparently peculiarly adapted to red foxes, as shown by the development there of these animals—good illustrations of the relative increase in size and vigor of animals in a specially favorable environment.

As noted in the general account of the red foxes, the occurrence of the black phase is sporadic, and the relative number of dark individuals varies greatly in different parts of their range. The region about the upper Yukon and its tributaries and the Mackenzie River basin are noted for the number of black foxes produced, apparently a decidedly greater proportion than in any other similarly large area. The prices for which these black skins sell in the London market prove them to be of equal quality with those from any other area.

Like other red foxes, the Alaskan species digs its burrows, with several entrances, in some dry secluded spot, where both male and female share in the care of the young. In northern wilds the food problem differs from that in a settled country. There the surrounding wild life is the only dependence, and varying hares, lemmings, and other mice are usually to be had by the possessor of a keen scent and an active body. In summer many nesting wild-fowl and their young are easy prey, while heathberries and other northern fruits are also available.

Winter brings a season of scarcity, when life requires the exercise of every trained faculty. The snow-white ptarmigan is then a prize to be gained only by the most skillful stalking, and the white hare is almost equally difficult to secure. At this season foxes wander many miles each day, their erratic tracks in the snow telling the tale of their industrious search for prey in every likely spot. It is in this season of insistent hunger that many of them fall victims to the wiles of trappers or to the unscrupulous hunter who scatters poisoned baits.

Fortunately the season for trapping these and other fur-bearers in Alaska is now limited by law and the use of poisons is forbidden. These measures will aid in preserving one of the valuable natural assets of these northern wilds.

Gray foxes average about the size of common red foxes, but are longer and more slender in body, with longer legs and a longer, thinner tail. They are peculiar to America, where they have a wide range—from New Hampshire, Wisconsin, and Oregon south through Mexico and Central America to Colombia. Within this area there are numerous geographic forms closely alike in color and general appearance, but varying much in size; the largest of all, larger than the red fox, occupying the New England States.

Gray foxes inhabit wooded and brush-grown country and are much more numerous in the arid or semiarid regions of the southwestern United States and western Mexico than elsewhere. In parts of California they are far more numerous than red foxes ever become. They do not regularly dig a den, but occupy a hollow tree or cavity in the rocks, where they bring forth from three to five young each spring. As with other foxes, the cubs are born blind and helpless, and are also almost blackish in color, entirely unlike the adults. The parents, 418 419 420 as usual with all members of the dog family, are devoted to their young and care for them with the utmost solicitude.

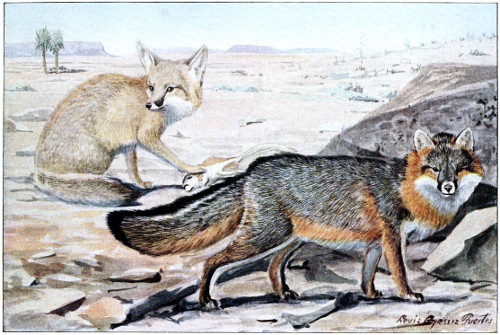

CROSS FOX RED FOX SILVER FOX

The precious black and silver gray foxes are merely color phases occurring in litters of the ordinary red animal (see text, page 416).

ALASKA RED FOX

DESERT FOX GRAY FOX

BADGER

Like other members of the tribe, they are omnivorous and feed upon mice, squirrels, rabbits, birds, and large insects, in addition to acorns or other nuts and fruits of all kinds. In Lower California they are very common about the date-palm orchards, which they visit nightly for fallen fruit. They also make nocturnal visits to poultry yards.

In some parts of the West they are called “tree foxes,” because when pursued by dogs they often climb into the tops of small branching trees.

On one occasion in Arizona I saw a gray fox standing in the top of a large, leaning mesquite tree, about thirty feet from the ground, quietly gazing in various directions, as though he had chosen this as a lookout point. As soon as he saw me he came down at a run and swiftly disappeared.

In the same region I found a den in the hollow base of an old live-oak containing three young only a few days old. The mother was shot as she sprang from the hole on my approach and the young taken to camp. There the skin of the old fox, well wrapped in paper, was placed on the ground at one side of the tent, and an open hunting bag containing the young placed on the opposite side, about ten feet away. On returning an hour later, I was amazed to find that all three of the young, so small they could crawl only with the utmost difficulty, and totally blind, had crossed the tent and managed to work their way through the paper to the skin of their mother, thus showing that the acute sense of smell in these foxes becomes of service to them at a surprisingly early age.

A small fox, akin to the kit fox or swift of the western plains, frequents the arid cactus-grown desert region of the Southwest. It is found from the southern parts of New Mexico, Arizona, and California south into the adjacent parts of Mexico. The desert fox is a beautiful species, slender in form, and extraordinarily quick and graceful in its movements, but so generally nocturnal in habits as to be rarely seen by the desert traveler. On the rare occasions when one is encountered abroad by day, if it thinks itself unobserved by the traveler it usually flattens itself on the ground beside any small object which breaks the surface, and thus obscured will permit a horseman to ride within a few rods without moving. If the traveler indicates by any action that he has seen it, the fox darts away at extraordinary speed, running with a smooth, floating motion which seems as effortless as that of a drifting thistledown before a breeze.

The desert fox digs a burrow, with several entrances, in a small mound, or at times on an open flat, and there rears four or five young each year. Its main food consists of kangaroo rats, pocket mice, small ground-squirrels, and a variety of other small desert mammals. In early morning fox tracks, about the size of those of a house-cat, may be seen along sandy arroyos and similar places where these small carnivores have wandered in search of prey.

Like the kit, the desert fox has little of the sophisticated mental ability of the red fox and falls an easy prey to the trapper. It is nowhere numerous and occupies such a thinly inhabited region that there is little danger of its numbers greatly decreasing in the near future.

The favorite home of the badger is on grassy, brush-grown plains, where there is an abundance of mice, pocket gophers, ground-squirrels, prairie-dogs, or other small mammals. There it wanders far and wide at night searching for the burrows of the small rodents, which are its chief prey. When its acute sense of smell announces that a burrow is occupied, it sets to work with sharp claws and powerful fore legs and digs down to the terrified inmate in an amazingly short time.

The trail of a badger for a single night is often marked by hole after hole, each with a mound of fresh earth containing the tracks of the marauder. As a consequence, if several of these animals are in the neighborhood, their burrows, 6 or 8 inches in diameter, soon become so numerous that it is dangerous to ride rapidly through their haunts on horseback.