MR. AND MRS. DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

Internationally beloved and known to millions the world over.

Title: Behind the Screen

Author: Samuel Goldwyn

Release date: June 11, 2019 [eBook #59730]

Most recently updated: July 7, 2019

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Tim Lindell, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

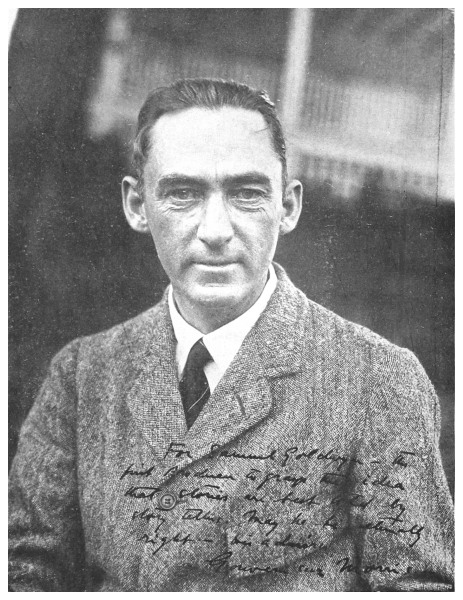

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

MR. AND MRS. DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS

Internationally beloved and known to millions the world over.

BEHIND

THE SCREEN

BY

SAMUEL GOLDWYN

NEW  YORK

YORK

GEORGE H. DORAN COMPANY

Copyright, 1923,

By George H. Doran Company

Copyright, 1923,

By The Pictorial Review Company

BEHIND THE SCREEN. I

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

TO THE MOTION PICTURE INDUSTRY

WHICH HAS BROUGHT ME SOME SUCCESS, A WORLD OF GOOD FRIENDS AND PLEASANT ASSOCIATES, AND, ABOVE ALL, THE SUPREME SATISFACTION OF DOING THAT WHICH I LOVE BEST TO DO, THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED. IN GRATEFUL APPRECIATION, I LIKEWISE DEDICATE TO THAT INDUSTRY

MY SINCEREST EFFORTS FOR THE FUTURE.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I want to acknowledge the co-operation of Miss Corinne Lowe in the preparation of these articles. But for her enthusiasm, her patience, and her splendid co-operation given me in every way, this series could never have been written.

S. G.

ix

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| One: | IN WHICH IS FILMED THE BIRTH OF A NOTION | 15 |

| Two: | RECORDS THE SUCCESS OF AN IDEA | 23 |

| Three: | MARY PICKFORD | 30 |

| Four: | FASCINATING FANNY WARD | 50 |

| Five: | MARGUERITE CLARK MISSES FIRE AND EDNA GOODRICH DOESN’T IGNITE AT ALL | 60 |

| Six: | THE MISCHIEVOUSNESS OF MAE MURRAY | 73 |

| Seven: | GERALDINE THE GREAT | 81 |

| Eight: | THE DISCOVERY OF CHARLIE CHAPLIN | 97 |

| Nine: | STARS, STARS, STARS! | 108 |

| Ten: | THE MAGIC OF MARY GARDEN | 127 |

| Eleven: | MAXINE ELLIOTT AND PAULINE FREDERICK | 137 |

| Twelve: | A MARRIAGE OF TWO MINDS | 149 |

| Thirteen: | THE REAL CHAPLIN | 158 |

| Fourteen: | JACKIE COOGAN AND “THE KID” | 169 |

| Fifteen: | DOUG AND MARY | 179 |

| Sixteen: | RODOLPH VALENTINO | 186 |

| Seventeen: | ROMANTIC TRUE STORIES OF SOME SCREEN FAVORITES | 196 |

| Eighteen: | POLA NEGRI | 212 |

| Nineteen: | THE TWO TALMADGES | 219 |

| Twenty: | GOOD OLD WILL ROGERS | 229 |

| Twenty-One: | SOME AUTHORS WHO HAVE TRAVELLED TO HOLLYWOOD | 235 |

xi

| Mr. and Mrs. Douglas Fairbanks | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| Elsie Ferguson | 16 |

| Mr. Goldwyn, Mabel Normand and Charlie Chaplin | 17 |

| Alice Terry | 32 |

| Bert Lytell | 33 |

| Mr. Goldwyn, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford | 48 |

| Barbara La Marr | 49 |

| Clara Kimball Young | 64 |

| Mr. Goldwyn Acting as Host and Waiter | 65 |

| Lou Tellegen and Geraldine Farrar | 88 |

| Theda Bara | 89 |

| Mabel Normand | 112 |

| Maxine Elliott | 113 |

| Mary Garden and Geraldine Farrar | 128 |

| Will Rogers Bids Pauline Frederick Goodbye | 129 |

| Charlie Chaplin | 160 |

| Rupert Hughes | 161 |

| Jackie Coogan | 176 |

| George Fitzmaurice | 177 |

| Rodolph Valentino | 192 |

| Maurice Maeterlinck | 193xii |

| Eric von Stroheim | 208 |

| “Charlie,” “Doug” and “Mary” | 209 |

| Constance Talmadge | 224 |

| Norma Talmadge | 225 |

| Samuel Goldwyn and Seven Famous Authors He Won to the Screen | 240 |

| Gouverneur Morris | 241 |

15

It was something more than nine years ago that I walked into a little motion-picture theatre on Broadway. I paid ten cents admission. As I took my seat a player-piano was digging viciously into a waltz. Upon the floor a squalid statuette lay under its rain of peanut-shells.

And all around me men, women, and children were divided between the sustained comfort of chewing-gum and the sharp, fleeting rapture of the nut.

Only a decade ago! Yet this was a representative setting and audience for motion-pictures. Likewise typical was the film itself. For, as were practically all productions of that day, this was only one or two reels. And, faithful to the prevailing tradition, the drama of to-night was Western.

I looked at the cowboys galloping over the Western plains, and in their place there rose before me Henry Esmond crossing swords with the Young16 Pretender, wiry young D’Artagnan riding out from Gascony on his pony to the Paris of Richelieu, Carmen on her way to the bull-fight where Don José waited to stab her.

Why not? Here was the most wonderful medium of expression in the world. Through it every great novel, every great drama, might be uttered in the one language that needs no translation. Why get nothing from this medium save situations which were just about as fresh and unexpected as the multiplication tables?

When I went into that theatre I had no idea of ever going into the film business. When I went out I was glowing with the sudden realisation of my way to fortune. I could hardly wait until I told my idea to my brother-in-law, Jesse Lasky.

“Lasky, do you want to make a fortune?” With these words I burst in upon him that evening.

Lasky, who was at that time in the vaudeville business, indicated that he had no morbid dread of the responsibility of great wealth.

“Very well, then,” I continued. “Put up some money.”

“In what?”

“In motion-pictures,” I answered.

“Motion-pictures!” scoffed he. “You and I would be a fine pair in that business—me, a vaudeville man, and you, a glove salesman! What do we17 know about the game? Besides, how about the trust?”

ELSIE FERGUSON

Dignified stage star who lost none of her lustre on the screen.

MR. GOLDWYN, MABEL NORMAND AND CHARLIE CHAPLIN

His last words touched upon a vital issue in the screen industry of that period. The truth of it was that motion-picture theatres throughout the country were practically at the mercy of ten companies which, for the privilege of showing pictures, collected a weekly license fee of two dollars each, from fifteen thousand theatres. I shall not enter here into the argument by which the combine justified their taxation. I shall merely remark that the existent system presented an obstacle worthy of consideration. However, all the way home I had been preparing an answer to this protest of Lasky’s, and now I eagerly put it forth.

“Give the public fine pictures,” I urged. “Show them something different from Western stuff and slap-stick comedies and you’ll find out what will become of the trust. And why should your entertainment have to be so short? If it’s a good story there’s no reason why it couldn’t run through five reels. I tell you the possibilities of the motion-picture business have never been touched. We could sell good films and long films all over the world.”

Eventually Lasky was convinced that my idea presented at least a good betting proposition, and he agreed to add ten thousand dollars to the equal18 amount which I put up, provided he be relieved of any active management. Considering that in those days many of the two-reelers were made for less than a thousand dollars, our original capital seemed not only adequate to the immediate cost of production, but to a handsome margin for recovery from a possible first failure. With this assumption of strength we took our next logical step. We hunted for somebody who would make our pictures for us.

It was natural that the first person of whom we should think in this connection was Mr. D. W. Griffith. He was then directing for the Biograph Company, one of the units of the motion-picture trust, and he had already experimented with the longer picture in “Judith of Bethulia.” Indeed, I wish to say right here that I lay no claim to pioneer thought in realising that the screen was susceptible of longer and more varied treatment, for, in addition to our American “Judith of Bethulia,” one or two foreign pictures had heralded the new era. Any possible credit to me, therefore, must be accorded to my conception of the new sort of photoplay as a systematic performance rather than as a sporadic spectacle. Indeed, I was to find out later that even this idea was not an exclusive visitation. Lasky and I had supposed that we were the only ones in the field, but it was not long before we discovered19 that even previous to us another man had acted on the same idea.

But to go back to my interview with Mr. Griffith. I met him for lunch, and I was impressed immediately by the personality which has since lifted him into his place as the greatest of screen directors. Tall and spare and quite stooped, Mr. Griffith’s figure suggests by its very lack of erectness that reserve of energy which transforms him in the studio to the tireless, almost demoniacal worker. His features are clear-cut, and to the suggestion of the eagle in his profile the clear blue eyes—eyes which you could never possibly mistake for gray even across a room—contribute a final authority. These eyes while he is at work, so people tell me, glow with enthusiasm, but during the chance interview they join with the mouth in a look of amused observation.

With this expression he heard me make my proposition that day. When he finally spoke it was to quench any hope that Mr. Griffith might ever become associated with Lasky and me.

“A very interesting project,” he commented, “and if you can show me a bank deposit of two hundred and fifty thousand dollars I think we might talk.”

I did not betray the meagre conversational basis which I had to offer. Instead, Lasky and I now20 approached a friend of ours, Cecil de Mille. Mr. de Mille, although very little more than thirty years of age at this time, was already known as a playwright of considerable skill. His father had been Belasco’s partner and he himself had been associated with the celebrated theatrical producer in writing “The Return of Peter Grimm.” With all of his dramatic tradition and achievement Mr. de Mille had one limitation. At this time he had never directed a picture. More than this, he had never even seen one directed.

However, neither he nor we were daunted by this slight flaw in his equipment. And after a day or two spent in the Edison studios Mr. de Mille went out to California to “shoot” our first picture. For his services he was paid one hundred dollars a week and was promised, in addition, some stock in the company. When you reflect that to-day he receives approximately five thousand dollars a week, together with a large percentage of the returns on every production, it helps you to realise that the jinnee of the screen has functioned almost as well as did his ancestor of the “Arabian Nights.”

And in no place is the magic more apparent than in California. When De Mille went out to Los Angeles to look around for a site, Hollywood promised nothing of its present pomp. The vast studios, the beautiful villas, the famous pleasure-places—all21 have arisen in the past decade. It needs, indeed, only a flash-back from the Famous Players-Lasky studios of to-day to our humble residence of nine years ago to give you a complete sense of the growth of the industry.

The site which we finally selected was one floor of a livery-stable. Here in this space, out of which had been created, in addition to the studio, five small dressing-rooms, our director made that first film. The elaborate sets were then undreamed of. Painted backgrounds achieved their duties, and our scenic equipment consisted of four canvas wings and two pieces of canvas. Likewise absent was the modern complicated system of lighting. The sun was our only electrician in those days. And with the aid of three or four men De Mille set to work in a studio where the weekly pay-roll now numbers eleven hundred and fifty people.

Yet, in spite of such simplified conditions, it cost us forty-seven thousand dollars to make that first picture. Nowadays that sum is inadequate for any long production, but in those times it was unprecedented. Of course the cost of the motion-picture rights of our first drama accounted for this expenditure. This drama was “The Squaw Man,” recently revived by Mr. William Faversham, and for it we guaranteed royalty rights of ten thousand22 dollars. Ten thousand, and our capital was only ten thousand more!

On the twenty-ninth of December, 1913, De Mille began making the picture. But before he had even touched it I had got enough orders on that unmaterialized merchandise to insure the production of the second picture. I represented the executive end of our enterprise, and my first move had been to make newspaper announcement of the fact that the Lasky Company, as we had decided to call our organisation, was going to produce a yearly series of twelve five-reel pictures, beginning with “The Squaw Man.”

In New York I awaited results. Which would prevail—the trust or the new kind of picture?

I was not kept long in suspense. Almost immediately theatre managers and letters from theatre managers began to pour in. These functionaries had been partially paralysed by the trust, and their quick response to our announcement indicated just how eager they were for an opportunity to regain their prestige. Although I had, of course, counted upon such reaction, the swiftness and volume of those first orders overwhelmed me with incredulous joy.

23

I am compelled to say right here that life had not led me to expect any such facility. For I had been a poor boy—poor and often homeless. Of formal schooling I had practically none. At the age when most boys take arithmetic and a roof and three square meals as a matter of course I was fending for myself. When I got these things it was through odd jobs in blacksmith-shops and in glove-factories. Sometimes, of course, I did not get them at all. For example, I remember how once as a boy of twelve I wandered for a whole week through the streets of London with no more ardent guaranty of the future than a loaf of bread.

My early boyhood was spent in Europe and I was just fourteen when, absolutely alone and with no friend or relative to greet me, I arrived in New York City. From the city I went to Gloversville, N. Y., and there, after about four or five years spent in a glove-factory, I succeeded in persuading a firm that I could sell gloves. I can say without arrogance of heart that I did sell them. But there24 was no miracle of ease about this process. I travelled from coast to coast; I often worked eighteen hours a day; I put over my product in districts where it never sold before. As a result of all this I was making about fifteen thousand dollars a year at the time when I chanced in upon that little motion-picture theatre. I also owned stock in my company and, thanks to an expanded income, I had been able to supplement my fragmentary schooling by many lectures and concerts and by frequent trips to Europe.

But, although at thirty I was a comparatively successful man, I was not satisfied. I never had been satisfied. I can remember how when a boy in the cutting department I used to walk by the leading hotel in Gloversville and look at the “drummers” who cocked their feet up in the big plate-glass window. How I envied them—those splendid adventurers with their hats and their massive cigars both at an angle! For to me they represented the everlasting romance of the far horizon. And when at last I myself was admitted to this peerage I was sensible, of course, of another, greater goal. I have made many mistakes in my life, but I can honestly say that they were all results of an unceasing effort on my part to reach the bigger thing just beyond.

But to return to my story. It soon became apparent25 that we needed more money for the production of “The Squaw Man.” How were we going to raise that necessary twenty-five thousand dollars? Our first approach to the problem was a personal one. Lasky and I asked any number of people we knew if they didn’t want some stock in the Lasky Company. But all of them were skeptical. At last, however, we were able to borrow the needed funds out of bank. De Mille resumed work on the picture, and a few weeks afterward he returned to New York with the precious merchandise. Meanwhile he had wired us that there was something wrong with the film, but even this did not prepare me for my first glimpse of the production upon which I had staked everything.

Buzz! In the silence of that deserted studio we heard the machine begin its work. And then, as from a very far shore, I heard Lasky’s voice.

“We’re ruined,” he cried.

He was saying only what I myself had been too sick with horror to exclaim. For, like a mad dervish, the home of the noble English earl, together with all the titled ladies who moved therein, had jumped across the screen. Time refused to stabilise them. They went right on jumping. And with gathering despair we looked on what we supposed to be the wreck of forty-seven thousand dollars.

26 That it was not a wreck was due to the aid of some one from whom we had no right to expect it. At that time the late Sigismund Lubin of Philadelphia was head of one of the ten companies which we were fighting. Nevertheless it was to him I appealed for expert advice. I took the roll of film over to Philadelphia, and with a largeness of spirit which I shall never forget the old gentleman saved me, his threatened rival, from utter ruin. He pointed out that the time-stop was wrong. No, not an irremediable defect. In the joy of this discovery I overlooked the hardship of his cure. Yet this was to paste by hand new perforations on both edges of a film that was nearly a mile long.

The story of the beginning of the Lasky Company is now coming to a close. To it I might add a thousand picturesque and amusing details, but I realise that the chief interest of my reminiscences is focussed, not upon the development of the motion-picture industry—dramatic as that undoubtedly is—but upon the celebrated personalities with whom my life has brought me into contact. I have delayed this long the more vital communications because the transition from the former impoverished photoplays to the elaborate spectacle of to-day involved many producers and brought with it the rise of all our famous stars. To give a real insight into the lives of Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin,27 Norma Talmadge, Douglas Fairbanks, Wallace Reid, Harold Lloyd, Mabel Normand, and other famous screen artists obligates, in fact, the background of photoplay history involved in the start of the Lasky Company.

My last word here touches upon the reception of “The Squaw Man.” It scored an immediate success. Our second play established us even more firmly. This prosperity resulted logically in helping the overthrow of the trust. Beaten upon by the wave of new photoplay methods, some of its units were carried out to oblivion. Others rose to the surface only through conformity to the agent of destruction.

It was during an interview with one of the first exhibitors who came to my office that I heard the name of the man who, unknown to me, had already embarked on the very same enterprise that I had.

“So you’ve got this idea of the long film too?” remarked this exhibitor.

If one of the Indians who greeted Columbus had said, “So you’ve landed too?” the explorer would have felt probably as I did at that moment.

“What do you mean?” I asked him.

“Why,” said he, “haven’t you heard about the man that brought over Sarah Bernhardt’s first picture and produced ‘The Prisoner of Zenda’—a fellow by the name of Zukor?”

28 It was not until some months after this that I first met Mr. Adolph Zukor, then head of the Famous Players Company. I should like to have more space to devote to the eminent producer who, through years of alternating competition and co-operation, has touched my life at so many points, but I can pause only long enough for a few words. Mr. Zukor, like myself, started in the world as a poor boy. Unlike me, however, he started film-production with a background of experience. He had owned for some years a number of motion-picture theatres, and a more intimate dissatisfaction with available resources was back of his break from tradition. When he attempted to get financial backing for his project, however, he met with the same objections which I had heard, and he has often told me how the theatrical manager whose aid he attempted to enlist scoffed, “What do you want to show a long film for? People are not going to have the patience to sit through more than a thousand feet of film.”

I might marshal a great many adjectives and nouns to Mr. Zukor’s credit, but I feel that I can suggest his fundamental character more skilfully by recalling one incident. Several years after I had met him we were coming home from some entertainment together when we saw a blaze in the locality of the Famous Players’ studio which, unlike29 our own, was situated in New York. We were soon to discover that it was the studio itself. In it were thousands of dollars’ worth of undeveloped negatives—many of them of Mary Pickford. Their destruction would have meant financial ruin to Mr. Zukor. He himself realised this fully. Yet the only words that he said, the words which he kept repeating all through the crisis, were, “Oh, do you think anybody’s hurt?”

30

It was some months after I first met our competitor that I received my first impression of the most noted screen actress in America. As I walked into Mr. Zukor’s office one evening I noticed a girl talking to him. She was very small and her simple little navy suit contrasted with the jungle of fur coat from which peeped another woman.

“They’ve offered me five hundred for the use of my name,” I heard her say, “but do you really think that’s enough? After all, it means a lot to those cold-cream people.”

I looked at the lovely profile where every feature rhymes with every other feature. I listened to the lovely light voice. And I was struck by the disparity between sentiment and equipment.

Yet somehow she did invest these words of mere commerce with a quality quite apart from their substance. There was something in her tone, something in the big brown eyes, which made you think of a child asking whether it ought to give up its31 stick of candy for one marble or whether perhaps it could get two. As I saw her slight figure go out the door it was the appeal of her manner rather than the text of her question which made me ask immediately who she was.

“What!” Mr. Zukor exclaimed. “Didn’t you recognise her? Why, that was Mary Pickford.”

That was just about eight years ago. Miss Pickford was already a star, and she was twinkling under the auspices of Adolph Zukor; for, early in his career of producing, our competitor had been fortunate enough to secure the services of that great pantomime artiste who has undoubtedly contributed more than any other single person to his present eminence.

Mr. Zukor made Miss Pickford a star. This is a mere formal statement of the case. In reality she made herself, for no firmament could have long resisted any one possessing such standards of workmanship. I am aware that here I sound suspiciously like the press-agent, who invariably endows his client with “a passionate devotion to her work.” It is unfortunate, indeed, that the zeal of this functionary has calloused public consciousness to instances where the statement is based on fact. All screen stars are not animated by devotion to work. Mary Pickford is. To it she has sacrificed pleasures,32 personal contacts, all sorts of extraneous interests.

Several years before I walked into the theatre which inspired me with my idea, Mary Pickford was working under Mr. Griffith in the Biograph Company, which, you will remember, was a unit in the trust. Then she was not a star. She was getting twenty-five dollars a week, and the most vivid reflection of those early days of hers is afforded by a woman who used to work with her.

“How well I remember her,” this woman has told me, “as she sat there in the shabby old Biograph offices. She nearly always wore a plain little blue dress with a second-hand piece of fur about her throat.”

Not long ago I asked Mr. Griffith this question: “Did you have any idea in those days that Mary Pickford was destined for such a colossal success?” His answer was a decided negative.

“You understand, of course,” he immediately qualified, “my mind was always on the story—not on the star. However, I can say this: It was due to me that Miss Pickford was retained at all, for the management did not care for her especially. To speak plainly, they thought she was too chubby.”

I gasped at the impiety of the word. It was some time before I could rally to ask him another33 question: “Then was there anything that set her apart from other girls you were engaging at that time?”

ALICE TERRY

Wife of Rex Ingram, noted director whose work in “The Four Horsemen” compelled unusual attention.

BERT LYTELL

Who brought great stage tradition to the screen.

“Work,” he retorted promptly. “I soon began to notice that instead of running off as soon as her set was over, she’d stay to watch the others on theirs. She never stopped listening and looking. She was determined to learn everything she could about the business.”

While considering these remarks of the greatest screen director anent the greatest screen actress, it is interesting to parallel them with Miss Pickford’s comments upon Mr. Griffith. One evening not long ago I was entertained at the Fairbanks home at a dinner including Charlie Chaplin and Mr. Griffith. After the meal was served Doug took Mr. Griffith out to see his swimming-pool. Mary and I were left alone, and as we looked after the tall, bent figure of the director, I took advantage of our solitude to ask her a question which had often occurred to me. “Mary,” I asked her, “how did you ever come to break away from Griffith?”

“Well,” she answered promptly, “it was this way: I felt that I was getting to be a machine under Mr. Griffith. I got to be like an automatic doll. If he told me to move my left foot I moved it. When he said, ‘Look up’ I did that just as unquestioningly.34 So I make up my mind to see if I could really do anything by myself.”

I doubt if Mr. Zukor himself realised at first the tremendous potentiality of Mary Pickford. It was some months, indeed, before the Famous Players starred her, and Mr. Zukor has often told me how during that probationary time she used to say to him, “Oh, Mr. Zukor, if I could only see my name in electric lights I’d be the happiest girl in the world!”

When the great moment to which she had so long and so eagerly looked forward finally did come, the scenario-writer of Mary Pickford’s own life displayed a dramatic deftness of touch.

One day Mr. Zukor asked Miss Pickford if she would go out to dinner with him that evening. She agreed, and he appointed the Hotel Breslin on Broadway for their meeting. When they sat down at their table it was still light. At last when dusk began to fall Mr. Zukor rose and went over to the window.

“Come over here,” he called to the girl. “I want you to see something.”

Wonderingly she followed him. She looked out at the street where the swift Winter darkness was dimming the familiar outlines, and then she looked back to his face.

“What is it?” said she. “I don’t see anything.”

35 “Wait,” he commanded.

As he spoke the lights of many windows began to brush like golden flakes against the blurred buildings. And then across the street at Proctor’s there suddenly leaped in letters of frosty fire these words:

She had never suspected that she was to be starred in this play. And it is not surprising that at the revelation of her success she burst into tears such as have moved her audiences all over the world.

“Can it really, really be true?”—this might have been the subtitle of that big scene in the drama of Mary Pickford’s life.

It was a moment after this first shock of incredulous joy that she said to Mr. Zukor, “Oh, what will mother say when she hears this?”

Any one who knows Mary will not be surprised at this almost instantaneous thought of her mother. I have met the average number of daughters in my life and I can truthfully say that none of them ever gave a mother such devotion as does she. Until the time Mary married Douglas Fairbanks Mrs.36 Pickford was the one dominating influence in her daughter’s life. In the vividness of this relationship you will find perhaps the reason for one outstanding lack in Mary Pickford’s life. There are many women who admire her. Of men pals, such as Marshall Neilan, the celebrated director, she has a score. But to my knowledge there is only one woman who has approached—and she very tentatively—the position of intimate friend.

“Ma” Pickford, as she is known familiarly, is now her daughter’s business manager. But in the old shabby days of the Biograph studio her activities, although more limited, were equally pronounced. Every single day she came with Mary to the studio and stayed with her until she left. She watched every move she made. She gave her suggestions about her work. She sat with the faithful make-up box while Mary was on a set. In the Famous Players’ studio it was the same. Of course, stage and screen supply numerous other instances of brooding maternal solicitude.

I am now approaching a phase of the noted pantomimist’s career which points to many adventures in which I myself have been involved. When Mary Pickford first went with Mr. Zukor he paid her five hundred dollars a week. Her success was so marked that before her contract had expired he37 voluntarily raised this to a thousand dollars. After this—but I am anticipating.

Whenever I saw Mr. Zukor looking homeless as a small-town man in house-cleaning time I knew what was the matter.

“How much does she want now?” I used to ask him laughingly.

“We’re fixing up the contract,” he would answer with a significant lift of the eyebrows.

It often took longer to make one of Mary’s contracts than it did to make one of Mary’s pictures. Yet, strangely enough, the beneficiary herself took no hand in the enterprise. The warfare of clauses was waged entirely by her mother and her lawyer. Indeed, Mr. Zukor has often told me that Mary Pickford had never asked him for a cent.

“Then how do you know she’s discontented?” I once inquired of him. “How does she act?”

“Like a perfect lady,” responded Mr. Zukor stoically.

I made no comment, but I have always understood that one of the advantages of being a perfect lady is that you can create a certain atmosphere without creating the basis for any definite accusations.

During the time that this contract was being negotiated the newspapers published an item to the effect that Charlie Chaplin had just signed a new38 contract whereby he was to receive $670,000 a year. Right here was where Mr. Zukor experienced a most acute manifestation of his periodic disorder.

When the Chaplin contract was announced every film-producer knew that Mary Pickford was negotiating a new contract, and I know of one specific offer she received at fifteen thousand dollars a week.

On account of the pleasant relations that had always existed between Mary Pickford and Mr. Zukor, however, she finally accepted the new contract with him, in which Lasky and I joined with Mr. Zukor, as the contract for ten thousand dollars a week, to apply on fifty per cent. of the profits of the picture, seemed unusually large.

During this period of dissatisfaction she spoke to me one day about the Chaplin contract. “Just think of it,” said she, “there he is getting all that money and here I am, after all my hard work, not making one half that much.”

This reminds me that, some time after the contract was made, Mary Pickford started working on her first picture, entitled “Less Than Dust,” and I saw more of her than I ever did before. As the enterprise was so large we decided to have a separate unit for her, which meant a separate studio that no one else worked in but Miss Pickford. As there was trouble one day, and Mr. Zukor being39 away, I went over to see her. Until that time any difficulties were always straightened out with Mr. Zukor. While I was there she make this remark to me: “What do you think? They all seem to be excited around here over my getting this money. As a matter of fact, one of your officials said: ‘Watch her walk through this set. For ten thousand dollars a week she ought to be running.’”

But to recur to the Chaplin contract: I was struck by the appeal in these words about dollars and cents. Again she seemed to me like a child, and this time all a child’s sense of injustice at what she considered an ungenerous return for her services spoke in the big brown eyes. If, indeed, my last paragraphs have cast the great screen artiste in any doubtful light, I hasten to remind you that all her tremendous professional pride was at stake in securing a concrete reward. Certainly there can be no doubt—and I am sure Mr. Zukor would be the first to admit this—that she was worth all the money she ever received. In fact, there are many who will consider this a very conservative statement.

Then, too, it will be remembered that my early impressions of Mary Pickford were received from Mr. Zukor and that, although he has always had the highest admiration for her both as a woman and as an artiste, his interpretation of various episodes40 was doubtless affected by the strain of financial adjustment. One memory of mine serves to establish this point.

On a certain day when I met our rival producer for lunch he was wearing what I had come to know as his “Mary” expression.

“What’s up now?” I asked him.

He shook his head. “She’s very balky over ‘Madame Butterfly,’” he responded. “This morning she stopped acting because she said the shoes weren’t right. In fact, nothing’s right about the whole play.”

Mr. Zukor attributed this mood to another crisis in wage fixation, but I am quite sure that salary was, at the most, only a partial factor in her dissatisfaction with that particular play. For not long ago she confided to a friend of mine: “The only quarrel I can ever remember having with a director was over ‘Madame Butterfly.’ It ought to have been called ‘Madame Snail.’ It had no movement in it, no contrasts at all. Now, my idea was to have the first scenes showing Pinkerton teaching the Japanese girl some American game like baseball. But would the director listen to me? Not a bit of it.”

Continuing with this same reminiscence, Mary Pickford spoke of her friend Marshall Neilan. “Micky was playing with me in ‘Madame Butterfly,’”41 she said. “And how well I remember the way we’d grouch after we left the studio. We used to leave work in an old car that we called Cactus Kate or Tuna Lil, and as we bumped into New York we’d invent together all sorts of business that we thought might tone up poor ‘Madame Butterfly.’ I was so impressed by Micky’s idea that I went to Mr. Zukor and said: ‘Do you know you ought to make Micky Neilan a director? He’d be worth at least a hundred and twenty-five dollars a week to you.’”

I quote this last as a testimony to the almost unerring acumen which Mary Pickford displays in her profession. Later on I myself engaged Marshall Neilan for the Lasky Company, and he has developed into one of the four or five great directors in the country. Incidentally I may mention that the Goldwyn Company now pays him twenty-five thousand dollars a picture, together with fifty per cent. of the profits. He produces four pictures a year.

My first long talk with Mary Pickford was almost a year after I caught my first glimpse of her in Zukor’s office. The conversation centred almost entirely upon work, and I shall never forget my amazement as I listened to her. There was no detail of film-production which she, this girl, still in her early twenties, had not grasped more thoroughly42 than any man to whom I ever talked. She knew pictures, not only from the standpoint of the studio, but from that of the box-office. Back of those lovely brown eyes, disguised by that lyric profile, is the mind of a captain of industry. In appearance so typically feminine, Mary Pickford gives to the romance of business all of a man’s response. Certainly she would have had no trouble in filling a diplomatic post. I realised this as, sitting with her one evening in the Knickerbocker Hotel restaurant, where I had taken her to dinner, I heard her speak for the first time of the Lasky studio. She was only twenty-two.

“I can’t tell you,” said she, “how I admire your photography.” And then she went on to laud other features until I tingled with pride to think that I belonged to such a superior organisation.

“It must be a wonderful pleasure to work in such a studio,” she concluded in a voice soft as the southern wind.

Of course I may be mistaken, but it seemed to me that Mary was conveying the impression that she would not be awfully offended if I made her an offer from the Lasky Company. However, as this impression was created after she had praised Zukor in the highest possible terms—indeed, she always spoke well of him—it avoided all the disadvantages of a direct statement.

43 I may mention incidentally that she did have offers from many producers. Therefore when she was ready to make a new contract with Zukor she had a very firm foundation of argument. “So-and-so’s willing to give me so much. Also So-and-so”—this was the lever applied by her mother and her lawyer.

There was another revelation made by that first evening. She and her mother were living at the time in a little apartment on One Hundred and Fifth Street. When I entered it I was never more surprised in my life, for the room into which I was ushered contained only a few plain pieces of furniture, and in its centre stood an inexpensive-looking trunk.

As I waited for Miss Pickford I wondered to myself, “What in the world is this girl doing with her thousand a week?”

For you must remember this was no transient abode. Here in these quarters, where Japanese ideas of elimination had been applied so thoroughly, the famous star had been living for months. As I thus speculated upon the destiny of Mary’s dollars the door opened and I looked up to see a short, rather stout figure and a face where could be traced some resemblance to that of the celebrity for whom I waited. It was Mrs. Pickford.

She greeted me cordially and then she turned to44 the trunk. From it I saw her take the gown her daughter was going to wear that evening, and I could not help observing the simplicity of this garment. Many a girl who makes fifty dollars a week would have considered it too plain for herself.

On another occasion when Mrs. Pickford accompanied us to dinner I heard the answer to my unspoken query in the meagre little room. She was investing Mary’s savings. Most of these investments were made in Canada, where Mary was born and brought up, and I was surprised to learn the extent they had already attained.

I have spoken of the famous star as being, in reality, a captain of industry. In the thrift to which I was introduced this first evening you find a reinforcement of the statement. I was soon to discover that waste of any kind offends Mary Pickford as much as it does John D. Rockefeller.

But if Mary is controlled in her general expenditure, if she has never been able to rebound from the fear of poverty impressed upon her by the straitened days of her childhood and early youth, she displays no similar restraint in one particular instance. Her family! Not only to her mother, but to her brother Jack and her sister Lottie she has been the soul of generosity.

In manner she is perfectly simple and unaffected. Unlike many other screen actresses whom45 I have known, she does not act after working hours. And when she is in the studio she is always courteous and considerate. There on the set, where the soul-meter registers so true, Mary Pickford never indulges in the spasms of ego which the afflicted themselves are wont to call their temperament. Methodically as if she were Mary Jones arriving in the office for dictation, she appears on the Fairbanks lot.

There is absolutely no swank about her. An illustration of the quality which has so endeared her to many other members of her profession is found in a benefit performance given last year at Hollywood. Space was limited and when the dressing-rooms were assigned no such poignant cry of outraged property rights has been uttered since the little bear whimpered, “Who’s been sitting in my chair?”

“What!” cried one of the motion-picture duchesses only just recently elevated to the peerage. “Do you mean to say that I have to dress in a room with three other people?”

Miss Pickford, however, whose audiences number twenty-five to this other star’s one, sat down good-humoredly in a room with several other performers.

“How jolly!” said she, according to report.46 “This reminds me of the old days at the Biograph when I was getting twenty-five a week.”

If Miss Pickford has, indeed, any vanity, it is focussed more upon her sense of being a good business woman than it is upon her ability as an actress. All of her friends realise this, and Charlie Chaplin, upon whose warm personal friendship with Douglas Fairbanks and his wife I shall dwell in a later chapter, is very fond of teasing her upon this one vulnerable point.

“Where do you get this idea that you’re such a fine business woman, Mary,” Charlie asked her laughingly one evening.

“Why, I am,” she retorted indignantly. “Everybody knows it.”

“I can’t see it,” announced Charlie. “You have something the public wants and you get the market price for it.

“And then,” recounts Charlie gleefully, “I wish you had seen Doug. He looked as if he were going to hit me.”

A year or so ago I was at one of the big hotels in Hollywood with an author making his first visit to the place. He looked around at the dining-room with the faces of so many famous motion-picture folks, and then he turned to me.

“I don’t see Mary and Doug,” he remarked. “Where are they?”

47 “No,” said I, “and if you live in Hollywood for a year you’ll probably never see them—unless you go to their home.”

Poor chap! If he had gone to Switzerland and been told that the Alps never came out he could not have looked more disappointed.

One evening I was invited to dinner at the beautiful home of Mary and Doug in Beverly Hills. The idol of the screen, arrayed in a beautiful evening gown, met me with a manuscript in her hand.

“Well, well, what are you doing?” I asked her.

“Oh,” she said, “I’m working on my story.”

We ate a dinner where the talk was all dedicated to pictures. Then as soon as it was over Mary turned to me. “I’d like you to see my new picture this evening,” she announced. “I’m awfully anxious to know what you think of it and to find out if you have any suggestions to make.”

I smiled a little as I was led into the projection-room, where almost every evening the star and her husband turn on their consistent diet of amusement, for I realised that in this clever way Mary was going on with her work under cover of entertaining me.

This incident is typical of the whole-souled concentration which I am trying to point out. Every night after dinner the star and her husband see some picture—either one of their own or that of48 somebody else. In order to accomplish this they have installed in their home a machine and, just as in the ordinary household you turn on the phonograph, one of their men servants tunes up the silver-sheet. This home, by the way, presents in its luxury a very different setting from the little room where the star first entertained me, for since her marriage to Douglas Fairbanks there has been a marked expansion in her mode of living.

At eight o’clock in the morning Miss Pickford appears in the studio. It is often late in the evening when she leaves it. As to her working environment, this has been so often reproduced that I shall pass over the uproar, the glaring lights, the heat, the long waits, the monotonous repetitions of every scene—all those features which make a motion-picture day the most wearing in the world. Nor is the work less exacting when she is not engaged in actual reproduction. For, after the careful sifting of hundreds of stories, her final choice demands innumerable preliminaries of costume, lighting, directing, scenario-writing, and casting. And always, always she is thinking up bits of business for her next play.

But, the reader may protest, you have given us Mary Pickford chiefly in the terms of work. Can this be all? Is it merely a captain of industry who, in the guise of the wistful, appealing, dark-eyed49 slip of a girl, has played upon the heart-strings of the world? Decidedly not! On the screen you can not humbug any of the people any of the time. The camera shows, as the speaking stage does not, the fundamental quality of the human soul. It has not deceived you, therefore, when you exclaim involuntarily, “Isn’t she sweet?” the minute you see Mary’s face on the screen.

MR. GOLDWYN, DOUGLAS FAIRBANKS AND MARY PICKFORD AT THE STUDIO

BARBARA LA MARR

Whose work in “The Eternal City” stamped her as an actress of stellar size.

Mary Pickford has a real sweetness of spirit. Furthermore, it is a woman’s sweetness. You find it in the look she bends upon her mother, in her greetings to those who work with her, in her love of children and of animals. It was that which led her to write to Mr. Zukor when, after their long career of contract-making, she finally left his organisation, the most affectionate and appreciative of letters. It was certainly that which made the first words I ever heard her utter seem not just a commercial inquiry, but the appealing wonder of a child.

Not only this. She possesses all a woman’s capacity for lyric response fused with her man’s capacity for epic response. The great romance of Mary Pickford’s life is undoubtedly Douglas Fairbanks, and upon this I shall touch when I come to speak of Fairbanks himself.

50

Before I happened into Adolph Zukor’s office that evening, of which I had spoken previously, when Mary Pickford was consulting him about the proper recompense for her indorsement of the cold-cream, I was, of course, already launched on my own adventures with the stellar world.

Through my account of the difficulties experienced by Mr. Zukor and Mary Pickford in arriving at a mutual understanding of a satisfactory wage, the reader may perhaps have gathered that the intercourse between producer and star is often clouded by the individual view-point. A story of my own contacts will not weaken that impression. In fact, before the Lasky Company was six months old I had discovered that the need for adjustment between these two supreme functionaries of the motion-picture world covers a wide ground, where salary represents only a limited space.

Among the first of the stars whom I engaged was Fanny Ward. It was shortly after we made our51 first picture that I chanced to meet this widely known actress in the elevator of the Hotel Claridge, New York. Fanny was not in her first youth. There was nothing, however, except her birth certificate to indicate this fact. If Ponce de Leon in his search for the Fountain of Youth had seen her that day he surely would have cried, “Ho, man, we’re getting warm!”

I was so struck by that air of youthful witchery which she has so often conveyed on the screen that I ultimately asked her if she would not make some pictures for us. Up to this time her fame had been confined to the speaking stage. But she was at once enthusiastic about the opportunity I presented to her, and in a short time we concluded arrangements for her trip.

The vehicle which we selected for her was “The Marriage of Kitty.” But, alas and alack! The vehicle was unequipped with shock-absorbers or even ordinary springs. After some very rough going in California, during which time Mr. de Mille had expressed by wire his dissatisfaction with my newly found star, the picture was sent back East. And along with the picture was shipped Fanny herself.

Almost immediately I was apprised of the latter fact. “Miss Ward phoned you just now,” announced my secretary on an otherwise pleasant52 morning. “She wants you to call her immediately.”

That I did not heed this request was due to a misplaced confidence on my part in the healing quality of Time. When the actress finally succeeded in seeing me I found that Time had done no more for Fanny than it does for a fireless cooker. Instead of cooling it had merely conserved those inner fires.

I had just ordered my dinner on that night when she consummated my capture, and as I saw her bear down upon my table I resigned myself to the inevitable. The inevitable was punctual. “You!” cried she, glaring up at me: “what have you done?”

I was, however, given no time for this solicited autobiography. Instantaneously the actress proceeded to enlighten me upon the one predominant and vital activity of my career. “You have disgraced me in the eyes of Hollywood and New York,” she asserted; “that’s what you have done. Did I ask to go into pictures? Not much! I had a big reputation on the stage, and then—you come along! You tell me what a future I have in pictures; you persuade me to leave New York and go to California, and now here I am, disgraced, absolutely made a laughing-stock——”

I took advantage of this, her first pause. “There, there,” murmured I, fully conscious of the limitations53 of my soothing technique, “what’s the matter?”

“Matter!” she stormed. “Everything’s the matter. Your photography’s rotten—absolutely no good. And as for your director—say, haven’t I been on the stage some years—oughtn’t I to know something about the game? And am I to be told what’s what by Cecil de Mille?” Et cetera. Et cetera.

The dinner cooled. Not so, Fanny. For fully half an hour the outraged star poured into my ears the tale of her wrongs in that far-away studio. Only my assurance that I would look at the film, which had arrived simultaneously with her, succeeded in stemming the flood-gates.

I did look at it, and my impression was much more favourable than I had hoped. It seemed to me that she had screened well and I wired to De Mille and Lasky to ask a second opportunity for Fanny. When I communicated this decision to Miss Ward she was so happy and so grateful for my intervention that I felt quite reckless about any financial outcome.

As it happened, however, the Lasky Company was not penalised for giving Fanny her second chance. The next play we assigned her was “The Cheat.” This film did four things. Its court scene where Fanny dramatically exposed the brand on54 her shoulder established her as an eminent artiste of the screen. It provided a wonderful vehicle for Sessue Hayakawa, the Japanese pantomimist, whom we engaged then for the first time, and was indeed responsible for the rapidity for his ascent to fortune. It also brought Cecil de Mille to the front. And to the Lasky Company it meant a first real “knockout” after a number of moderate successes. Everybody talked about “The Cheat,” Fanny Ward, and Sessue.

While making this play Miss Ward was the victim of a studio accident which provided the source of innocent merriment for the entire screen colony in Hollywood. When the cry of “Camera” was given Miss Ward got into action on a rustic bridge spanning a pool. She was attired in a costly ermine coat, a plumed hat, and a Paris gown. Sustained by the consciousness of these assets, as well as by her usual dramatic fervor, she began to trip across the edifice. For a few moments the tripping was good. Then suddenly there was a creak of boards. The creak was followed by a loud ripping noise, the bridge fell, and a moment later the camera, that remorseless Boswell, had recorded Fanny sitting in the pool below.

It was a somewhat inglorious attitude for any heroine, and Fanny was not slow to realise it. Sitting there in her soaked ermine coat with her55 plumed hat all awry, she relieved her feelings in a manner highly satisfactory both to herself and to those about her.

“At last,” commented one of her fellow actors, hearing this outburst of indignation, “we have seen it—the lake of fire and brimstone.”

But it was only a moment after this that the victim was laughing quite as heartily as the spectators. Indeed, among the various tempers which I have looked over in my career as producer, Fanny Ward’s variety comes nearest to the ideal recognised as “lovable.” Not only is her anger short-lived, but it is accompanied by such warmth of heart and generosity of spirit and it is followed so swiftly by her infectious laugh that one never remembers her stormy moods except with an affectionate smile.

Certainly her residence in Hollywood did much to dispel the horror which the mere mention of California evoked in the minds of many screen performers of that day. Into that former community with its few shops and its unpretentious homes Fanny moved with a suggestion of Eastern pomp. Having been married to a wealthy man and being therefore independent of her salary, she took the largest house in Hollywood and filled it with a fine blend of gold plate, servants, and bric-à-brac.

This home became the rendezvous of the picture-making56 colony. If you entered it on Sunday afternoon you found that forty-nine people had preceded you. No hostess could have been more delightful and gracious.

Whatever may be later sources of inspiration in motion-picture festivities those at Fanny Ward’s did not wander far from childhood’s happy hour. Once, I remember, a donkey-party was tendered. On this occasion Eva Tanguay did everything she could to sustain a famous self-characterisation. She did a bit of comedy work for which this nonsensical game offers such wide scope, convulsing us all with the innocent blundering she so well knows how to simulate.

There was one personal prejudice of Fanny’s which is recalled with amusement by all those who used to be invited to those parties. No matter what she served her guests at dinner—lobster, or quail, or turkey—she herself always ate frankfurters. Furthermore, she liked a mob scene of these “hot dogs,” and I can see her now as she sat before one of her famous gold platters heaped high with the incongruous fare.

Every other type of refreshment at the Ward home sprang from an equally liberal source. Witness to this fact is supplied by a dinner given by Fanny just previous to a discussion arranged by the Lasky Company, the Famous Players, and the57 Triangle Company with a view toward a merger of these organisations. A representative of one of the two rival companies sat beside me while a relentless hospitality was being waged. At last he turned to me pleadingly.

“For Heaven’s sake,” he whispered, “I want a clear head for our talk. Won’t you tell that butler to stop filling my glass?”

“Butler!” I whispered back, almost congealed with horror. “Sh! That’s Miss Ward’s husband.”

This husband, by the way, was Jack Deane, her leading man, whom she married after coming to Hollywood.

Fanny’s expenditures began at home, but they did not stay there. She made the same opulent gesture in the studio. Thus I remember that when Percy Hilburn, the cameraman who used to film her, threatened to leave us because we would not raise his salary from one hundred to two hundred a week, the actress made up the extra amount out of her own purse.

“What,” she exclaimed, “have Percy leave the place while I am here! A man that can make you look as beautiful as he does me!”

There was, of course, a great deal in what she said. For an expert cameraman can be as flattering as a pink sunshade. However, Fanny was dependent upon his ministrations.

58 Her sustained ability to look young was especially definite in “Heart’s Ease,” a Bret Harte story in which she played a seventeen-year-old part. As Fanny’s own daughter was at the time just about this same age, newspapers everywhere saw the opportunity for much good-natured fun, and it was after such far-flung propaganda that her close friend Nora Bayes greeted her with a sally I have never forgotten.

The famous comédienne just mentioned was opening up on a certain night in the Orpheum Theatre at Los Angeles. Fanny gave a large dinner that night, including Charlie Chaplin, Marie Doro, and De Wolf Hopper, and after the dinner she asked me if I would not drive into Los Angeles with her to Nora’s opening. I did so, and before the comédienne’s appearance Fanny took me back of the scenes. Nora came down the stairs to greet us and when she caught sight of her friend she cried, “Why, Fanny Ward, I expected to find you with a rattle in your hand!”

For several years Fanny’s screen popularity continued. Then quite gradually she began to go under an eclipse. Why was it? Perhaps she may not have forgotten the proper dramatic mediums. More probably the public failed in its former response to her type of acting. Be that as it may, this decline in popularity—so tragically familiar in the59 motion-picture world—left Fanny behind us, a pleasant memory. However, the Lasky Company had always prided itself on fidelity to contract, and we did not depart from this standard in our dealings with Miss Ward. It was she who finally severed our business relations.

I have dwelt upon the career of Fanny Ward at this length, not only because hers is one of the vivid and lovable personalities in the screen world, but because the social atmosphere which she created forms a cherished background for the recollections of many a screen star. To-day if you find yourself in a crowd where Mae Murray, Tommy Meighan, Mabel Normand, and other famous stars are gathered together, you are sure to hear, “Oh, do you remember that evening at Fanny’s when she did so and so?”

60

Meanwhile, of course, I had been negotiating with various other stars. Among this number was Marguerite Clark. Miss Clark, you remember, had stirred the public deeply by her beautiful performance in “Prunella,” and this success of the speaking stage resulted in a competition between Mr. Zukor and ourselves for her services on the screen. Our final compromise indicates how ably we lived up to the friendly-enemy ideal of conduct.

“See here,” called Mr. Zukor over the phone, “I hear you’re negotiating with Marguerite Clark. Now I want to tell you something. I’m going to get her, no matter what I have to pay. So you’ll do me a favor if you don’t bid me up any higher.”

I agreed to withdraw, but upon one condition only. The Lasky Company had just secured the rights to Harold McGrath’s “The Goose Girl,” and we had been thinking for some time that Marguerite would be ideal for the part. My final understanding with my competitor accordingly was61 that he should lend us the coveted star for this single picture. In this arrangement, however, we reckoned without Marguerite herself. “What, Marguerite go all the way out to California!” exclaimed the star’s sister when I called at the Clark apartment that first evening.

An Astor or a Vanderbilt ordered to go out and hoe potatoes, a Russian nobleman sentenced to Siberia—neither of these could have expressed more profound emotion. Nor was the prejudice of Miss Clark’s sister an isolated one. I quote this exclamation, indeed, as significant of an almost universal obstacle I encountered in those early days. Stars did not want to leave New York for California.

I soon suspected that in Marguerite’s case the prejudice was a more deep-seated one than could be explained by climate or landscape. The very morning after she agreed to go out to the Lasky studios a young man in the employ of Mr. Zukor came to my office. His name was Harold Lockwood and he will be remembered for his work in some of Mary Pickford’s earlier stories, and later as a famous star for the Metro Company.

After a little preliminary clearing of his throat the handsome Harold suggested the purpose of his call. “Ahem,” began he, “I hear you’ve engaged Miss Clark to do a picture for you?”

62 “Yes, yes, so I have,” retorted I, leafing over a pamphlet.

More pronounced symptoms of nervousness by Harold before he could proceed. “Ahem—well—I just thought—of course you may not be looking for anybody—but——”

We did not take advantage of Harold’s willingness to share Miss Clark’s banishment, but there are numerous parallel situations where we found the pressure more forceful. Sometimes, in fact, we have been obliged to take a constellation in order to secure the services of the one particular star which graced it. Our engagement of Blanche Sweet, of Pauline Frederick, and later experiences with Geraldine Farrar—these episodes to which I am coming presently—reveal the extent to which some emotional preference influences the contract of the feminine star.

Well, Miss Clark did go to California and she made for the Lasky Company its successful play of “The Goose Girl.” The performance was not, however, devoid of friction. From the studio across the continent to my office in New York came constant mutterings of disagreements between Miss Clark and her director, Fred Thompson. Once I wired to De Mille to ask him how the play was coming along, and his answer to the telegram was as follows:

63 “Don’t know much about the play, but geese and photography both looked great.”

I have mentioned that Marguerite’s sister met me that evening I went up to her apartment. This sister, who was some years older than her celebrated relative, was almost as constant a phenomenon as was Mary Pickford’s mother. Indeed, many feminine luminaries of the screen possess one of these adhesive relatives. There is nearly always a mother or brother or sister or husband standing around back of the screens to see that justice is administered.

There was one time when Mary Pickford’s supremacy was seriously threatened by the success of this other Famous Players’ star. “Is Mary jealous of Marguerite?” I asked Mr. Zukor at this period.

He shook his head. “No,” said he. And then he added swiftly, “But it comes to the surface through Mrs. Pickford and Marguerite’s sister.”

From this remark I gathered that the two doughty supporters of opposing causes used to look at each other about as pleasantly as did the Montagues and Capulets. And if you possess any flair, like Landor, for imaginary conversations, you can easily construct a dialogue between the twain based on their respective claims to the most mail, the most unappeasable demands of exhibitors, the most appreciation from Mr. Zukor.

64 Yet Mary long outlasted her fair rival. Why was this? Marguerite Clark was beautiful, she was exquisitely graceful, and she brought to the screen a more finished stage technique and a more spacious background than did Miss Pickford. My answer to this question, so often propounded to me, applies not only to Miss Clark, but to all the other actresses who have flashed, meteor-like, across the screen horizon. First of all, she did not have Mary Pickford’s absorbing passion for work. Secondly, she did not possess the other artiste’s capacity for portraying fundamental human emotion. Simple and direct and poignant, Mary goes to the heart much as does a Foster melody. Herein is the real success of a popularity so phenomenally sustained.

Previous to engaging Miss Ward and Miss Clark, the Lasky Company had secured the services of Blanche Sweet. The performance of this actress in Griffith’s “Judith and Bethulia” had lingered in my memory, and almost as soon as we organized I took Lasky to see that film. He was so much impressed that we wired at once to De Mille to negotiate with Miss Sweet, then working under Mr. Griffith in California.

From the first she did not seem satisfied with her new environment. After some days, in fact, she came to me and begged that she be allowed to leave us. She wanted to go back to New York.

CLARA KIMBALL YOUNG

Easily the screen’s most beautiful brunette, and whose eyes are known the world over.

MR. GOLDWYN ACTING AS HOST AND WAITER

John Bowers, Molly Malone and Will Rogers at the table. Chaplin is serving root beer.

65 “But why?” I pressed her.

After some hesitancy she finally confided the reason of her unrest. Marshall Neilan, whom I have mentioned as playing with Mary Pickford, had been unable to find work in Los Angeles and was taking the train back East the very next day. The result of this conversation was that I sent for Mr. Neilan, and so impressed was I by his intelligence that I engaged him as a director at two hundred and fifty dollars a week. His success was marked from the first and I have already indicated his rapid ascent to fortune.

As to Blanche, who eight years later became Mrs. Marshall Neilan, it was not until she began to work under Mr. Neilan’s direction that she justified our expectations of her. I shall never, indeed, forget my disappointment at seeing her first Lasky film.

“What!” thought I. “Can this be the same girl who was so effective in that Griffith picture?”

It was my introduction to a recurrent tragedy in my career as producer. Various times I have been attracted by Griffith successes only to find that they could not thrive in another environment. Just like Trilby when no longer confronted by the hypnotic baton of Svengali, so many of the men and women who have worked under Mr. Griffith can not perform when deprived of his inspiring force.

Meanwhile the Lasky Company had been expanding66 tremendously. Like an octopus it clutched at all the landscape available in the vicinity of the original livery-stable. New buildings kept going up. New people were being added. So swift was the pace of progress that De Mille’s brother William, whom we had sent out meanwhile as a scenario-writer, frequently voiced his leading plaint. He liked to work by himself in a little building away out in a field, but to save his life he could not move that little building fast enough. “I wake up in the morning after I’ve just staked a fresh claim,” he used to say, “and the doggone studio has caught up with me in the night!”

A tremendous impetus was given to both Mr. Zukor and the Lasky Company by an organisation of the distributers who had been handling our films. About six months after Lasky and I went into business these functionaries decided that in order to make themselves a real force they would have to guarantee to theatrical managers throughout the country a larger number of pictures. Their organization, under the name of the Paramount Pictures Corporation, requisitioned one hundred and four films a year, of which our company agreed to supply thirty-six. As this was just three times the number we had planned to produce, you will see the urgency of growth. It is equally evident why our capitalisation now increased from the original67 twenty thousand to two hundred and fifty thousand dollars.

But the domestic market by no means exhausted our outlet. Always I have been penetrated by a sense of international possibilities in the film industry. That this Esperanto of the stage could be communicated to foreign countries—here was the idea which in the early Summer of 1914 sent me speeding to Europe.

I was interested in placing not Lasky products alone, for before my departure Mr. Zukor had asked me if I would not look after his interests also.

Until this time we had engaged in no concentrated drive of the sort. For, although Mr. Zukor had a representative in London, the agency waged only a haphazard, picture-by-picture campaign. Nor was my first important interview pregnant with hope of more systematic sales.

Great Britain had always been active in picture-production and her leading distributer was William Jury, who has since been knighted. Mr. Zukor’s London representative arranged my meeting with this personage, and from almost the minute I began talking to him I saw that Mr. Jury believed that Britannia rules the films as well as the waves. After he had listened to my enthusiastic praise of both Zukor and Lasky products, he told me that no American company could possibly be as great as I68 said we were going to be. To this I retorted that no one so lacking in confidence in a product could possibly be able to sell it. Having thus clarified our views, Mr. Jury and I parted. Almost immediately afterward I helped finance Mr. J. D. Walker to handle both Famous Players and Lasky Films in Great Britain. Under my contract with him he was to take the output of both studios and to pay us ten thousand dollars advance against sixty-five per cent. gross.

After this my progress was comparatively easy. Sweden, Norway, and Denmark promised to buy all the pictures we made at something in the neighbourhood of three thousand dollars each. I closed a deal with Australia guaranteeing to take our complete output at thirty-five hundred dollars a film; Germany put in the same large order at an even higher rate—four thousand each; Belgium and Switzerland contributed their quota, and although France represented our poorest customer, even she did not withhold her mite.

Is it any wonder that as I rode from Berlin to Paris my head reeled with the magnitude of our success? Could this really be I, the poor boy who a short time before had wandered over these very countries with hardly a sou in his pocket?

Yet mine was no miracle of success. I traveled in Europe day and night. I pitted all my enthusiasm69 against many citadels of prejudice and scepticism. When, indeed, I finally sailed from Liverpool I was physically prostrated by the long strain of it all.

Even the triumph which I have just chronicled was doomed to only a partial realisation. I could not anticipate, of course, on that Summer day when, riding from Berlin to Paris, I counted up my thousands, that in a few short weeks a bomb would explode in Sarajevo which would change the map and the psychology and the industrial conditions of the whole world. And I certainly could not foresee, therefore, the broken contracts and the difficulty of obtaining ships to fulfil contracts which followed the declaration of war.

While in Europe I was constantly on the lookout for actors, and one of the results of my search was Edna Goodrich. Miss Goodrich had three assets at this time. She was beautiful; she had created a sensation on the London stage, and she had recently joined the famous recessional of wives of the late Nat Goodwin. Eventually Miss Goodrich made a picture for us at five thousand dollars, with the understanding that if it were successful we should have the first option on her second venture.

Too bad for Miss Goodrich! Too bad for the Lasky Company! Almost the minute De Mille70 started to work with her he wired me, “Goodrich too cold.”

In the film world this is an epitaph. Nor did Miss Goodrich live down her obituary. Time refused to thaw her, and I was then initiated into the profound truth that many an actress whom individuality of voice and beauty of colouring render glowing on the stage are absolutely calcimined by the camera.

However, my interview with Miss Goodrich resulted profitably in another way. While dining with her at the Carlton in London I was introduced to a tall, broad-shouldered, manly-looking chap with a mop of chestnut-brown curls. From the moment that I saw him I was struck with Tommy Meighan’s possibilities for the screen, and when he came to America I wired Lasky to look him over. We engaged him, and Tommy went to California to make his first picture, “The Fighting Hope.”

“Tommy no good”; this was the telephoned verdict which De Mille rendered after this initial performance. I was then in San Francisco, and when I arrived in Los Angeles the defendant got to me before the prosecutor.

“See here,” announced Tommy ruefully, “they say I’m no good around this place, so I guess I’ll clear out. The Universal has made me an offer, anyhow.”

71 “Do nothing of the sort,” I commanded. “Wait until I see your picture first.”

My view of that picture convinced me that our chief director’s opinion had been conceived too hastily. And the outcome of my intercession was a very distinct gain. A year or so planted this star on terra firma. To-day he is one of the most popular actors of the screen.

All this happened in 1914. The next year was one especially significant in motion-picture circles. Among the events contributing to its impressiveness was that Titanic conception of the silver-sheet, “The Birth of a Nation.” This Griffith picture which, by the way, was the first screen performance where two dollars a seat was asked, might also have been called “The Birth of Numerous Stars.” Mae Marsh, the Gish girls, perhaps a dozen luminaries who have since flashed across the public consciousness, owe their success to parts in the giant canvas.

It was during this year that De Mille and I went to a dinner given to Raymond Hitchcock, at Levy’s Café in Los Angeles. We were half-way through when we were attracted simultaneously by a young man who had just sat down at an adjacent table. One look at the clear-cut face and we exclaimed in unison, “Isn’t he attractive! Wouldn’t he be wonderful in pictures!”

He was wonderful in pictures. For his name72 was Wallace Reid. The very next day we engaged him at a salary of one hundred dollars a week, and it was not until this first meeting that we discovered he had already worked at pictures under Mr. Griffith’s direction. The untimely death of this gifted and attractive young man, whose future held so much of promise, brought to his profession an irreparable loss.

73

In this same eventful year the Lasky Company engaged another actress whose name is now familiar to the motion-picture population of the world. The Ziegfeld Follies of 1915 contained for the first time a screen episode introduced for the presentation of an auto race. From the moment when I saw Mae Murray romp across this incidental screen I saw her possibilities. When I got in touch with her, however, I discovered that several other producers had been inspired by the same belief.

That our organisation was the lucky competitor was due to a very advantageous connection which the Lasky Company had formed some time previously. The chief concern of both Mr. Zukor and our organisation was to get big stories, big plays, and to this end Mr. Zukor and I engaged in a memorable skirmish over Mr. David Belasco. It is apparent, of course, at first glance why the production of this, the most eminent producer of the spoken drama, should have assumed such importance in our eyes. Both of us felt that if we could74 only have the screen rights to the Belasco plays we should be placed in an invulnerable position.

In our rival efforts Mr. Zukor had the first advantage, for he had earlier formed a connection with Mr. Daniel Frohman, and through this alliance he was enabled to get into direct touch with Mr. Belasco. I, on the contrary, made all overtures through the great producer’s business manager. In spite of Mr. Zukor’s lead, the result hung in the balance for many days.

At last, just when I was beginning to despair, Mr. Belasco announced that he would see me. How well I remember that day when with beating heart I sat in the producer’s private office awaiting the decision so vital to my organisation! It seemed an eternity that I listened for the opening of a door, and when at last I heard it Mr. Belasco’s entrance was as dramatic as that of a hero in one of his own plays. The majestic head with its mop of white hair sunk a trifle forward, the one hand carried inside of his coat—I can see now this picture of him, as slowly, without a word, he descended the stair to greet me.

After I had gathered together my courage I began to talk to him about De Mille and Lasky and our organisation, and he seemed impressed from the first by my enthusiasm. I think he liked the fact that we were all such young men. Indeed, he75 said so. And it was this, I am sure, which influenced his decision. He made it that very day, and when I went out of his door my head was swimming with my triumph. Mr. Belasco had promised the Lasky Company the screen rights to all his plays. For these rights, I may mention, we promised him twenty-five thousand dollars advance against fifty per cent. of the profits.

I saw my esteemed but defeated rival at lunch on this very same day, and when I told him the news his face grew white. It was, indeed, a terrific blow. But a reversed decision would have meant even more to me. For such plays as “The Girl of the Golden West” and “Rose of the Rancho” merely helped to offset our leading competitor’s tremendous advantage in the possession of such stars as Mary Pickford and Marguerite Clark.

The promise of the Belasco plays influenced favorably many a screen actor of the time, and it was, in fact, my assurance to Mae Murray that she should play “Sweet Kitty Bellairs” which weighed against more dazzling offers from other studios.

Before Mae departed for California she came to me with trouble clouding that fair young brow. “I can’t do it,” said she.

“Can’t do what?” I inquired apprehensively.

“Why, this contract you’ve made with me; it says that I get one hundred a week and that the company76 buys my clothes. Now I can’t trust anybody else to pick out what I wear. Clothes are part of my personality and I’d much rather have more salary and have the privilege of buying my own wardrobe.”

I yielded the point and allowed her an extra one hundred a week to cover this expenditure. Incidentally, I may remark that Mae could not have saved many nickels from her allowance. There is a tradition that one evening at the Hollywood Hotel the charming little actress changed her evening wrap four times. I can not verify this legend, but I can say that Mae never changes from bad to worse. She is regarded as one of the most beautifully dressed women of the screen.

The clothes-cloud was dispelled from Mae’s horizon. Unfortunately, however, more severe storms awaited her in California. First of all, she was rent by the commands of a director whose conception of her talents had nothing in common with Mae’s own.

“Be more dignified. Remember that you are a lady, not a hoyden”; this was the spirit if not the substance of guidance.

At some such suggestion Mae would protest angrily. “But I’m a dancer—that’s the reason I was engaged. And now you want to turn me into something different. I tell you I’ll be an utter failure if you go on like this.”