Title: The Campaigns and History of the Royal Irish Regiment, [v. 1,] from 1684 to 1902

Author: G. le M. Gretton

Release date: June 19, 2019 [eBook #59779]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Brian Coe, John Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/campaignshistory00gret |

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

Basic fractions are displayed as ½ ⅓ ¼ etc; other fractions are shown in the form a/b, for example 1/320.

All dates in this book use the modern (NS) Gregorian calendar, except for quotations from regimental historians, who use old style (OS) Julian dates. See Footnote[12].

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

The Campaigns and History

of the

Royal Irish Regiment

From 1684 to 1902

BY

Lieutenant-Colonel G. le M. GRETTON

LATE 3RD BATTALION, LEICESTERSHIRE REGIMENT

| NAMUR, 1695 | BLENHEIM | RAMILLIES |

| OUDENARDE | MALPLAQUET | EGYPT |

| CHINA | PEGU | SEVASTOPOL |

| NEW ZEALAND | AFGHANISTAN, 1879-80 | EGYPT, 1882 |

| TEL-EL-KEBIR | NILE, 1884-5 | SOUTH AFRICA, 1900-02 |

William Blackwood and Sons

Edinburgh and London

1911

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

This history of the war services of the Royal Irish regiment has been written at the request of the officers of that very distinguished corps. When I accepted the task, I knew that I had undertaken a delightful but difficult piece of work, for it is no easy matter to do justice to the achievements of a regiment which has fought in Europe, in Asia, in Africa, in America, and in Australasia. After serving with credit in William III.’s war in Ireland, the Royal Irish won undying laurels in the Siege of Namur in 1695. They formed part of the British contingent in the army commanded by Marlborough in the Low Countries and in Germany, and fought, not only at the great battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, and Malplaquet, but in the long series of desperate but now forgotten sieges by which fortress after fortress was wrested from the French. A detachment took part in the defence of Gibraltar in 1727: the whole regiment was involved in the disasters of the campaign of 1745: the flank companies encountered foemen worthy of their steel at Lexington and Bunker’s Hill. In the first phase of the great war with France the Royal Irish were in the Mediterranean: they served in the defence of Toulon; they helped Nelson and Moore to expel the French from Corsica, and they were sent to the mainland of Italy where for some months they established themselves firmly at Piombino, a port on the Tuscan coast. A few years later they fought under Abercromby in Egypt, but then their good luck changed, for they were ordered to the West Indies, where they remained till the end of the Napoleonic war.

In 1840, the outbreak of the first war with China re-opened the gates of the Temple of Janus to the XVIIIth; and during the last sixty years almost every decade has seen the regiment employed on active service, for after the Chinese war came the second war in Burma; the Crimea; the Indian Mutiny; the New Zealand war; the second Afghan war; the campaign of Tel-el-Kebir; the Nile expedition; campaigns on the north-west frontier of India; and the war with the Dutch republics in South Africa.

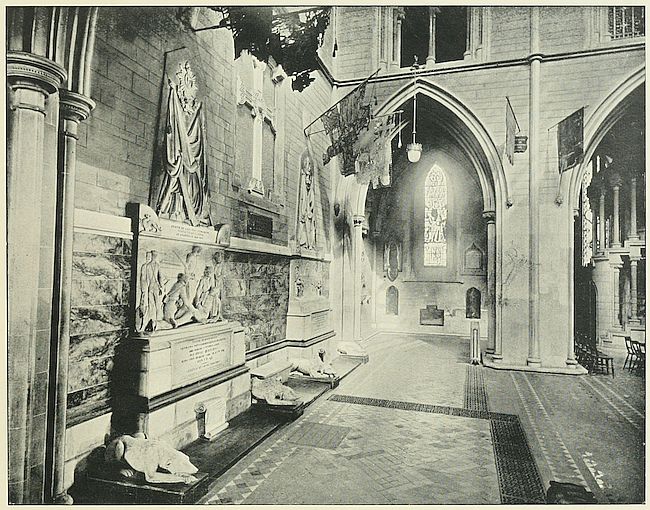

The Historical Committee had hoped that Field-Marshal Lord Wolseley would have written a preface to the history of the regiment, with which throughout his military career he has been associated closely. In Burma he won his spurs leading a charge of infantry among whom were many of the Royal Irish; as an acting Engineer at the siege of Sebastopol he frequently supervised the operations of the regiment in the trenches; in the Tel-el-Kebir campaign and the Nile expedition the Royal Irish formed part of the troops under his command; and for the last thirteen years he has been their Colonel-in-Chief. Ill health unfortunately has prevented Lord Wolseley from writing at any length, but in a letter to the Chairman of the Committee, he expressed his admiration for the regiment in the following words:—

“Hampton Court Palace, Middlesex,

19th June 1910.

My Dear Gregorie,—I am indeed very glad to hear that the History of the Royal Irish Regiment is soon to be published. Its story cannot fail to be a fine one. Every soldier who like myself, had the honour of fighting, I may say shoulder to shoulder with it, will read this new work with the deepest interest.

Were it to be my good fortune to lead a Storming party this afternoon I should indeed wish it were to be largely composed of your celebrated corps.

Believe me to be,

Very sincerely yours,

Wolseley.”

“To General C. F. Gregorie, C.B.,

Royal Irish Regiment.”

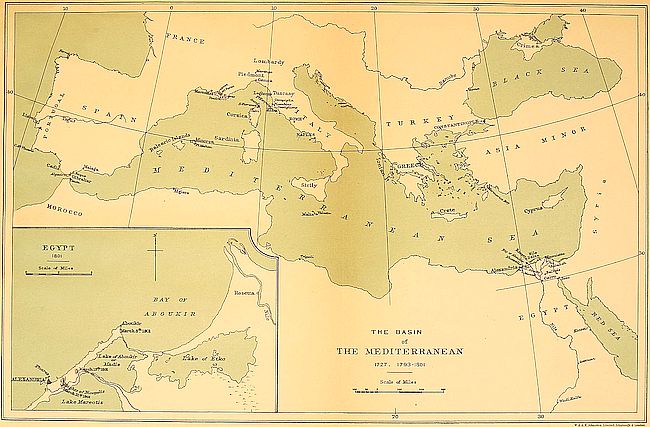

A lithographic reproduction of this letter will be found facing page viii.

This history has been prepared, not for the officers alone but for all ranks of the Royal Irish, and the Committee are supplying it to non-commissioned officers and private soldiers at a price so low that even the last joined recruit can buy it, and read of the gallant deeds of his predecessors in the regiment.

As I am fully impressed with the importance of recording the names, not of the officers only, but of all members of the regiment who on active service laid down their lives for their country, I have tried to mention in the Casualty appendix all ranks who were killed, or died from the effects of wounds or sickness in the many wars in which the Royal Irish have taken part. In the campaigns of the seventeenth and the greater part of the eighteenth centuries but few names are to be found, and it is not until the[vii] middle of the nineteenth century that those of wounded non-commissioned officers and men can be traced. In other appendices are lists of those who won medals for distinguished conduct in the field, and also those to whom medals for long service and good conduct have been awarded.

It has been my object to write this book as far as possible on the lines of a biography, and by quotations from regimental sources of information to let the Royal Irish describe their doings in their own words. In the wars of William III. and of Anne this was comparatively easy, for though the regiment has preserved no official records for the 17th and 18th centuries, during the first thirty years of its existence it produced four military historians, three of them officers, one a sergeant. Brigadier-General Kane, Captain Robert Parker, and Sergeant John Millner have left books, and Brigadier-General Robert Stearne a manuscript journal describing the events they witnessed. Unfortunately they all wrote for a public far more concerned in the general results of a battle or a siege than in the doings of an individual regiment; and though they gave excellent accounts of an engagement, they failed as a rule to describe the part played in it by the men under their command. Whether their laconic style was due to modesty—for the three officers were all distinguished soldiers—or to want of descriptive power, it is impossible to say, but the fact remains that they have bequeathed to their successors in the Royal Irish accounts singularly deficient in regimental detail. In some cases they failed to record the casualties among the XVIIIth in a battle or a siege, and when they remembered to do so, often forgot to give the names of killed or wounded officers. Their indifference to the losses of the lower ranks is characteristic of all armies in the 17th and 18th centuries; and they tell us nothing of the deaths by disease, or of the drafts of recruits by which the waste of war was made good. Sergeant Millner is equally unenlightening. If, instead of devoting his undoubted talents to the production of a sort of Quartermaster-General’s diary of Marlborough’s movements, he had written an account of the life of the regiment on active service, he would have left behind him a very interesting book, instead of a comparatively dull one.

The adventures of the XVIIIth in the campaign of 1745 in the Low Countries were described in the journal of one of the officers, whose name has not been preserved. For a hundred years the regiment produced no more authors, until, after the end of the first Chinese war, Lieutenant A. Murray wrote an interesting account of the Royal Irish in that campaign.

For the wars in the beginning and middle of Queen Victoria’s reign much valuable material was obtained from private sources by the honorary[viii] secretary of the Historical Committee, Lieutenant-Colonel A. R. Savile, who for many years devoted himself to the collection of information from officers who had served with the regiment in these campaigns. Probably no one but the man who has profited by Colonel Savile’s exertions can appreciate adequately the energy and perseverance he displayed in this labour of love for his regiment. He has also prepared two appendices; one giving an epitome of the services of the Colonels of the regiment, the other describing the memorials which have been raised by the officers and men of the Royal Irish to the memory of those of their comrades who died on active service. Nor is this all for which I have to thank him: his collection of historical matter relating to the regiment at all periods of its existence has proved of great help to me:—indeed in all honesty I may say that if this book meets with success a great part of that success will be due to the “spade work,” the results of which Colonel Savile has generously placed at my disposal.

Many of the past and present officers of the Royal Irish regiment have given me great assistance in the later campaigns by preparing for me statements recording their personal recollections, and by lending me their diaries and letters, written at the seat of war; and several non-commissioned officers have supplied me with interesting details about episodes in South Africa.

With the officers who form the Historical Committee I have worked in perfect harmony and identity of views, and I have to thank them warmly for the unfailing support they have given to me during the two years which it has taken me to prepare this book.

I have to express my sense of obligation to the Librarians of the War Office, the India Office, the United Service Institution, and the Royal Colonial Institute, and the officials at the Record Office for their friendly help.

To Mr Rudyard Kipling the warm thanks of the regiment are due for his kindness in allowing the reproduction of his ballad on the second battalion of the Royal Irish in the Black Mountain campaign.

In the compilation of this record very many books have been consulted. Among them stands out pre-eminently the ‘History of the British Army,’ by the Hon. John Fortescue, who, by his masterly descriptions of the campaigns he has dealt with up to the present, has made the path of a regimental historian comparatively smooth.

Sherborne, Dorset.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | v |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| 1684-1697. | |

| THE RAISING OF THE REGIMENT: AND THE WARS OF WILLIAM III. | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| 1701-1717. | |

| MARLBOROUGH’S CAMPAIGNS IN THE WAR OF THE SPANISH SUCCESSION | 25 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| 1718-1793. | |

| THE SECOND SIEGE OF GIBRALTAR—THE SIEGE OF OSTEND—LEXINGTON—BUNKER’S HILL | 65 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| 1793-1817. | |

| THE WAR WITH THE FRENCH REPUBLIC: TOULON—CORSICA—EGYPT. THE NAPOLEONIC WAR: THE WEST INDIES | 89 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| 1817-1848. | |

| THE FIRST WAR WITH CHINA | 120 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| 1848-1854. | |

| THE SECOND WAR WITH BURMA | 145 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| 1854-1856. | |

| THE WAR IN THE CRIMEA | 162 |

| [x] CHAPTER VIII. | |

| 1856-1859. | |

| OPERATIONS DURING THE MUTINY IN INDIA | 189 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| 1858-1882. | |

| RAISING OF THE SECOND BATTALION: THE WAR IN NEW ZEALAND | 193 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE FIRST BATTALION. | |

| 1865-1884. | |

| CHANGE IN ARMY ORGANISATION: THE SECOND AFGHAN WAR | 225 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE SECOND BATTALION. | |

| 1882-1883. | |

| THE WAR IN EGYPT | 232 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE FIRST BATTALION. | |

| 1884-1885. | |

| THE NILE EXPEDITION | 253 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE SECOND BATTALION. | |

| 1883-1902. | |

| THE BLACK MOUNTAIN EXPEDITION: THE TIRAH CAMPAIGN | 288 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE FIRST BATTALION. | |

| 1885-1900. | |

| MOUNTED INFANTRY IN MASHONALAND: THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA: COLESBERG AND BETHLEHEM | 305 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| THE FIRST BATTALION. | |

| 1900-1902. | |

| SOUTH AFRICA (CONTINUED): SLABBERT’S NEK: THE BRANDWATER BASIN: BERGENDAL: MONUMENT HILL: LYDENBURG: THE MOUNTED INFANTRY OF THE ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT | 332 |

APPENDICES.

| 1. THE MOVEMENTS OF THE XVIIIth ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT FROM THE TIME OF ITS FORMATION IN 1684 TO THE END OF THE WAR IN SOUTH AFRICA IN 1902, AND THE PLACES WHERE IT HAS BEEN QUARTERED IN TIME OF PEACE | 375 |

| 2. CASUALTY ROLL | 385 |

| 3. OFFICERS OF THE 1ST AND 2ND BATTALIONS WHO DIED IN THE WEST INDIES BETWEEN 1805 AND 1816 | 403 |

| 4. ROLL OF OFFICERS, WARRANT OFFICERS, NON-COMMISSIONED OFFICERS, AND MEN OF THE ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT TO WHOM HAVE BEEN AWARDED THE VICTORIA CROSS, MEDALS FOR DISTINGUISHED CONDUCT IN THE FIELD, FOR MERITORIOUS SERVICE, AND FOR LONG SERVICE AND GOOD CONDUCT | 404 |

| 5. THE TIRAH CAMPAIGN: COLONEL LAWRENCE’S ORDER OF JUNE 8, 1898 | 414 |

| 6. THE SOLDIER’S KIT IN SOUTH AFRICA | 416 |

| 7. INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE DEFENCE OF TRAINS | 417 |

| 8. DIARY SHOWING MOVEMENT OF THE FIRST BATTALION IN THE NORTH OF THE TRANSVAAL BETWEEN APRIL 12, 1901, AND SEPTEMBER 30, 1901 | 418 |

| 9. SUCCESSION OF COLONELS OF THE REGIMENT | 422 |

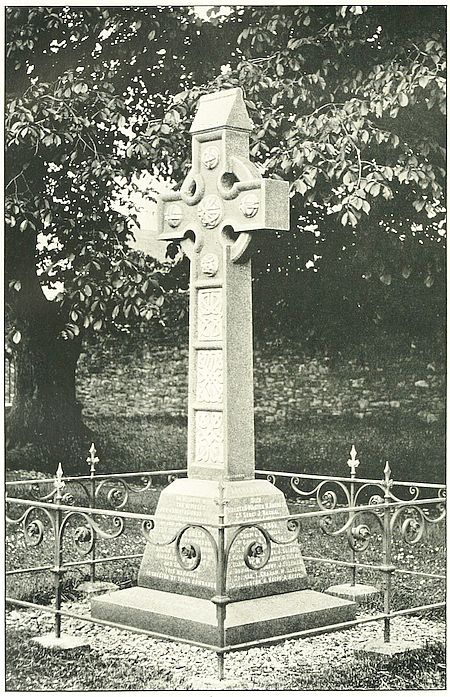

| 10. MEMORIALS OF THE ROYAL IRISH REGIMENT | 431 |

| 11. TABLE SHOWING THE FORMER NUMBERS AND PRESENT NAMES OF THE INFANTRY REGIMENTS OF THE REGULAR ARMY | 440 |

| ———— | |

| INDEX | 443 |

| PAGE | ||

| THE NORTH TRANSEPT OF ST PATRICK’S CATHEDRAL, DUBLIN | Frontispiece | |

| LITHOGRAPHIC REPRODUCTION OF LORD WOLSELEY’S LETTER | facing | viii |

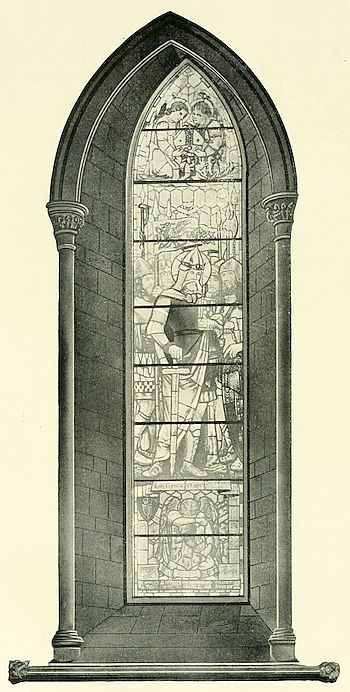

| MEMORIAL TO THOSE WHO DIED IN THE AFGHAN, EGYPTIAN, AND NILE CAMPAIGNS | 231 | |

| MEMORIALS TO THOSE WHO FELL IN SOUTH AFRICA | 305, 374 | |

| —————— | ||

| LIST OF MAPS. | ||

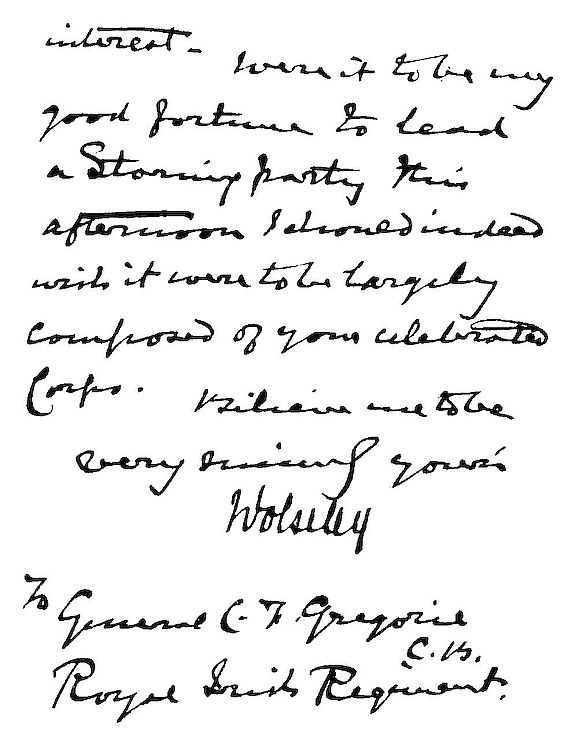

| NO. 1. BLENHEIM, RAMILLIES, OUDENARDE, AND MALPLAQUET | facing | 60 |

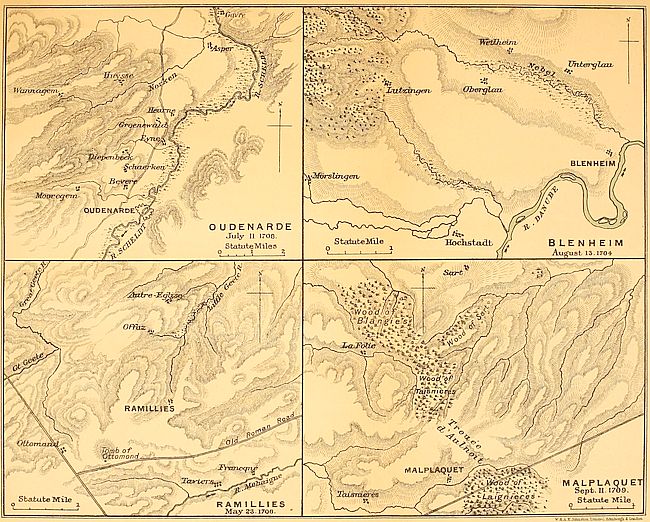

| NO. 2. THE LOW COUNTRIES | ” | 78 |

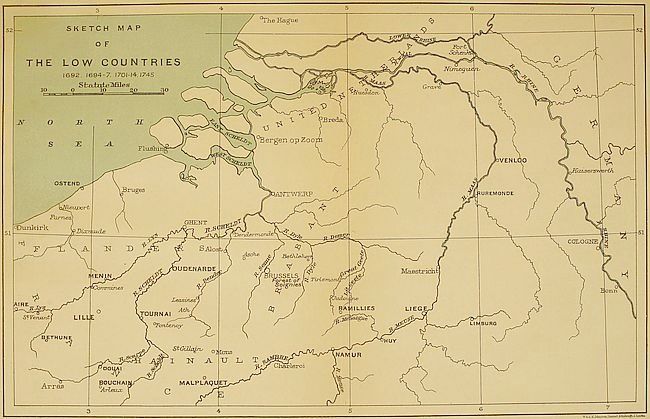

| NO. 3. BASIN OF THE MEDITERRANEAN | ” | 116 |

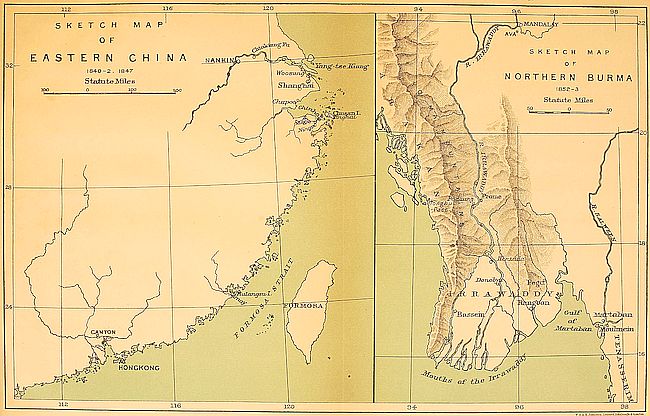

| NO. 4-5. CHINA AND BURMA | ” | 160 |

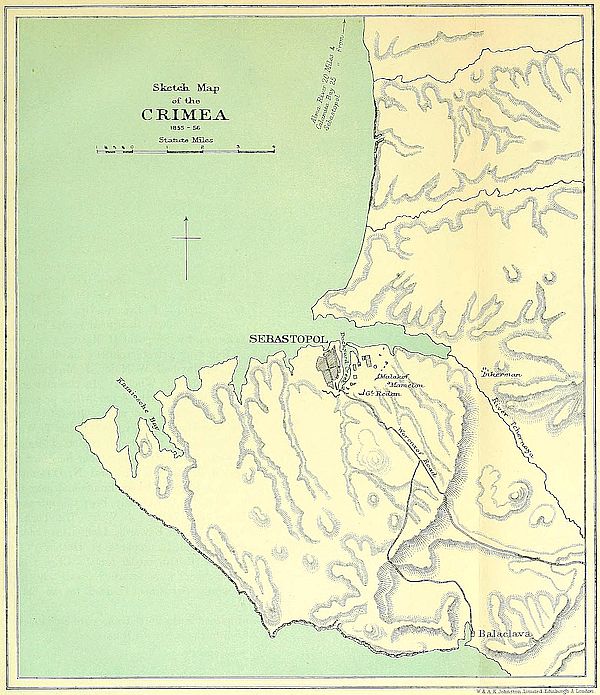

| NO. 6. THE CRIMEA | ” | 188 |

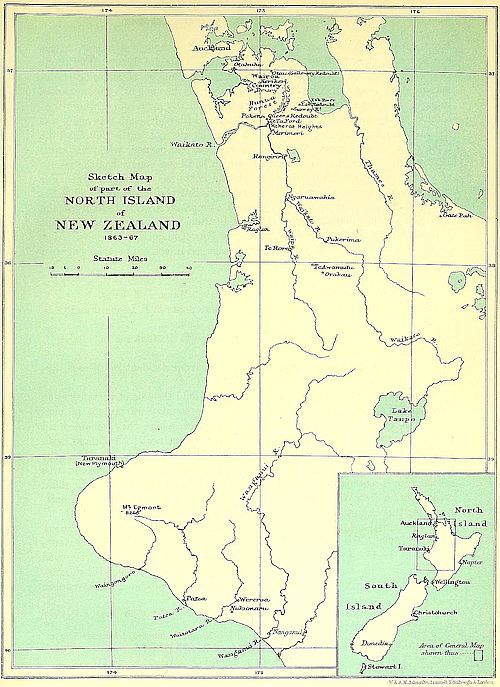

| NO. 7. NEW ZEALAND | ” | 220 |

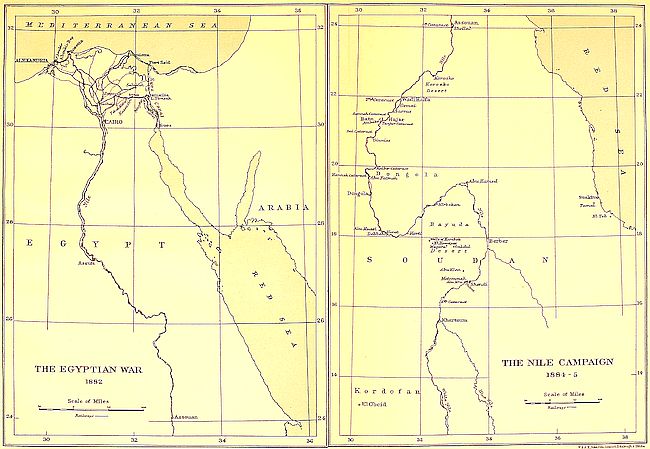

| NO. 8-9. THE WAR IN EGYPT, 1882—THE NILE EXPEDITION | ” | 286 |

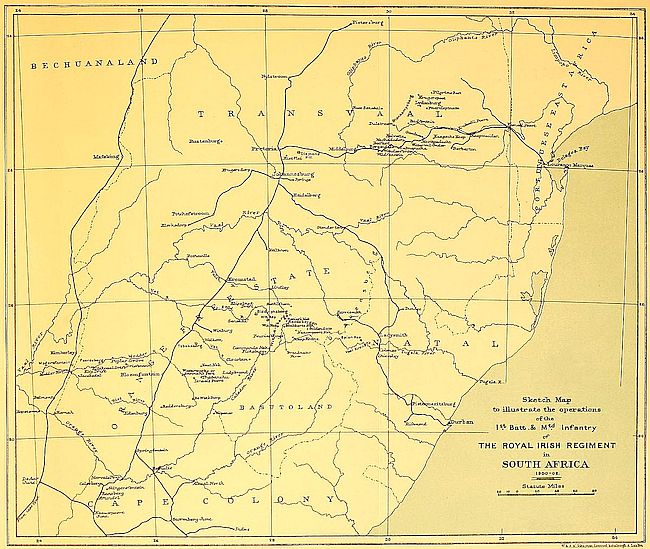

| NO. 10. SOUTH AFRICA | ” | 442 |

| page | line | |||||

| 40 | 24 | for | Lieut. G. Roberts | read | S. Roberts. | |

| 69 | 10 | ” | Colonel Crosby | ” | Cosby. | |

| 70 | 1 | of footnote | ” | ” ” | ” | ” |

| 121 | 10 | ” | ” | Lieut. D. Edwards | ” | Edwardes. |

| 128 | 4 | ” | ” | Lieut. C. W. Davis | ” | G. W. Davis. |

| { 3 | ” | ” | Lieut. H. J. Stephenson | ” | H. F. Stephenson. | |

| 147 | { 15 | ” | ” | Lieut. G. W. Stackpoole | ” | G. W. Stacpoole. |

| { 17 | ” | ” | Ens. T. E. Esmond | ” | T. E. Esmonde. | |

| 160 | 28 | ” | Lieut. W. F. Cockburn | ” | W. P. Cockburn. | |

| 165 | 4 | of footnote | ” | Capt. G. W. Stackpole | ” | G. W. Stacpoole. |

The Campaigns and History of

The Royal Irish Regiment.

The Royal Irish regiment was raised on April 1, 1684, by Charles II., when he reorganised the military forces of Ireland, which had hitherto consisted of a regiment of foot guards and a number of “independent” troops of cavalry and companies of infantry maintained to garrison various important points in the island. Charles formed these independent troops and companies into regiments of horse and foot; and as many of the officers had seen service on the Continent in foreign armies, and a large number of the rank and file were descendants of Cromwell’s veterans, Arthur, Earl of Granard,[1] when granted the commission of colonel in one of the newly raised infantry regiments, took command not of a mob of recruits with everything to learn, but of a body of soldiers of whom any officer might be proud. Of the corps thus raised all but one had an ephemeral existence. During the struggle between James II. and William III. for the possession of Ireland some followed the example of the foot guards, joined the Stuart king in a body, and then took service in France, while others broke up, officers and men ranging themselves as individuals on the side of the monarch with whose religious or political views they were in sympathy. The one bright exception was the regiment formed by Lord Granard, which under the successive names of Forbes’, Meath’s, Hamilton’s, the Royal regiment of Foot of Ireland, the XVIIIth, and the[2] Royal Irish regiment, has earned undying laurels in every part of the world.

Though brought over to England to help in the suppression of Monmouth’s rebellion against James II., Granard’s took no part in the operations by which the rising was crushed at Sedgemoor, and in the autumn of 1685 returned to Ireland,[2] where evil days awaited it. With James’s attempt against the liberties of his English subjects it is not the province of a regimental historian to deal; but it is necessary to explain that the King, desiring ardently to own an army upon which he could count to obey him blindly in the political campaign he was planning, proposed to drive from the Colours all officers and men upon whom he could not rely implicitly to carry out his schemes. He decided to begin operations in Ireland, where he gave the Earl of Tyrconnel unlimited power to remodel the personnel of the troops. In 1686, Tyrconnel summarily dismissed from many regiments all the Protestants in the ranks, whom he stripped of their uniforms and turned penniless and starving upon the world. The officers fared little better: two of Granard’s captains, John St Leger and Frederick Hamilton, were “disbanded” solely on account of their religious beliefs. As a protest against these proceedings Lord Granard resigned his commission, to which his son Arthur, Lord Forbes, was appointed on March 1, 1686. Next year the regiment “underwent a further purge,” thus described by Brigadier-General Stearne,[3] who was then one of Forbes’s officers. “Tyrconnel made a strict review of each troop and company, wherein he found a great many descendants of the ‘Cromelians,’ as he termed them, who must turn out also, and took the name of every man who was to be of the next disbandment, so that every soldier of an English name was marked down. As soon as the camp broke up and the army returned into winter quarters, most of the officers as well as soldiers were disbanded, and only a few kept in for a while to discipline those that supplied their places.” Tyrconnel rid himself of about four thousand of all ranks, or considerably more than half the Irish army; the men he replaced with peasants, good in physique but without discipline or training, while the officers he appointed were of a very inferior class, who in the war of 1690-91 failed in many cases to turn to good account the splendid fighting qualities of their soldiers. It is, however, only fair to Tyrconnel’s memory to mention that while he thus reduced the efficiency of the Irish army, he increased its power of expansion by devising a short service and reserve system by which many thousand men could be recalled to the Colours in case of need.

Thanks to the political influence and strong personality of Forbes, a “bold[3] and daring man,” who had learned the trade of war first in the army of France under the great Turenne, and later in a campaign against the Turks in Hungary, the regiment in the general ruin suffered less than any other corps. In defiance of Tyrconnel, Forbes succeeded in retaining more of his old officers and soldiers than any other colonel, and in 1688, when the regiment, 770 strong, was ordered to England to meet the invasion threatened by the Prince of Orange, it still contained a number of good officers, sergeants, and old soldiers, whose united efforts had welded into shape the mass of recruits recently poured into its ranks. For the next few months the strain upon these veterans must have been great, as they had to keep the young soldiers in order in a country where Irish troops at that time were looked upon with deep suspicion and hostility by the people, and not as now heartily welcomed by all classes. After being stationed for some time in London the regiment marched to Salisbury, where James had concentrated his troops to meet the Prince of Orange; and when the King, deserted by his generals, statesmen, and courtiers, abandoned his army and fled to France, Forbes kept his men together and returned to the neighbourhood of London, where he was quartered at the village of Colnbrook, near Hounslow. From the Prince of Orange, who by this time was actually, though not yet legally, King of England, Forbes received orders to disband the Roman Catholics of his regiment, and after five hundred officers and men had been disarmed and sent to Portsmouth en route for the Isle of Wight, several officers, many sergeants, corporals, and drummers, and about a hundred and thirty private soldiers, remained with the Colours.

Soon after this turning of the tables the regiment had an experience, probably unique in military history—an examination in theology, in which all ranks passed with high honours. The adventure is thus described in Stearne’s journal:—

“A report spread through the whole kingdom that the Irish were murdering, burning and destroying the whole country, insomuch that there was not one town in the whole nation that had not an account they were committing all these cruelties in the very next town or village to them. Sir John Edgworth, who was our major, commanded the regiment at this time (Lord Forbes being with the Prince of Orange in London); he was quartered at Lord Oslington’s house near Colnbrook, and upon the first of this flying report, sent for all the regiment to repair immediately to his quarters where there was a large walled court before the door, in which he drew them up with the design to keep them there until this rumour was over, but the country people, hearing that an Irish regiment was there, came flocking from all parts to knock us on the head: but Sir John bid them at their peril, not to approach, and told them we were not Irish Papists but true Church of England men; and seeing among the crowd a gentleman, called to him and desired he would send to the minister of the parish to read prayers to us, and if the[4] minister did not convince them we were all of the Church of England, we would submit to their mercy. The minister was soon sent for, and to prayers we went, repeating the responses of the Liturgy so well and so exactly that the minister declared to the mob he never before heard the responses of the Church of England prayers repeated so distinctly and with so much devotion, upon which the mob gave a huzza, and cried ‘Long live the Prince of Orange,’ and so returned home.”

In February 1689, the regiment was re-equipped,[4] and in anticipation of the recruits who in a few months began to refill its depleted ranks, weapons were issued for its full establishment. Five hundred and seventy-nine men were to be armed with flint-lock muskets and bayonets, while two hundred and forty were still to carry long pikes for the protection of the musketeers against cavalry on the battlefield and on the march. The pike, however, was a dying weapon, and was soon superseded completely by the bayonet. No mention is made of hand-grenades, though these missiles were already carried by the grenadier company, composed of men chosen from their comrades in the regiment for height, strength, and courage.

During the winter of 1688-89 Lord Forbes resigned his commission, on the ground that having sworn allegiance to James II. he could bear arms for no other king during his old master’s lifetime.[5] For a few weeks Major Sir John Edgworth replaced him, but owing to financial scandals compromising to himself and several of his subordinates he was obliged to retire,[6] and Edward, Earl of Meath, was appointed to the vacancy on May 1, 1689, when William III. completed his arrangements for re-officering the regiment, which was numbered the Eighteenth of the infantry of the line. He issued forty-one new commissions, some to the seniors who had escaped disbandment at Tyrconnel’s hands, others to officers who had been expelled from the army during James’s reign, others again to young men with no previous military experience. The names of the officers are given in the footnote.[7]

One of the results of the revolution by which James II. was deposed and William and Mary placed upon the throne was to plunge England into the vortex of Continental politics. As Prince of Orange, William had been the moving spirit in the coalition of States formed to curb the ambition of the French king, Louis XIV., who throughout his life strove to aggrandise himself at the expense of his neighbours; and when James II. took refuge in France, Louis saw his opportunity to strike a heavy blow at William. By long and careful attention to his navy he had made it superior to the combined fleets of the English and the Dutch—the great naval powers of the time—and, thanks to his command of the sea, was able to land James at Kinsale with five thousand excellent French soldiers to give backbone to the forty thousand men collected by Tyrconnel in anticipation of his Royal master’s arrival. So slow was communication in those days that, though James disembarked at Kinsale in March 1689, the news of the invasion did not reach England for several weeks, when William had already despatched most of his best troops to swell the forces of the Allies facing the French in the Low Countries. William hurriedly raised more regiments, but it was not until August that Marshal Schomberg, the veteran selected for the command of the expedition, landed near Belfast, where in a few days he was joined by Meath’s[8] regiment, which for some months had been quartered in Wales. The army was sent to Ireland utterly unprepared to take the field. There was no transport, the commissariat was wretched, the artillery was short of horses; guns, muskets, and powder, food, clothing, and shoes alike were bad. No wonder, therefore, that after taking the town of Carrickfergus, Schomberg refused to give battle to James, and fell back upon an entrenched camp at Dundalk to await reinforcements of every kind. Before the autumnal rains set in the General ordered his troops to build themselves huts, and the foreigners in William’s pay—old warriors, who had bought their experience in many campaigns—worked with a will; but the English regiments, composed of lazy, careless, and ignorant recruits, whose officers were no better soldiers[6] than their men, would not take the trouble to run up shelters or dig trenches to drain their camping-grounds. Fever soon broke out with appalling results. Out of the 14,000 troops assembled at Dundalk, 1700 died on the spot, 800 perished on the waggons in which the sick were carried to the coast, 3800 died in the hospitals of Belfast. The losses in the XVIIIth regiment are not known, but from Schomberg’s confidential report on the troops under his command it seems to have suffered less than other corps. Writing on October 23, 1689, the Marshal says: “Meath’s (18th Foot), best regiment of all the army, both as regards clothing and good order, and the officers generally good. The soldiers being all of this province, the campaign is not so hard on them as on others.”

Early in November James gave up the attempt to entice Schomberg out of his entrenchments and went into winter quarters. The Marshal promptly followed his example, holding the country between Lough Erne and Belfast with a chain of fortified posts, and establishing his headquarters at Lisburn, where the XVIIIth was placed in charge of his personal safety. The staff of the regiment must have been hard-worked in the spring of 1690, for recruits streamed in so fast that in June it was nearly the strongest corps in the British army, standing on parade six hundred and seventy-eight officers and men. For several months there was constant skirmishing along the line of outposts; but no movements of importance took place until June, when William III. arrived at Carrickfergus with two hundred and eighty-four transports and many vessels laden with stores. Though this great mass of shipping was escorted by a ludicrously small squadron of only six men-of-war, it was not attacked on the voyage, for the French had neglected to send a fleet to cruise in the Irish seas, thus leaving the line of communication across St George’s Channel uninterrupted. When the reinforcements brought by the King had landed, the army in Ireland reached the respectable total of about 37,000 men, of whom 21,000 were British, and the remainder Huguenots, Dutch, and Danes—continental mercenaries whom William had imported to lend solidity to his recently raised English regiments.

The French officers in James’s army had repeatedly urged him to retire into Connaught and defend the line of the Shannon, but on political grounds he declined to accept this excellent advice, and after some manœuvring took up a position on the river Boyne, near Oldbridge and Duleek. Here he entrenched himself, but on the 1st of July William attacked and routed him with considerable loss. As the XVIIIth regiment played no important part in the engagement, if, indeed, it came under fire at all, it is only necessary to say that though some of James’s troops fought with distinguished gallantry in this battle, others did not show the fine qualities they exhibited later at Limerick and Aughrim. Covered by a rear-guard of Frenchmen, the defeated army fell back upon the Shannon. James, for the second time,[7] deserted his soldiers and fled to France, while William occupied Dublin, and matured his plans for the next phase of the campaign. By a great victory over the Anglo-Dutch fleet at Beachy Head the King of France won for the moment the absolute command of the British Channel, and thus could throw reinforcements at will into the south and west of Ireland by the ports of Waterford, Cork, Kinsale, Limerick, and Galway. These towns were, therefore, essential to William; and hardly less important was Athlone, the entrance to the wild districts of Connaught, to which he hoped to confine the future operations of the war. A strong detachment under General Douglas was therefore sent against Athlone, while William himself led the greater part of his army towards Limerick, where a large number of James’s troops had been concentrated. Though these regiments had worked hard to improve the fortifications of the city, its defences were still so imperfect that when the French heard that William was approaching they pronounced the place to be untenable and moved off to Galway, leaving the Irish, about 20,000 strong, to defend it, under the command of General Boisleau, an officer who had learned to appreciate the good qualities of his allies, and Sarsfield, an Irish soldier of great brilliancy and courage. Reinforced by Douglas, whose detachment had failed to make any impression on Athlone, William appeared before Limerick on August 9, and after brushing away the enemy’s skirmishers pitched camp within a quarter of a mile of the city wall, expecting little resistance from a place so weak that the French had declared it “could be taken by throwing apples at it.” In eight days William opened his batteries, though with very inferior ordnance, for by a daring raid Sarsfield had swooped on the convoy bringing up his siege-train and destroyed nearly all his heavy guns. On the 20th the grenadiers of the XVIIIth and Cutts’s regiments greatly distinguished themselves by the capture of a strong redoubt near John’s Gate. A sudden rush from the trenches brought them to the foot of the work, into which they hurled a shower of hand-grenades, and then scrambling over the parapet under heavy fire, dislodged the defenders with the bayonet. As it was known that the redoubt had an open gorge, a quantity of fascines had been collected in the trenches, with which the grenadiers filled up the gap, and then held the redoubt against a determined sally until they were relieved by other troops. The affair cost the victors two hundred and seventy-one killed and wounded; but though it is known that the grenadiers suffered heavily, the only casualty recorded in the XVIIIth is the death of Captain Needham, who was killed by a random shot at the end of the engagement.

This success was followed by the capture of another outlying work; the trenches were pushed close to the walls, and six batteries played upon the defences, which, near John’s Gate, began to crumble under the bombardment. This breach William determined to assault, though he was warned[8] by some of his officers that Limerick was not yet sufficiently shaken to be stormed. According to many historians, his reasons for hurrying on the attack were that his supply of ammunition was running low, and that with the example of Dundalk before him, he could not venture to expose his troops to the terrible rains which had set in. “At times the downpour was such that the men could not work the guns, and to mount fresh batteries soon became an impossibility: the trenches were knee-deep in mud: the soldiers were never dry from morning till night and from night till morning: sickness, which had been prevalent in the camp before, increased to a plague: the tenting ground became a mere swamp, and those who could afford it kept down the overwhelming damp only by burning bowls of spirits under the canvas.”[9] On the 27th the breach appeared to be practicable, and William ordered Douglas to deliver the assault. Half the grenadiers of each regiment, five hundred men in all, were to lead, supported by the XVIIIth and five other infantry corps: on the left of the main attack was another column of infantry: and drawn up in rear stood a strong force of cavalry. At half-past three in the afternoon the grenadiers dashed out of the trenches, hurled themselves against the palisade of the counterscarp, and carried it after fierce fighting; then, gaining the covered way, they dropped into the ditch, scrambled up the breach, and pursued its defenders headlong into the town. So far all had gone well: the impetuous valour of the grenadiers had carried all before it, and victory was within William’s grasp, when a mistaken interpretation of orders ruined the day’s work. The supporting infantry should have followed the grenadiers up the breach, but, allowing themselves to be drawn into pursuit of some of the enemy along the covered way, they left the grenadiers without reinforcements. When the defenders saw that no more troops were pressing up the breach, they rallied, and, excited by witnessing the destruction of one of William’s foreign battalions by an accidental explosion, they drove the remnants of the grenadiers back into the covered way. If the failure to carry the breach was to be redeemed even partially, it was essential that the covered way should remain in the attackers’ hands, and round this part of the fortifications raged a fierce fight, in which both sides showed splendid courage; but, after three hours’ indecisive combat, Douglas found that his men had used nearly all their ammunition, and drew off to camp with a loss of at least five hundred dead and a thousand wounded. In this unsuccessful assault the XVIIIth suffered severely;[10] more than a hundred sergeants, corporals, and “sentinels” (as private soldiers were then termed) were killed or wounded, and, though the officers of the regiment who left accounts of this war are not agreed as to the exact casualties among the commissioned ranks, it appears certain that[9] six were killed and eight wounded.[11] Though all their names have not been recorded, it is known that Captain Charles Brabazon, Lieutenant P. Latham, and Ensign —— Smith were killed; Lieutenant-Colonel G. Newcomb (or Newcomen) died of his wounds, and Colonel the Earl of Meath, Lieutenants R. Blakeney and C. Hubblethorne, were wounded.

Dispirited by his reverse, William raised the siege, ordered his army into winter quarters, and after handing over the command to Ginkell, a Dutch general, returned to England after a campaign in which he had scored only one marked success—the victory at the Boyne. He had failed to capture Athlone and Limerick, and, with the exception of Waterford, all the ports in the south and west were still open to the French navy. In September, however, the arrival of Marlborough with an expedition from England improved the situation: Cork and Kinsale surrendered, and thus the harbours of Limerick and Galway alone remained available for the enemy’s operations. Ginkell’s first step was to establish himself on a line which, starting at Ballyshannon in the north-west, ran through Enniskillen, Longford, Mullingar, Cashel, and Fermoy to Castletown-Berehaven in the south-west. The regiment was ordered to Mullingar, where it passed the winter—very unpleasantly, according to Stearne, who states that, “in the month of December our garrison being reinforced by several regiments of Horse and Foot, marched towards the enemy’s frontier, where after having fatigued the troops for upwards of three months in this bad season of the year in ravaging and burning the country we returned to our quarters.”

Ginkell opened the campaign of 1691 by an attack on Athlone, a town built on both sides of the Shannon, and enclosed by walls, not in good condition but still by no means to be despised. On the right or Connaught bank a grim old castle frowned down upon a stone bridge, the only permanent means of communication across the river, for though there was a ford it was practicable only in very dry weather. After a short cannonade, Ginkell breached and stormed the defences on the Leinster side of the river, and, driving the enemy before him across the bridge, made himself master of the eastern half of Athlone. But now his real difficulties began. Batteries bristled on the bank above the ford; the guns of the castle commanded the bridge, which was so narrow that a few men could hold it against a regiment; and General St Ruth, a French officer of great experience, from his camp hard by could reinforce the garrison without hindrance from the besiegers. Ginkell rapidly threw up batteries, and opened so vigorous a fire with fifty guns and mortars that one side of the castle crumbled away and the houses on the Connaught bank were knocked to pieces. But until he had crossed the[10] river he could not close with his enemy; his pontoons were far behind him, and he had no transport to bring them to the front; and the defence of the bridge was so stubborn that he gained ground there only a few inches at a time. St Ruth scoffed at the idea of the place being in serious danger, decrying Ginkell as an old soldier who ought to know better than to waste time and men on a hopeless enterprise. “His master,” he said, “ought to hang him for trying to take Athlone, as my master ought to hang me if I lose it.” But the Dutch general determined to ascertain if the river was fordable, and, in the words of Stearne, instead of calling for volunteers,

“promised three Danish soldiers who lay under sentence of death, their lives and a reward if they would attempt fording the river, which they gladly accepted, and at noonday put on armour, and entered the river a little below the bridge, and went at some distance from each other; the enemy took them for deserters, and we from our trenches fired seemingly at them, but over their heads at the enemy; when they had passed the depth of the water, and almost on the other side, they turned back, which when the enemy perceived they fired at them as hard as they could, but our cannon which was reserved for that purpose, as also our small shot, fired so briskly upon them that they could not hold up their heads to take aim at the men, by which they were saved, two being only slightly wounded. The General finding the river fordable (which it had not been for many years) resolved to try and pass it, upon which he gave orders for 40 Grenadiers from each company and 80 choice men out of each Battalion of the whole army to march as privately as possible into the trenches, and the whole army to be under arms to sustain the attack should there be occasion.

“On the 20th June[12] the detachments marched into the trenches (I being one of the Captains who commanded ours) with all the privacy we could, but notwithstanding all our caution, St Ruth had notice of our motion and design by the appearance of crowds of people on the hills to see the action, upon which he marched down his whole army to the bank of his part of the town, and filled the Castle and trenches with as many men as it could well hold; our General perceiving this, put off the attack till another time, ordering our detachments back to Camp, but at the same time gave private orders that not a man should stir from his Regiment, or be put on any other duty, but to be all ready at a minute’s warning. St Ruth seeing us draw off, was persuaded that our General dare not pass the River at this time, and in this security marched his Army back to Camp, leaving only a slight body of men to guard their works and the Castle. The next day a soldier of our Army (whether sent by the General, or he went of himself, I can’t say) went over to the enemy and was carry’d before St Ruth, and told him that the common report in our Camp was that the General finding it was not practicable to pass the River at this time resolved to try what he could do at Banagher which lay ten miles down the River, and that everything was getting[11] ready for the march. St Ruth, easily persuaded with this notion, and finding all things very quiet in our Camp, made a splendid entertainment for all the Ladies and Gentlemen, the Officers of the Town, and the Camp. The same day, being 22nd June, our General sent private orders along the Line for all the detachments to march directly into the trenches, and to keep under all the cover they could, at the same time he posted several sentries on the hills to prevent anybody appearing to the enemy. About 3 o’clock, when St Ruth was at the height of his merryment, we began the attack by jumping into the River, and whilst we were wading over, our Cannon and small shot played with great fury over our heads on the enemy, insomuch that they did us but little hurt in passing, and when we got over they made but little or no resistance but fled immediately.

“At the same time we jumped into the River, part of our detachments attacked the Bridge, and laid planks over the arch that had been broken down upon our taking the first town, so that before St Ruth had any account of our design we were in possession of the town; however he marched his army down to try if he could force us back again, but he committed a grand error which he found out too late, and that was leaving the works at the back of the town stand, which became a fortification against himself, for had it not been for this, we should never have been able to maintain the town against his army, as we were not in possession of the Castle. When St Ruth found there was no forcing us back without a formal siege he returned to his camp, and those in the Castle seeing him march off immediately surrendered at discretion, and next day very early St Ruth decamped and marched off with great precipitation. In this action we had only 27 men killed, and about as many wounded, and not one Officer of note hurt.”

Ginkell now proposed to take the town of Galway and then turn southwards against Limerick, but before this plan could be put into execution it was necessary to dislodge St Ruth from the strong defensive position he had taken up near Ballinasloe, where he was determined to fight a pitched battle in the hope of retrieving the reputation he had lost on the banks of the Shannon. His left rested on the castle of Aughrim, a few miles south of Ballinasloe; his right was marked by the village of Urachree; his centre ran along the slopes of a green and fertile hill, well suited for counter-attacks by horse and foot. Much of the ground he occupied was surrounded by bogs, crossed by a few tracks, of which only two were fit for cavalry, while all were under the fire of his guns. Between the foot of the hill and the bogs were many little patches of cultivation enclosed by hedges and ditches, some of which St Ruth levelled to allow his cavalry free movement, while he left others intact in order to give cover to his marksmen, to break the enemy’s formations, and to conceal the movement of his troops upon the field of battle. The infantry held the centre; the cavalry were on the flanks with a strong reserve in rear of the left under Sarsfield, who had specific instructions not to move without a distinct order from St Ruth himself. On July 11, the armies, each about[12] 20,000 strong, were within touch, but owing to a heavy fog it was not until the afternoon of the 12th that the battle began with a sharp skirmish, which revealed to Ginkell the strength of St Ruth’s position, and convinced him that his only hope of success lay in turning the enemy’s left. He accordingly made a feigned attack upon the Frenchman’s right, launched the remainder of his infantry against the centre and left, and sent his cavalry to force their way past the Castle of Aughrim. The troops directed against the centre were to halt when they had crossed the bog, and on no account to push on until the column on their right was safely over the quagmire and the cavalry had turned the enemy at Aughrim. But when the soldiers, after floundering thigh-deep in mud and slime, reached firm ground they got out of hand, and forgetting their orders rushed forward, carrying everything before them until a sudden charge of cavalry swept them backwards in confusion, while the column for which they should have waited was still struggling in the bog. When this supporting column, of which the XVIIIth regiment formed part, had scrambled through the quagmire and re-formed its ranks, it moved towards the hill over a part of the field apparently deserted by the enemy, but really filled with sharpshooters, who, hidden in hedges and ditches, with admirable coolness held their fire until the leading companies were within twenty yards of them. Then a storm of bullets smote the head of the column; men dropped in scores, and for a moment the advance was checked, but the troops quickly rallied, and hurling themselves against the first hedge carried it against a resolute defence. Hedge after hedge, ditch after ditch, were charged and won, but by the time the last obstacle was surmounted the infantry had fallen into great confusion: the regiments “were so intermingled together that the officers were at a loss what to do,” and at that moment St Ruth’s cavalry came thundering down upon them. Under this charge the disorganised infantry gave way, and were being driven backwards into the bog, when St Ruth’s horsemen were themselves assailed in rear by some of Ginkell’s cavalry, who, after a daring march and still more daring passage of a stream under the walls of Aughrim Castle, reached the battlefield in time to save the foot soldiers from annihilation. During this cavalry combat occurred an interesting instance of the value of steady barrack-square drill. Throughout the winter of 1690-91 the infantry had been practised in regaining its formation rapidly after a charge, and now, when relieved from the pressure of the enemy, the battalions re-formed with comparative ease, and then attacked along the whole line. At this moment victory trembled in the balance, for though the losses on both sides had been heavy, the defenders, on the whole, had had the best of the day, and in Sarsfield’s strong body of cavalry they possessed a reserve which had not yet been called into action. Had Sarsfield then struck into the battle his troopers might have turned the scale, but he was fettered[13] by his instructions not to move except on St Ruth’s own order, and St Ruth, struck down by a stray cannon-ball, was lying a headless corpse upon the ground. The absence of the French general’s directing hand was soon felt, though his death was concealed as long as possible; and when the attacking infantry began to gain ground steadily, and the cavalry turning movement was fully developed, the men who for hours had so valiantly defended their position lost heart and began to fall back in disorder. Then their discipline failed them, and they broke, rushing in panic towards Limerick and Galway, with Ginkell’s cavalry and dragoons spurring fiercely after them.

The losses in this battle were very heavy. In William’s army 73 officers were killed and 109 wounded; of the other ranks 600 were killed and 908 wounded. The XVIIIth escaped lightly: only one officer, Captain —— Butler was killed; a major, a captain, and two subalterns were wounded; among the non-commissioned officers and men seven were killed and eight wounded.[13] On the subject of the casualties in the army commanded by St Ruth historians differ widely; but 7000 appears to be the number fixed upon by those least given to exaggeration. Whatever the actual figures were, however, there can be no doubt that James’s soldiers were so completely routed that in their retreat they strewed the roads with their discarded weapons. A reward of sixpence was offered for every musket brought into Ginkell’s camp; in a short time so many waggon-loads were collected that the price was reduced to twopence, and great numbers of firearms still came in.[14] The dispersal of St Ruth’s army was the death-blow to the Stuart cause: Galway made little resistance, and though the garrison of Limerick fought stoutly for a month it was obliged to surrender on October 3, 1691. The French officers were allowed to return to their own country, accompanied by those of James’s soldiers who wished to enter the French army, and with their departure ceased all organised opposition in Ireland to the rule of William III., who was thus free to transfer his troops to the Low Countries.

The regiment, however, did not go abroad at once. After wintering at Waterford it was ordered in the spring of 1692 to Portsmouth, to reinforce the garrison of England against an invasion threatened by Louis XIV., and after the French fleet had been beaten at the battle of Cape La Hogue the XVIIIth was one of the regiments selected for a raid against the seaport towns of France; but the coast proved so well guarded that it was impossible to land, and the transports sailed to the Downs and thence to Ostend, where the troops disembarked and marched towards the towns of Furnes and Dixmude, which the French evacuated without waiting to be attacked. While employed in strengthening the walls of Dixmude the[14] XVIIIth had a curious experience: there was an earthquake, so violent that the soldiers thought the French were blowing up the place with hidden mines, while the Flemish peasants, who were working as navvies, became paralysed with terror and declared that the end of the world was come. In a few weeks the greater part of the troops re-embarked for England, but not all reached land in safety, for a great storm scattered the transports, several of which went to the bottom. The XVIIIth regiment, however, was fortunate enough to escape all loss.

In the course of the winter Lord Meath retired,[15] and was succeeded in the colonelcy by Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Hamilton; Major Ormsby became Lieutenant-Colonel, and Captain Richard Stearne was promoted to the Majority. In 1693, the regiment, which now was known as Frederick Hamilton’s, was turned for a few months into a sea-going corps.

“In May, 1693, we marched to Portsmouth, and embarked on board the Grand Fleet, commanded by three joynt Admirals (viz., Sir Ralph Delaval, Sir Cloudesley Shovel, and Admiral Killigrew) when we served this summer as Marines. Our rendezvous was Spithead; in June we sailed to Torbay, where we waited for the Fleet which was to go under the command of Sir George Rooke who had twenty Men of War to convoy them up the Mediterranean. About the latter end of June Sir George joyned us, and the whole Fleet set sail together, and was looked upon to be the greatest that had been in one sea for many years; there being in all with Men of War and Merchantmen, English and Dutch, near 800 sail: the Men of War with their tenders stretching in one line between the Coast of France and the Merchantmen. The Grand Fleet kept Sir George company till they passed the Bay of Biscay, being the utmost limits of our Admirals’ orders, notwithstanding they very well knew that the French Fleet had sailed out of Brest, and was lying before them to intercept Sir George. Yet their orders were such that they dare not sail any farther, but then parted and returned to Torbay.

“The French, who never wanted intelligence from our Courtiers, had an exact account to what degree our Grand Fleet had orders to convoy Sir George, therefore lay by with their Grand Fleet about eighteen hours sail beyond the limit of our Grand Fleet; they upon first sight believed that our Grand Fleet had still kept Sir George company, which put them into such a consternation that for some time they stood away, which gave Sir George an opportunity of making signals to his Merchant ships to shift for themselves and make the best of their way back, whilst he with his Men of War sailed after them in very good order. As soon as the Enemy discovered their mistake they made all sail they could after him, but Sir George, keeping astern of his Merchant ships, made a running fight of it, by which means he saved his whole fleet except a few heavy sailers which were picked up by their Privateers.

“After this the French Fleet made the best of their way to Brest,[15] and the account coming to our Court, orders were sent to the Grand Fleet to sail immediately in quest of them, upon which our Admirals sailed immediately to Brest to try if they could get there before the enemy, but in vain, for they had got in several days before we left Torbay. This affair being over we returned to our port, and in September the Land Forces were put on shore. Our Regiment was landed part at Chatham and part at Southampton, and joyned at Norwich in October. In December we marched to London, and were reviewed in Hide Park by the King; two days after we embarked at Red House, and sailed for Flanders and landed at Ostend in December 1693.”[16]

The regiment was now to play a distinguished part in the war with France, which with a breathing space of five short years lasted until 1712. With the exception of the campaign of 1704 in Germany, the fighting in which the XVIIIth was concerned took place chiefly in the country now called Belgium, but then known as Flanders.[17] Its soil was fertile, and cultivated by a large and industrious population. Its numerous cities were celebrated throughout Europe for the wealth of their traders, whose merchandise was carried to the sea over a network of canals and navigable rivers. Every town was walled, and the whole country was studded with fortresses, with many of which the regiment was to become well acquainted in the course of the next twenty years. On the French side of the frontier a chain of forts stretched from Dunkirk to the Meuse, and Louis had further strengthened his border by a great line of field-works, in the hope of making an invasion of France impossible. In a country so highly fortified the war necessarily became one of sieges. Each side tried to breach the other’s line of defences by capturing fortresses. There were ceaseless marches and counter-marches, and gigantic attempts to relieve the besieged strongholds, met by equally strenuous efforts to prevent the relieving forces from fulfilling their mission. Flanders, however, was by no means the only part of Europe affected by the war, for sooner or later the French armies invaded nearly every country unfortunate enough to be within their reach. To describe the whole of Louis’s struggle for supremacy, and to explain the means by which he induced some of the Allies to abandon the coalition and range themselves on his side, would be far outside the scope of a regimental history. It is enough to say that though the conflict raged from the shores of the North Sea to the south of Spain, where a few thousand British soldiers served for several years, it was in Flanders that Marlborough won most of his splendid victories over the French.

The XVIIIth’s first campaign on the Continent—for the few weeks spent at Dixmude in 1692 cannot be dignified by this name—was uneventful. There were no great battles, and the only operation of importance was the[16] siege of Huy, where the regiment was employed with the covering force. In the spring of 1694 the order of precedence among the regiments of the British army was settled in a way very displeasing to Hamilton’s officers and men, who ever since the camp at Dundalk had claimed for their corps the numerical position due to its having been raised in April 1684.[18] Kane chronicles the decision in a few words.

“A Dispute arose about the Rank of our Regiment in particular, which were (sic) regimented 1 April 1684 from the old Independent Companies in Ireland, and had hitherto taken Rank of all the Regiments raised by King James the Second, but now those Regiments disputed Rank with us: the King referred the Affair to a Board of General Officers; and most of them being Colonels of those Regiments, would not allow us any other Rank than our first coming into England, which was some time before the King landed, when he came over Prince of Orange on the Revolution, by which we lost Rank of eleven Regiments, taking Rank after those raised by King James, and before all those raised by King William. The King thought the General Officers had acted with great Partiality, but as he had referred the Affair to them, he confirmed it.”

The whole question of precedence was re-opened in 1713, and the colonel of the XVIIIth made a strong effort to obtain rank for the regiment from the date of its formation in 1684, but without success.

When William III. took the field in 1695, he commanded an army of 124,000 men, composed of contingents from England, Holland, Denmark, and many of the German States. The British numbered about 29,000, and as the King employed them on every occasion when desperate courage and bull-dog tenacity were needed, it is clear that, however much he despised the English politicians who intrigued against him with Louis XIV., he appreciated his British soldiers at their true worth. As his object was the recapture of the fortress of Namur, taken by the French three years before, he began a series of manœuvres designed to decoy Marshal de Villeroi, the French Commander-in-Chief, so far into the western half of the theatre of war that the Allies would be able to dash upon Namur and invest it before their intention was discovered. William was so far successful that he was able to surround the fortress on June 23, but not before the French had thrown in strong reinforcements under Marshal de Boufflers, who took command of the garrison of thirteen or fourteen thousand excellent troops. The citadel stands on a rocky height at the end of the tongue of land formed by the junction of the rivers Sambre and Meuse. The town is built on the left bank of the Sambre; and in the fortification of both citadel and town the highest military art had been displayed—first, by the Dutch engineer Cohorn, who planned and built the works; and later, by his French rival Vauban, who had extended and improved them so greatly that Namur was now considered to be impregnable. A hundred and twenty-eight guns and mortars were mounted on its walls, and its arsenals and storehouses were well supplied in every way. On June 28th, William began his trenches, and five days later opened fire upon the town, which after desperate fighting surrendered on July 24, one of the conditions being that the garrison should be allowed to retire into the citadel with full power to take part in its defence.

During this, the first phase of the siege, the XVIIIth was part of the covering detachment of 20,000 men with which the Prince de Vaudemont, one of William’s trusted lieutenants, protected the operations of the besiegers so successfully that during several weeks he engrossed the attention of the French Commander-in-Chief’s vastly superior force of 90,000 troops. Before quoting Kane’s interesting account of the way de Vaudemont “sparred for time,” it must be explained that the French were in no hurry to relieve Namur, where they thought de Boufflers could hold his own indefinitely. De Villeroi accordingly marched against de Vaudemont, who had entrenched himself on the river Lys, nine or ten miles south of Ghent; but

“finding him stand his Ground, he proceeded with the more Caution, and halted about two Leagues short of him, till he had sent to Lille for some Battering-Cannon. This took up some Time which was what Vaudemont wanted to keep him in Play till the King could fix himself before Namur. At length Villeroy advanced within less than half a League of us, and[18] finding the Prince still keep his Ground, ordered a great many Fascines to be cut in order to attack us early next Morning. He also sent Lieutenant-General Montal with a strong Body of Horse round by our Right, to fall in our Rear, and cut off our Retreat from Ghent, which was three Leagues in the Rear of us. Now the Prince had three trusty Capuchin Fryars for his Spies, one of whom kept constantly about Villeroy’s Quarters, who found Means to inform himself of all his Designs; the other two plied constantly between both Camps without ever being suspected, who gave Vaudemont an Account of everything. Now the Prince having drawn Villeroy so near him, thought it high Time to make his Retreat; he therefore, as soon as Villeroy appeared, sent off all the heavy Baggage and Lumber of the Camp to Ghent, and about Eight in the Evening he ordered part of the Cavalry to dismount and take the Intrenchments, and the Infantry to march privately off with their Pikes and Colours under-hand, lest the Enemy should discover us drawing off; and as soon as it grew duskish the Cavalry mounted and marched after the Foot. Soon after Villeroy’s Advance-Guard finding our Works very quiet, ventured up to them; who finding the Birds fled, sent to acquaint the General; on which they marched after us as fast as they could. Montal, who by this time had got into our Rear, finding us marching off, thought to have fallen on our Flank; but Sir David Collier, with two Brigades of Foot, gave them so warm a Reception, that they were obliged to retire with considerable Loss. Next Morning all our Army got safe under the Works of Ghent, at which Time the Enemy’s Horse began to appear within a Mile of us; whereupon we past the Canal that runs from thence to Bruges, along which a Breast-Work had been thrown up.... Vaudemont had now a very difficult Part to act in Defence of this Canal against so powerful an Army. Villeroy marched immediately down to the Canal, where, for upwards of three Weeks, by Marches and Countermarches he harassed our small Army off their Legs; however, he could not make the least Movement, or form any Design, but the Prince had timely Notice of it; which was very surprising if we consider the Canal that was between us, so that the French said he dealt with the Devil.[19] Villeroy finding he could not pass the Canal on the Prince, at length turned towards Dixmude, where the Prince could give no manner of Assistance; here he succeeded beyond his most sanguine Expectations.”

After an easy victory at Dixmude, which the Governor surrendered without firing a shot, de Villeroi turned towards Brussels, where the wealth of the citizens promised much loot to his soldiers; but here he was again foiled by de Vaudemont, who out-marched him and took up a position which saved the city from capture, though not from a savage and unnecessary bombardment. After his artillery had devastated a large part of Brussels, de Villeroi drew off to await orders from Paris, thus giving the covering detachment the opportunity of joining hands with the main army before Namur, where William was assiduously battering the citadel with a[19] hundred and thirty-six heavy guns and fifty-eight mortars, whose fire towards the end of the siege cost de Boufflers three hundred men a day. On the 10th of August, the XVIIIth and three other British regiments were transferred to the besieging force, to replace corps shattered in the earlier operations, and at once began duty in the trenches. A few days later de Villeroi advanced, hoping to defeat William in a pitched battle, and thus to relieve the garrison which he had so long neglected, but he found the King so well posted and the covering army so heavily reinforced by the besieging troops that he did not venture to attack. While the French Commander-in-Chief was beginning to realise that in leaving de Boufflers so long unrescued he had made an irreparable mistake, William gave orders for a general assault upon the citadel, where the works had been breached in several places. During the night of the 19th, six thousand men from the covering detachment filed into the trenches, where before daybreak they were joined by the greater part of the besiegers. Seven hundred British grenadiers and four regiments—the 17th,[20] the XVIIIth, and Buchan’s and Mackay’s, two corps which have long since disappeared from the Army List,—under the command of General Lord Cutts, were to assault the work called the Terra Nova; while the Bavarians, Hessians, Brandenburgers,[21] and Dutch were to make simultaneous attacks on the other breaches. As the trenches could not hold all the troops poured into them, the XVIIIth and Buchan’s were sent to conceal themselves in the abbey of Salsine, about half a mile from the foot of the Terra Nova breach.

At 10 A.M. on August 20, the explosion of a barrel of gunpowder gave the signal for the attack, and from Cutts’s trenches began to emerge the red coats, to whom the most dangerous duty had, as usual, been entrusted; four sergeants, each followed by fifteen picked men, led the column; the grenadiers were close behind them; the 17th and Mackay’s followed in support, with the XVIIIth and Buchan’s in reserve. It was a desperate enterprise. Between the trenches and the Terra Nova was a stretch of several hundred yards of ground—smooth, coverless, and swept by frontal and cross fire, and before the grenadiers had crossed it they had left behind them a long trail of killed and wounded. Owing to a mistake in the organisation of the attack, the grenadiers and the 17th assailed the breach before the other regiments were at hand to support them, and by the time the XVIIIth came up the assault had been repulsed with heavy loss; many of the officers had been hit, and Cutts, the idol of the troops, was wounded and for the moment incapable of giving orders. Undismayed by the confusion and depression around them, the Irishmen with a yell rushed at the breach. At first they had to scramble over the bodies of those who[20] fell in the first attempt, but half-way up they reached the grenadiers’ high-water mark, and thence struggled upwards over ground covered by no corpses but those of the XVIIIth. From the neighbouring works they were tormented by cross fire, but yet pushed on, to the admiration of their foes who through the clouds of smoke watched them gradually winning their way up the breach, the Colours high in air, despite the carnage among the officers who carried them. Mad with excitement, determined to win at all cost, the regiment by a splendid effort reached the top of the breach, where the Colours were planted to show the King, who from a hill behind the abbey eagerly watched the progress of his British troops, that the Terra Nova was his. But as the men surged forward they found themselves faced by a retrenchment undamaged by the bombardment. The officers, holding their lives as nothing for the honour of their country and their corps, led rush after rush against this retrenchment, but in vain. They could not reach it; guns posted on the flank of the breach mowed down whole ranks; infantry fired into them at close range. All that men could do the XVIIIth had done, but nothing could withstand such a torrent of lead; the second attack failed, and the remnants of the regiment were driven backwards down the breach, and then charged by a counter-attack of horse and foot which the French let loose upon them.

Shaking themselves clear of the enemy, the survivors fell back towards the spot where Cutts, on resuming the command after his wound was dressed, had ordered his broken regiments to reassemble. While the British were retreating they learned that the Bavarians had not fared much better than themselves; badly led, they had missed their proper objective, the breach in a work called the Coehorne, and had attacked the covered way at a spot where the garrison was in great force; and after two hours’ hard fighting they reported that unless help came at once they could not hold their ground. Cutts, who from his love of a “hot fire” had earned for himself the nickname of the Salamander, instantly determined to go to the rescue of the Bavarians, and halting, turned towards the Coehorne and re-formed his column. To the onlookers it seemed impossible that troops fresh from the costly failure at the Terra Nova would face another breach, but Cutts knew what British soldiers could do, and his call for volunteers for a forlorn hope was answered by two hundred men, who headed this fresh attack, followed by Mackay’s, with the XVIIIth and the other regiments behind them in support. The assault was successful; the covered way was seized and held by the British, and all along the line victory smiled upon the Allies, who by five o’clock in the afternoon were lodged solidly within the enemy’s works.

To reward the XVIIIth for the magnificent courage it showed at the Terra Nova the King formally conferred upon it the title of the Royal[21] Regiment of Foot of Ireland, with the badge of the Lion of Nassau and the motto “Virtutis Namurcensis Præmium.”[22] In the year 1832, the Royal Irish received the somewhat belated official permission to emblazon this motto on their Colours; and it was not until 1910, two hundred and fifteen years after the capture of the fortress, that the regiments who took part in the siege were allowed to add Namur to their battle honours. In these matters our Government does not move with undue haste; it was only in 1882, that the Royal Irish were granted leave to commemorate on their Colours the fact that they had shared in the glories of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, and Malplaquet, the last of which was won in 1709!

The distinctions given by William were dearly earned, for though the authorities differ as to the actual numbers of the casualties in the XVIIIth, all agree that they were enormous. According to the army chaplain D’Auvergne, who wrote one of the best accounts of William III.’s wars in Flanders, the regiment lost twenty-five officers and two hundred and seventy-one non-commissioned officers and men. Parker and Kane give the same figures, but as both these officers were severely wounded it is probable that the returns had been sent in long before they came back to duty, and that in their books they adopted D’Auvergne’s numbers without investigation. In Stearne’s unpublished journal he states that twenty-six officers (whose names he does not mention) and three hundred and eighty of the other ranks were killed or wounded; and as Stearne was one of the few senior officers left with the regiment on the evening of the 20th of August, he must have had every opportunity of knowing the exact numbers. Two theories have been advanced to explain this discrepancy: the first, that Stearne included in his total all who were wounded, while the other historians took count only of the men who were gravely injured and admitted into the base hospital at Liege; the other is that among his four hundred and six casualties were the officers and men hit in the trenches after the XVIIIth joined the besieging army and before the day of the assault, or in other words that his figures show the regiment’s losses during the whole of the siege. But even taken on the lower, and therefore safer estimate, the percentage of loss is astonishingly high. At the beginning of a campaign a regiment was seldom more than 600 strong; indeed, many historians consider that 500 was the average strength. Since the XVIIIth had taken the field in June it had done much marching and[22] some work in the trenches, so that Hamilton’s ranks cannot have been quite full when he gave the order to storm the breach; but assuming that Hamilton had with him about 600 men, more than 49 per cent, or very nearly half the regiment, were killed or wounded on August 20, 1695. If the strength be taken at 500, the percentage shows that about six men out of every ten were hit; while if Stearne’s casualties are adopted the percentage is 81, more than eight men killed or wounded out of every ten who went into action. As it is impossible to ascertain definitely the strength of the XVIIIth, or to pronounce on the accuracy of the rival chroniclers, it is enough to say that the regiment suffered more heavily than any of the other British corps in Cutts’s column, whose losses, including those of the grenadiers, amounted at the least to thirteen hundred and forty-nine officers and men.[23]

In the XVIIIth Lieutenant-Colonel A. Ormsby; Captains B. Purefoy, H. Pinsent, and N. Carteret; Lieutenants C. Fitzmorris and S. Ramme; Ensigns A. Fettyplace, —— Blunt, H. Baker, and S. Hayter were killed. Captain John Southwell, Ensign B. Lister (or Leycester), and an officer whose name cannot be traced, died of their wounds. Colonel Frederick Hamilton; Captains R. Kane, F. Duroure, H. Seymour, and W. Southwell; Lieutenants L. La Planche, T. Brereton, C. Hybert (or Hibbert), and A. Rolleston; Ensigns T. Gifford, J. Ormsby, and W. Blakeney were wounded.[24]

The result of the assault convinced de Boufflers that he could not resist a renewed attack, and early on the 22nd he made signals of distress to de Villeroi, who finding it impossible to relieve him, retired to Mons, leaving the garrison of Namur to make the best terms it could. De Boufflers accordingly ordered his drummers to beat the Chamade, the recognised signal that a fortress desired to parley with the enemy, and after two or three days’ negotiations surrendered: the troops were to be allowed to return to France, the citadel, artillery, and stores remaining in the hands of the victors. On the 26th, the French, reduced by the two months’ siege[23] to less than five thousand effectives, marched out with all the honours of war—drums beating, Colours flying, and arms in their hands—and after filing through a double line of the allied troops were escorted to Givet, the fortress to which they had safe conduct. With the fall of Namur the campaign of 1695 virtually came to an end, for though there was some marching and counter-marching nothing came of these manœuvres, and the Allies went into winter quarters early in the autumn.

The campaigns of 1696 and 1697 were spent in operations unproductive of any affairs of importance, and the finances of all the combatants were so much exhausted by the strain of this long war that peace was signed at Ryswick in September of the latter year. The British contingent was sent to Ostend to await ships from England to take them home, and on December 10, the XVIIIth sailed on an adventurous voyage, thus described by Stearne.

“The ship I was in, with one more, having got near the Coast of Ireland, there came up with us a Sallee Man of War of about 18 guns, carrying Zealand colours.[25] When the master of our ship saw her bearing down upon us, he called up all the Officers and told us what danger we were in of being made slaves for ever. We thought it a very hard case after getting over so many dangers as we had gone through, upon which we all resolved to die rather than be taken, and having got all our men to arms, we made them lye close under the gunnel, that they might not discover what we were, and called to the other ship, and told them that in case she boarded us, that then they should lay her on board the other side, and that we would do the like in case they boarded them; and our Seamen were to be all ready with ropes to lash us together as soon as they laid us on board. At the same time we were to jump into her, and so take our fate. By the time she came up with us we had got everything ready to put our design in execution, but she fell in the wake of us, we being much the larger ship, and hailed our Master to go on board her, who answered that he would not leave his ship, and so kept on his course. The Sallee Man of War kept us company about an hour, and was once, as we thought, coming up to board us; however, she thought better of it, fell astern, and stood off without firing a shot, being prevented by the wind which blew very fresh, so that they could not put a gun out of their ports.