Title: Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, New York

Author: Charles W. Snell

Release date: June 30, 2019 [eBook #59839]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Stewart L. Udall, Secretary

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Conrad L. Wirth, Director

HISTORICAL HANDBOOK NUMBER THIRTY-TWO

This publication is one of a series of handbooks describing the historical and archeological areas in the National Park System administered by the National Park Service of the United States Department of the Interior. It is printed by the Government Printing Office and may be purchased from the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D.C. 20402. Price 60 cents.

by Charles W. Snell

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HISTORICAL HANDBOOK SERIES NO. 32

Washington, D.C., 1960

(Reprint 1961)

The National Park System, of which Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site is a unit, is dedicated to conserving the scenic, scientific, and historic heritage of the United States for the benefit and inspiration of its people.

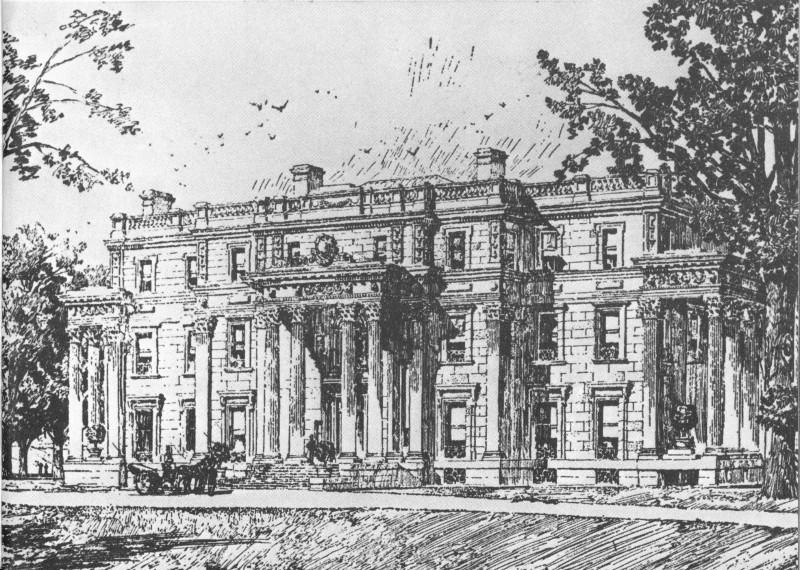

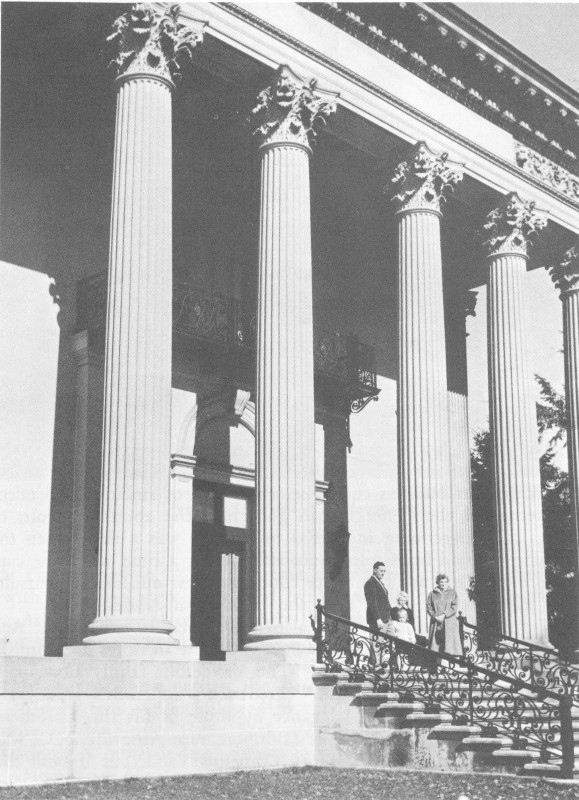

Vanderbilt Mansion.

Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, at Hyde Park, N. Y., is a monument to an era. It is a magnificent example of the palatial estates developed by financiers and industrialists in the period between the Civil War and World War I—a time when the United States surged into world prominence as an industrial nation and the new age of machines created great wealth that was almost untouched by taxation.

Focal point of the site is the mansion. Built in the Italian Renaissance style, its architecture and its furnishings show how strongly European art and culture influenced wealthy Americans at the turn of the 20th century. Vanderbilt Mansion is figuratively a palace transplanted from the Old World to the banks of the historic Hudson River.

The extensive grounds surrounding the mansion have been a part of great estates for almost two centuries. From natural terraces fronting the Hudson, the grounds level off to the open woods and lawns of an English-type park, then descend to forested seclusion in the valley of Crum Elbow Creek. Notable specimen trees dot the landscape, many of them from Europe and Asia. All these features combine to provide a setting worthy of the mansion itself.

Frederick William Vanderbilt made this estate his country home for 43 years, from 1895 until his death in 1938. Frederick was a grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt—the Commodore—who had founded the family fortune in shipping and railroading.

The name Vanderbilt (originally van der Bilt) was prominent throughout most of the 19th and early 20th centuries. This was largely due to the wealth of the family and the importance of its members in the transportation industry.

Cornelius Vanderbilt was a descendant of Dutch settlers who had migrated to America in the latter half of the 17th century. He first became interested in shipping while helping his father in odd jobs of boating and lightering around New York Harbor. When still a young man, he went into business for himself. He prospered, and soon his ships were calling at ports around the world.

Railroads were expanding rapidly at the time; but not until late in his life—at the urging of his eldest son, William Henry—did Cornelius Vanderbilt become interested in this new phase of transportation. Soon the name Vanderbilt was inseparable from railroading in the United States.

After the Commodore’s death in 1877, William expanded the Vanderbilt railroad interests in a number of systems, including the New York Central. When he died quite suddenly in 1885, several of his sons, left with substantial holdings of stock, increased their participation in the active management of the roads. One of these sons was Frederick William, future builder of Vanderbilt Mansion.

Born February 2, 1856, Frederick had attended Yale before entering his father’s office. In 1878 he had married Louise Holmes Anthony, daughter of Charles L. Anthony, prominent financier of New York City and Newport, R.I.

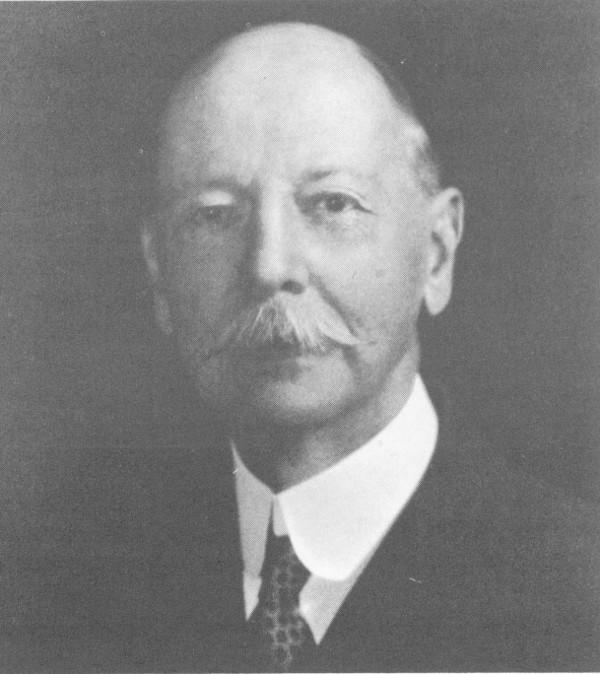

Aside from his business, Vanderbilt had few active interests, but was devoted to yachting. He was associated with Mrs. Vanderbilt in many philanthropic endeavors, particularly those related to young people; and he gave generously to several institutions of higher learning. Benefited during his lifetime and provided for in his will were Yale; Vanderbilt University at Nashville, Tenn.; and the Vanderbilt Clinic at Columbia University, built in memory of his father. Vanderbilt avoided personal exploitation of his benefactions just as he avoided membership in clubs and organizations of the type that might bring his name to public attention through officership or committee activity. This preference for anonymity continued until his death at Hyde Park on June 29, 1938, at the age of 82.

Vanderbilt was buried in the family mausoleum at New Dorp, Staten Island. He left no immediate survivors, for his wife had died in Paris 12 years earlier and they had had no children.

An accounting of the estate revealed that Vanderbilt, although retired for some years, had retained directorships in 22 railroads and many other corporations. His chief holdings were in the New 3 York Central railroad system, a Vanderbilt enterprise from its beginning. The fortune he left amounted to more than $78 million.

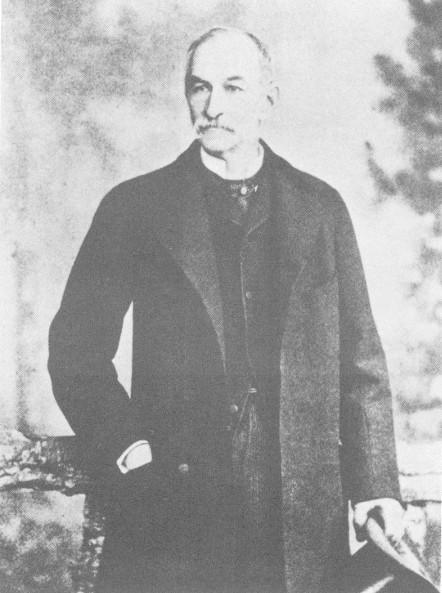

Frederick W. Vanderbilt as a young man.

When this headline of May 12, 1895, announced that another millionaire was coming to Dutchess County, residents of Hyde Park were not particularly impressed. For years the merchants of the village had been servicing the estates of wealthy men. Many of the townspeople were employed as gardeners, drivers, and domestics by the families of John Jacob Astor, Ogden Mills, Jacob Ruppert, Governor Levi P. Morton, James and John Roosevelt, and others prominent in the business and political worlds.

It was of interest, however, that the new neighbors, Mr. and Mrs. Frederick W. Vanderbilt, would occupy the Walter Langdon property, which they had purchased. It was also noteworthy that they planned extensive improvements to the mansion and grounds.

Langdon had acquired the property about 1852, buying out the interests of his mother and sisters and brothers with whom he had held joint title through a gift from his grandfather, John Jacob 4 Astor. During his ownership, Langdon had increased the size of the estate from 125 to 600 acres. He had also carried on the horticultural interests of earlier owners and had given the grounds a park-like atmosphere with walks, drives, and rustic walls and bridges. In later years, however, his interest seemed to have waned, and there were evidences of neglect all about.

The old Langdon House, built in 1847 and demolished to make way for Vanderbilt Mansion.

One reporter described the Vanderbilts’ new estate as “... a beautiful park all grown up to underbrush.” He noted that “There were hot houses ample but empty, the stables and farm buildings were in a state of extreme dilapidation, and the 40-room old mansion of the purest Greek architecture was painted a light pink....”

The new owner lost no time in getting started with his improvement program. He engaged the services of the famed New York architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White, and by the end of June their agents had completed measured drawings of the buildings on the estate.

It was decided that the former Langdon mansion would be remodeled. By September, architect Charles F. McKim had completed the plans. The north and south wings of the old structure were to be torn down and replaced. The central portion was to be retained under a new facade, and the rooms within it redecorated. Norcross Brothers, then the largest construction firm in the United States, moved in to begin work.

Remodeling of the mansion and other phases of the rehabilitation were obviously long-range programs. Some provision had to be made for a temporary residence for the Vanderbilts. The architect 5 and contractor accordingly directed their first efforts toward this end.

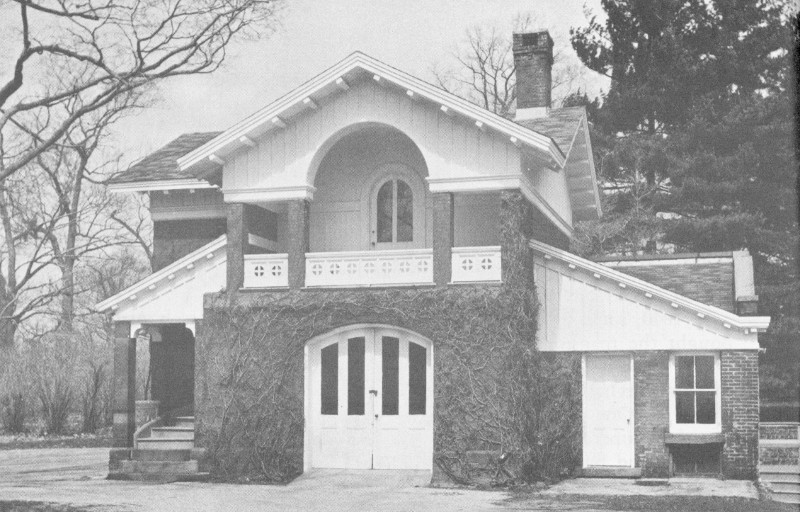

A carriage house of native field stone, probably erected in the late 1820’s, stood 540 feet north of the old mansion. Investigation revealed that the lime in the foundations and walls of this building had deteriorated to a point where the structure was unsafe, and it was decided to remove it completely. Plans were drawn for a pavilion to be erected on the same site. This would accommodate the Vanderbilts until the mansion was completed.

Time was at a premium if the new building was to be available for occupancy in the summer of 1896, and cost was no object. To speed the project, dynamite was placed under the four corners of the carriage house to bring it down, care being taken to protect nearby trees. The old structure was removed during the first week in September; and on November 24, 1895, just 66 working days later, the pavilion was completed. To accomplish this feat, the contractors had their carpenters working shoulder-to-shoulder.

Architect’s drawing of Vanderbilt Mansion.

For all the haste in its planning and building, the pavilion was an outstanding example of the owner’s desire to provide for the comfort of his gentleman friends when they visited him. This was the ultimate use for which the pavilion was planned, and no detail was overlooked. A large entrance hall, featuring an immense fireplace, was fitted for dining, general assembly, and congenial lounging. A butler’s pantry and kitchen for the preparation of game dinners, and several bathrooms equipped with showers for the convenience of guests were also on the first floor. From a balcony around the large central hall there opened the second floor rooms—bedrooms and servants’ quarters. A narrow staircase led to the roof, opening through a hatchway to a railed promenade or captain’s walk with a gunwale and a canvas-covered deck.

The pavilion.

West portico.

While Mrs. Vanderbilt resided there, the pavilion wore an aspect of “quiet domesticity.” One story told of her small rooms on the second floor “... brightened by a variety of exquisite feminine trifles.” Among these was a novel arrangement of rich portieres or doorway curtains that gracefully concealed the door.

Once the pavilion was completed, the contractor began, in January 1896, to remodel the Langdon mansion. Construction of two smaller houses for friends and relatives of the Vanderbilts was also started. (A gentleman of the press, evidently overwhelmed by the mansion, would later describe one of these smaller houses as “... a comparatively commonplace structure of red brick....” And, compared to the mansion, it was commonplace—a mere Georgian colonial house containing 16 rooms and 3 baths with a circular staircase leading from the front hall to the upper stories.)

Work had scarcely started on the mansion when serious structural defects were discovered in the walls of the center section. Complete demolition was deemed necessary. Vanderbilt balked at first, maintaining that he would have built along different lines had he felt there was nothing of the old house to be saved. Mrs. Vanderbilt was unhappy, too. In a letter to architect McKim, then in Egypt, his partner William R. Mead stated: “... when it was found the old house had to come down, Mrs. Vanderbilt kicked over the traces, and was disposed to build an English house, as she called it.”

But the architects prevailed. New plans were drawn with the center section rooms arranged along virtually the same lines as in the old house. The exterior features, including the projecting west portico that the Vanderbilts had particularly admired, were retained.

The new plans were ready in August 1896, and demolition of the old Langdon mansion was completed in September. Excavation of the deep basements for the new house was completed by hand and the foundations were finished before heavy snows in January 1897 forced suspension of the work.

As soon as the weather broke, activity resumed on the mansion project. Brickwork was completed by November, and electrical, plumbing, and heating systems were installed.

The heavy construction was barely completed when plasterers, stone carvers, and other artisans swarmed over the building. Working under the direction of the noted interior decorators, Ogden Codman and Georges A. Glaenzer, these men installed ceilings, wall tapestries, marble mantels, columns and pilasters, and beautiful mosaics and woodwork. Many of these items came from the Emperor Napoleon’s former chateau of Malmaison near Paris, also owned by Vanderbilt. A mural was painted by H. Siddons Mowbray on the drawing room ceiling.

The curious public was barred from the estate during these operations for fear of damage to the exquisite and costly decorations. But speculation concerning the interior of the mansion could not be stopped. One reporter, commenting on the number of skilled workmen and artists who daily tramped into the building, surmised that “... the inside will be as rich and beautiful as the outside is massive and splendid.” Another writer seemed gripped with nostalgia for a simpler day when he wrote: “The modest dwellings which satisfied wealthy landowners along the Hudson half a century ago ... are disappearing. On their sites are rising baronial halls fit for royalty....”

By April 1899, the furniture was being installed in the mansion, and on May 12 the Vanderbilts gave their first house party there. Guests for this auspicious occasion arrived at Hyde Park by special train.

Actual cost of the new mansion, unfurnished and without fixtures, was $660,000. The total cost of all construction and improvements, from May 1895 to March 1899, has been estimated at $2,250,000. And this was an age when a man worked all day for a dollar.

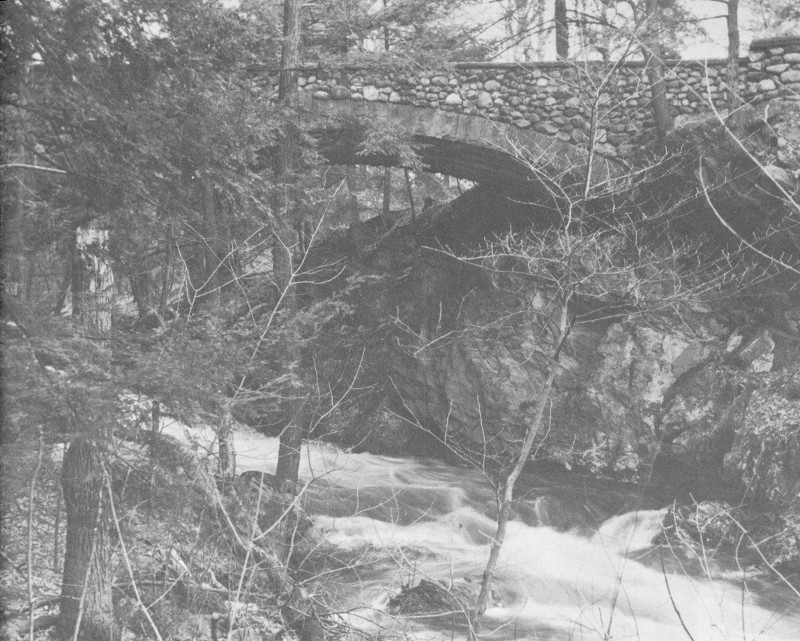

During the period when work on the mansion was at a standstill, and while work on the smaller houses was progressing, a large force of men was engaged in improvement of the grounds. In the larger portion of the estate lying east of the Albany Post Road, the order was to leave nature undisturbed to the greatest extent possible. Following the natural windings of a forest path, a carriage drive was laid out. A few obstructing rocks and trees were removed, and brooks were spanned, but generally the route of the drive was marked by outcropping ledges, overhanging forest trees, masses of ferns growing down to the wagon tracks, and a myriad of wildflowers. Readers of the Poughkeepsie Sunday Courier were regaled with this description of the drive: “As you wind along in the midst of its solitude and verdure, you might imagine yourself far away in the Adirondack forest, so sweet and still is the fragrant woodland....”

View of mansion from the north.

Brougham carriage used by the Vanderbilts.

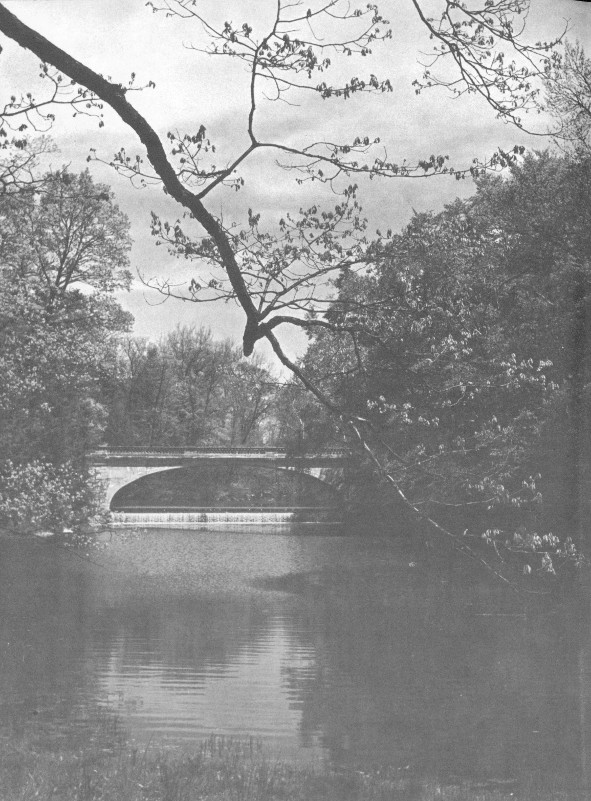

White Bridge from the south.

Stone bridge leading to coach house.

Some draining and grading was necessary to improve the land. A stagnant pond was cleaned out to create a miniature lake. The valuable muck, estimated at $30,000, was piled in a nearby field for later use as fertilizer.

In 1897, while work on the mansion went on apace, there was much activity on other fronts. A large standpipe, 10,000 feet of water pipe, and a large dam were installed to form a water system. Also completed was a powerhouse to generate all the electricity for the mansion and other estate buildings. On the grounds, extensive forestry operations, including trimming and replanting, were carried 12 out. Two new greenhouses were erected in line with a program for improving the extensive gardens.

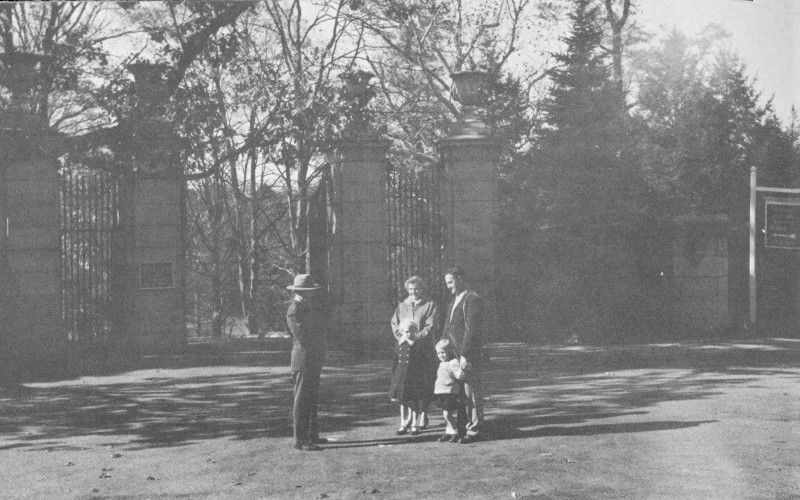

Main gate.

An old frame bridge crossing Crum Elbow Creek to the Post Road was replaced with the present White Bridge, for its time a very modern steel and concrete arch structure. A stable-coach house was built downstream. It was reached by a newly constructed rustic fieldstone bridge across the creek.

A contract for the erection of stone gatehouses was awarded in March 1898. These, together with gates and stone walls, were completed by the end of the year. The farm buildings on the east side of the Albany Post Road were repaired during the summer of 1899; roads were constructed on the farm section, and many large trees were transplanted.

Beginning in 1901, and continuing through the next 5 years, minor but important changes in and additions to the estate were made. The splendid barns, still standing on the farm section east of the Post Road, were erected. An Italian garden, starting from a point near the river entrance and laid out in terraces to the highest point 13 of the hill, was planned by James L. Greenleaf and executed under his direction.

South porch.

The grounds were enlarged in October 1905 when Vanderbilt purchased the estate of the late Samuel B. Sexton. This property of 64 acres, known as Torham, adjoined the Vanderbilt estate on the north and was considered a handsome addition. Sexton’s mansion 14 had been destroyed by fire several years before, but there remained some cottages, conservatories, a carriage house, a boathouse, barns, and other outbuildings. All of these, except the boathouse, were demolished in 1906 as part of a program to match the new property with the rest of the estate in what was called “the park plan.” The present north gate and stone walls were added to the new section at this time.

In the same year, final alteration of the mansion took place. Architect Whitney Warren of New York directed changes in the drawing room, main hall, and second floor hall. The Mowbray mural in the drawing room, which the Vanderbilts did not like, was removed.

With these changes, the mansion and estate began to look approximately as they do today.

In the 1890’s approximately nine-tenths of the wealth of the country was controlled by one-tenth of the population. It was an era of triumphant business enterprise when men of ambition and talent concentrated their energies on gathering the abundant fruits of America’s burgeoning industrial might. It was a time when the income tax had been ruled unconstitutional; a time when the captains of industry and commerce could use their millions for pursuits and pastimes that made even the wonders of Aladdin pale.

The great mansion was typical of these amazing enterprises. And typically, the owners ransacked Europe for art treasures and furnishings with which to fill them. The Vanderbilt family alone built four of these “baronial halls.” Frederick Vanderbilt’s Hyde Park mansion was matched in elegance by those of his three brothers: George Washington Vanderbilt’s Biltmore, near Asheville, N.C., was reputed to have cost $3 million; Cornelius Vanderbilt II built the elaborately decorated Breakers at Newport, R.I.; William K. Vanderbilt’s Spanish-Moorish mansion, Eagle’s Nest, is at Centerport, Long Island. Today, all are open to the public—museums of art, memorials to an age.

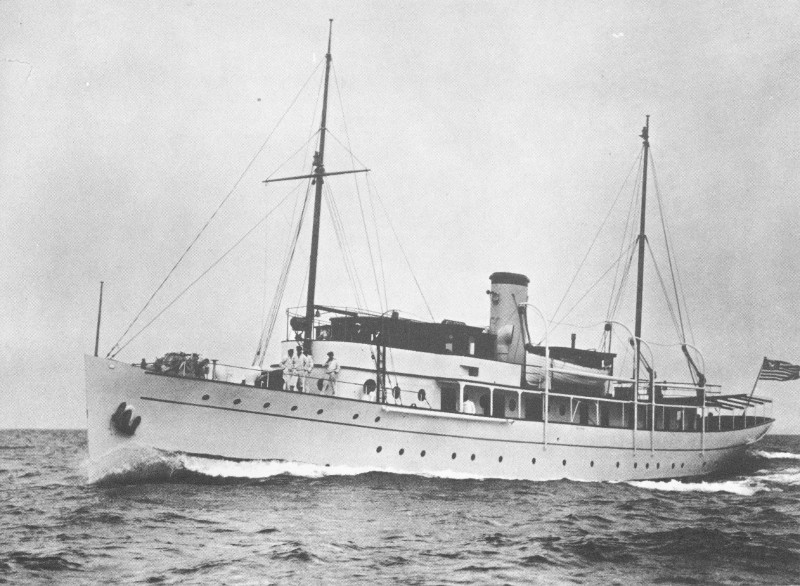

A favorite pastime of wealthy sportsmen was yachting—and in the Vanderbilt family, this was almost as fixed a tradition as railroading. From 1889 to 1938, Frederick Vanderbilt kept that tradition alive with a series of four large seagoing luxury craft. During World War I, he donated the third of these, Vedette I, to the United States Government, and it was used by the Navy for submarine patrol in the Atlantic. The fourth ship, Vedette II, was built 15 at Copenhagen in 1924. This twin-screw diesel craft—158 feet long with a 23-man crew—was used by Vanderbilt until his death.

Vedette II, Vanderbilt’s last yacht.

Aside from yacht owning, there were the international yacht races for such prizes as the America’s Cup. Several times Vanderbilt joined with other sportsmen in financing entries to these races. In 1934, one of these entries, the Rainbow, won the cup at Newport.

The pattern of life followed by the Vanderbilt’s was typical, not only of their own Hyde Park neighbors, but of others of their station. A more or less uniform cycle was followed year after year.

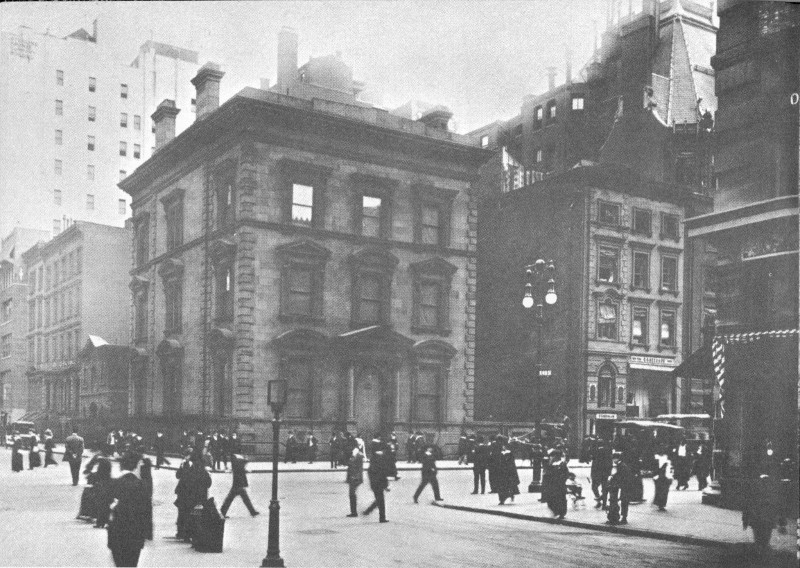

New York City was then the hub of the financial and business world, and here were centered the formal social interests of the wealthy. Consequently, it was essential that a townhouse be maintained there, though not necessarily as a principal residence. Depending upon their other interests, the members of this select group often moved about with the seasons.

About the middle of November, the Vanderbilts would go to New York for the opera and social season, staying at their townhouse until the end of January. On weekends in this period and at Christmas, they usually returned to Hyde Park, staying in the pavilion after the mansion was closed up about December 1.

The Frederick Vanderbilt townhouse at Fifth Avenue and 40th Street, New York City, razed in 1914. Courtesy Underhill Studio, New York.

March and April were generally spent at Palm Beach, Fla. Here the Vanderbilts and their guests would cruise on their yacht in southern waters. For variety they sometimes leased a large estate on the West Coast, the family making the trip there and back in its private railroad car. The Vanderbilts would return to Hyde Park about Easter, remaining until shortly after the Fourth of July. Between then and Labor Day, they usually went to one of the several summer mansions that they owned at various times. The first of these was Rough Point, at Newport, R.I. They also had a retreat which they called their Japanese Camp on Upper St. Regis Lake in the Adirondacks; it had been built by 15 “expert mechanics” brought over from Japan. From 1913 until Mrs. Vanderbilt’s death in 1926, they went to Cornfield, a residence at Bar Harbor, Maine.

Part of the summer might be spent in Europe. The Vanderbilts would cross the Atlantic on an ocean liner, having sent the yacht on ahead. Then they would pick up the yacht and cruise along the coast of Europe or in the Mediterranean. In his later years, Vanderbilt spent much of his time at Hyde Park, but would make an occasional summer trip on his yacht.

Frederick W. Vanderbilt in his later years.

There were several reasons why so many men of wealth chose the Hudson River Valley as the locale for their country estates. Scenic charm at a convenient distance from New York City attracted some. Others, like Vanderbilt, found the rolling countryside ideal for the pursuit of interests in purebred livestock and in horticulture.

Two events of great interest to these gentleman farmers were held each autumn. There was keen competition among them at the annual flower show of the Dutchess Horticultural Society in the State Armory at Poughkeepsie, and at the Dutchess County Fair, originally held at Poughkeepsie, and after 1919 at Rhinebeck. Vanderbilt always came away with his share of prizes for his plants and flowers, and for his garden produce, Belgian horses, and Jersey cattle.

For the sports-minded, the Hudson River provided both active and spectator events. Vanderbilt was a member of the Hudson River Yacht Club, some of whose members also enjoyed ice yachting on the frozen river. Sharing in this thrilling pastime were Archibald Rogers, John A. and Franklin D. Roosevelt, Samuel B. Sexton, Edward Wales, and Thomas Newbold.

The barns on the Vanderbilt estate, now privately owned.

A spring attraction that appealed to many of the Dutchess County residents was the college regatta held each year on the Hudson at Poughkeepsie. Vanderbilt was a regular contributor to this rowing event. The presence of his yacht in the spectator line was frequently mentioned in the papers.

The Vanderbilts enjoyed winter sports during their weekend visits at the pavilion. Their particular delight was sleighing. On a crisp winter day, the Post Road would be alive with handsome turnouts and highstepping horses. The air would then ring with the sound of sleighbells as the wealthy Hyde Parkers dashed about the snow-covered highways.

Spring and autumn found the members of the Dutchess Hunt Club riding to the hounds on their swiftest horses. All the fine livery of a pageant brightened these occasions.

Leading all other events for color and magnificence at the Hyde Park estates were the weekend house parties. The guest lists on these occasions included European nobility, and leaders in the fields of business, politics, and the arts.

Those invited to Vanderbilt Mansion were accommodated in lavishly appointed guest rooms, all of them furnished in 18th-century French style. Each room had its distinct color scheme, with the motif carried into the bathroom accessories. When the number of guests exceeded the number of guest rooms in the mansion, the overflow was housed in the pavilion.

Blue room, largest of the guest rooms.

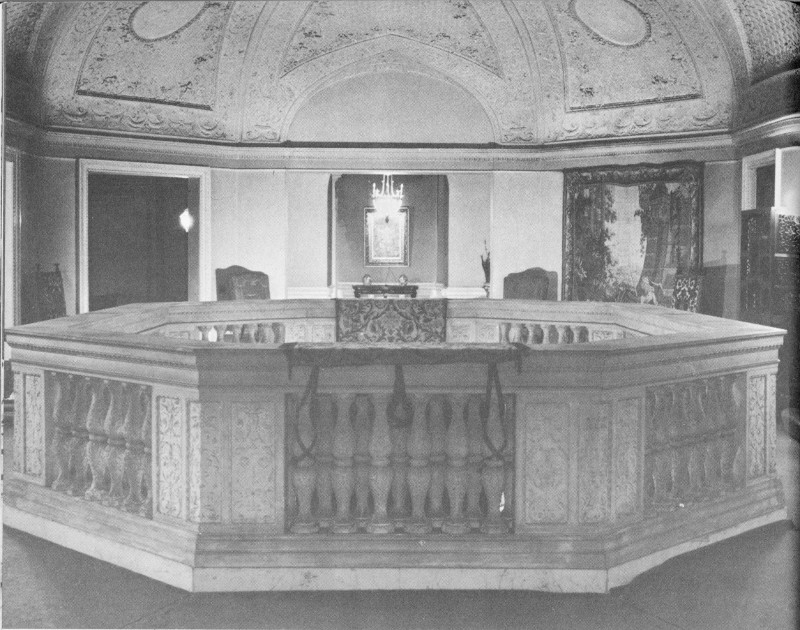

Dining room, family table at far end.

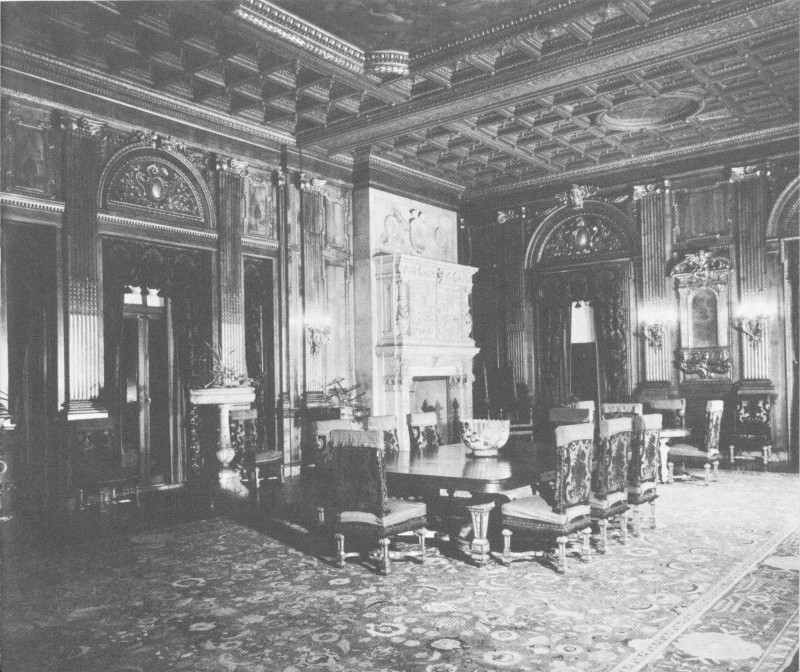

Drawing room.

Guests had the option of having breakfast in their rooms. The food would be served on special breakfast sets that matched the color scheme of the rooms. Those who preferred eating in the dining room found the small family table at the east end of the room covered with a white cloth and set with red china. In the center was a large swivel tray, or Lazy Susan, containing coffee and food for the meal. Guests were expected to seat themselves, turn the tray, and choose from it whatever they wished. If anyone was late, fresh coffee and warm food were brought up from the kitchen and placed on the tray.

When luncheon was served for the family or intimate friends, the small table was again used. If a formal luncheon was being served, the larger table in the center of the room, which could seat up to 30 people, would be set.

Details for formal affairs were arranged weeks in advance by Mrs. Vanderbilt with her cooks, butlers, and gardeners to avoid last-minute slip-ups. On such occasions, the hostess made it a point to blend the color of the flowers, the cloth, and the china. Thus, if yellow flowers were being used, the lace cloth would have a yellow satin undercover. The centerpiece might be an inlaid gold mirror and gilt vase, filled with fresh yellow roses. Scattered about the table would be six or eight smaller gold vases of flowers. The 21 service would be gold-plated, and the china would be white, with a gold stripe and the family monogram in the center.

The courses served at such a luncheon included hors d’œuvres, and an egg dish, followed by an entree. The main course would be a choice of chicken, turkey, or game. This was followed by an elaborate dessert, with cakes, fruits, and candies.

The family and intimate friends took their afternoon tea in the library. On more formal occasions, tea was served in the drawing room. Guests gathered in the gold room for sherry before dinner.

The color of the flowers, cloth, and china would again be blended for dinner. A monogrammed cloth covered the large table on the occasion of a formal dinner. The centerpiece might be a large silver bowl, a yachting trophy, filled with pink flowers, on a silver tray. Candelabra, fruit and bon-bon dishes, and the flatware would also be of silver. China would be of a fine Italian variety, engraved with pink flowers. Courses for a formal supper included soup, fish, and an entree. The main course was a choice of game, meat, or fowl. This was followed by dessert, fruit, and candies.

When finished at table, the ladies retired to the drawing room, where demitasse and liqueur were served. The gentlemen remained in the dining room for coffee, liqueur, and cigars. In about half an hour they would join the ladies in the drawing room for cards or other amusements.

Sometimes dinner was followed by a formal dance held in the drawing room. House guests were joined by other guests, neighbors, and their visitors. Music was furnished by an orchestra from New York City, and the dancing stopped promptly at midnight on a Saturday evening.

The immensity of the Vanderbilt estate at Hyde Park can best be gaged by realizing that at one time there were more than 60 full-time employees, directed by the estate superintendent. Of this number, 17 were employed in the house, 2 in the pavilion, and 44 on the grounds and farm—13 men cared for the gardens and lawns alone. When there were guests in the pavilion, additional cooks and maids were engaged from Hyde Park.

The fine herd of 24 Jersey cattle and the 15 Belgian draft horses maintained on the farm were all of the best breeding and show stock, as were the more than 2,000 white leghorn chickens and the Berkshire pigs. Entered in competition at the Dutchess County Fair, the animals took many honors. But they served a utilitarian purpose as well. Chickens supplied all of the eggs used in the kitchens, and non-layers were killed for table use. Cows furnished milk, and sweet butter was churned once a week. Pigs were slaughtered for meat. These products supplied both the mansion and the townhouse in New York City. The draft horses were used in farm work.

Vanderbilt coach house and stable.

Mrs. Frederick W. Vanderbilt.

In the era before the automobile, Vanderbilt’s entire stable of carriage horses usually arrived at Hyde Park from New York each year about May 1. Here they were stabled until about December 1, when they were returned to the city for the winter season in a special railroad car.

The vegetable gardens supplied fresh produce for mansion and townhouse. The quality of the produce must have been excellent, for year after year top honors at the Dutchess County Fair went to the estate superintendent for the 10 best varieties of vegetables grown by a professional gardener—and this in competition with entries from other great estates in the county.

The gardens and greenhouses supplied flowers for the mansion, and when the Vanderbilts were in residence at their townhouse in New York, fresh flowers were shipped there twice each week. Flowers were also sent twice a week to the hospitals in Poughkeepsie for distribution among the patients. In addition, the Vanderbilt, Roosevelt, and Rogers greenhouses supplied the lilies, palms, and other flowers to decorate the four churches of Hyde Park for Easter services.

All electricity for the estate was generated at the powerhouse, located on Crum Elbow Creek near the White Bridge. Wood for the fireplaces was cut on the estate, and the icehouses were filled from the ponds.

The great estates along the Hudson played an important role in the economy of the small communities nearby. Employment was provided for many residents, and the wealthy owners took a benevolent interest and provided a guiding hand in the affairs and welfare of the villages. The Vanderbilts may be cited as typical examples, and in the finest tradition.

Mrs. Vanderbilt knew personally almost every person living in Hyde Park. Her employees, as well as the doctors and ministers of the community, kept her informed of events taking place there. They told her of those in difficulty; Mrs. Vanderbilt then visited the family named. If there was illness, she called in a doctor and nurses; if there was poverty, she sent coal and groceries. Those suffering from tuberculosis she sent to Saranac Lake and took care of all expenses herself.

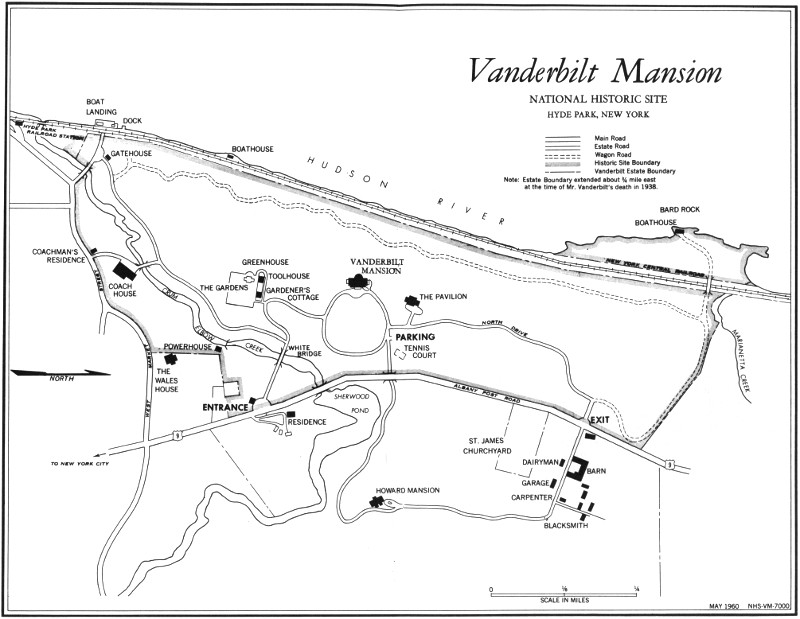

Vanderbilt Mansion

NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

HYDE PARK, NEW YORK

MAY 1960 NH5-VM-7000

Note: Estate Boundary extended about ¾ mile east at the time of Mr. Vanderbilt’s death in 1938.

She was interested in young people and saw to it that they had facilities for learning the domestic and industrial arts in the local school. For young men 13 and older, she organized and maintained a completely equipped clubroom in the village. For the young women in whom Mrs. Vanderbilt took a personal interest, she furnished funds for their complete education.

Each summer Mrs. Vanderbilt gave the school children of Hyde Park either a strawberry and ice cream festival or a cruise on the Hudson on a chartered steamer. Sometimes she joined forces with other wealthy residents and invited all the citizens of the town for a steamer cruise on the river; on one occasion this involved more than 700 people.

Through the Sunday Schools of the village, she arranged for each child to have needed clothes and toys at Christmas. And on Christmas day she would drive through the village in a sleigh loaded with gifts that she handed out to the children she met.

A reading room attached to St. James Chapel was established and maintained by Mrs. Vanderbilt for the people of the village. She was also responsible for bringing the Red Cross movement to Hyde Park in 1911; and in 1917, she was a prime mover in the establishment of the District Health Nurse Service.

With the outbreak of World War I, the Vanderbilts, James Roosevelt (a half brother of Franklin D. Roosevelt), and Thomas Newbold equipped, clothed, and armed for a 2-year period a Hyde Park Home Defense Company of 65 men. The Vanderbilts also arranged educational lectures, bringing to the townhall eminent authorities on various subjects. In 1920, Vanderbilt and Archibald Rogers jointly donated the money for a motion picture projector, thus bringing the first movies to Hyde Park. Other community projects drew Vanderbilt’s support, including an $18,000 donation for Hyde Park’s first stone bridge over Crum Elbow Creek on the Albany Post Road, just north of the village.

For their employees, the Vanderbilts sponsored a baseball team that, in its day, was one of the finest in the valley. Holiday parties for children and adults were held each year. Mrs. Vanderbilt sometimes visited the parties in person, mingling freely with the guests. Gifts to employees were the custom at Thanksgiving and Christmas.

The history of the 211-acre grounds surrounding the Vanderbilt Mansion goes back much further than that of the house.

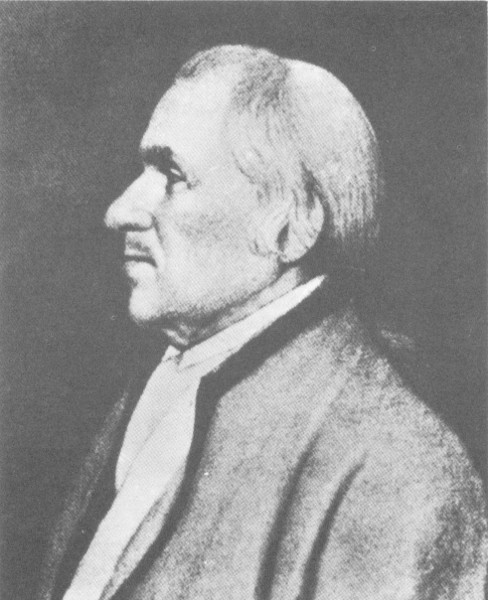

Pierre (Peter) Fauconnier.

Dr. John Bard.

On April 18, 1705, Peter Fauconnier and three other men were granted a patent for 3,600 acres of scenic land on the east side of the Hudson River. Fauconnier had fled his native France as a religious exile, arriving in America by way of England. Here he became secretary to Edward Hyde, Viscount Cornbury, Governor of the Province of New York, who signed the patent papers in the name of Her Majesty Queen Anne. The land was divided among the grantees; Fauconnier’s portion, undeveloped in his lifetime, appears to have passed at his death to his daughter, Magdalene Valleau. Mrs. Valleau sold her interest in the patent to her son-in-law, Dr. John Bard, who later purchased the entire patent.

The name Hyde Park was applied to the patent lands. Perhaps Fauconnier gave the name to his share out of respect for the Governor and it later extended to the holdings of Dr. Bard; or possibly the name came into use during the years of estate development by the Bard family. At any rate, the town of Hyde Park, established in 1821, took its name from the estate.

Dr. Bard, noted physician and pioneer in hygiene, had his first house built on the property about 1764. He continued to maintain his principal residence in New York City until about 1772, when he moved to Hyde Park. A new house, which he called the Red House, was built just north of the present St. James Episcopal Church, opposite the north gate of the National Historic Site. He 28 disposed of approximately 1,500 acres of the land, and developed the remainder as his estate.

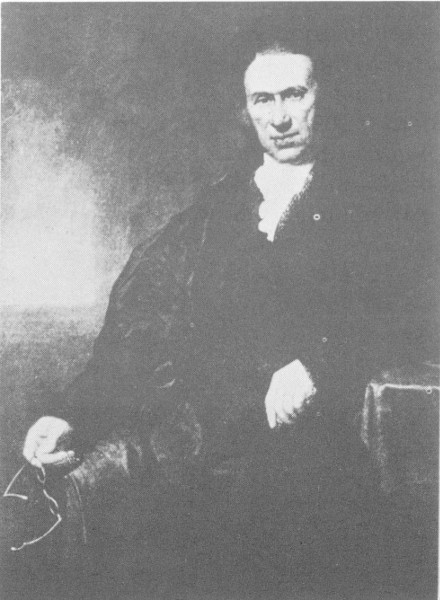

Dr. Samuel Bard.

Dr. David Hosack.

After the Revolution, Dr. Bard returned to private practice in New York City where he assisted his son, Dr. Samuel Bard, as attending physician to President George Washington. The elder Bard retired again to Hyde Park in 1798. Before his death a year later, the property was transferred to his son.

Dr. Samuel Bard built a house at Hyde Park in 1795, the first to stand on the site of Vanderbilt Mansion. A large house on the high elevation rising about 300 feet above the Hudson, it commanded a superb view of the river and of the mountains beyond. A garden was laid out on the land west of the Albany Post Road, and by 1820 a greenhouse, said to have been the first one in Dutchess County, was erected. In addition to his interest in trees and improvement of the grounds, Dr. Samuel Bard undertook experiments in horticulture and farming. He imported fruits from England, France, and Italy, and vines from Madeira. The Society of Dutchess County for the Promotion of Agriculture made him its first president in 1806. In this position he encouraged the use of clover as a crop and gypsum as a fertilizer. Dr. Samuel Bard lived at Hyde Park until his death in 1821 at the age of 79. His death followed within 24 hours that of his wife, Mary.

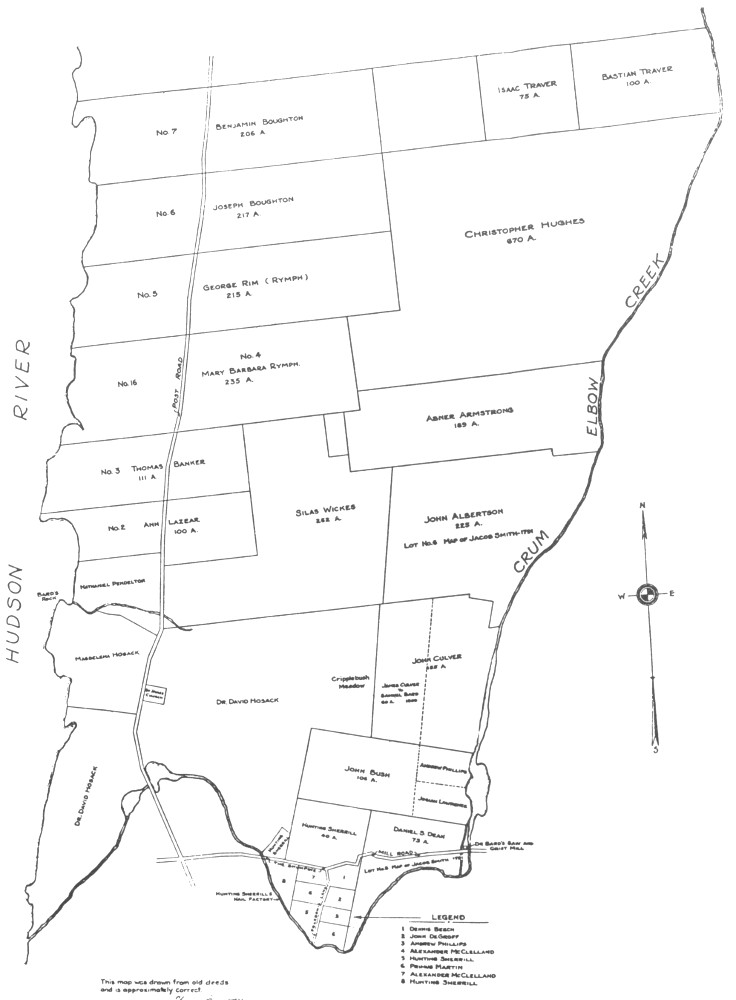

Map of the Hyde Park Patent, about 3,600 acres, showing land sales made by Dr. John Bard and Dr. Samuel Bard. In the time of Vanderbilt the estate comprised approximately the tracts labeled “Dr. David Hosack” and “Magdalene Hosack.” The National Historic Site comprises the land owned by Vanderbilt west of the Post Road and fronting the Hudson River.

Walter Langdon, Jr.

Their only surviving son, William Bard, inherited Hyde Park which had been reduced by land sales to 540 acres. He lived there only until 1828, when he sold the estate to Dr. David Hosack of New York City. A former professor of natural history at Columbia College, Dr. Hosack had become a partner of Dr. Samuel Bard and had taken over the latter’s medical practice when he retired.

Dr. Hosack spent vast sums of money for the improvement of his property. He was to create the first of the great Hudson Valley estates.

Deeply interested in botany, he revived horticultural experimentation and gardening at Hyde Park. Many of the rare specimens that today grace the lawns and gardens probably date from the period immediately following Dr. Hosack’s acquisition of the estate. Andre Parmentier, a Belgian landscape gardener, was engaged to lay out roads, walks, and scenic vistas.

In 1829, under the guidance of Martin E. Thompson of the architectural firm of Town and Thompson, Dr. Hosack remodeled and enlarged the house built by Dr. Samuel Bard in 1795. A new carriage house and gate lodges were also designed and constructed.

The new beauty of the Hyde Park estate carried its fame throughout this country and to Europe. Many notables came to Hyde Park to visit Dr. Hosack and to enjoy the scene. Among them were Philip Hone, diarist and former Mayor of New York; Washington Irving, noted author; the poet Fitz-Greene Halleck; Jared Sparks, American historian and editor of the North American Review; Capt. Thomas Hamilton, British novelist and adventurer; Harriet Martineau; Dr. James Thacher, physician and biographer; and the young English artist Thomas Kelah Wharton, who made several engravings of the estate.

In 1840, some 5 years after Dr. Hosack’s death, John Jacob Astor bought the mansion tract, containing about 125 acres of land west of the Albany Post Road. Astor almost immediately made a gift of this purchase to his daughter Dorothea Langdon and her five children. One of her sons, Walter Langdon, Jr., eventually bought out the property interests of his mother, sisters, and brothers, and by 1852 had become sole owner.

Gardener’s cottage.

The handsome house originally built by Dr. Samuel Bard, then enlarged by Dr. Hosack, was completely destroyed by fire in June 1845. A new mansion was built on the site of the destroyed house in 1847. By 1872, Langdon had reunited the farmland east of the Post Road through purchase. In October of that year, fire destroyed the splendid barns that had been Dr. Hosack’s pride. Three years later, Langdon built the gardener’s cottage and toolhouse, 32 the only buildings still standing that antedate the Vanderbilt era. Until late in life, the Langdons spent much of their time in Europe, and the Hyde Park mansion was closed for years. In 1882, however, Langdon returned to Hyde Park, living there the life of a country gentleman. There were no surviving children when he died in 1894 at the age of 72. When Hyde Park was offered for sale the next year, Frederick W. Vanderbilt purchased it.

Tool house.

Vanderbilt Mansion was designed by the firm of McKim, Mead, and White in 1896-98 in an Italian Renaissance style then popular with that firm. The mansion has about 50 rooms on 4 levels, including servants’ quarters and utility features like the kitchen and laundry. The entire construction of concrete and steel, faced with cut stone, is fireproof—except for the interior paneled walls and the furnishings.

This is a small, high-ceilinged room that leads from the imposing front portico of the mansion to the reception hall. It is without distinctive furnishings except for a pair of large Mediterranean green-glazed pottery jars.

Library and family living room.

Green and white marble imported from Italy is used with arresting effect for cornices and pilasters in this elliptically shaped room. Above the massive fireplace, which came from an Italian palace, is a Flemish tapestry bearing the insignia of the famous Italian Medici family of Renaissance times. In the center of the room is a French table with a porphyry top; upon it is a French clock with a matching porphyry base. Around the walls are high-backed Italian throne chairs. Two French Renaissance cabinets, in tooled walnut, stand at either side of the doorway. A pair of busts, male and female, are of Carrara marble. Many of these pieces are hundreds of years old.

Woodwork is Santo Domingo mahogany. Plates on the wall are Chinese, and a painting by the French artist, Lesrel, hangs over the desk. Above the fireplace, early Italian and Spanish flintlock pistols are grouped about an old Flemish clock. A hand-carved Renaissance panel forms the back of the desk chair. In the bookcase are about 400 volumes, mostly fiction and travel. Included 34 among these are the college textbooks that Frederick Vanderbilt used at Yale. From this room Vanderbilt conducted his estate affairs, such as tree culture and the operation of the greenhouses, gardens, and his 350-acre dairy and stock farm across the highway.

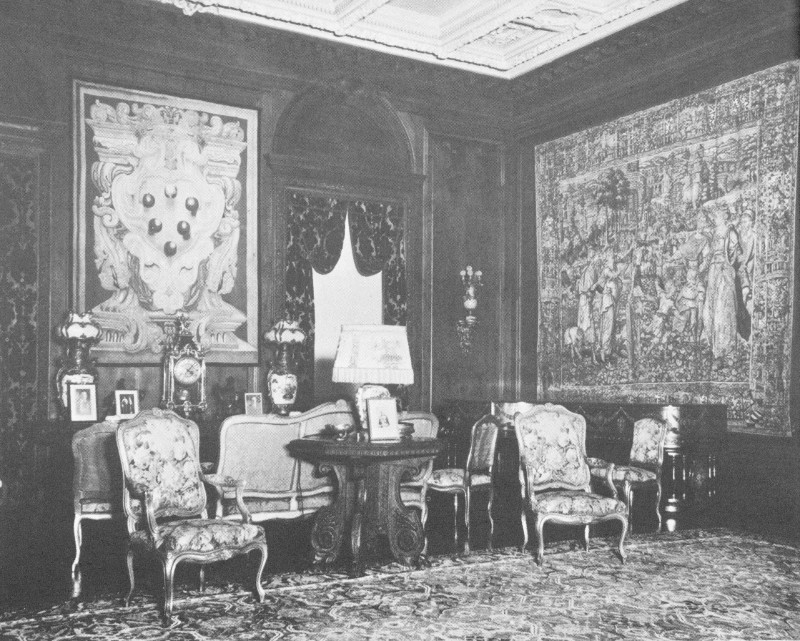

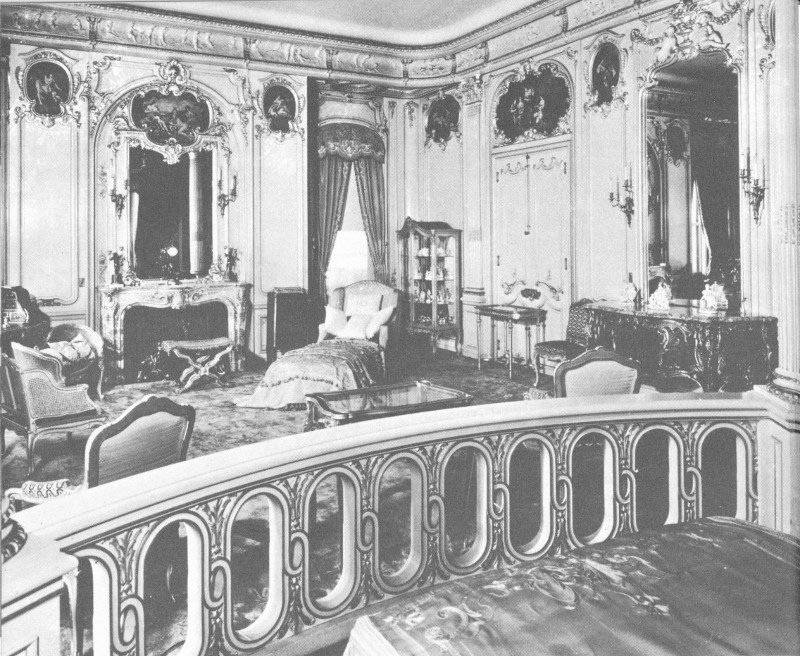

Drawing room, northwest corner.

This room reflects the work of decorator Georges A. Glaenzer of New York City. Hand-carved wood on the walls was done by Swiss artists brought to this country for that purpose. A vaulted section of the ceiling is molded plaster, made to simulate carved wood. The carved mantel of the fireplace is said to have come from a European church. A porcelain clock-and-candelabra set on the mantel was a gift from Mrs. Vanderbilt’s mother. Guns on the wall opposite the fireplace are antique Swiss wheel locks. More than 900 volumes on history, literature, natural science, and other subjects fill the bookcases in this room. This library was the family living room. Here the Vanderbilts and their intimate friends gathered for tea in the afternoon. Mrs. Vanderbilt used the table in this room to write letters to her friends. Frederick Vanderbilt’s favorite chair stands near a large window overlooking the grounds.

Gold room or French salon.

On one of the venerable Italian dower chests in this room is a model of Vanderbilt’s yacht, Warrior. On the other chest is a small bronze group depicting a Russian winter scene. Above the chests are two 16th-century Brussels tapestries showing incidents in the Trojan War. By the chests are a pair of Venetian torcheres and two small bronze chateau cannon.

Furniture in this room is predominantly French, except for two Italian refectory tables and a number of Chinese lamps. Two of these lamps have silk shades with hand-painted designs copied from the bases; this touch of luxury is repeated in other rooms, notably in Frederick Vanderbilt’s bedroom. The grand piano, an American Steinway, was decorated in Paris in goldleaf with the medallions of noted composers, it was originally used in the home of Vanderbilt’s father in New York City. Seventeenth-century Florentine tapestries on the end walls bear the coat of arms of the Medici family. Two 16th-century Brussels tapestries with more scenes from the Trojan War flank the doorway. Wall paneling is Circassian walnut. Twin fireplaces are Italian marble. As it now appears, this room represents the design of architect Whitney Warren, who redecorated the room in 1906. The original ceiling mural by H. Siddon Mowbray was removed at that time.

French doors open to a porch from which a path led to the Italian gardens. Formal entertaining in this room might include tea, after-dinner coffee, games of whist, and, on special occasions, a spring or autumn dance.

This French salon was designed by Georges A. Glaenzer after an 18th-century French drawing room. An inlaid tulipwood desk is Louis XV. A standing clock, made by Paul Sormani is a copy of one in the Louvre. One of the inset wall panels contains an Aubusson tapestry; two other panels (one above the marble fireplace) contain large mirrors which, reflecting in one another, provide a striking repetition of mirrors to infinity. As is evident from its gilded appearance, goldleaf was not spared in the room’s decoration. Here guests would gather for sherry before dinner.

In this room is a large Florentine storage chest of hand-carved wood, decorated with goldleaf and lacquer. Above the chest is a 17th-century Brussels tapestry. On the opposite wall is 37 an 18th-century Aubusson tapestry. Overhead is a Venetian lantern matching the one in the south foyer. In one corner is a large Chinese bowl with blue-dragon design against a white background; it rests on a Chinese teakwood stand.

Dining room.

This room is 30 by 50 feet. Its floor is covered by a huge Oriental (Ispahan) rug which measures 20 by 40 feet and is more than 300 years old. Furniture is a reproduction of Louis XIV period. The large dining table could be extended to seat 30 people. A smaller table at the east end of the room was used by the Vanderbilts when dining alone or with a few intimate friends. At such meals, Frederick Vanderbilt always sat on the south side of the table with Mrs. Vanderbilt opposite him on the north side. Across the room from the doorway are two 18th-century planetaria, made in London—instruments used for the study of the sun and planets. On the walls on either side of the door are a pair of French 17th-century tapestries, believed to be of Beauvais manufacture. Florentine chairs around the walls and two carved Renaissance mantels all emphasize the spaciousness of the room. Hand-painted and gilt panels decorate the ceiling. Two marble columns of the Ionic order flank the doorway, matching those in the drawing room. All original marble work in the mansion was done by Robert C. Fisher and Company, of New York City, then one of the largest importers of marble in the world.

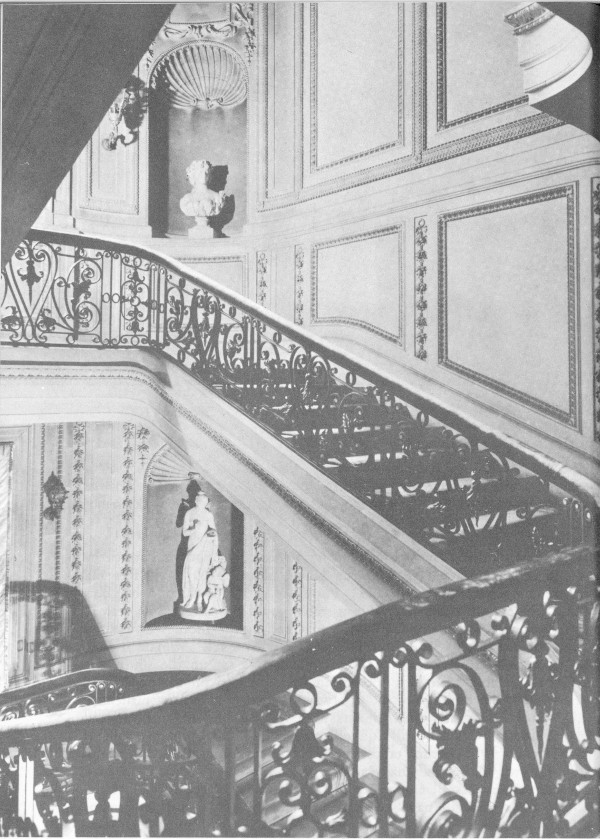

Grand stairway. Courtesy The New York Times Studio.

The hostess made it a point to blend the color of the flowers, the cloth, and the china. If yellow flowers were being used, the lace cloth would have a yellow undercover, the service would be gold-plated, and the china would be white with a gold stripe.

On the wall opposite the foot of the stairway is an 18th-century Flemish tapestry. The floor in the lower-stair hall is old Italian marble. A chair and marble fernery are Italian, and a large Chinese bowl of the Ming Dynasty is about 500 years old. Italian busts and statues occupy niches along the way. At one of the landings is a painting by the French artist, Adrien Moreau. An early 18th-century Beauvais tapestry hangs on the second-floor wall.

On a Louis XVI table stands an incense burner fashioned of marble and cloisonne. Overhead is a chandelier of beaded crystal; one of similar design is in the south foyer. Hanging here are original paintings by the 19th-century artists, Schreyer, Bougereau, and Villegas. Frederick Vanderbilt was more noted for the fine tapestries he collected than for outstanding paintings.

This is the largest of the guest rooms. Mrs. James Van Alen, the niece of Mrs. Vanderbilt who donated the mansion to the Federal Government, used this room during her visits to the Vanderbilts. The windows of this room command a splendid view of the Hudson and the mountains beyond. A white onyx French clock and companion pieces adorn the mantel, and a rare old (Ghiordes) prayer rug is spread before the fireplace.

Common to all guestrooms is the 18th-century French style of furniture and the use of a distinct color scheme. The guestrooms, unless otherwise noted, are believed to reflect the design of New York decorator Ogden Codman.

Most of the furnishings in this room are of French design. In the center of the room is a finely woven Persian dower rug. Pieces on the mantel are of the French Empire period. Each guestroom has a bath and one or more closets. The bathroom accessories always matched the color scheme of the guestroom.

In 1906, architect Whitney Warren installed the balustrade which now overlooks the reception hall.

Second floor hall.

In the second floor hall are three 18th-century Flemish tapestries, two Italian fringed and embroidered hangings draped over the balustrade, and two sets of matched high-backed chairs in walnut—one set of six chairs, one of four. A teakwood cabinet is of Chinese design.

These rooms open onto the second floor hall and are connected by a doorway to form a two-room suite. Furnishings are in the French style. A frieze on a Greek subject embellishes the 18th-century English Georgian mantel in the larger room.

This leads to the master bedrooms. French doors can be closed to separate this wing from the rest of the second floor. In the foyer are paintings by Kellar-Reutlingen and Firman-Girard.

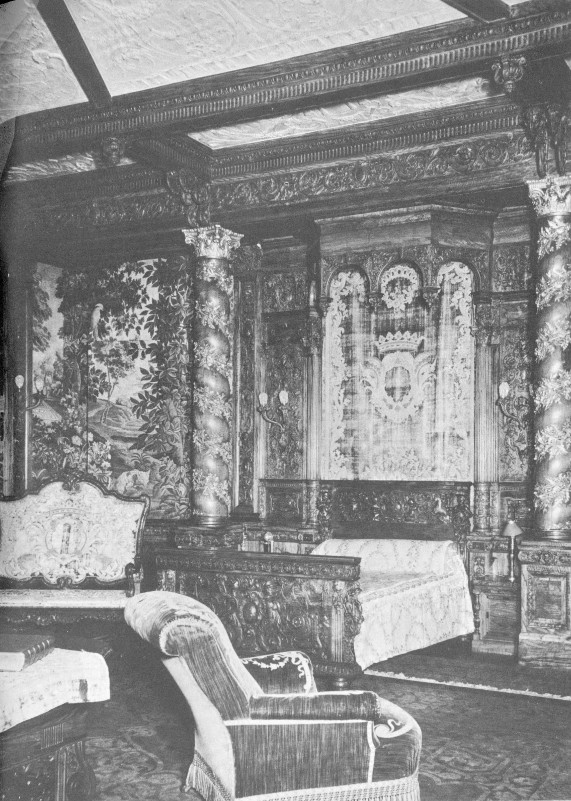

This room has carved woodwork of Circassian walnut. The bed and dresser were designed as part of the woodwork and were installed by Norcross Brothers. The room was designed by Georges A. Glaenzer. The walls and doors are covered with 17th-century Flemish tapestry. Hand-painted designs on the silk lampshades match those on the Chinese bases. The fireplace has a large carved mantel. On the floors are dark-red rugs made in India.

Frederick Vanderbilt’s room. Note tapestried walls.

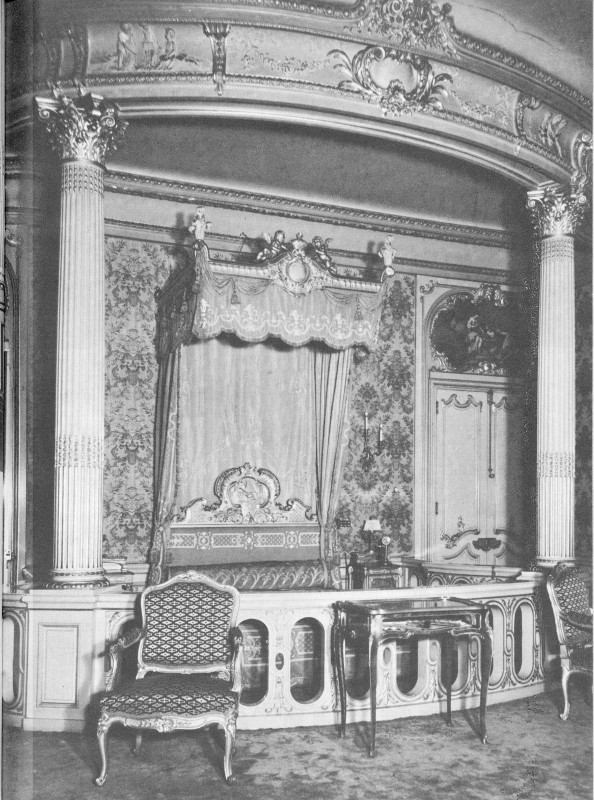

Mrs. Vanderbilt’s bedroom. Courtesy The New York Times Studio.

In this room, as in the Gold Room downstairs, there was an attempt at accurate reproduction. This room, designed by Ogden Codman, is a reproduction of a French queen’s bedroom of the Louis XV period. The bed is surrounded by a rail. (In French practice, courtiers gathered around the rail for morning levees.) The wall at the head of the bed is covered with hand-embroidered silk. Other walls are wood paneled and inset with French paintings. The heavily napped rug was made especially for this room; it weighs 2,300 pounds. Furniture is French 18th-century. Created by Paul Sormani, it is modeled on Louis XV period pieces. A curio case in front of the bedrail contains French fans and inside the rail is a prayer table and kneeling cushion.

Mrs. Vanderbilt’s bed.

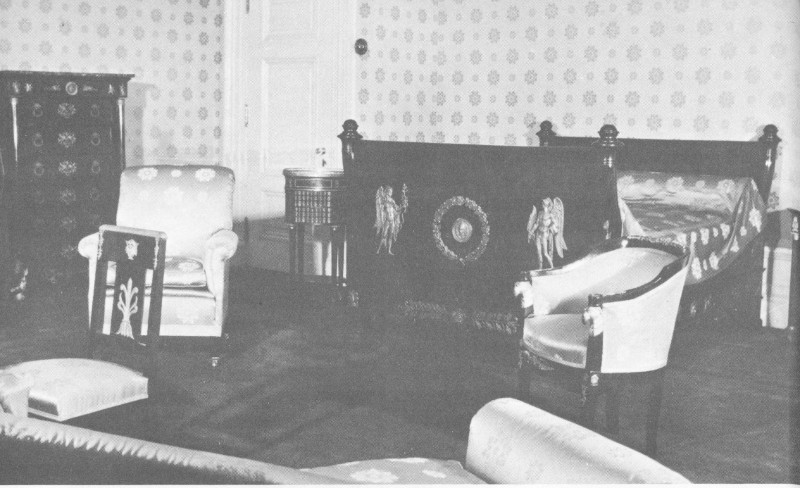

Empire room.

Adjoining the bedroom is the boudoir, furnished in the same motif. Notable pieces include a Dresden chandelier-and-candelabra set.

The third floor, which is closed to visitors, is divided into two sections; one contains five more guestrooms, and the other the servants’ quarters. The third floor guestrooms are as elaborate as any on the second floor and consist of the Pink Room, with white painted furniture—often used by Frederick Vanderbilt in the winter; the Little Mauve Room, furnished with oak furniture; the Empire Room, with French Empire period furniture and satin-covered walls to match the covering on the furniture and bed; and the White Room, with white furniture, drapes, and upholstery.

Female employees of the mansion were quartered in the servants’ rooms on the third floor. In addition to the housekeeper’s suite of two rooms, there were single rooms for seven maids, two cooks, and a kitchen girl, and a room for sewing and pressing. The maids’ rooms are, of course, simpler in decoration and furnishings than the guestrooms.

When the nine guestrooms in the mansion could not accommodate everyone present, the pavilion was used as a guesthouse.

The basement contains the rooms that were used by male employees of the mansion. There were single rooms for the three butlers, a room for visiting valets, and a room for the day and night men. In addition there were four storage rooms, two laundry rooms, a pressing room, a wine cellar, and an ice room. The kitchen was located under the dining room. Food prepared here was lifted via a large dumbwaiter to the butler’s pantry on the first floor, then carried from there into the dining room, where it was served. The servants’ hall, used as a recreation and dining room by the servants, was also located in the basement.

For almost two centuries these grounds have been part of country estates owned by influential and wealthy men. The magnificent specimen trees which they planted here may be ranked as a feature of interest second only to the mansion itself. Approximately two score species and varieties are represented, many of them from Europe and Asia.

Trees of foreign origin include European ash, European beech, English elm, Norway spruce, Norway maple, the red-leaved Japanese maple, and a ginkgo, or Chinese maidenhair-tree. This ginkgo is among the largest of that species in the United States.

Among the native American trees represented are sugar maple, flowering dogwood, eastern hemlock, Kentucky coffeetree, white oak, black oak, eastern white pine, and blue spruce. Other fine examples of their kind include large beeches, bur oak, and a great cucumber magnolia. Many of these trees are labeled.

Designed by McKim, Mead, and White, this building was erected by Norcross Brothers in 66 working days, September 8 to November 24, 1895, on the site of the old Langdon carriage house. Cost of the structure probably exceeded $50,000. The pavilion was used by the Vanderbilts during the construction and furnishing of the mansion, and, later, on weekends in the winter season when they came to Hyde Park for winter sports. The pavilion was also used to house the overflow of guests from the mansion.

The pavilion represents an adaption of classic Greek architecture. Certain liberties have been taken in the interest of functional arrangement, such as the placement of window openings and modifications necessary for the captain’s walk on the roof. The result is a pleasing combination of classic form and informal detail.

Ginkgo, or Chinese maidenhair-tree.

These two buildings, located south of the mansion, are the only structures on the estate that antedate the Vanderbilt era. Walter Langdon had them built in 1875 according to the design of John H. Sturgis and Charles Brigham, architects of Boston, Mass. Neither building is open to the public.

These gardens, which lay south of the mansion, may possibly date back as far as Dr. Samuel Bard’s era in 1795. They certainly existed in 1830 as a part of Dr. David Hosack’s estate, and the later owner, Walter Langdon, continued to maintain them. Landscape architect James L. Greenleaf radically revised and enlarged the gardens in 1902-3 for Frederick Vanderbilt.

The gardens thus represent several periods of development. They were divided into three units: The greenhouse gardens, the cherry walk and pool gardens, and the rose garden. The first of these consisted of three separate parterre gardens within a rectangle framed 47 on the west by the rose and palm houses and on the north by the toolhouse, carnation house, and gardener’s cottage. The cherry walk and pool gardens were located east of this group at a lower level, and progressed from the pergola to the garden house. The rose garden, still further east, had two terraces and contained panel beds.

The land north of the pavilion was added to the estate in 1905. From the north drive are unsurpassed views of the Hudson, the Shawangunk Range to the west, and the Catskill Mountains to the north. The north gate was erected in 1906. Directly opposite, on the east side of the Albany Post Road, are the Vanderbilt barns, built in 1901. This part of the estate is now in private ownership.

These structures date from 1898 and again represent the combination of McKim, Mead, and White-Norcross Brothers. The gatehouse is still used as a residence and is closed to the public.

Main gatehouse.

This bridge over Crum Elbow Creek was designed and constructed in 1897 by the New York City engineering firm 48 of W. T. Hiscox and Company. A Melan arch bridge, it was one of the first steel and concrete bridges in the United States.

River gatehouse.

The carriage road and Crum Elbow Creek proceed southward, ending near the Hyde Park railroad station at the Hudson River. Near this point is the river gate and gate lodge. These were designed by McKim, Mead, and White, and constructed by Norcross Brothers in 1898. The gatehouse is still used as a residence and is closed to the public.

Located on the river hill, a short distance east (or above) the river gate, is the coach house. It was designed by the New York City architect, R. H. Robertson, and erected by Norcross Brothers in 1897. In 1910, R. H. Robertson altered the coach house so it could also be used as a garage.

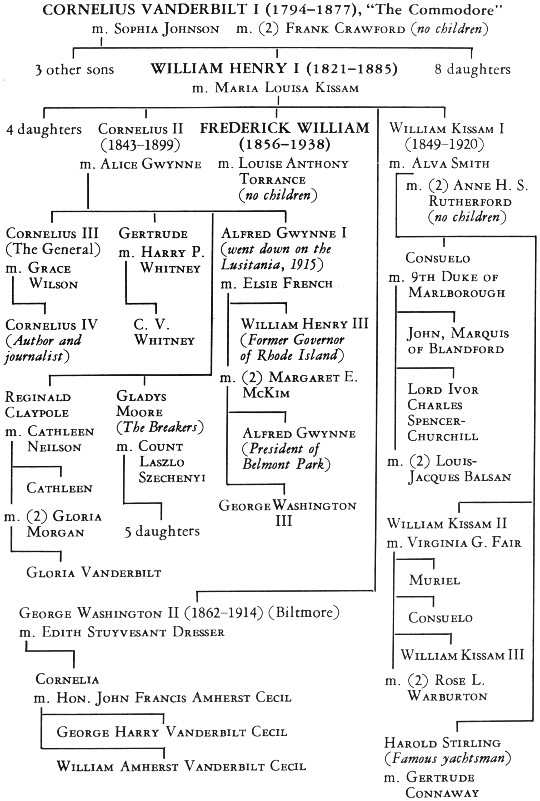

THE VANDERBILT FAMILY TREE

(Based on Andrews, Vanderbilt Legend, p. 79)

Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site is on the New York-Albany Post Road, U.S. 9, at the northern edge of Hyde Park, N.Y., about 6 miles north of Poughkeepsie, N.Y. From New York City, 82 miles away, you can reach it most conveniently by automobile over the Hendrick Hudson Parkway, the Saw Mill River Parkway, the Taconic State Parkway, U.S. 55, and U.S. 9. Approaches from the New York State Throughway and U.S. 9W on the west side of the Hudson River are by the Mid-Hudson Bridge at Poughkeepsie, the Rip Van Winkle Bridge at Catskill, or the Kingston-Rhinecliff Bridge at Kingston.

You enter the grounds by the main gate on U.S. 9, just north of the village of Hyde Park. You leave the site by the north drive and gate on U.S. 9, near St. James Church. The exit drive affords fine views of the Hudson River and the mountains to the west.

The grounds are open every day from 9 a.m. until dark. You are welcome to spend as much time as you wish viewing them.

The mansion is open every day during the summer, June 15 through Labor Day. It is closed Mondays at other seasons, and on Christmas Day. Visiting hours are from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. The nominal admission charge to the mansion does not apply to children under 12, nor to groups of elementary and high school children, regardless of age, and accompanying adults who assume responsibility for their safety and orderly conduct.

A self-guided tour system enables you to begin your tour of the mansion immediately upon arrival. Special guide service for groups may be arranged in advance through the superintendent.

There are no accommodations for picnicking or dining at the site. These services are available in the village of Hyde Park and at Norrie State Park, 4 miles north. Overnight accommodations are available in the village.

The Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site, administered jointly with this site, is 2 miles south of the village of Hyde Park on U.S. 9. It is open at the same times as Vanderbilt Mansion.

View from west lawn across the Hudson.

When Frederick W. Vanderbilt died in 1938, the Hyde Park estate was bequeathed to Mrs. James Van Alen, a niece of Mrs. Vanderbilt. Two years later, Mrs. Van Alen gave the estate to the Federal Government, and on December 18, 1940, it was designated a National Historic Site. Since that time it has been administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior.

A superintendent, whose address is Hyde Park, N.Y., is in immediate charge. His offices are in the pavilion.

Andrews, Wayne, The Vanderbilt Legend: The Story of the Vanderbilt Family, 1794-1940. Harcourt, Brace and Co., New York, 1941.

Croffut, W. A., The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune. Belford Clarke and Co., Chicago, 1886.

Lane, Wheaton J., Commodore Vanderbilt: An Epic of the Steam Age. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1942.

Langstaff, John Brett, Doctor Bard of Hyde Park: The Famous Physician of Revolutionary Times, The Man Who Saved Washington’s Life. E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., New York, 1942.

Holbrook, Stewart, Age of the Moguls. Doubleday and Co., Garden City, N.Y., 1953.

U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1973 O-517-151

FOR SALE BY THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS, U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON 25, D.C.