Title: Harper's Round Table, November 24, 1896

Author: Various

Release date: July 24, 2019 [eBook #59976]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

Copyright, 1896, by Harper & Brothers. All Rights Reserved.

| published weekly. | NEW YORK, TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1896. | five cents a copy. |

| vol. xviii.—no. 891. | two dollars a year. |

The Editor of the Round Table has asked me to relate some incident of my life which may be of interest to its readers. Will they permit me to tell them that episode in my life which gives me, when I recall it, the greatest pleasure?

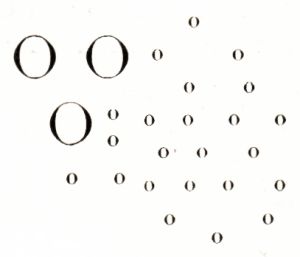

It is the old story of the pebble and the ever-widening circle in the water.

Do you remember how all through the autumn of 1893 there appeared in corners of newspapers, in telegraphic columns, then in editorial "briefs," sinister allusions to the total failure of the Russian crops and the menace of a famine? Do you remember how the dreary paragraphs expanded; how the menace became ghastly reality; how we grew to find, every morning, as we sat down to our bountiful American breakfasts, woful tales how men and women were dying of starvation fever, and little children turned wailing away from the horrible bread of weeds and refuse? I read as others read. And I read also of the titanic efforts of the Russian government and the wonderful generosity of the Russian people in that year of disaster. I experienced the momentary shudder of pity and horror that such tales excite, and, like other people, I thought "Somebody ought to do something"; and then pushed the hideous picture into the background of my mind.

One night Mr. Arthur M. Judy, the pastor of the Unitarian Church in Davenport, dined with us. The talk drifted to the famine in Russia. I told how a friend who had[Pg 74] passed through Russia in August described the look of the ruined wheat-fields and the sadness already settling over the villages.

"We ought to do something for those people," said he. "They came to our rescue during the civil war; they have always been friendly with us; we ought not to stand by idle now. We ought to do something, right here in Iowa."

We all agreed that it would be a good thing, but there was no definite plan proposed. Only later in the evening, as my mother, my sister, and I sat together before the fire, we talked of those starving people until it was uncomfortable. I found it hard to push the pictures of agony and death and piteous self-sacrifice into the background of my mind.

You perceive that the pebble had been thrown into the water.

Sunday, not long afterwards, we were having a little family dinner party, our own and my two brothers' families, and my elder brother's wife spoke of the famine. She is of English-Irish descent, and much of her life has been spent across the water. She has met many Russians, and she surprised us all by the intensity of her realization of the horrors of famine. Yet possibly it is not so strange. Early in the century her ancestors mortgaged their estates to fight the great Irish famine.

"It is horrible!" cried she; "and we sit here, while they are dying, eating and drinking. We talk of somebody doing something! Why don't we do something?"

"That's right," said my younger brother, cheerfully turning on me. "Sissy, why don't you do something?"

"I will," I answered, meekly; "I will go down to the Democrat office and ask Mr. Tillinghast to do something!"

Then we all laughed; but presently we were discussing the best manner in which to effect our purpose. The Democrat is the leading journal of our town, owned by Mr. D. N. Richardson, author of a delightful book of travels which ought to be on every round table, and his brother, J. J. Richardson, for many years the Iowa National Committeeman. Mr. Richardson and Mr. Tillinghast were the editors, Mr. Richardson being what one may call the consulting editor, and Mr. Tillinghast the active editor. Mr. Calkins, the new city editor, I had occasion to know later. I went to the Democrat. I stated our case.

I can see the editor now, his slender figure turning quickly in his chair as he threw his arm over the back of it, his dark eyes kindling, and his black brows meeting in a little frown of concentrated thought; and I can hear his leisurely, distinct tones as he spoke:

"I like the idea. I like it very much. But—you know there are difficulties. In the first place, we must discover whether the Russian government will accept our offering. We don't want to be lacking in courtesy any more than in generosity. In the second place, there are so many prejudices and so many falsehoods circulating about Russia that we want to select some channel of distribution which will be above suspicion."

"George thinks that the Red Cross and Clara Barton would satisfy every one."

"They would; and she is in Washington, where she can consult the Russian legation."

"And George says he will go with you any day this week to stir up Governor Boies to issue a proclamation and name a committee."

Thus lightly we entered on a work that was to absorb most of our time, our energies, and our hearts for the next three months.

The Governor was found already interested. His proclamation was issued immediately. Like all the Governor's state papers, it was dignified and to the point, but it contained in its brief lines a touch of pathos which is not often seen in state documents. Eleven of the most prominent citizens of the State were named as the Russian Famine Committee, the chairman being the Hon. Hiram Wheeler, Republican candidate for Governor in the campaign which had elected Mr. Boies. Mr. B. F. Tillinghast was named as secretary, and the Auditor of the State as treasurer. And it may be said here that upon the secretary and the treasurer fell the burden and the heat of the work of organizing an immense undertaking. Mr. Tillinghast, in especial, gave up almost his entire time, night and day, the owners of the Democrat loyally backing him up, and contributing not only the columns of the paper, but generous gifts of money and their own time. The first work was to organize enthusiasm—to spread the circle wider and wider. "First we must get the committee red hot, then they must get their committees red hot, and the press must keep up the fire," said Mr. Tillinghast. The press all over the State nobly responded, publishing anything bearing on the famine which the Famine Committee would furnish. Mr. Tillinghast every day culled from exchanges, American and foreign, from private letters and public letters, what seemed best calculated to rouse the public feeling. It was in itself an immense work. He, with his staff, was an entire literary bureau; but this was only a fraction of his work. He and a few others of us who were interested corresponded with hundreds of people, with the officers of the Red Cross, with Colonel Murphy and Buchanan and other corn experts (we had decided that our gift should be corn, and events proved the wisdom of our decision), with people in our own country, with the workers in Russia. Thousands of copies of the proclamation of the Famine Committee were printed, and thousands more slips of extracts from testimony from authentic sources regarding the sufferings of the peasants and the heroic relief-work of their country-men were also made ready. Almost the entire work of their selection and preparation was done by Mr. Tillinghast. At the same time he was holding in his hand all the reins of the different forces.

I remember that, accidentally, the "Horrors," as we used to call them, were printed on colored paper—red, orange, and blue. To our surprise, we found that the colors attracted so much attention that what began by accident continued by design. One of our best sources of information was the Northwestern Miller, which was advocating the sending of a cargo of wheat flour by the millers of the country. The generous millers raised the ship load, and Mr. Edgar, of the Northwestern Miller, accompanied it to Europe. He was thanked in person, for the evidence of friendship, by the Czarowitz, the present Czar.

Every Sunday night Mr. Tillinghast would come to my mother's house, the telephone would summon my two brothers and their wives, and a council of war would be held on the week's progress and the plans for the next week.

It was immediately after the meeting of the Famine Committee that my own mere active part in the work began. Mr. Tillinghast had reported the plan of campaign. He added: "Yes, the prospect is good. I think we can easily raise a train of corn. But I am more ambitious; I want to send a ship-load; and I think to do it we need to—interest the women." The women present said very little; but after he was gone, in the fashion of women, we "talked it over."

And that was the pebble that is responsible for the Iowa Women's Auxiliary to the Red Cross. First, I wrote to prominent women in society and in philanthropy all over the State, proposing the plan of an organization of women who should sign a pledge. The pledge is before me; it binds the subscriber to

Obey her superior officers.

Inform herself so far as in her power regarding the famine.

Influence her friends in favor of the objects of the Auxiliary, so far as in her lies.

Aid in any effort made by the Auxiliary to raise money for the Russian Famine Committee, by public entertainments.

The badge was a red cross on black satin ribbon, with the letters I.W.A. in gold above the cross. The officers generally decked the satin with gold fringe, and pinned a knot of ribbon in the Russian colors above. The admission fee was ten cents, which included the badge. Yet this sum more than paid all our expenses, principally because every member among the officers paid her own expenses. Never, perhaps, was a large charitable undertaking run more cheaply. All the committees worked for nothing, at their own charges; the railways donated passes, the telegraph companies donated their wires for the work, the newspapers[Pg 75] opened their columns, several owners of theatres and public halls offered them free for our entertainments in aid of the fund, the underwriters made a present of their charges, the very laborers who packed the cargo gave their labor. Two weeks sufficed to organize, to have lists signed all over the State petitioning the Governor to name a committee; and before three weeks had passed, the committee had met in Des Moines. The chairman was Mrs. William Larrabee, wife of ex-Governor Larrabee; and I took the position of secretary.

The members of the Central Committee were chosen as representing Congressional districts, that being the basis of representation in the Russian Famine Committee. They were Mrs. Francis Ketcham, Mrs. Charles Ashmead Schaeffer, Mrs. Matthew Parrott, Mrs. John F. Duncombe, Mrs. Ella Hamilton Durley, Mrs. Albert Swalm, Mrs. J. B. Harsh, Mrs. George West, Mrs. J. T. Stoneman, Mrs. Julian Phelps. We considered the officers of the Russian Famine Committee as our superior officers, and all moneys were turned in to them.

Miss Barton advised with us, and it was through her personal efforts that the ship that carried our corn was secured. The weeks that followed I have not the space to describe.

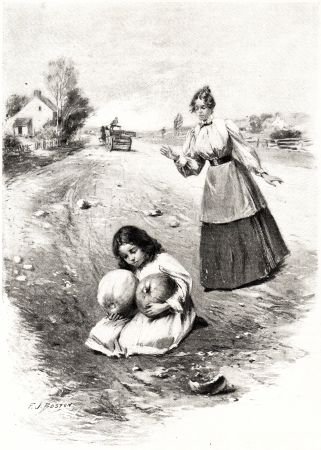

The president and secretary travelled among the districts; each district chairman travelled in her own district, organizing subcommittees and reporting to the secretary, who reported to the chairman. We held meetings in libraries and club-rooms and hotel parlors. There was always the same result; the simple recital of the misery, which we grew daily to feel more acutely the harder we worked to help it, was enough to stir the generous Western heart. Workers rose up all about us. They, in turn, inspired others. One old lady, enfeebled by rheumatism, a farmer's widow, wrote me for information, and carried the red and yellow slips which I sent her around among her neighbors, reading them, and collecting money. She raised $17. Sometimes, she said, it was hard for her to climb in and out of the wagon; but she thought of the poor starving creatures, and that gave her strength.

Two Swedish servant-girls added almost a hundred members to the Auxiliary by their own efforts. One of our most effective appeals was to tell (quoting our Russian informants) that a man or woman could be fed from then to the next harvest for the sum of $2.80. It seemed incredible, but Tolstoi and several others were our informants, and our Red Cross men later verified the statement. We used to say, "Will you not ask your friends to join with you and save one Russian life?" A poor seamstress came to one district chairman and offered her some money ($1.75), saying, "I can't save a grown-up Russian, but maybe this will save some child."

We raised money by different devices. Charity balls were given, and Russian receptions, and kind-hearted musicians sang. The opera of the Mikado, given in Davenport, helped our fund by over $800. There were other unions of the appeal to the sense of humanity and the appetite for amusement, but in general we simply asked for money in an honest, direct way, and it was given to us.

In the cities and towns we asked for money with which to buy corn; in the country we asked for corn itself. Mrs. Duncombe and Mrs. Ketcham sent out wagon solicitors, who drove from farm to farm. The Iowa farmers are very generous, and the wagons were heaped long before the circuit could be completed. The result of the united efforts of men and women was the largest ship-load of corn that ever sailed from our shores.

It is not only the result of our labors which makes the memory of that hard-working, anxious time precious; it is, most of all, the revelation that came to me, day after day, of the noble qualities of mine own people. I remember how, in one of the counties, a hail-storm had pelted the corn-fields and laid waste the harvest. We were questioning whether, at the same time that we were asking aid for others, we should ask for our own sufferers, when one of the chairmen received a letter from Adair, saying: "We're all right; we don't want anything. What are you thinking about? We've collected a car-load of corn for the Russians. Where shall we send it?"

And I remember very tenderly how the committees of women worked. Their tact, their enthusiasm, their unselfish loyalty, will always rise before me as I think of that time. And their virtues of omission were as shining as those of commission. We had our difficulties, our disappointments; we were harassed and discouraged, and a few times despairing; but in all that time, during which I had hundreds of letters and scores of meetings and innumerable private consultations with my comrades, I am not haunted by the humiliating spectre of even a single squabble. Nor did any of the chairmen report such a thing out of her own experience. Yet, for the credit of the sex, I would not wish to think that one of the husbands was right when he said: "You've broken the world's record. You haven't had a racket!"

But now is it not easy to understand why, of the experiences of my life, this is the one that is the jewel of my memory? And it is the old story of the pebble and the circle in the water.

There are a great many advantages in being born an American citizen. One can hope to become President of the United States and various other high and mighty things; but, after all, the greatest privilege is in being born among a people who are free from foolish superstitions. Suppose you had been born on the Congo River, for instance. How would you like that when you consider some of their beliefs? It is told by persons supposed to be well informed that the people inhabiting the district round the Congo River share with the Ashantees, of whom we have recently heard such a lot, the belief that if their high priest, the Chitome, were to die a natural death the whole world would follow suit at once, and would dissolve into air, for it is, according to them, only held together by his personal will.

Accordingly, when the pontiff falls ill, and the illness is serious enough to make a fatal termination probable, a successor is nominated, and he, so soon as he is consecrated, enters the high priest's hut and clubs him or strangles him to death. A somewhat similar custom obtains in Unyore when the King falls seriously ill, and seems likely to die, for his wives to kill him. The same rule is followed if he gets beyond a certain age, for an old Unyore prophecy states that the throne will pass away from the family in the event of the King dying a natural death.

"Look here! look here!" and mischievous Penelope rustled a handful of bank-bills before her mother, and the next second raised them above her head and waltzed around the room.

"What ails you, child, and where did you get that money?" was the ready inquiry, while Mrs. Thayer's admiring eyes followed her daughter's graceful, swift-moving figure.

All of a sudden Penelope's rosy face, flushed with exercise and radiant with happiness, burst into a merry laugh—one of the laughs that ripple all through the atmosphere, and prove so contagious that everybody within hearing of it laughs also.

Then stopping just before her mother, and again rustling the crisp bills, for they were bran-new, she this time teasingly said, "Guess."

"But I cannot."

"Well, then," and dragging a chair so as to be opposite[Pg 76] both her mother and Cousin Blanche—this cousin has been a young lady for over ten years, and makes her home with them—Penelope sat herself down, and with the tantalizing manner that she could assume on occasions, slowly counted, "One—two—three—four—five," and so on, laying one five-dollar bill over the other while doing so, until they numbered ten. Then satisfactorily surveying the pile before her, she raised her eyes, and looking full into the earnest faces of her listeners, exclaimed, with a wave of her hand in the money direction, "All mine!"

"You tantalizing, tormenting—" and Penelope's mother, trying to look severe, rose, and threw on the blazing log fire a paper which, until her daughter's entrance, she had been reading, and then with a swift backward turn of her head she concluded, "mischievous girl."

Mrs. Thayer was rarely known to have administered anything but caresses on any of her children, much less to her only daughter and youngest child. "Mother's pet," the boys called her, but people called her everybody's pet, for from her youngest brother to her eldest, and she had five of them, their first question was, "Where's Penelope?"

Therefore Mrs. Thayer was not at all surprised when her daughter finally told her that the money was a present from Uncle Dan. Uncle Dan was Mrs. Thayer's bachelor brother, and lived with them off and on, and Penelope farther explained, while delight streamed from every feature of her mobile face, "that uncle had given her the money to spend on a party"; and having told her story, she raised her gray-blue honest eyes to her mother, and asked,

"I could give a party for fifty dollars, couldn't I?"

"Of course you can! the loveliest sort of a party, too," was the assuring answer. Then, as that matter was arranged, Mrs. Thayer turned towards Blanche, who was quietly watching the interview but saying not a word. "Have you any scheme to suggest?" But before Blanche had an opportunity to reply Mrs. Thayer interjected, suddenly rising to give her dress a fresh smooth out, "Penelope, how would you like to give the party on your birthday?"

"I'd love to, mother," and very rapidly her little hands were clasped together while she added, "May I?"

"I don't see why not; your birthday is—let me count—just three weeks hence;" and with the most satisfied air Mrs. Thayer exclaimed, "Plenty of time. But run away now, dear, for we want to plan your party when you're not around."

And after a slight demur, for Penelope was thirteen years old and thought she should be taken into the consultation, she rose and gayly tripped out of the room.

"Now, Blanche," and Mrs. Thayer wheeled about to face her.

"You amuse me. What should I know about children's entertainments?"

"You're the very one that does know. Haven't you been all over the world nearly? Of course you know."

"Well, how do you think Penelope would enjoy a Delft party?"

Shaking her head slowly, Mrs. Thayer replied, "I never heard of one."

"Nor have I, and I am astonished that it has not been introduced long ago. As New York was settled by the Dutch, a Delft party could partake of the real Knickerbocker flavor—none of the sham kind;" and with this last word Cousin Blanche rose and walked nearer to the fire, adding, with a slight shiver, that she was cold.

Mrs. Thayer thereupon rang for the maid, who received orders to bring more wood, and as the fire crackled and blazed, Cousin Blanche talked steadily.

"Of course the word Delft suggests Holland, and we right away think of the large windmills everywhere visible. Some of these are built of stone, others of brick, and still others of wood. Many of them are thatched. Now my idea would be for the boys—Penelope's brothers, I mean—to form a tableau in which they would build windmills. The windmills could be cut out of card-board and pasted together. They could be painted to represent stone or brick. Ordinary straw could be used for thatching, and two or more of the boys might be putting the straw on. These windmills should be stood back of that large screen at the north end of the parlor before the children arrive."

"Then you wouldn't use a curtain?"

"No; we could arrange all the tableaux back of the screen, and so save a great deal of annoyance."

"How many tableaux do you think would be nice?"

"Three or four." And Cousin Blanche thoughtfully continued: "I would show only those that are thoroughly indicative of our Holland Dutch ancestors." And Blanche scrutinized Mrs. Thayer's face while she concluded, "Entertainment is always better when it is instructive."

"But I'm afraid"—and Mrs. Thayer acted fearful while she explained—"that the tableaux would be a terrible trouble."

"On the contrary, nothing could be easier;" and with a good-natured smile rippling over her face, Blanche continued, "Why not let me help you?"

"Help me? I expected you would. Why, Blanche!" and the forlorn tone of Mrs. Thayer's voice decided matters.

"I am thinking"—and Cousin Blanche's face was very bright, showing that her thought was satisfactory—"that it would be a good idea to show the tulip craze. This tableau would require girls and boys. Penelope could be one of the girls, and Fannie and Julia Mobray the others."

"They are quite getatable."

"That was my reason in selecting them. Living across the street as they do, they could easily run over for rehearsals."

"I did not know that the Hollanders were interested in tulips especially," Mrs. Thayer responded, slowly, and lifting her eyes so that they met the astonished ones of Cousin Blanche.

"Why," and without waiting for an explanation Cousin Blanche continued, "you've forgotten about it. The Hollanders spent immense sums of money in ornamenting their gardens with tulips; every new variety of the flower was sought for. They were produced in various shapes and unexpected colors. Indeed, a new color meant a fortune."

"Oh!" and Mrs. Thayer seemed greatly surprised. "But how would you show it?"

"I would group the children so that they looked pretty. They could wear green clothes to represent stalk and leaves, and have large colored-paper petals fastened to their waists, and with wire shaped and bent upward they[Pg 77] would look like veritable tulips. Then a few others could, in a previous tableau, show the act of planting tulip bulbs and watering some growing tulips."

"Suppose that you cannot get the tulips?"

"I can get tulips of some sort," was the assured response. "If I cannot buy natural ones, I can make paper ones."

Mrs. Thayer looked pleased, and then a pink flush suffused her face, while she replied, "I cannot frighten you, can I?"

"Not this time. Indeed, no one can afford to quietly accept things when arranging entertainments;" and Blanche rose and paced several times up and down the room. While she walked she added: "As for the other tableaux, one should certainly show a group of girls knitting and crocheting, and others painting pottery, tiles, etc. And then there should be a representation of storks and their nests."

"How would you get a stork?"

"Borrow one from a museum, if there is no other way. But I have friends who have fine specimens of storks, and stork nests also."

"Well, but what about the rest of the party?" And with a swift glance at her watch, Mrs. Thayer added, "I have an engagement."

"Delft games should be played. For example:

"Select a boy and hand him a knotted handkerchief. He must throw the handkerchief at a player, and before he can count aloud five the person to whom it is thrown must mention a round thing, such as an apple, a globe. If that person fails, he must change places with the one who has caught him, and throw the handkerchief at another. As no repetitions are allowed, it will soon be difficult to find an object that is round.

"Every player is seated. Turn to the person at your right, and ask, 'Will you come to breakfast?' To which the answer is, 'Yes.' When that question and answer have gone around the room, the first one must ask, 'What would you like for breakfast?' Perhaps the reply would be, 'Milk'; and he then puts the question to his right-hand neighbor, who perhaps would say, 'Oatmeal,' and so on, until no sensible answer can be made, for no repetitions can occur in this game, also. As the different players fail to respond they must stand.

"Give any letter of the alphabet—for example, S—to the company, also some paper and pencils. In five minutes' time they should write the names of three celebrated men, and also three sensible sentences, one for each man's name, as Shakespeare was born in Stratford on the Avon. Forfeits are required for failures.

"The games may be interspersed or followed by dances, and also by vocal or instrumental music."

"As you describe it, Blanche, I'm afraid the children wouldn't get home until morning."

"I am sure they will not want to. And, besides, it will be such a pretty party."

"That is so; but you haven't suggested any decorations."

"No, nor told you what you are to wear."

"I to wear?" and Mrs. Thayer almost screamed the words.

"Why, the party wouldn't be anywhere without costumes. You must"—and Blanche met Mrs. Thayer's face smilingly—"look over some Dutch portraits or photographs and decide which you will copy. Besides, you must wear a gown of Delft blue, as, indeed, I must also. And all the girls must wear Delft-blue colored frocks, and fashion them as closely as possible after the style of the young Dutch girls. Their hair should be worn flowing, and tied by the same colored ribbon, or worn in braids down their backs; and the boys must get the color in too some way; of course they could all wear Delft scarfs. And all the decorations should be of the same blue shade. That can readily be arranged by draperies and crêpe paper. And don't forget to have the caterer serve all confections and ices in form of dikes, windmills, ships, storks, etc. Indeed, we must have everything as Delft as possible."

When Penelope heard the scheme she could scarcely wait for her birthday night to come. But the days passed rapidly, after all, because everybody was very busy, and the night of all nights arrived at last.

And Uncle Dan, who did not enter the parlor until the games were in progress, exclaimed in amazement, as he turned towards Penelope,

"Well, if it be I, as I suppose it be,

I have a little dog at home, and he knows me."

And drawing his hand across his forehead in a dazed sort of way, he inquired: "Am I dreaming, child? I thought I was in America, but it seems I am in Holland, or perhaps time has gone backward, and it's the old Knickerbocker period."

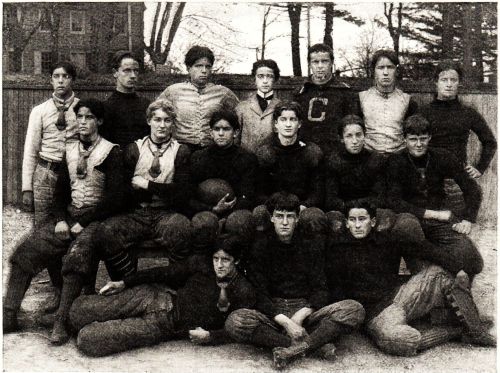

"It's outrageous!" said the pater, banging his fist down on the breakfast table in a way that made the mater, accustomed as she was to his ways, jump in spite of herself. "So that's the reason the young rascal's not going to be with us to-morrow until late in the evening. Listen to this;" and the pater began indignantly to read an extract from the morning paper:

"'An important change has been effected in the makeup of the Yale eleven. Teddie Larned, '99, has recently made such a fine showing at full-back that he will fill that position in the championship game against Princeton on Thanksgiving day. His punting and line-breaking are phenomenally good.'

"That's what I was afraid of when I sent him to college," continued the pater, solemnly, as he folded up the paper. "Football's a rough, brutal game, and those that play it become rough and brutal, when they don't injure themselves for life, as most of 'em do. I wouldn't have one of those young savages in my house. I'll just go up to that game early to-morrow afternoon," he went on, "and bring Teddie home with me. They'll have to get somebody else to fill his place in spite of his being such a phenomenal—er—line-smasher—whatever that is."

"Don't be too hasty," advised the mater, in whom Teddie, knowing his father's violent aversion to athletics, had confided. "This game means a great deal to our boy."

"Nonsense!" snorted Mr. Larned, indignantly; "it's nothing but a silly school-boy affair anyway. I'm astonished that grown men waste their time encouraging such things by going."

Long before the elevated train had reached Harlem it was packed and jammed to the doors with lusty college boys, pretty girls, and sedate heads of families, among whom Mr. Larned saw with astonishment many men of note. All were wearing college colors, all were filled with a delightful, suppressed excitement. Involuntarily the pater began to feel the contagion. But everybody was talking football, and their language sounded strangely to his ears.

"They say that Larned's a regular find for Yale," remarked a chrysanthemum-headed youth to his friend hanging to a strap beside him. "He kicked a goal from the field last week, when he was playing on the scrub, from the forty-five-yard line. You ought to see him buck a line!"

Teddie's name was on every one's lips, and the pater began, in spite of himself, to feel proud of his son, and to have a sneaking desire to see some of those accomplishments of his that other people seemed to know so much about.

Fighting his way through the crush at the gate, Mr. Larned finally found himself inside, albeit in a decidedly dishevelled condition. An official with a long flowing badge directed him to the training-quarters where the Yale team was reposing during the last hour before the game. At the door the pater was confronted by Mike, the grizzled old trainer.

"Of course Mr. Larned's here," he responded, surprisedly, to the former's inquiry, "but he can't see anybody just now."

"Tell him that his father wishes to speak with him at once," said the pater, authoritatively.

The trainer's manner became more respectful. "I'm very sorry, Mr. Larned," he said, firmly, "but the team can see no one before the game. The coachers are giving them a last talk now."

"Do you mean to tell me," the pater demanded, hotly, "that I can't see my own son?"

"Exactly, sir," replied the trainer, inexorably. "Just at present he's the full-back on the Yale eleven, and nothing else goes. And now, Mr. Larned, I'll write you out a pass to the grand stand, and then I must run back to the boys. After the game you can see your son aplenty—if there's anything left of him." And with this cheering suggestion, Mike scribbled a few words on a card, which he handed to Mr. Larned, and retired.

The latter stood speechless for a moment. That a power on the Street, a man whose name was among the great ones of Manhattan, should be treated thus cavalierly, and that by a hired trainer—

"Why, it's preposterous!" exclaimed the pater to himself; nor was his ruffled self-esteem soothed when he read the scrawl on the card: "This is Teddie Larned's father. He wants to see the game. Mike."

But then it proved an "open sesame," and the ushers, after reading the magic words, received him with the most marked attention, passed him along through the crowds of ordinary people who were not fathers to famous full-backs, and finally seated him in a front box which was specially reserved for the parents of the players—though Mr. Larned did not know this.

Next to him was seated a tall, ruddy-faced man, wearing the slouch hat which the old generation of Westerners still cling to. He was beaming with jollity, and joined a deep bass to some of the college songs that Yale voices were chanting all around him.

"Well, to-day's the day we watch the youngsters distinguish themselves," he remarked, cheerily, to Mr. Larned, during a lull in the cheering that was surging up and down the grand stand.

But before the pater could rebuff this friendly overture, as in his present state of mind he felt inclined to, a roar of cheers swept up and down the field, and the speaker sprang to his feet, waving his slouch hat frantically. Out on the brownish-green field trotted eleven shock-headed youths clad in dirty, heavily padded mole-skins, cleated shoes, and canvas jackets, frayed and torn, but each with the great varsity "Y" on its breast. An oval brown ball was hurled and caught with, what seemed to the pater's inexperienced eye, wonderful swiftness, and then as the ball rolled along the ground each man took his turn, as it came near, in sprawling down on it in a most comical manner. Suddenly it was passed nearly thirty yards, straight as an arrow into the arms of a short, chunky youngster, with an extremely dirty face, who seemed carved out of a solid block. With almost a single movement—so deftly was it done—the ball was caught and poised in both hands for the tiniest fraction of a second. Then came a hollow thump as the dropped oval was punted. Up, and up, and out in a tremendous parabola, almost the length of the field it soared. "AA! AA!" howled the Yale tiers. "Get on to that punt! What's the matter with Teddie Larned?"

The pater stared, at first incredulously, but sure enough that marvellous kicker was his own son Teddie, though disguised by the grime, the pads, and the tangled hair.

It must have been the excitement around him which made the pater stand up and watch with all his eyes every sky-scraping punt that the dirty-faced boy continued to make, and by a mere accident all at once he found himself saying "AA!" as loudly as any one before he had been on his feet a minute.

His companion was wild with excitement. "See that big chap?" he exclaimed, pointing out a young giant whose face looked like some monstrous mask, with its huge rubber nose-guard. "That's Bright, the centre rush. Ain't he a corker?"

"Looks too fat," said the pater, critically.

"Too fat, eh?" replied the other, excitedly. "Well, you just watch him play, and see if he's too fat. That little Larned's the one that's too fat. He punts all right, but a full-back ought not to be so round."

"Not at all! Not at all!" hotly responded the pater, who, though he did not know a full-back from a goal-post, was not going to sit by and hear his only son maligned. "A pull-back should always be thickset! They—er—pull better when they're like that. And—that's my son sir!"

The Westerner choked until he was nearly black in the face. "Well, shake, old man, and we'll call it square," he said, finally, when he had recovered breath enough to speak. "Bright happens to be my son, and in spite of their fat I think our two boys won't disgrace us this day—eh?"

And again it must have been the excitement of the game, for the dignified and somewhat exclusive Mr. Larned found himself shaking hands with a total stranger as if he had[Pg 79] been a life-long friend. All his bad temper had disappeared. He was aglow with excitement; the most delightful little thrills ran up and down his back, while an irresistible impulse to shout had taken possession of him.

"This is your first game, isn't it?" Mr. Bright questioned. But just then came another punt, and the pater found it much easier to stand up and yell "AA!" than to answer any such searching questions. Then all further conversation was made impossible by a torrent of cheers from the Princeton tiers, and eleven other men, with the same grimy, weather-beaten costumes, and the same businesslike air of deadly earnestness, spread across the field and went through similar preliminaries. Only their stockings were of a barber-pole pattern, with alternate rings of orange and black instead of a uniform blue, while a large orange "P" blazed on every breast in place of the Y.

And now there was no controlling the audience. Orange and black banners were confronted by yards of Yale blue. Yellow chrysanthemums glared at bunches of violets and bachelor's-buttons, while the wearers—men, women, and children—sent out volleys of cheers that made the grand stand shake. The pater and his newly found friend were on their feet with the rest. Near by was a crowd of Yale "rooters," as Mr. Bright graphically termed them, shouting a rhythmic cheer containing too many x's and other bewildering Greek consonants for the pater, while he invariably added an extra "Rah!" to the regulation cheer. But to his satisfaction he found that not even the deep-voiced Bright could shout "AA!" with more earnest emphasis and volume, and he fell back on that as his strong point.

Suddenly there is silence, a warning whistle blows. Yale has the ball, and the forwards group themselves in a curious zigzag formation, awaiting the kick off.

The short and chunky Teddie takes a run, his foot swings and strikes the ball with what seems hardly more than a gentle touch, but the oval is spinning clear down to the other end of the field, followed by the terrible rush of the whole Yale team. It is caught by a running Princeton man, who, with a swerve of his body, avoids the spring of one runner, hurls another aside with the "straight-arm," and comes tearing down the field like a deer. A tremendous shout from the wearers of the orange and black masses is bitten off with surprising abruptness. For Teddie smashes straight through the interference, and with a lightning-like dive, which there is no evading, tackles the runner just about the knees and hurls him headlong. In a flash the lined-up elevens are facing each other, and the fight is on.

"Too fat, eh? Just look at that!" chuckles Mr. Bright, slapping the erstwhile dignified Mr. Larned ecstatically on the back, as Yale's centre catches his opponent napping, hurls him aside, and downs a runner in his tracks.

Back and forth surges the tide of battle. The elevens are almost evenly matched, and though the ball has been dangerously close to either goal, it has always been kicked or rushed back in time. The pater marvels at Teddie. Where had his boy learned the daring, the coolness, and the self-reliance that characterize him that day? Time after time the Yale backs smash at the Princeton line and fail to make the necessary ground, and the ball is close to the goal, with only the swing of Teddie's right leg to ward off a touch-down. But the boy never falters. Unerringly he catches the ball, and just at the right moment when the rush of the opposing backs is almost upon him, the ball spins far out of danger, and a long-drawn breath of relief comes from the Yale seats. And once when Teddie dives into the line with the ball, and the great seething mass of arms and legs untangles itself, there is one that fails to rise with the rest. The little full-back lies very limp and still, and there is a cry for water, while old Mike rushes from the side-lines with a great blanket flapping in the breeze. The pater's face becomes all of a sudden drawn and white, and he trembles so that the great Westerner drops his arm across his shoulders.

"Steady, old man," he says, soothingly; "the boy's only had the wind pounded out of him. He'll be up and playing in a second." And maybe the two fathers don't join in the tremendous cheer that arises when Teddie trots back to his place—a little unsteadily, to be sure—and the game goes on.

"They're saving him," says Mr. Bright, after watching the play carefully for some time. "He's only been sent against the line three times this half, and now the other backs are doing most of the punting. They'll send him in to save the game in the last ten minutes."

The ball is back almost in the middle of the field again, when suddenly the warning whistle sounds shrilly, and the first half is over. A great buzz goes up from thousands of seats as the spectators discuss the details of the game, and, long before one expects them, the players are trooping back. Hair all adrip from the hurried sponging that the rubbers have given their grimy faces, bodies still atingle from the stinging alcohol rub-downs, with the hoarse, earnest, words of the graduate coachers still ringing in their ears, they line up for the bitter second half. From the start the advantage lies with the orange and black. The weight of their tremendous rush-line begins to make itself felt. Back and forth goes the ball, but—significant fact to the knowing ones—it stays constantly in Yale's territory. For the first time during the afternoon there is a dead silence, and the thud of the players' bodies as a back strikes the rush-line or tries to smash through the interference can be heard, and their sobbing breathing as again and again the confused heap untangles itself. The shrill voices of the quarter-backs as they call out the signal for the next play punctuates every struggle, and now and then one or the other of the Captains claps his muddy hands sharply together with a "Play hard, boys! Hit it up! Now show your sand!"

Above the struggling, changing mass hangs a thin white steam—truly a battle-mist. Finally, towards the end of the half, by a series of short, hard rushes, Princeton is on Yale's 20-yard line. But here the wearers of the blue stand like a stone wall, and, after three vain attempts, the ball goes to Yale on downs. Instantly it is passed back for a punt, and then—no one knows how it happened, perhaps the Yale guard was napping, perhaps the tackle was to blame—straight through the line, between tackle and guard, smashes the great right guard of Princeton and blocks the kick. The ball bounds from his broad chest clear across the line. In a flash one of the Princeton ends has followed, fallen on it, and the score is 4-0 in favor of Princeton. A crumb of comfort is it, but only a crumb to the Yale adherents, who sit gloomy and despondent amid a roaring storm of Princeton cheers, that no goal is kicked.

"Only seven minutes left," exclaims Mr. Bright, despairingly, "and that's not time to do anything against a rush-line like that. But the boys'll die a-trying, anyhow!"

Grim and unyielding the Yale men line up for these last stern minutes. They have failed. No matter the reason, the audience may call it a fluke, a piece of hard luck; but up on the Yale campus it is results that count—not excuses. In their hands is the honor of the college, and but seven minutes remain to wipe off the stain of defeat before thrice ten thousand people. Like a flash the eleven lines up. The battle opens with a last-resort flying-wedge play, too risky to try except at such a desperate time when every chance must be taken. When it is over the blue line is twelve yards nearer the Princeton goal; but two of the precious minutes are gone.

"Five, seven, twenty-nine!" shouts the quarter-back, hoarsely, and the ball goes back to Teddie, and smash he goes into the line. Like a flash the tangled mass dissolves, with the ball six yards nearer the goal. Nothing is harder to stand than the dumb furious rush of a despairing eleven, nerved by the sting of defeat, and seeing a chance to retrieve itself. No end plays now, but straight through the centre they go, and even Princeton's mighty rush-line wavers. Mr. Bright's prediction as to Teddie's having been held in reserve proves a true one. Back into his hands goes the ball for nearly every play, and gallantly that day does he sustain his reputation as the best line-breaker that has ever worn a Y. Sometimes it is a "turtle-back," or one of the huge guards makes a hole for him at the centre, or again, in a tandem play, Teddie follows the smashing rush of the heaviest back. But, whatever the play,[Pg 80] crashing through or even leaping over the opposing line, as they crouch for his approach, pushing, boring, squirming, with the weight of half a dozen men crushing the breath out of him, Teddie always gains ground. Sometimes the gains are small, to be sure, but always enough for Yale to keep the ball. Once there is a line-up by the side-line close to where the two fathers sit, and Mr. Larned looks down into Teddie's face scarce ten yards away. It shows very white now underneath the grime and sweat, while the blood, oozing from a cut in the forehead, clots blackly in little streams down the side of his face. But, strangely enough, the pater forgets to characterize the whole thing as brutal. In fact, his teeth are clinched as grimly as his son's as he leans far forward to see every move of the game, and his heart goes out to those "young savages" who are making such a dogged up-hill fight of it.

And now the ball is on the twenty-yard line, diagonally from the goal.

"Thirty seconds to play," shouts the umpire, poring over his stop-watch. "Thirty seconds to make one last attempt for Yale, and every man on the eleven nerves himself to hold against the Princeton rush-line as against death himself. As the quarter-back cries the signal, the right and left half-backs, from mere force of habit, crouch ostentatiously, as if prepared for a run round the end. But the feint is unnecessary. Every man on the Princeton eleven, every coacher on the side-lines, every football-player on the crowded grand stands, knows that a goal from the field is Yale's only chance, knows that on Teddie's coolness depends the fate of the day. Back goes the ball on a long, low, accurate pass from the wiry little quarter-back. And before it has reached Teddie's outstretched hands the crash comes, and against the sternly waiting line comes the full force of the Princeton rushers bent on breaking through and blocking the kick.

"Hold 'em, Yale!" gasps the Captain from his place at tackle, as he braces against the hard-pressed right-guard. And for a second Yale holds. Then the line wavers, and straight for Teddie, from as many different points, spring three men. But that second had been enough. Deftly and slowly, as if in practice, the ball is poised and dropped. Struck on the rebound by Teddie's foot, it spins up and out just above the outstretched fingers of the Princeton rushers, who leap high in the air to intercept it. The goal is a difficult, diagonal one to make, and every player forgets to breathe as the ball sails slowly on, until it just clears the cross-bar, making the score stand 5-4 in favor of Yale; the game has been won in the last quarter of a minute.

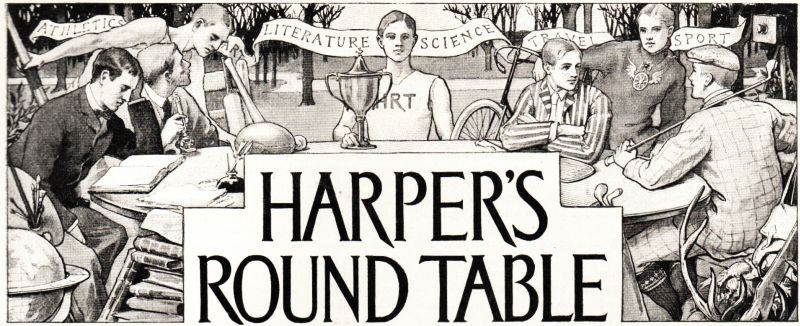

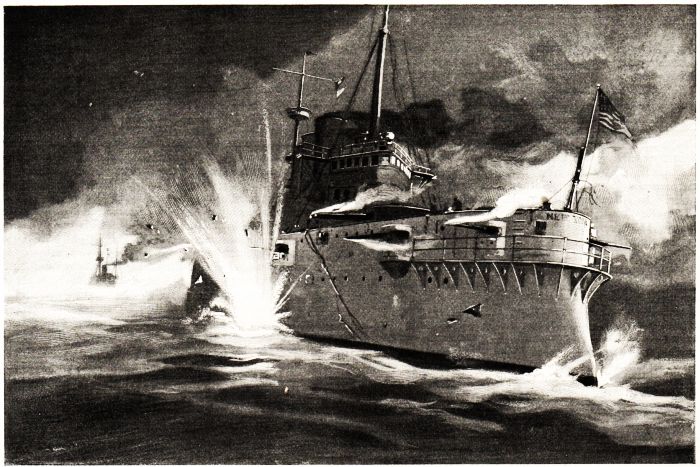

THE GAME HAS BEEN WON IN THE LAST QUARTER OF A MINUTE.

THE GAME HAS BEEN WON IN THE LAST QUARTER OF A MINUTE.

In such an indescribable turmoil as the one that followed, with every Yale sympathizer swarming out on the field to embrace the eleven which had so gallantly snatched a victory from the jaws of defeat, it was impossible to chronicle events with perfect accuracy; but it has been reported, on reliable authority, that shortly after the goal was kicked, a hatless and much dishevelled individual, bearing some faint resemblance to the dignified Mr. Larned, the well-known financier of New York, was seen enthusiastically hugging a muddy Yale player, supposed to be the full-back, pouring forth divers fragments of cheers the while, and at intervals embracing a tall man in a slouch hat who was performing a vigorous war-dance with variations. Both of these parties mentioned were also said to have been members of the group that carried the aforesaid full-back around the field on their shoulders in triumph. Undoubtedly the facts in the case have been much exaggerated, but it is certainly true that Mrs. Larned, to her unbounded amazement, received the following telegram from her husband late that evening:

"Teddie, my friend Bright, and four of the Yale eleven will eat Thanksgiving dinner with us to-night."

So we ran on with the wind holding fair until late in the evening, steering northeast by east. I had overcome a great deal of my timidity already, and had asked so many questions and paid such close attention to the way the brig was being handled, that by nightfall I thought I knew not a little about the working of a ship.

Captain Morrison, seeing my interest was so real, and put in a good-humor, as I have said, by the escape from the 74, explained to me something about steering by compass, and the wherefore of several orders.

The planter's wife had so far recovered from her indisposition as to take a seat at the swinging-table in the cabin, and we made a very jolly party at supper.

The skipper, warmed by a bottle of port which Mr. Chaffee had set upon the table, began to tell tales of the sea. I have heard many stories in my life, but I do not think that I have ever been thrilled or excited by any in the way that I was that evening.

Mrs. Chaffee must have noticed it, for she closed her hand over mine (that were tightly gripping the edge of the table), and stroked them gently in a motherly way. I resented this (although I am glad I did not show it), for was not I at that very time employed with the Captain in repelling an attack of a Barbary corsair? and Mrs. Chaffee's kindly touch recalled me to myself, and reminded me that I was but a boy, after all, who a few hours before had been almost in tears for the lack of what she had shown me—a little sympathy and the comfort of a kindly glance and touch.

The Captain had not finished his yarn-spinning—in fact, he was but in the middle of it—when the first mate thrust his head down the companionway.

"Will you come on deck, sir, and take a look at the glass on the way up?" he asked.

To my surprise, the Captain cast his tale adrift without an apology and hurried out, pausing for an instant only for a hasty glance at the barometer, which hung against the bulkhead at the foot of the ladder.

"It's evidently fallen calm," said Mr. Chaffee.

"And very glad am I that it has," answered his wife. "I think any more of that pitch and toss and I should have died."

For the last three-quarters of an hour, indeed, the Minetta had been stationary, heaving a little now and then, but in such a small way and keeping on such an even keel as scarcely to move the coffee in our cups. The Captain had been gone but a few minutes when we all went up on deck. The seas were round and oily, and the brown sails hung in lazy folds against the masts. The man at the wheel now and again gave the spokes a whirl this way and that, and he was forever casting his eye aloft as if by some motion of his he might catch a stray breath of wind.

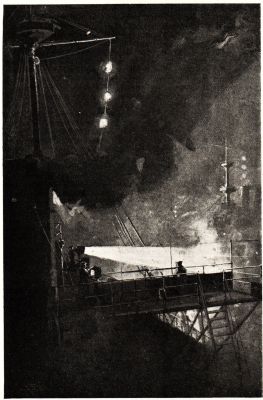

It was past sundown, and there was a strange, suffused glow everywhere, more like dawn than the twilight of evening. But off to the northwest towered a black tumble of clouds that were edged with a fringe of lighter color. They were stretching upwards and peering grandly above the horizon-line like a range of growing mountains.

Suddenly a quiver of light flashed all around, and then a streak of forked lightning ripped horizontally, like a tear in a heavy curtain, against the pit of the cloud. The Captain went below at this, to look at the barometer again.

"It's falling, Mr. Norcross," he said, raising his head. "Shorten sail, sir, and be lively!"

The men tumbled out from the deck-house. The top-sails which we had carried all the afternoon were taken in, and a reef put in the foresail and mainsail.

I watched all this bustling about with much delight, and then my attention was drawn to the sky. The clouds had now spread so that they were almost over us; a few big rain-drops fell and made little splotches on the surface of the water and spattered the deck in spots as big as dollars. They could be heard falling in the stillness against the dry sails overhead. Then, without a warning, there came another flash of lightning and a deafening thunder-roll. A slight puff of wind trailed the heavy blocks on the main boom rattling across the deck. The yards swung about with a complaining, creaking noise.

The Captain seized the glass and pointed to the westward; then he jumped to the wheel, jammed it over, and immediately began shouting orders to close the hatches, haul in the main-sheet, and make all snug. Every eye had followed the aiming of the telescope—a line of white below a wall of gray was coming toward us on the rush! A few more drops of rain fell softly, and then the thunder began to crash and roar on every hand.

Warned by the Captain, Mr. Chaffee and his wife went down to the cabin, both pale with fright. I, however, kept the deck, and in some way (I cannot account for it) was overlooked. And here nearly comes an ending to my story.

So suddenly and so fair abeam did the wind strike us that it was almost a knockdown then and there, and the first thing I knew I slid across the deck over against the lee bulwarks. The scuppers were running so full that I went under from head to foot; I thought surely I was going to be drowned—in fact, I think I took a few strokes and imagined myself overboard. The masts were extending over the water so far that the yard-arms almost dipped, the crew were hanging on by anything they could lay hand to, and the wind raised such a screeching in the rigging that the Captain, who was bawling at the top of his lungs, might as well have held silence; his voice apparently blew down his throat. Nevertheless, some of the crew must have understood him, for they clambered into the shrouds. This I noticed as I tried to crawl up the slope of the deck. Then there came a loud report; the foresail blew out into tatters, and the brig righted. A turn of the wheel, and she was put before it, crashing down into the sea (that came tumbling under her quarters), and now and then lifting her stern as if she would roll over like a ball—any which way.

I managed with difficulty to make the head of the after-ladder, and stumbled down it head first, some one slamming the sliding-hatch with a bang almost on my heels as they went over the combing. Looking about me, I found Mr. Chaffee and his wife engaged in prayer. They were much bruised from having been flung about the cabin, and were in great fear that we were about to founder.

But the Minetta was going so much steadier now that we all three sought our bunks, and managed to stay in them, and I had so much confidence in the Captain and crew, and was so unfamiliar with terror, that probably I did not recognize the nearness we had come to disaster, so after an hour or so I went to sleep.

When I awakened the sunlight was pouring in at the transoms, and we were gently heaving up and down. There was nothing to give me an idea of the time of day, but I could smell the brewing of coffee, and dressed hastily. No one was in the cabin, and the breakfast was untasted on the table; so, hearing the sounds of conversation, I went on deck. We were hove to, and within an eighth of a mile of us another vessel was coming up into the wind. She was very trim to look at, and I saw that a boat was being lowered over her side, and that she had the weather-gage of us.

The Captain was walking up and down with his arms folded, and our crew were gathered in the waist, muttering in surly and half-frightened voices.

"We are in for it this time, Master Hurdiss," said Mr. Chaffee, casting a bitter look over the taffrail at the stranger, from whose peak was flying the British Jack. "We are under the lion's paw, and no mistaking it."

Norcross, the mate, leaned over the rail and spoke to one of the men on the deck below him.

"Dash, do you know that vessel, my man?"

"Indeed I do, sir," was the reply from the light-haired seaman who had appeared so elated at the escape of the previous day. "It's his Majesty's sloop-of-war Little Belt, if I'm not mistaken, and she is a little floating hell, sir; that's what she is!"

Nevertheless, as I have said, she was a trim-looking craft, and I could not but admire the way the men tumbled into the boat and the long, well-timed sweep of the oars as they pulled toward us. When alongside, within a few yards, a young man in a huge cocked hat stood up in the stern-sheets.

"What brig is that?" he asked, brusquely.

Captain Morrison answered, giving our name and destination.

"I will board you," was the short reply of the cocked-hatted one, and he gave orders to the bowman, who was ready with his boat-hook, to make fast to the fore-chains.

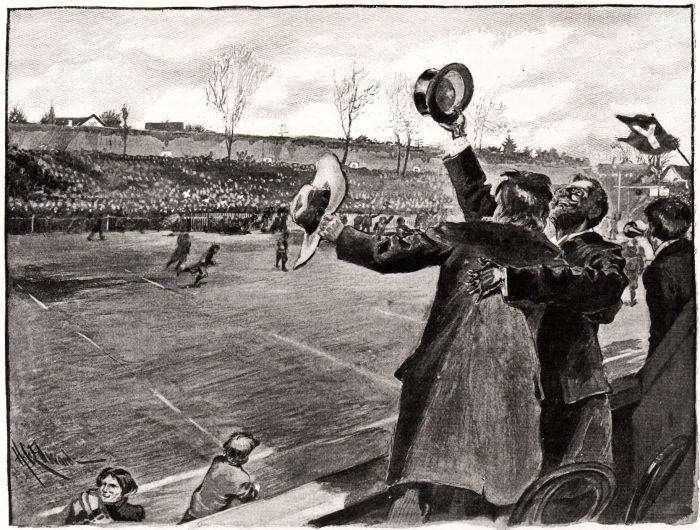

The English seamen, a sturdy-looking set, were all armed with cutlasses, and four or five of them followed their officer over the bulwarks.

The young Britisher's insolence must have been hard to stand.

"Muster your crew and let me see your papers," he ordered, with a toss of his head; "I would have a look at both of them."

Our Captain's politeness in replying, however, was quite as insulting.

"You have only to mention your wish, my courteous gentleman," he sneered. "Here are my papers and there are my crew. Will you help yourself to the cargo also? And pardon my not firing a salute, but we have a lady with us who objects to noise."

At this the English Lieutenant lifted his great hat, but he glared at the Captain as if he would have liked to lay hands on him; then he ordered two of the crew to rout out the forecastle (in a lower tone of voice), and two of them to give a look into the cabin and deck-house. He waited until they had returned, and then taking the papers that had been extended to him, he called off the names of the American seamen. Each one stepped forward in turn, but without saluting, and replied to the Lieutenant's questioning; apparently they all hailed from New England. Two of them, however, he told to stand over to the larboard side.

The men obeyed, and I have never seen such hate on any faces as they had on theirs.

But the scene, which was tragic enough in all conscience, despite the grinning of the armed man-o'-war's men who stood behind their leader, was to be broken by a climax as unexpected as a bolt from a clear sky.

"John Dash," read the officer. There was no answer, and he called it louder again, without result. "Where is this man?" he asked, impatiently.

The Captain made a low bow. "Thanks to your honor for your kind inquiry," he replied. "But the man failed to report on the morning of sailing."

It might have gone well had it not been for the interference of a low-visaged petty officer, who, with his fingers to his cap, here spoke.

"I saw a man go over the bow as we came up, sir," he said.

Two of the men hurried forward and leaned over the side. I, being near the rail, looked over also.

There was John Dash, holding on to the bobstay, his frightened face just above the surface of the water. In an instant he was hauled on board.

"Ah, there's where you've been all the time, Mr. Dash!" said Captain Morrison, sarcastically. "And how strange I not knowing it! This gentleman has been asking for you very kindly."

The poor man, dripping wet, was standing erect before the boarding-officer.

The titter that had run through the English sailors ceased as they saw the look on his face. He was drawing quick breaths, half-snarling like a dog, but he was trembling from head to foot.

"Oho!" said the servant of the King, lifting his eyebrows, "and here we are, eh? I think you know me, as I remember you, Charles Rice! You left us at the Port of Spain and forgot to return, you may remember. You owe his Majesty an accounting."

"I AM AN AMERICAN CITIZEN," RETURNED THE SAILOR,

HOARSELY.

"I AM AN AMERICAN CITIZEN," RETURNED THE SAILOR,

HOARSELY.

"I am an American citizen," returned the sailor, hoarsely, "born at Barnstable, Massachusetts! I was impressed from the ship Martha on the high seas, and owe accounting to no one."

"None of your insolence," cried the Englishman, drawing back his closed hand. "We'll see about that. You'll come with me, and these other two fine fellows also."

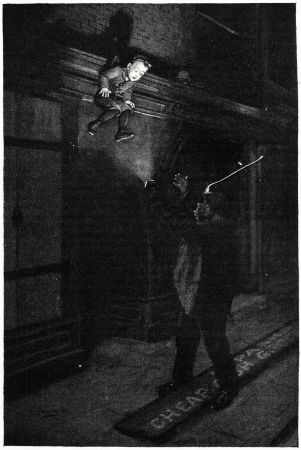

Dash, or Rice (I understood afterwards the latter was his real name), gave a leap backward and ran into the deck-house. The officer turned.

"Bring that man out," he said to two of his bullies.

Before they had crossed the deck something happened, and no one who witnessed it can ever shake it from his memory. The tall sailor appeared at the doorway. His hands were behind his back, and his blue eyes were absolutely rolling in his head.

"No, by the God of Heaven, you shall not be served!" he cried. "There is something you cannot command, at least, to do your bidding!" With a swift motion he drew his left arm from behind his back and flung something on the deck. It was his right hand, severed at the wrist!

Such a horror possessed us all that not a word was said. The planter's wife went in a heap to the deck, and as for myself, I went sick with the misery of it, and reeled to the side of the ship. The Lieutenant fell back as if struck a blow over the heart, and without a word, followed by his men, he clambered weakly down to his boat and shoved off. Dash lifted the bloody stump above his head; a curse broke from him, and then he fell into the arms of one of the black seamen. They carried him into the deck-house, and all hands followed, even the wheel being left deserted. As for myself, I crawled below into my bunk and wound the blankets about my head—Mrs. Chaffee was screaming in hysterics. Then and there was born in my heart such a hatred for the sight of the cross of St. George that I have never confounded my prejudice with patriotism, and this may account for some of my actions subsequently.

No one referred to the happening in our talk after this—it might not have occurred.

However, in such ways as we could we made the poor fellow comfortable; but John Dash, seaman, existed no longer; a poor, maimed, half-crazed hulk of a man was left of a gallant, noble fellow. But he had lived to teach a lesson.

A day later we sighted Sandy Hook, and beating up the bay, anchored in New York Harbor, where the planter and his wife and the heroic seaman were put on shore.

As the wind and tide were ripe to take us up the East River and through the narrows of Hell Gate into the Sound, we tarried but long enough to drop anchor and get it in again, and I caught only a panorama of houses and spires and the crowded wharfs of the city.

The voyage up the Sound was uneventful, and my landing in Connecticut and what followed I shall make another chapter.

But we passed many coasting-vessels and towns (whose number seemed past counting on both shores), and at last we entered the narrow sound of Fisher's Island and crept up close to the wharfs of Stonington. I made up my mind not to go ashore until the following morning, as it was after sunset before we had found a berth that suited the skipper.

Oh, I have forgotten to add that when I returned to my bunk, after being boarded by the party from the Little Belt, I had missed the miniature which I had left hanging by a nail driven into one of the stanchions. That one of the British sailors, on the hurried search of the cabin, had helped himself to it was beyond doubting.

Bleak, barren hills and cheerless plain,

All soaked and sodden with the rain;

No wood to bid the camp-fire glow,

No forest roof against the snow;—

Drear was the dying winter day

When the troops halted at Luray.

Not ev'n the draggled tents went up,

No chance to sleep, no chance to sup!

A few hours' rest upon their arms,

Then—who could tell what wild alarms?

"Halt until midnight," orders read;

"Then, if the storm holds, march ahead."

Tired and disheartened, faint and chill,

The soldiers, scattered o'er the hill,

Lay in their blankets. Scarce a word

In all the width of camp was heard.

Out of heart was the great blue host—

Out of that which they needed most,—

And the General's heart was a heavy load,

For well he knew what that hush must bode.

Forth from the town, as if heaven-sent,

Passed a child; and as on he went

Something moved him to sing a song

His mother taught him, while waiting long

For the loyal husband, who could not stay

When the first blue regiment passed that way!

Sweet, and flutelike, and childish clear,

The boy's voice rang through the valley drear:—

Tramp, tramp, tramp, the boys are marching;

Cheer up, comrades, they will come!

Every soldier along the hill

Felt his heart with the music thrill!

All forgotten the dreary night,

Hunger, and pillow frosted white.

One by one, as the child-voice sang,

Others joined, till the chorus rang

Deep as a mighty organ tone,

By the bellows of the storm-wind blown.

At midnight the order passed along:—

"March!" And they marched with their heart of song!

Needless to say how they fought, that day,

When the sun rose up over far Luray.

And the little singer—the loyal lad

Who gave, unconsciously, all he had

For his country's welfare—let none deny

His sovereign share in the victory!

If not from his song in the dreary night,

Whence came the courage to win the fight?

For a great many years—for as long, indeed, as either Bob or Jack could remember—there had been over the great fireplace in the office of the Mountain House, as its chief decorative feature, a huge moose-head, from either side of which rose up majestic antlers, concerning which Bob had once remarked that "they'd make a bully hat-rack."

To this sage remark Bob's father had replied that he thought so too; and he added that he thought it somewhat of a pity that Bob, when he chose his pets, should choose pug-dogs and rabbits, that were of no earthly use, instead of an occasional moose, which might be trained to sit in the hall and allow people to hang their hats on his horns.

"Just to think," he said, "what a convenience a real live walking hat-rack would be! When you wanted your hat, all you would have to do would be to whistle, and up the hat-rack would trot; you'd select the hat you wished to wear, and back would go the moose again to his accustomed place between the front door and the window."

"I'm willing," Bob had answered. "You buy me the moose, daddy, and I'll be glad to make a pet of him."

But it so happened that at the moment his father had something else to think about, and as a result Bob never got the moose.

Curiously enough, up to this particular summer of which I am writing, it had never occurred to either of the boys to inquire into the story of this especial moose, who had been so greatly honored by having his head stuffed and hung up to beautify the office of the hotel. They had both of them often wondered somewhat as to how it came to lose the rear portions of its body—that from its shoulders backward—but at such times it had so happened there had never been anybody about who could be counted upon to enlighten them on the subject. Now, however, it was different. Sandboys seemed always at hand, and considering that he had never failed them when they had asked for an explanation of this, that, or the other thing, they confidently broached the subject to him one afternoon during the music hour, and, as usual, Sandboys was ready with a "true story" for their satisfaction.

"Oh, that!" he said, when Bob had put the question. "Yes, I know all about it; and why shouldn't I? Didn't my father catch him? I guess!"

The boys were not quite sure whether the guess was correct or not, but they deemed it well to suppose that it was, and Sandboys went on.

"Some folks about here will tell you wonderful stories about that moose," he said. "Some will tell you it came from Maine; and some will tell you it came from Canady; and some will tell you they don't know nothin' at all about it; an' generally it'll be the last ones that tell the whole truth, though it did come from both Canady an' Maine; and, what's more, if it hadn't come, I wouldn't ha' been here. Nobody knows that but me, for up to now I haven't breathed a word about it to a soul, but I don't mind tellin' you boys the whole truth."

"You don't mean to say it got you your position here as a bell-boy, do you?" asked Jack.

"Yes, I do—that is, it did in a way, as you'll see when I've told you the whole story," returned Sandboys, and he began:

"My father, when he was a boy, used to live up in Canady. I don't recollect the name of the exact place. He told me its name lots o' times, but it was one o' them French-Canadian names with an accent to it I never could get the hang of. Names of English towns, like London or New York, I can always remember without much trouble, because I can spell 'em and pronounce 'em; but the minute they gets mixed in with a little foreign language, like French or Eyetalian, I can't spell 'em, pronounce 'em, or remember 'em to save my life. If anybody'd say to me, 'Remember the name o' that town or die,' I think that I'd simply have to stop breathin' an' die. I do remember, though, that it was a great place for salmon and mooses. My daddy used to tell me reg'lar slews of stories about 'em. Why, he told me the salmon was so thick in the river back of his father's barn, that if you took a bean-shooter and shot anywhere into the river, usin' pebbles instead o' beans, you couldn't help hittin' a salmon on the head and killin' it—or, rather, knockin' it unconscious, so's it would flop over and rise to the surface like it was dead, after which all you had to do was to catch it by the tail, chop its head off as you would a chicken's, cook it, and have your marketing done for two weeks."

"Jiminny!" said Bob. "It's too bad you can't remember the name of that place. A hotel at a place like that would be good as a mint."

"Oh no—it's all changed now," said Sandboys, sadly. "They've put a saw-mill in there now, and the salmon's mostly all gone. Sometimes they tell me they do catch one or two, and they're so big they cut 'em up in the saw-mill just like planks, and feed on 'em all through the winter."

"I've heard of planked shad," put in Bob, very anxious indeed to believe in the truth of Sandboys's statement, and searching in his mind for something in the way of a parallel which might give it a color of veracity.

"Hyops!" said Sandboys. "Planked shad is very good, but it can't hold a candle to planked salmon. But, as I was tellin' you, the place was full of moose too. They used to catch 'em and train 'em to go in harness. I don't believe anybody up there ever thought of buying a horse or a team of oxen to pull their wagons and plough their fields, moose were so plenty, and, when you could catch 'em hungry, so easy to tame. They'd hitch 'em to the plough, for instance, with ropes tied to their horns, and drive 'em around all day, and when night came they weren't a bit tired. But sometimes daddy said they'd strike a fearfully wild one, and then there'd be trouble. Pop told me he hitched one up to the harrow once, and the thing got a wild fit on and started across the field prancin' like a Rocky Mountain goat. He pulled up all the fences in his way with the harrow's teeth, and before he stopped he'd gone right through my grandfather's bay-window, into the dinin'-room, out the back door into the kitchen, takin' all the tables and chiny in the place with him. Where he went to nobody ever knew, though the harrow was found on top o' one of the mountains about sixty miles away, three years afterwards. I'd tell you the name of the mountain, only it had one o' those French-Canadian names too, so of course I can't.

"Time went on, and pop got to be a pretty big boy, and on his thirteenth birthday his father gave him the gun he'd used in the war—the war of the Revylation, I think it was, when George Washington was runnin' things. With it he gave him a powder-flask and some bullets, and I tell you pop was proud, and crazy to go huntin'. His father wasn't anxious to let him, though, until he thought pop knew enough about fire-arms to kill something besides himself, and he told him no, he couldn't. He must wait awhile. So pop tried to be good and obey, but that gun was too much for him. It kept hintin', 'Let's go huntin'—let's go huntin',' and one night pop could not resist it any longer. So after everybody'd gone to bed, he got up, sneaked down stairs into the parlor, took down the gun from the bricky-brack rack, and set out for the lonely woods.

"'If I don't kill nothin',' he said to himself, 'I'll get home before they wake up; and if I do kill somethin', pa will be so pleased an' proud he'll forgive me.' He little thought then he was leavin' home forever. He opened the door softly, an' in half an hour he was off on the mountain, 'longside of a great big lake. Pretty soon he heard a sound, and through the darkness he see two big eyes, flamin' like fire,[Pg 85] a-lookin' at where he was. It was that moose up there as was a-lookin' at him. For a minute he was scart to death, but he soon recovered, upped with his gun, an' fired—only he was too excited, and he didn't do any more than graze the moose's cheek. You can't see the scar. It's been mended. It was a tarrable exciting moment, for in a jiffy the moose was after him, head down. Pop tried to run, but couldn't. He stumbled, an' just as he stumbled he felt the big moose's breath hot on the back of his neck. He thought he was a goner for sure; but he wasn't, as it turned out, for as he rolled over and the moose tried to butt him to death, pop grabbed holt of his horns, and the first toss of his head the moose gave landed pop right between 'em, sittin' down as comfortably fixed as though he was in a rockin'-chair. If you'll look at the antlers you'll see how there's a place in between 'em scooped out just right for a small boy to sit in. That's where pop sat, hangin' on to those two upper prongs, with, his legs dangling down over the moose's cheeks."

"Phe-e-e-ew!" whispered Bob. "He was in a fix, wasn't he? What did the moose do?"

"Him?" said Sandboys. "He was absolutely flummoxed for a minute, and then he began to run. Pop held on. He had to. He didn't want to go travellin', but there warn't anything else he could do, so he kept holt. That moose run steady for three days, down over the Canadian border into Maine, takin' a short-cut over Maine into New Hampshire, droppin' dead with weariness two miles from Littleton, where I cum from. That let pop out. The moose was dead, and he wasn't afraid any more; so he climbed down, walked into Littleton, and sold the animal's carkiss to a man there, who cut off its head, and sent it up here to this hotel, an' it's been here ever since. Pop took the money and tried to get back home with it; but there wasn't enough, so he worked about Littleton until he had enough; and just then he met my mother, fell in love with her, married her, and settled down right there; and that's how it is that that moose-head is responsible for my bein' here. If the animal hadn't run away with dad, he'd never have met my mother, and I'd have been nowhere."

"It's very interesting," said Bob. "But I should think he'd have sent word to his father that he was all right."

"Oh, he did," said Sandboys; "and a year or two later the whole family came down and joined him, leavin' Canady and its French names forever."

And here the narrative, which might have been much longer, stopped, for the cross old lady near the elevator sent word that that "talkin' must stop," because while it was "goin' on" she "couldn't hear what tune it was the trumpeter was blowin'."

Chole (pronounced shōl) is a capital game for the enthusiastic golfer at this time of year, when the fields are brown and bare, and the careful green-keeper has closed the regular golf course for fear of harm to his precious putting greens. It is golf, and yet it is not golf, the essential difference being that but one ball is used, one player striving to advance it towards a certain agreed-upon goal, and his opponent as strenuously endeavoring to thwart him in the attempt. But, on the other hand, it is not hockey or anything resembling it. Each player has for the time being absolute possession of the ball, and cannot be interfered with while he is making his stroke. It is an old Belgian game, and undoubtedly one of the ancestors of our modern golf. As a matter of fact, it is still played in the Low Countries with rude iron clubs and an egg-shaped ball of birchwood. The following extract from a historical paper on the beginnings of golf explains very clearly the purpose and method of the play at chole:

If Tom Morris and Hugh Kircaldy were going to play a match at chole, they would first fix on an object which was to be hit. A church door at some five miles distance, cross country, seems to have been a favorite goal. This settled on, match-making began—a kind of game of brag: "I will back myself to hit the thing in five innings," Tom might say. (We will explain in a moment what an "innings" meant.) "Oh, I'll back myself to hit it in four," Hugh might answer. "Well, I'll say three, then," Tom might perhaps say, and that might be the finish of the bragging, for Hugh might not feel it in his power to do it in two, so he must let Tom try. Then Tom would hit off, and when he came to the ball he would tee it and hit it again, and so a third time. But when they reached the ball this third time, it would be no longer Tom's turn to hit, but Hugh's. He would be allowed to tee the ball up and dechole, as it was called—that is to say, to hit it back again as far as he could. Then Tom would begin again and have three more shots towards the object; after which Hugh would again have one shot back. Then if in the course of his third innings of three shots Tom were to hit the church door, he would win the match; if he failed, he would lose it.