Title: Under Six Flags: The Story of Texas

Author: M. E. M. Davis

Release date: August 21, 2019 [eBook #60144]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Ron Box and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

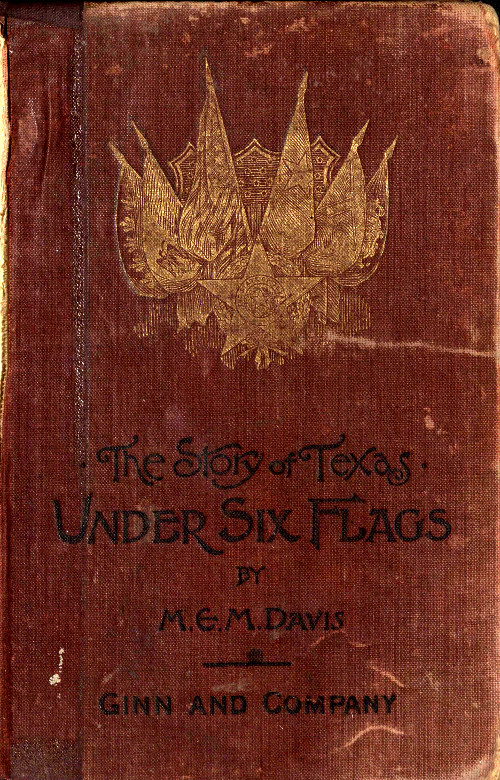

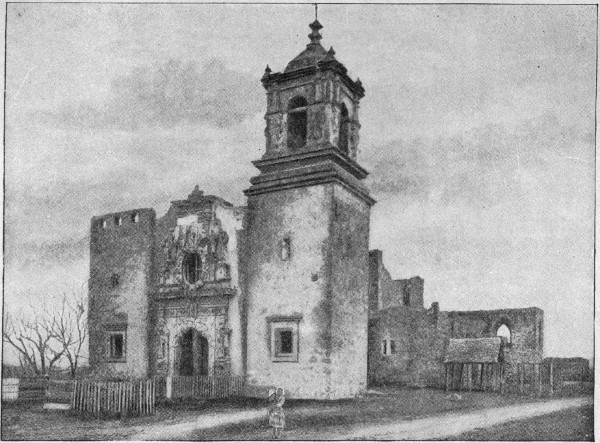

MAIN DOOR OF MISSION SAN JOSÉ, SAN ANTONIO.

BY

M. E. M. DAVIS

Author of “In War Times at La Rose Blanche,” “Under the Man-Fig,” “Minding the Gap,” etc., etc.

GINN & COMPANY

BOSTON · NEW YORK · CHICAGO · LONDON

Copyright, 1897

By M. E. M. DAVIS

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

26.5

The Athenæum Press

GINN & COMPANY · PROPRIETORS · BOSTON · U.S.A.

TO THE MEMORY

OF

E. H. Cushing

In the following pages I have endeavored to sketch, in rather bold outlines, the story of Texas. It is a story of knightly romance which calls the poet even as, in earlier days, the Land of the Tehas called across its borders the dreamers of dreams.

But the history of Texas is far more than a romantic legend. It is a record of bold conceptions and bolder deeds; the story of the discoverer penetrating unknown wildernesses; of the pioneer matching his strength against the savage; of the colonist struggling for his freedom and his rights.

It is the chronicle of the birth of a people; the history of the rise and progress of a great State.

I have tried in these simple readings so to arrange the salient points of a drama of two centuries as to present a consistent whole.

And I shall be happy if I shall succeed in awakening in the reader somewhat of the interest in Texas history which has inspired this work.

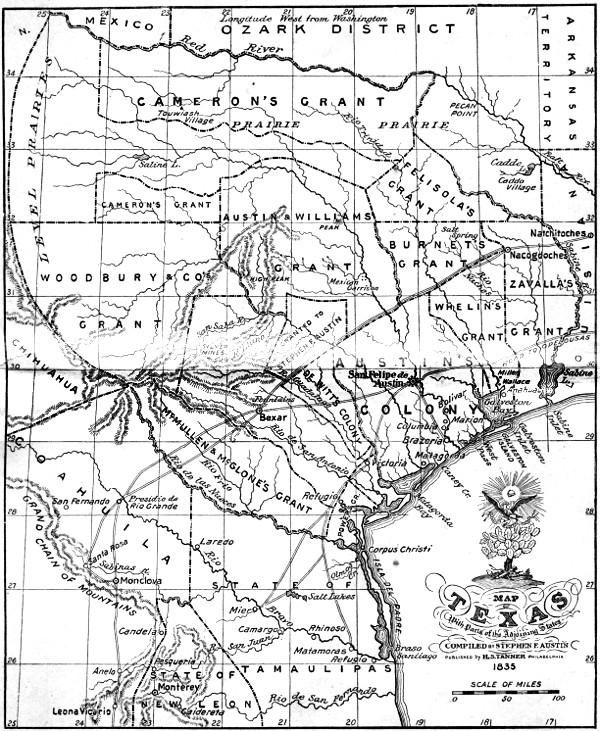

There are several features which mark Texas history as unique. One of these is the difference between the methods of colonization employed in Texas and those exercised elsewhere in the United States.

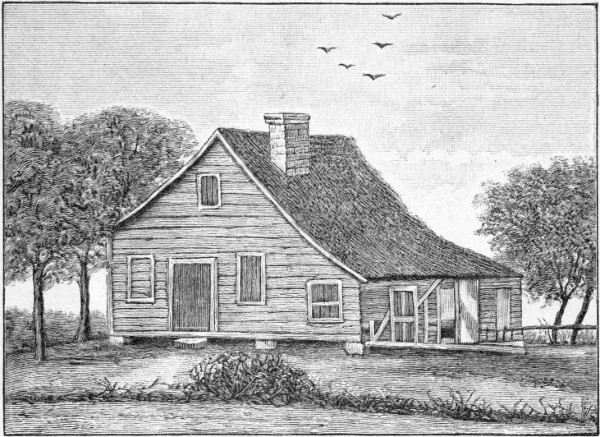

The pioneer with his cabin, his ever-spreading fields, his gardens and orchards—the idea of the home with its roots in the very soil, as represented by Austin and his followers—was preceded by a hundred barren years of fortress and soldier, the Spanish idea of conquest and military rule.

Again, its vast extent of territory and the ease with which its rich lands were acquired seemed to adapt Texas peculiarly to those communistic and utopian experiments which have been the delight of the visionary in every age of the world’s progress. A number of these have been tried upon its soil. The result has been to give a varied and original coloring to the shifting scenes.

The philosophical student will find these phases of our history well worth his consideration.

I desire in this place to express my thanks to the Texas teachers, to many of whom I am indebted for timely suggestions and for kindly encouragement; also my grateful obligation to Mr. William Beer, of the New Orleans Howard Memorial Library, for valuable assistance; and to the Library itself, which, under his able direction, has become particularly rich in documents and publications relating to the early history of Louisiana and Texas. M. E. M. DAVIS.

One morning early in the year 1684, Robert Cavalier, Sieur de la Salle, a gentleman in the King’s service, stood waiting in an antechamber of the royal palace at Versailles (Ver-sālz′). Behind the closed door, which was guarded by two of the King’s Musketeers in their showy uniforms, his Majesty Louis the Fourteenth was giving a private audience to the Count de Frontenac. This gentleman, late the governor of New France (Canada), was the friend and adviser of The Adventurer, as La Salle had been mockingly nicknamed by the idlers of the French court.

La Salle, who was headstrong and somewhat overbearing in character, more used, moreover, to command than to obey, frowned as he walked up and down the room, and glanced impatiently from time to time towards the king’s cabinet, where his fate hung in the balance. Months had passed since he had arrived in France from North America, with a great scheme already planned, and lacking only the consent of the king and his ministers. He had danced attendance at court until he was weary, rugged soldier that he was; now filled with hope when the ministers plied him with false promises, now sunk in despair when his enemies placed obstacles in his way. “Would I were back in the wilds of America, with Tonti of the Iron Hand and my red brothers,” he muttered, downcast and discouraged.

But at length the door opened, the tapestry was pushed aside, and Frontenac appeared. His eyes beamed with satisfaction. “Your application is granted,” he said, pressing La Salle’s hand. “His Majesty commissions you to plant a colony at the mouth of the great river where you have already raised the flag of France. Go, my friend; thank his gracious Majesty, and then hasten your preparations for departure.”

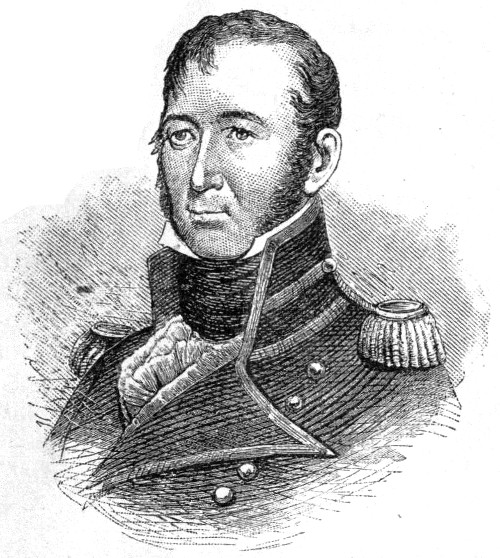

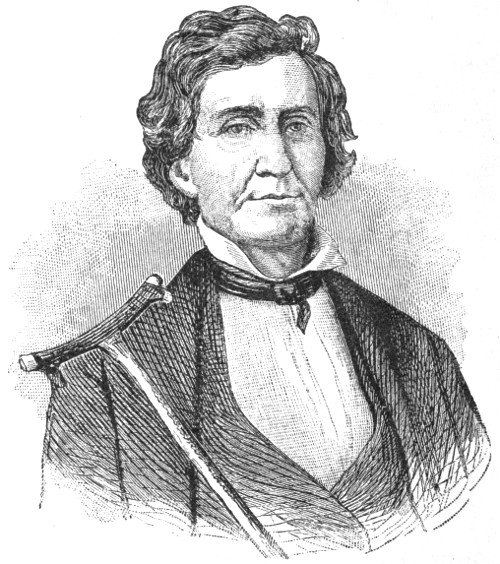

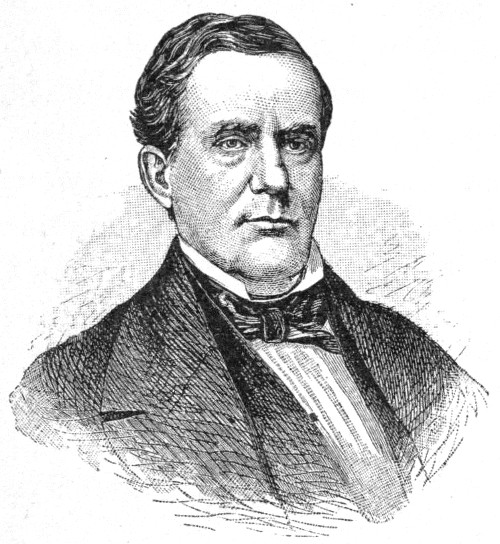

La Salle.

La Salle lost no time in obeying these directions. His heart throbbed with pride and satisfied ambition. For this was his dream: to colonize the beautiful wilderness watered by the lower Mississippi; to found a city on the banks of the mighty stream whose mouth it had been his good fortune to discover.

But this dream was never to be realized by him. It was the destiny of La Salle not to colonize Louisiana, but to become the discoverer of Texas.

After much trouble La Salle succeeded in perfecting the arrangements for his voyage. His little fleet was composed of four vessels: the Aimable (Ā-mah′-bl), the Joli (Zho-leé), the Belle, and the St. Francis. In these embarked over three hundred souls, including women, workmen, priests, and soldiers.

They sailed from Rochelle, France, on the 24th of July, 1684. The passage across the Atlantic was tedious and stormy; it was embittered by constant quarrels between La Salle and Beaujeu (Bo-zhuh′), the naval commandant of the squadron; and the fleet was crippled by the loss of the St. Francis, the store-ship, which was captured by the Spaniards. But toward the end of September the remaining vessels, in tolerable condition, entered the Gulf of Mexico. Here La Salle began a sharp lookout for the wide mouth of the river he aimed to enter.

He was full of confidence in himself, for he had spent years of his life tracking the savage wilderness of the north with his Indian guides, and he had the keen eye and the ready memory of the practiced scout.

But he had no exact chart of the pathless and unknown waters around him; the calculation of the experienced landsman stood him in little stead at sea. He lost his way, and sailing to the westward of the river known to us as the Mississippi,—but called by La Salle the St. Louis,—he came, on the 1st of January, 1685, in sight of the low-lying shores of Texas.

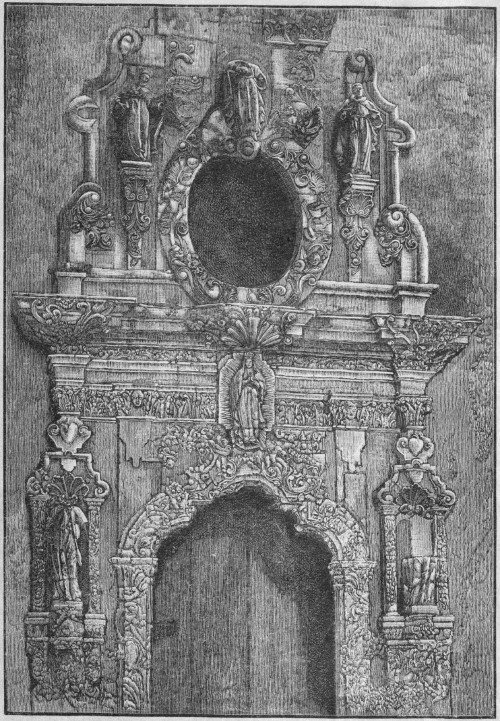

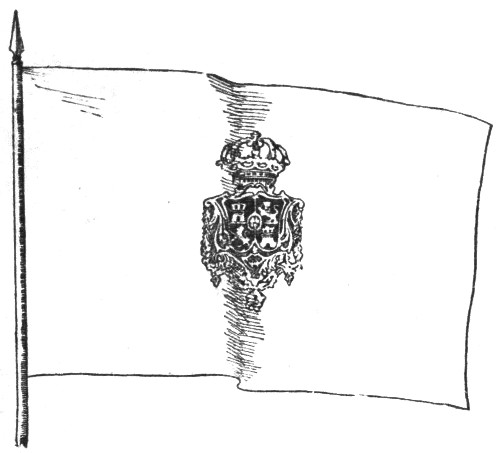

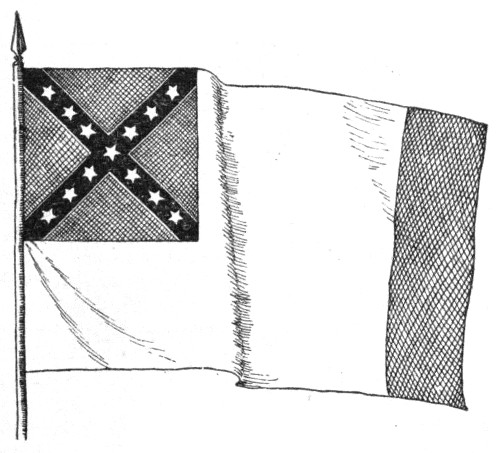

The Flag of France.

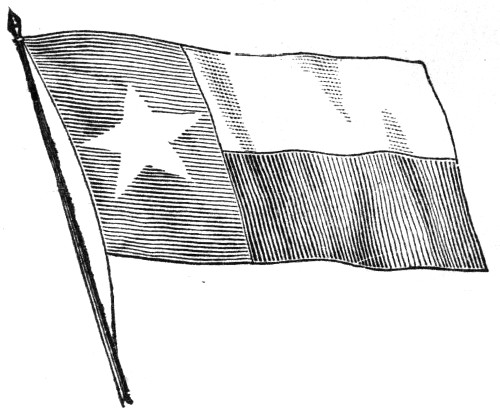

Some weeks later, the fleet anchored in the Gulf outside the beautiful land-locked bay of San Bernard (now Matagorda Bay); and La Salle, flag in hand, and attended by soldiers and priests, set foot on the new land, taking formal possession of it in the name of the King of France.

To the colonists, so long confined within the small ships and overwearied by the monotony of the voyage, it was a joy simply to feast their eyes on the green of the trees that lined the shore, and to breathe the fresh air that blew down, flower-scented, from the far western prairies. They longed to run like children on the sandy beach, to feel under their feet the firm turf. But La Salle’s experience among the Indians had taught him caution. He took the utmost care in landing his colonists, and in forming his temporary camps. Two temporary camps were established, one on Matagorda Island, where the lighthouse now stands; the other on the mainland, near the present site of Indianola.

His own heart, meantime, was heavy. He had missed his coveted and beloved river, though he still believed that the San Bernard Bay might be one of its mouths. The Aimable, in attempting to enter the harbor, had grounded upon a sandbank and gone to pieces. The Indians, who had swarmed to the coast in great numbers to greet the pale-faced strangers, had already become troublesome. They had, indeed, murdered two of the colonists, named Ory and Desloges. This was the first European blood shed upon Texas soil. The stock of provisions was running low, and finally, to crown all, Beaujeu, from the beginning hostile to La Salle, had hoisted sail, with scant warning, and returned to France, leaving the eight cannons and the powder belonging to the expedition, but carrying away with him all the cannon balls.

A less sturdy spirit might have been wholly disheartened; but La Salle, whatever he felt, gave no signs of weakness. He explored the country round about, and at the end of a short time he marked out the foundation of a fort beside a small stream which empties into the bay. He called the river Les Vaches (Cow River[1]), from the number of buffaloes which grazed along the banks. The spot[2] chosen for the site of the fort was a delightful one; the rolling prairies which stretched away northward were covered with rich grass and studded with belts of noble timber; southward lay the grey and misty line of the bay; birds of gay plumage sang in shadow of the grapevines that trailed from overhanging trees to the water’s edge; the clear stream reflected the blue and cloudless sky of southern Texas. Here the colonists set to work. La Salle with his own hands aided in hewing and laying the heavy beams of wall and of blockhouse. The curious savages, tall Lipans and scowling Carankawaes, hung about the place, peering forward with jealous eyes, and picking off the unwary workmen with their deadly arrows. But a day came at last when the little fortress, with its chapel, lodgings, and guardhouse, was completed. Amid the cheers of the colonists the flag of France loosened its folds to the wind; a hymn of thanksgiving and praise arose from the chapel; and La Salle, giving to the fort the name of St. Louis, dedicated it to France in the name of the King.

Several expeditions followed, in 1685 and 1686, the building of Fort St. Louis. La Salle not only cherished the hope of finding his lost river; he was lured northwestward by rumors obtained from the Cenis, the Nassonites, and other friendly Indians, of rich silver mines in the interior. He wished also to communicate, if possible, with his old friend, the Chevalier Tonti of the Iron Hand, whom he had left with a colony on the Illinois River. Tonti, having lost a hand in battle, used one made of iron; hence his title.

These journeys were both painful and perilous; the footsore explorers were obliged to swim swollen rivers; they traversed dangerous swamps and unknown forests; they encountered and fought with hostile Indians; they suffered the pangs of hunger and thirst; they were shaken with chills and parched with fever. It is marvelous, indeed, that a spark of courage should have remained in their hearts.

On returning to the fort after one of these expeditions, during which the commandant had lain for months helpless with fever in the lodge of a Cenis chief, he found matters there in a bad way. The last remaining vessel, the Belle, had been wrecked on a shoal in the bay. Food was scarce; ammunition was almost exhausted; and between death from sickness and losses in Indian skirmishes, the inmates were reduced to less than forty persons.

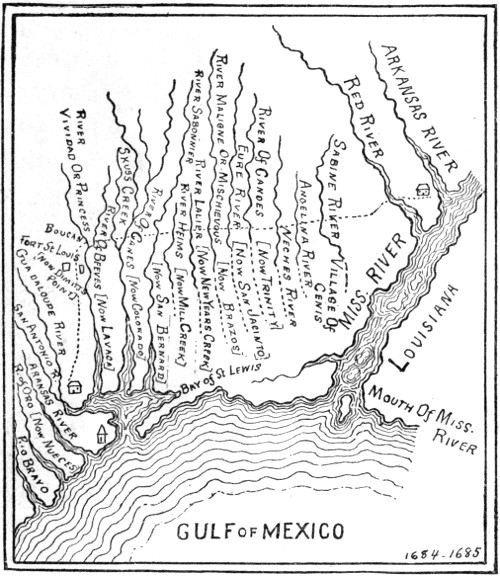

La Salle’s Map of Texas.

Despite all this, however, as the wayworn explorers drew near the walls, their ears were greeted with sounds of mirth and revelry. The Sieur Barbier and “one of the maidens”—as the chronicler relates—had just been married in the little chapel. The wedding party welcomed their chief with joyous shouts. We can well imagine how, removing his worn cap, he saluted the youthful pair with a stately bow. And the same evening, when the colonists gathered in the log-built hall of the commandant’s own quarters to make merry over the first European wedding on Texas soil, with what courtly grace did the Sieur de la Salle tread a measure with the blushing bride!

This was in October, 1686. On the 12th of January the following year, La Salle appeared in the open square of the Fort, dressed in his faded red uniform and equipped for traveling. His people pressed around him, listening with anxious hearts to his farewell words. For he was about starting once more across vast and unknown regions in search of Tonti—and help.

One by one he called to his side those whom he had chosen to accompany him. They numbered twenty—exactly half of the remnant of his colony. Among them were two of his own nephews and his brother, Cavalier; the faithful priest, Father Anastase; Joutel, the young historian of the colony; Liotot (Lee-o-to); L’Archevêque (Larsh-vāke′); Duhaut (Du-ho′); and Nika (Nee-ka), an Indian hunter who had followed La Salle to France from Canada.

Sieur Barbier was placed in command of the garrison; and, after an affectionate farewell, La Salle passed through the gate, which he was never to enter again, and plunged a last time into the forest.

Two months later, near the crossing of the Neches River, Moragnet (Mo-rä-nyā), La Salle’s nephew, who had been for some time on bad terms with L’Archevêque and Duhaut, was murdered by them while he was sleeping. Nika, who was with the party (which had been sent out after fresh buffalo meat), was killed at the same time. The murderers, fearful of La Salle’s just vengeance, determined to take his life also. They placed themselves in ambush; L’Archevêque, who was only sixteen years old, was detailed to lead their chief into the trap.

When La Salle appeared, in search of his nephew, he was fired upon and instantly killed (March 16, 1687).

Thus perished, by treacherous hands, the gallant and stout-hearted La Salle—the soldier, explorer, and dreamer. He was buried in the lonely spot where he fell. Father Anastase scooped out a shallow grave for his friend and benefactor, and pressed the grassy turf upon his breast. And so, within the borders of Texas—though the exact spot is unknown—repose the mortal remains of its discoverer.

Joutel with several of the band succeeded after many adventures in reaching one of Tonti’s settlements on the Arkansas River. Thence they made their way to Canada.

The assassins and their followers remained with the Indians, where, one after another, they nearly all met the same bloody and violent death they had meted out to their victims.

Five years later L’Archevêque with one companion was recaptured by the Spaniards from the savages and sent to Madrid.[3]

Tonti of the Iron Hand had waited long and anxiously for news of his friend. In 1684 he had gone in a canoe down the Mississippi to its mouth to meet the expedition from France. The expedition did not appear, and he returned to his post on the upper Mississippi. He questioned the Indian runners from the south and west as they passed his camp on their hunting raids. He could learn nothing of La Salle or his companions. That intrepid captain seemed to have vanished into the unknown west. At last, in 1689, he journeyed southward again in quest of his friend. Vague rumors reached him of men who had passed through his own forts and tarried to tell the story of La Salle’s death. But he would not believe them. He entered Texas and traveled as far as the wigwams of the friendly Cenis. From them he learned the fate of the man he loved; and the rugged soldier turned aside his head and wept.[4]

While these things were taking place in an obscure corner of the New World, there was commotion in the court of Spain. Word had come over from the “Golden West” that France had laid an unlawful hand upon some of the Spanish possessions there. Letters flew thick and fast between the Spanish viceroy in Mexico and the Spanish king’s[5] ministers. The Viceroy was ordered to punish the offenders as soon as ever they could be found; the dark-browed king of Spain was very angry.

All this stir was caused by the capture of the St. Francis, La Salle’s little store-ship in 1684. She was plainly on her way to some new colony. But where had that colony been planted? The wary captain of the St. Francis said that he did not know. Perhaps he told the truth. At any rate, it was not until 1686 and after a world of trouble that the Viceroy in Mexico located the spot of La Salle’s settlement. Spain considered herself at that time the legitimate owner of all that region which we now call Texas; she pretended, indeed, to own everything bordering on the Gulf of Mexico. A military council was therefore held at the new post of Monclova, and Captain Alonzo de Leon, the newly appointed governor of Coaquila (afterwards called Coahuila) (Co-ah-wee′-la), was dispatched to find and destroy La Salle and his colony. La Salle, with a bullet in his brain, had been lying for two years in his shallow grave near the Neches River; but the Viceroy did not know this.

Captain De Leon and his hundred soldiers marched gaily and confidently from Monclova in a northeasterly direction, across wild prairie and savage woodland. They were used to the ways of the Comanches, through whose hunting grounds they marched, and, at need, could take scalp for scalp; they were well fed and comfortably clad; the King’s pay jingled in their pockets,—a brave contrast truly to the starved, ragged, disheartened colonists at Fort St. Louis!

But when Captain De Leon and his men at length found the fort, the unfortunate French colonists, like their chief, had perished. Their bleaching bones lay scattered about the door of the blockhouse, where they had made their last desperate stand against the bloodthirsty Carankawaes. De Leon’s heart stirred with pity as he looked about him, thinking less, perhaps, of the men—for it is a soldier’s business to die—than of the delicate women who had shared their fate.

With the Cenis, into whose friendly wigwams they had escaped at the time of the massacre, De Leon found several of the colonists. These were afterwards sent back to their homes in France. But among them there is no mention of the Sieur Barbier and his young bride.

The Flag of Spain.

De Leon, it is said,—though this is a much disputed fact,—called the country about Fort St. Louis Texas, because of his kindly treatment by the Cenis Indians, the word Texas in their tongue meaning friends.[6] On his return to Monclova, he pictured this Texas as a paradise so fertile and so beautiful that the viceroy determined to establish there a mission and presidio,—that is to say, a church and stronghold,—for the double purpose of reducing and converting the Indians.

In 1690 Captain De Leon, with several priests added to his company of soldiers, marched again to Fort St. Louis. The broken walls were restored, and once more the air rang with the cheerful sounds of axe and hammer. The Mission of San Francisco was begun and dedicated; the Spanish flag fluttered in the breeze; a hymn of praise and thanksgiving arose from the chapel; and De Leon took formal possession of the country in the name of the King of Spain.

The Spaniards, harried by the Indians and too far from Monclova to receive regular supplies, were soon forced to abandon Fort St. Louis. Great was the rejoicing among the Lipans and the Carankawaes when the pale faces disappeared from among them, leaving the bay once more free to their own canoes, the prairies open to their moccasined feet.

Neither France nor Spain for a time seemed inclined to trouble herself further about this disputed property.

But in 1719 a French ship bound for the Mississippi drifted, like La Salle’s fleet, westward to the bay of San Bernard. Among those who went ashore for recreation, while the sailors were taking on fresh water, were Monsieur Belleisle, a French officer, and four of his friends. They did not reappear at the appointed signal, and the captain, after waiting for them for some hours, sailed away without them.

Belleisle and his companions were in despair at finding themselves thus abandoned; they wandered for weeks along the strange and lonely coast, living, as best they could, upon roots, berries, and insects. Finally four of the men died of starvation, leaving Belleisle alone. Weak and despairing, he made his way to the interior, where he soon fell into the hands of some Indians, whom he took at first to be cannibals. They stripped him and divided his clothing among themselves; but instead of eating him, as he expected they would do, they gave him to an old woman of the tribe, who made him her slave but who otherwise treated him with rude kindness. In time he learned the language of his captors and became a warrior, sometimes even leading their savage forays.

One day an embassy from another tribe came to the camp. Belleisle, listening to their talk, heard the name of St. Denis. Now St. Denis was one of his own former comrades-in-arms. Belleisle’s heart leaped. He wrote, with ink made of soot, a few lines on his officer’s commission,—which he had somehow kept,—and secretly bribed one of the strange Indians to carry this message to St. Denis. St. Denis happened at the time to be at Natchitoches (Nack-ee-tosh) beyond the Sabine River; when he read the note he was much affected. He immediately sent horses, arms, and clothing to the captive; Belleisle, by means of a strategy, escaped with the Indian guides and joined his friend.

This adventure of Monsieur Belleisle caused him later to become a part of the history of Fort St. Louis.

The unfortunate La Salle had died with his ardent and long-cherished dream unfulfilled. But after more than thirty years, another man had begun to realize that dream. Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville had sailed with French ships up the beloved river; his colonists were fast peopling the beautiful wilderness, and already the infant city of New Orleans lay strong and thriving on the bank of the Mississippi.

The commandant of Louisiana, though busied with his growing colony, kept yet a watchful eye upon the grasping Spaniards, who claimed the country eastward nearly to the Mississippi. But France claimed westward as far as the bay of San Bernard, by virtue of La Salle’s discovery. Bienville determined to make good the claim of France. In August, 1721, he fitted out a small vessel, the Subtile, told off a detachment of tried soldiers, and placed Bernard de la Harpe, an experienced captain, in command. The expedition set out at once to recover La Salle’s old fort. Belleisle, on account of his knowledge of the country and the Indian language, was sent along as guide.

The surprise and the rage of the Indians when they saw the hated flag waving again above the fort may be imagined. They threw themselves with such fury against the newcomers that La Harpe, seeing his small garrison in danger of massacre, withdrew quietly, and returned in October to New Orleans.

Fort St. Louis was left at last to a solitude never again to be broken. Vines grew over the crumbling walls and sprawled across the floors where human feet had passed; lizards basked in crevices of the blockhouse; and wild creatures from the wood took up their abode in the chapel. Day by day and year by year decay and change went on, until there came a time when nothing remained to tell of the place where the first settlers of Texas lived, suffered, rejoiced, and perished.

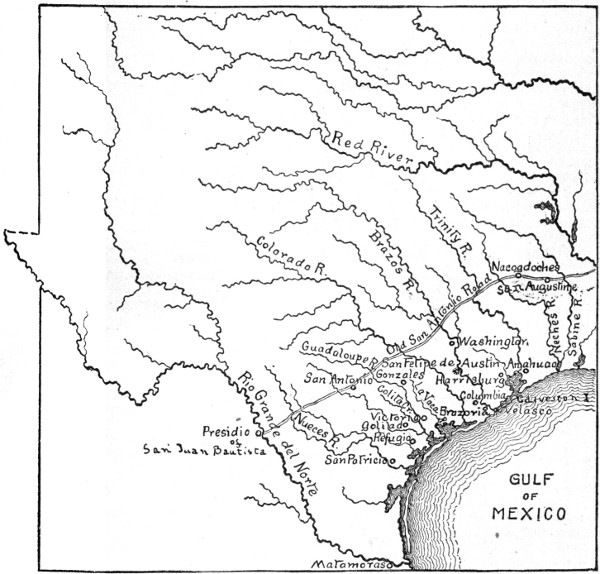

In 1714 Juchereau St. Denis rode across Texas, in an oblique line from a trading post in Louisiana to a presidio on the Rio Grande River. This was the same St. Denis who afterward, as already related, rescued his comrade-in-arms Belleisle from captivity. He had secret orders from Cadillac, the governor of Louisiana, and his busy brain was teeming with carefully laid plans of his own. His escort consisted of twelve white men and two or three Indians. He took his bearings as he went, carefully marking the way from river to river, from prairie to forest, from Indian village to buffalo range; thus sketching out that long thoroughfare which afterwards became famous as the “Old San Antonio Road.”

Much of the way lay through the lands of unfriendly Indians; but St. Denis rode as jauntily as if the men at his back were a thousand instead of a dozen.

And when one day he drew rein on the brow of a certain hill, and gazed down into the lovely cup-like valley where a few huts marked the beginnings of San Antonio, he might, for all signs of fatigue upon his handsome young face, have just quitted the governor’s residence.

“A beautiful site for a city,” he said to Jallot, his confidential servant. His pleased eyes roved over the smiling valley, through which the river ran like a silver thread. Graceful trees lined the river banks; the tender grass was studded with a thousand flowers of varied colors; there was a life-giving softness in the wind that came from the low mountains to the northward.

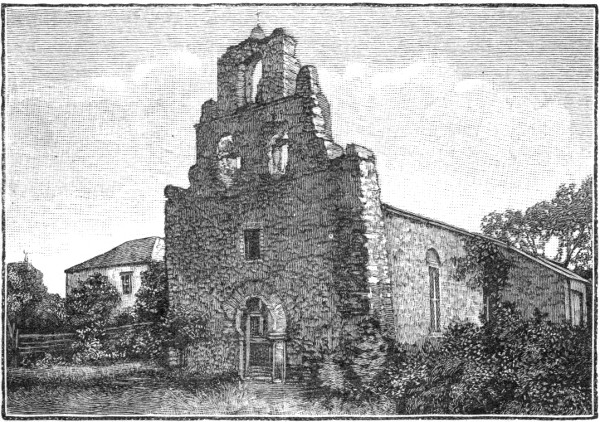

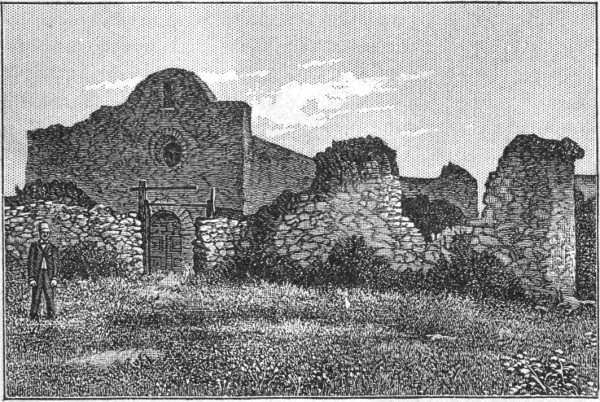

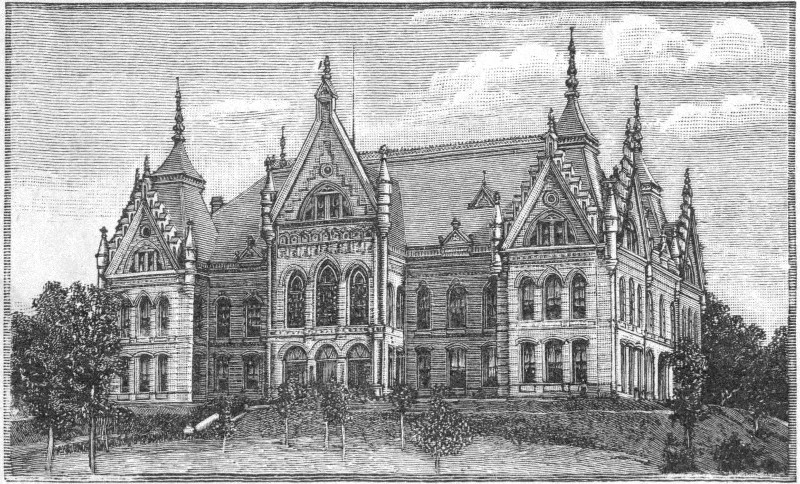

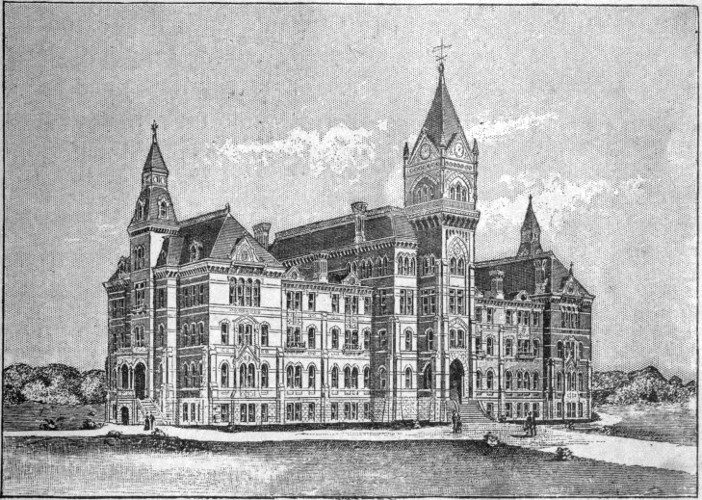

THE MISSION OF SAN JOSÉ.

St. Denis journeyed on to St. John the Baptist, carrying this lovely picture in his heart as he went. St. John the Baptist was a presidio on the Rio Grande River. It was built by Captain Alonzo de Leon, after his return from Fort St. Louis in 1689. Its commandant, at the time of the visit of St. Denis, was Don Pedro de Villescas. To Don Pedro St. Denis unfolded his mission—the opening of trade between Louisiana and Mexico. The friendly commandant could do nothing without first consulting his superiors; so he asked St. Denis to wait until a letter could be sent to the governor of the province at Monclova. St. Denis waited, and while he was waiting he fell in love with Donna Maria, the commandant’s daughter.

The young French officer was so dashing, so courtly, and withal so good looking, that it is no wonder Don Pedro’s daughter loved him in return; and there were at least two very happy persons at the Presidio of St. John the Baptist.

But when the courier came back from Monclova, St. Denis was seized by order of the governor, and was carried under guard to that city.

The governor of Coahuila was, as it happened, a rejected suitor of Donna Maria Villescas. Filled with jealous rage, he threw the young Frenchman into prison and threatened him with death unless he would give up all claim to his promised bride.

This St. Denis gallantly refused to do. After some months the governor sent him to the city of Mexico, denouncing him to the viceroy as a spy against the government. He was again placed in prison, where he was treated with great severity.

Donna Maria, however, was not idle all this time. She had sent several spirited letters to the governor at Monclova, and she now wrote to the viceroy himself. Her letter had the effect of loosening the chains of her lover.

Marquis de Linares, the viceroy, when he saw his prisoner, was so charmed that he offered the young Frenchman an important post in the Spanish army. But St. Denis would not consent to abandon his own flag. The viceroy then gave him a handsome horse, and parting from him with regret, sent him back to the presidio, where he married the loyal Donna Maria.

Before leaving the presidio on his return to Louisiana, he made secret arrangements for smuggling goods into Mexico.

The viceroy, having a hint of this, did not trouble St. Denis again; but he decided to establish posts and missions throughout the New Philippines—as Texas was still called—with garrisons armed to prevent contraband trade. Captain Domingo Ramon was appointed to carry on this work. He set out at once from St. John the Baptist for San Antonio, with a company of soldiers and several friars under his command. St. Denis, in high spirits and sure of his own success in spite of Captain Ramon, rode with him, acting as his guide.

Mission and presidio, as already stated, meant church and fortress. The places chosen for these buildings were generally in the very midst of populous and fierce Indian tribes. For the object of the builders was not only to hold the country against France, but also to reduce the savages and convert them to the Catholic religion.

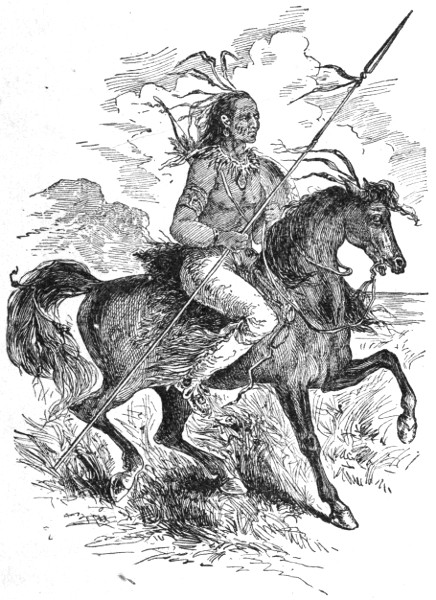

The Red Man had already his own rude belief in the Great Spirit who sat behind the clouds and watched over the flight of his arrows and the tasseling of his corn. He loved to tell about the Happy Hunting-grounds to which he would travel after death, attended by his horse and his dog.

It required a great deal of patience and perseverance on the part of the missionaries to make these wild creatures understand the meaning of the strange things they saw and heard: the hymns and prayers which broke the stillness at morning and at eventide, the candles blazing on the altar, the tinkling of bells, the movements of the priests, the humble attitude of the proud Spanish soldiers at mass. They crowded about the chapels, now accepting the new faith with childlike confidence, at other times seeking a chance to massacre priest and soldier in cold blood.

But these missionaries belonged to an order whose business it was to be patient. They were Franciscans from the monastery of St. Francis at Zacatecas in Mexico, and they were pledged to poverty and self-denial. Gentle, but sturdy, these barefooted friars, in their coarse woolen frocks and rope girdles, exercised a strange fascination over the Indians who fell under their influence.

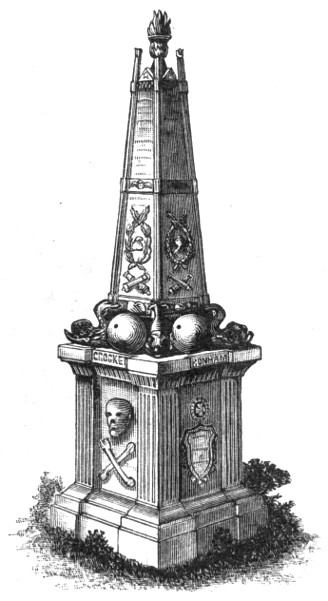

A Franciscan Father.

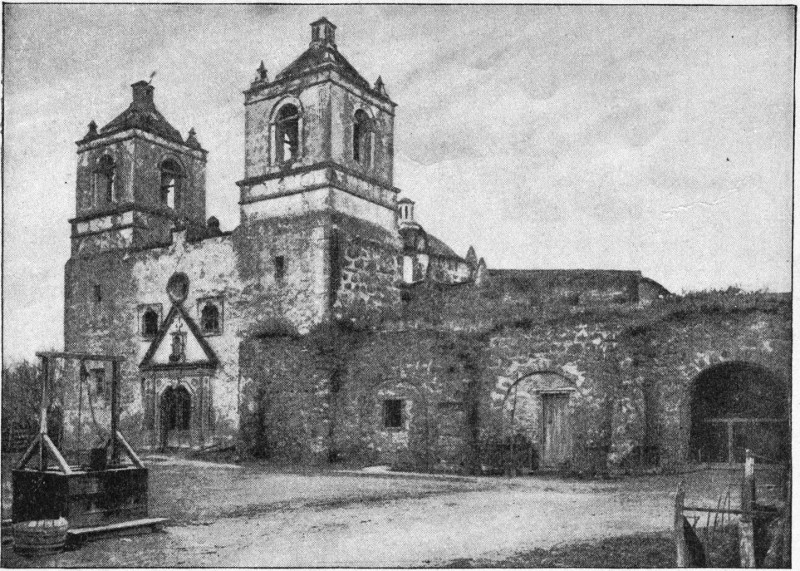

Captain Domingo Ramon went bravely to work with his soldiers and Franciscans. He was very much loved by the Indians. They adopted him into their tribes and cheerfully aided him in the hard labor of clearing and building. Within a few years the country was dotted with missions. Some of these were temporary structures, rude and frail; others were built of stone. The noble and majestic ruins of the latter fill the beholder to-day with wonder and delight. If the mission served also as a presidio, it was entitled to a garrison of two hundred and fifty soldiers; where there was no fortress, the church itself served as a stronghold. Among the earliest of the missions thus built were Our Lady of Guadalupe (Gwah-dah-loop′ā), at Victoria (1714); Mission Orquizacas (Or-kee-sa′-kass), on the San Jacinto River (1715); Mission Dolores near San Augustine (1716); Adaes, east of the Sabine River (1718); Nacogdoches (1715); and Espiritu Santo, at Goliad (La Bahia) (1718).

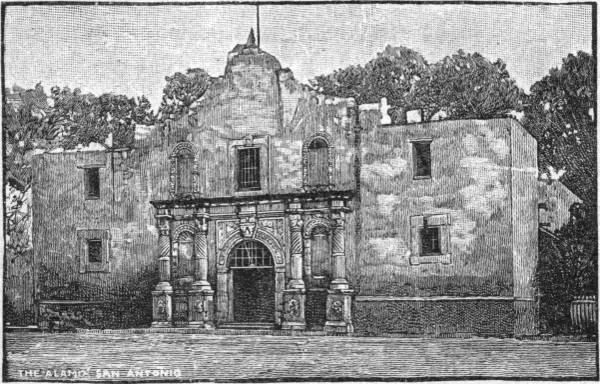

The Mission Alamo,[7] which was to play so prominent a part in the later history of Texas, was begun under another name, in 1703, on the Rio Grande River. It was removed to the San Pedro River at San Antonio in 1718. In 1744 it was finally built where its ruins now stand, on the Alamo Plaza in San Antonio, and was called the Church of the Alamo.

Early in 1718 the foundation of San José (Ho-sā′) de Aguayo, the largest and finest of all the missions, was laid near San Antonio. The little settlement which had so pleased the eye of St. Denis four years before had grown to a village. It had been laid off and named for the Duke de Bexar (Bair), a viceroy of Mexico; and St. Denis’ road, which linked it on the southwest with St. John the Baptist and on the northeast with Natchitoches in Louisiana, had already become a traveled highway. The Mission and Presidio of San José were therefore of the first importance.

Captain Ramon himself may have selected the site. It was a few miles below the town, on the limpid and swift-flowing river San Antonio. A day or two after the site was decided upon, a long procession wound across the beautiful open prairie from the village. It was headed by a venerable barefoot Franciscan father, who carried aloft a large wooden cross; on either side of him walked a friar of the same order, and behind them came acolytes and altar-boys bearing censer, bell, and vessels of holy water. Captain Ramon and his soldiers on horseback, and stiff and erect in their holiday uniforms, followed with the Spanish flag in their midst; the Mexicans who composed the slim population of San Antonio came next; then, grave and stately in their blankets and feathered headdresses and as proud as the Spaniards themselves, stalked a hundred or more converted Apache and Comanche warriors. A rabble of Indian squaws and papooses brought up the rear.

This procession went slowly along under the morning sun, now over the flower-set prairie, now through a strip of woodland. The river, breast-high to the women and boys, was forded, and as the foremost group reached the farther shore, the old Franciscan lifted his hand; a church hymn, sweet, powerful, resonant, arose from five hundred throats. Thus they came, singing, to the place where San José was to stand.

A large space was marked off; the ground plan of the great church was sketched on the turf,—perhaps with the point of Captain Domingo Ramon’s sword; the church prayers were said, and the corner-stone, already hewn and shaped, was sprinkled with holy water.

The scene on the spot daily thereafter for many years was a busy and picturesque one. Everybody worked with a will,—soldiers, priests, and Indians, all filled with a holy zeal. Even the Indian women fetched sand in their aprons, and the Indian children set their small brown bodies against the stones and helped push them into place. Tradition says that the people brought milk from their goats and cows to mix the mortar, thereby making it firmer and more lasting.

The beautiful twin towers went slowly up; the great dome was rounded over the main chapel; the double row of arched cloisters stretched their lovely length along the wall; the artist, Juan Huicar (wee′-car), sent out by the king of Spain, set his fine carvings above the wide doors.

At the same time the enclosing wall was raised; the fort with its flying buttresses, the guardhouse, the huts into which the Indian converts were locked at night—all these were completed. Orchards and gardens were planted, and irrigating ditches were dug. Again and again the work was interrupted by attacks from Indians; but when the fight was over the dead were buried, the wounded were cared for, and the building and planting went on as before.[8]

Such was the manner of the building of the Texas missions. It took sixty years to complete San José. In the meantime the handsome Mission of La Purissima Concepcion (Immaculate Conception) and San Francisco de la Espada (St. Francis of the Sword) were erected, both also on the San Antonio River.

The Mission of San Saba was built in 1734, on the San Saba River in what is now Menard County. The good fathers were at first very successful in converting the Apaches and the Comanches, who flocked to them in great numbers. But the reopening of Las Almagras (red ores), an old silver mine near the mission, brought into the neighborhood many reckless men; and quarrels soon arose between them and the Indians—quarrels which were one day to bear bitter fruit.

In 1719 St. Denis was at Natchitoches, which was one of the outposts of the French in Louisiana and close to the Texas border. He had traveled back and forth through Texas more than once since his first trip to the presidio on the Rio Grande; and he had spent much of his time in Mexican dungeons. But for that he bore the Spaniards no great ill-will. He had escaped from prison and brought his beautiful Mexican wife away with him; and when he made his flying journeys he turned aside, no doubt, to see his Spanish friend, Captain Domingo Ramon—who, by the way, was his wife’s uncle—and to admire the missions which were going up in every direction under that captain’s vigorous management. But now things were changed. A few months before, France and Spain, never on good terms with each other, had declared open war.

St. Denis, if the truth were told, was glad of a chance to fight somebody besides Indians. He was right weary of the skulking ways of the red warrior with his tomahawk, his paint and feathers, and his savage desire to carry scalps at his belt. He longed for a good honest brush with white men, who fought openly with gun and sword—men, for example, like his good friend Captain Ramon and his troop of jolly soldiers!

He leaped lightly into the saddle one morning and galloped out of Natchitoches at the head of a hundred and fifty men. Bernard de la Harpe, in joint command of the expedition, rode by his side.

They crossed the Sabine River and attacked the garrisons at the Missions of Nacogdoches, Aes, and Orquizacas, all of whom, surprised by the sudden onslaught, retreated before them. It was a lively chase across the vast territory, with a good deal of skirmishing; and it ended only when the Spaniards were safe inside the town of San Antonio.

St. Denis, drawing rein on the brow of the hill and gazing down once more into the lovely valley, saw a sort of orderly confusion on an open plaza in the heart of the town; horsemen were gathering, men were moving hurriedly about, and from the midst of the bustle the clear tones of a bell suddenly fell upon the air. It was the call to arms!

St. Denis smiled and turned to La Harpe: “It is high time we were riding homeward,” he said gaily, with a glance at their small band of wayworn troopers; and turning their horses’ heads they galloped away.

None too soon! For shortly afterwards the Marquis de Aguayo, governor of the province, came out of the town with a fresh troop of five hundred Spaniards, tried soldiers and eager recruits, and galloped in pursuit of the flying Frenchmen. It was another lively chase across the vast territory; but this time it was France who retreated, with Spain at her heels. Captain Ramon, quite as anxious for a tilt with civilized soldiers as his friendly enemy and nephew-in-law St. Denis, left the work of mission-building in the hands of his friars, and, as second in command, joined the governor-general in this pursuit.

Aguayo, following the example of St. Denis, did not pause until the intruders were safe in their own citadel at Natchitoches; then he replaced at the Missions of Orquizacas and Aes the men whom he had brought back with him, and he left for their protection a stout garrison at the Mission of Nuestra Señora del Pilar (Our Lady of the Font), about twenty miles west of Natchitoches.

He was as keenly alive as St. Denis himself to the natural beauty of the valley watered by the San Pedro and San Antonio Rivers; and on his return to San Antonio he set on foot many improvements, including the widening and deepening of the irrigating ditches.

These irrigating ditches were called acequias (a-sā′-kee-a). They are still in use, and many of them are very beautiful. One known as the Acequia Madre, or Mother Ditch, is as deep and wide as a small rivulet; the living waters, pure and cool, rush along a bed lined and parapeted with stone, and overhung with pomegranates and rustling banana leaves.

The water from the ditches is turned, by means of gates, into the fields and gardens which lie along its course. Each landowner is entitled to so much water a day, or at a stated period. This inflow of the crystal flood is called the saca de agua (taking the water), and is hailed with delight as it comes singing its way through corn-row, garden-patch, and rose-bower.

In the early days the completing of a water-ditch was celebrated as a feast. Rows of cactus were planted on its banks to keep off cattle, and shade-trees were set out along its course. A priest, attended by acolytes, blessed the water. The following day a drum was beaten at morning mass, and all those who had contributed in money or labor to the making of the ditch were summoned to the church to take part in the Suerte (soo-air′-ta),—a lottery for the drawing of the land watered by the new sluice. Tickets were placed in an urn and were drawn out by two children. The lucky holders of the highest numbers got the best lands. At night, by way of winding up the feast, there would be a procession and a fandango[9] on the plaza.

The good Marquis de Aguayo further recommended to the Spanish government at Madrid to send colonists to the province. “One family,” he said, “is better than a hundred soldiers.”

Then, having done all he could for the New Philippines, he went back to his official residence at Monclova, attended as far as St. John the Baptist by Captain Ramon.

The Spanish government, acting on the governor-general’s advice, ordered four hundred families to be sent out to the New Philippines from the Canary Islands. These islands, situated off the coast of Africa, belonged to Spain by right of conquest, and were settled by Spaniards of pure blood, noted for their honor and chastity, and for their devotion to the Catholic religion. Of the four hundred families only thirteen ever came. They reached San Antonio by way of Mexico in 1729, bringing with them their stores of clothing, silverware, and jewels. They built their dwellings around the present square of the Constitution, which they called Plaza de las Islas (Square of the Islands), in homesick memory of the sea-girt isles they had left behind.

Other colonists from Monterey and from Lake Teztuco, in Mexico, followed; houses sprung up beside the musical water-ways; vines were trained over the yellow adobe walls; semi-tropical vegetation made a paradise of the spreading fields and gardens. Finally, the newcomers, emulous of the growing walls of San José, laid on their plaza the foundation (1731) of San Fernando Church.

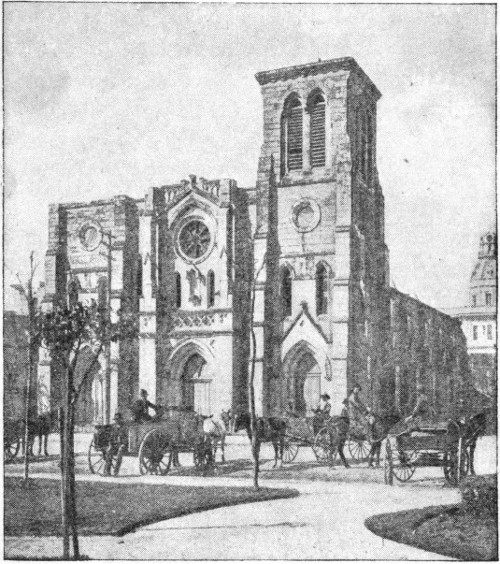

Enlarged and rebuilt on the same spot, San Fernando remains to this day the parish church of the Spanish-speaking Catholics of San Antonio.

But the settlers, or townspeople—as they may now be called—were full of anxiety in those troublous times. No more French soldiers, it is true, came riding across the border, chasing the Spanish troops to their very gates. But there were the Apaches and the Comanches. For in spite of the efforts of Spanish friars and Spanish soldiers, but few of the Apaches and Comanches had become Indios reducidos (converted Indians). Thousands of Indios bravos (wild Indians), as savage and cruel as if a mission had never been built, roamed the country, ready to swoop down at any moment upon the ill-guarded little post. A messenger would hurry in, perhaps from the missions below, which kept ever a keen lookout, breathless with the news that the Apaches were creeping stealthily upon the town. Or, suddenly and without warning, a ringing war-whoop would echo in the air, and leaping from cover to cover among the scattered houses, the Comanches, tomahawk in hand, would pursue their hapless victims to some last hiding-place; then, leaving death and desolation behind, they would vanish as suddenly as they had come.

At last the new settlers determined to put an end to this state of affairs. They organized themselves into a small army, and aided by the little garrison of soldiers then stationed there, they marched against their Indian foes, whom they defeated in a pitched battle.

THE MISSION OF LA PURISSIMA CONCEPCION.

This victory (in 1732) gave some security to the place. The Indian bravos still harried the country, killing those who ventured far from post and mission, and plundering where they could not kill. A number of years later (1752), after a fresh quarrel with the miners at Las Almagras, they fell upon the Mission of San Saba, and butchered every human creature within its walls. But rarely did they again venture near the dwellings of those determined pale-faces who had overcome them on their own hunting-grounds.

The years drifted on, peaceful and sluggish, towards the end of the eighteenth century. There were few happenings either in San Antonio itself or in the province, which was at last laid down on the map as Texas. There was no further dispute concerning boundary lines or property. Spain was the lawful owner of everything west of the Mississippi River. For Louis the Fifteenth of France, in 1762, for state reasons, presented to the King of Spain the handsome French province of Louisiana. The people of Louisiana were very angry when they learned—more than a year after the transfer—that they had been handed over without their knowledge or consent to the hated Spaniard. But Louis did not trouble himself in the least about what they thought or felt. Thus, the colonists being all Spanish subjects, were bound to peace among themselves. Even the dashing St. Denis, had he lived so long, could have found nobody to fight except the despised Indian. But that doughty warrior and courtly gentleman had long since fired his last shot on the field, and trod his last measure in the dance. According to the old chroniclers he remained to the end of his life “a devoted friend and a noble fighter.”

In 1729 a widespread plot was formed among the Indians in Texas and Louisiana to massacre all white people within reach, Spanish and French, men, women, and children. A friendly chief warned St. Denis of the plot. He gathered his troopers hastily together and rode out of Natchitoches, where he had continued in command, and in a short time defeated and scattered the tribes. After this they hated and feared him, but they looked upon him with awe, believing him to be protected by their own Manitou.

The Cathedral of San Fernando.

He was at length killed by the chief of the Natchez Indians. He lies buried near the town of Natchitoches.

In spite of the peace between Spain and France (1762)—or perhaps because of it—there was little progress in Texas. Spain forbade her colonists to trade with other nations; she did not allow them to manufacture anything that could be made in the mother-country, or to plant anything that could with profit be sent over from there. They were even forbidden to trade with their fellow-colonists in Louisiana.[10] Under these hard conditions settlers came in slowly. Texas remained almost neglected, peopled only by fierce savages.

But the little town in the southwest had a life of its own. Nearly everybody who had any business with Texas or Mexico traveled the Old San Antonio Road laid out by St. Denis in 1714; and all travelers halted at this lovely oasis in the wilderness. They were always loth to go away. For there were wonderful fiestas (feasts) in the Churches of the Alamo and San Fernando, and solemn processions to the grand Missions of Concepcion and San José; there were stately gatherings in the houses of the Island Spaniards, and merry boating parties on the blue-green waters of the river San Antonio. There were gay dances on the plaza at night to the music of guitar and castanet, and Mexican jugglers throwing balls and knives by the light of smoking torches. Bands of Mexican muleteers jingled in from the presidio on the Rio Grande, driving before them trains of mules loaded with ingots of silver, on their way to Natchitoches, four hundred miles distant; caravans traveling westward with bales of smuggled goods crawled lazily through the narrow streets. There was a continued coming and going of swarthy soldiers and black-gowned priests, governors, bishops, alcades, and christianized Indians; among them appeared, now and then, the fair face and wiry form of the American, the forerunner of that race which was one day to sweep all the others out of its path and to possess the land.

Once, in 1779, when Spain and England were at war with each other, there was even more than the usual stir on the Military Plaza. Nearly all the inhabitants of the town were gathered about the doors of the Church of the Alamo, where a priest was saying mass. Presently there was a burst of martial music, and a little company of soldiers came out; their heads were lifted proudly and their step was firm and assured. A cheer broke forth from the crowd; the soldiers sent back an answering shout as they mounted their waiting horses and rode away under the gaudy pennon of Leon and Castile.

Spain was at this time at war with England, and this handful of fighting men was the quota of troops furnished by the Spanish province of Texas to Don Galvez, the commander-in-chief of the army at New Orleans. They reached Louisiana in time to take an active part in the war and to rejoice with Galvez over his victories at Natchez, Mobile, and Pensacola.

In 1794 all the missions were secularized; that is, the control of them was taken away from the priests and given to the civil authorities. Upon this, the Missions of San José and Concepcion ceased to be the centers of activity they had been for nearly a century. San Antonio was shorn of a part of her glory. The majestic buildings remained, but the pomp and circumstance of fortress and chapel had forever departed.

One of the earliest missions planned by Captain Ramon was that of Our Lady of Nacogdoches (1715). It was built on the lands of the Naugodoches Indians, not far from the disputed boundary of Texas, and nearly on a line with the French post of Natchitoches in Louisiana. Some priests, whose duty it was to convert the Indians, were placed there, and with them a small garrison of Spanish soldiers to watch the French at Natchitoches. This was one of those garrisons surprised in 1718 by St. Denis, and driven to the gates of San Antonio. The soldiers were brought back and reinstated by Aguayo; and from that time on, to the close of the century, the little military post was kept up.

Monsieur de Pagès, a French gentleman who in 1766 passed across Texas on a voyage around the world, received from the missionary fathers at Aes, Adaes, and Nacogdoches a hospitable welcome. He describes particularly the Mission of “Naquadock” (Nacogdoches) with its “plaza and its pleasant trees,” and says that the “half-savage Spanish soldiers” at the presidio, when they were upon their horses, recalled to his mind the ancient chevaliers. The Spanish “bold-rider” wore a cuirass of antelope skin and carried a shield, a large sword, a carbine, and a pair of pistols. His arms and the equipment of his horse were very heavy and cumbersome, but he was an “amazing good fighter.” Monsieur de Pagès, who was an officer in the French navy, was also a correspondent of the Academy of Sciences at Paris. He took careful notes in all the countries through which he passed. He describes the soil and climate of Texas and the animals, especially the fine, robust horses. “A good horse,” he says, “may be had for a pair of shoes.” But his greatest interest is in the savages. He mentions the Comanches, the Apaches, the Adaes, and the Tehas tribes. The Tehas, he says, were a “corn-growing people.” He spent some time at the Mission of Nacogdoches (“Naquadock”) in company with a deposed governor of the province.

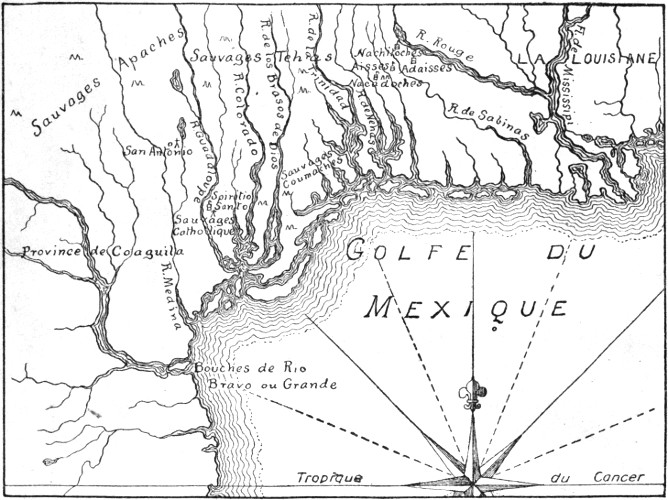

De Pagès’ Map of Texas.

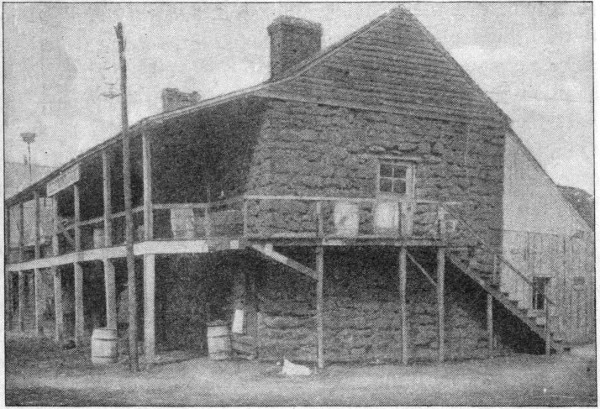

In 1778 a stone fort, which still stands, was built at Nacogdoches by Captain Gil Y Barbo for the accommodation of the Spanish soldiers. A few huts were clustered about the presidio, for it was on the Old San Antonio Road and was a stopping-place for travelers; but it was a dull and lonely spot.

Suddenly, with the birth of a new century, it awoke from its long slumber and became, in a way, the starting-point of Texas history. It was the gateway through which Anglo-American energy and ambition came in to Texas. From its plaza unrolled a panorama full of life and vigor: scenes in which adventurers, freebooters, patriots, and dreamers played their parts.

The panorama opens with Philip Nolan.

Philip Nolan, a young man of Irish descent, obtained in 1797 a permit from De Nava, the Spanish commandant-general of Texas, to collect in that province wild horses for the American army. He entered the province, made friends with the Indians, and succeeded in gathering twelve hundred mustangs, which he drove across the border. He drew and brought back with him at this time a map of Texas, the first one ever made. This map he gave to Baron Carondelet, the Spanish governor at New Orleans.[11]

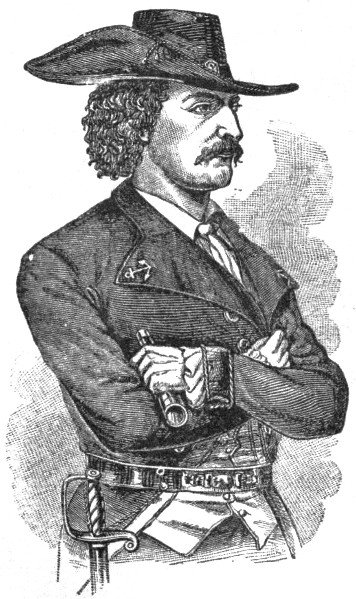

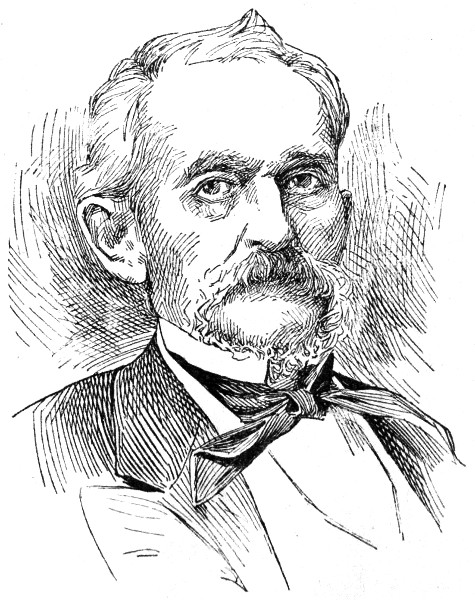

Three years later, with the same permit and ostensibly on the same errand, he started westward from Natchez, Mississippi. He had with him seventeen white men and one negro. His second in command was a nineteen-year-old lad named Ellis Bean. The men were all young, most of them being under thirty and many of them hardly more than twenty years of age.

They traveled on horseback across the wilderness, and some months later they encamped in the neighborhood of the present city of Waco, where they found “elk and deer plenty, some buffalo, and thousands of wild horses.”[12] In a short time they had caught and penned three hundred mustangs. The Indians were very friendly. At one time two hundred Comanches visited them in their camp. In return they spent a month in the wigwams of that tribe. Then they went back to their business of capturing wild horses.

But orders in the meantime had come from De Nava to Musquiz, the Spanish captain at Nacogdoches, to arrest Nolan at all hazards. He had been denounced to the Spanish government as a traitor, and it was believed that he had come to Texas for the purpose of setting up a republic of his own, or to further the plans of Aaron Burr.[13]

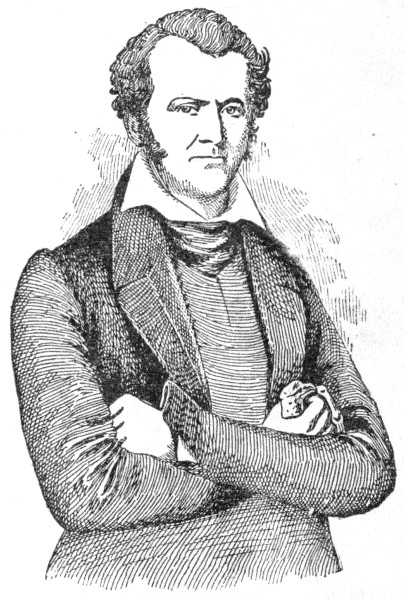

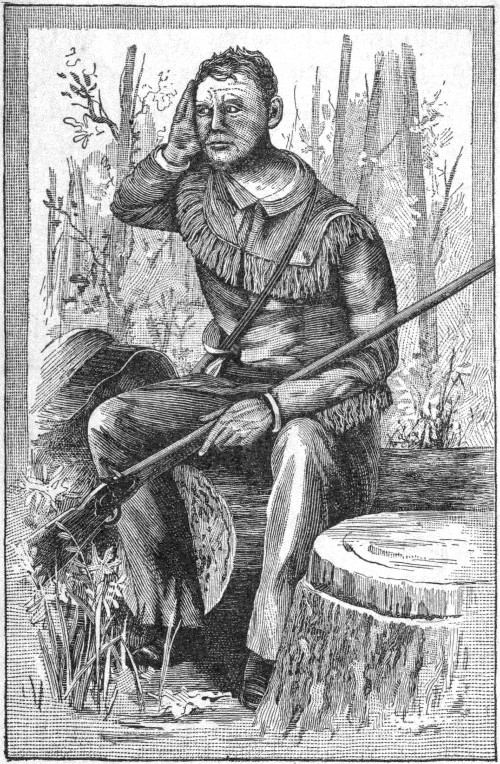

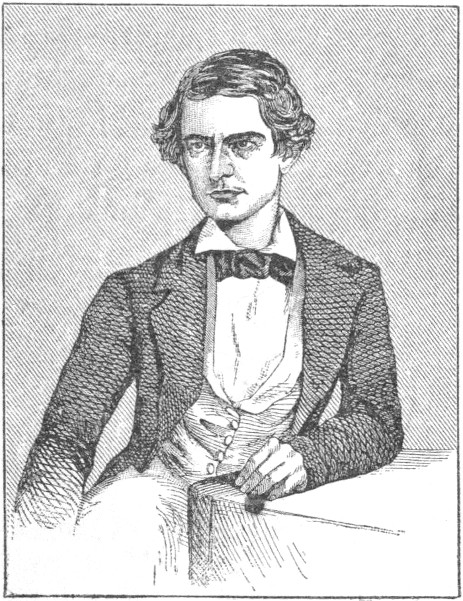

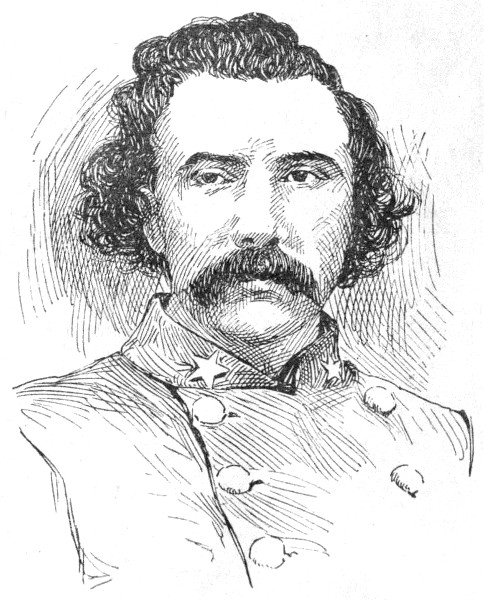

Ellis P. Bean.

Musquiz left Nacogdoches on the 4th of March, 1801, with one hundred soldiers, in search of the supposed conspirator. After a few days’ march he sent for El Blanco, a famous Indian chief, and offered him a large bribe if he would lead him to Nolan’s camp. El Blanco proudly spurned this base offer. Some Indian spies, however, served as guides, and at daybreak on the 22d of March Musquiz found the camp. He attacked Nolan and his men, who returned his fire from their rude blockhouse. Nolan, whose rifle had been stolen from him by a deserter from his own camp, was killed in a few moments. Bean took command and the fighting went on desperately for some time. Finally, on a promise from the Spaniards that they should be set free as soon as they reached Nacogdoches, the outnumbered Americans surrendered. They buried their gallant leader, whose dream of a republic, if he had one, died with him; and they set out with their captors for the Presidio of Nacogdoches. There, instead of the promised freedom, they found chains and captivity. They were heavily ironed and placed in close confinement. At the end of a month they were marched into the plaza, bound together, two and two. There was a beating of drums and a fluttering of Spanish pennons. The hearts of the poor young prisoners beat high with hope. Knowing that they had been guilty of no crime, they seemed already to feel their chains falling off, and they laughed joyfully, lifting their pallid faces to the free blue sky. But a harsh voice gave the order “Forward March!” and driven by brutal guards they limped painfully away to Mexican dungeons.

It was six years before the King of Spain found time to sentence these prisoners. A royal decree then came (1807) ordering every fifth man to be shot. By this time but nine were left alive, and the officer in charge decided that one only should suffer death.

The nine wretched captives threw dice to determine which of their number should die. The lot fell to Ephraim Blackburn, the oldest man among them. He was executed without delay.

Only one of the others ever breathed the blessed air of freedom again. Ellis Bean, after many strange and thrilling adventures, finally escaped. His companions, to a man, perished in loathsome Mexican prisons, some of them within a short time, others after a wretched captivity of more than fifteen years,—all ignorant to the last of the cause of their imprisonment.

While Nacogdoches was rubbing her sleepy eyes and staring at the Americanos, who kept coming into Texas in spite of the scant welcome they got there, a man was strutting about the court at Madrid in Spain, carrying Texas, so to speak, in his pocket. Manuel de Godoy, called El Principe de la Paz (The Prince of the Peace), who, from a private in the King’s Guards had come to be a grandee of Spain and first minister of the King’s council, was a corrupt courtier, cordially hated by the people, but a favorite both of the King and the Queen.[14] They had given him the highest honors and titles possible in Spain and finally they had made him a present of the territory of Texas. To this princely gift they added soldiers and ships and a large number of young women from the asylums in Spain. Godoy in his dreams already saw himself ruling in a semi-barbaric fashion over his kingdom in the “golden west.”

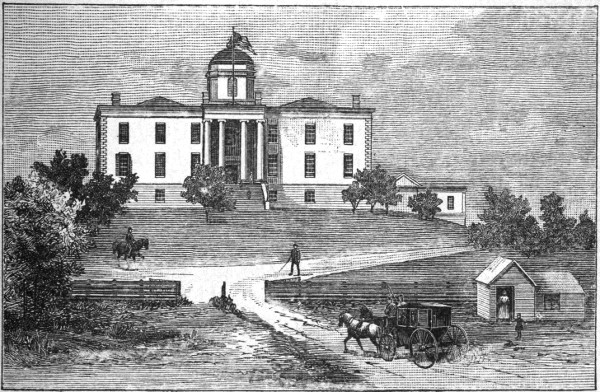

Old Stone Fort at Nacogdoches.

The attitude of Napoleon Bonaparte toward Spain put an end to this curious scheme. Soldiers and ships were ordered to another service; the young women were returned to their asylums; and Godoy was sent into dishonorable exile with his pocket empty, at least of Texas.

Spain, tired of the troublesome present she had received from Louis the Fifteenth, one fine day in 1800 handed Louisiana back to France. But before the French colonists had time to rejoice, Napoleon in 1803 sold them and their province to the United States. Again they were very angry; but, as before, nobody cared in the least what they thought or how they felt.

The old dispute concerning the boundary between Louisiana and Texas was revived by this transaction. Spain claimed eastward as far toward the Mississippi River as she dared. The United States would gladly have reached out westward to the Rio Grande. The quarrel at last grew so bitter that both countries prepared to go to war (1806).

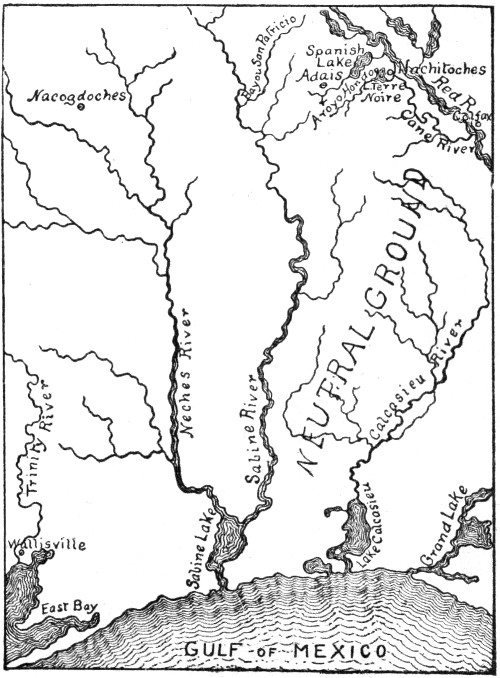

Nacogdoches and Natchitoches glared at each other across the Sabine River, like two watch-dogs snarling and showing their teeth.

Antonio Cordero, governor of Texas, hurried by way of the Old San Antonio Road from San Antonio to Nacogdoches. The lonely presidio then fairly thrilled; for fortifications were thrown up, provisions were brought in, and the place was put in a state of defense. Soldiers were also stationed at the mouth of the Trinity River, at the old fort at Adaes, and at other points. At length in August, 1806, Simon Herrera, commanding the Spanish troops with Cordero as his second, marched in with twelve hundred men at his back.

At Natchitoches also there was bustle and excitement. Governor Claiborne, followed at once by General Wilkinson of the United States army, had come up from New Orleans. Several angry messages passed between Generals Wilkinson and Herrera, but neither would yield an inch in his demands; and on the 22d of October General Wilkinson marched his troops to the east bank of the Sabine River and camped there. General Herrera’s camp was on the west bank, just opposite. The stream alone separated the two armies. On both sides everything was in readiness for a battle.

But in the hush of the night (November 5) the two generals met and held a secret council. The next day (Nov. 6, 1806), to the surprise of all and greatly to the disappointment of the American soldiers, it was announced that the affair had been peacefully settled. A strip of land between the Sabine River and a creek called the Arroyo Hondo seven miles west of Natchitoches, was declared neutral ground,—that is, ground to be occupied by neither country until the boundary line could be fixed by a state treaty.[15]

The Americans marched away, grumbling openly; the Spanish generals, having got more than they expected, returned well pleased to Nacogdoches.

Nacogdoches had ceased to be simply a stopping-place for travelers; it vied with its distant neighbor, San Antonio, in the gaiety of its social life. The Spanish officers, especially the commandant Herrera, were noted for their gracious and courtly manners. Some American families of position had moved in; there was even a hotel. The presidio had become a town.

One day in 1812 a young man—an American—wearing the uniform of the United States army crossed the Arroyo Hondo on horseback and entered the Neutral Ground. He withdrew a little from the road, dismounted, and seated himself upon a fallen log, seeming to await some one or something.

Soon a second rider appeared, threading his way through the forest trees. He was a Spaniard of soldierly bearing, and his somewhat stern features offered a marked contrast to the eager face of the first comer. He dismounted with a courteous greeting, sat down in his turn, and drawing a map from his pocket, he spread it upon his knees.

The Spaniard was Colonel Bernardo Gutierrez de Lara. The American was Lieutenant Augustus Magee.

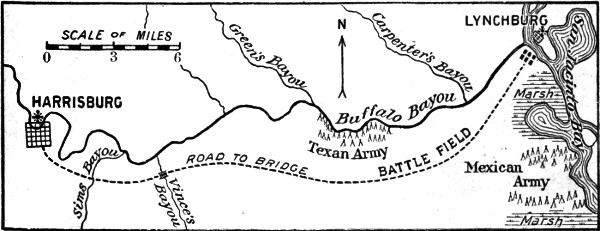

Map of The Neutral Ground.

The Neutral Ground from the moment of the treaty between Herrera and Wilkinson in 1806 became the resort of all sorts of lawless men, who, subject to no authority, robbed and murdered at will the travelers passing across this No Man’s Land. The danger at last became so great that the United States sent a squad of soldiers to serve as an escort to people whose business led them between the Sabine and Natchitoches. Lieutenant Magee was placed in command of this escort. He was a bold and gallant young fellow, within whose romantic brain soon came the idea of following out Nolan’s supposed plan of founding an independent republic in Texas.

He confided his project to Gutierrez, who had fled to Natchitoches after the failure of a similar attempt in Mexico, in which he had taken part. Gutierrez was delighted. He undertook to gain over the Mexicans in Texas. Magee resigned his position in the United States army and soon succeeded in forming a band composed of adventurers and desperadoes from the Neutral Ground, a number of Indians, some Mexicans, and a few Americans of good character. Gutierrez, on account of his influence over his countrymen, was put in command. Magee, however, was the leading spirit.

It was to talk over their scheme of invasion and conquest, to consult maps and arrange routes, that Magee and Gutierrez had met on the banks of the Arroyo Hondo.

Magee started soon after for New Orleans to get money and recruits. Gutierrez with a few men crossed the Sabine and took possession of Nacogdoches, which was at once abandoned by the Spaniards. From that place he marched to join Magee and the main army on the Trinity River.

The first movement of this army of republicans, which numbered several hundred men, was upon La Bahia (Goliad). The Spanish garrison in the fortress there joined them, surrendering, along with other military stores, the cannon brought over by La Salle in 1685.

Hardly, however, were the republicans within the fort when they were attacked by the Spanish army, under Governor Salcedo and General Herrera.

The fighting was at great odds, but the little band of republicans held their own during several months, their greatest loss being the death of their brave and spirited young leader, Magee, who, wasted with consumption, died in February, 1813.

Shortly afterwards a fierce hand-to-hand skirmish took place. In this the republicans were victorious. The Spaniards thereupon gave up the siege and retreated to San Antonio. The republicans followed under Colonel Kemper, who had succeeded Magee. On the 28th of March, 1813, a bloody battle took place on the Rosillo Creek, nine miles from San Antonio. The Spaniards were defeated with the loss of one thousand men. The victorious army marched into San Antonio, flying their flag in triumph. In the fortress of the Alamo they found seventeen prisoners, whom they released; the private soldiers taken prisoners at Rosillo were all set at liberty. The officers were at first paroled; but afterward by order of Gutierrez, or at least with his consent, they were marched by a company of Mexican soldiers to a place on the river below the town; there they were stripped, their hands were bound behind their backs, and their throats cut.

Among those thus brutally butchered were Salcedo, Governor of New Leon, Governor Cordero, and the brave and polished Herrera.

Many of the better class of Americans, among them the commanding officer, Colonel Kemper, disgusted with the savagery of Gutierrez, left the army. The republicans who remained were filled with triumph; intoxicated with success, they gave themselves up to rioting and rejoicing.

Their enthusiasm was increased by a victory over another Spanish force sent against them under the command of Don Y Elisondo (El-ee-son′do). In this battle, fought June 4, the Spaniards lost over a thousand men, dead, wounded, and prisoners.

But the tide of success had reached its height; it began to turn. Gutierrez having retired to Natchitoches, General Toledo (To-lā′do) was now in command of the republicans. On the 18th of August he marched out of San Antonio to attack a third Spanish army commanded by General Arredondo, who had thrown up breastworks on the Medina near the town.

The result was a terrific defeat for the republicans. Almost the entire army was destroyed; many were killed; those taken prisoners were butchered as cruelly as Herrera and his brother officers had been. Out of eight hundred and fifty Americans, only ninety-three escaped. One by one these stole through Nacogdoches on their way back to the safe thickets of the Neutral Ground.

Nacogdoches, it may be supposed, had grown accustomed to that dream of a Texas Republic which from time to time caused the air about her stone fort to thrill and vibrate; she was accustomed, too, to see that dream end in bloodshed and death.

So it was an old story when in 1819 some three hundred Americans came tramping in, ready, as they imagined, to convert Texas into a free and independent state. This new expedition, organized at Natchez, Mississippi, was conducted by Dr. James Long of Tennessee, an energetic patriot who had served as a surgeon in Jackson’s army at the battle of New Orleans.

General Long’s brother, David, accompanied him; and his wife and her sister followed, under the conduct of Randall Jones. They arrived at Nacogdoches soon after the new republicans had taken peaceful possession of the town.

A legislative body was formed. One of its members was Bernardo Gutierrez, who had continued to live at Natchitoches. The Republic of Texas was proclaimed, and land and revenue laws were passed. A newspaper, the first in Texas, was started by Horatio Bigelow, a member of the council.

General Long’s next step was to take possession of the country and strengthen the infant government. He placed detachments of men at various points on the Brazos and Trinity Rivers, opened trade with the Indians, and sent James Gaines, one of his lieutenants, to Galveston Island to get the assistance of Lafitte.

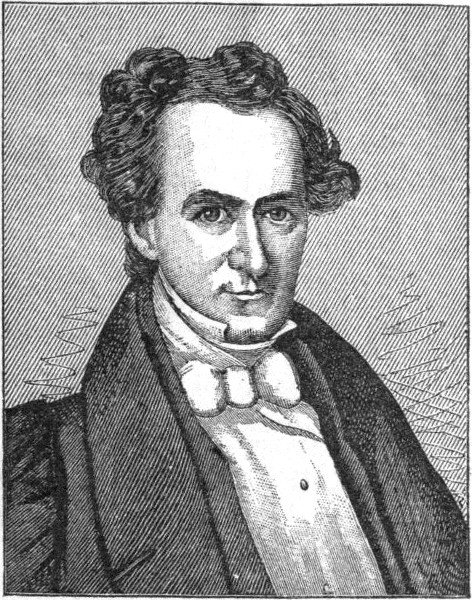

Jean Lafitte, a Frenchman by birth, had, while yet a mere lad, commanded a privateer which sailed the Gulf of Mexico. Later, with his two brothers, he had been, nominally, a blacksmith in New Orleans; but while hammering horseshoes and making wagon-tires, he was really engaged in smuggling. After a while, he dropped all pretense, and gathering together a band of reckless men he established himself in 1810 on the island of Grand Terre, a swampy lowland in Louisiana near the Gulf coast. From there he plied his unlawful trade. His band became finally so bold and troublesome that a reward was offered for their leader’s head. This proclamation, signed by Governor Claiborne, was posted about New Orleans; and more than once the daring freebooter was seen talking gaily with a group of friends, leaning the while with folded arms against a wall upon which flamed in big letters the governor’s mandate demanding his head. He was never captured.

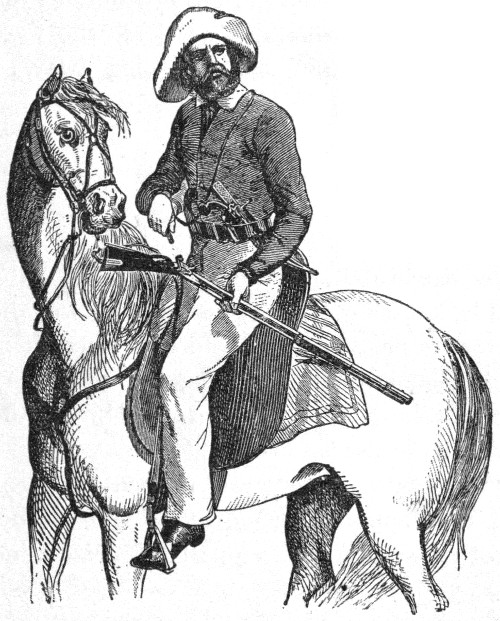

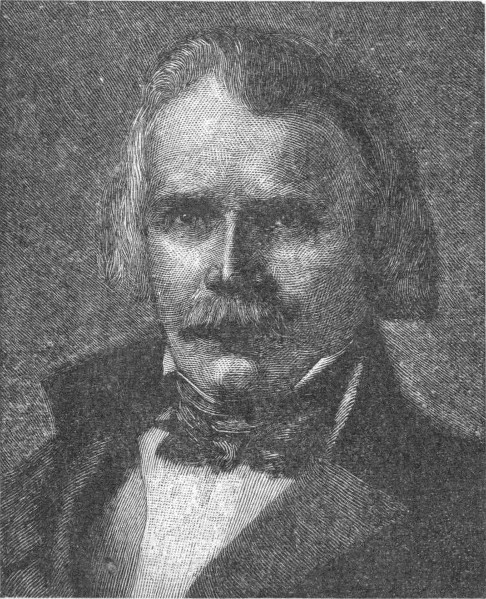

Jean Lafitte.

In 1814, when the United States and England were at war, a British officer visited Lafitte at Grand Terre and offered him the command of a frigate if he would join the British navy. Lafitte instead offered his services to General Jackson, fought gallantly at the battle of New Orleans, and received a full pardon from the United States government.

But his restless spirit would not long suffer him to remain inactive. In 1816 he fitted out a schooner (The Pride) and sailed to the uninhabited island of Galveston.

This island was discovered by La Salle as he coasted along the Gulf in 1684, seeking the Mississippi River. He called it the Island of St. Louis. It was afterward known as Snake Island, and received its present name, about 1775, in honor of Don José Galvez, governor of Louisiana and son of the viceroy of Mexico.

It had been occupied for a short time (1816) by a band of Mexican “republicans,” under Manuel Herrera and Xavier Mina. They were joined by Luis d’Aury, a Mexican naval officer, and Colonel Perry, an American who had taken part in Magee’s ill-fated expedition. They set up a sort of republic on the island. Their fleet of twelve armed vessels sailed the Gulf, and for a time the enterprise prospered. But the little republic did not last long. The leaders quarreled among themselves; the United States denounced their sailors as pirates; the settlement was broken up, and Galveston returned to its native solitude.

The island was covered with beautiful green grass; there were no shrubs, and the only trees were three live oaks clustered together about midway of the island. Its wide beach shone like silver in the sunlight. Here in a short time Lafitte had established a miniature kingdom. Adventurers came flocking to him from every direction, and in less than a year there were a thousand persons on the island. Lafitte, bearing the proud title of “Lord of Galveston,” held absolute sway over them. The fort and the town, which he named Campeachy, were kept under strict military rule. The bay harbored a fleet of swift vessels, sailed by fearless pirates who swept the Gulf, capturing and plundering Spanish ships and bringing the rich spoils to be divided by their chief. On the incoming Spanish barques there were bales of silks and satins, woven for the dark-eyed dames of Mexico, and soft carpets and priceless hangings for their houses; there were rare wines for the tables of the viceroys, and gold-embroidered altar-cloths for the churches. On outgoing Mexican vessels there were bars of silver and ingots of gold, tropical spices and dyes, uncut jewels, and beautiful skins of wild animals. All these treasures were unrolled and spread out on the open square of the fort, and each man was allotted his share. Lafitte was generous with the goods brought in by his freebooters. Once from a rich “haul” he took for his own share only a slim gold chain and seal which had been removed from the neck of a portly Mexican bishop on his way to visit Rome. This chain and seal were given by the pirate to Rezin Bowie, a brother of James Bowie. It remains in the Bowie family to this day.

Besides the regular business of piracy, which was politely called privateering, a brisk slave-trade was carried on between the island and the shores of Africa. Slave-ships came boldly into the harbor and landed their cargoes of black humanity at Campeachy. The negro gangs were driven into the fort, where they were sold by the pound. The price paid was generally one dollar a pound, though prices sometimes fell so low that an able-bodied man or woman could be bought for forty dollars. The purchasers hurried the unhappy Africans through the country to Baton Rouge and New Orleans, where they were resold at higher prices.

Lafitte was adored by his followers, though he ruled them as with a rod of iron. In person he was tall, dark, and handsome, with stern eyes and a winning smile. He wore a uniform of dark green cloth, a crimson sash, and an otter-skin cap. He lived in great state, in a richly furnished dwelling, called, from its color, the “Red House,” and entertained there in an almost princely manner the strangers whom business, curiosity, or misfortune brought to the island.

The Carankawae Indians, who had formerly held the strip of silver sand as their own fishing-ground, visited the newcomers, and gazed with wonder at their ships, their houses, and their cannon. But in a short time a quarrel arose between some of the freebooters and the chiefs, and four of Lafitte’s men were killed.

Lafitte hastened to avenge their death. He marched to the Three Trees, where three hundred Carankawaes were encamped. His own force numbered less than two hundred, but they were well armed and provided with two pieces of artillery. The Indians after three days of hard fighting were defeated, and withdrew to the mainland. This defeat increased their hatred of the whites. But they gave no further trouble to Lafitte.

The Lord of Galveston was at the height of his power in March, 1818, when a colony composed of his own countrymen sailed into the bay. They were led by General Lallemand, one of Napoleon Bonaparte’s old officers. The empire had fallen, Bonaparte was in exile at St. Helena, and Lallemand, no longer happy or safe in France, decided to form somewhere in the New World a Champ d’Asile (Place of Refuge). His choice finally fell upon Texas. He left France in October, 1817, with four hundred men and several women and children. He and his brother officer, General Rigaud (the latter being eighty years old), were received with stately courtesy by Lafitte, who assisted them greatly in their preparations for the journey to the place chosen for their colony.

This was on the banks of the Trinity River, about sixty miles from its mouth. When all was ready the two generals, with one hundred men, traveled thither by land; the others set out by water with a number of small boats carrying provisions, ammunition, etc.

After several days’ march the land party reached its destination, where the boats should have arrived before them. The boats were not there. Lallemand and his men were already without food, as they had started with an insufficient supply. They began to suffer the pangs of hunger, filled at the same time with anxiety about the missing boats. While in this condition they found in the woods around a sort of wild lettuce, large quantities of which they boiled and ate. No sooner had they eaten than they were seized with violent and deathlike convulsions. Lallemand, Rigaud, and one of the surgeons had not tasted the poisonous herb. But they were powerless to help, the medicines being on the boats.

Thus they were in despair when a Coushatti Indian, drawn by curiosity, came into the camp. He looked with amazement at the ninety-seven men stretched out and apparently dying on the ground. Lallemand, showing him the fatal herb, explained to him by signs what had happened. The Indian sprang swift as an arrow into the forest, and in a short time reappeared, his arms filled with a feather-like weed. It was the antidote of the poison the men had eaten; he boiled and made a drink of it; and, thanks to his skill and kindness, they all recovered.

Some days later the boats arrived. The voyagers had been unable at first to find the mouth of the river, hence the delay.

The colonists went to work with a will upon their settlement. They built four small forts,—Forts Charles and Henry, Middle Fort, and Fort Palanqua,—mounted eight cannons, and hoisted the French flag. Then they busied themselves with their own houses and fields.

They were very happy, these self-exiled French people. They labored in their fields and gardens by day; at night they sang and danced and made merry, looking forward to long and peaceful lives in their new home.

But the grain was hardly ripe in their fields when word came that Spanish soldiers from San Antonio and Goliad (La Bahia) were marching upon them to destroy them, or to drive them out of the country. They were not strong enough to resist such a force, so they abandoned their cabins and smiling gardens and returned to Galveston. A violent storm swept over the island a few days after their arrival there. Lafitte lost two brigs, three schooners, and a felucca; the unfortunate colonists lost not only their boats, but all their clothing and supplies.

Lafitte gave them the San Antonio, a small ship captured from the Spaniards, and provided them with food and clothes. Some of them sailed to New Orleans in the San Antonio; others made their way overland to Nacogdoches; thence to Natchitoches, to Baton Rouge, and at length to New Orleans, whence by the kindness of the citizens they were able to get back to France.

It was but a few months after Lafitte had so generously aided Lallemand and his colonists, when James Gaines, sent by General Long, came to the island. Lafitte entertained him royally at the Red House, but declined to join Long’s enterprise. He thought a Texas republic could be established only by the help of a large army, whereas General Long had but a handful of soldiers.

When Long received Lafitte’s reply he started to the island himself, in the hope of changing this decision. But hearing from his wife that a Spanish force under Colonel Perez was moving upon his outposts, he hurried back to Nacogdoches. He found that place deserted; everybody had fled panic-stricken across the Sabine at the approach of the Spaniards. In the meantime Perez attacked the forts on the Brazos and the Trinity, completely routing the garrisons. David Long was among the killed.

General Long’s spirit was unshaken. He joined his brave wife on the east side of the Sabine, and made his way with her to Bolivar Point, where the few followers left to him were encamped.

Just at this time Lafitte was ordered by the United States government to leave the island; his pirates had begun to meddle with American ships. He felt that resistance would be useless; so he gathered his men together, gave them each a handsome sum of money, and, having set fire to his fort and town, he sailed away in The Pride, with sixty of his buccaneers and a choice crew. He cruised for some years off the coast of Yucatan, and died at Sisal in 1826.

It was long believed that he buried fabulous treasures—gold, silver, and jewels—both at Grand Terre and at Galveston, but these treasures have never been found. There is a legend among superstitious people at Grand Terre which declares that several times swarthy, dark-bearded strangers have appeared there and dug in a certain place for the buried treasure. They have succeeded each time in uncovering a great iron chest; but as they were about to lift it out, some one has each time spoken, and at the sound the box instantly disappeared. It can be found and removed, the gossips add, only in the midst of perfect silence.

A prettier story is told of the treasure buried at Galveston. This story goes that on the night before he left the island forever, the pirate chief was heard to murmur, as he paced up and down the hall of the Red House: “I have buried my treasure under the three trees. In the shadow of the three lone trees I have buried my treasure.” Two of his men overheard him. They stole away down the beach, with picks and spades, determined to possess themselves of their leader’s treasure, which they knew must be priceless. They reached the spot, and in the pale moonlight they found the stake set to mark the hiding place. They shoveled the sand away, breathless and eager with greed. At length they found a long wooden box whose cover they pried open. Within, instead of piles of silver, caskets of jewels, and heaps of golden doubloons, they saw with awe and amazement the pale face and rigid form of the Chief’s beautiful young wife, who had died the day before. This was the treasure of Lafitte!