Title: Graham's Magazine, Vol. XL, No. 4, April 1852

Author: Various

Editor: George R. Graham

Release date: August 21, 2019 [eBook #60148]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Mardi Desjardins & the online Distributed

Proofreaders Canada team at https://www.pgdpcanada.net

from page images generously made available by Google Books

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. April, 1852. No. 4.

Contents

Transcriber’s Notes can be found at the end of this eBook.

GRAHAM’S MAGAZINE.

Vol. XL. PHILADELPHIA, APRIL, 1852. No. 4.

———

BY IGNATIUS L. DONNELLY.

———

Here the sinking sun hath broken through a forest close as night;

Plashing all the deepened darkness with its thick and wine-like light.

Shivered lies the broad, red sunbeam slant athwart the withered leaf,

Laughing back the startled shadows from their high and holy grief;

Down yon dusk-pool, slant, obliquely, shoots a line like sparry splinter,

As the waking flush of spring-time lightens up the eyes in winter:

Dimming as it straineth downward melts the red light of the sun,

Darkling pool and piercing beamlet mingling whitely into one.

Fallen rays, like broken crystals, spangle thick the shadowy ground,

Ragged fragments, glorious gushes scattered richly, redly round.

Where the lazy lilies languish, one intruding sunbeam creeps;

In the arms of slumberous shadow, like a child it sinks and sleeps;

And the quiet leaves around it seem to think it all their own,

’Mid the grass and lightened lilies sleeping silent and alone.

Here the dew-damp lingers longest ’mid the plushy fountain moss;

Here the bergamot’s red blossom leans the stilly stream across;

Here the shade is darkly silent; here the breeze is liquid cool,

And the very air seems married to the freshness of that pool.

See, where down its depths pellucid, Nature’s purest waters well,

Breaking up in curving current, wimpled line and bubbly swell;

While in swift and noiseless beauty, through the deep and dewy grass,

O’er the rock and down the valley, see the hurrying waters pass.

Oh, how dreamy grow my senses, as I couch me ’mid the flowers,

Oh, how still the blue sky looketh, oh, how noteless creep the hours;

Oh, how wide the silence seemeth, not a sound disturbing comes,

Save a drowsy, sleepy buzzing, that around continuous hums;

And I seem to float out loosely on weak slumber’s languid breast,

With a kind of half reluctance that sinks gradually to rest.

Distant faces group around me, kindly eyes look in my own,

And I hear, though indistinctly, voices of the lost and gone:

His whose bark went down in tempest; his whose life and death were gloom;

His whose hopes and young ambitions fell and faded on the tomb;

Oh, again his earnest language breaks upon my dreaming ear,

And I catch the tones that waking I shall never, never hear.

———

BY A. J. REQUIER.

———

Oh, with more than the pilgrim of Mecca’s devotion,

When he looks on the shrine which his worship endears,

Is the glance which we cast at the young heart’s devotion,

Its first rose of summer—the last which it bears;

Bright as a halo of sunshine reposing

At break of the morn on a billowless stream,

Where the wavering shadows are fitfully moving,

Or blush of a Peri that smiles in a dream.

Thus, thus must thou dwell on each glance of affection,

Each token of love I have strewed at thy shrine,

When thy bosom first heaved at the fear of detection,

And its secret alone was imparted to mine;

It is linked with each thought that is born in thy waking,

It embosoms each fancy that softens thy sleep,

And, if e’er it be wild as the waves in their breaking,

’Tis the image of Heaven that breaks on the deep!

For vainly the bosom whose pulses have throbbed

To the beat of a heart it had warmed with its fire,

Seeks to freeze the remembrance of tears it has sobbed,

And to smother the anguish of pining desire;

The remembrance will live, the remembrance will cling.

As the ever-green ivy encircles the oak,

And the tempest may strike with its withering wing,

But together they bend and together are broke!

Bright star of my soul! thus united we stand,

Intermingled in being and blended in breath,

Come fate with her darkest, her gloomiest band,

We will bend, we will break undivided in death;

’Twas Heaven decreed it, ’twas Heaven that wove

The tie which has bound us in home and in heart,

And this only we know, we live on but to love,

And thus loving we never, oh, never can part!

———

BY LYDIA L. A. VERY.

———

“ ’Tis in the morning that the church-yard of Memory gives up its dead.”

Let them rise from the heart’s tomb;

Spirits, not of sadness or gloom—

White-robed thoughts of Childhood’s truth,

Cherished hopes that filled our youth.

Let them rise a shining band

Coming from the Spirit-Land.

Let them rise! each well-known face,

Where so oft we loved to trace

Smiles that beamed for us alone,

Eyes o’er which Death’s veil is thrown—

Let them gather round our bed

All unheard their noiseless tread!

Let their eyes of love still speak,

Let their breath be on our cheek,

And their voice in our ear

Murmur words we loved to hear:

Let their spirits fair and bright

Visit us at morning light.

Death, who cometh thief-like, still

Taking Life’s bright gems at will;

With us early, with us late,

Making hearth-stones desolate—

Death, who visits all Life’s bowers.

Cannot gather Memory’s flowers!

FROM THE GERMAN.

“When will your bards be weary

Of rhyming on? How long

Ere it is sung and ended,

The old, eternal song?

“Is it not, long since, empty,

The horn of full supply;

And all the posies gathered,

And all the fountains dry?”

As long as the sun’s chariot

Yet keeps its azure track,

And but one human visage

Gives answering glances back;

As long as skies shall nourish

The thunderbolt and gale,

And, frightened at their fury,

One throbbing heart shall quail;

As long as after tempests

Shall spring one showery bow,

One breast with peaceful promise

And reconcilement glow;

As long as night the concave

Sows with its starry seed,

And but one man those letters

Of golden writ can read;

Long as a moonbeam glimmers,

Or bosom sighs a vow;

Long as the wood-leaves rustle

To cool a weary brow;

As long as roses blossom,

And earth is green in May;

As long as eyes shall sparkle,

And smile in pleasure’s ray;

As long as cypress shadows

The graves more mournful make,

Or one cheek’s wet with weeping,

Or one poor heart can break;—

So long on earth shall wander

The goddess Poesy,

And with her, one exulting

Her votarist to be.

And singing on, triumphing,

The old earth-mansion through,

Out marches the last minstrel;—

He is the last man too.

The Lord holds the creation

Forth in his hand meanwhile,

Like a fresh flower just opened,

And views it with a smile.

When once this Flower Giant

Begins to show decay,

And earths and suns are flying

Like blossom-dust away.

Then ask,—if of the question

Not weary yet,—“How long,

Ere it is sung and ended,

The old, eternal song?”

———

BY THOMAS MILNER, M. A.

———

It is convenient to place an indefinite title at the head of this article, in order to notice various classes of independent phenomena which immediately address themselves to the eye; and which are either plain developments of electrical action, or simply atmospheric meteors, or appearances resulting from its reflecting and refractive properties, or of obscure origin, but manifested in the atmosphere. To the former class the lightning belongs, beautifully playing among the distant clouds, or flashing with blinding glare and tremendous effect near the surface of the earth, warning man and beast of the presence of an agency able to extinguish animal and vegetable life in a moment, and utterly inappreciable in its swiftness, subtility and power. At the close of a hot, sultry day, over a level country, the igneous meteor often exhibits itself, in rapidly succeeding, broad, noiseless, and imposing sheets of flame, lighting up the whole range of the horizon, revealing for the moment the contour of the distant landscape upon which the shadows of the night have gathered, and discovering the outline of the clouds in the dusky sky. These displays, however startling to “the poor Indian, whose untutored mind” is alarmed at the slightest deviation from the ordinary aspect of things, are always harmless, and invite by their innocuousness and fascination the cultivated races to watch the bounding coruscations of the elastic element, besides contributing to render the fields of corn ripe unto the harvest. But it is otherwise when heat has overcharged the atmosphere with vapors, becoming piled into clouds of gigantic dimensions and massive architecture, which are often propelled by antagonist currents, and in different electrical conditions. After an unusual calm of nature, oppressive to the animal system, during which not a movement of the air is perceptible, and the leaves hang motionless upon the trees, while the brute creation indicate some intelligence of an impending change by their restlessness, an explosion commences. The flash is seen, the thunder heard, and the clouds open their watery store-house, a few distant and heavy drops increasing into a cataract of rain. Flash rapidly follows flash, and the interval between each appearance and the accompanying thunder peal becomes less. The pale hue of the lightning is exchanged for a vivid glare, in which a deep yellow, red, or blue is the predominant color, a variety of aberrations marking its course, the zigzag form showing that the fearful agent is near terrestrial objects. In this manner, “the detraction that wasteth at noonday” is frequently exhibited, now striking man and beast to the earth, or rending asunder the mighty oak of the forest, or firing the vessel of the hapless seaman, or shivering “the cloud-capt towers and gorgeous palaces,” the fanes of religion and the fortresses of war. Man has then a solemn sense of his helplessness and danger; and almost every creature sympathizes with him. The eel is restless in his muddy bed—the horse trembles beneath his rider—the cattle gather lowing to a covert—the eagle nestles in the cleft of the rock with folded wings—the hart looks wild and anxious: only the poor seal seems to experience agreeable sensations, for he will come out of his hiding-place in the deep, at the call of the thunder, and repose upon some overhanging ledge, as if calmly enjoying the convulsion of the elements.

Since the month of June 1752, when Franklin performed the celebrated kite experiment, by which he became the modern Prometheus, bringing down the celestial fire to the earth, the identity of lightning and electricity has been universally known. The theory of the electric fluid, as it is called, is to be sought for in philosophical treatises, our province being to notice its distribution, phenomena, and effects. That subtle principle which the Greeks denominated electricity, from elektron, amber, because the property was first noticed in that substance, appears to be a universally diffused agent, its presence having been detected in connection with the clouds, with hail, rain and snow, with vegetation, animals, and the interior strata of the earth. But undue accumulation transpires—the electrical equilibrium is disturbed; and the resulting phenomena of equalization are lightning and thunder. Thus two clouds, or a cloud and the earth, unequally electrified, tend to return to a condition of equality through a conducting medium, a metallic or moist body having the preference as a conductor, the discharge of electricity appearing in the form of a spark or flash, accompanied by a loud detonation according to its violence, the peal rebounding in echoes from cloud to cloud, and from hill to hill. Some regions of the globe are peculiarly subject to accumulations of electricity. Mr. Hamilton, in his work on Asia Minor, observes—“One of the most remarkable phenomena which I observed in Angora, was the great degree of electricity which seemed to pervade every thing. I observed it particularly in silk handkerchiefs, linen and woollen stuffs. At times, when I went to bed in the dark, the sparks which were emitted from the blanket gave it the appearance of a sheet of fire; when I took up a silk handkerchief, the crackling noise would resemble that of breaking a handful of dried leaves or grass; and on one or two occasions I clearly felt my hands and fingers tingle from the electric fluid. I could only attribute it to the extreme dryness of the atmosphere, and momentary friction. I did not observe that it was at all influenced by wind; the phenomena were the same, whether by night or by day, in wind or calm. Not a cloud was visible during the whole of my stay.”

Similar striking indications of the prevalence of electric action have frequently been observed by travelers when near the summits of high mountains, as by Sir W. J. Hooker on Ben Nevis, Saussure on Mont Blanc, and Tupper on Mount Etna. The latter, descending a field of snow, a good conductor, felt a slight shock upon entering a cloud which seemed electric, with a sensation of pain in the back. The hair of his head stood erect, and upon moving the hand near the head, a humming sound proceeded from it, which arose from a succession of sparks. Though a situation of great danger, yet we have several instances of such clouds having been traversed with impunity, when in the act of electrical explosion. The Abbé Richard, in August 1778, passed through a thunder-cloud on the small mountain called Boyer, between Chalons and Tournus. Before he entered the cloud, the thunder sounded, as it is wont to do, with a prolonged reverberation; but when enveloped in it, only single peals were heard, with intervals of silence, without any roll; and after he had passed above the cloud, it reverberated as before, and the lightning flashed. The sister of M. Arago was a party to a similar occurrence between Estagel and Limoux, and some officers of engineers likewise, during a trigonometrical survey on the Pyrenees.

The energy of atmospheric electricity appears to decrease as we recede from the equator to the poles, thus sympathizing with light and heat; for it is in tropical countries that the most terrific flashes of lightning and the loudest bursts of heaven’s artillery occur. Awful as these manifestations are occasionally in our temperate climate, they are but as a skirmishing of outposts to the general engagement of armies, when compared with inter-tropical displays. In Hindustan, in the Indian Ocean, along the African coast off Cape St. Verde, and in Central America, there is often a scene exhibited, which seems a rehearsal of the day “when the heavens being on fire shall pass away with a great noise.” Humboldt, during his residence at Cumana, witnessed a coincident development of electrical action, peculiar atmospheric phenomena, and terrestrial disturbance, during what is called the winter of that region. From the 10th of October to the 3d of November, a reddish vapor rose in the evening, and in a few minutes covered the sky. The hygrometer gave no indication of humidity; the diurnal heat was from 82·4° to 89·6°. The vapor disappeared occasionally in the middle of the night, when brilliantly white clouds formed in the zenith, extending toward the horizon. They were sometimes so transparent that they did not conceal stars even of the fourth magnitude, and the lunar spots were clearly distinguishable through the veil. The clouds were arranged in masses at equal distances, and seemed to be at a prodigious elevation. From the 28th of October to the 3d of November, the fog was thicker than it had been before; and the heat at night was stifling, though the thermometer indicated only 78·8°. There was no evening breeze. The sky appeared as if on fire, and the ground was every where cracked and dusty. About two o’clock in the afternoon of November 4th, large clouds of extraordinary blackness enveloped the mountains of the Brigantine and Tataraqual, extending gradually to the zenith. About four, thunder was heard overhead, but at an immense height, and with a dull and often interrupted sound. At the moment of the strongest electric explosion, two shocks of an earthquake, separated by an interval of fifteen seconds, were felt. The people in the streets filled the air with their cries. Boupland, who was examining plants, was nearly thrown upon the floor, and Humboldt, who was lying in his hammock, felt the concussion strongly. A few minutes before the first, there was a violent gust of wind followed by large drops of rain. The sky remained cloudy, and the blast was succeeded by a dead calm, which continued all night. The sunset was a scene of great magnificence. The dark atmospheric shroud was rent asunder close to the horizon, and the sun appeared at 12° of altitude on an indigo ground, his disc enormously enlarged and distorted. The clouds were gilded on the edges, and bundles of rays reflecting the most brilliant prismatic colors extended over the heavens. About nine in the evening there was a third shock, which, though much slighter, was evidently attended with a subterranean noise. In the night between the 3d and 4th of November, the red vapor before mentioned had been so thick, that the place of the moon could only be distinguished by a beautiful halo 20° in diameter. The vapor ceased to appear on the 7th; the atmosphere then assumed its former purity; and the night of the 11th was cool and extremely lovely. This account, with similar details from other observers, seems to indicate a more intimate relation than is generally admitted between the interior of the earth and its external atmosphere.

Among the regions peculiarly subject to electric phenomena is the country around the estuary of the Rio Plata. In the year 1793, one of the most destructive thunder-storms perhaps on record, happened at Buenos Ayres, when thirty-seven places in the city were struck by the lightning, and nineteen of the inhabitants killed. It is an observation of Mr. Darwin, founded on statements in books of travels, that thunder-storms are very common near the mouths of great rivers; and he conjectures that this may arise from the mixture of large bodies of fresh and salt water disturbing the electrical equilibrium. “Even,” he remarks, “during our occasional visit to this part of South America, we heard of a ship, two churches and a house, having been struck. Both the church and the house I saw shortly afterward. Some of the effects were curious: the paper, for nearly a foot on each side of the line where the bell-wires had run, was blackened. The metal had been fused, and although the room was about fifteen feet high, the globules, dropping on the chairs and furniture, had drilled in them a chain of minute holes. A part of the wall was shattered as if by gunpowder, and the fragments had been blown off with force sufficient to indent the wall on the opposite side of the room. The frame of a looking-glass was blackened; the gilding must have been volatilized, for a smelling-bottle, which stood on the chimney-piece, was coated with bright metallic particles, which adhered as firmly as if they had been enameled.” Near the shores of the Rio Plata, in a broad band of sand hillocks, he found those singular specimens of electric architecture, a group of vitrified siliceous tubes, formed by the lightning striking into loose sand. These tubes had a glossy surface, and were about two inches in circumference, the thickness of the wall of each tube varying from the twentieth to the thirtieth part of an inch. Four sets were noticed, probably not produced by successive distinct charges, but by the lightning dividing itself into separate branches before entering the ground. Similar cylindrical formations have been noticed in other places. Dr. Priestley has described, in the Philosophical Transactions, some siliceous tubes, which were found in digging into the ground, under a tree, where a man had been killed by lightning; and at Drigg, in Cumberland, three were observed within an area of fifteen yards, one of which was traced to a depth of not less than thirty feet. In the temperate climates electrical phenomena are most common, and usually most energetic in the summer season, and the displays are grander and more formidable in mountainous than in level countries. As we approach the poles, they become less striking; thunder is rarely heard in high northern latitudes, and only as a feeble detonation; and though lightning is more common, it is seldom destructive. In Iceland, in the winter, it often plays in the impressive but harmless manner which the natives call laptelltur. This is a fluctuating appearance of the whole sky, as if on fire, accompanied by a strong wind and drifting snow, but inflicting no further damage than that arising from the terrified cattle falling over the rocks in their efforts to escape from the phenomenon.

The rapidity of lightning, as measured by means of the camera lucida, M. Halvig estimates at probably eight or ten miles in a second, or about forty times greater velocity than that of sound; and according to M. Gay-Lussac, a flash sometimes darts more than three miles at once in a straight direction. M. Arago distinguishes three classes of lightning: First, luminous discharges characterized by a long streak of light, very thin, and well defined at the edges, of a white, violet, or purple hue, moving in a straight line, or deviating into a zigzag track, frequently dividing into two or more streams in striking terrestrial objects, but invariably proceeding from a single point. Secondly, he notices expanded flashes spreading over a vast surface without having any apparent depth, of a red, blue, or violet color, not so active as the former class, and generally confined to the edges of the clouds from which they appear to proceed. Thirdly, he mentions concentrated masses of light, which he terms globular lightning, which seem to occupy time, to endure for several seconds, and to have a progressive motion. Mr. Hearder of Plymouth describes a discharge of lightning of this kind on the Dartmouth hills, very near to him. Several vivid flashes had occurred before the mass of clouds approached the hill on which he was standing; and before he had time to retreat from his dangerous position, a tremendous crash and explosion burst close to him. The spark had the appearance of a nucleus of intensely ignited matter, followed by a flood of light. It struck the path near him, and dashed with fearful brilliancy down its whole length to a rivulet at the foot of the hill, where it terminated. Analogous to the discharges described as globular lightning are the fire-balls so often noticed, about which there has been no little scepticism; but the evidence cannot reasonably be doubted, that displays of electrical light have repeatedly occurred, conveying the impression of balls of fire to the observer. An instance is given by Mr. Chalmers while on board the Montague, of seventy-four guns, bearing the flag of Admiral Chambers. In the account read to the Royal Society, he states, that “on November 4th, 1749, while taking an observation on the quarter-deck, one of the quarter-masters requested him to look to windward, upon which he observed a large ball of blue fire rolling along on the surface of the water, as large as a mill-stone, at about three miles distance. Before they could raise the main-tack, the ball had reached within forty yards of the main-chains, when it rose perpendicularly with a fearful explosion, and shattered the main-topmast to pieces.” In an account of the fatal effects of lightning in June 1826, on the Malvern Hills, when two ladies were struck dead, it is stated, that the electric discharge appeared as a mass of fire rolling along the hill toward the building in which the party had taken shelter.

Mr. Snow Harris remarks upon the difficulty of explaining these appearances on the principles applicable to the ordinary electric spark. The amazing rapidity of the latter, and the momentary duration of the light, render it impossible that they should be identical with it; but he conjectures that there may be a “glow discharge” preceding the main shock, some of the atmospheric particles yielding up their electricity by a gradual process before a discharge of the whole system takes place. In this view, the distinct balls of fire of sensible duration which have been perceived, are produced in a given point or points of a charged system previously to the more general and rapid union of the electrical forces—a supposition which will apply as well to the Mariner’s Lights, or St. Elmo’s Fire, observed during storms of thunder and lightning at sea. Pliny mentions lights noticed by the Roman mariners during tempests, flickering about their vessels, to which Seneca likewise makes allusion. By the superstitions of modern times they have been converted into indications of the guardian presence of St. Elmo, the patron saint of the sailor, hence called cuerpo sante by the Spanish mariners. During the second voyage of Columbus among the West India islands, a sudden gust of heavy wind came on in the night, and his crew considered themselves in great peril, until they beheld several of these lambent flames playing about the tops of the masts, and gliding along the rigging, which they hailed as an assurance of their supernatural protector being near. Fernando Columbus records the circumstance in a manner strongly characteristic of the age in which he lived. “On the same Saturday, in the night, was seen St. Elmo, with seven lighted tapers, at the topmast. There was much rain and great thunder. I mean to say that those lights were seen which mariners affirm to be the body of St. Elmo, on beholding which they chanted many litanies and orisons, holding it for certain, that in the tempest in which he appears, no one is in danger.” A similar mention is made of this nautical superstition in the voyage of Magellan. During several great storms the presence of the saint was welcomed, appearing at the topmast with a lighted candle, and sometimes with two, upon which the people shed tears of joy, received great consolation, and saluted him according to the custom of the Catholic seamen; but he ungraciously vanished, disappearing with a great flash of lightning which nearly blinded the crew.

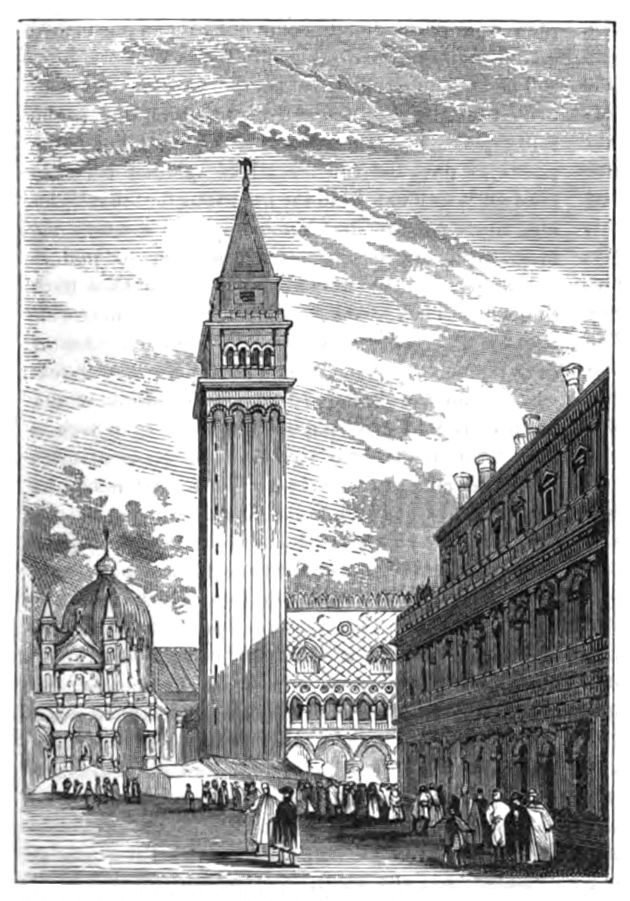

Tower of St. Mark’s, Venice.

It is a striking instance of the triumph of mind, that by the introduction of lightning conductors into different civilized states, the power of this most energetic agent of nature is controled, and comparative security provided for life and property, otherwise in imminent jeopardy, when a severe thunder-storm occurs. Experience has taught the prime importance of furnishing exposed or elevated structures with a conducting apparatus, and has sufficiently shown that the immunity from danger enjoyed by many an unprotected building has been merely accidental; for when the teeming thunder-cloud has been wafted within reach of the edifice hitherto unscathed, the delusion has vanished that man may carelessly and with impunity thrust up his handiwork into the region of storms, as if daring the fury of the tempest, and inviting down its vengeance. The fine tower of St. Mark’s, at Venice, rising to the height of 360 feet, terminates in a pyramid which was severely injured in 1388. In 1417 the pyramid was again struck, and set on fire, having been constructed of wood. The same event happened in 1489, when it was entirely consumed. After being rebuilt of stone, the fell lightning renewed its destructive stroke in 1548, 1565, 1653 and 1745; and on the last occasion the whole tower was rent in thirty-seven places, and almost destroyed. It was again ravaged in 1761 and 1762, but in 1766 a lightning rod was put up, which has since protected it from damage. At Glogau, in Silesia, an interesting example of the value of conductors occurred in the year 1782. On the 8th of May, about eight o’clock in the evening, a thunder-storm from the west approached the powder magazine established in the Galgnuburg. An intensely vivid flash of lightning took place, accompanied instantly with such a tremendous peal of thunder, that the sentinel on duty was stupefied, and remained for awhile senseless, but no disaster occurred. Some laborers at a short distance from the magazine saw the lightning issue from the cloud and strike the point of the conductor, which conveyed it in safety by the combustible material. A different result took place with reference to a large quantity of unprotected ammunition, belonging to the republic of Venice, deposited in the vaults of the church of St. Nazaire, at Brescia. The church was struck with lightning in the month of August, 1767, and the electric fluid, descending to the vaults, exploded upward of 207,600 lbs. of powder, reducing nearly one-sixth of the fine city to ruins, and destroying about 3000 of the inhabitants. The Indians, whenever the sky wears a lowering aspect, so as to threaten a severe thunder-storm, are said to leave their pursuits and take refuge under the nearest beech-tree, considering it a complete protection, as it is affirmed that no instance has occurred of the beech having been struck by atmospheric electricity, when other trees of the American forests have been shivered into splinters in its neighborhood.

For ages the inhabitants of the globe have seen the lightning flash and heard the thunder rattle; and some writers upon the occult sciences of the ancients, as Salverte, have supposed that, tutored by experience, without any understanding of the theory of the subject, they possessed the secret of warding off from their buildings the thunderbolt by a conducting apparatus. It is certain that extraordinary intimations to this effect may be culled from their writings. Pliny states that Tullus Hostilius, practicing Numa’s art of bringing down fire from heaven, and performing it incorrectly, was struck with lightning—a fate which Professor Richman of St. Petersburg experienced, while performing incautiously the sublime experiment of Franklin, measuring the strength of the electricity brought down by a metallic rod in a thunder-storm, being instantly killed. Pliny likewise mentions the laurel as the only earthly production which lightning does not strike; hence, as a protection, these trees were planted around the temple of Apollo. Columella, however, mentions white vines surrounding the house of Tarchon, the Etruscan, for the same purpose. These expedients may provoke a smile without deserving one; for there can be no doubt that trees sufficiently high around a temple, or succulent plants covering a dwelling, will exercise to some extent a protective power, and act as a regular system of conductors. Salverte mentions several medals which appear to have reference to this subject, particularly one which represents the temple of Juno, the goddess of the air, the roof of which is armed with pointed rods. He quotes also Michaelis, upon the temple of Jerusalem, to show that the Jews were not unacquainted with the art of protecting their public buildings—a position grounded upon the following facts: “1. That there is nothing to indicate that the lightning ever struck the temple of Jerusalem during the lapse of a thousand years.” This, of course, does not make the fact certain; but when, as M. Arago justly remarks, we consider how carefully the ancient authors recorded the cases in which their public buildings were injured by lightning, we may accept the silence observed respecting the temple of Jerusalem, as proof that it was never struck. For three centuries the cathedral of Geneva, the most elevated in the city, has enjoyed a similar immunity, although inferior buildings have been repeatedly damaged. Saussure discovered the reason of this, in the tower being entirely covered with tinned iron plates, connected with different masses of metal on the roof, and again communicating with the ground by means of metallic pipes. “2. That according to the account of Josephus, a forest of spikes with golden or gilt points, and very sharp, covered the roof of this temple; a remarkable feature of resemblance with the temple of Juno represented on the Roman medals. 3. That this roof communicated with the caverns in the hill of the temple, by means of metallic tubes, placed in connection with the thick gilding that covered the whole exterior of the building; the points of the spikes there necessarily producing the effect of lightning-rods. How are we to suppose that it was only by chance they discharged so important a function; that the advantage received from it had not been calculated; that the spikes were erected in such great numbers only to prevent the birds from lodging upon and defiling the roof of the temple? Yet this is the sole utility which the historian Josephus attributes to them.” Upon a sober review of these facts, it is difficult to resist the conclusion that the ancient world had some proficiency in the art of guiding the electric fluid from the bosom of the clouds, conducting it in a prescribed course, and thus disarming it of its terrors.

The subject of electrical agency is intimately connected with that of magnetism, to which this is the fittest place to glance—one of the most recondite points of physical science. The relation between the two is evident, from the notorious fact that lightning often renders steel magnetic, and disturbs the magnetism of the magnetised needle, so that in thunder-storms the compass needles of a ship have frequently been seriously injured. The magnetic agency, like electricity, has a general distribution over the earth, but the phenomena differ in different parts of the world, and are subject to periodical differences in the same place, the cause of which is very little understood. Every one is acquainted with the polarity of a freely suspended magnetic needle, or its tendency to lie parallel with the earth’s axis, pointing nearly north and south in every region of the globe. What is called the dip or inclination of the needle is its divergence from a perfectly horizontal position. Thus the north pole of the needle inclines downward in the latitude of London at an angle of 70°, but conveyed toward the equator, the dip diminishes, till no inclination at all appears. Transported farther toward the south, the dip again discovers itself, but in an opposite direction, the south pole of the needle inclining downward. “To understand the reason of this dip of the magnetic needle, and of its general direction, we have only to consider that the earth itself operates as a great magnet, the poles of which are situated beneath its surface. The directive property of the needle is owing to these poles; and when the needle is on the north side of the equator, the north pole of the earth having the greatest effect, the needle is attracted downward toward the north pole; hence exactly over the magnetic pole the needle would be vertical. Similar phenomena occur in the southern hemisphere; but here the south pole predominates, and of course depresses the corresponding pole of the needle; while at the magnetic equator, from the equal action of both poles, the needle will assume an exactly horizontal position.”

But neither the magnetic equator nor the magnetic poles coincide precisely with the geographical equator and poles, and this difference constitutes what is termed the variation of the needle. From calculation, the north magnetic pole had been fixed in latitude 70°, and longitude 98° 30′ west, a spot which Commander Ross approached within the distance of ten miles, in the year 1830, but was unable to verify the site, for want of the requisite instruments. Upon going through a long series of calculations afterward himself, he concluded the above position to have been erroneously assigned, and that the real point lay in latitude 70° 5′ 17″ north, and longitude 96° 46′ 45″ west, a spot on the western coast of Boothia, which he prepared to reach. On the first of June, 1831, at eight o’clock in the morning, he arrived at the site to which his calculations pointed, and found the same day the amount of the dip to be 89° 59′, only one minute less than 90°, the vertical position, which would have precisely indicated the polar station; and the horizontal needles, suspended in the most delicate manner possible, did not betray the slightest movement. The spot was an unattractive level site along the coast, rising into ridges from fifty to sixty feet high, about a mile inland. The wish expressed by the discoverer was natural, that a place so important had possessed more of mark or note, but Nature had erected no monument to denote the spot which she had chosen as the centre of one of her “great and dark powers.” A cairn of some magnitude was constructed by the adventurers, upon which the British flag was planted, and underneath, a canister was buried, containing a record of the interesting enterprise.

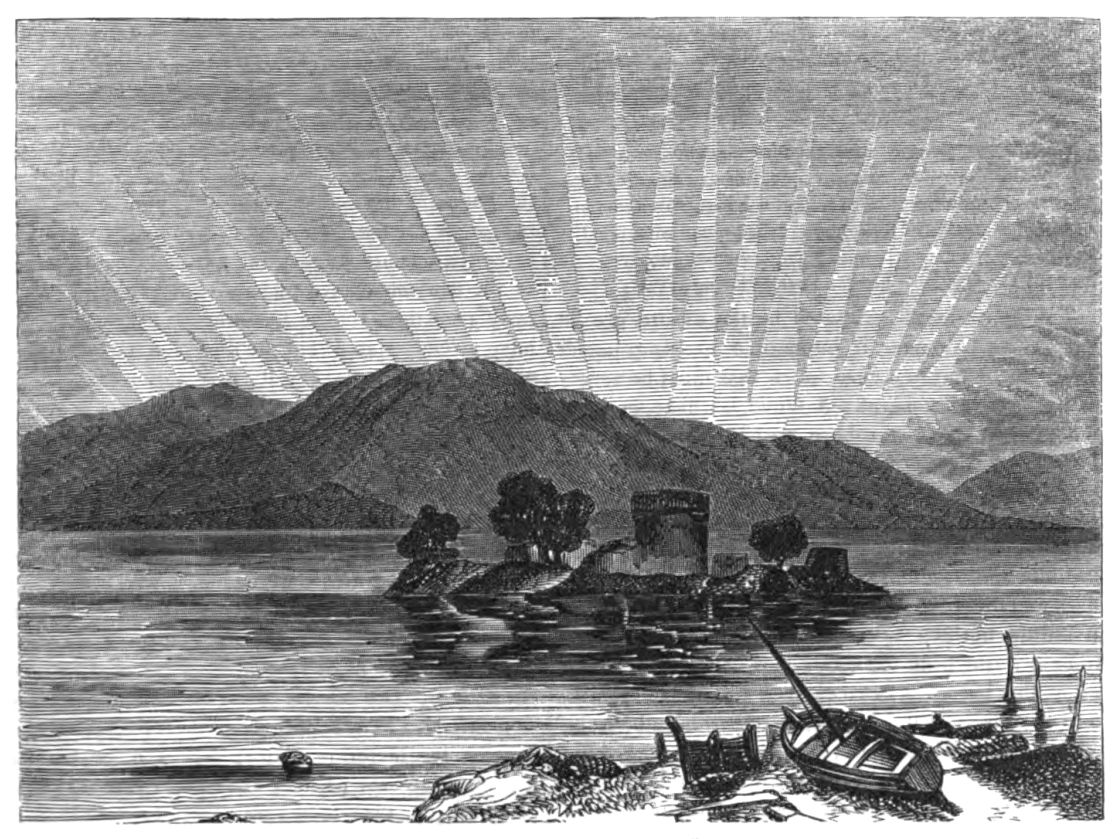

Aurora Borealis—Loch Leven.

The magnetic needle has frequently exhibited violent disturbance when the Aurora Borealis has appeared. This has led to the surmise that these brilliant lights are connected with the electric and magnetic properties of the earth, though in a manner which we cannot explain. It has been remarked that during the appearance of the aurora the electric fluid may often be readily collected from the air. If a current of electricity also be passed through an exhausted receiver, a very correct imitation of the auroral light will be produced, displaying the same variety of color and intensity, and the same undulating motions. It is highly probable, therefore, that the beautiful and fantastic meteoric display is connected with electricity; but great obscurity rests upon this department of meteorology.

Of all optical phenomena, the Aurora Borealis, or the northern day-break, is one of the most striking, especially in the regions where its full glory is revealed. The site of the appearance, in the north part of the heavens, and its close resemblance to the aspect of the sky before sunrise, have originated the name. The “Derwentwater Lights” was long the appellation common in the north of England, owing to their display on the night after the execution of the unfortunate earl of that name. The scene in the illustration is a picture of the auroral light, as observed from the neighborhood of Loch Leven—a scene in itself admirably calculated to exhibit the phenomenon; and to convey any adequate idea of its magical aspect, as seen in high latitudes, the painter’s hand and the poet’s art are needed. A native Russian, Lomonosov, thus refers to the spectacle:—

“Where are thy secret laws, O Nature, where?

Thy torch-lights dazzle in the wintry zone;

How dost thou light from ice thy torches there?

There has thy son some sacred, secret throne?

See in your frozen sea what glories have their birth;

Thence night leads forth the day t’ illuminate the earth.

“Come then, philosopher, whose privileged eye

Reads Nature’s hidden pages and decrees:

Come now, and tell us whence, and where, and why,

Earth’s icy regions glow with lights like these,

That fill our souls with awe; profound inquirer, say,

For thou dost count the stars, and trace the planet’s way.

“What fills with dazzling beams the illumined air?

What wakes the flames that light the firmament?

The lightning’s flash: there is no thunder there,

And earth and heaven with fiery sheets are blent;

The winter’s night now gleams with brighter, lovelier ray

Than ever yet adorned the golden summer’s day.

“Is there some vast, some hidden magazine,

Where the gross darkness flames of fire supplies?

Some phosphorous fabric, which the mountains screen,

Whose clouds of light above those mountains rise?

Where the winds rattle loud around the foaming sea,

And lift the waves to heaven in thundering revelry?”

The appearances exhibited by the aurora are so various as to render it impossible to comprehend every particular in a description that must be necessarily brief and general. A cloud, or haze, is commonly seen in the northern region of the heavens, but often bearing toward the east or west, assuming the form of an arc, seldom attaining a greater altitude than 40°, but varying in extent from 5° to 100°. The upper edge of the cloud is luminous, sometimes brilliant and irregular. The lower part is frequently dark and thick, with the clear sky appearing between it and the horizon. Streams of light shoot up in columnar forms from the upper part of the cloud, now extending but a few degrees, then as far as the zenith, and even beyond it. Instances occur in which the whole hemisphere is covered with these coruscations; but the brilliancy is the greatest, and the light the strongest, in the north, near the main body of the meteor. The streamers have in general a tremulous motion, and when close together present the appearance of waves, or sheets of light, following each other in rapid succession. But no rule obtains with reference to these streaks, which have acquired the name of “the merry dancers,” from their volatility, becoming more quick in their motions in stormy weather, as if sympathizing with the wildness of the blast. Such is the extraordinary aspect they present, that it is not surprising the rude Indians should gaze upon them as the spirits of their fathers roaming through the land of souls. They are variously white, pale red, or of a deep blood-color, and sometimes the appearance of the whole rainbow as to hue is presented. When several streamers emerging from different points unite at the zenith, a small and dense meteor is formed, which seems to burn with greater violence than the separate parts, and glows with a green, blue, or purple light. The display is over sometimes in a few minutes, or continues for hours, or through the whole night, and appears for several nights in succession. Captain Beechey remarked a sudden illumination to occur at one extremity of the auroral arch, the light passing along the belt with a tremulous hesitating movement toward the opposite end, exhibiting the colors of the rainbow; and as an illustration of this appearance, he refers to that presented by the rays of some molluscous animals in motion. Captain Parry notices the same effect as a common one with the aurora, and compares it, as far as its motion is concerned, to a person holding a long ribbon by one end, and giving it an undulatory movement through its whole length, though its general position remains the same. Captain Sabine likewise speaks of the arch being bent into convolutions, resembling those of a snake in motion. Both Parry, Franklin, and Beechey agree in the observation that no streamers were ever noticed shooting downward from the arch.

The preceding statement refers to aurora in high northern latitudes, where the full magnificence of the phenomenon is displayed. It forms a fine compensation for the long and dreary night to which these regions are subject, the gay and varying aspect of the heavens contrasting refreshingly with the repelling and monotonous appearance of the earth. We have already stated that the direction in which the aurora generally makes its first appearance, or the quarter in which the arch formed by this meteor is usually seen, is to the northward. But this does not hold good of very high latitudes, for by the expeditions which have wintered in the ice, it was almost always seen to the southward; while by Captain Beechey, in the Blossom, in Kotzerne Sound, 250 miles to the southward of the ice, it was always observed in a northern direction. It would appear, therefore, from this fact, that the margin of the region of packed ice is most favorable to the production of the meteor. The reports of the Greenland ships confirm this idea; for, according to their concurrent testimony, the meteoric display has a more brilliant aspect to vessels passing near the situation of the compact ice, than to others entered far within it. Instances, however, are not wanting, of the aurora appearing to the south of the zenith in comparatively low latitudes. Lieutenant Chappell, in his voyage to Hudson’s Bay, speaks of its forming in the zenith, in a shape resembling that of an umbrella, pouring down streams of light from all parts of its periphery, which fell vertically over the hemisphere in every direction. As we retire from the Pole, the phenomenon becomes a rarer occurrence, and is less perfectly and distinctly developed. In September, 1828, it was observed in England as a vast arch of silvery light, extending over nearly the whole of the heavens, transient gleams of light separating from the main body of the luminosity; but in September, 1827, its hues were red and brilliant. Dr. Dalton has furnished the following account of an aurora, as observed by him on the 15th of October, 1792:—“Attention,” he remarks, “was first excited by a remarkably red appearance of the clouds to the south, which afforded sufficient light to read by at 8 o’clock in the evening, though there was no moon nor light in the north. From half-past nine to ten there was a large, luminous, horizontal arch to the southward, and several faint concentric arches northward. It was particularly noticed that all the arches seemed exactly bisected by the plain of the magnetic meridian. At half-past ten o’clock streamers appeared, very low in the south-east, running to and fro from west to east. They increased in number, and began to approach the zenith apparently with an accelerated velocity, when all on a sudden the whole hemisphere was covered with them, and exhibited such an appearance as surpasses all description. The intensity of the light, the prodigious number and volatility of the beams, the grand intermixture of all the prismatic colors in their utmost splendor, variegating the glowing canopy with the most luxuriant and enchanting scenery, afforded an awful, but at the same time the most pleasing and sublime spectacle in nature. Every one gazed with astonishment, but the uncommon grandeur of the scene only lasted one minute. The variety of colors disappeared, and the beams lost their lateral motion, and were converted into the flashing radiations. The aurora continued for several hours.” A copious deposition of dew—hard gales in the English channel—and a sudden thaw after great cold in northern regions, are circumstances which have been frequently noticed in connection with auroral displays.

Aurora Borealis.

The sky of the southern hemisphere occasionally exhibits this strange and mysterious light, contrary to an old opinion upon the subject; and here it must be called Aurora Australis, the southern day-break. Its appearance, however, is far from being so common as in the northern zone, and is much less imposing. Don Antonio Ulloa, off Cape Horn, in the year 1745, witnessed the first appearance of the kind upon record in this region. Upon the clearing off of a thick mist, a light was observed in the southern horizon, extending to an elevation of about thirty degrees, sometimes of a reddish color, and sometimes like the light which precedes the rise of the moon, but occasionally more brilliant. Captain Cook, in the same latitudes, had more distinct views of the luminous streamers adorning the night-sky of the south. In the course of his second voyage he remarks, that on February the 17th, 1773, “a beautiful phenomenon was observed in the heavens. It consisted of long colors of a clear, white light, shooting up from the horizon, to the eastward, almost to the zenith, and spreading gradually over the whole southern part of the sky. These columns sometimes bent sideways at their upper extremity; and though in most respects similar to the northern lights, yet differed from them in being always of a whitish color, whereas ours assume various tints, especially those of a purple and fiery hue. The stars were sometimes hid by, and sometimes faintly to be seen through, the substance of these southern lights, Aurora Australis. The sky was generally clear when they appeared, and the air sharp and cold, the thermometer standing at the freezing point, the ship being in latitude 58° south.”

The history of auroral phenomena goes back to the time of Aristotle, who undoubtedly refers to the exhibition in his work on meteors, describing it as occurring on calm nights, having a resemblance to flame mingled with smoke, or to a distant view of burning stubble, purple, bright red, and blood-color, being the predominant hues. Notices of it are likewise found in many of the classical writers; and the accounts which occur in the chronicles of the middle ages, of surprising lights in the air, converted by the imagination of the vulgar into swords gleaming and armies fighting, are allusions to the play of the northern lights. There is strong reason to believe, though the fact is perfectly inscrutable, that the aurora has been much more common in the European region of the northern zone, during the last century and a half, than in former periods. A very brilliant appearance took place on the 6th of March, 1716, which forms the subject of a paper by Halley, who remarks, that nothing of the kind had occurred in England for more than eighty years, nor of the same magnitude since 1574, or about 140 years previous, in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, when Cambden and Stow were eye-witnesses of it. The latter states in his Annals, that on November 14th, “were seen in the air strange impressions of fire and smoke to proceed forth from a black cloud in the north toward the south—that the next night the heavens from all parts did seem to burn marvelous ragingly, and over our heads the flames from the horizon round about rising did meet, and there double and roll one in another, as if it had been in a clear furnace.” The year following, 1575, it was twice repeated in Holland, but not observed in England; and as a specimen of the tone of thought respecting the aurora, the description of Cornelius Gemma, a professor in the university of Louvain, may be given. Referring to the second instance of the year, and speaking in the language of the times, he remarks: “The form of the Chasma of the 28th of September following, immediately after sunset, was indeed less dreadful, but still more confused and various; for in it were seen a great many bright arches, out of which gradually issued spears, cities with towers and men in battle array; after that, there were excursions of rays every way, waves of clouds and battles mutually pursued and fled, and wheeling round in a surprising manner.” This phenomenon was repeatedly observed in the last century in Sweden, as at present; but prior to the year 1716, the inhabitants of Upsal considered it as a great rarity. Nothing is more common now in Iceland than the northern lights, exhibited during the winter with imposing grandeur and brilliance; but Torfæus, the historian of Denmark, an Icelander, who wrote in 1706, records his remembrance of the time when the meteor was an object of terror in his native island. It deserves remark, that its more frequent occurrence in the Atlantic regions has been accompanied by its diminution in the eastern parts of Asia, as Baron Von Wrangel was assured by the natives there, who added, that formerly it was brighter than at present, and frequently presented the vivid coloring of the rainbow.

Halos.

The simplest form of the halo is that of a white concentric ring surrounding the sun or moon, a very common appearance in our climate in relation to the moon, occasioned by very thin vapor, or minute particles of ice and snow, diffused through the atmosphere deflecting the rays of light. Double rings are occasionally seen, displaying the brightest hues of the rainbow. The colored ring is produced by globules of visible vapor, the resulting halo exhibiting a character of density, and appearing contiguous to the luminous body, according as the atmosphere is surcharged with humidity. Hence a dense halo close to the moon is universally and justly regarded as an indication of coming rain. It has been stated as an approximation, that the globules which occasion the appearance of colored circles, vary from the 5000th to the 50,000th part of an inch in diameter. Though seldom apparent around the sun in our climate, yet it is only necessary to remove that glare of light which makes delicate colors appear white, to perceive segments of beautifully tinted halos on most days when light fleecy clouds are present. The illustration shows a nearly complete and slightly eliptical ring around the sun, the lower portion hidden by the horizon, which was distinctly observed during the past summer in the neighborhood of Ipswich, of an extremely pale pink and blue tint. When Humboldt was at Cumana, a large double halo around the moon fixed the attention of the inhabitants, who considered it as the presage of a violent earthquake. The hygrometer denoted great humidity, yet the vapors appeared so perfectly in solution, or rather so elastic and uniformly disseminated, that they did not alter the transparency of the atmosphere. The moon arose after a storm of rain behind the Castle of St. Antonio. As soon as she appeared on the horizon, two circles were distinguished, one large and whitish, 44° in diameter, the other smaller, displaying all the colors of the rainbow. The space between the two circles was of the deepest azure. At the altitude of 4° they disappeared, while the meteorological instruments indicated not the slightest change in the lower regions of the air. The phenomenon was chiefly remarkable for the great brilliancy of its colors, and for the circumstance that, according to the measures taken with Ramsden’s sextant, the lunar disc was not exactly in the centre of the halos. Humboldt mentions likewise having seen at Mexico, in extremely fine weather, large bands spread along the vault of the sky, converging toward the lunar disc, displaying beautiful prismatic colors; and he remarks, that within the torrid zone, similar appearances are the common phenomena of the night, sometimes vanishing and returning in the space of a few minutes, which he assigns to the superior currents of air changing the state of the floating vapors, by which the light is refracted. Between latitude 15° of the equator, he records having observed small tinted halos around the planet Venus, the purple, orange, and violet being distinctly perceptible, which was never the case with Sirius, Canopus, or Acherner. In the northern regions solar and lunar halos are very common appearances, owing to the abundance of minute and highly crystallized spicula of ice floating in the atmosphere. The Arctic adventurers frequently mention the fall of icy particles during a clear sky and a bright sun, so small as scarcely to be visible to the naked eye, and most readily detected by their melting upon the skin.

———

BY MRS. E. L. CUSHING.

———

Hark to the silvery sound

Of the soft April shower

Telleth it not a pleasant tale

Of bird, and bee, and flower?

See, as the bright drops fall,

How swell the tiny buds

That gem each bare and leafless bough,

Like polished agate studs.

The elder by the brook,

Stands in her tusseled pride

And the pale willow decketh her

As might beseem a bride.

And round the old oak’s foot,

Where in their wintry play,

The winds have swept the withered leaves—

See, the Hepatria!

Its brown and mossy buds

Greet the first breath of spring,

And to her shrine, its clustered flowers,

The earliest offering bring.

In rocky cleft secure,

The gaudy columbine

Shoots forth, ere wintry snows have fled

A floral wreath to twine.

And many a bud lies hid

Beneath the foliage pent,

Waiting spring’s warm and wooing breath

To deck the vernal year.

When lo! sweet April comes,

The wild bird hears her voice,

And through the grove on glancing wing

Carols, “rejoice! rejoice!”

Forth from her earthy nest

The timid wood-mouse steals,

And the blithe squirrel on the bough

Her genial influence feels.

The purple hue of life

Flushes the teeming earth,

Above, around, beneath the feet,

Joy, beauty, spring to birth!

But on the distant verge

Of the cerulean sky,

Old Winter stands with angry frown

And bids the syren fly.

He waves his banner dark

Raises his icy hand,

And a fierce storm of sleet and hail,

Obey his stern command.

She feareth not his wrath,

But hides her sunny face

Behind a soft cloud’s fleecy fold

For a brief instant’s space,

Then looketh gayly forth

With smile of magic power,

That changeth all his icy darts

To a bright diamond shower.

Capricious April, hail!

Herald of all things fair,

’Tis thine to loose the imprisoned streams,

The young buds are thy care.

To unobservant eye

Thy charms are few, I ween;

But he who roves the woodland paths

Where thy blithe step hath been,

Will trace thee by the tufts

Of fragrant early flowers,

That thy sweet breath hath waked, to deck

The dreary forest bowers;

And by the bursting buds,

That at thy touch unfold

To clothe the tall tree’s naked arms

With beauty all untold,

Will hear thy tuneful voice

In the glad leaping streams,

And catch thy bland, yet fitful smile

In showers and sunny gleams.

Then welcome April, fair!

Bright harbinger of May!

Month of blue skies and perfumed air—

The young year’s holyday!

———

B. B.

———

Floateth in upon my senses now the melody of brooks,

And the drip of fragrant waters, far in solitary nooks—

O avaunt! ye tedious tasks! O get ye gone! ye irksome books.

Why to linger pent and stifled in this chamber small and low,

Through the casement on my temples thus to feel the breezes blow,

Bidding me to come and follow where at liberty they go?

Why amid this noisy Babel mingle in the petty strife,

In the wearying din and discord with which every day is rife,

While the full, free life within me yearns to greet its kindred life?

O, those boundless breadths of forest unrestrained to wander through,

Where the lofty pine mounts upward to the firmament of blue,

Where the swarth and stalwart savage paddles in his birch canoe.

O, to hear my ringing shout of exultation echo clear

In the woodland, by the moose-tramp and the covert of the deer,

Or where stalk the stately bison who have never known to fear,

On the broad and blooming pampas, with their fat and teeming soil

Never marred by human culture, never by unwilling toil,

Where the wild herds roam uninjured, and the gleaming serpents coil.

Or where crawls the full-fed Ganges down into his sandy bed,

And the sluggish hippopotamus uprears his clumsy head,

Where the beauty-bringing cestus of the torrid zone is spread.

Where many a glowing river rolls along its wealth of tide

Through the tangled vines and palm-trees bending down on either side,

With the orange bloom and citron, and the tall acacia’s pride.

Where the scaly cayman basking on the yellow bank is laid,

And the brilliant-plumaged song-birds call in every spicy glade,

There to hunt the spotted leopard in the jungle’s depth of shade.

Or beyond the spreading oceans, in some distant Paynim land,

Swifter than the fiery simoom sweep across the plains of sand,

On a fleet and naked barb, and wield a keenly flashing brand.

O for days of careless gladness, days that evermore are gone,

When the spirit-thrilling summons of the silver bugle-horn

Roused the green-clad host of merry men at break of dewy morn.

—Cease thy prating, foolish Fancy, Fancy wayward, unconfined,

List the mighty music rushing on the pinions of the wind,

’Tis the onward tread of nations, ’tis the endless march of mind.

Bowdoin College.

Each gentle word thy lip imparts,

Each glance of thy dear eye,

Is hidden in my heart of hearts

As in a treasury.

And, though but once in life we’ve met

And ne’er may meet again,

The memory of this hour, shall yet

Within my heart remain,

As the bright tinge of crimson dye,

When the red sun descends,

Long lingers in the western sky

And with the twilight blends.

Still let me cherish thoughts of thee

Till life’s sad hours are o’er;

Think of me, sometimes, tenderly—

I may not ask for more.

———

BY H. DIDIMUS.

———

The broad sun, red, and with softened beams, rose lazily upon the young earth. The wide sea, unruffled, heaved to and fro, mirroring in its depths the new-made canopy of azure and of gold spread by God’s hand, from limit to limit, over water and land, and all the stream of ocean. The herbage stood rank, thick, heavy, tall and motionless; and covered with vast shade mountain and valley and plain; for not yet had the revolving seasons, and storms, with falling rain abraded the soil, and bared rocks, and worn acclivities; nor the breath of heaven hastened in its course, circling the earth; nor the poles left their place to rise and fall, vibrating; but one unending spring ruled throughout the year. Rivers rolled—unvexed and noiseless—toward the bosom of their great mother; and the mountain stream scarce murmured as it fell, whitening, from sward to sward, to sleep in some still lake, happy with water-fowl. Herds of cattle—of horses and of deer, the elephant and the bison—wandered, uncared for, through fat pastures, beautiful with flowers; and the lion roamed at will, and crouched in every dingle, and in every glen, and took his prey. The air was vocal with the voice of birds, of birds innumerable, which saluted with morning hymn the growing day; and the hum of insects—which all night had drummed in the drowsy ear of silence—was hushed, and folding their wings, they slept. It is the primeval age.

Chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh-uh; oo-ugh, oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh—A white pigeon stood upon the lowest branch, heavy with foliage, of a noble oak, planted with creation, and arched his neck, and drooped his wings, and turned round and round, calling to his mate. Chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh-uh; oo-ugh; oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh—And the white pigeon looked out upon the sea, which rolled inward with its new voice, deep and hoarse, as it rolls now, and broke softly upon the glittering strand, just beneath his feet; and back to the wooded mountains, which showed blue and misty through the air, capped with silvery clouds; and beneath the arms of the forest trees, where the land rose gently from the shore, carpeted with green and gold, and all colors of the sun woven into flowers. Chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh-uh; oo-ugh; oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh—calling to his mate.

From a deep, embowered grot—half-hidden within a grove of oranges, and trellised with the woodbine and the grape, clustering—came a sweet voice, singing; not with the musical cadence and alliteration, and returning rhyme of later days, when intellect refined to weaken, but with the promptings of the soul, gushing, unmeasured, finding speech as it might.

“Call, call to your mate, happy bird, and she shall call to you again; but where is he who should call to me, in this day of joy? Erix, my Erix, rising like the sun in his strength, with broad shoulders, and a brow moulded by God! And the glory of his head, brighter than the beams of the morning; those curls which I, with merry fingers, have so often twisted, until they sprang from me with life and laughter, and clung about his neck, kissingly—why do they not dance before me, gladdening my sight? And those arms, like twisted vines, which hold and give every happiness—why are they not here to receive me? And those lips, which are so used to praise me, until I wonder at my own comeliness, and lose my breath in their thieving—why are they not here to bless me, with their music so subduing? And those eyes, so large and deep, those wells of passion, in which I live a double being, in which I see my own blushing—why are they not here, to kindle and to burn? Oh! Erix, my Erix, as flowers love the earth, as the earth loves the sun, as the sun loves its Maker, so is my love for thee, most beautiful and most excellent!”

And with the singing, came a fair maid, tripping into the outer air; large, lithe of limb, like the moon riding in mid-heaven, when seen in her full light, paling the stars. Her hair fell, unbound, even to her feet, covering half her shape; and about her waist was knit a robe of sables, which flowed downward, and concealed no excellence above the girdle. Her form was sister to the antelope, and her face, one, which Phidias would have chiseled for a Juno of giant make. Her glowing eyes, blue as the ether above them, rolled liquid as she sang, and bent the knee, and worshiped, extending her arms, which showed like wreaths of snow borne upon the wind, toward the mounting day—not ignorantly, for she was too near to God in time, to have forgotten him. Then rising, she also looked upon the sea, smiling in the sunlight, and loved it; for she was born upon its shores, and, with life, its roar filled her ears. She loved it—coming to her, from whence she knew not, from beyond the reach of space, which to her eye was bounded by the heavens, that bowed down and girdled the waters—and enticed, the robe of sables fell from her, and the glad brine received her, and mounting, laved all her beauty. Thus swimming, thus sporting, thus playing with young ocean, now floating, now dipping beneath his bosom heaving with great joy. The white pigeon left its perch, and sought a new rest, even the fair maid’s fair brow, rising from the wave, and arched its neck, and drooped its wings, and turned round and round, chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh uh; oo-ugh; oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh; calling to its mate.

The white pigeon nestled in the grot, and knew its mistress, and her caress; and when the maid would have taken it tenderly in her hand, smoothing its ruffled feathers, it flew upward, cleaving the air in circles, and descending, lighted upon her wrist, and pecked at her taper fingers, roseate with health, and arched its neck, and drooped its wings, and turned round and round; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh-uh; oo-ugh; oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh; calling to its mate.

“Call, call to your mate, happy bird, and she shall call to you again; but, where is he who should call to me, in this my bridal hour? Erix, my love, my life, my soul’s sole hope!”

The sound of merry horns, of laughter, and of shout, came leaping through the wood, and the fair maid started like a fawn, like a fawn tracked by the hunter, when it first scents its pursuer in the breeze; and hastening to the strand, she knit the robe of sables about her waist, and it fell down as before, concealing no excellence above the girdle. Fresh from the wave, she stood gazing, with hope and expectation her handmaids, who with nimble fingers adorned her, and covered her all over with tints from the blushing east. Her hair, long and damp, thick sown with pearly brine, showed gemmed; and parted lip, and flashing eye, the very tell-tales of passion, betrayed the beatings of her heart, her fears and her desire. When, in an after age, the poet wove this story into mythologic fable, he called her Venus, the Aphrodite, born of the foam of the sea; and the sculptor caught her as she stood, her feet like flocks of wool, the right advanced, the left raised at the heel, rushing, moving, white, and fair.

And now, far within the leafy vista, was seen approaching, descending toward the strand, a troop of maidens and young men. Crowned with chaplets of roses and the fruitful vine, they came on dancing, to shout and laughter, and the sound of merry horns; and he who led them was taller than the rest, herculean; and from his back hung a boar’s hide, and about his loins were girded the skins of foxes and of wolves, spoils of the chase. In his hand he held a bow, which he drew proudly at the sun; elated with the nearness of his supremest bliss. Child of the forest, greater than the sun, immortal, thou shall live when all of matter hath wholly passed away; draw then, thy bow, aspiring, if thou wilt; it is thy soul, conscious of its superiority, stirring within thee.

On, on; love gives fleetness to his feet. “Zella, Zella,” calling to his mate. And again the shout, the laughter, and the sound of merry horns; and again, “Zella, Zella,” calling to his mate.

But Zella called not to him again. Her heart was upon her tongue, and she could not speak; her strength had left her knees, and she stood transfixed; while “Zella, Zella,” sprang from every lip, echoed through the wood, and died afar off, amid the murmurs of the sea. Again, “Zella, Zella;” again the shout, the laughter, and the sound of merry horns; and Erix clasped the loved one to his breast.

“Zella!”

“Erix!”

“Now, may the ruler of the heavens and good earth so bless me, as I love thee, my soul’s choice! Closer, closer, my heart of hearts; thus twining, thus growing, no storm shall divide us; but, with equal step, we will move right onward through life, and beyond life, to gather new strength and a new glory, in a hereafter.”

The band of youths and fair maids danced around them, hand in hand, singing, “To the Mighty Giver of all good, praise. He sends the blossom and the fruit, praise. From Him come all our joys, praise. He made the day, and the night, with all her train of ever-burning fires, the fairest labor of His hand, praise. The sun is His servant, the moon His daughter, praise. He gave us the earth, with all its beauty of hill and valley, of water and of wood, praised be forever His holy name. Oh, happy, happy day! oh, happy, happy hour! Open, ye heavens! and let love from on high descend upon these two, brooding; that they may live, from generation to generation, renewed and renewing, to the end of time. Holy, holy, holy, is this compact instituted in the beginning. Now are ye of one flesh; hearts the same, wills the same, desires the same; of one body, of one mind. Praise Him, praise Him, praise the Mighty Giver of all good!”

Then hastening to the sea, they took up water, briny water, in shells, and poured it upon the lovers, and baptized them into a new life, and cast their chaplets upon them and covered them with flowers; still dancing, still singing: “The divided part has become old, put it off; the present is bright with every hope, enjoy it; the future shall be what you may make it, be not wanting; oh, happy, happy, happy pair! As ye are, so we would be; ever drinking draughts of pleasure through each revolving year.”

And now came forth the aged of the tribe, slow descending from the wood, and embraced them and blessed them; “Be fruitful and multiply—swear.” And Erix and Zella stretched out their hands toward heaven and swore, by the light, and by the orbs of the air, and by the ocean, far-rounding, illimitable, infinite, and by the solid earth, and by Him who moved upon the face of the waters and begat this glory, to be forever one. “What you receive, I will receive; what you reject, I will reject; your breath is my breath, and even as we are now, so death shall find us; leaving all else to cleave unto each other.”

The dance, the shout, the sound of merry horns, pointed to the grot, and Erix and Zella led the way. He, with head erect and willing feet, proud of his victory; she, with downcast eyes and halting gait, irresolute, resolved, like a coy maid, half-refusing, like a wife, wholly trusting, while youth and maiden, paired, in a long line, came sweeping after. And now they sway, first to the right then to the left, with measured step, beating upon the glad earth the bridal-song.

“Receive, receive thy children, Paradise, garden new found, not lost to us forever.”

“Who are these that come, beautiful with joy?”

“Receive, receive thy children, Paradise, garden new found, not lost to us forever.”

“Who are these that knock, pressing to tread upon holy ground?”

“Thy children, father; thy children, mother; open wide the gates that they may enter in. Praised be thy name, oh Adam! praised be thy name, oh Eve! these are thy offspring, joined as ye were joined, by the hand of God; open wide the gates that they may enter in.”

The grot received them, echoing; and shout, and laughter, and the sound of many horns, held riot over a feast of fruit, and the chase, and water from the brook, till the day went out and night crept slowly in, and stars spotted the sky, and the white pigeon descended nestling, timidly, to its couch, and arched its neck, and drooped its wings, and turned round and round; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-uh; chrr-oo-eh-uh; oo-ugh; oo-ugh; chrr-oo-uh; calling to its mate—and she, called to him again.

——

Ten circles have passed; ten circles of the earth about the sun; what are ten circles to life before the flood! The night is just yielding to the day, and in the farthest east streaks of gray light lie floating, dividing the ocean from the sky. How quiet the earth is; and seems to breathe, long and deep, in its huge slumber, not yet awakened. The murmur of the sea is infinite, ceaseless, and breaks, and returns, and breaks, in regular cadence upon the shore; ever speaking the same words—eternity and power. The sea and silent stars, which look down, twinkling, from heaven’s pavement, alone are watchful. How quiet the earth is! The owl sits moping upon her perch in some tall pine, and the wolf, whose cry, whetted by hunger, pierced the shades of night, gorged and reeking, has hastened to his lair. The dew, like rain, is upon the grass and all herbage, and hangs, globular, from every leaf. An incense rises, the incense of the morning, and fills the air; now known only to the wise and the poor, beloved of God. Hour most sweet; when day salutes the night, and night kisses day, to part and meet again.

At such an hour, Erix and Zella shook sleep from their eyelids and came forth, ready for the chase. Her hair no longer floated unbound, but, as became the matron, was twisted into a knot and confined with strings of coral, fashioned by the hand whose soft caress she returned with joys unspeakable. Upon her drooping shoulders, white and bare, rests a quiver well filled; and a belt of tiny sea-shells interwoven with fibres of the lichen, crosses transversely her breast, now full and rounded to completion. Sandals are upon her feet, and a tunic of shaggy hide covers her from the waist to the knee; all else, the morning air, invigorating, embraces. Thus seen, the poet of an after age, changed his story, and called her Dian, ruler of the night; and sang her praises in verse set to the babbling of brooks, the music of the wood, and sylvan sports. Erix, large, erect, perfect in manly beauty, with limbs well knit, proportional, combining activity and strength, was less incumbered than his mate, and carried, as his sole weapon, an ashen spear, charred and hardened at the point by fire. His was the front of Jove, the pagan, not yet won from mortality by intellect, or raised above mere matter, to express the soul’s labors and ambitions. And first, low bending, rose the morning prayer.

“Hail Father, Creator; Thou who gavest into our hands the earth, with its fullness; all hail! Thy children, fashioned after thine own excellence, we stand, rejoicing. Greater than the earth are we; greater than the sea, that vast stream which compasses all land, forever proclaiming thy praises; greater than the orbs of day and night; greater than the elements, thy ministers; for thou didst speak unto our fathers, and didst promise to raise the seed of Adam higher than the angels. The thunder serves us, obedient to thy will; and the quick lightning; and the clouds, pregnant with rain. In the air we find thy mercies, and every tree, and every flower speaks of thee. Accept, accept our great gratitude; and keep us, even as thou keepest all else.”

Again low bending, and Erix and Zella, light of foot, passed onward to the chase.

They skirt the wood, and narrowly inspect the dewy grass, to find new foot-prints of beast or heavy bird, seeking, with returning light, their accustomed food. No fairy ring, no shape of naiad or of dryad, no gnome, no sprite, met their pure vision, to turn them from their way; for not yet had the mind of man built up a superstition unto itself, and peopled the clefts of the earth, the water, and the air, giving to nothingness forms innumerable. Truth was too near and palpable, to be lost in imagination; to be moulded and cast anew, so changed as not to know itself; and poetry, the juggler and soul’s cheat, lay hid in matter, where God placed it, to be drawn thence for other purposes than those of error. It was not until man forgot his origin, that he sought out a new creator, even Beauty, the prime element in all God’s works, and so wrought with it, as to give strange life to all that is, and is not.

The wily hunters, skilled in their life’s trade, turn on every side, observe the lower boughs, fresh cropped, imitate the call of birds, the cry of deer, peer through the thick underwood which stood here and there in clumps, and plunged into the forest upon a trail which promised success.