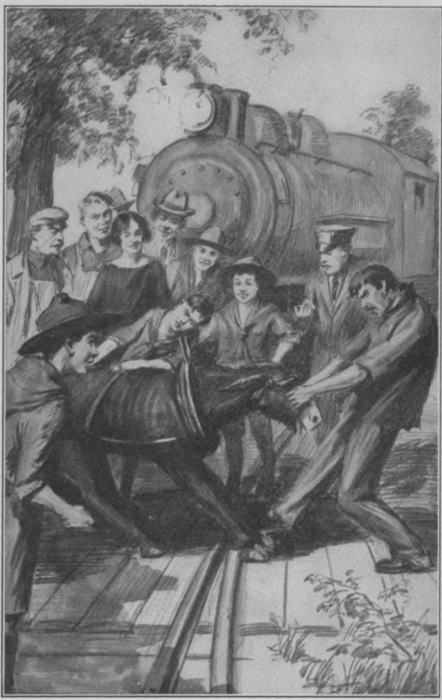

“OUT I WENT AGAIN WITH ALL OF THEM AFTER ME.”

Title: Roy Blakeley's Funny-bone Hike

Author: Percy Keese Fitzhugh

Illustrator: Harold S. Barbour

Release date: September 7, 2019 [eBook #60255]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Roger Frank and Sue Clark

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Roy Blakeley's Funny-bone Hike, by Percy Keese Fitzhugh, Illustrated by H. S. Barbour

“OUT I WENT AGAIN WITH ALL OF THEM AFTER ME.”

ROY BLAKELEY’S

FUNNY-BONE HIKE

BY

PERCY KEESE FITZHUGH

Author of

TOM SLADE, BOY SCOUT,

TOM SLADE AT TEMPLE CAMP,

ROY BLAKELEY, ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

H. S. BARBOUR

Published with the approval of

THE BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Made in the United States of America

Copyright, 1923

GROSSET & DUNLAP

CONTENTS

| I | We Go |

| II | We Start Back |

| III | We Go South |

| IV | We Go North |

| V | We Keep on Going North |

| VI | We Move Heaven and Earth |

| VII | We Reach the Fickle Guide Post |

| VIII | We Do a Good Turn |

| IX | We Follow Our Leader |

| X | We Retrace Our Steps |

| XI | We Wait for the Boat |

| XII | We Collect Toll |

| XIII | We Are Marooned on a Desert Island |

| XIV | We See a Sail |

| XV | We Form a Resolve |

| XVI | We Are Saved |

| XVII | We Cook the Duck |

| XVIII | We Meet a Friend |

| XIX | We Eat |

| XX | We Make a Promise |

| XXI | We Keep Still |

| XXII | We Hear a Voice |

| XXIII | We Go to the Rescue |

| XXIV | We Drop Dead—Almost |

| XXV | We Prove It |

| XXVI | We See a House |

| XXVII | We Lose Our Bearings |

| XXVIII | We Are Dead to the World |

| XXIX | We Wake Up |

| XXX | We Figure It Out |

| XXXI | We Make a Bargain |

| XXXII | We Become Bandits |

| XXXIII | We Win |

| XXXIV | We Start the Parade |

| XXXV | We End Our Hike |

| XXXVI | We Demobilize |

| Chapter the Last |

ROY BLAKELEY’S FUNNY-BONE HIKE

This is going to be the craziest story I ever wrote. But anyway every word of it is true—except a few small words. Even the punctuation is true. But I have to admit the story is crazy. It’s the craziest story ever written in this world or any other world. I don’t care how many worlds there are. The name I call it by is the Funny-bone Hike, but I should worry what you call it.

When you study first aid you have to know all about the different bones but the only bone I know anything about is my funny-bone. Anyway I don’t care so much about first aid—I like lemonade better.

But one thing, I’ve got the Safety First badge. To get that you have to think up a safety device in your home. I thought of a safety pin. I’ve got ten other merit badges, too. Next to laughing my specialty is cooking.

So now I’ll tell you about how all this crazy business started. It happened accidentally on purpose. Our troop was up at Temple Camp—that’s where we spend our summers. One morning six of us went down to Catskill Landing in the bus to get some fish-hooks and jaw-breakers; I’m crazy about those, I don’t mean fish-hooks.

The six scouts that happened to be along were Bert Winton, (he belongs out west) and Hervey Willetts, (gee whiz, he belongs everywhere I guess) and Garry Everson (he lives down the Hudson) and Warde Hollister (he’s in my patrol and my patrol is the Silver Foxes and they’re all crazier than each other, those fellows) and Pee-wee Harris (he’s one of the raving Ravens of our troop) and Roy Blakeley, that’s me, I mean I, correct, be seated. I was named after my sister because she was named before I was. I’m patrol leader of the Silver Foxes, but I’m not to blame, because they were wished onto me. I’m more to be pitied than blamed.

Now it’s about ten miles from Temple Camp to Catskill Landing. And it’s about three hundred and forty-eleven miles back from Catskill Landing to Temple Camp. I bet you’ll say that isn’t possible and I know it isn’t possible but it’s true just the same.

So this is the way it is. The first chapter of this story tells how we went to Catskill Landing and the next twenty or thirty chapters tell how we got back to Temple Camp. You can stay in Catskill Landing if you want to and not bother with the rest, I should worry. But the book includes the round trip only it wasn’t so round; it was kind of square like a circle and rectangular and right-angular and left angular, and every which way. It was shaped like a lot of wire all tangled up. The way back was so crooked that we met ourselves a lot of times going the other way.

So if you want to you can call this story The Tangled Trail. But I like the Funny-bone Hike better. Suit yourself.

The scout that was to blame for the whole thing was Hervey Willetts. Believe me, that fellow ought to be kept in a cage. He belongs to a patrol named the Reindeers but he ought to belong to the tomcats because half the time nobody knows where he is.

His scoutmaster says he wanders over the face of the earth but, believe me, he wanders across the head of the earth and down the neck of the earth; the face isn’t big enough for him. The scouts at camp call him the wandering minstrel because he goes all over and he’s all the time singing. It was just a streak of luck that we happened to have him with us that day. He wears a funny little hat without any brim and with holes cut in it so his thoughts can get out because they make him top-heavy when he’s climbing trees.

We were just starting to hike back from Catskill Landing when he said, “Come on, let’s make it snappy.”

“What do you mean, make it snappy?” I asked him.

“Let’s put some ginger in it,” he said.

“He means gingersnaps,” Pee-wee shouted; “let’s buy some.”

“A voice from the Animal Cracker Patrol,” Warde Hollister said; “here’s a couple of fish-hooks, and a package of tacks, eat those.”

“Put some ginger in what?” I asked Hervey. “I’d just as soon fill it up with ginger, only what?”

“The hike back,” he said. “Let’s start something.”

Already that fellow was suffering from remorse because he had sat quietly for half an hour or so in the bus.

I said, “If I knew of volcanoes or wild animals on the way back I’d lead you to them, but the only wild animal I know of around here is the mascot of the animal patrol.”

“Let’s play Follow Your Leader,” Hervey said.

“Not while we’re conscious,” Garry Everson spoke up; “not if you’re going to be the leader. I have to be home by Christmas.”

Bert Winton said, “I’m sorry, but school opens in a few weeks. Nothing doing.”

“I’ll follow you!” our little Animal Cracker shouted; “I don’t have to be home Christmas. I don’t have to be home till my birthday and that doesn’t come for four years because I was born in leap year.”

“Now we know why you’re so slow growing up,” Warde said.

“You’re a lot of tin horn sports!” Pee-wee shouted.

“I’m game,” I said. “I’ll die for the cause if anybody else will.”

Hervey said, “Listen.” Then he said, kind of sing-songy, so it made me want to walk:

Don’t ask where you’re headed for nobody knows,

Just keep your eyes open and follow your nose;

Be careful, don’t trip and go stubbing your toes,

But follow your leader wherever he goes.

Oh, boy, that started us off. We were like horses when they hear a brass band. Hervey gave me a shove and said, “Go ahead, start off, you’re the only patrol leader here, it’s up to you.”

“It’s your game,” I said.

“Go ahead, lead,” he began laughing, “and let’s keep it up till we get to Temple Camp. It’s no fun if you flunk.”

That was just like him, he didn’t care who led as long as he was moving. That fellow goes off in the woods a lot by himself and he doesn’t care anything about merit badges himself. He’s a funny kind of a scout but he’s awful generous. He can’t keep still, that’s one thing about him. Most scouts are always trying for things but all he cares about is action—he eats it alive.

So the first thing I knew I was marching along with the other fellows behind me and they were all singing those verses and kind of marching in step to them. Gee whiz, we couldn’t get those verses out of our heads. It was awfully funny to hear Pee-wee shouting them. Even now it seems as if I have to write them down and I guess there’ll have to be an operation to get them out of my mind. I lie awake at night and say them. If you once get those verses in your head, good night! Most all the rest of that day we were singing them. I guess the people in Catskill Landing thought we were a lot of lunatics. So now I’m going to write those verses down again But you want to be careful not to let them get you or you’ll come to be a raving maniac. If you do you can blame Hervey Willetts.

Don’t ask where you’re headed for nobody knows,

Just keep your eyes open and follow your nose;

Be careful, don’t trip and go stubbing your toes,

But follow your leader wherever he goes.

Don’t start to go back if it freezes or snows,

Don’t weaken or flunk or suggest or oppose;

Your job is to follow and not to suppose,

And follow your leader wherever he goes.

Don’t quit or complain at the stunts that he shows.

Don’t ask to go home if it rains or it blows;

Don’t start to ask questions, or hint, or propose,

But follow your leader wherever he goes!

When we started that crazy game we were near the landing. Maybe it would have been better if we had jumped into the Hudson. But instead of that I started marching up toward the railroad station with all the fellows after me, singing that song.

I went leap frog over a barrel and the rest of them did the same, singing, Follow your leader wherever he goes. All the while Pee-wee stuck on the top of the barrel because his legs were so short, but as long as he was the last one it didn’t make any difference.

“Take a demerit,” I shouted back at him. “What do you think you are? A statue?”

“He looks like a barrel buoy,” Garry shouted.

“Don’t look back, keep singing,” Hervey called to Garry. “Never mind what’s behind you.”

“Sure, think of the future,” Warde said. “And follow your leader wherever he goes.

Wherever he goes,

Wherever he goes,

Wherever he goes.”

I went waltzing into a candy store, and picked up a five cent chocolate bar and laid down a nickel and kept going in and out around the ice cream tables. All the people in there started laughing. One girl spilled a glass of root beer that she was drinking. All of us fellows had small change, we never have any large change, so nothing happened to block the parade.

Out I went again with all of them after me, holding the chocolate bar in my mouth. I took one bite of it and threw it in the trash can. I heard Hervey do the same, then Bert, and I knew Garry and Warde could be trusted.

“Keep your eye on Pee-wee,” I said.

“A scout isn’t supposed to waste anything,” the kid shouted, his mouth full of chocolate.

“None of that,” I shouted back. “How many bites did you take? Throw it away!”

“I took—I took one bite—in two sections,” the kid said.

“Come on,” I shouted.

Don’t quit or complain at the stunts that he shows,

Don’t ask to go home if it rains or it blows;

Don’t start to ask questions, or hint, or propose,

But follow your leader wherever he goes!

wherever he goes,

wherever he goes——

“Just keep your eyes open and follow your nose,” Warde said.

I kept going round and round a baby carriage till we were all dizzy and even the baby began to laugh. Then I went staggering in and out and over a lot of trunks at the station, and crawled under an express wagon and hopped on one leg along the platform. Everybody was screaming at us. We were shouting those verses good and loud.

There was an accommodation train standing at the station so we couldn’t get across the tracks. Gee whiz, I don’t call that very accommodating. I climbed up into the first car and started going back through the train, all the fellows after me, singing those crazy verses like a lot of wild Indians. The people in the cars stared at us. I dropped a cent in the slot and got a paper drinking cup and took a drink of water and then started carrying the cup full of water through the train. Along they came after me carrying cups of water.

All of a sudden, kerflop, the water spilled out on my face. That was because the train had started. I guess it happened to the rest of them because the people in the seats began to howl.

“Never laugh at another’s misfortune,” I said. “You may get your own faces washed some day.”

“Hurry up,” Garry shouted.

“What’s the difference?” Hervey said.

Somebody shouted, “The next stop is Alsen.”

“I hope it’s a good stop, we’ve had a good start, anyway,” Bert said.

We might have got out at the end of the car, only it was a vestibule car and all closed up.

“Now you see what you did,” Pee-wee shouted.

I said, “Don’t you care, you don’t have to get home for four years. We ought to reach Alsen in about a year and a half.”

“Hurry through to the next platform,” Garry said.

I sprinted through the next car and there was an open platform there but by that time the train was moving too fast for us to get off. Safety first, that’s our motto. Crazy but safe.

So then we had a meeting of the board of directors on the platform of that car till a brakeman made us go inside.

I said, “The plot grows thicker.”

“You’re a fine kind of a leader,” Pee-wee said, very contemptible like, I mean contemptuous. “What are we going to do now?”

“Be thankful I didn’t lead you onto an airship,” I said; “we’re going to Alsen, it’s a very nice place, houses and everything. Follow your leader wherever he goes.”

“We’re supposed to be headed for camp,” the kid said.

“We’re on our way there,” I told him. “We’re going west in a southerly direction.”

“Alsen is only about three miles,” Bert said.

“How do we know the engineer will see it when he gets there?” Garry wanted to know.

“Maybe he has a magnifying glass,” I said. “I hope there are some things in Alsen.”

“What kind of things?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“Things to do,” I told him.

“Where are we going to end?” he shouted.

“We’re not going to end,” I said.

“Temple Camp is west from here,” he yelled at me, because the train was making a lot of noise.

“Do you blame me for that?” I asked him. “I didn’t invent the compass, did I? If you’re not satisfied with where Temple Camp is you’d better complain to Mr. Temple, he put it there.”

“Oh, look at the big, high tree!” Hervey shouted. “Let’s climb up that on our way back.”

“Sure,” I said, “and jump off the top. You’d be going leap frog over the Woolworth Building if you were leader. Be thankful you’ve got a conservative leader.”

“A what?” the kid yelled. Just then he went backward off the arm of the seat plunk into a man’s lap.

“Tickets,” the conductor shouted.

I said, “Hey, mister, we’re on a funny-bone hike, and the train started before we had a chance to get off. We have to go to Alsen. Do you know if we can get ice cream cones there?”

He just laughed and said he’d have to collect our fares. It only costs ten cents from Catskill to Alsen.

I said to the fellows, “Well, so long as the engineer’s going to be our leader for a little while I’ll take a vacation.”

So I sat down and began looking out of the window.

Alsen is a tenderfoot village. It’s about as big as Pee-wee, only it’s more quiet. Pee-wee’s size is like Alsen but his noise is like New York.

The train stopped at Alsen and we got off. Right there was a train standing at the station headed north.

“Talk about luck,” Garry said. “I guess it was waiting for us.”

I said, “I enjoyed my trip south.”

“I was looking forward to hiking from here to camp,” Hervey said.

“Believe me, it’s nearer from Catskill,” I told him. “A train can go a long way in five minutes.”

“A comet can go billions of miles in a second,” the Animal Patrol piped up.

“If I see a comet I’ll get on it,” I told him; “follow your leader.”

“That’s one thing I never did; ride on a comet,” Hervey said.

“It’s about the only thing you haven’t done,” I told him. “Come on, follow your leader.”

I went marching up into one of the cars; Pee-wee tripped on the step.

“That’s a short trip to take,” Warde laughed at him.

“That could happen to the smartest man in the world,” the kid said.

“All right, here we go back again,” I said as we all tumbled into a couple of seats. Then I started to sing that crazy stuff about the Duke of Yorkshire:

There was the Duke of Yorkshire,

He had ten thousand men;

He marched them up the hill,

And he marched them down again.

And when they’re up, they’re up,

And when they’re down, they’re down;

And when they’re only half-way up,

They’re neither up nor down.

“Alsen is a mighty nice place, what I saw of it,” Garry said. “I couldn’t see it on account of the station. The happiest ten seconds of my life were spent there.”

I said, “I wish I could have spent a nickel there.”

“Are you going to start for camp when we get to Catskill?” the kid wanted to know. “I’m getting hungry.”

“I thought you didn’t have to eat for four years, that’s what you said,” I told him.

“What are you talking about?” he yelled.

I said, “When we get back to Catskill you’re going to follow your gallant leader in an east westerly direction till we come to the—North Pole, I mean the clothespole, outside the cooking shack at Temple Camp. We’re going to reach the pole like Doctor Cook didn’t do. When I hang my patrol scarf on the clothespole outside the cooking shack that’s a sign our journey is over. From the West Shore Line to the clothesline, that’s our motto.”

“We’re starting,” Warde said.

“Get your dimes ready,” Garry said.

“I haven’t got anything smaller than a cent,” I told him.

“You mean you haven’t got any sense,” Pee-wee shot at me.

“I’m poor but dishonest,” I said.

Just then I heard the door at the other end of the car slam shut and a brakeman came through shouting, “Albany the first stop, the first stop is Albany.”

“G-o-o-d night!” I said. “The plot grows thicker.”

“It’s petrified,” Warde said.

“We’re lost, strayed or stolen,” Garry began laughing.

We all made a dash for the platform, but it was too late. We were foiled again. The train was going at about forty-eleven miles an hour.

“Now what?” Pee-wee demanded, very dark and solemn like.

“Answered in the affirmative,” I said; “we don’t.”

“Don’t what?” he said.

“Don’t care,” Hervey spoke up. “We can do some stunts in the State Capital. We can jump over the seats in the Senate. Albany is only about thirty miles away.”

I said, “Posilutely; we can get back inside of four years and have a couple of centuries to spare. Follow your leader wherever he goes. I may jump over the governor’s head; they pass bills over his head. You learn that in uncivil government.”

“The more we start for camp the farther we get from it,” the kid said.

“Correct the first time,” I said; “be thankful you’re not on a comet.”

“What are we going to do?” he wanted to know.

“Is it a riddle?” I asked him.

“No, it isn’t a riddle!” he shot back at me.

“Because if it is, it’s a good one,” I said. “It’s about the best one I ever heard.”

“I like the West Shore Railroad,” Hervey said; “it’s full of pep; it goes scout pace.”

“You wanted ginger in our trip back to camp,” I said, “and you’ve got tabasco sauce. Gee whiz, you ought to be satisfied. We’ll go back to camp by way of the island of Yap.”

“You’re the leader,” Warde said.

One thing I’ll say for Hervey Willetts and that is that wherever he goes there is adventure. He carries it with him. He couldn’t just go on a hike, that fellow couldn’t. He always has to start something.

Garry said, “Well, things seem to be moving.”

“Oh, they’re moving all right,” Bert said.

Warde said, “There are only two directions left to go in.”

“Have patience,” I told him; “we’ll try them all; there are four, east and west and up and down.”

“And in and out,” Warde said.

“Sure,” I said, “that’s six. I wonder how much the fare to Albany is—the round trip?”

“It’s not so very round,” Pee-wee said.

“It’s a kind of triangular circle,” I told him. “If we pay our fare both ways we don’t get any dinner in Albany, we’ll have to walk back. And if we don’t have some dinner we can’t walk. So there you are; take your choice. It’s as clear as mud.”

“You’ve got us into a nice fix,” the kid said. “I knew you were crazy when you made us throw away those chocolate bars. The next thing you’ll have us in jail.”

“You should worry, you can eat the prison bars,” I told him.

“Let’s see how much money we’ve got,” Bert said.

I had about seventy-five cents and the cap of a fountain pen that I use for a whistle.

Pee-wee had fifty-two cents and a lot of junk; we had a little over seven dollars altogether. It was lucky that was enough for our fare to Albany. But we didn’t get much change. The conductor said the train went to Albany without change—I guess that’s why we didn’t get much.

“How can we hike back thirty miles to-day, tell me that?” the Animal Cracker wanted to know.

“That’s easy,” I said; “by doing two miles at a time, that makes fifteen. Are you getting frightened?”

“We don’t know where we’re going but we’re on our way,” Bert began singing.

“Maybe it won’t be so far back as it is there,” Garry said.

“Sure, because it’s always shorter going south,” I told him.

“Six of us ought to be able to earn seven dollars in Albany,” Warde said. “And we can take an evening train down.”

“I’m not going on any more trains,” Pee-wee yelled. “I’ve had enough of trains. If we come back on a train it won’t stop till it gets to Poughkeepsie, and then if we come up on another one it won’t stop till it gets to Montreal. You don’t catch me getting on another train.”

“Follow your leader,” I told him. “Follow your leader wherever he goes.”

Everybody in the train was laughing at us, but what did we care? It might have been worse, we might have been on the Erie.

“We’ve got enough left to wire to camp, if the worst comes to the worst,” Bert said.

“It’ll have to be worse than that before I’ll wire,” said Hervey.

“I’ll say so,” I told him. “I’m not worrying, this train knows where it’s going. If we forget to get out at Albany we’ll get out at Buffalo and you can follow your leader across Lake Ontario. That used to be in my geography.”

“I guess it’s there yet,” Garry said.

“Take a slap on the wrist for that,” I told him.

“You all make me tired,” Pee-wee said, very disgruntled.

“Well, you’re having a good rest,” I told him. “We’re on our way to Temple Camp, don’t worry. We’re only taking a long cut. Our trail is tied in a knot. We’ll get there when we get there—maybe a little sooner. All you have to do is follow your leader wherever he goes.”

“Absolutely, positively,” Warde said; “that’s understood.”

“Even if he goes to sleep,” I said; “excuse me while I take a nap. I expect to have a long walk this afternoon.”

Just then the train began slowing down and the whistle started blowing very loud and shrill. A brakeman with a red flag came hurrying through the car.

“I guess there must be a mosquito on the track,” Garry said.

“Maybe the engineer’s going to pick some blackberries,” Warde said.

All of a sudden—bang! the cars knocked against each other, the train stopped so suddenly. The whistle blew three or four times very quick and shrill.

In about one second I was on my feet. “Follow your leader,” I shouted. And through the aisle I went with the rest of them after me all singing those crazy rhymes that stuck in our minds like glue.

Don’t start to go back if it freezes or snows,

Don’t weaken or flunk or suggest or oppose;

Your job is to follow and not to suppose.

And follow your leader wherever he goes.

You can bet we didn’t lose much time getting off the train. “Follow your leader,” I said.

Garry said, “We’re in luck; we’re only about six or seven miles north of Catskill.”

“You don’t call that luck, do you?” Hervey said. “Just when I was counting on a nice trip to Albany.”

“I suppose you’d like to make a mistake and get on an ocean steamer,” I told him.

“Mistakes?” the kid shouted. “You’re the one that made mistakes famous.”

“Sure,” I said, “and you’re the one that put the wise crack in animal crackers.”

“The last syllable of a doughnut is named after you,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Always thinking about doughnuts,” I said. “Look on the track, there’s a friend of yours.” Right plunk across the track, about a couple of hundred feet ahead of the train was a donkey hitched to a funny kind of a wagon that was all machinery inside.

“I guess it goes by clockwork,” I said.

“It looks as if it doesn’t go at all,” Bert said.

“It did us a good turn anyway,” I said; “it made the train stop.”

Gee whiz, we had to laugh. The man that owned that outfit was an Italian and he was yelling Italian at the donkey and trying to make him start. I guess the donkey didn’t understand Italian.

“I GUESS THE DONKEY DIDN’T UNDERSTAND ITALIAN.”

A lot of people got out of the train and stood around watching and the engineer sat in his window looking as if he were very mad at the donkey. But anyway the donkey didn’t care. When we got close enough we could see that the wagon had emery wheels in it for grinding knives and scissors and scythes and things like that and they went by a gas engine.

The man was shouting, “Hey! Whater de mat? You go! Hey, whater de mat?”

I said, “We ought to have someone who can translate Italian. Suppose you shout at him, Pee-wee; if that doesn’t start him nothing will.”

The man kept jerking the donkey’s bit, all excited, and shouting, “Hey you, giddup, whater de mat?”

Two or three passengers started pulling and jerking the donkey, and one tried to push him, but it didn’t do any good. I felt mighty grateful to that donkey. Anyway he had a will of his own, that’s one sure thing. About a half a dozen passengers kept tugging at him but it didn’t do any good. He just braced his legs and let them pull.

I said, “Maybe if we hold some grass in front of him he’ll follow it.” But that didn’t work; I guess he wasn’t hungry.

Pretty soon Warde said, “I’ve got an idea; let’s move him with the gas engine. That engine’s about six horse power; it ought to be stronger than one donkey power.”

“It’s an insulation!” Pee-wee shouted.

“You mean an inspiration,” I told him.

“Hey, giddup; hey you,” the Italian kept shouting, all the time hitting the donkey with the whip.

I said, “Nix on that, it doesn’t do any good. What’s the use of licking a donkey when you’ve got a gas engine to move him with? You leave it to us, we’ll move him.”

The man said, “Mova de donk; hey boss, mova de donk!”

“Sure,” I said, “we’ll move him; we go to the movies and we know all about moving. Have you got some rope?”

I don’t know where the rope came from; maybe it came from the train and maybe it came from the wagon. Anyway we fastened it through one of the holes in the fly-wheel and wound it a couple of times round the shaft. Then we dragged the rope over to a tree on the edge of the woods, behind the wagon and tied it there. Everybody was laughing and the Italian was shouting, “Hey, maka de gas, boss! Pulla de donk!”

We told him to start the engine and let it run very slowly. Goodnight! Laugh? First there was a kind of straining and creaking, but we knew the engine was fixed solid because it was bolted right through a heavy engine bed to the floor of the wagon. The rope was so tight it looked as if it would snap. Pretty soon the donkey began to feel the pulling because he braced his hind legs; he looked awful funny.

“I bet on the donkey,” somebody shouted.

“I bet on the gas engine,” somebody else put in.

Everybody was laughing and the Italian was all excited, waving his whip in the air and running about shouting, “Hey, giva de gas! Pulla de donk!”

All of a sudden the donkey gave way and back he went after the wagon. He kept trying to brace himself but it wasn’t any use; the little engine went ck, ck, ck, ck, ck, ck, shaking and trembling, and back went the donkey after the wagon, till the whole outfit was off the track.

“He followed his leader all right,” Bert Winton shouted.

“Come on,” I said, “we have no time to be wasting here, let’s thank the donkey for the good turn he did us and then see if we can find out where we’re at. We’re probably somewhere.”

“Sure if we’re somewhere we ought to be able to get somewhere else,” Garry said.

“We don’t know which way to go,” Pee-wee said.

“We’ll go every which way,” I said, “and then we’ll be sure to strike the right way. One direction is just as good as another if not better. Come on, follow your leader.”

So off we marched into the woods singing:

Don’t ask where you’re headed for nobody knows,

Just keep your eyes open and follow your nose;

Be careful, don’t trip and go stubbing your toes,

But follow your leader wherever he goes.

As the train started all the passengers looked out of the windows laughing at us and waving their hands. Anyway we were more powerful than that train because a donkey could stop it and we could move him off the track, so it could get started, and that proves how smart boy scouts are even when they don’t know where they’re at.

“I’d like to know where we are,” Warde said.

“We’re in the Catskill Mountains,” I told him.

“You might as well say we’re in the universe,” Pee-wee said. “What good does that do us?”

“You mean to tell me it isn’t good to be in the universe?” I asked him.

“It’s one of the best places I know of,” Garry said.

“Sure it is,” I told him. “Anybody who isn’t satisfied with the universe——”

“You’re crazy!” Pee-wee yelled.

“Follow your leader,” I said. “Follow your leader wherever he goes.”

“Follow your nose,” Bert said.

“No wonder he goes up in the air so often if he follows that,” Garry said.

“Do you think I’m going to go marching around the country for the rest of my life?” the kid piped up.

“Don’t quit or complain at the stunts that he shows,” I said. “You want to go somewhere, don’t you? Well, I promise to lead you somewhere. That’s just where you want to go. What more can you ask?”

I kept marching in and out among the trees, touching some and not touching others, the other fellows after me. Pretty soon I hit into the road that crossed the track. We were about a quarter of a mile from the track then. I kept along that road, sometimes walking on the stone wall and sometimes going zigzag in the road. I knew we were going west and I was pretty sure that Temple Camp was southwest, but I didn’t know how far. I thought that pretty soon we would come to a crossroad and that there would be a sign there.

Pretty soon we did come to one and there was a sign there, all right. I was glad of that because the road we were on had made so many turns I didn’t know for certain which direction we were going in. Besides, the sky was all cloudy so I couldn’t tell anything by the sun.

“There’s a sign post!” one of the fellows shouted.

“Saved!” another fellow yelled.

I didn’t strain my eyes to see what was on the signboard, but as soon as I saw it I began passing in and out among the trees along the road, grabbing each tree and going around it. All the while we were singing those crazy rhymes. So that way I came to the sign post and grabbed hold of it and around I went, only, good night, the post went round with my hand.

“There’s a good turn,” I shouted.

“Now you didn’t do a thing but make the plot thicker,” Pee-wee yelled at me at the top of his voice. “Now you’ve got everything mixed up.”

“I changed the whole map of the Catskills,” I said. “That’s nothing; see how the map of Europe is changed. I don’t think much of a signboard that changes its mind.”

“I don’t think much of a scout that changes a signboard,” Pee-wee shouted.

We all stood there staring at the sign. On the top of that post were two boards crossways to each other and on each board two directions were printed with arrows pointing. On one board was printed COXSACKIE 8 M., with an arrow pointing one way, and ATHENS 5 M., with an arrow pointing the opposite way. On the other board was printed CAIRO 9 M., with an arrow pointing one way, and CLAYVILLE 7 M., with an arrow pointing the other way, and underneath that board was a little board with TEMPLE CAMP printed on it. I guess scouts put that there.

But a lot of good that sign did us because all we knew was that Temple Camp was in the same direction as Clayville and we didn’t know which direction Clayville was in.

“Follow your leader and you don’t know where you’re at,” Pee-wee said, very disgusted like.

“Wrong the first time,” I said. “The poem says follow your nose. Would you rather believe the guide post than that beautiful poem? The poem never changes but the guide post moves around. We know where we’re at, we’re right here; deny it if you dare. We’re smarter than the guide post.”

“You’re about as smart as a lunatic,” the kid shouted. “If you hadn’t touched that we’d know which way to go. Now where is Temple Camp?”

“That’s easy,” I told him; “it’s where it always was.”

“You mean you’re like you always were,” he said; “you’re crazy.”

“Let’s move it around again,” Hervey said, “and we’ll say the first verse and let go the post just as we finish. Then let’s go the way it says.”

“Good idea,” Warde said; “let’s all agree that we’ll go whichever way the Temple Camp arrow points.”

“There are four directions,” Pee-wee said. “We’ll stand just one chance in four of going the right way.”

“There are only two directions,” I said; “right and wrong. Deny it who can. So we stand a fifty-fifty chance of going right. Anybody that knows anything about arithmetic can tell that. Come on, follow your leader wherever he goes.”

I grabbed hold of the sign post and started walking around with the rest of them after me singing, “Follow your leader wherever he goes.” Some merry-go-round! We sang the first verse and I stopped short when we got to the word goes.

“Come on,” I said, “Temple Camp is right over that way. Follow your leader.”

“Trust to luck,” Hervey said; “if it’s wrong, so much the better. Let the guide post worry. They had no right to put a pinwheel here for a guide post.”

“Just what I say,” I told him.

“How about others coming along?” Warde wanted to know. That fellow makes me tired, he’s all the time using sense.

“Now what have you got to say?” Pee-wee yelled. “A scout is supposed to be helpful.”

“Sure, he’s supposed to help himself to all the cake he wants, like you,” I said.

Warde said, “As long as we’ve had all the fun we want here, let’s set the post right before we go.”

“We haven’t had all the fun we want,” Hervey said.

“Sure we haven’t,” I put in. “We haven’t begun to have any yet.”

“I care more about dinner than I do about fun,” Pee-wee said.

“Do you mean dinner isn’t fun?” Garry asked him.

“I’m just as crazy as you are,” Bert said to me, “but we might as well go crazy in the right direction if we can only find out what that is.”

“Carried by a large minority,” I said; “the board of directors is appointed to find out the direction, so we can go crazy in that direction.” Warde said, “The trouble is that other people that pass here are not so crazy as we are and they’d like to know which way is which. Some people are peculiar.”

“Some people are worse than peculiar,” the Animal Cracker shouted.

“The compliment is returned with thanks and not many of them, and we wish ourselves many happy returns of the way. If anybody knows the way this merry-go-round of a sign post is supposed to stand let him now speak or else forever after hold his peace.”

“Piece of what?” Pee-wee shouted.

“Piece of pie,” I said; “that’s what you usually hold, isn’t it?”

Warde just went up to the sign post kind of smiling and turned it around till he got it just where he wanted it.

“What’s the idea?” I asked him.

He said, “Well, there are a couple of ideas.” I said, “I didn’t know we could scare up as many as that among the whole lot of us.”

“Maybe I’m wrong,” Warde said, “but I think that the side of the post with dried mud on it should face the road. That mud was spattered by wagons and autos. And I think the side that isn’t sunbaked faced the woods where it’s damp and shady. And I think the board where the paint is faded is the one that faced the sun. And so I think that Cairo is over there, and Athens over there and Temple Camp over there. See?”

“Hip, hip, and a couple of hurrahs!” Hervey Willetts said. “That means we can cut through these woods and come out at the end of the old railroad branch. There’s a big apple tree over there, I fell out of it once. It’s all woods over there and we stand a pretty good chance of getting lost again.”

“What kind of apples are they?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“Baked apples,” I told him.

So then I started off with the rest of them after me, singing Follow your leader wherever he goes.

“There ought to be plenty of apples on that branch,” I said, as I went along.

“What branch?” the kid wanted to know.

“The old railroad branch,” I told him. “Don’t you know that apples grow on a branch?”

I guess none of us knew anything about that old branch but Hervey Willetts. That fellow knows about the funniest things and places. He can take you to old shacks in the woods and all places like that. He knows all the farmers for miles around camp. He knows where you can get dandy buttermilk. And he knows where you can get killed by quicksand and a lot of other peachy places. He says that’s the kind of sand he likes because it’s quick. He believes in action, that fellow.

I said, “As long as you know where we’re going suppose you be leader for a little while.”

“I’ll be leader,” Pee-wee shouted.

“Let Hervey be leader,” they all said.

So I fell behind and I was glad to get rid of the job of leading for a little while. But, oh boy, it was some job following! That fellow swung up into trees and turned somersaults over stone walls and hopped on one leg over big rocks—good night, we didn’t have any rest.

“You wanted ginger,” he said.

“Sure, but we didn’t want cayenne pepper,” I told him. “Have a heart.”

Gee whiz, that fellow didn’t miss anything, trees, rocks, fences, and all the while he kept singing:

Follow your leader,

Follow your leader;

Follow your leader true.

If he starts to roll,

Or falls in a hole;

Or shins up a tree or a telegraph pole.

You have to do it too,

you do;

You have to do it too.

I can’t tell you about all the crazy things that fellow did. It looked awful funny to see the rest of us following, especially Pee-wee with a scowl all over his face. I guessed Hervey knew where he was going all right because no matter what he did he always came back to a trail.

Pretty soon we came to the old railroad branch. A long time ago that used to go to some mines. We followed the old tracks through the woods. Hervey walked on one of the rails and we all tried to keep on it, but it was hard balancing ourselves he went so fast.

I guess maybe we went a half mile that way and then we saw ahead of us a funny kind of a car on the track. It wasn’t meant to carry people, it was meant to carry iron ore, I guess. It was about as long as a very young trolley car. A long iron bar, a funny kind of a coupling I guess it was, stuck out from it. It was all open, like a great big scuttle, kind of. There were piles of stones and earth and old holes all caved in nearby. Those were the old iron mines, Hervey said.

“Gee whiz,” I told him, “I’ve been to Temple Camp every summer and I never saw this place before. Christopher Columbus hasn’t got anything on you.”

“Follow your leader wherever he goes,” he said, and over the end of the car he went and, kerflop, down inside, all the rest of us after him. There was straw inside.

That fellow couldn’t sit down long. In about ten seconds up he jumped and shouted, “Follow your leader.”

I was so tired I could have just lain in that little car till Christmas, but I got up and so did the others, all except Pee-wee.

“Come on, follow your leader,” I said.

“Not much,” he said; “I’m going to lie here and take a rest. I’ve had enough funny-bone hiking. If you think I’m going to follow you all over the Catskill Mountains without any dinner, you’re mistaken. I know the way home from here, it’s easy. Go ahead and march into the Hudson River if you want to for all I care.”

“Which way do we go from here?” Hervey asked him.

“We follow the tracks straight along,” the kid said. “That will bring us to the turnpike and all we have to do is to go through Leeds. There, you think you’re so smart.”

“Righto,” Hervey said; “just climb out of the other end of the car and keep going, right along the track.”

“Smart kid,” I said.

“Do you think I’m going to be turning somersaults all the way home?” he wanted to know. “The next time I join a parade it won’t be with a lot of monkeys.”

“Those somersaults were all good turns,” Bert said.

“This place is good enough for me,” Pee-wee shot back at him.

So we left him there sprawled out on the straw and followed Hervey in and out of old holes, kind of like caves, and all around and over piles of earth and everything till pretty soon he stopped and said, panting good and hard, “What do you say to a plot?”

“I take them three times a day and before retiring,” I said. “What kind of a plot? A grass-plot?”

“Let’s have some fun with Pee-wee,” he said. “Did you hear him say he knows the way home from here? He thinks all he has to do is to climb out the other end of the car and keep going along the track to the turnpike.”

“Well, isn’t that right?” Warde asked.

“Sure it’s right,” Hervey said; “only it depends on where the other end of the car is. See? That car’s on a turntable if anybody should ask you.”

“If it were a dinner table it would interest Pee-wee more,” I said.

“I noticed there was a kind of platform under it with grass growing through the cracks,” Warde said.

“Come on, let’s see if he’s asleep and we’ll turn it around,” Hervey said. “The woods look the same no matter which way you go. Follow your leader.”

He started tiptoeing over to the tracks holding his finger against his lips and we all did just the same. I had to laugh, it seemed so funny. He kept singing, Follow your leader, in a whisper.

That fellow ought to be in my patrol, he’s so crazy.

There was Pee-wee, sprawled on the straw inside the little car, sound asleep. The funny-bone hike had been too much for him, I guess. Hervey got a stick and pushed with it against the rail right near the edge of the turntable. We had to all get sticks and push before we could budge it.

It squeaked as it went around, the part underneath was so rusty. We brought it to one full turn so that the car stood with the long coupling at the opposite side from where it had been before. We thought we might as well let Pee-wee sleep a little longer so we went to a tree that Hervey knew about and got some apples. Then we went back and sat in a line on the edge of the car with our feet hanging inside and started eating apples. After a little while we began singing, Follow your leader, and that woke Pee-wee up.

He opened one eye, then he stretched his arm, then opened the other eye and sat up, staring.

“Wheredgerget thabbles?” he wanted to know, rubbing his eyes.

I said, “Here, catch this and eat it.” Then I said, “Scout Harris of the raving Raven patrol, alias the Animal Cracker, you have been elected by an unanimous majority to lead the funny-bone hike. What say you? Yes or yes? Do you know the way to Temple Camp?”

“A fool knows the way to Temple Camp,” he said, very disgusted like.

“And you claim you’re a fool?” Warde asked him.

“I claim you’re a lot of lunatics,” Pee-wee said, sitting there and yawning and trying to eat an apple at the same time.

“It’s your turn to lead,” Garry said. “Our career of glory is over and we want to go home.”

“I’m tired of this crazy stuff and I don’t believe anybody here knows the way to camp,” Bert said.

“This branch crosses the turnpike,” Pee-wee said. “Don’t you know the little wooden bridge where the tracks cross the road?”

“Oh yes, the dear little wooden place,” I said; “how well I remember it!”

“You turn left on the turnpike and go through Leeds,” the kid said.

“Ah, but suppose the turnpike shouldn’t be there any more?” Garry said. “Some strange things have happened since we started in a north southerly direction from Catskill.”

“That’s because you had crazy leaders,” Pee-wee shot back. “If you’re sensible and want to go back to camp I’ll show you the way.”

“Oh we’re sensible,” I said.

“You’re the worst of the lot,” he shouted.

Hervey said, “My idea is, just like I said, to follow the track right along the same way we were going and that will bring us out at the turnpike.”

“If the turnpike hasn’t been turned around,” I said.

“We’ll be careful not to touch it with our hands when we get there,” Garry said.

“I’ll lead you,” Pee-wee said; “it’s easy from here; I could do it with my eyes closed.”

“If you’ll keep your mouth closed I’ll be satisfied,” I told him.

“But it isn’t going to be any funny-bone hike,” he said; “I’ll tell you that.”

“It’ll be a backbone hike—straight,” I said. “There’s no place like home.”

“Home is all right, it’s a good place to start from,” Hervey said.

“Well, then, take us home; I’m ready,” Bert spoke up. “I don’t want any more funny-bone hikes wished on me. Wish-bones are good enough, I’m hungry.”

So Pee-wee climbed over the end of the car, and started along and we all followed.

“Follow your leader wherever he goes,” I said.

“He’s going straight home,” Pee-wee said.

“Are you sure you got out of the right end of the car?” Hervey asked him.

Pee-wee was still kind of half-asleep, and he stopped and looked around. “Sure, we got in at the end where the coupling is,” he said. “Come on, follow me.”

“You can’t fool Scout Harris,” I said; “not even with a couple of cups of couplings. Forward march, follow your leader!” And we started singing:

Where’er we may roam,

There’s no place like home.

Pee-wee marched on ahead like a little soldier, munching an apple.

He marched along the tracks for about half a mile, through the woods. As he went along I remembered what Uncle Jeb said, that the woods look different when you’re going in the opposite direction from which you came. He said the way a tree looks depends on where you stand. And it’s the same with hills and everything. So that’s why the woods only look familiar when you’re going the same way that you went before. That’s the reason for blazing trails.

Uncle Jeb says a person looks different front and back and it’s the same with woods. Pee-wee marched along back the same way we had come, very bold and sure.

After a while he said, “I don’t know why we don’t come to the turnpike.”

“Maybe it’s because it isn’t here,” I said.

“Are you sure you’re going the right way?” Bert asked him.

“Sure I’m sure,” he said; “only it’s longer than I thought it was.”

“Maybe it got stretched,” I said.

Pee-wee just kept trudging along and he said, “Maybe it seems long because we’re kind of played out.”

“Oh, we don’t care as long as you get us home,” Garry said.

“We trust you implicitly,” Warde told him.

“You’re our guiding light,” Garry said.

Pee-wee just trudged on.

Pretty soon he said, “As long as you’re all so tired, maybe I can find—I think I know a short cut.”

“Take us the way the raven flies,” I said; “the shorter the quicker.”

“I can see a road over there through the trees,” he said. “That goes into the turnpike. It’ll be easier walking on the road.”

“As long as you know you’re going the right way,” I said.

“Sure I’m going the right way,” he said; “what’s the use of getting scared. We’ll be home in twenty minutes.”

“That’ll be nice,” Garry said.

“Won’t I be glad!” said Bert.

“Just you follow me,” Pee-wee said.

“We’re following,” I told him. “We’re following our leader wherever he goes. We know the animal cracker knows the woods. Have another apple?”

Next he left the tracks and cut over to the left where we could see a road through the trees. He hit into the road and hiked along.

“Sure you’re right?” Bert asked him.

“Do you think I don’t know the way?” the kid said, very disgusted.

“Don’t start to ask questions, or hint, or propose,” I said.

Pretty soon he came to a crossroad and g-o-o-d night magnolia! Right there, staring us in the face was the fickle signboard that I had turned around. Oh boy, you should have seen Pee-wee. The apple he was eating fell out of his hand and he just stood there staring. He couldn’t even speak.

“Don’t ask where you’re headed for nobody knows,” Hervey said.

I said, “Have no fear, our gallant leader is with us. Raving ravens do not get rattled. Trust to Scout Harris. He knows the way. Follow your leader.”

Maybe that signboard had been a pinwheel, but there it was at the very same spot where it had been before.

Warde said, “That’s one good thing about scouts, they always come back.”

I said, “Pee-wee led us the right way, only in the wrong direction.”

“Just as you said,” Garry put in, “the turnpike has disappeared. That’s why I never liked turnpikes, they’re so fickle.”

“There’s something wrong here!” the kid shouted.

“Sure,” I said, “it isn’t your fault, it’s the turnpike’s.”

“I started in the right direction,” Pee-wee shouted, “and I kept going in the right direction, you can’t deny it. I’d like to know how we got here?”

“That’s what I’d like to know,” I said.

“I suppose we just walked here,” Bert said; “we followed our leader.”

Hervey started singing:

The turnpike turned round

And the trail it got bent,

We followed our leader wherever he went.

“Anyway, I’m sure I started in the right direction,” the kid said; “I don’t care what anybody says.”

I said, “Sure, if the right direction changes its mind that isn’t your fault. Come on, let’s go back. It’s long past dinner-time.”

“Let Warde be leader,” Hervey said; “he’s the only one here who has any sense.”

So we started following Warde back along the trail till we came to the railroad tracks and along those to the little iron ore car.

Hervey said, “The best way to find out which way to go is to spin the car around and call the coupling the arrow-head and go whichever way that points.”

“You’re crazy,” Pee-wee shouted. “Will you talk sense and let’s start for camp? We’ve been starting for camp all morning.”

“That’s the right way to do,” I told him; “have a lot of different starts and if you can’t use one you can use another. Didn’t you ever hear of having two strings to your bow? A scout should never try to go anywhere without having two or three extra starts.”

Just then Hervey and Bert and Garry started moving the turntable around and, good night, you should have seen Pee-wee stare. All of a sudden he went up like a sky rocket.

“Now I know what you did!” he yelled. “You turned this around while I was asleep—you can’t deny it. You made the right direction the wrong one!”

I said, “The right direction is just as much right now as it ever was. You can’t blame us.”

“You’re all crazy!” he screamed. “Are we going to go home to camp and get something to eat or not? Do you think I’m going to starve?”

“Not while you’re conscious,” I said. “Would you like to lead the way foodward or shall we elect another leader? What say we all? Shall Pee-wee lead us to the promised land or not? Answer, not. You’re rejected by a large plurality.”

“Let Garry try it,” Hervey said. “Warde’s all right only he has too much sense.”

So that time we started in the right direction, following the old tracks toward the turnpike, with Garry leading us. We kept singing Follow your leader just the same as before.

Now this is the chapter where we’re all so hungry. It’s dedicated to Hoover. The name of it was “The Famine” only I decided to use another name. But believe me, in this chapter we’re hungrier than war-torn Europe. All that morning we had been marching around the country singing those crazy rhymes and we were having so much fun that we didn’t realize it was past dinner-time. All we had had was one bite of chocolate each except the two bites that Pee-wee took. Seven bites isn’t much for six scouts.

Pretty soon we came out into the turnpike and then we knew the way back to camp. It was a pretty long hike but we knew the way. All we had to do was to follow the turnpike south till we came to the blackberry road and that would take us into the road to camp.

I said, “I hope the camp is still there.”

Warde said, “If we get back in time for supper we’ll be lucky.”

“How about lunch?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“Nothing about it,” I said; “it just isn’t.”

“Do you think I’m going to walk ten miles with nothing to eat?” he shot back. “You call this a funny-bone hike, it’s a famine hike, that’s what it is. They’ll find our skeletons some day marching around through these woods——”

“Following our leader,” I said.

“That’ll be a funny-bone parade,” Garry said.

“It’ll be a bone parade all right,” I told him.

“Maybe we’ll strike a farmhouse,” Bert said.

Hervey said, “I know a better idea than that. What time is it?”

“Two o’clock,” I told him.

He said, “Good, I thought it was later. Do you like fish?”

“How many fish?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“Oh just about,” Hervey said.

“If you’re asking me,” I told him, “I could even eat some fish-hooks I’m so hungry. I could eat a whole school of fish.”

“I could eat a whole university of them,” Garry said.

“Do you like them fried?” Hervey asked us.

“M-m-m-mm,” I said; “I can just hear them sizzling now. Lead me to them.”

He said, “We’ll have to wait for them. Let’s hang out on the bridge and pretty soon the fishing boat will come along; it always comes up from the Hudson about this time. I know the men on that boat, I’ve been out fishing with them. They’ll give us a couple of fish and we can cook them. You leave it to me, I’ll fix it.”

“What kind of fish do they catch?” Pee-wee wanted to know.

“Smoked herring and salt codfish and canned salmon,” I told him, “and whales.”

“I could eat a whole whale,” he said.

“Sometimes they catch fish-balls,” Hervey said.

“Fish-balls or footballs or baseballs or masquerade balls, I don’t care, I could eat anything,” I said.

So then Hervey led the way along the turnpike till we came to the bridge across the creek. That creek is pretty wide and it empties into the Hudson. We were feeling all cheered-up on account of the chance of getting something to eat and we marched along shouting:

Don’t quit or complain at the stunts that he shows,

Don’t ask to go home if it rains or it snows;

Don’t start to ask questions, or hint, or propose,

But follow your leader wherever he goes.

Then Hervey started shouting:

We’re going to have our wish,

We’re going to get some fish.

Then Pee-wee began yelling:

I’m so hungry that I’m pale,

And I’d like to eat a whale.

Gee whiz, just as I told you, we were all crazy, especially Hervey Willetts; he was even crazier than I was and I was the craziest one there next to Bert and Warde and Garry. But one thing I’ll say for Hervey, he knows every place for miles around Temple Camp, and he knows everybody too, farmers and all.

In about five minutes we came to the bridge that the turnpike goes over. That bridge is a drawbridge and the creek under it is wide and deep and you can catch fish there only for one thing and that is that there aren’t any. There’s a big lever to turn the bridge around with.

“Let’s turn it around,” Hervey said.

“We’ve had enough turning around,” the kid shouted. “I’m not going to follow my leader any more till he starts eating fish.”

“Oh very well,” Hervey said, “I was just going to give you a free ride.”

“A free seat is good enough for me,” the kid said.

“I second the motion,” Warde said.

“There isn’t going to be any motion,” I said, quoth I. “This is going to be a case of sitting still.”

“Follow your leader,” Hervey said.

“What are you going to do? Stand on your head on the railing?” I asked him.

He just vaulted up onto the railing of the bridge and we all did the same and sat there swinging our legs and waiting for the fishing boat and singing those rhymes and changing them around. Pretty soon we were all shouting:

Don’t fall in the creek for the water’s quite wet,

But think of the fish that we’re soon going to get;

Mm-m

After about six weeks and ten years the fishing boat came chugging up the creek. Anyway it seemed as long as that before it came. The chugging of that engine sounded good.

“Now for the eats,” Garry said.

Hervey said, “They’ll have a lot of perch and some bass and maybe some soft-shell crabs.”

“Isn’t there anything in this creek?” the kid wanted to know.

“Nothing except water,” Hervey told him. “Anyway we haven’t got any fishline, have we? Thank goodness we’ve got some matches, we can start a fire.”

“We’ll fry them brown, hey?” Pee-wee said, all excited.

“Any color will suit me,” I told him.

“They won’t be any color at all when we get through with them,” Bert said.

By that time the boat was quite near and we could see a couple of baskets of fish in the cockpit, and there were two men. Oh boy, how I longed to eat them, I mean the fish. Pretty soon one of the men shouted for us to open the bridge, so they could pass.

I called, “Hey, mister, will you give us a couple of fish? We’re perched up here waiting for some perch.”

He laughed and said sure, but that we should open the bridge. Now the way to open that bridge was to walk around pushing a big iron handle like a crowbar only longer. It was kind of like a windlass. I guess one man could do it all right but it took three of us to get the bridge started. It wasn’t a very big bridge but I’m not saying anything about that because we’re not so big either except our appetites and maybe one reason we couldn’t push so well was because we were hungry.

Garry said, “I guess when the creek is nearly empty boats can go under this bridge all right.”

I said, “Don’t talk about being empty; I’m so full of emptiness it’s flowing over. Get your hands on this thing and push. If anything should go wrong now we’ll have to eat the Animal Cracker.”

So then we all started pushing the long iron handle—it was a lever, that’s what it was. All the while the boat was standing about twenty feet away from the bridge and one man was keeping her bow upstream with a big oar while the other man was kind of fumbling in one of the baskets picking out a nice big fish. Pretty soon he held one up all wet and dripping and, oh boy, it looked good. I guess it was nearly a foot long. He shouted, “How will that one do?”

“Mm-m-mm!” I said. “Lead me to it.”

“I know where there’s an old piece of tin in the woods,” Pee-wee said, all the while pushing the big lever for all he was worth; “a scout is observant.”

“I could eat a sheet of galvanized iron,” I told him. “A little salt and pepper and I could eat a piece of railroad track.”

“I mean to cook the fish on,” the kid said; “you’re crazy. Don’t you know how to fry a fish? I’m going to be the one to cook it because I’ve got the matches.”

“Hang on to them,” I said; “things are beginning to look better. Keep pushing; think of fried fish and keep pushing.”

Pee-wee began thinking harder and pushing harder; I could just see him thinking. And with one hand he felt in his pocket to make sure the matches were all safe. He carries matches in a box like a cylinder that shaving soap comes in.

It was kind of hard getting the bridge started but once it was started it kept moving slowly around. The reason you can move a bridge around like that is because it’s well balanced. But, gee whiz, I’m glad I’m not so well balanced because I wouldn’t have so much fun. Underneath the floor of the bridge were rollers on a track that went around in a circle. So pretty soon we had turned the bridge so that it was lengthways to the creek instead of across the creek and there was a passageway on either side of it where boats could pass.

“Marooned on a desert drawbridge,” Bert said.

“Poor, starving natives,” I said.

Garry said, “It’s like being on an island.”

“A merry-go-round, you mean,” Pee-wee said.

“Let’s call it Merry-go-round Island,” Hervey sang out.

Just then the boat came chugging very slowly along one side of the bridge and one of the men handed me the fish.

I said, “Many thanks and more of them, mister, you saved our lives.”

“Don’t let it slide out of your hands,” he said; “look out, it’s slippery.”

“If you let it slip out of your hands you’ll go in after it,” Pee-wee shouted.

Believe me, I kept tight hold of that fish. It was a dandy fish, it was big enough for about six people to have all they wanted.

The man said, “That will keep you quiet for a while; be sure to scrape all the scales off and clean him out good.”

“You leave that to us,” I told him, “we’re boy scouts. Cooking fish is our middle name. There’s only one thing we do better than cooking fish and that is eating them. We can eat them till the cows come home and sometimes the cows stay out all night where we live. Believe me, I never had much use for Henry Hudson in the history books, but I’m glad he discovered the Hudson River as well as the Hudson Boulevard.”

“That’s in Jersey City,” Pee-wee shouted. “Do you think that’s named after Henry Hudson?”

“It’s named after the Hudson automobile,” Garry said.

“Sure it is,” I told him, “just the same as the Hudson River is named after the Hudson River Day Line; you learn that in the fourth grade; here, take this fish while I help turn the merry-go-round around, around, around. Then we’ll eat.”

The boat went chugging up the creek, the men laughing and waving their hands at us. Pee-wee sat down on the floor of the bridge hugging the fish as if it were his long lost brother. The rest of us started pushing the lever.

But, oh boy, it didn’t push.

“Come on and help,” I said to Pee-wee.

“Suppose the fish jumps off the bridge,” he said. “Do you think I’m going to take any chances?”

“The strength of an Animal Cracker doesn’t count for much,” Garry said.

“Look out the fish doesn’t jump in the creek with you,” I told Pee-wee.

Well, we pushed and pushed and pushed and braced our feet and kept pushing for dear life, but we couldn’t budge that lever. Pee-wee held the fish tight under one arm and helped us but it wasn’t any use. We just couldn’t budge the lever.

“We’re marooned for fair,” Bert said.

“Boy Scouts Starve on Merry-go-round Island,” I said. “That would be a good heading for a newspaper article.”

“Merry-go-standstill you mean,” Hervey began laughing. “What do we care? It’s all in the game. Come ahead, give her one more push; follow your leader.”

“Do you call starving a game?” the kid fairly yelled at him. I had to laugh, he looked so funny standing there with the fish under his arm.

We tried some more but—no use. “The merry-go-round has stalled,” I said. “We’ve got Robinson Crusoe tearing his hair with jealousy.”

“We’re on a desert island in earnest,” Bert said. He was the last to give up.

“Don’t talk about desert, it reminds me of dessert,” I said.

“I’m not so much in earnest either,” Hervey began laughing. “Come on, follow your leader.” Then he started to jump up on the railing.

I said, “It’s a very good joke; he, he, ho, ho, and a couple of ha ha’s! But how about lunch? We can’t start a fire on this bridge without burning it up and besides we haven’t got any kindling.”

“The only way we can get off the bridge is to burn it up,” Hervey said. “The boy scout stood on the burning bridge——”

“Eating fish by the peck,” I said. “This is a new kind of a desert island—1921 model. We made it ourselves. But what care we? We have food. We care naught, quoth I.”

“What good is the food?” Pee-wee screamed. “You broke the bridge, that’s what you did! And now we’ve got to go hungry.”

“Go?” I said. “What do you mean by ‘go’? You mean we’ve got to stay here hungry. Our skeletons will be found on Merry-go-round Island——”

“Following their leader,” Hervey said.

“Along with the skeleton of a faithful fish,” Bert said. “That’s what happens to young boys when they go around too much.”

“That’s what happens when any one goes around with this bunch,” the kid shouted. “You’re so crazy that it’s catching; even the sign posts and bridges go crazy. The next time I go on a funny-bone hike I won’t go at all, but if I do I’ll bring my lunch you can bet.”

“What’ll we do next?” Hervey wanted to know.

I said, “Let’s have a feast, let’s feast our eyes on the fish. I can just kind of hear him sizzling over the fire.”

“You can’t eat sizzles,” the kid said, very disgusted like.

I said, “No, but you can think of them. Let’s all think how fine the fish would taste if we could only cook him. Do you remember how we moved a lunch wagon by the power of our appetites? Maybe we can move the bridge that way.”

“You make me tired,” Pee-wee yelled. “If you hadn’t started this crazy—look at the chocolate bars you made us throw away.”

“I’d like to have a look at them,” I said.

We all perched up on the railing of the bridge, Pee-wee holding the fish under one arm for fear it might flop off the bridge. Safety first. Sitting the way we did we were all facing the shore. There were woods there and dandy places to build a fire. There were twigs and things all around.

I said, “It would be fine over there. We could just get that piece of tin Pee-wee was telling us about and gather up some of those nice dry twigs and start a little fire and let the tin get red hot and then lay the fish on it——”

“Shut up!” the kid shouted.

“Only the trouble is we’re marooned on a desert island,” I said. “Anyway there’s one thing I like and that is adventure. I was always crazy to starve on a desert island.”

“You don’t have to tell us you’re crazy,” Pee-wee said.

“We followed you back to the sign post,” I told him, “and you promised to cook us a fish. Let’s see you do it. A scout’s honor is to be trusted, he’s supposed to keep his word—scout law number forty-eleven.”

“How about diving?” Hervey asked. “It’s the only way to get into the water; there isn’t any way to climb down off this thing; the underneath part of it is way inside.”

“Where did you expect it to be? Up in the air?” I asked him. “The underneath part is usually underneath.”

“Not always,” Bert said.

“Well, anyway,” I said, “I’m not going to risk my life diving into water that I don’t know anything about. Suppose I should break my skull; what good would a fish dinner be to me?”

“That’s a good argument,” Garry said.

“It’s a peach of an argument,” I told him.

“It’s what Pee-wee calls logic. Gee whiz, but I’m hungry.”

“Same here,” Bert said.

“Same here,” Garry said.

“Same here,” Hervey said.

“Same here,” Warde said.

“I’m as hungry as the whole five of you put together,” our young hero said. “I heard a story that a man can go forty days without food, but you can’t get me to swallow that.”

“It’s about the only thing that you wouldn’t swallow,” I told him. “I’m so hungry I’d swallow any argument I ever heard; I’d swallow any kind of a story, especially a fish story.”

“There you go again,” Bert said; “what’s the good of reminding us about it?”

“I’d swallow a serial story,” I told him; “any kind of cereal, oatmeal, cream of wheat, or anything.”

So we just sat there looking across the creek into the woods, and swinging our legs, but we were too hungry to sing.

“Let’s look for a sail on the horizon,” Hervey said. “That’s always the way people do when they’re starving on desert drawbridges. This would make a good movie play.”

“You mean a good standing still play,” I said; “the trouble with this hike is there isn’t any action in it.”

“You mean there isn’t any food in it,” Pee-wee piped up.

“Don’t you care,” I told him, “there’s a desert island. What more do you want? And we’ve got plenty of food only we can’t cook it. That’s better than being able to cook it and not having any. We should worry.”

Now after that last chapter are supposed to come about ten chapters where we don’t do anything except just be hungry. But believe me, that’s enough. We just sat there swinging our legs from the railing of that desert island, scanning the horizon for a sail.

I said, “I wonder if there’s any treasure buried on this desert island. Maybe Captain Kidd secreted some Liberty Bonds here; maybe he hid some bars of gold.”

“I wish he had left some bars of chocolate here,” Warde said.

“Or some small change, chicken feed, or anything we could eat,” Garry put in. “I’d be glad to eat a bale of hay or shredded wheat or a whisk-broom or anything else like that.”

“They’re just about getting ready to cook supper at Temple Camp now,” Warde said; “Chocolate Drop* is just about beginning to peel potatoes. Pretty soon he’ll be stirring up batter for cookies. I think they’re going to have strawberry jam and crullers to-night and—and cheese and—lemon pie. They’ll be having baked beans to-night, too, on account of it being Saturday. Oh boy, I can just see that nice slice of brown pork on top——”

“Will you keep still!” Pee-wee screamed.

“Sure,” said Hervey; “whatever it is, let’s do it. If we’re going to starve let’s get some fun out of it. I bet I can beat anybody starving.”

I said, “Pee-wee can beat you at that with both hands tied behind him, can’t you, Kid? Once I read about some men who were going to freeze to death in an ice cream freezer or somewhere; maybe it was up at the North Pole. So they wrote a note and stuck it up on a pole, maybe they stuck it on the North Pole, and they told what had become of them and how they had died a terrible death so that the world may be able to know about it. So let’s write a note and say that we starved here because we couldn’t cook a fish and that we hope our parents will take a lesson from us and not go round so much when they grow up. I was always wild, I used to ride on a runaway clotheshorse when I was a kid.”

“You’re a kid now,” our young hero shouted. “You think it’s funny, don’t you?”

“I know which is north and which is south,” I said, very sarcastic, “and anyway, I stay awake while I’m turning around. Do you think Cruson Robsoe got mad just because he was on a desert island? All he had was a footprint in the sand and we’ve got a fish—to look at. Isn’t he pretty? I bet there’s nice white meat inside of him, and a lot of bones. I wonder if he has a funny-bone? As long as we can’t get away from here let’s each tell our favorite dessert. I say let’s die bravely, like boy scouts, hungry to the end.”

All of a sudden, good night, Garry nearly fell off the railing; he was waving his hands and shouting, “A sail! A sail!”

“What kind of a sale?” Bert asked him. “A special sale or a cake sale or what? If it’s a cake sale lead me to it.”

Garry just kept shouting, “A sail! A sail! A sail on the horizon!”

“I don’t see any horizon,” I said. “Where is it?”

“Along there through the woods,” he said. “A sail! A sail! We are shaved!”

“What are you shouting about?” I said. “That isn’t a sail, it’s a Ford car! Hurrah! Hurrah! And a couple of hips!”

* The darky cook at Temple Camp.

We all started shouting, “We are shaved! We are shaved! A Fraud car! A Fraud car on the horizon!” I guess the driver of that Ford car thought we were crazy.

“I hope he’ll stop before he runs into the creek,” Warde said.

The car was coming along the turnpike at the rate of about a half a million miles a year and I shouted, “Hey, mister, whoever you are, please stop before you get here; it was raining last night and the water is wet.”

“Stop your fooling,” the kid said.

I said, “Do you think I want that car to come plunging into the creek? Suppose that driver is blind.”

“She’s coming under full sail,” Garry said.

“Hurrah!” they all shouted.

“She’s missing in one cylinder,” Bert said. Then we all started shouting, “Saved! At last we are saved!”

Just then, good night, that Ford car turned off into a side road and we couldn’t see it any more.

“Now you see what you get for fooling,” the kid shot at me. “If we had shouted ‘help’ all together as loud as we could he’d have come straight along. You think it’s fun being imprisoned here with nothing to eat; you make me tired. Maybe you don’t know that not much traffic comes along this old turnpike; that’s why they don’t have any bridge-tender here.”

“They have tenderfoot bridge-tenders,” I said.

“Maybe no one else will come along all night,” Pee-wee said, “and then what are we going to do? Suppose a wagon or an auto should come along after dark and we didn’t see it coming; it would plunge to death and then I hope you’d be satisfied.”

“That’s right,” Warde said, kind of serious, “we haven’t even got a lantern to swing. How could we warn anybody?”

“We can’t even shout if we don’t get something to eat,” the kid said.

“Sure,” Bert said, “we’ll be so weak we won’t even be able to lift our voices.”

“We’re in a desperate predicament,” Pee-wee said, very dark and serious like. I guess he got those words out of the movies.

“Maybe we could tie a note to the fish and throw him in the water,” I said. “When someone catches him they’ll find out we’re in distress.”

“No you don’t,” the kid yelled, hanging onto the fish while I tried to take it away from him.

“If we could only send up a signal,” Warde said. “It’s all very well joking but if it gets dark it will be mighty bad with this bridge open and no one standing guard at the ends of the road.”

“There’ll be a tragedy,” the kid said.

Gee whiz, when I heard Warde speak that way I realized that it might be pretty dangerous there after dark. And I was a little scared about it because it seemed that no one came along that road very much and maybe it would be night before anyone came.

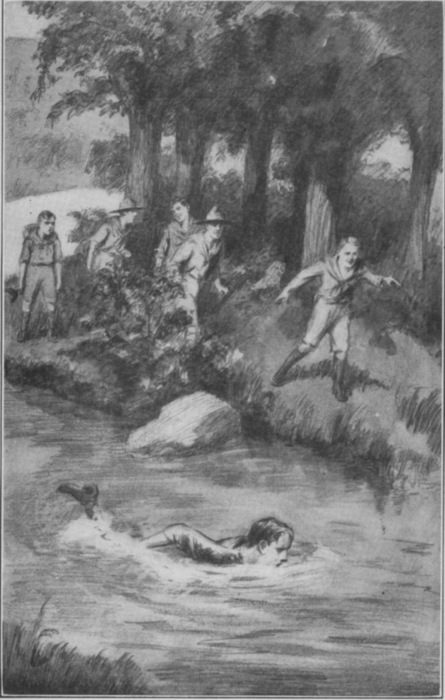

I said, “Well, if it gets toward night and no one comes either way I’ll take a chance and dive and swim to shore. One of you fellows will have to dive and swim to the other shore too.”

“I’ll do that,” Hervey sang out.

“But we’ll wait till it’s necessary,” I said.

Now maybe you think that because we are scouts we should have been able to get to shore easily enough, and if it were only a case of swimming that fish wouldn’t have anything on us. But we couldn’t get from that bridge into the water except by diving and diving is dangerous when you don’t know the water you’re diving into. Especially near a bridge it’s dangerous because there are apt to be piles sticking up under the surface of the water. So that’s why we have a rule never to dive unless we know about the place where we’re diving. But, gee whiz, if it’s a case of an auto plunging into the water or taking a chance myself, I’ll take the chance every time. And I know that Hervey Willetts would dive into the Hudson River from the top of the Woolworth Building if anybody dared him to do it.

“Anyway, let’s not lose our morale,” I said. “We’re here because we’re here. Scouts are supposed to be resourceful; let’s sit up on the railing again and think.”

“As soon as the sun goes down I’m going to dive,” Hervey said. “Do you see that big maple tree in the woods? As soon as I can’t count the leaves on that top branch any more I’m going to dive. I don’t know how deep it is or what’s under the water, but I’m going to stand guard down the road a ways. What do you say?”

“Are you asking me?” I asked him.

“I sure am,” he said; “you’re the only patrol leader here.”

I just said, “Well, if you want to know what I’m going to do I’ll tell you. I never broke up a game yet. I’m going to follow my leader wherever he goes. I’m going to take care of the other side of the road. I’m not going to ask where I’m headed for nobody knows. And I’m not going to weaken or flunk or suggest or oppose. And I’m not going to start to ask questions, or hint or propose. There are some scouts here that are not so stuck on this crazy game. But, believe me, it’s more of a game than I thought it was. You were the one that started it. No people are going to lose their lives on account of us. I’m going to follow my leader wherever he goes. So now you know.”

“Do you call me a quitter?” Pee-wee shouted in my face.

“Look out for the fish,” I said.

“I don’t care anything about the fish,” he yelled. “I’m not hungry. I’m in this funny-bone hike and I’ll follow Hervey Willetts if he—if he—if he—stands on his head on top of a bonfire—I will. So there!”

“He wouldn’t do such a thing, don’t worry,” I said. “He couldn’t keep still long enough. Pick up the fish before he flops off the desert island. Safety first, that’s our motto. Hey, Hervey?”

“That’s us,” Hervey said. “Let’s tell some riddles.”

So then we all sat on the railing of the desert island and sang Follow your leader, and Pee-wee joined in good and loud. He kept the fish under his arm. When it comes to a showdown Pee-wee is loyal. He can even be loyal to a fish.