Cover art

Title: The White Chief of the Ottawa

Author: Bertha Carr-Harris

Illustrator: John Innes

Release date: September 28, 2019 [eBook #60372]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

. . . By . . .

Bertha Wright Carr-Harris

With seven full-page illustrations

by John Innes

TORONTO

WILLIAM BRIGGS

1903

Entered according to Act of the Parliament of Canada, in the year

one thousand nine hundred and three, by BERTHA WRIGHT

CARR-HARRIS, at the Department of Agriculture.

PREFACE.

"The White Chief of the Ottawa" is not fiction. It is not a tale with a carefully concealed plot, meant to delude the reader at the beginning and to surprise him at the end. It is something stranger than fiction, a sketch of the life experiences of Philemon Wright and his family, the first settlers in the district of Ottawa. With the exception of the love of Abbie and Chrissy, which are based upon fact, the story is mainly a simple recital of actual facts which cannot be controverted.

The writer is indebted to the following for furnishing valuable data:

Diary and letters of Philemon Wright, 1806-1816.

Bouchette's Topographical Report.

"Travels in the North"—Sir Alexander Mackenzie, 1803.

"Three Years in Canada"—McTaggart, 1830.

"Shoe and Canoe"—Dr. Bigsby.

Parkman's History of Canada.

Also to traditions of old settlers collected at various times and places. May some of the pictures set forth in these pages inspire us with an ever-deepening appreciation of the self-sacrifice, the energy, the enterprise, of those whose loyalty to the British Crown led them to penetrate the dark recesses of our Canadian forests and brave the trials and vicissitudes of pioneer life.

To these conquering heroes Canada owes much of her prosperity and greatness.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

I.—A Weird Ceremony

II.—The White Chief

III.—Newitchewagan

IV.—An Indian Suitor

V.—Chrissy

VI.—Gay Voyageurs

VII.—"A Ministering Angel, Thou"

VIII.—Convent Days

IX.—The New Tutor

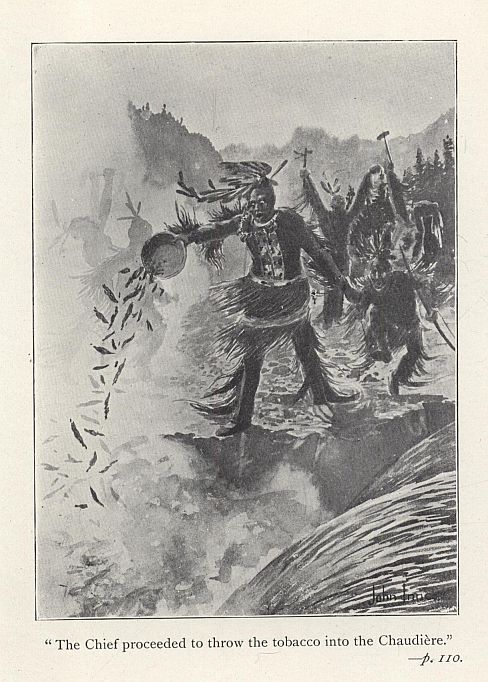

X.—Tobacco Offerings

XI.—Snares

XII.—Mrs. Bancroft's Sugaring Off

XIII.—Accidental and Confidential

XIV.—Machecawa Scalps the Englishman

XV.—A Romantic Wedding

XVI.—A Perilous Journey

XVII.—A Double Tragedy

XVIII.—An Exciting Moose Hunt

XIX.—After Many Days

XX.—Found Out

XXI.—Rideau Hall in the Thirties

XXII.—Light at Eventide

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

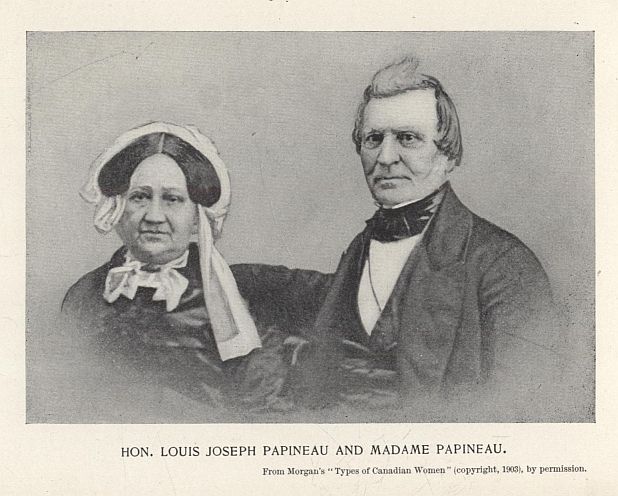

Philemon Wright and Mrs. Wright ... Frontispiece

"He stood there, a colossal statue in bronze"

"Oh, Machecawa, my brother, it is not well that you grieve"

"Soon twelve canoes rounded the headland"

"When Martin came up I went down"

Hon. Louis Joseph Papineau and Madame Papineau

"The Chief proceeded to throw the tobacco into the Chaudiere"

"I remained behind the tree, dodging round"

The White Chief of the Ottawa.

1800.

"De Beeg Chief he want to know, heem, by what autorité you fellers, you, cut down hees wood and tak' hees lan'?"

The speaker was a trapper named Brown, who had been in the employ of the Hudson's Bay Company for many years, and, though English by birth, spoke a mixed dialect, owing to his association with French trappers and traders and to the influence of his squaw wife. He had, however, retained a sufficient knowledge of English to be able to act as interpreter.

"Tell him," replied the leader of a group of settlers, "that the great father who lives on the other side of the water and Sir John Johnson, of Quebec, have authorized us to take this land."

"He say, heem," continued the interpreter, as he squirted the juices of his quid on the bronze carpet of pine needles, "dat you must tink dat dese chute and reever he want for hees beesnesse, an hees papoose she want eat someteeng. He want dis place, heem, pour chasse le mooshrat an' de moose, mak' le soucre an' ketch de feesh, an' hees afeard dat you tak' hees beaver, kill hees deer, break hees sucreries. You cut down hees tree for shure you kill hees beesnesse."

"The tools and materials we brought," replied the stranger, "are not for hunting or fishing, but for clearing land, and we shall endeavour to protect your beaver and fishing-grounds; but as for the sugaries, we must make use of them, because the land has already been given us, and if you will collect all your materials for making sugar we shall pay cash for them."

"De Beeg Chief he say," continued Brown, "dat white man seem bien bon, an' dat he will be so wit heem, an' if he pay cinq Louis he am geeve up all claim to de lan'."

"Very well," said the stranger, "we shall pay them thirty pounds if they will produce a deed or title to the lands."

"He comprends pas,"* said the interpreter. "L'agrement she was mak wit de fadder of hees fadder."

* Understands not.

Drawing a paper from his pocket the stranger read as follows:

"The Indians have consented to relinquish all claim to the land, in compensation for which they receive annual grants from the Government, which shall be withheld if they molest settlers."

For a time no one spoke, then the Big Chief, in a calm, deliberate and thoughtful manner, addressed the interpreter, who said:

"For shure he dunno, heem, how white man mak' dat papier hear an' speak dem words of long tam. Dis man he hav' someteeng dat he comprends pas."

A long consultation then took place among the dusky sons of the forest, and once more the interpreter turned to the stranger and said:

"Our tribe she tink like dis—Eenglishman he got someteeng he comprends pas at all; mabbe, he say, she wan beeg loup garou* and he tink it am better to be bon ami an' leeve in de sam' place dan be bad ennemi; so he am mak' you chief an' be de bess frien'."

* An indescribable monster, supposed to have supernatural powers.

The words were hardly finished when the Big Chief Machecawa (the strong one) advanced with slow and stately tread and implanted a kiss on the brow of the stranger. The Chief was a man in the prime of life, of great height and strength. As he stood there, still and motionless, he looked like a colossal statue in bronze, a perfect model, from his feathered head-dress to his beaded moccasins. He was followed by several subordinate chiefs who did likewise.

"He stood there, a colossal statue in bronze."

The Chief then spread a piece of well-dressed moose-skin, neatly painted, before him on the ground, upon which he opened a curious skin bag containing several mysterious looking articles, the principal one being a small carved image about eight inches long. Its first covering was of down, over which a piece of birch bark was closely tied, and the whole was enveloped in several folds of red and blue cloth. This little figure was evidently an object of the most pious regard. The next article taken from the bag was his war cap, which was decorated with feathers and plumes of rare birds, the claws of beaver, eagles, etc. Suspended from it was a quill for every enemy whom the owner had slain in battle. The remaining contents of the bag were a piece of tobacco and a pipe.

These articles all being exposed, and the stem of the pipe arranged upon two forks so as not to touch the ground, Machecawa motioned to his white brother to sit down opposite to him. The pipe was then filled and attached to the stem. A pair of wooden pinchers was provided to put fire into it. All arrangements having been completed, the Indians gathered round in a circle, awe and solemnity pervading all, while a subordinate chief, O'Jawescawa, took up the pipe, lighted it, and presented it to Machecawa, who received it standing and held it between both hands. He then turned to the east and drew a few whiffs which he blew to that point. The same ceremony was performed to the other three quarters, with his eyes directed upward during the whole of it. Then holding the stem about the middle between the three first fingers of both hands, and raising them upon a line with his forehead, he swung it three times round from the east with the sun, when, after pointing and balancing it in various directions, he laid it upon the forks. He then made a speech acknowledging past mercies and expressing the confidence that the blessing of peace would attend all their dealings with the stranger, upon whom he would now confer the title of "Wabisca Onodis," the White Chief.

He then sat down, while the whole company declared their approbation and thanks by uttering the word "Ho," with an emphatic prolongation of the last letter.

O'Jawescawa then took up the pipe and held it to the mouth of Machecawa, who, after smoking three whiffs out of it, uttered a short prayer and then went round with it, taking his course from east to west, to every man present, both Indians and white men, who could confidently affirm that they entertained no grudge against any of the assembled party, until the pipe was smoked out, when, after turning it three or four times round his head, he dropped it downwards and replaced it in its original position.

Machecawa then approached the stranger and the little band who were with him and uttered a short guttural sound, which the interpreter said meant, "Come and eat."

To refuse would be a grave offence, so the invitation was accepted by all, who followed the Big Chief through a narrow and winding path, which led to a small lake midway between the Gatineau River and the Chaudiere Falls. They arranged themselves in front of a number of huts made of bent boughs, some of which were covered with bark and some with deerskin, securely sewed and stretched tight as a drum. Following the example of the Indians they squatted on the ground in a circle.

Surrounded by a chattering group of squaws sat Newitchewagan, the wife of the Chief, with a child between her knees, while she hunted through the jungle of his hair with destroying thumb and finger. One old squaw, who was kneeling under a tree rubbing and twisting a moccasin between her hands, paused to fill her mouth with water, which she spurted in repeated jets over the moccasin. A little papoose, strapped to a flat piece of wood about three feet long spread with soft moss, was suspended to a branch of a tree. It crowed and laughed quite merrily as it was swayed to and fro by the cold wind. While the feast was in course of preparation the new Chief and his friends were entertained by songs of a most melancholy nature.

It was a strange scene that presented itself that cold and frosty evening in March. The snow-drifts were covered with a crust of frozen sleet, which crunched beneath the tread of moccasined feet. The bare branches of the maples were encased in ice, with long icicles attached, which glistened and reflected like a prism the rays of the setting sun. Small troughs of basswood, hollowed out in the middle by burning, stood at the trunk of almost every tree to catch the sap, which had ceased to run for several days owing to the "cold snap" which had taken place in the weather.

"How do you make sugar without pots?" asked the new Chief of the interpreter.

Pointing to a green hardwood stump he explained, in broken English, that the squaws burned a deep hole in the centre, into which they poured the sap which they had gathered. Stones heated on the fire were then dropped into the wooden cauldron, which caused the sap to boil. This operation was repeated until it was reduced to sugar.

There was little variation in the dress of the grotesque figures gathered round the fire. All had strips of deerskin tightly bound round their legs instead of trousers, and which were never removed unless to replace with new ones. Two aprons, one behind and one before, were fastened around their waist by girdles. Short shirts made of skin were fastened at the neck and arms, and were removed while portaging or paddling. They had very little hair—only a tuft on the top of the head, which was stuck full of feathers, wings and shells. Not a man among them could boast of a beard. The squaws were dressed in much the same fashion, except that the aprons were a trifle longer than those worn by the men, and their coarse black hair floated in the breeze.

Soon a young squaw drew from the ashes the charred remains of fully a score of partridges, which had not been divested of feathers nor cleaned internally. On removing the outer covering of charred feathers and ashes, she laid one for each man present before the Big Chief, who, with great solemnity, cast the first one into the fire as a sacrifice to the Great Spirit, the Master of Life. Pieces of bear-steak, which had been sizzling before the fire, were then served, while the Chief entertained his guests with strange monotonous songs, accompanied by the "shishiquoi," or rattle.

Full justice having been done to these and other Indian delicacies, Machecawa addressed the new Chief, the interpretation of his remarks being as follows:

"Our white brother will never inspire his enemies with feelings of awe or fear if he does not wear war-paint. Will the white-faced stranger consent to let us use our brush so as to make him such an object of terror that even his enemies will flee from him?"

"No! No!! No!!!" said the new Chief. "Soot and grease and ochre are for Indians, not for white men."

Whereupon the Indian said: "It is the custom of our chiefs to chose a manitou, who will protect them in times of danger and who will give them success in the chase."

"Tell them," replied the new Chief, "that the white man's Manitou is a Great Spirit whom we call 'Our Father,' and he saves and keeps and protects us by night and by day."

"Will the new Chief then permit us to graven on his body the form of this Great Spirit?"

"The form of the Spirit has been engraven on my body," he replied, "when He created me in His likeness."

The little group of settlers observed that a white dog, the mystic animal of many tribes, was being tied to the end of an upright pole. Presently the Chief, in a loud voice, began to pray to the 'Great Spirit Father,' the new Chief's Manitou, begging Him to accept the living sacrifice about to be offered. The Indians then rushed upon the animal in a state of frenzy and began to devour the raw, quivering flesh. This weird ceremony was a mystery to the assembled whites, and remained a mystery for some time.

This concluded the ceremonies of the day, and the new Chief and his friends returned to their shanties on the banks of the Ottawa, near the western point of the Gatineau, loaded with glory and Indian hospitality.

1800.

The hero of our sketch, Philemon Wright, was a man forty years of age. In appearance he was of a strong, broad build, and stood six feet in his stockings. A wealth of flaxen hair was brushed straight back from a high and noble brow. His face was profoundly meditative. Thick eyebrows shaded the eyes, which were wonderfully quick, observant and penetrating. His features indicated goodness and energy, strength of will and determination. His muscles were the envy of all who felt them.

Like all superior men, Philemon Wright nourished long his projects, but decision once made he set himself to realize them with ardor, obstacles only serving to intensify his energy, for he employed all the resources of his spirit and inflexible will to triumph over them. He was a worthy descendant of the men of Kent who followed Harold to victory through difficulties which to others would have been insurmountable.

His father, Thomas Wright, having sold his estates in Kent, settled in Woburn, twenty miles from Boston, in 1760, where Philemon, the fifth and youngest son, was born shortly afterwards. While a mere lad of fifteen he saw active service in the Revolutionary War, in the vicinity of Boston and New York, taking up arms as a British subject against the short-sighted rulers of the Motherland in the vain hope of wresting from them the rights which the revolutionists considered were their due.

Philemon married, at twenty-two, a Miss Wyman, of Irish descent, whose grand-nephews, Rufus and Joseph Choate, have since played so conspicuous a place in the drama of American history, and had seven promising children, who were known familiarly as Phil, Bearie, Chrissy, Abbie, Christie, Mary and Rug.

Philemon Wright was a man of indomitable courage, enterprise, industry and perseverance, and had acquired considerable property in the neighborhood of Boston. Finding a better market in Canada for farm produce, he went every fall to Montreal, and in 1796 determined to go on a tour of exploration on the Grand River, or the Utawas, as the Ottawa was then called.

A few settlements then existed for the first forty-five miles, up to the Long Sault Rapids, but beyond this point the seventy-five or eighty miles was a complete wilderness. He found that this part of the country was entirely unknown to the inhabitants of Montreal, excepting, of course, to the employees of the two great fur-trading companies, though its immense resources of fine timber were, he said, "sufficient to furnish supplies for any foreign market, even to load one thousand vessels."

Prominent members of the fur companies in Montreal drew his attention to their printed report, which stated that there was not five hundred acres of arable land on the extensive banks of the whole river.

"It may be to your interests to keep the Grand River from becoming settled," he said, "but you may bet your best beaver-skin on this, that there is at least five hundred thousand acres of uncleared land fit for cultivation on the banks of the Grand River."

In 1797 he again visited Canada, and examined the country from Quebec to Montreal, on both sides of the St. Lawrence, and then up the Ottawa as far as the Chaudiere Falls, studying carefully the navigation of the Ottawa, and its fitness for settlement.

In 1798 this enterprising but cautious man paid his third visit to his future home, and returned to Massachusetts with a full determination to commence a settlement. He failed, however, to inspire his neighbors with his own confidence in the scheme, and he therefore selected two respectable men from among them, and hired them to go with him the following summer to examine and report on what they saw. Their report, which was afterwards published in the Canadian Magazine of September, 1824, is as follows:

"We spent twenty days in October in exploring the Township of Hull. We climbed to the top of one hundred or more trees to view the situation of the country, which we accomplished in the following manner: We cut smaller trees in such a way as to fall slanting and to lodge in the branches of the larger ones, which we ascended until we arrived at the top. By this means we were enabled to view the country and also the timber, and by the timber we could judge the nature of the soil, which we found to answer our expectations. After having examined well the nature of the township, we descended the river and arrived, after much fatigue, at Montreal."

The report was so satisfactory to the people of Woburn that Mr. Wright was able to hire as many as he wished for the new settlement.

It was fully five hundred miles from Woburn to the Chaudiere, but the nineteenth century was hardly a month old when the little band braved the journey. Their leader assumed all risks himself, and with twenty-five men, five families, having a membership of thirty, fourteen horses, eight oxen, and seven sleighs loaded with mill irons, agricultural implements, carpenters' tools, household effects, provisions, left the quiet New England village. The route taken was the old stage road from Boston to Montreal, which passed through Woburn to Haverhill, thence to Concord, thence north-westward along the shore of Lake Memphremagog to Montreal, which was reached on the ninth day.

Montreal at that time was a very gloomy-looking little town, with a population of about seven thousand. It was surrounded by an old wall about fifteen feet high, with battlements and other fortifications. The houses were mostly built of grey stone, with sheet-iron roofs and iron window shutters, which gave them a prison-like appearance. The streets were narrow and crooked. Traineaux drawn by French ponies, and toboggans loaded with furs and drawn by several dogs in tandem, were frequently seen in the streets when this brave little band of New Englanders gazed in wonder upon the old historic French town.

The caravan then wended its way towards the north shore of the Ottawa. Its progress at first was slow, making only fifteen miles a day for the first three days, owing to the sleighs being wider than those used in Canada. On the third day they had reached the foot of the Long Sault and the terminus of the road. They were eighty miles from their destination, in a wilderness of snow and ice, and with no trace of a road.

"We proceeded to the head of the Sault," said Mr. Wright, in relating their experiences in the House of Assembly in 1820, "observing before night came on to fix upon some spot near water to encamp for the night, where there were no dry trees to fall upon us or our cattle. Then we cleared away the snow and cut down trees for fire for the night, the women and children sleeping in covered sleighs, the men with blankets around the fire, and the cattle made fast to the standing trees; and I never saw men more cheerful and happy, having no landlord to call upon them for expenses and no unclean floors to sleep upon, but the sweet ground which belongs to our Sovereign. We always prepared sufficient refreshment for the following day, so as to lose no time on our journey when daylight appeared. We kept our axemen forward cutting the road, and our foraging team next, and the families in the rear. In this way we proceeded on for three or four days, observing to look out for a good place for our camp, until we arrived at the head of the Long Sault, from whence we travelled the whole distance upon the ice until we reached our destination. My guide was unacquainted with the ice, as our former journeys were by water. We went very slowly lest we might lose our cattle, keeping the axemen forward trying every rod of the ice, which was covered with snow.

"I cannot pass over this account," continued Mr. Wright, "without referring to a sauvage, from whom we received great kindness. We met him with his wife drawing a child upon a bark sleigh. They looked at us with astonishment. They viewed us as though we had come from the clouds, walking around our teams and trying to talk with us concerning the ice, but not a word could we understand. We then observed him giving directions to his squaw, who immediately left him and went to the woods, while he proceeded to the head of our company, without promise of fee or reward, with his small axe trying the ice at almost every step. We proceeded in this way without meeting with any accident for about six days, when we arrived safely at the township of Hull. We had some trouble in cutting the brush and ascending the height, which is about twenty feet from the water. Our sauvage, after seeing us safely up the bank, spent the night with us and made us to understand that he must return to his squaw and child, and after receiving presents for his great services, took his departure."

What must have been the feelings of the pioneer settlers when they beheld for the first time the magnificent scenery of the Chaudiere, before its wild beauty was defaced by the woodman's axe or its sparkling waters used in slides and mill-races?

Three openings loomed up before them—the most distant one, to the left, a broad half-rapid, half-cascade, sweeping down among islands of pines; the middle passage seemed very narrow and carried away in a sort of creamy foam the waters of the Chaudiere proper; while the nearer or right passage led by a winding route to a rocky cove at the beginning of the portage road. Surely never had they beheld anything so picturesque, so indescribably grand, as it appeared to them on that bright and frosty evening! The precipices and rocky gorge of the opposite shore, green with pine and cedar to the river's brink, and covered with a mantle of beautiful snow; the volume of water, tossed, broken, dashed into foam, which floated down like miniature icebergs on the mighty rushing current till the natural ice-bridge was reached, made a scene not soon to be forgotten. The turrets, domes and battlements of the Dominion House of Parliament, which in a few short years was destined to crown the opposite cliffs, were a dream beyond the wildest imagination of our Pioneer.

1802.

Two years had slipped away. The ice moon had given place to the crescent whirlwind moon. The wild duck and geese had long since ceased their plash, plash in the water opposite "The Wigwam," as the children delighted to call their new home in the forest. The noble rivers, the picturesque falls, the monarchs of the forest towering heavenwards, the fragrance of pine and cedar, the lakes and rivers teeming with fish and fowl and fur-bearing animals, seemed to the children of the new Chief a paradise; nor were they alone in their views. The stern realities of pioneer life made it none the less enchanting to the man who gloried in overcoming difficulties and in braving hardships in one of the greatest conquests undertaken by man—the wresting of a wilderness from savagery to civilization.

The "Wigwam" was situated in the midst of an estate of twenty-two thousand acres, part of which had been received as a grant, but the greater portion being purchased from the Government, for the Chief had by no means suffered losses such as many U.E. Loyalists had borne, having brought with him a capital of nearly fifty thousand dollars.

The new home presented a strange contrast to the cosy, comfortable New England farmhouse. It was built of undressed tamarac logs in true rustic shanty fashion. The chinks between the logs and scoops of the roof were "caulked" with moss, driven in with a thin pointed handspike, over which a rude plaster of blue clay was daubed. The chimney was very wide and low, and was built above a huge boulder which formed the back of the fire-place. There was no upper story to the rude dwelling, which was partitioned off into bedrooms at each end, with a large living room, kitchen, dining-room all in one, in the centre.

A wild night had set in. It seemed as though all nature had gone mad. The wind struggled with doors and windows for an entrance to the humble home, but only served to intensify the warmth and light and joy within, for it made the great fire roar and crackle the merrier.

A group of happy children were popping corn before the glowing coals. Near them sat the Chief and Mrs. Wright conversing together in a low voice. Laying down her knitting, the latter looked earnestly into her husband's face.

"Philemon, Philemon," she said sadly, "How much more wisdom you are manifesting in the breaking-in of the farm colts than in the training of the boys. I am beginning to fear that you will be much better served by the former than by the latter. If you would but exercise your God-given authority over them and uphold mine we might hope for better results. The boys are getting beyond control, and why? Because, though I am teaching them in theory the right way, you are not insisting upon the practice of such theories. Words will not curb the exuberance of spirits nor check the waywardness of a young horse. If left to himself he will go where he wills. He must be trained with gentleness, but with firmness, and so with our children."

"My dear," he said, "your ideals are above me, and are as unlikely to be adopted by ordinary men of the world as the ideals of John Bunyan or Richard Baxter."

"I see, I see," she said, with a voice thrilling with emotion. "You hold up before them hopes of future greatness or wealth as a stimulant to goodness, studiousness, industry, that they may become 'ordinary men of the world.' My ambition has ever been to train them for God and His service."

"And you propose to do that," he said, coldly, "by coersion, canings, imprisonments, fines."

"Not at all," she replied. "A child trained from infancy in habits of obedience can generally be managed without chastisement and will obey from a sense of duty rather than from fear of chastisement."

"All very beautiful in theory," said the father, with a yawn, as he stretched himself to his full length, "but the Indian theory in my opinion is the best. They allow their children to do as they please and never check them, and what is the result? A self-reliant, independent people; a people who have not been deprived of strength of character or will power by constant subjection to the will of others; a people who, until spoiled by contact with unchristian whites, have followed the dictates of conscience rather than a code of prohibitory laws; a people who scorn mean, dishonorable transactions."

"Of two things I am convinced," said Mrs. Wright, thoughtfully, "'a child left to himself bringeth his mother to shame,' and his father also, for that matter, and that if we secure the formation of right principles at an early age we may with confidence give them their emancipation long before they grow up."

Suddenly the door opened and an Indian entered. Though covered with snow from head to foot, they recognized the chief, Machecawa. Without a word he drew through the open door a toboggan, upon which lay his squaw in an almost dying condition. At her bosom was a tiny babe, two days old.

Newitchewagan had had a severe chill. He had given her a vapor bath by heating boulders in the fire, dashing water on them, over which he had held her suspended in a blanket. For a time she seemed better, but not having sufficient covering, the keen north wind had caused a recurrence of chills, and notwithstanding the conjuring and charms of her friends she was evidently fast sinking, and the Chief, in his hour of sorrow, had fled for help to Mrs. Wright (whom the Indians regarded as possessing mysterious healing power), in the vain hope of finding some new way of saving her.

Mingled expressions of astonishment and pity came into the face of the mother of the household as she hastily left her seat by the side of her husband and assisted in removing the poor squaw to a comfortable bed.

Though not a popular type of New England beauty, there was a something about Mrs. Wright a certain expression so subtle as to escape definition, which gave her presence a strong personal magnetism, while her dignity and a marked grace of manner gave her an individuality which proclaimed her a queen among women. She was a woman of high ideals. "I fear not," she said, in a letter to her sister, "the wolves whose dismal howls echo and re-echo every night through the forest; I fear not the savages who walk into our home with as little ceremony as though it were their own; I fear not sickness nor death in this wilderness so far from medical aid. One thing only I fear, that I may fail in my duty to my husband, my children and my neighbors."

Her husband's "worldliness," her sons' lack of interest in religious matters and their tendency to adopt the language and expressions of the low and the vicious, afforded matter for constant reproof, rebuke and exhortation. Her efforts to develop in her children the highest ideals of Christian manhood and womanhood were not fully appreciated by the Chief, who was too feudal in his views of woman to understand a life like hers. The phenomenon of a woman superior to himself in mind and soul had never ceased to be a matter of perplexity to him. Her ideals were beyond his comprehension. He had not arrived at the conclusion that a wife should be allowed free scope for the exercise of her own individuality. Her position in the home was one of utter subjection and servitude. She was permitted to have no will but his, no plans but his, and to have no ideas but his. At the marriage ceremony "they two were made one," and that one was her lord and master.

Mrs. Wright's interest was not confined to her own family circle, for, notwithstanding the constant pressure of home duties, she had "a heart at leisure from itself to soothe and sympathize," and to the Indians and early settlers in their loneliness, their sorrows and sufferings, she was a mother, and more than a mother, for she was the only physician, the only clergyman, the only teacher that the little colony possessed for the first few years of its struggling existence. Her medical book and case of medicines, a gift from Dr. Green, of Woburn, brought relief to many sufferers. Her library, consisting of such volumes as "The Pilgrim's Progress," Baxter's "Saints' Rest," Young's "Night Thoughts," Hervey's "Meditations Among the Tombs," did much to enlighten, if not to cheer, darkened souls, while from the newest Boston school-books she trained the youth of the settlement in the elementary principles of the arts and sciences.

Such was the woman whom Machecawa sought in his hour of extremity.

All night long the noble chieftain of his people sat by the bedside with downcast eyes. The wind, having spent its force and fury, moaned and sobbed round the house; the flickering light from the hearth cast strange, weird shadows upon the wall when Newitchewagan opened her large dark eyes, gently stroked the little black head on her bosom, and with one affectionate look at him who had been her companion in hardships, heaved a deep sigh and was gone.

Machecawa, without uttering a word, hastily left the Wigwam, and in a short time returned with his face blackened and with several squaws, who tore their hair, scattered ashes on their heads, and raised their voices in wailing. They arranged to have the burial service take place in the evening, and it was well for the inmates of the Wigwam that it was not deferred for several days, for the wailing continued without cessation until all that was left of Newitchewagan was wrapped in birch bark and securely tied with a cord of deerskin, like a parcel, when it was borne by four young braves and laid upon a raised platform of boughs, between two fires which had been kindled a little distance from the Wigwam.

The Indians then squatted cross-legged in a large circle round the fires. Machecawa and his motherless children were seated close to the bier, their faces blackened, their hair and clothing torn and in disorder. The awful stillness was at length broken by old O'Jawescawa, who left his seat and, approaching the grief-stricken husband, said:

"O Machecawa, my brother, it is not well that you grieve. If Newitchewagan had lived she would many times have been hungry and cold and weary; but in the happy hunting-ground, whither she has gone, there is neither hunger nor cold nor weariness. Therefore you should be glad." He then drew his hunting-knife from his belt, and, slashing it through the birch-bark wrappings, cried:

"O Kitche Manitou! These places do I cut that our sister's spirit may come and go as she wills it, that she may visit us sometimes, that she may see our brother Machecawa when he is very sad."

"Oh, Machecawa, my brother, it is not well that you grieve."

Again he turned to his chief. "Our sister is gone, oh, my brother," he continued, "but you shall see her again. But she shall be changed, and you will not know her; but when you enter the Land of the Hereafter then you must sing always this little song, and so she will know you."

In a clear and true tenor old O'Jawescawa chanted a weird, minor air with tearful falling cadences.

"And when she hears that song," he went on, "then she will answer it with this"—and he sang through another little song.

The long-drawn, plaintive chords, the sense of awe inspired by the darkness and the firelight, and of the grave sad prayer, caused Mrs. Wright and her young flock to sob aloud.

"And so in that way," concluded O'Jawescawa, "you shall know each other."

The young men bore the remains to a grave that had been dug a short distance away in a pine grove. After the earth had been filled in, three of the women knelt and put together a miniature wigwam of birch-bark, complete in every detail. Then O'Jawescawa began again to speak, addressing the occupant of the grave in a low tone of confidence.

"O Newitchewagan, our sister," said he, "I place this bow and these arrows in your lodge that you may be armed on the Long Journey.

"O Niwitchiwagan, our sister, I place these snow-shoes in your lodge that you may be fleet on the Long Journey."*

* The writer is indebted to Mr. S. E. White for this account of the squaw's burial.

In like manner he deposited in the little wigwam extra moccasins, a model canoe and paddle, food, and a miniature robe. Then they all returned to their camp, all but Machecawa, who crouched on the ground by the grave, his blanket over his head, a silent, motionless figure of desolation. For three whole nights and days the Chief mourned for his squaw. Then he rose and went about his ordinary duties with unmoved countenance, and the grave was left to the sun and snow and rain and the mercy of all-forgetting Nature.

1803.

Machecawa and his friend O'Jawescawa became frequent visitors at the Wigwam. They would come in the morning, uninvited, and sit silently all day long before the open fire and observe all that was going on. The spinning-wheel and hand-loom were objects of unceasing interest to them, and though it proved a great distraction to the children in their studies, and to the girls in the performance of their domestic duties, to have them there, they were always treated not only with respect but with consideration and kindness.

One morning Machecawa stood gazing intently into the fire. His face wore an expression of perplexity. At length he turned to the White Chief, who was explaining a mathematical problem to one of his boys, and said:

"Big Injun, he want to speak his thoughts from books. He want to know white man's Manitou."

"May I teach him, father? Just for an hour every day?" said Chrissy, a tall, fair, thoughtful girl of seventeen, who was known throughout the settlement as the "Saint," for she had been led to take a serious view of life by a Quaker friend in the old school at Woburn. "It would be such a pleasure for me to lead him to a knowledge of the truth."

The father readily granted the request, and it was arranged that he should receive instruction from Chrissy every morning while the younger boys were having their lessons. Never had teacher a more apt, humble, or willing pupil. Never had pupil a more considerate, patient, kind-hearted instructor. Over and over again did she repeat words and sentences until at last the Indian found, to his unspeakable joy, that he was beginning to acquire the words pretty freely.

The morning hour with Machecawa proved of such interest that it was not an uncommon thing to see the White Chief and all the children listening intently to Chrissy and the Indian as they compared their respective creeds.

One morning, after she had been giving an account of the creation and the deluge, she said, "Now, tell me what you think of these things. Do the Indians ever think of how the world was made? Did they ever hear of a flood?"

Machecawa replied in broken English, the interpretation of which is as follows:

The Indian believes that the great Manabozo is king of all other animal kings. The West Wind is his father, and his mother is grand-daughter of the Moon. Sometimes he is a wolf; sometimes a hare; sometimes he is a wicked spirit. Manabozo was hunting with his brother, a wolf, who fell through the ice in a lake and was eaten by snakes. Manabozo was very cross and changed himself into the stump of a tree and surprised the king of the serpents and killed him. The snakes were all Manitous, and they made the water flood the world. Manabozo climbed a tree which grew and grew as the flood came up and was saved from the wicked spirits.

Manabozo looked over the waters and he saw a loon, and he cried to the loon for help to save the world. The loon went under the water to look for mud to build the world again, but he could not find the bottom. Then a muskrat tried, but he came up on his back nearly dead. Manabozo looked in his paws and found a little mud, and he took the mud and the dead body of the loon and with it created the world anew again.

"And do you believe that?" said the White Chief.

"Our tribe she believe like that," replied the Indian.

"What is that thing tied round your neck, Machecawa?" said Bearie, the second son, a short, well knit, sturdy-looking youth of eighteen, whose every expression reflected a bright, happy, generous disposition.

"She am my Manitou," replied the Indian.

"What is a Manitou? Every Indian you meet with seems to differ on the subject."

"Some tam she am wan ting, some tam she am anodder."

"That is evading the question," said Chrissy.

"What kind of a Manitou have you got inside of that little bag which is tied round your neck?" persisted Bearie. "Will you let me see it?"

"No! No!! No!!!" he said excitedly. "My Manitou she am not be pleese."

"Come, now, old man," he said. "Tell us all about it."

"What is it?"

"How did you get it?"

"What is it for?"

"Waal," he said, reluctantly, "When I am a boy, me, just become a man, my fadder, he say, 'Machecawa, tam you got a manitou.' My face he paint black, black. He say, heem, 'you no eat no teeng seex days.' By em by I am dream some teeng, me, dat some teeng she am my manitou. She help me kill beeg bear; she mak dem Iroquois dogs run like one wild moose. My fadder she am pleese; she make my manitou on my arm—see!" he said, rolling up his sleeve.

On his shoulder was the rude outline of a fish, which had been tatooed with sharp bones and with the juice of berries rubbed in.

"But what is in the little bag?" asked Bearie. "Will you let me see it?"

After a good deal of reluctance he gave in at last, and two curious boys untied the precious parcel, while the others, equally curious, looked over his shoulders at a few old broken fish bones which were all the little bag contained.

"Well, old man," said Bearie, slowly replacing the sacred relics, "we put our faith in something better than that. The white man trusts the Great Spirit in heaven to care for him and to take him to heaven when he dies."

"Any bear in hebben?" asked the Indian.

"No," said Bearie, "only good people."

"Dat hebben she am no good for big Injun," said Machecawa, sadly. "De happy hunting ground she am full of moose, buffalo, bear, beaver. She am far, far away at de end of land, where de sun she sleep—two, tree moons away. One beeg dog she am cross, an' she bark at dead Injun, but he go on, an' on, an' on, an' den he am glad."

It began to dawn upon the vigilant mother at length that it was not so much the wonders of civilization nor the desire to "speak his thoughts from books" that led Machecawa day after day to the Wigwam, as an ever-increasing interest in her fun-loving daughter, Abbie, who was a year younger than Chrissy, and who seemed unconscious of the fact that the eyes of the red chief were ever upon her.

Chrissy was at a loss to understand why he had suddenly lost all interest in the studies and seemed preoccupied with other thoughts. She was beginning to grow discouraged, and was sorely tempted to abandon any further attempts at instruction, when Machecawa suddenly left her one morning as she sat by the table with the open book, and, approaching his white brother, said, in broken English:

"Father, I love your daughter," pointing his forefinger at Abbie. "Will you give her to me that the small roots of her heart may entwine themselves with mine so that the strongest wind that blows may never separate them?"

For a moment there was silence in the room. The White Chief's face grew dark. The veins of his temples began to swell with rage. In a burst of passion he said:

"My child become your slave? Never! Never! The Indian wants woman to gather his wood, carry his burdens, dress his skins, make his clothes, build his house, cook his food, care for his children. No, no, Machecawa; no white woman would be happy to work like a squaw or to suffer as such."

Not a word could the Big Chief utter. He gave a deep sigh and gazed at Abbie fondly and admiringly. The inexpressible agony in his face touched the father's heart, and he added:

"My daughter is too young to marry, but when she is old enough to know her own mind she may answer for herself."

A ray of light and hope crept into the dark face, and drawing from a pouch a string of claws and teeth of rare birds and animals, he approached Abbie and fastened it about her snowy neck.

"You have conferred upon me a great honor, Machecawa," said Abbie, smiling, "but you shall have to wait for several years, for I have many things to learn before I could become the squaw of an Algonquin chief."

The chief then resumed his seat at the table and went on with his task with as much complacency as though nothing had happened, while Abbie and her brothers quietly withdrew in order to give vent to their feelings.

1804.

As the settlement did not afford any greater educational advantages than Mrs. Wright, with a multitude of other claims upon her time, was able to give to her daughters, Chrissy and Abbie were sent to a convent in Quebec, there being no other boarding-schools in Canada at this time.

Among their school friends was Sally Smith, whose mother invited them to spend Christmas with them at the officers' quarters at the Citadel.

"Just fancy!" said Mrs. Smith, addressing her husband, the Colonel, and his guest, a young Scotchman, as the girls entered the dining-room. "Shut up in a convent for sixteen months with nothing to vary the monotony of it! Do they not deserve a holiday?"

As they were introduced George Morrison and Chrissy looked at each other and bowed formally and composedly, and an awkward, embarrassing silence followed. For the first time in his life the presence of a fair and lovely girl cast a spell over him so extraordinary that, as he sat opposite to her at the dinner-table and watched her frank, bright, expressive face, his own responded to her every expression.

It would not be difficult to say which had made the most profound impression upon the mind of the honest young Scotchman, his distant kinsman, the Colonel, with his handsome, kindly face and his sturdy English character, or the tall, slight form before him, with sloping shoulders, tapering arms, and a face lovely in its spiritual contour.

George Morrison thought he had never met such a man as the Colonel, nor was the admiration unreciprocated, for his host took a great fancy to George. "He is one of those men," he remarked to his wife, "whom porridge and the Shorter Catechism have endowed with grit and backbone—just the sort of fellow for the Hudson's Bay Company's service. In dealing with traders and trappers men of nerve are needed, men of brain, men of muscle. George Morrison is not a man to be imposed upon. He can take his place at the head of a crowd of dare-devils and keep them under perfect control."

It is hardly possible in a way for a young man to live in the same house with a young and lovely woman like Chrissy without running more or less risk of entanglement. More especially is this so where the two have had little or no outside society to divert their attention from each other. George and Chrissy soon found it pleasant to be a good deal together. Before she had been a week in the house he had come to the conclusion that Chrissy was one of the most attractive women he had ever met, and one of the strangest. That she was clever and good he soon discovered from remarks she made from time to time; but that she had something that he did not possess was evident, and it puzzled him. So curious was he to fathom the mystery that he took every opportunity of associating with her in the hope of drawing from her the secret of her joyous, triumphant life.

They read together, sang together, walked together, and it seemed to them both that every word interchanged, every blending sound of their voices, every step they took, was welding together a bond which had existed since first they met at the Colonel's hospitable table. To George it seemed a natural sequence that when he had for the first time met the young woman who, he was convinced, was predestined by God to be his counter-part that the recognition should be mutual. He knew that she had a way of making him feel perfectly at ease in her society. When he was talking to her, or even sitting silently by her, he felt a sense of restfulness and reliance that he had never before experienced in the society of a woman, especially since he bade farewell to civilization to lead his men through the trackless maze of rivers, lakes and woods of the North-West.

It soon became evident to Chrissy that George liked her society. It never occurred to her what a boon it was to the rugged Nor'wester to be thrown, for the first time, into the society of a young woman not only of considerable intellectual attainments but of deep spirituality.

Chrissy did not think of love or marriage at first. What she did think of was the possibility of leading the young Scotchman into the highest realm of life—the spiritual.

They had just left the little old-fashioned church, and were walking the snowy streets in silence, when Chrissy spoke:

"Do you know," she said, shyly, "it's very strange, but you are the only man I have ever met to whom I could speak with confidence of the subject nearest my heart."

"And what may that be?" he asked, a ray of light and hope illumining his face.

"It is the realization of the love of the Unseen and Eternal. More to me than the sweetest earthly tie is One whom having not seen I love."

"It is all a mystery to me," he said. "In fact it is incomprehensible how anyone can manifest such enthusiasm and devotion to One unknown. Though I learned at mother's knee that 'man's chief end is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.' I have never been able to get beyond the theory of it."

"I am sorry for you," she said, her voice trembling with disappointment.

For several minutes neither spoke, when Chrissy said, slowly and thoughtfully:

"How oblivious the mineral kingdom is to the life of the world above it, and the vegetable kingdom to that of the animal. How much more so the man or woman having a mere physical existence to the life of the spiritual. They have not the faculty of comprehending its joys or its privileges any more than a stone can appreciate a flower, or a flower appreciate science or art. My heart yearns with unutterable pity for anyone to whom Christ and the things of the spiritual world are not a reality."

George made no response, and as they had reached the door of the Colonel's quarters, he grasped her hand.

"Chrissy, Chrissy," he said, "I must go. I dare not trust myself to speak," and he left her standing on the door-step.

The happy holidays had slipped away all too soon. Chrissy stood by a window gazing at the panorama before her. The moonlight poured through the window, filling the room with a soft radiance which rested upon her head with a kind of halo. The indescribable beauty of the scene without faded into insignificance compared with the scene which George Morrison contemplated—a young woman whose pure heart was mirrored in the beauty of her face and breathed in every accent of her gentle voice. Her earnest blue eyes looked as though they could see into that other world of which she so often spoke. Never before had he beheld a life so filled with fascinating grace as to pervade every gesture and accent. Never had he met a soul so permeated with love and devotion to God, and withal so simple, so natural, so sweet.

Chrissy was evidently oblivious to the presence of anyone, and started when George suddenly remarked:

"Pardon me, Miss Chrissy, if I intrude upon the sacredness of your meditations, but I understand you are going to leave us to-morrow. We may not meet again, for you will be shut up within the cloistered walls yonder and I shall be leaving in the spring for the great unknown land. I shall have cause to thank God through all eternity for your visit I am grateful, deeply grateful, for the loving interest you have manifested in my welfare, and I cannot part with you, dear Chrissy, without giving some expression of the intense love I have for you. It would be heaven begun on earth if I might only be permitted to walk life's pathway with you; but, alas! I am not in a position to offer you a home. I am not one of those white-shirt-fronted gentlemen such as we frequently meet with here, but, thank God, I can now offer you a heart that is white, a life that is pure. Life in the woods has rubbed off any of the veneer or polish that I may have brought with me from the Old Land, and I am just as you see me, Chrissy, a plain, rough man from the wilds of the West. Notwithstanding which, could you not give me a pledge that some time, somewhere, I may claim you as my own?"

For a moment Chrissy said nothing, but the expression of her face was more eloquent than any words. Her breast heaved with emotion as she said, slowly and calmly:

"I am convinced that such a union as you propose would be founded upon the only true basis, a mutual love for Christ. Unions such as this have only their beginning here; their full fruition is in eternity."

In a moment he was at her feet, and, pressing her hand to his lips, he poured forth expressions of happy gratitude to the Giver of all good.

To her lover she seemed as she stood before him an incarnation of love, of beauty, of goodness and grace, more like something belonging to another world—a subject of a higher power.

1805.

The river was scarcely free from ice-floes when Chrissy was summoned to the bedside of her mother, who had been hovering between life and death for several weeks. Weary and worn with nervous apprehension and the strain of the long and perilous journey, she entered the sick-room. The flickering light from the hearth fell upon the white face of the mother whom she loved as only a mother could be loved. She was sleeping soundly. Bending over her she laid her cool hand on the fevered brow, when the poor sufferer opened her eyes, but was too weak to speak. She smiled faintly, and again fell into a deep sleep. Through the long watches of the night, and oft through the day, she sat gazing at the sleeping form, inwardly praying that she might not be taken from them, that their home might not be left desolate.

At last there came a beautiful sunny morning in May when consciousness returned, and the patient began to show other signs of recovery. Naturally of a strong, vigorous constitution, Mrs. Wright soon became convalescent. One evening she was lying on a couch before the fire, when she observed the pallor of Chrissy's earnest face.

"You must go out more, my child," she said. "You have had a long siege of nursing. You look worn out."

"Come along, Chris," said Phil, her eldest brother. "Let us go for a stroll down to the shore."

It was a beautiful evening. The sun was just veiling his face behind the western hills, illuminating the sky with glory, when suddenly they were attracted by the sweet strains of a French song in the distance.

Soon twelve canoes rounded the headland, coming up the mighty current of the river, manned by men decked out in varied and brilliant colors. They sang as only Canadian voyageurs could sing, suiting the action of the paddles to the rhythm of the song:

"A la claire fontaine,

M'en allant, promener,

J'ai trouvé l'eau si belle,

Que je m'y suis baig-né,

Lui ya longstemps que je t'aime,

Jamais je ne t'oublierai."

Each verse was sung in solo, and then repeated by all in chorus, finishing with a piercing Indian shriek.

"Soon twelve canoes rounded the headland."

They followed them to the landing-place—a great flat rock on the north side of the river, at the beginning of the portage road—and found them preparing to bivouac there for the night, for all hands were busily engaged in kindling fires and unstrapping blankets. It was soon ascertained that it was one of the Hudson's Bay Company's brigades en route for the North, with supplies for the Company's forts, and that it was in command of a young Scotchman. Chrissy's pale face crimsoned as George Morrison approached her, and invited her and her brother to share his evening meal. At first glance he could have seen a resemblance between Phil and Chrissy, in feature, in manner and expression; both had the same quiet, thoughtful manner, the same calm, deliberate way of speaking, and the same reserved, proud bearing.

"I never dreamed of meeting you here," he said, "or I should have had a sumptuous repast ready. Fortunately I happen to have a tempting bit of beaver tail, which is considered a great delicacy to Nor'westers."

George Morrison was not slow to observe that Chrissy's face had an expression of sadness in it that he had never seen before.

"You seem melancholy and dispirited. What is on your mind, Chrissy?" he asked.

"I have been passing through a great trial," she responded, with quivering lips, "and I vowed a solemn vow when I thought that all hope of saving mother was gone, that if God would give her back, I would devote my whole life entirely and unreservedly to His service, even though it involved the severance of every earthly tie."

Phil, who never felt more ill at ease, more unresponsive, than when compelled to listen to a conversation which touched upon sacred themes, which were entirely beyond the range of his comprehension, quietly withdrew from the tent and strolled out to the fire, where a number of strange figures lay in the shadow of the dusky cliff. French voyageurs and coureurs des bois, white trappers and Indians, in a variety of lazy attitudes, reclined on buffalo robes and bearskins. Most of them, with bleared eye and bloated face, were puffing away at their pipes. Some had red handkerchiefs round their heads holding back their long black hair. Some wore buckskin smocks, fringed with bright colors and drawn tight at the waist by sashes of brilliant hue, with trousers of the same material with little bells fastened from knee to ankle.

"They're a' guid canoemen," said an old Scotchman, who had been for many years factor at one of the trading-stations, and who was en route to Moose Factory. "You should juist see them at wark. They wadna think twice o' takin' a canoe ower the Big Kettle yonner at this time o' the year. Whan they are in ony danger they faa' down on their knees an' caa' on the Virgin an' a' the holy angels tae save them, an' as sune as it is gane by they deny the verra exeestence o' Virgin or angels aither, an' sweer like troopers. The Government regairds them as kin' o' ne'er-do-weels' an' ootcasts. When they gang back tae ceevilization they spen' a' they've made in the fur trade on their claes an' in drucken bouts. As lang as their beaver-skins last they set nae bouns tae their riot. Mon, I've seen some o' thae verra men staulkin' thrae the streets o' Montreal as nakit as a Sioux. Tho' they're sic bauld dare-deevils they are verra usfu' tae oor company, for they gang hunners and hunners o' miles throu the leemitless maze o' lakes an' rivers in the far North in sairch o' furs. They dinna fear aither Iroquois nor Algonquins, Cree nor Sioux."

"He must have a lot of nerve," said Phil, pointing to the tent, "to place himself at the head of a crowd like that. I hope that he and you may never fall victims to the treachery of such a crew."

"Dinna be feart," he said, "but he'll keep a stiff upper han' o' 'em. They'll no verra readily try to ride ower him."

In the meantime a melancholy scene was taking place in the tent. Chrissy had signified her determination to follow in the footsteps of the sainted Marguerite de Bourgeois, Jogues, Jean de Brébeuf, and other early Canadian missionaries, who left the joys of home, the comforts of civilization, and, penetrating the back-woods beyond the protecting arms of the law, beyond the care of sympathetic friends, had lived and worked and laid down their lives as a sacrifice in seeking to convert the Indians to Christianity.

"But," protested George, "you are surely not going to take the veil like Marguerite de Bourgeois?"

"Certainly not."

"You are surely not going to wander off into the wild woods and lead the life of a squaw, are you?"

"Not exactly, but I hope to arrange with the Mission Board of the Dutch Reformed Church in New York, who are working among the Indians of Upper Canada, to take me as a teacher."

"But have not the Indians of Lower Canada, and especially the tribes scattered along your own river and its tributaries, a greater claim upon you? If your vow includes nothing less than martyrdom, the cannibals of the Nipissing or the Abbitibee tribes would be quite willing to aid you in carrying out your intentions," he said, a faint smile creeping over his serious face. "Chris, dear Chrissy," he said, as he stroked her soft flaxen hair, "I thought you had advanced too far in the Christ life to think of bartering with the Infinite. If He has given back your mother, receive her as a free gift, not to be paid for by the sacrifice of your own precious life, nor by the severing of earthly ties, but to be received and rejoiced in as a token of His free grace. Fulfil your vow, my noble girl; live for Him, work for Him, die for Him if need be, but one thing remember, that the highest destiny of woman lies in adorning the position God designed for her. It may please self to sever earthly ties, it may give you an inward feeling of being under no obligation to the Hearer and Answerer of prayer—a feeling that you are even with Him—but you will find that it is not the true road to happiness. Self is not your aim, nor is it comfort, nor enjoyment, nor social ambition; your chief end and mine is to glorify God and enjoy Him forever. If that sweetest of earthly ties formed at Quebec stands in the way of this, let us sever it here and now."

Tears were chasing each other down Chrissy's face as he spoke.

Few men can bear to see a woman in tears, and it was too much for George.

"Chrissy," he said, "don't cry, please, don't; but tell me, shall we sever it?" Her heart was too full for words, but every line of her face expressed remonstrance.

He stopped for a moment, as though waiting for an answer, when suddenly a shout went up which seemed to rend the very heavens, for it came from several hundred men. It brought George Morrison out of his tent in an instant. The crews of twenty-two large canoes belonging to the Company and twelve crews of Iroquois Indians, who were on their return from the winter hunt, with their families, furs, dogs, etc., had just arrived on the scene.

The bark canoes, measuring on an average thirty-six feet in length by six feet in width in the middle, which had been carried most tenderly over the portage on the naked shoulders of six men, were deposited in a semi-circle upside down.

The whole cargo of provisions and furs was carried in bundles or packs of ninety-five pounds each by means of pack-straps, called "tump-lines," arranged so that the middle or broad part of the strap rested against the forehead; the ends securing the load, which rested upon the shoulders. Each voyageur had one, two or three of these packs, which they had carried over the nine-mile portage at a slow trot, with the knees much bent, stopping for a few moments every half-hour for "a pipe," as the rest was called, until at last the landing-place was reached.

The crew of the second brigade almost out-rivalled those of the first in their appearance. They were the most extraordinary-looking individuals that Chrissy and Phil had ever beheld; mostly dark, gipsy-like men in blanket-coats with borders and sashes of brilliant hue, and hats with silver bands stuck full of feathers of a variety and brilliancy of color, all with long hair to protect their necks and faces from mosquitoes.

The clamour, jargoning and confusion of this wild, impetuous multitude cannot be described. The commander of the brigade was a Welshman, David Thompson, with a young Scotchman named Simon Fraser as assistant, whose names have been handed down to posterity as the discoverers of the Thompson and the Fraser Rivers.

Thompson was almost as extraordinary in his appearance as some of the members of his brigade. Though plainly and quietly dressed, his black hair was worn long all round and cut square, as if by one stroke of the scissors, just above the eyebrows. His figure was short and thick-set. His complexion was a ruddy brown, while the expression of his features was friendly and intelligent. His Bunyan-like hair and short nose gave him a very odd appearance. He had a powerful mind and had perfect command of his crew.

With them was a French priest, who had secured passage for Montreal in one of the Company's canoes.

The shout of greeting brought the Chief and his sons to the landing to see what was the matter, and they remained interested witnesses of the gay scene till nearly midnight, when the din ceased and all were soon asleep—the leaders in their tents; the men, some beneath their upturned canoes, some on blankets or skins spread on spruce boughs, and some just rolled in their blankets on the rocks before the fire, the cooks only remaining up to cook the hominy for the following day. Hominy was the regular fare for the voyageurs of the great fur-trading companies. It was made of dried corn, prepared by boiling in strong alkali to remove the outer husk. It was then carefully washed and dried, when it was fit for use. One quart of this was boiled for two hours over a moderate fire in a gallon of water, to which, when boiled, was added two ounces of melted suet. This caused the corn to split and form a thick pudding, which was a wholesome, palatable food, easy of digestion and easy of transportation, one quart being sufficient for a man's subsistence for twenty-four hours.

After taking leave of the Chief and Chrissy, George invited Phil, Bearie, Christie and Rug to remain all night, most of which was spent in conversation with the old Factor, who entertained them with accounts of the discoveries in the great unknown land.

"Eh, mon," he said, "it is a graund cuintree. My auld frien' Sandy Mackenzie, when juist a bit lad, cam' oot frae Inverness tae tak' a poseetion wi' Mr. Gregory at Fort Chipewyan, at the heed o' the Athabasca Lake, in the wild cuintree wast o' Hudson Bay. Sandy sune got wearied o' office life, an' got Greegory tae agree to let him gang explorin'; that ood be about twenty years sin'. Weel, sir, he took wi' 'im fower canoes wi' fower Indians an' twa squaws, an' they left the fort in June. In a week they had gotten the length o' Slave Lake, as muckle as fower hunner an' seeventy miles frae the Fort. After they had stoppit for some days they gaed on for about three weeks mair, an' gangin' roond the side of the lake frae the outgoing o' the river that has been ca'd aifter him, he gaed awa' doon the river, whar they had an unco time drawin' their canoes ower the frozen bits 'an gettin' them again intae the open watter, until at the hinner en' they foond 'oot that it emptit intae the North Sea."

"Did he see any polar bears?" asked Rug, who stood gazing intently at the rugged face of the speaker.

"Ay, lots o' them. I seen them mysel' in Davis Strait on the ice-floes comin' doon frae the North. We used to set a blubber fire burnin', an' they wad gether roond it, sniffin' an' smellin', at the bleezin' daintie. We wastit mony a boolit on them, but they didna seem tae mind it muckle. When ye cam' on them withoot waarnin', the only thing that ye could dae was tae roar oot as lood as ye could an' tae keep roarin'. Our men whiles triet tae catch them."

"How?" said Phil.

"They laid a rope wi' a lairge runnin' loop on the end o't alang the ice, an' laid a seal on't that had been tostit ower the fire. Verra sune the bears wad begin tae gether roond it. When one wad get inside o' the loop the men wad draw the rope, as the bear wad be hodden by the legs, than they wad turn the ither en' o' the rope roon' the capstan an' haul the beast on board. The growlin' an' the roarin' that resultit wad mak the hair o' your heed stan' on en'."

"Did your friend Mackenzie make any other discoveries?" asked Bearie.

"Ay, sir," replied the Scot. "He made the discoverie o' his life, when, three years aifter his comin' back tae the Fort, he set oot in sairch o' the Pacific Ocean, and foond it, tae. It was a thing that nae white mon had ever dune afore 'im, an' I doot if ony ane but Sandy could a stood the dangers an' deeficulties that he cam' through, what wi' a sulky crew that nearly drave him mad an' ither things. He was a brave, graun' mon, was Sandy. Weel, he left the Fort in October, an' gangin' up the Ungigah River, he gaed across the continent till he got tae the sea the next July, when he inscribed on the solid cliffs on the shore the fac' o' his discoverie."

Long before sunrise the chief cook gave a loud and startling shout, "Alerte!" No man dared linger for forty winks more, for after a hurried breakfast the North-bound crews shouldered their canoes and packs and commenced their long and tedious portage, and the return-crew launched their frail barques, and before pushing out into the mighty current, twenty paddlers in each boat—each squatting on his slender bag of necessaries—the priest pulled off his hat, and in a loud voice commenced a Latin prayer to the saints for a blessing on the voyage, to which the men responded in chorus.

"Qu'il me benisse."

After which they floated down the stream singing:

"En roulant ma boule roulant,

En roulant ma boule,

Derrièr chez nous ya t'un étang,

En roulant ma boule,

Trois beaux canards s'en vont baignant,

Rouli, roulant, ma boule roulant."

1808.

Two years had passed since the interrupted meeting in the tent. Not a word had Chrissy received from her lover. At length a report reached her, through a passing brigade, that George Morrison had been sent to the vicinity of Great Bear Lake to open a trading-post for his company, and that nothing had since been heard or seen of him.

Chrissy's devotion to her absent lover had grown deeper and stronger as month followed month. She never felt for an instant that he was dead to her. She did not think of him with hopes that were withered, with a tenderness frozen; the man whom she loved never once became a vague, dreamy idea to her, for to Chrissy George was a living, bright reality, who would come some day to fulfil his promise, when she would at last enter into the glorious consummation of her heart's deepest longing. It was this confidence that cheered and sustained her as she became her mother's most efficient coadjutor in missions of mercy and love. It was not an uncommon sight to see mother and daughter cantering over the rough woodland roads to distant clearances, in response to appeals for help from the sick and sorrowing.

On one occasion the appeal came from "Aunt" Allen, who lived on one of the back concession roads. As they approached the unpretentious but cosy little farm cottage, in the midst of a field of blackened stumps, Mrs. Allen came out to meet them.

"Oh, Mrs. Wright," she said, "I'm so thankful you have come. He's nearly mad with pain. In fact, I think the poor lad is agoin' out of his mind."

"How did it happen?" asked Mrs. Wright.

"You see," she said, "He had to sleep out nights in the woods when he was hauling timber to the drive, and an insect or somethin' must have got into his ear, for he could feel it a movin' and a crawlin' and"——.

"What have you done?" interrupted Mrs. Wright.

"We made him lie down with his ear on the pillow, but it was no good. Then we made him hold his ear down while we struck his head several hard blows to make it fall out, but it was no good. Then we put an onion poultice on it to draw it out, but that was no good, and now we don't know what more to do."

"I fear," said Mrs. Wright sadly, "that I shall not be much help to you, for my book does not mention what should be done in a case of that kind."

"But, mother," said Chrissy, "we cannot leave until we have done something. It is dreadful to see him suffer so."

"Physic will not touch it," she replied, "and they seem to have done everything that could be done."

At length Chrissy said:

"I've thought of a plan. Let us hold him with his head downwards, so that it may have a chance to drop on the floor; then let someone puff tobacco smoke up into the ear, and perhaps the smoke will cause the insect to become stupefied and it will fall out."

"Very good," said her mother. "The plan is worth trying, but who will do the smoking? There's not a man about the place."

"I'll do it myself," said Chrissy. "You have a pipe and tobacco, I suppose, Mrs. Allen?"

"Yes," she replied, "for the lad smokes."

The experiment was tried. Chrissy, kneeling on the clean sanded floor, puffed away vigorously at the strong old pipe, while her mother and Mrs. Allen held the young man's head over the fumes. Soon something dropped upon the floor, which proved to be a large red ant, and a shout of triumph went up as Mrs. Allen jumped upon it and ground it to nothingness. This brought instantaneous relief to the sufferer, who was very profuse in his expressions of gratitude.

Poor Mrs. Allen laughed and cried in turn as they took an affectionate farewell of one another, but Chrissy's face had an unusually pallid appearance, which, however, soon faded away as they galloped down the road to Mrs. Murphy's cottage.

They found the poor woman on a bed of suffering, where she had been for three months.

"Is it yersilf that's come, me lady?" she said, a slight flush of pleasure lighting up the pale, sad face.

"Yes, Bridget," said Mrs. Wright, "and I have brought my daughter, whom you have not seen for a long time."

"Ah, me darlint," she said, grasping Chrissy's hand, "Moike is a gud husband to me. He has a big, koind Irish heart, but one night when he came home he wasn't hisself, Moike wasn't, and he kicked me and the swate lamb there," pointing to a fat dumpling of a baby, "out of the door, and thin he locked it forninst me, Moike did; and I entrated him to let me in, but he would not; so I ran over the shnow through the fields to Joe Larocque's shanty, and I tuk off me skurt to roll the wee darlint in, for she was cryin' with the could, an' I ran to the shanty. For shure I was in my bare feet, an' when at last I reached Larocque's he was afeared to let me come in, he was, an' I prayed him for the sake o' the Blessed Virgin and all the holy angels to open the door, an' afther a long toime he did."

"Poor Moike," she said, with a look of agony in her face; "he's a gud man, a gud man, but he was not hisself—it was the dhrink that did it."

"There now, Bridget," said Mrs. Wright, "you have talked enough; you had better keep quite still while I remove these bandages."

The odor from the poor frozen hands and feet was frightful, but patiently and tenderly they removed the old bandages and applied new ones, after first saturating them in linseed oil and lime water. Before they had finished, the patient, overcome with exhaustion, sank back into a state of semi-unconsciousness, repeating the sad words over and over again:

"Poor Moike, he's gud, he's gud; but he wasn't hisself."

"I am afraid," whispered Mrs. Wright, "that mortification has set in. Did you observe that she had no feeling in the right foot while we were dressing it? Poor soul! Her sufferings will soon be over—perhaps to-night."

The tears streamed down Chrissy's face as she looked first at the poor sufferer, then at the innocent babe so soon to become motherless.

"I think, mother," she said, "that you had better leave me with her, for the Larocques can only come over once a day, and Mike has evidently no idea of how to take care of a sick woman, much less a baby. Could you not take him with you? Tell him that father wants him, for he said only this morning that he wanted more men."

It was finally decided that Chrissy should remain, and that the grief-stricken husband should ride her pony as far as the Columbia farm, where he was to remain until the Chief should give him leave to return.

It was nearly dark when Mrs. Wright reached Burns's, where several young men were standing round the door. Touching their hats respectfully to her as she entered, they soon followed her into a low room, permeated with the sickening odor of whisky and stale tobacco, where a young man lay with blackened eyes, a gash over the left temple, and a broken arm.

"So you've been fighting again, Andrew?" she said, "I thought after your last scrape that you would leave Jamaica rum alone."

Andrew was fully convinced in his own mind that his injuries would ultimately prove fatal, and his feelings alternated between vengeance on the one who had proved too strong for him and an uneasy apprehension of dissolution.

"It was not my fault; and if ever I lay hands on that villain again I'll thrash him within an inch of his life," he hissed through clenched teeth, his face white with rage; "I'll smash every bone in his body. Give me time, Mrs. Wright, to say a paternoster before you begin."

"How can you pray, 'Our Father which art in heaven, hallowed be Thy name,' and drink that which will cause His name to be profaned and blasphemed?" she said. "How can you pray, 'Thy kingdom come, Thy will be done,' and drink that which will be the greatest hindrance to the coming of His kingdom and the fulfilment of His will? How can you pray, 'Give us this day our daily bread,' and drink that which is depriving thousands of daily bread? How can you pray, 'Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors,' and take that which makes us unwilling to forgive our debtors? How can you pray, 'Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil,' and drink that which has proved temptation and evil to so many? I assure you, Andrew," she said, "that you cannot say a paternoster and drink strong drink."

Turning to the father of the young man, she said:

"It is a simple fracture, but it will have to be set, and it will need a strong man to do it. You can get a splint while I make the bandages. There now," she said, "take hold of the hand and pull it slowly and steadily—this way—see. Now, are you ready?"