Title: Elizabeth, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary

Author: Carl Küchler

Translator: George P. Upton

Release date: October 3, 2019 [eBook #60408]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by D A Alexander, Stephen Hutcheson, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(This file was produced from images generously made

available by The Internet Archive)

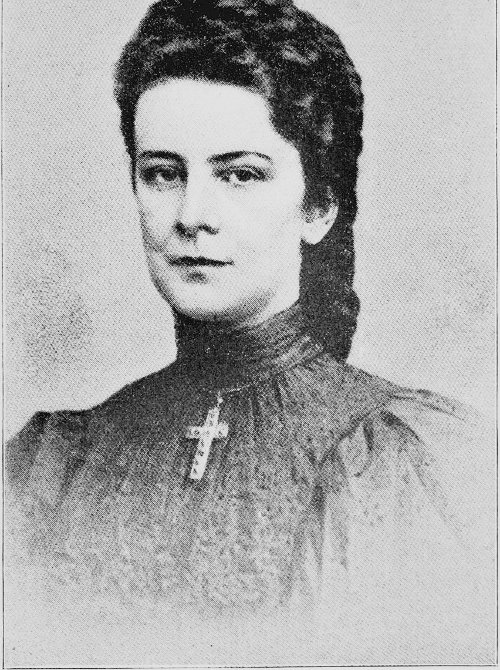

ELIZABETH as the young Empress

Life Stories for Young People

Translated from the German of

Carl Küchler

BY

GEORGE P. UPTON

Translator of “Memories,” “Immensee,” etc.

WITH FOUR ILLUSTRATIONS

CHICAGO

A. C. McCLURG & CO.

1909

Copyright

A. C. McClurg & Co.

1909

Published August 21, 1909

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

The story of the life of Elizabeth of Bavaria, Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary, is one of the saddest in the history of royalty, and in some respects recalls the story of the life of Marie Antoinette. Both their lives were sorrowful, both ended tragically, the one at the hands of an assassin, the other upon the guillotine. Elizabeth will not be remembered in history as a sovereign, for everything connected with the throne and with court life was distasteful to her, but rather as the beautiful, sorrowful daughter of the Wittelsbachs. She was not only one of the most beautiful women of her time, but an accomplished scholar and linguist, a good musician, and well versed in history, science, and art. She was a passionate lover of the woods and mountains, and was happiest when she was walking or riding among them, or associating with the Hungarian people. She was no more at home with the Viennese than was Marie Antoinette with the Parisians. Her domestic life was saddened by estrangement from her husband, by lack of sympathy among her relatives, by the terrible tragedy which ended the life of her son, Prince Rudolph, and by other tragedies which involved the happiness and sometimes the lives of those nearest to her. At last her sufferings were ended by the dagger of a cruel anarchist assassin. As the author of this volume says: “She died as she had often wished to die, swiftly and painlessly and under the open sky. Who can say that her last breath was not a sigh of thankfulness and peace?”

G. P. U.

Chicago, May 10, 1909.

On the ninth of September, 1888, an unusual event occurred in the princely house of Wittelsbach. Maximilian Joseph, the head of the ducal line of Vorpfalz-Zweibrücken-Birkenfeld, and his wife Ludovica (Louise), daughter of King Maximilian First of Bavaria and his second wife, Caroline of Baden, celebrated on that day their diamond wedding, both bride and groom having been barely twenty years old at the time of their marriage.

Few princely couples have been closely connected with so many of the reigning families of Europe. Their eldest son, Ludwig Wilhelm, renounced the succession to wed an actress, Henrietta Mendel, who had received the title of Countess Wallersee. Helene, the eldest daughter, married the Hereditary Prince of Thurn and Taxis, and their daughter Louise, by her alliance with Frederick of Hohenzollern, formed new ties between the Wittelsbachs and the royal house of Prussia. The next daughter was Elizabeth of Austria-Hungary, whose son in his turn took for his bride the King of Belgium’s daughter, Stephanie. After Elizabeth, in the family, came Karl Theodore, well known as an oculist, and, on his father’s death, the head of the ducal line of Wittelsbach. He first married his cousin Sophie, daughter of King John of Saxony; the second and present wife is Marie Josepha, Princess of Portugal. Two other daughters, Marie and Mathilde, allied themselves with the younger branch of the Bourbons. Marie became the wife of King Francis Second of Naples and Mathilde married his half-brother, Count Louis of Trani. The youngest daughter, Sophie, was betrothed at one time to her cousin, King Ludwig Second of Bavaria, but afterwards married Duke Ferdinand d’Alençon, nephew of Louis Philippe of France, while the youngest son, Max Emanuel, married Amélie of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, thereby becoming connected by marriage with Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria.

The Wittelsbachs have always been eccentric. Mental disorders have been common with them, and during the last century between twenty and thirty members of the family have died insane. Yet in spite of their peculiarities and eccentricities they have always been exceedingly popular with their subjects, as much for their personal charm as for their devotion to the happiness and welfare of their people. The annals of Bavaria have little to record of treason or conspiracy against the princes of the land, but tell much of the loyalty and sacrifices of life and property on the part of the people.

Duke Maximilian Joseph was born at Bamberg, December 4, 1808. He was the son of the weak-minded Duke Pius Augustus of Bavaria and his wife, Amélie Louise, Princess of Arenberg. “The good Duke Max,” as he was called by the people, was the only direct descendant of his grandfather, while his wife, on the other hand, was the youngest of a large family of sisters. Two had been princesses of Saxony and one a Queen of Prussia, while the fourth was the mother of the Emperor Francis Joseph of Austria-Hungary. King Ludwig First of Bavaria was a half-brother, and there were also two half-sisters. One was married first to the King of Würtemberg and afterwards to the Emperor Francis First of Austria-Hungary; the other became the wife of Napoleon’s stepson, Eugene Beauharnais, and the grandmother of Kings Charles Fifteenth and Oscar Second of Norway and Sweden.

Thus most of the dynasties of Europe were interested in the festivities in honor of the aged pair, and sent congratulations to the secluded spot on Starnberg Lake, where the event was celebrated, and where many touching proofs of the loyalty of the people of Bavaria were also received.

Maximilian Joseph belonged to the most eccentric and popular branch of the Bavarian royal family. Educated directly under the eye of his grandfather, his childhood had been spent partly in Bamberg, partly in Munich. At the age of eighteen he entered the University of Munich, where he applied himself assiduously to the study of history, natural science, and political economy, and on coming of age he was given, as provided by the Bavarian constitution, a seat in the Senate chamber. But he did not aspire to fame, either as orator or statesman; nor did he strive for military distinction, though at the age of thirty he was assigned to the command of a regiment of cavalry and in 1857 was invested with the rank of general. His natural love for science, literature, and art more often led him to exchange his uniform for the simple civilian dress.

During the youth of the Duke a musician, named Johann Petzmacher, created a great stir. He was born in 1803, the son of an innkeeper in Vienna, and in his eighteenth year accidentally learned to play the homely zither with which the mountaineers of the Austrian and Bavarian highlands accompany their folk songs. He soon became so absorbed in the possibilities of this instrument that he gave up everything else to devote himself to it. His fame as a performer soon spread far and wide. He played before the most select circles of Vienna and even at court, and made tours throughout Germany, being received everywhere with the greatest enthusiasm. Duke Max first heard him in 1837 at a concert in Bamberg, and determined to learn to play the zither under the master’s direction. Petzmacher was introduced to the would-be virtuoso, and from that time until his death made his home with his art-loving patron. The Duke in 1838 undertook a long journey through Asia and Africa, and his musician friend accompanied him. Savages listened with delight to his playing, and as the two friends sat on the top of the Egyptian pyramids or camped in the hot desert sands, the homely melodies carried their thoughts back to loved ones in Germany, and dangers and hardships were forgotten. While on this journey Duke Max wrote several musical compositions which were afterwards performed in public and received with great applause. Under the name of “Phantasus,” he wrote a collection of dramatic poems and novels that showed no small literary talent. More noteworthy than these, however, is his “Travels in the Orient,” a book of considerable merit. On his return to Bavaria he had a circus ring constructed in the rear of his palace in the Ludwigstrasse, at Munich, which aroused much curiosity, where he frequently made his appearance as ringmaster with members of the Bavarian nobility as circus riders and performers.

It was only during the winter months that he remained in Munich. All through the Summer and Autumn he lived with his family at his castle Possenhoffen, beautifully situated on Lake Starnberg. This picturesque region, shut in by a chain of lofty Alps, seems as if created to inspire poetical sentiment, and various members of the art-loving Bavarian royal family have built summer palaces there.

Max Joseph was an enthusiastic hunter and spent whole days roaming through the forests and mountains about Possenhoffen. Enjoyment of the beauties of nature was one of his passions, and he often came out in the Winter for a few days at a time. On these excursions he wore a simple hunting costume,—short gray jacket, open shirt with suspenders, feathered cap, knickerbockers with long stockings, and heavy-soled shoes. He generally went about on foot, but sometimes made use of the mail-coach, the usual mode of conveyance at that time. His fellow travellers seldom suspected that the good-natured huntsman who chatted so freely with them was a duke and the brother-in-law of their sovereign. He was continually besieged with petitions, and rarely did any one appeal in vain to the comparatively poor but warm-hearted prince. His benevolence was one of the chief causes for his popularity in Munich, though he was most beloved by the people as the gay zither player who with his instrument under his arm would enter their cottages quite like one of themselves, and play for the young people who were never weary of dancing to his music.

His wife was very different. She had not his artistic, impulsive temperament, and the good-humored simplicity with which he mingled with the common people did not altogether meet with her approval. The proper maintenance of her position seemed no more than a duty due to her high birth and rank, and for this reason she was never as popular as her husband, though her many admirable qualities commanded the greatest respect and admiration during the sixty years that she remained mistress of Possenhoffen. She was naturally endowed with a good mind and had been carefully educated. Honesty and love of truth were among her most marked characteristics, and all her life she held firmly to what after mature reflection she believed to be right. Like the Duke, she preferred the seclusion of the country to city life, and all through their happy married life she acted as a balance to her loving but restless husband as well as friend and adviser of her children, who adored and looked up to her always. Her glance was keen but kindly. Smiles came easily to her lips, and there was an air of distinction about her that sprang from true nobility of heart. She was one of those strong souls born to help others, but in little need of support themselves. She was by no means unambitious for her children, though the trials suffered because of them taught her by degrees to place less value upon outward splendor. She disliked to excite personal attention and cared only to live as quietly and modestly as possible.

It was the Christmas Eve of 1837. The bells of Munich were proclaiming the festival when Max Joseph, wandering about in one of the poorer quarters of the city, met a woman dragging herself painfully toward him with a bundle of firewood on her back. She addressed him with the usual Bavarian greeting,

“Praised be Jesus Christ!”

“For ever and ever, Amen!” replied the Duke, adding kindly, “Why are you carrying such a load upon your back this holy Christmas Eve?”

“I will tell you why, gracious Duke,” said the woman; “it is because my children have no Christmas gifts, and I have been in the forest gathering wood so that they may at least enjoy a warm room.”

“You did right,” returned the Duke. “As for me, I have already received my Christmas gift, for my wife presented me to-day with a charming little daughter who is to be called Liese, and I am so happy over it I wish you too to have a Merry Christmas.”

He wrote her name and address in his notebook, and after the darkness had fallen two servants appeared at the poor woman’s dwelling with two heavy baskets filled with food. At the bottom of each was a banknote for a considerable sum.

The child born on this day was Elizabeth, afterward Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary. In many countries it is regarded as a sign of misfortune to be born on Christmas Eve, but the happy childhood of the little princess had no foreshadowing of the experiences of her after life. Most of her early years were spent at Possenhoffen, which her father had bought some time before her birth. The great park and surrounding forests were the child’s first playgrounds, and developed in her sensitive soul a deep love of nature and of freedom.

The Duchess’s chief concern was the education of her eldest daughter, of whom she had great hopes. Helene was nearly four years older than her sister and was the favorite of the mother, whom she resembled both in character and appearance. Overshadowed by her seemingly superior talents, with no interest in books and ignorant of the requirements of court life, Elizabeth—or “Sissi,” as she was called—grew up almost unnoticed. She loved her sister with the enthusiasm of youth and with the natural tendency of the ignorant to look up to those more clever than themselves, but her father and brothers were dearer to her than either sister or mother.

The little girl was the darling of the Duke. She had inherited his love of nature, roamed about constantly with him through the mountains, visiting the peasants’ huts, and learned to look at life and people through his eyes. Her bringing up in no way fitted her for the high station she was afterward to occupy. At the end of her fifth year she was given a governess, but “Sissi,” though an unusually gentle and lovable child, soon learned how to wind her teacher round her finger and concerned herself little about study, for which she had no love. The Empress used to declare that in her youth she was the most ignorant princess in Europe, and the little she did know had been learned as she sat on her father’s knee. But if not over-taxed with lessons, her education in other branches was by no means neglected. The Duke was determined that his children should be well developed physically, and one of the best dancing masters of the time was summoned to Possenhoffen to teach Elizabeth and her sisters to dance and carry themselves properly. Even in her later years the Empress was an excellent walker and famous for her easy, graceful carriage.

“Walking never tires me,” she said once to one of her attendants, “and I have my father to thank for it. He was an indefatigable hunter and wanted my sisters and myself to be able to leap and spring like the chamois.” She also learned to swim and ride and dearly loved to sit a horse and feel the wind blowing through her hair. She was never happier than when riding about Lake Starnberg on her little pony, and in the winter, when forced to stay in the capital, it was her greatest joy to escape to the stables, where she would mount the most unmanageable horses that could be found. One day while playing circus, as she often did, she was thrown by a wild, full-blooded animal. Her governess uttered a shriek of terror, but Elizabeth quickly rose to her feet, neither frightened nor hurt, and laughingly besought permission to mount the horse again, which the terrified governess refused to grant. The happiest time in the whole year to her was when the warm spring days made it possible for them to return to Possenhoffen and she could enjoy unlimited freedom once more. She was passionately fond of flowers, and it is still told among the Bavarian Alps how “Liese of Possenhoffen” used to scramble about the wild unbeaten mountain paths to return at last with her arms full of edelweiss.

Her father taught her to play the zither, and she often went with him on long tramps among the Alps, stopping now and then for rest and refreshment at some hut where they would play dance music on their own instruments or on some they found there. On one occasion they had done this in a remote region where the huntsman and his daughter were not known, and the people gave the pretty child a piece of money in payment. Elizabeth always kept it. “It is the only money I ever earned,” she once said, when showing it to an acquaintance. There was never much pocket money for her to buy presents with, and she used often to spend the evenings knitting stockings for her mountain friends or sewing on some piece of needlework. The country folk about Possenhoffen idolized the little Liese, and when overtaken by one of the autumn storms she would often take refuge in their huts, quite alone, and sit down by the fire to chat and laugh with old or young. Her parents saw nothing amiss in this. Duke Max liked nothing better than to enter into the lives of his people, and when the mother was told how her daughter ran about with her brothers or played the zither in hovels while the peasants danced she but smiled indulgently, saying: “She is only a child. I will take her education in hand later on.”

This free life at Possenhoffen taught the little Elizabeth to regard the woods and mountains as her second home, and the most splendid halls of the palace seemed small and stifling to her in comparison. It no doubt exerted a marked influence on her later development, and possibly furnished a clue to her character as Empress of Austria. Had her childhood been different, she would unquestionably have been better fitted for the position she was soon to occupy.

One of the first journeys Elizabeth made with her parents and sisters was to Ischl. It was there that Franz Joseph’s parents were in the habit of spending the summer months, and the two sisters, the Archduchess Sophie and the Duchess Ludovica, had agreed to meet here in the Summer of 1853. The five years that had passed since the Emperor’s accession to the throne had been years of struggle and anxiety. Only a few months before, he had been wounded by the dagger of an assassin. The internal disorders of the Empire, however, had not prevented his name from being linked with that of various European princesses,—reports which were finally silenced by his clever and strong-willed mother, who swayed him completely and had determined that a princess of her own house should share her son’s double throne. This was natural enough. Both the Wittelsbachs and Hapsburgs are among the oldest reigning families of Europe, both have remained loyal to the Roman Catholic Church, and for six hundred years alliances between them have been common.

The Archduchess had heard much of the talent and amiability of her sister’s daughter Helene. She and the Duchess Ludovica were on the best of terms and had already secretly decided on the marriage. It only remained for the young people to meet and take a fancy to each other,—a matter of some concern to the Emperor, who, though an obedient son, was also a passionate admirer of the fair sex. It was certainly mutual attraction that drew Franz Joseph and Elizabeth together, though there are many tales told of how their betrothal came about. The following account, however, is probably nearest the truth.

On the sixteenth of August, 1853, the Emperor went to visit his parents at Ischl and meet Max Joseph’s family. As the travelling carriage rolled along the dusty highway, his adjutant suddenly uttered a cry of admiration:

“Look, your Majesty, look yonder!”

Franz Joseph drew out his field glass and caught a glimpse of a beautiful child playing with a flock of goats on a meadow near by. The next instant the road turned and the town appeared in sight.

An hour later he was sitting with his mother when a young girl burst into the room, unannounced, with a bunch of wild roses in her hand. She wore a short white frock, and a mass of silky chestnut hair fell in soft waves about her slender figure. It was the same youthful beauty he had seen from the carriage. It was the first time they had met, but she recognized him at once from the portraits she had seen, and without a trace of embarrassment approached and greeted him, saying heartily:

“How do you do, cousin?”

“Who are you?” inquired the Emperor, almost fearing lest the lovely apparition might vanish before his eyes.

“I am Elizabeth!”

The smile in the wonderful blue eyes won his heart upon the spot.

A few hours later he was presented to the Princess Helene, who, if not beautiful, was a bright, intelligent-looking girl with an air of great distinction. Had not Franz Joseph seen Elizabeth first, Helene would undoubtedly have become his Empress. The same day he was to dine with his aunt and uncle. As he entered their hotel in Ischl, he heard two voices from behind a half-closed door.

“I beg of you not to go out, Princess!” said one; “you know it has been forbidden.”

“That is the very reason why I want to,” retorted the other in soft girlish tones which he recognized; and the next moment Elizabeth stood before him, all smiles and blushes.

“Why must you not go out?” he asked.

“Because I am only a child and am not expected to appear till my older sister is married. It is all your fault, and I shall have to eat by myself, too!”

“Princess, what are you thinking of?” cried the governess, who now made her appearance, crimson with anger. “Pardon, your Majesty!” she added, turning to the Emperor, “but I have had strict orders.”

Without heeding her, he offered his arm to the young girl.

“Let us go out together, cousin,” he said.

“No, no, I dare not!” she replied in alarm. “Papa would be furious.”

“Come back!” cried the governess, and taking advantage of her pupil’s momentary hesitation, she drew her into the room and closed the door with a low courtesy to the Emperor.

At the close of the meal Franz Joseph turned to the Duke. “I have a favor to ask of my kind host,” he said. “Is it not the custom in Bavaria for the children to come in after dinner? I would like to become better acquainted with your second daughter, whom I saw for a moment at my mother’s this morning.”

All exchanged glances, and there was a moment’s silence, as Duchess Ludovica felt all her hopes for Helene slipping away. The Duke replied:

“It shall be as you wish, your Majesty,” and in a few moments Elizabeth made her appearance, blushing and frightened.

Franz Joseph had not a high opinion of women as a rule. Young as he was, he had already had some experience of them, but this lovely, innocent child wrought a sudden change in him, and through the political clouds that darkened the first years of his reign love flashed like lightning into his heart. That evening the Archduchess Sophie gave a ball at which both nieces were present. The court, suspecting that fateful events were brewing, watched the Bavarian princesses curiously. The Archduchess showed marked favor to Helene; the son devoted himself to both. When during the cotillion he handed Elizabeth a magnificent bouquet of roses, the interest increased. Would the mother yield to the son, or the son give way to the mother?

Franz Joseph’s choice was already made, however, and at the close of the ball he announced that he would have no one but Elizabeth for his wife. The Archduchess’ surprise and chagrin at the failure of her cherished plan knew no bounds, but she determined not to oppose her son’s choice. She had wanted him to marry her other niece, hoping to rule her as she did him; if the crown were to go to an immature child of sixteen instead of her clever sister of twenty, no doubt it would be so much the easier.

At nine o’clock the next morning the royal carriage stopped before Max Joseph’s door. The Emperor hastened up the steps, asked for an interview with the Duke and the Duchess, and then and there made a formal request for the hand of Princess Elizabeth. This was an affront to Helene that neither her father nor her mother found it easy to endure, but the suitor was persistent. If he could not have the one he loved, then he would not marry at all, and at length they were forced to yield. Franz Joseph wanted Elizabeth to be notified at once, but they would not consent to force her in any way. She was still as much a child in heart and feeling as in appearance, and when first told of the Emperor’s wishes she clasped her hands in dismay, exclaiming:

“It is impossible! I am much too young!”

Love had entered her dreams, however, even if her heart was not yet awakened. Franz Joseph’s impetuous wooing appealed to her impulsive nature. She was attracted by his person and his temperament, and without pausing to reflect, she joyfully promised to be his wife. The betrothal took place on the Emperor’s twenty-third birthday, August 18, 1853.

Great were the public rejoicings when the news reached Vienna. The glamour of romance that enveloped the affair appealed to the popular fancy, and a thousand tales were woven about the lovely child who was to be the bride of their young sovereign. Her pictures were scattered broadcast throughout the Empire, and people were never weary of dwelling on her beauty and the simple home life of her early days. During the month that the betrothed pair remained at Ischl with their parents, crowds flocked thither daily to gaze upon their future Empress, and returned full of praises of her modesty and charm.

On the twentieth of April, 1854, Elizabeth, accompanied by her parents and her two oldest sisters, started on her bridal journey to Vienna. Peasants from all the surrounding country thronged the streets of her native city through which she passed, and, overcome with the grief of parting, she stood up in her carriage and waved a tearful farewell to the cheering crowds.

The steamboat Stadt Regensburg conveyed the party from Straubing to Liutz. Work was everywhere suspended as on a holiday, and nothing was thought of but the coming of the long-awaited princess. At Liutz they had to go ashore to change boats, and there Franz Joseph met them, hurrying back to Vienna, however, so as to be there to welcome his bride. The town was buried in flowers. A magnificent arch had been erected. Bonfires burned on all the surrounding heights, while torchlight processions, theatrical performances, and serenades concluded the festivities of the day.

The next morning, April 22, the journey down the Danube was resumed. The Franz Joseph, which carried them from Liutz to Mussdorf, was covered with roses from stem to stern, the cabin hung with purple velvet, and the deck transformed into a flower garden. It was a beautiful spring morning. Banners waved from every roof and tower, and the river banks were lined on either side with cheering throngs, eager to catch a glimpse of their future Empress. What they saw was a slender, white-robed figure hastening from one side of the vessel to the other and bowing continually in response to the storms of greeting of which she never seemed to tire.

Meanwhile, at Mussdorf, the landing place for Vienna, great preparations had been made to welcome her. Since early morning crowds had been flocking thither, waiting with imperturbable patience and struggling to keep the places so hardly won. Near the bridge a pavilion had been erected with a wide portico whose gilded turrets and cupolas gleamed afar, and by noon it was filled with nobles, prelates, high officials, and deputies from the middle classes. Stationed upon a terrace to the right were the foreign ambassadors with their ladies; on the left sat representatives from Vienna and other cities under the Hapsburg rule. The weather had been threatening in the early part of the day, but towards noon heavy gusts of wind scattered the clouds, leaving the bluest of skies to welcome the bridal party. At half-past six the boat touched the shore amid the booming of cannon, strains of music, and the solemn pealing of bells. Franz Joseph hastened forward to embrace his bride, closely followed by his parents, the Archduke Franz Karl and the Archduchess Sophie, who embraced Elizabeth and then led her back to the bridegroom.

At last came the long-awaited moment when Elizabeth, leaning on the Emperor’s arm, entered the Austrian capital. From thousands of throats came the shout, “Long live the Emperor’s bride!” The sound was so overwhelming that Elizabeth stood for some moments by her lover’s side as if spellbound; then, as her glance swept slowly over the excited throng, she smiled charmingly and waved her handkerchief to the delighted spectators. Many years have passed since that day, many misfortunes have overtaken Austria and the house of Hapsburg, but eyewitnesses are still living who remember that moment and tell of the picture the fair young princess made as she then appeared in all her exquisite loveliness.

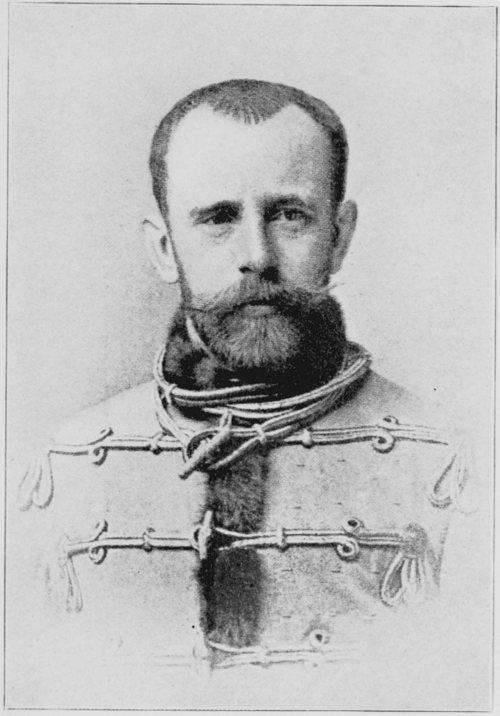

EMPEROR FRANZ JOSEPH in his twenty-eighth year

The progress from Mussdorf to Schönbrunn was a continuous ovation. At half-past seven they reached the gates of the old palace, where the Emperor once more bade his bride welcome before leading her up the great staircase, which was decorated from top to bottom with tropical plants and flowers. On the following day the state entry into Vienna took place. Every house had been decorated by loving hands, and the streets through which the bride was to pass were perfect rivers of flowers. The Elizabeth Bridge, which connected Vienna with the suburb of Wieden or “An der Wien,” was opened that day and given the name of the Empress.[1] Here the mayor and council of the city were stationed to welcome her. About the eight statues of famous men which adorned the bridge, thousands of rare shrubs and blossoms from the hothouses of Princes Lichtenstein and Schwarzenberg, the fragrance of which filled the whole town, had been effectively arranged. As far as the Corinthian gate stretched a triple wall of citizens, and at short intervals young girls stood strewing flowers.

The thunder of cannon and pealing of bells from every church tower in Vienna and its suburbs proclaimed the starting of the procession. The golden state coach was drawn by eight milk-white horses with tall white plumes on their heads; the harnesses were covered with gold, and the coachman, footmen, and postilions wore white wigs. On the back seat sat the bride with her mother. Her dress was of red satin, embroidered in silver, and over it she wore a white cloak trimmed with garlands of roses. About her neck was a lace handkerchief, and in her beautiful hair sparkled a circlet of diamonds, twined in which was a wreath of red roses. Never had Elizabeth more fitly deserved the name so often given her, never had she more perfectly looked “The Rose of Bavaria.”

Early on the morning of April 24, 1854, Te Deums were celebrated in all the churches of Vienna and the august pair attended high mass in the court chapel. By three o’clock in the afternoon the crowds about the Hofburg and the Church of the Augustins, where the ceremony was performed, were so great that barriers had to be erected to keep a way clear for the coaches to pass. From all parts of the Empire and of Europe guests had been pouring into the capital. On the preceding day alone, seventy-five thousand strangers arrived, a most extraordinary number for those days. Even the Orient—Alexandria, Smyrna, and Salonica—sent representatives to the wedding.

The famous old Church of the Augustins was gorgeously decorated for the occasion. Above the high altar rose a canopy of white velvet embroidered with gold, under which were placed two prie-dieux, also of white velvet. The walls and columns of the church were hung with damask and costly tapestry and the floor was carpeted. From a hundred candelabra countless tapers shed a soft but brilliant light. The Augustin Gallery, which led from the inner apartments of the Hofburg to the church, was similarly decorated and illuminated.

The marriage was to take place at seven o’clock in the evening. By six every available space in the church was filled with invited guests. The gay uniforms of the officers, the many-colored and picturesque court dresses of the Hungarian and Polish nobles, the sparkling jewels of the ladies, the gold-embroidered coats of the ministers and distinguished guests, the red robes of the cardinals, the fantastic costumes of many of the Oriental emissaries, all united to form a scene of incredible magnificence.

At the appointed time Prince Archbishop Rauscher, the Emperor’s former tutor, with more than seventy bishops and archbishops in their gold-embroidered vestments, assembled in the sacristy. The master of ceremonies informed his Majesty that all was ready, and the procession entered the Augustin Gallery. First came the pages, stewards, and gentlemen-in-waiting; next the privy councillors and high court officials; then the Archdukes with their chamberlains; and, last of all, the Emperor himself, in the uniform of a field marshal and wearing all his orders. Directly behind the bridegroom came his mother, leading the bride on her left. On Elizabeth’s left was her own mother, Duchess Ludovica, and after them followed the ladies of the court led by the Lord Chamberlain.

The bride of sixteen was radiant with all the beauty and happiness of youth. Her wedding gown was of heavy white silk, richly embroidered with gold and silver, over which she wore a loose garment of the same material with long sleeves. A diamond clasp held the long veil of Brussels point lace, and the bridal wreath of fresh myrtle and orange blossoms was secured by a magnificent coronet of diamonds which her mother-in-law had worn at her own marriage and given to Elizabeth as a wedding gift. A diamond necklace encircled her throat, and upon her breast she wore the Bavarian order of Theresa and the Austrian order of the Starry Cross, together with a bunch of white roses.

The Emperor and his bride were met at the door of the church by the Prince Archbishop, who sprinkled them with holy water, after which they knelt on the prie-dieux while the other members of the two royal families took their places. After a short prayer Franz Joseph and Elizabeth advanced to the high altar, made their responses, exchanged rings, and clasped hands. As the Archbishop pronounced the Church’s blessing at the close of the ritual, a salvo of musketry sounded from the regiment of infantry stationed on the Josephsplatz, and the next instant the thunder of cannon proclaimed that Austria had an Empress and Hungary a Queen.

At the time of her marriage Elizabeth was said to be not only the youngest but also the most beautiful Empress that had ever sat on the throne of the Hapsburgs. Her figure was tall and slender, her hands and feet small and well shaped, her features regular and delicate. She had a charming smile, wonderfully expressive dark blue eyes, a beautiful complexion, and a mass of waving chestnut hair that fell about her, when loosened, like a veil, and which she wore either hanging in eight heavy braids or wound like a coronet around her head. With no experience of the world and full of the confidence of youth, she looked forward to her married life as one long holiday. Crowned with love, all hearts should bow before her and she would be the good genius of her people.

But disappointment followed close upon the heels of the first intoxication. If the lower classes were charmed with their Empress, this was far from being the case with an aristocracy that claims to be the most exclusive in Europe, and there were many at court who felt that neither by age nor rank was this daughter of a non-royal Duke fitted to be their sovereign. Instead of being welcomed with open arms, therefore, she encountered only a wall of opposition and intrigue. Far from being the brilliant centre of homage and admiration, as she had dreamed, she was grieved and mortified to find those about her anxious only to deprive her of the honors and influence that were her due. It was most unfortunate that she should have been placed so early in a position requiring the utmost tact and knowledge without having had any training to fit her for it,—a poor bird that had left the home nest before it had learned to fly! In Bavaria she had been a happy, care-free child, beloved by every one and so full of the joy of life that she seemed to carry with her wherever she went a breath of those woods and mountains she so dearly loved. A Wittelsbach by both lines of descent, she had inherited the characteristics of the race, their pride and independence, honesty and courage, to a striking degree. Even these virtues, however, were but so many dangers, since they made it difficult for her to adapt herself to the rules laid down by court life. Her very youth and freshness were out of place at Schönbrunn and the Hofburg. Her ignorance and inexperience, which were well known in Vienna, made it seem probable that she would prove an easy tool at court, provided she were only amused and flattered sufficiently. But this error was soon discovered. With the peculiarities of her race she had also inherited their marked mental gifts, and young as she was, her mind was quick to grasp whatever interested her and to choose or reject with certainty.

Such a nature could not but rebel against the restraint and monotony of court life. Its pomps and ceremonies wearied her from the first, and little as she resembled Marie Antoinette in other ways, she hated etiquette even more than did that unfortunate Queen. The court of Vienna, which had lived by its conventional usages from time immemorial, regarded as natural and necessary the forms that Elizabeth considered ridiculous and childish. She once aroused a storm of indignation by refusing to appear at the customary state breakfast, which consisted of various hot dishes, and ordering some bread and sausage and a glass of Munich beer to be brought to her in her own apartments. On another occasion, when presiding at one of her first court ceremonials, she took off her gloves, contrary to all custom and tradition. An elderly court dame hastened to remind her of her mistake.

“Why should I not?” inquired the Empress.

“Because it is against the rules of etiquette,” was the answer.

“Then in future let it be proper to break the rule!” she declared.

No young husband could have been more devoted than Franz Joseph was to the bride he had found for himself without the aid of ambassador or envoy. “I am beloved as if I were a lieutenant, and as happy as a god!” he wrote to a friend just after the wedding.

And Elizabeth did truly love him, but not as he did her. In spite of the intensity of feeling that showed itself in after life, there was a certain inborn coldness in her nature that made it impossible for her to share his ardor or to understand him always. But it often taxed his devotion and patience to reconcile this freedom-loving child of nature to the restraints and obligations of her new position, and he was many times called upon to make peace between the older court ladies and their young mistress. He would gladly have loosened her bonds somewhat, but dared not introduce new ways and customs.

The Archduchess Sophie had hitherto reigned supreme at court. She was a remarkably clever woman, and all through the first difficult years of her son’s reign had proved a valuable support to him, and acquired an influence which she had no intention of surrendering into the hands of her seventeen-year-old niece. Two women, though of the same blood, could scarcely have been more different. The Archduchess was ambitious and worldly; the Empress cared nothing for place or power. Sophie was completely under the influence of the priesthood; Elizabeth worshipped God in nature, but avoided all religious ceremonies and hated priests. The older woman expected to find it easy to govern this child who had so unexpectedly received the imperial crown, through her vanity and inexperience, but finding herself mistaken, she resorted to other means. Elizabeth, as we have seen, had come to Vienna full of hopes and dreams, expecting naturally to occupy the first place in her husband’s life and court; but every attempt to assert her right as Empress was deliberately set aside by the Archduchess, who crushed her hopes and dispelled her dreams with a cruel hand, regardless of her feelings.

As for the court, “Madame Mère,” as she was called, was a power whose friendship it was prudent to possess. It was believed, moreover, that Franz Joseph, whose fickleness and susceptibility in matters of the heart were well known, would soon tire of his young wife. Elizabeth’s inexperience made it impossible for her to battle successfully with court intrigues, and it was plain that the mother-in-law would be victorious in the struggle between them. The Emperor always treated his wife with the greatest care and consideration, but misunderstandings gradually arose between them, fostered by wounded pride on her side and on his by the Archduchess Sophie’s constant efforts to lower her in the eyes of her son. Dearly as she loved Franz Joseph, Elizabeth held herself more and more aloof from him for fear of seeming the troublesome child her mother-in-law called her, and an expression of quiet sadness grew upon her. But there were moments, too, of hot revolt against the cold, selfish world in which she lived, and these did not mend matters for her. Rash and thoughtless, she struggled against this unceasing persecution. She treated the Archduchess’ followers with marked disdain and gave her confidence to others who deceived and betrayed her.

Nothing had been originally farther from the wishes of the young Empress than to fill her throne in solitary state, surrounded only by a few chosen families of noble birth. What she most wanted was to go about among the people and get acquainted with her new subjects, and during the early part of her married life she was often seen in the streets of Vienna. Wherever she went crowds gathered, struggling and pushing good-naturedly to get as near a view of her as possible. One day she went out to walk, accompanied only by one of her ladies-in-waiting and without informing any one of her intention. On one of the principal squares, seeing something in a window that attracted her, she entered the shop, but on turning to go out again was unpleasantly surprised to find hundreds of faces peering in at the door and windows, and it was only with the aid of the police that she was able to reach the street again. This incident excited the greatest disapproval at court.

“Her Majesty seems to imagine herself still in the mountains of Bavaria. She forgets that she is the Empress of Austria and what she owes to her husband’s position,” was whispered about her.

Discouraged at the result of her attempts to mingle with the people, she thenceforth avoided appearing in public as much as possible, confining her walks to the secluded portions of the palace gardens or the park about Schönbrunn. But even this did not satisfy the court, which now found fault with her for neglecting to show herself before the people on every possible occasion. This hostility and opposition that met the young Empress at every turn only made her retire the more within herself, and really inflicted an irreparable wrong, for it developed in her an inherited love of solitude that, once acquired, soon became too fixed ever to be renounced.

Meanwhile the outlying portions of the Empire—Bohemia, Moravia, Galicia, and Hungary—were waiting anxiously to welcome the imperial pair, and soon after the wedding they began a series of short journeys.

In September, 1856, they made a visit to the Austrian Alps that is still remembered and talked of even in the remotest mountain valleys. From Heiligenblut, where they spent the night, the Emperor and Empress climbed the Grossglockner. About four o’ clock in the morning, after hearing mass in the little parish church, they began the ascent, accompanied by two experienced guides, Elizabeth riding part of the way, while her husband walked. During the walk he gathered a bunch of edelweiss growing on a steep cliff and handed it to his wife, saying, “This is the first edelweiss I ever picked.”

At the Wallner Hut, as it was then called, the Empress stopped to rest, while Franz Joseph climbed to the lofty Glockner-saddle, and it was in remembrance of this visit that the Wallner Hut received the name of Elisabeth-ruhe. From there they went to Steiermark and thence to Gratz, where they arrived on the eleventh of September, and where, as at all other places, they were received with the greatest enthusiasm. In November of the same year they visited the Italian provinces which at that time formed part of their dominions. Owing to the political disturbances of the period and the feeling of the Italians against Austria, it was feared the sovereigns would meet with a cold reception; but the “mistress of the Adriatic” had decked herself magnificently to greet the young Empress. The streets and market-places were brilliantly illuminated and gorgeous masked balls were given in her honor. All hearts were won by Elizabeth’s beauty and charm of manner, and the delighted Emperor said to her:

“Your smile has done more toward conquering the people than all my armies have been able to accomplish!”

Franz Joseph, as we have seen, was a mere youth when his uncle, the Emperor Ferdinand, abdicated in his favor and retired to Prague to end his days. The young sovereign had scarcely ascended the throne when rebellion broke out in Hungary, and unable to quell the disturbance alone he was forced to seek aid from Russia. Czar Nicholas placed one hundred thousand men at his disposal, and the revolt of 1848-1849 was crushed with a firm hand. Countless towns, villages, and estates were laid in ashes, and the country was left bleeding from almost incurable wounds. The people bore their hard fate in sullen defiance, and five years later, when the Emperor married, time had done little to soften their hatred of Austria.

The pardon that Franz Joseph had granted on his wedding day to all political offenders in his dominions formed one step toward reconciliation, but the first real signs of a more friendly feeling were due not to him but to the Queen. It was her smile that finally appeased the wrath of the Hungarians, her beauty and goodness that laid the foundation of more amicable relations between them and their sovereign. She devoted herself assiduously to the study of their language, one of the most difficult in Europe, interested herself in the art and customs of the country, and showed such deep concern for their welfare that she is said to have wept on occasions when her husband refused to grant their wishes.

The reason for Elizabeth’s sudden and strong attachment to this hitherto unknown country could have been only a psychological one. When she first came to Vienna, she was impressed with the violent prejudice that existed at court against the Hungarians. Each attempt of that liberty-loving people to throw off their chains was regarded as a fresh crime by the Archduchess Sophie and her adherents, and the Empress heard much harsh criticism of her subjects beyond the Leytha. Her natural perversity and independence, however, led her to investigate the matter for herself, and she soon gained a very different idea of the open-hearted, chivalrous Hungarians, whose natural character was so like her own. Hoping to learn more of the inner life of the people by means of the language, she began the study of it with a zeal and industry that shrank from no difficulties till in time she acquired perfect mastery of it even to speaking it like a native.

“Queen Elizabeth speaks our language without a trace of foreign accent,” said the Hungarian poet, Maurus Jókai, “speaks it like a peasant woman and without any of the affectation common with most of our court ladies.”

Her first teacher was an old professor named Homokh, with whom she learned the grammar and to read easily. But this did not satisfy her. She wanted a thorough knowledge of Hungarian literature and engaged as her instructor Dr. Max Falk, at that time a journalist in Vienna. His methods were far less tedious than those of Homokh, and she began to read the best passages of Scripture, together with a history of the people. He also gave her for translation into Hungarian the French correspondence between Joseph Second of Austria and Catherine Second of Russia, published by Arnath, a task she found most delightful. Her tutor was charmed with her enthusiasm and the accuracy with which she performed her duties as pupil. One morning as she handed him her written translation, she said:

“All day yesterday my time was taken up with audiences, and in the evening there was a court concert. After that I was so tired I went directly to bed, but no sooner had I lain down than I remembered my Hungarian translation had not been written. So I tore a leaf from the almanac that lay on a table beside my bed and did it there. Excuse the pencil.”

It was not until May, 1857, however, that she made her first visit to Hungary. Her arrival was hailed with enthusiasm, and the young Queen was everywhere greeted with shouts of joy. An extensive tour of the country had been planned by the sovereigns, but a sad event forced them to abandon it.

The Emperor and Empress had two children at this time, the little Archduchesses Sophie and Gisela. Scarcely had the court established itself in the royal palace at Ofen when word was received of the illness of the two-year-old Sophie. The physicians’ first reports were reassuring, but on reaching Debreczin, May 28, the despatches announced a change for the worse. The anxious parents hastened back to Budapest, where on the next evening they heard that their oldest child was dead.

Elizabeth left Hungary with tears in her eyes. Her first great sorrow had befallen her on her first visit among the Magyars, and it may have been that grief attached her still more closely to this people whom in after years she loved so well and by whom she was adored as a sovereign and reverenced as a guardian angel.

Not only the Emperor and his family but the whole nation were anxious for an heir to the throne, and the disappointment was great when on May 5, 1855, the Empress gave birth to a daughter, who was called Sophie Dorothea, after the Emperor’s mother. Elizabeth was too young and inexperienced to understand this, though she could not fail to read the evidences of it in the faces of those about her. Still greater dissatisfaction greeted the birth of a second daughter, Gisela, in July, 1856. This daughter was married in 1873 to Prince Leopold of Bavaria, second son of the present Prince Regent.

The Empress looked forward to her maternal duties with the greatest happiness, and asked nothing more than to devote herself to her children. But even this was not to be allowed her. The Archduchess Sophie had the little girls removed almost immediately to a remote wing of the Hofburg, leaving the young mother alone in her splendid apartments, where she had always felt herself so much a stranger. Involuntarily she compared her lot with that of her mother, the mistress of Possenhoffen, whose busy life was filled with work and noble sacrifices for her flock of children, while the Empress of Austria had nothing left her but to preserve her beauty and exhibit her toilettes. The importance of providing the Empire with an heir was impressed upon her so constantly that she was puzzled and asked her own mother once in a moment of confidence:

“If I should have no son, do you suppose that Franz would follow Napoleon’s example and cause our marriage to be annulled?”

“Do not think of such things, my child,” replied the Duchess. “You know that Franz loves you devotedly.” Then she continued: “There are two sorts of women in this world,—those who always get their own way and those who never get it. You seem to me to be one of the latter. You have great abilities and do not lack character. But you have not the faculty of stooping to the level of your associates, or adapting yourself to your environment. You belong to another period, that in which saints and martyrs existed. Do not attract notice by being too obviously the first or break your own heart by fancying yourself the latter.”

At last, shortly before her twenty-first birthday, her dearest wishes were gratified, and on August 21, 1858, a son was born to the imperial pair, a beautiful child though somewhat delicate, in whose cradle the delighted father hastened to lay the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The next morning the good news was carried by telegraph to every corner of the world, a salute of a hundred and one guns was fired from all the fortresses in Austria and Hungary, and the signal was echoed from a million throats, while public enthusiasm was still further increased when the Crown Prince, at his christening, received the name of his great ancestor Rudolf of Hapsburg. The popularity of the Empress was at once restored. Her enemies were silenced, her mother-in-law contented, and she herself for a time was happy.

“No one has seemed to need me until now,” she declared pathetically, “not even my little girl whom they keep from me as much as possible. But I will not permit my boy to be taken away and given to the care of strangers. He will need me and we will be happy in each other.”

Again, however, she was mistaken. Rudolf was installed as soon as possible in a remote part of the palace, the Archduchess insisting that it was not suitable for the heir to a great empire to be brought up by a young mother who as yet did not even know how to conduct herself. When Elizabeth begged to be allowed the care of her own child and dwelt on the comfort it would be to her, her mother-in-law declared indignantly that it was absurd to talk of the need for comfort when she had everything in the world to make her happy. From Sophie’s point of view indeed this was perhaps true, but Elizabeth was of a different stamp, and no outward luxury could make up to her for disappointed hopes or an empty heart. Matters grew still worse for her when in the Summer of 1857 the Emperor’s second brother, Ferdinand Maximilian, married Charlotte, the daughter of King Leopold First of Belgium. This aspiring princess attached herself at once to the court party and became a great favorite with her mother-in-law.

Meanwhile heavy clouds were gathering on the political horizon. Among Franz Joseph’s Italian subjects the ferment was strongest, but throughout the whole Empire there was great discontent. It was well known that the Archduchess Sophie held the reins of power, and that it was she who declared war or concluded peace,—a state of things that caused much opposition in diplomatic circles, while all classes united in condemning this so-called “petticoat government.”

When the war with France and Sardinia broke out in 1859, it was less a question of the country’s incontestable rights than of the maintenance of the power of the Jesuits. Elizabeth plainly saw the mistake her husband was making in allowing himself to be guided so much by his mother in political matters and longed to use her influence with him to prevent it, but she was powerless. No one asked her advice, no one cared for her opinion; so she held her peace. While Franz Joseph was fighting at Solferino and his mother corresponded with foreign courts or held long conferences with statesmen and diplomats, the Empress had to content herself with visiting wounded soldiers and officers from the Italian battlefields. Like an angel of mercy she went about among the hospitals, tasting the food that had been prepared and distributing money and cigars. Her gentle words of pity and cheer carried the more weight since they had none of the sanctimonious tone so common at that time. The halo of piety with which the Archduchess Sophie enveloped all her actions was most distasteful to Elizabeth, who did not attempt to conceal her dislike of the clergy.

Once at a court ball, her train became entangled around the feet of the papal nuncio, who happened to be standing near. With an angry glance the Empress jerked it toward her with such force that the prelate barely escaped a fall,—a scene that was the cause of much suppressed merriment, for it was well known that Her Majesty would quite as gladly have deprived him of his influence at court as upset his person in the ball-room.

The estrangement between the Emperor and Empress gradually increased. Affairs of state, the distractions of court life, together with Franz Joseph’s growing disposition to return to the habits and pleasures of his bachelor life, all tended to widen the breach between them. The Emperor was naturally kind and affectionate, but he also had weaknesses which on closer acquaintance proved him to be far from the ideal character his young wife had imagined. She was too proud to stoop to unworthy means to retain his attachment for her, and her increasing sadness and reserve as well as her disinclination to take part in the festivities of the court, only wearied and helped to estrange him the more, as he felt in it a silent reproach.

Elizabeth had expected to find complete happiness in his love, and her solitary position at court in an atmosphere so hostile had made her cling yet more closely to this hope. By this time, however, reality had dispelled this illusion. She did not feel that she had lost her power over him or even his love, but her faith in him was shaken and her confidence destroyed. To be pitied was unendurable to the proud daughter of the Wittelsbachs. She hid her disappointment from the world and retired more and more within herself. At length her health began to give way. She struggled bravely against her growing weakness, but was finally seized with an illness which her physicians could neither understand nor cure. After repeated consultations it was decided that her lungs were affected, and a journey to Madeira was advised, that place being at the time regarded as the most favorable one for troubles of that kind. For a long time she refused to follow their advice, but finally early in the year 1861 she consented to go. Those who saw her start doubted whether she would ever return, and she herself had little hope of regaining her health.

She left Europe wrapped in mist and cold. When she landed in Madeira, a week later, she was greeted by blue skies, brilliant sunshine, and tropical vegetation. The villa she was to occupy was charmingly situated, with wide verandas, terraces overlooking the sea, and a chain of mountains stretching behind it. Under these new conditions the Empress began at once to improve and by the first of March was able to make daily excursions about the island, which was now ablaze with flowers. She even grew to look upon her illness as a deliverer. It had enabled her to escape from the oppression of court life, and the quiet solitude taught her patience and gave her strength to bear the trials still in store for her. She lived over the struggles of her life at Vienna, so different from the happy days of childhood in her peaceful Bavarian home, the memory of which, together with the tales and legends she had heard at her father’s knee, returned so often and so vividly to her mind.

She rose early every morning, studied, and practised her music, wrote daily letters to her husband and her parents, and took long walks upon the shore. Once during her stay on the island she had a visit from her sister Helene, who had married the Prince of Thurn and Taxis. Vessels rarely stopped there, and her life was most uneventful; but nature, which she had always loved, now became doubly dear. It was there too that she discovered a new interest in the world of poetry, and books soon became like friends to her. In the long solitary evenings she would take refuge in them from the restless longings of her heart and forget for the time her cares and troubles. Meanwhile, in Vienna, news of the Empress’ death was daily expected, but instead came word that her cough grew better, and at last it was announced that the climate of Madeira had done its work and she would be allowed to come back after a stay of four months.

On the way home in the middle of May a frightful storm arose, and the yacht Victoria and Albert (which had been loaned her by Queen Victoria of England for the return voyage) was tossed about like a nutshell on the angry sea. The Empress, however, refused to leave the deck in spite of all entreaties and the mountainous waves that threatened to sweep her over the side of the vessel. She even had herself fastened to the mast that she might safely enjoy the wonderful spectacle. On the eighteenth of May she was met off Trieste by the Emperor, who had come out on a warship to welcome her with an escort of five steamboats carrying notables and citizens with bands of music. At ten o’clock a shot from the castle announced the approach of the flotilla, and amid thundering salutes from batteries and warships the Emperor and Empress entered the harbor and landed near Miramar, the pleasure palace built for Archduke Maximilian, afterward Emperor of Mexico. A celebrated painting depicts the meeting between the young Archduchess Charlotte and Elizabeth on the great marble terrace overlooking the sea.

At Baden Elizabeth saw her mother-in-law and children again, and five days later the imperial pair entered Vienna, the railway station of which was decorated with flowers in honor of the occasion. They drove to the palace in an open carriage amid the cheers of the populace, whose joy over the Empress’ recovery found further expression the following day in praise services held in all the churches of the city.

Elizabeth’s sojourn in Madeira did not bring the permanent improvement that was hoped for. A few weeks after her return to Austria the cough returned, and fearing that the nature of her illness had been mistaken, her parents’ physician who had had the care of her in her youth was sent for. He decided that she was suffering from acute indigestion and that a change was imperative. This time the place of resort chosen was the island of Corfu, where she arrived safely soon afterward, accompanied by her physician. The Empress was charmed with the villa that had been secured for her, about half an hour’s drive from the capital. It was surrounded with gardens and large grounds, and in a shorter time even than at Madeira she began to show the beneficial effects of the climate.

Not far from the house was the mountain Aja Kyriahi, on the summit of which stood a small church surrounded with cypresses. Every morning before sunrise she climbed to this spot, and whenever in after years she came back to Corfu she always visited it.

At the end of two months her health was quite restored, and toward the close of October she left for Venice, where she held her court that Winter. Her return to Vienna the following August, after a sojourn in the Tyrol, was the occasion for almost as much enthusiasm as on her wedding day, the people everywhere showing the most touching proofs of their sympathy and devotion.

But again her stay in Vienna was destined to be of short duration, for after the lapse of a few weeks, unexpectedly and without confiding her intentions to any one, she left the capital, to seek refuge in travel from the troubles and complications of her position there. The Emperor followed to try and bring about a reconciliation, but she refused to meet him, and he returned at length to Vienna weary and disheartened. With her capacity for loving and her pride Elizabeth must have suffered intensely from the slights and disappointments of her married life, and fresh persecutions on the part of her mother-in-law, who had already succeeded in estranging her husband and children from her, no doubt led her to this step.

Months went by, and still the Empress continued her wanderings. There was a general feeling of sympathy for the Emperor, but in spite of this many began to take the part of his young wife, and when the Archduchess Sophie condemned her too harshly, believed that had it not been for “Madame Mère,” her daughter-in-law would never have gone away. The estrangement lasted for several years, but Elizabeth, at the urgent entreaties not only of the court but of her own family, agreed to return to Vienna once or twice a year to fulfil the state duties required of her. She remained no longer than necessary, however. The joys of travel had become too dear to her, the constraints of court life too irksome.

Franz Joseph meanwhile was growing more and more unreconciled to this state of affairs. The health of the Crown Prince was causing some anxiety, and his Majesty was urged to make his peace with the Empress. Elizabeth accordingly was approached by her mother, the Duchess Ludovica, for whose opinion she had the greatest respect, and who finally convinced her that it was her duty to go back to her children. Time and loneliness too had softened the bitterness of her feelings and awakened a mutual desire for reconciliation. Outside events also helped to bring about the reunion. Misfortune had overtaken Austria: the war of 1866 had driven the Hapsburgs from Italy and Germany, and Elizabeth, roused to sympathy, turned her face homeward, feeling that her place was with the Emperor and his people. Though still young in years her sorrows and trials had robbed her of her youth, and she came back a woman strong and self-reliant, caring little for court life, but devoting herself to hospital work among the wounded soldiers with an energy and self-sacrifice that earned her the reverence of all. Day after day she spent at the bedsides of the suffering, speaking to each in his own language and seeking to satisfy his wants. One man, named Joseph Feher, had refused to have his arm amputated, but the Empress begged him so earnestly to consent to the operation that he finally yielded, and she wrote to his mother that she would have her son taken to the palace of Laxenburg and provide for his future. Another day she came upon a soldier whose head had been so nearly severed that the physicians had no hope of saving him. Sitting down beside him, she asked if he had any last requests that she might fulfil for him. In a faltering voice he answered:

“Since I have had the happiness of seeing the Empress at my death-bed, there is nothing left to wish for in this world. I die happy!”

Wherever she appeared the weakest tried to lift themselves at her approach. Arms were outstretched to touch her as she passed, and when she left, there was a general murmur of—

“God bless our Elizabeth!”

Again the Archduchess Sophie’s schemes for the house of Hapsburg proved disastrous, and Franz Joseph’s eyes were opened at last to the fact that her sway had been as unfortunate for the country as it was fatal to his domestic happiness. In these bitter days of defeat and humiliation he learned to value the Empress at her true worth. She now became his real companion. In the latter years of her life he often consulted her in regard to affairs of state, and she might have exercised a much greater power in politics had she so desired. But the only matter of government in which she ever cared to have a voice was in regard to Hungary, in whose welfare she always felt the deepest interest. After the Austrian losses in 1866 she once said to Count Julius Andrassy:

“It distresses me to have things go wrong in Italy, but if anything were to happen to Hungary it would kill me!”

One Summer while visiting some baths, she climbed a near-by mountain on the summit of which a small chalet had been built. As they entered, her companion, seeing a visitor’s book on the table, wrote in it “Elizabeth, Empress of Austria.” Thereupon her mistress drew off her gloves and, taking the pen, added in Hungarian, “Elizabeth, Queen of Hungary.”

This mutual attachment proved a valuable safeguard during the war of 1866, when the Prussians threatened to advance on Vienna. It was thought safest for Elizabeth and the little Crown Prince to retire to Budapest, where she was received with an enthusiasm little short of Maria Theresa’s memorable reception. There is no doubt that the devotion of the people to the Queen was largely instrumental in bringing about a better feeling between Austria and Hungary, while still another proof of this devotion was their special request that she might be crowned together with the King, an event that had never before occurred in the history of the country.

It was not until the eighth of June, 1867, however, that the coronation took place. The ancient city of Pressburg had been the scene of all former coronations, but on this occasion the ceremonies were to be held for the first time in Ofen and Pesth, or Budapest, as it is now called, which had been made the capital in 1848. The city is one of the most beautifully situated in all Europe. On an almost perpendicular rock stands the royal castle, an imposing structure of great antiquity, and at its foot, surrounding it on three sides, lies Ofen. The flat and more modern town of Pesth is to the left, and beyond it extend boundless plains.

Both cities were in gala attire to welcome the sovereigns. In every direction as far as the eye could reach was a sea of waving flags and pennants, and on the spire of the Rathshaus gleamed a huge crown of St. Stephen. The evening before the ceremony was to take place Franz Joseph and his wife made a visit to the cathedral, which had been magnificently decorated for the occasion, and were greeted everywhere with the wildest enthusiasm. As they were about to leave the church an old man fell from a ladder on which he had perched himself in order to obtain a view of “the good Queen of Hungary.” Elizabeth, who saw him fall, hastened at once to his assistance,—an act that called forth renewed cheers when it reached the ears of those outside.

The town was crowded with Magyars from all parts of the kingdom, and sixty thousand troops lined the streets from the railway station to the royal castle, a distance of six kilometres. It was a most brilliant sight as the procession wound slowly down from the castle and crossed the bridge. Franz Joseph made a stately and imposing figure in his crown and coronation robes, but Elizabeth was the centre of all eyes. The sides of the coach were of glass so that she could be seen from all directions. It was surmounted by a large crown and drawn by six magnificent white horses, their long manes and tails interwoven with gold. Elizabeth at this time was in the prime of her majestic loveliness, having not yet reached her thirtieth year, and was considered the most beautiful princess in the whole civilized world. Deafening “Eljens” greeted her all the way to the cathedral, cannon thundered, and white-clad maidens showered roses in her path.

Immediately behind the Queen followed a mounted escort of two hundred young nobles in the gorgeous costume of the Hungarian magnate, covered with gold and precious stones. Their reins and stirrups were similarly adorned, and over the left shoulder they wore a leopard skin. The King and his suite had already taken their places in the cathedral when the Queen entered. She wore a dress of white brocaded satin and a black velvet bodice covered with diamonds. The coronation robe was also of black velvet, bordered with white satin. About her neck was a Hungarian necklace of diamonds, and on her head she wore the Hapsburg coronet that had been made originally for Maria Theresa. It is composed entirely of pearls and diamonds and is valued at three million gulden. While the King was being crowned, she remained seated with clasped hands absorbed in prayer, after which she in turn went through her part of the ceremony. As she resumed her place upon the throne beside the Emperor with orb and sceptre in hand, the whole assemblage joined in a mighty Te Deum which re-echoed from the vaulted roof of the old church.

The coronation ceremonies and the enthusiasm with which she was everywhere received made such an impression upon Elizabeth that she could never afterward speak of them without emotion and always regarded the occasion as one of the happiest times of her life.

The years following the coronation in Hungary were without doubt among the happiest of the Empress Elizabeth’s life. She interested herself in the details of her children’s education, shared her husband’s occupations and anxieties, and resumed her place at court with a dignity and loftiness of purpose that completely silenced her enemies. Conditions too had changed. The Archduchess Sophie had not only ceased to be a ruling power, but was completely crushed by the death of her second son, Maximilian, in Mexico, where he had been condemned to death and shot in 1867, after he had reluctantly accepted the throne. His unhappy wife, whose ambition was partly responsible for these tragic events, became hopelessly insane and it fell to Elizabeth’s lot to support and comfort the grief-stricken family.

The following year, April 22, 1868, another daughter was born to the imperial pair at the royal castle at Ofen. It was the first time for a century that a child of the royal house had been born in Hungary, and the enthusiasm of the Magyars knew no bounds. All night the streets were filled with excited throngs shouting “Eljens” for the King and Queen and the new-born Princess.

The Archduchess Marie Valerie, as she was christened, became the Empress’ favorite child. The two older ones had been kept away from her so long that at first they were completely estranged and it required much patience and devotion on her part to gain their affection and confidence. The Crown Prince, who was ten years old at that time, was a most interesting child and already a universal favorite, but under his grandmother’s influence he had developed a mixture of wayward pride and vanity that troubled his mother greatly and which she strove hard to correct. Fortunately, however, Rudolf was tender-hearted and easily influenced, and she succeeded at last to a large extent in overcoming the evil effects of the adulation and flattery with which the little heir had been surrounded. With Valerie she determined it should be different, and from earliest babyhood her training and education became the Empress’ chief care. She was a delicate child, and the mother watched over her with a devotion that seemed almost like a reparation for what she had failed to give her other children. She was present at the lessons of the two elder ones whenever possible and took the greatest interest in their education, repeatedly impressing on their teachers that she did not want them favored or spoiled. She taught the little girls to dance, and the first dance that Valerie learned was the Hungarian Czardas. She tried to implant in them her own love for Hungary and urged their tutors and governesses “to make them as little German as possible.”

Christmas was the most joyful time in the year for the imperial family, and Christmas Eve, being also Elizabeth’s birthday, was celebrated as a double feast. There were always two trees, the smaller of which the Empress decorated with her own hands for the children. She spent days looking for appropriate gifts for them and the Emperor, as well as the various members of the court, whose individual tastes she always tried to gratify. One day, shortly before Christmas, Marie Valerie came to her mother with a beseeching air and begged that the presents intended for her might be given to some poor children. Much touched by the idea, Elizabeth consented, and from that time there was always another tree laden with gifts for the unfortunates.

The Empress adored flowers. During her rambles she would gather whole armfuls, and even when riding would often spring from her horse to pick wild flowers and fasten them to the pommel of her saddle. Her rooms were always filled with them, and if any choice blossom chanced to please her especially she would carry it at night into her own bedroom. “Mutzerl,” as Marie Valerie was called, inherited this passion of her mother’s, and almost as soon as she could walk she started little gardens of her own at the different places where the court stayed in turn. She was her mother’s constant companion and there was the most touching sympathy and devotion between them. “Valerie is not only a daughter to me,” Elizabeth once said, “but my best friend and companion.”

The Archduchess was remarkable for her simplicity and lack of self-consciousness, as well as for her dignity and kindness of heart. Elizabeth was a firm believer in the virtues of physical exercise and had her daughter taught to ride, fence, and shoot; but Valerie did not altogether share her love of long walks and rides. She had the Wittelsbach love of art and literature, was devoted to poetry and even as a child wrote verses of some merit. Remembering the mortifications her own lack of education had caused her in her early married life, the Empress took special interest in Valerie’s education. She had her taught Latin and Greek, besides several modern languages, and shared her studies as much as possible, often poring over some difficult passage in Greek Scripture with her or learning by heart the most beautiful verses. The young poetess looked upon her mother as her most valuable critic and showed her all her poems which filled several volumes, deferring always to the Empress’ judgment and finding in her praise her greatest reward. She was devoted to both her parents, but as time went on became almost a second self to her mother—the living token of the reconciliation between herself and the Emperor, and a consolation for all her loneliness and suffering.