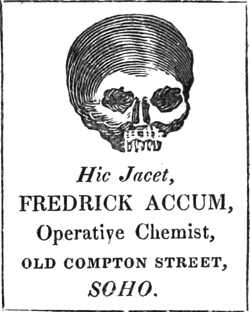

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Title: A treatise on the art of making good wholesome bread of wheat, oats, rye, barley and other farinaceous grains

Author: Friedrich Christian Accum

Release date: October 4, 2019 [eBook #60424]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by deaurider, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The object of this Treatise is to exhibit the chemical principles of the art of making good and wholesome Bread, of Wheat, Oats, Rye, Barley, Rice, Potatoes, and other farinaceous substances used for this purpose in different parts of the world.

I have first taken a view of the chemical constitution of the Alimentary Substances derived from the vegetable kingdom, and have added an Historical iiSketch of the Art of Making Bread. I have elucidated the chemical constitution of the substances of which Bread is made among civilized nations, as well as of various nutritive materials, besides Bread Corn, which are used in different countries as substitutes for Bread.

I have described the chemical analysis of Bread Flour, its immediate constituent parts, their proportions in different kinds of grain, and the method of separating them. I have pointed out the materials more particularly fitted for the fabrication of Bread; I have explained the reason why a variety of Alimentary Farinaceous Seeds, in common use, cannot be made into light and porous loaf-bread, although they are well calculated, under other forms, of being converted into highly nutritious food.

iiiI have explained the chemical distinction which exists between bread made with yeast, as well as with leaven, and bread made without either of these species of ferment; and, lastly, I have given specific directions for making the different kinds of Bread prepared from Wheat, Oats, Rye, Barley, Rice, Maize, Buck-wheat, Potatoes, and other farinaceous substances, as practised in various countries.

| PAGE | |

| PREFACE | i |

| CONTENTS | 1 |

| PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS, CHIEFLY WITH REGARD TO THE CHEMICAL CONSTITUTION AND NUTRITIVE QUALITY OF THE SUBSTANCES OF FOOD DERIVED FROM THE VEGETABLE KINGDOM | 7 |

| HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE ART OF MAKING BREAD | 25 |

| BREAD CORN | 30 |

| 2THE BREAD-FRUIT | 39 |

| SAGO BREAD, and SAGO | 41 |

| CASAVA BREAD, and TAPIOCA | 43 |

| PLANTAIN BREAD | 45 |

| BANANA BREAD | 46 |

| BREAD OF DRIED FISH | 47 |

| BREAD MADE OF MOSS | 49 |

| BREAD MADE OF EARTH | 50 |

| ——————— | |

| ANALYSIS OF BREAD FLOUR | 52 |

| QUANTITY OF FLOUR OBTAINABLE FROM VARIOUS KINDS OF CEREAL AND LEGUMINOUS SEEDS EMPLOYED IN THE FABRICATION OF BREAD, AND DIFFERENT KINDS OF FLOUR MANUFACTURED FROM WHEAT | 55 |

| 3REASON WHY OATS, PEASE, BEANS, RICE, MAIZE, MILLET, BUCKWHEAT, AND OTHER NUTRITIVE GRAINS CANNOT BE MADE INTO LIGHT AND POROUS BREAD | 58 |

| THEORY OF THE PANIFICATION OF BREAD FLOUR | 61 |

| ——————— | |

| UNLEAVENED BREAD | 66 |

| OATMEAL CAKES | 68 |

| MIXED OATMEAL AND PEASE BREAD | 69 |

| UNLEAVENED MAIZE BREAD | 70 |

| UNLEAVENED BEAN-FLOUR BREAD | 71 |

| UNLEAVENED BUCKWHEAT BREAD | 71 |

| UNLEAVENED ACORN BREAD | 72 |

| SEA BISCUIT | 73 |

| 4——————— | |

| LEAVENED BREAD | 79 |

| LEAVENED RYE BREAD | 83 |

| HUNGARIAN RYE BREAD | 85 |

| ——————— | |

| BREAD MADE WITH YEAST | 88 |

| METHOD OF MAKING WHEATEN BREAD, AS PRACTISED BY THE LONDON BAKERS | 93 |

| QUANTITY OF BREAD OBTAINABLE FROM A GIVEN QUANTITY OF WHEATEN FLOUR | 97 |

| HOME-MADE WHEATEN BREAD | 100 |

| TO MAKE PAN-BREAD | 102 |

| BROWN WHEATEN BREAD | 103 |

| MIXED WHEATEN BREAD | 104 |

| ROLLS | 105 |

| FRENCH BREAD | 105 |

| 5MUFFINS AND CRUMPETS | 105 |

| BARLEY BREAD | 109 |

| MIXED BARLEY BREAD | 111 |

| RYE BREAD | 112 |

| TURNIP BREAD | 114 |

| RICE BREAD | 116 |

| POTATOE BREAD | 121 |

| POTATOE ROLLS | 124 |

| APPLE BREAD | 125 |

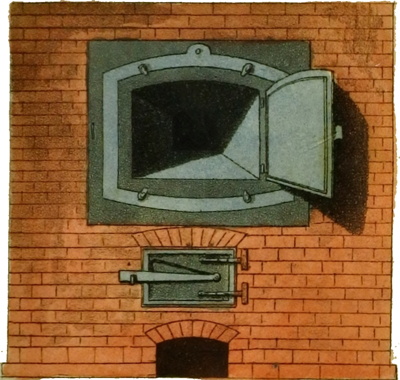

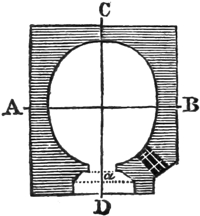

| DOMESTIC OVEN FOR BAKING BREAD | 126 |

| POPULAR ERRORS CONCERNING THE QUALITY OF BREAD | 133 |

| LAWS PROHIBITING THE ADULTERATION OF BREAD AND BREAD FLOUR | 149 |

| ECONOMICAL APPLICATION OF YEAST | 162 |

| ECONOMICAL PREPARATION OF YEAST | 165 |

| 6ECONOMICAL METHOD OF MAKING YEAST, RECOMMENDED BY DR. LETTSOM | 165 |

| POTATOE YEAST | 166 |

| METHOD OF PRESERVING YEAST | 167 |

To most animals nature has designed a limited range of aliment, when compared to the extensive choice allotted to man. If we look into the history of the human race, inhabiting the different parts of the globe, as far as we are acquainted with it, we find, that man appears to be designed by nature to eat of all substances that are 8capable of nourishing him: fruits, grains, roots, herbs, flesh, fish, reptiles, and fowls, all contribute to his sustenance. He can even subsist on every variety of these substances, under every mode of preparation, dried, preserved in salt, hardened in smoke, pickled in vegetable acids, &c.

The Author of Nature has so constructed our organs of digestion, that we can accommodate ourselves to every species of aliment; no kind of food injures us; we are capable of being habituated to every species, and of converting into nutriment almost every production of nature.

When we enquire more minutely into the chemical constitution of the different alimentary materials, which promote the growth, support the strength, and renew the waste of our body, we find that animal substances are not suited to form the whole of 9our daily food; and that, in fact, if long and extensively used, their stimulating effects at length exhausts and debilitates the system, which it at first invigorated and supported. Those, accordingly, who have lived for any great length of time on a diet composed entirely of animal matter, become oppressed, heavy, and indolent, the tone and excitability of their frame are impaired, they are affected with indigestion, the breathing is hurried on the smallest exercise, the gums become spongy, the breath is fœtid, and the limbs swell. We recognize in this description the approach of scurvy, a disease familiar to sailors, to the inhabitants of besieged towns, and, in general, to all who are wholly deprived of a just proportion of vegetable aliment.

On the other hand, vegetable food being less stimulating is also less nourishing; besides, 10this kind of aliment is, upon the whole, of more difficult assimilation than the food derived from the animal kingdom. Hence it is, perhaps, that nature has provided a greater extent of digestive organs for animals wholly herbivorous. It is insufficient to raise the human system to all the strength and vigour of which it is susceptible. Flatulency of the stomach, muscular and nervous debility, and a long series of disorders, are not unfrequently the consequences of this too sparing diet. Some Eastern nations, indeed, live almost entirely on vegetable substances; but these, it is remarked, are seldom so robust, so active, or so brave, as men who live on a mixed diet of animal and vegetable food. Few, at least, in the countries of Europe can be sufficiently nourished by vegetable food alone; and even those nations, and individuals, 11who are said to live exclusively on vegetables, because they do not eat the flesh of animals, generally make use of milk at least, of eggs, and butter and cheese.

Food composed of animal and vegetable materials is, in truth, that which is best suited to the nature and condition of man. The proportions in which these should be used it is not easy to determine, but generally the quantity of vegetables should exceed that of animal food. “On this head,” says Dr. Fothergill, “I have only one short caution to give. Those who think it necessary to pay any attention to their health, at table, should take care that the quantity of bread, of meat, and of pudding, and of greens, should not compose, each of them, a meal, as if some only were thrown in to make weight, but carefully to observe that the sum of, altogether, do not exceed due 12bounds or incroach upon the first feeling of satiety.”

All the products of the vegetable kingdom, used as aliment, are not equally nutritious. When we contemplate with a chemical eye the nutritive principles contained in vegetable substances, we soon perceive that they are but few in number, namely, starch, gluten, mucilage, jelly, fixed oil, sugar, and acids; and the different vegetable parts of them are nutritious, wholesome, and digestible, according to the nature and proportion of their principles contained in them. The starch and gluten appear the most nutritious, and together with mucilage at the same time, the most abundant ingredients contained in those vegetables from which man derives his subsistence. Hence, from time immemorial, and in all parts of the earth, man has used farinaceous seeds 13as part of his food, for they contain the above-mentioned materials in the greatest abundance. Of these the most nutritive are the seeds of the Cerealia, under which title are commonly comprehended the Gramineæ, or Culminiferous plants. Whilst the seeds of the Gramineæ supply the most important part of food furnished by the vegetable kingdom, in almost every part of the world, their leaves and young shoots support that class of animals hence called graminivorous, whose flesh is most generally eaten.

These vegetables are distributed so universally over the face of the earth, and have become to such a degree the object of culture, that they are very generally made into bread, or are employed instead of it; and, upon the whole, it appears that they are nutritive merely in the proportion to the 14quantity of farinaceous matter contained in them; but this substance exists in different combinations in different cereal and leguminous seeds. It is combined with gluten in wheat, with a saccharine matter in oats, and in many leguminous seeds, such as Harricot beans and pease, and with viscous mucilage in rye and Windsor beans.

Next to the Cerealia and Leguminosæ may be ranged the oily farinaceous seeds, such as almonds, walnuts, filberts, &c. These abound in starch and mucilage. The use of chocolate, which is prepared from the chocolate nut, growing in the West Indies, ground into a paste, with or without sugar, is in itself a nutritious substance, and to those with whom it agrees, it may be considered as a wholesome nutritious aliment. Yet the vegetable farina, in this state of existence, though highly 15nutritious, and to many palates very agreeable, is more difficult of digestion, and does not, upon the whole, afford a very wholesome alimentary substance. When too freely used, those kinds of seeds are sure to disagree, more especially if from age the oil has become rancid. They must be considered rather as a delicacy than as fitted to form a portion of our daily food, and with some particular stomachs they never agree.

Of the alimentary farinaceous roots, the potatoe, boiled or roasted, is one of the most useful, and perhaps after the Cerealia, one of the most wholesome and most nutritious vegetables in common use; its nourishing powers, there can be no doubt, depend upon the amylaceous fecula of which it is chiefly composed. The Jerusalem artichoke deserves likewise to be 16noticed here, as being a highly alimentary root, chiefly composed of farinaceous matter. Of the fruits rich in farinaceous and mucilaginous matter, few are indigenous. The chesnut, when roasted, affords an alimentary food, but in the East and West Indies the bread fruit, bananas, and the fruit of the plantain tree, are the substitutes for bread.

Scarcely any of the various alimentary substances employed by man are consumed in the raw and crude state in which they are presented to us by nature. Almost all of them are previously subjected to some kind of preparation, or change, by which for the most part they are rendered more wholesome and more digestible, and sometimes more nutritive. Accordingly, the observations we have made on the properties of different vegetable aliments, are to 17be considered as applied to them in the state in which they are commonly used among us.

When in the preparation of bread a baking heat is applied to the flour dough, a complete change is produced in the constitution of the mass. The new substance of bread differs materially from flour, it no longer forms a tenacious mass with water, nor can starch and gluten be any more separated from it.

By the application of heat to vegetables the more volatile and watery parts are in some cases dissipated. The different principles, according to their peculiar properties, are extracted, softened, dissolved, or coagulated; but most commonly they are changed into new combinations, so as to be no longer distinguishable by the forms and chemical properties which they originally possessed.

18In like manner the leguminous seeds, and farinaceous roots are greatly altered by the chemical action of heat. The raw potatoe is ill-flavoured, extremely indigestible, and even unwholesome. By roasting, or boiling, it becomes farinaceous, sweet, and agreeable to the taste, wholesome, digestible, and highly nutritious. Little is lost, and nothing is added to the potatoe by this process, yet its properties are greatly changed; its principles, in short, have suffered very remarkable chemical changes.

Even in the simple boiling of the various leguminous seeds, pot-herbs, and esculent roots, the effect does not seem confined to the mere softening of the fibres, the solution of some, and coagulation of other of their juices and principles; not only their texture, but their flavour, and other sensible 19qualities have undergone a change, by which their alimentary properties have been improved; the farinaceous matter by boiling is rendered soluble, the vegetable fibre softened. Saccharine matter is often formed, mucilage and jelly extracted and combined, and the product is rendered more palatable, wholesome, and nourishing. And, although every country has its own favourite articles of food, and modes of preparing them, and there is perhaps no subject in regard to which local prejudices are so strong, yet there can be no reason why the farinaceous matter of cereal seeds should always be consumed in the state of bread; many of them are not less agreeable, and not less wholesome in other forms of food.

In Scotland nine-tenths of those in the more humble walks of life live upon barleybroth, 20and there are not more healthy people to be found any where.—Cullen’s Materia Medica, v. I. p. 287.

It is chiefly to save the trouble of dressing any other kind of food, and that bread, from its portability and convenience of always being ready, has become the principal sustenance, but it is far from being the most economical method of using farinaceous grain. There can be no doubt that the same quantity of farinaceous matter made into bread might, in other forms, be used to a much greater advantage; for the great art of preparing good and wholesome food is to convert the alimentary matter into such a substance as to fill up the stomach and alimentary canal without overcharging it with more nutritive matter than is requisite for the support of the animal, and this may be done either by bread, or by converting 21the mealy substance of which it is composed into other forms, of which there is a great variety.

Persons who have travelled much on the continent are well aware that our neighbours have the art of throwing much more variety and gratification of the palate into the article of subsistence which has been emphatically called the staff of life, than we possess. The French and Germans convert the farinaceous flour of vegetables into a variety of excellent articles of food, and not serving, like our own, as a mere companion to pair off with so many mouthfuls of meat.

In speaking thus of the use of bread, I do not mean to deny that bread is highly alimentary, its nourishing powers are undoubtedly very great.

The finest bread, says an eminent physician (Dr. Buchan), is not always the best 22adapted for answering the purposes of nutrition. Household bread, which is made by grinding the whole grain, and only separating the coarse bran, is, without doubt, the most wholesome.

The people of South Britain generally prefer bread made of the finest wheat flour, while those of the Northern countries eat a mixture of flour and oatmeal, or rye bread. The common people of Scotland also eat a mixed bread, but more frequently bread made of oatmeal only.

In Germany the common bread is made of rye. The flour of millet is made in France, Spain, and Italy, into wholesome and nourishing pastry and puddings. The American and West Indian labourer thinks no bread so strengthening as that which is made of Indian corn.

The inhabitants of Westphalia, who are a hardy and robust people, capable of enduring 23the greatest fatigues, live on a coarse brown rye bread, which still retains the opprobrious name once given to it by a French traveller, “Bon pour Nicole—good for his horse Nichol.”

The great advantage of eating pure and genuine bread must be obvious; but bread is often spoiled to please the eye. I have elsewhere[1] shewn, that in the making of bread, more especially in London, various ingredients are occasionally mingled with the dough. The baker is obliged to suit the caprice of his customers, to have his bread light and porous, and of a pure white colour. It is impossible to produce this sort of bread from flour alone, unless it be of the finest quality. The best flour, however, being mostly used by the biscuit bakers and 24pastry cooks, it is only from the inferior sorts that bread is made; and it becomes necessary, in order to have it of that light and porous quality, and of a fine white, to mix alum with the dough. Without this ingredient the flour used by the London bakers would not yield so white a bread as that sold in this metropolis, and herein consists the fraud, that the baker is enabled by the use of this ingredient to produce, from bad materials, bread that is light, white, and porous, but of which the quality does not correspond to the appearance, and thus to impose upon the public.

1. Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, 2nd Edit. 1820, p. 130.

In the following pages I have enumerated the methods by which all the different kinds of farinaceous substances are made into good and wholesome bread, and are used in different countries as articles of daily sustenance.

Nothing appears so easy at first sight, as to grind corn, or other farinaceous substances, to knead the flour with water into dough, and to convert it, by baking, into porous bread. But, simple as these operations may now appear to us, the art of making loaf-bread was by no means one of the earliest among human inventions.

26For, however essential this species of food may be considered among us as an article of primary subsistence, it is perfectly certain, that men had long existed in a state of civilization, before bread was known among them.

It is evident that every species of corn must have been originally the spontaneous production of the earth; but as the grain, previous to cultivation, would grow but scantily, its importance as food might long escape observation, and mankind would naturally derive a more obvious, though less nutritive subsistence, from acorns, berries, and other fruits which were within their reach. Ages elapsed ere Ceres, according to the Grecian mythology, descended from heaven to teach mankind the use of agriculture.

In the early ages of society, according 27to some historians, men were satisfied with parching their corn for immediate use as food. The next advance appears to have been, to pulverize the grain in a mortar or handmill, and to form it, by the addition of water or milk, into a kind of porridge; or to make the bruised grain into dough, which was rendered eatable by baking on embers.

Even after the method of grinding corn into meal, and separating the bran by sifting, had become known, it was long before the art of fermenting the dough, in order to produce bread full of eyes and of a soft consistence, was discovered.

Like most other operations of primary importance, the origin of the art of making bread is lost in the darkness of ages past.

We are, however, certain that the Jews practised this art in the time of Moses; for 28we find in the Book of Exodus, chap. xii. v. 18, a prohibition to make use of leavened, that is, fermented bread, during the celebration of the Passover. But it does not appear that loaf-bread was known to Abraham, for in his history we read frequently of cakes, but not of fermented bread. It is, therefore, very probable, that the art of making fermented bread took its rise in the East, and that the Jews learned it from the Egyptians.

The Greeks attribute the art of making bread to the god Pan.

Bakers were unknown in Rome till the year of the city 850, or about 200 years before the Christian era. The Roman bakers, according to Pliny, came from Greece with the Macedonian army. Before this period, the Romans were often distinguished by the appellation of eaters of pap.

29At the time of Augustus, there were upwards of 300 baking houses in Rome, almost the whole of which were occupied by Greeks. The bakers enjoyed in ancient Rome great privileges. The public granaries were entrusted to their care; they formed a corporation, or kind of college, from which neither they nor their children were permitted to withdraw. They were exempted from guardianships and public services, which might interfere with their occupation. They were eligible to become Senators; and those who married the daughters of bakers, became members of the college.

From the establishment of bakers in Rome, the art of making loaf, or fermented bread, spread amongst the ancient Gauls; but its progress in the northern countries of Europe was slow, and in some northern 30districts, the luxury of eating fermented, or loaf-bread, is at this day not in general use. Some of the modern Italians consume the greatest part of their bread-flour in the state of macaroni and vermicelli, and in other forms of polenta, or soft pudding; and even at present millions of people neither sow nor reap, but content themselves with enjoying the spontaneous productions of the earth.

Properly so called, of which loaf-bread is chiefly made among cultivated nations, comprehends the seeds of the whole tribe of (cerealia), or gramineous plants; for they all contain a farinaceous substance, of a similar nature, and chiefly composed 31of starch. Those of the cerealia in common use are the following:

| Wheat | Triticum hybernum. |

| Barley | Hordeum vulgare. |

| Rye | Secale cereale. |

With us, wheat is chiefly employed for the fabrication of bread. It is, in fact, the only grain of which light porous bread can be made; but rye and barley are also used as bread-corn. The farina of the other cerealia afford also a nutritive and wholesome bread; though their flour is not so susceptible of the panary fermentation, it cannot be made into the white texture of the wheaten loaf. The bread formed from them is consequently much inferior to that prepared from wheat. The following seeds are chiefly employed to make a species of bread:

| 32 | |

| Oats | Avena Sativa. |

| Maize | Zea Mays. |

| Rice | Oriza Sativa. |

| Millet | Panicum milliaceum. |

Oats are used in the north of Europe for making a kind of bread, called oatmeal-cake, and particularly by the inhabitants of Scotland. Maize is frequently employed as bread-corn in North America.

Rice nourishes more human beings than all the other seeds together, used as food; and it is by many considered the most nutritive of all sorts of grain. A very ridiculous prejudice has existed with respect to rice, namely, that it is prejudicial to the sight, by causing diseases of the eye; but no authority can warrant this assertion: on the contrary, the opinion of the ablest men (Cullen’s Mat. Med. v. i. p. 229) may be quoted in favour of rice being a very 33healthy food: and the experience of all Asia and America may be adduced with sufficient weight to have answered this objection, if it had been supported by any thing more than vulgar prejudice, unsupported by facts. This grain is peculiarly calculated to diminish the evils of a scanty harvest, an inconvenience which must occasionally affect all countries, particularly those which are very populous. It is the most fitted of all food to be of use in relieving general distress in a bad season[2], because it comes from a part of the world where provisions are cheap and abundant; it is light, easy of carriage, keeps well for a long time, and contains a great deal of wholesome food within a small compass. Indeed, it has been ascertained that one 34part of rice contains as much food and useful nourishment as six of wheat.

2. Reports of the Society for bettering the Condition of the Poor, Vol. I. p. 137.

Next to the cerealia, the seeds of leguminous plants may be regarded as substitutes for bread corn. Their ripe seeds afford the greatest quantity of alimentary matter. Their meal has a sweetish taste, but they cannot be made into light and porous bread, without the addition of a portion of wheaten flour. Their meal, however, though it forms but a coarse and indifferent bread, neither very palatable nor very digestible, except by the most robust stomachs, is yet highly nutritive.

It is remarked by Dr. Cullen, that “on certain farms of this country, upon which the leguminous seeds are produced in great abundance, the labouring servants are much fed upon that kind of grain; but if such servants are removed to a farm upon 35which the leguminous seeds are not in such plenty, and therefore they are fed with the cerealia, they soon find a decay of strength; and it is common for servants, in making such removals, to insist on their being provided daily, or weekly, with a certain quantity of the leguminous meal.” We are not, however, to conclude from this observation, that pease-meal bread, is really more nutritive than wheaten bread, or than the meal of the other cerealia. We are rather disposed to regard it as an example of the effect of habit.

The leguminous seeds employed in the fabrication of bread, are

| Pease | Pisum Sativum. |

| Beans | Vicia faba. |

| Kidney Beans | Phaseolus vulgaris. |

The whole of this tribe afford a much 36more agreeable, though not a more nutritive aliment, when their seeds are used green, young, and tender, and simply boiled, than when fully ripened, and their flour baked.

It is remarked, that all the substances of which bread is made, as well as the substitutes for it, when chemically considered, are chiefly composed of one and the same identical material; namely, the farinaceous matter of the seeds, roots, fruits, or other products of vegetables, of different climates and soils; and that starch, or the amylaceous fecula, forms the most valuable part of all the materials used for making bread, and its substitutes.

This substance forms by far the most abundant, the most nourishing, and the most easy to be procured aliment, obtainable from the vegetable kingdom.

37“Whilst immense tribes of creatures devour the amylaceous fecula in the grain, as nature produces it, man knows how to give it different forms, from the most simple boiling to the most complicated delicacies of the arts of the confectioner and pastry-cook.

“It is singular that man should waste so valuable a substance for the purpose of hair-powder, a kind of custom perhaps ridiculous, in which modern nations imitate, without being aware of it, those people whom they term barbarous, and by which custom they lavish away a portion of the subsistence of a great number of families.”

This nutritive aliment, we find, exists in various combinations, in the roots, seeds, in the stems, and fruits of plants. Many roots abounding in the amylaceous fecula, yields a palatable and highly nutritious aliment.

38Hence the potatoe is a substance largely employed as a substitute for bread. Its nutritious qualities are fully ascertained by the experience of all Europe; it makes a considerable portion of the food of the poor; and in Ireland in particular, millions of people exist, who, from sufficient evidence, we are pretty certain live for years together almost wholly on this root and water, without any other seasoning than a little salt. It contains much amylaceous fecula, and when mixed with wheaten flour, may be formed into good and palatable bread. Other substances, besides the grains before mentioned, are in different parts of the world substituted for bread. These are the following:

The Bread-fruit Tree (Artocarpus incisa) affords the inhabitants of the South Pacific Ocean a substance resembling bread. They only climb the tree to gather the fruit, which is of a round shape, from five to six inches in diameter; it grows on boughs like apples, and, when quite ripe, is of a yellowish colour. The bread-fruit has a tough reticulated rind; there is neither seed nor stone in the inside of it. The eatable part, which lies between the skin and the core, is as white as snow, and of the consistence of new bread. The fruit is roasted on embers, or baked in an oven, which scorches the rind and turns it black; this is rasped off, and there remains a thin 40white crust, while the inside is soft and white, like crumbs of fine loaf-bread. It is eaten new, for if it is kept longer than twenty-four hours, it becomes harsh and unpalatable. It is also boiled, by which means the interior is rendered white, like a boiled potatoe. They make three dishes of it, by putting either water or the milk of the cocoa-nut to it, then beating it into a paste with a stone pestle, and afterwards mixing it with banana paste, which has been suffered to become sour.

The bread-fruit remains in season eight months in the year, during which time the natives eat no other sort of food of the bread kind; and the deficiency of the other four months of the year, is made up chiefly with cocoa-nuts, bananas, plantains, bread nuts (brosimum alicastrum), and other farinaceous fruits.

The Sago-Tree (Cycas Circinalis), which grows spontaneously in the East Indies, and particularly on the Coast of Malabar, furnishes to numerous Indian tribes their bread. In the Islands of Banda and Amboyna, they saw the body of the tree into small pieces, and, after bruising and beating them in a mortar, pour water upon the fragments; this is left for some hours undisturbed, to suffer the pithy farinaceous matter to subside. The water is then poured off, and the meal, being properly dried, is formed into cakes, or fermented and made into bread, which, it is said, eats nearly as well as wheaten bread.

The Hottentots make a kind of bread of 42another species of sago-tree (Cycas Resoluta). The pith, or medulla, which abounds in the trunk of this little palm, is collected and tied up in dressed calf’s or sheep’s skin, and then buried in the ground for several weeks, which renders it mellow and tender. It is then kneaded with water into dough, and made into small loaves or cakes, which are baked under embers. Other Hottentots, not quite so nice, merely dry and roast the farinaceous pith, and afterwards make it into a kind of frumety or porridge.

The same meal, or medulla, of the sago-tree, reduced into grain, by passing it whilst still moist through a kind of sieve, produces the sago of commerce, which receives its brown colour by being heated on hot stones.

In the Caribbee Islands they make bread of a very poisonous root (Jatropa Maniat), rendered wholesome by the extraction of its acrid juice, which the Indians use for poisoning their arrows. A tea-spoonful of the juice is sufficient to poison a man.

The root of the maniat, after being crashed, scraped clean, and grated in a tub, is enclosed in a sack of rushes, of very loose texture, which is suspended upon a stick placed upon two wooden forks. To the bottom of this sack a heavy vessel is suspended, which, by drawing the sack, presses the grated root and receives the juice that flows out of it. When the starch is well exhausted of its juice, it is exposed 44to smoke in order to dry it; and when well dried it is passed through a sieve. In this state it is termed Casava. It is baked into cakes, by spreading it on hot plates of iron or earth, turning it on both sides, in order to give it a good reddish colour.

The article of commerce, called tapioca, is the finest part of the farinaceous pith of the casava. It is separately collected and formed into small tears, by straining the mass while still moist, to form it into small irregular lumps.

The Plantain Tree (Musa Paradisiaca), which is a native of the East Indies and other parts of the Asiatic Continent, furnishes the inhabitants with a species of bread. The fruit of the plantain-tree is about a foot long, and from an inch and a half to two inches in diameter. It is at first green, but when ripe of a pale yellow. It has a tough skin, and within is a soft pulp of a sweet flavour. The fruit is generally cut before it is ripe; the green skin is peeled off, and the heart is roasted in a clear coal fire for a few minutes, and frequently turned; it is then scraped and served up as bread. This tree is cultivated on an extensive scale in Jamaica. Without 46this fruit, Dr. Wright says, the Islands would be scarcely inhabitable, as no species of provisions could supply its place. Even flour and bread itself would be less agreeable to the labouring Negro.

The fruit of the Banana Tree (Musa Sapientum), differs from the preceding, being shorter, straighter, and rounder. It is about four or five inches long, of the shape of a cucumber, and of a highly grateful flavour. Bananas grow in bunches that weigh twelve pounds and upwards. This fruit yields a softer pulp than the plantain-tree, and of a more luscious taste. It is never eaten green, but when ripe is a very pleasant food, either raw or fried in 47slices like fritters. It is relished by all ranks of people in the West Indies. When the natives of the West Indies undertake a voyage, they take the ripe fruit of the banana and make provisions of the paste; and, having squeezed it through a sieve, form the mass into loaves, which are dried in the sun or baked on hot ashes, after being previously wrapped up in leaves.

The Laplanders, who have no corn of their own, make a kind of bread of the inner soft bark of a pine tree, either mixed with the coarsest barley meal, or with dried fish beaten into powder. The bark is collected when the sap is rising, it is afterwards dried in the sun, or over a slow 48fire, and then mixed with the coarsest barley meal, or dried fish beaten into powder. The poorer people grind the chaff, and even some of the straw along with the barley.

Another kind of bread is made of dried fish and the root of the water dragon (Calla palustris), the root is taken up in the spring, before the leaves shoot out. It is dried, pounded, and boiled, till it becomes thick, like flummery, and after standing three or four days to lose its bitterness it is mixed with the powder of dried fish and the inner bark of the pine tree, and then made into a stiff paste, and baked over embers.

Some species of the tribe of Lichen, contain a considerable portion of starch, as the Lichen Rangiferinus, or rein-deer moss, which affords food to the stags and other fallow cattle of the North of Europe. The Icelanders form the lichen islandicus into bread, which is found to be extremely nutritious. The moss is collected in the summer, and, when dry, ground into powder, of which bread and gruel, or pottage, are made. It is sometimes also put whole into broth, or is boiled in whey, till it be converted into a jelly. In general, it is either previously steeped for some hours in warm water, or the water of the first boiling is rejected, in order to remove a part of the 50bitter extractive matter, which, if left, produces a disagreeable taste, and is apt to prove purgative.

The strangest substitute for bread that has ever been employed, is a sort of white earth. The poor in the Lordship of Moscoa in Upper Lusania, have been frequently compelled to make use of this earth as a substitute for bread.

The earth is dug out of a pit where saltpetre had formerly been worked; when exposed to the rays of the sun it splits and cracks, and small globules issue from it like meal, which ferments when mixed with flour. On this earth, baked into bread, many persons have subsisted a considerable 51time. A similar earth is met with near Genomu, in Catalonia.

In the western parts of Luisania too, the inhabitants have a most extraordinary custom of eating a white earth, mixed with clay and salt.

The rowers also, who ply on the river Mississippi, frequently drink large quantities of muddy water, which cannot fail to leave in the stomach a considerable quantity of earth. But it cannot be doubted, that a large quantity of earthy substances taken into the stomach would prove deleterious to health.

On examining bread corn, for instance wheat, we perceive an outside coating, which after the grain has been soaked in water, may readily be peeled off. This forms the bran of the flour. Immediately under it, is that part of the grain which affords the coarsest flour, it is soft to the touch, and not easily reduced to an impalpable powder, and of a sweetish taste. This constitutes about one half of the grain. Underneath this substance lies what is called by millers, the kernel or heart of the wheat, namely, a hard mealy substance, almost transparent. This part of the grain is capable of being speedily reduced to an 53impalpable powder, it ferments more readily than the outer layers, and it is this which produces the finest and best kind of wheaten flour. Such is the mechanical constitution of the grain. When chemically examined we find that the flour of wheat, rye, and barley, is composed of three ingredients, or immediate constituent parts, which may be separated by simple processes, viz. starch, gluten, and saccharine mucilage. The proportion of these differ materially in different kinds of corn. The method of separating them is as follows:

Make any quantity of wheaten flour into a stiff paste with cold water, and let it be kneaded and wrought in the hands under water; or put the flour into a coarse linen bag, and knead it between the hands whilst a small rill of cold water is suffered to pass 54over it. The water will carry away the starch in the form of a white powder, and the dough become more and more elastic, in proportion as the water carries off the starch; continue kneading the mass till the water runs off from the kneaded dough colourless. It will also be observed, that in proportion as the water carries off the starch, the paste in the bag assumes a more grey colour, less brilliant, as it were semi-transparent, and of a softer consistence, but, at the same time, more tenaceous, more viscid, more gluey, and more elastic.

Thus the flour is separated into three substances, by a method incapable of decomposing or altering any of its immediate constituent parts. The starch is precipitated in a white powder at the bottom of the water, from which it may readily be 55separated by suffering it to subside, and the supernatant liquid, contains in solution the saccharine mucilage; this may be obtained in the form of a syrup, by evaporating slowly in a warm place the clear decanted fluid; and the third substance, the gluten, remains in the bag, in the state of a soft, cohesive, and elastic substance.

In a similar manner the analysis of any species of bread corn may be effected.

QUANTITY OF FLOUR OBTAINABLE FROM VARIOUS KINDS OF CEREAL AND LEGUMINOUS SEEDS EMPLOYED IN THE FABRICATION OF BREAD, AND DIFFERENT KINDS OF FLOUR MANUFACTURED FROM WHEAT.

The Board of Agriculture, in order to ascertain what each of the various sorts of grain employed as substitutes for bread-corn 56would produce, when ground into flour, with only the broad bran taken out, caused a bushel of each of the undermentioned sorts of seeds to be ground for their inspection: the weight of the grain, as well as the bran and the flour, was as follows:

| Weight | Weight | ||

| Weighed. | of Flour. | of Bran. | |

| One Bushel of | lb. | lb. oz. | lb. oz. |

| Barley | 46 | 38 10½ | 5 10½ |

| Buckwheat | 46¼ | 38 9 | 5 5 |

| Rye | 54 | 43 0 | 9 5½ |

| Maize | 53 | 44 0 | 8 10½ |

| Rice | 61¼ | 60 5 | 0 0 |

| Oats | 38¼ | 23 5 | 13 10½ |

| Beans | 57¾ | 43 5½ | 12 5 |

| Pease | 61¾ | 47 0 | 12 5 |

A bushel of wheat, upon an average, weighs sixty-one pounds; when ground, the meal weighs 60¾ lbs.; this on being 57dressed, produces 46¾ lbs. of flour of the sort called seconds, which alone is used for the making of bread in London, and throughout the greater part of this country; and of pollard and bran 12¾ lbs., which quantity, when bolted, produces 3 lbs. of fine flour; this when sifted produces in good second flour 1¼ lb.

| lbs. | ||

| The whole quantity of bread-flour obtained from the bushel of wheat, weighs | 48 | |

| lbs. | ||

| Fine pollard | 4¼ | |

| Coarse pollard | 4 | 11 |

| Bran | 2¾ | |

| — | ||

| The whole together | 59 | |

| To which add the loss of weight in manufacturing the bushel of wheat | 2 | |

| — | ||

| Produces the original weight | 61 |

58REASON WHY OATS, PEASE, BEANS, RICE, MAIZE, MILLET, BUCKWHEAT, AND OTHER NUTRITIVE GRAINS CANNOT BE MADE INTO LIGHT AND POROUS BREAD.

Every person is acquainted with the difference there is between light well fermented bread, and that which is sodden, heavy, and badly risen, and the decided preference given to the former over the latter, as the most palatable, and easy of digestion.

The only substances for making loaf bread, by which term is meant, bread which is light, white, and porous, is the flour of wheat; and it is to the larger quantity of gluten, that wheat flour owes the property of being converted into loaf-bread. The average quantity of gluten contained in wheat flour, amounts to about one-fifth of 59the whole weight of the meal; but it varies in quantity in different kinds of wheat, according to the soil and season in which the corn has been reared, culture, and various other circumstances. Wheat kept in damp storehouses affords scarcely any gluten, and hence, in proportion as the flour of wheat is altered and deteriorated, which happens, as it is known, when it is kept too much compressed, without being occasionally stirred up and aired in hot and close granaries; in a word, as it undergoes a chemical change, its property of making good bread is diminished; and chemical analysis shows the quantity of gluten has become lessened under such circumstances; and when it is greatly diminished the meal forms no longer a tenaceous ductile dough. The spoiled flour produces a kind of bread which is heavy, harsh, and difficult of digestion.

60The greater the proportion of gluten, the easier the panification of bread-flour is effected, and the better is the bread. The wheat of the South of Europe generally contains a larger quantity of gluten, and is therefore more excellent for the manufacture of Maccaroni, Vermicelli, and other alimentary substances, requiring a glutenous paste.

Sir H. Davy found the flour of the wheat of this country to consist of from twenty to twenty-four per cent. of gluten. Barley contains six, and rye five per cent. of gluten.

We may now understand why potatoes, rice, beans, pease, buckwheat, millet, oats, and other nutritive cereal grains, abounding in starch, cannot be made into light and porous bread, although they are well calculated for being made into wholesome puddings, and why they only form crude, 61heavy, insipid cakes, when made into dough and baked, and not light porous loaf-bread.

In further confirmation of this statement it may be remarked, that if gluten of wheat, or only a portion of wheaten flour be incorporated by kneading with the before-named kinds of flour, a fermentable cohesive paste is produced, from which perfect bread may be made.

Bread, when chemically examined, is very different from flour; it no longer forms with water a tenaceous ductile mass, nor can starch, gluten, and saccharine mucilage be separated from it.

The chemical changes that take place in the panification of bread-flour, are by no 62means well understood. The saccharine mucilage, it appears, commences the fermentative chemical action that takes place in the dough, for without this substance, a mixture of flour, yeast, and water, cannot be made into true bread. The fermenting process when once commenced, is kept up by the gluten, forming the body of the paste through which the fecula and saccharine matter are diffused; and when the slight fermentation which it suffers, from changes in the saccharine matter, and supported by the presence of the gluten, has commenced, the paste becomes spongy and porous, from the disengagement of carbonic acid gas, while it still retains in some measure its elasticity; hence the lightness and porosity of well-baked wheaten bread; and hence bread, possessing these qualities, cannot be prepared 63from the flour of oats, barley, rye, or rice, or from any of the nutritive roots, as in all of these the quantity of gluten is considerably less, or entirely wanting, and no gluey elastic dough can be formed. The starch, which was merely diffused through the gluey dough, combines, during the baking, with a portion of water, into a stiff jelly, which renders the bread more digestible, and the gluten wholly disappears. A portion of carbonic acid gas, which becomes disengaged during the fermenting process, enlarges the bulk of the dough, which is thus rendered light, porous, and full of eyes, or cavities, in consequence of the extraction of the air bubbles, in the viscid glutenous matter; and the porosity of the bread is in proportion to the extent to which the rising of the dough is suffered to proceed.

64Some chemists persuade themselves that the fermentation of the flour dough differs materially from the fermentation of saccharine substances; namely, that the vinous, acetous, and putrefactive stages of the fermenting process take place simultaneously in the dough. They imagine the vinous fermentation to take place in the saccharine mucilage, the acetous in the starch, and the putrefactive in the gluten at the same time, and from the modification of each by the others, they consider that peculiar action to originate which converts paste into bread. Against this opinion, however, the following objections may be urged. In the first place, the quantity of saccharine mucilage is so extremely small as to produce no sensible effect alone on the whole mass, and what little there is probably passes speedily into the acetous 65fermentation. Secondly, the temperature that is required for bread-making is considerably lower than that at which starch dissolves in water, and where this is the case no alteration will take place, even in a long course of time: this is clearly shown by the usual process of starch-making, in which the bruised wheat is fermented for several days in large vats, in order to destroy the gluten, after which the starch is procured by simple deposition from the washings of the residue; and thirdly, no vestige whatever of the products evolved during the putrefactive fermentation of gluten, can be traced in any stage of the panification of bread flour.

Bread prepared by baking from the meal of farinaceous seeds kneaded with water into a dough and baked, is divided into three sorts, namely;—1. Unleavened bread; 2. Leavened bread; and, 3. Bread made with yeast.

Unleavened bread contains all the component parts of the flour but little altered. The meal is simply mixed with water, and baked into cakes. It is heavy, dry, friable, and not porous. The oatmeal bread of Scotland, is unleavened bread; as also sea biscuit, and all other kinds of biscuit.

The bread that is eaten by the Jews during the passover is unleavened. The usage of which was introduced in commemoration 67of their hasty departure from Egypt, [Exodus, chap. 12, v. 14 to 17.] when they had not leisure to bake leavened bread, but took the dough before it was fermented and baked unleavened cakes.

In Roman catholic countries it is still used, and prepared with the finest wheaten flour, moistened with water, and pressed between two plates, graven like wafer moulds, being first rubbed with wax to prevent the paste from sticking, and when dry it is used. Unleavened bread is hardly less nutritious than loaf or fermented bread, but it is generally speaking neither so wholesome nor so digestible.

To a peck of oatmeal add a few table-spoonsful of salt; knead the mixture into a stiff paste, with warm water, roll it out into thin cakes, and bake it in an oven or on embers.

In some cottages oatmeal bread undergoes a partial fermentation, whereby it is rendered lighter; but the generality of the people in the more humble walks of life, where oatmeal bread is eaten, merely soften their oatmeal with water, and having added to it a little salt, bake it into cakes. To strangers oatmeal bread has a dry, harsh, unpleasant taste, but the cottagers of Scotland, in particular, most commonly prefer it to wheaten bread.

To a peck of pease flour, and a like quantity of oatmeal, previously mixed by passing the flour through a sieve, add three or four ounces of salt, knead it into a stiff mass with warm water, roll it out into thin cakes, and bake them in an oven. In some parts of Lancashire and Scotland, this kind of bread is made into flattened rolls, and the cottagers usually bake them in an iron pot.

In Norway they make unleavened bread of oatmeal and barley, which keeps thirty or forty years, and is considered the better for being old, so that at the baptism of a child, bread is sometimes used which has been baked perhaps at the baptism of its great grandfather.

The bread made of maize flour, which is in common use in North America, is unleavened bread. The maize flour is kneaded with a little salt and water into a stiff mass; which, after being rolled out into thin cakes, is usually baked on a hot broad iron hoe.

Another kind of unleavened maize cakes, which is a North American bread, called Hoe cake, is made in the following manner.[3]

Take maize, boil it with a small proportion of kidney beans, until it becomes 71almost a pulp, and bake it over embers into a cake.

3. This and several other of the directions here given, for making various species of bread, are taken from Edlin’s excellent Treatise on bread making, a small work, long ago out of print.

Take a quarter of a peck of bean-flour and one ounce of salt, mix it into a thick batter with water, pour a sufficient quantity to make a cake into an iron kettle, and bake it over the fire, taking care to turn it frequently.

4. From the Reports of the Board of Agriculture.

Take a gallon of water, set it over a fire, and when it boils, let a peck of the flour of buckwheat be mixed with it, little by little, 72and keep the mixture constantly stirred, to prevent any lumps being formed till a thick batter is made. Then add two or three ounces of salt, set it over the fire again, and allow it to boil an hour and a half, pour the proper proportion for a cake into an iron kettle and bake it.

Take acorns, fully ripe, deprive them of their covers and beat them into a paste, let them lay in water for a night, and then press the water from them, which deprives the acorns entirely of their astringency. Then dry and powder the mass for use. When wanted, knead it up into a dough with water, and roll it out into thin cakes, which may be baked over embers.

73Bread made after this method is by no means disagreeable, and even to this day, it is said to be made use of in some countries.

The process of biscuit-baking for the British navy is as follows, and it is equally simple and ingenious. The meal, and every other article, being supplied with much certainty and simplicity, large lumps of dough, consisting merely of flour and water, are mixed up together; and as the quantity is so immense as to preclude, by any common process, a possibility of kneading it, a man manages, or, as it is termed, rides a machine, which is called a horse. This machine is a long roller, apparently 74about four or five inches in diameter, and about seven or eight feet in length. It has a play to a certain extension, by means of a staple in the wall, to which is inserted a kind of eye, making its action like the machine by which they cut chaff for horses. The lump of dough being placed exactly in the centre of a raised platform, the man sits upon the end of the machine, and literally rides up and down throughout its whole circular direction, till the dough is equally indented; and this is repeated till it is sufficiently kneaded; at which times, by the different positions of the lines, large or small circles are described, according as they are near to or distant from the wall.

The dough in this state is handed over to a second workman, who slices it with a prodigious knife; and it is then in a proper state for the use of those bakers who attend 75the oven. These are five in number; and their different departments are as well calculated for expedition and correctness, as the making of pins, or other mechanical employments. On each side of a large table, where the dough is laid, stands a workman; at a small table near the oven stands another; a fourth stands by the side of the oven, to receive the bread; and a fifth to supply the peel. By this arrangement the oven is as regularly filled and the whole exercise performed in as exact time, as a military evolution. The man on the further side of the large table, moulds the dough, having previously formed it into small pieces till it has the appearance of muffins, although rather thinner, and which he does two together, with each hand; and, as fast as he accomplishes this task, he delivers his work over to the man 76on the other side of the table, who stamps them with a docker on both sides with a mark. As he rids himself of this work, he throws the biscuits on the smaller table next the oven, where stands the third workman, whose business is merely to separate the different pieces into two, and place them immediately under the hand of him who supplies the oven, whose work of throwing, or rather chucking, the bread upon the peel, must be so exact, that if he looked round for a single moment, it is impossible he should perform it correctly. The fifth receives the biscuit on the peel, and arranges it in the oven; in which duty he is so very expert, that though the different pieces are thrown at the rate of seventy in a minute, the peel is always disengaged in time to receive them separately.

77As the oven stands open during the whole time of filling it, the biscuits first thrown in would be first baked, were there not some counteraction to such an inconvenience. The remedy lies in the ingenuity of the man who forms the pieces of dough, and who, by imperceptible degrees, proportionably diminishes their size, till the loss of that time, which is taken up during the filling of the oven, has no more effect to the disadvantage of one of the biscuits than to another.

So much critical exactness and neat activity occur in the exercise of this labour, that it is difficult to decide whether the palm of excellence is due to the moulder, the marker, the splitter, the chucker, or the depositor; all of them, like the wheels of a machine, seeming to be actuated by the same principle. The business is to deposit 78in the oven seventy biscuits in a minute; and this is accomplished with the regularity of a clock; the clack of the peel, during its motion in the oven, operating like the pendulum.

The biscuits thus baked, are dried in lofts over the oven till they are perfectly dry, to prevent them getting mouldy when stored for use.

One-hundred and twelve pounds of flour produce one hundred and two pounds of perfectly dry biscuits.

Or bread made with a portion of fermented sour dough, obtained by keeping some bread dough till the acetous fermentation takes place, when it swells, rarifies, and acquires a taste somewhat sour, and rather disagreeable. This fermented dough is well worked up with some fresh dough, which is, by that mixture and moderate heat, disposed to ferment; and by this fermentation the dough is attenuated and divided, carbonic acid is extricated, which being incapable of disengaging itself from the tenaceous and solid dough, forms it into small cavities, and raises and swells it; hence, the small quantity of fermented 80dough which disposes the rest of the mass to ferment is called leaven.

Most of the bread used by the people in the lower walks of life in France, Germany, Holland, and other European countries, is made in this manner.

Leavened bread, therefore, differs from unleavened bread, in being fermented by means of leaven, which is nothing more than a piece of dough kept in a warm place, till it undergoes a process of fermentation, swelling, becoming spongy, and full of air bubbles, and at length disengaging an acidulous vapour, and contracting a sour taste. Leaven must, therefore, be considered as dough which has fermented and become sour, but which is still in its progress towards greater acidity.

The addition of leaven, or this species of ferment to fresh dough, produces an 81important change in the bread, for when a small portion of leaven is intimately mixed with a large proportion of fresh dough, it gradually causes the whole mass to ferment throughout, a quantity of carbonic acid gas is extracted from the flour, but remaining entangled by the tenacity of the mass in which it is expanded by heat, this raises the dough, and as soon as the mass has acquired a due increase of bulk from the carbonic acid gas which endeavours to escape, it is judged to be sufficiently fermented and fit for the oven, the heat of which, by driving off the water, checks the fermentation, and forms a bread full of small cavities, entirely different from the heavy, compact, viscous masses, made by baking unfermented dough.

A great deal of nicety is required in conducting this operation, for if it is continued 82too long, the bread will be sour, and if too short a time has been allowed for the dough to ferment and rise, it will be heavy.

Bread raised by leaven is usually made of a mixture of wheat and rye, not very accurately cleared of the bran. It is distinguished by the name of rye bread; and the mixture of these two kinds of grain is called bread-corn, in many parts of the kingdom, where it is raised on one and the same piece of ground, and passes through all the processes of reaping, thrashing, grinding, &c. A mixture of one-hundred pounds of equal parts of wheat and rye flour, produce from one-hundred and fifty-four to one-hundred and fifty-six pounds of leavened bread.

Take a piece of dough, of about a pound weight, and keep it for use—it will keep several days very well. Mix this dough with some warm water, and knead it up with a portion of flour to ferment; then take half a bushel of flour, and divide it into four parts; mix a quarter of the flour with the leaven, and a sufficient quantity of water to make it into dough, and knead it well. Let this remain in a corner of your trough, covered with flannel, until it ferments and rises properly; then dilute it with more water, and add another quarter of the flour, and let it remain and rise. Do the same with the other two quarters of the flour, one quarter after another, 84taking particular care never to mix more flour till the last has risen properly. When finished, add six ounces of salt; then knead it again, and divide it into eight loaves, making them broad, and not so thick and high as is usually done, by which means they will be better baked. Let them remain to rise, in order to overcome the pressure of the hand in forming them; then put them in the oven, and reserve a piece of dough for the next baking. The dough thus kept, may with proper care, be prevented from spoiling, by mixing from time to time small quantities of fresh flour with it.

It requires some attention to be able to determine the exact quantity of leaven necessary for the proper fermentation of the dough. When it is deficient in quantity, the process of fermentation is interrupted, 85and the bread thus prepared is solid and heavy, and if too much leaven be used, it communicates to the bread a disagreeable sour taste.

Two large handfuls of hops are boiled in four quarts of water: this is poured upon as much wheaten bread as it will moisten, and to this are added four or five pounds of leaven. When the mass is warm, the several ingredients are worked together till well mixed. It is then deposited in a warm place for twenty-four hours, and afterwards divided into small pieces, about the size of a hen’s egg, which are dried by being placed on a board, and exposed to a dry air, but not to the sun; when dry, they are 86laid up for use, and may be kept half a year. The ferment, thus prepared, is applied in the following manner: for baking six large loaves, six good handfuls of these balls are dissolved in seven or eight quarts of warm water; this water is poured through a sieve into one end of the bread trough, and after it three quarts of warm water; the remaining mass being well pressed out. The liquor is mixed up with flour, sufficient to form a mass of the size of a large loaf; this is strewed over with flour: the sieve, with its contents, is put upon it, and the whole is covered up warm, and left till it has risen enough, and its surface has begun to crack; this forms the leaven. Fifteen quarts of warm water, in which six handfuls of salt has been dissolved, are then poured upon it through the sieve; the necessary quantity of flour is added, and mixed and 87kneaded with the leaven: this is covered up warm, and left for about half an hour. It is then formed into loaves, which are kept for another half-hour in a warm room; and after that they are put into the oven, where they remain two or three hours, according to their size.

The principal improvement that has been made in the art of fabricating bread, consists in the substitution of yeast, (or the froth that rises to the surface during the fermentation of malt liquors,) instead of common flour dough, in a state of acescency, called leaven, to rise the bread dough, made of flour and water, before it is baked. This substance very materially improves the bread. Yeast makes the dough rise more effectually than ordinary leaven, and the bread thus produced is much lighter, and free from that sour taste which may often be perceived in bread raised with leaven; because too much has been added to the paste, or because the 89dough has been allowed to advance too far in the process of fermentation before it was baked.

The discovery of the application of yeast, to improve the panification of bread flour, was made and first secretly adopted by the bakers of Paris; but when the practice was discovered, the College of Physicians there, in 1688, declared it prejudicial to health, and it was not till after a long time that the bakers succeeded in convincing the people, that bread made with yeast was superior to bread made with sour dough or leaven.

The bread used in this metropolis and in most other large towns in England, is made of wheaten flour, water, yeast, and salt. The average proportion are two pints by weight, of water, to three of flour, but the proportions vary considerably with 90the diversity of climate, years, season, age, and grinding of the wheat. There are some kinds of wheat flour that require precisely three-fourths of their weight of water. That flour is always the best which combines with the greatest possible quantity of water. Bakers and pastry-cooks judge of the quality of flour from the characters of the dough. The best flour forms instantly by the addition of water a very gluey elastic paste, whereas bad flour produces a dough that cannot be elongated without breaking.

The flour, in this case, being seldom mixed up oftener than twice, that is, the yeast previously diluted with water, is added to a part of the flour, and well kneaded; in a short time, swells and rises in the baking trough, and is called by the bakers, 91setting the sponge. The remainder of the flour is afterwards added, with a sufficient quantity of warm water to make it into a stiff dough, and then allowed to ferment. It is of essential consequence that the whole of the yeast should be intimately mixed with the two-thirds of the quantity of the flour put into the kneading trough, in order that the fermentation of the dough may commence in every part of the mass at the same time. The dough is then covered up, and the water which is mixed with the yeast being warm, speedily extricates air in an elastic state, and as it is now by kneading, diffused through every part of the dough, every particle must become raised, and the viscidity of the mass retains it, when it is again well kneaded and made up into loaves, and put into the oven. The heat 92converts the water also into an elastic vapour, and the loaf swells more and more, till at last it is perfectly porous.

During the baking, a still greater quantity of gazeous matter is extricated by the increased heat; and as the crust of the bread becomes formed, the air is prevented from escaping, the water is dissipated, the loaf rendered somewhat dry and solid, and between every particle of bread there is a particle of air, as appears from the spongy appearance of the bread.

It is curious that new flour does not afford bread of so good a quality as that which has been kept some months. The flour of grain too, which has suffered incipient germination, is much inferior in the quality of bread prepared from it: and from this principally appears to arise the injury which wheat sustains from a wet 93harvest. Various methods have been employed to remedy the imperfections of bread from inferior flour, such as washing the grain with hot water if it is musty, proposed by Mr. Hatchet;[5] drying and heating it even to a certain extent; adding various substances, such as magnesia, &c. Some experiments on this subject have been given by Mr. E. Davy. See a Treatise on Adulterations of Food, Second Edition, p.137.

5. See a Treatise on Adulterations of Food and Culinary Poisons, Second Edition, p. 143.

To make a sack of flour into bread, the baker pours the flour into the kneading trough, and sifts it through a fine wire sieve, which makes it lie very light, and 94serves to separate any impurities with which the flour may be mixed. Two ounces of alum are then dissolved in about a quart of boiling water, and the solution (technically called liquor,) is poured into the seasoning-tub. Four or five pounds of salt are likewise put into the tub, and a pailful of hot water. When this mixture has cooled to the temperature of about 84°, from three to four pints of yeast are added; the whole is mixed, strained through the seasoning sieve, emptied into a hole made in the mass of the flour, and mixed up with the requisite portion of it to the consistence of a thick batter. Some dry flour is then sprinkled over the top, and it is covered up with sacks or cloths. This operation is called setting quarter sponge.

In this situation it is left three or four hours. It gradually swells and breaks 95through the dry flour scattered on its surface. An additional quantity, (about one pailful,) of warm (liquor) water, in which one ounce of alum is dissolved, is now added, and the dough is made up into a paste as before; the whole is then covered up. In this situation it is left for four or five hours. This is called setting half sponge.

The whole is then intimately kneaded with more water, (about two pails full,) for upwards of an hour. The dough is cut into pieces with a knife, and penned to one side of the trough; some dry flour is sprinkled over it, and it is left to prove in this state for about four hours. It is then kneaded again for half an hour. The dough is now taken out of the trough, put on the lid, cut into pieces, and weighed, in order to furnish the requisite quantity for each loaf.

96The operation of moulding is peculiar, and can only be learnt by practice; it consists in cutting the mass of dough destined for a loaf, into two equal portions: they are kneaded either round or long, and one placed in a hollow made in the other, and the union is completed by a turn of the knuckles on the centre of the upper piece.

The loaves are left in the oven about two hours and a half, or three hours, when taken out of the oven, they are turned with their bottom side upwards to prevent them from splitting. They are then covered up with a blanket to cool slowly.

A sack of flour, weighing two hundred and eighty pounds, is made with five pounds of salt, and from three to four pints of yeast, into dough, with the requisite quantity of water, which varies according to the quality of the flour.

The older the flour, provided the wheat has been sound, and the flour well preserved, the greater will be the quantity of water required to convert it into a stiff dough, and the greater the produce of bread.

The quantity of flour for a quartern loaf is reckoned at an average, three pounds and a half, which produces, if the flour be of the best quality, five pounds avoirdupoise 98of dough. The quartern loaf produced from this quantity of flour weighs four pounds, five ounces and a half, and hence the dough loses, during baking, eleven ounces and a half.

The quantity of bread obtainable from the same quantity of flour is, however, much influenced by the manner in which the dough is fermented, and the skilful regulation of the heat employed for baking the bread.

A variation of temperature also makes a considerable difference to the baker’s profit or loss. In summer, a sack of flour will yield a quartern loaf more than in winter; and the sifting it, before it is wetted, if it does not make it produce more bread, certainly causes the loaves to be larger.

The loss of weight occasioned by the heat is proportional to the extent of the 99surface of the loaf, and to the length of time it remains in the oven. Hence the smaller the surface, or the nearer the figure of the loaf approaches to a globe, the smaller is the loss of weight sustained in baking; and the longer the loaf continues in the oven the greater is the loss.

A loaf that weighed just four pounds when taken out of the oven, after the usual baking, was put in again, and after ten minutes was found to have lost two ounces, and in ten minutes more it lost another ounce. The longer bread is kept the lighter it is, unless it be kept in a damp place, or wrapt round with a wet cloth, which is an excellent method of preserving bread fresh and free from mould, for a long time.

Take a bushel of wheaten flour, and put two third parts of it in one heap into a trough or tub; then dilute two pints of yeast with three or four pints of warm water, and add to this mixture from eight to ten ounces of salt. Make a hole in the middle of the heap of flour, pour the mixture of yeast, salt, and water into it, and knead the whole into an uniform stiff dough, with such an additional quantity of water as is requisite for that purpose, and suffer the dough to rise in a warm place.

When the dough has risen, and just begins again to subside, add to it gradually the remaining one third part of the flour; knead it again thoroughly, 101taking care to add gradually so much warm water as is sufficient to form the whole into a stiff tenaceous dough, and continue the kneading. At first the mass is very adhesive and clings to the fingers, but it becomes less so the longer the kneading is continued; and when the fist, on being withdrawn, leaves its perfect impression in the dough, none of it adhering to the fingers, the kneading may be discontinued. The dough may be then divided into loaf pieces, (of about 5lb. in weight). Knead each piece once more separately, and having made it up in the proper form, put it in a warm place, cover it up with a blanket to promote the last rising; and when this has taken place, put it into the oven. When the loaves are withdrawn they should be covered up with a blanket to cool as slowly as possible.

Mix up the flour, salt, and yeast, (See page 97), with the requisite portion of warm water, into a moderately stiff paste; but instead of causing part of the flour to ferment, (or setting the sponge), as stated in the preceding process, suffer the whole mass to rise at once. Then divide it into earthenware pans, or sheet iron moulds, and bake the loaves till nearly done, in a quick oven; at that time remove them out of the pans, or moulds, and set them on tins for a few minutes, in order that the crust may become brown, and when done wrap them up in flannel, and rasp them when cold.

Bread made in this manner is much 103more spongy or honeycombed, than bread made in the common way. It is essential that the dough be not so stiff, as when intended for common bread, moulded by the hand.

Suppose a Winchester bushel of good wheat weighs fifty-nine pounds, let it be sent to the mill and ground; including the bran, the meal will weigh fifty-eight pounds, for not more than a pound will be lost in grinding.

Mix it up with water, yeast, and salt, like the dough of common bread, (See page 97); the mass, before it is put into the oven, will weigh about eighty-eight pounds.

Divide it into eighteen loaves, and put 104them into the oven; when thoroughly baked, and after they are drawn out and left two hours to cool, they will weigh seventy-four pounds and a half.

Take a peck of wheaten flour, the same quantity of oatmeal, and half a peck of boiled potatoes, skinned and mashed; let the mass be kneaded into a dough, with a proper quantity of yeast, salt, and warm milk; make the dough into loaves, and put them into the oven to bake.

The bread, thus prepared, rises well in the oven, is of a light brown colour, and by no means of an unpleasant flavour; it tastes so little of the oatmeal, as to be taken, by those who are unacquainted with its composition, 105for barley or rye bread. It is sufficiently moist, and, if put in a proper place, keeps well for a week.

The dough of which rolls are made by the generality of the London bakers, is suffered to prove, that is to rise more, than dough intended to be made into loaf-bread. It is, therefore, left in the kneading trough, whilst the loaves made of the same dough are in the oven. During this period it rises more, and the fermentation is further promoted, by placing the rolls, when moulded, in a warm place, to cause the dough to expand as much as possible. When this has taken place, they are put in 106the oven to be baked, which is effected in about twenty or thirty minutes. When taken out of the oven they are slightly brushed over with a buttered brush, which gives the top crust a shining appearance, they are then covered up with flannel to cool gradually.

I have witnessed at a baker’s, who has the reputation for making excellent rolls, forty-eight pounds of dough moulded into one hundred (penny) rolls; they weighed, when drawn out of the oven, twenty-six pounds.

The bread called in this metropolis French rolls, and French bread, is made precisely in the same manner, namely, from common bread dough, but of a less stiff consistence; they are suffered to rise to a greater extent than dough intended for loaf-bread.

107Some bakers make rolls and French bread of a superior kind, for private families, in the following manner:

Put a peck of flour into the kneading trough, and sift it through a wire sieve, then rub in three quarters of a pound of butter, and, when it is intimately blended with the flour, mix up with it two quarts of warm milk, a quarter of a pound of salt, and a pint of yeast; let these be mixed with the flour, and a sufficient quantity of warm water to knead it into a dough; suffer it to stand two hours to prove, and then mould it into rolls, which are to be placed on tins, and set for an hour near the fire or in the proving closet. They are then put into a brisk oven for about twenty minutes, and when drawn, the crust is rasped.

108The cakes, called in this metropolis, muffins and crumpets, are baked, not in an oven, but on a hot iron plate.

For muffins, wheaten flour is made with water, or milk, into a batter or dough. To a quarter of a peck of flour is usually added three quarters of a pint of yeast, four ounces of salt, and so much water (or milk) slightly warmed, as is sufficient to form a dough of rather a soft consistence. Small portions of the dough are then put into holes, previously made in a layer of flour, about two inches thick, placed on a board, and the whole is covered up with a blanket and suffered to stand near a fire, to cause the muffin dough to rise. When this has been effected, the small cakes will exhibit a semi-globular shape. They are then carefully transferred on the heated iron plate to be baked, and when the bottom 109of the muffin begins to acquire a brown colour, they are turned and baked on the opposite side.

Crumpets are made of a batter composed of flour, water (or milk), and a small quantity of yeast. To one pound of the best wheaten flour is usually added three table-spoonsful of yeast. A portion of the liquid paste, after having been suffered to rise, is poured on a heated iron plate, and quickly baked, like pancakes in a frying pan.

Barley, next to wheat, is the most profitable of the farinaceous grains, and when mixed with a small proportion of wheat flour, may be made into bread. Barley bread is not spongy, and feels heavier in the hand than wheaten bread.

110To remedy this defect in part, it is always best to set the sponge with wheat flour only, for barley flour does not readily ferment with yeast, and adding the barley flour, when the dough is intended to be made. Bread made in this way requires to be kept a longer time in the oven than wheaten bread, and the heat of the oven should also be somewhat greater; but barley bread is sometimes made without the addition of wheaten flour.