Title: Historical Record of the Seventy-first Regiment, Highland Light Infantry

Author: Richard Cannon

Release date: October 7, 2019 [eBook #60449]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

At the front of the book, pages numbered [i] to [xvi] appear after those numbered [i] to [xix]; this numbering has been left unchanged.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each major section.

Repeated redundant headings and Sidenotes have been removed.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

HORSE GUARDS,

1st January, 1836.

His Majesty has been pleased to command that, with the view of doing the fullest justice to Regiments, as well as to Individuals who have distinguished themselves by their bravery in Action with the Enemy, an Account of the Services of every Regiment in the British Army shall be published under the superintendence and direction of the Adjutant-General; and that this Account shall contain the following particulars, viz.:—

—— The Period and Circumstances of the Original Formation of the Regiment; The Stations at which it has been from time to time employed; The Battles, Sieges, and other Military Operations in which it has been engaged, particularly specifying any Achievement it may have performed, and the Colours, Trophies, &c., it may have captured from the Enemy.

—— The Names of the Officers, and the number of Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates Killed or Wounded by the Enemy, specifying the Place and Date of the Action.

—— The Names of those Officers who, in consideration of their Gallant Services and Meritorious Conduct in Engagements with the Enemy, have been distinguished with Titles, Medals, or other Marks of His Majesty’s gracious favour.

—— The Names of all such Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers, and Privates, as may have specially signalized themselves in Action.

And,

—— The Badges and Devices which the Regiment may have been permitted to bear, and the Causes on account of which such Badges or Devices, or any other Marks of Distinction, have been granted.

By Command of the Right Honorable

GENERAL LORD HILL,

Commanding-in-Chief.

John Macdonald,

Adjutant-General.

The character and credit of the British Army must chiefly depend upon the zeal and ardour by which all who enter into its service are animated, and consequently it is of the highest importance that any measure calculated to excite the spirit of emulation, by which alone great and gallant actions are achieved, should be adopted.

Nothing can more fully tend to the accomplishment of this desirable object than a full display of the noble deeds with which the Military History of our country abounds. To hold forth these bright examples to the imitation of the youthful soldier, and thus to incite him to emulate the meritorious conduct of those who have preceded him in their honorable career, are among the motives that have given rise to the present publication.

The operations of the British Troops are, indeed, announced in the “London Gazette,” from whence they are transferred into the public prints: the achievements of our armies are thus made known at the time of their occurrence, and receive the tribute[iv] of praise and admiration to which they are entitled. On extraordinary occasions, the Houses of Parliament have been in the habit of conferring on the Commanders, and the Officers and Troops acting under their orders, expressions of approbation and of thanks for their skill and bravery; and these testimonials, confirmed by the high honour of their Sovereign’s approbation, constitute the reward which the soldier most highly prizes.

It has not, however, until late years, been the practice (which appears to have long prevailed in some of the Continental armies) for British Regiments to keep regular records of their services and achievements. Hence some difficulty has been experienced in obtaining, particularly from the old Regiments, an authentic account of their origin and subsequent services.

This defect will now be remedied, in consequence of His Majesty having been pleased to command that every Regiment shall, in future, keep a full and ample record of its services at home and abroad.

From the materials thus collected, the country will henceforth derive information as to the difficulties and privations which chequer the career of those who embrace the military profession. In Great Britain, where so large a number of persons are devoted to the active concerns of agriculture, manufactures, and commerce, and where these pursuits have, for so[v] long a period, been undisturbed by the presence of war, which few other countries have escaped, comparatively little is known of the vicissitudes of active service and of the casualties of climate, to which, even during peace, the British Troops are exposed in every part of the globe, with little or no interval of repose.

In their tranquil enjoyment of the blessings which the country derives from the industry and the enterprise of the agriculturist and the trader, its happy inhabitants may be supposed not often to reflect on the perilous duties of the soldier and the sailor,—on their sufferings,—and on the sacrifice of valuable life, by which so many national benefits are obtained and preserved.

The conduct of the British Troops, their valour, and endurance, have shone conspicuously under great and trying difficulties; and their character has been established in Continental warfare by the irresistible spirit with which they have effected debarkations in spite of the most formidable opposition, and by the gallantry and steadiness with which they have maintained their advantages against superior numbers.

In the Official Reports made by the respective Commanders, ample justice has generally been done to the gallant exertions of the Corps employed; but the details of their services and of acts of individual[vi] bravery can only be fully given in the Annals of the various Regiments.

These Records are now preparing for publication, under His Majesty’s special authority, by Mr. Richard Cannon, Principal Clerk of the Adjutant General’s Office; and while the perusal of them cannot fail to be useful and interesting to military men of every rank, it is considered that they will also afford entertainment and information to the general reader, particularly to those who may have served in the Army, or who have relatives in the Service.

There exists in the breasts of most of those who have served, or are serving, in the Army, an Esprit de Corps—an attachment to everything belonging to their Regiment; to such persons a narrative of the services of their own Corps cannot fail to prove interesting. Authentic accounts of the actions of the great, the valiant, the loyal, have always been of paramount interest with a brave and civilized people. Great Britain has produced a race of heroes who, in moments of danger and terror, have stood “firm as the rocks of their native shore:” and when half the world has been arrayed against them, they have fought the battles of their Country with unshaken fortitude. It is presumed that a record of achievements in war,—victories so complete and surprising, gained by our countrymen, our brothers,[vii] our fellow-citizens in arms,—a record which revives the memory of the brave, and brings their gallant deeds before us,—will certainly prove acceptable to the public.

Biographical Memoirs of the Colonels and other distinguished Officers will be introduced in the Records of their respective Regiments, and the Honorary Distinctions which have, from time to time, been conferred upon each Regiment, as testifying the value and importance of its services, will be faithfully set forth.

As a convenient mode of Publication, the Record of each Regiment will be printed in a distinct number, so that when the whole shall be completed the Parts may be bound up in numerical succession.

The natives of Britain have, at all periods, been celebrated for innate courage and unshaken firmness, and the national superiority of the British troops over those of other countries has been evinced in the midst of the most imminent perils. History contains so many proofs of extraordinary acts of bravery, that no doubts can be raised upon the facts which are recorded. It must therefore be admitted, that the distinguishing feature of the British soldier is Intrepidity. This quality was evinced by the inhabitants of England when their country was invaded by Julius Cæsar with a Roman army, on which occasion the undaunted Britons rushed into the sea to attack the Roman soldiers as they descended from their ships; and, although their discipline and arms were inferior to those of their adversaries, yet their fierce and dauntless bearing intimidated the flower of the Roman troops, including Cæsar’s favourite tenth legion. Their arms consisted of spears, short swords, and other weapons of rude construction. They had chariots, to the[x] axles of which were fastened sharp pieces of iron resembling scythe-blades, and infantry in long chariots resembling waggons, who alighted and fought on foot, and for change of ground, pursuit or retreat, sprang into the chariot and drove off with the speed of cavalry. These inventions were, however, unavailing against Cæsar’s legions: in the course of time a military system, with discipline and subordination, was introduced, and British courage, being thus regulated, was exerted to the greatest advantage; a full development of the national character followed, and it shone forth in all its native brilliancy.

The military force of the Anglo-Saxons consisted principally of infantry: Thanes, and other men of property, however, fought on horseback. The infantry were of two classes, heavy and light. The former carried large shields armed with spikes, long broad swords and spears; and the latter were armed with swords or spears only. They had also men armed with clubs, others with battle-axes and javelins.

The feudal troops established by William the Conqueror consisted (as already stated in the Introduction to the Cavalry) almost entirely of horse: but when the warlike barons and knights, with their trains of tenants and vassals, took the field, a proportion of men appeared on foot, and, although these were of inferior degree, they proved stout-hearted Britons of stanch fidelity. When stipendiary troops were employed, infantry always constituted a considerable portion of the military force;[xi] and this arme has since acquired, in every quarter of the globe, a celebrity never exceeded by the armies of any nation at any period.

The weapons carried by the infantry, during the several reigns succeeding the Conquest, were bows and arrows, half-pikes, lances, halberds, various kinds of battle-axes, swords, and daggers. Armour was worn on the head and body, and in course of time the practice became general for military men to be so completely cased in steel, that it was almost impossible to slay them.

The introduction of the use of gunpowder in the destructive purposes of war, in the early part of the fourteenth century, produced a change in the arms and equipment of the infantry-soldier. Bows and arrows gave place to various kinds of fire-arms, but British archers continued formidable adversaries; and, owing to the inconvenient construction and imperfect bore of the fire-arms when first introduced, a body of men, well trained in the use of the bow from their youth, was considered a valuable acquisition to every army, even as late as the sixteenth century.

During a great part of the reign of Queen Elizabeth each company of infantry usually consisted of men armed five different ways; in every hundred men forty were “men-at-arms,” and sixty “shot;” the “men-at-arms” were ten halberdiers, or battle-axe men, and thirty pikemen; and the “shot” were twenty archers, twenty musketeers, and twenty harquebusiers, and each man carried, besides his principal weapon, a sword and dagger.

Companies of infantry varied at this period in numbers from 150 to 300 men; each company had a colour or ensign, and the mode of formation recommended by an English military writer (Sir John Smithe) in 1590 was; the colour in the centre of the company guarded by the halberdiers; the pikemen in equal proportions, on each flank of the halberdiers; half the musketeers on each flank of the pikes; half the archers on each flank of the musketeers, and the harquebusiers (whose arms were much lighter than the muskets then in use) in equal proportions on each flank of the company for skirmishing.[1] It was customary to unite a number of companies into one body, called a Regiment, which frequently amounted to three thousand men; but each company continued to carry a colour. Numerous improvements were eventually introduced in the construction of fire-arms, and, it having been found impossible to make armour proof against the muskets then in use (which carried a very heavy ball) without its being too weighty for the soldier, armour was gradually laid aside by the infantry in the seventeenth century: bows and arrows also fell into disuse, and the infantry were reduced to two classes, viz.: musketeers, armed with matchlock muskets,[xiii] swords, and daggers; and pikemen, armed with pikes from fourteen to eighteen feet long, and swords.

In the early part of the seventeenth century Gustavus Adolphus, King of Sweden, reduced the strength of regiments to 1000 men. He caused the gunpowder, which had heretofore been carried in flasks, or in small wooden bandoliers, each containing a charge, to be made up into cartridges, and carried in pouches; and he formed each regiment into two wings of musketeers, and a centre division of Pikemen. He also adopted the practice of forming four regiments into a brigade; and the number of colours was afterwards reduced to three in each regiment. He formed his columns so compactly that his infantry could resist the charge of the celebrated Polish horsemen and Austrian cuirassiers; and his armies became the admiration of other nations. His mode of formation was copied by the English, French, and other European states; but so great was the prejudice in favour of ancient customs, that all his improvements were not adopted until near a century afterwards.

In 1664 King Charles II. raised a corps for sea-service, styled the Admiral’s regiment. In 1678 each company of 100 men usually consisted of 30 pikemen, 60 musketeers, and 10 men armed with light firelocks. In this year the King added a company of men armed with hand grenades to each of the old British regiments, which was designated the “grenadier company.” Daggers were so contrived as to fit in the muzzles of the muskets, and bayonets,[xiv] similar to those at present in use, were adopted about twenty years afterwards.

An Ordnance regiment was raised in 1685, by order of King James II., to guard the artillery, and was designated the Royal Fusiliers (now 7th Foot). This corps, and the companies of grenadiers, did not carry pikes.

King William III. incorporated the Admiral’s regiment in the second Foot Guards, and raised two Marine regiments for sea-service. During the war in this reign, each company of infantry (excepting the fusiliers and grenadiers) consisted of 14 pikemen and 46 musketeers; the captains carried pikes; lieutenants, partisans; ensigns, half-pikes; and serjeants, halberds. After the peace in 1697 the Marine regiments were disbanded, but were again formed on the breaking out of the war in 1702.[2]

During the reign of Queen Anne the pikes were laid aside, and every infantry soldier was armed with a musket, bayonet, and sword; the grenadiers ceased, about the same period, to carry hand grenades; and the regiments were directed to lay aside their third colour: the corps of Royal Artillery was first added to the Army in this reign.

About the year 1745, the men of the battalion companies of infantry ceased to carry swords; during[xv] the reign of George II. light companies were added to infantry regiments; and in 1764 a Board of General Officers recommended that the grenadiers should lay aside their swords, as that weapon had never been used during the Seven Years’ War. Since that period the arms of the infantry soldier have been limited to the musket and bayonet.

The arms and equipment of the British Troops have seldom differed materially, since the Conquest, from those of other European states; and in some respects the arming has, at certain periods, been allowed to be inferior to that of the nations with whom they have had to contend; yet, under this disadvantage, the bravery and superiority of the British infantry have been evinced on very many and most trying occasions, and splendid victories have been gained over very superior numbers.

Great Britain has produced a rate of lion-like champions who have dared to confront a host of foes, and have proved themselves valiant with any arms. At Crecy, King Edward III., at the head of about 30,000 men, defeated, on the 26th of August, 1346, Philip King of France, whose army is said to have amounted to 100,000 men; here British valour encountered veterans of renown:—the King of Bohemia, the King of Majorca, and many princes and nobles were slain, and the French army was routed and cut to pieces. Ten years afterwards, Edward Prince of Wales, who was designated the Black Prince, defeated at Poictiers, with 14,000 men, a French army of 60,000 horse, besides infantry, and took John I., King of France, and his son,[xvi] Philip, prisoners. On the 25th of October, 1415, King Henry V., with an army of about 13,000 men, although greatly exhausted by marches, privations, and sickness, defeated, at Agincourt, the Constable of France, at the head of the flower of the French nobility and an army said to amount to 60,000 men, and gained a complete victory.

During the seventy years’ war between the United Provinces of the Netherlands and the Spanish monarchy, which commenced in 1578 and terminated in 1648, the British infantry in the service of the States-General were celebrated for their unconquerable spirit and firmness;[3] and in the thirty years’ war between the Protestant Princes and the Emperor of Germany, the British Troops in the service of Sweden and other states were celebrated for deeds of heroism.[4] In the wars of Queen Anne, the fame of the British army under the great Marlborough was spread throughout the world; and if we glance at the achievements performed within the memory of persons now living, there is abundant proof that the Britons of the present age are not inferior to their ancestors in the qualities[xvii] which constitute good soldiers. Witness the deeds of the brave men, of whom there are many now surviving, who fought in Egypt in 1801, under the brave Abercromby, and compelled the French army, which had been vainly styled Invincible, to evacuate that country; also the services of the gallant Troops during the arduous campaigns in the Peninsula, under the immortal Wellington; and the determined stand made by the British Army at Waterloo, where Napoleon Bonaparte, who had long been the inveterate enemy of Great Britain, and had sought and planned her destruction by every means he could devise, was compelled to leave his vanquished legions to their fate, and to place himself at the disposal of the British Government. These achievements, with others of recent dates, in the distant climes of India, prove that the same valour and constancy which glowed in the breasts of the heroes of Crecy, Poictiers, Agincourt, Blenheim, and Ramilies, continue to animate the Britons of the nineteenth century.

The British Soldier is distinguished for a robust and muscular frame,—intrepidity which no danger can appal,—unconquerable spirit and resolution,—patience in fatigue and privation, and cheerful obedience to his superiors. These qualities, united with an excellent system of order and discipline to regulate and give a skilful direction to the energies and adventurous spirit of the hero, and a wise selection of officers of superior talent to command, whose presence inspires confidence,—have been the leading causes of the splendid victories gained by the British[xviii] arms.[5] The fame of the deeds of the past and present generations in the various battle-fields where the robust sons of Albion have fought and conquered, surrounds the British arms with a halo of glory; these achievements will live in the page of history to the end of time.

The records of the several regiments will be found to contain a detail of facts of an interesting character, connected with the hardships, sufferings, and gallant exploits of British soldiers in the various parts of the world where the calls of their Country and the commands of their Sovereign have required them to proceed in the execution of their duty, whether in[xix] active continental operations, or in maintaining colonial territories in distant and unfavourable climes.

The superiority of the British infantry has been pre-eminently set forth in the wars of six centuries, and admitted by the greatest commanders which Europe has produced. The formations and movements of this arme, as at present practised, while they are adapted to every species of warfare, and to all probable situations and circumstances of service, are calculated to show forth the brilliancy of military tactics calculated upon mathematical and scientific principles. Although the movements and evolutions have been copied from the continental armies, yet various improvements have from time to time been introduced, to ensure that simplicity and celerity by which the superiority of the national military character is maintained. The rank and influence which Great Britain has attained among the nations of the world, have in a great measure been purchased by the valour of the Army, and to persons who have the welfare of their country at heart, the records of the several regiments cannot fail to prove interesting.

[1] A company of 200 men would appear thus:—

| | |||||||||

| 20 | 20 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Harquebuses. | Muskets. | Halberds. | Muskets. | Harquebuses. | |||||

| Archers. | Pikes. | Pikes. | Archers. | ||||||

The musket carried a ball which weighed 1/10th of a pound; and the harquebus a ball which weighed 1/25th of a pound.

[2] The 30th, 31st, and 32nd Regiments were formed as Marine corps in 1702, and were employed as such during the wars in the reign of Queen Anne. The Marine corps were embarked in the Fleet under Admiral Sir George Rooke, and were at the taking of Gibraltar, and in its subsequent defence in 1704; they were afterwards employed at the siege of Barcelona in 1705.

[3] The brave Sir Roger Williams, in his Discourse on War, printed in 1590, observes:—“I persuade myself ten thousand of our nation would beat thirty thousand of theirs (the Spaniards) out of the field, let them be chosen where they list.” Yet at this time the Spanish infantry was allowed to be the best disciplined in Europe. For instances of valour displayed by the British Infantry during the seventy Years’ War, see the Historical Record of the Third Foot, or Buffs.

[4] Vide the Historical Record of the First, or Royal Regiment of Foot.

[5] “Under the blessing of Divine Providence, His Majesty ascribes the successes which have attended the exertions of his troops in Egypt to that determined bravery which is inherent in Britons; but His Majesty desires it may be most solemnly and forcibly impressed on the consideration of every part of the army, that it has been a strict observance of order, discipline, and military system, which has given the full energy to the native valour of the troops, and has enabled them proudly to assert the superiority of the national military character, in situations uncommonly arduous, and under circumstances of peculiar difficulty.”—General Orders in 1801.

In the General Orders issued by Lieut.-General Sir John Hope (afterwards Lord Hopetoun), congratulating the army upon the successful result of the Battle of Corunna, on the 16th of January 1809, it is stated:—“On no occasion has the undaunted valour of British troops ever been more manifest. At the termination of a severe and harassing march, rendered necessary by the superiority which the enemy had acquired, and which had materially impaired the efficiency of the troops, many disadvantages were to be encountered. These have all been surmounted by the conduct of the troops themselves: and the enemy has been taught, that whatever advantages of position or of numbers he may possess, there is inherent in the British officers and soldiers a bravery that knows not how to yield,—that no circumstances can appal,—and that will ensure victory, when it is to be obtained by the exertion of any human means.”

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE FORMATION OF THE REGIMENT

In 1777,

AND OF ITS SUBSEQUENT SERVICES

To 1852.

COMPILED BY

RICHARD CANNON, Esq.,

ADJUTANT-GENERAL’S OFFICE, HORSE GUARDS.

Illustrated with Plates.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY GEORGE E. EYRE AND WILLIAM SPOTTISWOODE,

PRINTERS TO THE QUEEN’S MOST EXCELLENT MAJESTY,

FOR HER MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE.

PUBLISHED BY PARKER, FURNIVALL, AND PARKER,

30, CHARING CROSS.

1852

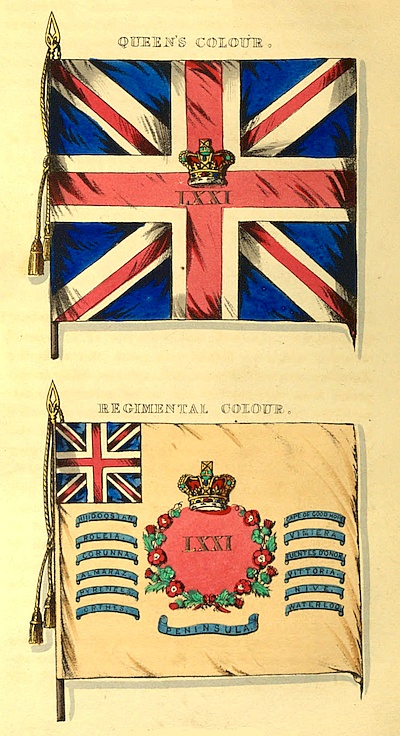

THE SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT

BEARS ON THE REGIMENTAL COLOUR AND

APPOINTMENTS

THE WORD “HINDOOSTAN,”

IN COMMEMORATION OF ITS DISTINGUISHED SERVICES

WHILE EMPLOYED IN INDIA FROM

1780 to 1797;

THE WORDS “CAPE OF GOOD HOPE,”

FOR THE CAPTURE OF THAT COLONY IN JANUARY

1806;

THE WORDS “ROLEIA,” “VIMIERA,”

“CORUNNA,” “FUENTES D’ONOR,” “ALMARAZ,”

“VITTORIA,” “PYRENEES,” “NIVE,”

“ORTHES,” AND “PENINSULA,”

IN TESTIMONY OF ITS GALLANTRY IN THE SEVERAL

ACTIONS FOUGHT DURING THE WAR IN PORTUGAL,

SPAIN, AND THE SOUTH OF FRANCE, FROM

1808 TO 1814;

AND

THE WORD “WATERLOO,”

IN COMMEMORATION OF ITS DISTINGUISHED SERVICES

AT THAT BATTLE ON THE 18TH OF JUNE

1815.

THE

SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT,

HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY.

OF THE

HISTORICAL RECORD.

| Year. | Page. | |

| Introduction | xiii | |

| 1777. | Formation of the Seventy-third regiment, afterwards numbered the Seventy-first Regiment | 2 |

| ” | John Lord Macleod appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1778. | War with France | 3 |

| ” | Removal of the regiment from North Britain to Guernsey and Jersey | ib. |

| ” | Proceeded to Portsmouth | ib. |

| ” | A second battalion added to the regiment | ib. |

| ” | Names of officers | 4 |

| 1779. | The first battalion embarked for India | 5 |

| ” | The second battalion removed from Scotland to Plymouth | ib. |

| ” | Siege of Gibraltar by the Spaniards | ib. |

| 1780. | The second battalion embarked for Gibraltar | 6 |

| ” | The first battalion arrived at Madras | 7 |

| ” | War with Hyder Ali | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion formed part of Major-General Sir Hector Munro’s army | 7 |

| ” | Siege of Arcot | 8 |

| ” | Action at Perambaukum | 9 |

| ” | The survivors of the British troops engaged in this unequal contest conveyed to Hyder Ali | 11 |

| ” | Attempts of the Spaniards against Gibraltar | 12 |

| 1781. | Progress of the War with Hyder Ali | 13 |

| ” | Battle of Porto Novo | 14 |

| ” | Presentation of silver pipes to the first battalion by Lieut.-General Sir Eyre Coote for its gallantry on that occasion | ib. |

| ” | Tripassoor retaken by the British | 15 |

| ” | Second action at Perambaukum, and defeat of the enemy | 16 |

| ” | Relief of Vellore | 17 |

| ” | Battle of Sholingur | ib. |

| ” | Gallant defence of Gibraltar | 18 |

| ” | Sortie of the garrison | 20 |

| 1782. | [vi] Vellore blockaded by Hyder Ali | 22 |

| ” | Advance of the British through the Sholingur Pass, and relief of Vellore | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Arnee | 24 |

| ” | Decease of Hyder Ali | 25 |

| ” | And succession of his son Tippoo Saib | ib. |

| ” | The combined attempts of France and Spain against Gibraltar | 26 |

| ” | Employment of red-hot shot by the garrison | ib. |

| ” | The expedient successful | 28 |

| ” | The garrison honored by His Majesty’s approbation | 29 |

| 1783. | Termination of the siege of Gibraltar | 30 |

| ” | Peace concluded between Great Britain, France, and Spain | ib. |

| ” | The second battalion sailed from Gibraltar for England | 31 |

| ” | Progress of the war with Tippoo Saib | ib. |

| ” | Siege of Cuddalore | ib. |

| ” | Unsuccessful sortie by the enemy | 33 |

| ” | Intelligence of the general peace received in India | ib. |

| ” | The second battalion disbanded | ib. |

| 1784. | Peace concluded with Tippoo Saib | 34 |

| ” | Restoration of the officers and men who had been made prisoners at the action of Perambaukum | ib. |

| 1785. | The regiment stationed at Madras | ib. |

| 1786. | The numerical title changed from Seventy-third to Seventy-first Regiment | ib. |

| 1787. | Stationed at Wallajohabad and Chingleput | 35 |

| 1788. | Embarked for Bombay | ib. |

| ” | Returned to Madras | ib. |

| 1789. | Major-General the Honorable William Gordon appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1790. | Hostilities commenced by Tippoo Saib | 36 |

| ” | The regiment marched towards Trichinopoly | ib. |

| ” | Siege of Palghautcherry | 37 |

| ” | Darraporam captured by the enemy | 38 |

| 1791. | Reviewed by General the Earl Cornwallis | 39 |

| ” | Action near Bangalore | 40 |

| ” | Capture of Bangalore by the British | 41 |

| ” | Advance towards Seringapatam | 42 |

| ” | Action with Tippoo’s troops | ib. |

| ” | Return of the army to Bangalore | 43 |

| ” | Capture of Nundydroog by the British | 45 |

| ” | ——— of Savendroog | 46 |

| ” | ——— of Outredroog, Ram Gurry, and Sheria Gurry | 47 |

| 1792. | Second advance of the British towards Seringapatam | ib. |

| ” | Successful attack upon the enemy | 48 |

| ” | Siege of Seringapatam | 49 |

| ” | Peace concluded with Tippoo Saib, and his two sons delivered as hostages | 50 |

| ” | Return of the regiment to Madras | 51 |

| 1793. | The French revolution, and declaration of war by the National Convention against Great Britain and Holland | ib. |

| ” | The flank companies engaged in the siege and capture of Pondicherry | 52 |

| 1794. | [vii] Contemplated expedition against the Mauritius | 52 |

| ” | The design relinquished, and march of the regiment to Tanjore | ib. |

| 1795. | Holland united to France, and styled the Batavian Republic | ib. |

| ” | The flank companies embarked for Ceylon | ib. |

| ” | Capture of the Island | 53 |

| 1796. | The regiment marched to Wallajohabad | ib. |

| 1797. | The regiment inspected by Major-General Clarke, and complimentary order on the occasion | ib. |

| ” | Embarked for England | 54 |

| 1798. | Disembarked at Woolwich | ib. |

| ” | Proceeded to Scotland | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Hindoostan” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| 1800. | Marched from Stirling, and embarked for Ireland | 55 |

| 1801.} | Stationed in Ireland | 56 |

| 1802.} | ||

| 1803. | Major-General Sir John Francis Cradock, K.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1804. | A second battalion added to the regiment | ib. |

| 1805. | The first battalion embarked on a secret expedition under Major-General Sir David Baird | 57 |

| ” | Arrival at the Cape of Good Hope | ib. |

| 1806. | Action at Bleuberg | 58 |

| ” | Surrender of the colony to the British | 59 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the words “Cape of Good Hope” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | Expedition to the Rio de la Plata | 60 |

| ” | Surrender of Buenos Ayres | 61 |

| ” | The city retaken by the enemy | 62 |

| ” | The first battalion taken prisoners and removed into the interior of the country | 63 |

| ” | Escape of Brigadier-General Beresford and Lieut.-Colonel Pack | ib. |

| 1807. | The second battalion removed from Ireland to Scotland | ib. |

| ” | Convention entered into by Lieut.-General Whitelocke, and release of the first battalion | 64 |

| ” | The first battalion arrived at Cork | ib. |

| 1808. | The second battalion embarked for Scotland | ib. |

| ” | Presentation of new colours | 65 |

| ” | Address of Lieut.-General John Floyd on that occasion | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion embarked for the Peninsula | 67 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the title of Glasgow Regiment, in addition to the appellation of Highland Regiment | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Roleia | 68 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Roleia” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Vimiera | 69 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Vimiera” on the regimental colour and appointments | 70 |

| ” | Convention of Cintra | ib. |

| ” | March of the troops into Spain | 71 |

| ” | Joined the army under Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | 72 |

| 1808. | [viii] Retreat on Corunna | 72 |

| 1809. | Lieut.-General Francis Dundas appointed colonel of the regiment | 73 |

| ” | Battle of Corunna | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Corunna” on the regimental colour and appointments | 74 |

| ” | The thanks of Parliament conferred on the troops | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion arrived in England | 75 |

| ” | Formed into a Light Infantry Regiment | 76 |

| ” | Expedition to the Scheldt | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion embarked at Portsmouth | ib. |

| ” | Action on landing | 77 |

| ” | Attack and capture of Ter Veer | 78 |

| ” | Siege and capitulation of Flushing | ib. |

| ” | Occupation of Ter Veer by the first battalion | 79 |

| ” | Return of the battalion to England | ib. |

| ” | Loss of the battalion on this expedition | ib. |

| 1810. | Permitted to retain such parts of the national dress as were not inconsistent with light infantry duties | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion again ordered for foreign service | 80 |

| ” | Embarked for Portugal | 81 |

| ” | Joined the army under Lieut.-General Viscount Wellington | ib. |

| ” | Actions at Sobral | 82 |

| ” | Occupied a position in the lines of Torres Vedras | ib. |

| ” | Marshal Massena retired to Santarem | 83 |

| ” | Advance of the first battalion | ib. |

| 1811. | Pursuit of Marshal Massena | 84 |

| ” | Battle of Fuentes d’Onor | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the words “Fuentes d’Onor” on the regimental colour and appointments | 85 |

| ” | The second battalion removed from Leith to South Britain | 86 |

| ” | The first battalion formed part of the army under Lieut.-General Rowland Hill | ib. |

| ” | Affair of Arroyo-del-Molinos | 87 |

| ” | The royal approbation conferred on the troops engaged | 88 |

| ” | Operations consequent on the preparations made by Viscount | |

| Wellington for the recapture of Ciudad Rodrigo | 89 | |

| 1812. | Third siege of Badajoz | ib. |

| ” | Capture of Badajoz | ib. |

| ” | Destruction of the enemy’s bridge of boats at Almaraz | 90 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Almaraz” on the regimental colour and appointments | 91 |

| ” | Subsequent operations | 92 |

| ” | Battle of Salamanca | 93 |

| ” | Retreat from Burgos | ib. |

| 1813. | Attempted surprise of Bejar by the French | 94 |

| ” | March of the first battalion to Bejar | ib. |

| ” | The second battalion returned to North Britain | 94 |

| ” | Battle of Vittoria | ib. |

| ” | Death of Colonel the Honorable Henry Cadogan, Lieut.-Colonel of the Seventy-first Regiment | 95 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Vittoria” on the regimental colour and appointments | 96 |

| ” | Advance on Pampeluna | 97 |

| ” | Skirmish at Elizondo | ib. |

| 1813. | [ix] Occupied positions in the Pyrenees | 97 |

| ” | Action at Maya | ib. |

| ” | ——— near Eguaros | ib. |

| ” | ——— at the Pass of Doña Maria | 99 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Pyrenees” on the regimental colour and appointments | 100 |

| ” | Encamped on the heights of Roncesvalles | 101 |

| ” | Gallant repulse of the French by a small party of the Seventy-first on the heights of Altobispo | ib. |

| ” | Advance to the French territory | ib. |

| ” | Battle of the Nivelle | 102 |

| ” | Passage of the Nive | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Nive” on the regimental colour and appointments | 103 |

| 1814. | Skirmishes at St. Hellette, heights of Garris, and St. Palais | 104 |

| ” | Action at Sauveterre | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Orthes | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Orthes” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | Affairs at Aire and Tarbes | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Toulouse | ib. |

| ” | Termination of the Peninsular War, and general order by the Duke of Wellington | 105 |

| ” | The first battalion embarked for England | ib. |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Peninsula” on the regimental colour and appointments | 106 |

| ” | The first battalion arrived at Cork | ib. |

| ” | The second battalion remained in North Britain | ib. |

| 1815. | Return of Napoleon to Paris, and renewal of the war | 107 |

| ” | The first battalion embarked for Ostend | ib. |

| ” | Battle of Waterloo | 108 |

| 1815. | Honors conferred on the army for the victory | 110 |

| ” | Authorized to bear the word “Waterloo” on the regimental colour and appointments | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion marched to Paris | ib. |

| ” | The second battalion disbanded | 111 |

| 1816. | Presentation of the Waterloo medals to the regiment | ib. |

| ” | Address of Colonel Reynell on that occasion | ib. |

| 1817. | Presentation of new colours by Major-General Sir Denis Pack, K.C.B., and his address to the regiment | 113 |

| 1818. | The regiment returned to England | 114 |

| 1819. | Inspected at Weedon by Major-General Sir John Byng | 115 |

| 1820. | Inspected by the Adjutant-General | ib. |

| 1822. | Embarked for Ireland | ib. |

| 1824. | Lieut.-General Sir Gordon Drummond, G.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | 116 |

| ” | The regiment embarked for Canada | ib. |

| 1825. | Formed into six service and four depôt companies | ib. |

| 1829. | The depôt companies proceeded to Berwick-on-Tweed | 118 |

| ” | Major-General Sir Colin Halkett, K.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| 1831. | [x] The service companies proceed from Quebec to Bermuda | 118 |

| 1834. | The Tartan Plaid Scarf restored to the Seventy-first Regiment | 119 |

| ” | The service companies arrived at Leith | ib. |

| 1835. | The regiment stationed at Edinburgh | ib. |

| 1836. | Embarked for Ireland | ib. |

| 1838. | Major-General Sir Samuel Ford Whittingham, K.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| ” | The service companies embarked for Canada | ib. |

| 1839. | The depôt companies removed from Ireland to North Britain | ib. |

| 1841. | Lieut.-General Sir Thomas Reynell, Bart., K.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | 120 |

| 1842. | The regiment formed into two battalions | ib. |

| ” | The Reserve battalion embarked for Canada | ib. |

| 1843. | The first battalion removed from Canada to the West Indies | ib. |

| 1846. | The first battalion embarked at Barbadoes for England | 121 |

| 1847. | Arrived at Portsmouth, and proceeded to Glasgow | ib. |

| 1848. | Lieut.-General Sir Thomas Arbuthnot, K.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| ” | The first battalion proceeded to Ireland | 122 |

| 1849. | Lieut.-General Sir James Macdonell, K.C.B., appointed colonel of the regiment | ib. |

| ” | The reserve battalion employed at Montreal in aid of the civil power | ib. |

| 1852. | Conclusion | 123 |

OF

THE SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT.

| Year. | Page. | |

| 1777. | John Lord Macleod | 125 |

| 1789. | The Honorable William Gordon | 126 |

| 1803. | Sir John Francis Cradock, G.C.B. | 127 |

| 1809. | Francis Dundas | 129 |

| 1824. | Sir Gordon Drummond, G.C.B. | 131 |

| 1829. | Sir Colin Halkett, K.C.B. | ib. |

| 1838. | Sir Samuel Ford Whittingham | ib. |

| 1841. | Sir Thomas Reynell, Bart., K.C.B. | 133 |

| 1848. | Sir Thomas Arbuthnot, K.C.B. | 140 |

| 1849. | Sir James Macdonell, K.C.B. and K.C.H. | 141 |

| Page. | |

| Memoir of Captain Philip Melvill | 143 |

| Memoir of General the Right Honorable Sir David Baird, Bart., G.C.B. | 144 |

| Memoir of Major-General Sir Denis Pack, K.C.B. | 151 |

| General orders of the 18th of January and 1st of February 1809, relating to the battle of Corunna and the death of Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | 161 |

| List of regiments which composed the army under Lieut.-General Sir John Moore | 165 |

| British and Hanoverian army at Waterloo on the 18th of June 1815 | 166 |

| Page. | ||

| Colours of the regiment | to face | 1 |

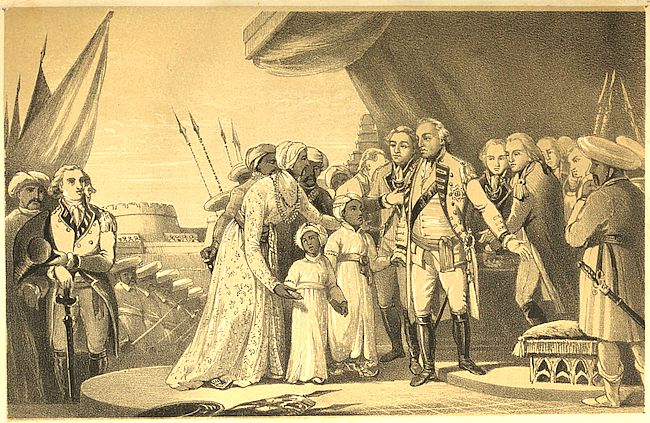

| The two sons of Tippoo Saib delivered as hostages to General the Earl Cornwallis | 50 | |

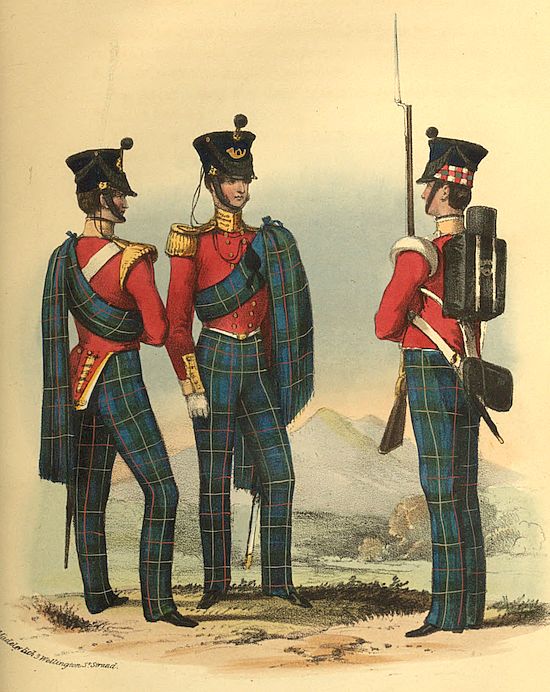

| Costume of the regiment | 124 |

TO THE

HISTORICAL RECORD

OF THE

SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT,

HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY.

During the last century several corps, at successive periods, have been borne on the establishment of the army, and numbered the SEVENTY-FIRST; the following details are therefore prefixed to the historical record of the services of the regiment which now bears that number, in order to prevent its being connected with those corps which have been designated by the same numerical title, but whose services have been totally distinct.

1. In the spring of 1758 the second battalions of fifteen regiments of infantry, from the 3d to the 37th, were directed to be formed into distinct regiments,[xiv] and to be numbered from the 61st to the 75th successively, as follows:—

Second Battalions.

| 3d | foot | constituted the | 61st | regiment. |

| 4th | ” | ” | 62d | ” |

| 8th | ” | ” | 63d | ” |

| 11th | ” | ” | 64th | ” |

| 12th | ” | ” | 65th | ” |

| 19th | ” | ” | 66th | ” |

| 20th | ” | ” | 67th | ” |

| 23d | ” | ” | 68th | ” |

| 24th | ” | ” | 69th | ” |

| 31st | ” | ” | 70th | ” |

| 32d | ” | ” | 71st | ” |

| 33d | ” | ” | 72d | ” |

| 34th | ” | ” | 73d | ” |

| 36th | ” | ” | 74th | ” |

| 37th | ” | ” | 75th | ” |

The 71st, 72d, 73d, 74th, and 75th regiments, thus formed, were disbanded in 1763, after the peace of Fontainebleau.

2. Several other corps were likewise disbanded in 1763, which occasioned a change in the numerical titles of the following regiments of Invalids, viz.:—

| The 81st regt | (Invalids) | was | numbered the | 71st. |

| 82d | ” | ” | ” | 72d. |

| 116th | ” | ” | ” | 73d. |

| 117th | ” | ” | ” | 74th. |

| 118th | ” | ” | ” | 75th. |

The 71st, 72d, 73d, 74th, and 75th regiments, thus numbered, were formed into independent companies[xv] of Invalids in the year 1769, which increased the number of Invalid companies from eight to twenty; they were appropriated to the following Garrisons, namely, four companies at Guernsey, four at Jersey, three at Hull, two at Chester, two at Tilbury Fort, two at Sheerness, one at Landguard Fort, one at Pendennis, and one in the Scilly Islands.

3. These numerical titles became thus extinct until October 1775, when another SEVENTY-FIRST regiment was raised for service in America by Major-General the Honorable Simon Fraser, which consisted of two battalions, and which performed eminent service during the war with the colonists. In December 1777, further augmentations were made to the army, and the regiments, which were directed to be raised, were numbered from the seventy-second to the eighty-third regiment.

The army was subsequently increased to one hundred and five regular regiments of infantry, exclusive of eleven unnumbered regiments, and thirty-six independent companies of Invalids.

The conclusion of the general peace in 1783 occasioned the disbandment of several regiments, commencing with the SEVENTY-FIRST regiment; the second battalion of which was disbanded on the 5th April 1783, and the first battalion on the 4th June 1784.

4. In 1786 the numerical titles of certain regiments, retained on the reduced establishment of the army, were changed, viz.:—

The seventy-third, which had been authorised to be[xvi] raised by John Lord Macleod in 1777, was directed to be numbered the SEVENTY-FIRST regiment.

The seventy-eighth, which had been authorised to be raised by the Earl of Seaforth in 1777, was directed to be numbered the SEVENTY-SECOND regiment.

The second battalion of the forty-second, which had been authorised to be raised in 1779, was directed to be constituted the SEVENTY-THIRD regiment.

These corps were denominated Highland regiments, and have since continued to form part of the regular army.

The details of the services of the present SEVENTY-FIRST regiment are contained in the following pages; the histories of the seventy-second and seventy-third regiments are given in distinct numbers.

QUEEN’S COLOUR.

REGIMENTAL COLOUR.

FOR CANNON’S MILITARY RECORDS.

Madeley lith. 3 Wellington St. Strand

OF THE

SEVENTY-FIRST REGIMENT,

HIGHLAND LIGHT INFANTRY;

ORIGINALLY NUMBERED

THE SEVENTY-THIRD REGIMENT.

The war between Great Britain and her American Colonies had, towards the end of the year 1777, assumed an aspect which was beheld with great interest by the European powers. France, although abstaining at this period from entering into the contest, privately encouraged the colonists, and several French officers proceeded to join the American standard. The influence of the British ministry then became employed in encouraging voluntary efforts for the raising of troops. Liverpool, Manchester, Edinburgh, and Glasgow, at their own expense, each raised a regiment of a thousand men, and several independent companies were levied in Wales. The livery of London and corporation of Bristol did not follow this example, but the monied interest in the metropolis showed its attachment to the administration by opening a subscription for procuring soldiers.

Fifteen thousand men were by these patriotic efforts raised and presented to the state; of this number upwards of two thirds were obtained from Scotland, and[2] principally from the Highland clans.[6] The hardy mountaineers of North Britain had been long celebrated for their military prowess, and the annals of warfare of subsequent years have added to their former renown, by affording them opportunities for sustaining their character for intrepidity and valour.

The present Seventy-first, Highland Light Infantry, was one of the regiments which owes its origin to the foregoing circumstances, and was raised under the following royal warrant, dated 19th December 1777, addressed to John Mackenzie, Esquire, commonly called John Lord Macleod, who was appointed its colonel.

“George R.

“Whereas we have thought fit to order a Highland regiment of foot to be forthwith raised under your command, to consist of ten companies, of five serjeants, five corporals, two drummers, and one hundred private men in each, with two pipers to the grenadier company, besides commissioned officers, these are to authorise you, by beat of drum or otherwise, to raise so many men in any county or part of our kingdom of Great Britain as shall be wanting to[3] complete the said regiment to the above-mentioned numbers; and all magistrates, justices of the peace, constables, and other our civil officers, whom it may concern, are hereby required to be assisting unto you, in providing quarters, impressing carriages, and otherwise, as there shall be occasion.

“Given at our Court at St. James’s, this 19th of December 1777, in the eighteenth year of our reign.

“By His Majesty’s command,

“Barrington.”

“To our trusty and well-beloved John Mackenzie, Esq., (commonly called John Lord Macleod), Colonel of a Highland Regiment of Foot to be forthwith raised, or to the Officer appointed by him to raise Men for our said Regiment.”

In February 1778 the Court of France concluded a treaty of defensive alliance with the American colonies, and Great Britain became involved in a war with France.

Lord Macleod’s efforts in raising the regiment were so successful that in April 1778 it was embodied at Elgin, under the denomination of “Macleod’s Highlanders,” and was numbered the “Seventy-third Regiment.”

In May the regiment, eleven hundred strong, embarked at Fort George, under the command of Colonel Lord Macleod, and proceeded to Guernsey and Jersey, in which islands it was stationed for six months. The regiment was subsequently removed to Portsmouth, and was cantoned during the remainder of the year in the neighbouring villages.

On the 24th of September, 1778, Colonel Lord Macleod received orders to raise a second battalion to the regiment. Each battalion was to consist of fifty serjeants, fifty corporals, twenty drummers and fifers, two pipers, and a thousand privates.

At this period the following officers had been appointed to the Seventy-third Highland Regiment.

First Battalion.

| Colonel, John Lord Macleod. | |

| Lieut.-Colonel, Duncan M‘Pherson. | |

| Majors. | |

| John Elphinston. | James Mackenzie. |

| Captains. | |

| George Mackenzie. | Hugh Lamont. |

| Alexander Gilchrist. | Hon. James Lindsay. |

| John Shaw. | David Baird. |

| Charles Dalrymple. | |

| Captain Lieutenant and Captain, David Campbell. | |

| Lieutenants. | |

| A. Geddes Mackenzie. | Simon Mackenzie. |

| Hon. John Lindsay. | Philip Melvill. |

| Abraham Mackenzie, Adjt. | John Mackenzie. |

| Alexander Mackenzie. | John Borthwick. |

| James Robertson. | William Gunn. |

| John Hamilton. | William Charles Gorrie. |

| John Hamilton. | Hugh Sibbald. |

| Lewis Urquhart. | David Rainnie. |

| George Ogilvie. | Charles Munro. |

| Innes Munro. | |

| Ensigns. | |

| James Duncan. | George Sutherland. |

| Simon Mackenzie. | James Thrail. |

| Alexander Mackenzie. | Hugh Dalrymple. |

| John Sinclair. | |

| Chaplain, Colin Mackenzie. | |

| Adjutant, Abraham Mackenzie. | |

| Quartermaster, John Lytrott. | |

| Surgeon, Alexander MacDougall. | |

Second Battalion.

| Colonel, John Lord Macleod. | |

| Lieut.-Colonel, the Hon. George Mackenzie. | |

| Majors. | |

| Hamilton Maxwell. | Norman Macleod. |

| Captains. | |

| Hon. Colin Lindsay. | Mackay Hugh Baillie. |

| John MacIntosh. | Stair Park Dalrymple. |

| James Foulis. | David Ross. |

| Robert Sinclair. | Adam Colt. |

| [5]Lieutenants. | |

| Norman Maclean. | Alexander Mackenzie. |

| John Irving. | Phipps Wharton. |

| Rod. Mackenzie senior. | Laughlan MacLaughlan. |

| Charles Douglas. | Kenneth Mackenzie. |

| Angus MacIntosh. | Murdoch Mackenzie. |

| John Fraser. | George Fraser. |

| Robert Arbuthnot. | John Mackenzie junior. |

| David MacCullock. | Martin Eccles Lindsay. |

| Rod. Mackenzie junior. | John Dallas. |

| Phineas MacIntosh. | David Ross. |

| John Mackenzie senior. | William Erskine. |

| Ensigns. | |

| John Fraser. | John Forbes. |

| John MacDougal. | Æneas Fraser. |

| Hugh Gray. | William Rose. |

| John Mackenzie. | Simon Fraser, Adjt. |

| Chaplain, Æneas Macleod. | |

| Adjutant, Simon Fraser. | |

| Quartermaster, Charles Clark. | |

| Surgeon, Andrew Cairncross. | |

In January 1779 the first battalion of the regiment, commanded by Colonel Lord John Macleod, embarked for the East Indies.

The second battalion, one thousand strong, embarked at Fort George in Scotland, in March 1779, under the command of Lieut.-Colonel the Hon. George Mackenzie (brother of Lord Macleod), and proceeded to Portsmouth, from thence it went on in transports to Plymouth, where the battalion landed, and was encamped upon Maker Heights until the 27th of November following.

The Court of Versailles had now engaged that of Madrid to take a part in the contest, and on the 16th of June 1779 the Spanish ambassador had presented a manifesto at St. James’s, equivalent to a declaration of war, and immediately departed from London. During the summer the siege of Gibraltar was commenced by the Spaniards, the reduction of that important fortress[6] being one of the principal objects of Spain in becoming a party to the war.

The vessels conveying the first battalion formed part of a fleet escorted by Rear-Admiral Sir Edward Hughes, which on the passage touched at Goree, upon the coast of Africa. Goree being evacuated by the French for the purpose of fortifying Senegal, which had been captured by them early in the year, was occupied by a British force, left for that purpose by Sir Edward Hughes.

After quitting Goree, the fleet proceeded to the Cape of Good Hope, at that time in possession of the Dutch, and there landed the sick. The fleet was detained for three months in Table Bay, for the purpose of refreshment and recovery of the sick, after which it sailed for India.

After the breaking up of the camp on Maker Heights, the second battalion embarked for Gibraltar in transports, under convoy of Admiral Sir George Rodney. When in the Bay of Biscay, the British encountered, on the 8th of January 1780, a valuable Spanish convoy belonging to the Caracca company, consisting of fifteen merchantmen, with a ship of sixty-four guns, and two frigates, the whole of which were captured. Sir George Rodney being compelled to employ many of the crews of the ships of war in manning the prizes, called upon Lieut.-Colonel the Hon. George Mackenzie for the services of the second battalion of the regiment as Marines. In a few days after the men were distributed for this purpose, the fleet defeated, on the 16th of January, off Cape St. Vincent, a squadron of eleven sail of the line, commanded by Admiral Don Juan de Langara. One Spanish ship of seventy guns blew up in the beginning of the action. The Spanish admiral’s ship of eighty guns, and three of seventy, were taken; one of seventy guns ran on shore, and another was lost on the breakers.

Nothing further transpired during the remainder of the voyage, and on the 18th of January 1780 the second battalion disembarked at Gibraltar, then closely blockaded by the Spaniards, who had despatched Don Juan de Langara to intercept the British admiral.

The first battalion had, in the meantime, continued on its voyage to India, and on the 20th of January 1780 anchored in Madras Roads, being twelve months from the time of leaving England. The battalion landed immediately at Fort St. George, and after remaining there about a month was removed to Poonamallee.

The intricate politics of India gave rise to a war in that country. Hyder Ali, the son of a petty chief in the Mysore, had risen to the chief command of the army of that state, and when the rajah died, leaving his eldest son a minor, Hyder assumed the guardianship of the youthful prince, whom he placed under restraint, and seized on the reins of government. Having a considerable territory under his control, he maintained a formidable military establishment, which he endeavoured to bring into a high state of discipline and efficiency. Hyder, now Sultan of Mysore, formed a league with the French, and entered into a confederacy with the Nizam of the Deccan, the Mahrattas, and other of the native powers, for the purpose of expelling the British from India.

In July 1780, Hyder Ali, having passed the Ghauts (as the passes in the mountains on both sides of the Indian peninsula are termed), burst like a torrent into the Carnatic, while his son, Tippoo Saib, advanced with a large body of cavalry against the northern Circars, and the villages in the vicinity of Madras were attacked by parties of the enemy’s horse.

These events occasioned the first battalion of the regiment to be ordered to proceed to join the army which was being assembled at St. Thomas’s Mount, under the command of Major-General Sir Hector[8] Munro, K.B., consisting entirely of the troops of the Honorable East India Company, with the exception of the Seventy-third, then about 800 strong.

Sir Hector Munro’s army amounted to upwards of 4,000 men, and was thus composed:—

| { Infantry | 1,000 | |

| European | { Artillery | 300 |

| { Dragoons | 30 | |

| Native | { Infantry | 3,250 |

| { Dragoons | 30 | |

| ——— | ||

| Total | 4,610 | |

| ===== |

With the army were also thirty field-pieces and howitzers, together with four battering twenty-four pounders.

The Anglo-Indian army marched to Conjeveram, sixty miles westward of Madras, where it was to be joined by a detachment from the northward, under the command of Lieut.-Colonel Baillie.

At this period the Sultan of Mysore was engaged in besieging Arcot, the capital of the Carnatic, which was invested by the enemy on the 21st of August. The movement of Sir Hector Munro’s force caused Hyder Ali to raise the siege; he then detached his son, Tippoo Saib, with a large body of horse and foot, amounting to 24,000 men and twelve guns, to intercept Lieut.-Colonel Baillie, whose junction with the main army had been ordered.

In this manœuvre Tippoo Saib succeeded, and Major-General Sir Hector Munro was compelled to detach Lieut.-Colonel Fletcher with a thousand men to reinforce Lieut.-Colonel Baillie. The flank companies of the first battalion of the Seventy-third formed part of this detachment; the grenadier company was commanded by Lieutenant the Honorable John Lindsay, and the light[9] company by Captain, afterwards General the Right Hon. Sir David Baird, Bart. and G.C.B.[7]

On the 6th of September, Lieut.-Colonel Baillie was attacked at Perambaukum by the division under Tippoo Saib, and on the 9th of that month was joined by the detachment under Lieut.-Colonel Fletcher. On the following day they were attacked by Hyder’s whole army, and the officers and men of this ill-fated detachment were either killed, taken, or dispersed.

The following graphic description of this unequal contest with Hyder’s whole army, the division under Tippoo Saib acting in concert, is given by Captain Innes Munro, of the Seventy-third, who published a “Narrative of the Military Operations on the Coromandel Coast from 1780 to 1784:”—

“Lieut.-Colonel Baillie could but make a feeble resistance against so superior a force; but his little band yet gallantly supported a very unequal fire, until their whole ammunition had either been blown up or expended, which of course silenced the British artillery. Hyder’s guns upon this drew nearer and nearer at every discharge, while each shot was attended with certain and deadly effect. Lieut.-Colonel Baillie’s detachment, seeing their artillery silenced and remaining inactive while exposed to certain destruction, very naturally became dismayed; which the enemy no sooner perceived than they made a movement for a general charge and advanced on all quarters to a close attack. At this dangerous and trying juncture, sufficient to damp the spirits of the most intrepid, all the camp-followers rushed in confusion through the ranks of every battalion, and in an instant threw the whole into disorder. The black troops, finding themselves in this calamitous[10] situation, relinquished every hope of success; and, notwithstanding the extraordinary exertions of their European officers, were no more to be rallied. But such of the Europeans as had fallen into disorder by this irregularity, quickly united again in compact order, headed by their gallant commander, who was at this time much wounded; and, being joined by all the Sepoy officers, planted themselves upon a rising bank of sand in their vicinity, where they valiantly resolved to defend themselves to the last extremity.

“History cannot produce an instance, for fortitude, cool intrepidity, and desperate resolution, to equal the exploits of this heroic band. In numbers, now reduced to five hundred, they were opposed by no less than one hundred thousand enraged barbarians, who seldom grant quarter. The mind, in the contemplation of such a scene, and such a situation as theirs was, is filled at once with admiration, with astonishment, with horror, and with awe. To behold formidable and impenetrable bodies of horse, of infantry, and of artillery, advancing from all quarters, flashing savage fury, levelling the numberless instruments of slaughter, and darting destruction around, was a scene to appal even something more than the strongest human resolution; but it was beheld by this little band with the most undaunted and immovable firmness. Distinct bodies of horse came on successively to the charge, with strong parties of infantry placed in the intervals, whose fire was discharged in showers; but the deliberate and well-leveled platoons of the British musketry had such a powerful effect as to repulse several different attacks. Like the swelling waves of the ocean, however, when agitated by a storm, fresh columns incessantly poured in upon them with redoubled fury, which at length brought so many to the ground, and weakened their fire so considerably, that they were unable longer to[11] withstand the dreadful and tremendous shock; and the field soon presented a picture of the most inhuman cruelties and unexampled carnage.

“The last and awful struggle was marked by the clashing of arms and shields, the snorting and kicking of horses, the snapping of spears, the glistening of bloody swords, oaths and imprecations; concluding with the groans and cries of bruised and mutilated men, wounded horses tumbling to the ground upon expiring soldiers, and the hideous roaring of elephants, stalking to and fro, and wielding their dreadful chains alike amongst friends and foes.

“Lieut.-Colonel Fletcher and twenty-nine European officers, with one hundred and fifty-five European rank and file, were killed; Lieut.-Colonel Baillie, with thirty-four officers, and almost all the European privates, were miserably wounded; sixteen officers and privates, from a Divine protection, and the generous clemency of the French hussars, remained unhurt, who, with the rest, were all made prisoners. The whole of the sepoys were either killed, taken, or dispersed.”

The flank companies were almost annihilated. Captain Baird received seven wounds, and Lieutenant the Hon. John Lindsay nine; both were made prisoners.

Lieutenant Philip Melvill[8] was totally disabled by his wounds, and was conveyed to Hyder’s camp, where many other wounded prisoners were crowded together in one tent, so as to prevent a moment’s ease or rest. They were afterwards confined at Bangalore, where they endured the greatest suffering for three years and a half, when, peace being concluded, the captives were released.

Lieutenant William Gunn, of the grenadiers, and[12] Lieutenant Geddes Mackenzie, of the light company, were killed.

These were the whole of the officers serving with the two companies. Of the non-commissioned officers and privates only two men joined the battalion, and those were found in the jungle desperately wounded.

The melancholy fate of these companies rendered it necessary for Colonel Lord Macleod to form two new flank companies from the battalion.

After the defeat of Lieut.-Colonel Baillie, Major General Sir Hector Munro retired with the army to Chingleput, much pressed on the march by the enemy. The wounded and sick being left at Chingleput, the army went into cantonments on Choultry Plain for the rainy season, which had set in. The troops in the retreat had suffered severely from fatigue and want of provisions.

Captain Alexander Gilchrist, of the grenadiers, whose ill-health prevented him from being with his company when Lieut.-Colonel Baillie was attacked, died at this period[9], and Lieutenant Alexander Mackenzie was wounded, together with several soldiers, in skirmishes with the enemy.

After the British fleet had departed from Gibraltar the Spaniards renewed the blockade by sea, and[13] attempted to destroy the vessels in the harbour by fire-ships, but failed. Towards the close of the year provisions again became short. A limited supply was occasionally obtained from the Moors. The effects of the scurvy were mitigated by cultivating vegetables on the rock; and the brave defenders of the fortress maintained their attitude of defiance to the power of Spain.

Mr. Laurens, late President of the American Congress, having been captured in his passage to Holland by the British, papers were found on him showing that a treaty of alliance was on the point of conclusion between the Americans and the States General. Great Britain in consequence declared war against Holland on the 20th of December, and thus became engaged with a fourth enemy, exclusive of the hostile powers in India.

Upon the 17th of January 1781, the army being re-assembled, took the field under the command of Lieut.-General Sir Eyre Coote, K.B., Commander-in-Chief in India. At this period the strength of the first battalion did not exceed five hundred men. Hyder Ali was then in the Tanjore country, committing every species of outrage and devastation.

On the 1st of June, 1781, Colonel Lord Macleod received the local rank of Major-General in the East Indies. In June Sir Eyre Coote moved the army along the coast southerly, towards Cuddalore, where his out-posts were attacked by Tippoo Saib, who was repulsed. The British commander afterwards marched his whole force to Chillumborem, upon the Coleroon, where the enemy had a large magazine of grain.

The pagoda was attacked by the piquets under the command of Captain John Shaw, of the first battalion, but the detachment was repulsed, and that officer wounded.

Hyder Ali, being apprehensive for the safety of Chillumborem, moved his army in the direction of that place from Tanjore and Trichinopoly, while Lieut.-General[14] Sir Eyre Coote, with the view of obtaining supplies from the shipping, proceeded towards Cuddalore. Hyder, by forced marches and manœuvres, had nearly surrounded the British on the plains of Porto Novo, about two days’ march to the southward of Cuddalore.

At four o’clock in the morning of the 1st of July, Sir Eyre Coote put his army of about 8,000 men in movement, while that of the enemy, computed at 100,000, was observed to range itself in order of battle.

The army of Lieut.-General Sir Eyre Coote formed on the plain in two lines; the first battalion was commanded by Colonel James Craufurd[10] (Lord Macleod having returned to England), and had its station in the first line under the orders of Major General Sir Hector Munro. Major General James Stuart commanded the second line. The action commenced by an advanced movement of the English troops, and the contest was sustained with great spirit by both parties until night, when the firing ceased, and the British remained masters of the field.

The veteran chief, Sir Eyre Coote, was so well pleased with the conduct of the battalion upon this occasion that he was heard to exclaim, addressing himself in the heat of the battle to one of the pipers, “Well done, my brave fellow, you shall have silver pipes when the battle is over!” The general did not forget his promise, and in addition to a general order expressive of his sense of the gallantry and steadiness of the battalion in the battle of Porto Novo, he presented a handsome pair of silver pipes (value one hundred pagodas[11]) to the corps, upon which was engraved a suitable inscription; this he desired might be preserved as a[15] lasting monument of his approbation of its conduct in that battle, the result of which enabled Sir Eyre Coote to reach Cuddalore, the point of destination, on the 4th of July.

Shortly afterwards the army was moved to St. Thomas’s Mount.

On the 3d of August the force from Bengal, under the orders of Colonel Pearse, arrived and formed a junction with Sir Eyre Coote’s army at Pulicat, to which place the army had moved in order to facilitate that important object. The British force now amounted to twelve thousand men.

The first brigade, composed entirely of Europeans, was commanded by Colonel Craufurd, of the present Seventy-first regiment, and had its station generally in the centre of the line. Major General Sir Hector Munro commanded the right wing, and Colonel Pearse the left.

In August, Major James Mackenzie of the battalion died, universally regretted. His exertions in the early part of the campaign had brought on illness, which terminated his career.

On the 16th of August the preparations that had been carried on for the siege of Arcot, which had been taken by Hyder Ali in the previous year, and for the relief of Vellore being completed, the Anglo-Indian army was put in movement. On the 20th of August Tripassoor was retaken, by which capture a very large supply of grain fell into the hands of the British. The camp of Hyder’s main army was at Conjeveram, and every exertion was made by his detachments to interrupt the progress of the British troops.

The British, on the 27th of August, came in sight of the enemy, drawn up in order of battle upon the very ground where Lieut.-Colonel Baillie had met his defeat, a position which the religious notions of Hyder Ali induced him to consider fortunate. Thus encouraged or[16] inspired, he seemed determined to hazard a second general action, and accordingly commenced the attack by a smart cannonade, when an obstinate contest ensued, which lasted the whole day, and which terminated in his defeat, and his being forced to retire from all his positions.

There was a circumstance peculiar to this field of battle which stamped it with aggravated horrors. It is ably and feelingly described by Captain Munro in his Narrative, from which the following is extracted.[12]

“Perhaps there come not within the wide range of human imagination scenes more affecting, or circumstances more touching, than many of our army had that day to witness and to bear. On the very spot where they stood lay strewed amongst their feet the relics of their dearest fellow soldiers and friends, who near twelve months before had been slain by the hands of those very inhuman monsters that now appeared a second time eager to complete the work of blood. One poor soldier, with the tear of affection glistening in his eye, picked up the decaying spatter-dash of his valued brother, with the name yet entire upon it, which the tinge of blood and effects of weather had kindly spared. Another discovered the club or plaited hair of his bosom friend, which he himself had helped to form, and knew by the tie and still remaining colour. A third mournfully recognised the feather which had decorated the cap of his inseparable companion. The scattered clothes and wings of the flank companies of the Seventy-third were everywhere perceptible, as also their helmets and skulls, both of which bore the marks of many furrowed cuts. These horrid spectacles, too melancholy to dwell upon, while[17] they melted the hardest hearts, inflamed our soldiers with an enthusiasm and thirst of revenge such as render men invincible; but their ardour was necessarily checked by the involved situation of the army.”

Upon this horrid spot the army halted two days, and it then retired to Tripassoor, to secure provisions. At this period the health of Major-General Sir Hector Munro compelled him to leave the army.

On the 19th of September, Lieut.-General Sir Eyre Coote made a movement towards Vellore, the relief of which place Hyder Ali appeared determined to oppose, by occupying in order of battle the Pass of Sholingur, at the same time making very spirited attacks against the fortress of Vellore.

Upon the 27th of September, Colonel Craufurd, now second in command, received the orders of the Commander-in-Chief to move the British army to the front.[13] Hyder, confident of success, made a forward movement to meet his opponents, when a general action commenced. A detachment, commanded by Colonel Edmonstone, (of which the flank companies of the first battalion formed part,) succeeded in turning the left flank of the enemy, and fell upon his camp and rear. The day closed by the total defeat of Hyder’s troops, who were pursued by the cavalry until sunset.

Under circumstances the most distressing and unpromising,[18] but with the hope of obtaining the supplies of provisions of which the army was quite destitute, and for which no previous arrangement had been made by the Government, Lieut. General Sir Eyre Coote, on the 1st of October, boldly pushed through the Sholingur Pass, and after a march of two days encamped at Altamancherry, in the Polygar country. Here, by the friendly aid and kindness of Bum-Raze, one of the Polygar princes, the troops were well supplied with every requisite.

The British camp was moved on the 26th of October to Pollipet, and the sick and wounded were sent to Tripassoor. Vellore was also relieved. This desirable object being effected, and the army reinforced by Colonel Laing with a hundred Europeans from Vellore, it proceeded to the attack of Chittoor, which, after a gallant resistance, capitulated.

With a view to get the British from a country so very inaccessible, Hyder Ali proceeded to the attack of Tripassoor, and on the 20th of November Sir Eyre Coote retired out of the Pollams, through the Naggary Pass, which obliged the enemy to raise the siege of Tripassoor, and to retire to Arcot. The campaign closed by the recapture of Chittoor by the enemy.

On the 2d of December, the monsoon having set in, the army broke up its camp on the Koilatoor Plain, and the different corps marched into cantonments in the neighbourhood of Madras.

During the campaign of 1781, the battalion was commanded by Captain John Shaw.

While the first battalion had been thus actively employed in India, the second battalion was engaged in the gallant defence of Gibraltar, the garrison of which was again relieved, in April 1781, by the arrival of a numerous fleet under Vice-Admiral Darby.

The Spaniards, relinquishing all hope of reducing[19] the fortress by blockade, resolved to try the power of their numerous artillery. Scarcely had the fleet cast anchor, when the enemy’s batteries opened, and the fire of upwards of one hundred guns and mortars enveloped the fortress in a storm of war; a number of gun-boats augmented the iron tempest which beat against the rock, and the houses of the inhabitants were soon in ruins. On the 8th of May, Captain James Foulis, of the second battalion of the regiment, was wounded in the lines.

On the night of the 17th of September the following incident relating to the battalion occurred in an attack of the enemy, the account of which is extracted from the “History of the Siege of Gibraltar,” by Colonel John Drinkwater, of the late Seventy-second Regiment, or Royal Manchester Volunteers:—

“A shell during the above attack fell in an embrasure opposite the King’s lines bomb-proof, killed one of the Seventy-third, and wounded another of the same corps. The case of the latter was singular, and will serve to enforce the maxim, that, even in the most dangerous cases, we should never despair of a recovery whilst life remains. This unfortunate man was knocked down by the wind of the shell, which, instantly bursting, killed his companion, and mangled him in a most dreadful manner. His head was terribly fractured, his left arm broken in two places, one of his legs shattered, the skin and muscles torn off part of his right hand, the middle finger broken to pieces, and his whole body most severely bruised, and marked with gunpowder. He presented so horrid an object to the surgeons, that they had not the smallest hopes of saving his life, and were at a loss what part to attend to first. He was that evening trepanned, a few days afterwards his leg was amputated, and other wounds and fractures dressed. Being possessed of a most excellent constitution,[20] nature performed wonders in his favour, and in eleven weeks the cure was completely effected. His name is Donald Ross, and he long continued to enjoy his sovereign’s bounty in a pension of ninepence a day for life.”

On the 4th of November, Lieutenant John Fraser, of the second battalion, had his leg shot off on Montague’s Bastion, and two of the soldiers of the battalion were likewise wounded by the enemy’s fire.

General Eliott, afterwards Lord Heathfield, which title was conferred for the services performed by him when Governor of Gibraltar, in order to free himself from the contiguity of the besiegers, resolved to make a sortie. The favourable opportunity presented itself; and, on the evening of the 26th of November, the following garrison order was issued:—