Title: Peggy's Giant

Author: Mary D. Maitland Kelly

Release date: October 12, 2019 [eBook #60475]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, David E. Brown, and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

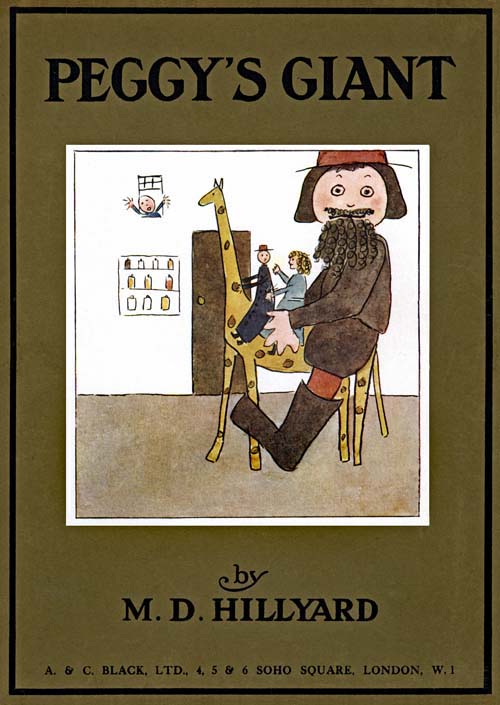

This is Peggy’s own drawing of what happened in the first

Adventure of the Ring. Everyone is very frightened in it.

Nurse has just sat down on seeing the Giant, and has

dropped Peggy’s brown holland frock behind her.

Peggy drew the frock very carefully, spreading it out

flat on the floor to get it exactly right. Mother helped her

with the Giant’s knee, and with the table. All the rest she

did herself. She knows Nurse is too small, but she was too

busy getting her surprised enough to remember to make

her bigger. Peggy is behind the Giant wondering what

to say. The little round things near the Giant’s foot are

the broken bits of the cup and saucer, and the black

dots are the currants in the cake. The curls in the Giant’s

beard were the most fun to do.

BY

M. D. HILLYARD

WITH SEVEN FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS IN COLOUR

DRAWN BY PEGGY

A. & C. BLACK, LTD.

4, 5 & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.1

1920

TO

PEGGY

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | What Peggy Found | 5 |

| II. | Disappearing | 9 |

| III. | A Daisy Field | 15 |

| IV. | The Sleepy Giant | 19 |

| V. | Sweets and Fairies | 22 |

| VI. | Fe-Fo-Fum! | 28 |

| VII. | Peggy Drives a Car | 35 |

| VIII. | The Mayor’s Outing | 39 |

| IX. | Down! | 43 |

| X. | Pixie Games | 49 |

| XI. | The Last Adventure | 54 |

| XII. | The Nicest Wish of All | 60 |

BY PEGGY

| What happened in the First Adventure of the Ring | Frontispiece |

| The Second Adventure | Facing page 20 |

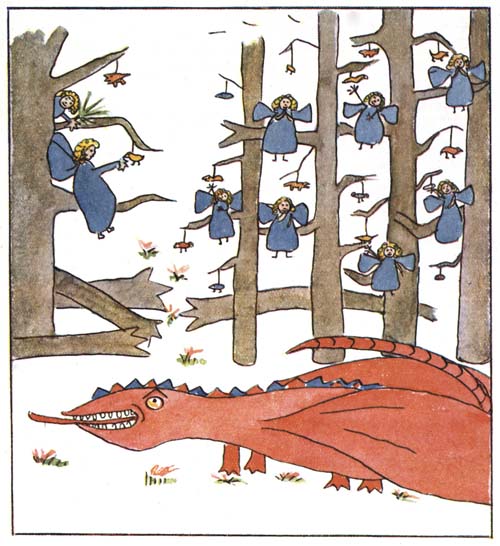

| What the Dragon looked like when Nurse said “You wouldn’t dare!” | ” 32 |

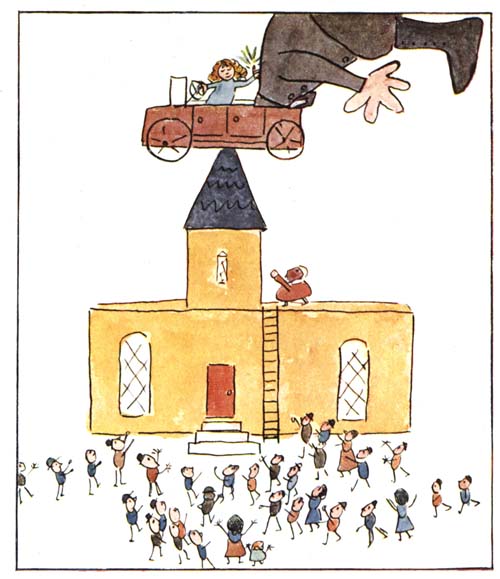

| Peggy just telling the Mayor that they’ve stuck | ” 40 |

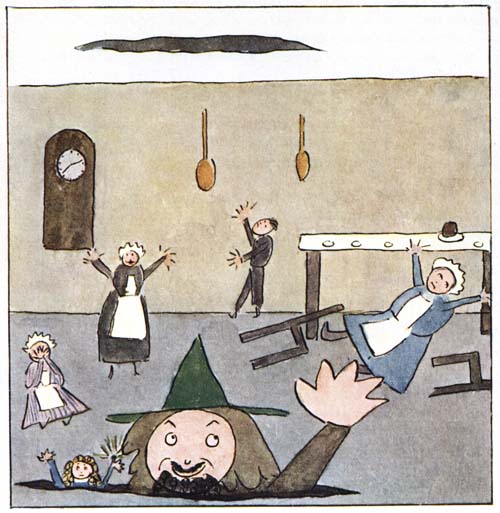

| Peggy and the Giant going down | ” 46 |

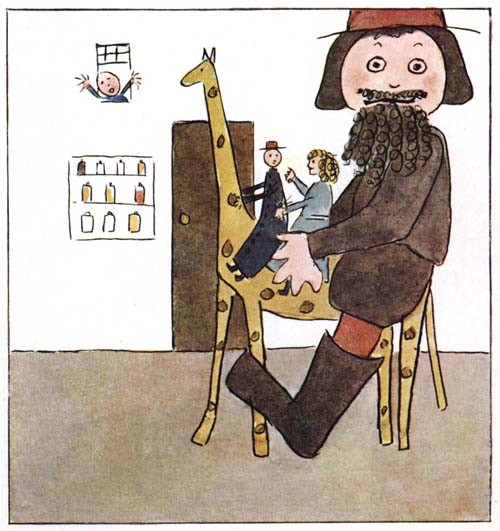

| The Giant and Peggy among the Pixies | ” 50 |

| Riding through the Village in the Sixth Adventure | ” 60 |

PEGGY’S GIANT

“It rattles!” said Peggy, shaking the last cracker, and looking up at Nurse.

“Well, pull it now, there’s a dear,” said Nurse, “and let me clear up this litter.”

Peggy had just finished her birthday tea up in the nursery alone with Nurse, as Mother was away. Of course it hadn’t been nearly so exciting as her last birthday tea—the only one she could remember—which had been downstairs with lots of other little girls and boys, who had all come to see Peggy. They hadn’t talked to her or to each other much, but had eaten lots of birthday cake, and Peggy had been taken up to bed before the last of them left, because she had had such a long and exciting birthday.

This year the only children who could come had suddenly started whooping-cough, and so there was no party at all. Still it was better than the usual dull nursery tea, for Mother had left a lot of crackers with Nurse for Peggy; and Cook had remembered to put six new candles on the new sponge cake, and they had all been lighted, and were doing their very best to look brighter than the sunshine pouring in through the nursery windows.

“Do guess what’s inside first, Nannie,” said Peggy, shaking the cracker again. “I guess it’s a little tiny cup and saucer for my doll’s house. Now, you guess.”

[6]“Oh, I don’t know—a whistle,” said Nannie, beginning to clear up the pieces of brightly-coloured paper that covered the table-cloth and floor, and that really looked a great deal too pretty to burn. “That’s generally what it is. But what’s the good of guessing when you’ll know in a minute? Come along and pull, I’m waiting.”

Peggy shut her eyes, and putting one hand over her ear—she was always uncomfortably startled by the bang—pulled hard with the other.

The thing inside immediately flew through the air, and rolled away under the toy cupboard. And Peggy followed as far as she could, lying flat on the floor and peering under. Then—“O Nannie, it sparkles!” she cried excitedly. “I do believe it’s a beautiful ring! I can see it quite plainly. Yes, it is. It’s a gold ring with a great big green stone in it! There, I’ve got it! O Nannie, look how it sparkles!”

“A bit of tin and glass,” said Nurse examining it and dropping it on the table. “What they want to put such rubbish in for passes my understanding! You can’t play with it, and it’ll only get left about. Now come and look at the paper blazing,” and she swept all the ends of the crackers into the fire.

Peggy was terrified that her ring would follow too, and she began in a great hurry to put it on all her fingers in turn to see which it would fit.

“It won’t fit any of them except my fum,” she remarked. “But just look how well it fits my fum!” and she waved her left hand to and fro proudly.

“You can’t wear a ring at your age,” said Nurse decidedly, “and no one ever wears them on their thumbs, as you very well know. Oh dear, your hair ribbon’s coming right off, as usual! Come here whilst I tie it on again.”

[7]“Just look how it sparkles!” repeated Peggy, stroking the green stone admiringly. And it certainly did. A bright green light spread from it all over that part of the nursery, just like the light in a beech wood in spring, when the sun is shining through the leaves; and it coloured and played over Nurse’s face and the cupboard and the roses on the wall-paper. “Do look, Nannie,” cried the child, “now the fireplace is green!”

“Very pretty,” said Nurse absentmindedly, not looking up as she brushed Peggy’s curls. “What a tangle your hair’s in, to be sure! Now I think I’ll take off this clean frock and put on your brown holland so that you can have a good game with all your toys out at once, as it’s your birthday.”

“Aren’t you going to play with me, too?” asked Peggy rather wistfully.

“I can’t,” said Nurse. “I’ve some letters to write, and post goes in half an hour—when it’ll be your bedtime. Grown-ups can’t spend all their time playing with little girls, you know. Here, slip your frock off and stay by the fire, whilst I fetch in your other,” and she bustled off into the night-nursery.

“I wish I was grown up,” said Peggy, twirling the ring round and round her thumb and staring into the fire. “Then I should drink strong tea, and eat birthday cake downstairs every day if I liked, and wear grand hats with fevvers in them!”

“I’m ready whenever you are,” said a voice behind her.

Peggy turned round quickly, and then nearly jumped out of her skin with astonishment.

For behind her, on the other side of the table, stood a Giant!

Peggy knew in a moment that he was a real Giant,[8] because he was the living image of the one on page 375 of the Blue Fairy Book, but instead of looking cross like that one does, he had a nice wide smile, and the kindest round twinkly blue eyes Peggy had ever seen. He was dressed all in brown, with bright scarlet stockings, his hair was thick and long, and so was his beard, and the nursery was so much too low for him that he had to bend nearly double, his great shoulders sending a cloud of plaster off the ceiling every time he moved. In one huge hand he held a cup of very black-looking tea, and in the other a bit of birthday cake with sugar on it and almond paste and little silver beads.

“You are a tall kind!” gasped Peggy, staring up at him. “I—I don’t think Nannie will be at all pleased!” and she glanced fearfully through the half-open door into the night-nursery.

“I know, that’s why I spoke,” said the Giant, sitting down on the floor and stretching himself—one foot went right out of the window in the process, and the other up the chimney, but he looked much more comfortable. The cup of tea and the cake he put carefully down by his side. “You rubbed the ring and wished, you know. How do you like your dress?”

Peggy looked down at herself and discovered she was wearing a striped white and yellow silk gown falling in heavy folds to the ground, and very high-waisted. On her arm was hanging, by its ribbon, a large white poke-bonnet, wreathed entirely around with a curling yellow feather.

“What are these things?” she asked in bewilderment.

“Why, you wished to be grown up, didn’t you?” said the Giant. “And you are. Or, at least, that’s the best I can do for you. But I’m a bit out of practice I know,” and he gazed with a rather disheartened air at the bonnet.

“I don’t know what Nannie will say,” said Peggy[9] uneasily. (She hadn’t the heart to tell the Giant that he hadn’t made her in the least the kind of grown-up she wanted to be.) “She never likes me dressing up!”

“Well then, wish about it,” said the Giant. “Say, ‘I wish Nurse to stay away half an hour.’ Hurry up, she’s coming.”

“I wish Nurse to stay away half an hour,” said Peggy obediently. “But what’s the good of that?” she added. “Here she is,” and so she was.

She came through the door hurriedly, with the frock in her hand, and when she saw the Giant she jumped right up high into the air, and then she sat down on the floor with a flop.

“Who is this, Miss Peggy?” she asked in an awful voice.

“Dear me!” said the Giant, struggling to his feet and knocking over the Rocking-Horse and three chairs in his hurry. “What can have gone wrong? The spells don’t work as they used to!” He looked at Nurse nervously; then—“You must stick to me,” he whispered hoarsely to Peggy, stepping back on the cup and saucer and grinding them to powder with his heel.

“He’s—he’s a friend of mine!” said Peggy bravely. She suddenly felt very sorry for the Giant, for though he was so extremely big he seemed somehow now just like a helpless baby. “He’s come to tea, Nannie, because it’s my birfday.” (Peggy still talked baby language when she got excited.)[10] “And he’s brought a lovely bit of cake like you said people had before the War,” she went on, pressing the ring tightly, and wondering when Nurse would speak. But the unfortunate woman continued to sit on the floor, glaring wildly at the Giant, and opening and shutting her mouth without a sound coming out of it.

“Oh dear, I wish something would happen,” at last came from Peggy desperately.

No sooner were the words out of her mouth than she felt the Giant tuck her under his arm and walk straight out of the window with her!

They went right over the garden and fields, the Giant striding along through the air with the greatest ease, and at such a pace that often the birds they met had no time to fly out of their way, and flew full tilt against them.

“Phew! that was a narrow shave!” said the Giant, stepping down at last into the middle of a great wood. He put Peggy down on some soft green moss, and leant against an oak tree, panting. “And after all, we left the tea and cake behind!” he added.

Peggy looked up at him. His head was right up above the branches, but she could see his long brown beard among the twigs.

“You squashed them both with your foot,” she said plaintively. “And I don’t understand anyfing! Why did you come at all? Though I like you very much,” she continued quickly. And indeed she had, from the very first moment. For he had such a kind face—though it was not what you would call a clever one exactly—and he was so different from every one else, and looked as though he would play games nicely.

“I came because you wished,” said the Giant. “That’s a Fairy Ring, that is. But it’s not once in a hundred years[11] any children find it—or, when they do, think of putting it on their thumb and wishing. By the way, where was it this time?”

“In a cracker,” said Peggy.

“Ah, I know those crackers,” said the Giant. “One Fairy one to ten million common ones is the average. Let me congratulate you! You’ll be allowed six visits from me, and six wishes each time, before the Ring disappears again. Very liberal, I call it.”

“Do you mean you can let me have everything I wish for, like what happens in the Fairy stories?” asked Peggy in a state of great excitement, and she began to jump about in a very un-grown-up way. “Oh, I wish—I wish this tree was made of chocolate!” she screamed. (You must remember she was rather over-excited, as it was her birthday.)

The Giant immediately handed her down a chocolate cream from one of the boughs; and Peggy noticed a bright shade of brown creeping all over the trunk and branches.

“Wish number three gone,” said the Giant with a sigh of relief. “Thank goodness, that wasn’t difficult. But I’m sorry to tell you I’ve grown rusty, very rusty indeed! It’s so many years since I’ve had anything of this sort to do, that I’ve forgotten how to manage the simplest things.” He sighed deeply till the branches clashed together over Peggy’s head. “I can see by your eye,” he went on gloomily, “that there’s something not quite up to date enough about your dress. And you must have noticed in the nursery that I’d quite forgotten how to disappear quickly. I shall lose my nerve at this rate, I know I shall!” and a large tear dropped at Peggy’s feet.

“Oh, no, you won’t!” said Peggy, putting her arms as far round one of his ankles as they would go, and hugging it. (The chocolate cream had been delicious, and she was in very[12] good spirits.) “I’d have hated you to disappear without me just now! Nannie would have been angry anyhow at my dress—and you managed beautifully after! But you shall practise disappearing now if you want to. We’ve lots of time, haven’t we? Go on. Try.”

So the Giant tried and tried—and then he rested—and then he tried and tried again, but it wasn’t the slightest good; he remained just as big and brown and there as ever. At last, with a stupendous effort, he almost succeeded, though he still showed a bit where the sun shone down against the trunk, whilst one of his huge boots remained quite visible, standing forlornly on the grass beside Peggy.

“It’s no good,” he remarked, reappearing again with startling suddenness. “There, I’m back again, you see, and I didn’t mean to be. Do use one of your wishes on it! Perhaps if I’d only disappeared once in the proper way, I should get into the hang of it all again. You’d better turn the Ring besides wishing, to make it more certain.”

Peggy did so, giving the Ring an extra turn in her zeal, and the Giant rolled completely up, and disappeared in a twinkling, to her great satisfaction. “That was splendid!” she cried. “You see it was quite easy! Now come back and do it again by yourself”—but the Giant didn’t answer at all.

A little cold wind blew right through the wood and rustled all the chocolate oak leaves above Peggy’s head, and a squirrel up in the branches threw a chocolate cream down on her, and then another, and they both squashed on her striped silk dress. Peggy was not easily frightened, but it all felt very lonely and queer, particularly as she didn’t know in the least where she was. She jumped to her feet and began running about the wood, shouting for the Giant as loudly as she could.

[13]It was only when she had been doing this for quite a long time, and getting no answer at all, that she remembered that she had not wished or turned the Ring. She at once did both, and, “Don’t tread on me for goodness’ sake!” said a squeaky voice near her foot.

Peggy looked down, and there amongst the leaves stood a tiny little figure reaching no higher than her instep. It was only when she had picked him up and peered closely into his face that she recognised the features of the Giant, distorted with rage.

“Oh dear,” she cried, “what has happened?”

“You should learn to manage your Ring better, before you treat me like this!” said the tiny Giant in an exceedingly cross voice. “Put me on a blade of grass at once, please,—thank you. I don’t like being held round the middle like that. Why did you turn the Ring more than once? I’ve never disappeared so uncomfortably fast before. And now look at the size I am! This is all I can manage after such a shock!”

“Well, it’s not my fault,” said Peggy with some spirit. “You ought to know the Ring better than I do. I only did what you told me!”

“I have got a broad outline of how the thing should be run,” said the Giant. “But I can’t fill in the details. You will have to learn by experience, I suppose.”

“What grand words you use,” said Peggy respectfully, but the Giant didn’t look mollified at all.

“Now we’ve used up the five wishes (not counting the failure) so you’d better wish yourself back in the nursery,” he said. “I don’t see that you’ve had much fun, and I know I haven’t. Goodness knows how I shall get back to my house!”

“Oh, but I want to do lots more,” said Peggy. “I[14] haven’t played at being grown up at all yet, and I haven’t had any more chocolates!”

“Never mind, there’s no time left—wish yourself home,” said the Giant. “Quick, now!”

He sounded so like Nurse at her crossest that Peggy hurriedly obeyed,—and the next instant she found herself standing alone in the nursery in her petticoat, and in the act of putting her ring into the toy cupboard.

“You must be cold!” said Nurse, coming in. “I thought I’d never find your old frock, and leaning over the drawer made me feel quite faint-like! There! now have a nice game with your dolls,” and she bustled over to draw the curtain.

“All the same I wish he hadn’t seemed so cross,” said Peggy to her Golliwog. “The only really nice part was the chocolate cream.”

“What are you grumbling about?” asked Nurse. “A chocolate cream, indeed, at this time of night! I think, if you ask me, that it’s time all little girls were in bed!” (She was that sort of Nurse.)

“All right,” said Peggy, jumping up at once. She even began to unbutton her frock and pull off her hair ribbon to Nurse’s great surprise; who, of course, couldn’t know that all Peggy wanted was for the next day to come quickly, so that she could see the Giant again.

“We’ll really find out the right way to manage the wishing to-morrow,” she thought as she cuddled down into bed. “It isn’t the dear old Giant’s fault if he’s forgotten things a little bit. It was really very clever of him to think of that dress at all! It’s the sort great-great-grandmother is wearing in the picture in the hall. Perhaps she was one of the little girls he played with. Fancy him remembering all that time ago, clever old thing!” She turned her head[15] and stared up at the ceiling, all golden with the firelight, and crossed with black crinkly bars from the reflection of the guard. “All the same I wish he hadn’t looked so cross,” she murmured, as she fell asleep.

Peggy sat curled up on the big window seat in the nursery reading Mary’s Meadow. At least, you couldn’t call it exactly reading, but mother had read out bits to her so often that she could remember most of them by heart.

Nurse was down in the kitchen talking to Cook; and the rain was pelting against the window-panes and the wind was blowing the trees all sideways and flattening down the plants in the garden, and screaming round and round the house trying to get in and blow Peggy about too.

Her little fat fingers moved along below the words as she read to herself in a slow whisper:

“We went there for flow-ers; we went there for mush-rooms and puff-balls; we went there to hear the night-in-gale.”

Peggy stopped, and looked out at the driving rain with a little sigh. “I wish I had a meadow of my very own!” she thought. And then she suddenly saw a bright green light coming from the cupboard in front of her, and at the same moment the Ring flew right through the wooden door, and straight on to her thumb!

Peggy gave a little shout of delight.

“I wish I was in my meadow with my Giant,” she cried[16] as fast as she could, for she heard Nurse’s step on the stairs. “And picking daisies, please,” she added, turning the Ring round, and rubbing it too, so as to make quite certain lots would happen.

“I’m perfectly delighted with this effect. My powers are returning, it seems!” said the Giant, speaking in his grandest though tiniest voice.

Peggy rubbed her eyes and tried to open them wide, but the sunshine was so dazzling that for a few seconds she was quite blinded by it.

Then she saw that she was in a great big green field, edged all round with a tall green hedge; and growing amongst the grass in the field were flowers, shaped like daisies of every kind and colour, big ones, little ones, tall ones, short ones, white, blue, pink, red, yellow, and purple ones, and even some of colours Peggy had only thought about sometimes but knew no name for. And the most lovely scent—a sort of mixture of honey and roses and pansies—came up from the whole field.

Peggy sat down amongst the flowers, clapping her hands. This was something like a wish! But where was the Giant?

“May I really pick a bunch?” she asked, looking towards the place where she thought his voice had come from.

“Yes, only be very careful of me!” said the Giant, and Peggy felt something tickling her hand.

She looked down and saw the Giant.

He was still very tiny, and was balancing on the yellow centre of a scarlet daisy, and reaching up to prick her hand with a bit of tasselled grass. He had a most roguish and[17] good-tempered expression on his little fat face, and the sun shone down on his curly beard till it made it look quite golden.

“Oh, what fun it must be to be small like that!” said Peggy, clasping her hands (she was so pleased to find the Giant wasn’t cross any longer). “I wish I could balance on a daisy too!”

She at once found herself standing amongst some thick bristling yellow stalks, like corn, whilst all around her spread up curving blue walls, stretching, it seemed, right up to the blue sky.

“What’s happened? Where am I?” she asked in a rather surprised voice.

“Balancing on a blue daisy,” said the Giant, jumping into the yellow stalks by her side. And Peggy noticed that they were now both exactly the same height. “Look out! Hold on!” he added excitedly, catching her hand. “There’s a breeze passing over the flowers. We’re going swinging!”

A great rustling sounded in the distance, which suddenly burst into a roar as a great wind swept by—and down they were flung on to the huge silky walls as the daisy bowed its head. Then with a tremendous jerk the flower righted itself, and sent them spinning off on to another daisy. This one shook its head and slid them on to another, and so on and on, half across the field, until at last, when they had learnt to balance, and were swinging dizzily to and fro on a large violet-coloured petal, the whole thing tilted more suddenly than usual, and shot them down on to the ground below.

“Oh, wasn’t it lovely!” cried Peggy, looking up through the dim light at the gigantic heads, still swaying to and fro[18] amongst the great blades of grass which looked as tall as trees. “What fun it is to be tiny like this!”

“I’m getting a bit tired of it,” said the Giant ruefully. He had knocked his knee on a little stone, and was sitting on the ground rubbing it. “You left me this size yesterday, you know—and I couldn’t remember the way to get back to my proper height! I think you’ll have to use up a wish on me now. After all, you’ve got four left still.”

“All right,” said Peggy obediently. (Anything to keep the Giant in such a good temper.) “I wish you were as tall as you were before.”

The Giant immediately shot up right through the grass and flowers, and apparently disappeared, for Peggy found herself left by an enormous black rock which barred the way, and quite shut out all the light there was in that dark place. She at once began trying to climb it, so as to find her way back to the Giant, but she had no sooner scrambled up the first ledge, than a voice that filled the air like several claps of thunder all sounding at once, bawled out:

“Get off my boot! I daren’t move. You can’t possibly stay as small as that!”

“Oh dear, it’s you I’m on, is it?” exclaimed Peggy. “I quite forgot that I was left so tiny! Now I must use up another wish, I suppose. What dreadful waste!” And of course there was nothing for it but to do so, as you can’t possibly have any fun with someone a million times taller than yourself.

The next moment she was sitting among the flowers, once more her proper size, with the Giant, once more his proper size too, standing by her.

“And now, may I begin to pick a bunch for Mummie?” she asked.

“Certainly,” said the Giant. “There’s no one to stop[19] you; they’re all your own.” He sat down on a hedge near by, which immediately sank with his weight, the trees that grew on it toppling down in all directions. “There, now I’m comfortable,” said he, “and I think I’ll have a nap. I never slept a wink last night.” And he lay down across what was left of the hedge, closed his eyes, and started snoring at once.

“Poor Giant,” said little Peggy, climbing up the hedge to look down at his round, good-tempered face, and wide-open mouth. “Sometimes he talks so grandly, but he’s not a bit grand really. I’ll let him stay asleep for a nice long time whilst I pick a huge, big bunch to send Mummie,” and she jumped down into the field again.

“I’ve only two wishes left now,” she thought to herself, as she ran in and out amongst the daisies. “Or really only one that’s any good, for I suppose I must use the last to get me home. I really think,” she went on, as she sat down to tie a bit of grass round a bunch of scarlet daisies, “that the Giant ought to get me home himself without making me waste a wish on it! I’m sure that’s always done in books. I’ll speak to him about it when he wakes.”

The running about in the hot sun had made Peggy quite thirsty, and after some searching she found a dear little stream running right through the field, at which a lot of butterflies were drinking. It was a beautiful golden colour, and when she tasted it she found it was the most delicious[20] lemonade, and it had crystallised rose leaves floating here and there upon it. The butterflies flew round her in hundreds and allowed her to stroke their soft red and blue and yellow wings, and when she suggested a game of hide-and-seek they were all delighted, and fluttered round in such quantities that she could scarcely breathe.

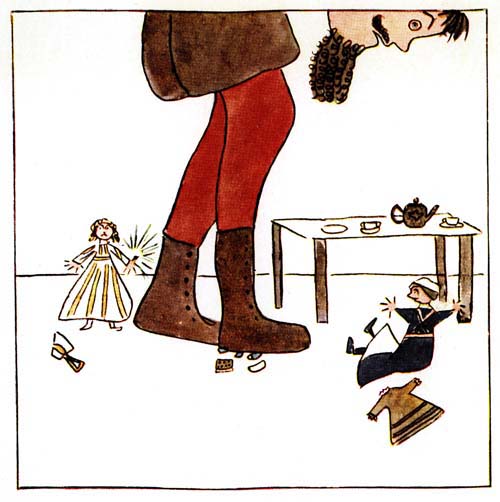

This is the picture Peggy drew of the Second Adventure. It was a very difficult one to do. The Butterflies are just coming up in hundreds and hundreds to try and wake the Giant. Mother showed Peggy how to draw the butterflies, but she did nearly all the rest quite by herself. The Giant sometimes wore that red hat, and sometimes a green pointed one. The Butterflies and Daisies were the most fun to paint. I hope you see the Ring.

It turned out a failure in the end, as not one butterfly could be induced to remain hidden long enough for the others to find him, but was always flitting in and out of his hiding-place, which, as everyone knows, completely spoils hide-and-seek.

However, they had a lovely romp, and it was quite a pretty sight to see several hundreds of them chasing Peggy back to “Home” (which was the Giant’s boot) after she had hidden.

“Oh, do let’s wake the Giant!” said Peggy, as they stopped for breath, “and make him play too! I know he’d love it!”

They all gathered round the sleeping Giant, who was lying just as Peggy had left him, snoring loudly, with his head comfortably pillowed amongst the spreading roots of a fallen tree.

But do you think they could wake him? Not they!

Peggy climbed the hedge and tickled his face with a branch. Then she tried to shake his arm, but of course couldn’t move it at all. Then she begged the butterflies to help, and they all flew round him with a great swishing of wings, making as much noise as they possibly could; but still the Giant lay there snoring, for he was not used to being up a whole night long, and was very, very tired.

A large blue and gold butterfly suggested pouring lemonade on to his face, and they fetched a good deal[21] between them all, but that wasn’t the least good, and only slid on to his beard and made it very wet and sticky.

“Oh, what am I to do?” cried Peggy. “It’s not fair! I never heard of such a thing happening in any Fairy Book! Nannie always lifts me out of bed when I won’t wake up. I only wish she was here to do it to him!”

And then she could have bitten her tongue out, for the butterflies suddenly wheeled round and flew away in a great cloud, and “He is a heavy weight, Miss Peggy,” said Nurse, appearing on the other side of the hedge, her face very red and hot. “But I’ll manage it in a moment. Now then, up with you! There he is, great heavy thing! He ought to be ashamed of himself, the big baby!”

Peggy felt dreadfully disappointed, and also rather angry, for though she didn’t mind getting annoyed with the Giant herself, it was a different thing hearing Nurse call him names. And now she’d wasted another wish entirely by accident, and must use her last up as quick as lightning, for Nurse was already beginning to look very puzzled and suspicious.

“I wish we were back in the nursery,” she whispered to the Giant, who was sitting up on the hedge, rubbing his eyes and staring at Nurse.... “And I’m very, very angry with you!” she added, as she found herself on the nursery window-seat again. But she was only answered by a rattle of raindrops on the panes.

“You’ve dropped your nice book on the floor,” said Nurse, coming in with a pile of aired linen in her arms and a deep frown on her face. “You’ll have to go back to rag-books again if you serve Mary’s Meadow like that!”

“Oh dear, I quite forgot the bunch of daisies!” said Peggy, aghast.

[22]“Now what daisies, Miss Peggy?” asked Nurse. “I can’t have you talking nonsense instead of attending to what I say. Pick that book up immediately. And you’ve got that Ring on your thumb again, I do declare! Mother wouldn’t like it at all, nasty common thing.”

“Oh, mayn’t I wear it sometimes, Nannie?” Peggy pleaded. “I know Mummie wouldn’t mind. She always lets me wear the bead necklaces I make.”

“No arguing!” said Nurse. “I’m going to put it in this cup on the bookshelf, and you can ask your mother when she comes back. Time enough to wear it then if she’ll let you.”

She did seem cross. No wonder, for, though she didn’t know it, she had just travelled very many million miles in about three seconds, and that’s very upsetting to the temper if you’re not used to it.

And Peggy looked sadly at the cup, for it was far out of her reach even if she stood on a chair.

“If I’d only had time to explain to the Giant!” she thought. “He couldn’t help sleeping so soundly, poor thing. Now perhaps I shall never see him again.” And she was very subdued indeed for the rest of the day.

But she needn’t have worried. You see she kept on forgetting it was a Fairy Ring.

“And if you don’t get muddy, but pick your way nicely, we’ll go to the village shop and buy a pennyworth of sweets,” said Nurse the next day, when they started out for their walk.

[23]“May I pick some primroses if I see them?” asked Peggy, dancing along.

There never were any on the high road, where Nurse generally chose to walk, but still there was always the chance there might be one day, and it was well to get permission beforehand.

“Yes, if you like,” said Nurse absentmindedly. She was very busy trying to see into a cab that had just passed, and didn’t really hear. Not that it mattered. There never were any primroses.

“There’s one—at least I fink there is!” said Peggy suddenly, when they had nearly reached the village. She stood on the edge of the ditch and peered up into the hedge. “Or is it a Fairy, perhaps? Do look, Nannie, it’s all white and shiny!”

“A Fairy indeed!” said Nurse, looking up too. “It’s an old bit of paper blown up there. Be careful, or you’ll be in the ditch!”

But she was too late, for Peggy lost her balance—or the side of the ditch gave way—and the next moment the two little gaitered legs were half hidden in dark brown muddy water!

“Very good!” said Nurse in a terrible voice. Then she dragged Peggy out, and walked her back along the road towards home, saying nothing in her most alarming manner.

Peggy really felt quite frightened.

“Nannie, you’re hurting my arm!” she said at last, trying to drag her hand away. She hated the dry feel of Nurse’s black cotton gloves pinched around her cold fingers. “Aren’t we going to buy any sweets after all?” she went on.

There was no answer.

[24]“Do you hear?” shouted Peggy desperately, and pulling harder.

“You should learn to do as you’re told,” said Nurse, taking a firmer grip, and walking faster still.

Peggy pulled harder still. She was beginning to feel really naughty. Besides, she knew it had been a Fairy, and who could think of stupid old ditches then? Nurse never understood.

“What have you got on your thumb?” asked Nurse, suddenly stopping, and dropping Peggy’s hand very quickly.

Peggy looked down, and there was the Fairy Ring sending out great sparkles of green light all over the muddy road! She could scarcely believe her eyes, and Nurse looked rather frightened.

Peggy felt there was not a second to lose.

“O Giant, I wish you’d take me away somewhere—and make Nurse nicer!” she whispered in a great hurry.

“You are a oner, you are!” said the Giant admiringly. “You nearly always ask for two things in one wish—but it never seems to matter—you get ’em! Now come along, we’ve got to hurry.”

Peggy and the Giant were walking along a wide silver road. The hedges, the gates, the trees, the flowers, even the birds that flew over their heads, were silver, all sparkling and gleaming in the light of a big silver moon in a blue sky. Peggy had never seen anything so beautiful, and she looked up at the Giant with very happy eyes as she danced along the road by his side.

“I shall always leave you to think of lovely places,” she said. “I should never have thought of coming here!”

“It’s the Ring as well,” said the Giant modestly. “But[25] we aren’t there yet. Sit on my hand; we shall get there quicker that way.”

“Why, where are we going?” asked Peggy, jumping up and holding on to his thumb.

“To Fairy-land,” said the Giant, stepping out briskly, “or at least to one little bit of it. It’s only as a great treat, because you couldn’t find a primrose, and never got your sweets. By the way, that was a Fairy in the hedge,” he added.

“I knew it was,” said Peggy. “But Nannie won’t see things sometimes. Oh, look! what is this coming?”

They had turned a corner, and saw far away above the hills something that appeared to be a great blue cloud edged with gold, advancing with a humming sound. As it came nearer Peggy discovered to her great excitement that it was really a multitude of Fairies all dressed in the palest blue dresses, their golden hair flowing out around them, and on their heads silver crowns studded with bright blue stones; and the humming sound was the rustle of their great blue wings which were bearing them along at a tremendous rate.

They made straight for Peggy, led by a tall, beautiful Fairy, whose blue dress was simply covered with sparkling stones. And there was something in her pretty smiling face which reminded Peggy of someone, but she couldn’t remember who. The next moment the Fairy was just above the Giant’s head; then she dropped suddenly, and catching Peggy up by the hand she and all the rest of the Fairies rose high in the air again and flew off by the way they had come.

Peggy clutched the Fairy’s hand very tightly for some time, for they were all going so fast that the rush of air made her feel quite breathless. But when she was rather more used to it, she turned her head to look at the[26] Fairies following, and suddenly saw that she had grown a magnificent pair of blue wings too!

She at once tried to flap them, and found she could do so quite well, though rather jerkily at first, and the Giant—who was striding along in the air just below her—looked up with a wide grin on his round face.

“Capital, capital!” he called out. “Well, how do you like flying?”

“It’s lovely!” shouted back Peggy. “You do think of splendid things! And so do you!” she added, looking up gratefully into the Fairy’s face.

And then she gave a great start, for, of course, she saw now who the Fairy was. She was Nurse!

Peggy gasped, and very nearly dropped right down. It was certainly Nurse, but Nurse looking happy, Nurse looking pleased with Peggy, Nurse seeming as though for once she was actually enjoying herself! It really seemed too good to be true, and Peggy darted another glance of great thankfulness down at the Giant.

“I’m glad you think it fun,” said Nurse, in a sweet, clear voice. “But you needn’t flap quite so hard. Look, give long, steady sweeps like this,” and she sprang forward even quicker into the air, and then showed Peggy exactly how it was done, till she had learnt perfectly.

The land was changing below them, or they were much higher up. It was sometimes bright and coloured like a rainbow, sometimes as red as fire, and sometimes so dark that they could see nothing below them. Once a terrible smell of smoke rose up, and Nurse called to everyone to mount higher.

“What a dreadful place that was,” said Peggy, when they once more saw the pretty rainbow land below them again. “Who lives there?”

[27]“Ogres,” said Nurse, “heaps of them. I hate passing their way, but it’s a short cut. That red country we passed just now was where the Dragons live. They’re even worse, nasty ill-bred creatures! However, we’ve passed them all now, and here we come down.”

They were right above a cleared space in a big black wood, and at a signal from Nurse, all the Fairies paused, and, half folding their wings, floated down amongst the trees. Peggy did so too, and balanced on a large branch, closing her wings up neatly as she saw the others doing.

“Now, each take a tree and begin,” called Nurse, who was flying about looking happier than ever, “and after that we’ll have some games!”

Then Peggy noticed what extraordinary trees they were all perched upon. For from every twig were hanging by silver strings the most fascinating little tiny sugar animals and birds of every colour and kind—blue elephants, mauve dogs, scarlet mice, yellow nightingales, and everything else you can think of. And all through the wood she could hear the Fairies calling and laughing to each other as they fluttered up and down the trees and ate the pretty things.

“May I?” asked Peggy, her fingers closing round a purple sparrow, and looking at Nurse who she hardly dared believe would be so changed as to allow her to eat as many sweets as she liked!

“Of course,” said Nurse smiling—and Peggy had never realised before how very nicely Nurse could smile. She also longed to tell her how pretty she looked with her golden hair all flying loose in the air. But she didn’t dare. “I advise you to try that pink cow just behind you,” went on Nurse. “No, not that one, the very big one by the trunk. That’s it. Now, isn’t that good?”

It was certainly too lovely for words. It had the[28] delicious taste that a strawberry ice has before you’ve eaten too many at a party, and it was also rather like pineapples and pear-drops and Tangerine oranges, and yet it was far better than any of them.

Peggy soon got quite good at half fluttering, half balancing along the branches like the others were doing, and trying each different sweet by turn.

(I’m afraid this sounds rather a greedy adventure of Peggy’s, but it wasn’t really, as it happened in Fairy-land, and there were enough sweets for everyone, and no one felt sick when they’d eaten too many.)

She had just bitten a pink sugar rabbit in half, and found it tasted just like meringues, when she remembered the Giant.

“Oh dear,” she cried, “where is the Giant? I’d quite forgotten him!”

Nurse looked very worried indeed.

“So had I,” she said. “We must have gone too fast for him!” And she flew up on to the top of a tree and gazed away across the hills. “He never will let us lend him wings,” she went on, “so he always gets left behind. He says his seven-leagued boots will last him out all right, and it’s no good arguing with him. Now, I expect he’s stuck somewhere, or has stumbled upon the Ogres and had a fight.”

“What!” cried Peggy in great horror. “My Giant[29] fighting? Oh, he’d sure to be beaten. What shall I do?” and she fluttered to and fro in great distress.

“Why, wish he were here, of course,” said Nurse. “You’ve five wishes left still, haven’t you?”

Peggy wished at once, and the Giant came crashing through the wood, upsetting the sugar trees in all directions.

“Oh, look!” said Nurse. “How careless you are!” (But she didn’t say it a bit in her old cross way.) “Plant those trees again before you do anything else!”

The Giant looked terribly knocked about and woebegone, and his coat was all in tatters, but he did as he was told at once, balancing the trees up again, and stamping in their roots well, like Peggy had seen the gardener do with his plants. Then he sat down on the ground and wiped his hot face with his pocket-handkerchief, and the Fairies all stopped eating sweets to hear what he had to say.

“Phew!” he gasped, “I’ve had an awful time! Whatever possessed you all to go at such a pace?”

“Well, I like that!” said Nurse. “When it was you who asked us to get to the sugar-wood before dark!”

“I wish I hadn’t now,” said the Giant. “Trying to catch you up I stumbled right into the middle of the Ogres, and I’d no sooner got away from them—after having my coat torn half off my back—than I stepped plump on to the Red Dragon, and you know what that means!”

“Dear, dear!” said Nurse. “Was he very vexed?”

“Vexed!” said the Giant. “He was in such a hideous passion that he made after me as fast as he could waddle—and then he started gliding. I was up in the air in a moment, I can tell you, striding along for all I was worth, and when he saw he couldn’t catch me from the ground he took to his wings and flew! And when a Dragon uses his wings—well—you know what you’ve got to expect![30] He’s after me now—and the Ogres are, too!” he added resignedly.

“Oh, they’ll never find you here!” said Nurse. “The Ring brought you along faster than any Ogre or Dragon could travel.”

“I thought an Ogre was almost the same as a Giant?” Peggy whispered to Nurse.

“Good gracious, no!” said she. “Don’t let the Giant hear you say that! They’re a set of vagabonds and ruffians who haunt the edge of Fairy-land. The kind with one eye in their foreheads, and the sort who say ‘Fe-Fo-Fum.’ You must have read about them? They can’t harm us Fairies, but any Giant, especially a really nice good one like yours, makes them simply mad!”

Peggy slid off her branch and flew to the Giant, perching on his shoulder and stroking his hair.

“I’ll take care of you,” she said, “if they do come. Don’t you be afraid! He’ll be all right, won’t he?” she added, turning to the Fairies.

But they were not listening.

They had all flown to the tops of their trees and were balancing on the topmost branches, bending forward and listening intently. For there was a soft humming, grumbling, hissing, bleating, gurgling sound coming from somewhere very far away!

“That’s the Ogres,” said Nurse, looking very grave—and the sound got a tiny bit louder.

Then a little cold, tinkling, rippling, singing, shivering, clinking sound began as well—so faint that it was just like a funny little whisper, and “That’s the Dragon and he’ll be here first!” cried all the Fairies together, looking graver still, and they began to flutter round Peggy and the Giant, staring at the Ring, which was winking and[31] flashing long green darts of light over everything and everybody.

“What shall I wish?” asked Peggy, glancing at the Giant, who was obviously too tired out to move another step. (The sounds were every second getting louder and louder.) “I—I should rather like to see them,” she added shyly, “if I can make the dear Giant quite safe.”

“Wish me to be invisible,” said the Giant wearily. “Then I shan’t have to get up. I’ve been practising it, so you won’t have any difficulty.”

“Yes, that’ll do nicely,” said Nurse. The noise had suddenly become so loud that Peggy could hardly hear her. “And you get as much behind the trunk as you can,” she went on to Peggy at the top of her voice, “and I’ll sit on a branch in front of you and hide you. If they do see you, you’ve only got to wish yourself invisible too.”

The noise had now changed to the rattling kind that a million luggage trains would make if they were all driven along in a row at once, and Peggy could hear tree after tree crashing to the ground. She had only just time to wish, and see the Giant disappear completely, when a great red creature plunged down through the branches above into the open space in front of the Fairies, and fell on his side, quite close to Peggy’s tree, lashing his tail and panting like a dog.

Tongues of red and blue fire flashed and darted up and down his scaly back, and his scarlet wings spreading across the grass withered it up at once. Peggy did feel glad she hadn’t missed the sight! But she took the precaution to wish that he should not crush the Giant, in case invisible Giants could be crushed.

In a few seconds the Dragon rolled on to his little short stubbly feet and waddled up to Nurse.

“Where’s the Giant?” he lisped in a high and very soft[32] voice. “I know he’s somewhere here, and I’ll flatten down every one of your sugar trees if you don’t tell me this minute!”

Peggy drew this to show what the Dragon looked like when Nurse said, “You wouldn’t dare!” Nurse is on the left and is just going to eat her sugar bird. Peggy is up above peeping from behind the tree. She wanted to draw the Ogres too, but there wasn’t any room. Mother only helped her with some of the branches, everything else she did by herself, and the Fairies took ages to do. They are sitting on the boughs eating the sugar animals and birds. It made the Dragon furious to see they weren’t afraid of him a bit. Those long things on the ground are the trees he knocked down, and the bits of red are the fires he started with his red-hot paws. The Giant is invisible sitting on the grass, just behind the Dragon’s tongue.

There was really something very frightening in his little polite voice!

“You wouldn’t dare!” said Nurse, laughing scornfully. “Run along and look about for him! He must be somewhere, as you rightly remark,” and she turned her back on him and began to nibble at a sugar bird.

The Dragon raised his eyebrows ironically, but finding Nurse was not looking at him any longer, he began to trot and glide about the wood, sticking his long red tongue under the fallen trees to lift them up, and hissing to himself more and more when he couldn’t find the Giant anywhere.

(And all the time the sound of the Ogres coming got louder and louder and louder!)

“There’s some magic going on!” said the Dragon at last, angrily, raising himself up on to the very tip of his tail and glaring over the tree-tops. “Ha, ha!” he added, “here come the others at last,” and he stretched out two welcoming paws to the two enormous Ogres who at that moment crashed into the wood.

Peggy nearly tumbled out of the tree in her excitement, for this was worth seeing indeed! One of the Ogres had only one eye in the middle of his forehead, just as she’d thought he would, and he did nothing but say “Fe-Fo-Fum!” over and over again, and stamp and growl and snarl.

The other one had three heads which all looked different ways, and he kept gnashing his three lots of teeth and snorting at the Dragon, who would go on smiling at him.

Then both Ogres advanced upon Nurse, brandishing their clubs.

[33]“We went miles out of our way!” they roared. “Where’s he gone to now?”

Nurse looked them over calmly from head to toe.

“Take your caps off this moment,” she said severely. “I think you forget who you’re speaking to!”

They looked rather cowed for the moment, and took their caps off sheepishly without saying a word, though the Dragon’s chuckle was enough to infuriate anybody. (The Ogre with the three heads had of course to take off three caps.)

“That’s better!” said Nurse. “Now, what do you want?”

“The Giant, of course,” growled the Ogre with one eye. “Fe-Fo-Fum! Fe-Fo-Fum!” and he trampled up and down restlessly.

It was more than Peggy could stand.

“Oh, do go on with the verse!” she called out imploringly, leaning forward right out of the tree. “You’ve said that line over and over again, and it’s not nearly all! You must remember how it goes on:

but she got no further, for with a scream of triumph the Dragon flung himself forward and seized her tree right up by the roots, and the nearest Ogre at the same moment plucked her out of it by his finger and thumb.

“Quick, Miss Peggy!” screamed Nurse, and Peggy did wish quick, ... and found herself back on the old muddy high road again, being dragged along it by Nurse. “For if you don’t hurry a bit more,” she went on, “you’ll catch your death of cold in those wet socks.”

Peggy burst into tears. Nurse was no longer a bit like[34] a nice Fairy, and it was all such a dreadfully sudden change, and everything felt so very flat. Even the stone in her Ring looked small, and as dull as a pebble.

“Oh dear, oh dear!” she sobbed. “And we never got to the games at all! And I’ve still got one wish left that I never used. Now it will be wasted!” and the tears poured fast down her cheeks.

Nurse looked down at her in astonishment, for Peggy never cried.

“What’s come over you all of a sudden?” she asked.

“I wish you were always nice like just now,” sobbed Peggy, quite forgetting Nurse never remembered anything about the adventures. “We were having such a lovely time! And then you went and made me leave at the most exciting bit.”

“I don’t think it’s very exciting to stand in a muddy ditch!” said Nurse, but her voice had all at once become very soft and gentle. “But never mind, Miss Peggy dear. I’ll tell you the story of the Three Bears now if you like, then we shall soon get home. And perhaps there’ll be a letter from Mother; I shouldn’t wonder!”

Peggy could scarcely believe her ears, for except in Fairy-land Nurse never really talked like that. Her tears were forgotten very quickly, for Nurse went on being like it all the rest of the day, laughing and playing and romping with Peggy right up till bedtime, and even a little while after!

Peggy couldn’t make it out.

You see she never noticed that she had used up her sixth wish after all.

“What’s that whizzing, Nurse?” asked Peggy, as she was picking a bunch of double snowdrops in the garden the next afternoon.

“A motor, I expect,” said Nurse, who was talking to the gardener—and she ran to peep down the drive through the bushes. “Callers, I’ll be bound. Yes, here it comes, a big red car. There’s a fat lady in behind, and a girl chauffeur driving it.”

“Let’s see,” said Peggy, pressing into the bushes too.

Nurse was not quite like she had been the evening before, because, of course, Peggy’s wishes never lasted on to the next day, but still she wasn’t nearly as cross as usual, and she had been playing hide-and-seek with Peggy quite half the afternoon, until the gardener came up to talk.

“Now they’ve heard your Mother’s not here, and are going away again,” Nurse went on. “There, look! They’ve stuck at the difficult turn, and the engine’s stopped! My, doesn’t that girl look cross? Get back, Miss Peggy, they’ll see us! Now you can hide once more if you like before tea. I’ll just finish giving John the message about the vegetables.”

“I wish I knew how to drive a motor,” thought Peggy longingly, as she trotted off to hide behind some laurels. “I’d go like the wind, and wouldn’t stop at any corners——Why—what’s happened?”

For she was driving the big red car as fast as lightning down the drive!

[36]“You never noticed you had the Ring on!” chuckled the Giant. “Well turned! Never mind the gate-post.”

He was sitting at the back, but with his legs sticking right out in front beyond the bonnet; and his elbows kept knocking great pieces out of the hedges as they whizzed along.

“What’s—what’s happened to the fat lady and the chauffeur?” gasped Peggy, clutching the steering-wheel for dear life, her cheeks scarlet, her hair streaming out behind her.

“I put them out in the drive,” said the Giant. “I expect they’ll follow us if they want to.”

“Weren’t they angry?” asked Peggy, bumping over a sheep because she didn’t know how to stop the car. “Oh dear, did I hurt him?”

“He’s all right, he’s up again,” said the Giant, turning round. “The Ring won’t let you hurt anything or anybody however much you knock into them. Angry? Oh, I really hadn’t time to stop and see. It’s all forgotten afterwards, you see. Look out for this corner. Oh well, never mind, we may as well be out of the road as in it!” For the car, not having been turned quick enough, had neatly leapt the hedge, and was now speeding across a ploughed field.

“Let her out, let her out!” said the Giant. “You said you wanted to go fast, I thought. Go on, let her out!”

Peggy didn’t know exactly what he meant, or what to do, but she whispered a wish that they might go still quicker, and the car rose in the air and raced along just a little above the level of the hedges.

“I think this is lovelier than anything we’ve done at all!” she shouted back to the Giant. “Oh, look! we’re coming to a town, I do believe! I wish I could drive through it just as though I was a real chauffeur. It would be so grand!”

[37]“Steady, steady! Wishes don’t grow on blackberry bushes,” cried the Giant warningly, but at once the car slowed down, and dropped into the high road, and Peggy found herself dressed exactly like the girl she had seen, and driving slowly along at the rate of about fifteen miles an hour. At first she tried to steer the car herself, but when she found that it guided itself when left alone, and that the horn sounded and the gear changed much better by themselves, she leant back and amused herself by staring at the people, and then at the shops, as they reached the principal streets of the town.

Suddenly she noticed that all the people they passed were beginning to behave in the most extraordinary manner, some of them racing away down side streets, screaming, others beginning to chase the car and shout at the top of their voices. Once they came on a line of policemen all standing in a row across the road with notebooks in their hands, but the car made very short work of them, scattering them in all directions, and though Peggy turned round and saw them picking themselves up at once and evidently not hurt in the very least, such a roar went up from the crowds in the streets that she asked the Giant in great perplexity why they were all so angry. Hadn’t they ever seen a lady chauffeur before?

“I expect it’s partly because of me,” said the Giant comfortably. “I knocked a piece right off the General Post Office just now with my elbow. You’d better rise again, I think.”

Peggy wished—but to her horror nothing happened, except that the car began to slow down, and crowds and crowds of people from all directions at once pressed around it, shouting and shaking their fists at the Giant.

“Goodness me!” said the Giant, who had no sooner[38] pushed away one lot than another came up. “The Magic’s gone wrong again! Turn the Ring quickly!”

Peggy did so, and the car rose with an awful jerk into the air and began to twist in and out amongst the chimney pots in an aimless sort of way till the Giant nearly toppled out, and Peggy felt quite giddy. At last she seized the wheel and tried to steer, and really felt they were making a little headway, when suddenly, without any warning, the car made a dart upwards, and then dropped on to the top of an ornamental steeple crowning the new Town Hall, where it stuck, the wheels turning madly.

“Now we are in a fix!” said the Giant uneasily. “I thought I’d remembered all about the wishing by now, but I’ve made a hash of it this time, and no mistake. You’d better wish we were safely home again. I can always manage that.”

“No, thank you!” said Peggy. “I did that yesterday before I’d used up all my wishes. I’m not going to do it again. I don’t mind it up here at all; I think it’s rather fun!”

“That’s not much fun!” said the Giant, looking down out of the car.

Peggy looked too—and could not help giving a little jump. Packed in the Square below them was the first crowd she had ever seen, and it was really rather frightening. Everybody was looking up and shouting and waving, and there was no doubt at all that they were very angry indeed. Still, in spite of the muddles the Giant so often made, Peggy always felt perfectly safe with him.

“I can’t hear what they say,” she said, “all talking at once like that! Do call down and ask them to speak clearer. They’ll hear you.”

[39]But the Giant was shaking with fright, and trying to hide himself under the seat, which, considering he was many sizes too big for the car, looked a hopeless task.

“Better leave them alone,” he muttered. “They’ll only get angrier still if we answer them.”

At that moment Peggy noticed a little fat man in a long red gown making his way through the crowd. Behind him came two men carrying a long ladder. This they put against the Town Hall, and the little fat man climbed to the top, and then off on to the roof just below the car. He was purple in the face with breathlessness and rage.

“That’s the Mayor, that is,” said the Giant in a terrified whisper, and he practically stood on his head in his efforts to wriggle part of his face under the seat. “If there is one thing that frightens me more than another it is a Mayor! I remember in 1615, or thereabouts—but that will keep till another time. Do you think he can see me? Can’t we go on now?”

“Certainly not!” said Peggy. “I want to hear what he’s going to say. He can’t do anything to us, you know. Really, I think this is the best adventure of all!”

“Hi!” called the Mayor. “Go on this moment, or we’ll make you!”

“We can’t!” shouted Peggy. “We’re stuck! A bit of the spire’s come right through the car!”

“Nonsense!” shouted the Mayor, “you can get off[40] perfectly well if you choose. The spire wasn’t built for the likes of you to go trapesing about on. Get off it!”

This is a painting of the Fourth Adventure. Peggy is just telling the Mayor that they’ve stuck. She’s rather afraid the Giant will fall out in a minute, that’s why she’s holding on to his back. You can see by her face she isn’t a bit frightened of the Mayor. This was Mother’s favourite picture. The Mayor was very difficult to draw, but he looked just like that Peggy said. None of the crowd had on red jackets really, but Peggy thought they looked pretty in a picture. You see the Ring, don’t you? Peggy quite forgot about the Giant’s red stockings till the picture was finished!

“We cant, I tell you!” cried Peggy, losing all patience. “Come up and look for yourself! Come on, climb on to the Giant’s boot!” For by this time the Giant had given up trying to hide himself, and was sitting on the car with his legs dangling into space, and looking the picture of misery.

“Stretch your foot down a little more,” said Peggy to him. “There,” as it dangled just above the Mayor’s head, “now jump this instant!”

“I won’t!” said the Mayor, ducking his head as the great boot hovered above it. “I never heard of such proceedings in my life!” He leant over the edge of the roof. “They won’t go on!” he shouted to the crowd below.

“Make ’em!” came in a perfect roar from the Square.

“Come along,” said Peggy coaxingly. (It would be something, she felt, to tell Nurse when she got back that she had had a real live Mayor in her car. Besides, it would be fun for him. But she wasn’t going to use up a wish on it. Peggy had grown very wary by this time.)

The Mayor stood looking very undecided, but when he saw the crowd beginning to shake their fists at him as well, he gave a jump, caught the Giant’s boot, and raised himself into a sitting position on the toe of it.

“Will you promise to do your best to get off if I come up and have a look?” he asked in a shaking voice.

“Of course we will,” said Peggy soothingly.—“Don’t look such a big frightened baby!” she added reprovingly to the Giant.—“Draw your boot up gently. There, that’s right”—as the Mayor was sidled carefully off into the front seat; “now I wish we could go on!”

The car shook itself all over, then leapt upwards, and once more set off at breakneck speed, but this time straight[41] upwards into the sky! Something at the same moment fell out with a heavy flop. Peggy turned her head hastily, just in time to see the Giant falling through the air behind them. But the car was rising upwards at such a pace that the next moment he and the whole town disappeared from view!

“Stop!” said a frightened voice at her side, and she turned and saw the Mayor, whom for the moment she had quite forgotten. His face was no longer purple, but as white as a sheet.

“I can’t!” said Peggy. “I’ve only one wish left, and that’s got to take me home. You asked me to get off the spire, you know, and I have! The Giant’s wearing his seven-leagued boots, so he’ll soon catch us up when he gets balanced again.” She skirted the edge of a pink sunset cloud as she spoke, and drove right up through a lemon-coloured one. “Oh, how lovely!” she went on delightedly. “I got a great chunk of it in my mouth, and it tasted just like pineapple. Did you?”

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” said the Mayor. “We’ve just been through an awful fog, and I insist on you stopping the car at once. If you can’t—and I see you don’t understand the first rudiments of driving—I can!”

He leant across her and seized the steering-wheel, but it at once came off in his hand, rolled down his arm, and jumped out of the car.

“There!” said Peggy triumphantly, to the now speechless Mayor. “See what comes of meddling!” (She felt quite like Nurse when she spoke like that.) “Never mind, my car goes just as well without that bit!” and she leant back in her seat and crossed her arms grandly. “The only thing I’m worrying about,” she went on, “is, if the Giant will ever find us! You don’t see him coming, do you? Look down through the hole in the car.”

[42]“Unless you stop, I shall jump out,” said the Mayor in a desperate voice. And he stood up and really looked as though he meant to!

“Oh, do sit down,” said Peggy. “You spoil everything. Just look, we’re going right on to this rainbow, I do believe! Yes, we’re on the purple part. Isn’t it a lovely smooth road? There, now, we’re off it and on the pink bit! Oh, why don’t you sit still and love it all as I do?”

“Because I’m going to get out,” said the Mayor, stepping over the door and lowering himself slowly till only his hand holding the step, and his very reproachful face showed themselves. “Now then,” he added, “you’ve only got till I count five; I shall let go then—perhaps”—he added in a whisper, being a truthful Mayor, but very softly so that she shouldn’t hear.

“Oh dear, it is mean of you to make me use up my last wish so soon!” said Peggy in a very vexed voice. “And I managed this drive especially for you, to make up for our having spoilt the Post Office and things.—Oh, very well,” she added crossly, as the Mayor reached four, and let go one hand, “I wish you were home and I was too, because you simply spoil everything when you won’t play properly!”...

“If I do, it’s not for you to say so, Miss Peggy,” was the reply, and Peggy found herself back in the garden again facing a rather red-faced and angry Nurse. “Just because I stop to speak to John for one moment, is no reason for you to think yourself neglected! I’m sure I never heard you call you were ready, so how was I to know? Then you come bouncing down on me like that!”

“Why, Nannie, did I bounce?” asked Peggy, very much interested. She had wondered before what her return looked like when the wishes were over.

[43]“Don’t repeat my words,” said Nurse crossly. “I was meaning the way you spoke, of course. How could you bounce down from behind the laurels? Now, come along into tea at once.”

“O Nannie, I’ve had such fun!” said Peggy, dancing along the path. “I went up, and up, and up——”

“There!” exclaimed Nurse. “One moment it’s grumble, grumble, the next all the other way! I won’t have you climbing trees either in hide-and-seek. You can’t expect to be found if you act like that. Now—not another word——”

“I’m afraid the Giant’s dreadfully lost this time!” thought Peggy, as she washed her hands for tea. “I don’t fink I was very kind to him! I do wonder if the fat lady minded the big hole in the car, and the wheel being lost. Oh, but I suppose that all comes right again, just as she forgets that the Giant sat her down in the drive! It would be lovely to tell Nannie that I’d driven a Mayor up a rainbow in a real motor car! But it’s no good trying to, she doesn’t understand the sensiblest things.”

And she ran into the day nursery to see which jam cook had sent up for tea.

“See me dance the polka!” went the old tune—and then again and again—and Peggy lay in bed listening to it and staring at the fire.

The children next door were having a party in their[44] hall, and every time the front door opened the sound of the music came crashing out, and jumped in through Peggy’s open window. Of course, she ought to have been at the party too, but, for one thing, she had had a cold all day, and for another, Nurse didn’t think the children next door had properly got over measles, so she was afraid to let Peggy go.

Peggy hadn’t much minded until now. Nurse had petted her all day and given her little bits of buttered toast at tea with apricot jam on them, and then had let the housemaid come up and play dominoes with her until bedtime, and now she had tucked her up warmly in bed with a hot-water bottle and told her to go to sleep quickly, so that she should be quite well before Mother came home the next day.

But go to sleep was just what Peggy couldn’t do. For one thing, thinking of Mother coming back was enough to make her keep wanting to jump out of bed and dance all over the room. And then the music too had begun to make her rather long to run into the house next door and play musical chairs with all the other children.

It was then that she suddenly felt the Ring pressing on her thumb, and realised that she had quite forgotten to wish at all that day!

“Oh dear, suppose it hadn’t come, I might have forgotten altogether,” she thought in dismay. “And now I’m rather frightened of seeing the Giant, in case he’s angry about the Mayor. I wonder what I’d better wish?”

She lay in bed thinking about it for quite a long time, until suddenly hearing some carriages driving off and the music stopping, she realised she was too late to wish to join the children’s party next door anyway.

[45]“Oh, I wish the Giant was here,” she said at last. “He can always think of lovely things to do.”

“Your window’s uncommonly small,” said the Giant, climbing in through it, and bringing with him big bits of the wall on each shoulder. “Gracious me, what a mess I’m in!” He shook himself and lay down on the floor with his face close to the fire. “I’ve been looking in at the party next door,” he went on. “Great fun—but they’re gone now. I saw ’em into their cabs. Why weren’t you there?”

“Because I’ve a cold,” said Peggy, sneezing three times. (The Giant seemed to have brought in all the cold night air with him.) “Nannie thinks I caught it hiding behind the laurels so long yesterday, but I know it was going through that lovely wet yellow cloud!”

The Giant’s face clouded over. “Least said soonest mended about that,” he said shortly. “I particularly told you of my aversion to Mayors, and you at once take one for a drive and leave me behind! That was not in the least what I meant. However, I will say no more. This is your last day but one with me, so we won’t waste it with quarrelling. What’s your wish? Be quick now, for this lovely hot fire makes me very sleepy.”

Peggy jumped out of bed, caught hold of the Giant’s little finger and hugged it.

“I’m so sorry,” she said coaxingly. “I like you better than any Mayor that ever was born, Giant darling. And I didn’t mean to leave you behind. Did you have an awful time?”

“Well, I went wandering about the sky for the rest of the night looking for you,” said the Giant. “I heard you’d been on the rainbow, but after that I lost all trace of you. Still, never mind; as you’re sorry, I don’t mind any more. Go on, wish away.”

[46]“It’s no good, I’ve tried to,” said Peggy. “We seem to have done everything exciting. We’ve been up——”

“How about going down for a change?” asked the Giant.

“Down?” said Peggy. “But we are down!”

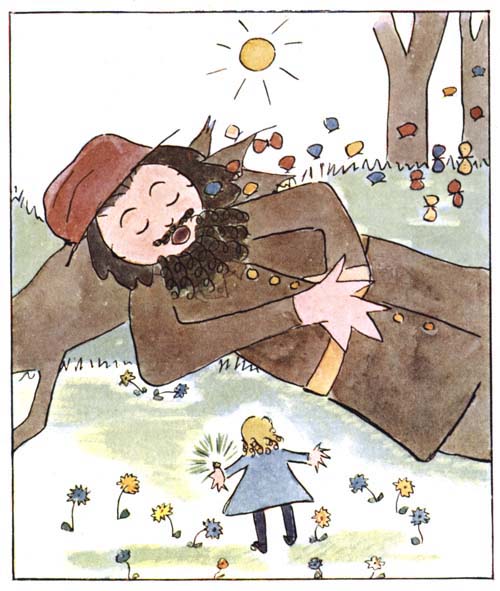

This is a picture of the fifth Adventure. The mark on the ceiling is the awful hole the Giant and Peggy made coming through. The Giant is waving his hand to Cook as they go down. The footman has only just seen the hole, and is showing it to everybody. The housemaid who played dominoes with Peggy is screaming out “Stop them, Cook!” and the scullery maid has sat down on the floor with her hands over her face. Cook is fainting by the table. She had just put a pudding on it for the servants supper. Peggy couldn’t put Nurse into the picture because she wasn’t sure if she was in the kitchen then or not. You do see the Ring, don’t you?

“Do you call this down?” said the Giant laughing. “Come along, get on my hand and wish,” and he laid his hand palm upwards on the hearthrug.

“Wish what?” asked Peggy, putting on her blue dressing-gown and slippers.

“To go down, of course,” said the Giant impatiently. “Has your cold made you deaf?”

“Oh, all right, I wish to go down,” said Peggy, clambering up on to the Giant’s hand. “But it sounds very dull—Gracious! Hold me tight!” for they both at once went right through the nursery floor and into the dining-room below.

“Oh, look!” said Peggy. “What a mess we’ve made of the ceiling. The table’s all covered with bits of it! Oughtn’t we to clear it up?”

“Don’t waste time,” said the Giant. “Come on,” and down through the carpet they went and right into the kitchen.

The servants were all at supper, but Peggy had only just time to catch sight of their terrified faces and to hear their chairs crashing to the floor as they all jumped up, before the Giant went right through that floor too!

After that they went down so fast that her curls flew up in a waving cone above her head, and the Giant’s beard flapped across her face and hid everything. She shut her eyes at last, until—“Open them, we’re down!” said the Giant, and they both flopped on to some long brown grass.

Peggy stared round in astonishment. They were sitting[47] in the middle of a great brown plain, edged all ground with little pointed brown hills rising up to a golden sky. And, “Oh, what ducky little houses!” cried Peggy, for nestling up the sides of every hill were hundreds of tiny brown thatched cottages, each with a dear little garden in front of it, full of vegetables and brightly coloured berries.

“Where on earth are we?” she asked.

“Nowhere,” said the Giant. “We’re in it. This is the Pixies’ country. Look, they’re coming out of their houses. Do you see them? They’ve heard us coming.”

A great opening of doors sounded from all around, and out poured the Pixies, and raced across the plain to Peggy and the Giant. Little fat brown fellows they were, dressed in dark shades of green and red, with round wrinkled faces and pointed caps. When they were quite near, they all stood in a crowd whispering and giggling, till two of them, holding a huge curled-up yellow leaf between them, were pushed forward towards Peggy.

“What have they got?” she whispered to the Giant.

“An invitation, I expect,” he whispered back, “for the party to-night.”

“What party?” asked Peggy, but “Hush, don’t, whisper, they’ll think you’re making personal remarks,” answered the Giant. “They’re very sensitive.” And certainly the Pixies carrying the leaf came to a dead stop, and, apparently overcome with shyness, dropped it on the ground, and raced back to their companions, where they stood sniggering and covering their faces with their hands, and peeping through their fingers at Peggy.

“How funny they are!” said Peggy in amazement. “Why do they do that?”

“I don’t know,” said the Giant. “I think it’s because they have so few holidays and see so few people. But[48] they’re a queer lot, and I don’t profess to understand them! You’d better read your invitation.”

Peggy picked the leaf up, and, unrolling it, read as follows: “We invite Peggy and the Giant to a Ball in the Distant Purple Caves in half an hour. Skating, Eating, Flitting, Mazing, Wending and other Amusements.”

“Oh dear, how exciting! Can I go?” asked Peggy, beginning to dance about all over the plain.

The Giant took the invitation and read it slowly.

“My goodness me, it is going to be a smart affair!” said he. “Yes, I think we can manage it all right. Only we shall have to dress up for it, I’m afraid. It wouldn’t do to look dowdy.”

“But what do Flitting, Mazing, and Wending mean?” asked Peggy, looking at the invitation again.

“Well, Flitting is flying round one after the other at the very top of the caves and copying everything the front Pixie does,” said the Giant, “and the one who goes on longest gets a prize. It’s tiring, but exciting; a sort of Follow-my-Leader, only a better game. And Wending is dancing up and down the Unexplored Passages and seeing who can pick up most diamonds first. They only have it at the very grandest parties. And Mazing is—now, what is Mazing? I’ve quite forgotten! However, I shall probably remember it in a minute or two.”

“Do you accept?” asked a tiny, shy voice at Peggy’s elbow, and she looked down to see a Pixie standing by her.

“Yes, we’d love to come, and it’s very kind of you to ask us,” said Peggy very politely. “I hope you’ll excuse my writing,” she added, having sometimes heard her mother say this.

“They’d love to come!” shouted the Pixie to the others, and “They’d love to come!” shouted the rest, till the hills[49] echoed with the sound, and then they all turned and raced back to their cottages, stopping now and then to giggle and snigger and look over their shoulders at Peggy and the Giant, before the little doors slammed again behind them.

“Very over-excited indeed,” remarked the Giant. “Now they’ll take the rest of the time dressing up. And, by the way, we ought to be getting ready too.”

“What did you think of wearing?” asked the Giant.

“Let me see,” said Peggy. “Yes—I think I wish to go as a Fairy, in pink. What would you like to be?”

“The wishes do work well now!” said the Giant in a gratified voice, for Peggy stood before him glittering in a rosy spangled frock and gleaming silver wings, with a star on her forehead and a wand in her hand all complete. “Well, if you’ll really be so kind as to use up another wish on me, I think I’d rather like to go as Little Boy Blue.”

“Certainly!” said Peggy, and the next instant the Giant, a good deal smaller than usual, and dressed all in blue, with a golden horn in his hand, stood on the plain. Unfortunately, however, his seven-leagued boots still remained their usual size, and his beard was as long and curly as ever, which gave him rather a strange appearance.

“Not quite so successful,” he remarked, glancing down at himself. “However, I shall pass in a crowd, I daresay. And now we must start. The Pixies will go under the hills, which takes a quarter of the time, but I daren’t take you[50] that way for fear of spoiling our clothes. Come along—fly on to my shoulder. That’s right! Shut your eyes and it won’t seem so far.” And off he walked at a great pace over the hills.

Peggy didn’t mean to do another picture of the fifth Adventure, but Mother particularly wanted one of the Pixies, so she had to do this, as the Ball-room one was too difficult to do. The Pixies are just shouting out, “This is Mazing, this is!” and Peggy is trying to catch two of them. You can see how tired and giddy the Giant must have got with wandering about amongst so many Snowmen. He is just wiping his face with his red handkerchief. Peggy made herself so very ugly by mistake, and didn’t know how to change it.

“Do try to remember as we go what ‘Mazing’ means,” said Peggy. “I wish I knew. It’s such a funny word!”

“I can’t talk or think of anything at present,” said the Giant. “I’ve got to try and find my way, and it’s no easy matter, I can assure you.” And a long silence ensued.

“Aren’t we there yet?” asked Peggy at last, after they had been travelling for over a quarter of an hour. She opened her eyes as she spoke, and then nearly fell off the Giant’s shoulder with astonishment.

For the brown hills had quite disappeared, and in their place a dazzling white country spread around. And a country filled with—could it be? Peggy rubbed her eyes, and stared again. Yes. Filled with snowmen! Snowmen towering up in all directions, one behind the other, hundreds and hundreds of them, and all exactly like the one Mother and Peggy had made in the garden last winter, with coals for eyes, and pipes in their mouths!

“Yes, I thought you’d be surprised!” said the Giant, stopping wearily. “I was. We’ve missed our way somehow, I believe, and it would really have been better if we had gone under the hills after all. This white country gets on my nerves. I must have a rest!”

He propped himself up against one of the snowmen as he spoke, and mopped his face with his red pocket-handkerchief. “Do fly up fairly high and see if there’s any way out of this,” he implored in an exhausted voice. “I’ve been walking in and out between the wretched things for ages. There seems no end to them!”

Peggy fluttered up and looked North, South, East and[51] West, but alas, there was nothing but hosts and hosts of snowmen in all directions.

“I believe it’s a trick of those nasty Pixies!” said the Giant angrily when she returned. “There—look! Wasn’t that one of them?” and he pointed behind her.

Peggy wheeled round, just in time to see a mischievous Pixie face peeping from behind a snowman.